Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1045. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in August 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Declan Murphy has received research funding from Shire (Basingstoke, UK) and leads the European Union (EU) Innovative Medicines Inititative consortium EU Autism Interventions – a Multicentre Study for Developing New Medications that receives funding from both the EU and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Ian Wong received a research grant from the European Commission, Hong Kong Research Grant Council and Janssen-Cilag Ltd (High Wycombe, UK) on research to investigate the safety of antipsychotic drugs and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder treatments. In addition, Ailsa Russell has a patent Authors Copyright – Treatment Manual Cognitive–Behavioural Therapy for Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder in Autism Spectrum Disorder pending. Susan Young has received honoraria for consultancy, travel, educational talks and/or research from the Cognitive Centre of Canada, Janssen Pharmaceutical (Raritan, NJ, USA), Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Novartis (Frimley, UK), HB Pharma (Sorø, Denmark), Flynn Pharma (Stevenage, UK) and Shire. Philip Asherson has received honoraria for consultancy, travel, educational talks and/or research from Janssen Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Novartis, HB Pharma, Flynn Pharma and Shire.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Murphy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

We need to develop better services and treatments for people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who are ‘in transition’ from childhood to adulthood.

People with ADHD have serious deficits in attention and are hyperactive. In contrast, those with ASD (autism, ‘atypical’ autism and Asperger syndrome) have stereotyped and obsessional behaviours and severe abnormalities in socioemotional behaviour and communication. They are different disorders, but have a lot in common. Thus, we studied them together.

Both ADHD and ASD are neurodevelopmental disorders (NDs) that have lifelong effects. They are of great public concern, much more common than previously thought, very frequently co-occur in the same person and are associated with serious comorbid mental health problems [e.g. drug abuse, anxiety, depression, learning disability (LD) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)]. This has a large social impact (e.g. the individual lifetime cost for ASD exceeds £2.4M and is significantly increased by comorbid LD).

People with ADHD and ASD have particular problems during the transition from children to adult services. Many ‘drop out’ and go untreated. In addition, few adult services are skilled in managing them, those already in these services are often misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated, and LD people are frequently excluded. This probably has an impact on the clinical outcome and costs – as treatment of the core disorders during childhood greatly reduces comorbidity. However, it is unknown (1) if this is true in young adults or those with LD and (2) if beneficial treatments developed in the general psychiatric population for the comorbid problems frequently found in ASD and ADHD are transferable to, and cost-effective, in these groups [e.g. cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for OCD].

Government policy calls for evidence-based practice, needs-led services and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines that stress psychological treatments. We have previously published instruments, which measure health needs, costs and consumption and gold standard research diagnostic tools. In addition, we carried out pilot studies in the treatment of comorbid disorders using both pharmacological approaches and CBT.

We therefore extended our work in two phases with the themes: (1) more effective services and (2) better treatments.

We used the following research questions to guide our work:

-

What are the needs of affected individuals and their carers and are these met by health services?

-

Are people with ADHD and ASD already in contact with clinical services recognised and treated by the services?

-

Can we improve the diagnosis of ADHD and ASD by clinical services?

-

Can we improve the treatment of ADHD and ASD by clinical services?

We included people with ADHD and/or ASD between the ages of 16 and 25 years during the ‘transition’ from child to adult services and those with a LD. In phase 1 (years 1–3) we worked to improve case identification and management. In phase 2 (years 3–5) we tested if effective treatments developed in the general population reduce comorbidity.

To develop more effective services we (1) developed simple protocols for case identification, (2) ascertained why people ‘drop out’ of services during the ‘transition’ and the consequences of that and (3) determined what interventions help adult services better identify, and meet the needs, of these people.

In this second part, we attempted to reduce disease burden by better use of current pharmacological and psychological treatments, and helping people who are often excluded. The drug studies initially focused on ADHD, as effective medications already existed that can be rapidly tested. In contrast, psychological interventions were aimed at common comorbid symptoms (OCD) in ASD.

We have constructed this report in five sections to match our programme design. In Section 1 (see Chapters 2–6), we present the patient and family perspective, and in Section 2 (see Chapters 7–13) we provide the service perspective. The third section (see Chapters 14–18) focuses on improving outcomes through better diagnosis, whereas the fourth section (see Chapters 19–23) focuses on improving outcomes through intervention. Section 5 (see Chapters 24 and 25) concludes the report by presenting our conclusions, recommendations for future research and examples of the impact of our work.

Within this report, some chapters or parts thereof have been previously published in the following papers:

Patient and public involvement

Our team involved users, carers and their representatives as co-applicants.

They identified the service and treatment priorities we addressed. In addition, they helped design this study and took an active part in carrying out the research. For example, we employed affected individuals as researchers. Furthermore, their representatives monitored our progress by serving on our Study Steering Board.

Dissemination materials and training packages have been prepared in collaboration with users and carers.

Section 1 Patient and family perspective

Chapter 2 Needs at the transition from child to adult services in ADHD and ASD: an overview of rationale and shared methods

Overall aims and objectives

Our aim was to investigate service use and needs among people with ADHD and ASD at the transition from adolescence to young adulthood (from ages 14 to 24 years). We wished to further understand (1) the demographic and medical correlates (e.g. age and comorbid conditions) of service use, (2) if current services are meeting the needs of young people with ADHD and ASD and (3) to what extent, and at what cost, family members of affected young people are able to meet these needs.

Background

Neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD and ADHD are of increasing concern given their high cost to health services, individuals and families. For example, recent estimates suggest that the cost to the UK economy of supporting children with an ASD is approximately £2.7B (US$4.4B) each year and the cost of supporting adults is much higher (US$40.4B each year). 7 Moreover, although ASD and ADHD are often thought of as childhood disorders, both can persist into adolescence and young adulthood. Approximately 96% of those diagnosed with an ASD as children still warrant diagnosis in young adulthood. 8 The figure is lower for ADHD, with persistence rates estimated between 15% and 65%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used. 9

Not only do young people (adolescents and young adults) with these disorders continue to experience symptoms, they also retain significant impairments. For example, most young people with an ASD show continued impairments in daily living skills, communication, social interaction, employment and education. 10–13 Young adults with ADHD tend to achieve greater independence than their peers with ASDs, but are still more likely than the general population to be unemployed,14 experience more frequent job losses,14,15 underachieve in education,16 experience instability in emotional relationships16,17 and display antisocial behaviours. 18–20

Even though symptoms and impairments continue among young people with ASD and ADHD, few services exist to support those with these disorders through adulthood. 21–23 Additionally, as these conditions have been found to be underdiagnosed among young adults,24,25 many are likely to remain solely reliant on family and friends for assistance. Thus, the situation for most young people with an ASD or ADHD is that they continue to experience symptoms and impairment, but have limited support from services and so rely on families.

Although many studies have investigated service use and needs of children with developmental disorders (e.g. ASD), to date little is known about the service use and needs of these groups as they reach adolescence and transition to adulthood. Nonetheless, concern has been expressed in the UK parliament about the perceived failure to provide effective transitioning because of:

-

inconsistency of referral and treatment criteria

-

poor communication between services

-

lack of continuity

-

conflict between the ‘child/family’ approaches of paediatric mental health services and the individual approach of adult mental health services

-

the disengagement of young adults who drop out of the health-care system. 26

In summary, there is the perception that there are significant problems in the provision of services for ‘youngsters’ as they transition into young adulthood. However, the evidence to help inform the debate is lacking. Hence, research into the needs of young adults with ASD or ADHD and their carers is important in order to design and implement appropriate and effective care programmes and support for carers as well as young adults with this disorder. This first section of our work therefore investigated the following in both ASD and ADHD: (1) service use, met and unmet needs, (2) the role of family members in meeting needs, (3) changes over time in service use and needs and (4) the consequences of these changes for the young person’s and the nominated family member’s well-being. Our approach was to use a core set of measures for both disorders when possible, but to use more appropriate disorder-specific measures when prudent.

Methods used that were common to both ADHD and ASD

We conducted an observational study based on face-to-face interviews and self-completion questionnaires with young people with ADHD and an ASD and their parents (usually mothers) at yearly intervals. The ADHD study was a 3-year prospective study; the ASD group was followed for 2 years [this difference in follow-up time arose owing to delay from Research Ethics Committees (RECs), resource constraints and time limits for the programme set by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR); for further details, please see Obstacles and solutions]. The study collected information on health service use, needs and social/demographic and health information relating to participants and their family member at the time of the interview. For the ADHD study, self-completion questionnaires were also administered to adolescents/young adults to obtain information regarding drug and alcohol use and problems with the police. Differences in the study design between the ADHD and ASD groups are highlighted in the sections that follow.

Study site

Data collection largely took place in participants’ homes or at the Institute of Psychiatry (IoP). Most participants were from Greater London; the remainder were spread throughout England, extending from Cornwall to Lincolnshire in the north-east.

Sample

Our study included 183 families consisting of young people aged 14–24 years (n = 82 with ADHD and n = 101 with ASD) and their parents. More detailed information on sample sizes is provided in Tables 1 and 4. Families were recruited through their children’s childhood clinical diagnoses of ADHD or an ASD from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and adult clinics, charities and research databases that form part of our clinical research networks. Clinical diagnosis of autism was confirmed in all cases using the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised27 (ADI-R) and ADHD (combined type) was defined using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), criteria. As participants in the ADHD group were originally recruited for the International Multi-Centre ADHD Genetics (IMAGE) programme, they were excluded if they had been diagnosed with autism, epilepsy, general learning difficulties, brain disorders and any genetic or medical disorder associated with externalising behaviours that might mimic ADHD based on both history and clinical assessment.

| Variable | % | Mean (SD) | Range | Missing (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YP age (years) | 17.50 (2.30) | 14–21 | 0 | |

| YP male | 89 | 0 | ||

| YP white or white British | 100 | 0 | ||

| YP education | ||||

| Full time | 57 | 0 | ||

| Part time | 7 | 0 | ||

| Not in education | 34 | 0 | ||

| PR education | ||||

| Low | 63 | 2 | ||

| High | 37 | 2 | ||

| YP accommodation | ||||

| Family home | 87 | 0 | ||

| Other | 13 | 0 | ||

| YP residing in Greater London | 56 | 0 | ||

| YP DIVA above cut-off point (> 6) | 73 | 2 | ||

| YP CIS-R | 7.90 (6.50) | 0–29 | 1 | |

| YP CIS-R above cut-off point (> 12) | 27 | 1 | ||

| YP impairments | 4.46 (2.72) | 0–10 | 3 | |

| YP total needs (parent report) | 5.05 (3.43) | 0–25 | 0 | |

| Met (parent report) | 2.58 (2.30) | 0–25 | 0 | |

| Unmet (parent report) | 2.48 (2.51) | 0–25 | ||

| YP AUDIT-C | 4.99 (3.89) | 0–12 | 6 | |

| YP AUDIT-C above cut-off point (> 4) | 65 | 0–12 | 6 | |

| YP drug use in past month | 24 | 7 | ||

| YP drug use ever | 48 | 7 | ||

| YP problems with police in past 12 months | 25 | 7 | ||

| YP exclusion from school | 50 | 0 | ||

| YP not in contact with services | 41 | 0 | ||

| YP in contact with services | ||||

| Children’s service | 33 | 0 | ||

| Adult service | 10 | 0 | ||

| ADHD service all ages | 16 | 0 | ||

| Childhood | ||||

| CD | 37 | 2 | ||

Recruitment for the ADHD sample began on 1 April 2009 and ended on 23 February 2011, for the ASD sample it began on 7 June 2010 and ended on 20 October 2011. Both studies received REC approval from the London – Camberwell St. Giles REC (previously known as the Joint South London and Maudsley and the IoP REC, South East London REC 4). The ASD REC reference is 04/H0807/71 and the ADHD REC reference is 08/H0807/68.

Instruments common to both ADHD and ASD studies

The instruments common to both studies are described below. Those used only in either the ADHD or the ASD elements of the project are described in the relevant disorder-specific section (see Chapters 2 and 3).

The level of need of the young person was captured using the Camberwell Assessment of Need for Adults with Developmental and Intellectual Disabilities (CANDID). 28 CANDID assesses needs across 25 domains, including social, physical, mental health, self-care and practical needs. For each domain, the young person and the parent were asked whether or not there was a significant need (coded as 1). If so, further questions were asked to ascertain if sufficient formal and/or informal support was being received. If adequate support was received, the need was classified as ‘met’ (regardless of whether or not it was met by formal or informal carers); if insufficient support was received the need was classified as ‘unmet’. Both met and unmet need scores were calculated by summing the number of domains where each was recorded. A total needs score (range 0–25) was calculated by summing the met and unmet need scores. 28

We adapted a brief series of questions on drug use from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) survey Mental Health of Children and Young People in Great Britain, 2004 Report. 29 Young people were asked to self-rate the frequency and nature of drug use from a range of drugs including cannabis, cocaine and heroin. For each individual drug, a question was asked regarding whether or not the participant had ever used this drug, even if just once. If the young person answered yes to this first opening question, two more questions were asked: (1) at what age the young person had first used this drug and (2) whether or not the young person had used this drug in the past month.

Alcohol use was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C), a brief and validated three-question screen that can help identify hazardous and harmful drinking. 30 The AUDIT-C is an abbreviated version of the 10-question Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT); the only screening instrument of hazardous alcohol use specifically designed for international use that is consistent with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), definitions of alcohol dependence and harmful alcohol use. Higher scores indicate greater likelihood of hazardous and harmful drinking and may reflect greater severity of alcohol problems and dependence, as well as a greater need for more intensive treatment.

Problems with police were examined through a series of questions based on those in the background information questionnaire used in the adult ADHD service at the Maudsley Hospital (adapted for this study). All participants were asked whether or not they had been in trouble with the police in the past 12 months. Those who answered yes were asked a brief series of questions regarding the nature and frequency of these problems (e.g. frequency of custodial sentences, times spent in a prison cell, appearances in court).

Caregiver burden was measured using the 12-item Zarit Burden Interview. 31 This captures the psychological and social impact of caring and asks respondents to rate the extent to which they agree or disagree with statements regarding their feelings about the results of caring on a five-point scale, with possible responses ranging from 0 (‘never’) to 4 (‘nearly always’). A total score (0–48) was calculated by summing the scores for each question. 31

We used a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) to capture service use. 32 In particular, participants were asked to state whether or not they were under the formal care of child or adult health services, with those answering yes recorded as currently being in touch with services (coded as 1). The CSRI was completed jointly by the parent and young person (where they took part).

Obstacles and solutions

Our main obstacles related to five main factors:

-

delays with REC approval and the need to submit separate ethics applications for both groups

-

reaching young people

-

attrition, a problem common to all longitudinal studies but of particular concern for the ADHD group

-

the online completion of the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) by parents of the ASD group

-

the lack of detail on prescribing patterns in an epidemiological sample that could be accessed in the time scale of this programme.

First, approval of the ASD research project for the purposes of the Mental Capacity Act 200533 led to significant delays due to the higher prevalence of LDs. As there is currently no standardised or accepted protocol for assessing whether or not a person lacks capacity to consent to take part in research it was necessary to develop a protocol for assessing capacity for this research project. Thus, a mental capacity assessment was adapted from one used in an earlier project under the same NIHR programme grant (REC 09/H0807/72). As this took some time to develop and to be approved by the local REC, the ASD study began 1 year after the ADHD study. This meant that ASD participants were followed for only 2 years (instead of 3 years, as for ADHD participants).

Second, our original design for the ADHD sample was based on contacting parents (as participants were contacted as children we only had contact details for parents). However, we soon amended the research design to be more inclusive in approach to young people, rather than approaching only via parents. To this effect, initial letters of invitation were sent both to parents and the adolescents/young adults at their parents’ homes.

Third, in order to reduce attrition (and non-response), especially among those with ADHD, we implemented a variety of measures. As participants were initially recruited through the IMAGE sample, the newsletter was revived and sent on an occasional basis to participants with summaries of the research and key findings (this has been led by Professor Asherson and his colleagues).

Fourth, we encountered difficulties in getting parents to complete the online DAWBA for their children with an ASD. This is because this online assessment is relatively time-consuming. We adopted several solutions to address this issue. Our researchers repeatedly contacted those with incomplete DAWBAs, reminding them of the need to provide this information. Furthermore, our researchers offered to assist parents in completing the forms. Finally, we offered parents a gift voucher of £20 in order to compensate them better for time taken to complete the DAWBAs.

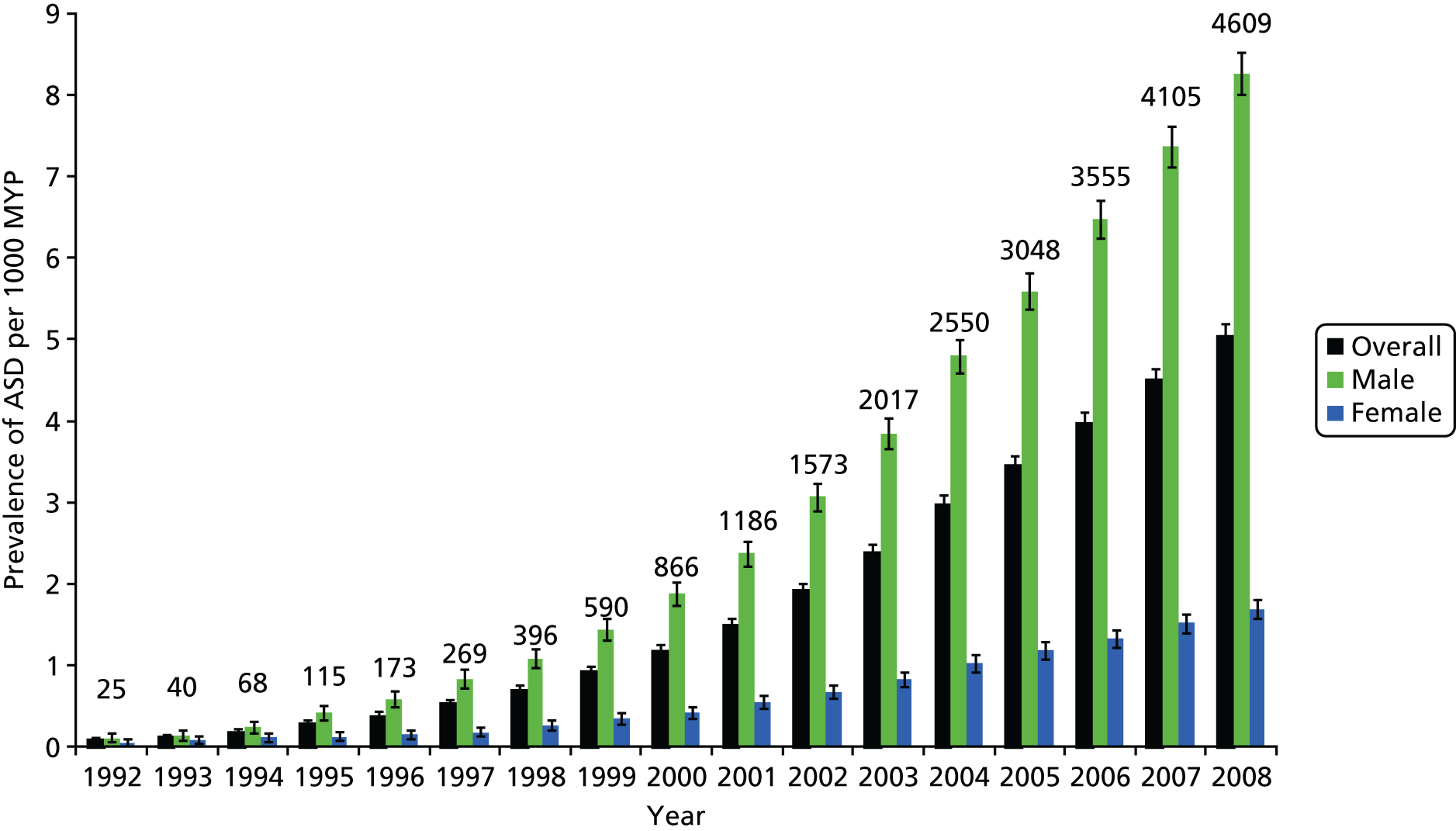

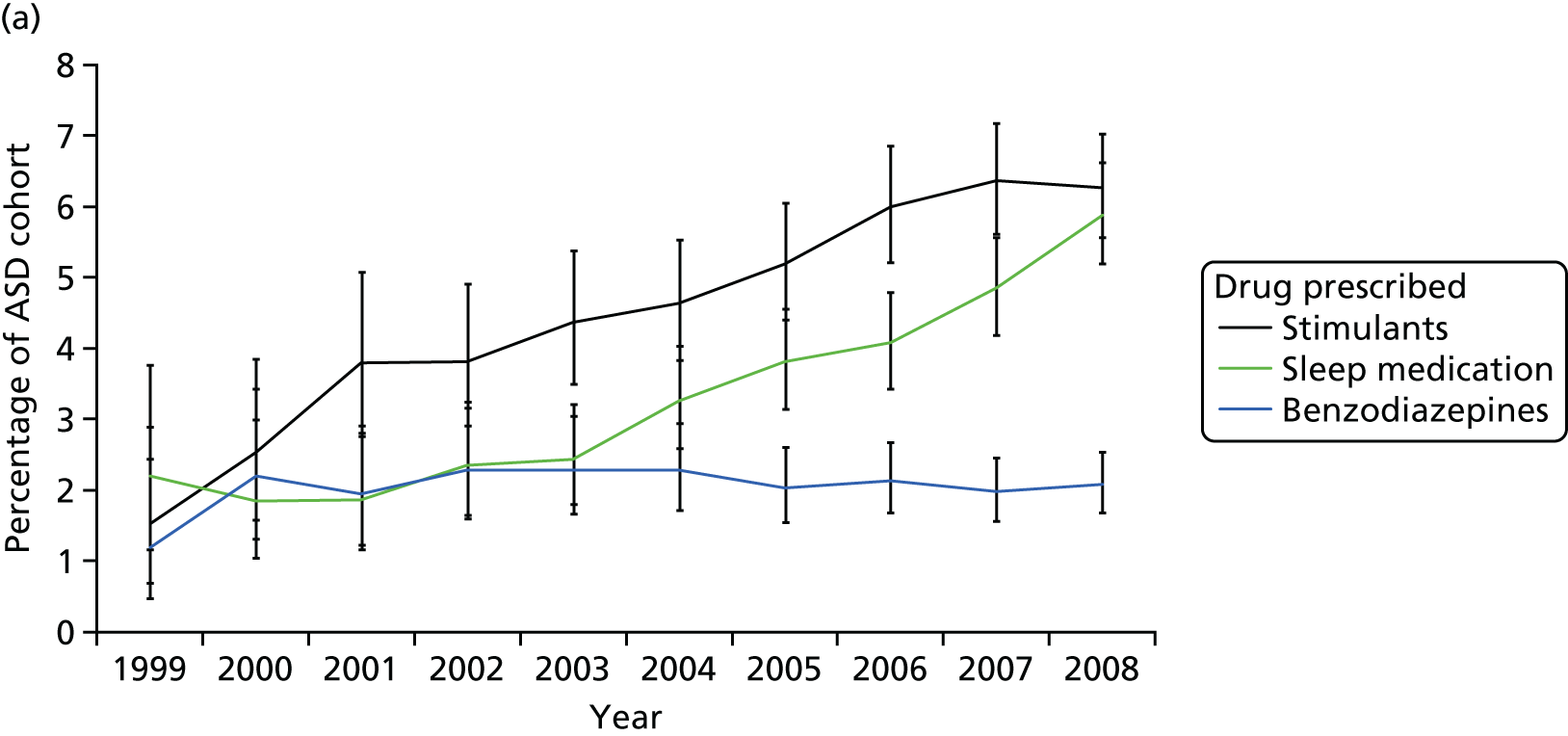

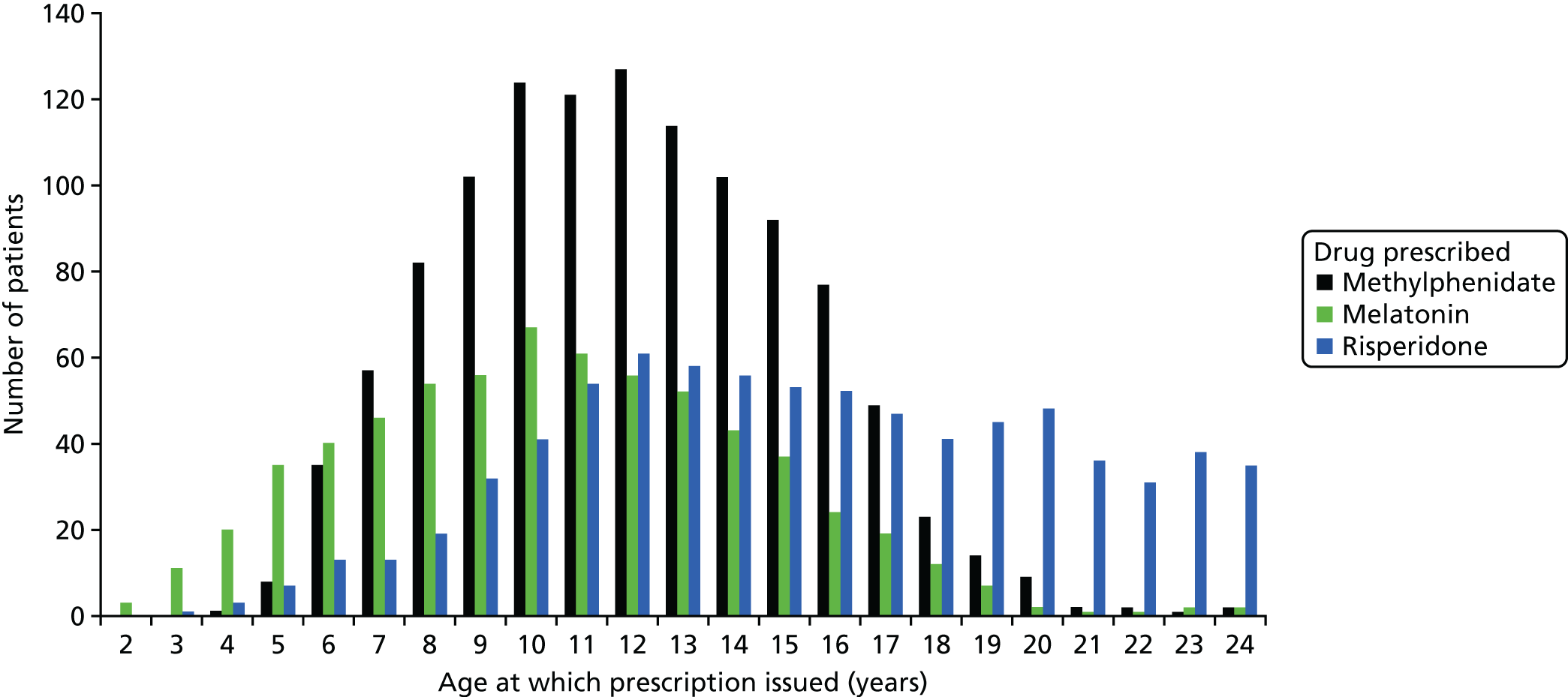

Furthermore, we were concerned by the lack of accurate prescribing data and an epidemiological sample that we could access – as this raises issues about the generalisability of our results. Hence, we developed a collaboration with Professor Ian Wong (who was then at the School of Pharmacy) to examine medication use in a nationally representative data set based on general practitioner (GP) records: The Health Improvement Network (THIN). The data for young people with ADHD have already been published and so we examined psychotropic drug prescribing and neuropsychiatric comorbidities among 0- to 24-year-olds with ASD between 1992 and 2008 in a nationally representative primary care database. Further details outlining the rationale for this component and our results are provided later in this report (see Chapter 20).

Chapter 3 Needs in ADHD at the ‘transition’

Study design

For the ADHD study three separate face-to-face interviews were administered and one self-completion questionnaire. The young person’s questionnaire consisted of:

-

a needs assessment based on the CANDID (i.e. a standardised needs-assessment instrument that assesses need in 25 life domains described above, see Chapter 2)

-

the Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R; a rating scale of comorbid psychological symptoms used in the ONS Psychiatric Morbidity surveys)

-

background information (e.g. current employment situation and educational circumstances).

Self-administered questionnaires gathered information from ADHD adolescents/young adults on:

-

the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale – IV (BAARS-IV; i.e. questions about attention and activity levels over the past 6 months)

-

the Center for Neurologic Study – Liability Scale (CNS-LS), a self-reported measure of the occurrence of moods in the past month and in the past 5 years

-

the AUDIT-C, a widely used self-reported measure of alcohol use described above (see Chapter 2)

-

a brief series of questions on drug use and police contact (e.g. if any problem with police in the past 12 months and number of formal police cautions and times spent in police cell and youth custody).

Parents were asked to:

-

complete the same questions about the their child’s level of symptoms or problems that co-occur with ADHD using the BAARS-IV

-

complete the same questions about their child’s needs using the CANDID

-

assess the impact of their child’s condition on their own employment situation and physical, psychological and social well-being

-

answer questions about the frequency and type of services they used

-

complete a widely used measure of carer burden (an abbreviated version of the Zarit Burden Interview)

-

provide background information (e.g. marital and tenure status, living arrangements).

A joint interview with both the young person and their parent consisted of:

-

the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults (DIVA) (this was conducted in the first year only)

-

the CSRI adapted for this clinical group asking information about the young person’s frequency and type of service use in the past 3 months, contact with transition teams and their experiences (and satisfaction) of transitioning from child to adult services (described in Chapter 2).

Each of the instruments specific to the ADHD study is described in more detail below.

Instruments specific to ADHD study

We used the DIVA,34 a diagnostic interview measure for adults with ADHD, recommended by the European ADHD Consensus Group,1 to measure current inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (that is in the past 6 months). Using the DIVA, three subtypes of ADHD can be identified: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive–impulsive and combined inattentive and hyperactive–impulsive. 34

Given that there is currently no measure of ADHD symptoms and impairments that is validated for use across the whole age range used in this study (i.e. 14–21 years), the DIVA was chosen for several reasons. First, despite being a relatively new measure, it was used in preference to existing published diagnostic interviews such as the Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID),35 because it is briefer, permitted greater freedom in responses and is used increasingly throughout Europe. Second, compared with the CAADID, which has items that are similar to the DIVA, the DIVA is also publicly available. Third, the items in the DIVA were considered to be more realistic for the diagnostic assessment of ADHD in adults by the European ADHD Consensus Group. 1 Finally, it was judged important to keep the outcome data the same across the whole sample, rather than choose one measure for adolescents and one for adults.

We also used the BAARS-IV (informant version),36 a standardised and widely used rating scale for the assessment, diagnosis and monitoring of treatment of ADHD in adults. It assesses 18 symptom items from the diagnostic criteria for ADHD in the DSM-IV and 10 items relating to impairment across different areas of functioning. The informant is asked to rate the frequency and severity of impairments with scores on a four-point scale ranging from 0 to 3 capturing the severity and frequency of the behaviours representing ‘0, not at all or rarely’; ‘1, sometimes’; ‘2, often’; and ‘3, very often’. Although both parent and young person ratings of impairments were obtained only the parent ratings are used here.

Psychiatric-associated conditions were assessed using the CIS-R. 37 It is a standardised, valid and reliable structured diagnostic instrument used for rating psychiatric symptoms across 14 domains (e.g. anxiety, depression), and is widely used in both clinical and the general populations. 37 Scores on each section can range from 0 to 4 (0–5 for the section on depressive ideas), with a total score ranging from 0 to 57. A total score of ≥ 12 is regarded as clinically significant. 37

Results

So far, our study of the ADHD group has focused on addressing the service use (and needs) of this clinical group at the transition to adolescence and young adulthood (that is ages 14–24 years). In addition, we explored the experiences of health-care transition (i.e. the process of moving from child to adult health services) from the young person’s and parents’ perspective.

Our framework for understanding service use among this clinical group was the Andersen–Newman Behavioural Model Of Health Service Use. 38–40 It is an established framework widely used by health economists, psychologists and medical sociologists to explain patterns of service utilisation among diverse populations. 41,42 The model organises service use into predisposing, enabling and need categories, whereby use of services is conceptualised as a function of predisposing (such as the person’s age), enabling (such as parental education) and need factors (such as ADHD symptoms, impairments, psychiatric comorbidities, needs and caregiver burden).

Sample characteristics

We included 82 individuals with ADHD. The average age of ADHD group was 17.5 years (see Table 1), and most were male (89%), still living at home (87%), unmarried (96%) and still in education (66%). Half reported having been excluded from school. Thirty-seven per cent of parents reported having achieved an educational level higher than A level (Advanced level).

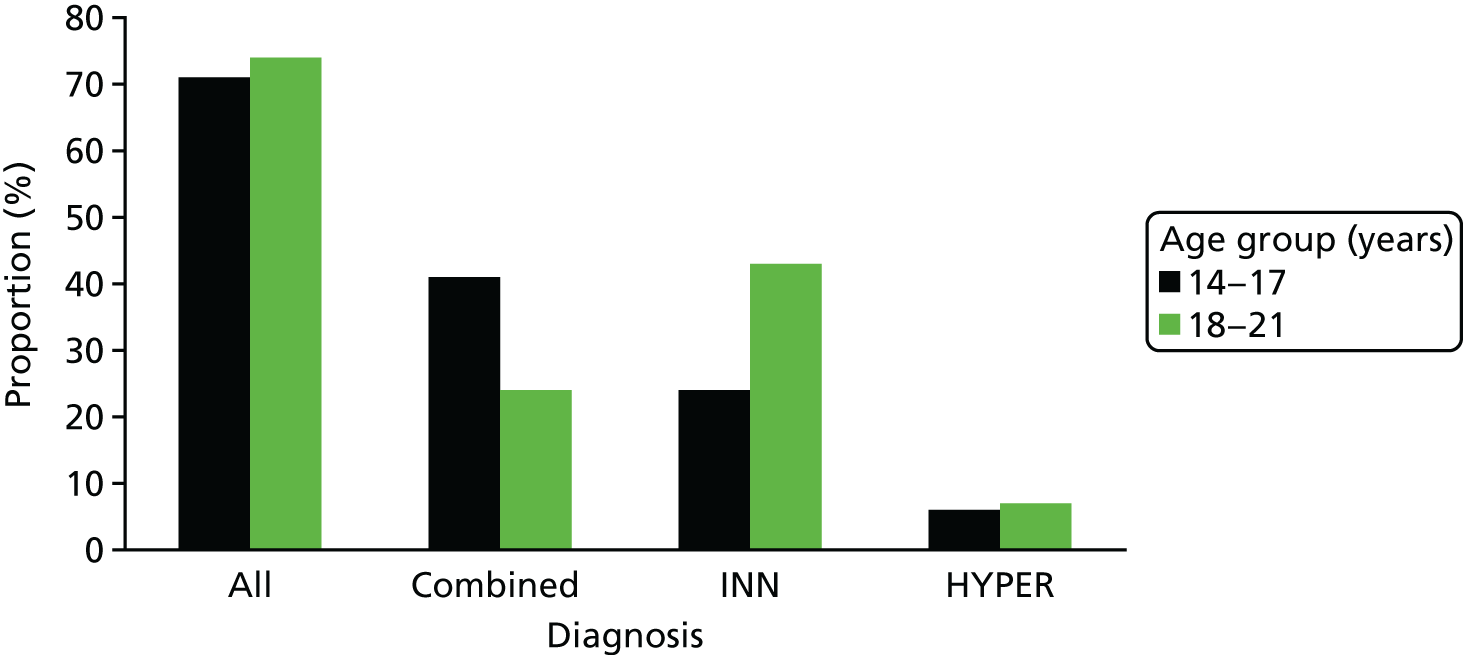

The majority (73%) still met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD. Overall, there was no significant difference between the younger (14–17 years) and the older (18–21 years) age groups in the percentage who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD (χ2 = 0.108; p = 0.742). However, a higher percentage of the younger group met criteria for combined ADHD (41% vs. 24%), whereas the predominantly inattentive subtype was more common in older individuals (44% vs. 24%) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of ADHD diagnoses by age according to DSM-IV criteria. HYPER, hyperactive–impulsive; INN, inattentive.

In addition, nearly two-thirds scored above the cut-off score on the AUDIT, suggesting high levels of alcohol consumption. Forty-eight per cent had used illegal drugs at some point and close to one in four had used drugs in the past month. Finally, 25% reported having been in trouble with the police within the past year.

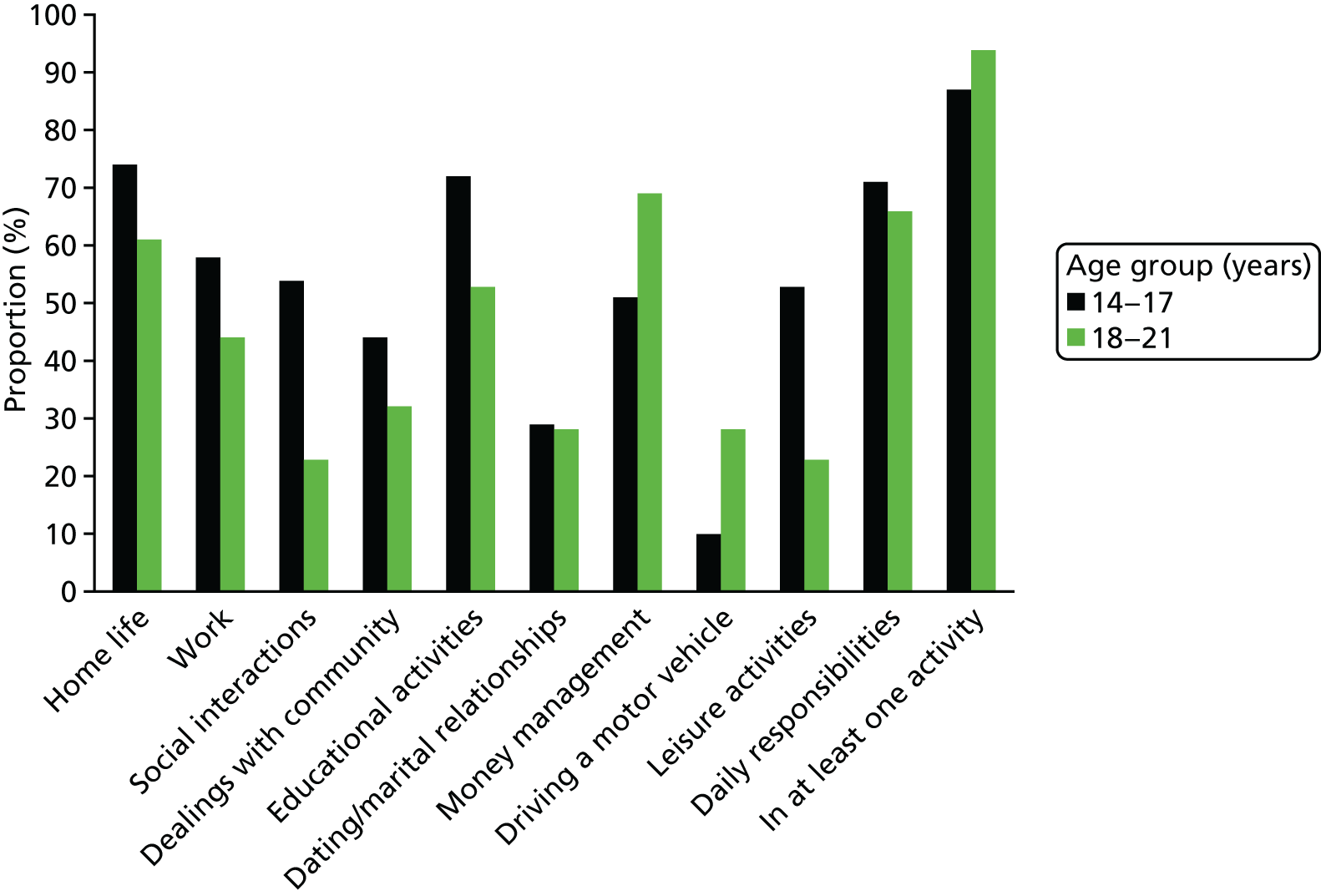

Impairments

In both age groups nearly all were impaired in at least one life activity (Figure 2). Overall, around two-thirds of parents reported significant impairments in their child’s management of daily responsibilities (68%), home life (67%), educational activities (62%) and money (61%); half of parents reported impairments among their children related to work (49%). There were no significant differences in percentages of impairments reported between the two age groups apart from in social interactions – where parents reported more impairments among those in the 14–17 years age group in comparison with those aged 18–21 years [χ2 = 10.48, degrees of freedom (df) = 3; p = 0.013]. In summary, impairments were not restricted to younger individuals with ADHD – both groups demonstrated marked impairments.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of impairments in daily activities by age.

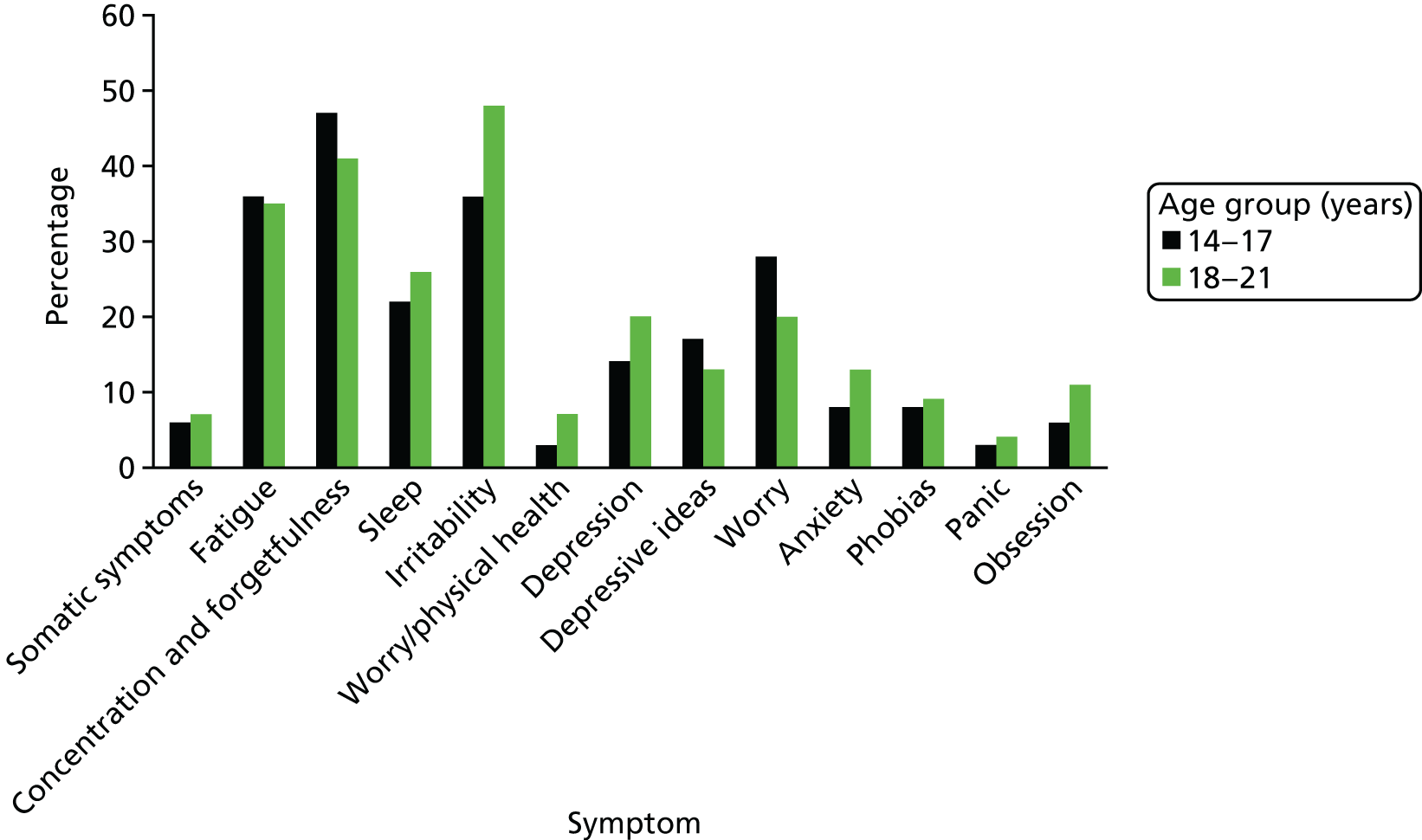

Associated psychiatric symptoms

Twenty-seven per cent scored above the cut-off score (> 12) on the CIS-R, indicating the likelihood of comorbid psychopathology. For example, over one-third of participants reported significant levels of fatigue and irritability and around one-quarter reported significant anxieties (Figure 3). There was no significant difference between the two age groups in the prevalence of associated mental health difficulties – including neurotic symptoms (t = –0.452, df = 79; p = 0.652).

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of neurotic symptoms by age according to CIS-R.

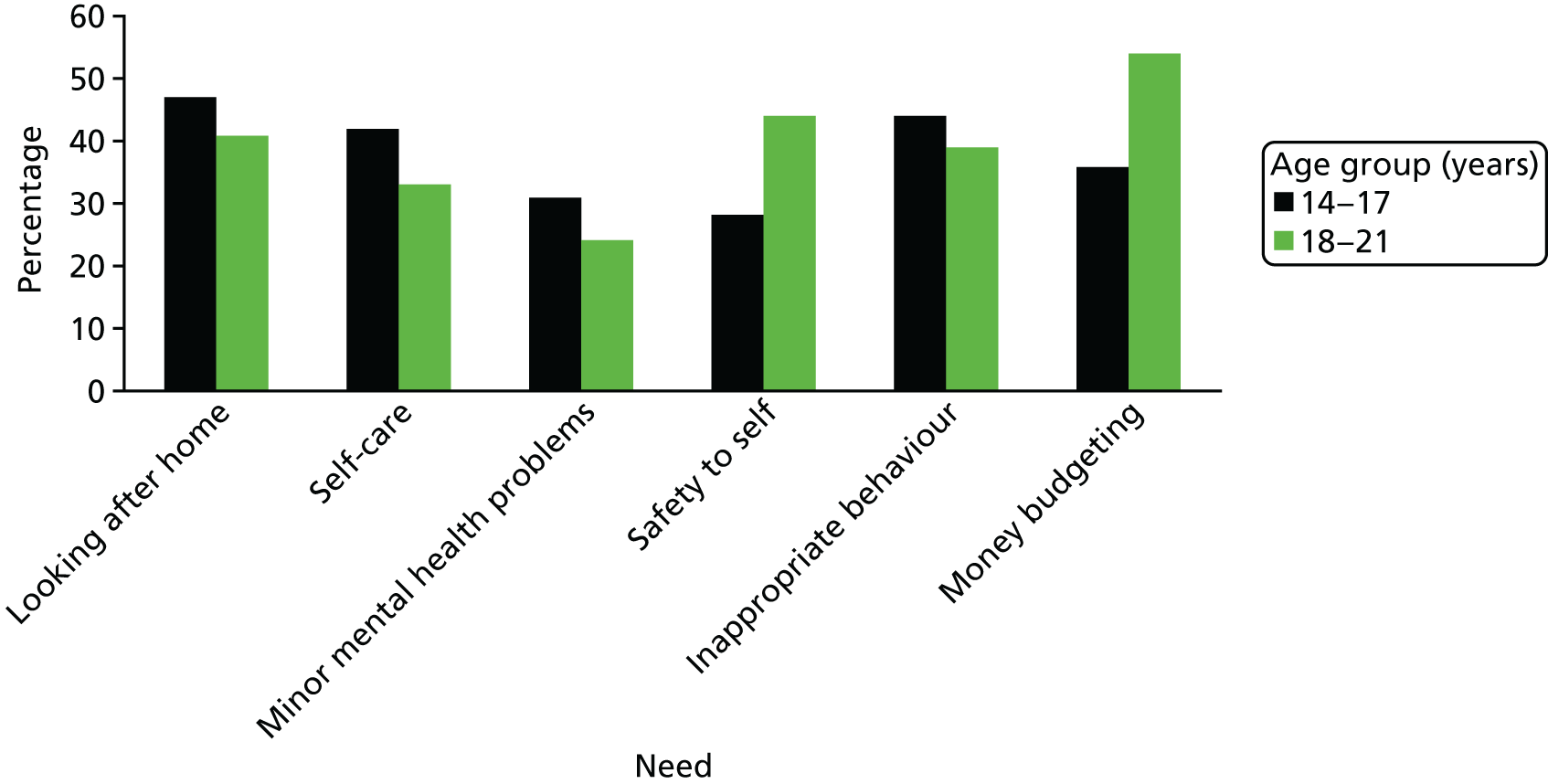

Needs

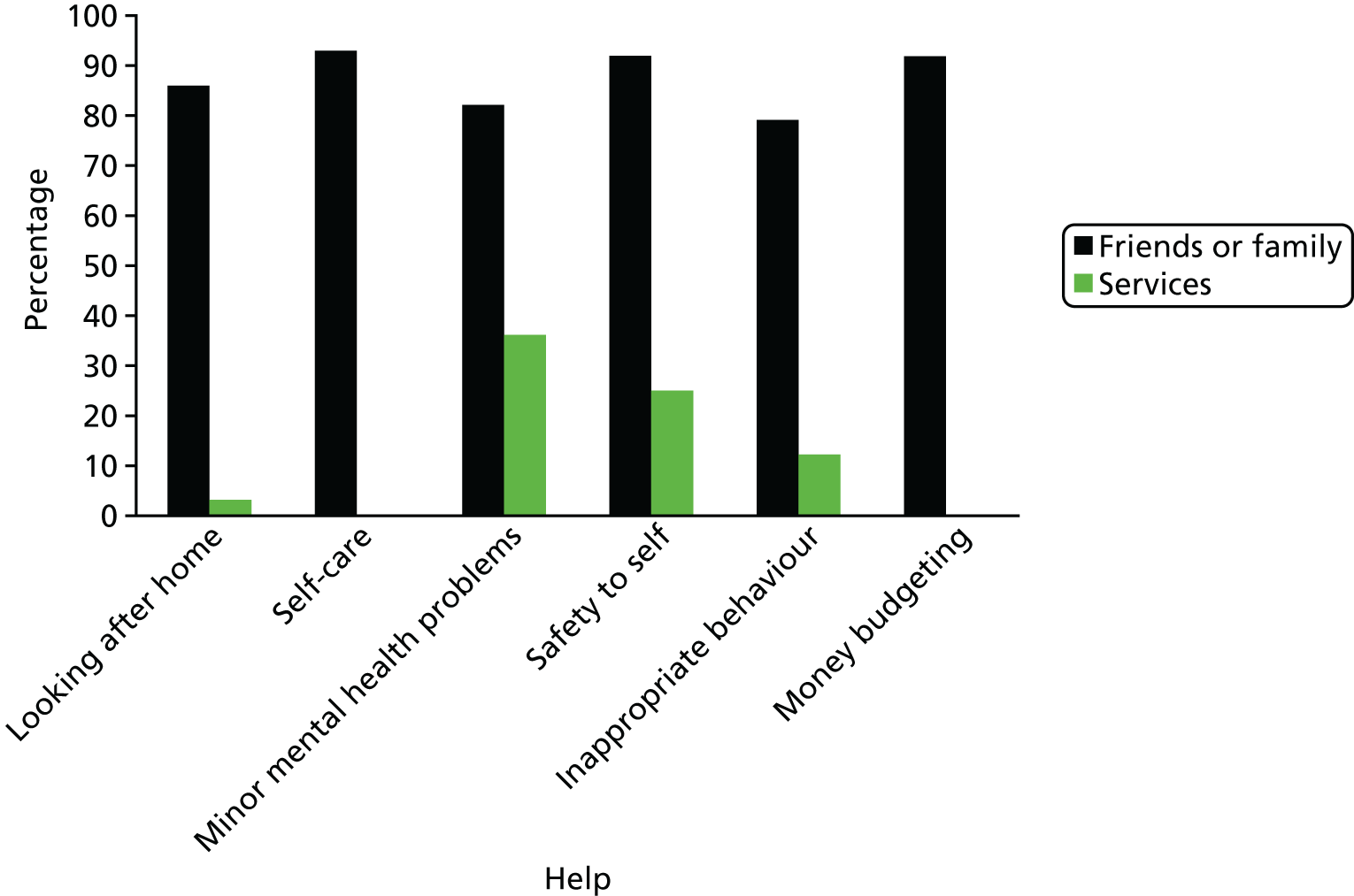

Parents reported that their child had a mean number of five needs (on average 2.58 of which were met and 2.48 of which were unmet; see Table 1). There was no significant difference between the younger and older age groups in the mean number of reported needs (5.25 vs. 4.89, t = 0.47; p = 0.64), met needs (2.78 vs. 2.41, t = 0.71; p = 0.48), or unmet needs (2.47 vs. 2.48, t = –0.01; p = 0.99). There was also no significant difference by age group in the percentages who reported needs within individual domains. The only exception being in the social contact domain, with parents of young people aged 14–17 years reporting more needs than parents of young people aged 18–21 years (χ2 = 6.20, df = 1; p = 0.01) (Figure 4). Most of the help received towards meeting these needs came from family or friends rather than from formal services (Figure 5). Overall, formal services provided little or no help towards needs other than those linked to the participant’s physical health, whereas families or friends or young people provided most of the help towards meeting young people’s needs. For example, whereas 88% of participants received some help from family and friends towards their reported need in the safety to others domain, only 12% reported receiving some help from formal services towards this reducing this need.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of needs by age.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of help received from friends or family and services towards meeting needs.

Service use

Despite a high prevalence of associated mental health symptoms, 41% of the sample reported that they were no longer in contact with services. Thirty-three per cent of the sample were in contact with children’s services and 16% reported regularly attending an ADHD service without age boundaries (that is one specialising in the management of children, adolescents and adults with neurodevelopmental difficulties). Only eight (10%) of the participants were seen by adult services (Table 2).

| Variable | In contact with servicesa | Significance test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Predisposing | |||

| YP age | 16.9 (2.1) | 18.4 (2.3) | df = 79, t = –3.32** |

| Enabling | |||

| PR (parent) education | |||

| Low | 27 (57) | 21 (44) | df = 1, χ2 = 0.041 |

| High | 17 (59) | 12 (41) | |

| Need | |||

| YP DIVA above cut-off point (> 6) | 35 (61) | 22 (39) | df = 1, χ2 = 0.849 |

| YP impairments | 5 (2.8) | 3.7 (2.5) | df = 76, t = 2.12* |

| YP CIS-R | 8.8 (6.8) | 6.8 (5.9) | df = 79, t = 1.39 |

| YP total needs | 5.5 (3.8) | 4.4 (2.9) | df = 79, t = 1.43 |

| YP childhood CD | 17 (57) | 13 (43) | df = 1, χ2 = 0.048 |

| PR carer burden | 19.7 (10.6) | 15.4 (6.8) | df = 79, t = 2.07* |

Those more likely to be in contact with services were younger, reported more impairments and higher parent–carer burden (Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression model used to analyse correlates of service use). The key outcome measure was whether or not the participant reported being currently seen by child, adult or tertiary services. The predictors captured predisposing (young person’s age), enabling (parental education) and need factors [ADHD symptoms, impairments, psychiatric comorbidities, parental caregiver burden and childhood conduct disorder (CD)]. Needs were not included in the model given their significant association with impairment (r = 0.51, df = 79; p < 0.01). Age was the only significant correlate of service use [odds ratio (OR) 0.62, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.46 to 0.83; p = 0.001], with a 1-year increase in the young person’s age reducing the odds of being seen by services by 38%. None of the other factors considered was significantly correlated with service use. The proportion of variance explained by the models was 0.24 using Cox and Snell R2 and 0.38 using Nagelkerke R2, indicating that between 24% and 38% of the variance is explained by this model. In summary, we found that in ADHD age (and not level of impairment) determines the chance of being seen by services.

| χ2 | 6.95* | |

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.24 | |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.38 | |

| Predictor | β | OR |

|---|---|---|

| Age | –0.476 | 0.62** |

| Parent education | 0.821 | 2.27 |

| Has ADHD | 0.304 | 1.36 |

| Impairment | 0.221 | 1.28 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | 0.057 | 1.06 |

| Carer burden | 0.017 | 1.02 |

| Childhood CD | –0.064 | 0.938 |

Health-care transition

As reported above, only 10% (n = 8) of participants reported having experienced a transfer to adult care. However, among this group, seven (≈85%) families reported not having received a written transition plan as recommended in clinical guidelines, and approximately 75% had not been spoken to by a professional about the move from child to adult services (and even the 25% who had said that this occurred reported that it been only a brief conversation). Around half of young people reported that they needed more help during the transition process to help them prepare for the move to adult services. Young people reported a need for more information to help them plan for the future (47%), someone to show them which services are available as they grow up (51%) and someone to explain the transition process to them (49%). In addition, around 70% of parents reported that their child needed more help in relation to information about future options (72%), having someone to talk to about transition (70%) and having someone to explain the transition process to them (69%). In addition, the majority (57%) of the those few young people and parents who had received some help in terms of transition reported that their transition had been poorly managed, with two-thirds reporting that they would have wanted more emotional and practical support.

Discussion

Our data indicate that two-thirds of adolescents and young adults with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD continue to meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria at follow-up. Many also present with associated psychiatric symptoms and impairments – as well as a wide range of health and social needs. Furthermore, there was no significant age-related difference in the overall prevalence of ADHD symptoms, impairments, psychiatric comorbidity or needs. Despite the continuing burden of symptoms and needs, reported service use decreased significantly with increasing age. For instance, a young person with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD reported 38% lower odds of service use at age 18 years than at age 17 years (irrespective of the severity of ADHD symptoms, impairments, comorbidities, carer burden or diagnosis of CD in childhood). This finding stresses the need for improving access to and/or use of health services among adolescents and young adults with ADHD.

In contrast, we found that most help towards meeting needs for adolescents and young adults came from friends and family rather than services (and families reported being provided with little or no help for the majority of domains). In addition, even where services were reported to have been involved, these were mainly targeted towards meeting the physical – rather than mental health or social – needs of this group.

Finally, we found considerable problems in health-care provision among this group that were specifically related to health-care transition. Only 10% of the sample had been transferred to adult services. Around half of all young people (and two-thirds of all parents) reported a need for more support from services in (1) accessing information regarding which services are available when they grow up, (2) the co-ordination of transition planning and (3) having someone to talk to about their practical as well as emotional needs. 43

Strengths and weaknesses

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis of needs and services use among those diagnosed with ADHD in childhood who are now at transition to adolescence and young adulthood. A key strength of our study includes the use of face-to-face interviews with both young people and their parents using reliable diagnostic and outcome measures. Moreover, our use of separate face-to-face interviews with young people and their parents enabled us to gain a more comprehensive picture of the wide range of needs among this group and to gauge the extent to which these needs are currently being met by services and family or friends. Another key strength of our study lies in our consideration of multiple potential factors that may correlate with service use among this group. This allowed us to better quantify the relative, and independent, contribution of factors that influence service use among this clinical group. Finally, our exploration of young people’s and their parents’ experiences of health-care transition, enabled us to identify key areas where improvements are necessary in health-care delivery. These are required from the perspective of both the affected person and their carers (e.g. a lack of access to sufficient information, problems with co-ordinating transition and lack of sufficient attention to the individual needs of young people and parents).

However, this was not an epidemiologically based sample and so our findings may not generalise. Nonetheless, we suggest that it is likely that the situation may be even worse in the general population, as our sample included individuals who had been in prior research studies of ADHD, and given that our sample had been in contact with CAMHS in childhood. Previous contact with such services may also have resulted in a bias towards presenting with higher levels of psychological problems at follow-up (e.g. in comparison with those in contact only with paediatric services in childhood). Nevertheless, rates of psychiatric comorbidity in our study are consistent with those reported in previous studies of ADHD. 44–48 Furthermore, as only those with a childhood intelligence quotient (IQ) of > 70 were included (with two exceptions), it is possible that our findings represent an underestimate of needs among those with intellectual disabilities. Likewise, as this study involved participants who were mostly males and from a Caucasian background it is not possible to say how representative the current findings are for women and those of ethnic minorities. Finally, due to our sample size we were likely underpowered to show significant effects of some of the predictor variables.

Conclusions

At transition, adolescents and young adults with ADHD represent a vulnerable group who are likely to have continuing needs that are currently poorly met by services. Key to improving transitional care are the health-care professionals and commissioners who design and run services. Without wider organisational support transitional health care is unlikely to become fully integrated into health services. Our initial results confirm Kennedy’s49 suggestion that changes could be made in policy, funding and training to enable the flexibility and continuity needed to put the young person at the centre of care. This comes at a cost. However, set against the considerable costs to the individual, family and society that are associated with untreated ADHD, there are clear clinical, ethical and financial arguments that suggest that investment in transition would realise long-term gains.

Age, rather than symptom severity, level of impairment or comorbidities, is the strongest correlate of service use in ADHD (with younger people being more likely to receive treatments).

Young people with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD at transition to adolescence and young adulthood suffer from persistent ADHD. In addition, they experience ongoing impairments and psychiatric comorbid symptoms. This leads to a wide range of health and social needs that would benefit from evidence-based treatment.

Most needs among adolescents and young adults with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD and their parents are poorly met by services. Most of the help received comes from families or friends.

Young people with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD and their parents report considerable unmet needs in health-care transition.

Chapter 4 Needs in ASD at the ‘transition’

Methods

As with the ADHD group, face-to-face interviews were conducted at yearly intervals with the ASD group. However, this study took place over a 2- rather than a 3-year period. In contrast to the ADHD study (see Chapter 3), interviews were largely undertaken with the parent and (whenever possible) with the young person themselves (we took parental advice into account on how best to manage the interviews in order not to cause any undue distress).

Thus, the first part of the parent interview consisted of a series of questions about their child (including the CANDID, their child’s alcohol and drug use and police contact if any). The second part collected information on the impact of their child’s disorder on their own situation and the final part, conducted when possible together with their child, asked questions about their child’s service use and transitions. When possible, the adolescent/young adult version of the ASD questionnaire consisted of questions on level of need, mood, drug and alcohol use and police contact. With few differences, we collected the same information for both young people and parents in the ASD group as we did for the ADHD group (e.g. the CANDID, the CSRI). The measures unique to the ASD group are briefly discussed below (i.e. those assessing ASD symptoms and associated comorbid psychiatric conditions). We included 101 individuals with ASD.

ASD-specific instruments

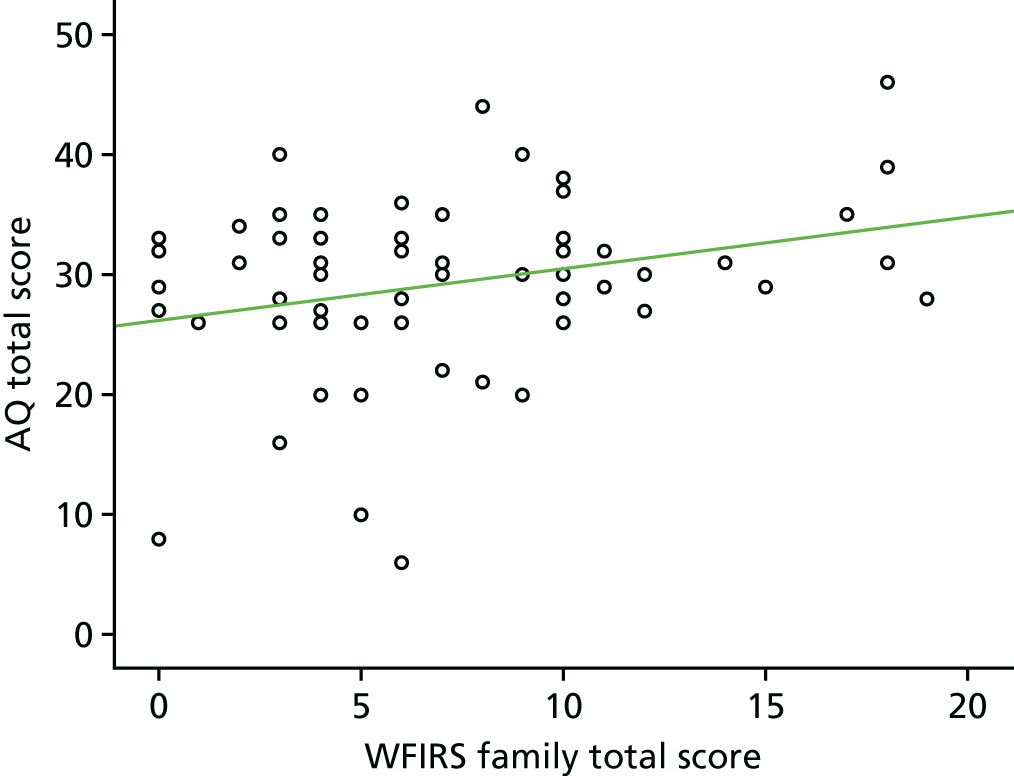

Current severity of ASD symptoms were captured using the Autism Quotient (AQ) – informant version. 50 It contains 50 items covering five different areas: social skills, attention switching, attention to detail, communication and imagination. For each question respondents report whether they ‘slightly agree’, ‘definitely agree’, ‘slightly disagree’ or ‘definitely disagree’ that a described behaviour is exhibited. Each question is scored 1 if the respondent reports the autistic symptom (by either ‘definitely’ or ‘slightly’ endorsing the symptom) and 0 if not. A total score (0–50) is calculated by summing the scores for each question. Scores over a cut-off point of 32 are indicative of an ASD. 50

Information on psychological co-occurring mental health symptoms was assessed using the DAWBA. 51 We did not use the CIS-R (as we did in the ADHD study) because there is no informant version of this instrument. The DAWBA assesses psychiatric symptoms and their impact across a number of domains through structured and open-ended questions, which cover the criteria required for a diagnosis according to both DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. The domains assessed were specific phobia, social phobia, panic, agoraphobia, OCD, generalised anxiety, depression, deliberate self-harm, impulsivity/hyperactivity and tics/Tourette syndrome. The DAWBA was completed online (www.dawba.net) by parents and young people when possible. Two trained raters (both psychiatrists) reviewed each case and produced consensus diagnoses based on the information provided by both parent and young person (where available). All conditions were rated according to ICD-10 criteria except ADHD, which was rated using DSM-IV criteria (as ADHD is not covered by ICD-10). An additional variable was derived from this measure stating whether or not the young person met criteria for one or more comorbid conditions [e.g. ADHD, Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD)].

Mental capacity issues

The ASD (but not ADHD) sample included individuals with intellectual disability (ID). Given the nature of the research, some of those who were eligible to participate lacked capacity to consent. We are aware that the baseline position is that capacity to consent is assumed unless there is reason to suppose otherwise. However, some neurological, psychological and/or behavioural markers may suggest lack of capacity for some things at some times. We also recognise that capacity is fluid in time and with respect to subject.

Indicators of potential lack of capacity include (but are not restricted to) the diagnosis of a LD, an IQ of < 70, significant deficits in adaptive functioning or other signs or symptoms of mental disorder that might compromise capacity to give informed consent. This was of particular concern for the ASD group as we did not exclude participants who had a LD (as was the case for the ADHD group, see above). All individuals with capacity gave informed consent.

Where there were doubts about the capacity of a young adult to give consent the study introduced an easy-read version of the information sheet and a capacity assessment was carried out by a trained researcher. The capacity assessment tool addressed the following questions, which are based on the principles outlined in Section 3 (1) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005:33

-

Can the person understand the information relevant to the decision?

-

Can the person retain that information?

-

Can the person use or weigh that information as part of the process of making the decision?

-

Can the person communicate his/her decision (whether by talking, using sign language or any other means)?

When it was established that the participant did not have capacity, but showed willingness to take part in the study, a relative or close friend (other than the carer) was approached to act as a personal consultee. The role of the consultee is to consider what the wishes and feelings of the participant would be if they had capacity, and if they judge that the person would want to take part, to consent on their behalf. We did our best to ensure that the consultee had no conflict of interest. If there were concerns about a conflict of interest then the parent was asked to contact the research team, at which stage a member of the research team spoke to them about the possibility of finding an alternative personal consultee.

The researchers who interviewed the ASD participants all received training from Dr Dene Robertson (consultant psychiatrist at the Mental Impairment and Evaluation Service, Bethlem Hospital) in assessing mental capacity to consent. In addition, they also undertook additional training; for example, they attended short courses on the Mental Health Act 200533 and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards awareness training, as well as training on protection of vulnerable adults and the Protection of Children Act 1978. 52 When possible, the researchers conducted assessments in collaboration with a member of the health-care team, known to the potential participant, with experience in assessing mental capacity.

Results

Service use (and needs) among those with an ASD in adolescence and young adulthood

As with the ADHD group, our focus so far has been on addressing the first research question, the correlates of service use. In addition, similar to ADHD, there is a lack of adult services for those with an ASD [and in particular among those with high-functioning autism (HFA) who have ongoing needs and functional impairments]. Appropriate and effective planning of care programmes requires knowledge of the needs of this population (and their carers).

Consequently, our aim was to investigate needs and correlates of service use (e.g. medical and demographic) among those diagnosed with ASD in adolescence and young adulthood (aged 14–24 years), to help identify how they are supported while they move from adolescence to young adulthood.

Similar to the analysis of the ADHD group, we used the Andersen–Newman Behavioural Model of Health Service (see Chapter 3, Results) to investigate the correlates of health service use among young people with an ASD.

ASD sample characteristics

Similar to the ADHD sample the young people were predominantly male (92%) and still living at home (87%). Seventy-three per cent met criteria on the DAWBA for an associated psychiatric condition and 13% had a clinically defined LD. Most of the total sample were still in education (77%) and had received a statement of special educational needs (70%); 40% had been excluded from school at some point in their education. Parental education was assessed and 60% reported a high level of achievement – that is they had received A-level qualifications or above.

Service and medication use

Fifty-six per cent of participants (Table 4) reported currently being in contact with child (33%), adult (22%) or tertiary services (1%). The services most commonly seen in the past 3 months were a GP (used by 43% of participants), psychiatrist (26%), key worker (22%) or psychologist (17%). Those who stated they were in contact with child, adult or tertiary services were significantly more likely than those who were not in contact with formal services to report having seen a psychiatrist (χ2 = 3.66; p = 0.001) or a mental health key worker in the past 3 months (χ2 = 7.92; p = 0.005).

| Variable | % | Mean (SD) | Range | Missing, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YP age (years) | 17.67 (2.9) | 14–24 | 0 | |

| YP male | 92 | 0 | ||

| YP education | ||||

| Full time | 70 | 0 | ||

| Part time | 07 | |||

| Not in education | 23 | |||

| YP employed (of those not in education) | 35 | 0 | ||

| Parental education | ||||

| Low | 41 | 0 | ||

| High | 59 | |||

| YP ethnicity | 1 | |||

| White | 85 | |||

| Black/Asian/other | 14 | |||

| YP accommodation | ||||

| Family home | 87 | 1 | ||

| Other | 12 | |||

| YP symptoms | ||||

| YP AQ symptoms | 35.85 (5.74) | 22–46 | 1 | |

| YP met criteria on DAWBA for one or more psychiatric condition | 73 | 12 | ||

| YP LD | 13 | 3 | ||

| YP needs | ||||

| Total needs (parent rated) | 9.58 (3.64) | 0–18 | 0 | |

| Unmet needs (parent rated) | 3.25 (2.88) | 0–11 | ||

| Met needs (parent rated) | 6.34 (2.72) | 0–12 | ||

| YP service use | ||||

| Children’s services | 33 | 0 | ||

| Adults | 22 | |||

| Tertiary | 1 | |||

| None/do not know | 45 | |||

Thirty-eight per cent of participants were currently taking at least one prescribed medication (Table 5). The most common prescribed medication was for ADHD (taken by 9% of participants), followed by antidepressants (8%) and sleep medication (8%). On average participants were prescribed 0.64 medications.

| Participant information | % | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently using medication | 38 | ||

| Number of medications prescribed | 0.64 (0.48) | 0–4 | |

| Type of medication used | |||

| ADHD | 9 | ||

| Antidepressant | 8 | ||

| Sleep medication | 8 | ||

| Antihistamine | 7 | ||

| Respiratory | 5 | ||

| Epilepsy | 3 | ||

| Beta-blockers | 3 | ||

| Antipsychotic | 2 | ||

Psychiatric associated symptoms

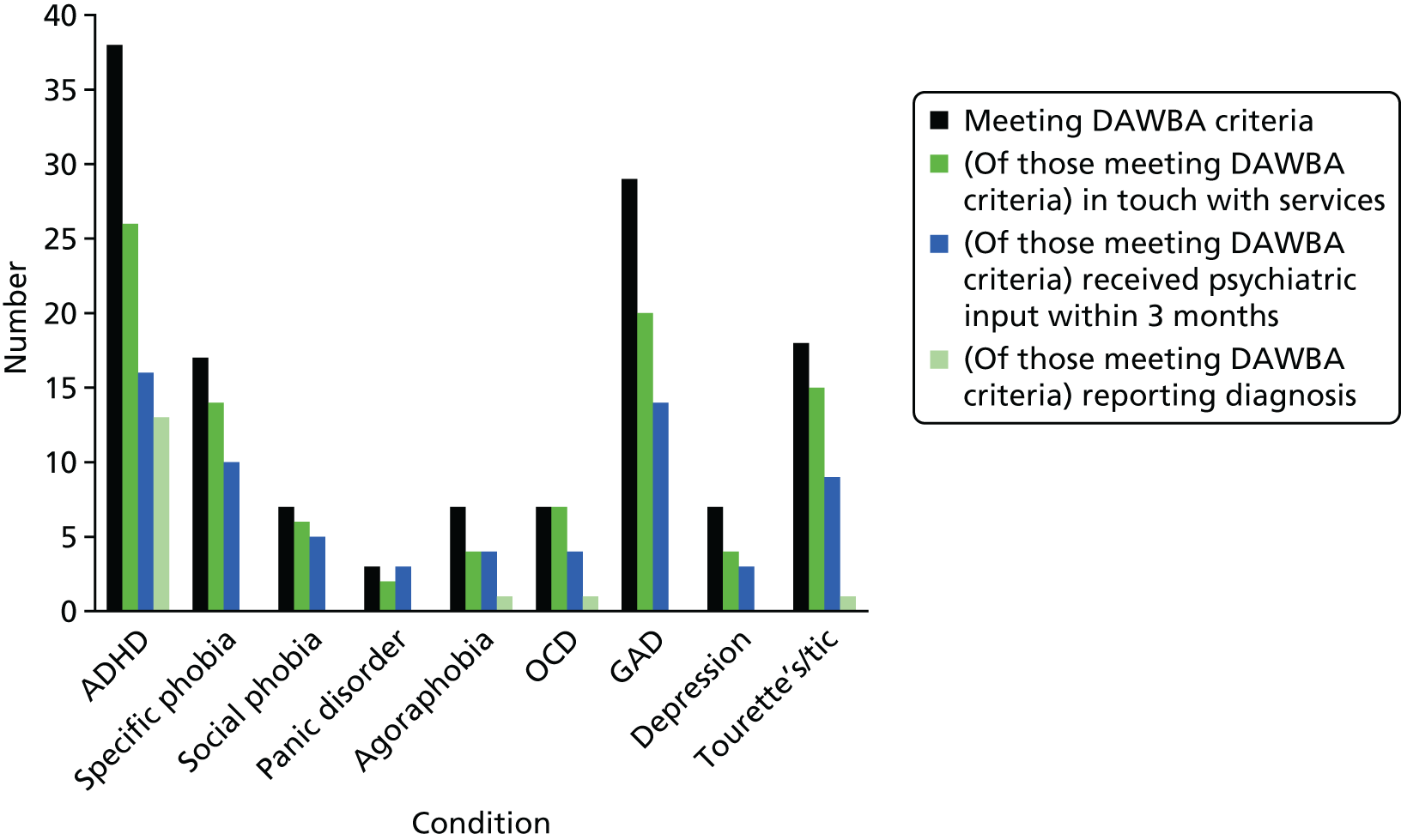

Figure 6 shows the number of ASD participants who also met criteria on the DAWBA for common psychiatric conditions. Figure 6 shows, for those who met the criteria for each condition, the numbers who were in touch with services; had saw a psychiatrist, psychiatric nurse, psychologist or counsellor in the past 3 months; and whose parents reported that their children had previously received a clinical diagnosis for an associated psychiatric disorder. Results show that 43% of the sample met clinical research diagnostic criteria for ADHD (38/89), 33% for GAD (29/89), 19% for a specific phobia (17/89) and 20% for tic/Tourette syndrome (18/89). In addition, a large proportion met criteria for more than one mental health problem. For instance, nearly half (47%) of participants met criteria for two or more co-occurring mental health disorders. However, relatively few of the parents whose children met the criteria for a co-occurring mental health disorder reported having previously been told that their child had a clinical diagnosis of the disorder. The most common additional diagnoses that parents had been made aware of are ADHD [36% (14/39)], agoraphobia [11% (1/9)], OCD [14% (1/7)] and tic/Tourette syndrome [6% (1/18)]. Young people with an ASD who met criteria on the DAWBA for at least one psychiatric disorder were more likely than those who did not to be in touch with services (χ2 = 10.67; p = 0.001). However, of those who currently met criteria for at least one additional psychiatric condition, one-third stated that they were not currently being seen by any services and over half had not seen any psychological or psychiatric services in the past 3 months (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Number of participants meeting criteria for one or more psychiatric conditions on the DAWBA (n = 89).

Need

Parents reported that their child had a mean number of 10 needs (on average six of which were met and three of which were unmet; see Table 4).

Figure 7 shows the needs most commonly reported by parents and the number of participants who were receiving help from family or services. Eighty-three per cent of parents reported that their child had a need relating to exploitation risk, 73% reported a need related to food, 72% reported a need related to money budgeting and 63% reported social needs. Few of the young people were receiving help for these needs from services; in contrast, almost all were receiving some help for them from friends or families.

FIGURE 7.

Met and unmet needs most frequently reported by participants and help received from family and services (n = 101).

As expected, younger people with an ASD with higher levels of need were more likely to be in contact with services than those who were not [mean 10.54, standard deviation (SD) 3.60, in contact vs. mean 8.14, SD 3.57, not in contact, t = –3.13; p = 0.002].

Correlates of service use

Table 6 shows the results of the logistic regression model used to analyse correlates of service use. The dependent variable was whether or not the participant stated that they were currently being seen by child, adult or tertiary health-care services. The predictors captured predisposing (young person’s age), enabling (parental education) and need factors (that is the level of ASD symptomology, total level of need, whether or not they met criteria on the DAWBA for any associated psychiatric conditions and the presence of a LD). The only significant correlate of service use was whether or not the young person met criteria on the DAWBA for one or more psychiatric conditions. For instance, the odds of young people with an ASD and an associated psychiatric condition being in touch with services are four times higher than for those without such a condition. The proportion of variance explained by the model was 0.18 using Cox and Snell R2 and 0.24 using Nagelkerke R2, indicating that between 18% and 24% of the variance in service use is explained by this model.

| Predictor | β | SE | OR | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR education (0 = high) | 0.774 | 0.522 | 2.168 | 0.145 |

| YP age | –0.090 | 0.085 | 0.914 | 0.289 |

| YP autism symptoms (AQ) | 0.002 | 0.044 | 0.998 | 0.973 |

| YP total need (parent rated) | 0.124 | 074 | 1.132 | 0.095 |

| YP met criteria on DAWBA for any condition | 1.353 | 0.587 | 3.870 | 0.021 |

Service use, diagnosis and treatment of comorbid psychiatric conditions

Table 7 examines the relationship between being in touch with services and diagnosis and treatment (in terms of reporting any psychiatric input in the past 3 months and receiving relevant medications), for the two most prevalent psychiatric symptoms (ADHD and GAD). We would expect that those who met criteria for a psychiatric condition and who were in touch with services would be more likely to report having received a clinical diagnosis and treatment. However, we found no such relationship (albeit with one exception). Among those with an ASD meeting DAWBA criteria for an anxiety disorder, 98% (43/44) reported that they had not been informed of (or diagnosed with) this additional problem by any service, 52% (23/44) had received no psychiatric input in the past 3 months and 86% (38/44) reported that they were receiving no relevant medication for anxiety. Only for those with an ASD who met criteria for ADHD was being in touch with services significantly associated with receiving psychiatric input in the past 3 months (see Table 7). However, even among this group, 65% (22/34) reported not having received a clinical diagnosis and 85% (29/34) were not being prescribed relevant medication.

| DAWBA condition | In touch with services | Reporting diagnosis | Fisher’s exact | Any psychiatric input in past 3 months | Fisher’s exact test | Reporting relevant medication | χ2 | Row total for number meeting DAWBA criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||||

| ADHD | Yes | 10, 38.5% | 16, 61.5% | 14, 53.8% | 12, 41.2% | 4, 18.5% | 22, 81.5% | 26 | |||

| No | 2, 25.0% | 6, 75.0% | 0, 0.0% | 8, 100.0% | 1, 12.5% | 7, 87.5% | 8 | ||||

| Total | 12, 35.3% | 22, 64.7% | p = 0.68 | 14, 41.2% | 20, 58.8% | p = 0.01 | 5, 14.7% | 29, 85.3% | p = 1.00 | 34 | |

| GAD | Yes | 0, 0.0% | 32, 100.0% | 17, 53.1% | 15, 46.9% | 6, 18.8% | 26, 81.2% | 32 | |||

| No | 1, 8.3% | 11, 91.7% | 4, 33.3% | 8, 66.7% | 1, 8.3% | 11, 91.7% | 12 | ||||

| Total | 1, 2.3% | 43, 97.7% | p = 0.27 | 21, 47.7% | 23, 52.3% | p = 0.32 | 7, 15.9% | 38, 84.1% | p = 0.65 | 44 | |

Discussion

We found that young adults with an ASD have a high burden of associated psychiatric symptoms, including ADHD, and this is one of the main drivers of their service use. Even so, 45% were not using any services. In addition, among those who were, most of their parents reported that their children had not been clinically diagnosed or treated for the mental health problem(s) that (we detected) they suffered from. Among our sample, we found that, of those participants reaching DAWBA criteria for GAD and who were in touch with services, no parents had reported that their child had received a formal clinical diagnosis. Eighty-one per cent did not report any relevant medication use for their children. Close to half (49%) reported that their child had no psychiatric input in the past 3 months. Similarly, 85% of those with both ASD and ADHD were untreated.

In addition, we found a very high level of need among this group – and these were more likely to be met by family and friends rather than by services. These needs mainly pertained to core daily living activities and independence and are highlighted in the recent NICE guidelines for adults as important to preparing adults on the spectrum as they transition into adulthood. 53

Our findings support those from a recent study highlighting the lack of treatment and services for adults living with severe and enduring mental health difficulties, including depressive and anxiety disorders and ADHD (URL: http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/special/cepsp26.pdf). The report concludes that living with a mental illness such as GAD can be even more debilitating than most chronic physical conditions even though three-quarters get no treatment (URL: http://cep.lse.ac.uk). Thus, our findings highlight the need for better recognition, referral and treatment of psychiatric comorbid conditions among young people with an ASD.

There are few recognised ASD-specific treatments. However, there are a number of effective treatments for ADHD, GAD and depression that have been developed in the general population. In addition, there is recognised success in treating some of the associated psychiatric conditions in developmental disorders. For example, the effective use of optimal dosing of methylphenidate (Concerta XL®; Janssen-Cilag Ltd, High Wycombe, UK) in children with hyperkinetic disorder and ID, ASD54 and for higher-functioning ASD. 55 Yet, despite this, we found very few affected individuals reported that they had been diagnosed or were being treated.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study has a number of limitations. First, the sex balance is not representative of the ASD population as > 90% of our sample is male, compared with a sex ratio of approximately 4 : 1 typically found by others. Second, our sample included relatively high-functioning individuals compared with the ASD samples investigated in other studies. For example, approximately 15% of our sample was diagnosed with a LD compared with a prevalence of 56% in a population cohort of children. 56 Even so, there is increasing recognition that many individuals with an ASD do not have an ID, but still report high prevalence of functional impairments, psychological comorbid disorders and needs. 57,58 Finally, this initial report is from a cross-sectional study and is therefore able to examine associations of need and service use at only one point in time and so causality cannot be inferred.

Nevertheless, this study has significant strengths in comparison with earlier research. Our study is one of the few to focus on adolescents and young adults with an ASD – whereas most studies concentrate on children. 59,60 In addition, our diagnostic assessment, the ADI-R, is a widely recognised and well-validated informant-based (so-called ‘gold standard’) measure of ASD and so the sample contains ‘true’ cases.

Our study has shown a high prevalence of unrecognised psychiatric associated conditions and needs among adolescents and young adults with an ASD. Many of the young people in this clinical group have needs that are met not by services but largely by family and friends. Moreover, our findings show that only severity of psychiatric conditions is associated with service use, and not ASD symptomology. Even those young people with an ASD who met criteria for an additional psychiatric condition and were in touch with services are no more likely to report appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Yet, further research is required into the appropriate use, efficacy and long-term safety of antipsychotics and stimulants in the autistic population before moving towards standardised pharmacological treatments (see Chapter 19). Too few services are ‘autism focused’ and geared towards programmes to help those with an ASD to maintain independence and sustain employment. 61 Our data suggest that needs-led services are required which can meet the complexities of ASD, including the core symptoms (e.g. difficulties with reciprocal social interaction and communication, repetitive behaviours and interests), but which can also diagnose and treat severe associated conditions such as ADHD, anxiety and depression, and thus reduce both the challenges facing the young person and the burden they place on caregivers.

Despite a high prevalence of associated psychiatric symptoms, many adolescents and young adults with an ASD are not being helped by services.

Our findings suggest that needs-led services are required to meet the complexities associated with lifelong disorders.

Chapter 5 Carer burden as people with ASD and ADHD ‘transition’ into adolescence and adulthood in the UK

Background

Here we address the third research question – that is to define the relationship between symptomology, need and service use among people with ADHD or an ASD at transition to adolescence and young adulthood and carer burden. Previous research focused largely on burden to carers of young children with ASD; few studies used adult samples.

The few available studies in ASD reported high levels of caregiver stress and burden; this was greater than in parents caring for adults with other disabilities such as fragile X syndrome and Down syndrome. 62,63 However, to our knowledge, no studies compared levels of burden for ADHD and ASD.

Methods

We used a modified stress appraisal model64 to examine correlates of burden. The model includes the following components as potential correlates of caregiver burden: (1) family background characteristics (parental education), (2) primary stressors (ADHD or ASD symptoms, a LD and measures of psychiatric comorbidities), (3) a primary appraisal (a measure of need) and (4) resources (use of services). This model was based on the stress appraisal model65 incorporating the two main theories regarding caregiver burden: the appraisal model66 and the stress process model. 67 Yates and colleagues’ stress-appraisal model65 consisted of five components: (1) primary stressors (e.g. level and type of disability), (2) primary appraisal (the caregiver’s subjective appraisal of care need), (3) resources (individual and societal resources that may affect the stressor such as the level of formal help), (4) secondary appraisal (often measured as caregiver burden) and (5) outcome (psychological well-being). Casado and Sacco64 altered this model by adding a family background component from Pearlin and colleagues’67 stress process model (family sociodemographic background) and by conceptualising caregiver burden as an outcome. Thus, we propose that family background, the young person’s level of symptoms and psychological comorbidities, and parental perceptions regarding the need for care and resources lead to perceptions of burden.

Results

Sample characteristics

We included 89 individuals with ASD and 81 individuals with ADHD. Young people in the two groups were similar in age, sex (≈90% male), education (≈70% in education) and accommodation (≈90% lived at home) (Table 8). Caregiver sociodemographic characteristics in the two groups were also broadly similar (see Table 8). All of the caregivers were either a biological or an adoptive parent. Caregivers from the two samples showed similar sex and marital status distributions (72% of ASD caregivers were married vs. 78% of ADHD caregivers, χ2 = 0.77; p = 0.38). In addition, around 35% of parents in both groups provided care for someone else aside from their child with ASD/ADHD (χ2 = 0.28; p = 0.60). Caregivers from the two samples were also comparable in terms of age (ASD mean 49 years, SD 6 years vs. ADHD mean 48 years, SD 5 years, t = 1.65; p = 0.10). There were, however, significant differences in occupation of the two caregiver groups: parents of ASD were in higher occupational groups (managerial/professional and associate professional/administrative) (55% ASD vs. 42% ADHD, χ2 = 12.54; p = 0.01).

| Variable | ASD | ADHD | Significance test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Mean (SD) | Range | % | Mean (SD) | Range | ||

| YP age (years) | 17.57 (2.87) | 14–24 | 17.47 (2.28) | 14–22 | df = 168, t = 0.26 | ||

| YP male | 92 | 89 | df = 1, χ2 = 0.52 | ||||

| PR age (years) | 49.02 (5.89) | 38–64 | 47.60 (5.44) | 36–59 | df = 167, t = 1.65 | ||

| PR female | 93 | 96 | df = 1, χ2 = 0.33 | ||||

| YP education | df = 2, χ2 = 1.67 | ||||||

| Full time | 67 | 57 | |||||

| Part time | 8 | 9 | |||||

| Not in education | 25 | 35 | |||||

| PR education | df = 1, χ2 = 12.58*** | ||||||

| Low | 38 | 65 | |||||

| High | 62 | 35 | |||||

| YP accommodation | df = 1, χ2 = 0.19 | ||||||

| Family home | 90 | 88 | |||||

| Other | 10 | 12 | |||||

| YP symptoms | |||||||

| YP AQ symptoms | 35.56 (5.54) | 22–46 | |||||

| YP ADHD symptoms | 10.63 (4.73) | 0–18 | |||||

| YP LD | 15 | 0 | |||||

| YP SDQ total | 20.51 (7.04) | 4–36 | |||||

| YP CIS-R | 7.85 (6.34) | 0–29 | |||||

| YP needs | |||||||

| YP total needs | 9.90 (3.55) | 0–18 | 5.01 (3.12) | 0–14 | df = 168, t = 9.51*** | ||

| Met | 6.58 (2.72) | 0–12 | 2.60 (2.31) | 0–11 | df = 167.26, t = 10.31*** | ||

| Unmet | 3.31 (2.89) | 0–11 | 2.41 (2.23) | 0–9 | df = 163.70, t = 2.30* | ||

| Service contact and needs | |||||||

| YP In contact with services | 58 | 56 | df = 1, χ2 = 0.14 | ||||

| Zarit Burden Interview | 22.66 (8.84) | 4–41 | 17.80 (9.18) | 0–38 | df = 168, t = 3.52** | ||

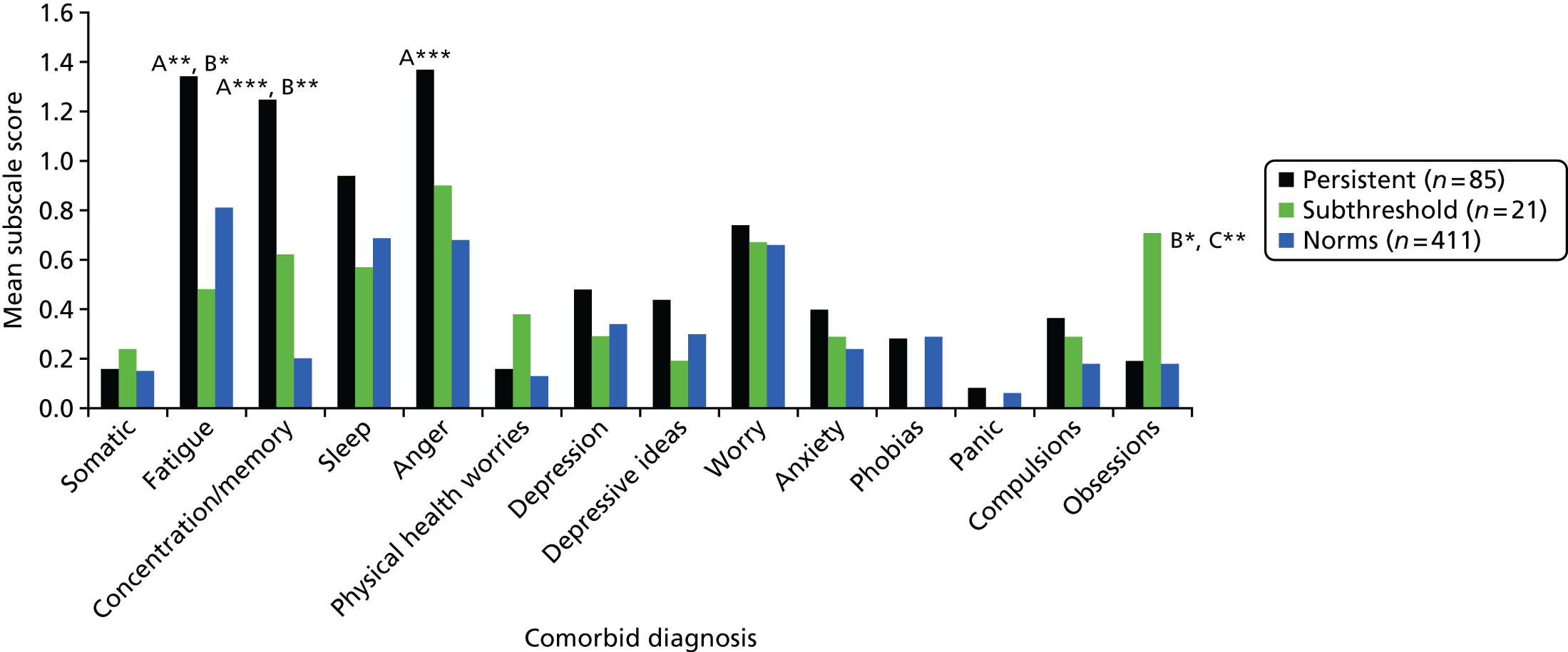

Caregiver burden and study variables

Caregiver burden was high in both68,69 groups, but it was significantly higher in ASD than ADHD (ASD mean 22.66, SD 8.84 vs. ADHD mean 17.80, SD 9.18, t = 3.52; p = 0.001). Family background (parental education) was significantly different, with 62% of parents in the ASD group being in the highest educational category, compared with 35% in ADHD (χ2 = 12.58; p < 0.001). Primary stressors (i.e. symptoms, LDs and psychiatric comorbidities) also showed significant differences between the two groups. The mean current severity of ASD as measured by AQ score for the ASD group was 36 (SD 6), with 73% of this group showing AQ scores above the suggested cut-off point of 32. The mean BAARS-IV current symptom score for the ADHD group was 10.63 (SD 4.73). Using a cut-off point of > 5 on the BAARS-IV current symptom score, 58% met threshold for inattentiveness, 42% for hyperactivity and 36% for combined ADHD. Fifteen per cent of the ASD group had been previously diagnosed with a LD, compared with none of the ADHD group. In terms of psychiatric comorbidities, the mean Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) score for the ASD group was 21 (SD 7), with 70% scoring in the abnormal range (> 16). Fifty-five per cent of the autism group also scored in the abnormal range on the hyperactivity subscale of the SDQ (> 6). The mean CIS-R score for the ADHD group was 8 (SD 6), with 27% per cent of the ADHD group scoring ≥ 12, indicating the presence of a common mental disorder.

Need, our measure of primary appraisal, also showed significant differences between the two groups, with the needs of those with an ASD (as rated by caregivers) being significantly higher (ASD mean 9.90, SD 3.55, vs. ADHD mean 5.01, SD 3.12, t = 9.51; p < 0.001). We used service use to conceptualise resources. There was little difference in this indicator between the two groups; 58% of the ASD group and 56% of the ADHD group were currently being seen by health services.

Tables 9–11 present the sequential multiple regression models used to examine the correlates of caregiver burden. Separate models were produced for each condition, as well as a model combining both conditions. Variables representing family background characteristics (parental education) were first entered into the model, followed by those capturing primary stressors (symptoms, a LD for ASD and psychiatric comorbidities), primary appraisal (need) and resources (use of services). For both samples, caregiver-rated need was a significant correlate of burden even after other factors were controlled for (see Tables 9–11). In addition, once need was controlled for, severity of disorder symptoms was no longer a significant predictor of burden for ASD, but remained significant for ADHD (see Table 10, model 3). Conversely, although psychiatric comorbidities were a significant predictor of burden for ASD, they were not for ADHD. Given that approximately half of the ASD group also met the threshold on the SDQ hyperactivity scale, we also investigated whether or not ADHD symptomology was associated with burden for the ASD group. When the SDQ hyperactivity subscale was included as a separate variable in the model (along with a variable comprising the total score from the other three subscales), the hyperactivity subscale was not significantly associated with burden.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.34 | ||||

| F change | 0.49 | 9.56*** | 10.37*** | 8.61*** | ||||

| ASD | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β |

| Correlates (reference groups) | ||||||||

| Family background | ||||||||

| Parent education (high) | –1.36 | –0.08 | –2.64 | –0.15 | –2.31 | –0.13 | –2.44 | –0.14 |

| Primary stressor | ||||||||

| LD | 0.36 | 0.01 | –1.01 | –0.04 | –0.99 | –0.04 | ||

| ASD symptoms | 0.03 | 0.02 | –0.00 | –0.00 | –0.00 | –0.00 | ||

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 0.70*** | 0.56 | 0.52*** | 0.41 | 0.51*** | 0.41 | ||

| Primary appraisal | ||||||||

| Need | 0.77** | 0.31 | 0.74** | 0.30 | ||||

| Resources | ||||||||

| Service use (no service use) | 0.86 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | –0.01 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.23 | ||||

| F change | 0.20 | 5.99** | 6.97*** | 5.75*** | ||||

| ADHD | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β |

| Correlates (reference group) | ||||||||

| Family background | ||||||||

| Parent education (high) | –0.30 | –0.02 | 0.29 | 0.02 | –0.26 | –0.01 | –0.13 | –0.01 |

| Primary stressor | ||||||||

| ADHD symptoms | 0.69** | 0.36 | 0.48* | 0.25 | 0.44* | 0.23 | ||

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 0.34* | 0.24 | 0.29* | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.19 | ||

| Primary appraisal | ||||||||

| Need | 0.90** | 0.31 | 0.88** | 0.30 | ||||

| Resources | ||||||||

| Service use (no service use) | 1.78 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.29 | ||||

| F change | 2.23 | 6.79*** | 12.25*** | 10.87*** | ||||

| ASD and ADHD | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β |

| Correlates (reference group) | ||||||||

| Family background | ||||||||

| Parent education (high) | –2.12 | –0.12 | –0.14 | –0.01 | –0.64 | 0.03 | –0.72 | 0.04 |

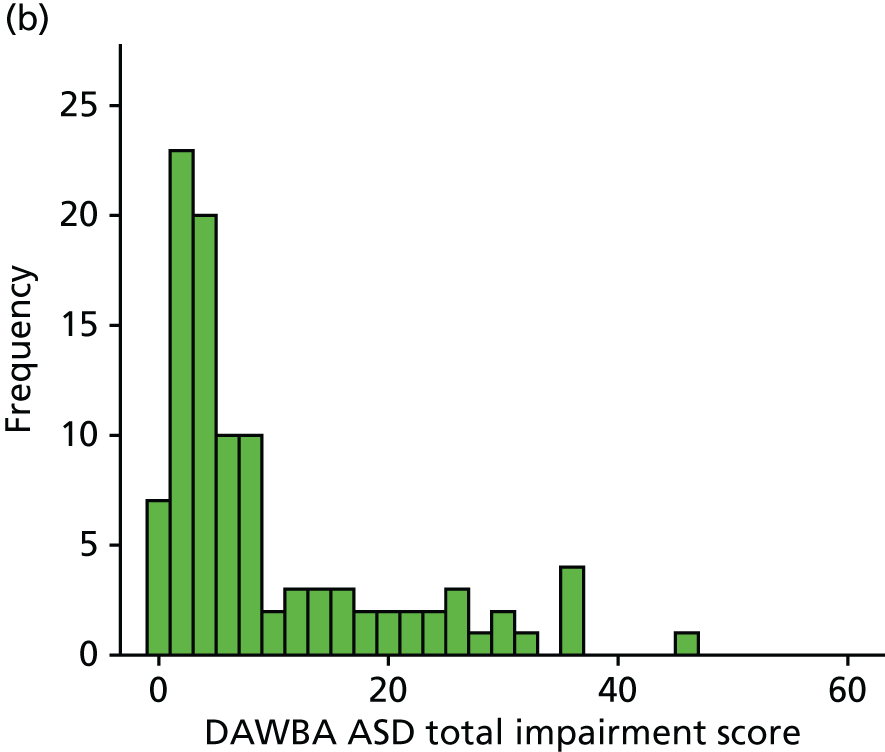

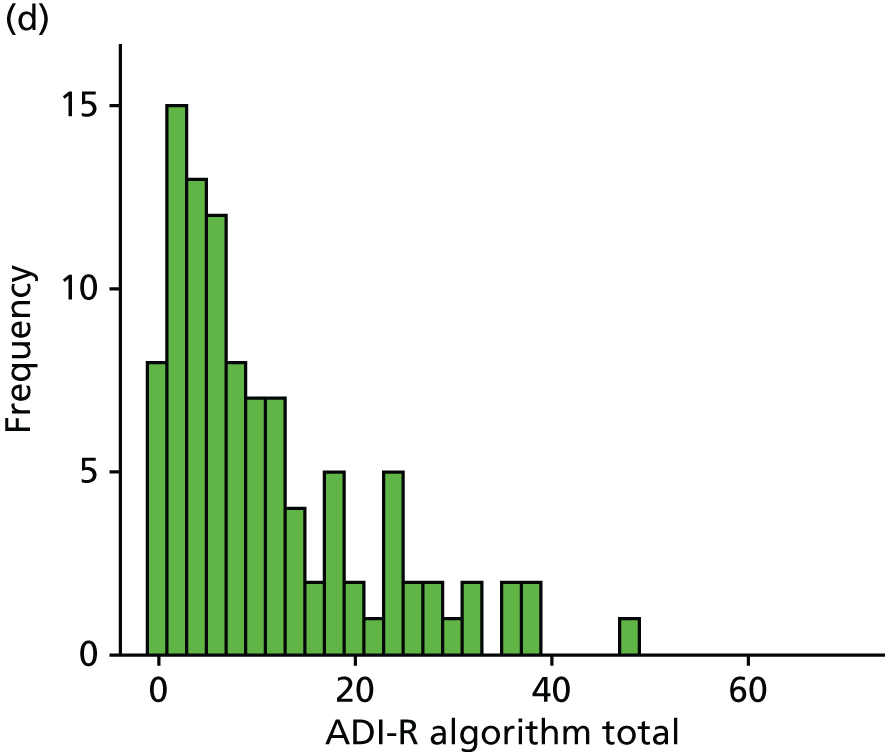

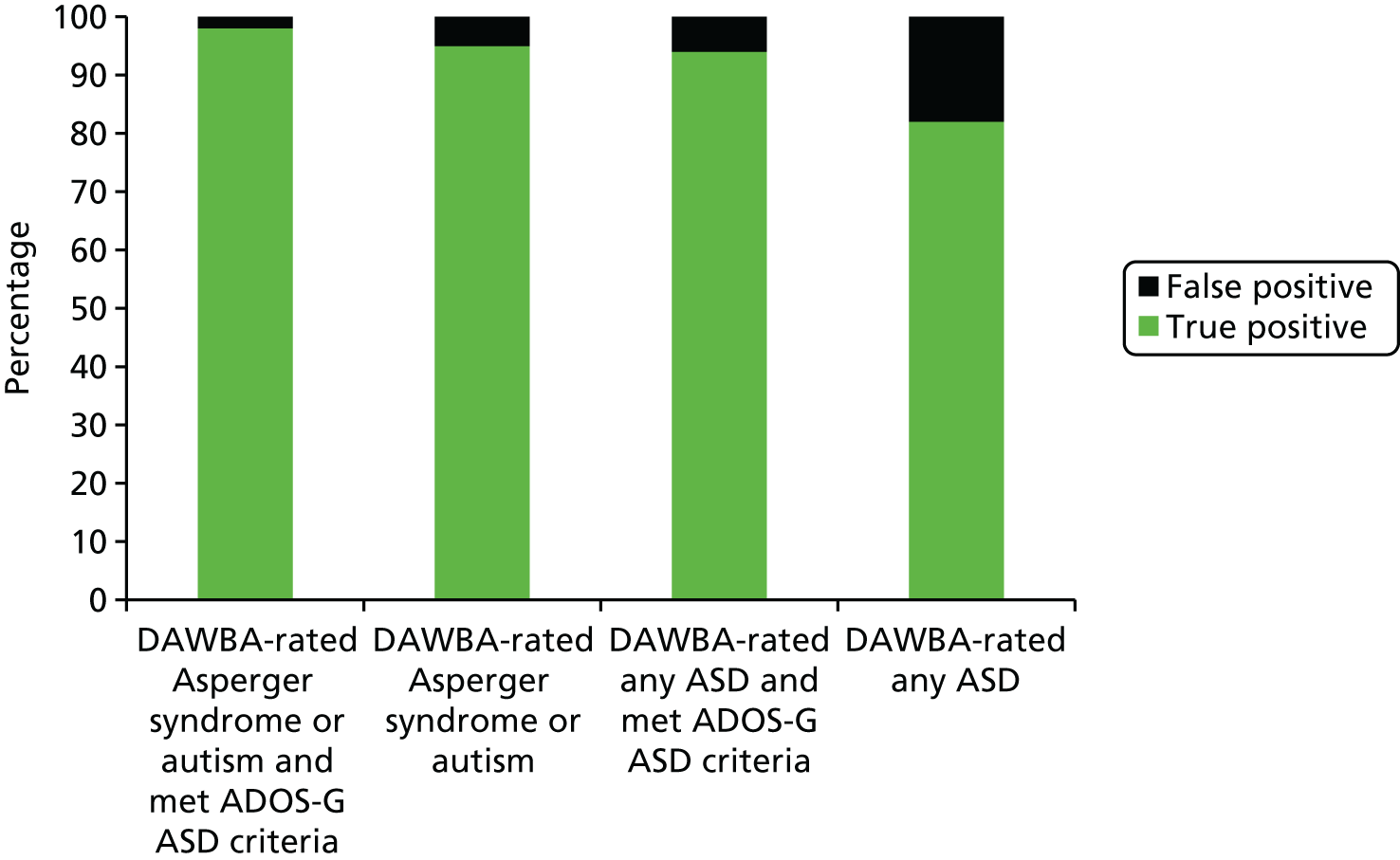

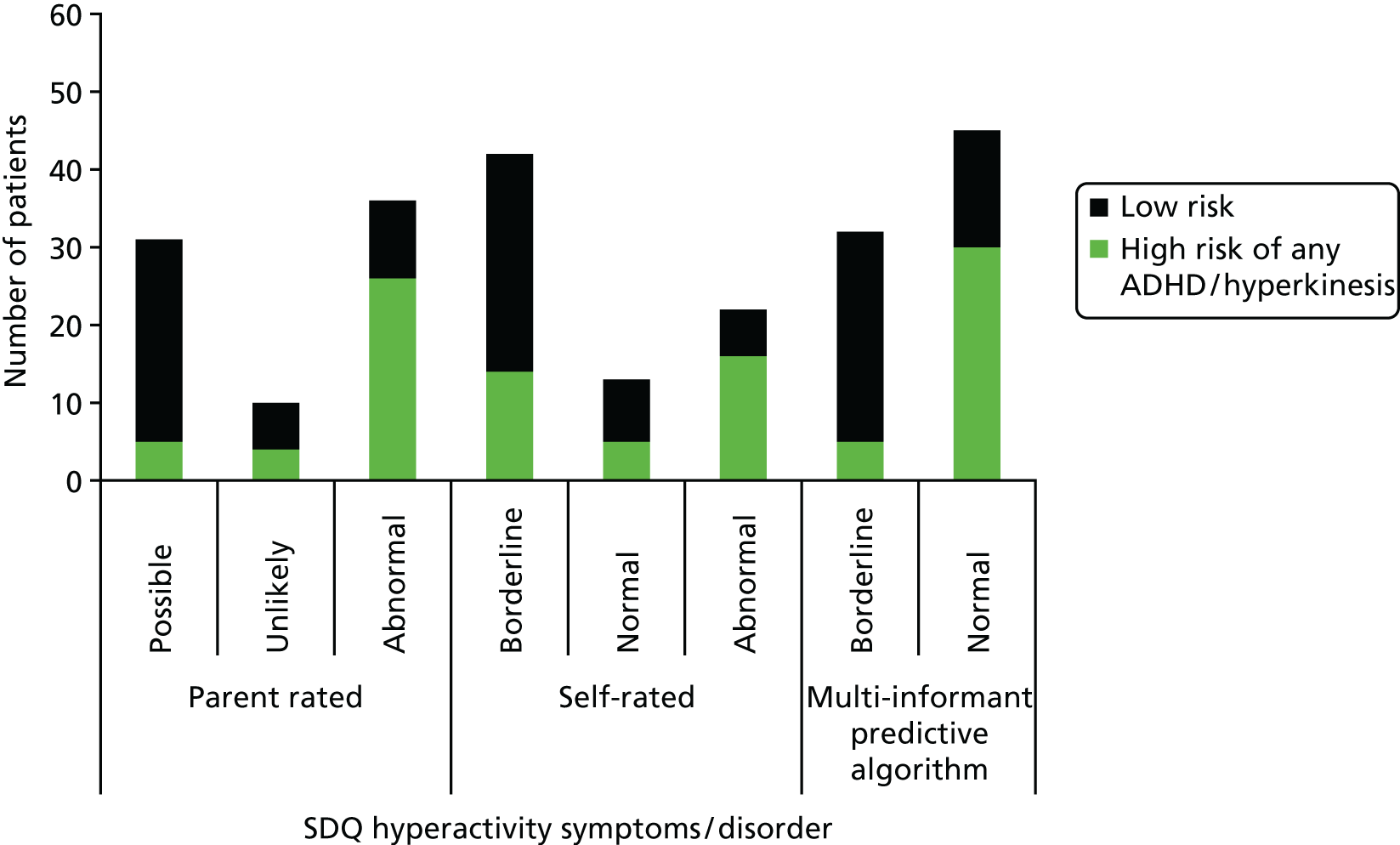

| Primary stressor | ||||||||