Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0109-10078. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The final report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The following authors had clinical/professional involvement in crisis teams during the course of the Crisis resolution team Optimisation and RElapse prevention (CORE) programme of research: David Osborn, Claire Henderson, Stephen Pilling, Fiona Nolan, Kathleen Kelly, Nicky Goater, Alyssa Milton and Ellie Brown. The following authors declare multiple research grants as chief investigator or co-applicant from the National Institute for Health Research during the course of the CORE programme of research: Brynmor Lloyd-Evans, David Osborn, Gareth Ambler, Louise Marston, Oliver Mason, Nicola Morant, Claire Henderson, Stephen Pilling, Fiona Nolan, Richard Gray, Tim Weaver and Sonia Johnson.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Lloyd-Evans et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background

Crisis resolution teams (CRTs) were mandated in the UK in 2000 under The NHS Plan: A Plan for Investment. A Plan for Reform. 1 They remained mandatory for almost a decade and, subsequently, have continued to be the preferred model of community crisis response in most mental health catchment areas. There has been a large workforce movement into these teams: several thousand mental health professionals now work in them. 2 Sometimes called home treatment or crisis assessment teams, CRTs provide rapid assessment in mental health crises and, if feasible, offer intensive home treatment as an alternative to hospital admission. 3 CRTs typically aim to offer 24-hour access and a ‘gatekeeping’ function, controlling access to inpatient beds and assessing suitability for home treatment before admission. 4 CRTs’ primary purpose is to reduce the use of hospital beds to manage crises. Reasons for this include the high cost of hospital admissions and the unpopularity of psychiatric hospitals with many service users. 5 Pioneers have also suggested that community management of crises can result in opportunities for service users to develop, in their normal living context, skills and insights, which will help them to cope better with future crises. 6,7 In addition, home treatment potentially offers more scope for working with social networks and addressing the social antecedents of crises in the community. 8,9 Therapeutic alliances between CRT staff and patients are based more on negotiation and equal partnerships than relationships between staff and patients in hospital are. 10 Therefore, a patient who has experienced effective home management of a crisis may subsequently be more able to manage their own health effectively, remain engaged with services and seek help at an early stage when warning signs of another crisis emerge. 11

Although the evidence base for CRTs was criticised as scant when they first became national policy,12,13 some positive findings had already been reported at the time this study was conceived. A national investigation14 into the early stages of CRT policy implementation indicated a mean reduction of 10% in admissions in areas where CRTs were available, rising to 20% when they operated for 24 hours a day. Moreover, naturalistic investigations of CRT introduction to catchment areas,15–17 as well as a randomised trial,18 suggest that CRTs can reduce hospital admissions. Two health economic assessments have shown lower health-care costs when CRTs are available. 19,20 There is also some evidence that service user satisfaction with acute care is higher when CRTs are available. 15,18 Little is known about the views of carers regarding the current UK model of CRTs. Outcomes, such as symptoms and social functioning, appear similar with or without CRT care. 15,18 A survey of London CRT staff was reassuring regarding workforce impact, suggesting fairly good satisfaction and low burnout. 21

Despite indications of the CRT model’s potential clinical effectiveness, there have been considerable reservations about its delivery in routine settings. 22,23 A national survey24 of CRTs found that only 40% of teams described themselves as fully established, with one-third of teams not involved in gatekeeping, as in some areas many hospital admissions take place without CRT assessment. The same survey24 showed that only just over half of teams offered a 24-hour, 7-day home-visiting service. Ward managers and CRT leaders still view a significant minority of hospital admissions as unnecessary. 25 Impact on bed use also varies between trusts26,27 and reductions in bed-days tend to be less marked than those in the number of hospital admissions. 13,17 Moreover, a reanalysis of the data from the national investigation of CRT implementation reported above13 suggested that the impact of CRT implementation on admissions cannot be disentangled from that of concomitant cuts in available inpatient beds, leading to uncertainty about the extent to which the new CRTs may be responsible for reduced admissions. 14 The Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Mental Health Act Commission have highlighted continuing difficulties with bed overoccupancy in a number of hospitals, and reports from both bodies express doubt as to whether or not CRTs have achieved their intended effects throughout the country. 27,28 Furthermore, any impact of CRTs seems thus far to be on voluntary admissions, and some evidence suggests that use of the Mental Health Act29 may even increase with CRTs in place. 13,30 There is a need to develop and implement well-integrated pathways through the acute care system that are clearly understood by CRT staff, managers and primary and secondary care referrers. 23

Service users and carers, although positive overall about receiving care in their own homes, report some dissatisfaction with CRTs,22,31 especially regarding continuity of care and relationships with staff. Specifically, they are concerned about having too many staff involved in each episode of care, with contacts often being fleeting and superficial. Information and planning of care are not sufficiently shared between staff and services. Discharge is often abrupt, with support for recovery falling off rapidly after the immediate crisis period. Some also report that the range of interventions offered is too narrow and focused on short-term symptom control. Other types of support, such as help in addressing practical and social problems that are often antecedents of crises32,33 and in developing better strategies for maintaining well-being and avoiding future crises, are highly valued, but insufficiently available.

Thus, CRTs appear to be potentially effective in meeting their goals of reducing inpatient admissions and improving service user experiences, but their implementation and the outcomes achieved seem to be very variable in practice. The difficulties in implementing new forms of treatment with demonstrated efficacy in trials in routine settings have been extensively described. 34,35 Facilitators of implementation include leadership in teams and from senior managers within organisations, financial and other incentives, systems for monitoring fidelity, a consistent set of local policies and guidelines that support the practice, and practitioner training. Interventions involving a single facilitating factor, such as training, rarely achieve change; packages with multiple measures and continuing measures to sustain change are usually required.

A potential barrier to effective implementation of the CRT model, alongside resource constraints, is the loosely specified nature of the model. There is only limited evidence available on critical ingredients and specific interventions associated with good outcomes. 6 The underdeveloped nature of the CRT model is apparent when comparing it with other complex service-level interventions, which have been the focus of programmes aimed at establishing and disseminating models of good practice. Most prominent in mental health is the US National evidence-based practices (EBP) project,36 which offers a model for evaluating whether or not complex service-level interventions operate as intended for achieving quality improvement in mental health settings. The EBP project has been applied to practices including assertive community treatment and individual placement and support.

Key stages in the EBP project are the development of a fidelity measure specific to the practice and the development of implementation resource kits designed to enable services to achieve high fidelity, followed by testing of whether or not they succeed. 37 Fidelity scales measure how far a service adheres to a model based on the best evidence about the most effective practice. 38 Once a fidelity scale has been established, further research can be conducted to test whether or not model adherence does indeed result in better outcomes, so that fidelity scale development and outcome measurement may be an iterative process as such evidence accumulates. The Supported Employment Fidelity Scale, for example, assesses 15 items relating to employment services’ staffing, organisation and service provision. 39 Evaluations have repeatedly found positive associations between model fidelity and employment outcomes. 40–44

Crisis resolution teams are comparable with models in the EBP project in that there is some evidence for their efficacy in the right conditions. However, an evidence-based and tested method of assessing and improving fidelity to a model of good practice is lacking, as the tools needed for widespread implementation of an optimal model of CRT practice are still lacking. Developing and testing such tools for CRTs, using a strategy based on the EBP project, is therefore of high interest for policy-makers and service planners.

As mentioned previously, service users have criticised the lack of continuity of care between services during and following a period of CRT care. 31 There is a documented gap in mental health care post discharge, with service users feeling that they are suddenly left to deal with their recovery without any support. 45 This is likely to be one of the factors contributing to the relatively high rates of re-admission to acute care found in CRTs, a limiting factor regarding their capacity to reduce overall admission numbers and acute care costs. Recent work on self-management interventions provides promising evidence for the clinical effectiveness of such programmes and their potential to bridge this gap. In chronic physical illnesses, supporting patients to learn to manage their own health has resulted in some benefits to quality of care and, in some cases, health outcomes. 46 In mental health, this approach has produced a new generation of interventions aimed at helping service users to better manage their condition and achieve their individual goals. Some examples are the Wellness Recovery Action Plan,47 the Recovery Workbook48 and the Pathways to Recovery: Workbook. 49 These programmes differ in structure and degree of clinician involvement but share an emphasis on peer facilitation and support and a focus on people’s own strengths, goals and resources. Most of these approaches incorporate relapse prevention work, aimed at helping service users and their carers to recognise and respond to early warning signs of deterioration in their mental health. 50

According to the recovery model,51 hope, social inclusion, meaningful activity and supportive relationships often matter more to service users than managing symptoms. Reflecting this, self-management interventions include not only relapse prevention work but also plans for maintaining general well-being and achieving personal recovery goals. Self-management approaches, both simple relapse prevention planning and broader recovery-focused interventions, are widely advocated in mental health, supporters including the Royal College of Psychiatrists,52 the NHS’s The Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide3 and the charity Rethink Mental Illness. 53 A limited number of small US studies demonstrate successful recruitment to studies of such interventions and some positive changes. 48,54 However, there is not enough evidence to establish whether or not self-management interventions achieve their intended goals with people with serious mental health problems.

The CORE programme

The CORE (Crisis resolution team Optimisation and RElapse prevention) study is a 6-year programme comprising two workstreams. Workstream 1 aims to deliver a means of optimising CRTs at a team level, through investigating what constitutes best practice in CRTs and developing and testing a fidelity measure and a service improvement programme for achieving high fidelity.

Workstream 1 focuses on team-level change, whereas workstream 2 addresses limitations in CRT care at an individual level by developing and testing an intervention for service users leaving CRT care. As described previously (see Background), pioneers of the CRT model argue that crises present an opportunity to work towards change in service users’ and their networks’ abilities to manage their mental health and respond to crises. 8 This fits with the priorities of service users, who report that episodes of CRT care currently seem to end without adequate support for longer-term recovery in place. 45 We thus aimed to investigate whether or not extending CRT management through the addition of a peer-supported self-management intervention can prevent future crises and improve service user experiences and outcomes.

The main substantial UK studies of the last decade regarding CRTs involved members of the CORE programme team, including a naturalistic investigation of the intervention’s impact on a range of social and clinical outcomes,15 the only randomised trial,18 health economic studies,19,20 an investigation of patient factors associated with being admitted rather than treated at home,55 a workforce study21 and the CRT national survey. 24 Thus, the current project is the next step in a continuing programme of investigation of community acute alternatives to hospital admission.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the CORE study was to establish evidence at both the team and individual service user level as to how CRT functioning may be optimised to reduce reliance on inpatient care and to enhance recovery.

The objectives of the CORE study were to:

-

define best practice in CRTs, drawing on empirical evidence when possible, and on the views of service users, carers, professionals and experts when such empirical evidence is not available

-

formulate a model for achieving best practice in CRT organisation and operation, and a fidelity measure to assess whether or not this is achieved

-

develop a service improvement programme for achieving high-fidelity care and conduct a mixed-methods investigation of its impact

-

develop, pilot and assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a peer-supported self-management intervention, designed to reduce relapse and enhance progress towards personal recovery goals among CRT service users.

Workstream 1 addresses objectives 1–3, aiming to develop and test a means of optimising CRT functioning. Evidence was investigated regarding the critical ingredients of CRT care and the perspectives of CRT stakeholders on good practice. This informed the formulation of a model of best practice in CRT care. Based on this, a CRT fidelity scale and a strategy for improving fidelity based on a service improvement programme were developed. Higher team fidelity was then explored to establish whether or not it is associated with better individual outcomes, and a preliminary investigation of the programme’s impact was conducted.

Workstream 2 addresses objective 4, aiming to test whether or not a self-management intervention, initiated at the point of discharge, can reduce relapse and use of acute services and enhance service user experiences and outcomes. The three stages of workstream 2 are the selection of the intervention and adaptation to a CRT context, testing its feasibility and acceptability, and investigation of its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in a randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Overview of the programme

The research was conducted between April 2011 and April 2017.

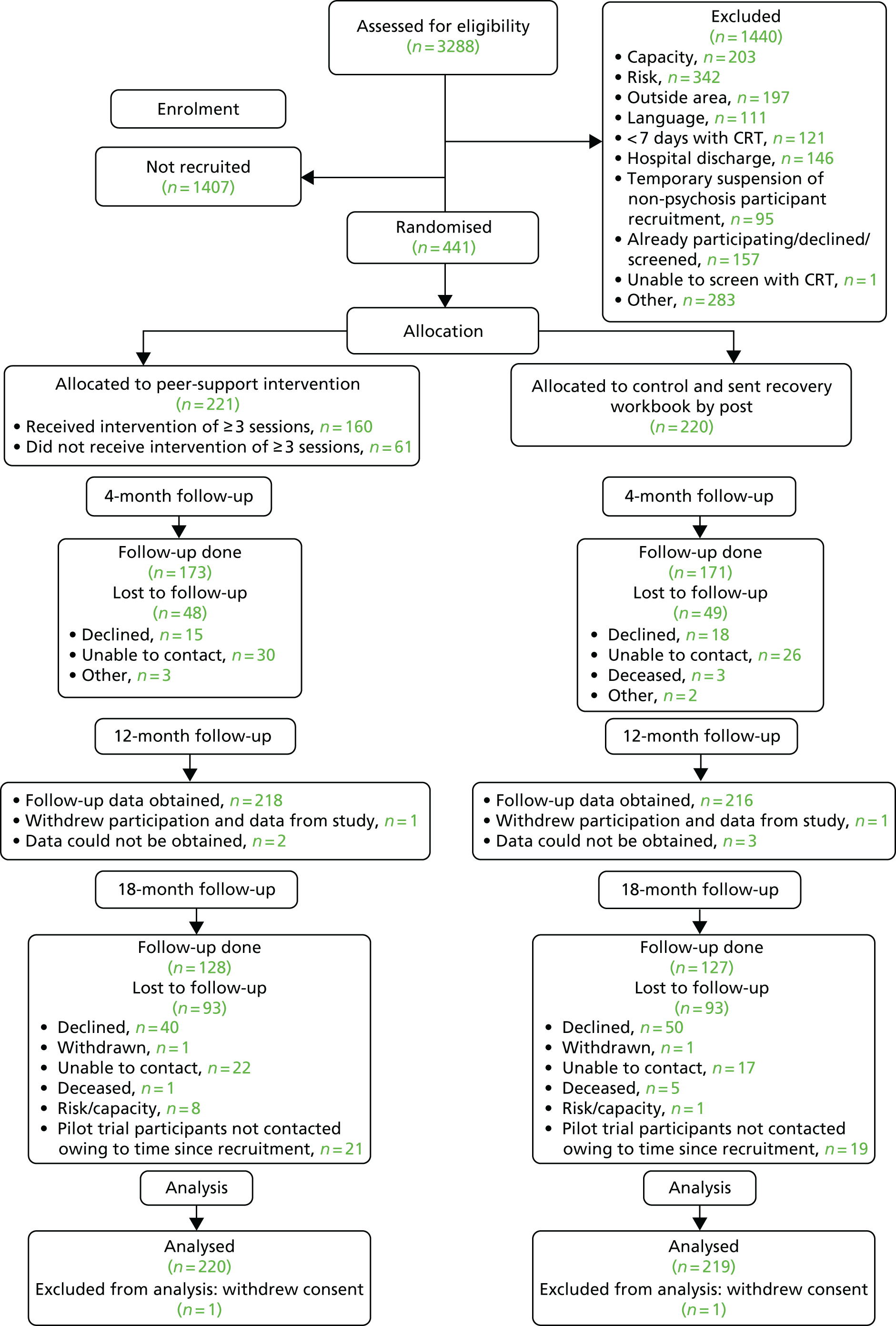

Figure 1 provides an overview of the CORE programme and the components of each workstream. The studies in the two workstreams were conducted in parallel and comprised six modules, providing within each workstream progression from pre-clinical/theoretical stages to development of each programme and then evaluation in RCTs. The only direct inter-relationship between the two workstreams was between module 1 and module 4, as some of the feedback obtained from qualitative interviews with CRT service users informed the development of the peer-supported intervention. Thus, methods and results for the two workstreams are reported separately.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the CORE programme. SMI, severe mental illness.

Patient and public involvement structures in the CORE study

The high priority that service users and carers attach to crisis care and their reservations regarding CRT implementation were the main drivers for the CORE programme. Public involvement was an integral part of planning and conducting the research throughout the CORE project.

In this section, the structures through which patient and public involvement (PPI) was facilitated during the CORE study are summarised, including the types of PPI activity undertaken. The impacts of public involvement on the study are briefly discussed in Public involvement activities. In addition, interviews with members of the CORE study service user and carer working groups on the experience and impact of PPI in the study were conducted by an independent researcher. A report summarising feedback from these interviews is also provided at the end of the synopsis (see Impact of public involvement on the study).

Patient and public involvement structures in the CORE study

-

A service user researcher co-applicant. An experienced service user consultant advised the study pre funding and was a co-applicant. Her contributions to the study included (1) overall planning and design, (2) leading training in interviewing skills for service user and carer working group members, (3) contributing to the selection and modification of the self-management recovery plan used in the workstream 2 trial, and (4) supporting and supervising the study public involvement co-ordinator. She elected not to remain fully involved in the study in years 4–6 of the project, although she continued to support the study public involvement co-ordinator until the end of his employment in the study.

-

A public involvement co-ordinator. A public involvement co-ordinator was funded for 1 day a week for the duration of the study. Key functions of the post were to manage and support the work of the working groups and front the public involvement in the study. Although funded from the start of the research, the appointment did not start until 1 year into the study because of the difficulties getting the innovative job matched to an appropriate NHS pay band.

-

Study service user and carer working groups. In the first year of the study, people with lived experience of using mental health services or caring for people using services were recruited to two working groups: one for service users and one for carers. These opportunities were advertised through the (former) Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), the National Service User Survivors Network, Rethink Mental Illness, and local service user groups Service User Research Forum (SURF), South Essex Service User Research Group and Service User and Carer Advisory Group Advising on Research (SUGAR). Twenty-three service users and 13 carers applied. Interviews were offered to 14 service users and 13 were appointed. Twelve carers were interviewed and seven were appointed. Two additional carers were recruited in 2013 (to replace two group members who left the study.) Priority was given to applicants with direct experience of CRTs and some previous involvement in research. Although some working group members contributed to only parts of the study, nine service users and six carers remained involved as working group members throughout.

Working groups were conducted separately for service users, and for carers, on five occasions. In addition, 12 joint meetings, two interviewer training days and three interviewer supervision sessions have been held. Additional consultations on specific topics were carried out via e-mail. About 2 years into the study, the two working groups elected to merge and hold joint meetings (having worked together as peer interviewers and in developing the CRT fidelity scale).

Working group meetings were used for members to contribute advice on the planning and conduct of the research in general. They also allowed planning and reflection on the specific study PPI activities listed later in this report. All working group meetings were attended by the programme manager who, along with the study public involvement co-ordinator, ensured that advice and suggestions from the working group were shared with others in the study team and fed into planning the study.

-

Service user and carer representation on the study steering committee. One service user and one carer with previous research experience were recruited to the CORE study steering committee [via SURF, the University College London (UCL) service user research group and SUGAR]. They participated in annual steering committee meetings that provided independent oversight and guidance for the study.

-

Research assistants with lived experience. During the course of the study, three research assistants with significant lived experience of mental health problems and two more with significant caring experience were recruited. This was not a deliberate strategy, although personal experience of mental health problems and mental health services was listed as a desirable criterion on research assistant person specifications, and adverts stated that applications from people with personal experience of mental health problems were welcome. These researchers were, however, able to bring their relevant lived experience to the role, for instance acting as peer interviewers or peer fidelity reviewers when necessary, and helping to support the working group and public involvement co-ordinator.

-

CRT staff involvement in the study. A working group of eight CRT clinicians was recruited from the 10 NHS trusts participating in module 1 interviews. This group met four times in 2011/12 and contributed to selecting a self-management resource for use in workstream 2 and the development of the CRT fidelity scale in module 2. A virtual working group of 11 CRT developers – international experts with experience of planning or managing CRT services – were recruited and contributed to the development of the CRT fidelity scale in modules 1 and 2. Further input from mental health staff with experience of working in or with CRTs was provided by clinical academic study applicants, and two CRT clinicians from participating NHS trusts who attended study meetings throughout the project. Extra input from clinicians from the lead NHS trust was sought for specific activities (e.g. the concept mapping process used to develop the CRT fidelity scale in module 2).

A budget for public involvement in the study was included in the grant awarded by the funders. The study public involvement co-ordinator post was funded as a NHS band 5 role. Working group members were offered paid involvement at a rate of £15 per hour (time to review study documents prior to meetings was included in payments). Working group members’ travel costs to meetings were also reimbursed.

The service users in the research group (led by Thomas Kabir) from the now-disbanded MHRN were a valuable source of advice with PPI arrangements on the study, regarding recruitment and payment arrangements and facilitating access to free benefits advice for working group members. The MHRN also helped set up two consultation meetings with service users and carers during preparation of the research grant, allowing service user and carer involvement with initial study planning.

Workstream 1

The CRT model has not been highly specified in the literature, as its critical ingredients are not yet established. 6 There is limited evidence about how best to implement CRTs and what type of interventions to deliver within them. 4 Workstream 1 developed the CRT model by investigating what constitutes best practice in CRTs and how difficulties in CRT model implementation identified in recent reports may be addressed.

The approach that was adopted in workstream 1 was based on the US EBP programme. 36 Central to the EBP method is the development of a fidelity scale, based, when available, on empirical evidence on components of the model associated with clinical effectiveness, and on stakeholder qualitative evidence and expert consultation when this is unavailable. Development of fidelity measures for complex interventions in mental health has been advocated not only as a means to define an intervention and measure services’ adherence to the model specified, but also to support service improvement. 56 Following fidelity scale development, a service improvement programme including manuals, training materials and guidance on implementation was designed to help teams achieve high fidelity and hence best practice.

The first part (module 1) of workstream 1 focused on investigating and defining best practice in CRTs. First, we reviewed current evidence regarding critical ingredients of CRT care and of relevant guidance. Second, we conducted a national survey of CRT managers in order to examine current service organisation and delivery and any initiatives to improve CRT practice. Third, we explored the perspective of service users, carers, professionals and experts on best CRT practice and their suggestions for service improvement. Findings from these studies were used to inform the emerging development of a model of CRT practice.

In module 2,we aimed to develop and test a CRT fidelity scale, designed to assess how far best practice as defined following module 1 is achieved. The fidelity scale was developed through a rigorous and systematic process, using stakeholders’ views to prioritise potential fidelity items drawn from the available evidence. The CRT fidelity scale was subsequently tested in a national survey of CRT model fidelity. We then developed a service improvement programme (SIP) for CRTs, with the fidelity programme as the central framework. The CORE SIP was modelled on the EBP project’s implementation resource kits,57 with content derived from the fidelity scale and provision of good-practice examples from the national survey.

The final stage in workstream 1 (module 3) involved a mixed-methods assessment of the impact of the SIP for achieving high fidelity to the CORE-defined model of good practice. Methods for this evaluation were finalised in the previous modules to ensure that it corresponded to key goals embodied in the CRT fidelity scale and SIP. Twenty-five CRTs were recruited to participate in a cluster randomised trial, with teams as the unit of randomisation: 15 of these were randomly allocated to the experimental intervention and 10 were randomly allocated to the control intervention. The aims were to establish (1) whether or not fidelity scores increase following the SIP, (2) whether or not teams receiving the SIP (the experimental intervention) achieve better service user experiences and better performance on key indicators of service use and (3) whether or not higher fidelity scores are associated with better outcomes at a team level. In addition, qualitative methods were used to explore participant experiences of the SIP.

Module 1.1: implementation of the crisis resolution team model in adult mental health settings – a systematic review

See Appendix 1 for the published report of this work. 58 The report is accessible at the following URL: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-015-0441-x (accessed 28 March 2019).

The review is registered with PROSPERO as CRD42013006415.

Aim

The aim of this review was to systematically acquire and synthesise evidence regarding critical components and key organisational principles of CRT services. In the review, quantitative evidence on associations between specific CRT characteristics and outcomes was prioritised. However, initial searches confirmed the belief that clear empirical evidence was likely to be limited. Literature on the views of stakeholders, including service users, carers, clinicians and service leaders, about best practice in CRTs was reviewed. In addition, the recommendations that government and expert organisations make about CRT service delivery and organisation were examined.

Methods for data collection

A systematic review was conducted. The databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Web of Science were searched to November 2013, without time limit or geographical restrictions. Studies were included from anywhere in the world and in any language. A further web-based search was conducted for published government and expert guidelines on CRT services; this was restricted to England. Full search terms are provided in the published report. 58

The following types of study were included:

-

quantitative studies comparing outcomes between CRTs with different characteristics, or between CRTs and other service models

-

national or regional surveys reporting associations between CRT characteristics and outcomes

-

qualitative studies exploring the views of stakeholders, including service users, carers and clinicians, of what makes a good CRT service

-

published guidelines from statutory and non-statutory bodies making recommendations for effective, good-quality CRT care in the NHS in England.

Analysis

A narrative synthesis was conducted, based on guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 59 Each of the above types of study was separately investigated. Statistical meta-analysis was not feasible because of the heterogeneity of included studies with regard to study aims and design, outcomes assessed, service settings and characteristics. The mixed-methods appraisal tool (MMAT),60 a tool that allows quality rating of a variety of types of study, was used to assess the quality of individual studies.

Key findings

Sixty-nine studies and documents were included in the review. The composition and activities of CRTs varied substantially across studies. Studies also varied in quality, with the total mean score on the MMAT scale60 indicating moderately high quality.

Overall, quantitative comparison studies and CRT surveys provide relatively little evidence regarding the specific characteristics of CRTs that are associated with positive outcomes. Many studies of CRT outcomes give relatively little detail regarding the characteristics of the CRTs, making it very difficult to draw conclusions about associations between service elements and outcomes. One comparison of two CRT models found the presence of a psychiatrist within the team to be associated with reduced admissions, and a national survey suggested an association between 24-hour opening and lower admissions. Little other relevant evidence was obtained.

Qualitative studies and government and expert guidelines provide more detailed specification of best practice in CRTs. Stakeholders emphasised accessibility, integration with other local mental health services, provision of time to talk and practical help, treatment at home when possible and continuity of care. CRT guidelines prioritised the provision of a 24-hour, 7 days per week multidisciplinary service, including a psychiatrist and medical prescriber, relapse prevention planning on discharge from the CRT and a gatekeeping role for CRTs in controlling inpatient admissions. The need for adequate staffing to meet service demands and high quality of staff training were also frequently emphasised.

Strengths and limitations

In order to establish the critical ingredients of CRTs, this review used a systematic search strategy to identify all available types of evidence. The multidatabase search for relevant research studies was supplemented with hand-searching of reference lists and contacting authors about conference abstracts. Although this search included international literature regarding CRT services and closely related models, the search for government and expert guidelines was confined to England because of resource limitations and challenges in identifying and accessing such sources.

Another limitation was the fact that because of the wide variation among studies and incomplete reporting of CRT characteristics, it was not feasible to conduct quantitative synthesis of results or compare the clinical effectiveness of CRTs across studies. Furthermore, the MMAT60 is a relatively unsophisticated means of assessing quality, even though it is probably the best available single measure for synthesising the quality of studies using a mixture of methods. The tool treats different methodologies as equivalent and merges different components of quality into a single score, which is potentially reductive and misleading. 61

The review did not exclude any papers on the basis of quality, as it was wished to fully assess the current evidence base regarding CRT services. As a result, some studies with lower quality scores were included, which may potentially compromise the strength of the conclusions. However, steps were taken to take account of the variability in the quality of included studies in our synthesis of the evidence.

Recommendations for future research

This extent to which empirically based critical ingredients of CRT good practice can be identified is constrained by the fact that only a very small number of studies address this question. Interpretation and synthesis of the studies that have been conducted are impeded by wide variations in models and outcomes investigated and lack of detailed information on service characteristics. Future studies of CRTs should provide a more comprehensive description of the CRT and comparison services, as recommended by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 62 Although there was relatively little quantitative evidence regarding the critical ingredients associated with good CRT outcomes, there was a high degree of consensus from stakeholders and policy guidance about an optimal CRT model, broadly corroborating initial government guidance accompanying the national mandate to introduce CRTs. 3 This provides a basis for development of a more highly specified CRT model and of a means to assess adherence to this model: a priority for CRT research. It would now be valuable to conduct further research into the characteristics of CRTs associated with good outcomes and good patient experiences.

Module 1.2: national implementation of a mental health service model – a survey of crisis resolution teams in England

See Appendix 2 for the published report of this work. 63 The report is accessible at the following URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/inm.12311/abstract (accessed 28 March 2019).

Aims

A national survey of CRT managers was conducted in 2011/12. The aims of the survey were to map the provision of all CRTs in England and describe CRT organisation and service delivery, explore the teams’ adherence to key policy recommendations3 and compare CRT managers’ views on actual and desirable CRT characteristics.

Methods for data collection

Between November 2011 and July 2012, the manager of every crisis resolution/home treatment team (or equivalent) in England was invited to complete an electronic survey. If a team manager could not be reached or wished to delegate the survey, another senior member of the team was invited to participate. The survey consisted of a 90-item questionnaire, which was based on previous national surveys of crisis services24,64 and was further refined after a pilot in four CRTs. The questionnaire covered a range of aspects of CRT organisation and service delivery, including exploring which interventions are available from CRTs. In addition, reports were elicited on local initiatives and priorities for service improvement, and views regarding ideal characteristics of CRTs. The survey could be completed online or as a telephone interview with a researcher. Data from the questionnaire were entered directly into a secure online system and were downloaded into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet and transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis.

Analysis

There were three stages of data analysis:

-

Data regarding CRTs’ organisation and service delivery were summarised using descriptive statistics. Any free-text responses were coded to allow quantitative description of the most frequent responses.

-

When data directly related to recommendations from the original CRT guidance,3 questionnaire variables were recoded or combined in order to examine the degree to which CRTs were adhering to guidance in three domains – referral criteria and access, interventions and staffing. The extent to which CRTs adhered to guidance in each domain was reported.

-

In order to investigate any discrepancies between actual and perceived desirable CRT practice, the proportion of CRTs in which a service characteristic was present was compared with the proportion in which a service characteristic was rated by managers as fairly or very useful.

Key findings

Through service mapping, we identified a total of 218 CRTs, with some CRT provision in all 65 mental health NHS trusts in England. One hundred and ninety-two CRTs (88%) took part in the survey and 184 respondents (84%) completed at least two-thirds of the questionnaire.

Table 1 shows the composition of CRTs: nurses and psychiatrists were employed in almost all teams, but representation of other professions varied greatly from team to team.

| Staff professional group/type | CRTs teams employing, or with dedicated time from, staff of this type, n/N (%) |

|---|---|

| Consultant psychiatrist | 148/171 (87) |

| Psychiatrist (other grade) | 129/171 (75) |

| Nurse | 171/171 (100) |

| Social worker | 122/171 (71) |

| Occupational therapist | 72/171 (42) |

| Psychologist | 50/171 (29) |

| Pharmacist | 29/171 (17) |

| Graduate mental health worker | 10/171 (6) |

| Other support worker/staff without a mental health professional qualification | 145/171 (85) |

| Approved mental health professional | 109/173 (63) |

| Non-medical prescriber | 79/168 (47) |

| Number of clinical staff in CRT team (full-time equivalent) (n = 171) | Mean 20.8 (SD 8.7; range 4.4–53.6) |

The survey also enquired about delivered interventions (Table 2). These were most often focused on prescription and delivery of medication, rather than on psychological, social or practical interventions.

| Type of intervention | Number of CRTs reporting providing this intervention to most or all service users who need it, n/N (%) |

|---|---|

| During CRT care | |

| Prescribing medication | 164/181 (91) |

| Delivering medication | 139/181 (77) |

| Supervising service users taking medication | 147/181 (81) |

| Going shopping with/for service users | 74/181 (41) |

| Preparing food with service users | 35/181 (19) |

| Helping service users to clean their home | 23/181 (12) |

| Helping with problems with welfare benefits | 106/181 (59) |

| Helping with debt problems | 94/181 (52) |

| Accompanying service users to the police station or court | 30/181 (17) |

| Accompanying service users to GP appointments | 58/181 (32) |

| Physical health checks | 118/181 (65) |

| Staying with service users for extended periods to ensure safety or mitigate isolation | 64/181 (35) |

| Discharge support | |

| Formulating written relapse prevention plans with service users | 116/184 (63) |

| Using advance directives or crisis cards | 68/184 (37) |

| Using self-management programmes (e.g. a Wellness Recovery Action Plan) | 68/184 (37) |

| Offering follow-up telephone calls or visits post discharge | 83/184 (45) |

Only one-third of CRTs (62/187, 33%) reported always acting as gatekeepers to inpatient beds, as stipulated in the original policy implementation guidance. 3 An even smaller proportion of CRTs (35/187, 19%) reported always attending formal assessments for compulsary admission under the Mental Health Act. 29 Most CRTs (186/188, 99%) were also engaged in early discharge work, identifying inpatients who could go home earlier with support from the CRT.

Team managers were asked to rate whether or not a number of aspects of service delivery were important, and to report whether or not they were actually able to provide these at present. Table 3 shows the results and indicates many discrepancies between actual and desired provision, for example in being able to provide practical support of various types to service users and in being able to spend extended periods of time with them. Thus, from the perspective of our work, the important overarching theme is that, although there are many gaps in areas such as psychological and social interventions and capacity to spend extended time with service users, such gaps do not result from these aspects of provision being seen as low priority. Rather, it appears that managers who were surveyed would have liked to deliver a much richer service than was possible in practice.

| CRT characteristic | Percentage of CRTs providing this (to most or all service users where needed) | Percentage of respondents rating this as very or fairly important for CRTs to provide | Discrepancy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accompanying service users to GP appointments | 32 | 85 | 53 |

| Staying with service users for extended periods to ensure safety or mitigate isolation | 36 | 85 | 49 |

| Helping service users to clean their home | 12 | 59 | 47 |

| Preparing food with service users | 19 | 69 | 40 |

| Accompanying service users to the police station or court | 17 | 67 | 40 |

| Employing carers as staff | 16 | 55 | 39 |

| Employing service users as staff | 26 | 64 | 38 |

| Helping service users with debt problems | 52 | 89 | 37 |

| Going shopping with/for service users | 41 | 78 | 37 |

| Client-held records | 43 | 79 | 36 |

| Minimum duration for staff visits | 13 | 48 | 35 |

| Minimum frequency for staff visits | 37 | 72 | 35 |

| Helping with problems with welfare benefits | 59 | 91 | 32 |

| Accepting self-referrals from service users not previously known to services | 21 | 44 | 23 |

| Providing physical health checks | 65 | 88 | 23 |

| Attending Mental Health Act29 assessments | 48 | 70 | 22 |

| Working with people with learning difficulties | 58 | 36 | −22 |

| Working with people with a personality disorder | 79 | 52 | −27 |

Strengths and limitations

This survey had a high response rate (88%), which gives confidence that the sample of respondents is representative of senior CRT staff in England. However, there are two main limitations. First, the use of self-reporting may have resulted in an over-reporting of CRT implementation because of social desirability bias. Second, the survey was cross-sectional in nature, thus shedding no light on changes over time.

Recommendations for future research

The survey suggested that the original policy mandate and guidance were not sufficient to achieve nationwide CRT implementation as intended. This supports conclusions from the US EBP programme36 that high fidelity to good practice is unlikely to be achieved without regular structured assessment of implementation. A need was thus identified for future research to develop and test tools to support implementation and monitoring of CRTs. CRT stakeholders’ views and priorities, including those of service users and carers, should also be investigated and taken into account in developing an empirically based optimum model of CRT care. Tracking service delivery nationwide by repeated surveys over time will also be important to achieving and sustaining implementation of a CRT model matching perceived needs.

Module 1.3: a qualitative study of stakeholders’ views on critical ingredients of crisis resolution teams and their implementation

See Appendix 3 for a link to the full report of this work. 65 The report is also accessible at https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-017-1421-0/open-peer-review (accessed 28 March 2019).

Aim

Previous research has shown that there is insufficient empirical evidence regarding the critical ingredients of CRTs (see Module 1.1) and that CRTs are not fully implemented as intended (see Module 1.2). The EBP programme36 recommends drawing on a broad range of stakeholder views in which empirical evidence linking service content to outcome is limited. Therefore, in this qualitative study, the aim was to examine stakeholders’ experiences of CRTs and their views regarding best practice.

Methods of data collection

Semistructured interviews and focus groups were conducted with different groups of CRT stakeholders: service users (n = 41 individual interviews), carers (n = 20 interviews) and practitioners (n = 147, comprising CRT staff, managers and referrers; nine individual interviews and 26 focus groups were conducted). The referrers group included clinicians from community mental health services, inpatient wards, liaison psychiatry services and general practitioners, thus representing a range of common referrers to CRT services. Participants were drawn from 10 mental health catchment areas across England. In addition, key experts (n = 11), involved in the development of CRTs internationally, were interviewed in order to provide a broad perspective on the history and theoretical origins of CRTs and on their intended aims and characteristics.

Topic guides were developed in collaboration with project advisory groups of service users, carers and clinicians, representing CRT stakeholders, to make sure that priority issues and the concerns of each group regarding CRT practice were covered. The overall aim was to explore views from all perspectives about what constitutes best practice in CRTs. Aspects of CRT care identified by previous research as problematic were included. Interviews with service users and carers were conducted by trained peer researchers (service users and/or carers) whenever available; the rest were conducted by non-peer study researchers. Data from practitioners were collected via focus groups, when feasible, or via individual interviews if it proved too difficult to convene focus groups. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Analysis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis66 supported by NVivo 9 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Using this analytical strategy, aspects of CRT work were explored that were perceived to be important, successful and unsuccessful, using both inductive and deductive approaches. Owing to the large corpus of data, a staged approach was used. An initial basic set of themes was developed, based on a small subsample of transcripts, in order to capture broad areas and organise the data. This set of themes was progressively elaborated through group discussions and an iterative process of reading and coding further transcripts. Later stages of analysis were focused on developing a nuanced understanding of parts of the data corpus relevant to our aims. Peer researchers, as well as members of project advisory groups representing all stakeholder groups, were involved in all the stages of the analysis. These collective processes can enhance validity by promoting reflexivity67 and ensuring that the perspectives of all stakeholder groups are considered in the analysis. 68

Key findings

There was a high level of agreement between stakeholder groups, with 11 features of CRT work identified as important across the groups. These were organised into three broad domains: (1) organisation of care, (2) the content of CRT work and (3) the role of CRTs within the acute and continuing care systems. For each feature, similarities and variations in stakeholders’ views on successful and unsuccessful aspects of current CRT practice and implementation were considered. Findings are summarised below.

-

Organisation of care:

-

Ease of access and speed of response were identified as being among the most important aspects of initial CRT contact for service users and carers. The need for 24-hour, 7-day access was emphasised, although the resource challenges of this were acknowledged. All stakeholder groups recognised the benefits of self-referral for known clients. Accident and emergency departments were viewed as the least satisfactory referral pathway.

-

Regularity, reliability and clarity were valued by stakeholders as these facilitate trust, emotional support and monitoring of risk and change. A few service users reported poor communication and infrequent visits from staff as the least helpful aspect of their care, whereas a small minority of service users and carers described large negative impacts when staff were not reliable.

-

Flexibility for referrals, timing of visits, forms of support and duration of contact were advocated by all stakeholder groups, with service users particularly valuing flexible timing of visits and involvement in their planning. Implementation issues identified include resource limitations and difficulties with predicting workloads.

-

Staff continuity was greatly valued by service users and carers as it can facilitate trust and relationship building, whereas the lack of it was one of the least helpful aspects of CRT contact. Practitioners and CRT developers were aware of the importance of staff continuity and the need to improve it. Several strategies to prioritise continuity within a shift-working system were discussed.

-

Staff mix and experience – service users and carers valued staff experienced in crisis work and CRT-specific staff training was viewed as essential by practitioners. CRT staff and developers identified multidisciplinary staff mix as one of the most important aspects of good practice. However, only a minority of CRT staff groups described their own teams as multidisciplinary. Practitioners often described overall staffing levels as stretched or inadequate because of resource limitations.

-

-

The content of CRT work:

-

Involving the whole family – CRT developers and practitioners described family involvement at initial assessments as valuable in helping them to develop a holistic view of the crisis and to decide on the suitability of home treatment and CRT interventions. Although family involvement was valued by carers, many often felt excluded from decisions about treatment and support.

-

Emotional support was extremely important for service users and many described this as the most helpful aspect of their CRT contact. Staff with excellent basic emotional skills, such as kindness and empathy, and staffing continuity, with opportunities to develop therapeutic relationships, were identified as facilitating provision of high-quality emotional support. A few service users and carers said that they had not received any emotional support, as their contacts with CRT staff were brief and focused on organising care or medication.

-

CRT interventions – medication supervision was identified as the principal intervention, although stakeholders agreed that CRTs were often too narrowly focused on this at the expense of other forms of support. Practical interventions were valued, but their availability was often limited by time and resources. Psychological input, self-management and physical health checks were also valued but not frequently provided.

-

-

The role of CRTs within the acute and continuing care systems:

-

Gatekeeping hospital admissions was seen as the most important function of CRTs by developers, with CRT capacity to prevent admissions under threat when this did not take place.

-

Providing home-based treatment was valued across stakeholders for preserving freedom, social contacts and daily routines, and allowing greater privacy and safety for service users. Stakeholders from all groups were concerned about whether or not home treatment decisions were based on clinical need or a requirement to reduce hospital admissions.

-

Continuity and communication with other services around discharge were seen as particularly important by stakeholders. However, all stakeholder groups reported problems in continuity of care and effective interservice communication. Almost all practitioners and developers reported misunderstandings and lack of knowledge about CRTs among referrers. A number of strategies were suggested to help improve working relationships and continuity with other services.

-

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this was the first study to provide an in-depth, multiperspective qualitative exploration of the successes and failures of CRTs across a wide range of contexts, covering trusts in urban, suburban and rural areas of England. The perspectives and experiences of all relevant stakeholder groups were explored and compared. The large number of qualitative data and the diverse demographic, clinical, service use and professional characteristics of the study’s sample help ensure that the common themes identified generally reflect the views of these stakeholder groups.

Given that service users were recruited through CRT clinicians, it is likely that the study’s sample under-represents service users who were not very engaged with services or who had generally negative experiences of CRTs. Because of the challenges of reporting concisely on such a large data corpus, the study focused on common themes and prevailing views within each stakeholder group. Thus, some less common concerns or views have not been thoroughly explored in depth, and the approach in this initial analysis of a very large number of interviews is necessarily broad rather than in-depth.

Recommendations for future research

Many of the findings from this study had direct implications for the development of a more highly specified CRT model, especially in relation to improving service user and carer experiences. Priority areas for service improvement and for further research in optimising team function and outcomes include continuity of care, provision of emotional and practical support, carer involvement, and the quantity and quality of contact with CRT staff. Findings also highlight challenges to CRT implementation in contexts of stringent resource limitations and complex service configurations. Most previous UK CRT research has been conducted in urban areas; some stakeholders in our interviews raised challenges to implementing the CRT model fully in more rural areas (e.g. in achieving a rapid response service and providing frequent home visits). Further research is needed to understand and assess barriers of, and facilitators to, successful implementation of good CRT care in different contexts. In relation to initiatives for CRT improvement, qualitative research including multiple stakeholder perspectives is a rich source for understanding the impact of initiatives and barriers of, and facilitators to, achieving intended improvements. Use of implementation science methodologies in understanding how to overcome barriers and achieve change is a priority for future research.

Module 2.1: development and piloting of a crisis resolution team fidelity scale

See Appendix 4 for the published report of this work. 69 The report is accessible at the following URL: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-016-1139-4 (accessed 28 March 2019).

Aims

Fidelity scales are measures of the extent to which services adhere to a model of high-quality care, based on evidence and on stakeholder consensus. They are designed as tools to support quality improvement. 56 There is evidence for some fidelity scales of an association between higher fidelity and superior service outcomes. 70 Fidelity scales have been developed for use in some mental health service models,71 especially in the USA, but none exist for CRTs.

The aim of this study was to develop a highly defined and validated fidelity scale for CRTs. The study aimed to (1) systemically develop a CRT fidelity scale, (2) test its feasibility and utility in practice and (3) conduct an initial investigation of its psychometric properties.

Methods

Concept mapping72 was used to construct the CRT fidelity scale. This is a method used in the development of measures to identify and group into relevant domains a set of priority items based on stakeholder consensus. Potential service model characteristics were identified from module 1 (the literature review),58 the national survey of CRT managers63 and a qualitative investigation of CRT stakeholder perspectives. All yielded potential items for inclusion in a longlist of characteristics of high-quality CRT delivery. Next, this longlist of characteristics, identified as associated with good practice in CRTs, was condensed and combined into a list of fidelity scale statements by a group of academic, service user and clinician stakeholders by, for example, removing duplicates and combining closely related items. Following this, a series of concept mapping meetings involving stakeholders with different perspectives was held. Participants were asked to prioritise statements in terms of their importance for CRT best practice and to sort statements into groups of conceptually related statements. Specialist Ariadne concept mapping software (version 1.0; Talcott, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was then used to analyse participants’ grouping of statements, using a form of cluster analysis, to generate a series of ‘cluster solutions’, which distinguished domains of CRT fidelity to reflect how participants grouped statements. The software also generated a mean importance rating for each statement from participants’ prioritisation of statements, which allowed the fidelity statements considered most important by stakeholders within each conceptual domain to be identified. Cluster solutions generated by the software were then reviewed by a small group of stakeholders, who selected the cluster solution that produced the most conceptually coherent set of domains of CRT fidelity, and named each domain, reaching consensus through discussion. The chosen cluster solution, that is, the final concept map, was then used to develop the CRT fidelity scale. Statements representing each fidelity domain were selected for inclusion in the fidelity scale. Statements of higher importance within each domain were selected for inclusion. Operational definitions were developed for each statement and anchor points specified for scoring, with reference to the development work carried out in module 1. Adherence to fidelity items is measured on a five-point scale. In common with other fidelity scales,70 a score of 5 on each item was taken to represent excellent model fidelity, that is, a service was adherent to best practice standards for this item. A score of 3 was taken to represent moderate fidelity, that is, a service was adhering to some essential requirements for best practice in this area, but not achieving all desirable elements of best practice for this item. The measure was thus able to distinguish services with ‘good’ overall model fidelity (i.e. a mean score of ≥ 4 per item) and services with ‘fair’ model fidelity (i.e. a mean score of 3–4 per item). At each stage of development, further stakeholder consultation was sought.

A fidelity review process was developed and piloted for collection of fidelity scale data. Reviews took place over 1 full day and were carried out by three reviewers: one clinician, one service user/carer and one researcher. CRT managers were contacted before the review to identify required documents and to establish the schedule. The review day involved interviews with managers, staff, liaising service staff, service users and carers; reviewing 10 anonymised case records; and reviewing service policies and records. Reviewers collected data using checklists and interview schedules, and scored fidelity items together at the end of the review. A draft fidelity review report was sent to team managers for clarifications before a final report and fidelity score were provided. Pilot reviews were initially conducted in four CRTs, followed by a 75-team review with CRTs from different parts of England, Scotland and Wales (see Crisis resolution team fidelity survey). Following reviews, researchers sought feedback from managers regarding the acceptability of the fidelity review and the validity and clarity of the fidelity scale.

Three psychometric properties of the fidelity scale were investigated:

-

Face validity was assessed through feedback from managers of CRTs participating in the pilot.

-

The presence of floor or ceiling effects and the ability of items to discriminate between higher and lower fidelity teams were investigated by assessing the range of scores from the 75-team review.

-

Inter-rater reliability was investigated using an extended vignette designed by researchers using mock fidelity review records.

Results

To construct the scale, an initial list of 232 identified service model characteristics was condensed to 72 fidelity scale statements by examining them for duplication and overlap. Sixty-eight participants were then involved in concept mapping, including representatives from all stakeholder groups (including service users, carers, CRT clinicians and managers, and CRT researchers). A four-cluster solution was chosen as the most coherent concept map. The clusters were named as (1) referrals and access, (2) content and delivery of care, (3) staffing and team procedures and (4) location and timing of care. Thirty-nine statements receiving a high level of endorsement were included in the final fidelity scale, representing each of the four clusters.

The three broad stakeholder groups in the process were service users and carers, CRT clinicians and others (including CRT researchers). All statements that were rated as very important (i.e. a mean score of > 4) by any of the three groups or as moderately important (i.e. a mean score of > 2.5) by more than one stakeholder group were included in the scale, either as a distinct item or among item-scoring criteria. Table 4 summarises the four clusters of items (subscales) defined through the process and the mean importance score for the items in each.

| Cluster | Number of statements from concept mapping (N = 72), n (%) | Mean of mean importance scores for statements in this cluster | Number of statements in the CRT fidelity scale (N = 39), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Referrals and access | 14 (19) | 3.41 | 10 (26) |

| 2. Content and delivery of care | 26 (36) | 2.84 | 16 (41) |

| 3. Staffing and team organisation | 25 (35) | 2.98 | 10 (26) |

| 4. Location and timing of care | 7 (10) | 3.15 | 3 (8) |

The first version of the fidelity scale was piloted in 75 teams in a range of urban and rural locations and catchment sizes. Feedback indicated that fidelity reviews and reports received afterwards were perceived as acceptable and helpful, although reviews were time-consuming. The first version of the fidelity scale was reviewed after 50 reviews. All 39 items were retained, with minor changes made to 19 items in creating version 2 of the fidelity scale. Version 2 was piloted alongside the original version in nine CRTs.

Seventeen reviewers participated in the inter-rater reliability exercise, using version 2 of the fidelity scale. An estimated kappa correlation of 0.65 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 0.76] between ratings was identified, indicating moderately high similarity between ratings within an item. The estimated intraclass correlation (ICC) averaged over the 16 raters was very high, at a value of 0.97 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.98). Consistency of agreement ICCs produced nearly identical values (i.e. an ICC of 0.97), equivalent to Cronbach’s alpha.

Results indicate that the fidelity scale distinguished between higher- and lower-fidelity CRTs, with a wide range of scores obtained on each item. Piloting version 2 of the scale generated modest changes to fidelity scores compared with version 1 piloting, but increased scale clarity.

Strengths and limitations

Using concept mapping, the study systematically developed the first CRT fidelity scale, based on best available evidence and stakeholder input. The so-far inconsistent implementation of CRTs has limited the potential benefits of providing this service model. 24 The CORE fidelity scale has potential to support CRT model implementation and aid quality improvement work by providing a clear specification of this service model. This addresses the study’s overarching aim of improving the care provided to service users experiencing an acute mental health crisis.

There were two limitations of the study’s CRT fidelity scale development: the scope of stakeholder consultation and the degree of testing of psychometric properties conducted.

It was aimed to include stakeholder views at all stages of development. However, during concept mapping, clinicians outnumbered service users and carers in terms of input, and some stakeholder groups (e.g. primary care referrers to CRTs and emergency services) were not represented. Stakeholder input was largely from the UK, so it is not known how far the fidelity scale represents views of international stakeholders and how appropriate it is for use outside the UK.

Research implications

The content and criterion validity of the study’s fidelity scale require investigation to demonstrate the legitimacy of the scale as a measure of service quality, and further testing of the scale’s inter-rater and test–retest reliability is also a priority. A clinical need to develop and evaluate a resource manual to help CRTs achieve service standards and aid quality improvement38 has been addressed in the (module 3) CORE SIP trial. 73 There is also a need to explore the feasibility and utility of the fidelity scale in international contexts where the model is used, such as in Norway and the Netherlands.

The development of the CRT fidelity scale has demonstrated concept mapping to be a feasible method in developing and defining the CRT service model. The development and piloting of the study’s CRT fidelity scale provides a model of PPI in research and audit. 74

Crisis resolution team fidelity survey

As well as serving to pilot the CORE CRT fidelity scale, the 75-team survey provided useful information about implementation of the CRT model nationally in England. See Appendix 4 for a reference to the published results of this work. 69

Forty-seven NHS trusts were approached, with 149 CRTs within their catchment areas. Of these, 75 CRTs from 27 trusts took part in the survey. The study sample of 75 teams comprised 70 teams in England, one team in Scotland and four teams in Wales.

In the 75 teams surveyed, the total scores ranged from 73 to 151 (possible range 39–195). The median score was 122 and the interquartile range (IQR) was 111–132 (these two findings were not reported in the published paper69 on the development of the scale; see Appendix 4). Higher scores indicate higher model fidelity.

The median scores per item across all 75 teams for each subscale within the CRT fidelity scale are provided in Table 5. The low score for the ‘location and timing of help’ subscale reflects the fact that many CRT teams had no access to residential crisis houses or acute day units, and typically provide a less intensive service (i.e. less frequent visits to service users) than recommended in the CORE scale and in the original CRT guidance.

| CRT fidelity scale subscale | Median score | Interquartile range |

|---|---|---|

| Referrals and access (10 items) | 3.40 | 2.73–3.71 |

| Content and delivery of care (16 items) | 2.86 | 2.22–3.50 |

| Staffing and team procedures (10 items) | 3.25 | 1.49–2.48 |

| Location and timing of help (3 items) | 1.85 | 2.36–3.94 |

The fidelity items for which teams typically showed poor fidelity to the CORE CRT model (median score of 1 or 2) and the items for which teams typically showed good model fidelity (median score of 4 or 5) are presented in Table 6.

| CRT fidelity scale items with | |

|---|---|

| Low fidelity in most CRT teams (median score of 1–2) | High fidelity in most CRT teams (median score of 4–5) |

| 1. The CRT responds quickly to new referrals | 2. The CRT is easily accessible to all eligible referrers |

| 14. The CRT assesses carers’ needs and offers carers emotional and practical support | 4. The CRT will consider working with anyone who would otherwise be admitted to an adult acute psychiatric hospital |

| 16. The CRT promotes service users’ and carers’ understanding of illness and medication and addresses concerns about medication | 5. The CRT provides a 24-hour, 7-day service |

| 17. The CRT provides psychological interventions | 6. The CRT has a fully implemented ‘gatekeeping’ role |

| 18. The CRT considers and addresses service users’ physical health needs | 8. The CRT provides explanation and direction to other services for service users, carers and referrers regarding referrals that are not accepted |

| 22. The CRT prioritises good therapeutic relationships between staff and service users and carers | 10. The CRT is a distinct service that only provides crisis assessment and brief home treatment |

| 24. The CRT helps plan service users’ and service’s responses to future crises | 11. The CRT assertively engages and comprehensively assesses all service users accepted for CRT support |

| 29. The CRT is a full multidisciplinary staff team | 15. The CRT reviews, prescribes and delivers medication for all service users when needed |

| 31. The CRT has comprehensive risk assessment and risk management procedures | 19. The CRT helps service users with social and practical problems |

| 36. The CRT has systems to provide consistency of staff and support to a service user during a period of CRT care | 23. The CRT offers service users choice regarding location, timing and types of support |

| 37. The CRT can access a range of crisis services to help provide an alternative to hospital admission | 27. The CRT has adequate staffing levels |

| 38. The CRT provides frequent visits to service users | 28. The CRT has a psychiatrist or psychiatrists in the CRT team, with adequate staffing levels |

| 32. The CRT has systems to ensure the safety of CRT staff members | |

| 33. The CRT has effective record keeping and communication procedures to promote teamwork and information sharing between CRT staff | |

| 35. The CRT takes account of equality and diversity in all aspects of service provision | |

| 39. The CRT mostly assesses and supports service users in their home | |

There are three main findings from this survey regarding implementation of the CRT model in practice in England. First, CRTs typically achieve only moderate fidelity in adhering to an optimal CRT model: teams’ scores ranged from low to moderately high fidelity; no team achieved an average item score of > 4, which would indicate very good model fidelity. Second, the range of scores achieved for each item suggests that the CRT fidelity scale is not unrealistically rigorous: all items were being delivered with high fidelity in some CRTs and, therefore, are achievable in routine care. Third, although areas of strength and limitations regarding CRT model adherence varied from team to team, the study’s survey shows that CRT teams typically struggled to provide core elements of the CRT model specified in government guidance,3 such as rapid response, a range of care from a multidisciplinary team and help with planning recovery and future crisis response.

This study thus corroborates the findings of previous surveys that relied on CRT managers’ reports of their teams’ organisation and service delivery,24,63 and suggests that the CRT model has been inconsistently and only partially implemented in England. It suggests that a national mandate and policy guidance may in themselves be insufficient to ensure implementation of a complex service model as planned. It reinforces the need to develop effective resources to support implementation and service improvement in CRTs.

Module 2.2: development of the service improvement programme

A CRT SIP was developed to support teams in improving adherence to the CRT model, as defined in the CORE CRT fidelity scale.

See Appendix 5 for the published report of this work. 73 The report is also accessible at the following URL: https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-016-1283-7 (accessed 28 March 2019).

The CORE CRT SIP was designed to support CRT teams in identifying target areas for service improvement and in developing and implementing plans to improve current practice. It was modelled on the US EBP programme’s implementation resource kits,57 with content informed by module 1 and by the content of the fidelity scale. Development of the SIP was led by a co-applicant (Steve Onyett), who brought expertise in promoting leadership and change management in health settings, and the study principal research associate (Elaine Johnston), who brought experience of working as a clinical psychologist in CRT teams. The SIP’s content was developed and refined iteratively, with input from the study team and consultants, and advice from senior clinicians with relevant CRT experience from local NHS trusts.

Structures and resources included in the SIP are available in the online CRT resource pack and are accessible at the following URL: www.ucl.ac.uk/core-resource-pack (accessed 7 March 2019). The structures and resources include:

-

Assessment of adherence to current CRT best practice measured by the CORE CRT fidelity scale. The stipulated time points for fidelity reviews were at baseline, 6 months and at the end of the 12-month study period, with detailed feedback provided to teams on their strengths, areas of low fidelity and changes in team fidelity since previous reviews. This was designed to help identify targets for service improvement, to inform planning for how to achieve them and to provide positive reinforcement for any implementation successes achieved during the previous 6 months.

-

Structures to guide service improvement work. A number of structures based on the EBP framework were adopted to guide service improvement. These included a 1-day, whole-team-scoping event for each CRT to kick-start the SIP feedback on the fidelity review, service improvement groups of managers and clinical leaders within each CRT meeting regularly to develop service improvement plans, and collaboration between CRT managers and staff in teams receiving the intervention, which will be promoted by the research team. Collaboration activities will include an online forum, regular bulletins from the research team about implementation progress at study sites and at least two meetings/events during the study period to promote sharing of experience, knowledge and best practice. Evidence suggests that these types of collaborative learning events have the potential to support improvements in the quality of services. 75

-

Access to a CRT facilitator (0.1 full-time equivalent for each team) to help teams develop and implement their service improvement plans. Facilitators were managers or senior clinicians with experience of working in or with CRTs, but not necessarily with experience within the team in which they had this role. Facilitators were provided with initial and follow-up group training and individual coaching; they were invited to regular implementation meetings with the study team to feedback how on the intervention was progressing and discuss ways of overcoming barriers to service improvement. Facilitators were encouraged to adopt a solution-focused approach76 in working with teams, building on teams’ existing strengths and focusing on achievable goals, rather than dwelling on the development and consequences of potentially intractable problems.

-