Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0609-10156. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The final report began editorial review in September 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Thomas Craig reports personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Europe Ltd, Wexham, UK. Richard Holt reports personal fees from Eli Lilly and Company (IN, USA), Jannssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium), Sunovion, Pharmaceuticals Inc. (MA, USA) and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Europe Ltd and is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Women and Children’s Health Panel. Thomas Barnes reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Newron Pharmaceuticals SpA (Bresso, Italy), and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan) and Lundbeck, Copenhagen, Denmark Kate Walters was a member of the Disease Prevention Panel and the Primary Care Commissioning Panel. Susan Michie was a member of the HTA Pandemic Influenza Board. Michael King was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded Clinical Trials Units (CTUs), Rapid Trials and Add-on Studies Board. Irwin Nazareth’s membership includes CTUs funded by NIHR, the Disease Prevention Panel, HTA Commissioning Board, HTA Commissioning Sub-board (Expression of Interest) and the HTA Primary Care Themed Call. Rumana Omar was a member of the HTA General Board. Steve Morris sat as a member on the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) board, HSDR Commissioning Board, HSDR Evidence Synthesis Sub-board, HTA Commissioning Board and Public Health Research Research Funding Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Osborn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Synopsis

Background

Burden of cardiovascular disease in people with severe mental illnesses

People with severe mental illnesses (SMI), including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychoses, make up around 2% of the UK population. 1

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most important physical problem in people with SMI,2 and those aged < 50 years are three times more likely to die from CVD than those without SMI, whereas those aged 50–75 years have a twofold risk. 3 People with SMI die from CVD up to 20 years earlier than the general population3–6 and recent studies have shown that the mortality gap for people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is widening. 7,8

The reasons for increased CVD are multifaceted, including increased levels of smoking, diabetes mellitus, obesity and dyslipidaemia in people with SMI compared with general practice controls. 9,10 Systematic reviews conclude that components of metabolic syndrome (being overweight, abnormal lipids, hypertension and abnormal glucose) are more common in people with SMI. 11 Research has also shown that people with SMI ate a higher-fat diet, ate less fibre and were less likely to participate in physical activity. 12,13 Antipsychotic medications, such as olanzapine and clozapine, have been linked to increased appetite and subsequent weight gain as well as abnormalities of lipid and glucose metabolism. 14 Another theory is that long-term stress of SMI exerts cardiovascular risk via the hypothalamic pituitary axis. 15

Current NHS provision of cardiovascular disease care in severe mental illness

The majority of people with SMI use primary care services and see a general practitioner (GP) more often than people without SMI. 6,16 Routine annual CVD risk screening for people with SMI is recommended in national guidelines17,18 and the responsibility for CVD risk prevention is placed within primary care, while those prescribed antipsychotics should be monitored more regularly. 19

The primary care quality outcomes framework pays GPs for providing an annual physical health review to people with SMI. Indicators for this review have changed over the past few years and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and cholesterol measurements were retired in 2014/15. The 2017/18 indicators consist of a recording of blood pressure, smoking status and alcohol consumption. 20

Studies have shown that if CVD screening is offered to people with SMI, then they are as likely to attend the screening as people without SMI. 21,22 However, in primary care, people with schizophrenia were significantly less likely to receive blood pressure or cholesterol screening than practice controls,23 and BMI and blood pressure recording rates were significantly lower in people with SMI than for those with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. 24 This study also found that exception reporting rates were higher for people with SMI.

Cardiovascular disease risk prediction tools for people with severe mental illnesses

Cardiovascular risk tools are widely used clinically to predict an individual’s risk of developing CVD, usually over a 5- or 10-year period. The risk scores are algorithms of conventional risk factors, such as smoking, blood pressure and lipids, and the predictive ability of the combined models is greater than that of each single risk factor. The resulting risk scores are also used to determine thresholds at which different risk reduction strategies, such as statins, should be employed.

It is noted in the 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for CVD disease, risk and reduction that people with SMI constitute a high-risk group for CVD and existing risk prediction tools may underestimate their CVD risk, a picture similar to that observed in South Asian people and people aged < 40 years. 25 Ethnicity-adjusted risk scores have been developed as a result,26 but this has not yet been done for SMI. People with SMI were excluded from the original cohorts, such as the Framingham cohort, from which existing risk scores have been derived. The 10-year risk needs to be accurately determined for CVD scores for people with SMI in order to decide the thresholds at which to intervene.

Evidence for treatments to reduce cardiovascular risk in severe mental illness

Although the evidence shows that there are higher rates of CVD risk factors and higher mortality in people with SMI, we know far less about interventions to decrease this risk. There is a lack of high-quality evidence on CVD risk-reduction strategies in people with SMI.

Statins have been found to reduce severe dyslipidaemia in people with SMI in small studies focused on particularly high-risk populations. 27,28 The best trials of smoking cessation show small changes in smoking and quit rates,29 and studies have shown that medication and behavioural interventions are effective for weight loss. 30,31 A feasibility trial in secondary care to improve screening for CVD risk factors, testing a nurse-led service working across primary and secondary care, improved screening rates, but was too short in duration to reduce CVD risk. 32 Systematic reviews of interventions to increase uptake of lifestyle behaviours found some beneficial impact on CVD risk factors; however, the methodological quality of many of the included studies was low. 33–35

Most studies target single-risk factors and do not seek to address the full CVD risk profile of patients with SMI. Only one trial was found that tested a life goals collaborative care intervention involving management strategies for mental health symptoms and CVD risk factors. The findings were that the intervention improved the primary outcome of quality of life (physical health) compared with usual care. CVD risk factors were measured only as secondary outcomes with significantly lower levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in the intervention arm than usual treatment at follow-up, but no significant differences in blood pressure, BMI, waist circumference or other lipid parameters. 36

The Primrose programme overview

The aim of this National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme was to develop and test better methods to predict and reduce the risk of excess CVD in people with SMI across three work packages.

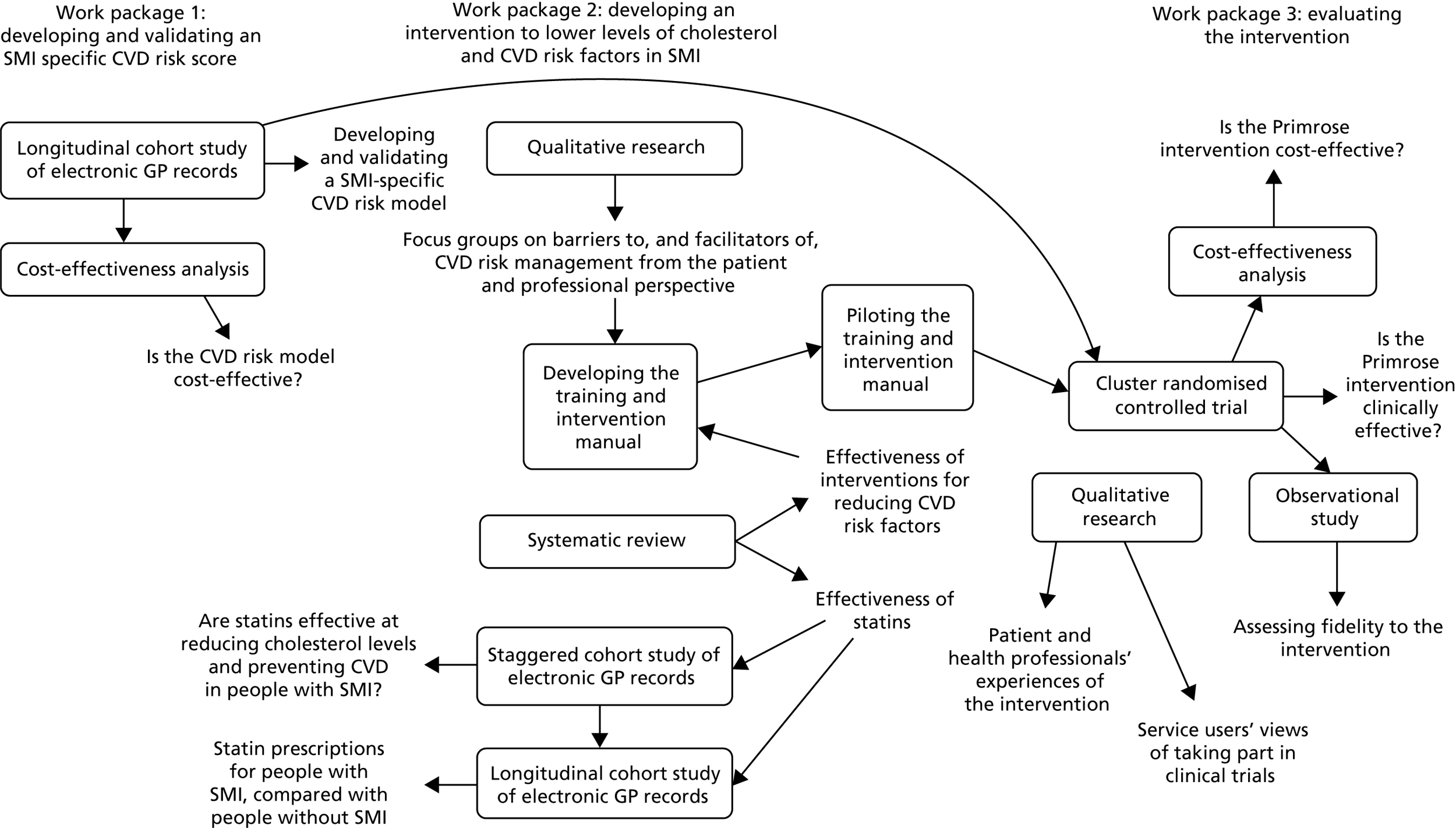

The research was carried out between May 2011 and July 2017. In years 1–2 (May 2011 to May 2013), we developed and validated a CVD risk score tool specifically for people with SMI. We then developed an intervention in primary care to lower levels of cholesterol and reduce CVD risk factors in people with SMI through an update of a systematic review of the literature, focus groups and workshops with clinical and lived experience advisors (years 1–3: June 2011 to December 2013). We also explored statin prescription rates and the effectiveness of statins on lowering levels of cholesterol and preventing CVD in people with SMI using primary care databases (years 2–5: October 2012 to December 2015). Finally, we tested the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the new intervention in a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) and assessed the extent to which the intervention was delivered as intended (years 3–6: January 2014 to February 2017). The links between the three work packages are summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the Primrose programme.

Project management

The programme was overseen by a Programme Management Group (PMG) consisting of all authors of this report. The PMG met every 6 months. Subgroups that were drawn from the PMG members met more regularly to deliver each individual work package. A trial management group was formed to oversee the trial delivery and met every 3–6 months. An external trial steering committee was also formed to monitor the conduct of the trial and the trial was supported by the UCL PRIMENT clinical trials unit (www.ucl.ac.uk/priment).

Work package 1: development and validation of a risk model for predicting cardiovascular disease events in people with severe mental illnesses

Work package 1 aimed to address the following research aims during the first 2 years of the Primrose research programme:

-

to develop a CVD risk score tool, specifically for people with SMI and compare its performance with that of existing general population CVD risk tools.

-

to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the CVD risk score tool.

Effectiveness of a cardiovascular risk prediction algorithm for people with severe mental illnesses

The work package was completed on time and the results have been published in one of the highest-impact international psychiatry journals (JAMA Psychiatry) in 2015 (with an impact factor of 16.6 at the time of writing). 37 To date, this has been cited 30 times on Web of Science and 42 times on Google Scholar. The link to this paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 1. 37 The algorithm has been developed and published as a web-based tool [www.ucl.ac.uk/primrose-risk-score (accessed 5 September 2018)].

The published work closely followed the proposed methods in our original funding application. It was a risk score development and validation study.

We used The Health Improvement Network (THIN) UK GP research database to identify a large cohort of 38,824 people with a GP-recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia, other psychoses or bipolar disorder, between 1995 and 2010. We identified 2324 new-onset cardiovascular events within this cohort.

We built a model to predict new-onset CVD using standard regression techniques. We included all the variables usually present in traditional risk scores (e.g. smoking, diabetes mellitus and cholesterol level) and then added SMI-specific variables in addition. These included use of first- and second-generation antipsychotics, use of antidepressants, type of SMI diagnosis and heavy alcohol use.

We developed one model that included blood test results for levels of cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol: the ‘Primrose lipid model’. We created another ‘Primrose BMI model’, which did not require these results. We compared these new models with the most widely used international models: the Cox Framingham models. We used a variety of methods to assess the performance of our new models in forecasting CVD, using a variety of accepted techniques to create multiple imputed data sets, and by dividing the data up into sections to allow ‘internal cross-validation’.

The validation results demonstrated that the new Primrose models performed better than the existing Cox Framingham models, in both men and women, in predicting future CVD events. In men, the D-statistic for the Primrose lipid model was 1.92 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.80 to 2.03] and the c-statistic was 0.80 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.83). For published Framingham scores in men, the D-statistic was 1.74 (95% CI 1.54 to 1.86) and the c-statistic was 0.78 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.82). In women, the D-statistic for the Primrose lipid model was 1.87 (95% CI 1.76 to 1.98) and the c-statistic was 0.80 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.83). For published Framingham scores in women, the c-statistic was 1.58 (95% CI 1.48 to 1.68) and the D-statistic was 0.76 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.80).

To assess whether or not this superiority of the new Primrose models reflected a difference in international models (between the US Framingham model and the UK Primrose model), a UK general population risk score model was created from the THIN database. This model would be very similar to UK models, such as QRISK® (University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK and EMIS Health, Leeds, UK), for which the parameters were not available at the time. The Primrose models still performed better than the UK general population models, which suggested that SMI-specific models are best, although all models performed quite well.

It is concluded that the new Primrose models were the most accurate, but that better evidence is needed regarding their potential impact before they could be recommended for replacing scores, such as the QRISK score or Cox Framingham, as these were models performing at an acceptable level in the SMI cohort and great effort would be required to implement new models across the clinical landscape. The inferior performance of general population algorithms has now been highlighted in clinical guidelines for managing the physical health of people with SMI. Examples are the NHS England Lester tool38 and the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) guidelines on antipsychotic induced weight gain. 39

A limitation of the study was that there may be more missing predictor variables within routine clinical data than in data collected for the purpose of research. In addition, the effectiveness of the CVD risk score models was not evaluated for people from different ethnic backgrounds owing to poor recording.

One risk score study is not sufficient to implement a full change in policy and screening practice for CVD. Therefore, in the Primrose cluster randomised trial, tested in work package 3, our data collection included the variables and calculations for the QRISK score as well as the Primrose new risk scores. Neither risk score was used to determine participant eligibility for the trial, but the risk score work was reassuring that either of the risk scores could be used within the trial for determining 10-year risk and relevant interventions in people with SMI. The risk scores were also used as secondary outcome measures in the trial.

We conducted a further health economics analysis to compare which of Primrose, QRISK or Framingham CVD risk scores would be most cost-effective if combined with statin prescriptions for people with a CVD risk of > 10% over 10 years. The results are outlined in the next section and they show some superiority for the Primrose BMI model in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and net monetary benefit (NMB).

Cost-effectiveness of a cardiovascular risk prediction algorithm for people with severe mental illnesses

The aim of this work package was to evaluate the 10-year cost-effectiveness of the SMI-specific risk algorithm (Primrose) described in the previous section37 compared with a general population CVD risk algorithm. To evaluate this, a 10-year decision model of costs was developed and consequences of CVD in patients with SMI in the UK primary care population were assessed. The full manuscript for this work package has been published in BMJ Open in 2017. 40 The link to this paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 1. 40

A patient-level simulation was developed to hypothetically model the progress of people with SMI over 10 years, which was composed of (1) a decision tree to identify those at a risk of CVD over 10 years and eligible for statin therapy and (2) a Markov state transition model of 10 1-year cycles. The patient population in the model was composed of a random sample of 1000 real primary care patients extracted from the THIN UK GP research database.

A CVD risk score was calculated for each of the 1000 patients using four different CVD risk algorithms in four separate analyses. 40 The risk algorithms assessed were:

-

a general population lipid algorithm

-

a general population BMI algorithm

-

a SMI-specific lipid algorithm

-

a SMI-specific BMI algorithm. 40

Algorithms (1) and (2) were based on an adaptation of the widely used Cox Framingham algorithm,41 herein referred to as the general algorithm, which was created and validated using THIN data. 40 Algorithms (3) and (4) were derived from UK SMI patients in THIN, aged 30–90 years. 37,40 The primary analysis was based on a CVD risk threshold of 10%. The primary CVD prevention strategy used was prescription of a statin for patients above the risk threshold. A fifth analysis using no CVD risk algorithm was included to estimate the costs and consequences of not intervening.

The patient-specific probability of having a primary CVD event and the probability of dying in each cycle were based on algorithms developed using the same data set that was used to develop the Primrose risk algorithm37 (38,824 people in THIN with SMI and aged > 18 years). The probability of having a secondary CVD event was calculated from the model in the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health Registry. 42

The benefits of statin therapy were modelled by applying the relative risk reduction of CVD from statin use from a Cochrane review (0.73 and 0.78 for coronary heart disease and stroke respectively)43 to the predicted risks of CVD for all patients newly prescribed statins. Costs included in our model were the cost of administering the CVD risk algorithm, CVD risk management and CVD events. All costs were reported in Great British pounds at 2012/13 values, inflated using conversion rates in Curtis (2013). 44

The mortality and morbidity impact was evaluated using QALYs as recommended by NICE,45 in which patients were allocated a utility score assigned to patients with SMI whose symptoms are being managed (0.865). 46 If a patient had a non-fatal CVD event, a utility decrement was applied. All future benefits (QALYs) and costs were discounted at 3.5% per annum. 45

Cost-effectiveness was calculated using the NMB approach47 and probabilistic sensitivity analysis to calculate the probability that each option was cost-effective for a willingness to pay (WTP) for a QALY.

The SMI-specific BMI algorithm classified the highest number of patients as at a ‘high risk’ of CVD (326 patients at 10% and 117 patients at 20%) and resulted in the greatest number of new statin prescriptions (255 patients at 10% and 81 patients at 20%). 40 The general BMI algorithm classified the lowest number of patients as ‘high risk’ (222 patients at 10% and 65 patients at 20%) and generated the lowest number of new statin prescriptions (175 patients at 10% and 44 patients at 20%). 40 The general SMI-specific BMI algorithm also prevented the greatest number of primary CVD events (13 events), equivalent to a 4–6% reduction in primary CVD events, and the highest NMB than the general lipid algorithm, and all other algorithms. 40

The results show that the provision of a relatively low-cost identification tool (the Primrose risk algorithm) and relatively low-cost intervention (statins) compared with the high cost of CVD events means that these combined interventions save up to £53,000 per 1000 patients over 10 years, or £53 per patient administered the Primrose CVD risk algorithm. The Primrose BMI model also gave 15 extra QALYs. The general population-derived lipid model was the next best performing algorithm with 13 extra QALYs and £46,000 saved.

A limitation of the study was that it was not possible to compare the performance of the Primrose models with that of the UK QRISK model, as the algorithm parameters were not available.

Work package 2: development of a practice nurse-/health-care assistant-led intervention for lowering levels of cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular disease risk in people with severe mental illnesses

Work package 2 aimed to address the following research questions using three different methodologies:

-

What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, lowering cardiovascular risk in people with SMI? (Focus groups.)

-

What evidence is there for effective pharmacological and behavioural interventions to manage cardiovascular risk factors in people with SMI? (Update of a systematic review.)

-

What are the patterns of statin prescribing for people with SMI and the general population? (Primary care database study.)

-

What is the effectiveness of statins in people with SMI? (Systematic review and primary care database study.)

The findings from the systematic review and focus group studies were brought together to inform the development of a CVD risk-lowering intervention and training programme for practice nurses and HCAs in primary care (Primrose intervention).

Focus groups with health professionals, patients and carers on the barriers to, and facilitators of, cardiovascular disease prevention in primary care for people with severe mental illnesses

Focus groups were conducted to explore current practices, barriers to, and facilitators of, delivering and accessing CVD risk-lowering interventions for people with SMI in primary care. This work was delivered according to the original programme protocol and was published in the journal PLOS ONE in 2015. 48 The link to this paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 2. 48 The findings were used to inform the development of the Primrose intervention and training programme.

A total of 14 focus groups were run with 75 participants, including 32 health professionals working in general practices, 11 staff from community mental health settings, 25 service users with SMI and 7 carers of people with SMI. Topic guides were used to guide the focus group discussions and were developed using domains from an established theoretical domains framework (TDF) for identifying facilitators and barriers to intervention delivery and behaviour change in health-care settings. 49 For this study, the TDF was used to design questions that would help elicit the barriers to, and facilitators of, lowering CVD risk for people with SMI from both the health-care professional and the patient perspective. More specifically, the topic guides were used to explore the resources, systems and training required by health professionals to lower CVD risk in SMI and, to explore with people with SMI and their carers the accessibility of services, motivation and capability to lower their CVD risk. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study and focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using a framework analysis approach. 50

A number of factors were identified that may prevent but also encourage people with SMI to access and engage with CVD risk-lowering interventions in general practice. A need for more systematic approaches to delivering CVD risk prevention in this setting was identified; however, the majority of people interviewed agreed that CVD risk monitoring and intervention delivery was the responsibility of health professionals working in general practice.

A number of barriers to CVD risk prevention were identified, including difficulties delivering preventative physical health care because of consultations focusing on mental health rather than physical health problems, scepticism among some health professionals about the effectiveness of stop smoking and weight loss interventions for people with SMI, and limited confidence and training for practice nurses to work with people with SMI. The negative side effects of psychiatric medications, a lack of motivation due to mental health problems and a lack of engagement with CVD risk-lowering interventions and primary care services were all identified as barriers to enacting CVD risk-lowering behaviours in people with SMI.

Potential facilitators were also identified that sought to address some of the barriers. These included practical ideas to increase attendance and engagement (e.g. afternoon appointments, appointment reminders); to involve family members, friends or support workers; to have a named contact at the general practice to ensure continuity; to provide healthy lifestyle advice during appointments; and to agree on and work towards realistic goals.

Stakeholders from different backgrounds and both urban and rural locations attended the focus groups, making the findings applicable to UK general practice. The service users who attended the focus groups may not have been representative of all service users, as they were active participants in their use of health services. It is likely that for people who are not well or not engaged, attending primary care services may be more difficult.

Systematic review of pharmacological and behavioural interventions for reducing cardiovascular disease risk in people with severe mental illnesses

To inform the development of the intervention, we planned to update existing systematic reviews, rather than conduct a review de novo. The updated review was presented and published as a conference abstract at The Lancet Public Health Science Conference51 and the results of the review were incorporated into the Primrose intervention training programme to inform health professionals about effective interventions for losing weight and stopping smoking in people with SMI.

A systematic review was conducted to evaluate and narratively synthesise evidence from published systematic reviews and individual RCTs on the effectiveness of pharmacological and behavioural interventions for reducing modifiable CVD risk factors in people with SMI. A meta-analysis of findings from individual RCTs was not possible because of the heterogeneity of reporting of interventions and outcome measures (see Appendix 1). 31,52–100

The Cochrane Library was searched for existing systematic reviews. The Cochrane Schizophrenia and Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group Trial Registers were then searched between 1966 and 2014 for additional RCTs not included in the identified reviews. Interventions to manage the following were searched: levels of cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, weight, smoking and alcohol consumption.

Fifteen systematic reviews and 28 additional RCTs were included in the review, from 11,028 references. The synthesised data demonstrated that bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy were effective interventions for smoking cessation, or reduction, as was a standardised smoking cessation programme. There was evidence that metformin and topiramate were effective pharmacological interventions for weight loss, and that behavioural interventions aimed at individuals (rather than groups) addressing diet and physical activity were most effective in reducing BMI. Only three trials reported effective interventions to reduce alcohol intake. No trials were found on interventions targeting levels of cholesterol, diabetes mellitus or hypertension as the primary outcome.

Study limitations were that the setting for most of the trials was secondary care, which limits their generalisability to primary care. It was also difficult to synthesise evidence from a wide range of intervention studies that targeted different CVD risk factors and measured outcomes in different ways.

Evidence was found that CVD risk attributable to weight and smoking can be managed effectively in people with SMI using pharmacological and behavioural approaches; however, limited or no evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to manage levels of cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, alcohol misuse or multiple CVD risk factors was identified in this population. These findings were taken forward into the development work and used within the training programme.

Investigating patterns of statin prescribing among people with, and without, severe mental illnesses

The aim of this study was to explore the statin prescription rate in people with SMI compared with people without SMI in primary care. This work was published in the journal Schizophrenia Research in 2017 (with an impact factor of 3.958 at the time of writing). 101 The link to this paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 2. 101

The uptake of physical health checks in primary care among people with SMI has increased substantially over time, reflecting the introduction of policies and incentives, such as the Quality Outcomes Framework. 20 However, the impact on cardiovascular interventions, such as statin prescribing, was unknown. We used data from THIN to examine the rate of new statin prescriptions in people with, and without, SMI over a 10-year time period. Overall, rates of initiating a statin were at least doubled in people aged 30–59 years with SMI than in those without, even after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors. Among people 60–74 years, rates were generally similar for people with and without SMI. However, among the oldest (aged ≥ 75 years) with schizophrenia (but not bipolar disorder), the rate of statin prescribing was around 20% lower (IRR 0.81, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.98) relative to those without SMI. These findings suggest that older individuals with schizophrenia are less likely to be initiated on a statin than people of a comparable age without SMI, and that this group may therefore benefit from additional measures to prevent CVD. The higher rate of statin prescribing among 30- to 59-year-olds with SMI (relative to people with SMI) demonstrates that statin prescribing is an important element of CVD prevention for this group and highlights the need for further evaluation.

Estimating the effectiveness of statin prescribing for people with severe mental illnesses

This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of statins for people with SMI through a systematic review of existing evidence and a series of staggered cohort studies designed to estimate the effectiveness of statins for the prevention of CVD and for modifying lipids in people with SMI. 102 This study was published in the journal BMJ Open in 2017. 102 The link to this paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 2. 102

Although statins form a core part of CVD primary prevention in the general population, this evidence base was not readily transferable to people with SMI. This is because it is not known whether or not patterns of medication adherence differ. Furthermore, some antipsychotic agents interact with sterol regulatory binding elements (which control lipid synthesis) and might therefore counteract the cholesterol-lowering action of statins. In addition, some of the largest statin trials have excluded participants with psychological conditions or excluded individuals perceived as less likely to be compliant with treatment.

Therefore, a systematic review was undertaken to examine the effectiveness of statins for primary prevention of CVD among people with SMI. This review did not identify any information on CVD events, mortality or long-term statin use in people with SMI. However, two studies provided evidence that statin therapy is associated with significant reductions in levels of total cholesterol (decreases of 11%28 and 35%27 for pravastatin and rosuvastatin, respectively) and LDL cholesterol (decreases of 20%28 and 49%27 for pravastatin and rosuvastatin, respectively) over 12 weeks in 60–100 individuals with SMI. These findings suggested that a large-scale study to evaluate the long-term impact of statin prescribing, particularly on CVD outcomes, was needed.

To explore the effectiveness of prescribing statins to people with SMI, we used UK primary care data from THIN to develop a series of cohort studies. These cohorts included 16,854 people aged 40–84 years who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and did not have pre-existing CVD. Cardiovascular outcomes of statin users and non-users were compared for (1) combined first myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke (primary outcome), (2) all-cause mortality and (3) change in total cholesterol concentration at 1 and 2 years after initiating a statin. We adjusted our results for a wide range of characteristics (such as blood pressure) that are associated with being prescribed a statin and the risk of developing CVD. In the main analysis we used multiple imputation to estimate the value of unobserved data and also conducted a complete-case analysis (for individuals with fully observed data), which produced very similar results to the analysis of the imputed data.

We did not identify statistically significant reductions in the rate of combined MI and stroke [incident rate ratio (IRR) 0.89, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.15] or all-cause mortality (IRR 0.89, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.02) associated with statin prescribing. However, it was found that statin prescribing was associated with statistically significant reductions (equivalent to a 20% decrease) in the level of total cholesterol 2 years after initiating a statin (IRR 1.2 mmol/l, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.3 mmol/l). This finding is similar to the reduction in cholesterol level observed in trial participants without SMI (IRR 1.1 mmol/l, 95% CI 0.8 to 1.4 mmol/l) and suggests that medication adherence in people with SMI is sufficient to support effective lipid modification. This translates to approximately a 25% decrease in mortality and 30% decrease in CVD events. 103

The study investigated a wide range of confounders for which data were captured in THIN; however, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding due to factors (such as diet and exercise) that were unmeasured within our data set. Of note, our estimates of effect for statins were compatible with those from randomised trials examining non-SMI populations, suggesting that the likely impact of unmeasured confounding on our results may be small.

Bringing the evidence together to develop and test the Primrose trial intervention and training programme

The following section describes the development of the Primrose intervention manual and training programme for health professionals working in primary care.

First, the barriers to, and facilitators of, enacting both health professional and patient behaviours for lowering CVD risk in SMI were identified in the focus group work, described in Conclusions and recommendations, Focus groups with health professionals, patients and carers on the barriers and facilitators to cardiovascular disease prevention in primary care for people with severe mental illness, using questions derived from a theory-informed approach for identifying the causes of behaviour (TDF). 49 The identified barriers and facilitators were then mapped to potential intervention components that sought to overcome the identified barriers and harness the facilitators (see Appendix 4, Table 15).

This evidence was supplemented with findings from the systematic review described in Conclusions and recommendations, Systematic review of pharmacological and behavioural interventions for reducing cardiovascular disease risk in people with severe mental illness, and recommendations from workshops with academic, health professionals and lived experience experts. Key intervention components were combined to form an intervention manual and training programme. The key components of the intervention and training programme are described in this section, and supporting tables and figures can be found in Appendix 4. The intervention manual developed as a result of the evidence synthesis can be downloaded on the project web page [(www.ucl.ac.uk/primrose/primrose_manual (accessed 5 September 2018)].

A subgroup consisting of experts in mental health, primary care, behaviour change, expertise from experience and health service research was formed to bring together the evidence into a study manual and 2-day training programme. A logic model was developed by the group to explain the relationship between factors that might influence the effectiveness and implementation of a primary care nurse-HCA-delivered behaviour change intervention. This was also used to guide the clinical and practical aspects of the intervention development and training content (see Appendix 4, Figure 4).

An evidence-based, theory-informed approach (the TDF)49 for identifying factors that might influence behaviour was used to map the barriers and facilitators for lowering CVD risk for people with SMI identified by focus group participants, to potential intervention components. Intervention components were then selected using an established taxonomy of behaviour change techniques104 as well as practical suggestions to address the barriers and incorporate the facilitators identified by the focus group discussions (see Appendix 4, Table 15).

The findings from the systematic review were used in the training programme to educate health professionals on effective interventions for weight reduction and stopping smoking in people with SMI.

Additional workshops were run with academic clinicians and lived experience advisors to elicit expert views on the final design of the intervention and training programme [see Patient and public involvement for a list of recommendations incorporated into the final intervention and training programme from the Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP)]. 105 A review of relevant policy and clinical guidelines was also undertaken to ensure that the intervention followed best clinical practice on CVD prevention in SMI with the aim of addressing the proximal outcomes (behaviours) identified in our logic model (see Appendix 4, Figure 4).

Piloting the Primrose trial intervention and training programme

Seven practice nurses/HCAs attended a pilot session of the training programme before the start of the trial. Some minor changes were suggested that were incorporated into the final training programme, including more opportunities for role play of Primrose appointments and more simplified explanations of the theoretical frameworks used to explain behaviour change.

The first intervention appointment was then piloted with two members of the LEAP. The practice nurse responsible for delivering the training met with each LEAP member and conducted the appointment using the study manual. Feedback from these sessions was incorporated into the final version of the manual and training programme. This included an emphasis on goals being patient led and a need to consider and understand aspects of the person’s life that may make behaviour change difficult.

The Primrose trial intervention and training components

The final intervention consisted of 8–12 appointments with a practice nurse/HCA over 6 months. Nurses/HCAs were trained to support patients to identify and monitor progress with goals on cardiovascular health, including taking medication, improving diet, increasing physical activity, stopping smoking or reducing drinking. They were encouraged to compile a local resource directory and refer patients on to existing support services if available in the local area (e.g. weight management or Stop Smoking Services), or provide support directly if services were unavailable or if the patient requested one-to-one support. They were also encouraged to actively follow-up and monitor attendance at services and progress made towards achieving health goals.

Nurses/HCAs were given a manual to take away with them, which included step-by-step appointment delivery flow charts, help sheets on managing different CVD risk factors and help sheets on strategies to help patients to stay motivated and engaged. A health plan was also given to patients to take away and use in between appointments. The health plan was used to record chosen goals, create an action plan and record progress towards achieving the goal.

The training programme was delivered to between four and eight practice nurses and HCAs at one of six training sessions by a practice nurse with expertise in mental health, a health psychologist, a lived experience trainer and the programme manager. The training comprised lectures and active learning through group discussion and role play of appointments. There were 2 days of learning, which were 2 weeks apart so that the nurses/HCAs could deliver an appointment between sessions and bring any difficulties they might have experienced or areas they felt less confident with to practise at session 2.

Training session 1 consisted of (1) discussing the link between CVD risk and SMI, (2) mental health awareness, (3) effective interventions for lowering CVD risk, (4) behaviour change techniques and (5) practical strategies to encourage motivation and engagement. Appendix 4, Table 16, contains a more detailed description of the content of training session 1. Training session 2 was led by the trainees and involved discussing the appointments that they had delivered and practising strategies and appointment delivery through role play and discussion.

In conclusion, an evidence-based manual and training programme was developed using clinician, patient and clinical academic advice from focus groups and workshops alongside reviews of the best available evidence in both policy and RCTs of CVD risk-lowering interventions. The resulting manual and training programme were piloted with health professionals and patients and found to be acceptable and deliverable. The intervention was then tested in a cluster RCT described in Work package 3.

Work package 3: evaluation of a practice nurse-/health-care assistant-led intervention for lowering levels of cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular disease risk in people with severe mental illnesses in primary care – a cluster randomised controlled trial

This work package evolved from the development work in work package 2 that integrated published evidence, the focus groups and then the work of the PMG and lived experience advisory group (LEAP) to design the nurse-/HCA-led intervention.

Work package 3 took this intervention and subjected it to a full clinical and economic evaluation in a cluster randomised trial, as planned in the original Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) funding application.

Work package 3 had the following research aims:

-

to establish whether or not the new Primrose intervention reduces levels of total cholesterol in people with SMI over a 12-month period compared with treatment as usual (TAU)

-

to determine whether or not the intervention improves other CVD risk factors over a 12-month period compared with TAU

-

to determine whether or not the intervention is cost-effective when compared with TAU

-

to assess the fidelity of intervention delivery in the Primrose intervention arm.

Clinical effectiveness of an intervention for lowering levels of cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular disease risk for people with severe mental illnesses

The full trial protocol for the cluster randomised trial106 was published in Trials in 2016. This protocol included the final sample size calculations for the trial as well as a description of the interventions and all trial procedures. The link to the protocol paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 3. 106

The trial was published in the journal Lancet Psychiatry in 2018. 107 The link to this paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 3. 107

The methods and results from the analysis of the cluster randomised trial in terms of clinical effectiveness are summarised below.

Methods

We successfully delivered a cluster randomised trial within which 76 GP practices across England were recruited and then randomised to either the Primrose intervention (n = 38) or the TAU (n = 38) arm. This total number of practices was larger than specified in the original grant application as the numbers of participants (cluster size) recruited in each practice was smaller than expected (mean 4.3 participants).

Participants in the trial were aged 30–75 years with a GP record of SMI, in line with the definitions already outlined in this report. They had a raised lipid profile defined as a cholesterol level of > 5.0 mmol/l or a total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio of > 4 mmol/l; and they needed to have one other cardiovascular risk factor, including hypertension, smoking, obesity, raised HbA1c levels or diabetes mellitus.

For the practices in the intervention arm, allocated nurses or HCAs were trained on two occasions to deliver the Primrose intervention that was developed in the earlier stages of the research programme (work package 2). Briefly, this involved arranging up to 12 appointments with each participant to target the most relevant CVD risk factor and using agreed evidence-based approaches, and established behavioural techniques to maximise the chance of successful risk reduction. In the treatment-as-usual arm, the nurses were not trained in the intervention but they were allowed to offer standard treatment for CVD risk factors in line with routine practice.

Patients and staff could not be masked to the intervention, but researchers were not informed of the allocation. The analysis plan was predetermined and random-effects linear regression (adjusting for baseline characteristics) was performed on the primary outcome of total cholesterol level at 12 months to account for clustering within general practice. Secondary outcomes included CVD risk scores and other cardiometabolic parameters including glucose, smoking, blood pressure and diabetes mellitus as well as BMI. We also included validated measures of well-being, diet and physical activity, patient satisfaction with services and adherence to both psychotropic and physical health medication.

Results

We recruited 327 participants with SMI: 155 participants in the 38 practices within the Primrose intervention arm and 172 participants within the TAU arm. Attrition in the study at 12 months was lower than predicted (12% as opposed to 20%) so that the total number of patients with follow-up data at 12 months (for the primary outcome of total cholesterol level) was greater than the sample size calculation requirements. In general, the patients had a high level of CVD risk factors, as would be expected by the inclusion criteria. For instance, half were current smokers and the mean BMI was above the threshold for obesity in both arms.

For the primary outcome of total cholesterol level there were no differences between arms at 12 months (5.4 mmol/l Primrose vs. 5.5mmol/l TAU; coefficient 0.03, 95% CI –0.22 to 0.29). This remained the case when additional analyses were performed, adjusting for baseline cholesterol levels or for characteristics that differed between arms at baseline. Total cholesterol levels did decrease over 12 months in both arms (mean decrease Primrose 0.22 mmol/l; mean decrease TAU 0.39 mmol/l).

There were also no differences between arms on the secondary outcomes listed in the methods section above, including the cardiometabolic parameters, patient satisfaction with services or adherence to medications. Statin prescriptions were low and did not increase at 12 months in either the Primrose or the TAU arm.

A total of 30 serious adverse events were reported for 25 people. There were fewer serious adverse events in the intervention arm (seven events for seven patients, including one death, three psychiatric admissions and three general admissions) than in the TAU arm (23 events for 18 patients including three deaths, 11 psychiatric admissions for nine people, seven general admissions for six people, one admission to a crisis house and one diagnosis of cancer).

Participant attendance rates at Primrose appointments were moderately good, with only 32 (21%) participants attending no appointments. A total of 72 (46%) participants attended more than six appointments over the 6-month intervention period and 36 (23%) participants attended between two and five appointments, with the remaining 15 participants (10%) attending one appointment.

Care in the TAU arm may have been better than standard general practice care as the GP practices in the study had identified people with raised CVD risk factors, for whom they may have then clinically intervened. Furthermore, participants and the practices were motivated to take part in the trial and to reduce CVD risk factors. This may have minimised the chance to show superiority for the more intensive Primrose intervention.

The choice of primary outcome measure for the trial was a challenge given that the intervention was designed to target multiple CVD risk factors. Nurses/HCAs were trained to discuss cholesterol levels and statin intervention and adherence in the first instance and then move on to other goals relevant to CVD risk reduction; however, this may have been in conflict with goal-setting being patient-led. If other behavioural goals were chosen instead of statins, then they may have had less impact on levels of cholesterol. However, differences were not demonstrated in any other CVD risk factors.

Conclusion

Nurses and HCAs were successfully trained in the Primrose intervention and delivered it to the majority of patients. However, participants in the intervention arm did not do better on the primary or secondary outcomes than participants in the TAU arm in UK primary care. This may reflect good care in both arms, as cholesterol levels did decrease over the study period and satisfaction with services on the validated client satisfaction questionnaire-8 was high in both groups.

This was a pragmatic trial in which participants exhibited a range of clinical characteristics and CVD risk factors, and it may be that this variability made it less likely that the primary outcome of total cholesterol level was targeted by the nurses/participants or that the most effective interventions, especially statins, were chosen. This possibility will be explored in further fidelity and health economics work.

Cost-effectiveness of an intervention for lowering levels of cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular disease risk for people with severe mental illnesses

The trial protocol for the cluster RCT106 was published in Trials in 2016 and included the cost-effectiveness analysis plan. The link to the protocol paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 3. 106

The full cost-effectiveness analysis was published as supplementary material to the trial in the journal Lancet Psychiatry in 2018. 107 The link to this paper can be found in Appendix 3, Work package 3. 107 The methods and preliminary results from this paper are summarised below.

Methods

The aim of the economic evaluation was to evaluate if the Primrose intervention was cost-effective compared with TAU, for a range of values of WTP for a QALY gained from a health-care cost perspective over the duration of the trial (12 months).

To calculate QALYs, EuroQol EQ-5D 5 level (EQ-5D-5L) data were collected at baseline, 6 months and 12 months and calculated as the area under the curve adjusting for baseline differences. Data were collected using patient-completed questionnaires asking about health promotion activities over the past 6 months at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. Health promotion activities included services for hazardous and harmful drinking, Stop Smoking Services, nicotine replacement therapy, diabetes mellitus and weight management services. Primary and secondary care resource use was collected from patient medical records for the duration of the trial. The cost of the Primrose intervention was calculated from data collected as part of the trial on the number and duration of Primrose appointments attended, missed appointments and who delivered the intervention (primary care nurse, HCA or GP). Information on the cost of training was also collected.

Results

The Primrose intervention arm showed a mean of 0.769 QALYs (95% CI 0.751 to 0.787) compared with a mean of 0.780 QALYs for TAU (95% CI 0.764 to 0.796). The difference in QALYs was –0.011 (95% CI –0.034 to 0.011).

The total health-care cost for the Primrose intervention group was £1286, with a total cost of £2182 for TAU (mean difference –895, 95% CI –£1631 to –£160; p = 0.012). These lower health costs were mostly a result of fewer mental health inpatient stays and costs (£157 in the Primrose intervention vs. £956 in TAU; –£799, 95% CI –£1480 to –£117; p = 0.018). The total mean 12-month health-care cost per patient for the Primrose intervention (including intervention costs but excluding those who did not attend and training) was £2580 (95% CI £1899 to £3261), with a total mean cost of £3404 (95% CI £2467 to £4340) for TAU. This gave a cost difference of –£824 (95% CI –£568 to £1079) in favour of Primrose. The total incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (–£824/–0.011) is £76,245.

There is some uncertainty as to whether or not using the EQ-5D-5L to calculate QALYs is a suitable methodology for health promotion interventions.

Conclusion

The potential effect of increased contact with a primary care health professional on mental health inpatient admissions warrants further investigation.

Fidelity assessment of the Primrose intervention delivery

We assessed the extent to which the intervention and training programme were delivered as intended through an analysis of a randomly selected sample of transcribed audio-recordings of intervention appointments. The full report of this work can be found in Appendix 2.

Methods

To enhance fidelity in the intervention arm, we developed a study manual in which the detail of each component of the intervention was described. Nurses/HCAs were trained on delivering the intervention through strict adherence to the details provided in the manual. This facilitated the standardised delivery of the intervention across 41 providers in all 38 participating GP practices in the intervention arm.

Nurses/HCAs in the intervention arm were trained in procedures for audio-recording all of their appointments with recruited Primrose patients. After gaining consent from the patients and nurses/HCAs in the intervention arm, nurses/HCAs were asked to record all of their Primrose intervention appointments.

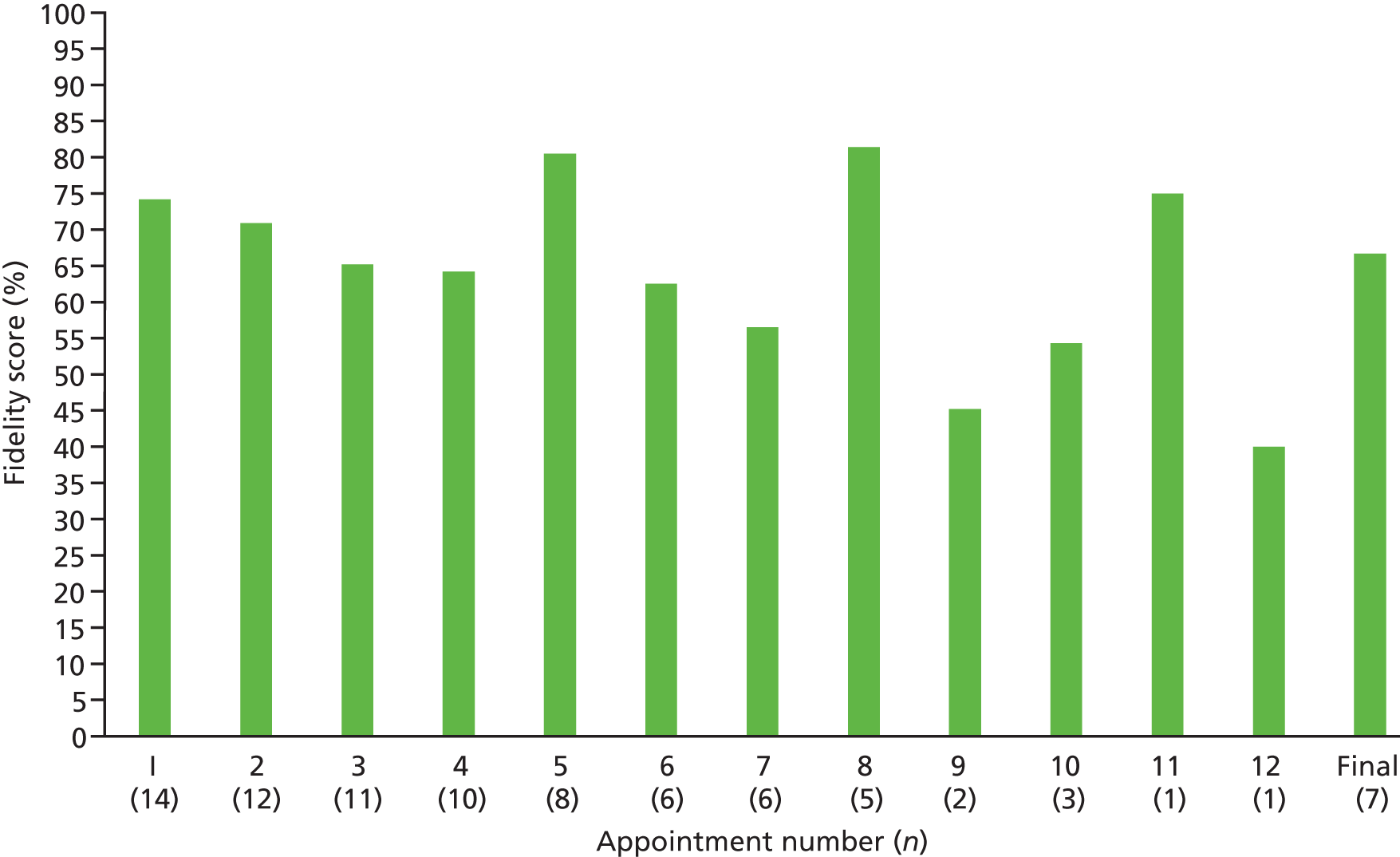

A random 20% sample of audio-recordings was selected for the fidelity assessment as specified in the original grant application. Fidelity was assessed by two independent researchers using first appointment and subsequent appointment checklists adapted from a reliable fidelity assessment method developed for behavioural interventions. 108,109 A score of ‘2’ was assigned if a provider behaviour was achieved, a score of ‘1’ when a provider behaviour was achieved to some extent, a ‘0’ when the provider behaviour was judged appropriate to do but was not delivered, and ‘not applicable’ for provider behaviours judged not appropriate. This scoring system was applied to the appointment transcripts, deriving a percentage fidelity score for each intervention component, appointment and provider. We also derived an overall fidelity percentage score for all sampled appointments and all providers combined. Inter-rater reliability for coding between the two researchers was 86% with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.668 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.70).

Results

One or more appointment audio files were returned by 33 out of 41 (80.5%) providers for 90 out of 123 (73.1%) patients. Out of 831 attended appointments, 431 (53%) audio-recordings were returned. A random selection of 86 out of 431 (20%) audio-recordings covering 23 out of 33 (69.7%) providers and 52 out of 123 (42.3%) patients were transcribed verbatim.

A total of 67.7% of intervention manual-specified components were delivered across all appointments indicating moderate fidelity, with considerable variation among activities. Fidelity was higher in appointment 1 (72.5%) than in subsequent appointments (66.6%). Fidelity also varied between intervention components and was lowest for ‘forming habits’ (47.8%) and highest for ‘reviewing progress’ (90.2%).

Out of 14 first appointments, none of the patients identified a goal that addressed statin adherence or initiation. Eight (57.1%) patients wanted to address diet or physical activity, three (21.4%) patients set a goal around reducing smoking, and two (14.3%) patients chose to reduce their alcohol intake. One patient did not set a goal. Nurses had higher fidelity than HCAs, with 79.5% of intervention components delivered by nurses compared with 64.3% by HCAs. This difference was significant [t(20) = 2.32; p = 0.037].

A potential limitation of the study was whether or not the fidelity sample of intervention practice nurses/HCAs was representative of the trial sample. Nurses were over-represented in the fidelity sample (60.9% vs. 43.9% in the trial) as were providers with previous research experience (52.2% vs. 39% in trial); however, the fidelity sample was randomly generated by an independent statistician.

Conclusion

Observed fidelity to the Primrose intervention was moderate, with some intervention components being delivered more than others. These results are comparable to other fidelity assessments of cardiovascular prevention programmes. 110 Statins were not focused on in initial appointments, which concurs with the main RCT findings in which few statins were initiated. HCAs had a lower fidelity of intervention delivery than practice nurses, which may have implications for future clinical and research work in this field.

Conclusions and recommendations

This section brings together the main conclusions from the Primrose research programme. It reflects on the successes and difficulties we faced over the 6 years, in the context of the original aims and objectives of the funded grant proposal. It then describes the implications of the research findings, the plans for future research building on the programme, and opportunities for other work in the field of cardiovascular comorbidity in people with SMI.

Summary of successes and challenges

We achieved all our main research objectives from our final PGfAR proposal and delivered some additional pieces of work related to cardiovascular health in people with SMI. The risk score work and development work were all delivered and most of that work has been published in peer-reviewed journals and/or presented at scientific meetings. The trial was also completed within a revised timeframe for the larger trial in terms of the increased number of required clusters.

The objectives were achieved despite a number of challenges, especially two major changes in national GP research infrastructure after funding was awarded, namely the closure of both the Medical Research Council General Practice Research Framework (MRC GPRF) and then the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN). We were one of the first research teams to fully run a primary care trial within the new Clinical Research Network (CRN) structure.

The timeframe for the trial in work package 3 required the Primrose programme to run for an additional 15 months to achieve the numbers required in our sample size calculation, mainly because of the challenges of recruiting sufficient participants in each general practice. This meant that we needed to recruit 76 GP practices rather than the original 40. All this was achieved despite a small number of permanent staff in our budget (one programme manager and one research assistant). It is testimony to their skills and hard work that the trial achieved its aims with 76 practices recruited across England, all requiring site initiation, training, liaison with practices and research network staff as well as co-ordination of follow-up data collection and study closure.

Work package 1: development and validation of a risk model for predicting cardiovascular disease events in people with severe mental illnesses

The work package 1 risk score work developed new models for predicting CVD in SMI. These were delivered on time, using all the methods specified in the original proposal. We developed bespoke new Primrose models for predicting CVD in SMI and these performed well in people with SMI. However, existing models from the general population also performed fairly well and we did not generate the objective evidence to suggest that existing CVD risk scores in general practice should be replaced immediately with the bespoke SMI specific models.

A limitation of the study was that the performance of the CVD risk score models among different ethnic groups was not assessed, but the availability of routine ethnicity data is limited and this could be a focus of future work if data quality improves.

Given that a range of guidelines have referenced our work, it is likely that many clinicians are aware that standard risk scores may underestimate risk in people with SMI.

Work package 1: additional economic modelling work over and above the original protocol

The health economics modelling work regarding the new Primrose risk scores has recently been peer reviewed and published. 40 It uses the more recently recommended threshold of 10% CVD 10-year risk to explore which risk models would be better for people with SMI if used to drive statin prescribing. The Primrose BMI models provided the best economic results, which may have been a result of its classification of more individuals at a high risk of CVD and eligible for statin therapy than other algorithms, although the UK QRISK models also performed well.

Given that there was a small difference between the two tools economically, the decision regarding which algorithm to use in routine clinical practice becomes one of implementation, advocacy and ease of use. One could argue in favour of using a general population-derived lipid model as these are already used in UK general practice and hence require no change. On the other hand, the SMI-specific BMI model, although potentially requiring additional training and implementation costs, could confer additional benefit by raising awareness of the need to improve CVD outcomes in people with SMI, and providing a model that requires no blood test to estimate risk, a limitation of other CVD risk algorithms as many people, with and without SMI, decline blood tests. 111 The ease of implementation and delivery of the SMI-specific BMI model means it could be used in any setting, including mental health care and non-clinical settings without blood results. This is particularly important as many people with SMI do not attend primary care and monitoring of CVD risk factors remains low in other settings. 19,111–114 The SMI-specific BMI model provides an opportunity to target more people with SMI, to increase identification of those at a high risk of CVD and decrease the physical, social and financial burden associated with CVD.

We have made the Primrose model available on the internet so that it can be used by interested stakeholders. 40

Although the Primrose risk score results were delivered (and published) on time, the initial validation results were not strikingly different from current CVD screening practice for us to include the new algorithms in the Primrose intervention work or to use them as inclusion criteria for the trial as originally planned. 37 This was partly a timing issue as the risk score work occurred in parallel to the development work packages 2.1–2.3, which involved bringing together this intensive development work to finalise the training and content of the Primrose intervention.

Work package 2: development of a practice nurse-/health-care assistant-led intervention for lowering levels of cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular disease in people with severe mental illnesses

Three major pieces of research were performed to help design the nurse-led intervention for the main trial, as detailed in our original research protocol.

We also worked closely with our patient and public involvement (PPI) LEAP panel throughout this part of the programme and won a national prize for our PPI work, from the NIHR Mental Health Research Network (MHRN).

Focus groups with health professionals, patients and carers on the barriers to, and facilitators of, cardiovascular disease prevention in primary care for people with severe mental illnesses

We had always planned to augment our previous work with stakeholders to derive up-to-date information on the best ways to deliver the Primrose training and the intervention itself in primary care.

We conducted focus groups with nurses, GPs, service users and other stakeholders as planned. This work was peer reviewed and published in PLOS ONE in 2015. 48 We used behavioural science theory49,104 to identify barriers to, and facilitators of, nurses delivering the intervention to reduce CVD risk in people with SMI. A range of important factors emerged and these were incorporated into the intervention for the trial.

Systematic review of pharmacological and behavioural interventions for reducing cardiovascular disease risk in people with severe mental illnesses

As there were existing systematic reviews in this field (for single risk factors, such as weight and smoking), it had only ever been planned to update and summarise this evidence so that the latest research could be incorporated into the training package and intervention. This evidence would include SMI-specific research that targeted the main CVD risk factors in people with SMI, namely levels of cholesterol, blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, raised CVD risk scores, weight/obesity, smoking and diabetes mellitus.

The updated, extensive review was delivered on time and was utilised in the workshops, training and other activities that informed the final content of our intervention for the trial. It did not find many additional pieces of evidence to warrant a new publication.

The findings of our review were specifically useful in demonstrating that smoking and weight reduction interventions have been successful in people with SMI. This was a positive message to incorporate into the intervention training, particularly aimed at tackling negative attitudes towards behaviour change in people with SMI. 27,115–117

The review was presented at a public health conference and the abstract published in The Lancet. 51

Investigating patterns of statin prescribing among people with, and without, severe mental illnesses

We completed primary care database research that showed that statins are generally being used equitably (or at higher levels) in people with SMI, compared with age-matched individuals without SMI, except in older people with schizophrenia for whom there is a disparity and underprescribing of statins. This is an important finding as this age group has the highest absolute rates of CVD.

This work was emerging as the trial and intervention design was under way; therefore, we maintained statins at the top of our hierarchy of interventions for the nurses to focus on in the Primrose intervention arm if the patients met the criteria for statin prescription, which changed to 10% rather than 20% risk at the beginning of the trial in 2014. 25

Additional piece of pharmacological epidemiology: estimating the effectiveness of statin prescribing for people with severe mental illnesses

This work involved a relatively novel methodological approach to assessing the effectiveness of statins in real life for people with SMI, again using the UK THIN database.

The staggered cohort design allowed us to show that after adjusting for multiple factors in the analysis, statins have similar effects on levels of total cholesterol at 12 months, as would be seen in the general population. In other words, statins do work and people with SMI do seem to take them when they are prescribed. This is sometimes questioned given issues around adherence and the multiple risk factor challenges that face people with SMI.

The work has been peer reviewed and published in BMJ Open (with an impact factor of 2.413 at the time of writing). 101,102 The work within work package 2.3 was also the content of a successful PhD awarded to Ruth Blackburn in 2016 as part of Primrose. 118

Bringing the evidence together to develop and test the Primrose trial intervention and training programme

At the end of the development work packages, we entered an intensive period of work, synthesising the evidence that we had identified, running workshops and developing the manual and training programme for the Primrose nurse-led intervention.

We were able to use a rich combination of existing data, expertise, novel research findings and existing clinical guidance to create a contemporary evidence-based intervention.

The intervention appointment structure was piloted with two LEAP members and the training programme was piloted with seven nurses. Feedback was generally positive with suggestions incorporated into the final versions of the manual and training programme. The final intervention included a structure of 8–12 appointments delivered fortnightly over a 6-month period, a 2-day training programme, the manual for the nurses and its component instructions. This specified a hierarchy of risk factors to address during the Primrose appointments, with guidance on how to choose collaborative goals, which were likely to have an impact on CVD risk. The manual and training programme also addressed a range of behavioural techniques to guide the nurses/HCAs through each appointment including goal-setting, creating an action plan and involving supportive others.

Each of the developed products received feedback and input from the full range of Primrose stakeholders including service users, practitioners, researchers and experts in behavioural science, nursing and cardiovascular health. Developing a complex intervention involving different stakeholders from a range of backgrounds was challenging at times, particularly when views on the content of the intervention and training programme were in conflict. One particular area of contention was around statin prescriptions, with clinicians and policy favouring statins as a first-line clinically effective treatment for CVD prevention, but patients expressing concerns about medication and a preference for patient-led behavioural approaches. We decided to maintain our emphasis on statins and statin adherence as the first-line treatment within the intervention, while also emphasising the need to work in partnership with the patient to determine how to tackle raised cholesterol levels and CVD risk, with the option of considering behavioural approaches around diet and physical activity, smoking and alcohol use.

This development process was very comprehensive and it was felt that the resulting intervention had been developed extremely thoroughly and included a high level of scientific and practical specification.

Work package 3: evaluation of a practice nurse-/health-care assistant-led intervention for lowering levels of cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular disease risk in people with severe mental illnesses – a cluster randomised controlled trial

Ethics approval and trial registration were successfully achieved on time to start the trial in 2013. The trial protocol was peer reviewed and published in 2016,106 before any analysis occurred.

The trial commenced in the north London locality and it soon became clear that recruitment procedures for the trial involved large amounts of work to screen for people with SMI in primary care, to check eligibility in terms of cardiovascular risk factors and to invite them to take part. Some potential participants did not have all the required information on CVD risk factors, so they needed to be invited to their GP practice to check eligibility. This was a rate limiting step to recruitment.

We realised that the numbers likely to take part per practice were somewhat smaller than expected, and required a lot of time and effort in the absence of the MRC GPRF and PCRN infrastructure. We therefore decided to increase the number of practices from 40 to a final total of 76, which increased the delivery time of the trial. However, we successfully recruited and retained enough people with SMI and CVD risk factors to achieve the final number of participants with primary outcome data at the 12-month follow-up (total n = 289), meeting the requirements of our published sample size calculation.

This was the first fully powered trial of a primary care-based intervention for lowering CVD risk in people with SMI. The successful delivery demonstrates that there is an appetite for this field in UK primary care and also that the CRNs were able to support this type of work. The large number of GP practices recruited and the geographical spread across both rural and urban areas in England is also a strength in terms of external validity.

The trial finished follow-up on time within our revised timeline (6 months ahead of the end of the overall programme funding as planned), allowing time for data cleaning and analysis of the results.

The training and intervention were successfully delivered across the general practices, and seemed acceptable to providers and participants with almost half attending six or more appointments in the Primrose intervention arm. This contradicts the negative attitudes that are sometimes voiced about uptake of this work in SMI.

The main results showed no differences in the primary outcome of total cholesterol levels at the 12-month follow-up. Furthermore, the trial did not show differences in any of the main secondary outcomes related to cardiometabolic risk factors, such as blood pressure, glucose, weight or smoking. Diet and exercise levels were similar in both arms and levels of satisfaction with services were high in both arms.

The richness and volume of the objective medical records data collected for the economic evaluation of the cluster randomised control trial was a strength of the study, but we did not have the time to conduct all of the analyses we were interested in. Additional work will include an analysis of 12-month data using multiple imputation to account for missing data and an analysis of the relationship between health inputs (health promotion activities) and health outputs (QALYs, reduction in unplanned health-care resource use).

In the assessment of fidelity using the audiotaped appointments, there was evidence that many of the behavioural techniques had been utilised within the appointments. This was true across providers, although fidelity seemed even higher for nurses than for HCAs. There was some evidence that when statin adherence or prescription should have been reviewed and targeted, the participant and provider did not choose statins as their primary focus.

The initial intervention had been envisaged as a nurse-led intervention, but in practice many GPs were unable to provide a nurse with time available to be trained in the Primrose intervention, so a health-care assistant (HCA) was identified instead. These practitioners do deliver CVD screening work to other populations, therefore, it was agreed that they would be trained in Primrose, partly to reflect real life and partly to allow the trial to be delivered practically and on time.

There is evidence in the primary care mental health literature that interventions that include supervision from a physician are more likely to reduce disease risk factors in people with depression,119 but this approach has not been tested in people with SMI. Future intervention studies may wish to test whether or not more intensive supervision and support for staff results in improved outcomes for patients; however, there may be cost implications of additional support.

There were some design issues that are a challenge to the external validity of the trial findings. This included generalisability, as both the GPs and the participants were people interested in physical health in SMI but perhaps not representative of the overall UK population and primary care landscape. A second issue was the cluster design and the fact that practices (and participants) allocated to the TAU arm were aware that there were Primrose participants with identified CVD risk factors who would not receive the Primrose intervention. Therefore, these participants may have received superior, or at least different, care to those undergoing standard care in usual UK general practice, by virtue of the screening process for the trial. In other words, TAU may not have been a ‘fair’ comparison with the Primrose intervention. The finding that levels of total cholesterol were reduced in both the intervention and the TAU arms despite a lack of focus on statins would support this.