Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0707-10010. The contractual start date was in January 2009. The final report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in December 2018. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sonia Saxena was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Career Development Fellowship (CDF) (NIHR-CDF-2011-04-048). CNAM is funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England and the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) programme. Kate Costeloe reports that she was a member of the Neonatal Data Analysis Unit Board throughout this research programme. No authors have any financial or business relationships with Clevermed Ltd.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Modi et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Creating the infrastructure: the National Neonatal Research Database

Abstract

Background: Successive UK governments have highlighted the potential of clinical data to advance patient care. Difficulties experienced by high-profile projects exemplify the challenges, including limited population coverage and clinical engagement, unknown data quality and public disquiet.

Aims: To develop the use of electronic patient record (EPR) data to improve neonatal specialised care, a high-cost NHS service.

Methods: We secured approvals from Caldicott Guardians, Lead Clinicians, the National Research Ethics Service and the Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group. We established a UK Neonatal Collaborative of provider NHS trusts. We collaborated with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and the national charity Bliss to develop a parent information leaflet. We conducted a systematic review to identify neonatal databases globally. We improved data completeness and quality through close interaction with clinical teams.

Results: We achieved 100% coverage of NHS neonatal units in England, Wales and Scotland (n = 185). We created a new NHS information standard, the Neonatal Data Set (ISB1595) and a National Neonatal Research Database (NNRD) containing a defined extract from real-time, point-of-care, clinician-entered EPRs. The NNRD is now used for a wide range and growing range of purposes including clinical and health services research, quality improvement programmes, national audit, commissioning support and national and regional benchmarking.

Conclusions: We have established proof of principle that EPR data may be employed to support patient care and clinical services through research and evaluation, and reduce the burden placed on busy clinical teams by providing a single national data source to service multiple outputs.

Background

Electronic patient records

Electronic patient records have been used increasingly over the last two to three decades and represent a rich data resource. Successive UK governments have recognised the potential of NHS clinical data to improve patient care and outcomes. 1–3 However, these aspirations have been slow to be adequately realised.

The challenges faced in harnessing the power of clinical data in health care are perhaps exemplified by the lessons of care.data and other high-profile UK projects. These include limited population coverage, weak clinical engagement, unknown data quality, regulatory uncertainty and public disquiet. Confidence in the concept of clinical data as a resource to improve patient care, despite an ambition to use these to improve standards, quality of care, accountability and patient choice, has been further damaged by escalating costs, critical media reports, breaches of data security and loss of public confidence by reports that personal data would be ‘sold’ to commercial organisations.

Neonatal specialised services

In the UK, neonatal specialised services (i.e. services for newborn infants requiring care over and above normal care) are currently provided by neonatal units operating in a series of mature clinical networks, each comprising around six to eight neonatal units. Neonatal networks were introduced as part of the restructuring of neonatal services in response to a report by the Department of Health and Social Care in 2002. Each neonatal network was to be largely self-sufficient in providing care across the complete range of intensities (the traditional intensive, high dependency and special care levels). As a result, large numbers of infants were transferred between neonatal units providing different levels of care in accordance with their care requirements, with ultimate ‘repatriation’ to a neonatal unit closest to home in preparation for discharge. The concurrent need for clinical information to be readily transferable between NHS provider trusts was a cardinal driver for the introduction of EPR technologies into neonatal units.

Prior to the restructuring of neonatal services into networks, the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) had commenced developing a ‘minimum’ Neonatal Data Set. 4 Neonatologists had long recognised the benefits of a uniform approach to recording clinical information, including the the ability to evaluate outcomes consistently at a national level. Over the period of the restructuring and subsequently, successive BAPM working parties made refinements to the ‘minimum’ Neonatal Data Set. 4

Neonatal electronic patient records

Over the last decades, a UK-based commercial firm had developed a technical platform for neonatal data in close consultation with neonatal clinicians. This platform has evolved, with successive versions introduced into use over the years. Electronic systems were introduced across all NHS provider trusts from 2005 onwards. The EPR system in most widespread use includes fixed-choice and free-text items, with the NHS number as the principal identifier. Data are recorded daily throughout the neonatal inpatient stay. Clinician-entered diagnoses are converted to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) codes. 5

Thus, the reorganisation of neonatal services into managed clinical networks, an established, commercially available technical platform with a user front-end developed in close collaboration with neonatal clinicians, and a ‘minimum’ Neonatal Data Set established by a professional organisation, provided the three prime underpinning requirements on which to develop electronic clinical data for secondary purpose, including research and evaluation. Members of the Medicines for Neonates investigator group had been involved in several of the developments in relation to neonatal data described above, and electronic records more widely (e.g. as members of successive BAPM data working parties) and, hence, brought a wealth of experiential knowledge to the programme.

Aims

Our aim was to develop the use of EPR data for secondary purposes to support neonatal services and facilitate research to improve newborn care and outcomes. We also aimed to secure strong clinician engagement and parental support, implement measures to assess data quality systematically, and establish a new national resource.

Methods

We established a Programme Steering Committee comprising the Medicines for Neonates investigator group, an independent chairperson and independent members, including a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative. We conducted a systematic review to identify and describe existing neonatal databases. We investigated the regulatory processes required, and considered and tested ways in which to establish close clinical engagement, evaluate and improve data completeness and quality, and provide information to parents nationally.

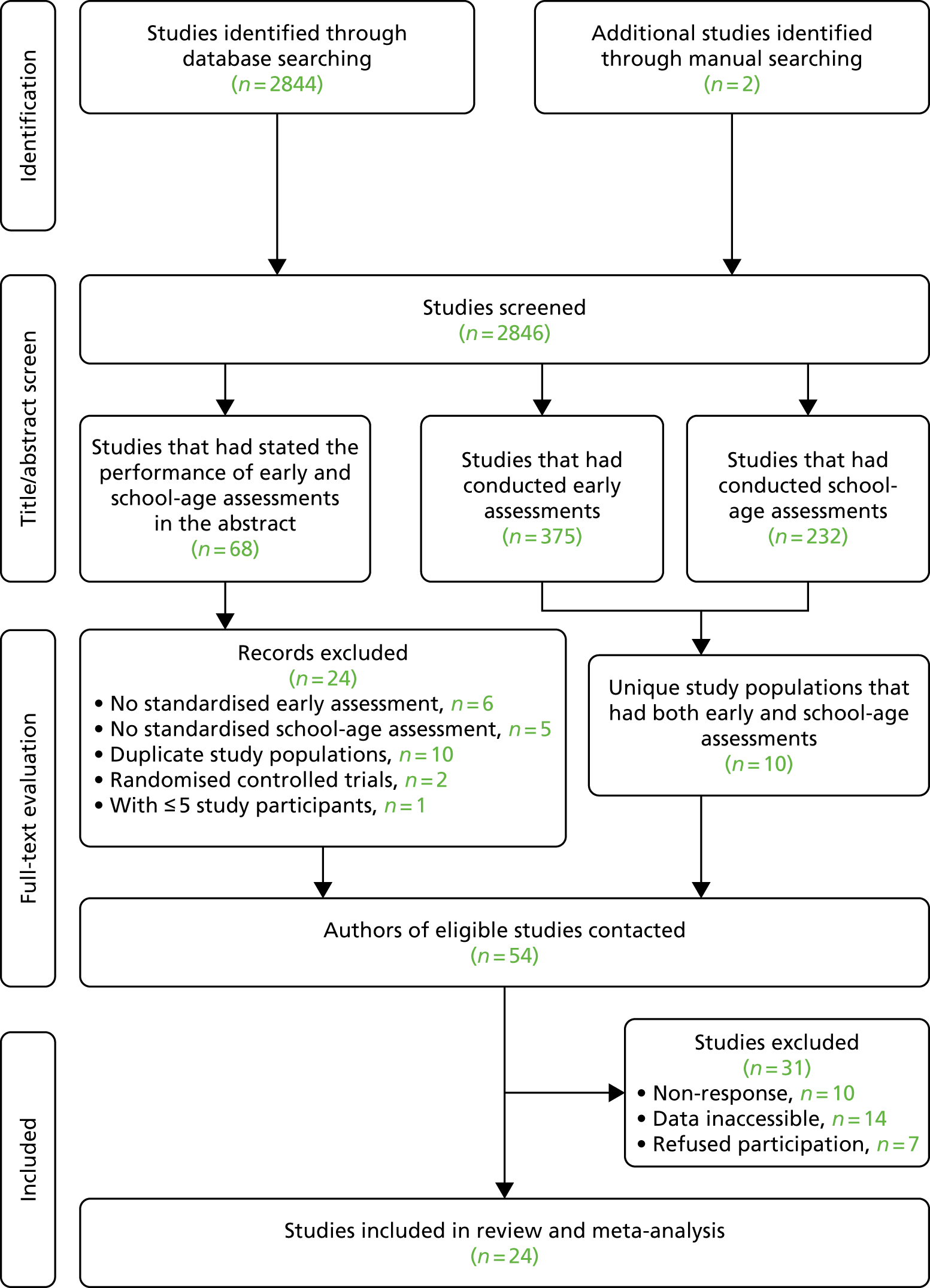

Systematic review methods

We carried out an electronic search on MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; via Athena), of publications covering the period 1 January 2000 to 15 March 2015. We applied language restrictions, including only English, French, German, Italian, Russian and Spanish articles. We employed the following search terms: ‘intensive care units, neonatal/’ OR ‘intensive care, neonatal/’ OR ‘neonatal intensive care units’ OR ‘NNU’ OR ‘NICU’ OR ‘neonatal ICU’ AND ‘infant/’ OR ‘neonat$’ AND ‘database$’ or ‘registry’ OR ‘registries’ OR ‘dataset$’ OR ‘data set$’ OR ‘vital statistics’. The literature search strategy is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Literature search strategy.

We carried out grey literature searches on the Web of Science and the Ovid Maternity and Infant Care Databases using the free-text terms ‘neonatal intensive care unit’ AND ‘infant’ AND ‘database’.

We exported results, including abstracts, into EndNote X7 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA]. Two researchers reviewed titles and abstracts to identify relevant publications and remove duplicate results. We retained publications that mentioned databases of patient-level information (administrative or clinical) and specified that data covered populations of infants from more than one neonatal unit. We reviewed full-text articles, references and websites. We entered extracted predefined information into Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) (Table 1).

| Name | Original definition from PROSPERO submission | Updated definition for final systematic review |

|---|---|---|

| Study identification | To include main author and year of publication (e.g. Smith, John et al. 2015) | Same as original but also includes websites for databases |

| Database name | The name of the database | No change |

| Primary purpose | Administrative, clinical, research, audit, other | No change |

| Country | Free text for country where database is based | No change |

| Scope | Regional, national or international | No change |

| Scope name | Free text to specify the region of country or countries | No change |

| Population limit | Admissions in hospital, births in hospital | Admission to neonatal units, all infants included in admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point, admissions or births in enrolled hospitals, health insurance enrolment, no limitations, entire region included |

| Data source | Recorded specifically for database or secondary-use database | Secondary-use database broken down as data extracted from clinical source (electronic health records) or data extracted from administrative source |

| Number of infants reported | Number | No change |

| Time period for number of infants reported | The range of years that the database spans from earliest time period that could be identified to the present (e.g. 2000–15) | Includes if database is still enrolling patients |

| Maternal characteristics | Mother’s ethnicity (yes/no), mother’s age (yes/no), mother’s education (yes/no), mode of delivery (yes/no) | No change |

| Infant characteristics | Gestational age in weeks (yes/no), gestational age in days (yes/no), gestational age definition (free text), birthweight (yes/no), sex (yes/no), multiplicity (yes/no), infant identification (yes/no), infant identification type (free text), intervention (yes/no), intervention type (free text), diagnoses (yes/no), diagnoses coded (yes/no), laboratory samples (yes/no), abdominal X-rays (yes/no), retinopathy of prematurity (yes/no), cranial ultrasound (yes/no), post-discharge information (free text) | Same as before except for the following changes: gestational age definition (yes/no), post-discharge information (yes/no) and blood cultures (yes/no) instead of laboratory samples (yes/no) |

| Funding | Not collected | Hospital subscription, insurance, mixed funding including support from public body. No current funding support identified. Support from public body |

Creating the Neonatal Data Set

We built on and extended the BAPM ‘minimum’ Neonatal Data Set (data items used to derive daily level of care, the currency underpinning the commissioning of neonatal specialised care services) and the mandated National Critical Care Minimum Data Set (NCC-MDS) (used for deriving neonatal Healthcare Resource Groups) to build a national ‘Neonatal Data Set’. This comprised basic demographic details (e.g. date of birth, birthweight), clinical interventions captured daily (e.g. respiratory support, type of feeds, surgical procedures, high-cost drugs), clinical outcomes and diagnoses. Each data item is clearly defined in an accompanying metadata set, and mapped to existing national standards as well as ICD codes. There was a preliminary assessment of the compatibility of Neonatal Data Set items for conversion to Snomed computed tomography (CT) terminology (international medical nomenclature); the conclusion was that the Neonatal Data Set is compatible, but conversion would require clinical and technical resourcing.

With the support of the NHS Information Standards Board (now NHS Digital), we submitted the Neonatal Data Set for approval as a national NHS standard. Following initial submission, the Information Standards Board issued an ‘advance notice’ of the Neonatal Data Set standard. In the process to becoming a national standard, the Neonatal Data Set evolved through changes that came about following public consultation, review by terminology experts at the NHS data dictionary, and alignment to other national data sets. As a result, 25 data items were added to the revised Neonatal Data Set and an existing 28 items were recoded to reflect data dictionary terminology or other national criteria. Full approval of the standard was obtained in December 2013. The stages leading to approval are shown in Table 2. The current approved Neonatal Data Set (SCCI1595) for standard items and age 2 years items are provided as Appendix 3.

| Submission stage | Document reference | Document title | Version | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needs | Needs stage | National Neonatal Data Set Needs Stage Submission | 1.7 | 7 September 2012 |

| Requirements gathering | Requirements stage | National Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Requirements Stage Submissions | 0.4 | 6 December 2012 |

| Draft and full approval | Review of central returns approval | Review of Central Returns Approval notification OR 2027 FT6 0001PMAND | 1 | 13 August 2013 |

| Draft and full approval | Submission | Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Submission | 1.4 | 16 October 2013 |

| Draft and full approval | Specification | Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Specification | 0.5 | 16 October 2013 |

| Draft and full approval | Data set | Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Release 1 | 2.1 | 16 October 2013 |

| Draft and full approval | Evidence of consultation | Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Evidence of consultation | 0.7 | 16 October 2013 |

| Draft and full approval | Data discovery | Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Data Discovery | 2.5 | 16 October 2013 |

| Draft and full approval | Implementation and maintenance plan | Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Implementation and Maintenance Plan | 0.5 | 16 October 2013 |

| Draft and full approval | Issues and risks | Neonatal Data Set ISB 1595 Issues Log & Risk Register | 10 | 16 October 2013 |

Results

Systematic review

Search results

The search yielded 2037 unique papers. Following a review of the titles and abstracts, 415 papers met our prespecified criteria. From these, we identified 82 databases and, for 52, data were recorded specifically for the database. In 21 papers, data were obtained from a primary administrative source and in nine papers data were obtained from a clinical source (Figure 2). Five countries accounted for the location of more than half (47/82) of all identified databases: the USA (n = 24), Canada (n = 11), the UK (n = 7) and Australia/New Zealand (n = 5). We provide details of the databases identified in Table 3.

FIGURE 2.

Data flows into the Neonatal Data Analysis Unit.

| Number | Name | Primary purpose | Country | Scope | Population limits | Data source | Time period covered by publication (database still enrolling patients) | Maternal variables | Infant variables | Funding source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alberta Perinatal Health Program Database6 | A | Canada | Regional (Alberta) | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 2002–4 (yes) | Mother’s age, mode of delivery | Birthweight, sex, multiplicity | Support from public body |

| 2 | Alere or Matria Health care/Paradigm7,8 | C | USA | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2003–7 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Hospital subscription |

| 3 | Arizona Newborn Intensive Care Program9 | A | USA | Regional (Arizona) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Extracted from administrative data source | 1994–8 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, identifier, intervention, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 4 | Asian Network on Maternal and Newborn Health10 | R | Asia (Malaysia, Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore) | International | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2003–6 (yes) | Mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, diagnoses, abdominal X-rays, cranial ultrasound | Support from public body |

| 5 | AUDIOPOG Sentinel Network11 | C | France | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 1994–2008 (yes) | Mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | No current funding support identified |

| 6 | Australia and New Zealand Neonatal Network12 | C | Australia/New Zealand | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1994–2012 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, blood cultures, ROP, post-discharge information | Mixed funding, including support from public body |

| 7 | Better Outcomes Registry and Network13 | A | Canada | Regional (Ontario) | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2006–10 (yes) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 8 | California Patient Discharge Linked Birth Cohort Database14,15 | A | USA | Regional (California) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from administrative data source | 1999–2004 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity | Support from public body |

| 9 | California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative16 | C | USA | Regional (California) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2005–11 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 10 | Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database17 | A | Canada | National | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 2002–10 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, identifier, intervention, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 11 | Canadian Neonatal Follow-Up Network18 | C | Canada | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2010–11 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, diagnoses, blood cultures, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 12 | Canadian Neonatal Network19 | C | Canada | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2013–14 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, diagnoses, blood cultures | Support from public body |

| 13 | Canadian Paediatric Surgery Network20 | C | Canada | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2013–14 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, identifier, intervention, diagnoses, abdominal X-rays, cranial ultrasound | Support from public body |

| 14 | Children’s Hospital Neonatal Database21 | C | USA | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2010–11 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Hospital subscription |

| 15 | Colorado Birth Certificate Database22 | A | USA | Regional (Colorado) | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2007–12 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 16 | Consortium of Safe Labor Database23 | R | USA | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 2002–8 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 17 | Croatian Intensive Care network24 | C | Croatia | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2004–5 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Identifier | Support from public body |

| 18 | Danish Medical Birth Registry25 | A | Denmark | National | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 1997–2008 (yes) | Mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 19 | Danish Neonatal Clinical Database (NeoBase)26 | C | Denmark | Regional (North And South Jutland) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 2005–6 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 20 | Emilia-Romagna Health Agency27 | A | Italy | Regional (Emilia-Romagna) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2002–9 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks | Support from public body |

| 21 | EPICure28 | R | UK | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2006–7 (no) | Mother’s ethnicity, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, intervention, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 22 | Erie County Register29 | A | USA | Regional (Erie County, New York) | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2006–8 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 23 | EuroNeoNet30 | C | European | International (Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Turkey and the UK) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2006–11 (yes) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 24 | Florida birth registry31 | A | USA | Regional (Florida) | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2009–10 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 25 | Intermountain Health care32 | C | USA | Regional (Utah) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 2003–5 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Birthweight | Hospital subscription |

| 26 | Israel National VLBW Infant Database33 | C | Israel | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1995–2003 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 27 | Japanese Vital Statistics34 | A | Japan | National | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 1999–2008 (yes) | Mother’s age | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity | Support from public body |

| 28 | Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program35,36 | C | USA | Regional (Northern California and Boston, Massachusetts) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 1995–6 (yes) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Hospital subscription |

| 29 | Kids’ Inpatient Databases37 | R | USA | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2003–12 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity | Birthweight, sex | Support from public body |

| 30 | Linked Emergency Management and Research Institute – Department of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Gujarat38 | A | India | Regional (Gujarat) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from administrative data source | 2008–9 (yes) | Mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks | Support from public body |

| 31 | London Neonatal Transfer Service39 | C | UK | Regional (London) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2005–11 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight | Support from public body |

| 32 | Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile (MassCHIP) and PELL40,41 | A | USA | Regional (Massachusetts) | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 2002–10 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age | Gestational age in weeks, multiplicity, intervention | Support from public body |

| 33 | Malaysian National Neonatal Registry42 | C | Malaysia | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2006–7 (yes) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, blood cultures, abdominal X-rays, cranial ultrasound | Support from public body |

| 34 | Medicaid Analytic eXtract43 | A | USA | National | Health insurance enrolment | Extracted from administrative data source | 2006–8 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Identifier | Support from public body |

| 35 | Memorial Care Medical Centres: Perinatal database, Quality Improvement Database44 | C | USA | Regional (California) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2002–3 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, identifier, intervention | Hospital subscription |

| 36 | Michigan Linked Records45 | A | USA | Regional (Michigan) | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 2003–4 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 37 | National Centre for Health Statistics linked live birth and infant death cohort file46 | A | USA | National | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 1998–9 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity | Support from public body |

| 38 | National Collaborative Perinatal Neonatal Network47 | C | Lebanon | Regional (Greater Beirut) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2009–10 (not identified) | Mother’s age, mother’s education | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity | Support from public body |

| 39 | National Institute for Health and Welfare: Medical Birth Register48 | A | Finland | National | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2012–13 (yes) | Mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 40 | National Neonatal Database SEN150049 | C | Spain | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2002–5 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, diagnoses, blood cultures, abdominal X-rays, cranial ultrasound | Support from public body |

| 41 | National Neonatal Perinatal Database50 | C | India | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2002–3 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, intervention | Support from public body |

| 42 | NNRD51 | C | UK | National | Admission to neonatal units, all infants included | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 2009–11 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, diagnoses, blood cultures, abdominal X-rays, ROP, cranial ultrasound, post-discharge information | No current funding support identified |

| 43 | National Perinatal Information Centre52 | A | USA | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2004–8 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, sex, identifier | Support from public body |

| 44 | National Perinatal Registry of Slovenia53 | A | Slovenia | National | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2012–13 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks | Support from public body |

| 45 | National Perinatal Registry, the Netherlands54 | C | The Netherlands | National | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2003–7 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 46 | National Perinatal Data Collection55 | A | Australia/New Zealand | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Extracted from administrative data source | 2001–5 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 47 | National Registry of Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Romania56 | C | Romania | National | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2011–12 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 48 | Neonatal Intensive Care Outcomes and Research Evaluation57 | C | UK | Regional (Northern Ireland) | Admission to neonatal units, all infants included | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 1999–2000 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, blood cultures, abdominal X-rays, cranial ultrasound | Support from public body |

| 49 | Neonatal Research Network of Japan58 | R | Japan | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2003–8 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, intervention, blood cultures | Support from public body |

| 50 | NEOSANO’s Perinatal Network in Mexico59 | A | Mexico | Regional (Mexico City, Tlaxcala City and Oaxaca City) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2006–9 (yes) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, multiplicity | Support from public body |

| 51 | New Jersey Perinatal Linked Data-Set60 | A | USA | Regional (New Jersey) | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 1997–2005 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, identifier | Support from public body |

| 52 | New South Wales Newborn and Paediatric Emergency Transport Service61 | C | Australia/New Zealand | Regional (New South Wales) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 1992–2001 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, intervention | Support from public body |

| 53 | New York State-wide Perinatal Data System62 | A | USA | Regional (New York) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from administrative data source | 1996–2003 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 54 | Newfoundland and Labrador Provincial Perinatal Program Database63 | C | Canada | Regional (Newfoundland and Labrador) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from administrative data source | 2001–9 (yes) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity | Support from public body |

| 55 | NICHD Neonatal Research Network Generic Database64 | R | USA | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1998–2009 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 56 | Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database65 | A | Canada | Regional (Nova Scotia) | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 2002–11 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 57 | NSW Pregnancy and Newborn Services Network66 | C | Australia/New Zealand | Regional (New South Wales And Australian Centralised Territory) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1997–2006 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, intervention | Support from public body |

| 58 | Pediatrix BabySteps Clinical Data Warehouse67 | C | USA | National | Admission to neonatal units, all infants included | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 1996–2010 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, blood cultures | Hospital subscription |

| 59 | Perinatal and Neonatal Surveys in Saxony68 | C | Germany | Regional (Saxony) | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2001–5 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 60 | Perinatal database of Middlesex Country, Canada69 | C | Canada | Regional (Middlesex County, Ontario) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 2002–11 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex | Support from public body |

| 61 | Perinatal Revision South70 | C | Sweden | Regional (Southern Sweden) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Recorded specifically for database | 1995–6 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, identifier | Support from public body |

| 62 | Perinatal Services British Columbia71 | A | Canada | Regional (British Columbia) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from administrative data source | 2004–14 (yes) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 63 | Population Health Research Data Repository72 | A | Canada | Regional (Manitoba) | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 2004–9 (yes) | Mother’s age | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 64 | Scottish Administrative Linked Data73 | A | UK | National | No limitations, entire region included | Extracted from administrative data source | 1981–2007 (yes) | Mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 65 | Seguro Medico para una Nueve Generacio74 | A | Mexico | National | Health insurance enrolment | Recorded specifically for database | 2008–9 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, sex, identifier | Support from public body |

| 66 | Swedish Neonatal Quality Register75,76 | C | Sweden | National | Admission to neonatal units, all infants included | Extracted from administrative data source | 2001–2 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, blood cultures, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 67 | Swiss Neonatal Network77 | C | Switzerland | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1996–2008 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, intervention, blood cultures, ROP, post-discharge information | Hospital subscription |

| 68 | Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database78 | A | Taiwan | National | Health insurance enrolment | Extracted from administrative data source | 1998–2001 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, intervention, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 69 | Tennessee Hospital Discharge Data System79 | A | USA | Regional (Tennessee) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from administrative data source | 2003–5 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity | Birthweight, sex, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 70 | The National Neonatology Database80 | C | The Netherlands | National | Admission to neonatal units, all infants included | Recorded specifically for database | 2003–5 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 71 | The Neonatal Survey81 | C | UK | Regional (East Midlands and Yorkshire) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2008–10 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, infant identification, intervention, diagnoses, laboratory samples, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 72 | The WHO’s Global Survey for Maternal and Perinatal Health82,83 | S | International [Africa (Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Algeria, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria and Uganda), Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay and Peru) and Asia (Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam)] | International | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2004–8 (no) | Mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 73 | Vermont Oxford Network84 | C | International (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Columbia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Kuwait, Malaysia, Namibia, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, the UK and the USA) | International | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1990–2012 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention, blood cultures, abdominal X-rays, cranial ultrasound | Hospital subscription |

| 74 | Victorian Perinatal Data Collection Unit85 | R | Australia/New Zealand | Regional (Victoria) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1979–97 (no) | No variables identified from those sought | Birthweight, sex, identifier, ROP, post-discharge information | Support from public body |

| 75 | West Midlands Perinatal Institute86 | C | UK | Regional (West Midlands) | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 2008–9 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | No variables identified from those sought | No current funding support identified |

| 76 | Wisconsin Linked Birth Record File87 | A | USA | Regional (Wisconsin) | Health insurance enrolment | Extracted from administrative data source | 2001–2 (yes) | Mother’s ethnicity, mother’s age, mother’s education, mode of delivery | Birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier | Support from public body |

| 77 | AOK National Insurance Entries88 | A | Germany | National | Health insurance enrolment | Recorded specifically for database | 2002–6 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | No variables identified from those sought | Insurance |

| 78 | Regional Census Data89 | A | Germany | Regional (Westfalen Lippe) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 1990–6 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Blood cultures | Support from public body |

| 79 | Neonatal Quality Assurance System90 | A | Germany | Regional (Baden Wuertemberg) | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2003–4 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | No variables identified from those sought | Support from public body |

| 80 | Bourgogne database91 | A | France | Regional (Bourgogne) | Admissions or births in enrolled hospitals | Extracted from clinical data source (electronic health records) | 2000–1 (yes) | Mode of delivery | Gestational age in weeks, birthweight, sex, multiplicity, identifier, intervention | Support from public body |

| 81 | Multicentre national database92 | R | France | National | Admission to neonatal units, gestational age and/or birthweight cut-off point | Recorded specifically for database | 2005–6 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | Gestational age in weeks, sex, intervention | Support from public body |

| 82 | Hessen Neonatal Register93 | A | Germany | Regional (Hessen) | No limitations, entire region included | Recorded specifically for database | 1989–2012 (yes) | No variables identified from those sought | No variables identified from those sought | Support from public body |

Primary purpose of databases

Of the 38 national databases, the primary purpose was clinical in 18, administrative in 13 and research in seven. Of the 40 regional databases 15 were clinical, 23 were administrative and two were research orientated. We identified four international databases (two were clinical, one was research and one was surveillance).

Data sources

Specific data collection is required for 28 out of 38 national databases. Data are extracted from a primary administrative source for seven databases, and from a primary clinical source for three databases (UK: NNRD; USA: Consortium of Safe Labor Database and Pediatrix BabySteps Clinical Data Warehouse) (see Table 3). Twenty-one of the 40 regional databases require specific data collection and, for 14, the source is an administrative database and, for 5, the source is clinical (see Table 3). All four international databases require specific data recording.

Population coverage

Twenty-seven databases hold data on all admissions to neonatal units, and the remaining databases restrict data by gestational and/or birthweight cut-off points, and/or enrolment or insurance cover.

Funding sources

Of the 82 databases identified, 71 receive funding from public sources, eight are funded through hospital subscriptions and one is funded through private insurance. We were unable to identify the funding source for the French AUDIPOG (Association des Utilisateurs de Dossiers Informatisés en Pédiatrie, Obstétrique et Gynécologie) Network;11 the NNRD was developed in part through public research funding, but has no ongoing funding support.

Summary

The NNRD is one of six national neonatal databases with ongoing data acquisition, primarily developed to support research. Uniquely, and in contrast to each of the other five (databases 16, 29, 49, 55 and 81 in Table 3), data in the NNRD are extracted from EPRs rather than being recorded specifically. There is complete national coverage of all admissions to neonatal units and no gestational age, birthweight, insurance cover or other restrictions.

Regulatory approvals

We obtained National Research Ethics Service approval in 2010 to establish a NNRD from extracts from EPRs, undertake projects within the Medicines for Neonates Programme, and employ the NNRD for NHS service evaluations and other research studies (REC reference number 10/H0803/151; provided as Appendices 5 and 6). We obtained approval in 2010 from the Confidentiality Advisory Group of the Health Research Authority [formerly Ethics and Confidentiality Committee of the National Information Governance Board; reference number ECC 8–05(f)/2010; provided as Appendix 4] to receive specific patient identifiers for the purpose of linking to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data.

Under standard operating procedures for Research Ethics Committees, site-specific approval is not required for studies conducted using research databases. There is no requirement for specific ethics approval for data collection centres that provide data because, under the Research Governance Framework, data collection centres are not regarded as research sites. NHS trust approval (‘R&D’ approval) is only required from the NNRD host institution (i.e. not from each data collection centre). However, we were informed that ‘local collaborators at Data Collection Centres within the NHS will require internal permission from their NHS care organisation to collect and supply data relating to NHS patients’. 94 We addressed this requirement by seeking Caldicott Guardian and Lead Neonatal Clinician approval from every NHS trust providing neonatal specialised care, to receive a defined extract from their neonatal EPRs, to hold these in the NNRD and to use these in NHS service evaluations and Research Ethics Committee-approved research studies. We obtained approvals incrementally and all NHS trusts in England, Wales and Scotland have now granted approval.

The National Neonatal Research Database

The data items constituting the Neonatal Data Set (NND) are extracted from EPRs created by clinical staff on all admissions to neonatal units in England, Wales and Scotland. Neonatal units in Northern Ireland utilise the same EPR platform but, to date, the regulatory approvals governing data transfer into the NNRD have not been sought. Following receipt of the necessary approvals, retrospective data extraction was undertaken so that the NNRD contains data from 2007 to the present. The NNRD is updated quarterly, and to date it contains data on approximately half a million infants and > 5 million care days. All neonatal units across England, Wales and Scotland have approved the release of Neonatal Data Set data items for inclusion in the NNRD (the total number of neonatal units is approximately 200, which has fluctuated over the course of the Medicines for Neonates programme as neonatal units have merged or reorganised).

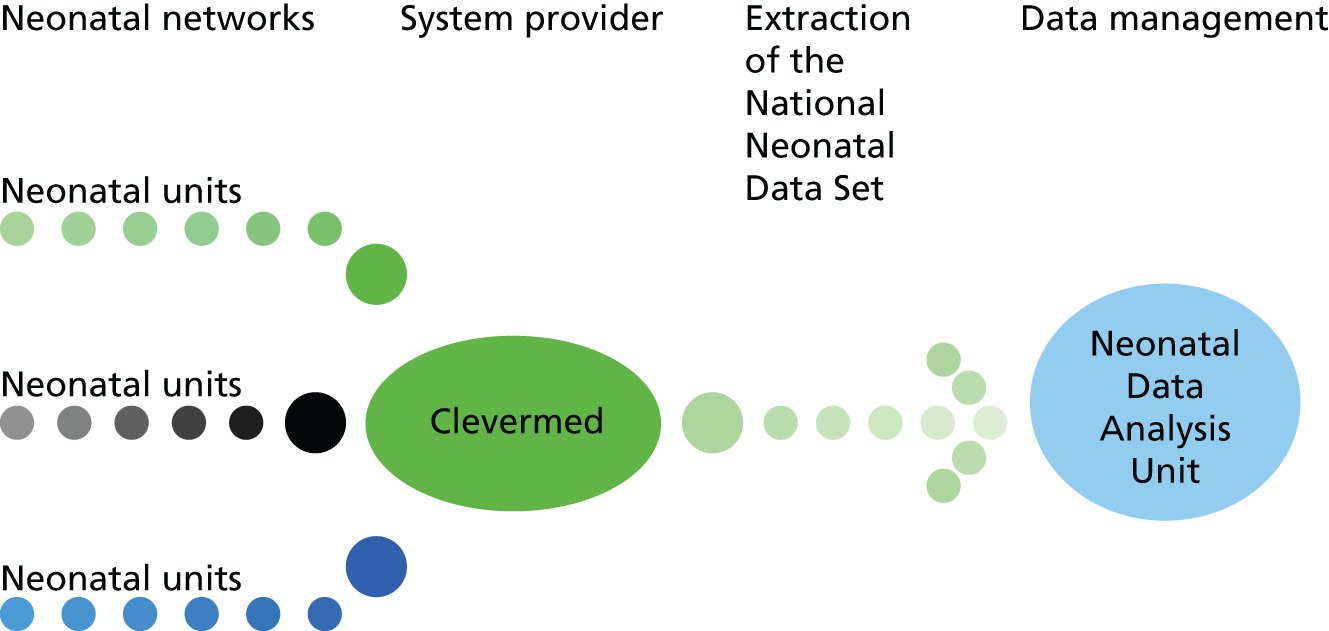

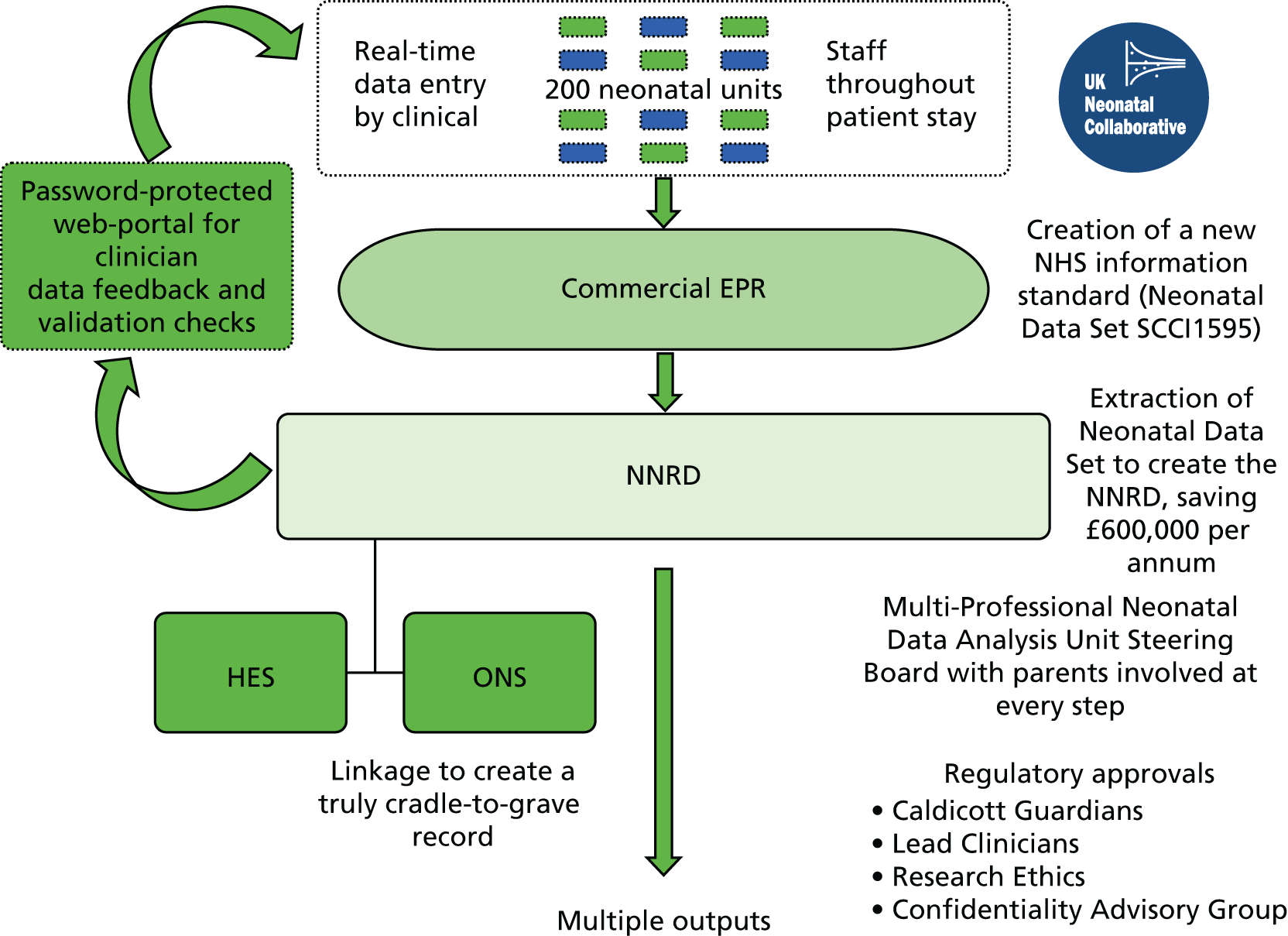

An NHS approved supplier, Clevermed Ltd (Edinburgh, UK), provides a web-based data capture platform known as Neonatal.Net or BadgerNet. Data held by Clevermed Ltd are stored on a secure N3 server and transmitted to the Neonatal Data Analysis Unit (NDAU) where they are used to create the NNRD after merging and cleaning of files. The NNRD is held on the NHS servers of Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust. Data flows are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

FIGURE 3.

Data flows to create the NNRD. ONS, Office for National Statistics.

Data management

At the NDAU, all data extracted from the neonatal EPRS are interrogated to identify duplicate, missing and potentially erroneous entries. Items are considered potentially erroneous if they fail a series of out of range, internal logic, and internal inconsistency checks.

A web-based portal was created to notify neonatal unit lead clinicians of missing or potentially erroneous entries. If clinical teams amend errors or complete missing fields, this is done in the baby’s EPR and this is sent to the NDAU at the next download. Initially, this process was confined to the data items (approximately 60 items) used for analyses for the National Neonatal Audit Programme. In addition, as the NNRD has become used for research studies, if key data items are required for specific projects then these are also subjected to the feedback loop process.

At the NDAU, patient episodes across multiple neonatal units are also merged to create a single file for each infant.

Clinician engagement

We termed NHS neonatal units contributing data to the NNRD the ‘UK Neonatal Collaborative’. Of note was that, although only site-specific approval and NHS approvals are required for the NNRD host institution, we would adopt a policy of seeking the approval of each NHS trust’s lead neonatal clinician for their data to be included in research studies. We adopted this practice in order to grow clinician engagement with the concept of the NNRD as a national resource and in recognition of their crucial contribution to acquiring the data.

Parent information leaflet

We collaborated with the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, the national charity Bliss and the parents of newborn babies receiving specialised neonatal care to develop a parent information leaflet (‘A Guide for Parents and Carers’) that explains the multiple uses of the NNRD. This was approved by the National Research Ethics Service and the Ethics and Confidentiality Committee of the National Information Governance Board.

If the parent or carer of the infant does not wish for EPR data on their infant to be extracted for the NNRD, then they can notify the neonatal unit staff who will then notify the data entry system supplier to prevent the flow of the data. To date, no parent or carer has asked that their infant’s data not be extracted.

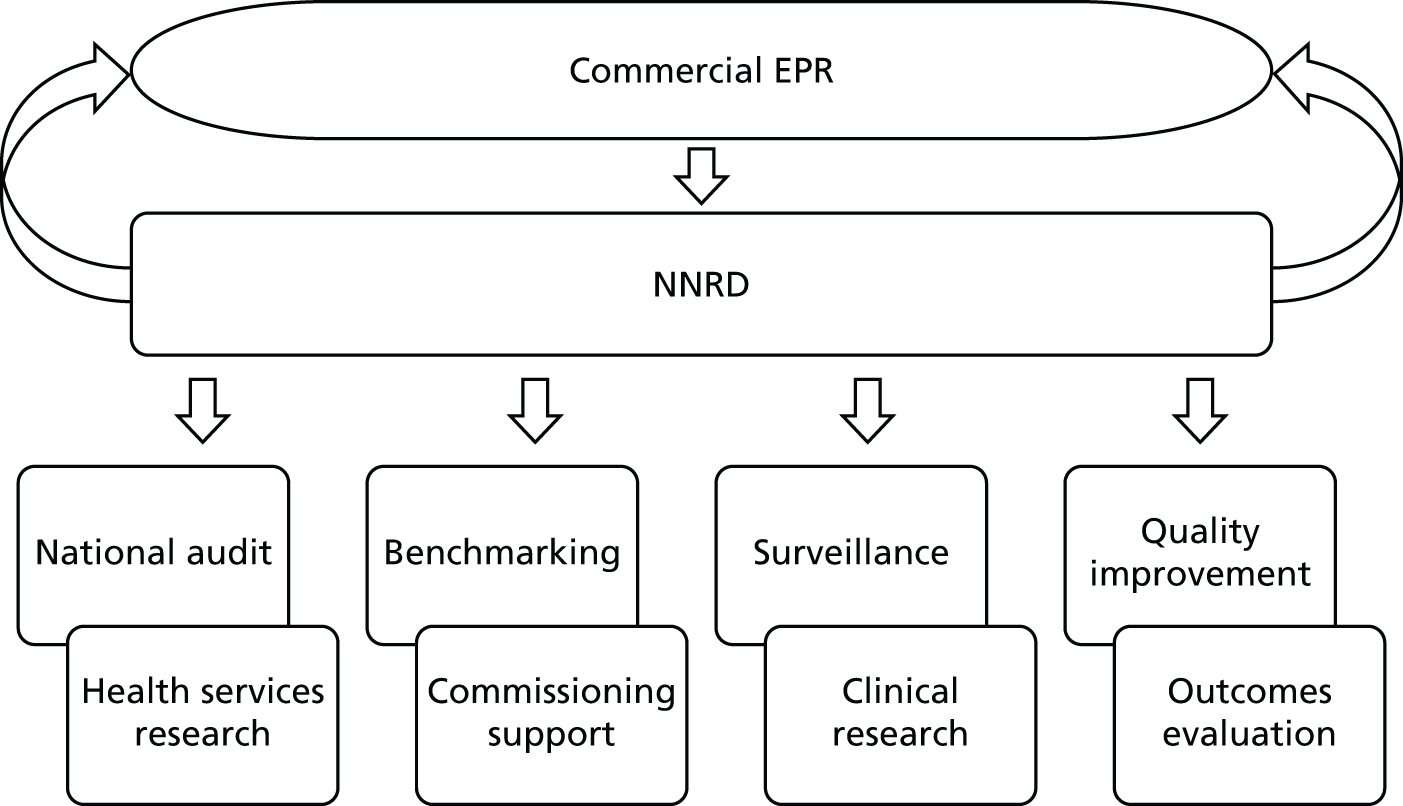

Uses and outputs of the National Neonatal Research Database to date

The use of the NNRD to support a wide range of outputs grew rapidly over the course of the Medicines for Neonates Programme, and continues to expand. Examples of the multiple outputs from the NNRD are shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Examples of multiple outputs from the NNRD.

Conclusions

We have shown that it is possible to create a national data resource, the NNRD, from extractions from EPRs, which brings multiple benefits. This eliminates the need for multiple individual collections, with repetitive capture of many commonly required data items. This in turn reduces the burden of data capture all too often imposed on busy clinical teams, and reduces the risk of transcription errors and other errors.

Our literature search identified 82 databases worldwide that hold neonatal information. The NNRD is one of only six national neonatal databases primarily developed to support research, with ongoing data acquisition. Uniquely, data in the NNRD are extracted from EPRs rather than being recorded specifically and there is complete national coverage of all admissions to neonatal units with no gestational age, birthweight, insurance cover or other restrictions.

The Neonatal Data Set incorporates data required to fulfil all currently mandated UK requirements. In addition, the Neonatal Data Set is sufficiently comprehensive to make the need for subsequent addition of new national data items unlikely in the immediate future. However, should this be required, the process for incorporation of new items into the EPR is straightforward (see Chapter 2, Research on an exemplar condition).

We have demonstrated that the approach we have adopted has been successful. The NNRD is now used for a growing number of purposes by a growing number of research groups, professional organisations and government bodies. In effect, our approach has gone a considerable way towards fulfilling the vision set out by Florence Nightingale more than 100 years ago and, more recently, the principles set out in successive national information strategies. These include the Council for Science and Technology report Better Use of Personal Information: Opportunities and Risks,95 the UK Clinical Research Collaboration Research and Development Advisory Group to Connecting for Health,96 the Academy of Medical Sciences report entitled Personal Data for Public Good: Using Health Information in Medical Research,97 the Department of Health and Social Care’s entitled Toolkit for High Quality Neonatal Services,98 and the aspiration articulated by the then Prime Minister, in numerous references to ‘big data’. We believe that the NNRD may reasonably be termed an example of ‘big data’. Although the term has been defined in various ways, Wang and Krishnan99 state that ‘A popular definition of big data is the “3V” model proposed by Gartner, which attributes three fundamental features to big data: high volume of data mass, high velocity of data flow, and high variety of data types’. The data in the NNRD does encompass each of these elements to varying extents, in contrast with many other clinical data sets that are much simpler.

In conclusion, we have established proof of the principle that EPR data may be employed successfully to support patient care and clinical services through research and a range of evaluations. We have shown that it is possible to reduce the burden placed on busy clinical teams by providing a single national data source to service multiple outputs.

Other Medicines for Neonates workstreams deal with issues of data quality, utility and patient (parent) involvement.

Implications for health care

The Medicines or Neonates programme has also established proof of concept for the use of EPR-derived clinical data in a wide range of research and health service evaluations. This opens up the possibility of adapting the road map that we have established for other specialty areas with potential to bring about NHS savings.

The NNRD has been developed and is currently maintained through academic endeavour, but processes to secure the stability of EPR-derived databases as national resources and their ongoing management are uncertain.

Research recommendations

A next step towards seizing the full potential of our approach for the benefit of the NHS and patient care would be to formally test the creation of another specialty database from EPRs using the road map that we have developed.

Chapter 2 Research on an exemplar condition: the use of the National Neonatal Research Database to study neonatal necrotising enterocolitis

Abstract

Background: Necrotising enterocolitis is a feared gastrointestinal inflammatory disease that predominantly affects preterm infants. The aetiology is uncertain and population incidence data are scant. Treatment is supportive and it includes surgery, but research is constrained by the relative rarity of the disease.

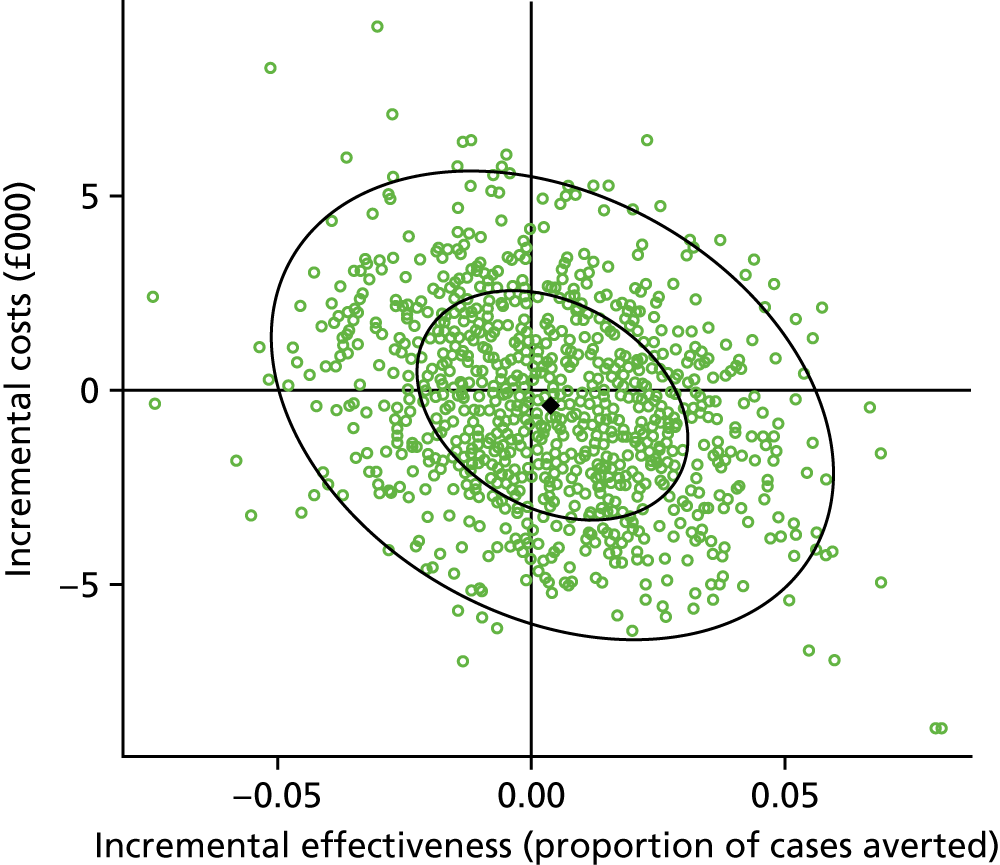

Aims and objectives: We utilised EPR-derived data to conduct population surveillance of severe NEC in England. Additional objectives were to inform the development of future clinical trials by identifying factors associated with severe NEC.

Methods: We secured the participation of every NHS neonatal unit in England in a prospective study. We extracted relevant data from the NNRD. We also obtained outcome data for infants who received NEC surgery or died from NEC at stand-alone paediatric surgical centres that do not use the neonatal EPRS.

Results: We identified 531 infants (462 who were born at < 32 weeks’ gestation) with severe NEC (resulting in surgery and/or death) over the complete 2-year period 2013–14. Among the infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation, neonatal network incidence ranged from 19.8 [95% confidence interval (CI) 9.1 to 30.4] to 47.4 (95% CI 32.5 to 62.4) per 1000 babies. We identified no strong evidence of variation between networks following adjustment for gestational age and birthweight standard deviation score (SDS), which were the only factors found to be independently associated with the disease.

Conclusions: The NNRD provides opportunity for rapid population surveillance of neonatal conditions and a source of baseline information to inform clinical trials but it requires strong clinician engagement.

Background

Necrotising enterocolitis is a feared gastrointestinal inflammatory disease that predominantly, but not exclusively, affects preterm infants. NEC is a principal cause of mortality and morbidity in very preterm infants. 100,101 The aetiology of NEC is uncertain and is likely to be multifactorial. Some studies have suggested that the most significant factor in determining NEC incidence is the neonatal unit in which an infant receives care, with the implication that variations in care affect risk. 102,103 In particular, there is a widespread view that enteral feeding regimens, including type of milk, affect the risk of NEC. However, lack of good evidence for specific feed-related interventions that affect the risk of NEC has resulted in variation in neonatal practice, entrenched clinical opinion and bewilderment among parents. Evidence is conflicting regarding whether or not antenatal steroid exposure, a strong predictor of neonatal survival, is associated with NEC. 102,104–110 A further difficulty is that the diagnosis of NEC can be difficult as signs are often non-specific and presentation is variable. No internationally agreed case definition exists, which makes comparisons between studies unreliable. The most frequently applied definitions include modified Bell’s criteria,111,112 which, although developed as criteria for staging after the diagnosis is made, have been widely adopted as a definition worldwide. There are also definitions from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) or IC-10 codes, the Vermont Oxford Network (VON), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and definitions from individual study authors. None has been developed through evidence-based methodology or has undergone validation.

In the absence of evidence from randomised trials, an approach that is widely believed to be of benefit is to identify variation in NEC incidence between neonatal units or networks, in the hope that this might help highlight potentially beneficial clinical practices that can then be tested in future randomised controlled trials.

Aims

We aimed to build on the establishment of the UK Neonatal Collaborative and the existence of the neonatal EPRS and NNRD to examine aspects of this serious disease. Our objectives were to:

-

conduct population surveillance of severe NEC

-

identify factors associated with severe NEC

-

evaluate variation in incidence across neonatal networks in England.

We also aimed to build engagement with local clinical staff responsible for recording neonatal data, through demonstration of the utility of EPR data in national research in an area considered a priority by parents and clinicians alike.

Methods

Approvals and agreements

We sought and obtained research ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service (Dulwich Research Ethics Committee; reference number 11/LO/1430) and inclusion into the UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio (ID 11853). We invited the participation of all neonatal units in England. We sought agreement from the local UK Neonatal Collaborative lead clinicians to utilise data from their neonatal unit held in the NNRD on all live-born infants admitted over the complete 2-year period 2012–13.

In order to promote maximal engagement with the neonatal community and optimise data quality and completeness, we asked local clinical staff to ensure that the following data items were recorded in each infant’s EPR: birthweight, gestational age, sex, mother’s race, antenatal steroids, and clinical and abdominal X-ray (AXR) findings for infants in whom abdominal signs were being investigated. We excluded infants of mothers that were unbooked, booked in non-English networks, or for whom network of booking was unknown.

Identifying babies with severe necrotising enterocolitis in the National Neonatal Research Database

We defined ‘severe NEC’ as NEC confirmed at surgery or post-mortem or resulting in death (death certification and/or verified by neonatal team). We initially intended to capture outcomes on a specific section of the neonatal EPRs, the screen used to record details of abdominal X-rays taken to investigate clinical signs consistent with gastrointestinal pathology. However, despite regular quarterly feedback of data completeness to neonatal units, we found that only 25% of infants who proceeded to NEC surgery had completed this screen; hence, sole use of these data would underestimate the incidence of severe NEC. Therefore, we used data from the NNRD to identify infants who may have received surgery for NEC or died from NEC, and verified these outcomes with clinicians at neonatal units. In addition, outcomes were sought for infants who received NEC surgery or who died at the four stand-alone paediatric surgical centres which do not use the BadgerNet neonatal EPRs (Great Ormond Street, Sheffield, Alder Hey and Birmingham Children’s Hospitals). Here, we describe the steps taken to identify and verify infants with severe NEC.

Step 1: data extraction

The variables extracted from the NNRD comprised static data (discharge/died status, cause of death, whether or not the post-mortem-confirmed NEC); daily data (NEC treatment: medical or surgical); episodic data (gastrointestinal diagnoses, discharge diagnoses, procedures during stay); AXR screen (whether or not surgery was required, whether surgery was required but the patient was too sick, whether or not the surgery-confirmed NEC, whether or not histology-confirmed NEC).

Step 2: data verification

We identified infants from the following EPR locations using the predefined field listed:

Discharge diagnoses

-

‘Necrotising enterocolitis – perforated’

-

‘Necrotising enterocolitis – proven (on X-ray or at surgery)’

-

‘Necrotising enterocolitis – confirmed’

-

‘Cause of death includes necrotising enterocolitis’.

Abdominal X-ray screen

-

‘Laparotomy-confirmed NEC’

-

‘Histology-confirmed NEC’

-

‘Post-mortem-confirmed NEC’

-

‘Procedures screen’

-

‘Laparotomy approach NEC’

-

‘Colectomy and ileostomy NEC’

-

‘NEC surgery performed’.

Combinations

-

‘Necrotising enterocolitis’ in ‘Discharge diagnoses’ and ‘Laparotomy’ in ‘Procedures’

-

‘Necrotising enterocolitis’ and ‘died’ in discharge status field.

Step 3

The study lead at each neonatal unit or paediatric stand-alone hospital where the surgery was performed or where the infant died was contacted to verify data. The following data were verified:

-

Gestation weeks and days.

-

Birthweight.

-

Did infant die in neonatal unit? (Yes/no.)

-

Age of infant at surgery for NEC (if applicable).

-

Was laparotomy performed? (Yes/no/required but too sick.)

-

Did visualisation confirm NEC? (Yes/no.)

-

Did histology confirm NEC? (Yes/no.)

-

Was a peritoneal drain inserted? (Yes/no.)

-

Was a post-mortem done? (Yes/no.)

-

If yes, did the post-mortem confirm NEC? (Yes/no.)

-

Was NEC a cause of death? (Yes/no).

Other data extraction from the National Neonatal Research Database: data management

We extracted the following data for all babies from the NNRD: booking network, gestational age in completed weeks and days, birthweight, fetus number, antenatal steroids, maternal pyrexia in labour, whether or not mother received antibiotics, mode of delivery, maternal chorioamnionitis and maternal infection. We calculated birthweight SDS, standardised for sex and gestational age from UK World Health Organization (WHO) reference data. 113 We considered a birthweight SDS of < –4 or > 4 to be erroneous, and we treated these as missing values.

Analyses

Incidence and absolute numbers of cases of severe necrotising enterocolitis

We expected all very preterm infants (born before 32 weeks’ gestation) to be admitted to a neonatal unit and, hence, derived the population incidence of severe NEC for this group. To ensure that this is a valid assumption, we compared the numbers of infants for whom data were present in the NNRD against the equivalent number obtained from the most recently available data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) as this contains complete birth registrations. For preterm infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation, we report the incidence of severe NEC (95% CIs) per 1000 infants admitted to neonatal care. In contrast, not all infants born at a gestational age of ≥ 32 weeks will necessarily be admitted to a neonatal unit and so, for this group, we only present the absolute numbers of cases of severe NEC. For infants who received surgery for NEC, we will report the median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for postnatal age and postmenstrual age for the day of surgery by gestational bands.

Factors associated with severe necrotising enterocolitis in infants born at a gestational age of < 32 weeks

For preterm infants, we compared baseline characteristics for gestational age in completed weeks, birthweight SDS, fetus number, antenatal steroids, maternal pyrexia in labour, whether or not mother received antibiotics, mode of delivery, maternal chorioamnionitis and maternal infection between those with severe NEC and those who did not develop the condition. We used the chi-squared test, the application of Yate’s correction and the t-test, as appropriate. We performed a stepwise multiple logistic regression; variables found to be significantly associated with severe NEC in the univariate logistic regression analysis (p < 0.15) were considered candidate variables for the multivariable logistic regression model. For the final multivariable model, we retained only variables that were significant independent predictors of NEC. We further investigated the effect of retaining and excluding antenatal steroid exposure in the final multivariable model. The level of statistical significance for all analyses was set at p < 0.05 using two-tailed comparisons.

Variation in the incidence of severe necrotising enterocolitis among infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation

For preterm infants, we report the incidence of severe NEC (95% CIs) per 1000 infants admitted to neonatal care by network of booking. We assessed whether or not there was variation in the incidence of severe NEC at network level in two ways. First, we compared the rate in each neonatal network against the average incidence across England. Second, we compared each individual network against a reference network. We selected the reference as the network contributing the largest number of infants, to minimise the standard errors.

In the first approach, we used methods analogous to those used to calculate standardised mortality ratios (SMRs), assigning infants to the neonatal network of booking. We calculated the standardised severe NEC ratio (SNR) by dividing the observed number of severe NEC cases by the expected number of severe NEC cases. For the unadjusted SNR, the expected number of severe NEC cases was calculated as the total number of infants in the booking network multiplied by the overall severe NEC rate across England. For the adjusted SNR, the expected number of severe NEC cases was calculated by first estimating the probability of severe NEC for each infant using logistic regression, and adding up the probabilities to obtain the expected number of severe NEC cases in each network. The 95% CIs for the SNR were calculated using Byar’s approximation114 with correction for multiple testing, controlling the false discovery rate at 5%. 115 Variables included in the logistic regression to estimate the probability of severe NEC for each infant were gestational age (in completed weeks), birthweight SDS and antenatal steroids.

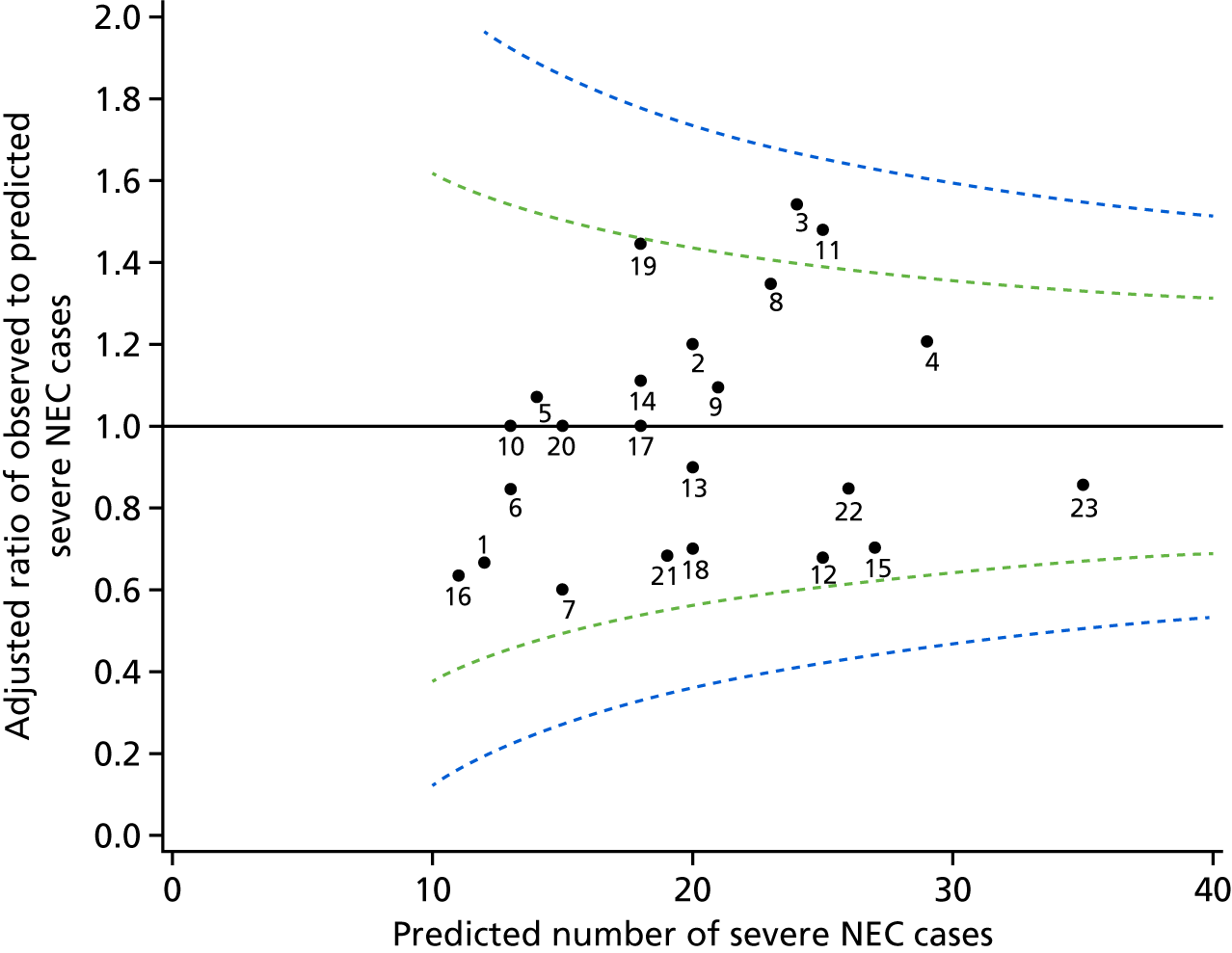

Funnel plots were used to illustrate the SNR at network level. The prediction limits were drawn corresponding to 95% (SD 2) 99.8% (SD 3) from the target SNR of 1, assuming the observed severe NEC rates follow a Poisson distribution. The limits were adjusted for multiple testing controlling the false discovery rate of 5%.

We expect 5% of networks to lie outside the 95% prediction limits, and 0.2% to lie outside the 99.8% prediction limits. For the second approach, we used multivariable logistic regression adjusted for antenatal steroid exposure and variables independently associated with severe NEC to derive the odds ratio (OR) for severe NEC in each network relative to the reference network. We corrected for multiple testing using the Bonferroni method. All p-values reported are two sided. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS® software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Data validation

We compared data from the NNRD with data from paper medical notes as part of a project evaluating a quality improvement project conducted by the East of England Neonatal Networks. 116 In brief, between 2011 and 2013, we assessed and fed back completeness and accuracy of NNRD data to participating neonatal teams involving 17 neonatal units. The study lead at each neonatal unit extracted a selection of data items from medical notes for two randomly selected infants discharged in the previous month. These data were sent to the NDAU and compared with NNRD data.

Results

Incidence and numbers of cases of severe necrotising enterocolitis

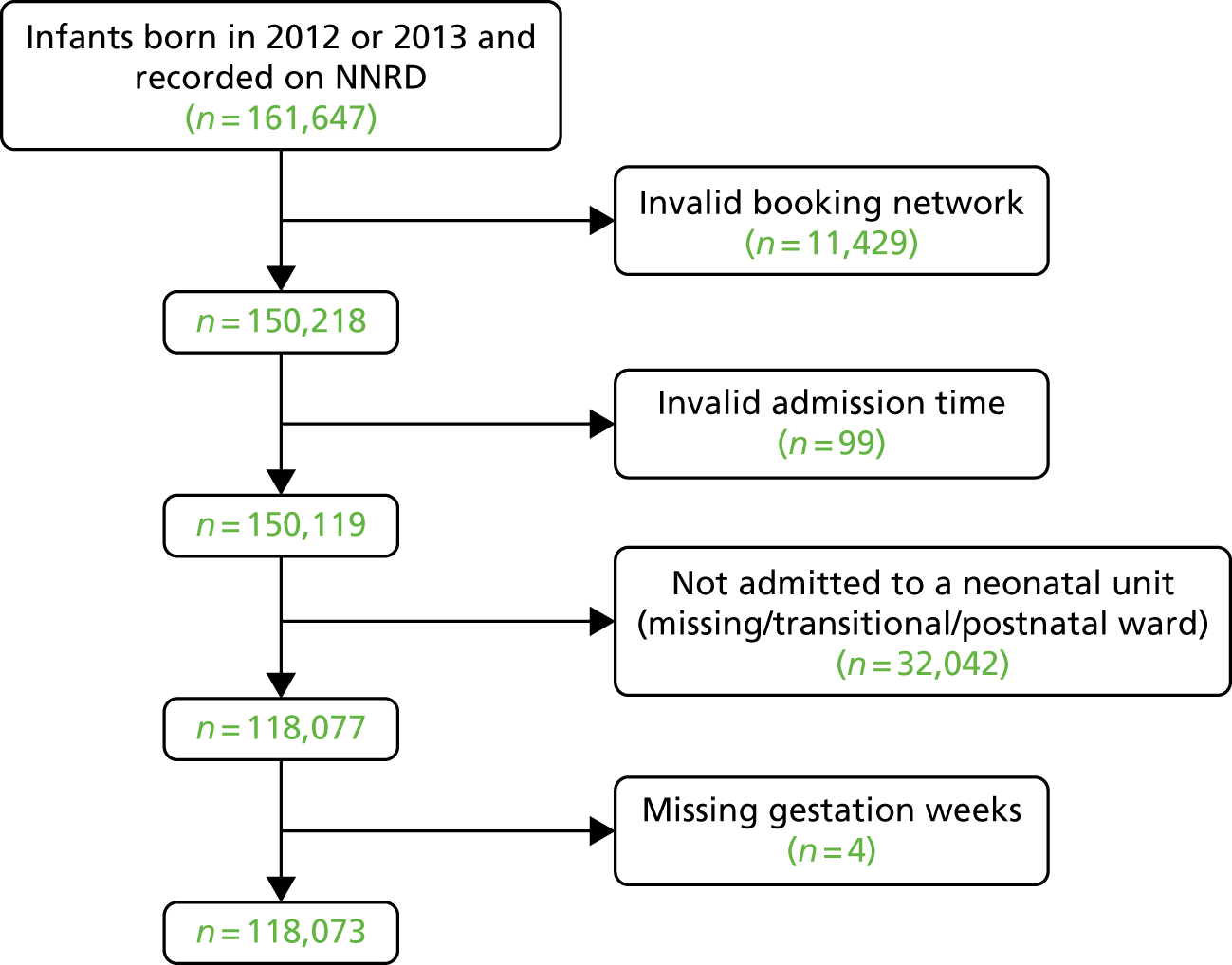

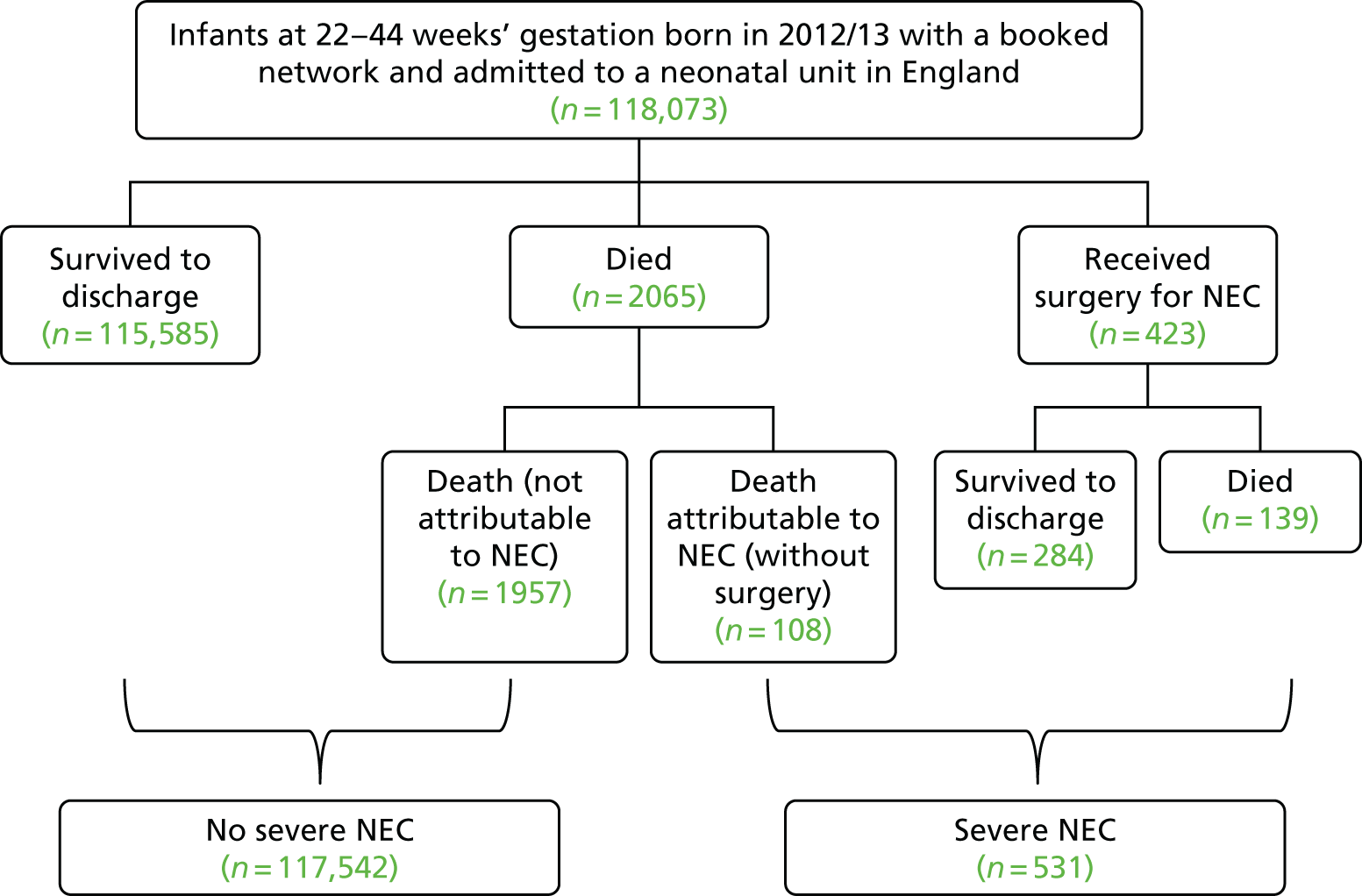

We extracted data on a total population cohort of 118,073 infants (Figure 5). We identified 531 infants with severe NEC. Table 4 shows the proportion of infants with severe NEC who had surgery and survived to discharge from neonatal care, who had surgery and died, and who died without surgery, by gestational age bands. Of the total number of infants with severe NEC 79.7% (423/531) had surgery; of those who had surgery 32.9% (139/423) died; 20.3% (108/531) of infants with severe NEC had died without surgery (Figure 6).

FIGURE 5.

Flow chart showing derivation of the study population.

| Gestation (completed weeks) | Infants with severe NEC (N = 531), n | Total, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery and survived | Surgery and died | Died without surgery | ||

| 22+0 to 25+6 (n = 2035) | 101 | 58 | 41 | 200 |

| 25+0 to 28+6 (n = 4331) | 97 | 56 | 42 | 195 |

| 29+0 to 31+6 (n = 8312) | 42 | 12 | 13 | 67 |

| 32+0 to 36+6 (n = 42,169) | 29 | 11 | 12 | 52 |

| ≥ 37+0 (n = 61,226) | 15 | 2 | 0 | 17 |

| All gestations (n = 118,073) | 284 | 139 | 108 | 531 |

FIGURE 6.

Flow chart showing the population with severe NEC.

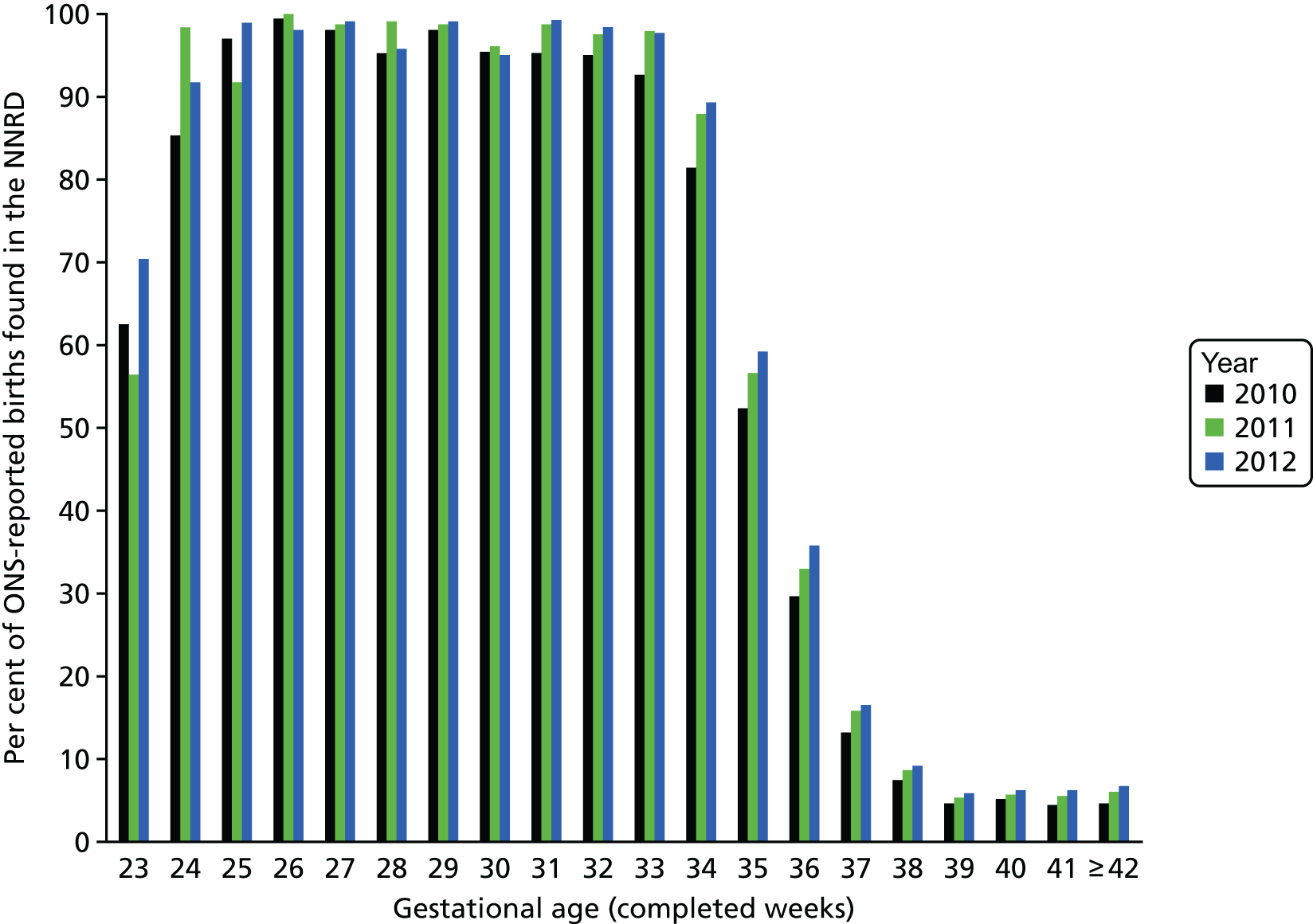

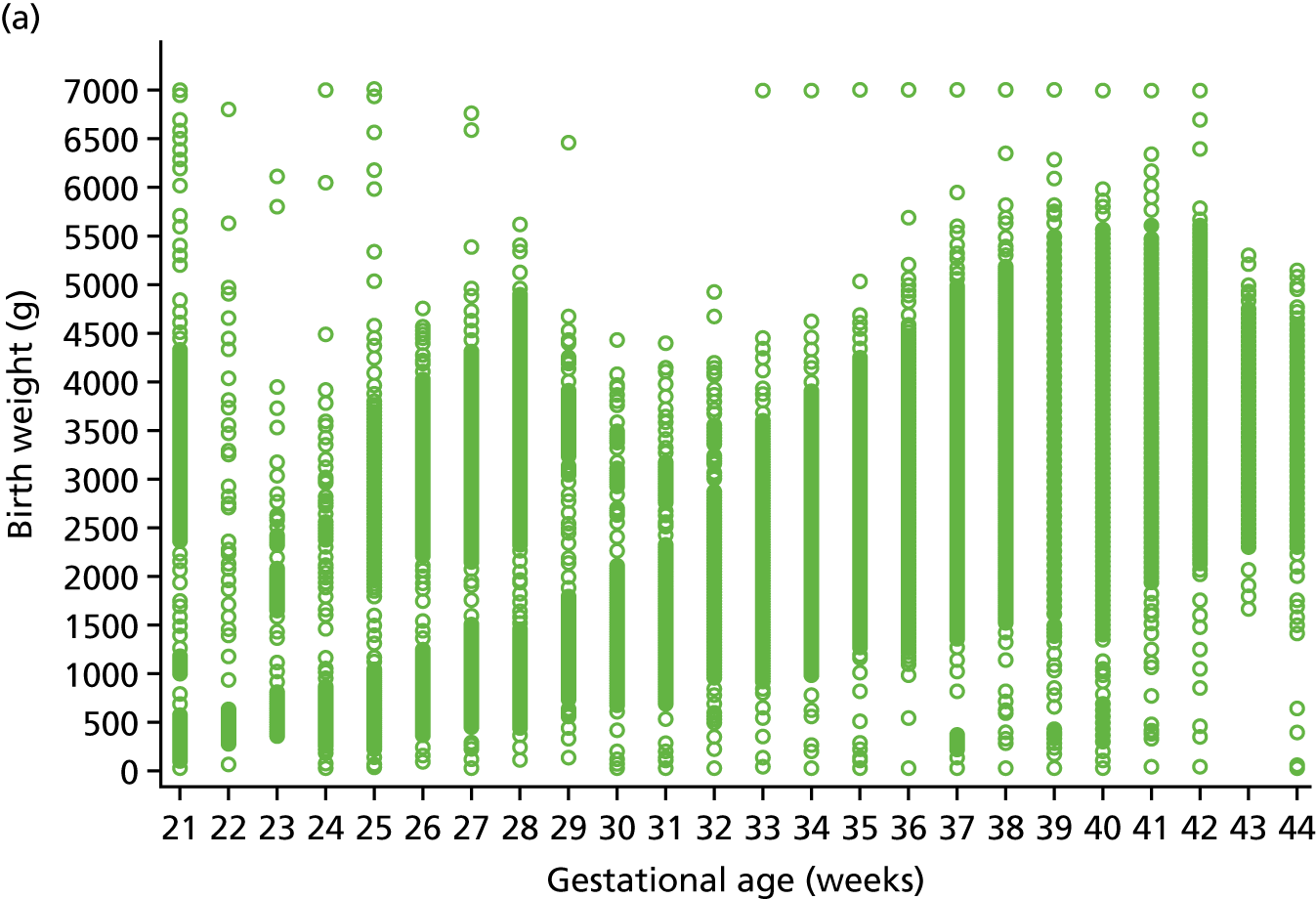

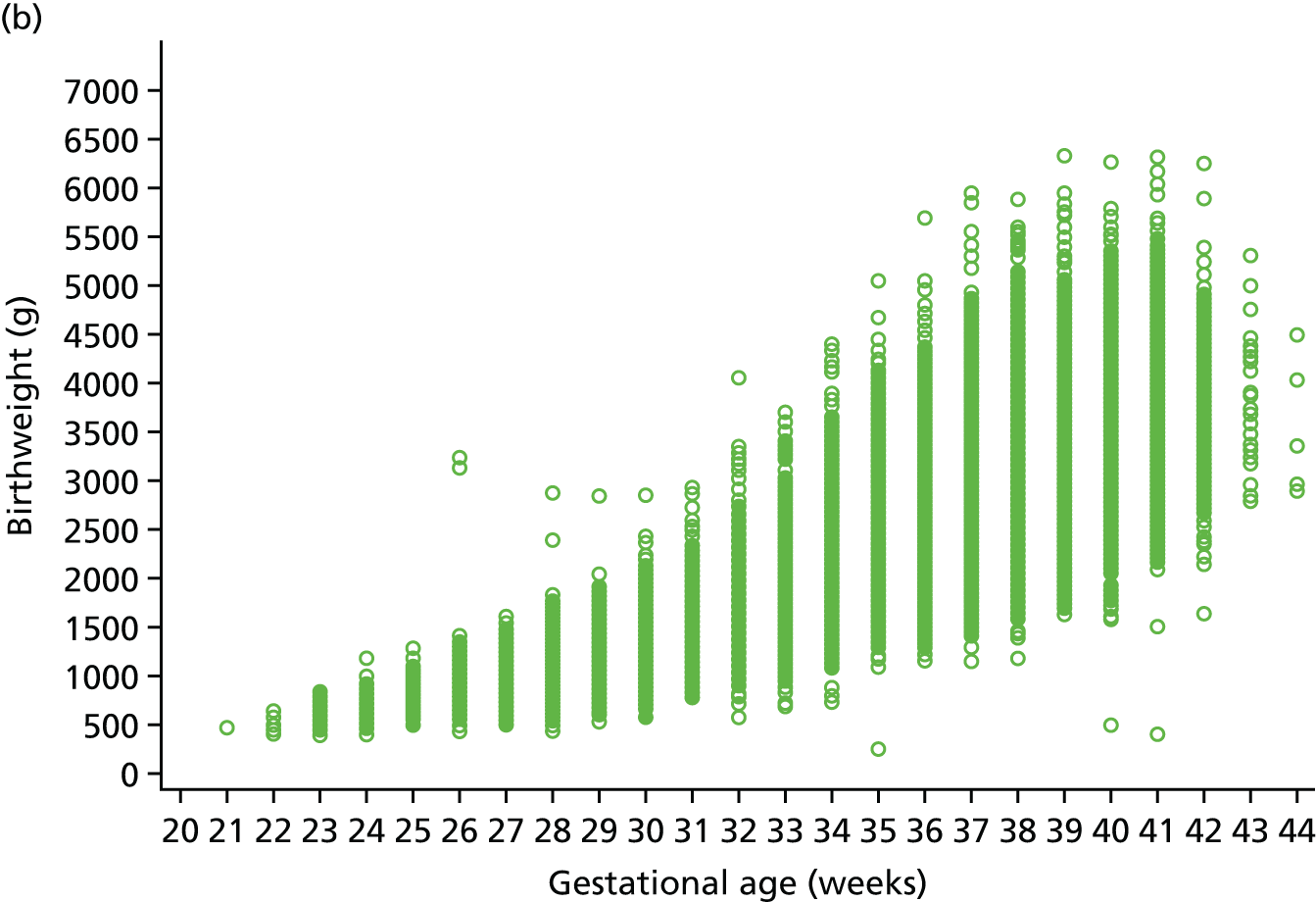

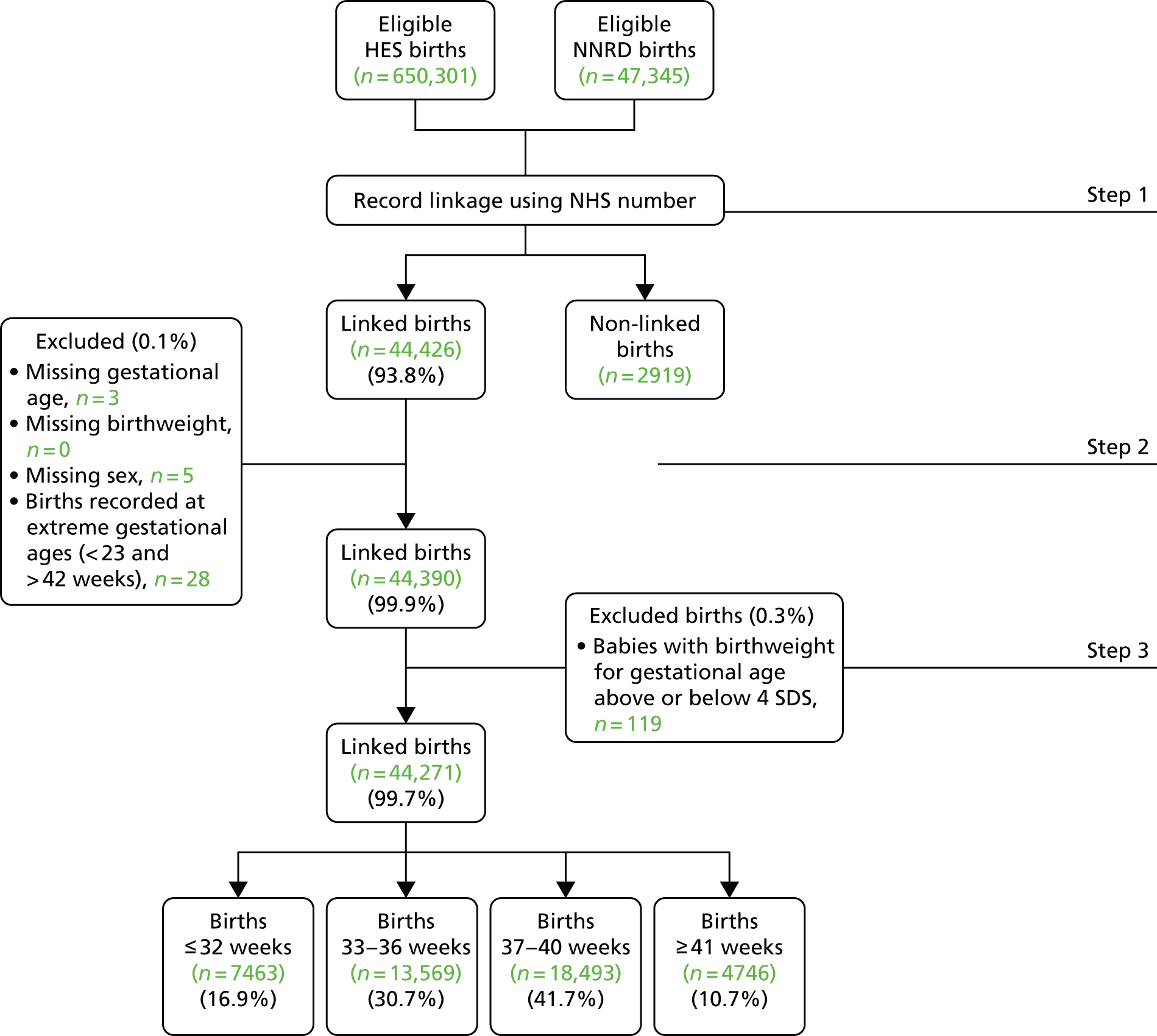

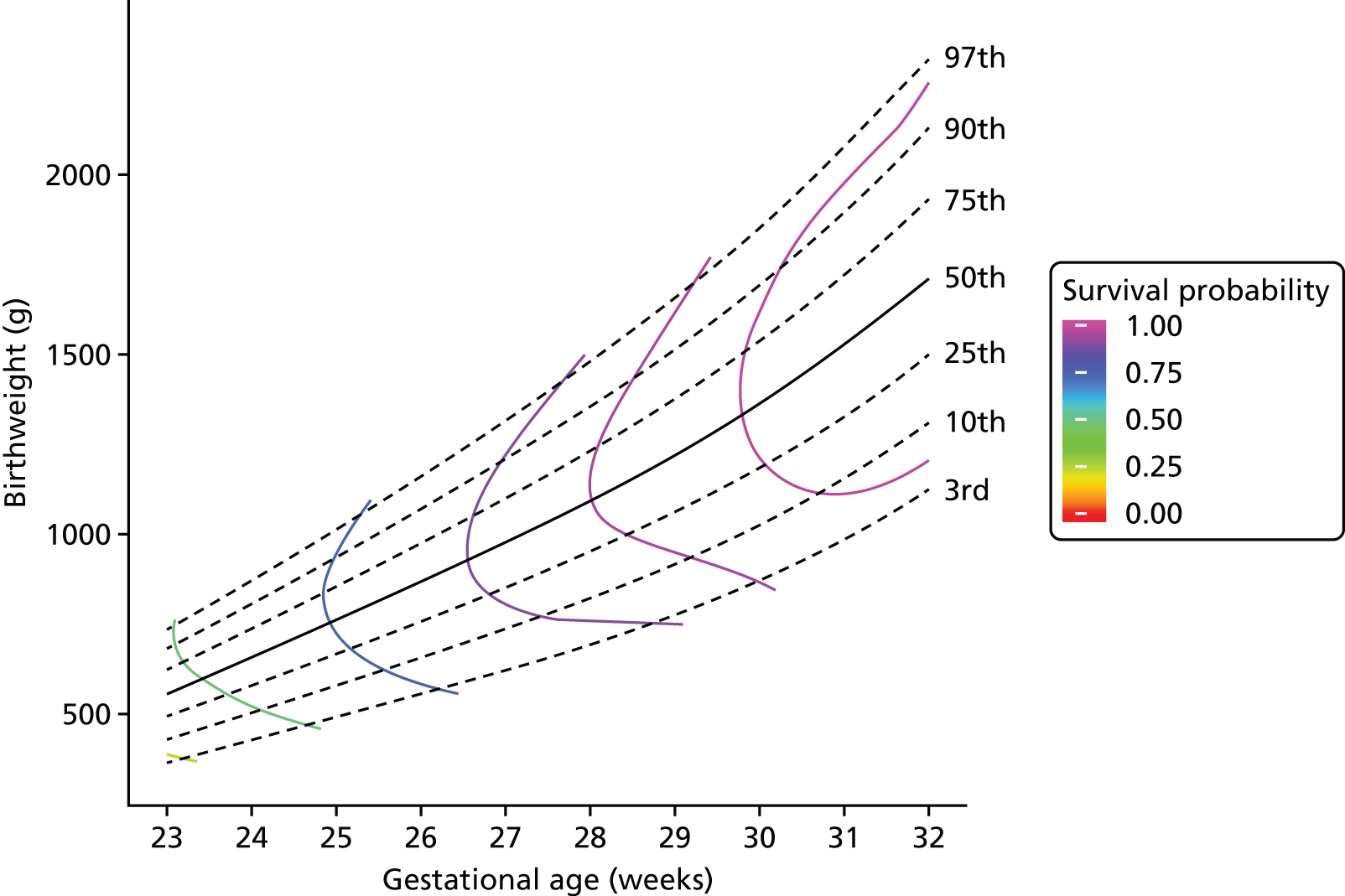

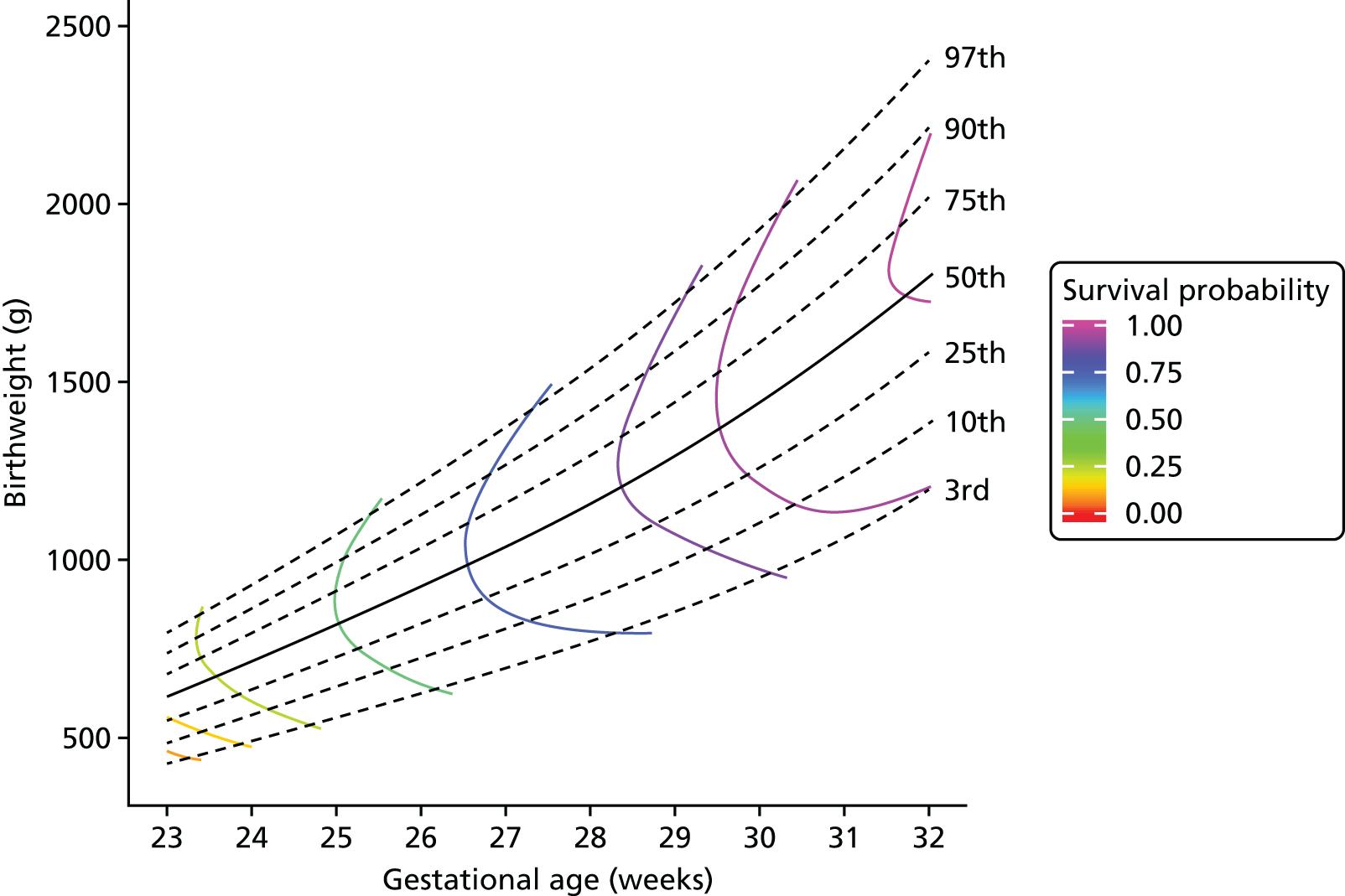

Comparing ONS data with NNRD data from 2012 shows that of the infants who were born alive in England between the gestational ages of 25 and 31+6 weeks, 96–99% were admitted to a neonatal unit (Figure 7); the corresponding figures are 92% and 70% of infants born at 24 and at 23 weeks’ gestation, respectively. The percentage of infants who were admitted to a neonatal unit starts to fall after 32 weeks’ gestation. Therefore, as we have population data for infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation, we present the incidence for these infants; but for infants who were born after 32 weeks’ gestation, we present only the raw numbers.

FIGURE 7.

Percentage of ONS-reported live births in the NNRD.

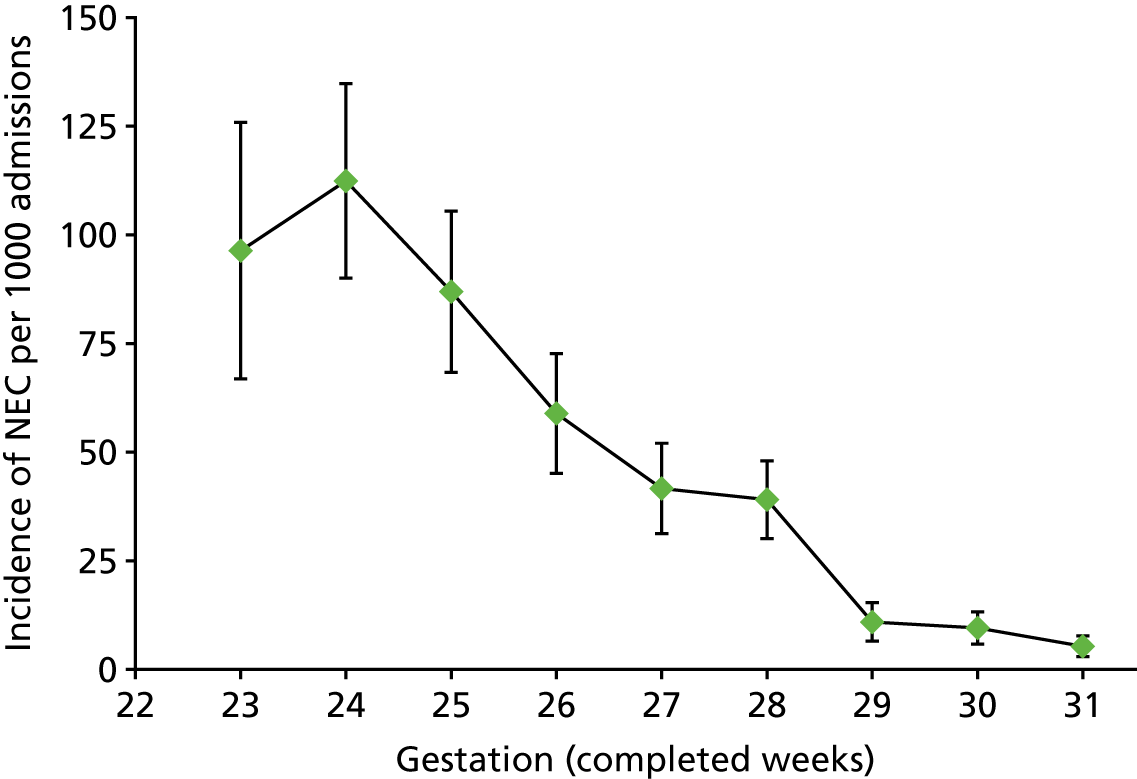

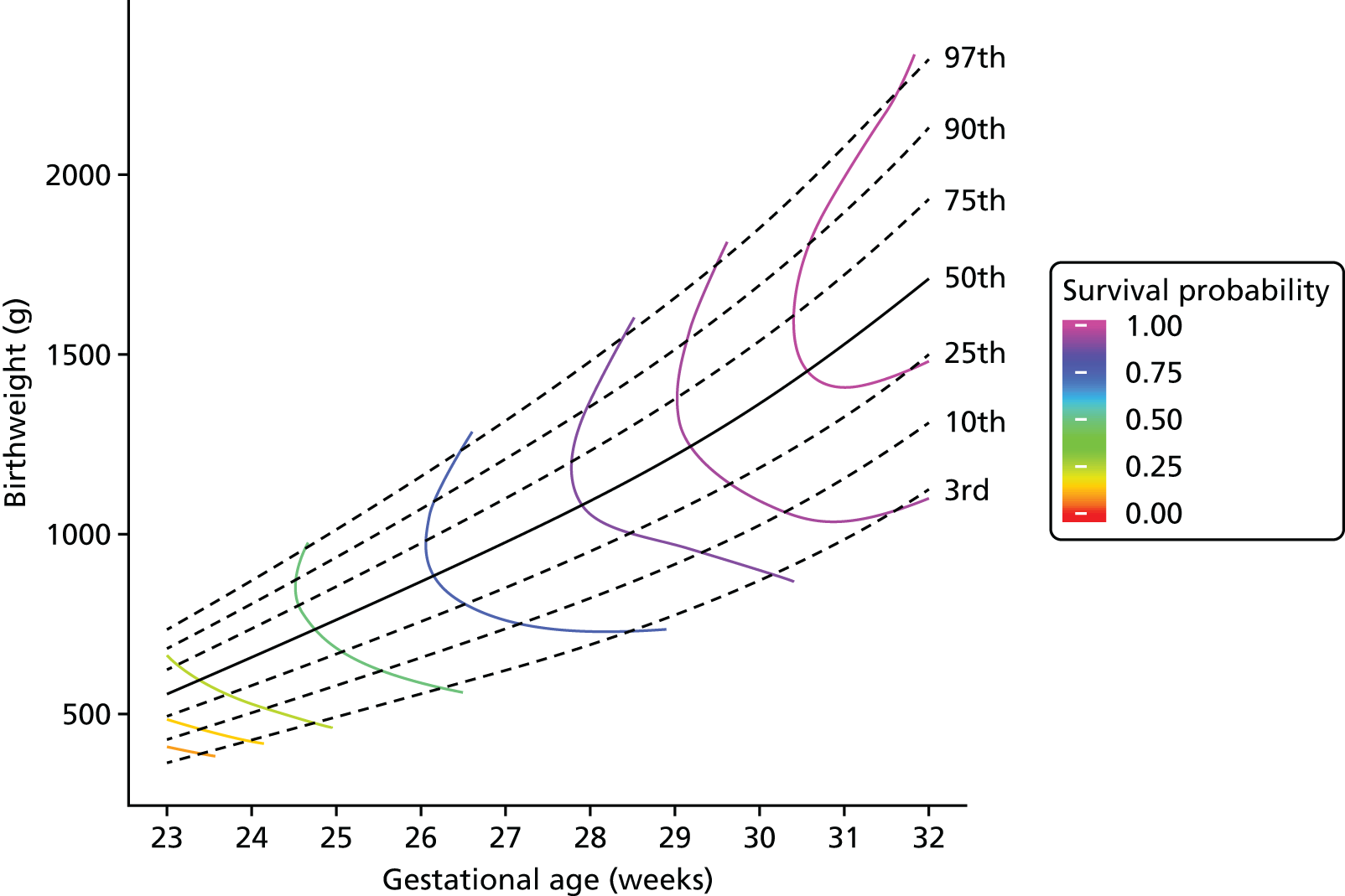

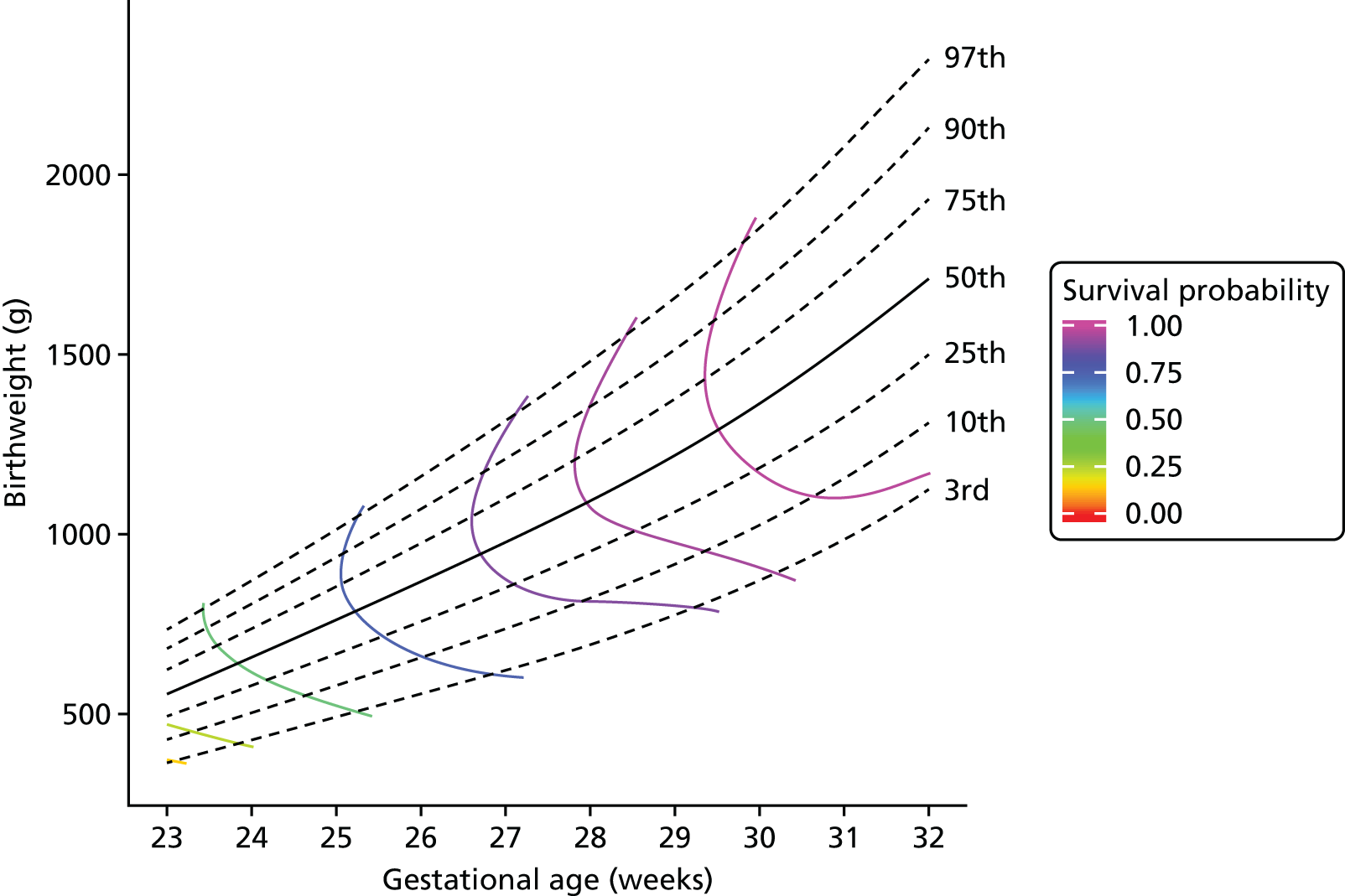

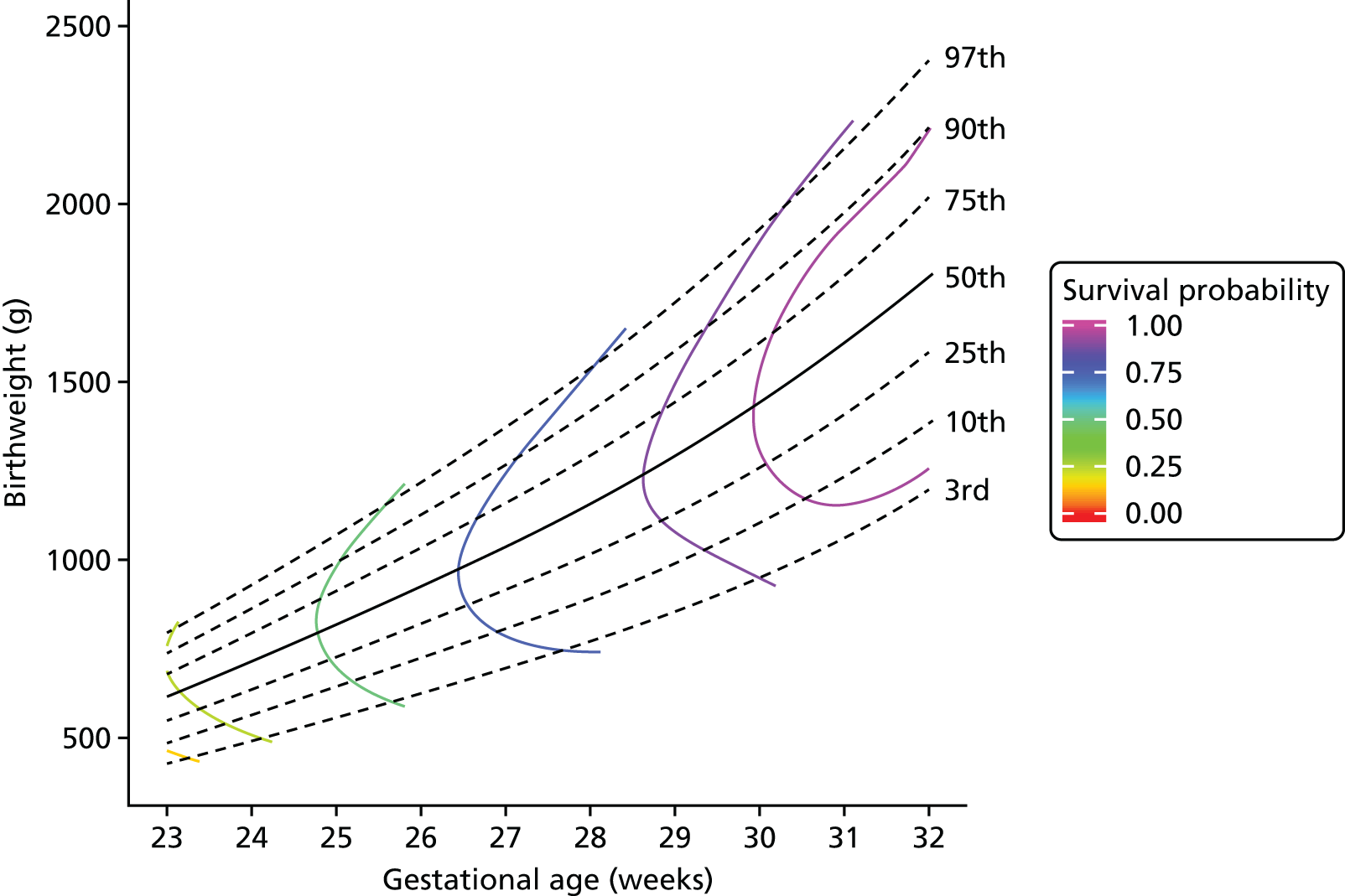

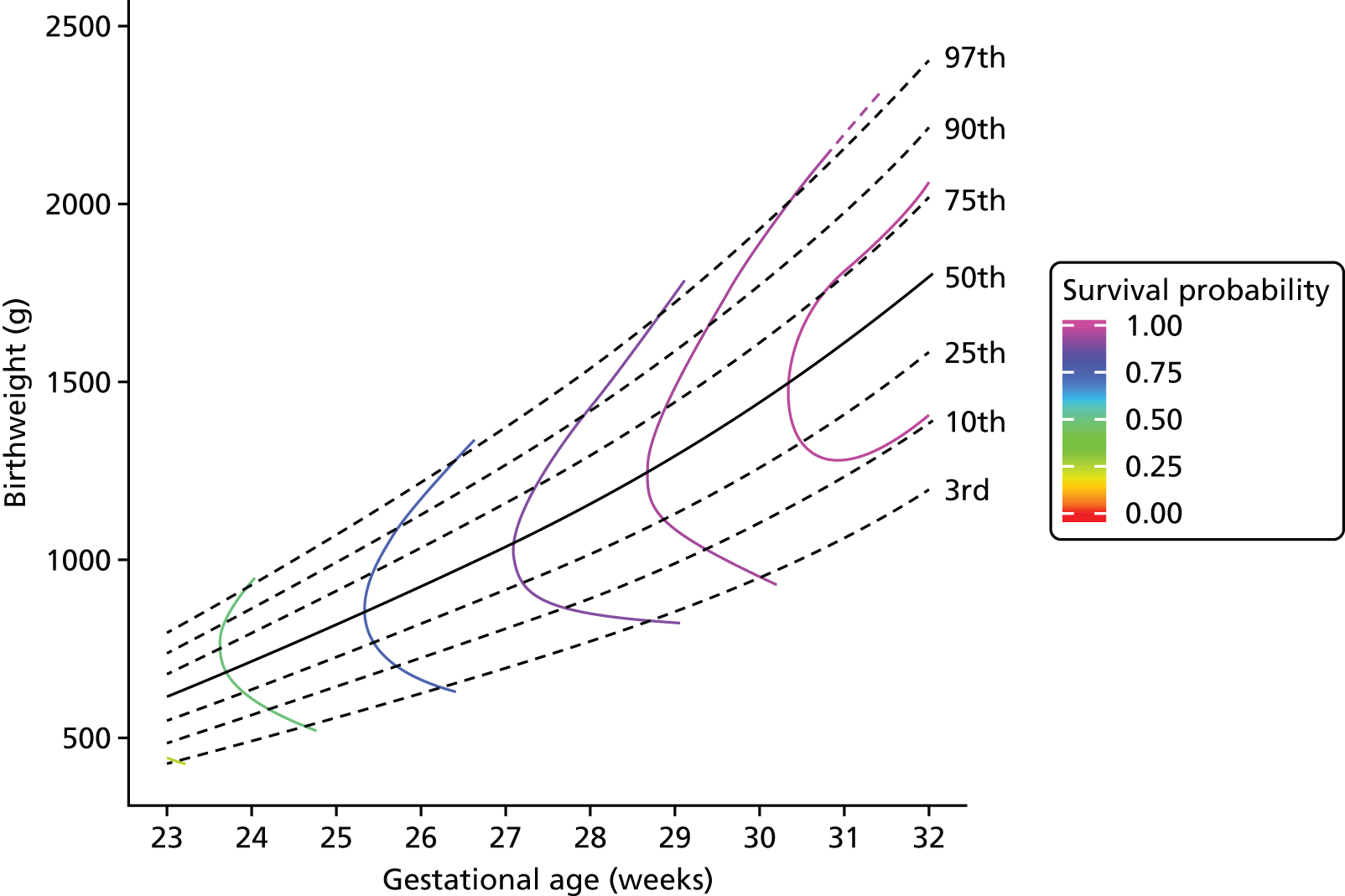

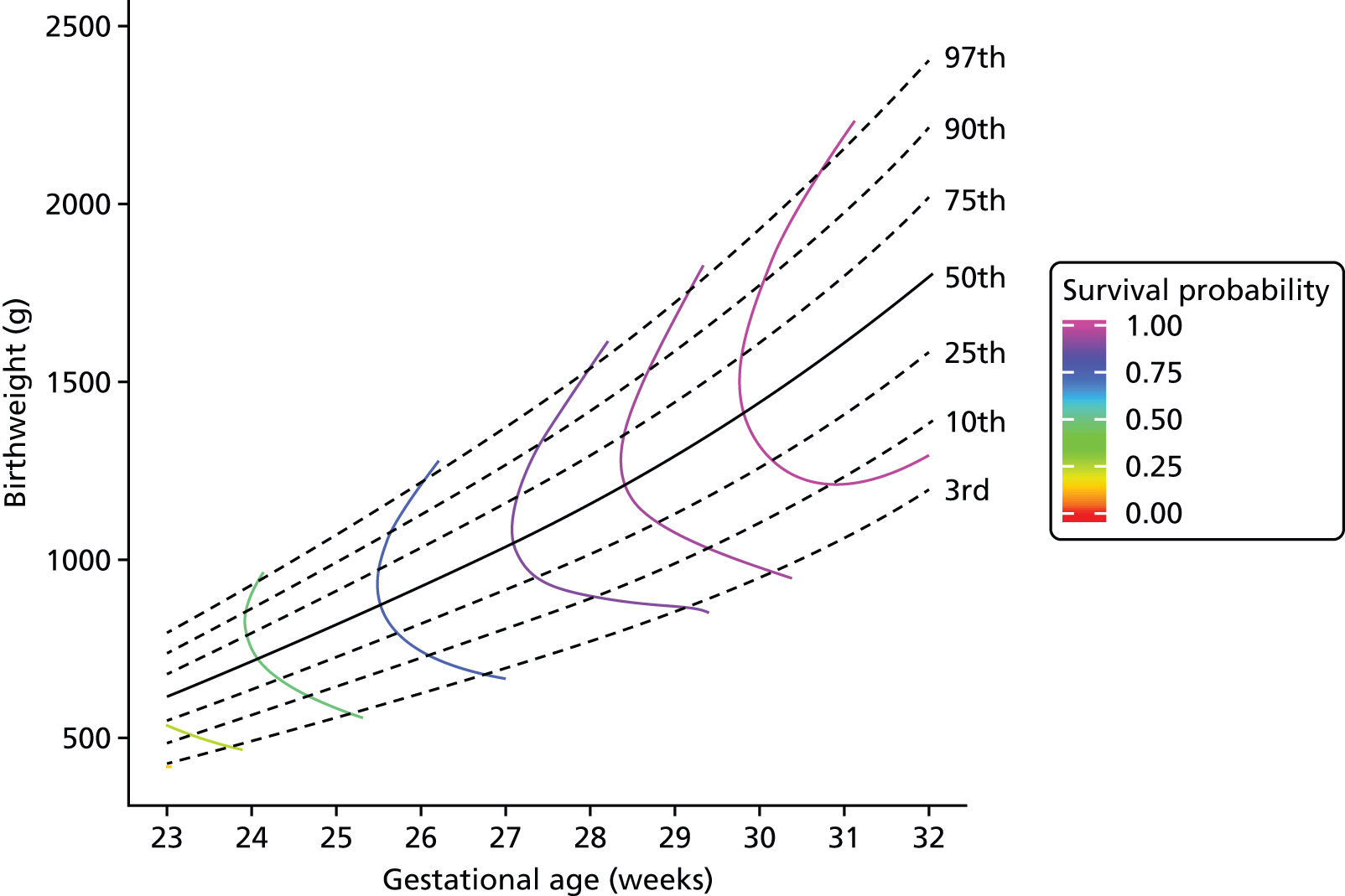

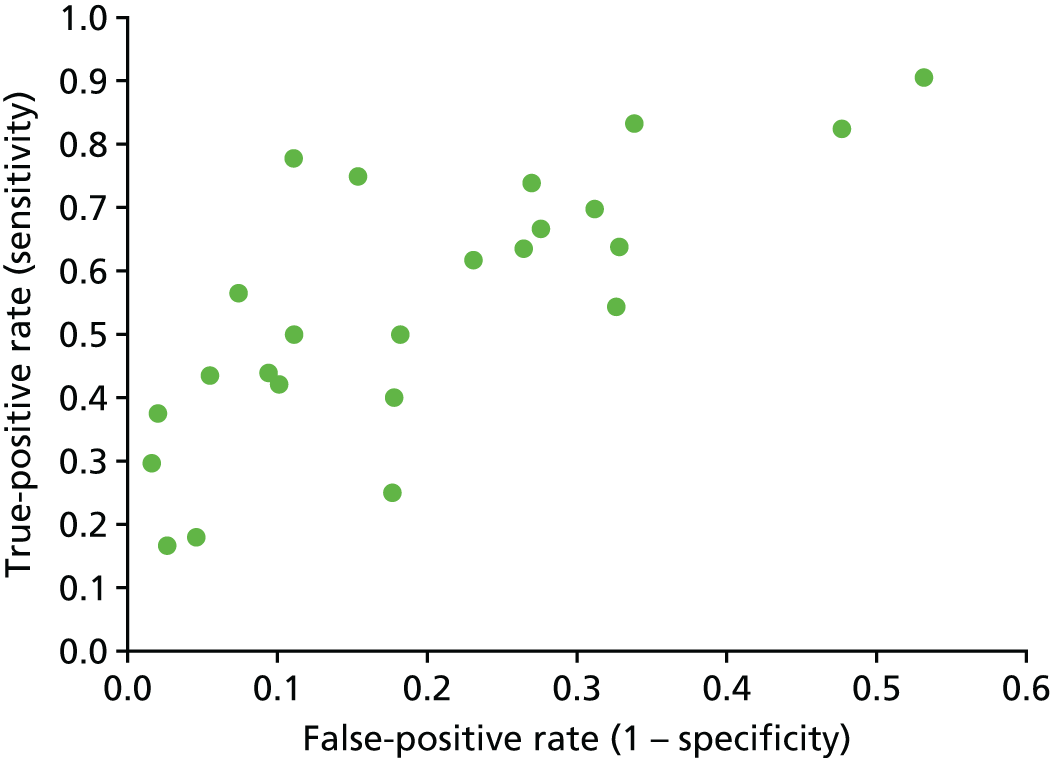

The incidence of severe NEC was inversely related with gestational age (p < 0.001, test for trend). The highest incidence of severe NEC occurred in infants born at 24 weeks’ gestation. The incidence per 1000 infants for all infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation is 31.5 per 1000 (95% CI 28.7 to 34.3 per 1000), and by gestational age is as follows: 23 weeks, 96.4 (95% CI 66.8 to 125.9); 24 weeks, 112.4 (95% CI 90.0 to 134.8); 25 weeks, 86.9 (95% CI 68.4 to 105.5); 26 weeks, 58.9 (95% CI 45.1 to 72.7); 27 weeks, 41.0 (95% CI 30.6 to 51.3); 28 weeks, 39.0 (95% CI 30.1 to 48.0); 29 weeks, 10.9 (95% CI 6.5 to 15.3); 30 weeks, 9.5 (95% CI 5.8 to 13.2); and 31 weeks, 5.3 (95% CI 2.9 to 7.7). Figure 8 shows that there is a sharp decline in the incidence of severe NEC at 29 weeks’ gestation.

FIGURE 8.

Incidence of severe NEC, infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation. Incidence derived from raw data; bars are 95% CI; gestation category labelled 23 weeks represents 22 and 23 weeks (14 infants born at 22 weeks, none with severe NEC).

Of the 531 infants with severe NEC, 462 (87%) were born before 32 weeks’ gestation, of whom 366 received surgery. Table 5 shows the postnatal and postmenstrual age at NEC surgery for infants < 32 weeks’ gestation. There is an inverse relationship between gestational age at birth and postnatal age at surgery (log-rank test < 0.001). The most immature infants born, before 26 weeks’ gestation, receive surgery for NEC around the third to fourth week of life; in contrast infants who are born at 30–31 weeks’ gestation undergo surgery in the second week of life.

| Gestational age (weeks) | Number of infants | Age (days) at NEC surgery (median, IQR) | Postmenstrual age (completed weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | 29 | 25 (12–37) | 27 (25–29) |

| 24 | 66 | 20 (12–38) | 27 (26–30) |

| 25 | 64 | 31 (12–53) | 29 (26–32) |

| 26 | 55 | 29 (15–39) | 30 (28–31) |

| 27 | 41 | 13 (9–31) | 29 (28–31) |

| 28 | 57 | 24 (14–36) | 31 (30–33) |

| 29 | 19 | 18 (9–32) | 32 (30–33) |

| 30 | 19 | 11 (7–25) | 32 (31–33) |

| 31 | 16 | 10 (8–17) | 32 (32–33) |

| Total | 366 | 22 (11–37) | 30 (27–32) |

Factors associated with severe necrotising enterocolitis for infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation

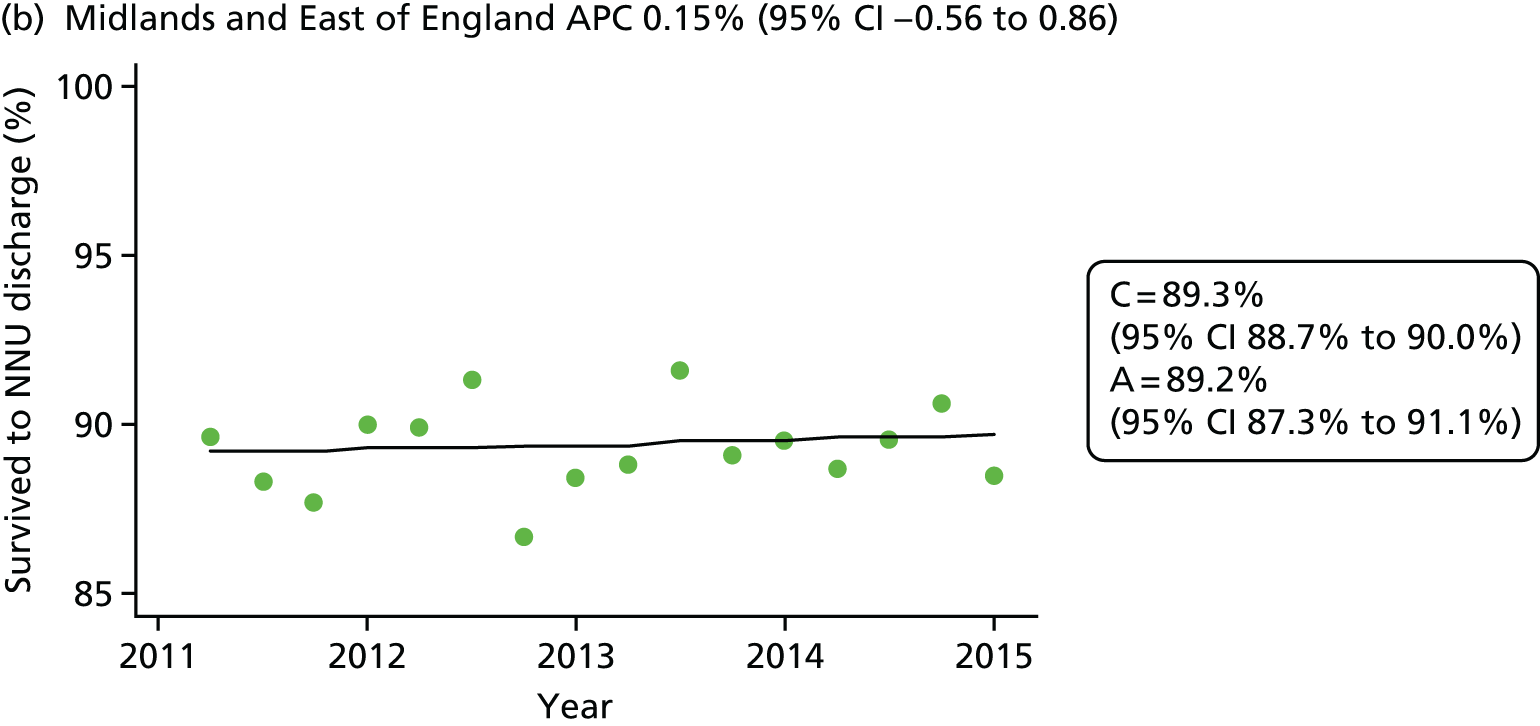

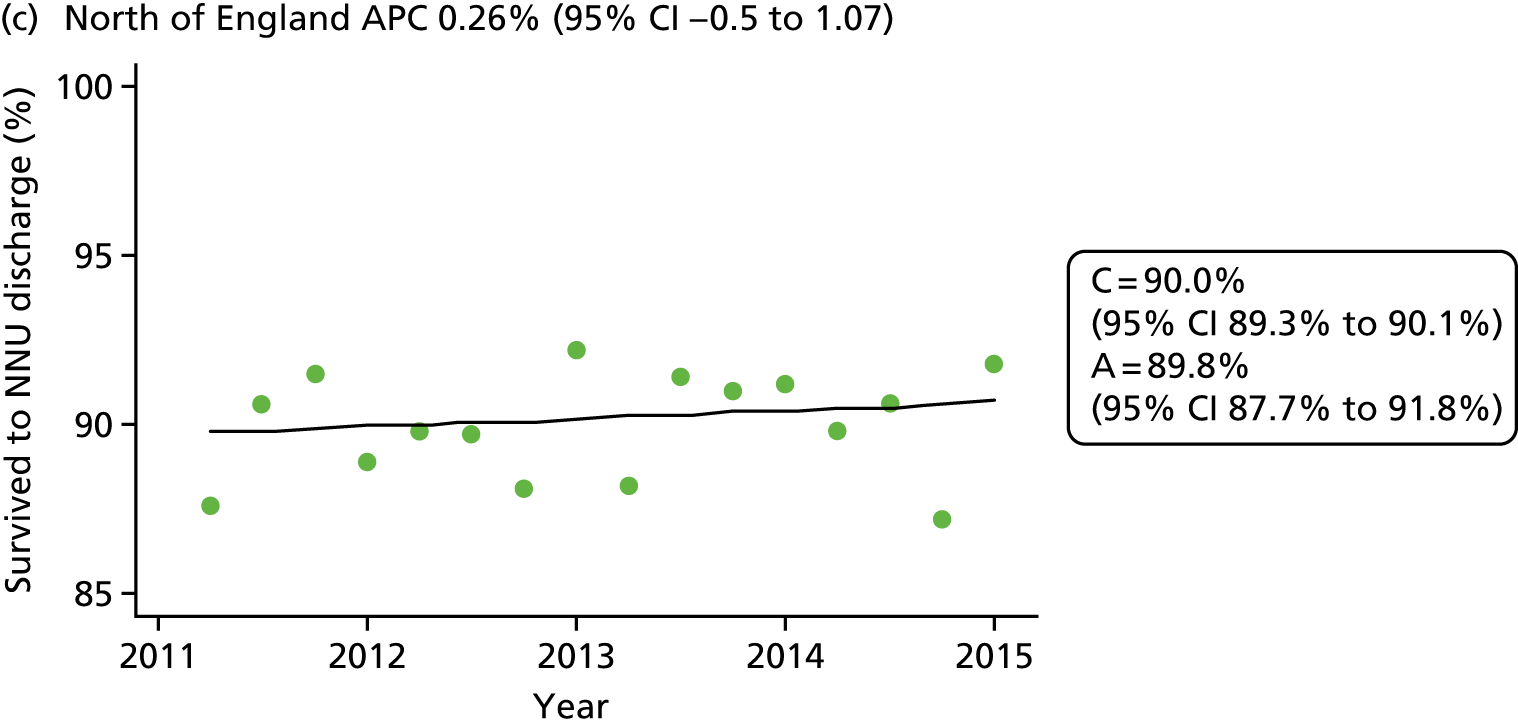

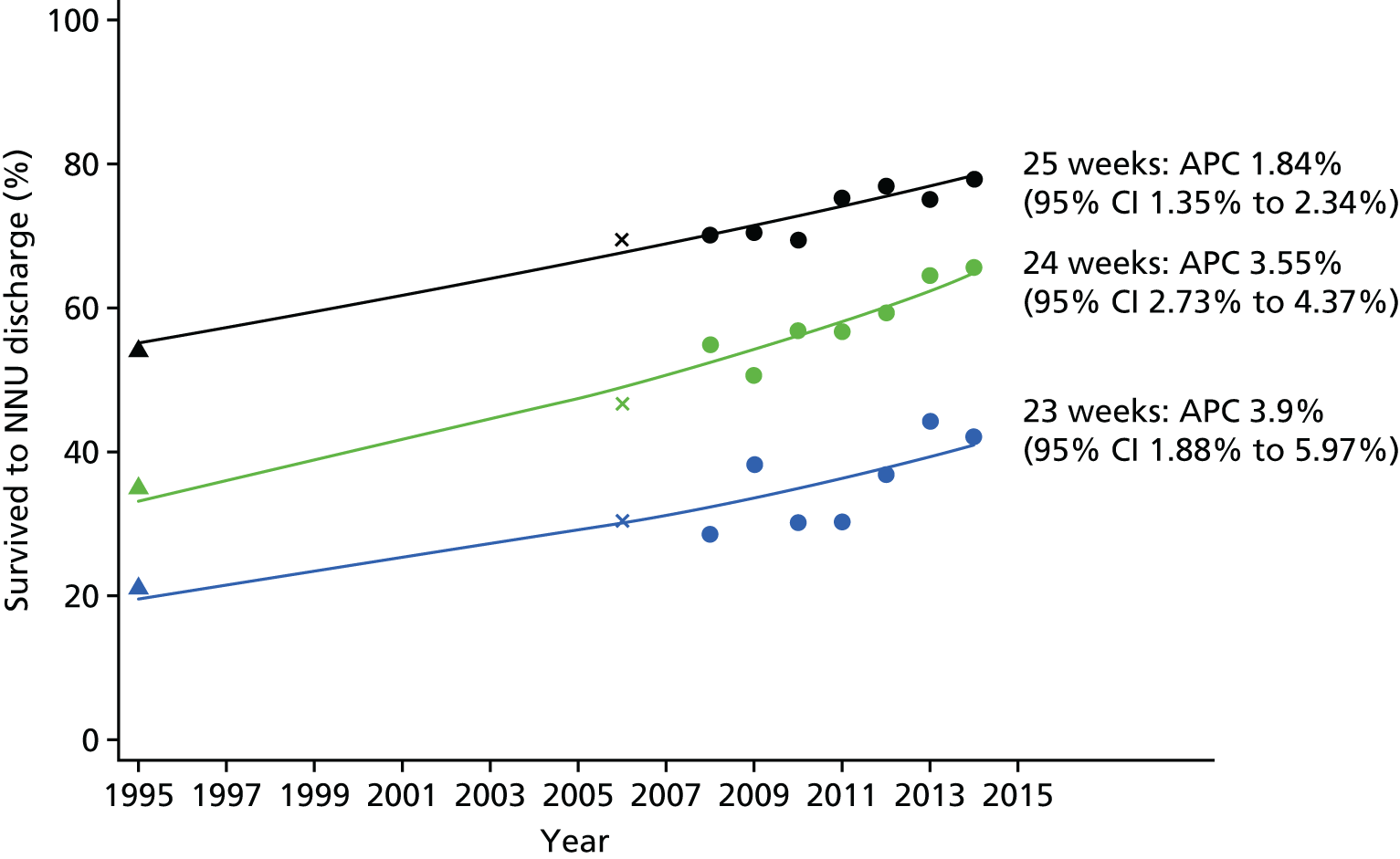

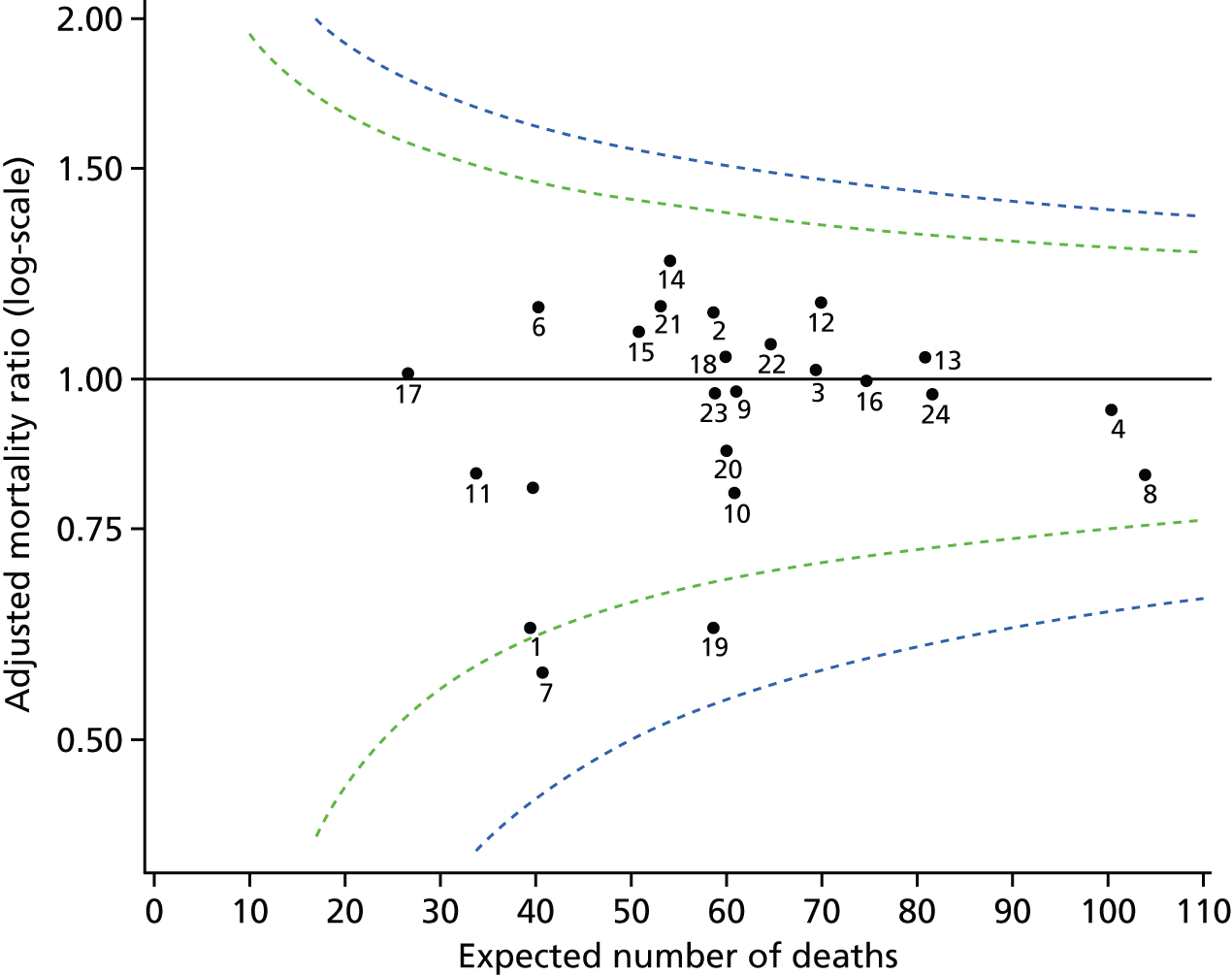

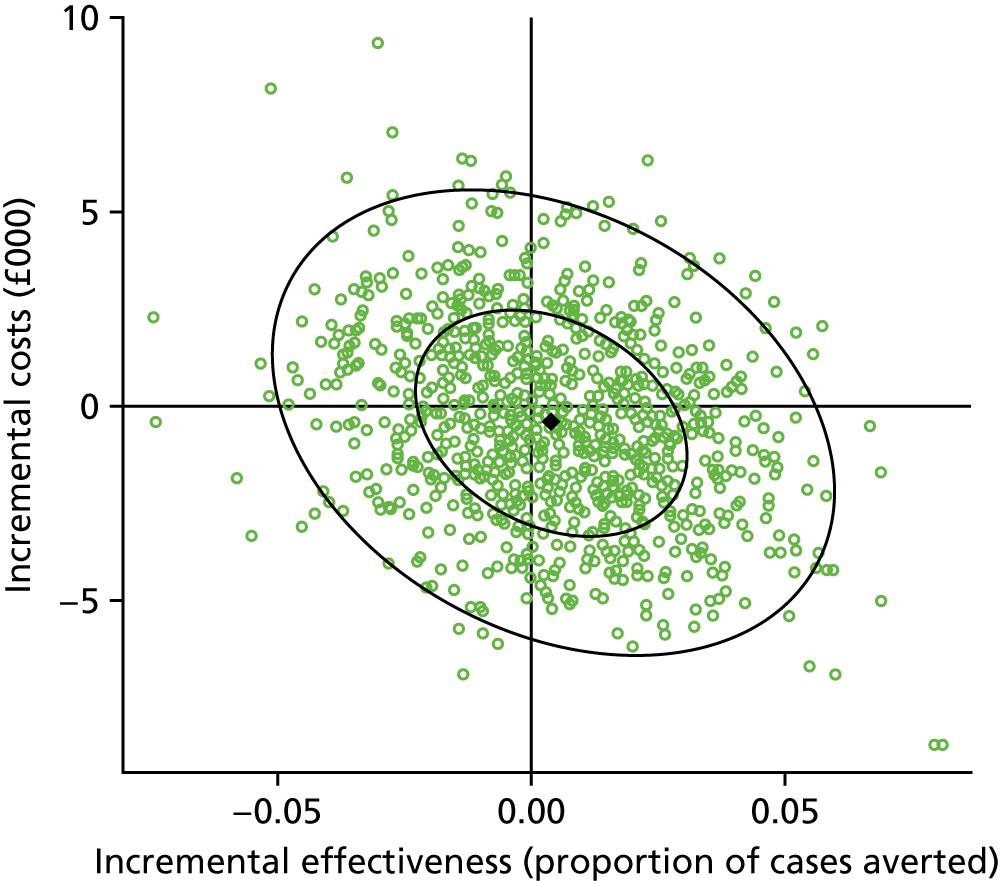

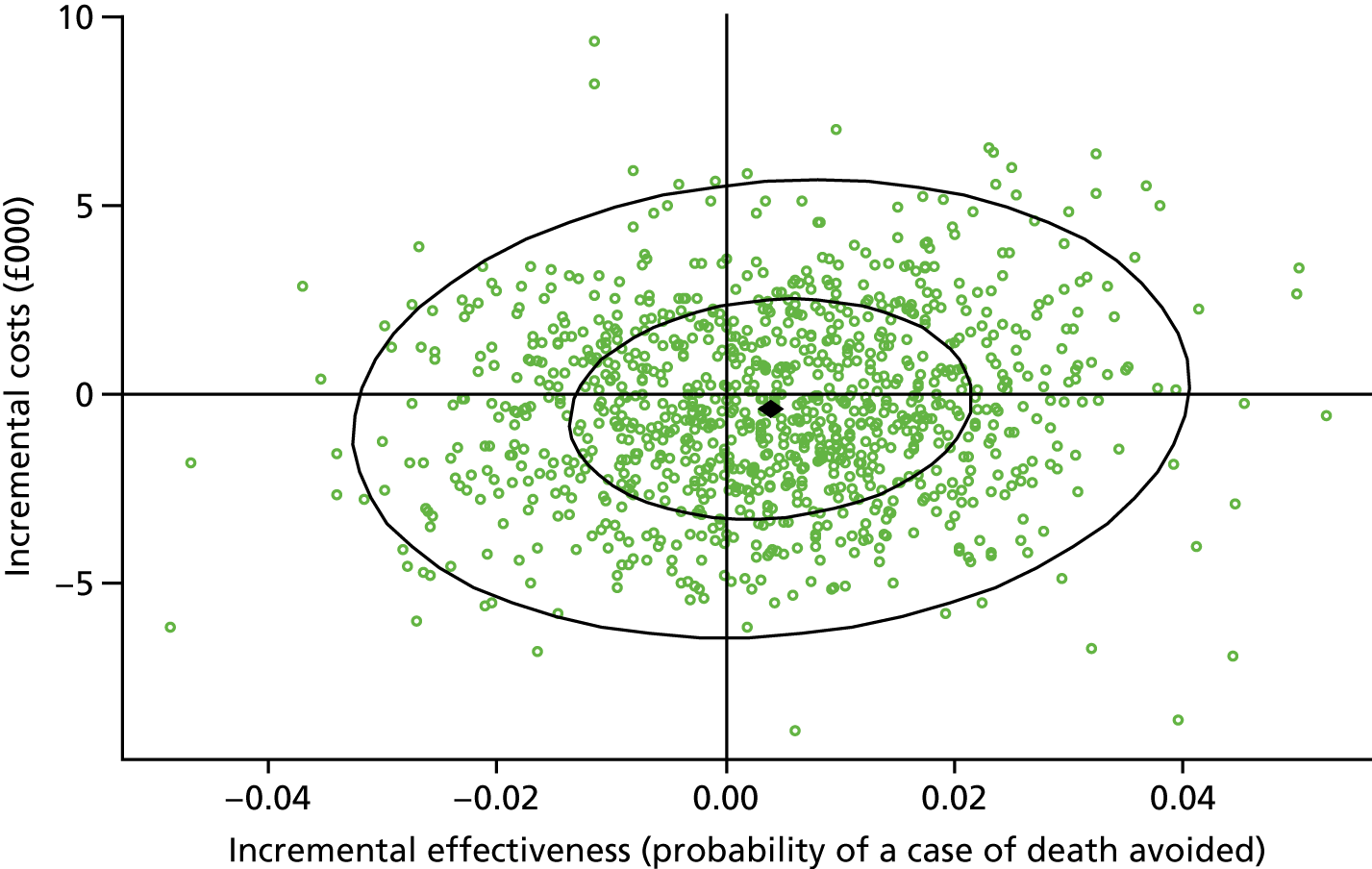

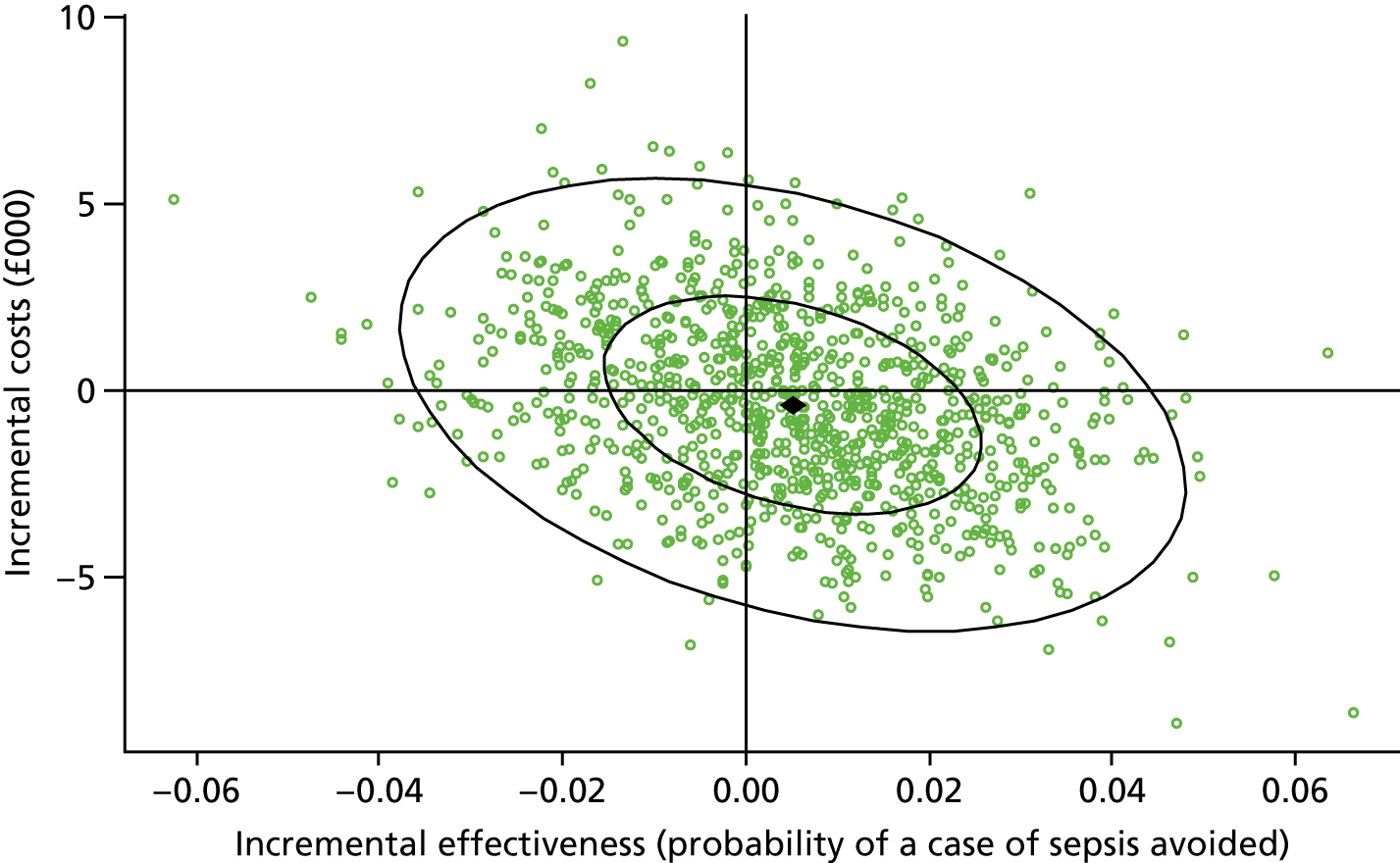

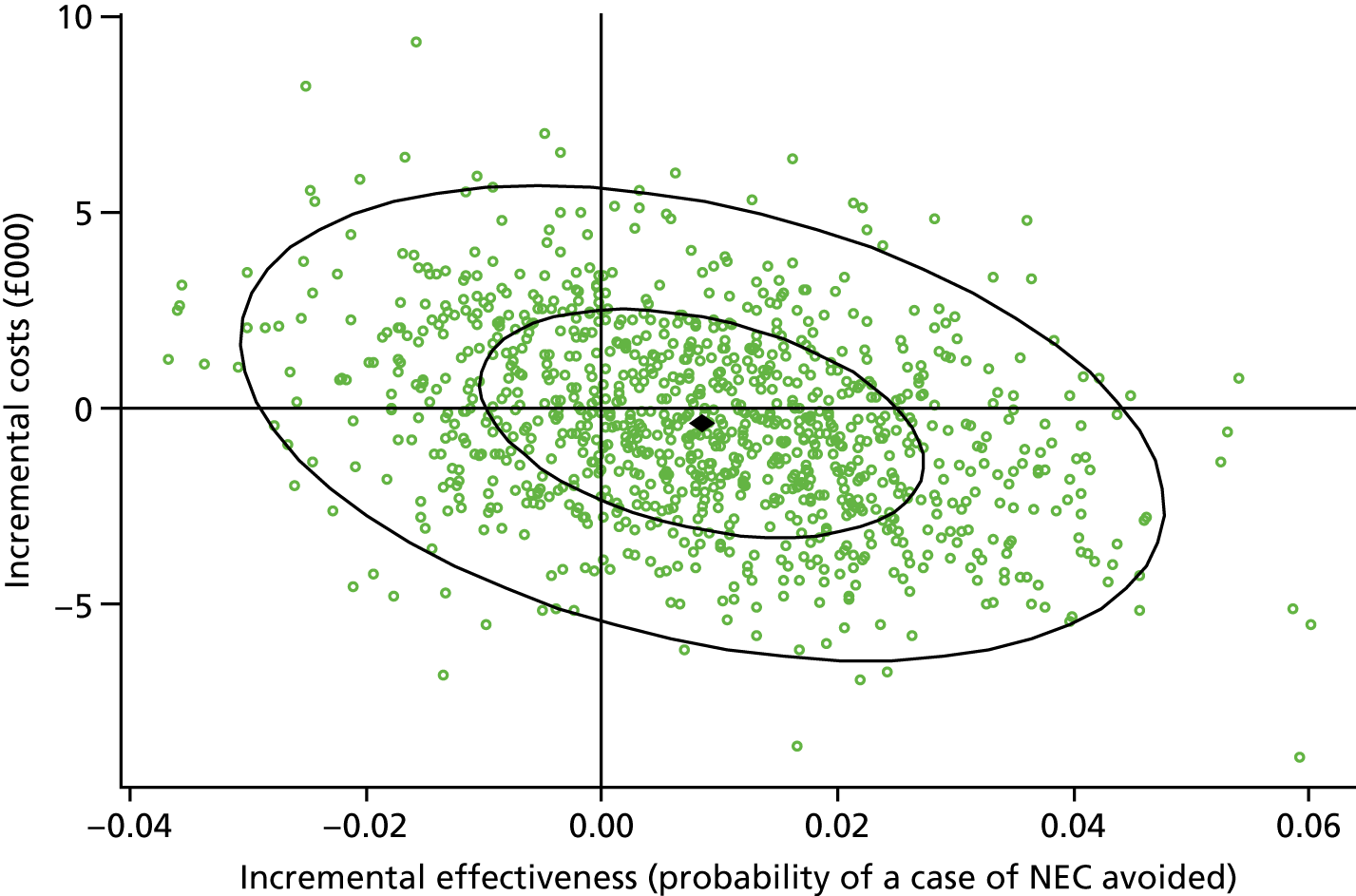

We compared the patient characteristics of the 462 preterm infants who developed severe NEC against the 14,216 preterm infants without severe NEC. Infants who developed severe NEC were more immature, with a mean gestational age of 26.2 weeks compared with 28.5 weeks (p < 0.001). Gestational age, birthweight, birthweight SDS, fetus number, whether or not the mother received antibiotics in labour, and mode of delivery were significantly different between the two groups (see Appendix 1, Table 53).