Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0610-10097. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None of the authors has any professional interests in the services studied in this research programme that could constitute a conflict of interest. Sandra Eldridge reports membership of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Board and the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee. Stefan Priebe reports previous membership of the HTA Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health Panel (2013–2018).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Killaspy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Introduction

We report on results from the QuEST (Quality and Effectiveness of Supported Tenancies for people with mental health problems) study, a national programme of research into mental health supported accommodation services in England. Many of those who use these services have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychosis, with associated difficulties in managing everyday activities. Specialist mental health supported accommodation services are a key component of the ‘whole-system care pathway’ for people with complex and longer-term mental health problems, often providing support to people on discharge to the community after lengthy or recurrent hospital admissions. We estimate that around 60,000 people in England live in supported accommodation at considerable cost to the tax payer. 1,2 Despite this, there has been little research to guide practitioners and commissioners in the most effective models and the support that should be provided. This research aimed to address this gap by providing evidence on the current provision, quality, cost and effectiveness of supported accommodation for people with mental health problems in England.

Background

The NHS Hospital Plan of 19623 heralded the process of deinstitutionalisation in England and Wales and the development of community-based mental health care, a key component of which is supported accommodation. In England, around one-third of working-age adults with severe mental health problems reside in supported accommodation provided by health and social services, voluntary organisations, housing associations and other independent providers. These include nursing and residential care homes, group homes, hostels, blocks of individual or shared tenancies with staff on site, and independent tenancies with ‘floating’ or outreach support from staff. Local statutory community mental health services provide care co-ordination and clinical expertise to the residents and staff of supported accommodation projects through the Care Programme Approach. 4 In 2006, around 12,500 people with mental health problems in England were in a nursing or residential care home1 and around 40,000 were receiving floating outreach. 2

The majority of those who require these services have complex mental health needs and functional impairments that have an impact on their ability to manage activities of daily living. Despite medication, many experience ongoing symptoms of their illness and impairments in cognition associated with long-term severe psychosis, reducing their motivation and organisational skills. 5 They may require assistance to manage their medication, bills, personal care, shopping, cooking, cleaning and laundry. However, the majority have been shown to be able to sustain community tenure with support and many gain skills and can manage with less support over time. 6,7 Nevertheless, most are unemployed and socially isolated. 8 In short, despite the move towards community-based care, this group remains one of the most socially excluded in society. 9 Supported accommodation services have a very important role in assisting people with complex mental health problems to live in the community, but despite this and the large resources dedicated to these services, there has been very little research to investigate their effectiveness. 10

The only survey of mental health supported accommodation to be carried out in England (led by co-investigator SP) found few differences in the characteristics of service users in different types of setting or in the support offered. 11 This survey sampled 12 nationally representative regions and identified a total of 481 projects, of which 250 were randomly sampled. Of these, 153 responded to a postal survey; 57 were nursing/residential care homes (with a mean of 16 residents), 61 were individual or shared flats with on-site staff support (with a mean of 13 service users) and 30 provided floating outreach to a mean of 34 service users in their own flats, usually rented from the local authority or a housing association. The majority were male, 80% had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and 48% also had a history of substance misuse. There were no differences in service user characteristics between service types. Around 40% of those in supported housing or receiving floating outreach were participating in some form of community activity (compared with 25% of those in residential care) but similar numbers of hours were spent by service users across all settings in education or work (mean 13 hours per week) and only 3% were in open employment. Staff made contact with users an average of 6 days per week in supported housing and 4 days per week in floating outreach services. Between four and six service users (18–25%) moved on from each service annually. Almost all service users were prescribed medication and all services provided support with activities of daily living. The costs of services appeared to be driven by the local tradition of provision rather than clinical need. Shepherd and Macpherson12 have also commented that the development of local supported accommodation provision appears to be largely determined by history, the sociodemographic context of the area and the support available from primary care and secondary mental health services.

Although the previous survey did not find major differences between the content of care provided in supported housing and floating outreach services, many areas of the UK operate supported accommodation pathways where service users move from higher- to lower-staffed settings as their skills improve. This allows for graduated ‘testing’ but necessitates repeated moves. A number of studies have identified discrepancies between stakeholder views on the level of support required, with service users tending to prefer more independent accommodation and staff and family members tending to prefer the person to live in a staffed environment. 13–15 An important criticism of more highly staffed settings is the use of institutional regimes and impaired facilitation of service users’ autonomy through over-support and a poor rehabilitative culture. 16 Conversely, some service users have reported that independent tenancies are lonely. 16,17

At the time that we developed the QuEST programme, there had been no trials investigating the effectiveness of supported accommodation services for people with mental health problems18 and few good-quality studies investigating the effectiveness of these services. 10 The paucity of research reflects the logistic difficulties in researching this area. Randomisation to different types of housing support may be resisted by clinicians who feel that service users require a staged process, moving from higher- to lower-supported settings as their skills and confidence increase, and by service users with clear preferences for particular services. It also seems that the availability of supported housing stock is more influential than clinical need in determining accommodation allocation. The lack of evidence means that we do not know whether or not individuals are following the most clinically effective and cost-effective routes to independence. Recently, the results of a major trial in Canada comparing usual care with ‘Housing First’ (a floating outreach model that targets individuals with mental health problems who are homeless) found that Housing First was associated with greater housing stability, but other gains in clinical and social outcomes were less clear. 19 The QuEST programme aimed to address this gap in the evidence.

Objectives of the QuEST programme

-

To adapt the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care (QuIRC) and an existing patient-reported outcome measure, the Client Assessment of Treatment (CAT) scale, for use in mental health supported accommodation.

-

To assess quality and costs of supported accommodation services in England and the proportion of people who successfully move on to more independent settings.

-

To identify service and service user factors (including costs) associated with greater quality of life, autonomy, satisfaction with care and move-on.

-

To assess the feasibility, required sample size and appropriate outcomes and costs for a randomised evaluation of two models of supported accommodation. One provides a constant level of staff support on-site (supported housing) and the other provides outreach support of flexible intensity to people in independent tenancies (floating outreach).

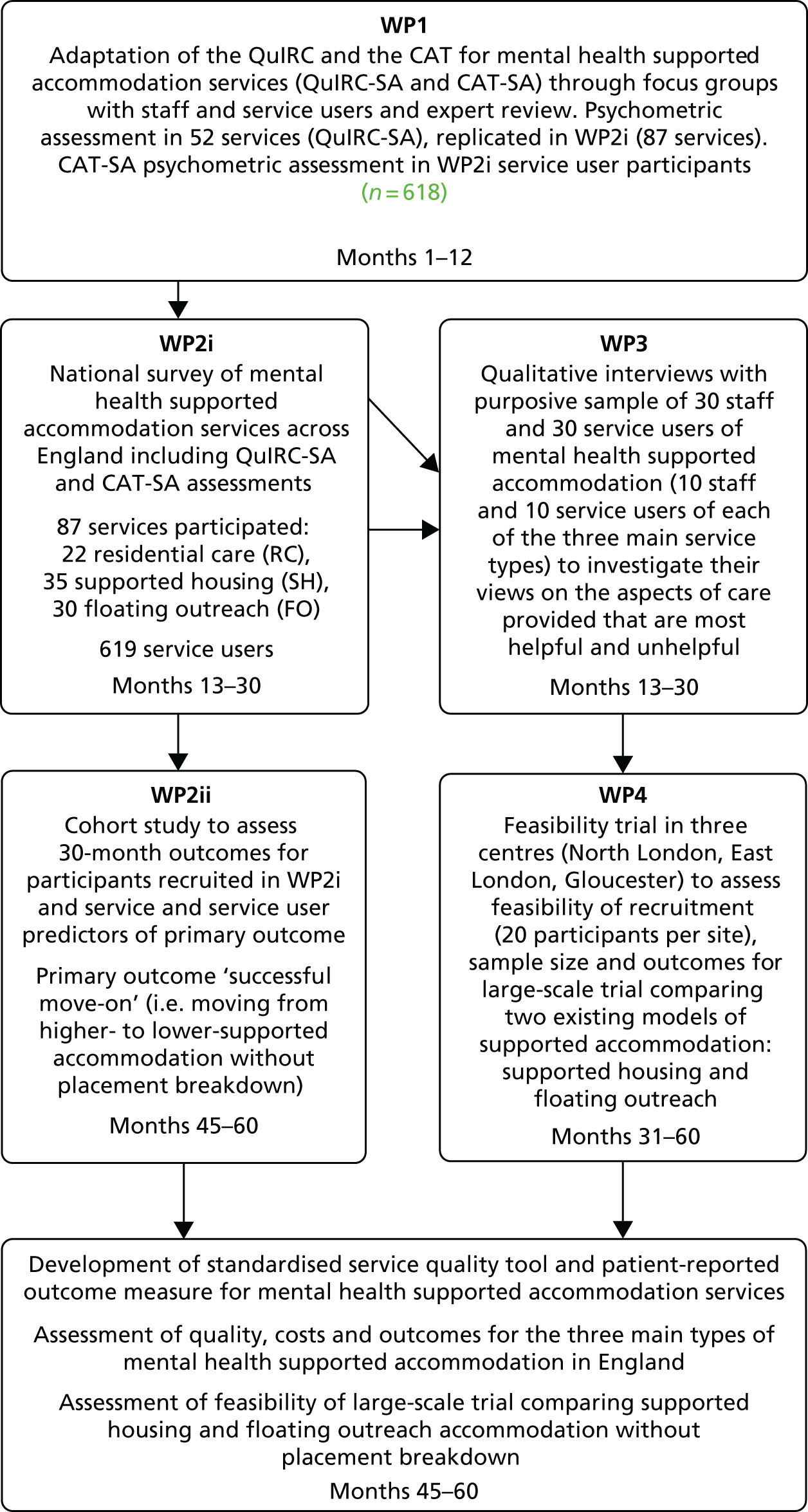

Figure 1 illustrates the interconnecting work packages (WPs) and timelines.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing relationships between WPs. CAT-SA, Client Assessment of Treatment for Supported Accomodation; FO, floating outreach; QuIRC-SA, Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care: Supported Accommodation; SH, supported housing; WP, work package.

Objective 1 was addressed in the first WP (WP1) of the programme: adaptation of an existing standardised quality assessment tool used in longer-term mental health units, and an existing patient-report outcome measure, for use in mental health supported accommodation settings.

Objectives 2 and 3 were addressed through WP2 and WP3.

WP2 comprised two components:

-

survey of a nationally representative sample of supported accommodation services across England that used the standardised tools adapted in WP1, together with additional descriptive data collected from staff and a random sample of service users to describe and compare the content and costs of care delivered in the three main types of supported accommodation service provided in England (residential care, supported housing and floating outreach)

-

Longitudinal follow-up of the random sample of service users recruited in WP2i over 30 months to identify service and service user factors associated with our primary outcome – move-on to less supported accommodation.

Work package 3 comprised in-depth qualitative evaluation of staff and service user perspectives on the aspects of care considered most beneficial in supporting recovery and the barriers to providing these.

Objective 4 was addressed in WP4: an evaluation of the feasibility of a randomised trial to compare two existing models of supported accommodation (supported housing and floating outreach).

Study preparation

Recruitment of research team

-

Ms Sarah Dowling: Project Manager, University College London – started 18 September 2012.

-

Dr Sima Sandhu: Researcher, Queen Mary University of London – started 1 September 2012.

-

Dr Rose McGranahan: Researcher, Queen Mary University of London – started 1 January 2016.

-

Dr Peter McPherson: Research Associate, University College London – started 4 October 2012.

-

Dr Joanna Krotofil: Research Associate, University College London – started 1 January 2013.

-

Ms Isobel Harrison: Research Associate, University College London – provided maternity cover for Joanna Krotofil from January to July 2014 and remained involved with the project through North Thames Clinical Research Network funding.

No-cost extension

The National Institute for Health Research kindly agreed a 6-month no-cost extension to our contract to acknowledge the time lag between the official contract start date and the date when the relevant subcontracts were agreed that enabled recruitment of the research team.

Ethics approval

Application for ethics approval for WP1–3 of the programme was made in November 2012 and approval was received on 4 February 2013 from the Harrow Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/LO/2009). Ethics approval for WP4 was sought on 12 March 2015 and approval was received on 7 April 2015 from Liverpool Central Research Ethics Committee (reference 15/NW/0252).

Research governance

The research was conducted in keeping with usual research governance guidance and processes. The chief investigator and researchers prepared appropriate standard operating procedures for all WPs. The researchers were trained in the use of the study materials by Helen Killaspy and piloted these prior to use. In 2014, the research was audited by North London Central Research Consortium and no concerns were identified.

Programme management

The chief investigator and programme manager managed the day-to-day running of the programme, overseen by the Programme Management Group (PMG), which met quarterly to review study progress and address managerial and scientific issues as they arose. The Programme Steering Group (PSG) provided an objective ‘quality assurance’ process, reviewing progress and advising the PMG if problems arose that might have an impact on the successful completion of the research. We also recruited a Service User Reference Group to provide an independent view on aspects of the research that were of particular relevance to users of supported accommodation services. The PMG also consulted with an independent group of clinical and policy experts in the field of supported accommodation at relevant stages of the programme, particularly in relation to the adaptations to the service quality tool in WP1 and recruitment in WP4. In addition, a dissemination event and stakeholder roundtable event were held at the end of the programme, attended by members of this expert group, to discuss the implications of the programme findings for future practice and policy.

Patient and public involvement

We recognised that the involvement of service user expertise was key to the success of the programme and included PPI throughout, from design to dissemination. The co-investigator Gerard Leavey co-ordinated these activities. We consulted with the North London Service User Research Forum (SURF) about the focus and design of the study prior to submitting the proposal for funding and incorporated suggestions into the application (e.g. having an independent service user reference group to consult throughout). We further consulted the SURF in relation to the adaptation of the tools in WP1, the interpretation of the results in WP2, the development of the topic guides in WP3 and WP4 and addressing recruitment issues in WP4.

One of our co-applicants (MA) has lived experienced of severe mental illness and of living in supported accommodation. He has worked closely with our group on previous studies in the field of complex psychosis and contributed to our lay summary at the design/application stage and throughout the programme as a member of the PMG. He was also the service user expert on our PSG. After funding for our programme was agreed, we recruited a second service user expert to join Maurice Arbuthnott on the PMG. Service user representatives in the PMG were actively involved in commenting on the delivery of the research programme, reviewing progress and assisting in the development of plans to disseminate the research findings.

We also recruited three lay members with experience of severe mental health problems and supported accommodation services to our Service User Reference Group. This group was facilitated by Gerard Leavey and met every 6 months to provide an independent view on all aspects of the research that were of particular relevance to users of supported accommodation services.

The PSG meetings were held every 6 months to provide oversight to the research programme, reviewing its progress and advising the PMG if problems arose that might have an impact on its successful completion. The service user representative on this group contributed to these discussions.

All service user experts were paid £50 per meeting plus travel expenses.

Study progress (start date: 1 October 2012)

Work package 1: project months 1–12

Data collection in WP1 was completed on time. However, it was decided that further analysis of the psychometric properties of the adapted QuIRC using the larger sample of service managers and service users recruited in WP2 was indicated. The results were published in April 2016 in BMC Psychiatry. 20 Adaptation of the CAT scale was completed on time and the results were published in March 2016 in BMC Psychiatry. 21

Work package 2i: project months 13–30

The first component of WP2 (national survey) was completed on time and the main quantitative results comparing the three main types of supported accommodation were published in November 2016 in Lancet Psychiatry. 22

Work package 2ii: project months 45–60

The second component (30-month follow-up of service users’ progress) commenced in June 2016 and data collection was completed in August 2017. Researchers tracked service users through 3-monthly contact with their supported accommodation service manager to minimise loss to follow-up. The results were published in The British Journal of Psychiatry. 23,24

Work package 3: project months 13–24

Work package 3 was completed on time and the results were published in July 2017 in BMC Health Services Research. 25

Work package 1: adaptation of the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care and Client Assessment of Treatment scale for use in supported accommodation services

The aim of WP1 was to adapt an existing quality assessment tool and an existing patient-rated outcome measure for use in supported accommodation services. The QuIRC26 is an international, standardised tool that assesses quality of care in longer-term mental health facilities. It is completed by the service manager and provides descriptive data and quality ratings, expressed as percentages, for seven domains of care (living environment, therapeutic environment, treatments and interventions, self-management and autonomy, social interface, human rights, and recovery-based practice). It has excellent inter-rater reliability and domain ratings are positively associated with standardised measures of service users’ autonomy and experiences of care. 26,27 Therefore, it can provide a proxy assessment of service users’ views of a facility even though it is completed by the unit manager. It is freely available as a web-based resource (www.quirc.eu). Table 1 provides a summary of the tool content and structure.

| Domain | Number of items scoring domain | Examples of areas covered | Example of item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living environment | 22 | Privacy, décor, cleanliness, meals, mobility access, access to laundry facilities, access to outside space | Is there a private room for patients/residents to meet with their visitors? |

| Therapeutic environment | 35 | Staffing, aims of service, therapeutic optimism, service user involvement in decisions about the service, staff supervision | How hopeful are you that the majority of your current patients/residents will show improvement in their general functioning over the next 2 years? |

| Treatments and interventions | 27 | Staff training, facilitating access to evidence-based interventions, managing challenging behaviour, processes for review of treatment and care | How often are therapeutic effects and side effects of psychiatric medication reviewed? |

| Self-management and autonomy | 27 | Facilitating service user involvement in decisions about own care, supporting service users to gain skills for more independent living, avoidance of ‘blanket restrictions’ | Is there a process for supporting patients to manage their own medication? |

| Social interface | 10 | Facilitating access to community resources, engaging with family, supporting service users’ friendships, providing support to vote in elections | How many of your patients/residents regularly take part in activities in the community? |

| Human rights | 24 | Access to advocacy and legal representation, formal complaints process in place, case notes kept securely and confidentially | Is a welfare/benefits advice service available to your patients/residents? |

| Recovery-based practice | 19 | Individualised and collaborative care planning, ex-service users employed in the service, working towards successful move-on to more independent accommodation | Please estimate the number of your patients/residents who have moved on from your unit to more independent accommodation in the last 2 years? |

The CAT scale is a seven-item, international, standardised, patient-reported outcome measure with good psychometric properties28 that was originally developed for inpatient mental health care (see Appendix 1). Each item is rated from 0 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (entirely satisfied).

Methods

Tool content review and adaptations

The content of the QuIRC was first reviewed by the research team to identify obviously problematic items (e.g. irrelevant items or those requiring rephrasing). Three focus groups with staff and service users recruited from North London were held, one of each focus group from each of the three main types of supported accommodation in England (residential care, supported housing and floating outreach) to gain participants’ views on the relevance of individual QuIRC (staff) and CAT (service user) items. Focus groups were facilitated by the researchers under the supervision of Gerard Leavey. The relevant QuIRC items (staff focus groups) and all seven CAT items (service user focus groups) were used to structure and focus the discussion, which aimed to identify items that required amendment/deletion and additional items. The focus groups were recorded and transcribed and the researchers collated responses.

The findings were supplemented by the advice of three panels of experts who also reviewed the QuIRC and CAT. The first panel comprised five members with expertise in supported accommodation (two senior clinicians, a service manager, a senior policy advisor and a Care Quality Commission senior adviser). The second expert panel was our QuEST study service user reference group, which comprised three members with lived experience of specialist mental health supported accommodation and services. The third expert panel was the North London SURF, which comprised 12 members with lived experience of mental health problems and expertise in mental health services research. All three expert panels were sent the original QuIRC and CAT and a document summarising the comments from the focus groups. They were asked for their opinion about the suggested amendments and any additional amendments. The researchers collated all responses from the focus groups and expert panels, identifying items where there was consensus for adaptation, deletion or a new item. These were reviewed by the QuEST PMG to gain final agreement on changes. The revised QuIRC was then piloted with three service managers (one of each of the three types of supported accommodation) in North London and final amendments to wording were made.

Psychometric property assessment of the adapted Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care

To assess the psychometric properties (item response spread, internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, sampling adequacy) of the adapted QuIRC, supported accommodation services were randomly selected from a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database of all supported accommodation services (residential care, supported housing and floating outreach) in each of 14 nationally representative areas of England (see Work package 2 for further details of area selection and scoping of services). Two services of each of the three types were randomly selected from each of the 14 areas with the aim of recruiting 20 managers from each type of service (60 in total). The researchers contacted service managers to gain their informed consent for participation. Two researchers attended a face-to-face interview with participating service managers. One researcher led the interview and both researchers independently rated the adapted QuIRC from the answers given by the unit manager.

Data analyses were conducted by Sarah White, statistician from St George’s University London, who was involved in the development of the original QuIRC. Items were considered to have inadequate response spread if > 90% of service managers gave the same response. Internal consistency of domain scores was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and considered acceptable if > 0.6. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using kappa coefficients for categorical data (weighted kappa if more than two categories) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for normally distributed, continuous data, and considered acceptable if > 0.7.

Psychometric property assessment of the adapted Client Assessment of Treatment

The psychometric properties of the adapted CAT were assessed in the 618 service users who participated in the national survey of supported accommodation services in WP2 (see Work package 2 for full details of the approach to sampling and recruitment). Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Convergent validity was assessed through correlation with ratings of participants’ subjective quality of life using the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA),29 which has a total maximum mean score between 1 and 7.

Results

Each staff focus group comprised four members (the service manager plus three support workers). The three service user focus groups had five or six members (residential care, n = 6; supported housing, n = 5; floating outreach, n = 5).

Adapted Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care

A total of 28 QuIRC items were rephrased, 20 items were deleted and 10 items were added. For example, item 77 from the original QuIRC was adapted to better reflect the nature of support within these settings (original item: ‘How many of your staff are trained in control and restraint techniques?’; amended item: ‘How many of your staff are trained in breakaway techniques?’), whereas item 116 was simply omitted (‘Are patients/residents free to send and receive uncensored mail or email?’). The final version had 143 items. It was also agreed that because floating outreach services are not ‘building based’ but provide support to people living in an independent tenancy, the items relating to the living environment of the service were not relevant and, therefore, the adapted QuIRC would not be able to provide a rating on this domain for these services.

Inter-rater reliability of the QuIRC was carried out with managers of 14 residential care homes, 21 supported housing services and 17 floating outreach services (52 services in total).

Only 16 out of the 143 items showed a poor response spread. Internal consistency was inadequate for all domains except therapeutic environment and treatments and interventions. However, the analysis was limited by a relatively small sample size and the lack of variability in response to some items. With regard to inter-rater reliability, 70 ICC analyses were conducted and only one item was found to be unreliable. A total of 186 kappa coefficient analyses were conducted and four items were found to be unreliable (κ < 0.7). In addition, there were 14 items where analyses could not be conducted because there were too few cases (five items), zero variance (two items) or where variables were constants (seven items). The full results of these assessments are available in Killaspy et al. 20

The PMG agreed amendments to the adapted QuIRC in response to the results. It was decided to keep items with inadequate variance because (1) to drop them would have disrupted the logical flow of the tool content and (2) greater variance might be achieved in future development of the tool for use in settings outside the UK. Additional explanatory information was added to improve the reliability of one item, one item was dropped completely and unreliable response options were dropped for three items.

It was also agreed that internal consistency would be reassessed using the larger sample of 87 services participating in WP2 along with an assessment of sampling adequacy (the proportion of variance among the variables that might be common variance) using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic. Hair30 suggested a KMO value of ≥ 0.5 to evaluate whether or not a sample of data has sufficient common variance to make exploratory factor analysis appropriate.

Internal consistency improved on all domains with the larger sample (Table 2). All domains met the KMO > 0.5 criterion of sampling adequacy. It should be noted however that both Cronbach’s alpha and the KMO statistic are influenced by sample size and in this analysis the sample size was still smaller than desirable for robust estimates of both properties (generally 300 observations). However, we were able to investigate whether or not there was adequate common variance within the domain items to assume that the domain had coherence. We replicated the approach taken in the original development of the QuIRC, where items were considered to load onto a factor (domain) if they scored > ± 0.3. As some items had zero variance, they were removed before analysis (living environment: two items; self-management and autonomy: three items; human rights: four items). All items loaded onto a factor within that domain at the > ± 0.3 level (i.e. each item was contributing to the common variance within the domain).

| Domain | Number of items scoring domain | WP1 services (n = 52) | WP2 services (n = 87) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) domain score | Range | Cronbach’s alpha | Mean (SD) domain score | Range | Cronbach’s alpha | KMO | ||

| Living environment | 20 | 81.0 (7.1) | 62.3–94.3 | 0.39 | 81.2 (8.7) | 53.9–96.2 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Therapeutic environment | 33 | 62.2 (7.3) | 48.5–78.9 | 0.66 | 61.4 (6.9) | 38.2–75.4 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| Treatments and interventions | 27 | 55.1 (8.4) | 36.7–76.3 | 0.66 | 54.2 (8.1) | 35.1–73.2 | 0.64 | 0.61 |

| Self-management and autonomy | 33 | 69.0 (5.8) | 53.7–81.8 | 0.40 | 68.0 (6.9) | 39.3–83.8 | 0.62 | 0.58 |

| Social interface | 7 | 59.0 (10.8) | 33.9–89.7 | 0.27 | 58.9 (12.1) | 37.6–85.6 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

| Human rights | 21 | 86.7 (5.0) | 71.4–96.7 | 0.09 | 85.5 (6.9) | 66.1–97.5 | 0.37 | 0.53 |

| Recovery-based practice | 18 | 71.7 (8.2) | 51.9–91.4 | 0.53 | 69.2 (9.9) | 31.8–90.5 | 0.67 | 0.57 |

We engaged the same information technology specialist who developed the web-based version of QuIRC to develop a similar application for the adapted QuIRC for supported accommodation services. This increases its accessibility, reduces the time required to complete it compared with a face-to-face interview, and provides a built-in scoring algorithm. It has a similar facility to the original QuIRC application in producing a printable report for the service manager about the performance of their service on the adapted QuIRC domains, comparison benchmarking data for similar services and suggestions for how to improve performance. The final version of the adapted QuIRC was named the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care: Supported Accomodation (QuIRC-SA).

Adapted Client Assessment of Treatment

All seven CAT items were considered relevant by the focus group participants and expert reference group members, with only slight modification of the wording required (e.g. ‘treatment/care’ was changed to ‘support/care’). No items were deleted or added. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89. With regard to convergent validity, scores on the adapted CAT were positively correlated with the mean total MANSA (quality of life) score (rs = 0.35; p < 0.001). Full results are available in Sandhu et al. 21

Links to other work packages

The QuIRC-SA and CAT-SA were used to assess service quality and service user experience in the national survey of supported accommodation services (WP2i), the prospective cohort study (WP2ii) and the feasibility trial comparing supported housing and floating outreach (WP4).

Limitations

Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care: Supported Accommodation

One of the limitations of the QuIRC-SA was the inadequate internal consistency. Although the domains were coherent [as measured by sampling variance (KMO statistic)], it is possible that the estimates of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) may have been influenced by our sample size; a sample size of 300 to 400 is desirable in order to obtain robust estimates of internal consistency. The decision to retain items with inadequate response variance may be considered a limitation of the tool. Although it could be argued that the retention of these items unnecessarily increases the size and administration time of the QuIRC-SA, omitting them would have disrupted the logical flow of the tool. We were not intervening to improve service quality during the QuEST programme and we therefore did not assess the tool’s sensitivity to change. Test–retest reliability was not assessed as we felt that this was too onerous for busy service managers (as the tool takes 1 hour to complete). Both should be assessed in future studies, but their omission had no influence on the findings of later phases of the QuEST programme as we used only baseline QuIRC-SA assessments.

Client Assessment of Treatment for Supported Accommodation

Although the development and testing procedures for the CAT-SA were rigorous, a number of limitations must be acknowledged. First, we did not collect data on symptoms or clinical profile when assessing the psychometric properties of the measure, which negates the possibility of investigating potential relationships between CAT-SA ratings and symptomology. Second, owing to the nature of our investigations, test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change have not been assessed. Third, additional validation procedures are needed to establish its validity in countries outside England. Finally, service user experience/appraisals on the CAT-SA may be influenced by support received outside the supported accommodation setting.

Key findings

Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care: Supported Accommodation

-

The QuIRC-SA is the first standardised tool for quality assessment of specialist mental health supported accommodation services.

-

Of 143 items, only 18 showed a narrow response range, and five had poor inter-rater reliability.

-

The QuIRC-SA had excellent inter-rater reliability and exploratory factor analysis showed that items loaded onto the domains to which they had been allocated.

-

The QuIRC-SA can be recommended as a self-report quality assessment tool for supported accommodation services.

-

A digital version is available, free to use, at www.quirc.eu.

Client Assessment of Treatment for Supported Accommodation

-

All items of the CAT were considered relevant to mental health supported accommodation services; slight changes to wording were made.

-

The CAT-SA demonstrated good internal consistency and convergent validity.

-

The CAT-SA can be recommended as a ‘patient-reported outcome measure’ for use in mental health supported accommodation services.

Work package 2: national survey of supported accommodation services across England (work package 2i) and cohort study to investigate service user outcomes (work package 2ii)

The aim of this WP was to describe supported accommodation in England and factors associated with positive outcomes and costs.

The main objective of the national cross-sectional survey (WP2i) was to describe the provision and quality of supported accommodation for people with mental health problems in England and to investigate service and service user factors associated with service users’ quality of life, autonomy and satisfaction with care. Specifically, we investigated the following research questions:

-

Is there a difference in service users’ quality of life, autonomy, ratings of the therapeutic milieu of services and satisfaction with care between the three main types of supported accommodation (i.e. residential care, supported housing and floating outreach services)?

-

Can any variation in these be explained by service and service user characteristics?

Work package 2i: national survey of supported accommodation services

Methods

Our sample size was estimated to assess the difference in proportion of people moving on from each of the three types of supported accommodation 30 months after recruitment (assessed in the second component of WP2 – the cohort study). Our original estimate was that we needed to recruit 90 services (30 of each type) and 450 service users (five from each service) from 14 nationally representative areas based on an intraservice cluster correlation coefficient of 0.07 and a mean cluster size of five. We selected the 14 areas using an index developed by Priebe et al. 11 for their postal survey of supported accommodation, which ranks local authority areas on the basis of mental health morbidity, social deprivation, urbanicity, provision of community mental health care, supported accommodation, local authority mental health-care spend and housing demand. Recruitment was carried out between 1 October 2013 and 31 October 2014.

The researchers contacted key personnel working in housing departments in each of the 14 areas to first scope the local provision of mental health supported accommodation services and the number of places available in each. Residential care homes for adults with mental health problems in each area were also identified from the Care Quality Commission (the registration authority for care homes in England and Wales) website to ensure that none was missed (www.cqc.org). Services that were unusually large (> 80 service users) or small (< 6 service users) were excluded to increase generalisability of the sample. Five areas were replaced with another area closest on the sampling index: three because the area had no residential care services and two because the researchers were unable to clarify local supported accommodation provision (see Appendix 2, Table 5).

After 15 services of each of the three types were recruited, we reviewed our sampling strategy. We recalculated our intraservice correlation coefficient using responses to one item of the managers’ research interview [their estimate of the proportion of service users who had moved to more independent accommodation (residential care and supported housing) or required less support (floating outreach) in the last 12 months] and found it to be 0.18. A larger service user sample (624 rather than 450) was thus required. Owing to the relatively small number of residential care services identified, the number of services needed was adjusted to 21 residential care, 35 supported housing and 35 floating outreach, and the number of service user participants per service was increased to a maximum of 10.

The researchers randomly ordered the services in each area and within each of the three service types and contacted service managers sequentially to invite their participation. Service managers were given up to 4 weeks to reply. When the target number of services of each type had been recruited or the list exhausted for each area, the researchers moved on to the next area (see flow chart in Killaspy et al. 22).

Where service managers responded to the initial contact, the researchers arranged a time to discuss the study further by telephone. If the manager was willing for their service to participate, the researchers arranged a face-to-face meeting to explain the study to staff. A list of potentially eligible service users was then obtained from the service manager (excluding those they considered to be unable to give informed consent to participate and those absent from the accommodation for any reason). Each potentially eligible service user was allocated a unique identifier code. The service user list for each service was randomly ordered by the researchers in blocks of six. Service users in the first block were approached in any order by the researchers to seek their participation and subsequent blocks were generated until five service users had been recruited or the list was exhausted for each service. All potential participants received a participant information sheet about the study and had at least 2 days to read it and address queries to the researchers before giving their informed consent to participate.

Data collection

The researchers completed face-to-face interviews with the service manager, keyworkers and service users at which the following data were collected.

Service manager: description of the service

-

Service quality was assessed using the QuIRC-SA. 20

-

A proforma was used to gather details of the annual budget, referral processes and input from local mental health services.

Keyworker staff: service user assessments

-

A pro forma was used to collect service user participants’ clinical and risk history.

-

A Likert-type scale assessed the staff member’s expectation of the service user moving on (residential care/supported housing clients) or managing with less support (floating outreach clients) in the next 12 months.

-

Challenging behaviours were assessed with the Special Problems Rating Scale (SPRS),31 which records the presence and severity of 14 challenging behaviours, giving a total mean score of 0 to 2.

-

Needs were assessed with the Camberwell Assessment of Needs Short Assessment Scale (CANSAS),32 which rates 22 domains of care on a 3-point scale (0 = no need, 1 = met need, 2 = unmet need).

-

Use of substances was rated with the Clinician Alcohol and Drugs Scale (CADS),33 from which a dichotomous problematic/non-problematic score can be derived.

-

Social functioning was assessed with the Life Skills Profile (LSP). 34 The 39 items rate various aspects of the service user’s social and everyday functioning from 1 to 4. Higher scores denote better functioning. A total score (from 39 to 156) and five subdomain scores can be derived.

-

The adapted version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)35 was used to collect contacts with professionals/services within and outside the supported accommodation service, details of any medical and/or psychiatric admissions and contacts with family members over the past 3 months. These data were used in the health economic assessment.

Service users

-

A pro forma was used to collect sociodemographic details and details of any incidents of abuse (verbal, physical or sexual abuse), self-harm or exploitation by others from within or outside the service over the last 12 months.

-

Quality of life was assessed with the MANSA;29 the service user rates 12 life domains on a scale from 1 (could not be worse) to 7 (could not be better). A total mean score between 1 and 7 is generated.

-

Social inclusion was assessed with the Social Outcome Index (SIX),36 which gives a rating from 0 to 6 from four social domains [i.e. employment, housing, living alone or with family/partner, and contact with friend(s)].

-

Service users rated their autonomy using the Resident Choice Scale (RCS). 37 The degree to which they have choice over 22 aspects of daily activities is rated on a four-point scale, giving a maximum possible score of 88.

-

Users of residential care and supported housing services rated the therapeutic milieu of the service with the Good Milieu Index (GMI). 38 General satisfaction with the service and the degree to which it facilitates confidence and abilities are rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with higher scores denoting greater satisfaction.

-

Satisfaction with care was assessed with the CAT-SA. 21

Data analysis

Data were entered into a purpose designed database by the researchers. After data cleaning, data were transferred to Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software for analysis. Differences between services, including the adapted QuIRC domain scores, service user characteristics and ratings of standardised assessments were investigated using simple descriptive statistics and regression analyses. Multilevel regression was used to investigate the association between service factors (adapted QuIRC domain ratings and contextual factors) and service user factors (sociodemographic characteristics, clinical history, social functioning, needs, substance misuse and challenging behaviours) with service user ratings of quality of life, autonomy, good milieu of the service and satisfaction with care (see www.ucl.ac.uk/psychiatry/research/epidemiology-and-applied-clinical-research-depa/projects/quest-project for full details of the analysis plan). We assumed the convention that in any regression analysis at least 10–20 participants for each predictor should be entered into the model.

Results

A total of 22 residential care, 35 supported housing and 30 floating outreach services were recruited. From these 87 services, 619 users were recruited (residential care, n = 159; supported housing, n = 251; floating outreach, n = 209). A total of 193 keyworkers completed ratings on service users.

The full characteristics of the three types of service and their users are shown in tables 1 and 2 of Killaspy et al. 22

In summary, floating outreach provided more places than the other two types of service. Both floating outreach and supported housing services expected to work with their users for a median of 2 years, whereas for residential care this was 5 years. All three types of service used similar processes to assess new referrals. Almost all services had clinical input from a community mental health team or community rehabilitation team, despite the fact that only one-third of floating outreach clients were subject to the Care Programme Approach (vs. almost all residential care and supported housing clients). Supported housing services scored highest on six of the seven domains of the QuIRC (floating outreach scored slightly higher for human rights).

Most service users were male (66%), single (66%) and unemployed (82%). Users of residential care services were older and had been known to mental health services longer than users of the other two types of service. Most (68%) had a primary diagnosis of psychosis but one-third of floating outreach service users had depression/anxiety. The proportion of service users with substance misuse problems was relatively small (16% alcohol, 12% drugs), with the lowest prevalence among residential care service users. Users of residential care and supported housing had slightly more previous admissions than users of floating outreach and more were subject to a community treatment/restriction order. Overall, 40% of service users had committed an act of violence at some time, but there were few serious incidents of risk to others in the last 2 years. More users of supported housing (26%) and floating outreach (21%) had self-harmed within the last 2 years than users of residential care (4%). Risk of serious self-neglect was reported for 57% overall (72% for users of residential care services and at least 50% for users of the other two types of services). Vulnerability to exploitation was reported for around one-third of users in supported housing and floating outreach services and for 41% of those in residential care. Overall, 67% to 78% of service users across the three types of accommodation were considered a risk to themself or others.

There were few differences in social function and challenging behaviours between service users in the three types of accommodation, but those in residential care, unsurprisingly, had more needs than those in supported housing or floating outreach. However, there were few unmet needs across the three types of accommodation. Users of supported housing and floating outreach were more likely to report having been a victim of crime in the last 12 months than those in residential care (residential care 8%, supported housing 25%, floating outreach 22%) and around half of these incidents involved physical assault. Residential care service users had higher ratings of satisfaction with their safety than users of the other two types of service.

Regression analyses that took account of clustering by area and service showed lower quality-of-life scores for those in floating outreach and supported housing than for those in residential care services, but higher levels of autonomy in both supported housing and floating outreach than in residential care (see table 3 in Killaspy et al. 22). In these analyses, the therapeutic milieu (which could not be assessed in floating outreach services) was rated higher by users of supported housing than by users of residential care [mean difference 0.973, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.126 to 1.821; p = 0.024], yet there were no statistically significant differences between the three service types in terms of satisfaction with the care received.

Appendix 2, Tables 6 and 7, show the results of the regression analyses that investigated service and service user characteristics associated with service users’ quality of life, autonomy, ratings of the therapeutic milieu (residential care and supported housing only) and satisfaction with care. The QuIRC domains therapeutic environment and recovery-based practice were found to be highly correlated. It was decided to keep recovery-based practice in the models as this domain had been found to be a predictor of successful discharge from inpatient mental health rehabilitation units in a previous study. 39 As data could not be collected for living environment domain scores for floating outreach services, this domain was also dropped from the regression models. The 19 variables included (see Appendix 2, Tables 6 and 7) were agreed by the PMG on the basis of those where differences were found in the summary statistics and where there was clinical justification.

In these analyses, which accounted for differences in service user characteristics, service users’ quality of life (MANSA) did not differ between supported housing and residential care but remained lower for those in floating outreach than for those in residential care. Supported housing was still predictive of higher autonomy (RCS) than residential care but floating outreach was not. In addition, positive associations were found between service users’ quality of life and the mental health morbidity/housing index of the local area, service user age, primary diagnosis (psychosis vs. non-psychosis) and problematic drug use. Negative associations were found with the number of places occupied per service, the adapted QuIRC recovery-based practice domain score and the number of unmet needs. However, the small size of the coefficients suggests that these associations had very little clinical impact. Service users’ autonomy was negatively associated with the QuIRC-SA domain treatments and interventions score and unmet needs, but, again, small coefficients suggest that these associations were of limited clinical significance. For each additional occupied place per service, there was a small reduction in service users’ ratings of satisfaction with care (CAT-SA) and the therapeutic milieu (GMI). The GMI ratings were positively associated with the QuIRC-SA human rights domain score, service users’ age, staff ratings of their social function (LSP) and risk history. Once again, small coefficients limit the clinical relevance of these findings.

Health economic component

Methods

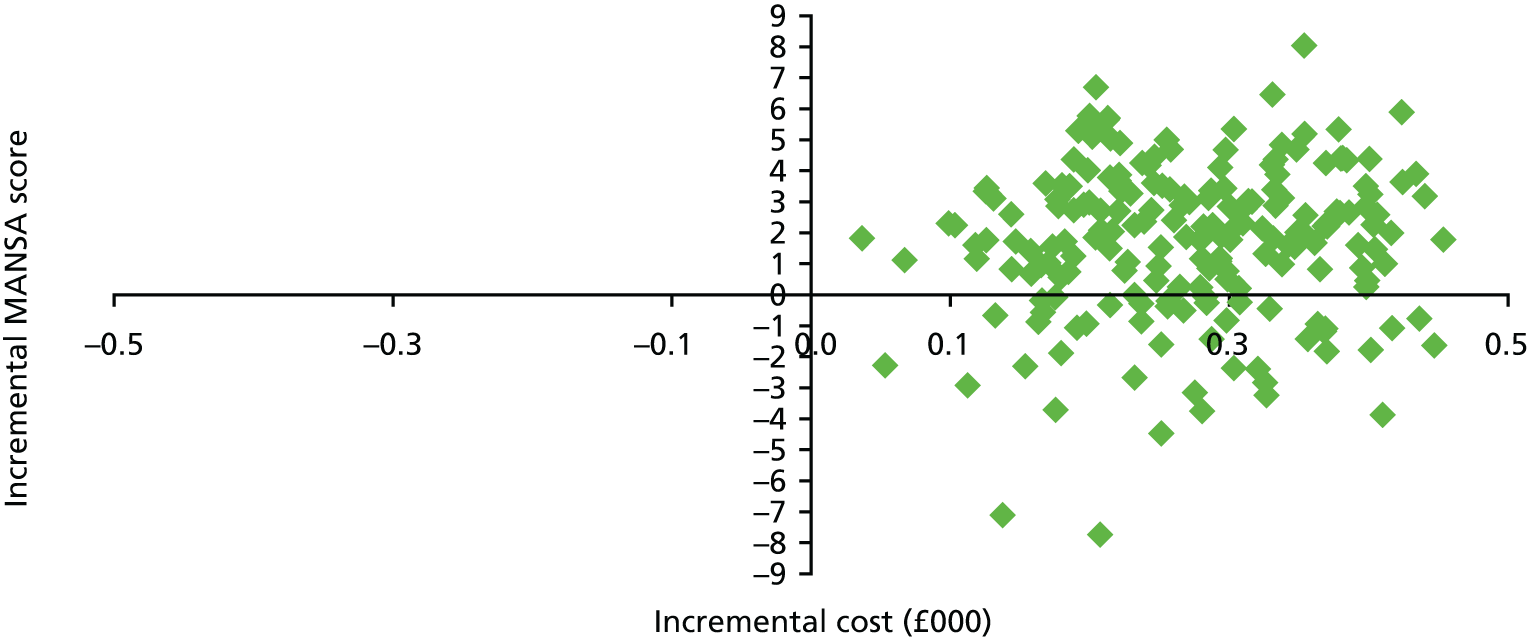

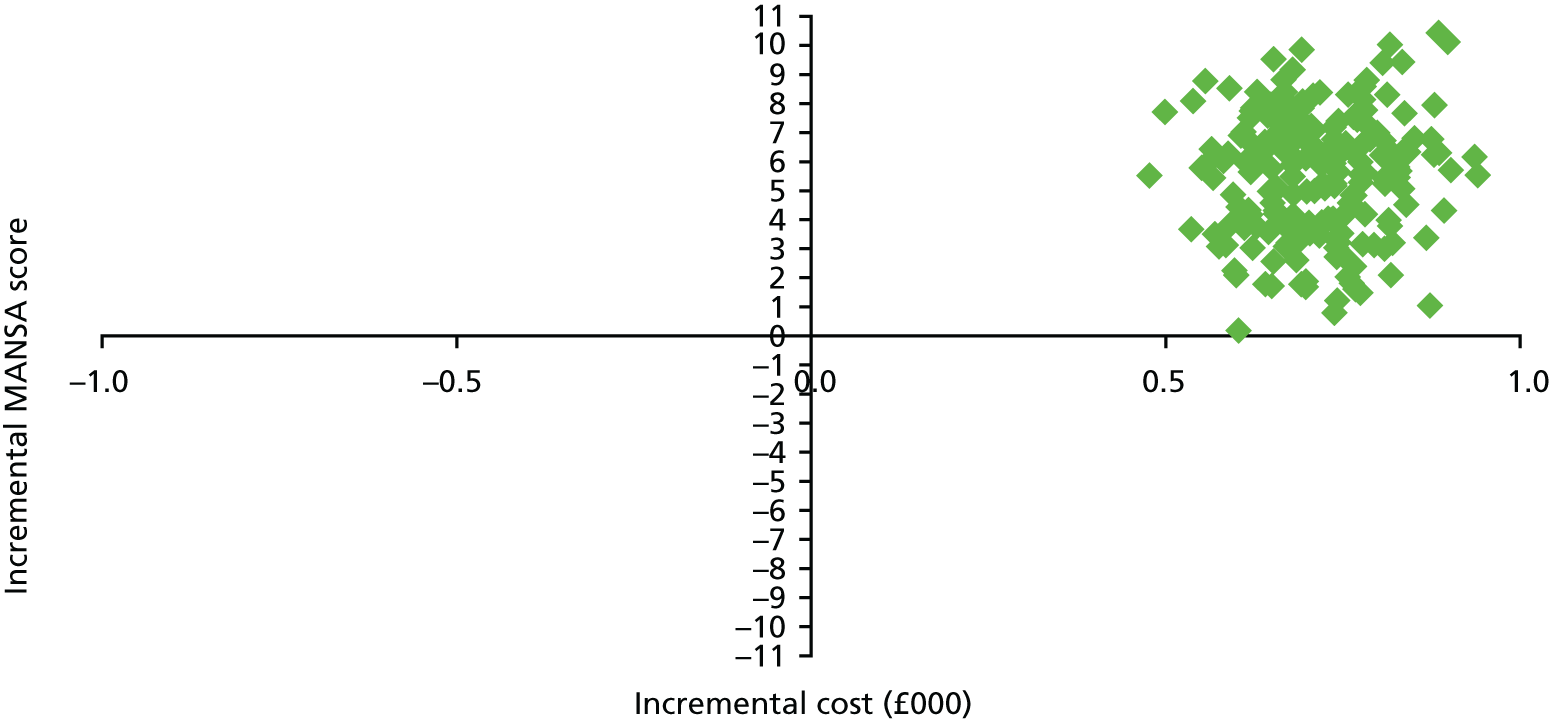

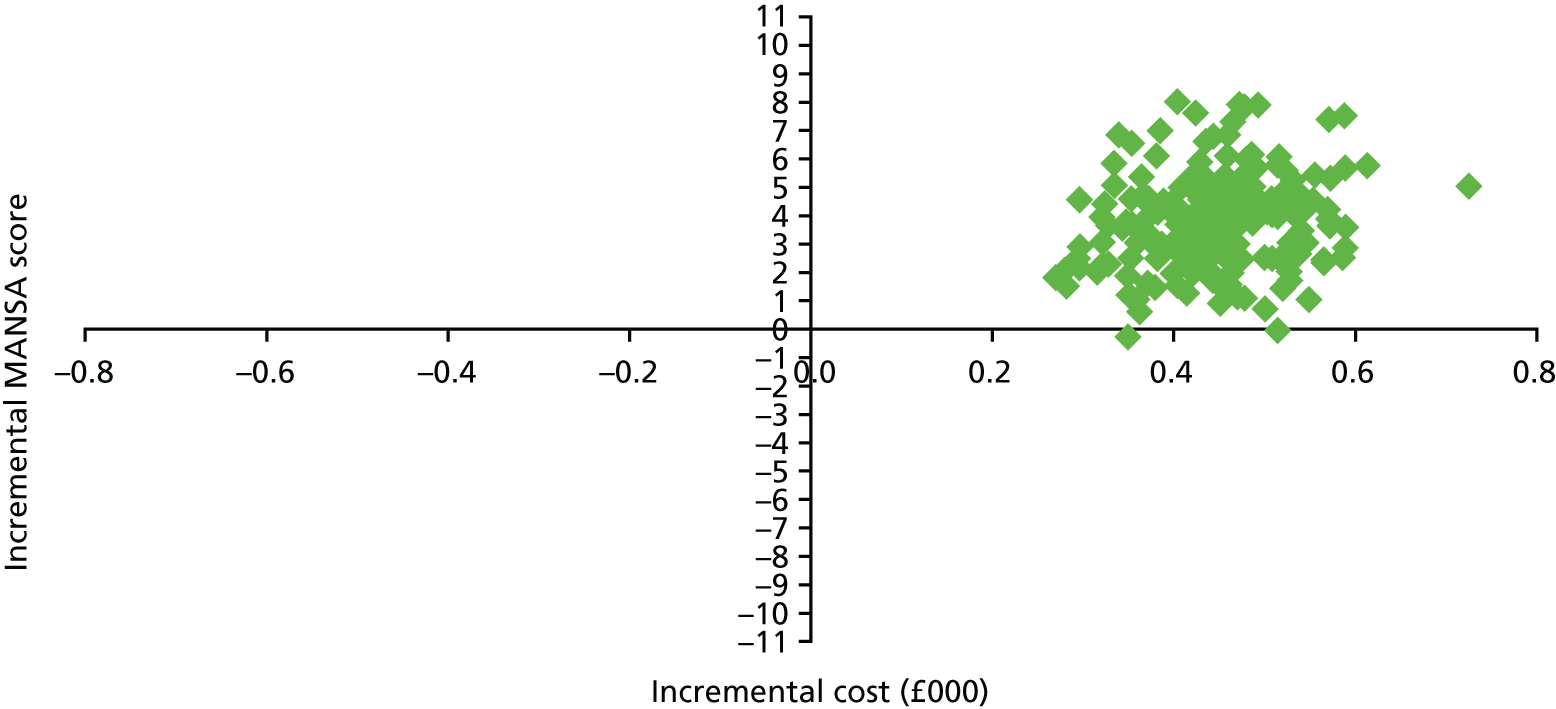

The use of services was estimated from staff and service user interviews using an adapted version of the CSRI. 35 Both health-care and social care costs were included in the analyses. Services included those provided externally as well as contacts with staff of the supported accommodation service. Participants provided information on whether or not specific professionals had been seen in the previous 3 months, how often they had been seen and whether or not this was in a group setting. Information relating to the previous 3 months was obtained on contacts with care co-ordinators, psychiatrists, other doctors, psychologists, community mental health nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, counsellors and art therapists. Contacts with staff of the supported accommodation service were broken down into face-to-face contacts, group sessions and personal care. It was assumed that group sessions consisted of four participants. In addition, details of admissions to hospital in the previous 12 months for mental health or physical health reasons were provided. Service costs were calculated by combining the service use data with appropriate unit cost information. 40 Total costs of services used in the previous 3 months were calculated, as were total inpatient costs for the previous 12 months. An overall total for the previous year was calculated by multiplying the 3-month costs by 4 and adding to the inpatient costs. Comparisons in terms of service use and costs were made between the three groups (i.e. residential care, supported housing, floating outreach). Total cost differences were assessed using a mixed-effects multilevel regression model, controlling for clinical and demographic factors. To generate cost-effectiveness, planes we used a bootstrapped linear regression model for both the cost and the MANSA score, and controlled for area. One thousand cost-outcome differences between (1) residential care and supported housing and (2) residential care and floating outreach were generated and plotted.

Results

There were clear differences in the proportion of each group using specific services (see tables 4 and 5 and the appendix of Killaspy et al. 22). Those in residential care were most likely to receive input from the supported accommodation staff through group sessions and to be in receipt of personal care. Those in supported housing and floating outreach had similar levels of face-to-face and group contacts with supported accommodation staff. Users of supported housing had the highest input from community team care co-ordinators (79% vs. 64% of residential care and 45% of floating outreach service users) and the highest rate of psychiatric admission (24% vs. 11% of residential care and 9% of floating outreach service users). Floating outreach service users generally had lower levels of service use than those in the other two groups. Of those who used specific services, the intensity of use did not differ markedly between the groups for most services. However, those in residential care had more nurse contacts, face-to-face sessions and personal care contacts than users of the other two services. They also had longer stays in hospital for mental health reasons, although this was influenced by some outliers.

The services with the highest costs were inpatient care and face-to-face contact with supported accommodation staff. Excluding inpatient care, the costs of service use during the previous 3 months were highest for users of residential care, followed by those receiving floating outreach. Inpatient costs were lowest in the floating outreach group and similar in the other two groups. This was also reflected in the total costs pertaining to a 1-year period such that total costs were highest for residential care service users and lowest for floating outreach service users.

The multilevel models showed that after making adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics, the residential care group had costs that were, on average, £1483 more than for supported housing and £5381 more than for floating outreach. The average costs for supported housing were £3898 more than for floating outreach. We found that residential care service users had a quality-of-life (MANSA) score that was 0.274 points higher than users of supported housing and 0.722 higher than users of floating outreach, and those in supported housing had a score that was 0.449 points higher than for those in floating outreach (see table 3 in Killaspy et al. 22). These figures suggest that it costs £5412 to achieve an extra 1-point improvement on the MANSA (representing a clinical improvement of > 14%) if residential care is chosen rather supported housing, £7453 if residential care is chosen rather than floating outreach and £8682 if supported housing is chosen rather than floating outreach. Appendix 2, Figure 4, shows the uncertainty around these point estimates and indicates that although residential care is most likely to generate higher costs and better outcomes (quality of life) than supported housing, there is still a reasonable probability of lower costs and better outcomes for supported housing. Appendix 2, Figures 5 and 6, show that residential care and supported housing are both highly likely to produce better outcomes but higher costs than floating outreach.

With regard to service users’ autonomy, both supported housing and floating outreach produced better outcomes than residential care and were less expensive. That is to say that they were ‘dominant’. Supported housing was more expensive than floating outreach but it was associated with greater autonomy, with a cost of £46,405 for every extra unit improvement in autonomy achieved.

Links to other work packages

The QuIRC-SA and CAT-SA, developed in WP1, were used to assess service quality and service user experiences in WP2i. Service users in supported housing and floating outreach had similar levels of risk, social functioning, challenging behaviours and autonomy, and received similar levels of input from their supported accommodation support workers, suggesting equipoise between the two service types, which supported the rationale for a comparison of these two service models in the feasibility trial (WP4).

Limitations

A number of limitations must be acknowledged. In spite of using a sampling strategy explicitly designed to minimise bias and produce a nationally representative sample, service users who declined to participate or who lacked capacity to consent may have introduced a sampling bias. In addition, our findings cannot be generalised to supported accommodation services and systems outside England. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of WP2i means that we cannot infer causality from our findings.

Key findings

-

Compared with floating outreach, service users in residential care and supported housing had more severe mental health problems.

-

Over half of all service users were at risk of serious self-neglect and over one-third had been vulnerable to exploitation over the previous 2 years.

-

One-quarter of those in supported housing and one-fifth of those receiving floating outreach services had been the victim of crime in the last year, compared with 8% of those in residential care.

-

Residential care was the most expensive service and floating outreach was the cheapest. Residential care and supported housing were both highly likely to produce better outcomes but had higher costs than floating outreach.

-

As assessed by the QuIRC-SA, supported housing demonstrated the best quality of care compared with the other two service types.

-

After adjusting for clinical differences between service users, quality of life was similar for those in residential care and supported housing, but lower for those in floating outreach. Autonomy was greater for those in supported housing than in residential care and floating outreach. Satisfaction with care was similar across service types.

Work package 2ii: cohort study

The aim of WP2ii was to assess the proportion of people in supported accommodation who successfully moved on to more independent accommodation over 30 months and to identify service and service user factors (including costs) associated with move-on.

The primary outcome, ‘successful move-on’, was defined as the proportion of participants in each service type who moved to more independent accommodation successfully without placement breakdown over the 30-month follow-up period. Because floating outreach is provided to people living in a permanent tenancy, for this service type, the primary outcome was defined as managing with fewer hours of support per week rather than moving home.

Our specific research questions were:

-

What proportion moved on to more independent accommodation overall and by service type?

-

What proportion moved on to more independent accommodation and sustained it for the 30-month follow-up (i.e. did not move back to more supported accommodation)?

-

How much of the variation in outcome was due to service type and service quality (measured by the QuIRC-SA domains), before and after accounting for service user characteristics (age, sex, diagnosis, length of stay, morbidity)?

We also investigated a secondary outcome, defined as the proportion of participants who moved on to more independent accommodation and sustained it for 30 months (i.e. without placement breakdown, any move back to more supported accommodation or any hospital admission) overall and by service type.

To minimise the influence of time in service and clinical differences between service users in different types of supported accommodation, we planned to undertake further investigation of service user level outcomes for the subgroup of individuals in the main cohort who had been living in supported accommodation for < 9 months at recruitment. Nine months was chosen as a pragmatic balance between being relatively new to the service and being there long enough for staff and service users to be able to rate the various outcome measures. For this subgroup, we aimed to investigate the following research questions:

-

Is there a difference in service users’ quality of life, autonomy and staff-rated social function at the30-month follow-up between users of different types of service, after adjusting for the baseline score of each outcome?

-

Is there a difference in service users’ quality of life, autonomy and staff-rated social function at the30-month follow-up between users of different types of service after adjusting for baseline score, service quality and service user characteristics?

-

How much of the variation in these outcomes is due to service type and quality, after accounting for service user characteristics?

-

Are there differences in service use and costs at the 30-month follow-up?

Methods

Data collection

After participants were recruited in WP2i, the researchers maintained contact with the relevant service manager every 3 months to monitor whether or not the service user had moved on to less supported accommodation, moved to more supported accommodation or had any admission(s) to hospital. For those who had moved, details of the new supported accommodation service were obtained and contact was made with the new service staff. If the service user moved on to a fully independent accommodation, with no supported accommodation staff involvement, their care co-ordinator (when applicable) was contacted to provide ongoing monitoring of their accommodation status. This process was continued over the 30-month follow-up period.

At the 30-month follow-up point, the researchers completed telephone interviews with supported accommodation staff or care co-ordinators and confirmed details of any moves to alternative supported or independent accommodation during the 30-month period and the length of time in each accommodation. From these data, an overall assessment of whether or not the person had progressed successfully was made [i.e. moved to less supported accommodation (for those in floating outreach services, this was operationalised as having fewer hours of support per week) without placement breakdown].

If a relevant staff member could not be identified (e.g. if the service user had moved to a fully independent tenancy without floating outreach support and been discharged from mental health services), NHS case records were accessed to collect primary outcome data on move-on. For all participants who were reported to have had a hospital admission, case notes were also checked to clarify this. The researchers also completed the adapted version of the CSRI35 with the staff member, corroborating the length of any admissions from the case notes for the health economic analysis where possible.

For the cohort of participants who had been in their accommodation for < 9 months at recruitment, researchers conducted additional face-to-face interviews with service users and their support workers or care co-ordinators. If the service user had moved on to fully independent accommodation and had no contact with supported accommodation or mental health staff, only the service user interview could be completed. These interviews comprised the same measures completed at recruitment, assessing, (1) from staff interviews, social functioning (LSP),34 substance use (CADS),33 challenging behaviours (SPRS)31 and needs (CANSAS),32 and, (2) from service user interviews, quality of life (MANSA),29 social outcomes (SIX),36 autonomy (RCS),37 therapeutic milieu (GMI)38 and satisfaction with care (CAT-SA). 21

Data analysis

Data were entered into a purpose designed database by the researchers. Data checks were completed on all records, comparing the recorded data with the data entered into the database. After cleaning, data were transferred to Stata statistical software for analysis. Descriptive analyses were conducted for all variables.

Primary outcome

For the primary outcome, a logistic mixed-effects model was fitted using xtmelogit, with a random intercept for service and a fixed effect for area as this was used in the sampling frame as a design variable. Univariate analysis was used to identify service and service user variables with a significant association (p < 10%) with the primary outcome for inclusion in multilevel models investigating predictors of the primary outcome. As the analysis of baseline data showed that the QuIRC-SA domains therapeutic environment and recovery-based practice were very highly correlated (Spearman’s rho = 0.87) and the variance inflation factor exceeded 10, it was decided to dispense with the therapeutic environment domain score as the recovery-based practice domain score had previously been shown to predict successful discharge from inpatient rehabilitation services. 39 The QuIRC-SA domains included in the univariable analysis were therefore restricted to treatments and interventions, self-management and autonomy, social interface, human rights, and recovery-based practice. Living environment was excluded as it does not apply to floating outreach services.

Service user variables included in the univariate analysis included sociodemographic and clinical characteristics [age, sex, clinical history, diagnosis (non-psychotic vs. psychotic disorder), length of stay with service], social functioning (LSP), total unmet needs (CANSAS), substance misuse (CADS), challenging behaviours (SPRS), risk of self-neglect and/or vulnerability to exploitation, risk to others and risk of self-harm. Variables were examined for collinearity. Those that did not allow discrimination between service users because the counts were too high or too low were excluded.

Selected variables were included separately in the univariable model to ascertain whether or not there was a difference in successful move-on between service types after adjusting for these variables. Those that showed a significant association (p = 10%) were included in the multivariable model. In our multivariable models, we assumed the convention that at least 10–20 participants for each predictor should be entered.

Sensitivity analyses

To address factors that may have influenced our primary outcome (clinical profile of service users, geographical location of service, definition of primary outcome for floating outreach, service user time in service), the following sensitivity analyses were conducted on the primary outcome by service type:

-

a propensity score analysis that collated an average treatment effect from the following variables: social function – LSP score,34 age, diagnosis of psychosis/no psychosis and a composite risk variable (vulnerability to risk of exploitation with or without risk to others, with or without self-harm in the last 2 years)

-

excluding participants who did not have a diagnosis of psychosis

-

replacing the geographical area variable with the geographic area sampling index score

-

only categorising floating outreach service users as having a positive outcome if the number of hours per week of support had reduced by at least 50% since recruitment

-

comparing service users who had been in the supported accommodation for < 9 months at recruitment with those who had been there for ≥ 9 months.

Secondary outcome

A logistic mixed-effects model was fitted using xtmelogit, with a random intercept for service and a fixed effect for area to assess the secondary outcome by service type.

Subgroup analysis

We planned to use multilevel models to investigate factors associated with service user ratings of quality of life, autonomy and satisfaction with care in the subcohort of participants who had been living in their accommodation for < 9 months at recruitment. However, the sample for whom data were available was too small and thus only descriptive data are presented.

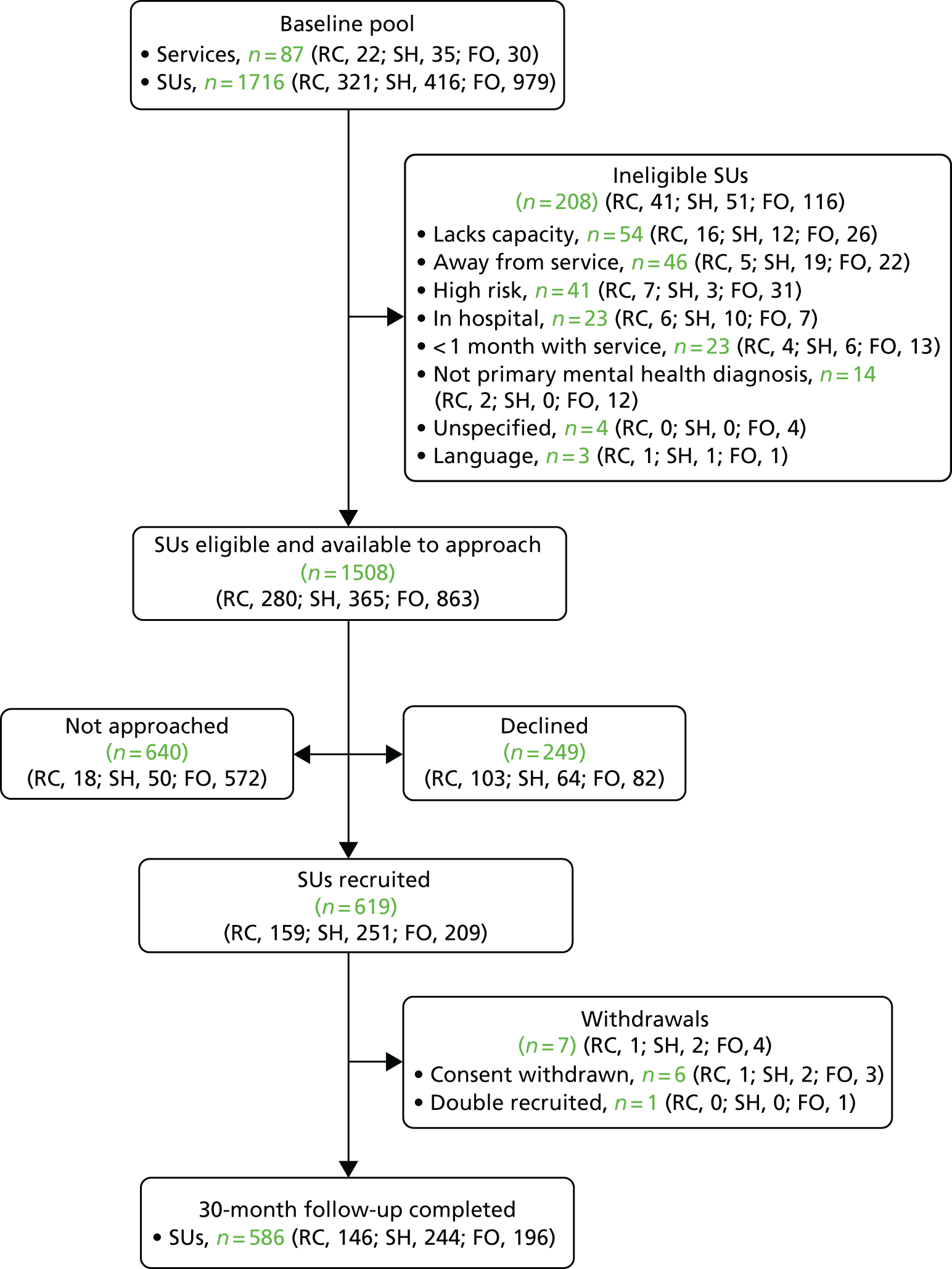

Results

Participant flows in the cohort are shown in Figure 2. After accounting for withdrawals (n = 7) and deaths (n = 26), we followed up 586 out of 619 (95%) participants over 30 months (residential care n = 146; supported housing n = 244; floating outreach n = 196).

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow during the prospective study. FO, floating outreach; RC, residential care; SH, supported housing; SU, service user.

Descriptive data

Descriptive data for participants at follow-up by service type are shown in Appendix 3, Table 8. Overall, 110 out of 586 participants (18.8%) had a hospital admission during the 30-month period. Incidents of risk to others were highest among users of residential care (14% vs. 11.5% for users of supported housing and 4.1% for those in receipt of floating outreach). Episodes of self-harm were highest among users of supported housing (17.3% vs. 14.8% receiving floating outreach and 4.2% in residential care). Around one-third (30.5%) of supported housing service users who had not moved on were considered by staff as ready for move-on, compared with 8.5% of those in residential care and 6.9% of those receiving floating outreach.

Missing data

Overall, there were very little missing primary or secondary outcome data (see Appendix 3, Table 8).

Primary outcome

In total, 243 out of 586 participants (41.5%) achieved the primary outcome of successful move-on to less supported accommodation. The proportions achieving the primary outcome in residential care, supported housing and floating outreach were 15 out of 146 (10.3%), 96 out of 244 (39.3%) and 132 out of 196 (67.3%) participants, respectively. The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of achieving the primary outcome for users of floating outreach compared with residential care was 28.81 (95% CI 11.53 to 72.02; p < 0.001). For floating outreach compared with supported housing service users, the OR was 5.11 (95% CI 2.47 to 10.57; p < 0.001). The unadjusted OR of achieving the primary outcome for users of supported housing versus residential care was 5.64 (95% CI 2.30 to 13.84; p < 0.001) (see Appendix 3, Table 9).

The univariable analysis identified positive associations with the primary outcome for the QuIRC-SA service quality domain scores for human rights (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.16; p = 0.007) and recovery-based practice (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.08; p = 0.054), as assessed at recruitment. The QuIRC-SA social interface domain score was negatively associated with the primary outcome (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.98; p = 0.001). Service user total unmet needs, length of time in the supported accommodation service and a composite risk variable (risk of vulnerability to exploitation with or without risk of self-harm) at recruitment were also negatively associated with the primary outcome (see Appendix 3, Table 9).

After adjusting for these variables in the multilevel model, users of floating outreach services were almost eight times more likely to be managing with less support at follow-up than users of residential care (OR 7.96, 95% CI 2.92 to 21.69; p < 0.001) and almost three times more likely than supported housing service users (OR 2.74, 95% CI 1.01 to 7.41; p < 0.001). Users of supported housing were almost three times more likely to have moved on to less supported accommodation than those in residential care (OR 2.90, 95% CI 1.05 to 8.04; p = 0.04).

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the sensitivity analyses are shown in Appendix 3, Tables 10 and 11. All analyses showed a similar pattern of results to the main adjusted and unadjusted models, with higher odds of floating outreach service users achieving the primary outcome than users of supported housing and residential care, and higher odds of supported housing service users achieving the primary outcome than those in residential care.

Secondary outcome

Few (17/243, 7%) individuals who moved on had an admission after they had moved. This was most likely among supported housing service users, among whom 12 out of the 96 (12.5%) who moved on had a subsequent hospital admission [vs. none of the 15 who moved on from residential care and 5/132 (3.8%) of those who moved on from floating outreach]. The results of the analysis of our secondary outcome multivariable model are shown in Appendix 3, Table 12.

Subgroup analyses

The subgroup analyses results are shown in Appendix 3, Tables 13 and 14. The mean satisfaction with care (CAT-SA) scores were highest in residential care [mean 8.2, standard deviation (SD) 2.0]. There was little difference in mean quality-of-life (MANSA) and autonomy (RCS) scores between users of the three service types. Social function (LSP) was lowest in residential care (mean 118.3, SD 19.4) and highest in floating outreach (mean 127.2, SD 12.1).

Health economic component

Methods

Data on services used by residents were collected from staff at the 30-month follow-up with a short version of the CSRI. For the subcohort of participants who had been in the service for < 9 months at baseline, data were also collected from service users directly. Costs were calculated as described in Work package 2, Health economic component, and a similar multilevel model was used for analysing cost differences for the full sample. Information on inpatient use during the whole 30-month follow-up was available. We did not extrapolate the 3-month non-inpatient costs across the 30-month period.

The association between the primary outcome measure and costs was investigated in two ways. First, costs were compared for each group among those who achieved the outcome and those who did not. Second, the primary outcome variable was entered into the multilevel models to investigate the overall relationship with cost. We do need to be cautious in interpreting the results though because it is to be expected that those who do move to a lower level of care will have correspondingly lower costs. Adjusting for participant characteristics does allow us to quantify the impact more precisely.

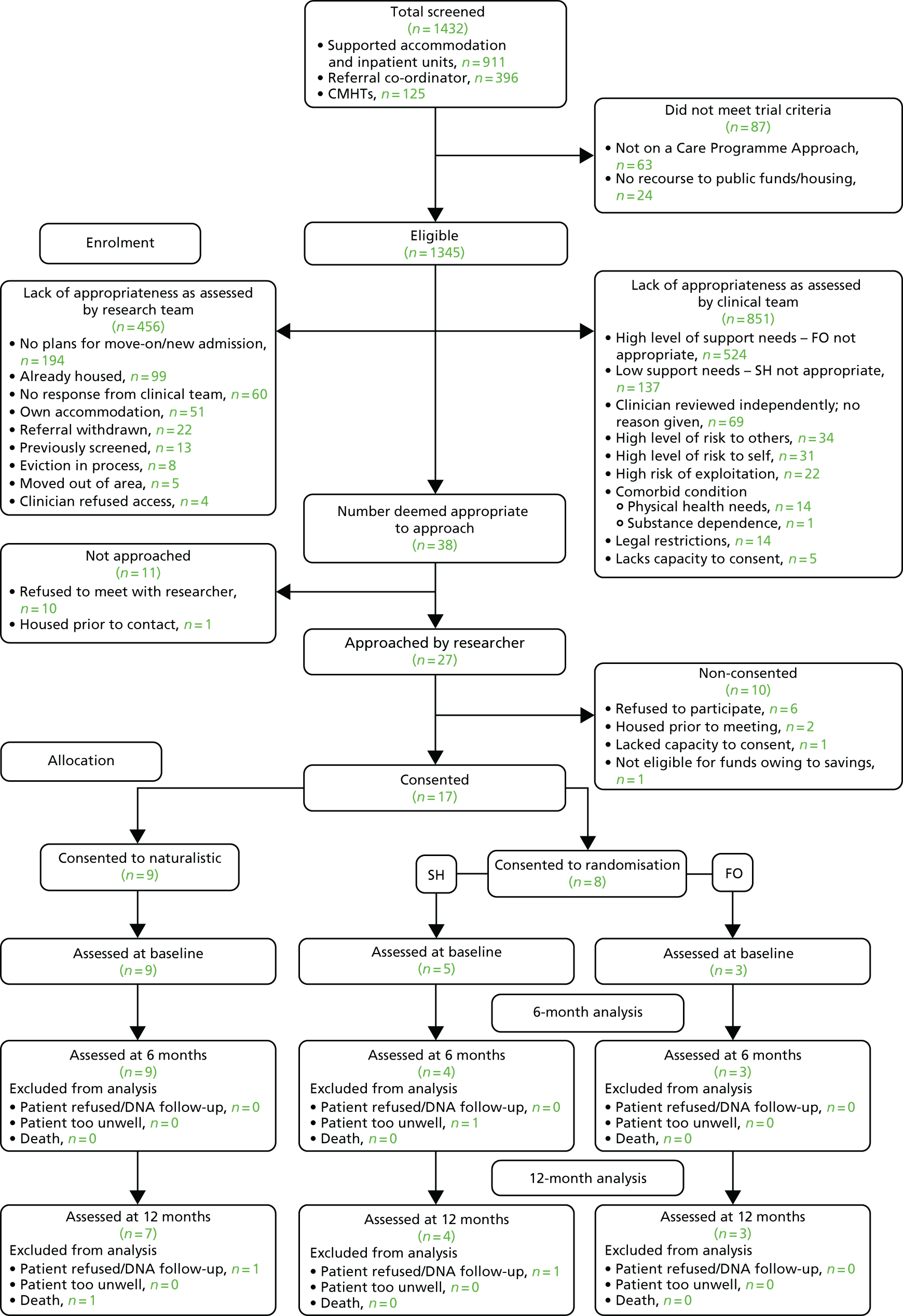

Results