Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0609-10107. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Lelia Duley reports National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Trials Unit support funding. Jon Dorling reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study, grants from NIHR and grants from Nutrinia Ltd (Ramat Gran, Israel) outside the submitted work. He also reports membership to the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Efficient Study Designs 2015–16, HTA General Board 2016–19, HTA Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health (MNCH) Methods Group 2014–18, HTA MNCH Panel 2013–18, and HTA Post Board Funding Teleconference 2015–18. Andrew Weeks reports grants from Liverpool Women’s Hospital Charity during the conduct of the study. Gill Gyte reports personal fees from Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group outside the submitted work. Jim Thornton reports membership of HTA Clinical Trials Board 2010–15, HTA and EME Editorial Board 2016–18, Rapid Trials and Add on Studies 2012, CPR Decision-Making Committee. David Field reports HTA Commissioning Board 2013–2018, HTA and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Editorial Board 2012–18. William McGuire reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study, and membership of the HTA Commissioning Board 2013–present and the HTA and EME Editorial Board 2012–present.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Duley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background

Being born too early (preterm birth) has a major impact on survival and quality of life for the child, on psychosocial and emotional stress on the family, and on costs for health services and society. 1–3 Mortality is highest for infants born very preterm, before 32 weeks’ gestation. In the UK, infant mortality (deaths in the first year of life) for babies born very preterm is 144 deaths per 1000 live births, compared with 1.8 deaths per 1000 live births at term. 4 Although only 1.4% of live births in the UK are very preterm, these babies account for 51% of infant deaths. 4

The costs of neonatal care for infants born very preterm are high. For those born before 28 weeks’ gestation, duration of hospital stay is 85 times that for term births and hospital inpatient costs are £15,000 higher. For those born at 28 to 31 weeks, duration of hospital stay is 16 times that for term births and hospital inpatient costs are £12,000 higher. 5 Morbidity among children born very preterm who survive is also higher than those born at term. 3 Of very preterm infants who survive, around 5% develop cerebral palsy and those without severe disability have a twofold or greater increased risk for developmental, cognitive and behavioural difficulties. 1,2 These impairments may persist into adolescence and early adulthood. 6,7 Even modest improvements in outcome would be of substantial benefit to the children, their families and the health services.

Aims and objectives

The aims of this programme were to improve the quality of immediate care at very preterm birth, enhance family-centred care, and improve outcome for infants born very premature and their families.

Specific objectives were to:

-

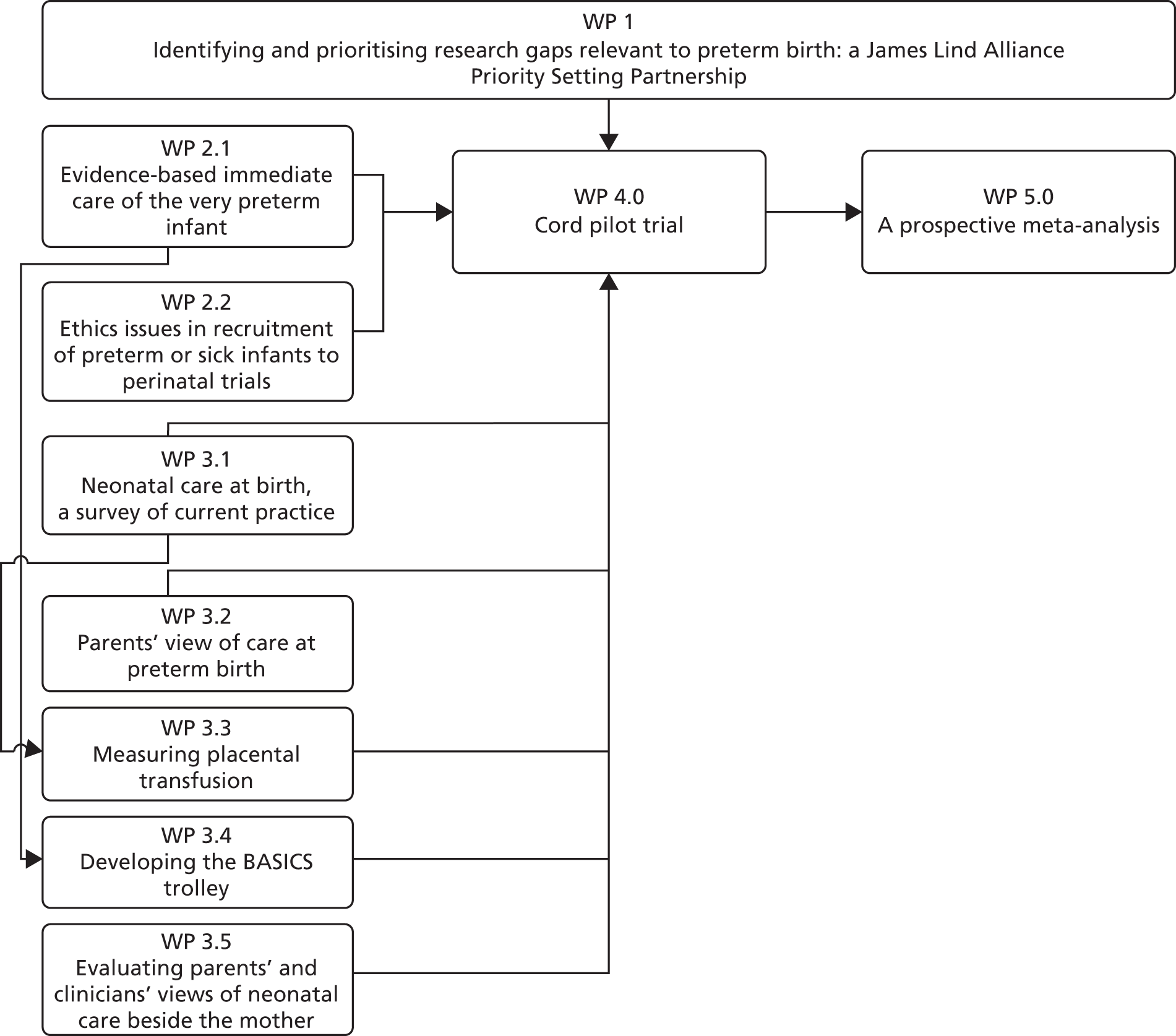

Develop a James Lind Alliance (JLA) Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) between service users and clinicians to identify and prioritise treatment uncertainties relevant to preterm birth (work package 1; Figure 1) and to:

-

identify and prioritise research gaps for preterm birth, using the methods developed by the JLA

-

describe how service users and clinicians interact when making collective decisions about research priorities, and how they communicate when deciding research priorities together.

-

-

Develop strategies for providing initial neonatal care at birth beside the mother, rather than away from the mother, for preterm or sick babies by:

-

conducting a survey of current practice for initial neonatal care with the cord intact at NHS hospitals (work package 3.1)

-

describing parents’ experiences and views of care at very preterm birth, and developing a questionnaire tool to assess their views of care at very preterm birth (work package 3.2)

-

improving understanding of the physiology of transition from fetal to neonatal circulation by measuring umbilical flow at preterm birth and assessing how it varies with gestation (work package 3.3)

-

conducting systematic reviews and overviews (umbrella review) to assess the evidence for delivery room transitional assessment and support, and to identify research gaps (work package 2.1)

-

developing a mobile Bedside Assessment, Stabilisation and Initial Circulatory Support (BASICS) trolley to support providing newborn life support beside the mother, and with the cord intact (work package 3.4)

-

describing parents’ and clinicians’ experiences and views of neonatal care at birth beside the mother, and of the BASICS trolley (work package 3.5).

-

-

Generate information that will inform the design of a high-quality large multicentre UK trial comparing a policy for very preterm births of deferred cord clamping and initial neonatal care with umbilical cord intact, against immediate clamping and initial neonatal care after cord clamping, by:

-

conducting a narrative systematic review (framework synthesis) to identify the ethical challenges and their potential solutions in consent to recruitment of preterm or sick infants to clinical trials (work package 2.2)

-

conducting a pilot randomised trial comparing deferred cord clamping and initial neonatal care with the cord intact, against immediate clamping and initial neonatal care after cord clamping for very preterm births, including follow-up of the women for 1 year and until 2 years of age (corrected for gestation at birth) for the children (work package 4)

-

establishing a collaborative group to conduct a prospective meta-analysis of trials evaluating alternative strategies to influence placental transfusion at preterm birth, and developing the protocol for this analysis (work package 5).

-

FIGURE 1.

Overview of work packages. WP, work package.

The prioritisation process ran in parallel to other work packages. It was added to the programme in response to feedback from the funding board at stage 1 of the grant application process. Hence, other work packages were not dependent on its outcomes. Although cord clamping did emerge as a top priority, we had already identified this as a priority via an informal process.

Priority setting for future preterm birth research

In the past, the health-care research agenda was determined primarily by researchers, and the processes for priority setting in research lacked transparency. 8 Often, research does not address the questions about treatments that are of greatest importance to patients, their carers and practising clinicians. 9,10 Many research questions have not been investigated and for many more the existing evidence is incomplete. The JLA (www.lindalliance.org/; accessed 24 January 2019) has developed methods for bringing patients and clinicians together to establish PSPs that then identify and prioritise ‘treatment uncertainties’ to inform publicly funded research. 11 This approach has been used successfully for a wide range of topics including asthma,12 urinary incontinence,13 vitiligo,14 prostate cancer15,16 and schizophrenia. 17 For urinary incontinence, of the top 10 priorities, five came from clinicians, four from patients and one from researchers. 13

When uncertainty about the effects of treatments relates to preterm birth, it seems particularly pertinent that research should address the most important priorities, and the most pressing needs, of these vulnerable children and their families and clinicians. Failure to identify and prioritise these uncertainties may result in suffering and death. 18 Examples in perinatal care where this failure to identify and prioritise important uncertainties has happened include the use of caffeine, which was shown to reduce the risk of cerebral palsy and developmental delay, and so was widely taken up in clinical practice, but only 30 years after being suggested for prevention of apnoea in premature babies. 19,20 In addition, the use of magnesium sulphate, which, after 60 years of controversy, was finally shown to be better for women with eclampsia than either diazepam or phenytoin. 21–23 Although the importance of women and their clinicians contributing to the perinatal research agenda is well established,8 we proposed the first PSP in the perinatal field.

To establish a PSP required bringing together representatives of women and their families and of clinicians and other health-care workers. Understanding of how people interact and make collective decisions in groups or committees with members from diverse organisations comes from health research, and from social psychology and business administration. 24 Larger groups may increase membership diversity,25 although this may be offset by a reduction in reliability of decision-making. The chairperson is crucial for establishing inclusiveness, openness and trust in the discussion. 25–28 If time is short, less knowledge is shared and evaluated and then decisions result more from judgement based on prior preferences than problem-solving,29 which may mean that they are more influenced by an individual’s status within the group. 25

When we planned the Preterm Birth PSP, evidence about how service users and clinicians make joint decisions on research priorities was lacking. 24 Improved understanding of how such partnerships work (e.g. if expertise based on qualifications, experience or problem-solving skills influences decisions30 or if the way arguments are framed changes as consensus develops) may offer insight into how the process could be improved.

The Preterm Birth PSP published a list of the top 15 research priorities,31 which is being used by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and by researchers in planning new research. Study of the groups’ working processes has also led to recommendations about how decision-making might be improved.

Parents’ views and experiences of very preterm birth

Very preterm birth and subsequent hospitalisation of the baby can be an extremely distressing time for parents. 1,32 There has been little research into parents’ experiences at the time of very preterm birth, or their satisfaction with their care during the birth. In addition, previous work has often failed to include fathers. Women’s views and experiences during labour and childbirth are increasingly important to health-care providers and policy-makers,33 and may have an impact on subsequent health and well-being for the woman and her baby. 34,35

To ensure a strong parent focus throughout our programme, we planned qualitative interviews to explore parents’ experiences of very preterm birth and their first moments with their baby. 36–38 Regular multidisciplinary project meetings to plan these interviews, and to discuss the emerging themes and verbatim transcripts, were immensely valuable for subsequent work packages. These were particularly valuable for developing strategies for neonatal care beside the mother, and for planning the pilot trial. Our experience in conducting these interviews also contributed to further qualitative work exploring the views of both parents and clinicians of neonatal care at birth beside the mother,39,40 and of the new two-stage consent pathway in our pilot trial. 41,42

A number of instruments have been developed to assess women’s satisfaction with care during childbirth. When planning our programme we were not aware that any of these were designed to be used following very preterm birth, which is usually a different experience from giving birth to a healthy term baby. To confirm this we conducted a systematic review of available measures to assess parents’ satisfaction with care during labour and birth. 43 Having demonstrated there was not a suitable tool for very preterm birth, we developed a 20-item questionnaire called Preterm Birth experience and Satisfaction Scale (P-BESS) for use in this situation. 44 We used this questionnaire for the follow-up of women recruited to our pilot trial. It has been translated into Spanish and Portuguese.

Placental transfusion and neonatal transition

At birth, if the umbilical cord is not clamped then blood flow between the baby and the placenta may continue for several minutes. 45–48 This umbilical flow is part of the physiological transition from fetal to neonatal circulation, which, for very preterm infants, may improve resilience during this transition. 49–51 ‘Placental transfusion’ refers to the net transfer of blood to the baby between birth and cord clamping.

Cord clamping before umbilical flow ceases may restrict neonatal blood volume and red cell mass, and/or disrupt transition from fetal to neonatal circulation. For term births, umbilical flow usually continues for 2 minutes, but may continue for over 5 minutes. 46,48 The mean volume of placental transfusion at term is 100 ml, which is 29 ml/kg birthweight and 36% of neonatal blood volume at birth. 48 For preterm births, umbilical flow may continue for longer than for term births52 and is incomplete if the cord is clamped in 30–90 seconds. 53 This corresponds with development during gestation; at term, two-thirds of the fetoplacental circulation is in the infant, whereas for those born below 30 weeks’ gestation, a greater proportion of the fetoplacental circulation is in the placenta. 45 In addition, the preterm umbilical vein is smaller than at term, and uterine contraction less efficient; therefore, transition from the fetal to the neonatal circulation may be slower. Cord milking or ‘stripping’ seems to be an attractive option for preterm births, as potentially it increases neonatal blood volume without the need to defer cord clamping. 54 However, cord milking over-rides the infant’s physiological control of its own blood volume and blood pressure, and it interrupts transition to the neonatal circulation. 55

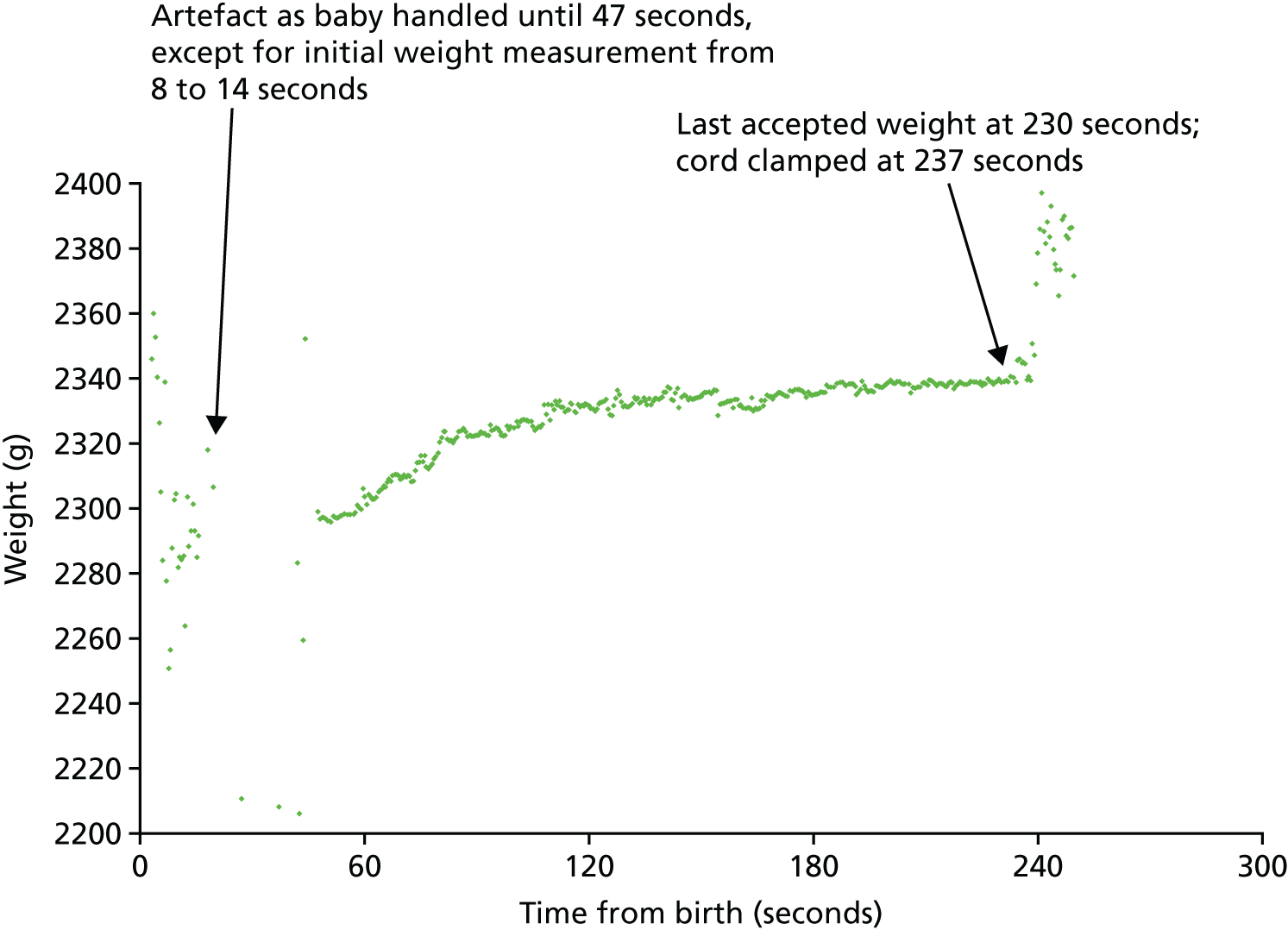

To improve understanding of the physiology of placental transfusion and assess when might be the best time to clamp the cord for preterm births, we measured umbilical flow at preterm birth. Although this proved to be more challenging than we had anticipated, the resulting data helped to inform the decision to wait at least 2 minutes before clamping the cord in the pilot trial.

Neonatal stabilisation and resuscitation at birth beside the mother

In the UK, about one-third of all newborn babies are attended at birth by neonatal resuscitation staff. For most, all that happens is an assessment, stimulation, thermal care and simple airway management. However, around 15% of these babies receive active stabilisation and/or resuscitation at birth, such as mask ventilation, intubation, cardiac massage or drug administration.

Transition to the neonatal circulation begins at birth when pulmonary vascular resistance falls as the lungs expand and fill with air, pulmonary blood flow increases and ductal blood flow declines as peripheral resistance falls. 56 Stabilisation at very preterm birth aims to assist this transition, and recommendations for newborn life support for very preterm infants are to prioritise establishment of respiration and a resting lung volume. 57 Traditionally, this was facilitated by immediate cord clamping, allowing the baby to be transferred quickly away from the mother for interventions such as airway opening manoeuvres, continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) and tracheal intubation with or without prophylactic surfactant administration.

Providing initial neonatal stabilisation and resuscitation for very preterm or sick infants beside the mother would potentially allow newborn life support to be provided with the cord intact, facilitating a longer period before cord clamping than was possible at the time when we were planning this programme. It would also allow the woman and her partner to share the first moments of their child’s life, a more family-centred approach to care at birth. 58,59 Family-centred care in neonatal units, with improved communication and involvement of parents in their baby’s care, appears to benefit babies, is welcomed by parents60 and has been prioritised by the NHS. 61 Providing initial neonatal care beside the mother also has parallels with family presence during resuscitation of adults and children, an approach that is preferred by families and clinicians, and that appears to be beneficial. 62–65 Should the baby subsequently die, this time spent with the parents may prove to be an important factor in their experience of the life of their baby, and could potentially be of benefit in bereavement.

At the start of our programme, information about neonatal care beside the mother within the UK was anecdotal. 53,66 Therefore, we began by describing current practice at that time for care at birth67,68 and by assessing the evidence from randomised trials for delivery room neonatal interventions. We then developed and piloted strategies for providing initial neonatal care beside the mother, and assessed whether or not this was acceptable to parents and clinicians. This included both developing a new mobile trolley designed specifically for this purpose69 and adapting the existing equipment. 70 Our work demonstrating that providing newborn life support beside the mother is valued by parents and clinicians,39,40 and that care with the cord intact is feasible, contributed to the success of the Cord pilot trial. 71 Providing neonatal care beside the mother, with the cord intact, compared with after clamping and cutting the cord, has growing interest nationally and internationally. 72,73

Ethics issues in recruitment of preterm or sick infants to perinatal trials

Recruitment of preterm or sick infants to clinical trials requires approaching parents at a particularly difficult time, often with a tight time scale for making a decision. This raises challenges for obtaining informed consent to such research, especially issues regarding competence for consent, understanding of complex issues, insufficient time for parents to consider participation, and voluntariness if parents have a sense of obligation or feeling of debt to the clinician-researcher who is caring for their child. 74 On the other hand, if the problem of consent is not successfully addressed, this risks becoming an ‘orphan’ area of research. That is, if ethically permissible research cannot be designed, then this area of medical research will be abandoned.

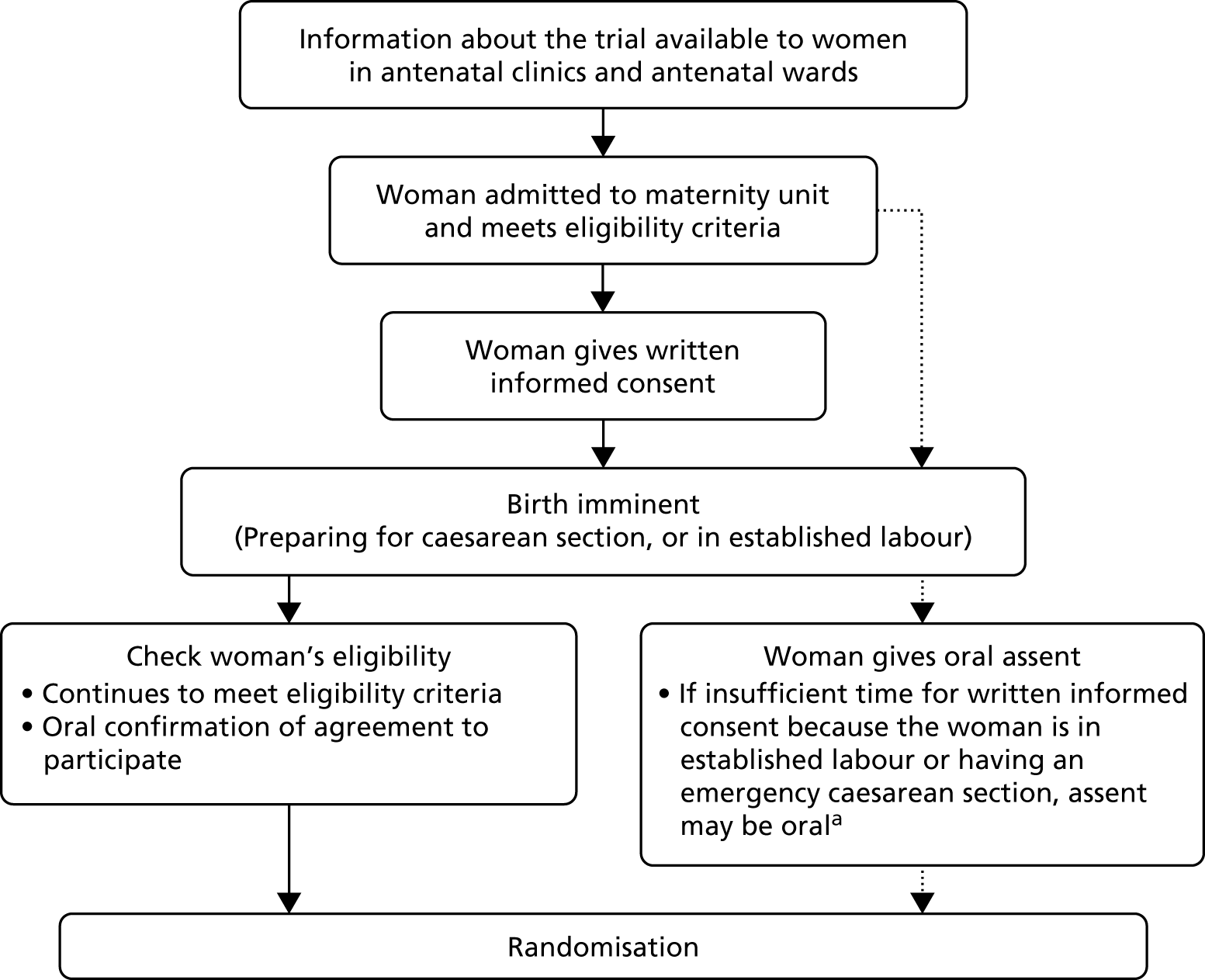

Earlier work has explored these difficulties, specifically in the neonatal context. 74 Discussion of both the nature and the importance of consent, as well as empirical work on methods of obtaining consent and parental experience of those methods, has continued. 75–77 Hence, when we planned our programme it seemed timely to review understanding of these ethics issues in the light of this expanding literature, and of both the changing regulation for clinical trials and the increased public expectations of the conduct of research. Our overall aim was to identify a way of conducting ethical neonatal research in those circumstances where obtaining valid consent from parents has proved to be a significant challenge. The goal was to identify both the challenges to an ethically defensible consent process and their potential solutions. 78,79 This led to the development of a two-stage pathway for consent used and evaluated in the Cord pilot trial. This pathway accounted for almost one-third of recruitment to the trial, and was viewed positively by both parents and clinicians. 41,42 It was rapidly included in updated guidance for intrapartum research from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 80,81 The same two-stage approach has also been adapted for use in an acute stroke trial, for which randomisation is within 8 hours of the stroke. 82

Systematic review of timing of cord clamping at very preterm birth

Thirty years ago, it was first suggested that immediate cord clamping for preterm babies might increase the risk of intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH). 83 Postulated mechanisms for this increase were hypovolaemia or increased fluctuation in blood pressure during the abrupt transition from fetal to neonatal circulation.

At the time that we planned this programme, the Cochrane review of timing of cord clamping and other strategies for influencing placental transfusion at preterm birth included 10 trials, with 454 mother–infant pairs largely recruited before 33 weeks’ gestation. 84,85 In these trials, deferred cord clamping ranged from 31 to 120 seconds and immediate cord clamping ranged from 5 to 20 seconds. Many outcomes were reported by only a few studies, with potential for reporting bias. Immediate clamping was associated with an increased risk of transfusion for anaemia [relative risk (RR) 1.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.14 to 2.16; four trials, 183 infants] or hypotension (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.06 to 3.54; 3 trials, 90 infants) compared with deferred clamping. The risk of IVH on ultrasound scan was also higher for babies allocated immediate clamping (RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.27 to 2.84; seven trials, 329 infants), but for severe IVH (grade 3 or 4), a more reliable predictor of long-term outcome, there was no clear difference (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.27 to 5.02; five trials, 269 infants). There was no clear difference between the groups in temperature on admission to a neonatal unit, but only three trials (143 infants) reported this outcome. One study had reported follow-up at a median age of 7 months for 58 out of 67 surviving infants, with no clear differences between the groups. 86

Alternative policies for timing of cord clamping at very preterm birth

In previous trials for deferred clamping, the decision about when to clamp the cord was usually a balance between allowing some umbilical flow and what was perceived as an acceptable delay in transferring the baby to the neonatal team. As standard practice was for the neonatal team to be located either at the side of the room or in a room nearby, this necessitated early clamping and cutting of the cord, particularly for infants requiring stabilisation or resuscitation at birth. Therefore, providing initial neonatal care at birth with the cord intact would make it feasible to defer cord clamping for longer than had previously been possible, including for high-risk infants who have the most potential for benefit.

Our programme to improve the quality of care and outcome at very preterm birth focused on care at the time of birth. We reviewed evidence from systematic reviews 36–38,67,68,70,78,79,87 relevant to delivery room neonatal care, surveyed current practice, described parent experiences, measured umbilical blood flow, developed strategies for providing newborn life support beside the mother, and reviewed ethics issues in recruitment of preterm and sick babies to clinical trials. These work packages all contributed to the design and conduct of the Cord pilot trial, a pilot randomised trial to assess the feasibility of conducting a large UK trial comparing alternative strategies for cord clamping. To provide adequate power for long-term follow-up of the children and inform the design of a large definitive trial, we planned a prospective meta-analysis of similar studies.

This focus on the time of birth and cord clamping was identified as a priority by informal discussion with parent representatives,88 and parent representatives worked in partnership with clinicians and researchers to develop the application and conduct the research. The topic had also been identified as a research priority by researchers,58,84,85,89 obstetricians,90 midwives,90 neonatologists (Duley L, Farrar D, McGuire W, Oddie S. Survey of the Extended Neonatal Network to Assess Views on Timing of Cord Clamping and Placental Transfusion: Report Prepared for the Extended Neonatal Network. 2009. Unpublished), the National Institute for Care Excellence (NICE),91,92 and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 59 Therefore, it was unsurprising that this uncertainty was included in the list of top priorities from our JLA Preterm Birth PSP. 31

Changes from the original programme plan

The phrase ‘preterm birth’ is broad. Our programme had a specific focus on care around the time of birth, and our intention was that this would be reflected in the scope of our JLA PSP (work package 1). However, from the initial scoping meeting, it was clear that both service users and clinicians had a different view and the discussion ranged from risk factors to prognosis and the grandparent perspective. This continued at the first meeting of the partnership steering group. As the partnership was between service users and clinicians, the researchers agreed that their views should determine scope. The challenge of too wide a scope led to delays in progressing the priority setting, and the process progressed only once it was agreed that this should be narrowed. This delay and the resource demands of the priority setting process meant that it was not possible to conduct the planned work on outcomes.

Although our sampling frame for the qualitative interviews with parents (work package 3.2) included one hospital where deferred cord clamping was in routine practice for very preterm birth, no parents interviewed had experienced neonatal care beside the mother. It was, therefore, not possible at that time to assess their experiences of this type of care. Instead, we did this by assessing parent and clinician experiences of neonatal care beside the mother using semistructured interviews, rather than the planned focus groups (work package 3.5). This was in order to gain more detailed accounts of the events and experiences than would be available in a focus group. In addition, because in focus groups individuals might be reluctant to disagree with the dominant view, you get a socially constructed view rather than people’s individual views and experiences.

Measuring placental transfusion at preterm birth proved to be far more challenging than our earlier work at term birth. 48 This was primarily because of the unpredictability of preterm birth, which made it difficult for the research team to be present and with the equipment set up in time for the birth. As we secured funding to assess feasibility of a similar trial in low and middle income countries, this study was replicated successfully in India. 47

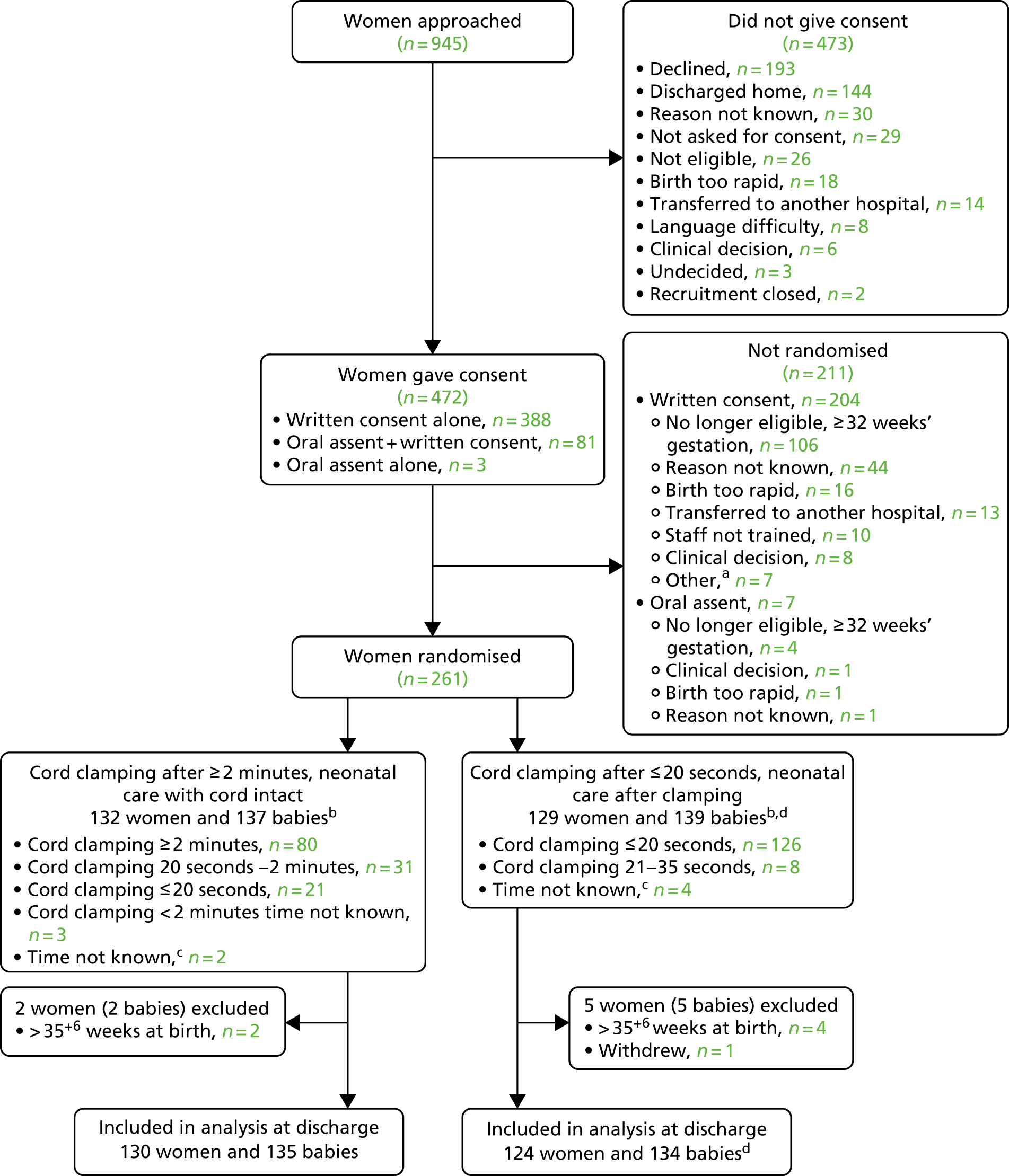

The Cord pilot trial was conducted as planned. Added value of this multidisciplinary programme led to several additional elements. First, innovative methods for consent to participate in emergency perinatal trials was identified as a research gap by the ethics framework review. This led to the development of a two-stage oral assent pathway used in the trial when birth was imminent, which boosted recruitment. Second, to evaluate this pathway we used our experience of semistructured interviews with parents and clinicians (work packages 3.2 and 3.5) and of the framework analysis of ethics issues (work package 2.2) to design and conduct qualitative interviews with women and clinicians who had experience of consent in the Cord pilot trial. Finally, excellent recruitment contributed to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) assessment that feasibility had been demonstrated and that we should seek funding to progress to the definitive trial. The TSC also recommended that recruitment continue while funding was sought, to avoid ‘stop/start’. Hence, recruitment was extended and only closed when the funding application was rejected. To maximise the value of this additional recruitment, follow-up of both women and children was also extended and data for all those randomised are presented here.

For the prospective meta-analysis, the first cycle of analysis had been planned within the programme. However, as data from the two largest studies (Cord pilot trial93 and the Australian Placental Transfusion Study94) were not available within the time scale of the programme, this analysis has been postponed. In addition, the collaborative group of triallists has agreed to expand the protocol to a retrospective individual participant meta-analysis with nested prospective meta-analysis.

Programme management

The co-applicants formed a programme steering group to oversee implementation of the research programme as well as integration and timely delivery of the work packages. This group met every 4 months for the first 3 years, and every 6 months thereafter. A project management group of coinvestigators supported each work package. In addition, the JLA Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) formed a steering group from membership organisations and stakeholders, and independent oversight of the Cord pilot trial was by an independent TSC and Data Monitoring Committee.

Patient and public involvement

Throughout this report, we use the term ‘service users’ to describe patient and public involvement. Because having a baby is a physiological event, pregnant women and parents are not ‘patients’. The topic of when to clamp the umbilical cord at very preterm birth was identified through discussion with parent representatives, including Gill Gyte, offering perspectives from the National Childbirth Trust (NCT). Consultation with parents, through Bliss, quickly made clear that parents viewed change in practice at this difficult time with considerable caution. A strong parent perspective throughout the planning and conduct of our research was clearly essential to ensure relevance, quality and a timely delivery. This was achieved through partnership with representatives of the NCT (https://www.nct.org.uk/) (GG) and Bliss (https://www.bliss.org.uk/) (Jane Abbott and Zoe Chivers). Their input included being co-applicants in the grant application, membership of the programme steering group, membership of most project management groups, co-authorship of many programme publications, and active dissemination of outputs through their organisations. Success of this collaboration was reflected in a Bliss ‘Advancing care through research’ award for the programme.

Additional patient and public involvement contributed to the JLA Preterm Birth PSP, which involved both service user organisations and service users (parents and adults born premature). A personal reflection from one service user member of the steering group demonstrates both the value and the challenges of such involvement (Box 1). In addition, the TSC for the Cord pilot trial included two independent parent representatives, and parents commented on information for participants.

In the early part of 2012, I received an e-mail in my work capacity at the charity KIDS. Attached to the introductory e-mail was a survey about preterm birth research, which I circulated to my caseload of parents in the London borough of Camden. I then completed the survey myself, as I also happen to be a parent of a daughter who was born 11 weeks prematurely.

I was at the time just completing a Master’s degree and my research dissertation regarded an aspect of preterm birth and the development of Cerebral Palsy. With this added interest, I contacted the researcher who had sent out the survey in order to discuss the research further. During our meeting, she mentioned that a fundamental part of this project was for service users and health-care professionals to come together to set priorities and that my involvement, as a parent, within the steering group would be most welcome.

The journey that followed was both fascinating and rewarding. There was a steep learning curve about a process like this – which saw the identification of unanswered questions about causes, care and treatment of preterm birth through to the prioritisation by service users, clinicians and researchers of the Top 15 issues for future research. There was also great validation in being a respected and involved participant of the steering group throughout the process, culminating in my presentation of the parent perspective on this piece of work at the European Congress of Perinatal Medicine in Florence (where our work won a prize in the top 6)!

Having felt incredibly held and supported during steering group meetings where my contribution was encouraged and valued, there were times, particularly during group conference calls or in the e-mail rounds, when I wondered whether my input was necessary or appropriate and I often felt quite overwhelmed by the scientific complexity of the overall process and project. This seems pertinent to acknowledge in a field that has patients at its centre, but often has to go beyond their sphere of understanding or comfort.

Initially it felt that my value was to bring in my personal experience, and I was often called on to reflect my perspective as someone who had been impacted by preterm birth. However, at times it was hard to know how to pitch this within the high level of theoretical rhetoric, both from a medical and a research position. I did often wonder at how the personal voice can be lost in the higher level of complexities and detail.

All of that said, the overarching feeling has been one of being embraced and encouraged, with the reminder that this sort of collaborative work brings together individuals with very different skills and experience for a reason. The process as a whole felt empowering and the knowledge that my personal experience was playing a vital part in bringing fresh understanding was validating.

Bev Chambers

Reproduced with permission from Bev Chambers.

Work package 1: identifying and prioritising research gaps relevant to preterm birth – a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership

See Appendices 2–4 for the published and unpublished reports of this work.

Research aims

Our aims were to:

-

identify and prioritise research gaps relevant to preterm birth that are most important to people affected by preterm birth and health-care practitioners in the UK

-

describe how service users and clinicians interact when making collective decisions about research priorities, and how they communicate when deciding research priorities together.

Identifying and prioritising research gaps relevant to preterm birth

Prioritisation process

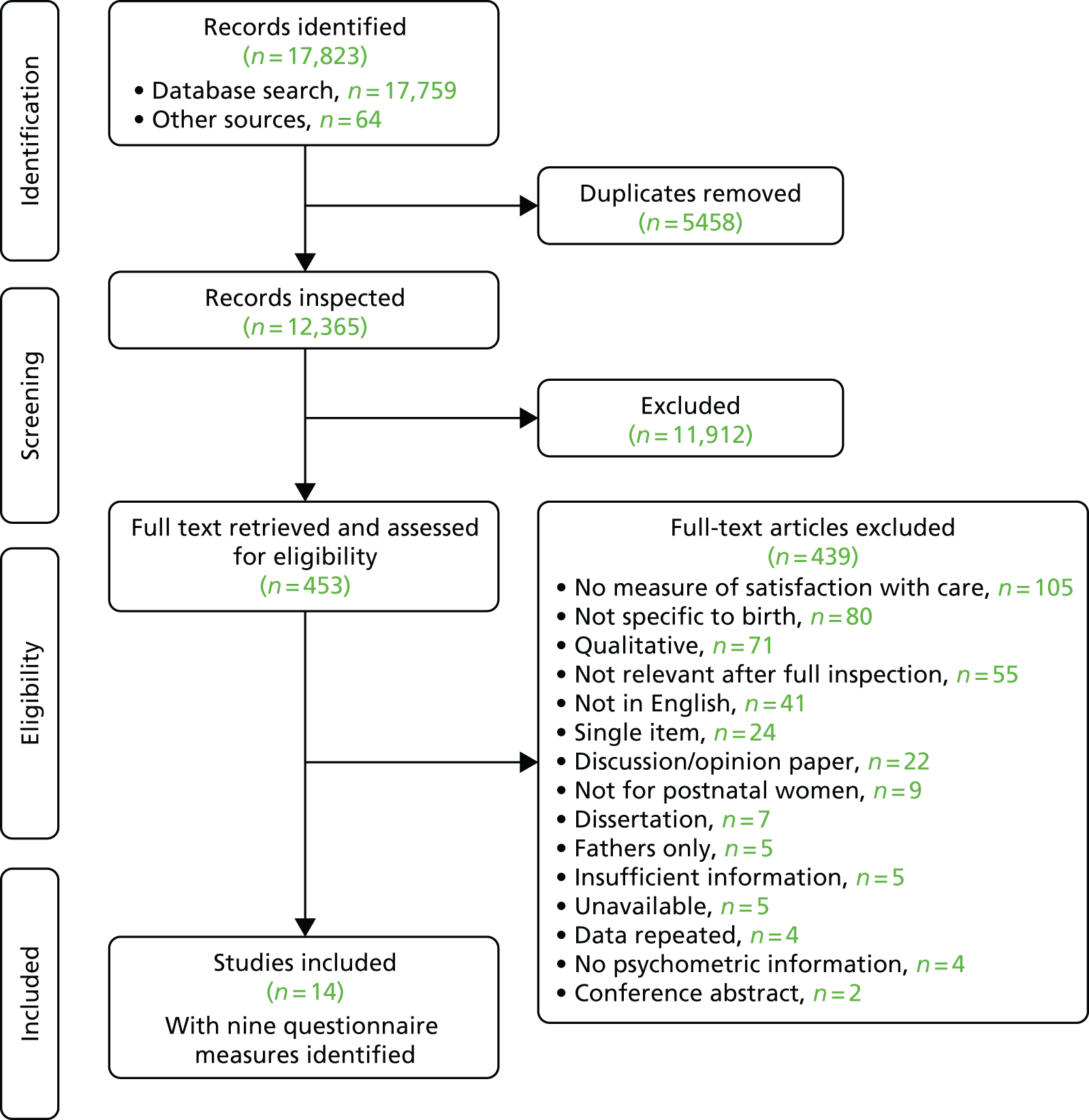

Using methods established by the JLA,95 we first identified unanswered questions about the prevention and treatment of preterm birth from people affected by preterm birth, clinicians and researchers. Then we prioritised those questions that people affected by preterm birth and clinicians agreed are the most important (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of the JLA Preterm Birth PSP. HP, health professional; PaPB, people affected by preterm birth.

Initiation of the partnership

The Preterm Birth PSP was initiated in November 2011, following an earlier introductory meeting of potential stakeholders. The 29 participating organisations were asked to complete a declaration of interests, and a steering group was convened that included members from nine of these organisations. At the introductory workshop it was clear that many participants felt that the scope of the partnership should be wider than was initially envisaged, for example including uncertainties about the causes of preterm birth, the prognosis following being born preterm, and interventions long before birth.

Consultation

As widening the scope too far risked making the prioritisation unachievable, the steering group restricted the scope to uncertainties about treatments and to interventions during pregnancy and around the time of birth or shortly afterwards (taken up to the time of hospital discharge for the baby after birth).

Research questions were gathered from people affected by preterm birth, clinicians and researchers using methods developed by the JLA. 95 This included a survey completed online by 349 people, and in paper format by 37 women attending specialist preterm birth antenatal clinics at two tertiary level hospitals and parents visiting two neonatal intensive care units. These 386 responses contained 593 potential research questions. In addition, 540 potentially relevant research questions were identified from systematic reviews of existing research and from national UK clinical guidelines. 96–107

Collation

All questions were screened to identify those sufficiently similar to either merge or group into broader questions and to remove any that were out of scope, unclear or being answered by a subsequent or in-progress randomised trial. This left 70 unanswered questions from the survey, 28 from systematic reviews and 24 from clinical guidelines remaining in the process. Of these 122 questions, 18 overlapped with other questions and were merged to give a final ‘long list’ of 104 unanswered research questions.

Prioritisation

This was a two-stage process. First, the long list of 104 questions was sent out for voting on the top 10 questions, online and in paper format, using a modified Delphi survey. The steering group reviewed ranking by the 507 people who voted, overall and by stakeholder group. They removed remaining overlap or repetition between questions, before agreeing the shortlist of 30 questions to go forward to the second stage: a prioritisation workshop. This workshop had 34 participants, including representatives from people affected by preterm birth and clinician organisations as well as parents of babies born preterm and adults who were born preterm. At the workshop, nominal group technique95 was used to achieve consensus on ranking the 30 questions.

Key findings

We identified 104 unanswered research questions (Oliver S, Duley L, Uhm S, Crowe S, David A, James CP, et al. Top Research Priorities for Preterm Birth: Results of a Prioritisation Partnership Between People Affected by Preterm Birth and Healthcare Professionals. Unpublished). Consensus was not achieved on a top 10, and so a top 15 research priorities was agreed (Box 2). 31 This top 15 had significant differences to the ranking following public voting. The most noticeable were two questions ranked 18 (How do stress, trauma and physical workload contribute to the risk of preterm birth, are there effective ways to reduce those risks and does modifying those risks alter outcome?) and 26 (What treatments can predict reliably the likelihood of subsequent infants being preterm?) at the workshop. These were outside the top 15 but had been ranked 3 and 4, respectively, in the public vote.

-

Which interventions are most effective to predict or prevent preterm birth?

-

How can infection in preterm babies be better prevented?

-

Which interventions are most effective to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in premature babies?

-

What is the best treatment for lung damage in premature babies?

-

What should be included in packages of care to support parents and families/carers when a premature baby is discharged from hospital?

-

What is the optimum milk-feeding strategy and guidance (including quantity and speed of feeding and use of donor and formula milk) for the best long-term outcomes of premature babies?

-

What is the best way to judge whether or not a premature baby is feeling pain (for example, by their face, behaviours or brain activities)?

-

Which treatments are most effective to prevent early-onset pre-eclampsia?

-

What emotional and practical support improves attachment and bonding, and does the provision of such support improve outcomes for premature babies and their families?

-

Which treatments are most effective for preterm premature rupture of membranes?

-

When is the best time to clamp the umbilical cord in preterm birth?

-

What type of support is most effective at improving breast feeding for premature babies?

-

Which interventions are most effective to treat necrotising enterocolitis in premature babies?

-

Does specialist antenatal care for women at risk of preterm birth improve outcomes for mother and baby?

-

What are the best ways to optimise the environment (such as light and noise) in order to improve outcomes for premature babies?

Reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 383, Duley et al. ,31 Top 15 UK research priorities for preterm birth, pp. 2041–2, © 2014, with permission from Elsevier.

Describing how service users and health-care professionals interact when making collective decisions about research priorities

Methods for data collection

The study sample comprised attendees at 13 meetings of the Preterm Birth PSP: 12 steering group meetings (three conference calls, nine face to face) and the final prioritisation workshop. These were all recorded and transcribed. An ethnographical approach108 was adopted with participant observation109 and discourse analysis110 of the recordings, field notes and analysis of documentary records of meetings and steering group activities.

Analysis

Transcribed data were coded using an analytical framework based on the Elaboration Likelihood Model111–113 using NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software. We coded discussion as using either a central route (rational argument with evidence) for persuasion or a peripheral route (relying on emotional responses to cues such as authority, commitment, consistency, liking, reciprocation, social proof or scarcity). For example, prioritising a treatment because the speaker ‘wanted to know if there would be better outcomes’ was coded as ‘central’ because of its rational approach. Asserting ‘I think this topic has to be number one because that is sort of nice’ was coded as ‘peripheral’ with a ‘liking’ cue.

To investigate decision-making based on values, transcripts were coded into three types of discussion:114 informational (facilitator encourages participants to speak, defers controversy and lets participants know their ideas will not be evaluated), problematical (participants consider the information and/or values needed to address the issue intelligently) and reflexive (participants discuss their own discussion to learn from the process).

To understand the process of consensus development, the JLA approach was compared with the ‘Group Development Model’115 (Figure 3), which argues that every group experiences these five stages before becoming a self-reliant unit. At each stage, the dynamics of the group change from periods of inefficiency and uneasiness through to a period of high performance.

FIGURE 3.

Group Development Model versus JLA stages of partnership working.

Key findings

Throughout their meetings, steering group members used a central route pathway (281/502, 56%) more often than a peripheral route (221/502, 44%), and the peripheral cues they used most were ‘commitment’ and ‘consistency’. During the final workshop, ‘social proof’ (i.e. peer pressure, ‘we do this in our group’) was used most frequently. Health-care professionals used the central route (n = 33) more than service users (n = 15), and service users used the peripheral route (n = 23) more often than health-care professionals (n = 17).

The main types of discussion were ‘informational’ and ‘problematical’, with ‘problematical’ increasing over time. For the first 18 months (up to compiling the long list of uncertainties) there were no ‘reflexive’ discussions, and these remained less frequent (n = 9) than ‘informational’ (n = 104) and ‘problematical’ (n = 169). For both ‘informational’ and ‘problematical’ discussion, speakers used central routes more often than peripheral ones. When they used peripheral routes, for ‘informational’ discussion they used all the peripheral cues. For ‘problematical’ discussion, cues used the most were ‘consistency’ during steering group meetings, and ‘social proof’ during the final workshop. ‘Scarcity’ was more common later in the process when there was more time pressure. Participants were less likely to accept peripheral route messages, although when supported by a central route message from another speaker it became more persuasive.

Four questions ranked in the top 10 after public voting were outside the final top 15. These were stress and physical workload, preventing subsequent preterm birth, screening in the first trimester and multiple birth. The last three moved down the ranking based on the argument that they were included in the overarching top ranked question ‘Which interventions are most effective to predict or prevent preterm birth?’. Arguments against ‘stress and physical workload’ were that it was similar to another question and that it is not a conventional treatment and would be difficult to define or change.

There were similarities between the Group Development Model stages and the JLA PSP process, in particular that ‘forming’ (or team building) was comparable with ‘initiation’, and ‘adjourning’116 was comparable with ‘reporting’. At ‘storming’, team members were comfortable expressing discontent and challenging other opinions, and at ‘norming’ they had a common goal and shared responsibility for achieving it. In the PSP, these two stages were difficult to distinguish because the group repeated ‘storming’ after ‘norming’. At ‘performing’, team members were competent, autonomous and able to handle the decision-making process, which was similar to ‘prioritisation’ in the PSP. However, when new members joined for the final workshop, this returned the group to an early development stage (‘forming’), as they needed to get to know each other and define their roles and tasks. Only then could the group begin to ‘perform’ and prioritise the research questions. This discrepancy in terms of group development between steering group members and the new participants may have influenced the quality of the final consensus.

Strengths

Strengths of this Preterm Birth PSP include the large numbers of participants in the process and the range of stakeholders involved. Although several of the top priorities are already well recognised as important, such as what is the optimum milk-feeding regimen for preterm infants, others are indicative of areas previously under-represented in research (e.g. packages of care to support families after discharge and the role of stress, trauma and physical workload in the risk of preterm birth). This is in keeping with findings from previous JLA partnerships and highlights the value of shared decision-making. 117

Challenges

Preterm birth is associated with factors such as lower socioeconomic status, ethnicity and maternal age. 118 Despite implementing strategies to reach a representative population, our respondents remained primarily white and with a relatively high proportion of homeowners and so were not representative of those most affected by preterm birth. This may limit the relevance of these priorities to other populations.

The JLA PSP process uses a modified Delphi with individual voting, followed by a face-to-face workshop using Nominal Group Technique. Combining these two methods aims to maximise the advantages of both while minimising their disadvantages. The ‘lost priorities’ demonstrate that merging the two methods may, in some instances, weaken the benefits of each method. Large changes in ranking between individual voting and the final workshop appeared to be related to difficulty in the perspective of people affected by preterm birth being heard in the large group session, and a difference in the priorities of two key groups of health professionals (neonatologists and obstetricians).

Maintaining balanced representation between people affected by preterm birth and the different groups of health professionals for the final prioritisation workshop was challenging, and may have influenced the final ranking. The difficulty in achieving consensus underlines the complexity of priority setting for research, particularly for preterm birth. Pregnancy is not an illness or disease, and it involves at least two people (mother and child); preterm birth can have lifelong consequences for them and their families, as well as for the health services and society. This complexity and the differing priorities of different stakeholders make it important to consider the top 30 list, and the long list of 104 questions (Oliver et al. , unpublished), as well as the top 15 priorities, when planning and funding new research. 31

Implications for future research

These 15 top priorities provide guidance for researchers and funding bodies to ensure that future preterm birth research addresses questions that are important both to service users and to clinicians. Although people affected by preterm birth and health-care professionals had many shared priorities, they had different perspectives on some questions. Priorities may also change over time and in different settings. Therefore, when planning and funding research it is important to consider not only the top 15 priorities but also the top 30 ranked by those affected by preterm birth and the top 30 ranked by health-care professionals.

Future prioritisation processes, particularly those with a similar wide range of health-care professionals, should endeavour to anticipate potential different perspectives and mitigate any imbalance where possible, and should report voting separately by ‘service users’ and health-care professionals. Health-care professionals who are also researchers should declare this potential conflict before participating in the prioritisation workshop, so that it can be taken into account.

Work package 2.1: evidence-based immediate care of the very preterm infant

Newborn infants who have delay in establishing independent respiratory effort after birth may require transition support in the delivery room. To support development of guidance for providing initial neonatal care beside the mother, and also to provide a context for determining how deferred cord clamping might be integrated with evidence-based transitional assessment and support practices in the Cord pilot trial, we conducted an overview or ‘umbrella review’ of relevant Cochrane reviews.

See Appendix 5 for the unpublished report of this work.

Research aims

Our aims were to identify Cochrane reviews of delivery room transition support interventions, appraise review quality and identify important gaps in the evidence.

Methods for data collection

We undertook a systematic overview (umbrella review) using the standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 119,120 We registered the overview on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42012003038). We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews121 (Issue 6, 2015) for reviews evaluating any intervention for delivery room support of newborn infants. We excluded reviews of interventions that are more usually or feasibly delivered following admission to the neonatal unit, and those administered to all infants as part of routine practice.

Analysis

For each review, two reviewers independently extracted information on review quality characteristics, and on the participants, treatment and control interventions, and outcomes. Review quality was assessed using the 11-item AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic reviews) tool. 122,123

Key findings

Eighteen Cochrane reviews were identified. Broadly, these reviews assessed delivery room interventions for airway management, respiratory or circulatory support (four reviews); surfactant replacement therapy for preterm infants with or at risk of respiratory distress syndrome (eight reviews); supplemental oxygen or other drugs for infants compromised at birth (five reviews); and strategies for influencing placental transfusion (one review). The overall quality of reviews was good, but methodological quality of the included trials varied greatly. Four reviews had no included trials. The most commonly prespecified primary outcomes were death, incidence of chronic lung disease and neurodisability. Two reviews prespecified surrogate outcomes, such as physiological measures, rather than clinically important primary outcomes. There are few data on long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Of the four reviews that assessed interventions to support the infant airway and breathing, two did not find any eligible trials and one included only a single small trial. 124–126 The fourth review assessed delivery room airway support for infants at risk of meconium aspiration (four trials, 2884 participants) and concluded that there is no evidence that routine endotracheal intubation reduces mortality or morbidity in vigorous term babies with meconium staining compared with standard resuscitation. 127

The strongest evidence supported type and timing of surfactant administration for preterm infants. Two reviews, originally published in 1997, provided strong evidence that for very preterm infants, surfactant replacement reduced the risk of death by about 40%. 128,129 A related review concludes that natural surfactant is more effective than synthetic surfactant for reducing the risk of death. 130 These reviews are now regarded as ‘complete’, as further trials would be unlikely to change their conclusions. Subsequent reviews found evidence that early surfactant administration with brief ventilation reduces the need for mechanical ventilation and associated morbidity, but that prophylactic (delivery room) administration is not more effective than delayed selective administration when infants have prophylactic nasal continuous positive airway pressure support. 131,132 Uncertainty remains about the comparative effects of newer synthetic surfactants that contain surfactant protein mimics, and of novel non-invasive routes for administering these. 133,134

Five reviews assessed supplemental oxygen or other drugs for infants compromised at birth. One compared using air rather than 100% oxygen for newborn resuscitation at birth. 135 Five trials were identified (three were quasi-randomised), but the review concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for using either intervention. Three reviews assessed other drug interventions. 136–138 Of these, two assessed adrenaline or sodium bicarbonate during resuscitation and found insufficient evidence for reliable conclusions. 136,137 The third review assessed naloxone for infants exposed in utero to opiates and identified nine trials, but none assessed clinically important outcomes. 138 The fifth review examined interventions to prevent hypothermia in newborn very preterm infants,139 and it concluded that various measures, including plastic wraps or bags and warming mattresses, reduce the risk of delivery room hypothermia, but found insufficient data to assess effects on infant morbidity and mortality.

One review assessed timing of cord clamping and other strategies for influencing placental transfusion at preterm birth. 140 This review found evidence that deferring cord clamping for 30–120 seconds, rather than clamping before 30 seconds, probably reduced the need for blood transfusion and possibly reduced the risk of IVH. Data from 13 out of the 15 included trials did not identify a statistically significant effect on risk of death. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes were not reported.

Implications for research

Some reviews identified key evidence gaps. These were mainly related to pharmacological intervention for transition support or resuscitation of newborn infants, and the effectiveness of new, less invasive forms of airway management (and related issues regarding surfactant delivery).

Work package 2.2: ethics issues in recruitment of preterm or sick infants to perinatal trials

The recruitment of very preterm or sick infants to clinical trials requires approaching parents at a difficult time, often with a tight time scale for making a decision. This raises challenges for obtaining valid informed consent to such research.

See Appendices 6 and 7 for the published reports of this work.

Research aims

We aimed to synthesise:

-

Observational and qualitative studies that explored the process of recruitment and consent, and reported parents’ and clinicians’ views and experiences.

-

Analytical (or philosophical) studies that have examined the pertinent ethical questions. These concern the validity of consent, the proper understanding of the parental role in giving or withholding consent, varied possible methods of seeking consent, the best interests of those involved, issues of risk, and the parallels between consent processes in relevant research and clinical contexts.

The goal was to identify both the challenges to an ethically defensible consent process and their potential solutions. Ideally, these solutions would include strategies that we could implement to improve the consent process in the Cord pilot trial.

Methods for data collection

The methods used for this review conformed to those set out for a framework synthesis. 141 The first stage was the development of a tentative initial conceptual framework based on prior knowledge of the existing philosophical literature on informed consent, including in neonatal research. 142,143 This initial framework informed the criteria for including studies and it suggested terms for the literature searches. After refining the framework in the light of the literature from the first searches, the second searches were developed. All searches were updated (for examples of search strategies, see Appendices 6 and 7).

Analysis

Empirical studies

For the empirical studies, the conceptual framework was modified to focus on specific questions prioritised by the authors, and further searches devised, guided by bioethics review methods studies. 144,145 We screened abstracts of the papers from identified citations for inclusion, using the five criteria from the modified framework:

-

parents’ views of neonatal trials

-

clinicians’ views of neonatal trials

-

parents’ and clinicians’ views of parental consent/decision-making in clinical practice if the articles concerned the validity of the consent in an emergency situation, or during or soon after labour

-

validity of consent

-

other options for gaining consent.

Analytical studies

For the analytical studies, discussion of the initial themes that were identified confirmed the conceptual framework. Further searches were informed by this framework and by bioethics review methods studies. 144–146 We screened abstracts of papers from identified citations for inclusion, using the five criteria from the confirmed framework:

-

consent, participation or recruitment for neonatal research (relevant to clinical trials)

-

parental decision-making for treatment of, or research with, sick or preterm neonates

-

parental decision-making for birth and/or labour

-

methodology in emergency/urgent neonatal research

-

alternative ways of gaining consent for neonatal research.

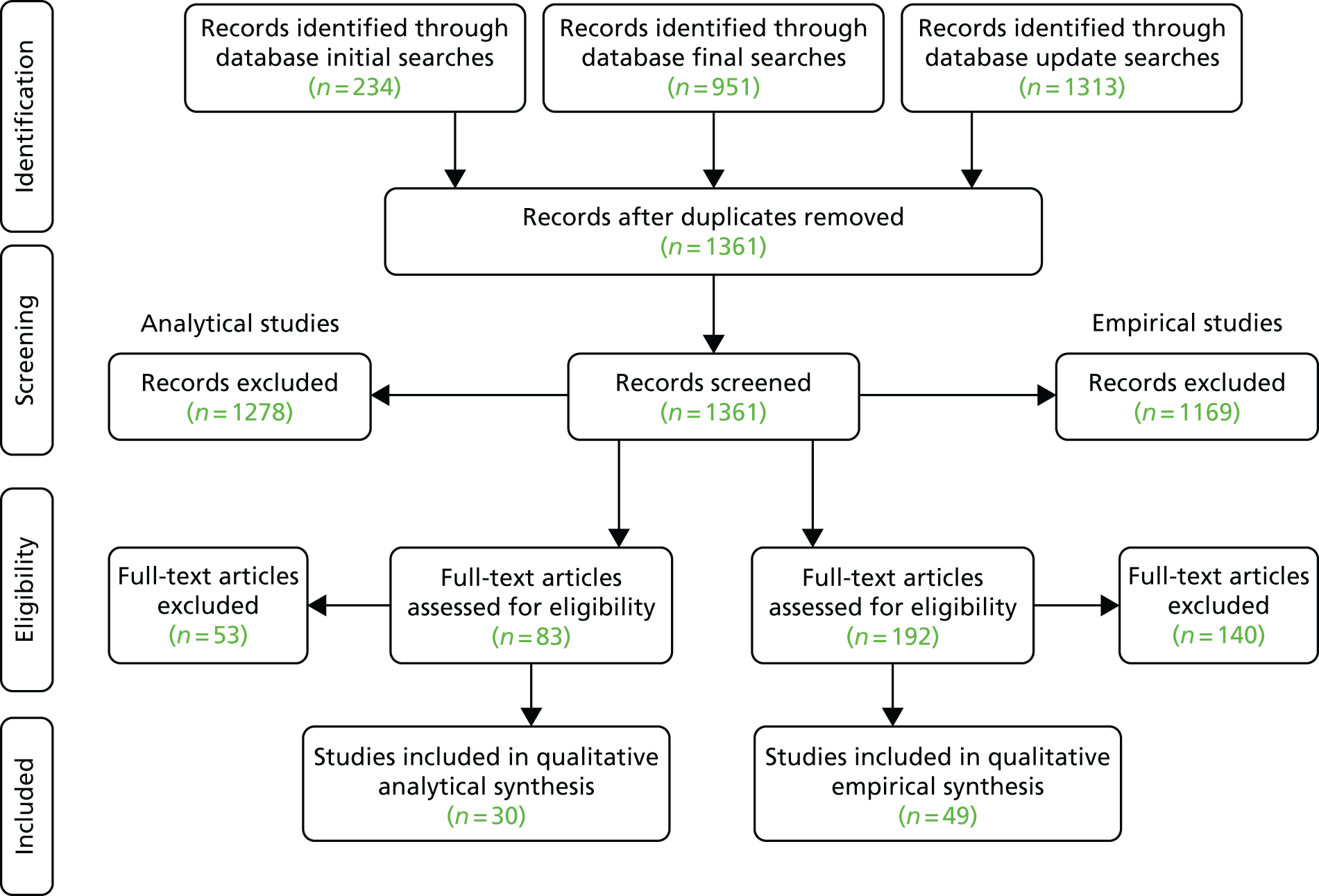

Overall, we ‘included’ 49 empirical papers and 30 analytical papers (Figure 4). All studies met the quality assessment criteria. For the empirical papers, we identified five themes: (1) attitudes of parents, (2) attitudes of clinicians, (3) validity of consent, (4) different consent processes and (5) miscellaneous topics. For the analytical papers we identified four themes: (1) ethical basis of parental informed consent for neonatal research, (2) validity of parental consent, (3) other options for gaining consent, and (4) risk and the double standard between consent for treatment and consent for research. We coded articles and tabulated them against these themes.

FIGURE 4.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram for the framework synthesis. Derived from Wilman et al. 79 [© Wilman et al. , 2015. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated] and Megone et al. 78 [© The Authors, 2016. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated].

Key findings

Empirical research

Our review found that the stated motivations for parents to consent were altruistic: the benefit entering the trial might bring to others; the possibility of some benefit for their baby, or themselves; or the trial bringing some hope in a hopeless situation. 79 Motivations to decline participation in research were inconvenience to parents, burden to their child, or worries about risks, particularly for the baby. Some parents felt that they did not have enough time to decide. Severity of illness of the infant did not appear to affect trial participation.

Parents felt that formal consent for research was necessary and protected their child. Most parents felt that they ought to make the decision about whether or not their child participated in research. They wanted to feel informed and involved, and considered it their responsibility to make this sort of decision. However, many parents also wanted input from others before making the decision, including family and their doctor. Some parents did not want to make the decision. Others felt that being approached about a trial added to their stress and anxiety, particularly if they were approached at an inappropriate time.

Clinicians respected parental authority and largely felt that parental consent was necessary for trials. Reasons for this were that it respects ‘parental rights’, parents are best placed to act in the best interests of their child, and parents must live with the long-term outcomes of their decision. On the other hand, some clinicians felt that clinicians are the best decision-makers for sick babies, and some wanted to spare parents the burden of making this decision.

Clinicians felt that consent forms protected researchers (by providing confirmation that information was given), and aided communication with parents. However, clinicians also worried that too much information added to parents’ burden, and noted barriers to effective communication (e.g. intimidation of parents, and lack of care and support for them). Clinicians raised concerns about balancing their responsibility to the trial with their responsibilities to the parents. Some considered these ‘equal responsibilities’ and felt that it was possible to discharge both. Others saw the possibility of ‘divided responsibilities’ causing anxiety to clinicians, or saw the need for ‘prioritised responsibility’ in which clinicians put parents’ interests before the interests of the trial.

Interviews with parents who had given consent for neonatal trials suggested that this consent was valid for only 59% in terms of voluntariness, competence and informedness. Some parents reported feeling pressure to participate, whereas others felt no pressure. Competence, or capacity, to give valid consent may be affected by factors such as emotional state, understanding and time available to decide. Parents reported being calm when they made the decision, but some felt that they had been anxious or stressed. Some parents reported not making a proper decision because of the pain or anxiety, others reported making considered decisions despite pain, time pressure or anxiety. Some parents had clear understanding of a trial, but others reported problems with understanding a trial about which they were asked for consent. Some parents felt that they could make a genuine decision even with suboptimal understanding. Communication skills of the clinician affected understanding. Although parents largely felt that they had adequate time, in the circumstances, to make the decision, a significant minority did not. Parents made rapid decisions regardless of how much time was available, and they needed more time if there was a greater risk. Parents largely received satisfactory information; however, some parents reported problems with the information that they were given. The information sheet was often unread, although in some studies parents remembered being given the sheet and used it when making their decision.

In general, mothers acknowledged the difficulties for researchers in finding the ‘right time’ to approach them for consent for perinatal research. Some parents would prefer antenatal consent rather than consent during, or after, labour, and would like information earlier in pregnancy even if not recruited then. However, parents were not completely comfortable with antenatal consent as they reported not seeing the relevance of the trial at that time, and felt greater anxiety if told about the trial earlier in pregnancy. Some parents were comfortable with consent in labour, but some were not. Parents were not comfortable with waived consent.

Opting out is when consent is presumed unless the parent explicitly opts out of the trial. Although some parents were comfortable with opting out, others were not. For continuous consent, there is initial agreement to participate with further discussion and information after recruitment. Validity of the later ‘continued’ consent improves when discussion continues after recruitment. Some parents approve of continuous consent, but some have concerns about receiving further information at a later stage when that might have affected their original decision. One study reported a staged consent process in which consent (oral or written) is sought antenatally and the consent is sought again at the point of intervention. However, at present this is only reported, not discussed.

The main conclusions are that:

-

there is widely held agreement that it is important that parents do give or decline consent for neonatal participation in trials, but that

-

there is evidence that existing consent procedures are unsatisfactory, and that

-

none of the proposed alternative consent processes reviewed by the research is satisfactory

-

there are some significant gaps in the empirical research in this area.

Analytical research

The analytical research addressed the justification for seeking consent from a parent (or parents) to neonatal or perinatal trials. 78 This issue arises because it may be thought that it is not sensible to seek consent when the most affected party is unable to give consent, in which case the focus should simply be on that individual’s best interests. Hence, it is relevant to query the basis for consent being given, or declined, by the parent. Justification for parental consent includes the importance of autonomy, such as parental autonomy, or the parents’ own rights to make decisions about their child. A similar claim holds that parenting decisions are part of deciding how to conduct one’s own life, while another defence suggests that fetal rights are part of maternal autonomy. However, others have rejected any defence of parental consent that appeals to autonomy, arguing that a parent’s interest in autonomous parenting may not outweigh the child’s interests, or that parents do not ‘own’ their children.

A second claim in defence of parental consent is that parents should be seen as surrogate or proxy decision-makers, where ‘proxy’ means not simply someone who acts on behalf of another but one who represents another’s views. Some suggest that there might be reason for a parent to give consent even if an appeal to autonomy or rights is rejected. Thus, it is held that it is not appropriate to think of the ‘autonomy’ of a neonate and, therefore, it is not appropriate to think of ‘informed consent’ for a child. Another line of argument is that consent in the neonatal context is a case of ‘family decision-making’, because it is not appropriate to consider the child’s decision in isolation. In addition, it is suggested that parents should give consent because they will bear the consequences of the decision. However, some claim that the requirement for parental consent rests on the value of beneficence; as the purpose of informed consent is protection of the best interests of the child, it is the responsibility of parents to make decisions as a way of promoting their child’s best interests, so they should give consent. Some have argued that parents should be allowed to make the decision only when it is in the best interests of their child. In reply to this, it is argued that the protection of the child’s best interests should not rest entirely or even mainly on informed consent. It is the responsibility of the researcher or the ethics review process to protect the participant’s best interests (therefore, it is inappropriate to defend parental consent by an appeal to the protection of those interests). In addition, the concept of parental consent is a misnomer; for neonates, what should be discussed is parental permission (or authorisation).

An important theme was whether or not, in the neonatal and perinatal context, parental consent is valid, and to what extent validity matters. Potential barriers to obtaining valid consent in these circumstances include time limitations, which adversely affect the amount and quality of the information given; stress, anxiety or pain of the parents; and the mother’s sedation. However, some writers have claimed that these features can also contribute (positively) to an autonomous decision process. Parental desperation or fear may affect the voluntariness of any consent given. Parents may also see the researcher as a figure of authority, which may affect the voluntariness of their decision. A more indirect problem for gaining valid consent is that the consent process itself increases parental anxiety.

Barriers to informed consent in this context have implications for respect for the principle of autonomy, if that is the basis for seeking parental consent. Some argue that parental autonomy will be violated if there is a defect in the consent process, whereas others suggest that parents are being used as a means to an end in a consent process that may be flawed. A further argument is that the principle of beneficence (acting for the benefit of the child and/or mother) becomes a more important ethical principle in research with neonates because informed consent is not possible. Another response to the difficulties with and barriers to consent is that we must strive for improvements in what we do to seek consent, and attempt to get the best possible consent even when perfect informed consent is not possible.

The analytical research has examined a cluster of issues around risk in medical research and clinical treatment. There are disagreements about the nature of the risks involved in research. One claim is that if the context for the clinical trial is a potentially life-threatening condition, and the outcome of the intervention is unknown, then the trial intervention should itself be viewed as a significant risk for the participant. An opposing claim in this situation is that this is a risk of the disease and/or the situation, and not of the trial, so it should not be viewed as a risk of the trial intervention. Another view is that fully informed consent is not possible for clinical trials because the very information needed for fully informed consent is that which is uncertain and under investigation.

Other ways of addressing the consent requirement include a claim that defends the idea of a waiver of consent in emergencies. The suggestion is that consent can be waived, but that provisional assent must be given at the time of being invited to participate, and there should be community involvement at the design stage. The aim is to make research possible for the benefit of patients, so this waiver should not be used to make research easier for researchers. Another approach defends a method by which consent is achieved through giving women antenatal notification of the intended clinical trial, and then seeking consent if they meet the criteria for trial entry. A third option discussed is that of deferred or continuing consent. This is a process in which, if the parents are absent or affected by situational incapacity, they are assumed to give initial consent and then provide consent when they are capable of taking in the information and making the decision. However, this leaves open the possibility that consent is not given, in which case the trial intervention would have constituted assault. Retrospective consent is argued to be ‘logically incongruent’ and, if consent is retrospectively withheld, the researcher is left in the position of never having had consent. Another option is the Zelen method, in which parents are not informed if the novel ‘intervention’ will not be offered to the child. This final suggestion is the opt-out method for giving consent. This may lessen the burden on parents, increase recruitment and increase understanding, but autonomy may be overridden, for example if a participant fails to exercise their opt-out right by default rather than opting out autonomously. All of these approaches involve a parent giving (or waiving) consent, but a final alternative is to have a consent process in which an independent proxy gives consent for the child.

These results reveal five key points about the consent process and highlight one important gap in the research. The key points are as follows:

-

There is a variety of possible defences for seeking parental ‘consent’ to neonatal and/or perinatal trials, and these are consistent with the strongly and widely held view that it is important that parents do give (or decline) consent for such research, as found in the empirical literature.

-

In giving parental ‘consent’ in a perinatal context, parents are authorising infant participation, not giving ‘proxy consent’.

-

There are philosophical reasons for supposing that at least some parents will fail to give valid consent in a neonatal context. These support concerns about the consent process raised in the empirical literature.

-

None of the existing consent processes reviewed by the research is satisfactory. This matches the findings of the empirical research.

-

There are reasons for giving weight to both parental ‘consent’ and the infant’s best interests in both research and clinical treatment, but also reasons to treat these factors differently in the two contexts, and this may be partly attributable to the differing relevance of risk in each case.

The significant gap in the philosophical literature is the lack of any detailed discussion of a process of emergency and/or urgent assent followed by later full consent. This matches a gap found in the empirical literature.

Successes

This is the first review focusing on the ethics issues around consent to neonatal or perinatal research. Other reviews have focused on methods for increasing recruitment or improving how information is conveyed, but none has focused directly on the ethics issues. 61,147–151

Challenges

The key challenge lay in this project being a relatively novel departure for systematic review methods, as it involved reviewing systematically across the disciplinary boundaries between philosophy, social science and medicine. To address this, the multidisciplinary team included expertise in philosophy, clinical practice, social science, information science and advocacy for parents. For the philosophers, the systematic review methods were somewhat different from those that are conventionally adopted in work on ethics. The notion of a systematic review is uncommon, indeed almost unknown, as a method for conducting research in philosophy, both in philosophy as a whole and in philosophical medical ethics in particular. 144,152 On the other hand, for the social scientists and clinicians the standard philosophical means for resolving ethics problems were unconventional. As a result, the whole process of developing a systematic review in ethics through interdisciplinary collaboration has given rise to considerable reflection in its own right.

Implications for future research

We identified three important gaps relevant to consent for perinatal trials:

-