Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number rp-pg-1210-12007. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The final report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in December 2018. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Karina Lovell, Peter Bower, Penny Bee, Richard Drake, Patrick Callaghan, Andrew Grundy, Anne Rogers, Helen Brooks and Linda Davies report holding other grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of this study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Lovell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

The problem we set out to address

For the last two decades, mental health policy and ethos have placed increasing emphasis on involving services users, and their carers, in their own care. This vision is in part driven by a strong moral argument that health-care delivery should be shaped and informed by the very people whom it aims to affect. Service users and carers, by virtue of their lived experience, can bring a wealth of experiential knowledge and expertise to mental health-care management.

Research evidence is accumulating to confirm that increased service user and carer involvement can lead to positive outcomes for both health-care systems and their users. 1–5 Service user involvement has been shown to enhance service quality and care engagement, reduce rates of enforced treatment and readmission and lessen social isolation and stigma. 6–8

Care planning is one area of contemporary practice that is conducive to service user involvement. 5–12 Mental health-care planning has been defined as ‘the process through which services in relation to an individual’s care are “assessed, planned, co-ordinated and reviewed“’13 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that people using mental health services should develop a care plan with mental health and social care professionals, and be given a copy of this care plan with an agreed date for review. 14 The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health15 upholds collaborative care planning as a priority goal for mental health services, and an essential Care Quality Commission (CQC) standard. 16

Although principles of service user and carer involvement are embedded in policy ideologies, evidence suggests that they have been suboptimally translated in practice. Service users and carers consistently report feeling unsupported by care planning processes and continue to request greater involvement in their care. 7,16,17 Dissatisfaction is evident across a variety of service settings and with a range of professional roles. 18,19 A recent CQC review of care involvement has highlighted ‘longstanding concerns’ with care planning involvement, concluding that routine practice can diverge quite substantially from policy recommendations for ‘person-centred care’20 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0).

Identified barriers to service user and carer involvement in mental health services include poor information exchange,5 ritualised practices that limit opportunities for involvement,5,17 inhibitions or misconceptions regarding patient confidentiality and/or professional resistance to sharing decision-making power. Importantly, our recent systematic review5 found conceptual differences in the interpretation and meaning of involvement between service users and professionals. Although professionals tended to focus on objective evidence of service user involvement, such as ensuring that care plans were shared with and signed by service users, service users and carers tended to prioritise the qualitative experience of their involvement, specifically the consistency and quality of their care planning relationships.

If meaningful service user and carer involvement in care planning is to be achieved, then there is a pressing need to agree and foster a system-wide, user-centred model of collaboration and involvement. 21,22 Our research programme aimed to address the gap between policy and practice by addressing this need.

Aims of the programme

The Enhancing the Quality of User and Carer Involvement in Care Planning (EQUIP) programme was led by the University of Manchester and Manchester Mental Health and Social Care NHS Trust (now Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust) in collaboration with the University of Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. Prior to the programme grant award, we were awarded a Programme Development Grant (RP-DG-1209-10020) to undertake preparatory work, including a literature review, delivering a research methods course for service users and carers to increase service user and carer capacity to engage with the proposed research (see Appendix 1). In our programme of work, we aimed to develop, evaluate, implement and disseminate a co-produced and co-delivered training intervention for mental health professionals to improve service user and carer involvement in care planning.

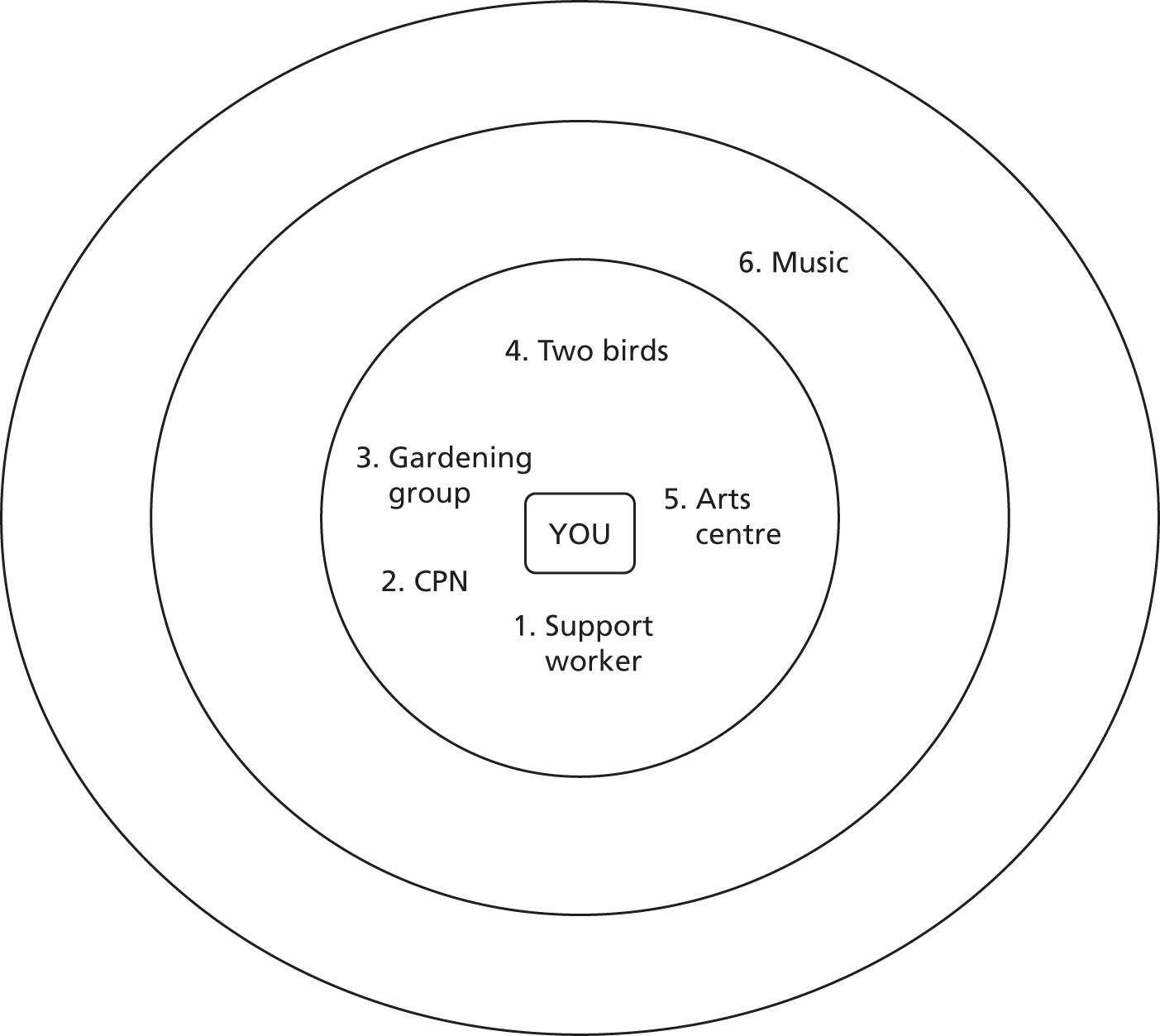

This work was divided into four separate but inter-related workstreams (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The EQUIP programme. Blue arrows denote service user and carer advisory group involvement. Dark blue boxes denote direct service user and carer advisory group input/output. Green arrows and boxes indicate significant input from service user and carer co-applicants/researchers. AMA, Ask Me Anything; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Workstream 1

-

Develop a co-produced training intervention to improve service user and carer involvement in care planning for mental health professionals.

-

Develop and validate a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) of service user involvement in care planning, develop an audit tool and assess individual preferences for key aspects of care planning involvement.

Workstream 2

-

Evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a co-delivered training package to enhance service user and carer involvement in care planning in secondary care mental health services.

Workstream 3

-

Understand the contextual, individual and organisational barriers and facilitators, and examine the processes involved in the development and use of service user- and carer-involved care planning.

Workstream 4

-

Disseminate our findings, training intervention materials and patient-mediated resources produced during the programme to all relevant stakeholders using multiple methods.

Programme management

The programme was sponsored by Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust, and the EQUIP multidisciplinary team was based across two sites (University of Manchester and University of Nottingham) and collectively formed the Programme Management Group, which met quarterly to monitor programme progression. The chief investigator was responsible for the overall leadership, management and output from the programme, and there was a designated lead for each workstream. Each site had a principal investigator, who led monthly team meetings with all programme site staff. A full risk assessment of the programme was conducted by the chief investigator and the trial manager, and a risk register was developed. The risk register was managed and monitored by the trial manager and the chief investigator, and was a standing agenda item at each Programme Management Group meeting. A Programme Steering Committee was established, comprising an independent chairperson with expertise in programme grants and care planning, and three other independent members including a service user and a clinician with experience of working in community teams. The Programme Steering Committee met biannually throughout the duration of the programme.

Ethics

The programme received a favourable ethics opinion from the National Research Ethics Service on 8 August 2014 (National Research Ethics Service Committee North West Lancaster, Research Ethics Committee reference 14/NW/0297; Integrated Research Application System project ID 125899).

Patient and public involvement

In our programme development grant (RP-DG-1209-10020), we developed and delivered a 6-day interactive training course on research methods for service users and carers to facilitate active engagement in the research programme. From this cohort, two service users and a carer became co-applicants on the programme grant, and others formed the service user and carer advisory group (SUCAG). Two service users were appointed (0.5 whole-time equivalent) for the duration of the programme and the carer (through personal choice) was appointed on a casual basis.

The service user and carer co-applicants have been integral to the research design, data collection, analysis and dissemination in workstreams 1 and 3, co-developing and delivering the training in workstream 2 and disseminating in workstream 4. The co-applicants have been supported to lead on writing papers and presenting at conferences, and to facilitate this process each service user and carer co-applicant was paired with a writing mentor. Three of the EQUIP papers16,17,23 have been led by co-applicants and all have developed considerable research skills; Andrew Grundy has completed the first year of a PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) qualification.

The service user co-applicants have also been fundamental in the provision of the research methods training, which we continued to deliver throughout the programme. A research methods book based on the training with significant contribution from service users and carers has been developed.

A SUCAG was convened at the start of the programme grant and held 11 meetings between March 2013 and April 2017. Members of the SUCAG were recruited from the first two cohorts of the service user and carer research methods training course, and those with similar experience from the Nottingham area. An independent chairperson of the group was recruited via expression of interest from the pool of trained service users and carers.

Members of the SUCAG (14 in total) have had a primary role in advising the study team throughout the grant. Activities have included confirming outcome measures for the trial across a range of domains that were identified by service users and carers as part of the programme development work; informing development of the PROM through identification of key questions of ‘quality in care planning’; co-developing a definition of care planning; contributing to the methodological development of workstream 3, particularly in relation to the use of diaries and observations of care planning meetings; contributing to the development of the trial outcome measure packs (advice on presentation and ordering of measures to reduce participant fatigue); contributing case studies for intervention training; and reviewing all the participant trial documentation, for example by providing reviews of the participant information sheets and covering letters prior to submission for ethics review.

The SUCAG meetings have also provided a regular opportunity for the research team to provide feedback on the programme progress and to explain the funder reporting requirements, for example the 24-month checkpoint reporting process.

Members of the SUCAG were invited to apply to become trainers to co-deliver the training intervention for health professionals in workstream 2. The rationale for running a ‘train the trainers’ course was that few had any experience in training and expressed fears and concerns about training mental health professionals. Nine people applied and all were offered places on a ‘train the trainers’ course (with the view that six would co-deliver the training and three would be held in reserve in case of sickness/absence).

Throughout the programme grant, we have used the EQUIP website (http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/equip), Twitter (https://twitter.com/Care_Plan) (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) and regular study newsletters to engage with interested parties and to keep them up to date with the programme. We have also sought to use online and innovative media platforms to actively engage with service users, carers and health professionals via our patient-mediated materials (e.g. the service user 10Cs16 animation of care planning and accompanying EQUIP cards, http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/equip/10Cs, and the award-winning carers animation, http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/equip/mentalhealthcareplanning). With the SUCAG, we have developed a video dissemination of patient and public involvement (PPI) in the study to ensure that it is accessible to a wider public audience beyond our research participants and colleagues in health and academia.

The strength of PPI throughout the programme grant has been underpinned by having a nominated lead for PPI in place to co-ordinate PPI activities across the four workstreams, to liaise with the SUCAG and to provide support to co-applicants with lived experience of mental health difficulties. We were awarded the Mental Health Research Network award for outstanding carer involvement in March 2014. In 2018, we were awarded the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN) McPin MQ Service User & Carer Involvement in Mental Health Research Award. Notably, all of our SUCAG members have taken up advisory group roles in other studies.

We have all benefited and feel privileged to have worked with service users and carers. There is little doubt that the quality of the programme has been much enhanced by our co-development, delivery, production and dissemination activities.

Workstream 1: development

The aims of workstream 1 were to develop a:

-

training intervention to enhance service user and carer involvement in care planning in secondary care mental health services

-

PROM that better meets user and carer requirements for quantifying the extent of their care planning involvement in UK mental health services.

Key findings from a systematic review conducted as part of the programme development grant (RP-DG-1209-10020; see Appendix 1) created a foundation on which to build up evidence through the workstream using focus groups (study 1) and interviews (study 2) with service users, carers and mental health professionals. Following data collection, findings were synthesised by the whole research team during a ‘synthesis day’ and key material was generated with which to develop training material for a course for health professionals. The data collected were also used to inform the content for a PROM and the audit tool (study 3) and a stated preference survey (study 4) to measure service user and carer involvement in care planning.

Outputs

The findings of the systematic review are published in Bee et al. 24 (see Appendix 2).

Study 1

The aim of study 1 was to develop the content, delivery mode and length of a user- and carer-led training intervention for health professionals, and to improve user and carer involvement in care planning.

Methods

Focus groups were conducted with a range of stakeholders (service users, carers and mental health professionals). Focus group interview schedules were informed by the systematic review5 and developed by the research team, with input from academics, clinicians and service users and carers from the research programme and the SUCAG. Schedules covered current perspectives on user involvement in care planning, the process and outcomes of care planning, prior experiences of service user and carer involvement and potential training requirements. Focus groups lasted approximately 60–90 minutes and were undertaken at a range of locations to support participation: at university campuses, trust sites and community locations (e.g. at carers’ centres and participants’ homes). Participants received high-street gift vouchers worth £25 for taking part.

Participants were recruited purposively from Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust using a range of methods (trust intranet advertisements, press releases, posters in trust premises and information distributed through carer and service user networks and forums). An initial target to conduct six focus groups was exceeded, with a total of nine focus groups taking place, involving 61 participants across the groups. Four focus groups were conducted with service users and carers (n = 34), four were with health professionals (n = 18) and there was one mixed group with users, carers and professionals (n = 9).

Focus groups were recorded, transcribed and anonymised, then analysed using a qualitative framework approach,25 an acknowledged method of analysing primary qualitative data pertaining to health-care practices with policy relevance. 26 Data from the focus groups were synthesised with further data from individual interviews (study 2) and key findings are reported in study 2.

Study 2

The aim of study 2 was to determine the priorities and core concepts underpinning service user and carer engagement and involvement in care planning in mental health services.

Methods

Individual qualitative interviews were conducted with service users, carers and mental health professionals.

Data from individual interviews were collected with the intention to combine with study 1 data to prevent missing any issues that participants might be reluctant to raise in a focus group situation. 27 Participants were recruited as per study 1, with further recruitment from Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust via poster displays, trust newsletters and the intranet, university press releases, oral presentations at service user and carer groups and via service user and carer news bulletins and websites. Interviews lasted approximately 60–90 minutes and were undertaken at a range of locations to support participation: at university campuses, trust sites and community locations (e.g. at carers’ centres and participants’ homes). Participants received high-street gift vouchers worth £25 for taking part. A total of 74 interviews across Manchester (n = 43) and Nottingham (n = 31) were completed (22 service users, 21 carers, 3 user/carers and 28 professionals). A number of interview participants also took part in the focus groups in study 1 (n = 22).

Interviews were recorded, transcribed and anonymised, and analysed in combination with data from study 1 using framework analysis. Framework analysis is commonly used within qualitative health research and allows for both inductive and deductive coding to be incorporated into the analysis process, which means that codes emerging from the data can be combined with important codes that were identified prior to the study. The analysis team comprised service user and carer co-applicants working alongside experienced qualitative researchers for independent coding purposes. The team read their transcripts on multiple occasions to familiarise themselves with the data before starting to code the transcripts. The data and analysis were managed using a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database comprising participant characteristics, along with a Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) document containing emerging themes from each transcript, to provide a data trail. The team met regularly to discuss their own emergent codes, to develop a provisional coding framework, to discuss alternative explanations of interpretations and to ensure that the emerging codes remained grounded in the original data for purposes of validity. This approach to analysis meant that during the constant comparison of new data, the provisional framework was amended and re-shaped to enable the introduction of new codes, and allowed for the removal of other codes that became superfluous over the course of the analysis. The resultant framework contained only those codes agreed on by the whole analysis team. Previous iterations of the coding framework were stored for purposes of transparency and the research team agreed as a whole when data saturation had occurred and no new themes were emerging from the data. In order to further strengthen the validity of the qualitative findings, the final coding framework was presented to the wider study team, which was asked to comment on whether the framework seemed grounded in the data, on any omissions in the framework or any ambiguities.

Key findings

The combined data from studies 1 and 2 were divided into separate categories for user and carer data and health professional data.

Health professionals

A clear training need was identified by health professionals, with strong support for the idea of user and carer involvement in that training, and for whole-team training for greater impact. A range of barriers to service user involvement were identified, including individual barriers, such as skills deficits and staff understanding of user-involved care planning, and organisational barriers, including workload/resource pressures, the current key performance indicator/target culture of the NHS and difficulties balancing involvement with risk management.

Service users and carers

In accordance with the professional data, users and carers identified a need for training for all mental health staff, but there was a feeling that senior clinicians might benefit most. There were suggestions that training should prioritise skills in active listening and communication, assertiveness and time for reflection. Participants believed that the training should be mandatory, accredited and updated regularly, and should be co-delivered in order to value the expertise of service users and carers. Potential barriers to effective training were also raised, including staff workload and attitude, lack of accountability and reluctance among service users and carers to be involved as trainers. Issues around care plans also emerged, where care plans were seen as meaningless, not tailored to individuals and not taking into account service users’ and carers’ wishes, experiences or needs. Participants felt that good involvement is facilitated by good relationships with and between staff, effective communication, partnership working and allowing sufficient time during care planning. Barriers to involvement were highlighted as frequent staff changes, workload, lack of knowledge about services by all parties, unhelpful staff attitudes and episodes of severe illness.

Outputs

A full description of the methods, analysis and results have been published in Bee et al. ,24 Cree et al. 17 and Grundy et al. 16 (see Appendix 2).

Strengths and limitations

We examined care planning issues with contemporary mental health services in depth across a large sample and from multiple stakeholder perspectives, maximising the transferability of our findings. We included service users and carers in analysis (independent coders) and presented our coding manuals to the SUCAG to optimise the rigour of our analysis. It is likely that the health professionals who took part in these studies were those who were motivated to achieve ‘good’ care planning and/or were open to organisational and individual change. The data also reflect only the views of health professionals within only two NHS trusts and may not be generalisable to other individuals, settings or localities. In terms of service user and carer data, we interviewed a self-selected sample of participants, many of whom had particularly strong views on the shortcomings of the care planning process. Despite efforts to recruit directly from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) third-sector organisations, there was only a small minority of participants from BAME groups.

What the studies add

Health professional data show that a combination of individual and organisational factors currently hinder successful service user and carer involvement in care planning, and highlight a clear need to deliver training to increase the quality and consistency of care planning procedures. The studies also draw attention tothe fact that service users and carers are concerned about the way in which care plans are created and implemented, and that there is a shared perception between service users and carers of a reluctance among health professionals to involve them in the care planning process.

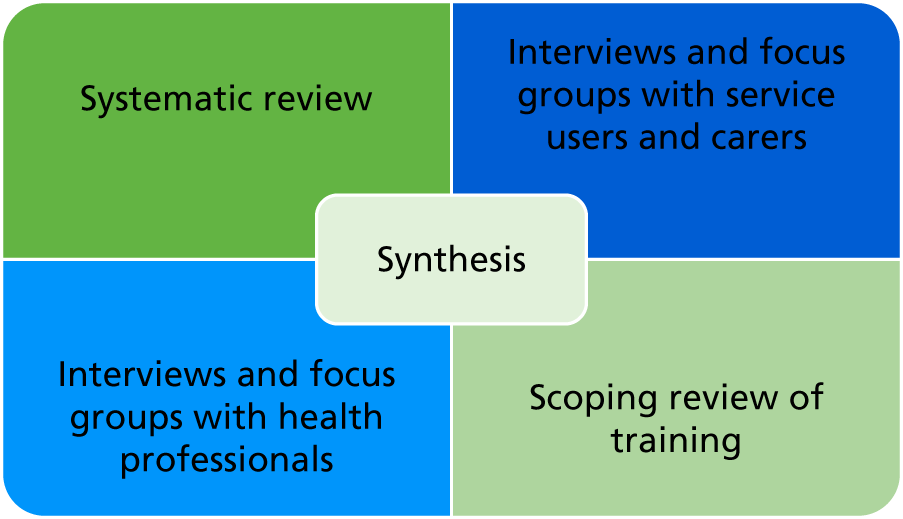

Scoping review of training

Building on the evidence gathered for training content, a scoping review was conducted to identify relevant work that could inform the development, delivery and implementation of the training courses. Three key reviews were identified. 28–30 The exercise produced a number of key findings relevant to the development of the training programme, including that small interactive groups are more effective than large didactic groups; educational outreach (supervision) is effective; improving collaboration between health professionals might be helpful; multifaceted interventions are likely to be better than single-strand intervention; and providing patient materials may help implementation.

Data synthesis

A synthesis day was held with all study applicants and researchers in November 2013.

The two key aims of the synthesis day were to:

-

synthesise the evidence from workstream 1 to develop the training intervention for health professionals

-

develop a ‘train the trainers’ course for service users and carers to co-deliver the training intervention.

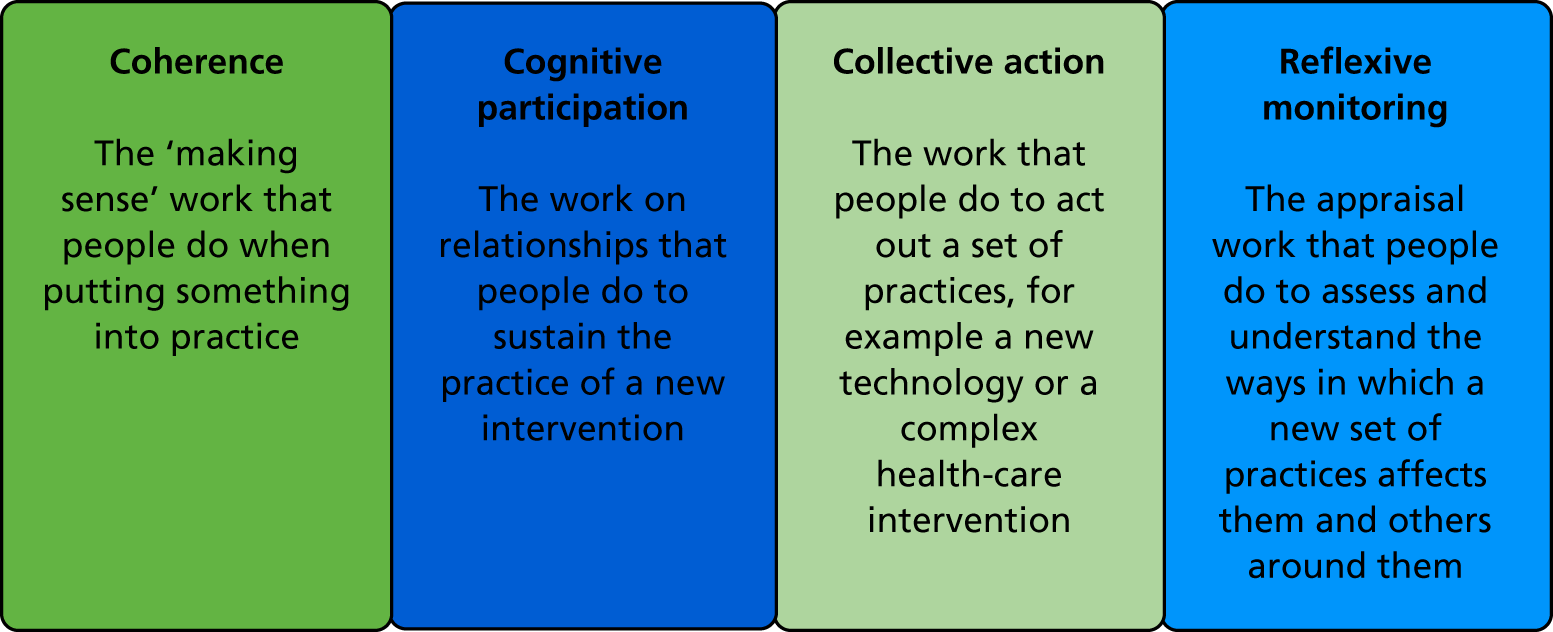

Structured summaries of key findings from the systematic review, focus groups and interviews with service users, carers and health professionals, and from the scoping review of training interventions, were distributed by study leads to the group (see Appendix 2). Our synthesis (Figure 2) followed a similar format to formats of previous studies, where we successfully synthesised a variety of data sources. 31–33 A group discussion involved tabulating key evidence statements within a matrix where each row referred to the results from each dataset and each column represented one of the core training components for both the training intervention and the ‘train the trainers’ course (see Appendix 2).

FIGURE 2.

Synthesis of multiple data sources.

Training intervention for health professionals

The core training components included the content, attendance, duration, delivery mode, resources needed and system requirements that we wished to address. The matrix provided the platform for a structured discussion between the programme team to derive the final training intervention and ‘train the trainers’ course. Those components that did not provide evidence or were ambiguous were discussed by applicants in small teams until a consensus was reached.

The training intervention is detailed in accordance with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guidelines in Box 1. 34

Why: our aim was to co-develop, co-produce and co-deliver (with service users/carers) a best-evidence, acceptable and feasible training programme for mental health professionals to enhance user and carer involvement in care planning. Two reviews were conducted, including a narrative synthesis (Bee et al. 5), which examined how user-involved care planning is operationalised within mental health services and to establish where, how and why challenges to user involvement occur; and a scoping review of training reviews and interventions that change clinician behaviour. In addition, focus groups and individual interviews with service users, carers and health professionals were conducted to ascertain training content and delivery requirements and to determine the priorities and components of adequate user and carer involvement in care planning. The evidence from the reviews and qualitative data were synthesised to develop and design the training.

What: a range of training materials have been developed for the training, including Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides, case scenarios, audio-recordings from health professionals, service users and carers and a trainer’s manual.

Who: the synthesis identified that the training should be multidisciplinary, including all health professionals and psychiatrists. Team training was seen as optimal and, as far as possible, teams will be trained together. The training will be delivered by two of the co-applicants (both academics with teaching experience) and three or four service users and carers who have attended a 4-day ‘train the trainers’ course.

How: the synthesis indicated that training should include a range of formats: face to face, self-directed learning and follow-up supervision. The consensus exercise indicated a minimum of 15 hours and maximum of 30 hours. The course will run for 2 days (12 hours) plus 6 hours’ follow-up supervision and 8 hours’ self-directed learning (optional). Hence, each health professional will receive 18 hours of facilitated training and an additional optional 8 hours’ self-directed learning.

Where: consensus was reached that the training venue should be outside the clinical area, geographically convenient, provide good catering and in a venue with appropriate training resources.

When and how: the training will be delivered to each cluster randomised to the training intervention over 2 days. In recruiting teams, we ask that 80% of the care co-ordinators within each team attend the training. The training will be delivered within 6 weeks of service users being recruited into the trial.

Tailoring: the intervention has been tailored for health professionals.

Modifications: only minor modifications will be made in the light of feedback during the trial. If the trial is successful and we implement the training across other NHS trusts, modifications will be made in the light of feedback collected from the process evaluation.

How well: fidelity of the training has been ensured by the careful development and synthesis work described earlier, the ‘train the trainers’ course, the development of a detailed manual and the delivery of training by the same groups of trainers.

The core components of the training were a training package including a training manual, training materials, presentations, and group exercise materials consisting of 2 days’ face-to-face training (12 hours in total), an 8-hour optional self-directed learning package and 6 hours’ supervision per team in the 6 months post training.

The 2-day training intervention included interactive presentations, audio-visual clips, small group exercises, skills practice exercises (including role play), live demonstrations of good practice, and working with anonymised care plans or anonymised examples from professionals’ caseloads. We wanted to move away from the ‘sharing personal stories’ model of user/carer ‘involvement’ in delivering training; thus, although the academic researcher was the lead facilitator, the service users and the carers facilitated group work, shared both positive and negative experiences of care planning and shared ideas around good and poor practice with the wider group throughout the 2 days.

The training team consisted of two academic researchers, six service users and one carer. We delivered the initial training as a whole team to ensure consistency; subsequent training sessions comprised one academic researcher and two or three service users and carers. Over the duration of the study, some of the service users and carers took leading roles in the training. The training was designed to be a co-produced and co-delivered training resource.

‘Train the trainers’ course

The synthesis contributed to the development of the ‘train the trainers’ course. A 4-day course was designed to train service users and carers to deliver the training course to health professionals. The underlying philosophy of the programme was participatory learning and andragogy (adult learning) and aimed to enable participants to understand the principles of training and identify the attributes and values of an effective trainer. The training focused on core educational principles of delivering high-quality training, including facilitating small and large groups, engaging and empowering trainees and maximising the use of training materials. The fourth day of training included a review of the EQUIP professional training intervention for health professionals and an opportunity to practice presentation and facilitation skills.

In addition to our three service user and carer co-applicants, we recruited six service users and carers from our SUCAG with the aim of having a core team of six trainers and three reserves in case of sickness/absence. The course was delivered by the study team in June 2014 and incorporated 2 days of educational principles, 1 day of micro-teaching with peer feedback and a final day focusing on delivering the training intervention for health professionals. (Training materials are available on request from the authors.)

Evaluation of the ‘train the trainers’ course

The aim of the study was to obtain views from service users and carers who attended the ‘train the trainers’ course 1 year following completion of the course, when participants had had exposure of delivering the training. In particular, the team wanted to elicit feedback on training facilitation, content and preparedness for undertaking a trainer role on the EQUIP care planning training intervention for mental health professionals.

Methods

Individual semistructured interviews to explore participants’ views on training acceptability were used. Letters of invitation to take part in the evaluation were sent to all nine trainees approximately 7 months after the completion of training. Participants had to opt in (by e-mailing or phoning). All nine trainees agreed to take part and provided written informed consent. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Of the nine participants, there were six service users (four female, two male) and three carers (two female, one male). Transcripts were analysed independently by two members of the trial team using thematic inductive coding of themes emerging to uncover meaning in participants’ accounts of their involvement in the training process. 35 The team met to review themes and reach agreement on the coding of the data and the overarching themes.

Key findings

Course content was rated highly but may benefit from review and/or extension to allow the range of topics and resulting professional training programme to be covered in more depth. Trainees who delivered the training intervention to health professionals were positive about their support experiences, preparedness and personal impacts. Service users and carers wanted to gain new skills and confidence in presentation/facilitation as well as to make a difference to health-care practice. We also found that service users desired different levels of involvement in training facilitation – some wanted to take a more active role than others.

Outputs

A full description of the methods, analysis and results has been published in Fraser et al. 36 (see Appendix 2).

Study 3

The aim of study 3 was to co-develop, with service users and carers, a PROM to assess user/carer involvement in mental health-care planning and an audit tool for mental health services.

Patient-reported outcome measure

We undertook a systematic review reporting the use, development and/or validation of user- and/or carer-reported outcome measures of involvement in mental health-care planning. 37 The review revealed a lack of care planning measures that are able to meet service user nominated acceptability criteria alongside published standards for psychometric quality. Our aim was to co-develop a PROM to assess user and carer involvement in care planning and the SUCAG suggested that the measure should include the following attributes: suitable for use in the UK; developed via service user and carer collaboration; available in a self-report format for both service users and carers; rated by both service users and carers; based on a social and recovery model; continuous rather than a dichotomous scale; and between 12 and 15 items long.

Audit tool

We developed an audit tool to inform clinicians, services, auditors and researchers who want to quantify levels of user and carer involvement in care planning.

Methods

Potential PROM items were generated from data collected in workstream 1 (studies 1 and 2); 70 candidate items were developed. Face validity was examined with a mixed sample of 16 members of the SUCAG using cognitive interviewing. Nine items were removed because the SUCAG found their language or wording unclear or hard to understand.

The remaining 61 items constituted the nascent scale. Members of the SUCAG were also asked to comment on potential response formats. Consensus was reached for a five-point Likert scale with named anchors of ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘strongly agree’ and a middle neutral value with the label ‘neither agree nor disagree’.

We recruited self-identified service users with severe and enduring mental health problems and carers to complete the emerging PROM, using multiple recruitment strategies (including advertising on NHS trust intranets, newsletter and press releases; posters displayed on trust premises, local trust-based and third-sector study advocates, via Twitter and re-tweeted by local and national mental health charities across the UK and local and national service user and carer forums). Data were collected using online (SelectSurvey version 4.5; ClassApps, Kansas City, MO, USA), postal and face-to-face modalities.

In total, 402 participants completed the 61-item PROM. A randomly selected sample of the 402 were approached to undertake a second completion 4 weeks after baseline, to assess test–retest validity, and 59 test–retest PROMs were completed.

For Rasch analysis, a minimum sample size of 250 allows for > 99% confidence that item calibrations are stable to within ± 0.5 logits, irrespective of scale targeting. This minimum sample size was also deemed sufficient. Prior to statistical analysis, data were double entered and a 5% accuracy check was made. Less than 0.1% errors were detected during the double-entry procedure.

Psychometric and statistical analysis of the data were conducted, involving exploratory factor analysis, Mokken analysis,38 Rasch analysis,39 category threshold analysis, differential item functioning, local dependency, scale reliability, unidimensionality and test–retest reliability. An iterative process of item removal reduced the remaining 61 items to a final 14-item scale (Table 1). The final scale has acceptable scalability (H0 = 0.69), reliability (α = 0.92), fit to the Rasch model [χ2(70) = 97.25, p = 0.02], and no differential item functioning or locally dependent items. Scores remained stable over the 4-week follow-up period, indicating good test–retest reliability.

| Item | Completely disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Completely agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The care plan has a clear objective | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. I am satisfied with the care plan | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. I am happy with all of the information on the care plan | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. The contents of the care plan were agreed on | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Care is received as it is described in the care plan | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. The care plan is helpful | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. My preferences for care are included in the care plan | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. The care plan is personalised | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. The care plan addresses important issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. The care plan helps me to manage risk | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. The information provided in the care plan is complete | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. The care plan is worded in a respectful way | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Important decisions are explained to me | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. The care plan caters for all the important aspects of my life | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

For the audit tool (Table 2), we completed a three-round consensus exercise with our SUCAG (n = 16) and reduced the 61 candidate PROM items to form a shorter six-item audit tool. In round 1, items were presented to the SUCAG members (n = 16), who were each asked to select the top 10 PROM items that they felt were most important to include in an audit tool. A total of 27 items were identified by the group. In round 2, these 27 items were discussed, with individuals providing verbal reasoning for their choices. The 27 items were then re-rated for importance based on the group discussion, reducing the pool down to 10 items. In round 3, these 10 items were identified and discussed further until consensus was reached on six audit tool priorities. Psychometric assessment assessed the performance of the six items identified by the SUCAG using a combination of classical test, Mokken and Rasch analyses. Test–retest reliability was calculated using t-tests of interval level scores between baseline and 2- and 4-week follow-up.

| Item | Completely disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Completely agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I am satisfied with the care plan | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. My preferences for care are included in the care plan | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. The care plan helps me to manage risk | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. The information provided in the care plan is complete | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Important decisions are explained to me | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. The care plan caters for all the important aspects of my life | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Key findings

The 14-item PROM ‘Enhancing the Quality of User and Carer Involvement in Care Planning (EQUIP)’ scale displays excellent psychometric properties and is capable of unidimensional linear measurement. The scale is short, user- and carer-centred and will be of direct benefit to clinicians, services, auditors and researchers wishing to quantify levels of user and carer involvement in care planning (see Table 1). A six-item audit tool was also developed for NHS trusts (see Table 2).

Strengths and limitations

We undertook a stringent, methodological process leading to an initial PROM measure of 61 items, developed in conjunction with service users and carers, and reduced to a 14-item psychometrically validated PROM. Measure length and ease of completion were identified as key user-nominated attributes for PROM acceptability. However, the utility of any measure depends on its validity, reliability, sensitivity and feasibility of completion and a trade-off between these criteria is often necessary. It is possible that some concepts that were originally conceived as important to service users during item generation were not adequately represented by the items retained in the final measure. This accepted, the final measure encompassed a breadth of items that represented a multiplicity of user responses. The attributes selected as most important for the audit tool were chosen by our SUCAG and may lack a diverse or representative sample of individuals using secondary care mental health services.

What this study adds

Current measures, such as those used by the UK CQC, focus on objective indicators of care planning administration rather than those aspects of care planning that service users value most. Our 14-item PROM ‘Enhancing the Quality of User and Carer Involvement in Care Planning (EQUIP)’ addresses this gap. The scale is short, user- and carer-centred and will be of direct benefit to clinicians, services, auditors and researchers wishing to quantify levels of user and carer involvement in care planning.

Outputs

The systematic review reporting the outcome measures of involvement in mental health-care planning has been published in Gibbons et al. 37 (see Appendix 2).

The description of analysis, methods and results of the PROM has been published in Bee et al. 40 (see Appendix 2).

Study 4

The aim of study 4 was to use a stated preference survey to estimate the strength of user/carer preferences and weights for key items included in the audit tool.

Methods

We used a binary discrete choice experiment with five attributes (i.e. whether or not preferences for care are included in the care plan; whether or not the care plan helps me manage risk; completeness of the information in the care plan; whether or not important decisions are explained to me; and whether or not all important aspects of my life are catered for) and an additional attribute describing the time per person spent on care planning related activities. Each attribute had five levels. Each level described how the service might be described by service users, from completely disagree (the reference level) to completely agree. Table 3 shows an example choice question; 13 choice questions were designed, with each choice question describing two alternative care planning approaches for participants to choose their preferred option.

| Which care plan do you prefer? (tick one) | Care plan A | Care plan B |

|---|---|---|

| My preferences for care are included in the care plan | Completely disagree | Completely agree |

| The care plan helps me to manage risk | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree |

| The information provided in the care plan is complete | Completely agree | Agree |

| Important decisions are explained to me | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree |

| The care plan caters for all the important aspects of my life | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree |

| The average time you spend each month to prepare for, attend or follow up on care planning meetings is . . . | 2 hours | 4 hours |

Service user and carer participants were recruited from adult secondary care mental health services in two NHS trusts, and online via social media. Participant characteristics were summarised with descriptive statistics. The analyses included all participants who completed one or more choice set. For the analysis, the completely disagree level of each attribute was used as the reference level for each of the audit tool attributes. This gives an indication of the value to participants of moving from the worst to an improved level of involvement in the care planning process.

This first step was to summarise and describe the data and inform further analysis. Accordingly, it was hypothesised that higher levels for the audit tool attributes (e.g. agree or completely agree) would be preferred to lower levels (e.g. disagree or completely disagree). In contrast, it was thought that participants would prefer to spend less rather than more time per month on care planning activities. A conditional logit regression using maximum likelihood estimation was used as the starting point for the analysis. 41,42 However, participants’ preferences may vary because of factors that are observed, such as sociodemographic characteristics, type of respondent (service user or carer), design factors (e.g. postal vs. online survey), or because of unobserved factors. To account for this, a random-effects, mixed logistic regression model was used for the main analysis. 43 The analysis treated all attributes as random.

A marginal rate of substitution was calculated using the time spent per month on care planning related activities to estimate the amount of time each person is willing to trade to gain their preferred levels of each audit tool attribute.

Stata® version 15 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all the analyses reported here. The mixed logistic regression used the published mixlogit and wtp (delta) user commands developed for Stata. 44,45

Key findings

We recruited 232 participants, of whom 89% completed all choice questions. Most responses were from service users (n = 132/215, 61%), carers (n = 49/215, 23%) and people identifying themselves as both service users and carers (n = 34/215, 16%). Seventeen participants did not report if they were services users or carers. The mixed logit regression results are summarised in Table 4.

| Attribute | Coefficient (SE) | p-value | MRS (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| My preferences for care are included in the care plan | |||

| Completely disagree | Reference level | ||

| Disagree | –0.539 (0.080) | < 0.001 | –4.6 (–7.9 to –1.4) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.102 (0.069) | 0.141 | 0.9 (–0.4 to 2.2) |

| Agree | 0.567 (0.083) | < 0.001 | 4.9 (1.4 to 8.3) |

| Completely agree | 0.797 (0.103) | < 0.001 | 6.8 (2.1 to 11.5) |

| The care plan helps me to manage risk | |||

| Completely disagree | Reference level | ||

| Disagree | –0.508 (0.076) | < 0.001 | –4.4 (–7.7 to –1.0) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.209 (0.082) | 0.011 | 1.8 (0.2 to 3.4) |

| Agree | 0.532 (0.083) | < 0.001 | 4.6 (1.3 to 7.9) |

| Completely agree | 0.484 (0.099) | < 0.001 | 4.2 (0.4 to 7.9) |

| The information provided in the care plan is complete | |||

| Completely disagree | Reference level | ||

| Disagree | –0.116 (0.071) | 0.102 | –1.0 (–2.3 to 0.3) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | –0.002 (0.077) | 0.979 | 0.0 (–1.3 to 1.3) |

| Agree | 0.115 (0.083) | 0.165 | 1.0 (0.0 to 2.5) |

| Completely agree | 0.188 (0.077) | 0.015 | 1.6 (0.1 to 3.1) |

| Important decisions are explained to me | |||

| Completely disagree | Reference level | ||

| Disagree | –0.230 (0.070) | 0.001 | –2.0 (–3.7 to –0.2) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.077 (0.064) | 0.227 | 0.7 (–0.5 to 1.8) |

| Agree/completely agree | 0.577 (0.076) | < 0.001 | 4.9 (1.6 to 8.3) |

| The care plan caters for all the important aspects of my life | |||

| Completely disagree | Reference level | ||

| Disagree | –0.216 (0.070) | 0.002 | –1.9 (–3.6 to –0.1) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.049 (0.063) | 0.436 | 0.4 (–0.7 to 1.5) |

| Agree/completely agree | 0.519 (0.079) | < 0.001 | 4.5 (1.2 to 7.7) |

| Average time you spend each month to prepare for, attend or follow up on care planning meetings | |||

| Time | –0.002 (0.001) | 0.005 | Not applicable |

The data suggested that preferences were strongest for the attribute ‘my preferences for care are included in the care plan’, with service users prepared to spend 5 hours [95% confidence interval (CI) 1 to 8 hours] and 7 hours (95% CI 2 to 12 hours) per month for improvements compared with the reference level. The least preferred attribute was whether or not the information included in the care plan was complete, with participants willing to spend 1.5 hours (95% CI 0.1 to 3.0 hours) for improvements, compared with the reference level.

Strengths and limitations

Service users and carers were involved in the design of the discrete choice experiment, survey materials and recruitment. Our recruitment methods increased the chance of self-selection into the study and may reduce the representativeness of participants and we used analysis methods to help account for variation in participants’ preferences because of unobserved factors or individual characteristics. In addition, survey respondents were based in the UK and were predominantly female and white British. Thus, the results may not be generalisable within and outside the UK. We used a main effects design that means that important interactions between the study attributes were not accounted for, reducing the robustness of the results.

What this study adds

To our knowledge, this is one of the first large, full-profile, discrete choice experiments conducted with people with serious mental illness. The study results demonstrated that participants preferred care plans that emphasised their involvement by including their preferences, helping them to manage risk, catering for all of the important aspects of their life and by having important decisions explained to them. The completeness of information included in the care plan was the least preferred attribute. The marginal rates of substitution suggested that service users are willing to spend time for improvements to the way in which they are involved in their care planning. Our findings could be used to help services target improvements in care planning to the aspects most important to service users.

Outputs

The full results of the stated preference survey are reported in Appendix 2.

Workstream 2: evaluation

Study 5

The aim of workstream 2 (study 5) was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a training intervention to enhance service user and carer involvement in care planning in secondary care mental health services.

Methods

We conducted a pragmatic cluster trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the training intervention to enhance service user- and carer-involved care planning compared with controls in UK NHS community mental health services. The trial used cohort and cross-sectional samples to reduce risks to recruitment and retention. The cluster cohort was recruited at baseline and followed over the 6 months of the trial, whereas the cluster cross-section was recruited at the end of the trial. Consenting service users cared for by each community mental health team (CMHT) were recruited and carers were recruited from consenting service users. Each CMHT was randomised to either intervention (training in care planning) or control (usual-care planning). The CMHTs randomised to intervention received the training package.

We recruited service users and carers from CMHTs between July 2014 and December 2015 from 10 NHS trusts across the UK. Service users were aged ≥ 18 years with a severe mental illness under the care of participating CMHTs. CMHTs screened lists and excluded patients who were not deemed to have capacity to provide fully informed consent or who were too unwell at the time of recruitment. The primary outcome was patient self-reported ‘autonomy support’ measured using the Health Care Climate Questionnaire (HCCQ-10). 46 The HCCQ-10 is a self-report scale based on self-determination theory and measures ‘autonomy support’, defined as patient perceptions of the degree to which they experience their health professionals as supporting choice and ensuring that their behaviour (and behaviour change) is congruent with their values. The scale has 10 items, examples of which include ‘I feel that my mental health-care provider team has provided me with choices and options’ and ‘My mental health-care provider team has worked with me to develop a mental health-care plan’. Items are scored on a seven-point scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. An overall score is calculated as the mean of the items (expressed out of 100), with a higher score indicating greater ‘autonomy support’.

Secondary outcomes included patient self-reported involvement in decisions (EQUIP PROM);40 satisfaction with services [Verona Service Satisfaction Scale (VSS54)];47 side effects of antipsychotic medication [Glasgow Antipsychotic Side Effects Scale (GASS)];48,49 well-being [Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS)];48 recovery and hope [Developing Recovery Enhancing Environment Measure (DREEM)];50 anxiety and depression [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)];51 alliance and engagement [California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (CALPAS)];52 quality of life [World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) questionnaire];53 carer satisfaction [Carer and User Expectations of Services (CUES)];54 quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs); and use of services. Measures were completed at baseline (pre training) and at 6 months post training (cohort sample), and at 6 months post training only (cross-sectional sample).

Outcomes for the cross-sectional sample included the HCCQ-1046 and the PROM. 40 Carer measures included the EQUIP PROM40 and WHOQOL53 and carer satisfaction was measured using the Carers’ and Users’ Expectations of Services – Carer version (CUES-C). 54 A summary of outcome measures, including scoring ranges, can be found in Table 5.

| Outcome measures | Baseline | 6-month follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort design | Cross-sectional sample | ||

| Primary outcome measure | Autonomy support | HCCQ-1046

|

HCCQ-10 |

| Secondary outcome measures | User and carer involvement | EQUIP PROM40

|

EQUIP PROM (short version)

|

| Satisfaction | VSSS-5447

|

||

| Medication side effects | GASS48

|

||

| Well-being | WEMWBS49

|

||

| Recovery and hope | DREEM50

|

||

| Mental health symptoms | HADS51

|

||

| Alliance/engagement | CALPAS-1252

|

||

| Quality of life | WHOQOL-BREF53

|

||

To recruit service users into the cluster cohort, clinical studies officers (CSOs) sent out an introductory letter, participant information sheet and consent to contact form. On receipt of the consent to contact form, service users were invited to interview to complete baseline measures. Consenting service users were asked to nominate a carer to be included in the study who, if nominated, was provided with a questionnaire pack (including introductory letter, information sheet, questionnaire, prepaid envelope and consent to contact at 6-month follow-up form).

Service users were recruited to the cluster cross-section by a postal survey, distributed by CSOs to all service users in CMHTs (excluding those already in the cluster trial) recruited to the cluster cohort 6 months following randomisation.

Following recruitment of service users and carers, clusters were allocated randomly to either intervention or usual-care by the clinical trials unit of the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre.

The trial protocol was published55 (the original trial protocol and a summary of amendments can be found in Appendix 3).

Intervention

All consenting CMHTs allocated to the intervention received the training intervention. We asked that at least 80% of staff designated as ‘care co-ordinators’ (i.e. those with a caseload) committed to attending the training. Training was delivered within 6 weeks of service users being recruited into the trial. Clusters allocated to the control condition of ‘usual practice in care planning’ did not have access to the training intervention training.

Sample size and statistical methods

The original sample size calculation was for 24 clusters and 480 patients. Recruitment issues identified early in the trial meant that a decision was made to increase the number of clusters to 36 to ensure sufficient power. The recruitment methods used in EQUIP meant that the proportions of patients responding to the study was variable within sites (from 5% to 30%) and difficult to predict. Therefore, increasing the numbers of clusters to 18 meant that recruitment of more patients than the planned 480 was likely, unless specific measures were taken to reduce the numbers of patients per site (e.g. sampling patients within clusters, or limiting the numbers of patients per cluster). Such additional measures would have proven difficult in practice. Therefore, the decision to increase the number of clusters to 36 led to recruitment of 609 patients. The low-risk and non-invasive nature of the intervention and because the cluster design meant that all patients were exposed whether or not they formally participated in the trial means that it is unlikely that any participants had faced additional risk of harm because of the decision to increase cluster numbers and the subsequent increase in the total sample size.

We wrote to the Research Ethics Committee outlining the recruitment numbers at the end of the trial and the committee raised no issues, but we accept that this issue should have been stated explicitly to the Research Ethics Committee when we raised the cluster numbers.

The Research Ethics Committee’s response was as follows:

The Committee has reviewed your letter regarding the over recruitment into this study. Although they acknowledged that nothing could be done since the study has been declared closed, they pointed out that it was not clear from your letter why the cluster was increased. They stated that whilst the design meant that the numbers in each cluster were difficult to control, the CI [chief investigator] had overall responsibility of the study and should have been aware of the overall recruitment and when a possibility of over recruitment became apparent, the REC [Research Ethics Committee] should have been notified immediately. They concluded that although no actual harm had occurred at this time, they strongly advised that if this happens in the future, you must notify the REC immediately the participant numbers are likely above what had been approved by the REC and submit an amendment.

National Research Ethics Service Committee Northwest Preston (Health Research Authority), 2019, personal communication.

The primary outcome was the HCCQ-10,46 but data on the use of this scale by people with severe mental illness were limited, so we used a standardised effect to calculate sample size for the cluster trial. Twelve clusters per arm and a mean of 20 service users per cluster (total sample size of 480 participants) would have > 80% power to detect a standardised effect size of 0.4. This assumes an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05 and an 80% follow-up rate, providing 384 participants with complete data in the analysis. For the cross-sectional study, we required the same number of patients in each cluster.

Analysis was completed using Stata version 13 and followed a statistical analysis plan prepared prior to analysis and approved by the independent Programme Steering Committee. The plan identified the cluster trial as the primary analysis, with the cluster cross-section and combined analyses to be presented as secondary analyses. For the cluster trial, intervention effects were estimated using a linear mixed model with a random intercept for teams. Analysis of outcomes followed intention-to-treat principles with outcome data included for all patients irrespective of receipt of the intervention or completion of care planning during the time scale of the trial. The pattern of missing data was assessed in terms of baseline characteristics of service users to check for differential non-response. Predictors of non-response were included as covariates in each model to satisfy the missing at random assumption of maximum likelihood used in estimating linear mixed models. Missing baseline data for the cohort sample were cluster mean imputed.

Participant flow

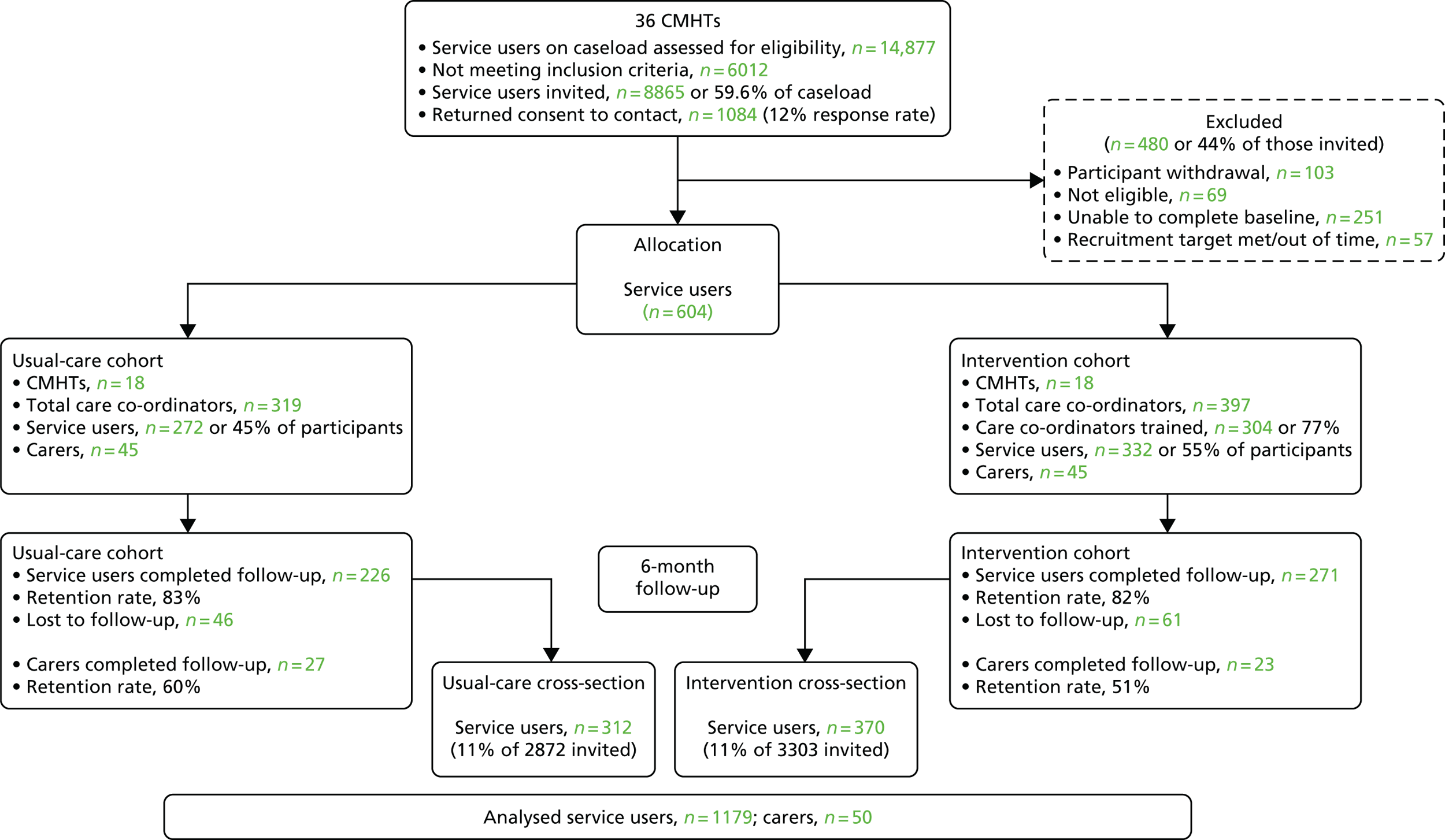

Participant flow for the cluster trial and cross-sectional sample is shown in Figure 3. During recruitment, the number of service users per cluster was smaller than estimated in the sample size calculation. We increased the number of clusters from 12 to 18 per arm to ensure sufficient power, and 36 teams were randomised to either the intervention (n = 18) or the usual-care (n = 18) group. There was appreciable uncertainty regarding the effect size for the outcome, which is indicated by the use of a standardised rather than absolute effect size and also the adoption of an ICC of 0.05. Given that there was minimal cost to continuation, it seemed appropriate to continue recruitment of centres rather than termination to protect the power of the trial against the ICC being larger than expected. The Programme Steering Committee, Research Ethics Committee and NIHR approved continued recruitment beyond the target size. In total, 604 service users and 90 carers were recruited to the cluster cohort. Ten out of the 18 CMHTs demonstrated ≥ 80% attendance of care co-ordinators at the training (range 48–100%). Retention at the 6-month follow-up for service users in each CMHT ranged from 76% to 93%, with an overall mean of 82% (n = 497). Retention of carers was limited, ranging from 0% to 100% between clusters, with an overall mean of 56% (n = 50). For the cross-sectional study, 682 service users were recruited [mean number per CMHT was 19.5 service users, standard deviation (SD) 14.0 service users].

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for cluster randomised controlled trial and cluster cross-section.

Demographics

Combining the cluster trial and cross-sectional samples (n = 1286), 58% of service users were female, 48% were aged between 45 and 64 years, 38% were aged between 25 and 44 years, 87% described themselves as white and only 13% were employed (Table 6). Demographics were broadly similar between the cluster cohort and cross-sectional samples and between intervention and usual care (Tables 6 and 7). Of the 90 carers in the cluster trial, just over half were female and most were white (Table 8).

| Demographic variable | Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 271) | Intervention (N = 333) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 156 | 58 | 199 | 60 |

| Non-female | 107 | 39 | 128 | 38 | |

| Missing | 8 | 3 | 6 | 2 | |

| Ethnic group | White | 232 | 86 | 295 | 89 |

| Non-white | 33 | 12 | 32 | 10 | |

| Missing | 6 | 2. | 6 | 2 | |

| Education | Secondary school | 108 | 40 | 129 | 39 |

| Higher education | 153 | 56 | 182 | 55 | |

| Missing | 10 | 4 | 22 | 7 | |

| Accommodation | Owner-occupier | 85 | 31 | 97 | 29 |

| Other | 176 | 65 | 227 | 68 | |

| Missing | 10 | 4 | 10 | 3 | |

| Living arrangements | Alone or with a pet | 191 | 70 | 225 | 68 |

| With someone else | 75 | 28 | 102 | 30.63 | |

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | |

| Employment | Employed | 37 | 14 | 45 | 14 |

| Other | 230 | 85 | 281 | 84 | |

| Missing | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | |

| Demographic variable | Cross-sectional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 309) | Intervention (N = 373) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 172 | 56 | 225 | 60 |

| Non-female | 131 | 42 | 141 | 38 | |

| Missing | 6 | 2 | 7 | 2 | |

| Ethnic group | White | 275 | 89 | 314 | 84 |

| Non-white | 28 | 9 | 45 | 12 | |

| Missing | 6 | 2 | 14 | 4 | |

| Education | Secondary school | 147 | 48 | 167 | 45 |

| Higher education | 112 | 36 | 151 | 40 | |

| Missing | 50 | 16 | 55 | 15 | |

| Accommodation | Owner-occupier | 84 | 27 | 113 | 30 |

| Other | 217 | 70 | 246 | 66 | |

| Missing | 8 | 3 | 14 | 4 | |

| Living arrangements | Alone or with a pet | 164 | 53 | 197 | 53 |

| With someone else | 142 | 46 | 170 | 46 | |

| Missing | 3 | 1 | 6 | 2 | |

| Employment | Employed | 40 | 13 | 55 | 15 |

| Other | 265 | 86 | 306 | 84 | |

| Missing | 4 | 1 | 12 | 3 | |

| Demographic variable | Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 44) | Intervention (N = 46) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 22 | 50 | 25 | 54.35 |

| Non-female | 22 | 50 | 20 | 43.48 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.17 | |

| Ethnic group | White | 39 | 89 | 40 | 87 |

| Non-white | 5 | 11 | 6 | 13 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Education | Secondary school | 17 | 39 | 20 | 43 |

| Higher education | 22 | 50 | 23 | 50 | |

| Missing | 5 | 11 | 3 | 7 | |

| Accommodation | Owner-occupier | 25 | 57 | 32 | 70 |

| Other | 19 | 43 | 14 | 30 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Living arrangements | Alone or with a pet | 13 | 30 | 14 | 30 |

| With someone else | 31 | 70 | 31 | 67 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Employment | Employed | 15 | 34 | 23 | 50 |

| Other | 29 | 66 | 22 | 48 | |

| Missing | 31 | 70 | 1 | 2 | |

Cluster trial (service users)

Primary outcome Health Care Climate Questionnaire (cluster cohort)

The HCCQ-1046 was the primary outcome measure. High scores represent higher appraisals of care. The mean and SD in the intervention and usual-care group are given in Table 9 with the adjusted mean difference and 95% CI. Results show no difference in HCCQ-10 scores between intervention and usual care at 6 months. The ICC indicates that approximately 2% of the variation of HCCQ-10 at 6 months is between teams, showing little difference in HCCQ-10 scores between teams.

| Time point | Usual care | Intervention | Adjusteda mean difference (intervention – usual care) | 95% CI | p-value | ICC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |||||

| Baseline | 5.06 | 1.66 | 271 | 5.27 | 1.48 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 4.93 | 1.78 | 226 | 5.01 | 1.70 | 270 | –0.064 | –0.343 to 0.215 | 0.653 | 0.02 |

Secondary outcomes (cluster trial)

The results of the secondary outcomes (Table 10) in the cluster trial showed no significant difference between the intervention and usual care at 6 months, except for VSSS-54. The adjusted mean difference indicates that the intervention group had higher (meaning more satisfied) VSSS-54 scores than the usual-care group, which showed a small, statistically significant difference at the 5% level. The 95% CIs are wide and, therefore, the true effect is potentially negligible. With all secondary outcomes, the ICC demonstrates very little variation between CMHTs.

| Outcome | Time point | Usual care | Intervention | Adjusteda mean difference (intervention – usual care) | 95% CI | p-value | ICC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | ||||||

| PROMa | Baseline | 22.81 | 8.78 | 271 | 22.07 | 8.58 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 21.64 | 11.18 | 152 | 21.32 | 9.62 | 193 | 0.396 | –1.817 to 2.609 | 0.726 | 0.05 | |

| HADS-A (anxiety)a,b | Baseline | 11.37 | 5.36 | 271 | 12.23 | 5.18 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 10.85 | 5.86 | 171 | 12.10 | 5.37 | 209 | 0.430 | –0.334 to 1.194 | 0.270 | 0.00 | |

| HADS-D (depression)a,b | Baseline | 9.19 | 5.31 | 271 | 10.03 | 5.18 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 8.91 | 5.83 | 171 | 9.81 | 5.49 | 209 | –0.001 | –0.861 to 0.858 | 0.998 | 0.00 | |

| VSSS-54a,b | Baseline | 3.58 | 0.62 | 271 | 3.53 | 0.61 | 331 | ||||

| 6 months | 3.53 | 0.80 | 155 | 3.51 | 0.72 | 192 | 0.120 | 0.001 to 0.239 | 0.049 | 0.01 | |

| CALPASa,b | Baseline | 4.98 | 1.27 | 271 | 5.06 | 1.19 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 4.87 | 1.45 | 151 | 4.81 | 1.38 | 192 | –0.010 | –0.259 to 0.239 | 0.935 | 0.01 | |

| GASS | Baseline | 17.73 | 10.37 | 271 | 18.30 | 8.93 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 17.80 | 11.57 | 114 | 19.80 | 10.28 | 144 | 1.316 | –1.075 to 3.708 | 0.281 | 0.05 | |

| WHOQOLa | Baseline | 3.03 | 1.02 | 271 | 3.04 | 1.05 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 3.20 | 1.19 | 157 | 3.16 | 1.11 | 201 | 0.024 | –0.170 to 0.218 | 0.808 | 0.00 | |

| DREEMa | Baseline | 39.20 | 12.32 | 271 | 38.81 | 11.86 | 334 | ||||

| 6 months | 41.07 | 13.78 | 161 | 38.83 | 13.29 | 204 | –0.661 | –2.600 to 1.278 | 0.504 | 0.002 | |

Cluster trial (carers)

The three outcomes completed by carers were the 14-item EQUIP PROM, WHOQOL and CUES-C. The results showed no significant difference in PROM or CUES-C scores between intervention and usual care at 6 months. There was a slight difference in WHOQOL scores, indicating that the intervention improves quality of life by approximately half a unit on the 1–5 scale (0.484), but the CI for this estimate is wide, suggesting potentially negligible difference. Controlling for baseline variables, the between-cluster variation in all three measures is negligible and so the ICC is effectively zero, showing no difference between CMHTs (Table 11).

| Outcome | Time point | Usual care | Intervention | Adjusteda mean difference (intervention – usual care) | 95% CI | p-value | ICC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | ||||||

| PROM | Baseline | 19.48 | 10.96 | 44 | 20.97 | 12.64 | 20 | ||||

| 6 months | 16.45 | 10.86 | 46 | 20.10 | 8.00 | 22 | 0.392 | –5.676 to 6.460 | 0.899 | 0.00 | |

| WHOQOL | Baseline | 3.45 | 0.90 | 44 | 3.69 | 0.81 | 46 | ||||

| 6 months | 3.27 | 1.15 | 26 | 3.91 | 1.00 | 23 | 0.484 | 0.009 to 0.959 | 0.046 | 0.00 | |

| CUES-C | Baseline | 24.68 | 8.02 | 44 | 24.67 | 8.28 | 46 | ||||

| 6 months | 24.12 | 9.97 | 26 | 22.71 | 9.08 | 24 | –0.972 | –4.4383 to 2.440 | 0.577 | 0.00 | |

Outcomes for cross-sectional study

The two outcomes completed by service users and carers were the HCCQ-10 and the PROM. Results show no significant difference in the HCCQ-10 and the PROM between intervention and usual care at 6 months. The mean and SD in the intervention and usual-care group are given in Table 12 with the adjusted mean difference and 95% CI. Controlling for baseline variables, the between-cluster variation in all three measures is negligible and so the ICC is effectively zero, showing no variation between CMHTs.

| Outcome | Time point | Usual care | Intervention | Adjusteda mean difference (intervention – usual care) | 95% CI | p-value | ICC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | ||||||

| HCCQ-10 | 6 months | 5.10 | 1.72 | 284 | 5.08 | 1.72 | 344 | –0.132 | –0.511 to 0.247 | 0.495 | 0.05 |

| PROM | 6 months | 25.25 | 13.60 | 242 | 25.62 | 13.46 | 309 | –0.691 | –4.068 to 2.686 | 0.688 | 0.07 |

Key findings

The results showed no statistically significant difference in HCCQ-10 scores between the intervention and usual care at 6 months. The ICC indicates that only 2% of the variation of HCCQ-10 at 6 months was between teams.

The results of the ‘cluster cross-section’ and combined analyses were similar to the primary analysis, with no statistically significant difference on the primary outcome between the intervention and usual care at6 months. Analyses of secondary outcomes in the ‘cluster cohort’ found a significant effect on a single outcome of service satisfaction. However, the 95% CIs are wide and, therefore, the true effect is potentially negligible. In terms of opportunities to use the training in routine contacts with patients, data from patient self-report suggested that 79% of patients providing data saw their CMHT during the 6-month follow-up, with a mean of 12.3 contacts. Our intervention to improve user- and carer-involved care planning in community mental health services was well attended and acceptable to staff, but had no significant effects on patient perceptions of autonomy support, or other outcomes.

Cost-effectiveness

An economic evaluation was integrated into the clinical trial to assess whether or not the EQUIP training intervention was cost-effective at each of the different levels that decision-makers may be willing to pay in order to gain 1 unit of health benefit.

Methods

Service use data were collected at baseline and the 6-month follow-up for all service users who participated in the cluster trial, as were health status data [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)]. The service use data were collected using a survey adapted for the EQUIP trial. The service use data were combined with published national unit costs to estimate costs. 56,57 The costs of delivering the intervention were estimated from the costs incurred in the trial and the number of people trained. They included the costs of health-care professionals’ time to attend the training and the costs of trainers’ time to deliver the training. The costs of consumables and room hire were also included. The QALYs were estimated by combining the EQ-5D-5L data with UK-specific utility weights using the crosswalk methodology recommended by NICE at the time of the evaluation. 58,59 The analysis used the perspective of the NHS and social care (costs) and service users (QALYs). The time horizon for the primary analysis was the 6-month follow-up point of the trial. Analysis of the economic data was based on intention-to-treat principles, and missing data (owing to incomplete observations and missing follow-up) were imputed using multiple imputation. Regression analyses were used to estimate the net costs and outcomes of the EQUIP training intervention, adjusting for participant sociodemographic characteristics and team cluster (baseline covariates) that may influence costs and QALYs. A generalised linear regression model, with a gamma distribution and log-link, was used to account for the skewed nature of the cost data. An ordinary least squares regression model was used to estimate net QALYs. This required the assumption that the QALY data were normally distributed, which was tested in the sensitivity analysis. The net cost and QALY were bootstrapped to estimate the probability that the EQUIP training intervention was cost-effective at different hypothetical amounts decision-makers may be willing to pay to gain an additional QALY. Sensitivity analysis explored the relative cost-effectiveness of the training intervention if different choices were made about the study methods. These included using different measures of benefit, alternative estimates of the unit cost of the intervention, complete-case analysis and the use of a beta distribution to estimate net QALYs.

Key findings