Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0610-10048. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The final report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rachel Churchill reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (Programme Grants for Applied Research programme) during the conduct of the study. Simon Gilbody serves as deputy chairperson of the NIHR Health Technology Commissioning Board, but was not involved in the commissioning of this programme of research. Catherine Harmer reports personal fees from P1vital (Wallingford, UK), grants from UCB Pharma (Brussels, Belgium), grants and personal fees from Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, NJ, USA), and personal fees from H. Lundbeck A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark), Servier Laboratories (Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) and Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) outside the submitted work. Tony Kendrick reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Marcus Munafo reports grants and personal fees from Cambridge Cognition (Cambridge, UK) and personal fees from Jericoe Ltd (Bristol, UK) outside the submitted work. Tim Peters reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Howard Thom reports personal fees from Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland), Pfizer Inc., Roche Holding AG (Basel, Switzerland) and Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA) outside the submitted work. Nicky Welton reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study; and she is the principal investigator on a Medical Research Council-funded project in collaboration with Pfizer Inc. Pfizer Inc. part funded a junior researcher on the project. The project is purely methodological using historical data on pain relief, and unrelated to this work. Nicola Wiles reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Glyn Lewis reports grants from University College London during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Fortitude Law (London, UK) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Duffy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background

Depression is the leading cause of disability globally. 1 Most people with depression or depressive symptoms are treated in primary care and antidepressants are often the first-line treatment. There were over 70 million antidepressent prescriptions in England in 2018. 2 There is much uncertainty about when people with depression might benefit from an antidepressant and concern that antidepressants are overprescribed. General practitioners (GPs) often feel under pressure to provide some treatment and have to make a difficult decision about whether or not an individual will benefit from an antidepressant. The existing guidelines use terms such as ‘mild’ or ‘moderate’ depression to guide prescription but do not specify what this means, and such guidelines are not based on empirical studies. Identifying the patients who are most likely to respond to an antidepressant would improve the management of depression in primary care as well as in other clinical settings. This would reduce the inappropriate prescription of antidepressants in those less likely to respond, and increase appropriate prescription in those more likely to respond.

The minimal clinically important difference

To make informed recommendations about when treatments are of benefit to patients, we must decide what constitutes a clinically important treatment effect. There is no consensus about the size of a ‘clinically important difference’ on continuous outcome scales. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline group, which includes service users, suggested that this difference was three points on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD),3 but did not provide any empirical justification. 4 We need to decide on a clinically important treatment effect before we can make recommendations about when selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are of benefit and to estimate the sample size of a study. There have been previous attempts to determine clinically important differences5,6 but these have relied on classifying people as ‘well’ or ‘ill’ and then calculating the differences in score between the groups. However, these metrics do not take into account the perspectives of the patient. We were interested in participants’ own views about improvement to determine a clinically important difference. Our approach was to ask people to rate their own improvement and then use this to calculate the difference in scores corresponding to a change. This method has been used in relation to quality-of-life scales but, as far as we are aware, not in relation to depression. 7 There has been work comparing the results of self-administered questionnaires with psychiatric diagnostic assessments. 8 Our approach was therefore in contrast to these methods and emphasises the patient’s perspective.

Measurement of depression

Another barrier to the development of evidence-based guidelines for antidepressant prescription in primary care is the lack of a standardised measure of depressive symptoms that is easily implemented. Existing studies on antidepressants mostly use rating scales, such as HAMD, that are difficult to standardise, are designed for clinician administration and require training. It is extremely unlikely that these scales would ever be used in primary care and this has never been proposed, to our knowledge. Shorter self-administered scales, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),8 have been used in UK primary care and in the NHS Improving Access to Psychological Treatment services. However, it is widely thought that the PHQ-9 does not provide sufficiently good data to guide prescribing even if it is useful as an outcome measure. The NICE CG90 depression guideline9 explicitly recommends not using the PHQ-9 and similar scales alone for the purpose of guiding treatment.

Short questionnaires, such as the PHQ-9, are unlikely to give accurate information to guide prescription, but evidence suggests that they do perform well as a measure of outcome or change. 10 However, this symptom-based approach to measuring outcome has been challenged by the growing literature about ‘recovery’, largely from the perspective of people with psychosis. Two areas highlighted in this literature include the concepts of hope and empowerment, the notion that the patient feels able to change. 11 We are aware of only a limited literature concerned with ‘recovery’ in people who have experienced depression. 12 Malpass et al. 13 have also interviewed people recovering from depression in relation to change on the PHQ-9 and did identify some areas that were not well covered in that questionnaire. These included anxiety along with ‘awareness’ and ‘ability to make changes’.

There is still some uncertainty about how antidepressants work but Harmer et al. 14 have found that antidepressants lead to changes early on in the processing of emotional information. Beck et al. 15 first proposed that negative interpretations, beliefs and memories play a key role in depression and developed cognitive–behavioural therapy. Subsequently, the cognitive neuropsychological model of depression has proposed that lower-level changes in emotional processing play a causal role in the genesis of symptoms and precede changes in depressive symptoms. 14 Simple tests, such as face recognition and word recall, could be used alongside symptom measures to investigate changes in depression and complement measures of symptoms. Existing studies have been small and used case–control designs that are prone to selection bias. If we could confirm that emotion-processing tasks were related to depressive symptoms, future research could see if the response to emotion-processing tasks could be used to predict clinical response. We therefore also investigated associations between depressive symptom severity and emotional processing and how this might change in recovery.

There are a wide range of existing outcome assessments of depressive symptoms, for example HAMD, PHQ-9, Beck Depression Inventory, version 2 (BDI-II)16 and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 17 It would be useful to know how these scales inter-relate so that the results of clinical trials can be compared with each other. 18,19 If we could ‘map’ the scores on the scales against each other, this would help with the interpretation of existing data and in the application of existing and future results to clinical practice.

What factors are associated with response to antidepressants?

It has been proposed that antidepressants are more effective for patients with more severe depression, but the evidence for this is inconsistent20–25 and recent large studies of individual patient data suggest no influence of depression severity. 23–25 On the other hand, a systematic review of patients with depressive symptoms not meeting diagnostic criteria26 did not find evidence that antidepressants were effective. However, the majority of the existing trials were not designed to investigate this hypothesis and exclude patients who are below a certain severity threshold. 27,28 A more general criticism is that the current evidence is dominated by trials performed for regulatory purposes so it is difficult to generalise their results to patients currently receiving treatment, mainly provided in primary care.

To help GPs decide whether or not to prescribe SSRIs, it is important to compare a SSRI with a placebo. This becomes more rather than less important in less severe depression as the differences between placebo and active medication are likely to be smaller than for more severe depression. 20 By ‘response’ to antidepressants, we refer to the difference between the antidepressant and the placebo.

The two main diagnostic manuals, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10),29 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),30 have similar, but not identical, diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode (ICD-10) and major depression (DSM-IV). DSM-IV also has a category of minor depression that requires fewer symptoms. As a rule, GPs do not use these diagnostic criteria and there is currently little empirical evidence that meeting either of these diagnostic criteria can alone indicate whether or not antidepressants will be beneficial. There is a consensus that depressive symptoms can be viewed along a continuum of severity, and, in population terms, ‘subthreshold’ symptoms are still a public health concern. 31,32 It is therefore important to assess the severity of symptoms along this continuum. People who do not meet diagnostic criteria might still benefit from antidepressant treatment, or the converse.

There is evidence that antidepressants can be effective for people with dysthymia. 33,34 Dysthymia is a US term used in DSM-IV but not in ICD-10. It describes depressive symptoms of long duration (≥ 2 years) but not meeting the diagnostic criteria for depression. NICE guidelines19 recommend SSRIs for persistent subthreshold depressive symptoms but give no guidance on the duration of the persistence. We proposed, as adopted by current UK guidelines,19,35 that symptom severity and duration of symptoms are two separate dimensions that both might help to predict response to antidepressants.

The PANDA research programme

The overall aim of the PANDA (What are the indications for Prescribing ANtiDepressAnts that will lead to a clinical benefit?) research programme was to provide GPs or other clinicians with improved guidance about when antidepressants are most likely to result in a clinical benefit for patients with depressive symptoms in primary care and be cost-effective for the NHS. The main hypothesis was that response to antidepressants (compared with placebo) would increase with both the severity and duration of depressive symptoms. The programme aimed to investigate whether or not there are thresholds of severity and duration above which a clinically important response to antidepressants is most likely. In line with growing emphasis on patient-centred care, ‘clinically important’ was defined as a reduction in depressive symptoms large enough that patients would detect feeling better. An additional aim was therefore to establish, for the first time, the reduction in depressive symptoms on self-administered depression questionnaires that is required for patients to feel better. To assess severity and duration, we used a detailed, self-administered, computerised assessment that could be easily implemented in primary care. Finally, we also wanted to investigate how patients interpreted the questions in the current self-administered scales, to investigate how that related to self-reported improvement and to investigate the relationship between depressive symptoms and the underlying cognitive biases that are characteristic of depression.

A new randomised controlled trial (RCT) was required to provide this information, despite the wealth of data available from previous placebo-controlled studies that have largely been carried out by the pharmaceutical industry and are comprehensively summarised in Cipriani et al. 28 First, the existing data were mostly of a poor quality and were carried out decades ago for regulatory purposes rather than to study clinical indications. Cipriani et al. 28 noted that 78% of trials were industry funded and that, overall, trials were of poor quality and small, with a mean sample size of 224 (across arms). In addition, 82% of trials were also at moderate or high risk of bias and the larger more recent placebo-controlled trials reported smaller effect sizes, perhaps reflecting more rigorous methods. Second, existing results on the influence of depression severity on antidepressant response are in terms of HAMD scores. This is not useful in primary care because of the training required. Even though we should be able to calculate equivalent scores on measures such as the PHQ-9, more detailed assessments would provide a better predictor of response than brief questionnaires. Third, existing data are unlikely to generalise to the population currently receiving antidepressants in primary care in the UK or in other countries. Most of the trials excluded people at lower levels of severity and the recruitment methods are usually unknown. Finally, we are not aware of any existing data from previous studies on the influence of duration of illness.

The objectives of the PANDA research programme

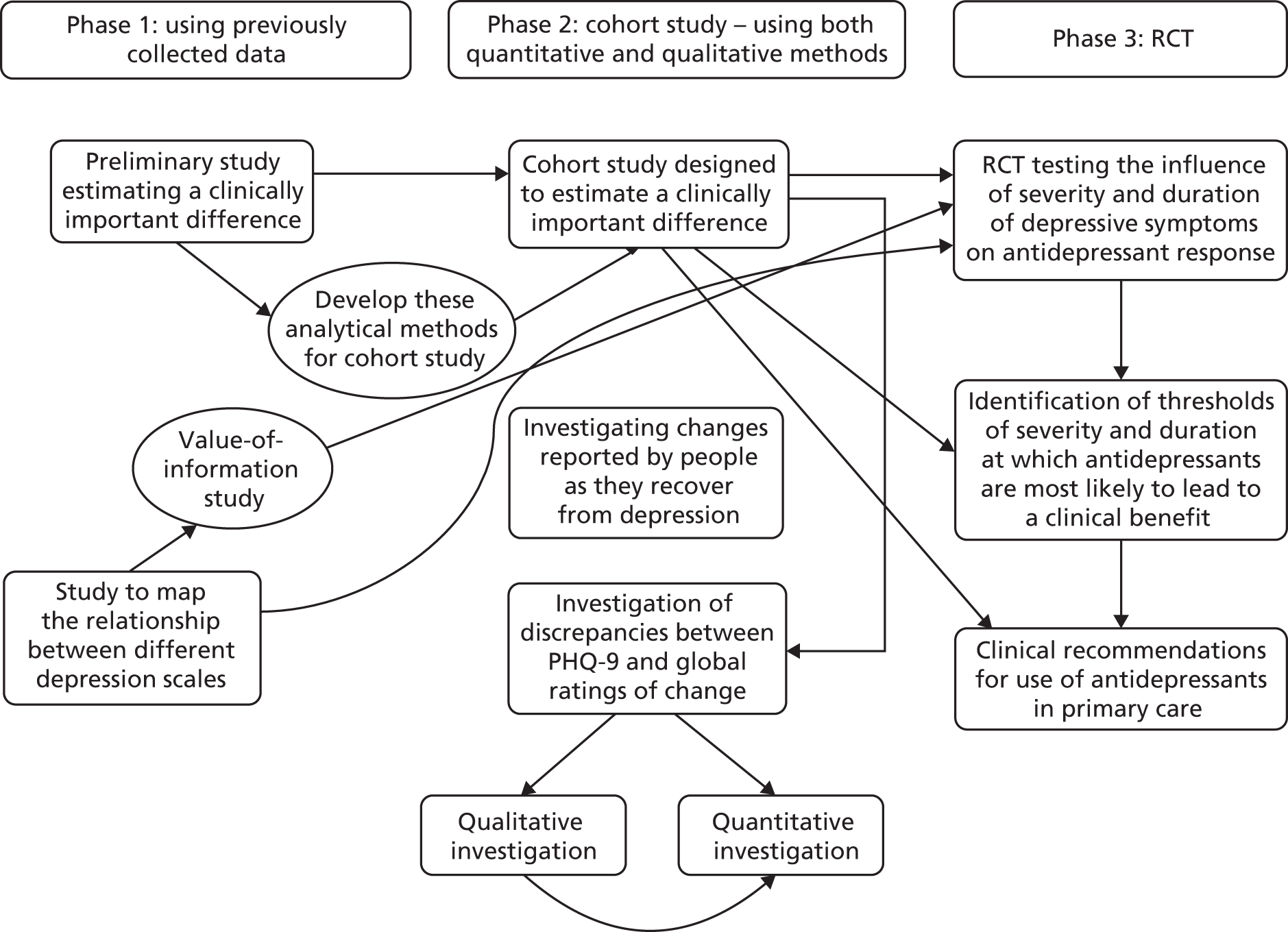

The PANDA research programme consisted of three phases; the aims of each phase and the title of corresponding PANDA papers are listed below.

Phase 1: using previously collected data

Aim 1a: to use existing data to estimate the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the BDI-II.

-

See Appendix 1: Button et al. 36

Aim 1b: to ‘map’ the relationship between different depression scales to estimate the scores on each scale that correspond to the same severity of symptoms.

-

See Appendix 2: Kounali et al. 37

Aim 1c: to carry out a value-of-information study to estimate the probable benefit of carrying out a RCT as described in phase 3.

-

See Appendix 3: Thom et al. 38

Phase 2: cohort study – using both quantitative and qualitative methods

Aim 2a: to estimate the MCID in commonly used self-administered questionnaires for depressive symptoms.

-

See Appendix 4

Aim 2b: to investigate the changes reported by patients as they recover from depression.

-

See Appendix 5: Malpass et al. 39

-

See Appendix 6: Bone et al. 40

-

See Appendix 7: Lewis et al. 41

Aim 2c: to investigate disagreement between self-reported improvement and changes in the scores on depressive symptom questionnaires.

-

See Appendix 8: Robinson et al. 42

-

See Appendix 9

Phase 3: randomised controlled trial

Aim 3: to investigate the severity and duration of depressive symptoms that are associated with a clinically important response to sertraline in people with depression and whether or not these factors are associated with the cost-effectiveness of sertraline.

-

See Appendix 10: Salaminios et al. 43

-

See Appendix 11: Lewis et al. 44

-

See Appendix 12: Hollingworth et al. 45

The inter-relationships between the three phases are summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The inter-relationships between the three phases.

Changes to the programme

-

In our research proposal, we originally had aimed to carry out a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis to investigate the relationship between the severity of depressive symptoms and the response to antidepressants. However, after the research programme was funded, an individual patient data meta-analysis was published by Gibbons et al. 23 using data provided by the pharmaceutical industry and there have been more recent replications. 24,25 Gibbons et al. 23 analysed all the placebo-controlled studies of the antidepressants fluoxetine and venlafaxine that were sponsored by the relevant pharmaceutical company and had therefore obtained a complete and unbiased sample of the placebo-controlled trials. As a result, we decided to abandon the original proposal for a systematic review in this area based on literature searching and approaching authors for individual patient data.

-

With the resources that had originally been earmarked for the individual patient data meta-analysis, we carried out an analysis of existing data to begin our study of the MCID (aim 1a and see Appendix 1) and a value-of-information study (aim 1c and see Appendix 3). Previously published economic models including that used in the NICE CG9019 did not consider treatment by baseline severity and none modelled depression severity itself, so this required the development of an economic model in which severity of depression was part of the decision-making process.

-

We also included some simple emotion-processing tasks in the PANDA cohort study. These tasks are influenced by antidepressant medication and might indicate changes that occur during recovery from depression that are not currently assessed by self-administered questionnaires. These tasks therefore extended aim 2b and the relationship with depressive symptoms and changes in symptoms are reported in Appendices 6 and 7.

-

When originally devised, the primary aim of the RCT was to investigate the severity and duration of symptoms associated with a clinically important response to sertraline, as stated in the protocol paper43 and on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry. However, it was apparent towards the later stages of designing the RCT and in formulating the detailed analysis plan46 (uploaded before any analyses were performed to http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk and approved by the Trial Steering Committee) that we would have insufficient statistical power to estimate plausible interaction effects that would allow us to investigate those aims. Our power calculation and primary analysis (as stated in the analysis plan46) are therefore based on a primary aim to examine the clinical effectiveness of sertraline versus placebo. Interactions between severity and duration at baseline and treatment response were planned as exploratory.

-

In the original funding application, we used citalopram as our choice of antidepressant. However, during the set-up stage, new guidance was released informing clinicians that citalopram can prolong the QT interval, especially in higher doses. Although the risk was low, we decided to change the study medication to sertraline, another commonly prescribed SSRI that is no longer under patent. There are very few pharmacological differences between the SSRIs and we believe that the results of our study can be applied to all SSRIs.

Phase 1: using previously collected data

Aim 1a: to use existing data to estimate minimal clinically important difference from the patient perspective

Research aims

The aim of this study was to use existing data to estimate the MCID from the patient’s perspective, and to investigate whether or not the MCID varied according to how severely ill patients were to begin with, which we have called ‘baseline dependency’.

Methods for data collection

We used existing data from three RCTs [GENetic and clinical Predictors Of treatment response in Depression (GenPod), TREAting Depression with physical activity (TREAD) and Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive Behavioural Therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in primary care (CoBalT)],47–49 in which we had asked patients a Global Rating of Change (GRC) question. All these studies recruited individuals who met the ICD-10 criteria for depression. GENPOD compared citalopram and reboxetine, TREAD evaluated an intervention designed to increase physical activity and CoBalt investigated cognitive–behavioural therapy as an adjunctive treatment in people who had not responded to antidepressants. As far as we are aware, these are the only trials that used the GRC. Each trial used the BDI-II as the primary outcome, which provided an opportunity to estimate the MCID for the BDI-II. Each RCT investigated treatment options for depression and followed participants over several months providing at least two time periods for analysis. Data from 1039 patients who met the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression were analysed.

Analysis

To test whether or not the MCID varied according to baseline severity, we assessed change in BDI-II scores as both absolute (difference) and proportional reduction. Participants were dichotomised into ‘better’ and ‘not better’ (combining feeling the same and feeling worse) using the GRC. To examine whether or not the MCID varied according to baseline severity of depression, and thus determine whether or not MCID was best assessed in terms of absolute change or per cent reduction in scores from baseline, we used generalised linear models. We used receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis to find the change in BDI-II score (the ‘cut-off point’ or threshold) that optimally classifies those individuals who felt better and those who did not.

Key findings

We found strong evidence that the size of the MCID depended on the initial severity of depressive symptoms. Patients with more severe depressive symptoms at baseline required a larger change in their BDI-II scores to report feeling better. Participants in the CoBalt study whose symptoms had not responded to antidepressants needed to experience larger changes on the BDI-II (on average) to report feeling better. Overall, for every 10-point increase in baseline severity on the BDI-II, the mean score associated with feeling better increased by 4.8 points [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.9 to 8.5 points] on the BDI-II. There was statistical evidence that the MICD was best assessed as a proportional reduction of scores rather than an absolute fixed value.

Our best estimate for the MCID based on the ROC analyses provide the best estimates of MCID, with an improvement from baseline of 17%, 18% and 32% for GenPod, TREAD and CoBalT, respectively. As noted above, the MCID for CoBalt, in which the participants had depression that had not responded to antidepressants, was larger than for the other two studies.

Limitations

The study was a secondary data analysis from existing trials and the use of RCT data introduced regression to the mean and this complicated the interpretation of the changes. The trials included only those who met the ICD-10 criteria for depression so there were fewer data at lower levels of severity where there is more controversy about the MCID.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

This study allowed us to develop our approach towards estimating the MCID in preparation for the PANDA cohort study in phase 2. The MCID was also used to inform our power calculation for the RCT in phase 3. The MCID estimate was also used for aim 2c, in which we investigated disagreements between self-reported improvement and the changes in self-administered depression scales.

Aim 1b: ‘mapping’ the relationship between different depression scales

Research aims

The aim was to estimate the relative responsiveness of commonly used scales for depressive symptoms. This allows comparison of treatment effects across different studies and also allowed us to draw conclusions about the relative responsiveness of outcome measures that might not have been directly compared.

Methods for data collection

A search for all measures of depression, anxiety and quality-of-life outcomes was conducted in May 2011 in studies on the Cochrane Depression Anxiety and Neurosis review group’s register. We identified 31 placebo and usual-care controlled studies with clearly defined treatment and control groups that reported two or more outcome measures of depression or quality of life. Eleven of the studies were drug trials and the remaining studies were of psychological therapies. The depression measures included were the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), PHQ-9, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression-17 items (HAMD-17),50 Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression-24 items (HAMD-24)50 and Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). 51 We also examined the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),52 Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) mental capacity score and SF-36 physical capacity score. 53

Analysis

We used a new meta-analytic method that had been developed by our co-investigators54 that can be interpreted as estimating the relative responsiveness of different scales. The data used in the study were the mean treatment differences between active and control arms after 12 weeks’ follow-up or as close as possible to that. If this was unavailable, we used the difference between the mean score at baseline and follow-up. The pooled standard deviation (SD) at follow-up was used for standardisation, if available. If this was not available, the pooled SD on the difference between the mean score at baseline and follow-up was used. The analysis used methods that allowed for simultaneous estimation of treatment effects on continuous outcomes and the ‘mappings’ between treatment effects in a Bayesian framework. The mappings are ratios of the underlying treatment effects on their original scales. The mappings between standardised effects are reported as relative responsiveness ratios.

Key findings

We found evidence that the PHQ-9 was most responsive to change following treatment of the depression scales investigated. For example, a 1-SD unit treatment effect of BDI-II was equivalent to a 1.52-SD unit effect on the PHQ-9 (95% credibility interval 1.17 to 2.05) and a 1.31-SD unit effect on HAMD-17 (95% credibility interval 1.04 to 1.69). This is evidence that the PHQ-9 is more responsive to treatment changes than the BDI, by a factor of 1.52, and the HAMD-17 is more responsive than the BDI, by a factor of 1.31. The finding that the PHQ-9 was superior to the BDI agrees with a previous finding. 55 There was evidence that the generic EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and SF-36 measures were less sensitive to change than the BDI.

Limitations

Findings from this study are limited by its small size, the unrepresentative sample of trials that were selected and the ability to generalise to other clinical situations.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

This study provided evidence that the PHQ-9 was more responsive to change after treatment than other depression measures, supporting its use as an outcome measure in the PANDA RCT. The mapping coefficients were also used in the value-of-information study (aim 1c) as the mapping coefficients can be used to estimate quality-of-life differences when only depression measures have been used in the study.

Aim 1c: to assess the value of information from carrying out a randomised controlled trial of antidepressants in depression of mild severity

Research aims

Our aims were to develop an economic model that incorporates the severity of depression as part of decision-making processes. This would lead to a recommendation of the most cost-effective threshold above which to prescribe antidepressants and also an estimate of the value of a trial aiming to reduce uncertainty in this decision.

Methods

We extracted trial data from those identified in earlier systematic reviews by Kirsch et al. ,20 Fournier et al. 22 and Gibbons et al. 23 Cipriani et al. 56 provided evidence on discontinuation rate in the first 12 weeks of treatment. To address gaps in evidence for our economic model we obtained expert clinical opinion.

Analysis

The model is split into two components. The first was a continuous estimate of HAMD at the end of the initial 12 weeks as a function of the initial score. This was based on a metaregression of the extracted trials reporting treatment effect and baseline depression severity conducted using the Bayesian software WinBUGS version 1.4.3 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). 57 This metaregression estimated proportional treatment and placebo effects on depression severity on the HAMD scale.

This outcome of this model was then categorised into four depression severities: well is 0–7 HAMD, mild is 8–13 HAMD, moderate is 14–18 HAMD, and severe and very severe are > 19 HAMD. These four states formed a Markov model58 that extrapolated patient progress over a further 2 years in eight 12-week cycles. The HAMD for each state was mapped to the EQ-5D using the results of aim 1b, giving quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for each cycle. Total QALYs and costs were calculated and gave the incremental net benefit for each treatment strategy. The expected value of partial perfect information (EVPPI), which is the improvement to decision-making if uncertainty on a selection of input parameters to the model were removed, was used to determine an upper bound on the value of collecting further evidence. 59

Key findings

The metaregression estimated that patients on antidepressants had an additional 12% (95% credibility interval 3% to 21%) decrease in 6-week HAMD versus placebo. The economic model determined that treating patients with a severity score of ≥ 2 on HAMD had the highest probability (> 65%) of being cost-effective at a £20,000 willingness-to-pay threshold.

A short-term trial investigating the relation between treatment effect and severity and quality of life in depression patients had an EVPPI of £67.7M over a 10-year time horizon. This suggested that the proposed PANDA trial was potentially cost-effective.

Limitations

There was little evidence on treatment effects in low-severity patients, but our analysis had assumed that the relationship with severity held across the whole range of HAMD scores. We were reliant on clinical opinion for some important values affecting costs. Finally, the EVPPI provides an upper bound on the value of a trial as it assumes the removal of all uncertainty on a subset of parameters. Expected value of sample information estimates the value of reduced uncertainty on a subset and is related to a specified sample size and trial design; expected value of sample information would be necessary for a more accurate assessment of trial value. 60

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

We estimated that the PANDA RCT (phase 3 of the programme grant) had the potential to be cost-effective and the absolute expected value of perfect information estimates would vary from approximately £70M to £95M between the models. The metaregression results of previous trials informed our power calculations for the RCT.

Phase 2: the PANDA cohort study – using both quantitative and qualitative methods

Aim 2a: estimating a clinically important difference in commonly used self-administered questionnaires for depressive symptoms

Research aims

The aim of this study was to estimate the MCID for the PHQ-9, the BDI-II and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) using an anchoring method in which participants were asked to retrospectively report improvement or worsening on a GRC question. We also investigated whether or not the MCID varied according to the initial severity of symptoms.

Methods for data collection

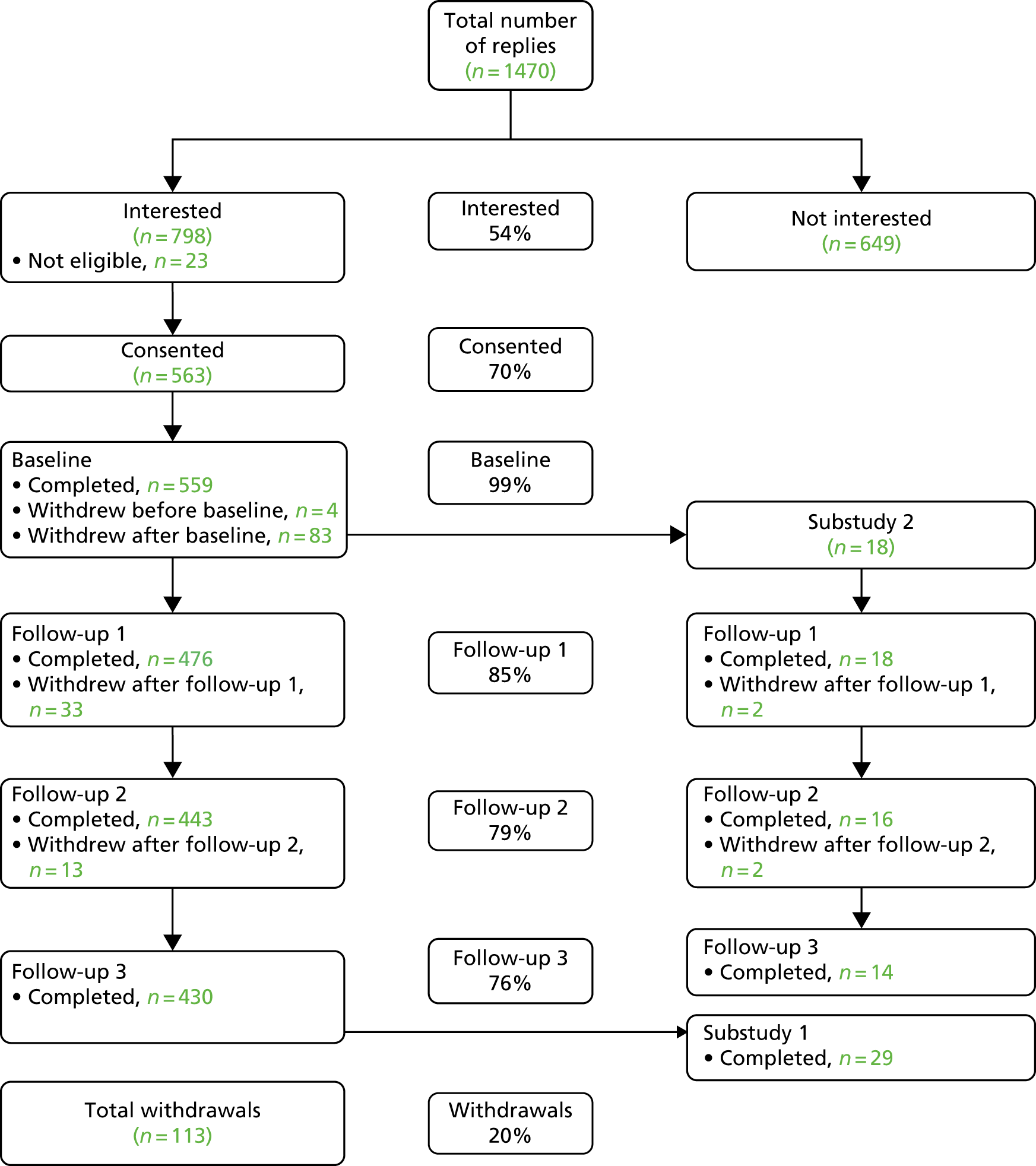

The PANDA cohort consisted of patients who had presented to UK primary care surgeries with depressive symptoms or disorder, or depressed mood, during the previous year. Participants had a range of depressive symptoms and were recruited from one population, reducing selection bias. Overall, 7721 patients were sent an information letter in the post and 1470 (19%) replied (Figure 2). Of these, 821 were willing to be contacted, 23 (3%) of whom were ineligible. The remaining 798 were contacted to arrange an interview and 563 consented to take part in the cohort study. Data on our measures were collected at four time points. At time 1, 559 people provided data (four could not be contacted), with corresponding figures at follow-up at 2, 4 and 6 weeks of 476 (85%), 443 (79%) and 430 (77%), respectively. For this analysis we used data from 400 participants who gave complete data on all follow-ups.

FIGURE 2.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram: PANDA cohort study.

The participants were asked to rate their own improvement using a GRC question. The GRC was assessed by asking patients ‘compared to when we last saw you 2 weeks ago, how have your moods and feelings changed?’ Response options were ‘I feel a lot better’ (1), ‘I feel slightly better’ (2), ‘I feel about the same’ (3), ‘I feel slightly worse’ (4) and ‘I feel a lot worse’ (5). These ratings were compared with the changes in the score on the self-administered questionnaires BDI-II, PHQ-9 and GAD-7. This enabled us to calculate the change in scores (on the questionnaires) that corresponded to an improvement in patients’ GRC. To assess the reliability of the GRC, the question was completed twice by the participants at each time point. The participants completed the Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R)61 at baseline only. The data were used to derive the diagnosis of depression and its severity.

Analysis

We analysed data from 400 participants with complete data on the CIS-R, PHQ-9, BDI-II, GAD-7 and GRC. We assessed reliability of the GRC scale by quantifying the two repeated assessments completed by the participant at each follow-up in absolute and relative terms. We used beta regression to estimate the changes in depressive symptoms measured by the BDI-II and the PHQ-9 over three follow-ups in each GRC category and according to three categories of the CIS-R score. This was an improvement on our previous analysis as it allowed us to model variability and means.

Key findings

We estimated the threshold below which the participant was more likely to report feeling better than feeling the same using a ROC analysis. The estimates were provided for three severity bands, determined by the baseline CIS-R score. The average initial scores for the three bands on the PHQ-9 were 4.1, 7.8 and 12.2. The range of scores therefore extended our study of MCID to lower ranges of severity than our earlier study (aim 1a, see Appendix 1). The MCID as a percentage appeared to increase for the lower severities. For example, in the lowest severity band, the MCID for the PHQ-9 was 48% (95% CI 37% to 65%), whereas in the most severe band it was 19% (95% CI 16% to 24%). There was still considerable uncertainty about the MCID at lower severities. For the GAD-7, the corresponding figures were 72% (95% CI 55% to 97%) and 9% (95% CI 7% to 11%).

Limitations

There was relatively low power in this cohort because there was little change in symptoms between the follow-up points. We had a low response rate in the cohort, but one would not expect any selection bias to affect the estimates. The participants who ‘felt the same’ on the GRC still had a drop in score and it is not clear why this occurred.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

The MCID is essential if we are to give guidance to patients and doctors about whether or not antidepressants should be prescribed. The aim of both MCID studies (aims 1a and 2a) was to develop, for the first time, a patient-centred measure of the change in depressive symptoms required to achieve a clinical benefit. These data will be able to help interpret the results of the PANDA RCT as well as being an output in their own right for other investigators.

Our approach towards estimating the MCID was based on an average within-person change related to improvement. However, the results from RCTs provide an estimate based on a comparison between groups. Applying our MCID estimate to a RCT result therefore rests on a counterfactual argument in which the outcome were that individual to receive a placebo is contrasted with the outcome were that individual to receive the active treatment. In other words, the patient is told ‘if you received the treatment you would (on average) be X points lower on the PHQ-9 and (on average) that is a difference that people regard as important’. Using this argument allows clinicians to make treatment recommendations for individual patients under counterfactual arguments resting on the trial’s generalisability. We describe the probability that a patient who ‘feels better’ has a reduction in depression score scale of greater than or equal to the MCID. It is natural to compare the expected benefit from an intervention tested in a RCT with that minimum difference. It gives us an idea of the improvement needed for the patient to perceive any benefit.

Aim 2b: to investigate the changes reported by patients as they recover from depression

We carried out three studies to investigate this aim. First, we carried out a qualitative investigation of the meaningfulness of the PHQ-9 in determining meaningful symptoms of low mood. We also examined the processing of emotional information and how this varied with depressive symptoms and over time. Emotion-processing is a key abnormality in depression and influenced by antidepressant medication. 14 The second study investigated the variation of emotional face recognition in relation to depressive symptoms. Finally, the third study examined variation in recall of socially rewarding information according to depressive symptoms.

Study 1: a qualitative investigation of the meaningfulness of the PHQ-9 in determining meaningful symptoms of low mood

Research aims

To explore differences between the way patients comprehend and map their answer to the options on the questionnaire. A secondary aim was to investigate whether or not patients shift over time in how they comprehend items on the questionnaire or find them problematic to answer, in relation to their own changing symptoms. The substudy also examined the content of responses and their meaning to the participants.

Methods of data collection

This was a longitudinal qualitative substudy nested within the PANDA cohort study, which included 18 participants who completed the baseline appointment at the Bristol site. A purposive sampling strategy was used to ensure that there was a range of participants of differing ethnicity and sex and sociodemographic differences were presented. The participants were interviewed using cognitive interviewing techniques at 2, 4 and 6 weeks after their baseline. At each interview the participants were invited to complete the GRC question and the PHQ-9 while thinking aloud what was going through their minds. Non-directive, open verbal probing as well as observation probes were used (e.g. ‘You’re hesitating; can you tell me why?’, which was followed by targeted probes, such as ‘What does that term mean to you?’). Forty-eight digitally recorded interviews were recorded and analysed.

Analysis

The analysis used was consistent to that used in cognitive interview framework analysis. 62 A Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) grid was created to analyse the digital audio files; the grid contained 18 column headings, each heading denoting ‘comprehension’ or ‘answer mapping’ for each item on the PHQ-9. Additional columns summarised the data from the card-sorting exercise and the GRC question. Participants were listed in rows, where each row represented a different time point.

Key findings

The study provided evidence that the PHQ-9 may be missing the presence and/or intensity of certain symptoms that are meaningful to patients. For instance, participants translated the options on frequency into their own meaningful measure of intensity; for example, ‘several days’ was used to represent a low level of intensity rather than the actual number of days a certain symptom was present. The triple- or double-barrelled questions were problematic for participants who felt that they could respond differently to each part of the question. For example, item 9 on the PHQ-9 asks if patients have been bothered with ‘thoughts that you would be better off dead, or hurting yourself in some way’. The participants regarded the GRC as a good way of summarising their situation overall, in contrast to the PHQ-9, which addressed only some of the important changes.

Limitations

The cognitive interviewing technique is still developing as a framework and the approaches to analysis of the data collected of cognitive interview data are being debated. 63 This was a small sample looking at a limited range of questions.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

This study helps us to understand some of the limitations of the PHQ-9 from the perspective of patients. It provides evidence that the GRC item has validity from the perspective of the patients and indicates the weaknesses of the PHQ-9 in assessing individual change.

Study 2: variation in emotional face recognition and depressive symptom severity

Research aims

The aim was to investigate whether or not processing of happy and sad facial expressions was associated with the severity of depressive symptoms, cross-sectionally and longitudinally.

Methods of data collection

In this study, we examined the data from the computerised facial recognition task that was completed by the PANDA cohort participants (n = 509) at baseline, then at 2 and 4 weeks. The participants were presented with ‘morphed’ faces with varying degrees of emotional intensity. The correct responses were classified as ‘hits’ and incorrect responses as ‘false alarms’. Accuracy and response bias were measures for facial expressions of varying emotional intensities.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using multilevel or mixed-effects linear regression models to calculate concurrent and longitudinal associations between hits, false alarms and depressive symptoms separately for happy and sad faces.

Key findings

For every additional face incorrectly classified as happy (positive emotion bias), concurrent PHQ-9 scores reduced by 0.05 of a point (95% CI –0.10 to 0.002; p = 0.06). This association was strongest for more ambiguous facial expressions. There was no evidence for associations between sad face recognition and concurrent depressive symptoms, or between happy or sad face recognition and subsequent depressive symptoms or antidepressant use. We concluded that as the severity of depressive symptoms increased there was a reduced tendency to see positive images but there was no influence on negative images.

Limitations

The sample excluded people with depression who had not visited their GP and we had a low response rate. However, the inclusion of participants did not depend on emotion recognition, so this is unlikely to have biased any associations between emotion recognition and depressive symptoms. There was little change in our cohort so we cannot exclude the possibility of longitudinal associations between facial expression recognition and depressive symptoms.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

The results indicated that, as depressive symptoms increased, people became less likely to report that an ambiguous facial expression was happy. This has important implications for understanding how people with depression might respond to social circumstances. We demonstrated that this effect occurred over the whole range of depressive symptom severity. Future research could identify whether or not emotion-processing performance could be used to predict response to antidepressants.

Study 3: variation in the recall of socially rewarding information and depressive symptom severity

Research aims

The aim was to investigate whether depressive symptoms are associated with recall for socially rewarding (positive) or socially critical (negative) information.

Methods of data collection

This study also used the data from the PANDA cohort and, as in the previous study of facial recognition, positive and negative recall were assessed at three time points: baseline and 2 and 4 weeks. On each occasion, participants were presented with 20 likeable and 20 unlikeable faces on a computer screen in a random order. Participants had to rate whether these were likeable or unlikeable and, after a short gap, were asked to recall any of the words that were presented.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using multilevel mixed-effects models to calculate concurrent and longitudinal associations between the number of positive and negative words recalled and depressive symptoms, before and after adjustment for confounders (n = 524).

Key findings

We found evidence for a concurrent association between increased recall of positive words and reduced severity of depressive symptoms: for every increase in two positive words recalled, depressive symptoms reduced by 0.6 (95% CI –1.0 to –0.2) BDI points. There was no evidence of an association between depressive symptoms and negative recall (–0.1, 95% CI –0.5 to 0.3). Longitudinally, we found more evidence that increased positive recall was associated with reduced depressive symptoms than vice versa.

Limitations

Although the analysis was conducted on the largest sample to date of emotional processing and depressive symptoms, the cohort study had a low response rate, which might have introduced a selection bias. Although different words were used at each time point, after the first assessment participants would have expected the incidental recall task. This could have led to increased recall, but we did not observe this.

Aim 2c: to investigate disagreement between self-reported improvement and changes in the scores on depressive symptom questionnaires

We used quantitative and qualitative methods to identify those aspects of recovery that are currently missed by questionnaires.

Study 1: why are there discrepancies between depressed patients’ Global Rating of Change and scores on the PHQ-9 depression module? A qualitative study in primary care

Research aims

The aim of this qualitative study was to investigate why there are discrepancies between depressed patients’ GRC in their mood and their scores on the PHQ-9. Patients were interviewed regarding the source and meaning of mismatches between their GRC and their PHQ-9 scores.

Methods of data collection

This study was nested within the larger PANDA cohort study in which participants completed the GRC and a PHQ-9 at four time points, each 2 weeks apart. We examined data from the first 86 participants in Liverpool who had completed all study assessments. ‘Mismatch’ was defined as a disagreement between a patient’s GRC and a meaningful change in their PHQ-9 scores between that time point and the preceding one. We classified a meaningful change as a 15% reduction or increase in scores, based on preliminary MCID estimates from the programme. Of the 86 participants selected, 44 (51%) were identified as cases of mismatch. The 32 participants with the most pronounced mismatch were invited to participate in the qualitative substudy. Qualitative interviews were audiotaped and transcribed with 29 participants. The interview centred on five key topics: experiences of depression, experiences and expectations of treatments, how effective they thought the questionnaires were (e.g. the PHQ-9), reasons for their mismatch and social factors.

Analysis

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was used to guide the analysis. This enabled us to focus on the individual accounts before moving to identify more general themes in the data. All transcripts were coded to identify initial themes, and then further analysed to formulate superordinate and subthemes.

Key findings

We identified four superordinate themes as explanations for disagreement:

-

There were limitations in the questions asked by the PHQ-9 and a lack of questioning about intensity such that the GRC provided a more accurate assessment of current mental state. The PHQ-9 does not ask about some depressive symptoms, such as interacting with people, lack of libido and inability to cope at work. It also does not enquire about comorbid symptoms such as anxiety, PTSD symptoms and physical illnesses.

-

The impact of recent positive or negative life events could affect their responses but was not captured by the PHQ-9.

-

Variation in mood was ‘normal’ so was not seen as a global change in mood. Participants had underscored responses in the hope that their symptoms would improve or did not want to admit how they were feeling. Participants sometimes omit items on suicidality to avoid possible intervention.

-

Some participants observed that they found it difficult to recall what they were doing or how they were feeling from one day to the next.

Limitations

This was a relatively small sample and it is not possible to infer how common the reasons for disagreement might be in a more representative sample. The MCID estimate was based on preliminary results.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

This study helps to further understand some of the limitations of the PHQ-9 in assessing change. It supports the view that the PHQ-9 should not be used alone to assess improvement in individuals. Such self-administered scales need to be supplemented with further clinical assessment. Further clinical assessment is needed if the PHQ-9 is to be used in clinical practice. This study supported the validity of the GRC, but some respondents found the retrospective recall required by the question was difficult.

Study 2: changes in self-administered measures of depression severity and patients’ own perceptions of changes in their mood – a prospective cohort study

Research aims

The aim was to examine the extent to which changes in scores from self-administered depression questionnaires (PHQ-9 and BDI-II) disagree with patients’ own self-rated improvement in mood, and investigate factors that influence this relationship.

Methods of data collection

We used data on the BDI-II and the PHQ-9 and the GRC completed by the PANDA cohort participants at baseline and at the 2-, 4- and 6-week follow-ups.

Analysis

The change scores for the BDI-II and the PHQ-9 at the 2-, 4- and 6-week follow-ups were calculated by subtraction from the previous time point. We used a MCID of 20% to create categories of meaningful improvement, no change and deterioration that could be compared with the GRC. We used logistic regression models to test whether or not anxiety symptoms, mental and physical health-related quality of life, negative life events, and social support influenced response to the GRC after adjustment for the change scores on the BDI-II or the PHQ-9.

Key findings

About half of the patients exhibited disagreement between their response on the GRC and the categories of meaningful change that we calculated. For the PHQ-9 we found that 51% (95% CI 46% to 55%) showed disagreement and for the BDI-II we found that 55% (95% CI 51% to 60%) showed disagreement. We also found that patients with more severe anxiety symptoms were less likely to report feeling better on the GRC, having taking account of the change in depressive symptoms. Patients with a better mental health-related quality of life were more likely to report feeling better in a similar analysis. Thus, anxiety and health-related quality of life contribute to the perception of improvement over and above any change in depressive symptoms.

Limitations

The PANDA cohort had a low response rate that might have introduced a selection bias. However, as our selection of patients did not depend on any of the exposure variables, it is unlikely to have biased the associations we have reported.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

The results of this quantitative study supported our finding from the qualitative PANDA studies that clinicians working in primary care and other clinical settings should be cautious in interpreting changes in questionnaire scores without further clinical assessment. The study indicated areas where depressive symptoms questionnaires are not assessing aspects of mental health important to patients. In a RCT, any variation between individuals should not affect the comparison as the randomisation should lead to comparable groups.

Phase 3: the PANDA randomised controlled trial

Research aims

The aim of the RCT was to investigate the severity and duration of depressive symptoms that are associated with a clinically important response to sertraline and cost-effectiveness (compared with placebo) in people with depression who present to primary care. The main hypothesis was that response to antidepressants would increase with both severity and duration of depressive symptoms. Our primary analysis was a comparison between sertraline and placebo at 6 weeks.

Methods for data collection

We used broad and pragmatic inclusion criteria, recruiting people who had sought treatment for depressive symptoms of any severity or duration in primary care. The key entry criterion was that GPs and/or patients were uncertain about the potential benefits of an antidepressant and we did not set any severity or duration thresholds as exclusions. Patients were recruited from primary care surgeries in four UK sites (i.e. Bristol, London, Liverpool and York) and identified by GPs, who either invited patients during a consultation or conducted a database search and then sent an invitation in the post. Participants were randomised to 100 mg of sertraline or an identical placebo and followed up at 2, 6 and 12 weeks.

Figure 3 is a flow diagram of the progress through the trial.

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram: PANDA RCT.

Analysis

The primary outcome was the PHQ-9 at the 6-week follow-up. Interactions terms of a realistic size, that are smaller than the main effect, require very large sample sizes for adequate power. As a result, we modelled the treatment effect on log-transformed PHQ-9 scores (continuous outcome) using an intention-to-treat analysis. The exponentiated regression coefficient is the proportional (or percentage) change in PHQ-9 scores between randomised groups. Evidence of a treatment effect using a proportional model implies that the treatment effect expressed as a mean difference would increase with severity. In sensitivity analyses we fitted an additive model using absolute depression scores (non-logged PHQ-9) and calculated an interaction between treatment allocation and baseline CIS-R depression severity score. However, we expected the power of this analysis to be low.

Secondary outcomes at 2, 6 and 12 weeks were depressive symptoms and remission assessed using the PHQ-9 and the BDI-II, generalised anxiety disorder symptoms, mental and physical health-related quality of life and self-reported global improvement. We used linear multilevel models for repeated measures of continuous secondary outcomes at 2, 6 and 12 weeks (PHQ-9, BDI-II, GAD-7 and Short Form questionnaire-12 items physical and mental health-related quality of life). Logistic multilevel models were calculated for repeated measures of binary secondary outcomes at 2, 6, and 12 weeks (remission on the PHQ-9, the BDI-II and feeling better on the GRC scale).

We undertook a cost-effectiveness analysis from the perspective of the NHS and Personal and Social Services alongside the PANDA RCT. Quality-of-life data were collected at baseline and 2, 6 and 12 weeks post randomisation using EQ-5D-5L, from which we calculated QALYs. Costs were collected using patient records and from resource use questionnaires administered at each follow-up interval. Differences in mean costs and mean QALYs and net monetary benefits were estimated. Our primary analysis used net monetary benefit regressions to identify any interaction between the cost-effectiveness of sertraline and subgroups defined by baseline symptom severity (0 to 11; 12 to 19; ≥ 20 on the CIS-R) and, separately, duration of symptoms (greater or less than 2 years’ duration). A secondary analysis estimated the cost-effectiveness of sertraline versus placebo. In sensitivity analyses, we (1) performed a complete-case analysis to check the robustness of our findings to missing data, (2) examined the impact of excluding costs that were not judged to be directly related to the treatment of depression and (3) excluded all secondary care costs from total NHS and Personal and Social Services costs to assess whether or not our findings were robust to infrequent but expensive hospitalisations.

Key findings

We found no evidence that the antidepressant sertraline reduced depressive symptoms at 6 weeks. In the sertraline group, PHQ-9 scores were 5% (95% CI –7% to 15%; p = 0.41) lower than those in the placebo group. In the sensitivity analyses using additive models, there was no evidence of an interaction with severity or duration of depressive symptoms with treatment effect, but these analyses would have lacked statistical power.

Of the secondary outcomes, there was strong evidence that sertraline reduced anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 score reduced by 17%, 95% CI 9% to 25%; p < 0.000046) and improved mental but not physical health-related quality of life as well as self-reported global improvement. There was weak evidence that depressive symptoms were reduced by sertraline at 12 weeks for both the PHQ-9 and the BDI-II. Given our findings, we also investigated whether or not the treatment effect for anxiety symptoms was influenced by baseline severity. We found no evidence that the effect of sertraline on anxiety symptoms varied according to the severity of anxiety or depressive symptoms. The number needed to treat in order to feel better according to our self-reported global improvement question was 8.5 (95% CI 5.2 to 22.1) people at 6 weeks and 6.4 (95% CI 4.6 to 10.3) people at 12 weeks.

There was no evidence of an association between the baseline severity of depressive symptoms and the cost-effectiveness of sertraline. Compared with patients with low symptom severity, the expected net benefits in patients with moderate symptoms were £64 (95% CI –£312 to £441) and the expected net benefits in patients with high symptom severity were –£51 (95% CI –£389 to £287). Patients who had a longer history of depressive symptoms at baseline had lower expected net benefits from sertraline than those with a shorter history; however, the difference was uncertain (–£132, 95% CI –£431 to £167). In the secondary analysis, patients treated with sertraline had higher expected net benefits (£118.37, 95% CI –£23.39 to £260.14) than those in the placebo group. Sertraline had a high probability (> 90%) of being cost-effective if the health system was willing to pay at least £20,000 per QALY gained.

Limitations

We had broad inclusion criteria and some participants had very few symptoms. This may have reduced the treatment effect, but our methods of analysis using a proportional approach should have helped to take account of this. There was attrition of nearly 20% by 12 weeks, although this did not differ by study arm, and when we investigated the impact of missing data, this did not appear to explain the findings. We had limited statistical power to explore interactions between treatment response and symptom severity or duration. It is possible that subgroups in which sertraline was more cost-effective might have become more evident with a larger sample size or longer follow-up.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

The RCT did not find evidence of an early antidepressant effect of sertraline on depressive symptoms in the population studied. There was, however, evidence that sertraline reduced anxiety symptoms and was more likely to lead to a clinically important benefit. The results of the trial and those from the MCID can be used to provide some initial guidance about the likely cost-effectiveness of sertraline and other SSRI antidepressants in primary care.

Conclusion

We chose the PHQ-9 as our primary outcome in the PANDA trial. The PHQ-9 is widely used in primary care and there is evidence that it is better at detecting changes in depressive symptoms after treatment than other measures. 37,55 It also avoids the observer bias that affects clinician-rated HAMD and MADRS scores. However, our qualitative research identified a number of reasons for disagreement between the PHQ-9 and the self-reported GRC, as well as indicating that up to 50% of patients might show disagreement between self-reported change and the results of questionnaires. Our findings indicate that the processes and motivations behind completing the PHQ-9 are complex and influenced by ongoing physical, social and emotional issues. Our findings suggest that PHQ-9 and, by implication, other self-administered questionnaires should not be used alone to assess improvement or deterioration. Their use should be supplemented with further clinical assessment and the use of more open-ended questions.

The MCID is the smallest change in symptoms that is considered clinically worthwhile by the patient. Our MCID research in phases 1 and 2 has enabled us to develop appropriate analytical methods for estimating the MCID and to provide values for the MCID in a primary care population for the first time. We can apply our MCID estimates to the results of the PANDA trial, but we acknowledge that our estimates of MCID are still uncertain.

When we initially formulated our research questions we assumed that the treatment effect varied according to depression severity but that the MCID was a fixed value, irrespective of depression severity. Our results, if anything, now point in the opposite direction, at least when we estimate treatment effects and MCID using a proportional approach. Our results suggest that sertraline has a similar (proportional) effect size over the whole range of depression (and anxiety) severity and it is the MCID that changes and gets larger, proportionally, at lower levels of severity. We have found that, at higher levels of severity, the proportional approach works better for the MCID. The proportional approach also has attractions when analysing clinical trial data. It avoids the assumption that the same absolute treatment effect is observed regardless of whether a person scores 5 or 25 on a scale. This seems unlikely and a proportional reduction approach appears more plausible as well as providing a better statistical fit to the data.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis in the PANDA trial, we found no evidence of a clinically important effect of sertraline on depressive symptoms. We found a 5% reduction in the sertraline group at 6 weeks, and this is considerably smaller than the MCID estimates for the PHQ-9 we have obtained. We cannot exclude the possibility that sertraline led to a clinically important improvement at 12 weeks, as we found a 13% (95% CI 3% to 21%) reduction in PHQ-9, but this is still well below our MCID. In contrast we found strong evidence that sertraline reduced anxiety symptoms on the GAD-7, with a reduction of 21% (95% CI 11% to 30%) at 6 weeks. This is consistent with some of our estimates of the MCID for GAD-7 (see Appendix 4) and suggests that this change is clinically important. We found insufficient evidence of an interaction between the cost-effectiveness of sertraline and severity or symptom duration that GPs could use to efficiently target prescribing. There was no evidence of a substantial treatment effect of sertraline on quality of life, as measured by the EQ-5D-5L. However, sertraline is an inexpensive intervention that has a high probability of being cost-effective compared with placebo across primary care patients with depression or low mood.

Our MCID estimates are based on an average within-person change related to improvement; however, a RCT compares groups. Application of our results has therefore required a counterfactual argument in which researchers compare the same individual(s) who receive placebo but who might have received the active treatment. The MCID estimated from a within-person calculation can then be applied to the between-group differences in a clinical trial.

Our estimates of MCID could be used to guide decisions about whether or not a treatment will benefit an individual. For this, one needs to be able to predict the likely score for that person on the proposed outcome measure were they not to receive that treatment. In other words, we need to know the likely value of an individual’s PHQ-9 or GAD-7 score at follow-up, 6 or 12 weeks later, if they were to receive a placebo. The expected value of the placebo at follow-up can then be used to determine the appropriate initial value for the MCID and thus decide if the proportional reduction expected from a treatment would be larger than the MCID for such a person. For this to be feasible, we would need more precise estimates of MCID and also the ability to predict future scores of patients on the basis of their clinical and other characteristics.

Finally, we can make some very approximate estimate of what proportion of participants in the PANDA cohort would probably have benefited from treatment. From our results in Appendix 4, it is clear that those with a GAD-7 score of 3 at 6 weeks have a MCID of about 50%. It is highly unlikely that those individuals would have experienced any benefit from sertraline. In the PANDA RCT, about 30% of participants scored ≤ 3 at 6 weeks. However, we cannot conclude this with any confidence at this stage. We do not know the distribution of symptoms in those receiving antidepressants in the UK and our estimates of MCID are approximate. Our overall results are reassuring in indicating that, on average, patients in the PANDA RCT are benefiting from sertraline. However, it is probable that a substantial proportion or patients receiving antidepressants are not experiencing any individual benefit. For clinicians to be confident about recommending treatment to patients, we need accurate information on individualised treatment effects and the outcome without treatment as well as MCID. Of course, any recommendations for treatment will also have to take account of any risks and adverse effects that result from the treatment as well as patient preference.

Recommendations for future research

Our finding that sertraline seems to be effective for anxiety but not depressive symptoms has a potential implication for understanding the mechanisms of antidepressant treatment as well as the clinical benefit that patient’s will experience.

Research recommendation 1

Future research into the mechanism of action of antidepressants should examine the biology of anxiety symptoms.

The result of the RCT also questions the reliance of current clinical guidelines on existing placebo-controlled studies that have been conducted largely for regulatory purposes. Cipriani et al. ’s review28 highlights the poor quality of the existing research. Antidepressants are commonly used medications and it is concerning that we still have a number of outstanding questions about their efficacy and clinical indication many years after they were introduced. The use of behavioural tasks such as face recognition and memory for words might be a useful way to investigate these mechanistic aspects.

Research recommendation 2

Future studies should investigate the clinical effectiveness of antidepressants for anxiety disorders in UK primary care population.

We would recommend that future investigation of antidepressant efficacy should have longer follow-ups to see if there are longer-term benefits for depressive symptoms as well as anxiety symptoms. We would encourage use of more detailed outcome measures, using self-reported information, to ensure that the whole range of symptoms that are common in depression and anxiety are studied. The use of self-reported improvement (GRC) seems a valuable outcome measure in clinical trials.

Research recommendation 3

Further investigation of minimal clinically important differences.

Further research is needed to investigate the size of the MCID and the factors that might influence whether or not patients report improvement. We need more precise estimates to guide decision-making. We have provided evidence that patients’ reporting of feeling better can be affected by various other factors, such as anxiety and physical changes. Further investigation of this will also help inform how MCIDs could be used clinically to provide treatment recommendations.

Implications for practice and any lessons learned

The PHQ-9 and similar self-administered questionnaires should not be used alone in assessing improvement or deterioration. It is important to supplement such standardised measures with a clinical assessment.

Sertraline is effective and cost-effective in reducing anxiety symptoms such as worry and restlessness in the first 6 weeks of treatment in people who present with depressive symptoms. Any effect on depressive symptoms takes longer to emerge; although an improvement in anxious symptoms in someone presenting with depressive symptoms could lead to a clinical benefit. Patients who present to primary care with depressive symptoms have a wide range of severity of symptoms. Overall, this population is likely to benefit from SSRI antidepressants. Our findings support the prescription of SSRI antidepressants in a wider group of participants than previously thought, including those who do not meet diagnostic criteria for depression or generalised anxiety disorder, especially when anxiety symptoms such as worry and restlessness are present.

Patient and public involvement

Paul Lanham, a service user and a co-applicant, was also a member of the independent steering committee during phase 3 of the programme and was involved in PANDA for over 6 years. Paul Lanham and Derek Riozzie have also contributed to PANDA annual meetings where all co-applicants and researchers discuss progress, review the protocols and discuss any findings. They made important contributions to the discussion and influenced the interpretation of the results and decisions about study design. All study documentations have been revised and commented on by Paul, Derek and the user group co-ordinated by Derek at Liverpool University. In addition, we enlisted the support of the North London Service Users Research Forum (SURF). The SURF was co-founded in 2007 by service users and clinical academic psychiatrists at University College London to provide meaningful consultation on research. It has 12 members with mental health problems. Since 2007, it has consulted on > 50 projects and SURF members have been invited to join steering/management groups on many of these. As a result, the group is very experienced and confident about the advice and input they provide; their comments on the trial paperwork have been invaluable. The letter templates, patient information sheets and the questionnaire were amended to reflect the patient and public involvement (PPI) feedback. We also consulted on the protocol concerning self-harm or risk of self-harm, which we used if patients reported this in the course of the cohort and RCT. Having close involvement of the PPI for the duration of the programme (i.e. over 6 years) has been invaluable for its success. It has also enabled us to build on it and we have recruited a PANDA RCT participant to represent PPI on a different depression trial: ANTidepressants to prevent reLapse in dEpRession (ANTLER). 64 We plan to carry on using the services users’ comments in the design, documentation and analysis of any future studies.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients who took part in the PANDA studies. We would like to thank the GPs and GP surgery staff who supported recruitment for this research. We have been supported by the following Clinical Research Networks (CRNs): North Thames CRN, CRN North West London, CRN South London, North West Coast CRN, Greater Manchester CRN, West Midlands CRN, West of England CRN, Yorkshire and Humber CRN and North East and Cumbria CRN.

We would like to acknowledge the particular input of the CRN research nurses and CSOs: Dawn Adams, Heather Tinker, Lynsey Wilson, Tara Harvey, Khatiba Raja, Zara Prem, Beena Bauluck, Yvonne Foreshaw, Cynthia Sajani, Jahnese Maya, Anna Townsend-Rose, Emily Clare, Rachel Nixon, Pam Clark and Irene Sambath.

We would also like to acknowledge Vivien Jones for providing administrative support at the Bristol site; Rebecca Rawlinson at the Liverpool site; Bryony Thomson and Yvonne Donkor at University College London; and Wendy Cattle at York. Jodi Prem was instrumental in recruitment at York.

We also thank Carolyn Chew-Graham, Ian Anderson, Anne Rogers, Evan Kontopantelis, Paul Lanham, Christopher Williams, Richard Bying and Obi Ukoumunne for generously agreeing to sit on the Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee.

Ethics approval and sponsorships

For the PANDA cohort study, ethics approval was obtained from National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee South West-Central Bristol. The University of Bristol acted as sponsor for the study.

The PANDA RCT was approved by NRES Committee East of England – Cambridge South (reference number 13/EE/0418). The Joint Research Office, University College London acted as sponsor for the RCT.

Contributions of authors

Larisa Duffy was the programme manager and with Gemma Lewis was responsible for drafting the report.

Larisa Duffy, Gemma Lewis, Anthony Ades, Ricardo Araya, Jessica Bone, Sally Brabyn, Katherine Button, Rachel Churchill, Tim Croudace, Catherine Derrick, Padraig Dixon, Christopher Dowrick, Christopher Fawsitt, Louise Fusco, Simon Gilbody, Catherine Harmer, Catherine Hobbs, William Hollingworth, Vivien Jones, Tony Kendrick, David Kessler, Naila Khan, Daphne Kounali, Paul Lanham, Alice Malpass, Marcus Munafo, Jodi Pervin, Tim Peters, Derek Riozzie, Jude Robinson, George Salaminios, Debbie Sharp, Howard Thom, Laura Thomas, Nicky Welton, Nicola Wiles, Rebecca Woodhouse and Glyn Lewis contributed to the constituent papers in the appendices. The papers included as appendices each have its own lists of authors.

Anthony Ades, Ricardo Araya, Rachel Churchill, Tim Croudace, Christopher Dowrick, Simon Gilbody, William Hollingworth, Tony Kendrick, David Kessler, Paul Lanham, Alice Malpass, Tim Peters, Jude Robinson, Debbie Sharp, Nicky Welton, Nicola Wiles and Glyn Lewis were responsible for the original proposal and for securing funding.

Glyn Lewis was chief investigator of the programme and had clinical responsibly for the RCT recruitment at the London site.

All authors have provided substantial contributions to the conception and design of the PANDA programme and interpretation of data and had input into drafting the report and/or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to available anonymised data may be granted following review.

Patient data

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. There is huge potential to make better use of information from people’s patient records, to understand more about disease, develop new treatments, monitor safety, and plan NHS services. Patient data should be kept safe and secure, to protect everyone’s privacy, and it’s important that there are safeguards to make sure that it is stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data are used. #datasaveslives You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation.

Disclaimers