Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0608-10035. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stephen Morris is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Board. Irwin Nazareth is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board. Sonia Saxena was funded by a NIHR Career Development fellowship (NIHR CDF-2011-04-048). Min Hae Park received grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study and received personal fees from Research Consultancy for Marie Stopes International (London, UK). Anthony S Kessel is the director of International Public Health at Public Health England.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Viner et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report details the methods and findings of the PROMISE programme grant, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and undertaken by the investigator team between March 2010 and September 2015.

Rationale

Obesity in children and young people (CYP) has been an enduring public health and clinical priority throughout the early 21st century. Growing concerns about a ‘childhood obesity epidemic’ in the first decade of this century prompted the undertaking of this research programme. 1–3 It remains a high priority in 2019/20; the Chief Medical Officer focused much of her 2012–13 annual report Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays4 on prevention of childhood obesity. The UK government published Childhood Obesity: A Plan for Action in 2016. 5 Chapter 2 was published in 2018, with the aim of halving childhood obesity by 2030.

Since the start of this programme in 2010, there has been some evidence that child and adolescent obesity rates may be stabilising;6 however, the proportion of obese young people in the latest Health Survey for England7 remains worryingly high: 17% and 22% for 13- to 15-year-old boys and girls, respectively. The National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) shows similar obesity rates, with 21% of girls and 17% of boys in Year 6 being classified as obese in 2013. 8

The rationale for concern about childhood obesity is supported by some key publications from this programme team. Childhood obesity is associated with increased adult morbidity and mortality. 9 Overweight and obesity also track strongly into adult life: ≈ 85% of females and ≈ 92% of males who were overweight or obese in childhood were also overweight or obese at two or more time points between 26 and 42 years of age. 10

It is neither appropriate nor necessary to give greater background information on the epidemiology, complications or manifestations, or the prevention or treatment, of child and adolescent obesity here. Further background information relevant to each substudy is given in the introduction to each chapter. The rationale for the programme and how this report will be structured are outlined here.

Development of the PROMISE programme

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published its first guidance on management of childhood obesity in 2006, as part of wider guidance on the prevention and management of obesity issued in December 2006. 11 This guidance has been updated in several ways, with new guidance on identification and management of obesity in children and adults issued in November 2014,12 and new prevention guidance issued in March 2015. 13

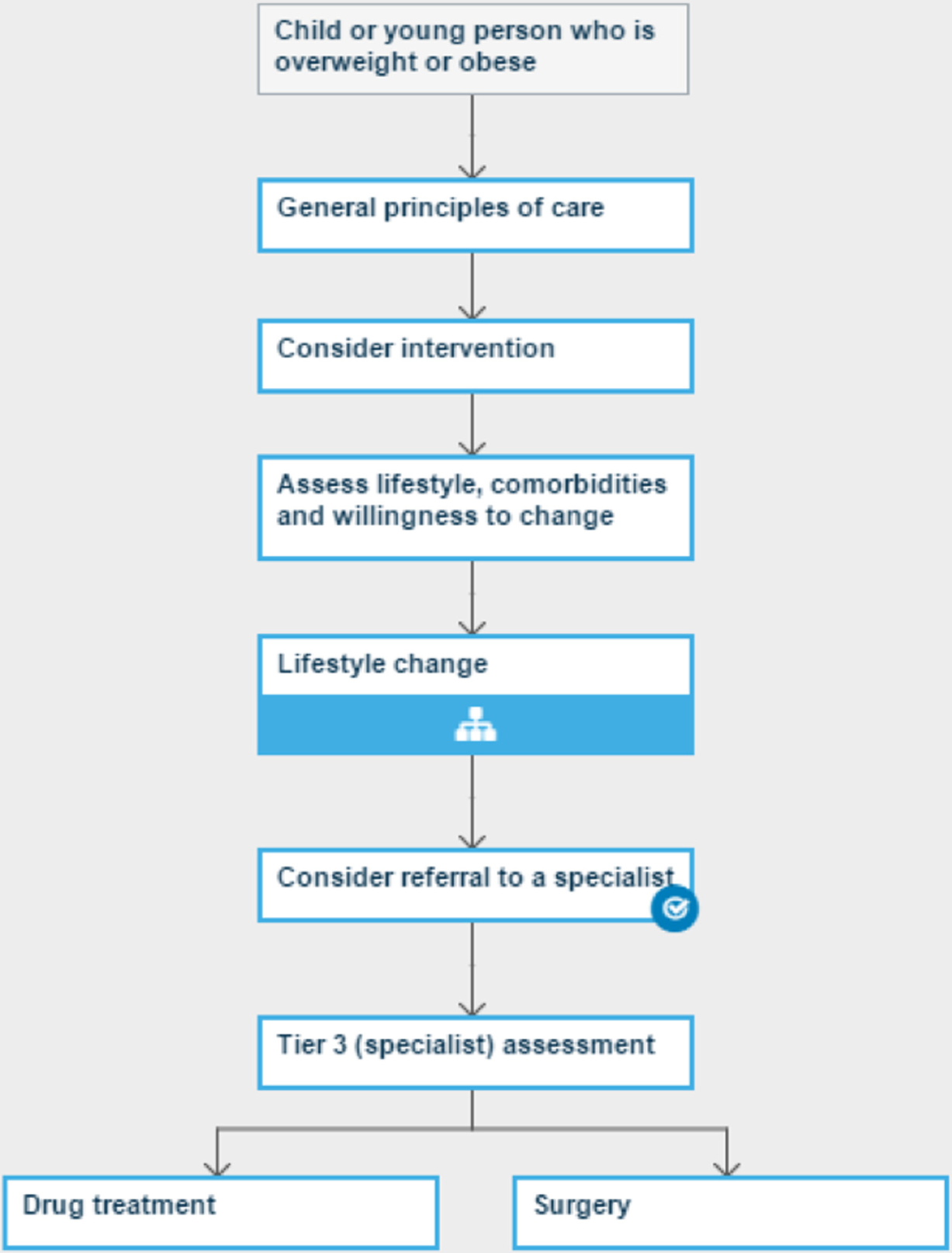

The childhood obesity pathway, first outlined by NICE in 2006,11 has become the basis of childhood obesity prevention and management plans in most parts of England and Wales since that time, as developed by (initially) primary care trusts (PCTs) and their successor organisations, Clinical Commissioning Groups.

The 2006 NICE pathway11 commenced with assessment and guidance by front-line staff in primary care. The 2009/10 NHS Operating Framework14 directed that, from summer 2009, the NCMP feedback and parental responses to feedback (in terms of behaviour change and seeking help) would form the first step in identification, assessment and management for many obese children. However, the impact of NCMP feedback on parental behaviour and help-seeking, and the resultant burden on primary and secondary care, is unknown.

Optimal therapy was outlined by NICE as multicomponent lifestyle modification programmes, and anti-obesity drug (AOD) therapy and bariatric surgery were identified as appropriate for older adolescents with severe obesity and comorbidities.

Contemporary epidemiological data at the time suggested that 10–15% of children and adolescents were obese by the definition used by NICE [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 98th centile] and were therefore eligible for lifestyle modification treatment. It was estimated that of these, approximately one-third (i.e. 3–5%) would fail lifestyle modification and meet the NICE criteria for AOD therapy, with a further 0.5–1.0% of adolescents meeting the NICE criteria for bariatric surgery. It was noted that paediatric services in the UK were, at the time, poorly developed and unprepared to provide services to this number of children.

The development of the research questions in Paediatric Research in Obesity Multi-modal Intervention and Service Evaluation (PROMISE) was explicitly stimulated by gaps in the evidence for the NICE childhood obesity pathway. Areas were identified for which additional evidence was needed or for which the application of existing knowledge could support public health or NHS staff to provide the best care to overweight children. A programme of five linked substudies was created, which integrated public health and clinical perspectives, focusing on apparent gaps in evidence. These were as follows:

-

Study A investigated the impact of the NCMP on families and on health service use in obese children. The NCMP was very new at that time (the first wave of data collection occurred in 2006/7) and few data were available on its effect on families and behavioural change.

-

Study B developed a brief evidence-based electronic tool to improve management of obesity by front-line staff [e.g. general practitioners (GPs)]. At the time of programme development, GPs were not very involved in childhood obesity management and there were major concerns that identification of overweight and obese children through the new NCMP would impose a large new burden for primary care.

-

Study C tested a novel community-delivered lifestyle modification programme for obese adolescents. At the time of programme development, there were very few weight management programmes specifically aimed at adolescents, who have different developmental needs to children and to adults.

-

Study D investigated AOD use, safety and potential clinical effectiveness in children and adolescents in the NHS. The 2006 NICE guidance11 endorsed the use of AODs in those aged ≥ 12 years with significant obesity comorbidities. Data on safety and effectiveness in adolescents are very limited. There are no published data on acceptability and clincal effectiveness in NHS practice.

-

Study E investigated the safety and outcomes of bariatric surgery in adolescents in the NHS. The 2006 NICE guidelines11 endorsed bariatric surgery in adolescents within specialist centres, yet there were no available outcome data on adolescent bariatric surgery within the NHS.

A final implementation work package within the programme ensured the dissemination of findings to key audiences to maximise potential patient benefit within 3–5 years of the end of the programme.

Application for funding for PROMISE was made to NIHR in late 2008, with outline agreement for funding obtained in July 2009. The programme began in January 2010. The initial end of the programme of 30 March 2015 was extended to 15 December 2015.

Structure of this report

This report first describes each of the five studies and substudies in detail (see Chapters 2–6), including a brief background, methods, results and discussion section for each substudy. Chapter 7 describes the impact and dissemination, as well as the patient and public involvement (PPI) work undertaken for the whole programme. The implications of the programme for public health and policy, clinical practice and research, as well as the limitations and overall conclusions, are discussed in Chapter 8. Chapter 9 outlines future research recommendations.

Chapter 2 Study A: scoping the impact of the National Child Measurement Programme on the Childhood Obesity Pathway

Parts of this chapter were reproduced from (1) Falconer et al. 15 © Falconer et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd, 2014. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited; and (2) Syrad et al. 16 © 2014 The Authors. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of British Dietetic Association. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/), which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is noncommercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.

Abstract

The provision of feedback letters to parents about their child’s weight status following measurement for the NCMP has been recommended by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) since 2008, with the aim of engaging the families of overweight children and supporting them to make healthy behaviour changes. This study aimed to assess the impact of NCMP feedback on parental recognition of childhood overweight, perceptions of the health risks associated with their child’s overweight status, and lifestyle behaviours and health service use. A longitudinal study was conducted of 1844 parents of children aged 4–5 and 10–11 years who received weight feedback as part of the 2010–11 NCMP in five PCTs in England. Self-completed questionnaires were administered before and after feedback. Positive effects of feedback on parental recognition of childhood overweight and its associated health risks were observed, but there were minimal effects on lifestyle behaviours (e.g. diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviour). More than one-third of parents of overweight or obese children sought further information regarding their child’s weight. There were no observable effects of feedback on child self-esteem or teasing. In qualitative interviews with a subsample of parents with overweight or obese children, perceptions of child health in terms of emotional well-being and physical health, irrespective of weight, were identified as a major barrier to behaviour change. There was evidence to suggest that ‘proactive’ feedback in the form of telephone calls or face-to-face meetings could have greater impact on changing parental perceptions than the letter alone, but there was no effect on behaviours, and parents preferred written feedback.

Key findings

At baseline (i.e. before NCMP feedback):

-

Three-quarters of parents of overweight and obese children do not recognise their child to be overweight. Before they received NCMP feedback, only 14% of parents with overweight children and 35% of parents with obese children perceived their child to be overweight. Parents were likely to classify their children as overweight only if their BMI was ≥ 99.7th centile (much higher than the standard 95th centile used by the NCMP).

-

Many parents do not consider their child’s overweight status to be a health risk: 41% of parents who acknowledged their child to be overweight did not perceive this to be a health risk. Interviews with parents suggested that parental definitions of health frequently did not include weight; some parents did not consider the NCMP result to be credible because it did not take into account their child’s background or lifestyle.

-

Cultural factors, as well as deprivation, may explain high levels of obesity among black and South Asian children in England. After accounting for deprivation and other sociodemographic characteristics, black and South Asian children were three times more likely to have an obesogenic lifestyle than white children. Qualitative work indicated that being overweight was not viewed negatively by some non-white parents.

After NCMP feedback:

-

The majority (87%) of parents found NCMP feedback to be helpful. More than one-fifth of parents of overweight children reported feeling upset, but only 1.8% of parents stated that they would withdraw their child from the NCMP in the future.

-

One-quarter of parents of overweight children and half of parents of obese children sought further information regarding their child’s weight: the most frequently reported sources of information were friends and family (reported by 14.4% of parents), the internet (9.9%), the GP (8.9%) and the school nurse (8.4%).

-

NCMP feedback has positive effects on parental knowledge, perceptions and intentions. After receiving NCMP feedback, parents’ general knowledge about the health risks associated with child overweight improved, particularly among non-white parents. The proportion of parents who recognised their child to be overweight nearly doubled after feedback, but remained low, at 38%. Nearly three-quarters of parents reported an intention to change lifestyle behaviours following NCMP feedback.

-

However, NCMP feedback has little impact on actual lifestyle behaviours. After feedback, there were no changes in reported dietary behaviours or screen time. There was a slight increase in the proportion of obese children meeting recommended levels for physical activity.

-

‘Proactive’ feedback may be more effective than letters alone. In areas where ‘proactive’ NCMP feedback (telephone call or face-to-face meeting) was given to parents of obese children in addition to the letter, there was a greater improvement in parental recognition of child overweight and health risks. However, telephonic feedback required additional resources (£9.50 vs. £1.24 per child) and most parents reported a preference for feedback by letter.

Background

The ‘Healthy Lives, Healthy People’17 cross-government strategy on obesity places strong emphasis on reducing the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity in the UK, and highlights the instrumental role of primary and secondary prevention efforts in achieving this goal. In line with the strategy, the NCMP was established in 2006 by the DHSC to measure the height and weight of children in Reception (aged 4–5 years) and Year 6 (aged 10–11 years) at state-maintained schools in England. The aims of the NCMP are to gather data for population-level surveillance of childhood obesity levels and trends, and to inform local planning of services for children and families. Until March 2013, responsibility for delivery of the NCMP lay with PCTs, with guidance on implementation provided by the DHSC. From 1 April 2013, local authorities (LAs) became responsible for the collection of NCMP data, with guidance from Public Health England (PHE).

Since 2008, the DHSC and PHE have recommended the provision of NCMP results (weight feedback) to parents, with the aim of engaging families of overweight and obese children and supporting them to make healthy behaviour changes. Template letters for weight feedback have been developed by the DHSC and PHE, which contain the child’s weight, height and BMI centile category (i.e. underweight, healthy weight, overweight, very overweight). Some LAs (and previously PCTs) produce their own letters, and others additionally offer ‘proactive feedback’ in the form of telephone calls or face-to-face consultations for families of children with a BMI outside the healthy weight range.

More than half of parents of overweight and obese children underestimate their child’s weight status,18,19 and many parents who consider their child to be overweight are unconcerned about the health implications of excess weight. 20,21 Given that risk perception is associated with readiness to change health behaviours, widespread parental underestimation of childhood weight and health risk could compromise the success of childhood obesity interventions. 22,23 The provision of accurate information to parents in the form of weight feedback through the NCMP has been proposed as a way to increase parental recognition of childhood overweight and obesity, and to encourage families to make positive lifestyle changes. 24 However, to date there has been limited evidence that routine weight feedback of this nature leads to changes in parental perceptions or lifestyle behaviours. An early evaluation of NCMP feedback showed that one-third of parents planned to make lifestyle changes as a result of the written feedback,25 but this cross-sectional study did not assess effects on actual behaviour change and did not evaluate proactive forms of feedback. Small-scale studies have indicated that written feedback can improve parental awareness of their child’s overweight status,26 but benefits in terms of direct health outcomes have not been robustly demonstrated. A systematic review27 of the evidence concluded that there was a lack of data on the effectiveness of BMI screening for childhood overweight and obesity. In addition, the potential for harmful effects has not been fully explored; for example, there is a risk that weight feedback could lead to excessive weight concern or distress among families and precipitate unhealthy behaviours such as dietary restriction. Despite the lack of longitudinal evidence on the effects of population-based weight screening and feedback on parental perceptions and behaviours, over 1 million children are measured as part of the NCMP each year and their parents are provided with weight feedback. This study aimed to address this evidence gap and provide data that could inform future development of NCMP feedback and its delivery.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to scope the impact of the NCMP on families and on health service use in overweight and obese children, with four specific objectives:

-

to estimate the effects of NCMP feedback on parental recognition of childhood overweight, parental perceptions of the health risks associated with their child’s weight status, and weight-related lifestyle behaviours and health service use

-

to compare the effects of different forms of weight feedback (letter vs. proactive feedback)

-

to identify barriers to behaviour change and health service use, particularly among deprived and ethnic minority groups

-

to produce preliminary data on NHS costs associated with NCMP feedback.

Methods

A longitudinal study was conducted of parents of children taking part in the NCMP in five PCTs in England [Redbridge, Islington, West Essex, Bath and North East Somerset (BANES) and Sandwell], using a series of self-administered questionnaire surveys to follow up parents over 1 year (objectives 1 and 2). Qualitative interviews were also conducted with a subset of parents to explore barriers to health behaviour change (objective 3). Preliminary data on the costs of different types of NCMP feedback were generated as part of an economic evaluation (objective 4).

National Childhood Measurement Programme measurement and feedback

During the study, PCTs carried out their usual NCMP measurement and feedback procedures: PCTs sent letters to parents outlining the aims of the NCMP and measurement process, and provided an opportunity for parents to withdraw their child from the measurement. Eligible children had their height and weight measured at school by trained staff. Within 6 weeks of the measurement, written feedback was mailed to parents with information about their child’s BMI category, defined using centiles of the UK 1990 growth curves28 and cut-off points at the 2nd, 91st and 98th BMI centiles to define underweight, healthy weight, overweight and obese (described to parents as ‘very overweight’), respectively. Parents of underweight, overweight and obese children were provided with information about the health risks associated with their child’s weight status (see Appendix 1). Feedback also included information about healthy lifestyles from the DHSC’s Change4Life campaign,29 and information about local health and leisure services. A telephone number for the NCMP team was provided for parents who required further information and support. Redbridge, BANES and Sandwell PCTs supplemented the written feedback with proactive feedback in the form of telephone calls to parents of children identified as obese, during which parents were informed by a member of the measurement team (usually a school nurse) about their child’s result, and were able to get advice and support as required. Parents in Redbridge PCT were also offered a face-to-face appointment with a school nurse in a local clinic, during which families were provided with advice to support lifestyle change.

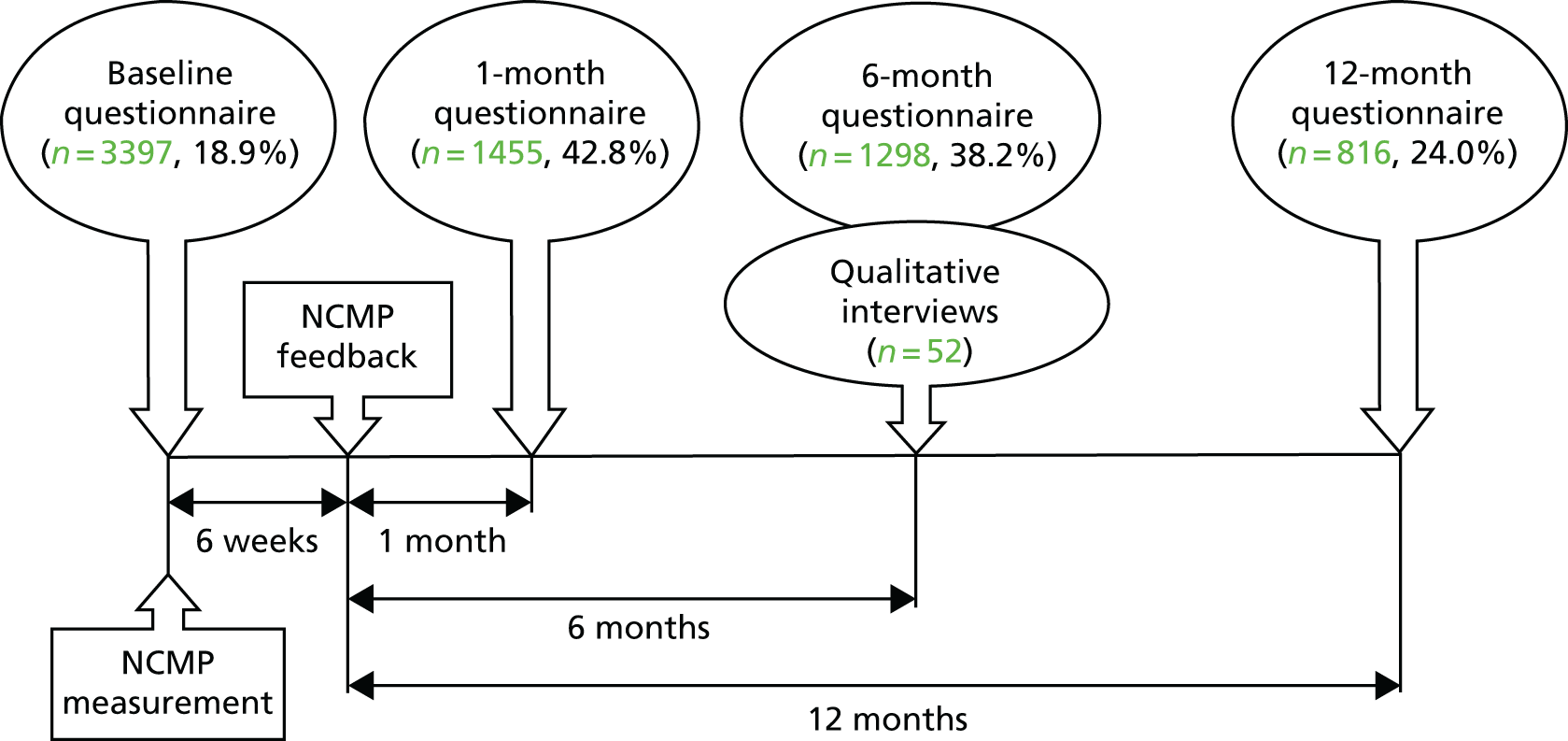

Survey questionnaires

Parents of all children participating in the NCMP in the five selected PCTs in 2010–11 (n = 18,000) were invited to participate in the study. Questionnaires were administered at baseline (approximately 6 weeks before parents received weight feedback), and at 1, 6 and 12 months after weight feedback (Figure 1). Baseline questionnaires were distributed through schools on the day of the NCMP measurements, between February and July 2011, and responses were returned to the study team in prepaid envelopes. The questionnaire assessed parental knowledge and perceptions of their child’s weight and health, and lifestyle behaviours (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The questionnaire was made available online also, and reminder postcards and e-mails were sent to parents via schools. To encourage participation, all respondents were entered into a free prize draw to win a Nintendo Wii (Nintendo Co. Ltd, Kyoto, Japan).

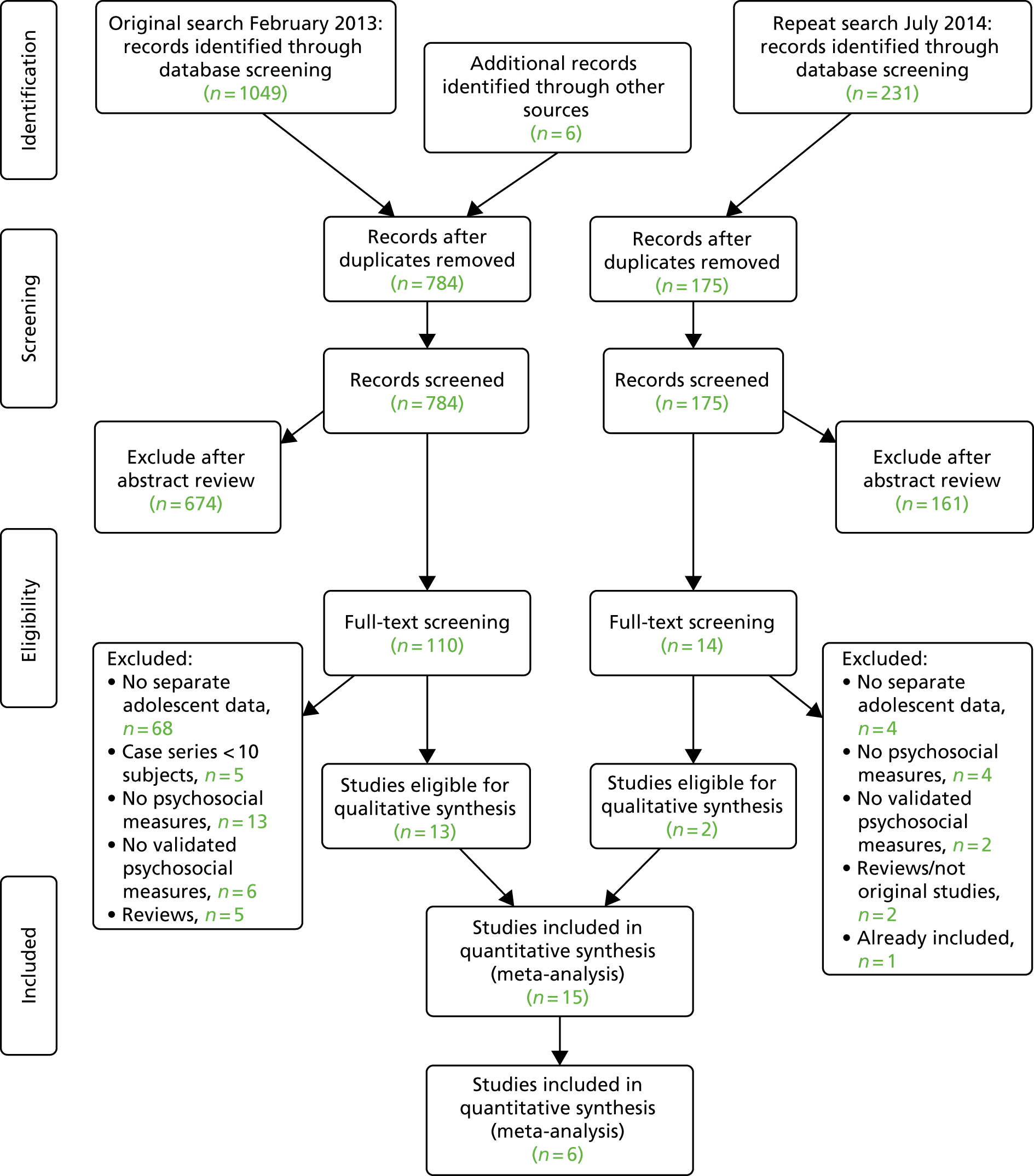

FIGURE 1.

Timeline for data collection in NCMP evaluation study, showing sample sizes and response rates. Figures in brackets show response rates as percentage of target population. Modified from Falconer et al. 15 © Falconer et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd, 2014. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

Follow-up questionnaires at 1, 3 and 12 months were mailed directly to parents who had completed a baseline questionnaire. In addition to the questions in the baseline questionnaire, follow-up questionnaires included questions to assess parents’ feelings and behaviours in response to NCMP feedback (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Up to two reminder contacts in the form of e-mails, text messages and telephone calls were made to non-responders. Questionnaire responses were linked to children’s NCMP data, including anthropometric measures, ethnicity and deprivation data [Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score, a measure of local area deprivation based on a respondent’s postcode30] using a Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) macro to match children based on their name and date of birth. Children who could not be matched automatically were identified using manual searches. The matching was carried out within the PCT and an anonymised linked data set was provided to the study team. All survey data were checked and entered electronically into a Stata®, release 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) database.

Main outcome measures

The following outcomes were assessed at baseline and at 1, 6 and 12 months’ follow-up:

-

Parents’ general knowledge of childhood obesity as a health problem, assessed using the question ‘Do you think that being overweight increases a child’s future risk of any of the following: diabetes mellitus (DM), cancers, heart disease, high blood pressure, and arthritis?’. Parents who correctly identified four or more conditions were considered to have good knowledge.

-

The child’s diet, based on parent-reported frequency of consumption of fruits, vegetables, sugary drinks, sweet and savoury snacks (categories ranged from less than once a week to at least three times a day). 31 Each food category was assigned a score from 1 to 7, with a higher score indicating more frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables, and lower consumption of sugary drinks and snacks. A healthy eating score was derived as a mean of these subscores, with a score of ≥ 5 indicating a healthy diet.

-

The child’s daily physical activity, assessed with the question ‘On average, how many minutes of physical activity (described as any activity that increases heart rate and makes the child get out of breath) does your child do?’. Children who met the national physical activity recommendation of at least 1 hour per day were categorised as engaging in adequate physical activity.

-

The child’s daily screen time (the number of hours spent watching television or playing video games). Responses were categorised by whether or not children met screen time recommendations of < 2 hours per day. 32

The following outcomes were assessed in the parents of overweight and obese children only:

-

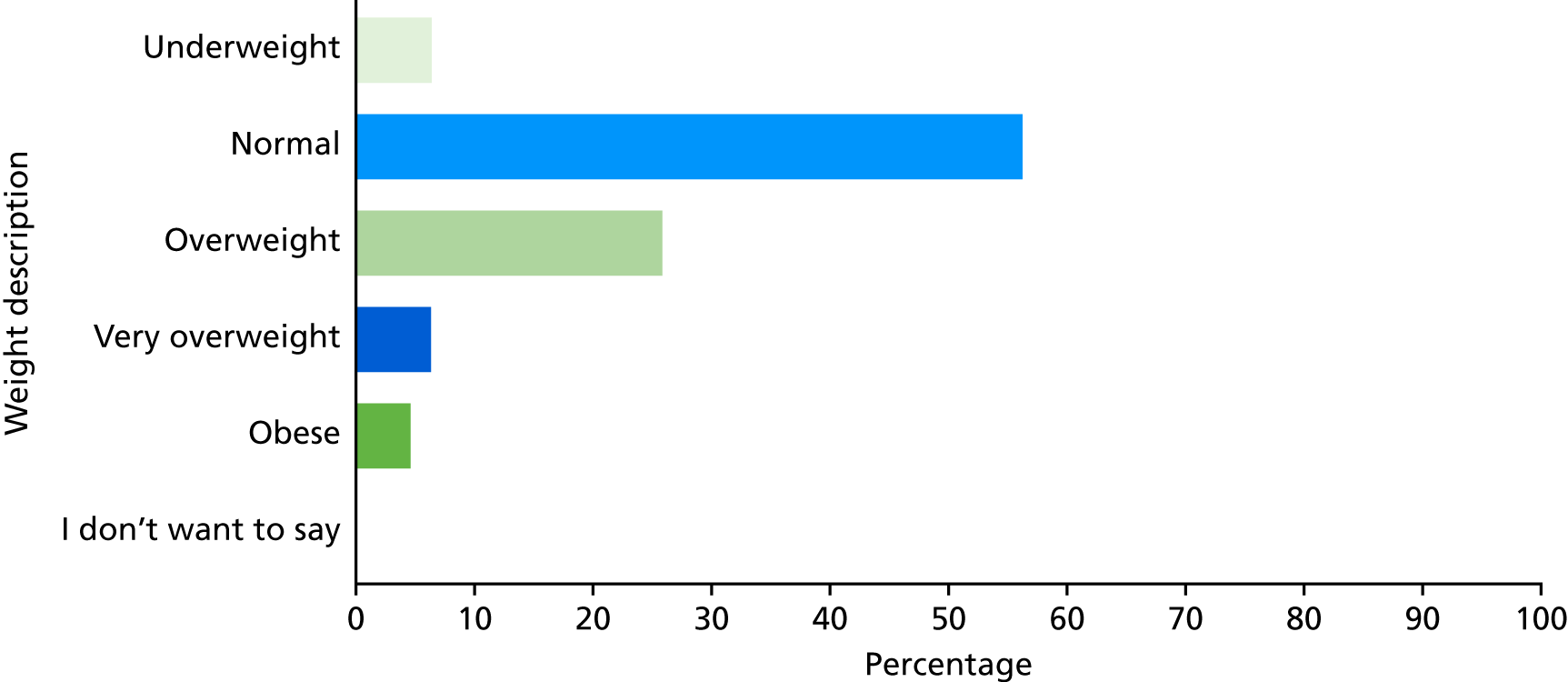

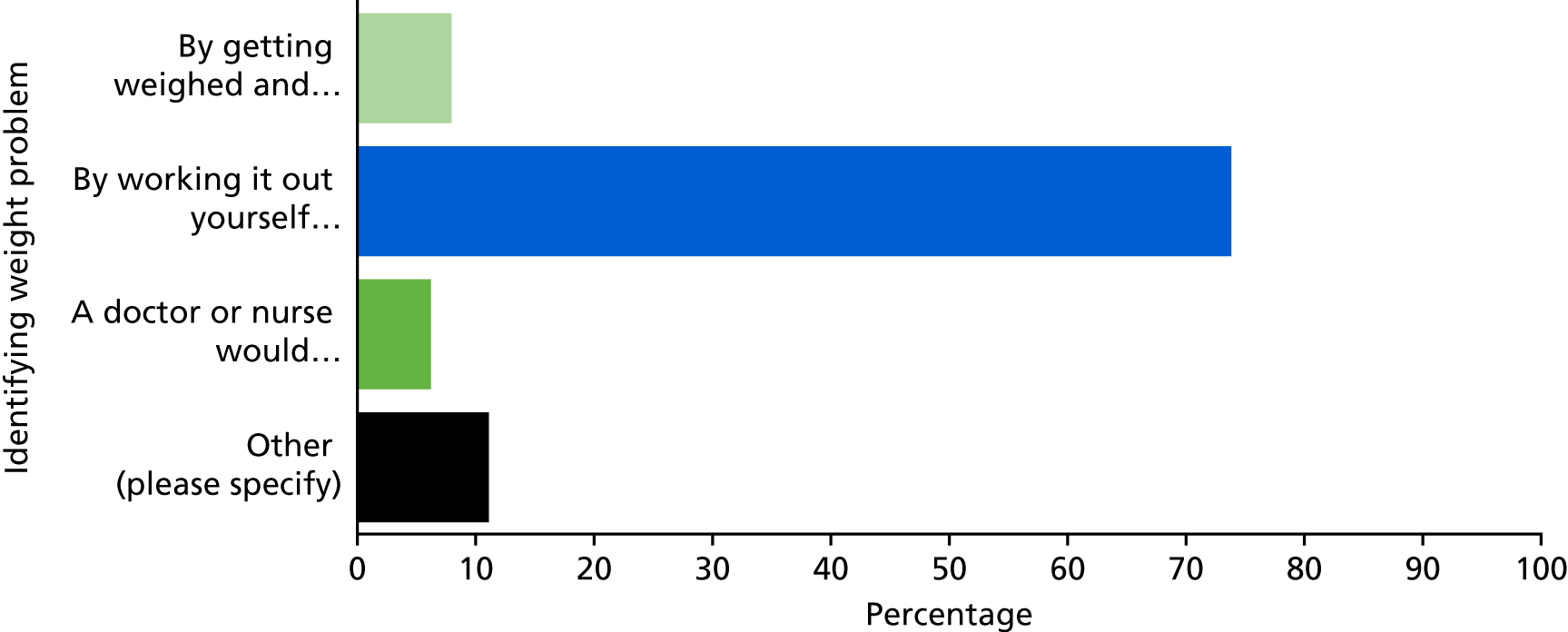

Parental recognition of their child’s overweight status (child described as ‘overweight’ or ‘very overweight’) in response to the question ‘How would you describe your child’s weight at the moment?’.

-

Parental perception of the health risks associated with their child’s overweight status (parent answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you think your child’s current weight is a health risk?’).

-

Weight-related teasing, assessed using the Teasing/Marginalisation subscale from Sizing Them Up, a validated parent-proxy measure of obesity-specific health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) scale. 33 A score of ≥ 50 represented frequent weight-related teasing.

-

The child’s self-esteem, assessed using the Emotional Functioning subscale of the Sizing Them Up scale. A score of ≥ 50 indicated frequent episodes of low self-esteem.

At follow-up, all parents were asked whether or not they had sought further information regarding their child’s weight, from sources including the school nurse, GP, pharmacist, or friends and family. Parents were also asked about the emotions that they experienced in response to the feedback (e.g. surprised, guilty, proud, pleased, upset, angry, ashamed, judged or indifferent).

Qualitative interviews

Qualitative interviews were conducted with a subsample of parents of overweight or obese children, who were purposively selected on the basis of their responses to the questionnaire surveys at follow-up; the sample was selected so that equal proportions did and did not perceive their child’s weight to pose a risk to their health. The sample was also selected to ensure that a range of socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds were represented (around half of the sample were from deprived and ethnic minority households), and equal proportions of parents with children in Reception year and Year 6 were selected. Semistructured interviews were conducted by a researcher with considerable experience in conducting qualitative interviews with parents of school-aged children. Interviews were conducted either at the participant’s home or by telephone, at the parent’s request. The majority (81%) of interviews took place at the participant’s home. The interview schedule was developed to explore the barriers to behaviour change following receipt of the NCMP feedback, and consisted of open-ended questions with prompts as required (see Appendix 2). Each interview lasted ≈ 30 minutes on average. Interviews were audio-recorded using a digital voice-recorder and transcribed verbatim. A thematic analysis was carried out using the software package NVivo Version 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to identify emergent themes: transcripts were read and reread, and initial codes were drawn from the data. With input from three experienced researchers, these initial codes were collated into themes and a coding frame was developed for data analysis.

Economic evaluation

The costs of delivering NCMP feedback were estimated using data on staff time and resource requirements associated with the feedback provided by PCTs. Staff costs were estimated using the NHS Agenda for Change 2012 pay rates. 34 Total costs for each PCT were divided by the number of children measured for the NCMP in the PCT, to derive a cost per child, and costs associated with different forms of feedback (written and proactive) were compared. The mean cost per child of providing routine written feedback across all PCTs was calculated to provide an England-wide estimate.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of survey respondents were described using summary statistics (means and proportions), and compared with anonymised data on weight status, ethnicity, age and IMD score for all children participating in the NCMP in the five PCTs.

Parental perceptions were explored in analyses comparing parent-perceived and objectively derived assessments of child weight status in the study sample at baseline. A multinomial model of parental-perceived weight status was used, with three categories of perceived weight status: (1) underweight, (2) healthy weight and (3) overweight (including obese). A child’s BMI (calculated from measured weight and height), expressed as a z-score from the UK 1990 reference population,35 was the only independent variable included in the model. Using this model, cut-off scores were obtained that represented the points at which a child’s BMI z-score was equally likely to be classified by parents into two adjoining weight status categories, identifying BMI z-scores (expressed as centiles) at which parents were equally as likely to describe their child as underweight as healthy weight, or healthy weight as overweight. Analyses stratified by school year and sex produced little variability in the estimates across models, indicating that an unadjusted model was appropriate. To explore whether or not ethnic group, IMD quintile, child’s sex or school year might predict parental misclassification of child weight status (two outcomes: underestimation or overestimation), logistic regression was used. Standard population-level weight status cut-off points (underweight < 2nd, overweight > 85th, very overweight > 95th centile), rather than clinical cut-off points, were used for comparison with parent-reported categories, as parents are more likely to have been exposed to these population cut-off points before receiving NCMP feedback. Standard errors were adjusted for school-level clustering.

The main analyses (objective 1) were restricted to respondents with longitudinal data (data at baseline and at least one follow-up at 1 or 6 months). If parents had completed a questionnaire at the 1- and 6-month follow-ups, precedence was given to data at 1 month to reflect the immediate impact of feedback. A sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of including responses at 6 months (n = 452; 24.5%) showed no difference compared with restricting to responses at 1 month only; therefore, results for the combined data are presented. The proportions of parents reporting each outcome at baseline and follow-up were calculated. The difference between pre- and post-feedback proportions was assessed using McNemar’s test, and results are presented as the change in proportion between baseline and follow-up (a positive value indicates an increase from baseline to follow-up, and a negative value indicates a decrease).

Analyses of the differences were stratified by the following sociodemographic characteristics to assess potential effect modification: PCT, child’s sex, school year, ethnicity (categorised as white or non-white owing to small numbers from individual ethnic minority groups), deprivation (quintiles of IMD score) and child’s weight category (three categories: healthy weight and underweight combined, overweight or obese). Among parents of obese children, analyses were also stratified by type of feedback: letter only or letter plus proactive feedback (objective 2). Differences in the outcomes by sociodemographic characteristics and type of feedback were assessed using chi-squared tests. The potential effect of seasonality on outcomes, particularly physical activity and sedentary behaviour, was also explored by stratifying and comparing outcomes by season (March–May, June–August, September–November, December–February). To account for potential clustering by PCT, random-effects logistic regression models were fitted for each outcome, including PCT as a variable in the model. Interaction terms were included to assess potential modification of the main effect by feedback type, gender, ethnicity and deprivation. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software Stata, version 12.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee.

Results

A total of 3397 parents responded to the baseline questionnaire (a response rate of 18.9%). Of these, 1844 parents completed at least one follow-up questionnaire at 1 month (n = 1455; a response rate of 42.8%) or 6 months (n = 1298; a response rate of 38.2%) and formed the sample for the main analyses. At 12 months, 816 participants (24.0%) returned a questionnaire; this was considered too small a sample for further analysis here. Among the parents of obese children (n = 105), 61.9% received proactive feedback in addition to the letter.

Comparison with target population

Compared with the whole population of children participating in the NCMP in the five PCTs, the study sample had lower proportions of overweight and obese children (15.4% vs. 22.1%; p-value from chi-squared tests for difference < 0.01), Year 6 children (44.5% vs. 50.9%; p < 0.01), parents from the most deprived areas (43.7% from the two most deprived quintiles vs. 49.1%; p < 0.01) and children from ethnic minority groups (34.0% vs. 45.5%; p < 0.01) (Table 1). Parents from these groups were also more likely to drop out of the study, resulting in greater differences at follow-up: at 6 months, 13.4% of children were overweight or obese, 40.2% were from the most deprived areas and 30.0% were from ethnic minority groups.

| Characteristic | Percentage | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study sample (n = 1844) | NCMP population (n = 18,000) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 49.7 | 48.4 | 0.29 |

| Female | 50.3 | 51.6 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 66.0 | 54.5 | < 0.01 |

| Asian | 5.5 | 10.8 | |

| Black | 15.7 | 21.2 | |

| Mixed/other | 12.8 | 13.5 | |

| School year | |||

| Reception (4–5 years) | 55.5 | 49.1 | < 0.01 |

| Year 6 (10–11 years) | 44.5 | 50.9 | |

| Weight status | |||

| Underweight | 1.9 | 1.4 | < 0.01 |

| Healthy weight | 82.8 | 76.5 | |

| Overweight | 9.7 | 12.5 | |

| Obese | 5.7 | 9.6 | |

| Deprivation quintileb | |||

| 1 | 19.1 | 20.3 | < 0.01 |

| 2 | 24.6 | 28.8 | |

| 3 | 19.9 | 21.6 | |

| 4 | 16.7 | 15.7 | |

| 5 | 19.7 | 13.7 | |

Of the 285 parents of overweight or obese children who had responded to the questionnaire survey, 108 were invited (by letter) to participate in the qualitative interviews. Interviews were carried out with 52 parents (43%). Theoretical saturation of the data was achieved with 40 interviews, with no new themes emerging in the final 12 interviews. The demographic characteristics of interview participants are presented in Table 2.

| Characteristic | % (n) (N = 52) |

|---|---|

| Parent sex | |

| Male | 17.0 (9) |

| Female | 83.0 (43) |

| Parent ethnicity | |

| White | 50.0 (26) |

| Non-white | 50.0 (26) |

| Socioeconomic deprivationa | |

| Deprived (IMD 1/2) | 44.0 (23) |

| Not deprived (IMD 3/4/5) | 56.0 (29) |

| PCT | |

| Islington | 15.4 (8) |

| Redbridge | 34.6 (18) |

| West Essex | 19.2 (10) |

| BANES | 13.5 (7) |

| Sandwell | 17.3 (9) |

| Child school year | |

| Reception (4–5 years) | 50.0 (26) |

| Year 6 (10–11 years) | 50.0 (26) |

| Child sex | |

| Male | 56.0 (29) |

| Female | 44.0 (23) |

| Child weight status | |

| Overweight | 37.0 (19) |

| Obese | 63.0 (33) |

| Parent perceives their child’s overweight status to pose a health risk | |

| Yes | 43.0 (22) |

| No | 57.0 (30) |

Parental knowledge, perceptions and lifestyle behaviours at baseline

At baseline, 72.3% of parents were able to identify the common health conditions associated with childhood overweight; this proportion was higher among parents with healthy weight and underweight children [74.8%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 72.5% to 77.1%] than among those with overweight (61.9%, 95% CI 54.2% to 69.7%) or obese (57.8%, 95% CI 47.4% to 68.2%) children. Parental knowledge also varied with ethnicity; just 59% of parents of children from non-white ethnic groups correctly identified common childhood obesity comorbidities, compared with 79% of parents of white children.

About half of the children were reported to meet dietary (48.7%) and screen time (53.4%) recommendations, and about one-third (36.3%) achieved recommended levels of physical activity. Compared with their healthy weight and underweight peers, levels of physical activity were lower and screen time was higher among overweight and obese children; the proportion achieving a healthy diet was lower among obese (but not overweight) children.

Among the parents of overweight and obese children (n = 285), the proportion who considered their child to be overweight was low: 14% of parents of overweight children and 35% of parents of obese children described their child as overweight. Similarly, 11.0% of parents of overweight children and 38.6% of parents of obese children considered their child’s weight status to pose a health risk. A small proportion of parents of overweight and obese children (8.9%; n = 10) reported frequent weight-related teasing, and 1.8% (n = 2) reported low self-esteem.

When parent-perceived weight cut-off points were estimated, the point at which a parent was equally likely to recognise underweight as healthy weight was when their child had a BMI at the 0.8th centile (95% CI 0.4 to 1.1 centile). A parent was more likely to classify their child as overweight rather than healthy weight when their child had a BMI of ≥ 99.7th centile (95% CI 99.3 to 99.9 centile). Based on population-based cut-off points for weight status, 915 (31%) parents underestimated and 25 (< 1%) overestimated their child’s weight status. Parents were more likely to underestimate their child’s weight status if they were black [reference group: white, odds ratio (OR) 1.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.1], south Asian (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.0), male (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.6) or in the older age group (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.5). Parents from less deprived areas were less likely to underestimate their child’s weight status (OR for each quintile less deprived, OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.9). Overestimation of weight status was more likely for Year 6 than Reception children (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.2 to 8.5). Ethnic group, deprivation and a child’s sex did not predict parental overestimation of weight status.

Objective 1: the impact of National Child Measurement Programme feedback

Parental knowledge

The proportion of parents with good general knowledge about the health conditions associated with childhood obesity increased following NCMP feedback (7.7%, 95% CI 5.1% to 10.3%). Variation in parental knowledge by child’s weight status and ethnicity remained, with parents of overweight and obese children and those from non-white ethnic groups having lower levels of knowledge. Detailed data by weight status can be seen in Table 3.

| Outcome | Weight status, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy weight and underweight (n = 1574) | Overweight (n = 180) | Obese (n = 105) | |||||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | Difference in proportiona | Baseline | Follow-up | Difference in proportiona | Baseline | Follow-up | Difference in proportiona | |

| Good parental knowledge of the health risks of child overweightb | 74.8 (72.5 to 77.1) | 81.9 (79.9 to 83.4) | 7.1 (4.6 to 9.6) | 61.9 (54.2 to 69.7) | 70.3 (63.1 to 77.6) | 8.4 (–0.4 to 17.2) | 57.8 (47.4 to 68.2) | 65.6 (55.5 to 75.6) | 7.8 (–4.5 to 20.1) |

| Parental recognition of child overweight | NA | NA | NA | 14.0 (8.8 to 19.3) | 25.1 (18.6 to 31.7) | 11.1 (4.0 to 18.3) | 35.3 (25.9 to 44.7) | 58.8 (49.1 to 68.5) | 23.5 (12.7 to 34.3) |

| Parental recognition of the health risks associated with child’s overweight | NA | NA | NA | 11.1 (6.4 to 15.9) | 18.1 (12.3 to 24.0) | 7.0 (1.4 to 12.6) | 38.0 (28.3 to 47.7) | 43.0 (33.1 to 52.9) | 5.0 (–6.9 to 16.9) |

| Child achieves a healthy dietc | 49.6 (47.0 to 52.2) | 48.9 (46.3 to 51.5) | –0.7 (–3.4 to 2.0) | 50.6 (42.8 to 58.4) | 46.3 (38.5 to 54.1) | –4.3 (–12.7 to 4.0) | 41.3 (31.1 to 51.6) | 41.3 (31.1 to 51.6) | 0 (–10.6 to 10.6) |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption (≥ 5 portions/day) | 32.5 (30.2 to 34.8) | 33.0 (30.6 to 35.3) | 0.5 (–2.0 to 2.8) | 27.8 (21.2 to 34.4) | 25.0 (18.6 to 31.4) | –2.8 (–10.4 to 4.7) | 22.9 (14.7 to 31.0) | 28.6 (19.8 to 37.4) | 5.7 (–3.5 to 14.9) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption (< 1/day) | 71.0 (68.7 to 73.3) | 70.0 (67.7 to 72.4) | –1.0 (–3.5 to 1.5) | 77.3 (71.0 to 83.5) | 75.6 (69.2 to 82.0) | –1.7 (–9.9 to 6.5) | 63.6 (54.0 to 73.3) | 66.7 (57.2 to 76.1) | 3.0 (–8.6 to 14.7) |

| Child achieves adequate physical activity (≥ 1 hour/day) | 38.1 (35.6 to 40.5) | 39.1 (36.7 to 41.5) | 1.0 (–1.6 to 3.6) | 27.9 (21.1 to 34.7) | 28.5 (21.7 to 35.3) | 0.6 (–6.1 to 7.3) | 25.2 (16.7 to 33.8) | 37.9 (28.3 to 47.4) | 12.6 (2.5 to 22.8) |

| Child achieves appropriate screen time behaviour (≤ 2 hours/day) | 55.4 (52.9 to 57.9) | 51.5 (48.9 to 54.0) | –4.0 (–6.6 to –1.4) | 45.5 (38.0 to 52.9) | 39.2 (31.9 to 46.5) | –6.3 (–14.2 to 17.3) | 41.6 (31.8 to 51.4) | 31.7 (22.5 to 40.9) | –9.9 (–20.6 to 0.8) |

| Weight-related teasingd | NA | NA | NA | 4.3 (–1.7 to 10.2) | 10.6 (1.5 to 19.8) | 6.4 (–2.7 to 15.5) | 19.0 (0.7 to 37.4) | 14.3 (–2.0 to 30.6) | –4.8 (–25.6 to 16.0) |

| Low self-esteeme | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.0 (–4.4 to 24.4) | 5 (–5.5 to 15.5) | –5.0 (–26.8 to 16.8) |

Parental perceptions

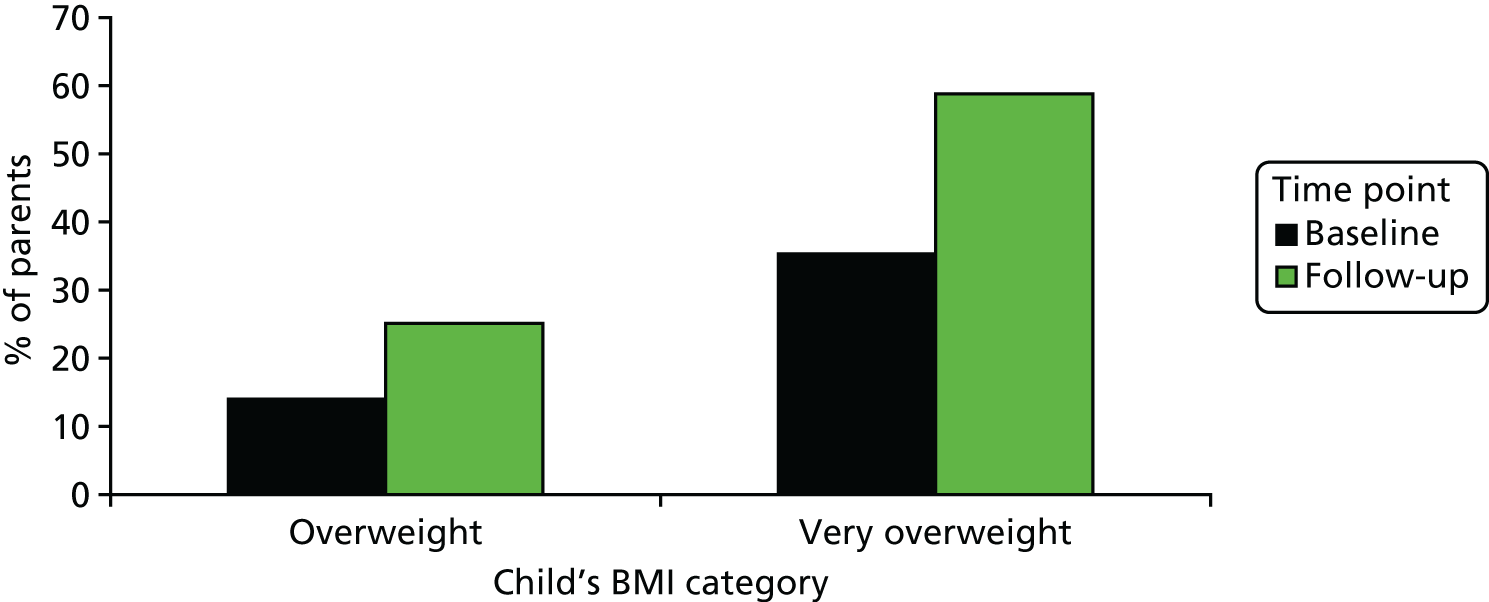

The proportion of parents of overweight and obese children who recognised their child’s overweight status increased post feedback (+15.8%, 95% CI 9.8% to 21.7%), with a greater increase among the parents of obese children (+23.5%) than among parents of overweight children (+11.1%) (Figure 2). However, 41% of parents of obese children and 75% of parents of overweight children continued to perceive their child to have a healthy weight after receiving NCMP feedback.

FIGURE 2.

The proportion of parents of overweight and obese (very overweight) children who considered their child to be overweight, before and after receiving NCMP feedback.

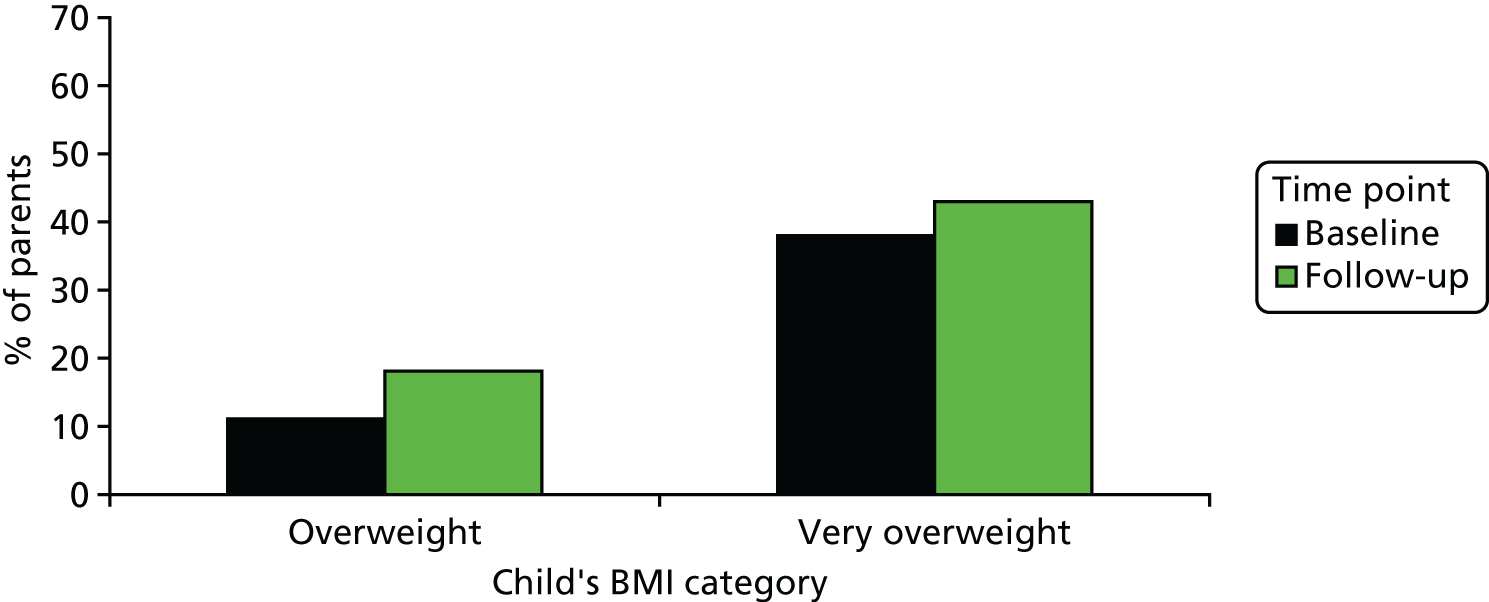

The increase in the proportion of parents who considered their child’s overweight status to pose a health risk was modest for both overweight (+7.0%, 95% CI 1.4% to 12.6%) and obese children (+5.0%, 95% CI –6.9% to 16.9%) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The proportion of parents of overweight and obese (very overweight) children who considered their child’s weight to pose a health risk, before and after receiving NCMP feedback.

Lifestyle behaviours

Neither consumption of fruit and vegetables nor consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages changed following feedback. Physical activity levels increased among obese children (+12.6%, 95% CI 2.5% to 22.8%), but not among children in other weight categories. The proportion of children engaging in recommended levels of screen time was lower after feedback (–4.6%, 95% CI –7.0% to –2.2%). There was no strong evidence for an effect of season on lifestyle behaviours. Detailed data by weight status can be seen in Table 3.

Health service use

One-quarter of parents of overweight children (26.9%) and half of parents of obese children (49.4%) sought further information or help regarding their child’s weight following receipt of the NCMP written feedback (compared with 12% of parents of healthy weight children). The most frequently reported sources of information were friends and family (reported by 14.4% of parents), the internet (9.9%), GPs (8.9%) and school nurses (8.4%). Attendance at a GP practice owing to concerns about their child’s weight was reported by 6% of parents of overweight children and 15% of parents of obese children.

Teasing and self-esteem

Frequent weight-related teasing was reported by 10% of parents of overweight and obese children at baseline, compared with 2% of parents of healthy weight children. Low child self-esteem was reported by 4% of parents of overweight and obese children and 1% of parents of healthy weight children. Both weight-related teasing and low self-esteem were more prevalent among obese children than among overweight children at both time points, but there was no apparent effect of NCMP feedback on either. The proportion of parents reporting weight-related teasing or low self-esteem did not change substantially after feedback.

Parents’ reactions to National Child Measurement Programme feedback

Parents reported experiencing a wide range of emotions in response to receiving NCMP feedback, which varied considerably by the child’s weight category. The most common reaction among parents of healthy weight children was ‘pleased’ (reported by 65.0% of parents) and 21.0% felt proud of their child’s result. Among the parents of overweight and obese children, the most commonly reported emotions were surprise (reported by 35.0%), upset (24.1%), guilt (15.4%) and shock or anger (14.8%).

Despite some negative emotional reactions to the feedback among the parents of overweight or obese children, the majority of parents across all child weight categories (87.2%) reported that they found the NCMP feedback to be either ‘somewhat helpful’ or ‘very helpful’. Parents of overweight children were most likely to find the feedback ‘not at all helpful’ (Figure 4). The majority of parents (70.0%) reported that they would encourage future participation in the NCMP for their child or child’s siblings. Only 1.8% said that they would withdraw their child from the programme in the future.

FIGURE 4.

The proportions of parents who found the NCMP feedback to be helpful, by child’s weight category.

Talking with children about National Child Measurement Programme feedback

Half of all parents (52%) had discussed their child’s weight status with their child. Parents of obese children were over two times more likely to have discussed the result with their child than parents of healthy weight children (adjusted OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.5 to 4.5). In all weight categories, the parents of children in Year 6 were more likely than parents of Reception-aged children to have discussed the result with their child (adjusted OR 4.4, 95% CI 3.4 to 5.8).

Among those parents who did discuss the result with their child, parents of underweight and healthy weight children mainly discussed the actual result, whereas parents of overweight and obese children mainly discussed making lifestyle changes or seeking help. Parents of overweight and obese children often chose not to discuss the weight result with their child, and during interviews some parents mentioned that this was because of a fear of inducing an eating disorder or low self-esteem.

Almost all parents of healthy weight children found talking to their child about the result to be easy (95.5%). More parents of overweight and obese children found talking to their child to be ‘a little difficult’ (30.4%) but very few reported it to be ‘difficult’ (3.2%). Among overweight and obese children, parents of boys more commonly reported finding the conversation to be easy.

Effects of sociodemographic characteristics on the impact of National Child Measurement Programme feedback

There was a larger increase in the proportion of parents who recognised the health risks associated with their child’s overweight status among those with children from non-white ethnic groups than those with white children (Table 4). In adjusted analyses, the parents of children from non-white ethnic groups were eight times more likely to have changed their recognition of the weight-related health risks (OR 8.6, 95% CI 1.9 to 39.8). The proportion of parents who reported an improvement in their child’s diet was larger among those with children in Year 6 than those with children in Reception year. There were no statistically significant effects of other sociodemographic characteristics (sex and deprivation) on any outcomes.

| Characteristic | Parental recognition of overweight | Parental recognition of health risks associated with child’s overweight | Child achieves a healthy diet | Child undertakes adequate physical activity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in proportion, % (95% CI)a | p-valueb | Difference in proportion, % (95% CI)a | p-valueb | Difference in proportion, % (95% CI)a | p-valueb | Difference in proportion, % (95% CI)a | p-valueb | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 12.6 (5.6 to 19.6) | 0.24 | –3.3 (–8.7 to 2.1) | < 0.01 | –2.9 (–10.9 to 5.1) | 0.98 | 7.3 (0.3 to 14.4) | 0.37 |

| Non-white | 19.3 (10.1 to 28.6) | 17.9 (8.8 to 27.1) | –2.7 (–12.0 to 6.6) | 2.5 (–5.7 to 10.6) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 14.8 (6.4 to 23.3) | 0.75 | 5.8 (–2.3 to 14.1) | 0.88 | –3.9 (–12.2 to 4.4) | 0.71 | 2.2 (–3.7 to 8.1) | 0.27 |

| Male | 16.7 (9.2 to 24.2) | 6.7 (0.4 to 13.0) | –1.6 (–10.5 to 7.3) | 8.1 (–.07 to 16.7) | ||||

| School year | ||||||||

| Reception (age 4–5 years) | 16.9 (9.3 to 24.5) | 0.69 | 8.1 (1.2 to 15.1) | 0.48 | –10.5 (–18.9 to –2.1) | 0.01 | 5.9 (–1.5 to 13.4) | 0.76 |

| Year 6 (age 10–11 years) | 14.6 (6.3 to 22.9) | 4.4 (–3.3 to 12.1) | 4.6 (–4.0 to 13.2) | 4.3 (–3.2 to 11.8) | ||||

| Deprivation quintilec | ||||||||

| 1 | 13.3 (0.3 to 26.3) | 0.54 | 3.8 (–5.2 to 12.7) | 0.41 | 6.8 (–4.4 to 18.1) | 0.82 | 6.3 (–3.3 to 15.8) | 0.58 |

| 2 | 14.8 (4.3 to 25.4) | 5.6 (–3.0 to 14.1) | –5.9 (–16.1 to 4.3) | 10.9 (0.03 to 21.7) | ||||

| 3 | 26.4 (13.0 to 29.8) | 13.0 (–0.07 to 26.0) | –3.8 (–17.3 to 9.6) | –1.8 (–11.5 to 7.9) | ||||

| 4 | 13.6 (0.4 to 27.7) | 11.4 (–0.4 to 23.1) | –4.8 (–22.9 to 13.4) | 6.8 (–6.9 to 20.6) | ||||

| 5 | 11.1 (5.6 to 27.8) | –3.9 (–17.7 to 10.1) | –4.0 (–22.8 to 14.8) | 11.1 (–8.9 to 31.1) | ||||

Objective 2: the effects of different forms of weight feedback

Proactive feedback was implemented in Redbridge, BANES and Sandwell PCTs. In Redbridge PCT, approximately 60% of parents of obese children were successfully contacted by telephone and offered a face-to-face appointment; 69% of these parents accepted the appointment. Corresponding numbers for BANES and Sandwell PCTs could not be ascertained. There was some evidence to suggest that proactive forms of feedback may be more effective than written feedback alone in changing perceptions among the parents of obese children (Table 5). Parents who lived in PCTs offering proactive feedback demonstrated greater improvements in parental recognition of their child’s overweight status (32% vs. 10%) and greater recognition of the associated health risks (13% vs. –8%) than patients in all PCTs in the study taken as a whole. There was no effect of type of feedback on lifestyle behaviours or health service use.

| Outcome | Difference in proportion, % (95% CI)a | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Written feedback only | Proactive feedback | ||

| Parental recognition of overweight | 10.0 (–7.4 to 27.4) | 32.3 (20.2 to 44.2) | 0.03 |

| Parental recognition of health risks associated with child’s overweight | –7.9 (–27.2 to 11.4) | 12.9 (–0.5 to 26.3) | 0.07 |

| Child achieves a healthy diet | –8.8 (–24.6 to 6.9) | 5.2 (–7.3 to 17.7) | 0.17 |

| Child partakes in adequate levels of physical activity | 15.0 (–2.1 to 32.1) | 11.1 (–0.1 to 22.2) | 0.69 |

Parents expressed a strong preference for written feedback over other forms of feedback, with 84.5% of all parents preferring feedback by letter, whereas 3.0% preferred feedback by telephone. Among the parents of obese children, the type of feedback received during the study was not associated with preferences for future forms of weight feedback.

Objective 3: barriers to behaviour change and health service use

Qualitative interviews with parents of overweight and obese children identified several barriers to health-related behaviour change: (1) parental perceptions of their child’s health, weight and appearance, (2) cultural differences, (3) access to and availability of local services, (4) contradictory advice from health professionals, (5) relevance of lifestyle advice and (6) limits to parental control.

Barrier 1: parental perceptions of their child’s health, weight and appearance

Many parents did not consider the NCMP result and its associated health concerns to reflect their child’s situation. The predominant theme that arose during analysis was that parents had broad definitions of health, with a variety of features other than weight being considered to determine whether or not a child was healthy. Parents placed more importance on their child’s emotional and physical health than on weight per se:

No he’s a happy boy, he’s a proper happy little boy. He’s not concerned about anything . . . he doesn’t get picked on in any way by anybody.

Parent 20024; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

I think if he is happy with the way that he looks and he’s happy with himself, I think then that’s absolutely fine.

Parent 20031; obese 10- to 11-year-old child

Many parents considered a healthy lifestyle to be more important than weight as an indicator of health and well-being:

I never thought of the weight side particularly, I just looked at what the lifestyle was. He does exercise and he does eat well.

Parent 20022; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

If she’s not active I would be worried but she’s active, she runs, she do all of them things so I’m not worried about her health.

Parent 20021; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

For some parents, this discrepancy made the NCMP feedback less credible:

It only measures weight-to-height ratio and doesn’t take into account their lifestyle, their activity and things like that.

Parent 20010; overweight 10- to 11-year-old child

Another barrier to changing perceptions was that excess weight in their child was viewed by many parents to be puppy fat, which their child would grow out of as they got older:

I look at him and I see puppy fat, I don’t see overweight fat, I think they’re two different things.

Parent 30004; overweight 10- to 11-year-old child

It’s not a huge concern at the moment because I think we’ve got to get through puberty and see how she goes and how she grows.

Parent 30001; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

Some parents felt that their child was genetically predisposed to be heavy and, therefore, being overweight was not entirely within their control:

Some of it is down to poor diet from us but a lot of it has got to be to do with genetics.

Parent 20035; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

Many parents viewed their child’s weight status in comparison with that of other children and extreme examples of overweight, and, therefore, did not consider their child to look overweight:

I don’t think when you look at her you don’t look at her and think she’s overweight. She doesn’t have that overweight look feature-wise.

Parent 20001; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

He honestly doesn’t really look overweight to me so you see children in the street and they’re little round puddings. He’s not one of them.

Parent 20024; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

Barrier 2: cultural differences

Although results from the analysis of interview data were generally universal across parents (regardless of gender, age or ethnicity), there were some cultural influences that affected parents’ responses to the NCMP feedback. Some parents of non-white ethnicity described a disparity between the predominant ‘British’ views of overweight and those of their culture, in which overweight was not viewed negatively:

Back in my country, saying a child is overweight means it is a good thing.

Parent 20017; obese 4- to 5-year-old child

Barrier 3: access to and availability of local services

Around half of parents of obese children and three-quarters of parents of overweight children did not seek further help or information after receiving NCMP feedback. The most commonly reported barrier to seeking help was a lack of knowledge about where to go for help:

If there was literature sent out to parents with children with weight problems and they listed the organisations or the services as you say that are available, then that would give parents more ideas of where to go.

Parent 20006; obese 5- to 6-year-old child

Some parents described limited availability of services when they did follow up health advice:

The health visitor gave me the number of one of the sport centres and they offer 12 weeks’ activity but I put her name down and they haven’t . . . they said they don’t have enough people to do that course, so they haven’t let me know yet and it’s been 5–6 months now.

Parent 20008; overweight 11- to 12-year-old child

Others expressed concern about the perceived costs associated with services:

At the local sports centre, they have things going on but things are so expensive, to pay for that is a lot . . . I always keep thinking, ‘oh I want him to do another thing’, but we just don’t have the funds to do that.

Parent 20022; obese 6- to 7-year-old child

Barrier 4: contradictory advice from health professionals

Although not commonly reported, some parents who sought advice from a health professional were reassured that their child was not overweight, which undermined the NCMP feedback:

I took both children to the clinic at that time and [the] doctor checked both of them and said, ‘I can’t understand why they send them in the first place because they’re not overweight’. Maybe they sound overweight according to their age, but according to their structure, their height, they are not overweight . . . when a specialist like a doctor or someone tells something it takes more effect and she was a bit relieved that I’m not fat.

Parent 20007; overweight 10- to 11-year-old child

Barrier 5: relevance of lifestyle advice

Some parents dismissed the lifestyle advice provided in the NCMP feedback letter because they felt that they were already leading healthy lifestyles:

I felt it was talking to the person who feeds their child crisps every day and has fizzy drinks, and is going to, of course, just be feeding their child to a real budget and that’s really hard. I was thinking from my point of view this isn’t very helpful . . . I can’t remember what it said really ‘cause I felt it wasn’t even relevant to me.

Parent 20032; overweight 5- to 6-year-old child

Barrier 6: limits to parental control

Several parents described the difficulties of controlling all aspects of their child’s lifestyle, citing influences such as the child’s school, other family members and the child’s own preferences as obstacles to modifying lifestyle behaviours:

I don’t want to sound conceited, but I knew exactly how to eat healthily but we had a child who likes her sweet stuff and her snacks and her crisps.

Parent 30001; overweight 11- to 12-year-old child

I had always struggled with my partner about feeding our daughter. I felt he made inappropriate decisions regarding her portion sizes, and the amount of food that he allowed her to eat . . . the issue that I felt was the real impediment so any change was my partner, and I didn’t feel that I needed any advice as to how I could overcome . . . change his behaviour. I mean he’s going to behave the way he behaves and sadly he doesn’t really listen to me or anyone else to some extent.

Parent 20011; overweight, 6- to 7-year-old child

Objective 4: NHS costs associated with National Child Measurement Programme feedback

The cost of providing routine written feedback letters to parents was estimated at £1.24 per child, compared with £9.50 per child for telephone feedback and £41 per child for face-to-face appointments. The higher costs were attributable to the additional staff time required to deliver proactive feedback (Table 6). Based on these estimated costs and the national prevalence of obesity among children taking part in the NCMP, the mean cost per child of providing written feedback letters to all parents and a telephone call to the parents of all obese children was £2.03 (on average an additional £0.79 per child compared with written feedback only).

| Feedback type | Breakdown of tasks required | Staff involved | Cost per child (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Letter |

|

|

1.24 |

| Proactive telephone callsa |

|

|

9.50 |

| Proactive telephone calls plus face-to-face consultationa (Redbridge PCT) |

|

|

41.00 |

Discussion

We report findings from the first large-scale evaluation of the NCMP feedback and its impact on parental perceptions of their child’s weight status and health, and lifestyle behaviours and health service use. This study has shown that parents’ general knowledge about childhood obesity comorbidities increased following NCMP feedback, as did recognition of childhood overweight among parents of overweight and obese children. However, a sizable proportion of parents with obese children and the majority of parents of overweight children continued to perceive their child to have a healthy weight after receiving information to the contrary. Analysis of baseline data showed the sizeable discrepancy between parent-perceived and objectively assessed weight status cut-off points (99.7th centile compared with 91st centile used in NCMP feedback). The proportion of parents of overweight and obese children who perceived their child’s weight status to be a health risk increased after feedback, but remained low at follow-up; those parents who did change their perception of their child’s health may be more likely to engage with child weight issues and be prompted to make positive changes. 24,36 Parents of ethnic minority group children, boys and older children, and parents from more deprived areas, were more likely to underestimate their child’s weight at baseline. Research to understand how parental perceptions of their child’s weight status and health are formed in different groups may identify ways to more effectively communicate information to parents.

The parents of ethnic minority children demonstrated a larger change in recognition of the health risks than parents of white children. A similar effect has been observed in other studies, with ethnic minority groups reporting greater changes to lifestyle and plans for help-seeking following weight feedback. 37,38 Although this variation by ethnic group requires further investigation, these findings are encouraging, as many ethnic minority groups are at increased risk of obesity and its comorbidities,39 and typically have lower rates of participation in obesity prevention initiatives than white populations. 40,41 Qualitative interviews with parents also highlighted cultural influences on parental perceptions of child overweight, suggesting that there may be value in developing culturally specific feedback.

In this study, there was no observed effect of weight feedback on dietary behaviours, and a positive effect on physical activity was observed only among obese children. A previous evaluation of NCMP feedback showed that many parents plan to make changes to behaviour following feedback,25 but our study indicates that actual behaviour changes may be small and limited to certain groups. Given the low-intensity nature of routine weight feedback as an intervention, it may be expected that changes in behaviour would not be large. 42 In the case of screen time behaviour, fewer children met the screen time recommendations after feedback than before. A possible explanation for this unexpected finding is that the information provided with weight feedback does not make explicit recommendations about screen time; inclusion of screen time recommendations could be included in weight feedback in the future.

More than one-third of parents of overweight and obese children reported seeking further information regarding their child’s weight in response to the feedback. Informal sources of help (i.e. friends and family, the internet) were most commonly consulted; parents may feel more comfortable approaching these sources than more official sources of information, and interviews indicated that limited availability of services presented a barrier to seeking help. An implication of this finding is that the quality of information that parents receive may be difficult to monitor, and parents may be more likely to receive misinformation or advice; further work to explore the types of health information that parents access from informal sources may inform the development of resources for parents. Fifteen per cent of parents of obese children reported seeking help from a GP; in interviews, some parents described receiving advice from health professionals that contradicted the NCMP feedback. This finding highlights the importance of adequate training for primary care professionals to deal with childhood overweight and obesity. The capacity of local services to cope with increased help-seeking as a result of NCMP feedback also needs to be assessed, and taken into consideration when implementing the programme.

More than half of parents reported discussing the feedback with their child; however, we found no adverse effects on self-esteem and weight-related teasing in overweight and obese children. 43 The majority of parents found weight feedback to be helpful and reported that they would encourage future participation in the NCMP for their child. A small number of parents reported feeling upset or angry in response to the feedback. Consideration of the sensitive nature of weight issues should be a priority when devising feedback. 44

When written letters were supplemented by proactive weight feedback (i.e. telephone calls or face to face), there were greater improvements in parental recognition of their child’s overweight status and recognition of the associated health risks, but no effect on lifestyle behaviours or health service use. The success of proactive feedback may have been limited by relatively low contact rates; for example, in Redbridge PCT, just 60% of parents of obese children were contacted successfully by telephone, although the results reflect the logistical difficulties associated with this type of feedback. In general, more intensive behaviour change interventions have greater success and this may be applicable in the context of weight feedback provision. 42,45 However, the potential benefits of proactive feedback must be balanced against the higher costs, parents’ preference for written feedback over proactive modes of delivery and difficulties in contacting parents by telephone.

A major barrier to behaviour change among parents of overweight and obese children was that parents perceived their child’s health in terms of a variety of features other than weight, particularly emotional well-being and physical health. This was reflected in the low levels of parental recognition of overweight and the associated health risks in their children. Other barriers that were identified included limited availability and perceived high cost of local services, contradictory advice from health professionals and limits to parental influence over their children’s lifestyles. These barriers should be taken into consideration when developing weight feedback; an emphasis on healthy lifestyles and ways to encourage positive behaviours in all children, regardless of their weight status, may be a priority for future interventions, particularly in the context of low levels of recognition of the NCMP result among parents of overweight and obese children.

Strengths and limitations

This study was conducted in a large, population-based and sociodemographically diverse sample, which enabled examination of the effects of weight feedback in different weight and sociodemographic groups. To account for the lack of a comparison group, a short time interval was selected between baseline and follow-up questionnaires (≈ 3 months) to minimise potential changes in outcomes that may have occurred independently of the intervention.

The main limitation of this study was the low response rate and high attrition, which raise the possibility of a biased sample. It is plausible that parents who are more engaged with issues relating to their child’s health would be more likely to participate in the study and respond to feedback than parents who are not engaged with these issues, which would lead to an overestimation of the effect of weight feedback. Comparison of the study sample with all children taking part in the NCMP in the five PCTs revealed a slight under-representation of children from ethnic minorities, children from Year 6, children from deprived areas and overweight/obese children in our sample, which may limit the generalisability of the study findings to the UK NCMP population. However, the lifestyle behaviours of the study sample were similar to those previously observed in national surveys of primary school-aged children. 46–48 To keep the questionnaires concise, brief measures of behaviour and potential harms were used, not all of which are validated. Lifestyle behaviours are difficult to measure accurately,49 and self-reported measures of behaviours may be subject to misreporting. The reported lack of a change in lifestyle behaviours in this study argues against this being an issue;50 however, this does not discount the possibility of systematic social desirability bias, for example parents over-reporting fruit and vegetable consumption at both time points. The dietary measures used have been previously assessed using test–retest methods and found to be reasonably reliable. 31 In addition, parental perceptions of overweight and health risk were evaluated using questions that have been used in previous evaluations of weight feedback. 43 Questionnaires were not translated into other languages, as it was not standard practice to translate the feedback letters in any of the PCTs involved in the study. Consequently, the study does not reflect the impact of NCMP feedback on non-English-speaking households.

We did not collect data on parental weight as this would have only been by self-report, which is highly prone to bias. We did not collect data on disordered eating among children because of contraints of questionnaire length; however, this would have added to our understanding of the impact of NCMP feedback.

Conclusions

The NCMP feedback had a positive impact on parents’ general knowledge about childhood obesity, and parental recognition of overweight and the associated health risks in their own children. However, there were no improvements in children’s lifestyle behaviours following provision of feedback, suggesting that the impact on prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity is likely to be minimal. A number of barriers to behaviour change were identified in interviews with parents. A notable barrier was parents’ perceptions of health, which often did not take account of weight. However, the majority of parents found the feedback to be helpful and were happy to take part in the NCMP in the future. Proactive feedback appeared to offer some additional benefit in terms of changing parental perceptions, but was logistically complex to implement, and written feedback was preferred by parents. The mixed results of this study suggest that the NCMP may have a role in changing parental perceptions and health knowledge in the general population, but other initiatives may be required to precipitate lifestyle behaviour changes that will reduce childhood obesity prevalence. This includes provision and evaluation of online resources to support weight change for children and families.

Chapter 3 Study B: developing a new electronic tool to improve childhood obesity management in primary care

This chapter has been reproduced from Park et al. 51 Published by the BMJ Publishing Group Limited. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Abstract

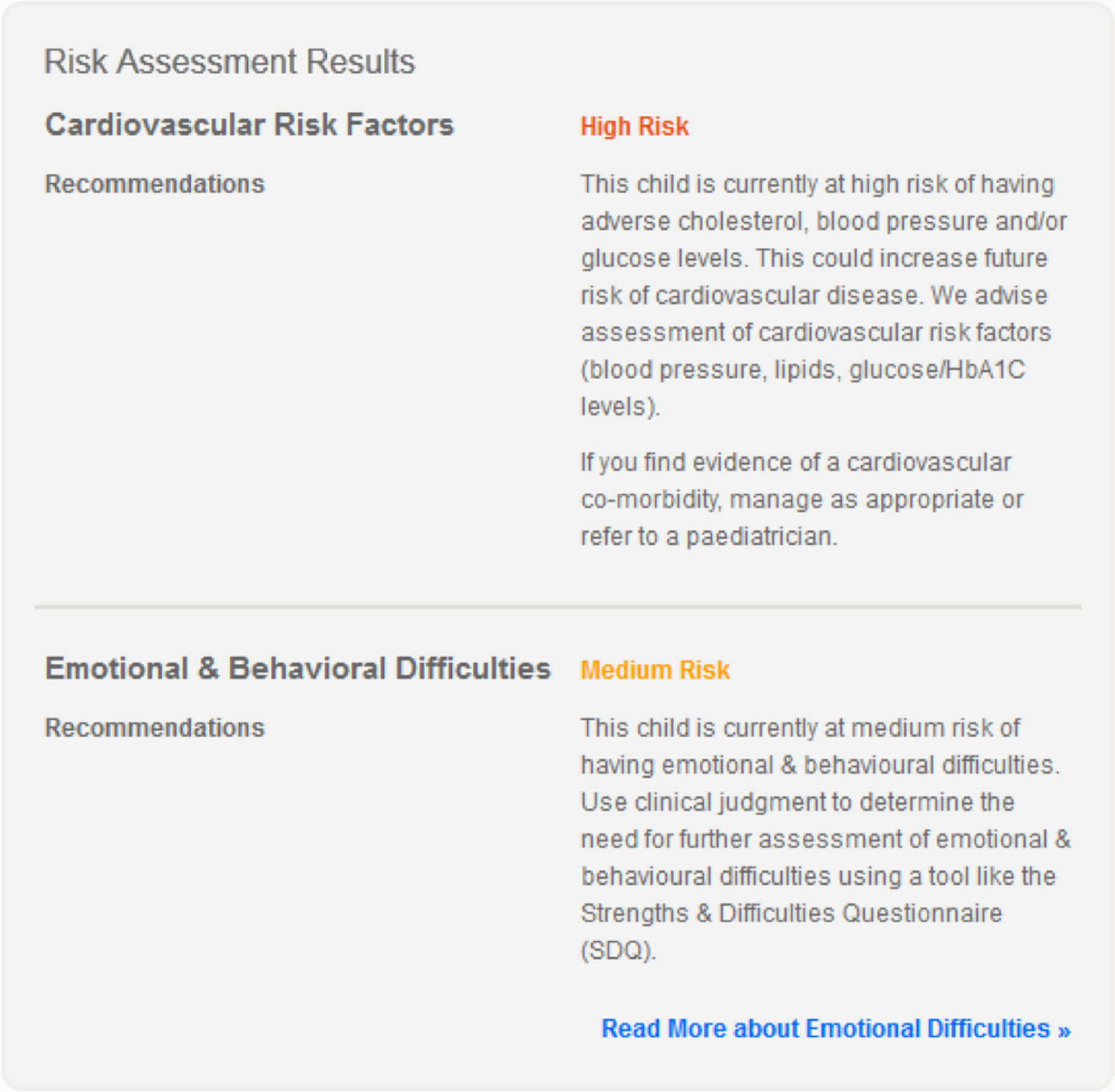

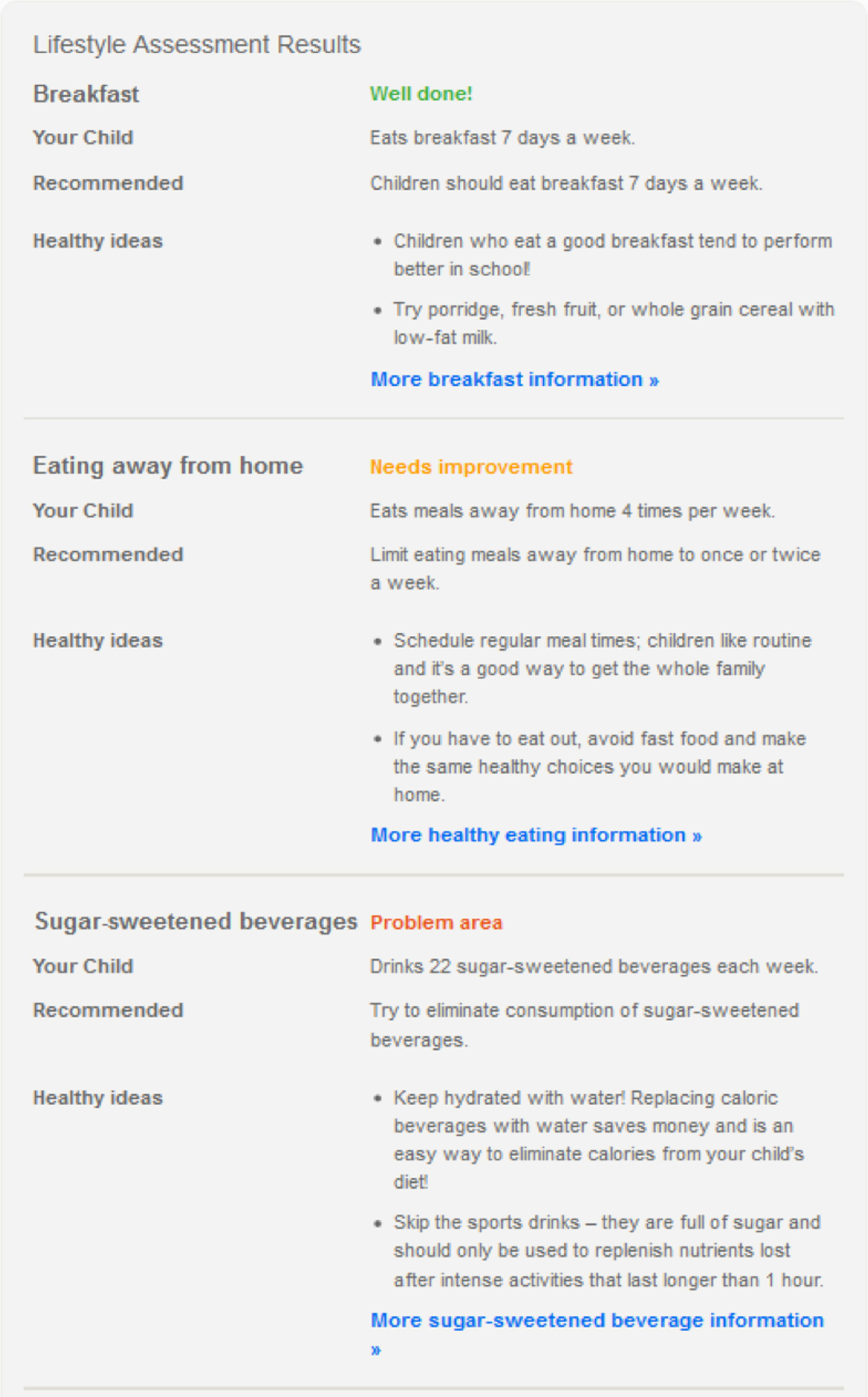

Effective screening and management of childhood obesity in primary care is limited by time constraints and a lack of specialist training. The use of appropriate evidence-based technologies could improve treatment of overweight children in this setting. We developed a simple online tool, Computer-Assisted Treatment of CHildren (CATCH), to aid primary care practitioners in assessing and treating childhood obesity, and evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of implementing this tool in general practice. The tool incorporates risk estimation models, developed from analysis of large population-based data sets to identify children at risk of obesity-related comorbidities who may need referral to secondary care, and provides families with tailored, evidence-based lifestyle advice. An uncontrolled pilot study with integral process evaluation was conducted at three general practices in north-west London to evaluate the feasibility of using CATCH in primary care, and to assess the acceptability of tool-assisted consultations to families and practitioners. Families with concerns about excess weight in a child aged 5–18 years (n = 14 children) had a consultation with a GP or practice nurse using CATCH. Families and practitioners completed questionnaires to assess the acceptability and usefulness of the consultation, and participated in semistructured interviews that explored user experiences. Most families and practitioners were satisfied with the tool-assisted consultations, and reported that the tool was easy to use, the personalised lifestyle advice was useful and the use of visual aids was beneficial. Families and practitioners identified a need for practical, structured support for weight management following the consultation. However, CATCH was trialled in only three practices in one city and warrants investigation in different settings.

Key findings

-

Risk estimation models for cardiovascular and emotional/behavioural obesity-related comorbidities perform moderately well to stratify risk in overweight and obese CYP in primary care, although further work is needed to improve models.

-

A consultation using an online tool is acceptable to families presenting at a GP clinic with concerns about excess weight in a child: the majority of families (n = 12; 86%) were satisfied with the CATCH-assisted consultations, and all respondents found the personalised lifestyle advice useful or somewhat useful.

-

In interviews, parents described the consultation as informative, and several referred to the consultation as a ‘wake-up call’ that alerted them to the severity of their child’s weight problem.

-

Parents felt that the use of visual aids, such as the BMI chart, to show the child’s weight status and printed lifestyle advice reinforced the practitioner’s message. Similarly, practitioners felt that the tool could enhance the impact of their advice. It was suggested that the tool could be used as positive reinforcement for patients with BMIs in the healthy range and who had a healthy lifestyle.

-

Practitioners were satisfied with the tool-assisted consultation and reported that the tool was easy to use.

-

All practitioners were in agreement that the tool (or a version of it) would be something that they would continue to use in the future and would like to see integrated into their clinical software system.

-

Families and practitioners identified a need for practical, structured support for weight management following the consultation: several parents suggested that follow-up appointments for monitoring and guidance on weight management would be beneficial.

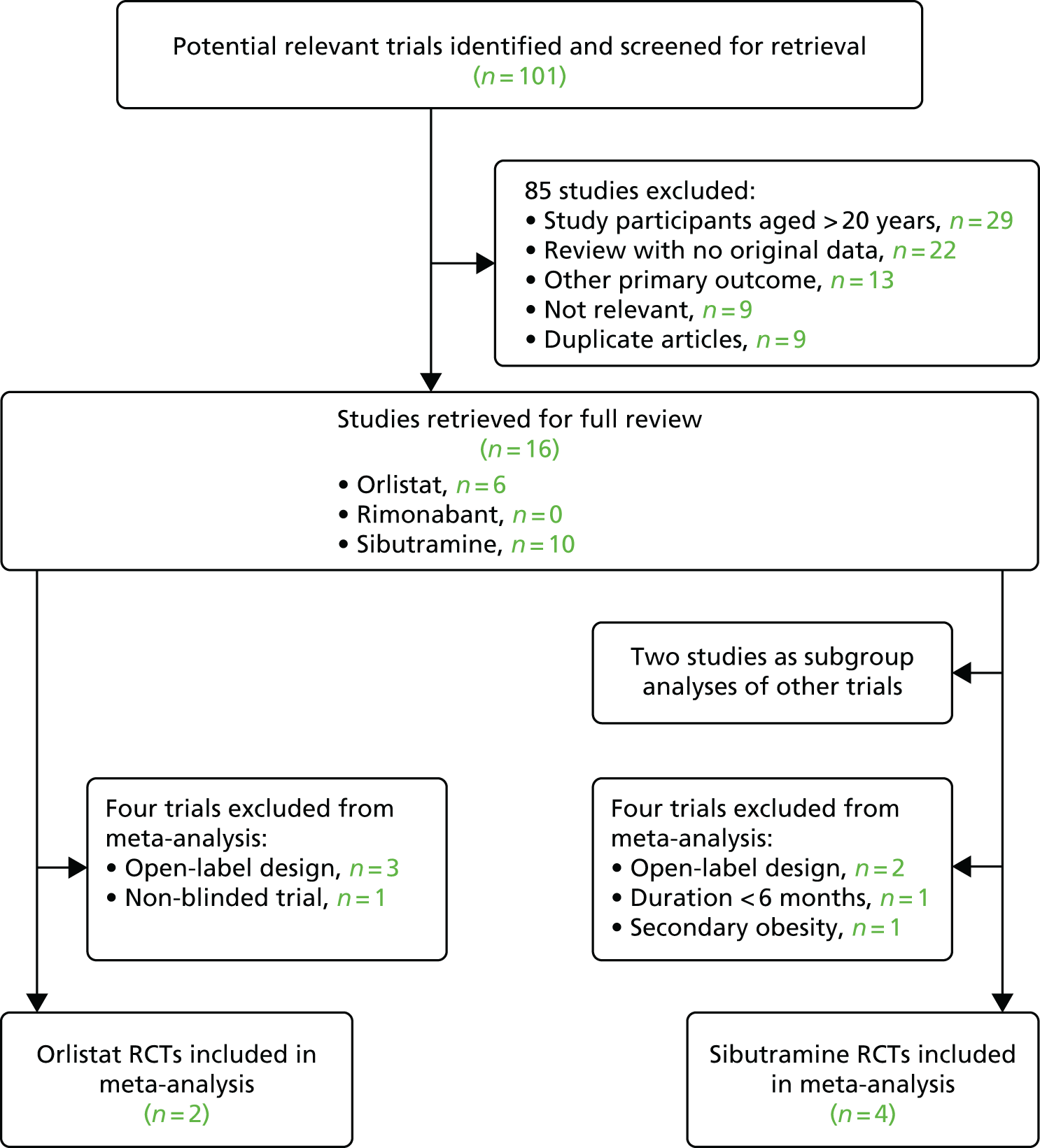

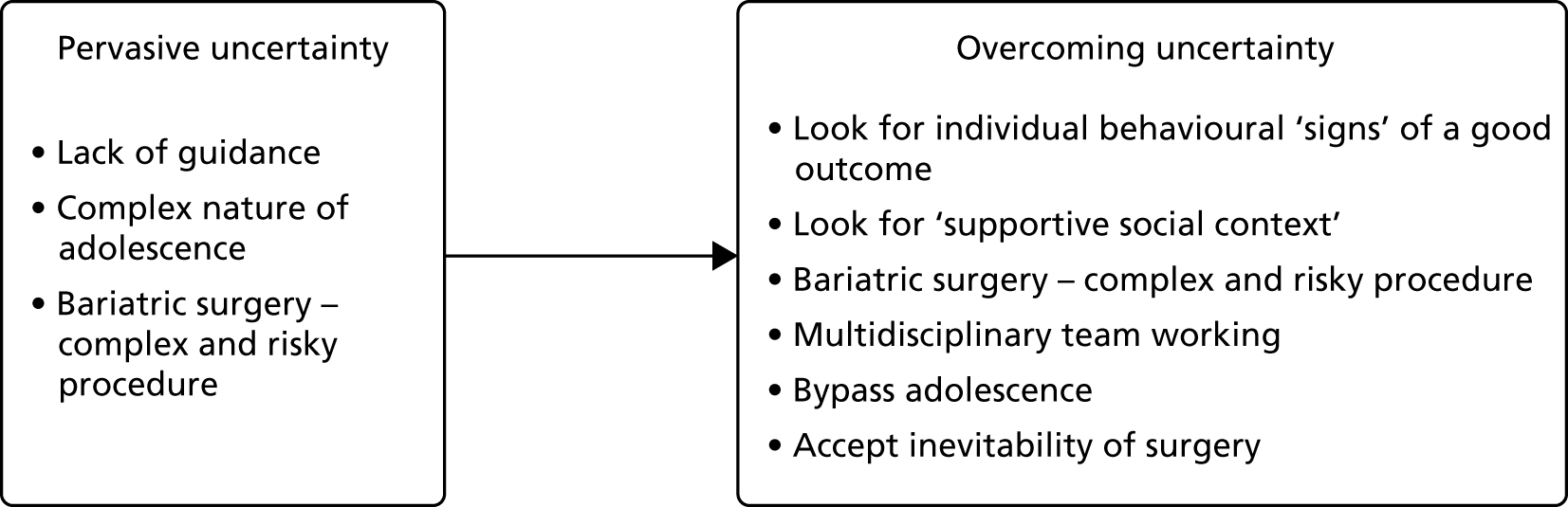

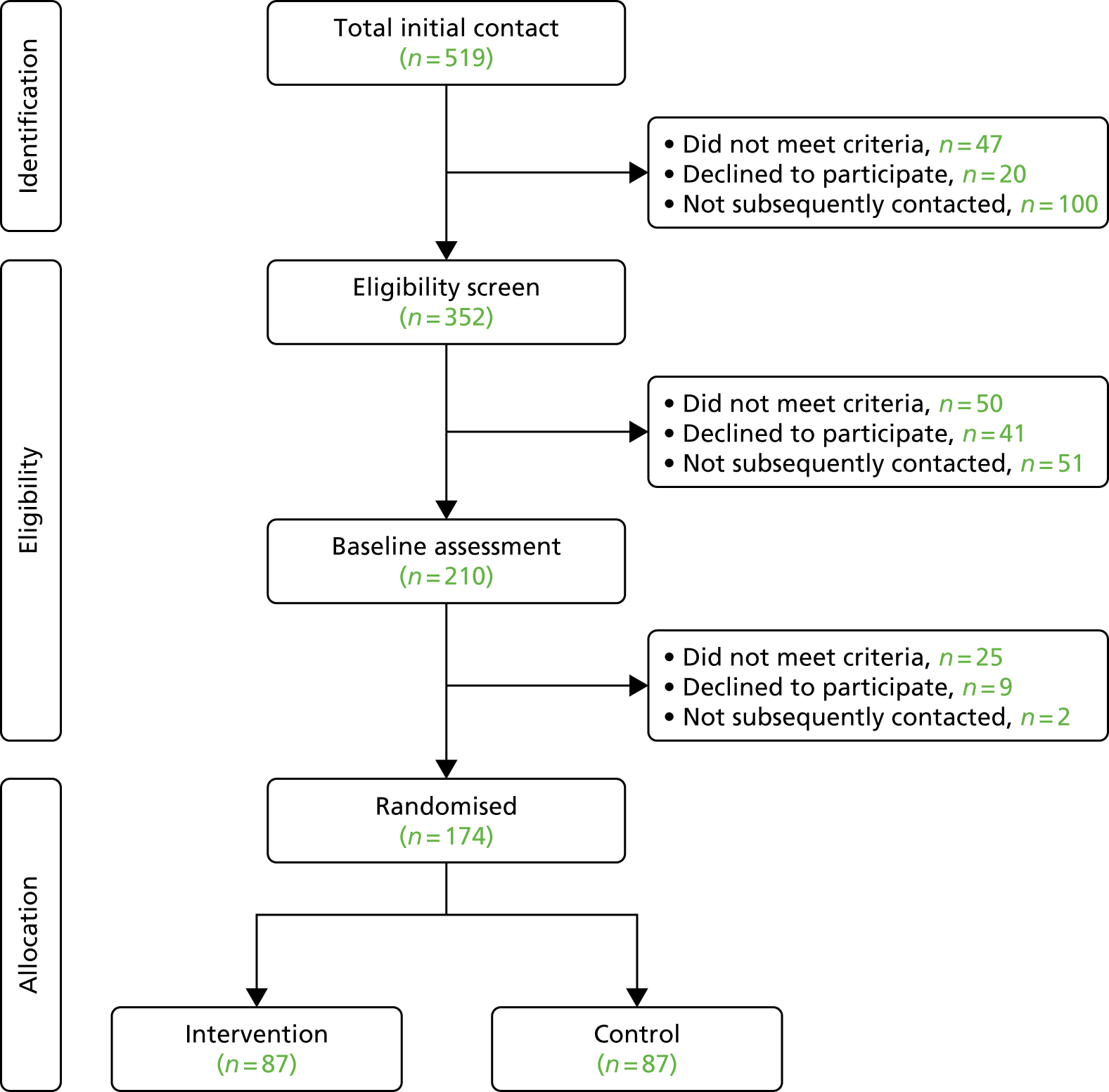

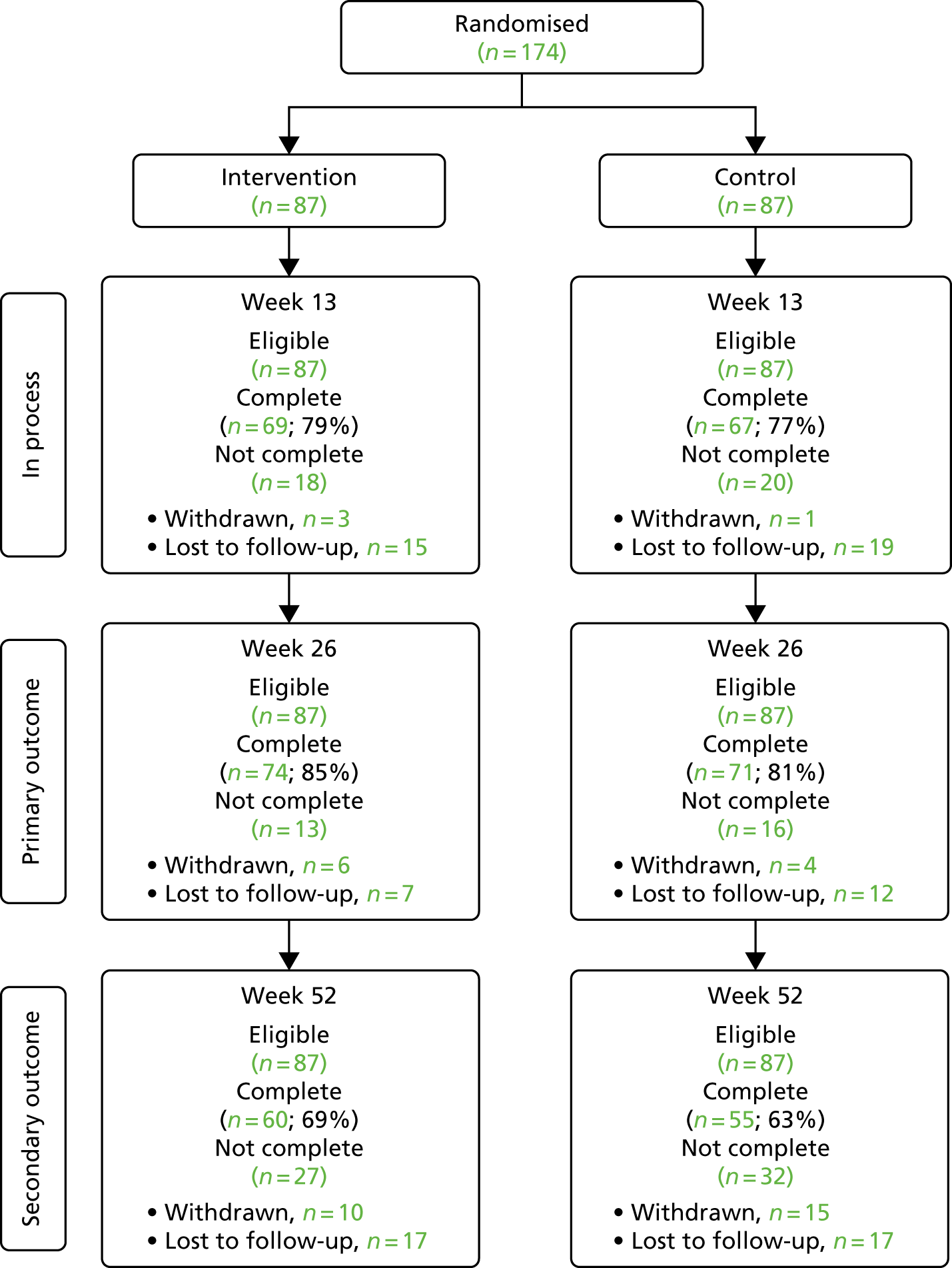

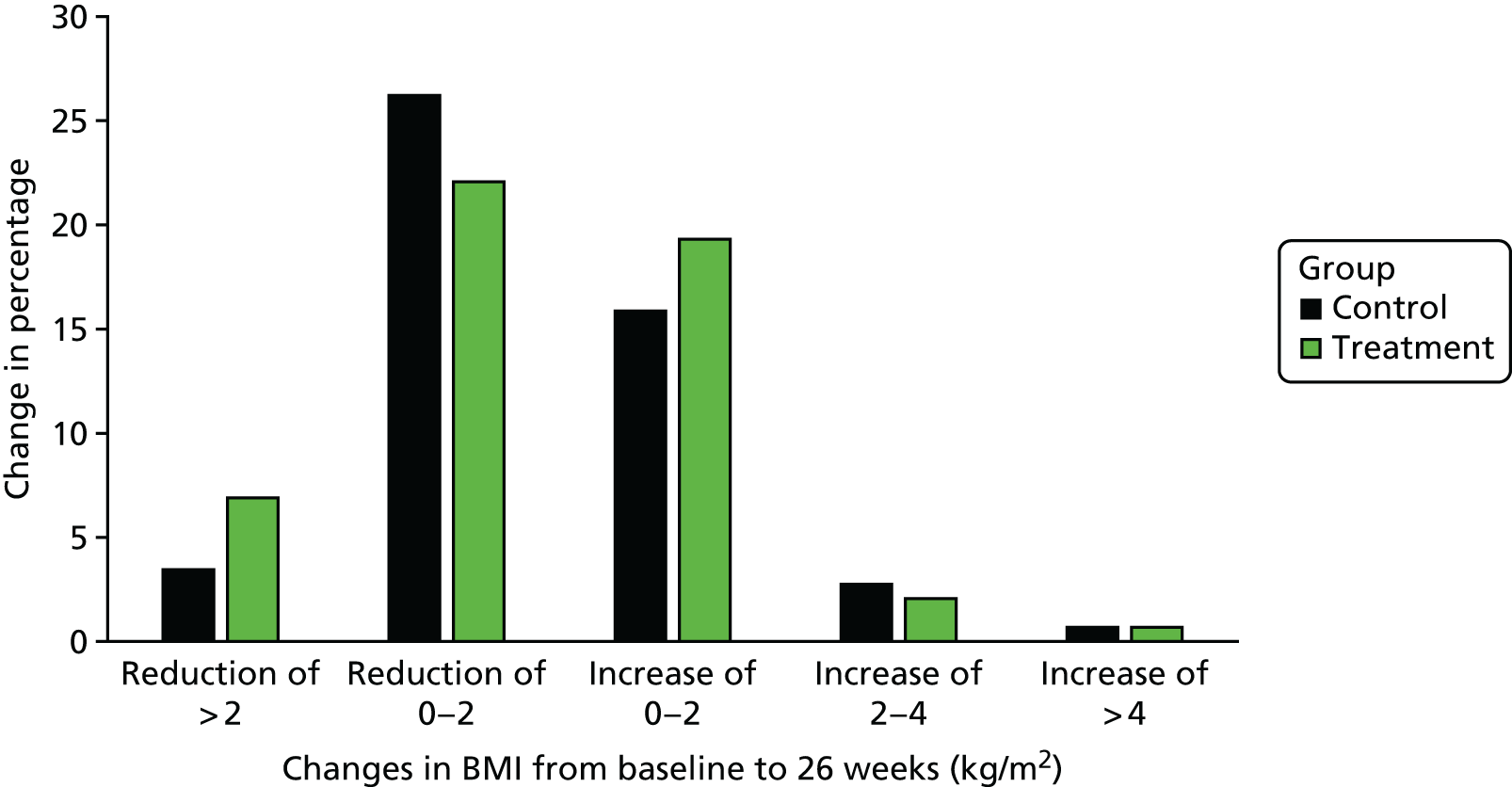

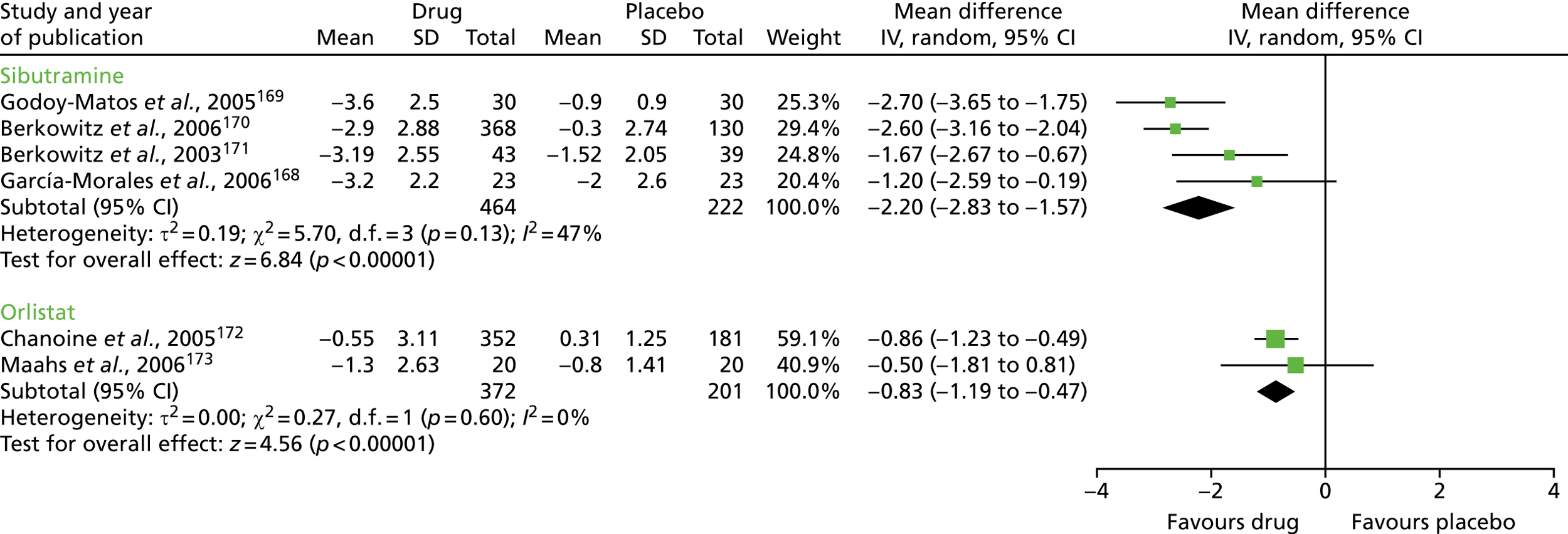

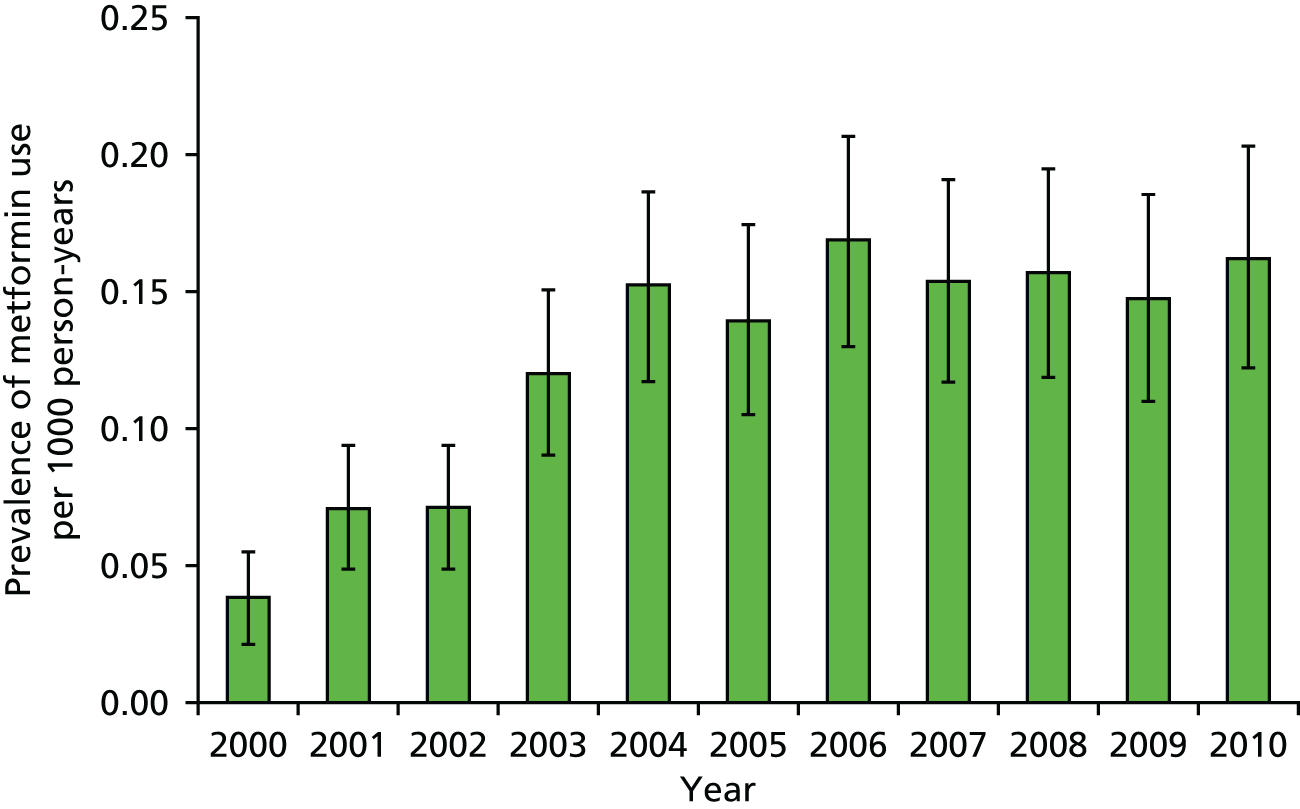

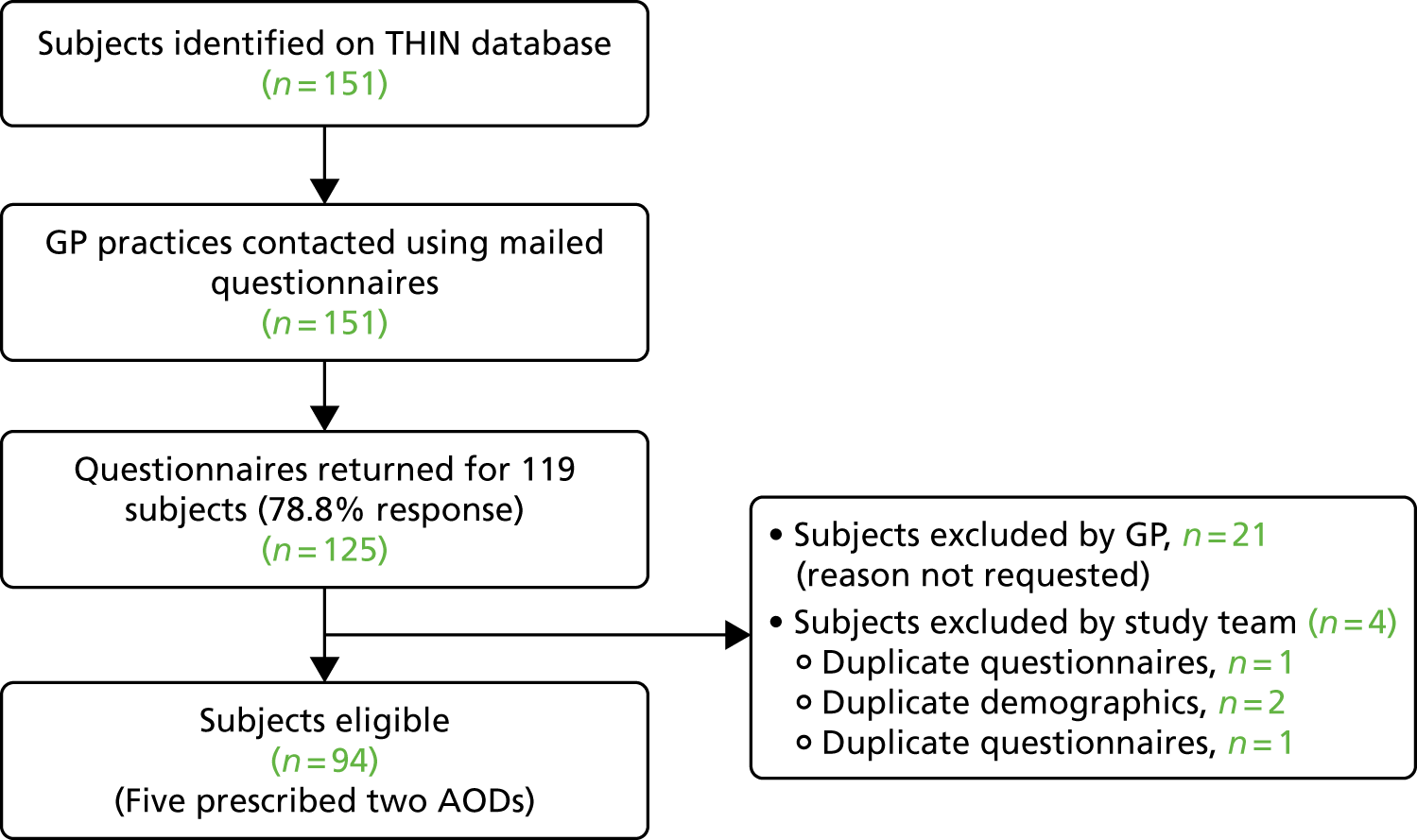

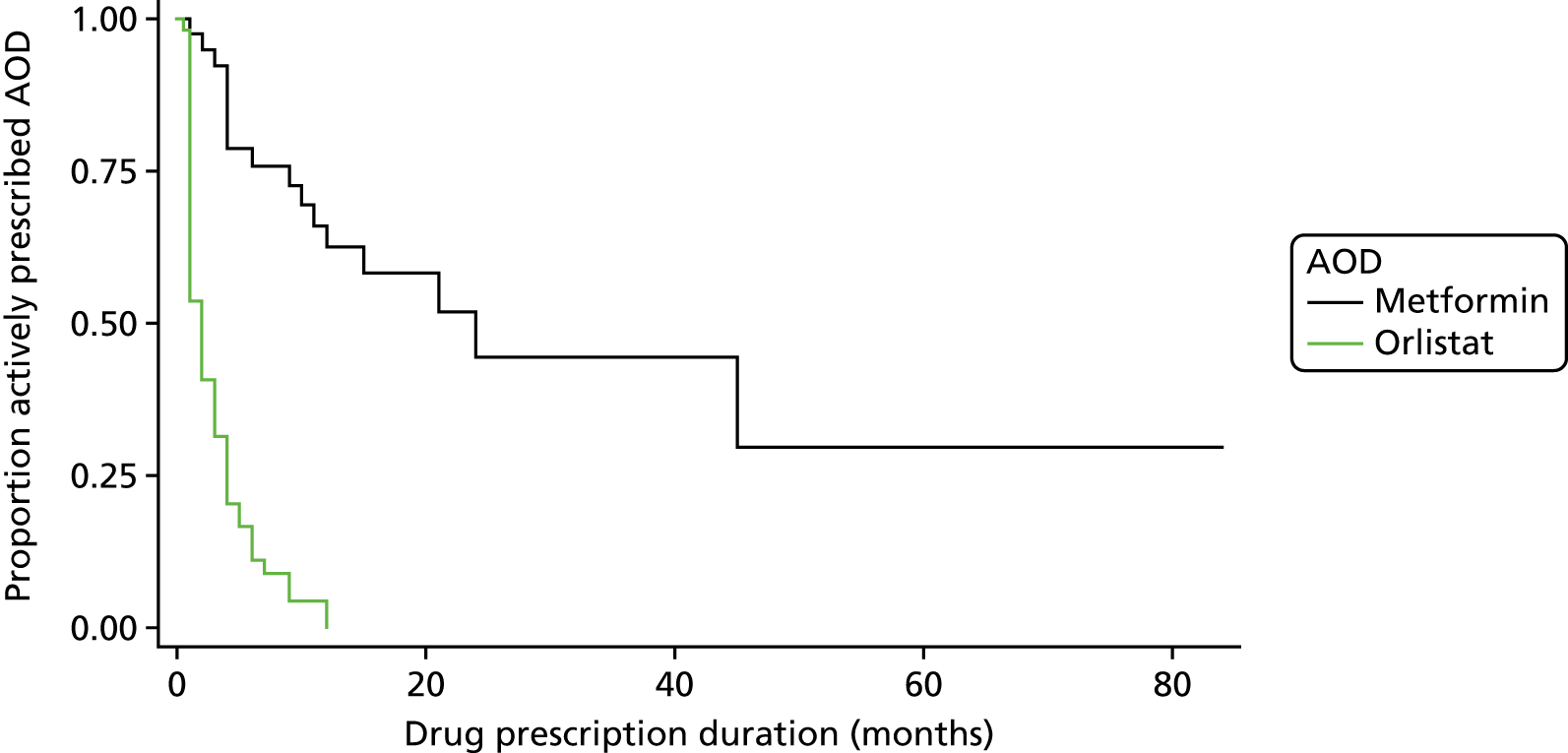

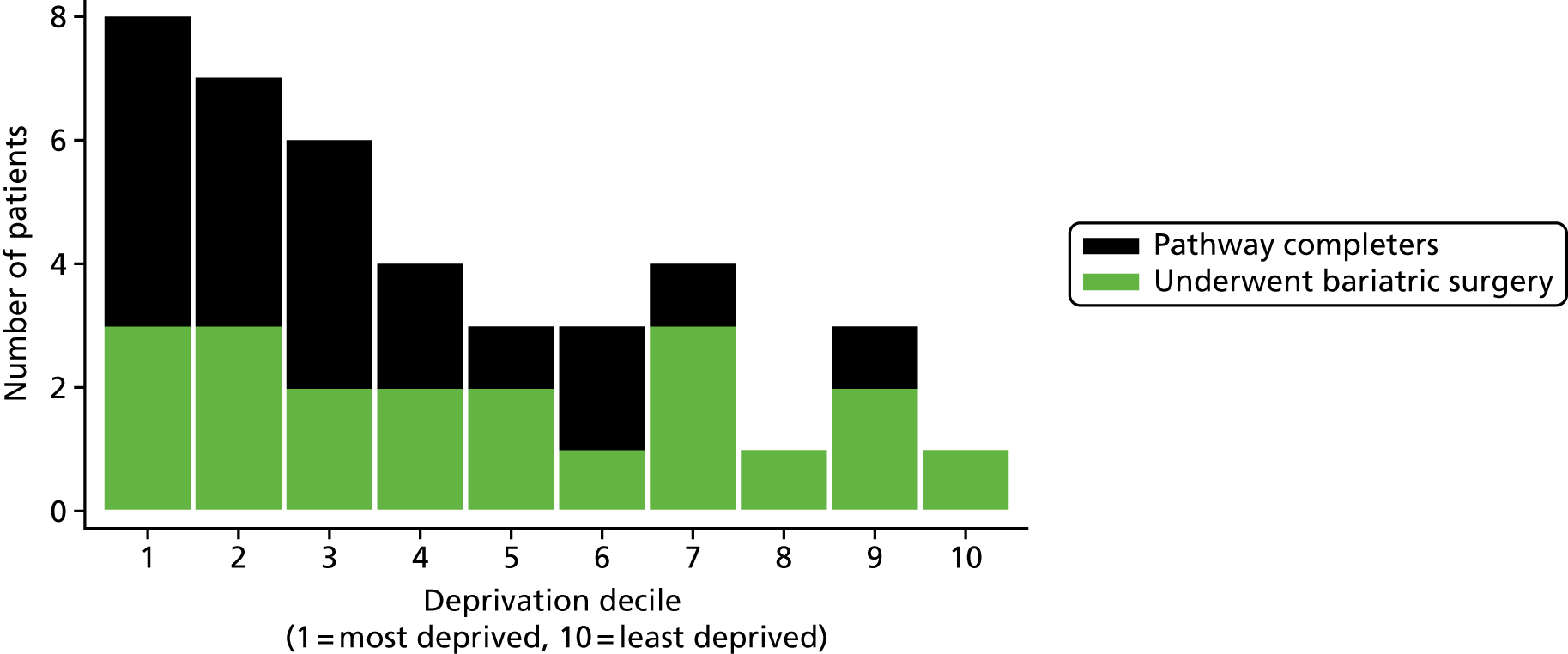

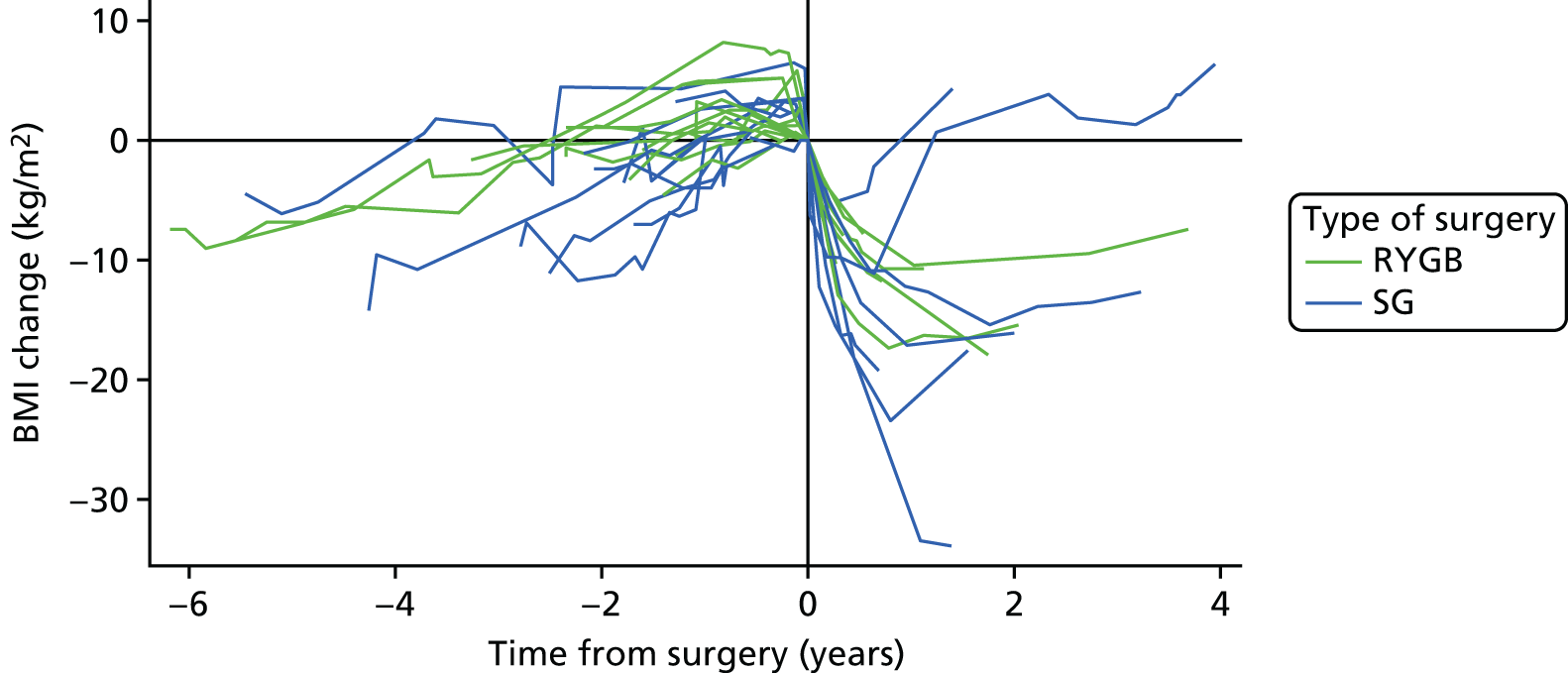

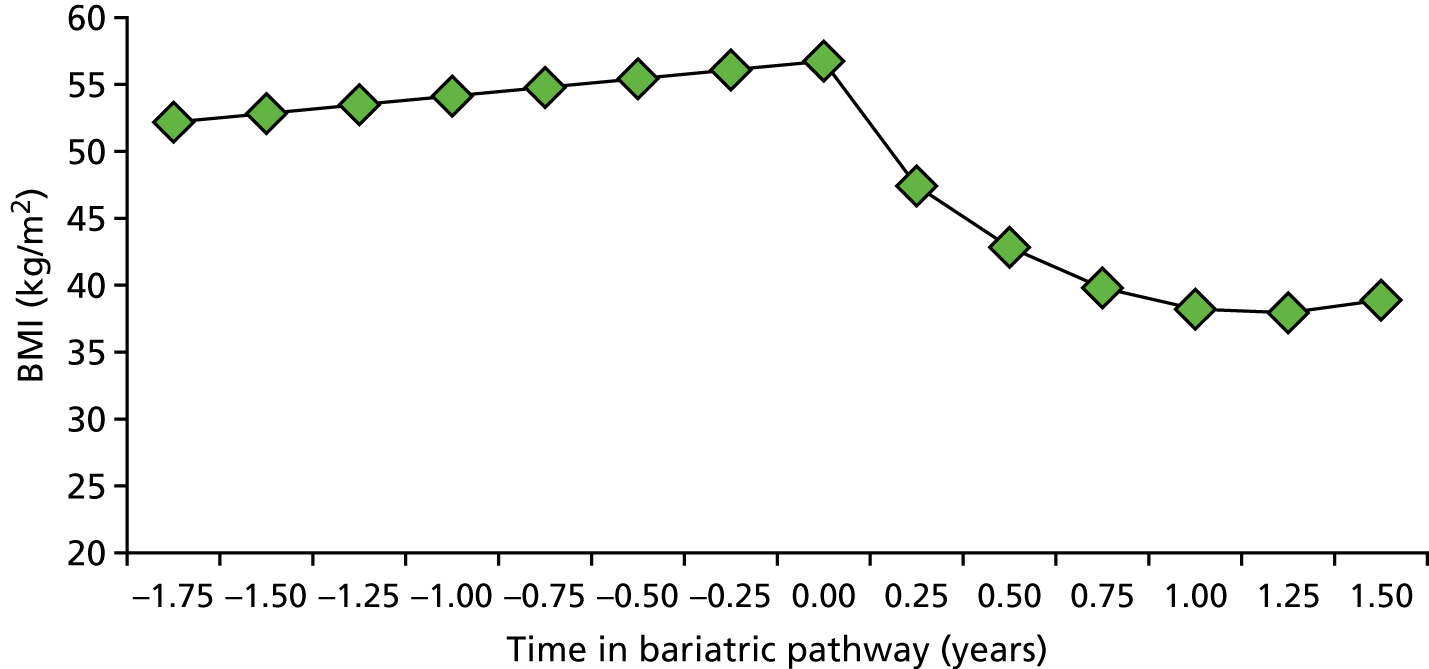

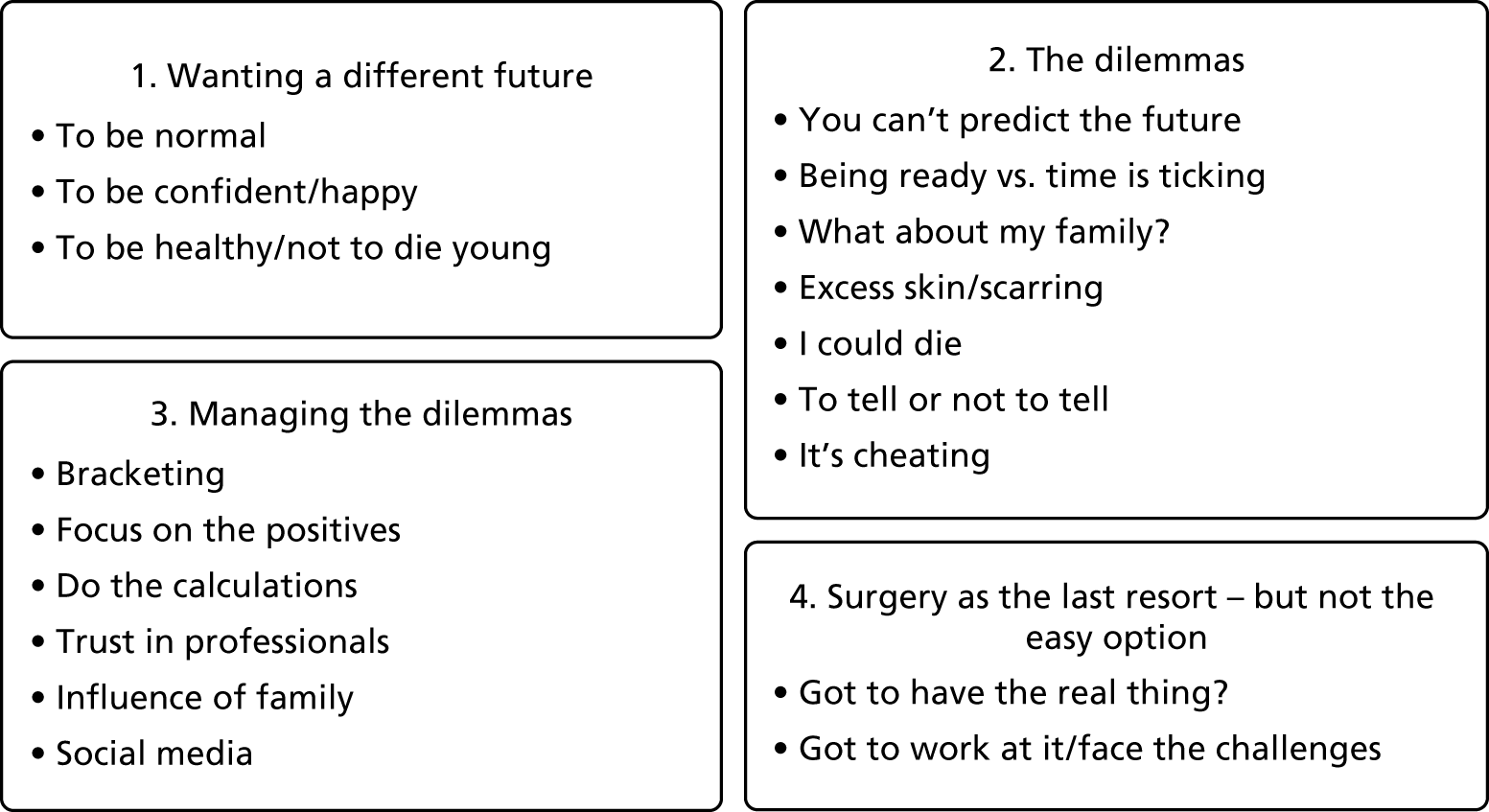

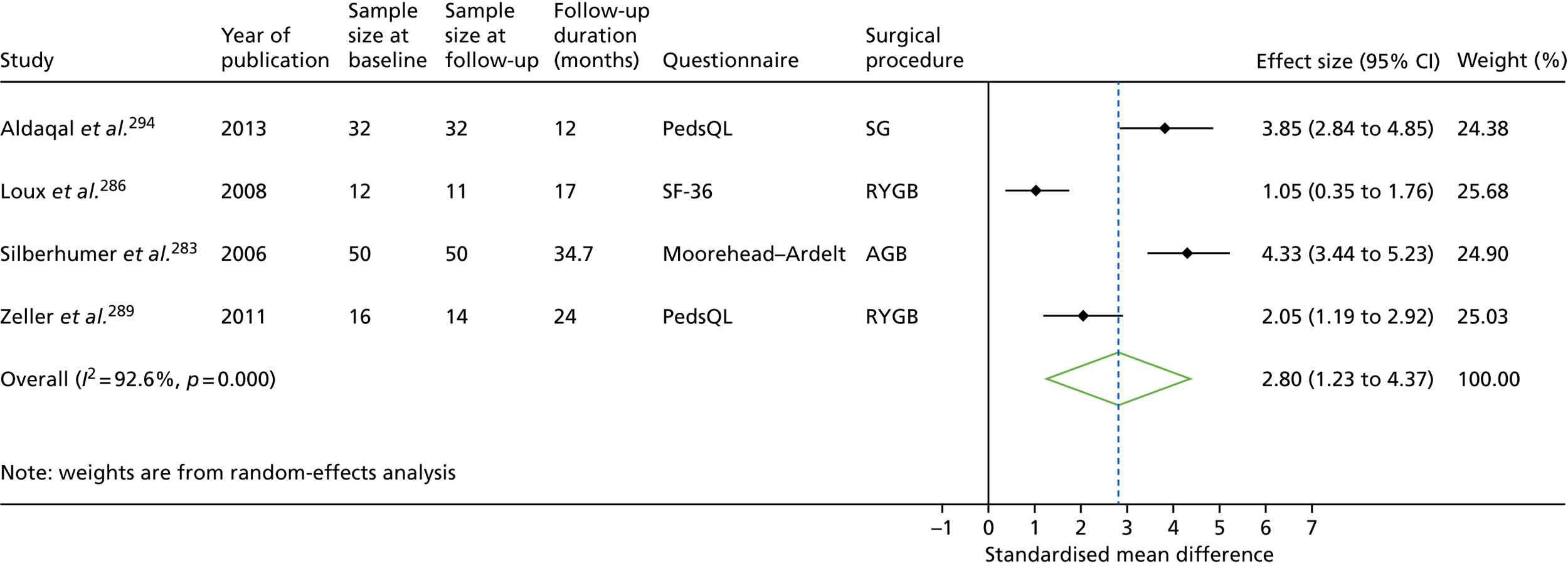

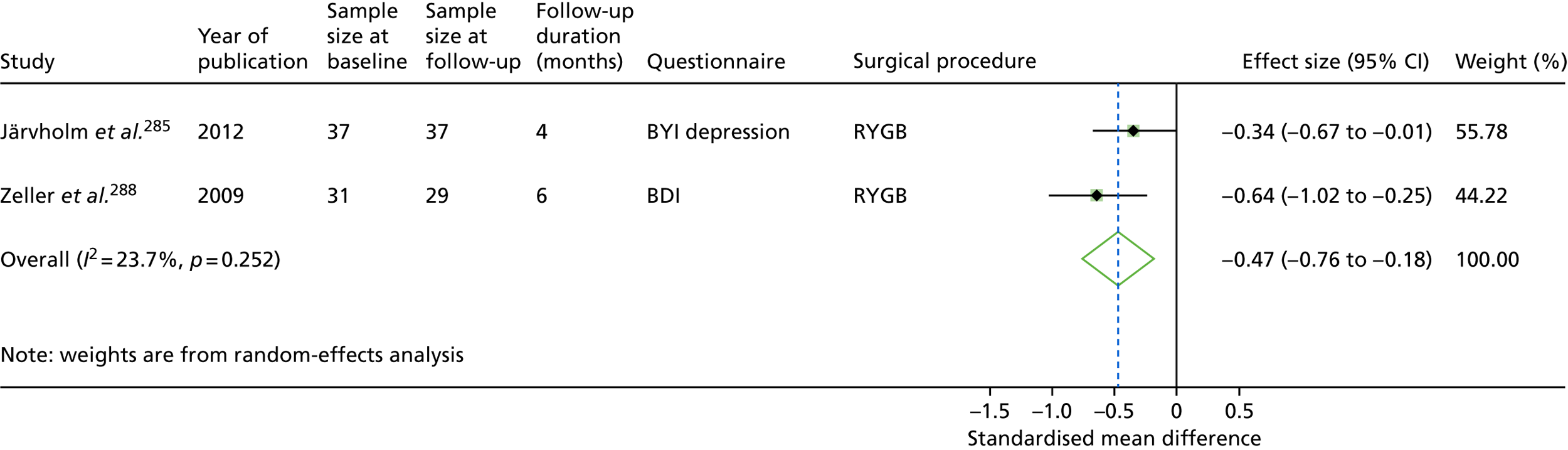

Background