Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0609-10171. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Karl Claxton reports personal fees from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd (Basel, Switzerland) and personal fees from HERON (Parexcel, Walton, MA, USA), outside the submitted work. Nicky Cullum reports non-financial support from Kinetic Concepts, Inc. (KCI; San Antonio, TX, USA), outside the submitted work. David Torgerson reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), outside the submitted work, and is director of a clinical trial unit funded by NIHR. Nicky Welton reports grants from NIHR, during the conduct of the study, and she is principal investigator for a research grant jointly funded by the Medical Research Council and Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Chetter et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Introduction

More than 10 million surgical operations are conducted every year in the NHS, with the majority of these involving a wound created by surgical incision. 1 Most incised surgical wounds heal by primary intention, when the wound edges are closely apposed and sutured, clipped or glued together. However, not all surgical wounds heal in this way; some wounds are left open after surgery and heal from the bottom up by the formation of granulation tissue (known as healing by secondary intention). The surgical wounds healing by secondary intention (SWHSIs) may be planned (e.g. after significant tissue loss for which primary closure is not possible, or in the presence of infection). Alternatively, healing by secondary intention may be unplanned when a primarily closed wound opens or ‘dehisces’ (full or partial separation of wound edges). These SWHSIs, also called ‘open surgical wounds’, may remain open for many months, are prone to infection, may prolong hospital stays, and necessitate further hospital admissions and surgeries (delayed primary closure) or skin grafting,2 all adversely affecting patients’ quality of life and incurring substantial NHS costs.

Prevalence of SWHSIs

Although SWHSIs are thought to be relatively common, when we planned this research there were few national or international data regarding their epidemiology. Two published studies estimated that SWHSIs constituted approximately 28% of all prevalent surgical wounds. 3,4 From data collected in Hull and East Yorkshire, UK, Srinivasaiah et al. 4 reported 136 open surgical wounds and 74 dehisced surgical wounds, from a total population of 590,000 (a point prevalence of 0.36/1000 population). Further UK cross-sectional data from Bradford, UK, reported 111 wounds that were classed by the study authors as open surgical wounds and a further 88 that were classed by the study authors as having broken down post surgery. 3 However, the size of the underlying population and, hence, point prevalence for these wounds was not reported. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of SWHSIs alongside in-depth investigation of their origin, natural history, typical treatments and impact on patients and health services was needed.

Details of patient and wound characteristics

Previous research on wound prevalence by Vowden and Vowden3 and Srinivasaiah et al. 4 focused on all wounds, rather than specific wound types. To the best of our knowledge, when we began this research, there was no high-quality information (national or international) describing patients with a SWHSI (age, sex, comorbidities, concomitant medications, surgical speciality); wound characteristics (site, size location, aetiology, whether or not the wounds were planned to be left open before surgery, frequency of wound infection); SWHSI treatments or healing rates in general and for specific patient groups (e.g. those with diabetes mellitus). Robust time to healing data were also limited and reports frequently presented inaccurately analysed data. 5–10 The generalisability of the existing research was also limited, as many trials reported time to healing rates in relation to subpopulations of SWHSI patients and treatments: one trial5 of perineal wounds and foam dressing, two trials7,8 of pilonidal sinus wounds and silastic foam dressing, and one trial10 of below-knee amputation wounds and plaster cast with silicone sleeve or elastic compression. The lack of systematic data describing SWHSIs and their treatment and outcomes was matched by a lack of knowledge about the impact of SWHSIs on patients’ quality of life or daily functioning, as well as the impact of these wounds on the use of health-care resources. This, in combination, made it almost impossible to assess the impact of SWHSIs and their treatments on patients, or to plan new research studies to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of potential new or alternative treatments or interventions.

The treatment of SWHSIs

Management of SWHSIs often involves daily or more frequent dressing changes, sometimes with packing of the wound cavity. Many different dressing options are available, from simple dressings such as gauze (which can be painful to remove) to more modern options such as foam, hydrocolloid and alginate dressings. Wounds may also be treated by debridement (the removal of foreign material and devitalised tissue) or by skin grafting. When this research was conceived, the type and frequency of treatments being used for SWHSIs was not known. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in SWHSI patients are infrequent and often poorly designed, underpowered, utilise surrogate outcomes and often report limited or incorrectly analysed healing data, making interpretation of these data incredibly difficult. For example, a multicentre RCT comparing the effects of zinc oxide with placebo mesh on secondary-healing pilonidal wounds was underpowered, recruiting only 64 participants (n = 33 zinc and n = 31 placebo), and although it did not detect a difference in median healing times (54 days, interquartile range 42–71 days for zinc; 62 days, interquartile range 55–82 days for placebo; p = 0.32), this may have been due to the lack of power. In the same study, fewer postoperative antibiotics (a surrogate marker of wound infection) were prescribed in the zinc oxide group (n = 3) than in the placebo group (n = 12) (p = 0.005). 11

In terms of evidence of effectiveness of different treatment options, Vermeulen et al. 12 explored the relative effects of dressings and topical agents for SWHSIs in a systematic review. They found only 13 RCTs, all of which were small, of poor quality and often conducted > 10 years previously. There was no evidence to indicate that the choice of dressing or topical treatment offered any benefit in terms of wound healing time, but the data were sparse. A systematic review, conducted to inform National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines on surgical site infection, investigated the effects of topical antiseptics and antibiotics (including impregnated dressings) on the risk of wound infection in SWHSIs. 13 The four included studies were small and provided generally uncertain evidence on a range of uncommon treatment options. The guidelines recommend that chlorinated lime and boric acid [Edinburgh University Solution of Lime (EUSOL)] and gauze, moist cotton gauze or mercuric antiseptic solutions should not be used to prevent surgical site infection in the management of SWHSIs. 13

Increasingly, more advanced and costly wound treatments have been extensively adopted into clinical practice, with inadequate supporting evidence. One example is negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT), a device that applies a carefully controlled negative pressure (or vacuum) to the dressing, moving tissue fluid away from the treated wound area into a disposable canister. 14 The canister is removed and replaced either when it becomes full or at least once per week. The device is generally used as part of the SWHSI treatment pathway, rather than to the point of healing, and can be administered and removed by both nurses and surgeons.

Cost of treating SWHSIs

Surgical wounds healing by secondary intention can be large and may produce a significant volume of exudate, which can be difficult to manage, and frequent, time-consuming, dressing changes are common. In addition, SWHSIs must also be protected from infection and trauma during healing. It has been suggested that SWHSIs are at high risk of postoperative infection, with the wound providing an ideal environment for bacterial proliferation, which may be associated with delayed healing. 15 These factors, and the possible need for further surgery, suggest that the costs of treating patients with SWHSIs could be substantial. The lack of available epidemiological evidence in relation to SWHSIs had, however, made it difficult to ascertain the health and social care costs of treating these wounds.

SWHSIs: the patients’ perspective

The lack of systematic data describing SWHSIs, their treatment and outcomes was matched by a scarcity of knowledge about the impact of SWHSIs on patients’ quality of life. Little was known regarding patients’ perspectives and experiences of living with a SWHSI, or their views, expectations and concerns regarding management and outcomes.

SWHSIs: the clinicians’ perspective

A variety of clinicians, including surgeons, tissue viability nurses and general practice nurses, are all commonly involved in the management of patients with SWHSIs. As previously stated, there is a dearth of high-level evidence to guide the management of these patients, particularly regarding the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different treatments or interventions. Greater clarity is required regarding assessment of these wounds and the factors that influence management decisions.

Summary

In summary, this research programme was undertaken recognising that SWHSIs may be common and costly but that there was a need for further exploration of the extent, nature, outcomes and impact of these wounds. The lack of international epidemiological data regarding these patients seriously impairs the development of new research studies in this area. There was also huge uncertainty regarding SWHSI management. Options ranged from inexpensive simple dressings to the more complex and costly NPWT, but accurate data regarding the frequency of use of specific treatments was non-existent. In addition, all treatment options for SWHSIs lacked robust, supportive evidence bases in terms of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and the impact on patients’ quality of life. As a result, clinicians and patients were uninformed about how to care for SWHSIs and, specifically, which treatment options were most effective and offered the best value for money. The need for research to fill these evidence gaps was also highlighted by the NICE guidance. 13

Given the number of treatment options available, it is important that patients, carers and health professionals are involved in trial design, including the selection of significant outcome measures, and that research is conducted through sufficiently powered trials to detect significant differences in healing rates between treatments. However, the enormous cost of conducting the trials required to fill the evidence gaps means that a rush to undertake such studies, before obtaining additional key intelligence, would be hugely inefficient. There were several important unknowns: information about the natural history and epidemiology of SWHSIs; which treatments were being used most commonly and, thus, should be evaluated; whether or not the decision uncertainty associated with various treatments justifies an expensive trial; and whether or not a trial is feasible. In addition, little was known about which outcomes matter to patients with SWHSIs and what the desirable treatment characteristics are from the perspective of the staff treating them. We have undertaken research to generate vital data regarding an important, costly and hugely under-researched health problem. The research findings will aid in planning service delivery and future research, including economic modelling and primary studies.

Aims

We aimed to characterise and quantify SWHSIs, their outcomes and impact, and to begin to identify effective SWHSI treatments. The core aims of the research were achieved via four interdependent workstreams. The links between the four workstreams are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the whole research programme and its inter-relationships.

Workstream 1

Workstream 1 aimed to describe the number, characteristics, current treatments, impacts and health outcomes of patients with SWHSIs. This was achieved using an initial prevalence survey and a subsequent inception cohort of patients with a SWHSI to collect naturalistic data regarding treatments used, rates of healing, adverse events and quality-of-life changes.

Workstream 2

Workstream 2 aimed to use all available research data to estimate the cost-effectiveness of current treatments for SWHSIs, as identified in workstream 1, and was completed using evidence synthesis and decision-analytic modelling. If assessments of cost-effectiveness suggested that there was decision uncertainty (i.e. uncertainty about which treatment offers best value to the NHS), we would extend analyses to assess whether or not investment in future research on treatments for SWHSIs was likely to be worthwhile and, if so, what research would offer best value for money.

Workstream 3

Workstream 3 aimed to determine the impact of SWHSIs on patients, specifically their perspectives and experiences of living with a SWHSI, of wound management and relevant wound outcomes. In addition, this workstream aimed to determine NHS professionals’ views about SWHSI treatments and important outcomes to measure treatment effects. This was achieved through qualitative interviews with both patients and NHS professionals.

Workstream 4

Workstream 4 aimed to determine the feasibility of conducting further primary research on SWHSIs through a pilot, feasibility RCT.

This synopsis describes the results of our findings from all four workstreams. Publications arising from this research programme are listed in the Acknowledgements.

Patient and carer involvement

Involvement of patients and carers was identified at the outset as a priority for this research.

In workstream 1, two patient representatives contributed to the design of documentation for the cohort study and provided their perspective on study processes, questions and data interpretation through attendance at associated workstream meetings. A dedicated section of the meeting was devoted to patient feedback and the meeting was followed by an informal discussion between the research lead, a study research nurse and the patient representatives. When possible, any comments received from the patient representatives were incorporated into relevant study documentation or procedures. A newsletter to inform participants about the progress of the research was initiated by the patient representatives who assisted in the design and review of this document.

In workstream 3, the input of patient and carer representatives was crucial in the design and piloting of the interview topic guide, and the interpretation of the findings arising from the qualitative interviews, including review of the main study findings and input into the writing of the results. A summary of the results of the qualitative work was subsequently sent to participants, following review by the patient representatives.

Patient and carer involvement for this programme of work culminated in the development of a ‘Patient User Group’, convened at the start of workstream 4. This group was developed, following experiences in workstream 1, to increase the number of patient representatives involved and so reduce any burden on the two initial representatives involved. Ten patients or carers with experience of SWHSIs were invited to attend the inaugural meeting in March 2015, with five representatives subsequently attending. This resulted in a diverse group, with a mix of age, sex, SWHSI history and previous research experience. A further two meetings were convened during workstream 4 to provide comment on patient-facing documentation and study procedures and to discuss the interpretation of the results of the pilot, feasibility RCT. As in workstream 1, when possible, any comments received from the patient representatives were incorporated into study documentation or procedures. One member of the group was subsequently recruited to act as a patient and public representative for the workstream 4 Management Group meetings. The member provided a patient perspective on the trial processes and documentation, and made substantial contributions. This patient representative also contributed to and reviewed the summary of workstream 4 for this report and the associated papers arising from this workstream. In addition, a lay representative was also included in the workstream 4 Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee to provide patient input on data quality and patient safety and to advise on any issues arising during the trial.

The inclusion of patient and carer representatives has been instrumental in shaping this research programme and will undoubtedly be beneficial in shaping future research in this area. The mix of patients and carers providing input to the individual workstreams and in the Patient User Group provided the research programme team with a diverse range of experiences to draw on and consider when making decisions in relation to this research programme. Given the number of patient and public members involved in the various stages of this programme, there was naturally a range of views noted regarding patient and carer experiences, study procedures and documentation; however, in the vast majority of cases there was a consensus of opinion regarding progression of this research.

Workstream 1: cross-sectional survey and cohort study of SWHSIs

The dearth of national and international clinical and research information regarding the prevalence, patient characteristics and treatments for SWHSIs meant that we did not know the extent and nature of these wounds, how and where they were managed or the associated outcomes. To enable accurate assessment of time to healing and treatment use, we planned an inception cohort study to address key uncertainties. An inception cohort approach was essential to allow accurate assessment of SWHSI duration. Planning the cohort study was difficult, however, as there were no data regarding where most SWHSIs occurred. For example, were most SWHSIs left open in theatre or did they subsequently break down in hospital or in the community? We needed basic information regarding the numbers of patients with SWHSIs and their location in order to put adequate resources in place for the inception cohort study. We therefore preceded the cohort study with a cross-sectional survey. This approach facilitated the gathering of initial intelligence to support subsequent work and, in addition, the use of a cross-sectional design allowed us to estimate a point prevalence estimate for SWHSIs. The cross-sectional survey has been published (see Appendix 1). 16 The cohort study has also been published (see Appendix 2). 17

Cross-sectional survey

Objectives

The cross-sectional survey aimed to capture information to aid the design of the cohort study. This included the:

-

number of patients with a SWHSI (point prevalence), their characteristics and the NHS settings where they were receiving treatment

-

proportions of SWHSIs planned prior to surgery and those that occurred as a result of wound breakdown (dehisced) after surgery.

Information was also collected on typical durations of SWHSIs, the types of surgery preceding the SWHSI and the treatments received by patients.

Methods

The cross-sectional survey was conducted over a 2-week period (spring 2012) in primary, secondary and community care settings in Hull and the East Riding of Yorkshire, UK. We asked health-care professionals to identify patients on their case load who had at least one SWHSI (i.e. a wound deliberately left open owing to infection, swelling, contamination or empty tissue space, a wound initially closed but subsequently dehisced or a wound arising from surgical debridement). When patients had multiple SWHSIs, the largest wound was deemed to be the ‘reference SWHSI’. Detailed data were collected, including patient and wound characteristics, health-care provider, clinical and surgery details, and treatment events (see Appendix 3). As this survey was limited to secondary use of routinely collected information, Research Ethics Committee approval was not required. 18 Approval was, however, obtained from associated NHS trusts prior to commencement of data collection.

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were summarised as frequencies and proportions, whereas continuous variables were summarised as medians and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and ranges. The usual resident regional population aged ≥ 20 years, as taken from the 2011 census, was used as the denominator when calculating point prevalence. 19

Results

Following removal of duplicate cases (identified through age, ethnicity and wound characteristics), data were analysed for 187 patients with a SWHSI. In total, 62% of patients were male, 95.2% were of white British ethnicity and the median age was 58.0 years (range 19–90 years), as detailed in Table 1.

| Variable | Patients (N = 187) |

|---|---|

| Sex, n/N (%) | |

| Male | 116/187 (62.0) |

| Female | 62/187 (33.2) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median (95% CI) | 58.0 (55 to 61) |

| Minimum–maximum | 19.0–90.0 |

| Missing, n/N (%) | 3/187 (1.6) |

| Ethnicity, n/N (%) | |

| White British | 178/187 (95.2) |

| Asian Indian, Asian other, black other, other mixed background, white other, white and Asian and not specified | 7/187 (3.7) |

| Missing | 2/187 (1.1) |

| Number of SWHSI per patient, n/N (%) | |

| 1 | 164/187 (87.7) |

| 2 | 16/187 (8.6) |

| 3 | 4/187 (2.1) |

| 4 | 1/187 (0.5) |

| Missing | 2/187 (1.1) |

We estimated the point prevalence of treated SWHSIs as 4.1 per 10,000 population (95% CI 3.5 to 4.7 per 10,000 population), using the resident regional population value as the denominator. 19 The observed maximum number of SWHSIs per patient was four (1/187, 0.5%), with the majority of patients (164/187, 87.7%) having only one SWHSI. Patients were more frequently treated in community than in secondary care settings (109/187, 58.3% vs. 56/187, 29.9%, respectively), with the remaining patients treated within primary care (8/187, 4.3%) or other care settings (2/187, 1.1%). There were 12 patients (12/187, 6.4%) for whom treatment location was not recorded.

We found that almost half of the SWHSIs were planned to heal by secondary intention (n = 89, 47.6%) and 77 (41.2%) were primarily closed wounds that had subsequently dehisced. A further six wounds (3.2%) were surgically opened, six (3.2%) arose for other reasons [surgical debridement (n = 2, 1.1%), sutures removed and left open to heal (n = 1, 0.5%), skin graft failure (n = 1, 0.5%), non-healing wound (n = 1, 0.5%) and necrotising fasciitis requiring debridement (n = 1, 0.5%)] and for nine patients (4.8%) the information was not known or was missing. The median time from surgery to wound breakdown was 9 (95% CI 7 to 10) days.

In addition, we found that the median duration of wounds at the point of survey was 28 days (95% CI 21 to 35 days). Fully dehisced SWHSIs had the longest median duration (35 days, 95% CI 15 to 150 days), and those with long wound durations were most frequently treated within primary care (median duration 112 days, 95% CI 21 to 469 days) and community settings (median duration 35 days, 95% CI 28 to 56 days) (Table 2).

| Wound duration (days)a | Treatment setting | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Community | Secondary care | Primary care | |

| n/N | 89/109 | 56/56 | 7/8 |

| Median (95% CI) | 35.0 (28 to 56) | 14.5 (6 to 21) | 112.0 (21 to 469) |

| Minimum–maximum | 1–560 | 1–238 | 21–896 |

| Missing, n (%) | 20 (18.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) |

In total, we identified 43 different surgical procedures that preceded the development of a SWHSI. The most common surgical procedures were for pilonidal sinuses/abscesses (28/187, 15.0%), lower-limb amputations (19/187, 10.2%) and laparotomy with bowel resection (19/187, 10.2%). As detailed in Table 3, the most common surgical specialties associated with SWHSIs were colorectal (80/187, 42.8%), plastic (24/187, 12.8%) and vascular (22/187, 11.8%) surgery.

| Surgical specialty | Wound category (n) | Total (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned | Partially dehisceda | Fully dehisceda | Surgically openeda | Other | Not known | Missing | ||

| Colorectal | 51 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 80 |

| Plastics | 5 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 24 | |||

| Vascular | 14 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 22 | |||

| Orthopaedic | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 14 | |

| Upper GI tract | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 13 | ||

| Cardiothoracic | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |||

| Urology | 3 | 3 | 6 | |||||

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Otherb | 5 | 1 | 6 | |||||

| Breast | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Missing | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||||

At the time of the survey, most patients (184/187, 98.4%) were receiving active treatment for their wound. Dressings were the most common single treatment, being received by 169 (93.4%) patients. Eleven (6.1%) patients were receiving NPWT (10 patients in secondary care and one patient in the community setting). One patient (0.5%) was receiving larval therapy.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study is the first to characterise SWHSI patients and their wound origin, duration and treatment.

This study provided initial data on wound and treatment characteristics, for which there were limited data when the research programme was conceived. Identifying common surgical specialties (within secondary care) that lead to SWHSI, that almost 50% of SWHSIs were planned and that the most common treatment location was the community helped us to plan recruitment strategies (i.e. identification of planned SWHSIs in advance of surgery) and time frames for both the cohort study and the subsequent pilot, feasibility RCT (workstream 4), and will also help to inform research studies in the future.

A total of 43 surgical procedures preceding SWHSIs were identified, with common associated surgical specialties being colorectal, plastic and vascular surgeries. SWHSIs occur in a wide range of specialties; however, there are specific populations in whom SWHSIs more frequently occur and so these may be appropriate as the focus of further research.

Data collected in relation to wound duration at the point of the survey have enabled us to estimate the duration of follow-up required to capture healing events. Again, this information helped to inform our design of the cohort study and pilot, feasibility RCT (workstream 4).

When this research programme commenced, we had identified the need for a rigorous population-based estimate of SWHSI prevalence. This study has provided a population-based estimate of treated SWHSI prevalence, which has suggested that these wounds are relatively common. Given the prevalence observed, this therefore supports the need for further research into SWHSI epidemiology and treatments.

Cohort study

Objectives

Following the cross-sectional survey, we conducted a prospective, inception cohort study with the following objectives:

-

to investigate the clinical characteristics of patients with SWHSIs from the point of inception of the wound

-

to clearly delineate the clinical outcomes of patients with SWHSIs over the lifetime of their wound, with a particular focus on time to wound healing and associated determinants

-

to describe the types of treatments received by those with a SWHSI

-

to assess the measurable impact SWHSIs have on patients’ quality of life.

Methods

The cohort study was conducted over a 21-month period (18 February 2013 to 30 November 2014) in primary, secondary and community care settings at eight study sites across Yorkshire and the Humber, UK. Prior to commencement of the study, approval was obtained from Yorkshire and Humber – Humber Bridge Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/YH/0350) and from the associated NHS trusts.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had a SWHSI, defined as ‘an acute (< 3 weeks’ duration) open wound, resulting from surgery and requiring treatment, which was healing from the bottom up by the formation of granulation tissue’. When patients had multiple SWHSIs, the largest wound was deemed to be the ‘reference SWHSI’ and detailed data were collected for this one wound. Health-care professionals in primary, secondary and community care settings initially identified and screened patients for eligibility. Clinical areas identified as having a high prevalence of SWHSIs were targeted for recruitment, including colorectal and vascular surgical wards. Patients meeting the eligibility criteria were approached for informed consent by a research nurse before any data collection. A formal sample size calculation was not required for this study, although it was anticipated that 443 participants could be recruited over a 6-month period.

Data, including patient, surgery and wound information, quality of life and a wound photograph (used to assess wound features), were collected at baseline. Participants were followed up every 1–2 weeks for a minimum of 12 months and a maximum of 21 months to collect key clinical outcome data [including healing through either participant self-reporting or clinician observation, defined as ‘complete epithelial cover in the absence of a scab (eschar)’]; key clinical events such as surgical site infection (in accordance with Public Health England guidance on surgical site infection surveillance) or hospital admission;20 SWHSI treatments received; and any changes to a participant’s study involvement, including death. To ensure accurate data collection, healing status was further verified through a home visit to a sample of patients (10–20%). Participants also completed quality-of-life [Short Form questionnaire-12 item (SF-12)21 and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)22] and pain [Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)23] assessments via postal questionnaires at 3-monthly intervals for a minimum of 12 months and a maximum of 21 months.

Data analysis was conducted using Stata® version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Summary statistics for all variables were generated. Association with healing was examined for prespecified variables and multivariate logistic regression analyses conducted. Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards model analyses were used to examine time to event data. SF-12,21 EQ-5D-3L22 and BPI23 data were summarised, with SF-1221 data subsequently analysed using linear mixed models.

Results

A total of 396 patients were recruited to the cohort study from primary and acute care settings in Yorkshire, UK, with 393 participants included in data analysis (three patients were found to be ineligible following recruitment and so were excluded from the analysis). Just over half of participants were male (n = 222, 56.5%), participants had a median age of 55 (range 19–95) years and 69.5% of the study population were classed as overweight or obese (31.3% and 38.17%, respectively). Current smokers made up 28.5% of participants (i.e. were currently smoking or had quit within the last year).

The most common comorbidities we observed were cardiovascular disease (n = 151, 38.4%), followed by diabetes mellitus (n = 103, 26.2%) and peripheral vascular disease (n = 57, 14.5%). The majority of participants had no previous history of SWHSIs (n = 93, 72.0%) and had only one SWHSI (n = 358, 91.0%), and their surgical wound had been planned to heal by secondary intention (n = 236, 60.1%). The median area of the reference SWHSI at baseline was 6 cm2 (range 0.01–1200 cm2). SWHSI location varied; however, the most common sites were the abdomen (n = 132, 33.6%), foot (n = 59, 15.0%) and leg (n = 58, 14.8%), linking the commonly represented surgical specialities of colorectal (n = 136, 39.7%) and vascular (n = 82, 20.9%). At baseline, 164 patients (41.7%) were receiving hydrofibre dressings and 89 patients (22.7%) were receiving NPWT. Further details of baseline demographics (patient, wound and surgery) and treatments received are presented in Tables 4–7.

| Variable | Patients (N = 393) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 55.0 (19.0–95.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 222 (56.5) |

| Female | 171 (43.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.9 (6.6) |

| History of SWHSI, n (%) | |

| Yes | 93 (23.7) |

| No | 283 (72.0) |

| Do not know | 17 (4.3) |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | |

| None in last 10 years | 219 (55.7) |

| None current, but in last 10 years | 62 (15.8) |

| Current (less than one pack/day) or quit in last year | 84 (21.4) |

| Current (more than one pack/day) | 28 (7.1) |

| Baseline comorbidities | Patients (N = 286), n (%)a |

| Cardiovascular disease | 151 (38.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 103 (26.2) |

| Airways (e.g. asthma) | 69 (17.6) |

| Arthritis | 65 (16.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 57 (14.5) |

| Cancer | 51 (13.0) |

| Orthopaedic (e.g. fractures) | 27 (6.9) |

| Stroke | 20 (5.1) |

| Autoimmune | 19 (4.8) |

| Neurological | 11 (2.8) |

| Other | 31 (7.9) |

| Medications used | Patients (N = 272), n (%)b |

| Anticoagulants/antiplatelets | 196 (49.9) |

| Vasodilator | 111 (28.2) |

| NSAIDs | 66 (16.8) |

| Corticosteroids | 11 (2.8) |

| Immunosuppressant | 9 (2.3) |

| Cytotoxic | 5 (1.3) |

| Variable | Patients (N = 393) |

|---|---|

| Number of SWHSIs, median (range) | 1 (1–6) |

| Area (cm2), median (range) | 6 (0.01–1200) |

| SWHSI location, n (%) | |

| Abdomen | 132 (33.6) |

| Foot | 59 (15.0) |

| Leg | 58 (14.8) |

| Perianal | 34 (8.7) |

| Back | 19 (4.8) |

| Natal cleft | 16 (4.1) |

| Buttocks | 16 (4.1) |

| Breast | 7 (1.8) |

| Arm | 5 (1.3) |

| Perineum | 5 (1.3) |

| Head | 3 (0.8) |

| Hand | 2 (0.5) |

| Neck | 2 (0.5) |

| Missing | 35 (8.9) |

| Aetiology, n (%) | |

| Planned | 236 (60.0) |

| Dehisced | 141 (35.9) |

| Surgically opened | 16 (4.1) |

| Tissue involvement, n (%) | |

| Full thickness | 235 (59.8) |

| Muscle, tendon or bone exposed | 120 (30.5) |

| Organ exposed | 1 (0.3) |

| Unsure | 35 (8.9) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) |

| Infection at baseline, n (%) | |

| Yes | 79 (20.1) |

| No | 314 (79.9) |

| Antibiotics used, n (%) | |

| Yes | 182 (46.3) |

| No | 211 (53.7) |

| Dressing, n (%) | |

| Hydrofibre/spun hydrocolloid | 164 (41.7) |

| Other | 129 (32.8) |

| Wound contact | 114 (29.0) |

| NPWT | 89 (22.7) |

| Foam | 36 (9.2) |

| Alginate | 27 (6.9) |

| Silver containing | 23 (5.9) |

| Iodine | 19 (4.8) |

| Soft polymer | 19 (4.8) |

| Hydrocolloid | 10 (2.5) |

| Superabsorbent | 7 (1.8) |

| Cavity foam | 4 (1.0) |

| Hydrogel | 1 (0.3) |

| Silver sulfadiazine | 1 (0.3) |

| Treatment environment, n (%) | |

| Hospital inpatient | 229 (58.3) |

| Home | 88 (22.4) |

| GP | 55 (14.0) |

| Hospital outpatient | 11 (2.8) |

| Other | 8 (2.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) |

| Variable | Patients (N = 393), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Subspecialty | |

| Colorectal | 156 (39.7) |

| Vascular | 82 (20.9) |

| Other | 50 (12.7) |

| Plastics | 33 (8.4) |

| Orthopaedic | 17 (4.3) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 13 (3.3) |

| Surgical debridement | 11 (2.8) |

| Upper GI tract | 7 (1.8) |

| Urology | 7 (1.8) |

| Cardiothoracic | 7 (1.8) |

| Neurosurgery | 3 (0.8) |

| Thoracic | 3 (0.8) |

| Breast | 2 (0.5) |

| Trauma | 1 (0.3) |

| Oral and maxillofacial | 1 (0.3) |

| Surgery type | |

| Emergency | 236 (60.1) |

| Elective | 135 (34.4) |

| Missing | 22 (5.6) |

| Contamination level | |

| Dirty | 247 (62.9) |

| Contaminated | 65 (16.5) |

| Clean-contaminated | 51 (13.0) |

| Clean | 26 (6.6) |

| Missing | 4 (1.0) |

| Treatment dressings received (at any time) | Patients (N = 393), n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Hydrofibre | 259 (65.9) |

| Basic wound contact dressing | 212 (53.9) |

| Other | 196 (49.9) |

| NPWT | 115 (29.3) |

| Foam | 113 (28.8) |

| Silver-containing dressing | 89 (22.7) |

| Soft polymer dressing | 73 (18.6) |

| Iodine-containing dressing | 71 (18.1) |

| Alginate dressing | 49 (12.5) |

| Hydrogel | 23 (5.9) |

| Hydrocolloid | 22 (5.6) |

| Superabsorbent | 21 (5.3) |

| Cavity | 12 (3.1) |

| Polyhexamethylene biguanide dressing | 8 (2.0) |

The mean length of participant follow-up was 499 days [standard deviation (SD) 127.4 days], with a range of 13–651 days (median 528 days). Sixty-six participants (16.8%) were not followed up for the entire study duration (31 withdrew, 29 died and six were lost to follow-up). When the reference SWHSI was situated on a limb, this was amputated for 3.3% of participants (n = 13), of whom 61.5% had experienced an infection during follow-up (n = 8) and 76.9% had diabetes mellitus (n = 10). Infections were experienced by 32.1% of study participants (n = 126). Hospital admissions were reported for 97 participants (24.7%), of which 66 participants (68.0%) returned to the operating theatre. Thirty-six cases (38.1%) of hospital admissions were related to SWHSIs.

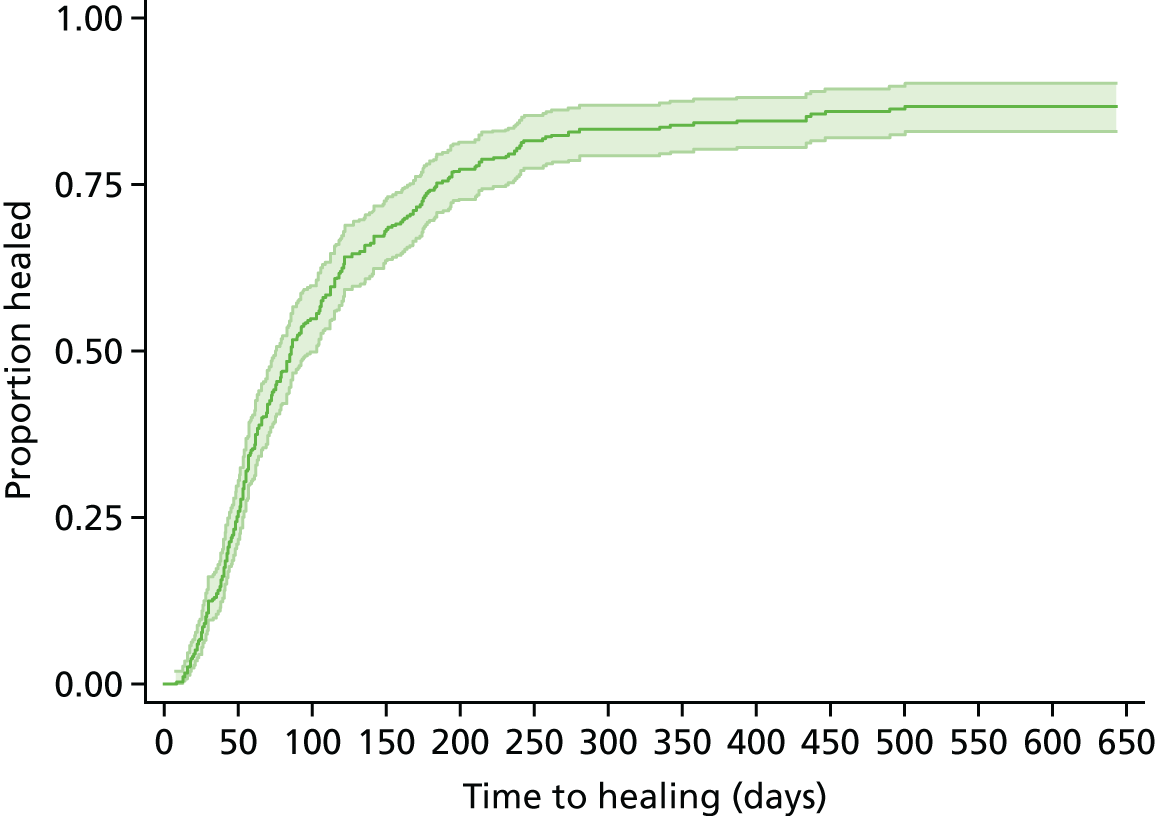

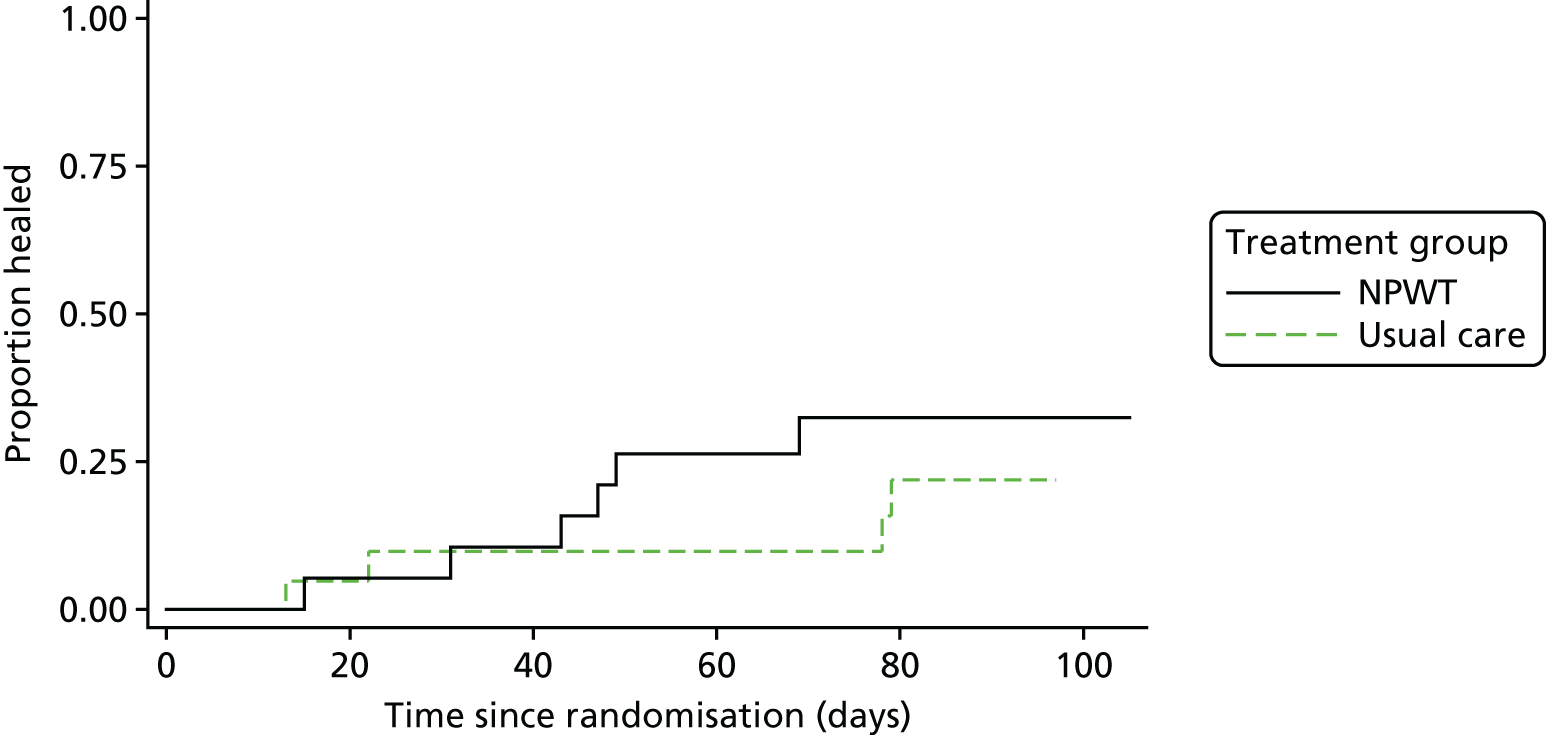

Data indicated that the reference SWHSI healed for 81.4% of participants (n = 320) during the study. Agreement between patient self-report and nurse assessment of healing status verification was relatively high (77.8% at 6 months and 74.2% at 12 months). Disagreements were present for four participants: three patients had healing confirmed during a visit but paperwork was not completed to this effect and one participant was not healed at the verification visit but healed shortly afterwards. The median time to healing for all cohort participants was 86 (95% CI 75 to 103) days, as presented in Figure 2. When we assessed time to healing against baseline participant and wound characteristics in a Cox proportional hazards model, baseline wound area above median (p < 0.01) and surgical wound contamination level as determined at the point of surgery (p = 0.04) were significant predictors of prolonged time to healing (see Appendix 4). Infection at any point was also found to be a significant predictor of prolonged time to healing (p < 0.01).

FIGURE 2.

Cohort study: Kaplan–Meier curve of time to healing in days.

The most commonly received treatment throughout the study was hydrofibre dressings, with 65.9% (n = 259) of participants receiving this treatment at least once. Nearly one-third (n = 115, 29.3%) of participants received NPWT at some point during the study.

Health utility scores captured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) measure22 (in which 0 = death and 1 = perfect health) were a mean of 0.5 (SD 0.4) at baseline, increasing to a mean of 0.6 (SD 0.4) at 6 months and 0.6 (SD 0.4) at 12 months. Further details are provided in Table 8.

| Time point | Overall | Healing status | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healed | Not healed | |||

| Baseline, n | 383 | 311 | 72 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.37) | 0.4 (0.42) | 0.07 |

| 3 months, n | 258 | 223 | 35 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.38) | 0.6 (0.33) | 0.58 |

| 6 months, n | 219 | 191 | 28 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.37) | 0.5 (0.34) | 0.08 |

| 12 months, n | 185 | 166 | 19 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.35) | 0.6 (0.38) | 0.31 |

Pain, measured as BPI scores for pain severity (in which 0 = no pain and 10 = pain as bad as you can imagine) and pain interference (in which 0 = does not interfere and 10 = completely interferes)23 reduced slightly over time. Mean pain severity reduced from 3.7 (SD 2.54) at baseline to 3.0 (SD 3.0) by 15 months; similarly, mean pain interference scores reduced from 4.2 (SD 2.54) at baseline to 3.1 (SD 3.17) at 15 months. Further details are provided in Table 9.

| Time point | BPI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain severity | Interference | |||||||

| Overall | Healing status | p-value | Overall | Healing status | p-value | |||

| Healed | Not healed | Healed | Not healed | |||||

| Baseline, n | 385 | 313 | 72 | 390 | 318 | 72 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.54) | 3.6 (2.53) | 4.0 (2.53) | 0.28 | 4.2 (3.12) | 4.2 (3.14) | 4.4 (3.05) | 0.63 |

| 3 months, n | 257 | 220 | 37 | 260 | 223 | 37 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (2.63) | 3.3 (2.70) | 3.4 (2.17) | 0.83 | 3.8 (3.12) | 3.7 (3.13) | 4.3 (3.08) | 0.30 |

| 6 months, n | 210 | 182 | 28 | 214 | 186 | 28 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.67) | 3.3 (2.71) | 3.9 (2.38) | 0.22 | 3.8 (3.18) | 3.7 (3.20) | 4.6 (2.97) | 0.13 |

| 12 months, n | 179 | 161 | 18 | 179 | 161 | 18 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.66) | 3.3 (2.70) | 4.0 (2.32) | 0.29 | 3.6 (3.18) | 3.5 (3.20) | 4.3 (2.97) | 0.36 |

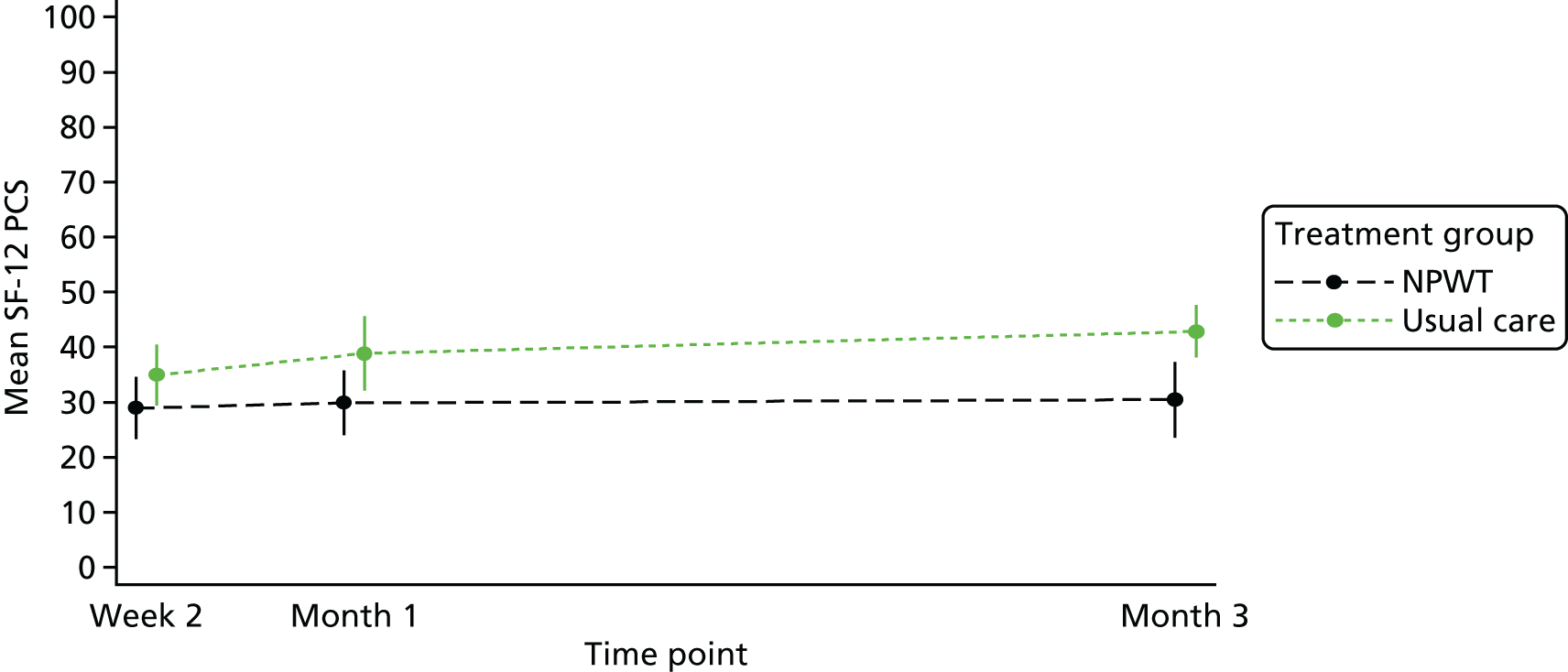

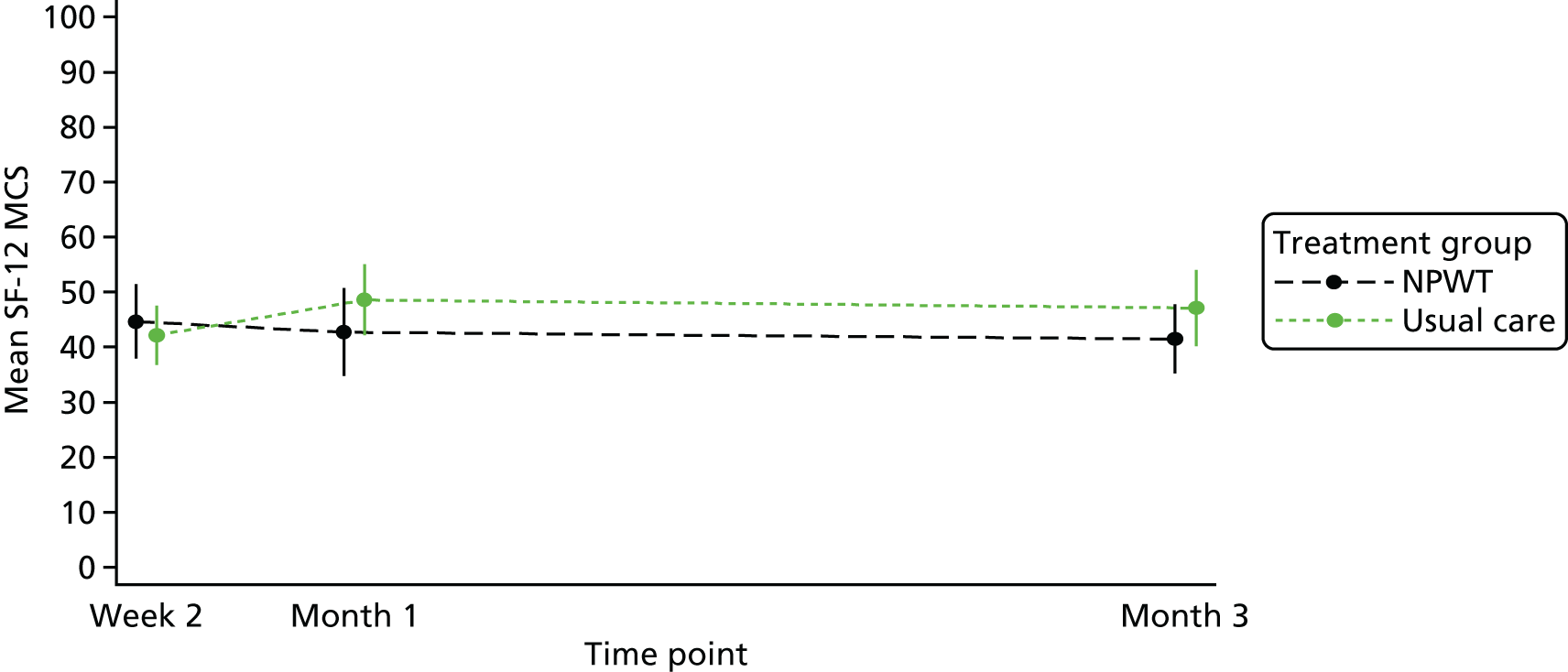

Quality of life was measured using the SF-12 and presented as SF-12 physical component scores (PCSs) and mental component scores (MCSs). 21 At baseline, the mean PCS was 33.1 (SD 10.7) and the mean MCS was 42.2 (SD 12.35). At 15 months’ follow-up, the mean PCS was 40.8 (SD 13.46) and the mean MCS was 48.3 (SD 10.73). Further details are provided in Table 10. A linear mixed model, adjusting for duration of SWHSI, baseline SWHSI area, location, participant age and baseline SF-12 subscale score, found follow-up time point, baseline score, age and SWHSI duration to be significant predictors of PCS (p < 0.001 in all cases) and MCS (p = 0.03 for time point and p < 0.01 for age, baseline score and SWHSI duration).

| Time point | SF-12 dimensions (overall population) | |

|---|---|---|

| PCS | MCS | |

| Baseline, n | 390 | 390 |

| Mean (SD) | 33.1 (10.17) | 42.2 (12.35) |

| 3 months, n | 255 | 255 |

| Mean (SD) | 37.7 (13.15) | 45.1 (11.69) |

| 6 months, n | 223 | 223 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.2 (12.91) | 45.1 (12.13) |

| 9 months, n | 210 | 210 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.4 (12.89) | 46.4 (11.28) |

| 12 months, n | 187 | 187 |

| Mean (SD) | 38.8 (13.11) | 47.2 (11.58) |

| 15 months, n | 147 | 147 |

| Mean (SD) | 40.8 (13.46) | 48.3 (10.73) |

| 18 months, n | 78 | 78 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.4 (13.52) | 47.3 (11.12) |

Conclusions

This prospective inception cohort study in patients with SWHSIs is the first we have identified. Broad patient groups (patients undergoing abdominal colorectal surgery, lower-limb vascular surgery and a mixed group of other procedures and specialities) were identified, which were similar to those identified in our cross-sectional survey. This information flags populations of clinical relevance, as well as those likely to be the focus of further research.

The median time to healing for these wounds, of approximately 3 months, is new information, which highlights the extended period of time that patients might expect to cope with open surgical wounds. There was high variability, with time to healing ranging from 8 days to 1 year and 4 months (prior to censoring) and from 5 days to 1 year and 7 months (following censoring). The chronicity of these wounds is crucial for patients and carers to appreciate, in order for them to have realistic expectations regarding wound healing. The cohort also highlights the large number of adverse events that occur in SWHSI patients, with wound infection and readmission to hospital (with the associated care costs) being particularly common. This cohort study data clearly demonstrated that SWHSIs pose a distinctive management challenge that was previously unsupported by high-level evidence.

Adjusted analyses provide further initial insights into possible patient and wound ‘risk’ factors that might have a detrimental impact on healing, including wound infection at any point, baseline wound area and higher levels of surgical wound contamination, as determined at the point of surgery. The predictive baseline factors may be important for the stratification of randomisation or adjustment for prognostic factors in future trials; however, it should be noted that there are many other covariates that are associated and correlate with these predictors. The SF-12 data indicate that, at baseline, SWHSI patients have quality-of-life limitations comparable to patients with congestive cardiac failure; however, they were significantly younger. 24 This therefore demonstrates the potential impact that SWHSIs have on patient quality of life. However, as the improvements in SF-12 scores during the study demonstrate, quality of life may be improved by time or wound healing. The research to date is therefore building a picture of a relatively common wound type that takes a prolonged time to heal, negatively impacts quality of life and puts patients at high risk of infection and other adverse events.

The common treatments for SWHSIs, in the centres involved in this cohort that were treating SWHSI patients across Yorkshire and the Humber, UK, were dressings and NPWT. There is currently limited and generally low-quality evidence on how effective dressings are in terms of wound management and promoting optimal clinical outcomes in a cost-effective way. 14 A recent Cochrane systematic review found only two RCTs, with a total of 69 participants, that had investigated the relative effectiveness of NPWT on SWHSIs, both reporting limited outcome data, which prevents any firm conclusions to be made. 14 Given that all SWHSI patients in this cohort were receiving dressings and/or NPWT, further research to explore clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these treatments in one or more of the common surgical groups identified seems warranted, and so was considered appropriate for further assessment in workstream 2.

The prospective and observational design of this study allowed us to follow patients over time and to collect the important natural history, treatment and outcome data presented here. Although we tried to maintain a representative sample, the need for consent meant that the subset recruited might differ in some systematic way from the wider SWHSI patient population. Comparison of the cohort and the cross-sectional survey data may be useful here, as the survey data were captured away from the patient’s bedside, did not require consent and thus may provide a more epidemiologically complete overview of the SWHSI population. In terms of patient, epidemiological, wound and surgery data, the populations in the survey and cohort appear similar; however, the findings from the survey may have influenced specific areas for focused recruitment into the cohort study (e.g. subspecialty-specific hospital wards). Some patient groups for whom wound problems are recognised nationally seem under-represented in the cohort study (e.g. post-caesarean wounds, for which dehiscence rates as high as 6% have been reported). 25

The cohort study was conducted in a single geographical area (two large centres in Yorkshire, UK), and therefore the patient groups and the treatment availability observed may not be reflective of national or international patient populations or treatment availability. However, we have no reason to suspect that there are huge differences between these surgical patients and those elsewhere, particularly given the breadth of our inclusion criteria.

We also note that our analyses exploring the impact of factors on time to healing are based on our observational data set and thus these cannot be assumed to be causal relationships. Thus, firm conclusions regarding factors that may affect healing cannot be drawn. However, we are able to report the associations found between observed covariates and healing, and reflect on them. From the outset of the study, there was careful consideration regarding measured study variables, with the aim of capturing important data, including factors that had the potential to be prognostic in relation to healing. We consulted widely with clinical experts and extensively scoped the literature, with the aim of providing the most comprehensive analysis possible.

The further research conducted as part of this research programme (workstreams 2–4) focused on further investigation of interventions that may offer clinical effectiveness and cost-effective treatment options for SWHSIs (workstream 2), as well as more detailed exploration of patients’ experiences of living with SWHSIs and health professionals’ views of delivering care to patients with these challenging wounds.

Workstream 2: using evidence from observational research to estimate the value of negative-pressure wound therapy in SWHSIs

Following characterisation of SWHSI patients and their treatment in workstream 1, the evidence gap regarding the cost-effectiveness of SWHSI treatments remained. Data collected in workstream 1 indicated that a variety of interventions are used when treating and managing SWHSIs. Although the majority of participants in the cohort study received dressings throughout follow-up, 29.3% (115/393) received a significantly more expensive technology: NPWT.

Negative-pressure wound therapy devices apply a carefully controlled negative pressure (or vacuum) to a dressing, creating an air-tight seal and removing tissue fluid from the treated wound area into a disposable canister. 14 The canister is removed and replaced either when it becomes full or at least once a week. The device is generally used as part of the SWHSI treatment pathway, rather than to the point of healing, and can be administered and removed by both nurses and surgeons. It has been claimed that NPWT speeds up wound healing by removing excess fluid, increasing tissue perfusion and removing bacteria. 26 However, although a recent Cochrane systematic review identified two RCTs investigating the relative effectiveness of NPWT on SWHSIs,14 it could not draw any conclusions, as the outcome data reported in both studies were very limited.

Given the current level of clinical use on SWHSIs, the cohort data collected in workstream 1 have been used here to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of NPWT for the healing of SWHSIs (the clinical outcome of wound treatments most valued by patients)27 and the value of a future RCT. From this work, a paper highlighting methodological challenges of analysing observational evidence in this context has been published (see Appendix 5). The current chapter presents the clinical implications of the research.

Objectives

-

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of NPWT compared with wound dressings for the healing of SWHSIs, using cohort data from workstream 1.

-

To assess whether or not investment in further research on treatments for SWHSIs is likely to be worthwhile.

Methods

In this workstream, we evaluated if, after adjustment, NPWT was clinically effective and cost-effective when compared with standard dressings. For clinical effectiveness, we used wound healing as the outcome; for cost-effectiveness, we quantified the impact of differences in time to healing on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). This approach assumed that no mortality differences existed and, thus, any improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were associated with accelerated time to healing only. We also noted that any additional HRQoL improvements that may have arisen from treatment (independent of healing status) were expected to be transient and not to have a significant impact on HRQoL (which is a multidimensional concept that includes domains related to physical, mental, emotional and social functioning). For this reason, such effects were not considered here.

We hypothesised that NPWT could be cost-effective by reducing healing time, improving HRQoL and reducing treatment costs (via reduced healing time). We envisaged that if the total costs of treatment were higher with NPWT than for comparator treatments, NPWT would only be cost-effective if the incremental costs to QALY gains fell below the standard NICE £20,000–30,000 per QALY threshold.

Specifically, the cost-effectiveness analysis used cost per QALY gained as the cost-effectiveness outcome. A 1 year time horizon was considered and a NHS perspective was adopted. Formally, we aimed to quantify the impact of NPWT in expected time to healing. The difference in QALYs between the interventions was derived from the expected time to healing and the EQ-5D index score while healed/unhealed, the latter estimated using the multilevel model (described in supplementary material in Appendix 5). Incremental disease costs were calculated in an analogous way to incremental QALYs, making use of the cost estimates derived in the multilevel two-part modelling approach (see Appendix 5). Treatment-related costs considered that patients received some form of treatment up to healing. The daily costs associated with the ‘non-NPWT’ group were based on average costs of dressings in participants who had received other treatments and were calculated by multiplying this cost by the difference in time to healing. For patients receiving NPWT, an average daily cost of NPWT was applied to the mean time on NPWT treatment in the cohort study. In the remaining time, patients were assumed to use dressings, with a daily cost equal to patients in the ‘non-NPWT’ group.

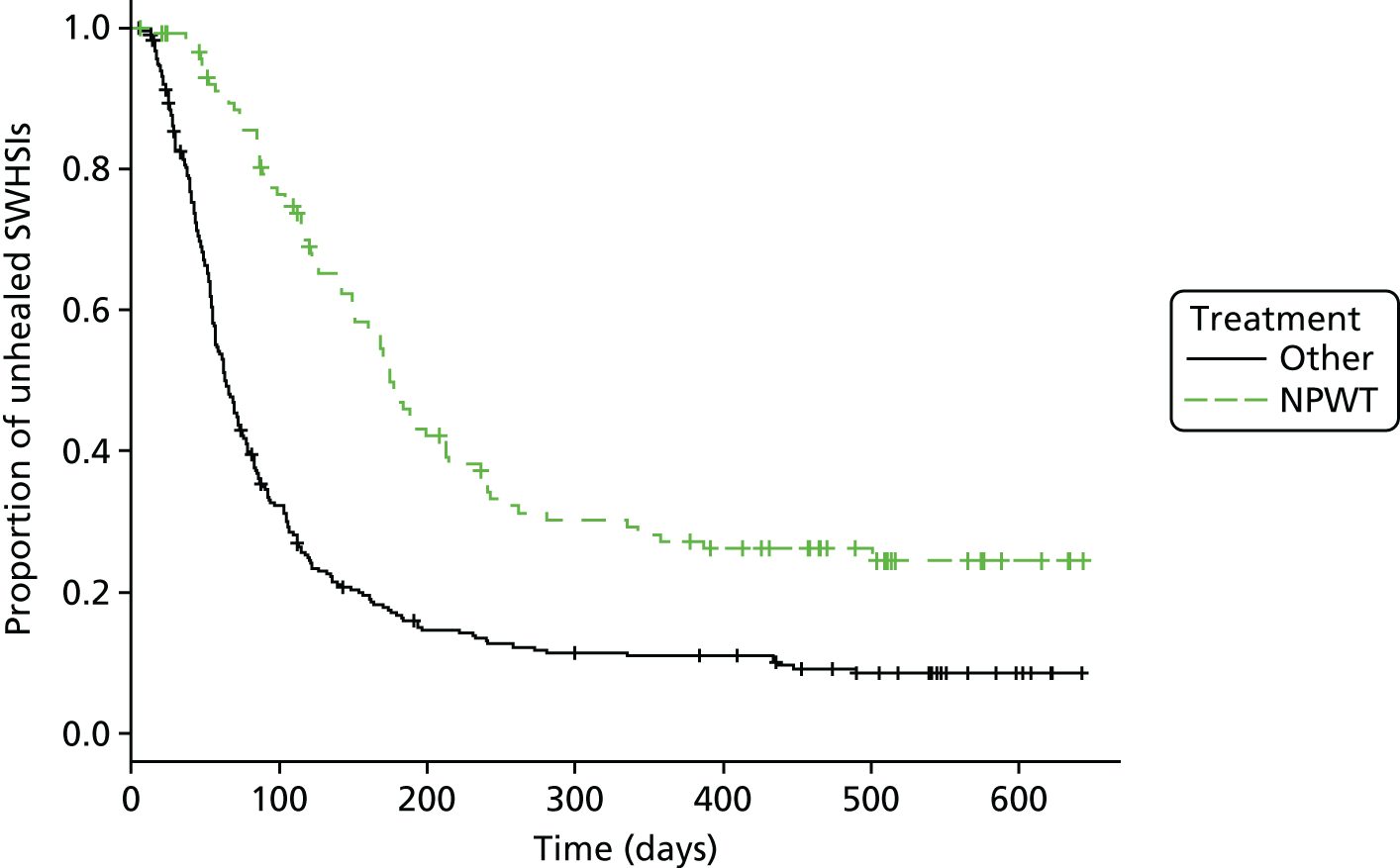

The cohort data were analysed for evidence regarding the various aspects of treatment and wound healing, including the impact of treatment (NPWT vs. dressings) on the time to healing and the impact of this SWHSI healing on disease-specific costs and HRQoL, as is presented in Figure 3. To estimate the effect of treatment on healing, we attempted to control the confounding (and selection bias) inherent when using observational data in this context. We adjusted for observed confounding (i.e. for characteristics observed within the cohort study sample that determine time to healing and may have differed between the groups). We also attempted to account for any potential confounding from unobserved sources.

FIGURE 3.

Time to healing: descriptive Kaplan–Meier curve. Reproduced with permission from Saramago et al. 28 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Health-related quality of life was assessed in the cohort study using the EQ-5D index score, obtained through a self-reported questionnaire, comprising five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression). 22 Participants were also asked to complete a resource use questionnaire quarterly. This questionnaire was developed for this study to allow costing of NHS resources specifically attributable to the SWHSIs and included collection of number of contacts with general practitioners (GPs), nurses and doctors in NHS institutions or the patient’s home, as well as the number of nights spent as an inpatient between study follow-up time points. The costing used national sources and 2014 prices. 29

Analyses required the application of econometric models to the cohort data. A Bayesian approach to inferences was utilised, computed using Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation, using WinBUGS version 1.4.3 (Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). 30

Identification of external evidence to supplement cohort data

To evaluate the existence of any external evidence to complement the cohort data, we also conducted the following range of systematic literature searches.

We conducted Cochrane systematic reviews of RCTs evaluating the treatment of SWHSIs, with any recognised form of NPWT. 14,31

Using the general review methods and with the support of an information specialist and an expert systematic reviewer, we conducted systematic searches and identification of the following studies:

-

any cohort studies evaluating the use of NPWT for SWHSIs

-

any EQ-5D or related health utility data for people with SWHSIs

-

any previous modelling work for the treatments of SWHSIs that might inform the planned work.

Details of the search strategies used are detailed in Appendix 6.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions index scores and disease-specific costs

A multilevel (or panel data) approach was used to model both EQ-5D index scores and quarterly costs that accounted not just for between-participant variation but also for within-participant variation across the quarterly observations. A time-dependent indicator of whether the participant had healed or not at each time point was used to capture the effect of healing. Changes from baseline EQ-5D index scores were modelled using a standard multilevel model based on the normal distribution (random intercept). For cost data, due to a high proportion of zero observations and the typical skewness associated with these data, a two-part model was used: the first part was a multilevel logistic regression (to explain the probability of observing zero costs over time) and the second was mixed gamma model with log-transformed costs (to evaluate the expected value of the non-zero observations). Both parts were multilevel models, to account for the repeated observations per participant.

We calculated the average daily cost of NPWT as £31.78 (according to centre-specific costings). For dressings, a unit cost of £2.39 per day was calculated (based on the mix of dressings used within the cohort data). The duration of NPWT treatment was evaluated from the cohort data (mean 37 days, SD 64.6 days) and was assumed to be independent of time to wound healing, as this treatment is rarely used up to the point of wound healing. NPWT patients were assumed to receive only dressings for the remainder of time unhealed.

Results indicated that healing was associated with a small (but statistically significant) increase in EQ-5D index score [mean 0.055, standard error (SE) 0.02]. Cost data, as presented in Table 11, indicated that healing significantly reduced quarterly wound-related costs (mean £865, SE £112).

| Model | Mean | 95% CrI |

|---|---|---|

| Expected EQ-5D (unhealed) | 0.091 | 0.036 to 0.146 |

| Expected EQ-5D (healed) | 0.091 + 0.055 = 0.146 | 0.098 to 0.193 |

| Difference in EQ-5D attributed to healing | 0.055 | 0.015 to 0.094 |

| Expected costs (£) (unhealed) | 1124.45 | 916.9 to 1359.1 |

| Expected costs (£) (healed) | 258.91 | 208.1 to 317.7 |

| Difference in costs (£) attributed to healing | 865 | 674.2 to 1126.5 |

Relative effectiveness (time to healing) of negative-pressure wound therapy and dressing-treated wounds

Based on the cohort data, we took two different approaches to modelling the time to healing and assessed robustness of our conclusions to the approach taken.

Modelling strategy A: ordinary least squares with imputation

Modelling strategy A used ordinary least squares (OLS) (or linear regression) to describe time to healing. OLS methods do not deal with censoring and 73 participants did not heal within the study follow-up period. To generate a complete data set on time to healing, the censored observations on time to wound healing were imputed, assuming their follow-up time plus an additional quantity, either 1 day (i.e. participants were conservatively assumed to have healed the day after they were censored) or expected healing time (data elicited from three experienced clinicians and pooled) (see Appendix 5). Note that by attributing an additional time to healing, elicited by clinical experts, to patients who have been censored in the study, we are also extrapolating beyond the study follow-up. Such extrapolation is required to allow achieving an unrestricted estimate of the effects of NPWT on mean time to healing, required for cost-effectiveness analysis.

Modelling strategy B: two-stage model

A second, more complex, modelling strategy (modelling strategy B) was also implemented, which explicitly considered the unhealed participants. Instead of OLS, it used a two-step modelling approach: a logistic regression estimated the probability of healing within the follow-up for each treatment, followed by linear regression, which estimated the expected time to healing for the population that healed within follow-up. This strategy reflected the possibility of there being a group of ‘long-term non-healers’ and allowed exploration of different determinants of the probability of healing and of time to wound healing, conditional on having healed in the adjustment for observables.

In terms of adjustment for observed confounding, and in the absence of evidence on determinants of healing in this patient group, a comprehensive variable selection process was undertaken using the cohort data sample. It aimed to identify predictors of treatment assignment with NPWT, predictors of healing and treatment effect modifiers. The selection criterion was based on goodness of fit (using the deviance information criteria at a widely used cut-off point of 5 deviance information criterion points). 32 All the predictors identified were used as adjustment covariates in the regression model for time to healing.

To account for unobservable confounding, instrumental variable (IV) regression was used. This method uses a variable (the instrument) that is associated with treatment assignment but not with outcome (except for any indirect effect on treatment assignment) to adjust for unobservable confounding. A range of instruments focused on the decisions of health professionals to use NPWT, that is use of NPWT on previous patient treated, perceptions of NPWT as effective treatment, likelihood of NPWT use for patients, desire to use NPWT more frequently, perceptions of NPWT as affordable and value for money, and company representative input, were considered (see Appendix 5). The selection of instruments was based on frequentist tests aimed at assessing aspects of validity and relevance (see Appendix 5). Previous treatment used by the treating health professional was the best-performing instrument.

The IV model used two regressions (two stages). The first stage regressed treatment allocation by the instrument and the set of relevant predictors of outcome (logistic regression) to predict the probability of each individual participant being assigned to NPWT. The predictions were then used as a covariate in the second-stage regression(s), which, again, conditions on the set of relevant predictors of outcome. Inferences were obtained using a Bayesian framework, so that uncertainty over predictions of treatment allocation was fully considered. Any external evidence located (from previous research) was to have been used as prior evidence to update the data obtained from the cohort.

Cost-effectiveness of negative-pressure wound therapy

The cost-effectiveness analysis uses cost per QALY gained as the cost-effectiveness outcome. A 1-year time horizon was considered and a NHS perspective was adopted. Formally, we aimed to quantify the impact of NPWT in expected time to healing. The difference in QALYs between the interventions was derived from the expected time to healing and the EQ-5D index score while healed or unhealed, the latter estimated by the multilevel model (described in the supplementary material in Appendix 5). Incremental disease costs were calculated in an analogous way to incremental QALYs, making use of the cost estimates derived in the multilevel two-part modelling approach described above (see Appendix 5). Treatment-related costs considered that patients received some form of treatment up to healing. The daily costs associated with the ‘non-NPWT’ group were based on average costs of dressings in participants who had received other treatments and were calculated by multiplying this cost by the difference in time to healing. For patients receiving NPWT, an average daily cost of NPWT was applied to the mean time on NPWT treatment in the cohort study. In the remaining time, patients were assumed to use dressings, with a daily cost equal to that for patients in the ‘non-NPWT’ group.

Results

Identification of external evidence to supplement cohort data

We screened 1477 citations from the literature searches and found no existing health utility data collected from patients with SWHSIs that could be used. Neither did we find any relevant published models exploring either the clinical effectiveness or the cost-effectiveness of treatments for SWHSIs. In terms of relative effects for NPWT compared with alternative treatments on healing, we located four potentially relevant RCTs33–36 and no observational data.

Of the four trials, two explored the use of NPWT compared with standard dressings to treat foot wounds in patients with diabetes mellitus. 33,34 One trial33 included 162 adult patients who had undergone a transmetatarsal amputation of the foot. It was not clear from the study whether or not the wounds had been left open following surgery. A second trial34 included 342 adult patients who had undergone debridement of a foot wound and were randomised to receive NPWT or dressings (predominantly hydrogels and alginates). Although it was not clear whether or not the debridement of these wounds was surgical, we were advised by local clinicians that it was likely to be. Both trials of NPWT in foot wounds reported time to healing data; however, the data appeared to include wounds that had been closed by surgery following treatment with NPWT or dressings. The two trials were considered to be at high risk of performance bias, as unblinded health professionals had made key decisions regarding the treatment of wounds, such as closure surgery. This issue has been noted previously and the validity of combining wounds closed by secondary intention and those closed by surgery has been questioned. 37 The potential for high risk of bias in these studies, combined with the fact that the data from these trials related to only a subset of the heterogeneous group of patients of interest, meant that we felt that the relative healing data could not be reasonably combined with the adjusted estimates of the cohort data.

Two further trials were identified. 35,36 The first study,35 with 20 participants, compared NPWT with an alginate dressing in the treatment of open, infected groin wounds. The second study,36 with 49 participants, compared NPWT with a silicone dressing in the treatment of excised pilonidal sinus. No useable healing data were reported in either trial. For this reason, these studies did not provide relevant evidence to complement the cohort data.

Effectiveness results when adjusting for observables

Modelling strategy A: ordinary least squares with imputation

Relevant associations found with predictors of treatment assignment with NPWT were wound area > 25 cm2, skin and subcutaneous tissue loss (a measure of tissue involvement) and inpatient (vs. outpatient) management. Relevant associations found with predictors of healing were inpatient (vs. outpatient) management and previous history of a SWHSI. The data also suggested that history of a SWHSI could be a relevant treatment effect modifier. Predictors of treatment assignment and predictors of healing were used to adjust all regressions within modelling strategy A.

In the model in which treatment effect modifiers were not considered, and censored observations were assumed to heal 1 day after follow-up, participants treated with NPWT were expected to take longer to heal than those who did not receive NPWT, on average 73 days longer [95% credible interval (CrI) 33.8 to 112.8 days longer] (Table 12). The addition of the interaction term between treatment and SWHSI history indicated that NPWT was still expected to increase time to healing compared with the use of dressings alone, but the magnitude of effect differed between the groups (181 days for participants with history of SWHSIs vs. 42 days for patients without history of a SWHSI). Results were similar when elicited expert opinion was used to impute censored healing times; however, the point estimates were even less favourable for NPWT (requiring, on average, 114 days additional days to wound healing compared with the use of standard dressings) and uncertainty was significantly increased.

| Model ID | Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Instrument used, z | None | None | None | Previous treatment | Previous treatment with interaction |

| Equation | TTH | TTH | TTH | (Stage 2) TTH | (Stage 2) TTH |

| Adjustment covariates | None | Observables | Observables + interaction | Observables | Observables + interaction |

| Area (> 25 cm2), x1 | 18.0 (95% CrI –23.1 to 58.0) | 21.1 (95% CrI –20.3 to 62.1) | 23.8 (95% CrI 29.8 to 43.7) | 36.2 (95% CrI –23.7 to 56.3) | |

| Treatment location,a x2 | 45.3 (95% CrI 11.3 to 79.2) | 43.8 (95% CrI 9.9 to 76.8) | 48.9 (95% CrI 3.0 to 63.8) | 55.3 (95% CrI 10.8 to 70.8) | |

| Tissue involvement,b x3 | 31.9 (95% CrI –1.5 to 65.0) | 26.6 (95% CrI –5.3 to 58.7) | 33.8 (95% CrI –8.0 to 73.1) | 37.2 (95% CrI –2.0 to 50.6) | |

| History, w | 7.5 (95% CrI –28.4 to 42.9) | –29.3 (95% CrI –71.5 to 12.1) | 7.2 (95% CrI –29.5 to 44.6) | –10.3 (95% CrI –61.4 to 7.4) | |

| NPWT, t | 108.0 (95% CrI 73.6 to 142.2) | 73.2 (95% CrI 33.8 to 112.8) | 41.9 (95% CrI –1.1 to 84.1) | 56.9 (95% CrI –71.7 to 192.8) | 9.1 (95% CrI –120.2 to 55.9) |

| NPWT × history, w.t | 138.7 (95% CrI 56.9 to 221.8) | 69.4 (95% CrI –67.5 to 118.0) | |||

| Constant | 116.8 (95% CrI 97.9 to 135.2) | 81.4 (95% CrI 53.3 to 110.0) | 92.7 (95% CrI 64.5 to 120.8) | 81.1 (95% CrI 52.3 to 109.1) | 86.7 (95% CrI 56.7 to 97.0) |

| Observations | 393 | 372 | 372 | 372 | 372 |

Modelling strategy B: two-stage model

This modelling approach explicitly modelled the probability of healing within follow-up and, in addition to the predictors of treatment assignment mentioned in Modelling strategy A: ordinary least squares with imputation, it identified associations with body mass index (BMI) and wound location being the foot (vs. other locations). For those healing within follow-up, time to healing was associated with surgery type (colorectal vs. other surgeries), wound duration and diabetic foot wounds. No evidence of relevant interaction terms was found. As detailed in Table 13, results indicated that participants treated with NPWT were estimated to have lower probability of healing than those who did not receive NPWT [odds ratio (OR) of healing with NPWT was 0.59 (95% CrI 0.28 to 1.12)]. The expected time to healing of NPWT-treated participants who healed compared with participants treated with dressings alone was an additional 46 days (95% CrI 19.6 to 72.5 days).

| Model ID | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b0 | b1 | |||

| Equation | (Stage 2A) OR for healing | (Stage 2B) TTH | (Stage 2A) OR for healing | (Stage 2B) TTH |

| Type of regression model | Logit | OLS | IV, logit | IV, OLS |

| Adjustment | None | None | Adjustment set | Adjustment set |

| Area (> 25 cm2), x1 | 0.52 (95% CrI 0.24 to 0.99) | 27.7 (95% CrI 0.6 to 54.5) | ||

| Treatment location,a x2 | 0.52 (95% CrI 0.22 to 1.04) | 30.9 (95% CrI 9.2 to 52.3) | ||

| Tissue involvement,b x3 | 0.50 (95% CrI 0.25 to 0.91) | 11.4 (95% CrI –8.1 to 30.9) | ||

| BMI (kg/m3), v1 | 1.04 (95% CrI 1.00 to 1.09) | |||

| Location: foot, v2 | 0.34 (95% CrI 0.16 to 0.64) | 30.1 (95% CrI 9.2 to 52.3) | ||

| Surgery type, v3 | 13.1 (95% CrI –6.1 to 32.4) | |||

| SWHSI duration (days), v4 | 2.3 (95% CrI 0.6 to 4.0) | |||

| Diabetic feet, v5 | 42.8 (95% CrI 9.1 to 76.3) | |||

| NPWT, t | 0.35 (95% CrI 0.20 to 0.57) | 69.0 (95% CrI 48.2 to 89.1) | 0.59 (95% CrI 0.28 to 1.12) | 46.0 (95% CrI 19.6 to 72.5) |

| Constant, γ1 | 6.56 (95% CrI 4.70 to 9.37) | 82.0 (95% CrI 71.9 to 92.1) | 6.98 (95% CrI 1.62 to 29.55) | 36.9 (95% CrI 12.4 to 61.3) |

| Observations | 393 | 354 | ||

Effectiveness results when adjusting for observables and unobservables

Overall, conclusions were similar using modelling strategies A and B, and treatment effect estimates adjusted for unobservables were broadly consistent with the results we observed when adjusting only for observables. Participants treated with NPWT were predicted to take longer to heal, albeit with a high level of uncertainty in the estimates [e.g. modelling strategy B, second-stage regression: 46 days longer (95% CrI 19.6 to 72.5 days longer)].

Cost-effectiveness of negative-pressure wound therapy

The results for healing, utilities and costs were combined to generate cost-effectiveness estimates for NPWT. Evidence relating to the additional days until healing after censoring for unhealed patients within the follow-up period was elicited from three experts and used in an extended analysis, the results of which are shown in Table 14. Irrespective of the adjustment made (on either observables or unobservables), the results indicated that treatment with NPWT was expected to be less effective and a more costly use of NHS resources than treatment with standard dressings alone: associated incremental QALYs of –0.012 (SE 0.005) (model A, observables), –0.008 (SE 0.011) (model A, unobservables), –0.007 (SE 0.004) (model B, observables) and –0.027 (SE 0.017) (model B, unobservables). There was little decision uncertainty in this result. When losses arising from the displaced health-care resources were added to the direct health effects (by valuing 1 QALY at £20,000), the health consequences of using NPWT were evaluated at –0.111 (model A, observables), –0.095 (model A, unobservables), –0.087 (model B, observables) and –0.183 (model B, unobservables).

| Elicited | Fitted values for parameters of a gamma distribution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50th percentile (days) | 90th percentile (days) | Shape, first and third quartiles | Scale, first and third quartiles | Mean (days), first and third quartiles | 50th percentile (days), first and third quartiles | 90th percentile, (days), first and third quartiles | |

| Expert 1 | 1044 | 3234 | 1.12 | 1290 | 1445 | 1031 | 3322 |

| Expert 2 | 496 | 679 | 15.3 | 33.1 | 506 | 495 | 683 |

| Expert 3 | 180 | 3650 | 0.23 | 5222 | 1201 | 176 | 3176 |

| Pooled using formal synthesis (95% CrI) | 1.79 (0.03 to 54.5) | 615 (241 to 1615) | 1038 (29 to 39,065) | 559 (0 to 28,011) | 1820 (15 to 37,161) | ||

Data and analyses of the cohort study indicate, with little uncertainty, that treatment with NPWT is less effective and more costly than treatment with standard dressings alone.

Value of a future randomised controlled trial

Although there is uncertainty in the incremental cost and QALY estimates, our analyses consistently indicate that there is little uncertainty in the optimal decision (i.e. the probability of treatment with NPWT being considered cost-effective to the UK NHS was close to zero). This means that conducting a future study in order to reduce the associated uncertainty (in the costs and QALYs) would not change the optimal decision and therefore there is no value in conducting such a study for this purpose. For this reason, the value of information analyses originally planned were redundant: the value of information is zero.

Negative-pressure wound therapy is currently widely used in clinical practice. The results from the observational study may contradict beliefs with regards the effectiveness of NPWT, but, given that our findings have been derived from observational research, there is the potential for unresolved confounding to affect the results and reduce confidence in them and the associated conclusions drawn. This lack of confidence may lead decision-makers and funders to justify calls for definitive evidence from a RCT. The value of conducting such research, to obtain definitive evidence, will be looked at next.