Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1210-12004. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in March 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2020. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. This report has been published following a shortened production process and, therefore, did not undergo the usual number of proof stages and opportunities for correction. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Dalal et al. This work was produced by Dalal et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Dalal et al.

SYNOPSIS

Research summary

Our original proposal stated that the Rehabilitation Enablement in Chronic Heart Failure (REACH-HF) programme of research would include four linked work packages (WPs) that aim to:

-

develop an evidence-informed, home-based, self-care cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programme for people with heart failure (HF) and their caregivers (‘the REACH-HF intervention’)

-

conduct a pilot trial to assess the feasibility of a definitive trial of the REACH-HF intervention in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)

-

conduct a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention versus usual care in people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and their carers

-

undertake evidence synthesis/modelling to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention versus centre-based CR in people with HFrEF.

Our original research questions were:

-

WP1 –

-

What are the necessary intervention components of a home-based, self-care manual for patients with HF?

-

What are the necessary intervention components of a home-based, self-care manual for caregivers of patients with HF?

-

-

WP2 –

-

How feasible is the REACH-HF intervention in patients with HFpEF?

-

-

WP3 –

-

What are the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention compared with usual care in patients with HFrEF?

-

What is the impact for caregivers of using the intervention versus usual care?

-

-

WP4 –

-

What are the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention versus centre-based CR in patients with HFrEF?

-

What is the expected value of information for future research, including a RCT of the REACH-HF intervention versus centre-based CR in patients with HFrEF?

-

Over the 6 years of our programme of applied research, we were able to complete all four WPs as per our original research questions, although we had to modify our economic evaluation in WP4. Given the paucity of direct head-to-head RCTs in the HF population identified by the updated Cochrane review1 of home- versus hospital-based CR (four RCTs in a total of 295 patients, with only one single-centre study undertaken in a UK setting) and that the data were too limited to directly estimate the longer-term cost-effectiveness of home- versus hospital-based CR, we decided to restrict our economic modelling to examine the questions of the longer cost-effectiveness of:

-

the REACH-HF intervention versus usual care

-

home-based CR versus usual care

-

centre-based CR versus usual care.

In summary, the only change that we made to our original proposal was to WP4, for which we modified the economic modelling, as we were not able to make a direct comparison of the effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention versus centre-based CR in people with HFrEF. Instead, our modelling compared home- and centre-based CR versus usual care.

Setting the scene

The burden of heart failure

Chronic HF is a burgeoning global health challenge that affects about 64 million people worldwide,2,3 including nearly 5 million people in the USA4 and about 900,000 people in the UK. 5 In the Western world, 1–2% of adults are living with the condition,6 and the prevalence is predicted to increase with the ageing population. 3,7 Low- and middle-income countries are also seeing an increase in prevalence, as people in these countries adopt Western lifestyles, leading to higher rates of obesity, diabetes and hypertension – morbidities that contribute to development of HF. 8,9

An editorial in The Lancet highlighted the negative impact of HF, describing it as ‘a dangerous, debilitating, and common disease, subjecting patients, carers, and doctors to a substantial burden. The need for admission to hospital and provision of specialist care, often for extended periods, means that the costs to health systems are correspondingly great’. 3 In 2002, the annual NHS spend on HF was £716M – just less than 2% of the total NHS expenditure of nearly £40B. Globally, the economic burden is predicted to grow to more than US$108B [£82B, conversion as at 27 June 2018: 1 US$ =$ 0.760133 Great British pounds (GBP)] as the population ages and nations become more industrialised. Hospital admissions are a key driver of the rising costs related to HF in high-income countries: in people > 65 years of age, it is the most common reason for hospital admission in the USA, where about 1 million admissions per year are related to HF, which is comparable to annual admissions for HF in Europe. 3

With the prevalence of HF predicted to increase as a result of increased life expectancy and a corresponding increase in the elderly population,3 care needed by elderly people, especially those with long-term conditions and multimorbidities, will also increase. Nearly 80% of patients with HF have three or more comorbidities, with the most common preceding a diagnosis of HF being hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, osteoarthritis and atrial fibrillation (AF). 7 A recent population-based study in the UK assessed the interval need (a measure of dependency and an assessment of demand) that was being met by carers for generational cohorts of elderly people and identified a change in care needs between 1991 and 2011, with an increase in elderly people being cared for in the community, creating more responsibilities for family and friends. 10

People with HF are commonly categorised on the basis of their left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (typically LVEF < 40–45%) have ‘systolic’ HF due to impaired left ventricular contraction, while those with normal LVEF (typically > 45–50%) have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). 11,12 Although individuals with HFpEF are thought to account for more than half of all patients with HF, most trials have recruited only patients with HFrEF – probably because patients with HFpEF tend to be older and have multiple comorbidities and historically there has been a lack of consensus on the exact definition of HFpEF. The prevalence of HFrEF is decreasing, whereas the prevalence of HFpEF is increasing.

Both forms of chronic HF can cause several symptoms, including shortness of breath, fatigue, fluid retention, impaired cognitive function and appetite disturbance. People with HF consequently experience exercise intolerance, poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL), increased hospital admissions, increased mortality and higher health-care costs, which seem to be similar for those with HFrEF and HFpEF. 4,13 Historically, 5-year survival rates for patients with HF have been worse than for the most common cancers. With the increasing cost of hospitalisations, the focus of treatment over the past two decades has been on pharmacological therapies and devices (biventricular pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators), which have resulted in improvements in survival and fewer hospitalisations, mainly in patients with HFrEF. 3

Poor HRQoL in people with HF13 is multifaceted and involves complex interactions across a range of measures, including severity of HF, extent of comorbidity (e.g. pulmonary disease and chronic kidney disease), exercise capacity, physical activity status, activities of daily living14,15 and depressive symptoms, which alone are evident in up to 42% of patients with HF. 16 As survival rates in people with HFrEF have improved, HRQoL is becoming a key patient-reported outcome measure. 3,17,18 Better management of HF can reduce uncertainty and anxiety and may improve quality of life. 19

The evidence base for cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure

Cardiac rehabilitation has, in its broadest sense, been defined as the sum of activities required to:

. . . influence favourably the underlying cause of cardiovascular disease, as well as to provide the best possible physical, mental and social conditions, so that the patients may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume optimal functioning in their community and through improved health behaviour, slow or reverse progression of disease.

Although exercise training remains a key component of CR, current practice guidelines consistently recommend ‘comprehensive rehabilitation’ programmes that contain the core components necessary to optimise cardiovascular risk reduction, foster health promotion behaviour patterns and their maintenance over time, reduce disability, and promote an active lifestyle. Guideline-based CR consists of three key elements: exercise to rebuild physical capacity and heart health, psychological support to help manage the emotional consequences of living with a heart condition, and support for key self-care behaviours. In the context of HF, key self-care behaviours include taking medications, engaging in (long-term) exercise, managing stress/anxiety and monitoring/managing fluid build-up. 21 Friends and family can have a key role in supporting patients to engage in and maintain these key self-care behaviours. CR for HF supports patients and carers to achieve or maintain good HRQoL as part of managing HF symptoms and HF-related self-care.

In 2004, the first Cochrane systematic review22 of exercise-based interventions for HF in 29 studies (1126 randomised participants) with up to 12-month follow-up reported that exercise training significantly improved exercise capacity compared with no exercise training. Only one study examined the effect of exercise on mortality and morbidity, and only nine out of 29 RCTs measured HRQoL, with seven of these reporting an improvement in exercise capacity. An updated Cochrane review14 published in 2010 focused on trials with follow-up of 6 months or longer that reported on HRQoL and clinical events – that is, mortality and hospitalisation. This review, which included data from a trial-level aggregate of 19 RCTs involving 3647 participants, found no difference in short- or long-term all-cause mortality between exercise and no exercise; however, exercise therapy resulted in a reduction in HF-related hospitalisations [risk ratio 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 0.99] and an improvement in patient-reported HRQoL (standardised mean difference 20.63, 95% CI 20.37 to 20.80). However, most of the trials recruited predominantly men (median 87%) and, although more recent studies have included women, they were limited to people with mild or moderate HF – that is, class II or III of the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, which is used to categorise the severity of HF based on symptoms and functional exercise capacity, but not severe disease. 11,23 None of the trials included people with HFpEF, and the interventions in 14 out of 19 RCTs were delivered in centre-based settings.

A further update of the Cochrane review in 2014 reassessed the effectiveness of exercise-based rehabilitation on mortality, hospital admissions, morbidity and HRQoL in people with HF compared with no exercise training. 24 It also sought to identify additional evidence, including cost and cost-effectiveness, for those individuals poorly represented in previous reviews (i.e. older people, women and people with HFpEF) and the interventions specifically delivered in a home- or community-based setting. This review, which included 33 trials involving 4740 people with HF, identified no difference in pooled mortality between exercise-based rehabilitation and no exercise in trials with up to 12-months’ follow-up [relative risk (RR) 0.93, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.27]. However, there was a trend towards a reduction in mortality for exercise-based rehabilitation alone after more than 12 months of follow-up (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.02). Compared with no CR, exercise training reduced the rate of overall hospitalisation (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.92) and HF-specific hospitalisation (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.80). A change of 5 points in the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) score is considered clinically important (higher scores indicate poorer HF-related HRQoL), and inclusion of exercise in rehabilitation programmes resulted in a greater improvement in this disease-specific measure of HRQoL (13 trials, 1270 participants, mean difference –5.8 points, 95% CI –9.2 to –2.4 points). Univariate meta-regression analysis showed that the benefits of exercise-based CR are independent of participants’ age, sex or degree of left ventricular dysfunction, type of CR (exercise only versus comprehensive), mean dose of exercise intervention, length of follow-up, overall risk of bias and trial publication date. Most of the participants included in this review had HFrEF and were categorised as having NYHA class II or III disease. 15,24 The more recent trials included people with HFpEF and NYHA class IV disease and greater proportions of women and older patients. Evidence from two trials supported the cost-effectiveness of exercise-based CR in terms of gain in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and life-years saved. 25,26 Although Cochrane reviews of RCTs are not conclusive about the mortality benefits of CR, data from national audits show that patients referred to CR have better survival; however, observational analyses like these should be interpreted with caution, as they are subject to selection bias and confounding.

On the basis of evidence accumulating on the clinical benefits of CR, in 2010 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended supervised, group-format, exercise-based rehabilitation for people with HF. 27 Similarly, other international guidelines on the management of HF, including those published by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), recommend CR as an effective and safe intervention. 11,28 The ESC recommends that CR must be integrated into the overall provision of care for patients with HF based on class IA evidence, which shows that regular aerobic exercise improves functional capacity and symptoms in people with HFrEF and also reduces the risk of hospitalisations in these patients. 11

Current provision of cardiac rehabilitation

Historically, CR after myocardial infarction (MI) and revascularisation (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft) has been provided for groups of patients in centre-based settings, such as hospitals. The 2017 annual statistical report from the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) states that, overall, 51% of eligible patients who had a MI, percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft participated in CR in England, Northern Ireland and Wales. 29 Lower rates of uptake in these groups led to innovative ways of delivering CR, such as home-based CR using the Heart Manual. 30 This step-by-step guide is supported by a trained nurse facilitator and directs the patient through a 6-week programme of exercise, stress management and education (www.theheartmanual.com; accessed 20 February 2020). Supervised group-based interventions, as recommended by NICE,5,31 may be difficult for patients to access,32 and home-based CR programmes, such as the Heart Manual, are no less clinically effective than centre-based programmes but equally cost-effective. Patients like to have a choice of CR, and studies have shown that choice can enhance uptake.

The CR needs of people with HF can be more complex than for patients after uncomplicated MI or revascularisation – the settings in which CR was first used. People with HF are prone to greater levels of disability, as disease progression leads to increasing incapacity and deconditioning. 33 Activities of daily living are limited by symptoms such as shortness of breath and fatigue, thus affecting HRQoL. 13

The 2017 National Heart Failure Audit stated that there is underprovision of CR in the UK, with < 20% of patients with HF being referred to CR during hospitalisation. 34 According to the 2016 and 2017 reports from the NACR, people with HF make up < 10% of all patients who participate in CR. 35 The 2017 standards of the British Association for Cardiac Prevention (BACPR) recommend that HF should be a priority area and that CR providers should consider offering alternatives to centre-based CR to improve the current low uptake of CR in people with HF. 20

Importance and relevance of programme

The underprovision of CR has been evident for several years, with a national survey undertaken as part of the programme development application for the REACH-HF programme showing that only one in seven (35/224, 16%) CR centres in England, Wales and Northern Ireland provided a dedicated HF programme in 2009–10. A European survey conducted around the same time showed that < 20% of patients with HF were involved in CR. A recent registry study from the USA reported that only 10% of eligible patients with HF were referred for CR after hospital discharge, although this proportion increased between 2005 and 2014. 36

Despite good evidence (see The evidence base for cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure), the importance of CR in HF is not acknowledged in major clinical reviews. A key potential strategy for commissioners to improve on the current poor provision of CR in HF and address this important unmet need is to offer individuals choice by including a home-based CR intervention that is evidence based and provides an alternative to centre-based CR.

Involvement of caregivers

Despite recommendations that family members or caregivers should be included in discussions about care, few evaluations of supportive interventions for individuals caring for someone with HF have been published to date. There have, however, been calls for research to develop interventions with caregivers to improve quality of care, reduce costs and improve patients’ HRQoL. 37

Caregivers have an important role in supporting the management of chronic disease, although this often comes at considerable personal cost, and many caregivers are uncertain about how best to provide this support. Most caregivers have health and well-being problems of their own – either pre-existing conditions or issues arising from the burden of their caregiving activities. Caregiver burden is due to the tasks of caring (objective burden) and the distress associated with the role (subjective burden). The objective burden comes from activities that include physical tasks such as washing, dressing, feeding and assistance with mobility, which are often performed at night. Other caregiving activities support self-care of chronic conditions such as HF, including assisting with identification of signs and symptoms of deterioration, taking action during an emergency, and assisting with blood pressure monitoring and medication management. Caregivers also support adherence to dietary restrictions, support emotional needs, promote exercise and physical activity, provide transport, maintain safety, and liaise with health-care professionals (HCPs).

Innovation

We set out to design and develop a novel HF rehabilitation intervention/approach that would (1) provide information that is individually tailored rather than a one-size-fits-all approach; (2) include facilitation and careful monitoring of the development of self-care skills and strategies by a specially trained facilitator; (3) offer near-patient care in the patient’s home rather than requiring attendance at hospital clinics; (4) employ theoretically informed and evidence-based practice to support behaviour change; and (5) provide an intervention strongly informed by service-user consultation at every stage of its development. Overall, the intervention package was expected to offer a higher standard of care, and we hypothesised that it would result in improved self-care. 38

Original aims, objectives and outputs

The overarching aim of this programme was to improve the body of evidence-based knowledge of CR for HF to enhance the current low uptake of CR in HF and to inform future service commissioning.

Our specific objectives were to:

-

develop an evidence-informed, home-based, self-care CR programme for patients with HF and their caregivers (‘the REACH-HF intervention’)

-

conduct a pilot trial to assess the feasibility of a full trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention in addition to usual care in patients with HFpEF

-

assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention in addition to usual care in patients with HFrEF and their caregivers

-

assess cost-effectiveness over the longer term of the REACH-HF intervention, other home-based CR and centre-based CR versus usual care in patients with HFrEF.

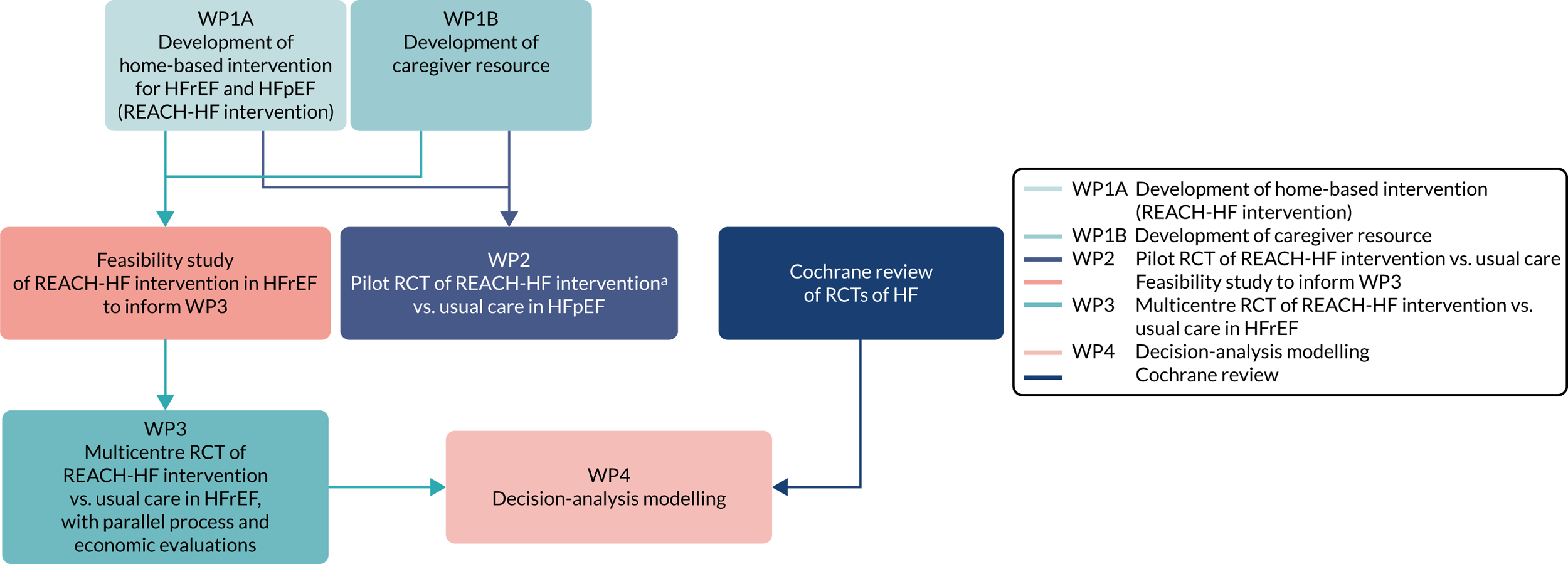

To meet these objectives, we developed a series of inter-related WPs (Figure 1):

-

WP1 – to develop a novel, evidence-informed, facilitated, self-care home-based rehabilitation intervention (‘the REACH-HF intervention’) for people with HF (see WP1A) and their caregivers (see WP1B) and undertake an uncontrolled feasibility study in patients with HfrEF.

-

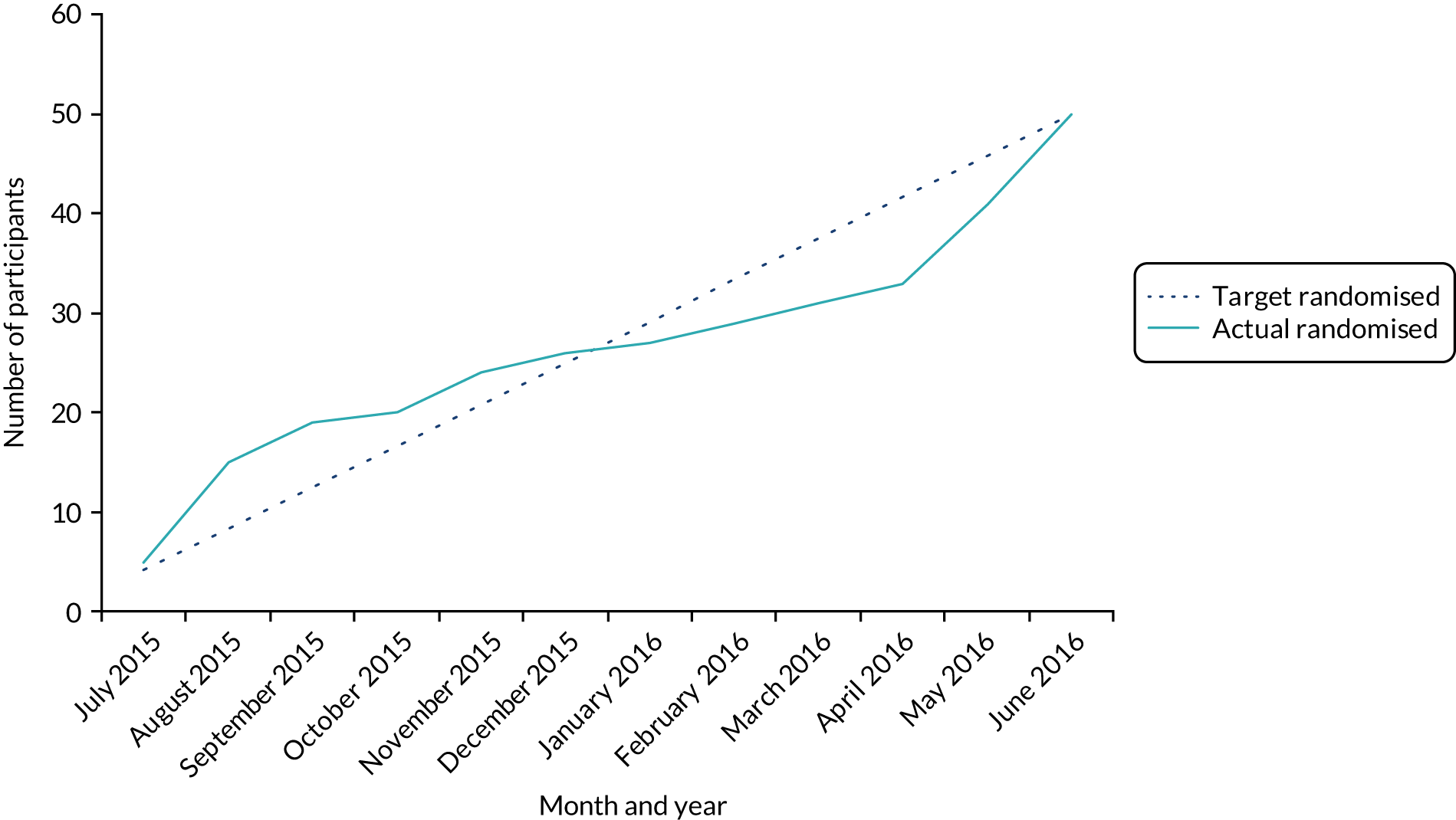

WP2 – to conduct a single-centre, pilot RCT of the REACH-HF intervention to determine the feasibility of a full trial of its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in addition to usual care in patients with HFpEF (see Work package 2: single-centre, pilot randomised controlled trial of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction).

-

WP3 – to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention in addition to usual care in patients with HFrEF and their caregivers in a multicentre RCT (see Work package 3: multicentre randomised controlled trial of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction).

-

WP4 – to assess the longer-term cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention, other home-based CR and centre-based CR versus usual care in people with HFrEF by using evidence synthesis and modelling methods to bring together evidence on home- and centre-based CR (see Work package 4: model-based cost-effectiveness analysis).

FIGURE 1.

Diagram depicting the REACH-HF programme and its inter-relationships. a, Adapted for patients with HFpEF for pilot RCT.

We were able to fully meet the programme objectives:

-

We co-designed the REACH-HF intervention with stakeholders including patients, caregivers, clinicians and commissioners.

-

Both WP2 and WP3 trials recruited to target and had excellent retention.

-

We successfully completed an updated evidence synthesis and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home- and centre-based CR.

Table 1 summarises the publication outputs from this programme.

| Programme objectives | Synopsis: research development | Programme outputs |

|---|---|---|

| WP1 – to develop an evidence-informed, home-based, self-care CR programme for patients with HF and their caregivers (‘the REACH-HF intervention’) |

WP1A: systematic intervention mapping methods to develop a facilitated home-based, self-help intervention for patients with HFrEF (‘the REACH-HF intervention’) WP1B: individual qualitative interviews and focus group interviews in participants’ homes to systematically develop a theoretically robust, home-based resource for caregivers of people with HF The REACH-HF intervention was also evaluated in a feasibility study in patients with HFrEF with parallel process evaluation |

REACH-HF intervention, comprising HF Manual, participant Progress Tracker booklet, Family and Friends Resource for caregivers, and facilitation by cardiac nurses or physiotherapists (details available from investigator team) Greaves et al. 39 (see Appendix 1) Wingham et al. 40 (see Appendix 1) |

| WP2 – to conduct a pilot trial to assess the feasibility of undertaking a full trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention in addition to usual care in patients with HFpEF | WP2: pilot trial to assess the effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with HFpEF |

Eyre et al. 41 (see Appendix 1) Lang et al. 42 (see Appendix 1) Smith et al. 43 (see Appendix 1) |

| WP3 – to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention in addition to usual care in patients with HFrEF and their caregivers | WP3: RCT and process evaluation to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the REACH-HF intervention in addition to usual care vs. usual care alone in patients with HFrEF |

Taylor et al. 38 (see Appendix 1) Dalal et al. 44 (see Appendix 1) Wingham et al. 10 (see Appendix 1) Frost et al. 45 (see Appendix 1) Report on trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis (unpublished report, see Appendix 3) |

| WP4 – to assess cost-effectiveness over the longer term of the REACH-HF intervention, home-based CR and centre-based CR vs. usual care in people with HFrEF | WP4: evidence synthesis/modelling to assess the cost-effectiveness over the longer term of the REACH-HF intervention, home-based CR and centre-based CR vs. usual care in people with HFrEF |

Long et al. 1 (see Appendix 1) Taylor et al. 46 (see Appendix 1) Report on model based on cost-effectiveness analysis (unpublished report, see Appendix 3) |

Work package 1: intervention development and feasibility study

Some parts of these sections have been reproduced with permission from Greaves et al. 39 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Work package 1: overview

We used a systematic intervention development framework – intervention mapping47 – to develop a novel, evidence-informed, facilitated, home-based, self-care manual for people with HFrEF (‘the REACH-HF intervention’) (see WP1A) and their caregivers (see WP1B) and evaluated this intervention in a feasibility study in patients with HFrEF. This included the use of formal and informal literature reviewing, individual qualitative interviews, focus groups and workshops with a range of stakeholders (patients, caregivers, service providers and experts in the field) to develop a model of targets for change and intended processes of change (a logic model). Following this, we identified and ‘mapped’ change techniques to each intended process of change and strategically organised the intervention components. This resulted in a comprehensive, theory-based, user-centred, home-based, self-care support programme for people with HF and their caregivers. We collaborated closely with our patient and public involvement (PPI) advisory group throughout, such that the intervention can be considered to have been co-created with patients with HF and their caregivers. The resulting REACH-HF intervention includes three core printed components (i.e. the Heart Failure Manual, a Family and Friends Resource for caregivers and a Progress Tracker booklet), a choice of two exercise programmes for patients and a training course for facilitators. The intervention was delivered by trained facilitators (cardiac nurses or physiotherapists with experience of delivering CR programmes). We stipulated that, in most cases, patients should receive a minimum of two face-to-face sessions and around six contacts in total over the course of 12 weeks. The methods used to develop the novel REACH-HF intervention and a detailed description of the intervention and its theoretical basis have been published. 39 This paper included a supplemental file with data on the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention for patients and caregivers but with data on changes in outcome measures redacted (these data were considered sensitive at the time, as the main trial was under way). We now include the previously unpublished results of the feasibility study in Report Supplementary Material 2. The REACH-HF intervention was trialled in a feasibility study in patients with HFrEF and was used successfully in both of our RCTs (see Work package 2: single-centre, pilot randomised controlled trial of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and Work package 3: multicentre randomised controlled trial of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction). In both studies, it was well accepted by study participants and HCP facilitators.

Work package 1: introduction

To manage HF effectively, patients need to engage in a number of self-care behaviours including exercise-based CR, which is recommended nationally and internationally. 48 However, participation in CR remains suboptimal in people with HF, which has been attributed to difficulties in patients accessing hospital- or centre-based CR and lack of support for caregivers. Consequently, there have been calls for alternative ways of delivering CR for patients with HF to improve the poor uptake.

Work package 1 concerned the development and feasibility testing of a novel, home-based intervention – ‘the REACH-HF intervention’ – for people with HF (WP1A) and their caregivers (WP1B). A detailed report of the development process and content of the intervention and its theoretical basis has been published (see Appendix 1). Report Supplementary Material 2 provides the results of a single-arm feasibility study designed to test the acceptability of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with HFrEF and the research methods for the main trial (see Work package 3: multicentre randomised controlled trial of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) and to identify ways to improve/optimise the intervention ready for further evaluation. The intervention’s development and its content are further described below.

Work package 1: research aims

Intervention development aims (work packages 1A and 1B combined)

The aims of the intervention development were to:

-

establish the support needs of people with HF and their caregivers

-

use a systematic intervention development framework (intervention mapping) to develop a home-based CR intervention that is theory based and evidence informed, involving people with HF and their caregivers

-

develop a training course to support intervention delivery.

Feasibility study aims

The aims of the feasibility study were to:

-

assess the feasibility and acceptability of adding the REACH-HF intervention to usual care for patients with HFrEF, their caregivers and intervention facilitators

-

assess the fidelity (quality) of delivery of the REACH-HF intervention

-

assess the feasibility of outcome data collection processes and measure completion/attrition rates

-

identify any changes needed in the REACH-HF intervention or facilitator training.

Work package 1: methods

Framework for intervention development

Following the UK Medical Research Council guidance for developing complex health-care interventions,49 we used a systematic, evidence-informed approach to develop the REACH-HF intervention. Our approach was based on intervention mapping – a six-step systematic framework for intervention development:50

-

Step 1 – ‘needs assessment’ to identify targets for change.

-

Step 2 – building matrices to ‘map’ change targets against determinants of the desired changes.

-

Step 3 – selection of appropriate behaviour change techniques and strategies to address each determinant identified in step 2.

-

Step 4 – production of detailed intervention and training materials.

-

Step 5 – anticipating adoption and implementation of the intervention.

-

Step 6 – plans for evaluation of processes and effects.

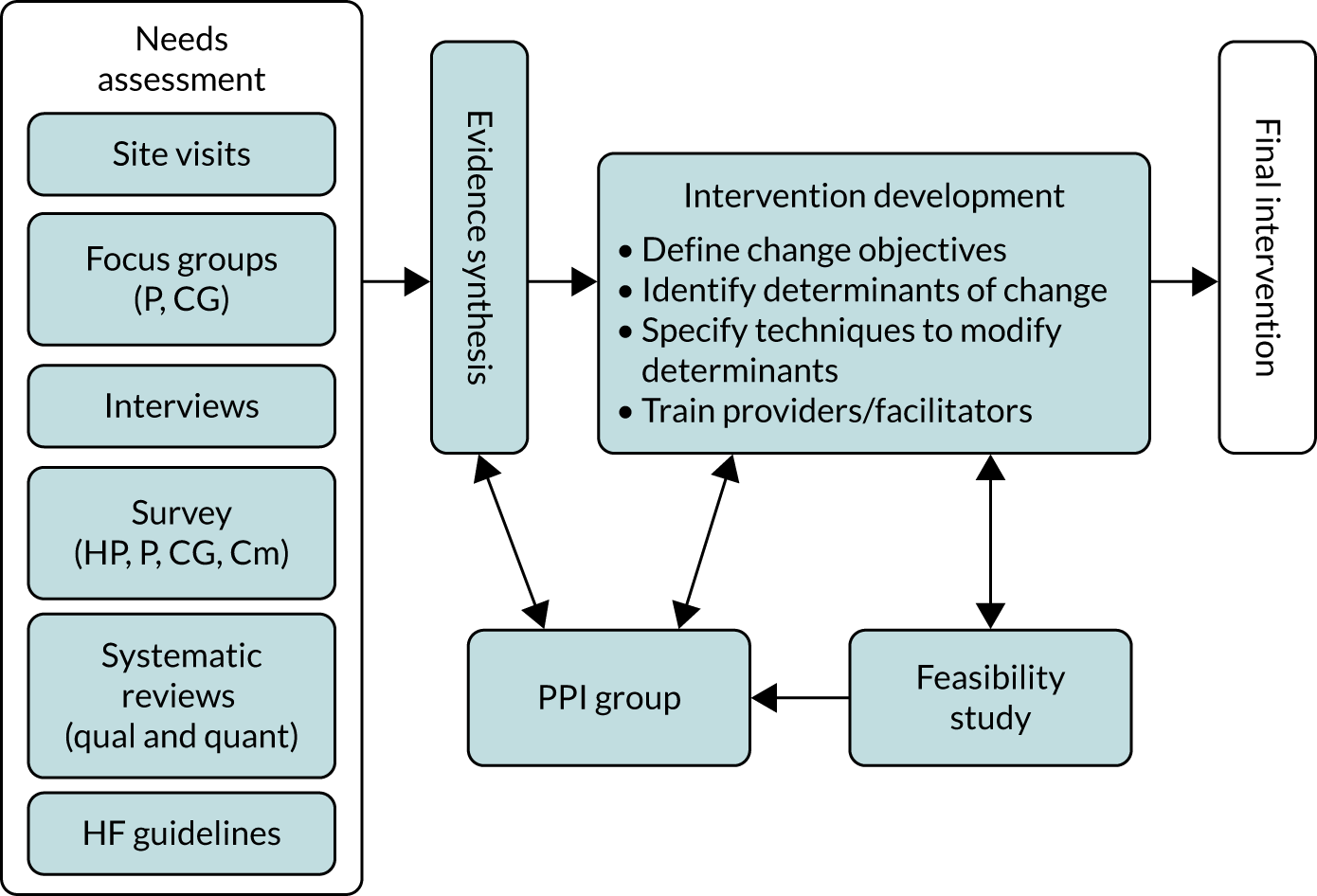

Intervention mapping seeks to ground the intervention in the context and the population to be targeted, as well as the existing evidence base. A key element of the intervention development process was the inclusion of the REACH-HF PPI group, which consisted of six people from Cornwall with a range of experiences with HF and three caregivers of people with HF. An overview of the intervention development process is provided in Figure 2, and the following sections provide a summary of the first five steps of the intervention mapping process. The process evaluation plans (step 6) are described elsewhere (see Report Supplementary Material 3 and Work package 3: process evaluation). 39

FIGURE 2.

Development of the REACH-HF intervention. CG, caregivers; Cm, commissioners; HP, health-care providers (e.g. general practitioners, cardio specialists, nurses); P, patients; qual, qualitative; quant, quantitative.

Step 1: needs assessment/identifying targets for change

The process began by assessing the needs of patients with HF, their caregivers and the service providers. This included gathering information on the problem, its causes and the target population and then developing a ‘causal model’ outlining the main modifiable factors that might contribute to an improvement in HRQoL for people with HF (see Figure 2).

Reviews of qualitative and quantitative literature provided a starting point for assessing the self-care support needs of patients and caregivers. An ongoing literature search (updated every 2–3 months) identified published reviews of self-care and rehabilitation interventions for people with HF from 1994 onwards. In addition, two de novo systematic reviews were undertaken by the project team: a meta-ethnographic synthesis of qualitative literature on the attitudes, beliefs and expectations of people with HF receiving CR51 and a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of CR in people with HFpEF. 52 We also reviewed national and international clinical guidelines for HF recommended by our project management group, including the ESC21 and NICE practice guidelines. 27 The key recommendations on behaviour change, information needs or other changes needed to improve the HRQoL of patients or caregivers were extracted, along with potential self-care strategies and potential determinants of such changes.

A number of systematic reviews and guidelines highlighted the importance of exercise-based rehabilitation as a central element in driving positive outcomes in HF. 14,21,27,52 As a result, a specialist working subgroup of project team members (PD, SS, KJ, JA, CG and RT) met several times (along with extensive e-mail interaction) to develop and refine the exercise and physical activity components of the intervention.

We conducted focus group interviews with two community-based HF support groups and attendees at a hospital-based rehabilitation class. Each group included 12–20 patients and 6–10 caregivers. The main topic areas were ‘coming to terms with heart failure’; benefits of and barriers to exercise/physical activity; problems and solutions associated with taking medications; information and support needs; advice for family members or caregivers; and how the REACH-HF intervention should be delivered.

To further elicit the views of key stakeholders, a needs assessment questionnaire was circulated to 10 people with HF and 24 other experts in the field, including two behavioural scientists, 14 specialist nurses (HF, CR and primary care cardiac nurses), two cardiologists, two general practitioners (GPs), two exercise physiologists with CR experience and two pharmacists. This was an opportunity sample based on contacts known to the REACH-HF project management group and people in the focus groups who had volunteered to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire (which is published alongside the intervention development paper39) included questions about what outcomes are important for people with HF; self-care behaviours that should be targeted; information and support needs; suggested content and delivery formats; and who might deliver the intervention. Respondents were also asked how the manual could be adapted for a range of users, including those with HFpEF.

The REACH-HF PPI group helped to design the topic guide for the focus group interviews, completed and commented on the needs assessment survey and commented on summaries of information from the focus groups. The group met every 2 months throughout the 12-month needs assessment stage, with additional e-mail and postal correspondence between meetings.

A qualitative research study involving face-to-face, semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of 26 caregivers of people with HF with a range of sex, age and socioeconomic status was also conducted to specifically identify caregivers’ needs. 40

Understanding the context or community in which an intervention is delivered is another important aspect of needs assessment. 50 A member of the research team (Wendy Armitage from the Heart Manual Department) conducted site visits to HF treatment centres and a range of staff at four sites (Truro, York, Birmingham and Abergavenny) and administered a questionnaire on current service provision. 53 This identified existing strengths, limitations, competencies and capacities of potential providers.

Two team members (Carolyn Deighan and Michelle Clark from the Heart Manual Department) reviewed further literature to identify evidence on the effectiveness of relaxation and mindfulness interventions for people with HF (and other chronic illnesses) to inform the stress management component of the Heart Failure Manual. Finally (just prior to implementation in the feasibility study), a training needs questionnaire was sent to HCPs who had been selected to deliver the intervention to assess their current state of knowledge/expertise with regard to key elements of the intervention. This was used to tailor the training course in step 4.

A key challenge was to summarise and integrate the data and ideas from many diverse sources. We did this using a framework for mixed-mode evidence synthesis called triangulation protocol. 54 First, a thematic synthesis of the needs assessment documents and recordings was used to generate a ‘needs assessment’ table, which listed the key recommendations from each evidence component. We then considered where the recommendations from each source agreed (convergence), offered complementary information on the same issue (complementarity) or seemed to be contradictory (dissonance). Where there was dissonance, we resolved this through further discussion with the members of the project management and PPI groups. The focus of the data synthesis was on identifying (1) targets for change and (2) modifiable determinants of the changes suggested. This analytical process was conducted separately for patients and caregivers.

The themes identified by the above synthesis were organised into a logic model55 for the intervention (Figure 3). This was developed by grouping the targets for change into broad themes (behavioural, environmental, social and psychological) and mapping them onto a generic causal modelling framework for intervention development (the PRECEDE model50,56). It was acknowledged that environmental and contextual factors (e.g. home environment, social support networks) might affect HRQoL directly or indirectly (via interaction with behavioural or psychological factors).

FIGURE 3.

Logic model/behavioural specification for the REACH-HF intervention. ADL, activities of daily living.

The targets for change (Box 1) were then prioritised through a process that included noting the level of agreement between stakeholders from the needs assessment table, consultation with the project PPI group and further discussion within the project team. We took into account the strength of the evidence base and the potential for improving HRQoL. The highest priority targets for change (shown in dark blue in Box 1) were then grouped into the following five categories:

-

engaging in exercise training to build (and maintain) cardiovascular fitness

-

managing stress, breathlessness and anxiety

-

HF symptom monitoring (and associated help-seeking), particularly in terms of managing fluid status

-

taking prescribed medications

-

understanding HF.

Engage in exercise training (to improve cardiovascular fitness).

Longer-term physical activity (to maintain cardiovascular fitness).

Manage stress/anxiety.

Manage fluid status (over and under hydration).

Monitor signs and symptoms: seek help appropriately.

Take medications.

Manage breathlessness.

Understand HF.

Manage low mood.

Manage fatigue.

Healthy eating.

Manage/live with uncertainty (about possible deterioration/decompensation events/end of life).

Sleep well.

Maintain social activities/social roles.

Weight management.

Manage severe depression.

Stop smoking.

Manage alcohol intake.

Manage/organise the home and work environments.

Manage financial burden/organising benefits.

Manage comorbidities (other illnesses) that might affect the ability to manage HF.

Manage and respond appropriately to devices (e.g. implantable cardiac defibrillator, cardiac resynchronisation therapy), including managing anxiety around devices.

Understand medications/treatments.

Get vaccinations.

Engage in sexual activity if desired.

Dark blue font indicates full coverage (core topic and important for all).

Light blue font indicates needs-based intervention (topic important for some but not all patients).

Orange font indicates case management approach (topic important for some but needing external input).

Light orange font indicates information only (topic peripheral or of relatively minor importance in most cases).

Item 5 (understanding HF) was included following step 3 (see below), as it was identified as a core determinant underpinning engagement with the first four targets for change.

The project management group and PPI group agreed that the above core priorities should receive strong focused support from the intervention facilitator and that the intervention manual should contain interactive elements to support change in these areas (e.g. for exercise training, we included a choice of a walking programme or chair-based exercise programme, as well as interactive tools for goal-setting and self-monitoring).

A second set of targets (the light blue text in Box 1) were identified as important for some but not all patients (e.g. smoking cessation and healthy eating). It was agreed that these aspects should be assessed and (briefer) intervention from the facilitator provided if needed.

A third set of targets, although important for some patients, were deemed to be outside the remit of the provider (e.g. management of severe depression) or possible to address through existing services (e.g. smoking cessation). It was agreed that these topics would be dealt with using a case-management approach.

A fourth set of targets were categorised as peripheral or minor topics, such as vaccination. For these topics, the patient was assessed, given some information and, if needed, signposted to further agencies or information (e.g. websites).

The core priorities for the caregiver resource were to:

-

facilitate improvement in HRQoL for the person with HF by helping them to achieve the core priorities for change for patients (see Box 1)

-

improve the quality of life for caregivers by acting to maintain their own health and well-being.

The target of ‘understanding heart failure’ was also felt to be of core importance in underpinning engagement with the above targets. The targets for change for caregivers that emerged from the needs assessment process are shown in Box 2. A focus group with four caregivers was conducted to prioritise the targets in the same way as described for the patient manual (see Analysis and integration of needs assessment data).

Support monitoring and management of signs/symptoms of HFa (e.g. when to ‘step in’).

Understand HF. a

Understand and manage medicines. a

Exercise/physical activity promotiona (facilitate the HF Manual exercise programme as well as maintenance).

Provide emotional support to help manage patient’s mood, anxiety, stress.

Manage caregiver stress and emotional consequences.

Manage own physical healtha (including physical activity/lifestyle, health problems, safe lifting).

Become a caregiver (psychological and practical adaptation, role negotiation).

Sleep well.

Deal with emergencies (including resuscitation issues).

Communication with health professionals.

Manage/organise the home and work environments – daily hassles.

Maintain own social activities/social roles.

Monitor signs/symptoms of depression of cared-for person. a

Understand and manage comorbidities. a

Provide and engage social support (e.g. offer information, encouragement and practical support; engage friends, relatives, carer groups).

Live with uncertaintya (e.g. possible deterioration/decompensation events, end-of-life issues).

Attend to physical needs of the cared-for person (practical tips).

Manage and respond appropriately to devices (e.g. implantable cardioverter defibrillator, cardiac resynchronisation therapy), including managing anxiety around devices. a

Engage social services (e.g. carer needs assessment).

Manage financial burden/organising benefits for caregiver.

These self-care issues are also dealt with in the HF Manual, and relevant sections are referenced from the caregiver resource.

Dark blue font indicates full coverage (core topic and important for all).

Light blue font indicates brief, needs-based intervention (topic important for some but not all patients).

Orange font indicates case management approach (topic important for some but needing external input).

Step 2: specifying performance objectives/identifying determinants of change

The behavioural, environmental, social and psychological targets for change resulting from needs assessment (see Boxes 1 and 2) were broken down into more proximal ‘performance objectives’. Performance objectives are statements of who needs to change and what behaviours or thought processes need to be changed (and in what circumstances) to achieve each target. 50 For each performance objective, modifiable determinants of change were identified using several parallel methods:

-

Existing evidence (e.g. process evaluations in rehabilitation studies).

-

Theories of behaviour change and psychological adaptation. 51,57–63

-

Evidence identified during the needs assessment stage (e.g. qualitative data, needs assessment questionnaire).

-

A structured 1-day workshop with a panel of experts in the field (two exercise/rehabilitation specialists, two cardiac specialist nurses, two GPs with cardiac special interest, two cardiologists and three behavioural scientists).

-

Similar structured workshops (three separate 2-hour sessions) with the PPI group. The consultation workshops focused on the ‘core priority’ change targets.

In the workshops, the ‘core priority’ targets for change and their associated performance objectives were presented to the expert panel and the PPI group. For each performance objective, the panel were asked:

-

What will help people to achieve this target?

-

What will stop people achieving this target? What will get in the way?

-

How could we help people to overcome any barriers and achieve this target?

A facilitated group discussion resulted in a list of modifiable determinants (barriers and facilitators) relating to each objective.

The performance objectives and determinants were then used to construct a set of ‘mapping matrices’ or tables. The first two columns in Table 2 show the performance objective and determinants for performance objective 1: ‘Engage in exercise training sessions 2–3 times per week’ as an example. Separate matrices of performance objectives and determinants were constructed for the caregiver intervention.

| Performance objective | Modifiable determinants | Change techniques | Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Engage in exercise training sessions two or three times per weekb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

The intervention design team specified a theoretical basis that (1) provided sufficient range to incorporate all the determinants of change identified for each change target, and (2) was as parsimonious as possible.

Step 3: specification of change techniques and strategies

Step 3 of the intervention mapping process involved the selection of change techniques (e.g. behaviour change and psychological intervention techniques) targeting each of the determinants of change identified in step 2. In addition to expert opinion and experience, this work drew on an existing taxonomy of behaviour change techniques64 and the expertise of the REACH-HF collaborators in developing disease management programmes and CR programmes to identify potentially successful strategies for patients with HF and their caregivers. The PPI group were asked about the strategies that they had found to be successful and reviewed the selected change strategies (and the final programme materials) to ensure that they were likely to be feasible and acceptable for patients and caregivers.

Step 4: production of detailed intervention and training materials

The outputs from the first three stages of the intervention mapping process were used to generate detailed intervention materials and a training course for facilitators. These are described in Work package 1: results. The PPI group commented on the materials in terms of both format and content.

Step 5: anticipating adoption and implementation issues – the REACH-HF feasibility study

We conducted a single-arm feasibility study (ISRCTN25032672) with a parallel process evaluation across four sites (Birmingham, Cornwall, Gwent and York) to (1) assess the feasibility and acceptability of adding the REACH-HF intervention to usual care for patients with HFrEF, their caregivers and intervention facilitators, (2) help refine the intervention in advance of the main trial and (3) assess the quality of intervention delivery. 39

The REACH-HF intervention was delivered to 23 patients (and 12 caregivers) by seven trained intervention facilitators at four sites (Cornwall, Abergavenny, Birmingham and York) over a period of 12 weeks in addition to usual care. Process data to help assess feasibility, acceptability and quality of intervention delivery (intervention fidelity) were collected from multiple sources:

-

Qualitative methods were used to explore the stakeholder experiences of using and delivering the intervention. Brief semistructured interviews with 13 patients and seven caregivers about their experiences of receiving the REACH-HF intervention were conducted by telephone or face to face. These were undertaken at 6 weeks (halfway through the intervention period) and at around 15 weeks (at the end of the intervention period). The seven intervention facilitators completed feedback forms at the end of each session. They documented what went well or not well and also participated in up to three (audio-recorded) debriefing/feedback sessions during intervention delivery and a focus group at the end of the intervention period. Topic guides (see Report Supplementary Material 1) were developed in consultation with the intervention development team, the REACH-HF investigators and our PPI Advisory Group.

-

A 13-item intervention fidelity checklist was applied to audio-recordings of all intervention sessions for 18 participants to assess the quality of intervention delivery (see Appendix 1). This produced a score of 0–6 for each (predefined) key component of the intervention process. Two members of the intervention design team (from a pool of three team members) independently rated intervention fidelity for each recording. To improve inter-rater reliability, prior to rating all the recordings, the three coders (Anna Sansom, Colin J Greaves and Jennifer Wingham) coded the same four audio-recordings and had debrief meetings to compare scores and agree principles to identify examples of adequate, excellent or poor delivery for scoring going forwards. A detailed instruction set was developed and is available in Appendix 1. 39

-

Patient and caregiver outcome measures planned for the main RCT were collected before and after the intervention (3 months after baseline) to assess their feasibility and acceptability. Serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events that were potentially related to the intervention were recorded for patients (not for caregivers).

Work package 1: analysis

The recorded interview data, facilitator feedback forms and other qualitative data were subjected to simple thematic analysis. 65 Data were transcribed verbatim and analysed to extract concepts, which were then grouped into higher-level themes using a constant comparison approach. Data were organised using NVivo version 11.0 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Two researchers independently analysed a sample of interviews and then conferred to develop an initial coding framework (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Quantitative outcome measures were summarised using basic descriptive statistics, with mean pre–post change scores for outcomes presented alongside CIs, as well as completion rates. Fidelity scores were summarised across participants for each checklist item and also broken down by facilitator.

Work package 1: results

Feasibility study results

A summary of the findings is available in Appendix 1. The feasibility study recruited 23 patients and 12 caregivers, and seven intervention facilitators provided the intervention.

-

Patients and caregivers were highly satisfied with the REACH-HF intervention and attendance at sessions was high (all patients attended at least three face-to-face sessions and typically received four telephone contacts).

-

A number of potential modifications to the content of the manual and facilitator training were identified.

-

Intervention fidelity scoring of all of the delivered consultations for 18 cases indicated adequate delivery for most aspects of the intervention by all facilitators [mean scores ranged from 2.6 (item 11, caregiver health and well-being) to 5.0 (item 1, person-centred delivery)] and are presented in in the feasibility study report (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table A).

-

Two items [addressing emotional consequences of being a caregiver (item 10) and caregiver health and well-being (item 11)] had suboptimal delivery–fidelity scores.

-

We also computed fidelity scores collated per facilitator, and these are presented in Table 5. These represent delivery for only three patients per facilitator and so should be treated with caution. Despite this, we observed reasonable consistency between facilitators on most items.

-

Levels of outcome completion were generally excellent, and patients/caregivers perceived relatively low measurement burden.

-

A number of patient and caregiver outcomes following the REACH-HF intervention showed evidence of improvement (with all of the caveats of a small population of selected participants and uncontrolled comparisons).

-

No patient or caregiver safety concerns were identified.

-

Physical fitness [measured through the Incremental Shuttle Walk Test (ISWT)] was successfully carried out by the majority of patients. As per previous studies, older patients with multiple comorbidities showed some improvement, but this did not achieve statistical significance over time.

A number of ideas for improving the text of the HF Manual and the training were identified, such as changing the name of the original ‘Caregiver Resource’ to ‘Family and Friends Resource’ to promote engagement with the intervention, as many cohabitees did not identify themselves as a ‘caregiver’. Following processing of the above data, the HF Manual (including the Family and Friends Resource and Progress Tracker) and training course were substantially revised. This final version was then evaluated in Work package 3: multicentre randomised controlled trial of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

The REACH-HF intervention

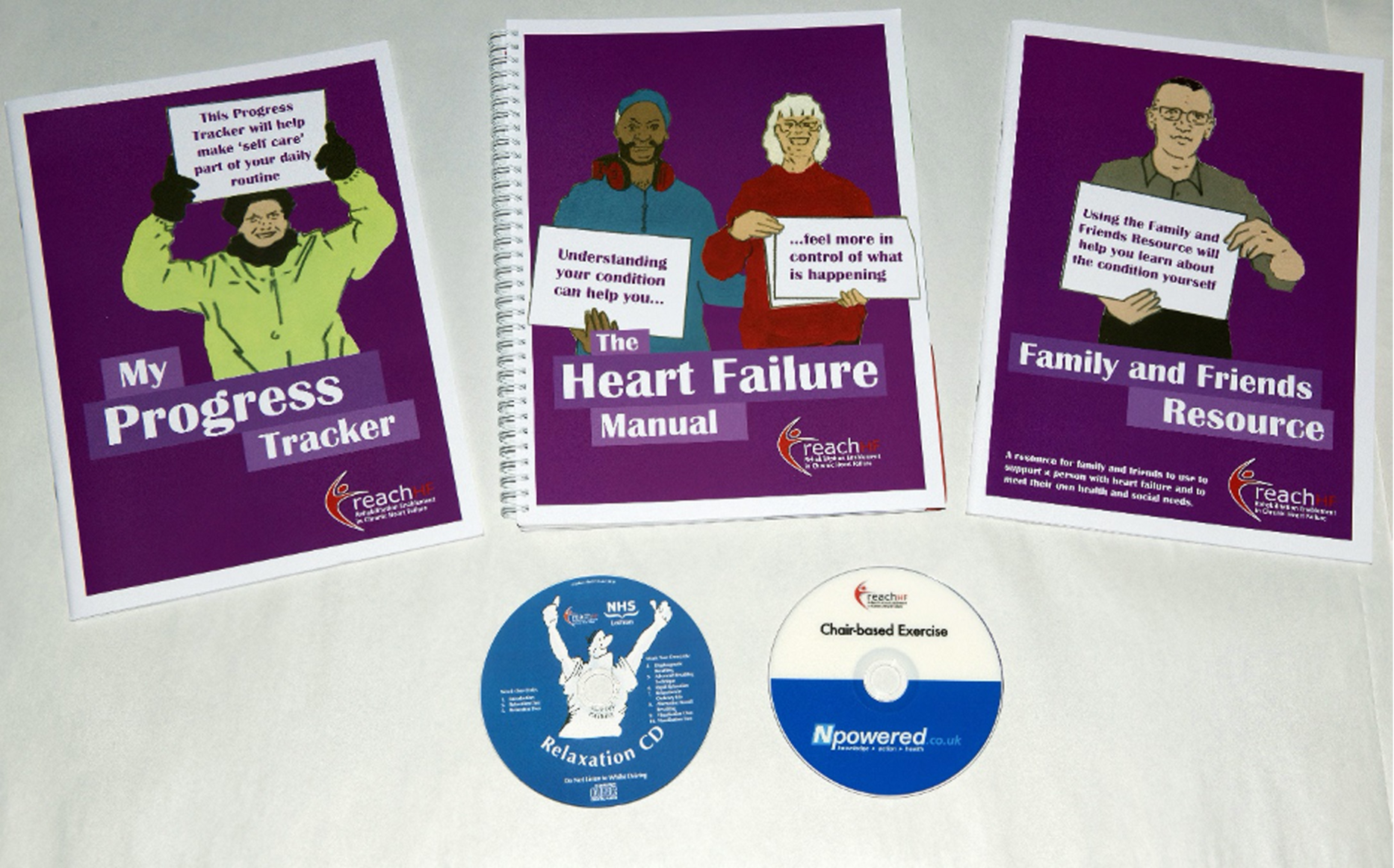

The REACH-HF intervention is a comprehensive self-care support programme comprising the ‘HF Manual’, including a choice of two exercise programmes for patients, a Family and Friends Resource for caregivers, a Progress Tracker booklet and a facilitator training course. For patients, the main self-care targets are engaging in exercise training, monitoring for symptom deterioration, managing stress and anxiety, managing medications and understanding HF (see Box 1 for an expanded list). Secondary targets include managing low mood and smoking cessation (where relevant). For caregivers, the main intervention targets are supporting self-care for the patient and looking after their own physical and mental health (see Box 2). The intervention is facilitated by trained HCPs with specialist cardiac experience (e.g. a HF nurse or physiotherapist) over 12 weeks via home and telephone contacts. The four main REACH-HF intervention elements as described in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

The REACH-HF intervention materials.

Heart Failure Manual

This is a self-help resource for use by patients and their caregivers. The HF Manual includes patient-focused/plain English explanations of what HF is and how people can learn to live with the condition to maximise their quality of life. The text aims to improve understanding of HF in terms of the identity of the illness, as well as causes, consequences, control/treatment and timeline, in line with Leventhal’s common sense model of illness. 61 It includes sections on taking medications, fluid management (including a traffic-light guide on recognising when to seek help), managing stress, managing changes in symptoms and a choice of two structured exercise programmes (see REACH-HF exercise programme). The manual also includes a compact disc (CD) with relaxation and breathing control exercises from the existing Heart Manual30 and appendices offering self-care advice on other self-care behaviours, such as smoking cessation, implanted devices, managing low mood and healthy eating.

Progress Tracker

This is an interactive booklet designed to facilitate learning from experience/over time and build understanding about the impact self-care activities have on symptoms, emotional well-being and quality of life through practice, self-monitoring of progress and (facilitated) problem-solving.

Family and Friends Resource

This is a manual for use by caregivers. It aims to increase caregiver understanding and skills both to help the person with HF and to look after their own physical and mental well-being. The resource is divided into three main sections: (1) supporting the patient’s self-management of HF (‘Providing support’), (2) caring for the caregiver (‘Being a caregiver’) and (3) practical advice, including mobilising social support, accessing benefits and other formal and voluntary support (‘Getting help’).

Training course for facilitators

A training manual/syllabus for a 3-day training course for the REACH-HF intervention facilitators was developed. Facilitators were defined as professionals with experience in CR or cardiac nursing. The facilitation role is crucial to the success of the REACH-HF programme. As well as being the main delivery process, it enables tailoring of the REACH-HF intervention resources to the individual needs of patients and their caregivers. The course includes the theory and process of facilitation (building rapport using patient-centred counselling techniques,66 empowerment and support of self-management, building understanding of the condition61); using behaviour change techniques; techniques for managing stress and anxiety; contents of the manual; supporting exercise and physical activity using the intervention materials; and facilitation of the Family and Friends Resource and medical/nursing issues. The training was linked by three case studies of patients with HF and opportunities to practise facilitation techniques and to problem-solve potentially difficult situations.

A set of quotations or ‘patient voices’ selected by patients and caregivers in the PPI group from our prior qualitative work was incorporated throughout the written resources in the form of speech bubbles to help illustrate key points (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Extract from the HF Manual showing a ‘patient voice’ callout.

REACH-HF exercise programme

Patients were offered a choice of two exercise programmes:

-

A chair-based exercise programme and digital versatile disc (DVD) that had been previously developed by Professor Patrick Doherty, who is a REACH-HF co-investigator and was principal investigator at the York trial site. The DVD includes seven levels of aerobic and resistance exercise with progressively increasing intensity. The exercises are designed to avoid undue breathlessness, build cardiovascular fitness, improve efficiency of movement and strengthen muscles to facilitate functional activities associated with daily living. The chair-based exercise programme was integrated into the REACH-HF intervention and facilitators received training on how to support patients in using the chair-based exercise DVD. The intellectual property for the chair-based exercise programme belongs to Professor Doherty who, as part of the REACH-HF and NIHR intellectual property agreement, licensed the chair-based exercise programme DVD to REACH-HF for the main trial and subsequent dissemination of REACH-HF.

-

A progressive walking-training programme based on increasing walk duration and intensity over time to build cardiovascular fitness and lower limb muscle strength.

The starting level (for the DVD) or walking time/distance (for the walking programme) was agreed (by patient and facilitator) based on results from an ISWT in conjunction with data and metabolic equivalent (MET) values for each of the known fitness level (METs) for each of the seven chair-based exercise programme levels. The proposed chair-based exercise level would start patients at around 65–70% of their ISWT MET, which is an expression of physical fitness. Values for ISWT (e.g. metres walked or speed achieved) were used to guide the walking exercise programme, using mostly distance-walked targets or speed of walking, where that suited the patient’s ability and goals.

Patients were also given pragmatic instructions on how to work at a moderate intensity. We wanted to ensure that the initial exercise prescription for patients was in the range of 65–70% of their maximal fitness derived from the ISWT. In addition, we sought to avoid reliance on the use of heart rate monitors by helping patients to become familiar with and skilful at using a self-rating scale of perceived effort (scored 1–10 from ‘nothing’ to ‘exhausted’) and advised patients to work at an effort level of 4–6. We also encouraged them to monitor their breathing and to work at a level that resulted in breathing heavier, feeling warmer and having a faster heartbeat. Instructions for warming up and cooling down were given, and, where possible, the facilitator observed the patient doing some exercise (using the DVD or walking) to ensure that the patient understood the level of intensity required. We advised that patients should be a little out of breath but still able to carry on a conversation. Patients were allowed to ‘mix and match’ between the two programmes if desired and were encouraged to engage with one of the exercise options every other day, or at least three times per week.

Intervention delivery

Based on existing CR practice and clinical guidelines, 12 weeks was considered an appropriate duration for delivery, with a minimum of three face-to-face contacts with a facilitator (plus telephone contacts) during this time. The face-to-face contacts were designed to be delivered in the patient’s home. The number of contacts was not specified exactly to allow tailoring of the delivery to patient needs, and no maximum number of sessions was stipulated. However, we stated that, in most cases, patients should receive a minimum of two face-to-face sessions and about six contacts in total over the course of 12 weeks. In practice (see Work package 3: multicentre randomised controlled trial of the REACH-HF intervention in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction), a mean of four face-to-face contacts and a mean of 6.5 contacts were delivered in total.

Theoretical basis

As different barriers and enablers (processes of change) were identified for different change targets, the resulting intervention drew on multiple theoretical perspectives. Despite this, several common theoretical processes for supporting the targeted changes in behaviour and psychological processes were identified (Table 3). Key principles included building an understanding of the condition to provide a rationale for change (Leventhal’s common sense model61); building intrinsic motivation and promoting autonomy (self-determination theory57); promoting adaptation to living with HF and an active approach to coping;51,63 and encouraging learning from experience through engagement in self-care activities (control theory68). The elements were aimed at managing stress and anxiety used psychological intervention processes based on cognitive–behavioural therapy70 and mindfulness therapy. 71,72

| Process (and theoretical basis) | Key features and intervention facilitation techniques |

|---|---|

| Active patient involvement (motivational interviewing66/self-determination theory57) | The facilitator should encourage the participant to be actively involved in the consultation. The idea is to maximise the participant’s autonomy as the main agent of change, developing intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation. However, the consultation should be guided. Empathy-building skills (open questions, affirmation, reflective listening, summaries) and individual tailoring should be used throughout the consultations. Reflective listening may be used to direct the conversation or highlight key strengths or barriers. A collaborative/shared decision-making style is appropriate, and the facilitator may share their own expertise and ideas. The Ask–Tell–Discuss technique should be used to exchange information (e.g. to address misconceptions or offer helpful new information). Overall, the participant should be increasingly empowered to take control of her/his self-care behaviour. Interactions should be encouraging, respectful and non-judgemental. The interaction should also be individually tailored to the patient’s specific information needs, beliefs, skills, and priorities |

| Assessing the patient’s current situation and needs (motivational interviewing,66 individual tailoring67) | The facilitator should use patient-centred communication techniques (as above), which may include the Ask–Tell–Discuss and open-ended questions to explore the patient’s current situation. This should include all of the following:

|

| Formulating an individualised treatment plan (self-regulation/control theory,68 individual tailoring67) | The facilitator should use patient-centred communication techniques (as above) to formulate an appropriate treatment plan based on the patient’s current situation (as assessed above). The treatment plan will be staged over time, aiming to work on a few topics initially and introducing other elements as the programme continues. This should be set up as an experiment to see how feasible the proposed actions are and whether or not they help the patient’s situation. An element of guiding to ensure the inclusion of clinical priorities (e.g. medication issues, exercise), as well as patient priorities, may be appropriate. The facilitator and participant should formulate a specific written action plan (using the template in the Progress Tracker) for exercise-training based on a choice of the two REACH-HF exercise-training programmes. The patient and caregiver should be ‘signposted’ to relevant sections of the manual. The facilitator may also employ some problem-solving techniques at this stage to pre-empt and address potential problems |

| Building the patient’s understanding of HF/their situation (Leventhal’s common sense model,61 theories of illness adaptation63) |

The facilitator should elicit the patient’s and caregiver’s current understanding of HF and seek to build their ‘illness model’ in terms of understanding the identity, causes, consequences, cure/control options and timeline associated with the condition. This process may take several weeks and should be reinforced as the programme progresses Facilitators will signpost the patient and caregiver to relevant sections of the manual, including the ‘Understanding heart failure’ section and use patient-centred communication techniques (as above) to elicit and build understanding. The Ask–Tell–Discuss technique and reflective listening will be used to exchange information to reinforce elements of the patient’s understanding that predispose positive self-care behaviours (e.g. understanding the link between physical fitness and symptoms of HF). The facilitator should seek to reframe negative attitudes and exchange information to address misconceptions or address important gaps in understanding. Learning should be reflected on/reinforced at subsequent sessions |

| Supporting self-regulation skills (self-regulation/control theory,68 relapse prevention,69 theories of illness adaptation63) |

The facilitator should discuss and encourage the use of the ‘Progress Tracker’ workbook in the HF Manual to keep track of progress and as a way of recording and addressing any problems completing the activities and any benefits that might be associated with the planned activities. At subsequent meetings, the facilitator and participant should review progress with all planned changes to exercise/physical activity and other self-care activities. The facilitator should reinforce and reflect on any successes. The participant and facilitator should discuss any setbacks, encourage identification and problem-solving of barriers to self-care, and the patient’s plans should be revised accordingly. Reframing should be used to normalise setbacks and see them as an opportunity to learn from experience (trial and error) rather than as failures Problem-solving should use OARS and information exchange (Ask–Tell–Discuss) techniques to identify barriers and explore ways to overcome them. Problem-solving may specifically focus on issues of connectedness (social influences, involvement of others in supporting activities) and long-term sustainability or on breaking the problem down into more manageable chunks |

| Addressing emotional consequences of HF (cognitive–behavioural therapy,70 mindfulness,71 theories of illness adaptation63) | The facilitator should help the patient recognise and address any significant stress, anxiety, anger or depression that is related to having HF. They should seek to normalise such feelings and help the patient to access and facilitate use of the cognitive–behavioural therapy techniques and stress management techniques within the manual. If depression, anxiety or other emotional problems are severe, a referral to appropriate clinical services should be facilitated |

| Caregiver involvement (if applicable) (literature on caregiver needs40) |

The facilitator should engage the caregiver as much as possible as a co-facilitator of the intervention. The facilitator should tailor the intervention to work with the caregiver’s abilities and availability. Person-centred counselling techniques (OARS) should be used for caregiver assessment and to exchange information to build the caregiver’s understanding of the situation and help them recognise and manage their own health needs, including mental health, physical health and social needs. The facilitator should facilitate a conversation between the patient and the caregiver to agree their roles and responsibilities and how these might change if the patient’s condition declines. Attention should be given to the caregiver’s needs and concerns about being a caregiver/providing care, as well as those of the patient The facilitator should help the caregiver to recognise and address any significant stress, anxiety, anger or depression related to supporting someone with HF and facilitate the use of the cognitive–behavioural therapy techniques and stress management techniques within the manual, as needed. This includes facilitating a referral for a carer’s assessment if the caregiver wishes, as well as referral to other relevant care services as appropriate The facilitator should help the caregiver to prioritise and look after their own health and well-being |

| Bringing the programme to a close (Leventhal’s common sense model,61 theories of illness adaptation,63 self-regulation/control theory,68 relapse prevention69) | Progress should be consolidated and reinforced. Plans for long-term sustainability of activities and strategies learned for managing HF should be discussed. The facilitator will review progress since the start of the intervention and reinforce what has been learnt. Useful strategies that were helpful should be identified. Plans to stay well/prevent relapse should be discussed, as well as ‘cues for action’ and plans to revisit the manual in the future. The facilitator will discuss plans to sustain any new activities, identifying any potential problems and coping strategies to overcome these. The possibility of good and bad days should be discussed and normalised |

Work package 1: discussion

Summary

Intervention mapping gave a clear structure and process for developing the REACH-HF intervention and the associated training programme for intervention facilitators. The process took into account the needs of a range of stakeholders, including patients with HF, their caregivers, HCPs, potential facilitators and health-care commissioners.

The construction of a causal model as part of the intervention mapping method (see Figure 2) was useful as a framework to integrate the identified needs and define the intervention’s ‘targets for change’. However, as reported by other studies that have used intervention mapping to develop complex health-care interventions,73–75 the overall process was time-consuming and resource intensive.

Successes

To our knowledge, this is the only publication that provides a detailed description of the theoretical and evidentiary basis, intervention techniques and strategies for an intervention to promote quality of life in people with HF. The intervention was co-developed with patients, caregivers, clinicians and academics to optimise it for use with patients with HF in real-world CR settings, and this was a particular strength of the research. In particular, PPI ensured that the intervention was tailored to individual needs based on a diverse range of patient backgrounds, knowledge levels and severity of HF.

Limitations

The complexity of the intervention development process may affect replicability, and it is unlikely that a different team of collaborators using the same methods would have produced exactly the same intervention.

Conclusions

We developed a comprehensive, evidence-informed, theoretically driven, self-care and rehabilitation intervention that is grounded in the needs of patients and caregivers. The intervention was well received by patients and caregivers and was feasible for and acceptable to the nurses and physiotherapists who delivered it. The intervention was delivered to an acceptable standard, although some revisions to the intervention and its associated training course were suggested. After these revisions, the REACH-HF intervention was ready for evaluation in a full-scale trial.