Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1210-12003. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The final report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in September 2020. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Perera et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background

Advances in health promotion and better prevention, detection and treatment of diseases have led to important demographic changes in the UK, with consistent increases in healthy life expectancy. Paradoxically, this also means that a greater number of people are now living longer with one or more long-term conditions, such as diabetes, kidney disease or coronary heart disease. 1,2 In the UK, the management of these conditions has shifted from secondary care to primary care, partly because of the continuity of care that primary care provides, but also because of the generalist approach used in primary care to deal with multiple, not necessarily related, conditions. 3 A major aspect of the good management of these conditions is long-term monitoring. However, despite the considerable economic cost for most of these conditions, there is no or poor evidence on the monitoring strategies used, for example how, what and when to monitor. 4

In particular, the frequency of monitoring has received little attention. A higher frequency of monitoring does not necessarily lead to better management. 5 Besides the financial costs, there are considerable downsides to overfrequent measurement. There are personal costs, such as the time spent, the need for invasive tests, the extra levels of anxiety and sometimes unnecessary hospital visits. More directly relevant, a higher frequency of monitoring increases the potential for inadequate management based on test results showing, incorrectly, deterioration when, in reality, the observed change is due to measurement variability only. 5,6 The overall aim of this programme was to develop a better understanding, extend the methods, increase the evidence base and improve the practice of clinical monitoring in UK primary care.

As background for this programme, our group, and others, had already developed evidence in the areas of cardiovascular disease (CVD) monitoring (cholesterol and blood pressure), warfarin monitoring and the monitoring of diabetic nephropathy. 5,7–10 This programme extended this work to other important clinical areas in primary care that represent two extremes in the way monitoring is carried out in primary care: renal monitoring in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and monitoring people with chronic heart failure (CHF). In the renal monitoring workstream (WS), we emphasised the non-diabetic population with CKD, to complement our previous report on diabetic nephropathy. 7

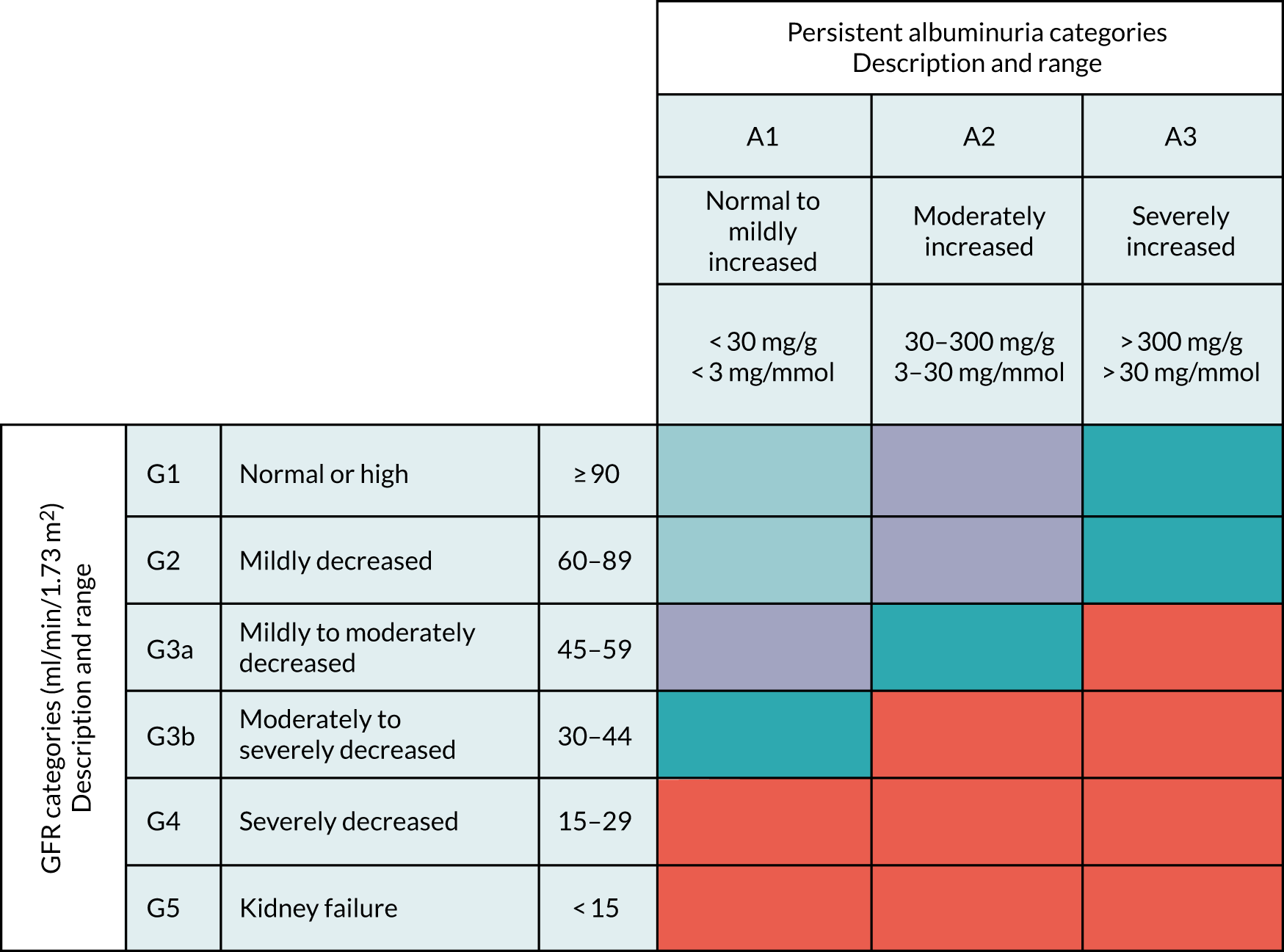

Diagnosis and management of CKD is based around estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) measurements (creatinine and cystatin C based). Measurement of eGFR-creatinine (i.e. eGFR based on a creatinine measure) is recommended whenever a request for serum creatinine is made;11 as laboratory testing in primary care has seen a 9% annual increase in the previous two decades,12 the majority of those classified with CKD will have mild/moderate disease [G1 to G3b, based on eGFR-creatinine, and A1/A2 based on albumin–creatinine ratio (ACR)]. Therefore, most of the management/monitoring for CKD carried out in primary care will be in this group, with the final stages of disease (renal failure needing dialysis or transplantation) occurring rarely or only after many years. Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for the management of CKD11 recommends that monitoring should be based around measurements of eGFR-creatinine and ACR, with the frequency determined jointly by the patient and the health practitioner, but suggests at least one test per year for those with mild or moderate reduction in kidney function (G3a or higher) or for those with moderately increased ACR (A2).

For CHF, on the other hand, diagnosis is carried out by a heart failure multidisciplinary team based around symptoms, signs and investigations. N-terminal prohormone of B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is currently the only recommended test used as part of this diagnostic process, but there are high levels of uncertainty regarding the threshold used for this. 13 Although some improvement in the management of this condition has been made, the outlook after diagnosis is still poor; therefore, the majority of monitoring, even when carried out in primary care, is conducted in the later stages of disease. 14 There is, however, strong evidence of the prognostic association between NT-proBNP level and survival,15 as well as evidence that treatment of heart failure can improve patient quality of life, in terms of both physical and emotional well-being. 16 With regard to monitoring, NICE recommends that this should be based around clinical reviews and recommends the use of NT-proBNP as part of treatment optimisation only in a specialist care setting for people with CHF aged < 75 years who have a reduced ejection fraction and who do not have CKD of G3a or higher. 13

The research programme

The overall aim of this programme is to improve the management of long-term conditions in primary care by optimising the utility and frequency of tests used for monitoring. To achieve this, we carried out a series of inter-related projects on two specific areas, arranged as two WSs: WS1 – CKD and WS2 – CHF. Each WS was designed to (1) provide a summary of current practice and current evidence in this area, (2) generate new quantitative and qualitative evidence for monitoring these conditions and (3) provide a cost-effectiveness framework (or full model) to integrate this evidence.

The programme was integrated by a series of studies using different methodological approaches: systematic reviews, analysis of electronic health records, cohort and feasibility studies, interviews and focus groups, and statistical and health economic modelling. These studies were carried out to answer the following research questions:

-

Does the choice of biomarker for the monitoring of CKD in a primary care population better predict renal function decline and is this choice cost-effective?

-

Can the number of tests that are used to monitor individuals with stage G2 and G3 CKD be reduced, and hence the associated costs?

-

Is it useful to monitor CHF in primary care using natriuretic peptide (NP) or weight as markers?

-

Is it feasible and affordable to use point-of-care (POC) NP measurement as part of a monitoring strategy in primary care?

-

What is the acceptability and impact of alternative monitoring regimes among individuals experiencing these conditions?

The research was carried out between January 2013 and May 2019.

The links between the different WSs and the different projects in each WS are summarised in Figure 1. There was shared methodology in both WSs and a single stakeholder group, which provided guidance and direction throughout.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the programme. BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide.

Workstream 1: chronic kidney disease

Prevalence rates from the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) England returns indicate that > 1.8 million adults are classified as having moderate to severe CKD (defined as persistent proteinuria or eGFR from serum creatinine), representing 4.09% of those aged ≥ 18 years. 17 CKD (see Appendix 1 for the five main stages) is associated with increased CVD risk (predominantly stroke, ischaemic heart disease and heart failure)2,18–21 and increased all-cause mortality. 2,19,21

Given that prevalence of CKD rises exponentially with age, published estimates vary according to the populations used to derive them. Less severe stages of early CKD are likely to be more prevalent, as suggested by US data that estimated that approximately 14% of the population could be classified as having stage G1, 10% as having stage G2, 6.7% as having stage G3 and 0.5% as having stages G4 and G5. Nevertheless, the majority of studies focus only on moderate or severe renal impairment, at the level of CKD stage G3+, which means that there is a lack of evidence for the management of the majority of those with CKD.

Most patients with CKD are managed in primary care (98%) using a multifactorial approach of repeated monitoring, maintenance of blood pressure below agreed guideline limits (140/90 mmHg, or < 130/80 mmHg in those with diabetes or raised proteinuria), treatment of hypertension with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and encouragement to lead a healthy lifestyle. 11 Current NICE guidance for the management of CKD11 recommends that monitoring should be based around measurements of eGFR-creatinine and ACR, with the frequency determined jointly by the patient and the health practitioner and tailored to take into account several factors, but suggests at least one test per year in those with mild or moderate reduction in kidney function (stage G3a or higher) or those with moderately increased ACR (stage A2). One of the reasons given for monitoring people with CKD is to be able to identify accelerated progression, which is currently defined as a sustained decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of ≥ 25% and change in GFR category within 12 months, or a sustained decrease in GFR of 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2 in ≥ 1 year. Accelerated CKD progression is one of several potential criteria for hospital referral. 11

What questions are being addressed?

We studied current practice in monitoring CKD to establish a point of reference for our subsequent research, and we reviewed the evidence for treatment options in CKD, because the value of monitoring depends, in large part, on the availability of actions that can be taken when disease has progressed. The value of monitoring also depends on the strength of the signal (true change) compared with the noise (apparent change due to imprecision in laboratory tests). We therefore studied the signal and noise of the current monitoring test, eGFR-creatinine, using different equations, and used this to compare the value of longer versus shorter intervals between laboratory tests. Furthermore, we established a cohort study in which to compare the laboratory test currently used to calculate eGFR-creatinine with a promising alternative using eGFR-cystatin C (i.e. eGFR based on a cystatin C measure). We accompanied these quantitative studies of the overall properties of CKD monitoring with detailed investigation of the experience of CKD monitoring in practice from patients and health practitioners. This WS addressed the following questions:

-

What is current practice in monitoring kidney disease in primary care?

-

Is there evidence for preferring the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) or Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation when estimating eGFR-creatinine?

-

What interventions are known to slow the progression of early-stage CKD?

-

What are the properties of CKD monitoring based on eGFR-creatinine, in particular the rate of change and the accuracy of diagnosed CKD stages?

-

Does the use of serum cystatin C (instead of serum creatinine) to estimate GFR improve the predictive value of CKD monitoring?

-

What are the views from patients and health practitioners on how monitoring CKD is carried out in primary care and the acceptability of any changes from current practice?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of different monitoring strategies for CKD in primary care?

Current practice

Serum creatinine testing 1993–2013 in Oxfordshire (Oke et al.22)

To determine if the frequency of kidney function testing has changed over time, we looked at who is tested and how frequently these tests are conducted (see Appendix 2). We obtained details of serum creatinine tests sent to the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Clinical Biochemistry laboratories from both primary and secondary care in Oxfordshire (> 1.2 million people) over a 20-year period (1993–2013). To determine the frequency of monitoring, we used Poisson regression models to adjust for the initial level of kidney function, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) testing, evidence of albuminuria or proteinuria, sex and age.

We found that the number of serum creatinine tests ordered from primary and secondary care steadily increased over the 20-year period (reaching > 220,000 in 2013 in primary care alone). Increased rates of testing were attributed, in part, to the expansion of the area that the laboratory serves and the ageing population, but trends did not seem to be affected by guideline changes or incentive payments. Older people with higher HbA1c levels and people with reduced kidney function were tested most frequently.

This analysis did not include data on patient history, prescriptions or reasons for test ordering, and so was unable to determine whether the tests were for diagnosis or monitoring or whether or not they were ordered with appropriate frequency. As the data are from a single region of the UK, we were unable to comment on whether or not these represent nationwide trends.

Therefore, we looked at national data to examine kidney function testing using data from > 600 general practices across the UK.

UK primary care kidney function testing 2005–2013 (Feakins et al.23)

To comment on regional variation in kidney function testing rates and how these differ by chronic diseases and prescriptions, we used routinely collected data from 4,573,275 patients from 630 UK general practices contributing to the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) between 2005 and 2013 (see Appendices 3 and 4). The analyses were based on serum creatinine and urinary protein measures as markers of kidney function, and codes indicating the presence of chronic conditions, as well as drug prescriptions for which kidney monitoring is recommended.

We found that the rate of serum creatinine testing increased linearly across all age groups year on year, and the rate of proteinuria testing increased sharply in the 2009–10 financial year, but only for patients aged ≥ 60 years. For patients with established CKD, creatinine testing increased rapidly in 2006–7 and 2007–8, and urinary protein measurement increased rapidly in 2009–10, aligning with the introduction of respective QOF indicators. In adjusted analyses, the presence of a Read code for CKD was associated with up to a twofold increase in the rate of serum creatinine testing, whereas the presence of other chronic conditions and the prescription of potentially nephrotoxic drugs were associated with up to a sixfold increase. Regional variation in the rate of serum creatinine testing predominantly reflected country boundaries; in particular, Northern Ireland had higher rates of testing than other UK regions.

These findings suggest that the significant increases in the number of patients having kidney function tests annually and the frequency of testing are driven by changes in the recommended management of CKD in primary care, namely the QOF. Future studies should address whether or not increased testing has led to better outcomes.

Current evidence

Comparison of the bias and accuracy of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Equations (McFadden et al.24)

Measuring eGFR is important in primary care as it determines the stage of CKD, referral decisions and changes to doses of commonly prescribed medicines. However, there is uncertainty over the optimal eGFR-creatinine equation to be used in community-based populations because the existing equations for eGFR-creatinine are derived mainly from younger patients with renal disease, whereas, in community populations, the patients are older and have a lower prevalence of established renal disease. We set out to examine how eGFR from existing equations, the CKD-EPI and MDRD, differ from measured glomerular filtration rate (mGFR) in populations that are equivalent to a primary care population (see Appendix 5). We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies (up to June 2017) that recruited patients similar to a primary care population, extracting data on the difference between estimated and measured GFR for CKD-EPI and MDRD equations. We also developed methods for meta-analysis to combine data on differences into summary statistics.

We found that the MDRD equation underestimates true renal function by 4.7 ml/minute/m2 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8 to 8.7 ml/minute/m2], and the CKD-EPI equation is more accurate in community-based populations. At higher levels of mGFR, which reflect community populations, the MDRD equation was less accurate (by 4.6%, 95% CI 2.9% to 6.2%) and more biased (by 3.2 ml/minute/1.73 m2, 95% CI 1.6 to 4.8 ml/minute/1.73 m2) than the CKD-EPI equation. Our data were limited in that the quality rating was not deemed high in many studies that were single centre, and the recruitment methods were not always clearly stated. This work allowed us to have a baseline of bias and accuracy for creatinine-based estimates of GFR in primary care.

Effects of medication on the progression of stages G3 and G4 chronic kidney disease (Taylor et al.25)

Treatment of people with CKD aims to prevent or reduce disease progression, prevent complications and minimise the risk of CVD (see Appendix 6). We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (March 1999 to July 2018) to examine and compare the effects on the progression of CKD of four classes of drugs: antihypertensives, lipid-modifying drugs, glycaemic-control medications in patients with diabetes, and sodium bicarbonate. Our focus was on patients managed in primary care or by shared care with specialist nephrology services. The review summarised 35 studies including > 51,000 patients: 12 studies of antihypertensive drugs, 14 of lipid-modifying drugs, one study of an antihypertensive drug and a lipid-modifying drug, six studies of glycaemic-control drugs, and two of sodium bicarbonate. Nineteen studies provided summary data based on populations with CKD of stages G3 and G4 only. None of these studies provided data on sodium bicarbonate medication. Pooled estimates from these showed that, for antihypertensive drugs, there were no significant differences in renal function, and that eGFR was 4% higher in those taking lipid-modifying drugs (ratio of means 1.04, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.08) and 6% higher (ratio of means 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.10) in those taking glycaemic-control drugs (no studies provided data on sodium bicarbonate medication). Furthermore, and as expected, treatment with lipid-modifying drugs led to a significant reduction in the risk of CVD [risk ratio (RR) 0.64, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.80] and all-cause mortality (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.98). There were no significant differences in cardiovascular events or mortality in studies of antihypertensive and glycaemic-control drugs. We found some evidence that glycaemic-control and lipid-modifying drugs slow the progression of CKD, and no evidence of renal benefit or harm from antihypertensive drugs.

New quantitative evidence

Modelling deterioration of kidney function (Oke et al.26)

This project (see Appendix 7) aimed to estimate the rates of progression of renal function stratified by urine albumin status, age and sex in a general population of people attending primary care.

We used the CPRD and constructed four cohorts based on their urine albumin status at baseline. The statistical method specified in the protocol (based on linear models6,27) proved unsuccessful; instead, a method for categorical data (i.e. a hidden Markov model27) was used to estimate the true underlying kidney function while accounting for measurement error and within-person variability due to eGFR-creatinine. Models were adjusted for age, sex, heart failure and previous diagnosis of cancer, and stratified by albuminuria status (< 3 mg/mmol vs. 3–30 mg/mmol vs. > 30 mg/mmol) at baseline.

The estimated rate of true transition from one CKD stage to the next, per year, was approximately 2% for people with normal urine albumin, between 3% and 5% for people with microalbuminuria (urine albumin of 3–30 mg/mmol) and between 3% and 12% for people with macroalbuminuria (> 30 mg/mmol). Misclassification of CKD stage due to measurement variability in serum creatinine, and hence eGFR-creatinine, is estimated to occur in between 12% and 15% of all tests in primary care. Progression of kidney function becomes faster with increasing age, and is faster among men, among people with elevated urine albumin and among patients with heart failure or with a previous diagnosis of cancer.

The true rate of progression of CKD is relatively slow, and eGFR-creatinine is an imperfect measurement that can lead to misclassification of disease stage every time it is used. This suggests that, when annual monitoring detects an apparent change of disease stage, this is more likely to be attributable to the imperfections of the measurement than to a true change.

Limitations of this analysis include missing data, which arise from the use of routinely collected electronic health records data rather than a clinical study. See the following section for a further study of the progression of CKD.

Prospective cohort study of monitoring chronic kidney disease

Cross-sectional evidence suggests that cystatin C provides better estimates of current kidney function than serum creatinine. We designed a study [Frequency Of Renal Monitoring – Creatinine and Cystatin C (FORM-2C)] to investigate whether or not cystatin C also provides better prognostic information than serum creatinine for future change in renal function. Because direct (radiological) measurement of GFR is invasive and expensive, making large studies impractical, we used change in eGFR (respectively eGFR-creatinine and eGFR-cystatin C) as the study outcome: the study report in Appendix 8 gives more details.

A cohort of 747 patients with an eGFR-creatinine of 30–89 ml/minute/1.73 m2 was recruited and followed up for 2 years, with blood samples taken at recruitment, 2 weeks and 12 weeks to establish baseline eGFR (both measures), and at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after recruitment to measure the change in eGFR (both measures) over time. There were sufficient data from 629 patients to carry out analysis. When using serum creatinine to estimate GFR, baseline eGFR-creatinine had a concordance statistic (c-statistic) (also known as concordance index) of 0.495 (95% CI 0.471 to 0.521) for predicting future change in eGFR-creatinine. When using cystatin C to estimate GFR, baseline eGFR-cystatin C had a c-statistic of 0.500 (95% CI 0.474 to 0.525) for predicting future change in eGFR-cystatin C. Similar results were seen in sensitivity analyses, as described in Appendix 8. Either method of estimating baseline eGFR was predictive of the 2-year value [c-statistic for eGFR-creatinine 0.833 (95% CI 0.811 to 0.851) and for eGFR-cystatin C 0.889 (95% CI 0.877 to 0.898)], because there was, on average, little change over 2 years (see Appendix 8, Table 9).

Regardless of the method of estimation, eGFR (both measures) does not appear to usefully predict future change in eGFR (both measures). This is relevant, as change in eGFR has been shown to be significantly associated with all-cause mortality, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and cardiovascular events beyond that observed for mGFR. 28,29 The study is limited by the use of surrogate measurements of renal function in the outcome, as well as in the index tests. One study using radiological measurement of kidney function is due to report in June 2021. If confirmed, our preliminary results suggest that the rate of change of renal status does not depend strongly on current state: there is no ‘acceleration’ of renal decline, at least across CKD stages G2 and G3a, which dominate our cohort.

New qualitative evidence

Qualitative evaluation for chronic kidney disease

To understand the acceptability and impact of current monitoring regimes among individuals with CKD, we used a mixture of patient interviews and focus groups with health professionals30 (see Appendices 9 and 10). For the patient interviews, we sought to recruit people who were having regular checks of their kidney function because they had stage G1–3 CKD. For the focus groups with health professionals, we used a variety of methods to recruit participants, mainly drawn from practices in Oxfordshire and the wider Thames Valley area. Participant numbers for the focus groups were small, so the views expressed may not necessarily be regarded as representative of these professions.

Forty-six people were recruited for the patient interviews; one withdrew after interview. Stage of CKD was unknown for seven participants, 35 had stage G3, two had stage G2 and two had been recently referred to specialist care because of more advanced kidney disease. The main findings were published in 2015 on https://healthtalk.org/ (accessed 5 May 2020) as ‘topic summaries’. 31 Sixteen people participated in four health professionals’ focus groups.

A gap was revealed between what health professionals seek to explain about CKD and what patients may understand. Primary care professionals often avoided using the term ‘CKD’ when talking to patients with early-stage kidney impairment in an attempt to avoid causing unnecessary anxiety. Patients’ accounts of receiving information about their kidney health echoed the phrases described by health professionals. However, patient interpretations showed some of these phrases to be unhelpful, raising further questions and adding to, rather than diminishing, initial concerns. The use of phrases such as ‘kidney damage’ or ‘kidney failure’ could be frightening, and the term ‘chronic’ was sometimes misinterpreted as meaning serious, whereas a description of the decrease in kidney function as a percentage or stage seemed less alarming. However, the exact meaning of the test results was often unclear, and those who were told their CKD stage did not always understand what this meant. Some patients found it difficult to understand that they had been diagnosed with CKD when they did not experience symptoms. Attempting to reassure patients that their kidney impairment was nothing to worry about, without providing explanatory information about the condition, could leave patients concerned and wanting to know more about possible causes, the meaning of test results and whether or not they could do anything to prevent further decline.

The GPs all confessed to being unfamiliar with the latest updates to NICE guidelines for either CHF or CKD or both, arguing that work pressures did not allow time to read these for all conditions. NICE’s website was considered confusing and difficult to navigate, and GPs were more likely to learn about patient management recommendations from other sources, such as the Clinical Commissioning Group or QOF alerts. On the current CKD guidelines,11 specifically, there was confusion about when ACRs should be requested from the laboratory and how the results should be interpreted and acted on.

Our research led to a mixed-methods study that calls for a rethink in how doctors talk to patients with reduced kidney health, replacing the term ‘CKD’ with different bands of kidney age (see Appendix 11).

Economic models

Review of economic models

We asked the following questions: what is known, from existing models, about the cost-effectiveness of monitoring of CKD? What can be inferred about the cost-effectiveness of CKD monitoring from the results of our CKD WS project (described above)? To what extent has the cost-effectiveness of CKD monitoring been studied, and, in particular, what modes of CKD monitoring have been studied? What modes of CKD monitoring should be prioritised for study (see Appendix 12)?

We reviewed the literature to identify existing cost-effectiveness models in CKD that could be suitable for such an assessment (up to January 2019). Although there are many model-based evaluations of interventions in CKD, we included only models that could be useful to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of CKD monitoring in the context of current clinical guidelines. Therefore, a lifetime cost-effectiveness model was reviewed if (1) CKD stages were defined using eGFR-creatinine (i.e. not exclusively based on proteinuria status), (2) at least two distinct states prior to renal replacement therapy (RRT) (i.e. renal dialysis or renal transplant) were included (i.e. the model states were not simply ‘pre RRT’ and ‘RRT’) and (3) the incidence of important cardiovascular events was modelled.

A pearl-growing search strategy was used to identify eligible cost-effective models. First, four suitable key studies (‘pearls’) were identified32–36 by the authors using their previous experience, including the development of one of these models. 36 The reference lists and citations of each included study were reviewed. One additional study was included37 and classified as a new pearl, and the search was repeated for another iteration, as a result of which no relevant papers were identified. To ensure that no important manuscripts were missed, a quick scoping search was performed in Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) (using the search line ‘cost-effectiveness “chronic kidney disease” progression’), followed by a review of the references included in an in-house review of models of CKD progression (Iryna Schlackow, University of Oxford, 2018, personal communication). These reviews did not yield further eligible studies.

Thus, five long-term cost-effectiveness models potentially useful to assess CKD monitoring were reviewed. Detailed descriptions of the models included in our review are presented in Appendix 12. Of the five models, two were developed to assess the cost-effectiveness of CVD prevention interventions (e.g. statins) in CKD,32,36 two were developed in the context of screening for CKD/proteinuria in general population33,37 and one aimed to accommodate both CKD identification and treatment. 35 Parameters of the models were mostly collated from published literature and/or derived from different data sources,32,33,35,37 with only one model based largely on individual patient-level data. 36 Only two models separate the ESRD state into dialysis and renal transplant states, which are associated with different outcomes and costs. 35,36 All models included validation of their performance, but this validation was not in the context of a general CKD population. Only the screening models included early CKD stages (e.g. CKD stage G2, which constitutes the bulk of the CKD population in a primary care setting) in their target populations. 33,35,37 The CVD prevention models considered only CKD stage G3 and beyond. 32,36 In the screening models, effects of ACE inhibitors and ARB treatments were implemented, but in only one model were these treatments assumed to affect CVD risks;37 in the other two models, these treatments were assumed to affect only CKD progression and mortality. 33,35 Only one model considered heart failure as an end point,35 but it was unclear how the treatment effect on heart failure was implemented, and what the impact of this treatment on other transitional probabilities was. None of the identified studies assessed effects of monitoring eGFR.

In summary, none of the identified models included the elements required for the assessment of cost-effectiveness of monitoring strategies in UK primary care. Therefore, it was decided to develop a new cost-effectiveness model to support the evaluation of CKD monitoring.

Cost-effectiveness of monitoring kidney function in UK primary care (Schlackow et al.38 and Appendix 14)

We sought to incorporate the findings from the programme into a model of the cost-effectiveness of monitoring CKD in primary care. We assessed the following frequencies of GFR monitoring: no monitoring, monitoring every 5, 4, 3 and 2 years and annual monitoring. Based on the systematic review of interventions (see Appendix 6),25 other published meta-analyses39–41 and discussions with clinicians and stakeholders, it was agreed that a key objective of eGFR monitoring in primary care is to guide treatments to reduce CVD risk among people with reduced kidney function. To project health outcomes, we supplemented the model of variability and progression (see Appendix 7)26 with additional modelling that included CVD risk equations with a term for stage of eGFR. Full details of the model, including estimated cost and quality-of-life impact of cardiovascular outcomes, are given in Schlackow et al. 38

Appendix 14 gives details of the application of the model to GFR monitoring, including the assumptions made about monitoring costs and prescription costs, and assumptions made about treatment. Current clinical guidelines recommend that CVD preventative treatments (i.e. statin, antihypertensive or antiplatelet drugs) be considered for patients with reduced kidney function and, therefore, in the cost-effectiveness analysis we studied the impact of GFR monitoring on their use. Based on the systematic review of interventions (see Appendix 6),25 we assumed statin treatment to be the most relevant.

We could not justify monitoring in people with CKD to guide cardiovascular prevention as changes in eGFR did not trigger changes in CVD treatment recommendations (see Appendix 14). Briefly, this arises because, for people with clinical CKD [i.e. meeting the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)42 definition], statin treatment is recommended;43 many of them are also indicated for antihypertensive treatment44 and, if they have a history of CVD, for antiplatelet therapy. 44 These therapies are also widely recommended in people with CVD. 43 Therefore, under current guidelines,11 monitoring the eGFR among patients with clinical CKD or with a history of CVD would largely not change indicated cardiovascular therapies.

We also considered eGFR monitoring in people with impaired eGFR (i.e. an eGFR of < 90 ml/minute/1.73 m2) but no CKD (defined as macro/microalbuminuria or an eGFR of < 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2). For some of these people, monitoring eGFR to detect CKD is potentially beneficial, compared with no monitoring, but the model does not currently separate potential harms of overdiagnosis. The optimal (i.e. most cost-effective) interval of eGFR monitoring in this group depends on a patient’s age and our analyses indicate that, at £20,000 per QALY cost-effectiveness threshold, that is about every 3 years for people aged < 60 years, every 4 years for people aged 60 to 69 years, and no monitoring among those aged ≥ 70 years.

Conclusions

This WS focused on management/monitoring of CKD in primary care, researching current practice and providing new evidence to guide this management. In particular, we concluded that:

-

Over the last decade, renal function testing has increased in volume at the national level. Specifically, for those with CKD, this increase is driven by national guidance for reporting monitoring.

-

At higher levels of mGFR, which reflects primary care populations, the MDRD equation was less accurate and more biased than the CKD-EPI equation.

-

Lipid-modifying and glycaemic-control medications are possibly beneficial to slow the progression of early-stage CKD. However, evidence of glycaemic control exists only in diabetic populations.

-

The rate of change in eGFR is slow, and misclassification is more common than real change.

-

The rate of change in eGFR is slow, regardless of the baseline eGFR, in patients in primary care. Cystatin C is not a better predictor of change than creatinine.

-

The terminology around ‘chronic’ and ‘disease’ is problematic for patients and GPs when communicating about early stage, or small decreases in renal function.

-

Before this programme, there were no models available that were able to assess the cost-effectiveness of monitoring strategies in UK primary care, to our knowledge.

-

A new cost-effectiveness model to assess frequency of eGFR modelling was developed in this programme; people with an eGFR of between 60 and 90 ml/minute/1.73 m2 were identified as a group for whom monitoring could potentially be beneficial.

-

Application of our cost-effectiveness model to those with an eGFR of between 60 and 90 ml/minute/1.73 m2 suggests that monitoring eGFR in people aged < 70 years and without cardiovascular disease every 3–4 years to guide cardiovascular prevention may be cost-effective.

Research recommendations

-

Estimates of the bias, and accuracy, of eGFR-creatinine equations varied greatly (statistical heterogeneity) between studies in our systematic review. It would benefit the NHS to determine when (in what settings) and how (with what protocol) the most accurate results can be obtained and which protocol should be recommended nationwide.

-

High variability in eGFR-creatinine, and hence inaccuracy in CKD staging, suggest a probable benefit to combining eGFR measurements (several creatinine and/or several cystatin C), rather than simply repeating them and acting on the most recent; this potential route to better management should be researched.

-

Cystatin C appears to have some advantages over serum creatinine for estimating GFR, for example in predicting rapid progression; these findings, from secondary analyses only, should be confirmed.

-

At least one alternative to the term ‘CKD’ has now been proposed, in response to our qualitative work and patient and public involvement (PPI), and its potential to improve communication should be investigated (see Patient and public involvement).

-

Closing the gap (identified in the systematic review of interventions) of evidenced interventions that specifically protect renal function would have the greatest potential to improve the cost-effectiveness of CKD monitoring.

Overall, these can be summarised as three key questions:

-

When and how can the most accurate estimates of GFR be obtained?

-

What is the longer-term relationship between current eGFR (either measure) and future progression of CKD?

-

How can the progression of CKD be prevented or delayed in patients at risk?

Implications for practice

-

Laboratories could improve the accuracy of eGFR testing by switching to the CKD-EPI equation for its calculation, as recommended by NICE,11 if they have not done so already.

-

Potential treatments that might positively affect kidney function are lipid-modifying treatment and glycaemic-control medication.

-

The rate of change of kidney function in a primary care population is slow, and most apparent changes will be due to measurement noise (error) and not real change.

-

This rate of change is slow regardless of the initial CKD stage (in a primary care population).

-

The terms ‘chronic’ and ‘disease’ act as barriers in the communication between health practitioners and patients. A potential solution is the use of alternative terms, such as ‘kidney age’. 45

-

Monitoring individuals with CKD is difficult to justify by the usual logic of treatment initiation or titration. Alternative ways of quantifying its benefit might be required.

Reflections

We find that CKD monitoring, using blood tests in particular, but also urine tests, has been a huge growth area in the NHS. However, our research highlighted a substantial gap in the evidence base for this monitoring. The usual rationale for monitoring a clinical condition includes an action, typically a treatment change, that can be taken in response to the results of monitoring tests. In a large systematic review, we found no evidence that antihypertensive treatment or administration of sodium bicarbonate are useful actions to slow progression of kidney disease, and the treatments that might slow progression, in particular lipid-modifying treatments, are likely to be in use already in patients with CKD, particularly those with stage G3 disease onwards. Following these findings through to a full model of cost-effectiveness emphasised that monitoring of CKD in primary care, especially as frequently (i.e. annually) as currently recommended, cannot be rationalised as monitoring to guide treatment. This complements our previous finding that monitoring diabetic nephropathy as frequently as annually is unlikely to be cost-effective. 7

It would, however, be premature to abandon all monitoring of CKD. Arguments may be made that monitoring CKD (e.g. in stage G3) could encourage lifestyle changes, promote adherence to already indicated medications, help avoid nephrotoxic treatments such as ibuprofen in primary care and help avoid sudden descent from apparent full kidney health into late-stage kidney disease in secondary care. These benefits will be harder to quantify than an obvious treatment for CKD, but such a research effort is needed to provide a sound rationale for monitoring and to design a cost-effective monitoring schedule. Current practice, that is annual monitoring, has become a growing cost to the NHS, yet lacks a clear evidence base.

The other major finding to emerge from this work was the problematic terminology ‘CKD’, which is misunderstood by patients and avoided or used with reluctance by GPs. This emerged from our formal qualitative research, but it emerged also, and sooner, from the reactions of patients approached to take part in our studies, and from the patient and public members of our stakeholder group. We return to this in Patient and public involvement.

Workstream 2: chronic heart failure

A 2002 report suggested that ≈ 900,000 people in the UK had CHF. 46 Since then, the prevalence of heart failure in the UK has been increasing, probably as a result of demographic changes and improvement in the management of CHF, with an observed increase of 23% between 2002 and 2014. 47 In a prospective community screening study,48 definitive CHF, according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) criteria,49 was present in 2.3% of the population, of whom the proportion with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of < 40% was 41%; the prevalence of definitive CHF rose to 8% in those aged > 75 years. 50

The incidence in the UK is less clear, but the crude rate has been estimated to be 1.3 cases per 1000 population per year for those aged ≥ 25 years, reaching 7.4 cases per 1000 population per year for those aged 75–84 years and 11.6 cases per 1000 per year for those aged ≥ 85 years. 48 The absolute incidence of CHF in the UK has also increased considerably since 2002 (12% between 2002 and 2014), even though the age-standardised incidence is actually decreasing. 47 Overall, a GP with a patient population of 2000 will care for approximately 40 to 50 patients with heart failure and see two or three new cases each year.

Early diagnosis is seen as critical because early-stage heart failure may be reversible. However, the diagnosis and management of CHF remains challenging. For example, although CHF is frequently diagnosed by GPs, it is confirmed by echocardiography in only approximately one-third of cases. 51 NICE13 recommends that a heart failure multidisciplinary team carry out the CHF diagnosis using a combination of symptoms, signs and investigations. The use of a NT-proBNP measure is the only biomarker recommended as part of this diagnostic process, but with recognition of the uncertainty regarding the absolute threshold used. 13 Despite recent improvements, patients diagnosed with heart failure have a poor prognosis: approximately 40% of patients diagnosed die within the first year. After that, the mortality rate decreases to approximately 10% per year. 52–54 Survival rates are worse than those of cancer of the breast or prostate. 55

People diagnosed with heart failure have high levels of use of health-care resources not only in terms of GP consultations and community-based drug therapies, but also because of referrals to outpatient clinics and inpatient bed-days. Heart failure accounts for 5% of all emergency medical admissions; it is estimated that the total annual cost of heart failure to the NHS is approximately 2% of the total budget, with approximately 70% of this total attributable to the costs of hospitalisation. 56,57 Moreover, re-admissions are common, with approximately one in four patients re-admitted within 3 months. 58,59 Patients also report a dramatic decrease in their quality of life, with a consequent impact not only on agencies such as social services and the benefits system, but also on their families and caregivers. 58 There is, however, considerable evidence58,60,61 that pharmacological treatments can improve the prognosis of heart failure. Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments can improve patient quality of life, in terms of both physical functioning and well-being. 58

With regard to monitoring, NICE13 recommends that this should be based around clinical reviews, and recommends the use of NT-proBNP as part of treatment optimisation only in a specialist care setting for people with CHF aged < 75 years who have reduced ejection fraction and who do not have CKD of stage G3a or higher. 13 Increased levels of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and NT-proBNP in patients with heart failure have been demonstrated, in some studies,62,63 to have, not only diagnostic, but also prognostic, utility.

Previous work has identified BNP as having large clinical variation in non-severe populations, thereby probably reducing its utility for monitoring CHF. 64 POC NP testing has been suggested as an alternative method to reduce this variability. 65 At the same time, POC NP testing would enable GPs to rapidly refer the appropriate patients or, if CHF can be excluded, investigate alternative causes of clinical symptoms (e.g. dyspnoea).

What questions are being addressed?

We reviewed the evidence for NP-guided treatment in CHF, including how a potential intervention using this approach could be implemented, because this has been the most promising area for which monitoring of this group could be effective. For NP monitoring to be of use, the noise (i.e. within-person variability) should be relatively small compared with the signal (true change). We therefore studied the noise of NP measures based on a secondary analysis of a clinical trial. As an alternative strategy, to minimise NP variability, we studied the accuracy of available POC NP devices, as well as testing the feasibility of their use in a general practice. To understand where monitoring should take place, we summarised the evidence relating to strategies for remote monitoring (RM) (from home) in this population. As for the CKD WS, we carried out a detailed investigation of the experience of CHF monitoring in practice from the perspectives of patients and health practitioners. Finally, we summarised the evidence available regarding health economic models to evaluate monitoring strategies in CHF and provided a framework to carry out this assessment. This WS addressed the following questions:

-

Is there evidence to suggest that NP-guided treatment improves outcomes in patients with CHF?

-

What would be the relevant components of an intervention to implement NP-guided treatment?

-

What are the properties of NP measures used when monitoring CHF, in particular, the within-person coefficient of variation (CV)?

-

Are POC NP measures accurate and, of the devices available for measuring POC NP, which would be best to use?

-

Is it feasible to implement a POC NP test/device in a primary care practice?

-

What is the evidence regarding the efficacy of RM in CHF?

-

What are the views from patients and health practitioners of how monitoring CHF is carried out in primary care and the acceptability of any changes to current practice?

-

What health economic models have been used, and what issues need to be addressed, to study the cost-effectiveness of monitoring CHF in UK primary care?

Current practice

Although the age-adjusted heart failure incidence in the UK is decreasing, the absolute incidence and prevalence have seen a substantial increase over the previous decade, potentially due to demographic changes and improvement in management. 47 Recommended management of CHF patients is based around a multidisciplinary team working in collaboration with primary care, with the primary care team taking over routine management once the patient has stabilised. 13 Measurement of patient NT-proBNP is also recommended as part of the diagnostic pathway and as part of a monitoring strategy to optimise treatment, but only in a specialist setting for people aged < 75 years with heart failure, with reduced ejection fraction and with an eGFR of > 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2.

An analysis of current management of CHF patients in primary care66 identified that, at least until 2013, only a small proportion of those with a current diagnosis of CHF have ever had NP measured in a primary care setting (4.85%, 95% CI 4.71% to 4.99%); that most of these measurements are probably used as part of a diagnostic strategy (74% of individuals with a single NP measurement); and that the type of NP most commonly used in primary care since 2007 is NT-proBNP. This analysis66 confirmed the strong association observed between high levels of NPs and all-cause mortality in this group. It also suggests that measurements of NP are underused in primary care as part of the diagnostic pathway (not consistent with NICE guidance13) and not used as part of a monitoring strategy (consistent with NICE guidance13). 66

Current evidence

Natriuretic peptide-guided management of heart failure (McLellan et al.67,68)

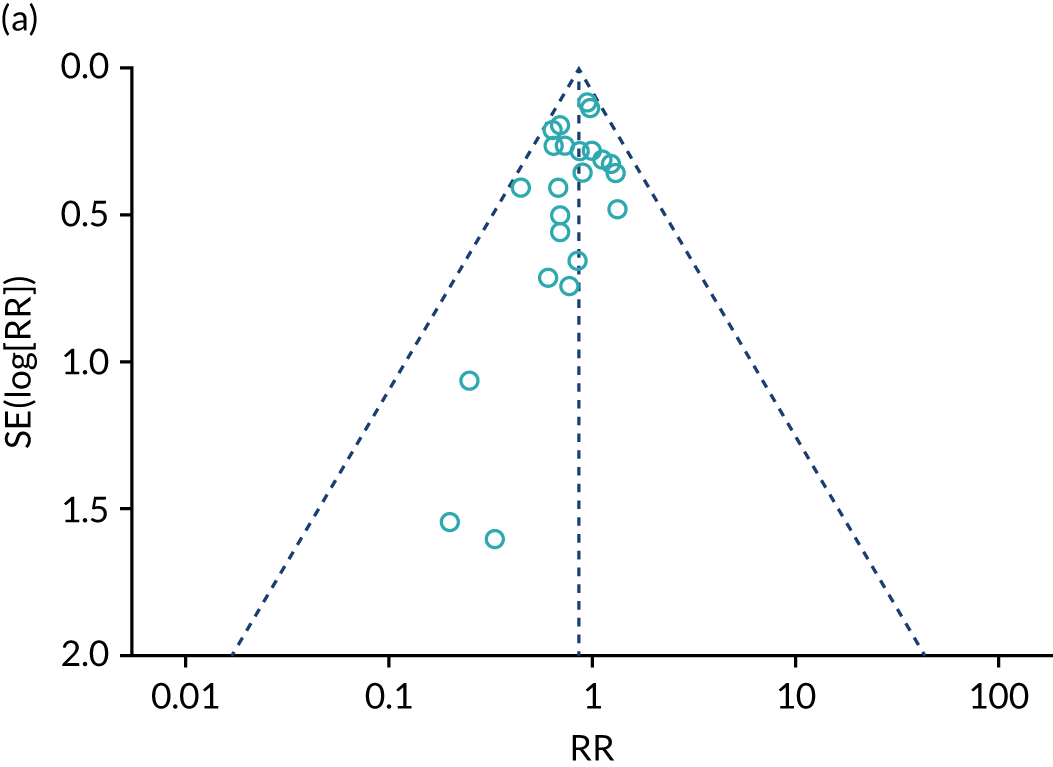

We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis (see Appendices 15 and 16) to assess whether or not treatment guided by serial NP monitoring improves outcomes, compared with treatment guided by clinical assessment alone (up to November 2017). In 2016, we found inconclusive evidence for a reduction in all-cause mortality (13%) and heart failure mortality (16%). Heart failure admission was reduced 30% by NP-guided treatment, but the evidence was inconclusive for all-cause admission. Six studies reported on adverse events; however, the results could not be pooled. Only four studies provided results for cost of treatment: three of these studies reported a lower cost for NP-guided treatment, whereas one reported a higher cost. The evidence showed uncertainty for quality-of-life data. Heterogeneity was low for all outcomes bar heart failure admission, which was substantial.

In 2017, the addition of the Guiding Evidence Based Therapy Using Biomarker Intensified Treatment in Heart Failure (GUIDE-IT) study69 increased the total number of participants by 24% and substantially increased the precision of the estimates. This altered the findings of the Cochrane systematic review,67 and the evidence now indicated that NP-guided treatment could improve all-cause mortality by 13%. The effect on heart failure admission was a relative reduction of 20%, whereas the findings for all other outcomes were similar to those from the Cochrane systematic review.

We concluded that the current pooled evidence indicates a beneficial effect of NP-guided therapy on all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions. However, despite the publication of the GUIDE-IT study,69 the largest in this field, the effectiveness estimated from the meta-analysis is marginal and the conclusions are not yet robust, with a high chance that these will change as new evidence emerges.

Effectiveness of remote monitoring for heart failure

Remote monitoring, a collective term for telemonitoring (TM) and structured telephone support (STS), of heart failure is increasingly becoming an option for patients, as a result of the ongoing advancement in technology and familiarity with its use (see Appendix 17). RM aims to collect and transmit physiological data through devices in the patient’s own home that could potentially increase early detection of clinical deterioration, improve patients’ quality of life and decrease health-care delivery costs.

Despite the lack of NICE-recommended use of RM (201070 and 201813 guidelines), the NHS Technology Enabled Care Services Resource for Commissioners,71 in response to the NHS Five Year Forward View,72 recognised that RM technology would be important in the future.

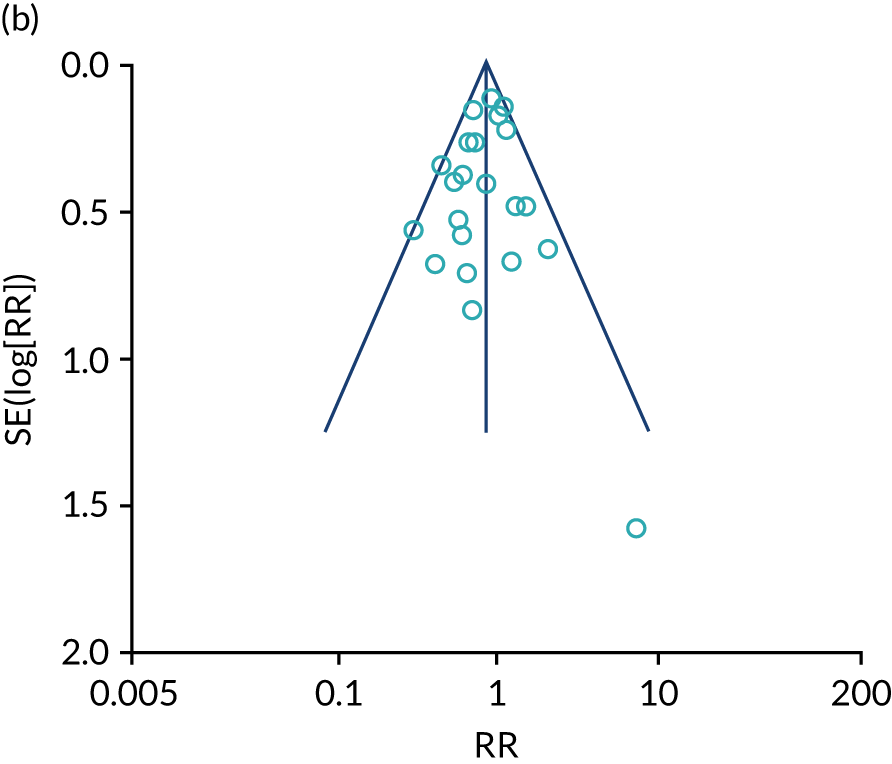

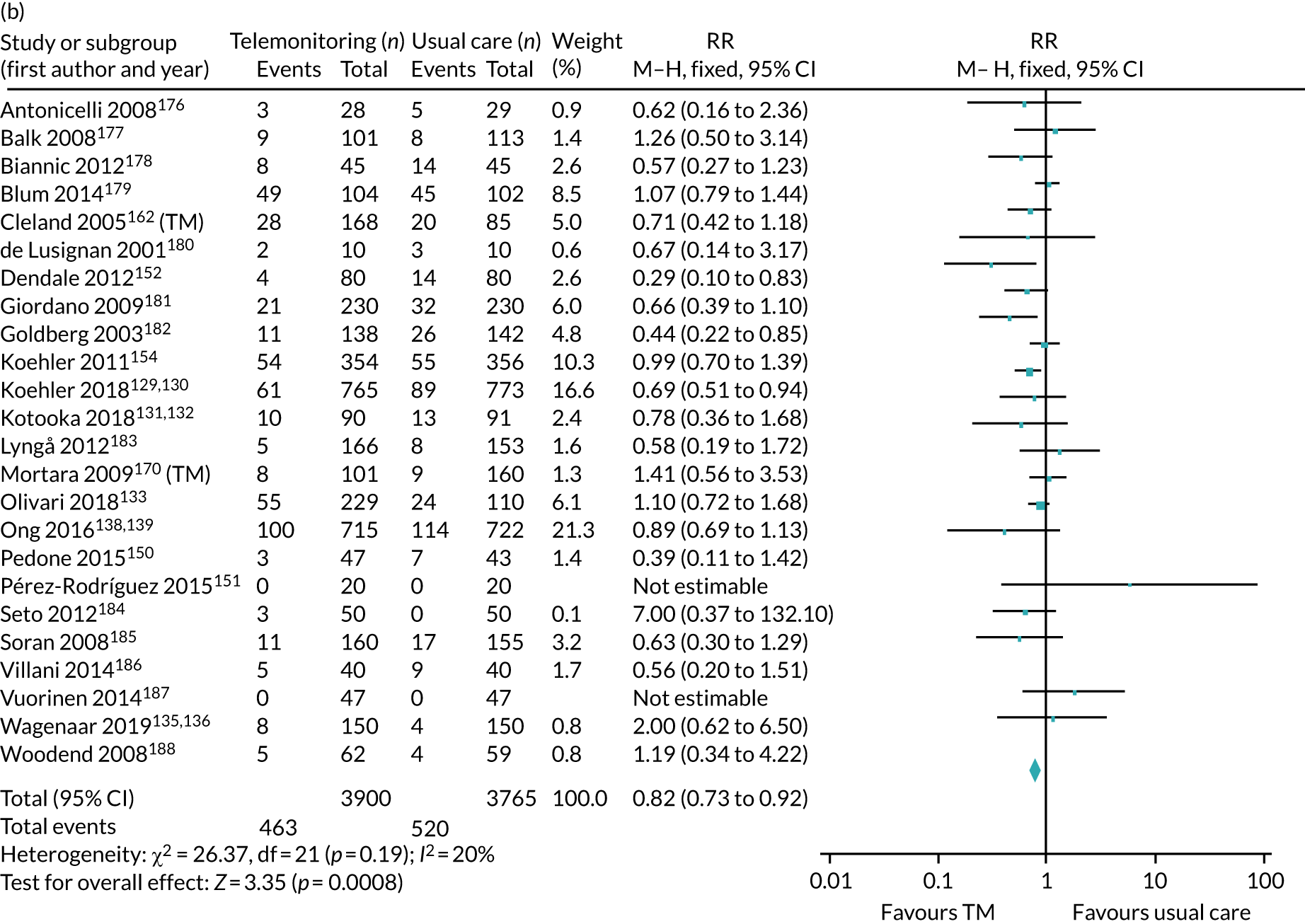

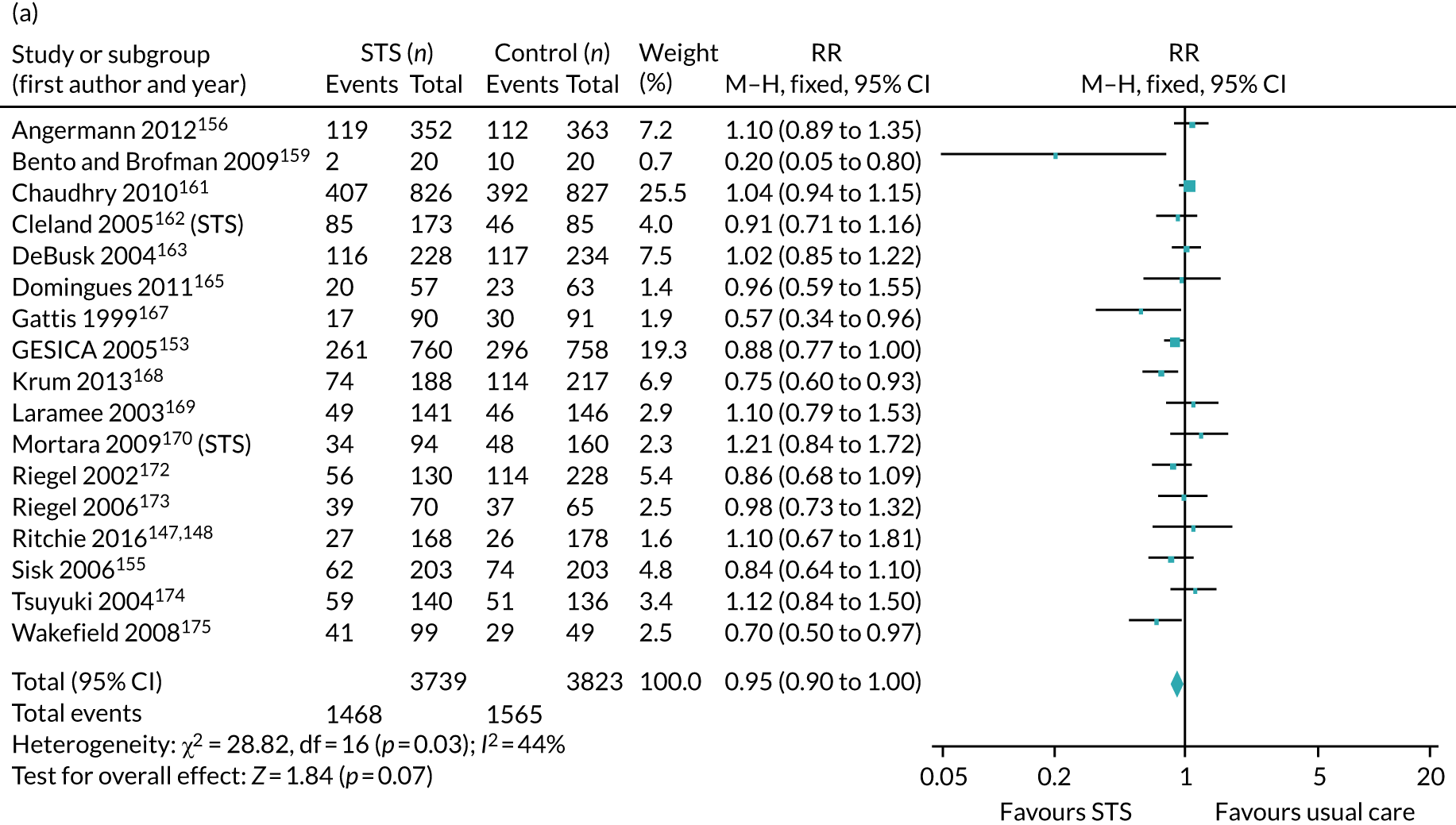

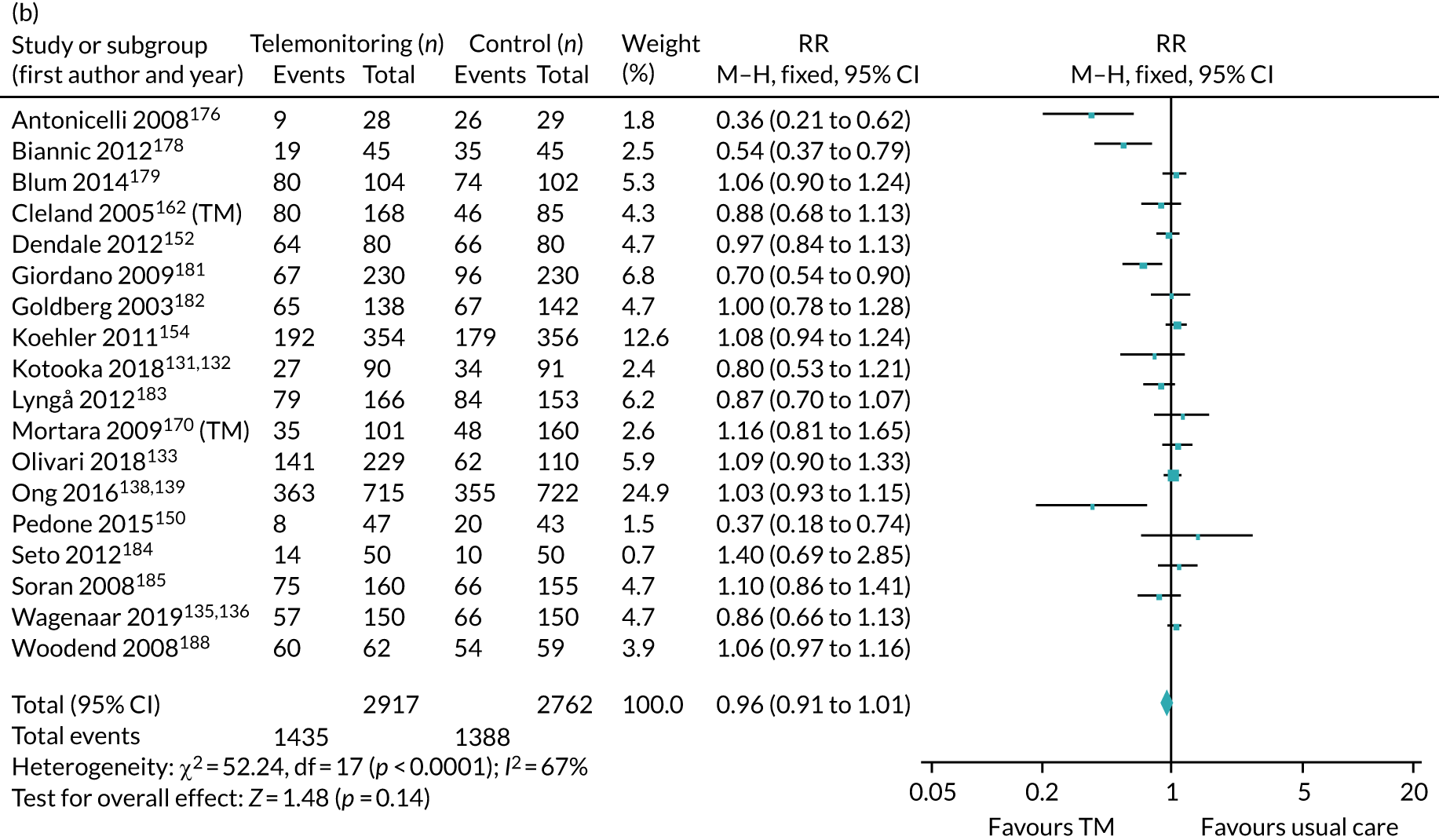

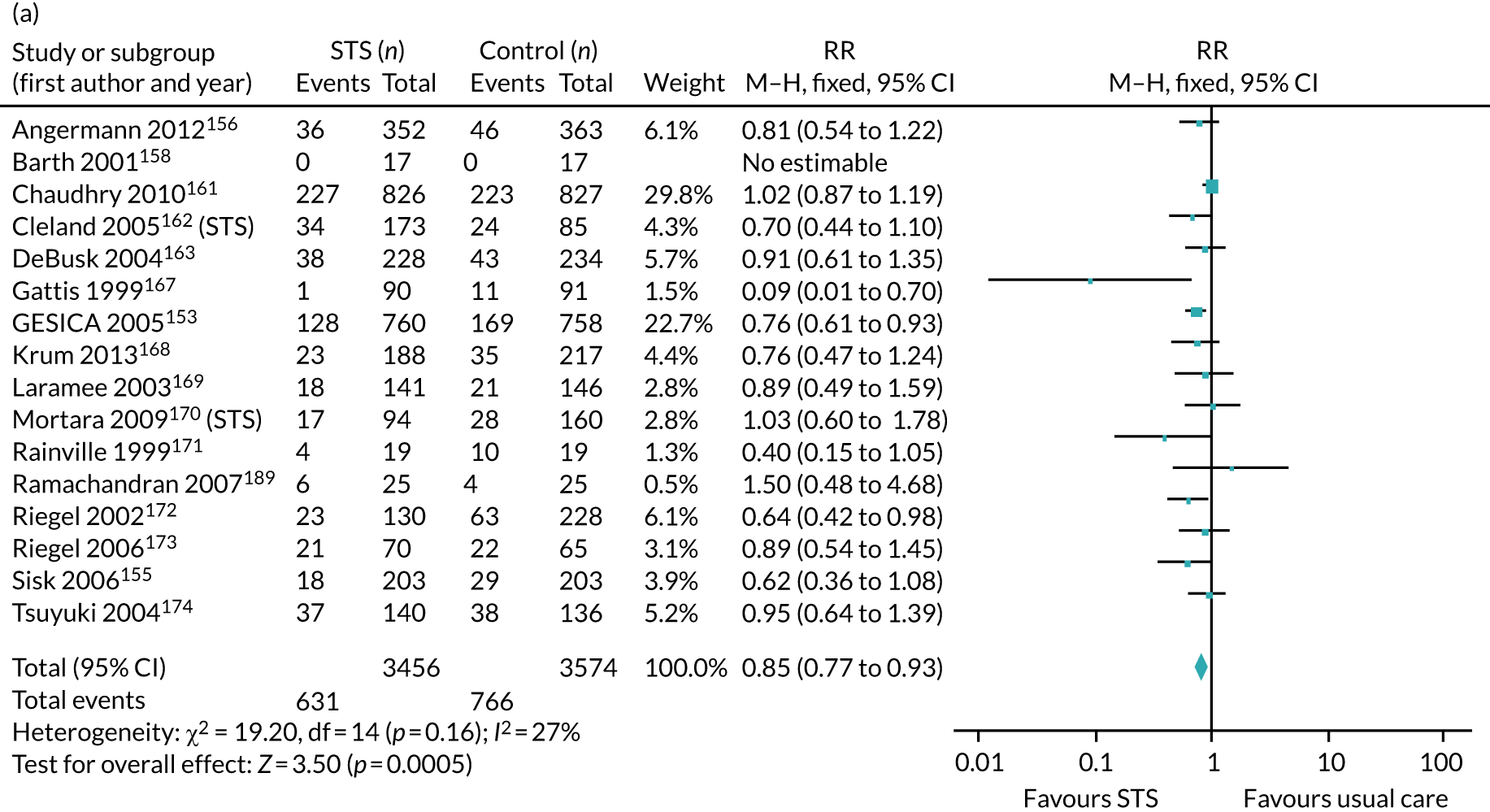

This systematic review and meta-analysis (up to February 2019) aimed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of home TM and/or STS interventions, compared with standard care, among adults with heart failure for all-cause mortality, all-cause hospital admission, heart failure hospital admission, length of stay, health-related quality of life, adherence, acceptability, heart failure knowledge and self-care. This was an update of a previous review by Inglis et al. 73

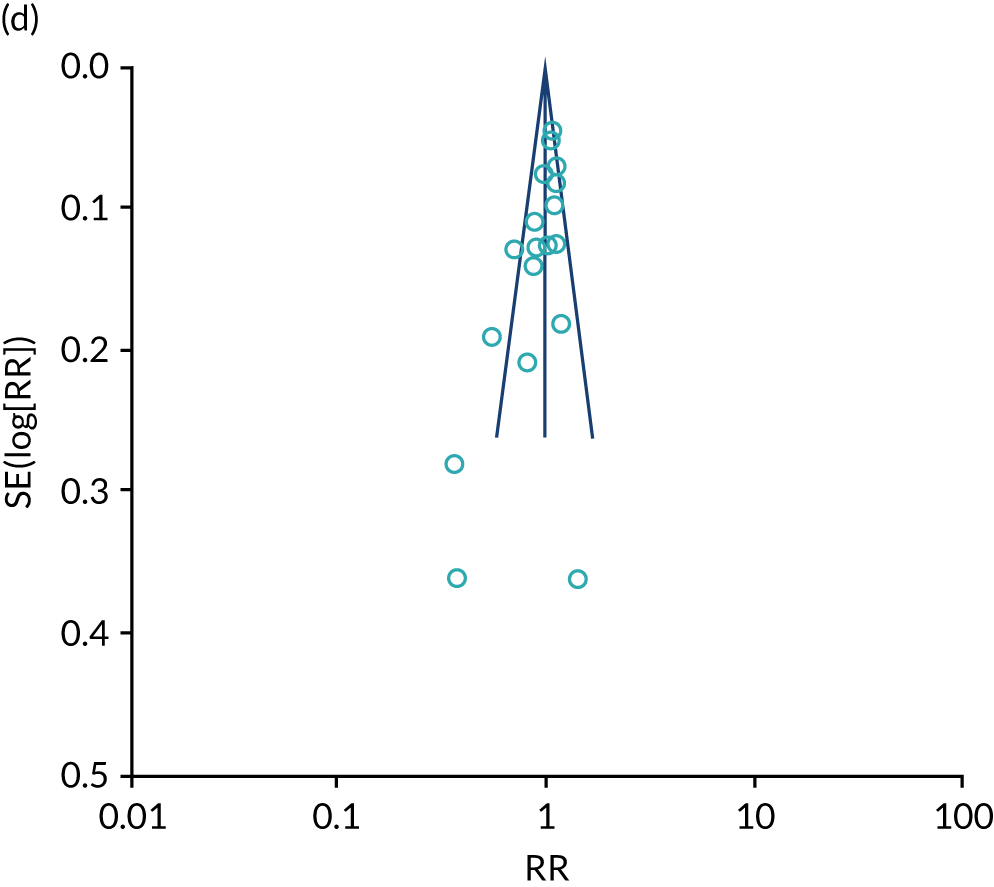

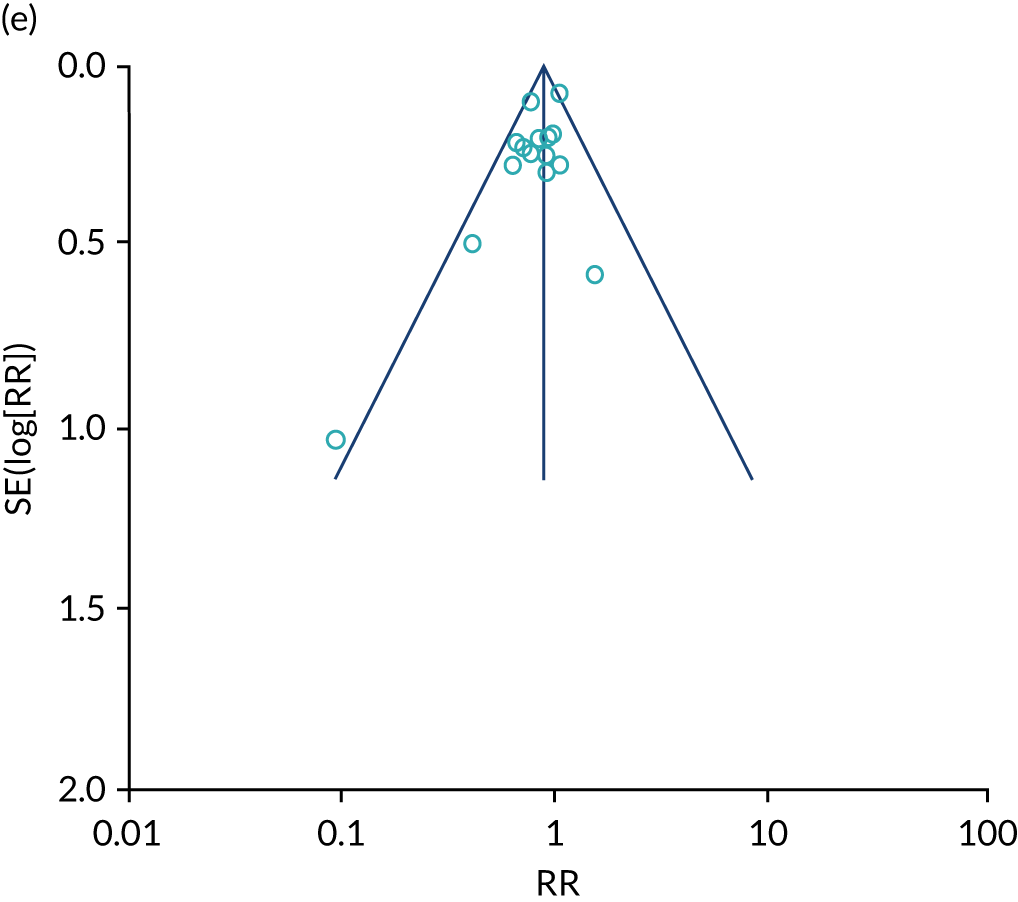

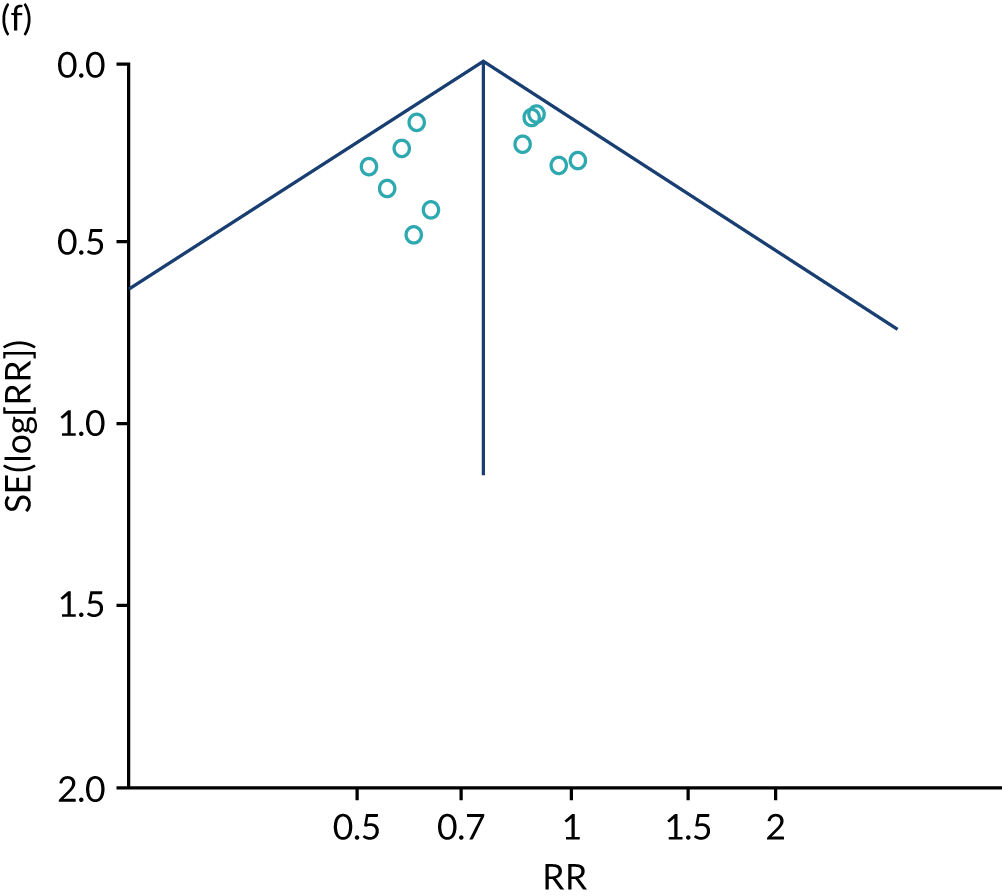

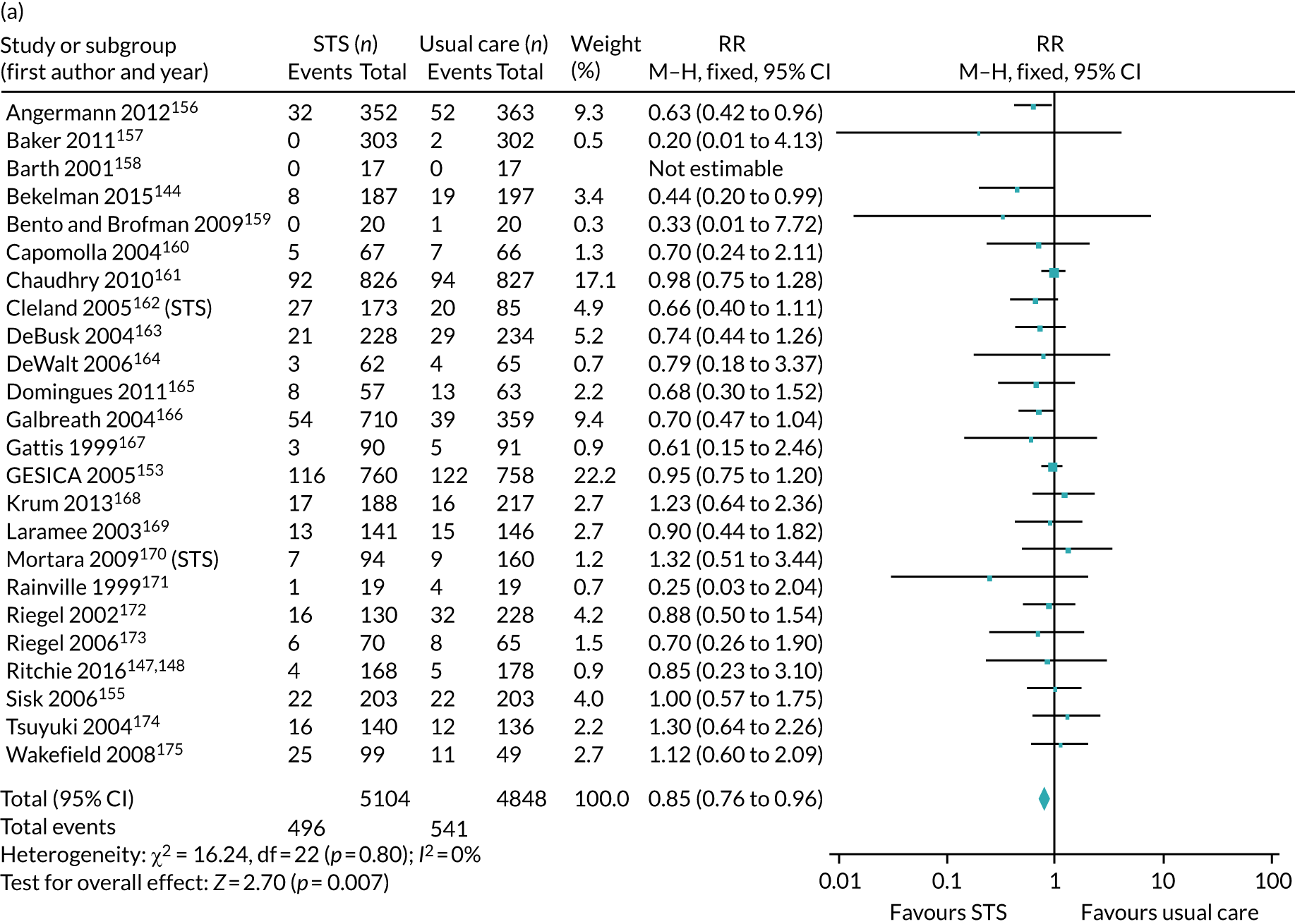

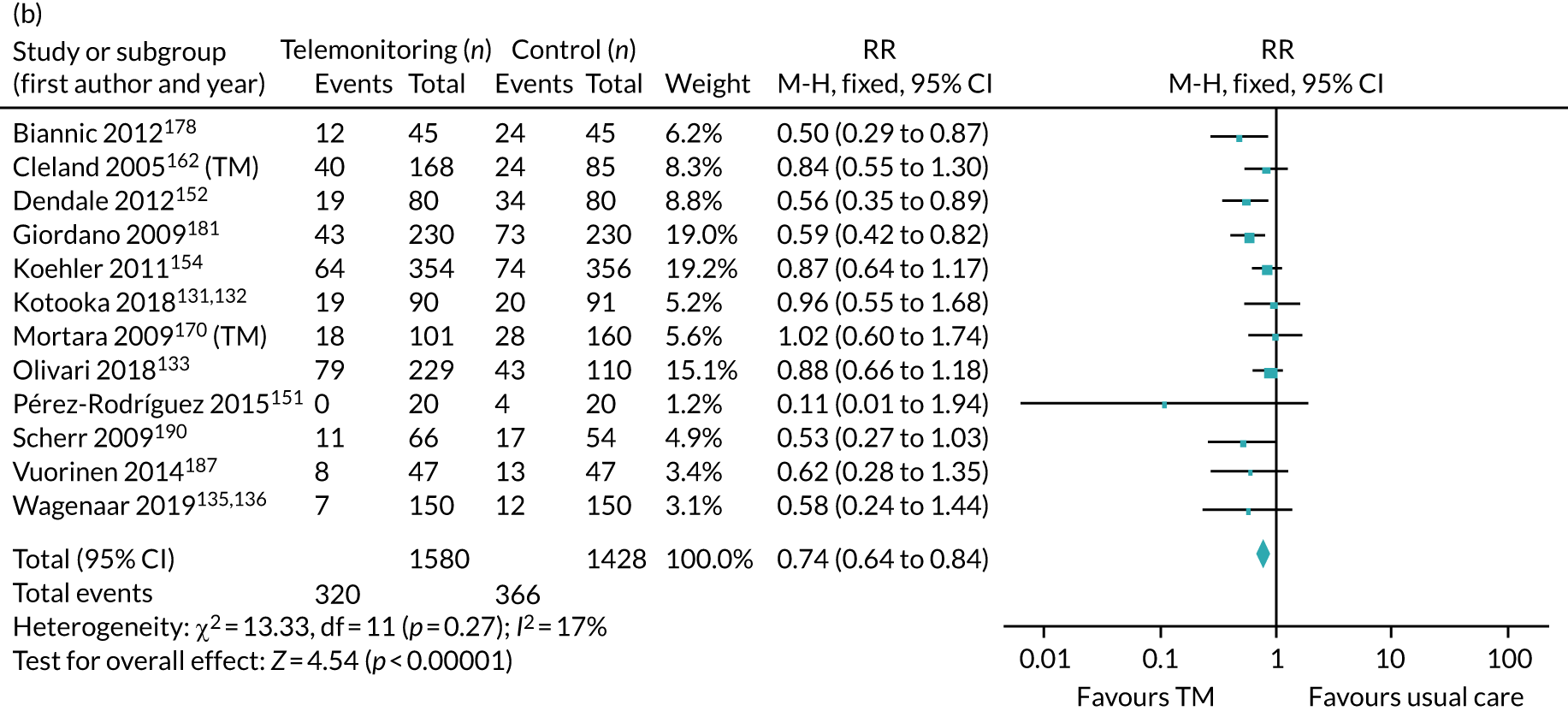

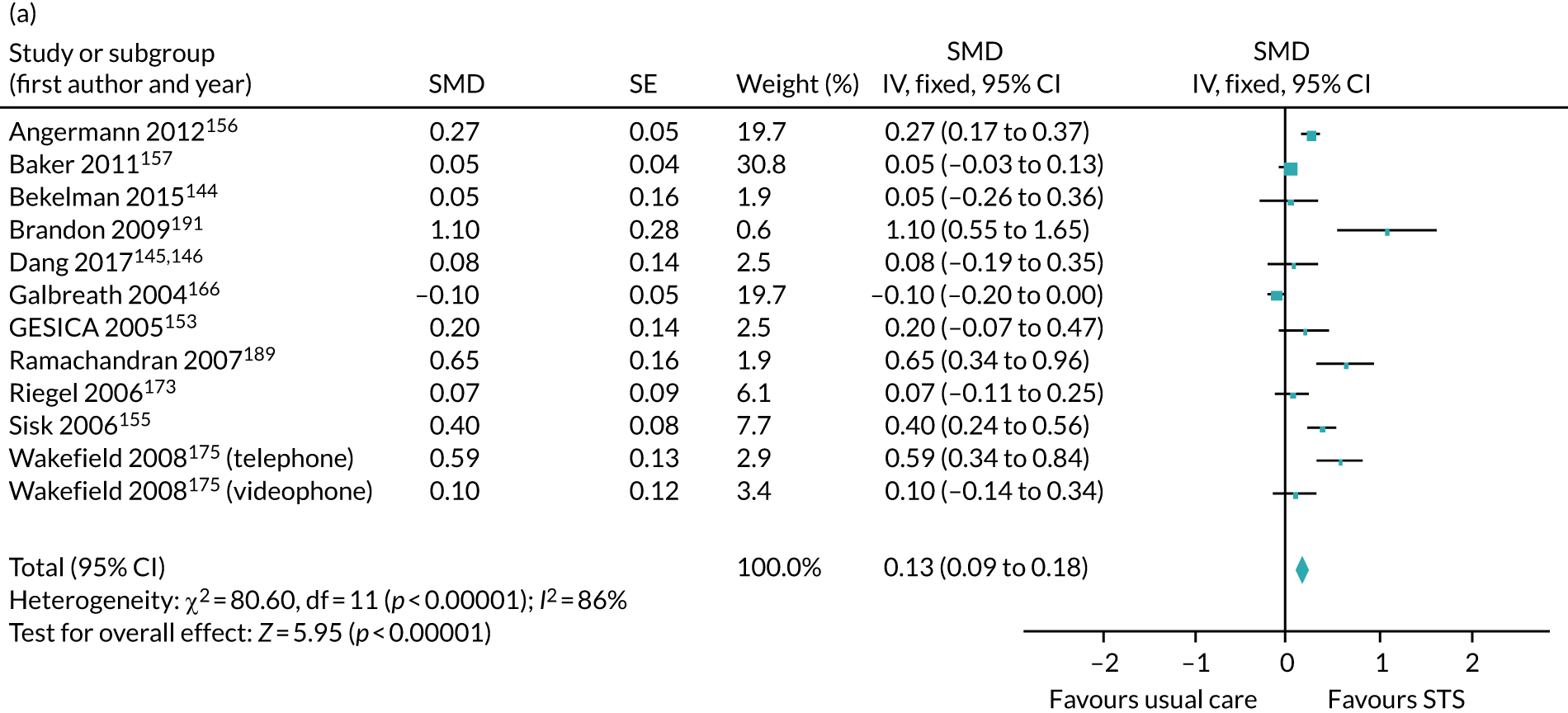

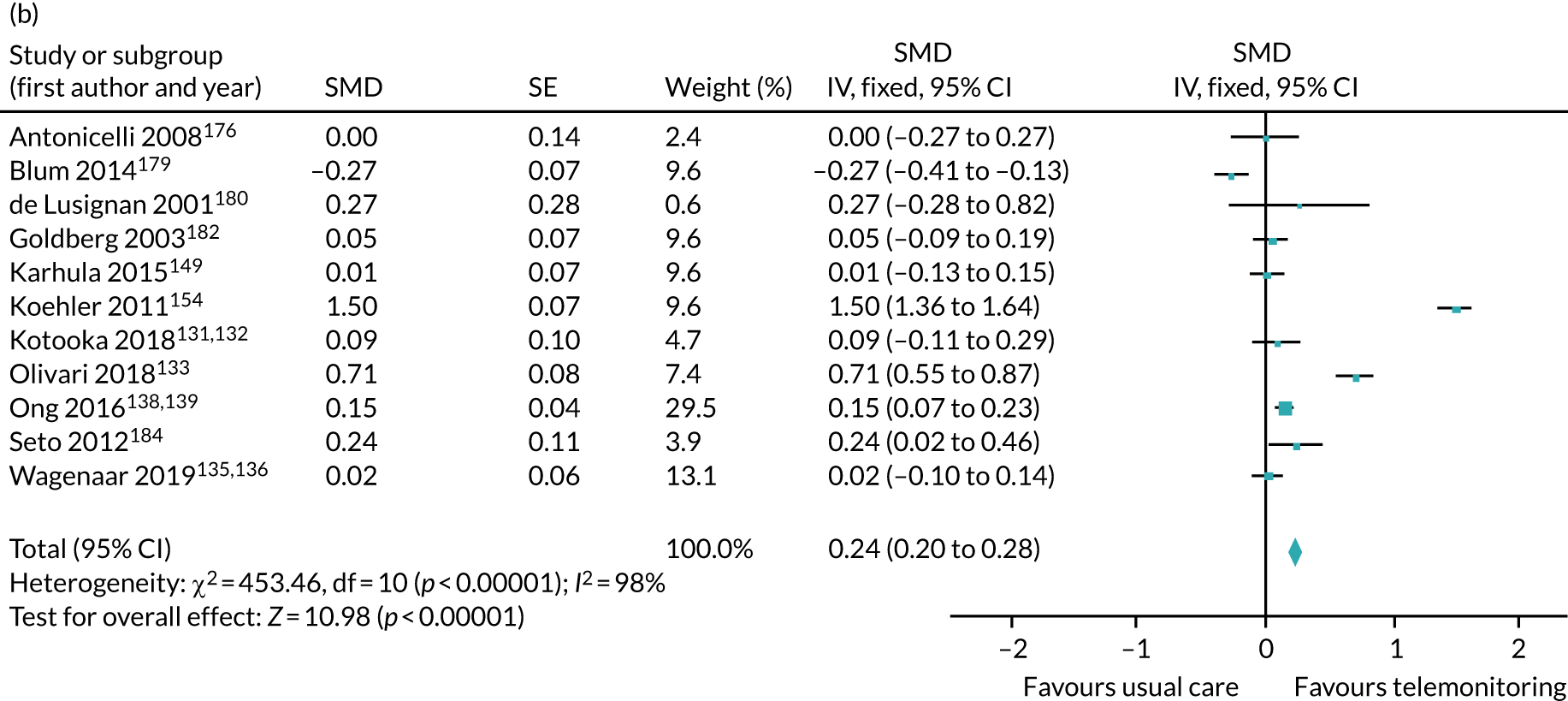

We identified 12 new RCTs, including the second- and fourth-largest studies to date, to our knowledge, to add to the existing 41 RCTs previously identified by Inglis et al. 73 in 2015. Screening and data extraction were carried out by two co-authors. For binary outcomes, we used fixed-effects meta-analyses to estimate the RR; for continuous outcomes, the standardised mean difference (SMD) was used.

The pooled results suggest that the rates of all-cause mortality and heart failure hospital admissions were reduced and quality of life was improved with the use of RM (all-cause mortality: STS – RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.96; I2 = 0%; TM – RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.92; I2 = 20%; heart failure admission: STS – RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.93; I2 = 27%; TM – RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.84; I2 = 17%; quality of life: STS – SMD 0.13, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.18; I2 = 86%; TM – SMD 0.24, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.28; I2 = 98%). However, although there was a suggestion that the rate of all-cause hospital admissions may be reduced by RM, this was not statistically significant. It was not possible to pool data for length of stay, adherence, acceptability, heart failure knowledge or self-care. For the outcomes of all-cause mortality and heart failure hospital admission, the heterogeneity was low and, although moderate for all-cause hospital admission, no particular explanation for the higher heterogeneity was revealed by subgroup analysis or meta-regression. The findings for quality of life should be viewed with caution as the heterogeneity was very high and testing of the robustness of the effect estimate by using a random-effects model resulted in the TM finding no longer being statistically significant.

This is a rapidly changing area of research, and a further 24 studies were recorded as ongoing; therefore, the evidence will continue to need updating as these are published. Furthermore, the technology continues to advance, meaning further updates will be required. Many RM interventions are complex, and further investigation of these using component analysis would be beneficial.

Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care natriuretic peptide tests for chronic heart failure (Taylor et al.74)

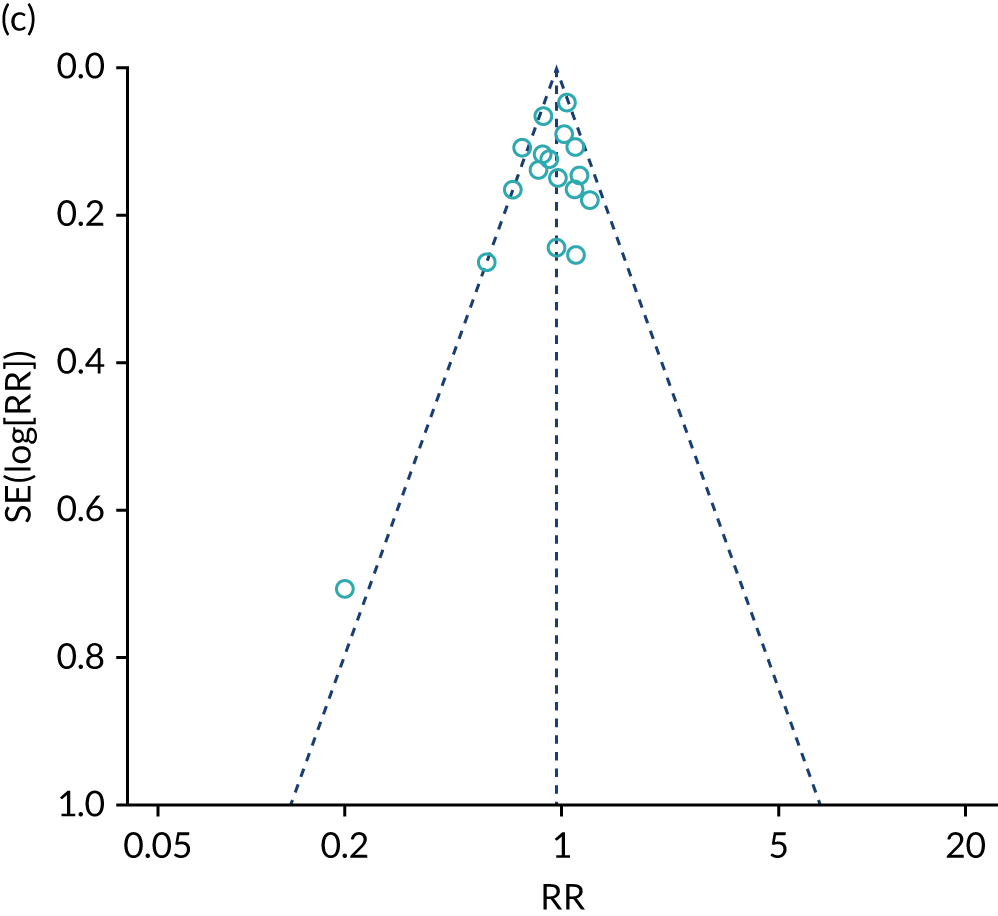

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of POC tests compared with echocardiography, clinical examination or combinations of these, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis (up to March 2017) of all POC NP diagnostic accuracy studies (see Appendix 18). We included only studies that were carried out in primary care or other ambulatory care settings, as this is where the test would be used in practice.

We identified 42 publications of 39 individual studies and included 37 studies in the analysis. These studies assessed the diagnostic accuracy of two different natriuretic tests (BNP and NT-proBNP); only five studies had been undertaken in primary care. The studies varied considerably in the types of patients they included, the health-care settings and the thresholds used. There was a wide range of sensitivity and specificity at different thresholds reported in the various studies. For the BNP test, the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.95 (95% CI 0.91 to 0.97) and 0.57 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.70), respectively, whereas, for NT-proBNP, pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.99 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.00) and 0.60 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.74), respectively. However, it was important to note that the sensitivity was more variable in the studies conducted in primary care.

Our review showed that NP tests have variable ability to exclude CHF in patients in ambulatory care. A positive test would need to be confirmed with cardiac imaging and also appropriate follow-up. We also highlighted that certain thresholds recommended by guidelines might be relevant, but further research is needed to confirm which thresholds are the most appropriate in an ambulatory care setting and whether or not implementing them can improve patient care.

Limitations of the analysis were that very few data were available in primary care settings and only a small number of studies were conducted using NT-proBNP. Several included studies were also at unclear risk of bias, which may potentially lead to an overestimate of the accuracy measures. The heterogeneity across the studies may also affect the generalisability of the results.

Given the lack of studies in primary care and the methodological limitations we identified in the studies, high-quality evidence in the form of randomised trials is needed to better guide the use of POC NP tests in the primary care and ambulatory care setting. Such studies should also clarify the appropriate thresholds to improve outcomes in patients with CHF. As part of this programme grant, a study in primary care of the accuracy of POC NT-proBNP tests was undertaken to address this research gap.

New quantitative evidence

Essential components in natriuretic peptide-guided management of heart failure (Oke et al.75)

This work aimed to identify the key components of NP-guided treatment interventions that reduced rates of hospitalisation in patients with heart failure (see Appendix 19). We extracted detailed information on the components of interventions from studies of NP-guided treatment of heart failure identified in a systematic review67,68 (see Appendices 15 and 16).

Detailed information on the interventions used in the studies was extracted from the papers in the review. We looked at univariate associations between components of the interventions and the strength of the reduction in the rate of heart failure hospitalisations and all-cause mortality. We compared intervention options in studies with significant and non-significant results to find components common to the more effective forms of the intervention.

We identified eight components across 10 studies that reported heart failure hospitalisation rates. The common-components analysis identified four components: a predefined treatment protocol, the locale of the heart failure clinic, setting a stringent NP target and incorporating a relative target as potential key components to reducing heart failure hospitalisations using NP-guided therapy.

The extent of what we could say about the effective components was limited by the number of studies that reported heart failure hospitalisations. Being unable to control for patient-level differences across studies may have masked the active components. Future studies should be conducted using individual patient data for their analyses.

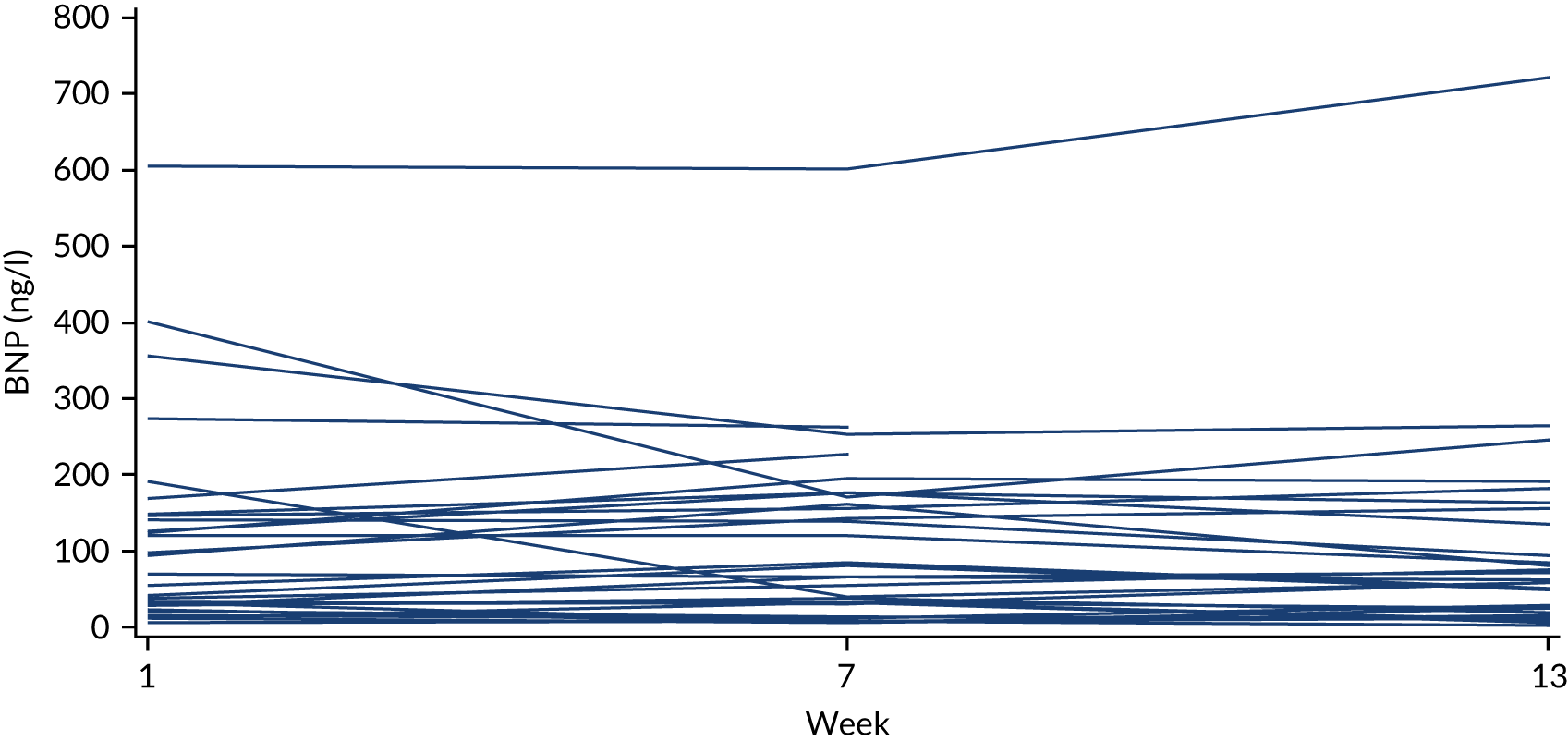

Estimation of the variability of B-type natriuretic peptide and weight

To investigate variability in BNP concentrations and weight in patients with heart failure, we analysed data from the control arm of a RCT among patients with stable New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or III CHF (see Appendix 20). The data were collected over 13 weeks of follow-up. Thirty patients in the control arm reported weight measurements weekly. BNP was measured every 6 weeks at 1, 7 and 13 weeks. The influence of age and obesity was investigated.

The between-person CV of weight was < 26% and of BNP was 137%. Between-person variation in BNP was higher for younger patients than for older patients with heart failure (the CV was 170% for age < 55 years and 88% for age ≥ 55 years), but did not appear to be related to obesity. Within-person variation was also substantial, but was smaller than between-person variation (the CV was 46% for BNP and 1.2% for weight).

The results suggest that monitoring over 3 months is unlikely to detect true BNP change against background noise in this small, chronically stable, heart failure population.

Feasibility study of the use of point-of-care natriuretic peptide testing in primary care

It has been postulated that routine monitoring of NP could assist in improving the care of patients with heart failure in the community. 70 Recent advances in technology provide the possibility of POC NP testing, but there is currently no evidence to support the use of such devices as part of routine care of patients with heart failure in primary care.

The primary aim of this study was to determine the variability in NP measurements made using POC NP technology in patients with heart failure in primary care settings, including both between- and within-person variability. Secondary outcomes assessing feasibility included the proportion of planned tests for which results were available (see Appendix 21).

We recruited adults with a recorded confirmed diagnosis of heart failure from three general practices in Oxfordshire between 20 February and 28 March 2018; follow-up was to 29 March 2019. Participants attended three scheduled visits at 0, 6 and 12 months from baseline. At all three visits, three venous blood samples were taken: one for POC NT-proBNP measurement (cobas® h 232 POC system; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), and two to be sent to the local laboratory for NT-proBNP and renal function testing.

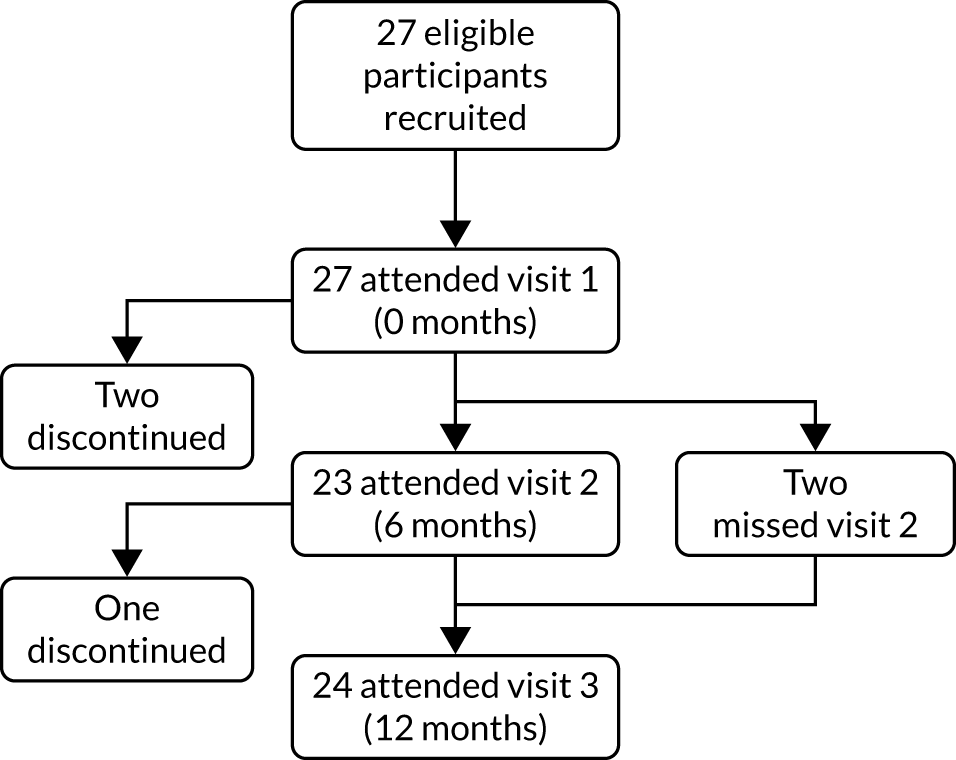

Of 27 recruited participants, all attended visit 1, 23 attended visit 2 and 24 attended visit 3 (see Appendix 21). POC NT-proBNP measurements were successfully obtained at all visits attended by participants.

Within-person variability in POC NT-proBNP over 12 months was 881 pg/ml (95% CI 380 to 1382 pg/ml). Between-person variability was calculated using data from all 27 participants. Between-person variability in POC NT-proBNP over 12 months was 1972 pg/ml (95% CI 1525 to 2791 pg/ml).

We found that it was feasible to carry out POC NT-proBNP testing in primary care, with testing successfully carried out in 100% of planned study visits. However, no tests were carried out during routine primary care visits by the study participants. Between-person variability in POC NT-proBNP was around twice as large as within-person variability over 12 months. This would indicate that deviations from individual set points for NT-proBNP are likely to be more helpful than population-level thresholds when considering a monitoring strategy.

New qualitative evidence

Qualitative evaluation for chronic heart failure

To understand the acceptability and impact of current monitoring regimes in individuals with CHF, we used a mixture of patients’ interviews and focus groups with health professionals (see Appendix 9). We used existing interviews conducted between 2003 and 2013, as well as new interviews focusing on monitoring. Participants for the focus groups with health professionals were recruited using a variety of methods, but were mainly drawn from practices from Oxfordshire and the wider Thames Valley area. Participant numbers for the focus groups were small, so the views expressed cannot be regarded as being representative of these professions.

Forty-three previously existing interviews and 16 new ones were analysed. The analysis aimed to focus on patients’ attitudes to both the content and frequency of monitoring, adherence to and understanding of medications, and triggers of consultation. The analyses of the original and new interviews were published in (respectively) 2014 and 2016. 76 Sixteen health professionals participated in four focus groups: two consisting of community heart failure nurses (CHFNs), one of GPs and one of practice nurses.

A range of strategies was reported, with some people monitoring their weight and blood pressure at home, and some using TM. Monitoring could take place in either primary or secondary care (or both); care by specialist nurses was particularly valued. Frequency of check-ups ranged from yearly to weekly. Being monitored provided people with reassurance. A few expressed criticisms, which were minor, about their current regime, although, for some, titrating medication to optimal levels took too long. Advice about when to seek help did not seem to have been given other than for emergency situations. Approval for hypothetical future changes to monitoring regimens would be forthcoming, provided the rationale was explained. Increased reliance on blood testing in future would be acceptable, and POC testing in GPs’ surgeries would be appreciated by people who would become anxious waiting days or weeks for test results.

As expected, CHF nurses were fully cognisant of the NICE guidelines for managing people with CHF, and used them daily to guide their care, with adjustment based on patient complexity (comorbidities). GPs and practice nurses expressed unfamiliarity with the latest updates to NICE guidelines. NICE’s website was considered confusing and difficult to navigate, and both GPs and practice nurses were more likely to learn about patient management recommendations from other sources, such as the Clinical Commissioning Group or QOF alerts. Given this, CHF nurses mentioned that they usually lead on treatment plans.

Chronic heart failure patients are regularly seen by practice nurses, but only as part of their management for other long-term conditions (driven by the QOF). GPs were unsure what tests they should be doing, and when and how to interpret and act on the results. Although they would welcome specific guidance from specialists about how to manage individual patients discharged from secondary care, they felt criticised by cardiologists for up-titrating a patient’s medicines too slowly, when, in reality, this process could be challenging as a result of patient factors beyond their control.

Generally, both GPs and CHF nurses recognise NP as a useful diagnostic test for CHF, but CHF nurses could see no benefit of measuring NP as part of routine monitoring, instead suggesting that any changes in severity would be reflected in patients’ symptoms. All groups believed that the cost of the test (both financial and in terms of professionals’ time and extra blood samples required from the patient) would outweigh any potential benefits.

Economic issues

We aimed to identify health economic models used to address research questions related to monitoring heart failure in primary care, and hence to identify key issues. We reviewed the research questions addressed, the model structures and the data sources used to populate the models (see Appendix 22). A previous review by Goehler et al. 77 (including studies published be June 2010) was updated to August 2018 to identify analytical frameworks developed to evaluate heart failure interventions and management programmes in primary care. Studies were excluded if the research question was based fully within secondary care or if they reported local non-UK adaptations of already-included models.

Forty studies were identified: three focused on diagnosing heart failure, 11 focused on management strategies and 26 focused on drug interventions. Thirty-one studies used Markov model specifications with several different model structures. There was limited use of individual patient characteristics in the models. The data used to populate the parameters of the economic models were sourced predominantly from RCTs (undertaken several years ago) among patients with CHF recruited in hospitals.

Different models have been used to evaluate primary care interventions for patients with CHF. Despite the small number of studies that took into account patient characteristics, this appears to be increasing over time. Data from RCTs are widely used for estimating disease risks, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and costs. Participants in these trials, frequently completed some years previously, were unlikely to be representative of the general CHF population in primary care. Future work should consider individual patient risk factors and include more recent data from CHF patients in primary care.

Three key issues were identified. First, the model structures were not generally sufficiently detailed to allow assessment of subtle improvements in disease monitoring. Second, a very small number of models accounted for individual patient characteristics and risks; however, this problem appears to be increasingly tackled in more recent models. Third, data to parameterise the economic models almost exclusively came from RCTs, many of which were completed some years previously and recruited patients exclusively in hospitals. Therefore, these data are unlikely to be representative of the target CHF population in primary care in the UK. Future work should consider individual patient risk factors and source more recent data from primary care.

Conclusions

This WS focused on management/monitoring of CHF in primary care, researching current practice and providing new evidence to guide this management. In particular, we concluded that:

-

NP tests appear to be underused in primary care as part of diagnostic pathways (at least until 2013), which is not consistent with NICE guidance,13 and are not used as part of a monitoring strategy (consistent with NICE guidance).

-

NP-guided treatment might be beneficial in this population in reducing all-cause mortality and the rate of heart failure hospital admissions, although some uncertainty remains with regard to the size and robustness of this effect.

-

We identified three components (plus being located in a specialist setting) that may be essential for NP-guided therapy in reducing the rate of heart failure hospitalisations – (1) using a predefined treatment protocol, (2) setting a stringent target and (3) the use of patient-specific targets.

-

TM and STS in this population reduce the rate of all-cause mortality and hospital admission. Quality of life might also be improved by RM, although large levels of heterogeneity reduce our confidence in this beneficial effect.

-

Within-person variability of BNP and weight is large, thereby reducing the chances of identifying true change in the condition using these measures.

-

POC NP tests have variable ability to exclude CHF in patients in ambulatory care at low thresholds, but the ESC threshold for non-acute care for NT-proBNP might be an appropriate cut-off point for POC testing in this setting.

-

It is feasible to carry out POC NT-proBNP testing in primary care, with testing successfully carried out in 100% of planned study visits. However, no opportunistic tests were conducted.

-

Between-person variability in POC NT-proBNP is around twice as large as within-person variability over 12 months.

-

Professionals consider the use of NP tests for monitoring expensive, of limited benefit and, potentially, a waste of scarce resources.

-

Health economic studies increasingly consider individual patient factors, but are limited by a lack of data from CHF patients typically seen in primary care.

Research recommendations

-

Further studies evaluating the efficacy of NP-guided treatment in CHF are needed. Based on a 13% relative reduction from a 15% mortality (baseline), an excess of 10,000 participants will be required to have a sufficiently powered (≥ 80%) study. Current systematic reviews/meta-analyses include just over 4000 participants.

-

Any such studies should collect resource data on length of hospital stay and re-admission rates, which are critical for the health service and will facilitate assessment of cost-effectiveness.

-

The potential mechanisms for an effect on mortality, such as increased patient and physician adherence to treatment regimens, should be explored.

-

New and ongoing studies of RM need to be incorporated promptly to systematic reviews; these should consider changes in the technologies used for this purpose.

-

Determining the appropriate threshold for the use of POC NP testing is needed if this technology is to be incorporated as part of a diagnostic or monitoring pathway.

-

Exploring the barriers to the routine use of NP and POC NP testing is needed to increase health practitioners’ use of these tests.

-

More detailed data on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, including disease progression and health-care use, from CHF patient cohorts in primary care are required to inform assessments of monitoring strategies.

Implications for practice

-

If NP tests are not currently used as part a diagnostic pathway in primary care, which goes against the NICE recommendation, their use could be incentivised.

-

RM, using either TM or STS, in the care of CHF should be considered, as it is likely to reduce the rates of all-cause mortality and heart failure hospital admissions, and may improve quality of life.

-

NP tests have variable ability to exclude CHF in patients in ambulatory care at low thresholds, but the ESC threshold for non-acute care for NT-proBNP might be an appropriate cut-off point for POC testing in this setting.

-

As between-person variability in POC NT-proBNP was around twice as large as within-person variability over 12 months, this indicates that deviations from individual targets for NT-proBNP are likely to be more helpful than population-level thresholds when considering a monitoring strategy.

-

Both NP and weight are highly variable measures; therefore, any change observed should be interpreted with caution.

-

Use of POC tests to measure NP in general practice is feasible, but does not lead to reductions in observed variability.

-

There are substantial barriers to the implementation of NP-guided treatment in primary care. In particular, the perception from health practitioners, both nurses and clinicians, is that the use of NP measures may not be beneficial.

Reflections

Pharmacological treatments for heart failure in primary care are well established, but must be managed (titrated) with great care and may temporarily worsen patient quality of life. This may contribute to the major underuse of evidence-based therapies in routine practice, which may, in turn, increase the likelihood of urgent admissions with worsening heart failure. Identifying ways of detecting heart failure deterioration is therefore likely to be important for patients and health-care systems. There is, therefore, strong prima facie evidence for a role for monitoring, but we find that the candidate monitoring measures – NP, and also weight – have relatively high within-measurement variability. In this context, it is perhaps not surprising that we find encouraging, but inconsistent, evidence from trials that monitoring to guide treatment, by clinicians or at home, is potentially life-saving. Future research should investigate the settings and methods in which monitoring has the most benefit, and we suggest that refining the reliability of measurements, whether through new biochemical methods or through averaging several measurements to reduce noise, is a promising direction in which to start.

Patient and public involvement

Background