Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1209-10013. The contractual start date was in December 2011. The final report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Taylor et al. This work was produced by Taylor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Taylor et al.

SYNOPSIS

Setting the scene

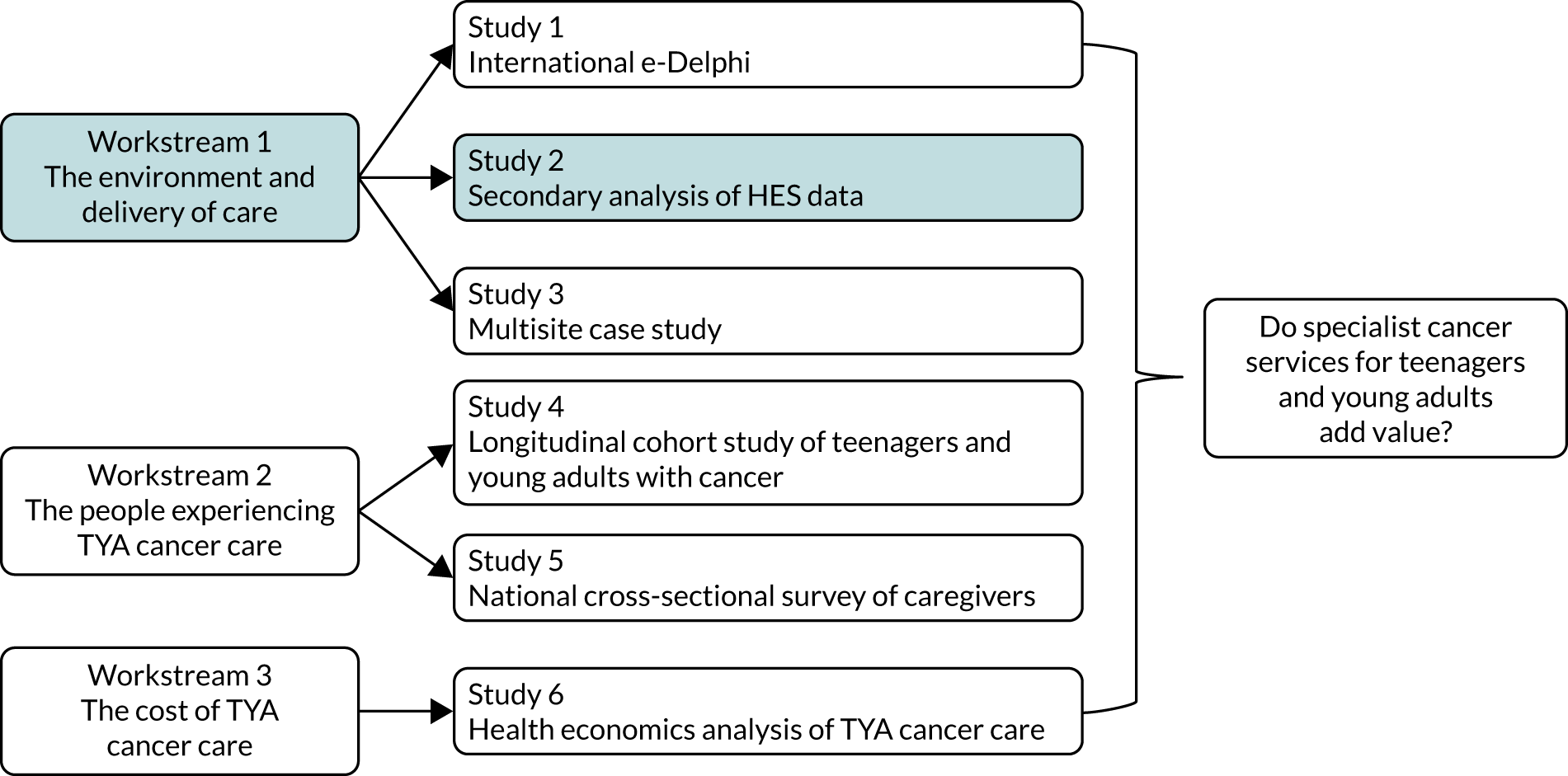

Young people have unique needs that differ from those of children or older adults, yet traditional policy and services serve children and young people as a single population. Consequently, teenagers and young adults can find themselves being treated in a children’s service or can become lost within adult health services. 1–3 The impact of this was identified in teenagers and young adults, who account for just 1% of all cancer diagnoses, but in whom cancer is the highest non-accidental cause of death. 4,5 Outcomes for young people are also documented to be poorer than for children and older adults. 6 The reason for this is multifactorial, including the range of cancer types (Figure 1); prolonged time to diagnosis; unfavourable tumour biology, as increasing age within this range is associated with worsening survival in certain cancers; inconsistent use of molecular diagnostics that may be central to optimal care;7 limited access to clinical trials;6,8,9 lack of concordance with treatment protocols;10 and a lack of specialist supportive care. 6,11 In addition, young people themselves have described unsatisfactory experiences of care, which include lack of recognition of their autonomy, failure to maintain their need to continue to meet normal life goals during treatment, lack of peer support, care by staff with little experience of young people, and inappropriate care environments. 12,13 The additional unique psychosocial and health-care needs of this specific population are also being increasingly highlighted in the international literature. 14–17 Place of treatment and cancer care, in terms of both disease and age-appropriate specialist settings, is increasingly acknowledged as significant to the outcome for teenagers and young adults with cancer. 17–19

FIGURE 1.

The distribution of tumour types in young people is unique and not replicated in other age groups (adapted with permission from Lorna A Fern, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 2021, personal communication, based on the data from Birch et al. 4). CNS, central nervous system.

Provision of teenage and young adult cancer care in England

Specialised teenage and young adult (TYA) cancer services in the UK have evolved over the past 30 years, with much input from the charity Teenage Cancer Trust. 20,21 Since the 1960s, a model of delivering cancer care to children has been established,11 and in 2001 adult cancer services were reconfigured into cancer networks, resulting in improvements in both patient experience and outcomes. 22 The first teenage cancer unit opened in the Middlesex Hospital in 1990, but it was not until 2005 that national policy was published that formalised the configuration of services specifically for teenagers and young adults. 23

The release of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) improving outcomes guidance (IOG) for children and young people with cancer in 200523 was a significant landmark on the landscape of English TYA cancer service development. This outlined detail about the provision of services for teenagers and young adults, such as clinical organisation, facilities, and diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. 23 Although this guidance supported subsequent service delivery, the evidence review that underpinned it was a collation of evidence on child and adult cancer services, some of which was assessed to be of fair to poor quality. Of the 15 pieces of evidence reviewed, only two were specific to teenagers and young adults. 24

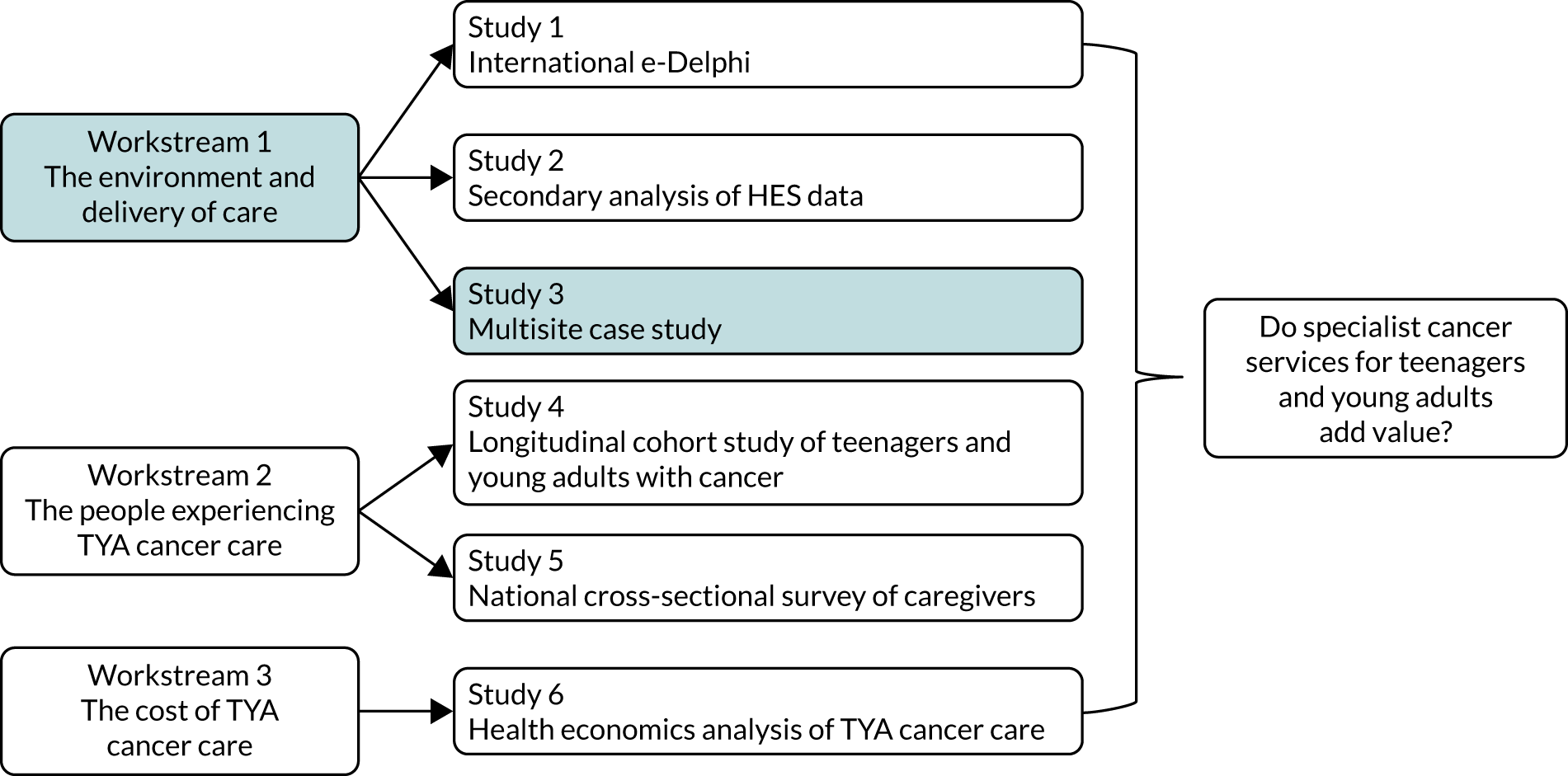

Despite the evolution and development of UK cancer services for young people, there continued to be variation regarding where young people with cancer received their care. 25 Even with government recommendations advocating ‘young person-friendly’ health services,26 many young people in the UK were cared for on adult wards27 or in children’s services28 (Figure 2). It was suggested that it was ‘inappropriate’ to deliver care to young people in either child or adult environments of care,30,31 or in settings not equipped to meet their needs. 32

FIGURE 2.

An illustration of the three types of health service where young people with cancer may be cared for. Reproduced with permission from Sarah Lea. 29 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure. Images reproduced from Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, 2017 with permission (Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, 2021, personal communication).

Prior to the release and implementation of the IOG, approximately 52% of young people in England had been receiving care in a hospital that became a principal treatment centre (PTC). This group mainly comprised teenagers (aged 15–18 years) rather than young adults (aged 19–24 years). The place of care was a key focus within the IOG,23 which stated young people should be treated in an ‘age-appropriate environment’ and have access to ‘age-appropriate’ facilities. What made an environment or facility age-appropriate was not defined. However, specialist services could not be mandated without sufficient evidence to underpin them. This led to the process of designation (i.e. cancer services for young people in England were structured into networks of care with a central TYA-PTC as a ‘hub’ of expertise and hospitals with adult cancer services surrounding the TYA-PTC could apply to be ‘designated’ to provide cancer care to young people aged 19–24 years).

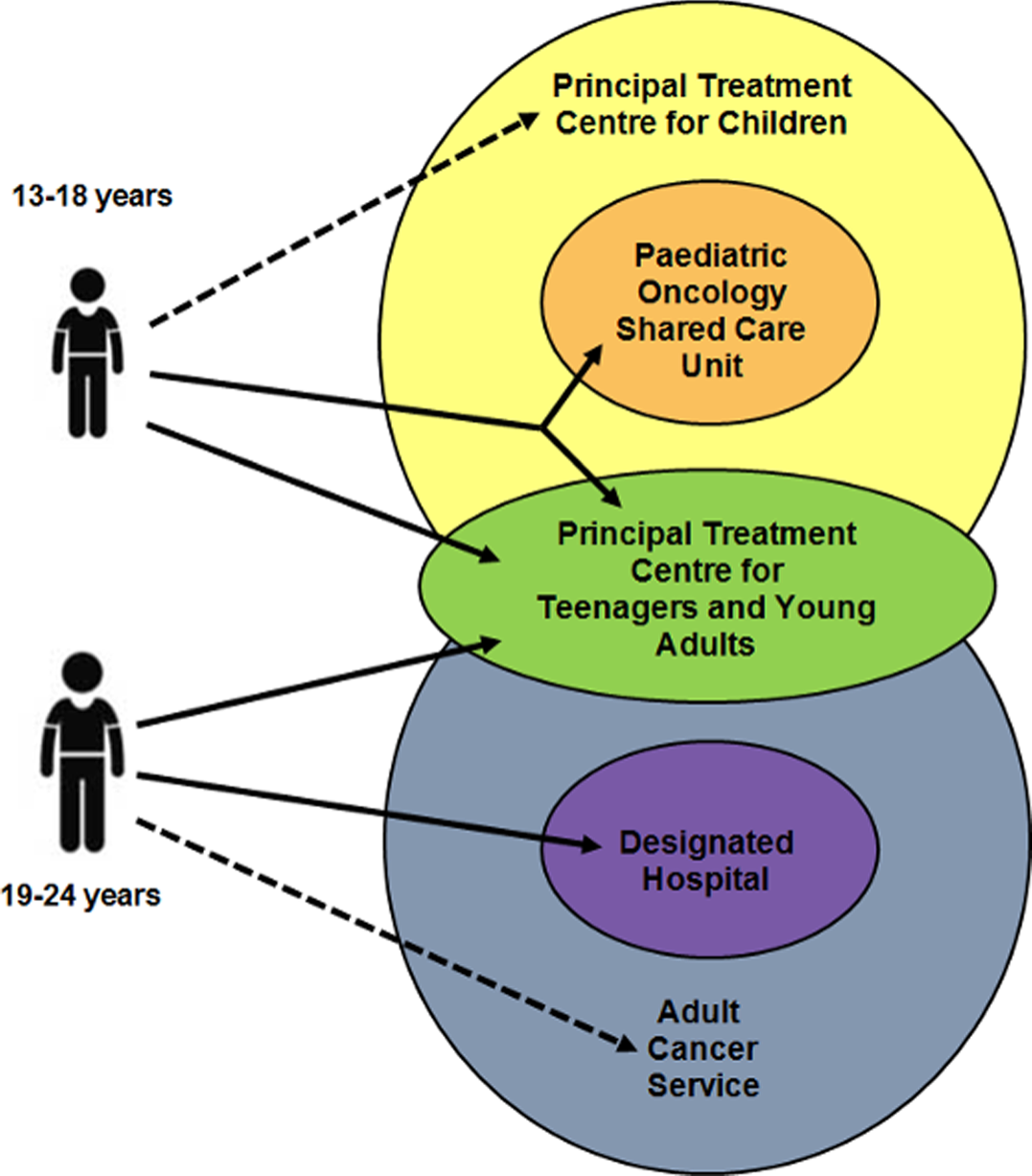

The model of service delivery for young people with cancer in England in 2012, when this programme of work began, consisted of 13 TYA networks of care with a TYA-PTC and varying numbers of associated designated hospitals (Figure 3). The TYA-PTC provided treatment expertise across the range of cancers common in young people, supported by a dedicated TYA multidisciplinary team (MDT) to meet the psychosocial needs of this population, within an environment that was tailored to the developmental and social needs of young people. 21 Young people aged up to 16 years could receive care in a children’s PTC or a paediatric oncology shared care unit that was authorised to provide certain aspects of supportive care, such as administration of blood products or simple chemotherapy drugs. Young people aged 19–24 years were to have ‘unhindered access’ to age-appropriate care and had the choice of being referred to a TYA-PTC or to stay in an adult cancer unit in a designated hospital within the network (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Map of the location of the 13 TYA cancer networks in England. (1) Cambridge, (2) Bristol, (3) Oxford, (4) Liverpool, (5) Newcastle, (6) East Midlands, (7) Birmingham, (8) Southampton, (9) Leeds, (10) Manchester, (11) South Thames, (12) North Thames and (13) Sheffield.

FIGURE 4.

The range of places where a young person with cancer may receive their care, dependent on whether they are aged 13–18 or 19–24 years. Young people may receive access to specialist TYA cancer care (highlighted by the solid arrows), but young people may still be cared for in either child or adult cancer services (highlighted by the dashed arrows). Reproduced with permission from Sarah Lea. 29 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

There was a requirement that designated hospitals would notify the TYA-PTC of young people newly diagnosed with cancer so that there was ‘sharing of responsibility for patient management’ between the tumour site-specific clinical team at the designated hospital and the experts at the TYA-PTC. 33 Moreover, young people at designated hospitals should have ‘unhindered access’ to the support of the wider MDT via outreach work performed by the specialist professionals from the TYA-PTC (e.g. young people’s social workers). 23 Within each network there were also hospitals that were not allocated to provide care to TYA (non-designated hospitals). A proportion of teenagers and young adults continued to be cared for in these non-designated hospitals without access to the age-specific expertise of the TYA MDT at the PTC or access to age-appropriate care throughout their entire cancer journey. 34

Although there was a variety of services in which a young person may receive their cancer care, dependent on their disease, age, location and availability of services, there was variation in how this was translated and implemented across England. Of the 76 hospitals that were designated to deliver TYA cancer care, in 2013 approximately one-third were unable to deliver ≥ 50% of the standards that had been specified for being designated. 35 There were no consequences of this, and these hospitals have remained designated for teenagers and young adults, despite lacking many elements of a young adult-friendly cancer service. 36

BRIGHTLIGHT

The guidance and policy directing TYA cancer services in England in 2010 was not based on evidence and there was a lack of research evaluating how well these TYA cancer care networks operated. BRIGHTLIGHT is the applied health research programme providing this evaluation, which evolved from feasibility work in the Essence of Care study in 2009/10 that informed the methods for BRIGHTLIGHT. 37–41 During the Essence of Care study, we identified wide variation in the delivery of care across England, which informed the need for all the studies within the programme to be multicentre as well as containing longitudinal aspects. Although we have achieved this, we have been challenged by recruitment to the cohort and changes in regulatory processes throughout the study period, resulting in delays and preventing the detailed analysis of the cohort data necessary to fully understand the results. As a result, we provide a tentative conclusion in the knowledge that further work may be required to further inform answers to the overarching question: do specialist cancer services for teenagers and young adults add value?

Objectives

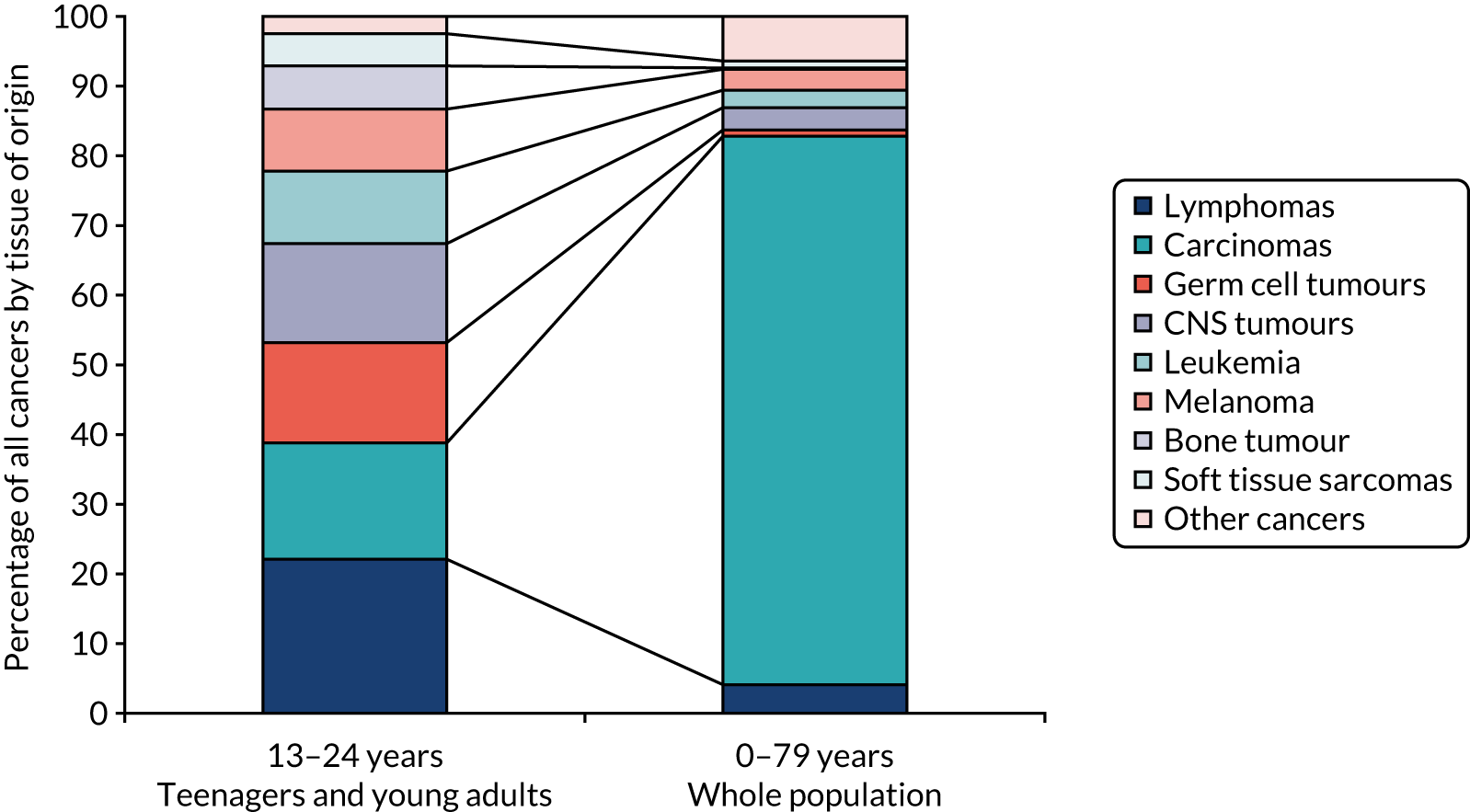

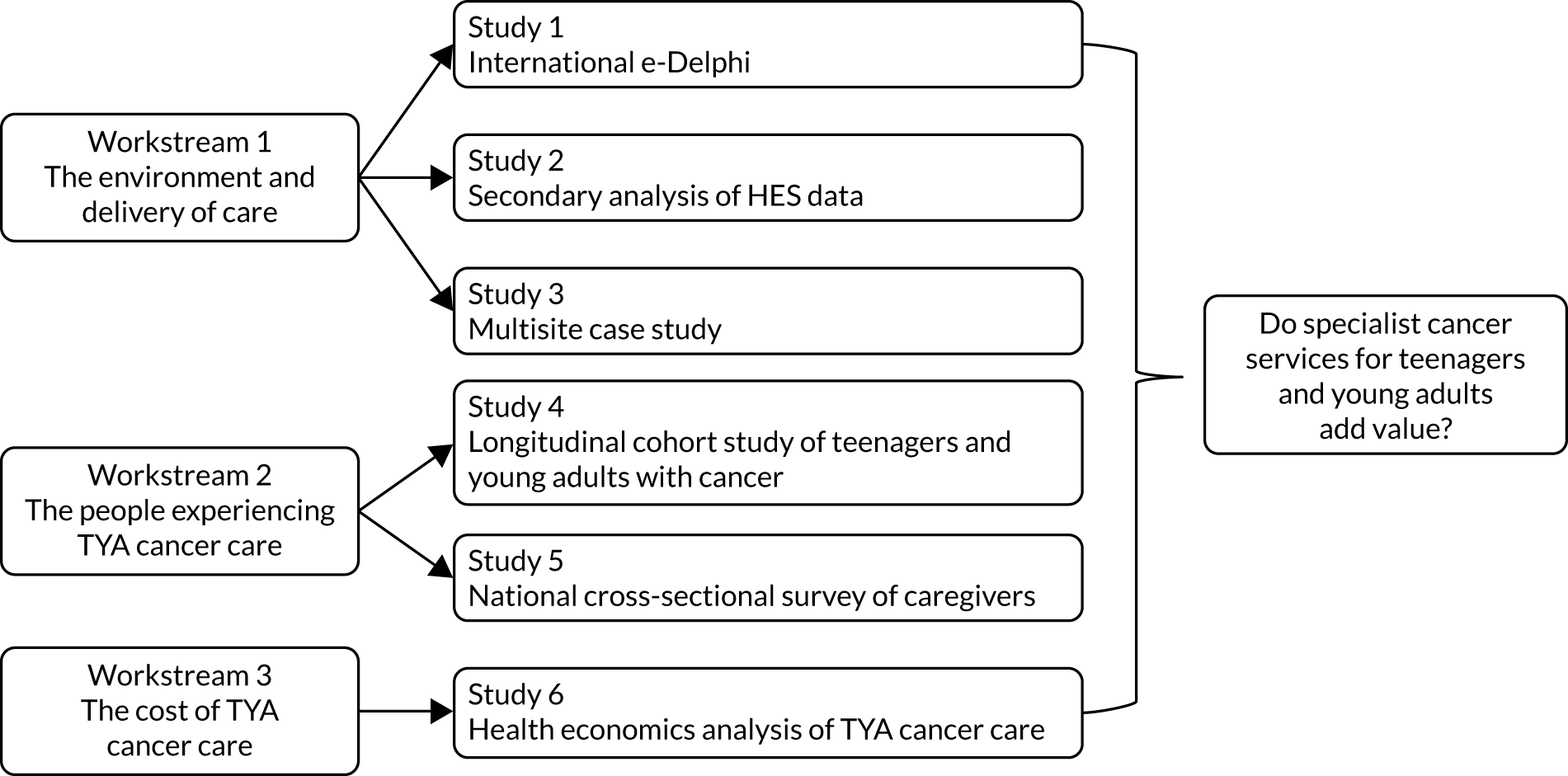

The programme of research was divided into three workstreams (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Flow diagram depicting the inter-relationships between the workstreams. HES, Hospital Episode Statistics.

Workstream 1: establishes the description of teenage and young adult cancer care including specialist care

-

1.1. Explore the culture of care through non-participant observation, semistructured interviews and analysis of departmental documents.

-

1.2. Identify the specialist competencies and added value of specialist health professionals through an international Delphi survey.

-

1.3. Develop the TYA Cancer Specialism Scale to categorise three levels of TYA care and apply to individual patient-level data.

Workstream 2: examines care of young people with cancer in a cohort study

-

2.1. Relate the level of cancer care received by teenagers and young adults to quality of life (QoL), satisfaction with care, clinical processes and clinical outcomes (overall, by age group and by tumour type).

-

2.2. Examine young people’s experience of cancer care through a longitudinal descriptive survey.

-

2.3. Compare social and educational milestones among young people receiving different levels of TYA cancer care.

-

2.4. Examine geographic and sociodemographic inequalities in access to TYA cancer care.

Workstream 3: examines the economics of the levels of teenage and young adult cancer care

-

3.1. Calculate detailed costs to the NHS and Personal Social Services of teenagers and young adults receiving different levels of cancer care.

-

3.2. Estimate the cost incurred by teenagers and young adults and families receiving different levels of cancer care.

-

3.3. Calculate the cost-effectiveness of different levels of cancer care.

Programme management

A core group was responsible for the day-to-day management of the programme, including the chief investigator (Jeremy Whelan), programme lead (Rachel Taylor), lead for patient and public involvement (PPI) (Lorna Fern) and representation from each workstream (Faith Gibson, Sarah Lea and Nishma Patel). The core team met on a monthly basis to discuss study progress and address issues that needed attention, such as recruitment into the cohort. A wider executive team comprised the co-applicants of the programme who provided methodological expertise as required (Julie Barber, Stephen Morris, Richard Feltbower, Dan Stark, Louise Hooker and Rosalind Raine). The executive team had an annual meeting to discuss study progress, review results and discuss future study conduct. BRIGHTLIGHT was developed with young people and the young advisory panel (YAP), comprising 23 young people, who met yearly for a face-to-face workshop and were consulted on all impending changes through a closed Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) page. Additional meetings with YAP members involved in specific projects were held either face to face or by teleconference (see Acknowledgements). Finally, we had a steering committee, chaired by William Van’t Hoff (Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust), which comprised experts in QoL (Meriel Jenney, Children’s Hospital for Wales, Cardiff), longitudinal research (Lisa Calderwood, Centre for Longitudinal Studies), TYA cancer care (Laura Clark, Teenage Cancer Trust) and research delivery (Zoe Coombe and Jocelyn Walters, Comprehensive Research Network managers).

A summary of the alterations to the programme

Two additional studies were added to the programme at no additional cost. One of these was a mosaic study, mapping TYA-PTC services, which was used to inform the selection of cases in study 3. Data from caregivers (study 5) were made possible through a mechanism used by the contract research company to reduce family interference during the face-to-face interviews in study 4.

Four contract variations have been approved by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Central Commissioning Facility, including three extensions to the grant. As a result, rather than ending in December 2016, the grant ended in December 2019. This was to accommodate the unanticipated difficulty in recruiting to the cohort (study 4) and to ensure that we had enough time for longitudinal data collection and for the required analyses. The third variation in contract allowed for removal of workstream 4, which had been directed towards implementation of changes within the duration of the grant. Because of the delays described above, the methods suggested in the grant application could not be implemented. However, we had developed additional studies and secured funding for a number of these early in the process (see Work arising from the grant).

The fourth variation in contract provided funding for support for analysis for objectives 2.3 (study 4), and secondary data analysis. There have been challenges beyond our control appointing to this post, so these analyses are not included in the report but are ongoing.

Alterations to the original plan also included analyses that we were not able to undertake in study 4 (the cohort study). We were not able to explore geographic and sociodemographic inequalities in access to TYA care as we reduced our sample size and recruited a fifth of the total population diagnosed with cancer. We were also unable to conduct the planned granular analysis of age and cancer type for this reason.

Patient, public and carer involvement in BRIGHTLIGHT

Involvement prior to submission of the research proposal

The initial idea to evaluate specialist cancer care for young people was professionally driven. However, recognising the unique challenges that this group faces, we felt that a successful programme grant would hinge on involving young people throughout the process. BRIGHTLIGHT is a study about young people with cancer, designed and driven by young people with cancer. Five young people worked as co-researchers during the feasibility work, which was instrumental to the study design, the development of survey materials and the identification of suitable outcome measures. Young people were also integral to dissemination, including co-authoring papers. 37,39

With such an extensive programme we began making links with communities involved in young people’s care and research delivery prior to protocol submission. Our PPI partners also included parents, siblings, professionals caring for young people, charitable organisations and research networks. We worked with partner groups to optimise the acceptability of study design, delivery, research question and outcomes.

Our experience of PPI prior to submission prepared us well for the commitment and resources required for a successful PPI strategy. In addition to the PPI lead, we employed a cohort manager to manage PPI activities. One young person joined us as a co-applicant. However, as is often the case with young people who finish treatment and move on to full time employment, she had other day-to-day commitments. Thirteen years had passed since her diagnosis and her role came to a natural end.

We recently published our 10-year PPI experience. 42

Establishing our patient, public involvement group and networks

Young people

Young people working as co-researchers during the feasibility work lent itself well to this short intensive piece of work. However, we felt that the sustainability of this model was not viable given the life-stage commitments of young people and the length of the proposed programme. Our application stated:

An initial workshop will be held with the Young Persons Reference Group; thereafter they will be consulted using options such as email discussion rather than face-to-face meetings, recognising the range of life stage commitments of TYA [teenagers and young adults].

Discussions with young people between December 2011 and August 2012 revealed that e-mail would not be an appropriate or responsive method of involvement, as e-mail was no longer ‘vogue’ (YAP workshop participant) and had been replaced by Facebook. Young people also advocated some face-to-face contact to foster relationships between themselves and the research team. We opted for a closed Facebook page, which took 14 months to be approved by our NHS trust and opened in October 2013, 13 months after the 2012 workshop. This delay was unfortunate, as it meant that many young people who attended the 2011/12 groups had moved on/changed contact details in this time.

We accessed young people through the conference ‘Find Your Sense of Tumour (FYSOT)’. 43 Annually between 2008 and 2017, we consulted around 200 young people aged 13–24 years on study design, suitability of research questions, outcome, recruitment approach and dissemination. 42,44,45 Young people gave their opinions individually and anonymously through handheld device surveys. We also recruited four young people from FYSOT to perform in our dissemination event ‘There is a Light’.

Parents and siblings

We planned to include parents and siblings and, following notification of funding, we visited existing groups of young people (Leeds/Birmingham) and family events (Cambridge). The Cambridge event involved focus groups with young people and parents/siblings. In our original plan, we stated our intention to report back to parents annually. In response to recruitment problems we focused efforts on understanding the barriers to recruitment from young people and professionals. Additionally, we added a further strand of data collection in response to our PPI work to more fully understand the experiences of carers.

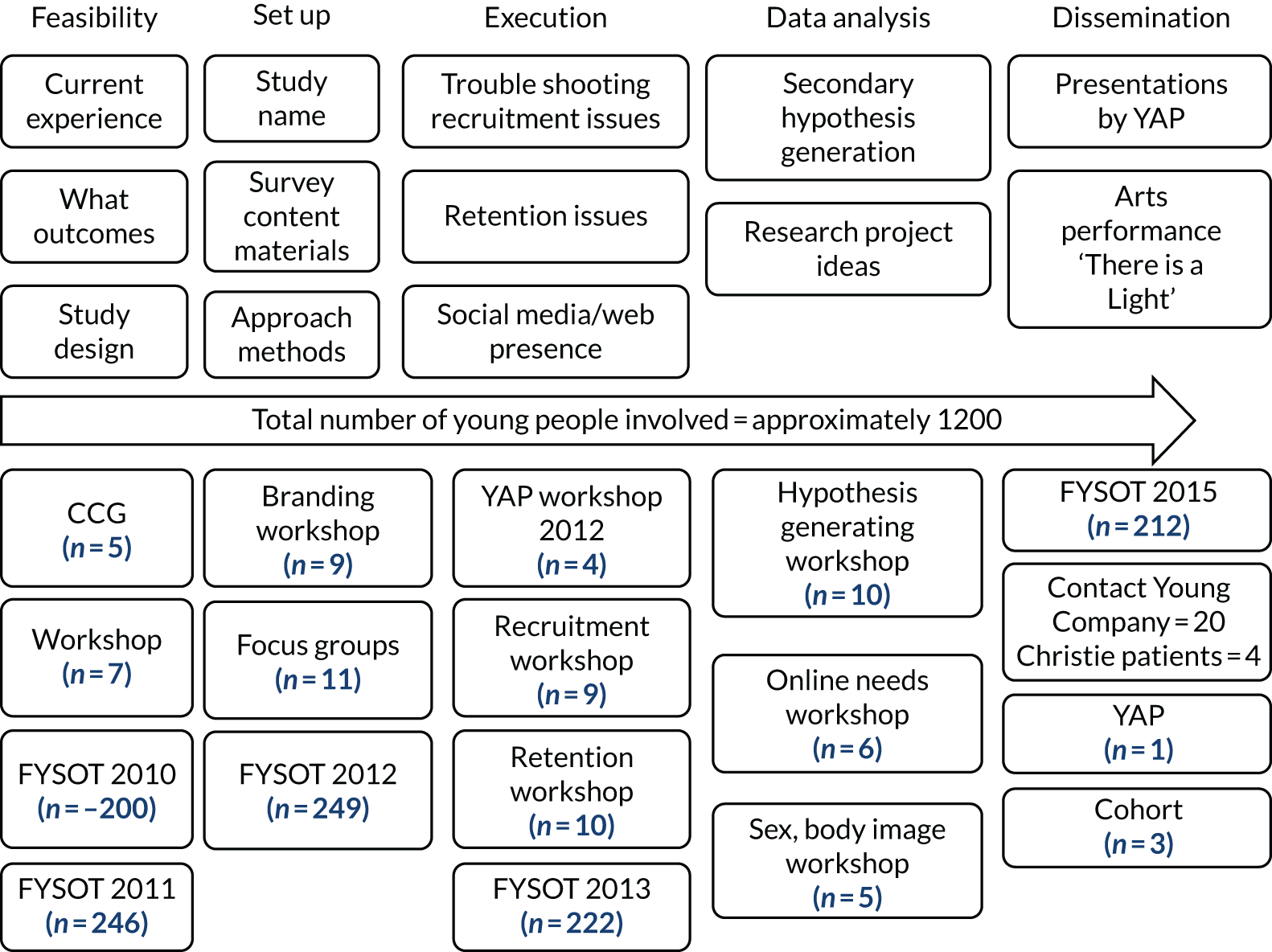

We have involved around 1200 people in our PPI strategy (not including professionals) (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

A schematic diagram of BRIGHTLIGHT PPI involvement.

Networks

The care of young people is complex with low incidence rates, multiple cancer types and care delivered across children, TYA and adult services in over 100 NHS trusts; consequently, project delivery was always going to be challenging. In anticipation of this we developed a third PPI group of ‘networks’. These included clinical/non-clinical staff delivering care, research network staff, adult PPI groups and charitable organisations.

Patient and public involvement aims

The aim is that PPI would contribute to developing all aspects of the research programme and contributing to the evidence supporting PPI through publishing our experiences and evaluations.

Methods

Patient and public involvement was undertaken through group work in participatory workshops.

The YAP remains connected through the closed Facebook page, which was monitored daily by the lead for PPI or a delegated team member. Contact was predominantly via group messenger to advertise workshops, post questions and advertise relevant activities and opportunities to participate in other projects. On only one occasion did the lead for PPI have to intervene because of inappropriate postings.

Workshops

Workshops have evolved in response to feedback from young people. 46 Changes included sending out the full aims, objectives and agenda prior to the workshop, allowing more time for young people to network, trying to engage a wider group of young people, varying the times, days and location of workshops and playing quiet music during activities and breaks. The typical workshop structure can be seen in Appendix 1:

The staff were amazing, very informative. Made me feel included throughout. It was a relaxed informal atmosphere which didn’t make the goal of the day seem to [sic] strenuous or daunting. Also thanks for the voucher MERRY CHRISTMAS [drawing of love heart].

The research team were actively involved in workshops, taking part in role play to illustrate some of the issues around recruitment. We piloted this in 2013 as an alternative to updating young people on the progress of the study through a presentation using PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), and it received favourable feedback. In 2014, we re-enacted a meeting held with the NIHR to illustrate further points about recruitment/retention. Workshops were followed up within 48 hours with an e-mail from the PPI lead to enquire about any distress/upset. No distress was reported, with young people reporting that they felt that the workshops were therapeutic and enjoyed the opportunity to contribute to the research agenda and meet with other young people.

The role of the young advisory panel in programme management

Review of documents and development of survey materials

The YAP contributed to survey development and approach materials through focus groups and telephone cognitive interviewing. 47 During the set-up of study 4, comments from young people included amending the approach period, wording on the patient information leaflet and formatting of the consent forms allowing young people to tick boxes rather than initialling, and we have now introduced this to all our consent forms. Parents also commented on survey materials during set-up and appeared more sensitive to questions than young people. Questions that parents felt were insensitive were double-checked with young people who had no problem with them.

Branding

The YAP were responsible for rebranding the study from the ‘2012 TYA Cancer Cohort Study’ to BRIGHTLIGHT in response to young people noting that the study name needed to be memorable. 44

Interventions for recruitment

Recruitment to BRIGHTLIGHT began in July 2012, with early signs of lower than anticipated recruitment. Despite this, our acceptance rate by patients approached to participate was 80% and we believe this high level of acceptability was due to our extensive PPI strategy during study design and set-up. We turned to our PPI partners for recruitment advice. Young people suggested a more appealing patient information sheet, audiovisual information, advocating informed choice by publicising that professionals should facilitate young people’s awareness of all research studies available to them and recruitment by other members of the treatment team. In response to these suggestions, we designed a shorter patient information sheet, which was given out with the paper document, videos of the information sheet and a ‘meet the team’ section on the website. Recognising that the YAP are an engaged group, we sought validation of suggestions around approach and recruitment with participants of FYSOT in 2013. 45 We also trained a group of social workers/youth support workers to gain consent. Lastly, we held a workshop with youth support co-ordinators and enrolled our networkers to contribute to a weekly Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) recruitment campaign. However, this was not as successful as Twitter recruitment had proved for research on other diseases. 48–50

Interventions for retention

Uptake to participate in the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort among those approached was higher than anticipated, as was retention at wave 2 (i.e. 12 months after diagnosis). However, we noted falling retention rates at wave 3 (i.e. 18 months after diagnosis) to around 30%. In response, we focused our 2014 workshop on strategies to improve retention and introduced interventions including personalised letters to participants and feedback of results using info graphics. After implementation of these measures, retention rates increased to 60%. 51

Dissemination and publicity

The YAP have contributed to our dissemination and publicity programme, including presentation of emerging results by two YAP members at FYSOT (link to FYSOT presentation52); chairing the BRIGHTLIGHT/TYAC (Teenage and Young Adult with Cancer professional organisation) conference in July 2017; and an interview on BBC Radio 5 Live (BBC, London, UK). National dissemination by a novel route was achieved through collaboration with Dr Brian Lobel, Contact Young Company and four young people with a previous cancer diagnosis. 53 The collaboration involved a series of workshops with the research team, young people and theatre group to create an artistic interpretation of emerging BRIGHTLIGHT results. Additional funding was secured from the Wellcome Trust and Macmillan Cancer Support, which allowed the performance to tour professional and patient conferences, including FYSOT in 2017. The performance received great reviews in terms of content, artistic talent and accessibility of results. 54 The young people participating also expressed benefit from being part of the team. 55

New studies

The YAP have contributed to new study development, which addressed online information needs,56 end-of-treatment concerns57 and the development of a sarcoma-specific patient-reported outcome measure. 58,59 Additionally, the YAP commented that the impact of cancer on sex, body image and relationships was poorly addressed; thus, we held two workshops with a view to new study development. 60 This has resulted in a patient-initiated study examining sexual health in young people with cancer, which was unsuccessful in the first grant submission but further applications for funding are planned. YAP members who wish to pursue a research career are co-applicants on new studies.

We do not have any negative effects to report from our PPI strategy. However, we do recognise the commitment and resource required from the research team to ensure that young people are included effectively in the study.

Discussion and conclusions

BRIGHTLIGHT was designed by young people with cancer for young people with cancer. Their involvement has been integral to study success and we will continue to engage with them as we interpret and disseminate the results and create new projects. Over 10 years we have optimised our engagement strategies in response to young people and changing technology,42 especially social media. Despite this, there are some areas where we feel we did not quite achieve complete success.

Diversity

The gender balance of the YAP was predominantly female, a phenomenon not unique to BRIGHTLIGHT. Although we had some ethnic variation within the group (around 20% of the YAP were ethnic minorities), it did not always reflect this diversity due to the variability of workshop attendance. Attendance at workshops was generally in the region of 9–10 young people, which was around half of our YAP. We sought feedback and were given multiple reasons including ‘too rainy to attend’, ‘hottest day of year, too hot to attend’, ‘would be better in summer holidays’, ‘would be better if not in summer holidays’. After several attempts of varying the times, calendar month and location, we felt that there was no real preference and workshops are now held on a Friday/Saturday in London (all expenses are paid and a voucher is given for attendance).

Bereavement

There is always a risk when bringing young people with cancer together over time that bereavements may occur within the group. Three deaths occurred within our group. We arranged for the local Macmillan Support and Information Service to offer bereavement support; however, this was not taken up (to our knowledge) and because of patient confidentiality, we would not be told of any young people who had approached the service.

Unanticipated events

Several unexpected events occurred. First, the lengthy and bureaucratic NHS processes meant that some of the suggestions that young people wanted could not be implemented or took considerable amounts of time: for example, shortening the patient information sheets, implementation of the Facebook page and utilising social workers/youth support co-ordinators for recruitment. Meeting expectations of the YAP, particularly around the use of emerging technology and social media, was constrained by resources and internal governance issues. After the Facebook page was established, young people requested Twitter, then Instagram (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.instagram.com), then Snapchat (Snap Inc., Santa Monica, CA; www.snapchat.com), curation of which would have required a dedicated communications team. Therefore, we did not implement a Snapchat account and our Instagram account did not really flourish.

Following our feasibility work, policies were put in place for codes of conduct (e.g. alcohol, smoking, drug use) and expenses. Further to this, several policies were implemented in response to events. An ‘out-of-hours’ policy was introduced in response to a young person having to make an emergency trip home late at night following sickness of her child during a 2-day workshop. Second, a ‘sickness policy’ was implemented after a young person (> 16 years) was admitted to hospital via accident and emergency (A&E) during a workshop and refused to give a next of kin contact. Finally, although no distress has been reported after the workshops, in response to an e-mail follow-up after a workshop, we had one incident of significant distress during dinner after a workshop. This young person was referred to their treatment team for support.

Reflections/critical perspective

We feel that we have successfully integrated the contributions of young people into our programme of research. This has been dependent on several things but mainly commitment and dedication from the research team to the principle that involving young people is worthwhile. Budgeting adequate funding within the grant has also been pivotal to our PPI success, with dedicated personnel to deal with some of the administration behind user involvement. We have shown that given appropriate support, young people can make a valuable contribution to research and we hope that our experience inspires other research teams to reach out to ‘hard-to-reach’ groups and involve them in research.

We would like to extend our thanks to the young people and PPI partners who have contributed to BRIGHTLIGHT since 2008.

Defining the competence of health-care professionals caring for teenagers and young adults with cancer

Aims

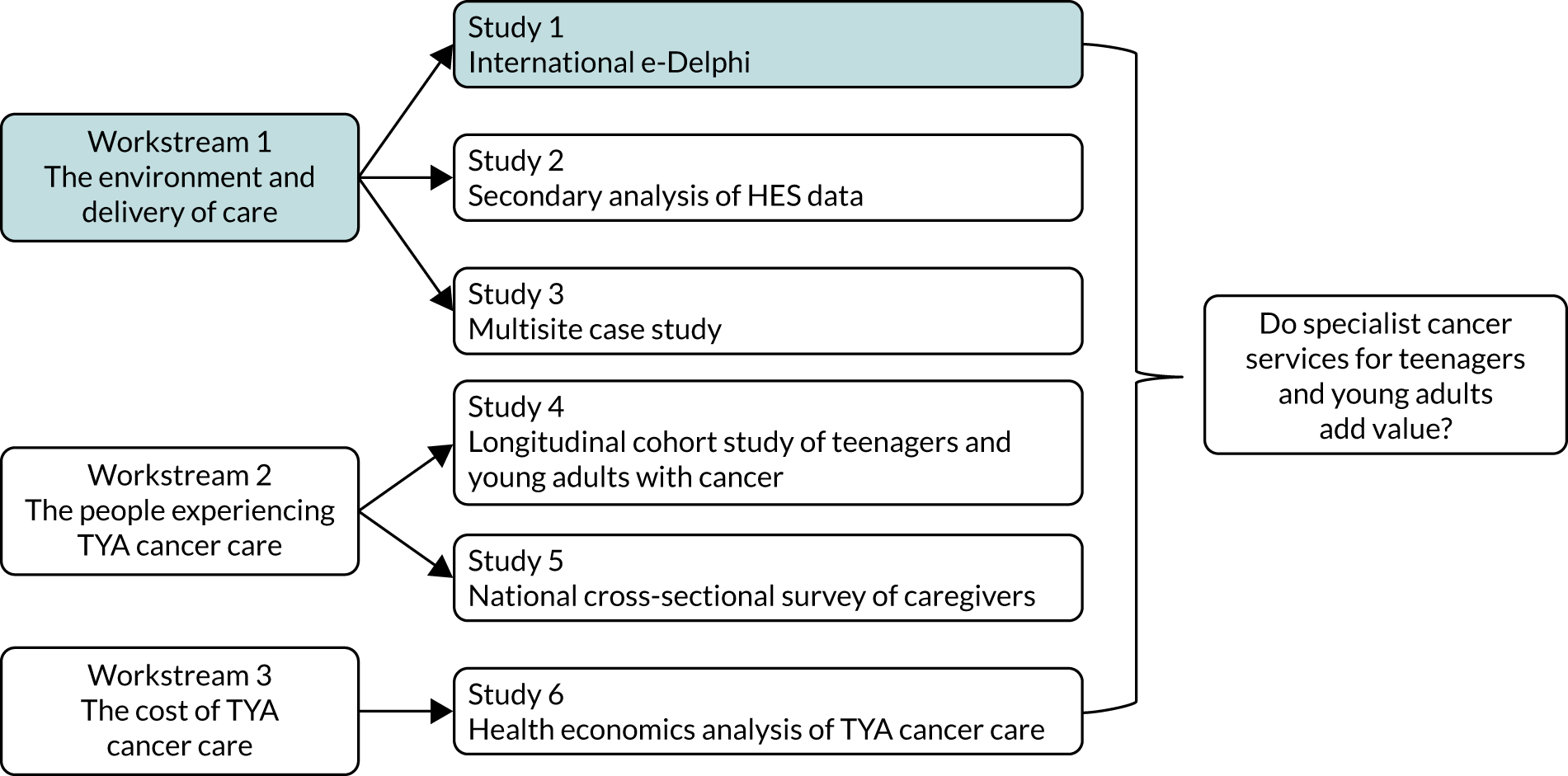

The relationship of study 1 to the rest of the programme is shown in Figure 7. We aimed to identify the specialist competencies and added value of specialist TYA health-care professionals through an international Delphi survey.

FIGURE 7.

Flow diagram highlighting the study referred to in Defining the competence of health-care professionals caring for teenagers and young adults with cancer. HES, Hospital Episode Statistics.

Methods

We sought to use a consensus approach and selected a Delphi technique, which normally involves two or more rounds of postal or online questionnaires. The Delphi technique employs ‘experts’ as panel members. There is little consensus as what defines an ‘expert’61 and, therefore, ‘expert’ for the Delphi study reported here was defined as any health professional working in TYA cancer care for a minimum of 12 months.

Round 1 questionnaire

A comprehensive list of competencies was generated from our preliminary study,38 and this formed the content for the first round of this Delphi survey. These were subdivided into skills, knowledge, attitudes and communication. All the questions had closed-ended responses using 9-point Likert scales (i.e. strongly agree to strongly disagree). However, as the competency list was initially generated by health-care professionals based in the UK, several open-ended questions were included to ensure that the survey would accommodate the opinions of professionals in other countries. The questionnaire was administered through a web-based survey programme.

Round 2 questionnaire

Only items for which there was no agreement were included in the round 2 questionnaire. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyse responses to open-ended questions. Panel members were also requested to identify five skills, areas of knowledge, and attitudes that they considered the most important.

Data analysis

Items were ranked and reported according to medians. Medians of 7–9 were defined as strong support, 4–6.5 as moderate support and 1–3.5 as weak support. The mean absolute deviation from the median was calculated and the level of agreement was categorised according to thirds of the mean absolute deviation from the median (low > 1.41, moderate 1.08–1.41, high < 1.08). These summaries were also calculated according to profession (medical doctor, nurse, other health-care professional) and differences determined using chi-squared tests to compare the number of respondents who had strong agreement (consensus).

Key findings

Study 1 is reported in full. 62 In summary, a total of 179 health-care professionals registered to be members of the expert panel, of whom 159 (89%) returned the round 1 questionnaire. Valid responses were available from 158 (88%) professionals, and 136 (86%) of these 158 responded to round 2. The majority of these professionals were nurses or medical doctors from Europe and North America. In round 1, consistent high levels of agreement were reached on all statements related to skills (n = 27), knowledge (n = 18), attitudes (n = 24) and communication (n = 19). In round 2, there was highest consensus on being able to discuss sensitive subjects; knowing about current therapies; knowing normal TYA physical and psychological development; knowing about the impact of cancer on psychological development; knowing about the side effects of treatment and how this differs from children and older adults; and knowing about fertility preservation.

There were aspects that all professional groups agreed were important. Most agreement was in the attitudes required for caring for young people with cancer: being friendly and approachable, being honest, being respectful and being committed to caring for young people with cancer. Other areas of agreement included being able to identify the impact of disease on young people’s life and working in partnership with young people; knowing how to provide age appropriate care; and knowing the side effects of treatment and how this was different for children or older adults. There was agreement that key aspects of communication were being able to listen to young people’s concerns, talking about difficult issues and being able to speak to young people using familiar language while retaining a professional boundary.

Limitations

A limitation was that the composition of the expert panel was predominantly experts working in Europe or North America; therefore, our results may reflect a Western perspective. ‘Expert’ was defined as working with teenagers and young adults for a minimum of 12 months, but we did not specify the age of the TYA population. As international variation exists, this could have influenced the importance assigned to areas of competence. In addition, the process used to create our expert panel may have excluded those who were not members of professional organisations or had published in this area.

A further limitation was that the survey was available in English only. Finally, we did not ask participants about their training background and, therefore, we could not examine the differences between those who were child trained and those who were adult trained.

Inter-relationship with the rest of the programme

This provided the context for understanding the complex elements of the multiprofessional role for study 3.

Quantifying specialist care

Aims

The relationship of study 2 to the rest of the programme is shown in Figure 8. We aimed to develop a TYA Cancer Specialism Scale to quantify and categorise the levels of TYA cancer care and then apply this to individual patient-level data.

Methods

Details of the development of the metric to quantify specialist care have been reported as supplemental file 2 in Taylor et al. 63 In summary, this metric was developed from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) admitted patient care (APC) data. NHS trusts containing a TYA-PTC were defined and the trust code was identified from NHS Digital HES records. For all the patients in the cohort study (study 4), every APC spell was assigned to be either specialist TYA-PTC care (based on the trust code) or care elsewhere. A proportion of TYA care was calculated for each member of the cohort at 6 and 12 months after diagnosis.

Key findings

The inpatient HES data were successfully linked to 1074 out of 1114 young people recruited. The distribution of the proportion of care by 6 and 12 months after diagnosis suggested that there were three natural groups occurring within the data. Categories of care were calculated based on the proportion of specialist care received: all care received in a TYA-PTC (ALL-TYA-PTC), some care in a TYA-PTC and some care in either a children’s or adult cancer centre (SOME-TYA-PTC), or no care received in a TYA-PTC (NONE-TYA-PTC).

Limitations

Assigning ‘specialist’ care to the whole trust code rather than the hospital within the trust, we assumed that the young person would receive care from the TYA MDT wherever they were cared for within the trust. The metric was developed using APC data only, which did not account for any care delivered in outpatient units. There was a further assumption that all TYA-PTCs were the same, and we did not account for the difference in TYA-specific services each provided. For example, some were better developed with a TYA environment, employed TYA-specific staff (e.g. youth support co-ordinators) and had established relationships with the designated hospitals in their network, whereas others did not have any of this in place at the time of study. Finally, there was a large variation in the proportion of TYA-PTC care in the SOME-TYA-PTC group, ranging from 3% to 99%. If a young person, for example, was admitted to a local hospital for febrile neutropenia but had all their remaining care in ALL or NONE-TYA-PTC, then they were assigned to the SOME group.

Inter-relationship with the rest of the programme

This metric was the exposure variable for studies 4–6 (see Identifying the outcomes associated with specialist teenage and young adult cancer care to Calculating the cost of specialist teenage and young adult cancer care).

Understanding the culture of care

Aims

The relationship of study 3 to the rest of the programme is shown in Figure 9. We aimed to explore the culture of TYA cancer care to answer three specific research questions:

-

How does the context of each TYA-PTC and its network shape young people’s individual experience of care?

-

What is different and what is common across the culture of TYA cancer care in the four TYA-PTCs and networks of care?

-

What are the perceptions of care of young people and professionals in each TYA-PTC and its network?

Methods

This was a multiple case study conducted across four TYA cancer networks in England. The cases were informed from our feasibility work describing the unique history of the TYA-PTC, the environment and patient population that shaped care delivery. 41 In addition to the four TYA-PTCs, 20 hospitals linked to these were also included and young people were recruited in 17. Young people were aged 13–24 years with a confirmed cancer diagnosis and undergoing treatment. Health-care professionals delivering care to young people were also included and purposively sampled to represent the range of professions in the MDT. Data were collected through semistructured interviews, tours and shadowing with health-care professionals, and participant observation. Thematic analysis was used to identify themes between, within and across the four cases – deconstructing and reconstructing the components of the culture of care that emerged, thereby enabling synthesis and contextualisation of data.

Key findings

The results for study 3 are available in full. 29,64,65 Twenty-nine young people and 41 health-care professionals were interviewed, and there were 120 hours of observation. Young people were predominantly in the TYA-PTC group (n = 22; 76%); and health-care professionals included ward-based nurses (n = 9), clinical nurse specialists (n = 8), nurse leaders/managers (n = 9), youth support co-ordinators (n = 4), social workers (n = 3), medical doctors (n = 3), non-nurse service managers (n = 2), education roles (n = 2) and allied health professionals (n = 1).

An initial analysis was undertaken of the interviews with young people and health-care professionals, which were synthesised with existing literature to develop a definition of age-appropriate care. 64 It was not possible to provide a simple definition as age-appropriate care was identified as a more complex entity comprising seven core components: best treatment; health-care professional knowledge; communication, interactions and relationships; recognising individuality; empowering young people; promoting normality; and the environment. These formed a conceptual model with each core component comprising a number of subthemes, with the relationships between the components being interlinked. Defining age-appropriate care highlighted the aspects that have the potential to enhance care. These are potentially the components to focus on to improve the delivery of care. For example, providing the best treatment relies on having access to clinical trials.

The study findings brought together data from all sources and settings to explore the culture of care for young people with cancer. They were broadly divided into three categories: the physical and social environments of care; communication and core values; and the development of health-care professional holistic competence and the culture of care.

The physical and social environments of care

The décor, structure, function and facilities of a physical environment tailored specifically to the needs of young people were highlighted as important. Health-care professionals and teenagers and young adults agreed on similar aesthetic features, for example colourful décor that created a less clinical atmosphere. Professionals described how wards in the TYA-PTC provided modern, colourful and well-resourced environments, and these settings facilitated health-care professionals to enjoy interactions with their patients and colleagues. Health-care professionals identified that the physical surroundings in which they interacted with their patients had an impact on the conversations that they had. Young people described the atmosphere on these wards as calm, relaxed and homely, which promoted normality.

There was a relationship between the physical environments in which young people were cared for, their experiences of care and the social relationships that they built with those around them. The dedicated social spaces provided in the TYA-PTC enabled youth support co-ordinators to better fulfil their role, where the environment provided the space and facilities to bring young people together.

Communication and core values

Communication was the major visible process of care that occurred between young people and professionals, both at an individual level and within groups. Three types of communication emerged:

-

Interpersonal – young people recognised effective communication, and they identified and valued the relationships they built with health-care professionals. Young people recognised and valued the meaningful interactions that they had with health-care professionals, both within TYA-PTCs and designated hospitals. Young people described continuity and consistency with health-care professionals as advantageous, enabling them to build relationships with those caring for them. Likewise, health-care professionals acknowledged that continuity of care was important. Youth support co-ordinators described an essential part of their role was being a ‘constant’ for patients. Continuity of staff and the implementation of routine communication processes, such as effective handovers between professionals, meetings and discussion groups provided opportunities for a united and knowledgeable health-care team to form and to flourish.

-

Intra-hospital – there were multiple and separate circles of intraprofessional communication about care within a hospital, involving all members of the direct care team and others. Processes described by health-care professionals were more complex where multiple teams were involved. Young people spoke specifically about the role of the clinical nurse specialist and their part in ensuring care was not disjointed.

-

Hospital to hospital – communication was back and forth between the teams at the designated hospitals, shared care hospitals and the TYA-PTC, ensuring that both the young person’s clinical and their psychosocial needs were being met. There was variation in processes that affected overall experience.

Three core values emerged: recognising individuality, promoting normality and empowering young people. These core values were an essential part of the less visible ‘below the surface’ culture, and were values that underpinned TYA cancer care across all settings. Delivery of care tailored to the individual patient’s needs and effective provision of information were highlighted as important by young people and professionals. Health-care professionals sought to encourage those young people who were cognitively able to have some control over their care and the decisions made about it.

The development of health-care professional holistic competence and the culture of care

The formation and sharing of a culture where care was responsive to the unique needs of the teenagers and young adults was influenced by four factors: a consistent volume of young people using services, effective leadership, an appropriate and accepting attitude, and patience.

Consistency and a large number of young people using a service was important in the formation of an age-appropriate, young person-centred culture of care. The TYA-PTCs hosted a consistent, concentrated volume of young people, compared with many of the children’s and adult cancer settings. In all contexts, leadership was essential to shape and perpetuate the culture of care. Leaders were vital in bringing together the whole team, creating a culture in which all health-care professionals communicated with each other effectively. Leaders were important in assisting the formation of trusting relationships between all members of the team. Shared beliefs and ‘buy-in’ of health-care professionals into what was different and special about caring for young people with cancer were core to the culture of care. It took considerable time for such connections and knowledge about caring for young people to develop on both a network and a local level, particularly as these networks could span a variety of specialties: adult, child and a wide range of tumour site-specific teams.

The importance of the core values that underpin care, and the need for education, effective leadership and multidisciplinary teamworking was described as essential. These should be prioritised when developing and evaluating interventions that contribute to the delivery of care. Care delivered in an environment that promotes normality through facilitating socialisation with peers was described as essential to the delivery of optimal holistic and young person-centred care. Growing and nurturing a culture of care that meets the unique needs of young people with cancer and improves their experiences of care takes time and commitment.

Limitations

Although purposeful sampling was planned and employed where possible, the willingness and availability of study participants affected the final sample. For these reasons, younger teenagers, those with a brain tumour and those with melanoma are all examples of under-represented patient groups.

A limitation was that eligibility for participation included being able to speak English. In addition, health-care professionals were frequently time-limited and busy with their clinical and support roles, which was particularly so for medical staff. Furthermore, some methods of data collection proved challenging, such as walking interviews, and the observations undertaken did not provide opportunity for complete research immersion into the sites visited, as would have been possible with traditional ethnographic techniques.

Inter-relationship with the rest of the programme

Study 3 provided the qualitative evaluation of the delivery of care in which the quantitative data gathered in study 4 could be compared and contextualised.

Identifying the outcomes associated with specialist teenage and young adult cancer care

Aims

The relationship of study 4 to the rest of the programme is shown in Figure 10. Our aim for study 4 was to establish a cohort of teenagers and young adults who were newly diagnosed with cancer to determine the outcomes associated with category of care. This included:

-

relating the category of cancer care to QoL, satisfaction with care, and clinical processes and clinical outcomes

-

examining young people’s experience of care.

FIGURE 10.

Flow diagram highlighting the study referred to in Identifying the outcomes associated with specialist teenage and young adult cancer care.

Methods

Details of recruitment into the cohort and a description of the cohort are reported. 63,66,67 In summary, the cohort study was conducted across England, recruiting in 109 NHS trusts, of which 97 recruited at least one young person. Young people were eligible to participate if they were aged 13–24 years and had a new diagnosis of cancer.

Data were collected from young people using a bespoke questionnaire, the BRIGHTLIGHT survey, which contained five validated patient-reported outcome measures, and 169 patient experience questions related to pre-diagnosis experience, diagnostic experience, place of care, contact with health-care professionals, treatment experience, fertility, involvement in clinical trials, adherence, communication and co-ordination of care, education, employment, well-being, and relationships. 37,47 The BRIGHTLIGHT surveys are freely available under licences detailed in the following links: [https://xip.uclb.com/product/brightlight_wave1; https://xip.uclb.com/product/brightlight_waves2-4; and https://xip.uclb.com/product/brightlight_wave5 (accessed 1 June 2021)]. The survey was administered five times in 3 years by an independent research organisation through face-to-face interviews in young people’s homes during wave 1 (i.e. 4–7 months after diagnosis) then either online or through a telephone interview at waves 2–5 (i.e. 12, 18, 24 and 36 months after diagnosis). Data about young people’s cancer and clinical care were obtained from their medical records and the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service. Comparisons were made between young people treated in NONE-TYA-PTC, SOME-TYA-PTC or ALL-TYA-PTC.

Key findings

The results for study 4 are reported in full68,69 and additional results are reported in Appendix 2. A total of 1126 young people were recruited, and valid consents were available for 1114. A description of the cohort is reported in full. 63 The group mean total QoL improved for all patients, but was 5.63 points higher (95% CI 2.77 to 8.49 points) for young people receiving SOME-TYA-PTC care, and 4.17 points higher (95% CI 1.07 to 7.28 points) compared with ALL-TYA-PTC care. These differences were greatest 6 months after diagnosis, but reduced over time and did not meet the 8-point level that is clinically significant. The rate of improvement was significantly greater in the ALL-TYA-PTC and SOME-TYA-PTC groups so there was minimal difference between the ALL-TYA-PTC and NONE-TYA-PTC by 3 years after diagnosis. Young people receiving NONE-TYA-PTC care were more likely to have been offered a choice of place of care, be older, be from more deprived areas, be in work and have less severe disease. However, multivariable analyses of measured confounding factors did not explain the differences observed.

Young people who had NONE-TYA-PTC care had the highest survival, followed by those who received ALL-TYA-PTC and SOME-TYA-PTC care. Adjusted analyses showed no significant difference according to the category of care. Clinical records linked to levels of care were available in 1009 young people receiving NONE-TYA-PTC care and indicated they were less likely to have a molecular diagnosis (where relevant), be reviewed by a children’s or TYA MDT, have an assessment by supportive care services or discuss fertility than those treated in SOME-TYA-PTC or ALL-TYA-PTC.

There was no difference in perceived social support anxiety or depression between the three groups, but young people in the SOME-TYA-PTC and ALL-TYA-PTC groups had higher illness perception than those in the NONE-TYA-PTC group (i.e. they were more likely to perceive themselves as ill). Finally, there were no differences in young people’s experience of care, and the majority were satisfied irrespective of where they were treated.

Limitations

Young people in the cohort had significantly lower survival than those not recruited, which suggested that there was recruitment bias. 63 Potentially, these patients were in hospital longer, thus facilitating more opportunities for recruitment. Only one-fifth of the population was recruited, so the results of the cohort do not necessarily reflect those of the rest of the population. The limitations of the TYA Cancer Specialism Scale were discussed in Quantifying specialist care, which includes the limitations of the results from the cohort. The BRIGHTLIGHT survey was administered face to face at the first wave, as this increase’s retention into longitudinal research47 and at waves 2–5 there was the option of a telephone interview or online completion. This may have introduced response and/or social desirability bias. 70 Finally, we used the only measure of QoL that was available in 2011 that had been validated across the ages 13–24 years. Although the PedsQL is well established for measuring outcome, as a generic measure of QoL this may not have been sensitive enough to detect differences according to the place of care. Age is one of the key factors determining where young people are treated, but the PedsQL does not have significant changes across the various age versions to reflect the developmental differences [i.e. there is little difference in the wording between the child (8–12 years), teen (13–18 years) version and young adult versions].

Inter-relationship with the rest of the programme

Patient experience is a central tenet of health-care policy and is important to how quality of care is measured. Establishing the cohort and study 4 were therefore central to evaluating specialist cancer services. Study 4 also enabled study 5 to be conducted (caregivers were identified and nominated by young people) and data for study 6 were collected from the cohort at the time as the survey was administered.

Determining if specialist teenage and young adult services support caregiver’s information and support needs

Aims

The relationship of study 5 to the rest of the programme is shown in Figure 11. The aim of study 5 was to evaluate whether or not caregivers of teenagers and young adults with cancer had unmet information and support needs, and if this varies by level of care category.

FIGURE 11.

Flow diagram highlighting the study referred to in Determining if specialist teenage and young adult services support caregiver’s information and support needs.

Caregivers play an important role in providing support for young people when they have a cancer diagnosis. 71 In our development work underpinning the programme grant, we showed one of the skills in caring for this population is the unique pattern of communication, which is unlike children’s or adult cancer care. Communication with children is focused mainly on parents, whereas communication with adults is directed at the person affected with cancer. However, with young people, professionals need to involve those caring for young people, whether it be parents, partners or friends, while also being cognisant of the young person’s right to confidentiality. 38

In our original application, the lack of caregiver perspective was a criticism from one of the reviewers, but was an aspect of TYA cancer care that we were unable to evaluate because of limited resources. However, during the set-up of study 4, the contract research company administering the BRIGHTLIGHT survey suggested that a paper questionnaire could be administered at the time of the first wave of data collection (this is a method used to limit involvement of other members of the household during face-to-face survey administration). A scoping review of the literature identified no study on caregivers of teenagers and young adults with cancer. Much of the early literature examining caregivers of children and older adults focused on unmet needs. This was therefore the focus of study 5.

Methods

The methods for study 5 have been reported in full. 72

The BRIGHTLIGHT Carer Questionnaire (BCQ) was developed based on caregiver unmet need questionnaires and was developed for caregivers of children and older adults. The BCQ has 15 multi-item questions covering four domains: information needs; experience of the cancer treatment centre and contact with health-care professionals; emotional well-being and relationship with the young person; and support for completing practice tasks. Responses are on a range of 3-, 4- and 5-point Likert scales. The BCQ is freely available under the following licence: https://xip.uclb.com/i/healthcare_tools/brightlight_carer.html (accessed 1 June 2021). The BCQ was administered as a paper questionnaire to the person who young people nominated as being their main caregiver. If this person was not in the property at the time of the young person’s interview, it was left for the young person to administer. The BCQ was returned in a free-post envelope; no reminders were given.

Principal component analysis was used to reduce 22 items from the BCQ into five domains: (1) the support that caregivers received, (2) satisfaction with support, (3) information provided, (4) opportunities to make decisions about treatment (5) and services provided for caregivers. Caregiver data were linked to young person data though a unique study code so that comparisons could be made between the three categories of care: NONE-TYA-PTC, SOME-TYA-PTC and ALL-TYA-PTC.

Analysis

Comparisons between the three categories of care described in study 4 (i.e. ALL-TYA-PTC, SOME-TYA-PTC and NONE-TYA-PTC) were made using cross-tabulation and chi-squared tests.

Key findings

A total of 518 caregivers returned the BCQ, and 514 of these could be linked to young people’s data in the cohort. Study 5 is reported in full in Martins et al. 72 The majority were white (90%), mothers (81%) aged between 35 and 54 years (71%). Regression analysis, adjusting for caregiver and young person characteristics, indicated that there was no difference in the support that caregivers received depending on where the young person was treated. Caregivers of patients in ALL-TYA-PTC care had greater satisfaction with the support. Where care was delivered in SOME-TYA-PTC care, caregivers received the most amount of information; however, they had fewer opportunities to make decisions. Finally, satisfaction in services provided specifically for caregivers were reported mostly by caregivers who had ALL-TYA-PTC care.

Limitations

Participants were predominantly female, white and mothers, so their needs may not represent those of fathers, partners and members of other ethnic groups. There was no validated questionnaire available for caregivers of teenagers and young adults, so a measure was developed based on existing literature. Although content validity was confirmed, and later analysis confirmed construct validity, the BCQ may not include all of the issues that caring for a young person with cancer could entail. Analysis of the BCQ was limited to 22 items that were selected on the basis that they had the potential to be influenced by specialist care; other aspects of unmet needs, such as emotional well-being, were not included but could be an important aspect of care delivered in a TYA-PTC.

Inter-relationship with the rest of the programme

Study 5 enabled us to evaluate the value of specialist care on caregivers who are an important source of support for young people.

Calculating the cost of specialist teenage and young adult cancer care

Aims

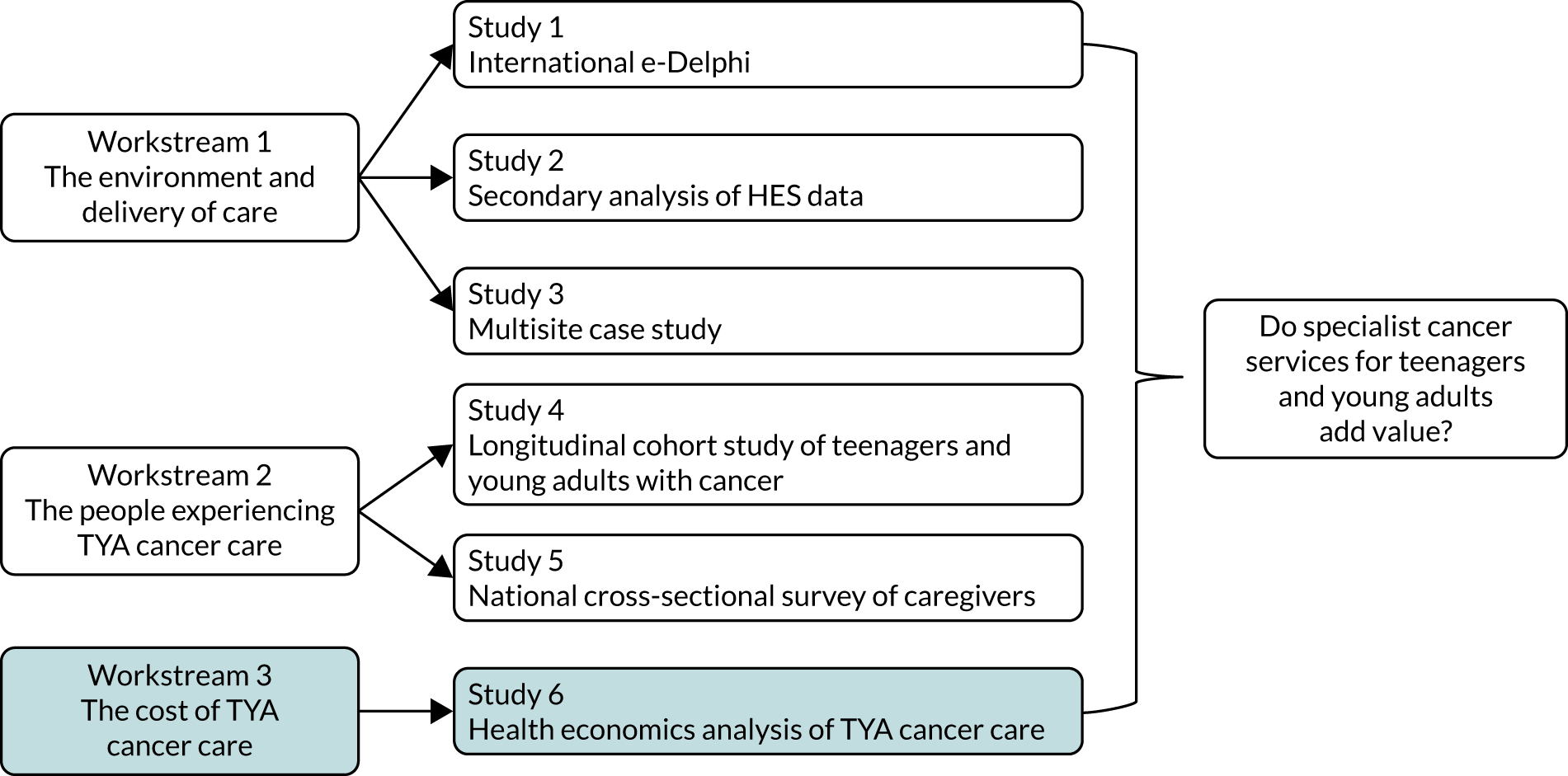

The relationship of study 6 to the rest of the programme is shown in Figure 12. The aim of study 6 was to examine the economics of the categories of TYA cancer care. Specific objectives were to:

-

calculate detailed costs to the NHS and personal social services of teenagers and young adults

-

estimate the cost incurred by teenagers and young adults, and families

-

calculate the cost-effectiveness of the different categories of care.

FIGURE 12.

Flow diagram highlighting the study referred to in Calculating the cost of specialist teenage and young adult cancer care.

Methods

Details of study 6 are included in Appendix 3. In summary, data for the health economics analysis were collected from the cohort in study 4. Young people completed a Cost of Care Questionnaire (CoCQ) at the time of interview that comprised nine multi-item questions on additional costs incurred as a result of a cancer diagnosis. This asked respondents to reflect on the time from diagnosis to the interview. Young people were also asked to complete a cost record, which contained the same information but recorded weekly in 3-monthly cycles at 9 and 12 months after diagnosis. These questionnaires were paper self-report versions returned in a freepost envelope. No reminders were sent. The CoCQ and cost record are freely available to download under the following licence: https://xip.uclb.com/i/healthcare_tools/brightlight_healtheconomics.html (accessed 1 June 2021). Analysis of HES data was undertaken to calculate hospital costs and to calculate young people’s travel costs in the first 12 months after diagnosis (see Appendix 3 for details of the methods).

Key findings

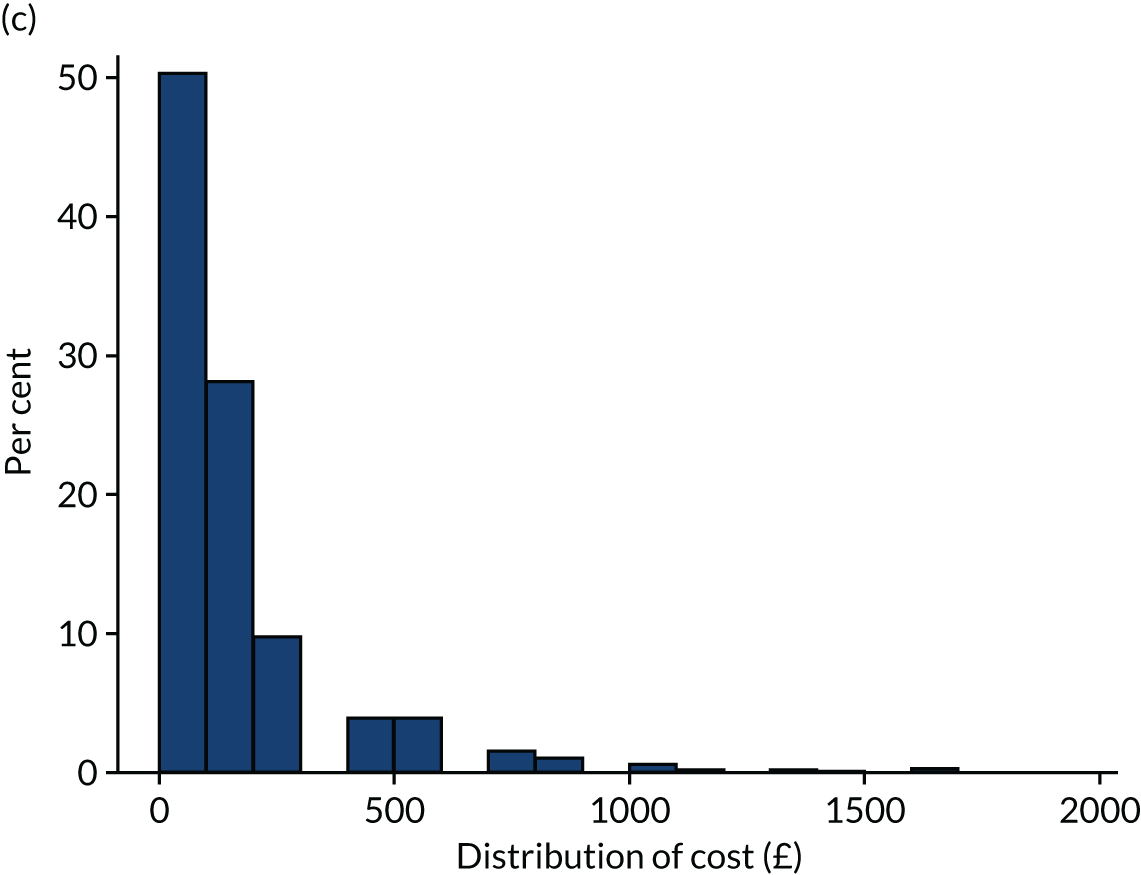

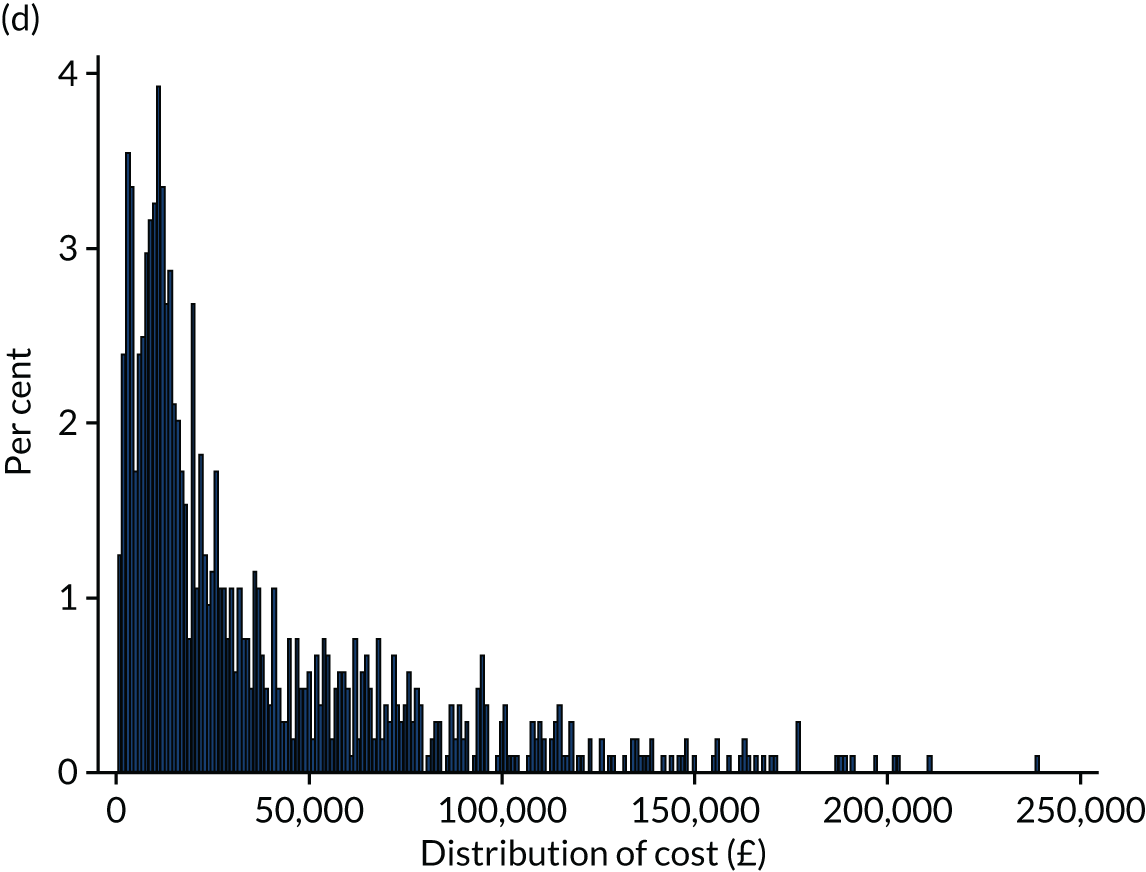

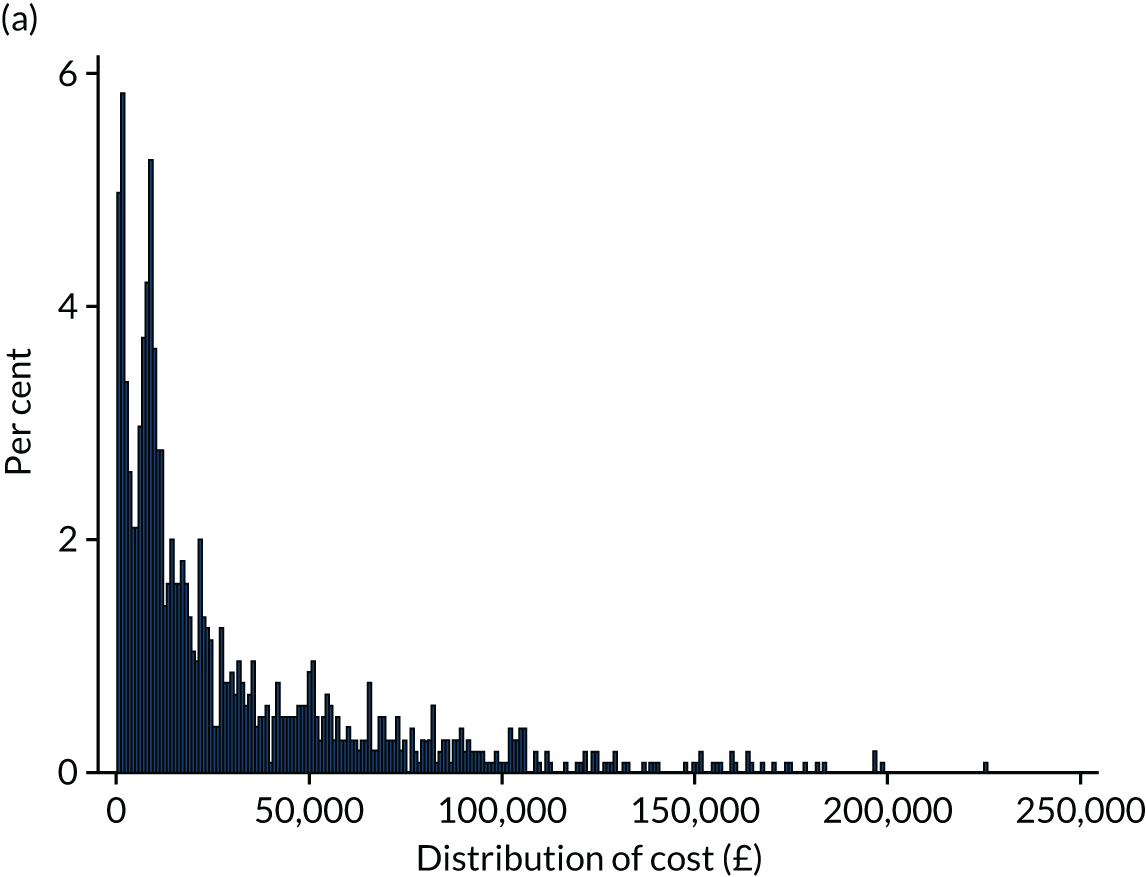

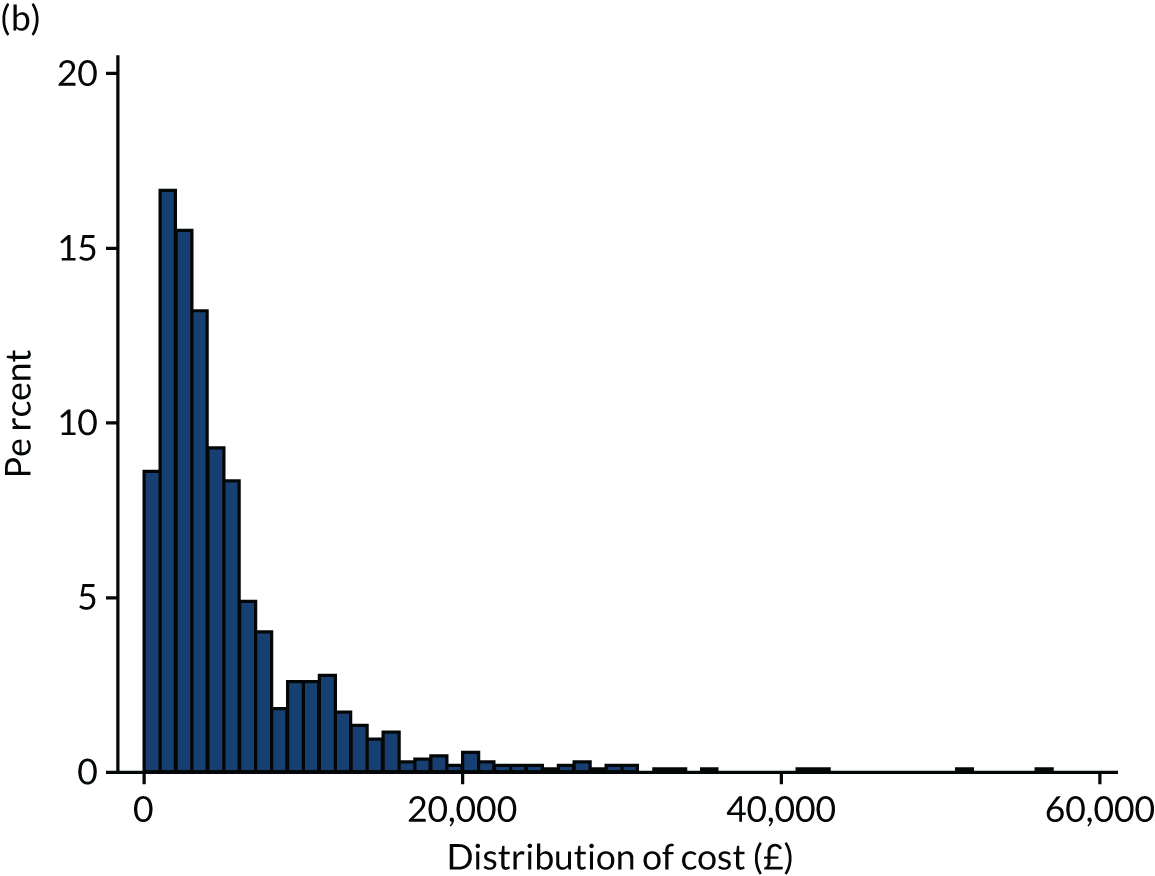

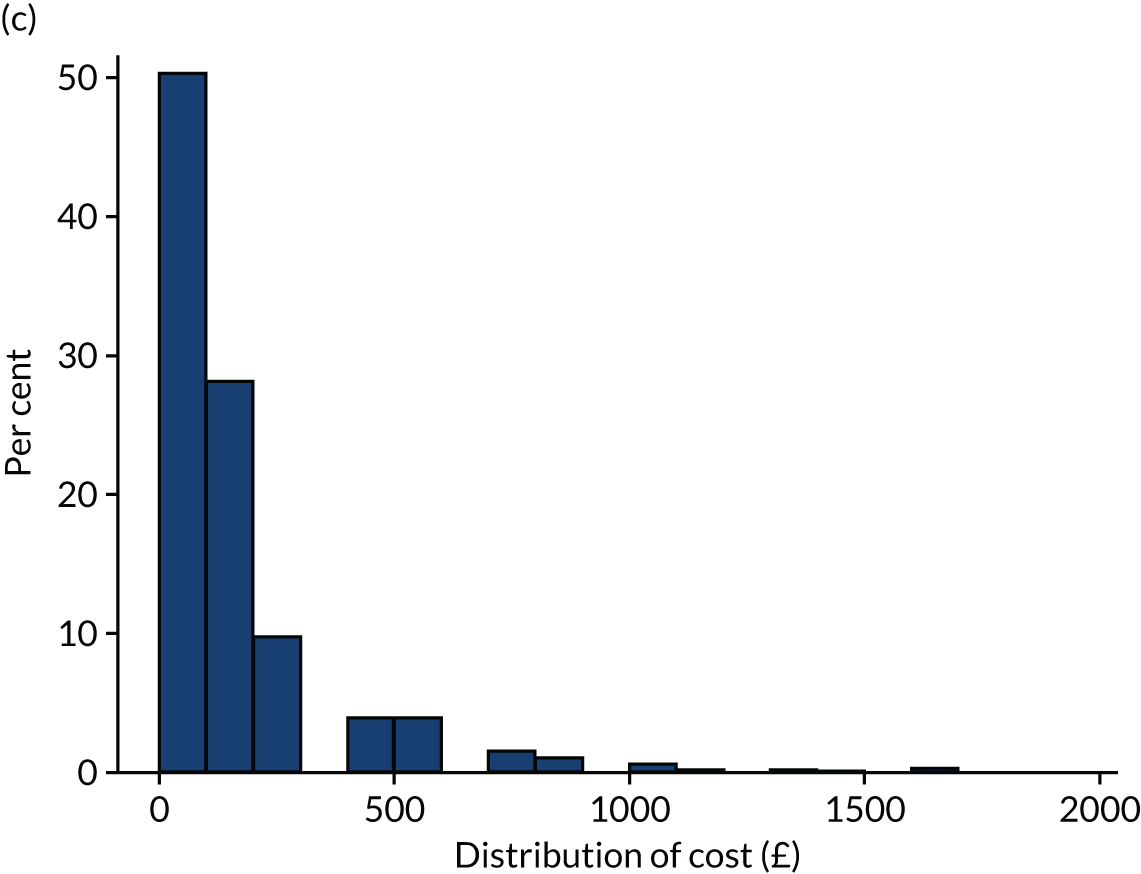

The results are presented in detail in Appendix 3. HES data were available for 1044 young people. The mean hospital costs in the first 12 months after diagnosis were highest among patients receiving SOME-TYA-PTC care (mean £43,000, 95% confidence interval £39,831 to £46,169); there were no significant differences in costs between the NONE-TYA-PTC and SOME-TYA-PTC groups. Findings in the adjusted analysis showed that the highest cost was incurred by the SOME-TYA-PTC group, followed by the ALL-TYA-PTC group, with the lowest cost incurred by the NONE-TYA-PTC group. These differences were statistically significant.

In the fully adjusted analysis for calculating travel costs, the sample size was 733 and the SOME-TYA-PTC group continued to incur the highest cost, followed by the ALL-TYA-PTC and NONE-TYA-PTC groups. The mean of out-of-pocket expenses for patients receiving NONE-TYA-PTC care, SOME-TYA-PTC care and ALL-TYA-PTC care for the first 6 months from diagnosis were £284.77, £743.83 and £976.46, respectively. Similarly, out-of-pocket expenses for patients receiving NONE-TYA-PTC care, SOME-TYA-PTC care and ALL-TYA-PTC care at 6–9 months were £58.52, £280.58 and £122.14, respectively. At 10–12 months, these out-of-pocket expenses were £398.66, £98.17 and £179.40, respectively. Food purchased as a result of hospitalisation was the highest cost item. The mean number of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained per patient was 2.45 (95% CI 2.28 to 2.62) for patients receiving NONE-TYA-PTC care, 2.15 (95% CI 1.74 to 2.14) for those receiving SOME-TYA-PTC care and 2.20 (95% CI 1.94 to 2.28) for ALL-TYA-PTC care, which were not significant.

Limitations

Only a proportion of the cohort completed the CoCQ and there was a low response rate to the cost record; therefore, out-of-pocket expenses could be under- or overestimates of the true costs to patients. The health economics assessment utilised data collected in study 4 only, so no assessment of the cost of the environment of care or staffing specialised units was undertaken. Much of the infrastructure and staffing in the TYA-PTCs is provided through charitable funding, which the hospital cost analysis does not account for. The hospital costs were higher in the SOME-TYA-PTC and ALL-TYA-PTC groups, but these may not be higher to the NHS if they were to some degree offset by charitable funding.

Inter-relationship with the rest of the programme

Study 6 provided the health economic analysis for the whole programme.

Work arising from the grant

As referred to in Setting the scene, a planned fourth workstream included in the original grant application was changed to reflect the gradual inclusion of several linked projects. A summary of these and progress throughout the programme are summarised in Table 1.

| Theme | Project description | Progress |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic pathways |

REFER_ME Perceived poor diagnostic timeliness is a consistently reported and significant concern for young people, which they themselves have highlighted as a research priority. 73 Young people wanted questions on the pre-diagnostic experience included in the BRIGHTLIGHT survey, but these did not relate to the main objectives of the study. However, inclusion afforded us the opportunity to explore in detail in a large sample, routes to diagnosis |

Collaboration with Epidemiology of Cancer Healthcare and Outcomes group at University College London Two publications accepted74,75 Funding from CRUK_EDAG received in 2019 to undertake additional analysis (Lorna A Fern, personal communication) |

| Access to research |

RECRUIT_ME Recruitment to the cohort study was more challenging than we had anticipated. Fern et al. 76 have previously developed a model to support strategies to improve recruitment of teenagers and young adults to clinical trials. We have now expanded on this work to look at access to all research, especially the barrier and facilitators. 45,66,77 This also links to the NHS long-term plan, which specifies a target to recruit 50% of young people to clinical trials by 202578 |

Collaboration with the NIHR TYA cancer lead and multiple sites across England The YAP co-hosted a NIHR TYA research summit in 2018 to set the agenda for increasing access to research A NIHR RfPB application was rejected in 2019 and a NIHR programme development grant was rejected in 2021 An application will be submitted to UKRI in 2021 |

| Cancer care in specific populations |

RELEASE_ME Young people in prison were excluded from participation in the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort because of the extreme challenges of access, consent and data collection. However, health-care professionals informally reported the inequality of access to care, the impact of a prisoner-patient population on service delivery, the negative impact on care experience and also the concern about whether or not outcomes for this population were as good as the outcomes for those not in prison |

Led by Dr Elizabeth Davis at King’s College London NIHR HSDR funding was received in 2018 to explore this through analysis of NHS data, in-depth interviews with patient-prisoners, and workshops to develop a strategy to change practice (grant reference 16/52/53)79 |

|

Developing a SAM Sarcoma is a common cancer type in young people and is well represented in the cohort. There are QoL measures available specifically for many types of cancer, but not for sarcoma, which may be due to the heterogeneity of sarcoma (affecting soft tissue and bone, across all areas of the body). A disease-specific QoL measure is often recommended to capture the issues specific to a defined population. Without knowing the patient-report experience, it is not possible develop a measure of QoL that accurate reflects patients QoL. QoL is an important outcome for patients; if we are developing interventions to improve young people’s psychosocial outcomes, it would be helpful to have a measure available to use as an outcome |

Collaboration with members of the Psychosocial and survivorships, and sarcoma clinical studies group at the NCRI Funding was awarded from Sarcoma UK in 2016 (grant reference SUK102.2016LG). Data collection is now complete, and analysis is anticipated to be complete in 2021. 58,80,81 Additional funding from Sarcoma UK was awarded in 2019 to undertake secondary analysis of the qualitative data to understand the route to diagnosis (grant reference SUK203.018), and in 2020 for a study to develop an intervention for fear of recurrence (grant reference SUK201.2019), also using secondary analysis of SAM data |

|

| Supporting psychosocial outcomes |

INFORM_ME Imparting information through the internet is commonplace and is often deemed more acceptable to young people. However, reviews82,83 have shown that interventions used to support psychological well-being, mostly utilising technology, and technology interventions used to support various outcomes have mostly shown no benefit, for reasons including no involvement of patients in the development of the intervention and interventions being developed independent of theory. We anticipate that many interventions we will be developing in the future will be delivered online or will embrace digital technology. Therefore, we wanted to understand more about how young people use the internet |

Collaboration with nurse consultants from Leeds and Bristol Funding was awarded from Teenage Cancer Trust in 2016 and is completed56,84 |

|

End of treatment The end of treatment is known to be a transition point generating high anxiety for young people and was identified by the YAP and in our early feasibility work as a priority for further understanding and support |

Collaboration with nurse consultants from Leeds and London, and principal lecturers from Coventry University Funding was awarded from Teenage Cancer Trust in 2018 and is completed57,85,86 |

|

|

Social reintegration In addition to the end-of-treatment study outline above, a more detailed investigation into social reintegration is being undertaken. This project is using education, employment and social engagement data from the British Household Panel Survey and the UK Household Longitudinal Study databases to provide the non-cancer controls for the same secondary analysis that will be undertaken with BRIGHTLIGHT data. A cohort of 400 young people aged 16–39 years will also be established |

Led by Professor Dan Stark at the University of Leeds Funding was awarded by the Economic and Social Research Council in 2019 (grant reference ES/S00565X/1) and the study commenced in 2020 |

|

|

Sexuality and intimacy This was a subject the YAP identified as an issue that was under-researched and not adequately addressed by clinical teams |

Led by Professor Brian Lobel at Rose Bruford and the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama A grant application was rejected by the British Academy in 2020 |

|

|

Caregiver information and support needs The unmet needs have been described, but additional analysis is planned to understand more of emotional needs and factors that could predict caregiver needs that could inform an intervention to support caregivers |

Led by Nicky Pettitt, Nurse Consultant at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Trust. A proposal was submitted as part of a MRES. Support is being provided for the analysis and submission to a NIHR HEE/ICA CDRF | |

| Delivery of health care |

When cure is not likely We undertook a study to understand the needs of young adults in the last year of life. This study collected a data set from patients, their nominated carer and health-care professional, linking this through workshops to the reflections of other patients, families and health-care professionals. This has expanded our understanding of the challenges specific to the delivery of excellent end-of-life-care to young adults with cancer |

Collaboration with teams in Leeds and Southampton Funding was awarded from Marie Curie in 2013 (grant reference 15722). The study is complete87,88 |

|

BRIGHTLIGHT extension study The results of BRIGHTLIGHT are all about the delivery of specialist TYA cancer care. There have been changes to the way services are delivered for young people in England so the TYA-PTC links to hospitals designated in the region to deliver care |

A NIHR post-doctoral fellowship was rejected in 2018. An application for a similar project was awarded in 2020 through the NIHR Policy Research Programme (grant reference NIHR201438) to commence in 2021 | |

| Patient and public involvement and engagement |

Using the arts to inform health-care research BRIGHTLIGHT was developed with young people and they have been integral in study management. As noted above, they have also identified issues that need further exploration. They have also played a role in dissemination where we have been exploring more novel ways of disseminating our results, so they are more meaningful to people who do not necessarily understand graphs and the scientific way results are traditionally presented |

Led by Professor Brian Lobel at Rose Bruford and the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama Funding was awarded by the Wellcome Trust in 2016 to develop a theatrical performance (grant reference 204162/Z/16/Z). There is a Light: BRIGHTLIGHT played for 11 nights in seven cities across the UK in 2017. The evaluation was accepted for publication in 202089 A NIHR programme development grant was rejected in 2020 to extend dissemination of BRIGHTLIGHT through enhanced engagement. This was resubmitted in May 2021 |

Do specialist cancer services for teenagers and young adults add value?

The question that subtitles the BRIGHTLIGHT programme of research, ‘Do specialist cancer services for teenagers and young adults add value?’, was initially posed in response to concerns raised by opposing groups and individuals. These included professionals and advocates who were directly involved in the early development of cancer services that were specifically aimed to address the needs of teenagers and young adults, and also concerns raised by others, who, in these early stages, questioned the appropriateness or necessity of such services. The motives were both intellectually inquisitorial and, perhaps especially in the context of constrained health-care resources, practical.