Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0109-10061. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The final report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in February 2020. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Adab et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic progressive respiratory condition with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 9.21–11.7%2 in adults aged ≥ 30 years. However, at least half of all people with COPD (depending on the diagnostic criteria) remain undiagnosed, representing a large number with potentially unmet need. 3,4 COPD is defined by the presence of airflow obstruction among those with relevant risk factors but there is increasing recognition that the disease is heterogeneous, with different causative factors, phenotypic characteristics and varying prognosis. 5,6 A substantial proportion of those with COPD are of working age, and there is some evidence that they have poorer employment history,7 higher rates of sickness absence8 and poorer work performance [because of presenteeism (working while unwell)]9 compared with the general population. In the UK, COPD is estimated to cost the NHS around £1.5B (2011 costs),10,11 with total costs (including societal and intangible costs) nearing £48.5B (2014 costs)12 per year. This compares with estimates of around US$49.9B in the USA (2010 prices)13 and €48.4B in the European Union (2011 prices). 14

At the time of developing this proposal in 2009/10, there was much uncertainty about the natural history of COPD,5,15 how to approach early identification of patients16,17 and what interventions were effective for early-stage disease. During the conduct of the programme, both the UK National Screening Committee and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) highlighted the lack of randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence that showed that screening for COPD is beneficial. We therefore sought a variation to our contract to undertake additional work to that proposed in the original funded application: to follow up trial participants to examine the impact of screening on clinical outcomes. There was also little information on the impact that having COPD has on work performance and occupation. Furthermore, most of the previous research to explore prognosis and natural history of COPD were based on people with COPD recruited through secondary care and specialised settings, rather than within primary care. 18–20 The overall aim of this programme was therefore to recruit a unique UK primary care COPD cohort to address some of these uncertainties and, as a platform for future research, to test novel health service interventions.

Overview of research programme

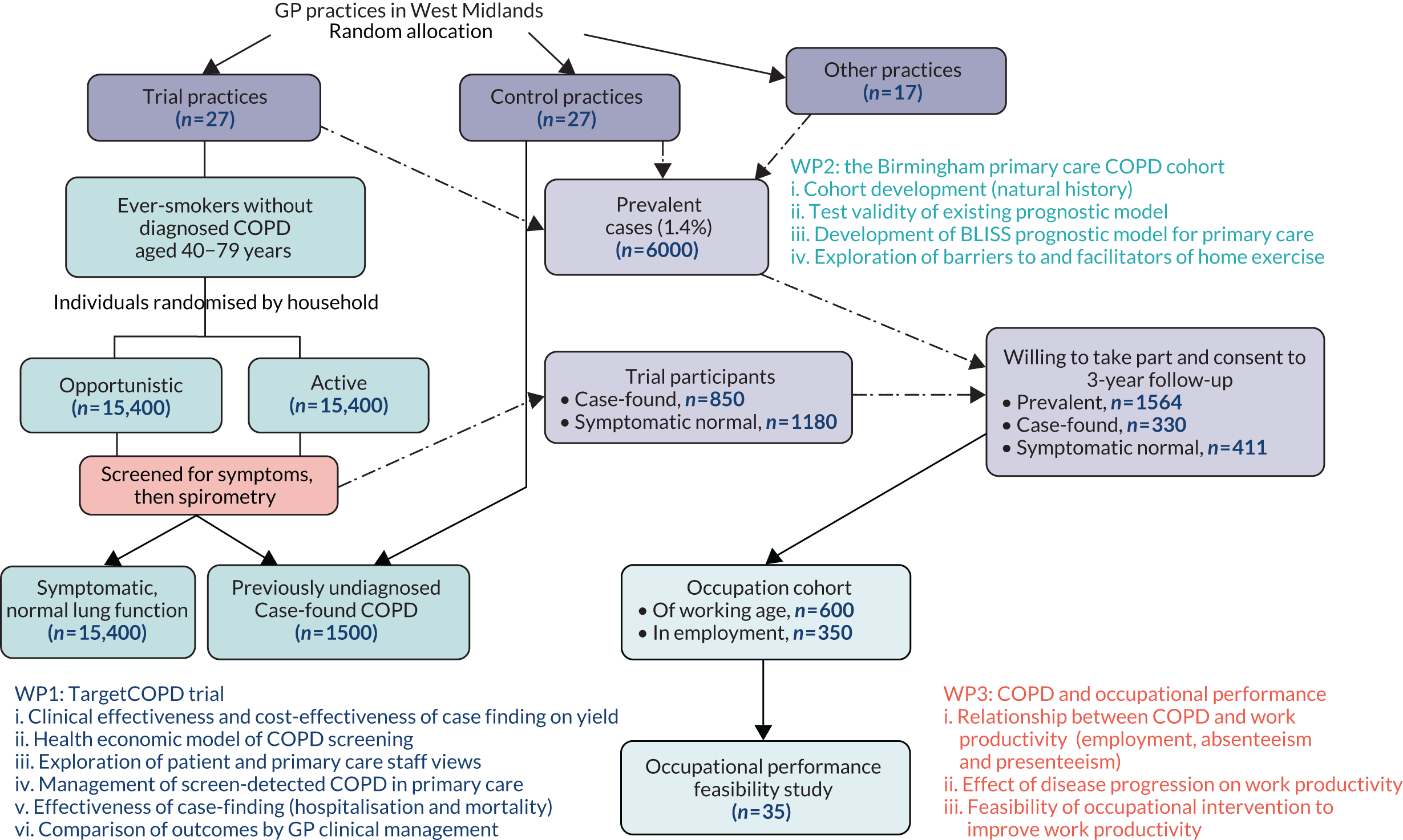

The programme consisted of three inter-related work packages (WPs), each addressing several research questions. Figure 1 provides an overview of the linked WPs in the programme, which are briefly described below. Each WP is then described in more detail, outlining the rationale, the research questions addressed and a summary of the findings and outputs linked to the original programme objectives. A full list of publications arising from our programme is available in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the programme of work. BLISS, Birmingham Lung Improvement StudieS.

Work package 1: clinical trial to evaluate case-finding; TargetCOPD trial

The aim of this WP was to ascertain the most clinically effective and cost-effective approach to identifying undiagnosed COPD. Initially, this was considered in terms of yield (WP1i), but with additional follow-up (in a variation to the contract) in terms of clinical outcomes (WP1v and vi). A Markov model was also developed to estimate the long-term cost-effectiveness of a systematic screening programme for undiagnosed COPD. Finally, we explored the views of patients on the process and outcomes of case-finding and the perspective of staff in primary care on the concept of case-finding and percieved implications for their practice.

The objectives were to:

-

ascertain the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of targeted case-finding (opportunistic or active) compared with routine care

-

develop a Markov model to compare the cost-effectiveness of systematic case-finding with current practice

-

explore the views of patients and primary care staff on COPD case-finding

-

describe the clinical management of screen-detected COPD patients in primary care

-

assess the long-term effectiveness of COPD case-finding on respiratory hospitalisations and mortality

-

compare outcomes among screen-detected COPD patients who were adequately managed by their general practitioner (GP) with those among patients who were not.

Work package 2: Birmingham primary care chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort

The aim of this WP was to develop a cohort of more than 2000 people with COPD who would be representative of those in a primary care setting, including more people with mild/moderate disease than included in previous cohorts. Participants were recruited from COPD registers in general practices as well as from participants in the TargetCOPD trial in WP1. This included those who were identified through case-finding and those who took part in the case-finding trial and reported respiratory symptoms but did not have COPD based on spirometry.

The participants were followed up every 6 months for around 3 years (2012–16) and their data were linked to routine data on hospitalisation and mortality obtained from NHS Digital. We used these data to externally validate an established prognostic model [the age, dyspnoea, airflow obstruction (ADO) prognostic score] in predicting mortality. In addition, we developed a new prognostic model [the Birmingham Lung Improvement StudieS (BLISS) index] to predict the risk of respiratory hospitalisation in this primary care population.

A sample of 26 cohort participants were also invited to attend focus groups to explore barriers to and facilitators of undertaking physical activity (PA), which is one of the most important components of treatment for people with COPD.

The establishment of the cohort also provides an opportunity for testing novel interventions in future.

The objectives were to:

-

recruit a primary care cohort of 2000 new and existing COPD patients

-

test the validity of existing COPD prognostic models in a primary care COPD population

-

develop a prognostic model (BLISS index) to predict respiratory hospitalisations suitable for a primary care population

-

explore barriers to and facilitators of PA participation among people with COPD.

Work package 3: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and occupational performance

The aims of this WP were to (1) examine the relationship between clinical characteristics and severity of COPD and occupational outcomes, including employment, work absenteeism and presenteeism (working while unwell); (2) examine whether or not disease progression over time is associated with occupational outcomes; and (3) assess the feasibility and benefits of offering formal occupational health (OH) assessment and subsequent recommendations aimed at improving work-based indices. Participants in this WP were a subsample of the larger cohort recruited in WP2.

The objectives were to:

-

examine factors associated with occupational performance (employment, absenteeism and presenteeism) among COPD patients of working age

-

examine how disease progression (lung function decline, exacerbation) over time is associated with occupational performance (employment, absenteeism and presenteeism) among COPD patients in employment

-

assess the feasibility of offering OH assessment with recommendations to people with COPD.

Work package 1: clinical trial to evaluate case-finding – TargetCOPD trial

Objective (i): to ascertain the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of targeted case-finding (opportunistic or active) compared with routine primary care (work package 1i, published trial report)21

Parts of this section are based on Jordan et al. 21 Reprinted from The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Vol. 4, Rachel E Jordan, Peymané Adab, Alice Sitch, Alexandra Enocson, Deirdre Blissett, Sue Jowett, et al. , Targeted case finding for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease versus routine practice in primary care (TargetCOPD): a cluster-randomised controlled trial, pp. 720–30, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

Rationale

Several reports from the UK government and health charities22,23 have highlighted the burden of COPD, the extent of underdiagnosis and the variation in access to and participation in relevant services. The Department of Health and Social Care published an outcomes strategy for people with COPD in 2011 that recommended opportunist and the systematic case-finding to minimise late diagnosis. 22 However, the most clinically effective and cost-effective approach for identifying undiagnosed cases was not known. Although some published studies reported the yield from either active24–26 or opportunistic27–29 approaches to case-finding using spirometry, these were limited because of a lack of comparison groups, the restricted number and range of participants, a lack of follow-up and different target populations (e.g. specific age groups; all current smokers or people who have smoked; whether or not symptoms were considered prior to spirometry). Furthermore, general population screening using spirometry was not recommended16 because it would identify many people without clinically important disease, for whom there is little evidence of effective interventions. 30 We therefore sought to evaluate different approaches to case-finding for undiagnosed COPD, focusing on yield and cost-effectiveness (from a health-care perspective). To our knowledge, this was the first major trial to compare different targeted recruitment approaches with case-finding with routine care.

What we did

We recruited 54 GP practices across the West Midlands (10 August 2012–22 June 2013) to take part in the 12-month trial and randomised these clusters to case-finding or to continue with routine care. All patients on the practice registers aged 40–79 years who had no existing diagnosis of COPD and had ever smoked (based on GP electronic records) were eligible for and included in the trial. Using a computer-generated randomisation sequence, we randomised practices (balanced on practice characteristics) and in the intervention case-finding arm we randomised individual households of patients to receive one of two approaches to case-finding: opportunistic (offered screening opportunistically when they visited the practice for any reason) or active (additionally offered screening through a postal invitation). Screening was carried out in two stages, with an initial questionnaire (see Appendix 2) followed by an invitation to attend for diagnostic spirometry for those who reported relevant chronic respiratory symptoms. Our study case definition of 1-year incident COPD was either (1) a new diagnosis of COPD by the GP (based on new entry on practice COPD register) or (2) the presence of airflow obstruction on screening [defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.7 post bronchodilator, in line with recommendations from the guidelines31 produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)] in patients with chronic respiratory symptoms. Sample sizes were based on estimates from our published model (see published paper21 for full details) and required 27,768 patients per group. Primary outcomes were analysed using appropriate regression analyses adjusted for practice-level deprivation, ethnicity and age. The active versus opportunistic comparison required logistic regression with fixed effects and the targeted versus routine comparison required multilevel models with random effects. We undertook a within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis to calculate the cost per additional case detected of both strategies versus routine care, and we undertook a detailed cost analysis of the screening processes using standard NHS32,33 and trial-specific costs34 (2013 prices), including set-up costs and training costs. Equipment and training costs were amortised over 3–5 years using a discount rate of 3.5%. Sensitivity analyses considered patient costs, alternative case-finding scenarios and models of care (GP, community or secondary care led).

What we found

A flow diagram of participants is available in the published paper. 21 We found that very few new cases of COPD were diagnosed in the routine care practices (n = 337; 0.8%). The odds of finding new cases were seven times higher using the targeted approach than with routine care [n = 1278 (4%); adjusted odds ratio (OR) 7.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.80 to 11.55; p < 0.0001], and active case-finding (combining opportunistic and active postal invitation to screening) was twice as effective as opportunistic-only [n = 822 (5%) vs. n = 370 (2%); adjusted OR 2.34, 95% CI 2.06 to 2.66; p < 0.0001]. Active case-finding may also be more cost-effective than the opportunistic approach (£333 vs. £376 per additional case detected, respectively). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for active case-finding was £573 per additional case detected compared with opportunistic case-finding. Sensitivity analyses made little difference, although a secondary care-led service was more expensive.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this was the first RCT to compare yield of undiagnosed COPD from a comparison of different screening approaches with routine practice and to estimate their cost-effectiveness. However, the efficiency of screening could have been improved by using different screening tests, or pre-screening algorithms applied to electronic health records (EHRs) to target screening invitations to those at highest risk. Even with the most intensive screening approach, only 38% of those invited for screening responded, and not all those who responded and had symptoms attended for diagnostic spirometry. Further research should focus on how to maximise screening coverage and uptake and improve the efficiency of the screening process.

Objective (ii): to develop a model (using Markov decision analysis) to compare the cost-effectiveness of a systematic case-finding programme with current practice (work package 1ii, published)35

Rationale

The TargetCOPD trial confirmed that active approaches to screening result in a higher proportion of undiagnosed COPD patients being identified compared with routine care. People with screen-detected COPD are expected to benefit from treatment resulting in improved quality of life, increased survival and reduction in hospital admissions. To provide data for policy-makers to consider the longer term benefits of screening for COPD in relation to investment in other health services, a cost-utility model is needed. Published economic evaluations in COPD have primarily considered interventions for the disease rather than for those who are screen detected,36 and others have concentrated on the costs of COPD in burden of illness studies. 37 No trial-based economic evaluation had considered case-finding. NICE guidelines38 included a simple decision tree-based modelling to determine the cost-effectiveness of opportunistic case-finding among people aged > 35 years who have smoked and have a chronic cough. However, the model was simplistic and included many assumptions for which evidence was limited. We developed a model-based economic evaluation of the long-term costs and benefits of screening for undiagnosed COPD.

What we did

We used costs (using 2015 prices39) and outcome data from the TargetCOPD trial, in combination with the best available published data, and additional information from our linked Birmingham COPD cohort study (WP2) to develop a Markov decision-analytic model to address this objective. The model compared the cost-effectiveness of a 3-yearly systematic case-finding programme aimed at people aged > 50 years who have smoked with current practice because the yield of new cases was very small in younger age groups. The model had a time cycle of 3 months, which was short enough to capture important COPD-related events, and a time horizon of 50 years, assuming a maximum age of 100 years. Patient-level data on case-finding pathways were obtained from our TargetCOPD RCT. The model outcome was cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, from a health service perspective. Discounting was applied to costs and outcomes at 3.5%. Multiple one-way sensitivity analyses assessed what impact modification of key parameters had on the results. We considered varying the starting age, screening interval and time horizon as well as the screening processes (questionnaire response, spirometry attendance rate), treatment initiation rates and effectiveness of treatments.

What we found

We estimated the ICER of systematic case-finding compared with routine care to be £16,596 per additional QALY gained. Using the commonly used willingness-to-pay threshold in the UK (£20,000 per QALY), we estimated there was 78% probability of cost-effectiveness. The estimate was robust to sensitivity analyses, with the main cost-driver being uptake of screening. The most cost-effective age to begin screening was around 60 years. Better ascertainment of treatment effectiveness will help improve precision but, using the best current estimates from the literature,40,41 screening is likely to be cost-effective provided that at least 12% respond to a screening questionnaire, > 26% attend spirometry and > 8% of screen-detected patients are adequately treated and managed.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first economic model to evaluate the long-term cost-effectiveness of a COPD case-finding strategy, using contemporaneous data sources to inform estimates and using multiple sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the model. However, the validity of some of the assumptions underlying the model is unknown. In particular, there is uncertainty around the effect of treatment on progression and the natural history of COPD. Future research should refine the model based on data from studies that provide more accurate estimates of effectiveness and consider additional costs, such as those to the health service, of pathways to deal with a larger number of identified cases.

Objective (iii): to explore the views of (a) patients invited to take part in case-finding, in terms of the process and outcomes (work package 1iii, published),42 and (b) primary care staff, in relation to case-finding (work package 1iii, published)43

Rationale

Although there has been much research examining the yield from different case-finding activities, few previous studies have examined other aspects related to the development of a screening programme. One important aspect is the acceptability of screening and understanding the perspective of both patients and those who provide screening. We undertook two studies: one to explore the views of patients who had been invited for screening as part of the TargetCOPD trial, about the screening process and outcomes, and another to understand the process from the perspective of primary care staff who would manage those who are case-found.

What we did

For the patient perspective, we invited for interview people who had been invited for screening in either the active or opportunistic arm as part of the TargetCOPD trial (i.e. adults aged ≥ 40 years with a smoking history who had been considered eligible for the trial by their GP). We invited four groups of patients: those who (1) were invited and consented to take part in screening, (2) were invited and declined, (3) attended screening but did not have COPD and (4) attended and had abnormal lung function suggesting COPD. We sought their views on the screening process and their reflections on the outcomes of screening.

For the primary care staff perspective, we invited 20 staff, including GPs, nurses and managers in practices that had taken part in the TargetCOPD trial. Participants were invited to share their views on COPD case-finding, including their perceptions of the benefits, harms, and barriers to and facilitators of implementing a screening programme in primary care.

For both studies, interviews were transcribed and analysed using the framework approach.

What we found

Forty-three patients and 20 health-care staff were interviewed. Patients generally considered screening to be a good thing, and the presence of symptoms on prompting facilitated their attendance. The importance of ensuring that the screening process is convenient was highlighted, and patients worried that GPs did not have the time to follow up after screening.

Barriers to attending screening included psychological and practical factors. The former related to denial and failure to recognise symptoms, fear of the ‘test’ and perceiving lung disease as less important within the hierarchy of their health problems. Practical barriers included lack of time, inability to access GP appointments and having caring and other responsibilities that were considered more important.

Among primary care staff, although they also generally supported screening for undiagnosed COPD, they also commented on concerns around potential negative consequences, including an increase in workload for GPs and overdiagnosis in patients. Some commented that, currently, diagnosed patients were not being adequately treated. Perceived barriers to implementing screening included lack of resources and limited access to diagnostic services. However, potential solutions, including better support from secondary care, an increase in specialist COPD nurses and better community respiratory service provision, were also discussed. Poor knowledge of COPD in terms of recognising symptoms and how to manage those with the disease was also highlighted as a problem that needs to be addressed.

For a screening programme to be implemented and have high uptake, it is important to raise patient awareness of COPD risk factors and symptoms and provide training and additional resources for primary care. In particular, it is important to ensure that management pathways for diagnosed COPD patients are optimised before further cases are identified.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this was the first study to explore perceptions of patients and health-care providers on different stages of case-finding. However, we did not explore experiences of the approach to recruitment for screening (questionnaire at GP surgery or by post) and no participant commented on this. In addition, we did not invite and have not captured the views of people who reported no chronic respiratory symptoms as part of screening. Furthermore, inviting patients in the context of research may not reflect views on screening in practice. For health-care staff, those who participated are likely to be more engaged in case-finding and their views may represent those who are more proactive in management of case-found COPD.

Objective (iv): to describe the clinical management of screen-detected chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in primary care and compare management in those who were versus those who were not on the practice chronic obstructive pulmonary disease registers (work package 1iv, manuscript submitted)

Rationale

From a public health perspective, screening is more than a screening test. To have an impact on clinical outcomes, a number of criteria need to be fulfilled and, in the UK, the National Screening Committee considers these carefully before recommending commencement of a population screening programme. The criteria relate to the condition, the screening test, the treatments available for those who are screen detected and the characteristics of the programme and its implementation. In relation to the programme implementation, it is important to ensure that resources are available and pathways are in place to manage screen-detected individuals. In the UK, NICE has set out a pathway for the diagnosis and management of people with COPD. 31 As part of the TargetCOPD trial, patients with chronic respiratory symptoms who attended spirometry screening had their results fed back to their GP, with a note for them to follow NICE guidelines for further management. However, there are few studies that have examined how patients diagnosed with COPD are subsequently managed and whether or not primary care staff follow recommended pathways for managing these patients. We therefore obtained data from GP EHRs and self-reported data from case-found patients (those with airflow obstruction on spirometry who fulfil the NICE recommended criteria for diagnosing COPD) to describe the clinical management of case-found COPD patients (identified through the TargetCOPD trial) and compare this with that of patients newly diagnosed with COPD through routine care. In addition, we compared characteristics and management for those who were or were not entered on to the practice COPD register.

What we did

We identified patients who had been newly diagnosed with COPD (case-finding, n = 857; routinely diagnosed, n = 764) during the period August 2012 to June 2014 in the 54 GP practices that took part in the TargetCOPD trial. Data on demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as a range of clinical assessments and interventions recommended by NICE for people with COPD, were extracted from EHRs for a subset of patients covering the period April 2011 to September 2017. In addition, patients who had been identified through case-finding were invited to complete a health questionnaire around 5 years after their first diagnosis, in March 2018, with a reminder 2 months later.

For all patients, we determined whether or not they had been added to the practice COPD register used in reporting for the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) by the end of the TargetCOPD trial period. The number of COPD-related clinical assessments and interventions were summed to form a clinical management score. Multilevel logistic regression was used to assess for associations between participant characteristics and the likelihood of being added to a disease register, comparing those who were identified through case-finding with those routinely diagnosed. Multilevel linear regression was used to assess associations between participant characteristics, COPD disease registration and the clinical management score.

What we found

Figure 2 shows a summary of participants included in these analyses. The primary analysis showed that just over one-fifth (182/857; 21.2%) of case-found patients, but almost all of the routinely diagnosed patients (708/764; 92.7%), had been added to the QOF COPD register within 12 months of assessment [median time from trial spirometry assessment to COPD registration 152 days, interquartile range (IQR) 72–258]. Factors associated with a higher likelihood of COPD registration among case-found patients were current and former smoking (adjusted OR 8.68, 95% CI 2.53 to 29.82, vs. OR 6.32, 95% CI 1.88 to 21.29, respectively) and lower percentage of predicted FEV1 (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.95 to 0.98).

FIGURE 2.

Flow of participants contributing to analyses for this study. a, Included in current study.

Electronic health record data were available for 532 out of 1629 patients (identified through case-finding, n = 344; identified through usual care, n = 188) (Table 1). The characteristics of participants with and without EHR data were broadly similar. Factors associated with a higher clinical management score were being on the COPD register (adjusted β 5.06, 95% CI 4.36 to 5.75, which means that the score was on average 5 units higher for those on the COPD register than for those not on the register) and a higher number of comorbidities (adjusted β 0.38, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.65, which means that the score increased by 0.38 units for each additional comorbidity). Although of only borderline statistical significance, there was also a negative association with being case-found rather than routinely diagnosed (adjusted β –0.69, 95% CI –1.44 to 0.07).

| Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-finding (N = 344) | Usual care (N = 188) | |||

| n a | % | n a | % | |

| Clinical assessment | ||||

| MRC dyspnoea score recorded | 98 | 28.5 | 171 | 91.0 |

| CAT score recorded | 36 | 10.5 | 94 | 50.0 |

| Spirometry undertaken | 48 | 14.0 | 79 | 42.0 |

| COPD severity recorded | 33 | 9.6 | 96 | 51.1 |

| BMI recorded | 244 | 70.9 | 168 | 89.4 |

| Oxygen saturations recorded | 41 | 11.9 | 55 | 29.3 |

| Chest X-ray undertaken | 13 | 3.8 | 9 | 4.8 |

| Depression screen undertaken | 54 | 15.7 | 55 | 29.3 |

| Clinical intervention | ||||

| Listed on COPD register | 78 | 22.7 | 175 | 93.1 |

| Care plan recorded | 38 | 11.0 | 97 | 51.6 |

| Annual review undertaken | 91 | 26.5 | 170 | 90.4 |

| Smoking cessation counselling provided | 157 | 45.6 | 139 | 73.9 |

| Nicotine replacement therapy | 27 | 7.8 | 17 | 9.0 |

| Influenza vaccination provided | 240 | 69.8 | 138 | 73.4 |

| Pneumococcal vaccine provided | 19 | 5.6 | 23 | 12.2 |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation provided | 17 | 4.9 | 42 | 22.3 |

| Inhaler technique assessed | 56 | 16.3 | 116 | 61.7 |

| Inhaler prescribed | ||||

| Salbutamol | 128 | 37.2 | 152 | 80.9 |

| Ipratropium | 5 | 1.5 | 10 | 5.3 |

| Salmeterol | 3 | 0.9 | 10 | 5.3 |

| Fluticasone | 3 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Budesonide | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Beclometasone | 20 | 5.8 | 13 | 6.9 |

| Fluticasone/salmeterol | 33 | 9.7 | 70 | 37.2 |

| Budesonide/formoterol | 12 | 3.5 | 23 | 12.2 |

| Any of the above inhalers | 134 | 39.0 | 163 | 86.7 |

| Antibiotic rescue pack | 10 | 2.9 | 43 | 22.9 |

| Prednisolone | 51 | 14.8 | 96 | 51.1 |

| Clinical management score | ||||

| < 5 | 225 | 65.4 | 17 | 9.0 |

| 5 to 9 | 83 | 24.1 | 73 | 38.8 |

| ≥ 10 | 33 | 9.6 | 98 | 52.1 |

| Median (IQR) | 3 | 2–5 | 10 | 7–12 |

Self-reported questionnaire data were available for 375 out of 857 case-found patients. Only one-fifth of these patients were on the COPD register and, overall, one-third were aware of their diagnosis through their GP (88.5% of those on the COPD register vs. 17.5% of those not on the register). Around 45% had attended a COPD annual review, with the proportion being higher for those on the COPD register (83.3% vs. 34.7%). Factors associated with a higher clinical management score in this group were having a larger number of comorbidities (adjusted β 0.38,95% CI 0.10 to 0.65), higher COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score (adjusted β 0.05, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.08) and lower percentage of predicted FEV1 (adjusted β –0.03, 95% CI –0.04 to –0.01). Being on the COPD register was also significantly associated with a higher management score (adjusted β 3.48, 95% CI 2.81 to 4.15).

A proportionately high number of case-found patients with COPD were not added to practice COPD registers and these patients were less likely to receive recommended effective treatments for their condition. Overall, even those who were on the COPD register did not receive all recommended interventions, including smoking cessation advice or referral to pulmonary rehabilitation.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of the largest studies to evaluate the clinical management of screen-detected COPD patients in primary care. The lack of availability of EHR data on all trial participants was a limitation, and the validity of the EHR data is dependent on the clinical coding practices used. Nevertheless, the missing data are likely to be random, based on similarity of characteristics between those with and without data. Furthermore, the self-reported data from those who responded to questionnaires broadly verified the findings from health records.

Objective (v): to assess the long-term effectiveness of case-finding for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on respiratory hospitalisations and mortality (work package 1v, manuscript in preparation) and objective (vi): to compare outcomes (including health-related quality of life) among screen-detected chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in primary care who were managed adequately by their general practitioner (based on the practice chronic obstructive pulmonary disease registers) with those who were not

Rationale

Since starting our programme of work, the UK National Screening Committee undertook a review to consider screening for COPD44,45 and the USPSTF updated their review. 46 Both recommended against screening for the time being, citing the need to establish evidence on clinical effectiveness of early identification before recommending systematic programmes for screening. The benefits of case-finding in improving health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and QALY gains has also not been previously studied.

Through our original trial, the infrastructure was in place to assess whether or not screening and early detection of COPD benefited patients in the longer term. We therefore sought a variation to the contract to extend follow-up and to link data on all patients who were part of the original trial with routinely available data. We obtained data on all eligible participants from NHS Digital on hospitalisations [through Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data] and mortality, from the start of the trial until the last date available. We also sought approval from the National Research Ethics Committee and legal approval from the Confidentiality Advisory Group to obtain relevant patient identifiable data from GP practice records through an opt-out process and hold these temporarily to allow data linkage with the data obtained from NHS Digital. We were then able to compare outcomes among those who were in practices where active screening took place with those in the routine care arm practices (WP1v).

Additionally, to improve the input into the health economic model developed previously, we sought to obtain additional data on quality of life among screen-detected COPD patients some years after diagnosis and to compare outcomes among those who were managed in accordance with NICE guidelines with outcomes among those who were not.

What we did

Data on mortality and hospitalisations (all-cause and respiratory) were obtained for all eligible patients (who were alive at the start of the intervention, n = 74,693) from 54 participating practices in the TargetCOPD trial. Patient demographic data and information on whether or not the patient was on the practice QOF COPD register within 12 months of the trial were obtained from GP records. We also administered a questionnaire in 2017/18 to all case-found patients identified through the TargetCOPD trial to invite them to respond to questions on quality of life as well as their health and treatments received for COPD. Cox proportional hazard models, using random effects to account for clusters and adjusted for potential confounding factors, were used to model the time to event outcomes (death, first all-cause hospital admission and first respiratory hospital admission) in the intervention (active or targeted) and routine care arms. The time to event was censored at the death (for admission outcomes) or data extraction (30 September 2017 for hospital admissions and 13 October 2017 for deaths) if no event occurred. We also compared outcomes for the two intervention arms (active and opportunistic). Finally, for screen-detected cases, we compared mortality and hospitalisation as well as HRQoL measures [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and CAT scores] among those who were or were not added to the practice QOF register. Based on data from objective v, we used addition to the practice COPD register as a proxy measure for being better managed and treated for COPD. Analyses were adjusted for baseline values as well as for a range of potential confounders, including age, sex, ethnicity and baseline values for lung function, comorbidities and smoking status.

What we found

Among the 32,743 participants in the case-finding arms, 1557 had a respiratory hospitalisation compared with 1899 among the 41,950 participants in the routine arm over a mean follow-up period of 4.3 years [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 1.04, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.47]. The corresponding HR for all-cause hospitalisation and mortality were 1.06 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.71) and 1.15 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.61), respectively, suggesting that, overall, there was no significant difference in risk of first hospitalisation and mortality between those who were in the screening arm compared with those in the routine care arm of the trial.

Within the two intervention groups in the case-finding arm there was no statistically significant difference between groups in terms of overall hospitalisations and mortality (adjusted HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.04, and adjusted HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.20, respectively). The adjusted HR for respiratory hospitalisation in the active group compared with the opportunistic group was 1.14 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.27), indicating an increased hazard of respiratory admissions in the former group (where yield from screening was higher).

Comparison of outcomes for screen-detected patients who were on the QOF COPD register with those who were not also showed no statistically significant difference in relation to all-cause hospitalisation (adjusted HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.11), respiratory hospitalisation (adjusted HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.73) and mortality (adjusted HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.12).

Thus, despite screening resulting in a higher yield of undiagnosed cases of COPD, there was no difference between those who were in practices with or without screening in terms of clinical outcomes at 4 years. The poor clinical management of COPD generally, and very low addition of case-found patients (particularly those with less severe disease) to the practice COPD register, may be an explanation for the findings. Given these results, we did not undertake a health economic analysis to examine cost per hospital admission avoided or cost per life-year saved.

In the adjusted analyses examining HRQoL, there was no statistically significant difference in EQ-5D scores between the two groups (adjusted mean difference –0.006, 95% CI –0.048 to 0.036). The adjusted mean CAT score was statistically significantly and clinically higher in those who were on the COPD register than in those who were not (mean difference 2.317, 95% CI 0.481 to 4.153), indicating a greater impact of COPD on their life and poorer quality of life. This difference is likely to reflect the more severe disease and characteristics of those who are added to the COPD register compared with those who are not, rather than being a result of how they were managed.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first trial to report clinical outcomes from a large trial of screening for undiagnosed COPD. The trial was not powered to detect clinical outcomes because that was not the primary aim, but, nevertheless, it has provided reasonable effect estimates. The poor clinical management of people with screen-detected COPD limits the ability of detecting any potential benefits and thus the interpretation of findings. The low proportion of screen-detected patients being entered on the COPD register may explain the observed lack of effectiveness of screening.

Additional outputs and published analyses related to work package 1

The main TargetCOPD trial paper was disseminated more widely at respiratory conferences internationally and won the following awards:

-

Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) award for ‘best paper of the year 2016’ in Category 2 (CVD, Renal, Respiratory, Oral, ENT & Ophthalmology).

-

European Respiratory Society (ERS) best abstract in primary care 2015.

-

American Thoracic Society (ATS) best abstract Clinical Problems Assembly 2015.

-

Society for Academic Primary Care nomination for best abstract 2015.

Additional related papers include the following.

Jordan et al.47

This was the protocol for the TargetCOPD trial, outlining the rationale, methods and analysis plan.

Miller et al.48

In this analysis we used data from the TargetCOPD trial and compared how the application of two different definitions of airflow obstruction would impact on the clinical characteristics of the population who would be labelled as having COPD. The definition used in the trial was based on the ratio of FEV1/FVC < 0.7 [the fixed ratio (FR)], which is recommended by NICE. The second definition was based on using the lower limit of normal (LLN) that is increasingly being recommended. We found that, among 2607 people who attended for spirometry, around one-third had airflow obstruction using the FR definition compared with 20% using the LLN definition. There was overlap between the two groups. However, those identified by the FR and not the LLN definition were older, had better lung function and fewer respiratory symptoms, but had a higher rate of heart disease. Overall, we demonstrated that using the FR rather than LLN identifies a greater proportion of individuals with cardiac, rather than respiratory, clinical characteristics.

Haroon et al.49

This analysis used data from the TargetCOPD trial to develop a validated algorithm and risk score to target case-finding on those at highest risk of undiagnosed COPD and thus improve the efficiency of any future case-finding process. Although other COPD risk scores have been developed, this was the first that was based on identifying case-found COPD (rather than incident clinical COPD diagnosed through routine care) and is therefore more useful in the context of case-finding in primary care.

Haroon et al.50

In this analysis we used a case–control study design to match incident COPD cases from 340 GP practice registers (using the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink) to two controls (based on age, sex and practice). Predictive risk factors for COPD were identified from practice records and used to develop a clinical risk score. The risk score was validated using a sample from a further 20 practices. The model, including smoking status, history of asthma and lower respiratory tract infections, and prescription of salbutamol in the previous 3 years, resulted in reasonable prediction (c-statistic 0.85, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.86).

Haroon et al.51

This systematic review (based on studies from 1997 to 2013) summarised the uptake and yield from different approaches to screening for undiagnosed COPD in primary care. Data from three RCTs, one non-randomised trial and 35 uncontrolled studies showed that all approaches result in identification of new undiagnosed cases. The review suggested that targeting higher-risk individuals (e.g. smokers) and using questionnaires or handheld flow meters prior to diagnostic screening was likely to increase yield. However, it also highlighted the need for well-conducted RCTs.

Haroon et al.52

This review compared the diagnostic accuracy of different COPD screening tests in primary care. A total of 10 studies were identified from 1997 to 2013 and included use of screening questionnaires [mainly the COPD Diagnostic Questionnaire (CDQ)], handheld flow meters [e.g. the copd-6 (Vitalograph Ltd, Buckingham, UK)] or a combination. Handheld flow meters demonstrated higher test accuracy than questionnaires but the review highlighted the need for high-quality evaluation of comparative screening strategies.

Work package 2: the Birmingham primary care chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort

Objective (i): to recruit a cohort of 2000 new and existing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients from general practices in the West Midlands (work package 2, linked to work package 1, published)53

Rationale

The natural history of COPD is still not understood, and several expert reviews have highlighted a need to further investigate both old and new longitudinal data. 5,15 Prior to this programme, a number of relevant COPD disease cohorts had been established,54–56 but these included patients with more advanced disease from secondary care settings, with short duration of follow-up, and were mainly of small size. Other large population cohorts have also been used to address questions relevant to COPD. 57–60 However, because these were not specifically set up to address COPD, not all relevant measures were undertaken and the quality of lung function was not always prioritised. There were no UK primary care COPD cohorts with patients representing the range of disease severity, particularly including people with mild/moderate disease, or a diverse socioeconomic mix. Furthermore, existing cohort studies included neither people with COPD who were identified through case-finding nor patients reporting respiratory symptoms but who had normal lung function [former Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 0]. 61 The evidence on progression to COPD in the latter group is limited and contradictory,62–64 and methods for assessing symptoms are inconsistent. 62,65 The clinical relevance and natural history for this patient group and screen-detected cases are unclear.

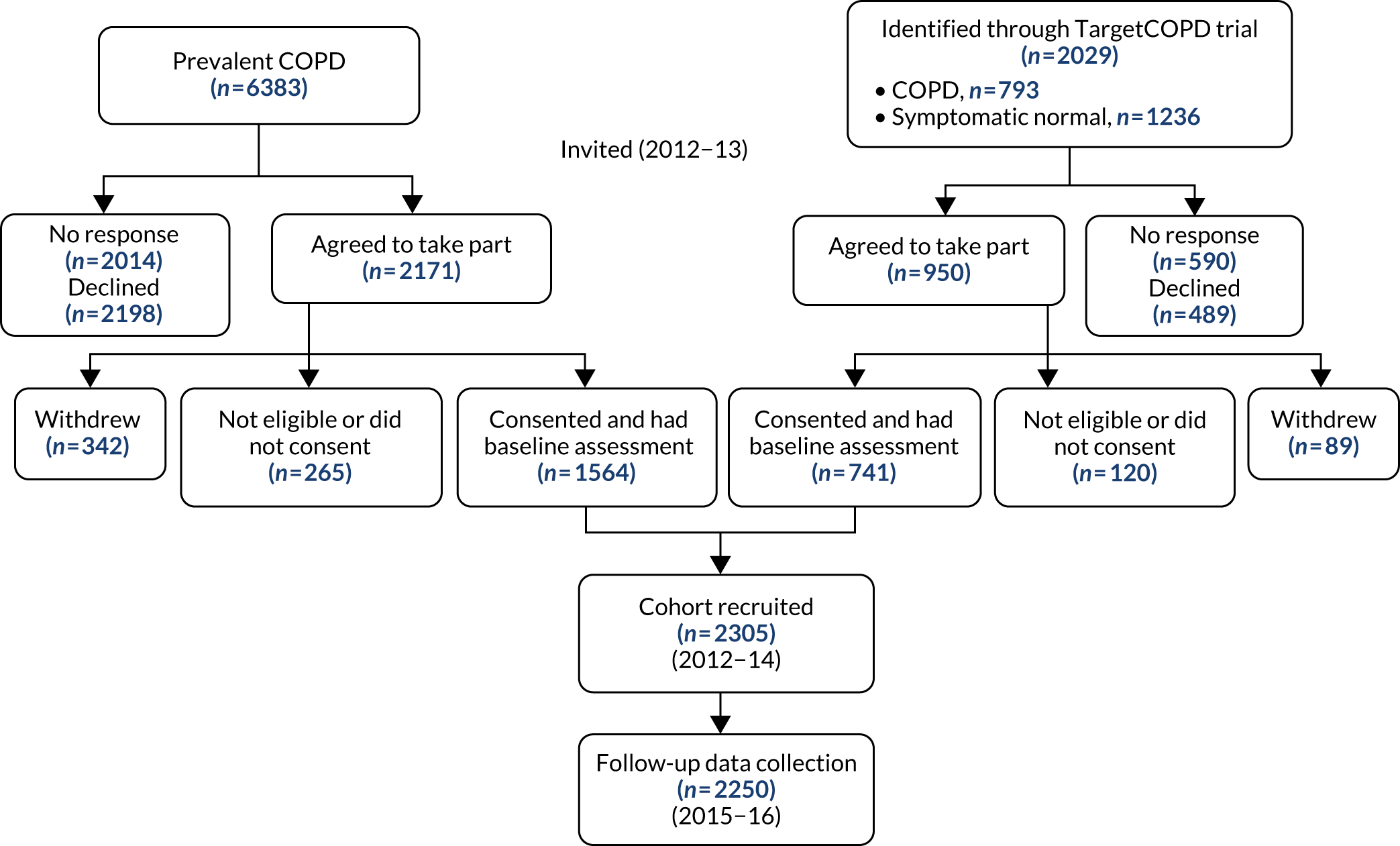

What we did

We recruited 2305 patients aged ≥ 40 years from 71 practices across the West Midlands (Figure 3), comprising 1564 patients with previously diagnosed COPD, 330 previously undiagnosed patients with respiratory symptoms and airflow obstruction confirmed by spirometry (case-found COPD) and 411 symptomatic patients with normal lung function confirmed by spirometry. 53

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of patient recruitment and assessment for the Birmingham COPD cohort study.

Baseline assessments were undertaken by trained researchers using standardised protocols between 2012 and 2014 (Figure 4). Assessments included high-quality pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry using an ndd EasyOne® spirometer (ndd Medizintechnik AG, Zurich, Switzerland). Other measurements included height and weight, body fat percentage estimation using the Tanita BC-420SMA Body Composition Analyser (Tanita Europe BV, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), assessment of grip strength using a Saehan Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer (Saehan Corp., Masan, Republic of Korea) and assessment of exercise capacity using the sit-to-stand test. In addition, trained researchers used face-to-face interviews to obtain occupational history. Information on skill content of occupations was used to assign a four-digit standard occupational classification (SOC2010)66 code for current or main occupation using the CASCOT (computer assisted structured coding tool) software (online version, Office for National Statistics, Newport, UK).

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative number of cohort participants recruited and having baseline assessments by month.

Participants were also asked to complete questionnaires that sought data on demographic characteristics, lifestyle (smoking history and exercise habits), symptoms, exacerbation history, general health, diagnosed medical conditions, health-care usage and the home environment (see Appendix 3). HRQoL was assessed using disease-specific (CAT)67 and generic (EQ5D)68 instruments, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)69 instrument was used to screen for depression. Work productivity was assessed through questions on work absence and presenteeism using the Stanford Presenteeism Scale (SPS-6)70 and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI). 71

At 6-monthly intervals, patients were sent follow-up questionnaires by post. All follow-up questionnaires included items on employment, general health, lung health, exacerbations, new diagnoses, attendance at pulmonary rehabilitation, health-care utilisation, smoking history, medications, depression and HRQoL. Some questionnaires included additional items, which are summarised in Table 2.

| Questionnaire | Special items in questionnaire | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 6 months | Self-management, exercise, COPD knowledge, major events | 73.0 |

| 12 months | Major events | 67.6 |

| 18 months | Handwashing, diet | 69.2 |

| 24 months | Self-management, handwashing, exercise, self-efficacy | 66.1 |

| 30 months | Pain symptoms, fatigue | 62.8 |

| Follow-up assessment | Exercise, smoking cessation, e-cigarette use, major events, sleep, vitamin use | 88.3 |

| Supplementary | Anxiety, illness perception, self-perception | 78.8 |

Patients were invited for a final assessment visit around 3 years after baseline (2015–16). In addition to post-bronchodilator spirometry, other baseline assessment measures and questionnaires were repeated. Cohort participants’ routine data on comorbidities and medications were extracted from GP records. Linked data on hospital episodes and mortality were also obtained from NHS Digital for the period 1 April 2012 to 31 March 2016.

Establishment of this cohort allowed important questions of relevance to patient benefit to be addressed (WP2i).

What we found

Follow-up data were available for 2250 patients (97.6%), and almost two-thirds (1469, 63.7%) returned for face-to-face follow-up assessment. Six-monthly questionnaires were completed by around two-thirds of patients (62.8–73.0%; see Table 2). In the initial 2 years of follow-up, 267 (12%) patients had at least one respiratory-related hospital admission, based on HES data. Over the entire period of follow-up (minimum 1.8 years, maximum 3.8 years), 382 patients (17%) had at least one respiratory hospital admission and 170 (7%) had died at the time data were obtained from NHS Digital.

Strengths and limitations

We established one of the largest primary care COPD cohorts, which is novel in that it includes case-found patients. A limitation was that fewer than one-third of case-found patients agreed to join the cohort. Our recruitment strategy resulted in an over-representation of patients with less severe disease because patients had to be ambulatory. Despite attempts to include patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds, the majority were white.

Objective (ii): to test the validity of existing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prognostic models in a primary care chronic obstructive pulmonary disease population (work package 2, published);72 and objective (iii): to develop a prognostic model (BLISS index) to predict respiratory hospitalisations suitable for a primary care population (work package 2, drafted, see Appendix 4)

Rationale

A better understanding of factors predicting prognosis and the development of a prognostic model can facilitate doctor–patient consultations and inform management decisions and health service planning. For COPD, a simple measure of lung function, FEV1, has historically been used to grade severity. However, there is increasing recognition that this measure is not a good predictor of clinical outcomes. Alternative measures of lung function may improve diagnostic73 and prognostic ability. 74,75

A number of studies have also described a range of factors other than lung function that are associated with COPD progression, deriving prognostic indices. The first [BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnoea, and exercise) index] was developed to predict mortality risk in those with COPD. 56 However, the method of development was not clear, its validity has not always been confirmed and not all measures are practical in non-specialist settings. 76 Since then, several other prognostic models have been developed and, since we started the programme, a number of systematic reviews have been undertaken to summarise these. 77–79 The reviews show that existing prognostic models are heterogeneous in terms of the number and type of predictors, the prognostic outcome, time horizon and statistical approach. Most focus on predicting mortality risk,56,76,80–82 although others were developed to predict additional outcomes such as exacerbations,83,84 COPD-related hospitalisation,85 respiratory hospital attendance/admission86 and exacerbation or hospitalisation. 87,88 Only three indices84,87,88 were derived from primary care populations, despite this being where most COPD patients are managed, and most included patients with more severe established disease. No models were developed in populations that included case-found patients. Few studies were validated or used recommended statistical approaches for deriving the model.

The most recent review showed that the ADO index was most discriminatory in predicting mortality. 78 For a prognostic model to be used by clinicians, it needs to be simple and capture the required patient data with minimum resource;89 the ADO index fulfils these criteria. We therefore undertook validation of the ADO index for mortality within our cohort (WP2, objective ii).

However, in relation to predicting respiratory hospitalisation, which is an important outcome to consider, current models have moderate discriminative ability. This suggests that other relevant predictors are missing from these prognostic models. We therefore derived a new COPD prognostic model, the BLISS index, for use in a primary care population (with 2-year respiratory hospitalisation as primary outcome and all-cause hospitalisation, exacerbations, primary care consultations and mortality as secondary outcomes), using recommended statistical techniques (WP2, objective iii, draft paper; see Appendix 4).

What we did (objective ii)

We validated the ADO index using data from 1701 patients from the Birmingham COPD cohort study (case-found or on the practice COPD register) who had complete data for the variables required for this study. We externally validated the ADO index for predicting 3-year mortality, with 1- and 2-year mortality as secondary end points. Discrimination was calculated using area under the curve (AUC), also known as the c-statistic, and calibration was assessed using a calibration plot with locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) and measures such as the calibration slope. In sensitivity analyses, we included only patients with existing COPD and those with complete data.

What we found (objective ii)

The ADO index was discriminatory for predicting 3-year mortality (c-statistic 0.74, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.79), with similar discriminatory ability for 1- and 2-year mortality (c-statistic 0.73, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.80, and c-statistic 0.72, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.76, respectively). The ADO index overpredicted mortality at each time point, which was more pronounced at 1- and 2-year mortality time points (calibration slopes 0.95, 0.79 and 0.79 for 3-, 2- and 1-year mortality, respectively) and in those with higher baseline ADO scores. Thus, although the ADO index shows promising discrimination in a primary care population, the model may need to be recalibrated if the ADO index is used to provide well-calibrated risk predictions for 1- or 2-year mortality. Discrimination and calibration were similar in sensitivity analyses.

What we did (objective iii)

To develop and internally validate a new prognostic model in primary care to predict respiratory hospital admissions within 2 years, we linked self-reported and clinical data for all patients with COPD from the Birmingham COPD cohort (331 case-found and 1558 previously diagnosed) with routine HES obtained through NHS Digital. The primary outcome for the prognostic model was the occurrence of a respiratory-related hospital admission (using primary diagnostic codes) from entry to the cohort study up to 2 years (May 2012 to June 2014). Secondary analysis considered outcomes during the full period until the NHS Digital data were obtained (1 April 2016). The maximum follow-up time was around 4 years.

A list of 23 candidate variables was drawn up based on those included in other models for COPD, along with other variables identified by a consensus panel comprising study investigators, clinicians and patients. The degree of airflow obstruction was deemed clinically important but, owing to the documented statistical problems with the commonly used FEV1% predicted (FEV1 as a percentage of what would be predicted as normal),75 the best variable to be included in the model was not clear. We therefore tested three variables as candidate predictors in the model [FEV1% predicted, forced expiratory volume in 1 second quotient (FEV1Q), and FEV1/height2]. With 267 events for the primary outcome, up to 26 candidate variables could be used, based on the rule of thumb of 10 events per candidate variable. 90

The model was developed using backward elimination with p < 0.157 for retention. Fractional polynomials were considered and multiple imputation using chained equations was used for missing data. Discrimination was assessed using the c-statistic and calibration was also assessed. Bootstrapping was used for internal validation and the optimum-adjusted performance statistics were presented. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using only those with previously diagnosed COPD.

What we found (objective iii)

Over a median follow-up of 2.9 years (range 1.8 to 3.8 years), 382 participants (16%) had a respiratory admission and 267 (12%) had a respiratory admission in the primary 2-year period. Participants with hospitalisations were more likely to be older (70.3 vs. 67.0 years; p < 0.001), be male (66% vs. 59%; p = 0.017), be more deprived [median Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score of 30.3 vs. 24.4; p = 0.0025], have a lower body mass index (BMI) (mean 28.2 vs. 28.8 kg/m2; p = 0.108), have more severe airflow obstruction (mean FEV1% predicted 56.5% vs. 75.2%), have worse dyspnoea [Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea grade 3 57.5% vs. 51%; p < 0.001] and have worse quality-of-life scores (median CAT score 24 vs. 17; p < 0.001). They were more likely to report previous exacerbations based on the use of antibiotics or steroids (60% vs. 43%; p < 0.001) and to report previous hospitalisations in the previous 12 months (18.4% vs. 2.6%; p < 0.001). Participants with hospitalisations were also more likely to report a higher rate of vapours, gases, dusts or fumes (VGDF) (71% vs. 62%; p = 0.004), to report exposure to smoking (31% vs. 27% current smokers; p = 0.019) and to have diabetes (24% vs. 15%; p = 0.001) and cardiovascular disease (20% vs. 15% with coronary heart disease; p = 0.049).

Using a pragmatic approach to model development, and including only variables that are widely available or feasible to obtain in primary care, six variables were retained in the final developed model: age, CAT score, respiratory admissions in the previous 12 months, BMI, diabetes and FEV1% predicted. After adjustment for optimism, the primary model performed well in discriminating between those who will and those who will not have 2-year respiratory admissions (c-statistic 0.75, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.79). Four further variables were included in the secondary analysis but had similar score performance. Sensitivity analysis with prevalent COPD cases resulted in an identical apparent c-statistic but included smoking status in addition to the six variables in the primary model. Overall, the BLISS score may perform better in predicting respiratory admissions than the scores currently available, but further research is required to compare this model with existing ones in other data sets. Important next steps are external validation, proposing and evaluating a model of use to guide patient management, and exploration of the best ways to implement such a score in primary care practice.

Strengths and limitations

We used recommended and up-to-date approaches for our validation study and model development, overcoming limitations of previous studies. Using data from a research cohort (the Birmingham primary care COPD cohort) meant that measurements were of high quality and undertaken at prescribed time points. However, the cohort population may not be fully generalisable to primary care because patients with more severe disease who were housebound were excluded. Including screen-detected patients was a strength and limitation but sensitivity analyses excluding these patients did not substantially alter the findings. For model development, although the variable components for the score are relatively simple, these may not be routinely collected or available, and calculation of the score requires software.

Objective (iv): to explore barriers to and enablers of participation in physical activity among people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care (work package 2, published)91

Rationale

Although the majority of people with COPD who are likely to be detected through case-finding could be offered evidence-based interventions, there are few effective interventions for those with milder disease. One intervention that has received increasing interest is exercise. Observational studies have reported an association between higher PA levels and lower morbidity92–94 across the full range of COPD severity. Exercise is the cornerstone of pulmonary rehabilitation programmes (PRPs), which have been shown to have a positive impact on COPD symptoms and prognosis. 95 However, PRP provision is limited and uptake is low. 96 To better understand the motivation for PA engagement among people with COPD in the community, we explored perceived barriers and facilitators among people with COPD using the framework from social cognitive theory.

What we did

A purposive sample of 26 patients (age range 50–89 years; men, n = 15) from the Birmingham COPD cohort study, with a range of COPD severity, was recruited to participate in one of four focus groups. Thematic analysis was undertaken to identify key concepts related to their self-efficacy beliefs.

What we found

Several barriers to and enablers of PA closely related to self-efficacy beliefs and symptom severity were identified. The main barriers were health-related (fatigue, mobility problems, breathing issues caused by the weather), psychological (embarrassment, fear, frustration/disappointment), attitudinal (lack of feeling in control of their condition, disregard of PA benefits, older age perception) and motivational. The main enabling factors were related to motivation (PA as part of caring duties, deriving enjoyment from activity or the social aspects), attitudes (positive view of PA), self-regulation (e.g. keeping to a routine) and performance accomplishments (sense of achievement in fulfilling personal goals). This information can help to tailor management of people with COPD.

Strengths and limitations

The use of social cognitive theory in this study was novel, and allowed the identification of personal barriers related to perceptions, motivation and attitudes towards physical activity, which went beyond the external barriers identified in previous studies. This understanding can inform interventions that have the potential to improve attendance and adherence. Furthermore, by including distinct subgroups of patients, we identified context-specific factors, such as barriers specific to those who are in paid employment, thereby informing the tailoring of future interventions.

However, the study participants predominantly had mild to moderate COPD and so the findings may not reflect the views of those with more severe disease. Furthermore, the voluntary nature of participation may have meant that the views of some who were less interested in PA were not included. The emergence of themes may also have been influenced by the use of social cognitive theory, and potentially different themes might have dominated had a different theoretical framework been used.

Other collaborations and analyses of cohort data

One of the aims of establishing a cohort was to allow it to become a platform for testing other hypotheses and interventions. As a result, several groups, including postgraduate students and other collaborators, worked with us to introduce discrete questions in some of the follow-up questionnaires or undertook analyses from the data collected for the cohort study. The main substudies are described below.

Cohort data used for analyses leading to a PhD thesis: Buni97

Rationale

There has long been uncertainty about the nature and prognosis of people with chronic respiratory symptoms who do not yet meet the accepted airflow obstruction criteria for COPD. 98 In 2001, the GOLD committee included an additional ‘at-risk’ stage in the description of COPD patients with a view to considering early interventions. Patients in this stage (known as GOLD stage 0) were thought to be ‘at risk’ of developing COPD in the future. 61 However, in 2006, GOLD stage 0 was removed from the classification owing to a lack of supporting evidence regarding progression to diagnosed COPD. Nevertheless, there remain many patients (particularly smokers) in the population with such symptoms; some patients even carry a formal diagnosis of COPD and are therefore potentially ‘overdiagnosed’. It is debated whether these patients represent a group with ‘pre-clinical’ COPD or if they have other conditions that explain their symptoms. We undertook a range of primary and secondary data analyses to help answer these questions.

What we did

We undertook three linked systematic reviews to identify and assess published studies that (1) examined the risk of developing COPD among GOLD stage 0 patients compared with the normal population, (2) examined the prognosis of GOLD 0 patients compared with established COPD patients and/or (3) evaluated factors that affected the prognosis of GOLD 0 patients. The primary studies included analysis of (a) data from the 2010 Health Survey for England (HSE)99 to evaluate the independent effect of respiratory symptoms by airflow obstruction on quality of life, (b) cross-sectional data from the Birmingham COPD cohort study to compare the characteristics and health outcomes of GOLD 0 patients with newly diagnosed (case-found) COPD patients who had airflow obstruction and (c) cross-sectional data from the Birmingham COPD cohort study to compare the characteristics and health outcomes of people on the GP COPD register who did not have airflow obstruction (overdiagnosed) with those of people who had spirometric obstruction.

What we found

The systematic reviews revealed very few published studies evaluating the prognosis of people with GOLD 0 symptoms, and the studies that were found were heterogeneous in design, populations and outcomes. A tentative conclusion was that those with GOLD 0 symptoms may show faster decline in FEV1 than the normal population, but the risk of developing COPD was not consistent. Persistent GOLD 0 symptoms may be an important predictor of development of COPD and FEV1 decline. Persistent symptoms were associated with continued smoking and, in some studies, the presence of metabolic syndrome. GOLD 0 patients had similar risks of mortality to GOLD 1 patients, and those who were current smokers had similar risks to GOLD 2 patients. GOLD 0 patients often had similar health-care use to established COPD patients.

The HSE analyses revealed a gradient of effect on quality of life from ‘normal’ to those with COPD. Asymptomatic patients with airflow obstruction only were much more similar to ‘normals’, and those with GOLD 0 were more similar to those with both symptoms and airflow obstruction (i.e. defined as COPD). Dyspnoea and wheeze were more strongly associated with poor quality of life than chronic productive cough.

Analyses of the Birmingham COPD cohort showed that GOLD 0 patients had similar consumption of health-care resources to those newly identified with COPD, additionally indicating similar quality of life, exercise capacity and exacerbation-like events in these two groups. GOLD 0 patients were more likely to be female, to be obese and to have multiple comorbidities (e.g. cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes and depression) than diagnosed COPD patients, but they were not more likely to have either diagnosed or undiagnosed asthma (assessed using GOLD/ATS definition of bronchodilator reversibility; a change of > 12% of baseline FEV1 if this exceeds 200 ml). Overall, 10% had reversible airflow obstruction suggestive of asthma.

Overdiagnosed COPD patients (≈14% on UK COPD registers) were also more likely to be female, to have never smoked and to be obese (19% had restrictive pattern disease) and were slightly more likely to have multiple comorbidities. Around 20% of these patients had spirometric abnormalities consistent with restrictive lung disease. Their quality of life, exacerbation history, exercise capacity and health-care utilisation were very similar to those of GOLD 0 patients.

In conclusion, the presence of respiratory symptoms is epidemiologically and clinically relevant. GOLD 0 patients have similar poor quality of life and health-care consumption to those with mild COPD. It is still uncertain whether this group will develop COPD or if they are ill because they have other conditions. It is also possible that spirometric criteria for defining COPD need to be reconsidered. Future longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate GOLD stage 0 and to inform management guidelines that may include earlier interventions. This is important to help improve patients’ quality of life, reduce the risk of misdiagnosis and reduce inappropriate health-care resource use.

Collaboration with Professor Mike Thomas from the University of Southampton: Brien et al.100

This analysis explored demographic factors, lung function/COPD-related symptoms and psychosocial/behavioural factors associated with quality-of-life impairment (using COPD CAT scores) in people with COPD. In a multivariable model, we showed that dyspnoea, illness perception, dysfunctional breathing symptoms and depression explained most of the impairment in quality of life. Thus, interventions targeting psychological factors could improve outcomes in people with COPD.

Linked trial funded through the NIHR National School of Primary Care Research: Jolly et al.101

This trial was a modification of a WP in the original programme grant, with additional funding. Overall, 577 people with earlier-stage COPD (MRC dyspnoea grade 1 or 2) were recruited from general practices (2014–15). Participants were randomised to a nurse-delivered telephone health coaching intervention (smoking cessation, increasing PA, medication management and action-planning) or usual care. Compared with usual care, participants in the intervention group reported significantly greater PA at 6 months.

Dickens et al.102

We obtained additional funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School of Primary Care Research to undertake a linked study to assess the accuracy of microspirometry as a screening tool for undiagnosed COPD. The relevant measurements were undertaken during cohort participants’ visits. We compared lung function measures obtained from the Vitalograph® (Vitalograph Ltd, Buckingham, UK) lung monitor with post-bronchodilator confirmatory spirometry. We found that the optimal cut-off point for the lung monitor was a FEV1/FEV6 of < 0.78, resulting in sensitivity of 82.8% (95% CI 78.3% to 86.7%) and specificity of 85.0% (95% CI 79.4% to 89.6%).

Cohort data used by Master of Public Health students: Khan et al.103

In this analysis, the extent of self-management behaviour and support reported by cohort participants was described. The majority of 1078 responders reported taking medications as instructed and receiving annual influenza vaccinations. However, only 40% had self-management plans and half reported never having received advice on diet/exercise. Fewer than half of current smokers had been offered help to quit in the previous year. Having a self-management plan was associated with better medication adherence and better disease knowledge.

Cohort data used as part of a PhD thesis: Kosteli104

One chapter is dedicated to the focus groups exploring the views of COPD patients on PA.

Work package 3: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and occupational performance

Objective (i): to examine factors associated with employment (published), absenteeism and presenteeism (published) among COPD patients of working age (work package 3)105,106

Rationale

Among those with COPD in the UK, approximately 40% are below retirement age; of these, 25% are not able to work. 107 Among those who continue to work, COPD is likely to affect work capability through sickness absence (9% of all certified absences) and working while unwell (presenteeism). 108 Data from other countries suggest that people with COPD (including undiagnosed109 and mild disease110) have a poorer employment history and retire earlier than people with normal lung function,111 but there were no data quantifying this in the UK, and no studies to examine presenteeism or productivity among working adults with COPD. Indirect societal costs attributable to COPD (largely owing to absenteeism) are high. Studies based on other conditions suggest that presenteeism costs may exceed those associated with absenteeism. 112 Few studies have examined which factors among people with COPD are associated with lower employment and work productivity. This information could inform future interventions, which could, in turn, improve patients’ work experience, thereby reducing the burden and societal costs related to COPD.

What we did

We undertook cross-sectional analysis of baseline data of patients from the Birmingham COPD cohort who were of working age. We compared the characteristics of those who were in paid employment with those who were not. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effects of sociodemographic, clinical and occupational characteristics on the likelihood of being employed. Using the subsample in paid employment, we examined characteristics associated with absenteeism (defined by self-report over the previous 12 months) and presenteeism (assessed using the Stanford Presenteeism Scale).

What we found

Among the 1889 people in the cohort who had COPD, 608 were of working age, of whom 248 (40.8%) were in work. Older age (60–64 years vs. 30–49 years: OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.65), lower educational level (no formal qualification vs. degree/higher level: OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.97), poorer prognostic score [highest vs. lowest quartile of modified BODE score: OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.33] and history of high occupational exposure to VGDF (high VGDF vs. no VGDF exposure: OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.85) were associated with a lower probability of being employed. Only the degree of breathlessness component within the BODE score was significantly associated with employment. Among those who were in paid employment, degree of breathlessness was the only factor associated with both absenteeism (high absenteeism in severe vs. mild dyspnoea: OR 1.84, 95% CI 0.54 to 6.27; p < 0.01) and presenteeism (working while unwell in severe vs. mild dyspnoea: OR 18.11, 95% CI 2.93 to 112.21; p < 0.01). Additionally, increasing history of occupational exposure to VGDF was independently associated with presenteeism (poor presenteeism in medium/high exposure vs. no exposure: OR 4.34, 95% CI 1.26 to 14.93; p < 0.01).

Based on these findings, future interventions should focus on managing breathlessness and reducing occupational exposures to VGDF to improve work capability among those with COPD.

Strengths and limitations

The inclusion of a wide range of patients with COPD from primary care, including case-found patients, was novel. The assessment of occupation in detail and linking with a job exposure matrix to estimate VGDF exposure was a strength. However, overall, the sample of participants in paid employment was small and the wide CIs for several estimates suggest that there was insufficient power to clarify associations. We did not have objective measures of absenteeism and some other measures were also based on self-report, which may introduce errors.

Objective (ii): to examine how disease progression (lung function decline, exacerbation) over time is associated with occupational performance (employment, absenteeism and presenteeism) among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in employment (work package 3, manuscript in preparation)

Rationale

The burden of COPD on the working population is high. The relationship between sickness and disability and unemployment is poorly understood and could be better informed by longitudinal follow-up. A number of factors, including sociodemographic characteristics, the general economic environment and the severity of chronic disease, have an impact on employment and an individual’s ability to work. We undertook longitudinal analysis to examine how disease progression is associated with occupational outcomes, adjusting for clinical, sociodemographic, occupational and labour market factors.

What we did