Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1210-12015. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Murtagh et al. This work was produced by Murtagh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Murtagh et al.

SYNOPSIS

Background

The clinical challenge

People in the last year of life often suffer complex and multiple symptoms and distress because of their illness or impending death. 1–3 Functional status often deteriorates as the illness progresses, leading to increased dependency and greater care needs. 4 The families of those affected experience their own fears and losses. 5

This occurs across a wide range of different life-limiting illnesses. Symptoms, distress, functional trajectories and family support needs have been most widely studied in cancer, but other life-limiting conditions (e.g. advanced cardiac and respiratory diseases, progressive neurological conditions, dementia, end-stage kidney disease and advanced liver disease) bring equally challenging symptoms and support needs. 6,7 Family support is particularly important if bereavement is to be well negotiated8 and future psychological health maintained. 9

As the population age distribution changes, these needs are also extending over longer time periods as the length of time living with advanced illness increases. 10

Specialist palliative care: provision and inequities

Palliative care has developed to meet these complex needs of patients and families facing advanced progressive illness. It addresses physical and psychological symptoms and gives social, practical and spiritual support in the last months of life. 11 The UK ranked first in the 2015 Quality of Death Index, a measure of the quality of dying across 80 countries,12 with UK hospices leading the way internationally, providing a world-leading model of excellence in palliative care.

However, the work of UK hospices – which deliver both inpatient and home-based specialist palliative care – has often come from grass-roots and local initiatives, meaning that there are marked geographical inequities in provision across England. Much of hospice and specialist palliative care is funded from the charitable sector; in 2018, charities contributed £3 for every £1 from the NHS. 13 The balance between NHS and charitable funding varies markedly around the country;13 this and other factors has led to major inequities in palliative care provision.

A UK government-commissioned review into specialist palliative care14 found high levels of inequity in the provision of palliative and end-of-life care. There was diversity in the type and range of providers in any one geographical area15 and inequity in both the amount of funding (with money spent by the NHS in 2010 ranging from £186 to £6213 per person who died) and the source of funding (with the proportion funding coming from the NHS varying from 0% to 62%). 14 This could not be accounted for by variations in the populations served. 14

Even more marked variation in the commissioning of palliative services across England has been demonstrated more recently. 16 A ‘north–south’ divide has been identified,17 with substantial differences in the average time from referral to death between providers in the north and south of England. This is important: the benefits of specialist palliative care are notably greater if delivered earlier in the illness trajectory. 18

Older people and those with non-cancer diagnoses are also less likely to access specialist palliative care,19,20 often resulting in a poor match between individual needs, the resources provided to meet those needs and the health outcomes achieved.

Substantial differences in the approach to commissioning services suggests provision rather than population demographics account for a large component of the variation. 16

The research gap

One major challenge in improving our ability to better match resources to needs is the lack of research into what accounts for these apparent inequities in provision and – in particular – a lack of a standardised way to assess and monitor palliative care needs. With growing constraints on resources, it is becoming imperative for individual-level needs to be mapped accurately to reduce inequities, match resources to needs and improve the quality, consistency of provision, and efficiency of palliative care. This has been endorsed as a high priority nationally,14 but there is very limited evidence available to inform the best ways to match individual-level needs to resources. Most importantly, there is no ‘standard’ way to assess, capture and report the palliative care needs of individual people with advanced illness. This programme of research directly addresses this research gap.

What we already know

Illness in the last year of life places major resource burden on the NHS. Up to 20% of healthcare expenditure is spent on the last year of life. 21 Total NHS expenditure in 2017/18 was around £122B in England22 – roughly £2200 per person – indicating that around £25B per year is spent on health care in the last year of life. Much of this is on acute care, but it is estimated that palliative care is needed for about 75% of all those approaching death. 23

The amount of health and social care resources spent on those in the last year of their life is increasing and will increase further in coming years. Ageing populations, greater co-morbidity and longer chronic disease trajectories are all increasing this demand. 24,25 However, this is not a simple relationship; commonly used approximations of health, such as age or mortality, are not enough to capture the complex dynamics in healthcare requirements. 26 Population ageing particularly increases expenditures on acute and long-term care. 27 In this context, it is increasingly important to recognise palliative care needs and ensure they are effectively addressed with the best possible use of scarce resources.

Palliative care needs

Assessment of patients’ needs plays an important role in improving outcomes in palliative care. Patient-reported outcomes – where ‘outcome’ here is defined as a ‘change in current or future health status following intervention’28 – are a way of measuring the changes in patients’ health that they themselves perceive over time. These outcomes allow for assessment of intervention effectiveness. In terms of addressing needs, there is increasing evidence that home, hospital and inpatient specialist palliative care is effective and significantly improves patient outcomes, particularly for cancer patients with reduced pain and other symptoms, reduced anxiety, and reduced hospital admissions. 29 Similar evidence is emerging for patients with non-malignant disease. 30–32

Further systematic reviews,29,33,34 including meta-analyses and Cochrane reviews,35,36 and randomised controlled trials of specialist palliative care services30,37 provide consistent evidence of the effectiveness of palliative care services in improving symptoms, reducing family burden, improving satisfaction with care and preventing depression. There is wide acknowledgement that palliative care should be available to all, based on need not diagnosis and extending across settings,38,39 and these principles underpin the NHS End of Life Care Strategy. 40

Given the complexity of problems experienced in the last year of life, it is not surprising that a high proportion of healthcare resources is spent during this time: as much as 20% of all healthcare expenditure. 21 However, some of this may be poorly spent: hospital admissions may be prevented by better anticipatory symptom control, better family support and earlier facilitation of advance discussions about patient and family preferences for treatment and care. 41,42 Robust studies demonstrate improved patient outcomes and reduced costs when palliative care is provided early30,37,43 and a systematic review of trials of palliative care interventions shows greatest positive impact on quality of life when these interventions are provided early. 18

Casemix classifications: a potential way forward

Within health care, there is increasing use of casemix classifications to help gain a better understanding of how healthcare resources might be allocated in an equitable yet efficient way. Casemix classifications are based on patient-level criteria, which allow the grouping of patients into classes in terms of the resources needed to meet their needs. 44 Casemix is defined as ‘a means to classify patients into groups in order to provide a useful measure to make meaningful performance comparisons, to cost healthcare, or to fund it’ (information from NHS Digital, licenced under the current version of the Open Government Licence). 45 Casemix classifications are defined as ‘a system assigning each person [patient] into a hierarchical system of groups or classes, according to various individual casemix criteria. Each group or class is associated with higher or lower resource requirement to meet needs.’46

The USA developed such casemix classifications, including diagnosis-related groups (DRGs)47 and these have been used to develop prospective payment systems globally. 48 DRGs are a useful classification of healthcare needs driven by the diagnosis, but have been shown to be inappropriate for some areas of health care, such as mental health,49 primary care50 and palliative care. 46,51

Palliative care needs are not diagnosis-driven, but instead by factors such as functional status, physical symptoms and emotional burden. 51 Palliative care needs a consistent method of classifying types of patients with complexity of needs, treatment and costs, using casemix criteria. 52–54 Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs) underpin the main casemix classification adopted in England. 44

It is necessary therefore to identify those with more complex palliative needs and requiring more resources. 55 An Australian casemix classification for palliative care was developed in 1997, empirically tested and progressively refined over time. 52–54 The Australian casemix classification consists of classes defined by five criteria most strongly predictive of resource use: Phase of Illness, problem severity, functional status and dependency, age and model of care. 55 Full class definition and categorizations are available at https://ahsri.uow.edu.au/pcoc/index.html (accessed 12 December 2021). Its implementation proved it was possible to consistently and routinely collect casemix data nationally;56 this has enabled consistent casemix adjustment in outcome measurement, with year-on-year improvement in outcomes at a national level and a funding model which matches patient’s needs. 51,57 Palliative care funding pilots in the UK have also suggested casemix data may be useful for these purposes. 58 However, it is unclear whether or not, and how, any existing palliative care classification can be easily applied to the UK to address unmet needs and reduce inequities.

What we do not know

Although casemix classifications have been widely used to manage resources across health care, they have rarely been applied to palliative care. Existing classifications (i.e. DRGs and HRGs) are based on diagnoses, but for patients receiving palliative care the priority is not on diagnosis but enhancement of well-being and quality of life, and the maintenance or maximisation of current health status in the face of advanced incurable illness. 52 A palliative care casemix classification must reflect these different goals. 53,54,57

Australia is the only country to have developed such a casemix classification for palliative care. 57 Diagnosis and procedure criteria were found to be ineffective in classifying the complexity of needs for those receiving palliative care. 53 Instead, palliative Phase of Illness and ‘problem severity’ were better indicators of increased complexity and consequent greater resource use. 56,59 Despite these advances, key questions remain unanswered:

-

How can the wide range of patient needs in palliative care provision best be classified across conditions and settings, so that services can be resourced to meet individual needs and deliver best outcomes? Without such a classification, it is difficult to ensure that sufficient resources can be matched to the right patient at the right time.

-

Within such a classification, how is complexity best understood/captured so that commissioners can commission, and providers can deliver, the optimal mix of services?

-

What are the best criteria for palliative care casemix? It is internationally acknowledged that diagnosis and procedures are not useful criteria in palliative care casemix categorisation53,57 and UK specialist palliative care providers seek a model more attuned to patient needs across wide-ranging levels of complexity.

-

What are the most useful patient-level data in palliative care? There is a lack of specific patient-level data in palliative care with which to model casemix and resource use. 14 This is especially true in community settings, where provision cuts across the NHS and voluntary sectors. 60,61

-

What evidence do we have to build on? Some work has been undertaken in recent palliative care funding pilots,58 but no evidence has been published from these to help determine which casemix criteria are optimal for use in England.

Rationale for our approach

This programme responds to these challenges by developing a palliative care casemix classification across conditions and settings. Recent UK initiatives to improve the provision of high-quality palliative care40,62 have not addressed the challenges of classifying needs and costs.

Worldwide, different palliative care funding models exist,63 but a formal palliative care casemix classification has been developed only in Australia. This Australian casemix classification incorporates functional status/dependency with problem severity and palliative Phase of Illness,57 and adopts a blended funding model. 64 There is no existing palliative care classification easily transferable to the UK, but the Australian model is a valuable starting point.

This programme leads directly to patient benefit through the improved matching of resources to needs at the individual patient-level, with corresponding outcome measurement, along with more effective and cost-effective use of resources through the following work:

-

the development of better patient-centred outcome measures that are relevant and meaningful for patients with advanced illness and their families

-

the development of a ‘standard’ way to assess, capture, and report the palliative care needs of individual people with advanced illness

-

the development of a casemix classification – casemix ‘classes’ based on individual-level criteria – which can predict the resources needed to address the symptoms/concerns of people with advanced illness needing specialist palliative care.

This approach has been directly recommended by the Palliative Care Funding Review,14 and we have liaised closely with NHS England in progressing this work.

Aims and objectives of the C-CHANGE programme

Aims

The aims of the C-CHANGE programme were to report the costs of specialist palliative care; develop and test a person-centred, nationally applicable casemix classification for adult specialist palliative care provision in England; accurately capture the complex needs of patients with advanced disease in last year of life; better quantify those needs; and support more equitable allocation of resources to meet them.

The programme also aimed to identify ways to measure the improvements in health status and well-being which patients and families experience following specialist palliative care so that the casemix classification could be developed, but also so that quality and effectiveness of services can be more readily demonstrated to patients, families, commissioners and services.

Objectives

The C-CHANGE programme had five objectives:

-

to refine, validate or test new and existing person-centred outcome measures to assess the main health status and symptoms/concerns of, and services received by, patients and families receiving specialist palliative care

-

to utilise the perspectives of key stakeholders (i.e. patients, families, professional caregivers, commissioners and policy-makers) on complexity in palliative care to inform subsequent casemix development

-

to understand the criteria which distinguish different models of palliative care to help inform how a casemix classification and per-patient funding models can best be utilised across different models of specialist palliative care

-

to develop a person-centred palliative care casemix classification, based on individual patient and family needs and costs of care, for adults with both cancer and non-cancer conditions in the last year of life

-

to test this person-centred palliative care casemix classification in terms of its ability to predict resource use in last year of life and to better understand transitions between services in order to improve care.

Overall design of the C-CHANGE programme

The C-CHANGE programme comprised six workstreams (see Figure 1):

-

Workstreams 1, 2, 3 and 4 ran consecutively.

-

Workstream 5 ran concurrently with workstreams 1, 2, 3 and 4 to integrate each workstream into the overall programme of work.

-

Workstream 6 also ran concurrently with workstreams 1, 2, 3 and 4, to maximise dissemination and outputs throughout the programme.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram for the C-CHANGE programme.

Changes to the overall programme design

We amended/expanded three components of the original workplan:

-

In workstream 1, emerging psychometric evidence changed the extent to which we needed to undertake validation of the different measures. We added a study of Phase of Illness, as new evidence56 confirmed Phase of Illness would potentially be a key casemix criteria.

-

During workstreams 1 and 2, as a direct result of input from our patient and public involvement (PPI) group, we added a patient experience measure and included an additional secondary analysis to understand the role of uncertainty in the care needs of patients and families with advanced illness.

-

Within workstreams 3 and 4, we studied the models of specialist palliative care operating at the participating sites in more detail; the need for this became apparent as we tried to characterise models of palliative care in the context of a rapidly changing healthcare environment.

Workstream 1: measures and training

Workstream 1 (‘measures and training’) was designed to meet objective 1: to refine, validate or test new and existing person-centred outcome measures to assess the main health status and symptoms/concerns of, and services received by, patients and families receiving specialist palliative care (for use in workstreams 3 and 4).

As planned, we undertook full validation of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS), which was the key measure of patients’ symptoms and other concerns in workstreams 3 and 4. We also undertook further testing of the palliative Phase of Illness measure, which had limited previous psychometric assessment, mostly of reliability. 59 After discussion with our PPI group, we also adapted and tested an experience measure: Views on Care (VoC).

The following other measures adopted for workstreams 3 and 4 already had published validation work (or this work emerged before the commencement of workstream 1):

-

the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI),65 including adaption for palliative care66

-

the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview – validity of the short version with 6 items,67 including in advanced illness68

-

the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form –12 (+ 4),69 including in advanced disease70

-

the Australian-modified Karnofsky Performance Scale (AKPS) – an adapted version of the widely-used Karnofsky Index to measure functional status and activity. 71

We also undertook training of all participating sites in the use of the measures for workstreams 3 and 4, as planned.

An added component of workstream 1 – at the request of our PPI group – was a secondary analysis of existing qualitative data to understand the role of uncertainty in assessing the care needs of patients and families with advanced progressive illness.

More details of the measures are available in Appendix 1.

Validation and testing of measures

Validation of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale– cognitive testing

This work has also been published in Schildmann et al. 72 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aim

Our aim was to explore patients’ views on the IPOS, with a focus on comprehensibility and acceptability, and to subsequently refine the questionnaire.

Methods

We carried out a cognitive interview study using ‘think aloud’ and verbal probing techniques. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. The IPOS was then refined according to findings. Purposively sampled patients were recruited from four palliative care teams across different settings.

Results

A total of 25 interviews were conducted. Overall, comprehension and acceptability of the IPOS were good. Identified difficulties comprised (1) comprehension problems with specific terms (e.g. ‘mouth problems’) and length of answer options; (2) judgement difficulties owing to, for example, the recall period; and (3) layout problems.

Validation of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale: full validation study

This work has also been published in Murtagh et al. 73

Aim

Our aim was to validate the IPOS, a measure underpinned by early psychometric development, by evaluating its validity, reliability and responsiveness to change. 73

Design

We designed a validation study for both the patient self-report and staff proxy-report versions of the IPOS. We tested construct validity (factor analysis, known-group comparisons and correlational analysis), reliability (internal consistency, agreement and test–retest reliability) and responsiveness (through longitudinal evaluation of change).

Results

We recruited 376 adults receiving palliative care and 161 clinicians from a range of palliative care settings. We confirmed a three-factor structure (physical symptoms, emotional symptoms and communication/practical issues). 73 The IPOS showed a strong ability to distinguish between clinically relevant groups; total IPOS and IPOS subscale scores were higher (i.e. reflected more problems) in those patients with ‘unstable’ or ‘deteriorating’ versus ‘stable’ Phase of Illness (F = 15.1; p < 0.001). Good convergent and discriminant validity was found for hypothesised items and subscales of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General. 73 The IPOS showed good internal consistency (α = 0.77) and acceptable-to-good test–retest reliability (60% of items kw > 0.60). Longitudinal validity in the form of responsiveness to change was good.

To assess how palliative Phase of Illness related to the other measures

This work has also been published in Mather et al. 74

Aims

Our aim was to describe function, symptoms and other palliative care needs according to Phase of Illness, and to consider the strength of associations between these measures and Phase of Illness.

Design and setting

We performed a secondary analysis of patient-level data for a total of 1317 patients in three settings. Function was measured using the AKPS. Pain, other physical problems, psycho-spiritual problems and family and carer support needs were measured using the Palliative Care Problem Severity Scale (https://documents.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@chsd/documents/doc/uow272193.pdf; accessed 21 August 2023).

Results

The AKPS and Palliative Care Problem Severity Scale items varied significantly by Phase of Illness. Mean function was highest in the stable phase [65.9, 95% confidence interval (CI) 63.4 to 68.3] and lowest in the dying phase (16.6, 95% CI 15.3 to 17.8). Mean pain was highest in the unstable phase (1.43, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.51). In multinomial regression, psycho-spiritual problems were not associated with Phase of Illness (χ2 = 2.940, df = 3; p = 0.401). Family and carer support needs were greater in the deteriorating phase than the unstable phase [odds ratio (deteriorating vs. unstable) 1.23, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.49]. Overall, 49% of variance in Phase of Illness is explained by the AKPS and Palliative Care Problem Severity Scale.

A patient experience measure: Views on Care

This work has also been published in Pinto et al. 75

Context

When patients face advanced illness, their experience of care is especially important. In palliative care, we often rely on the accounts of bereaved relatives to report the quality of end-of-life care, and there are no patient-reported measures of the experience of care. Our PPI group challenged us to consider and address this omission. We derived and tested a new questionnaire, called Views on Care (VoC), to address this gap.

Measure development

After research team, PPI group, and steering group discussions, VoC was derived from four questions selected from St Christopher’s Index of Patient Priorities76 that address patients’ evaluation of changes in experience of palliative services, and quality of life [the quality of life items are adapted from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire – 15 items measure (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL), which is well-validated in advanced illness]. 77 The St Christopher’s Index of Patient Priorities itself was considered too long.

Methods

We conducted a survey to examine patients’ views on care and the relationship between these views and changes in health status. Participants were adults receiving specialist palliative care in eight hospital, hospice inpatient and community settings across England. We collected demographic details, plus a patient-reported survey at baseline and follow-up. We reported VoC at follow-up, and change in health status (measured using the IPOS) between baseline and follow-up. Descriptive statistics characterise sample demographics and VoC responses, and the chi-squared statistic tests the association between VoC scores and IPOS change scores. IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used throughout. Ethics approval was obtained from the Dulwich National Research Ethics Committee (REC), London, UK (reference number 124991).

Results

A total of 212 participants were recruited, with a mean age of 65.84 years [standard deviation (SD) 13.5 years]; 137 participants completed both baseline and follow-up surveys. Responses to VoC items 1, 3 and 4 were reasonably normally distributed. Responses to VoC item 2 were positively skewed with most participants indicating that palliative care was giving positive benefit. Participants reporting that ‘things had got better’ (item 1) were more likely to have improved overall outcomes (reduction in IPOS total score: χ2 = 6.057; p = 0.48). With regard to IPOS subscales, there was significant positive association between those reporting that ‘things had got better’ (item 1) and improved outcomes on the IPOS physical symptoms subscale (χ2 = 11.254; p = 0.004). Patients reporting benefit from palliative services (item 2) were more likely to have improved scores on the IPOS communication/practical issues subscale (χ2 4.743; p = 0.051).

Exploring uncertainty in relation to palliative care needs

This section has been reproduced with permission from Etkind et al. 78 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aim

Our aim was to understand patient experiences of uncertainty in advanced illness and develop a typology of patients’ responses and preferences to inform subsequent research in this programme.

Design

We performed a secondary analysis of qualitative interview transcripts. 78 Studies were assessed for inclusion and interviews were sampled using maximum variation sampling. Analysis used a thematic approach with 10% of coding cross-checked to enhance reliability. Qualitative interviews from six studies were analysed, comprising patients with advanced heart failure, end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, end-stage renal disease, advanced cancer and advanced liver failure. 78

Results

A total of 30 transcripts were analysed. The median patient age was 75 years (range 43–95 years) and 12 patients were women. The impact of uncertainty was frequently discussed: the main related themes were engagement with illness, information preferences, patient priorities and the period of time that patients focused their attention on (temporal focus). A typology of patient responses to uncertainty was developed from these themes (see Figure 2). 78

FIGURE 2.

Two different examples of patient responses to uncertainty, dependent on level of engagement, information preferences and temporal focus. Reproduced with permission from Etkind et al. 78 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Workstream 2: stakeholders’ perspectives on measuring complexity

This work has also been published in Pask et al. 79

Workstream 2 (‘stakeholders’ perspectives on measuring complexity’) was planned to meet objective 2: to utilise the perspectives of key stakeholders (i.e. patients, families, professional caregivers, commissioners and policy-makers) on complexity in palliative care to inform subsequent casemix development.

Aim

Our aim was to explore the perspectives of key stakeholders on complexity in palliative care to inform subsequent casemix development.

Methods

Design

We designed a qualitative study using semistructured interviews with key stakeholders in specialist palliative care.

Recruitment and consent

We undertook audio-recorded, individual interviews with various stakeholders across specialist palliative care. Participants were either recruited from one of the C-CHANGE participating sites for workstreams 3 and 4 or – for policy and national leads – sought out by the wider research team at the Cicely Saunders Institute (the leading UK research institute for palliative care). Within this frame, participants were sampled purposively, by personal and/or professional background, geographical location and experiences of settings of care (hospital, hospice and community).

Data collection

A topic guide was developed from a review of evidence on complexity, potential criteria for casemix already used46 or proposed,58 existing casemix classifications in palliative care57 and predictors of resource use in the last year of life. It was refined by our PPI group, by the research team, and through discussion with and feedback from the Programme Steering Committee.

Face-to-face, semistructured interviews were conducted by C-CHANGE researchers in the participant’s preferred setting. To increase the credibility of the data, interviewers summarised the interview back to each respondent, to allow the participant to verify the data and clarify any misconceptions or add additional information. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded, anonymised and transcribed verbatim to ensure confidentiality.

Analysis

Interviews were analysed independently by two researchers from the C-CHANGE team using the five analytical steps of framework analysis: (1) familiarisation, (2) identifying a thematic framework, (3) indexing, (4) charting and (5) mapping and interpretation. Framework analysis was considered the optimal approach to allow both an inductive and deductive approach, which would facilitate comparison across stakeholder groups and support the service delivery and policy focus of this research. Emerging themes were discussed with the whole C-CHANGE research team to improve the confirmability and dependability of the findings. Charts were created for each theme, grouped by stakeholder type, and were used to explore stakeholder assonance and dissonance among perspectives on each theme and subtheme. Analysis was managed using NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The framework was presented to the PPI advisory group, the Project Steering Committee and other qualitative research experts to refine and improve the presentation of the developed framework.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was gained from the King’s College London REC (BDM/14/15–2).

Results

Sixty-five participants – including patients and families – were recruited and interviewed (see Pask et al. 79 for full details of participant characteristics). Participants provided valuable insights into how complexity might best be understood. They largely understood and valued any use of individual person-level criteria to determine complexity and had nuanced perspectives on how this might be undertaken.

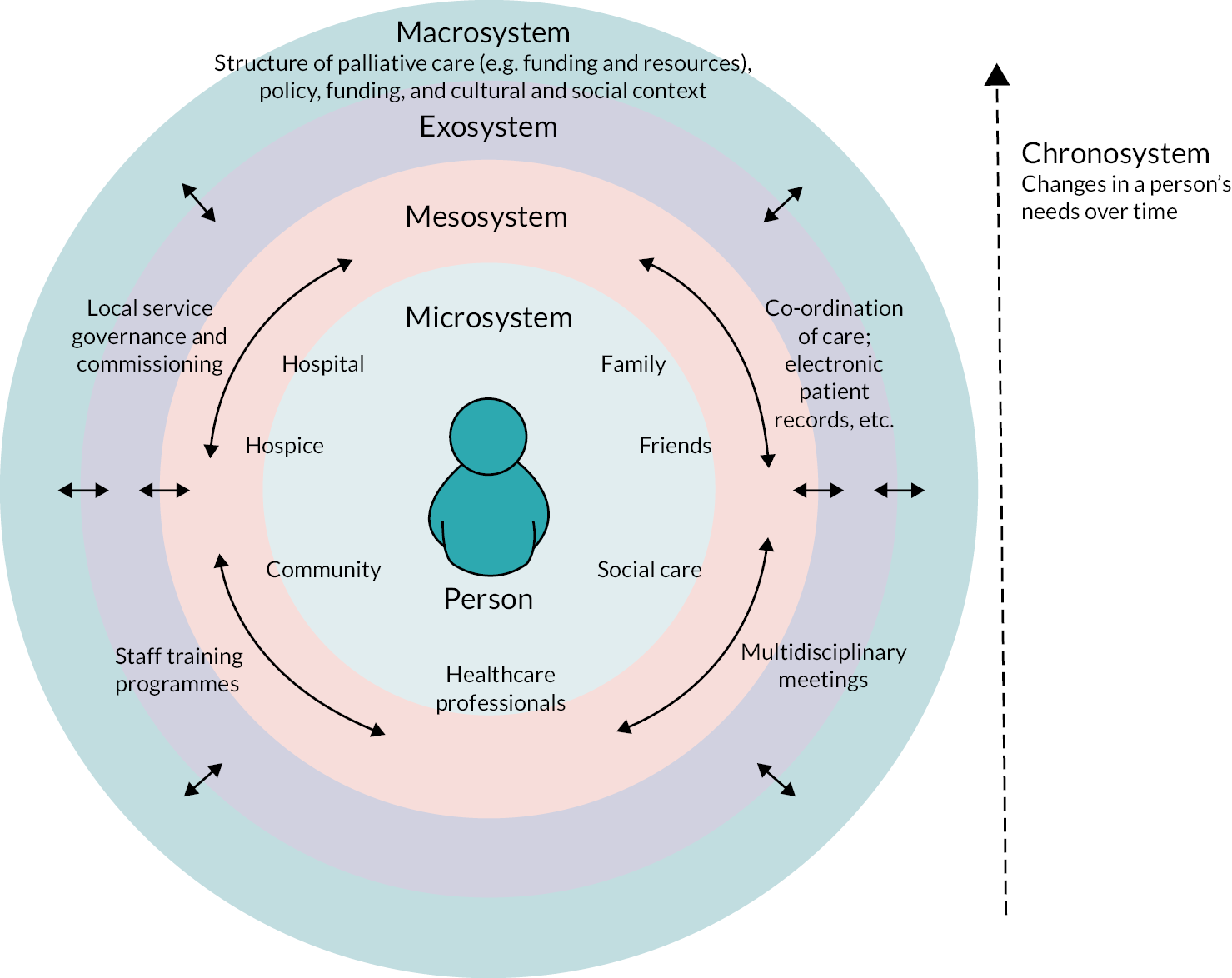

Based on these qualitative findings, we developed a theoretical framework – adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory80 – directly using the interview data provided by patient, family and professional participants to help understand complexity in specialist palliative care (see Figure 3). This framework emphasises that considering physical, psychological, social and spiritual domains (a classic approach in specialist palliative care) is not enough to characterise complexity. Other aspects – such as ‘pre-existing’ (often social), ‘cumulative’ and ‘invisible’ (such as unrecognised depression in the context of physical illness) complexity – are important too, yet frequently overlooked.

FIGURE 3.

A theoretical framework of complexity in the palliative care context. Reproduced with permission from Pask et al. 79 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The way in which professionals and services interact with people and their families was also considered to be crucial to assessing, understanding and responding appropriately to complexity. Number, severity, range and temporality of needs – as well as ‘hidden’ or overlooked aspects of complexity, as noted above – all needed to be considered in the development of a meaningful casemix classification for specialist palliative care.

Workstream 2: models of specialist palliative care

This work has also been published in Firth et al. 81

This work in workstream 2 (‘models of specialist palliative care’) was extended from that proposed in our original bid to meet objective 3: to understand the criteria which distinguish different models of palliative care, to help inform how a casemix classification and per-patient funding models can best be utilised across different models of specialist palliative care.

The originally planned work needed to be expanded to understand and describe the different models of palliative care, which were rapidly evolving in a changing healthcare environment (especially in community settings). This change was fully supported by the Programme Steering Committee and PPI group.

Aim

We aimed to understand the criteria which characterise and distinguish different models of palliative care. 81

Methods

Design

We developed a mixed-methods study with (1) semistructured interviews to identify criteria for models of care, (2) a two-round Delphi study to rank/refine these criteria and (3) structured interviews to test the acceptability and feasibility of these criteria. 81

Semistructured interviews

A rapid scoping review was conducted to identify literature related to models of palliative care. Original papers and reviews were examined for possible criteria which could help define models of specialist palliative care and a topic guide was created covering the 28 preliminary criteria identified from this literature. Semistructured interviews using a pre-specified topic guide were conducted with a range of palliative care service leads across organisations. 81

Delphi study

We selected Delphi survey methods for this second stage because it enabled us to present potential criteria derived from the semistructured interviews to all respondents, allowed them time to absorb this complex information at their own pace and enabled us to sample a wide range of views in a way that gave all opinions equal weight. A two-round Delphi survey of UK clinical, policy or PPI leads were invited from the Outcome Assessment and Complexity Collaborative network (a multidisciplinary network of professionals engaged in the implementation of outcome measures in specialist palliative care in England), and the national C-CHANGE sites. Participants were advised that we were aiming to establish a list of key criteria to describe and compare models of care. The Delphi survey was conducted to refine the criteria from the semistructured interviews, identify any additional criteria, achieve consensus on how each criterion was defined and rank the criteria in terms of importance. 81 CREDES (Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies in palliative care) guidelines were followed. 82

An online survey was developed using Bristol Online Survey (BOS) v1.0 Bristol, UK. 83 The survey was piloted for face validity prior to going live.

In the first Delphi round, panel members were presented with a list of 34 criteria. Participants were asked to state whether or not they agreed with the inclusion of each criterion as an important criterion for describing and comparing models of specialist palliative care (answering ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’) and their reasons for this. They were also asked to comment on the phrasing and clarity of the criterion, as well as the answer options listed. Finally, participants were asked to suggest any additional criteria they thought should be included. 81

Each criterion was retained if at least 75% participants answered ‘yes’. Free-text comments were analysed using content analysis and used to refine and expand the set of criteria.

In round 2 of the Delphi process, participants received anonymised feedback from round 1 and the amended list of criteria for further refinement and ranking. Participants were asked to rate the importance of each criterion for characterising and comparing different models of care on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important; 2 = not very important; 3 = important; 4 = very important; 5 = extremely important). In addition to the rating scales, participants were also given the opportunity to add additional free-text comments to help refine criteria and answer options. 81

Responses were analysed to capture both central tendency (median rating) and dispersion [interquartile range (IQR)]. Consensus was deemed to have been reached for criteria that received aggregated responses with an IQR of ≤ 1 and a median of 4 or 5. Both methods are considered to offer robust measurements for Delphi surveys. 84,85 Criteria reaching this consensus were then included in the final set.

Ranking responses were collated and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22. Free-text responses underwent content analysis and were used to refine the criteria and response options.

Structured interviews to test for acceptability and feasibility of the criteria

The criteria developed from the Delphi survey component were then tested with clinical leads from three different specialist palliative care settings (hospice inpatient care, hospital advisory teams and community-based care) using structured interviews. Participants consented to be interviewed and audio-recorded. The data from these interviews were classified according to the criteria used, and entered into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to identify whether or not the criteria could discriminate between services. 81

Ethics approval

Prior ethics approval for all three components was gained from the King’s College London REC (LRS-15/16–2449).

Results

Semistructured interviews

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 14 service leads from eight organisations, discussing 12 settings of care (five hospice inpatient units, two hospital advisory teams and five community teams).

An early finding was that the clinical leads struggled to know at which level within the organisation to describe their models of care. 81 It was often confusing when an organisation covered multiple settings of care (i.e. hospice inpatient, community, hospital inpatient and day services) and also provided multiple services within each setting, which often overlapped. For example, a hospice may have inpatient hospice, home care and ambulatory settings. Within any one of these settings, multiple services or teams were often operating. Within the day services there may be a physiotherapy clinic, a lymphoedema service and a day service, all operating with different models of care.

After all interviews were completed, out of the 28 criteria in the topic guide, 11 were not reported as useful and were removed; 17 criteria were refined; and a further 17 criteria were created. This resulted in 34 criteria to take forward to the Delphi survey. 81

Delphi survey

A total of 190 participants were invited to take part in the Delphi survey. Of the 190 clinical, policy and PPI leads contacted, 54 agreed to participate (response rate 28.4%).

Results of Delphi round 1

Out of thirty-four criteria, six were removed due to not reaching the 75% consensus rate, and one removed due to poor comprehension. Three new criteria were added:

-

How many referrals are accepted and seen annually by this service/team? (to reflect the size of service)

-

Does this service/team accept patient or family self-referrals? (to reflect the approach to self-referral)

-

Who undertakes the first assessment? (to reflect whether the model of care was doctor-led, nurse-led or another kind of model).

The out-of-hours criteria were heavily refined to improve comprehension and four new criteria relating to ‘out-of-hours’ were created. This resulted in a refined list of 34 criteria. 81

Results of Delphi round 2

Thirty participants (out of 54 in round 1) completed round 2 (60% response rate). In round 2, the 34 revised criteria from round 1 were ranked and rated, and criteria not meeting the predetermined consensus level were excluded. Sixteen criteria reached consensus (see Box 1).

-

Setting of care (inpatient hospital, inpatient hospice, home based, etc.)

-

Type of care delivered (‘hands on’ or advisory)

-

Size of service (measured by number of referrals accepted annually)

-

Number of disciplines delivering the care

-

Mode of care (face-to-face, telephone or other remote delivery)

-

Number of interventions available

-

Whether or not out-of-hours referrals are accepted

-

Whether or not out-of-hours care is available to patients already known to the service

-

Time when out-of-hours care available

-

Out-of-hours mode (face to face or advisory)

-

Type of out-of-hours provision (‘hands on’ or advisory)

-

Extent of education/training provided to external professionals

-

Whether or not outcome and experience measures are used in the service

-

Whether or not standard bereavement follow-up is provided

-

Whether or not complex grief follow-up is provided

-

The primary diagnosis of those patients receiving care (cancer/non-cancer)

-

Is the service a publicly funded or voluntary funded service?

-

Whether or not there are patient or family self-referrals

-

Whether or not there are standard discharge criteria

-

Purpose of care provided.

Copyright © 2023 Murtagh et al.

Structured interviews

Interviews were conducted with 21 service leads from 19 different services (six hospice inpatient, four hospital advisory and nine community settings). The responses to each criterion were compared to see if the criteria could distinguish and discriminate effectively between services. A further four criteria relating to context were also added (see Box 1); these were reported by the clinical leads as providing important context for the practical application of the criteria. These four contextual criteria were the purpose of the team, who funds/manages the team, the ability to self-refer and the discharging of patients. 81

Workstream 3: development of the casemix classification

The protocol for this study has been published55 was planned to meet objective 4: to develop a patient-centred palliative care casemix classification, based on individual patient and family needs, for adults with both cancer and non-cancer conditions in the last year of life.

Aim

Our aim was to develop a casemix classification for UK specialist palliative care, for use in hospital-based palliative care, inpatient hospices (palliative care units) and home-based palliative care.

Methods

Design

We designed a multicentre prospective cohort study, following patients during episodes of specialist palliative care and reported according to the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement. 86

Definitions

We defined an episode of care as a ‘period of contact between a patient and palliative care service provider or team of providers that occurs in one setting’. 87 A new referral into palliative care or change of setting (e.g. re-location into an inpatient setting from home/care home, or vice versa) signalled the start of an episode of palliative care. Discharge from palliative care, change of setting or death signalled the end of an episode of care. We defined the setting of care as one of three types: hospital advisory (hospital-based specialist palliative care teams providing an advisory or consultant service), inpatient hospice (where patients are admitted to a hospice or specialist palliative care unit for an overnight stay of one or more days) or community-based specialist palliative care (where the patient receives care in their usual place of residence, either at home or in a care home).

Population and settings

Patients were recruited from 14 organisations providing specialist palliative care services in England: four hospital advisory services, five inpatient hospice services and seven community-based services (some organisations provided more than one setting of care). Sites were selected to ensure our study sample was representative of UK palliative care patients and services in terms of participant age, ethnic background, service size, proportion of cancer/non-cancer patients and urban–rural balance. We included more community services than hospital or inpatient hospital services.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included consecutive adult patients (≥ 18 years) receiving specialist palliative care at all participating sites. Exclusion criteria comprised patients aged < 18 years, those who declined participation and/or those who previously expressed a wish not to participate in research.

Data collection and primary outcome

Data were collected from clinicians between July 2015 and October 2016, with completion of follow-up at the end of January 2017; no data were collected directly from patients. Collected data included demographic and clinical variables, episode start and end dates, potential casemix variables, and data on patient-level and other costs of providing specialist palliative care. All participants received the usual specialist palliative care at that site, including a multidisciplinary team with specialist training delivering holistic care focused on physical and psychological symptom management, social/family support, planning ahead around priorities and preferences, and care into the dying phase including post-death care of the family, where relevant.

Potential casemix variables were selected based on (1) being patient-level attributes and (2) existing evidence of association with casemix/complexity. 88 The key casemix variables included were age, sex, ethnicity, living circumstances, need for interpreter, primary diagnosis, palliative Phase of Illness, functional status, dependency and symptoms/problem severity.

Details of the measures used are presented in Appendix 1.

Our primary outcome was the cost of specialist palliative care per day. We adopted a (palliative) provider perspective for costs. The costs of acute hospital care, primary care, generic end-of-life care (i.e. provided by non-specialist teams), and informal care costs were excluded, not because these are unimportant, but because we sought casemix criteria relevant to specialist palliative care. A broader perspective on costs is planned for future work.

Palliative Phase of Illness was assessed daily for people receiving inpatient (hospital or inpatient unit) care and at every contact for those receiving community-based care. Each change in Phase of Illness (or end of episode) triggered the collection of the AKPS, IPOS or Palliative Care Problem Severity Score (PCPSS), and the Barthel Index. All staff involved in patient care recorded the time spent delivering care to participants at the patient level using the staff activity matrix.

We collected data from participating sites on the costs of delivering their services and patient-level resource use data from the staff activity matrix to derive actual patient-level costs according to a standard costing methodology based on current NHS costing principles. 89 Note that costs captured for the hospital advisory and community-based settings represented the additional or ‘top-up’ costs for adding palliative care support to the hospital or community setting (and thus are reasonably compared). In contrast, the costs for inpatient hospices represented all the costs of inpatient care (and so are more reasonably compared with the costs of acute hospital admission). The full costing methodology (how costs were collected, classified and compiled) is available from the corresponding author on request.

Sample size

Based on standard recommendations for fitting multivariate models, a minimum of 50 + 8 × m cases for testing multiple correlation (where m is the number of predictors) are required to test the null hypothesis that the population multiple correlation equals zero with a power of 80%, α = 5% and a medium effect size for the regression analysis (R2 = 0.13). 90,91 The unit of analysis was episodes within sites; therefore, 10 predictors required 130 episodes per site. Allowing an additional 15% for episodes with missing data and 20% for cost outliers, we estimated that a target of 2674 episodes of care (191 episodes × 14 sites) was required.

Data handling

Data were collected prospectively at each site, recorded on an electronic database, cleaned and checked. Checked data were transferred to statistical software [Stata® standard edition (SE) V.12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and MATLAB® 8.2 (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA)] for analysis.

Analysis

An exploratory data analysis was undertaken first, examining variables of interest one at a time. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, medians, ranges and correlations) were calculated. Comparative box plots were constructed to investigate the differences between sites, episodes and phases. Cost of care was used as the response variable, measured as the total cost per episode.

The aim of the analysis was to form distinct groups within the data, such that patients within each group were similar to each other, but different from patients in the other groups.

To discover which baseline casemix variables could best predict the cost of a particular episode of care, the following nine steps were then undertaken:

-

We removed incomplete episodes, retaining only the complete episodes of care.

-

Following a previously adopted approach,46 high- and low-cost outliers were identified and removed using a trimming algorithm based on the IQR with the upper trim point at Q3 + 1.5 IQR and the lower trim point at Q1 – 1.5 IQR (where Q1 is first quartile and Q3 is third quartile). 46 The trimming algorithm was applied to each setting separately.

-

We examined the distribution of costs of specialist palliative care, by setting.

-

Then, following the same approach as the development of the Australian casemix classification,88 we developed and validated a cost-predictive model using classification and regression tree (CART) analysis, which constructs decision rules in a hierarchical manner to form a branching classification.

-

We used CART analysis to enable the more complex interactions between the predictor variables (both categorical and continuous) to be explored. CART has the advantage of being non-parametric and is not significantly impacted by outliers in the input variables. It enables the use of each variable more than once, if required for the optimal regression tree.

-

Explanatory variables were compared to find the one which could best split the data into two homogeneous groups that were as different from one another as possible. These two groups would then be further split, using the same or another explanatory variable. Successive binary splits were performed on the data until there was no further improvement to be made and the best possible classification solution was reached.

-

The best CART was deemed to be that which accounted for the largest proportion of variation in the cost of care (the response variable). The criterion used to compare the different ‘trees’ was the proportion of the variance of the response variable that could be explained by the selected groups.

-

Costs were log-transformed for better modelling and back-transformed for providing mean costs per class or at each terminal node. Decisions about rules for splitting were informed by clinical utility (for instance, allowing branches that made clinical – as well as statistical – sense), as well as statistical performance as outlined in 7. We selected a maximum of four branches and a minimum of 30 cases per branch, for reasons of clinical utility. 10–fold cross-validation was used to prevent overfitting of the developed classification. No recalibration was undertaken. The analysis was done in R 3.5 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the rpart, caret and (for bagging the trees) RWeka packages.

-

For each setting, we reported the variance explained by the CART model and the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) (i.e. the square root of the variance of the residuals). The RMSE indicates the absolute (rather than relative, as with R2) fit of the model to the data.

Ethics approval

The trial registration number is ISRCTN90752212. Ethics approval was received from the Camberwell St Giles National Research Ethics Service REC on 2 July 2015 [REC Reference: 15/LO/0887, Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) Project ID:172938].

Results

Subject characteristics

A total of 2469 patients were recruited, providing data on 2968 complete episodes of specialist palliative care (12 incomplete episodes were removed prior to analysis); 2087 participants contributed one episode of care, 283 participants contributed two episodes and 99 contributed three or more episodes. Demographic and clinical characteristics for the 2469 participants are reported in Table 1. No participants withdrew after recruitment. Further details are available in Appendix 2.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic details | |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 71.6 (13.9) |

| Median (range) | 73 (20–104) |

| < 65 years | 740 (30.0) |

| ≥ 65 years | 1729 (70.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1258 (51.0) |

| Female | 1205 (48.8) |

| Missing | 6 (0.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 1825 (73.9) |

| Black African or Black Caribbean | 217 (8.8) |

| Asian | 151 (6.1) |

| Mixed ethnic background | 118 (4.8) |

| Other | 32 (1.3) |

| Missing | 126 (5.1) |

| Living alone | |

| Yes | 548 (22.2) |

| No | 1921 (77.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Interpreter needed | |

| Yes | 22 (0.9) |

| No | 2447 (99.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Cancer | 1857 (75.2) |

| Lip, oral cavity and pharynx | 83 (3.4) |

| Digestive organs | 392 (15.9) |

| Liver and biliary | 73 (3.0) |

| Pancreas | 119 (4.8) |

| Respiratory and intrathoracic | 349 (14.1) |

| Bone, skin and mesothelial | 93 (3.8) |

| Breast | 150 (6.1) |

| Female genital organs | 116 (4.7) |

| Male genital organs, including prostate | 142 (5.7) |

| Urinary tract | 75 (3.0) |

| Brain, eye and other central nervous system | 72 (2.9) |

| Unknown primary | 52 (2.1) |

| Lymphoid and haematopoietic | 131 (5.3) |

| Independent multiple sites | 10 (0.4) |

| Non-cancer | 612 (24.8) |

| HIV/AIDS | 13 (0.5) |

| Motor neurone disease/ALS | 9 (0.4) |

| Dementia, including Alzheimer’s | 45 (1.8) |

| Neurological (excluding MND) | 7 (0.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (0.2) |

| Heart failure | 17 (0.8) |

| Stroke, infarction or haemorrhagic | 3 (0.1) |

| Other heart or circulatory | 12 (0.5) |

| Chronic respiratory including COPD | 39 (1.6) |

| Liver failure or chronic liver disease | 12 (0.5) |

| Renal failure | 8 (0.3) |

| All other non-cancer conditions | 433 (17.5) |

| Multiple non-cancer conditions | 8 (0.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

Episode characteristics

Details of the 2968 complete episodes of care and related casemix variables are reported in Table 2.

| Episode characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Setting | |

| Hospital advisory | 767 (25.9) |

| Inpatient hospice | 764 (25.7) |

| Community | 1437 (48.4) |

| Total | 2968 (100.0) |

| Palliative Phase of Illness at episode start | |

| Stable | 451 (15.2) |

| Unstable | 1422 (47.9) |

| Deteriorating | 834 (28.1) |

| Dying | 261 (8.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| AKPS score at episode start | |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 45.9 (19.9) [10–100] |

| 0–50 | 1759 (59.2) |

| 60–100 | 934 (31.5) |

| Missing | 275 (9.3) |

| Modified Barthel Index score at episode start | |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 8.28 (6.6) [0–20] |

| Missing | 1395/2469 (56.5)a |

| PCPSS at episode start | |

| Pain | |

| Mean score (SD) [range] | 1.5 (1.06) [0–3] |

| Absent | 615 (20.7) |

| Mild | 703 (23.7) |

| Moderate | 724 (24.4) |

| Severe | 515 (17.4) |

| Missing | 411 (13.8) |

| Other physical symptoms | |

| Mean score (SD) [range] | 1.9 (0.88) [0–3] |

| Absent | 188 (7.0) |

| Mild | 630 (23.4) |

| Moderate | 1096 (40.6) |

| Severe | 659 (24.4) |

| Missing | 125 (4.6) |

| Psychological symptoms | |

| Mean score (SD) [range] | 1.8 (0.92) [0–3] |

| Absent | 335 (11.3) |

| Mild | 827 (27.9) |

| Moderate | 932 (31.4) |

| Severe | 423 (14.2) |

| Missing | 451 (15.2) |

| Family concerns | |

| Mean score (SD) [range] | 1.8 (0.92) [0–3] |

| Absent | 273 (9.2) |

| Mild | 592 (20.0) |

| Moderate | 1057 (35.6) |

| Severe | 552 (18.6) |

| Missing | 494 (16.6) |

| Length of episode (days) | |

| Hospital advisory | |

| Mean (SD) | 19.3 (39.01) |

| Median (range) | 8 (1–402) |

| Inpatient hospice | |

| Mean (SD) | 15.6 (15.77) |

| Median (range) | 12 (1–140) |

| Community | |

| Mean (SD) | 50.4 (53.95) |

| Median (range) | 30 (1–313) |

Outliers

Using the trimming algorithm described in Methods, Analysis, 123 (16.0%) hospital advisory episodes, 185 (24.2%) inpatient hospice episodes and 305 (21.2%) community episodes were removed to ensure that the principal cost and classification reporting was not based on outliers (a common challenge in costing studies).

Costs of specialist palliative care

The distribution of the total cost of specialist palliative care episodes, derived from the trimmed data set, is shown in Table 3; costs are shown (1) by day, (2) by day, broken down by Phase of Illness, and (3) by episode of care, together with details of length of episodes.

| Setting of care | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital advisory | 644 | 27.3 |

| Inpatient hospice | 579 | 24.6 |

| Community | 1132 | 48.1 |

| Total | 2335 | 100.0 |

| Mean (SD) | Median | |

| Hospital advisory | ||

| Cost per day: all episodes (£) | 72.65 (57.18) | 56.15 (31.22–100.03) |

| Cost per day by Phase of Illness (£)a | ||

| Stable | 60.03 (49.54) | 48.11 (24.91–78.34) |

| Unstable | 76.41 (58.71) | 58.61 (35.20–105.71) |

| Deteriorating | 68.55 (52.85) | 53.87 (31.54–95.77) |

| Dying | 81.28 (63.88) | 61.76 (33.00–119.90) |

| Length of episode: all episodes (days) | 15.18 (32.32) | 7 (3–15) |

| Length of episode, by Phase of Illness (days)a | ||

| Stable | 26.35 (59.22) | 7 (2–18) |

| Unstable | 16.47 (30.91) | 8 (4–17) |

| Deteriorating | 10.90 (24.35) | 6 (3–11.5) |

| Dying | 7.58 (16.83) | 3 (1–6) |

| Cost per episode: all episodes (£) | 507.36 (446.38) | 385.84 (176.15–698.85) |

| Cost per episode, by Phase of Illness (£)a | ||

| Stable | 387.57 (415.61) | 244.67 (116.38–508.32) |

| Unstable | 585.26 (268.11) | 458.01 (229.71–839.04) |

| Deteriorating | 431.33 (416.19) | 307.33 (146.68–558.59) |

| Dying | 335.53 (299.38) | 206.89 (106.59–521.89) |

| Inpatient hospice | ||

| Cost per day: all episodes (£) | 716.38 (765.04) | 434.33 (365.72–664.50) |

| Cost per day, by Phase of Illness (£)a | ||

| Stable | 669.55 (783.49) | 407.69 (292.81–588.00) |

| Unstable | 690.28 (726.03) | 428.38 (388.53–527.13) |

| Deteriorating | 832.60 (879.18) | 458.01 (353.11–967.66) |

| Dying | 645.08 (647.98) | 453.44 (364.51–606.52) |

| Length of episode: all episodes (days) | 14.74 (15.69) | 11 (5–19) |

| Length of episode, by Phase of Illness (days)a | ||

| Stable | 19.55 (22.70) | 12 (6–22.5) |

| Unstable | 16.68 (16.25) | 13 (6–22) |

| Deteriorating | 12.29 (10.02) | 10 (6–16) |

| Dying | 9.17 (17.66) | 6 (2–11) |

| Cost per episode: all episodes (£) | 7202.25 (7679.24) | 4428.28 (1601.00–10,533.93) |

| Cost per episode, by Phase of Illness (£)a | ||

| Stable | 8001.18 (9082.44) | 4179.83 (2054.33–9346.56) |

| Unstable | 7731.80 (7644.43 | 5345.43 (2069.59–10,654.10) |

| Deteriorating | 7654.97 (7839.31) | 4623.73 (1716.47–11,947.12) |

| Dying | 3119.63 (4948.30) | 1021.32 (463.39–2957.72) |

| Community | ||

| Cost per day: all episodes (£) | 35.76 (40.49) | 21.37 (6.23–49.13) |

| Cost per day, by Phase of Illness (£)a | ||

| Stable | 23.20 (32.60) | 10.58 (3.21–28.35) |

| Unstable | 33.97 (38.13) | 21.52 (6.23–47.03) |

| Deteriorating | 40.02 (43.28) | 24.01 (8.14–54.22) |

| Dying | 61.86 (44.84) | 55.87 (24.91–88.46) |

| Length of episode: all episodes (days) | 49.45 (51.53) | 30.5 (12–68) |

| Length of episode, by Phase of Illness (days)a | ||

| Stable | 65.03 (58.02) | 46.5 (20.5–90) |

| Unstable | 50.80 (50.91) | 32 (15–70) |

| Deteriorating | 45.42 (47.15) | 28 (12–61.5) |

| Dying | 16.67 (33.48) | 5 (2–19) |

| Cost per episode: all episodes (£) | 858.43 (780.77) | 624.18 (264.18–1230.44) |

| Cost per episode, by Phase of Illness (£)a | ||

| Stable | 818.91 (798.19) | 569.97 (207.24–1187.43) |

| Unstable | 879.57 (782.01) | 607.70 (282.47–1257.20) |

| Deteriorating | 870.39 (781.96) | 641.70 (274.30–1215.15) |

| Dying | 806.66 (725.88) | 577.93 (224.56–1230.57) |

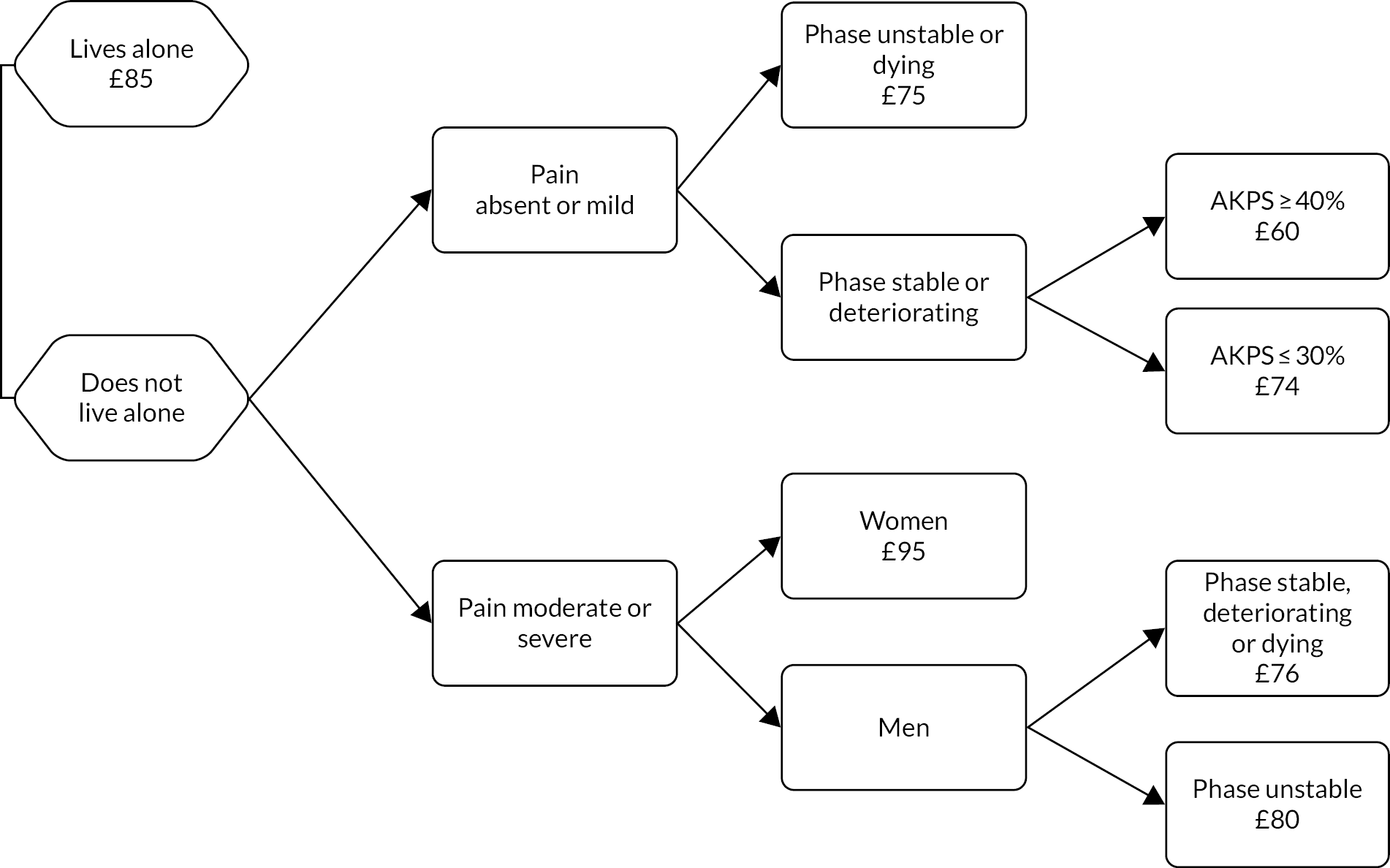

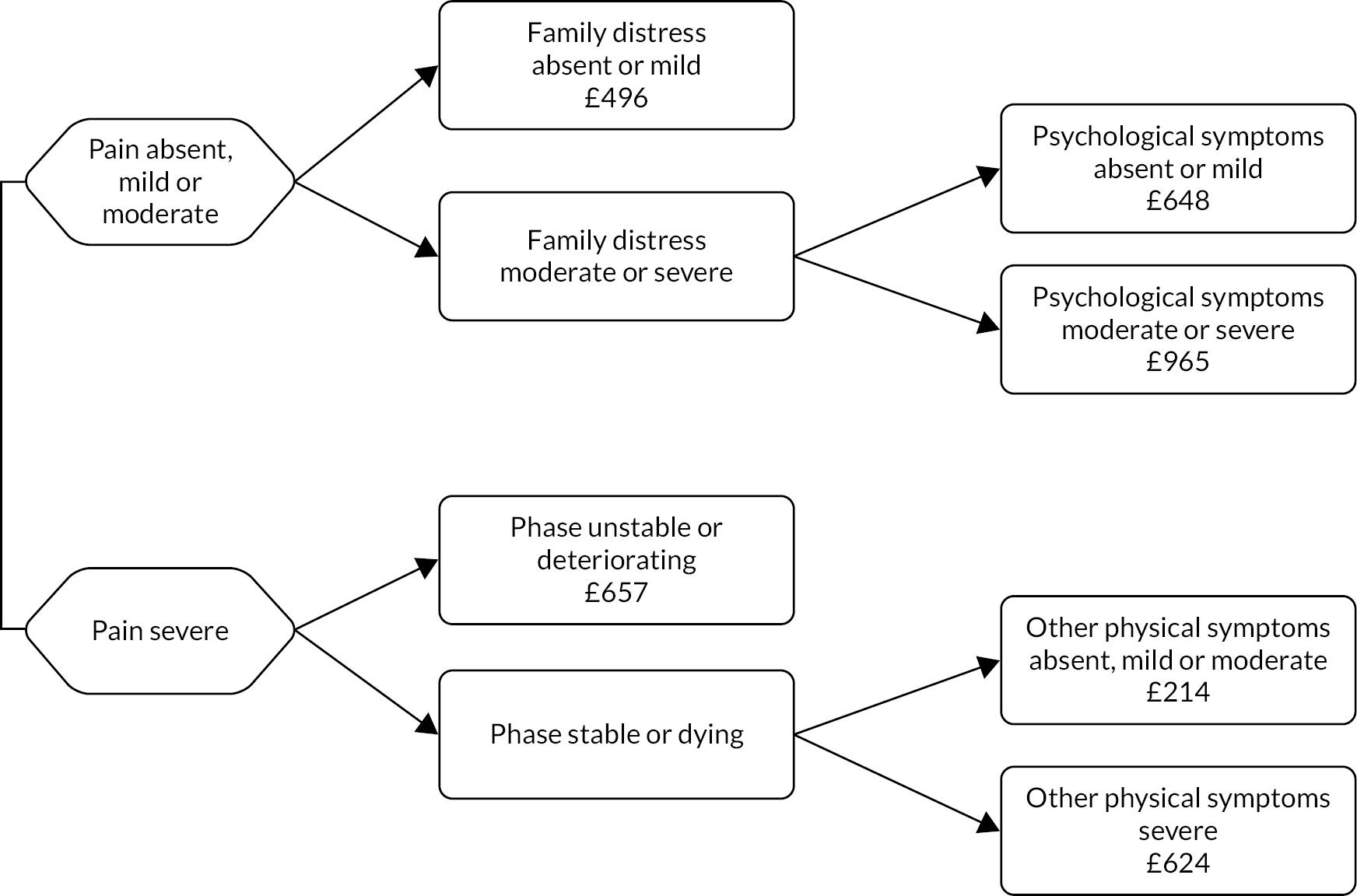

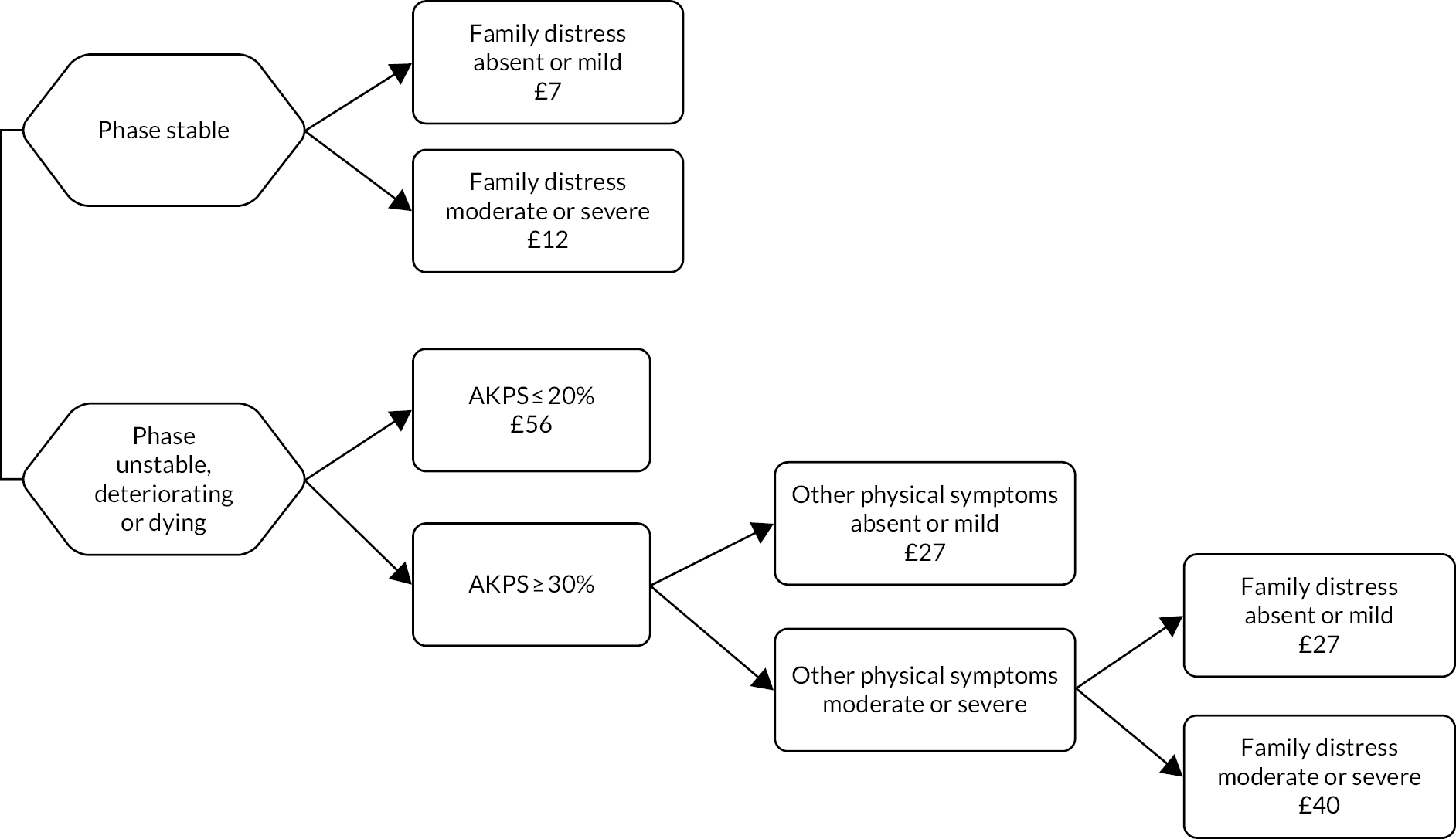

Classification and regression tree analysis

Figures 4–6 show the CARTs for each setting. The per cent variance explained (and RMSE) were 20% (RMSE = 0.30), 51% (RMSE = 0.51) and 27% (RMSE = 0.36), for hospital advisory, inpatient hospice and community episodes, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Classification tree of casemix criteria for hospital advisory episodes of specialist palliative care (costs per day reported for each class).

FIGURE 5.

Classification tree of casemix criteria for inpatient hospice episodes of specialist palliative care (costs per day reported for each class).

FIGURE 6.

Classification tree of casemix criteria for community episodes of specialist palliative care (costs per day reported for each class).

Seven different casemix variables provide the optimal combination to develop classes for each of the settings. Table 4 shows which variables were used and how they were combined to constitute the casemix classes, including cost weights.

| Class | Living situation | Pain | Functional status | Palliative Phase of Illness | Family distress | Physical symptoms other than pain | Psychological symptoms | Sex | Class cost per day (£) | Cost weighta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classes for hospital advisory episodes of care | ||||||||||

| A | Lives alone | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 85 | 1.4 |

| B | Does not live alone | Absent or mild | – | Unstable or dying | – | – | – | – | 75 | 1.3 |

| C | Does not live alone | Absent or mild | AKPS ≥ 40% | Stable or deteriorating | – | – | – | – | 60 | 1.0 |

| D | Does not live alone | Absent or mild | AKPS ≤ 30% | Stable or deteriorating | – | – | – | – | 74 | 1.2 |

| E | Does not live alone | Moderate or severe | – | – | – | – | – | Female | 95 | 1.6 |

| F | Does not live alone | Moderate or severe | – | Stable, deteriorating or dying | – | – | – | Male | 76 | 1.3 |

| G | Does not live alone | Moderate or severe | – | Unstable | – | – | – | Male | 80 | 1.3 |

| Classes for inpatient hospice episodes of care | ||||||||||

| A | – | Absent, mild or moderate | – | – | Absent or mild | – | – | – | 496 | 2.3 |

| B | – | Absent, mild or moderate | – | – | Moderate or severe | – | Absent or mild | – | 648 | 3.0 |

| C | – | Absent, mild or moderate | – | – | Moderate or severe | – | Moderate or severe | – | 965 | 4.5 |

| D | – | Severe | – | Unstable or deteriorating | – | – | – | – | 657 | 3.1 |

| E | – | Severe | – | Stable or dying | – | Absent, mild or moderate | – | – | 214 | 1.0 |

| F | – | Severe | – | Stable or dying | – | Severe | – | – | 624 | 2.9 |

| Classes for community episodes of care | ||||||||||

| A | – | – | – | Stable | Absent or mild | – | – | – | 20 | 1.0 |

| B | – | – | – | Stable | Moderate or severe | – | – | – | 24 | 1.2 |

| C | – | – | AKPS ≤ 20% | Unstable, deteriorating or dying | – | – | – | – | 56 | 2.8 |

| D | – | – | AKPS ≥ 30% | Unstable, deteriorating or dying | – | Absent or mild | – | – | 27 | 1.4 |

| E | – | – | AKPS ≥ 30% | Unstable, deteriorating or dying | Absent or mild | Moderate or severe | – | – | 27 | 1.4 |

| F | – | – | AKPS ≥ 30% | Unstable, deteriorating or dying | Moderate or severe | Moderate or severe | – | – | 40 | 2.0 |

Workstream 4: testing of the casemix classification

This work has also been published in Guo et al. 92

Workstream 4 (testing the casemix classification) was planned to meet objective 5: to test this person-centred palliative care casemix classification in terms of its ability to predict resource use in the last year of life, and to better understand transitions between services in order to improve care.

Aim

Our aim was to test the palliative care casemix classification developed in workstream 3 in terms of its ability to predict resource use for patients receiving episodes of specialist palliative care, and to explore the experience of transitions between care settings for those receiving specialist palliative care.

Methods

Design

We designed a multicentre prospective cohort study, following patients during episodes of specialist palliative care, with a qualitative nested component (interviews with a subsample of participants to better understand the experience of transitions between care settings).

Definitions

We defined both an episode of care and the setting of care as in Workstream 3: development of the casemix classification, Definitions.

Population and settings

Patients were recruited from 12 organisations providing specialist palliative care services in England, comprising three hospital advisory services, eight inpatient hospice services and five community-based services (some organisations provided more than one setting of care). Sites were selected for diversity in terms of participant age, ethnic background, service size, proportion of cancer/non-cancer patients and urban–rural balance

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria comprised adult patients aged ≥ 18 years who were able to consent and receiving specialist palliative care at any of the participating sites. The exclusion criteria were patients aged < 18 years and those unable to consent.

Data collection and primary outcome

Data were collected from patient participants and clinicians between December 2016 and May 2018. Collected data included demographic and clinical variables, episode start and end dates, casemix variables as required for the casemix classification developed in workstream 3, and data on patient-level and other costs of providing specialist palliative care. All participants received the usual specialist palliative care at that site, including a multidisciplinary team with specialist training delivering holistic care focused on physical and psychological symptom management, social/family support, planning ahead around priorities and preferences, and care into the dying phase including post-death care of the family, where relevant. Details of the measures used are presented in Appendix 1.

Palliative Phase of Illness was assessed daily for people receiving inpatient (hospital or inpatient unit) care and at every contact for those receiving community-based care. Each change in Phase of Illness (or end of episode) triggered the collection of the AKPS, IPOS or PCPSS and Barthel Index score. All staff involved in patient care recorded the time spent delivering care to patient participants at a patient level using the staff activity matrix.

We also collected data from participating sites on the costs of delivering their services, plus patient-level resource use data, as in workstream 3.

A subsample of participants who had experienced at least two transitions between care settings were invited for interview. A purposive sampling approach was used to include participants from a range of age groups, sex, diagnoses, types of transitions in either direction and geographical areas.

Data handling

Quantitative data were collected prospectively at each site, recorded on an electronic database, cleaned and checked. Checked data were transferred to statistical software (Stata SE V.12) for analysis. Qualitative data were recorded, transcribed verbatim and handled using NVivo version 12.

Analysis

For the quantitative data, the casemix classes developed in Workstream 3 were applied to predict costs for episodes of care and this was contrasted with the actual costs captured for each episode of care. For the qualitative data we adopted a similar approach to Pinnock et al.’s qualitative study,93 undertaking a thematic94 and narrative analysis of interviews, exploring how perspectives on transitions evolve over time, with detailed attention to patient and family perspectives on their experience of care in each setting and during transitions, including their experience of interventions that potentially influenced changes in settings of care.

Ethics

The trial registration number is ISRCTN90752212. Written or oral witnessed consent was taken and documented for each participant, and continuing consent was confirmed at follow-up. Ethics approval was received from Bromley REC on 5 September 2016 (REC Reference: 16/LO/1021, IRAS Project ID: 204926).

Quantitative results

Subject characteristics

A total of 309 patients were recruited, providing data on 751 episodes of specialist palliative care. Of these participants, 309 contributed one episode of care, 177 (57%) contributed a second episode of care and 119 (39%) contributed a third episode of care. Only 63 (20%) participants contributed four or more episodes of care. Demographic and clinical characteristics for the 309 participants are reported in Table 5. Just over three-quarters (76%) of participants had cancer, but we were able to recruit one-fifth with a range of different non-cancer conditions.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic details a | |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 66.9 (13.15) |

| Median (range) | 68 (18–96) |

| < 65 years | 117 (37.9) |

| ≥ 65 years | 183 (59.2) |

| Missing or prefer not to say | 9 (2.9) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 134 (43.4) |

| Female | 170 (55.0) |

| Missing or prefer not to say | 5 (1.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 265 (85.8) |

| Black African or Black Caribbean | 9 (2.9) |

| Asian | 8 (2.6) |

| Mixed ethnic background | 9 (2.9) |

| Other | 11 (3.6) |

| Missing or prefer not to say | 7 (2.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or partner | 165 (53.4) |

| Separated or divorced | 43 (13.9) |

| Widowed | 46 (14.9) |

| Single | 46 (14.9) |

| Missing or prefer not to say | 9 (2.9) |

| Living alone | |

| Yes | 107 (34.6) |

| No | 191 (61.8) |

| Missing or prefer not to say | 11 (3.6) |

| Interpreter neededb | |

| Yes | 2 (0.6) |

| No | 302 (97.8) |

| Missing | 5 (1.6) |

| Primary diagnosis b | |

| Cancer | 237 (76.7) |

| Lip, oral cavity and pharynx | 1 (0.3) |

| Digestive organs | 55 (17.8) |

| Liver and biliary | 8 (2.6) |

| Pancreas | 10 (3.2) |

| Respiratory and intrathoracic | 46 (14.9) |

| Bone, skin and mesothelial | 11 (3.6) |

| Breast | 28 (9.1) |

| Female genital organs | 16 (5.1) |

| Male genital organs including prostate | 25 (8.1) |

| Urinary tract | 11 (3.6) |

| Brain, eye and other central nervous system | 4 (1.3) |

| Unknown primary | 7 (2.3) |

| Lymphoid and haematopoietic | 15 (4.8) |

| Independent multiple sites | 0 (0.0) |

| Non-cancer | 59 (19.1) |

| HIV/AIDS | 1 (0.3) |

| Motor neurone disease/ALS | 11 (3.6) |

| Dementia including Alzheimer’s | 0 (0.0) |

| Neurological (excluding MND) | 8 (2.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0) |

| Heart failure | 5 (1.6) |

| Stroke, infarction or haemorrhagic | 0 (0.0) |

| Other heart or circulatory | 0 (0.0) |

| Chronic respiratory including COPD | 28 (9.1) |

| Liver failure or chronic liver disease | 1 (0.3) |

| Renal failure | 1 (0.3) |

| All other or multiple non-cancer conditions | 4 (1.3) |

| Missing | 13 (4.2) |

Episode characteristics