Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0610-10108. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Wenborn et al. This work was produced by Wenborn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Wenborn et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction: setting the scene

Defining dementia

‘Dementia is a term used to describe a range of cognitive and behavioural symptoms that can include memory loss, problems with reasoning and communication and change in personality, and a reduction in a person’s ability to carry out daily activities, such as shopping, washing, dressing and cooking’ (© NICE 2018. Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication). 1 There are a range of conditions that cause dementia, the most common in the UK being Alzheimer’s disease, as well as vascular dementia, mixed dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia amongst others. A person with dementia finds it increasingly difficult to remember, know where they are, know who other people are, keep track of time, organise themselves and their activities, understand what is being said, communicate with other people, make decisions, or learn new things. As a result, the person experiences increasing difficulty in carrying out activities of daily living (ADL) and other valued and meaningful activities; they progressively need more and more assistance from family and friends, as well as from professional carers. The way in which carers support a person with dementia to cope with their impairments can either optimise or decrease the individual’s performance and as a result can dictate the degree of disability and lack of agency or sense of control that is experienced. 2,3

The number of people living with dementia

It is estimated that 47 million people worldwide were living with dementia in 2015 and, although the number is still rising globally owing to an ageing population, the incidence is decreasing in some countries because of the take up of public health information to adopt healthier lifestyles. 4 The 2015 UK figure was estimated to be 850,000 people living with dementia, with almost two-thirds living in the community. 5

The impact of caring for a person living with dementia

The current financial cost to the NHS, local authorities and families in England is £26.3B per year, of which £11.6B is attributable to the support provided by unpaid carers (i.e. primarily family members). 5 Indeed, unpaid care accounts for three-quarters of the total cost for people living with dementia within the community. 5 The impact of caring for someone living with dementia is not only financial, but can also be both physically and psychologically demanding. As the person with dementia loses the ability to carry out everyday tasks and their former activities and roles, family carers often experience a feeling of increased burden and stress. About 40% of family carers of people with dementia have clinically significant depression or anxiety; carers can also have poorer physical health, more absences from work and lower quality of life than non-carers. 4 Carer stress predicts care home admission and elder abuse. 4

Living Well with Dementia: a policy priority

Several UK Government policies aim to improve health and social care service provision for people with dementia and their carers. A watershed point in England was the publication of Living Well with Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy,6 the first significant policy document to address these issues. This strategy had three main aims: (1) raise awareness and understanding, (2) provide earlier diagnosis and support, and (3) maximise living well with dementia. The strategy was underpinned by 17 objectives to be achieved over 5 years. The subsequent Prime Minister’s Challenges7,8 urged action to do more to achieve the strategy first by 2015, and then by 2020, and thus raised the profile of dementia as being a clinical and research priority. 7,8 The UK Government subsequently pledged to provide community-based programmes that aimed to improve quality of life for people with dementia and their carers. 9

Training and supporting carers and tailoring psychosocial interventions to meet the specific needs of individuals are key components to achieving the dementia strategy objectives. Personalised interventions can improve family carers’ well-being, delay admission to care homes and reduce the risk of institutionalisation by up to one-third. 10,11 More recently, and following on from the drive for earlier diagnosis,12 the importance of providing psychosocial interventions for people with dementia has been emphasised both internationally13 and nationally. 14

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial interventions, which include physical, cognitive or social activities, can have positive and cost-effective outcomes on cognition, quality of life and institutionalisation. 15,16 Since this research programme commenced (2012), funding for psychosocial dementia research has increased and a range of interventions have been, and are being, developed and evaluated through randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and other methodologies. UK-funded studies cover a range of interventions, for example Dementia And Physical Activity,17 brief interventions to promote independence18 and tailored activities. Furthermore, a multicentre RCT of goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation (the GREAT trial) demonstrated good achievement of goals but no benefit to validated outcomes,19 and an implementation study is about to commence.

Defining occupational therapy

Humans have an innate need to engage in personally meaningful activities to maintain physical and mental health and well-being. People who have dementia increasingly need support to engage in such activities. 2 Occupational therapy is a complex, dynamic process that comprises multiple practices, the implementation of which is individualised, with the relationship between the person(s) and the therapist being fundamental because the process necessitates the active involvement of the person(s) and therapist working in partnership. 20 Occupational therapists utilise core skills to engage people in personally meaningful occupation. They collaborate with the client (often including the client’s family and/or carer as well) in assessment, enablement, problem-solving, environmental assessment and adaptation, and use activity as a therapeutic tool. 21 Hence, engaging in meaningful activity is both the means and the outcome of the occupational therapy process and intervention.

Community Occupational Therapy in Dementia

In the Netherlands, Graff et al. 22 developed the Community Occupational Therapy in Dementia (COTiD) programme. It comprises 10 1-hour sessions of home-based occupational therapy provided over 5 weeks by an occupational therapist who works in partnership with the person who has dementia and their family caregiver on individualised goals to improve skills in meaningful daily activities through the use of effective strategies, adaptation of the (physical and social) environment, and developing the caregivers’ abilities and sense of competence. A single-site RCT of 135 pairs of people with mild to moderate dementia and their family caregivers (n = 270) compared COTiD with treatment as usual (TAU), which did not include any occupational therapy provision. The study demonstrated improved ADL skills, quality of life and mood in people with dementia, and improved quality of life, mood and sense of competence in family caregivers. 23,24 COTiD was also found to be cost-effective. 25 A subsequent study in Germany found no difference between providing COTiD and providing a single consultation visit by an occupational therapist. 26 Although the comparator group in this latter trial was different, the integral process evaluation highlighted the need not only to translate but also to adapt complex interventions to the local context for evaluation and cross-national comparison to be effective. 27 COTiD is now being translated, adapted and evaluated in other European countries. A pilot study is under way in France, and a prospective cohort study in Italy has demonstrated positive effect on caregiver burden, as well as improved activities performance and satisfaction for people with dementia. 28

UK occupational therapy practice

Currently, people with dementia living in England may or may not see an occupational therapist at the point of diagnosis and, if they do, only briefly, primarily for assessment of risk and support needs. Traditionally, occupational therapy has been provided later on in the dementia pathway; however, this is changing as a result of implementation of the previously described policy that promotes earlier diagnosis and easy access to post-diagnostic support services. At whatever point the occupational therapy is provided, the focus is invariably on the person with dementia, with their family carers’ needs considered primarily in terms of their ability to support the person with dementia within their role as a carer. Occupational therapy is not often geared towards meeting the carer’s personal or occupational needs.

The Graff study23–25 demonstrated the potential value of the occupational therapy intervention being provided at an earlier point, with a focus not only on the person with dementia but also on enabling and skilling up their family carer, who will inevitably be required to provide increasing support for the person with dementia if they are to remain engaged in meaningful activities, while also meeting their own needs, including occupational balance. It therefore appeared that COTiD had great potential for adoption in the UK. However, the culture, health and social care service provision and context differs between the Netherlands and England. At the time of the Graff study, people in the Netherlands were diagnosed with dementia by either a neurologist or a geriatrician within an outpatient clinic. There was no community occupational therapy nor older people’s mental health service provision for people with dementia within the Dutch insurance-based model of health care. Within the UK, health care has long been provided free at the point of delivery through the NHS. At the point of designing this research programme, specialist older people’s mental health services were well established, with multiprofessional teams, including occupational therapists, providing assessment and intervention services within hospital and community settings, including people’s own homes. Memory Assessment Services were just being established to provide early diagnosis and access to a range of support for people with dementia and their family carers. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that occupational therapy should be considered to support functional ability in people living with mild to moderate dementia. 1 The current Memory Services National Accreditation Programme standard 6, ‘psychosocial interventions’, requires services to provide timely access to psychosocial interventions for occupational and functional aspects of dementia, including access to occupational therapy, and access to advice and support on assistive and telecare solutions designed to assist people with ADL: a core domain of occupational therapy practice. 29

Therefore, this applied research programme, Valuing Active Life in Dementia (VALID), was funded to translate, adapt, develop, evaluate and implement a community occupational therapy intervention for people with mild to moderate dementia and their family carers in England.

Chapter 2 The VALID applied research programme

Programme aim

The aim of the VALID programme was to translate, adapt, develop, evaluate and implement a community occupational therapy intervention that will promote independence, meaningful activity and quality of life for people with mild to moderate dementia and their family carers within England.

Programme objectives

The VALID programme objectives were to:

-

translate and adapt COTiD into the Community Occupational Therapy in Dementia – the UK version (COTiD-UK) intervention and training programme and optimise it for use in the UK

-

test the feasibility of implementing COTiD within UK health and social care services

-

field test the proposed outcome measures through an internal pilot trial of COTiD-UK compared with TAU

-

estimate the effectiveness of COTiD-UK in improving the functional independence of people with mild to moderate dementia through a multicentre, pragmatic, single-blind, RCT

-

evaluate the cost-effectiveness of COTiD-UK compared with TAU

-

assess the implementation of COTiD-UK through monitoring and budget impact analysis

-

disseminate the findings of the VALID research programme widely.

Programme structure

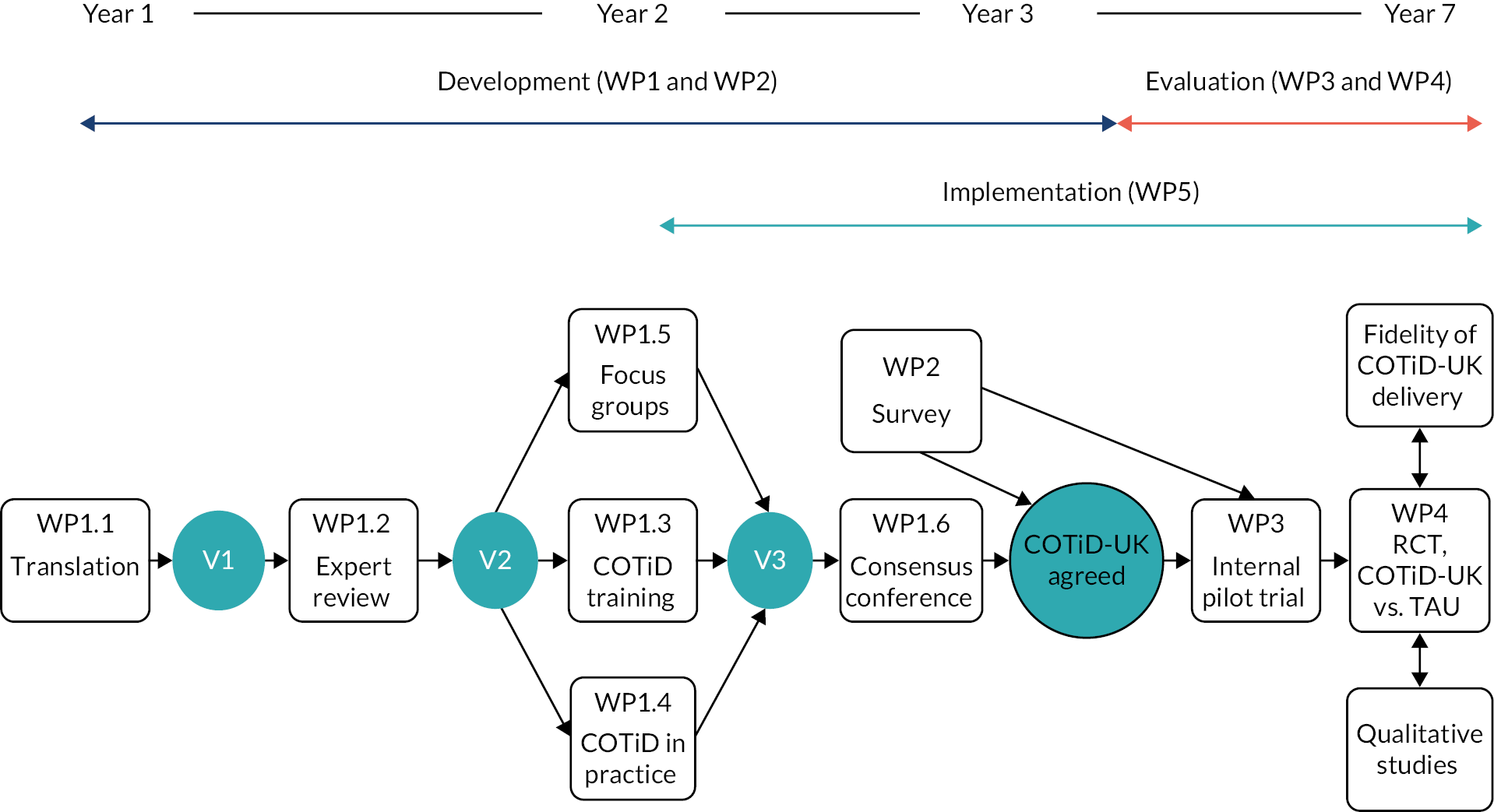

The VALID programme followed the Medical Research Council framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions30 and comprised three phases and five associated work packages (WPs): development (WP1 and WP2), piloting and evaluation (WP3 and WP4), and implementation (WP5). Figure 1 illustrates the sequence of WPs and activities across the programme. Table 1 summarises the WPs and their respective aims and activities.

FIGURE 1.

The VALID research pathway diagram.

| Phase (WP) aim | Activity | Data collected |

|---|---|---|

| Development phase (1/2) | ||

| To translate and adapt the COTiD guideline and training package to maximise its suitability for use within the UK, and to produce the COTiD-UK intervention in readiness for evaluation in WP3 and WP4 | WP1 | |

| 1.1 Translation of Dutch intervention manual and the training materials (including subtitling DVD) to produce version 1 of the manual | Comments from review of translation | |

| 1.2 Expert review and amendment of translated manual to produce version 2 of the manual | Expert opinion feedback sheets | |

| 1.3 COTiD training using version 2 of the manual and materials | COTiD training: | |

|

||

| 1.4 COTiD put into practice using version 2 of manual | COTiD in practice: | |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| 1.5 Focus groups conducted with people with dementia and with family carers who did not receive COTiD | Focus group transcripts and field notes | |

| 1.6 Consensus conference held to consider version 3 of the manual | Record of group discussions | |

| WP2 | ||

| 2.1 Online survey | Survey responses (quantitative and qualitative) | |

| Piloting phase (3) | ||

| To field test the outcome measures and trial procedures, and finalise the COTiD-UK intervention mode of delivery, training and supervision | Internal pilot trial of COTiD-UK compared with TAU across three research sites | ACCEPT review |

| Evaluation (4) | ||

| To determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of COTiD-UK compared with TAU | Multisite RCT | Outcome measures data including: |

|

||

|

||

| Qualitative studies | ||

| 1. Taking part in the COTiD-UK intervention | Semistructured interviews with dyads and occupational therapists who took part in COTiD-UK | |

| 2. Why people declined to take part in the trial | Semistructured interviews with family carers who had declined to take part in the VALID RCT | |

| Economic evaluation | COTiD-UK training and provision costs. Service receipt costs and quality-of-life measure | |

| Implementation (5) | ||

| To determine the feasibility and effectiveness of COTiD-UK in usual clinical practice | Assessing the fidelity of COTiD-UK delivery | COTiD-UK session transcripts |

| Review of data using the Theoretical Domains Framework | Evaluation phase: | |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Piloting and evaluation phases | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

Changes to the original research plan

The research aim and six out of the seven objectives remained the same; however, the timing and design of the programme were revised, as described in the following section.

Development phase

The time needed to translate the Dutch COTiD manual and training materials (including subtitling the training videos) was initially underestimated. Completion of the task was further delayed until the original Dutch author was available to check the translated materials for accuracy. Hence, the task took nearly 1 year, rather than 6 months, as originally scheduled. This, together with delays in agreeing occupational therapist capacity and funding to cover their time at the 10 participating research sites, delayed the start of the COTiD training by a further 6 months. Further delays in setting up research sites and obtaining the relevant local governance approvals then delayed the intervention being provided in practice: this was originally scheduled to start following the first training day in January 2013 but actually started at the first sites in April 2013. Further delays in gaining management agreement at some sites to release the occupational therapists meant that in some sites, the intervention did not start until July 2013. A series of information technology (IT) and information governance challenges and complicating issues delayed some of the occupational therapists’ video-recorded data being transferred to the research team. This subsequently delayed their analysis and provision of feedback to the occupational therapists on their performance. Other activities, therefore, had to be rescheduled; specifically, the occupational therapy focus groups, which were initially scheduled for the final training day in June 2013. These needed to be deferred by 3–4 months to ensure that participants had some experience of providing the intervention in practice so as to be able to discuss it. Hence, the consensus event could not run until after the intervention had been provided and, therefore, took place in September 2013. Completing the analysis of the development phase data to finalise the COTiD-UK intervention in readiness for the trial then took a further 6 months. Therefore, the development phase took twice as long as originally scheduled.

Piloting and evaluation phase

The delays outlined above, plus unexpected staff absence (May to July 2014), meant that the internal pilot trial (WP3) started nearly 2 years later than scheduled. Having moved from the internal pilot trial to the full RCT (WP4), a range of challenges hampered its completion to time and target. These included delays in recruiting research sites because of the complex nature of the trial, which required both researcher and occupational therapist capacity to deliver, then the recruitment of pairs rather than individual participants.

Several interested sites were not able to proceed because of lack of researcher and/or occupational therapist capacity. Research support required funding from the local Clinical Research Network (CRN), which was not always forthcoming, and not all NHS trusts agreed to free up occupational therapists’ time so that they could take part in the study. It should be noted that only 2 out of 15 sites managed to obtain excess treatment costs, namely the additional funding that is required within the UK to deliver the clinical intervention being evaluated, as this is not included in the research grant award. This was despite the initial award of subvention funding for the programme as a whole because no trust met the threshold needed to reclaim the costs. This inevitably reduced the capacity to deliver the intervention in a timely way in some sites because the occupational therapists’ availability was dependent on the goodwill of their service managers, who had to balance their support for the study with the need to provide the level of service commissioned. This restricted the occupational therapist capacity such that more research sites than originally planned had to be recruited to achieve the dyad recruitment target within the time frame agreed with the funder.

In addition to this, additional occupational therapists had to be trained throughout the trial period to deliver the intervention as new sites were recruited, and one-quarter of those originally recruited later dropped out as a result of changing jobs, service reconfiguration or sick leave. The complexity of liaising with clinical teams to recruit dyads in tandem with occupational therapists’ capacity to deliver the intervention within the protocol time scale, while maintaining researcher masking and in many cases with limited occupational therapist time being available, resulted in trial recruitment taking longer than expected. Therefore, the trial recruitment period was initially extended by 6 months and then a further 9 months to the end of June 2017, following a successful variation-to-contract application to the funders for an 18-month extension to the programme. The final data were collected towards the end of January 2018. Hence, the RCT took 40, rather than 36 months to complete, as originally planned.

The original plan was to collect follow-up data for all participants at 12, 26 and 52 weeks, and for the first 40% of those recruited at 78 weeks (n = 192). The 18-month variation-to-contract extension was calculated to enable the 26-week follow-up data to be collected for all participants, while the percentage of 52-week follow-ups had to be reduced from 100% (n = 480) to 77% (n = 368) to complete the RCT within the revised time scale.

Implementation phase

It was originally planned to complete the implementation phase (WP5) after the RCT had finished, to fulfil objective 6, but this structure and objective was changed because of a number of factors.

First, developments within the growing field of implementation science since the grant application was submitted recommended that implementation should be integrated throughout a programme of research such as this, rather than be left as a stand-alone package at the end. 31 Second, as the development phase had over-run as described, thus delaying the piloting and evaluation phases, it was not feasible to complete the implementation phase as planned.

However, the range and depth of data collected within the development, piloting and evaluation phases strongly contributed to this aspect of the programme, and the learning from these resulted in some of the activities originally and specifically planned for WP5 no longer being necessary. Therefore, the implementation phase was revised to consist of (1) a descriptive study to assess the fidelity of delivery of the COTiD-UK intervention within the RCT, and (2) an exploratory study to understand why the intervention was or was not delivered as planned by reviewing data collected during the development, pilot and evaluation phases using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). 32 The revised plan is described in more detail in Chapter 7.

A budget impact analysis was not carried out because the statistical results indicated a low probability that the intervention would be cost-effective and, therefore, that the intervention was not likely to be implemented.

Programme management and governance

Programme Steering Committee

An independent Programme Steering Committee (PSC) acted as the oversight body on behalf of the Sponsor [North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT)] and funder [National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)]. The role of the PSC was to provide expert advice that was independent of the research team, monitor progress, advise on proposed changes to the programme’s plans in the light of new evidence or other unanticipated development, and provide written support for any requests for additional funding or time extensions. It comprised an independent chairperson, statistical and clinical advisors, a person living with dementia, a former spousal carer and, on occasion, a funder representative. Relevant members of the research team attended as requested to provide information and progress reports.

Programme Management Group

A Programme Management Group (PMG) had operational responsibility to deliver the programme of research. It was chaired by the chief investigator (MO) and comprised the majority of co-applicants, plus members of the research team and other collaborators as required and invited. The PMG met face to face or over the telephone at varying intervals depending on the stage of the research programme.

On some occasions, a smaller group (referred to as the Principal Investigators Group) involving the chief investigator (MO); Sheffield (GM) and Humber (EMC) research centre Principal Investigators; qualitative/patient and public involvement (PPI) lead (FP); and programme manager (JW) met, usually over the telephone, to consider research, recruitment and dissemination activities in more practical detail. They were also joined by other members of the team as and when relevant, for example, they were joined by the trial manager to discuss site and participant recruitment.

Occupational Therapy Reference Group

An Occupational Therapy Reference Group (OTRG) comprising UK occupational therapists with experience of working with people with dementia and their family carers provided independent specialist occupational therapy advice to the research team to ensure that the proposed research activities were relevant and feasible in terms of current UK occupational therapy service provision and practice. It was chaired by the clinical occupational therapist co-applicant (SR), supported by the programme manager and reported to the PSC.

Trial management and governance (work packages 3 and 4 only)

The RCT was run by the NIHR UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC)-registered Priment Clinical Trials Unit at University College London (UCL), which provides specialist expertise in the design, conduct and analyses of trials in primary care and mental health. The trial was set up and conducted in accordance with Priment quality management systems and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for non-Clinical Trials Of An Investigational Medicinal Product.

Trial Management Team

Day-to-day responsibility was delegated by the chief investigator to the programme manager and the trial manager and relevant members of the trial team. The Trial Management Team (TMT) ensured that the trial was conducted, recorded and reported in accordance with the protocol, good clinical practice, all regulatory requirements and other essential procedures for running trials, as documented by the SOPs developed by the Priment clinical trials unit and the sponsor.

Trial Management Group

A Trial Management Group (TMG) consisting of the chief investigator, members of the TMT and Priment met at regular intervals to monitor the conduct and progress of the trial, with the frequency of meeting depending on the stage of the study. The division of responsibilities was defined following clinical trials unit/sponsor SOPs and conducted accordingly.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

An independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) was responsible for safeguarding the interests of trial participants, assessing the safety and efficacy of the interventions during the trial, and monitoring the overall conduct of the clinical trial. The DMEC reported to the PSC.

Chapter 3 Development phase: developing COTiD-UK (work packages 1 and 2)

Aims

The aims of the development phase were to translate and adapt the COTiD guidelines and training package to maximise its suitability and feasibility for use within the UK and to produce the COTiD-UK intervention in readiness for evaluation in a RCT.

There were two WPs:

-

WP1 – translation and adaptation of the COTiD intervention and training package

-

WP2 – online survey to scope current community occupational therapy service provision and practice for people with dementia and their family carers in the UK.

Ethics approval

Full ethics approval for WP1 and WP2 was gained from NRES Committee Yorkshire & the Humber – Leeds West on 28.11.12, Ref No 12/YH/0492. Five amendments (four substantial and one non-substantial) were approved to cover protocol and documentation updates, and new documents as needed. Local research and development governance approvals were obtained at each research site as appropriate. Informed consent was received from all participants.

The COTiD guideline and training package

As described earlier, the COTiD guideline and training package was developed in the Netherlands and published in Dutch,23 and subsequently in French33 and Italian. 34

The COTiD intervention

The aim of the COTiD intervention is to improve the person with dementia’s ability to carry out daily activities, improve the family carer’s sense of competence and, thereby, enhance the quality of life for both parties. COTiD consists of 10 1-hour sessions delivered over 5 weeks. The person with dementia and their carer are both clients and, for this reason, are both actively involved and work in partnership with the occupational therapist.

There are three phases.

Strengths, needs and case formulation phase (sessions 1–4)

Following an introductory session (number 1) to establish rapport and explain the format of the intervention, this phase comprises:

-

an occupational performance history interview35 with the person who has dementia

-

an ethnographic interview36 with the carer

-

recording the dyad’s daily routine/schedule using a diary sheet

-

skills observation to assess the person with dementia’s motor and process skills and the carer’s communication, interaction skills and coping skills

-

strategy observation to assess the person with dementia’s current strategies

-

environmental assessment

-

summarising and interpreting the information in readiness for the next phase (the occupational therapist does this in preparation for phase 2, it does not constitute one of the COTiD sessions).

Goal-setting phase (session 5)

In session 5, the occupational therapist summarises the information gained from the narrative interviews conducted with the person with dementia and with the family carer, plus the completed environmental assessment, activity and strategy observations. Then, together with the person who has dementia and their family carer, they list and prioritise the goals to be addressed during the intervention phase (shared decision-making). Goals may be joint or individual to either party.

Implementation of the intervention plan phase (sessions 6–10)

During sessions 6–10, the person with dementia and their carer work through the agreed intervention plan activities using either strategy training or external compensation to enable the person with dementia’s occupational performance. The occupational therapist also uses the consultation advice model to coach the carer in problem-solving skills. 37 The carer is encouraged to consider and implement effective strategies using the ‘how can you achieve that’ approach to best enable the person with dementia to carry out activities by effectively using their remaining strategies and adaptations made to the physical and social environment, while also reducing their care burden and meeting their own needs. The sessions primarily take place where the person with dementia lives. The ethnographic interview may take place in the carer’s home, and some implementation sessions may take place outside the home, that is within the local community, depending on the goals that have been set.

The COTiD training package

In the Netherlands, 4 training days are provided; the first 3 days each run 1 month apart, followed by a fourth day 3 months later. The first 3 days cover the three phases of the intervention, respectively. Content includes didactic teaching and practising some of the skills needed, for example the activity and strategy assessments. A case study is used, with participants role-playing the part of the occupational therapist, while actors simulate the role of the dyad. A carousel format is used, that is participants take it in turns to ask the actor(s) questions, with the actors providing feedback at the end regarding their experience. Participants practise their new skills in between the training days by providing sessions to dyads. These sessions are video-recorded and the recordings are brought to the next training day for trainer and peer feedback, during which discussion is framed by a checklist devised for evaluating the occupational therapist skills. The fourth day covers how to market the intervention and again features participants using role play to explain the purpose and value of COTiD to a range of potential stakeholders, for example a consultant psychiatrist, team manager and service commissioner. The COTiD knowledge questionnaire, COTiD vignettes and COTiD training evaluation are completed during this last training day.

Development of COTiD-UK

Introduction

A mixed-methods approach was used and included the following activities: translation and expert review of the manual and training materials; evaluation of the COTiD training for occupational therapists and COTiD delivery in practice; focus groups; semistructured interviews; a consensus conference; and an online survey. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analysed to develop COTiD-UK. Some of the data were further analysed within the implementation phase (WP5) and those results are, therefore, reported in Chapter 7.

Work package 1: translation and adaptation of the COTiD intervention and training package

Step 1.1: translation

The COTiD Dutch manual was translated into English by a commercial company,22 checked for accuracy by MG (original author) and then edited by JW to ensure that it contained commonly used UK language and occupational therapy terminology. This resulted in the first version of the manual.

Step 1.2: expert review and amendment

Method

Version 1 was reviewed by the VALID OTRG in terms of the content, language, occupational therapy terminology and intervention components. Comments were reviewed independently, discussed by JW, SH and SR, and then discussed with MG.

Results

All suggested amendments were agreed, including renaming some of the COTiD phases to better reflect UK occupational therapy terminology; substituting the Model of Human Occupation Screening Tool (MOHOST) assessment38 for the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) assessment39 as it is a more widely used assessment tool within UK occupational therapy practice; and the practical activity examples were made culturally relevant. This resulted in the second version of the manual, which was used in steps 1.3 and 1.4.

Step 1.3: COTiD training

Method

Three training days were held at monthly intervals in each of the three main study centres (Hull, London and Sheffield). MG delivered the training, supported by JW, using training materials and subtitled video clips translated from the original Dutch materials. In between training days, the occupational therapists started practising and video-recording their new skills (each were provided with a small digital video camera). The recordings were brought to the following training days for peer and trainer feedback. A fourth training day was held at each site 3 months later to discuss their progress.

The following data were collected from each occupational therapist participant:

-

COTiD Knowledge Questionnaire – translated from Dutch and comprising six multiple-choice questions aimed at checking the respondents’ knowledge of the COTiD intervention. It was completed during training day 4.

-

COTiD vignettes – two translated vignettes each describing a dyad taking part in COTiD were completed online following training day 4. The aim was to assess participants’ understanding of putting COTiD into practice by completing seven questions related to the COTiD process, using free text. The potential score ranged from 0 to 112, with higher scores reflecting higher understanding. JW and SH assessed the responses, using a translated checklist, based on a ‘model’ answer having achieved 100% inter-rater reliability.

COTiD training evaluation

A translated questionnaire was completed during training day 4 to collect participants’ views through quantitative and qualitative responses.

Results

Participants

Occupational therapists (n = 44) were recruited from across the three main study centres, covering 10 organisations, of whom 33 completed all four training days.

COTiD knowledge acquisition

Thirty-three participants completed the COTiD knowledge questionnaire. The number of correctly answered questions ranged from one to four, with just under one-fifth of respondents (n = 6, 18.2%) obtaining the higher mark and 15% obtaining the lower mark. Fourteen occupational therapists (42% of those who attended the final training day) completed the COTiD vignettes exercise with scores ranging from 20 to 79, with a mean score of 58 and median score of 59.

COTiD training evaluation

The majority felt that the course length was adequate, but nearly half felt that there was insufficient time between the training days to absorb the information provided. Half of the participants agreed/strongly agreed that the content was clear, whereas others would have liked more content focused on the less familiar aspects, for example conducting the occupational performance history interview and ethnographic interviews. The video feedback was valued in principle but considered to have become repetitive, taking up too high a proportion of the training days.

Step 1.4: delivering COTiD in practice

Method

Dyads comprising a person with dementia and a family carer were recruited at local sites to take part in the COTiD intervention. The aim was to identify how the intervention needed to be adapted in readiness for delivery within the piloting and evaluation phases. The following data were collected.

Video-recordings of COTiD sessions

The occupational therapists video-recorded two COTiD sessions with each dyad. The recordings were evaluated by one of four occupational therapist researchers familiar with the COTiD intervention (two in the UK and two in the Netherlands) to assess the occupational therapists’ COTiD skill development and level of competence using a translated checklist.

COTiD provision checklists

Data regarding the dyads’ demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as the duration and content of the COTiD sessions delivered, were collected via a checklist. A descriptive statistical analysis was completed to establish the participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics, and a thematic analysis of the intervention goals set and activities engaged in by the dyad with the occupational therapist during the sessions was conducted.

Semistructured interviews with dyads, managers and referrers

Semistructured interviews, using an Indicative Topic Guide, were conducted with dyads who had taken part in COTiD to explore dyads’ views of the COTiD intervention. These dyads were purposively sampled to represent as wide a range of experiences across the three sites, including: relationship between the dyad (i.e. spousal or non-spousal), gender, age. These interviews were conducted face to face at the person with dementia’s home.

Managers of occupational therapists who had taken part in the COTiD training and delivered the COTiD sessions were interviewed over the telephone, using an Indicative Topic Guide, to explore the organisational and managerial issues of delivering COTiD at the service level. People who had contributed by referring potential participants to the study team were interviewed in order to explore study recruitment issues, including the suitability of promotional materials and information provided and timing of the invitation. Referrers were purposively sampled to represent a range of professional background/role across the three sites.

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy and anonymised. The interview transcripts were coded and organised using NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) by two researchers who developed a coding framework and completed a thematic analysis of (1) the dyad interview data set and (2) the manager and referrer interview data set.

Focus groups with occupational therapists

Focus groups were held with occupational therapists after the fourth training day to explore their views on the training provided, COTiD intervention and delivery requirements, and barriers to and facilitators of putting COTiD into practice within the UK. Four researchers were involved, with two facilitating each group and completing field notes and reflective accounts during and immediately after the groups to capture non-verbal communication observed and their own reflections and interpretations. The groups were audio-recorded and the recordings were independently transcribed. Transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis, with each researcher reading one or two transcripts, assigning codes, categories and then themes to the data. The team discussed and iteratively checked these against the transcripts to strengthen trustworthiness. Once there was overall agreement on codes, categories and themes, these were then applied to all the transcripts.

Results

Participants

In total, 130 people with dementia together with a family carer (n = 260) across 9 of the 10 sites consented to take part in the COTiD intervention. Nineteen dyads either withdrew before completing the sessions or did not receive the intervention owing to lack of occupational therapist availability to deliver it.

The age of people living with dementia ranged from 54 to 94 years, with a mean age of 79 years, and the age of family carers ranged from 22 to 95 years, with a mean age of 65 years. In total, 51% of people living with dementia were male and 61% of family carers were female. A total of 72.6% of the dyads were spousal couples and 22.2% were parent–adult child pairs, and 64% of the family carers co-habited with the person living with dementia. The majority of dyads were white British.

Video-recordings of COTiD sessions

In total, 28 of the 33 occupational therapists provided at least one video. The total number of recordings received was 196. Inter-rater reliability of at least 80% was achieved by the four assessors. In practice it proved impracticable to assess the strategy observation videos because the assessors did not have access to the strategy observation checklist that should have been completed by the occupational therapist. In addition, nearly 10% of the videos could not be categorised for assessment because the occupational therapists had not named the file correctly. The level of competence in delivering the intervention was originally set at 80%, but the mean scores ranged from 60% to 78%. However, the raters’ feedback suggested that certain checklist items were not well correlated with the total score and, therefore, did not truly reflect the therapists’ level of competence to deliver COTiD.

Using the video cameras was challenging to some, and many found the IT and information governance processes very difficult to adhere to, not least because at some of the sites the only available equipment was outdated.

COTiD provision checklists

Forty-one checklists were analysed. In total, 161 activities were listed, with the most utilised activities being (in order of the most frequently utilised) domestic, home-based leisure, memory/orientation, personal care, physical activity and social contact. Fifty-seven goal-setting forms (number of goals, n = 153) were analysed. The range of goals set included (in order of the most frequently cited) increasing enjoyable home-based activity, carer education, domestic activities, personal care, physical activity, increased time for carer, community-based leisure, increasing social contact and improving memory/orientation. The format used to write goals varied tremendously, ranging from using just one word, for example ‘Diary’, through to more detailed goals, for example ‘to be able to dress in appropriate clothing for occasion and time of year’. It was not always clear as to who the goal related to: the person with dementia, the family carer or the dyad. Some goals were worded in the negative, for example ‘X will stop doing Y’.

Semistructured interviews with dyads, managers and referrers

Nine dyads were interviewed; all but one dyad were spousal dyads who co-habited. Dyads reported often struggling to identify ‘valued’ activities that they might pursue separately or together. In addition, in relation to the balance between talking and actually carrying out activities during the sessions, dyads wanted more and earlier ‘doing’. Their views were mainly positive. Suggested improvements included providing more support and guidance for identification of goals and subsequent activities.

Five referrers and four managers were interviewed. Given that the themes relate primarily to implementation of COTiD in practice, they are reported within Chapter 7.

Focus groups with the occupational therapists who had delivered the COTiD intervention

Five focus groups were conducted, with between five and eight participants in each; a total of 28 occupational therapists from eight of the participating organisations took part. Three main themes were identified from the data, each with subthemes:

-

COTiD training – timing, content and practising skills

-

COTiD intervention – benefits, challenges, follow-up, occupational therapy support workers, manual and structure

-

participation in the research process.

The third theme, regarding participants’ experience of taking part in the research process, in terms of what enabled or challenged their input, has been reported elsewhere. 40

Occupational therapists felt that the training needed to be provided as near as possible to the actual delivery of the intervention and needed to include more UK-relevant examples and more complex case studies. The COTiD intervention was seen to be truly client centred, occupational therapy specific and involving carers in their own right, and was referred to as ‘being the bedrock of OT [occupational therapist] practice, almost giving us permission to be OTs again’. It was felt that session frequency and length needed to be much more flexible because it was usually not possible to provide the 10 sessions within the stipulated 5 weeks, as a result of either occupational therapist capacity and/or dyad availability. In addition, it was also felt that dyads needed longer between the latter COTiD sessions to actually put planned goals and activities into practice before reviewing progress at the next session with the occupational therapist.

Step 1.5: focus groups with people with dementia and family carers of people with dementia who had not received the COTiD intervention

The aim of these focus groups was to elicit views of the COTiD programme from people with dementia and family carers and the extent to which the programme might meet their needs and preferences, and identify any aspects that may require changes to make the programme suitable for use in the UK.

Method

Separate focus groups were conducted with people living with dementia and with family carers who were currently supporting people living with dementia or had done so in the previous 2 years. No one who participated had received the COTiD intervention. Each group was run by an experienced facilitator, supported by a scribe who observed, recorded non-verbal communication and made field notes. The groups were audio-recorded, and the recordings were then transcribed and an inductive, data-driven thematic analysis was completed.

Results

Six focus groups were conducted: three with people with dementia and three with family carers (n = 39). Three themes emerged, with positive, negative and ambivalent views of COTiD running across all three themes: loss and living with dementia, ‘what helped us’, and consistency and continuity.

In summary, participants suggested that COTiD delivery needed to be flexible in terms of timing and length of the intervention; fit into their existing demands; include the person living with dementia and their family carer as partners within the process; include a focus on previous occupations; and be provided at the appropriate (i.e. early) stage of their dementia pathway.

A more detailed description and discussion of these focus groups has been reported elsewhere. 41

In addition, the COTiD training and provision costs were identified and are reported in the economic evaluation section (see Chapter 6).

The manual was updated in light of the data collected above to produce version 3.

Step 1.6: consensus conference

Method

A consensus conference was held to agree the content of the COTiD-UK intervention. Participants included people with dementia and family carers, some of whom had taken part in the COTiD intervention and others who had not; occupational therapists who had attended the COTiD training, some of whom had subsequently delivered the COTiD intervention in practice; multidisciplinary team members, including those who had referred dyads to take part in the COTiD intervention; and managers of occupational therapists involved in the training and intervention delivery.

Version 3 of the COTiD manual was circulated in advance of the event, including an abbreviated version for people living with dementia that mainly comprised the information sheets to be provided to participants during the intervention. Following presentations from the research team, participants were asked to discuss three questions, in mixed groups of approximately eight participants each. The questions were (1) ‘How relevant do you think the COTiD manual is for addressing problems in daily living experienced by people living with dementia in the UK?’; (2) ‘How appropriate do you think the intervention is for people and how could it be improved?’; and (3) ‘How well do you think the structure of the intervention fits the UK context?’. Two researchers joined each group: one to facilitate the discussion and one to take notes. The discussion notes were transcribed and analysed thematically.

Results

Thirty-one participants attended the event. There was consensus that COTiD fits the UK context well and could be beneficial in reducing risks and preventing crises. There was a view that it ‘fills a significant gap’ that existed at that time, and that providing an evidence base for COTiD in the UK would ‘futureproof’ it. There was also discussion about the importance of ensuring that there is funding available for COTiD in the light of the ever-changing commissioning processes and priorities.

In summary, key messages related to the importance of the intervention being delivered in a timely and flexible manner; concern about what would happen in practice after the intervention finishes; the fact that COTiD ‘legitimises . . . spending time getting to know people before beginning intervention’ (occupational therapist participant), a practice that was felt to have been discouraged in recent years; the importance of considering the terminology used in the manual; and the potential benefit of COTiD to people with dementia.

Work package 2: online survey to scope current community occupational therapy service provision and practice for people with dementia and their family carers in the UK

The aims of the online survey were to identify current UK occupational therapy service provision and practice for people living with dementia and their family carers, and to explore the potential facilitators of and barriers to implementing COTiD in the UK.

Method

A questionnaire was developed through reviewing the literature, researcher knowledge and consultation with the VALID OTRG. It was piloted with the local occupational therapy service and subsequently amended. To identify current practice, participants were asked about their occupational therapist role, local service provision, referral routes, access to assistive technology and use of assessment tools, using open and closed questions and Likert scales. Descriptive statistics were calculated, including totals (n) and percentages, as well as the ranges, medians, means and standard deviations. To explore the potential implementation of COTiD in UK practice, respondents were asked to reply to four questions, using free text. A thematic analysis of the responses was conducted. An optional section invited participants to provide demographic and contact details, which would be entered into a gift voucher prize draw. The survey was conducted online over 4 months. Recruitment of occupational therapists working with people living with dementia was through direct invitation to community mental health teams listed on the Personal Social Services Research Unit database and via the Memory Services National Accreditation Programme, primarily by e-mail containing a link to the questionnaire. The questionnaire was also promoted via established local and national professional networks, relevant websites and newsletters.

Results

In total, 230 occupational therapists consented to take part, of whom 197 provided quantitative data and 138 also provided qualitative data. A detailed description and discussion of the quantitative data that related to current service provision at the time of the survey has been reported elsewhere. 42

In summary, the key findings were that over half of the respondents undertook primarily profession-specific work; occupational therapy-specific assessments were the most common profession-specific task – two-thirds of referrals for initial assessments were for people with mild to moderate dementia; the median time spent per person with dementia was 2.5 hours; and most respondents could prescribe equipment to support personal care activities, as well as telecare, but not for reminiscence or leisure activities. This information informed the revised intervention and training content. It also informed the development of the template document used to collect TAU information from the research sites that took part in the RCT.

Finalising the COTiD-UK intervention and training package in readiness for the evaluation phase

The COTiD-UK intervention

The UK intervention is designed to be delivered more flexibly in terms of timing (up to 10 hours over approximately 10 weeks) to maximise the availability of both occupational therapists and dyads, and to provide dyads with time to put their agreed activities and plans into practice in between sessions with the occupational therapist. The content is similar to the COTiD intervention, but its delivery is less prescriptive; for example, occupational therapists complete the physical and social environmental assessments and the activity and strategy analyses but use the assessment tools that they usually use in their own practice/service, rather than the translated COTiD checklists and tools. The one-to-one narrative interviews are conducted in the same way but follow on from the introductory session to start building rapport with the dyad and provide opportunity to discuss what is important to them as soon as possible. There is an emphasis on engaging in activity earlier and more frequently within the sessions. Goals are set in the same way, through discussion between the dyad and the occupational therapist, but can be evaluated and added to throughout the sessions if dyads’ views and/or circumstances change over time. The sessions usually take place where the person with dementia lives but, depending on the goals, may also take place in the local community, for example the sports club, local library or garden centre. During the final session, the dyad and occupational therapist evaluate the success in achieving the goals and plan ahead for the future.

The COTiD-UK training programme

The COTiD-UK training programme was restructured into 3 days because it was felt that the content could realistically be covered in this time; this also made it more affordable and feasible for services to release occupational therapists to attend. Days 1 and 2 ran consecutively, and day 3 took place after participants had put COTiD-UK into practice. The content was revised from the original to include more complex case examples, presented in the form of role plays with the occupational therapists taking on all roles, rather than incurring the cost of employing actors to perform the dyad roles. Time to practise the narrative interviews and goal-setting sessions, along with actually using the audio-recording equipment, was included, plus more time and emphasis on setting and writing specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound (SMART) goals,43 including a group exercise. The COTiD knowledge questionnaire was refined to make it more easily understood and more accurately reflect the revised COTiD-UK intervention. The online COTiD vignette task was dropped from the COTiD-UK training because of the low response rate and reported difficulty that participants had in understanding and completing it.

Audio-recordings were used instead of video-recordings, and updated IT and information governance guidance was provided to participants. Before delivering COTiD-UK in the RCT, occupational therapists were required to complete a ‘training dyad’, which incorporated audio-recording as many sessions as practicable. These recordings were then reviewed by a COTiD-UK trainer using a refined checklist to assess the occupational therapists’ competence. These checklists later became the basis from which fidelity measures for the RCT were developed (see Implementation phase). A supervision structure was put in place for the intervention providers, with supervision provided by either a COTiD-UK trainer or a local supervisor who had also completed the COTiD-UK training.

Development phase: conclusion

Analysis of the data collected through the sequence of activities described above resulted in the COTiD intervention being translated and adapted to maximise its suitability and feasibility for use within the UK context, specifically the health and social care sector, and hereafter is referred to as COTiD-UK. This version was then ready to be evaluated in an internal pilot and subsequent full RCT (i.e. WP3 and WP4), as reported in Piloting and evaluation phases: internal pilot and randomised controlled trial of COTiD-UK compared with treatment as usual (work packages 3 and 4).

The dyad recruitment materials and processes were also refined in readiness for the evaluation phase. For example, participant feedback indicated that some people were not comfortable with using the term ‘family carer’ at the post-diagnostic stage. As a result, the term ‘supporter’ was used on future participant recruitment documents, such as information sheets and consent forms, and when communicating with dyads. The term ‘family carer’ continued to be used within study protocols and published outputs.

This phase took twice as long to complete as originally planned but reflects the range of activities used and depth of data collected, which importantly included the perspectives of people with dementia and family carers, as well as occupational therapists and other professional groups. A number of logistical challenges arose, including delays in recruiting research sites, occupational therapists and dyads; IT and information governance difficulties experienced at some sites; and obtaining the necessary governance approvals at some sites to actually deliver the COTiD intervention. However, it was important that the intervention was not only translated but also adapted to maximise its suitability and feasibility for use within the UK culture, and health and social care provision.

Chapter 4 Piloting and evaluation phase: internal pilot and randomised controlled trial of COTiD-UK compared with treatment as usual (work packages 3 and 4)

Aim

The aim of this phase was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the COTiD-UK intervention compared with TAU.

There were two WPs:

-

WP3 – internal pilot trial.

-

WP4 – full RCT.

Hypotheses

It was hypothesised that, compared with TAU, COTiD-UK would:

-

significantly improve ADL in people with dementia

-

significantly improve quality of life for the people with dementia and their family carers

-

demonstrate cost-effectiveness.

Ethics approval

NHS ethics approval for WP3 and WP4 was gained from the NRES Committee London – Camberwell St Giles on 14 July 2014 (reference number 14/LO/0736). Eighteen amendments (13 non-substantial and five substantial) were approved to cover protocol and trial documentation updates; the addition of new trial sites and participant identification centres, registration with Join Dementia Research and new trial documentation as required; and postgraduate student studies linked to the VALID programme (as outlined in Development of research capacity). The appropriate local research and development governance approvals were obtained at each research site.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Work package 3: internal pilot trial

The aim of WP3 was to conduct an internal pilot trial of COTiD-UK compared with TAU to:

-

field test the outcome measures to be used to measure the effectiveness of COTiD-UK

-

finalise the intervention modes of delivery and associated training and supervision of those delivering COTiD-UK

-

field test trial procedures.

Work package 4: full randomised controlled trial

The aim of WP4 was to conduct a RCT to:

-

determine the clinical effectiveness of COTiD-UK compared with TAU

-

determine the cost-effectiveness of COTiD-UK compared with TAU.

Work package 3 was designed as an internal pilot, with the intention of moving forward into WP4, the full RCT, if predefined success criteria based on the Acceptance Checklist for Clinical Effectiveness Pilot Trials (ACCEPT) model were met. 44 This checklist provides a systematic basis for assessing whether or not a pilot trial has adequately tested a study design, methods and procedures, and, therefore, whether or not the pilot data can be integrated into the full trial data set without compromising trial integrity. There are three potential outcomes:

-

Unequivocal acceptance of pilot data – the design and methods are confirmed as being feasible and appropriate except for minor details; therefore, pilot data can be carried forward to the main trial data set.

-

Conditional acceptance – the design and methods are found to be feasible and appropriate in principle but need refinement; therefore, a decision including the pilot data must be delayed until the variation in procedures for the full pragmatic trial is known.

-

Non-acceptance of pilot data – the need for substantial change is identified; therefore, the pilot data cannot be carried forward to the main trial data set.

Moving from internal pilot to the full randomised controlled trial

The internal pilot trial ran from September 2014 to April 2015 in the three main research sites (Hull, NELFT and Sheffield). The internal pilot trial procedures and data set were reviewed by the central research team against the predefined ACCEPT criteria,44 and were presented to the independent PSC in April 2015. The criteria assessed were trial design; sample size; intervention training and fidelity of delivery; participants’ recruitment strategy and eligibility criteria; consent procedures; randomisation process; blinding data collection, quality and management; research governance; and data analysis.

The research team reported that no significant changes had been made to the study design. Recruitment had initially been slower than expected, with 44 dyads (88% of the target of 50 dyads) having been consented by April 2015. However, the recruitment rate was picking up, and retention at the 12-week follow-up, at the first site, was 89%. It was agreed that more sites and occupational therapists than originally planned would need to be recruited to enable the recruitment of the target sample of 480 dyads to be achieved within time.

It was decided to omit the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure:45 partly because it was felt that the number of measures needed to be reduced to lessen the burden on participants and partly because of the feedback from research staff about the difficulties experienced in administering this assessment in a consistent, reliable way over time and between assessors. Some refinements were made to the web-based database, and a data entry handbook was written to maximise consistency of data collection and entry across time points and research sites.

The outcome of this review confirmed that the design and methods were feasible and appropriate except for minor details, and resulted in the PSC supporting the unequivocal acceptance of the internal pilot data within the full trial data set.

The methodology and results reported here, therefore, derive from the trial procedures used and the data set collected during the internal pilot and full RCT. This study is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. 46 The trial protocol and outcomes are reported elsewhere in detail47,48 and, therefore, are summarised here.

Method

Study design

The study design was a multicentre, pragmatic, two-arm, parallel-group, single-blind individually RCT with an internal pilot. People with mild to moderate dementia were recruited along with an identified family carer (a dyad or pair). Recruited dyads were individually randomised and allocated to receive either TAU or the COTiD-UK intervention in addition to TAU, which may or may not have included occupational therapy provision depending on usual practice at the recruiting sites. The intention was to recruit 50 dyads for the internal pilot and a further 430 dyads for the RCT. The study ran in NHS trusts across England, and participants were primarily recruited from older adult community mental health teams and memory services across inner city, urban and rural areas.

Recruitment

In March 2015, during the COTiD-UK evaluation phase, VALID joined the Join Dementia Research register, and 22% of the RCT participants were recruited via this route, although the percentage varied across research sites. This NIHR initiative, in partnership with the Alzheimer’s Society (London, UK), Alzheimer’s Scotland (Edinburgh, UK) and Alzheimer’s Research UK (Cambridge, UK), enables people to register their interest in taking part in dementia research and, thereby, be matched to relevant studies. 49

Recruitment of dyads to the RCT involved local participant-relevant organisations as appropriate at each research site. For example, within NELFT, dyads were recruited via the local Alzheimer’s Society and Age UK (London, UK) branches through attending events, such as dementia cafés, carer support groups, early intervention services and cognitive stimulation groups. However, the level and nature of this involvement varied from site to site, according to what community support services were provided locally and by whom, and the recruitment procedures usually utilised within the site.

Interventions

COTiD-UK

The COTiD-UK intervention consists of up to 10 hours of community occupational therapy delivered over 10 weeks to the dyad, primarily at the person with dementia’s home and in their local community. The content, as well as the training and supervision model, are described in detail at the end of Chapter 3, Development phase: developing COTiD-UK (work packages 1 and 2).

Adherence to the intervention was defined as dyads reaching the goal-setting phase, as agreed through discussion between the occupational therapist researchers and the COTiD-UK trainers, which indicated that the initial core elements of the intervention had been delivered.

Treatment as usual

The TAU group received standard clinical care, usually provided in the recruiting site, which may or may not have included standard occupational therapy. Given that usual service provision varied between and within the recruiting trusts, each site completed a template detailing the usual treatment offered.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures were selected to replicate the Dutch23–25 and German26 studies where possible, while also using tools more commonly used within UK studies. The primary outcome measure was the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS),50 with the primary end point at 26 weeks. This retained the focus on the ability to perform ADL as the primary outcome, given that it was not feasible to use the AMPS as Graff and colleagues23 had because of the lack of AMPS-trained occupational therapists in the UK and the potential resource implications for using this across a much larger sample size with more follow-up data collection points. Secondary outcome measures for the person with dementia were selected to assess cognition (Mini Mental State Examination),51 ADL ability (Interview of Deterioration in Daily activities of Dementia),52 condition-specific quality of life [Dementia Quality of Life (DEMQOL) scale]53 and mood (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia). 54

Secondary outcome measures for the family carer assessed sense of competence (Sense of Competence Questionnaire)55 and mood [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)]. 56

Social contacts, leisure activities and serious adverse events were recorded for all participants. Self-reported quality of life data [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)] were collected for both the person with dementia and their carer,57 and resource use data [Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)]58 were collected for all participants to facilitate the economic evaluation [reported in Chapter 6, Economic evaluation (work packages 1, 3 and 4)].

Therefore, the majority of the outcome measures replicated those used in the Dutch23–25 and German26 studies.

Procedure

Data were collected through a face-to-face interview with the dyad at the person with dementia’s home at baseline and at 12 and 26 weeks post randomisation. A reduced data set was collected through a telephone interview with the family carer at 52 and 78 weeks. This comprised, in the case of the person with dementia and the family carer, the BADLS total score, plus the occurrence of any serious adverse events, the CSRI score, information on social contacts and leisure activities, as reported by the family carer, plus, in the case of the family carer only, HADS and EQ-5D-5L scores. As explained previously (see Chapter 2, The VALID applied research programme), the original intention was to collect data for all dyads at 52 weeks and the first 40% of dyads recruited at 78 weeks (n = 192); however, as part of the variation to contract, this was revised to following up the first 77% of dyads recruited at 52 weeks, while the target sample at 78 weeks remained the same. Follow-up data collection was undertaken by site-based research staff masked to the dyad’s allocation.

The target sample size was based on a standardised mean difference of 0.35 in the BADLS total score between the COTiD-UK and the TAU groups, with the anticipated effect size determined using the clinical expertise of the applicant group and based on the DOMINO group consensus advice regarding the minimum clinically important difference using the BADLS. 59 To detect this difference using a two-sample t-test with 90% power and a significance level of 5%, and after adjusting for 15% attrition, 5% non-adherence in the TAU group and the clustering of dyads by occupational therapist in the COTiD-UK group [assumed intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) with an average of 10 dyads per therapist], we planned to recruit 256 dyads to the COTiD-UK group and 224 dyads to the TAU group.

Statistical analysis followed a predefined statistical analysis plan with no interim analysis and used Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Occupational therapists delivering the COTiD-UK intervention completed a COTiD-UK checklist for each dyad to quantify the number, frequency, length and content of sessions provided, and audio-recorded all sessions where it was practicable. These data enabled the intervention costs to be calculated for the economic evaluation [see Economic evaluation (work packages 1, 3 and 4)], the intervention fidelity to be assessed (see Implementation phase) and the percentage of goals achieved, partially achieved and not achieved to be calculated (see Results section).

Results

Recruitment of sites, occupational therapists and dyads

Approximately 30 NHS trusts expressed interest in taking part in the study, 15 of which were set up as research sites between September 2014 and May 2017, although one did not proceed to recruiting dyads. Forty-four occupational therapists were trained to deliver COTiD-UK, 32 of whom proceeded to the RCT and were allocated at least one dyad each; however, one occupational therapist was subsequently unavailable to provide the intervention as planned owing to ill health. Reasons for dropout of occupational therapists included the employing organisation not being recruited as a site or the site’s failure to recruit participants, sickness, job turnover or not being made available because of service and organisational constraints. Dyad recruitment took place between September 2014 and July 2017, and the last follow-up assessment was completed in January 2018 when the study shut to recruitment in line with the revised funding agreement. The recruitment and retention rate varied across sites, with some sites exceeding their recruitment target whilst more sites did not achieve their initial target, a challenge that we have reported in more detail elsewhere. 60

Baseline data

In total, 468 dyads were randomised, with 249 dyads assigned to COTiD-UK and 219 assigned to TAU. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups were very similar at baseline. The people with dementia ranged in age from 55 to 97 years, with a mean of 78.6 years, and family carers ranged in age from 29 to 94 years, with a mean of 69.1 years. The vast majority of participants were white British. Of the people with dementia, three-quarters were married and about one-quarter lived alone. In addition, half had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, one-fifth had vascular dementia and just over 10% had a mixed presentation. About 85% were categorised as having mild dementia. About three-quarters of the family carers were spouses, with most of the rest being adult children.

Outcomes at 26 weeks

At 26 weeks, 406 dyads remained in the trial (86.7%), giving an attrition rate of 13.3%. Outcome data were collected and analysed for 368 dyads (78.6% of the total sample; COTiD-UK, n = 207; TAU, n = 161), giving an attrition rate of 21.4%.

At 26 weeks, the BADLS total score did not differ at the 5% level when comparing the two groups, with an adjusted mean difference estimate of 0.35 [95% confidence interval (CI) –0.81 to 1.51; p = 0.55]. The adjusted (for baseline BADLS total score and randomised group) ICC estimate for the primary outcome at week 26 was 0.043. This reflects the level of correlation between the BADLS total scores for dyads treated by the same occupational therapist within the COTiD-UK group. When considering the within-dyad mean BADLS total score, to account for missing items, the mean difference estimate was 0.02 (95% CI –0.04 to 0.07). Predictors of missingness were identified as the ethnicity of the person with dementia and marital status of the family carer. When also adjusting for predictors of missing data, the mean difference estimate in BADLS total score was 0.34 (95% CI –0.82 to 1.49). The complier-average causal effect, which provides a measure of the effect of the COTiD-UK intervention in the population that took part and reached the goal-setting phase of the intervention, at week 26 was estimated as 0.42 (95% CI –0.77 to 1.60).

Secondary outcomes were similar between the two groups at week 26. For continuous outcomes, all effect estimates were close to zero. For the numbers of leisure and social contacts, intensity rate ratio estimates were close to 1.

At the 26-week follow-up, research staff collecting outcome data were reported as having been unmasked as to the dyad allocation for 45 of the 338 assessments (13.3%).

Adherence and goal achievement