Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as award number RP-PG-1211-20011. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2022 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Wells et al. This work was produced by Wells et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Wells et al.

Synopsis

Background

Cardiovascular disease and cardiac rehabilitation

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are associated with approximately 25% (168,000) of all deaths each year in the UK. Survival rates are improving, with an estimated 7.64 million people in the UK living with heart or circulatory diseases. 1 Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is recommended by the UK Department of Health and Social Care, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR) for eligible patients following a cardiovascular event. Components of CR focus on health behaviour change and education, lifestyle risk factor management and psychosocial management. 2 CR has been shown to be a cost-effective intervention that leads to a reduction in cardiovascular mortality and risk of hospital admissions, while also improving health-related quality of life. 3,4

Mental health provision in cardiac rehabilitation

The psychological impacts of CVD are considerable, with patients reporting high levels of anxiety and depression that have been linked to increased mortality, poorer quality of life, greater social problems and higher healthcare costs. In a recent analysis,5 19% of patients entering CR were classed as having borderline or clinical depression and 28% were classed as having borderline or clinical anxiety on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). An analysis of health records showed that 54.5% of CVD patients who reported consistently high levels of anxiety and depression were referred to a specialist or had active psychological management with a general practitioner (GP). 6 There is no standardised approach for psychological interventions in CR, and interventions can vary between stress management, counselling, relaxation, meditation and cognitive challenging of negative thoughts. Research on psychological interventions within CR is generally of low quality, with usually small reductions of psychological symptoms reported and limited improvement seen in anxiety, low mood and health-related quality of life. 7

Novel applications of metacognitive therapy: a translational approach

Metacognitive therapy (MCT)8 is a treatment approach based on the hypothesis that anxiety and depression are maintained by a common maladaptive thinking style, called cognitive attentional syndrome (CAS), of sustained, repetitive negative thinking, increased attention to threat and dysfunctional coping mechanisms. CAS is linked to biased metacognition, which is that part of cognition responsible for regulating thinking. Important components of metacognition are the beliefs a person holds about thinking, which in the metacognitive model can be defined as positive or negative. Positive metacognitive beliefs concern the usefulness of worry as a coping strategy (e.g. ‘worrying helps me find answers to my problems’), whereas negative metacognitive beliefs concern the uncontrollability and danger of thoughts and feelings (e.g. ‘I cannot stop worrying about the future’ or ‘thinking like this means I am losing my mind’). Such beliefs are considered to underlie unhelpful reactions to negative thoughts about life events, such as the thought ‘what if I have another heart attack?’. In comparison with other treatment approaches, MCT does not require in-depth analysis and challenging of the content of negative thoughts or worry, instead focusing on reducing unhelpful processing styles (e.g. reducing worry frequency and duration) in response to negative thoughts. 8 MCT has been demonstrated as highly effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression and maladaptive metacognitions in people with mental health problems. 9–12 In a recent meta-analysis in mental health, MCT was found to be more effective in reducing anxiety and depression symptoms than other psychological therapies such as cognitive–behavioural therapies (CBT). 13

The chief investigator of this programme of research, Adrian Wells, is the originator of MCT and the director of the Metacognitive Therapy Institute. Therefore, it is important to draw attention to the steps taken throughout the PATHWAY research programme to maintain objectivity. These steps included masking to patient allocation, data management undertaken by a separate clinical trials unit, prespecified data analysis plans, pre-trial registration, the publication of trial protocols and project monitoring by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

The PATHWAY study

Current CR approaches vary considerably in the level and type of psychological interventions used, with many CR services offering little or no psychological input. Furthermore, trials investigating the efficacy of specific psychological interventions and techniques in heart disease are often of low quality. 7 In line with guidelines from BACPR, CR programmes offer a choice of treatment approaches in order to deliver a menu-based strategy to meet individual patient needs. 2 Currently, 75.4% of patients choose to undertake group-based CR, with 8.8% choosing home-based treatment, while 42.2% of patients engage with two or more modes of CR delivery. 5 Therefore, psychological interventions might offer similar variation in treatment delivery, providing the option for group- and home-based treatment to be integrated into existing CR and to maintain improved access to psychological treatment.

The PATHWAY programme aimed to improve access to more effective psychological interventions for patients attending CR services. This was approached through investigating the effects associated with introducing MCT alongside CR in group- and home-based formats.

Aims and objectives of PATHWAY

The primary aim of PATHWAY was to improve access to more effective psychological interventions for a range of heart disease patients attending CR services. We aimed to integrate two metacognitive interventions: a group intervention and a home-based intervention. The project set out to achieve the following objectives:

-

Conduct a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a group MCT (Group-MCT) for patients with depression and/or anxiety.

-

Establish evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Group-MCT in a full- scale RCT.

-

Produce a rigorous, well-specified Group-MCT package.

-

Develop a home-based metacognitive intervention (Home-MCT) for patients with depression and/or anxiety.

-

Establish the feasibility and acceptability of integrating Home-MCT into the CR pathway.

-

Establish provisional evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Home-MCT.

-

Develop a protocol and manual to inform a full-scale RCT of Home-MCT.

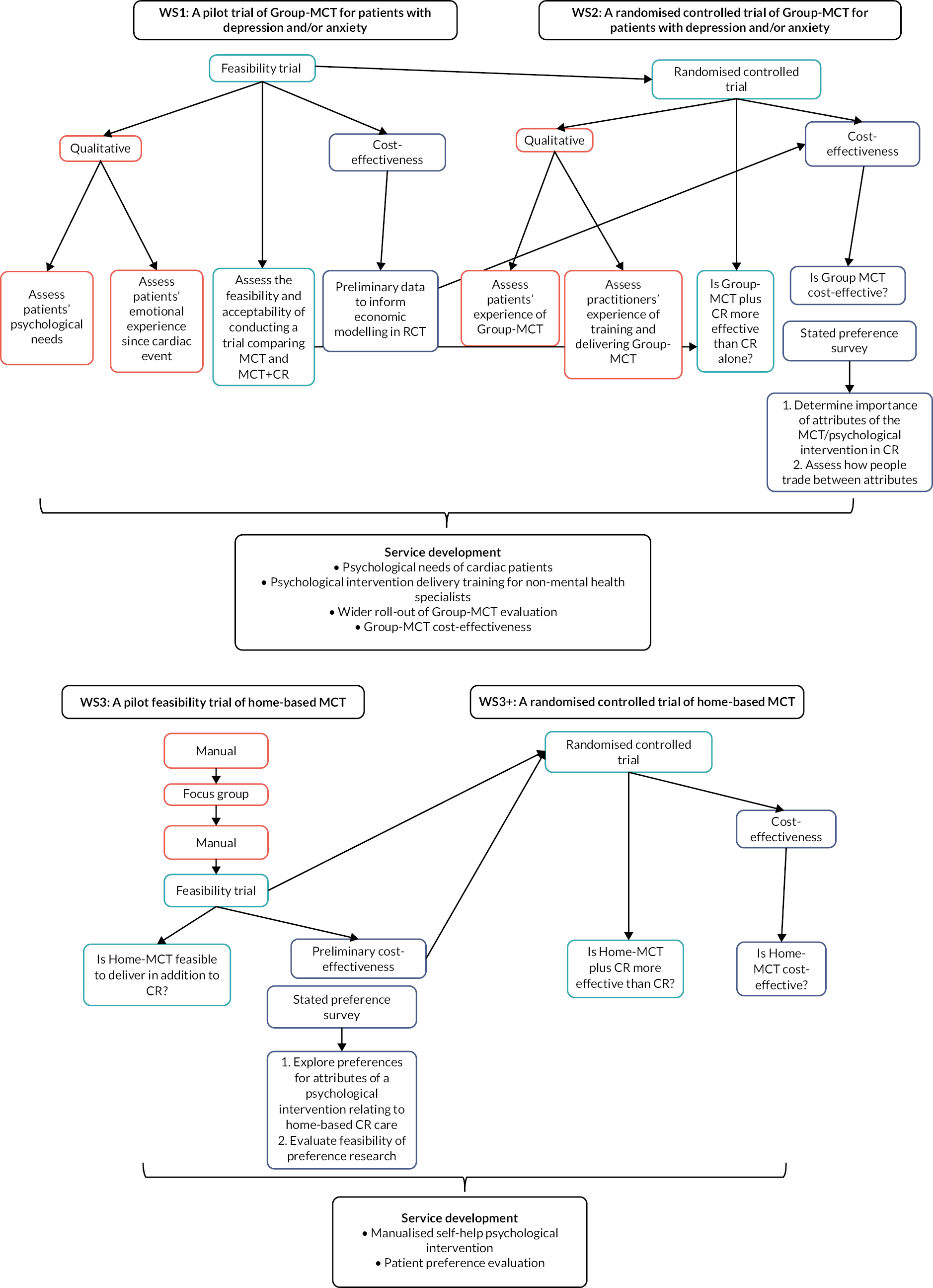

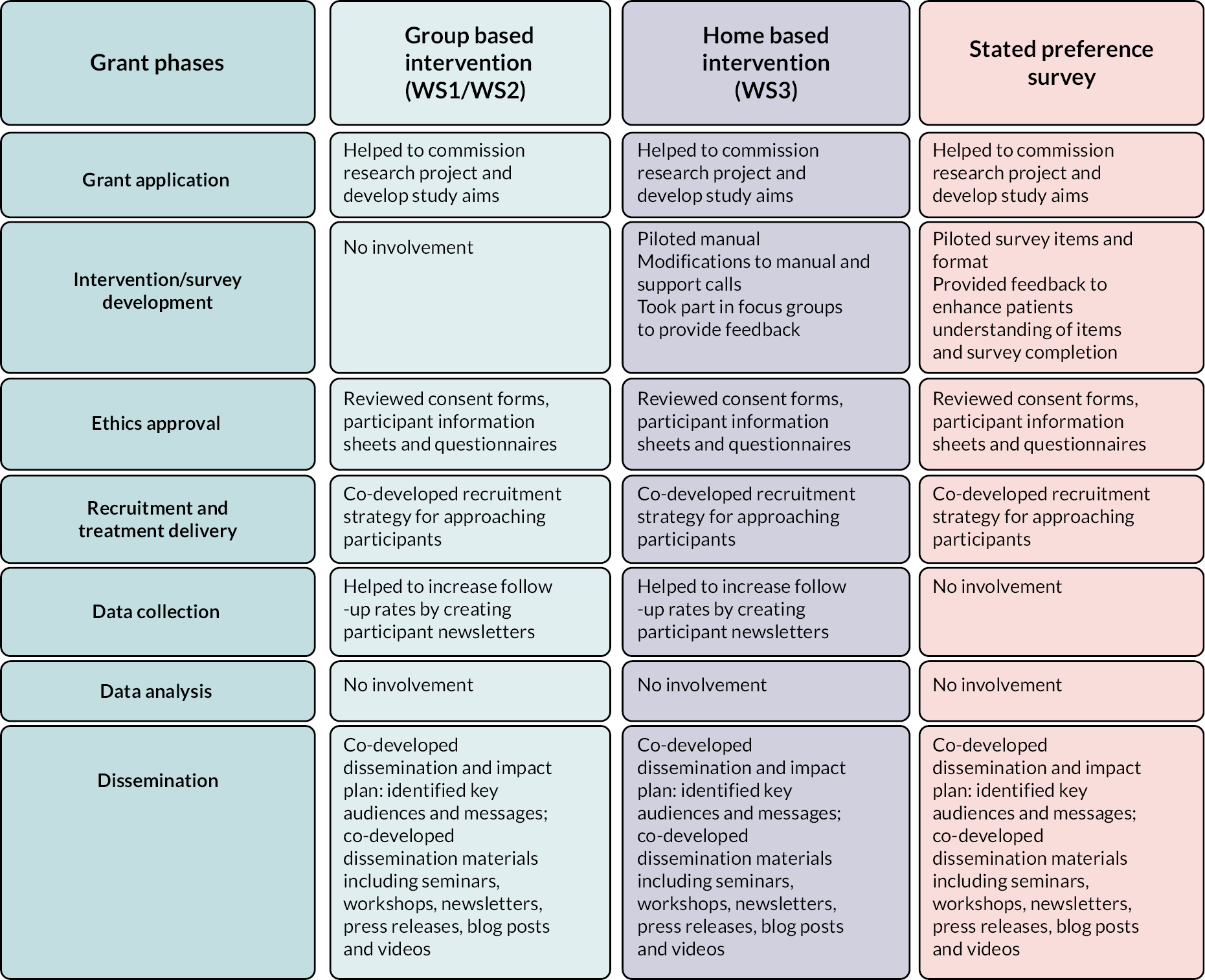

To meet these objectives, we developed a series of work streams (WSs) with integrated qualitative and health economic evaluations. Figure 1 shows the research pathway diagram and Table 1 gives an overview of the original programme objectives, WSs and outputs.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram.

| Programme objectives | Research activity | Programme outputs |

|---|---|---|

| WS1: to conduct a pilot trial of Group-MCT for patients with depression and/or anxiety | Development of Group-MCT manual | Group-MCT intervention including treatment manual for practitioners, patient booklet and practitioner training |

| Qualitative interviews | McPhillips et al.1 McPhillips et al.15 |

|

| Pilot trial to assess the acceptability and feasibility of conducting a study in CR | Wells et al.16 Wells and Faija17 |

|

| WS2: to conduct a full-scale RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Group-MCT + usual CR compared with usual CR alone | RCT to assess the effects associated with and cost-effectiveness of Group-MCT + usual CR vs. usual CR alone Discrete choice experiment to investigate preferences for the delivery psychological therapy intervention in CR (clinic-based) PPI evaluation and framework |

Wells et al.18 Wells et al.19 Shields et al.3 Shields et al.20 Shields et al.21 McPhillips et al.;22 Anderson et al.23 Shields et al. (see Appendix 2) Wells et al.24 Wells et al.25 Shields et al.26 Capobianco et al.27 |

| WS3: to develop a home-based MCT intervention (Home-MCT) and then evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of integrating Home-MCT into the CR pathway in a feasibility trial | Development of Home-MCT manual | Home-MCT manual comprising six modules accompanied by three telephone support calls from MCT-trained CR staff |

| Feasibility trial to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of Home-MCT Qualitative interview and focus groups |

Wells et al.28 Wells et al.29 Supplementary WS2/3 outputs: Faija et al.30,31 Capobianco et al.32 |

|

| Pilot discrete choice experiment to investigate preferences for delivery of psychological therapy intervention in CR (home-based) | Shields et al.33 | |

| WS3+: to conduct a full-scale RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Home-MCT + usual CR vs. usual CR alone | RCT to assess the effects associated with Home-MCT + usual CR vs. usual CR alone | Wells et al.34 |

Work stream 1 was a pilot trial of Group-MCT for patients with depression and/or anxiety. We undertook an initial small-scale pilot trial to establish the acceptability to CR patients and therapists (CR staff trained to deliver the manualised MCT treatment) of adding MCT to usual CR. The pilot also evaluated the feasibility of conducting a full-scale RCT of the intervention.

Work stream 2 was a full-scale RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Group-MCT plus usual CR compared with usual CR alone. Progression to WS2 depended on the findings of WS1 with regard to the acceptability and feasibility of delivering MCT and implementing a full-scale RCT.

Work stream 3 was to develop a home-based MCT intervention (Home-MCT) and then evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of integrating Home-MCT into the CR pathway in a feasibility trial.

We were able to fully meet the programme objectives:

-

WS1 demonstrated that a trial of Group-MCT added to usual CR was feasible and acceptable and confirmed our original sample size estimate.

-

The WS2 and WS3 trials recruited to target and had excellent retention.

-

Group-MCT + CR was found to be more effective than CR alone at 4- and 12-month follow-up.

-

Home-MCT + CR was found to be feasible and acceptable and was extended to a full-scale trial under a variation to contract (VTC) to utilise a study underspend.

-

The full-scale trial of Home-MCT demonstrated that the treatment was associated with significantly improved psychological outcomes when added to usual CR.

-

We co-designed the Home-MCT intervention with patients and clinicians.

-

We completed a cost-effectiveness analysis of group- and home-based MCT.

Summary of changes to original aims

Following the completion of WS3, we submitted a VTC on 29 January 2019 to progress WS3 from a feasibility trial to a full-scale RCT (WS3+). The VTC was awarded on 12 March 2019. The following was added as the aim of WS3+: to assess the effects associated with home-based MCT.

Work stream 1 a pilot trial of Group-MCT for patients with depression and/or anxiety

Some parts of the sections that follow have been reproduced with permission from Wells et al. 16 and McPhillips et al. 14,15 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Work stream 1 overview

Anxiety and depression are common among CR patients. However, existing psychological interventions used in CR produce only modest reductions in emotional distress. An alternative therapy currently not used in CR, MCT, has shown promising results in improving anxiety and depression in mental health settings and in patients with physical illnesses. WS1 aimed to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of delivering Group-MCT to CR patients experiencing anxiety and depression.

Work stream 1 was a multicentre pilot feasibility study with 4- and 12-month follow-up comparing Group-MCT plus usual CR (intervention) with usual CR alone (control). The study was designed as an internal pilot of the full-scale RCT (WS2). Prespecified criteria for progression to a full RCT were (1) a mean recruitment rate of 8.7 per month, with a rate of 10 per month being desirable; (2) ≥ 65% of participants in the MCT arm attending at least four of the six Group-MCT sessions; and (3) 75% retention at 4-month follow-up. Additionally, the pooling of data collected under the pilot with those collected under the full RCT in the final analysis depended on no substantial changes being made to the trial procedures (e.g. patient eligibility criteria, follow-up schedule) or the trial instruments (e.g. outcome measures) as a result of the pilot. Both study progression and the pooling of data sets required the agreement of the TSC and NIHR as the funding body. The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service of the NHS (reference 15/NW/0163) and registered with a clinical trial database (ISRCTN reference ISRCTN74643496).

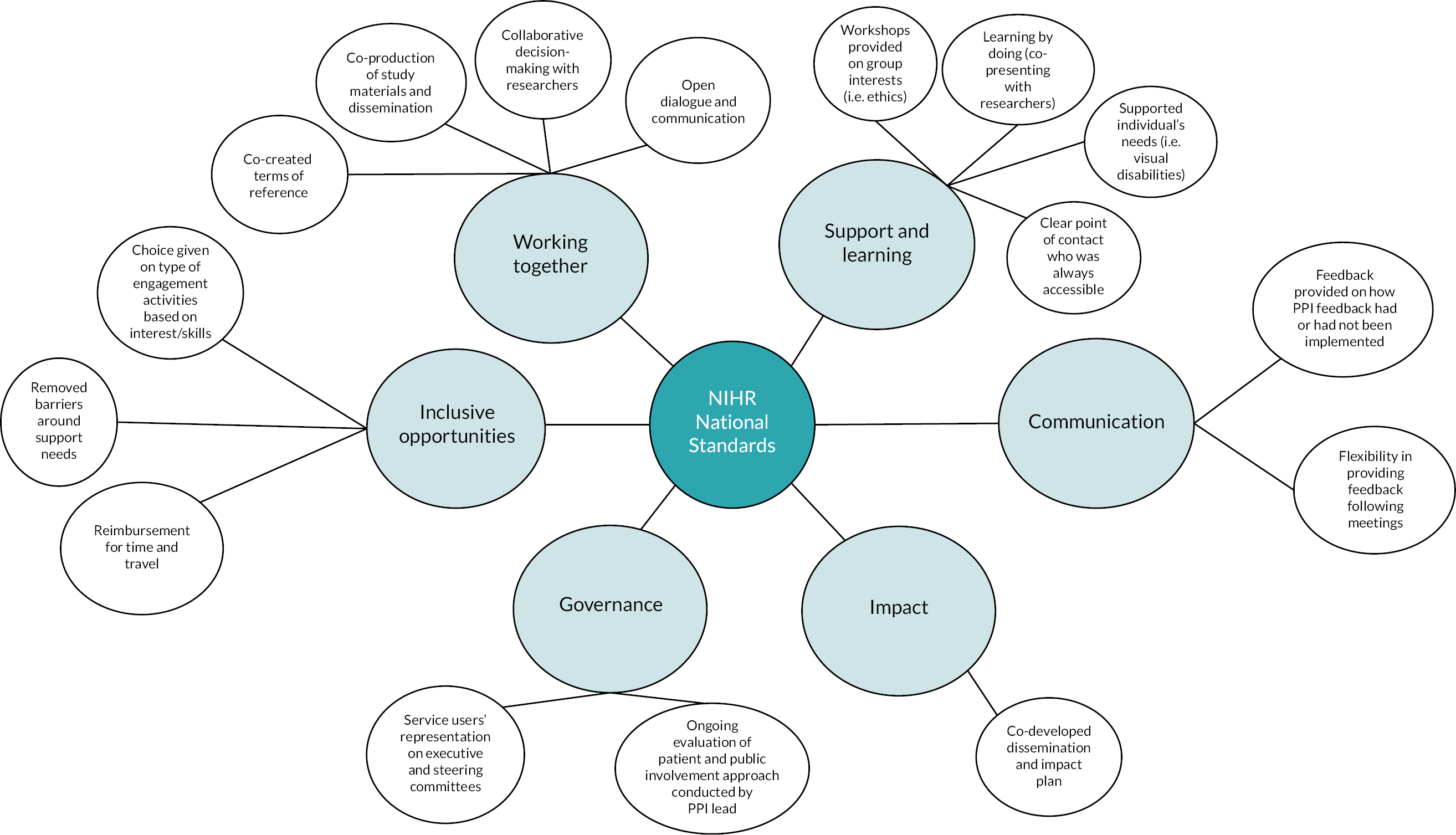

Collaboration with our patient and public involvement (PPI) advisory group took place throughout the study, with PPI members involved at every stage. WS1 recruited 52 CR patients who had elevated anxiety and depression scores on the HADS. Patients were recruited from three NHS trusts in north-west England: University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and East Cheshire NHS Foundation Trust.

The results of the pilot study provided evidence that Group-MCT was acceptable and feasible to deliver within CR. With the agreement of the TSC and NIHR, we progressed directly to a full-scale randomised trial of adding Group-MCT to CR (WS2). The pilot study found that no substantial changes to the trial procedures or instruments were required; therefore, agreement was also given to merge the pilot and main trial data in the RCT analysis. The re-estimation of the full trial sample size based on the pilot data and available resources resulted in a decision to increase the total recruitment target to 332, providing 90% power to detect the desired 0.4 effect size.

Aims and objectives

-

Confirm procedures for recruitment, randomisation, intervention delivery and data collection prior to a full-scale trial.

-

Collect data on recruitment and retention rates, and variability and clustering, in outcome measures, to confirm the sample size calculation and timeline for the full-scale trial.

-

Obtain preliminary economic data to inform economic modelling in the full-scale trial.

-

Include outcome data in analysis of the full-scale trial if no changes are required to the key features of the trial following the pilot.

-

Interview Group-MCT patients, including those who declined to participate or dropped out, to assess their (1) emotional experience since the index event, (2) interaction of emotional state with clinical care, (3) reactions and expectations on being offered the intervention and (4) for those engaged, their perceptions of the intervention.

-

Interview control patients to assess their (1) emotional experience since the index event and (2) interaction of emotional state with clinical care.

Methods

Work stream 1 was delivered in accordance with the grant proposal and employed a randomised pilot feasibility study with 4- and 12-month follow-up comparing Group-MCT plus usual CR (intervention) with usual CR alone (control). The study was designed as an internal pilot of the full-scale RCT (WS2).

Fifty-two CR patients with elevated anxiety and/or depression were recruited to a single-blind randomised feasibility trial between July 2015 and February 2016 from three NHS trusts in north-west England (University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and East Cheshire NHS Foundation Trust). The target sample size was originally 50 patients (25 per arm), determined as sufficient to evaluate recruitment and retention rates for a full-scale trial as well as rates of completion of the intervention. This sample was also adequate for estimating variability in outcome measures for which samples of 40 are generally considered sufficient. However, parallel recruitment across sites meant that 52 patients had consented by the end of the recruitment period and were included in the sample.

After giving informed consent, patients were randomly allocated to a trial condition in a 1 : 1 ratio using a minimisation algorithm that incorporated a random component in order to maximise balance between the arms in sex distribution, HADS anxiety and depression scores, and hospital site. Randomisation was conducted via a telephone link to the Manchester University Clinical Trial Unit (Manchester CTU).

The acceptability and feasibility of adding Group-MCT to CR was evaluated with respect to recruitment rates; attrition by the primary end point of 4 months; number of MCT and CR sessions attended; completion of follow-up questionnaires; and ability of the outcome measures to discriminate between patients. The study was also used to re-estimate the required sample size for a full-scale trial. We also examined the extent to which non-specialists in mental health (i.e. CR health providers) adhered to the Group-MCT protocol. For details of the data collection method, see the protocol. 17

Trial population

The following inclusion criteria were applied:

-

Fulfilment of Department of Health and Social Care and/or BACPR CR eligibility criteria (acute coronary syndrome, revascularisation, stable heart failure, stable angina, implantation of cardioverter defibrillators/cardiac resynchronisation devices, heart valve repair/replacement, heart transplantation and ventricular assist devices, adult congenital heart disease, other atypical heart presentation)

-

A score of ≥ 8 on either the depression or the anxiety subscale of the HADS35

-

Age ≥ 18 years

-

A competent level of English-language skills (able to read, understand and complete questionnaires in English).

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

-

Cognitive impairment that precludes informed consent or ability to participate

-

Life expectancy of < 12 months

-

Acute suicidality

-

Active psychotic disorders

-

Current drug or alcohol abuse

-

Antidepressant or anxiolytic medications initiated in the previous 8 weeks

-

Concurrent psychological intervention for emotional distress.

Cardiac rehabilitation (treatment as usual)

Usual CR programmes comprise two components: exercise and educational sessions. CR programmes vary in content by site; however, all participating sites are offered core components (BACPR Standards and Core Components2) primarily using group-based delivery as part of outpatient provision in hospital or community settings supported by a multidisciplinary team. CR programmes across all sites ran weekly over 8–10 weeks. Exercise sessions were delivered in groups, with a therapist-to-patient ratio of 1 : 5 for low- and moderate-risk patients and 1 : 3 for high-risk patients. Educational seminars lasted 45–60 minutes and covered lifestyle and medical risk factor management. Additionally, all sites provided psychosocial intervention, including stress management and relaxation talks. Relaxation sessions at all sites included breathing techniques and progressive muscle relaxation. Two sites delivered psychoeducational talks on stress, while three sites included cognitive therapy methods for stress management (i.e. challenging negative thoughts, worry decision tree, behavioural activation). One site offered a 4-week stress management course as part of CR.

Group-metacognitive therapy

The MCT + CR intervention received group-based MCT in addition to the usual CR programme at their site. Group-MCT was delivered in six sessions lasting 60–90 minutes each, held once per week and facilitated by two CR professionals (i.e. physiotherapist, CR nurses and occupational therapists) or research nurses depending on the site. CR staff received basic training in implementing the treatment manual. Therapists completed a 2-day workshop delivered by the developer of MCT (AW). Training included didactic teaching, role-play, discussion and studying of the treatment manual. In addition, therapists delivered the intervention to a pilot group of volunteers along with an additional 1-day workshop that focused on enhancing initial skills. Therapists received ongoing supervision on an occasional basis while they were delivering the intervention.

Group-MCT focused on helping participants identify thoughts leading to the processes of worry, rumination and unhelpful coping behaviours. Participants were then guided through the practice of specific techniques to aid flexibility of and control over extended negative thinking patterns. Homework practice of the techniques was featured throughout the programme. At the end of treatment, patients received a ‘helpful behaviours’ prescription summarising what they had learned. Therapists’ adherence to the trial protocol was assessed through their completion at the end of each session of a checklist identifying the protocol components that had been implemented.

Data monitoring

Data monitoring, quality and handling were undertaken by the Manchester Clinical Trials unit and project oversight was conducted by an independent TSC.

Analysis

We assessed the feasibility and acceptability of adding Group-MCT to usual CR.

Feasibility outcomes included:

-

Completion of follow-up questionnaires (proportions of missing values, both overall and within-trial arms)

-

Ability of the outcome measures to discriminate between patients (range of scores, floor or ceiling effects)

-

Re-estimation of the required sample size based on the findings of this study (number of recruited patients required to detect an effect size of 0.4 on HADS total score at 80% power, controlling for baseline scores and allowing for attrition and clustering of patients within therapy groups)

-

Therapist adherence to study protocol

Acceptability outcomes included:

-

Study recruitment rate (number agreeing to participate out of those approached, and number recruited per month)

-

Withdrawal or drop-out by the primary end point of 4 months (attrition rate)

-

Numbers of MCT and CR sessions attended

-

Therapist adherence to study protocol

Results

Feasibility and acceptability of a trial of Group-MCT

The results of the feasibility study have been published. 16 Participants were recruited between July 2015 and February 2016, and 38% of eligible patients were consented and randomised to the study, resulting in a recruitment rate of approximately 6.5 patients per month. Fifty-two participants (33 male and 19 female) were recruited, with 23 participants allocated to Group-MCT + CR and 29 allocated to CR alone. The mean age of participants was 58.67 years (standard deviation 9.47 years, range 38–79 years).

Retention at both 4- and 12-month follow-up was reasonable. At 4-month follow-up, 72.4% of patients in the control arm returned follow-up questionnaires; one (3.5%) participant withdrew from the study, six (20.7%) participants did not return the questionnaires and one (3.5%) questionnaire pack was lost in the post. The return rate of the intervention arm questionnaires was 69.6%; four (17.4%) participants formally withdrew from the study, two (8.8%) participants did not return the questionnaires and one (4.4%) questionnaire pack was lost in the post.

All questionnaires demonstrated a good range of observed scores, covering the majority of the possible score range, and with little in the way of floor or ceiling effects.

The trial did not negatively impact on attendance at usual CR, which was much the same in both trial arms. Participants attended a median of six sessions, with 58.6% of the CR-alone arm and 52.2% of the Group-MCT + CR attending at least six sessions of CR.

Among those allocated to the Group-MCT intervention, 56.5% of patients (n = 13) attended at least four of the six sessions, 21.7% (n = 5) attended one or two sessions and 21.7% (n = 5) did not attend any sessions. Therapist adherence to the MCT treatment protocol was monitored using an adherence checklist. Therapists were asked to indicate if specific components of the intervention had been completed at each session. Adherence was high at an average rating of 98.2% across all sites, with all sites deviating from the protocol only once.

Progression to a full randomised controlled trial

The decision to progress or not to a full RCT was made based on the data available at the time of submission of the study milestone report. At this point all patients had been recruited but only 18 had reached the 4-month follow-up point. The results at this point differed somewhat from those given above for the full study sample. The study’s overall recruitment rate of 6.5 patients per month reflected a slow start, followed by an average of nine patients recruited per month over the final 3 months. Seventeen patients (94%) had returned the 4-month follow-up questionnaire. Of 10 patients in the Group-MCT + CR arm, 6 (60%) had attended at least four treatment sessions: although slightly below the target of 65%, the small sample made this figure subject to large uncertainty. On the basis of these results and other evidence for acceptability and feasibility, including the qualitative work with patients and therapists, the NIHR as funder agreed that the research could progress to a full-scale RCT. To address the shortfall due to slow early recruitment, the study was expanded to include an additional two sites.

Sample size

Under assumptions of 25% attrition, a correlation of 0.5 between baseline and follow-up outcome scores, mean therapy group size of 5.75, and intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, we originally estimated that a total recruitment sample of 230 patients for the main trial would provide 80% power to detect a treatment effect size of 0.4. As no substantial changes were made to the trial procedures or instruments following the pilot, with the consent of our TSC and NIHR as the funder the decision was taken to merge the pilot data with those of the main trial. Considering the updated parameters from WS1 [a 35% attrition rate, correlation of 0.5 (unchanged), mean group size of 3 and ICC of 0.05 (assumed)] and available resources, we revised the total recruitment target to 332 to give the full study 90% power to detect the desired 0.4 effect size.

Conclusion

The results suggested that a full-scale trial of Group-MCT within CR was feasible and acceptable to deliver.

Qualitative evaluations

Study participants (intervention and control) were interviewed in semi-structured qualitative interviews to explore the potential enablers of/barriers to recruitment/retention at several levels: patient (e.g. attitudes to emotional needs and support), intervention (e.g. comprehensibility) and service (e.g. practices or staff communications that contradict or support the intervention).

Some parts of these sections have been reproduced with permission from McPhillips et al. 14 and McPhillips et al. 15 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Ethics approval was obtained from NRES Committee Northwest REC (reference 15/NW/0163). All participants provided written informed consent prior to being interviewed. Qualitative interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and pseudonymised. Analysis varied depending on the research question.

Analysis of the data to determine CR patients’ emotional distress and psychological needs followed a constant comparative approach that occurred in parallel with interviews to develop a thematic framework. The framework was further developed with subsequent interview transcripts. 14 The analysis was evaluated based on its ‘catalytic’ and ‘theoretical’ validity, whereby findings had practical implications and connected with broader theory. The analysis was inductive in that they presented features of patients’ accounts based on emerging data/transcripts rather than on the significance for a priori theories. Theoretical frameworks were drawn on after the analysis was complete to consider the implications of the findings. 14,36

Analysis of qualitative interviews also aimed to understand patient distress from the perspectives of CBT and MCT and comprised three stages: inductive analysis followed by a constant comparative approach, and, finally, reviewing transcripts combining deductive and inductive elements. 15 The exploration of patients’ experience of MCT used thematic analysis. Using a systematic approach, codes were produced by grouping similar concepts together to identify key themes.

Psychological experiences and psychological needs of cardiac rehabilitation patients

We conducted a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews of 46 CR patients who had elevated symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. 14 The study aims included:

-

Understanding how distressed cardiac patients describe their emotional needs

-

Understanding how CR patients described and understood their distress

-

Exploring patients’ thoughts about how well they thought their current CR and routine care addressed their psychological needs and their views on the role of formal psychological interventions

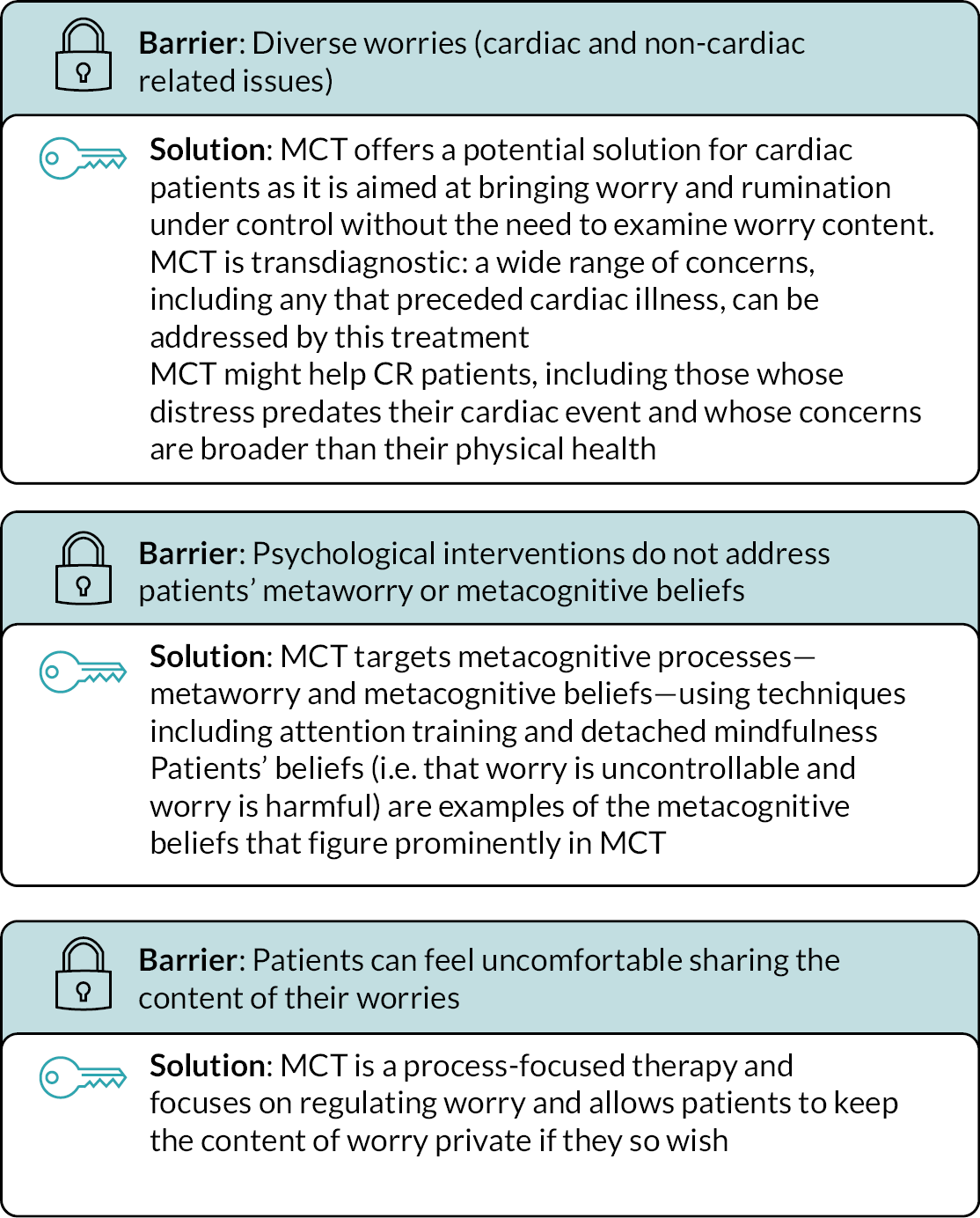

Patients often described their emotional experience since their cardiac event as negative, reporting how they felt low in mood and often engaged in worrying about and dwelling on a range of concerns, including ones that were unrelated to their health and predated their cardiac event. 14 We did not find differences in accounts between men and women or between patients from different centres.

While patients were found to worry about and dwell on a range of topics, which is in line with findings of previous studies,36,37 they also described how they believed that worrying was uncontrollable and harmful, and they worried about worry (a process known as metaworry). The concerns CR patients have about worry (i.e. metaworry) have not been described previously; however, they are central to the metacognitive model38–40 and clarify how CR patients’ distress might be better addressed.

Patients described how they wanted to ‘get back to normal’ and stop worrying. 14 They felt that they lacked a way to achieve this other than waiting for time to pass, and when they did seek support, they sought reassurance from staff and peers to check that they were responding ‘normally’. 14 However, the effects of reassurance were generally transient and, consistent with previous findings, appeared to have little benefit for patients with cardiac symptoms. 41,42 A new and potentially important finding was that, despite wanting reassurance, most patients were reluctant to talk about their worries in the context of CR unless they had been previously socialised into psychological interventions. 1 Furthermore, despite being troubled by worry, most were dismissive of stress management and guided relaxation techniques offered in the context of existing CR. These techniques seemed superficial and difficult to apply in real life and needed more practice than CR provided. Patients also noted that they associated CR primarily with exercise classes and physical rehabilitation, which is in line with previous research, which may be a barrier to using CR as a setting to support mental health. 43

Using MCT may overcome some of the barriers associated with current psychological approaches in CR, as summarised in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Barriers faced in current CR psychological treatment and solutions provided by MCT: a visual summary of discussion in our qualitative study. 14

Assessing the ‘fit’ of the metacognitive model versus the cognitive–behavioural model in dealing with anxiety and depression in cardiac rehabilitation

The acceptability of the metacognitive model for CR patients was assessed both alone and comparatively with a model more frequently used in NHS services, CBT. 15 Although CBT achieves moderate effects in CR for patients experiencing anxiety and depression,7 it may be that a psychological theory that does not focus on the content of patients’ negative thoughts (e.g. ‘I might have another heart attack’) but instead focuses on regulating worry and rumination may be better able to moderate the diverse range of concerns linked to anxiety and depression. By comparing patients’ perspectives via an interview guide designed to assess their concerns and causes of distress, it became apparent that worry and rumination exacerbated distress and that this perseverative negative thinking often began with a realistic negative thought, for example ‘I’ll never get back to full fitness, I’ll never live a full life in the same way’. Although it is evidently the case that CR patients will experience such thoughts, it is not always the case that they will continue to think those thoughts. CBT seeks to challenge such realistic thoughts, which is frequently unachievable. MCT would enable patients not to further engage with such thoughts, thereby limiting the time spent ruminating and having the positive effect of reducing the extent of negative thinking. Findings from the study15 illustrated that MCT may have a better fit with the experiences of CR patients; this overall conclusion was based on a sample of 49 patients who took part in a thematic interview. 15 This group of patients reported a diverse range of worries but were reluctant to discuss them, offering the ideal opportunity for MCT to be used to overcome the distress of these patients as with this approach there is no need to discuss the content of worries. Conceptualising patients’ distress from the perspective of CBT involved applying many distinct categories to describe specific details of patients’ talk, particularly the diversity of their concerns and the multiple types of cognitive distortion. It also required distinction between realistic and unrealistic thoughts, which was difficult when thoughts were associated with the risk or consequences of cardiac events. From the perspective of MCT, a single category – perseverative negative thinking – was sufficient to understand all this talk, regardless of whether it indicated realistic or unrealistic thoughts, and could also be applied to some talk that did not seem relevant from a CBT perspective.

Work stream 2 a randomised controlled trial of Group-MCT for patients with depression and/or anxiety

Some parts of these sections have been reproduced with permission from Wells et al. 19 This is an Open Access article, distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Work stream 2 overview

A full-scale, two-arm, single-blind RCT with a nested qualitative study was conducted to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness associated with the Group-MCT intervention plus usual CR (MCT + CR). CR services from five NHS trusts across north-west England (University Hospital of South Manchester, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, East Cheshire NHS Trust, Stockport NHS Foundation Trust and Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust) recruited 332 patients attending CR with symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Participants were randomly assigned to receive MCT + CR or usual CR alone. Patients assigned to receive MCT + CR attended six additional weekly sessions of Group-MCT led by two CR staff members, with each session lasting 60–90 minutes. The primary outcome was level of anxiety/depression as measured by total HADS score at 4-month follow-up. Secondary outcomes included HADS score at 12 months plus scores on the Impact of Events Scale Revised (IES-R), Metacognitive Beliefs Questionnaire-30 (MCQ-30), EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) and Cognitive Attentional Syndrome Scale-1 Revised (CAS-1R) at 4- and 12-month follow-up. At 4 months, patients in the MCT + CR arm had significantly reduced total HADS scores compared with those in the CR-alone arm. At 12 months, the group difference was reduced but still statistically significant (p < 0.01). The results for most secondary outcomes also favoured the MCT + CR arm at both 4 and 12 months. The protocol of this trial and the principal results have been published. 17,19

A qualitative interview study found Group-MCT to be effective, positive and beneficial. Patients identified advantages of the group format linked to non-specific supportive factors, and they valued the techniques used in treatment and supported delivery of the intervention by non-mental health specialists. The full qualitative results have been published. 22

Work stream 2 aims

-

Evaluate the effectiveness of MCT + CR compared with usual CR alone in alleviating depression and/or anxiety in patients attending CR.

-

Evaluate the impact of Group-MCT on secondary outcomes including post-traumatic stress, metacognitive beliefs, health status, adherence to CR, health and social care utilisation and work resumption.

-

Assess the durability of treatment outcomes at 4- and 12-month follow-up.

-

Obtain patient qualitative data to help interpret evidence of effectiveness, including processes that might underpin or compromise effectiveness or explain heterogeneity in effectiveness.

-

Obtain practitioner qualitative data to evaluate practitioner experience of Group-MCT delivery and understanding of patients’ emotional needs and identify potential enablers of/barriers to the recruitment and retention of patients.

-

Obtain data from a stated preferences survey about participants’ relative preferences, utility and willingness to pay (WTP) for components of Group-MCT to inform future policy and commissioning decisions.

-

Establish the cost-effectiveness of Group-MCT.

Methods

We conducted a multicentre, two-arm, single-blind RCT with 4- and 12-month follow-up comparing Group-MCT plus usual CR (MCT + CR) with usual CR alone.

Participants were recruited from CR centres across five NHS trusts in north-west England (University Hospital of South Manchester, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, East Cheshire NHS Trust, Stockport NHS Foundation Trust and Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust). No changes were made to the study eligibility criteria following WS1; see WS1 for a full description. For details of patient recruitment and study eligibility, see the published trial protocol. 17 Patients were randomly allocated to the trial arms by Manchester Academic Health Science Centre Clinical Trials Co-ordination Unit using a computer in a 1 : 1 ratio using a minimisation algorithm to balance the trial arms with respect to hospital site, sex and HADS scores. Patients were informed of their trial arm allocation by a member of the research team. The trial chief investigator, trial statistician and research assistants collecting assessment data were masked to treatment allocation.

Group-MCT intervention (MCT + CR)

No changes were made to the Group-MCT intervention following WS1 (pilot feasibility study); see WS1 for a description of the intervention.

Usual CR

Usual CR was delivered as described above.

Data collection and outcomes

Data collection and outcomes mirrored the pilot study; see the trial protocol for details. 17

Analysis

Analysis was conducted in accordance with a prespecified analysis plan specifying the analytical models, primary and secondary outcomes, choice of covariates, sensitivity analyses and other key aspects of the analysis. Prior to data analysis or unmasking, the analysis plan was finalised and approved by the TSC.

The primary outcome was:

-

HADS total score at 4-month follow-up (after treatment).

The secondary outcomes included:

-

HADS total score at 12-month follow-up

-

Post-traumatic stress symptoms measured on the IES-R at 4- and 12-month follow-up

-

Metacognitive beliefs measured on the MCQ-30 total and uncontrollability and danger subscale at 4- and 12-month follow-up

-

Health status measured on the EQ-5D-5L at 4- and 12-month follow-up

-

Repetitive negative thinking and coping mechanisms measured on the CAS-1R at 4- and 12-month follow-up

-

Adverse events related or unrelated to the study

The primary analyses used intention-to-treat principles. A linear mixed-effects regression model was applied for continuous outcomes, incorporating all three time points (baseline, 4 months and 12 months). The prespecified covariates used were randomisation factors (hospital site, sex, baseline total HADS score), age and medication for depression or anxiety (never taken/currently taking/taken in the past). All other potential covariates were below predefined imbalance criteria for sensitivity testing [standardised mean difference (SMD) > 0.25 or category difference of > 10% between arms]. We applied hierarchical regression models with random effects at the levels of the patient and the CR (or MCT + CR) course attended. The covariance matrix for the model was chosen as either unstructured or first-order autoregressive depending on whichever gave the lower Bayesian information criteria score.

The effects associated with the intervention at 4- and 12-month follow-up were examined using the treatment-group-by-time-point interaction terms from the mixed-effects model analysis, where time point was a categorical variable to provide independent tests of effect at 4 and 12 months. No adjustments for multiple testing were applied, and an alpha value of 5% was used throughout. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using multiple imputation (MI) to assess the robustness of the results against missing values. There were very few missing values at baseline (one missing outcome value and a maximum of three missing values on any covariate); therefore, these were imputed by simple regression imputation using all available variables at baseline but excluding trial arm. MI was then used to impute missing outcome values at 4 and 12 months using the full set of variables and including the interaction term between trial arm and time point (for consistency with the analysis model). The chained-equations MI procedure was used and 20 MI data sets.

A mixed-effects logistic regression was conducted to assess the differences between the arms in engagement in economic activity (as a binary outcome) at 4- and 12-month follow-up. Covariates in the model were the same as for the continuous outcome measures.

All outcome measures demonstrated skewness and kurtosis below the threshold of 1.0 specified in the analysis plan and so sensitivity against non-normality was not assessed. The trial eligibility criteria allowed the inclusion of participants without clinically relevant anxiety provided they had at least mild depression, and vice versa; 23% and 40% of participants respectively fell into these categories at baseline, closely balanced between the arms. To determine how this might have impacted on analysis results for HADS anxiety and depression as separate outcomes we conducted sensitivity analyses excluding these individuals. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Participants: overview

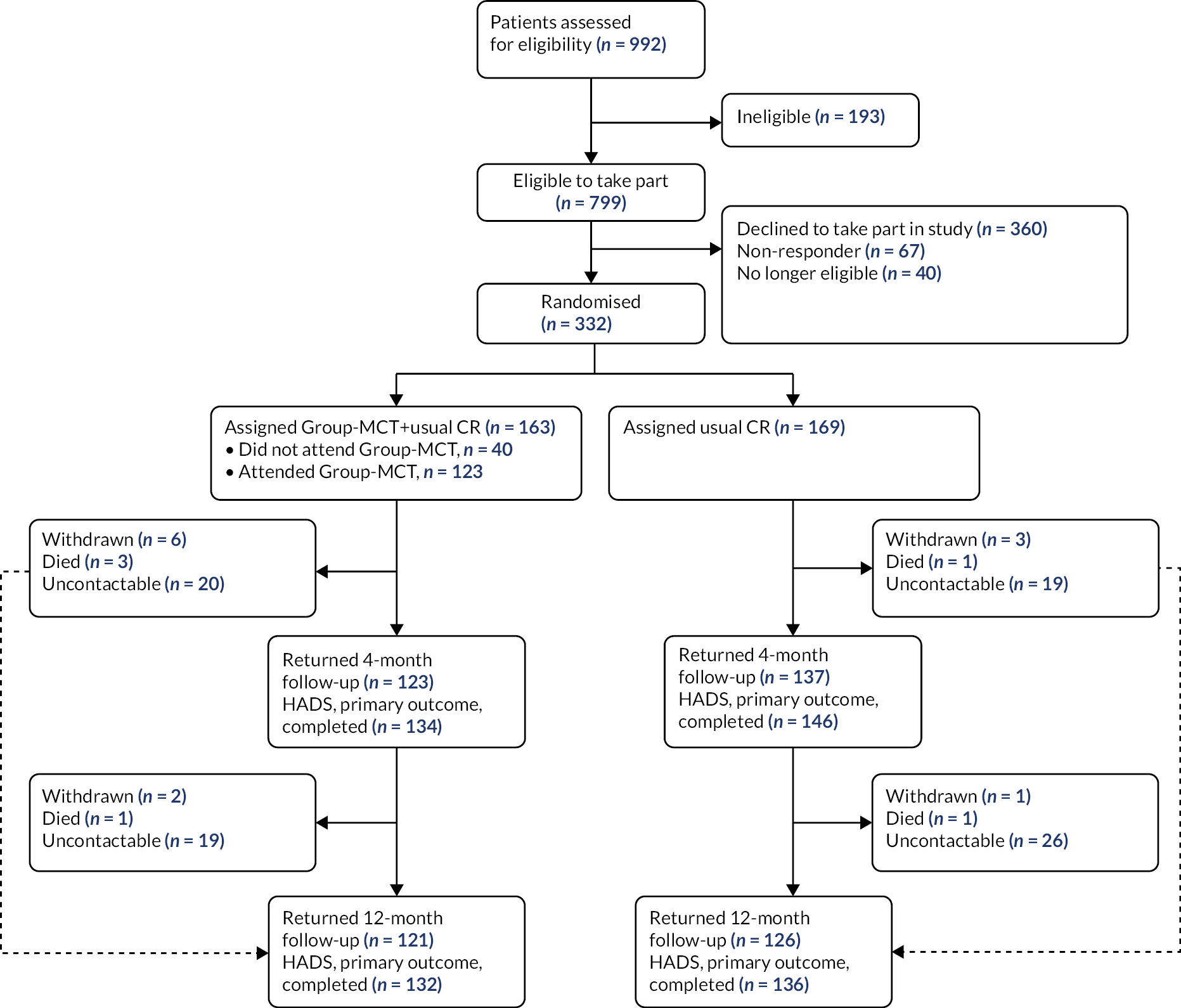

Between July 2015 and January 2018, 3808 patients were referred to CR across all five sites. A total of 992 patients had a score of ≥ 8 on the HADS subscales; of these, 332 were consented to the trial following eligibility screening and initial contact. One hundred and sixty-three patients were randomly allocated to MCT + CR and 169 patients were randomly allocated to usual CR alone (see Figure 3). For further details, see Wells et al. 19

FIGURE 3.

Work stream 2 trial profile. Figure reproduced with permission from Wells et al. 19 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

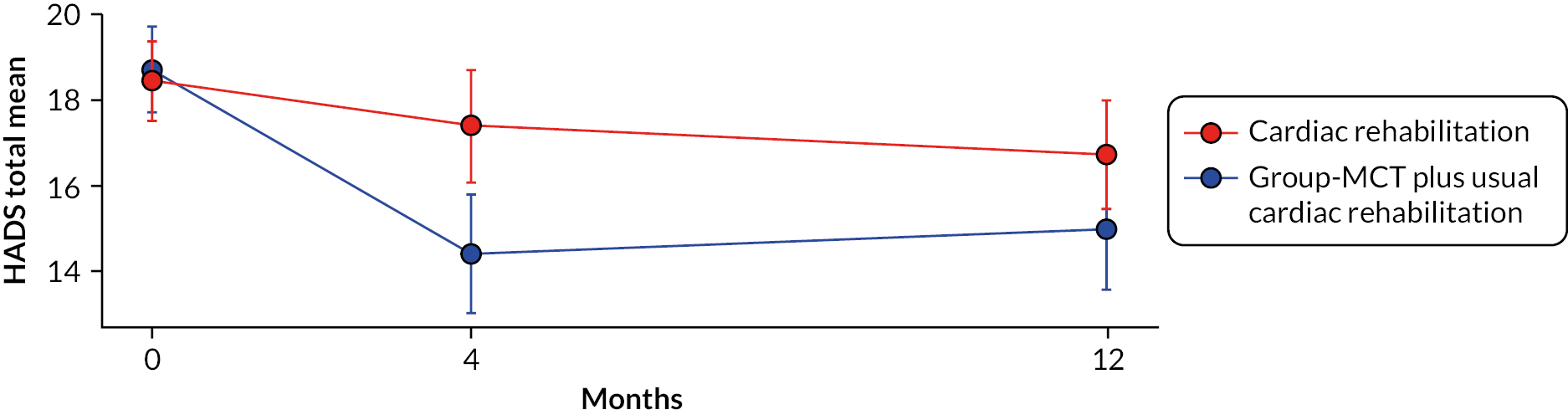

Effects associated with Group-MCT

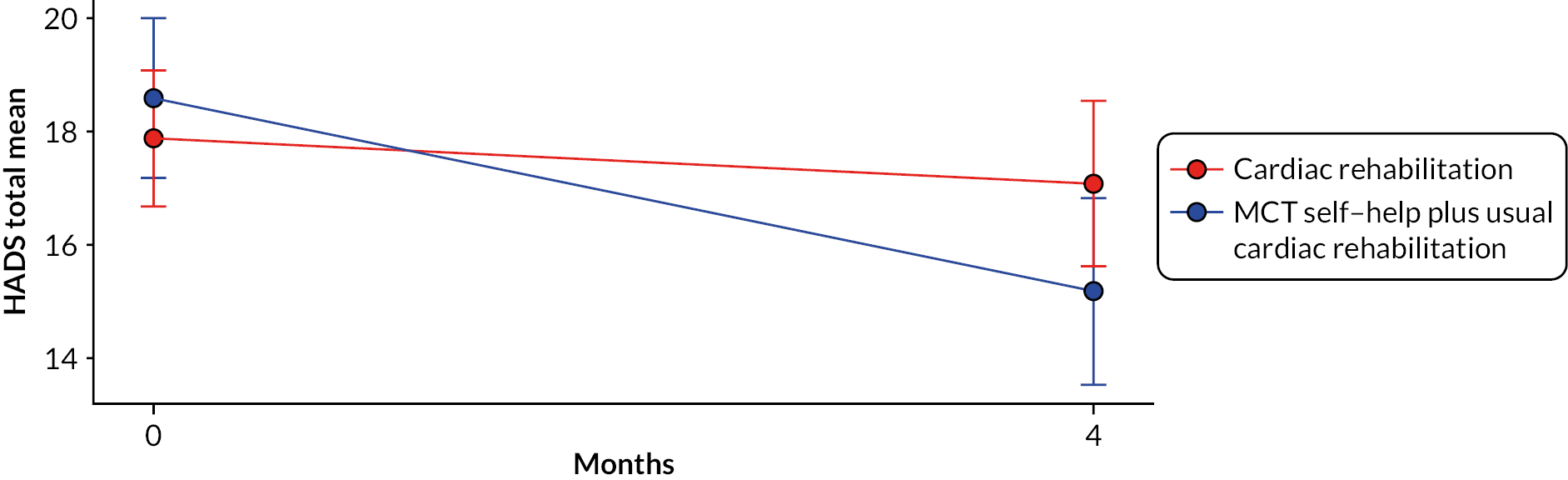

Mean HADS total scores and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each trial arm at pre- and post-treatment assessment points are presented in Figure 4. The mean HADS total score under CR alone declined gradually over time in an almost linear fashion, compared with a large reduction over the first 4 months under MCT + CR followed by a plateauing of scores. On the primary outcome – HADS total at 4 months – the results significantly favoured MCT + CR [adjusted mean difference (AMD) −3.24, 95% CI −4.67 to −1.81, p < 0.001; SMD 0.52]. The between-group difference in HADS remained significant at 12 months, albeit at a lower level (AMD −2.19, 95% CI −3.72 to −0.66, p = 0.005; SMD 0.33). Mean HADS anxiety was significantly lower in patients in the MCT + CR arm at 4 months (AMD −1.67, 95% CI −2.54 to −0.81, p < 0.001; SMD 0.44) and 12 months (AMD −1.35, 95% CI −2.22 to −0.48, p = 0.002; SMD 0.34). MCT + CR patients achieved a lower HADS depression mean score at 4 months (AMD −1.58, 95% CI −2.37 to −0.79, p < 0.001; SMD 0.47) but not at 12 months (AMD −0.85, 95% CI −1.75 to 0.05, p = 0.065; SMD 0.23).

FIGURE 4.

Unadjusted mean total HADS scores at baseline and at 4- and 12-month follow-up. Note: bars are 95% CIs. Figure reproduced with permission from Wells et al. 19 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Most other outcomes also favoured the MCT intervention: adjusted mean IES-R scores were lower with MCT + CR at 4 months (AMD −4.92, 95% CI −9.04 to −0.81; p = 0.019) but not at 12 months (AMD −3.28, 95% CI −7.92 to 1.36; p = 0.166); MCQ-30 total scores were lower at both 4 and 12 months (AMD −8.57, 95% CI −11.95 to −5.18, p < 0.001; AMD −7.37, 95% CI −11.24 to −3.50, p < 0.001, respectively); MCQ-30 negative beliefs subscale scores were lower at both time points (AMD −3.15, 95% CI −4.16 to −2.14, p < 0.001; AMD −2.35, 95% CI −3.43 to −1.26, p < 0.001) and the CAS-1R was also lower with MCT + CR at both 4 and 12 months (AMD −126.25, 95% CI −165.83 to −86.67, p < 0.001; AMD −116.29, 95% CI −159.13 to −73.45, p < 0.001). EQ-5D-5L utility scores showed no statistically significant group difference at 4 months (AMD 0.03, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.09; p = 0.200) or 12 months (AMD 0.03, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.10; p = 0.201); the difference on the EQ-5D-VAS was not significant at either time point (4 months: AMD 4.62, 95% CI −0.10 to 9.34, p = 0.055; 12 months: AMD 0.66, 95% CI −4.12 to 5.45, p = 0.786). Sensitivity analysis using MI changed the statistical significance of one secondary outcome, the IES-R at 4 months, which ceased to be statistically significant (p > 0.05). There was no significant difference between the arms in engagement in economic activity at 4-month (odds ratio 0.94, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.47; p = 0.93) or 12-month follow-up (odds ratio 1.10, 95% CI 0.24 to 4.99; p = 0.90).

To aid in the interpretation of the clinical impact of findings, the Reliable Change Index (RCI)44 was computed for the primary outcome. The RCI represents the difference between two measurements made in a single individual that would be statistically significant at a p-value of < 0.05. It was computed for the HADS total score at the primary 4-month follow-up. Using the control sample, we calculated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 at 4 months for the HADS to estimate reliability for the usual CR population. Based on this, a reduction of 6 points in an individual’s score was defined as statistically reliable improvement, while an increase in 6 points was defined as a reliable worsening of symptoms. Calculations of the HADS total score at 4-month follow-up showed that 21% of patients in the CR-alone arm reliably improved compared with 33% of patients in the MCT + CR arm. The proportion of patients exhibiting psychological deterioration was 15% in the CR-alone arm compared with 4% in the MCT + CR arm.

Qualitative evaluation: overview

From the intervention arm of the trial, 32 patients took part in qualitative interviews prior to starting Group-MCT but during CR [time point 1 (T1)]. Patients who attended four or more Group-MCT sessions were defined a priori as having completed a minimal dose of the intervention likely to produce benefit. Among intervention patients who consented to take part in qualitative interviews, 22 completed the intervention, with 20 completing time point 2 (T2) interviews. Ten did not complete the intervention but five completed T2 interviews; four of these patients attended two or more Group-MCT sessions and their interviews were included in the analysis, and one patient interviewed did not attend any Group-MCT sessions due to work commitments and therefore was excluded from the analysis.

Interviews were conducted at T1 and T2 and were conversational in nature. Topic guides with a mixture of open and closed questions with open-ended prompts were used to encourage patients to share experiences and probe specific points. T1 interviews are discussed in WS1. Data gathered in T1 interviews were used to inform T2 interviews, which explored patients’ emotional experiences since T1, their views and experiences of Group-MCT, and their engagement with techniques from the intervention. Interviews were tailored to the individual, drawing on specifics from T1 interviews. Interview guides were modified iteratively as the interviews and analysis proceeded so that developing ideas could be tested. The interviews lasted an average of 52 minutes (range 14–88 minutes). The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and pseudonymised. Full detailed results have been published. 22

Ten CR staff delivering MCT were interviewed about their experiences of training in and delivery of Group-MCT. Group-MCT was initially delivered by seven CR practitioners across three CR services participating in PATHWAY. Six of these practitioners were interviewed before training, with one practitioner declining to be interviewed at this point. However, all seven were interviewed during training and after they had delivered Group-MCT, as the practitioner who had originally declined later contacted the research team to take part. Two more CR services later joined the study. Two CR practitioners from one of these services and two clinical research nurses (CRNs) were trained in Group-MCT. The two CR practitioners provided written informed consent and were interviewed during training and after they had delivered Group-MCT. One CRN was interviewed during training only, as she left the study shortly afterwards, and the other CRN declined to take part in the study.

Qualitative studies received ethics approval from NRES Committee Northwest REC (reference 15/NW/0163). All participants provided written informed consent prior to being interviewed.

Qualitative data analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was used. Data in each transcript were coded to explore patients’ experiences and understanding of Group-MCT. Generated codes were discussed within the research team and discrepancies were resolved during discussion. Coded data were reviewed and collated into candidate themes. Candidate themes were discussed by the research team and on agreement semantic themes were identified.

Patients experience of Group-MCT

Two main themes were identified in patient experience of Group-MCT: general therapy factors and MCT-specific factors. The first theme concerned general therapy factors central to positive experiences of treatment, with subthemes of interaction with other CR patients and CR staff’s delivery of the intervention. Interaction with other CR patients was an important factor to most patients, providing reassurance, normalisation of feelings in a positive environment and facilitation of the intervention. Patients who were in small groups found that this negatively impacted their experience of Group-MCT, as small groups affected the delivery of the therapy. This highlighted the importance of having a minimum of three or four patients in a group to optimise patient experience. The delivery of the therapy by CR staff was generally received positively by patients as it enabled a positive and relaxing environment. For some patients, CR staff’s specific knowledge and experience of cardiology was important to their delivery of the therapy. However, a minority of patients criticised the staff’s delivery by because of a perceived lack of knowledge and the style of delivery. Patients’ perceptions of CR staff’s delivery were overall positive and demonstrated that CR staff, who were not mental health specialists, established and maintained a therapeutic alliance valued by patients.

The second theme related to MCT-specific factors, with subthemes of patients’ perceptions and understanding of the aims, experiences of individual techniques and perceptions of effectiveness of Group-MCT. Accounts of the aims of Group-MCT varied from those consistent with the model to those that were ‘off-model’. Patients who did not complete Group-MCT had negative perceptions of the aims of the therapy. Patients who correctly understood the aims of the therapy appeared to demonstrate a greater flexibility in their reaction to worry. All patients who completed the intervention were positive about the techniques introduced in MCT. Most patients were able to use these techniques in a manner consistent with the therapy model. However, in some cases techniques were used in a manner not consistent with the model. The results suggest that the techniques used in Group-MCT are largely understood and beneficial; however, therapists should be mindful of patients’ potential misinterpretation and inappropriate use of the techniques based on these narratives.

Practitioners experience of training and delivery of Group-MCT

Aim

To assess CR staff’s experience of learning and delivering MCT.

Methodology

Cardiac rehabilitation staff were interviewed at three time points: before Group-MCT training, in the middle of training, and after delivering Group-MCT. A topic guide was developed and used to guide the interviews.

Nine CR staff delivering MCT were interviewed about their experiences of training in and delivery of Group-MCT. See Appendix 1, Table 4, for an overview of therapist demographic characteristics.

For the results, see Appendix 1.

Cost-effectiveness of group-metacognitive therapy

Aims

A within-trial economic evaluation aimed to compare the cost-effectiveness of MCT plus usual care (CR) with that of CR alone from a health and social care perspective in the UK. The protocol of the cost-effectiveness evaluation has been published21 and details of the findings of the evaluation are reported in Appendix 2.

Methods

The economic evaluation used intention-to-treat and estimates total costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for the trial follow-up (cost–utility analysis). An NHS and social care perspective was taken. The time horizon of the primary analysis was 12 months to incorporate sufficient time for any impact of MCT on service use and health status. Unit costs are reported in Appendix 3.

Analysis

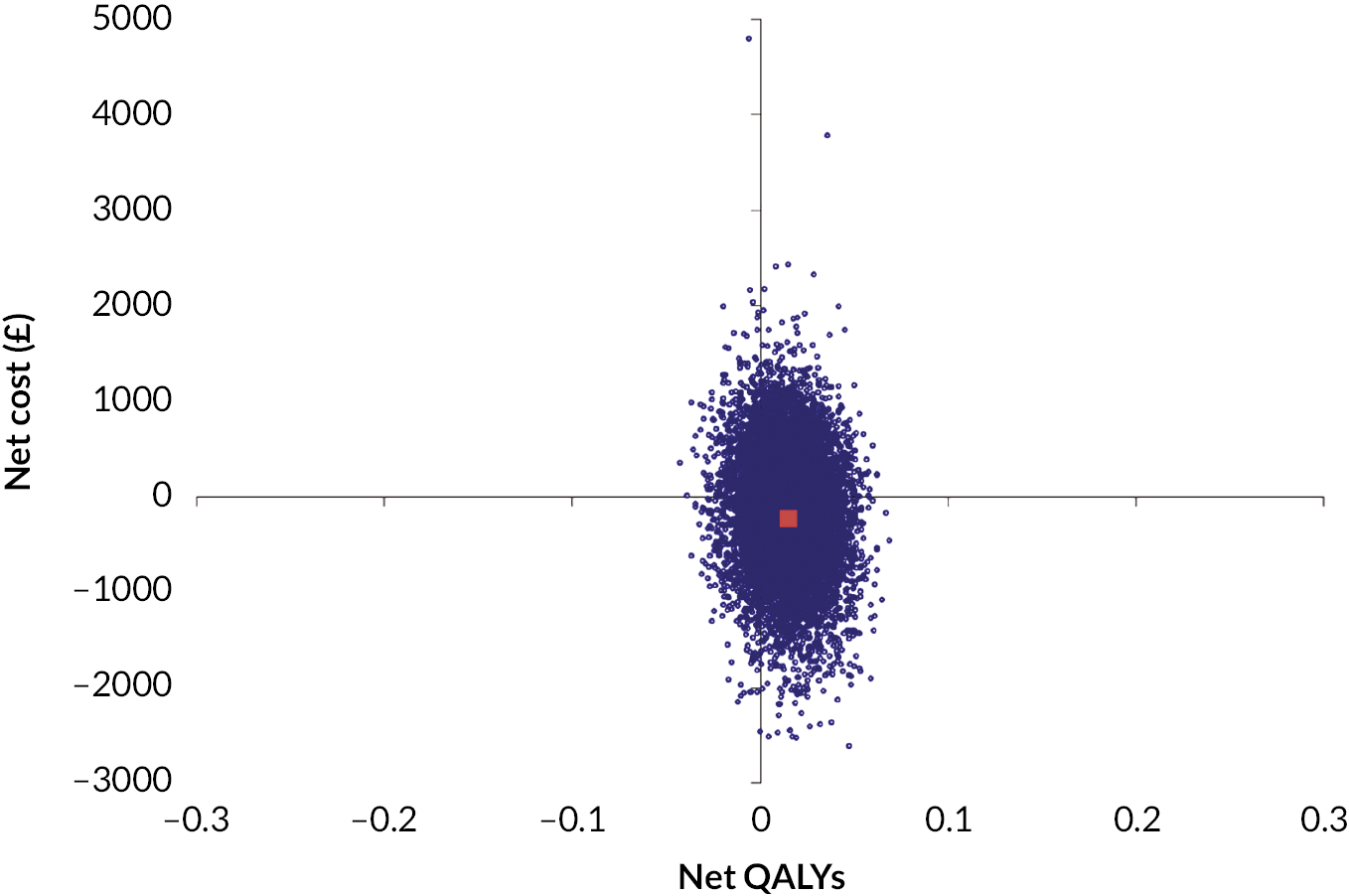

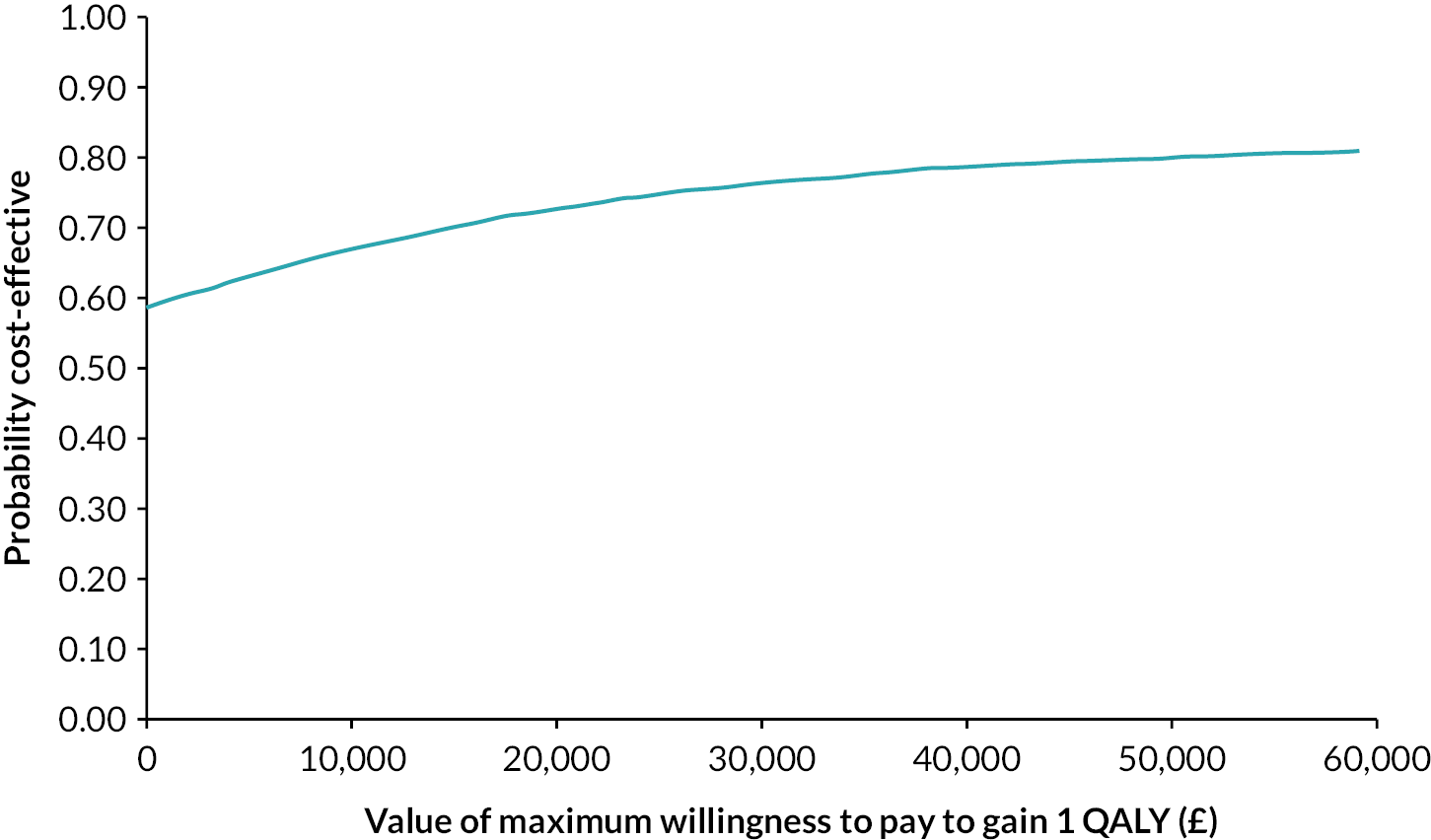

Quality-adjusted life-years were estimated using the EQ-5D-5L, which was collected at baseline and at 4- and 12-month follow-up. Data on health and social care use were collected using an economic patient questionnaire adapted from other trials. This captured secondary, primary, community and social care use. Unit costs of NHS and social care services were taken from national average unit cost data, and the price year was 2019. 45,46 Single imputation was used to impute missing baseline variables, with MI used to impute values missing at follow-up. Costs were imputed by category and utility by individual EQ-5D-5L domain to use all available data. The primary outcome of interest is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Regression analysis was used to estimate net costs and net QALYs and these estimates were bootstrapped to generate 10,000 net pairs of costs and QALYs to inform the probability of cost-effectiveness. Sensitivity analyses tested the impact of the study design and assumptions on the ICER and cost-effectiveness acceptability analysis. See Appendix 2, Table 5, for the sensitivity analysis rationale.

Results

In the primary cost-effectiveness analysis, the MCT intervention is dominant, meaning it is both cost saving (net cost −£219, 95% CI −£1446 to £1007) and health increasing (net QALY 0.015, 95% CI −0.015 to 0.045). However, the CIs are wide and overlap zero, indicating high level of variability in the data and uncertainty in the estimates. The primary analysis found that at a willingness-to-pay threshold (WTPT) of £30,000 per QALY the MCT intervention is around 76% likely to be cost-effective, again reflecting uncertainty. See Appendix 2, Tables 5–7, for further details; see Appendix 2, Figure 9, for the cost-effectiveness plane; and see Appendix 2, Figure 10, for the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the results at 4-month follow-up were similar to those of the primary analysis, and the complete-case analysis or the use of different assumptions around the cost of MCT did not affect conclusions. In these sensitivity analyses MCT remained dominant but with CIs wide and overlapping zero, demonstrating significant uncertainty.

Conclusion

Although the primary cost-effectiveness analysis and the majority of sensitivity analysis indicate that the MCT intervention may be cost saving and health increasing, or below typically accepted thresholds, the wide CIs that overlap zero indicate a high level of variability and uncertainty in the estimates. Further research should aim to reduce the uncertainty in the findings, for example with larger sample sizes and alternative measures used to produce utilities. In addition, research should explore how cost-effectiveness differs according to the implementation of MCT within CR.

Stated preferences survey

Aims

A discrete choice experiment (DCE) aimed to explore preferences for different characteristics of a clinic-based psychological intervention added to CR. The PPI work to develop the stated preference study has been published as a case study,20 and the analysis of the survey has been published. 33 An example of survey materials is included in Appendix 4.

Methods

A DCE was conducted and recruited a general population sample and a trial sample. DCE attributes included the modality (group or individual), the healthcare professional providing care, information provided prior to therapy, the location, and the cost to the NHS. Participants were asked to choose between two hypothetical designs of therapy, with a separate opt-out included. A mixed logit model was used to analyse preferences. The cost to the NHS was used to estimate the WTP for aspects of the intervention design/delivery. The study recruited a range of participants, including members of the UK general public aged ≥ 18 years, recruited via a commercial survey sample provider, as well as Group-MCT trial participants.

Analysis

The DCE was analysed using individual choice responses as the dependent variable in the model. 47 Owing to the presence of potential scale and preference heterogeneity (confirmed by a Swait and Louviere plot) a mixed logit model was used for analysis; this model assumes that parameters vary between individuals and accounts for heterogeneity across samples. Random utility theory assumes that a participant chooses between two options by interpreting the information described as a set of characteristics and selecting the one that provides the highest overall utility or value to them. Therefore, characteristic coefficients indicate the direction of preference. Marginal rates of substitution for each attribute were estimated by dividing the coefficient for that characteristic by the inverse of the NHS cost coefficient.

Results

Three hundred and four participants completed the DCE, the majority of whom were a sample of the general public (n = 262). The general population appeared to favour individual therapy (WTP £213, 95% CI £160 to £266) delivered by a CR professional (WTP £48, 95% CI £4 to £93) and at a lower cost to the NHS (β = −0.002; p = 0.000). Participants preferred to avoid options where no information was received prior to starting therapy (WTP −£106, 95% CI −£153 to −£59). The results for the location attribute were variable and challenging to interpret.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates a preference for psychological therapy as part of a programme of CR, as participants were more likely to opt in to therapy than they were to opt out. The results indicate that some aspects of the delivery that may be important to participants can be used to design a tailored psychological therapy that reflects preferences. However, preference heterogeneity is an issue that may prevent a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to psychological therapy delivery in CR. The COVID-19 pandemic (during which recruitment took place) is likely to have affected the DCE.

Work stream 3: the development and evaluation of Home-MCT

Work stream 3 overview

BACPR suggests that CR should employ a menu-based approach to CR, allowing a choice of home-based programmes. 2 Although CR offers home-based CR programmes, this has not been applied to psychological support, which has predominantly been delivered and evaluated in face-to-face formats. 48

Home-based psychological support may increase access to psychological help, especially for CR patients who may not be able or willing to attend face-to-face treatment or may be returning to work. Current self-help psychological therapies for cardiac patients are focused on applying relaxation techniques and CBT7 and are limited in efficacy. 48–50 As current home-based psychological options have variable effects, there is room to develop more effective alternatives.

While MCT has demonstrated efficacy in face-to-face delivery, a self-help version of MCT has yet to be evaluated. We therefore set out to develop and evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of home-based MCT.

Work stream 3 aims

-

Develop a home-based metacognitive intervention (Home-MCT) for CR patients with depression and/or anxiety.

-

Establish the acceptability and feasibility of integrating Home-MCT into the CR pathway.

-

Establish provisional evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Home-MCT.

-

Obtain qualitative data to help refine the presentation and delivery or Home-MCT for a full-scale trial.

-

Obtain data from a stated preferences survey about participants’ relative preferences, utility and WTP for components of the intervention to inform the design of a full-scale trial.

-

Collect data on patient variables and outcome measures to inform the design of a full-scale trial.

Methods

The PATHWAY Home-MCT feasibility study is a multicentre RCT with 4- and 12-month follow-up comparing home-based MCT plus usual CR (intervention) with usual CR alone (control). The trial received full ethics approval from the Northwest – Greater Manchester West Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/NW/0786, IRAS ID 186990) and was registered with a clinical trials database (ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier number NCT03129282). Participants were recruited from two NHS CR services (Bolton NHS Foundation Trust and Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust). For further details of the trial protocol, including participant assessment and recruitment, see Wells et al. 28

Trial population

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Fulfil Department of Health and Social Care and/or BACPR CR eligibility criteria. Thus, the patient was to have at least one of the following: acute coronary syndrome, revascularisation, stable heart failure, stable angina, implantation of cardioverter defibrillators/cardiac resynchronisation devices, heart valve repair/replacement, heart transplantation and ventricular assist devices, adult congenital heart disease, other atypical heart presentation

-

A score of ≥ 8 on the anxiety and/or depression subscales of the HADS (screening HADS)35

-

Minimum of 18 years old

-

A competent level of English-language skills (able to read, understand and complete questionnaires in English)

Participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

-

Cognitive impairment that precludes informed consent or ability to participate

-

Acute suicidality

-

Active psychotic disorders (i.e. two or more of the following: delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech, grossly disorganised or catatonic behaviour, negative symptoms)

-

Current drug/alcohol abuse (a maladaptive pattern of drinking, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress)

-

Concurrent psychological intervention for emotional distress that is not part of usual care

-

Antidepressant or anxiolytic medications initiated in the previous 8 weeks

-

Life expectancy of < 12 months

Self-help metacognitive therapy (Home-MCT)

Home-MCT is a self-help paper manual that consists of six modules. Modules focus on developing a case formulation, developing new strategies to regulate worry and rumination, and challenging metacognitive beliefs that maintain maladaptive patterns of thinking. In addition, participants received three telephone support calls lasting up to 30 minutes each. Call 1 was introductory; during this call, the manual and format were explained to patients and calls 2 and 3 were scheduled. Calls 2 and 3 were made after the completion of modules 2 and 4 and focused on reviewing the key learning points and providing support and guidance on the modules and implementing MCT strategies. Support calls followed a structured script, and staff were reminded that their role was to provide support and guidance on completing Home-MCT. Home-MCT was offered in addition to usual CR.

Development of Home-MCT

The treatment manual was developed by the PATHWAY chief investigator (Adrian Wells) and based on the Group-MCT manual. Before the Home-MCT manual was used in the feasibility trial, the manual and telephone support calls were tested with our PPI group, and after this, focus groups were conducted to review the manual and calls.

During the focus group, PPI members noted that the manual was easy to use and modules were easily to follow and flexible and encouraged adherence to the intervention. However, they felt that the size of the manual may deter patients from using it.

Patient and public involvement feedback on individual modules was as described below.

Piloting the manual with the PPI group provided important insight into patient experience of the intervention and the timing and content of telephone support calls prior to participant recruitment. This resulted in alterations to the manual, including adding information on what to expect from the intervention and what to do when the manual was received by post, emphasising that patients could complete the different modules at their own pace, increasing simplicity of instructions for completing the homework sections, and making a clearer differentiation between anxiety and stress. Amendments were also made to the telephone support scripts. Feedback from the PPI group was addressed prior to trialling Home-MCT, and PPI members were informed of how all the changes were addressed.

Analysis

With a view to the potential for the study to act as an internal pilot for a subsequent definitive trial (i.e. the data would be combined with subsequent data if the trial were extended and no changes were made to the methods), data analysis was restricted so that it was primarily descriptive, with no between-group analysis of outcome measures, thereby ensuring that masking to treatment allocation would be maintained if the trial were extended.

Acceptability of adding Home-MCT to usual CR was assessed by:

-

Recruitment into the study (number of patients agreeing to participate out of those approached, and number recruited per month)

-

Withdrawal or drop-out by the primary end point of 4 months and by 12-month follow-up (attrition rates)

-

Numbers of MCT modules completed (including time spent on each module)

-

Number of CR sessions attended

The feasibility of conducting a full trial was assessed by:

-

Completion of follow-up questionnaires (proportions of missing values)

-

Ability of the outcome measures to discriminate between patients (range of scores; floor or ceiling effects)

-

Re-estimation of the sample size for a definitive trial based on the findings of this study

Unlike the WS1 pilot, specific thresholds for progression to a full RCT were not defined for WS3, as our original protocol was not designed to continue to a full RCT within the research programme. However, we found ourselves in the position of being able to progress to a full-scale evaluation at no extra cost and did so following consultation with the TSC and NIHR under a ‘variation to contract’. The results of the full trial (WS3+) are reported later in this report.

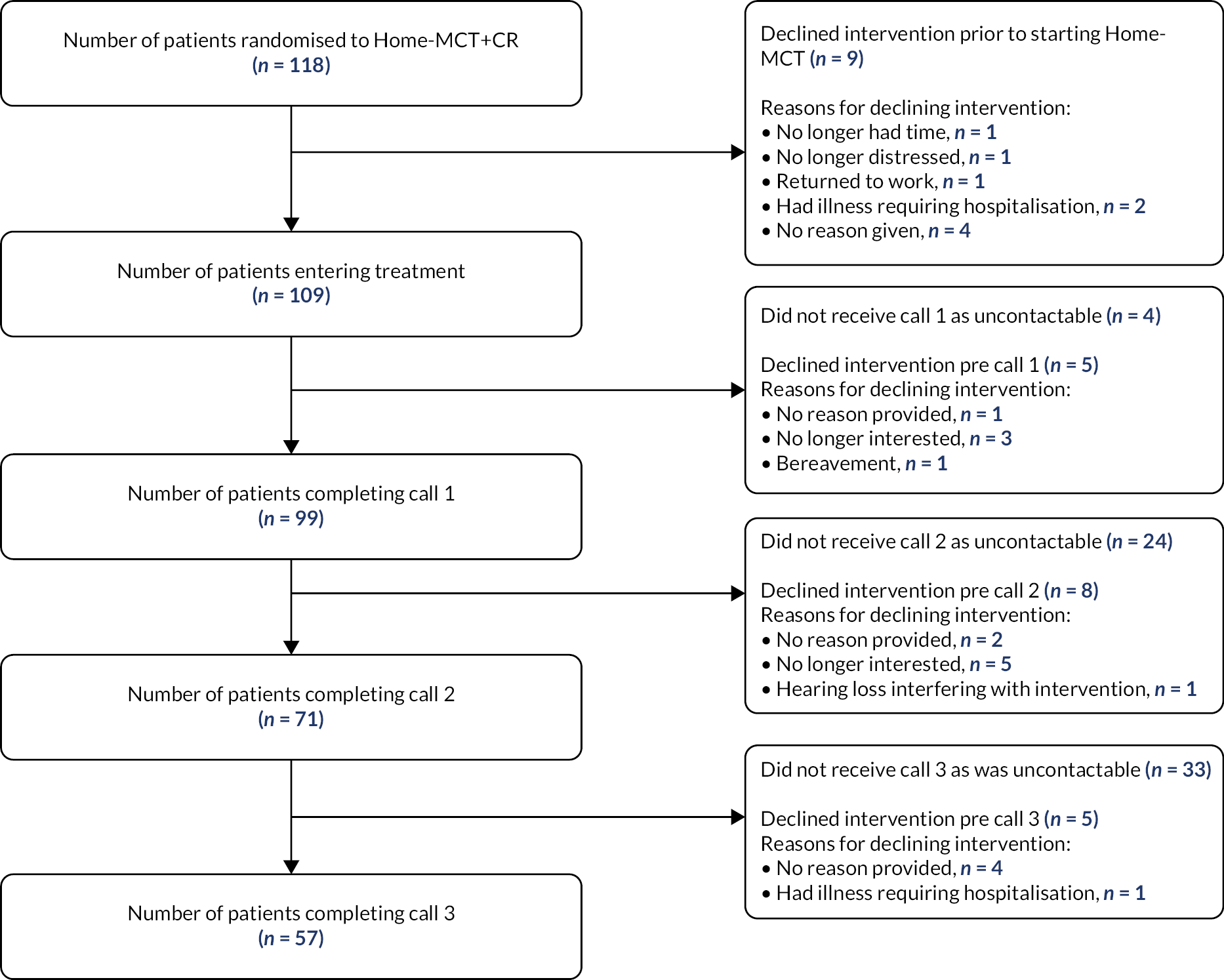

Results (work stream 3)

Participant overview

Between 1 April 2017 and 26 February 2018, 632 patients were referred to CR services, of whom 200 (31.6%) were eligible to take part. One hundred and eight patients (69 male and 39 female) agreed to participate and were consented and randomised to the study. Patients had a mean age of 59.9 years (standard deviation 9.7 years, range 40–84 years).

Acceptability and feasibility trial of Home-MCT

The study achieved a recruitment rate of approximately 10.8 patients per month.

Retention at 4-month follow-up was > 80% for both arms. In the control arm, 52 (96.3%) patients returned 4-month follow-up data, 2 patients died and no patients withdrew from the study. In the intervention arm, 45 (83.3%) patients returned follow-up data, 4 patients withdrew, 4 patients did not return data, and 1 patient died. Attrition was therefore higher in the MCT + CR arm, at 16.7% compared with 3.7% in the CR-alone arm. Retention remained high at 12 months, but with a similar difference between the arms, with 90.7% of control and 81.5% of intervention participants returning follow-up data.

All questionnaires demonstrated a good range of observed scores, covering the majority of the possible score range, with little in the way of floor or ceiling effects.

Attendance at CR was high in both arms; 89% of CR-alone patients attended CR exercise classes and 85% attended educational seminars on health-related topics. Only 11% did not attend any CR exercise sessions and 15% did not attend any educational seminars. In the Home-MCT + CR arm, 80% of patients attended CR exercise classes and 78% of patients attended educational seminars. A higher proportion of intervention group participants did not attend exercise sessions, at 20%, and 22% did not attend educational seminars.

Information on engagement with the Home-MCT manual was collected via an end-of-study questionnaire mailed to participants, which had a 69% response rate. In total, 72.7% of patients who returned the end-of-study questionnaire completed four or more of the six modules, although owing to attrition these were just 45.3% of all Home-MCT patients still alive at 4 months. Although most patients reported completing a module in 60 minutes, individual times for doing this varied, ranging from 40 to 105 minutes.

Among those who returned the questionnaire, Home-MCT demonstrated high credibility. After completing the manual, patients were assessed on how user-friendly they found Home-MCT. Home-MCT was rated highly, with patients stating that they found the manual easy to use and understand (median rating of 80 out of 100), that the homework was easy to follow (median rating of 85 out of 100), and that the exercise SpACE was easy to use (median rating of 90 out of 100). When patients were asked if they found that they needed the telephone support calls, results were mixed: 40% said they did not need the support calls, while 40% stated they did. No adverse events were reported.

Verification of estimated sample size

Under assumptions of 20% attrition and a 0.5 correlation between baseline and 4-month follow-up, we provisionally estimated that a total recruitment sample of 246 patients would be required for a definitive trial, subject to revision based on the findings of this feasibility study. In the event, this feasibility study had an overall attrition rate of 10% at 4 months and a baseline-to-follow-up correlation of 0.58. However, there was evidence of greater attrition in the Home-MCT group at 17%, so for conservative reasons we chose to retain our original sample size estimate for a main trial.

Summary of findings of work stream 3

Overall, Home-MCT was found to be an acceptable and feasible addition to CR. No adverse events were reported in either trial arm. These results suggested that we could progress to a full-scale RCT to evaluate the efficacy of Home-MCT. The full trial would also provide a more definitive evaluation of the tendencies seen in the pilot for retainment in the trial and attendance at usual care to be somewhat lower among those offered Home-MCT. The success of the feasibility study supported a VTC to extend recruitment to a full-scale RCT.

Stated preference survey

Introduction

A pilot stated preference survey, using a DCE design, was conducted to explore the preferences of participants in the Home-MCT feasibility study for attributes of a psychological therapy intervention, relevant to home-based care, delivered in CR. The objectives were to evaluate the feasibility of preference research, estimate the sample size needed for a full study and explore preliminary preferences for included attributes. The paper has been published. 33

Methods

Following a review of qualitative feedback, PPI feedback and iterative discussion with the trial team, attributes and levels were selected for the DCE. A fractional factorial design was chosen, using a published design catalogue (http://neilsloane.com/oadir/oa.16.5.4.2.txt) and modulo arithmetic. 47,51 Participants were asked to choose their preferred scenario from two hypothetical options, and then whether they would choose this scenario or no psychological therapy (opt-out). Data were analysed using individual choice responses as the dependent variable in the model with a conditional logit using maximum likelihood estimation. 47 Results were used to estimate the sample size that would be required to calculate significant preference coefficients in a full study, generated for D-efficient and Bayesian designs in the experimental design software Ngene (Choice-Metrics, Sydney, NSW, Australia). 52

Results