Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0614-20009. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The final report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2023. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Estcourt et al. This work was produced by Estcourt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Estcourt et al.

Synopsis

Structure of the Programme

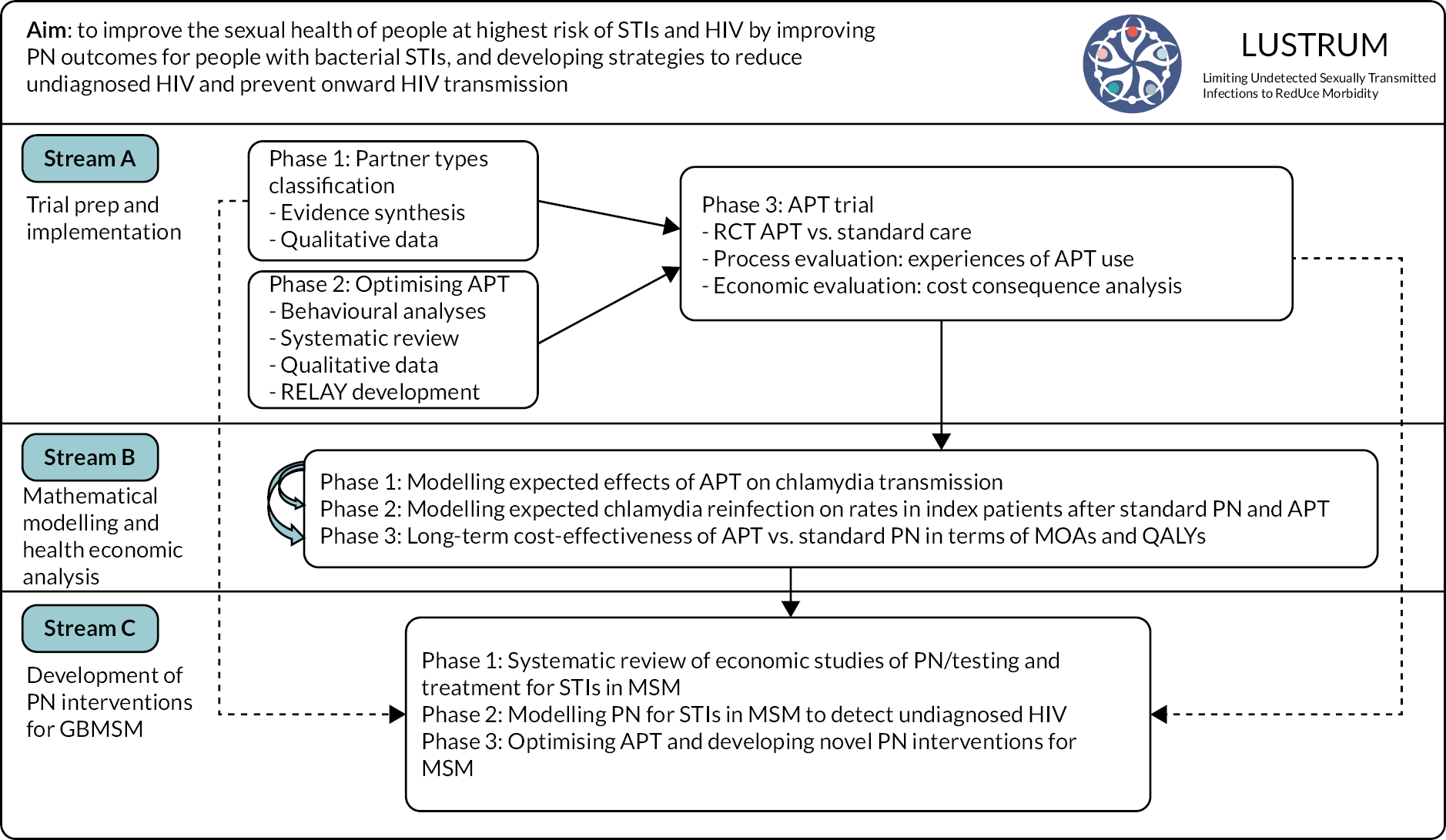

This Programme aims to improve the sexual health of people in Britain at highest risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by improving partner notification (PN) outcomes for people with bacterial STIs through three inter-related research streams (see Research pathway diagram in Figure 1).

Research pathway diagram

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram showing the inter-related workstreams within the LUSTRUM Research Programme. APT, accelerated partner therapy; GBMSM, gay and bisexual men who have sex with men; IP, index patient; MOAs, major outcomes averted; MSM, men who have sex with men; QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RELAY, a clinical management and partner notification data collection system.

Changes to the Programme

To maximise utility and impact of the research, changes were made in areas as follows:

Firstly, we delayed the trial to avoid overlapping with another sexual health clinic-based National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) funded trial. 1 The durations of intervention and control phases were extended by 2 months with a 2-week washout period instead of 1 month, to increase index patient (IP) recruitment. The target sample size was reduced from 5880 to 5440 to account for the inclusion of three additional clusters.

Secondly, the content of Stream C was updated to keep pace with scientific developments and in light of findings from the pre-trial phase (Stream A). Instead of a single online survey of one stakeholder group, we delivered a three-phased approach involving a wider spectrum of stakeholders. This included a literature review and stakeholder workshop, empirical qualitative work and intervention specification using programme theory. 2 We also switched to virtual rather than face-to-face focus groups with an additional group of men who have sex with men (MSM) instead of healthcare professionals (HCPs) due to COVID-19-related restrictions in April 2020. Although the online format worked well, it was more time-consuming and so we chose to focus on PN for bacterial STIs rather than including HIV. The issues for HIV PN are different and complex and therefore need separate discussion.

Finally, the Programme end date was extended by 4 months to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on working patterns across the whole team.

This report is structured to reflect the way we conducted the Programme of research as shown in the Research pathway diagram, which differs slightly from some subheadings and numbering within the original bid document.

Stream A phase 1: qualitative studies – sex partner types and optimising accelerated partner therapy

Qualitative studies–developing a classification of sex partner types

Aim and objectives

To develop a classification of sex partner (SP) types for use in PN and other interventions to prevent STIs.

To conduct a synthesis of existing knowledge on partner types from published literature; establish contemporary evidence of public, patient and HCP staff beliefs about partner types; consult with multidisciplinary experts on the developing classification.

Methods for data collection and analysis

Firstly, we conducted an iterative synthesis of diverse sources of evidence to generate an initial comprehensive classification. Evidence sources included:

-

analysis of data from National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal) 33

-

analysis of relationship types in 259 dating applications (apps)4

-

scoping review of social and health sciences literature on partner types (56 studies). 5

Secondly, we conducted qualitative interviews with public, patients and health professionals [57 patient and public participants (male n = 34; female n = 23)]. 6

Finally, we operationalised and sought external endorsement for the sex partnership classification through multidisciplinary clinical expert consultation at dedicated workshops facilitated by the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH),7 later in the Programme, we piloted the revised classification in sexual health clinics during a randomised controlled trial (RCT). 8,9

Limitations

The diverse data types that were synthesised precluded a standardised approach to meta-analysis and relied on more qualitative approaches from meta-synthesis.

Key findings

We identified a spectrum of partner types and noted the malleability of partner types as relationships develop and across the life course.

We created a novel five-category classification, broadly predicated on duration of the relationship, likelihood of future sex and degree of emotional connection. 10 This was used successfully by sexual HCPs to record partner types within the RCT. 8

Stage 1: collating diverse evidence

We analysed data on partnership types from the Natsal-3 survey11 and used these findings within our review of published evidence (Evidence source 2).

Evidence source 1: We applied a systematic review approach to examine the top 500 downloaded dating apps in Britain to determine how they described and organised sexual relationships. After deduplication and full content screening, 259 apps were examined in detail. We extracted data on the architecture of dating apps, such as the options available to dating app users as they made connections with others. Most dating apps are designed for specific user populations, typically grouped according to sexual preferences, social commonalities or individual characteristics. We conducted a cluster analysis to explore if dating apps could be grouped along a range of shared denominators. Two clusters emerged – unfocused and ambiguous, and highly specific – catering to the different needs of possibly the same dating app users. We did not collect any information on dating app users, nor dating app designers. 4

Evidence source 2: Using a systematic search strategy, we examined 56 out of 15,592 papers which detailed types of sexual relationships and partnerships. Most studies were published within the 21st century in the USA and used a range of primarily quantitative designs. We extracted and detailed the partnership types described in each of the included papers. We found that studies tended to have a close focus on one kind of relationship/partner (e.g. ‘casual’) rather than explore a large range of diverse partnership types. Subsequently we synthesised the types of relationship/partner detailed within the literature by extracting and interpreting the commonalities and differences among reported partnership types. In this way, we were able to develop a spectrum of eight mutually exclusive categories of relationships. These categories were: (1) ‘married/committed’; (2) ‘main partner’/‘serious partner’/‘stable’ or ‘long term’; (3) ‘established’; (4) ‘girlfriend’/‘boyfriend’; (5) ‘dating’/‘going out’; (6) ‘friends with benefits’; (7) ‘**** buddies’ and ‘booty calls’; and finally (8) ‘super casual’, ‘hook-ups’, ‘meets and one-night stands’. 5

Evidence source 3: We conducted qualitative interviews with members of the public and sexual health clinic patients (male n = 34; female n = 23). After an initial thematic analysis, we subsequently explored our findings further in terms of resonance with key constructs from sexual script theory. 12 We showed how the ways people perceive and talk about their relationships relate to the changing and multilayered social organisation of their relationships. Our findings emphasise how recent, labile, sociocultural scenarios are shaping fluid and emerging interpersonal and intrapsychic sexual scripts leading to both new uncertainties and opportunities in the ways we relate to each other sexually. 6

Stage 2: integration and synthesis of diverse evidence

Using the constant comparative method and data visualisation, we synthesised these diverse findings to shape a pragmatic classification of partner types that could be useful within clinical practice and within the RCT itself. We identified five main partner types: ‘Established partner’, ‘New partner’, ‘Occasional partner’, ‘One-off partner’ and ‘Sex worker’. 10

Multidisciplinary clinical expert consultation to revise the classification – During a series of interactive workshops and meetings with diverse sexual health professionals and other experts, we iteratively tested and adapted the classification to ensure that it made sense, had face and ecological validity and could be used within clinical practice.

Piloting of the revised classification in sexual health clinics during a RCT of PN – We piloted the novel classification by implementing it into routine practice ahead of the trial and during the phase of stable data collection at the beginning of the RCT within a clinical management and PN data collection system (RELAY) (see Stream A phase 2: optimising accelerated partner therapy). Healthcare professionals were able to assign all SPs to a category without difficulty and no further changes were needed. 10

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

The classification of partner types was used within the RCT to categorise SPs and thereby enabled determination of trial outcomes by partner type. The classification was also instrumental in shaping the intervention development focus of Stream C, in that it highlighted that APT was unlikely to be a useful approach with one-off partners and shifted our focus to alternative approaches.

Stream A phase 2: optimising accelerated partner therapy

Accelerated partner therapy barriers and facilitators and optimising accelerated partner therapy

Aim and objectives

To optimise APT and produce a manualised intervention, a complementary training package and a specific range of intervention resources.

To detail the behavioural system of APT; analyse videos of APT, conduct a synthesis of published evidence concerning the behavioural elements of APT and related interventions; establish in-depth behaviourally informed evidence concerning the barriers and facilitators to receiving/delivering APT including focused work with those likely to struggle with APT; specify the key components of APT and operationalise them within an APT manual, training package, a series of on-line videos (for staff and SPs using the self-sampling and treatment pack) and other intervention resources (optimised pack contents and laminated materials for HCPs and for IPs).

Methods for data collection and analysis

Insights from several contributing studies were combined to optimise APT. These included:

-

An analysis of the behavioural system of APT from videos of role play based on previous APT work. 13

-

A systematic review of PN intervention content (K = 14). 14

-

Qualitative interviews with public, patients and health professionals, including both heterosexuals and MSM with initial thematic analysis. 15

-

Application of the behaviour change wheel (BCW)16 and normalisation process theory (NPT)17 to specify the intervention in terms of its key components and associated mechanisms.

-

Further qualitative interviews and focus groups with people with mild to moderate learning disabilities addressed the intervention amongst those who may particularly struggle with APT. 18

-

Focus groups with diverse HCPs to explore the acceptability and pertinent barriers and facilitators to implementing APT.

-

We used the APEASE (acceptability, practicability, effectiveness, affordability, side-effects, equity) criteria19 to finalise the content of the intervention and operationalise it within the manual, the training packages, the videos and intervention materials.

-

Finally, we worked iteratively with the software development company (Epigenesys) to incorporate key stages of the APT intervention into RELAY (please see Stream A phase 3), which was used by HCPs during the RCT. 9

We adopted a user-centred approach with multiple pre-design and prototype testing phases to further develop the functionality and design of the bespoke web-based referral and data collection tool created and refined in previous studies. 20,21 RELAY supported the APT patient pathway, enabling rapid communication between the clinics and the research health advisers (RHAs) and pharmacy services.

Limitations

We relied only on qualitative data to optimise APT; participants for the interviews and focus groups chose to take part so may have different views to some end-users of APT.

Key findings

Building upon previous accelerated partner therapy work to detail the behavioural system of accelerated partner therapy through video analysis of accelerated partner therapy

We detailed the behavioural structure of APT across its key actors, the central behavioural domains addressed and the specific behaviours required for each of APTs key steps. 13,14

Systematic review of partner notification intervention content and behavioural steps

Fourteen studies met our inclusion criteria. Most focused on treating Chlamydia trachomatis through a series of sequential steps dependent on local context and policies resulting in relatively heterogeneous intervention steps although with considerable overlap. Analysis of intervention content showed commonly reported behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were ‘adding objects to the environment’, ‘credible source’ and ‘instruction on how to perform a behaviour’. Systematic review registration number: CRD42016051178. 14

Qualitative interviews with public, patients and health professionals to understand barriers and facilitators to delivery and uptake

There were diverse and varied barriers and facilitators for each step of APT and for each actor (e.g., HCP vs. IP or SP) and their distinct behavioural domains. Facilitators outnumbered reported barriers.

For IPs and SPs, many of the barriers related to psychosocial consequences of engaging in APT, confidence and skills needed to deliver and use the STI and HIV self-sampling pack and a lack of understanding of sexual health, and PN.

From the HCP perspectives, perceived barriers related to their own levels of knowledge and perceived competence in telephone consultations, perceived skills and beliefs (e.g. the safety of remote prescribing), and also the contexts in which they worked [e.g. need for dedicated space and time within busy sexual health services (SHSs)].

Optimising the intervention

To address the identified barriers, we systematically developed a comprehensive package of optimal intervention components. These components were all specified in terms of the causal mechanisms they moderated and the BCTs and intervention functions they employed. Analysis using the BCW showed that to support HCPs in delivering APT a combination of education, training and environmental restructuring would be particularly important.

Equally, for both IPs and SPs, enablement, education, persuasion and modelling were perceived to be particularly important. These key intervention functions were also detailed in terms of the BCTs they employed. Following the use of the APEASE criteria19 with expert team members, the intervention was specified and operationalised in the form of a manual for trial sites, training materials for face-to-face and on-line use, on-line videos for staff, IPs and SPs, and additional intervention materials such as laminated sheets to support both the HCP and the IP within APT. 13

Qualitative studies with people with mild to moderate learning disabilities

All participants found at least one element of the self-sampling pack challenging or impossible to use but welcomed the opportunity to undertake sexual health screening without attending a clinic. Reported barriers to correct use of the pack included perceived overly complex STI/blood-borne virus (BBV) information and instructions, feeling overwhelmed and the manual dexterity required for blood sampling. Many female participants struggled interpreting anatomical diagrams depicting vulvo-vaginal swabbing. Facilitators included pre-existing STI/BBV knowledge, familiarity with self-management, good social support and knowing that the service afforded privacy. 18

RELAY

RELAY functioned well as a web-based clinical management and PN data collection tool to support the APT patient pathway, and enabled rapid communication between the clinics, the supporting RHAs, and testing laboratory (for the IP repeat testing in the RCT). We are working with several trial clinics to explore options for retaining RELAY as a long-term clinic-wide PN system for all STIs.

Stable data collection and piloting of definitions

We successfully introduced RELAY into each clinical service for 2–4 weeks before the start of the trial for sexual HCPs to record PN consultations and outcomes of existing methods of PN and clinical data on SPs using the new SP classification. 10 Minor amendments were made to the webtool following user feedback.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

The optimised version of APT is central to the RCT. It is also important for understanding the specific focus of Stream Cs intervention development which focused on PN with ‘one-off partners’ as the work reported here showed viability of APT with ‘Established partner’, ‘New partner’, ‘Occasional partner’ amongst MSM.

Stream A phase 3: trial delivery, analyses and interpretation

Background

APT is a PN method whereby during the IP’s clinic attendance, HCPs assess SPs by telephone consultation, before sending out or giving the IP antibiotics and STI and HIV self-sampling kits to deliver to their SP(s). APT has shown promise in pilot trials. 20,21

Aim and objectives

Aim: to determine the effectiveness of APT in improving outcomes of PN for genital chlamydia in heterosexuals in a cluster crossover RCT.

Specific objectives are to determine:

-

The effect of APT on the proportion of IPs who test positive for chlamydia 12–16 weeks after the PN consultation (the gold standard outcome in PN trials).

-

The effect of APT on the proportion of SPs treated.

-

The effects of APT according to SP type.

-

The effect of APT on the proportion of SPs notified.

-

Whether APT is associated with faster treatment than standard PN.

Methods for data collection and analysis

Trial design: a cluster crossover RCT of APT offered as an additional PN method compared with standard PN alone. 9 The APT intervention was offered at the level of the sexual health clinic, with randomisation of each clinic to either intervention or control arm in the first phase of the trial.

The trial was accompanied by an economic evaluation, transmission dynamic modelling and a qualitative process evaluation.

Clusters were 17 sexual health clinics (publicly funded) in areas of Britain with contrasting patient demographics.

Participants were heterosexual women and men, aged ≥ 16 years with a positive test for C. trachomatis and/or clinical diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or cervicitis (women) or non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) or epididymo-orchitis (men) and reporting at least one contactable sexual partner in the past 6 months.

Recruitment: during the initial PN consultation with the IP, the HCP assessed eligibility for the study. As this was a low-risk health intervention, consent was provided at service level.

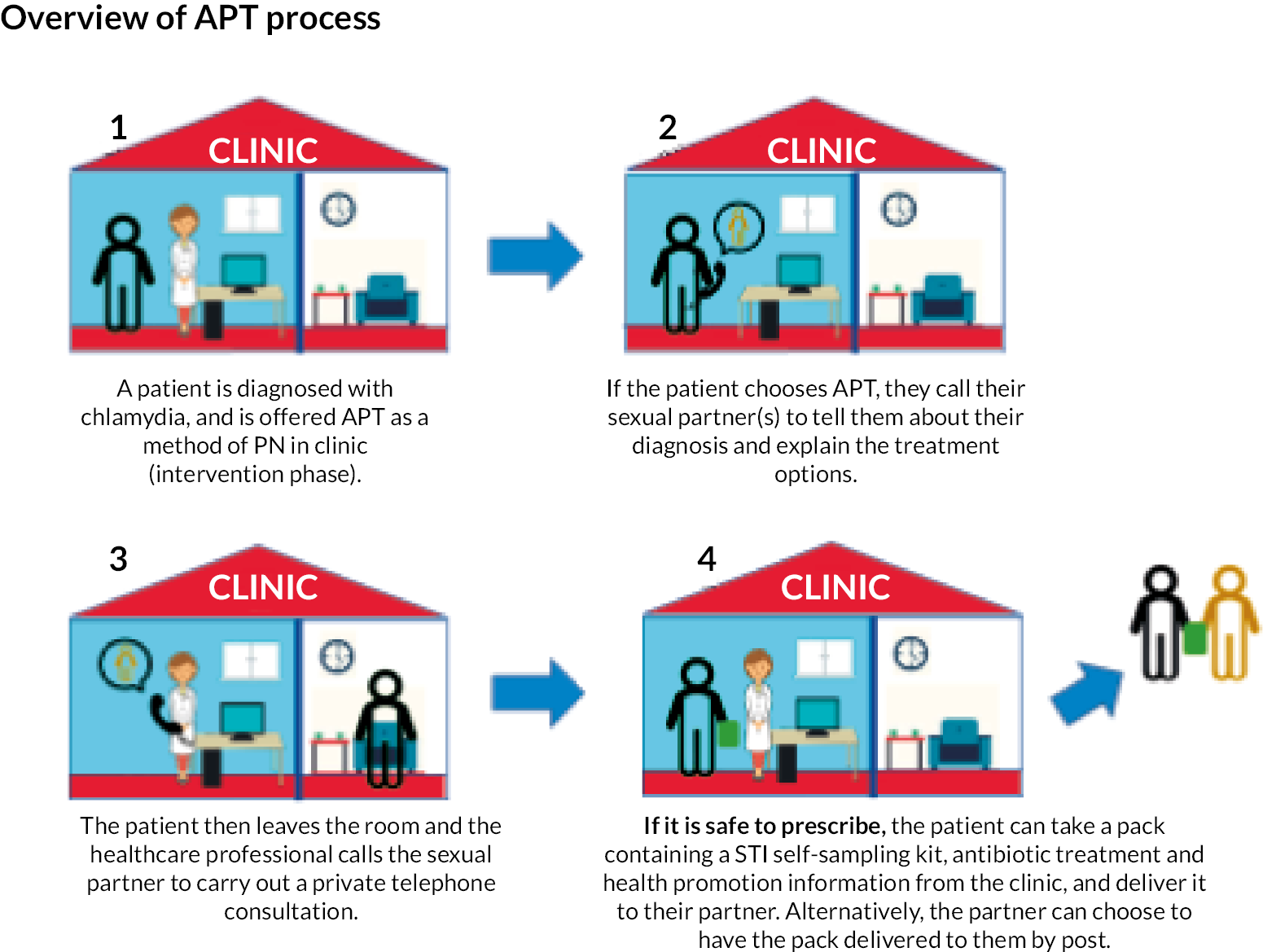

Intervention: APT offered as an additional PN method compared with standard PN alone (see the APT overview film22). The APT intervention was offered at the level of the sexual health clinic, with randomisation of each clinic to either intervention or control arm in the first phase of the trial (random permutation). Figure 2 shows an overview of the APT process.

FIGURE 2.

Diagram showing the steps of the APT process.

Control: standard PN, which was enhanced patient referral in which HCPs asked the IP to inform their SP(s) of the need for testing and treatment, supplemented by written or website information.

Trial periods: there was a 4-month run-in period (July–October 2018), consisting of rolling clinic set-up including training for HCPs and a period of at least 2 weeks of baseline data collection when HCPs used RELAY to record standard PN data. Then nine clinics entered intervention phase while eight entered control phase, according to the randomisation schedule. At the end of the first 6-month trial phase (November 2018 to April 2019), there was a 2-week washout period where clinics did not offer APT to patients and followed their standard PN procedures. Then clinics crossed over to the opposite arm (intervention or control) for phase two (for 6 months, May–November 2019). The total duration of the trial was 19 months, allowing for a 3-month follow-up period to enable outcome data collection to be completed for all patients in the second trial phase. Clinics which did not start phase one of the trial in November 2018 completed recruitment in November 2019 and trial phases were condensed.

The primary outcome was the proportion of IPs testing positive for C. trachomatis 12–24 weeks after the PN consultation. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of SPs treated; the proportion of SPs notified; cost effectiveness; model-predicted chlamydia prevalence; SP and HCP experiences of APT.

The primary outcome analysis was by intention to treat, fitting random-effects logistic regression models that account for clustering of IPs within clinics and trial periods. The statistician carried out analysis of the primary outcome blinded to allocation.

Trial registration: This trial is registered as ISRCTN 15996256.

Development of APT web tool: we adopted a user-centred approach to further develop the functionality and design of RELAY created and refined in previous studies. 20,21 Clinic HCPs entered clinical data and any data collected for research purposes directly onto RELAY during the PN consultation. RELAY supported the APT patient pathway, enabling rapid communication between the clinics and the supporting RHAs. A new function enabled a clinical summary to be downloaded and incorporated into the patients’ clinic electronic patient records.

We undertook an extensive pre-design (product testing) phase and rounds of iterative development with health professionals and sexual health clinic health advisers to ensure that the tool met their needs, current activity, and work habits.

We also ‘stress tested’ RELAY and performed a dummy data retrieval exercise, in which an independent company comprehensively tested the system for errors and its ability to extract all relevant data variables needed for the statistical analysis plan for the trial.

RELAY had been developed to exceed all contemporary NHS data storage and transfer standards and NHS information governance compliance with strict adherence to the Caldicott principles of confidentiality, as outlined in the Caldicott report 1997. 23 However, the process for research and development (R&D) and Information Governance approval in several of our trial sites was extremely arduous, created substantial delays in some cases and almost prevented participation in one site.

Ethical approval and the General Data Protection Regulation paradox: Ethical approval for the trial was provided by London – Chelsea Research Ethics Committee (18/LO/0773) and approved us to seek consent for trial participation from lead clinicians at participating clinics (service-level) rather than seeking individual informed consent from IPs other than for the process evaluation studies. Following Weijer et al. ,24 we believed that APT is a complex, ‘low-risk’ healthcare delivery intervention. APT is offered in addition to standard PN and operationalised as a supplement to usual care; thus, IPs have the choice of taking up APT or not. It is widely accepted that individual consent may not be essential in such trials,25 in which the situation is analogous to the introduction of changed processes in routine services. 26 This was important for the RCT as individual-level consent is thought to have contributed to low recruitment numbers in a previous study of APT. 21

However, the newly introduced General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) required that individuals have the option to choose whether their data may be used for research. This presents a challenge when consent has been given by the clinical service and not by individual service users. We developed a pragmatic opt-out solution to this consent paradox. 27 Our approach supported the individual’s right to withhold their data from trial analysis while routinely offering the same care to all patients.

Selection of clinics: we selected 17 NHS (publicly funded, free to access) specialist sexual health clinics (clusters) across England and Scotland from those expressing interest. Selection was based on numbers of reported chlamydia diagnoses data in the Public Health England Genitourinary Medicine Clinical Activity Dataset for STI surveillance28 (England) and geographical diversity (Scotland) to create three strata: London, non-London metropolitan ‘cities’ and non-London urban ‘towns’. A full list of study sites is included in the published study protocol. 9

Training of clinic staff and site set-up and support: multidisciplinary members of the trial team (researchers, research heath advisers and clinicians) made a study initiation visit to each clinic prior to randomisation to train staff in intervention delivery, the use of RELAY and the novel classification of SP types needed for data collection. The training consisted of (1) a whole clinic presentation explaining an overview of the trial, (2) small group interactive APT training using observed and participatory role plays and use of the intervention manual, (3) training and quizzes on use of the new partner type classification and (4) one-to-one or small group training in use of RELAY.

In addition, we created a series of training videos which enabled those who were unable to attend, new staff who joined during the study period, staff from clinics which entered intervention phase second to learn/refresh their skills and knowledge. We have subsequently made all resources available on our website and YouTube channel.

The trial team liaised with and supported clinics extensively. Typically, this included a weekly telephone call with each site lead, refresher training either on site or remotely when clinics switched from control phase to intervention phase and ad hoc as requested by the clinics or if recruitment appeared to slow.

Stable data collection: we introduced RELAY into each clinic 1 month before the start of the trial. Clinic health advisers used RELAY as their routine method of recording PN consultations and outcomes of existing methods of PN and clinical data on SPs using the new SP classification.

Limitations

Overall enrolment and follow-up were lower than expected20,21 and statistical power was lower than assumed. APT uptake itself was not a part of the power calculations, but we expected more IPs to choose it. We were unable to determine whether APT was associated with faster treatment because only small number of IPs knew when, as opposed to whether, their SPs had been treated.

The pragmatic trial design was intended to ensure that the effectiveness of APT would be evaluated under real-life clinical conditions. However, trial procedures meant that APT required additional data collection regardless of whether the patient accepted the APT intervention. This, together with wider operational factors (see Stream A phase 3: process evaluation), meant that it was seldom offered routinely. 29

Key findings

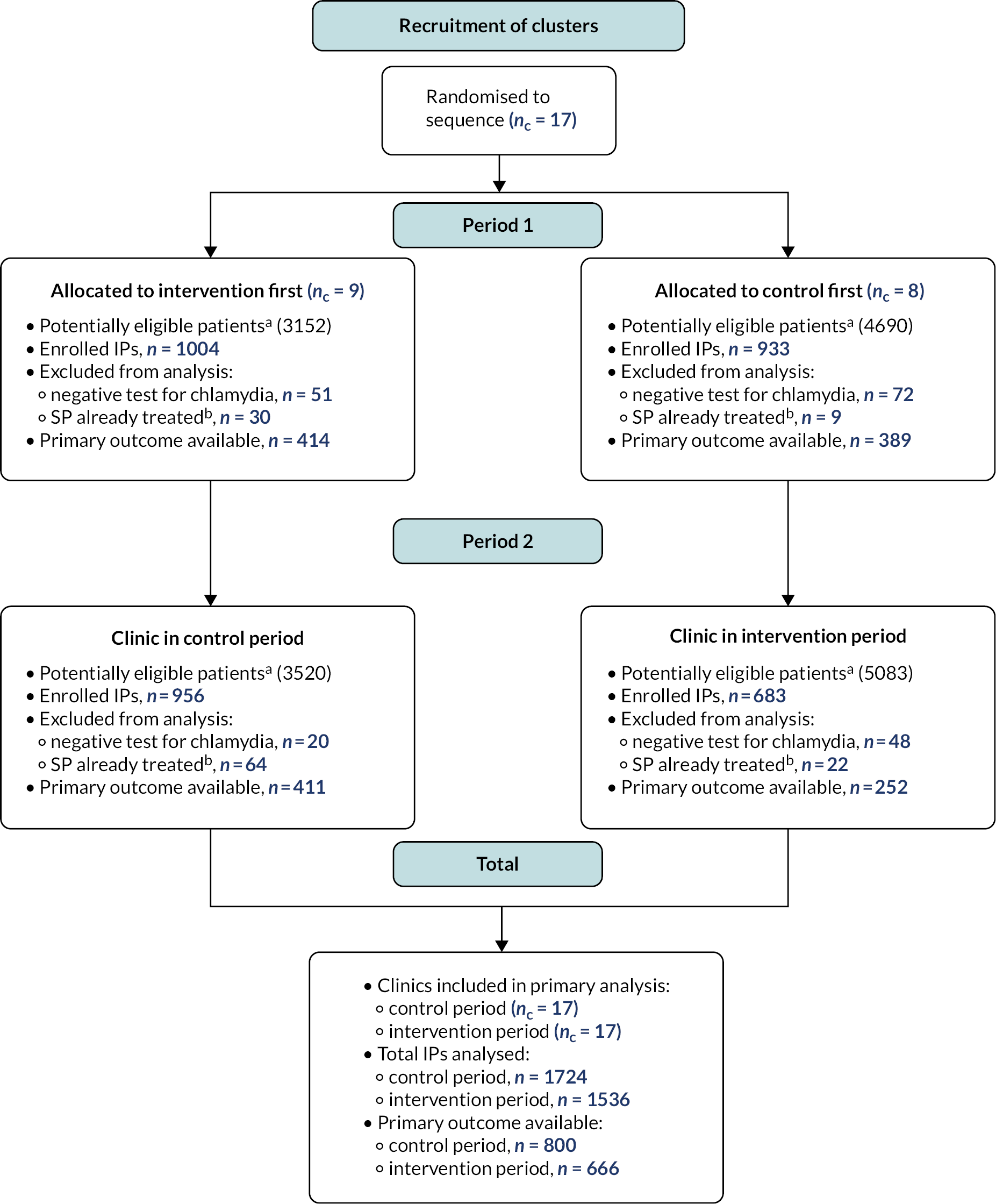

Figure 3 provides an overview of the trial.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of enrolment by clinic randomisation status and period. a, Administrative service data on all chlamydia diagnoses within trial period in non-MSM patients aged ≥ 16 years not attending as PN contact; b, All potentially eligible SPs treated prior to clinic consultation of IP.

All clinics completed both periods. One thousand five hundred and thirty-six and 1724 IPs provided data in intervention and control phases. In intervention and control phases, 666 (43.4%) and 800 (46.4%) IPs were tested for C. trachomatis; 31 (4.7%) and 53 (6.6%) were positive, adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.66 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.41 to 1.04; p = 0.07]. In total, 4807 SPs were reported, of whom 1636 (34.0%) were committed/established partners. Characteristics of index cases and partners were balanced. Overall, 293/1536 (19.1%) of IPs chose APT for a total of 305 partners, of whom 248 accepted. The proportion of IPs with one or more SPs notified was 1123/1150 (97.7%) in the intervention phase and 1185/1218 (97.3%) in the control phase (aOR 1.18, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.00; p = 0.54), while the proportion of all partners notified was 95% in both phases (aOR 0.80, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.29; p = 0.35). The proportion with ≥ 1 SP treated was 775/881 (88.0%) in intervention and 760/898 (84.6%) in the control phase, aOR 1.27 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.68; p = 0.10).

One thousand five hundred and thirty-six IPs with 2218 partners were enrolled in APT intervention phases, but APT could not be offered by the clinic in 81/2218 of these. The IP selected APT for 305/2137 (14.3%) partners when available. Of these, 166/305 (54.4%) were committed/established, 85/305 (27.9%) were new, 45/305 (14.8%) were occasional and 9/305 (3.0%) were one-off partners. Common index reasons for declining APT included: preference for face-to-face conversation 400/1832 (21.8%), partner already in clinic 388/1832 (21.2%), unwilling to engage with partner 206/1832 (11.2%), preferring partner to attend clinic 202/1832 (11.0%), partner overseas 150/1832 (8.2%). Of 241 partners sent APT packs, 120/241 (49.8%) returned chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing samples, of which 78/119 (65.5%) were positive for chlamydia (no result obtained for one returned sample), but only 60/241 (24.9%) HIV and syphilis samples (all negative). Of 106 IPs offered APT, which was accepted ≥ 1 partners, and tested for chlamydia at 12–24 weeks, only 2 (1.9%) were positive. This contrasts with 6.6% (53/800) in the control arm and 5.2% (29/560) in IPs not selecting APT or whose partners refused. There were seven adverse events reported (see Report Supplementary Material 1), all deemed to be of low severity and managed through discussion with the Trial Steering Group and Trial Management Group.

Tables 1–8 show the trial data and outcomes.

| Variable | Control period, n (%) or median (IQR) | Intervention period, n (%) or median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of IPs | 1724 | 1536 | |

| Sociodemographic factors | |||

| Age | Years [median (IQR, range)] | 24 (21–28, 17–62) | 24 (21–28, 16–72) |

| IP sex at birtha | Male | 547 (32) | 522 (34) |

| Female | 1177 (68) | 1014 (66) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Enrolment of IP based on | Diagnosed chlamydia | 1678 (97) | 1506 (98) |

| PID | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.06) | |

| Cervicitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| NGU | 37 (2.1) | 27 (1.7) | |

| Epididymo-orchitis | 2 (0.12) | 2 (0.13) | |

| Ethnicity | White British or Irish | 829 (48) | 707 (46) |

| White other | 199 (12) | 181 (12) | |

| Black/Black British | 368 (21) | 377 (25) | |

| Asian/British Asian | 100 (6) | 92 (6) | |

| Mixed ethnicity | 193 (11) | 134 (9) | |

| Other ethnicity | 35 (2) | 45 (3) | |

| SPs per IP | |||

| SPs last 12 months | Count [median (IQR, range)] | 2 (1–3, 1–100) | 2 (1–4, 1–60) |

| New SPs last 12 months | Count [median (IQR, range)] | 2 (1–3, 0–99) | 1 (1–3, 0–50) |

| SPs in 1/3/6-month look-backb | Count [median (IQR, range)] | 2 (1–2, 1–25) | 1 (1–2, 1–39) |

| SPs included in analysis | Count [median (IQR, range)] | 1 (1–2, 1–20) | 1 (1–2, 1–10) |

| Variable | Control period, n (%) | Intervention period, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of SPs | 2589 | 2218 | |

| Sociodemographic factors | |||

| Gender identitya | Male | 1699 (66) | 1419 (64) |

| Female | 890 (34) | 799 (36) | |

| Partner typeb | Committed/established | 880 (34) | 756 (34) |

| New relationship | 342 (13) | 343 (15) | |

| Occasional partner | 687 (27) | 610 (28) | |

| One-off partner | 680 (26) | 509 (23) | |

| Condom use with this partner | Always | 293 (11) | 202 (9) |

| Sometimes | 870 (34) | 800 (36) | |

| Never | 1426 (55) | 1216 (55) | |

| Likelihood of future sex with this partner | No | 1066 (41) | 844 (38) |

| Not sure | 614 (24) | 458 (21) | |

| Yes | 909 (35) | 916 (42) | |

| Control period | Intervention period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measures | n (%)a | n (%)a | OR (95% CI); p-value | aOR (95% CI); p-value |

| Number of IPs | 1724 | 1536 | ||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| IP chlamydia test 12–24 weeks (observed data) | ||||

| Positive | 53 (6.6) | 31 (4.7) | 0.67 (0.42 to 1.06); 0.08 | 0.66 (0.41 to 1.04); 0.07 |

| Negative | 747 (93.4) | 635 (95.3) | – | – |

| No testb | 924 | 870 | Excludedb | Excludedb |

| IP chlamydia test 12–24 weeks (MAR MI) | ||||

| Positive | 116 (6.7) | 73 (4.8) | 0.67 (0.40 to 1.14); 0.14 | 0.67 (0.39 to 1.14); 0.14 |

| Negative | 1608 (93.3) | 1463 (95.2) | – | – |

| IP chlamydia test 12–24 weeks [MNAR MI: δ = loge(0.5)] | ||||

| Positive | 154 (8.9) | 86 (5.6) | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.92); 0.02 | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.92); 0.02 |

| Negative | 1570 (91.1) | 1450 (94.4) | – | – |

| IP chlamydia test 12–24 weeks [MNAR MI: δ = loge(2)] | ||||

| Positive | 98 (5.7) | 55 (3.6) | 0.57 (0.38 to 0.88); 0.01 | 0.57 (0.37 to 0.88); 0.01 |

| Negative | 1626 (94.3) | 1481 (96.4) | – | – |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| ≥ 1 SP treated for chlamydia (observed data) | ||||

| Yesc | 760 (84.6) | 775 (88.0) | 1.25 (0.94 to 1.64); 0.12 | 1.27 (0.96 to 1.68); 0.10 |

| Nod | 138 (15.4) | 106 (12.0) | – | – |

| Not knownb | 826 | 655 | Excludedb | Excludedb |

| ≥ 1 SP treated for chlamydia (MAR MI) | ||||

| Yes | 1452 (84.2) | 1344 (87.5) | 1.29 (0.94 to 1.77); 0.12 | 1.30 (0.94 to 1.81); 0.12 |

| Noe | 272 (15.8) | 192 (12.5) | – | – |

| ≥ 1 SP notified (observed data) | ||||

| Yesc | 1185 (97.3) | 1123 (97.7) | 1.17 (0.69 to 1.97); 0.56 | 1.18 (0.70 to 2.00); 0.54 |

| Nod | 33 (2.7) | 27 (2.3) | – | – |

| Not knownb | 506 | 386 | Excludedb | Excludedb |

| Control period | Intervention period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measures | n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI); p-value | aOR (95% CI); p-value |

| Total number of SPs | 2589 | 2218 | ||

| Treated at 2 weeks (observed data) | ||||

| Yesa | 859 (79.6) | 842 (83.6) | 1.31 (0.94 to 1.83); 0.11 | 1.25 (0.88 to 1.77); 0.20 |

| No | 220 (20.4) | 165 (16.4) | – | – |

| Not known by IPb | 699 | 538 | Excludedb | Excludedb |

| Follow-up not recordedb | 811 | 673 | Excludedb | Excludedb |

| Known to be treated at 2 weeks | ||||

| Yesa | 859 (33.2) | 842 (38.0) | 1.50 (1.08 to 2.10); 0.01 | 1.27 (0.99 to 1.65); 0.06 |

| No | 1730 (66.8) | 1376 (62.0) | – | – |

| Notified at 2 weeks (observed data) | ||||

| Yes | 1700 (95.0) | 1514 (95.0) | 0.93 (0.58-1.47); 0.75 | 0.80 (0.49-1.29); 0.35 |

| No | 89 (5.0) | 79 (5.0) | – | – |

| Follow-up not recordedb | 800 | 625 | Excludedb | Excludedb |

| With stratification by relationship type | ||||

| Treated at 2 weeks (observed data) | ||||

| Yesa: committed establishedc | 400/478 (83.7) (n = 880) | 400/447 (89.5) (n = 756) | 1.74 (1.04 to 2.91); 0.04 | 1.65 (0.96 to 2.82); 0.07 |

| Yesa: new relationshipc | 151/176 (85.8) (n = 342) | 182/200 (91.0) (n = 343) | 1.83 (0.79 to 4.24); 0.16 | 1.72 (0.72 to 4.14); 0.22 |

| Yesa: occasional partnerc | 175/232 (75.4) (n = 687) | 162/207 (78.3) (n = 610) | 1.19 (0.62 to 2.28); 0.59 | 1.16 (0.59 to 2.29); 0.66 |

| Yesa: one-off partnerc | 133/193 (68.9) (n = 680) | 98/153 (64.1) (n = 509) | 0.64 (0.32 to 1.27); 0.20 | 0.65 (0.32 to 1.32); 0.23 |

| n/N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Per IP summary | ||

| APT uptake | Total IP s in intervention period | 1536 |

| APT not selected for any partner | 1243 (80.9) | |

| APT selected by IP for ≥ 1 partner | 293 (19.1) | |

| APT accepted by ≥ 1 partner | 244 (15.9) | |

| Per SP summary | ||

| APT pathway | Total SPs in intervention period | 2218 |

| APT not offered by clinic | 81/2218 (3.7) | |

| Staffing limitations | 68/81 (84.0) | |

| Drug supply issues | 13/81 (16.0) | |

| APT not selected by IP | 1832/2137 (85.7) | |

| IP prefers to have the conversation with the partner face-to-face | 400/1832 (21.8) | |

| Partner is in clinic to be treateda | 388/1832 (21.2) | |

| IP doesn’t want to talk or see partner | 206/1832 (11.2) | |

| IP prefers the partner to visit the clinic | 202/1832 (11.0) | |

| Partner is overseas | 150/1832 (8.2) | |

| IP doesn’t have partner’s phone number | 59/1832 (3.2) | |

| IP is worried about partner’s reaction | 57/1832 (3.1) | |

| IP does not understand how APT works | 1/1832 (0.1) | |

| Other/missing | 369/1832 (20.1) | |

| APT selected by IP | 305/2137 (14.3) | |

| No answer to phone call | 49/305 (16.1) | |

| SP declined APT | 8/305 (2.6) | |

| APT accepted | 248/305 (81.3) | |

| APT not clinically appropriate | 7/248 (2.8) | |

| Receipt of APT pack | ||

| Not known | 36/241 (14.9) | |

| Confirmedb | 205/241 (85.1) | |

| STI and HIV testing | ||

| Chlamydia | Test returnedc | 120/241 (49.8) |

| Positive | 78/120 (65.0) | |

| No result obtained | 1/120 (0.8) | |

| Gonorrhoea | Test returnedc | 120/241 (49.8) |

| Positive | 1/120 (0.8) | |

| No result obtained | 1/120 (0.8) | |

| Syphilis | Test returnedc | 60/241 (24.9) |

| Positive | 0/60 (0) | |

| No result obtained | 0/60 (0) | |

| HIV | Test returnedc | 60/241 (24.9) |

| Positive | 0/60 (0) | |

| No result obtained | 0/60 (0) | |

| Control period | Intervention period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measures | n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI); p-value | aOR (95% CI); p-value |

| Number of IPs | 828 | 586 | ||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| IP chlamydia test 12–24 weeks (observed data) | ||||

| Positive | 30 (7.8) | 12 (5.0) | 0.59 (0.29 to 1.18); 0.12 | 0.56 (0.28 to 1.13); 0.09 |

| Negative | 357 (92.2) | 229 (95.0) | – | – |

| Not knowna | 441 | 345 | Excludeda | Excludeda |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| ≥ 1 SP treated for chlamydia (observed data) | ||||

| Yesb | 342 (83.8) | 318 (90.1) | 1.72 (1.09 to 2.73); 0.02 | 1.72 (1.08 to 2.72); 0.02 |

| Noc | 66 (16.2) | 35 (9.9) | – | – |

| Not knowna | 420 | 233 | Excludeda | Excludeda |

| C. trachomatis test result at 12–24 weeks, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Negative result | Positive result | Missing | |

| Sociodemographic factors of IP | ||||

| Ethnicity | White British or Irish | 655 (42.6) | 34 (2.2) | 847 (55.1) |

| White other | 173 (45.5) | 8 (2.1) | 199 (52.4) | |

| Black/Black British | 313 (42.0) | 25 (3.4) | 407 (54.6) | |

| Asian/British Asian | 69 (35.9) | 6 (3.1) | 117 (60.9) | |

| Mixed ethnicity | 134 (41.0) | 9 (2.8) | 184 (56.3) | |

| Other ethnicity | 38 (47.5) | 2 (2.5) | 40 (50.0) | |

| Age (years) | 16–20 | 259 (39.8) | 23 (3.5) | 369 (56.7) |

| 21–24 | 475 (42.6) | 27 (2.4) | 613 (55.0) | |

| 25–29 | 351 (42.3) | 19 (2.3) | 460 (55.4) | |

| 30+ | 297 (44.7) | 15 (2.3) | 352 (53.0) | |

| APT selected for one or more SP, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No | Yes | |

| Sociodemographic factors of IP | |||

| Ethnicity | White British or Irish | 543 (76.8) | 164 (23.2) |

| White other | 155 (85.6) | 26 (14.4) | |

| Black/Black British | 321 (85.2) | 56 (14.9) | |

| Asian/British Asian | 81 (88.0) | 11 (12.0) | |

| Mixed ethnicity | 105 (78.4) | 29 (21.6) | |

| Other ethnicity | 38 (84.4) | 7 (15.6) | |

| Age (years) | 16–20 | 248 (78.2) | 69 (21.8) |

| 21–24 | 422 (80.7) | 101 (19.3) | |

| 25–29 | 315 (84.5) | 58 (15.6) | |

| 30+ | 258 (79.9) | 65 (20.1) | |

Conclusions

APT is a safe, feasible and effective way of clinically managing SPs of people with chlamydia as part of a menu of contact tracing and management options. While APT uptake was low among patients assessed for eligibility, it was associated with a small reduction in chlamydia positivity in IPs at 4 months and a higher number of partners treated. In almost all instances where APT was accepted, this was for established/committed relationships, while one-off partnerships made up only 1 in 30 APT decisions, although these amounted to 1 in 5 partnerships in the intervention period.

More work is needed to increase engagement of the SPs with self-sampling for STIs including syphilis and HIV so that opportunities for screening are not lost. The trial was not powered to evaluate differences in APT uptake according to ethnicity or age, but data from the trial indicate that this may be lower in ethnic minority groups.

Accelerated partner therapy processes could be adapted for use in other groups such as MSM, trans and transgender people, but they are only feasible for infections routinely treated by oral medication. The first-line therapies for both gonorrhoea and syphilis are currently parenteral in many countries. 30 More broadly, we need to consider the partners who will not be reached by APT (one-off partners with whom future sex is not anticipated). Although not a risk to the IP, they are likely to make an important contribution to community transmission. New interventions are needed to directly target this group.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

Earlier intervention optimisation and associated studies provided the trial with a new classification of SP types used in collection of outcome data, an optimised APT intervention within a fully manualised intervention and HCP training package, RELAY, a bespoke data collection and clinical management webtool, to manage IPs and SPs during the trial. Trial data informed the health economics evaluation and the mathematical model (Stream B). New knowledge gained from the prospective logic model and its retrospective application to assist interpretation of trial and Programme findings caused us to move away from basing our novel PN intervention for MSM with one-off sexual partners on APT. The finding that APT appealed to people in relationships with a greater degree of emotional connection but much less so within one-off or short duration partnerships paved the way for a different approach in Stream C.

Stream A phase 3: process evaluation

Aim and objectives

To conduct a qualitative process evaluation to understand IPs’, SPs’ and HCPs’ experiences of APT, the trial and its key contexts.

Specific objectives were:

-

to use programme theory to detail assumptions and expectations about how APT would work within SHSs and the wider context before data collection and analysis

-

to use qualitative analyses from multiple stakeholders to explore the relative role of the context, issues of intervention fidelity and the actual contribution of varied putative intervention mechanisms in shaping intervention outcomes, both intended and unintended.

Methods for data collection and analysis

Data collection

Qualitative data: collected through six focus groups and individual interviews (n = 10) with purposively sampled HCPs (n = 34 from 14 sites), IPs (n = 15) and SPs who received APT (n = 17). 29

Data analysis

Qualitative process evaluation study: we developed initial programme theory iteratively combining results of the pre-trial studies of video analysis of APT and the systematic review of PN interventions with input from the wider interdisciplinary trial team. We created a narrative account and visualised it within logic models. We conducted subsequent analyses as data became available and these were independent of trial results.

We undertook deductive thematic analysis15 to focus on the key elements of programme theory. These primary thematic structures addressed questions of context, context dependency in relation to local implementation, fidelity and adaptions, experiences and perceptions of the relative functioning of putative intervention mechanisms as well as perceived outcomes (both anticipated and unanticipated). Within these primary thematic structures, more inductive themes were identified driven by the data. PF and FM conducted all analyses and audited each other’s work, discussed the findings with the wider team and came to agreement about the final coding. Finally, we used these analyses to illustrate the dynamic functioning of the programme theory using colour-coded visualisations within the logic model.

Limitations

Limitations relate to the inherent biases within the sampling (e.g. self-selected). Furthermore, if we had been able to collect data within both trial arms (rather than via single retrospective recall), it may have been possible to delineate trial burden from intervention more clearly.

Key findings

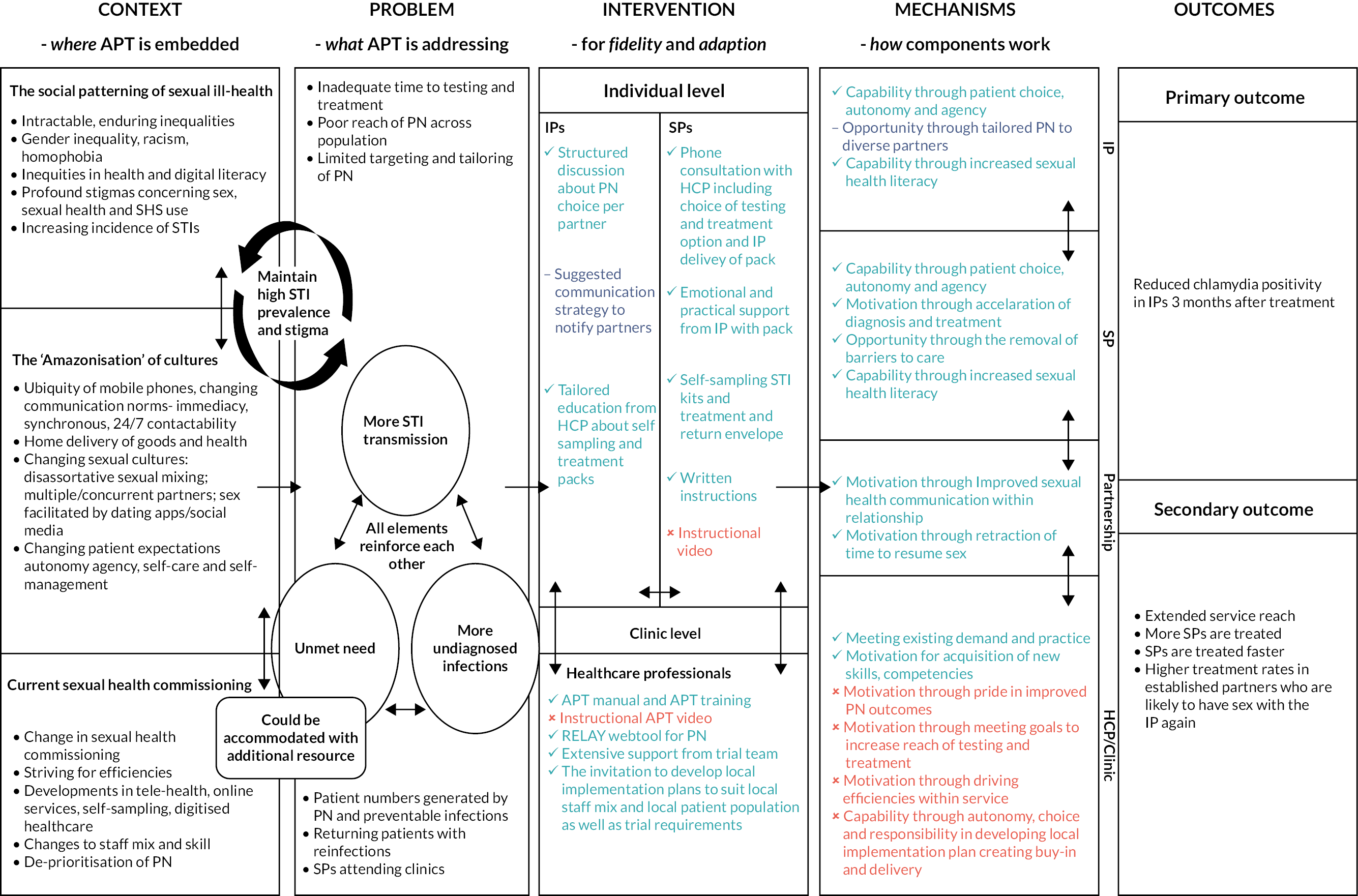

We developed initial programme theory and an accompanying logic model to describe how APT was imagined to work and we detailed various intervention mechanisms using behavioural and implementation science. 29 Preliminary work showed that APT was anticipated to primarily change key interactions and SHS organisation to accommodate accelerated and safe remote care to lead to reductions in IP reinfection. We theorised these mechanisms at various levels, drawing on behaviour change perspectives, implementation science and systems perspectives.

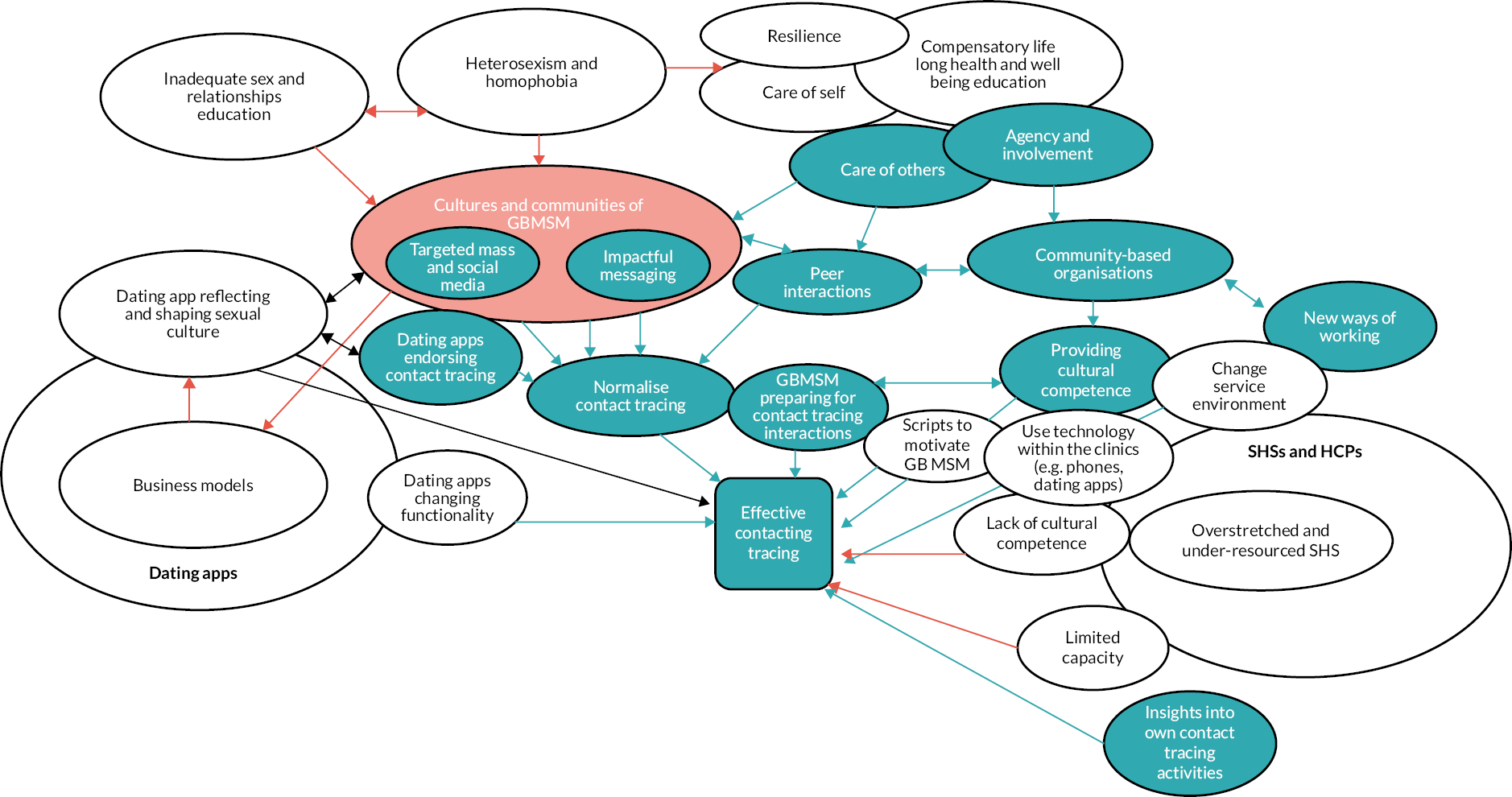

Subsequently, using the deductive thematic analysis, we used programme theory to create an evidence-based, theoretically informed overview of how APT worked dynamically within the context of the trial and within British SHSs. This is visualised in the colour-coded overview logic model (see Figure 4). We found APT training and resources (especially RELAY) transformed key interactions as anticipated. Overall intervention fidelity was good, and APT was well-liked by those who delivered and received it. Equally putative intervention mechanisms worked mostly as expected, although those concerned with local implementation sometimes worked counter to expectations because of contextual interdependencies. The trial struggled to be implemented at scale across all sites. Considerable external pressures drove all services to constantly adapt to achieve efficiencies. In some services, APT was perceived as time-consuming and without palpable impact. This seemed to be because APT did not visibly reduce patients ‘in the waiting room’. As such, the ‘invisibility’ of the effectiveness of APT curtailed the establishment of positive feedback loops driving normalisation within services.

FIGURE 4.

An overview of findings from the qualitative process evaluation shown through a colour-coded logic model of APT.

Text in light blue shows where our initial programme theory was supported through process evaluation data. Text in dark blue shows mixed findings in relation to supporting our initial programme theory. Text in red shows where our initial programme theory was not supported through process evaluation data.

Index patients and SPs who used APT primarily did so within established relationships. APT was particularly beneficial when one partner experienced barriers to attending face-to-face sexual health care (such as STI stigma, work constraints). Despite including a consultation with an appropriate HCP, APT necessitates a shift in responsibilities away from staff within services and onto patients and their partners. This worked well for some who felt more empowered and in control of their care, but others struggled with the burden of information and new processes. For example, some SPs took the treatment immediately but waited until treatment was completed to use the self-sampling kits as a ‘test of cure’ and others reported difficulties in doing finger-prick blood sampling. There was also confusion about the rationale for testing for STIs other than chlamydia despite provision of verbal and written explanations. The intended support to mitigate some of these aspects of APT was disrupted by NHS data communication constraints, which prevented HCPs from sending direct links to short YouTube videos we had created to assist engagement with APT processes. Overall, we found a mixed picture of a well-liked, intuitive, coherent intervention struggling to gain traction within already pressured services.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

These analyses helped us understand and contextualise the RCT findings and were informative for the intervention development work with MSM (Stream C). Notably, findings illustrated the key pressures that SHSs were experiencing at the time of the RCT and the apparent systemic deprioritisation of PN activities. As a result, this led to the team reconsidering their approach to intervention development with MSM and the decision to avoid an intervention which relied upon the work and activities of SHSs alone. Drawing upon concepts from systems science, we decided to conceptualise a future PN intervention for MSM in a more distributed way, including the activities of wider stakeholders such as MSM themselves, community-based organisations and those who provide dating apps/dating sites to facilitate sexual mixing. In this way, with a range of agents distributed across the system driving poor PN amongst MSM, it was feasible to avoid intervention components which risked placing undue burden on SHSs.

Stream A phase 3: health economics

Background

Economic evaluations are typically conducted to inform decisions on the best intervention among a given set of alternatives. 31 Most infections are asymptomatic leading to a delay in detection and treatment and onward transmission. Untreated chlamydia can cause reproductive health complications. 32 Chlamydia imposes a considerable economic burden on healthcare systems mostly attributed to complications of non-treatment and re-infections. 33 In Britain, the economic burden of chlamydia to the NHS is approximately £100 million per annum. 33

We conducted a cost-consequence analysis (CCA) alongside the trial. We considered a CCA as an appropriate method because the predetermined trial outcome of ‘cases of reinfection avoided for the index patient’ is deemed as an intermediate outcome for health economics since the full impact of infection, for both the individual and the population, given the infectious nature of the disease, cannot be fully assessed based on this outcome. The longer-term impact and the related cost effectiveness of the APT intervention are evaluated using appropriate methods34 as part of the LUSTRUM Programme and are reported elsewhere.

Aim and objectives

To compare the costs and outcomes of APT versus standard PN for avoiding reinfections in IPs with chlamydia.

Methods for data collection and analysis

The CCA adopted the perspective of the NHS; hence, only direct healthcare costs were considered. We collected data on costs and resource use prospectively during the trial – from the initial consultation up until 24 weeks post intervention. We drew unit costs primarily from the trial and the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) costs35 and we applied weighted averages to these costs where appropriate. All costs were reported in 2019–20 British pounds. We inflated Sterling values and cost estimates from previous years using the NHS cost Inflation Index (NHSCII). 35

Resource use data were recorded on RELAY by various cadres of HCPs. The key categories of resource use data for the IPs were:

-

Initial consultations: this included data on HCPs’ pay grade (bands) and the length of the consultation. A precise measurement of the initial consultation duration within the trial was not feasible; hence, assumptions were made based on clinical advice and estimates from a convenience sample of the trial HCPs. All estimates included time for trial-related tasks but did not include any telephone consultations with the SPs.

-

Two week follow-up calls: to determine IP reported PN outcomes, follow-up calls were made 2 weeks after initial consultations by two RHAs. Cost estimates included the average wage/hour 6 length of call and additional time for administrative tasks.

-

Retesting: to provide the primary outcome, IPs were retested for chlamydia at 12–24 weeks. This was either self-testing (using a self-sampling kit posted to them) or testing in the clinic. The costs of the retest pack were obtained from the trial. For retest in a clinic, we assumed standard practice for staff band and test duration. 36

-

Text message: we used text messaging service costs for a large London hospital trust as a proxy. 37

The key categories of resource use data for the SPs who accepted APT were:

-

Telephone Consultation: trial data provided the average duration of a telephone consultation. The cost of a phone call was sourced from a National UK telephone Company (BT). In estimating costs, additional time used by the HCP for patient-related administrative work was included.

-

The content of APT packs: we estimated the costs of the APT packs based on information collected during the trial. A breakdown of these costs is provided.

For SPs during the control phase, we sought data on the number of contactable SPs, clinic attendance for consultations and tests, and test outcome when available and made assumptions if data were not available.

A CCA is typically the first step in an economic evaluation in which costs and outcomes are assessed in a disaggregated manner to see if any intervention shows clear dominance. The result of the CCA analysis is presented as the total costs for PN. We conducted a further analysis of the SPs. We did not apply discounting to either the costs or outcomes due to the short duration of the trial. The reporting is in line with the consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. 38 We performed statistical analyses using STATA 15.0®39 or Excel Spreadsheet.

We conducted one-way deterministic sensitivity analyses (see Appendix, Table 11) to assess the impact of changes to the base-case assumptions and included variations in:

-

pay band/grade of the staff for the initial consultation

-

duration of the initial consultation

-

follow-up calls.

Limitations

The CCA benefited from the robustness of the main analyses as shown by the sensitivity analyses. We were unable to use data from RELAY on the duration of initial consultations due to wide variations in data quality between sites. However, we made assumptions based on trial evidence and hence were able to conduct analyses with practical values.

A CCA provides a breakdown of costs and outcomes only – it can sometimes be used to inform decision-making, if the decision-maker can make judgements on the ranges of cost and outcome presented. 40,41 However, in this case, we caution against any such interpretation.

This is because the CCA is based on an intermediate outcome only, and the full impact of the intervention on the transmission of the STIs across the population and its impact on sequelae associated with the disease can only be assessed by modelling the impact on the transmission flow using a transmission dynamic model. 33,34

Key findings

We estimated the costs and outcomes of APT versus standard PN in avoiding reinfection based on negative tests at trial end. The primary outcome was available for 809 IPs in the control phase and 671 IPs in the intervention phase inclusive of 125 patients that selected APT for their SPs. Amongst these, 747 (92%) patients in the control phase and 513 (94%) patients without APT and 122 (98%) (with APT) in the intervention phase had a negative test result, an indication that re-infection was avoided. The total costs of PN for the IPs were estimated as £71.26 for the control phase, and as £91.23 and £74.83 for the intervention phase, with and without APT, respectively. The total cost of PN was £33.17 for SPs who utilised APT and £39.58 for the SPs in the control phase. The sensitivity analyses showed that for all scenarios explored, the results made no substantial difference to the base-case results.

The CCA provides preliminary results only, hence at this stage, no judgement can be made on the cost effectiveness of the intervention. The outcome (reinfections avoided) is an intermediate outcome since it is impossible to know how the outcome would impact on the final outcome and the ultimate sequelae caused by the infection.

The preliminary results show that the APT intervention was more costly than the standard PN (£91.23 vs. £75.21). The intervention with APT accepted avoided re-infections in 98% of patients, compared with 92% for standard PN. The findings suggest that APT could provide an effective addition to the current standard PN practice in Britain.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

The findings of the economic evaluation will provide costs and resource use input for the health economic analysis of Stream B which will evaluate the long-term effects of APT versus standard PN.

Stream B: mathematical modelling and health economics

We used mathematical modelling and health economic analyses to investigate (1) the expected effects of APT on chlamydia transmission, (2) the expected rates of chlamydia reinfection in index cases after standard PN and APT, (3) the long-term cost effectiveness of APT versus standard PN in terms of major outcomes averted (MOA) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and (4) whether improving outcomes of PN for gonorrhoea in MSM could reduce undiagnosed HIV. The four related studies are described in more detail below.

Stream B phase 1: modelling the effects of accelerated partner therapy on chlamydia transmission

Aim and objectives

While the direct effects of standard PN and APT on the identification of new chlamydia infections are well-documented42 and can be observed in the RCT, the indirect population-level effects on incidence and prevalence of chlamydia are less clear. 43 In order to better understand and interpret the outcomes of the RCT, we estimated the expected proportions of chlamydia positivity in partners of people with diagnosed chlamydia (index cases) and quantified the effects of APT on chlamydia prevalence compared with standard PN in Britain.

Methods for data collection and analysis

We developed a novel deterministic, population-based chlamydia transmission model (see Figure 5). 44 A dedicated PN module allowed us to track the most recent partners of index cases and to identify the index–partner combinations that result in the largest effect of PN on reducing chlamydia prevalence. We considered a population aged 16–34 years and calibrated the model to sexual behaviour data between people of the opposite sex and chlamydia prevalence data reported by 3671 participants in Britain’s third (Natsal-3, 2010–12)3,45 using approximate Bayesian computation (ABC). In different scenarios, we calibrated the model to sex- and activity group-specific prevalence in the presence (current situation) and absence of control interventions. We simulated the effects of APT on chlamydia transmission by (1) increasing the number of treated partners by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20% and 25%, and (2) reducing the time to partner treatment by 1, 2 and 3 days compared to standard PN. We then calculated the relative reduction in prevalence 5 years after the implementation of APT.

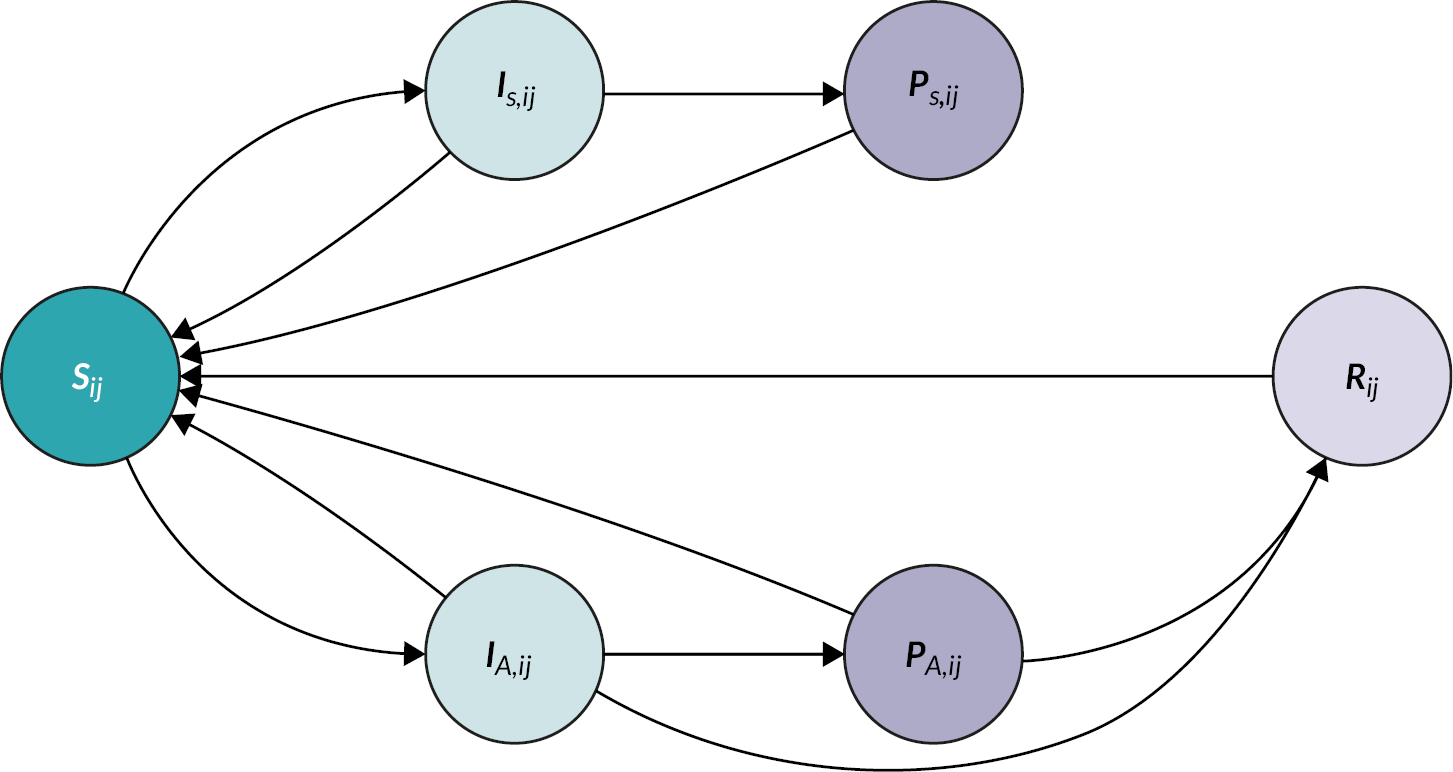

FIGURE 5.

Schematic illustration of chlamydia transmission model.

Susceptible individuals Sij can become symptomatically and asymptomatically infected (IS,ij and IA,ij). Infected individuals can then become notified (PS,ij and PA,ij) by their partners. All infected individuals can receive treatment to become susceptible again, or acquire temporary immunity (Rij) through spontaneous clearance of the infection. Movement of individuals into and out of the population is omitted in the scheme. Subscripts i and j denote sex and sexual activity groups, respectively. A more detailed description of the model structure is given in Althaus et al. 44

Limitations

First, we considered notification of the index case’s most recent partner only. This was a necessary simplification of our modelling framework. As the average number of notified partners is typically below one, we expect that including notification of additional partners in our model would not substantially affect our results. Second, we did not consider reinfection of index cases by untreated partners. This aspect was investigated in a separate study (study 2 of Stream B). Finally, the model does not include data from the RCT as the studies were run in parallel.

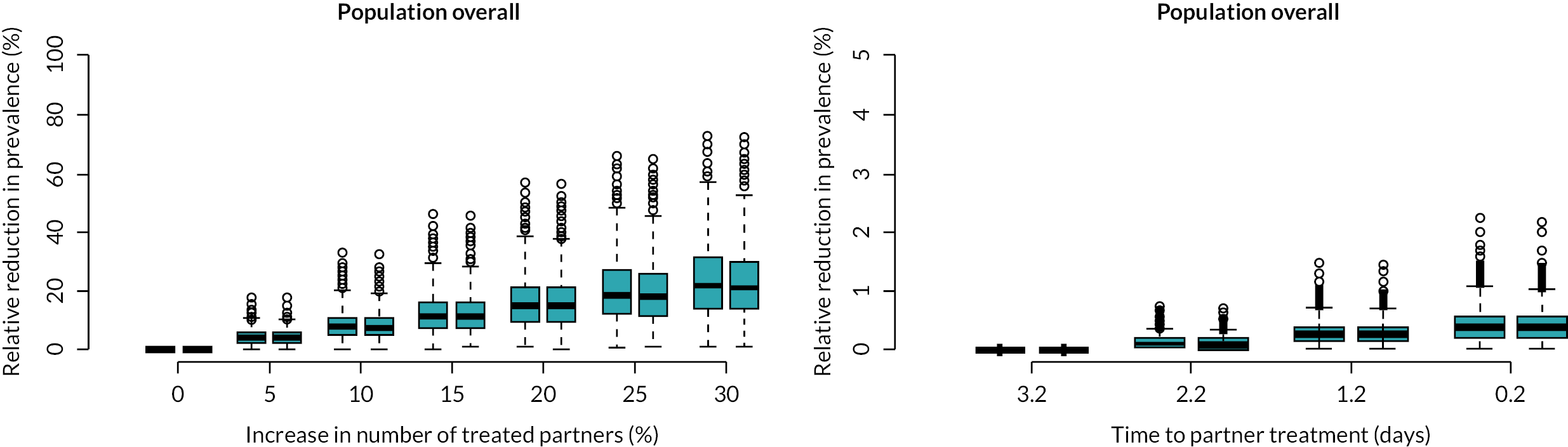

Key findings

We found that chlamydia positivity is highest in partners of symptomatic index cases with low sexual activity, whereas the infected partners are typically asymptomatic and highly sexually active. Conducting PN for this particular index–partner combination will thus be most effective for preventing further transmission. Increasing the number of treated partners from current levels in Britain [0.51, 95% credible interval (CrI) 0.21 to 0.80] by 25% would reduce chlamydia prevalence by 18% (95% CrI 5% to 44%) in both women and men within 5 years (see Figure 5). In contrast, reducing the time to partner treatment alone had a minor effect on reducing prevalence. Together, these results suggest that PN typically identifies sexual partners that are likely to further transmit chlamydia, and that APT in particular has the potential to further reduce prevalence through an increase in PN uptake.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

First, the results of this study on chlamydia positivity in partners of index cases help to better interpret the outcomes of the RCT. Second, simulated data from the model were used as input parameters for modelling reinfection with chlamydia (study 2 in Stream B) and the cost-effectiveness analysis (study 3 in Stream B).

The projected effect of APT on chlamydia prevalence after 5 years is shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Projected effect of APT on chlamydia prevalence after 5 years.

APT is modelled as an increase in the number of treated partners (left) or a reduction in the time to partner treatment (right). Changes in prevalence are given for females (red) and males (blue). Note the difference in scales of the axes between the left and right panels.

Stream B phase 2: modelling reinfection with chlamydia after standard partner notification and accelerated partner therapy

Aim and objectives

The expected effects of APT on the reinfection of treated index cases by untreated partners with chlamydia remain unclear. We did not consider reinfection of treated index cases in the transmission model (study 1 of Stream B). Here, we analysed data from the RCT using another mathematical model and quantified the effects of offering APT on the probability of successful partner treatment.

Methods for data collection and analysis

We extended a previously developed mathematical model42 to compute the probability of chlamydia reinfection of index cases by their untreated partners with chlamydia. We fitted the model to data from the RCT and estimated the probability of successful treatment of the partner of index cases in a Bayesian framework.

Limitations

The model does not distinguish between reinfection in women and men and considers reinfection by a single partner only. Furthermore, the remaining uncertainty in some key parameters together with the relatively small numbers in the primary outcome of the RCT result in considerable uncertainty of the modelling results.

Key findings

We estimated the median probability of reinfection at 16.2% (50% CrI 12.7 to 20.0%) without partner treatment and 2.3% (50% CrI 1.7% to 3.6%) when partner treatment is 100% successful. The observed rates of reinfection in the RCT correspond to a median probability of successful partner treatment of 63% (50% CrI 47% to 75%) during the control period and 77% (50% CrI 64% to 87%) during the intervention period, where APT was offered in addition to standard PN. Hence, the study suggests that the observed reduction in reinfection with chlamydia when offering APT is consistent with a higher probability of successful partner treatment.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

The results of this modelling study help to better interpret the effect of offering APT on the primary outcome of the RCT (Stream A).

Stream B Phase 3: cost-effectiveness analysis of accelerated partner therapy versus standard partner notification

Aims and objectives

We estimated the cost effectiveness of APT compared with standard PN in terms of MOA and QALYs gained to assess the long-term impact of APT on chlamydia and its sequelae at the population level.

Methods of data collection and analysis

We developed a static spreadsheet-based model using output from the chlamydia PN model (Stream B phase 1) to estimate the impact of APT on healthcare costs and numerous health outcomes: mild and severe PID, ectopic pregnancy, tubal factor infertility, chronic pelvic pain, epididymitis and QALYs in a population of 100,000 adults aged 16–34. 46 Estimates of resource use and unit costs were drawn from the Stream A within-trial CCA and suitable published secondary sources. Probability values relating to the complication were drawn from suitable published secondary sources. Utility values informing QALYs were obtained from a primary study (for female complications) and published literature (for epididymitis). Our base-case analysis assumed that APT increased the number of partners treated from current levels by 25%.

We calculated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for APT versus standard PN in terms of cost per MOA and cost per QALY gained. We then conducted extensive deterministic sensitivity analyses and a probabilistic sensitivity analysis to assess parameter uncertainty. Lastly, we conducted scenario analyses whereby the increase in the number of partners treated by APT was lowered to 15%, 10% and 5%, respectively.

Limitations

Firstly, the analysis did not consider the effect that repeat or persistent chlamydia/PID would have on tubal damage. Secondly, only an IP’s most recent partner was considered in the analysis. Thirdly, due to a lack of availability, robust utility values were not used for epididymitis. Lastly, the analysis made no comparisons for different forms of APT (e.g. APT Pharmacy,20 which was considered by a previous CCA36).

Key findings

The base-case results, which assume that APT increases the number of partners treated by 25%, showed that APT is less costly and more effective in terms of MOA and QALYs than standard PN, hence is cost-saving. Deterministic sensitivity analyses found that APT remained either cost-saving or cost-effective, the latter with ICERs that were very low and well within acceptable thresholds. APT remained cost-effective when the increase in the number of partners treated by APT was lowered to 15% and 5%, respectively; however, it was more costly than standard PN.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

The health economic analysis of Stream B models the long-term effects of APT versus standard PN and thereby complements the trial and CCA from Stream A that measure the short-term effects. It additionally draws estimates of resource use and unit costs from the Stream A CCA. The cost-effectiveness model relies on simulated data about the long-term effects of standard PN and APT from the dynamic transmission model (Stream B phase 1). 44

Stream C: development of optimal partner notification interventions for men who have sex with men with bacterial sexually transmitted infections

Men who have sex with men are disproportionately affected by STIs and HIV. Patterns of sexual partnership for MSM tend to differ from heterosexual patterns; MSM tend to report higher numbers of SPs and a greater proportion of one-off partners who contribute disproportionately to onward transmission.

Little research has focused on PN amongst MSM possibly because of the challenges associated with reaching one-off partners. Different PN strategies which appeal to MSM, and their one-off partners are needed. This has become particularly important in recent years given the emergence of increasing antimicrobial resistance to Neisseria gonorrhoea, the causative agent of gonorrhoea for which the majority of British cases are reported in MSM. Furthermore, more effective PN for MSM with a bacterial STI could identify MSM at particularly high risk of HIV acquisition because patterns of infection overlap. The ability to identify MSM at HIV risk provides opportunities for targeted HIV prevention and health promotion in the form of STI and HIV testing, appropriate vaccinations and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Stream C phase 1: identifying and evaluating existing economic studies about partner notification and/or testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections/human immunodeficiency virus

Economic research on PN has typically focused on heterosexuals, with a lack of evidence on effectiveness in MSM. Novel PN interventions for MSM need to be grounded in economic reality.

Aim and objectives

We conducted a systematic review of economic studies of PN interventions for STIs in MSM. PN often involves testing and treatment of SPs; hence, to ensure a comprehensive inclusion of all PN-related interventions, we also explored studies associated with testing and treatment strategies.

Methods for data collection and analysis

We undertook a systematic review according to the guidelines of the UK‘s Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)47 and reported this following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 48 A search strategy was developed using the population, intervention, comparison and outcomes (PICO) framework. 49 A scoping search was carried out on Google Scholar and MEDLINE. This was followed by a search on six electronic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), HIMC and cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature (CINAHL), up to June 2020. The reference lists of potentially key papers were hand-searched to identify additional papers. Search results were entered into the endnote database manager,50 to exclude irrelevant studies and code relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: formal economic evaluation and cost-analysis studies were included if participants were MSM who had any STI and/or HIV and the intervention was related to PN, testing or treatment. Studies were excluded if they were editorials, reviews or reports on the use of technology for interventions not related to PN, such as health promotion and education.

Study selection: a two-stage process was used to screen studies for inclusion using published methods. 51,52 Studies were categorised independently by two reviewers. A formal quality appraisal was not conducted because the review’s objectives required a description of all economic evidence but not a methodological assessment.

Data extraction and synthesis: a bespoke data extraction form was developed based on the study objectives and subsequent planned analysis. Data were extracted and checked for consistency by two reviewers. Relevant information was tabulated to facilitate comparison across studies and evidence was summarised using a narrative synthesis.

Limitations

The systematic review benefited from a comprehensive search using best practices. The review provides useful information on the cost of PN for STIs/HIV in MSM that could potentially be used as model inputs for any future model-based analyses. We had anticipated that evidence from this review would be used to develop a preliminary decision-analytic model to explore the cost effectiveness of alternate pathways developed in the Programme. However, this was possible because we did not identify any consistent pathways to evaluate. Furthermore, we identified no studies focusing on the costs and outcomes associated with digital technologies for PN.

Key findings

The systematic review selected 26 studies out of a possible 1909. Overall, 11 studies included PN strategies in the assessment, while 15 studies focused on testing and/or treatment, 16 papers focused on MSM, but only 3 of these were on PN, indicating a paucity of PN studies in this population. The review did not identify any PN studies on MSM for curable STIs, including chlamydia. However, two studies on HIV that reported on PN in this population were identified. Few studies reported on patients’ characteristics and settings.

The studies (22) were mostly formal economic evaluations, with only four cost analyses. The majority of the economic evaluations were cost-utility analyses with outcomes reported as QALYs which were derived from studies on heterosexual people due to a lack of data on MSM. These may not be directly relevant to MSM given the different patterns of SPs reported by these two groups. Few studies reported cost components or types of resource use to identify the costs none of these cost studies was relevant to digital PN. The studies mostly derived their data from secondary sources and only six used data from primary sources. Information on partner types or digital PN was not available within the selected studies. There was also little information on using a digital tool for PN, with just one paper53 reporting the use of an online PN tool. The lack of evidence on efficient approaches for MSM supports the need for new interventions with parallel economic evaluation.

Interrelation with other parts of the Programme

The dearth of appropriate economic evidence highlighted by this review supports a call for future research in this area to embed economic evaluation and associated appropriate data collection so that the process evaluation as outlined in Stream C can be used to develop models to explore a novel PN approach for MSM with STIs and aid decision-making.

Stream C phase 2: investigating partner notification for bacterial sexually transmitted infection to increase detection of undiagnosed human immunodeficiency virus in men who have sex with men

Aim and objectives

The original aim was to investigate the effects of improved PN interventions in MSM with gonorrhoea on identifying sexual partners that are infected with Neisseria gonorrhoea, HIV or both. In recent years, the research questions with respect to PN in MSM have changed due to the introduction of HIV PrEP which has become an accepted biomedical HIV prevention intervention. 54 We aimed to develop a gonorrhoea/HIV co-infection model for MSM.

Furthermore, we summarise the recent modelling literature on PN and PrEP in MSM to identify future research questions.

Methods of data collection and analysis

We attempted to extend the modelling framework from Stream B (phase 1) to include gonorrhoea/HIV co-infection and fit it to incidence and prevalence of gonorrhoea and HIV. We searched the literature for novel mathematical modelling studies on bacterial STIs, HIV, PN and PrEP.

Limitations

The development of the gonorrhoea/HIV co-infection model did not extend beyond an experimental phase. First, fitting the model to data about both infections, using the same method as in Stream B (phase 1), did not result in convergence of posterior parameter distributions. Second, the PN module could not be easily extended to co-infections within the time frame of the project. The existing literature on modelling PN in MSM focuses on expedited partner therapy (EPT)55–57 as carried out in the USA, in which an IP is given additional (oral) antibiotics to deliver to SPs. The findings are thus not generalisable because current treatment for gonorrhoea in many countries is parenteral due to the concerns about the efficacy of oral cefixime treatment.

Key findings