Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1211-20012. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The final report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Price et al. This work was produced by Price et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Price et al.

SYNOPSIS

Content and changes during the programme

The programme had two work packages (WPs) with matching objectives.

Work package 1

The aim was to determine the content, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an enhanced Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment (PASTA) trial to facilitate emergency stroke treatment.

The objectives were to:

-

develop an enhanced paramedic role for assessment of patients with acute stroke symptoms by a review of relevant literature and qualitative assessment of factors influencing the role from public and professional perspectives

-

examine the paramedic intervention by a cluster randomised trial of cost-effectiveness and qualitative process evaluation of professional and public experiences

-

report a within-trial economic evaluation of the enhanced role compared with standard care.

Work package 2

The aim was to determine the clinical effectiveness, costs, cost-effectiveness and affordability of delivering intra-arterial therapy (IAT) for acute ischaemic stroke patients in England.

The objectives were to:

-

develop a conceptual model of potential care pathways for IAT patients across NHS services, including pre-hospital, secondary and tertiary care settings

-

convert the conceptual model into a mathematical model, identify the evidence for parameterising key decision points and estimate outcomes

-

understand patient, public and relevant professional groups’ views on possible IAT service designs

-

estimate the effectiveness, incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) and other outcomes from an NHS and societal perspective of a national IAT service for stroke

-

develop an implementation plan for IAT in English stroke services that optimises access.

During the programme, there were a number of changes made in response to emerging evidence for treatment effectiveness, evolution of clinical services and challenges for trial recruitment. These are summarised below.

Changes to work package 1

-

The original proposal included a short phase to test the feasibility of delivering the intervention and data collection in a clinical setting. However, because of the logistical and training challenges created by designing and delivering a separate pilot study within part of a participating ambulance service, the objectives were incorporated into the main clinical trial as an internal pilot phase. This was approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Recruitment began in December 2015 and the pre-set pilot criteria were confirmed by the TSC as achieved in April 2016.

-

During the main PASTA trial phase examining the cost-effectiveness of an enhanced ambulance stroke pathway, there were delays in training sufficient numbers of intervention paramedics to achieve the planned recruitment target. In April 2017, it was agreed with the funder that the primary outcome should change from a health outcome [i.e. 3-month modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score] to a process outcome (i.e. administration of thrombolysis), as the latter measured the intended impact of the intervention, but required fewer patients to show a clinically important impact. The original sample size of 3640 patients was replaced by a new estimate of 1297. A major amendment was approved by NHS Ethics in October 2017.

-

During the parallel process evaluation, it quickly became evident that patients who had recently experience acute stroke were unable to provide views on the PASTA intervention that might inform its acceptability. After discussion with the Programme Steering Committee, it was agreed that attempts to identify patients for this purpose should cease, and notification was given to NHS Ethics.

Changes to work package 2

There were no significant changes to the planned model purpose or development, but the following aspects were altered in response to events outside the programme:

-

The systematic review of IAT effectiveness also included a trial sequential analysis to understand the impact of the most recent trials. 1–3

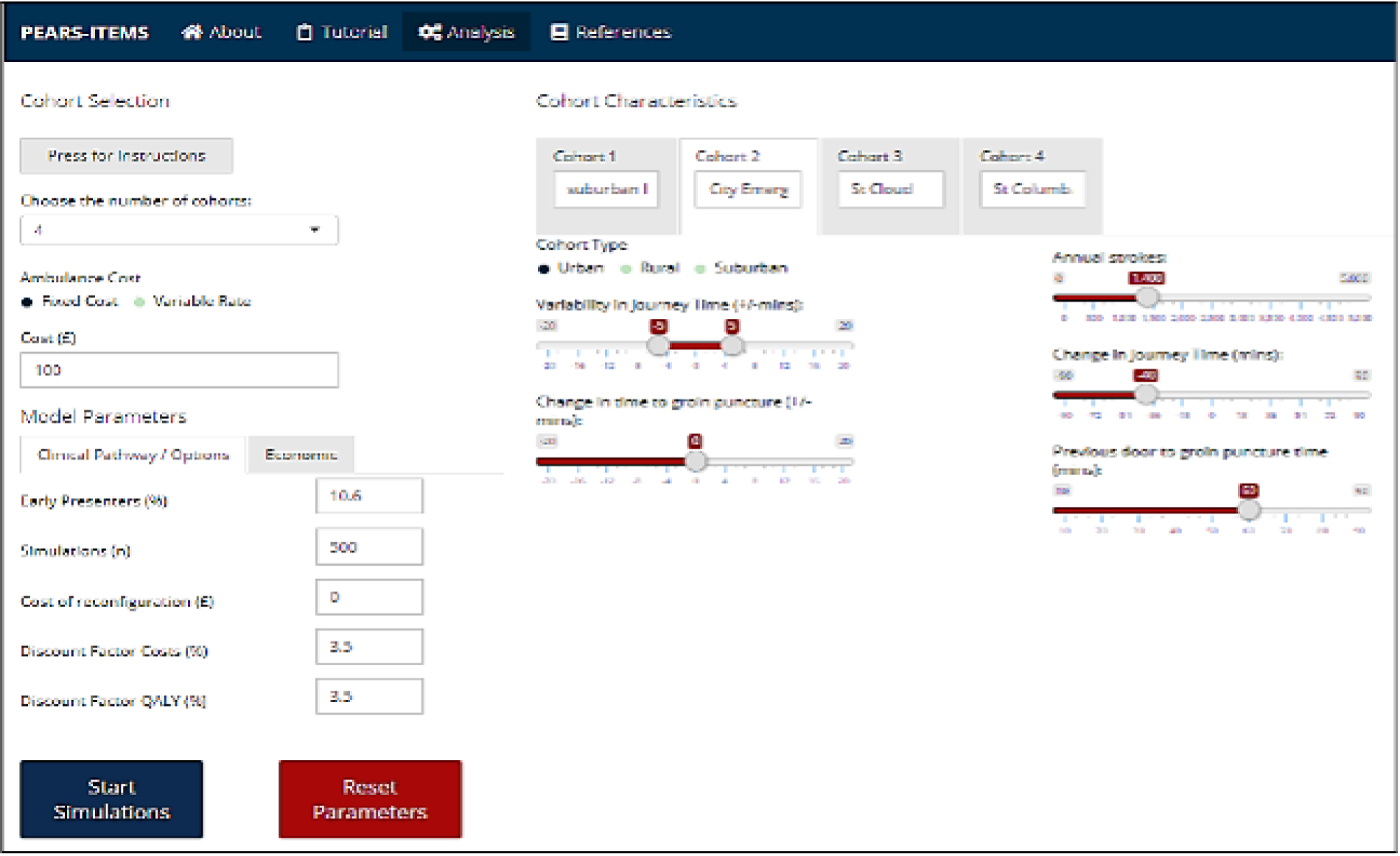

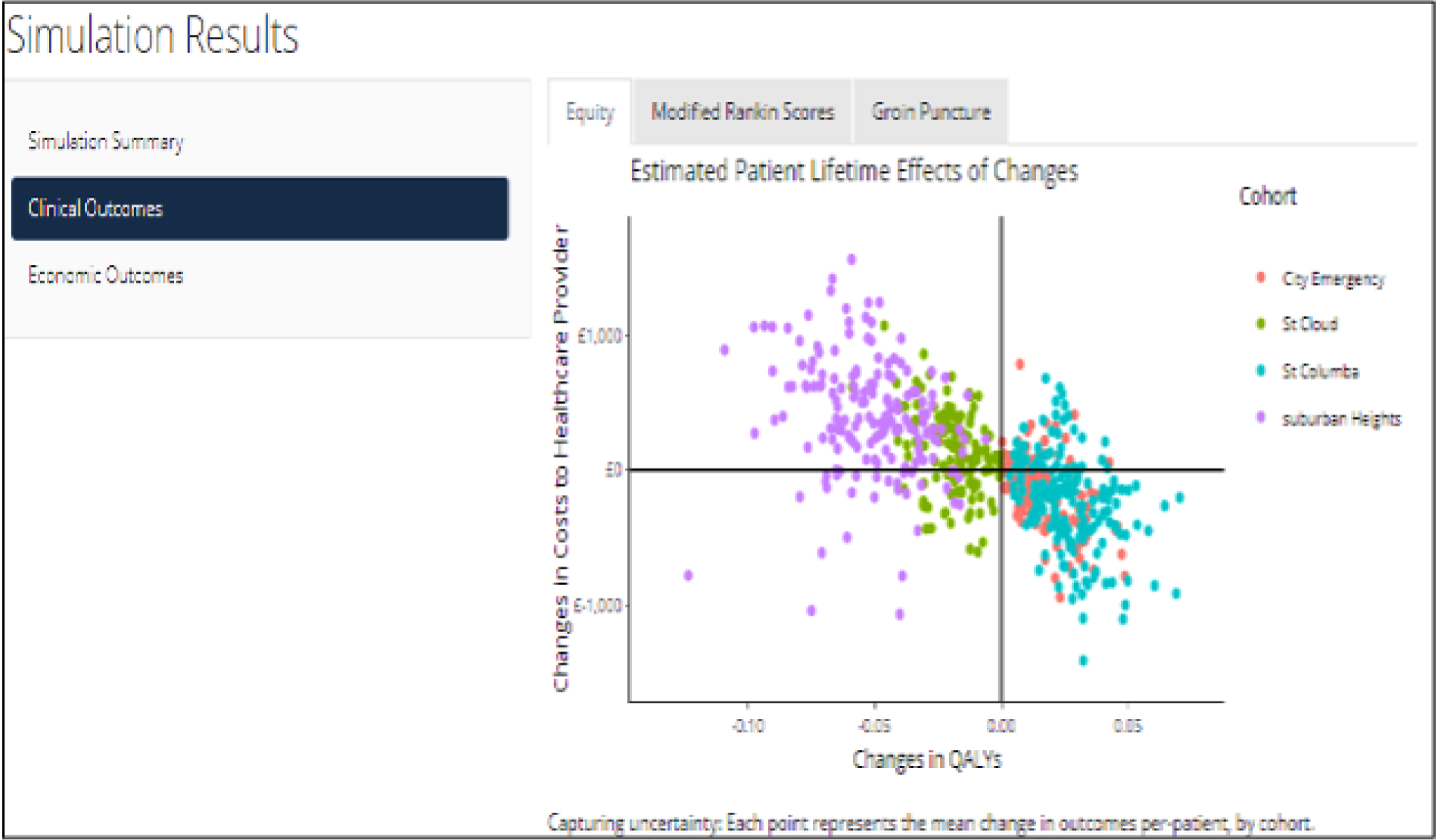

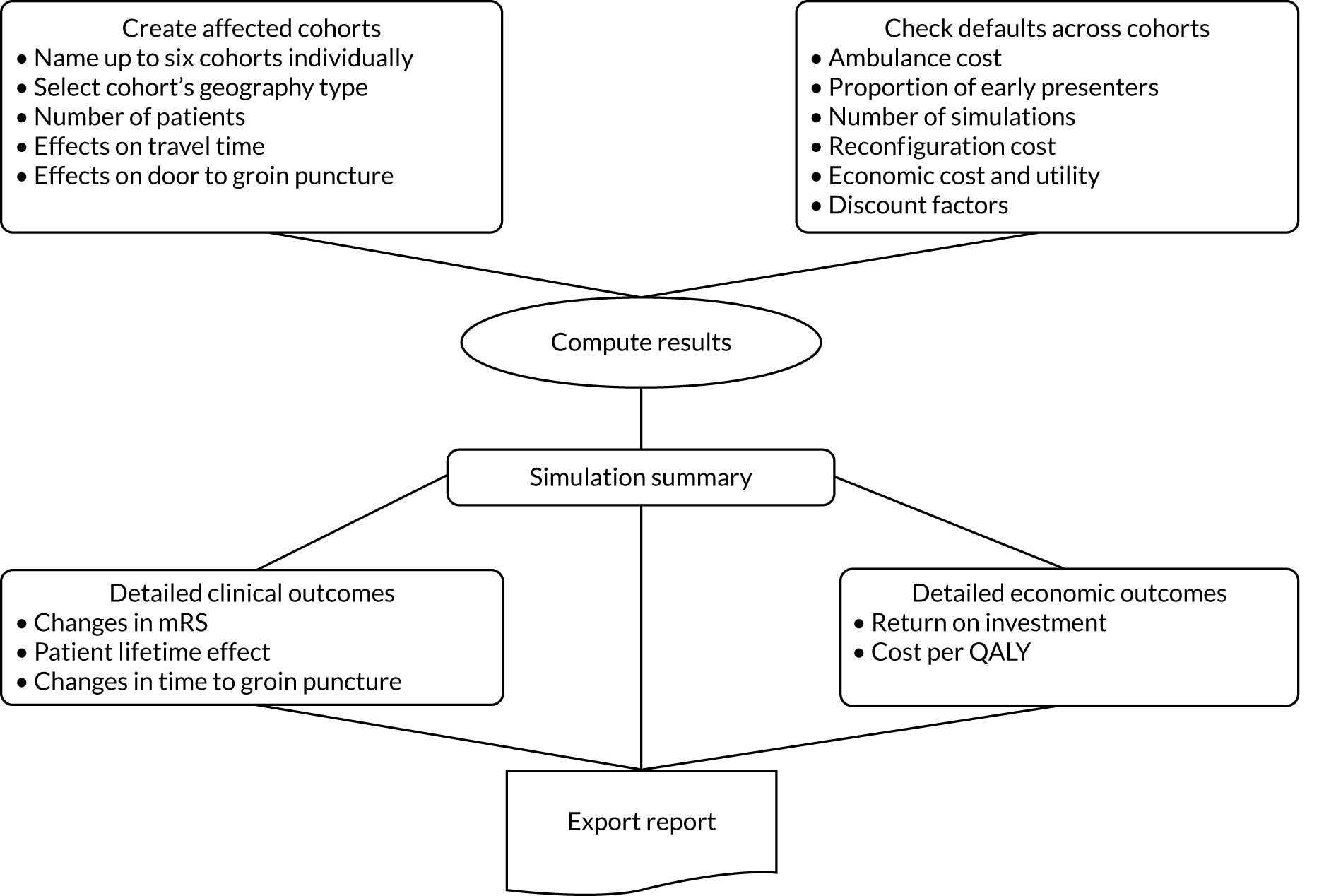

-

NHS England issued guidance4 for commissioners during the programme (featuring early work undertaken in the programme), which pre-empted part of the intended dissemination activity. The dissemination focus changed to providing commissioners with directly relevant information about choices for their area via an online configurable tool: Interface for Thrombectomy Economic Modelling and outcomeS in stroke (ITEMS).

These changes were agreed by the Programme Steering Committee. There were no implications for research permissions.

Background

Stroke is the single largest cause of adult disability and the third leading cause of death in England, but outcomes are significantly improved when patients are quickly admitted to specialist care for time-critical treatments and multidisciplinary care. 5,6 Acute stroke management across the NHS improved substantially following the publication of a National Stroke Strategy in 2007 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance in 2008,7,8 but emergency provision of the only licensed emergency drug treatment has remained variable and below aspirational targets. Known as ‘intravenous thrombolysis’, effective treatment requires administration of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator to selected ischaemic stroke cases within 4.5 hours of symptom onset, thereby promoting breakdown of any thrombus responsible for a sudden reduction in cerebral blood flow. Earlier treatment is more likely to reduce future dependency, but there is also a 3% risk of deterioration as a result of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage. 9 As well as requiring rapid assessment, individual patients must be carefully selected based on a combination of clinical and brain-imaging information, which provides an indication of their potential to benefit from treatment.

At a service level, thrombolysis delivery is challenging because both brain imaging and specialist assessment must be rapidly available to confirm treatment eligibility, achieve optimal treatment outcomes and avoid harm. Despite wide dissemination of the National Strategy, NICE guidelines and corresponding national clinical guidelines,10 and significant reorganisation of services in some regions,11,12 the national audit has continued to show large variations in the rate and speed of thrombolysis delivery between services and diurnal variations within services. 6,13 At the start of the programme in 2014, only 11% of total stroke admissions in the NHS were being treated against an aspirational target of 20%, with a median door-to-treatment time of 54 minutes, despite a target of < 40 minutes. 6 This largely remained unchanged by the end of the programme in 2019, implying that further improvements are unlikely to be achieved by focusing solely on the process of care delivery within hospitals. Even if stroke patients are unsuitable for thrombolysis after rapid processing, they might still benefit from other aspects of early specialist management to avoid complications, such as intravenous blood pressure lowering or reversal of anticoagulation medication, to reduce the risk of intracerebral haematoma expansion. 10

Ambulance stroke assessment

The NHS ambulance assessment of suspected stroke patients consists of initial symptom recognition using the Face, Arm, Speech Test (FAST),14 exclusion of hypoglycaemia and urgent transfer with pre-notification to the nearest hyperacute stroke unit (HASU) if onset is believed to be within 4 hours. 10 Local pathway variations exist according to the location of the specialist HASU, but the role of the paramedic has fundamentally remained the same for 15 years. Despite proximity to the patient and audit data showing scope for improvement in overall service delivery, the pre-hospital content of the emergency stroke pathway and related training has not been further optimised for thrombolysis decision-making. There have been reports that additional pre-hospital-phase interventions can facilitate thrombolysis treatment, including multiprofessional workforce training,15 raising the service priority level for suspected stroke16 and personalised feedback to paramedics about care quality. 17 However, studies were setting specific and/or observational, and generally described short-term improvements in thrombolysis-naive services.

In other specialties, evidence is increasing that imposing a structure on interactions within multidisciplinary teams at specific points along a clinical pathway has a major bearing on the efficiency of care delivery. Simple tools can standardise communication of key information and confirm whether or not essential tasks have been undertaken, including structured formats for paramedic handover to emergency department (ED) staff18,19 and multidisciplinary care process checklists for pre- or post-care delivery. 20,21 Enhanced handover and team checklists might, therefore, be valuable during the specific scenario of assessment for thrombolysis eligibility, as well as improving access to other stroke treatments and organised stroke care.

In view of the potential for ambulance personnel to play a more significant role during the initial assessment of suspected stroke patients who may be suitable for thrombolysis, WP1 developed and evaluated an enhanced PASTA pathway.

Intra-arterial thrombectomy

Although clinical services were seeking effective implementation of thrombolysis provision, an evidence base was rapidly developing for a powerful additional treatment suitable for selected patients with moderate to severe ischaemic stroke as a result of large artery occlusion (LAO), known as IAT. Although thrombolysis reduces long-term disability, restoration of cerebral blood flow occurs in only 50% of patients and in only 10% with LAO,22 thereby limiting its effectiveness. During IAT, an arterial catheter is guided into the cerebral circulation by a trained interventionist to extract the thrombus directly, thereby achieving greater success in restoring the blood supply. To reduce disability, this must also be performed as soon as possible, usually within 6 hours of symptom onset and following initial treatment with thrombolysis. 23,24

As the IAT procedure requires interventionists and facilities currently only available at regional neuroscience centres, the clinical pathway is more complicated than thrombolysis and the majority of IAT-eligible patients require rapid secondary transfer to the centre following initial assessment at a local HASU. 25,26 Advanced symptom checklists for ambulance personnel have been developed in an attempt to identify patients who are more likely to have LAO for selective redirection, but, so far, these have not shown acceptable levels of accuracy for widespread clinical deployment. 27,28

At the start of this programme, in 2014, there was no commissioned provision of IAT across > 120 HASUs. Critical issues were still unclear, including how many patients were suitable for IAT based on emerging trial data, the optimal configuration of HASU and IAT centres, and stakeholder preferences regarding the inevitable trade-off between possible health gains at a central site relative to additional travel distance and displacement. This information was essential for services and commissioners to prepare for IAT implementation, but required presentation in a format facilitating comparison of options in a local service context. Hence, WP2 sought to determine the clinical effectiveness, costs, cost-effectiveness and affordability of delivering IAT for acute ischaemic stroke patients.

Work package 1

Development of the Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment

Material throughout this section has been reproduced with permission from Flynn et al. 29 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Systematic literature review

The completed review has been published. 29

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-compliant protocol30 was registered online as PROSPERO CRD42014010785.

To develop an enhanced paramedic assessment capable of supporting hospital thrombolysis of appropriately selected stroke patients, it was first necessary to understand challenges and successes reported during pre-hospital roles for any condition with known time-sensitive outcomes (i.e. trauma, myocardial infarction and stroke).

Therefore, an electronic search of published literature (from January 1990 to September 2016) was conducted across eight bibliographic databases that focused on (1) generic or specific structured handovers between ambulance and hospital personnel and (2) paramedic-initiated care processes at handover or post handover.

A narrative review of 36 studies shortlisted at the full-text stage indicated that (1) enhanced paramedic skills might supplement handover information as there would be a greater shared understanding of what information is important for the receiving medical team; (2) structured handover tools and feedback on performance can improve clinical communication during emergency transfer of patient care; and (3) enhanced paramedic roles following arrival at hospital were limited to ‘direct transportation’ of patients to imaging/specialist care facilities, and there were no examples of paramedics continuing to assist with patient care after handover. No descriptions were identified for pre-hospital thrombolysis-specific information collection tools or stroke-specific handover formats, but the review provided general support for the development of an enhanced paramedic role containing these elements.

Stakeholder engagement

To develop an intervention that was likely to be acceptable and feasible within UK ambulance and stroke services, relevant stakeholders were formally engaged in the design process. Fifteen focus groups and interviews were undertaken over the first 12 months of the programme in north-east England, north-west England and Wales, involving patient representatives (n = 20) and health-care professionals (n = 103), comprising paramedics and ED and HASU clinicians. 31 Digital recordings were transcribed, anonymised and analysed using open and then focused coding with constant comparison. 32,33 During four iterative rounds of data collection, themes were developed to understand barriers to and facilitators of the adoption of the paramedic intervention and the developing enhanced role/PASTA pathway material was amended accordingly.

In summary, paramedics, hospital clinicians and patients welcomed the use of enhanced skills during pre-hospital stroke assessment. Paramedics believed that they were capable of undertaking more detailed clinical assessments aimed at thrombolysis eligibility, but were unsure if their experience and skills would be recognised by hospital teams. Both professional groups strongly supported the use of a standardised handover format to enable new skills to be more effective and minimise the possibility of thrombolysis potential not being recognised by hospital triage staff receiving the patient. To encourage a joint working approach, there was general support for paramedics providing reminders about key time targets for brain imaging and treatment administration during handover.

All participants were uncertain about the feasibility of paramedics spending extra time in the hospital to assist the clinical team because of the wider implications for ambulance service response times. However, as there could be times when few hospital staff were available for initial care processes post handover, they agreed that it may be beneficial to assist with practical tasks as part of the intervention for up to 15 minutes (the standard service target interval between ambulance handover and departure). There was no system in place for paramedics to routinely receive feedback about their assessment process, but all professional groups were interested in the evidence showing that simple individual feedback could improve pre-hospital stroke care quality,17 and were enthusiastic for this to be incorporated.

During the fourth round of interviews, there were no additional changes to the proposed PASTA pathway or concerns from public representatives, and the Programme Steering Committee agreed that WP1 should progress towards delivery of the main trial.

The Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment intervention

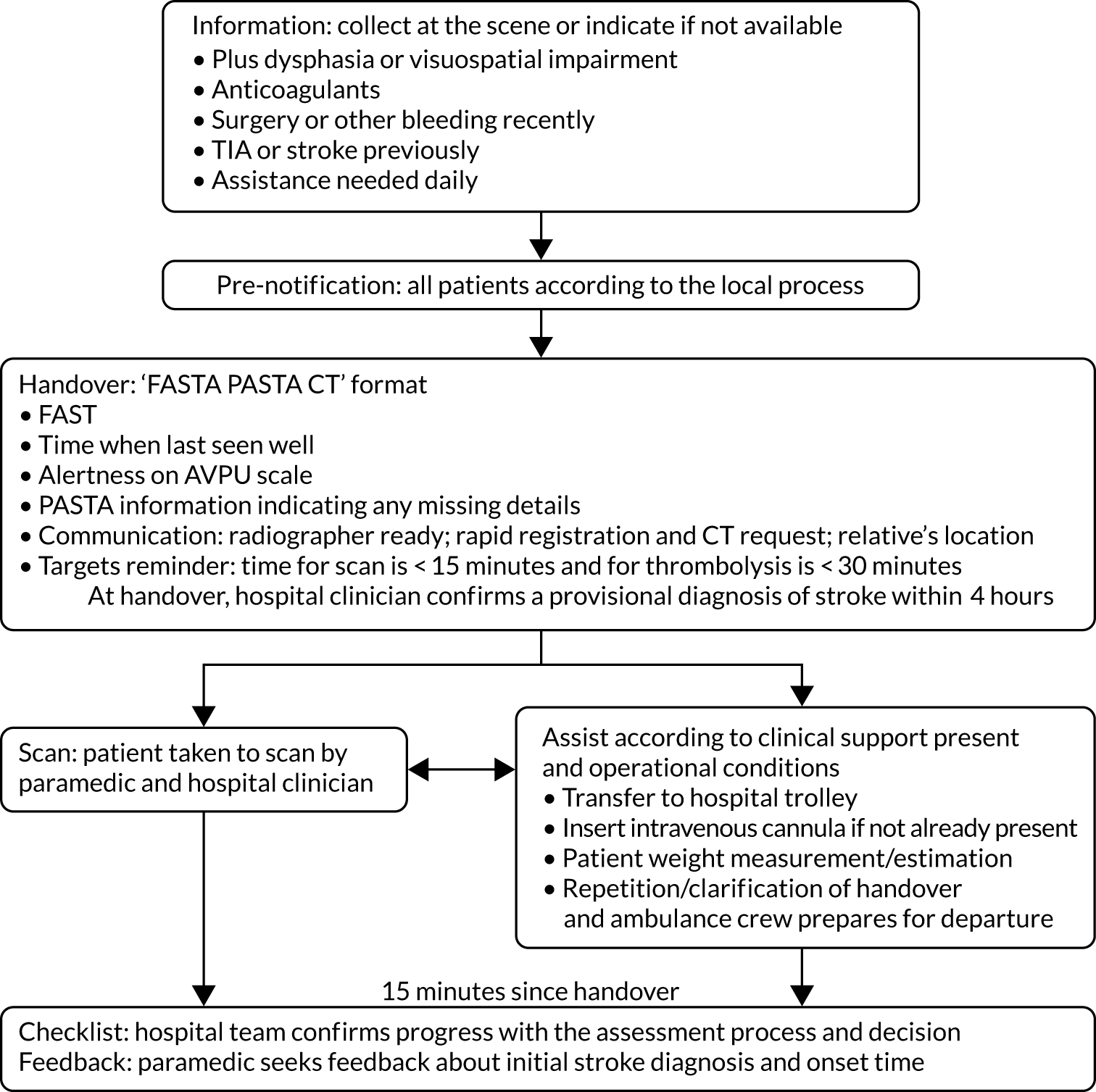

The PASTA pathway consisted of the following components (Figure 1):

-

Information – the paramedic seeks additional information at the scene, which is routinely considered during thrombolysis treatment decisions but typically is not obtained until after hospital admission (e.g. prescription of anticoagulant medication).

-

Pre-notification – although this is an expected component of standard care, the PASTA paramedics were specifically reminded to pre-alert the destination hospital.

-

Handover – on arrival at the hospital, the paramedic provided a standardised handover of stroke-specific details to the hospital team, including FAST, onset time, patient alertness as measured using the Alert, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive (AVPU) scale34 and PASTA information.

-

Scan – if the computed tomography (CT) scanner was immediately available, the paramedic assisted with patient transfer to radiology.

-

Assist – up until 15 minutes after arrival, the paramedic undertook the following tasks as required: insertion of an intravenous cannula, obtaining the patient’s weight and repetition/clarification of clinical information for the arriving stroke team members.

-

Checklist – at 15 minutes after handover, the paramedic asked a member of the hospital team to confirm progress with key tasks (e.g. status of the scan request).

-

Feedback – the paramedic requested feedback from a hospital clinician about the accuracy of their provisional stroke diagnosis and onset time estimation.

FIGURE 1.

The PASTA pathway intervention. FASTA PASTA CT, Face, Arm, Speech, Time, Alertness Plus Anticoagulants Surgery TIA Assistance Communication Targets; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Examination of the Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment pathway intervention clinical effectiveness: a cluster randomised trial

The published study protocol35 and the main study report36 have been published.

Material throughout this section has been reproduced with permission from Price et al. 35 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Material throughout this section has been reproduced with permission from Flynn et al. 36 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 1.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The PASTA trial objectives were to:

-

determine whether or not the PASTA pathway increased the proportion of patients receiving thrombolysis (the primary outcome)

-

describe the impact of the PASTA pathway on key time intervals during delivery of care

-

describe the number and subsequent diagnoses of suspected stroke patients who travelled to the hospital with a study paramedic but, following assessment at hospital, were not given a diagnosis of stroke (‘stroke mimics’).

Methods

A pragmatic multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) design was chosen to reduce contamination of standard care by the intervention and avoid potential delays in care due to individual randomisation. Ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Committee North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 (reference 15/NE/0309).

The study was hosted by three ambulance services (i.e. north-east England, north-west England and Wales) with similar clinical pathways for standard care that reflected national clinical guidelines. 10 These served 15 study hospital sites. Important acute activity and workforce characteristics are shown in Appendix 1, Table 6. Clusters were individual paramedics based within pre-randomised ambulance stations stratified by service, size and distance of station from the nearest study hospital. Paramedics who were based at stations randomised to the PASTA trial only became involved following successful completion of study-specific training (i.e. an online video and knowledge assessment). Paramedics based at standard care stations were simply informed that their clinical record entries would be supporting a study of pre-hospital assessment. Patients received the PASTA intervention or standard care according to which paramedic attended to them. Participating hospitals were not randomised and received both PASTA and standard care patients.

Participants

Patients were identified and recruited after completion of the thrombolysis assessment in participating hospitals if the following criteria were met:

-

they travelled to hospital with a study paramedic

-

they were aged ≥ 18 years

-

they received a diagnosis of stroke from a hospital specialist

-

they were within 4 hours of stroke onset (onset time determined by the hospital stroke team) when assessed by the study paramedic.

Intervention

Trained paramedics were requested to provide the PASTA pathway intervention (see Figure 1) to patients who they suspected were suffering a stroke and were within 4 hours of symptom onset. Initial paramedic stroke identification processes were unchanged. A study-specific ambulance data collection form was completed to record delivery of the different PASTA components. The patients attended by paramedics who were randomised to the standard care group received routine assessment and treatment. 10

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients receiving thrombolysis. The secondary outcomes included key time intervals during assessment and thrombolysis treatment, stroke severity 24 hours after thrombolysis [as measured on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)],37 delivery of other components of acute care, day 90 death or dependency (mRS) score38,39 and complications after thrombolysis. 40

Statistical analysis

Based on the effects reported by previous studies and our eligibility criteria, the sample size estimation considered that a change from 43% to 53% of study-eligible patients receiving thrombolysis would be clinically important. At 90% power, a 5% significance, an average cluster size (patients per paramedic) of five patients, an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.02, an imbalance of two control patients per intervention patient (reflecting delays in the PASTA training uptake) and attrition of 1%, it was calculated that 1297 patients were required (standard care, n = 865; PASTA intervention, n = 432). However, the study protocol allowed for the final recruitment target to be kept under review and adjusted to reflect any changes in the underlying assumptions. The final required number of patients was 1149 based on a cluster size of three and a standard care-to-PASTA group imbalance of 8 : 5 patients.

Analysis was by ‘treatment allocated’ (i.e. the study group allocation of the station base for the attending paramedic). Imputation was used for missing NIHSS scores and day 90 mRS scores.

The primary analysis used logistic regression allowing for clustering by paramedic, with adjustment for clinically important and statistically significant covariates and factors to estimate an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for the proportion of all patients receiving thrombolysis. The mRS was dichotomised into ‘favourable outcome’ (mRS score 0–2) or ‘poor outcome’ (mRS score 3–6) and an aOR of a ‘poor outcome’ was calculated. Other comparisons used odds ratios (ORs) by logistic regression and t-tests as appropriate. Cox proportional hazard regression estimated a hazard ratio for the combined impact of the intervention on thrombolysis and time to treatment since the emergency call.

A post hoc analysis considered whether or not routine hospital specialist availability for thrombolysis decision-making had any bearing on the treatment received in each study group. Workforce information reported in the 2016 Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) Acute Organisational Audit6 was used to categorise hospitals as compliant or non-compliant with the current national standard regarding hospital provision of a specialist thrombolysis service [i.e. there should be a minimum of six specialists trained in emergency stroke care providing a continuous rota without input from non-specialists, so that all treatment decisions are made by a stroke specialist (see Appendix 1, Table 6)].

Results

At 62 PASTA stations, 453 of 817 (55%) paramedics completed training. At 59 standard care stations, 700 of 723 (97%) paramedics agreed to assist. Between 10 December 2015 and 31 July 2018, 11,478 stroke patients travelling by ambulance were screened, 1391 fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were approached, and 1214 patients were enrolled. Of these, 500 were assessed by 242 PASTA paramedics (2.1 patients per paramedic) and 714 were assessed by 355 standard care paramedics (2.0 patients per paramedic). The follow-up is shown as per Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting recommendations in Figure 2. Primary outcome data were available for all patients.

FIGURE 2.

Trial profile. a, Eight paramedics allocated to standard care completed the PASTA training during the study.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were very similar in the two study groups for all patients (see Appendix 1, Table 7). The mean age was 74.7 [standard deviation (SD) 13.2] years, women comprised 48% of the patient group and the median/mean admission NIHSS score was 9.0/11.4. Appendix 1, Table 8, shows the demographics and clinical characteristics according to the study group and receipt of thrombolysis.

The PASTA paramedics took an average of 13.4 minutes longer [95% confidence interval (CI) 9.4 to 17.4 minutes longer; p < 0.001] than the standard care paramedics to complete patient care episodes (i.e. ‘clear’ a patient), mainly because an additional 8.8 minutes was spent in the hospital (95% CI 6.5 to 11.0 additional minutes; p < 0.001). There was no significant difference between the groups for paramedic time spent on scene (PASTA intervention, 26.0 minutes; standard care, 24.2 minutes; difference 1.61 minutes, 95% CI –0.2 to 3.4; p = 0.08). There was no evidence of other differences between time intervals (see Appendix 1, Table 9).

There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients who received thrombolysis (Table 1) in the PASTA [197/500 (39.4%)] and standard care groups [319/714 (44.7%)], but there was a possible trend in the opposite direction to that of the anticipated intervention effect (aOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.08; p = 0.15; intracluster correlation coefficient 0.00). Among thrombolysis-treated patients, a PASTA paramedic assessment to assign a patient to thrombolysis was longer by an average of 8.5 minutes (95% CI 2.1 to 13.9 minutes longer; p = 0.01) than that of a standard care paramedic. The Cox regression analysis of time from the 999 call to treatment for the PASTA intervention group compared with standard care group reported an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.02; coefficient –0.17; p = 0.07), indicating that thrombolysis in the PASTA intervention group was less likely at any time point after the start of the emergency care pathway. After thrombolysis, there were no significant differences evident between groups for reduction in stroke severity or any treatment complication, but the number of events was small (see Table 1). No evidence for significant differences was observed for other individual acute care processes delivered to all patients (see Appendix 1, Table 10).

| Group | Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PASTA intervention | Standard care | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | |

| Thrombolysis treatment, n/N (%) | ||||

| All patients | 197/500 (39.4) | 319/714 (44.7) | 0.81 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.02; p = 0.07) | 0.81 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.08; p = 0.15) |

| Ischaemic stroke only | 196a/409 (47.9) | 319/607 (52.6) | 0.83 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.07; p = 0.15) | 0.84 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.17; p = 0.30) |

| Times | N = 197 | N = 319 | Difference in mean PASTA minus standard care | |

| Onset to treatment time (minutes) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 154.4 (55.3) | 149.9 (51.7) | 4.47 (95% CI –4.97 to 13.93; p = 0.35) | – |

| Median (IQR) | 146 (110–194) | 137 (110–190) | – | |

| Paramedic assessment to treatment time (minutes) | N = 194 | N = 315 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 98.1 (37.6) | 89.6 (31.1) | 8.50 (95% CI 2.10 to 14.80; p = 0.01) | – |

| Median (IQR) | 90 (72–114) | 86 (68–107) | – | |

| Hospital arrival to treatment time (minutes) | N = 176 | N = 286 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 58.9 (33.4) | 54.2 (26.9) | 4.69 (95% CI –1.20 to 10.55; p = 0.12) | – |

| Median (IQR) | 48.5 (35–75) | 48.5 (36–65) | – | |

| Stroke severity (NIHSS) | ||||

| After treatment (24–48 hours) | N = 193 | N = 307 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8.5 (9.0) | 9.6 (9.3) | –1.12 (95% CI –2.7 to 0.54; p = 0.19) | – |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (1–14) | 6 (2–15) | – | |

| Reduction after treatment | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (6.5) | 2.8 (7.2) | 0.90 (95% CI –0.35 to 2.2; p = 0.16) | – |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (0–7) | 3 (0–7) | – | |

| Complications, n (%) | N = 196 | N = 319 | ||

| Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage | 4 (2.0) | 10 (3.1) | 0.64 (95% CI 0.20 to 2.10; p = 0.46) | – |

| Extracranial haemorrhage | 6 (3.1) | 6 (1.9) | 1.65 (95% CI 0.52 to 5.20; p = 0.39) | – |

| Angiooedema | 2 (1.0) | 7 (2.2) | 0.46 (95% CI 0.10 to 2.24; p = 0.32) | – |

| Other complication | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 3.30 (95% CI 0.30 to 36.40; p = 0.56) | – |

| Any complication | 13 (6.6) | 24 (7.5) | 0.87 (95% CI 0.43 to 1.76; p = 0.70) | – |

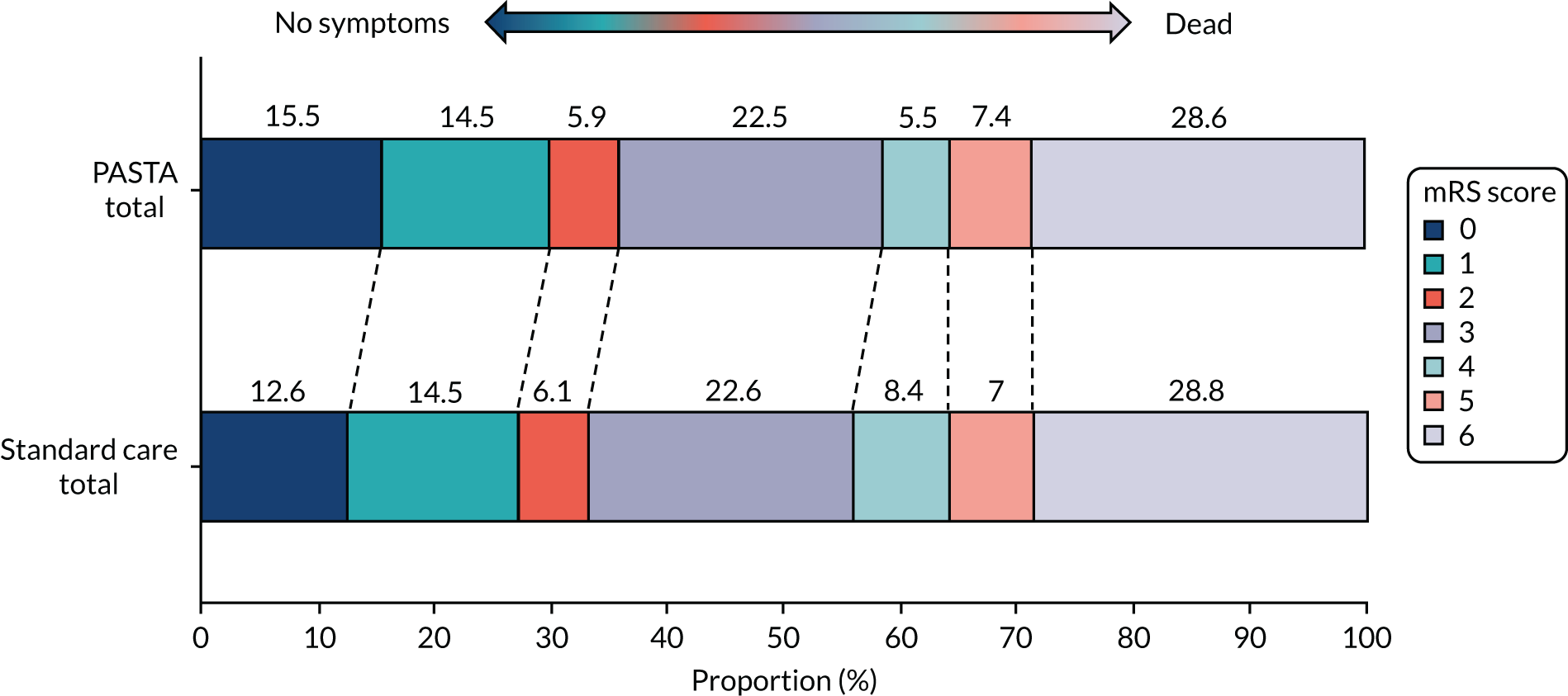

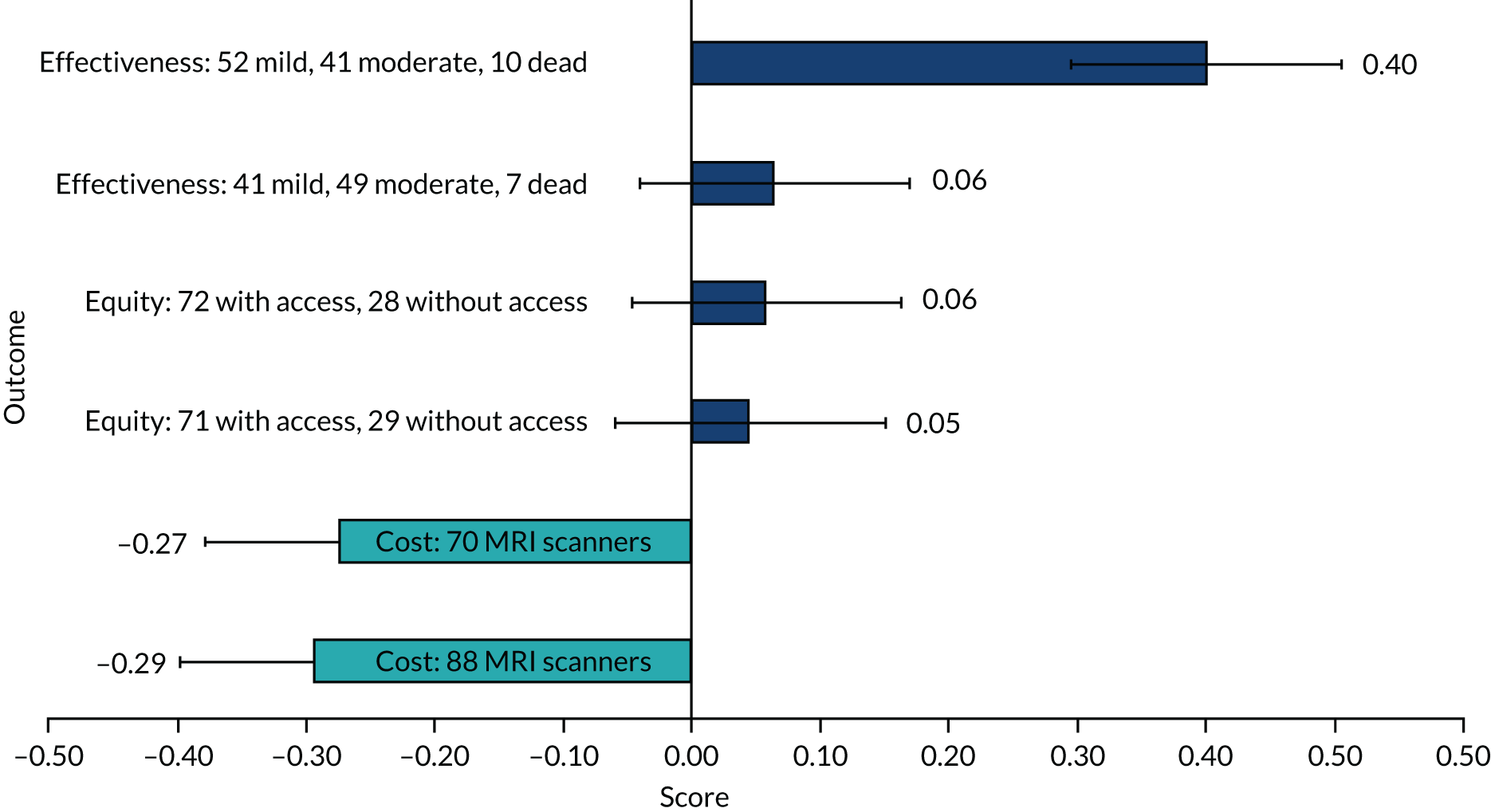

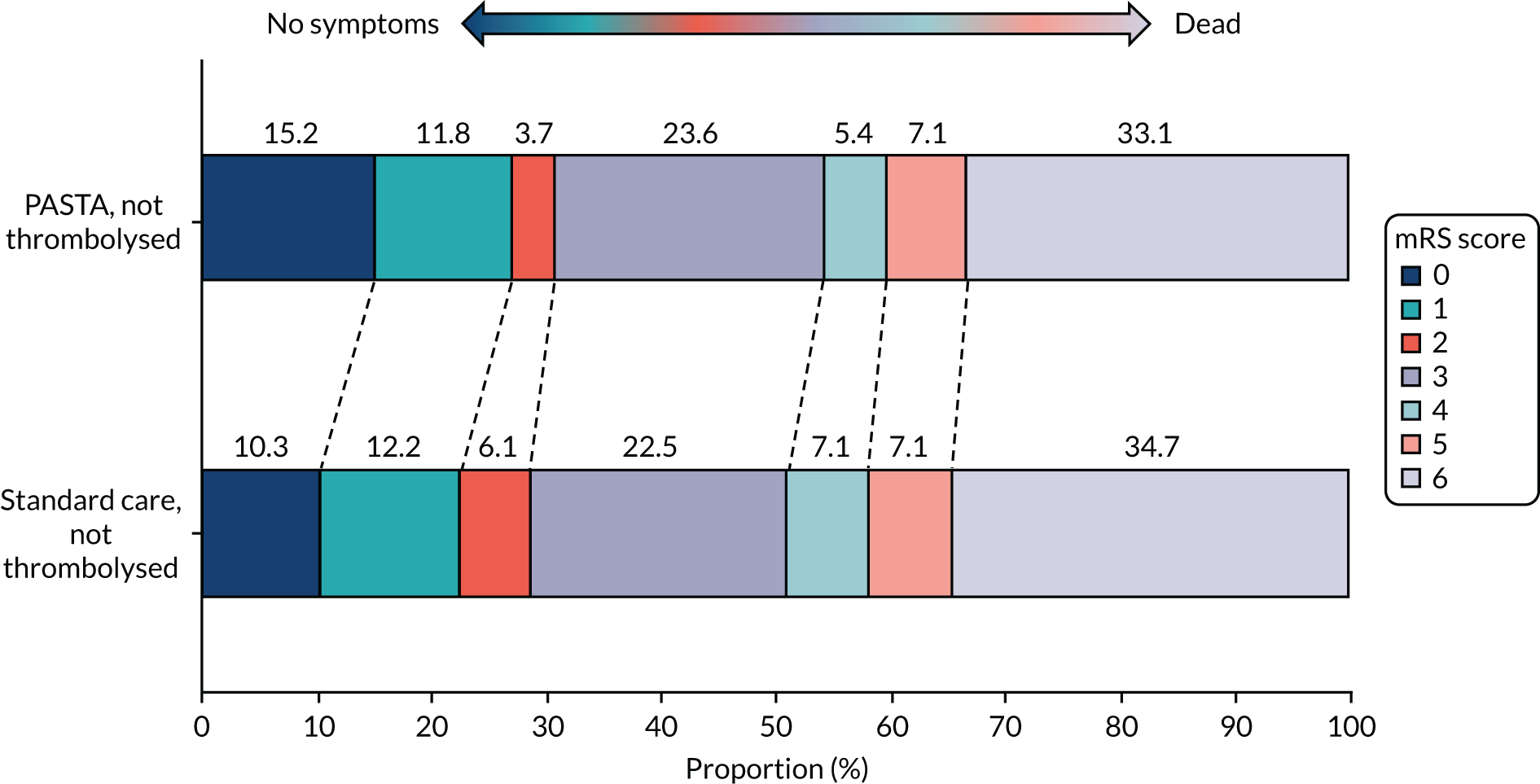

At day 90, there was no significant difference between groups for mortality [the PASTA intervention, 140/499 (28.1%); standard care, 199/712 (27.9%); OR 1.00 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.30); p = 0.97)]. Figure 3 shows the distribution of mRS score values at day 90. Although the CIs were wide enough to include clinically important differences favouring either group, there was an unexpected non-significant trend towards fewer poor outcomes (i.e. a mRS score ≥ 3) at day 90 among the PASTA intervention patients [PASTA intervention, 313/489 (64.0%); standard care, 461/690 (66.8%); aOR 0.86 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.2); p = 0.39], which was also seen among those who received thrombolysis [PASTA intervention, 108/193 (56.0%); standard care, 191/312 (61.2%); aOR 0.78 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.30); p = 0.34].

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of day 90 mRS scores for all patients.

Similar day 90 mRS score distributions for thrombolysis and non-thrombolysis groups are shown in Appendix 1, Figures 14 and 15. The serious adverse events were recorded from 81 PASTA patients (16%; total of 94 events) and 136 standard care patients (19%; total of 161 events). None of the serious adverse events had a causal link to the study intervention.

Eight hospitals were not fully compliant with the national standard for local specialist availability (see Appendix 1, Table 6). In the post hoc analysis, these non-compliant services showed a statistically significant 9.8% absolute reduction in the PASTA thrombolysis treatment rate compared with the standard care thrombolysis treatment rate [PASTA intervention, 99/276 (35.9%); standard care, 105/230 (45.7%); unadjusted OR 0.67 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.95); p = 0.03], whereas there was no difference at the seven compliant hospitals [PASTA intervention, 98/224 (43.8%); standard care, 214/484 (44.2%); unadjusted OR 0.98 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.35); p = 0.91].

Study-specific ambulance data collection forms recording delivery of the PASTA pathway were located for 227 out of 500 (45.5%) intervention patients. Use of the structured handover was recorded for 59.0% and use of the individual components of the checklist ranged from 57.3% to 90.3%. Full data are shown in Appendix 1, Table 11.

Although patients with symptoms mimicking stroke were not enrolled in the trial, hospital research support staff recorded that 1596 such patients were transferred by a study paramedic. The most common non-stroke diagnoses were transient ischaemic attack (TIA) (34.5%), headache/neurological (13.1%), epilepsy/seizure (10.3%), infection/sepsis (9.0%), syncope/circulation (6.1%), functional (4.1%), brain imaging diagnosis [e.g. tumour (3.5%)] and metabolic disturbances (3.3%).

Discussion

This multisite pragmatic trial showed that a paramedic-initiated thrombolysis-focused emergency stroke assessment that extended beyond hospital handover did not increase thrombolysis rates. Instead, there was a trend towards less thrombolysis administration. Although there was a longer initial paramedic assessment process, it is unlikely that the PASTA intervention resulted in patients simply ‘timing out’ of treatment as this was, proportionally, a minor extension of the whole emergency pathway, and the Cox regression analysis indicated that intervention thrombolysis was probably less likely at any time point since the emergency call.

It may be surprising that these results show that the PASTA pathway did not improve thrombolysis delivery when simpler pre-hospital interventions have increased treatment rates (e.g. raising the ambulance priority level for suspected stroke)16 and reduced hospital treatment delays (e.g. pre-notification),41 but the service context of each report is likely to be relevant. Previously, additional thrombolysis activity was observed at four out of six US centres following a multilevel intervention comprising public awareness activities, a paramedic symptom checklist and competitive benchmarking. 15 The two unchanged centres had high baseline treatment rates and may have already achieved optimal performance. A similar ceiling effect may explain the lack of effect among the PASTA sites, which were already established thrombolysis providers. A multisite Scandinavian trial16 randomised 942 suspected stroke/TIA patients to a higher and standard response level after multidisciplinary training. The study reported a thrombolysis rate of 24%, compared with 10% among controls. Like the PASTA intervention, there was no significant change in door-to-needle time, suggesting that delays following admission relate to logistical factors such as scan capacity, image reporting and specialist availability.

Despite the intervention group showing a surprising trend towards fewer thrombolysis treatments, outcomes were not adversely affected and there was a counter-intuitive trend towards better health. If indicative of a genuine effect, one possible hypothesis is an influence on case selection, that is structured communication of directly relevant and timely information by the PASTA paramedics might increase clinician confidence about withholding treatment when there is borderline benefit, higher than average risk or uncertainty about key details, such as onset time. The post hoc analysis showed that intervention group thrombolysis was significantly less likely across services with specialist availability below the level recommended by national guidelines. 6 Relatively inexperienced clinicians under time pressure may tend towards overtreatment rather than undertreatment of borderline cases, which could be moderated by the PASTA handover and/or checklist, whereas services with greater specialist continuity may already apply a more systematic approach to case selection. Being an unexpected finding, we had not collected the required data describing clinical and radiological quality of individual treatment decisions to confirm this hypothesis. However, previous ED studies have reported that, typically, less than half of pertinent items of information are shared during standard handover of mixed patient groups,42 with significant variation due to the level of experience of the clinicians involved. 18,43 The relevance and clarity of handover can be improved by introduction of simple generic formats19,29 while multidisciplinary team checklists make care safer through clarification of information and reinforcement of important standards. 20,21

The distribution of mimic conditions observed was typical of previous ambulance studies and clinical reports,44 providing reassurance that the suspected stroke cohort underpinning the trial was representative of the wider clinical population.

Examination of the Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment pathway intervention cost-effectiveness

The main study report has been published. 45

Material throughout this section has been reproduced with permission from Bhattarai et al. 45 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

A within-trial health economic analysis estimated the cost-effectiveness of the PASTA intervention, compared with standard care, over 90 days of follow-up. As the trial post hoc analysis showed that thrombolysis varied according to specialist availability, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken to determine if costs and cost-effectiveness varied by site-level specialist availability. The economic evaluation was reported following best practice guidelines conforming to the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS).

Methods

Outcomes were QALYs and cost per participant reported in 2017/18 Great British pounds from an NHS and social service perspective. QALYs were based on health utility scores generated from mapping discharge and day 90 mRS scores to EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version, values. 46 These were converted into QALYs using the area under the curve method, controlling for pre-stroke disability, age and sex. Costs were derived from prospectively captured resource utilisation data, including paramedic time, acute medical treatments, bed-days, post-discharge rehabilitation, social services involvement (paid carers at home and in social care settings) and hospital re-admissions. Standard unit costs were used in calculations. 47,48 As the time horizon was 90 days, discounting of costs and outcomes was not required.

A complete-case data set and an imputed data set were analysed. Missing cost and utility data were imputed using predictive mean matching within the multiple imputation generated by chained equations. Generalised linear model regressions with gamma family link function estimated marginal costs while controlling for age, sex and pre-stroke disability clustered by site. 49 Stochastic sensitivity analysis used non-parametric bootstrapping to quantify and explore the impact of statistical imprecision surrounding the point estimates of costs, QALYs and cost-effectiveness. The likelihood that the PASTA intervention would be cost-effective, compared with standard care, was reported over a range of willingness-to-pay (WTP) values.

Results

The unadjusted differences for complete-case mean mRS scores, utility, QALYs and total cost estimates between the PASTA intervention and standard care are shown in Appendix 2, Table 12. Over the 90-day follow-up period, there was no evidence of QALY differences between groups in either complete-case (0.007, 95% CI –0.003 to 0.018) or imputed data (0.005, 95% CI –0.004 to 0.015) (Table 2). There were lower total costs in the PASTA intervention group for both complete-case (–£1473, 95% CI –£2736 to –£219) and imputed data sets (–£1086, 95% CI –£2236 to –£13).

| Outcome measure | Data, mean (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete case | Imputation | |||

| Standard care | PASTA intervention | Standard care | PASTA intervention | |

| QALYs | 0.100 (0.093 to 0.108) | 0.108 (0.099 to 0.116) | 0.104 (0.097 to 0.110) | 0.109 (0.102 to 0.117) |

| ΔQALY | 0.007 (–0.003 to 0.018) | 0.005 (–0.004 to 0.015) | ||

| Total costs (£) | 13,103 (12,292 to 14,019) | 11,630 (10,702 to 12,586) | 13,106 (12,421 to 13,904) | 12,019 (11,223 to 12,865) |

| ΔTotal costs (£) | –1473 (–2736 to –219) | –1086 (–2236 to –13) | ||

| ICER (ΔCost/ΔQALY) | Dominant | Dominant | ||

| Probability of being cost-effective at £20,000 WTP for a QALY (%) | 1 | 99 | 1.9 | 98.1 |

| Probability of being cost-effective at £30,000 WTP for a QALY (%) | 0.3 | 99.7 | 1.7 | 98.3 |

Detailed descriptive costs from the complete-case data set are shown in Appendix 2, Table 13. Although there was a greater mean cost for paramedic training time and longer patient episode duration in the PASTA intervention group than in the standard care group, there were savings from less use of thrombolysis medication, reductions in length of hospital stay and reductions in the duration of rehabilitation and provision of social care support. The costs for other acute stroke treatments were slightly higher among the PASTA patients.

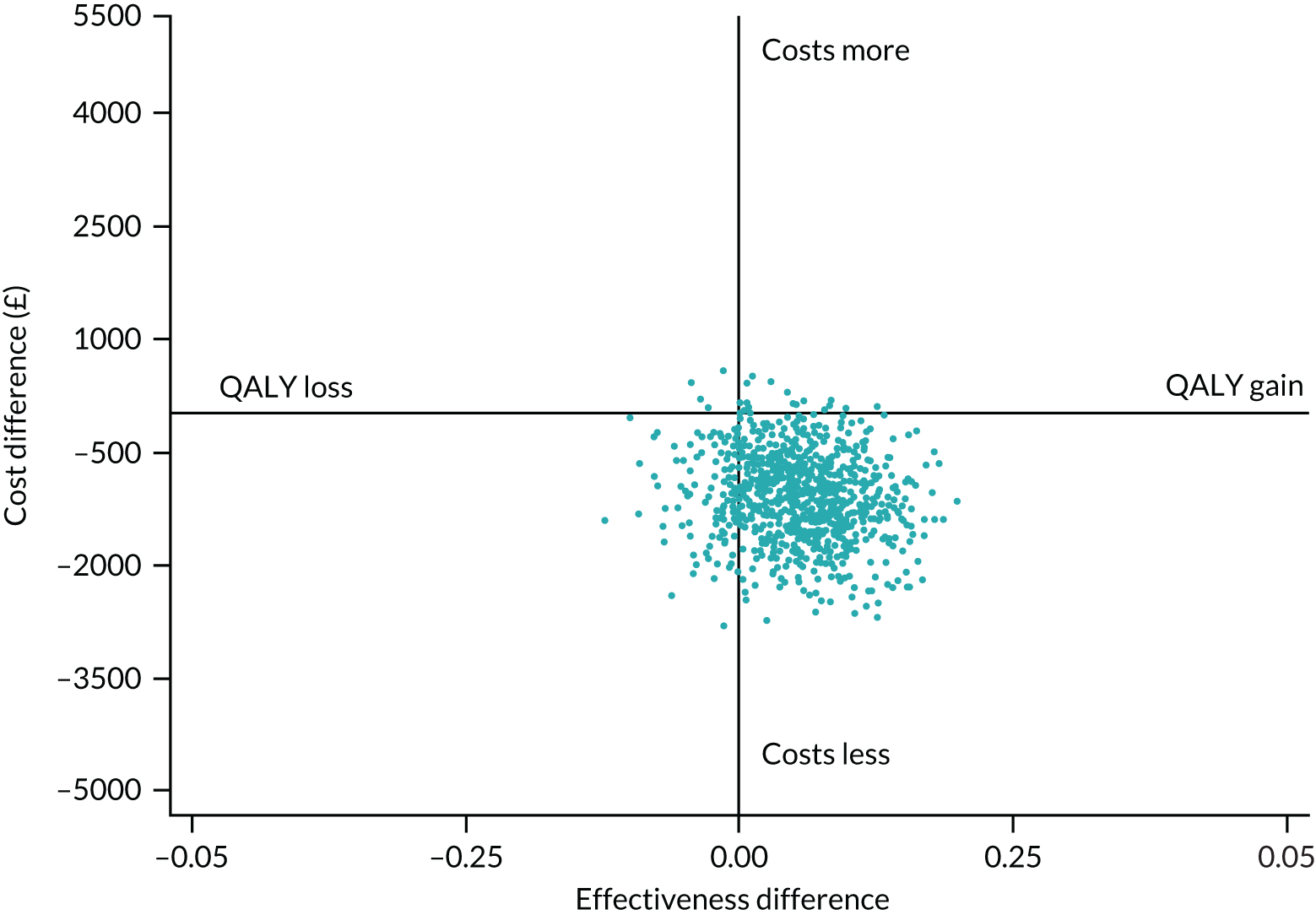

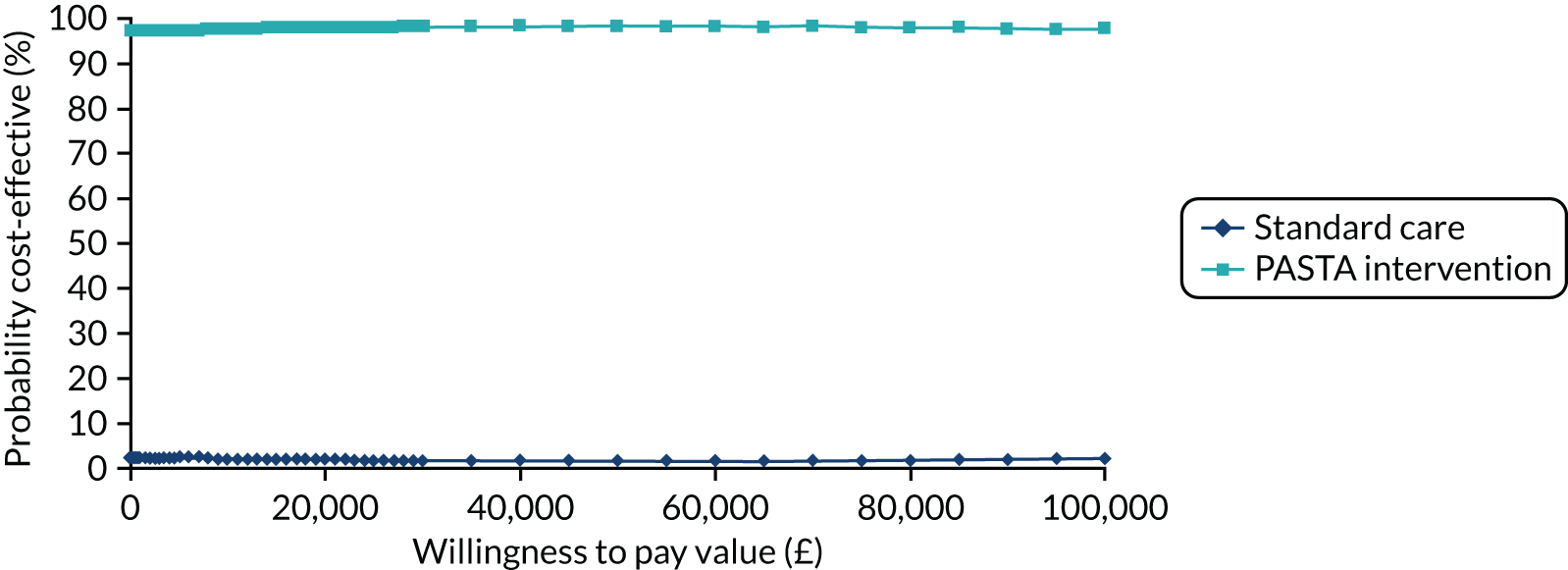

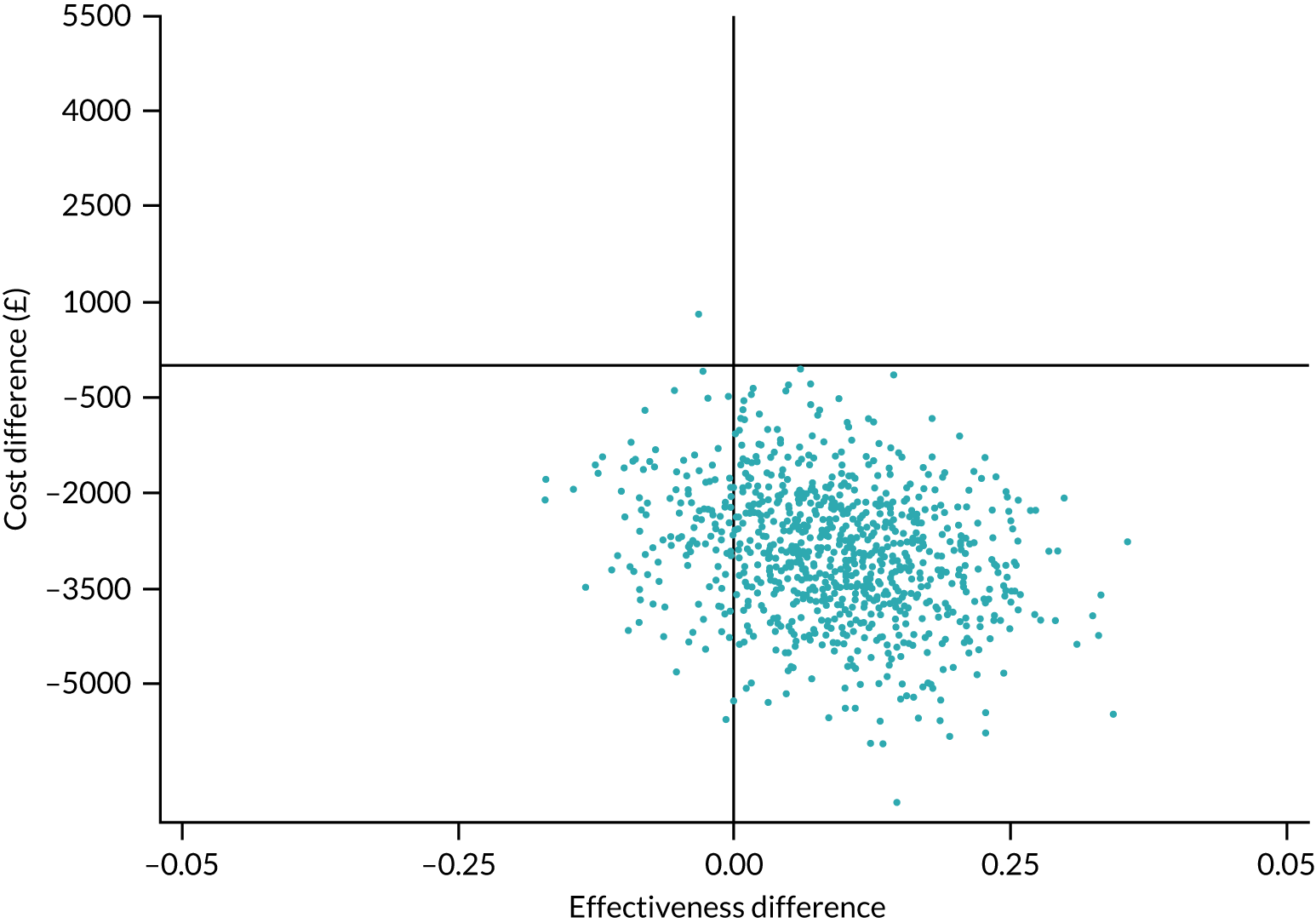

A plot of bootstrapped differences in mean costs and QALYs for the imputed data set showed that for most iterations (91.3%), the PASTA intervention was less costly and more effective than standard care (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Cost-effectiveness plane for imputed data.

Over the range of values for society’s WTP for 1 QALY, there was a > 97.5% chance that the PASTA intervention group would be considered cost-effective (see Appendix 2, Figure 16).

The post hoc economic sensitivity analysis results are shown in Appendix 2, Table 14. The seven compliant hospitals where there was no evidence of a thrombolysis rate difference between the PASTA and standard care groups showed no evidence of a difference in QALYs (0.005, 95% CI –0.008 to 0.018) or costs (–£423, 95% CI –£2220 to £1362). The eight non-compliant hospitals that together had a thrombolysis reduction in the PASTA intervention group provided no evidence of a difference in QALYs (0.009, 95% CI –0.008 to 0.025), but costs were lower for the PASTA patients than for standard care patients (–£2952, 95% CI –£4988 to –£917)]. Cost-effectiveness planes for the compliant and non-compliant hospitals are shown in Appendix 2, Figures 17 and 18.

Discussion

Although the paramedic-led thrombolysis-focused emergency stroke assessment used in the PASTA trial did not increase thrombolysis rates, the economic evaluation showed a cost saving associated with the PASTA intervention group. The QALY differences were, on average, small and there was no evidence of differences, but, overall, there was a very high chance that the PASTA intervention would be cost-effective across all WTP threshold values.

Although it is not surprising that fewer thrombolysis treatments resulted in lower costs, it was unexpected to observe the PASTA intervention group savings in other aspects of care, including length of hospital stay, rehabilitation and social care. Although these data require cautious interpretation, patients with better health following emergency assessment would require lower costs for each of these resources in turn. 50 However, it is important to acknowledge that the health difference was non-significant, small and short term.

Although the economic results are not intuitive, previous triallists have proposed that costs of care can be more sensitive indicators of all consequences (expected and unexpected) of a complex intervention in a pragmatic trial than a pre-chosen primary end point that focuses on one anticipated impact only. 51 This proposal is consistent with the idea that the PASTA intervention could have a mixed effect on patient care.

In the post hoc analysis, a reduction in costs up until 90 days was particularly evident for the PASTA patients across services with specialist availability below the level recommended by national guidelines. This is consistent with the earlier hypothesis (see Examination of the Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment pathway intervention clinical effectiveness: a cluster randomised trial, Discussion) that relative inexperience normally leads to overtreatment rather than undertreatment of borderline cases by non-specialists. Better clinical acumen would not only save costs by preventing futile thrombolysis, but could also avoid a longer length of stay associated with essential monitoring after treatment and rehabilitation following harmful complications.

Impact of the Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment intervention on ambulance response times

During funding of the programme and development of the PASTA intervention (see Development of the Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment, Stakeholder engagement), concerns were raised by reviewers and ambulance personnel regarding any negative impact from the additional time that intervention paramedics could spend in the hospital post handover, rather than becoming ‘clear’ again for another emergency call. To identify any effect on ambulance service responsiveness as a result of the PASTA intervention delivery, we undertook a retrospective observational study of the North East Ambulance Service (NEAS)’s emergency performance in parallel with the PASTA trial.

Methods

The NEAS was selected because all hospitals within the boundary of the service were trial sites, and the likelihood of finding any effect would, therefore, be higher than in regions with only partial coverage (i.e. north-west England and Wales). Until October 2017, for each patient consented to the trial, NEAS provided audit compliance information regarding any ‘Red 1’ (suspected cardiac arrest requiring an 8-minute response) and ‘Red 2’ calls (any other serious emergency requiring an 8-minute response time) occurring in the service 1 hour before the trial patient was attended by a study paramedic, and hourly afterwards for the next 3 hours. This allowed examination of whether or not the PASTA intervention had a wider impact on the service response by comparing, between the PASTA and standard groups, whether or not national audit targets for any parallel Red 1 and Red 2 calls were achieved (i.e. an appropriate ambulance vehicle arrived for those patients within 8 minutes of the 999 call). It was not possible to continue this evaluation after October 2017 as national ambulance metrics changed and data were no longer available.

Results

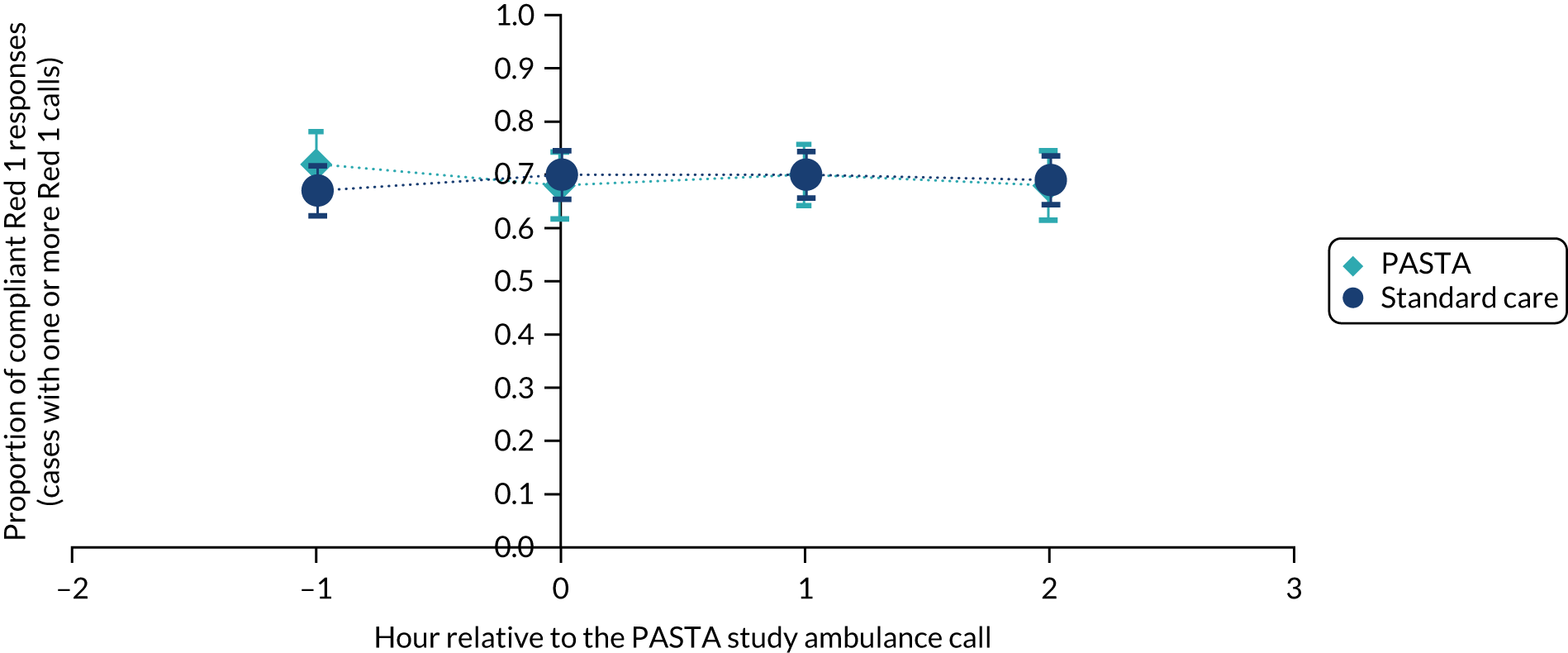

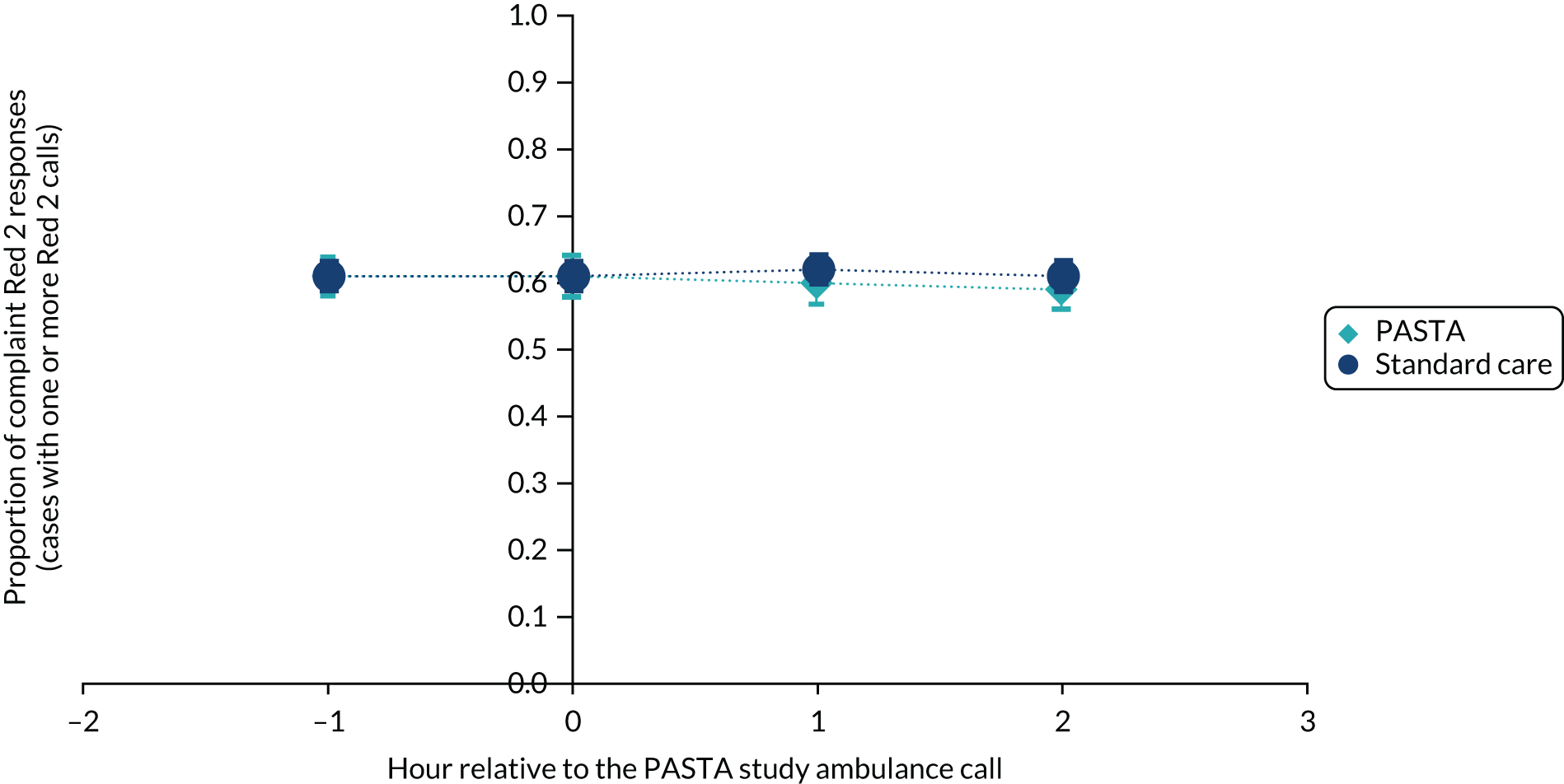

Between December 2015 and October 2017 (i.e. for 23 months), in the 1 hour before and 3 hours after any enrolled trial patient being attended by a study paramedic, there were a total of 831 and 2533 Red 1 calls, and 12,155 and 38,708 Red 2 calls, respectively (see Appendix 3, Tables 15 and 16). The average compliance across all patients was 68.7% for Red 1 and 61.1% for Red 2. As shown in Figures 5 and 6, after removal of hours when Red calls did not occur, there were no significant differences between the PASTA and standard care groups in the proportion of compliant Red 1 or Red 2 calls achieved by the service at any hourly time point in relation to an enrolled patient being attended by a study paramedic.

FIGURE 5.

Proportion of compliant Red 1 ambulance responses in the 1 hour before and 3 hours after a study patient was attended by a paramedic. The dark blue circles show the standard care and the light blue diamonds show the PASTA study groups.

FIGURE 6.

Proportion of compliant Red 2 ambulance responses in the 1 hour before and 3 hours after a study patient was attended by a paramedic. The dark blue circles show the standard care and the light blue diamonds show the PASTA study groups.

Discussion

The results provide reassurance that, despite engaging paramedics for an average of 13.4 minutes longer with trial patients, the PASTA intervention did not cause decompensation of the ambulance service’s ability to respond to its highest priority calls. This is not surprising as this time interval fell within the 15 minutes’ tolerance for ambulance departure after hospital handover, and suspected stroke is a relatively small proportion (approximately 3%) of ambulance service activity, so should not create a service-wide capacity issue. It is important to recognise that these data reflect calls related to patients who were consented to the trial and not all suspected stroke patients who were attended by study paramedics, but the results support the ongoing hosting of stroke research by ambulance services.

Process evaluation of the Paramedic Acute Stroke Treatment Assessment intervention

The main study report has been published. 52

Material throughout this section has been reproduced with permission from Lally et al. 52 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

There were three groups involved in a process evaluation that intended to describe the acceptability and feasibility of the PASTA pathway in the clinical setting: intervention paramedics, hospital clinicians and intervention group patients.

Methods

Participants were invited to semistructured interviews (in person or over the telephone). Hospital research support staff sought medically stable patients who were attended by a NEAS intervention paramedic within the last 7 days. Interviews were audio-recorded, anonymised and transcribed. Data collection and analysis was an iterative process, following the combined principles of the constant comparative32 and thematic analysis. 33 Two researchers coded transcripts independently, which were then compared and further analysed during data sessions. Approval was given by the National Health Service Research Ethics Committee Newcastle and North Tyneside (reference 15/NE/0309).

Results: intervention paramedics

In total, 26 interviews were conducted across the three ambulance services (north-east England, n = 11; north-west England, n = 10; and Wales, n = 5). Participants’ length of service ranged from 14 months to 27 years, with qualifications up to postgraduate degree level.

Iterative data analysis identified four key themes, which reflected paramedics’ experiences at different stages of the intervention care pathway:

-

Enhanced assessment at scene – paramedics reported that the PASTA intervention complemented their skill set and confidence, and the trial training allowed them to feel well prepared. Illustrative quotations are shown in Appendix 4, Box 1.

-

The pre-alert to the hospital – when local standard care pathways permitted conveyance of additional patient details, pre-notification contained more detailed and appropriate information as a result of the PASTA enhanced assessment. Illustrative quotations are shown in Appendix 4, Box 2.

-

Handover to hospital team – the standard ‘scripted’ format for handover of thrombolysis-specific information was viewed as the primary benefit of the PASTA pathway. Paramedics felt more confident during communication with the hospital team, and felt that they were less likely to forget important details. Illustrative quotations are shown in Appendix 4, Box 3.

-

Assisting in the hospital and feedback – owing to traditional professional boundaries, paramedics found these aspects harder to achieve, although feedback from the clinical team was valued when available. Illustrative quotations are shown in Appendix 4, Box 4.

Results: hospital clinicians

Seven focus groups and one telephone interview were conducted across the three study regions. A total of 25 staff participated, including stroke specialist nurses, ED nurses and stroke consultants.

The following main themes were identified, also reflecting key stages of the pathway:

-

Enhanced paramedic role – hospital staff perceived that paramedics generally seemed to enjoy the role and receiving feedback (see Appendix 4, Box 5: quotations 1 and 2). They reported that there were not as many paramedics trained as they had expected.

-

Handover value – staff who had directly experienced the handover viewed it positively. They reported that the PASTA paramedics required fewer prompts from the stroke or ED team to get the details they needed, and the information was provided in the appropriate order (see Appendix 4, Box 5: quotations 3 and 4).

-

Post-handover uncertainty – in a few settings, it was valued that the PASTA paramedics assisted with practical tasks after handover, such as taking the patient for urgent brain imaging, as this freed up the hospital staff to prepare for the possibility of thrombolysis treatment (see Appendix 4, Box 5: quotation 5). However, this assistance was not always required by the hospital staff or consistently offered by the paramedics, who may have found it difficult to initiate (see Appendix 4, Box 5: quotation 6). Even if extra assistance was not needed, feedback to paramedics was viewed positively (see Appendix 4, Box 5: quotation 7).

Results: intervention patients

Six patients (five male and one female) were interviewed, after which a decision was made by the TSC to stop further patient recruitment because of the limited information being obtained about the PASTA intervention. Some patients could not remember any specific details, and those who could provide an account of their admission to hospital could not recall any specific details of paramedic actions. This may reflect the nature of acute stroke on perception or memory and the emotional state of patients at the time, but it is also likely that patients had no prior knowledge of paramedic care processes that would have enabled them to identify any actions that were related to the intervention.

Discussion

Even though there was overlap with existing practice, participating paramedics and hospital staff valued the structure of the PASTA pathway. The pathway was considered to enhance paramedic confidence and shared care, although there was less value post handover because help was not always required and traditional boundaries were harder to overcome.

Strong support was expressed for the structured patient assessment and corresponding information handover. A review of 12 studies examining structured patient assessment frameworks found evidence of improved documentation,53 but no examples from pre-hospital care. The general need to improve emergency handover has been highlighted by a review of 21 studies, which identified concerns about communication in the chaotic ED environment, exacerbated by a lack of time and resources. 18 More recently, there have been reports in support of structured generic handovers19 and a version for trauma care,54–56 but there have been no previous descriptions of a stroke-specific handover. 29

On completion of the PASTA pathway checklist, paramedics welcomed the opportunity to receive immediate feedback, which hospital staff were happy to provide. Previous interviews with Canadian paramedics also found positive perceptions of feedback, but this was described as informal and opportunistic. 57 Feedback to individual paramedics has been shown to encourage adherence to standard stroke care assessment, but was not in given real time and did not allow clarification by the recipient. 17

Work package 2

Baseline characteristics of intra-arterial thrombectomy service provision in England

A full report has been published and parts of this section have been reproduced from the report. 58 Flynn D, Ford GA, McMeekin PJ, White P. International Journal of Stroke (volume 11, issue 8), pp. NP85–85, copyright © 2016 by World Stroke Organization. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications.

Results from randomised trials demonstrating that rapid IAT treatment reduced dependency for selected stroke patients became available in 201523,24 and led to interventional procedure guidance being issued by NICE in March 2016,59 but very few UK hospitals were able to provide this service. Most treatments were opportunistic in the absence of clearly defined clinical pathways, and there was no information about how interventional neuroradiologists (INRs) performing the procedure were interpreting the evidence. Understanding baseline service provision and patient selection processes was an essential first step towards modelling optimal NHS service provision.

Methods

In November/December 2014, a survey was sent to clinical leads in all 24 regional INR services in England to obtain data on current provision of IAT, IAT patient selection and diagnostic imaging criteria, and centre opinions on future IAT service provision.

Results

Eighteen centres (75%) responded that provided INR services to a population of ≈ 43 million. No centres reported delivery by non-INRs. Ten centres (56%) had formal IAT protocols and six (33%) had protocols for interhospital transfers. A median of 10 [interquartile range (IQR) 16] stroke patients underwent IAT per centre during the previous year. One centre had 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (24/7) IAT provision, two centres had 7-day provision during normal hours, 12 delivered IAT on weekdays and three had no regular provision at all. There was substantial variation in the patient selection criteria and protocols for provision of IAT (Table 3). For future IAT services, there was clear support for centralisation of provision into large HASUs at neuroscience centres (89%) with ‘drip and ship’ interhospital transfers across a formal network (94%).

| Question | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Time window for INR accepting anterior circulation stroke for IAT | |

| < 4.5 hours | 13 (72) |

| 4.5 to < 6 hours | 3 (17) |

| > 6 hours | 0 (0) |

| Not time based | 2 (12) |

| Patient category considered for IAT | |

| Perform IAT only when thrombolysis contraindicated | 1 (6) |

| Perform IAT only in accordance with the 2013 NICE guidelines | 7 (39) |

| Will perform IAT outside 2013 NICE criteria | 8 (44) |

| No response | 2 (11) |

| Referral source | |

| Stroke physician/neurologist (own hospital) | 8 (44) |

| Stroke physician/neurologist (all hospitals) | 8 (44) |

| Referrals from wider range of specialties/grades | 1 (6) |

| No response | 1 (6) |

| Evidence for arterial occlusion before accepting the patient | |

| Accept patients with clinically/plain CT-suspected LAO | 8 (44) |

| Only accept patients for IAT where LAO is confirmed by CT angiography/MRA | 8 (44) |

| No response | 2 (11) |

| Anaesthetic technique | |

| General anaesthesia | 4 (22) |

| Conscious sedation with or without general anaesthesia | 10 (55) |

| No response | 4 (22) |

| Local primary IAT therapeutic strategy | |

| ‘Stentriever’ device alone | 8 (44) |

| ‘Stentriever’ device with balloon guide catheter | 3 (17) |

| Direct aspiration alone | 1 (6) |

| Varies between operators | 5 (28) |

| No response | 1 (6) |

Conclusions

Most centres in England in 2014 were limited to weekday ad hoc provision of IAT. There was considerable variation across centres in imaging and patient selection for IAT, but the responses to questions about the organisation of future service provision for IAT in England showed a degree of consensus.

Updated estimates of certainty for intra-arterial thrombectomy effectiveness and safety

The full systematic review has been published and parts of this section have been reproduced from the review. 60 Flynn D, Francis R, Halvorsrud K, Gonzalo-Almorox E, Craig D, Robalino S, et al. European Stroke Journal (volume 2, issue 4), pp. 308–18, copyright © 2017 by European Stroke Organization. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications.

The PRISMA-compliant protocol61 was registered online as PROSPERO CRD42015016649.

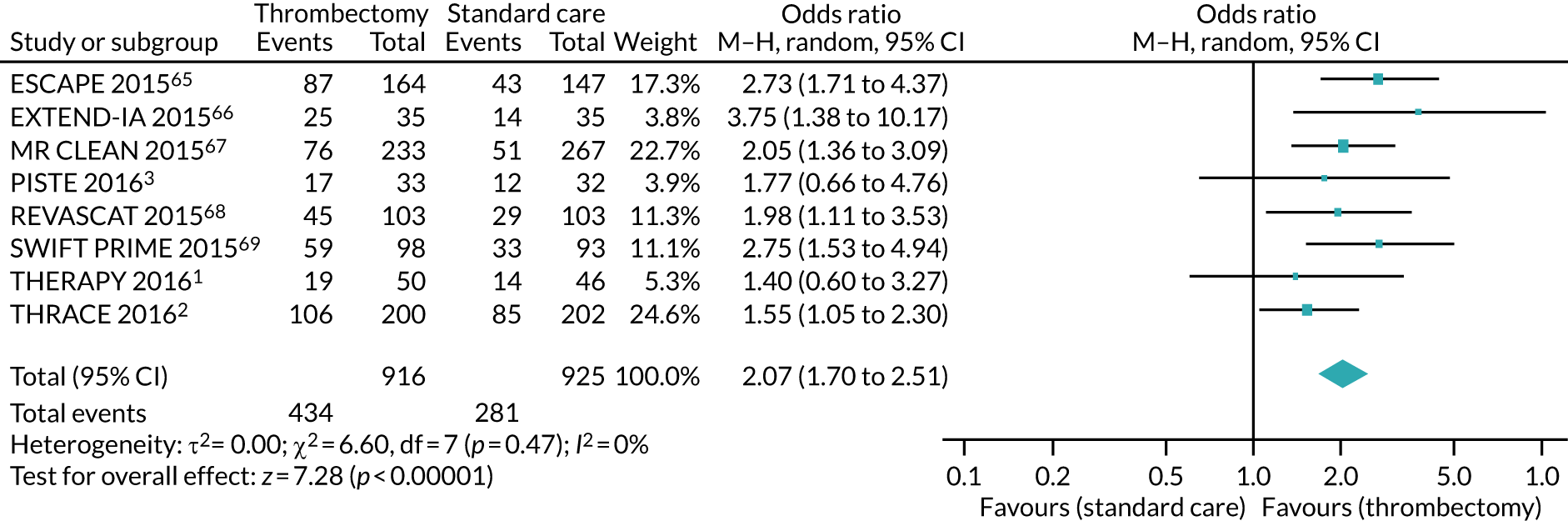

Soon after the programme started, several meta-analyses of IAT RCTs were published,23,24,62,63 each of which had taken a slightly different approach, but all found that IAT is an effective treatment. The most robust of these was the academic collaborative triallists (the HERMES group) individual patient record meta-analysis. 23 However, the evidence base to define the safety and effectiveness of IAT had expanded by ≈ 45%, with THERAPY (The Randomized, Concurrent Controlled Trial to Assess the Penumbra System’s Safety and Effectiveness in the Treatment of Acute Stroke),1 THRACE (The Contribution of Intra-arterial Thrombectomy in Acute Ischemic Stroke in Patients Treated With Intravenous Thrombolysis)2 and PISTE (Pragmatic Ischaemic Stroke Thrombectomy Evaluation)3 trials all reporting later in 2016. Therefore, an updated evidence synthesis was warranted. A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis (TSA) was conducted to understand the impact of trials reporting in 2016 on the magnitude/certainty of the estimates for effectiveness and safety of IAT.

In parallel with this systematic review looking at efficacy and safety, a detailed narrative review was undertaken of IAT complications. 64

Methods

The search strategy is shown in Appendix 5. Random-effects models were conducted of RCTs comparing IAT with/without adjuvant thrombolysis against thrombolysis and other forms of best medical care in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. The TSA established the strength of the evidence derived from the meta-analyses.

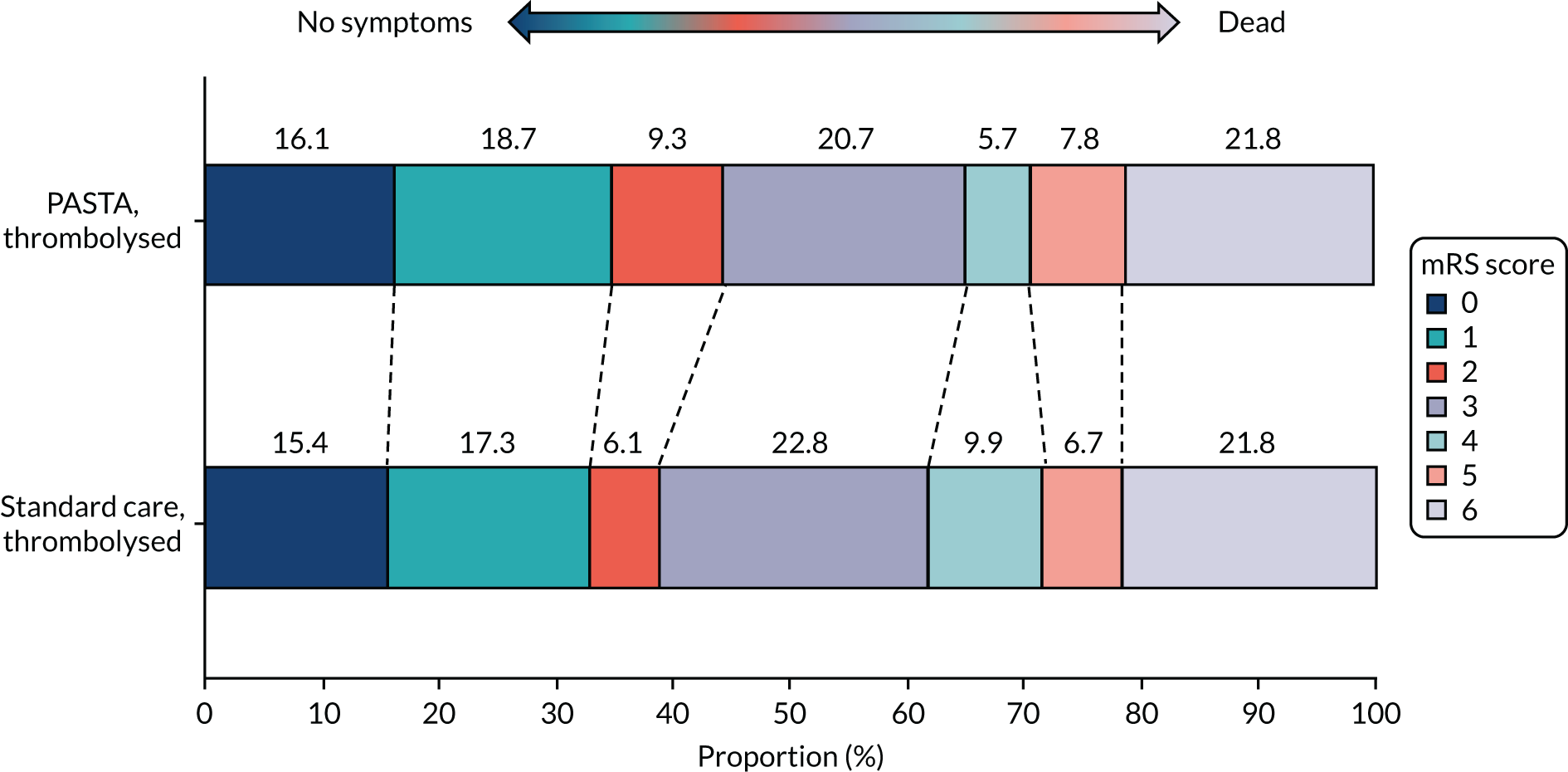

Results

Patients treated with IAT were significantly more likely to be functionally independent (mRS score of 0–2) at 90 days’ follow-up (OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.88 to 3.04). As shown in Figure 7, the impact of the three 2016 trials1–3 was a slightly decreased pooled effect size, but increased certainty of the mid-point estimate (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.70 to 2.51).

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot for functional independence. M–H, Mantel–Haenszel. Reproduced with permission from Flynn et al. 60 Flynn D, Francis R, Halvorsrud K, Gonzalo-Almoroz E, Craig D, Robalino S, et al. , European Stroke Journal (Volume 2, Issue 4), pp. 308–18, copyright © 2017 by SAGE Publications Ltd. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications Ltd.

Intra-arterial thrombectomy, compared with best medical care, did not show any effect on mortality or symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage at 90-days’ follow-up. Results of the TSA satisfied the criterion for ‘sufficient evidence’ on effectiveness; however, uncertainty remains as to whether IAT is associated with lower mortality or increased risk of symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage.

Conclusions

The expanded evidence base for IAT yielded a more precise assessment of effectiveness, but uncertainty remained as to the net effect of IAT on mortality and symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage.

Expert consensus on preferred implementation option for intra-arterial thrombectomy services

A full description is available in Halvorsrud et al. 70 Parts of this text have been reproduced with permission from Halvorsrud et al. 70 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Although there was evidence supporting IAT therapeutically, there was no consensus on how it should be made available within clinical services. The aim was to establish consensus on options for future organisation of IAT services, based on agreement among physicians with clinical expertise in LAO stroke management.

Methods

A survey questionnaire was developed with 12 options (propositions) for future organisation of thrombectomy services in England (see Appendix 6, Box 6). The British Association of Stroke Physicians (BASP) facilitated recruitment of panellists to provide representative ratings of options (by location and experience). Consensus was defined as ≥ 75% of ratings for each option falling within three categories (i.e. approve, quite strongly approve or very strongly approve) on a seven-point Likert scale. Wider BASP membership and members of the British Society of Neuroradiologists (BSNR) then ranked those propositions on a seven-point Likert scale, reaching consensus following two initial assessment rounds. Data was collected from November 2015 to March 2016, and participation was pseudo-anonymous.

Results

Eleven respondents completed two rounds. 71 Three options achieved consensus:

-

selective transfer to nearest neuroscience centre for INR-delivered IAT (100% approve)

-

local imaging then transfer to nearest neuroscience centre for INR-delivered IAT (91% approve)

-

local imaging then transfer to nearest neuroscience centre for advanced imaging and INR-delivered IAT (82% approve).

Subsequently, the wider group of BASP and BSNR members (n = 64) assigned the highest approval ranking for transferring LAO stroke patients to the nearest neuroscience centre for thrombectomy based on the results of local CT/computed tomography angiography (CTA) (option 2).

Conclusions

The Delphi exercise by clinical and imaging stroke experts in England established consensus on a ‘simple’ imaging-driven option, which advocates the secondary transfer of patients (‘drip and ship’) with LAO stroke for thrombectomy based on local CT/CTA alone.

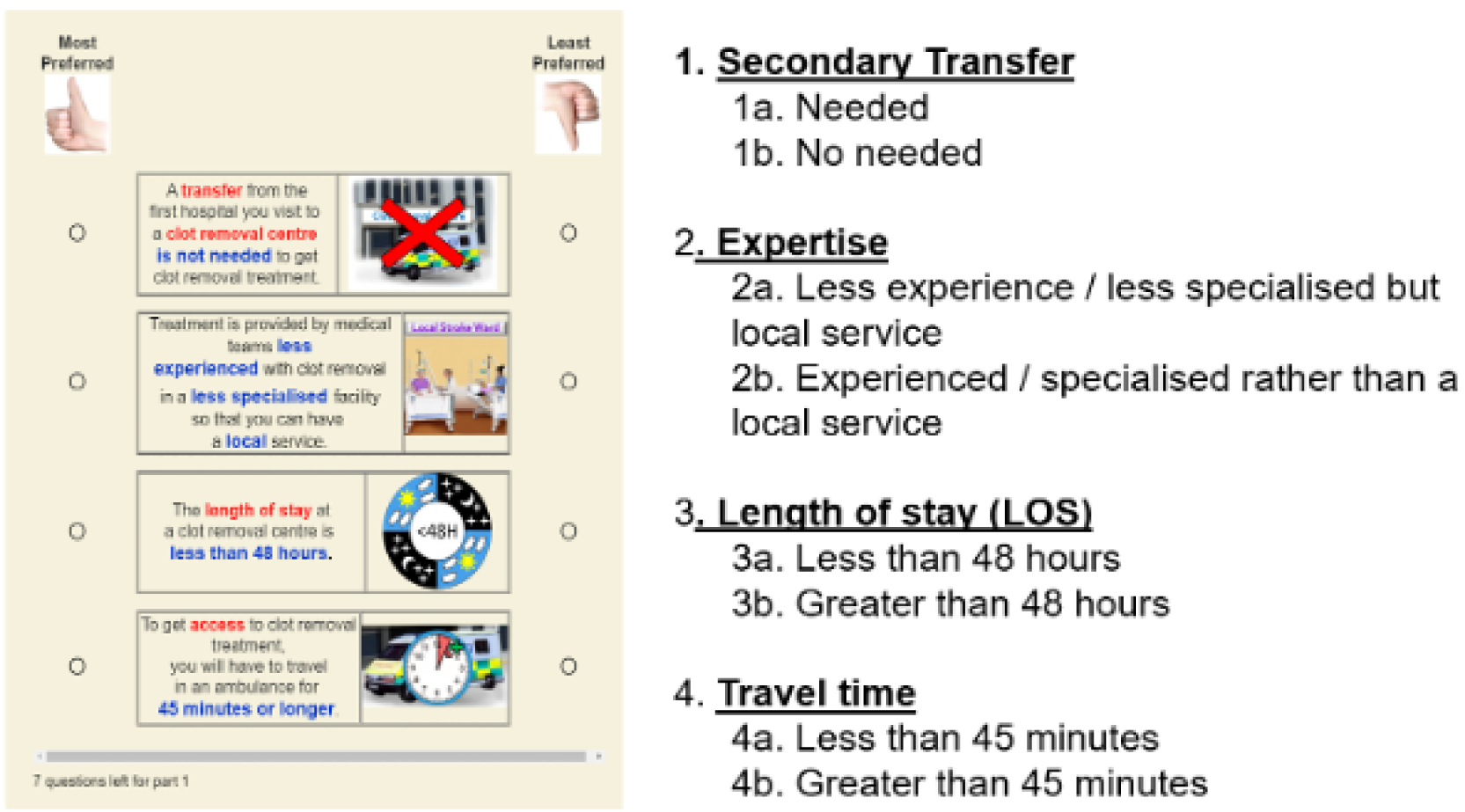

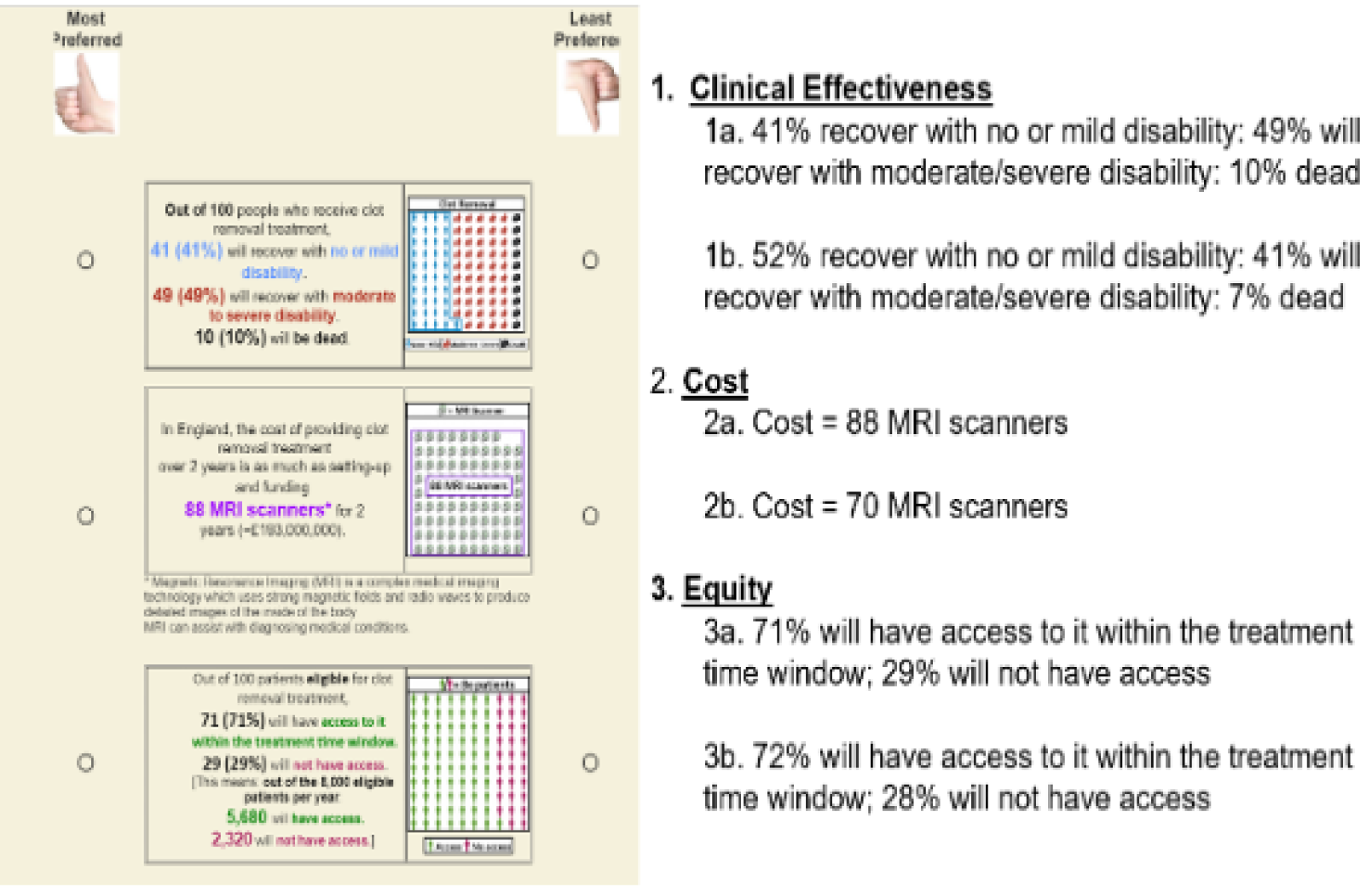

Patient and public preferences on attributes of intra-arterial thrombectomy service organisation

To integrate the opinions of stroke survivors/relatives/carers and the public into the outputs of a health economic model for IAT in England, their preferences were elicited regarding attributes of IAT service provision, including thresholds for additional travel time in the context of this time-critical emergency.

Methods

The research programme patient and public involvement (PPI) representative facilitated recruitment of 14 stroke survivors and their relatives/carers from a stroke PPI panel to engage in an iterative process to develop an inclusive and accessible ‘aphasia-friendly’ survey. Interactive meetings were convened to obtain feedback on an (1) initial draft of the survey and (2) updated version with graphics and textual presentation that adhered to guidance on developing resources for people with aphasia. 72 Subsequent testing was undertaken with 10 stroke survivors/carers and local PPI panels. The resulting anonymous survey was hosted and advertised on the Stroke Association website73 (from January 2017 to May 2017) with information on IAT, including the time sensitive nature of outcomes, limited number of specialist facilities and delays that can occur during secondary transfer from a local stroke unit.

Results

Responses were received from 147 individuals [mean age 49 (SD 16) years; 61% female]: 27 stroke survivors (18%), 51 relatives/carers of stroke survivors (35%) and 69 other members of the public (47%). The majority of stroke survivors were male and the majority of the other groups were female. Respondents were spread across England (50% were resident in north-east England). Full details of respondents are in Appendix 7, Table 17. The survey results are show in Table 4. Differences in proportions for each survey item as a function of participant type were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), indicating that experience of stroke did not influence responses.

| Question | Number of respondents (%) |

|---|---|

| Thrombectomy can be delivered only at specialist centres. Would you agree to be transferred from your local hospital to such a centre to undergo thrombectomy? (N = 142) | |

| Yes | 138 (97) |

| No | 4 (3) |

| How long would you be prepared to travel via an emergency (999) ambulance for thrombectomy? (N = 145) | |

| 1: up to 20 miles/29 minutes | 36 (25) |

| 2: up to 30 miles/41 minutes | 46 (32) |

| 3: up to 40 miles/53 minutes | 17 (12) |

| 4: up to 50 miles/65 minutes | 46 (32) |

| How long would you be prepared to stay at the specialist centre for thrombectomy before you are returned to your local centre/hospital? (N = 144) | |

| 24 hours | 8 (6) |

| 48 hours | 26 (18) |

| > 48 hours | 110 (76) |

| Should a thrombectomy service be made available in your local stroke unit, even if this meant that thrombectomy would be carried out by a less experienced stroke team? (N = 144) | |

| Yes | 33 (23) |

| No | 57 (40) |

| Uncertain | 54 (38) |

Conclusions

In agreement with expert views favouring centralised provision of IAT with secondary transfer as appropriate, 97% of respondents would accept hospital transfer and 75% would be prepared to travel up to 30 miles to access IAT.

Establishing the number of stroke patients eligible for intra-arterial thrombectomy

A full report has been published. 74

Material throughout this section has been reproduced with permission from McMeekin et al. 74 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

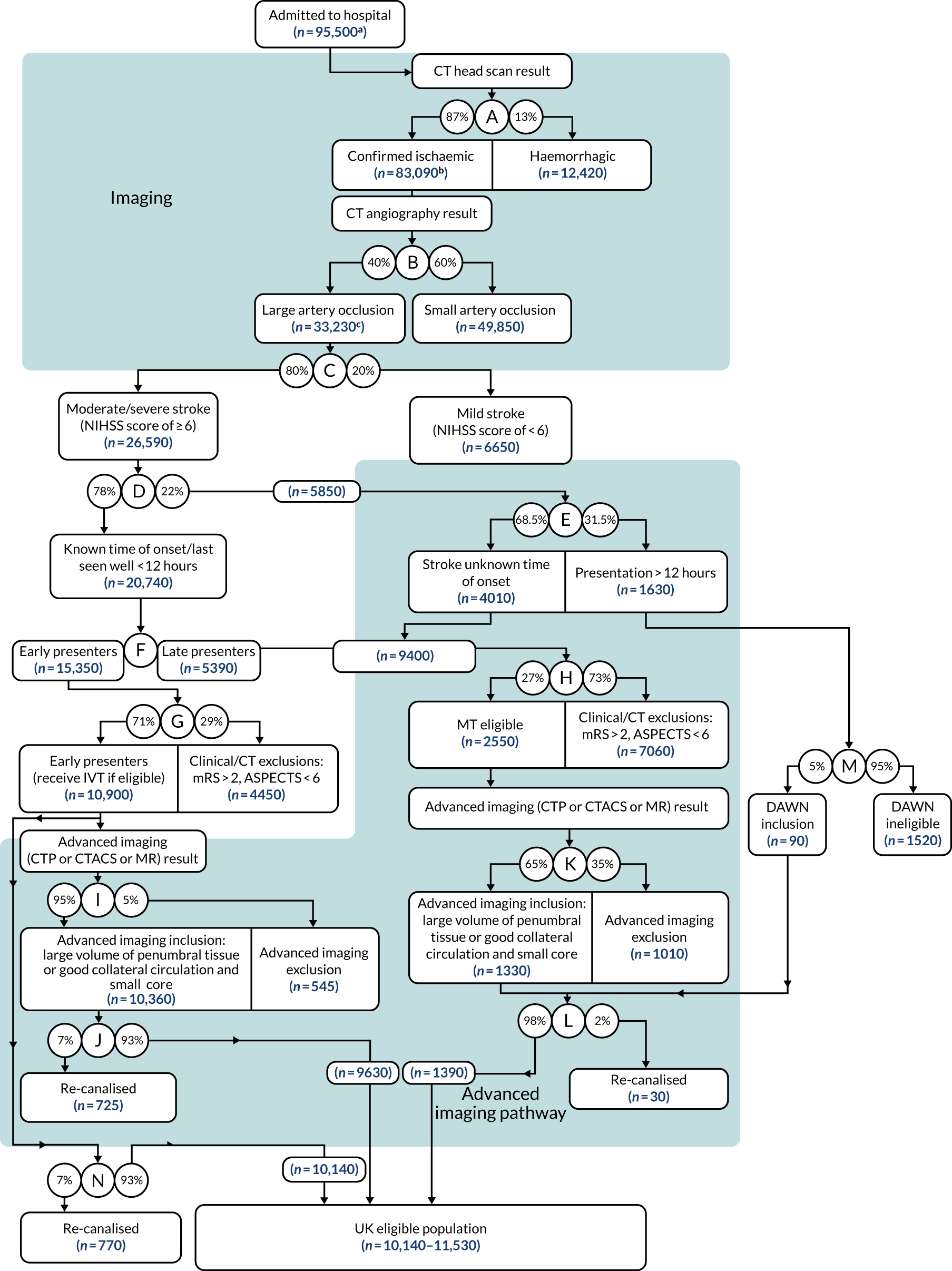

To model optimal national service configurations, it was necessary to first estimate the proportion of UK stroke patients eligible for IAT, as this had not previously been established at a population level.

Methods

Using national registry data from the SSNAP for England, Wales and Northern Ireland,6 adjusted for Scotland using data from the Scottish Stroke Care Audit,75 a decision tree with 14 nodes (A–N) was constructed from published trials74 depicting eligibility for IAT, regardless of geographical or service constraints. An updated version in 201876 included two new reports describing IAT efficacy among late presenters. 77,78

Results

The updated decision tree is presented in Figure 8. 74 The eligible population includes (1) the total UK population, even if currently geographically inaccessible; (2) patients with a confirmed infarct, excluding patients with unconfirmed status (≈ 2%); and (3) patients with basilar artery occlusions eligible for treatment. Patients in the large, lower blue-shaded box are selected by advanced imaging. It was originally estimated that between 9620 and 10,920 UK stroke patients would be eligible for treatment. The revised estimate based on new evidence was that an additional 490 early-presenting and 205 late-presenting patients would be eligible for IAT (i.e. between 10,140 and 11,530 patients). The largest increase was a result of new evidence of IAT benefit for patients with Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (ASPECTS) of ≥ 5,80 with a smaller contribution from the treatment of patients presenting between 12 and 24 hours. 77,78

FIGURE 8.

Updated estimate of the number of stroke patients eligible for IAT. ASPECTS,79 Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score; CTP, computed tomography perfusion; CTACS, computed tomography angiography collateral scoring; DAWN,78 DWI or CTP Assessment with Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake-Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neutrointervention with Trevo; IVT, intravenous thrombolysis; MR, magnetic resonance; MT, mechanical thrombectomy. a, Total UK population, including those deemed to be geographically inaccessible; b, confirmed infarcts, excluding ≈ 2% of patients whose status is unconfirmed. Note that totals between levels in the tree may differ slightly due to decimal rounding. Reproduced with permission from McMeekin et al. 74 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Conclusion

Up to 12% (11,530/95,500) of UK stroke admissions are eligible for IAT based on treatment criteria from randomised clinical trials.

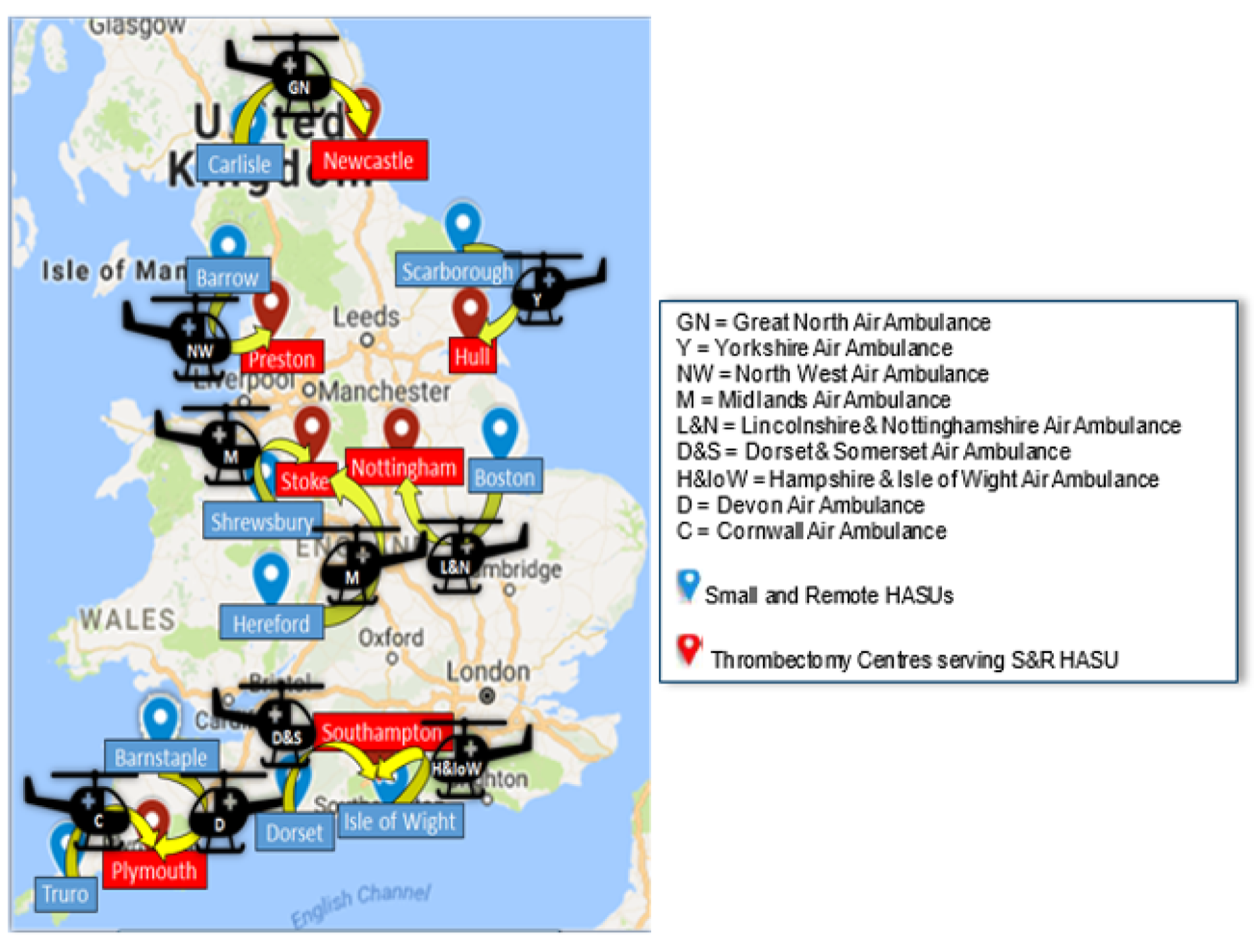

Helicopter Emergency Medical Services survey

While undertaking the survey of INR centres (see Baseline characteristics of intra-arterial thrombectomy service provision in England), it became apparent that some parts of the population live remotely from a hospital able to provide IAT. However, many hospitals are served by the air ambulance network, which could provide an approach to improve access to treatment. A survey of Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) was undertaken to parameterise a health economic model for the cost-effectiveness of HEMS compared with ground-based ambulances providing secondary transfer of stroke patients for IAT.

Methods

An online survey was sent to the clinical leads of nine HEMS serving ‘unavoidably small and remote’ hospitals (NHS England definition: < 200,000 population and > 1 hour of travel from nearest major hospital)81 (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Unavoidably small and remote hospitals in England with HEMS. Reproduced with permission from Google Maps (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). Map data © 2021 Google GeoBasis-DE/BKG (© 2009).

The survey gathered data on the number of helicopters, time in operation, number of hospitals served, average travel times by air, fit for purpose helipads, availability (09.00 to 17.00, 24/7 or other) and conditions under which flight is permitted.

Results

Responses were received from all nine HEMS (Table 5).

| Characteristic | Median | Range | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual number of stroke transfers | 2.5 | 11 | 5.5 |

| Number of helicopters | 2 | 1–3 | 1.5 |

| Operational hours (per day) | 14 | 7 | 6.5 |

| Response time (minutes) | 4 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Cost per mission (£) | 2750 | 750 | 375 |

All HEMS were willing to provide secondary transfers for IAT. HEMS operated a median of 14 hours per day, with extensions to operational hours being planned in two HEMS. The median response time from notification to take-off was 4 minutes and the cost per mission was £2750 (range £2500–3500). Most HEMS (eight of the nine) were Instrument Flight Rules-approved82 for flying in low-visibility conditions. To deliver transfer for IAT robustly, three of the nine HEMS indicated additional funding and/or organisational changes would be required.

Microcosting study to establish true cost of intra-arterial thrombectomy

The full report has been published and parts of this section have been reproduced from this report. 83 Republished with permission of Royal College of Physicians, from The cost of providing mechanical thrombectomy in the UK NHS: a micro-costing study, Balami JS, Coughlan D, White PM, McMeekin P, Flynn D, Roffe C, et al. , volume 20, edition 3, 2020; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

To estimate cost-effectiveness of national implementation, it was first necessary to establish the cost of providing IAT within the first 72 hours since stroke onset and to explore resource and costs variations across UK centres.

Methods