Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as award number NIHR200625. The contractual start date was in June 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2022 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Plappert et al. This work was produced by Plappert et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Plappert et al.

Synopsis

Background

Bipolar, schizophrenia and other psychoses are the single largest cause of disability in the UK,1 and yet probably one-quarter to half of people receive no specialist mental health care. 2 The prevalence of bipolar, schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, defined as the number of people on the general practice Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) registers for severe mental illness, was 0.8% for QOF year 2011–23 and has since risen to 1%. 4 Such numbers have a considerable impact on the economy, with total service costs for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and bipolar estimated as £3.8 billion in 2007 and likely to rise to £6.3 billion by 2026. 5

People with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or psychosis have a significantly reduced life expectancy compared with the general population. 6 Two-thirds of the mortality gap can be explained by physical disorders. 7 This is primarily due to a combination of lifestyle factors and medication side effects contributing to cardiovascular and respiratory risk. Additionally, the diagnosis of other significant illnesses may be delayed because of diagnostic overshadowing.

The NHS England policy The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health highlights the low level of primary care engagement with this group: ‘We should have fewer cases where people are unable to get physical care due to mental health problems … we need provision of mental health support in physical health care settings – especially primary care’ (p. 11; Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 8

Poor continuity of care and lack of information exchange between primary and secondary care also create barriers to effective support. The PARTNERS1 review of primary care records found that approximately 31% of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or other psychosis in the UK were seen only in the primary care setting and that those seen in secondary care received only minimal support. 2 Primary care practitioners find it difficult to effectively support patients with serious mental illness (SMI), often lacking the necessary time and training to address these patients’ mental health needs. 9–11 Furthermore, access to health prevention and promotion activities in primary care is reduced for people with SMI. 12,13

Recent UK policy has promoted joined-up care, including the integration of primary and secondary services to provide better care for harder-to-reach groups. 14 The recent NHS Community Mental Health Transformation policy15 also aims to address this problem by ensuring that all those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or other psychosis and requiring care are well supported, ideally by collaboration between primary care, secondary services and third-sector organisations. This is also consistent with person-centred care (e.g. the Comprehensive Model of Personalised Care),16 which offers an integrated approach to health care for people with complex needs and provides proactive support for physical health conditions.

A collaborative care model, whereby a specialist healthcare professional works in primary care forging collaboration between primary and secondary care, is a potential approach to achieving better integration between separate parts of the health and social care system. 1 Collaborative care has been shown to be effective in improving mental, physical and social functioning across a range of mental health conditions. 2,17,18

Most of the collaborative care evidence for SMI has been developed and evaluated in the USA, where the nature of service user populations and of service use differs from the way we fund, structure and use NHS England. 19 Although there is considerable evidence of effectiveness, this largely relates to depression. 18

While those with severe symptoms of psychosis generally receive significant attention from services, it is clear that for those at lower risk care is much more haphazard. This is aggravated further by the increases in discharges from specialist services over recent years. There have been sustainable approaches to providing specialist mental health input for those with psychosis in primary care in only a few settings, such as East London. 20

Studies over time report that primary care practitioners find it difficult to effectively support this group of patients, often lacking the necessary time and training. 9–11 There is often poor continuity within primary care teams and poor co-ordination with secondary care.

In light of the above, this research programme aims to further understanding of the nature of current care, decide which outcomes are important, and then develop and test a collaborative, person-centred intervention to address deficits in care. It focuses on the estimated 70% of adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar who are currently seen and treated in primary care alone, or those currently seen in secondary care with lower levels of risk (operationalised as diagnostic clusters 11 and 12). Risk in this context refers to self-harm, self-neglect, suicide or harm to others.

How to navigate the PARTNERS2 research programme report

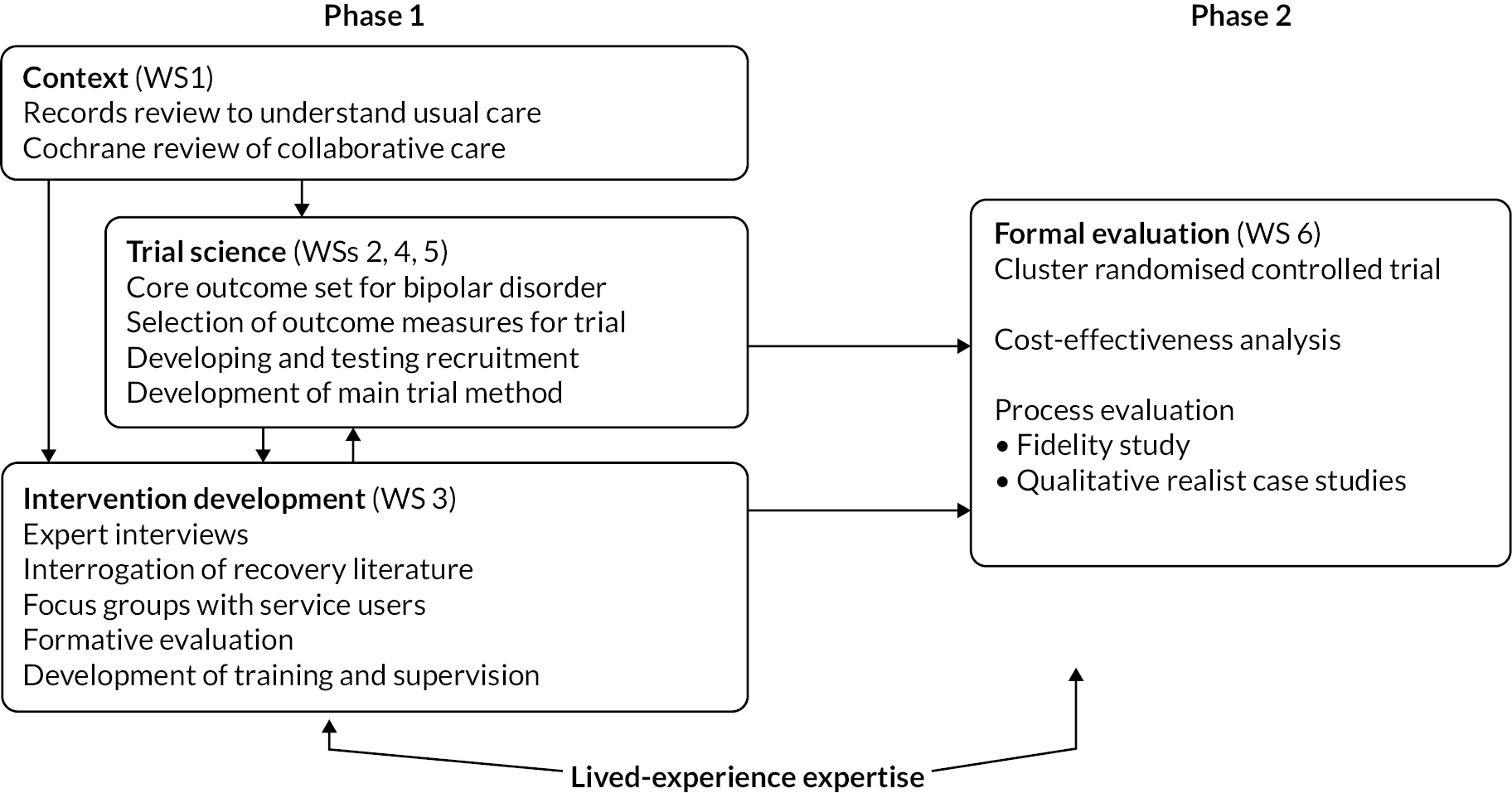

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded PARTNERS2 programme ran between 2014 and 2021, across two phases consisting of a total of six workstreams (WSs) (Figure 1), all supported by three Lived Experience Advisory Panels (LEAPs).

FIGURE 1.

The PARTNERS2 programme.

Phase 1: context of research (workstream 1)

-

an observational retrospective cohort study of primary and secondary care medical notes

-

an update of our original Cochrane review ‘Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness’. 21

In parallel, we also developed the initial model of intervention (WS 3) through:

-

a systematic review of literature on collaborative care and personal recovery

-

interviews with key leaders in collaborative care and personal recovery

-

focus groups with service users

-

a formative evaluation of initial model of collaborative care to identify facilitators/barriers and refinement for implementation in main trial.

And trial methodology (WSs 2, 4 and 5):

-

development of a core outcome set (COS) for bipolar

-

development of recruitment methods.

Phase 2: randomised trial, cost-effectiveness study and integrated process evaluation (workstream 6)

In this stage we conducted:

-

a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT)

-

a cost-effectiveness study

-

a mixed-methods process evaluation.

Public involvement underpinned all of the WS activity through the study LEAPs during the programme life cycle and the employment of service user researchers in the project team.

Alterations to the programme

The original programme proposed an external pilot trial of 300 participants from 60 general practitioner (GP) practices across three sites and did not include any effect sizes, power analysis or primary outcome. In 2016, a request was made to change the original design to carry out a definitive trial within the programme remit. The changes were agreed, converting the external pilot to an internal pilot trial with the following modifications:

-

agreement of a primary outcome and re-estimation of required sample size

-

reappraisal of sample size based io internal pilot

-

conversion to a definitive trial including stop–go rules set prior to trial onset [in conjunction with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and NIHR].

The trial arm of the programme [now split into two phases: development of feasibility stage (formative evaluation) and RCT (including with internal pilot)] is detailed in Table 1.

| Stage and key aims | Duration | Key dates |

|---|---|---|

| Develop feasibility stage: Aims: To develop and refine the intervention model To agree outcome measures To test recruitment processes |

24 months | 2014–6 |

| Convert internal pilot trial to full trial | VTC approved July 2016 | |

| RCT: internal pilot: Aims: To further test feasibility of both recruitment and the intervention delivery for patients and GP practices To assess recruitment against objectives: |

6 months | Trial started: 1 October 2017 Trial registered: 16 October 2017 First participant recruited: 8 June 2018 |

|

||

| To assess delivery and safety of intervention – e.g. intervention delivery (care partners in place) and adverse events such as crisis care (home treatment teams), admissions (psychiatric) To review initial sample size target of 336 participants |

||

| Change in CTU transition phase | 4 months | Decision November 2018. Handover period December 2018–February 2019 |

| Conversion to full trial | Stage 2 application submitted November 2018 Bridge funding period March 2019–May 2019 Funding award approved April 2019 Programme extension period June 2019–February 2021 |

|

| RCT (completion of RCT following internal pilot): Aim: To establish the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of primary-care-based collaborative care for people with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or other types of psychosis Note: revised recruitment target of 204 participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or other types of psychosis from ≈34 clusters (GP practices), based on per-protocol sample size recalculation (December 2019) and funder requirements (January 2020) |

Completion of recruitment Follow-up: 10–12 months |

Recruitment end date: 28 February 2020 Follow-up end: 28 December 2020 Data collection end date: 31 March 2020 Study end date: 30 April 2021 |

Early in the programme, the COS work was expanded and streamlined. Instead of creating a COS for SMI, after consultation with service users, carers and practitioners a decision was made that both a COS for bipolar and a COS for schizophrenia were needed. This was because two outcome sets for bipolar and schizophrenia emerged during the preliminary qualitative work. The decision was made that the final COS would relate to bipolar only rather than to schizophrenia or to SMI generally (the PARTNERS2trial population). This was because of the larger number of available data on and greater research and advisory team expertise relating to bipolar. Within the resources of the PARTNERS2 programme, it was possible to create only one COS using robust methods and including user involvement. A COS for bipolar was selected and created.

During the formative evaluation phase, flexible approaches for recruitment were tested. However, Health Research Authority guidance changes meant that these processes were no longer permitted in the second phase due to confidentiality concerns. Additional changes in one of the host NHS trusts (Lancashire Care Foundation Trust) causing financial and time pressures meant that the site had to withdraw during the set-up phase. The programme was allowed to continue along with a change in the co-ordinating Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) (from Birmingham to Plymouth, in line with RB taking on a co-chief investigator role). At this stage it was also agreed that the health economics modelling and stated preference survey planned for phase 1 would not proceed, with resources reallocated to the trial. Alternative sites were recruited [Somerset Partnership Trust and Livewell Southwest Trust (Plymouth)].

Following slower-than-hoped recruitment, a re-estimation of sample size (as per protocol for internal pilot) and changes in power, requirements decided following input from the Programme Steering Committee and the funder meant that we were able to stop recruitment in January 2020, completing the trial within the funding envelope. Table 1 details the trial development, including changes.

After recruitment closed and during intervention delivery and follow-up, the COVID-19 pandemic and UK national lockdown necessitated significant programme changes. After consultation with the Programme Steering Committee and the funder, the research team adapted methods for intervention delivery, follow-up data collection and the ongoing process evaluation (Table 2). The changes were tested for an 8-week period. Once they were shown to be successful, and after risk assessments were conducted for both service users and practitioners, the decision was made to continue remote delivery, where possible, both of the intervention and of follow-up and process evaluation data collection, until the end of the trial.

| Challenges | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Adapting the intervention to remote delivery | Delivery via telephone or video conferencing software. Intervention practitioners received training on using video conferencing software and delivering interventions remotely. Coaching and goal setting were adjusted to be appropriate to a lockdown environment. The majority of participants found it acceptable to continue the intervention after adaptation to remote delivery. Practitioners delivering the intervention reported they were able to continue collaborating with primary care by remote means |

| Collecting data remotely | Follow-up data and process evaluation data collected via telephone, video conferencing or post. For the secondary outcome of time use, data collection was adjusted to include activities participants conducted remotely, for example attending church via video conferencing |

| Understanding the feasibility and acceptability of continuing the intervention, and collecting data, remotely. This included acceptability to participants and the feasibility of collaborating with primary care | 8-week trial phase, including rapid realist evaluation. This realist evaluation considered (1) the experiences of the intervention practitioners delivering the intervention during COVID-19 restrictions; and (2) during routine audio-assisted recall interviews with service users, exploring their experiences of engaging with the intervention by remote methods |

Phase 1: developmental and preparatory studies

Phase 1 included research to further understand the context (WS1), trial science work (WSs 2, 4 and 5) and intervention development (WS3).

Context-related research (workstream 1)

Assessment of local care pathways and current services

Background

Workstream 1 aimed to define the current status of integration and collaboration after the introduction of the QOF and identify where the strengths and weaknesses of integration lie. This was to inform better long-term solutions by describing the process of current care and help us target those who could benefit from collaborative care. It addressed a weakness in the PARTNERS1 study2 of primary care records that did not pick up all secondary care contacts. Three key questions addressed were:

-

What is the current level of primary care and secondary mental health care contact for those individuals with SMI who were taken on for specialist care?

-

What is the level of longitudinal continuity of care within primary and secondary care for those under secondary care?

-

What health risks were recorded and what physical healthcare monitoring was undertaken for this group?

This work has been published in Reilly et al. 22 (this is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited) and informed the development of the theoretical model for the PARTNERS2 intervention [see Development of theoretical model of the intervention (workstream 3)].

Methods

A multisite, epidemiological review of primary and secondary care contacts in participating mental health services was undertaken. Three host NHS trust sites were invited to participate (Birmingham, Lancashire and Devon). Five Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) and a subsequent 33 GP practices referring into these CMHTs were recruited. GP practices were stratified according to size. We aimed to identify 100 randomly selected eligible cases per secondary care site who met the inclusion criteria on 1 September 2014. This required individuals to be under secondary care and to have diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar or other psychoses.

Data were manually extracted from electronic secondary mental health care and primary care medical records between October 2014 and June 2016. The data extraction tools developed in the PARTNERS1 study were expanded for this purpose in consultation with our LEAP members and service user researchers.

Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics and measures of variance were derived relating to individual demographics, number and type of medications, number of comorbidities, direct service contacts and reasons for contacts. Continuity of care in primary care was measured using the Modified, Modified Continuity Index (MMCI), which measures the number of GPs seen; a higher continuity score occurs when there are larger numbers of visits with a smaller number of GPs. The type and frequency of contacts with primary and secondary care were also measured, as were the proportions of individuals who had no contact with primary care and the time between contacts in primary and secondary care.

Results

Among the 297 individuals included in the study, the average age was 47 years and 56% were male (see Table 1); 33% of individuals were from ethnic minority communities, and around half (53%) were smokers and 16% were ex-smokers; smoking cessation advice was reported to have been given to 66% of those who were smokers.

The majority of care in this group of individuals under specialist services at the eligibility point was provided by secondary care practitioners; of the 18,210 direct contacts recorded, 76% were from secondary care (median 36.5, interquartile range 14–68) and 24% were from primary care (median 10, interquartile range 5–20). There was evidence of poor longitudinal continuity; in primary care, 31% of people had poor longitudinal continuity (MMCI ≤ 0.5), and 43% had a single named care co-ordinator in secondary care services over the 2 years.

Thirty-seven (12%) individuals had been discharged to primary care within the 2-year period but were on the secondary care caseload when the sample was taken. Of these, 15 (41%) had been discharged more than once. A high proportion of individuals (44%) had seven or more GP contacts (25% had three to six and 17% had one or two contacts) and 7% of cases did not have any contact with a GP (6% were missing). The majority of primary care contacts were at the practice (72%) or by telephone (27%), of which 63% were with a GP, just over one-quarter (27%) were with a nurse and 10% were with another health professional.

The majority (88%) of individuals had had one or more contacts with a secondary mental health care professional, meaning that 12% had not. Over one-quarter of individuals had had a mental health admission over the 2 years and 16% had had a non-mental health admission.

In conclusion, three-quarters of all direct contacts recorded across primary and secondary care were from secondary care. For most individuals with SMI who are in contact with secondary mental health services, these services are central to their care. Individuals were seen on average every 2 weeks by specialist care practitioners, albeit with much variability. By contrast, these individuals were also seen on average every 6 weeks in primary care. Greater knowledge of how care is organised presents an opportunity to ensure some rebalancing of the care that all people with SMI receive when it is required.

Update of Cochrane review of collaborative care

Background

Collaborative care is a community-based intervention that promotes interdisciplinary working across primary and secondary care and typically consists of a number of components focused on improving the physical and/or mental health care of individuals, in this case those with SMI.

Since the publication of the original Cochrane review ‘Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness’,21 there has been a substantial increase in the number of published and relevant RCTs, and a refinement in defining collaborative care and working models. The update to the original review has been conducted; it includes an additional seven studies and has been published in Reilly et al. 21

Objective

The objective was to assess the effectiveness of collaborative care approaches in comparison with standard care for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or other psychosis who are living in the community. The primary outcomes of interest were quality of life (QoL), mental state, personal recovery and psychiatric admissions. These were selected by the review team and our LEAPs as the most suitable outcomes for all stakeholders.

Methods

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Study-Based Register (18 April 2011; 20 February 2015; 12 August 2016; 28 January 2019; 28 January 2020; 10 February 2021) including clinical trial registries. We contacted 51 (in 2011) and 48 (in 2016) experts. We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMD) controlled trials register (all available years to 6 June 2016).

Subsequent searches in Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycInfo® together with the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (with an overlap) were run on 6 June 2020 and 17 December 2021.

We identified RCTs where interventions described as ‘collaborative care’ were compared with ‘standard care’ for adults (aged ≥18 years) living in the community with a diagnosis of SMI. SMI was defined as schizophrenia, other types of schizophrenia-like psychosis or bipolar affective disorder.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of authors independently extracted and assessed the quality of data. The quality and certainty of the evidence was assessed using the Risk of Bias 2.0 (for the primary outcomes) and GRADE. Treatment effects were compared between collaborative care and standard care. We divided outcomes into short term (up to 6 months), medium term (7–12 months) and long term (over 12 months). For dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratio (RR); for continuous data, we calculated standardised mean differences (SMD), presented alongside 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Random-effects meta-analyses were used because there were substantial levels of heterogeneity across trials. We created a ‘summary of findings’ table using GRADE. 23

Results

We included eight RCTs24–31 (1165 participants) in this review, two of which met a strict definition of collaborative care. The composition and purpose of the interventions varied across studies. Most outcomes provided low-quality or very-low-quality evidence.

We found three studies (28,29,31) assessing QoL of participants at 12 months. QoL was measured using the Short Form Questionnaire-12 items,28,29 and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version,31 and the mean end-point mental health component scores were reported for 12 months. Very-low-certainty evidence did not show a difference between collaborative care and standard care in medium-term QoL (mental health domain at 12 months: SMD 0.03, 95% CI −0.26 to 0.32; 3 RCTs, 227 participants) and nor did low-certainty evidence (physical health domain at 12 months between collaborative care and standard care: SMD 0.08, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.33; 3 RCTs, 237 participants).

Furthermore, low-certainty evidence did not show a difference in medium-term mental state (binary) at 12 months between collaborative care and standard care (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.28; 1 RCT, 253 participants); in medium-term mental state (depressive symptoms) at 12 months between collaborative care and standard care (SMD −0.17, 95% CI −0.53 to 0.18; 3 RCTs, 227 participants); in medium-term mental state (manic symptoms) at 12 months between collaborative care and standard care (SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.38 to 0.22; 3 RCTs, 227 participants); or in the risk of being admitted to psychiatric hospital at 12 months in the collaborative care group compared with standard care (RR 5.15, 95% CI 0.67 to 39.57; 1 RCT, 253 participants). There was some low-certainty evidence of a reduction in the risk of psychiatric hospital admission at 2 years in the collaborative care arm compared with usual care (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.99; 1 RCT, 306 participants), but no evidence of a difference in the risk of psychiatric hospital admission was observed at 3 years (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.01; 1 RCT, 306 participants). One study indicated an improvement in disability (proxy for social functioning) at 12 months in the collaborative care arm compared with usual care (OR 1.69, 95% CI 0.98 to 2.91; 1 RCT, 253 participants); we deemed this low-certainty evidence.

Personal recovery and experience of care outcomes were not reported in any of the included studies. The data from one study indicated that the collaborative care treatment was more expensive than standard care [mean difference (MD) I$493.00, 95% CI I$345.41 to I$640.59] in the short term. Another study found the collaborative care intervention to be slightly less expensive at 3 years.

In conclusion, this review does not provide evidence that collaborative care is more effective than standard care in the medium term in relation to our primary outcomes. Dropout rates suggest no evidence of a difference between collaborative care and standard care in short-, medium- or longer-term treatment acceptability. However, our confidence in these findings is extremely limited due to the low certainty of evidence. Evidence would be improved by better reporting, higher-quality RCTs and an assessment of the underlying mechanisms of collaborative care. We advise caution when using the information in this review to assess the effectiveness of collaborative care.

Development of theoretical model of the intervention (workstream 3)

Initial programme theory development

The PARTNERS2 programme theory for the final intervention model was developed over three phases:32

-

drafting of an initial model and development into a prototype

-

refinement of the prototype model through formative evaluation into the trial intervention model

-

further refinement of the intervention model through the RCT with parallel process evaluation.

The process of developing the initial PARTNERS2 model has been published in Gwernan-Jones et al. (2019),32 which includes a supplementary file of the explanatory statements making up the intervention.

Stakeholder involvement events included regular consultation meetings with LEAP members over the full period of the research project (2014–21); two consultation meetings with LEAP members, researchers (including service user researchers), practitioners and policy-makers during the development of the initial model (November 2014 and January 2015); and a stakeholder meeting (October 2016) during the formative evaluation attended by researchers, practitioners delivering the partners service and LEAP members. Stakeholder input fed into model development by contextualising, shaping and providing feedback on the practicality and relevance of proposed aspects of the intervention.

An intervention was proposed in the original research programme funding application based on a recent systematic review of collaborative care for psychosis21 and the model of chronic care33 framed by concepts of personal recovery. 34 Using this proposal as a foundation, and drawing on a realist approach,35 a directory of 453 explanatory statements was iteratively created that articulated a rationale for why, how and for whom it was perceived the different aspects of the intervention would work. This directory of explanatory statements drew on a number of data sources:

-

literature on collaborative care for mental health, and personal recovery literature

-

11 telephone interviews with key leaders in collaborative care and personal recovery to explore their perceptions of best practice

-

six focus groups with 33 participants living with psychosis (13 women and 20 men) about their experiences of care.

Through cycles of discussion and consensus building, researchers and stakeholders debated the proposed approaches to delivering the intervention, and their decisions guided consolidation of 106 explanatory statements and graphic and written representation of the programme theory in the form of a prototype model. Finally, the prototype model was interrogated internally (by comparing the explanatory statements with the practitioner manual) and externally (by comparing the explanatory statements with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines), and then through debate across the research team, refined to establish consistency and rigour within the model and across the supporting documents. A manual for practitioners (care partners and supervisors) and guides for service users and their friends and family were developed.

Formative evaluation of the PARTNERS service

Background

The prototype model was then tested during a pilot formative evaluation, conducted from November 2015 to April 2017, to:

-

assess the extent to which delivery of the intervention matched the model

-

identify issues that fostered or prevented delivery of the model as intended

-

identify any additional support for implementation required in the main trial

-

evaluate and refine the initial model by comparing the perceived effects of the intervention with the programme theory.

Methods

During the formative evaluation, the Partners Service (a name chosen by the LEAP) was delivered at three sites (Northern England, the Midlands and the South West; two urban sites and one urban/rural site) over a period of 8–10 months. Secondary care practitioners (‘care partners’) were trained to deliver a collaborative coaching model. We called these practitioners ‘care partners’ to emphasise the collaborative nature of the role. Thirty-seven semistructured interviews were conducted with care partners (n = 4), service users (n = 14), care partner supervisors (n = 4), friends and family of service users (n = 5), GPs (n = 4) and other primary or secondary care practitioners (n = 6). We also recorded eight care partner–service user sessions and followed these up by interviewing the care partner (n = 7) and service user (n = 7) individually to explore their experiences during the recorded session (interpersonal process recall). 37

Preliminary analysis of the data involved ongoing descriptive coding to identify issues that prevented delivery of the model as intended; these were fed back to the Partners Service delivery teams to improve the service during the pilot period. A secondary analysis, using the framework method,38 focused on the extent to which the actual provision aligned with the mechanisms and outcomes predicted by the PARTNERS prototype model. At the end, a stakeholder meeting in October 2016 informed the development of strategies to improve theory for both what should be delivered and the implementation strategies to be used for the main trial.

Results

Key components of the prototype model that were not delivered as intended by one or more of the care partners or in one or more of the sites included:

-

a lack of support from secondary care to care partners, including no protected time and irregular supervision

-

limited interaction and integration of care partners into primary care sites, including difficulties with access and poor evidence of record-keeping

-

a lack of evidence for some care partners of a collaborative approach to interacting with service users, consistent monitoring of mental health and/or follow-up of service users, and the use of intervention resources for coaching and motivational approaches.

Factors that prevented implementation according to the initial model included:

-

systemic problems with communication, for example within primary care

-

care partner understanding, capacity for and/or willingness to engage with a collaborative coaching and goal-setting approach

-

capacity for and/or understanding about how to provide PARTNERS2 supervision to care partners.

These findings prompted refinement for implementation, including:

-

support to increase the integration of care partners into primary care through researcher facilitation

-

improved care partner understanding and skills in relation to coaching, goal setting and working collaboratively, using increased levels of training and a revised, clearer practitioner manual. It was anticipated that, through better understanding of the Partners Service approach, care partners would be able to address barriers to service user motivation to work on goals.

Delivery of the prototype model was partial, and data availability limited the extent to which the operation of mechanisms and outcomes could be fully evaluated. Where there was evidence of intervention delivery as intended, mechanisms and outcomes seemed to operate as anticipated. Therefore, the programme theory was adapted not in relation to the way the intervention was understood to work, but only with regard to the way it was implemented. Further evaluation of the validity of the programme theory was conducted during the clinical trial and process evaluation.

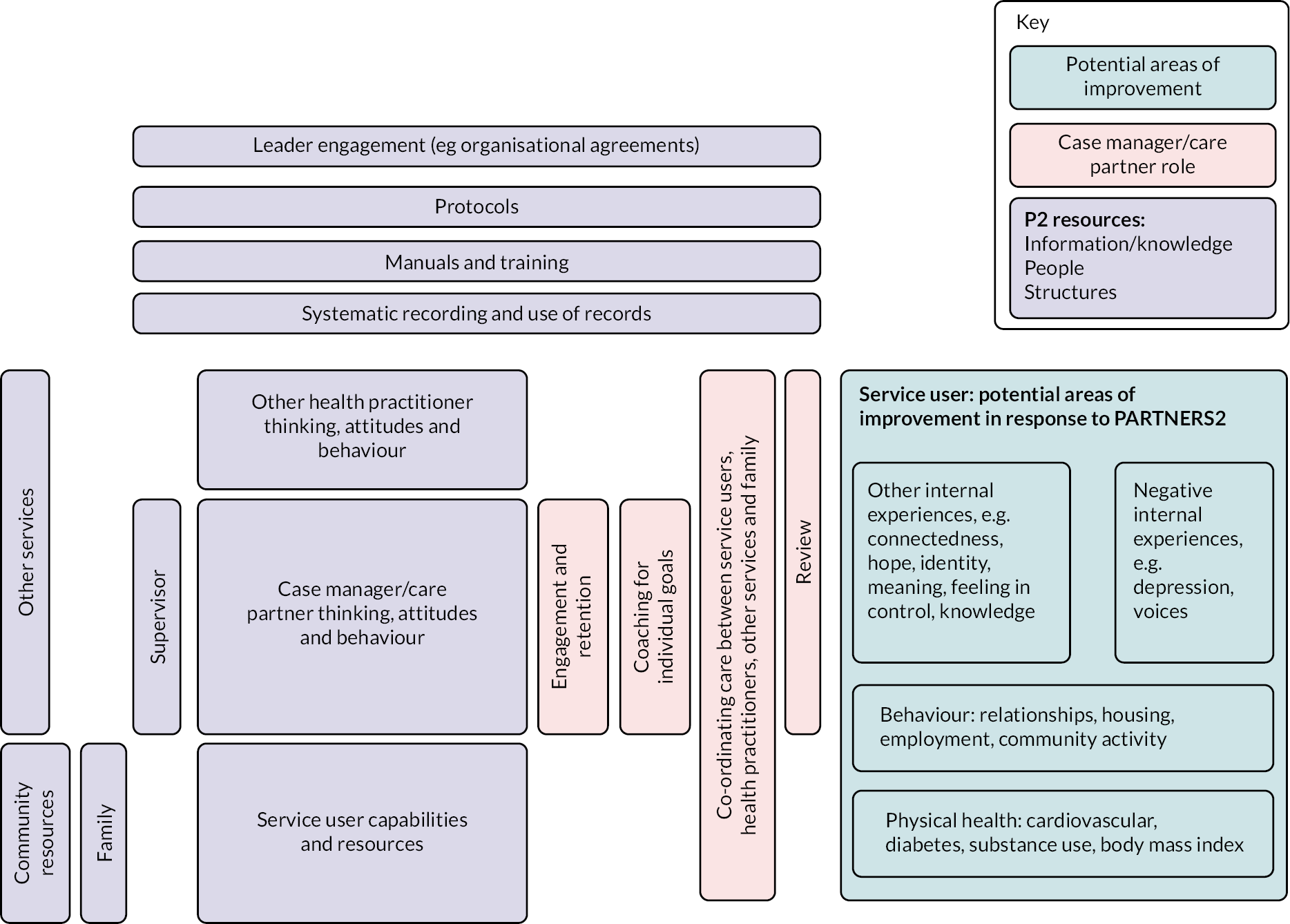

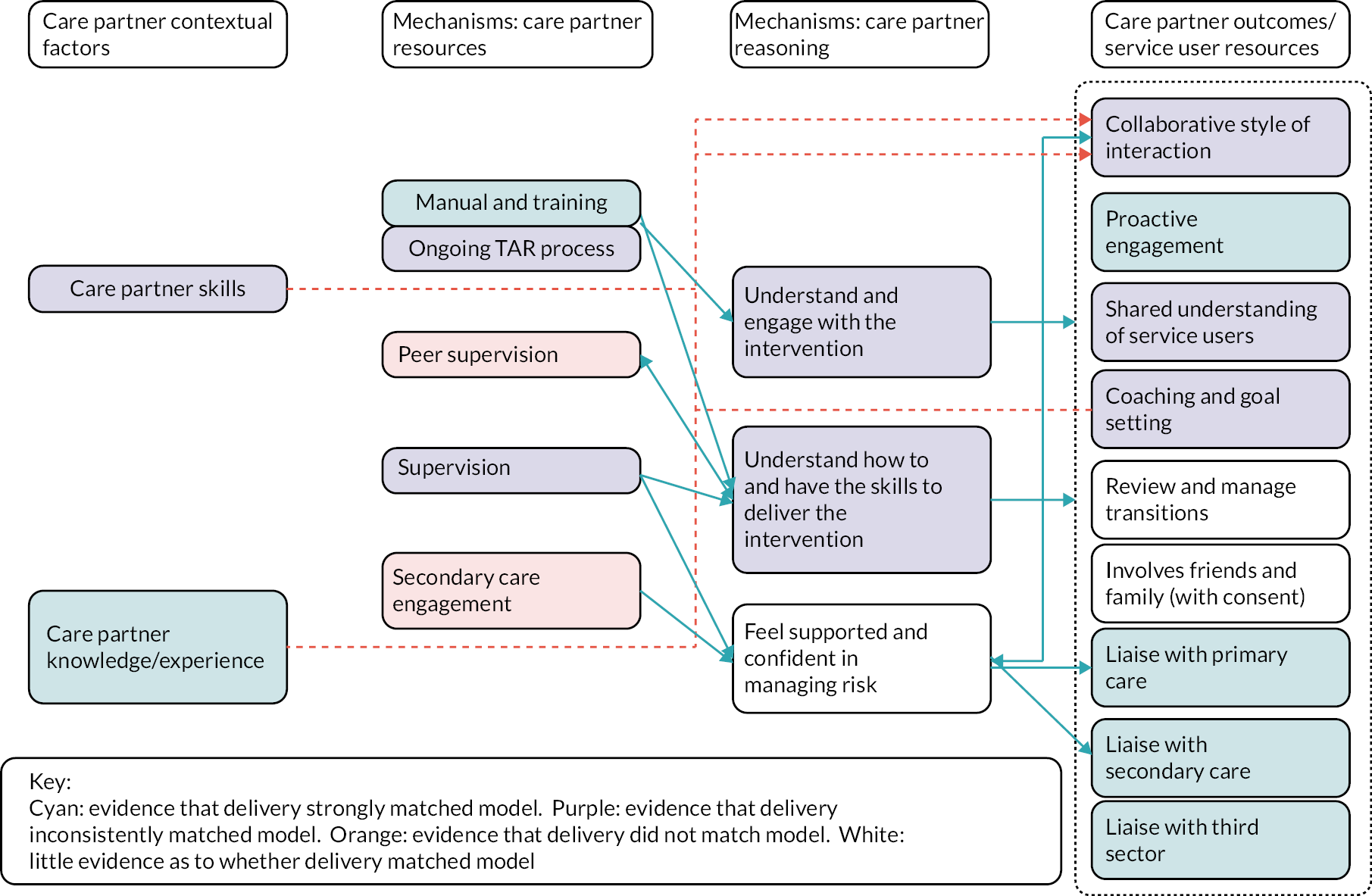

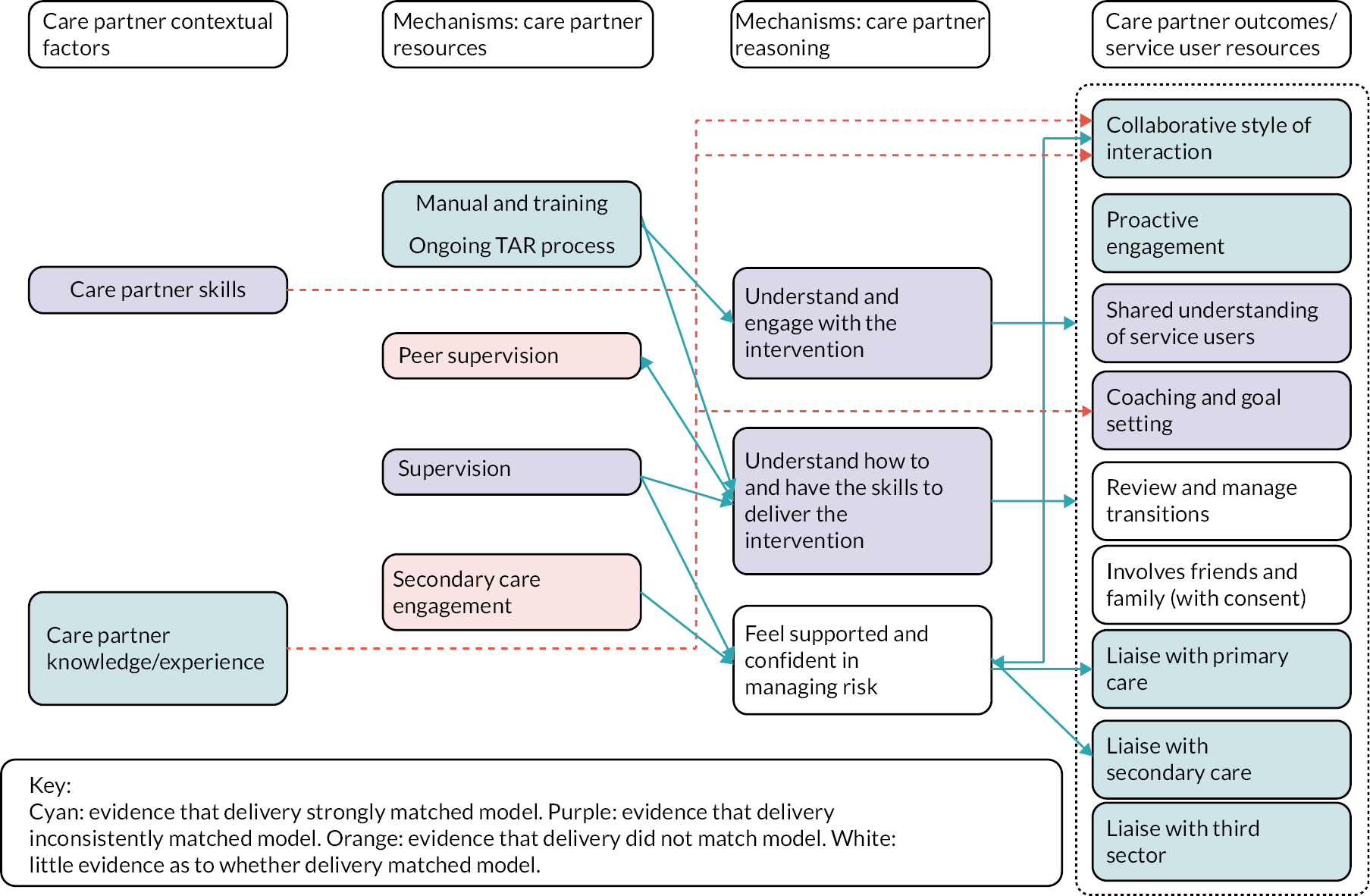

Description of the PARTNERS2 intervention

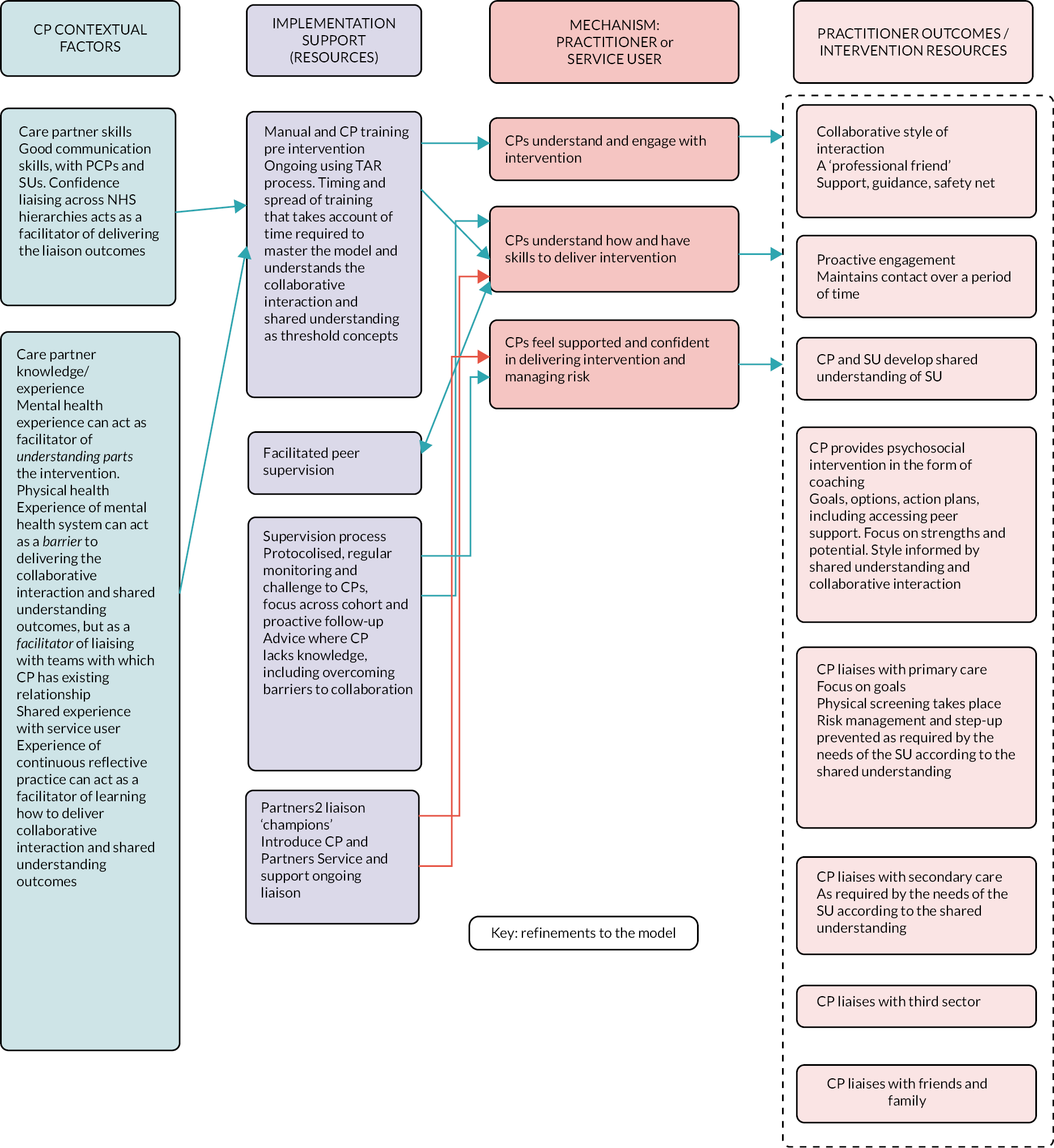

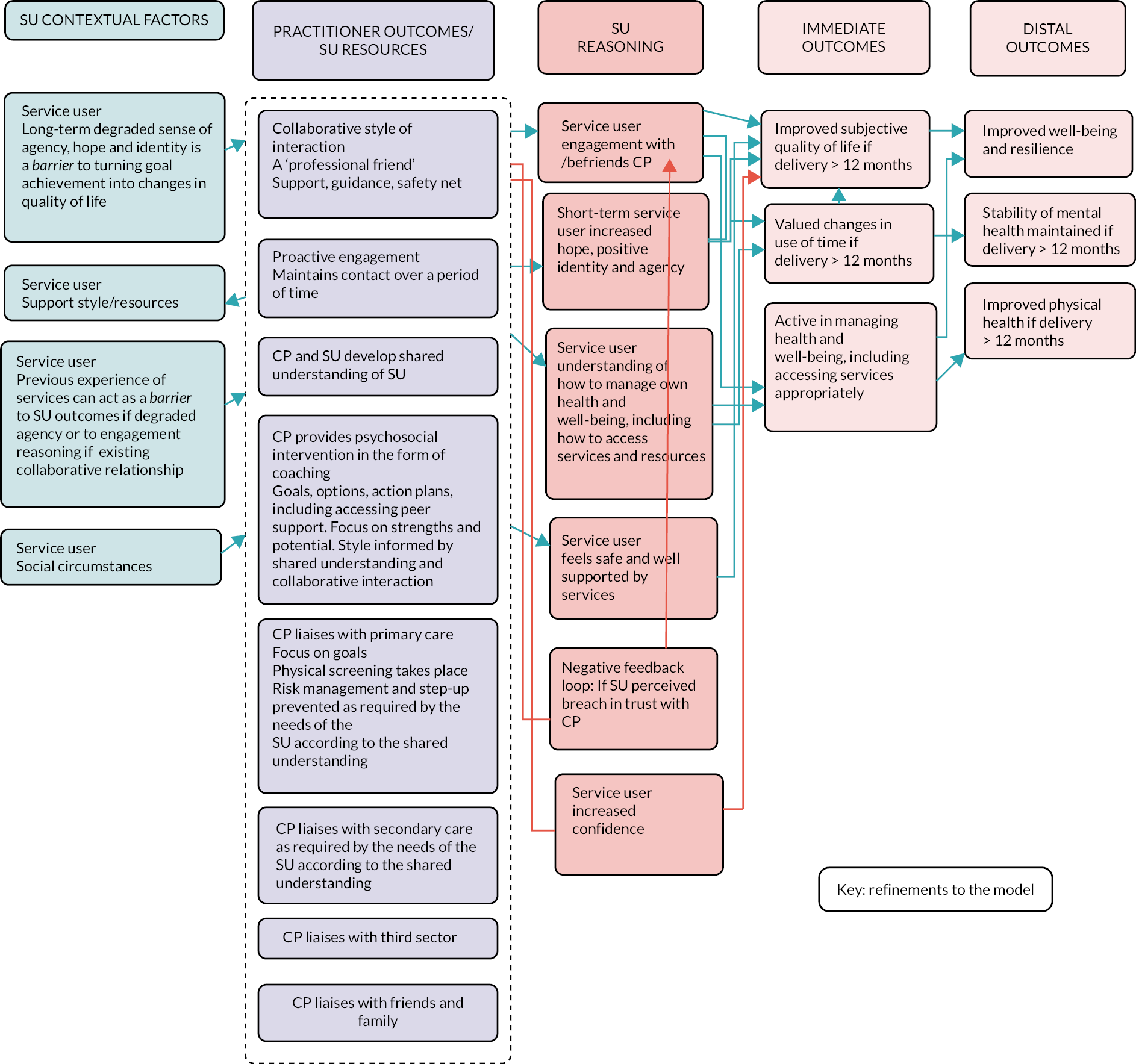

The intervention is complex, involving change at three levels, namely institutional level (secondary care trusts/CMHTs and primary care), practitioner level (care partners, supervisors, other primary and secondary care staff, third-sector and community organisational staff) and service user level (service users and friends and family, where there is consent). The 14 components are described in Table 3, and the relationships between contexts, resources, mechanisms (reasoning and reactions) and intermediate and intervention outcomes are shown in Figure 2. The manual is available as a supplementary file.

| PARTNERS2 intervention model component | Description |

|---|---|

| Underpinning conceptual models of collaboration | Wagner’s Chronic Care Model,33 the CHIME framework of personal recovery34 and coaching for mental health recovery39 |

| Identification of patients: method | Screening of patient records against inclusion criteria ensures a systematic approach to patient caseload |

| Identification of patients: setting | Primary and secondary care |

| Provider integration | Specialist mental health practitioner (a ‘care partner’) from a CMHT is sited in primary care practices |

| Multidisciplinary working | The care partner works alongside primary care practitioners under the supervision of a qualified mental health practitioner (from any mental health profession). The supervisor is based in a local secondary care CMHT. A linked psychiatrist is available if required |

| Systematic communication between providers | Care partners share patient records including progress notes and care plans; co-location supports face-to-face communication between care partners and primary care practitioners |

| Case management | Care partners co-ordinate care, liaising with other practitioners (primary and secondary care; third-sector and other community organisations) and friends and family to make sure an individual’s needs are met |

| Study protocols/treatment algorithms | Manuals (care partners, supervisors, GPs, service users, friends and family) describe the principles and approaches of the Partners Service, which includes flexible response to individual needs. A supervision protocol specifies clinical, caseload and pastoral guidance and support |

| Systematic monitoring and follow-up | Service users are reviewed regularly at negotiated intervals; session intensity and interval are varied according to an individual’s need. Minimal support is three telephone contacts per year; standard service involves more frequent face-to-face contact. Care partners routinely monitor mental health through standardised scales and/or patient notes |

| Pharmacological intervention | Pharmacological intervention is part of the PARTNERS model only when desired by the service user as a goal, and could involve an action plan or review by the linked psychiatrist or GP |

| Psychological intervention | Care partners follow principles of coaching to work with service users towards personally meaningful goals. These might necessitate more social or more medical care. Additionally, elements of motivational interviewing are included, for example to support individuals to consider changes in lifestyle. Individualised action plans identify relevant resources and agreed steps to support service users to take action to work towards goals |

| Education for mental health/primary care practitioners | Two-day training before start of practice for care partners and supervisors, based on the practitioner manual; regular follow-up training for care partners; training provided by research team including lived experience panel. Primary care induction for staff members to familiarise them with the PARTNERS model |

| Patient education/promoting self-management | Care partner provides information and draws on motivational interviewing approaches to increase knowledge of self-management strategies and motivation to improve physical and mental health |

| Collaborative relationship with patients | Care partners adopt a collaborative, egalitarian style of interaction with service users following coaching principles, to support the empowerment of service users in relation to CHIME (connectedness, hope, identity, meaning and empowerment) principles |

FIGURE 2.

Depiction of the PARTNERS2 initial model.

Development of trial methodology (phase 1: workstreams 2, 4 and 5)

Development of a set of outcomes for a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the PARTNERS2 intervention (workstream 2)

Background

A COS was developed for use in community-based bipolar trials. The protocol and results papers have been published as Keeley et al. 40 and Retzer et al. 41 Our aim was to suggest a small number of agreed outcomes to be collected and reported in all trials within this research area.

Methods

The method was a three-stage process:

-

a long list of outcomes was derived from (1) focus groups with people with a bipolar diagnosis and friends/family, (2) interviews with healthcare professionals and (3) a rapid review of outcomes listed in bipolar trials in the Cochrane database

-

an expert panel of people with personal and/or professional experience of bipolar participated in a modified Delphi process; Reproduced with permission from Retzer et al. 41 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

-

a consensus meeting was held to finalise the COS.

Focus group and interview recordings were transcribed and analysed together as the purpose of analysis was to identify all possible outcomes. Transcripts were uploaded to Dedoose42 online qualitative data management software to manage and support data analysis. Dedoose was used to organise the qualitative data collected during the focus groups and one-to-one interviews to generate the outcome longlist, and descriptive accounts of the interviews and focus group discussions. Reproduced with permission from Retzer et al. 41 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. The Cochrane database was accessed in March 2015, and two researchers independently performed a complete search of all pre-categorised titles listed under the bipolar reviews on the Cochrane database for systematic reviews. The outcome list was then reviewed during a multidisciplinary stakeholder meeting composed of academic researchers, LEAP members and a carer.

Participants from the UK were invited to complete a two-round Delphi survey co-developed with service user researchers. People with a bipolar diagnosis and carers were recruited nationally through local support groups, electronic advertisement via third-sector organisations and social media. Health and social care professionals and researchers were recruited through the professional networks of the PARTNERS2 research team. Purposive sampling was used to capture a range of professional roles and supplemented as required through snowball sampling. A screening tool was developed to monitor sample diversity and inform and direct recruitment. A paper-based version of the survey was available on request.

The Delphi survey was hosted by Delphi Manager software. 43 Participants were asked to rate each of the outcomes on a nine-point Likert scale and invited to suggest outcomes they considered were absent from the stage 1 and 2 longlist. Suggestions were automatically included for rating in round 2. Following the closure of round 1, the software internally calculated the stakeholder group's ratings of each outcome.

A consensus meeting44 was attended by the research team, LEAP members, participants of the Delphi survey and people who had been unable to participate in the Delphi but had expressed an interest in attending the meeting.

Results

Three focus group discussions were held, ranging in size from four to eight people between July 2014 and March 2015. Telephone interviews with healthcare professionals and researchers (n = 16) took place between July and November 2014. In total, 76 outcomes were identified (including 20 duplicates).

Data were extracted from 17 bipolar reviews in the Cochrane database, and a further 45 outcomes were identified. Following the multidisciplinary stakeholder meeting to review the 101 outcomes, 47 were merged and 12 more were added.

Fifty Delphi participants were recruited to participate in round 1 of the Delphi survey between September and December 2016, and round 2 was open from December 2016 to February 2017.

Sixty-six outcomes were included in the survey, and a further 13 were added by participants during round 1. Three of the suggested outcomes were rated as important by participants in round 2 and so were included in the consensus meeting discussion. The consensus meeting was attended by 14 people (six healthcare professionals, five people with a bipolar diagnosis, two carers and one researcher) and took place in September 2017.

The final COS comprised 11 outcome domains: personal recovery; connectedness; clinical recovery of bipolar symptoms; mental health; well-being; physical health; self-monitoring and management; medication effects; QoL; service outcomes; service user experience of care; and use of coercion.

Additional work to select primary outcome for PARTNERS2 trial

To account for the wider psychosis target population in PARTNERS2, and the nature of the intervention, we undertook an additional and separate more pragmatic stakeholder consultation to select outcomes and measures for use in the trial. This involved service users and carers, practitioners and researchers. A presentation of key decisions was followed by a discussion, ensuring that everyone’s views were registered. The aim was to select a set of outcomes, with associated validated measures, that reflected the needs of individuals and would also assess the effectiveness of the intervention model. We needed a primary outcome measure that was sensitive to change and had good psychometric properties and face validity for stakeholders; and also a set of measures that not only reflected outcomes desired by service users (as in COS work) but could be delivered by the intervention according to its internal logic.

Quality of life was selected. It is a common outcome in trials of SMI, although it was not prioritised in our COS work. Relevant measures of QoL were reviewed, and the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) was selected because it was clinically relevant to the target population and potentially amenable to change by the intervention. The MANSA has good validity and reasonable internal consistency. 45 A range of other secondary measures were also agreed as described in the trial protocol paper,46 covering several of the COS domains identified, including QoL, recovery and experience of care.

Development of recruitment processes (workstream 4)

Background

Recruitment to trials is often slow, and feasibility needs to be tested. The PARTNERS collaborative care intervention necessitated the recruitment of secondary care providers, GP practice clusters and individual participants. In the feasibility phase, we tested the recruitment of practices and participants alongside the formative evaluation of the intervention (workstream 3).

Methods

Potential participants were identified by clinical research network (CRN) staff and clinicians screening patient lists in primary and secondary care. Those eligible from secondary care were approached by a clinician known to them. Those seen in primary care were sent an invitation letter with an expression-of-interest form by the GP practice. Those indicating interest were contacted by the research team. Recognising difficulties in recruiting the target population, we trialled two strategies to improve recruitment, both of which were acceptable to participants and improved response rates:

-

Those who did not respond to initial contacts received a telephone call from a clinician or the research team to discuss the study (Lancashire and Devon).

-

Those who did not respond to initial contact received a ‘rapid invite appointment letter’ inviting them to a short meeting with a member of the research team to discuss the study (Devon and Birmingham).

The research objective in this stage was to recruit participants to receive the intervention and to collect qualitative data to refine the intervention. Therefore, we did not test collection of quantitative outcome measures. Instead, trial outcome measures were piloted with LEAP members.

Results

Table 4 shows the feasibility stage recruitment numbers.

| Secondary care provider | GP practices | Individual participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number approached | Number recruited | Number eligible | Number recruited | |

| Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust | 4 | 1 | Data missing | 6 |

| Lancashire Care Foundation Trust | 3 | 3 | 70 | 21 |

| Devon Partnership NHS Trust | 2 | 2 | 67 | 10 |

Pragmatic recruitment of secondary care providers utilised existing relationships, with the intention of covering a range of sociogeographic demographics. GP practice recruitment was also pragmatic, based on ease of location access and existing relationships. Where there was no existing relationship, practices were initially approached by letter and telephone call, with a follow-up face-to-face meeting with the practice team. Supporting this process was a study website built with our LEAP members, containing videos and information to describe the trial: www.partners2.net

Setting up the randomised controlled trial (workstream 5)

Transfer of both the intervention and the trial procedures to the RCT was not straightforward because of a combination of NHS pressures and the implementation of more stringent national research governance measures.

We had assumed that secondary care partners in the feasibility study would continue their participation into the RCT stage. However, changing NHS financial landscapes, staffing resource pressures, and GP (clusters) recruitment delays led to two trusts (Devon and then Lancashire) withdrawing. Consequently, we lost care partners who had been trained over a period of 2 years, including in the feasibility phase. Replacement sites to identify and train care partners were approached based on access considerations for the research team, and maintaining sociogeographic demographics (e.g. an urban/rural mix). We required substantially greater numbers of GP practices for the RCT. Although our approach mirrored the feasibility stage, it had not been possible to test the time and staff resource required or the local variation in response when recruiting a larger sample.

We intended to identify potential participants for the trial using the process trialled in the feasibility stage. However, local, changing, interpretations of research and information governance requirements meant that it was deemed inappropriate for the research team to view patient records prior to patient consent, even with permission from the practice and ensuring that no data left the practice. Therefore, primary/secondary care staff were required to identify potential participants. This is a time-consuming task, the reallocation of which led to a delay in participant recruitment. The onerous nature of this task also adversely affected practice recruitment. There were differences across regions in whether CRN-funded NHS research staff could and should support hard-pressed practice staff to carry out this screening of patient records.

We also sought ethics permission to send an invitation letter, followed by an accompanying telephone call, to potential participants who had not returned an expression of interest. The follow-up telephone call had to be undertaken by a clinician because of the governance changes noted above. Not all sites had the resource to provide this call; later in the programme, permission was obtained for NHS research staff to make these calls, which was associated with a boost in recruitment.

Phase 2

Phase 2 consisted of a RCT (initially an internal pilot trial), a health economics cost-effectiveness analysis and a mixed-methods parallel process evaluation.

Randomised controlled trial, cost-effectiveness study and process evaluation (workstream 6)

Cluster randomised controlled trial

Background

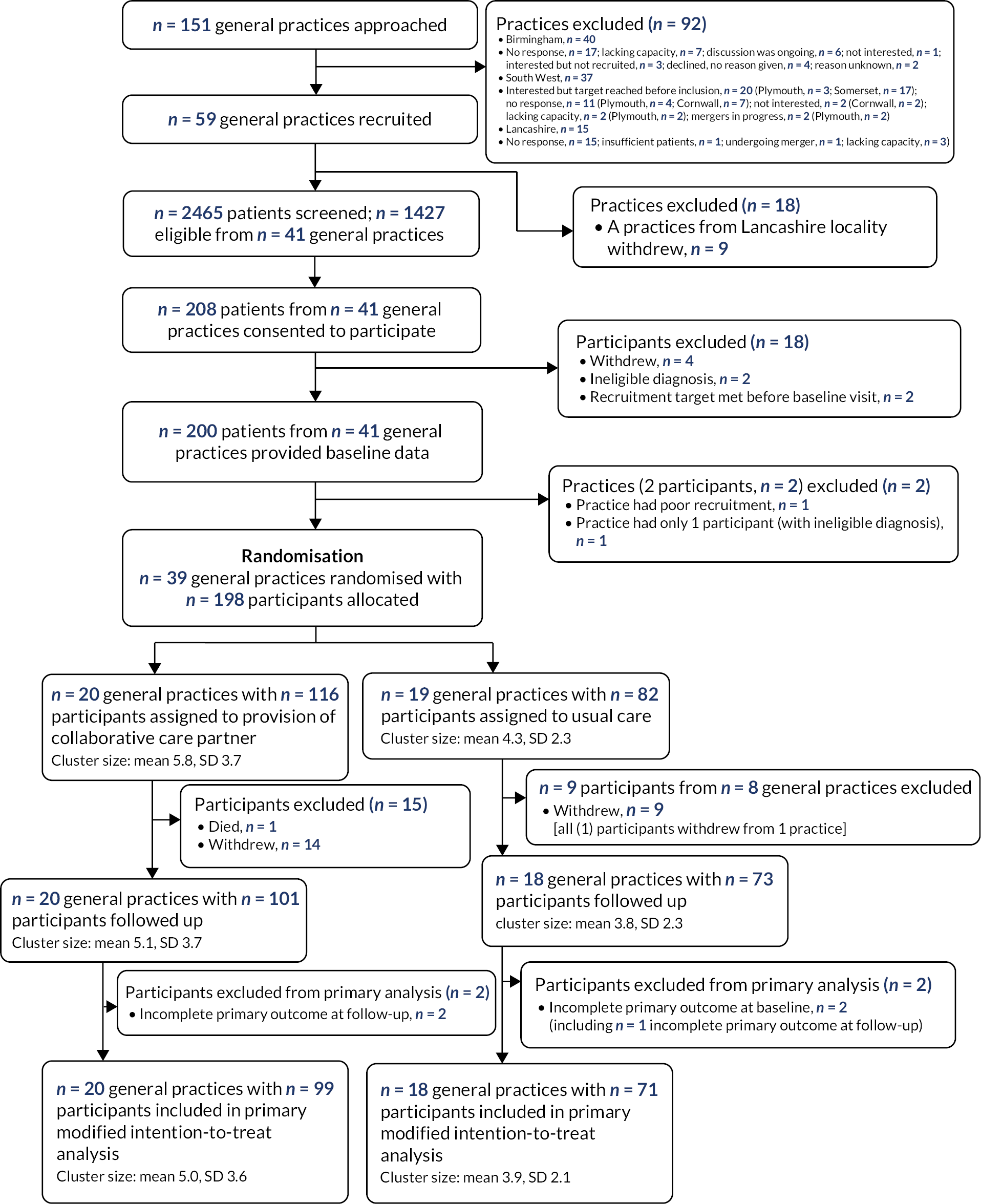

The aim of the definitive trial was to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the developed primary-care-based collaborative model (PARTNERS) for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or other psychoses on improving QoL. The protocol paper for the trial has been published as Plappert et al. 46 A paper detailing the trial results has been accepted for publication (Byng et al. ; Figure 3). 47

FIGURE 3.

CONSORT diagram. SD, standard deviation.

Method

The study used a cluster randomised controlled superiority trial design, the clusters being general practices in regions in England. Participants had to be consented and have their baseline measures collected before the practice was allocated (1 : 1) to either the PARTNERS (intervention) or the care as usual (control) group. Allocation was minimised on region and practice size.

The PARTNERS intervention (see Table 3) was compared with care as usual, which was the support being provided by primary and secondary care services at the time. Participants allocated to the PARTNERS2 intervention received up to 12 months of the intervention, including a 2-month transition back to care as usual. Care partners included nurses and support workers. Follow-up was planned at 10 months post unmasking but was brought forwards to 9 months for the final participants.

The primary outcome measure was the participant-reported overall MANSA score,45 measured at baseline and follow-up. Secondary outcome measures included Time Use Survey (TUS),50 Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR-15),49 the full and short version of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale [(S)WEMWBS],39 Brief-INSPIRE,51 ICEpop CAPability (ICECAP-A)52 and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 53 All participant-reported outcomes were collected at baseline and follow-up during an interview with a research assistant. Research assistants asked participants to also fill in self-complete measures; self-reported lifestyle outcomes included smoking, alcohol consumption, cannabis use and healthcare monitoring, as well as safety outcomes [number of psychiatric hospital admissions; number of days as an inpatient as a result of psychiatric admission; number of episodes under home treatment and total days under home treatment (crisis care); and serious adverse events (SAEs)].

Participants who experienced COVID-19-related restrictions during their study involvement were asked additional questions at follow-up to increase understanding of how lockdown and social distancing impacted on their mental health, access to physical health care and usual activities.

Primary analyses were on an intention-to-treat basis. The target between-group difference was 0.45 points in the overall MANSA score and assuming a standard deviation of 0.9. This is equivalent to a standardised effect size of 0.5. The original recruitment target was 336 participants from ≈ 56 clusters (each with a mean of six participants recruited) to achieve 90% power. This was revised to a target of 204 participants from ≈ 34 practices to achieve 80% power.

Analyses were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan,54 approved by the TSC prior to database lock. In summary, outcomes were analysed using a Gaussian random-effects regression models, including the cluster-level minimisation factors (region and practice size), individual-level baseline score as fixed-effects covariates, and GP practice as a random effect. Prespecified subgroup analyses of the primary outcome added the interaction effect of allocated group and the subgroup [(1) region, (2) practice size, (3) diagnostic group and (4) usual care provider at screening]. Four sets of sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome were originally planned; a further three were prespecified to explore the potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the primary outcome and the secondary outcome of TUS.

Results

Thirty-nine general practices were recruited and randomised: 20 to the intervention group (116 individual participants recruited) and 19 to the care as usual group (82 individual participants). Around two-thirds of participants were under primary care for their mental health needs at the time of recruitment, just over one-fifth (22%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 58% had a diagnosis of bipolar. Over 60% of participants were female and around 40% were single at recruitment. Only eight (4.1%) were black, five (2.5%) Asian, four (2.55%) mixed and one (0.5%) other.

The two groups were reasonably balanced in terms of individual-level baseline characteristics. Over 87% of recruited participants were followed up (101 in the intervention group and 73 in the care as usual group).

At baseline, the mean overall MANSA score in the intervention group was 4.29 (SD 0.88) points and 4.33 (SD 0.99) in the care as usual group. At follow-up, mean scores in both groups improved slightly, to 4.54 (SD 0.82) and 4.51 (SD 1.01) in the intervention and care as usual group, respectively. The change in overall MANSA (primary outcome) could be calculated for 99 (85%) participants in the PARTNERS2 intervention group [mean change 0.25 (SD 0.73)] and 71 (87%) participants in the care as usual group [mean change 0.21 (SD 0.86)]. The improvements in mean overall MANSA score did not differ significantly between the groups, with the fully adjusted mean between-group difference of 0.03 [95% CI (intervention minus care as usual) −0.25 to 0.33; p = 0.819]. All sensitivity analyses, including complier-average causal effect (CACE) analyses, were in agreement with the primary analysis. There was no evidence of a differential intervention effect in any of the four prespecified subgroup analyses.

There was no evidence of statistically significant differences between allocated groups in terms of the secondary outcomes. Numbers and patterns of missing data in the Brief-INSPIRE measure at both baseline and follow-up meant that these data were only summarised descriptively.

While there were some differences in the summary statistics of participants who completed the trial before COVID-19 and those who were followed up during the pandemic, there was no evidence of a statistically significant impact of COVID-19 from any of the associated, prespecified, sensitivity analyses for either MANSA or TUS. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the planned review of primary care notes was possible for only 31 participants and so we were unable to obtain data on healthcare monitoring.

Seven participants had one recorded mental health episode each, of which three occurred after at least one recorded interaction with a care partner. Twenty-eight SAEs were reported in total, in 18 participants, with 11 categorised as mental health problems and none deemed to be related to PARTNERS2. Thirteen of the SAEs were reported in participants after they had had at least one recorded interaction with a care partner.

Health economics analysis

The health economics study comprised a set of cost-effectiveness analyses. This is described below and in Appendix 1.

Cost-effectiveness study

Background

The economic evaluation aimed to estimate the cost-effectiveness of PARTNERS2 compared with usual care, from the NHS and social care (costs) perspective, over the scheduled follow-up of 10 months.

Method

Quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) measured health benefit, as recommended by NICE. 55–57 Patient-level service use data were costed using national unit costs58,59 for 2019–20. The primary outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which combines service use costs and health benefit.

Participant-reported service use at follow-up was collected for a 3-month, rather than 10-month, recall period to reduce the burden to participants of recalling service use over a longer period and to balance complete service use data against incomplete recall, inconsistent or missing data, and limited resources for data collection. An audit of primary and secondary care notes was planned to collect (1) key high-cost psychiatric secondary and crisis care services that may not be used within the 3-month recall period at follow-up and (2) GP, practice nurse and other GP practice consultations. However, the latter was not feasible given the impact of COVID-19 on access to practices.

A generalised linear model (gamma, log) predicted a cost per day of participant-reported service use at follow-up for the pooled data, adjusting for baseline covariates. This was combined with the costs of mental health related admissions and crisis care from the secondary care audit to estimate the full cost from baseline to the end of follow-up. Missing baseline measures of cost, utility and clinical indicators were single imputed with indicators for missing demographic data60 costs and QALYs for the pooled data set were multiple imputed. 61

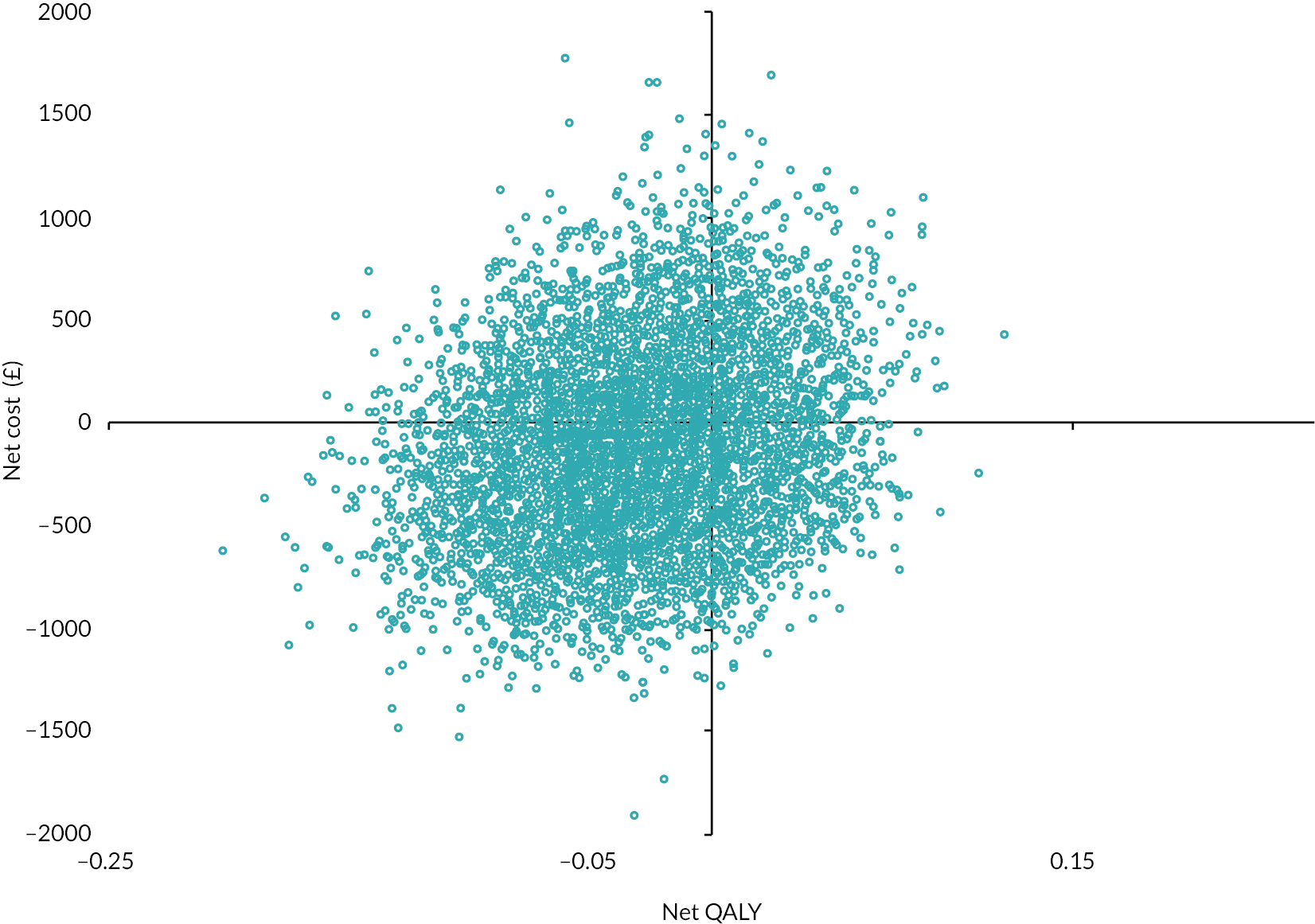

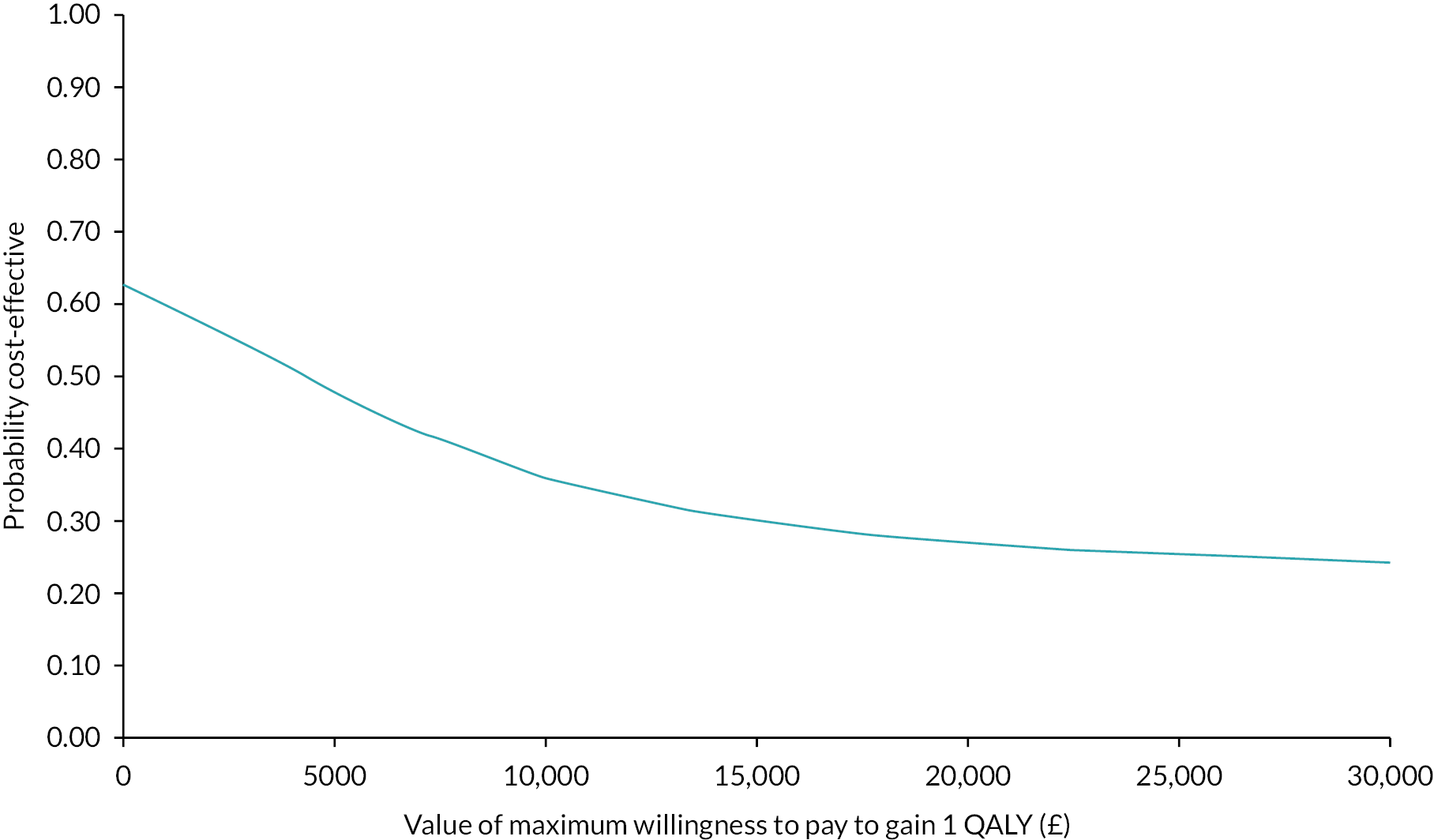

Results

Regression analysis estimated the net costs and QALYs of PARTNERS2, adjusting for key covariates. These estimated costs and outcomes were bootstrapped to estimate the probability that the PARTNERS2 intervention is cost-effective. Prespecified sensitivity analyses assessed whether alternative measures or analyses could change the conclusions of the economic analysis. Using the multiple imputed data, the average QALYs (usual care: mean 0.55, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.61; PARTNERS2: mean 0.51, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.57) and costs (usual care: mean £2689, 95% CI £999 to £4378; PARTNERS2: mean £1743, 95% CI £1149 to £2338) were similar for the two groups. Overall, the 95% CIs are wide and overlap, indicating a high level of variance and uncertainty. The net, bootstrapped QALYs (−0.007, 95% CI −0.086 to 0.071) and costs (−£213, 95% CI −£1030 to £603) were similarly inconclusive, with wide 95% CIs that overlapped zero. At the prespecified willingness-to-pay threshold (WTPT) of £15,000 to gain one additional QALY, the probability that the PARTNERS2 intervention is cost-effective is < 50% for the primary and all sensitivity analyses.

The major limitation to the economic evaluation is that the service use data available to generate cost estimates for the full follow-up period were restricted by the fact it was not possible to complete the service audit of primary care records. Consequently, the costs of the full follow-up period were predicted from the 3-month participant-reported costs combined with the secondary care audit. The data constraints and uncertainty in the data mean that there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about the overall cost-effectiveness of PARTNERS2.

Parallel process evaluation

Delivery and fidelity analysis

Background

The monitoring, measurement and assessment of intervention delivery and fidelity are important, as it has been demonstrated that fidelity can be a mediator of study outcomes. If interventions fail to produce a desired or expected outcome, this could be due to poor implementation rather than a lack of effectiveness of the intervention. In recent years, a science of intervention fidelity has grown, but a debate continues about the nature of the core elements to be measured. Behaviour change taxonomies have been developed62 in an attempt to standardise approaches when studying complex interventions in community settings.

Increasingly sophisticated work has identified five domains of fidelity: study design, training, intervention delivery, intervention receipt by participants and intervention enactment, defined as the extent to which participants apply the skills learnt. Receipt and enactment have been defined as ‘engagement’ by some authors. 63 Despite some real progress, no gold standard for engagement exists, and psychometric properties of fidelity scales are infrequently reported. 64

Method

Two methods were used. First, a set of research instruments was developed to capture the extent and reach of delivery by the care partners (see Appendix 2). These included details of when and how contacts were made, the key activities delivered in sessions and the extent of supervision. They were completed by care partners with support from researchers. We also documented periods of care partner absence.

Second, the PARTNERS2 Collaborative Care Fidelity instrument was designed to capture the intervention programme theory: what it was meant to do from the perspective of the individual receiving the intervention. The research team developed the instrument by following the steps outlined by Walton et al. 63 These steps include the following: (1) reviewing previous measures, (2) analysing intervention components and developing a framework outlining the content of the intervention, (3) developing fidelity checklists and coding guidelines, (4) obtaining feedback about the content and wording of checklists and guidelines and (5) piloting and refining checklists and coding guidelines to assess and improve reliability. Reproduced with permission from Walton et al. 63 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. The instrument was piloted by LEAP members and contained 26 items relating to various aspects of intervention delivery and impact.

Results

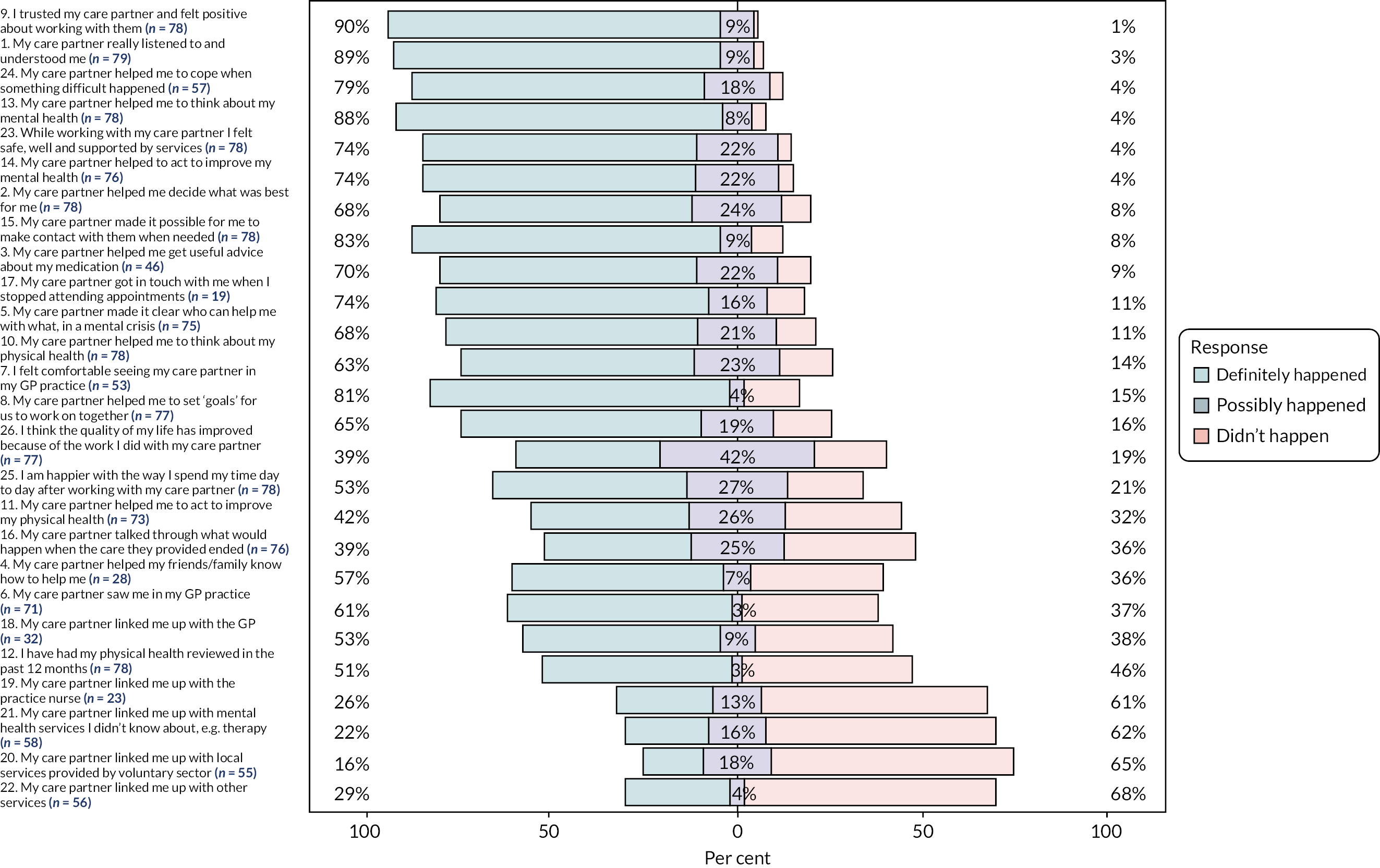

A care partner was in place for at least 70% of the intervention period for 75% (15/20) of the intervention practices, and the majority of intervention group participants (91%) had at least one care partner interaction of any type. Care partners reported discussing goals with 101 participants (87%).

Of the 116 participants in the intervention group, fidelity questionnaire data were available for 81 (71%). The distribution of responses (frequencies and per cent) to individual items is reported in Table 11 (see Appendix 2). Figure 4, from which ‘not applicable’ responses were excluded, shows the proportion of those receiving the intervention (and who considered the question applicable to them) who recognised if they had received key components. Over half of the respondents to the fidelity instrument reported that 19 out of 26 items definitely happened. Overall, the data suggested that fidelity to the PARTNERS model was more likely to have occurred with interpersonal practices (e.g. listening and understanding, 89% of those who considered this question applicable to them, n = 70/79) than activities related to the co-ordination of care (e.g. linked to GP, 53% of those who considered this question applicable to them, n = 17/32).

FIGURE 4.

Participant responses to the fidelity questionnaire. Figure excludes ‘not applicable’ responses. Questions 1–14: 0 = didn’t happen, 1 = possibly happened, 2 = definitely happened; questions 15–26: 0 = no, 1 = to some extent, 2 = yes.

Future work will investigate the psychometric properties of the PARTNERS2 Collaborative Care Fidelity instrument, including divergent (or discriminant) validity, item homogeneity and data reduction analyses.

Realist process evaluation

Background

An integrated realist qualitative process evaluation was designed to assess delivery against programme theory, evaluate changes in care partner understanding and behaviour over time, and further develop the programme theory for implementation.

Methods

We purposively sampled care partners, supervisors, service users, friends and family members, and relevant health professionals from the four participating final trial sites. All care partners and supervisors were invited to take part. Service users were purposively sampled to capture geographical locations, demographics and interim data analysis.

Data collection comprised semistructured interviews; audio-recordings of intervention sessions between care partners and service users; tape-assisted recall interviews conducted separately with the participating care partners and service users; audio-recorded supervision meetings; reflective practice logs; and researchers’ observations and field notes, initial training and local top-up training sessions. COVID-19 pandemic restrictions led to changes in both remote data collection to incorporate more telephone interviews and recordings, and separate rapid realist evaluation of video-based interactions for remote delivery.

Data analysis involved the construction of case studies for care partners and service users, drawing on the above data sources. Evaluative coding and then within- and cross-case analyses enabled the exploration of delivery compared with the theory model, and the subsequent refinement of programme theory for implementation. LEAP members were involved in designing data collection tools, analysis and interpretation. A COVID-19 substudy examined delivery during the pandemic. Data collection and preliminary analysis were completed before the trial results were know in order to minimise interpretive bias.

Results

Semistructured interviews (n = 46) were conducted. Ten intervention sessions were recorded, followed by tape-assisted recall interviews with care partners and service users. Eight in-depth case studies for care partners and 15 in-depth case studies with service users were constructed.

We identified that practitioners need time to make changes to their practice in order to adopt more equitable relationships and shared understandings with service users. Having experience in reflective practice acted as a facilitator of making these changes. Previous experience working in mental health care may necessitate the unlearning of existing practice. Liaison with primary and secondary care was enabled by supplementary support, from existing relationships, strong introductions, or having a ‘PARTNERS champion’ within the primary or secondary care team. We have less information regarding supervision, because of inconsistent delivery, or the involvement of friends and family members, as most service users declined the involvement of these.

Service users sometimes framed their relationship with their care partner as that of a ‘professional friend’ or similar, and they valued the development of a collaborative relationship and shared understanding. These relational aspects of the PARTNERS service were important for fostering confidence, agency and identity, which were necessary conditions for thinking about and developing goals. Long-term poor agency and identity were barriers to working on goals.

The COVID-19 substudy identified that remote delivery was possible, although to be optimal it required a skilled care partner who had extensive experience of PARTNERS and was confident in using digital technologies, or who was comfortable modelling their vulnerability with technologies to service users. Some service users preferred telephone. Some individuals who lacked access to digital technologies appear to have been disenfranchised from the advantages of video.

Suggested theory refinement

Previous experience working in mental health care may act as a barrier to adopting care partner practice but as a facilitator of liaising. Care partner building of relationships with primary and secondary care can be facilitated by staff within these teams. Training and supervision should account for these factors. Core processes are the development of a collaborative relationship and shared understanding. Developing positive identity, improved agency and resilience are key interim outcomes for some service users. These are necessary for working towards goals and can be more important than goal attainment.

At an institutional level, supervisors need to be allocated sufficient time to understand the model and to support care partners. Care partners need not necessarily hold specific mental health experience; existing ways of working may act as a barrier to learning the model, whereas existing relationships with other practitioners may be a facilitator. This may be different if system-wide cultural changes in practice have taken place, as suggested by the new Community Mental Health Framework (CMHF) (NHS, 2019). 15 The difficulties in increasing identity, agency and resilience for long-term service users need to be acknowledged.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was embedded across the PARTNERS2 programme from the outset. Original co-applicants included both an applicant with bipolar and a McPin Foundation director. Patient involvement in PARTNERS2 has been an integrated element with clear decision-making responsibilities:65 LEAPs, service user research assistants (SURAs), TSC and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) members. Across the research team, including at co-applicant level, others also drew on lived-experience expertise where appropriate. Reflections on this have been published by the PARTNERS 2 writing collective (2020). 66

To embed PPI, we co-produced a ‘ways of working’ document in collaboration with all members of the study team to frame and help develop working practices guided by the National Survivor User Network 4PIs. 67 PPI has been crucial in PARTNERS2. Some significant contributions are highlighted below.

Three LEAPs, consisting of service users and carers, were recruited in 2014, and included individuals with a range of diagnoses. Members were selected for their life skills as well as mental health experiences matched to a role description specification. Each study site – Lancashire, Birmingham and Devon – had its own LEAP, which met quarterly. An impact log was kept to track ideas and decisions. Members also attended full team sessions with the research and clinical team on an annual basis. Over time members took on more responsibilities for agendas and chairing meetings. LEAPs contributed to the development of the intervention and the trial design, as well as working across the different PARTNERS2 WSs. Meetings were held to problem-solve local issues, such as recruitment or engagement challenges, and to reflect on emerging findings. Membership remained stable throughout the study. Nineteen members worked collaboratively with the research team on a range of projects, developing recruitment materials, selecting the primary outcome and trial outcome measures, piloting outcome measures, reviewing data, and inputting to manuals for both service users and care partners. They also developed our study website design and content, contributing videos and scripts.

Three part-time SURAs, one per study site for the first 3 years of the study, worked alongside a PPI co-ordinator. Expertise from experience was used in various ways, including co-facilitating and co-chairing COS workshops and meetings; developing the intervention, including training care partners; writing recruitment materials, including a study leaflet containing SURA profiles; and recruiting trial participants. SURAs acted as a bridge between the LEAP members and the academic team, providing a dual perspective with their experiential expertise and research skills. We explored how SURAs, LEAP members and other members of the research team worked together in a peer-reviewed paper addressing PPI and co-production approaches. 67

In 2018, PARTNERS2 jointly won the NIHR Service User and Carer Involvement in Research Award in recognition of its PPI programme. We made some changes to the programme when we lost the Lancashire site in 2019, moving regional LEAP meetings to central sessions. During COVID-19 restrictions, the format of LEAP meetings was changed from face to face to online. Over time, research assistant staffing on the project changed as staff, including SURAs, left. We formally had only one SURA at the end of the study, but other team members drew on expertise from experience without carrying a specific peer or service user job title.

Discussion

Reflections on what was and was not successful in the programme

Key successes of the programme included iterative development of a theory-based intervention valued by individuals; an in-depth quantitative description of standard care; a COS for bipolar; an analysis of our partnership with service user researchers and the LEAPs; methodological innovations for complex intervention evaluation; and the delivery of a cluster RCT in adverse conditions. We report by WS and then more general reflections to provide a narrative over the life of the programme.

Workstream 1: understanding the context

We completed one of only a handful of quantitative descriptions of usual care for psychosis in the UK. However, hand-searching electronic health records from primary and secondary care to determine the nature of usual care was painstaking and time-consuming. The current lack of joined-up electronic health records both between secondary and primary care and within secondary care made this harder. We were unable to access social care and voluntary-sector records. We were able to provide new insights into the type of care received, showing that many people received high volumes of specialist mental health contacts and others much less, and also how the three locality health systems had distinct organisational patterns. The process of collecting the data, and delays in data transfer combined with the inconsistent nature of the data, meant that it was not possible to clearly identify pathways of care to develop the structure of the economic decision-analytic model as originally planned. Initial work indicated the need for a complex model that could account for the interactions between care providers in primary and secondary care as well as social care, and between participants and care providers. Limited data with which to populate such a model, combined with limited resources for the main trial, led to the decision to transfer the funding for this work to the trial.

The Cochrane review of collaborative care documented the range of interventions and outcomes measured and generated across diverse collaborative care type interventions for psychosis internationally. It is surprising how little knowledge there is about collaborative care – one of the only combined clinical and organisational models of care likely to support the integration for individuals with psychosis promoted by NHS policy. The review addresses this gap in knowledge, although the heterogeneity of studies limited clear conclusions about which components and underlying mechanisms may be responsible for benefit and which may be unhelpful or even counterproductive. The review also highlighted the low quality of existing evidence, underlining the importance of the PARTNERS2 trial.

Workstream 2: core outcome set work