Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/93/10. The contractual start date was in February 2015. The final report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Bywater et al. This work was produced by Bywater et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Bywater et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Social and emotional well-being

Social and emotional well-being in childhood refers to the ability of a child to express and manage their emotions in socially and culturally appropriate ways and to develop positive relationships with their parents, other adult caregivers and peers. 1,2 The development of social and emotional well-being requires many foundational competencies, skills and characteristics, including, for example, inhibitory control, emotion regulation, self-confidence, perspective-taking and attachment. 1,3 Throughout infancy and toddlerhood, the typically developing child experiences rapid cognitive and maturational changes that support the accomplishment of increasingly complex developmental tasks in social and emotional domains of development. 2 By age 20 months, infants can respond to their own name, recognise themselves, display interest in other people (e.g. adults and peers) and are able to engage in co-ordinated interaction with them. In addition, infants at this age can form attachments with their caregivers and develop internal working models of relationships, are capable of expressing basic emotions and can also regulate their emotions through self-soothing with support from adults. 3 These social and emotional competencies form the foundations of healthy development and school readiness.

There are strong continuities between infant social and emotional well-being and later life outcomes. Impaired social and emotional well-being in the early years increases the risks of negative outcomes throughout childhood and into adulthood. For example, longitudinal studies document increased risks of poor mental health, as well as increased risks of antisocial behaviour and criminality, and poor educational and employment outcomes. 4–6 Conversely, positive social and emotional well-being in the early years is associated with good health and development outcomes throughout the life course and provides a basis for adaptive resilience to future adversities. 4,7,8 Evidence suggests that promoting social and emotional well-being in the early years is more effective, and less costly, than interventions delivered later in life once difficulties are more entrenched. 9

Parent–child relationships play a critical role in the development of social and emotional well-being. Parenting practices, styles, skills and knowledge, as well as parental mental health, can have an impact on the quality of parent–child relationships and attachment bonds. Unresponsive parenting (e.g. when a parent is under stress or experiencing depression) can lead to ineffective parenting strategies and (inadvertent) emotional neglect. 2 Although the majority of research has been conducted with mothers, there is a growing field also documenting the influential role of fathers and other co-parents, such as grandparents, in the development of children’s social and emotional well-being. 10,11

Parenting interventions to promote infant social and emotional well-being

Parenting programmes are effective in reducing behavioural, social and emotional difficulties in school-aged children,12,13 as well as improving parent psychosocial health. 14 However, as highlighted by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2012, there is a gap in our understanding of the extent to which parenting and family-focused interventions are effective in enhancing social and emotional well-being specifically in infants. 15 An earlier systematic review found some preliminary support for the use of group-based parenting programmes to improve the emotional and behavioural adjustment of children aged < 3 years. 16 However, there was insufficient evidence to support any firm conclusions and further research on parenting programmes for younger age groups was recommended. 16 Although there is significant policy interest and increasing research in the area of early intervention and prevention [with the subsequent establishment of the Early Intervention Foundation (London, UK) and the 1001 Critical Days Manifesto movement], the evidence gap identified by NICE still exists.

The case of proportionate universal interventions

There has been a particular call for research on interventions provided to families within a framework of ‘proportionate universalism’. Proportionate universalism was first proposed in the Marmot review (2010)17 and refers to services designed to be delivered universally, but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of need or disadvantage. Proportionate universalism is a response to an overwhelming body of evidence highlighting social gradients of health, whereby people at the top have less threat to health than the deprived people at the lower end of the gradient. 29 A proportionate universalism approach argues that services will not reduce health inequalities if they are focused solely on the most disadvantaged in society; however, if we solely concentrate on the most disadvantaged then the health gradient will not decrease and will only tackle a small part of the problem’. 17

The Marmot review’s call to action included strategic objectives concerning the provision of proportionate universal parenting services. 17 Although there are numerous examples of parenting programmes for young children in the UK (see the Early Intervention Foundation’s Guidebook18), many such programmes are targeted at high-risk families or children who are already experiencing difficulties. Targeted approaches, although potentially effective, have been criticised for causing stigma towards parents experiencing disadvantage and, in turn, affecting the uptake of services. In addition, it has also been argued that targeted approaches often do not identify all children and families in need of additional support. 8 Proportionate universal approaches that embed interventions within existing universal services may improve uptake and interaction with, and access to, care. 8,16

Lack of proportionate universal interventions and evidence base

Despite clear potential, there is a large gap in the evidence base for proportionate universal interventions. A recent systematic review of universal parenting interventions for 0- to 2-year-olds reported a lack of evidence for effectiveness of interventions in the postpartum to 24-month period. 8 Although the quality of evidence was low, previous controlled studies reported no differences between intervention families and controls. The authors8 speculate that one reason for the lack of intervention effects may be a lack of behaviour change content in the programme theory for included interventions, despite their reliance on parental behaviour change as a mechanism for improving social and emotional well-being in infants. Hurt et al. 8 concluded that ‘there is an urgent need for robust evaluation of existing interventions, and to develop and evaluate novel interventions to enhance the offer to all families’.

The Incredible Years® parenting programmes

The Incredible Years® (IY) parenting programmes [URL: www.incredibleyears.com (accessed 6 January 2022)] are parent interventions that are underpinned by social learning theory and are designed to enhance the social and emotional well-being of children (aged 0–12 years). The programmes encourage rewards for behaviours in children parents want to see more of, while ignoring behaviours parents want to see less of. The IY programmes are manualised and delivered by trained leaders to groups of 10–12 parents for 2 hours a week for 10–14 weeks. The Incredible Years infant programme (IY-I) and Incredible Years toddler programme (IY-T) versions for 0- to 1-year-olds and 1- to 3-year-olds, respectively, build on decades of research evidence that demonstrate the effectiveness of the IY programmes for parents of children aged ≥ 3 years. Previously, the older-age IY programmes have demonstrated effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and transportability in independent trials across several countries/contexts. 12 Meta-analyses suggest that IY may be beneficial to younger children and their parents,19 and that families with severe depression and severe conduct problems demonstrate co-occurring changes for the better. 20 An analysis of data pooled from several IY trials suggested a large moderating effect for depression and that IY was more beneficial for children where parents were more depressed. 21

Evidence for the IY-I is slowly growing. 22 A small (n = 80) randomised non-targeted study in Wales, UK, showed that control mothers were significantly less sensitive during play with their baby at a 6-month follow-up. 23 In addition, a small trial in Denmark, delivered universally, found differential outcomes for the lowest and highest functioning families, suggesting that IY-I should be targeted (as originally designed). 24 Results from 12 IY-I groups (n = 79 group participants) showed parental benefits of improved mental health and parenting confidence post course (pre–post only, no comparator) and influenced a rural county in East Wales to scale delivery of IY-I. 25

Two IY-T trials, one in the UK26 and one in the USA,27 were inconclusive. The UK trial26 was a small community-based trial in Wales. The trial26 relied on geographical targeting to disadvantaged ‘Flying Start’ areas and did not always reach families that needed most support. The US trial27 delivered IY-T through primary care (i.e. paediatric practices), rather than community settings.

Both the IY-I and IY-T require further evaluation to establish their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness and to inform the evidence base. Neither IY or similar parenting programmes [e.g. the Positive Parenting Program (Triple P)28] have, to date, been delivered or tested using a targeted proportionate universal approach delivered in community settings.

Introduction to the E-SEE Steps model and its components

The Enhancing Social–Emotional Health and Well-being in the Early Years (E-SEE) Steps model is a unique multilayer intervention delivery model that combines three elements of existing IY programmes in a proportionate universal approach. The universal dose is the Incredible Babies book (IY-B), with two targeted group-based programmes (i.e. IY-I and IY-T) providing support at a greater intensity for those with greater need at different points in their child’s development.

The IY age-appropriate programmes lend themselves well to a proportionate universal delivery model, as they can be delivered in cumulative ‘doses’ according to need. 29 The E-SEE Steps model has the potential to provide robust evidence and inform NICE guidance. Recent research30 on child outcomes using longitudinal data has demonstrated the usefulness of using ‘stacked’ early interventions across the early years of children’s lives to maximise impacts on child outcomes. In addition, a recent systematic review31 suggested that a proportionate universal approach, although underutilised, is useful for mental health interventions and, given previous evidence for older age IY programmes, this intervention may be useful when delivered in this way.

Explanation of rationale

Although there is significant policy interest, there is a lack of robust UK evidence for promoting social and emotional well-being and for programmes specifically designed to prevent later mental health issues developing in children aged ≤ 2 years. The early years are a critical period of development for children, during which empathic and responsive parenting promotes positive outcomes. However, the majority of parenting programmes are designed for older children for whom social, emotional and behavioural difficulties are identifiable. Recent UK policy and guidance has placed emphasis on a whole family approach (i.e. including fathers and grandparents in an integrated proportionate approach).

The proposed study will evaluate a preventative approach for parents of very young children at a time when the child may show no obvious signs of mental health or behavioural difficulties (or at least these signs are difficult to detect), although risk factors, such as parent or co-parent depression, may be present. The IY basic programme (for parents of children aged ≥ 3 years) has demonstrated substantial post-intervention improvements in a variety of parent and child outcomes and has a robust evidence base in the UK. 32 However, although IY-I and IY-T have been developed with the same successful format and support infrastructure as the basic programme, they have not yet been evaluated in a proportionate delivery model within a community-based trial.

Specific objectives

The E-SEE study comprised two phases: (1) a pilot trial and (2) a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT). The pilot phase informed the main trial design and trial procedures. The main trial was designed to (1) establish the effectiveness of the E-SEE Steps model on clinical outcomes, (2) evaluate the processes around service delivery and (3) assess cost-effectiveness.

The primary research questions were:

-

Does the E-SEE Steps model enhance child social and emotional well-being at 20 months of age when compared with services as usual (SAU)?

-

Can IY be delivered as a proportionate universal model, and what are the organisational, or systems-level, barriers to and facilitators of delivering in this way, with fidelity?

-

Is IY, and the proposed delivery model, cost-effective in enhancing child social and emotional well-being at 20 months when compared with SAU?

Alongside the outcome, process and economic studies designed to answer these questions (see Chapters 3–5, respectively), a series of substudies were planned (see Appendix 10), including (1) a study exploring the experiences of co-parents, (2) a study exploring hospital visits and admissions and (3) a study exploring comparisons with a similar trial conducted in Ireland.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from Bywater et al. 33 © 2022 Bywater et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This report is concordant with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. 34

Pilot phase

The study was funded as a two-phase RCT, comprising an internal 18-month pilot conducted in two local authority (LA) areas and followed by a 30-month pragmatic two-arm RCT conducted in four LAs. 35 The study met stop/go criteria to progress to a main trial phase; however, the pilot identified design changes needed to ensure viability [e.g. changes to programme materials, the addition of another screener and more flexibility for the delivery of the model by one organisation (i.e. health or LA) as opposed to the originally required two organisations (i.e. health and LA)].

Table 1 summarises the progression criteria, associated measures and assessment of the pilot, and consequent changes to study design and/or implementation.

| Progression criterion | End point/measure | Assessment of criterion | Implications for design of definitive RCT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment: recruit and randomise at least 144 participants at each site (n = 288) to achieve 192 participants at final follow-up | Sample size (recruited and randomised) achieved at baseline | Not achieved: n = 205, representing 71% of the target baseline sample of 288. Although recruitment was below target, high rates of retention mitigated this (at FU3 n = 181, i.e. 94% of original FU3 target of n = 192) |

Develop site recruitment targets/expectations and document in site-level agreements Create awareness-raising materials to promote the study among referring practitioners Utilise QuinteT approach Recruitment challenges suggest an alternative design, consisting of a single research question ‘Do the scores of children in the IY arm, on average, stay below those scores for children in SAU over the three follow-up measures?’, which reduces the sample size required in a definitive trial and increases statistical power |

| Retention: maximum 12% loss at each data collection (follow-up) time point (equivalent to 32% overall loss) | Sample size at the three follow-up data collection time points (i.e. FU1, FU2 and FU3) | Achieved: 181 participants were retained by the end of FU3 (12% overall loss). There was an average of 4% loss at each data collection point. This was much lower than the 12% loss at each time point and the 32% overall loss that was anticipated |

Replicate piloted strategies for retaining parents Change of address procedures Branded tokens with study contact details on PAC input to data collector training Consistent data collector across time points Appointment by letter procedures Re-attempt contact with those lost to follow-up at next time point Consider SWAT to explore differential effectiveness |

|

Intervention delivery: books received by parents and ability for local sites to successfully deliver the required number of groups (to include identification and training of group leaders and suitable venues for groups) IY-I planned: four groups per site IY-T planned: two groups per site Intervention groups consist of a viable number (minimum eight parents invited, with five parents in attendance > 50% of sessions) |

Book receipt monitored via track and trace postage Programme monitoring data collated by the study team on IY training attendance, group venue and number of groups delivered in each site Parent contact logs completed by group leaders |

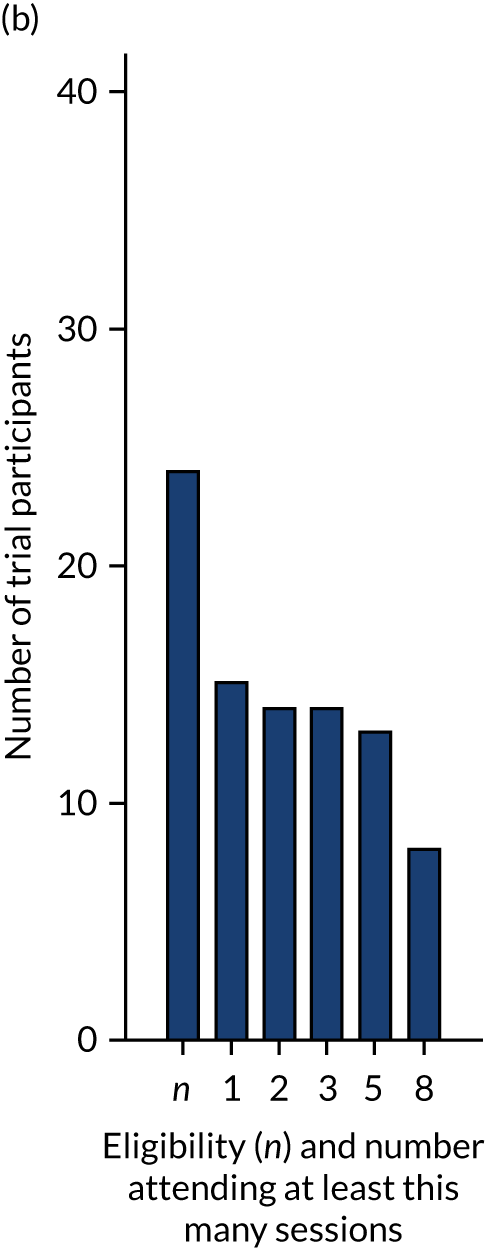

Partially achieved: all parents in the intervention arm received an IY-B. Sufficient practitioners identified, trained in IY-I and IY-T and attended supervision in each site Suitable venues used (all groups delivered in children’s centres) Viable group size was impacted by initial identification and recruitment issues and staff capacity to run groups at times convenient for parents and, therefore, was not achieved in all groups IY-I: two groups ran in site 1 (n = 6). Two groups started in site 2, which were combined to one group (n = 3) IY-T: two groups ran in site 1 (n = 2 in both groups). Two groups ran in site 2 (n = 3 and n = 7) Spaces offered to eight or more eligible participants in most groups IY-I site 1: n = 15 eligible, n = 6 accepted and attended IY-I site 2: n = 12 eligible, n = 4 accepted and attended IY-T site 1: n = 24 eligible, n = 8 accepted, n = 4 attended IY-T site 2: n = 31 eligible, n = 17 accepted, n = 10 attended |

Replicate postage and delivery procedures Ensure minimum of 10 practitioners trained in each programme in each site Allow flexibility in group delivery (could be health visitors only or LA only or combination) Ensure that referring practitioners offer an application to the study to all parents of children aged ≤ 8 weeks Supplement the PHQ-9 (scores ≥ 5) with ASQ:SE-2 scores (in the monitoring or refer zones) when determining eligibility for targeted IY-I and IY-T Emphasise need for crèche, transport, flexible timing and wrap-around support in service design processes for IY-I and IY-T Utilise matched non-research participants to supplement groups where needed to ensure minimum group sizes Revise sample calculation from 3 : 1 (intervention to control) to 5 : 1 to facilitate the identification of eligible parents and viable group size |

|

Intervention acceptability: IY retention levels to reach 70% at IY-I and IY-T end Parent satisfaction (supplements data on retention levels) |

Parent contact logs completed by group leaders Satisfaction forms completed weekly after each group session and at the end of the programme |

Achieved: achieved when viewed as the percentage of parents retained when parents attended at least one session. Retention lower when calculated as percentage of anyone initially accepting a place (this included ‘no shows’) IY-I: average weekly attendance as a percentage total of those parents attending at least one session = 73% IY-T: average weekly attendance as a percentage total of those parents attending at least one session = 87% Parent satisfaction forms completed by parents indicate a positive and high level of parent satisfaction |

Efforts should be focused on increasing uptake of groups among eligible parents (see above) Some suggestions from parents included increasing group sizes, ensuring locations are accessible/providing transport and timing the groups so that they start when children are younger Additional feedback from parents in relation to increasing the length of the programme and each session need further exploration |

| Intervention fidelity: adherence and quality of delivery assessment of 80% in each LA across co-leaders | Group leader weekly self-report checklist (adherence) and PPIC completed independently by the study team (quality of delivery) |

Achieved: overall adherence to key components of IY-I and IY-T ranged from 80% to 96% according to self-report checklists completed by group leaders The PPIC tool shows acceptable threshold of 80% was exceeded for quality of delivery for IY-I and IY-T. Overall PPIC scores for fidelity were good for IY-I (73%) and IY-T (78%) |

Retain independent measure of intervention fidelity alongside standard self-report checklists Provide accredited IY training and fortnightly supervision to group leaders and promote delivery ‘dry runs’ through service design processes |

A recalculation of sample size for the main trial was also undertaken using data collected during the pilot phase.

Although the overarching design remained the same, the pilot was reclassified as an external pilot. A full account of the pilot phase of the study and how the learning informed the main trial design is provided in Blower et al. 36

Main trial design

The trial was designed as a pragmatic two-arm RCT and economic appraisal, with an embedded process evaluation to examine the outcomes, implementation and cost-effectiveness of the intervention, and intervention uptake.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Eligible trial participants were parents (or primary caregivers) with the main parenting responsibility for the index child (aged ≤ 8 weeks) and their co-parent (if appropriate).

Primary caregiver is used here as an umbrella term to describe any person (e.g. biological parents, step-parents, foster parents, grandparents or legal guardians) who has the primary parental responsibilities of a child. English law states that if the child lives with their mother, then the mother is recognised as the primary carer.

Co-parent is a term used to describe any individual who may or may not be the ‘biological’ parent of the child, but who is involved in the upbringing of the child alongside the child’s primary caregiver (i.e. the father, or a parent by partnership or marriage to one of the child’s biological parents, such as stepmother). One co-parent could be recruited for each recruited primary carer.

Parents with a child aged ≤ 8 weeks were approached by health visitors or family and child service staff/services to see if they wished to hear more about the E-SEE study. For those who were interested, a form was completed, giving permission for the research team to receive their contact details, assess their eligibility and to contact the parent to make an appointment to visit them in their home (or an alternative venue to suit the parent) to discuss the trial further. Parents then decided if they wished to participate in the trial or not. Recruitment, therefore, was conducted within the home by the research team, with written informed consent being given by parents and co-parents wishing to participate. Parents could also self-refer if they had heard about the study via other channels (e.g. community groups and forums).

Non-eligible parents were provided with information about how to access local children centres and health service provision. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of participants throughout the trial.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants through the main trial. Note that ‘unwilling’ is defined as not wishing to attend the intervention and ‘unable’ is defined as unable to attend (e.g. because of lack of child care, returned to work or time the intervention was delivered).

Parents were eligible if they:

-

had the main parental responsibility for a child aged ≤ 8 weeks at initial engagement

-

were willing to participate in the research

-

were willing to be randomised and, if allocated to intervention, were able to receive IY services offered

-

were not enrolled in another group parenting programme at consent stage

-

were fully competent to give consent.

Co-parents were eligible if the primary carer agreed to their involvement and if they lived with the index child or looked after them for at least three evenings each week.

The exclusion criteria were the opposite of the above and, in addition, parents were excluded if:

-

the child had obvious organic or developmental difficulties or had been diagnosed with the same.

Settings and locations where data were collected

Expressions of interest, via completed proformas, were received from 16 potential sites in England. The proformas and initial discussions with sites were used to establish (1) levels of local deprivation, (2) sufficient live birth rates per year to allow recruitment of eligible and interested families, and to achieve an adequate randomisation sample with viable numbers for group delivery, and (3) willingness to support staff and intervention delivery costs and time. A number of interested sites were unable to participate because of limits on health visitor capacity/contracts or because sites were already delivering the IY-I or IY-T or were committed to running other parenting programmes. Four trial sites were selected that met the requirements. Two sites were in the north of England, both with council and NHS IY delivery, one site was in the Midlands of England, involving LA-only delivery (although health visitors also approached potential participants), and one site from the south of England, involving an NHS-only provider.

Intervention

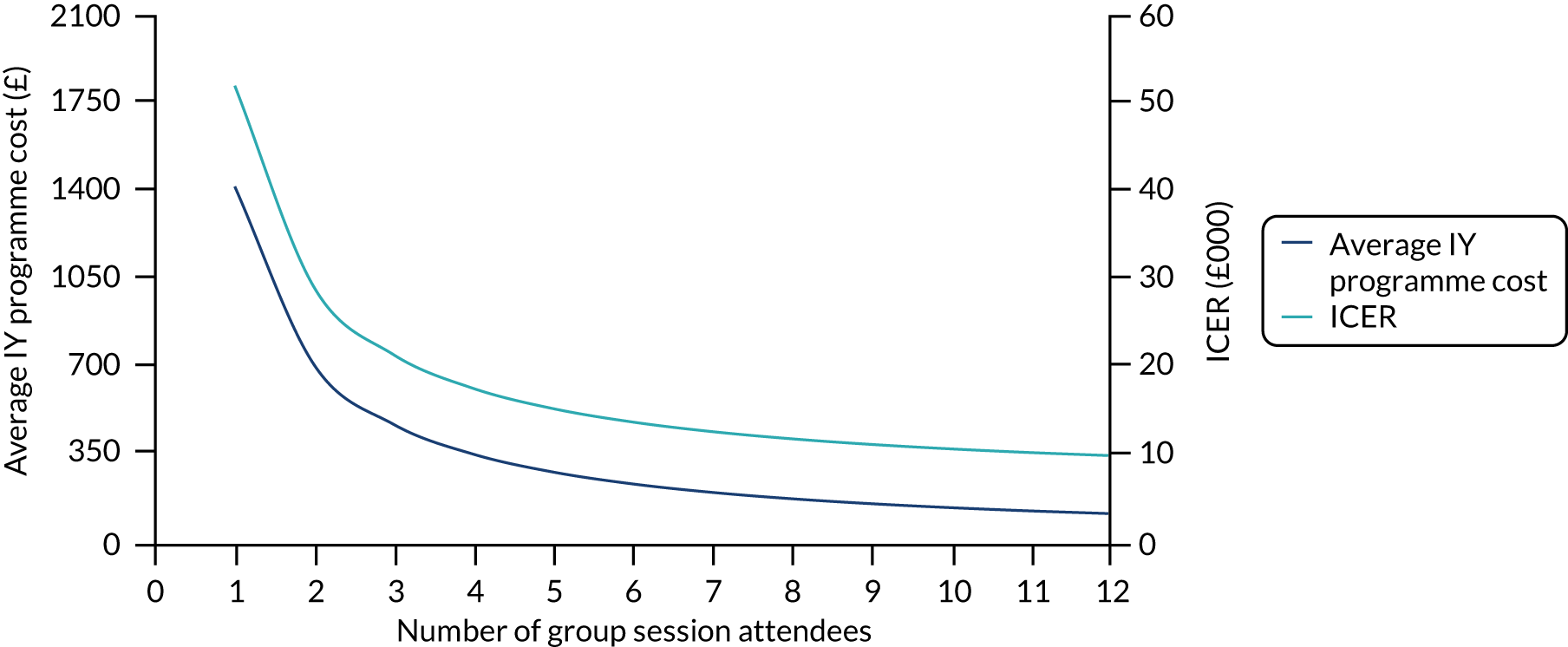

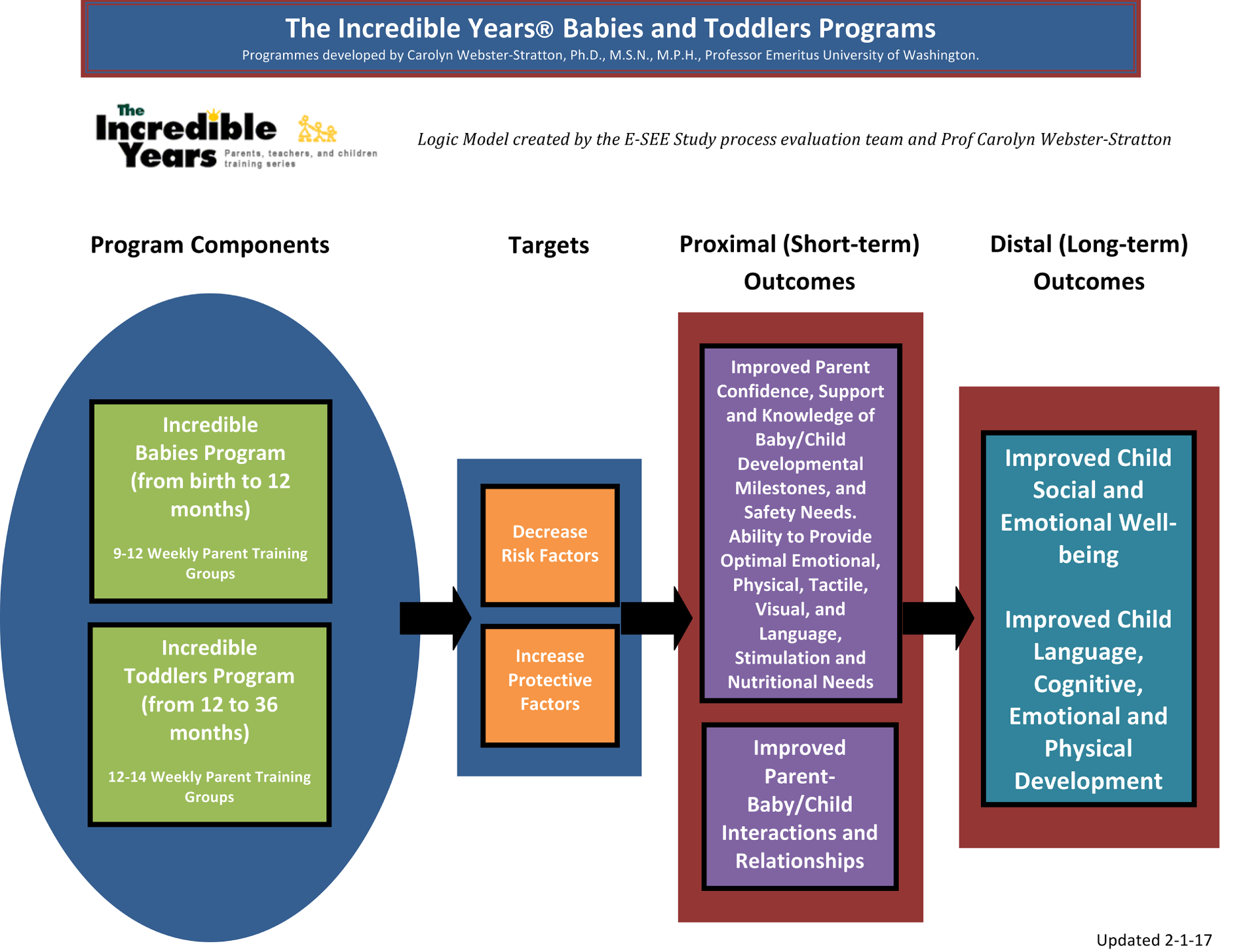

The E-SEE Steps model adopts the IY series [URL: www.incredibleyears.com (accessed 7 January 2022)] of programmes for parents, children and teachers to enhance social and emotional well-being in children aged 0–12 years as content for the different levels of intervention. Two new programmes have been developed for parents of children aged 0–2 years: the IY-I and the IY-T (see Appendix 1, Figure 11, for the IY-I and IY-T logic model). Each programme is accompanied by a parenting book (i.e. the IY-B), reflecting the content of the programmes delivered in group sessions, with activity and journal pages. In addition, the E-SEE Steps model used the IY-B as a universal educational resource to increase parental knowledge and understanding about babies and toddlers’ social and emotional development. All intervention parents received this book immediately following randomisation to intervention and postal tracking numbers were used to establish receipt of the book. There is evidence37,38 to support a link between parents’ knowledge and their practice/parenting behaviour. Within the universal proportionate framework, three levels of the IY parenting programme were investigated in this RCT.

Incredible Babies book

The IY-B is guide and journal of a baby’s first year. The IY-B provides information on how to promote and understand a baby’s physical, social, emotional and language development, and includes safety alerts, developmental principles and a journal section to record progress.

Incredible Years infant programme

In the infant group-based programme, parents learn how to help their babies feel loved, safe and secure. Parents learn how to encourage their babies’ physical and language development. The programme involves parents attending a 2-hour session with their babies once per week for 10 weeks in groups of 8–10 parents (the standard IY-I is 8 weeks; however, developer guidance suggests that the content should be delivered over 10 weeks for ‘high-need’ families). The programme uses video clips of real-life situations to support the training and there are opportunities for group discussions and practice exercises for parents to do with their babies. Key content covered in the IY-I includes ‘getting to know your baby’, ‘babies as intelligent learners’, ‘providing physical, tactile and visual stimulation’, ‘parents learning to read babies’ minds’ and ‘gaining support’. The programme is delivered by two trained IY group leaders.

Incredible Years toddler programme

In the toddler group-based programme, parents learn how to help their toddlers feel loved and secure, how to encourage their toddler’s language, social and emotional development, how to establish clear and predictable routines, how to handle separations and reunions and how to use positive discipline to manage misbehaviour. The programme (delivered by two trained group leaders) involves parents attending a 2-hour session once a week for 12 weeks in groups of 10–14 parents. A crèche may be provided during each session. Key IY-T content includes ‘playing with your child’, ‘supporting your child’s social, emotional and language development’, ‘using praise to encourage positive child behaviour’, ‘reinforcing positive behaviour’, ‘setting limits’, ‘handling separations’ and ‘managing unwanted behaviour’.

Universal proportionate delivery of the intervention

Following baseline data collection, the universal-level intervention dose (i.e. the IY-B) was posted to all intervention families to read and use at home. Postal tracking was used to establish receipt of the book. An active placebo (e.g. another type of book) was not specifically given to the control arm, as the control arm received SAU.

The IY-I and IY-T were targeted using two screener measures. Eligibility was based on the primary parent’s level of depression, as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9), and/or the child’s social and emotional well-being score, as measured by the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social and Emotional, 2nd edition (ASQ:SE-2). Eligibility for the IY-I and IY-T were assessed at follow-up 1 (2 months post baseline) (FU1) and follow-up 2 (9 months post baseline) (FU2), respectively, during home data collection visits. Eligible parents (and their co-parent if applicable) were invited to attend the IY-I and/or IY-T. The IY developer recommends home visits to eligible parents before the group sessions begin to better understand the family’s needs and to build rapport and engagement.

In an attempt to ensure viable group size (i.e. a minimum of five parents), non-research parents could be invited to the groups. These parents were invited by service staff based on professional judgement/assessment. We did not collect data for these parents, as they attended as they would for any other parenting intervention delivered at that site. This is accepted practice in types of research interventions that require viable group size. The intervention families could also access all SAU.

Setting for intervention delivery

Both IY-I and IY-T were delivered in convenient community venues and locations to reduce participant travel time, burden and drop-out. Travel and crèche facilities were provided by sites, where possible, and provision monitored. Each IY group was delivered by two IY-trained staff from health/LA staff, such as health visitors, infant mental health practitioners, children centre staff and nursery nurses. Group leaders attended separate 3-day training workshops for IY-I and IY-T that were delivered by accredited UK-based IY trainers. Sites were advised to deliver a ‘dry run’ practice of an IY-I or IY-T group prior to delivering the research groups. In addition, the IY developer recommended regular peer review and/or delivery supervision for facilitators for effective implementation and encouraged agencies to support accreditation of group leaders. Further details on training and supervision are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Control treatment

Control parents/co-parents had access to SAU. IY-I and IY-T did not form SAU in participating sites, although other parenting programmes may have been available. We documented the nature of SAU in each locality and collected data on which health (and social) services families had accessed via completion of an adapted Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). A waiting list control design was not feasible, as children of control group parents would exceed the IY-I and IY-T age range after intervention group completion. Implementation partners were asked to consider offering the IY-T book or IY basic programme to control parents at the trial end.

Outcomes and measures

Questionnaire packs were pre-tested with non-research parent representatives of the ethnic and socioeconomic profiles of the regions in the study [facilitated by the E-SEE Parent Advisory Committee (PAC)] to assess user-friendliness and comprehension of the questionnaire materials and length of time for completing them. Measure selection was also informed by a suite of systematic reviews of the measurement properties of outcome measures frequently used in RCTs of parenting programmes for children in the early years. 39,40 The child and parent measures presented were administered at all time points [i.e. baseline, FU1, FU2 and follow-up 3 (18 months post baseline) (FU3)] unless otherwise stated. Provenance, properties and rationale for all measures are presented in the trial protocol. 41 All measures were completed by parents, with the exception of the Infant CARE-Index observational measure and, in addition, researchers completed the CSRI and demographic form based on parent responses.

Child primary outcome

Social and emotional well-being

The parent-reported ASQ:SE-242 was used to establish effectiveness of the overall proportionate delivery of the E-SEE Steps model. This questionnaire was completed by the primary parent only. Population norms for ASQ:SE-2 are provided in Appendix 2, Table 33.

Key secondary parent outcome

Depression

The parent-reported PHQ-943 was used to establish effectiveness of the proportionate delivery of the overall E-SEE Steps model. The PHQ-9 was completed by primary and co-parents. Population norms for the PHQ-9 are provided in Appendix 2, Table 34, along with a copy of the measure.

Other secondary outcomes for primary and co-parents

Parent–child attachment/interaction

Parent–child attachment/interaction was measured at FU3 using the primary and co-parent-completed Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale (MPAS) and/or Paternal Postnatal Attachment Scale (PPAS). 44,45

Parenting skill

Parenting skill was assessed by the primary and co-parent-completed Parent Sense of Competence (PSOC) scale. 46

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured by the primary and co-parent-completed EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 47

Service use

Service use was assessed using an adapted CSRI48 for the primary parent only.

Child secondary outcomes

Behaviour

Behaviour was measured at FU3 using the primary and co-parent-completed Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). 49

Cognitive development

Cognitive development was measured at FU3 using the primary and co-parent-completed Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL™) infant scale. 50

Health (quality of life)

Health (quality of life) was measured at FU3 using the primary and co-parent completed PedsQL Infant Scale. 50

Service use

Service use was captured by the primary parent-completed CSRI. 48

Parent–child dyad secondary outcome measures

Dyadic synchrony

Dyadic synchrony was assessed using the Infant CARE-Index (PM Crittenden, Family Relations Institute, 2010) observational report solely conducted with the primary parent–child dyad. Researchers filmed interactions in the home and videos were coded by researchers trained in the Infant CARE-Index.

Other measures

Demographics

A bespoke parent/co-parent demographics report form was developed specifically for the study, capturing key information on age, ethnicity, religion, income, marital status and parent/co-parent education. The form also contained questions on breastfeeding and other feeding practices. The co-parent and follow-up demographics forms were a shorter version of the baseline form.

Quality of relationships

The quality of relationships between parents (if applicable) was assessed via parent self-report using a very brief form developed specifically for the study.

Further measures for the process and economic evaluation are described in Chapters 4 and 5, respectively.

Changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced

Use of the Eyberg Child Behaviours Inventory was provided as an example child secondary measure to be used in the FU3 visits with participants. However, following work on a systematic review of measures in relevant domains/constructs as part of E-SEE study,40 the SDQ was found to be more appropriate for the study. The SDQ is available in multiple languages, has a subscale of emotional well-being, is free of charge and is more widely available to services. In protocol version 10, the PHQ-9 is described as the ‘parent and co-parent primary outcome’. That description is technically incorrect, as the trial is powered on ASQ:SE-2 alone. PHQ-9 is now described as the key secondary outcome. In addition, in protocol version 10, the Infant CARE-Index is described as a child attachment measure and listed as a child secondary outcome. Child attachment is just one part of the index and we will use the overall dyadic synchrony score, which is a parent–child dyad measure.

Data collection

Data collection took place in the participant’s own home. All data collectors were educated to postgraduate level (or with equivalent experience) and had prior experience working with children or families. All data collectors attended a study-specific training delivered by the E-SEE trial co-ordinator and E-SEE York trial manager prior to data collection. Data collectors also undertook safeguarding training and good clinical practice training. Further detail on training and data collection procedures can be found in the study protocol version 10. 41

Sample size

Sample size was calculated on the child primary outcome of social and emotional well-being using the ASQ:SE-2. The study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the whole E-SEE Steps model (i.e. ‘Do the scores of children in the E-SEE Steps arm, on average, stay below those scores for children in the SAU arm over the three follow-up measures?’). Parents were eligible to be offered the proportionate intervention if they scored ≥ 5 on the PHQ-9 or their child scored within the monitoring or cause for concern range on the ASQ:SE-2. We defined the minimal clinically important difference at FU3 to be 5 units on the ASQ:SE-2 in the E-SEE Steps arm compared with the SAU arm. We expected this effect to be consistently seen over the three follow-up points. Assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 18 units on the ASQ:SE-2 at FU3, the correlation between baseline and FU3 scores is 0.26, and between pairs of measurements after baseline is 0.40. For a design effect of 1.25 for the intervention arm, two-sided 5% significance level and 90% power, we would require the study to have retained 441 intervention participants and 92 control participants. Allowing for overall attrition of 12%, this would require 606 parents to be randomised with an allocation ratio of 5 : 1. The high allocation ratio was required to ensure that a sufficient number of parents were eligible and able to attend IY groups. Assuming the attrition rate of 12%, we expected 151 parents to be eligible for IY-I, with 50 parents attending, and 147 parents to be eligible for IY-T, with 48 parents attending, based on our pilot data.

Additional information about the ASQ:SE-2

The ASQ:SE-2 thresholds for concern are shown in Table 2. For interventions aimed at improving the mental health of parents, a minimal(ly) clinically important difference of 5 has been suggested; however, given that this is an intervention aimed at child behaviour, it is not appropriate here but is provided for reference.

| Threshold for concern | Age interval (version of ASQ:SE-2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 months | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | |

| Monitor: it is close to the cut-off point (review behaviours of concern and monitor) | 25–34 | 30–44 | 40–49 | 50–64 |

| Refer: it is above the cut-off point (further assessment with a professional may be needed) | 35+ | 45+ | 50+ | 65+ |

Randomisation

Randomisation was at the individual level, using a web-based randomisation system developed by the Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (Sheffield, UK) in collaboration with epiGenesys (Sheffield, UK) and using a randomisation sequence prepared by the trial statistician. E-SEE Step participants were randomised in a 5 : 1 ratio (intervention to control arms) stratified by sex of child, sex of carer, recruitment site and PHQ-9 baseline score or ASQ:SE-2 baseline score (with the last two variables representing level of need).

Randomisation occurred after eligibility had been established, informed consent obtained and baseline measures collected from parents to reduce initial attrition. The allocation schedule was concealed and the intervention arm was confirmed only once eligibility and consent were confirmed by researchers. A member of the research team inputted participant information to the online system to enable randomisation, with allocation results returned immediately. The trial co-ordinator informed families of allocation to condition.

Parent–child dyads were randomly allocated to intervention or control arms and stratified according to level of need based on the depression score of the parent with the main parenting responsibility or the child’s social and emotional well-being (assessed using ASQ:SE-2), sex of the child and primary parent, and recruitment site. The co-parent was automatically assigned the same allocation as the parent.

If the parent had missing depression data, measured using the PHQ-9, then randomisation was not possible. We did not randomise participants who had missed three or more of the main questions on the PHQ-9 measure at baseline.

Blinding

Participants and group leaders delivering the intervention were not blind. Data managers and research staff involved in recruitment, initial assessments and fidelity/process assessment were also not blind to allocation. Production of ongoing Trial Management Group (TMG), Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) reports was undertaken by unblinded programmers. The trial statistician remained blind while the study was in progress, but was unblinded when conducting the final analysis. All data collectors were blind to the research questions and condition allocation. Unblinding of blinded members of the E-SEE team was made known to study management via the protocol non-compliance procedure and logged. Further information on steps to ensure the maintenance of blinding can be found in our full protocol. 41

Statistical methods

Information on the calculation of the sample size for the main trial and the clinical meaning of intervention effects has been provided in Sample size. Information on the analysis for the ancillary substudies is included in the study protocol, which is available along with the E-SEE main trial statistical analysis plan (SAP) and pilot SAP. 41

Effectiveness was assessed using intention-to-treat analysis, accounting for the repeated measurements of individuals at FU1, FU2 and FU3 using general estimating equations. Membership of the IY-I and IY-T groups is confounded with outcome at FU1 and FU2 and so programme group clustering was unaccounted for because it is not possible to do this appropriately without biasing the treatment effect estimate in the methods we have explored. This is also current practice in the wider community. 31 Simulations conducted during SAP development suggested that estimates from our chosen model are robust to intracluster coefficients (ICCs) < 0.2.

Treatment effectiveness

The overall effectiveness of the proportionate delivery of IY was assessed by intention-to-treat analysis using a marginal model fitted using general estimating equations with a Gaussian family, identity link and autoregressive covariance structure of order 1 AR(1). AR(1) means that each observation in the time series is directly related to the observation that preceded it. Model estimates with standard errors that are robust to the non-normality and non-independence of observations were computed. Statistical analyses used Stata®/MP 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Inclusion of covariates

There were no major differences between the groups at baseline. Covariates included were baseline PHQ-9 and ASQ:SE-2 scores, whether or not the parent had a degree, whether or not the parent was in a relationship, the primary parent’s ethnicity, the child’s sex, follow-up time and delivery site. Site fixed effects were included to minimise unexplained variance in site-specific effects and facilitate generalisability by capturing factors that explain why effects vary across sites (e.g. differences in parental recruitment and retention, and implementation fidelity).

Missing data

Full case and survey item non-response were explored. Item non-response was imputed using questionnaire developer rules. Sensitivity to missing outcome data and missing information on whether or not the primary parent held a degree was explored using chained equations to impute 25 multiply imputed data sets using a logit model and a multivariate normal mode for the repeated-measure outcome variable. Covariates were the same as those in the primary analysis model plus randomisation group and whether or not the dyad met the criteria for inclusion in the IY-I and IY-T groups.

Analysis populations

Inequalities

We conducted a simple moderator analysis to explore the extent to which intervention effectiveness differed between distinct subpopulations by testing the significance of the interaction between randomised treatment group and subgroup (e.g. parent education level, first child, sex of child, site).

Intervention components

The impact of individual components (i.e. IY-B, IY-I and IY-T) was investigated using non-randomised observational analysis where participants in the control arm with outcome scores above the eligibility threshold were used as a pseudo-control group.

Additional analyses

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of the outcome analysis, the primary analysis was repeated with alternative specifications of the primary outcome measure and using multiple imputation (MI). Per-protocol and complier-average causal effect analyses were not conducted, as there is no satisfactory way of defining compliers without biasing the estimated impact of IY-I and IY-T on compliers because of the conditional design whereby eligible participants have already scored highly on the outcome measure. A descriptive analysis of the characteristics associated with compliance was undertaken.

Study oversight and management

The University of York (York, UK) was the trial sponsor. A TSC comprised an independent chairperson, a member with early years expertise, an independent statistician and lay representatives (including a member of the PAC when available). The TMG comprised the chief investigator, trial managers, a trial statistician, a data manager, a health economist and other co-investigators. The DMEC included an independent chairperson, a professor of psychology and an independent trial statistician. These committees functioned in accordance with Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit standard operating procedures.

Ethics arrangements

This study was approved by NHS Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 (Bangor, UK) on 22 May 2015 (reference 15/WA/0178 and IRAS 173946). Health Research Authority approval, which was issued on the basis of an existing assessment of regulatory compliance, was received on 13 September 2016 (i.e. a letter of Health Research Authority approval for a study processed through pre-Health Research Authority approval systems). The chief investigator’s departmental ethics committee at the University of York required submission of project documentation and approval was given on 10 August 2015 (reference FC15/03).

Changes to protocol

Version 10 is the final version of the protocol. Please refer to the protocol for a full list of amendments. 41 Significant amendments (i.e. those not related to simple language and terminology) to the protocol in the main trial phase (i.e. versions 5–10) are detailed below. All amendments were approved by the Research Ethics Committee, E-SEE TSC and DMEC, and were accepted by the funder.

Version 5: 23 February 2017

-

Section 4 (Gantt chart and key milestones): removal of study Gantt chart to allow flexible timing of group programme delivery. Milestones table updated to reflect access of health data at end of study only.

-

Section 5 (ancillary substudies): change made to access health records at a single time point at the end of the study, rather than during pilot and at the end of study, in the light of NHS Digital costs.

-

Section 6 (selection, recruitment and withdrawal of participants): parents may be given/sent a reminder card about the focus groups/interviews.

-

Section 8 (intervention): change made under ‘setting and delivery’ to allow a more flexible approach to intervention delivery, which will be guided by each site/service provider.

-

Section 9 (assessments and procedures): the Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory was replaced by the SDQ as the child secondary outcome measure.

Version 6: 8 May 2017

Trial design, sample size, randomisation and statistical sections of the protocol were amended because of changes to the main trial, as informed by the pilot phase:

-

The pilot was external with references to internal pilot removed.

-

Inclusion of the ASQ:SE-2 as an eligibility screener (protocol version 4) meant that ASQ:SE-2 would be used as a stratification variable in the main phase. Clarification added that recruitment site is a stratification variable (pilot and main phase).

-

Strategy of lowering the PHQ-9 eligibility threshold in the pilot would not be used in the main trial.

-

Change to sample size calculations for the main trial. Calculations for the pilot and main phase are presented separately in section 6.

-

Allocation ratio of 4.8 : 1 applied in the main trial.

-

Adaptation of the statistical design to look at effectiveness of the programme overall, rather than at each stage of the IY programme.

-

Removal of the requirement to calculate ICC for the pilot (protocol version 4) meant that an independent statistician is no longer required at that stage.

Version 7: 16 May 2017

-

Section 6 (selection, recruitment and withdrawal of participants): parents and co-parents who have taken part in the pilot phase will not be eligible to take part in the main phase of the trial.

Version 8: 7 November 2017

-

Study summary, section 6 (sample size calculation) and section 7 (randomisation): adjustment of the allocation ratio from 4.8 : 1 to 5 : 1.

Version 9: 8 November 2018

-

Section 6 (selection, recruitment and withdrawal of participants): minor amendment to allow inclusion of non-research participants to the group intervention based on professional judgement/assessment made by of service staff.

Version 10: 17 June 2019

-

Section 9 (assessment and procedures): clarification that the effectiveness of the proportionate delivery of the IY E-SEE Steps model overall (i.e. three levels of IY-B, IY-I and IY-T) will be determined through use of the ASQ:SE-2 and PHQ-9. Footnote 4 added to the parent and co-parent primary outcome. Infant CARE-Index videos will be coded by trained members of the research team.

In addition to the amendments above, three changes were made to the analysis model in the protocol. These changes were justified and agreed by all stakeholders (i.e. the National Institute for Health Research, DMEC and TSC) prior to database close and unblinding. First, we replaced a multilevel mixed model with treatment group and participants as random effects, with a marginal model fitted using general estimating equations.

Second, we no longer accounted for treatment group clustering because the offer of IY-I and IY-T was conditional on outcome at FU1 and FU2 and, therefore, clustering was confounded with treatment effect, leading to biased estimation of the latter. We used a marginal model fitted using general estimating equations because accounting for repeated measures using a mixed model inflates the type I error (random intercept-only model) or gives a biased estimate of the treatment effect (random intercept and slope model). Simulations conducted during SAP development suggested that estimates from this alternative model are robust to ICCs < 0.2.

Third, cluster-level analysis using summary measures was no longer included because participants can get IY-I alone, IY-T alone or both IY-I and IY-T and, therefore, there was no way of grouping participants into clusters that remain stable throughout the intervention. The sex of primary caregiver covariate was not used because findings from the pilot showed too few male primary caregivers for the associated model parameter to be estimated.

Patient and public involvement

The involvement of parents and caregivers of very young children has been integral to the E-SEE trial. In this section we outline the different ways that patient and public involvement has contributed to the E-SEE model, from the planning stages through to the dissemination of trial findings. Reflections on what worked well and not so well are also provided.

Pre-funding preparation

We conducted focus groups with family and children service staff and fathers to establish how to be ‘father inclusive’ when inviting fathers to groups, and how best to retain them. We also asked for fathers’ opinions on the developing study design and the importance of the research questions. The meetings were informative and a brief report was produced to summarise the key learning. 51

Post-funding preparatory work

A PAC was established with members from two study sites. Members included mothers, fathers, step-parents and grandparents with children of similar ages to the trial index children. The group was ethnically diverse. The main roles of the PAC were to advise and support researchers on recruitment to the trial and advise on, and assist with, training in the measures to be used (e.g. the PAC supported the training of E-SEE data collectors by role playing data collection visits with the researchers). The PAC also advised on trial retention strategies, and on publicity and dissemination. PAC members received training for their committee role.

Throughout the pilot and main trial

The PAC raised awareness of the trial through community events in their local communities, sharing flyers with local groups, and also kept the research team informed of local events and groups targeted at the trial population of interest. In addition, the PAC contributed to the E-SEE trial website design and had their own E-SEE Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) page to enhance engagement with each other and the research team. One PAC member became a lay member on the TSC for a period of time.

Dissemination

Pre COVID-19, PAC members were scheduled to participate in and support site dissemination events. PAC members contributed to pilot site awareness events and parent and staff end-of-pilot events. Infographics for participating families have been reviewed by the PAC for levels of understanding and acceptability. PAC members reviewed the Plain English summary of this report.

Reflections on what worked well and not so well

Ensuring representation of parents from all our study sites was not possible, despite several attempts to recruit PAC members via social media adverts, e-mails to existing networks and groups, and posters in local children’s centres. However, we were successful in recruiting PAC members from two of our sites through local voluntary organisations working with families. PAC members’ local knowledge of where the best places/groups to raise awareness were was very useful. It was particularly useful to get the PAC members’ views on measure choice (e.g. if a measure looked simple and nicely laid out then it was preferred to a shorter measure that looked less professional or attractive). The wording of questions was also scrutinised for understanding and informed our choice. Having PAC members support E-SEE data collectors in role play was invaluable, as it gave ‘real-life’ experience of trying to complete measures with parents while children demanded their parents’ attention.

Although we were well informed by father groups pre funding and offered some father inclusivity training, few fathers were recruited to the trial and fewer still attended groups when their partner was eligible to attend. We write more about this in our substudy in Appendix 10.

Chapter 3 Outcome evaluation results

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from Bywater et al. 33 © 2022 Bywater et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Details of the sample recruited and retention of participants across time points are available in Figure 1.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was child social and emotional well-being using the ASQ:SE-2. Higher values of ASQ:SE-2 indicate a higher degree of risk in terms of the social and emotional well-being of children. The key secondary outcome was the PHQ-9 depression module for the primary carer, subsequently referred to as PHQ-9. Higher values on the PHQ-9 indicate higher levels of depression for the parent. Therefore, for both the primary and key secondary outcome, we were looking for the difference in average scores between the treatment and control group to be negative for the results to indicate efficacy. We were powered on the primary outcome only and so present findings in terms of significance for ASQ:SE-2 and trends or confidence intervals (CIs) for PHQ-9.

There are age-appropriate versions of the ASQ:SE-2. Three versions were used in this trial.

Data completeness

The trial had very high levels of response to all surveys at all follow-up points both in terms of the number of surveys returned and the number of items completed on each survey (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Therefore, very little imputation was required.

Baseline covariates

No major imbalance between arms at baseline was found, both in terms of covariates (Table 3) and baseline outcome scores (see Appendix 3, Table 35). Mean ASQ:SE-2 score at baseline was moderately lower in the treatment group than in the control group, but this was adjusted for in the primary analysis, as baseline ASQ:SE-2 was a planned covariate.

| Variable | Treatment arm | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | ||

| Child | N = 285 | N = 56 | N = 341 |

| Categorical variable, n (%) | |||

| Sex of child | |||

| Male | 145 (51) | 29 (52) | 174 (51) |

| Female | 140 (49) | 27 (48) | 167 (49) |

| Child’s ethnicity | |||

| English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 215 (75) | 37 (66) | 252 (74) |

| Any other white background | 9 (3) | 4 (7) | 13 (4) |

| White and black Caribbean | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 3 (1) |

| White and black African | 3 (1) | 1 (2) | 4 (1) |

| White and Asian | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (1) |

| Any other mixed/multiple ethnic group | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 6 (2) |

| Indian | 14 (5) | 6 (11) | 20 (6) |

| Pakistani | 19 (7) | 5 (9) | 24 (7) |

| Bangladeshi | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) |

| Any other Asian background | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| African | 5 (2) | 1 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Any other ethnic group | 1 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Premature | |||

| No | 274 (96) | 53 (95) | 327 (96) |

| Yes | 9 (3) | 3 (5) | 12 (4) |

| Missing data | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Difficulties at birth | |||

| No | 132 (46) | 26 (46) | 158 (46) |

| Yes | 153 (54) | 30 (54) | 183 (54) |

| Continuous variable | |||

| Child’s age (weeks) | |||

| n (%) | 285 (100) | 56 (100) | 341 (100) |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (2.1) | 5.9 (2.2) | 6.0 (2.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–8) |

| Minimum, maximum | 2, 11 | 2, 10 | 2, 11 |

| Primary caregiver | N = 285 | N = 56 | N = 341 |

| Categorical variable, n (%) | |||

| Parent’s age group (years) | |||

| 18–21 | 9 (3) | 2 (4) | 11 (3) |

| 22–25 | 36 (13) | 7 (13) | 43 (13) |

| 26–30 | 88 (31) | 15 (27) | 103 (30) |

| 31–35 | 95 (33) | 21 (38) | 116 (34) |

| ≥ 36 | 57 (20) | 11 (20) | 68 (20) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 285 (100) | 56 (100) | 341 (100) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 218 (76) | 38 (68) | 256 (75) |

| Irish | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Any other white background | 12 (4) | 4 (7) | 16 (5) |

| White and black Caribbean | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| White and black African | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (0) |

| White and Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (0) |

| Any other mixed/multiple ethnic group | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (1) |

| Indian | 15 (5) | 7 (13) | 22 (6) |

| Pakistani | 18 (6) | 3 (5) | 21 (6) |

| Bangladeshi | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) |

| Any other Asian background | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| African | 7 (2) | 1 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Any other ethnic group | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (0) |

| Highest qualification previously achieved | |||

| Post-doctorate qualification | 8 (3) | 0 (0) | 8 (2) |

| Master’s degree | 28 (10) | 8 (14) | 36 (11) |

| Undergraduate degree (e.g. BA or BSc) | 96 (34) | 14 (25) | 110 (32) |

| A certificate or diploma in higher education | 33 (12) | 5 (9) | 38 (11) |

| A, AS or S Levels | 19 (7) | 7 (13) | 26 (8) |

| O Levels or GCSE: five or more | 15 (5) | 6 (11) | 21 (6) |

| O Levels or GCSE: four or fewer | 9 (3) | 3 (5) | 12 (4) |

| Overseas qualifications | 10 (4) | 2 (4) | 12 (4) |

| Vocational qualifications | 53 (19) | 8 (14) | 61 (18) |

| None of these qualifications | 14 (5) | 1 (2) | 15 (4) |

| Missing data | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (1) |

| Relationship status | |||

| Married and living together | 184 (65) | 38 (68) | 222 (65) |

| Cohabiting/living together | 70 (25) | 12 (21) | 82 (24) |

| Living together part of the time | 4 (1) | 3 (5) | 7 (2) |

| Separated | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) |

| A couple but not living together | 13 (5) | 0 (0) | 13 (4) |

| Dating | 1 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Not in a relationship | 9 (3) | 2 (4) | 11 (3) |

| Continuous variable | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| n (%) | 285 (100) | 56 (100) | 341 (100) |

| Mean (SD) | 30.9 (5.1) | 31.1 (5.0) | 30.9 (5.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 31 (28–35) | 32 (27–34) | 31 (28–34) |

| Minimum, maximum | 18, 43 | 20, 40 | 18, 43 |

| Baseline weekly income (£) | |||

| n (%) | 226 (79) | 43 (77) | 269 (79) |

| Mean (SD) | 733.1 (470.7) | 766.9 (454.4) | 738.5 (467.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 603 (400–950) | 710 (400–1000) | 630 (400–973) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 2500 | 151, 1850 | 0, 2500 |

| Co-parent | N = 53 | N = 15 | N = 68 |

| Categorical variable, n (%) | |||

| Parent’s age group (years) | |||

| 18–21 | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| 22–25 | 1 (2) | 2 (13) | 3 (4) |

| 26–30 | 13 (25) | 2 (13) | 15 (22) |

| 31–35 | 13 (25) | 5 (33) | 18 (26) |

| ≥ 36 | 22 (42) | 5 (33) | 27 (40) |

| Missing data | 2 (4) | 1 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 51 (96) | 15 (10) | 66 (97) |

| Female | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Missing data | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Relationship status | |||

| Married and living together | 39 (74) | 13 (87) | 52 (76) |

| Cohabiting/living together | 12 (23) | 1 (7) | 13 (19) |

| Living together part of the time | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 1 (1) |

| A couple but not living together | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Missing data | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Highest qualification previously achieved | |||

| Post-doctorate qualification | 1 (2) | 1 (7) | 2 (3) |

| Master’s degree | 7 (13) | 0 (0) | 7 (10) |

| Undergraduate degree (e.g. BA or BSc) | 16 (30) | 3 (20) | 19 (28) |

| A certificate or diploma in higher education | 6 (11) | 4 (27) | 10 (15) |

| A, AS or S Levels | 1 (2) | 2 (13) | 3 (4) |

| O Levels or GCSE: five or more | 6 (11) | 1 (7) | 7 (10) |

| O Levels or GCSE: four or fewer | 4 (8) | 1 (7) | 5 (7) |

| Overseas qualifications | 1 (2) | 1 (7) | 2 (3) |

| Vocational qualifications | 8 (15) | 2 (13) | 10 (15) |

| None of these qualifications | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Missing data | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Continuous variable | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| n (%) | 51 (96) | 14 (93) | 65 (96) |

| Mean (SD) | 34.5 (8.3) | 35.1 (8.2) | 34.6 (8.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 33 (29–39) | 35 (30–40) | 34 (29–39) |

| Minimum, maximum | 18, 68 | 24, 55 | 18, 68 |

| Baseline weekly income (£) | |||

| n (%) | 44 (83) | 11 (73) | 55 (81) |

| Mean (SD) | 915.8 (895.9) | 690.4 (483.4) | 870.7 (831.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 760 (460–1079) | 600 (250–1000) | 700 (450–1058) |

| Minimum, maximum | 93, 6000 | 115, 1645 | 93, 6000 |

Although we assessed imbalance between the arms, we did not assess representativeness of the sample to local or national population data. What was noticeable here was the large number of E-SEE parents in live-in relationships (90% and 89% of intervention and control parents, respectively, with 65% and 68% married, respectively). According to the Office for National Statistics,52 marriage prevalence is 50% and 60% of the population (aged ≥ 16 years) were living as a couple in 2019, the majority of whom were married. Only 3% and 4% of parents (intervention and control, respectively) said that they were not in a relationship, which is below the national average of 25% of families being lone-parent families. The numbers were too small to conduct subgroup analyses.

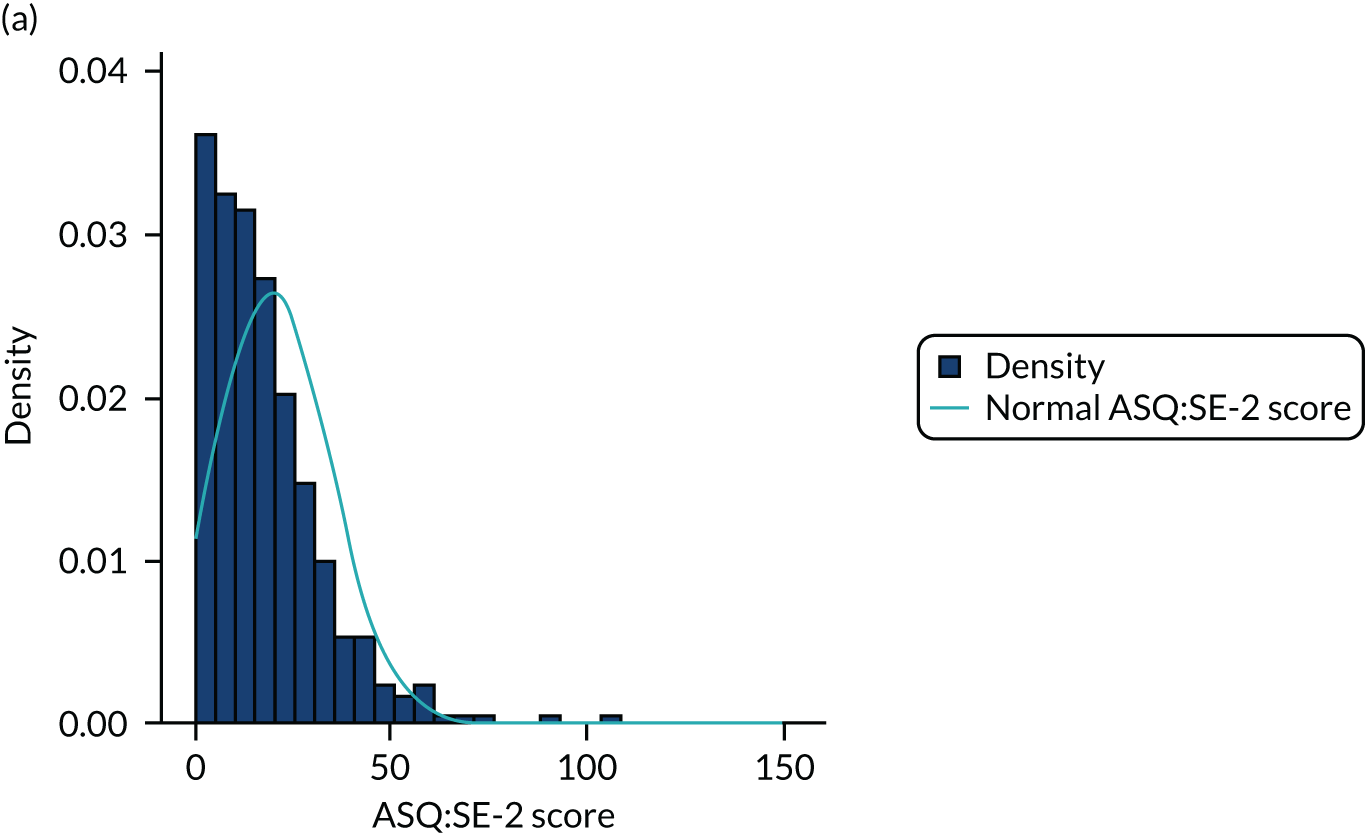

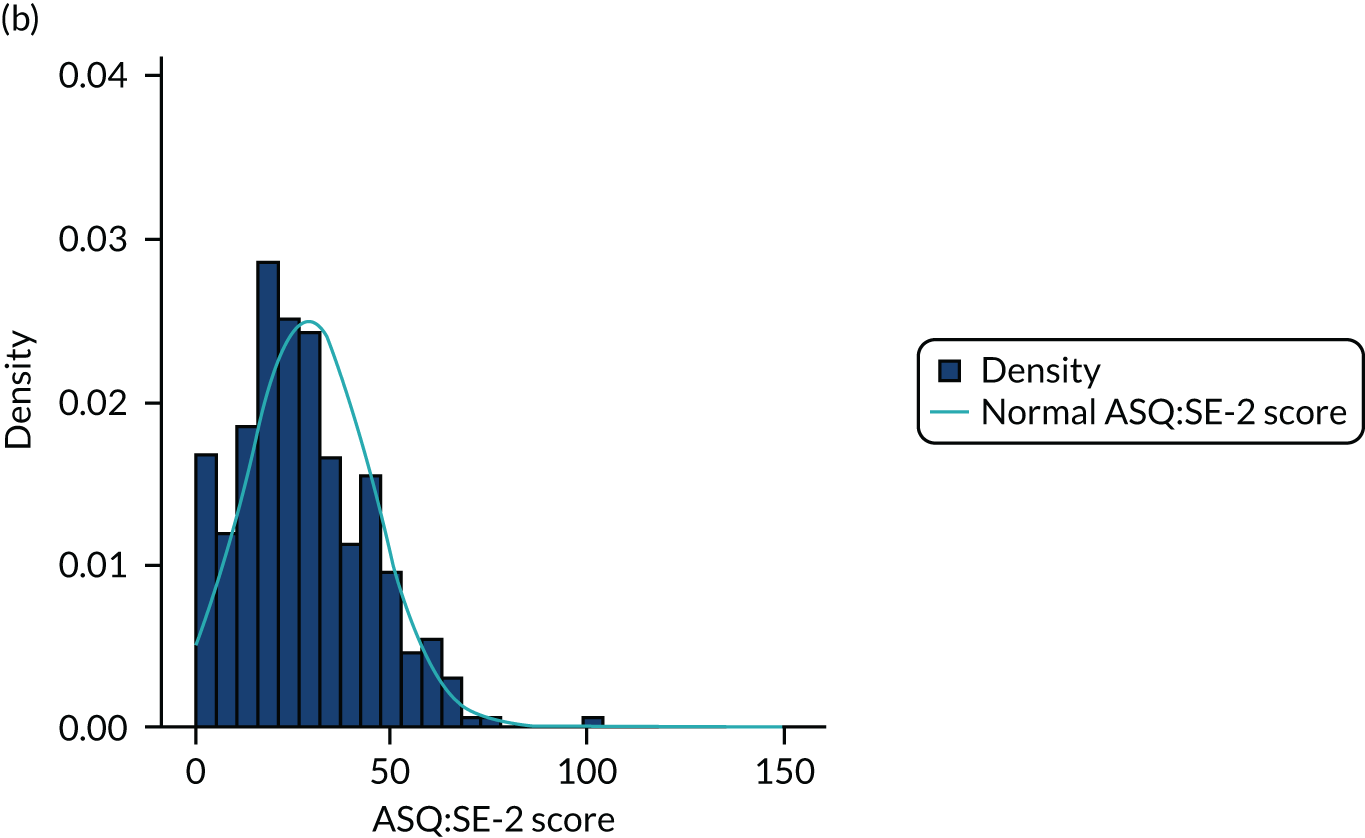

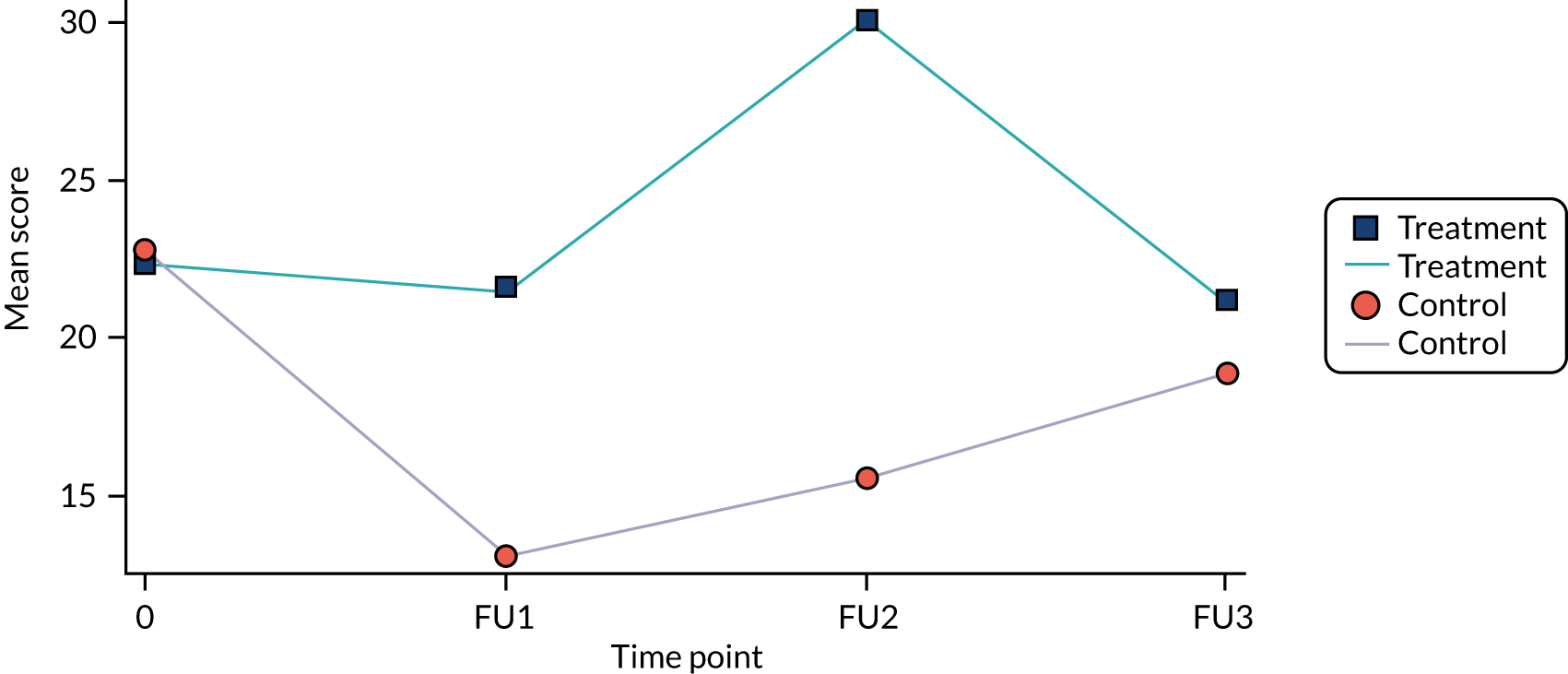

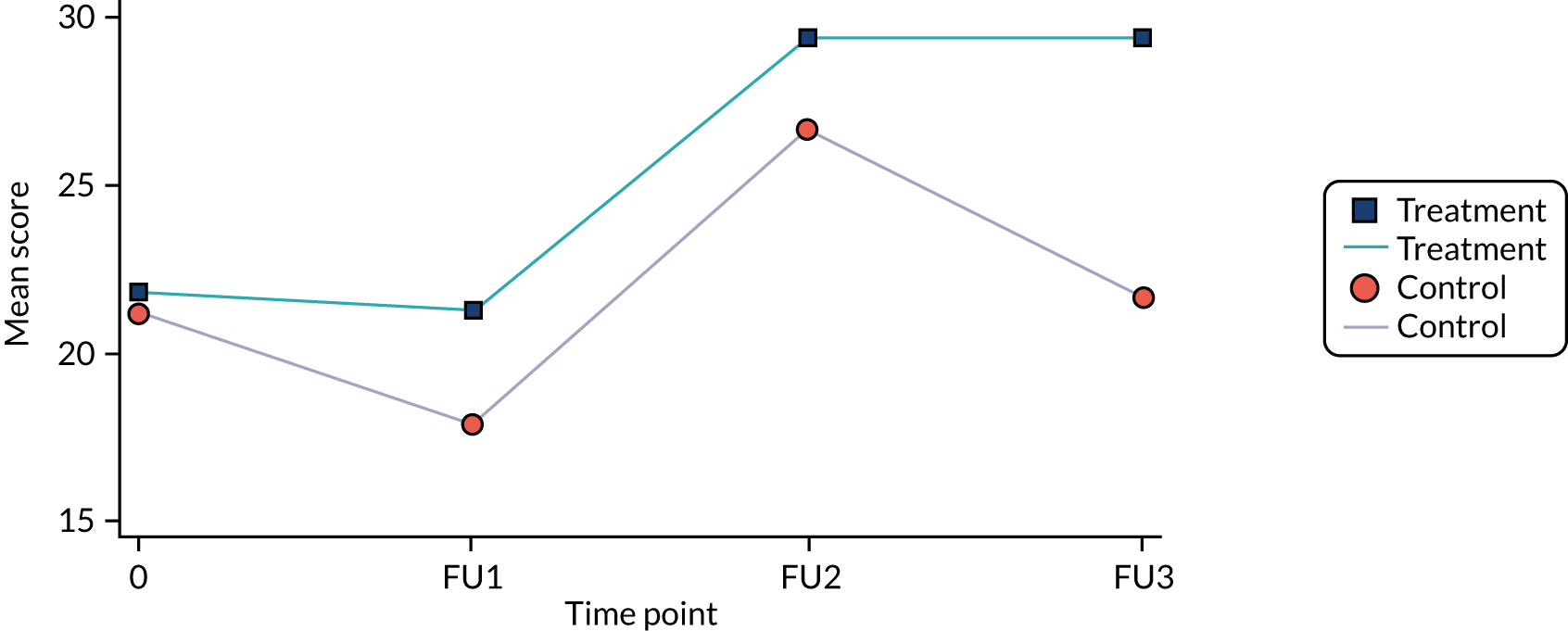

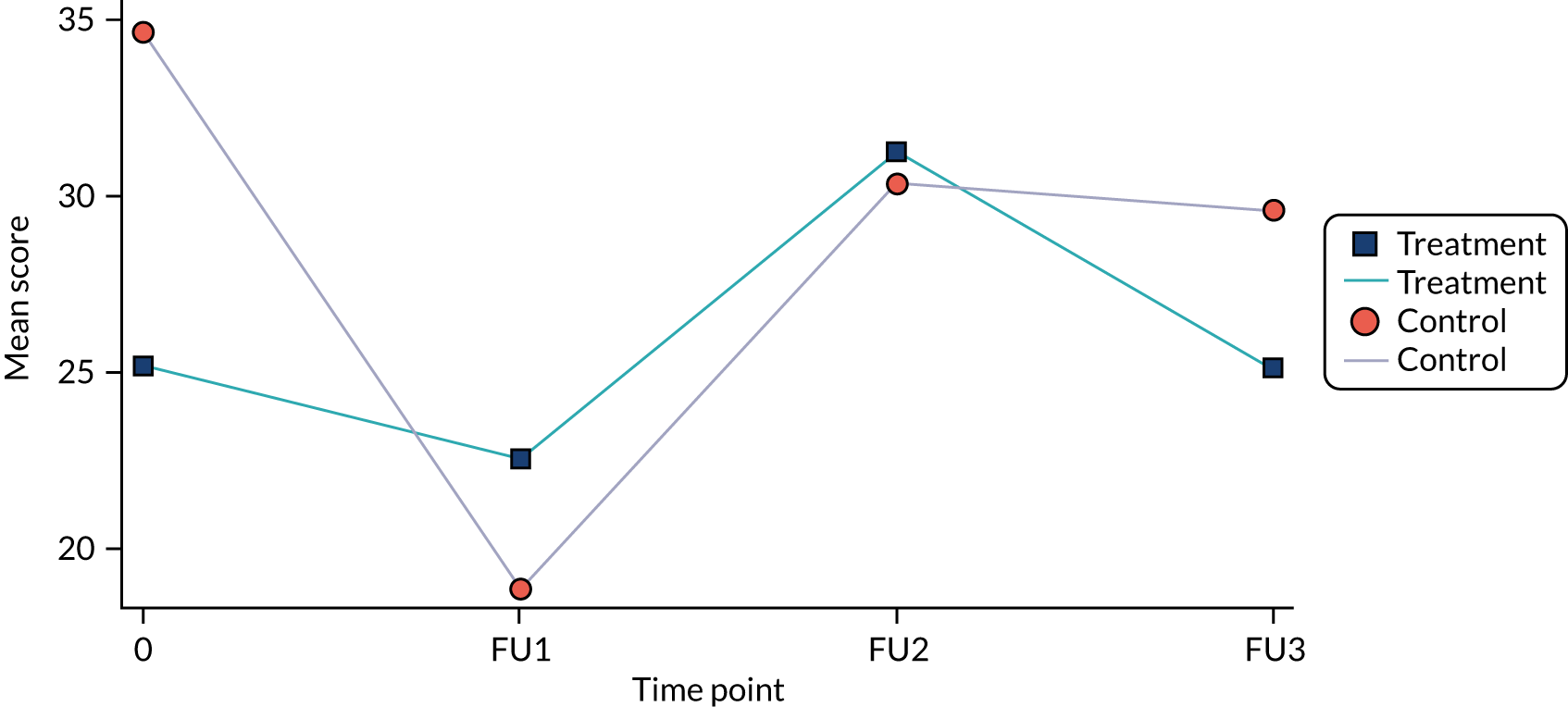

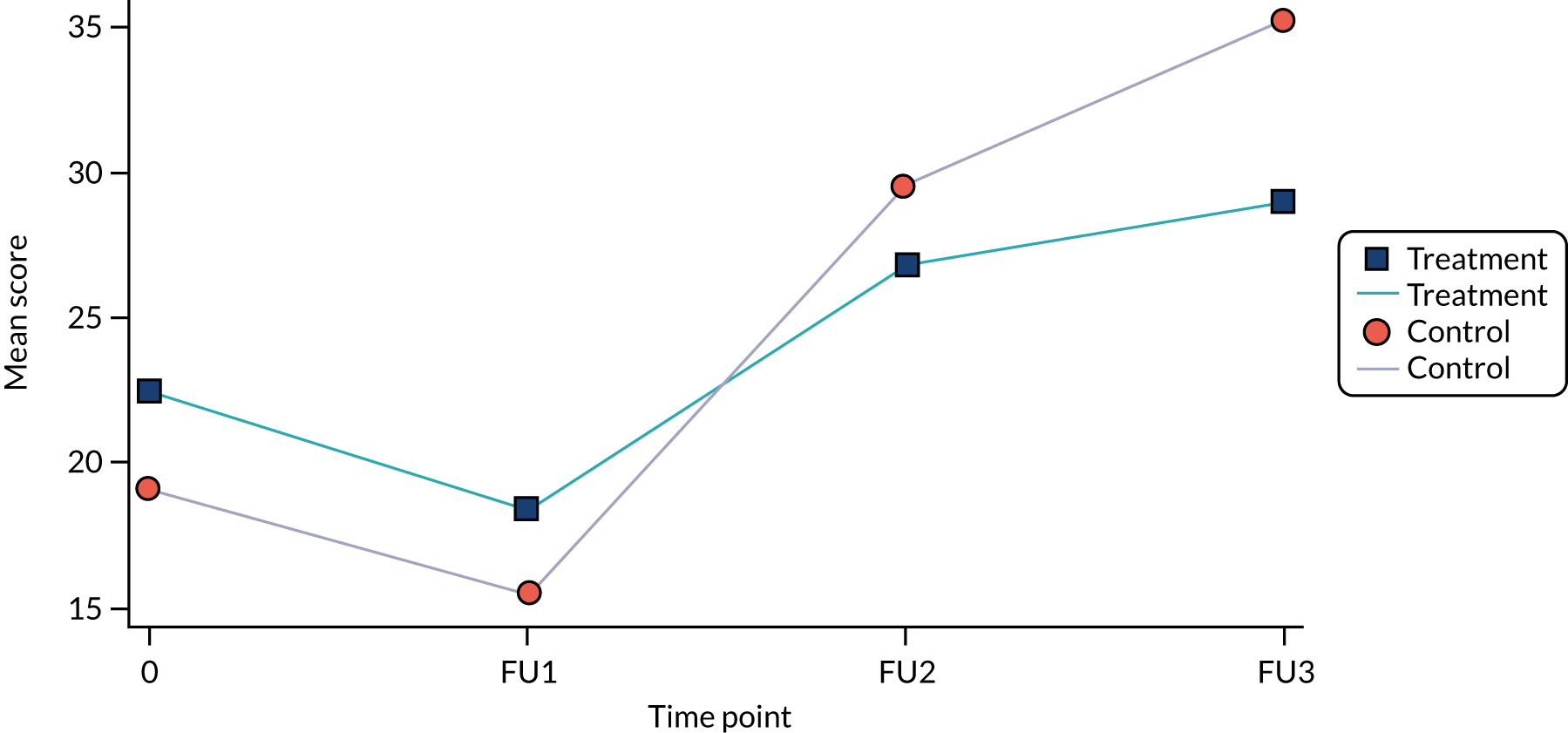

Primary analysis of primary outcome: ASQ:SE-2

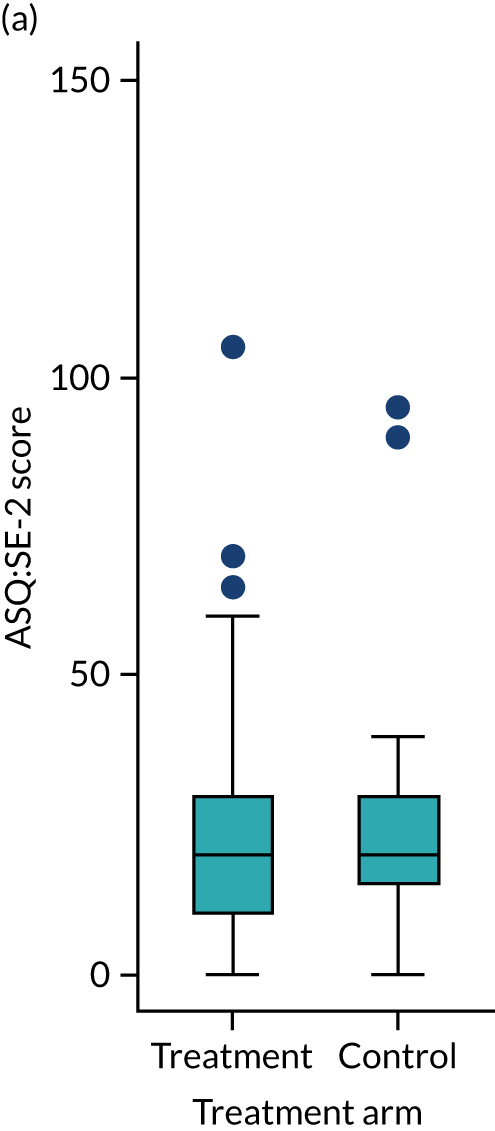

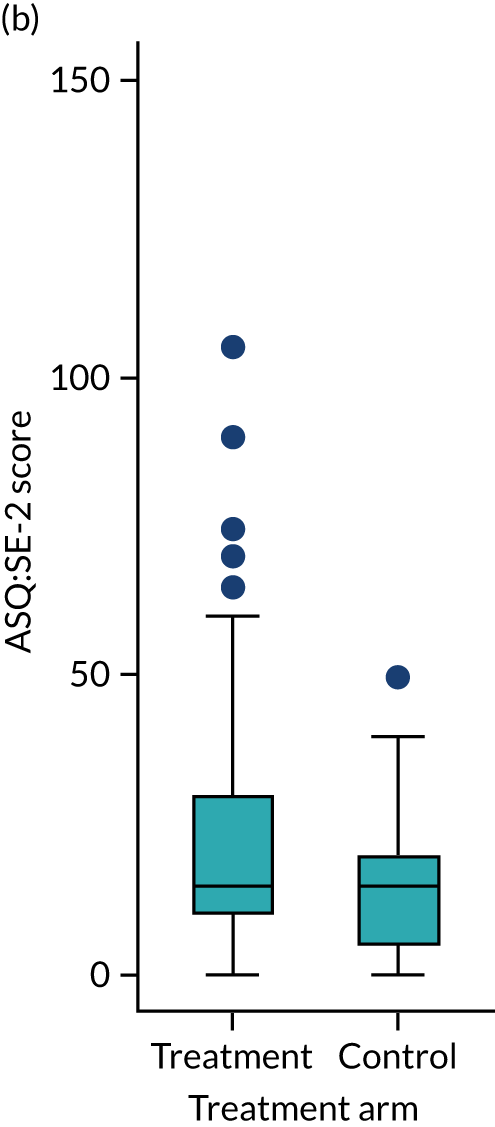

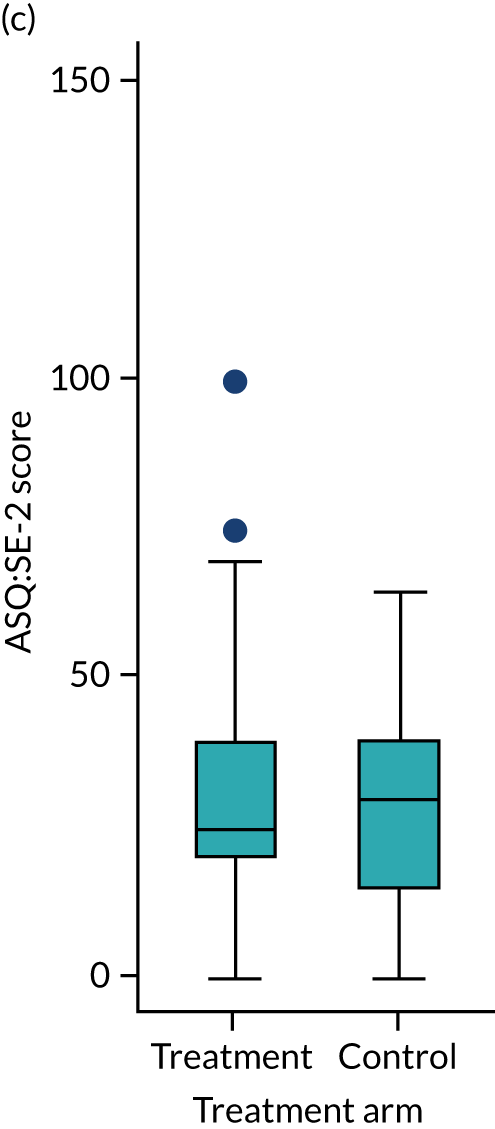

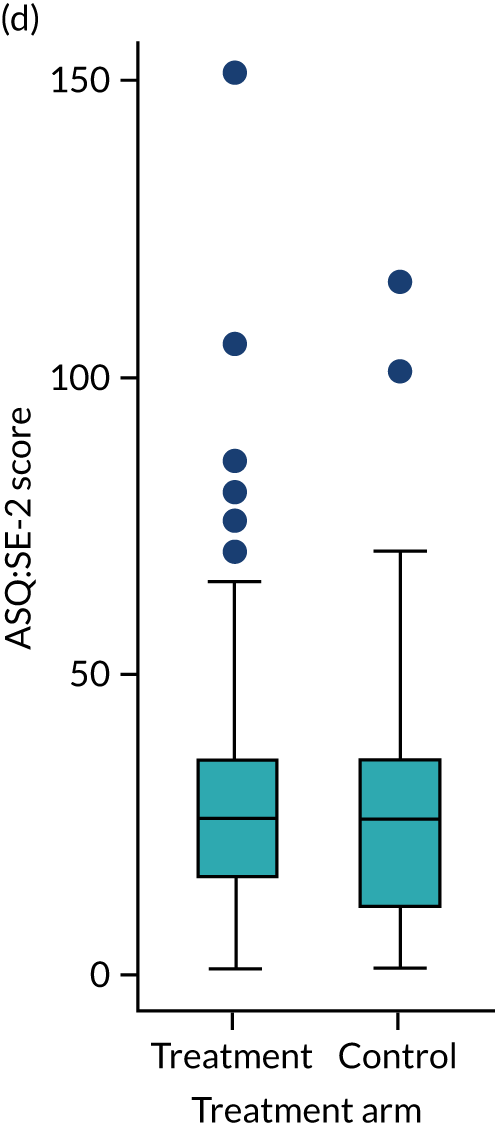

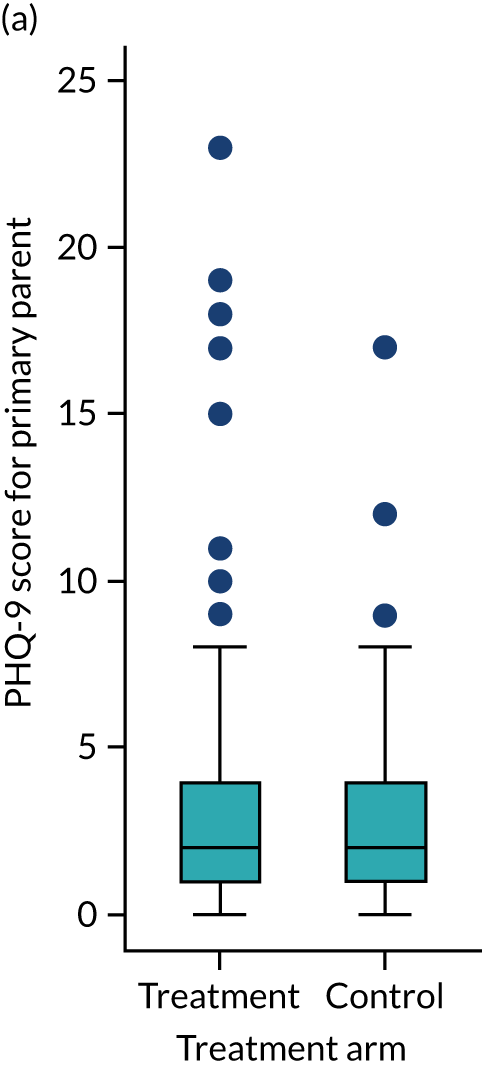

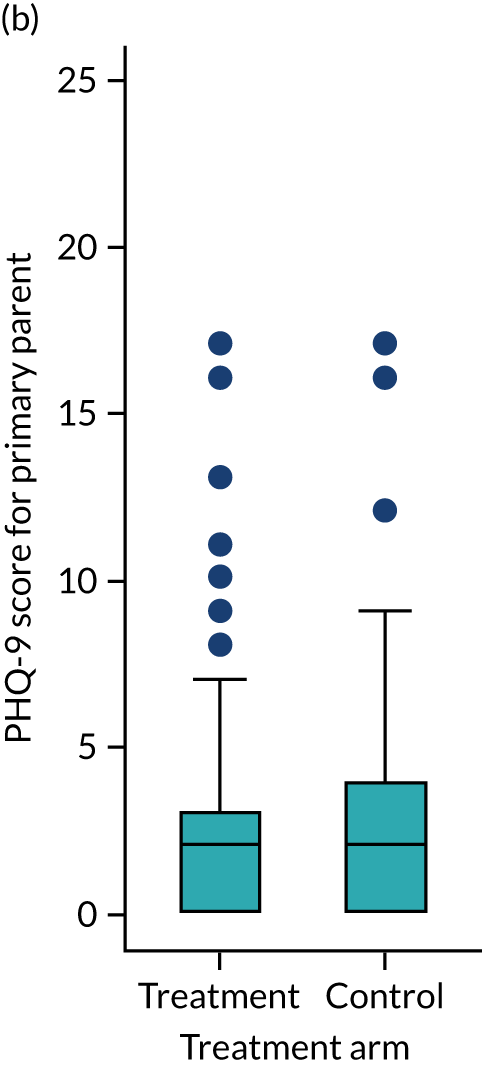

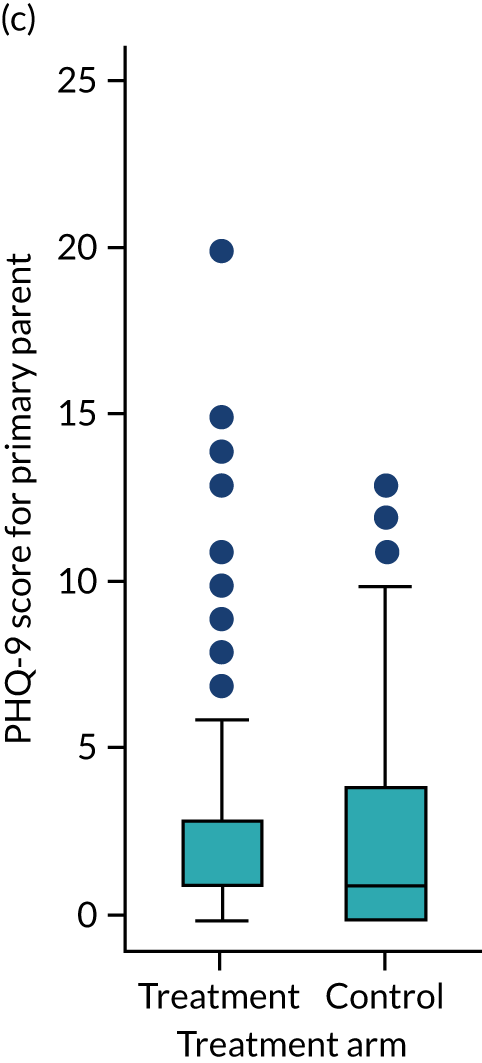

The mean ASQ:SE-2 score was higher in the treatment group than in the control group at all follow-up points apart from FU3. As higher scores relate to poorer outcomes, this provides no evidence in the direction of efficacy (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Summary of overall ASQ:SE-2 scores by follow-up point. (a) Baseline; (b) FU1; (c) FU2; and (d) FU3.

There was a borderline statistically significant positive difference in ASQ:SE-2 scores between arms after controlling for baseline covariates and stratification variables, suggesting that the intervention may have a detrimental effect (3.02, 95% CI –0.03 to 6.08) (Table 4).

| Time point | Treatment arm | All (n = 341) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (n = 285) | Control (n = 56) | ||||

| Baseline | |||||

| n (%) | 285 (100) | 56 (100) | 341 (100) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 22.8 (15.1) | 23.8 (16.6) | 23.0 (15.4) | –0.91 (–5.32 to 3.50) | |

| Median (IQR) | 20 (10–30) | 20 (15–30) | 20 (15–30) | ||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 105 | 0, 95 | 0, 105 | ||

| FU1 | |||||

| n (%) | 270 (95) | 55 (98) | 325 (95) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 20.5 (15.7) | 16.5 (10.9) | 19.8 (15.1) | 4.06 (–0.29 to 8.41) | |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (10–30) | 15 (5–20) | 15 (10–25) | ||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 105 | 0, 50 | 0, 105 | ||

| FU2 | |||||

| n (%) | 269 (94) | 55 (98) | 324 (95) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 29.0 (16.2) | 26.8 (14.7) | 28.6 (16.0) | 2.14 (–2.50 to 6.78) | |

| Median (IQR) | 25 (20–40) | 30 (15–40) | 25 (20–40) | ||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 100 | 0, 65 | 0, 100 | ||

| FU3 | |||||

| n (%) | 268 (94) | 53 (95) | 321 (94) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 26.8 (19.5) | 28.1 (23.6) | 27.0 (20.2) | –1.30 (–7.26 to 4.66) | |

| Median (IQR) | 25 (15–35) | 25 (10–35) | 25 (15–35) | ||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 150 | 0, 115 | 0, 150 | ||

| Overall | 3.02 (–0.03 to 6.08); 0.052 | ||||

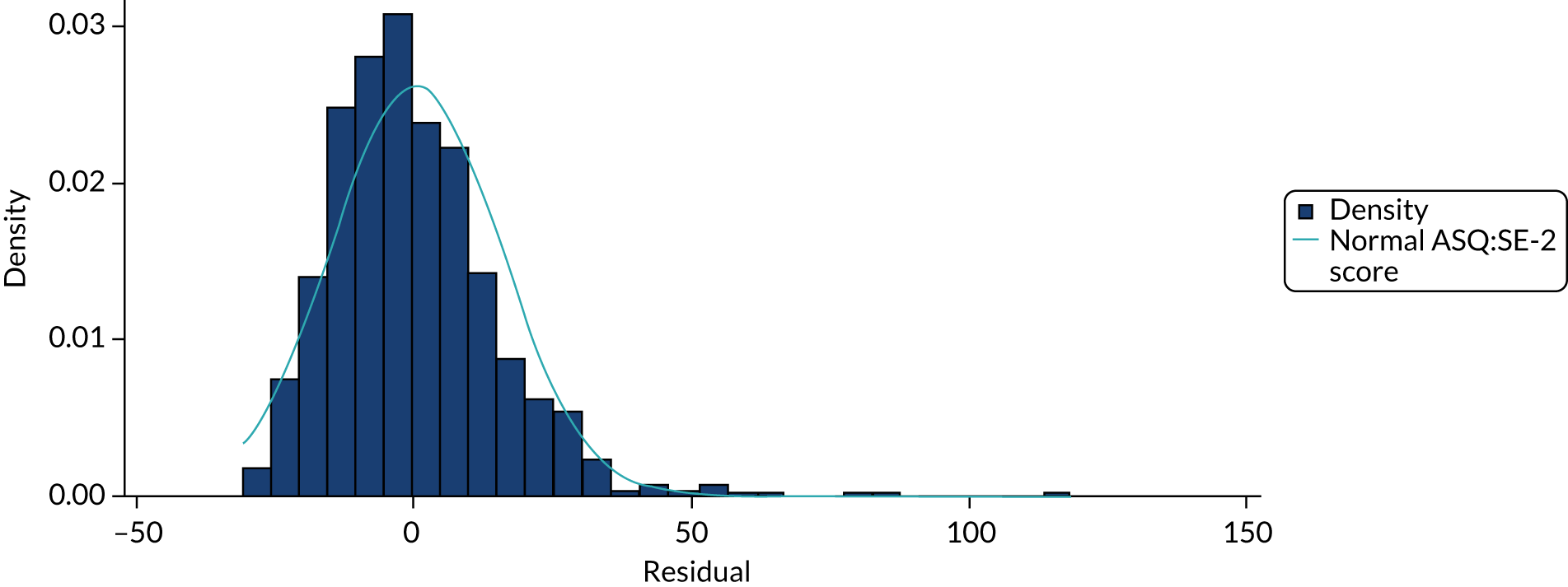

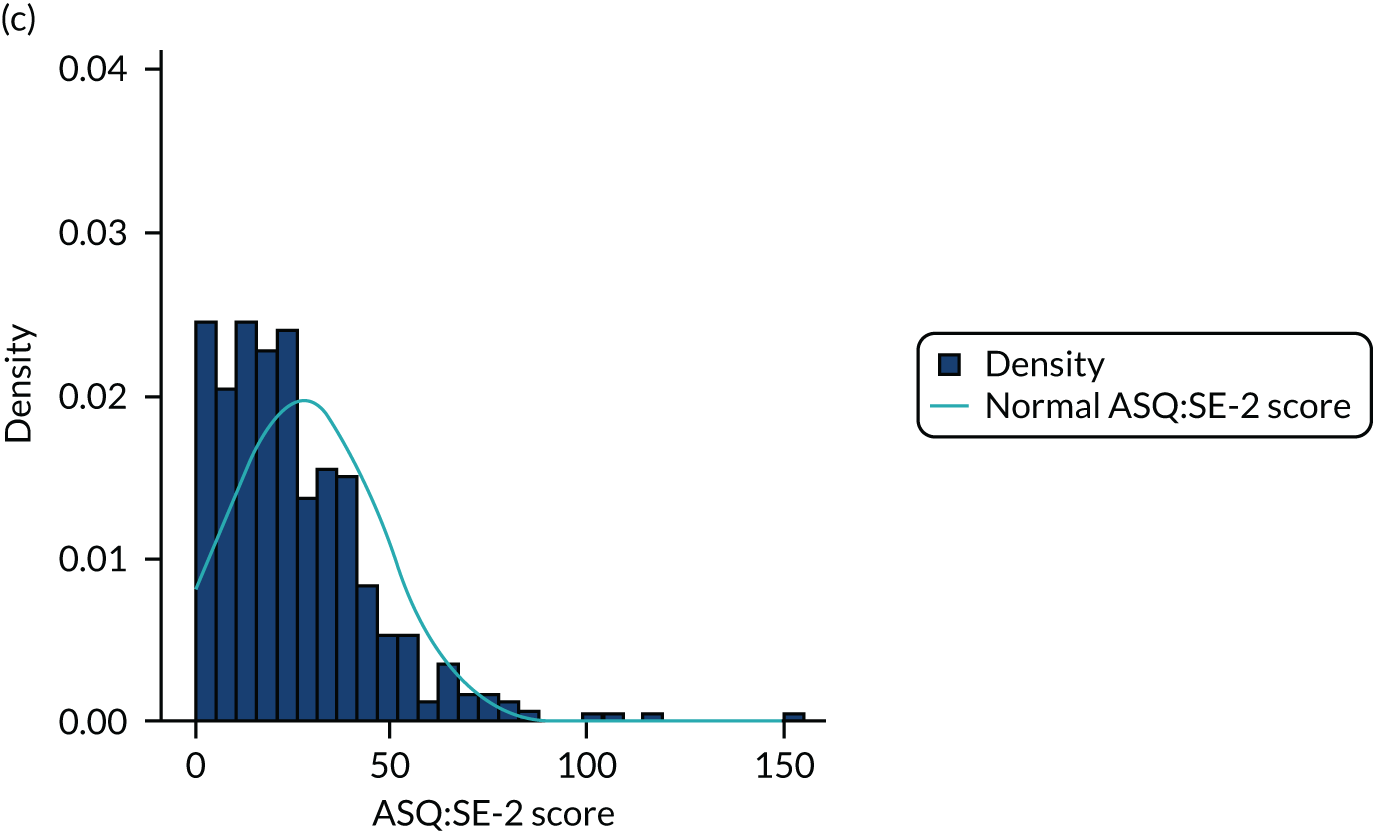

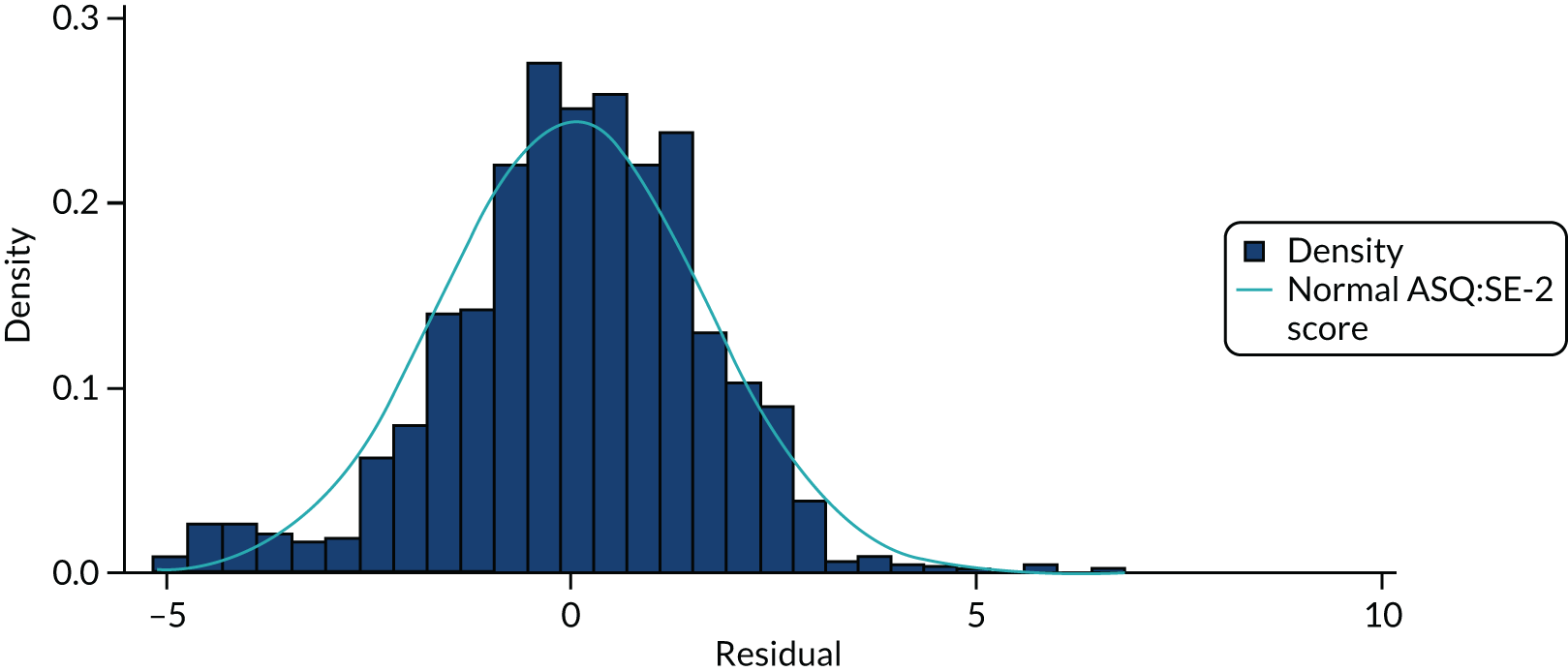

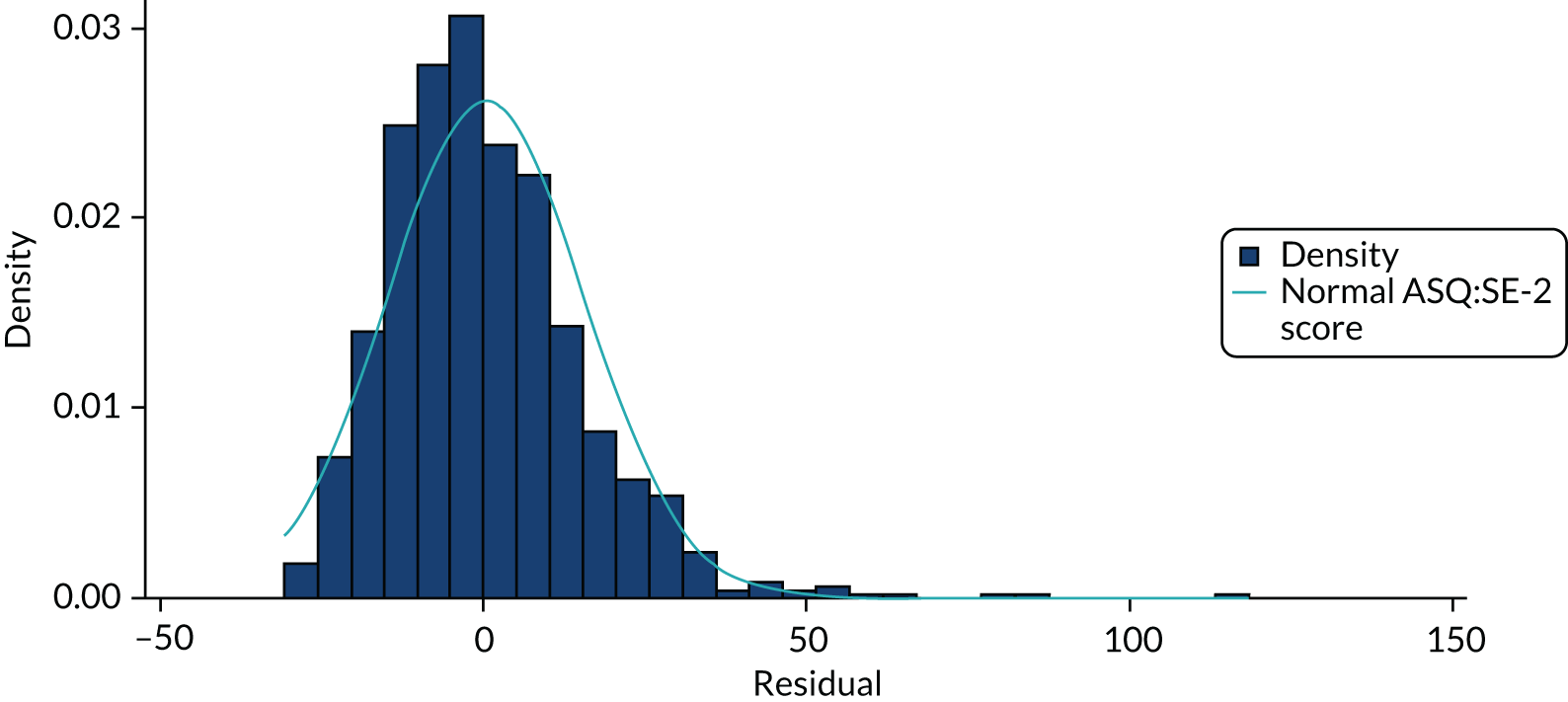

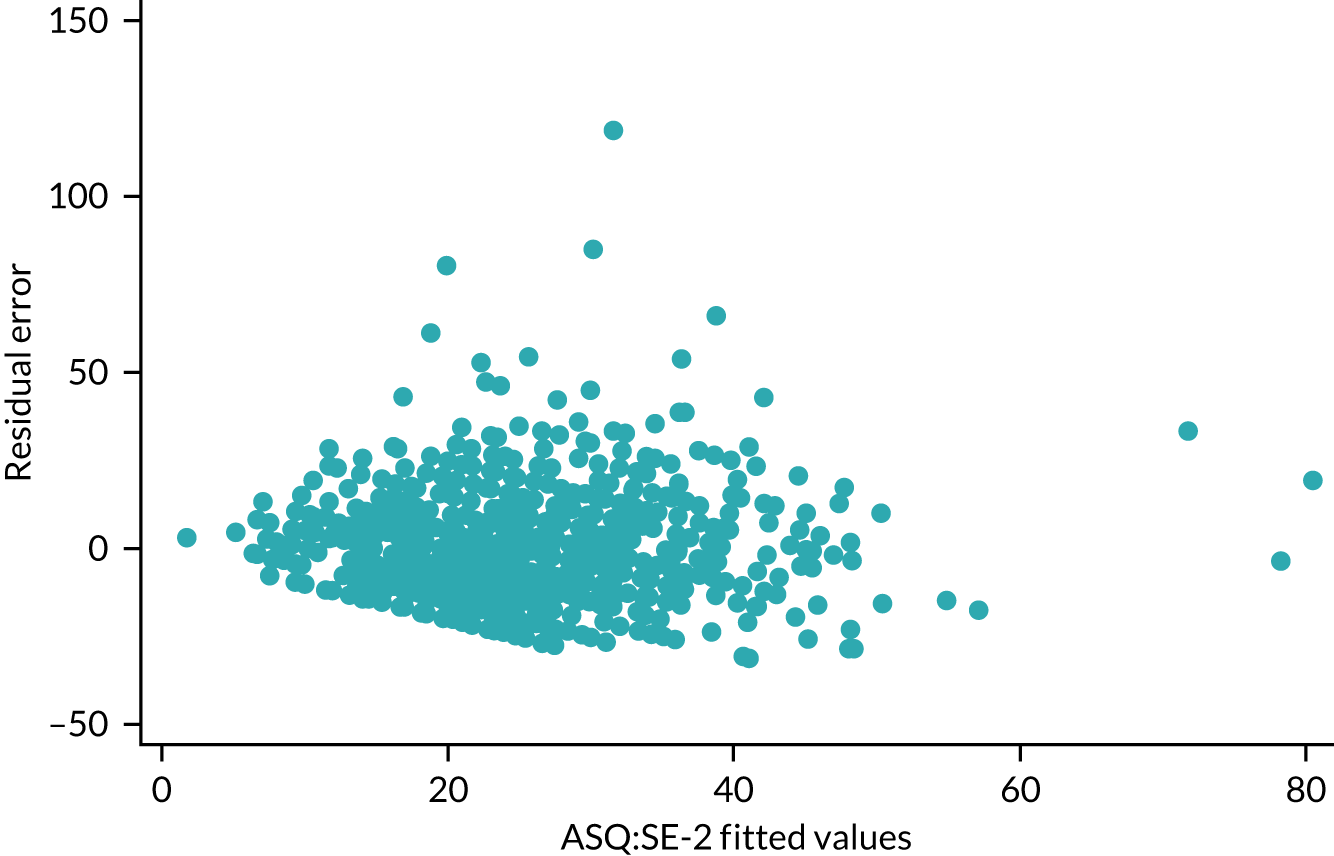

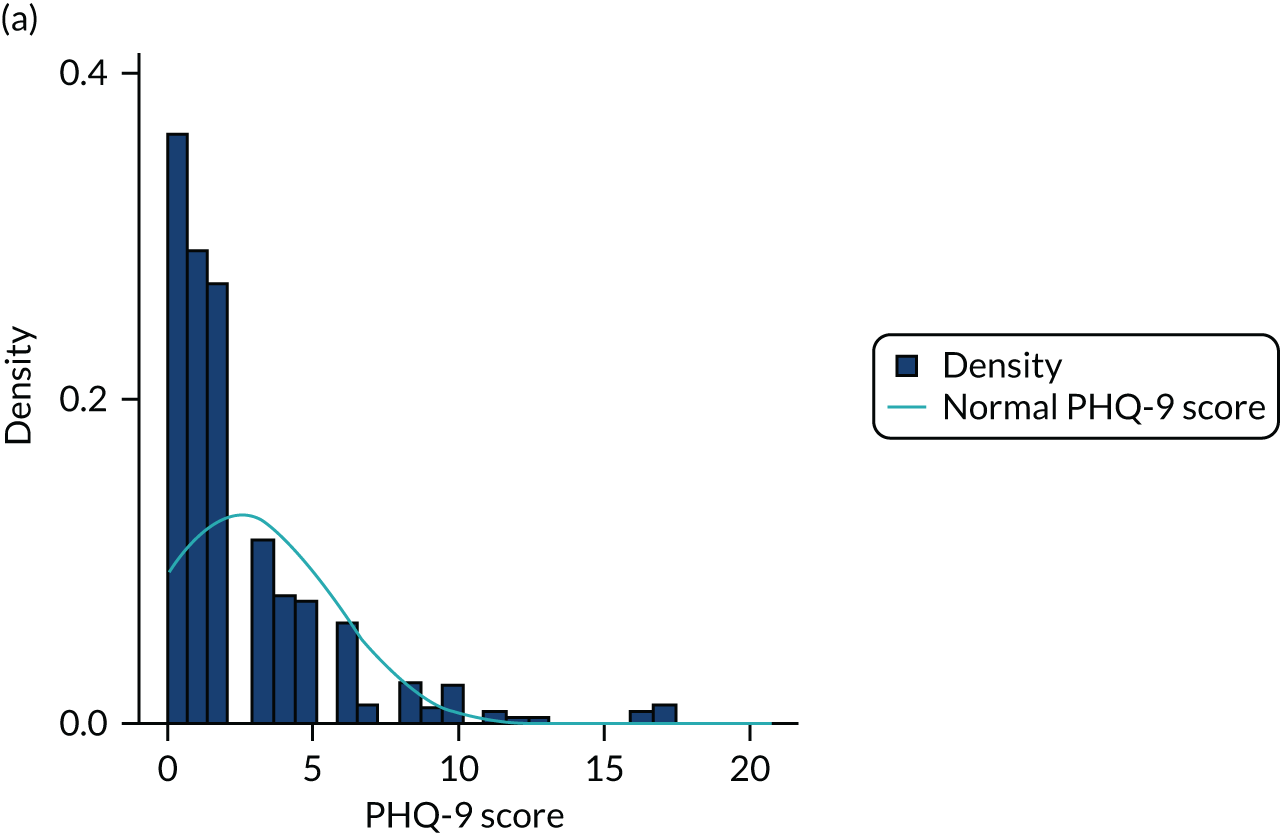

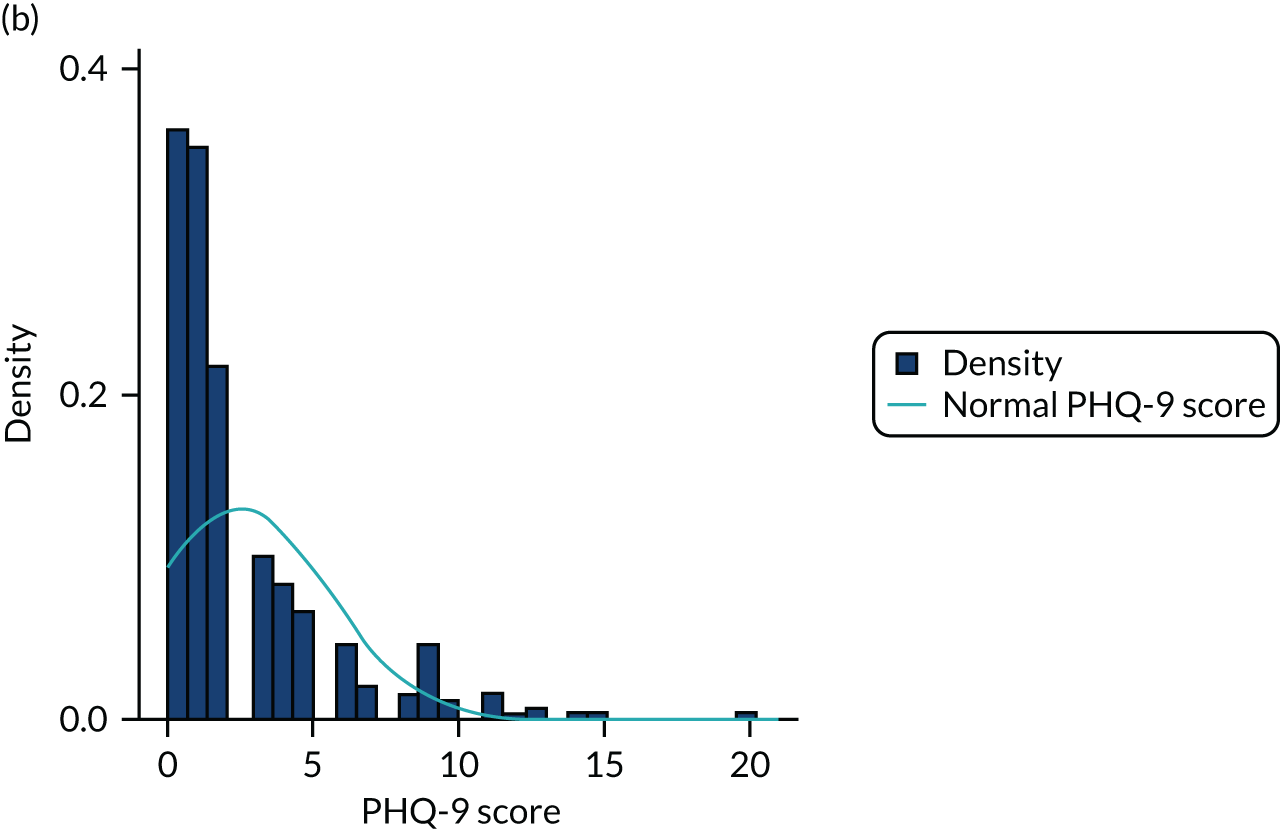

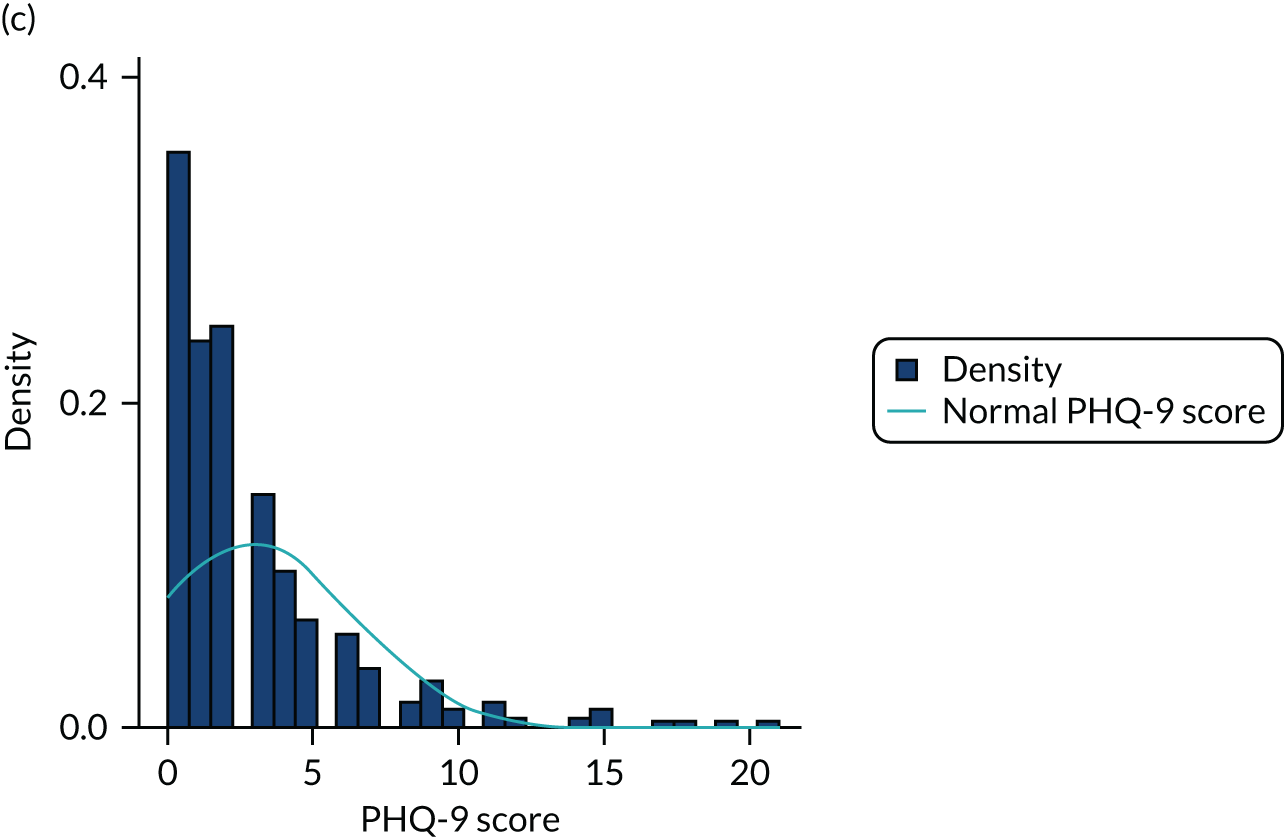

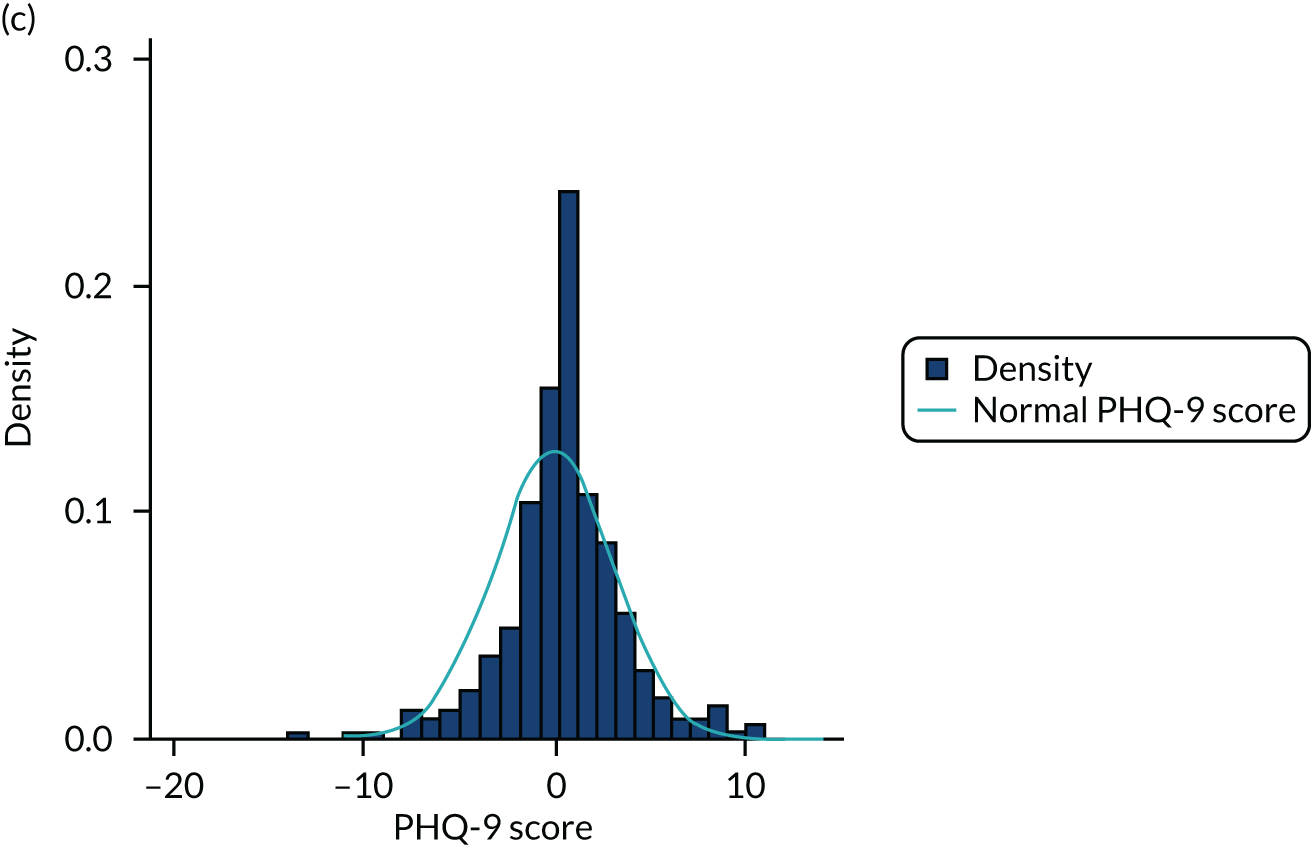

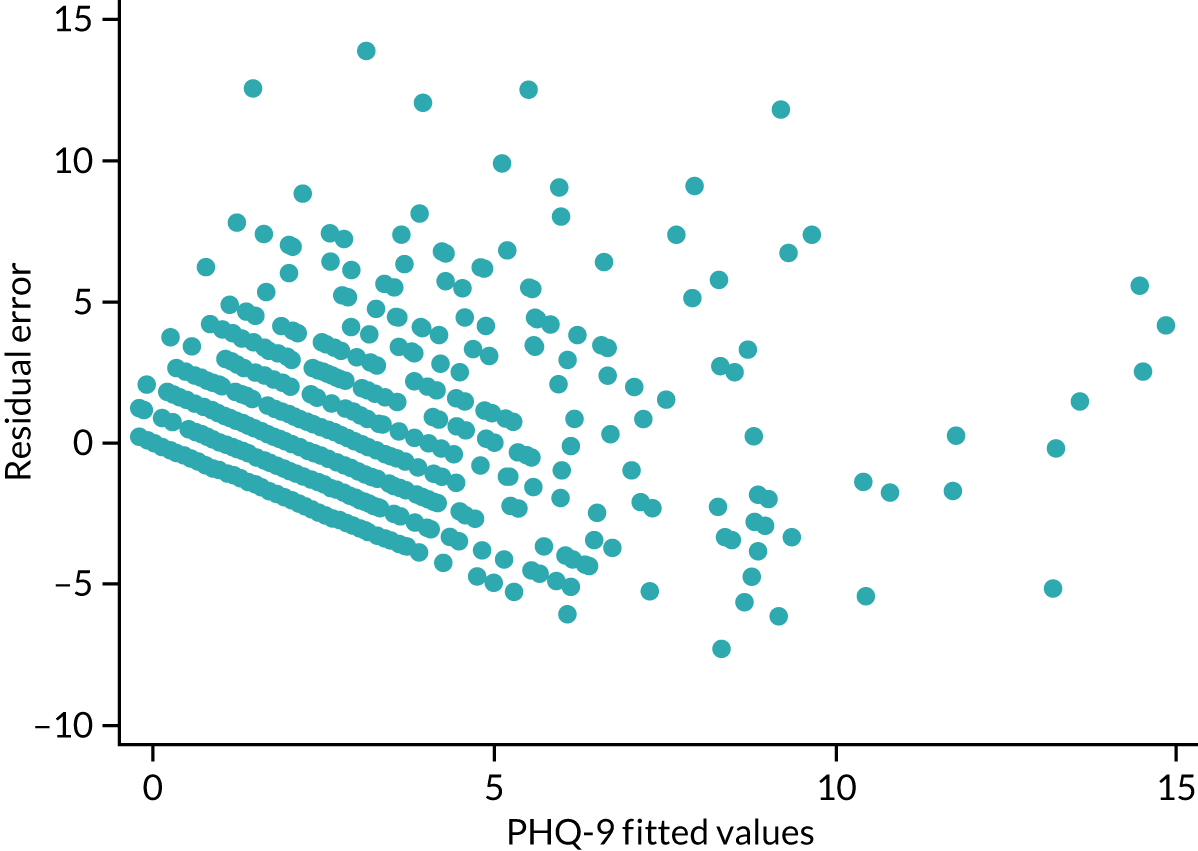

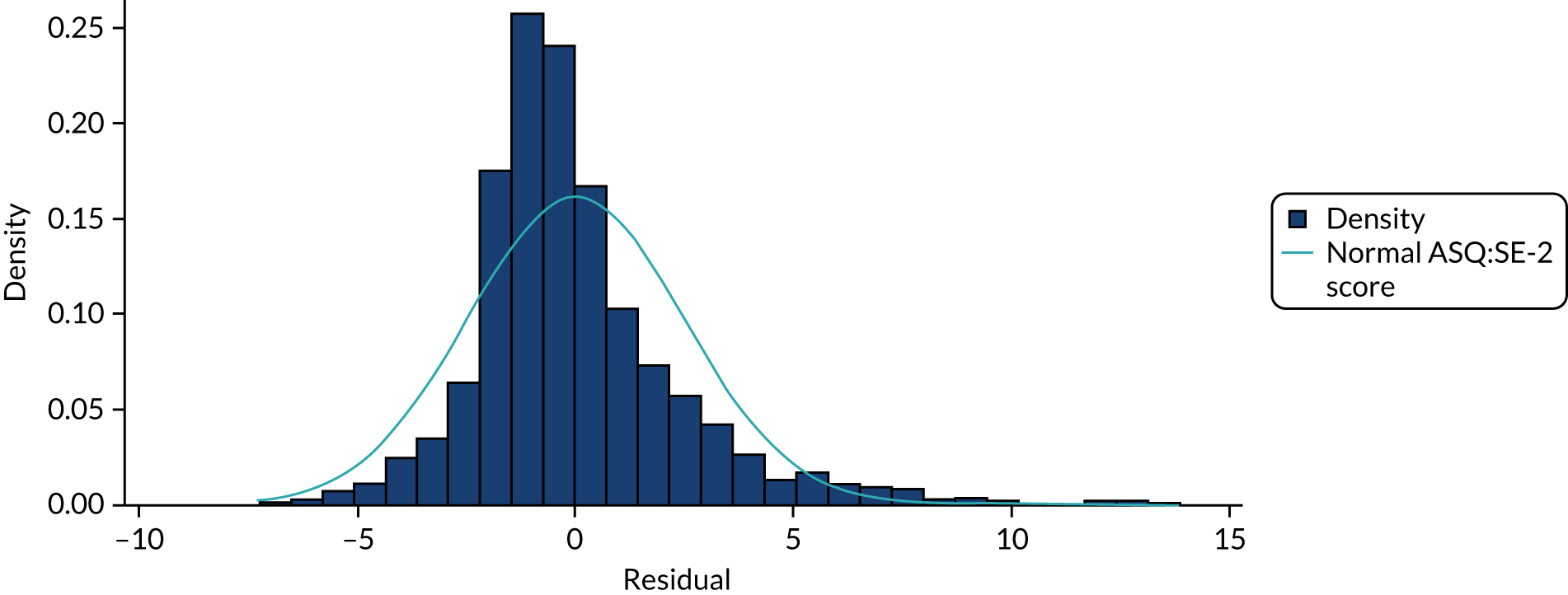

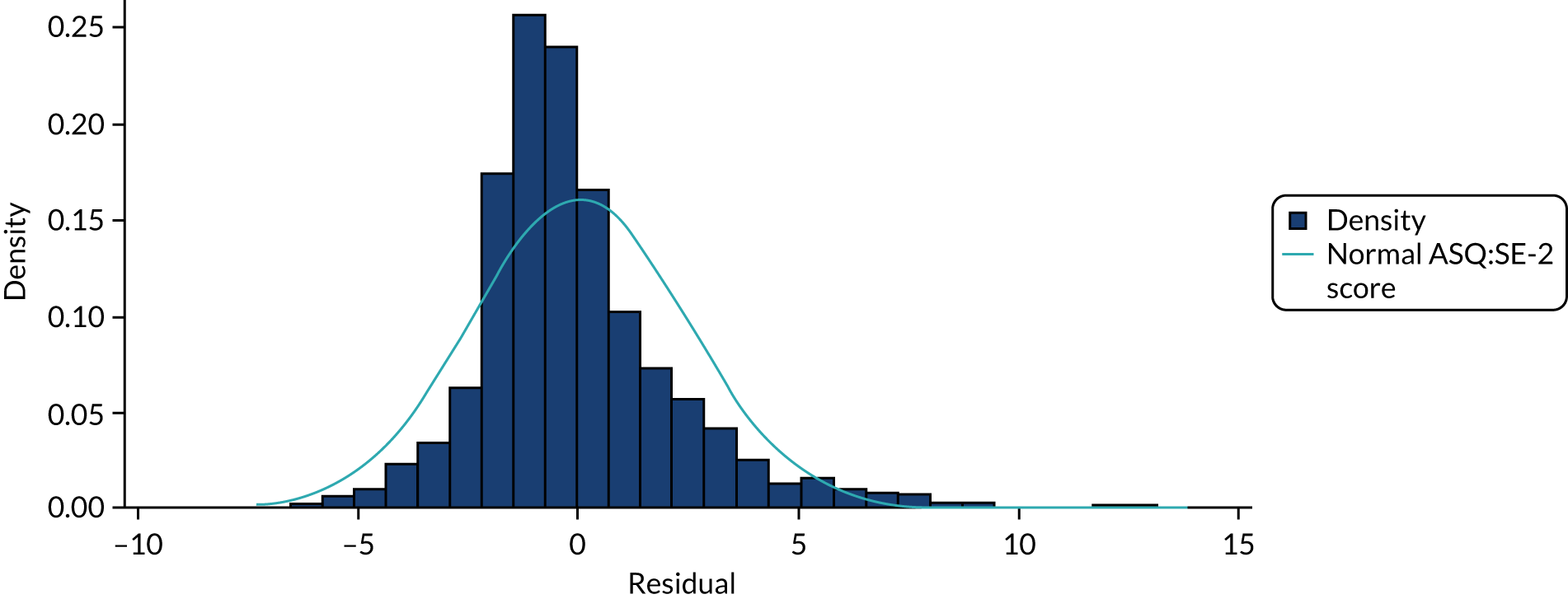

Residuals from the primary analysis model were not perfectly normal, as they were symmetric around zero, with no outlying or overtly influential values (see Appendix 4, Figure 12). The validity of the primary analysis was, nevertheless, investigated using a sensitivity analysis because the ASQ:SE-2 itself has a positively skewed distribution and, together with the extreme imbalance in allocation the type I error, may be increased because there is a heightened risk that, by chance, we observe more extreme values in the larger treatment arm.

Sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome

In addition to the pre-planned sensitivity analysis outlined in the SAP [see URL: www.york.ac.uk/healthsciences/research/public-health/projects/e-see-trial/#tab-3 (accessed 10 January 2022)], unplanned additional sensitivity analyses were undertaken because of the two issues above.

The first planned sensitivity analysis refitted the primary analysis model after transforming ASQ:SE-2 to z-scores and percentage scores (where percentage score is the difference from minimum score expressed as a percentage of the difference between the minimum and maximum scores possible). This transformation, to some extent, also addressed the issue that three different (age-specific) ASQ:SE-2 versions were used over the follow-up periods. The second planned sensitivity analysis was MI. However, because of the skewed distribution of the outcome and concerns over inflated type I error rates due to unbalanced allocation, we felt that further sensitivity analyses were justified.

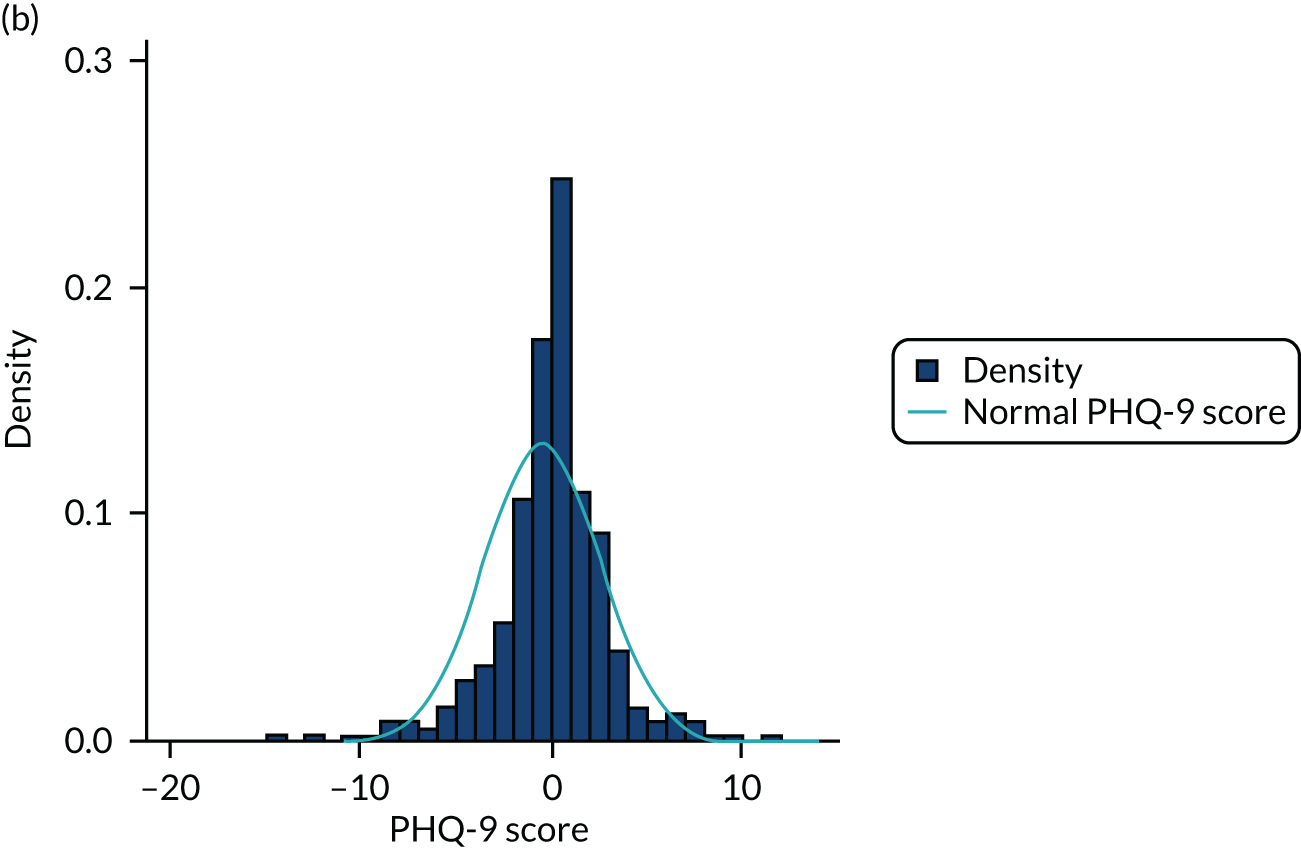

Four types of unplanned sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, we re-ran the primary analysis on square root-transformed primary outcome scores. Appendix 4, Table 36, shows that the residuals for this model are less skewed. Second, we re-ran the primary analysis model, assuming an unstructured rather than auto-correlated structure (see Appendix 4, Table 37). This allowed more of these data to be used because Stata omitted participants who do not have data for at least two adjacent follow-up points. Third, owing to the skewed raw data and imbalance in the size of each arm, a permutation test was carried out. We permuted the allocation to arm 1000 times, keeping all other variables unchanged, and calculated the proportion of times we observed an effect estimate greater than or equal to the actual effect estimate to calculate a permutation-based p-value.

Finally, MI was undertaken using the difference between each participant’s ASQ:SE-2 follow-up score and baseline ASQ:SE-2 score. MI on this ‘differenced’ data removed much of the skew in these data because participants with extreme ASQ:SE-2 values at follow-up typically had similarly extreme values for ASQ:SE-2 at baseline and so the differences were more normally distributed. The MI was conducted using chained equations and 25 replications, with qualification imputed using a logit model and ASQ:SE-2 imputed using a multivariate normal model by treating each time point as a separate variable in the chain. Complete data were available for all other variables in the primary analysis model.

Table 5 summarises the outputs from all models (primary and sensitivity) and Figure 3 shows a forest plot for all analyses, with results transformed into original ASQ:SE-2 units. The sensitivity analyses suggest that the results were not particularly sensitive to the imbalance between arms and the skewed distribution of the primary outcome. However, the strength of the signal diminishes when methods that allow for missing and incomplete data are employed. To understand why the additional observations had this effect, we explored some features of the missing data by comparing baseline ASQ:SE-2 scores and treatment allocation between the missing and non-missing observations (see Appendix 5, Table 38). It is difficult to draw any conclusion from this comparison because of the complex relationship between missing data, time point, allocation and effect.

| Analysis | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis model | 3.02 (–0.03 to 6.08) | 0.052 |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||

| z-score transformation | 0.19 (0.01 to 0.36) | 0.036 |

| Percentage transformation | 0.81 (0.06 to 1.56) | 0.035 |

| Primary with unstructured correlation | 2.56 (–0.69 to 5.80) | 0.122 |

| Permutation test | 0.069 | |

| Difference from baseline: MI | 1.97 (–1.22 to 5.17) | 0.23 |

FIGURE 3.

Forrest plot for primary analysis models on original scale. MCID, minimum clinically important difference.

Exploratory analysis of the primary outcome

It is interesting to note that comparing the unadjusted differences between arms at each follow-up point suggested a stronger early effect in favour of SAU, which tended to diminish over time (see Table 4). Most of the weight of the signal in the overall effect was due to the larger difference seen at FU1, which then diminished over time. This might suggest that the book alone increased the primary outcome in the treatment group compared with the control group. This pattern was more pronounced after subtracting the baseline score from the score at each follow-up point and looking at unadjusted differences between arms. In this adjusted analysis, the size of the effect decreased from 4.6 at FU1 to 2.9 at FU2 and –0.9 at FU3.

Two planned and one unplanned exploratory analysis were conducted. First, the subgroup analysis was conducted for social and economic background (using ‘primary parent educated to degree level’ as a proxy), whether or not the index child was the first child, sex of the child and site by adding an interaction between treatment group and subgroup into the primary analysis model. For ‘first child’, the main effect was additionally included because it is not a covariate. There was weakly significant evidence of an interaction with treatment for site (p = 0.06), but no evidence of a significant interaction for the other three subgroups (Table 6). The site-level control groups were too small for additional statistical analysis (Figures 17–20 in Appendix 6 do not suggest better scores in the treatment groups compared with control for any of the sites).

| Subgroup | Interaction coefficient (95% CI) | Interaction p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Below degree level | –2.88 (–9.19 to 3.43) | 0.37 |

| Male (child) | –0.23 (–6.28 to 5.81) | 0.94 |

| Not first child | 1.95 (–4.15 to 8.06) | 0.53 |

| Site | ||

| 1 | –9.99 (–17.25 to –2.74) | |

| 2 | –3.49 (–9.9 to 2.93) | |

| 3 | –6.80 (–14.43 to 0.83) | |

| 4 | Omitted | |

| Overall site interaction | 0.06 | |

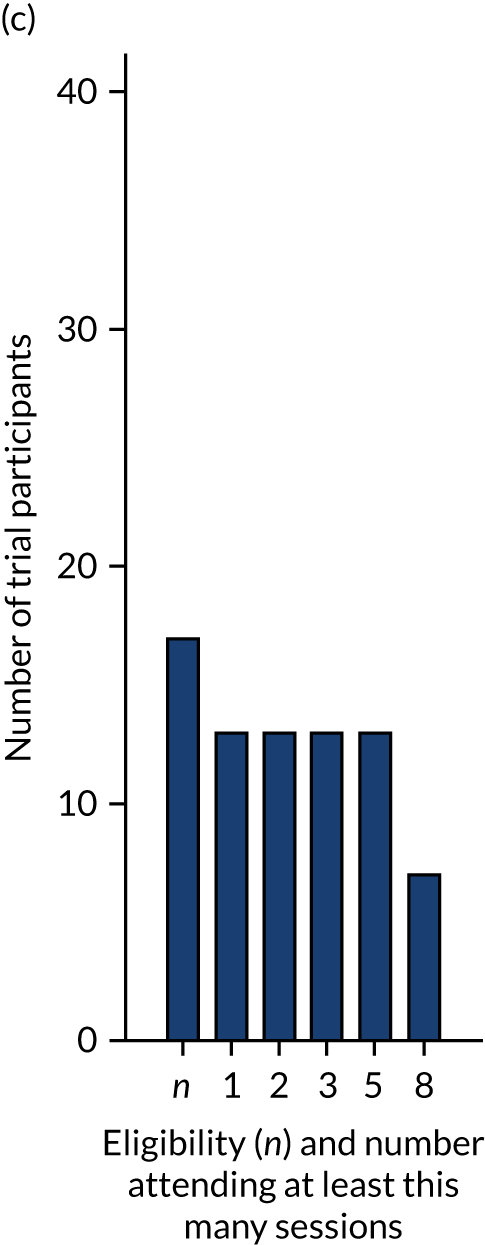

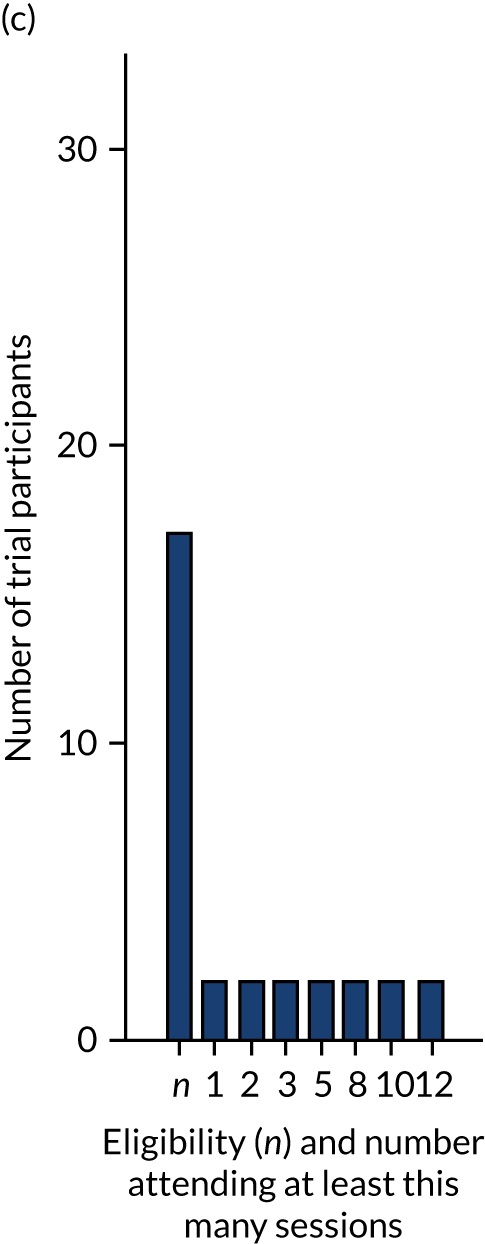

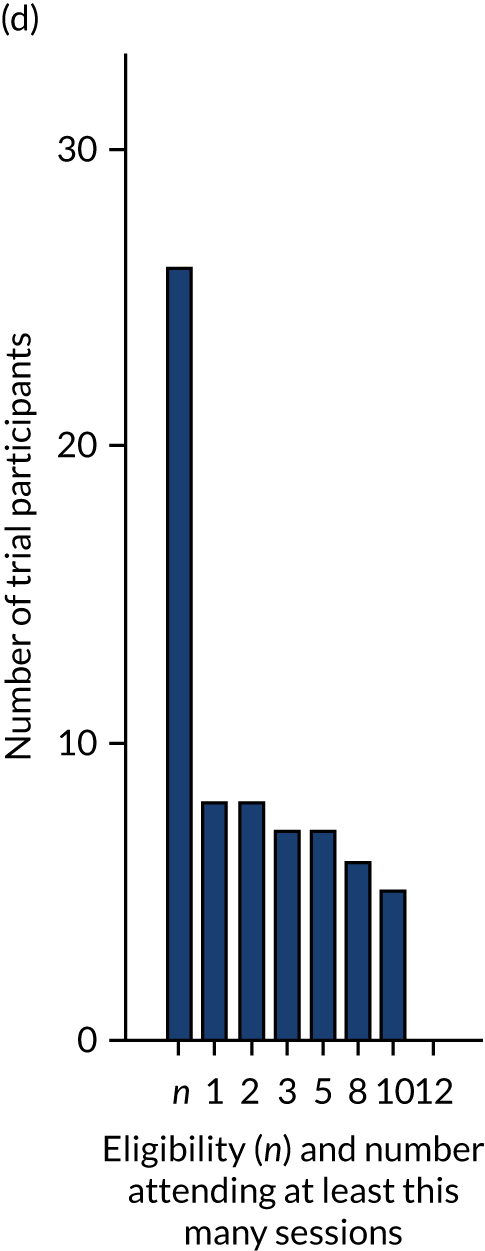

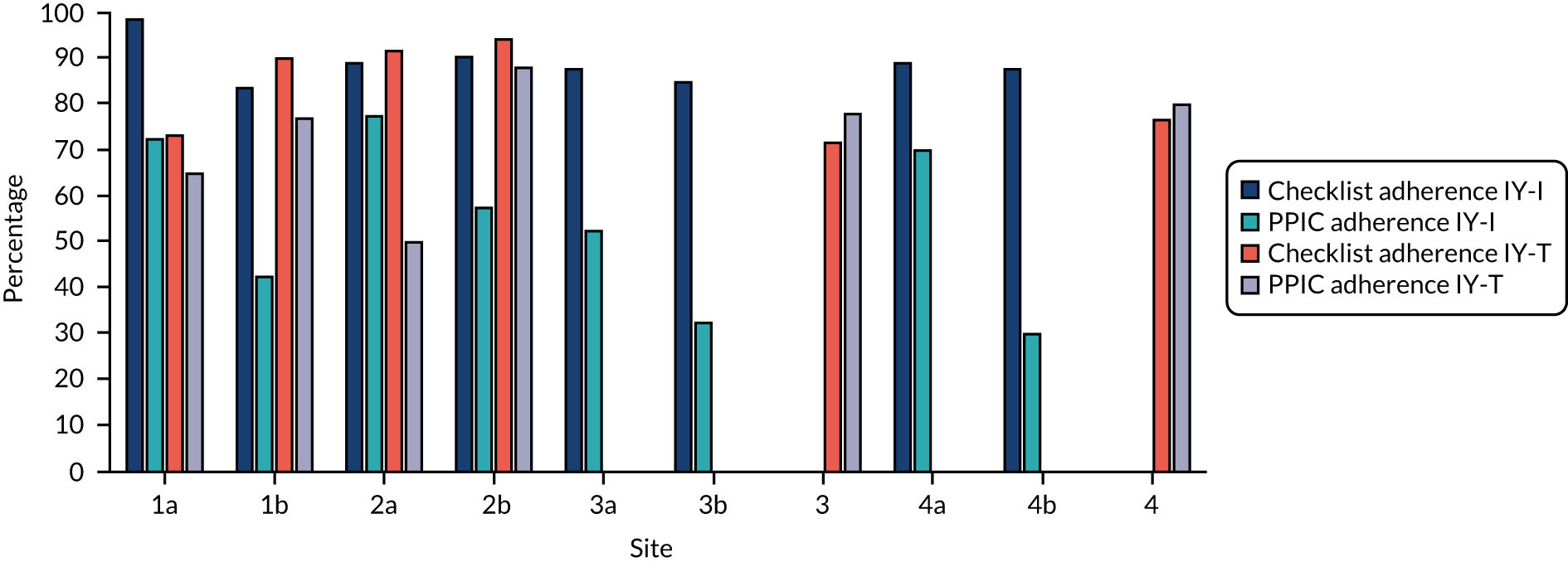

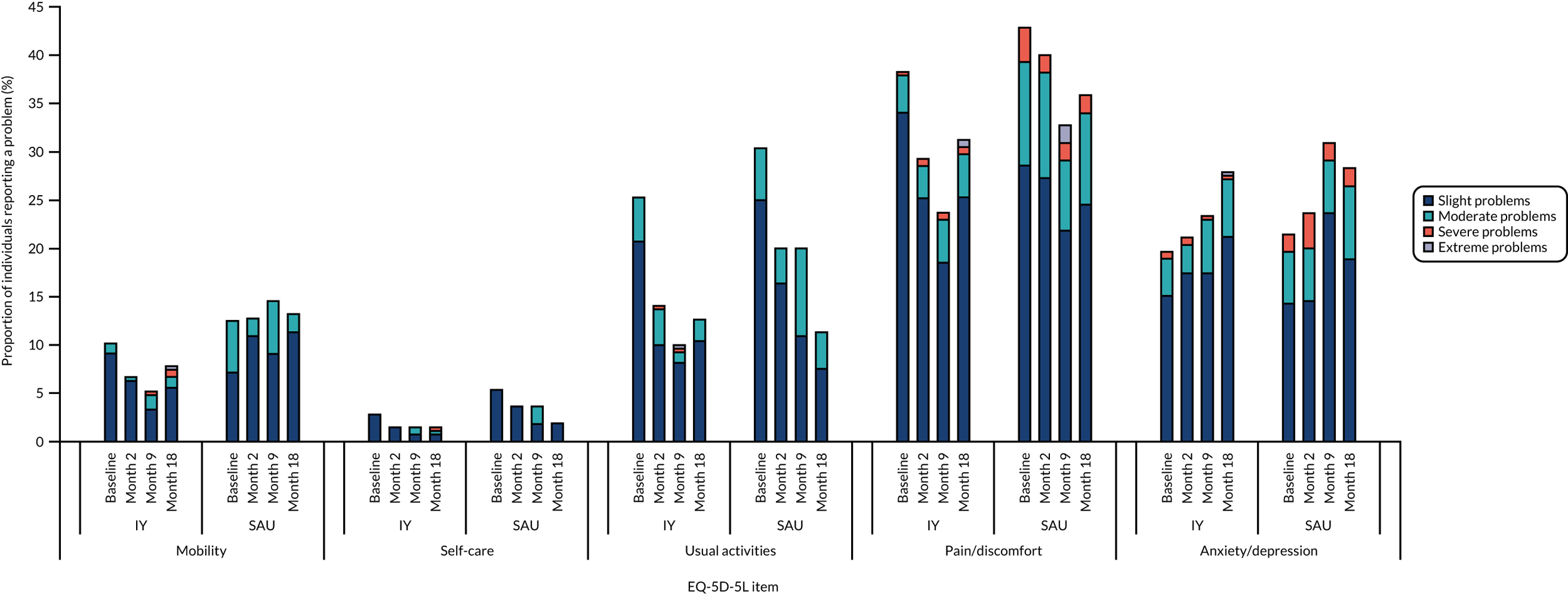

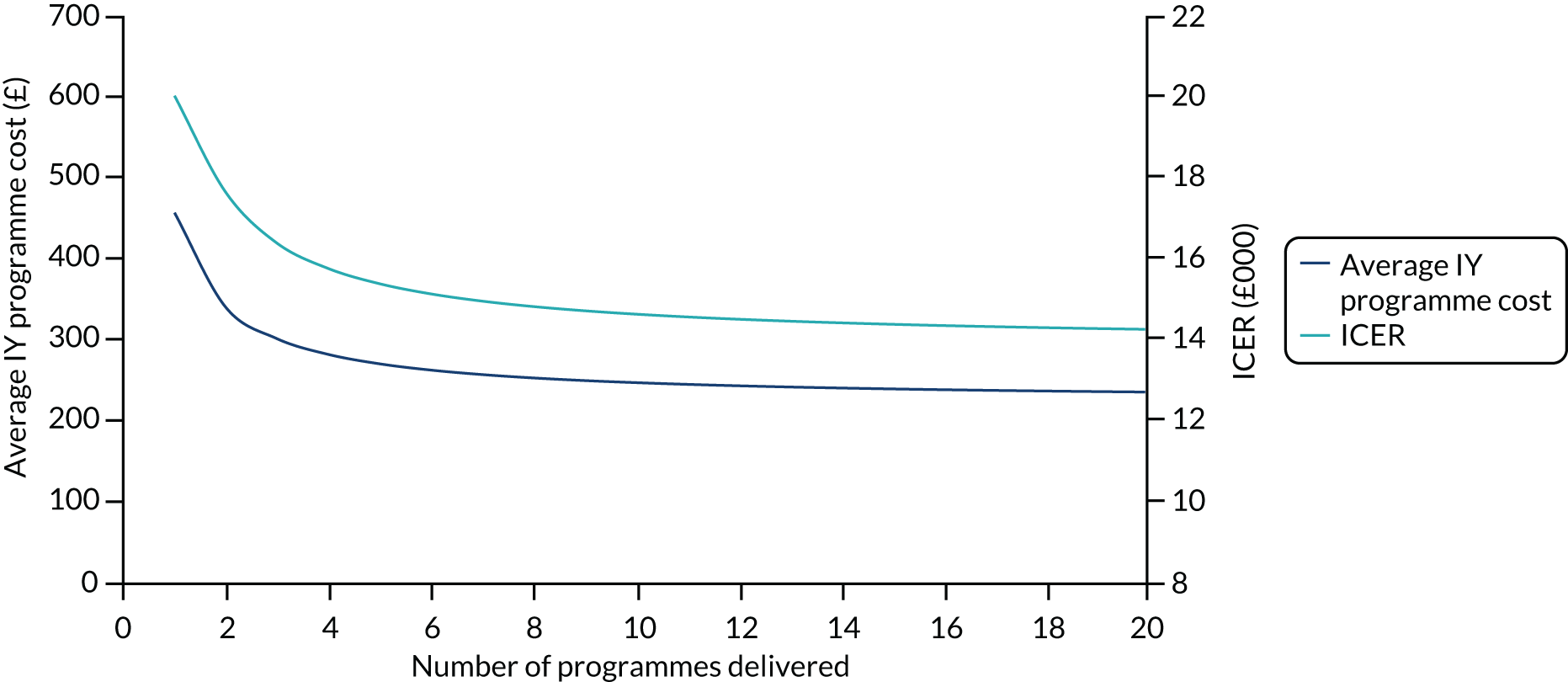

Second, planned indicative analysis of whether or not the baby and toddler groups had an impact were undertaken. This analysis is indicative only because allocation to group programme occurs after randomisation. Eligibility for group programme is determined by ASQ:SE-2 and PHQ-9 scores at FU1 for IY-I and at FU2 for IY-T. The indicative analysis compared the eligible participants with the subgroups of control participants that had ASQ:SE-2 and PHQ-9 scores in the eligible range for the groups (referred to a pseudo-controls), using the same model as used for the primary outcome. The analysis found no evidence of a difference between group programme participants and the pseudo-controls (see Appendix 7, Table 39).