Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 16/09/13. The contractual start date was in March 2018. The final report began editorial review in January 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Popay et al. This work was produced by Popay et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Popay et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2016 the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) sought to commission research to address urgent gaps in the evidence on which interventions, using a community engagement approach, are effective in improving health and well-being and reducing health inequalities. The research reported here was funded under that initiative. It was the third phase of the Communities in Control (CiC) study: a longitudinal mixed-methods study that began in 2014 and aimed to evaluate the social and health impacts of England’s largest area-based community empowerment initiative to date – Big Local (BL). Two earlier phases of the CiC study were funded by the NIHR School for Public Health Research (SPHR) (CiC1: 2014–15 and CiC2: 2015–17). 1–3 These earlier phases were the foundation for the phase 3 research reported here (CiC3), enabling the construction of longitudinal qualitative and quantitative data sets and providing early insights into both process and impacts. CiC3 began in March 2018 and was originally to end in May 2021. However, in response to pandemic-related disruptions, described at various points in the report, a short no-cost extension to September 2021 was agreed.

The BL initiative, funded by the then Big Lottery Fund (now the National Lottery Community Fund), was launched in 2010 and began to be implemented in 2011. It was initially due to run for 10 years but has since been extended. The programme gave each of 150 relatively disadvantaged neighbourhoods around England £1M for residents to spend to ‘make their neighbourhood an even better place to live’. 4 Though not an explicit objective, the BL initiative has the potential to influence health outcomes of residents of these neighbourhoods via various pathways. The CiC study has focused on the potential indirect health impacts of communities of place having greater collective control over decisions and actions to improve the areas in which they live, and the direct health impacts of any improvements in the social determinants of health and health equity residents deliver in their neighbourhoods.

Communities in Control (CiC3) has investigated the medium-term social and health impacts of BL on the populations of the 150 areas in England where the programme was implemented and on the most engaged residents in these areas; assessed changes over time in the collective control BL residents had over decisions and actions that aimed to improve social determinants of health in BL areas; explored pathways to any changes in collective control and social and health outcomes identified; and conducted an economic evaluation. We also aimed to draw out policy, practice and research implications for future community engagement strategies.

It is important to note that our research has been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The lives of our respondents and members of our research team have been disrupted by the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 lockdown and particularly by home working and the closure of schools, nurseries and so forth. While most research staff continued working, their productivity was impacted, affecting the research in ways that are difficult to quantify. Other challenges and delays to the project, partly or wholly due to the pandemic, can be identified. Access to the Office for National Statistics Annual Population Survey (ONS APS) for research on the social and health impacts of BL at the area population level was delayed for almost 2 years, leaving ˂ 2 months to complete the analysis of our primary outcome. This caused severe delays for the economics analyses, which were dependent on the findings from the APS analysis, leading to major redesign of this work. Wave 2 interviews in work package (WP) 3 were halted entirely for 3 months, and when fieldwork began again it was clear that many residents of BL areas would not be able to continue to participate due to disruptions in their lives, severely disrupting recruitment. Notwithstanding these challenges, we believe that the findings described in this report will make a valuable contribution to the development of future public health action with those communities and groups that bear the brunt of social inequalities.

In Chapter 2 we consider the context for the research. This chapter looks in turn at the key underpinning concepts (empowerment, control and community); changes over the past 25 years in policy perspectives on place-based initiatives (PBIs) in which, like BL, community involvement is central; and current evidence on the social and health impacts of these initiatives. The CiC3 study is then described in Chapter 3, including the theoretical framework underpinning the research and our original plans for public involvement. Changes since the research was funded are highlighted, including the impact of the pandemic (the impacts of public involvement are considered in the final chapter). The next six chapters present the main findings. Drawing on a series of interviews with national key informants, Chapter 4 describes how the programme has changed over time and the relationship of BL to the national policy context. Chapter 5 presents the quantitative findings on population-level social and health impacts in BL areas. Quantitative findings on the impacts on the health and well-being of the most engaged residents are presented in Chapter 6. Chapters 7 and 8 draw on our longitudinal qualitative data to explore pathways to changes in collective control in BL communities and to health impacts. Appendix 7 summarises the methods and findings from the earlier phases of the CiC study, some of which are integrated into the report where relevant. Chapter 9 presents findings from our work on the economics of BL. Finally, in Chapter 10 we summarise the main findings from the research and discuss the implications for future policy, practice and research focused on place-based initiatives that aim to ‘empower’ disadvantaged communities to engage in action to reduce social and health inequalities.

Chapter 2 Place-based approaches to address social and health inequalities: concepts, policy and evidence

The conceptual context: empowerment, control and community

Over the past quarter-century, place-based approaches to promote public participation in policy decision-making and empower communities to have more control over their lives have become mainstream, featuring in global, national and local health and social policies (e.g. UN Economic and Social Council 20195). However, the concepts of empowerment, communities and collective control – central to these policies – are subject to multiple and sometimes conflicting interpretations.

Empowerment

Many contemporary understandings of empowerment link it to improvements in individual self-help. For example, in the health field it is linked to personal management of chronic health conditions and/or the adoption of ‘healthier’ behaviours. In contrast, drawing on the work of Freire and Gramsci6,7 and the civil rights and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, others understand empowerment as involving sociopolitical processes that support people bearing the brunt of social injustice to exercise greater collective control over decisions and actions impacting on their lives and health, and in so doing, contributing to greater social equity in society. As Eyben puts it: ‘empowerment happens when individuals and organised groups are able to imagine their world differently and to realise that vision by changing the relations of power that have kept them in poverty, restricted their voice and deprived them of their autonomy’. 8

Like empowerment, ‘control’ is often understood as an individual outcome of successful empowerment. ‘Collective control’, in contrast, is presented as the outcome of successful empowerment at a community or group level, when people act together in their common interest. As we describe in Chapter 7, in the CiC study, the capabilities associated with collective control have been operationalised as different forms of power. 9

Examples of this more political expression of community empowerment find their most radical form in the popular epidemiology examined by Brown,10,11 where people spontaneously and collectively respond to resist a shared threat to their well-being. Brown has studied local people’s resistance to exposure to toxic waste, including, for instance, the action by residents in Woburn, Massachusetts, to try to prove a link between industrial toxins in their water supply and high rates of childhood leukaemia. 10

These different understandings of empowerment sit at the extremes of a continuum along which the significance varies between a focus on individual self-help versus collective action; on changes in personal circumstances/behaviour versus in proximal living and working conditions; of action to increase internal capabilities of individuals/groups to improve their lives versus action on wider political and social change for greater equity.

Elsewhere we have argued that the construct of collective control understood as the outcome of empowerment processes has greater analytical and practical advantage for health policy and practice than the commonly used concept of ‘community empowerment’. 9 In particular, it can help move policy, practice and research beyond the ‘inward gaze’ dominating many contemporary community initiatives, which focuses on developing the internal capabilities of disadvantaged communities in order to better enable them to ‘cope’ with their proximal living circumstances. This inward gaze is embedded, for example, in concepts such as community competencies, capacities, assets, resilience and social capital. Clearly, it is important that people experiencing the brunt of inequalities (however defined) are supported to develop their internal capabilities. It is also important, however, that this inward gaze is complemented by an ‘outward gaze’ aimed at supporting communities to mobilise these capabilities to collectively take more control over the external structures and conditions that drive social, economic and health inequalities. The concept of collective control helps strengthen this outward gaze by placing power and social change at the centre of place-based policy and practice.

Community

The term collective also avoids the ambiguous and contested concept of community. 12 Some 50 years ago, Bell and Newby identified 98 different definitions of community. 13 As Dominelli notes, communities ‘are constantly changing entities with shifting and contested boundaries … because individuals belong to more than one community simultaneously.’14 Communities are self-defined and can be international, national or local. They provide a sense of belonging for ‘members’ sharing an affinity to a particular place, interest or identity but can feel exclusionary to those who do not ‘meet’ the membership criteria. Communities can also be deeply gendered. Women are primarily responsible for constructing the threads that bind local place-based communities together – albeit the relational work they do in these communities is often invisible.

For much of the past 25 years, public policy and practice focused on reducing social and health inequalities in England has been dominated by a focus on place-based communities and particularly people living in the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods. However, as we discuss in the next section, there have also been significant differences in the nature of these policies over time.

The policy context: English place-based community initiatives since 1997

Since the 1960s, numerous PBIs in the UK have aimed to tackle social and geographical inequalities by regenerating disadvantaged areas and improving the lives of the people who live there15–17 (see Box 1 for a timeline of policy developments relevant to community empowerment). These are often collectively referred to as area-based initiatives (ABIs), but in this report we use the more generic term PBIs. Improving health outcomes has not always been a primary focus of these policies, and the role of local government has changed over time, but the active involvement of local people has always been central to how such initiatives are meant to be delivered on the ground, albeit the approaches to community involvement have varied within and between policy initiatives. 18–20

Place-based initiatives gained particular prominence during the Labour administration of 1997–2010. Shortly after the 1997 election, a national strategy for neighbourhood renewal which focused on disadvantaged areas was published; it gave local government the lead role in promoting community empowerment, a role later enshrined in the 2006 Local Government Act. There was also a growing policy emphasis on the role of civil society organisations as partners with local authorities in supporting community empowerment and as providers of publicly funded services. The policy discourse also increasingly emphasised people’s responsibility to contribute to the well-being of their communities alongside their right to receive services and support.

The English place-based New Deal for Communities (NDC) programme, launched in 1998, was a central plank of the Neighbourhood Renewal Strategy. It aimed to reduce the gaps between 39 of the poorest neighbourhoods and the rest of the country in six domains: health, education, worklessness, crime, housing and the community. 21 Each NDC neighbourhood received £50M to achieve outcomes in these domains and had to establish a multisector partnership board to oversee expenditure over 10 years (a longer time period than any previous PBI). Community involvement was central. Residents were a majority on 31 of the 39 NDC partnership boards (in some cases chairing these), which included representatives from the local authority, police, the NHS and civil society agencies. The NDCs had a particular focus on physical regeneration and, driven by central government policy, sought to increase the diversity of local populations through housing improvements. However, implementation varied considerably. Some areas saw large-scale demolition and renewal; others focused on improving existing infrastructure. Despite the community empowerment rhetoric, as with other PBIs during this period, local authorities were accountable for the funds and had considerable influence over the NDC local programmes, while central government set the outcomes to be achieved and became more controlling over time. 21

The Neighbourhood Renewal Action Plan published in 2001 provided funding for community participation in a further 88 neighbourhood renewal areas across England. This plan included the ChangeUp programme (£231M), which supported community associations to access a range of training and support opportunities, and the establishment of community empowerment networks (CENs). These networks of local voluntary, community, faith and social enterprise (VCFSE) agencies were intended to work in partnership with local government in neighbourhood renewal areas to promote community participation in decision-making, though research suggests that at least some local authorities were unwilling to give the CENs a significant community empowerment role. 22 Other initiatives at this time adopted a more targeted focus on health (e.g. Health Action Zones and Healthy Living Centres)23,24 or on particular groups in the community (e.g. Sure Start centres for families with young children). 25

The Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government in power from 2010 to 2015 retained a strong policy focus on PBIs in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. However, there was a significant move away from central government involvement and major investment in physical infrastructure. Rather than directly funding or directing community action, the national government’s role shifted to one of creating an enabling environment in which place-based communities could take the initiative for themselves. The leading position of local government was replaced with an even stronger role for civil society organisations in supporting community empowerment and delivering publicly funded services, together with increased involvement of the private sector. 26

The coalition’s initial flagship policy, announced prior to the 2010 election, was the Big Society initiative. Between 2010 and 2012, this comprised a range of measures to encourage people to take an active role in their community and to take more responsibility for local decisions and services in order to achieve ‘fairness and opportunity for all’. 27 In 2011, the Community Organisers programme was launched to recruit and train 500 senior community organisers, to be paid £20,000 for their first year, and 4500 part-time voluntary organisers. 28 These organisers were to help communities, particularly in disadvantaged areas, take advantage of Big Society initiatives established by the 2011 Localism Act that aimed to ‘achieve a substantial and lasting shift in power away from central government and towards local people’. 29 Big Society initiatives included the right to buy public assets for community use and the right to bid to run public services. There was also an emphasis on community members setting up social enterprises that would reinvest their profits back into their business, creating local employment, or into the community to tackle local problems. In 2012 Big Society Capital, a social impact investment initiative, was set up. Run by the four main UK banks – Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group and NatWest Group – it used funds from dormant bank accounts to provide loans for social enterprises and community projects.

The Big Society initiative disappeared around 2012. However, together with the Neighbourhood Renewal programme, it fed into a growing debate about the relative merits of supporting civil society organisations and community associations to strengthen community cohesion and deliver publicly funded services, compared with top-down, state-led action. From 2015 onwards, while policies have affirmed the continued importance of PBIs to address social and health inequalities, they have also clearly established the state’s role locally and nationally as less directive and more enabling. This is exemplified in the Civil Society Strategy published in 2018, which continued the emphasis on building a society ‘where people have a sense of control over their future and that of their community’ and on shifting the civil society–state relationship to give greater power and responsibility for service delivery to local people and third-sector organisations. 30

There is considerable literature on the limitations of both the Neighbourhood Renewal and Big Society approaches to place-based community empowerment. Bridle, for example, has argued that there is no evidence that either model led to improvements in volunteering, community action or public services. 31 Additionally, Balazard et al. suggest that between 2010 and 2015, public funding for smaller community associations was reduced, as it was for local government, with most funds going to large civil society organisations and private companies. 32 Other commentators have highlighted problems associated with a lack of funding for ‘social infrastructure’ to support civil society and community action. For example, Wills argued that because the localism agenda failed to provide local structures that enabled common interests to be identified in diverse populations and supported people to mobilise and shift local power dynamics, community empowerment could not be sustained. 33 Additionally, it has been argued that the increasing involvement of civil society organisations in public service delivery has undermined their role in community organising.

The election of a new government in 2019, the UK’s departure from the EU (‘Brexit’) and the COVID-19 pandemic have been accompanied by a reframed policy focus on the ‘levelling up’ of communities. The 2018 Civil Society strategy remains in place. However, in the context of the extensive community mobilisation that was seen during the first COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in England in 2020,34 the Conservative MP Danny Kruger was commissioned to ‘develop proposals to maximise the role of volunteers, community groups, faith groups, charities and social enterprises to contribute effectively to the government’s levelling up agenda’. 35

Published in September 2020, and based on wide consultation with organisations and individuals with experience of place-based/community initiatives, Kruger’s report sets out a series of proposals centred around a new ‘community power’ paradigm. 35 These reflect the broad policy direction embedded in the Big Society initiative and the 2011 Localism Act, but they also address many of the criticisms of previous place-based approaches to reduce social inequalities. For example, it is proposed that while decisions should be devolved to allow residents to ‘make great places “from within” rather than by outside interventions’, small-scale community associations, social enterprises and local groups should be favoured over the large civil society and private sector organisations that have had major roles in the past. 35 Similarly, the role of national and local government as ‘convenors and enablers’, not ‘inhibitors’ of community action is highlighted alongside a call for the central government to invest in renewing and modernising social infrastructure. The report recommends that significant resources be allocated to community associations and local civil society groups (with no strings attached) via a Levelling up Communities Fund (using dormant bank and insurance accounts). A new Community Power Act is proposed to establish a ‘community right to serve’, extending the rights for communities, charities and social enterprises to be involved in the design or delivery of a wide array of public services, and a new national Civil Society Improvement Agency to allocate funds to local organisations to help develop capacity for collective action in communities. Finally, the report argues for a revaluation of social infrastructure and the intangible social benefits of civil society to be included in the Treasury Review of the Green Book and for the development of a new Index of Social Infrastructure that can inform local and national policy-making.

The research context: social and health impacts of place-based community initiatives

Syme termed the theory underpinning policies that aim to empower individuals and/or communities ‘control over one’s destiny’. 36 A number of pathways are embedded in theories linking inequities in ‘control over destiny’ to inequities in health. 37

-

Living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods can produce a sense of collective threat and powerlessness. Over time, these chronic stressors can lead to anxiety, anger or depression – all known to damage mental and physical health. 38

-

Empowerment processes could trigger collective action by residents that successfully challenge local health hazards; for example, by preventing the siting of a toxic waste facility in a neighbourhood. 39,40

-

Members of disadvantaged groups could use their experiential knowledge to identify more appropriate and acceptable ways to address the health risks they face. 37,41–43

-

Participation in collective activities can reduce social isolation and foster greater social connectedness, improving mental and physical health. 39,44–47

-

Individuals participating in collective action can also benefit from an improved sense of self-efficacy and control, which research has linked to better health. 37,48

-

Empowerment processes may lead to increased political understanding and engagement (e.g. increasing voting rates). This could increase public pressure for more accountability in politics and more socially just policies.

High-quality empirical evidence testing these theoretical pathways demonstrates that the level of control an individual has over their life circumstances is a significant determinant of individual-level health outcomes. 49–52 There is also growing evidence on the impact of collective control on population health and on unequal collective control across diverse communities as a determinant of health inequities. For example, research has found positive impacts of collective control by communities on the social determinants of health; for example, social cohesion and environmental improvements. 37,53–56 Evidence for direct impacts of collective control by communities on health outcomes is more limited, but longitudinal studies have reported a positive association with health improvement. Chandlers et al. , for example, found that lower rates of youth suicide among First Nations people in Canada were significantly associated with increased ‘cultural continuity’, measured in terms of the success of land claims, degree of self-government, community control of local services and access to dedicated cultural facilities. 57 Similarly, Baba et al. found significant associations between measures of empowerment, general health and mental health among 4000 adult households in 15 Glasgow neighbourhoods undergoing regeneration. 58

Though limited in number, there are also some high-quality evaluations of the social and health impacts of interventions that aim to increase collective control. Orton et al. , for instance, identified direct health benefits arising from microfinance interventions that increased collective control among women in South Africa, Peru and Bangladesh, including reduced violence against women; reductions in infant mortality that were greater for those in the scheme compared with poor and richer women outside the scheme; and improved nutritional status in children, especially girls. 59 Evaluations of initiatives with a primary focus on community development, mostly small-scale case studies, have also reported positive impacts at individual, community and organisational levels. This has included outcomes for participating individuals such as increased confidence and influence over decision-making,60,61 impacts on social isolation and community connectedness and cohesion,60 and impacts on the capacity for local community organisations and groups to create change. 62,63 Some studies have looked at the effects of community-led initiatives on health outcomes. For example, a survey of communities undergoing regeneration in Glasgow found that residents’ perceptions of their ability to influence decisions where they lived were positively associated with mental health outcomes. 58 Similarly, a study of neighbourhood belonging found moderate associations with well-being stemming from greater social participation and increased feelings of belonging to the neighbourhood. 64

Research also suggests that the potential for PBIs to positively impact on social and health outcomes may be linked to their approach to community involvement. For example, while English policy initiatives such as Health Action Zones, Sure Start centres and Healthy Living centres enabled community members to participate successfully in specific health improvement initiatives and service delivery, evaluations reported there was little community influence over the strategic direction of these initiatives. 20,24,65,66 Factors influencing the degree and nature of collective control by residents in such initiatives are wide-ranging but include the extent to which priorities are conceived to have been ‘top-down’ (e.g. directed by local or national government policies). 67

Approaches to community involvement can also vary across areas within a single programme, producing differential empowerment outcomes and different social and health impacts. For example, in evaluations of regeneration programmes conducted in Scotland and England, despite the presence of engagement processes, lower levels of resident empowerment were observed in neighbourhoods undergoing major redevelopment (e.g. demolition and rebuilding of housing stock) compared to areas with regeneration plans focused on improving existing infrastructure and housing. 68 Similarly, an evaluation of the health equity impacts of the English NDC programme suggests there were greater improvements in mental health/well-being and social cohesion in NDC areas that adopted structures and processes that gave local people significant control over decisions. While few findings were statistically significant, they were consistent with theories about the pathways from empowerment to health and social outcomes. 68 Interestingly, lower levels of empowerment have also been reported when control of social housing has been transferred to resident-led community housing associations. As the quote below highlights, these results point to poor-quality involvement processes but also to a potential mismatch between the nature and scale of the problems facing residents who get involved in decision-making, the degree of control they have over these problems and the level of support they receive:

community engagement processes can be … unable to respond to variations in circumstances faced by communities living in different places. The result is that individual residents may not derive a sense of empowerment from either their participation in, or the ripple effects of, collective community engagement processes. 58

Finally, there is some limited evidence that PBIs that aim to empower local people may have differential impacts depending on the socioeconomic ‘status’ of neighbourhoods, potentially enhancing collective control over decisions in more affluent communities, while undermining capabilities for collective control in more disadvantaged groups. For example, on the basis of an evaluation of four local empowerment initiatives in England, Rolfe concluded that while communities can have control over decisions and actions:

the level of agency in each situation is shaped by community capacity [which] seems to demonstrate a distinct socioeconomic gradient, reinforcing concerns that community participation policies can become regressive, imposing greater risks and responsibilities upon more disadvantaged communities in return for lower levels of power. 69

Conclusion

There is growing evidence supporting the theory that increasing collective control by communities of interest/place over decisions and actions could have positive impacts on their lives and health. However, variations in the type and level of collective control communities are given appear to impact on the potential for positive outcomes, and more disadvantaged communities may be particularly disadvantaged if empowerment processes are not appropriately designed and supportive.

However, it remains the case that, overall, the evidence base on the impact of PBIs on the collective control communities have over decisions and actions, and in turn on social and health outcomes, needs to be strengthened. While a recent non-systematic review highlighted a multitude of studies of community empowerment initiatives reporting positive social and health outcomes, these are generally very small-scale, cover a short time period and rarely include controls or comparators. 70 There is also a lack of attention to health outcomes in many evaluations of interventions aiming to improve neighbourhoods by increasing residents’ collective control over decisions/actions. This is partly because policy-makers, those delivering the intervention, and evaluators do not anticipate health impacts; and partly due to challenges in capturing the impacts on outcomes in complex social initiatives. 71,72

Robust evaluation studies are needed that assess: (1) whether specific community empowerment initiatives actually lead to increased collective control by communities over decisions that impact on their neighbourhood; (2) the factors that enable and/or constrain the development of collective control in communities; and (3) whether initiatives that do enhance collective control can do so in ways that lead to better health-related outcomes and ultimately have the potential to reduce health inequalities. In particular, the studies need to be sensitive to the possibility of negative impacts and to differential impacts across different communities and neighbourhoods. The research reported here aimed to address these questions by evaluating a large community empowerment programme in England, utilising a design that recognised the methodological challenges and built on the latest developments in theory and research on PBIs. 73–75 In the next chapter we describe the Big Local intervention and the CiC study in more detail.

Chapter 3 The Communities in Control study

Introduction

The standard approach to evaluation of social and health interventions is to ask questions about what ‘works’ or ‘does not work’, for whom and in what contexts. The answers to these types of questions, however, while important, are not sufficient when the focus is on complex, socially-embedded, place-based community empowerment interventions like BL, where programme elements vary across place and time, pathways to impact are never linear or predictable and the context varies and is often unstable. As Petticrew argues, in addition to asking ‘what works’, evaluation should also ask ‘what happens’ when an intervention is ‘implemented across a range of contexts, populations and subpopulations, and how have these effects come about?’. 76 This shifts the focus of evaluation towards investigating the chain of events flowing from the introduction of an intervention in a complex, adaptive system and producing evidence that informs decisions about how to make things happen more effectively in the future. 74,77–79

The CiC study adopted this approach to an evaluation of BL and was underpinned by the system-informed theory of change described below. Initially the research was to run for 39 months, but a 4-month extension was granted to deal with some of the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Big Local intervention

Background

In 2010, the National Lottery Community Fund (then Big Lottery Fund) announced funding of £271M for the BL programme. The scale of funding allocated, although small compared to government-funded initiatives such as NDC (approximately £2B over 10 years), was the largest ever investment by a non-government funder in a place-based community empowerment programme, and in 2020 remained ‘the biggest ever single-purpose National Lottery-funded endowment’. 80

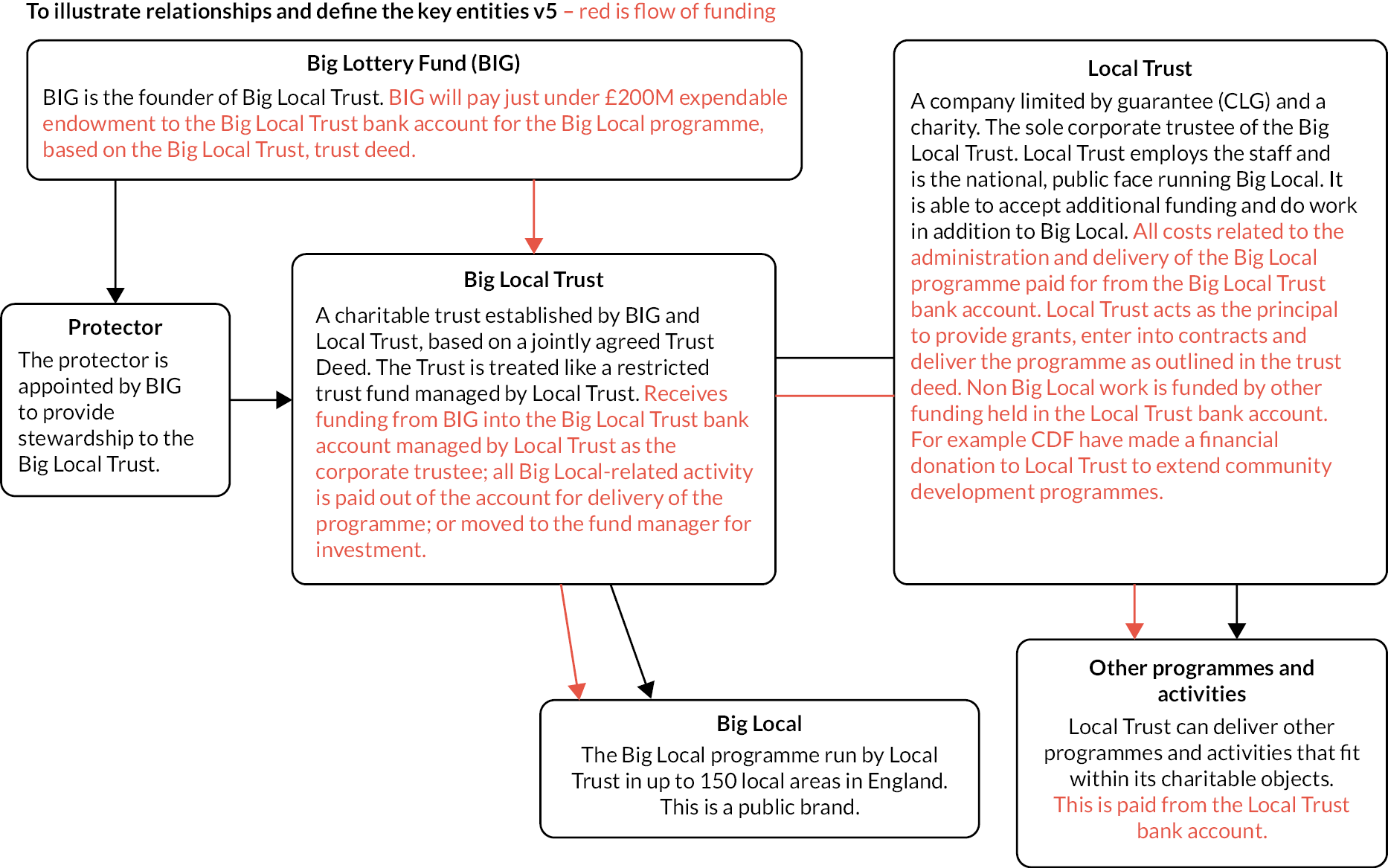

Following a tendering process,81 the Community Development Foundation was appointed to lead a consortium of national organisations to set up a new organisation that would act as the Corporate Trustee for a BL Trust. 82 Consequently, Local Trust (LT) was formed, taking over management of BL from the original consortium in March 2012. Figure 1 outlines the relationship of BL to its key entities: the funder (Big Lottery/National Lottery Community Fund), LT, BL Trust and the legal protector (providing stewardship of the BL Trust). BL Trust was set up as a charitable trust with a jointly agreed trust deed between the National Lottery Community Fund and LT. 83 LT is the sole corporate trustee of the BL Trust. In its role, LT ensures BL is delivered in a way that is in keeping with the trust deed. A key stipulation of the deed was that the total endowment should be committed by a date about 10 years from when the trust was set up, subsequently agreed to be 2026. 83 The trust deed also requires the use of BL funding to be additional to public funding for activities that national/local government is required to provide as part of statutory functions.

FIGURE 1.

Relationship between key BL programme entities. Reproduced with permission of Local Trust.

Selection of areas to be included in the Big Local programme

In total, 150 areas in England were selected for funding in three waves (July 2010, February 2012 and December 2012). The Big Lottery Fund decided on the areas following consultation with local partners (e.g. local authorities). 84 Local areas were selected on the basis that they had historically missed out on lottery and other community funding. 80 Early guidance published in 2010 indicates that the targeted localities were ‘all places where many people face multiple barriers to meeting their needs, and which have not had great success in gaining resources to help’. 81 While all BL areas are relatively disadvantaged, in practice they vary across a range of geographical and demographic characteristics, with local populations ranging from 3000 to 12,000, with most being between 6000 and 7000. There is also considerable variation in the extent to which BL area boundaries are contiguous with pre-existing formal or social boundaries (e.g. a ward or housing estate). 2 Earlier phases of the CiC study found that this influenced the speed and nature of early roll-out of the programme in local areas. 2 This included the ways in which residents were able to engage with other residents and professionals and act collectively to make decisions about how to spend the £1M to improve their neighbourhood. 3

Big Local programme outcomes and framework

The funder set four outcomes for the BL programme, which are listed below. These were intentionally broad, enabling local communities to set their own priorities:81

-

Communities will be better able to identify local needs and take action in response to these.

-

People will have increased skills and confidence so that they continue to identify and respond to needs in the future.

-

The community will make a difference to the needs it prioritises.

-

People will feel that their area is an even better place to live.

Once established, and in consultation with partners, LT developed a programme theory and framework to guide the delivery of BL locally. Central to this was a seven-stage pathway which all areas are expected to move through, albeit iteratively and at their own pace. Although LT no longer refers explicitly to a ‘pathway’ in its guidance for local areas, these key components of the programme framework, shown in Box 2, remain in place.

-

Getting people involved: To spread work about BL and make sure residents know how to get involved.

-

Exploring your BL vision: To understand local aspirations, needs and priorities and develop a shared vision for the area.

-

Forming your BL partnership: To oversee the local programme – guidance says 51% of members must be residents so local community is in majority.

-

Creating a local plan: To describe how BL partnership will improve the neighbourhood, building on identified vision and local priorities. Reviewed and endorsed by LT before funds released to partnership to be managed by a locally trusted organisation (LTO). Plans can change.

-

Delivering your local plan: BL partnerships oversee delivery of actions in the plan, often working with other organisations/groups.

-

Collecting the evidence: To enable BL partnerships to assess and communicate progress and achievements to wider community. LT has produced resources to support partnerships to measure impacts.

-

Reviewing BL plan and partnership: Conduct at least one review when plan is active and submit to LT before submitting new or updated plan requesting further funds. Each BL area also has a BL rep who conducts annual review of partnership.

Initially, each local area received a small grant of £20,000 to consult with residents and produce their plans. Across areas, engagement, consultations and plan development occurred approximately in the first 2 years, before BL partnerships began to draw down the main grant after their initial plans were endorsed by LT. Although there is no formal time frame for expenditure by local areas (e.g. no set date for submission of local plans), all BL partnerships had had their first plan endorsed by 2015. Each area has been allocated approximately £1.1M over time, with an additional £50,000 released to each area in March 2020 to enable BL partnerships to provide additional support to local communities during the pandemic. These additional funds are derived from growth in the BL Trust endowment, which is invested.

National support and management functions for Big Local

Local Trust, and national organisations commissioned by them, provide a range of support for BL partnerships. Firstly, each BL area receives professional support through a BL rep who acts as a ‘critical friend’, helping BL partnerships to develop and deliver their plans. Reps also contribute to a two-way flow of information between LT and the BL partnership; for example, disseminating information about new opportunities (e.g. events, training) as well as updating LT on progress or local issues. Secondly, each BL partnership is required to identify a LTO to manage its funds; these include organisations such as community voluntary services, local civil society organisations, housing associations and parish councils. While not compulsory, many BL partnerships also employ people or organisations to undertake specific tasks (e.g. to run engagement events and/or manage projects). Thirdly, partnerships can secure optional support or expertise such as training and learning opportunities for residents and organisations involved in BL and topic support related to delivering plans (e.g. social investment, managing land assets). Finally, network events are organised nationally and regionally to encourage the exchange of knowledge between BL partnerships and organisations with relevant expertise. We do not have the space in this report to describe the wide range of approaches adopted in BL areas to engage the wider population in the programme – we have written about these elsewhere85 – nor the diverse actions taken to improve the neighbourhoods, which are described on the LT website (https://localtrust.org.uk).

While the broad programme framework described above has remained constant over time, the speed of spend has varied across BL areas. Some are likely to have spent all their funding before 2026; other areas have spent more slowly. Additionally, our fieldwork in this third phase of CiC has identified ways in which programme arrangements have evolved over time, from early stages of set-up to delivering plans and spending money. These changes are explored in more depth in Chapter 4.

The Communities in Control study: theoretical framework

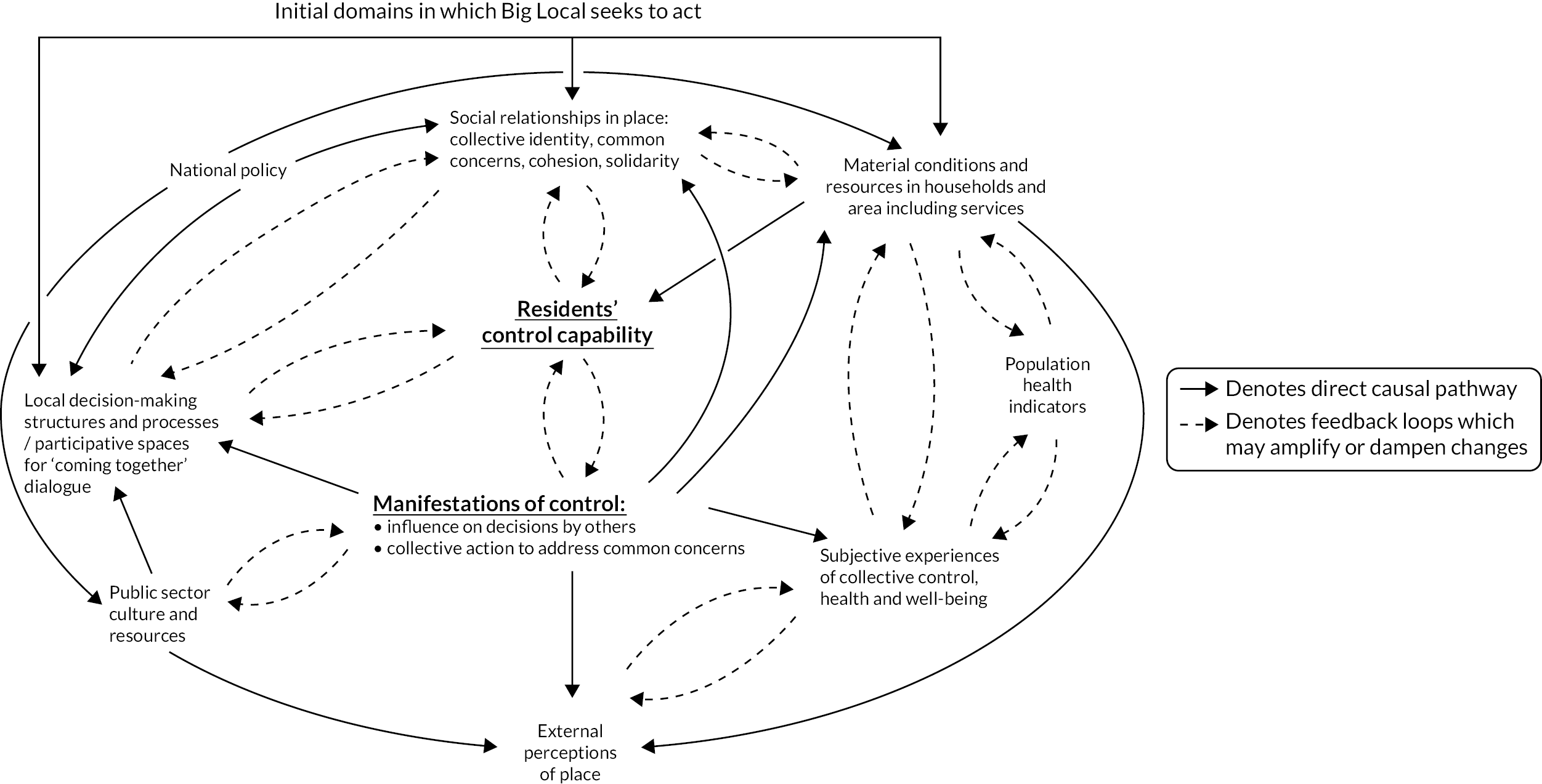

The CiC study is a longitudinal mixed-methods evaluation. Two earlier phases, funded by the NIHR SPHR, ran from 2014 to 2017. During phase 1 we developed a novel theoretical framework for the evaluation, the Collective Control Influence System (CCIS), shown in Figure 2. This diagram depicts the processes and feedback loops that may be triggered by BL, which could enable and/or constrain (in systems language – amplify or dampen) residents’ attempts to improve the conditions in which they live and the pathways that could lead from these improvements to health improvements.

FIGURE 2.

Collective Control Influence System (CCIS).

Our system-informed theory of change starts from the premise that various elements of the BL programme may increase capabilities for collective control among those residents who are most actively engaged. If, in gaining greater collective control, residents are able to act together (with or without others) to prevent or mitigate exposure to health-damaging living and working conditions, then direct health effects may ensue for the active residents and for the wider population, through making their neighbourhood a healthier, better place to live.

The three straight arrows at the top of Figure 2 show the points in the CCIS where the initial impacts of BL would be expected to be felt: on social relationships in place, local decision-making structures and processes, and material resources in households and the environment. Various complex interactions between elements of the system flow from these initial impacts. Proposed direct causal links between different elements of the CCIS are shown with a solid line and arrow, while feedback loops between these are shown with a dotted line.

There may also be indirect health improvements arising from the reduction in social isolation and improvement in mental health that participation in community action can bring about. Finally, increased control may lead indirectly to physical health benefits. Evidence from the work environment shows that employees who experience high job demands but low control over their working conditions are at higher risk of psychosocial stress, which has been linked to physical conditions such as coronary heart disease. Furthermore, exposure to low job control increases with decreasing social position and may have contributed to the observed social inequalities in coronary heart disease incidence. 37 Changes in physical health conditions such as coronary heart disease would only be expected to emerge in the longer term, unlikely in the lifespan of this research. The theory also allows for the possibility that the processes set in train may have negative health impacts, particularly on the residents who are most actively involved. We used this system-informed theory of change, particularly in our analysis of qualitative data, to examine these various processes and to understand how the feedback loops operated in BL areas.

Public involvement in the Communities in Control study

Big Local residents have been involved in the CiC study since it began in 2014. They have contributed to fieldwork design, developing research tools and interpreting findings, particularly but not exclusively in relation to the qualitative research in WP3 described below. We have had regular dialogues with members of BL partnership boards and other residents and workers in our local fieldwork areas. The purpose of these dialogues has been to ensure that local evidence priorities were acknowledged and integrated into the research where possible, that local knowledge of the neighbourhood and of BL informed the fieldwork and that data-gathering methods were acceptable. We have also had regular meetings with LT, the national organisation managing BL, and contributed to their regular engagement events.

Our original plan for ongoing involvement included two or three annual meetings of the BL resident network established in phase 1 of CiC, with other involvement taking place in our fieldwork sites. Members of the network contributed to the original research proposal and the project’s plain English summary, and advised on the ethics approval documentation. Subsequently, they have supported the testing and refining of interview topic guides and contributed to plans for recruitment of respondents and consent processes. BL residents also made a major contribution to the study website (www.communitiesincontrol.uk), including a short video of a CiC public adviser talking about his experience of involvement (https://youtu.be/4auqXfEWbWw). They have also commented on the kinds and formats of outputs to be shared with the BL communities in the future and on the plain English summary for this report. However, following discussions with network members and LT in 2018, we moved away from resident network meetings to activities at a regional and local level. For example, members of our team have worked with BL reps at the regional level to develop and deliver several learning events for BL partnerships in person and online.

The issue of reciprocity emerged as a recurring concern in discussions with members of BL partnerships. This is an ethical issue, with some community members arguing that the research risked ‘taking from’ or ‘gaining from’ the communities studied unless there was an offer of reciprocity. We have endeavoured to meet these reciprocity obligations in various ways. For example, staff have attended and spoken at local stakeholder events, provided advice to partnerships on how to evaluate their work, reviewed funding applications, supported partnerships in their mid-term plan reviews, and identified evidence they could use to show the impact of their work (e.g. the social and health impact of outdoor gyms). Involvement of BL residents in and beyond our fieldwork sites was not possible for much of 2020 and into 2021. Some partnerships put all their time and energies into responding to the needs of their local communities; others stopped meeting, as individuals struggled with their own challenges. However, we were able to support some of the COVID-19 work of partnerships; for example, by providing evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on minority ethnic groups.

Details of our past and future activities aimed at involving BL residents and wider public in interpreting and disseminating our findings are included in Chapter 10.

Communities in Control study: phase 3 study design

From an evaluation perspective, BL is a ‘natural experiment’ in community empowerment. By ‘natural experiment’, we refer to the Medical Research Council’s definition of ‘events, interventions and policies that are not under the control of the researchers, but which are amenable to research using the variation in exposure that they generate to analyse their impact’. 86 No aspect of the BL initiative was under the control of the CiC researchers, but while the function of the programme is standardised, there is considerable variation in the form it has taken across the 150 areas that we have been able to exploit for evaluation purposes. Firstly, there are differences in the social, economic and political contexts in which local programmes are rolled out. These differing contexts could lead to differences in the impact of BL on health and other outcomes. Secondly, the funding can be used flexibly, such as to make social investments, develop projects, award grants or negotiate in-kind support from other organisations (e.g. local authorities). 3 Thirdly, BL plans may include a wide range of actions relevant to local priorities and needs. These include actions to improve the physical and built environment,87 challenge place stigma,88 strengthen social relationships between residents,85,89 and reduce poverty and improve the local economy. 3 As part of planning for sustainability beyond 2026, some BL partnerships have also sought to invest in, or take over management of, assets such as community hubs or public land. Fourthly, while not formally required to do so, the BL partnerships often engage with local public, private and/or third-sector agencies (e.g. NHS organisations and local government) to attain their goals, though the nature and extent of this engagement varies at the local level. Lastly, as there is no fixed BL timescale, there is variation in the pace and scale of roll-out over time. BL areas may also adapt their plans over time, in response to changing local needs.

The objectives of phase 3 of the CiC study were to:

-

investigate longer-term population-level health and social outcomes of BL

-

investigate impacts of BL on health and well-being of engaged residents

-

assess changes in collective control among BL residents and pathways to changes identified

-

illuminate residents’ perspectives on health and well-being impacts and pathways to these

-

conduct an economic evaluation of BL

-

draw out implications for future design and evaluation of PBIs that aim to increase collective control, particularly in disadvantaged communities.

The study comprised four WPs, which are described below.

Work package 1: population-level impacts on health and social outcomes

This WP sought to assess whether the intervention had any positive impacts on social and health outcomes for the populations in BL neighbourhoods. The methods used in this work are described here, and the findings are reported in Chapter 5.

The Big Local intervention start date

The areas in which the programme was implemented were selected between 2010 and 2012 and received a small grant in the initial period, but most did not start to draw down substantial amounts of money until their plans were approved in 2015. For the analysis of population impacts, we therefore defined 2016 as the start date – that is, the earliest date from which it is plausible that the BL initiative could start to have an impact on population health outcomes. We examined the timing of impacts using alternative start years in the analysis (see below).

Data and sample size

The analysis utilised data from the ONS APS for the years 2011–1990,91 and various secondary sources. The APS is the largest representative household survey in the UK, with a sample size of 320,000. It combines data from four successive quarters of the Labour Force Survey with rolling-year data from the English, Welsh and Scottish Local Labour Force Survey. The sampling frame is the Royal Mail postcode address file and the NHS communal accommodation register, and sampling is stratified to ensure it is representative at the regional level. Where possible, every adult aged 16 and over in a household is interviewed. Where there are other individuals in the household who can answer on behalf of an absent respondent, proxy responses are also collected. Well-being measures (see Outcomes below) are only collected on non-proxy respondents, of which there are approximately 165,000 per year. New respondents in the sample are interviewed face to face, while subsequent interviews are conducted over the telephone where possible.

We used the secure access version of this data set which includes an indicator of the Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) of each respondent. LSOAs are small geographical areas used by the UK’s ONS, each typically containing a population of about 1500 people. This LSOA indicator was used to identify respondents in BL and in comparator areas (see below). This provided a total sample of 26,440 non-proxy respondents in BL areas and 75,580 in comparator areas from 2011 to 2019 (see Appendix 1, Table 13 for annual sample sizes). This was similar to our estimated sample size in our pre-registered protocol of 108,000 respondents over the 9 years. We used simulation methods to investigate the power that this sample would provide across a range of effect sizes, taking into account weights for the study design and using robust clustered standard errors to account for clustering within areas and serial correlation in the data. 92

As Table 1 shows, we would be able to detect an absolute reduction of two percentage points in our primary outcome – the proportion of the population reporting high levels of anxiety – with a power of 83% (at α = 0.05). A two-percentage-point reduction would mean that the proportion of the population reporting high levels of anxiety drops from the estimated baseline level of 21% to 19% in BL areas. For the analysis of secondary outcomes, we used a number of routine data sources to construct a panel of aggregate data for the 880 LSOAs that lie within BL areas and the matched 2640 comparator LSOAs over 9 years (2011–19), providing 31,680 observations for the analysis. These data are based on the total populations and not a sample survey.

| True effect size (risk difference), % | Power (at α = 0.05), % |

|---|---|

| 3 | 99 |

| 2 | 83 |

| 1.5 | 61 |

| 1.2 | 44 |

| 1 | 37 |

| 0.5 | 17 |

Outcomes and control variables

Outcome 1: Our primary outcome was high levels of anxiety self-reported in the APS, measured as the proportion of people reporting a score of > 6 in response to the question ‘Overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?’, where 0 is ‘not at all anxious’ and 10 is ‘completely anxious’. A threshold of > 6 on the 11-point scale has been identified by the ONS as a measure of high anxiety levels. 93

Outcome 2: The Small Area Mental Health Index (SAMHI) is a composite annual measure of population mental health that we developed for each LSOA in England. The data and methods used to compile the index are available through the open data portal Place-based Longitudinal Data Resource. 94 The SAMHI combines data on mental health from multiple routine sources into a single index, including antidepressant prescribing data from NHS Digital,95 mental health-related hospital attendances as defined below, diagnoses of depression in primary care from the Quality and Outcomes Framework,96 and claims for Incapacity Benefit and Employment Support Allowance for mental illness. 97 Each indicator was individually standardised by rescaling data to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (z-scores). Maximum likelihood factor analysis was used to combine these indicators (by finding appropriate weights) into a single score based on the intercorrelations between all the indicators. The SAMHI is an indicator of poor mental health; a higher score indicates worse population mental health.

Outcome 3: Antidepressant prescribing measured as the average daily quantity of antidepressants prescribed per 1000 population per year using general practitioner (GP) practice prescribing data provided by NHS Digital. 98 This indicator was standardised by rescaling data to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 (z-scores).

Outcome 4: Mental health-related hospital attendances per 1000 population using Hospital Episode Statistics provided through a data sharing agreement with NHS Digital (DARS-NIC-16656-D9B5T-v3.10). This measure consists of A&E attendances and admitted patient care for alcohol misuse, drug misuse, self-harm, and common mental disorders. Specifically, it includes a count of all admissions with a primary diagnostic ICD-10 code of X60*–X84*, Y10*–Y34*, F00–F99, E244, F10, G312, G621, G721, I426, K292, K70, K852, K860, Q860, R780, T510, T511, T519, X45, X65, Y15, Y90, Y91 but excluding Y33.9*, and Y87*, plus a count of all A&E attendances for self-harm (codes 141–144, 35, 37) in each year for each LSOA, divided by the annual population estimate. This indicator was standardised by rescaling data to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 (z-scores).

Outcome 5: Recorded crimes and incidents of antisocial behaviour (ASB) per 1000 population for the offence categories violence and sexual offences, burglary, criminal damage and ASB using Open Data from the UK government. 99 The combined indicator was used and additionally each category of crime was analysed separately. These indicators were standardised by rescaling data to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 (z-scores).

Outcomes 6–8: We also included the three other measures of subjective well-being included in the ONS well-being set – ‘low satisfaction’, ‘low happiness’ and ‘not worthwhile’ – measured as a score of < 7/11 in response to the questions: ‘Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?’, ‘Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?’ and ‘Overall, to what extent do you feel that the things you do in your life are worthwhile?’.

In analysis of the APS, we used age and sex plus a number of variables to adjust for potential confounders. Respondents were defined as employed if they reported that they were either an employee or self-employed in the survey week. Socioeconomic status was defined using the National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification (NS-SEC),100 grouped into three categories: (1) higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations; (2) intermediate occupations; and (3) routine and manual occupations or never worked/long-term unemployed. Respondents were defined as coming from a black, Asian or other minority ethnic group if they identified as Asian/Asian British mixed/black/African/Caribbean/black British/Chinese/Arab/multiple ethnic groups/other ethnic group. Education status was defined in three categories based on highest educational qualifications: (1) degree or equivalent, (2) some qualifications but less than a degree, or (3) no qualifications. Marital status was defined as married/civil partnership or other. Respondents were defined as having a disability if they reported a long-standing illness that limited work or other daily activities. We also used survey data on housing tenure. Survey questions related to education and disability are only asked for respondents of working age (aged 16–64) and therefore these variables were only included in analysis limited to this age group.

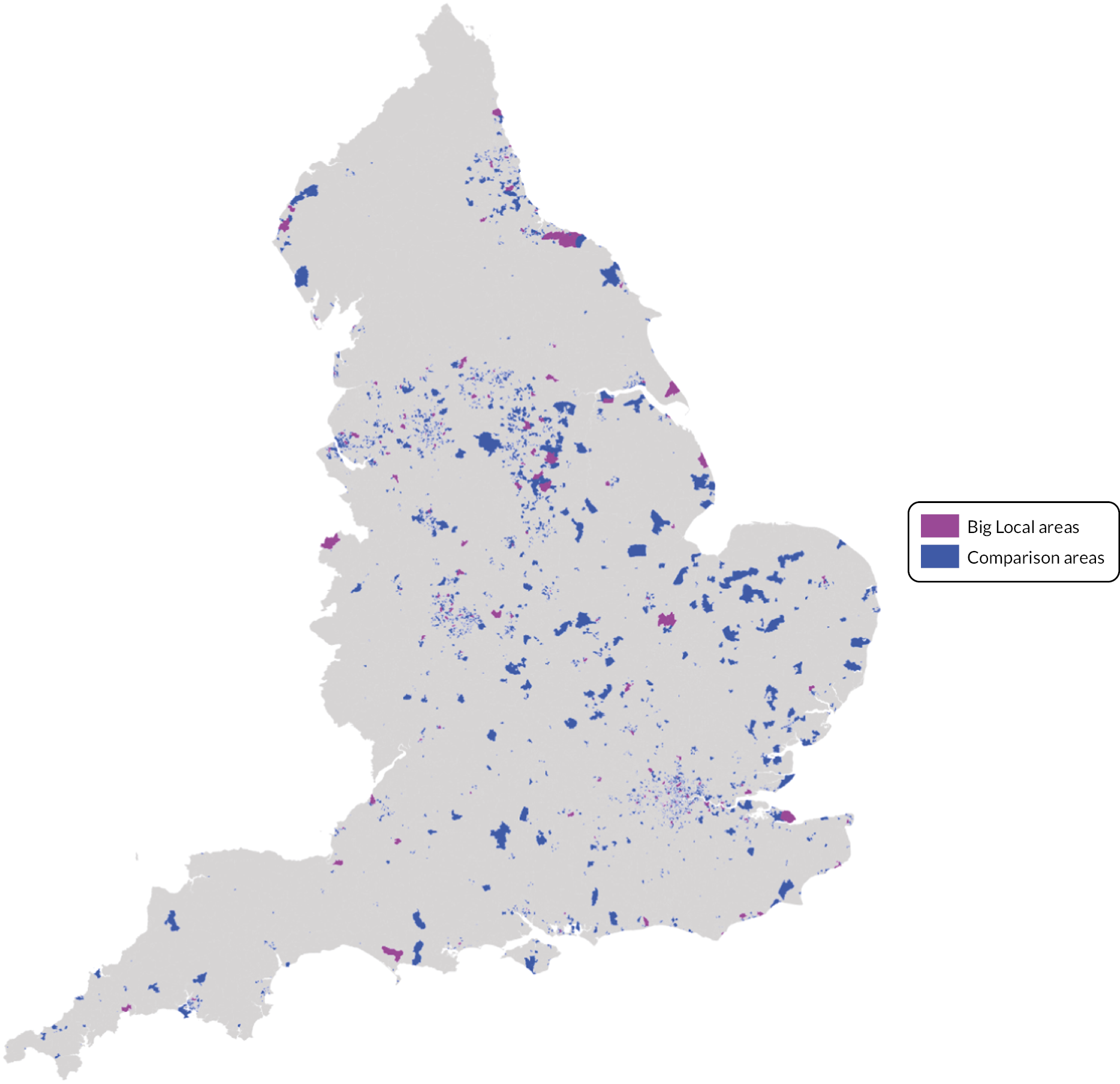

Matching to define the comparison areas used data on Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2015 domains of income, health, crime and environment;101 the Community Needs Index 2019 developed by LT;102 the ethnic and age profile of the population using data from the 2011 census; the average distance to the nearest GP practice, hospital and green space, using data from the Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards Index (AHAH),103 the distance to the coast; the ONS area classification based on eight subgroups (affluent England; business, education and heritage centres; countryside living; ethnically diverse metropolitan living; London cosmopolitan; services and industrial legacy; town and country living; and urban settlements);100 and region.

As additional control variables in the LSOA level analysis we used annual estimates of the distance to the nearest GP practice and hospital to account for potential changes in access to health services that might lead to bias in our outcomes that are based on health service utilisation (antidepressant prescribing and mental health-related hospital attendances). To account for potential divergence in the trends in economic conditions in BL and comparator areas, we additionally controlled for the annual unemployment claimant rate using data from the Department for Work and Pensions. 97

Statistical methods

Firstly, we defined our comparator areas based on a set of LSOAs matched with the LSOAs included within BL areas. The entire population of the intervention area (150 BL areas) consists of 880 LSOAs. Each of these intervention LSOAs was matched with three control LSOAs located within England, providing 2640 matched control LSOAs. We used propensity score matching104 to ensure that these comparator areas had similar observed characteristics to the intervention LSOAs in the time period before the start date for the intervention (2011–15). The matching was based on the variables outlined above, along with the prior values of the four secondary outcomes (SAMHI, antidepressant prescribing rate, mental health related hospital admissions, recorded crimes). The nearest neighbour method was used for matching, which selects controls with propensity scores that are closest to that of the intervention LSOAs.

We then used difference-in-differences (DiD) methods105 to compare the change in health and social outcomes in BL areas to those in non-BL areas. The estimate of the effect of the BL programme was therefore calculated as the difference between the change in the outcome in the BL areas and the change in the outcome in the comparator areas. This DiD approach uses a comparison both within and between areas – accounting for secular trends in our outcomes and unobserved time-invariant differences between areas that could confound findings. The primary assumption is that trends in outcomes would have been parallel in the BL and comparator areas in the absence of the BL programme. This is a reasonable assumption as the comparator areas are very similar to the BL areas at baseline and therefore likely to be affected in a similar way as the BL areas by wider national factors such as welfare reforms, austerity measures and economic change.

This involved estimating a regression based on the following formula:

where Yiat is the outcome reported by individual or LSOA i in area a at time t, BLa is a dummy variable taking the value 1 for BL areas and the value 0 for the comparator areas, and AFTERt is a dummy variable taking the value 1 for time periods after 2015. Xiat is a vector of control variables for individual/LSOA i in area a at time t. The coefficient of interest is β3, the coefficient on the interaction term AFTERt∗BLa, sometimes referred to as the DiD parameter. It indicates the change in outcomes in the BL areas relative to the change in outcomes in the comparator areas, that is, the effect of the programme on the outcome. As this interaction term cannot be interpreted as the programme effect in non-linear models, we used linear regression models, even for our binary well-being outcomes, to estimate the DiD parameter. 106 To check the robustness of this approach, we additionally estimated logistic regression models for the binary outcomes and then calculated the contrast of the predicted margins from these models, that is, the equivalent to the interaction term in a linear model. 106

Subgroup and lagged and lead analysis

To investigate differences in effect by sociodemographic conditions, the analysis of our primary outcome using APS data was repeated for subgroups defined by socioeconomic status, ethnicity and for the working-age population (16–64 years). The analysis of our secondary outcomes was repeated for subgroups of BL areas, as the LSOA-level data provided sufficient numbers of observations in each subgroup’s BL area. This subgroup analysis was not possible with the primary outcome, as the APS sample within each BL area was not sufficient.

The analysis of subgroups of BL areas included rematching each subgroup to a comparison group of areas to ensure balance was maintained within subgroups. To investigate whether effects differed according to the scale and type of activity in each BL area, we repeated the analysis including only those BL areas that had spent more than 80% of their grant by 2019/20 (30 BL areas). These areas had progressed furthest with implementation and therefore we might expect that any effects on social and health outcomes would be greatest in these areas. To investigate whether differences in the type of activities in each BL area influenced outcomes, we repeated the analysis for four groups of BL areas defined by the type of activities they prioritised for expenditure. These activities were classified into a fourfold typology based on the determinants of health that they targeted: economic (e.g. money advice, poverty reduction and skills development interventions), social (e.g. arts and culture, community spaces, loneliness interventions), environmental (e.g. community safety, housing and transport interventions) and lifestyle (e.g. sport and physical activity, and health and well-being interventions).

Most BL areas prioritised funding of activities across more than one of these types, and so we replicated our analysis for each group if they had included that activity type in their offer (e.g. environmental interventions). So BL areas could be included in more than one group if they included activities across multiple types in their offer. To understand potential combined effects of the scale and types of activity on outcomes, we repeated the analysis for our four groups of BL areas defined by their type of activity, while also limiting this analysis to those that had spent more than 80% of their grant.

To investigate whether contextual factors influence the effectiveness of the BL programme and potential impacts on social and health outcomes, we repeated the analysis for: (1) three groups of BL areas defined by baseline deprivation using the IMD 2015 income domain score; (2) three groups defined by the proportion of people from ethnic minority groups; and (3) three groups based on the age profile of the population (proportion of people under 16 and over 75).

We also checked the timing of impacts using lags for the 2 years after the BL implementation start date of 2016 and investigated whether impacts happened before this implementation year using leads for the 3 years before this date. Finally, to examine the sensitivity of our models to dichotomising the well-being outcomes, we repeated the analysis for the full scale (0–10) for all four well-being outcomes.

Work package 2: the impact of active engagement with Big Local on health and social outcomes among engaged residents

This WP sought to assess whether the intervention had any positive impacts on health outcomes for the most actively engaged residents in BL neighbourhoods. The methods used in this work are described here, and the findings are reported in Chapter 6.

Data sources

This WP used data from three waves (2016, 2018 and 2020) of a biannual longitudinal survey of those most actively engaged in BL – all BL partnership members in all 150 BL areas. This was conducted by LT. As already noted, BL partnerships have a majority of resident members plus members from local organisations including the local authority, the NHS, and/or faith and other third-sector organisations.

A survey is delivered by the LT every 2 years, online and by post, to all the individuals actively involved as the members of the 150 BL partnerships in England. These include non-residents and residents. We refer to the latter in our reporting as ‘active residents’. The survey was initially developed internally by LT to meet programme and learning requirements of the organisation. However, through our partnership with LT, the CiC research team were able to add additional questions relating to mental well-being, self-rated general health, collective and/individual control, social cohesion and area perception. The BL partnership survey is a repeat cross-sectional survey. Although the survey was conducted in 2014, it was only in 2016 that we were able to insert questions on health, place or experience of collective control. For our purposes, the first-wave survey was therefore in 2016 (baseline, wave 1). Potential respondents were identified using a common sampling frame: all BL partnership members who submitted contact details (over 1200) as part of the annual partnership review carried out by LT were approached via e-mail (for an online questionnaire submission). BL reps were also sent physical copies of questionnaires by post to distribute, to reach as many other partnership members (~400) as possible. This gave a total potential sample of over 1600 partnership members across all 150 BL areas. A total of 862 participants submitted a completed wave 1 questionnaire in 2016, a baseline response rate of over 50%. In 2020 (wave 3), the questionnaire was distributed – online only – to all 1664 current partnership members, and 1018 responses were received, leading to a response of around 61%. These repeated samples provided the basis for a nested cohort, whereby individual records were linked over the three waves (2016, 2018 and 2020). As anticipated in our proposal, the final sample size of the nested cohort was small, with only 217 participants providing linked data over all three waves, and so we also analysed the total responses at each wave using a repeat cross-section design. The repeat cross-sectional survey had samples of n = 862 in wave 1, n = 1011 in wave 2 and n = 1023 at wave 3. Our analytical sample at each wave (comprising those who provided responses across all our variables) was 500, 654 and 636. The analyses also looked separately at resident and non-resident partnership members.

Types of Big Local programmes

Using data provided by LT, we were able to undertake subgroup analyses on the basis of the extent and type of BL activity in each of the 150 BL areas. We used a threefold classification of the amount of funds spent on activities up to 2019/20 – low (spent ˂ 50% of £1M), medium (spent 50–80% of the £1M) and high spend (spent > 80% of the £1M) – and the fourfold typology of activities described earlier. This was based on the determinants of health that BL expenditure targeted: economic (e.g. money advice, poverty reduction and skills development interventions), social (e.g. arts and culture, community spaces, loneliness interventions), environmental (e.g. community safety, housing and transport interventions), and lifestyle (e.g. sport and physical activity, and health and well-being interventions). Most BL areas funded activities across more than one of these groups. In the WP2 analyses, outcomes for partnership members in areas that included a specific expenditure type in their programme plans were compared to those in areas that did not include that specific type but had planned expenditure in any/all of the other three activity groups.

Obtaining and managing the data

Local Trust collated the survey responses and sent them to the research team in an anonymised SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) spreadsheet in October 2018 and October 2020 (we already had baseline data from 2016 from earlier phases of CiC). 107 The anonymised data were uploaded to a shared Box folder which was only accessible to named collaborators. Individual records were linked over the three waves via unique numerical identifiers for the purpose of the nested cohort. The repeat cross-sectional element included area-level data linkage. The data were stored in electronic form on secure university servers and were accessed through password-protected networked PCs and laptops.

Outcome measures

The survey collected data on the characteristics of BL partnership members [demographic data, socioeconomic status (education), perception of individual and collective control and perception of the BL area, levels of participation (number of unpaid hours per week on BL activities) and self-perceived health] using two validated measures: the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS) and Census General Health. A copy of the questionnaire is included in the accompanying project documentation.

Our primary outcome was the score from SWEMWBS, which is designed to measure positive mental health states (as opposed to symptoms of mental ill-health such as anxiety and depression). The scale has seven domains, and scores range from 7 to 35, with higher scores indicating higher positive mental well-being. The scale has been validated for the general population. 108 Questions include the degree to which a participant ‘feels useful’ or ‘feels relaxed’, or agrees with the statements ‘I think that I deal with problems well’, ‘I feel close to other people’ and ‘I have been able to make up my mind about things’.

Our secondary outcome was ‘self-rated general health status’ (the census measure), which asks ‘How is your health in general? Would you say it was very good, good, fair, bad, very bad?’ This was recoded with ‘very good’ and ‘good’ coded as ‘good’ and fair, and with ‘bad’ and ‘very bad’ coded as ‘not good health’.

Explanatory variables

Based on our theory of change, engaged residents could be expected to experience improvements in mental well-being and general health as a result of reductions in social isolation as they participate in BL activities, through an improved perception of community, as well as through feeling that they have greater control over decisions that affect their daily lives. At baseline, we therefore examined any association for our two health outcomes with: (1) whether respondents felt able to influence decisions affecting their area, either with others (collective control) or as individuals (individual control); (2) social cohesion around involvement (feels good to know more people in the area, feels more connected, feels more positive about BL area, feels stronger sense of community) and area perception (feels people in the BL area can be trusted, feels people in their BL area are willing to help each other, feels they belong to the area); and (3) hours of involvement among participants. Only the explanatory variables that were significantly statistically associated with our primary outcome at baseline were then included in the follow-up analyses. Typology data on the extent and type of BL activities in different areas were also included in the follow-up analysis to examine whether different levels of expenditure or types of activity were more/less associated with any changes in our primary outcome.

Analysis

We examined whether our primary and secondary health outcome measures changed over time across the three waves using both the repeat cross-sectional and cohort designs.

Baseline analysis

Survey data for 2016 for 862 people involved in the 150 BL areas in England were summarised using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation for continuous variables, percentages for categorical variables). Our explanatory factors were then examined for bivariate associations with both the health outcomes, and the initial model included those with p ≤ 0.25. The final parsimonious model retained variables with significant associations – adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, educational status, resident status and hours volunteered. A random-effects linear model was used to examine the associations between SWEMWBS, demographics and our explanatory variables. Similarly, a generalised estimating equation (GEE) model was used to examine the associations with our secondary outcome of self-rated general health.

We also investigated whether there were differences across a number of predefined groups. Firstly, we investigated health inequalities by analysing whether any health associations at baseline differed by education or gender. Secondly, we investigated any differences in terms of levels of participation in the BL (measured using hours involved) to see whether there was a graded association between participation and our health outcomes. Thirdly, we also examined differences by resident versus non-resident status of BL partnership members.