Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/126/11. The contractual start date was in January 2018. The final report began editorial review in June 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Coulman et al. This work was produced by Coulman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Coulman et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Background to the research

Intellectual disability (often referred to as learning disability in UK health settings) is described in International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision, as a disorder of intellectual development. 1 Consistent with contemporary definitions, intellectual disability emerges during the ‘developmental period’ (usually taken to mean before age 18 years) and is characterised by low cognitive ability (i.e. an intelligence quotient of < 70) and low levels of adaptive behaviour (such as communication, and social and independence skills, assessed using standardised tools). Prevalence studies internationally suggest that approximately 2–3% of children and adolescents have an intellectual disability. 2 Based on Department for Education data published from the National Pupil Database (NPD), there are approximately 300,000 children of school age with an intellectual disability in England. 3 Data from the Global Burden of Disease Study suggest that approximately 1.43% of children aged < 5 years in the UK have an intellectual disability. 4

Owing to challenges in intelligence quotient testing in younger children, especially for disabled children, the term global developmental delay is often used to refer to children who, when older than 5 years of age, are likely to attract a label of intellectual disability. 5 Global developmental delay is defined in terms of a delay in two or more developmental domains (from among the following five) in children aged < 5 years: (1) gross and/or fine motor skills, (2) speech and language, (3) cognition, (4) social and personal skills, and (5) daily living skills or activities. 5 Children with intellectual disability/global developmental delay may also have other diagnoses, including Down syndrome, other genetic syndromes (e.g. fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome) or autism. For example, in the UK, children with an intellectual disability may be 33 times more likely than children without an intellectual disability to meet diagnostic criteria for autism. 6

Young children with an intellectual disability face, by definition, cognitive, learning, social and everyday living challenges. These children also experience a range of other social, health and educational inequalities. 7 For example, at aged 3 years, children with intellectual disability have lower levels of prosocial behaviours and higher levels of both internalising and externalising problems than children without intellectual disability, and these disparities generally increase throughout early and middle childhood. 8 In the physical health domain, children with intellectual disability are up to 70% more likely to be obese, which in turn increases the long-term risk of obesity-related health problems. 9 Children with an intellectual disability and their families are also more likely to be exposed to multiple social and economic risks, including poverty and negative life events. 6

Parents of children with intellectual disability also often have elevated levels of stress, mental and physical health problems themselves. Meta-analyses and results from higher-quality research designs (such as population-based national samples) have suggested, for example, that mothers of children with intellectual disability are about 1.5 times more likely than other mothers to experience depression10 and, similarly, 1.4 times more likely than other mothers to have high levels of psychological symptoms indicative of mental health problems. 11 Data from the UK Millennium Cohort Study (a population-representative birth cohort) also show that fathers of young children with intellectual disability are twice as likely to score above the cut-off point on a psychiatric disorder screen when compared with fathers of other young children. 12 The day-to-day burden of care for a child with intellectual disability is also high even when compared with other carers (e.g. dementia family carers). 13 Longitudinal research further suggests that the severity of the needs of children with intellectual disability can be associated with the well-being of their family members, especially parents. In particular, increased behavioural and emotional problems in children with intellectual disabilities also leads to deterioration in parental well-being over time, and typically vice versa. 14

Despite significant needs, access to supports and services for families of children with intellectual disability is fraught with negative experiences and is often described as ‘battling’ against the system. 15 Access to services and professionals is also limited. For example, < 30% of parents of children with an intellectual disability who also had a diagnosable mental health problem had access to mental health services in the preceding 12 months. 16 Therefore, children with intellectual disability and their parents face significant health inequalities and potential problems with accessing appropriate support.

Moving beyond parents’ well-being, there is also intellectual disability family research that applies family systems theory to examine putative effects on other family members and on family subsystems. 17,18 Siblings of children with an intellectual disability, for example, may be at a small, but elevated, risk for behavioural and emotional problems compared with other children who do not have a brother or sister with intellectual disability. 19 In addition, parental relationship problems, parent–child relationships, sibling relationships and overall family functioning may all be adversely affected in families of children with an intellectual disability. 14

Given this research evidence, interventions and supports are needed that target both parental or family well-being and developmental outcomes for the child with intellectual disability. Developmental challenges for children with an intellectual disability, and inequalities affecting their families, emerge early in life (certainly by ages 3–5 years), and so early intervention and support is important as both an individual family and larger policy priority. 20 In addition to parental well-being, what parents do with their child with intellectual disability and the relationships they build with them have been shown to be crucial for the development of children with intellectual disability (as they are for all children). The parent–child relationship quality at age 3 years, for example, predicted behaviour problems when children with intellectual disability were aged 5 years. 21 Negative dimensions of parenting in the early years period (i.e. aged 3–5 years) also mediated the effects of maternal well-being on the behaviour problems of children with an intellectual disability at aged 7 and 11 years. 22 Therefore, interventions that also target parenting practices/strategies and parent–child relationships could have significant potential to support families of young children with intellectual disability.

Rationale for the current study

The existing evidence base for early family/parent-based interventions for families of children with intellectual disability is significantly limited. There is some evidence relating to early intervention approaches that focus only on teaching new or extended skills to children with intellectual disability (e.g. Eldevik et al. 23), without any additional support for family members. 23 Similarly, there are some potentially effective intervention strategies from a psychological therapy perspective (such as cognitive–behavioural therapy and, more recently, mindfulness-based approaches) to reduce parental psychological distress in families of children with intellectual disabilities, where the interventions do not also focus on child outcomes. 24,25 Psychoeducation interventions may also be used in UK services, typically addressing one or more of three components: (1) information about disability, (2) information about services and supports available to families and (3) potentially a brief psychoeducational perspective on well-being. 26 Although such psychoeducation interventions have been evaluated with parents of pre-school children,27 parents of adolescents approaching transition28 and with parents of adults,29 the evaluations are small in size and rarely use randomised controlled trial (RCT) designs. 26 Other psychoeducation programmes have had a focus on services and improving access to services only,30 including by increasing parents’ confidence to access services. 31

Parenting interventions, which can focus on both child and parental outcomes, have recently been systematically reviewed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to inform the Mental Health Problems in People with Learning Disabilities: Prevention, Assessment, and Management clinical guideline. 32 The NICE guidance reviewed 15 RCTs of parenting programmes that involved parents of children with intellectual disability. These programmes were not developed for parents of children with intellectual disability [but were adapted from mainstream parenting programmes, e.g. Stepping Stones Triple P33 (Triple P International Pty Ltd, Brisbane, QLD, Australia)] and the programmes were not targeted at families of young children with intellectual disability. The single exception with an early intervention focus was a RCT of an individual family-delivered positive behavioural support intervention for young children with intellectual disability and severe behaviour problems. The RCT compared the intervention alone to a version that included a parent optimism component. 34 The parenting programmes reviewed by NICE also did not explicitly target parent well-being, but focused on a problem related to the child (e.g. behaviour problems). In terms of evidence gaps, NICE found no evidence relating to group parenting programmes designed specifically for parents of young children with intellectual disability, without a specific focus on a problem related to the child and with the explicit aim of improving parent psychosocial well-being. Therefore, there is a gap in both the availability of suitable group parenting programmes as well as an established gap in the evidence base.

A further limitation in the evidence base is the lack of approaches that have involved co-production with families35 or those including family members themselves as partners in supporting other families that have a child with an intellectual disability. This is despite evidence that parents’ lived experience can be beneficial in supports for families of disabled children more generally. For example, a recent systematic qualitative synthesis36 of research in which parents offer peer support to other parents of children with disabilities identified four themes describing the benefits of peer–peer support: (1) shared social contact with other parents, (2) learning from the experiences of other parents, (3) parent supporters gaining self-confidence and expertise, and (4) all participants valuing the opportunity to support others in group contexts. 36

Parenting programmes for families of children with intellectual disability are likely to remain a priority for UK services for several decades. In England, learning (intellectual) disability services across the NHS, local authorities and the for-profit and third sector are undergoing considerable change as a result of the government’s transforming care programme. The service model from the transforming care programme identifies early intervention/early support and support and skills training for parents as a part of a regional/community response to better services for families of children with intellectual disability. 37 In Scotland, parenting interventions are also a priority and are seen as a key way to improve the life chances of disadvantaged groups, including children with intellectual disability. The Scottish Government has proposed a co-ordinated parenting strategy across statutory and third-sector organisations, with partners from the third sector taking a lead in delivering parenting interventions. 38

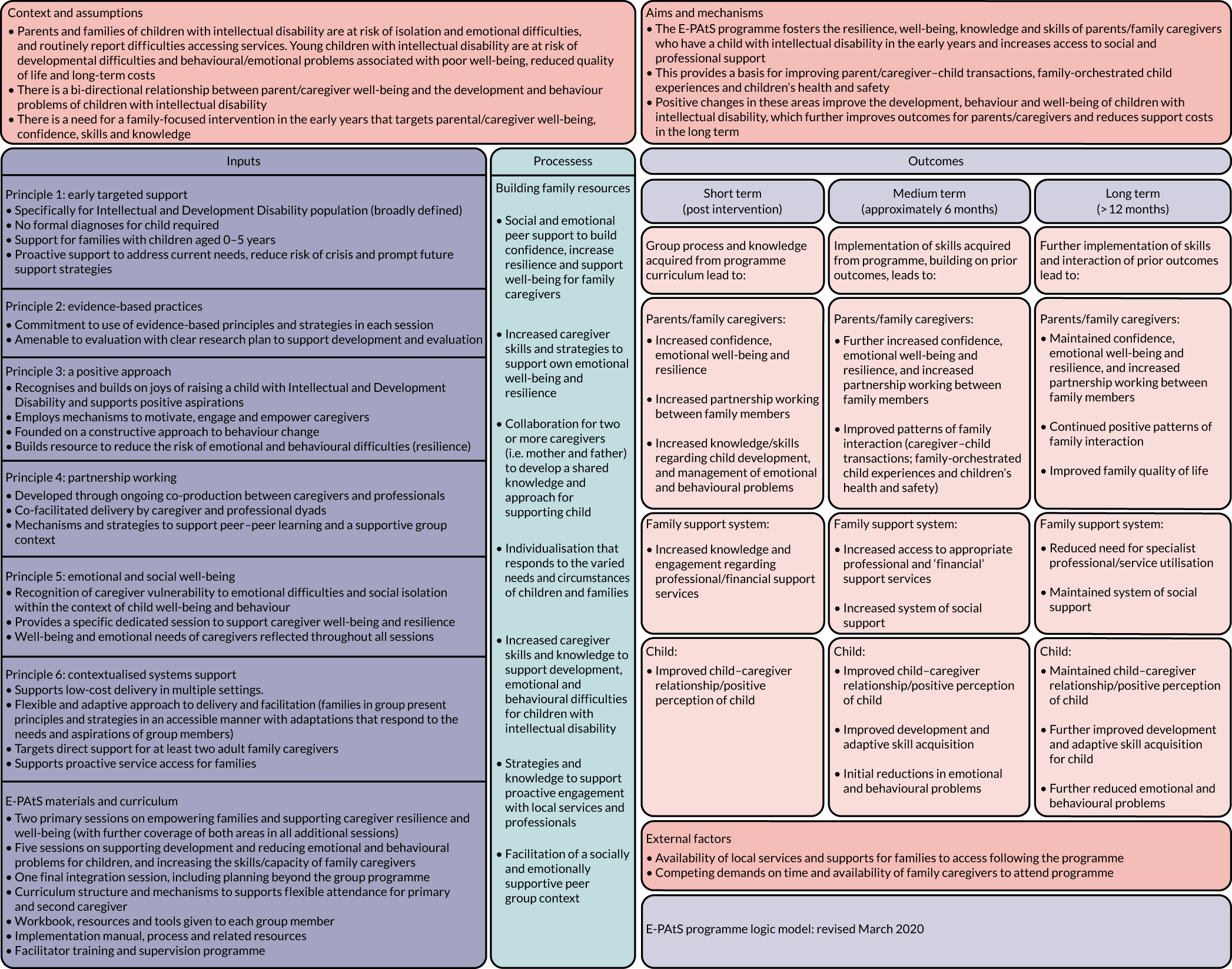

In response to the identified needs and gaps in the existing evidence base, we previously co-produced (with family carers) the Early Positive Approaches to Support (E-PAtS) programme. The E-PAtS programme is designed as a group parenting programme that is suitable for all families of young children with intellectual disability, and addresses issues for parents and the child that may already be experienced or will be likely to emerge during the course of the child’s development. The E-PAtS programme is a bespoke parenting programme that is specifically informed by intellectual disability research. The programme is co-delivered by a trained family carer facilitator and a professional facilitator across eight group sessions. The primary focus is to enhance parental psychosocial well-being. A detailed description of the E-PAtS programme is provided in Chapter 2 and the logic model is presented in Appendix 1.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the E-PAtS feasibility RCT was to assess the feasibility of delivering the E-PAtS programme to family carers of children with an intellectual disability by community parenting support service provider organisations. The study will contribute to the evidence base on the well-being of families with a young child with intellectual disability. Importantly, the study will inform a potential, definitive RCT of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the E-PAtS programme.

The study primary objectives were to assess the following:

-

the feasibility of recruiting eligible participants to the study and the most effective recruitment pathways to identify families of young children with intellectual disability

-

the feasibility of recruiting suitable intervention providers and facilitators to deliver the E-PAtS intervention

-

recruitment rates and retention through the 3- and 12-month post-randomisation follow-up data collection

-

the acceptability of study processes, including randomisation, to service provider organisations, facilitators and family carers through qualitative interviews

-

the acceptability of intervention delivery to service provider organisations, facilitators and family carers through qualitative interviews

-

adherence to the intervention, reach and fidelity of implementation of the E-PAtS intervention through attendance records, evaluation of session recordings and participant/facilitator qualitative interviews

-

usual practice in this setting and use of services/support by intervention and control participants

-

acceptability of collecting and analysing routinely collected data within a definitive RCT

-

service provider organisation willingness to participate in a definitive trial

-

the feasibility and acceptability of the –

-

proposed primary outcome measure for a definitive trial as methods to measure the effectiveness of the intervention [i.e. the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) at 12 months post randomisation]

-

proposed secondary outcome measures for a definitive trial, including resource use and health-related quality of life data, as methods to measure effectiveness of the intervention and to conduct an embedded health economic evaluation within a definitive RCT.

-

Chapter 2 Intervention

The E-PAtS programme

The E-PAtS programme is a group parenting programme for parents/family carers of children with an intellectual disability. The E-PAtS programme has been developed in response to the contexts, research and theoretical assumptions discussed in Chapter 1 to provide timely, effective and sensitive support to families of children with an intellectual disability. The programme aims to bolster family resources and resilience to achieve positive outcomes for parents who attend, as well as for their children and other family members. The components of the intervention (i.e. the six key principles of the E-PAtS programme and the programme materials and curriculums) are described in the E-PAtS logic model (see Appendix 1) alongside the main mechanisms of impact, potential outcomes (used to inform the methods of the current research) and longer-term outcomes that could be examined in a later study.

The E-PAtS programme was developed by Nick Gore, starting in 2011/12, in collaboration with a patient and public involvement (PPI) partner [i.e. the Challenging Behaviour Foundation (CBF) (Chatham, UK)], parents of children with intellectual disability, and intellectual disability professionals and researchers (including research team members Richard Hastings and Jill Bradshaw). The original programme content and rationale for the E-PAtS intervention was informed by the development of a framework that summarised relevant research evidence in the intellectual disability field39 by early intervention theory, especially the developmental systems model,40 and by the principles of co-production, both in designing the programme and also in its delivery (i.e. using a family carer co-facilitator working jointly with a professional).

Development process for the E-PAtS intervention

Key topic areas for inclusion in the E-PAtS intervention curriculum were developed using a workshop model. An initial 1-day workshop was held in January 2013 and involved a total of 17 participants, all of whom had attended prior initial meetings with Nick Gore to discuss the programme development. Workshop participants were a mix of parents and professionals with expertise in the proposed curriculum topic area (e.g. sleep). The task of the initial workshop group was to design 2.5-hour sessions that would serve as an evidenced-based introduction to a topic area, including practical skills or tools that would be needed in the first group that families might attend after a diagnosis or soon after suspicions are first raised about a child’s development. The workshop group were also given context informed by the emerging intervention logic (e.g. the session content should help to prepare families for the future emergence of problems and how to engage with professionals and services to obtain support).

The workshop content was edited, revised and manualised by Nick Gore during 2013. In this period, the original workshop members provided commentary and editorship to multiple editions of the materials that were developed. Feedback to support development of the programme was also gained from a parent/family carer focus group (comprising six additional family carers) via presentation and discussion with several multiprofessional groups (who were additional to the original workshop group) and a series of six in-depth development meetings between Nick Gore and a parent/carer who participated in the first workshop and later became a programme facilitator. The E-PAtS programme was pilot tested three times over the following 4 years, with more than 94 families participating (once led by Nick Gore and a parent facilitator and twice with Nick Gore training new facilitators). Following the second pilot, and a subsequent focus group that comprised programme facilitators, the E-PAtS programme materials and manuals were refined further. Therefore, the programme tested in the current research had been robustly developed and pilot tested prior to this study.

E-PAtS programme content and structure

The E-PAtS programme is fully manualised (comprising a programme manual and a programme implementation manual) and is typically delivered over an 8-week period. The programme is delivered in a group format to up to 12 parents/family carers, representing a maximum of eight families. Two parents/family carers from each family are invited to attend, but typically both family members attend approximately one half of the same sessions. Programme facilitators are typically professionals who are employed by third-sector organisations, but have included a range of health and social care professionals (and could include education professionals). Each programme is also delivered with a parent/family carer co-facilitator employed by the organisation specifically to deliver the E-PAtS programme. Facilitators deliver the programme in pairs (one professional and one parent/family carer facilitator) after completing a 5-day training programme and a period of supervised practice. Supervised practice consists of between two and three supervision meetings with the E-PAtS programme trainer during the first facilitation of a programme.

Facilitators are typically required to have prior experience of supporting children with intellectual disability and/or their families, but are likely to have a variety of professional roles and qualifications. Family carer facilitators are the parent of a child with an intellectual disability. The E-PAtS programme may be delivered in a range of community settings, including child development centres, community centres and church halls. In the current research, host organisations met the costs of programme delivery that relate to the training of facilitators, employment of facilitators, use of facilities and reproduction of materials. All E-PAtS materials, manuals and workbooks (including any future updates or revisions) are provided to trained host organisations for their continued and sole use at no cost.

All participating families attend a programme preparation session/interview with facilitators (undertaken by telephone in the current study) or other professionals from the host organisation (either face to face or by telephone) prior to the delivery of the programme curriculum as a standard part of E-PAtS programme implementation. This session helps prepare parents for the programme, ensures that it fits with their current needs and expectations, and identifies and proactively resolves any barriers regarding attendance and engagement for both parents/family carers from the family who are expecting to attend the groups. Carers also have opportunities throughout the programme to highlight any other factors that facilitators could address to support their engagement in the programme.

The E-PAtS programme comprises eight 2.5-hour group sessions, delivered at times of day determined by the provider according to the needs and preferences of participating families. A summary of E-PAtS programme sessions is provided in Table 1. The first two sessions of the E-PAtS curriculum predominantly focus on the emotional and well-being needs of parents/family carers together with the development of a family system of support. Session 1 provides an introduction to the programme and establishes group processes (see Table 1), before providing advice and strategies to support access to professional services and financial supports for families and their children. The second session focuses on the emotional vulnerabilities and needs of parents/family carers of children with intellectual disability, supports service access in relation to these and empowers parents/family carers to develop self-management and social support systems to reduce these vulnerabilities and needs and build resilience over the long term. Further consideration and support in relation to both building systems of family support and safeguarding the emotional well-being of parents/family carers is also included as a component of each subsequent session, and is further expanded on in the final session of the programme (i.e. session 8), which brings together all learning and supports to allow this to be continually used in the future.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | |

| Working together |

|

| Session 2 | |

| Looking after you and your family |

|

| Session 3 | |

| Supporting sleep |

|

| Session 4 | |

| Interaction and communication |

|

| Session 5 | |

| Supporting active development |

|

| Session 6 | |

| Supporting challenges 1 |

|

| Session 7 | |

| Supporting challenges 2 |

|

| Session 8 | |

| Bringing it all together |

|

Sessions 3–7 focus predominantly on supporting parent/family carer knowledge and confidence in responding to child-focused areas of need that are also associated with poor outcomes for parents and families of young children with intellectual disability. Session 3 provides advice and support in relation to sleep. Session 4 provides information to help children acquire effective functional communication and session 5 provides information to help children develop a range of adaptive skills. Sessions 6 and 7 draw on all previous sessions and provide additional curriculum content to help carers prevent and address problem behaviour currently displayed by their child or problem behaviour that they may be at risk of developing in future.

Each programme session is based on best practice developed through co-production with a range of professional experts and family carers. Sessions provide an overview of each area, with theoretical and practical considerations, to empower family carers with knowledge and activate improved patterns of family interaction (following the developmental systems model for early intervention). 40 Each session also includes further resources and signposting to support future advice and professional input for families that require this. The E-PAtS programme is designed as a cohesive programme curriculum rather than a menu of choices, with the expectation that parents/family carers attend the majority of sessions whether or not they or their child has support needs in the topic area. This is based on a premise that families and their children who attend the programme are at increased risk of experiencing complex needs across topic areas at some point in the child’s development, but that this could be reduced through early intervention and proactive support. In addition, it is considered that participating family carers will contribute towards the group process mechanisms, with the potential to support other group members in relation to one or more of the curriculum areas. This group process and mutual support may have potential benefits for both the carer in question and other group members.

Although the E-PAtS programme encourages and aims to facilitate full programme attendance, it is recognised that the complexity of family life for family carers supporting a child with intellectual disability may result in occasional non-attendance. The programme therefore incorporates a range of strategies to support families in such an instance. First, the programme provides a workbook of resources that provides access to important information and prompts development of bespoke strategies for families (relevant sections of which are provided to families even if a session is missed). Second, facilitators aim to accommodate any missed sessions, should these occur, by allocating time for brief catch-up discussions with families at the start or end of a subsequent session. Finally, as previously described, several core curriculum areas (and those associated with carer well-being in particular) run throughout all sessions (rather than being prescribed to a specific session), and so can be accessed by family carers even if an individual session is missed.

All of the E-PAtS curriculum components are delivered via a combination of oral and video presentations, group discussion and in-group exercises. The E-PAtS programme group process aims to create an emotionally and socially supportive setting that encourages engagement and addresses the well-being needs of family carers. First, meeting and working with peers who are experiencing similar challenges and needs, as well as being supported by a facilitator who is also a family carer, provides emotional validation and inspiration to group members. Second, programme facilitators have received training and supervision to develop therapeutic competencies to be used in conjunction with delivery of all curriculum areas. These skills help ensure that the emotional needs of family carers are recognised and responded to sensitively and constructively, and that supportive relationships are fostered between group members.

Presentation of materials and exercises is also designed to support family carer engagement, identify their particular needs and strengths, and empower them to build on these. Prior to delivery of each programme, facilitators are required to make localised adaptions to programme materials (e.g. information provided about current and local financial and service supports). Facilitators are also trained to respond to the specific needs of individual group members during delivery of each session (e.g. citing examples and strategies that are aligned with the presenting needs and circumstances of family carers who are in attendance and their children).

Family carers are given opportunities to rehearse and develop strategies and skills within sessions, but are not assigned tasks to complete between sessions. This is based on the assumption that participants will likely present with a range of different needs and circumstances and are likely to need to develop family support systems and personal resources as a prerequisite to implementing self-management and child-focused strategies at home. Implementation outside of the group setting may be possible for some participants within the time frame of programme delivery, but more typically this is expected to occur following programme completion.

All family carers are provided with a workbook that accompanies the programme. The workbook contains additional materials, tools and signposting to relevant resources in relation to each content area. The workbook is built around a ‘person-centred profile’, detailing the specific support needs for each family’s child. By completing the workbook throughout the programme, families are empowered to create a resource based on their knowledge and experience, combined with evidence-based practices, to inform broader systems of family and child support in the future. The workbook also allows information and learning from the programme to be shared with other family members who are unable to attend sessions directly. This is intended to contribute towards engagement with fathers and other family carers, and the development of a shared and collaborative family approach for supporting children.

In addition to the programme manual (focused on the delivery of each session and the session content and materials), the implementation manual includes practical elements that the provider organisation and facilitators need to deliver the E-PAtS programme. The implementation manual’s content includes role profiles for facilitators, practical suggestions about location set-up and all additional resources required to deliver the programme. There is also a training programme and manual for training facilitators to deliver the programme. The 5 days of training are guided by a manualised curriculum, comprising 1.5 days of teaching in relation to the evidence base, theory and ways of working that underpin the E-PAtS programme; 1.5 days of teaching regarding the programme curriculum for the programme; and 2 days of tutoring practice-based demonstration regarding curriculum delivery, group process and co-production in the delivery of the programme. Facilitators are required to be able to demonstrate necessary skills and understanding of the E-PAtS programme during the final training session prior to implementation, and receive two or three supervision sessions from the trainer (in addition to any supervision with the host organisation) during their first delivery of the programme. To date, all training has been provided by Nick Gore and/or Jill Bradshaw, but work is under way with regard to a ‘train-the-trainers’ programme training.

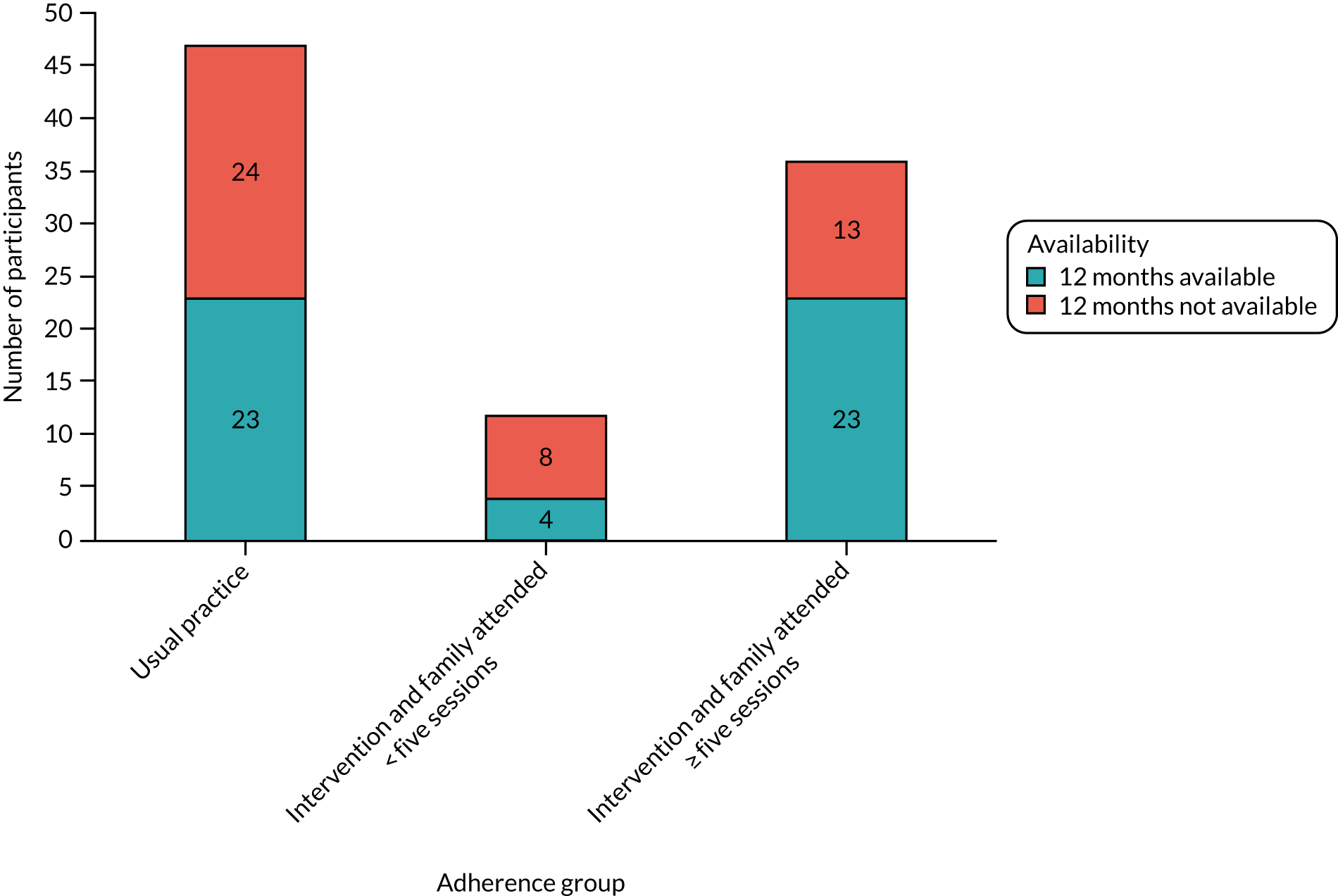

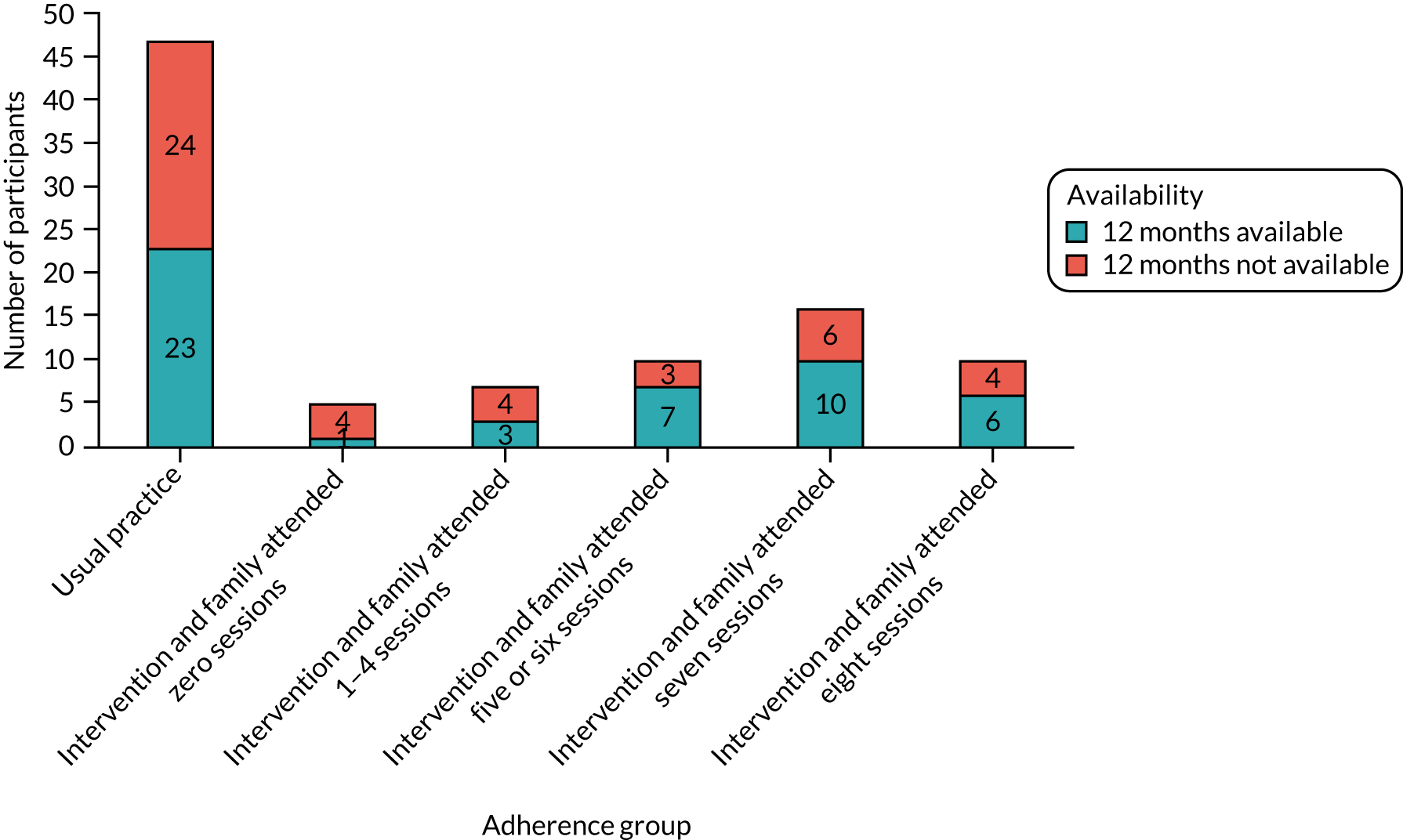

E-PAtS programme adherence

An initial definition of adherence to the E-PAtS intervention was focused on attending a total of five out of the eight sessions, but specified a pattern of attendance at the level of an individual family carer (i.e. one from the first two sessions, three of sessions 3–7 and the final session 8). During the course of the research, this definition was revised in two main ways: (1) to reflect that adherence was better described at the level of the family (in keeping with assumptions in the logic model) and (2) to simplify the definition to count any five sessions attended from the eight as representing adherence. This revised definition is used in the results and is discussed in Chapter 6.

Chapter 3 Methods

Design

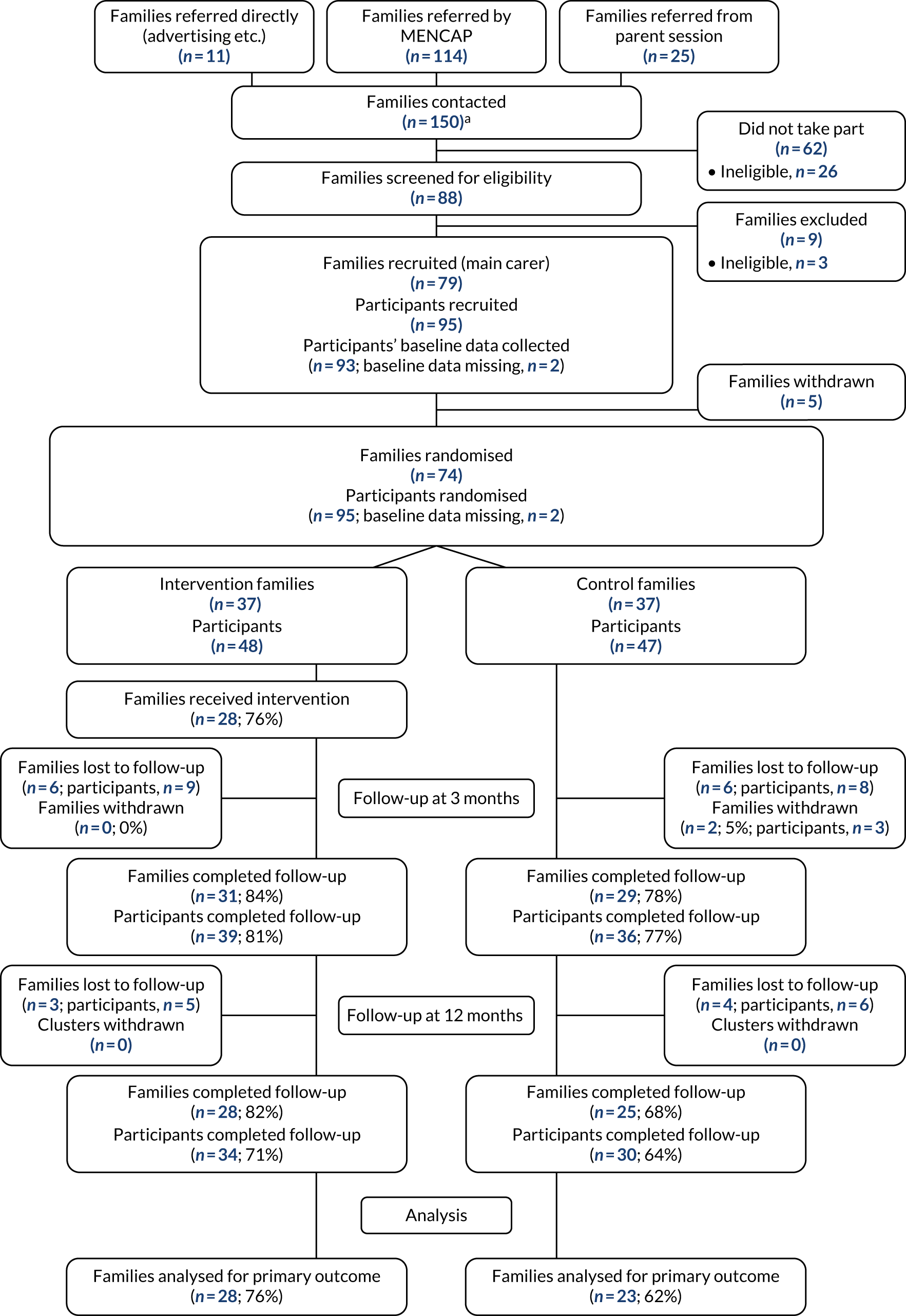

The study was a two-arm cluster (family carers in families) RCT with 1 : 1 randomisation using randomly permuted blocks, stratified by study site and choice of either study pathway. Primary participants selected one of two study pathways if they were randomised to the control arm: (1) pathway A families were offered the E-PAtS programme subsequent to the 12-month follow-up and (2) pathway B families were not offered the E-PAtS programme. Participants were recruited, asked to select study pathway A or B, and then randomised. Intervention participants were offered the E-PAtS programme immediately and all participants continued to have access to the usual support and advice services provided. The feasibility of using a range of established outcome measures proposed to test the intervention in a main trial was assessed. This study was not designed to test effectiveness. The acceptability of proposed outcome measures will inform the selection of outcome measures for a definitive trial.

Setting

The study was designed to take place in up to four study sites, defined as geographical areas where service provider organisations offer support services to parents.

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was given by the University of Warwick Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee on 14 December 2017 (reference number 30/17-18).

Usual practice

The comparator intervention was usual practice, with an optional waiting list for the E-PAtS programme. Usual practice includes any service (mainstream and specialised) provided to families and their children with intellectual disability as a part of an Education Health and Care Plan (or equivalent outside England) or via any other mechanism. Children with intellectual disability and their families could receive a wide variety of care and support from health, social and education sectors and the third sector, depending on their needs. Usual practice may vary by function (e.g. parent support, intervention for the child) and/or by the main recipient (e.g. the parent, the child with intellectual disability, the whole family). Usual practice may include parenting support or psychological therapy for psychosocial health, but we did not recruit primary family carers who were already receiving a recognisable parenting programme intervention or a psychological therapy for mental health problems at the time of baseline assessments (see Exclusion criteria). Participants were not asked to refrain from attending other interventions or therapies during the study. Usual practice was recorded through service use data. In addition, a question was included in an online UK survey of parents of young children with intellectual disability (n = 673), carried out by the research team at the University of Warwick (Coventry, UK), to record parents’ recent use of early years and early intervention services. These data enabled us to generally assess families’ level of access to interventions and describe the difference in content, delivery and value between usual practice and the E-PAtS programme. Usual-practice data will inform a later definitive trial and other future research.

Feasibility randomised controlled trial

Site selection

Service provider organisations were selected as sites for the E-PAtS feasibility study if they fulfilled the following selection criteria:

-

The site was prepared to refer a sufficient number of potential participants/families to the study team.

-

The site was prepared to deliver up to two E-PAtS courses at two periods throughout the study: (1) immediately following randomisation and (2) following data collection 12 months post randomisation for control participants.

Participant selection

Families were referred to the study team by service provider organisations in their local area following a flexible multipoint recruitment method, including established referral routes, local and national charitable support organisations, local authority services, special schools and nurseries, after school/weekend services for children with special educational needs and disabilities, parent/family support groups, social media, advertising in the media in local areas and self-referral.

The strategy was aimed to be flexible and collaborative. All potential participants confirmed interest in participating in the study either directly with the service provider organisation or by returning a completed reply slip to the study team. Potential participants were contacted by study team researchers to arrange a short screening/recruitment interview.

Participant screening

A screening interview was conducted either by telephone or face to face with a study team research assistant (see Eligibility criteria). Study processes, in particular the screening process, were fully explained and family carers were provided with a participant information sheet and given sufficient time to consider the information. Written consent or verbal consent was obtained in face-to-face or telephone screening interviews, respectively. Screening measures were taken to establish eligibility (see Eligibility criteria), including the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales (VABS)42 and the Brief Family Distress Scale. 43 Scoring of the VABS was conducted following the screening visit by the research assistant and this was quality checked by an additional trained member of the study team. The family carer was informed of their eligibility status and, if applicable, a recruitment interview was arranged.

Eligibility criteria

Clusters were family units with at least one young child with intellectual disability. For each cluster, a main family carer was recruited to the study. Subsequently, a second family carer was recruited to the study, if applicable.

The identified child with intellectual disability had to meet the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged 1.5–5 years (up to the day before the child’s 6th birthday).

-

An administrative label of any severity of intellectual disability (learning disability/ learning difficulties in UK terminology), referring to identification of the child within the education, health or social care systems as having intellectual disability, or as eligible for receipt of specialist intellectual disability services, or diagnoses indicating the presence of intellectual disability for younger children (e.g. ‘global developmental delay’).

-

A VABS44 composite score of < 80 (i.e. allowing for measurement error but still indicating significant developmental delay) at the time of the screening interview.

Exclusion criteria

-

The child is placed in a 24-hour residential placement at baseline.

-

The child is placed in a foster placement that is due to end before the 12-month post-randomisation follow-up data collection point.

-

The child had current child protection concerns identified.

The family unit and participants/family carers had to meet the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

A biological, step, adoptive or foster (if placement was planned to extend to 12 months’ follow-up) parent or adult family carer, including older siblings, grandparents or other family members who live in the family home.

-

Main family carer was available to attend the E-PAtS intervention.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Sufficient level of English language ability, enabling (verbal) completion of proposed outcome measures.

Exclusion criteria

-

Enrolled in a group-delivered or individually delivered parenting programme outside the study at baseline (main family carer only).

-

Enrolled in a programme of personal psychological therapeutic support at baseline (given that the E-PAtS programme is focused on family carer well-being).

-

If any family carer in the family had already participated in an E-PAtS intervention.

-

The family was recognised to be in a state of current crisis and unable to cope, indicated by a score of 9 or 10 on the 10-point Brief Family Distress Scale45 (assessed by primary family carer report only). Families in a state of crisis presented with needs that could not be addressed in a proactive programme and required urgent case management. Alternative forms of support were recommended to families in crisis.

Recruitment and consent

A recruitment interview was conducted either by telephone or face to face with a study team research assistant. All study processes were explained in detail, including randomisation and burden for the participant. Written or verbal consent was obtained in face-to-face or telephone interviews, respectively. In addition, the following data collection forms were completed: a participant’s contacts form that included multiple methods of contact (i.e. address, telephone, e-mail address) to minimise loss to follow-up; preferences for follow-up data collection (i.e. face-to-face interview completion, telephone-based completion or postal questionnaires); preferences for choice of study pathway (participants randomised to the control group who choose pathway A were invited to attend the E-PAtS programme at 12 months post randomisation and participants who choose pathway B were invited to an E-PAtS programme course); and a baseline questionnaire, including baseline demographics and proposed outcome measures.

Sample size

A target of 64 families (32 families in the usual-practice arm and 32 families in the intervention arm) were to be recruited to the study. As this was a feasibility study and the purpose was to provide estimates of key parameters for a future trial rather than to have enough power to detect statistically significant differences, a formal a priori power calculation was not conducted. 46 However, recruiting 64 families was to provide a certain level of precision around a 95% confidence interval (CI). For example, this precision is ± 9.8% for a consent rate of 80%, if 64 families are recruited.

Randomisation and masking

The E-PAtS trial is a two-arm, cluster RCT. Clusters were families with a child with intellectual disability and up to two parents/family carers were recruited per family. Families were randomised following recruitment and completion of all baseline measures. Families were randomised using randomly permuted blocks of size four, stratified by study site and choice of study pathway (A or B), with an equal allocation 1 : 1 to E-PAtS in addition to usual practice or usual practice alone. The study manager/data manager, neither of whom were involved in recruitment or data collection, conducted randomisation and informed participants and the service provider organisation of their allocation by telephone. Research assistants at sites responsible for collecting follow-up data and all remaining study team members (including the trial statistician) remained blind to participants’ allocation. At follow-up data collection, participants were asked not to reveal their allocation to the research assistants. However, if the participant’s allocation was revealed it was noted.

Study primary objectives

The following primary objectives were measured and used to inform the decision to progress to a definitive trial:

-

recruitment rates and effectiveness of recruitment pathways

-

study retention rates

-

adherence to the E-PAtS programme

-

fidelity of E-PAtS programme delivery

-

service provider organisation recruitment rates and willingness to participate in feasibility and definitive trial

-

assessment of the barriers and facilitating factors for recruitment, engagement and intervention delivery from the perspective of all stakeholders

-

measurement of usual practice

-

acceptability of collecting and analysing routinely collected data within a definitive trial.

The feasibility of using a range of established outcome measures proposed to test the intervention in a main trial was assessed. This study was not designed to test effectiveness. The acceptability of individual proposed outcome measures (via completion rates, quality of completion and qualitative data) informed the selection of outcome measures for a definitive trial. The proposed outcome measures included those for individual family members, subsystem relationships and overall family functioning. Proposed outcomes were chosen based on outcome areas prompted by the E-PAtS logic model; experience in research with families of young children with intellectual disability, including the total measurement load family carers have been willing to bear; brevity but with good psychometric properties; and potential comparisons with national data sets (e.g. Millennium Cohort Study47) to provide context for the meaning of scores obtained. All proposed outcome measures were administered to family carers. Table 2 shows details and timings of all proposed outcome measures for a definitive trial [Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) figure].

| Time point | Target of outcome | Screening | Study period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (up to 8 weeks prior to randomisation) | Randomisation (up to 5 weeks prior to intervention) | Follow-up | |||||

| 3 months post randomisation | 3–9 months post randomisation | 12 months post randomisation | |||||

| Enrolment | |||||||

| Consent for eligibility | F | ✗ | |||||

| Eligibility screening | F | ✗ | |||||

| VABS42 (full) | C | ✗ | |||||

| Brief Family Distress Scale | F | ✗ | |||||

| Informed consent | F | ✗ | |||||

| Contacts data | F | ||||||

| Randomisation allocation | N/A | ✗ | |||||

| Assessments | |||||||

| Demographic data | F | ||||||

| WEMWBS48 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| HADS49 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| EQ-5D-5L50 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Brief COPE51 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| CBCL52 | C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ version 4.0 generic core scales53 | C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Relationship Happiness Scale47 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Family APGAR Scale54 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire55 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Sibling Relationship Questionnaire (revised) (where relevant)56 | C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Family Support Scale57 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| FMSS58 | F and C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (seven items)59 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Positive Gains Scale60 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Disagreement over issues related to child,47 co-parenting44 | F | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| CPRS45 | F and C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Parent activities/involvement index | F and C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Group Cohesion Scale (eight items)61 | F | ✗ | |||||

| Client Service Receipt Inventory62 | F and C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| VABS42 (brief) | C | ✗ | |||||

| Participant views on use of routine collected data in future trial | F | ✗ | |||||

| Process evaluation: participant interviews | F | ✗ | |||||

| Process evaluation: facilitator interviews | N/A | ✗ | |||||

| Process evaluation: service provider organisation interviews | N/A | ✗ | |||||

Participants completed the VABS at baseline. A report consisting of the standard report generated by online VABS prefaced by an adapted two-page summary was provided to participants shortly following baseline completion. The two-page summary was designed by the research team, with PPI input provided by the advisory group. It consisted of an adapted description of the VABS, the method of collecting the data, and a description of current and next developmental level and ideas about how the child might be supported to achieve the next level. It also included information on the technical report, emphasising that it might be of use for professionals working with the child and noting that the report compared the child with typically developing children and that there can be many reasons why a child does not score high on a particular item.

Process evaluation

Medical Research Council guidance was used as a framework for the process evaluation to describe implementation processes, review the intervention logic model through examining intervention mechanisms, and consider the role of context in shaping intervention implementation and mechanisms. 63 The process evaluation employed a mixed-methods approach and focused on the study primary objectives. Qualitative interviews with facilitators, service provider organisations and family carers examined implementation processes, intervention mechanisms, the role of contextual factors and interrogate patterns in the quantitative data, as well as informing assessment of the feasibility of implementing the E-PAtS programme within a definitive trial.

Fidelity of intervention delivery was assessed by determining the proportion of key messages and activities that were completed as intended in each session in two ways. The primary measure of fidelity was completion of the E-PAtS programme observation checklist by a trained observer based on video-recorded or audio-recorded sessions delivered in the intervention arm. A separate observation checklist was available for each of the eight E-PAtS programme sessions. Checklists consisted of between 16 and 38 items (with an average of 29 items) that correspond to key activities, discussions and learning points that need to occur in a given session. Observers were required to rate whether or not an item was covered by the facilitator pair. The second measure of fidelity utilised self-completion checklists that are used as a standard part of the E-PAtS programme implementation by facilitators. A separate checklist was available for each of the eight sessions and was available for facilitators to complete after each session. Checklist items cover key activities and discussions (with some, but not complete, correspondence to the observations checklist) and were rated as either having been covered or not having been covered by facilitators.

Statistical methods/analysis plan

The study protocol follows SPIRIT guidelines and the analysis and reporting of this RCT is in accordance with the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) extension for randomised pilot and feasibility trials guidelines. Significance tests are not reported as the E-PAtS feasibility RCT was not powered to test hypotheses. The majority of outcome analyses are descriptive in nature. Continuous data are reported as means and standard deviations (SDs), or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), as appropriate. Categorical data are reported as frequencies and proportions. Feasibility outcomes were estimated with their associated 95% CIs. The main preliminary analyses of outcome measures are intention to treat based, accounting for clustering (family carers in families) using multilevel models. Single-carer families are included as a cluster of size one.

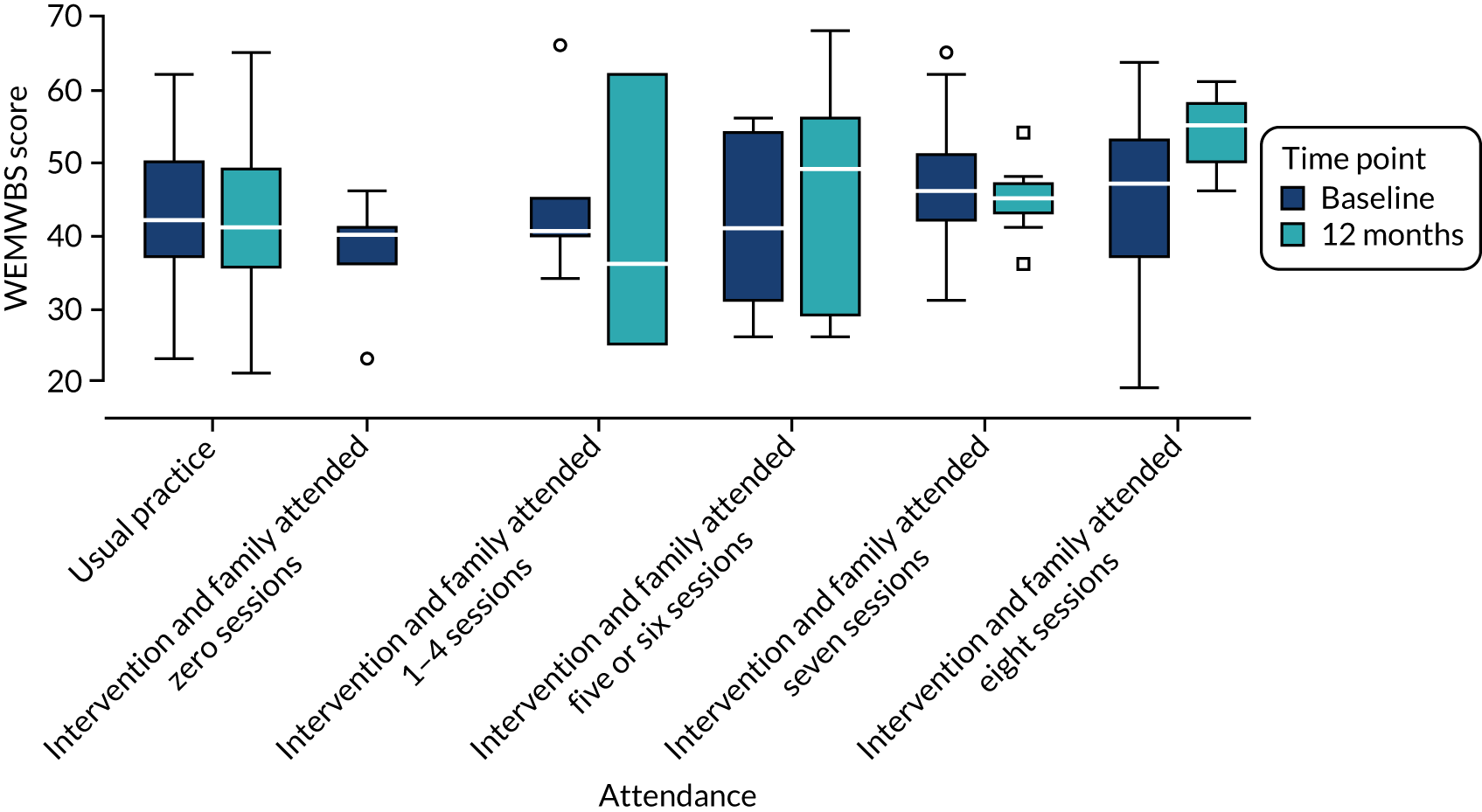

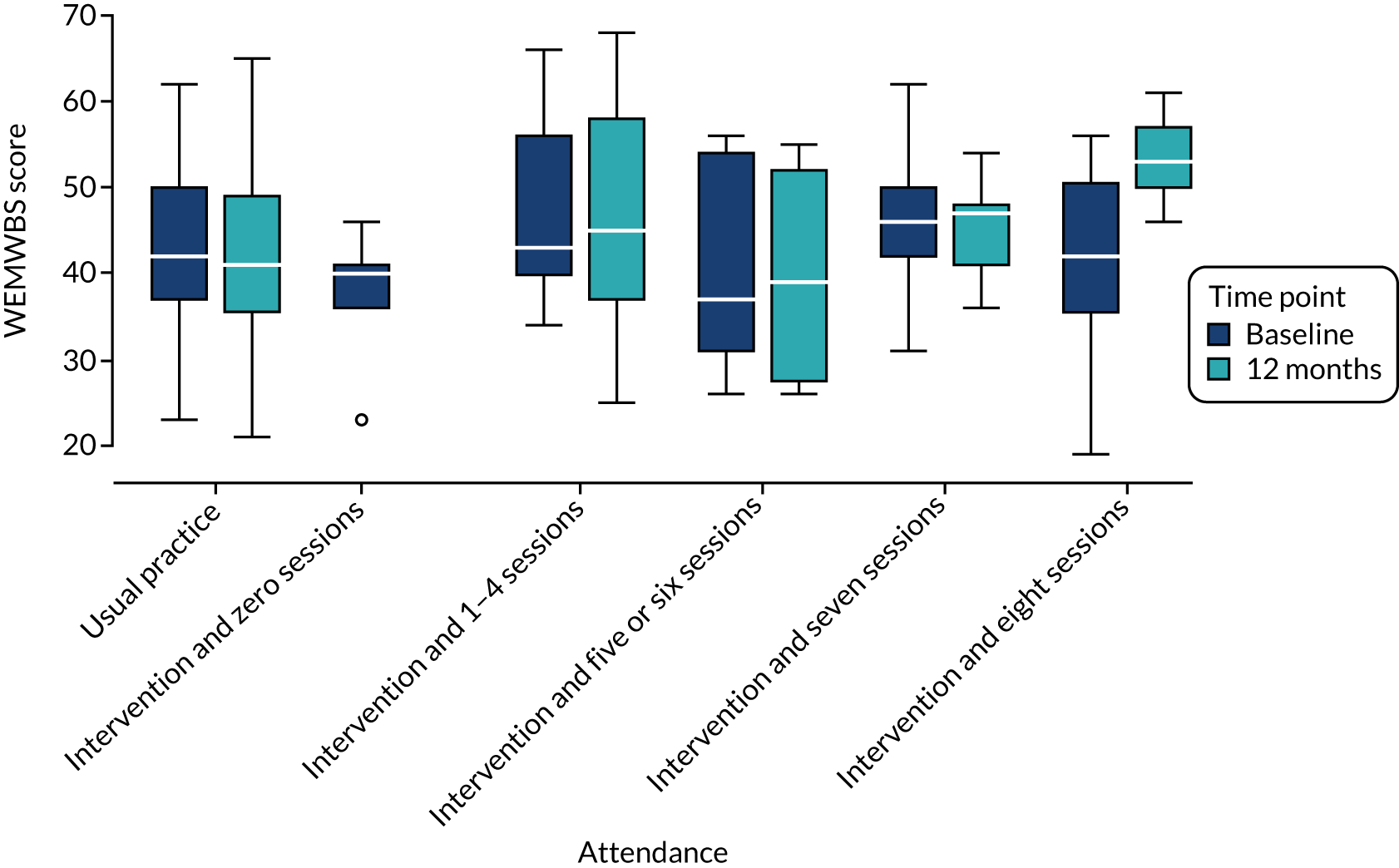

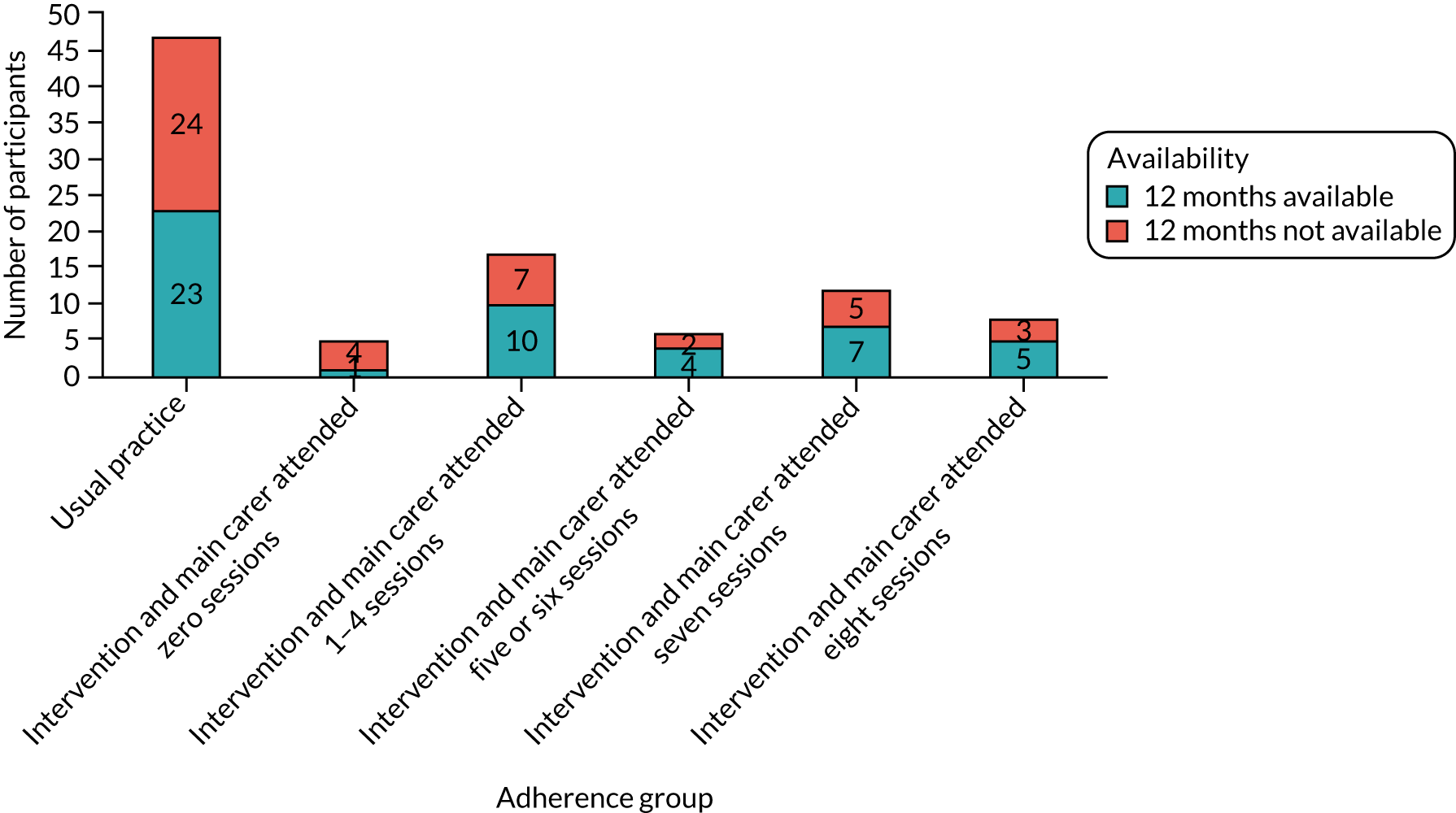

The analysis of the proposed primary outcome for a definitive trial examined mean WEMWBS scores between arms at 12 months post randomisation, with baseline WEMWBS scores included as a covariate. The analysis also adjusted for randomisation factors. Remaining potential outcome measures for a definitive trial were analysed similarly, with appropriate multilevel regression models. Results from all regression models are reported using point estimates and 95% CIs. Outcomes were also explored in relation to the definition of adherence to the E-PAtS programme (see Chapter 2 for definition of completion/adherence) and to consider two additional perspectives on family session attendance as additional exploratory analyses:

-

the actual number of sessions attended by a family unit (i.e. at least one family member), with any instances where both family carers attended the same session counting as one and not two

-

the actual number of sessions attended by the main family carer.

Box plots were used to illustrate differences in baseline and 12-month follow-up WEMWBS scores (i.e. the candidate primary outcome measure for a definitive trial) by adherence and session attendance.

Exploratory complier-average causal effect (CACE) analyses were conducted for our main adherence definition and our two measures of session attendance by fitting two-stage least squares instrumental variables regression models. Models included baseline WEMWBS scores and site as covariates, and accounted for the correlated nature of participants within families by including cluster robust standard errors (SEs). The purpose of these analyses was to explore the impact of accounting for adherence and session attendance on the intervention effect estimates, and to test the robustness of these findings to different perspectives associated with adherence. Estimates are reported as adjusted mean differences and associated 95% CIs. For session attendance, model coefficients were multiplied by eight to estimate the maximum efficacy.

Economic evaluation

The overall objective of the health economic component of the E-PAtS feasibility study was to provide early evidence on economic aspects of the E-PAtS programme and an assessment of the best possible ways of expressing the cost-effectiveness of the programme within a larger subsequent trial. This included (1) an early assessment of the economic costs associated with the programme; (2) an assessment of the broader resource use and health-related quality outcomes associated with the programme; (3) identification of appropriate sources of unit costs for potential resource consequences and an assessment of how much primary costing research will be required for the main study; (4) identification of available routine health and social data sources that could be used to complement and validate self-reported resource utilisation data; and (5) an assessment of the best possible way of expressing the cost-effectiveness of the E-PAtS programme using future preference-based approaches.

Economic costs associated with the E-PAtS programme

A focus of the economic evaluation in a future trial is to estimate the cost of delivering the E-PAtS programme in community settings, including the costs of employing the programme facilitators and costs of delivering the group sessions. This information was collected by asking both professional facilitators and family carer facilitators for the E-PAtS programme to complete detailed weekly activity logs, outlining the cost of delivering each E-PAtS session [including costs associated with programme delivery time, indirect administrative activities (e.g. paperwork), planning for groups, telephone calls and E-PAtS programme supervision activities]. The weekly activity logs also recorded the mode, distance and time spent on travelling by each facilitator as part of E-PAtS programme-related activities. The hourly employer costs for the E-PAtS facilitators were obtained from the E-PAtS programme manager and included salaries, employer on-costs and revenue and capital overheads. Travel costs per mile were obtained from the website of HM Revenue and Customs of the UK Government. 64 Additional expenditures, such as refreshments, participant travel and child-care costs associated with the E-PAtS intervention, were valued in accordance with what was recorded in the weekly activity logs.

This information was collected from E-PAtS professional facilitators and family carer facilitators in two of the study sites (this information was collected for sites 1 and 3 only). Detailed weekly activity logs were used, outlining the cost of delivering each E-PAtS session.

Routine data analysis

In response to reviewer comments suggesting linkage to routine data was explored in this feasibility study, we aimed to do the following: (1) map out the relevant data providers, data sets available and associated timescales that could be linked to a future trial population, (2) explore participant acceptance of linking to these data sources, (3) explore the possibility of routine data access for a definitive trail and (4) describe the logistics of linking, transferring and storing data. The decision was made to not consent participants to linkage of data as part of this feasibility study, but to explore the acceptability of consent with current participants at 12 months. It was not intended for the data to be reported as part of the feasibility study outcomes and so data applications were not submitted.

Qualitative methods/analysis plan

Thematic analysis was used to analyse each group of interviews (with providers, facilitators and family carers) separately and independently, followed by qualitative synthesis across all interviews to provide an overarching synthesis of family carers’ experiences and perceptions related to the study objectives. 65 A triangulation exercise was conducted, combining qualitative and quantitative data analysis results.

A full statistical and health economics analysis plan and a qualitative analysis plan were written by the statistician, health economist and qualitative researcher, and approved by the Study Management Group (SMG) and Study Steering Committee (SSC) prior to analysis taking place.

Retention strategy

A number of strategies were used to encourage participant retention:

-

At baseline, participants selected their preferred follow-up method for the 3- and 12-month follow-ups (i.e. post, telephone or face to face). Throughout the study, participants could change their follow-up method at any point by informing the study team.

-

Participant incentives (£10 for each main family carer and £15 for each second family carer) were sent to participants prior to follow-up data collection.

-

A systematic procedure was used to contact participants for each follow-up, ensuring that a minimum of three telephone contacts, plus additional contacts by e-mail or additional telephone numbers provided, were attempted for each participant.

-

For non-responding participants, a minimum data set [consisting of three prioritised outcome measures of WEMWBS, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) and the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale, aligning with the intervention logic model and taking into consideration participant burden] was offered to reduce participant burden and maximise follow-up rates.

Changes to the protocol

There was one amendment of note to the original protocol of the study. The exclusion criteria were updated to state that families would be excluded if they scored 9 or 10 (in crisis and unable to cope) on the 10-point Brief Family Distress Scale. The original exclusion criterion stated that the family were recognised to be in a state of current crisis with a score of ≥ 8. This change followed a SMG meeting where the team considered that families in crisis but able to cope could benefit from attending the E-PAtS groups and should therefore be included in the study. Any family considered at risk at any point in the study would be signposted to appropriate support services.

Chapter 4 Public and participant involvement

Public and participant involvement during this project focused on two main processes. First, a family carer was an independent member of the SSC appointed by the funder. Payment was offered to the family carer SSC member in addition to covering their expenses.

The second PPI process focused on a family carer advisory group that was managed by the PPI partner grant applicant organisation through the CBF. There were nine family carers in total recruited to the advisory group. They were recruited using a mixture of targeted recruitment (i.e. inviting family carers who had already been trained as E-PAtS facilitators, who would have insight into and experience of the intervention) and an open invitation for expressions of interest to the CBF network of families that were unlikely to have experience of the E-PAtS programme but who had relevant life experience (as they had children who might have benefited if the E-PAtS programme had been around when they were younger). Five members of the advisory group (four from Northern Ireland and one from England) were also E-PAtS facilitators, although they were not involved with E-PAtS delivery for this research. Four members of the group (from across England) were family carers with no experience of the E-PAtS programme. Two family carers were fathers and seven were mothers.

Once they had expressed an interest in joining the advisory group, family carers were contacted to arrange an initial telephone call or discussion in person by either the project manager from CBF or the family support manager from the Mencap in Northern Ireland (Belfast, UK). For those with no previous experience of the E-PAtS programme, the initial discussion involved:

-

an overview of the E-PAtS intervention

-

an overview of the feasibility study

-

a summary of the commitment involved in joining the advisory group

-

practical arrangements for the meetings.

For those who had been E-PAtS facilitators and were familiar with the intervention, the initial discussion covered the latter two areas. Family carers were invited to ask questions and share any particular interests they had relevant to the study. Telephone calls were followed up with a written summary of the information prepared by CBF, and carers were offered a subsequent telephone call if they wanted to discuss anything further once they had read the documents. Two family carers took up this offer of a subsequent telephone call. One group member had to step down from the group during the study (because of other demands) and two new members were recruited part-way through the project. Family carers were paid £50 in vouchers for each advisory group meeting, with additional payment for work on e-mail consultations between meetings.

Advisory group meetings were chaired by the PPI co-ordinator and attended by the lead researchers so that they could hear views of family carers and discuss with them directly. Meetings were on two sites – at the CBF offices (Chatham, UK) and the Mencap Children’s Centre (Belfast, UK) – and linked by Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Family carers unable to attend either site in person were also able to attend using Skype. At the first meeting, carers were asked if the meeting arrangements worked for them. They were also asked if one of them would like to chair the meetings in future. All were happy with the original set-up and preferred to focus on the content rather than chairing the meeting.

The first meeting was on 7 February 2018 and covered:

-

a presentation from the study chief investigators explaining the study (which was also intended to be used in recruitment events for participants)

-

the terms of reference for the group to be discussed, edited and agreed

-

input to the online UK survey that was being carried out to inform an understanding of usual practice

-

the measures proposed to gather service receipt data.

The second meeting planned for May 2019 had to be postponed as material was not ready for discussion by the advisory group in time and some consultation was carried out electronically instead. The second meeting was on 19 September 2019 and focused on the initial findings from the process evaluation. The third and final planned meeting took place using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA), due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in June 2020 to discuss materials intended to disseminate study findings to participants and facilitators. We also sought family carers’ views on priorities for dissemination and influencing policy/practice.

Advisory group members were asked to comment on a number of study documents by e-mail. Between two and four family carers responded to each of these requests, with often in-depth comments and suggestions. CBF staff members also commented on these study documents. All were offered the chance to discuss on the telephone with CBF if they wished. Requests for comments on study documents included:

-

comments on recruitment materials (January 2018)

-

comments on the wording of the VABS report (June 2018)

-

comments on sections of the questionnaire (September 2018)

-

comments on topic guides for interviews and the routine data questionnaire (January 2019)

-

comments on the 12-month follow-up questionnaire (May 2019)

-

feedback on the lay summary for the current report (June 2020).

When the May 2019 meeting was postponed, CBF staff requested that Nick Gore record a video, edited and shared by CBF, to update the advisory group members on study progress. Family carer advisors were invited to direct any questions to Nick Gore or to the CBF.

The PPI co-ordinator was a member of the SMG as a full participant and so was also to identify areas where family carer advisory group input may be helpful. Several of the e-mail consultations were agreed as a result of this involvement. The advisory group was a standing item on the SMG agenda and the involvement of the PPI co-ordinator was pivotal to ensuring that PPI was discussed at every meeting, both in terms of how to meaningfully engage the group and how to respond to the feedback from the advisory group. Feedback was also provided to the advisory group about recommendations that they had made and actions taken by the research team (or an explanation as to why a particular piece of advice was not actioned).

Key suggestions and feedback from the advisory group that directly affected the research included the following:

-

recommendations on how to explain the role of the study more effectively as part of the recruitment presentation (a new slide was added as a result)

-

changes to the structure, content and wording of the report on the VABS for parents

-

informing content for the online UK survey to assess usual practice and, in particular, the content and presentation of the service receipt questionnaire

-

informing content of interview topic guides, particularly about how to approach difficult topics with carers

-

clarity and suitability of terminology used in the study (e.g. main and second carer to be used)

-

identification of future research/development questions, such as whether a school-age version of the E-PAtS programme could be developed and how older siblings might be involved in E-PAtS groups

-

informing content for routine data questionnaire.

Routine data questionnaire at the 12-month follow-up

A questionnaire was developed with input from our PPI co-ordinator and the family carer advisory group, and this was one of the most detailed aspects of PPI involvement and advice. The questions aimed to explore the acceptability of linkage to different routine data sources, as well as linkage of their own data compared with their child’s data. An explanatory section at the start of the questionnaire introduced the concept of routine data followed by a number of questions.

Routine data questionnaire development

The questions and explanation for this questionnaire were redrafted twice. First, following feedback from our PPI co-ordinator to make the explanation clearer at the start of the questionnaire and second, following feedback from the advisory group. Feedback was collated from two members of the advisory group and some of the suggestions are shown below. All feedback was used to finalise the questionnaire and the SMG signed off the final version:

Don’t forget, a proportion of people filling out these questionnaires will have a learning disability themselves. Some may struggle with longer words/explanations. In addition to this, parents of children with disabilities usually hate paperwork as we are often inundated with it. The less parents feel they have to fill out, the more amenable they will be.

I think it’s also vital that whoever is presenting this information to the participants is well informed and explains it both in a non-threatening manner and consistently across the participants. Many parents will listen to what they’re being told as opposed to fully digesting the written information.

I think people may have some concern about why their information is needed – for example if someone has had mental health difficulties in the past they may be worried sharing this information could lead to involvement with social services – I know that you say the info is securely held and only used for the specific research project, but I wonder if this needs to be explained further to reassure people that this would not happen?

I particularly like the part about numbers and codes. I think this will reassure people. I also thought the part about having to prove the data is kept secure and not to be used for other purposes would reassure people.

Question 3 – this question may start to scare people off. Social services use the term ‘children’s services’ or ‘children’s social care’ for that reason. There’s a taboo around this area for sure. People don’t like to admit that their child is a CIN [Child in Need]. This is compounded by the fact that children who are under a CPO [Child Protection Order] or who are ‘at risk’ are also under the same umbrella term. Think about using another term or phrase here. Let’s be honest, if your child is a ‘looked after child’ or under CP [Child Protection], you’re hardly going to freely offer access to this information.

Much of the feedback was relevant to this specific patient population, which will be particularly useful for the development of the definitive trial participant information in relation to routine data.

Chapter 5 Results

Both quantitative and qualitative results are discussed in the context of the progression criteria and have been mapped on to the objectives of the study, as detailed in the study protocol. The results are reported in six main sections (Table 3).

| Objective | Results discussed |

|---|---|

| 1. Site and participant characteristics | |

|

|

| 2. The RCT | |

| The feasibility of recruiting eligible participants to the study and the most effective recruitment pathways to identify families of young children with intellectual disability |

|

| Recruitment rates and retention through 3-month and 12-month post-randomisation follow-up data collection |

|

| The acceptability of study processes, including randomisation, to service provider organisations, facilitators and family carers through qualitative interviews |

|

| 3. Piloted outcome measures proposed to test the effectiveness of the intervention in a main trial | |

| The feasibility and acceptability of the proposed outcome measures as methods to measure the effectiveness of the intervention and to conduct an embedded health economic evaluation within a definitive RCT |

|

| 4. Feasibility testing of the intervention | |

| The feasibility of recruiting suitable service provider organisations and facilitators to deliver the E-PAtS intervention |

|

| Adherence to the intervention, reach and fidelity of implementation of the E-PAtS intervention through attendance records, evaluation of session recordings and participant/facilitator qualitative interviews |

|

| The acceptability of intervention delivery to service provider organisations, facilitators and family carers through qualitative interviews |

|

| 5. Usual practice | |

| Usual practice in this setting and use of services/support by intervention and control participants |

|

| 6. Feasibility/recommendations for a future trial | |

| Service provider organisation willingness to participate in a definitive trial |

|

| The feasibility of conducting an embedded health economic analysis in a definitive trial |

|

| Acceptability of collecting and analysing routinely collected data within a definitive RCT |

|

| Progression criteria | |

Site and participant characteristics

Site/service provider organisations characteristics

Three sites were involved in the study to support recruitment of participants and deliver the E-PAtS intervention. Two sites were part of one service provider organisation, Mencap Northern Ireland, and one site was part of a second service provider organisation, an independent local Mencap group in England. The service provider organisations are third-sector organisations that support people with intellectual disabilities in an area of London and in Northern Ireland. Prior working relationships existed with two of the sites (Belfast and Derry) that supported recruitment to the study. The other site (Barnet) was recruited specifically for this study, with support from the Royal Mencap Society (London, UK). Two sites were characterised by urban contexts and one site was characterised by a mixture of urban and more rural contexts.

Belfast

Mencap Northern Ireland’s family support service has been running for 3.5 years. The focus of the work is to support families with children aged 0–7 years with intellectual disability, developmental delay and/or autism. The majority of the work with families takes place at the Mencap Children’s Centre in Belfast, where families can access a variety of supports. Prior to the current study, the E-PAtS programme had been delivered in Belfast on six occasions. A family support manager employed by Mencap Northern Ireland was available to support intervention implementation and research.

Barnet

Barnet Mencap (London, UK) provides a range of services and runs campaigns alongside people with intellectual disability, and people with autism and their families to secure good services and support in the borough. This includes provision of parenting programmes to families of children with intellectual disability. Barnet Mencap took part in piloting an early version of the E-PAtS programme, but had not otherwise delivered the programme (in its current form) prior to taking part in the study. A small degree of managerial support was available to support intervention implementation and research activities.

Derry

Family support services by Mencap Northern Ireland are also provided in Derry, largely with a community-based focus (and without a specific centre, as there is in Belfast). A family support worker operates within a wide range of local community, voluntary and statutory organisations to build links with relevant families. Prior to the current study, the E-PAtS programme had been delivered in Derry on one occasion. Support for the intervention implementation and research activities was available through the same manager employed by Mencap Northern Ireland, as in Belfast, and a manager based at Derry.

Participant characteristics

In total, 95 participants were recruited to the E-PAtS study. Table 4 details the characteristics of the study participants, which were broadly balanced between the control and intervention arms. The majority of participants were biological mothers (n = 65, 68%). Biological mothers accounted for 88% of main carers (n = 65). Of the 21 second carers, 86% were biological fathers (n = 18). Only four participants reported that their child with intellectual disability lived with them on a part-time basis. Overall, around three-quarters of participants classified themselves as being either white British or white Irish (n = 50). Twenty-three participants (41%) were educated to degree level or above. This compares with 27% of the UK population, according to the 2011 census. Overall, 45% of participants reported being employed or self-employed (n = 43), with 46% of main carers looking after the home and family (n = 34). Twelve participants (13%) were finding things difficult financially, with a further 25% ‘just about getting by’ (n = 24). There were some slight differences between arms in the financial question categories. For example, 11 intervention participants said that they could raise £2000 in a week for an emergency ‘easily’ and nine reported that they were ‘living comfortably’. This compares with three and two participants in the control group, respectively. By combining categories to avoid smaller numbers, however, 36% of both intervention and control participants said they could raise £2000 in a week (n = 34). The majority of participants considered themselves as being in ‘good’ or ‘very good’ health (n = 72, 76%).

| Characteristic | Main family carer | Second family carer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 37), n (%) | Intervention (N = 37), n (%) | Control (N = 10), n (%) | Intervention (N = 11), n (%) | |

| Relationship to child | ||||

| Biological mother | 30 (81) | 35 (95) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |