Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number 15/129/03. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The draft manuscript began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Burns et al. This work was produced by Burns et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Burns et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Cook et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The following text includes minor additions and changes to the original text.

Alcohol harm: a global concern

Reducing alcohol-related harm continues to be a global public health priority, with 5.3% of all global deaths and 5.1% of all disease and injuries being attributable to alcohol. 2 Use of alcohol is widely recognised to harm an individual’s health and social relationships, and increasing evidence highlights the scale of alcohol’s harm to others through second-hand effects. 3–5 It also harms society more generally, as urban areas can become less pleasant and less safe to visit,6 and crime may increase. 7,8 Moreover, the consumption of alcohol contributes significantly to health inequalities. A so-called ‘alcohol harm paradox’ exists where alcohol harm is higher among those living in more deprived areas, even when the amount of alcohol consumed is the same or less as those more advantaged. 9 This is due to patterns of consumption (e.g. heavy episodic binge drinking), lower access to health services, increased alcohol availability with fewer community assets and the accumulative effect of multiple risk factors (e.g. smoking, obesity). 10–12 Overall, alcohol use is a key risk factor for many non-communicable diseases13 (NCD) but currently, the global NCD target to reduce harmful use of alcohol by 10% by 2025 is on a poor trajectory. 14

Interventions to reduce intake and harm from alcohol

Interventions that are effective at reducing alcohol harm can be implemented at an individual level,15 community level16,17 and national level. 18 At the individual level, alcohol identification and brief advice (IBA), otherwise known as alcohol screening and brief interventions (ASBIs), aims to reduce alcohol-related harm through early identification of hazardous or harmful drinking in non-treatment-seeking populations. It has been shown in systematic reviews and meta-analyses to be effective among adults in a variety of settings15,19 with most trials located in primary care settings20 and emergency departments. 21,22 According to the traditional classification system of preventative interventions, ASBIs are a type of secondary prevention intervention designed to lower the prevalence of alcohol use disorders and reduce the potential for future harm by promoting early behaviour change. 23,24 The World Health Organization identifies ASBIs as a recommended ‘best buy’ intervention to reduce alcohol use. 25

However, evidence of implementation of ASBIs as a secondary prevention intervention in non-health community settings is limited. 26 Little is known as to whether alcohol IBA must always be delivered by a professional in order to be effective. While existing research demonstrates that lay health worker roles are an established approach,23 widely used for a range of public health priorities and population groups,27 no previous programmes with a specific focus on alcohol had been published in the literature.

At the community level, accessibility of alcohol is a key determinant of harm, and restricting physical access to alcohol is an additional World Health Organization ‘best buy’ as it is deemed effective, cost-effective and feasible to implement globally. 2,3,25 Internationally, systematic review evidence shows that increased alcohol outlet density and temporal availability are linked to higher levels of crime and poor health. Interventions in and around the alcohol environment that improve the serving practices and standards of licensed premises can lead to small reductions in acute alcohol-related harm. 18

In England, local authorities can address accessibility, serving practices and standards of operation of premises licensed to sell or supply alcohol using the regulatory framework of the Licensing Act 2003. 28 Each local licensing authority must publish a statement of its licensing policy every 5 years, promoting the four statutory objectives of the 2003 Act: the prevention of crime and disorder; public safety; the prevention of public nuisance; and the protection of children from harm. Longitudinal, area-level analysis of UK data sets has shown that, at borough level (i.e. lower-tier local authorities in England), both alcohol-related hospital admissions16 and crime17 reduced faster in areas where more restrictive licensing policies are in place. Using small area-level data [lower-layer super output areas (LSOAs) with a mean population of 1500 persons], alcohol outlet density in Wales has similarly been associated with alcohol-related hospital admissions and crime data. 8 Licensing action could reduce alcohol harm at a community population level through both primary and secondary prevention mechanisms of action since restricting the physical availability of alcohol can benefit the whole population universally, and targeted enforcement action can mitigate the impact of existing harm. 3,24

Powers exist for local people to influence licensing decisions, but such licensing action does not generally happen, and there is a paucity of published evidence on community engagement. 29 Lay people have the ability to influence local alcohol licensing policy and licensing decisions via the local licensing process, and legislation promotes greater community involvement in licensing decisions. Existing studies have identified the need to gain a better understanding of how to support community members to engage, especially those experiencing health inequalities. 29–31 Utilising ‘people power’ has represented a huge untapped resource in existing local regulatory systems; however evidence highlights asymmetries of power as one of the key barriers to community engagement32 and how licensing authorities may prioritise conflict resolution and compromise between licence applicants and members of the public rather than the promotion of existing licensing objectives. 33 Furthermore, where promoting community involvement in licensing decisions is not only ‘encouraged’ but is a legal requirement, concerns exist to ensure it is not tokenistic. Where there has been evidence of successful community-led alcohol controls reducing alcohol harm, further research is needed to develop and test context-specific menus of available powers communities can use, tailored to the specific identities of communities. 34

Asset-based community development

The Communities in Charge of Alcohol (CICA) intervention was designed using an asset-based community development (ABCD) approach, where a health asset is any factor which enhances the ability to create or sustain health and well-being. 35 This is in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on behaviour change, which advocates building on existing community resources and skills. 36 The principles of the approach are to: allow time for communities to realise and acknowledge their individual and collective assets and to rebuild their confidence and networks, enable local people to take the lead and build trust with communities by demonstrating that involvement leads to change. The approach seeks to build community networks, which are health promoting. At the time of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) commissioning brief in 2016, ABCD approaches were being promoted widely23 and were attractive in terms of current fiscal challenges and cuts to services, but there was relatively little evidence for their effectiveness. 37

Context to the Communities in Charge of Alcohol evaluation

In 2014, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) agreed a Greater Manchester (GM) Alcohol Strategy 2014–17, which included taking forward a programme of activity to reduce alcohol-related harm while retaining a focus on growth and reform, promoting effective practice within GM and challenging the status quo on key national issues. Within the strategy, there was a particular focus on the role of the community in reducing alcohol harm and the expanded use of licensing and regulatory powers to address alcohol availability. In pursuing these objectives, the GMCA entered into a partnership with the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) to develop training for and introduce alcohol health champions (AHCs) in all 10 GM local authority areas in 2017. The principle of community lay health champions has been well established;38–40 the focus on alcohol and the community’s role in licensing is the novel contribution of this study.

This was the first time that GM had attempted to co-ordinate an approach to building health champion capacity across all 10 local authorities. It was underpinned by the GM Health and Social Care Strategic Partnership’s commitment to a ‘Radical Upscale in Prevention’ as one of the four key programmes within the ‘GM Taking Charge’ Strategy. Thus, an important opportunity presented itself, coinciding with the commissioning brief from the NIHR Public Health Research (PHR) Board in 2016 identifying the need for research on the effectiveness of locally delivered interventions to reduce intake and harm caused by alcohol.

Research objectives

The main aim of the research was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost consequences of the community AHC programme, known as CICA.

Primary objective

To determine the effect of the CICA intervention on area-level key health and crime performance indicators.

Outcome evaluation objectives

-

Determine the effect on area-level key health performance indicators: alcohol-related hospital admissions, accident and emergency (A&E) attendances and ambulance call-outs.

-

Determine the effect on key crime indicators (street-level crime data).

-

Determine the effect on key antisocial behaviour (ASB) indicators.

Research questions

-

Does the intervention result in (statistically significant as well as relevant in absolute terms) improvement in health and crime indicators?

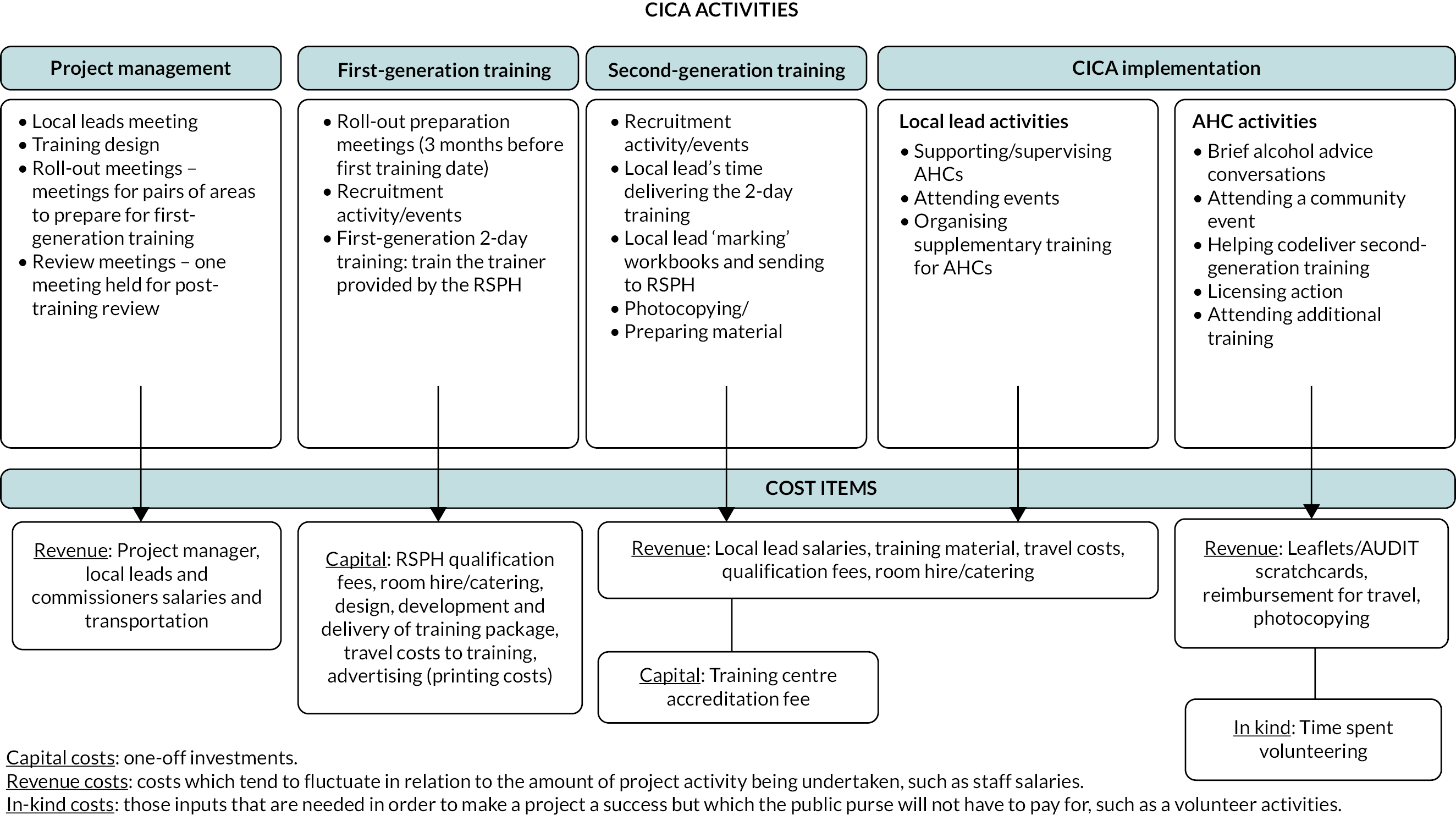

Economic evaluation objectives

-

Identify set-up and running costs using a standardised costing exercise (examination of commissioning documents and contracts).

-

Resolve costs by sector (health, ambulance and police) before, during and after CICA setup.

-

Quantify benefits due to reduced hospital admissions, ambulance call-outs, emergency department use, crime and ASB.

Research questions

-

What are the set-up/ongoing costs in terms of in-kind contributions (time of residents, public sector officers, councillors and voluntary organisations)?

-

How much did the set-up phase cost (venue hire, refreshments, training)?

-

How much per year will the process cost to run (advertising, venue hire, external facilitation)?

-

What are the savings in terms of reduced crime, hospital admissions and ambulance call-outs? What are the cost benefits and cost consequences of CICA?

Secondary objectives

To understand the context and factors that enable or hinder the implementation of the intervention, including establishing, operationalising and sustaining the CICA intervention.

Process evaluation objectives

-

Explore policy context and variation in licensing practice, including any impact of devolution in GM.

-

Explore barriers/facilitators at key stages of the intervention (recruitment of AHCs to initial training and cascade training; delivery of initial training and cascade training; using skills beyond the training in AHC activity; retention of AHCs).

-

Explore responses to AHC training, modelling of health behaviours, perceptions of community cohesion and development.

-

Determine the numbers of trainees, brief interventions applied and community awareness events organised/participated in.

-

Examine and quantify the amount and success of community involvement in licensing issues.

-

Determine whether there is a change in composite measures of alcohol availability.

Research questions

-

How was licensing policy operationalised in the local area prior to CICA? Does the context (devolution) impact on licensing?

-

What are the main barriers/critical success factors?

-

How many people were trained, did they engage with the training and did they put it to use?

-

How many brief interventions were applied?

-

Has licensing (and therefore alcohol availability) been influenced by community involvement?

-

Does citizen participation increase as a result of the intervention?

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Cook et al. 1 and from the CICA trial protocol (available from the NIHR project web page: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/15/129/03) and earlier papers on the process evaluation. 41–44 The CICA trial protocol is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The earlier process evaluation papers are published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerivatives (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), therefore these extracts have been reproduced exactly. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Study design

Communities in Charge of Alcohol was a complex community-level intervention. Since it was not amenable to conventional randomisation (as recognised in the complex interventions guidance45), it had a quasi-experimental design. 46 This fitted on the ‘continuum of evaluation’,47 which recognised the need for multiple methods/variants in experimental design. 48

Analysis of primary outcomes was made at the area level, comparing CICA areas with control areas. Each local authority defined its own CICA area by selecting pre-existing geographical communities defined by LSOA boundaries. The smallest intervention area encompassed one LSOA, and the largest contained three LSOAs (mid-year population estimates combined: 1600–5500).

With implementation already in the planning phase as part of the GM Alcohol Strategy 2014–17, this evaluation was researcher-influenced but not researcher-controlled. Although researchers had no control over the selection of the areas, the order of roll-out of intervention areas in each local authority was under researcher control. CICA was rolled out as a stepped-wedge randomised trial. It was evaluated using mixed methods to investigate health and crime outcomes, processes and economic effects.

Ethical approval, registrations and study monitoring

Ethical approval was received from the University of Salford Research Ethics Committee on 17/05/17 (reference number: HSR1617–135) and obtained from the University of Bristol (as the host of the outcome evaluation) on 16 May 2019 (reference number: 82762). The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN81942890. The trial protocol was published in April 2018,1 and protocol revisions were published here: www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/15/129/03.

A summary of the amendments to the protocol is listed within the evaluation methods. The Analytic Plan for the evaluation (version 3) described in this chapter was uploaded to the Open Science Framework prior to analysis (https://osf.io/9z65w/; dated 8 March 2021).

The outcome evaluation relied on analysis of secondary data from Local Alcohol Profiles for England (LAPE) (Public Health England), Hospital Episode Statistics [National Health Service (NHS) Digital], ambulance call-out data [North West Ambulance Service (NWAS)] and police data obtained initially at the LSOA level. In terms of sensitivity, police data are publicly available at street level. Hospital Episode Statistics are sensitive at LSOA level, although once alcohol-attributable fractions (AAFs) are applied to the data, they are deemed to represent a low risk of disclosure. Nevertheless, appropriate measures were taken to ensure the security of potentially sensitive data sets, including their storage only on secure university file servers. These data were aggregated to compile intervention areas (composed of one to three LSOAs) and their matched controls.

Participants were recruited to take part in the process evaluation and economic evaluation. All participants were provided with full information about the study (see project website) and provided written consent. Participants included volunteer AHCs, key informants and stakeholders in commissioning, service providers and licensing officer roles and members of the public. Alcohol health champions completed consent forms at their first training session prior to filling out the pre-training questionnaire. Potential participants for interviews and focus groups were given a minimum of 1 week to decide whether or not to take part, and written informed consent was obtained prior to the start of the interview or focus group. Data obtained within the process evaluation were anonymised, and each participant was given a unique code, stored separately to the main data file. Consent forms were stored in a separate location to the main data files. Transcripts used pseudonyms in place of real names and are used throughout the reported findings to protect participants’ anonymity. Data were stored on secure university file servers, accessible only to the research team.

To protect the anonymity of participants, since the intervention was at a small area (community) level, the locations of the study areas and the identity of the host local authority are not revealed in this report, and each area is given a (randomly generated) code between 1 and 10.

A protocol was established for local CICA leads to report incidents or adverse events using a standardised form. The process outlined responsibilities for monitoring and reporting from CICA local leads to the Greater Manchester Programme Manager, the research team at the University of Salford, Principal Investigator and Study Steering Committee (SSC). No adverse events or incidents were reported.

The study methods are reported in accordance with the Consolidation Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement.

Setting

All GM local authorities within the study setting had higher than England averages for alcohol-related mortality, ranging from 46.7 in Trafford to 71.9 per 100,000 in Manchester. 49 A fifth of all LSOAs in GM were in the highest decile of deprivation nationally (ranging from only 3% in the borough of Trafford to 28% in the City of Manchester). Greater Manchester was heterogeneous in terms of its application of licensing policy; only one local authority was classified as having high licensing policy intensity (two local authorities were medium, five low and two passive in terms of making use of cumulative impact areas and/or refusing licences16).

Intervention description

The description of the intervention is concordant with TIDieR:50 the Template for Intervention Description and Replication and the description below is structured according to the headings of the template.

Brief name

Communities in Charge of Alcohol.

Why (rationale/theory/goal)

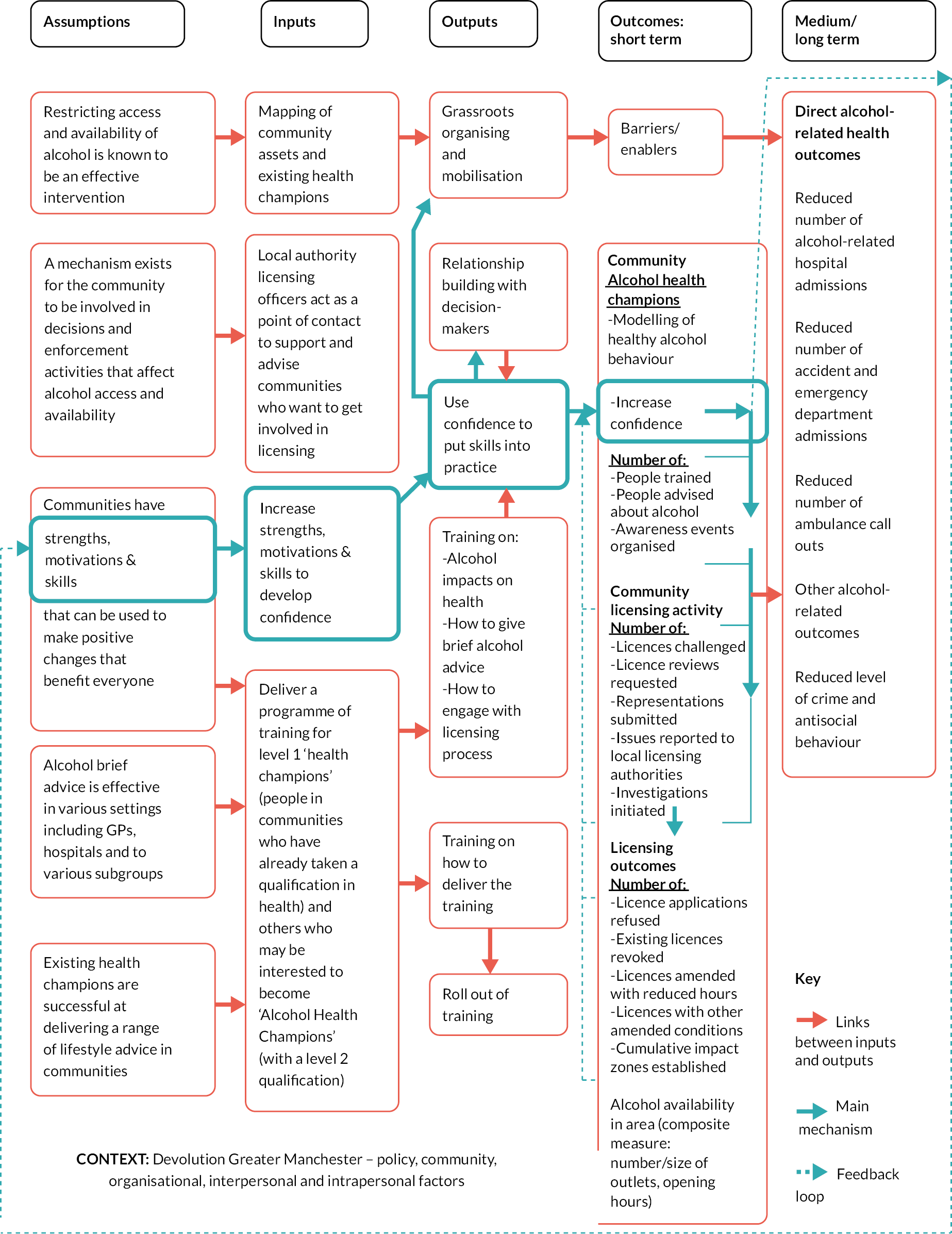

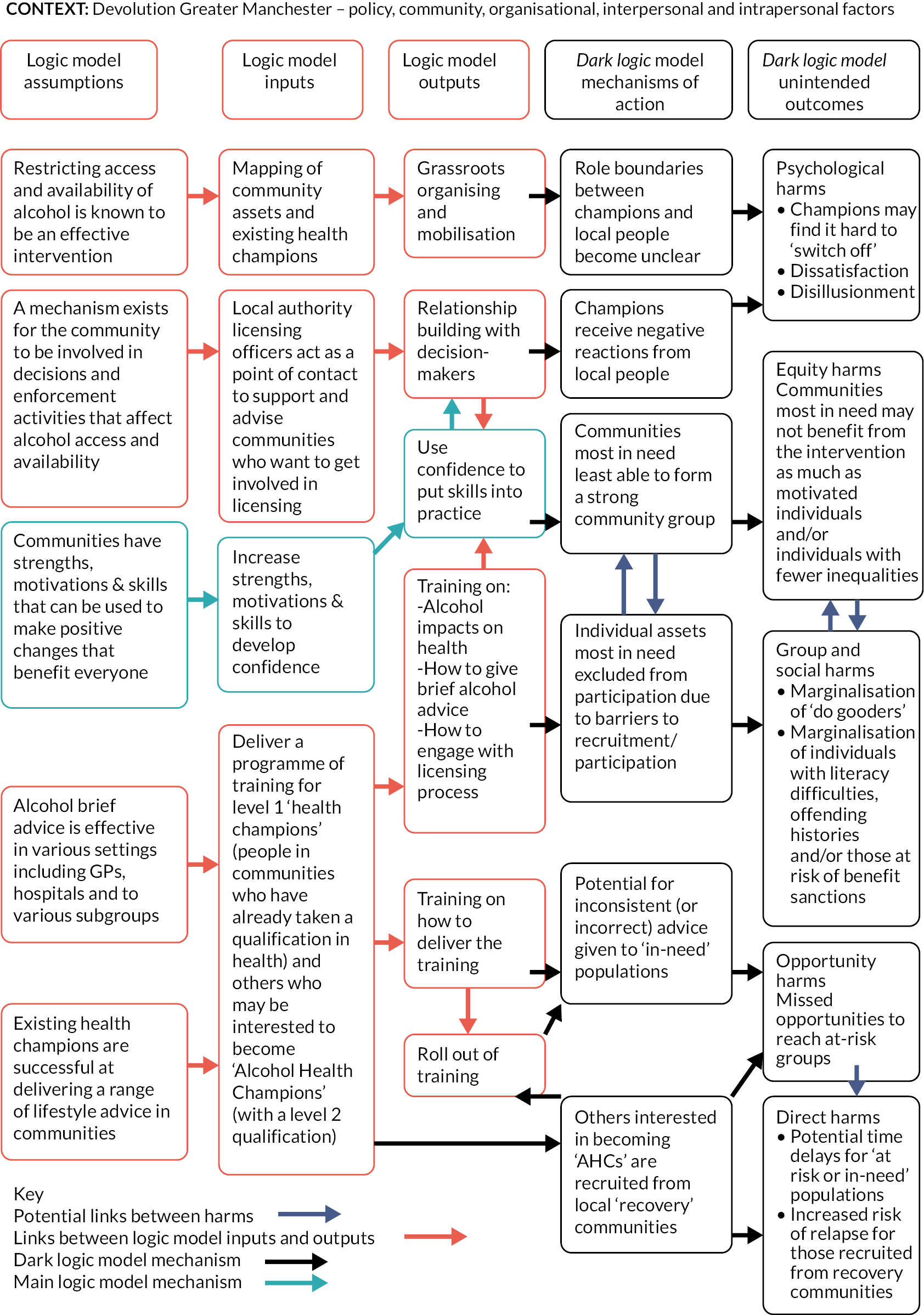

Communities in Charge of Alcohol is based on the principles of ABCD. The ABCD mechanism of action in CICA assumes that communities have strengths, motivations and skills to become AHCs who can reduce alcohol harm. This is based on existing health champion models which utilise lay health workers to work in a voluntary capacity to offer brief advice and brief interventions alongside their other daily activities. 23,40 Through CICA, champions are trained to focus on alcohol, receiving additional knowledge and skills to enable them to get involved in local licensing decisions. In ABCD theory, building an infrastructure of alcohol training and support to deliver alcohol harm reduction interventions will positively reinforce the strengths, motivations and skills of the community. See Appendix 1 for logic model.

What (materials)

An AHC role description advertises the CICA programme, and local co-ordinators recruit lay volunteers. Informational material explains the AHC role, what is involved, the requirements for the role and support that is available at all stages of the training and AHC activity (see Appendix 2).

Royal Society for Public Health ‘candidate workbooks’ are used within the training of AHCs (the ‘intervention providers’), which are assessed and externally verified to award successful participants with the Level 2 qualification in ‘Understanding Alcohol Misuse’. Supplies of the alcohol harm assessment tool, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – consumption (AUDIT-C), in scratchcard form (see Figure 1), are issued to AHCs to support them with informal, brief advice conversations. 51

FIGURE 1.

Alcohol use disorders identification test – consumption scratchcard used by AHCs as part of the CICA intervention. Source: Public Health England.

What (procedures)

Using a cascade training model, an accredited and standardised 2-day Train-the-Trainer course is delivered initially by the RSPH and local licensing officers, then cascaded by professionals with the support of the AHC community. In both the Train-the-Trainer and cascade training, delivery is face-to-face in small groups.

In the pre-implementation phase, professionals are designated to be local CICA co-ordinators who prepare for the roll-out of alcohol health training in their area before the first Train-the-Trainer event. They recruit lay volunteers on to AHC courses, support AHCs in developing confidence to put their knowledge and skills into practice and cascade the training to others. The CICA training programme aims to give lay AHCs the confidence and tools to understand and address alcohol use, take action on alcohol licensing and train others to become AHCs (see Table 1).

| Day | Topic/aims |

|---|---|

| Day 1 (full day) | Understanding alcohol misuse |

|

|

| Day 2 (half day) | Licensing action |

|

|

| Day 2 (half day) | Train-the-Trainer |

|

Alcohol health champion activities include: offering informal brief alcohol advice to promote behaviour change among family, friends, colleagues and with the wider community at community events and using the powers that exist in the Licensing Act 2003 that encourages communities to strengthen restrictions in the sale or supply of alcohol. Alcohol health champions are trained to use informal approaches to raise concerns and complaints directly with managers of licensed premises, as well as formal processes to report issues to local licensing authorities, submitting representations or requesting licensing reviews. A community hub approach at a place-based level created an infrastructure of support for AHCs through meetings facilitated by local CICA co-ordinators and attended by local licensing officers.

Who provided

Communities in Charge of Alcohol co-ordinators are professionals working in the intervention case area, employed by the local authority, private or voluntary sector. They are commissioned to provide health and well-being services or alcohol and drug treatment services. Their expertise in health improvement/health promotion or alcohol and drug treatment may or may not include a background in ABCD or working with volunteers. They receive the same training as AHCs, the standardised 2-day Train-the-Trainer course accredited by the RSPH.

Alcohol health champions are lay individuals who share the common place-based characteristic that they live or work within the intervention case area. They attend the accredited and standardised 2-day Train-the-Trainer course with the RSPH (first-generation training) or the two-date cascade training course delivered by the local CICA co-ordinator.

Lay volunteers are recruited from the intervention case areas, include adults aged 18 years and over, and are embedded in the community either through their residency or their work role.

How

Alcohol health champion intervention activities are provided individually or as a group. The AHC activity of providing informal, brief alcohol advice is provided face to face to individuals within the community where AHCs live or work. Alcohol health champions (with support from their co-ordinators) are responsible for deciding exactly how to operationalise the advice-giving. Examples included opportunistic conversations with friends, families, colleagues or community members, as well as more planned activities such as staffing stalls at drop-in community events. Informal licensing action is provided face to face to managers of licensed premises within the community where they live or work. Formal licensing action requires issues to be reported by telephone, on the internet or face to face to a local licensing officer. Formal representations require submission in writing to local authorities on the internet or by post.

Where

Each local authority’s public health team selects a target community to receive CICA, using the following guiding principles as inclusion criteria and making use of a standardised data set available to local authorities:52

-

an area of high alcohol-related harm (defined as high within the local authority rather than in comparison to regional or national average rates)

-

alcohol harm is considered in terms of a combination of indicators

-

alcohol-related crime and ASB

-

alcohol-related hospital admissions

-

weekend evening A&E attendances

-

users of local treatment services

-

hospital recording of location of violent incidents (if available)

-

density of licensed premises in the area or adjoining areas (if available).

A rationale was provided in writing by e-mail from local authority public health commissioning teams, summarising LSOA and middle-layer super output area (MSOA) data used to inform their decisions. The number and type of different alcohol harm indicators chosen varied from 2 to 5.

Of the nine authorities that rolled out CICA, the majority used alcohol hospital admissions as an indicator of high levels of alcohol harm (n = 8), followed by crime (n = 6), A&E attendances (n = 4), indices of multiple deprivation (IMD) (n = 4) and number of licensed premises (n = 4). Three public health teams used numbers in structured community-based alcohol treatment as recorded in the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS),53 previously referred to as Tier 3 interventions. 54 Considering the variation of data underpinning area selection for the CICA intervention, the process evaluation team (SCH) additionally extracted and compared available data on a wider set of area characteristics (all characteristics shown in Table 2). The intervention was planned in all 10 GM local authorities; thus, there were originally 10 sites. These are labelled by randomly generated codes rather than local authority names to protect the confidentiality of the stakeholders and AHC participants.

| Intervention areaa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Size of target area | |||||||||

| No. of LSOAs | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Mid-year population estimate55 | 2996 | 2139 | 2162 | 3259 | 4244 | 5586 | 3604 | 5220 | 3452 |

| Rationale for choosing area | |||||||||

| Alcohol hospital admissions | ✓b | ✓ | ✓b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| A&E attendances | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Crime | ✓b | ✓c | ✓c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Domestic violence incidents | ✓ | ||||||||

| No. in community (Tier 3) structured alcohol treatment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Prevalence of higher-risk drinking | ✓b | ||||||||

| % binge drinking adults (MSOA) | ✓b | ✓b | |||||||

| Engagement team presence | ✓ | ||||||||

| No. of licensed premises | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Indices of Deprivation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Characteristics of area | |||||||||

| Deprivation decile56 | 1, 1 | 1 | 1 | 1, 1 | 1,1 | 1, 2, 2 | 1,1 | 1, 4, 4 | 1, 2 |

| Population: men (%)55 | 48.7 | 56.6 | 46.4 | 45.7 | 47.6 | 48.3 | 50.7 | 49.5 | 53.0 |

| Population: women (%)55 | 51.3 | 43.4 | 53.6 | 54.3 | 52.4 | 51.7 | 49.3 | 50.5 | 47.0 |

| Ethnicity: white57 | 94.0 | 64.0 | 90.0 | 96.3 | 81.0 | 80.0 | 96.0 | 82.0 | 89.0 |

| Social housing (%)58 | 45.0 | 37.1 | 39.6 | 55.8 | 45.0 | 42.0 | 55.0 | 17.6 | 50.0 |

| Home ownership (%)58 | 38.0 | 29.0 | 31.5 | 33.9 | 28.8 | 45.0 | 36.4 | 56.0 | 35.0 |

| Access to health assets and hazards decile59 | 6th, 8th | 10th | 9th | 9th, 9th | 8th | 6th, 7th, 9th | 8th, 9th | 7th, 9th, 10th | 9th |

| No. of licensed premises | 8 | 59 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 17 | 9 | 22 | 20 |

Alcohol health champion activities take place within the geographical boundaries of the community where people live and work. Informal, brief advice conversations take place with family and friends in people’s own homes, at social events or with colleagues in the workplace. Community awareness events take place in local community centres, libraries, health centres or other public spaces. Informal licensing action takes place in licensed premises within the community. Formal licensing action could lead to a Licensing Sub-Committee hearing which would take place at local council offices.

When and how much

In keeping with the ABCD (bottom-up, community-led) approach, AHCs are free to do whatever they are comfortable with; the programme does not dictate where, when or how much activity should take place.

Tailoring

The Level 2 Understanding Alcohol Misuse course is defined as a Level 2 qualification (recognised by Ofqual/Council for the Curriculum, Examinations & Assessment and Qualification Wales) with a standardised syllabus and candidate workbook set by the RSPH. The licensing action half-day training is designed by a local licensing officer to then be adapted according to the regulatory and enforcement processes and procedures within each local authority as per their Statement of Licensing Policy. The Train-the-Trainer course is a 2-day course, whereas the cascade training can be delivered flexibly within the community. Support for AHCs provided by local CICA co-ordinators can be tailored as required.

Outcome evaluation methods

The effectiveness of CICA was measured through the following data and objectives:

-

Determine the effect of the intervention on area-level key health performance indicators: routinely collected alcohol-related hospital admissions (narrow indicator), A&E attendances and ambulance call-outs.

-

Determine the effect of the intervention on key crime indicators (street-level crime data).

-

Determine the effect of the intervention on key ASB indicators.

Key indicators of health and crime were determined based on the literature, discussion between the researchers and with stakeholders from GM and data availability.

Given the nature of the population intervention, which we were not able to randomise to specific areas (i.e. this study was, therefore, a natural experiment evaluation60 rather than a randomised controlled trial), and the relatively small average population effects we would expect from an intervention such as CICA (although for individual events a large impact might be possible), an important component of this evaluation is the application of different evaluation designs as well as different statistical methods (described below) to evaluate the same intervention. Methodological triangulation, following recommendations to improve such natural experiment evaluations for public health,60 strengthens the inferences about effectiveness by triangulating the results from methods and data sets, each with its own unique, inevitable sources of bias. 61

Data set

The intervention was planned to be rolled out across all 10 boroughs in the study at different points in time, in a random order. These areas are referred to as ‘intervention areas’, and each local authority had selected a small area (within their respective district) to target the intervention – these were areas of priority in terms of having high levels of alcohol-related harm and were also areas of significant economic and social deprivation. The random order of roll-out for the 10 areas was generated by the project’s lead statistician (FdV) using statistical software R, independent from the implementation and process evaluation teams.

For the purpose of this evaluation, data were aggregated to the geographical level of the LSOAs, which each have a minimum population of 1000 residents, with the mean population size being 1500. 62 This geographical aggregation level most closely approximates the areas of implementation, which were defined around pre-existing communities (and may therefore not necessarily map directly onto a LSOA). As such, all subsequent statistical analyses were also conducted on data aggregated at the LSOA level and counts or rates of events (see below). The intervention areas varied in size between one and three LSOAs and varied in population size from 1648 to 5586 (mid-year population estimates).

The evaluation covers a 10-year period, with about 7 years pre intervention and a maximum of 3 years after the start of the implementation follow-up until the end of January 2020. For reference, the implementation schedule for CICA is shown in Table 3.

| Area code | Training | Intervention | Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | End | ||

| Area 9 | September 2017 | October 2017 | September 2018 | September 2019 |

| Area 10 | September 2017 | October 2017 | September 2018 | September 2019 |

| Area 1 | November 2017 | December 2017 | November 2018 | November 2019 |

| Area 4 | November 2017 | December 2017 | November 2018 | November 2019 |

| Area 8 | January 2018 | February 2018 | January 2019 | January 2020 |

| Area 7 | January 2018 | February 2018 | October 2018 | January 2020 |

| Area 3 | Mar 2018 | April 2018 | September 2018 | January 2020 |

| Area 6 | May 2018 | June 2018 | May 2019 | January 2020 |

| Area 2 | May 2018 | June 2018 | May 2019 | January 2020 |

| Area 5a | January 2020 | |||

For each LSOA, we selected three local control LSOAs and three national control LSOAs for comparison. Further details can be found later in this chapter, in Evaluation and analytic designs.

During the pre-implementation phase of the project, it became clear that the CICA intervention would not be implemented in Area 5 in the time period relevant to the study, and as a result there were only nine areas that progressed to the initial implementation phase (made up of one to three LSOAs each). With the exception of the counterfactual analyses (see below), Area 5 and its matched controls were kept in the data set and served as an additional control set. For the counterfactual analyses, which are conducted at the individual area level prior to combining them to obtain the average effect, Area 5 was not included.

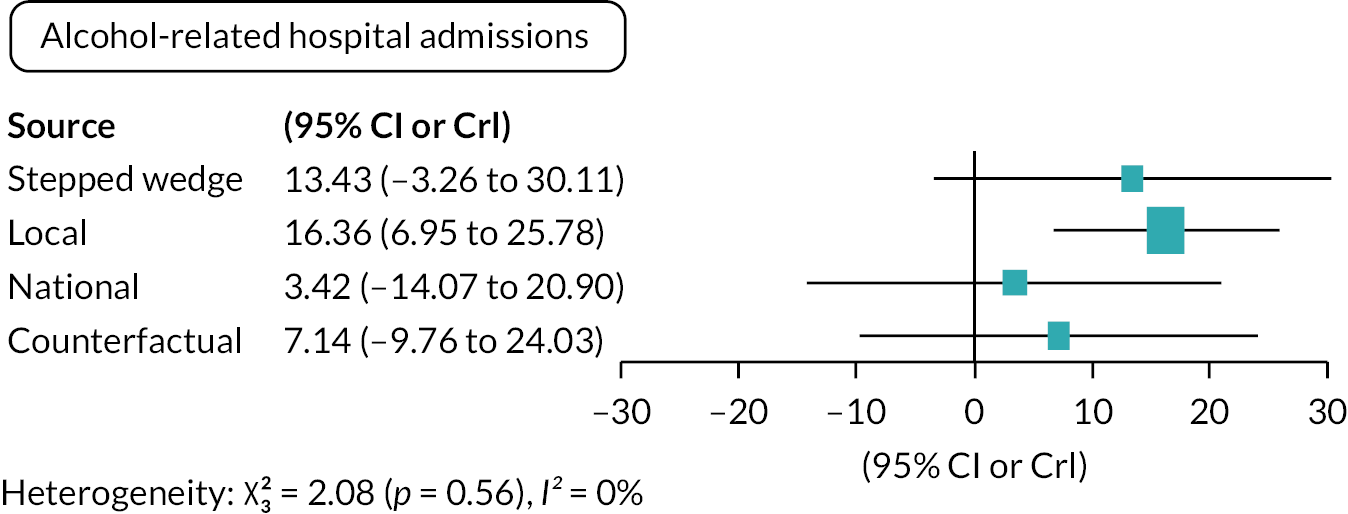

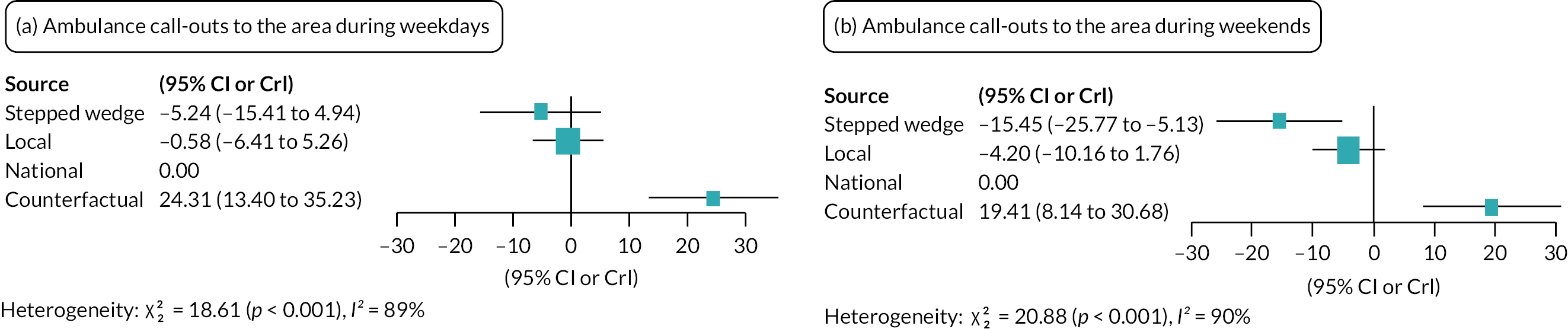

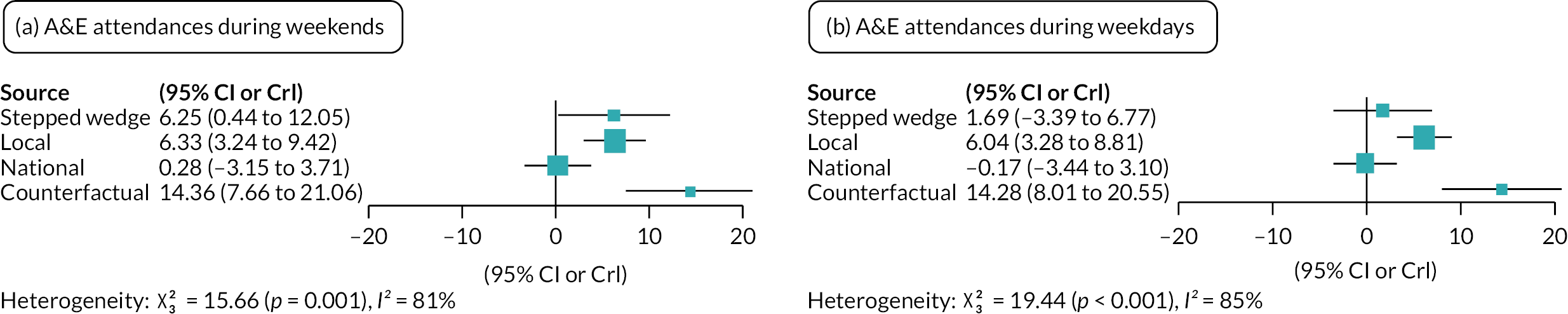

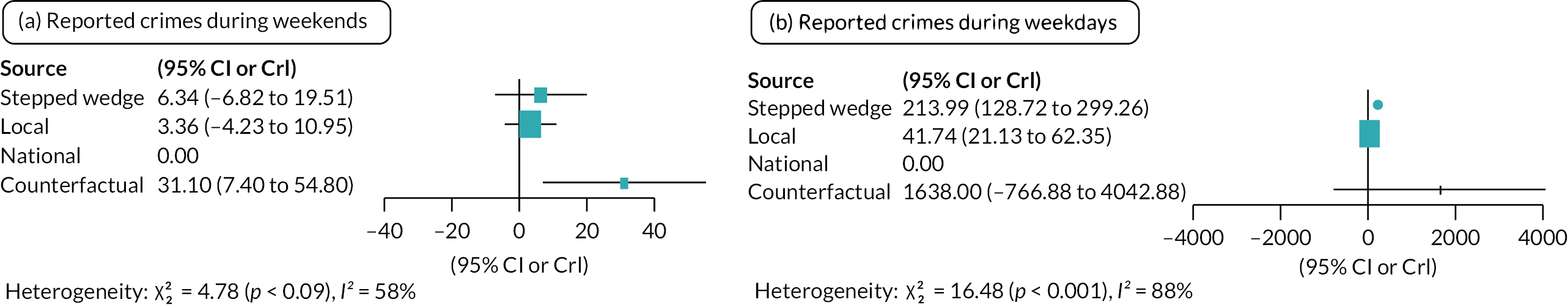

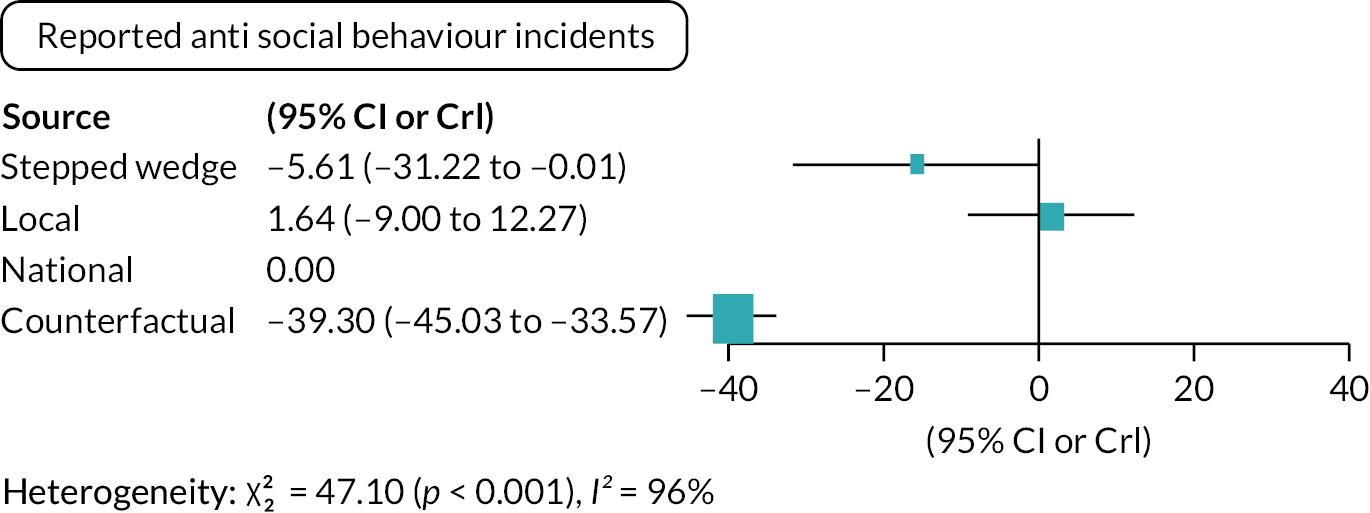

We selected four outcomes for evaluation of alcohol-related community harms, with ambulance call-outs, A&E attendances and numbers of crimes collected separately for weekends and weekdays. In addition, within the crime statistics, we also looked at the incidence of reported ASB separately. This resulted in a total of eight outcomes for evaluation, of which alcohol-related hospital admissions were considered the study’s primary outcome.

-

alcohol-related hospital admissions (narrow measure)

-

A&E attendances weekends

-

A&E attendances weekdays

-

call-outs for ambulance to the area services weekends

-

call-outs for ambulance to the area services weekdays

-

numbers of recorded crimes weekends

-

numbers of recorded crimes weekdays

-

number of recorded ASB incidents.

Alcohol-related hospital admissions were estimated as the AAF of total hospital admissions and were based on the narrow definition of alcohol-attributable. More details on this methodology can be found here. 63,64

A number of further decisions were made prior to analysis of the data. Crimes are more likely to be recorded as being related to alcohol over a weekend, with the Crime Survey of England and Wales also showing that, in 2013–14, victims of violent crime were more likely to report the offender to be under the influence of alcohol at the weekend (70% of crimes are related to alcohol) compared to overall (53%). 65 A similar pattern was observed for ambulance call-outs in the North East of England,66 and we hypothesise that a similar pattern might also be present for A&E attendances. We therefore a priori defined a time period where the likelihood of involvement of alcohol is highest (Friday 3 p.m.–Sunday 3 p.m.) and aggregated these ‘weekend incidents’. Conversely, ‘weekday’ incidents were those occurring from Monday to Friday between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. each day (note there was a small overlap in timings, but data indicate66 very few incidents occur in this 2-hour timeslot). Because of low numbers, we were not able to also do this for recorded ASB incidents.

Except for the primary outcome of alcohol-related hospital admissions, which necessarily is associated with an indication of the involvement of alcohol, for the other outcomes the involvement of alcohol was also recorded. However, from discussions with experts and initial exploration of this indicator in the GM crime statistics (in preparation of this study), it became clear that the quality of these ‘alcohol-flags’ was questionable and, in any case, missing for a significant proportion of incidents. We therefore included all incidents and did not use the alcohol flags.

In addition to outcome data, we obtained corresponding time series of resident population size, the LSOA-level English IMD56 and the average age of the LSOA residents. We further defined a new variable of the four quarters of each year to account for annual patterns in the outcome, and we defined a ‘time’ variable, which signifies each subsequent time point in the time series. And finally, we defined a 0/1 indicator variable for each time point in each intervention LSOA to indicate whether CICA has started (1) or not yet (0).

For the evaluation of each of the outcomes, we obtained time series data from 2010 through 2020. With the CICA roll-out introduced in 2017–18, this means that analyses are based on 7 full years of pre-intervention time series and up to 3 years of post-roll-out follow-up.

Data sources

Time series data were obtained from several different sources and linked to LSOA and month in one data set for analysis.

Alcohol-related hospital admissions were obtained at LSOA level from the Local Knowledge and Intelligence Service (LKIS) North West of the former Public Health England. For reference, data aggregated at higher levels is available from the LAPE. 49 The time series were aggregated by month and LSOA. LAPE are based on NHS Digital’s Hospital Episode Statistics, and we obtained the sum of AAFs based on the narrow definition from Public Health England. 63,64

Accident and emergency attendances and emergency admissions were obtained from the NHS Digital Hospital Episode Statistics A&E data set following a Data Access Request (DARS) Application (DARS-NIC-268750-B3T4W-v0). Requested data were monthly total numbers of A&E attendances by LSOAs (patients) in the GM area. Two outcomes were created: one for weekends and one for weekdays, as described above.

Data on ambulance call-outs to the LSOA were obtained from the NWAS following a data request to the HRA and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) (IRAS ID 261621). Data were all ‘see and treat’ and ‘see and convey’ events for GM aggregated by LSOA and month and for weekend and weekdays (using the same definition of weekends/weekdays as for A&E attendances and emergency admissions above).

Reported street-level crime incidents were obtained through data requested to the GM police authority and included recorded violent, sexual and public order offences (ASB incidents). Data requests were developed with the project collaborator from the GMCA. Reported incident data were aggregated from postal codes to corresponding LSOAs and from individual events to monthly counts. Weekday and weekend time series were generated following the same definition as for A&E attendances and emergency admissions above. Incidents of reported ASB incidents were extracted for separate analyses, as it was hypothesised these might be most likely to change most following the intervention.

Covariate data were obtained from publicly available national statistics data sets by the Office for National Statistics. 67

Prior power calculation

Based on the methodology for stepped-wedge randomised trials outlined by Hussey and Hughes,68 power calculations were performed for the primary outcome ‘alcohol-related hospital admission rates (narrow)’ obtained from the LAPE49 extracted for all 10 GM local authorities. Power analyses were conducted at larger local authority level rather than at the level of the intervention area because the exact areas and comparisons had not yet been determined. The mean standardised alcohol-related hospital admission rate for the year 2014 was 207 (per 100,000 people), with a maximum temporal standard deviation per site of 17.2 (range within sites 5–17) and a coefficient of variation across sites of 4.35. With 10 areas and 12-month follow-up (i.e. when all areas have received the intervention and a minimum of 1-month post-intervention follow-up), and a statistical significance level of 5% and statistical power of 90%, the proposed study would be able to detect a 10% average difference in rates compared to baseline. For an intervention to be effective and cost-effective, a minimal reduction in key indicators of 10% was reasonable. Power calculations for various alternative scenarios were also calculated and are provided in the Analyses Plan (https://osf.io/9z65w/).

Evaluation and analytic designs

As a complex community intervention, it was not possible to use a conventional randomised design (as recognised in the complex interventions guidance45). Communities in Charge of Alcohol was therefore evaluated as a natural experiment. 46 We evaluated the average intervention (treatment) effect (ATE) across all 10 boroughs using four different analytic designs or statistical methods. This form of methodological triangulation was done following recommendations to improve causal inference from natural experiment evaluations. 60 Its aim is to improve causal inference by comparing the results from different ways of obtaining the ATE through use of different study designs, control units and methods, thereby exploring similarities and differences in the different results. The hypothesis being that if different methods provide broadly comparable results in terms of direction of effect and effect size, this would increase our confidence in inferring that an effect might be the result of the intervention. Conversely, if there are differences in effect size, but in particular in direction of effects, this is most likely evidence of artefacts in the data rather than true effects. This way, we reduce the potential for bias from the use of a single study design or analytic method. However, note that analyses are still based on the same data and data generation process (see above), so there remains potential for bias even after triangulation.

Stepped-wedge cluster trial

Design

The stepped-wedge design describes the sequential roll-out of an intervention over time, or in other words, how the intervention is implemented in each of the intervention areas at some time point in the time series. Each intervention LSOA therefore changes from ‘control’ to ‘intervention’ and thus serves as its own control. 69

Analysis

The stepped-wedge design was analysed using hierarchical growth models (similar to previous work16,17) and analysed by multilevel mixed-effects models to account for the repeated measurements in the same areas (i.e. random intercepts), thereby accounting for different levels of the outcome in each area (e.g. alcohol-related hospital admissions in one LSOA will be ‘more similar’ than those in another LSOA, perhaps one with a much lower rate). Theoretically, it is also plausible that the temporal trend in each area differs from that in any other, which can be modelled using random slopes as well. However, exploratory analyses indicated there is insufficient statistical power to incorporate this. The outcome variables were LSOA-level counts and were analysed using mixed-effects negative binomial models (to account for overdispersion70). LSOA resident population sizes were used as offsets in the models. All models were further adjusted for quarter, area-level IMD score, average age in the area and time to account for the secular time trend across the time series. Exploratory analyses indicated that for none of the outcomes, this was a linear increase/decrease, and therefore the time trend was modelled using a basic cubic spline to account for non-linearity. Out of different potential model structures, the final models were determined based on assessment of assumptions regarding distributions of errors and model fit calculated by the Akaike information criterion. All analyses were done in R statistical software using the lme4 package for hierarchical growth modelling.

Local controls

Design

Each intervention area was matched to three other, comparable, control LSOAs. Comparable LSOAs were from the same district (lower tier local authority) but not neighbouring the case area, the latter to avoid bias in the effect estimates because of spillover effects as a result of the intervention. Matching of intervention to control areas was done using propensity score matching based on an a priori selected set of confounding variables (LSOA population density, deprivation, average age and baseline alcohol-related hospital admissions and crime rates) for the year prior to the start of CICA programme (2016). Note that although these are outcome measures, in contrast to propensity score matching, here the propensity scores are only used to identify the most similar control. Matching was done using the ‘nearest neighbours’ algorithm.

Analysis

The final data set contains the time series for 76 LSOAs (19 interventions and 57 matched controls). These have been analysed as controlled Interrupted Time series (cITS)71 using the same hierarchical growth modelling analytic method as used for the stepped-wedge cluster trial, with the difference being that in these analyses, results are not just internally compared but also against trends in the control LSOAs. Unmatched mixed-effects negative binomial models were conducted. All analyses were conducted in R, using the MatchIt package for propensity score matching and lme4 package for statistical analyses.

National controls

Design

The national control analyses are similar to the local control analyses, but each intervention LSOA was matched to a comparable control from the national data set. This was done so that local idiosyncrasies would not bias results and would also completely avoid any issues of spillover. 72 Matching was similarly done using propensity scores based on the 2016 values, although because of the large amount of data (there are 32,844 LSOAs in England56), a prior selection of areas was made based on similarities in the pre-2017 time series of the primary outcome only using ‘dynamic time warping’, which is a statistical methodology that can be used for matching time series. 73 Because of (lack of) data availability, the national control analyses were done only for hospital admissions and A&E admissions.

Analyses

Statistical analyses for the national controls are similar to those of the local controls, as described above. All analyses were conducted in R, using the dtw package for dynamic time-warping and lme4 package for statistical analyses.

Counterfactuals

Design

Alternative to the local control analyses described above, we also approached the evaluation of this design using a synthetic control approach74,75 to estimate counterfactuals of ‘what would have happened had there been no CICA intervention’ for each intervention LSOA separately (henceforth named “counterfactuals”). The difference between the counterfactual and the measured outcomes can then be interpreted as the impact of the intervention. This methodology was previously successfully used in other studies of the impact of local alcohol policies on health and crime. 16,76–78

Analyses

We used Bayesian structural time series to model the pre-intervention time series of the outcome in the intervention area from a weighted combination of the time series in the matched local controls. This model was then used together with the post-intervention time series in the controls to estimate the counterfactual in the intervention areas. The methodology has been described in detail79,80 and in summary. 81 Analyses were done for each intervention LSOA separately, and the LATE was estimated by combining the effects across all areas using meta-analysis. As flagged above, as Area 5 did not end up receiving the intervention, it is excluded from these analyses. All analyses were done in R using the bsts and CausalImpact packages. Meta-analysis was done using the metagen package in R.

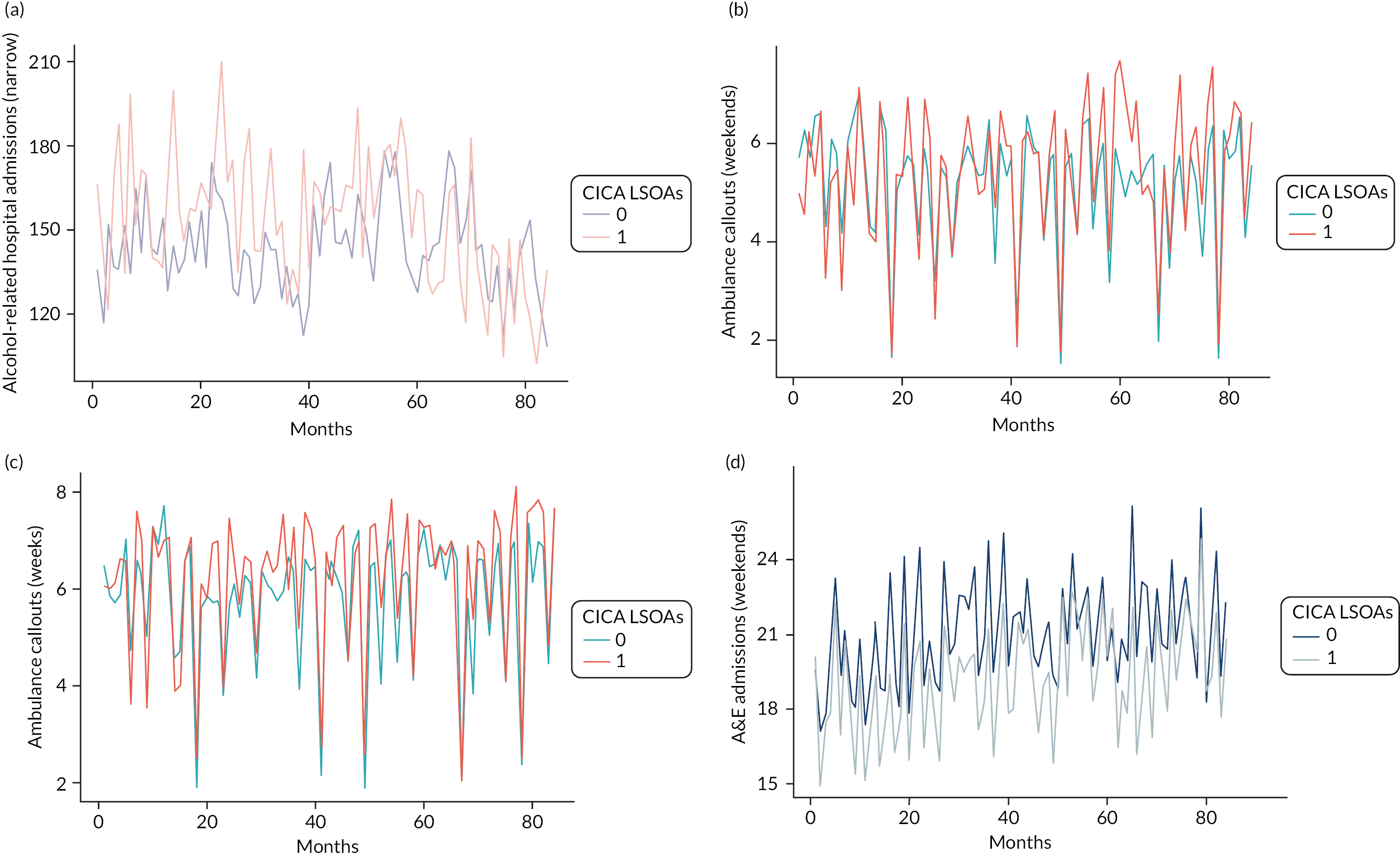

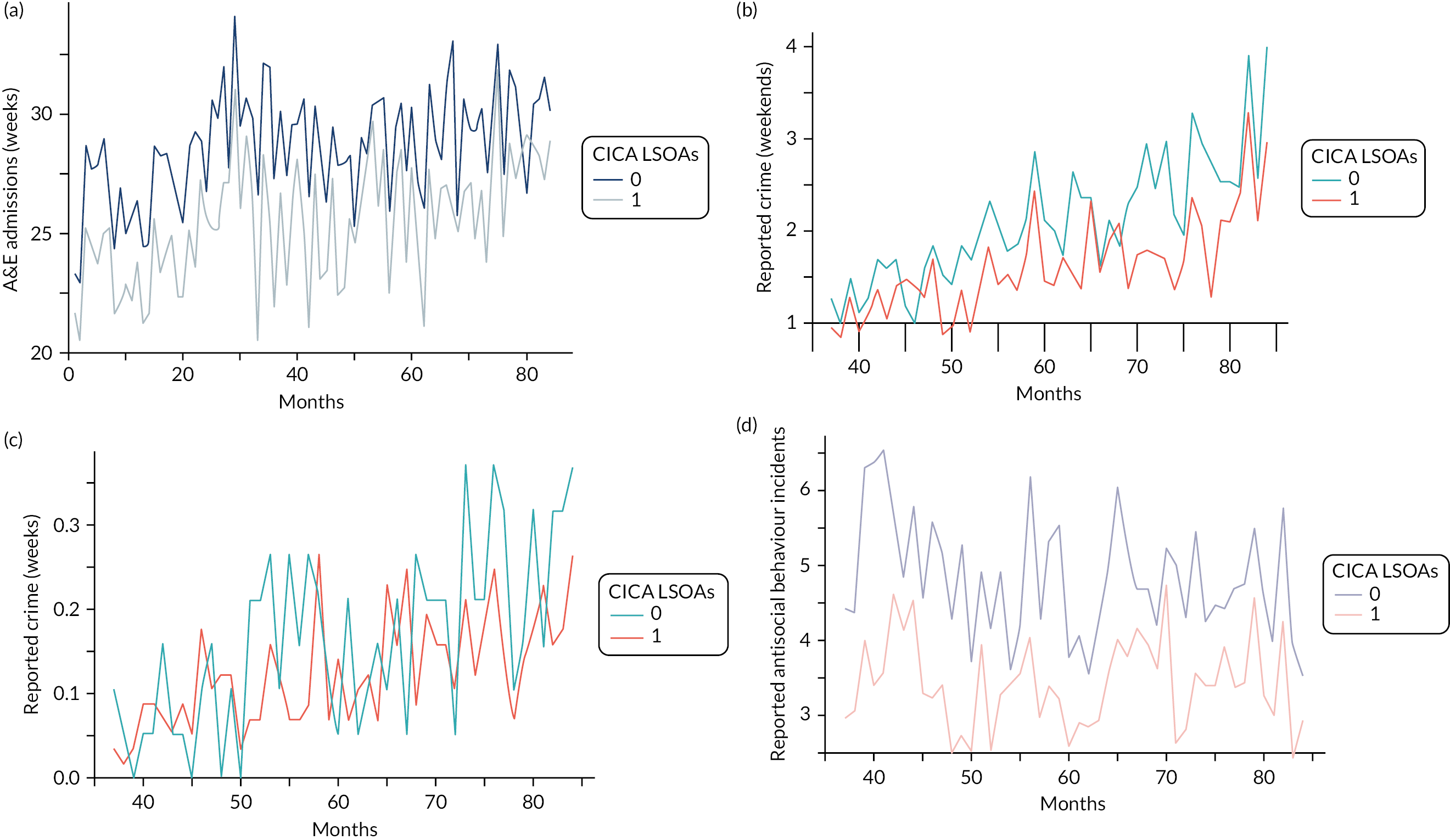

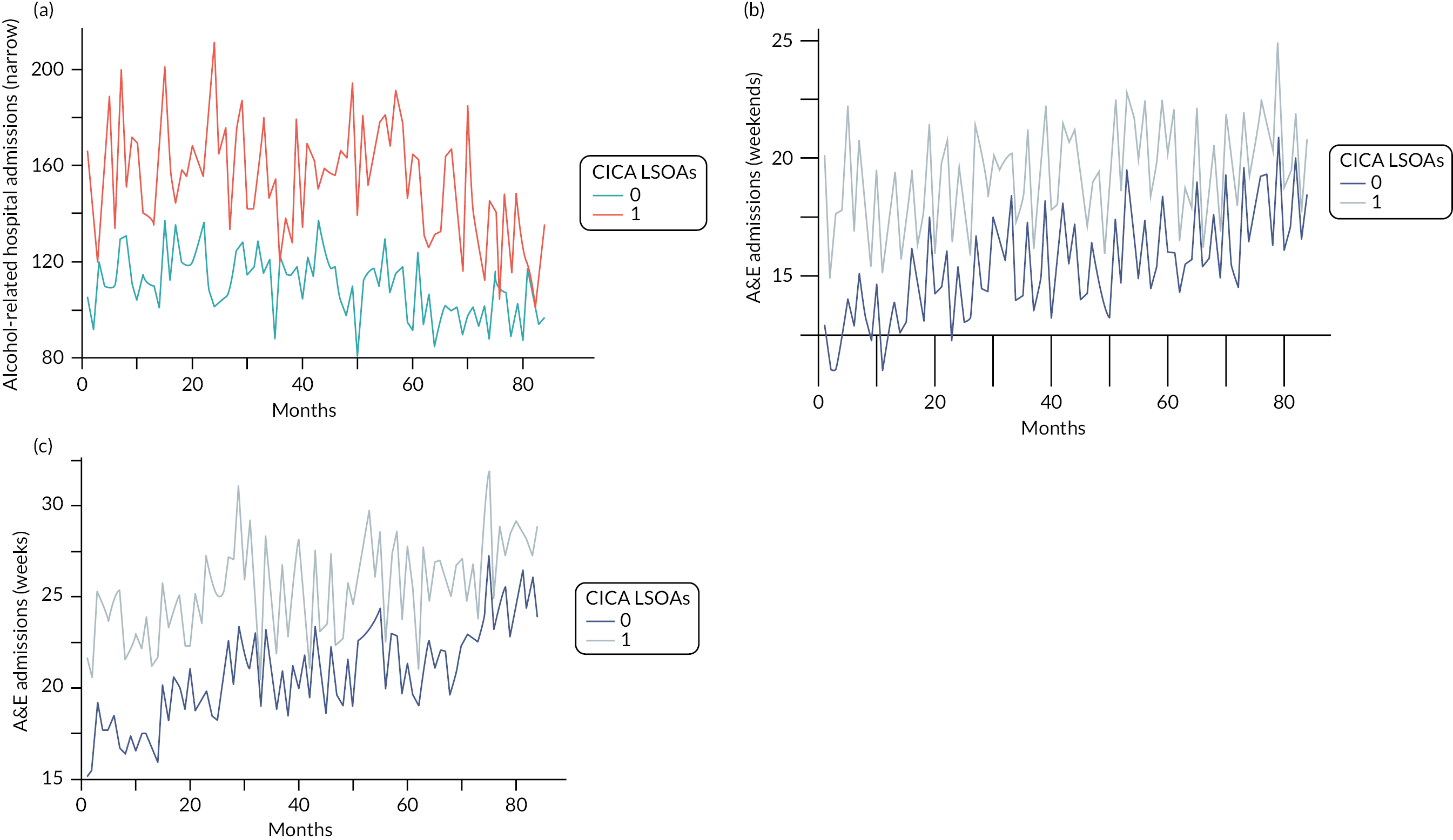

Presentation of results

Results are presented as percentage change as a result of the intervention, 95% confidence intervals and p-values. An important assumption for evaluation using cITS is that of parallel trends of the outcome in the intervention and control areas prior to the intervention (with the assumption that this would have continued had there not been an intervention). 71 These are presented – for convenience aggregated for intervention and control LSOAs – graphically in Chapter 3.

Results of Bayesian structural time series are presented as the average percentage change as a result of the intervention across all areas and 95% Bayesian credible intervals (CrIs). We also present the posterior tail area probabilities, calculated as the samples where the 95% CrI excluded the null and which can be interpreted as classical p-values. 79

For triangulation, and ease of comparison, all results of the different methods for each outcome are plotted as forest plots. Because these are not independent study estimates (as normally used in meta-analyses), the summary estimates and confidence intervals are not presented. Forest plots were generated using the meta R package.

Changes to the protocol

Following the withdrawal of an intervention case area in the pre-implementation phase, all references to 10 intervention areas in project documentation were changed to 9 areas. As this protocol change between version 2.0 and 2.1 amended the planned sample size, the statistical power calculations were updated. With only nine intervention areas, but with all other characteristics the same and using the same statistical power calculation methodology, with 90% power, the study was expected to be able to detect 10% differences (or 8% with 80% statistical power). The difference between 9 and 10 intervention areas was approximately 0.1%. The randomisation of areas for roll-out was updated to reflect one intervention area had been removed.

Follow-up of primary outcomes was originally due to end in May 2020. Between version 2.1 and version 3.0 of the protocol, follow-up timescales were reduced from 12 months to 9 months to remove the impact of the national lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which started in March 2020. This was because the lockdown was likely to have changed the nature and type of alcohol-related harms occurring in year 3 between March 2020 and May 2020.

Process evaluation methods

The design of the process evaluation was informed by Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for conducting process evaluation of complex public health interventions. 48 The aim was to explore the factors that enabled or hindered the implementation of the intervention. This included establishing, operationalising and sustaining the CICA intervention. The objectives of the process evaluation were as follows:

-

Exploring the policy context and variation in licensing practice, including any impact of devolution in GM.

-

Exploring the barriers/facilitators at key stages of implementing the intervention (recruitment of AHCs to initial training and cascade training, delivery of initial training and cascade training, use of skills beyond the training in AHC activity, retention of AHCs).

-

Exploring the response to AHC training, modelling of health behaviours, perceptions of community cohesion and development.

-

Determining the numbers of trainees, brief interventions applied and community awareness events organised/participated in.

-

Examining and quantifying the amount and success of community involvement in licensing issues.

-

Determining whether there was a change in composite measures of alcohol availability.

The aims and objectives of the process evaluation were achieved using mixed methods to examine the context, acceptability, facilitators and barriers to implementing the intervention (see Appendix 1). Appropriate process analysis techniques were selected for each method.

In the quasi-experimental study, the intervention was not implemented in exactly the same way in each locality. This depended on various local contextual factors, the specific skills, motivations and behaviour of the local AHCs, and the characteristics of the support network provided by the local CICA co-ordinator. The goal of the process evaluation was to capture key contextual factors relating to the recruitment, training and ongoing support of AHCs, in addition to pre-existing decision-making structures. 82

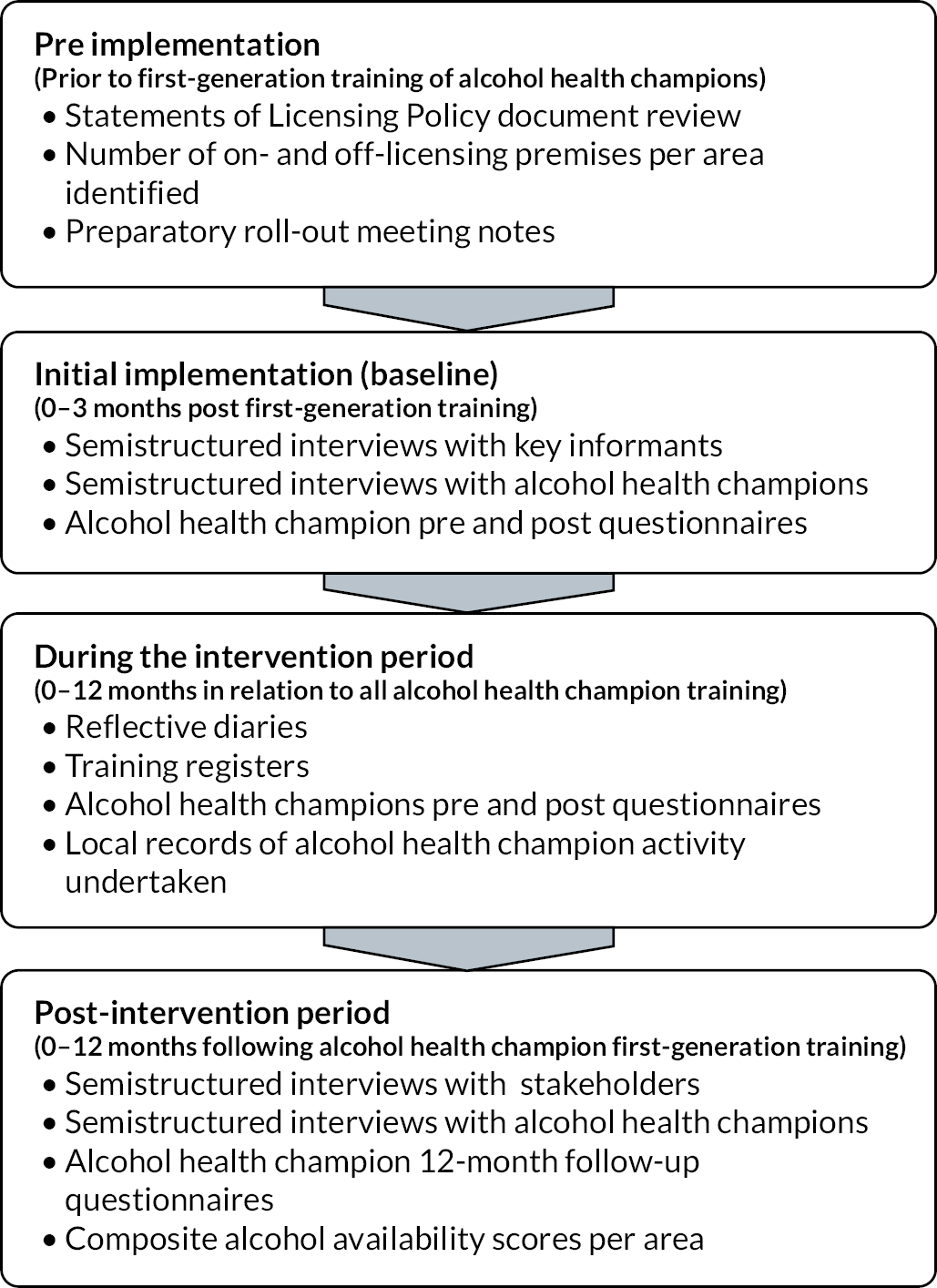

Each phase of the implementation process was explored through relevant and available data capture and methods. Figure 2 provides an overview of the data collection activities pre, during and post the roll-out of the intervention. Data collection required collaboration between stakeholders (AHCs, local co-ordinators and licensing leads) and researchers using mixed methods.

FIGURE 2.

Data collection materials used and processes undertaken across the timeline of the intervention.

Pre-implementation phase

The pre-implementation context was defined as the 2- to 3-month period before the official launch of CICA in each intervention case area. The launch of CICA was marked by the first RSPH Train-the-Trainer event. Data collection in the pre-implementation phase relied on document review and data extraction of secondary data.

Licensing policy context

The document review included a review of the licensing policy context (Statements of Licensing Policy) in each local authority to discover how licensing policy was enacted prior to intervention and the ongoing monitoring of the policy/practice context. A document review was carried out by EJB and SH [patient and public involvement (PPI) representative] on publicly available Statements of Licensing Policy from each of the 10 local authorities (n = 10). These local alcohol licensing policies are legally required to be published by each local Licensing Authority at least once every 5 years, detailing how they will carry out their administrative licensing functions in accordance with the 2003 Act to promote the four licensing objectives: prevention of crime and disorder; public safety; prevention of public nuisance; and the protection of children from harm. 28,83

Document analysis involved skimming (superficial examination), reading (thorough examination) and interpretation using content analysis as an iterative process to organise information into themes, categories and case examples. 84 A directed content analysis approach was taken using predetermined categories85 based on existing research assessing the context of alcohol licensing policy statements in Scotland. 86 These predetermined categories structured the standardised data extraction form used by both members of the research team.

Alcohol availability

Alcohol availability data for CICA intervention areas were obtained from Licensing Authority registers. Each local authority Licensing Unit is responsible for maintaining the register as per Section 8 of the 2003 Act. 28 Information was sought on the number of premises licences granted for both on- and off-licensed sales of alcohol, hours of alcohol sales and size/capacity of premises (where available). Our original protocol stated that we would calculate composite alcohol availability scores from these variables. However, there was no standardised database system shared by Licensing Authorities to maintain Licensing Registers. Therefore, details of hours of alcohol sales and size/capacity limit of premises were not consistently recorded, preventing composite alcohol availability scores from being calculated. Only one consistent data set available was used as the measure of alcohol availability: the number of premises licensed to sell or supply alcohol in each intervention area. Records were exported at a ward level in Microsoft Excel® form. Since ward-level records did not provide the granularity needed for CICA intervention areas, premises licence data were then transferred into Microsoft Access, creating a database file to enable multivalued ‘look up’ fields to obtain alcohol availability data at a LSOA level. Each local licensing authority’s web page was used to identify whether their Licensing Register28,83 was made available to the public to access online.

Preparatory roll-out meetings

Notes from preparatory roll-out meetings were used to explore infrastructure in place in all 10 areas a priori. These audio teleconferencing meetings were held between July 2017 and April 2018, each being held for 2–3 months leading up to each Train-the-Trainer event with key stakeholders from each area, convened by an overall programme manager supporting the co-ordinated implementation of CICA. Meetings were structured around a roll-out checklist created by stakeholders to guide preparation. Meeting notes were shared with the research team as secondary data and evaluated using content analysis by two researchers (EJB and SCH). Units of meaning were defined from items within the meeting checklists as ‘external contextual factors’, that were labelled, grouped into a category (categorisation matrix) and described as a theme. 85 This analysis from a priori qualitative data (2–3 months prior to roll-out) was then revisited as part of a longitudinal design of the process evaluation. At the follow-up phase, relationships were tested between external contextual factors and a key output indicator at the end of the intervention period: total numbers of lay people trained to be AHCs.

Initial implementation phase

The initial implementation context was defined as the baseline position at the start of CICA, captured within the first 3 months from the initial Train-the-Trainer event. Sampling was purposeful. All 22 stakeholders (see Table 4) from 10 local authorities (LA) who had committed to establishing the role of AHCs in their localities were eligible to participate. Two chose not to be interviewed.

| Stakeholder | Background and role in implementing CICA |

|---|---|

| Commissioning leads | Extensive experience of working in local government. Invited to participate in regular meetings prior to implementing the intervention in their area. Some commissioning leads could attend the RSPH Level 2 Understanding Alcohol Misuse training programme for AHCs. |

| Local operational co-ordinators | Employed by their local authority or by a service provider commissioned by their local authority. All operational co-ordinators had experience as practitioners with expertise in working with individuals with moderate/severe addiction difficulties. All were invited to participate in three meetings in advance of the training rolling out in their area. All attended both days of the RSPH training programme in their area, supporting their prospective AHCs. |

| Licensing leads | Licensing leads, employed by their local authorities, had extensive experience in alcohol licensing. Eight of the nine licensing leads attended the RSPH training programme on Day 2 to provide input about the Licensing Act 2003 to prospective AHCs. They were invited to attend the pre-meetings prior to the training rolling out in their area. |

Interviews with 20 of these key informants were held either in person (n = 19) or by telephone (n = 1). All had committed to establishing the role of AHCs in their localities. This included a key stakeholder from the local authority that withdrew from the CICA programme. All were known to the research team through preparatory roll-out meetings. Audio-recorded interviews lasted between 13 and 50 minutes (mean = 26.5 minutes) and were fully transcribed.

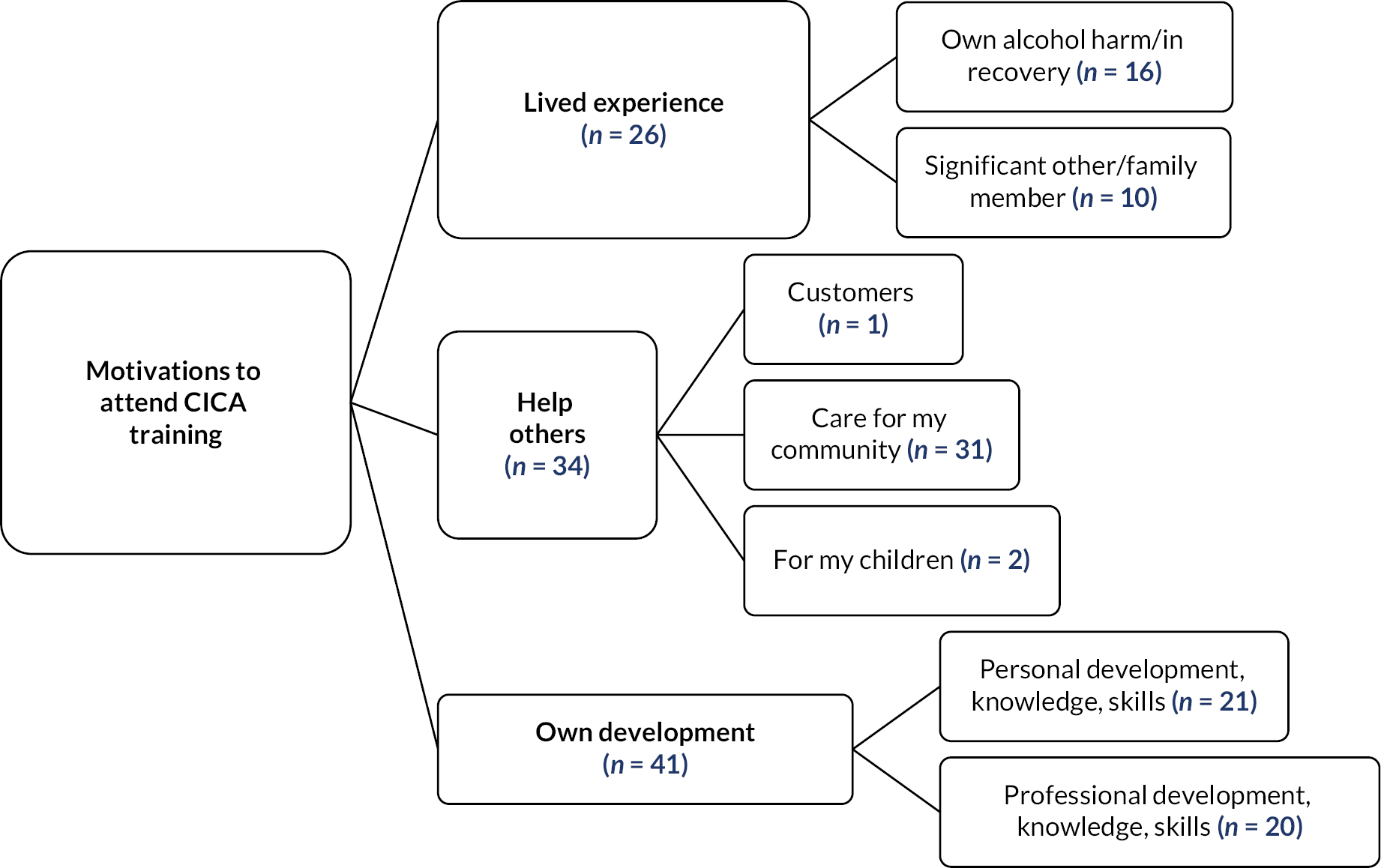

Response to alcohol health champion training

Training registers provided numbers of participants trained at all CICA training events as well as details of the role background of attendees (categorised as lay volunteers or paid professionals) to monitor the reach of the training to volunteers from within the target communities. Registers provided a timeline of the total number of CICA training events that took place within the 12-month intervention period, including how many times an intervention area carried out cascade training. Demographic questionnaires were completed by lay volunteers at the beginning of the first training day to record age, gender, ethnicity and highest educational attainment. The abbreviated alcohol screening tool AUDIT-C51 was used as a measure of healthy behaviours, and a free-text question captured reasons for participating in CICA.

Pre- and post-training attitudinal questionnaires surveyed participants’ perceived importance and confidence towards AHC activity on a 5-point Likert scale. Questions asked to what extent they agreed whether it was important to promote healthy lifestyles within their community and get involved in licensing decisions, and their perceived confidence in carrying out different aspects of the role (giving alcohol-related brief advice and/or raising issues about venues selling alcohol). Post-training questionnaires were completed at the end of the last day of training.

Interviews with a convenience sample of newly trained AHCs (n = 5 from n = 3 CICA areas) explored how they responded to the CICA intervention at an early stage to explore ‘sense-making work’ as defined in Normalisation Process Theory as a key component when operationalising a new set of practices. 87 This aimed to understand the intervention and how people begin to start collective action, for example, putting actions into place to enact the intervention. 88 Time since initial training ranged from 3 to 6 months. Data collection comprised a mix of telephone (n = 2) and face-to-face (n = 3) interviews, ranging from 23 to 47 minutes in length. They were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Face-to-face interviews took place in private spaces within community settings. A one-off payment to cover travel and time costs was given to interview participants.

Intervention phase

The intervention period commenced in the month subsequent to the initial Train-the-Trainer event and was ongoing for 12 months. Although targets were not imposed or a specified amount of activity expected, local co-ordinators were asked to keep a tally of AHC activity (five out of nine did so). Volunteer champions were invited to complete a reflective diary, which was not used as a tool to check for consistency with local co-ordinators’ tallies but instead to help explore barriers and enablers affecting their role. In other research, diaries have been used as a validation exercise where self-reported data have been assessed for bias;89 in CICA, we did not want the volunteers to feel watched or over-monitored. Reflective diaries were completed by AHCs who consented, and the detail was as much or as little as the AHCs were willing to provide. Diary participants had the choice of using their own online reflective diary, paper diary or a diary kept by their local co-ordinator recording the information on their behalf (a group diary).

Cascade training events were delivered by local CICA co-ordinators with the support of AHCs during the intervention period. Observations of cascade training events (n = 5) were recorded by the research team on a standard form to evaluate fidelity of cascaded training as well as any tailoring of the training.

Follow-up phase

Survey and semistructured interviews with alcohol health champions

The follow-up period within the process evaluation commenced after 12 months. Champions were invited to take part in a survey and interviews and were contacted by both their local co-ordinator as well as the research team. One year post-training, a follow-up questionnaire was sent to AHCs. Questionnaires (n = 11) were completed online (using the Bristol Online Survey Tool). Reasons for loss of champions at the follow-up phase were documented where known, along with factors affecting inactivity. Semistructured interviews were held with AHCs (n = 7) to capture experiences of the CICA intervention activities they took part in. We had originally intended to recruit a purposive sample of those who had or had not remained engaged with the programme. However, because of our earlier experience at 3 months, showing that recruitment for the interview could be problematic, all AHCs were invited to take part. Interviews ranging between 24.37 and 28 minutes (average 40.5 minutes) were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Semistructured interviews with stakeholders

Semistructured one-to-one interviews with local co-ordinators/stakeholders 12 months post implementation of CICA were carried out. Sampling was purposive. Eleven local co-ordinators, representing eight of the nine CICA areas responsible for operationalising CICA, were invited to participate in a telephone or face-to-face interview 12 months post implementation. In terms of role, four were public health practitioners; four were public health commissioners; and three were substance misuse practitioners. Local co-ordinators from all areas except Area 3 and Area 5 participated (the local co-ordinator from Area 3 was no longer in post, and the intervention did not take place in Area 5). Eleven interviews were conducted following written consent: nine face to face and two by telephone. Interviews ranging between 31 and 131 minutes (average 75.90 minutes) were audio-recorded and transcribed. Written consent was gained at the outset of interviews following a period of consideration of a participant information sheet.

Licensing leads

Sampling was purposeful. Licensing leads involved in AHC training from nine LAs were invited by e-mail to participate in a telephone or face-to-face interview 12 months after the first training session for AHCs. Licensing leads from Areas 1, 2, 6, 7, 9 and 10 participated (n = 6). Licensing leads from Areas 3, 4 and 8 did not respond to interview requests. Five telephone interviews were conducted by SCH and one face-to-face interview by EJB. Audio-recorded interviews ranged between 14.6 and 38.3 minutes (average 22.18 minutes).

Licensing records

Licensing records were extracted with local authority Licensing Units where available to validate activity around licensing. This included numbers of new applications for a premises licence (including minor variations), written representations, review applications and any changes to the local authority’s Statement of Licensing Policy.

Focus groups with the community

Community members within two intervention areas were invited to attend a focus group. Local CICA co-ordinators helped advertise the focus groups using adverts/posters in local public spaces and through wider promotion within existing community networks. Focus groups explored: perceptions of alcohol harm within the community, views and opinions about the AHC role and perceptions of community cohesion within the intervention area.

A convenience sample was drawn from two CICA intervention areas (Area 1 and Area 6). Members of the public were reached through adverts in public places (e.g. local library) and via e-mail to existing community networks. Local co-ordinators, familiar with the area, led on recruitment using an electronic PDF advert as well as printed copies of A3 posters and A5 flyers provided by the research team. Participants were unknown to the research team but knew in advance that the focus group was organised by the University of Salford and aimed to give people a chance to ‘have their say about alcohol’ in return for £20 as a token of appreciation.

Three single focus groups90 were facilitated in private rooms within local libraries. A total of 26 participants attended, and written consent was obtained before the start. Two focus groups were held on the same day in June 2019 (Area 1) and one more in February 2020 (Area 6). EJB was supported by CU (administrative support inside the focus group) and SCH (administrative support outside the focus group). EJB explained how the focus group would work, its purpose and ground rules and announced when the audio-recorder would be switched on. A short description was provided of the CICA programme and the role of an AHC. Discussions lasted 38.11–60 minutes (average 48.54 minutes). Audio-recordings were transcribed (field notes not taken). Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction as contact details were not obtained.

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative data from public licensing registers (e.g. on number of licensed premises) were extracted and described. Data from training registers were extracted and summarised. For the pre–post-training questionnaires with AHCs, descriptive statistics were used to summarise AHC demographic characteristics and current level of drinking as categorised by their AUDIT-C score. Related sample sign test statistics were conducted to ascertain changes in attitude following training. Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Training register data and loss at follow-up data were summarised descriptively using Microsoft Excel. A Spearman’s rank correlation test measured the association between the number of pre-implementation external contextual facilitating factors and the number of AHCs trained in the first year. This was followed by Mann–Whitney U-tests comparing the numbers of AHCs trained in areas with and without each individual external contextual factor.

Qualitative analysis

Analysis of documents

Analysis of documents used content analysis, and a summative, deductive approach was taken using the ‘surface structure’ (manifest analysis) – ‘what has been said’ rather than ‘what intended to be said’. Starting with the selection of a unit of analysis, five stages of data analysis were followed: stage one decontextualisation; stage two recontextualisation; stage three categorisation; and stage four compilation. This comprehensive review of the collected data enables information relevant to the research question to be identified. 91

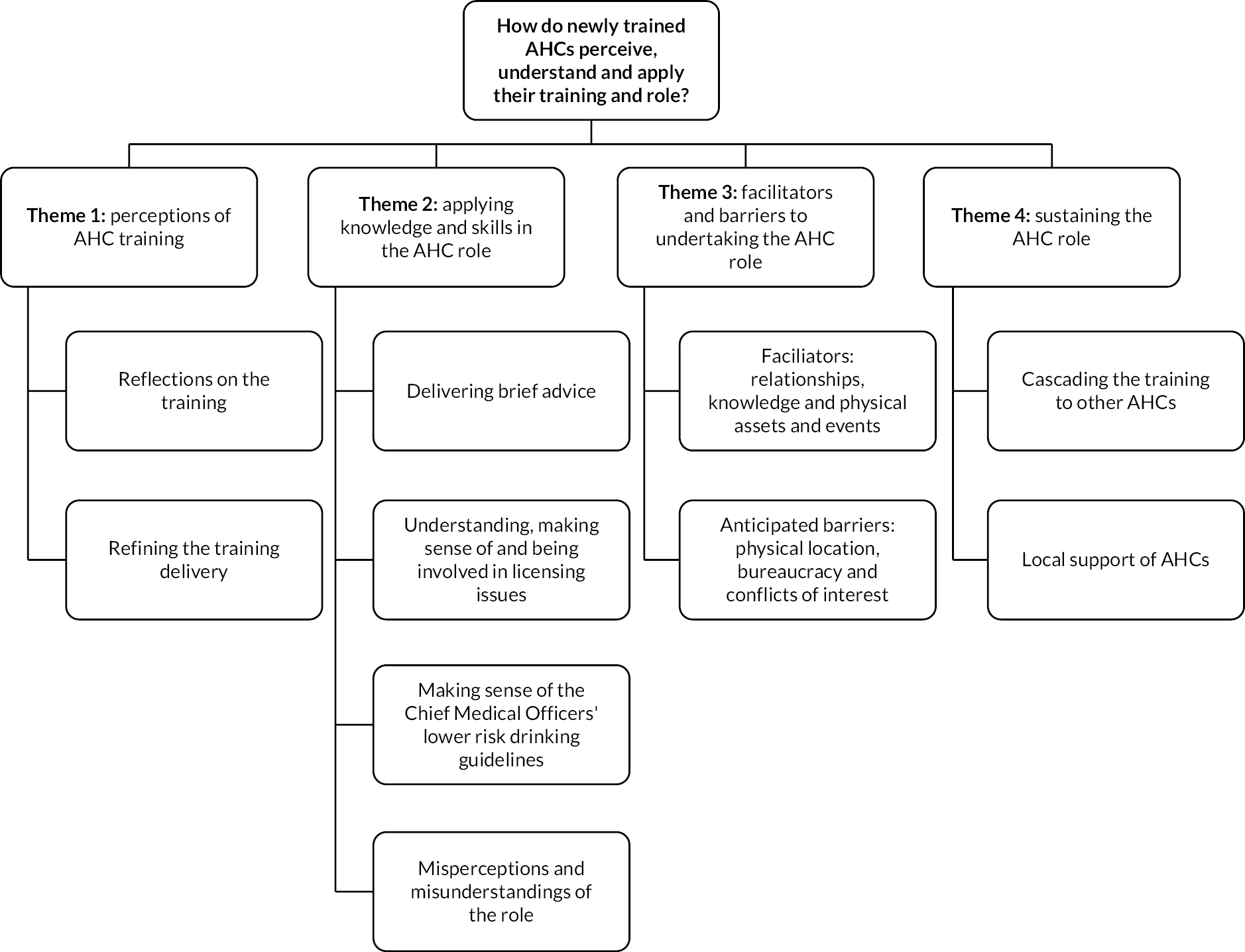

Analysis of interviews and focus groups

Semistructured interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded, fully transcribed verbatim by a transcription service and anonymised. The transcripts were returned as Microsoft Word (Version 2204) documents. A thematic framework method92,93 was used for data analysis. This approach enabled themes to develop both deductively from the research questions and inductively from participants’ testimonies. 94 All data were coded and analysed according to the five stages of framework analysis. Textual data were ‘charted’ in themes relating to key research questions and scrutinised for differences and similarities within themes, keeping in mind the context in which these arise. We used a predominantly inductive approach with both semantic and latent coding.

Familiarisation of the data was done by reading through all the transcripts once while listening to the original audio recordings. Notes were taken based on key recurring ideas that related to the research question. 95,96 An initial thematic framework of possible themes and subthemes was developed based on the interview schedule and emerging concepts from the notes taken. 97 All transcripts were coded according to this framework, a process known as indexing. This was done by inputting all transcripts into NVivo (Version 12 Plus) (QSR International, Warrington, UK) as a singular data set and applying codes to them using the ‘nodes’ feature.

A matrix of the framework was then developed in Microsoft Excel (Version 2206) where each column represents a theme or subtheme, and each row represents a participant. Codes were extracted from NVivo and charted into the framework in the appropriate intersections between the columns (themes) and the rows (participants). As data were charted, the framework was revised as needed, with themes and subthemes merged, split or removed in an iterative process. Summarising notes for each column (themes) and each row (participant) were added to the chart. Charting in this way allowed us to not only synthesise an interpretation of the overall data but also observe and form trends in the data for each participant and compare across participants. Researchers MC, SCH and CU (initial implementation phase) and PAC, CU, ND and EJB (follow-up phase) held review meetings to reflect on thematic development and refine the themes and subthemes. Each theme and subtheme were given a categorical label, and a map was devised to demonstrate the relationships between them. Other steps to maintain the quality of the process included: verbatim transcription, checking transcripts against recordings, being reflexive and exploring data in a nuanced manner. 98,99

Member checking

The findings were presented back to key stakeholders as well as AHCs at a conference, led by the process evaluation team, to share and discuss early CICA project findings. The presentation gained verbal input from attendees, who were invited to comment, in order to check the trustworthiness of findings. 100 The findings resonated with attendees, and no recommendations for amending the themes were suggested. Focus group findings could not be presented back to the public as contact details were not obtained.

Changes to the protocol

In the design stages of CICA, the training aspect of the intervention was intended to be a 3-day course, which had been reflected in version 1.0 of our protocol. Prior to roll-out preparation in each area, the GM Local Leads steering group changed the delivery mode of the training to 2 days. This was following consultation with the RSPH and local areas, who suggested that it would be easier to recruit people for a 2-day programme.

The 3-month interviews with AHCs were not part of our original protocol. This data source was added as an amendment following a discussion about Normalisation Process Theory with our SSC and how a snapshot of AHCs’ attitudes at the outset would contribute to recording their sense-making of the intervention. 87 We recognised that volunteer lay champions were driven by a range of personal motivations to get involved and aimed to explore whether their experience of key training messages (how to deliver brief advice and get involved in licensing activity) may or may not have been coherent with their own values and motivations.

We had initially planned to create a composite score of alcohol availability, making use of data on number of licensed premises, hours of sale and capacity (on-licensed premises only). In theory, this information forms part of licensing applications and should be recorded in the licensing register. However, there was no consistent format, so we were unable to do this. See the discussion chapter for a consideration of its implications.

At 1-year follow-up, we had planned to carry out two focus groups with people who had come into contact with AHCs, given the original premise that by this time each LSOA would have received a significant ‘dose’. However, it became evident that recruiting those who had received brief advice raised a range of issues which had not been anticipated, including ethical issues and potential bias in the sample.