Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number 17/44/11. The contractual start date was in December 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Holloway et al. This work was produced by Holloway et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Holloway et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Holloway et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

For individuals in contact with the criminal justice system, the prevalence of at-risk drinking is far higher than in the general population. There is very little evidence of efficacy or effectiveness of alcohol interventions in reducing risky drinking amongst those in the criminal justice system and in particular men on remand in prison. This is compounded by the limited evidence for the optimum timing of delivery, recommended length, content, implementation and economic benefit of an extended alcohol intervention in the prison setting. APPRAISE (A two-arm parallel group individually randomised Prison Pilot study of a male Remand Alcohol Intervention for Self-efficacy Enhancement) will therefore provide vital evidence to inform a future definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) of an extended alcohol intervention for men on remand in prison. The remainder of this chapter provides the background research and rationale for APPRAISE, presents the study aims and objectives, and concludes by describing the structure of the remaining chapters of this report.

Prevalence of at-risk drinking in the United Kingdom criminal justice system

Hazardous drinking is defined as a repeated pattern of drinking that increases the risk of psychological or physical problems,2 whereas harmful drinking is defined by the presence of these problems. 3 Drinking at hazardous or harmful levels is categorised as risky or at-risk drinking.

The prevalence of at-risk drinking, which includes drinking at levels that harm a person’s health, is far higher amongst those in contact with the criminal justice system (73%). 4–9 In the UK, between 51% and 83% of incarcerated people are classified as risky drinkers. 10 For those on remand in prison, the prevalence is between 62% and 68%. 8 This compares to 35% in the general population. 11 Furthermore, rates of alcohol dependence among those who are incarcerated (43%) are 10 times higher than for the general population. 8

Interventions

Parts of this section have been reproduced from Newbury-Birch et al.,8 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Alcohol brief interventions (ABIs) are a secondary prevention activity, which is aimed at people who are drinking in a pattern that is likely to be harmful to health and/or well-being. They have been frequently shown to be effective in primary health care,12,13 but they are typically delivered by practitioners who are not addiction specialists, to non-treatment, opportunistic populations. 14

ABIs largely consist of two different approaches: simple structured advice, which after screening raises awareness through provision of personalised feedback and advice on steps to reduce drinking behaviour and its adverse consequences; and an extended brief intervention, which generally involves behaviour-change counselling. Extended brief intervention introduces and evokes change by giving the participant the opportunity to explore their alcohol use, as well as their motivations and strategies for change. Both forms share the common aim of helping people to change drinking behaviour to promote health. 14

There is a wide variation in the duration and frequency of ABIs. However, typically they consist of between one and four sessions and are very short in nature (between 5 and 60 minutes). 15 They generally include personalised feedback on alcohol intake in relation to what the recommended limits are and discussion of both health and social risks, and may include setting personal targets which can include psychological and motivational interviewing. 15 One example of this is using the FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menus, Empathy, Self-efficacy) approach. 14

Due to the established links between risky drinking and crime and the costs to society, in both health and social care, it is important to find interventions that are effective. It has been shown that interventions that capitalise on the ‘teachable moment’ are conducive to behaviour change, for example where individuals consider their alcohol use within the context of their offending behaviour and its punitive consequences. 16,17

There is robust evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses to indicate that short alcohol interventions are effective in reducing alcohol consumption amongst risky drinkers in healthcare settings. 18,19 There is very little evidence of efficacy or effectiveness of alcohol interventions in reducing risky drinking amongst those in the criminal justice system, including the prison system, 20,21 and in particular remand prisoners. However, there has recently been evidence in the UK that alcohol (and drug) interventions can have an effect in reducing recidivism. 22 Furthermore, short alcohol interventions have been shown to reduce recidivism in the probation setting. 7 Nevertheless, there is limited evidence for the optimum timing of delivery, recommended length, content, implementation and economic benefit of an extended alcohol intervention in the prison setting. Likewise, there are weaknesses within the current evidence base with regard to the theoretical underpinnings of such interventions. This risks an intervention with a weak theoretical base and poorly specified ‘active’ ingredients, and which is less likely to deliver the desired outcomes.

Current evidence of alcohol interventions for those in the criminal justice system

A recent systematic review of the efficacy of psychosocial alcohol interventions for incarcerated people found that interventions in the prison setting have the potential to positively impact their relationship with and use of alcohol;21 however, because of small numbers and the use of different outcome measures it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis or generalise findings. Notably, none of the studies focused on men on remand, as compared with other subgroups within prisons. Remand refers to those who are either unconvicted or convicted and unsentenced, held in custody awaiting trial and/or sentencing.

Rationale for APPRAISE

In 2021, 16% of the prison population in England and Wales, and 19% in Scotland, were remand prisoners. 23,24 This equated to around 12,750 in England and Wales and 1700 in Scotland. Approximately 25% of individuals will not receive a custodial sentence. 25 People spend on average 10 weeks in custody while on remand. 26 During this time, many do not have the opportunity to access mainstream prison health or public health services. 27

It has been shown that there is a complex interplay between individual and contextual factors and risky drinking behaviours and alcohol-related crime. 28 Addressing alcohol harm in prisons, at what can be considered a ‘teachable moment’, where there is an opportunity for people to reflect on their risky drinking and their current position, could potentially reduce the risk of re-offending and costs to society, and help to address health inequalities. 29 While there is an inevitable uncertainty in estimating the costs of alcohol-related crime and disorder, most estimates suggest they represent a considerable economic burden.

A recent Cabinet Office estimate reported that alcohol-related crime in England cost society £21.5 billion. 30 However, this estimate is outdated and there are concerns regarding the assumptions and methodological judgements used in deriving this estimate. 31 Better-quality estimates from four high-income countries placed the total costs of alcohol at 2.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007, of which 3.5% was made up of law-enforcement costs. 32,33 It has been shown that intervening to reduce alcohol use is cost-effective, generating both long- and short-term savings. Public Health England (PHE) estimated that every £1 invested in effective alcohol treatment brings a social return of £5. Evidence estimates that health savings of £4.3 m and crime savings of £100 m per year can be made as a result of appropriate alcohol interventions. 34 It has also been suggested that providing effective treatment is likely to significantly reduce the costs relating to alcohol as well as increase individual social welfare. 35

In 2017, the Scottish Parliament Health and Sports Committee held an inquiry into prisoner health care to consider how health and social care and medicines in prison are accessed and the effectiveness of health and social care in prison. The Inquiry report set out recommendations for the Scottish government to prepare a strategic plan to address prison social and health care. 36 Furthermore, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines [NG57]37 for people in prison acknowledge that adequate healthcare provision for prisoners would reduce pressure on community services later.

Theoretical background

The intervention in this study (the APPRAISE study) builds on previous research which has explored the theoretical validity of a self-efficacy-enhancing alcohol intervention,38,39 and was originally tested as part of a pilot cluster RCT in a general hospital setting with evidence of a potential effect. 38 In our recently completed Medical Research Council Public Health Intervention Development (MRC-PHIND) funded PRISM-A (Alcohol Brief Interventions for Male Remand Prisoners) study, we undertook development and refinement of this self-efficacy-enhancing alcohol intervention within the prison setting, working with men on remand to include a synthesis of their views, with reviews of the evidence base and theoretical underpinnings. 40

This current study worked solely with men on remand. We acknowledge that there are also women prisoners who have alcohol-use disorders. There is evidence that women face different issues when imprisoned, and different barriers to services, which are important to note. 41,42

The PRISM-A study with men on remand, carried out in two prisons in the UK, showed a high prevalence of risky drinking [82% scored more than 8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Test (AUDIT)]. These numbers are comparable to other findings in the prison system in the UK,4–8 but more than three times as high as in primary care settings. 11 In the PRISM-A study, we were able to access, recruit, consent and identify those who were risky drinkers. We also found high levels of willingness of staff and participants to engage with the self-efficacy-enhancing intervention we tested for acceptability, and a willingness to participate in a trial that would involve follow-up at 6 and 12 months. Analysis of 24 in-depth interviews with male remand participants demonstrated strong substantiation that the intervention could help men on remand to develop skills and strategies that would be particularly useful on liberation. We also identified through the interviews a stronger preference amongst the participants for interventions of longer duration and that such interventions should incorporate a post-liberation component.

This is an under-researched area with large gaps in knowledge. A systematic review of alcohol interventions for offenders in the criminal justice setting identified a lack of evidence-based intervention strategies and highlighted the paucity of knowledge in this area, and in particular the lack of UK-based studies and the absence of rigorous studies focusing on men on remand. 8,21

Given the limited evidence on the effectiveness of psychosocial alcohol interventions for men on remand, we aimed to address this gap by carrying out a two-armed individually randomised pilot study to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a self-efficacy-enhancing intervention that had been developed during the PRISM-A study. 40 The results from this study will enable us to undertake a future definitive RCT evaluating its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

The study aligns to the MRC framework,43 using mixed methods with two linked phases conducted in two sites in the UK: Scotland and England.

Phase I involves a two-arm, parallel-group, individually randomised pilot study. The pilot evaluation provides data on feasibility and an assessment of the likely impact of the APPRAISE intervention to inform the feasibility of a future definitive multicentre RCT.

Phase II comprises a process evaluation. We have drawn on the MRC framework for process evaluation to guide the planning, design and proposed conduct of the process evaluation. 44 The aim of the process evaluation is threefold: first, to assess how the intervention was implemented, second, to undertake some preliminary exploration of change mechanisms underpinning the intervention and third, to assess the context within which the intervention is delivered.

An additional element was added to the study, as part of the study extension, during and in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following approval from National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), we carried out a survey of prisons in Scotland, England and Wales to ascertain what alcohol services are available in male remand prisons and how coronavirus disease discovered in 2019 (COVID-19) has affected these services.

Study aims and objectives

APPRAISE comprised a two-arm, parallel-group, individually randomised, pilot study of a self-efficacy-enhancing psychosocial alcohol intervention for men on remand in prison. It aimed to provide the evidence to support the design of a future definitive multicentre RCT for which new funding would be sought. APPRAISE had the following objectives and questions.

Objective 1: to pilot the study measures and evaluation methods to assess the feasibility of conducting a future definitive multicentre, pragmatic, parallel-group RCT.

-

Is it feasible to conduct a future multicentre RCT of a self-efficacy-enhancing psychosocial alcohol intervention for men on remand?

-

Can we obtain reasonable estimates of the parameters necessary to inform the design and sample size calculation for a future definitive multicentre RCT? This includes standard deviations of potential continuous primary outcomes and estimates of recruitment, retention and follow-up rates.

-

How well do participants complete the questionnaires necessary for a future definitive RCT?

-

Can we collect economic data needed for a future definitive RCT?

-

Can we access recidivism data from the Police National Computer (PNC) databases for trial participants?

-

Can we access health data from routine NHS data sources for trial participants?

Objective 2: to assess intervention fidelity.

-

What proportion of the interventions are delivered as per protocol?

-

Is there any evidence of contamination between the two conditions and/or between those workers delivering the intervention.

-

To what extent was the intervention changing process variables consistent with the underpinning theory?

Objective 3: to qualitatively explore the feasibility and acceptability of a self-efficacy-enhancing psychosocial alcohol intervention and study measures to staff and for men on remand and on liberation.

-

How acceptable are the trial and intervention procedures (including context and any barriers and facilitators) to the following key stakeholders: men on remand in prison and on liberation; prison staff (including healthcare staff); commissioners; policy-makers and third-sector partners?

Objective 4: to assess whether operational progression criteria for conducting a future definitive RCT are met across trial arms and study sites and, if so, develop a protocol for a future definitive trial. Operational progression criteria are based on previous research results. 7

-

Do the two prisons invited to the study agree to take part?

-

Based on knowledge from previous data, do at least 90 eligible participants consent to take part and be randomised across the trial arms?

-

Do at least 70% of participants who consent to the trial receive the intervention?

-

Are at least 60% of those who received the intervention followed up at 12 months across trial arms and study sites?

Objective 5: to carry out a survey to ascertain what alcohol services are available in male remand prisons and how COVID-19 has affected services.

Structure of the report

The report comprises nine chapters, providing details of the background to the study, the rationale for the study, and an account of the research design, methods and findings. Reporting of public patient involvement (PPI) involvement and on equality diversity and inclusion is included. The report concludes by answering whether the study met its aims and objectives, learning from the study, strengths and limitations, while reflecting on the impact of COVID-19 and details of the recommendations for a future definitive trial.

This first chapter has provided the background research and rationale for the study and presented the study aims and objectives. Chapter 2 details the development of the intervention, presents the various elements of the intervention and theoretical underpinnings, and aligns itself to the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework. 45 delivery mechanisms as well as the logic model. Intervention training is also described. Chapter 3 reports the pilot trial methods including the management of the study, governance as well as ethics and research clearance. Chapter 4 presents the pilot trial findings, addressing Objectives 1 and 4. Chapter 5 reports the qualitative process evaluation methods. Chapter 6 presents the qualitative process evaluation findings, addressing Objectives 2 and 3. Chapter 7 details the results of the collection and access of economic data and recidivism data for trial participants, addressing Objective 1. Chapter 8 presents the APPRAISE COVID-19 survey methods and results. This was an additional piece of work we agreed with NIHR to carry out during COVID-19 and as part of the study extension period. Chapter 9 presents the discussion, PPI overview, strengths and limitations, recommendations for future RCT and conclusion. The aim of PPI was to provide meaningful engagement with stakeholders who had direct experience of the prison system, ranging from those who have experience of incarceration to those who run third-sector organisations supporting people on release from prison. Our PPI co-applicant was present to contribute in all PMG meetings. The Guidance for Reporting Instrument of Patients and the Public – short form (GRIPP2) form46 identifies the PPI study engagement (see Appendix 1). Finally, recommendations for a future definitive trial are presented. Due to COVID-19, we faced unavoidable modifications to the APPRAISE study. These are reported across chapters at the relevant points. To support completeness of reporting these unavoidable and important modifications to the trial due to COVID-19 (extenuating circumstances), we also completed the CONSERVE checklist9 (see Appendix 2).

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Holloway et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter reports on the origins of the APPRAISE intervention and its theoretical underpinnings, and provides a detailed description of the study intervention itself and the nature of the training for those delivering it. For completeness of the APPRAISE intervention reporting and replicability, the TIDieR checklist is used to support the structure of the chapter (see Appendix 3). 45

Origins and development of the APPRAISE intervention

The APPRAISE intervention is an extended self-efficacy-enhancing alcohol intervention developed for men on remand with self-reported drinking that is harmful or hazardous. The APPRAISE intervention is based on previous ABI research focusing on self-efficacy as an appropriate basis for a single-session ABI intervention to enhance drinking refusal self-efficacy in a general hospital population. 38,39

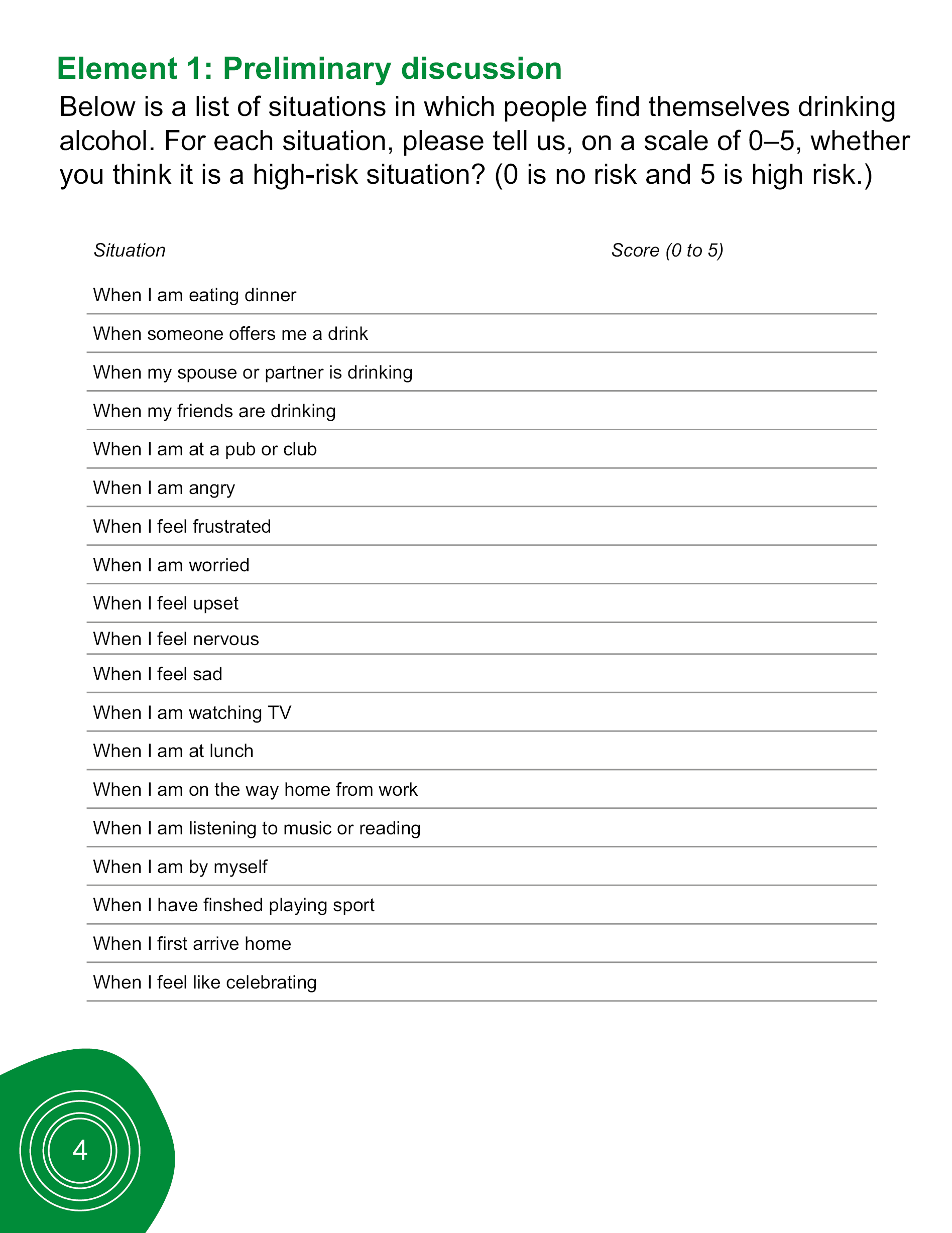

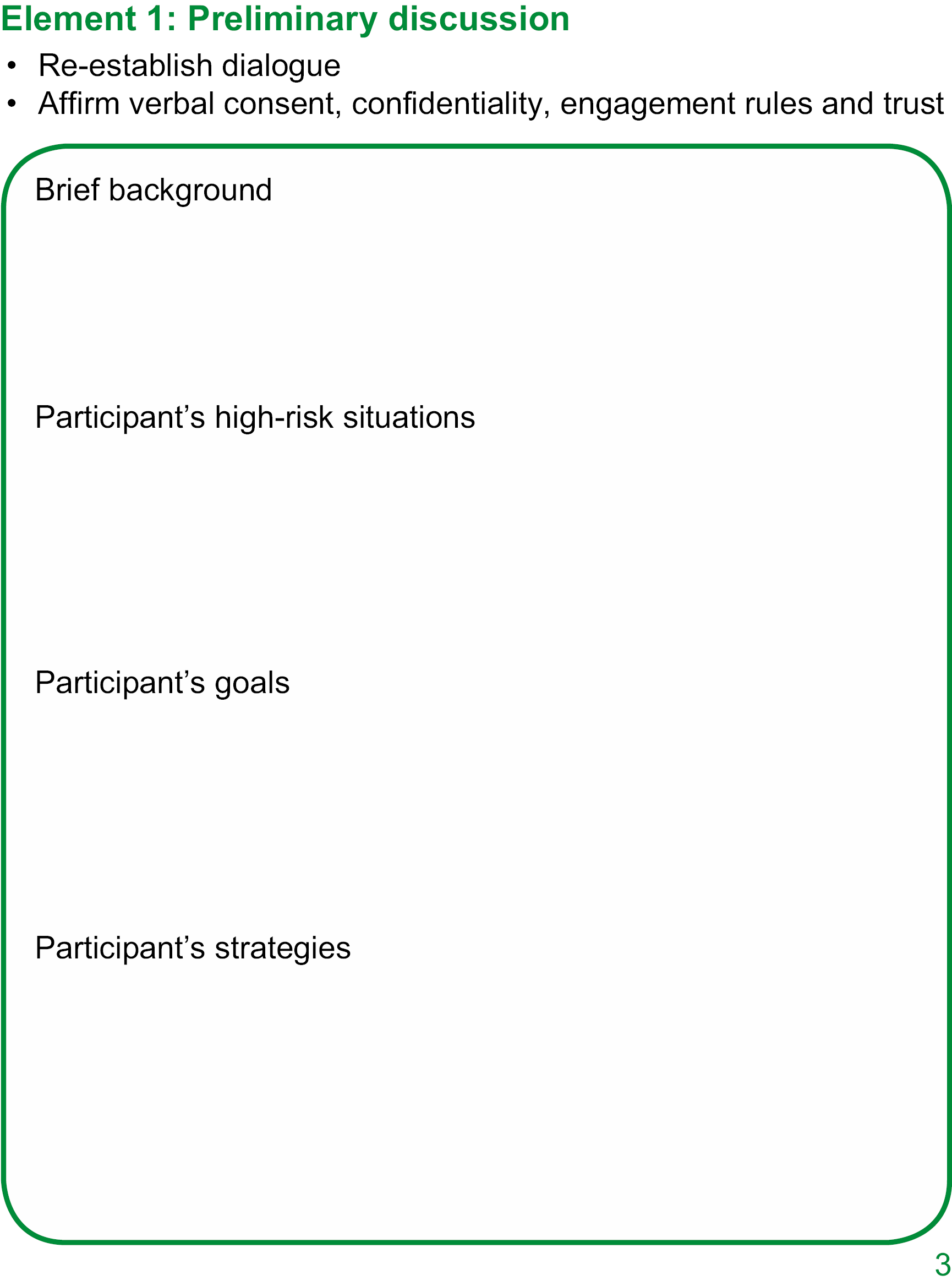

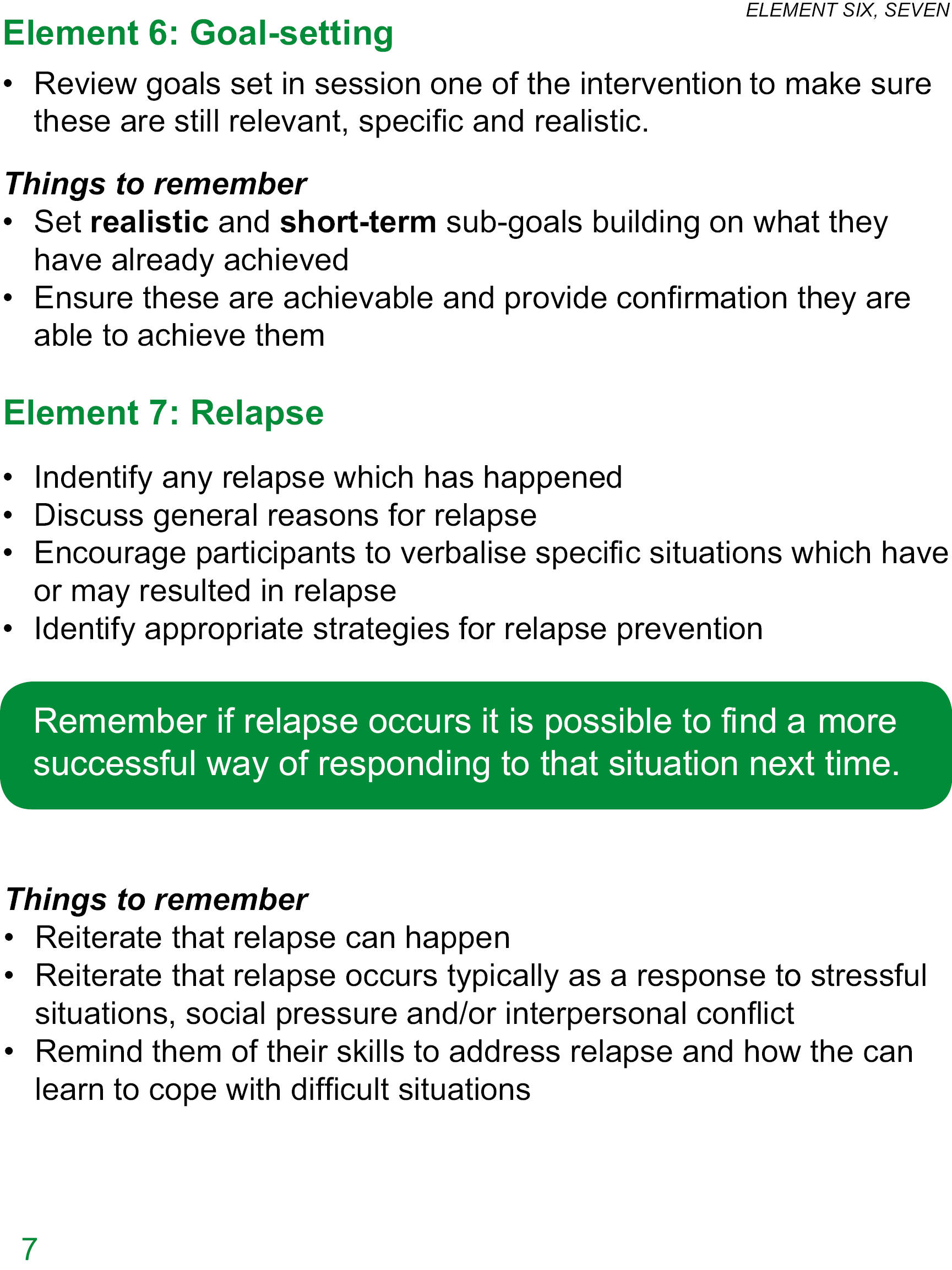

From this original work, additional intervention modification was undertaken as part of the PRISM-A study on the basis of our learning from interviews with men on remand (n = 24). 40 The aim of these interviews was to explore the acceptability of a self-efficacy-enhancing ABI,40 including listening to feedback regarding the nine elements of the intervention: (1) preliminary discussion, (2) acquiring and providing information, (3) self-monitoring, (4) increasing awareness, (5) situation appraisal and appropriate coping strategies, (6) goal-setting, (7) relapse, (8) self-evaluation/self-reinforcement and (9) culmination. 39,40

The nine intervention elements of the single-session delivery were found to be acceptable to men on remand who were interviewed as part of the PRISM-A study. Feedback regarding frequency and intensity of contact identified a preference for more than one session, with a desire for additional sessions being delivered in the community following liberation. The participants reported that this would provide the opportunity to put the skills gained as a result of the single-session intervention into practice, once liberated, in real-world situations in which alcohol is widely available to them.

This evidence subsequently informed the development and refinement of the single-session ABI to an extended four-session ABI, incorporating a single session to be delivered in the prison setting with the remaining three additional booster sessions to be delivered following liberation.

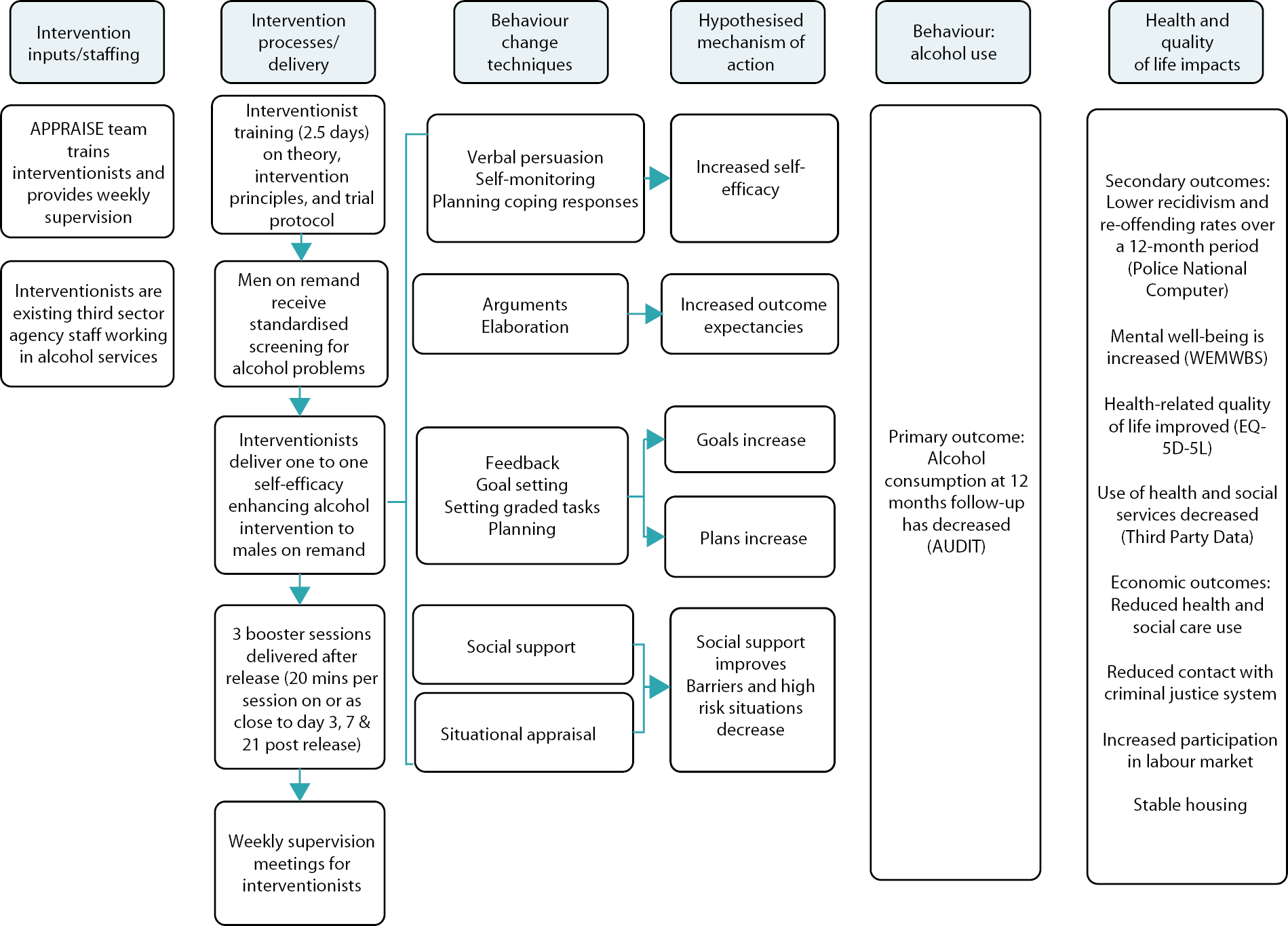

APPRAISE intervention: theory, elements and logic model

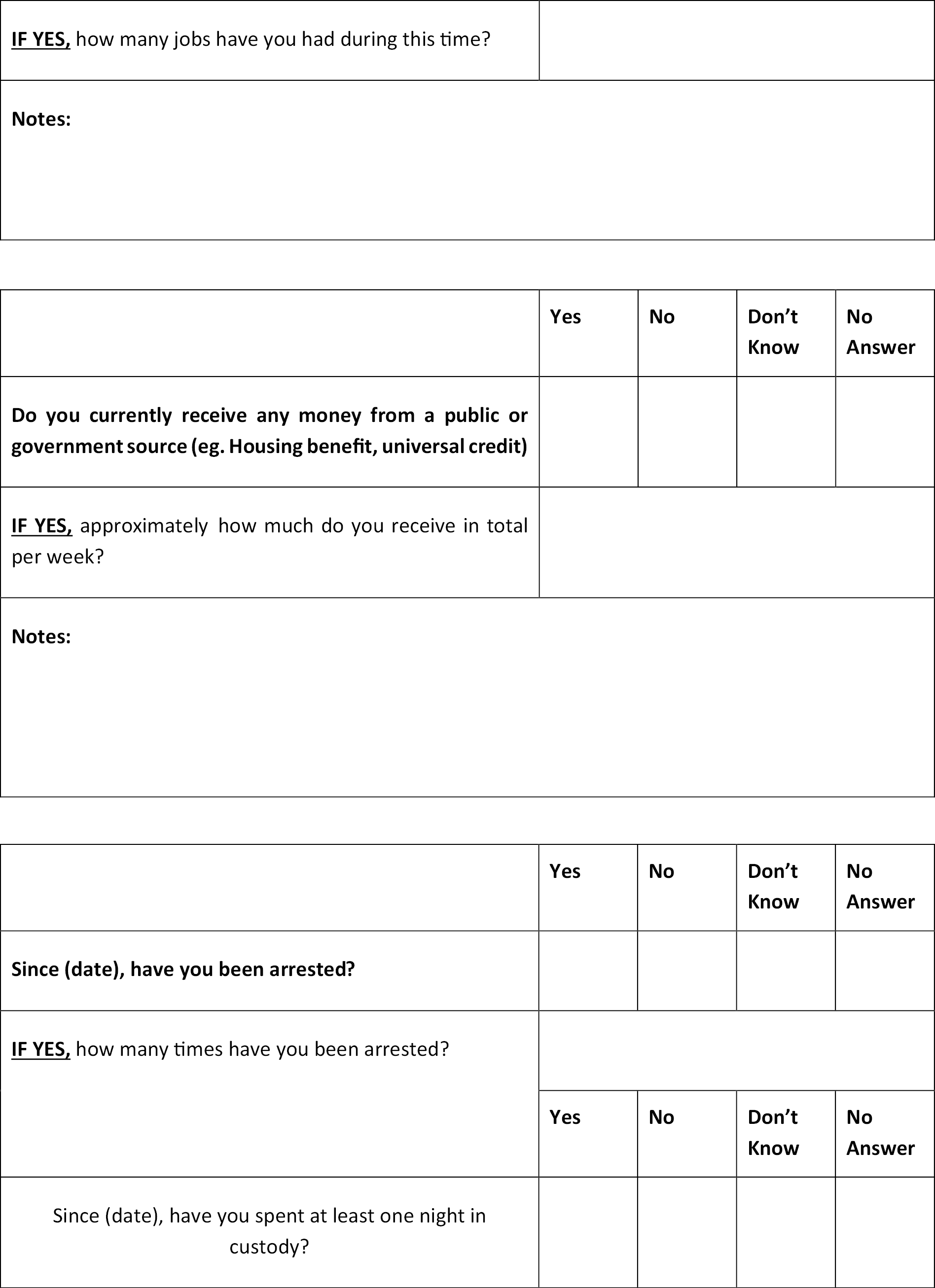

The APPRAISE intervention is based on Social Cognitive Theory and designed to increase self-efficacy and other self-regulatory skills to reduce alcohol consumption. Figure 1 illustrates this process in the APPRAISE logic model. According to the theory, self-efficacy is a central determinant of health behaviour change. 47 Primary sources of self-efficacy that can be targeted through interventions are mastery experience, verbal persuasion, vicarious experience and physiological state. 39,40,47 All these sources of self-efficacy were addressed in the intervention (see Table 1 for all elements of the APPRAISE intervention). Mastery experiences should become more likely due to intervention elements addressing feedback, goal-setting, planning for release, including plans for coping responses, and self-monitoring of the intervention. Verbal persuasion was delivered by the interventionist, as were ways to achieve a calmer physiological state during high-risk situations. The intervention was designed to also increase outcome expectations by delivering arguments and elaborations and seeking social support. The intervention aimed to develop better self-regulation skills, thus enabling individuals to address their alcohol consumption behaviour. Liberation then offered participants the opportunity to implement and act on the targeted behaviours learned in the intervention in their ‘real life’ social context. The aim was for participants to have the ability to develop and build upon these skills and self-belief through success and mastery, with their efforts leading to the adoption and maintenance of reduced alcohol consumption. Reducing alcohol consumption can provide a sense of achievement and success, which should further increase self-efficacy. 39

FIGURE 1.

APPRAISE logic model.

| Opening strategies | |

|---|---|

| Element 1: preliminary discussion | Introduction to APPRAISE study |

| Introduction to APPRAISE | |

| Consent, confidentiality, engagement rules, trust | |

| Element 2: acquiring and providing information | Feedback on AUDIT score |

| Establish perception of impact of alcohol on health and life | |

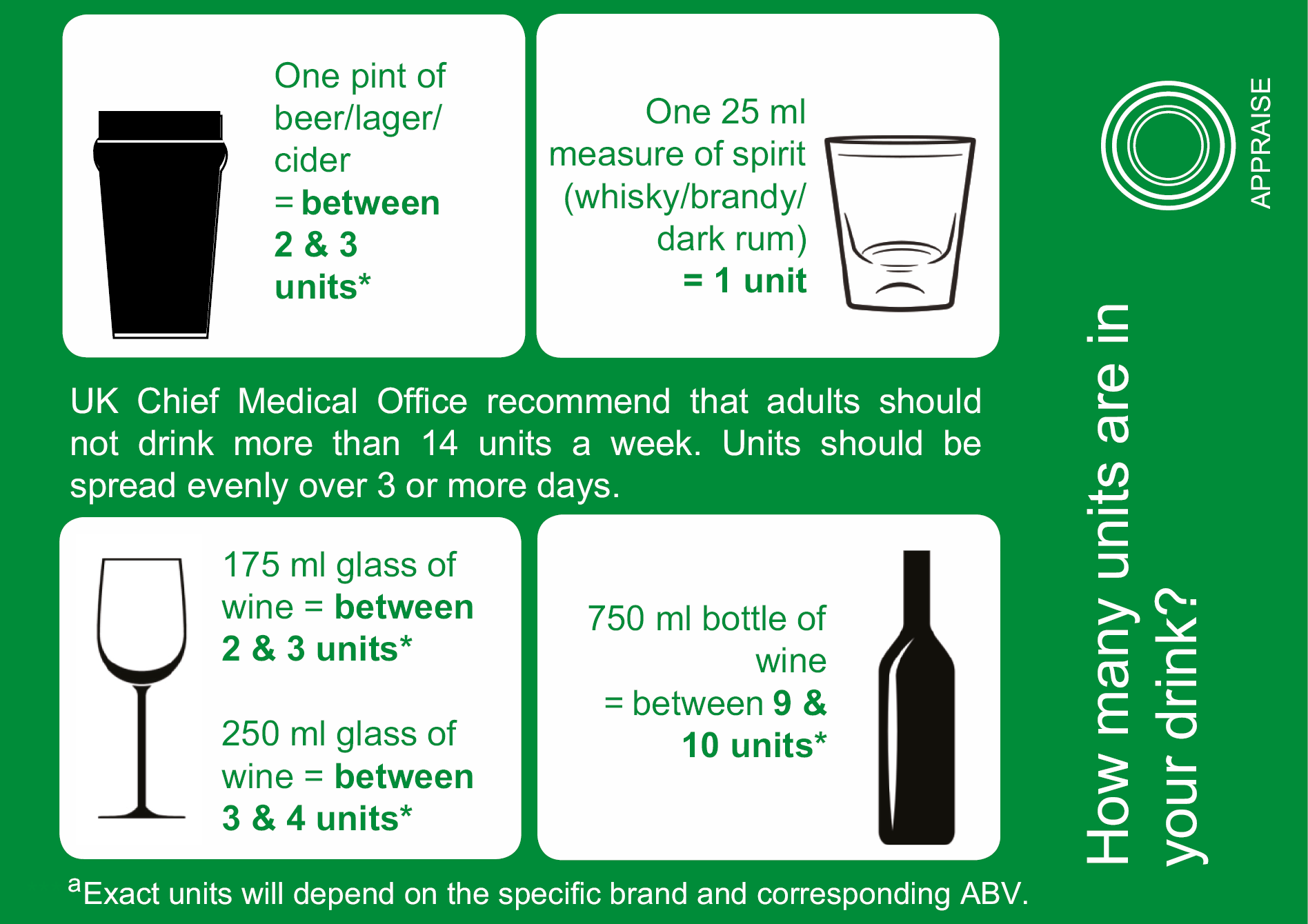

| Standard units of alcohol | |

| Recommended drinking levels | |

| Alcohol-related health problems | |

| Legal drink/drive limit | |

| Tips on reducing consumption | |

| Where to obtain information/support (prison and liberation) | |

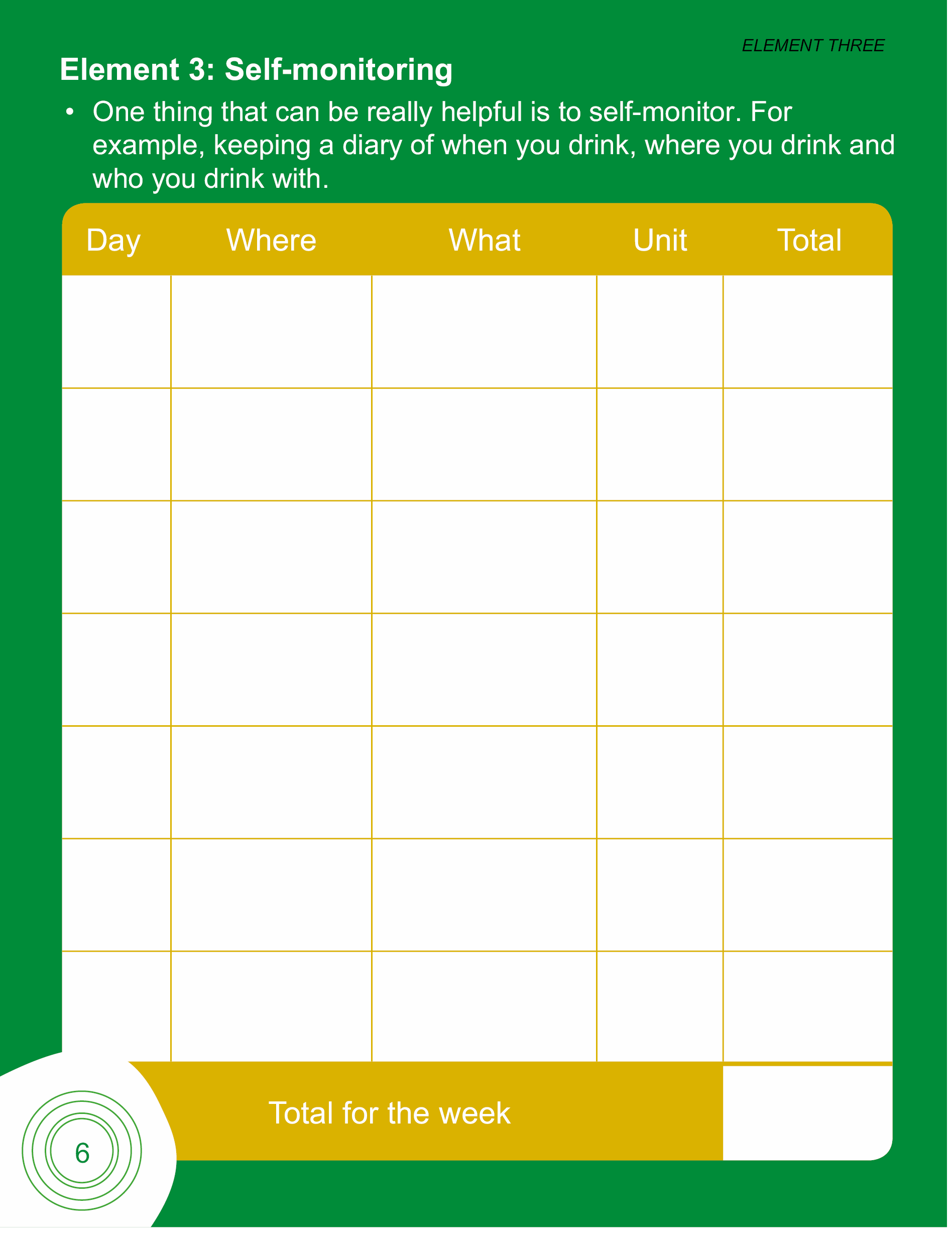

| Element 3: self-monitoring | Diary card – when, where, who, type of drink, why |

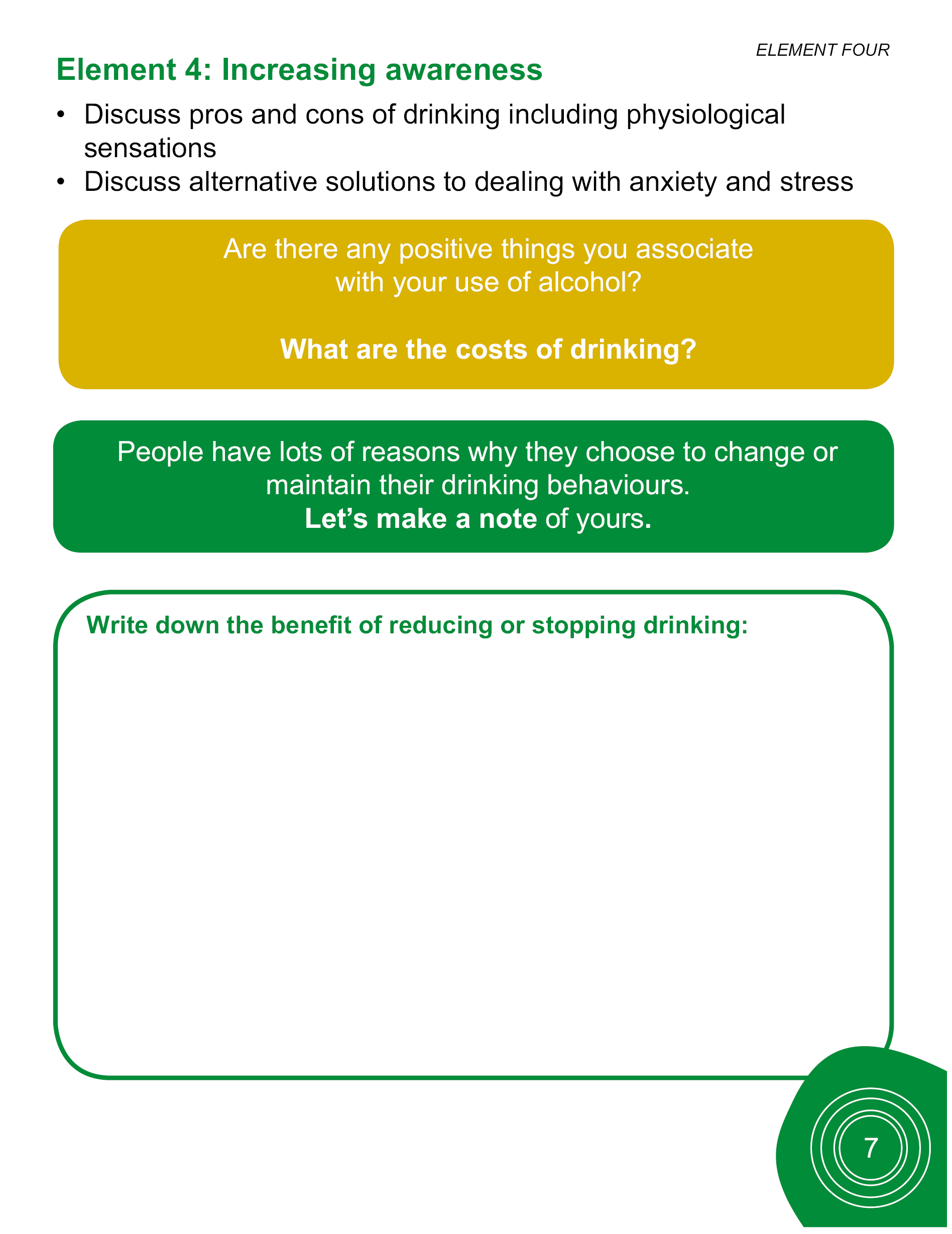

| Element 4: increasing awareness | Balance sheet – pros and cons of drinking |

| Physiological sensations identified | |

| Alternative appraisal of somatic sensations identified | |

| Strategies to reduce | |

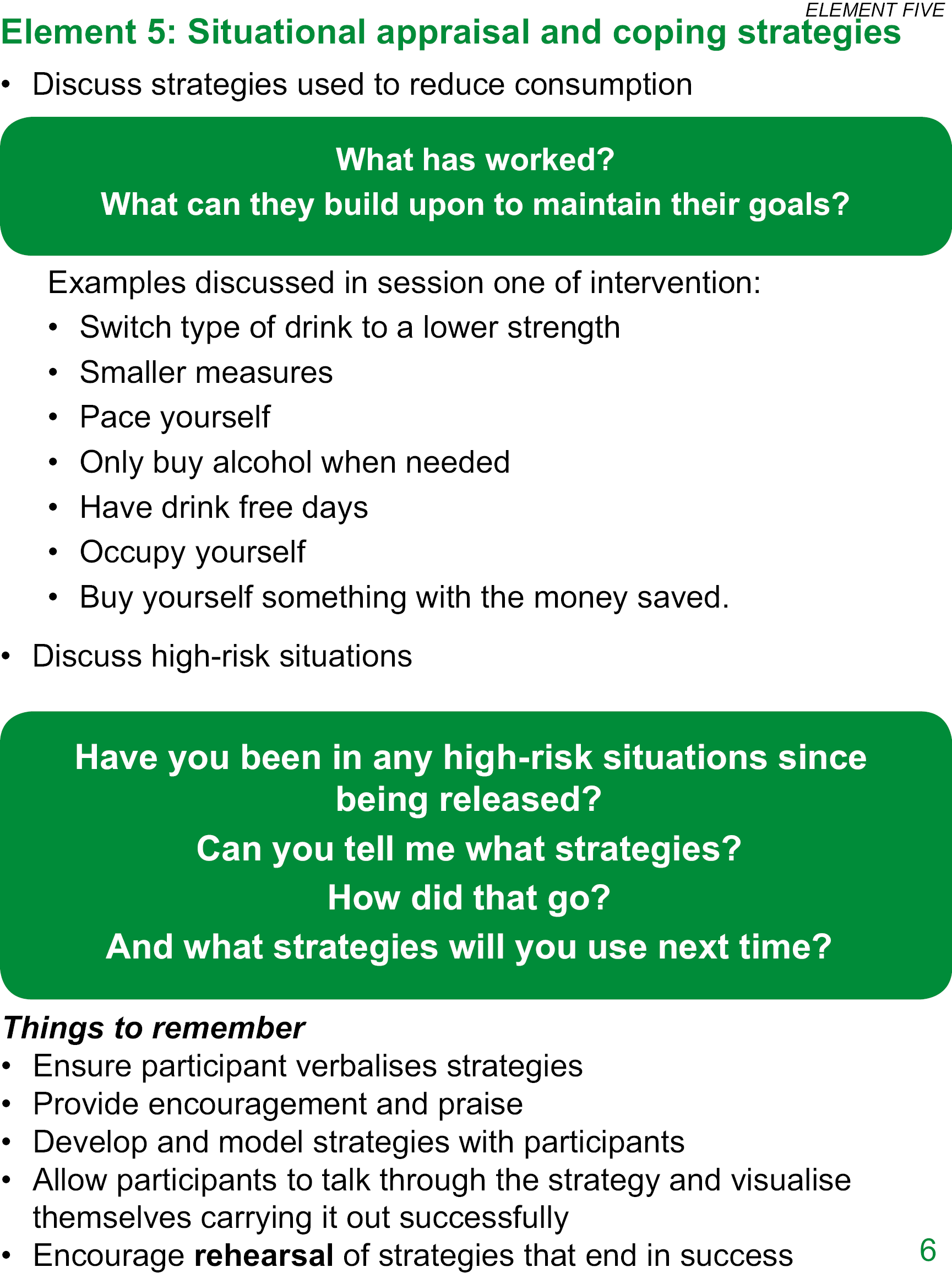

| Element 5: situation appraisal and appropriate coping strategies | High-risk situations and antecedents of over-drinking identified |

| Alternative coping strategies identified | |

| Coping strategies verbalised by participant | |

| Praise provided | |

| Strategies developed further through co-production | |

| Strategies modelled by interventionist | |

| Participant verbalises strategies and visualises them | |

| Plan for exposure to low-risk situations and avoidance of high-risk situations | |

| General control strategies: reduction in rate of drinking, sipping, drinking low-alcohol drinks and alternating between soft or low-alcohol drinks and higher-alcohol drinks | |

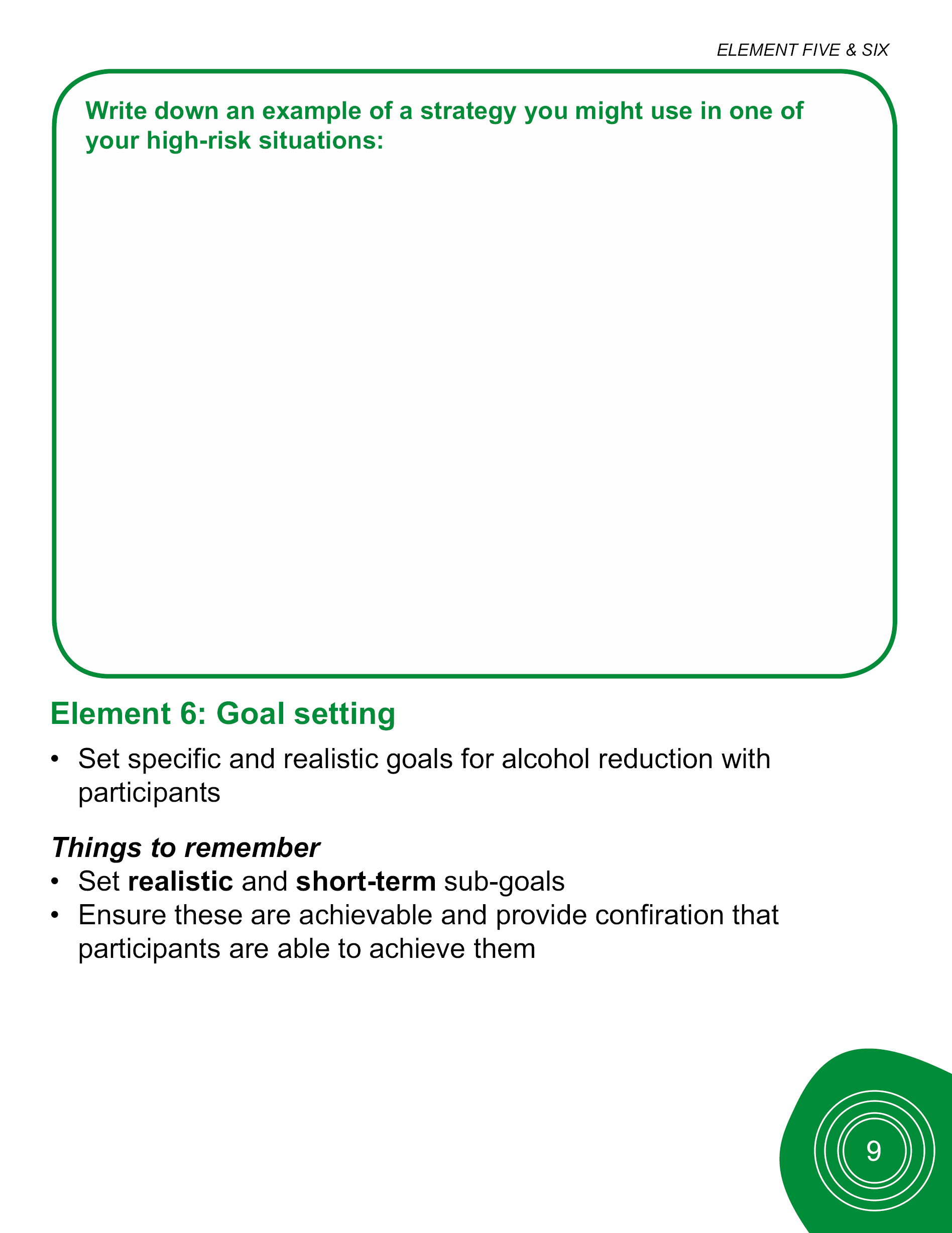

| Element 6: goal-setting | Setting realistic sub-goals (short-term) |

| Facilitating success and increasing motivation | |

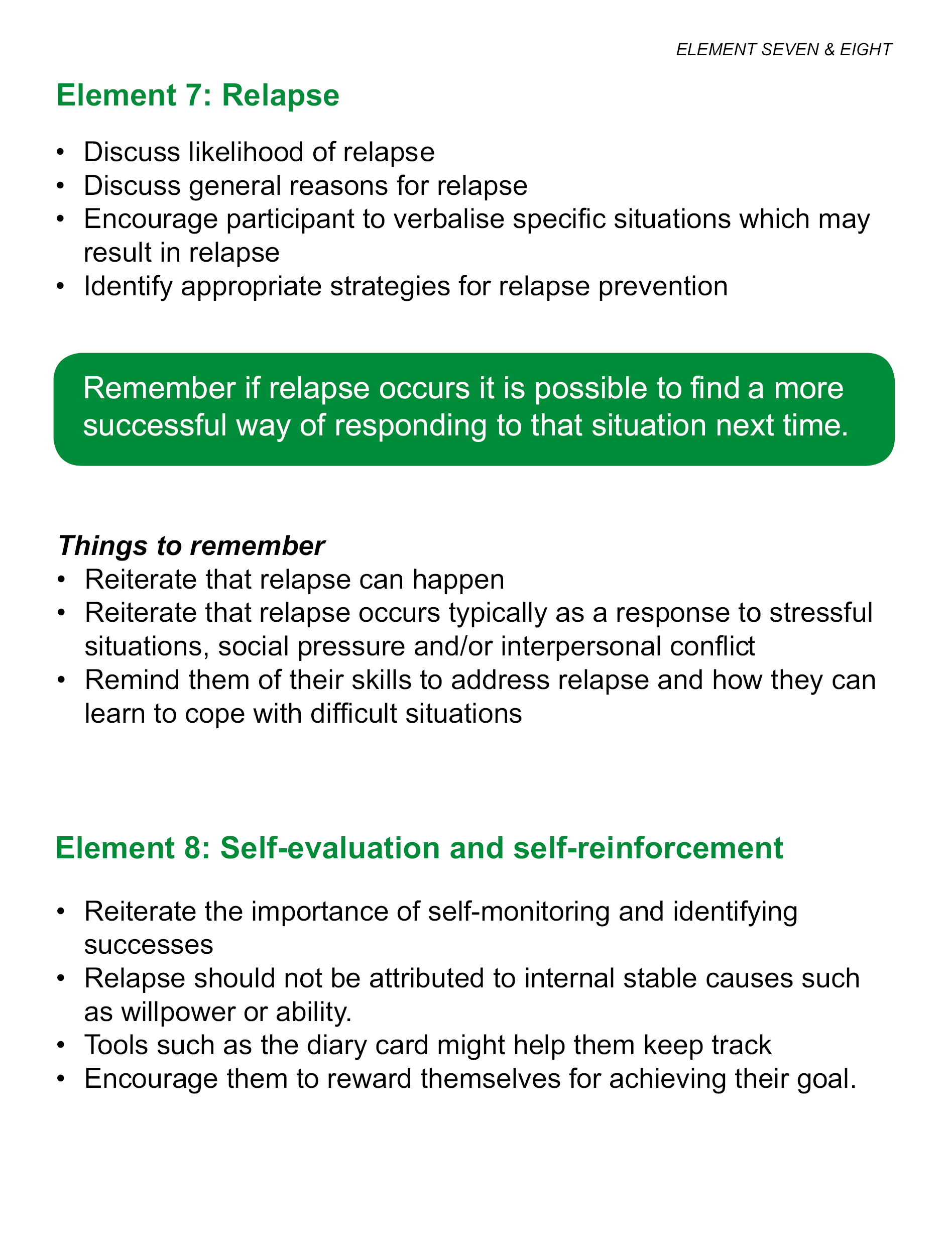

| Element 7: relapse | What happens if you relapse |

| What caused the relapse? | |

| How do I understand relapse? | |

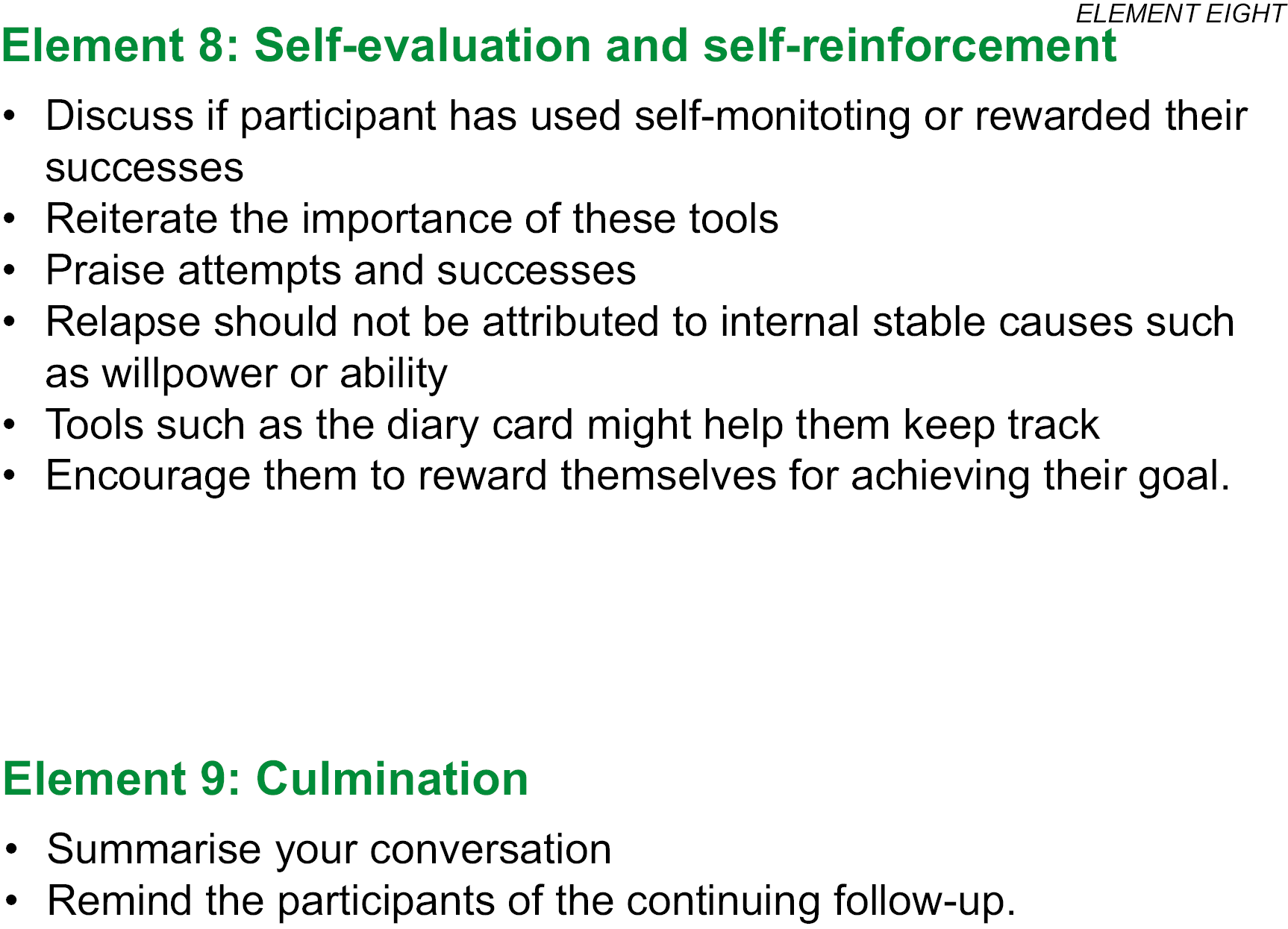

| Element 8: self-evaluation and self-reinforcement | Using my alcohol diary as a means of self-evaluation and self-reinforcement |

| Self-congratulations and rewarding my success | |

| What do I attribute my success to? | |

| Element 9: culmination | Reflections and conclusions. Plans and goals reiterated and confirmed |

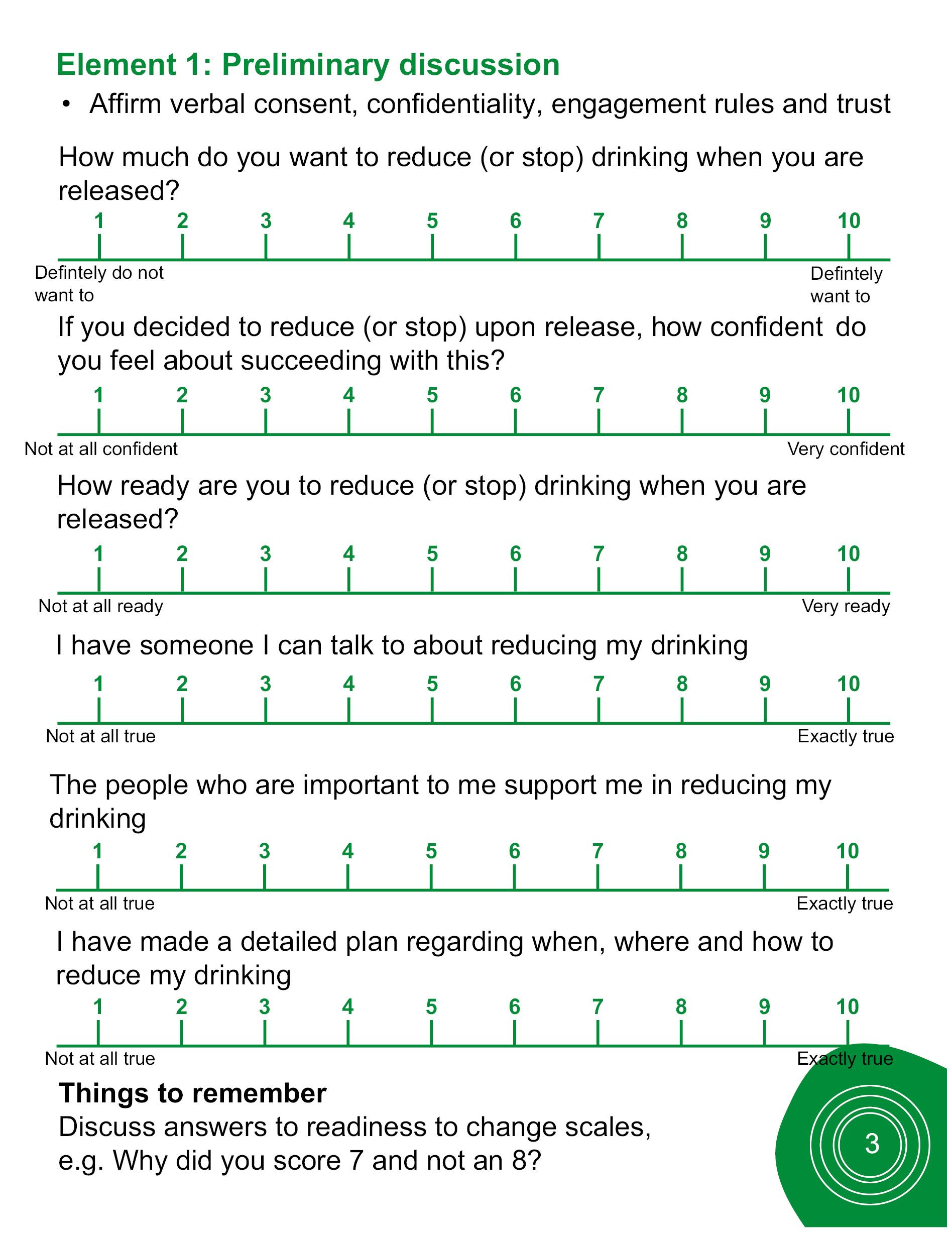

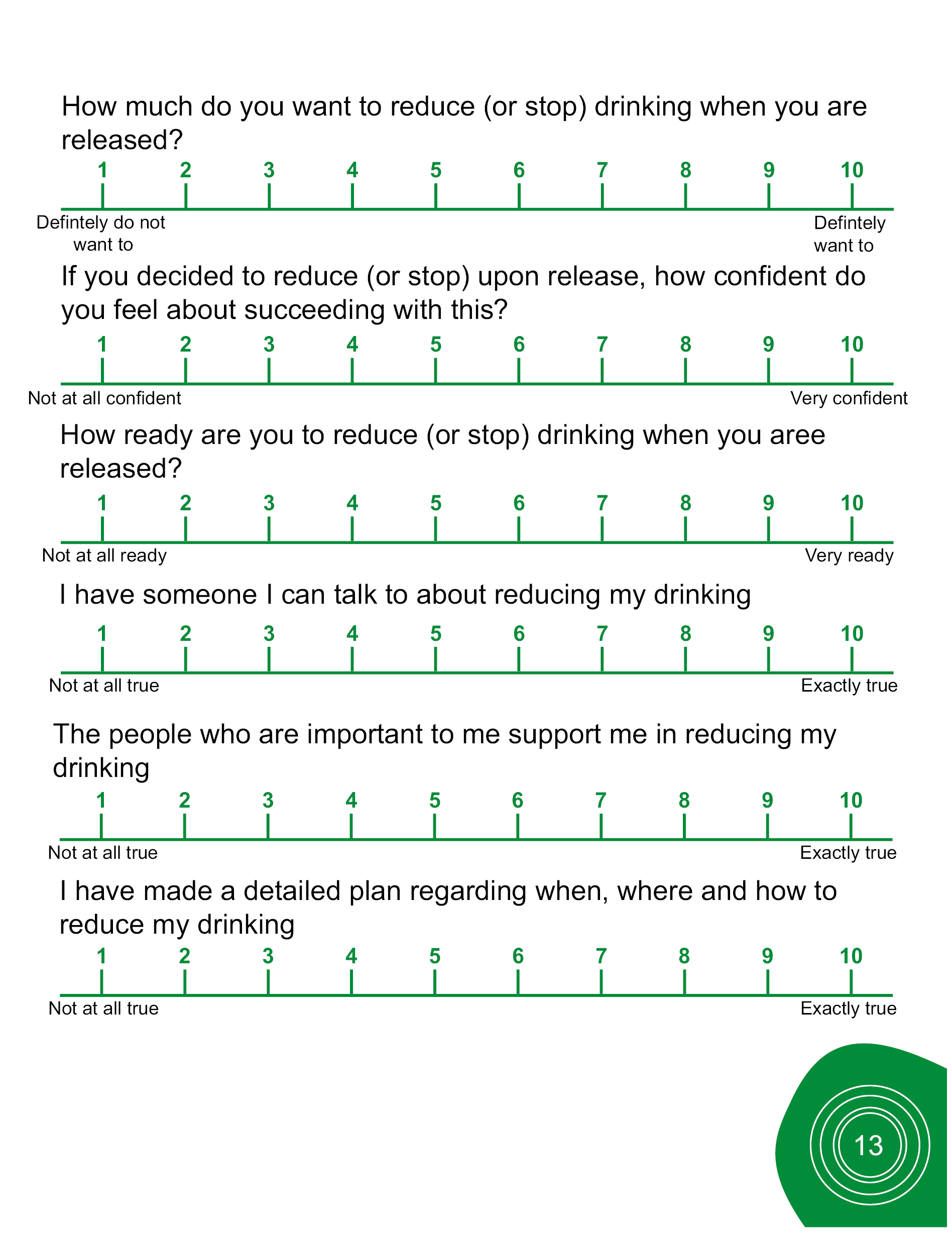

The six proposed mechanisms of change in the logic model are: self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals, plans, social support and high-risk situations.

-

Self-efficacy will be measured using: (i) an item on the Readiness to Change Ruler: ‘How confident are you that you could reduce (or stop) drinking when you are released?’ and separately (ii) the Drinking Refusal Self-efficacy Questionnaire.

-

Alcohol expectancy will be measured using the Negative Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire.

-

Goals will be measured using an item on the Readiness to Change Ruler: ‘How much do you want to reduce (or stop) drinking when you are released?’

-

Plans will be measured using: (i) an item on the Readiness to Change Ruler: ‘How ready are you to reduce (or stop) drinking when you are released?’ and (ii) ‘I have made a detailed plan regarding when, where and how to reduce my drinking’.

-

Social support will be measured using the following items: (i) ‘The people who are important to me support me in reducing my drinking’ and (ii) ‘I have someone I can talk to about reducing my drinking’ in the Readiness to Change Ruler.

-

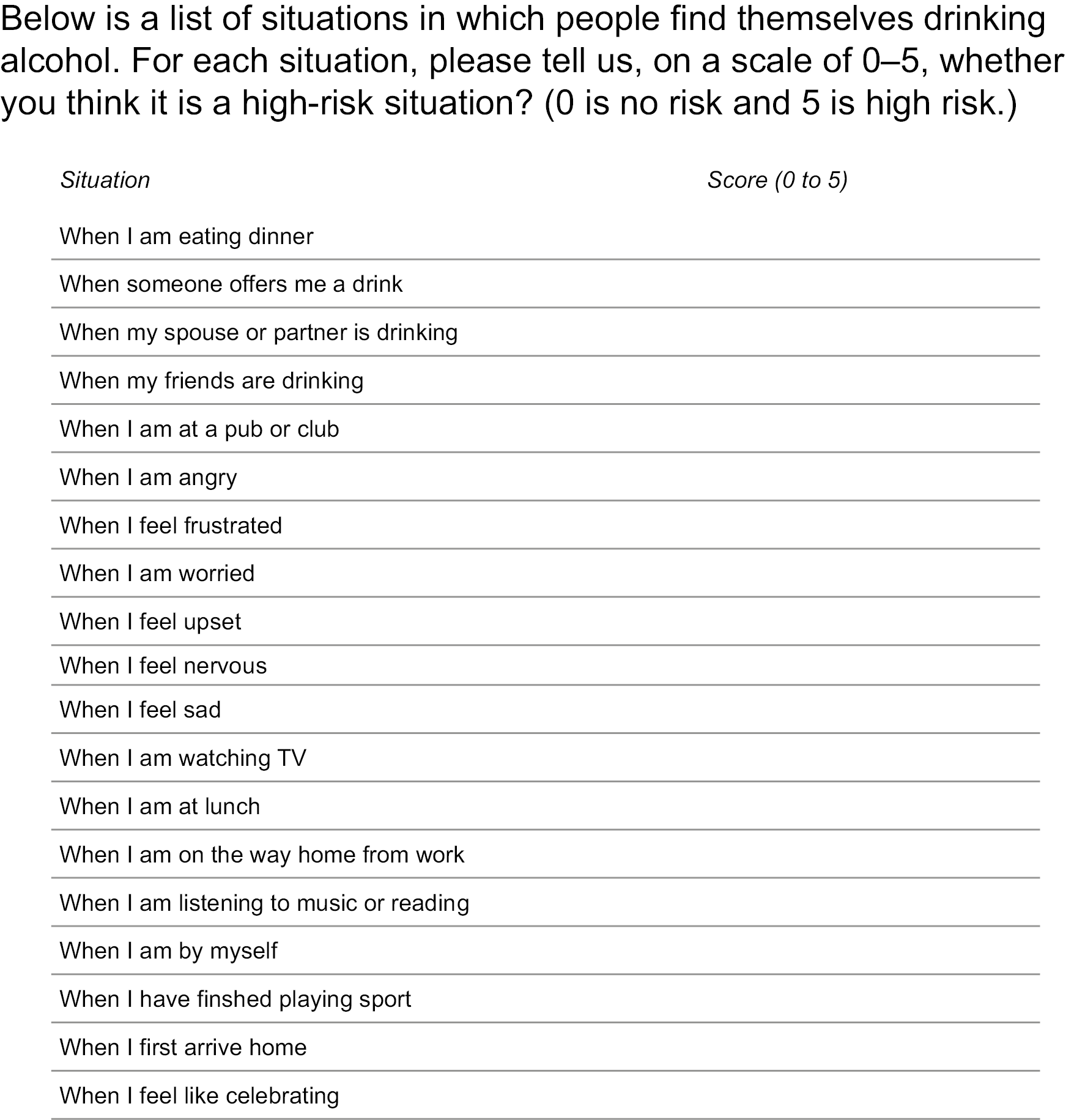

Barriers and high-risk situations will be measured using the following items: (i) ‘I know in which situations it will be difficult for me to reduce my drinking’ and separately (ii) the question ‘to what extent do you consider this to be a high-risk situation for you?’ in the Drinking Refusal Self-efficacy Questionnaire.

APPRAISE intervention materials

The APPRAISE intervention consisted of three documents:

-

APPRAISE Intervention Tool [V3_20October] (see Appendix 4)

-

Intervention Tool Postcard (Unit card) [V2_25Sept19] (see Appendix 5) and

-

Follow-up Manual [V1_25 Sept19] (see Appendix 6).

These documents together supported the delivery of the behaviour-change methods, linked directly to the determinants/mechanisms of change that focused on the targeted behaviour, in order to achieve the desired outcomes.

-

Document 1: the APPRAISE Intervention Tool was an eight-page, double-sided A5 booklet containing all nine Intervention Elements (Table 1: APPRAISE elements) and was the material used for the first intervention session.

-

Document 2: the Intervention Tool Postcard (Unit card) was postcard-sized and provided brief information about recommended drinking levels and units that was given to individuals to take away with them during Element 2 of the first intervention session.

-

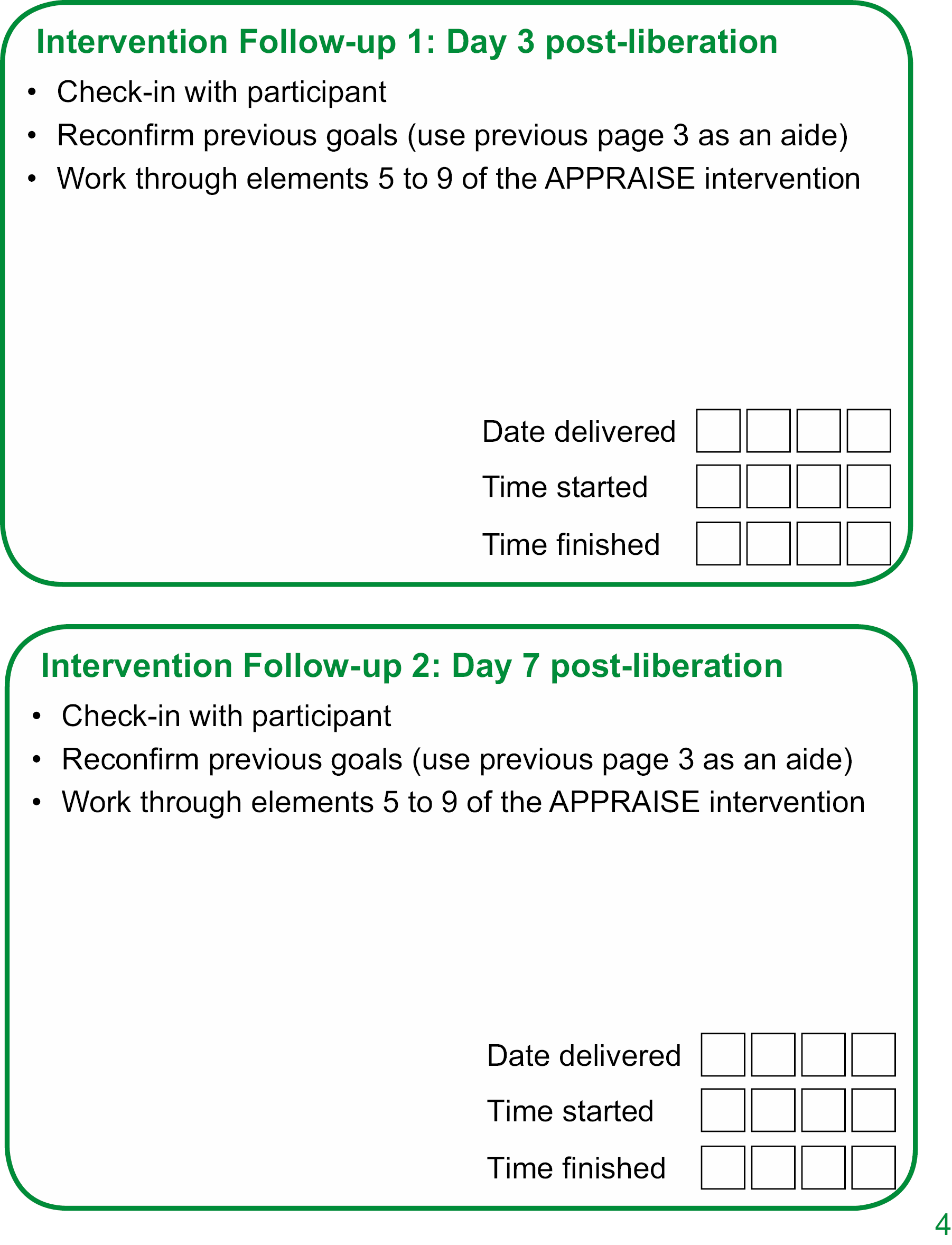

Document 3: the Follow-up Manual was a six-page double-sided A5 booklet for use during all three post-liberation follow-up intervention sessions (Day 3, Day 7 and Day 21). The manual contained Element 1 as a way of re-establishing dialogue following on from the first intervention session, followed by Elements 5–9 of the APPRAISE intervention.

APPRAISE intervention procedures

The APPRAISE intervention was delivered in a safe, non-judgemental environment where engagement rules and trust were affirmed. This was with the aim of enabling and supporting the intervention activities. The APPRAISE Intervention Tool booklet contained ‘Things to remember’ – notes for the interventionist to support the delivery of the intervention elements. This reminded the interventionist of the key areas within each element to be emphasised during intervention delivery. It also provided a mechanism of supporting intervention fidelity in relation to delivery of the intervention changing process variables consistent with the underpinning theory.

While the APPRAISE intervention has specific core elements, the intervention itself was person-centred in that it became individualised during the course of the participant-interventionist conversation and subsequent intervention delivery.

The starting point for this approach was assessing participants’ readiness to change by way of completion of the Readiness to Change Ruler. 48 The scoring then provided information and understanding as to where the participant was in relation to their readiness to change. Similarly high-risk drinking situations were identified during Element 1 to provide further information that would build upon all the elements moving forward. This initial discussion was key to ensuring the interventionist was able to understand, recognise and respond effectively in relation to gauging how participants perceived their drinking and their motivation to change and how they used alcohol in their lives. Discussing answers to both the Readiness to Change Ruler and high-risk situations supported the delivery of an individual realistic starting point for both participant and interventionist. Depending on the results of these elements, each element could then be individualised to participants’ particular needs.

The participants AUDIT score, obtained following screening, was shared with them during Element 2 to feedback and provide information on recommended drinking levels, units and the impact alcohol may have been having on themselves, others and their life on the whole. Giving the Intervention Tool Postcard (Unit card) to the participant provided an easy-to-carry postcard-size information resource which could be studied following intervention sessions and post liberation.

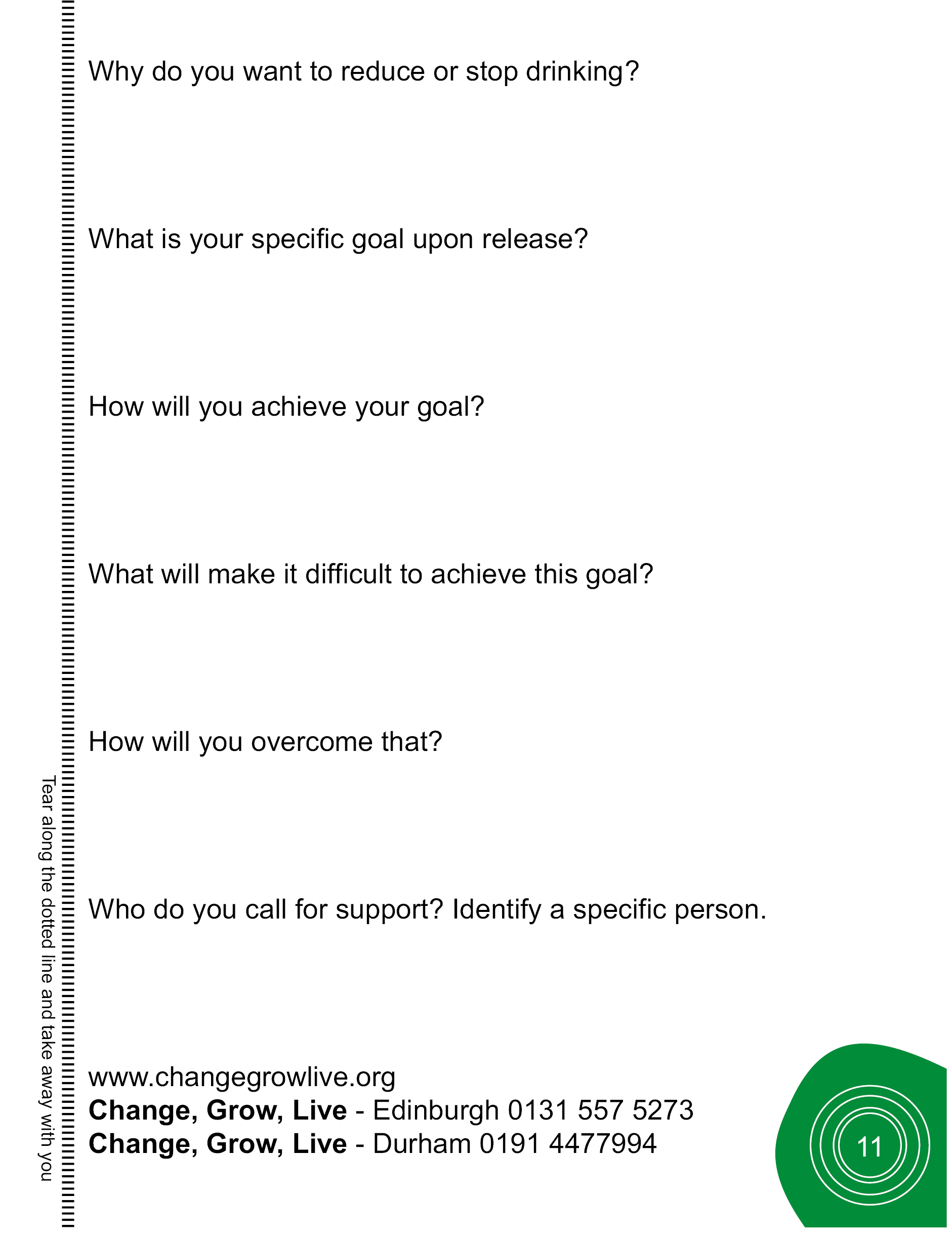

In addition, the booklet had a perforated page that was removed at the end of Element 8 and was given to and kept by the individual receiving the intervention. The page was a takeaway ‘personal planner’ with reinforcement triggers of the key behaviour-change methods and mechanisms.

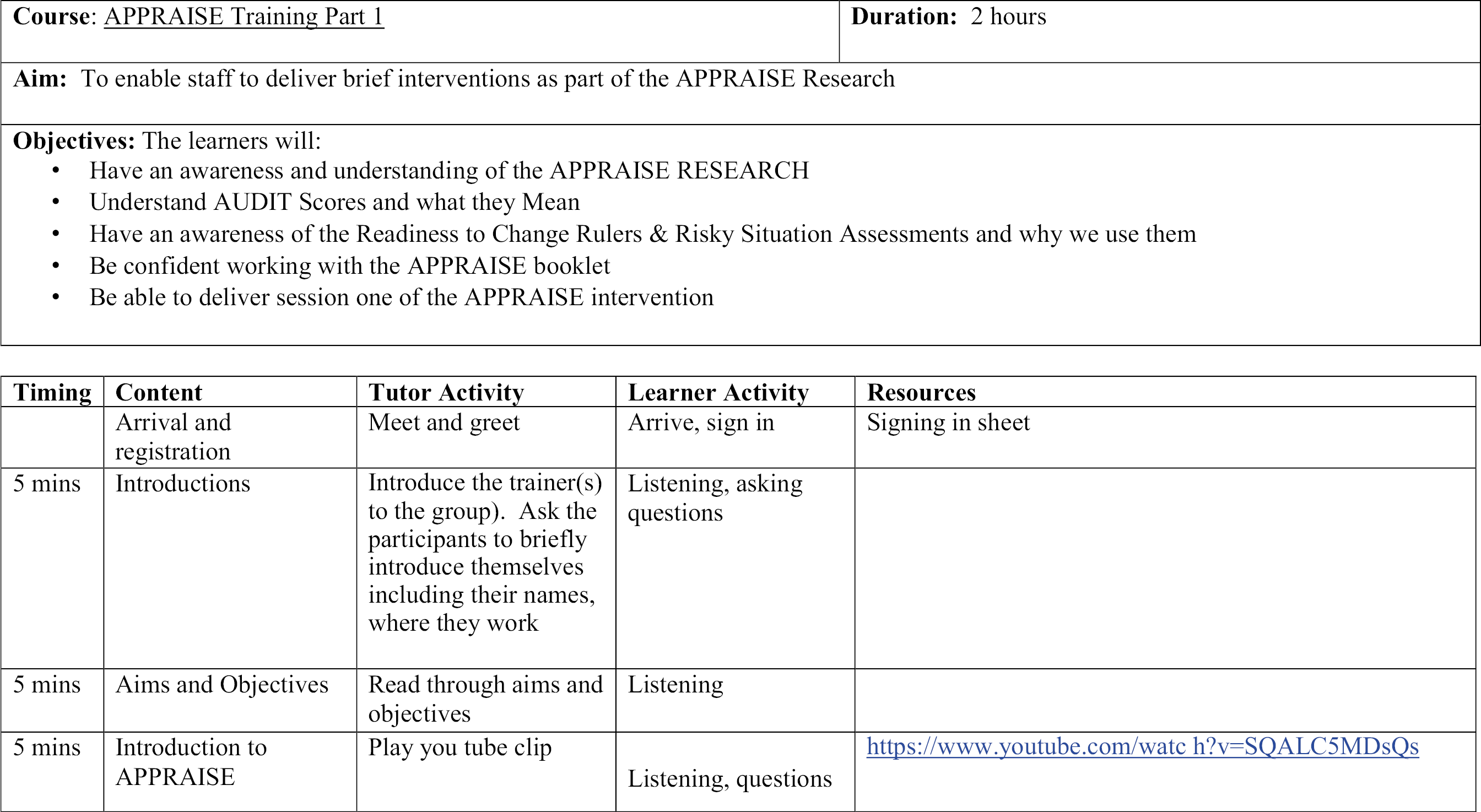

APPRAISE intervention training

Intervention training was provided at both study sites to members of the Change Grow Live (CGL) team who were supporting the delivery and which included those practitioners who would be delivering the APPRAISE intervention itself.

The aims of the training for interventionists were to:

-

have an awareness and understanding of the APPRAISE intervention

-

understand AUDIT Scores and what they mean

-

have an awareness of the Readiness to Change Ruler and Risky Situation Assessments and why we use them

-

be confident working with the APPRAISE booklet; and

-

be able to deliver the APPRAISE intervention.

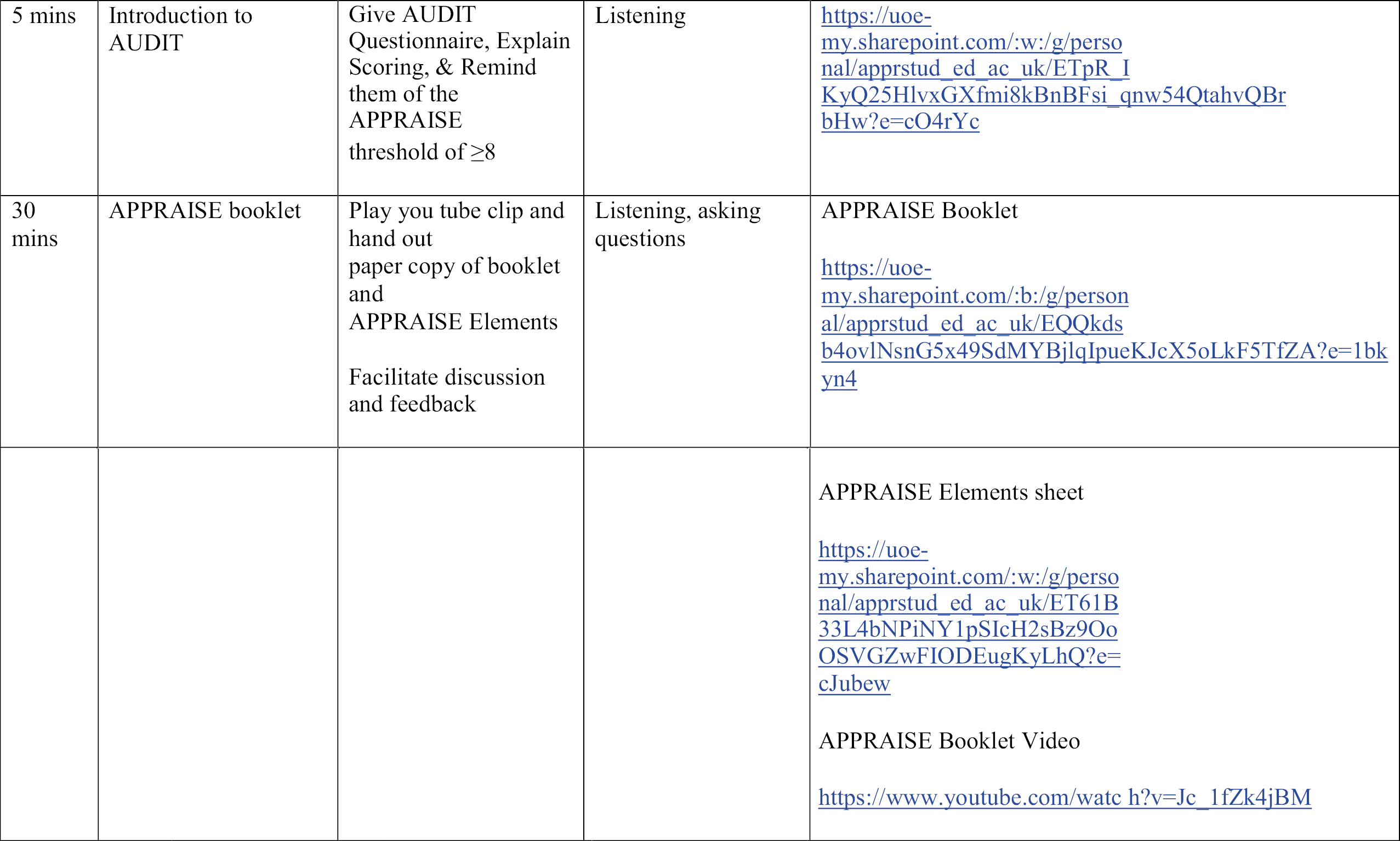

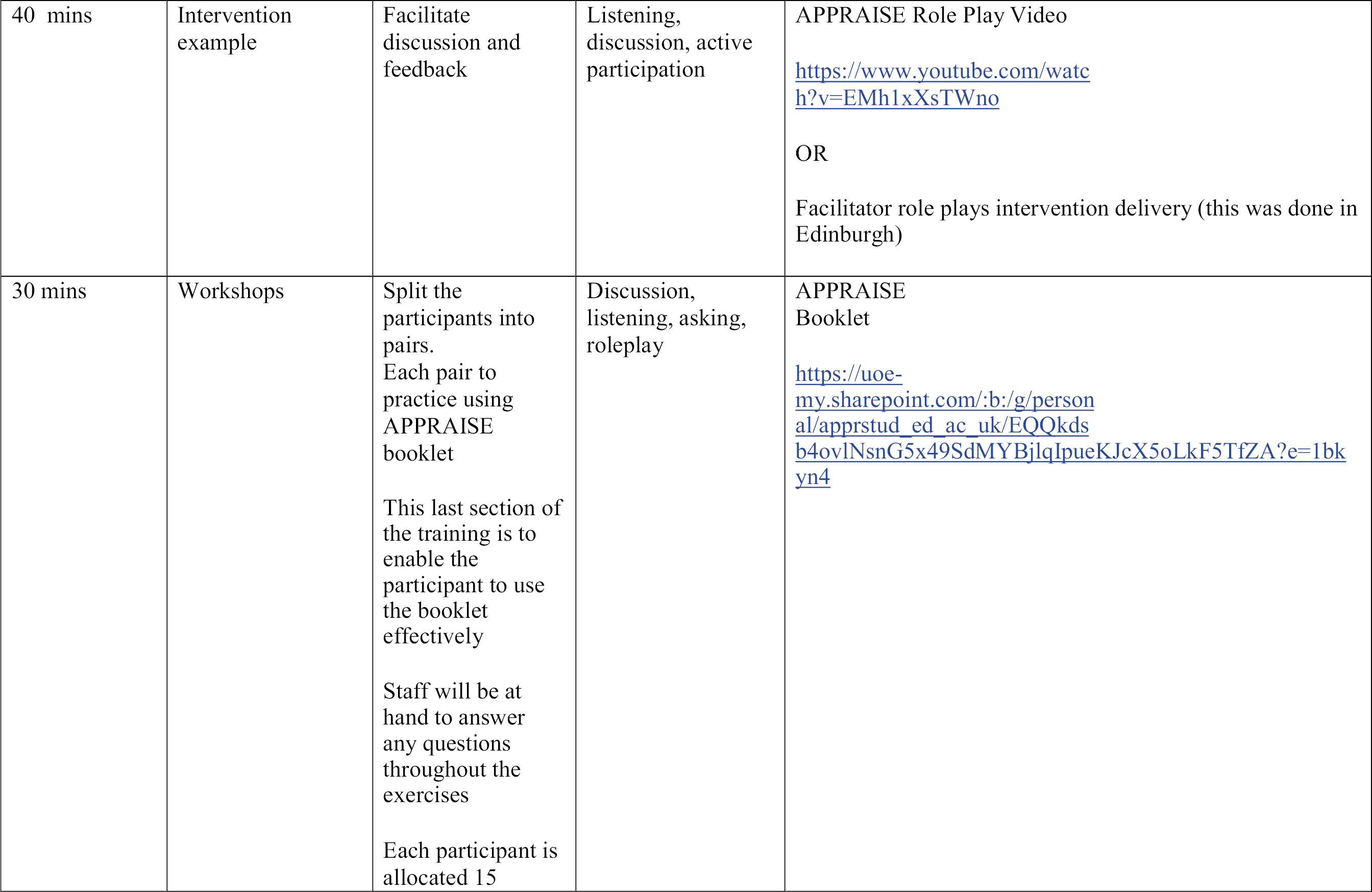

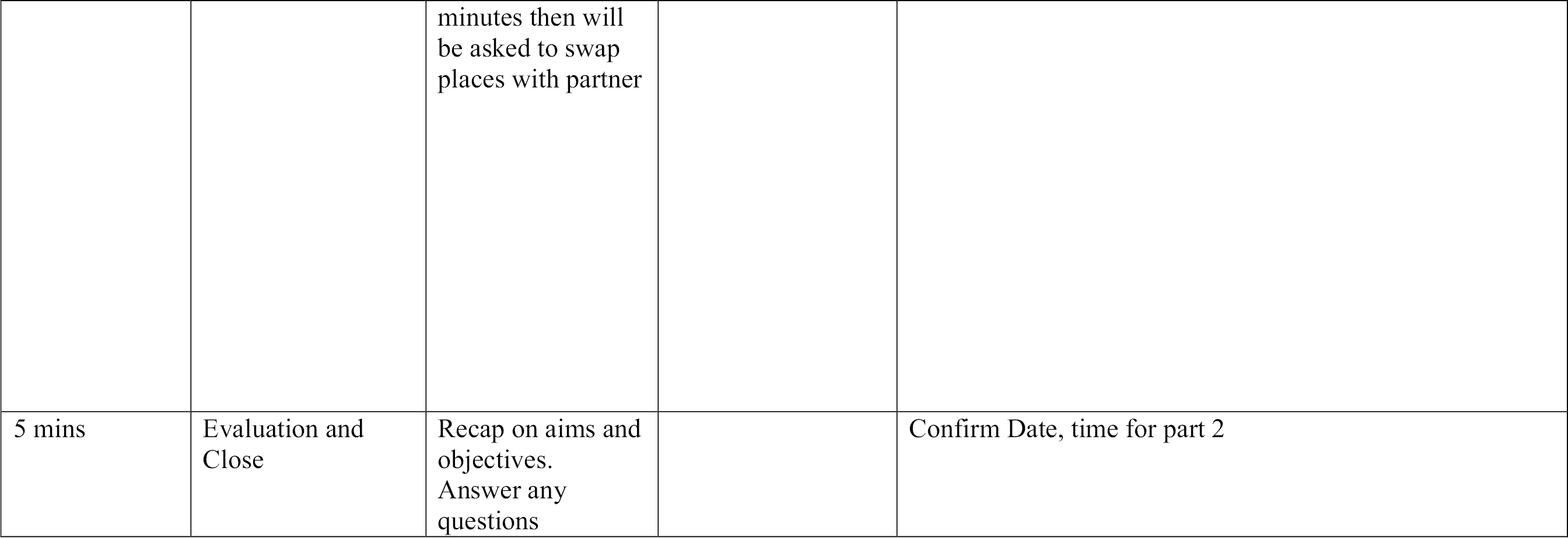

The training material ‘(APPRAISE training plan1_VG) (see Appendix 7) for the APPRAISE intervention provides interventionists with:

-

a written brief on the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention

-

paper copies of the three APPRAISE intervention documents

-

paper copy of the APPRAISE elements

-

online narrated review of the three APPRAISE intervention documents

-

intervention delivery video

-

paper copy of the AUDIT instrument; and

-

opportunity to engage in intervention delivery role-play exercises.

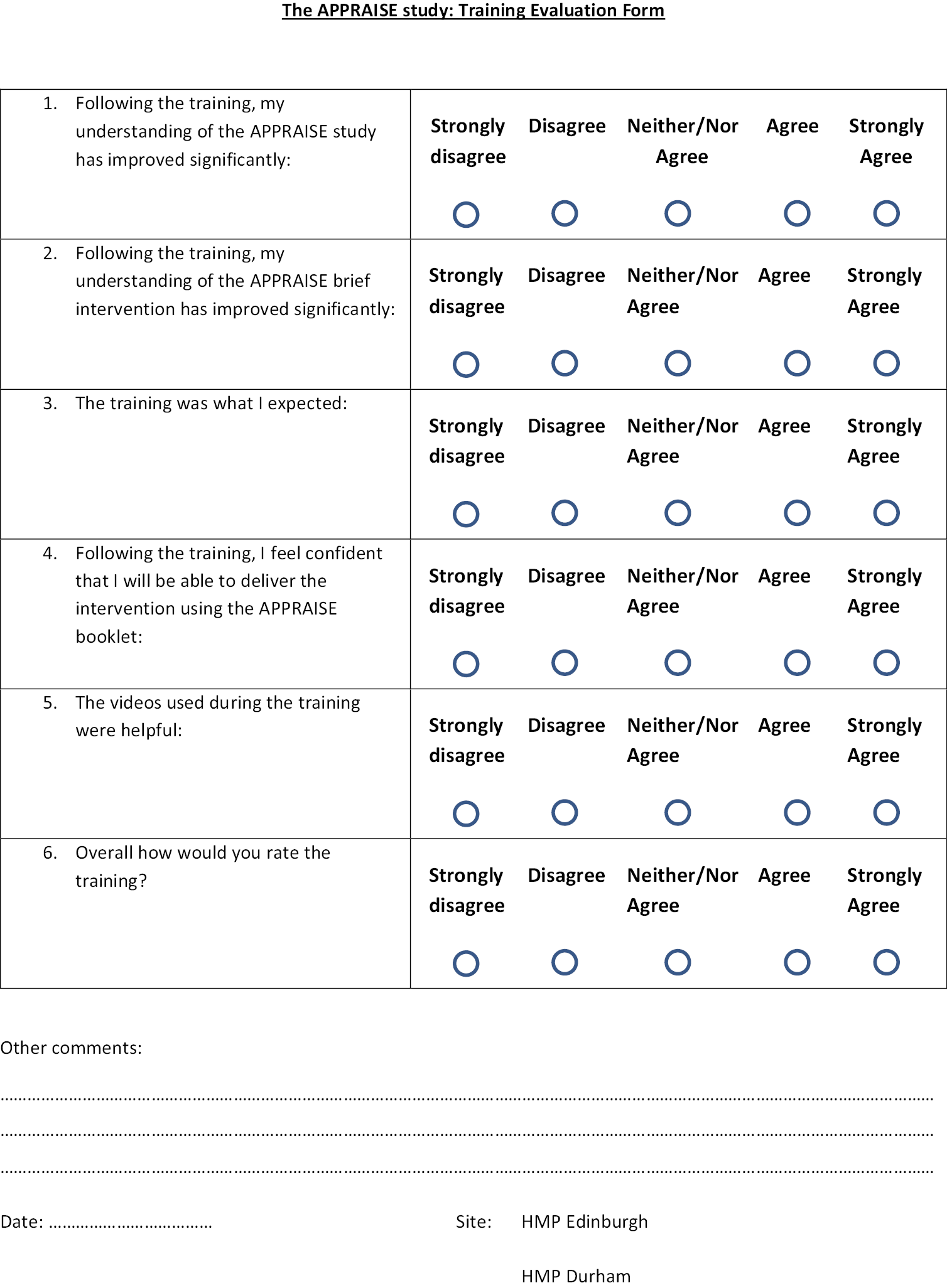

On completion of the training, a six-question Likert scale survey (see Appendix 8) as a form of evaluation of the training undertaken was self-completed by interventionists and CGL team members from both study sites (see Intervention implementation).

APPRAISE intervention delivery mode and location

Following completion of baseline assessments and randomisation, those allocated to the intervention arm were invited to attend their first of three intervention sessions. This was delivered face to face by the identified interventionist at each study site. It was delivered in a quiet room either on the residential wing, a landing or in one of the CGL designated rooms and was delivered at both sites by CGL interventionists. Four members of the CGL team from the England study site and two members from the Scotland study site attended the intervention delivery training.

At the beginning of data collection, both study sites had allocated two interventionists. Due to resource capacity and sick leave during the data-collection period, Scotland had one interventionist and England had two interventionists able to deliver the interventions.

We asked the three interventionists for details of their education and previous training experience. This request was made during COVID-19 when we were only able to communicate via e-mail. While there was a willingness to provide the information, due to the incapacity of interventionists to find the time we were unable to obtain that information.

The APPRAISE intervention comprises nine elements (Table 2) to be delivered in four steps: Step 1 comprises a 1 × 40-minute face-to-face session in which the nine elements are covered and delivered by a trained practitioner from CGL in the prison setting. Steps 2, 3 and 4 are 20-minute sessions conducted by phone, on or close to day 3, 7 and 21 post liberation. The post-liberation sessions include elements 1 (preliminary discussion), 5 (situation appraisal), 6 (goal-setting), 7 (relapse), 8 (self-evaluation/self-reinforcement) and 9 (culmination). Table 3 provides details of the intervention sessions, duration, intensity and dose.

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Element 1: preliminary discussion | Participants re-introduced to study and APPRAISE, made aware of the purpose of the engagement, emphasising confidentiality, consent and trust. Mirrored aspects of ‘Opening strategies’.48 Readiness to Change Ruler completed and list of high-risk drinking situations identified on a scale of 0–5. |

| Element 2: acquiring and providing information | Focus on participants reported level of alcohol consumption as per screening AUDIT score and their perception of the impact of alcohol on their health and life. Six key pieces of information provided: Standard units of alcohol; Recommended drinking levels; Alcohol-related health problems; Legal drink/drive limit; Tips on reducing consumption; Where to obtain information/support. Intervention Tool Postcard (Unit Card) given to keep. |

| Element 3: self-monitoring | Participant introduced to the idea of keeping a diary post liberation: they are guided through how they would complete the diary with the support of the interventionist. They are informed that the diary will encourage them to reflect and record when, where and with whom, if anyone, they have consumed alcohol, why and what type of drink to enable self-monitoring on liberation, acting as a source of self-evaluation and record of progress.49 |

| Element 4: increasing awareness | Pros and cons of drinking recorded on a balance sheet of drinking. Physiological drinking sensations experienced discussed with strategies to identify and reduce with alternative appraisal of somatic sensations identified, for example alternative stress-relieving strategies, such as relaxation techniques rather than alcoholic drink. |

| Element 5: situation appraisal and appropriate coping strategies | High-risk situations and antecedents of over-drinking identified and alternative coping strategies considered. Situations are identified in order that appropriate coping and response strategies are practised prior to the situation next occurring. Coping strategies verbalised by participant, praise provided and strategies developed further and modelled by interventionist. Participants talk through the strategy and visualise themselves carrying it out (covert modelling). The better ingrained and more automated the response is, the higher one’s self-efficacy and the lower the probability of relapse.50 Avoidance of high-risk situations may be necessary in the first instance (although can be unrealistic) until mastery with low-risk situations is achieved (progressive mastery). Core set of general control strategies also discussed: reduction in rate of drinking, sipping drinks, low-alcohol-content drinks and alternating between soft or low-alcohol and higher-alcohol drinks. |

| Element 6: goal-setting | Realistic sub-goals set, short-term so that unachievable goals initially avoided. Setting proximate goals in relation to self-efficacy development can facilitate success promptly with increase in motivation towards accession to distal goals. This approach likened to a stepladder approach of focusing on the few rungs in front of you. For example, goal may be to reduce quantity of alcohol consumption on certain days of the week. |

| Element 7: relapse | Likelihood of relapse discussed and importance of identifying the events that resulted in the relapse, not attributing relapse to stable causes, such as ability or uncontrollable causes as this can result in lowering of self-efficacy and expectation of future success. Attribution to relapse discussed and focus on appraisal due to unstable causes and not to a personal failure/ability. Majority of relapses occur as a result of emotional distress, social pressure and interpersonal conflicts, therefore appropriate relapse strategies are discussed and practised. |

| Element 8: self-evaluation and self-reinforcement | Reward for success through affective self-reaction, for example, self-congratulations. The alcohol diary is a means of self-evaluation and self-reinforcement, success is attributed to their ability and skill, resulting in feelings of pride. |

| Element 9: culmination | Reflection of preceding discussion, conclusions drawn, praise given on progress and decisions made. Plans and goals reiterated and confirmed. Agreement regarding mobile phone follow-up on liberation. |

| Element | Elements of intervention39 | Enhancing self-efficacy | Delivery mode and location | Number of sessions and location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preliminary discussion | Verbal persuasion | Face-to-face (P) Mobile phone (L) |

1 (P) 3 (L) |

| 2 | Acquiring and providing information | Verbal persuasion | Face-to-face (P) | 1 (P) |

| 3 | Self-monitoring | Verbal persuasion | Face-to-face (P) | 1 (P) |

| 4 | Increasing awareness | Physiological state | Face-to-face (P) | 1 (P) |

| 5 | Situation appraisal and appropriate coping strategiesa | Vicarious experience | Face-to-face (P) Mobile phone (L) |

1 (P) 3 (L) |

| 6 | Goal-settinga | Verbal persuasion | Face-to-face (P) Mobile phone (L) |

1 (P) 3 (L) |

| 7 | Relapsea | Performance attainment | Face-to-face (P) Mobile phone (L) |

1 (P) 3 (L) |

| 8 | Self-evaluation/self-reinforcementa | Performance attainment | Face-to-face (P) Mobile phone (L) |

1 (P) 3 (L) |

| 9 | Culmination | Performance attainment | Face-to-face (P) Mobile phone (L) |

1 (P) 3 (L) |

APPRAISE post-liberation intervention modifications due to coronavirus disease discovered in 2019

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the project. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, access to both study sites for the RAs and research team was halted. It became clear quite quickly that the impact of the pandemic resulted in there being limited or no capacity for the interventionists to follow up on liberation data of those in the intervention group or deliver post-liberation intervention. Prison staff were also unable to provide us with liberation data, as their focus was rightly on the COVID-19 response in prisons. Similarly, RAs were unable to go into the prisons and access liberation data.

Modifications on timing of the post-liberation intervention delivery were made in an attempt to provide flexibility, if there was an opportunity to deliver the post-release interventions. This meant that post-release intervention sessions could still be attempted where possible with the originally intended interval between them maintained to the extent possible (4 days between sessions 2 and 3, and 14 days between sessions 3 and 4).

Chapter 3 Pilot trial methods

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Holloway et al.,1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

APPRAISE was a two-arm, parallel-group, individually randomised pilot study of a self-efficacy-enhancing psychosocial alcohol intervention for men on remand in prison. 1 It was intended to provide the evidence to support the design of a future definitive multicentre RCT, for which new funding would be sought.

The study aligned to the MRC framework,43 using mixed methods with two linked phases.

-

Phase I involved a two-arm, parallel-group, individually randomised pilot study. The pilot evaluation provides data to inform the feasibility of a future definitive multicentre RCT.

-

Phase II comprised an embedded process evaluation. The MRC framework for process evaluation guided the planning, design and proposed conduct of the process evaluation. 44

This chapter presents the methods of the Phase I pilot trial with the pilot trial findings presented in Chapter 4, and relates to research Objectives 1 and 4 in our protocol. Objectives 2 and 3 are discussed in later chapters.

The primary research objectives of the Phase I pilot study were:

Objective 1: to pilot the study measures and evaluation methods to assess the feasibility of conducting a future definitive multicentre, pragmatic, parallel-group RCT.

-

Is it feasible to conduct a future multicentre RCT of a self-efficacy-enhancing psychosocial alcohol intervention for men on remand?

-

Can we obtain reasonable estimates of the parameters necessary to inform the design and sample size calculation for a future definitive multicentre RCT? This includes standard deviations of potential continuous primary outcomes and estimates of recruitment, retention and follow-up rates.

-

How well do participants complete the questionnaires necessary for a future definitive RCT?

-

Can we collect economic data needed for a future definitive RCT?

-

Can we access recidivism data from the PNC databases for trial participants?

-

Can we access health data from routine NHS data sources for trial participants?

Objective 4: to assess whether operational progression criteria for conducting a future definitive RCT are met across trial arms and study sites and, if so, develop a protocol for a future definitive trial. Operational progression criteria are based on previous research results. 7

-

Do the two prisons invited to the study agree to take part?

-

Based on knowledge from previous data, do at least 90 eligible participants consent to take part and be randomised across the trial arms?

-

Do at least 70% of participants who consent to the trial receive the intervention?

-

Do at least 60% of those who received the intervention get followed up at 12 months across trial arms and study sites?

Setting and site selection

The study occurred in two study sites hosting men on remand within the prison estate of the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) and His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS), one in Scotland and one in England respectively.

The complexity of the prison estate cannot be overestimated. Our learning from previous work had highlighted how essential it was to engage with our colleagues within the prison system with regard to the study. Prison governors and associated personnel at both prison sites were involved in discussions regarding the study while we were developing the initial funding application. We had built good operational knowledge as well as relationships with key personnel over the course of securing funding.

The prison governor at each site was the primary gatekeeper and contact for the study team. This proved vital in previous prison research work and again for this study. In the months leading up to data collection commencing, while waiting for ethics approval, we had several meetings with the governors at both study sites and also with appointed research study contacts for day-to-day operations. Visits were made to both prison sites to share details of the study with prison officers, health professionals and CGL over several months. The strong relationships formed were essential to our understanding of the complexities of the prison estates and the day-to-day work carried out there, providing insight into how we could undertake the research study with minimal disruption to the estate operations.

Eligibility criteria

Men detained on remand had to meet the following criteria:

-

Inclusion criteria

-

detained in either the SPS Scottish study site or His Majesty’s Prison Service (HMPS) North East England study site

-

have been in the prison setting for 3 months or less

-

aged 18 years and over

-

informed consent given

-

≥ 8 on the AUDIT screening tool51

-

-

Exclusion criteria

-

previously recruited to the study

-

unable to give informed consent or deemed incompetent/unable to make an informed decision regarding consent

-

identified as a risk to self and/or others by prison staff

-

judged to be under the influence of an illicit substance by prison or research staff

-

currently taking Antabuse

-

on a segregative rule under the prison rules

-

not able to understand the documents, which are in the English language, or agree to the research assistant (RA) working with them to understand them.

-

Prison and/or research staff were responsible for making a subjective judgement as to whether or not a remand person was under the influence of an illicit substance and whether the level of intoxication was likely to have an influence on risk or capacity to understand/consent.

Participant selection and recruitment

The prison staff were key to facilitating the selection and recruitment of study participants at both sites. At the England study site, peer induction workers were also key to this process. The RAs spent time developing good working relationships with prison staff and peer induction workers on the wing. Information regarding males on remand entering the estate was made available to the RA with the selection and recruitment process across both study sites, as outlined in Table 4.

| Scotland | England |

|---|---|

| Men on remand were given PIS by reception staff as part of their admittance. | Men on remand were held on the Induction wing. During the first 3 weeks, men on remand who were eligible were given PIS by the RA where possible. Thereafter, the RA was able to join the daily Induction session and provide the PIS and talk about the research with all new men on remand. |

| Review new arrival list sheet daily. Highlight initial eligibility of potential participants (< 3 months, high risk, Rule 95a). |

Drug and Alcohol Recovery Team (DART) provided list of new arrivals daily. RA reviewed the list. Highlighted initial eligibility of potential participants (< 3 months, high risk). |

| Arrive on wing with list and checked with prison officers any on the list eligible who may be at high risk/excluded/Rule 95. Prison officers would also identify to RA anyone who had expressed an interest to them about participating in the study. RA informed prison officer whom they wished to approach. | Arrive on wing with list and checked with prison officers any on the list eligible who may be at high risk/excluded. Prison officers and Peer Induction would also identify to RA anyone who has expressed an interest to them about participating in the study. RA informed prison officer whom they wished to approach. |

| If approval given, cell number identified and potential participant approached via door hatch. If they agreed to speak with RA, prison officer would open pad door and escort potential participant and RA to the interview room. | If approval given, cell number identified and potential participant approached via door hatch. If they agreed to speak with RA, prison officer would open pad door and escort potential participant and RA to the interview room. |

| Interview room on landing with window. RA would sit on seat nearest the door and potential participant on the other side of the table. RA reaffirmed study information, confirms exclusion and inclusion criteria and consents as appropriate. Following completion prison officer would escort participant back to the cell. If potential participant did not wish to participate, prison officer would escort them back to the cell. | Interview room glass room in middle of wing. RA reaffirmed study information, confirms exclusion and inclusion criteria and consents as appropriate. Following completion prison officer would escort participant back to the cell. If potential participant did not wish to participate, prison officer would escort them back to the cell. |

Consent

The RA at each site reviewed the Participant Information Sheet (PIS) with men on remand who met the eligibility criteria, provided a written and verbal description of the study, answered any questions or queries and then invited them to consider participating. The RA obtained informed consent from those willing to participate. Those who did not wish to participate at this point were thanked for their time and received no further interaction with regard to participating in the study.

We were aware that freedom of consent can easily be undermined for prisoners and those in the criminal justice system, which means these individuals may be more vulnerable to exploitation or abuse by researchers: learning disabilities, illiteracy and language barriers are prevalent within these populations. The prevalence of these characteristics alongside the power differential between researcher and potential participant meant that particular care was needed to ensure that valid, freely given and fully informed consent was achieved. For the purposes of this research, we considered valid consent as underpinned by adequate information being provided to the potential study participants and that they had the capacity to decide for themselves. A capable person would:

-

understand the purpose and nature of the research

-

understand what the research involves, its benefits (or lack of benefits), risks and burdens

-

understand the alternatives to taking part

-

be able to retain the information long enough to make an effective decision

-

be able to make a free choice; and

-

be capable of making this particular decision at the time it needs to be made.

Participants were asked to consent to their data being used for the present study as well as consenting to long-term follow-up (beyond this study) and for appropriate linkage to be conducted.

Stopping rule/discontinuation/withdrawal criteria

Participants were reminded during the trial that they were free to withdraw at any time without having to give a reason and without it affecting their care in the prison setting or on liberation. Where a participant wished to withdraw, we honoured their wish. We also made attempts to ascertain and document the reason for withdrawal, recording this within the case report form (CRF). Participants who requested withdrawal from the study intervention were asked if they would be willing to remain in the study for the purposes of follow-up data collection. Data provided at the point of withdrawal were retained and used in the study analysis, where the patient consented to this.

Potential reasons for participants being withdrawn from the study were: participant withdrawal of consent; RA discretion in the best interest of the participant to withdraw; the RA was informed by Prison, NHS or service staff that it was in the best interests of the participant to withdraw; an adverse event required discontinuation of participation in the trial; or termination of the trial by the sponsor.

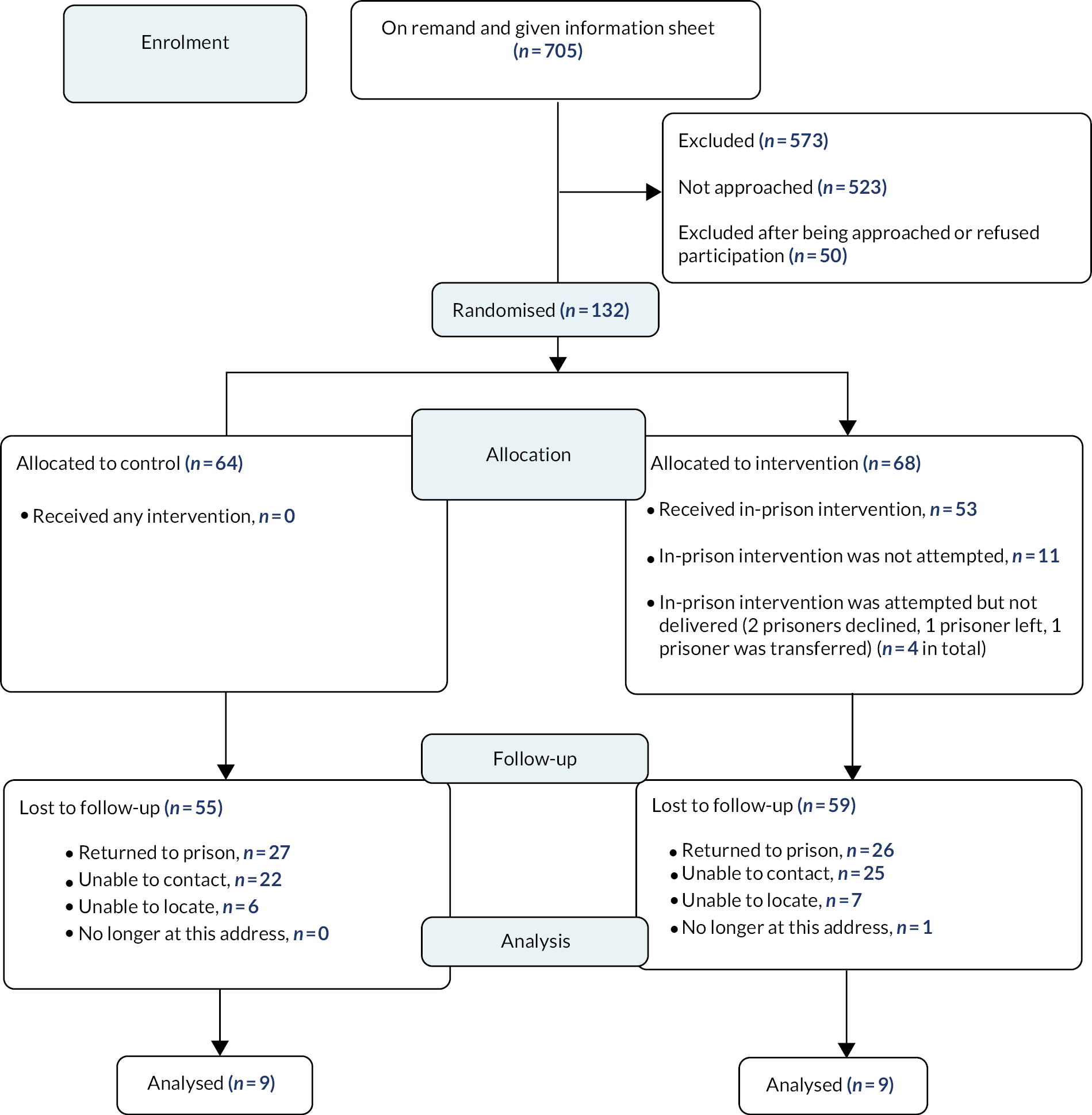

Sample size

The aim was to recruit at least 180 participants in total comprising 90 participants per study arm across the two study sites. From prison data obtained from correspondence with SPS and the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), we had estimated that approximately 50% of participants would be liberated while the rest would remain incarcerated, leaving 45 participants per study arm (90 in total) across the two study sites.

The target sample size

-

would enable us to calculate two-sided 95% confidence intervals around proportions recruited, liberated, and dropping out in each study arm with half-widths of < 0.15

-

exceeds the 30 per group recommendation of Lancaster et al.,53 and the 35 participants per group recommendation of Teare et al.,54 for estimating key unknown design parameters, for example standard deviation with sufficient precision when the primary outcome is continuous; and

-

would ensure that within each study arm within each site we were satisfying the minimum 12 per group rule of thumb of Julious for pilot trials. 55

Participant screening

The AUDIT tool51 is considered the ‘gold standard’ alcohol screening instrument and was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO). It is a 10-item screening tool designed to assess alcohol consumption, drinking behaviours and alcohol-related harms. The score is the total sum derived from the 10 questions. Scores range from 0 to 40. A score of 8–15 indicates hazardous/increasing-risk alcohol use, 16–19 indicates harmful/high-risk alcohol use and 20–40 indicates likely dependence. The AUDIT has been used previously in the criminal justice system,7 and was found to be feasible and acceptable with men on remand in the PRISM-A study. 40

After obtaining informed consent, the RAs screened all study participants using the AUDIT. Those with a score of ≥ 8 were considered eligible for the study. Those scoring < 8 on AUDIT were thanked for their time and took no further part in the study. Those with an AUDIT score of ≥ 8 completed the baseline assessment and measures and were then randomised.

Randomisation and blinding

The randomisation process was supported by the Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit (ECTU). Due to the restriction of the use of electronic equipment and no access to mobile phones by the research team and RAs while in the prison setting, we were unable to use a randomisation system, such as an interactive voice response telephone system or one accessed over the web. Allocation was conducted at the level of the participants, randomised to the active or control intervention using stratified block randomisation by site, via opaque sealed envelopes, based on a predetermined random number allocation carried out by the ECTU. Allocation was conducted by researchers opening the next sequential sealed opaque envelope after consent had been provided and the baseline assessment completed. Therefore, RAs were blind to group allocation at baseline.

The RAs were not involved in the delivery of the active and control interventions but were aware of study allocation of participants as the trial progressed. Allocation concealment was used whereby neither the person delivering the interventions nor the participant was aware of the study allocation until they were irrevocably entered into the trial. Both the trial statistician (RP) and health economists (AS, JB) were blind to group allocation prior to the final analysis and only had details of study participants by study number.

The trial statistician and health economists were only to be unblinded if requested to do so by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee Project Steering Group (DMEC), due to safety concerns. This was not necessary during the study and unblinding took place at the final analysis stage.

Self-report primary outcome measure

The proposed primary outcome measure for a future definitive study was total alcohol consumed (in units) in a 28-day period. This can be ascertained using the 28-day timeline followback questionnaire (TLFB-28). 43 Three other variables can be derived from the data: per cent days abstinent, drinks per drinking day (secondary outcome measures) and total number of days where alcoholic drinks are consumed. The TLFB-28 was to be conducted by the RA at time points (TP) 1 and 2.

Self-report secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes measures were to be completed at TP0 (baseline), TP1 (6 months) and TP2 (12 months).

Alcohol use frequency, quantity (on a typical occasion) and binge drinking were assessed using the AUDIT. 34 In order to assess the utility of using Average Drinks per Day derived from the AUDIT at 12 months as a primary outcome measure we planned to randomise the order of presentation of TLFB-28 and AUDIT and conduct a levels-of-agreement analysis, using TLFB-28 as a gold standard, to explore whether AUDIT is an acceptable proxy for TLFB-28. The order of presentation of TLFB and AUDIT was to be randomised in advance by a secure remote randomisation service. (See section ‘Follow-up plans post-COVID 19’ for changes to the use of AUDIT and TLFB-28 at TP1 and TP2.)

The following study measures were to be used across the three time points.

Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale

Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale56 comprises 14 items with five response categories, ranging from ‘None of the time’ to ‘All of the time’. The items are all worded positively and cover both feeling and functioning aspects of mental well-being. Items are scored on a range from 1 to 5, providing a total score between 14 and 70.

Drinking Refusal Self-efficacy Questionnaire – revised

This revised version of the DRSEQ57 assesses a person’s belief in his/her ability to resist alcohol. There are 19 items, each scored on a five-point Likert scale. Responses range from 1 (I am very sure I could NOT resist) to 6 (I am very sure I could resist), providing a total score between 19 and 114. A lower score indicates less self-efficacy.

Three subscales can also be calculated: Social Pressure (SP) (score range 5–30), Emotional Relief (ER) (score range 7–42) and Opportunistic (OP) (score range 7–42).

Negative Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire

The NAEQ58 assesses the extent to which people expect negative consequences to occur if they drink. There are 60 items in the questionnaire. Responses are measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1, which is ‘highly unlikely’, to 5, which is ‘highly likely’, providing a total score between 60 and 300. A lower score indicates more negative expectancies.

The items, themselves, are grouped onto three dimensions (same-day, next-day and continued-drinking expectations). The next-day and continued-drinking dimensions are combined to form the distal expectancy subscale (score range 39–195) and the same-day, the proximal subscale (score range 21–105).

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version

The EQ-5D-5L59 comprises two parts. The first is a visual analogue scale and the second is a descriptive system. There are five dimensions within the descriptive system: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression. Each has five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and extreme problems. Participants convey their health state by identifying the most appropriate statement in each of the five dimensions. Each dimension score is combined to describe health state. An X is used for the visual analogue score to identify the health of the participant on that particular day.

Readiness to Change Ruler

The Readiness to Change Ruler is used to assess a person’s readiness to change their alcohol use. 10 There are six readiness to change rulers on the assessment form. Each ruler represents a linear scale from 1 to 10, and the participant marks on the ruler their current position in the change process.

The Readiness to Change Ruler was completed immediately prior to and immediately following the initial intervention session. This was carried out by the interventionist as part of the initial intervention delivery.

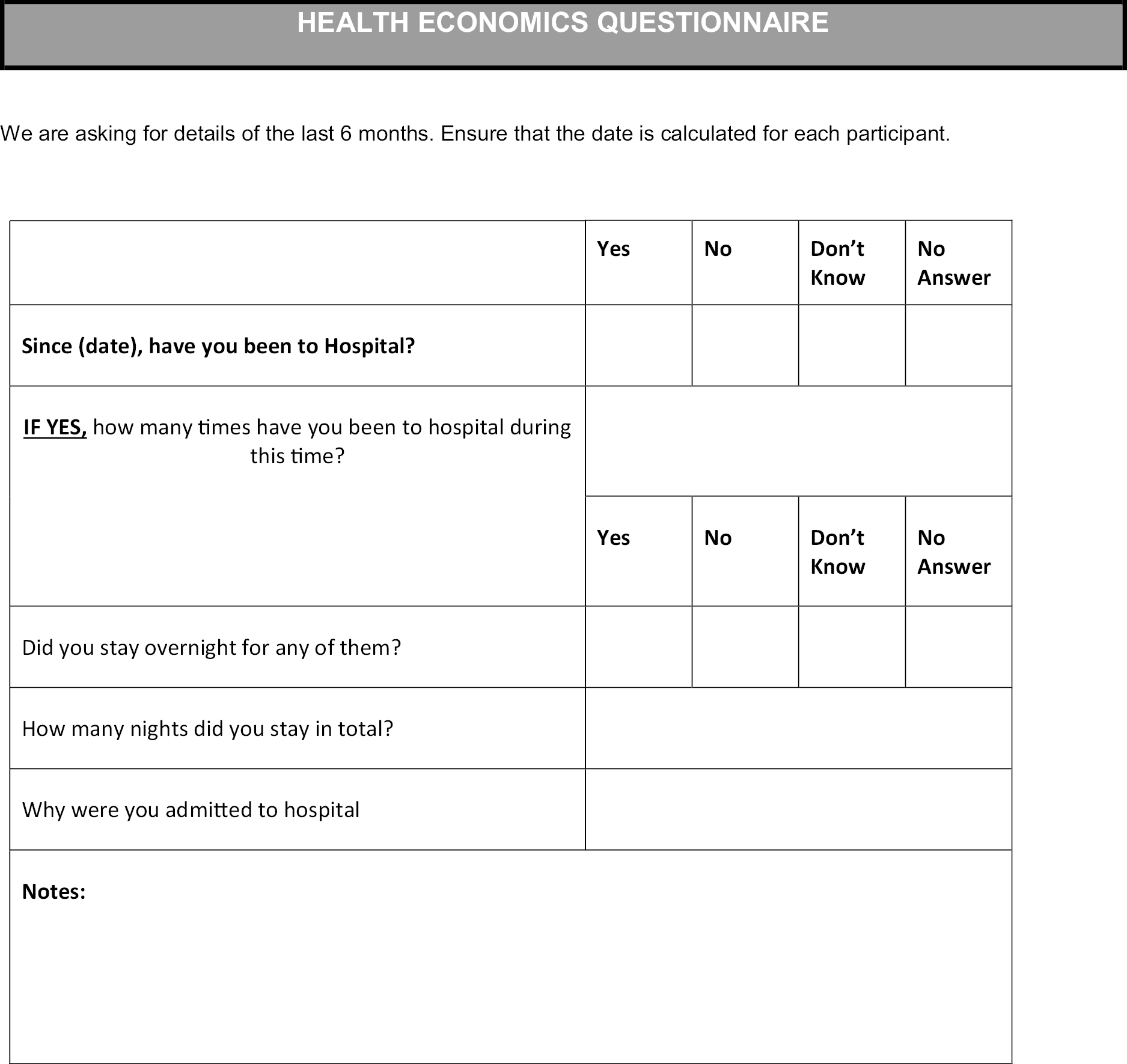

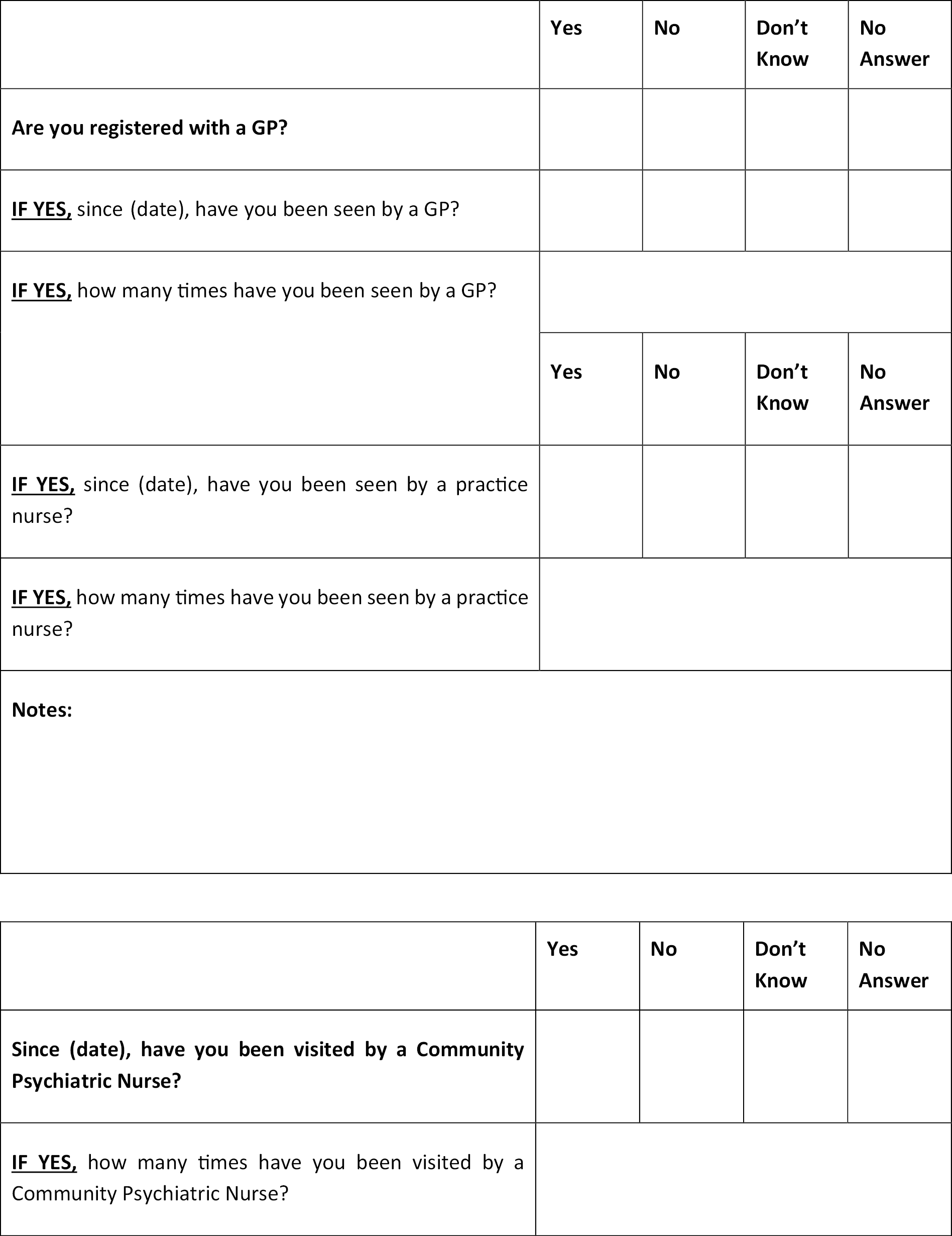

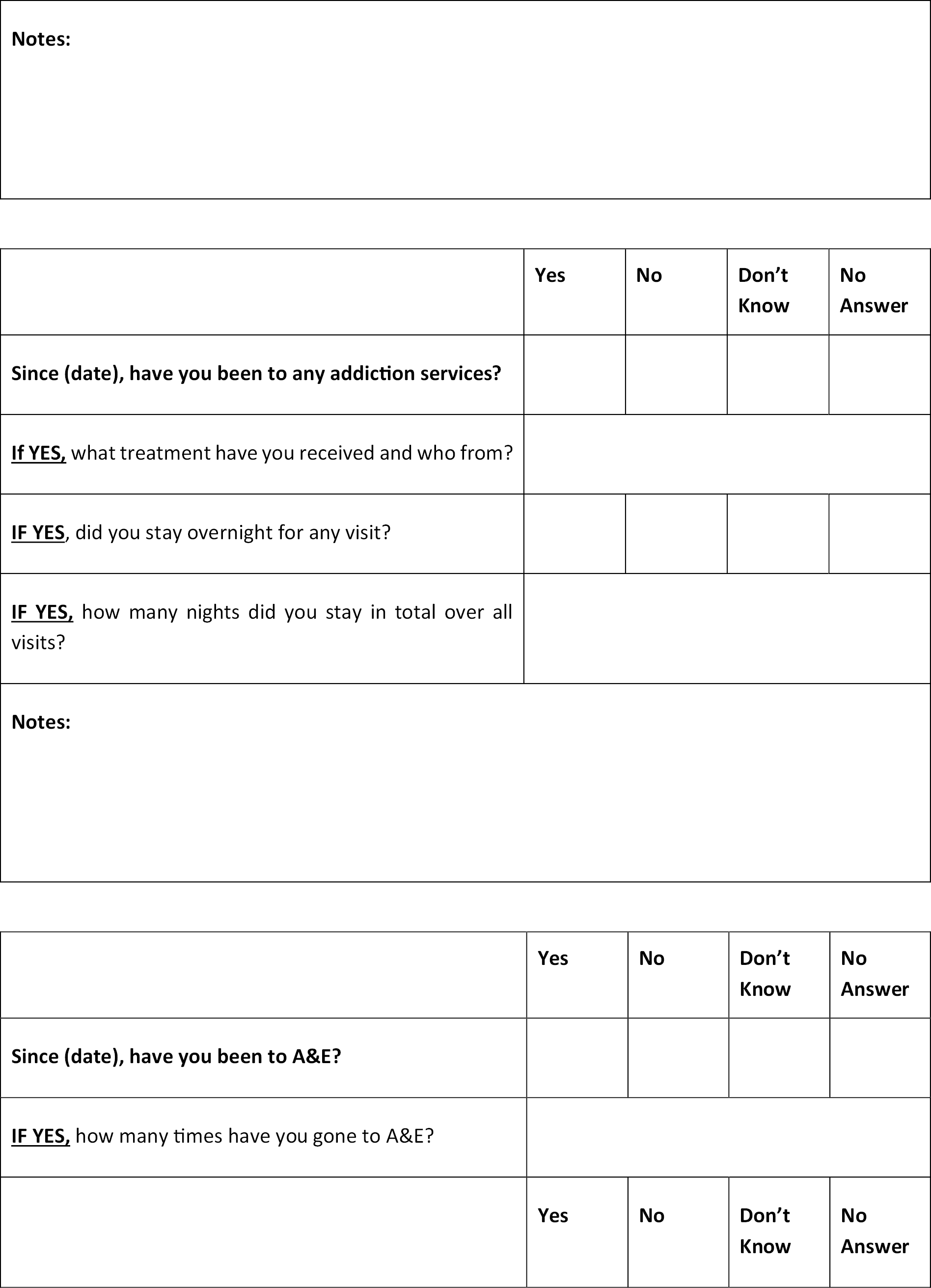

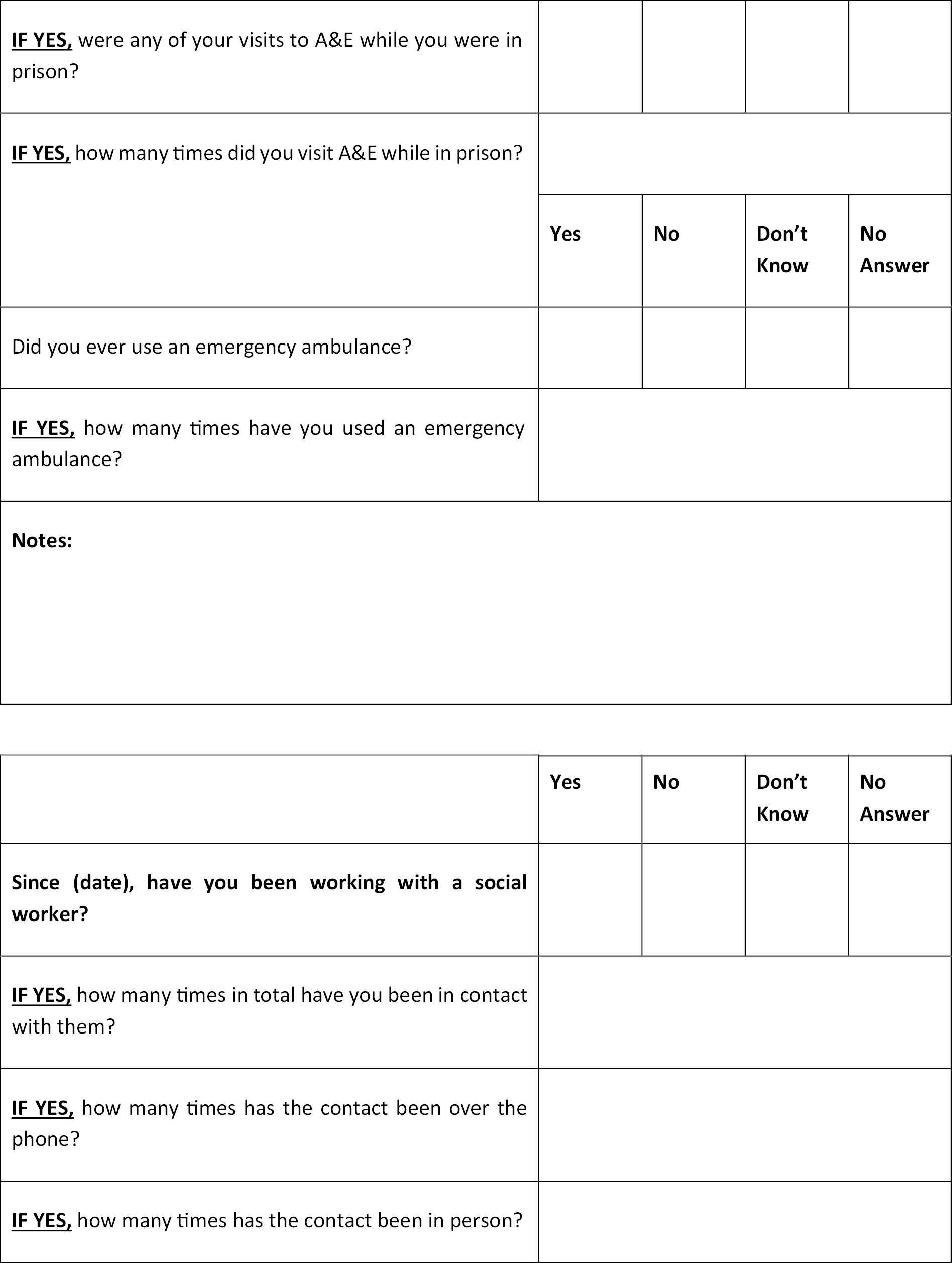

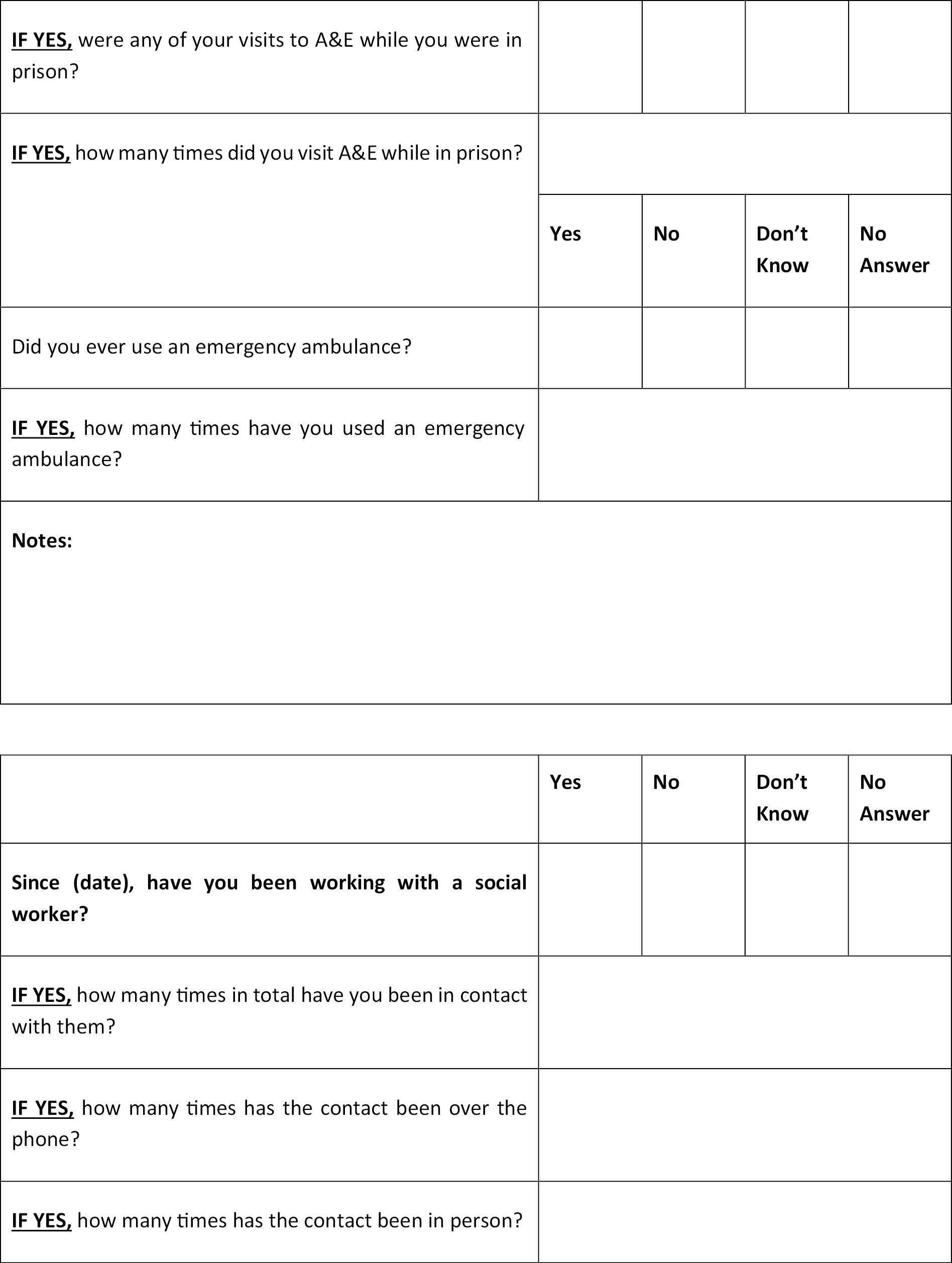

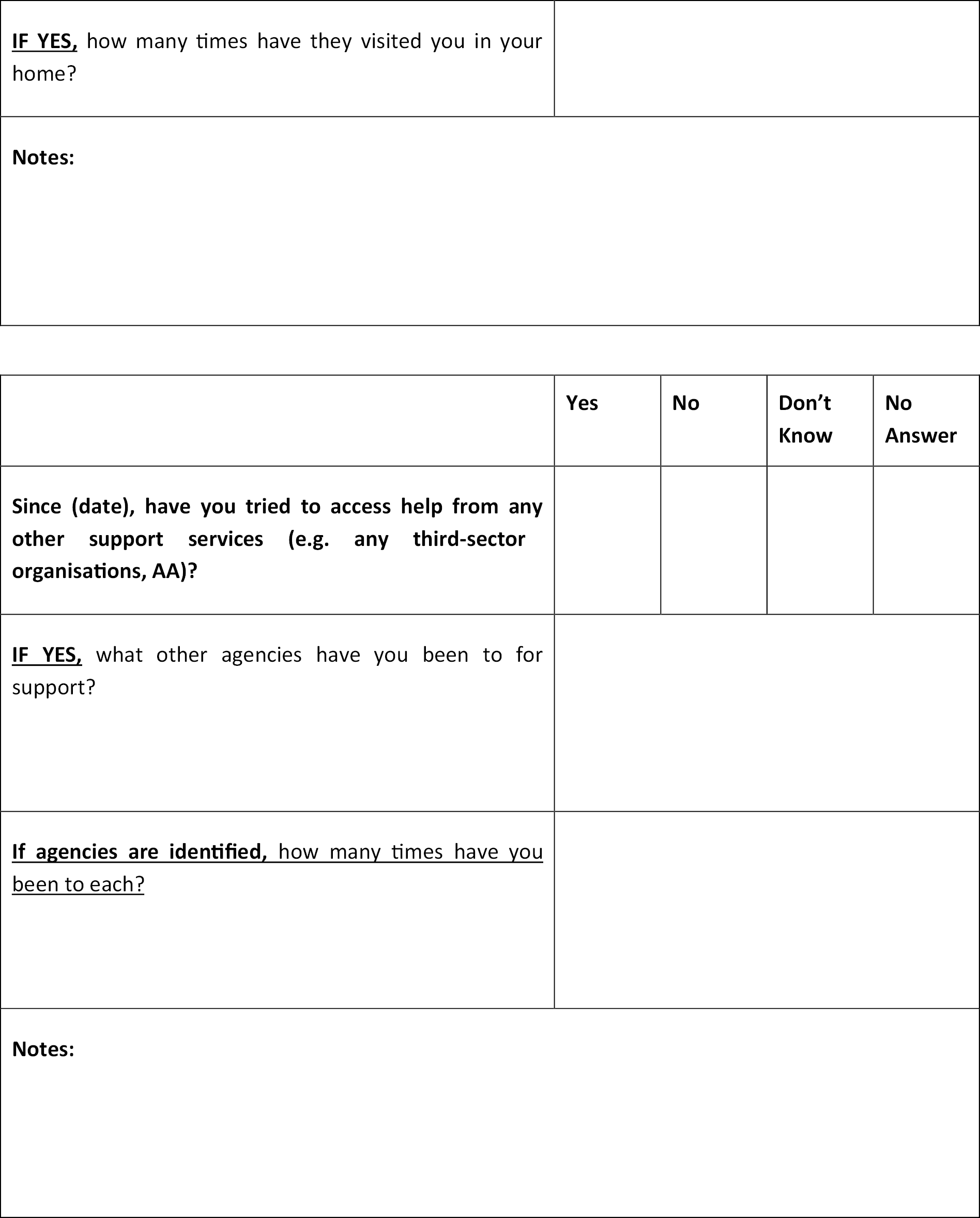

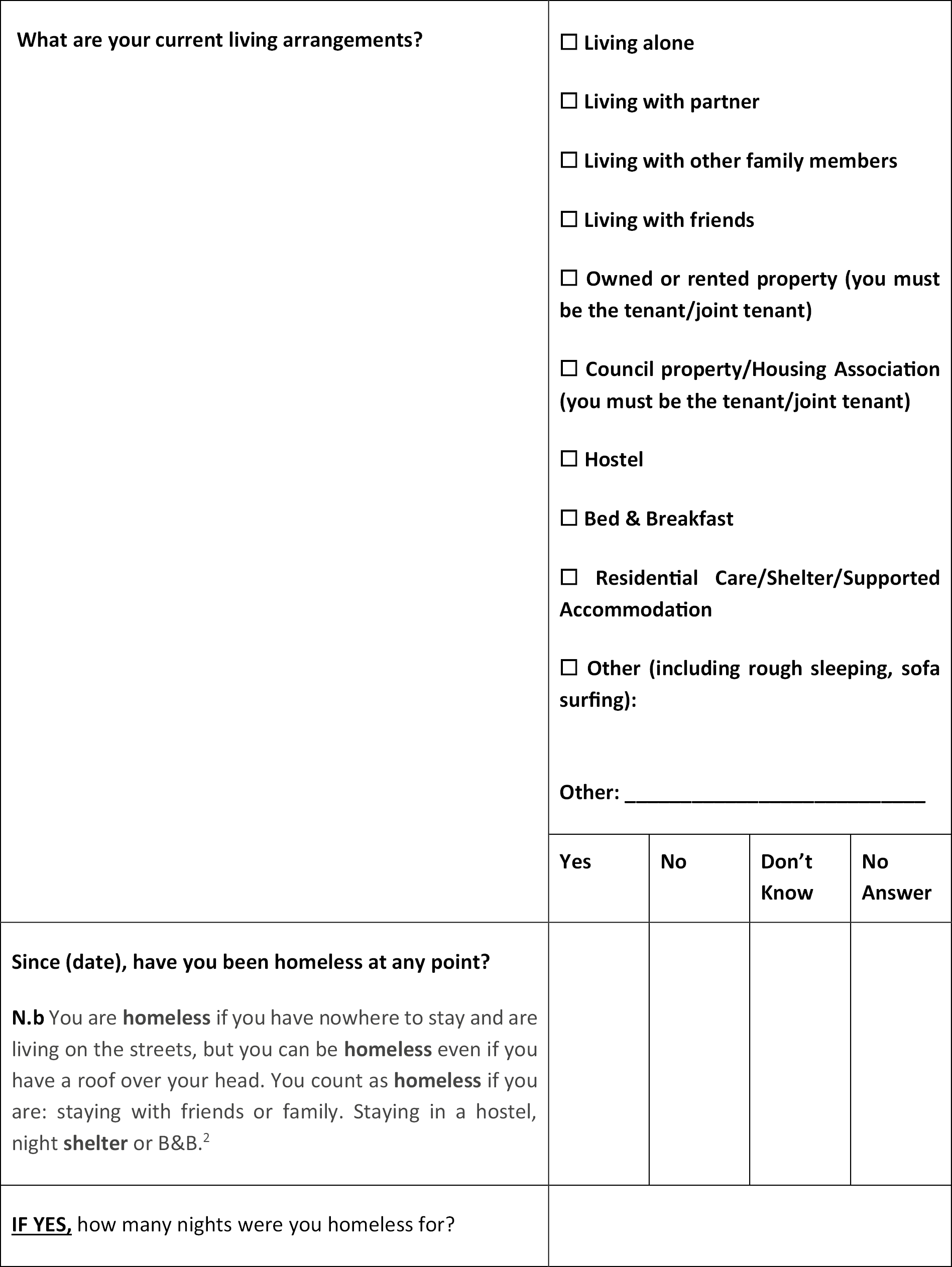

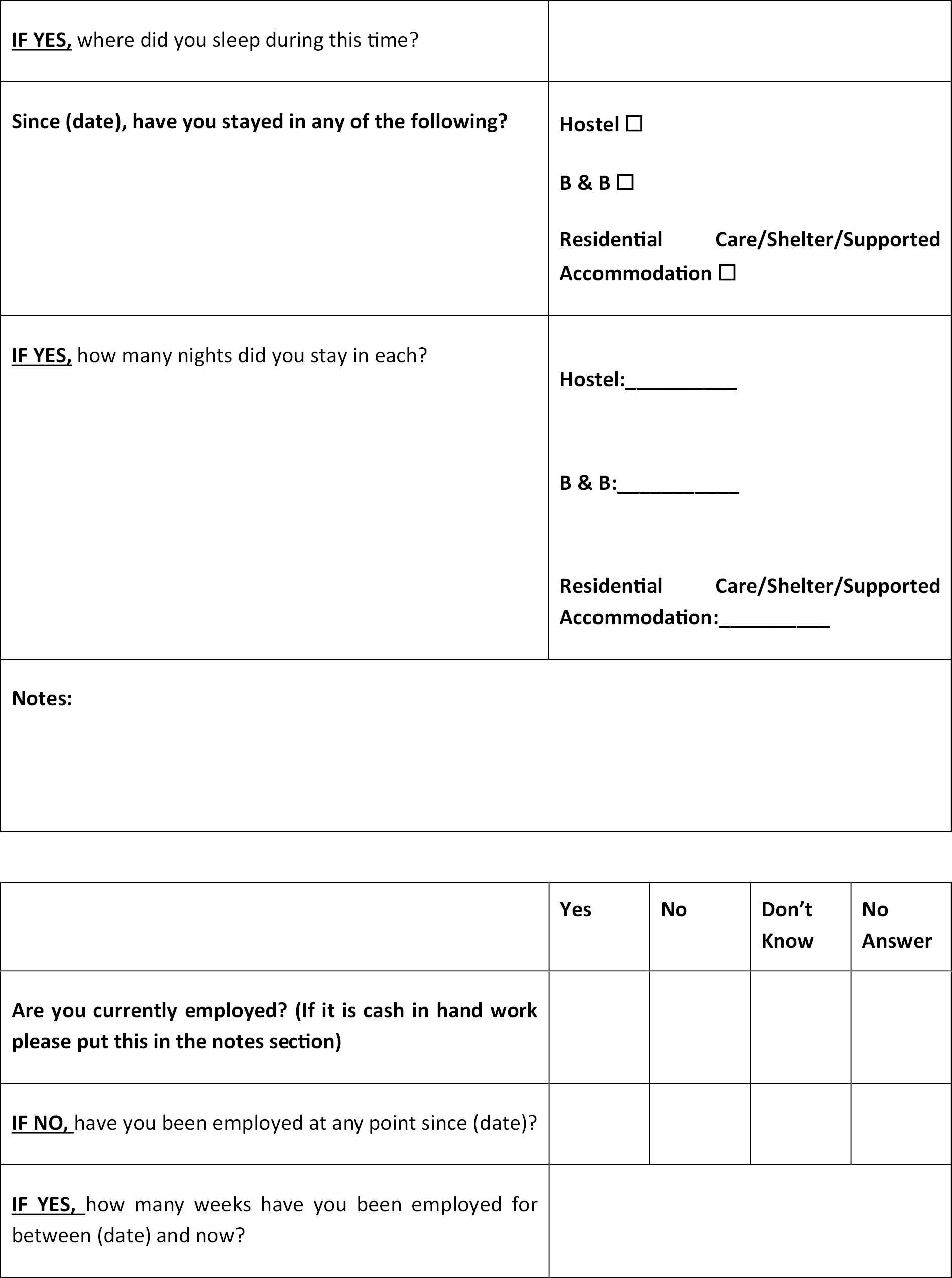

Economic Form 90

We adapted the terminology of the Economic Form 9060 (the Economic Form 90 was originally designed for American context) (see Chapter 7, Methods) to produce a service user questionnaire to determine social costs including in the domains of health and social care use, criminal justice involvement, unemployment, and welfare (see Appendix 9).

Baseline data collection and assessment of outcomes

Baseline data (TP0) collection was conducted prior to randomisation to prevent observer or respondent bias to questions asked or answered at baseline by knowledge of the randomisation group, with follow-up data collected at TP1 (6 months) and TP2 (12 months).

The baseline assessment data were collected via researcher-led completion of hard-copy questionnaires embedded within the Baseline CRF (TP0). Due to restrictions on the use of electronic equipment in the prison estate, we were unable to use electronic devices to record study data on site. The RA was able to answer any questions and offered clarification as needed. The baseline assessment took approximately 35 to 60 minutes. Participants also completed the Participant Locator Form (see Appendix 10). The Locator Form was used to collect information from participants about a range of methods, modes and formats of contacting them at follow-up if they were liberated. Immediately after, participants were randomised, informed of their allocation,61 and thanked for their time.

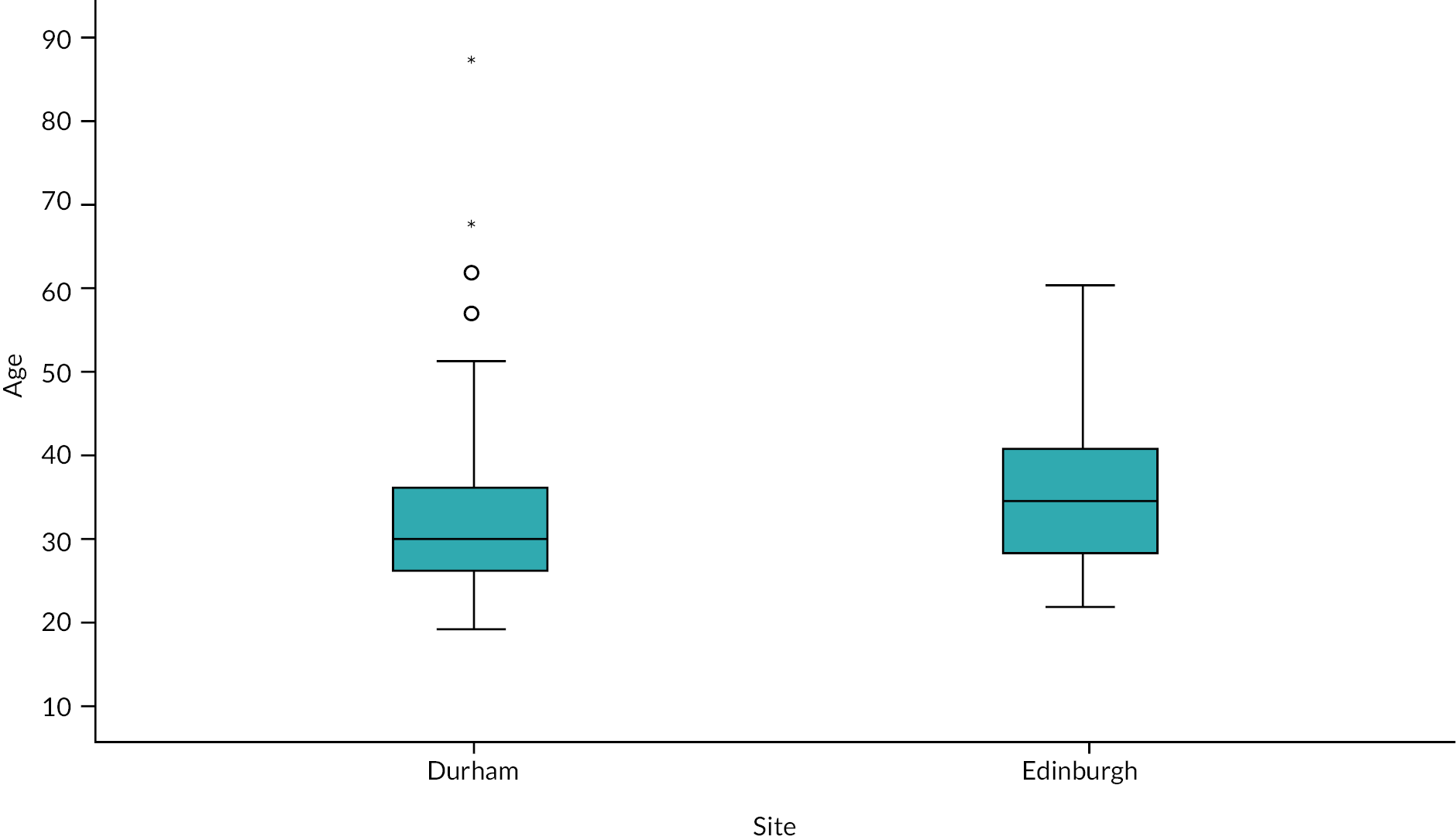

The baseline CRF recorded demographic data on age, known court dates, ethnicity, postcode [Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD)], relationship status, and educational achievement. In addition, baseline data on proposed secondary outcome measures were recorded via the Readiness to Change Ruler,10 the EQ-5D-5L,59 the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale,56 the Drinking Refusal Self-efficacy Questionnaire – revised,57 the Negative Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire,58 and a revised version of the Economic Form 90,60 which recorded data relating to hospital and or A/E visits, general practitioner (GP) registration and visits, engagement with Community Psychiatric Nurse, engagement with any addiction services, emergency ambulance use, engagement with social worker, current living arrangements, ever been homeless, employment status, number of arrests and number of court visits.

Control condition (care as usual)

The control condition (care as usual) consisted of similar components at both study sites.

England control condition

All men held on remand are screened by a reception nurse on reception. If a substance misuse need is identified in the screening, they are referred to the Drug and Alcohol Recovery Team (DART) and the team then sees them the following day to complete the triage and comprehensive assessment. Those men who decline the offer of the DART service are then revisited to be given harm-reduction information and a point of contact if they need to self-refer further into their sentence. Posters are displayed around all of the establishment and anyone or any service can refer an individual to DART.

They refer to the relevant community substance misuse treatment service for an individual’s release and ensure the service user understands when and where their appointment is. They also offer additional support through the gate with their Reconnect Navigators, who will support those individuals who are more complex and struggle to engage to their first appointment.

Scotland control condition

For those service users who expressed that they are looking for alcohol support, the support is person-centred and based on the person’s needs. Following assessment, individuals would agree a recovery plan with their worker, the recovery coordinator, and support Scotland Mental Well-Being Scalemay be alcohol awareness, harm reduction, motivational support and relapse prevention. The frequency of this would be dependent on the individuals’ needs and would not be time-limited. People with alcohol issues could be referred to the relevant region’s alcohol service for counselling support if they wanted this. If the individual was returning to the region where the prison was, they would be offered through-care support from a recovery support service. This would include practical support as well as substance misuse support to help them reintegrate back into the community.

Intervention condition

Following completion of baseline assessments and randomisation, those allocated to the intervention arm were invited to attend their first of three intervention sessions. This was delivered face to face by the identified interventionist at each study site. The APPRAISE intervention was delivered at both sites by CGL.

The in-prison and post-liberation elements of the APPRAISE intervention are described in full detail in Chapter 2.

Follow-up data collection

We worked with our PPI co-applicant and former community justice mentor, who mentored men in prison and on liberation, to advise on the strategies to maximise retention and follow-up. These strategies were based on her own experiences of following up her mentees on liberation and were also strategies used by CGL community justice workers. Each study participant provided their preferred method of follow-up by completing the Locator Form at baseline.

Follow-up assessments were to be attempted at 6 months (TP1) and 12 months (TP2) post-randomisation where the participant had been (a) not liberated, (b) liberated and in the community, or (c) liberated and then re-incarcerated. An 8-week window was in place for the follow-up to be completed for both of the time points. If a participant was not contacted at 6 months they were still approached again at 12 months. Follow-up was to be conducted by the RA at each study site. However, due to changes in personnel at both study sites during the study, all follow-ups for both study sites were not conducted by the RA who undertook recruitment and baseline measurements. Feedback from all RAs noted that participants responded to follow-up more positively when it was the RA they knew and remembered from recruitment and baseline. There was a sense of trust that had been built which was less evident when the new RAs were undertaking the follow-ups.

Follow-up plans pre-coronavirus disease discovered in 2019

Participants were initially followed up using one of the following methods, determined by the information they provided at baseline interview as part of the Locator Form completion:

-

by phone call (at varying times and days of the week)

-

via hard copies of the follow-up questionnaire sent by post with an accompanying letter to be completed and returned to the study team via a pre-paid envelope; two reminders were sent; or

-

via hard copy in prison for completion with the RA.

Follow-up plans post-coronavirus disease discovered in 2019

As a result of the impact of COVID-19 on the planned follow-up strategy, modifications were made to the follow-up method, procedures, data collection format, measures, and CRFs. These were discussed by the project management group (PMG) and then at the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Ethical approval for these amendments was sought and gained.

Additional follow-up approaches were added: text message, WhatsApp, Facebook and an electronic Qualtrics link to the survey sent by phone or e-mail. Follow-ups were to be conducted over the phone by the RA. Where study participants were identified as being incarcerated at follow-up, we would attempt to make appropriate arrangements with the relevant prison to establish if it was possible to visit and undertake the follow-up assessment. Due to the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, access to the England study site was still not possible and for the Scotland site, although access had started to return, it was restricted and was only possible in a few instances, by which time the study had concluded.

Participants who had given permission to use social media were also sought on Facebook and one attempt to contact them was carried out (we were limited to one attempt as per ethics committee stipulation).

COVID-19 restrictions meant that we were unable to undertake face-to-face interviews. We therefore developed alternative formats of CRFs for participants to complete at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Our amendment allowed us to send electronic copies via Qualtrics link to participants (if they had consented to us contacting them in this way) and would allow for self-completion using hard copies. We simplified the CRFs to accommodate this and removed the TLFB-28, which required in-person administration. We therefore replaced the AUDIT and TLFB-28 with the extended-item AUDIT-C questionnaire. Previous studies have shown AUDIT-C and the TLFB-28 demonstrating excellent levels of agreement on alcohol consumption. 4 An overall total score of ≥ 5 is deemed as AUDIT-C positive, and indicates increasing or higher-risk drinking. 62

The NAEQ includes three sub-sections. The final sub-section was removed as it was considered as having potential to cause distress when self-completed. This was discussed at length by the PMG and with particular input from our PPI co-applicant. The layout of the Health Econ Form was also simplified to support self-completion.

Statistical methods/analysis plan

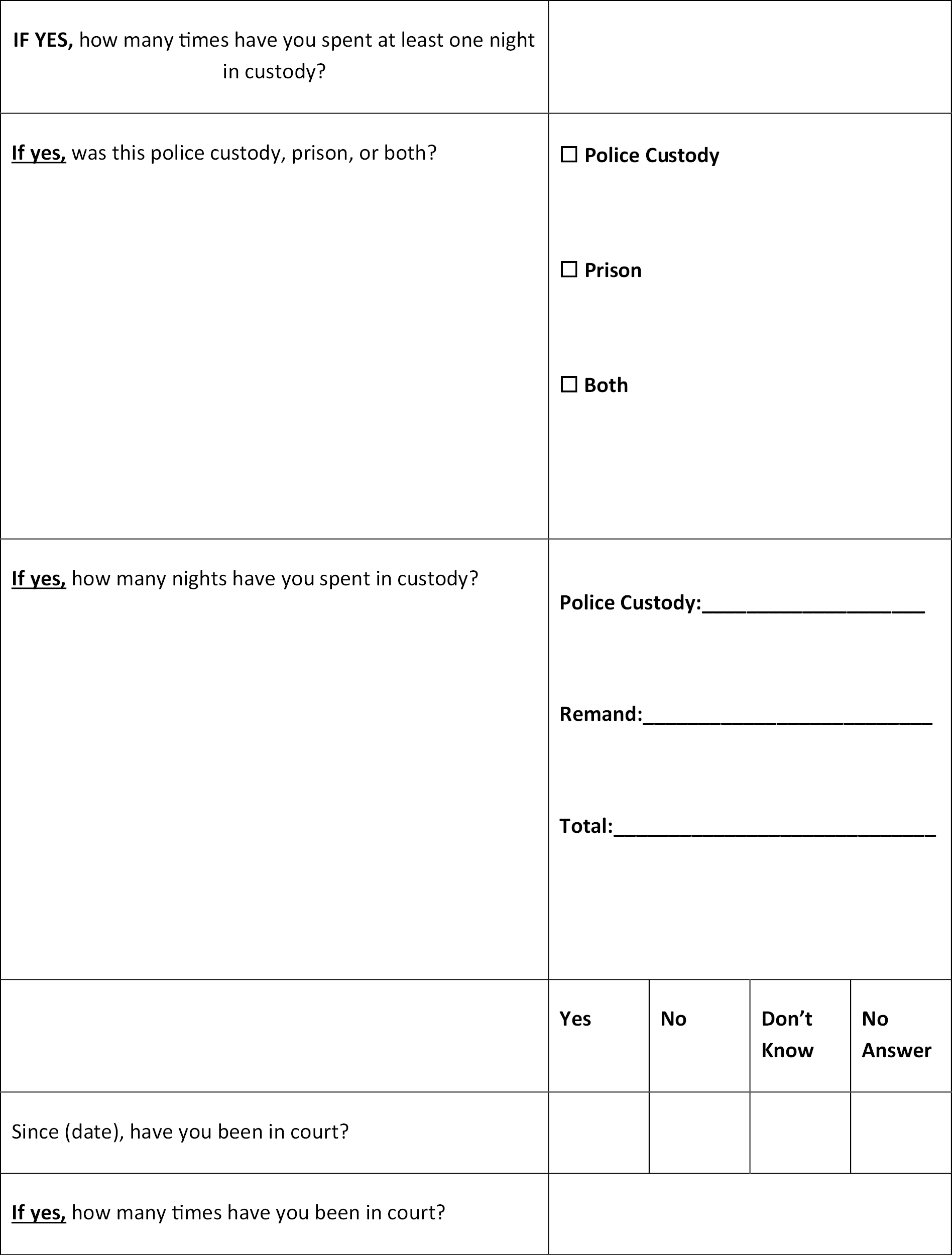

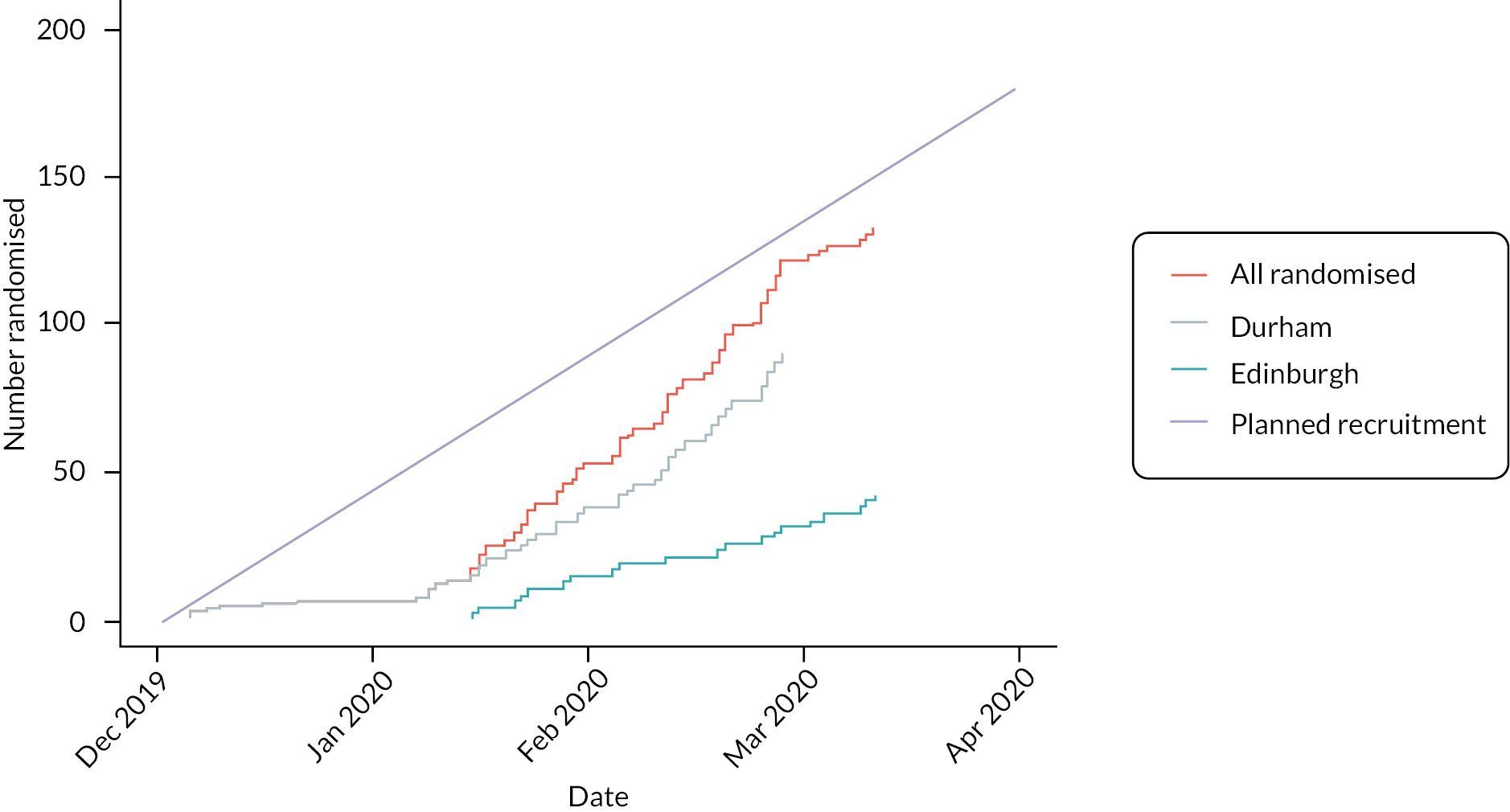

The progress of participants through the APPRAISE pilot trial is presented in accordance with CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines40 to allow descriptions of key parameters required for a future RCT: eligibility rates, consent, adherence, retention at follow-up and data completeness of outcome measures.

Overall statistical principles

Analyses were based on a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) population unless otherwise stated. The modified ITT population included all participants who were randomised into the APPRAISE study, if they had provided valid non-missing data for each outcome at the relevant time points. Participants were analysed according to the trial arm they were randomised to, irrespective of the treatment they received, continuing study eligibility, or compliance post randomisation. Participants who discontinued with the intervention, withdrew, or were non-compliant with the protocol were included in the ITT population, provided that valid outcome data were recorded for them.

It was assumed that any missing data were missing-completely-at-random (MCAR). Although a multiple imputation analysis was specified in the protocol paper, this approach is only valid when the proportion of missing data lies between 5% and 40%. 63 Very high amounts of missing data at follow-up meant that no multiple imputation was performed and all missing data were left as missing.

Lancaster et al. 53 recommend that the analysis of a pilot study should be mainly descriptive and focus on confidence intervals. Therefore, the analyses focused on calculating descriptive statistics and two-sided 95% confidence intervals rather than on hypothesis tests or p-values in general. Outliers were identified by viewing boxplots and/or histograms of the outcome variables of interest and were queried at the data-checking stage where an error had been suspected. All analyses included outliers as standard unless otherwise stated.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was to be collected at TP0, TP1 and TP2. The primary outcome for the pilot study was alcohol consumed in the 28 days prior to TP2, assessed using the extended Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C). This was calculated using questions 1 and 2 of the AUDIT-C, which address frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed. 64,65 Responses to question 1 were recoded; Never = 0, Monthly or less = 0.25, 2–4 times per month = 0.75, 2–3 times per week 2.5, 4–5 times per week = 4.5, 6 or more times per week = 7. Question 2 was recoded; 1–2 drinks = 1.5, 3–4 = 3.5, 5–6 = 5.5, 7–9 = 8, 10–12 = 11, 12–14 = 13 and more than 14 = 16. The weekly consumption was derived by multiplying the recoded values for question 1 and question 2 together and then multiplying the product by 4 to derive 28-day consumption.

The original AUDIT-C measure is known for right censoring quantity of consumption and as a consequence being less responsive to change in heavy drinkers. Extending the AUDIT-C response categories we aimed to have a trade-off between minimal completion burden and granular data. We initially tested our assumptions about categorisation of consumption in data sets that contained the extended AUDIT-C and TLFB and found minimal benefit of allocating a daily consumption value over 16 units per drinking day, something that has been further confirmed in other studies using the extended AUDIT-C to assess weekly consumption. 66

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures are the Readiness to Change Ruler,10 the EQ-5D-5L,59 the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale,67 the Drinking Refusal Self-efficacy Questionnaire – revised,57 the Negative Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire,58 and a revised version of the Economic Form 90. 60 Measurements were recorded at baseline (TP0) using a combination of self-completion and researcher-led completion of a hard-copy questionnaire. These measures were to be collected again at 6 months (TP1) and 12 months (TP2) post randomisation where participants were (a) not liberated, (b) liberated and in the community or (c) liberated but back in prison.

Recruitment, adherence and follow-up retention analyses

Trial management data, the Intervention Delivery Logs, and follow-up questionnaires were used to assess recruitment, eligibility, adherence, and retention at follow-up. For recruitment and eligibility, the following trial management data (recorded from the initiation of the trial until full recruitment is reached) were considered by each study site where possible:

-

number entering on remand

-

number given information sheet

-

number approached

-

number consented

-

number randomised and

-

number followed up at each time point.

These numbers were used to calculate appropriate proportions, which are reported for the entire study and by site. Exact 95% confidence intervals were calculated for key overall proportions relating to recruitment, adherence and retention.

Descriptive summaries

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the following variables:

-

baseline characteristics

-