Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number 16/122/20. The contractual start date was in March 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in December 2022 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Booth et al. This work was produced by Booth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Booth et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout this chapter has been reproduced from Cochrane et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes some additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Young adult offenders commonly have a range of health and social needs, making them vulnerable to mental health problems. 2,3 Those aged between 18 and 24, who have been investigated for a suspected low-level offence, may need to attend court and, if convicted, face penalties such as prison. However, many believe that more should be done to prevent young adults from entering the criminal justice system to begin with. Diversion is a process whereby an accused offender is formally moved into a programme in the community, such as an out-of-court community-based intervention (OCBI), instead of entering the criminal justice system. 4 Despite the use of diversion programmes in the UK, particularly among a younger population,4,5 the evidence base around the effectiveness, including health benefits, of diversion is still unclear.

The Gateway programme, an OCBI, was developed by Hampshire Constabulary (HC), in partnership with local third sector organisations with the aim of improving the life chances of young adult offenders. In the programme, a mentor (navigator) assesses the needs of each young adult and develops a pathway with referrals to healthcare and other local support services (e.g. housing). Young adults then take part in two workshops (LINX team) about empathy, and the causes and consequences of their behaviour. The components of the Gateway intervention are underpinned by theory and have been evaluated in isolation;6–12 there has been no previous attempt to evaluate the combination of elements as used in the Gateway programme.

Existing research on diversion and recidivism among young populations

A literature review of challenges to engagement, with diversion programmes aimed at promoting a public health approach to crime, was undertaken in January 2020. A summary is provided here and the full review is in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Literature searches were conducted using CINAHL, EMBASE, Europe PMC, MEDLINE, National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Library and Web of Science databases using the search terms: 'diversion', 'out-of-court disposals' and 'court diversion'. The 15 included studies on diversion have largely been undertaken outside the UK; the majority being conducted in the USA, with a few studies in Australia, New Zealand and the rest of Europe. Most of the studies focused on younger populations and on family treatment as a therapeutic intervention. For example, multisystemic therapy is a resource-intensive programme, which focuses on factors within the offender’s social network that contribute to their offending behaviour. 13 Treatment usually takes place within the community, such as at home or at school. A meta-analysis of diversion programmes for juvenile offenders was undertaken in 2012 and identified 28 studies involving 19,301 youths. 14 The most common outcome reported among the studies was recidivism, the tendency of the offender to reoffend. Of the five types of programmes included, a statistically significant reduction in recidivism was only observed for family treatment (OR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.82). Overall, there was high heterogeneity among the studies in terms of the research and programme design, as well as the quality of programme monitoring and implementation. The mean age of the population in studies identified by the meta-analysis ranged from 12.6 to 15.9 years of age. An evaluation of Checkpoint, a court diversion programme which does not respond to the needs of a particular age group but is aimed at adults, found a lower reoffending rate in comparison to the control cohort. 15 Despite the lack of robust evidence, the case for diversion among young adults is increasing, due to a growing recognition of their varying levels of maturity and complex needs. 16,17

According to HC statistics for 2018/20, the five main offence categories for this age group where formal action was taken by the police are possession of drugs, violence, shoplifting, criminal damage and public order offences. These young adults often represent a vulnerable population with a range of complex needs, such as mental health issues and substance misuse. They are more likely to come into contact with the police both as suspects and victims of crime and are significantly over-represented in the formal justice process, accounting for approximately one-third of police, probation and prison caseloads. 16

In the UK, several Police Forces are exploring the use of out-of-court disposals among 18–24-year-olds involved in less serious offending. 18 Out-of-court disposals are usually given where the offence is perceived to be a low-level crime. The aim is to divert the young adult away from their offending behaviour. However, evidence of the effectiveness of diversion interventions among this population remains limited.

Rationale for intervention and current study

The Gateway intervention model was conceived as a ‘culture changing initiative’ that sought to address the complex needs of young adult offenders aged 18–24. Central to this is the belief that transitions into adulthood are not linear and that more work is necessary to support desistance among this vulnerable population. By combining components shown to have an impact, at least in the short term, the Gateway programme aimed to provide a more comprehensive approach with longer-term impacts. HC understood the need to undertake a robust assessment of the cost and effectiveness of implementing the Gateway programme. In addition, to understand the potential generalisability, the study included a qualitative evaluation. This mixed-methods approach aimed to ensure the study evaluated the impact of the intervention on participants, account for the views of victims, assess the intervention itself and examine the cost-effectiveness of the Gateway programme. The study included a wide set of outcomes with a particular focus on health and well-being of offenders, victim satisfaction and reducing reoffending.

Research aims and objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Gateway programme issued as a conditional caution compared to a court appearance or a different conditional caution.

The study objectives were to:

-

Examine the effectiveness of the Gateway intervention on (1) health and well-being including alcohol and substance use, (2) access to and use of health and social services and (3) quality of life, among young adult offenders.

-

Explore the views and experiences of victims.

-

Assess the implementation of the Gateway intervention as delivered in the study and the generalisability of the findings.

-

Identify and measure all relevant consequences, both cost and benefits, of the Gateway intervention compared with usual process.

-

Examine the effectiveness of the Gateway intervention on reoffending.

Chapter 2 Effectiveness trial

Methods

Material throughout this section has been reproduced from Cochrane et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. The text below includes some additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

To assess effectiveness of the Gateway programme the researchers undertook a pragmatic, superiority randomised controlled trial (RCT) with participants aged 18–24 who had committed low-level offences and resided within Hampshire and Isle of Wight (IoW) area. There was an internal pilot and an economic evaluation was planned. RCTs provide the most robust method to establish whether an intervention is effective. Participants were randomised using a 1 : 1 allocation ratio to either the Gateway conditional caution (intervention) or disposal as usual to a court summons or a different conditional caution (usual process).

To capture the impact of the intervention on participants and other stakeholders, a qualitative evaluation was carried out (see Chapter 3).

Research aims and objectives

The aim of the trial was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Gateway programme issued as a conditional caution compared to court summons or a different conditional caution. The objectives addressed in this chapter were to:

-

Examine the effect of the Gateway intervention on: (1) health and well-being including, alcohol and substance use (2) access to and use of health and social services and (3) quality of life, among young adult offenders.

-

Identify and measure all relevant consequences, both cost and benefits, of the Gateway intervention compared with usual process.

-

Examine the effect of the Gateway intervention on reoffending.

Study sites

The four trial recruitment sites were Southampton Central Police Station, Portsmouth Central Police Station, Newport Police Station on the IoW and Northern Hampshire Police Investigation Centre in Basingstoke, with recruitment from across Hampshire and IoW.

Population

The study population were 18- to 24-year-old offenders residing within HC area. According to police statistics, the five main categories of offences for this age group are: violence; possession or trafficking of drugs; theft; criminal damage; and public order offences. These young adults represent a vulnerable population with a range of complex needs, such as mental health issues and drug and substance misuse. They are more likely to come into contact with the police both as suspects and victims of crime and are significantly over-represented in the formal justice process, accounting for approximately one-third of police, probation and prison caseloads. 16

Recruitment

The researchers’ process for recruitment acknowledged that the study population represented a vulnerable group with complex and overlapping health and social needs, therefore engaging with them was likely to be challenging. According to police estimates at the start of recruitment, an average of 23 individuals would be eligible to receive the Gateway intervention each month across all sites.

By law the police must know the destination for an offender at the time of disposal. As the intervention was one of the disposal options, randomisation had to take place at the time of disposal. It was agreed with HC that their investigators would be trained to identify and recruit participants. An approach used successfully for a previous study. 19

Police investigators, dealing with potential participants, received face-to-face and/or online training from the Gateway Inspector or Sergeant. The non-mandatory 1-hour training introduced the aims of the study and eligibility. Also covered were the consent process, and use of Alchemer (formerly SurveyGizmo), a web-based eligibility and randomisation tool, to ensure standardised recruitment and recording of eligibility criteria (see Randomisation).

The Police Gateway Team monitored recruitment daily, contacted investigators about potentially eligible cases to remind them about the Gateway caution and study, and discussed with investigators where a potential participant had been missed. All the Gateway and study documentation and information were readily available on the HC computer system. A variety of methods were used to raise and maintain awareness of the Gateway study within HC, such as computer screen savers, notices in police station offices and newsletter articles from the Deputy Chief Constable. Refresher training was offered throughout the study period.

Further information on recruitment is provided in Stage 1 consent.

Consenting participants

Participation was voluntary. It was not felt appropriate for police investigators to obtain fully informed consent because of the potential risk of coercion, nor was it practical given the timelines. The researchers therefore developed a two-stage consent procedure.

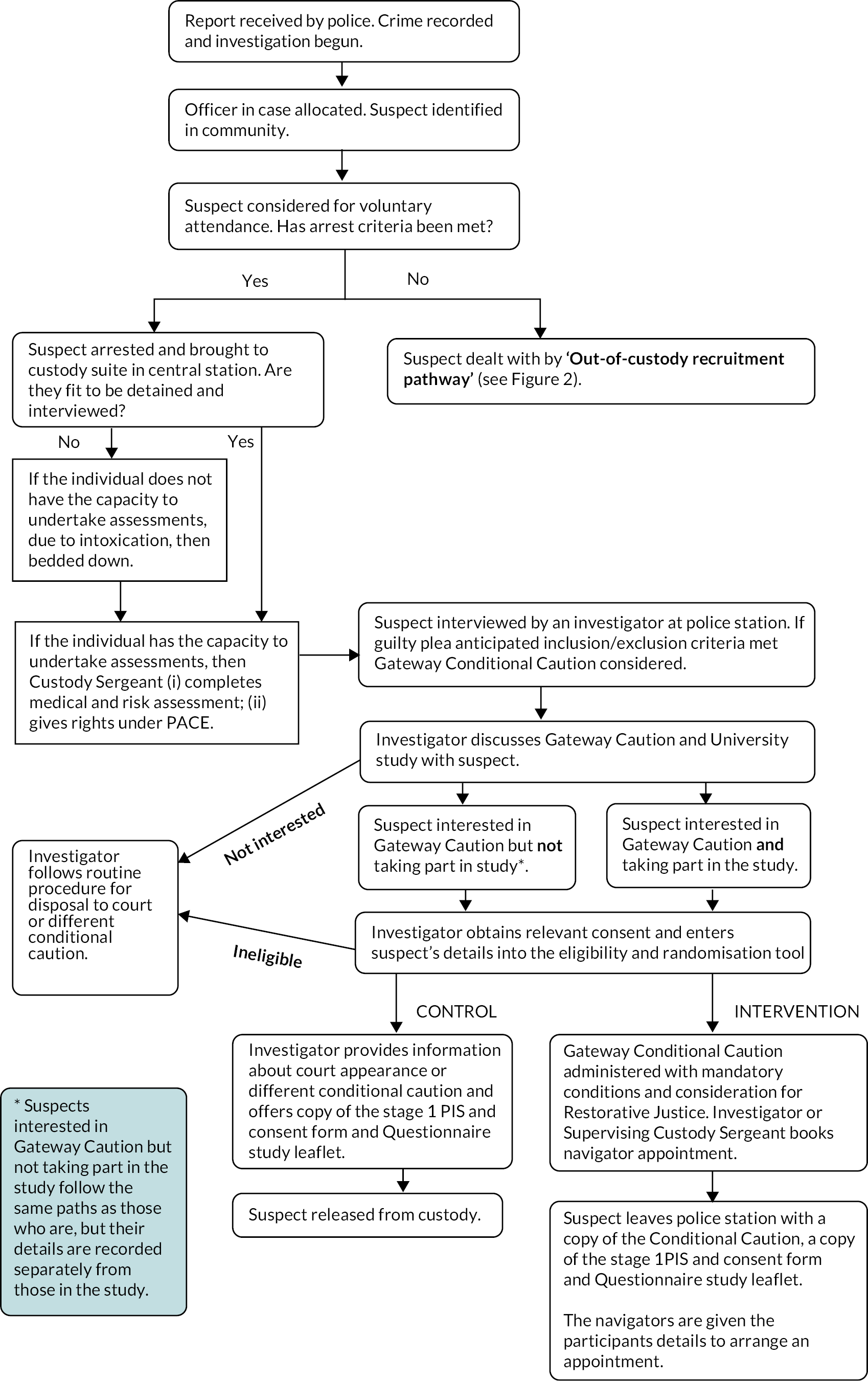

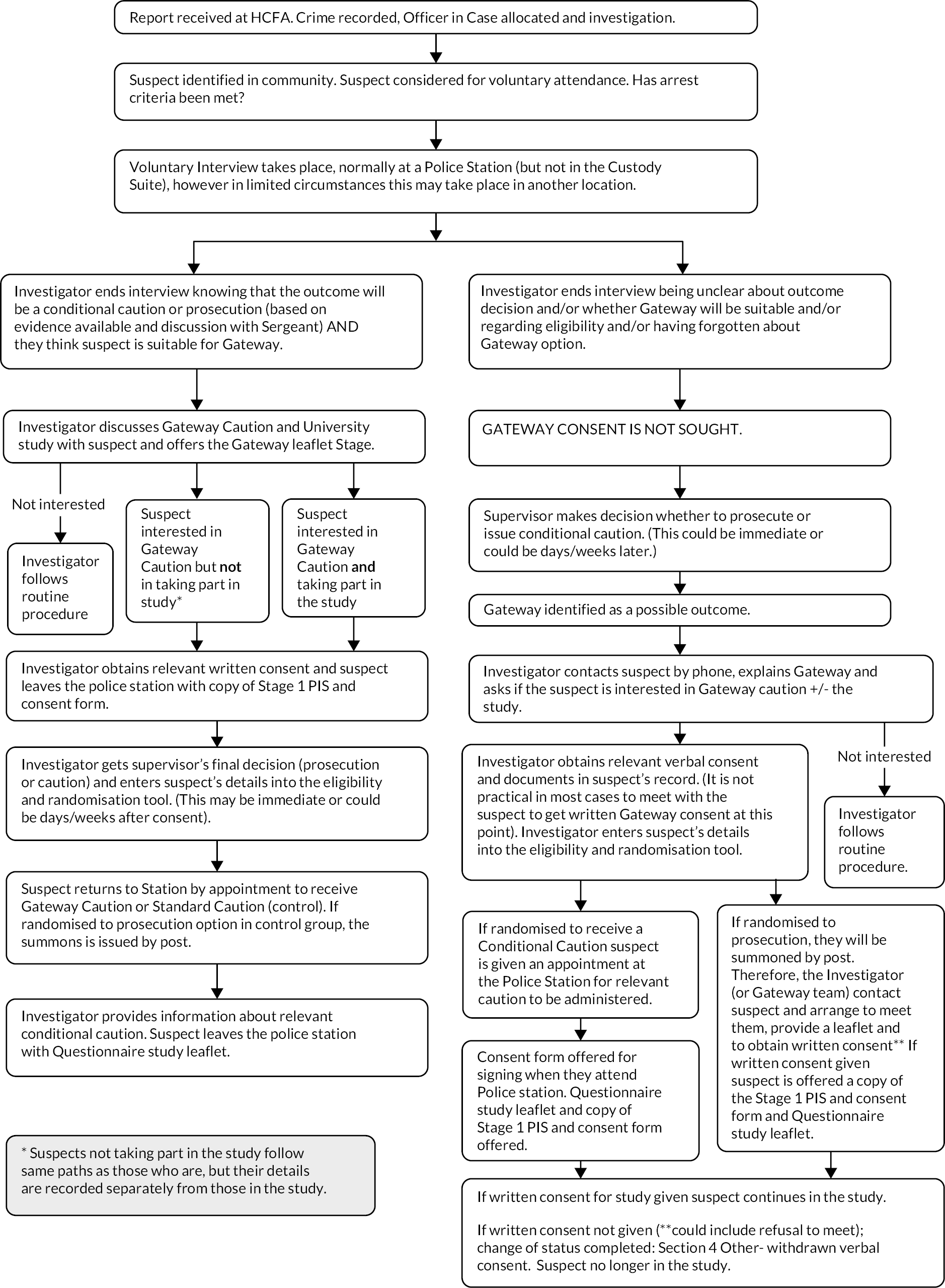

Stage 1 consent

During processing in custody, investigators identified potentially eligible participants (see Appendix 1, Figure 8) and discussed with them the Gateway programme. For legal reasons, the Gateway caution was initially offered as a potential disposal option independently of the study. If interest was shown, the offender was then informed about the ‘Questionnaire Study’ (terminology used in participant facing materials). A Gateway Caution information leaflet (produced by HC independently of the study) and a Questionnaire Study leaflet with link to a video (see Report Supplementary Material 2) were offered and/or e-mailed later. Potential participants were made aware that further details about the study would be provided by a university researcher and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. If the offender agreed to take part in Gateway and the study, the investigator obtained their signature on the combined Stage 1 participant information sheet (PIS) and consent form.

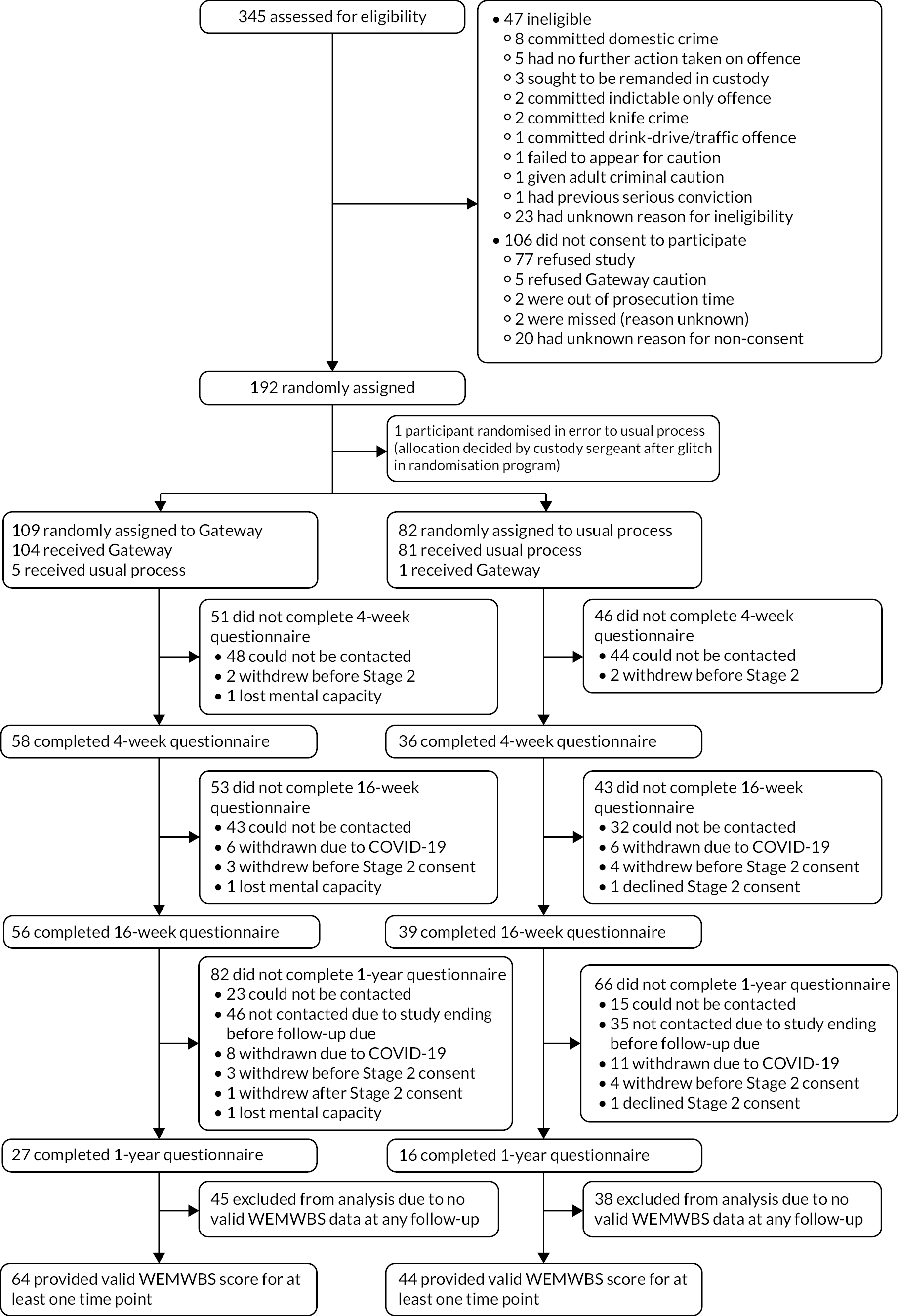

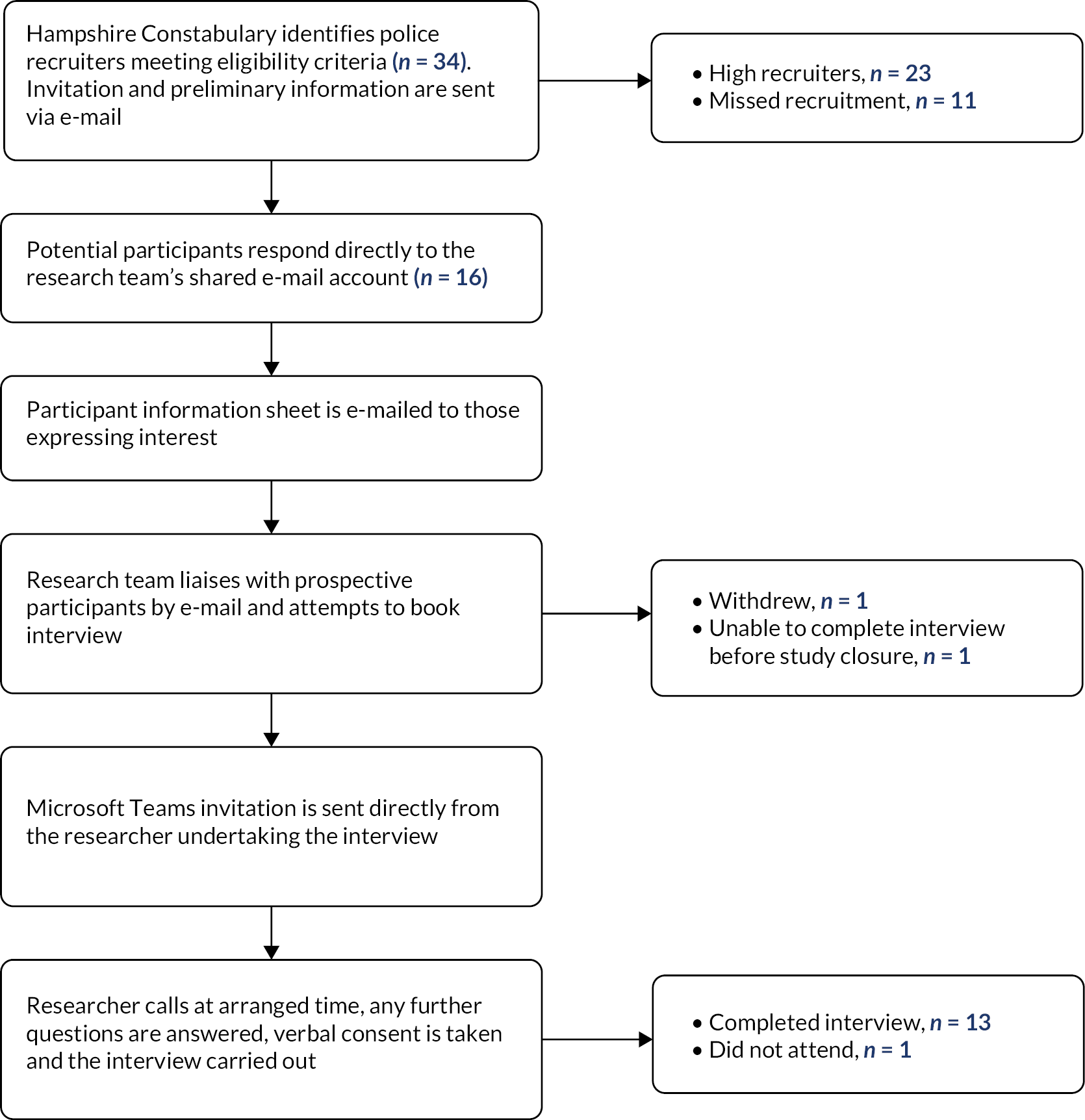

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram demonstrating the progression of participants through the trial.

A small number of participants were recruited through the out-of-custody process (see Appendix 1, Figure 9). The investigator followed the process for in-custody, where they were confident that although a disposal decision could not be made at that time, the young person would ultimately be eligible for the Gateway caution option. In these cases, the time between randomisation and disposal could vary. If contacted by telephone, they were asked to give verbal Stage 1 consent to participate. If given, this was recorded in the individual’s Police records management system (RMS) incident record. Written consent was subsequently sought prior to any trial-related activities for the participant. Anyone later declining consent in writing was withdrawn from the trial. This approach ensured all potentially eligible participants had the chance to join the study, in keeping with the pragmatic nature of this trial.

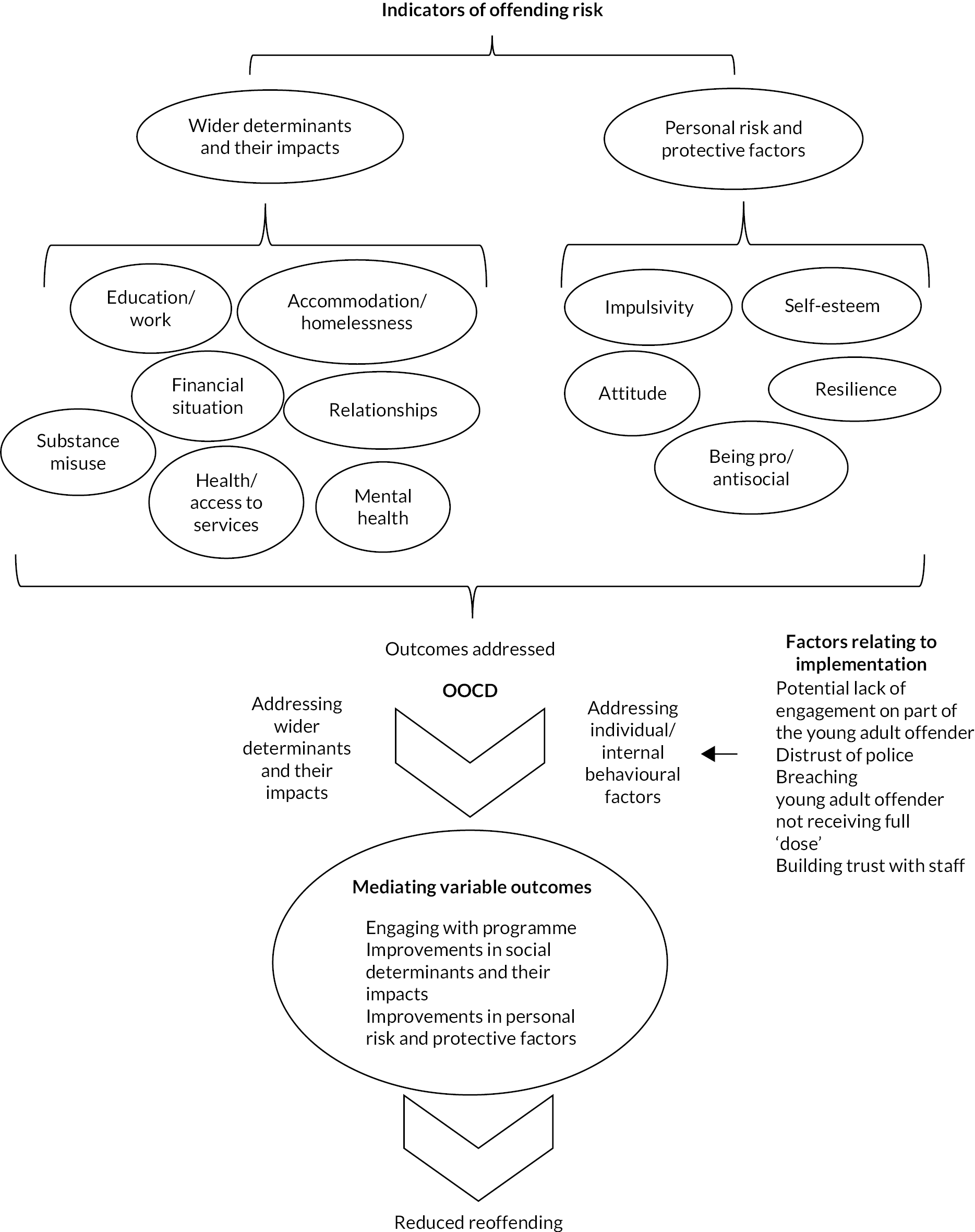

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual framework for determining risk of offending behaviour and role of OOCDs in reducing offending.

Stage 1 consent allowed the police to provide the University of Southampton (UoS) researchers with the participant’s contact details and to access their police records for data on variables such as age, gender and ethnicity and offending history, trigger offence and any subsequent reoffending. Investigators made it clear to potential participants that they would be provided with more details of the study later by the researchers and would have the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The personal contact details of participants who consented to take part in the study were passed to the research team.

Stage 2 consent

Participants who consented at Stage 1 were contacted by a member of the Gateway Team at Southampton Central Police Station within a week of recruitment to remind them about the study and check for changes to their phone numbers. The Questionnaire Study leaflet and a link to the video developed for the study were sent by e-mail at this time.

Ahead of the week 4 data collection time point, the researchers attempted to contact participants by phone, text, e-mail and/or post to arrange an interview. Once arranged, the Stage 2 PIS was e-mailed or posted to the participant.

At the interview the researcher went through the PIS providing explanations as required. Participants were provided with any other information required and had any queries answered. After time to consider their involvement, and if they decided to proceed, the researcher read out the statements in the consent form. If the participant agreed to a statement, the researcher put the participant’s initials in the corresponding box. When completed, the researcher added their own name, the participant’s name and the date of verbal consent. The completed consent form was saved as a PDF and a copy sent to the participant. Once consent had been given, data collection could occur at the same interview or on a subsequent day.

Participants were informed that they had the right to withhold consent or to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. To maximise data collection, if a participant took part in the week-16 interview having not taken part at week-4, verbal consent was obtained at that point.

Stage 2 consent included optional permission to access data from police records on reoffending for up to 10 years from their enrolment in the study. This was to facilitate a potential long-term assessment of reoffending as a separate follow-up at 10 years post-randomisation.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria

-

Suspect aged 18–24 years.

-

Suspect resided within HC area.

-

There was an anticipated guilty plea (i.e. they admitted the offence and said nothing which could be used as a defence or made no admission but had not denied the offence or otherwise indicated it would be contested).

-

Full code test met (i.e. there was sufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction and it was in the public interest to prosecute or offer a conditional caution to the suspect).

Exclusion criteria

-

Hate crime according to Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) Policy.

-

Domestic violence-related crime.

-

Domestic violence-related crime referred to CPS.

-

Sexual offence as defined by the CPS.

-

Knife crimes where a decision to prosecute was made.

-

Where on conviction the court was more likely to impose a custodial sentence (based on sentencing guides).

-

Remand in custody was sought.

-

Breach of court or sexual offences orders.

-

Any offence involving serious injury or death of another.

-

Any serious previous convictions within the last 2 years [i.e. serious violence, grievous bodily harm (GBH) or worse, serious sexual offences, robbery or indictable only offences].

-

Summary offences more than 4 months old.

-

Persons subject to Court bail, Prison Recall, Red Integrated Offender Management (IOM) or currently under Probation.

-

Indictable only offences.

-

All drink/drive or endorsable traffic offences.

-

Offender had already had a Gateway caution.

-

Offender needed an interpreter.

Intervention

The Gateway programme was a police-led intervention consisting of three parts: a needs assessment with a Gateway navigator (a trained support/case worker); attendance at two workshops/telephone interventions designed to aid development of cognitive and affective empathy; and an undertaking not to re-offend during the 16-week caution. Participation in the restorative justice (RJ) process was voluntary.

Developed as an OCBI, the Gateway programme was issued as part of a 16-week contract with set conditions, known as a conditional caution. The set conditions were to attend all the required elements of the Gateway programme, and to not reoffend during the 16-week caution. Other conditions such as a fine or writing a letter of apology could be added to individual cautions at the investigator’s discretion. A breach of any of the conditions, that is, where one or more of the conditions of the caution are not met, could have resulted in the offender being prosecuted for the original offence.

Part 1. Needs assessment

Within 3–5 working days of their disposal, the participant engaged with the Gateway navigator who conducted a thorough needs assessment. Based on identified needs, the navigator assisted the young adult into the appropriate services including with Gateway partner agencies such as alcohol, drug and mental health services. The Gateway navigators were provided by the third sector organisation No Limits and Southampton City Council. The navigators then mentored the individual through the programme. The navigators aimed to hold three face-to-face assessments: 1 at the start, 1 in the middle and the third at the end of the participant’s 16-week caution period. During COVID-19 pandemic restrictions assessments were carried out via phone or video calls. Follow up contact was predominantly via phone, text or video calls.

Part 2. The LINX workshops

The LINX workshops aim to assist young adults in the development of cognitive and affective empathy, accept the need to change attitudes and behaviours including offending and prevent future antisocial and/or violent behaviour. The workshops took place face-to-face in a neutral venue as accessible as possible. Because of COVID-19 social distancing measures, some of the workshops were modified and delivered by telephone or video calls. Details of the differences between the LINX workshops and the LINX telephone delivery are provided in Appendix 2.

LINX workshops for Gateway use carefully constructed experiential group work tools alongside a strong visual framework, ‘Making the LINX to rebuild my life’ wall. LINX workshops seek to enable the young adult to explore and share personal feelings on a variety of issues, particularly around their life experience. The various exercises and activities throughout delivery are designed to take the young adult on a journey, enabling them to see how an experience can create a feeling, which can be translated into a set of behaviours that, for these young adults, may create risk of harm to themselves or others, and thus risk of offending.

Day one workshop

Delivered between weeks 2 and 3 post randomisation, the first event addressed: the journey of offending; sentences and out-of-court disposals; empathy, rights, respect and responsibility; impact of offending behaviour on victims/self and collateral damage to wider society; positive communication and relationship; RJ options and personal risk. Materials designed to build and develop a relationship with the young adults’ personal navigator were used so the navigator could help the young adult identify risk factors leading to further offending.

Day two workshop

Delivered between weeks 5 and 6 post randomisation, the second event focused around the ‘Making the LINX to rebuild my life’ wall, which represents the nine pathways to offending. In addition to consolidating learning and building on the young adults’ strengths, the day helped promote an understanding of resilience and the part it plays in spinning life’s plates. Day 2 also included further examinations into personal risk and protective factors; the role self-esteem plays in keeping us and others safe; and identifying how positive communication can support the study’s goals and make amends. Workshop leaders and navigators used the session to assess for gaps, the need for new goals and support to ‘keep their wall in order’. Running parallel to both sessions the leaders of the LINX workshops built on the support that the navigators gave to the young adults and reinforced the motivation needed to access other services.

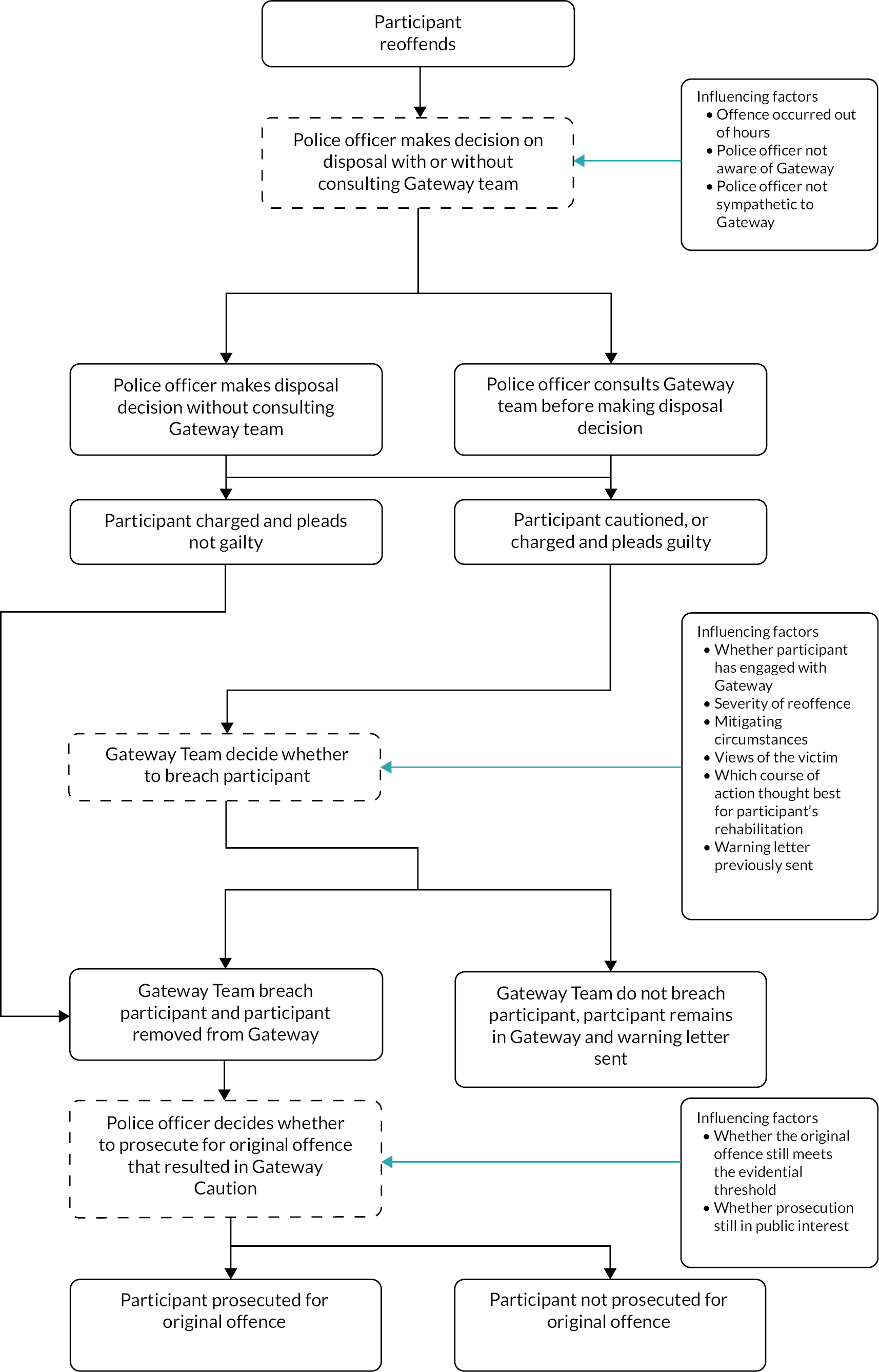

Part 3. Condition to not reoffend

If a participant reoffended during the period of their caution, the HC Gateway Team could use their discretion when deciding whether to ‘breach’ the participant (see Appendix 3, Figure 10). If a participant was considered to have breached the terms of the caution, they were withdrawn from the Gateway intervention, and the investigator who originally gave the Gateway Caution considered whether to prosecute the participant for the original offence. Participants who breached their Gateway Conditional Caution continued to be approached for data collection.

Restorative justice

Restorative justice could be added to the standard conditions of the Gateway Caution after discussion and agreement with the young person: the process is victim led, but voluntary for both the victim and the offender. Through RJ, victims can communicate with their offenders and convey the impact the crime has had on them, with the intent to empower the victim. If investigators referred the young person to the RJ process, the navigators and LINX team offered support to the young person, but the actual process was managed as a separate activity. If the victim agreed to RJ conferencing, the young adult would be encouraged to engage with the victim to take positive steps and make amends for the crime committed.

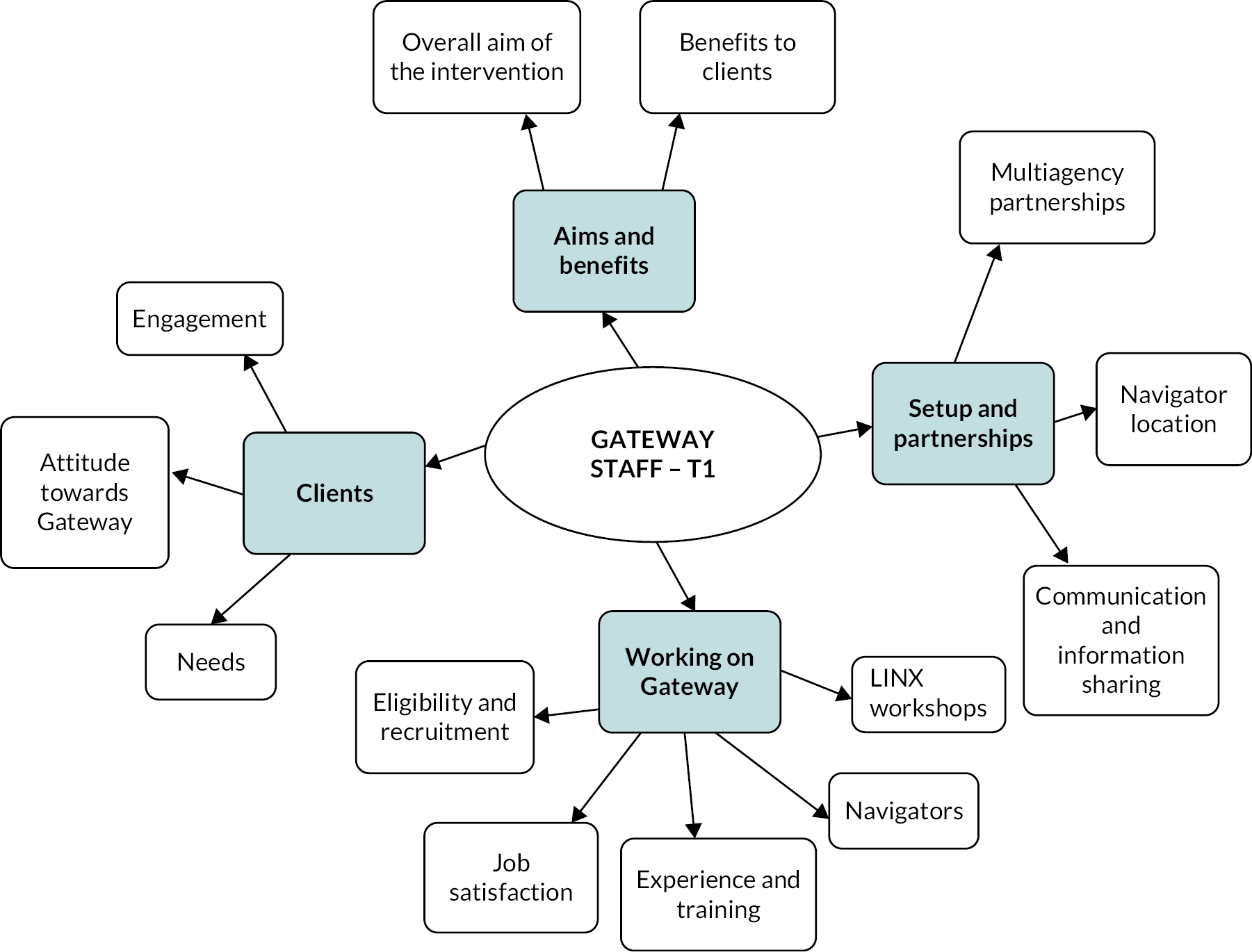

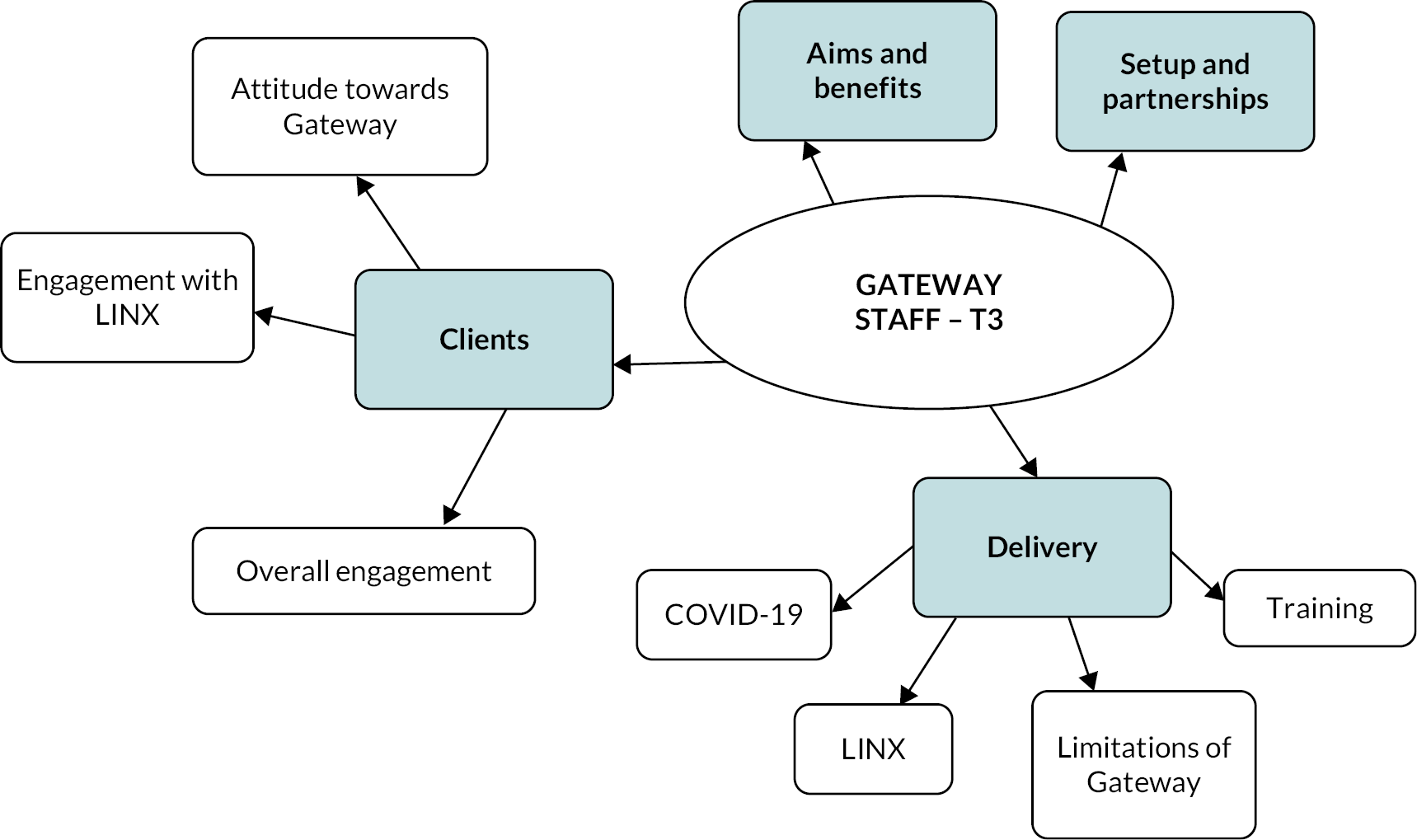

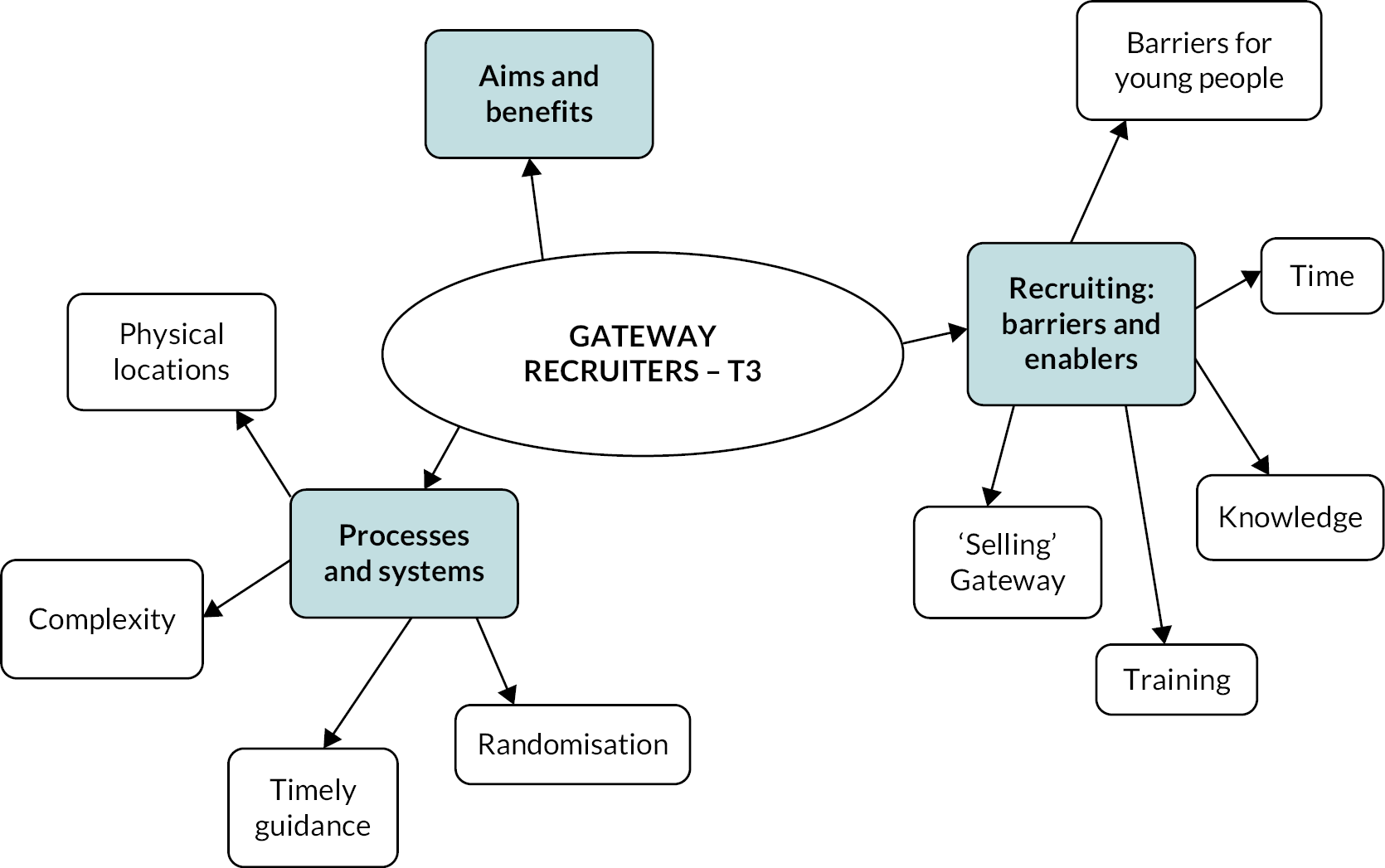

FIGURE 3.

Thematic analysis map – Gateway staff at T1.

Delivery of the Gateway programme

Delivery of the intervention was by a multiagency approach. No Limits, a third sector organisation that provides free advice, counselling, support and advocacy for under 26-year-olds, and Southampton City Council funded the Gateway navigators. Agencies accessed through the navigator triaging of needs included, The Prince’s Trust, Two Saints (housing) and local Community Mental Health Teams. Referral to these and other agencies was made where possible and appropriate.

The Hampton Trust, a third sector organisation with skills and expertise in developing community-based interventions for adults and young people, developed and delivered the LINX workshops/telephone interventions.

Restorative Solutions, a not-for-profit community interest company was commissioned by the Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) to offer RJ options.

Comparator

The comparator was usual process. Under current guidance, for young adults aged 18–24, where there is enough evidence for prosecution (known as Full Code Test) and where the individual admits responsibility, there are various possible outcomes. For less serious offences and where the offender has a limited background of convictions, they may receive a conditional caution. For more serious offences, or where the offender has a more in-depth background in relation to criminal convictions, the offender may be charged and given a court date.

Conditional caution

A conditional caution constitutes both an in-custody and out-of-custody process. In routine practice, where an offender has committed a lower-level crime, the full code test has been met and the offender accepts responsibility for the crime; it may be more proportionate for this to be dealt with through an out-of-court disposal such as a conditional caution. The supervising officer (usually the Custody Sergeant) is in charge of making the final disposal decision. A record of conditional cautions is kept by the police, but they are not the same as a criminal conviction.

Conditions attached to conditional cautions must be appropriate, proportionate and achievable and have an element of rehabilitation and/or reparation and/or punishment. 20 Conditional cautions may have a mixture of conditions and the victim is consulted before the disposal decision is finalised. All conditions must be achievable and agreed by the offender. Examples of standard conditions include apology letters, victim awareness courses, drug diversion courses, alcohol diversion courses and fines or compensation. Drug, alcohol and victim awareness courses are provided through various organisations and the cost is charged to the offender. Conditions must be capable of being completed within 16 weeks, and in the event of non-compliance, the option of prosecuting the original offence is considered.

Examples of routine practice conditions include, victim awareness, drug or alcohol diversion courses (cost is charged to the offender), apology letters and fines or compensation. The standard length of a conditional caution is 16 weeks; all conditions must be completed within that time. If an offender fails to complete the conditions attached to the caution, they will be considered for prosecution of the original offence.

Charge

This is an in-custody process. Where a young person is arrested and brought to custody, they will be interviewed by the investigating officer. If the evidence reaches the full code test and the offender is not suitable for a conditional caution, due to the nature of the offence or their previous convictions, the offender will be charged with the offence and given a court date before release from custody.

Court summons

This is an out-of-custody process. If it is not necessary to arrest an offender, that is detain them in custody, then they are dealt with by way of voluntary interview. The offender can be interviewed under caution without arrest which means that they are free to leave at any time. When the investigating officer reaches the full code test, the file is submitted to the supervisor for a disposal decision. A summons is sent by post to the offender with a date to attend court.

Monitoring adherence to allocations

Spreadsheets within the study case management system, Huddle, provided the Police Gateway Team with oversight of the number of active clients in Gateway, numbers breached, number completed, indicators of breaches/completers, time to date in Gateway and time before breached, discretions applied, monthly recruitment and the numbers refusing participation and cases missed.

An ‘Engagement with client’ spreadsheet was maintained by navigators to record adherence data and was available in Huddle. This spreadsheet included participant ID; type of contact, date of contact, whether participant responded to contact, duration of contact in minutes, name of referring agency and comments from the navigator. Third sector organisations liaised directly with the Police Gateway Team and navigators to report engagement updates in accordance with referrals.

The Hampton Trust provided attendance registers for the LINX workshops/video/calls as these were mandatory sessions for the intervention.

Standard police monitoring of adherence to alternative conditional cautions issued to participants in the usual care group was followed and the information about the conditions and any breaches recorded.

Participant follow up

Participation in the intervention was for 16 weeks from the time of disposal. All participants were asked to take part in telephone interviews at 4-weeks, 16-weeks and 1-year post-randomisation, with flexibility on timing to accommodate the target population. Participants missing one of the data collection points were followed up at the subsequent time point unless they formally withdrew from the study or were withdrawn by the study team during COVID-19 restrictions.

Ahead of each data collection time point, up to four attempts were made to establish contact via text and calls with the participants, with the aim of providing brief information about the study and gauge their availability. If the number was clearly incorrect or out of order, no further contact was attempted. If the researchers were unsuccessful after four attempts, an e-mail was sent to the participant to say that the researchers had been trying to contact them and providing a study phone number for the participant to call. The final contact attempt for non-responders was to send a letter to the participant.

Once an appointment had been booked and the details confirmed with the participant, a text confirmation was sent to their contact mobile number, followed by reminders the day before and the day of the appointment. Discretion was applied to frequency of reminders, guided by interactions with participants.

If the participant cancelled an interview or missed it without notice, the researchers made up to four attempts to re-establish contact and reschedule. If these attempts were unsuccessful, no further attempts were made until the next data collection time point, at which time the process restarted.

The number of contact attempts was indicative, rather than prescriptive. Similarly, flexibility was exercised in relation to the timing of data collection, to accommodate participants’ and researchers’ availability. If no interviews took place at week 4, 16 and 1-year the participant was deemed lost to follow up.

Follow-up data were collected up to 31 March 2022. Attempts to contact participants eligible for week 16 and/or year 1 data collection after the 31 March 2022 were made to inform them that no further involvement was required. A £10 voucher was offered as a gesture of good will.

Incentives to participate

The study population were mostly disadvantaged young adults, faced with previous and continuous adversity, such as unemployment, substance misuse, or exposure to abuse. The study’s recruitment process acknowledged that engaging this population was likely to be challenging. Initially, as a thank you for their time, the participants received a high street shopping voucher for £10 following completion of a case report form (CRF) (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Following difficulties in getting participation in week 4 interviews during the pilot phase the researchers’ patient and public involvement (PPI) representative advised that an increased amount was likely to improve the attendance rate and completion of the CRFs.

The researchers originally intended to change the voucher format to cash at face-to-face interviews, to increase the attractiveness of the incentive. However, when COVID-19 restrictions were imposed the study was changed to telephone interviews only. To reduce selection bias, the study allowed for three different ways to deliver paper vouchers. The aim was to boost recruitment of participants with unstable living arrangements, without a bank account or lacking access to e-mail or the Internet for whatever reason, meaning they would be unable to benefit from online shopping. Delivery mechanisms included via the Gateway navigator, tracked postal delivery or via a local partner organisation.

In the pilot the researchers learnt that it was common for their target population to frequently change phone numbers, without informing the researchers, or not answer phone calls or texts. To encourage continuing study participation, the researchers increased the initial payment and applied incremental payments, with vouchers to the value of £30 for week 4, £40 for week 16 and £50 for 1-year completed interviews.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). This was used to measure health and well-being among study participants. WEMWBS is a 14-item self-reported questionnaire that addresses mental health and well-being and has established valid reliable psychometric properties in adolescent populations. 21,22 Compared to other well-being indices, WEMWBS was tested for response bias and showed low correlation with both subscales of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding: Impression Management (p = 0.18*) and self-deception (p = 0.35**), which make it suitable for self-report. 23 WEMWBS was self-reported at 4-weeks, 16-weeks and 1-year post-randomisation (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Secondary outcomes measures

The following were the secondary outcome measures:

-

The Short Form 12 questionnaire (SF-12) was used to report health status. The 12 items of the SF-12 provide a representative sample of the content of the eight health concepts24 and the various operational definitions of those concepts, including what respondents are able to do, how they feel and how they evaluate their health status.

-

Risky alcohol use will be measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). The AUDIT tool is a simple screening tool that is used to identify the early signs of hazardous and harmful drinking and mild dependence. AUDIT has been validated among an adolescent population. 25,26

-

Drug use will be measured using the Adolescent Drug Involvement Scale (ADIS). The ADIS was deemed most appropriate, as it captures recent/current use, and has been validated within this population age group. 27

-

Reoffending type and frequency through access to routine data: police records have been used to examine the type and frequency of offence.

-

Data on resource use, including access to primary and secondary care health services and social care, was primarily to be used to inform the cost-consequence analysis (CCA).

Secondary outcome data were self-reported at 4-weeks, 16-weeks and 1-year post-randomisation.

The secondary outcome measures used to measure reoffending type and frequency were pre-specified in both v1.0 and v1.1 of the SAP as follows:

-

The total of the number of record management system (RMS) incidents and the number of police national computer (PNC) convictions up to 1-year post-randomisation.

-

The total of the number of RMS incidents resulting in being classed as a suspect and charged/cautioned and the number of PNC convictions up to 1-year post-randomisation.

-

Charged with a ‘summary’ or ‘either way’ offence up to 1-year post-randomisation.

-

Charged with an ‘indictable only’ offence up to 1-year post-randomisation.

However, after receiving the RMS and PNC data from the police, it became clear that because the RMS data is a subset of the PNC data, there was a risk of double counting crime incidents when combining the RMS and PNC data to form the first two measures of reoffending listed above. Therefore, the first two outcome measures listed above were split into the following:

-

number of RMS incidents up to 1-year post-randomisation;

-

number of RMS incidents resulting in being classed as a suspect and charged/cautioned up to 1-year post-randomisation; and

-

number of PNC convictions up to 1-year post-randomisation.

Adverse event reporting and harms

There were no anticipated adverse events or effects. Potential distress to participants from discussing personal issues or from reflecting on their own behaviour as part of the intervention was monitored by the researchers and the experienced support/case workers delivering the intervention. Referral to appropriate support services could be made where necessary. Participants were informed that if they disclosed any information about a crime the police were unaware of, this would have to be reported to the police.

Participant change of status and withdrawal

Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any point without giving a reason. Each PIS gave information on how a participant could withdraw, including who to contact. Forms for documenting type and reason for withdrawal and other applicable change-of-status categories were available for use by the Police Gateway Team and the UoS researchers.

Participants who consented to Stage 1 but withdrew before giving Stage 2 consent had their study details completely anonymised by the University researchers where personal details had been shared and no study assessments performed.

Participants who consented to Stage 1 but declined Stage 2 consent (without withdrawing) had no study assessments performed.

For participants who withdrew following Stage 2 consent, information already obtained up to that point was retained. To safeguard the individual’s rights under UK general data protection regulation (GDPR) only the minimum personally identifiable information was retained by the Universities. Personal data remained on Huddle, managed by HC, but no longer visible to the researchers and was not downloaded or processed for the purposes of the study. Participant withdrawal after Stage 1 consent required completion of a Change of Status CRF.

Participants who decided to withdraw from the study at any stage did not undergo any further follow-up related to the study.

Loss of capacity during participation in the study

Participants who lost mental capacity after consenting to take part were withdrawn from the study.

Internal pilots

The first 6 months of trial recruitment were designed as an internal pilot to assess feasibility. The study aimed to set up three sites and recruit 50 participants during the pilot. The imposition of a national lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic came at the end of the internal pilot. Progression against the criteria in Table 1 was agreed by the funders and the Study Steering Committee (SSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Substantial adaptations to delivery had to be made, so the 6 months after recruitment could safely restart were viewed as a second pilot phase and further progression criteria set (see Table 1).

| Recruitment rate | Progression decision |

|---|---|

| Internal pilot 1 (October 2019–March 2020) Target: 50 participants | |

| 90% (≥ 45 participants) | SSC/DMEC to confirm continuation of recruitment for a further 21 months or until the required 334 participants have been recruited.a |

| 70%–90% (35–45 participants) | SSC/DMEC to take into account whether all the sites had been set up and consider extending the recruitment period by 1–4 months.a |

| 60%–70% (30–35 participants) | SSC/DMEC to take into account whether all the sites had been set up and consider extending recruitment period by 4–6 months.a |

| ˂ 60% (< 30 participants) | SSC/DMEC to discuss closure of the study in collaboration with the funders |

| Internal pilot 2 (September 2020–February 2021) Target: 74 participants | |

| 90% (≥ 67 participants) | SSC/DMEC to confirm continuation of recruitment for a further 17 months or until the required 334 participants have been recruited.a,b |

| 70%–90% (52–66 participants) | SSC/DMEC to take into account sites set up and consider extending the overall recruitment period by an additional 1–4 months.a,b |

| 60%–70% (44–51 participants) | SSC/DMEC to take into account sites set up and consider extending the overall recruitment period by 4–6 months.a,b |

| ˂ 60% (43 participants) | SSC to meet and discuss closure of the study, in collaboration with the funders. |

Sample size

There is no widely accepted and established minimal clinically significant difference for the primary outcome, WEMWBS. It has been suggested that a change of three or more points is likely to be important to individuals, but different statistical approaches provide different estimates ranging from three to eight points (WEMWBS user guide22). There is also variation in the standard deviation (SD) of the WEMWBS with estimates ranging from 6 to 10.828 with the pooled estimate of 10 across all studies. Assuming 90% power, 5% two-sided statistical significance, mean difference of 4 points on WEMWBS and a SD of 10, 266 participants are required. Preliminary figures from The Hampton Trust’s skills/attitudes workshops for domestic abuse (RADAR intervention) suggest a drop-out rate of approximately 15%. Conservatively, assuming a 20% attrition rate, the study aimed to recruit and randomise 334 participants.

Randomisation

Sequence generation

Participants were allocated using simple randomisation with a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. The allocation sequence was created using computer-generated random numbers in Alchemer using a randomisation sequence approved by the trial statistician. The system was tested and verified by York Trials Unit (YTU) data management and the trial statisticians during the training of police investigators, prior to the start of recruitment to the study.

Concealment mechanism

Alchemer automatically generated and recorded the random allocation when a police investigator entered details for an eligible participant. It was not possible for investigators to predict or influence the allocation.

Implementation

The allocation was generated when a police investigator entered the details of a potential participant, and they met the eligibility criteria. The allocation of Gateway conditional caution or usual process was displayed on the screen. The police investigator then informed the participant of the allocation and proceeded with disposal using the allotted allocation. A similar method for randomisation was adopted in a RCT of domestic abuse perpetrator intervention (CARA) conducted in Southampton Police District, where they were able to successfully recruit a similar population group (n = 293). 19

Blinding

Consent for eligibility screening, Gateway consideration, sharing of contact details, and randomisation was undertaken by the police investigators, none of whom are involved in data collection for the study.

Research team members at UoS, involved in obtaining Stage 2 consent and data collection, were blinded as far as possible to the allocation. The CRFs included a tick box for the researcher to indicate whether they believed blinding had been compromised during assessment, or other communications such as when booking appointments, and if so which of the allocation groups they believe the participant to be in.

The statistician was not blinded to treatment allocation.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted in Stata® version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), and reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 29 Version 1.1 of the statistical analysis plan (SAP) was finalised and approved by the SSC/DMEC prior to the completion of data collection on 31 March 2022 (see Report Supplementary Material 4). Version 1.0 of the SAP outlined the planned analyses in order to assess the effectiveness of the Gateway intervention. However, once it was decided by the Trial Management Group (TMG) that due to retention and data collection rates, it was no longer feasible to assess effectiveness. Low retention rates mean a large number of participants would not be included in the primary and secondary analysis models. This is likely to introduce bias into the estimation of the treatment effect, as it is feasible that for this study population to know that whether their data that is missing is dependent on the data values themselves, for example, participants missing WEMWBS data may have lower levels of mental well-being. Version 1.1 of the SAP was therefore produced, removing all reference to formal hypothesis testing and outlining purely descriptive analyses. Continuous measures were summarised using counts, mean, SD, median, IQR, minimum and maximum. Categorical measures were summarised using counts and percentages. All participants were analysed according to their randomised group, unless otherwise stated.

Trial progression

The flow of participants from eligibility and randomisation to follow-up and analysis of the trial was presented in a CONSORT flow diagram. Reasons for ineligibility and non-consent were tabulated. The number of withdrawals and reasons for withdrawal at each time point were summarised descriptively by randomised treatment group.

Participant demographics

Participant demographics were summarised descriptively by randomised treatment group, both for all participants randomised and participants who provided the primary outcome for at least one time point. No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken between groups.

Intervention and usual care delivery

For those who received Gateway, the number of LINX workshops attended, delivery of LINX workshops, contacts attempted by the navigator, successful contacts made by the navigator and total duration of successful contacts were summarised descriptively.

For participants who were cautioned, the conditions attached to each caution were summarised descriptively by whether the participant received the Gateway conditional caution or a different caution.

Primary analysis

The primary outcome, WEMWBS, was summarised descriptively at each time point by randomised treatment group.

A challenge of working with this study population was that participants were difficult to contact, and therefore more flexibility was allowed, in terms of when a participant could complete their study questionnaire for example, if a researcher managed to contact a participant 14-weeks post-randomisation, they would still complete the 4-week CRF, even though this CRF would have been due 10 weeks earlier. However, in this scenario, the data from this CRF would have been collected closer to the 16-week follow-up due date than to the 4-week follow-up due date, and therefore rules for cut-off points were pre-specified in the SAP. Data from CRFs that did not lie in any of the pre-specified follow-up windows were not included in the primary and secondary analyses (excepting the analysis of contact data).

Secondary analyses

Treatment compliance

For participants randomised to the Gateway intervention, compliance as defined by the following definitions was summarised descriptively.

-

Minimal compliance: for a participant to be classed as having met the conditions for minimal compliance to the intervention, they should have:

-

engaged with their navigator for the initial, midway and final assessment

-

attended the two LINX workshops and

-

not been breached for reoffending during the duration of the conditional caution.

-

-

Full compliance: for a participant to be classed as having met the conditions for full compliance, they should have met the conditions for minimal compliance, and in addition engaged with external agencies organised by the navigator. Participants who met the conditions for minimal compliance, but for whom the navigator did not need to organise any interactions with external agencies, were classified as having met the conditions for full compliance.

Missing data

The amount of missing data among participants was summarised descriptively by randomised treatment group, along with reasons for missing data. The number of participants who were contactable at each time point was also summarised descriptively.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were summarised descriptively at each time point by randomised treatment group.

Analysis of exploratory outcomes

Accommodation status was dichotomised in the following manner:

-

Homeless:

-

rough sleeping

-

sofa surfing

-

direct access (self-referral) or emergency (agency referral) hostel.

-

-

Not homeless:

-

living with parent

-

housing association

-

private tenant

-

living with extended family

-

supported accommodation

-

shared living accommodation.

-

Dichotomised accommodation status at 4-weeks and 1-year post-randomisation was summarised descriptively by randomised treatment group.

Other analyses

Number of contacts to first conversation at each follow-up time point

For each follow-up time point, for participants who were contacted using a method other than letters, the number of contacts required to be able to hold a conversation about the study with the participant was presented by randomised treatment group. In addition, information on the type of contact used was presented descriptively by randomised treatment group.

The number and proportion of participants contacted using a letter was presented by randomised treatment group. In addition, the number and proportion of participants who could not be contacted was presented by randomised treatment group.

Participants informed of their disposal decision after their 4-week follow-up was due

The number and proportion of participants, informed of their disposal decision after their 4-week follow-up was due, were presented by randomised treatment group. For each participant the number of days between date of randomisation and date of disposal was summarised descriptively, alongside whether the participant attended their 4-week follow-up.

Reporting of the use of discretion in overriding the condition to not reoffend

The number and proportion of participants in the intervention group who violated the condition to reoffend was presented. For these participants, the number for whom discretion was considered before taking the decision to breach was reported.

Index of multiple drug use

The index of multiple drug use data were summarised descriptively at each time point by randomised treatment group.

Adverse childhood experiences questionnaire

The total number of adverse childhood experiences questionnaire (ACEs) reported at 16 weeks post-randomisation was summarised descriptively by randomised treatment group.

Health economic data

Health economic CRF data were summarised descriptively by randomised treatment group at each time point.

Economic evaluation

Due to the study not reaching its recruitment and data collection targets, it was decided that a health economic analysis was not feasible.

Data collection and management

Plans for assessment and collection of outcomes

Demographic and study outcome data were recorded in paper CRFs by researchers experienced in undertaking interviews. All three of the outcome data collection CRFs included WEMWBS, SF-12, AUDIT and ADIS measurement tools as well as the health economic data questionnaire developed for the study (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Following Stage 2 consent, the UoS researchers read out the questions and answer options as set out in the relevant CRF. Guidance was given if a question was not understood or required further clarification. The researcher hand-wrote the responses in the CRFs. Each CRF was identified with a unique participant ID, signed and dated by the researcher and posted to YTU data management in a pre-paid envelope. The UoS researchers tracked completion of each interview and CRF and YTU tracked CRFs received and the date of receipt.

A participant could be reported as withdrawing from the study either by a researcher or a member of the Gateway police team using a Change of Status CRF. The Police Gateway Team could also report a participant withdrawing from the Gateway intervention.

The study, Case Management System (Huddle), was maintained centrally by Southampton Police as a secure central location for storing documentation and linking the various sources of data for individuals together. For the purposes of analysis, data were pseudonymised, and for subsequent reports and publications, the data wholly anonymised. For the purposes of data management, once randomised, individual participants were identified using their unique study identification number, including an identifier for the site they were recruited from.

Trial data and study files were handled in accordance with good clinical practice (GCP) principles, the appropriate data management procedures and YTU standard operating procedures (SOPs).

Data entry and management

All staff involved in handling study data were trained in data protection and data security. Trial data were stored and transferred following YTU SOPs. Data were processed according to trial-specific procedures.

Paper CRFs received by the YTU data management team were scanned into OpenText Teleform, a secure form processing software application that minimises the risk of data entry errors. Data queries were raised with the UoS researchers and documented.

Data storage and archiving

Each site held data according to GDPR and Data Protection Act (Great Britain 2018); data storage was regularly reviewed to ensure compliance. Following Stage 2 consent, personal data and special category personal data were processed in connection with this study under the legal basis of Article 6(1)(e) and Article 9(2)(j) of the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for processing for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest, and as necessary for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes, with Article 9(2)(j) operating in conjunction with the safeguard requirements set out in Article 89(1) of the GDPR.

All study files were stored in accordance with GDPR guidelines. Study documents (paper and electronic) were retained in a secure (kept locked when not in use) location for the duration of the study. All essential documents, including source documents, will be retained for a minimum period of 10 years after study completion. The separate archiving of electronic data will be performed at the end of the study, to safeguard the data for the period(s) established by relevant regulatory requirements. All work will be conducted following the University of York Data Protection Policy. 30

Public involvement

Three separate approaches were used within the PPI, with the aim of representing all relevant stakeholders to ensure the research was carried out in a way that would be as effective as possible and produce meaningful outputs for those affected. These three areas were with service users (young adult offenders), victims and the public.

Patient and public involvement was embedded early on with the help of partners The Hampton Trust. Meetings with young adults on a Hampton Trust programme explored various aspects of the study, including importance, acceptability and feasibility. The groups fed back in detail around the logistics of the study: the process around consent and randomisation; ways to manage challenges following up the control arm; and opinion on assessment forms.

Once the study was underway, the PPI lead worked with partners to involve young adult representatives who had been through the Gateway programme and those who had been through the ‘usual process’. Consultation and input from these service users provided a clear understanding of the challenges and benefits that participants with and without prior experience of the criminal justice system might face. These PPI representatives worked closely with the PPI lead to develop consent forms, PISs, and initial information leaflets, plan recruitment strategies and consider the most effective ways of arranging interviews and qualitative work.

There were two public representatives on the SSC/DMEC. An ex-offender, working for Hampshire Youth Offenders Team as a peer mentor and support worker; and a victim advocate, working for a charity for victims of crime. They represented the voice of the service users and victims at Steering Group meetings, helping the group reflect on the realities of delivering the programme from the user perspective, reminding the group of some of the vulnerabilities and needs of this population, and ensuring the views of victims were considered.

These two representatives also worked closely with the study PPI lead, providing strategic input, advice and guidance throughout, with a particular focus on the logistics of getting the project underway, reviewing and adapting the protocol. The idea of a recruitment video was conceived by the ex-offender public representative, and the content was co-created with them.

Utilising links established through a local outreach programme, community leaders and members of the public were consulted. The researchers worked closely with these individuals to ensure that they understood the concerns and attitudes of the wider community. Additionally, they were able to provide input to public facing documentation and materials.

Patient and public involvement was able to help the research team consider some of the unique issues facing this vulnerable population. There were challenges, however, and PPI representatives often presented with similar chaotic lives as participants. As a result, involvement was often ad hoc or one-off, with representatives finding it difficult to commit consistently or in a longer term. Working with partners The Hampton Trust and Gateway navigators was invaluable when it came to building trust, identifying and collaborating with offending representatives.

Regulatory approvals and research governance

The outline proposal was submitted to the Hampshire Constabulary Ethics Committee, who agreed to support the study. Any subsequent ethical issues were referred for discussion by HC senior staff.

The study protocol and all associated study documents such as information sheets, consent forms, and questionnaires and subsequent amendments were submitted to the UoS Ethics and Research Governance Board for approval (ERGO Number: 31911).

Confirmation was obtained that the study did not require approvals from the Health Research Authority (HRA), Social Care or Her Majesty Prison Probation Service research ethics committees.

The governance structure for the study comprised the TMG and the independent SSC which also acted as the DMEC. The SSC/DMEC met six times during the course of the study; key meetings were to discuss the set up (October 2018), review of progression and the temporary suspension during COVID-19 restrictions (May 2020), progression following pilot 2 (April 2021) and completion of data collection for early closure of the trial (February 2022). The Chief Investigator had overall responsibility for the study, which was sponsored by the UoS. The TMG submitted regular reports to the funder, SSC/DMEC and sponsor.

Protocol changes and amendments

Protocol amendments were approved by the NIHR Public Health Research (PHR) programme manager, ethics committee and sponsor. A full list of all protocol amendments is provided in Appendix 4 and the rationale for some of the changes explained in Chapter 4.

Trial results

Overview

The first internal pilot phase began on 1 October 2019 and was due to end on 31 March 2020. However, due to social distancing and other measures introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, HC temporarily halted all out-of-court disposal activities that involved face-to-face interaction on 22 March 2020. This meant conditional cautions, including the Gateway caution, were not being issued. As a result, recruitment to the study was halted and the first internal pilot phase ended on 22 March 2020. On 15 June 2020, NIHR PHR, in agreement with the SSC, indicated they would support a second internal pilot phase starting from when it was judged safe by HC and the TMG.

The summer of 2020 was spent preparing to restart the study as soon as it was deemed safe. Alternative means of delivering the intervention were developed, in particular converting the LINX group workshops to telephone delivery. In July 2020 HC confirmed their intention to restart issuing Gateway cautions during August 2020 and recruitment to the trial restarted on 7 September 2020.

Due to issues with retention of participants, recruitment ended on 13 December 2021, and data collection ended on 31 March 2022.

Site set up

Three sites were opened during the first internal pilot phase, in Southampton, Portsmouth, and Basingstoke. All three sites reopened with the addition of IoW following the study pause. Southampton, Portsmouth and Basingstoke were each open for 22 months in total, and IoW for 16 months.

Eligibility, screening and recruitment of participants

The flow of participants through the trial is reported in a CONSORT flow diagram (see Figure 1).

In total, 345 potentially eligible participants were screened, of which 47 (13.6%) were ineligible. Of the 298 (89.4%) eligible participants, 106 (35.6%) did not consent to participate. Table 2 gives reasons for ineligibility and non-consent.

| Reason for ineligibility (n = 47) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Committed domestic crime | 8 (17.0) |

| Had no further action taken on offence | 5 (10.6) |

| Sought to be remanded in custody | 3 (6.4) |

| Committed indictable only offence | 2 (4.3) |

| Committed knife crime | 2 (4.3) |

| Committed drink-drive/traffic offence | 1 (2.1) |

| Failed to appear for caution | 1 (2.1) |

| Given adult criminal conviction | 1 (2.1) |

| Had previous serious conviction | 1 (2.1) |

| Reason not recorded in Alchemer | 23 (48.9) |

| Reason for non-consent ( n = 106) | |

| Refused study (after accepting Gateway caution) | 77 (72.6) |

| Refused Gateway caution | 5 (4.7) |

| Out of prosecution time | 2 (1.9) |

| Missed (reason unknown) | 2 (1.9) |

| Unknown | 20 (18.9) |

In total, 192 participants were randomised to the trial. One participant was randomised in error to usual process due to an error in the completion of the randomisation process, leading the custody sergeant to non-randomly assign the participant to usual process. This participant was excluded from all further analyses. Therefore, 191 participants were randomised to the trial and included in the analyses (Gateway 109; usual process 82).

Participant baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for all randomised participants and for all participants who provided a valid WEMWBS score for at least one time point are presented in Appendix 5, Table 16.

Thirty-nine (21.3%) participants were female, and the average age was 20.8 years old (SD 1.9 years). The vast majority of randomised participants were of white North European ethnicity (n = 170; 93.4%). The most commonly reported highest level of education among randomised participants for those who provided data (n = 110; 57.6%) was 2 or more A-levels (n = 32; 29.1%), with the next most common levels being 1–4 General Certificate of Secondary Educations (GCSEs) (n = 28; 25.5%), more than 5 GCSEs (n = 24; 21.8%) and no qualifications (n = 17; 15.5%).

The most common entry route into the study for randomised participants was via caution (n = 165; 90.7%). The median number of incidents in the police RMS that participants were involved in was 6 [interquartile range (IQR) 3 to 13]. There were 57 (31.5%) who had been involved in a RMS incident leading to a charge or caution, and 53 (29.3%) participants who had been convicted ˂ 1 year prior to randomisation.

Baseline characteristics of the randomised participants were generally well balanced between groups, with small imbalances in gender and highest level of education status.

Retention rates, calculated as number of participants consented and randomised at Stage 1 who were due to provide data compared to the number of completed WEMWEBS at March 2022 (when data collection stopped), were:

-

week 4: 49% (93 provided data of the 191 due)

-

week 16: 49% (93 provided data of the 191 due)

-

1-year: 37% (43 provided data of the 115 due).

Recruitment and data collection rates for each of the pilots and the main trial are presented in Table 3.

| Time point | Screened | Eligible | Target for period | Randomised (% of target) | Week 4 data | Week 16 data | 1-year data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot 1 (Oct 2019–March 2020) | 70 | 57 | 50 | 35 (70.0) | Due: 32 | Due: 16 | Due: 0 |

| Collected: 14 (43.8%) | Collected: 5 (31.3%) | Collected: N/A | |||||

| Pilot 2 (Sept 2020–Feb 2021) | 105 | 99 | 74 | 64 (86.4) | Due: 87 | Due: 58 | Due: 31 |

| Collected: 37 (42.5%) | Collected: 19 (32.8%) | Collected: 7 (22.6%) | |||||

| Main trial (March 2021–April 2021) | 170 | 142 | 140 | 93 (66.4) | Due: 192 | Due: 192 | Due: 115 |

| Collected: 95 (49.5%) | Collected: 96 (50.0%) | Collected: 43 (37.4%) | |||||

| Totals | 345 | 298 | 264 | 192 (72.7) | Due: 192 | Due: 192 | Due: 115 |

| Collected: 95 (49.5%) | Collected: 96 (50.0%) | Collected: 43 (37.4%) |

Randomised participants and randomised participants who provided a valid WEMWBS score for at least one time point had similar distributions of the following baseline characteristics: age, gender, ethnicity, Index of Multiple Deprivation, entry route, RMS incidents involved in and RMS incidents leading to charge or caution. However, there was a larger imbalance between groups in having been previously convicted in randomised participants who provided a valid WEMWBS score, compared to the randomised participants. The distribution of marital status and highest level of education were very similar between the randomised participants and randomised participants who provided a valid WEMWBS score. However, this is because marital status and highest level of education were collected via CRFs and could be collected at either 4-weeks, 16-weeks or 1-year post-randomisation only. The WEMWBS was also collected at these time points, and therefore if a participant provided a valid WEMWBS score then in the vast majority of cases they also provided their marital status and highest level of education.

Intervention and usual process delivery

Of the 109 participants randomly assigned to Gateway, 104 (95.4%) received Gateway, while for the 82 randomly assigned to usual process, 81 (98.8%) received usual process.

Of the five participants who did not receive Gateway, despite being randomly assigned to Gateway, four received a standard caution. Of the 81 participants who were randomly assigned to and received usual process, 76 (93.8%) entered the study via the caution route. Therefore 105 participants received a Gateway caution, and 80 received a standard caution. Table 4 provides information on the caution conditions attached, presented by the type of caution received.

| Gateway conditional caution (n = 105) | Usual process (n = 80) | |

|---|---|---|

| Conditions attached (multiple conditions possible), n (%) | ||

| Standard Gateway conditions (no additional conditions added) | 85 (81.0) | N/A |

| None (simple caution) | N/A | 5 (6.3) |

| Compensation | 18 (17.1) | 20 (25.0) |

| Letter of apology | 5 (4.8) | 10 (12.5) |

| Victim awareness course | 0 (0) | 14 (17.5) |

| Alcohol diversion course | 0 (0) | 11 (13.8) |

| Drugs diversion course | 0 (0) | 16 (20.0) |

| Not to enter specific premises | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Fine | 0 (0) | 5 (6.3) |

| Women and Desistance Empowerment programme | 0 (0) | 9 (11.3) |

| Restorative justice | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

The Gateway conditional caution was delivered as planned up until 23 March 2020, when the study was paused due to COVID-19. All activities relating to conditional cautions were also paused by HC on this date. The Gateway conditional caution restarted in August 2020 and recruitment to the trial in September 2020, with full remote working and no face-to-face contact with participants. This included converting the LINX workshops to delivery by telephone. Face-to-face working returned in May 2021, where appropriate and risk assessed.

Of the 105 participants who received Gateway, navigator logs were received for 76 (72.4%). Table 5 presents information on delivery of the Gateway intervention. There are four participants for whom the number of LINX workshops attended is unknown due to the participant withdrawing before Stage 2 consent was obtained or having withdrawn after giving Stage 2 consent.

| Received Gateway conditional caution (n = 105) | |

|---|---|

| LINX workshops attended (supplemented with change of status data) | |

| Number with data, n (%) | 101 (96.2) |

| 0 (Did not attend LINX workshops due to COVID-19 pause) | 4 (4.0) |

| 0 (participant chose not to attend LINX workshops) | 8 (7.9) |

| 1 (participant chose not to attend LINX workshop) | 1 (1.0) |

| 2 | 88 (87.1) |

| Delivery of LINX workshops | |

| Number with data, n (% of those who attended at least one workshop) | 80 (89.9%) |

| Face to face | 45 (56.3) |

| Telephone | 35 (43.8) |

| Contacts attempted by navigator (excluding LINX workshops) | |

| Number with data, n (%) | 76 (72.4) |

| Mean (SD) | 52.8 (25.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 42 (39–63) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 22, 168 |

| Successful contacts made by navigator (excluding LINX workshops) | |

| Number with data, n (%) | 76 (72.4) |

| Mean (SD) | 26.0 (20.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 19 (15–31) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 0, 108 |

| Total duration of successful contacts, minutes | |

| Number with data, n (%) | 70 (66.7) |

| Mean (SD) | 761.5 (594.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 626.5 (380–978) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 36, 2785 |

Primary analysis

Table 6 reports the WEMWBS score at 4-weeks, 16-weeks and 1-year post-randomisation. The WEMWBS score can take values between 14 and 70, where higher scores indicate a better state of mental health and well-being. The WEMWBS, SF-12, AUDIT and ADIS data for one participant in the Gateway group was excluded at week 4 due to the questionnaire being completed too early, while at week 16 the data for two participants in the Gateway group were excluded due to the questionnaires being completed too late.

| Gateway conditional caution (n = 109) | Usual process (n = 82) | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 57 (52.3) | 36 (43.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 44.1 (9.6) | 44.9 (7.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 45 (38–52) | 44 (41–49) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 19, 61 | 28, 62 |

| Week 16 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 54 (49.5) | 39 (47.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 48.6 (9.9) | 46.0 (8.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 49 (42–55) | 47 (40–53) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 27, 67 | 30, 60 |

| Year 1 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 27 (24.8) | 16 (19.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 48.4 (9.7) | 45.7 (7.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 49 (41–54) | 45.5 (41.5–50.5) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 29, 68 | 28, 58 |

Secondary analyses

Treatment compliance

Of the 105 participants randomly allocated to the Gateway conditional caution who did not withdraw before Stage 2 or withdraw Stage 2 consent, 81 (77.1%) met the definition for minimal compliance. Thirteen participants did not meet minimal compliance due to not attending the two LINX workshops, six did not meet minimal compliance due to breaching the condition to not reoffending during the period of the caution and five were given usual process despite being randomly assigned to the Gateway conditional caution.

No participants were withdrawn from the Gateway conditional caution because they failed to engage with partner/referral agencies identified by the navigator, therefore the number of participants meeting full compliance is 81 (77.1%).

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Table 7 reports the participant-reported secondary outcomes at 4-weeks, 16-weeks and 1-year post-randomisation. The SF-12 mental component can take values between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating a better level of mental health. The SF-12 physical component can take values between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating a better level of physical health. The AUDIT score can take values between 0 and 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of hazardous and harmful alcohol use. The ADIS score can take values between 0 and 184, with higher scores indicating higher levels of drug involvement.

| Gateway conditional caution (n = 109) | Usual process (n = 82) | |

|---|---|---|

| SF-12 Mental Component | ||

| Week 4 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 57 (52.3) | 36 (43.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 42.4 (12.0) | 43.5 (9.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 43.6 (35.7–53.1) | 43.8 (36.8–51.9) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 15.1, 58.8 | 22.1, 58.8 |

| Week 16 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 54 (49.5) | 39 (47.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 47.7 (7.6) | 45.0 (9.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 47.7 (41.7–54.6) | 45.8 (38.7–52.7) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 34.3, 58.8 | 20.7, 58.1 |

| Year 1 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 27 (24.8) | 16 (19.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 47.5 (7.5) | 46.1 (8.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 47.7 (39.5–54.6) | 47.5 (44.4–51.8) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 34.3, 58.8 | 20.7, 58.1 |

| SF-12 Physical Component | ||

| Week 4 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 57 (52.3) | 36 (43.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 54.5 (5.3) | 52.8 (6.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 55.5 (53.7–57.4) | 55.2 (51.2–56.8) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 36.8, 63.9 | 30.8, 59.2 |

| Week 16 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 54 (49.5) | 39 (47.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 52.5 (6.4) | 53.4 (5.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 54.5 (51.7–56.0) | 55.2 (52.4–56.9) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 26.1, 59.4 | 38.0, 60.1 |

| Year 1 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 27 (24.8) | 16 (19.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 51.9 (7.9) | 53.5 (6.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 54.5 (51.7–56.5) | 55.3 (52.5–58.2) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 26.1, 59.4 | 38.0, 58.9 |

| AUDIT | ||

| Week 4 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 57 (52.3) | 36 (43.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 12.9 (9.2) | 11.2 (7.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 11 (5–19) | 10.5 (5.5–16.5) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 0, 34 | 0, 28 |

| Week 16 | ||

| Number with data, n (%) | 54 (49.5) | 39 (47.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 11.6 (8.1) | 11.6 (8.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 9.5 (5–15) | 10 (4–16) |

| Minimum, Maximum | 0, 32 | 0, 36 |

| Year 1 | ||

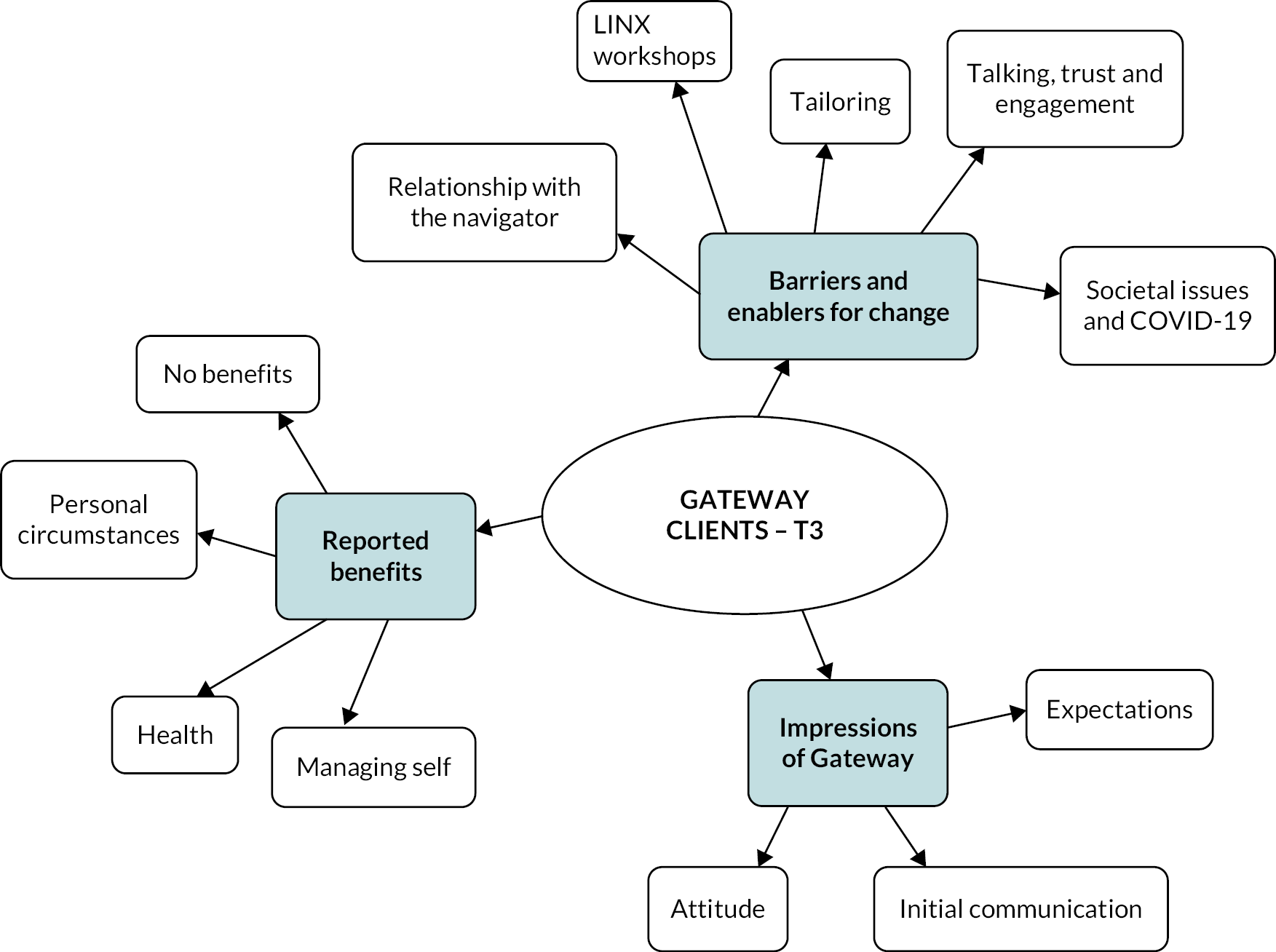

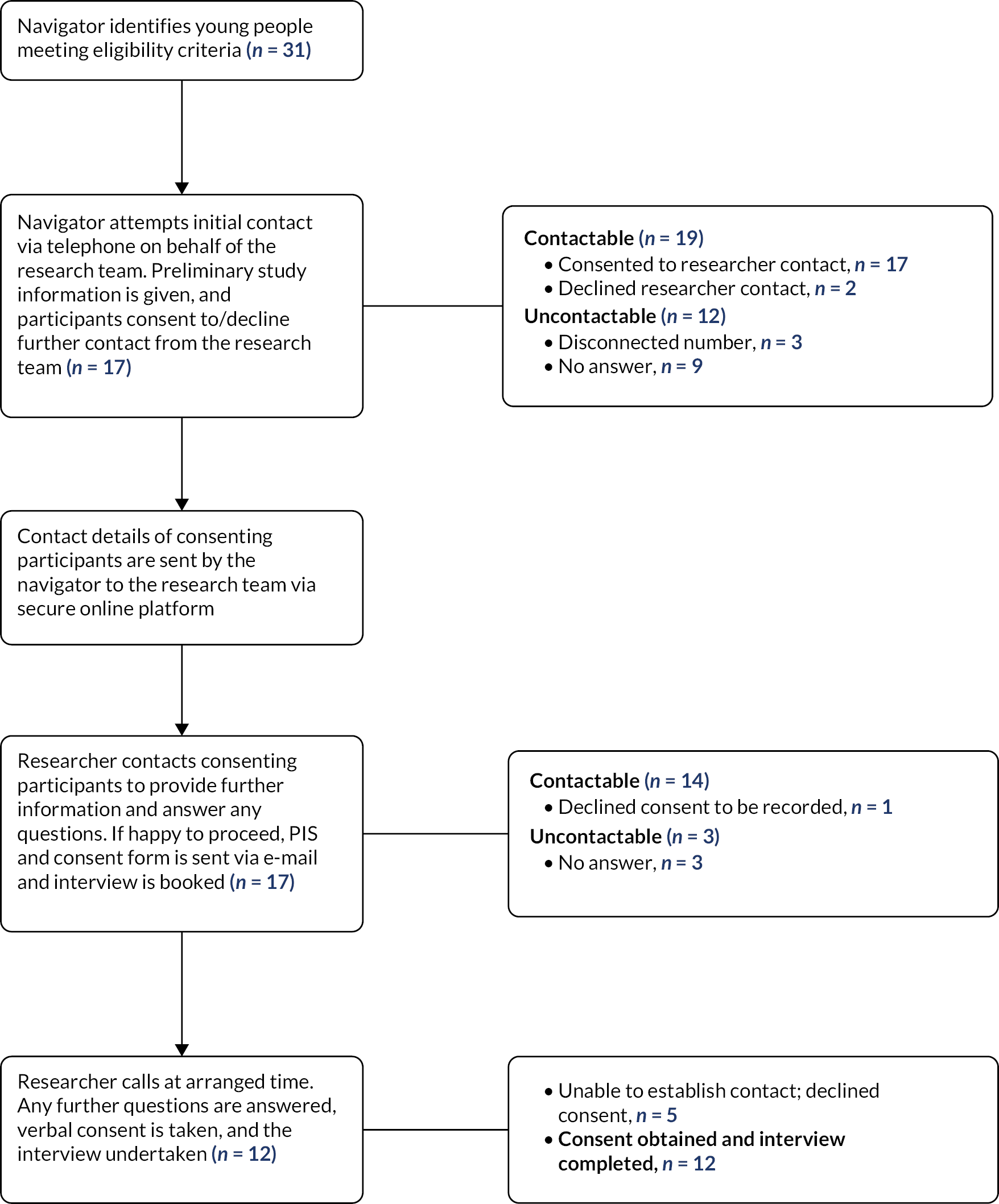

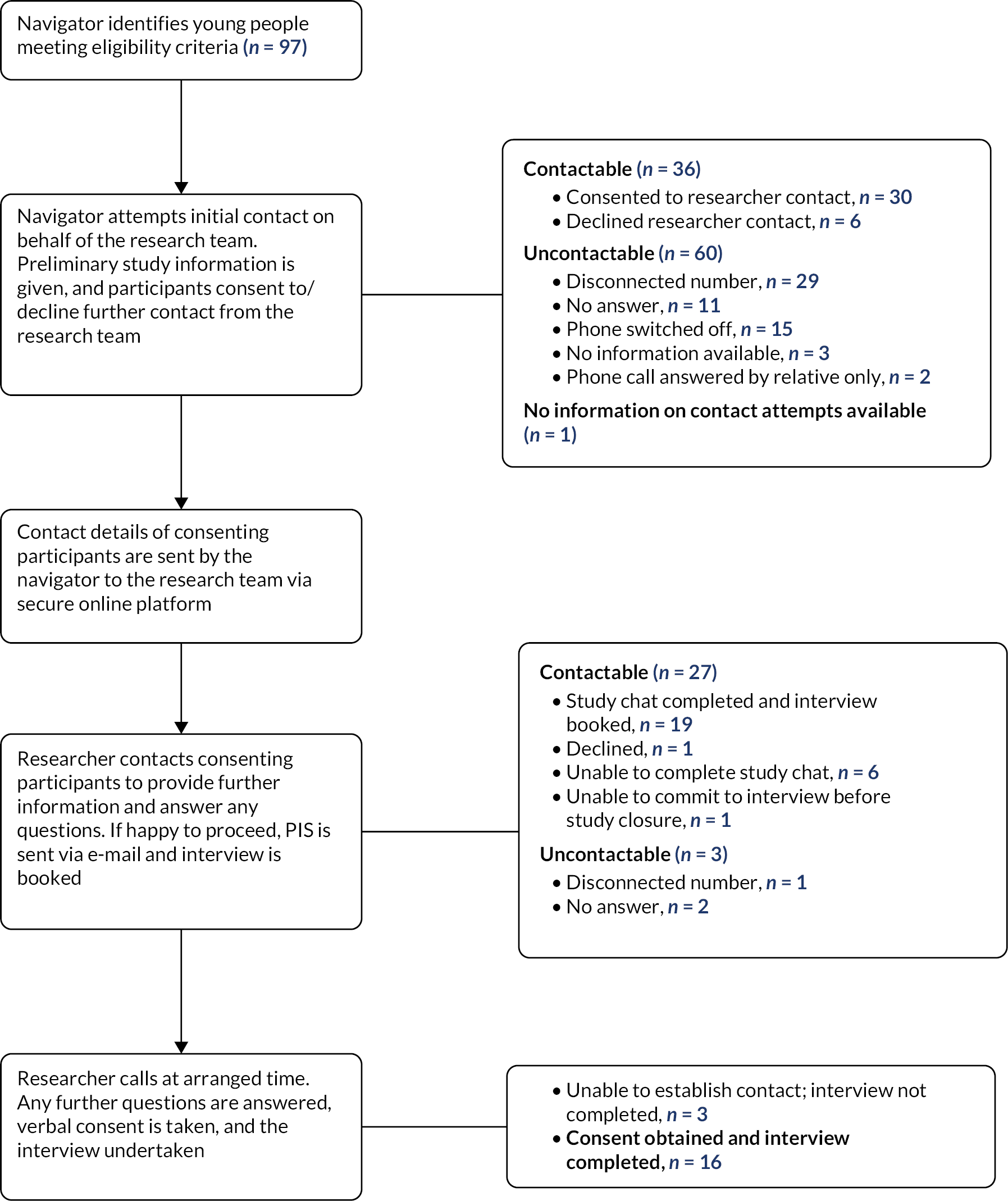

| Number with data, n (%) | 27 (24.8) | 16 (19.5) |