Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3002/08. The contractual start date was in March 2010. The final report began editorial review in March 2012 and was accepted for publication in October 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Adam Fletcher, James Thomas and Margaret Whitehead have received grants to their institution from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Rona Campbell has received grants to her institution, support for travel and payment for writing/reviewing from the NIHR Public Health Research programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Bonell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The importance of the school environment

Young people in the UK are among those with the worst health in Europe, and there are marked health inequalities, with considerable implications for later health and economic costs. 1,2 There are increasing suggestions that seemingly separate outcomes, such as substance use, violence and sexual risk, are interlinked, requiring common intervention strategies. 3,4 Health education delivered through the school curriculum and aiming to improve knowledge, develop skills and modify peer norms is now well established in schools, addressing smoking, drinking, drug use, sexual behaviour, physical activity and diet. However, systematic reviews suggest that such interventions have disappointing results. 5–11

A complementary approach to curriculum-based health education is to change the school environment to promote health and well-being. Although, traditionally, research has focused on individual and family risk and protective factors, there is increasing recognition that young people's health can be influenced by broader social factors. 12,13 A large body of educational research has explored ‘school effects’ on attainment and other outcomes. Such research originated in the 1970s with the work of Michael Rutter et al. ,14 which questioned the previous assumption that young people's educational attainment was determined mainly by their social background, with schools having little or no effect. 15 Rutter and others' work suggested that schools differ in student attainment and that factors such as strong leadership, student involvement, high expectations and frequent evaluation and praise appeared to explain some of these differences. 16–20 Different schools were described as having a different ‘ethos’, referring to the sets of values, attitudes and behaviours distinguishing one school from another. 20,21 As well as their social environments, schools differ in their physical environment, such as cleanliness, lighting, ventilation and aesthetic appeal, which may have important consequences for students' engagement and learning. 22

The school environment may also have profound effects on students' emotional and mental health, and opportunities to choose healthy lifestyles, a point first suggested by early studies showing significant differences in rates of health-related behaviours and outcomes between schools. 23 Rather than treating schools merely as sites for health education, ‘school environment’ interventions aim to modify how the school social and physical environment influences health. School environment interventions can address health directly, for example by modifying school policies (e.g. on smoking),24 improving catering25 or encouraging staff and students to walk or cycle to school. 26 Other actions aim to address factors such as disengagement and a lack of social support, which are risk factors for multiple adverse outcomes. 27,28 Such actions include increasing student participation in decision-making and providing staff with training on how to re-engage disaffected students. These interventions take a ‘socioecological’29 approach to promoting health, whereby health is understood to be influenced not only by individual characteristics and behaviours but also by the wider social, cultural and economic context.

An important influence on the development of school environment interventions has been the World Health Organization's (WHO) framework for Health Promoting Schools (HPS). 30 This was influenced by WHO's Ottawa Charter, which recognised the limited effectiveness of health education alone in promoting health. 31 The framework for HPS called for health to be promoted through the whole school environment, and not just through ‘health education’ in the curriculum. A ‘health promoting school’ aims to promote lifestyles conducive to good health; provide an environment that supports and encourages these lifestyles; and enable students and staff to take action for a healthier community and healthier living conditions. 32 In England, the previous government developed a National Healthy Schools Programme, informed by the WHO framework, to which all schools were to sign up; however, the current government has ceased providing national funding for this programme and rendered it optional for schools to participate.

The HPS model has been described in various ways in different documents. 33–40 Although some interventions are explicitly labelled as adopting a HPS model, others do not use this name but nonetheless are implicitly based on the same principles. In the USA, this approach is commonly referred to as a Coordinated School Health Program (CSHP). Both HPS and CSHP require change in three areas of school life: (1) formal health education curriculum, (2) environment and ethos and (3) links with the wider community.

Some approaches to HPS have been rigorously evaluated, but many have not. 34 Other trials have evaluated interventions that aim to modify the school environment to promote health but which are not explicitly informed by the HPS framework.

Rationale for the systematic review

Evidence concerning the effects of school environment interventions has not been comprehensively synthesised and reviews that have examined these interventions are now quite old. Existing reviews have also focused on interventions combining school environment change with curriculum components and so cannot assess the contribution of environmental change to any health effects detected. A decade-old systematic review of HPS interventions identified only 12 studies, four of which were randomised trials. It concluded that HPS interventions are promising, especially for promoting healthy eating, reducing bullying and improving mental and social well-being. 34 Other reviews of school-based interventions have similarly examined interventions addressing the school environment alongside other forms of intervention such as classroom curricula and counselling. A meta-analysis of school-based interventions to address a range of problem behaviours concluded that such interventions were effective in reducing alcohol and drug use,41 a point echoed in a more recent systematic review focused solely on whole-school interventions to prevent drug use. 42 Because existing reviews have examined interventions combining school environment with other components they cannot assess the specific effects on health of environment changes. Furthermore, no evidence syntheses have been carried out on the effects of school environment interventions in important areas such as sexual health, alcohol or smoking.

There has also been no synthesis of evidence on the school environment intervention process. Process evaluations examine the planning, delivery and receipt of school environment interventions and how these are influenced by local context, and are useful for informing decisions about the wider implementation of interventions. 43,44 Process evaluations can help explain how and under what conditions an intervention works and so can form a useful complement to randomised controlled trial (RCT) examination of whether or not and for whom an intervention works. 45

A further gap concerns the synthesis of evidence on the health effects of the school social and physical environment in the absence of specific interventions. Examining the impacts of such school-level factors on health outcomes is now a growing field of public health research that merits synthesis. 46 Although such observational studies provide less certain causal inference than experimental studies, those aiming to minimise confounding and other sources of bias could be used to identify promising areas for future intervention studies. This is important because, to date, school environment intervention studies appear to have addressed only some aspects of the school environment and neglected others, such as school leadership and approaches to learning.

An early review of the effects of anti-smoking policies on student smoking concluded that there was some evidence that these were effective; however, the review was hampered by its non-systematic design and admission of ecological alongside multilevel studies. Multilevel studies, unlike ecological studies, enable proper examination of how features of the school as an institution as opposed to the compositional features of the student body affect student health outcomes. 47 The review by Aveyard et al. 48 acknowledged the importance of multilevel evidence; however, it concluded that, although smoking prevalence differed markedly between schools, it was not yet possible to determine whether this was due to differences in student composition or to schools as institutions because of the poor methodology of studies. A particular problem was that studies did not adequately adjust for the potentially confounding effects of the families and neighbourhoods from which students were drawn, and overadjusted for factors that might actually mediate school-level effects on smoking, such as student attitudes to school and peer behaviours. This review used a simple set of database search terms, which may have made for an insensitive strategy, and the review authors noted that many of the articles included were found through the reference lists of included reports rather than from the database searches. Another review of multilevel studies of school effects on a range of student outcomes, including health as well as academic performance, involved a yet more rudimentary search strategy and no prespecified methods of quality appraising and synthesising studies. 49

Finally, qualitative research has also been used to explore how staff and students perceive their school environment, and the processes they see as influencing health. 50 This evidence would also be useful in informing future school environment interventions but remains unsynthesised.

Our review aimed to address these gaps. It was conducted in close collaboration with colleagues undertaking a Cochrane review that is updating the decade-old review of HPS interventions. 34 This Cochrane review focuses on interventions addressing each of the following areas: school curriculum; environment or ethos of the school; and links with parents/the wider community. 51 Our review instead focused only on school environment interventions that lack a health education curriculum component. This was a pragmatic means to provide our review with a focus distinct from that of the Cochrane review, but also allowed us to examine whether or not it is possible to attribute health effects to changes to schools' social and physical environments.

Chapter 2 Aim and research objectives

The initial, overarching purpose of this systematic review was to synthesise evidence relating to the effects of interventions addressing, and school-level measures of, schools' social and physical environments on the health and well-being of students and staff.

The research objectives and hypotheses were refined across two stages. In the first stage we developed broad research questions (RQs) geared towards developing a map of evidence and theories related to the review. These encompassed all aspect of schools' social and physical environments and the health and well-being of both students and teachers. These data were then presented to stakeholders (academics, people working in policy and practice and young people) whom we consulted with to help focus the review. We refined our research objectives in light of these consultations and in stage 2 focused specifically on student health and defined the school environment more narrowly in terms of how schools are organised/managed, how they teach, provide pastoral care and discipline students, and/or the school physical environment. We conducted five in-depth reviews of the evidence corresponding to the following RQs.

Research question 1

What theories and conceptual frameworks are most commonly used to inform school environment interventions or explain school-level influences on health? What testable hypotheses do these suggest?

Research question 2

What are the effects of school environment interventions (interventions aiming to promote health by modifying how schools are organised and managed; or how they teach, provide pastoral care to and discipline students; and/or the school physical environment) that do not include health education or health services as intervention components and which are evaluated using prospective experimental and quasi-experimental designs, compared with standard school practices, on student health [physical and emotional/mental health and well-being; intermediate health measures such as health behaviours, body mass index (BMI) and teenage pregnancy; and health promotion outcomes such as health-related knowledge and attitudes] and health inequalities among school staff and students aged 4–18 years? What are their direct and indirect costs?

Research question 3

How feasible and acceptable are the school environment interventions examined in studies addressing RQ2? How does context affect this, examined through process evaluations linked to outcome evaluations reported under RQ2 above?

Research question 4

What are the effects on health and health inequalities among school students aged 4–18 years of school-level measures of school organisation and management, teaching, pastoral care and discipline, student attitudes to school or relations with teachers, and/or the physical environment (measured using ‘objective’ data other than aggregate self-reports of the same individuals who provide data on outcomes), examined using multilevel quantitative designs?

Research question 5

Through what processes might these school-level influences occur, examined using qualitative research?

Protocol

The review protocol is available in Appendix 7. The published version can be freely accessed from the BioMed Central website (www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/453): Bonell C, Harden A, Wells H, Jamal F, Fletcher A, Petticrew M, et al. Protocol for systematic review of the effects of schools and school-environment interventions on health: evidence mapping and syntheses. BMC Public Health 2011;11:453.

Chapter 3 Report organisation and terminology

The report is organised according to the two stages of the research project. Stage 1: identifying and describing the references (see Chapter 5) presents the RQs, methods and findings of the evidence and theory map, and the stakeholder consultations. Stage 2: in-depth synthesis (see Chapters 6–10) presents the methods, results and discussions for the in-depth reviews for each RQ. Chapter 6 presents the in-depth review of the theories; Chapter 7 presents the in-depth review of the outcome evaluation studies; Chapter 8 presents the in-depth review of the process evaluation studies; Chapter 9 presents the in-depth review of the multilevel studies; and Chapter 10 presents the in-depth review of the qualitative studies. Each of these chapters lists the RQ investigated, explains our methods, gives an overview of the included reports and presents the results and discusses these in relation to the RQ at hand. In Chapter 11 we develop an overall synthesis in which we assess the primary and secondary review hypotheses developed in Chapter 6 in relation to the empirical evidence presented in Chapters 7–10. Chapter 11 also considers the strengths and weaknesses of the review, provides a summary of our findings and suggests implications of our review.

We use the term ‘report’ to refer to written publications included in the review. We use ‘study’ or ‘data set’ to refer to the research from which these arose. We use ‘reference’ to mean records of study reports included in the evidence map. ‘Statistically significant’ is used to indicate p < 0.05, except where otherwise indicated.

Chapter 4 Data management

We used EPPI-Reviewer 4 (ER4; Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, London, UK) to support the management and analyses of the references found and the data extracted for all stages of the review. 52 ER4 is a web-based systematic review program that supports the review process: downloading of bibliographic citations, application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, recording and storing free text and categorical and numerical data, and conducting statistical and qualitative synthesis. This specialist program also incorporates functions for comparing the independent assessments of reports from two or more reviewers. Therefore, ER4 helped to assure quality in our review and facilitated transparency and auditability.

Stage 1 Identifying and describing the references

Chapter 5 Evidence map, theory map and stakeholder consultations

Aim and research questions

The purpose of the map of evidence and theory and stakeholder consultations was to identify references that are potentially relevant to our review questions; to assess the nature of the references; and to refine our review questions for stage 2. The RQs for this initial mapping stage focused on all aspects of schools' social and physical environment and therefore were broader than the refined questions that we finally examined in our in-depth reviews.

Research question 1

What theories and conceptual frameworks are most commonly used to inform school environment interventions or explain school-level influences on health? What testable hypotheses do these suggest?

Research question 2

What are the effects of school environment interventions (interventions aiming to promote health by modifying the school's physical, social or cultural environment through actions focused on school policies and practices relating to education, pastoral care, sport, extracurricular activities, catering, travel to and from school and other aspects of school life) evaluated using experimental and quasi-experimental designs, compared with standard school practices, on health (physical and emotional/mental health and well-being; intermediate health measures such as health behaviours, BMI and teenage pregnancy; and health promotion outcomes such as health-related knowledge and attitudes) and health inequalities among school staff and students aged 4–18 years? What are their direct and indirect costs?

Research question 3

How feasible and acceptable are school environment interventions? How does context affect this?

Research question 4

What are the effects of other school-level factors on health and health inequalities among school staff and students aged 4–18 years, examined using multilevel and ecological (school) designs?

Research question 5

Through what processes might these school-level influences occur?

Methods

Database searching

Electronic databases searched

A total of 16 bibliographic databases were searched between 30 July 2010 and 23 September 2010, with no limits on language or date:

-

Australian Educational Index

-

British Educational Index

-

CAB Health (part of CAB Abstracts) – now known as Global Health

-

The Campbell (C2) Library

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

EMBASE

-

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC)

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC)

-

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS)

-

MEDLINE

-

PsycINFO

-

Social Policy and Practice (includes ChildData and Social Care Online)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Knowledge)

-

Sociological Abstracts

-

Dissertation Abstracts/Index to Theses.

EconLit and Public Affairs Information Services (PAIS) were also investigated, but trial searches produced no new material.

Search terms

A broad approach to database searching was used in stage 1 given the cross-disciplinary nature of the review, the wide range of study designs to be included and the variability with which references were indexed in bibliographic databases. A sensitive search was undertaken using a large number of natural-language phrases. The search terms were used to develop core searches that included the most relevant terms and in which references were to be scanned carefully, examining the full title/abstract in detail for inclusion; and non-core searches in which a broader set of ‘non-core’ (or marginal) terms were applied and scanning for inclusion was to be carried out slightly more rapidly (although in practice both were scrutinised carefully). Some additional intervention terms were added to the key terms as a third searching phase.

Core search

-

Setting (1) – school terms.

-

Population (2) – child terms.

-

Intervention/effect (3A) – key intervention/school-level effect terms.

-

Outcomes (4) – broad range of health outcomes.

-

Key phrases (5) – related to health and schools.

Search 1: Set 1 and Set 2 and Set 3A and Set 4 (setting/population and key interventions/effects and outcomes).

Search 2: Set 5 (HPS phrases).

Non-core search

-

Setting (1) – school terms.

-

Population (2) – child terms.

-

Intervention/effect (3B) – other non-key terms related to intervention/school-level effect (general free text).

-

Outcomes (4) – broad range of health outcomes.

-

Key phrases (5) – related to health and schools.

-

Key phrases (6) – simple phrases combined with Set 4 outcome terms.

Search 3: Set 6 and Set 4 (whole school phrases and outcomes).

Search 4: Set 1 and Set 2 and Set 3B and Set 4 (setting/population and key interventions/effects and outcomes).

Additional terms were added to Set 3B in the third phase of the search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included quantitative, qualitative and theoretical literature in the evidence map that theorised or empirically examined the effect of the school social and/or physical environment, interventions to address this and/or processes underlying these effects or interventions (not including the provision of health education or health-related goods or services) on the health or well-being outcomes of students (age 4–18 years) or staff. All references from the searches were uploaded into ER4 and duplicate references were removed (those scoring ≥ 0.85 on ER4's similarity score). Exclusion criteria were developed (Table 1) to remove irrelevant references and thereby identify relevant references. References were screened on title and abstract. A round of pilot screening was conducted by two reviewers on a sample of 200 abstracts to test and refine the criteria. The remaining references were divided between six reviewers (CB, HW, AH, CV, MP and FJ) and screened independently. After each reviewer had screened 2000 references, a random sample of 10% (n = 200) were double screened by another reviewer to ensure consistency in applying the criteria. A threshold of < 20 disagreements per 2000 references on whether to include/exclude was established.

It should be noted that, although these criteria were applied to most of the references, because of time constraints and the large number of references, those that were obviously to be excluded were marked ‘exclude only’ and not assigned an exclusion code.

| Exclusion criterion | Guidance |

|---|---|

| Exclude 1: general topic | The study is not about health/well-being or disease (including references solely focused on outcomes concerned only with education) |

| Exclude 2: setting and population | The study is not about the students or staff of schools (i.e. serving those aged 4–18 years) |

| Exclude 3: type of report | The study does not report primary research, a review of research or a theory |

| Exclude 4: study focus | Intervention (primary) references: The intervention is neither mainly delivered on the school site nor concerned with travel to and from schools (extracurricular interventions were included unless excluded based on any of the criteria below); neither about an intervention aiming to promote health/well-being or prevent disease nor reporting on the health/well-being outcomes of an intervention; involves only health education, information or counselling (regardless of who delivers this), school nursing, clinics or health checks, or health-related goods (medication, contraception, micronutrients, etc.), but interventions concerning school catering, sport or active transport would be included; and targeted only to some students on the basis of health-related needs (but interventions targeted on the basis of educational or social but not health needs would be included) |

| Non-intervention (primary) references: The study is not related to the effects of the school environment/school-level factors on health/well-being. We excluded reports comparing health outcomes between individuals with different educational experiences or attitudes because such references cannot be used to infer school-level effects | |

| Reviews and theoretical references: The study is not a review or theoretical paper with a focus on the school environment, interventions addressing this or school-level effects | |

| Exclude 5: study typea | Intervention (primary) references: The study is not an empirical outcome evaluation or process evaluation reporting on school environment intervention effects on health and/or cost, economic and econometric references examining school environment interventions |

| Non-intervention (primary) references: The study is not empirically examining school environment influences on health/well-being. If the study is a quantitative study it will be excluded if it is not reporting on school-level variables (but multilevel analyses including school-level analyses would be included); it is reporting only on school-level measures of students' social (e.g. socioeconomic status) or demographic (e.g. ethnicity) characteristics or students' social networks (but references examining student–staff relationships would be included); or it is reporting only on school-level measures of health education (regardless of who delivers this), school-based clinical health services or interventions targeted on the basis of health-related needs. If the study is a qualitative study it will be excluded if it is not reporting on the process by which schools might influence health | |

| Theoretical references: The study does not propose an abstracted, generalisable way in which features of schools are causally related to student/staff health. In other words, include only literature describing/explaining the theories and conceptual frameworks that are used to inform school environment interventions or explain school-level influences on health | |

| Reviews: The study is not a systematic review |

Evidence map: coding references

Included references were descriptively coded based on title and abstract. Descriptive coding involved identifying the following characteristics of each study:

-

relevance to RQs 1, 2, 3, 4 and/or 5

-

type of research

-

country where research was undertaken

-

research design

-

target population

-

health topic examined

-

level of school (e.g. high school, elementary school).

A round of pilot coding was conducted by four reviewers (CB, AH, HW and FJ) on a random sample of 40 references to ensure that the list of characteristics captured was comprehensive and relevant. Two reviewers (FJ and HW) double-coded the remaining references to ensure consistency in coding. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

As a result of the large number of references included at this stage, references were coded for the evidence map on the basis of title and abstract only. When screening references for inclusion in the evidence map we erred on the side of inclusion and so there were inevitably errors of overinclusion.

Theory map

A map of theories and conceptual frameworks used to inform school environment interventions or explain school-level influences on health was developed alongside the evidence map. We looked for theories while coding the first half of the references for the evidence map to obtain a broadly representative sample of theories. Those theories that were ‘named’ (e.g. ‘social learning theory’) and which were referenced in multiple references were identified. Summaries of the included theories were obtained through a Google search or were extracted from the original texts where they were first published.

Consultation with stakeholders

To refine the RQs and focus the review, we consulted with key stakeholders regarding the review topic and evidence and theory map.

Policy, practice and research

We presented the findings of the evidence map and theory synthesis to people working in policy (n = 3), practice (n = 1) and research (n = 2) on 1 April 2011. These individuals were purposively selected to ensure expertise regarding young people's health and education and generate diversity according to sector. Based on the evidence map we engaged in semistructured in-depth discussions about:

-

defining ‘school environment interventions’

-

determining the usefulness of theories in informing school interventions and explaining school-level effects

-

establishing priorities for the review in terms of types of interventions, health outcomes and theories of interest.

The evidence map was presented by CB and the session was chaired and facilitated by AH. Discussion lasted just over 2 hours with notes being taken by HW.

Young people

We consulted with an existing group of young people, brought together to advise on the conduct of public health research. We met with DECIPHer (Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement)'s Public Involvement Advisory Group, called ALPHA (Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement), on 25 September 2010 and again on 27 May 2011. We originally intended to consult with young people once on the evidence map and once on the draft final report, but we decided to front-load young people's participation at the start to ensure that we examined areas of priority to them. This group includes young people aged 14–19 years from across south Wales.

The first consultation was conducted at project inception when reviewers were first developing the protocol. The purpose of this consultation was to find out what the terms ‘health’ and ‘well-being’ meant to young people and to elicit their perspectives on how schools might impact on their health and well-being. A total of 13 young people participated in a face-to-face semistructured consultation that lasted just over 1 hour and it was facilitated by two researchers (AH and RL), with oversight from one youth worker. Notes were taken by AH.

For the second consultation we presented findings of the evidence map and theory synthesis to the group. The purpose was to engage in a prioritisation exercise to find out which of the health outcomes identified in the evidence map young people found most relevant to their experiences. A total of 13 young people from the group participated in the face-to-face semistructured consultation facilitated by two researchers (AH and FJ), with oversight from one youth worker. Notes were taken by FJ.

Online consultations through a social networking site (http://groups/youngpeopleinresearch; note that this website is no longer active) supplemented the face-to-face consultations. ALPHA members were invited to join the online group and provide any further views on the questions elicited from the face-to-face consultations, but this resulted in minimal additional data.

Results

Flow of literature: from database searching to evidence map

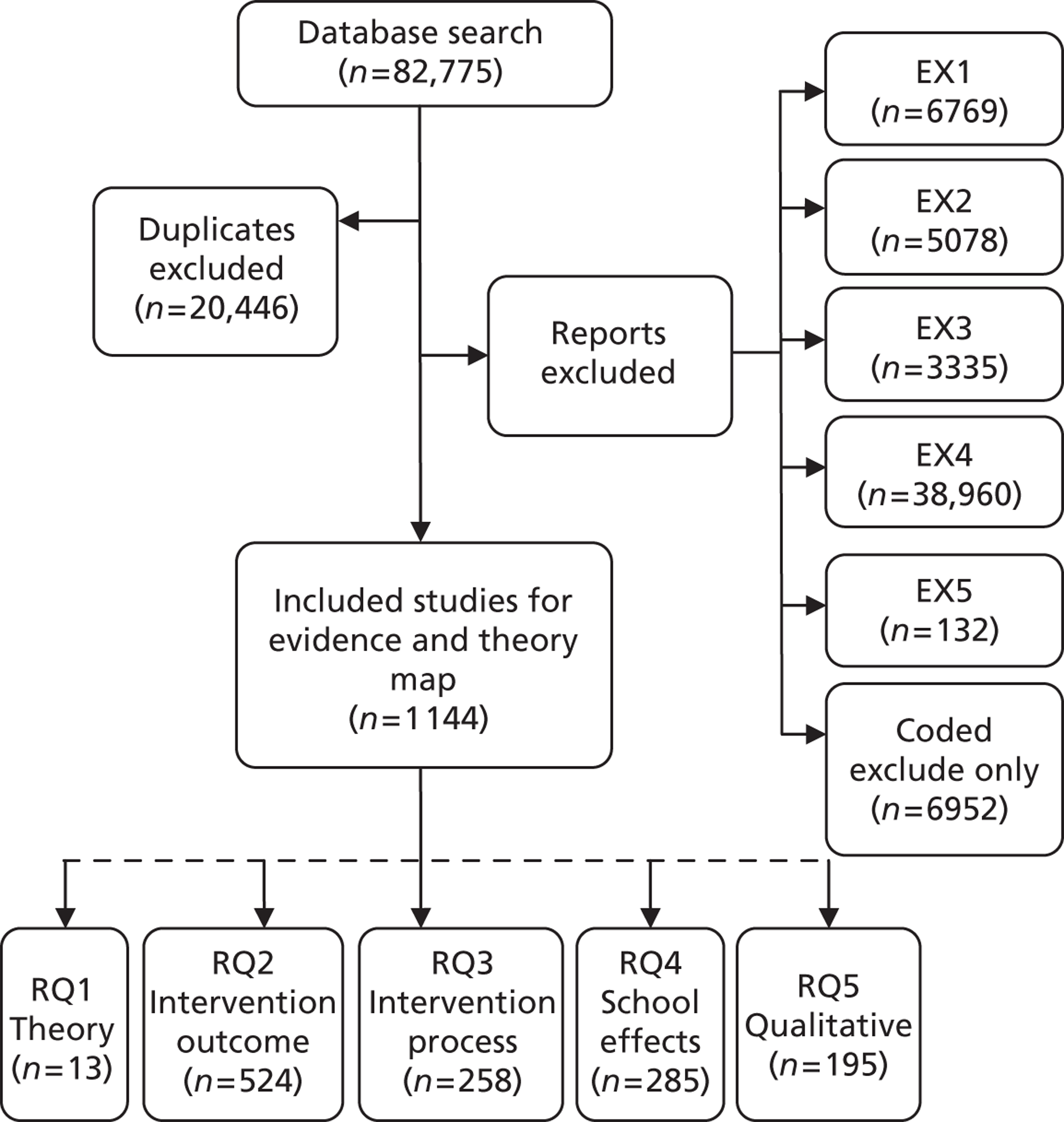

A total of 82,775 references were retrieved from the database searching. Of these, 20,446 were identified as duplicates: either ‘exact’ matches (n = 19,132) or very close matches (n = 1314). The remaining 62,329 references were screened on title and abstract and 61,185 (98.2%) were excluded. In total, 1144 references were included in the evidence map (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow of literature stage 1: evidence and theory map.

Literature from additional searches

Eight reports were identified for the stage 2 in-depth syntheses from additional searches (citation chasing and contacting authors and collaborators). One additional multilevel study of school effects on health was identified by contacting authors of included reports. 53 Two intervention outcome evaluation reports were referred to us by our Cochrane review collaborators. 54,55 Two additional theory references and one intervention outcome evaluation were identified by reference sifting. 56–58 Two additional intervention outcome/process evaluation reports were included as suggested by CB. 59,60 The reasons why these references were not captured in the database search were because they were published after our database search date,53,59 because of the reference type54 (conference paper) and/or because they were lacking relevant key wording. 55,58 Reports identified from additional searches are not presented in the results of the evidence map or flow of literature diagram because the additional searches were conducted after the map was produced.

Evidence map

The 1144 references were descriptively coded based on title and abstract to identify relevant characteristics of references. Because the references were coded for inclusion on title and abstract only, there are inevitably errors of overinclusion. Nonetheless, the evidence map provides a useful overview of the available evidence to inform our decisions about what references to prioritise for in-depth review in stage 2.

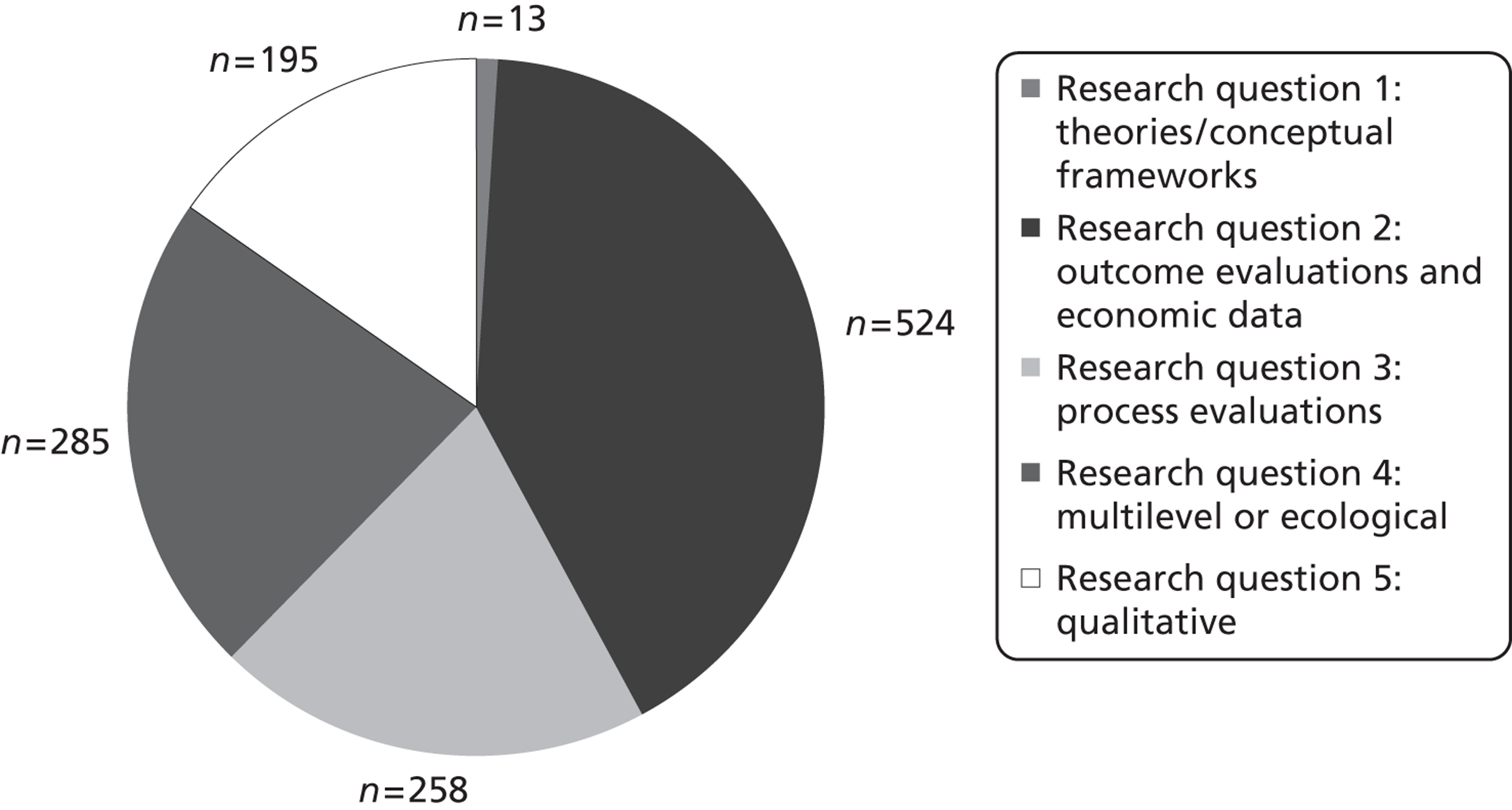

Relevant research question(s) of references included in the evidence map

Figure 2 indicates to which RQs references might be relevant. The total number of references, displayed in this figure, does not equal the total number of included references as categories were not mutually exclusive.

FIGURE 2.

Potential RQ(s) addressed by references in the evidence and theory map. RQ1: literature describing/explaining the theories and conceptual frameworks that were used to inform school environment interventions or explain school-level influences on health. RQ2: evaluation references reporting on school environment intervention effects on health, as well as cost, economic and econometric references examining the costs of school environment interventions. RQ3: process evaluations of school environment interventions. RQ4: multilevel or ecological (school) references examining school-level influences on health. RQ5: qualitative references exploring the process by which school-level factors might influence health.

Types of research

The vast majority of the references were coded as primary research (n = 1088). Very few systematic and other literature reviews (n = 68) were identified and even fewer stand-alone theory/conceptual references (n = 9).

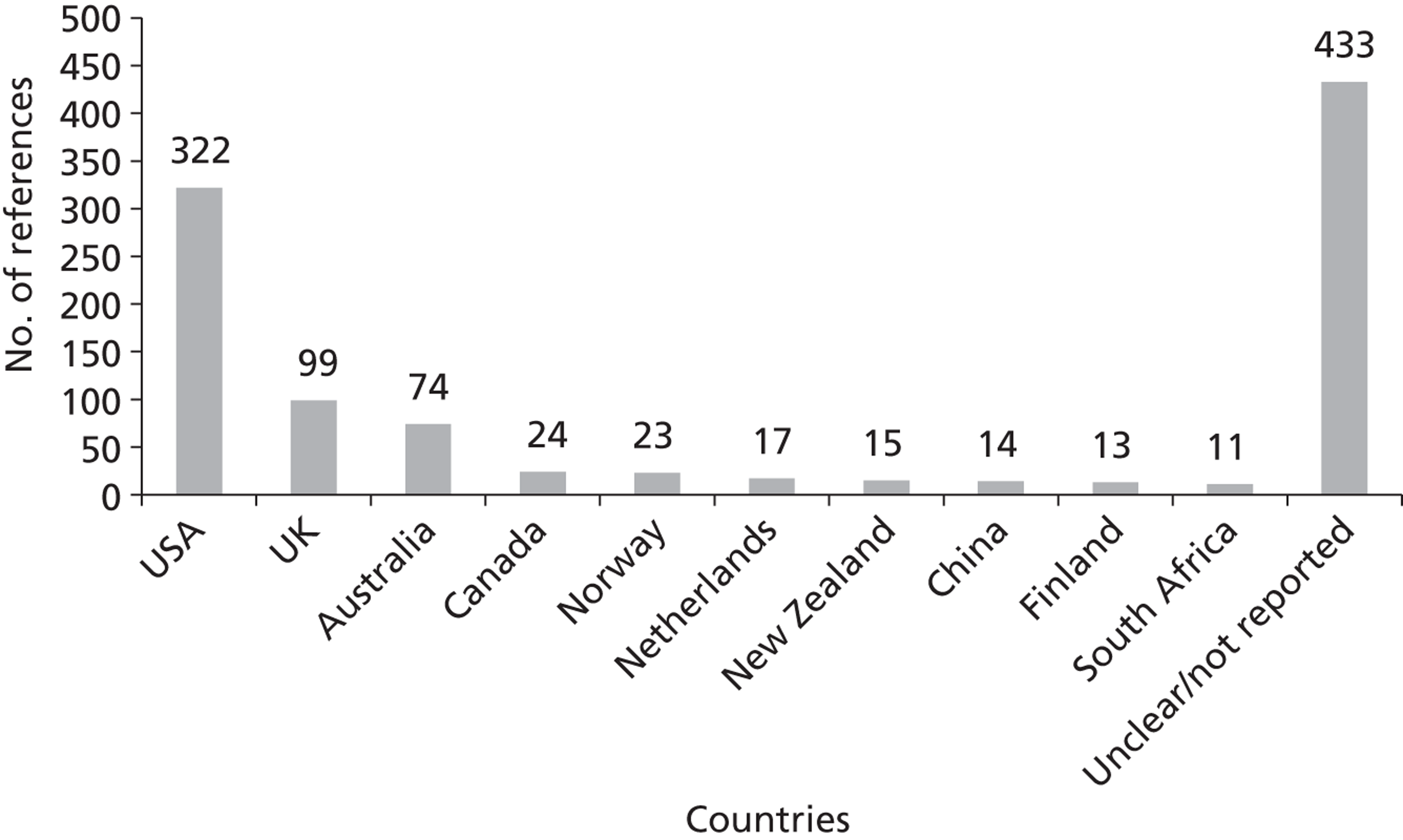

Country where research was undertaken

Figure 3 provides the distribution of research for the top 10 countries where research was conducted. Some references did not report the country of research in the title or abstract (n = 433). The total number of references, displayed in this figure, does not equal the total number of included references as categories were not mutually exclusive.

FIGURE 3.

Countries of primary research of studies included in the evidence map.

Research design

For references identified as outcome evaluation references reporting on the effects of school environment interventions on health, the primary research design was coded as follows:

-

RCTs (n = 143)

-

non-randomised comparison groups (n = 111)

-

before/after with no comparison groups (n = 74)

-

single cross-sectional survey (n = 20)

-

other [n = 7: potential quasi-experimental (n = 1), participatory action research project (n = 1), quantitative data evaluation (n = 1), focus groups (n = 2), meta-analysis (n = 1) and interrupted time series (n = 1)].

The research design was not clear from the title/abstract for 99 of the outcome evaluation references. Only nine references were identified as potentially including cost data or having conducted an economic analysis; the vast majority did not report this information in the title/abstract.

For references identified as potential multilevel or ecological (school) references examining school-level influences on health, the design was coded as follows:

-

single cross-sectional surveys (n = 198)

-

longitudinal cohort or repeat cross-sectional (n = 42)

-

other [n = 4: prospective diary design (n = 1), in-depth interview and focus group (n = 1), policy analysis (n = 1) and observational study (n = 1)].

The remaining multilevel/ecological study references (n = 39) did not clearly report the research design in the title/abstract.

Target population and health topics examined

Students were the target population studied for nearly all of the references included in the evidence map (n = 1093), with only 52 titles/abstracts mentioning staff as the target population.

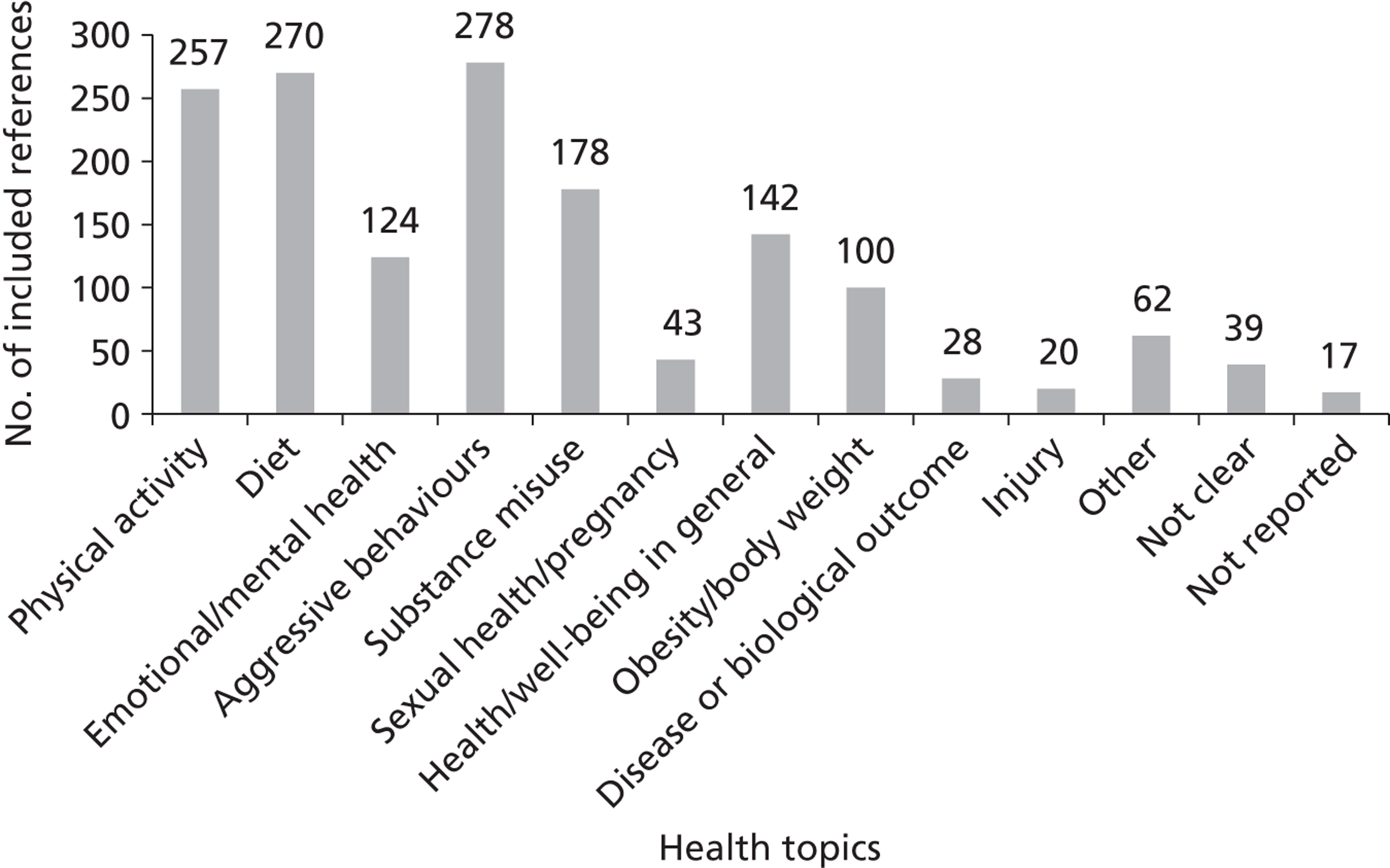

Most of the health topics identified were about violence, bullying and/or harassment (n = 278), eating/drinking (non-alcoholic; n = 270) or physical activity (n = 257). Figure 4 provides the distribution of the different health topics examined among included references. The total number of references displayed in the figure does not equal the total number of included references as categories were not mutually exclusive.

FIGURE 4.

Health topics of the references included in the evidence map.

School level/grade level reported

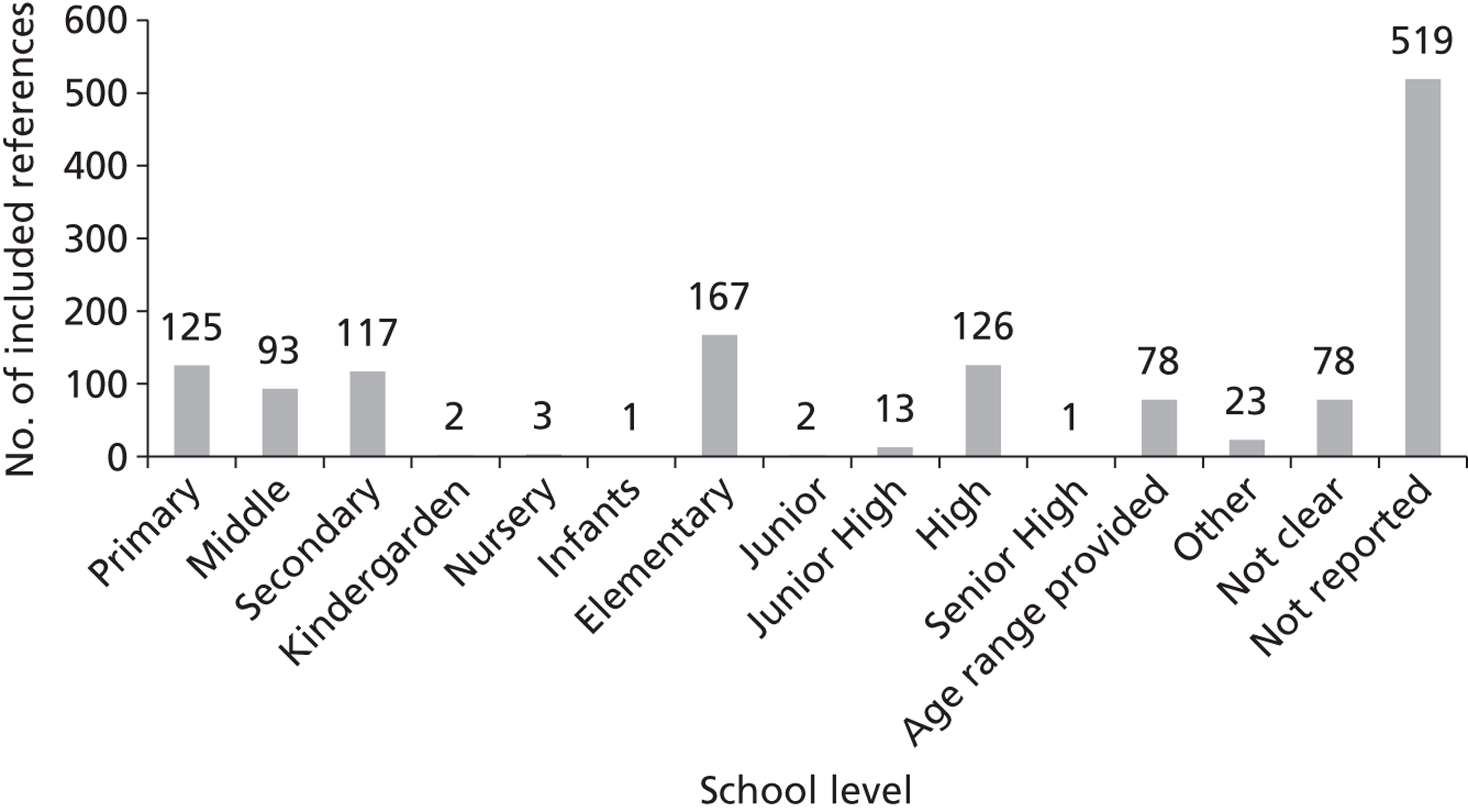

Most titles/abstracts did not report the school/grade level studied (n = 519). Of those that did, the majority of the research was conducted at elementary/primary schools (n = 167/125) or high/secondary schools (n = 126/117). Figure 5 provides the distribution of the different school/grade levels examined. The total number of references, displayed in the figure, does not equal the total number of included references as categories were not mutually exclusive.

FIGURE 5.

School/grade level of the references included in the evidence map.

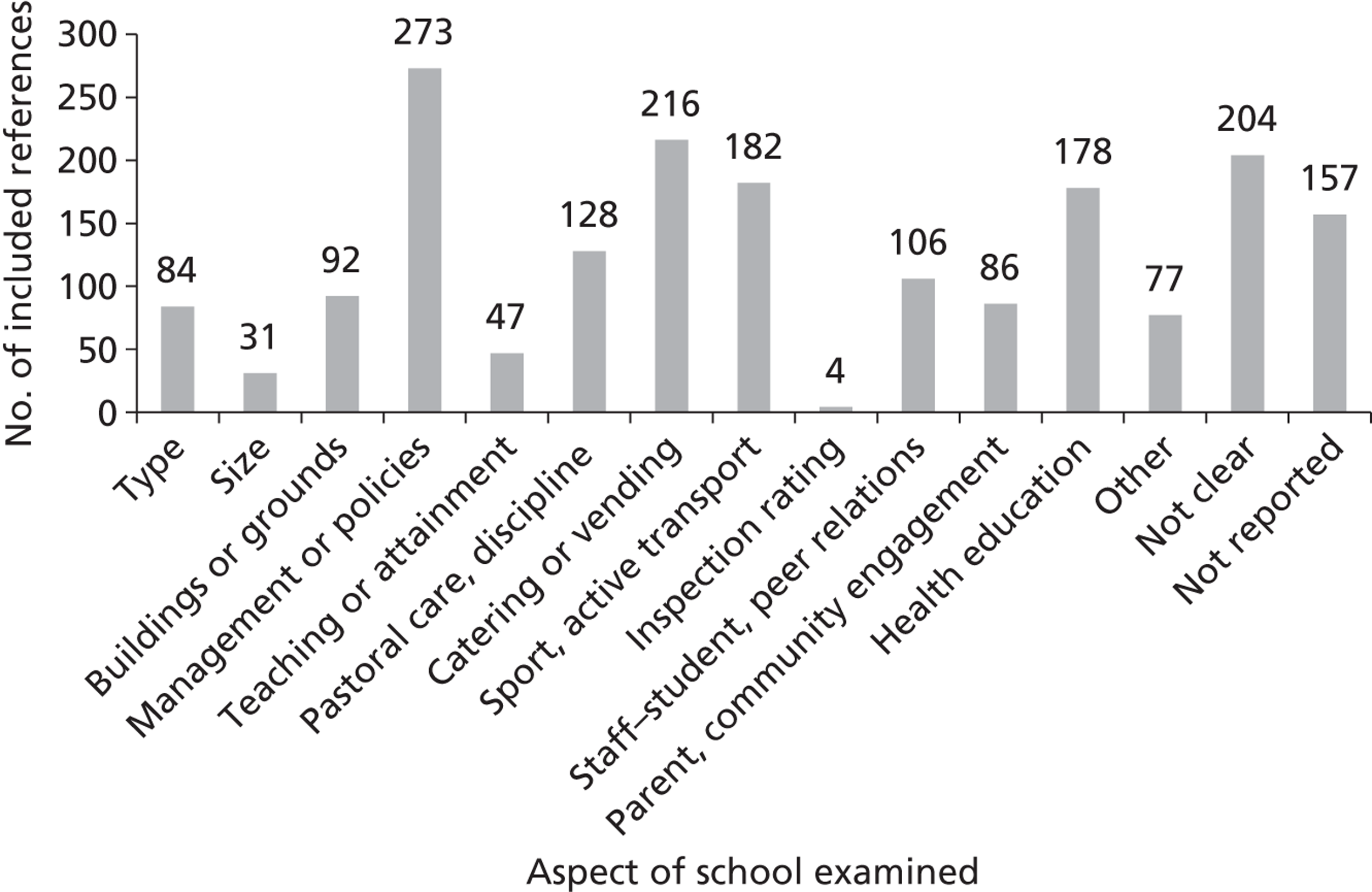

Aspect of the school examined

Figure 6 provides the distribution of the different aspects of schools examined among included references. Most reports focused on school management or polices (n = 273), catering or vending (n = 216) and sport or active transport (n = 182). We were unable to determine the aspect of the school examined for about one-quarter of the references based on the title/abstract alone (not clear n = 204; not reported n = 157). The total number of references, displayed in the figure, does not equal the total number of included references as categories were not mutually exclusive.

FIGURE 6.

Aspect of the school examined in the references included in the evidence map.

Theory map

A total of 12 theories/models were identified from the theory map. These include anomie theory, attachment theory, differential association theory, ecological systems theory, educational transmission of class theory, the health belief model, social cognitive theory, social control theory, the social development model, the social learning model, strain theory and the theory of reasoned action.

The theories suggest the potential importance of school-level determinants concerning or interventions addressing:

-

how schools structure norms (anomie theory)

-

relationships between staff and students (attachment theory, social learning theory)

-

the roles and opportunities that schools give to or withhold from students (social development model, strain theory)

-

teaching and learning (educational transmission of class theory)

-

school rules (social control theory)

-

health education (health belief model)

-

a combination of these (ecological systems theory).

Stakeholder consultation

The stakeholder consultation with policy-makers, teachers and academics suggested that we needed to define the school environment more clearly because otherwise it might be assumed to be the physical environment only. The consultation group suggested that, based on the presentation of the evidence map, we narrow our focus to:

-

policy and management (policies, systems)

-

social relationships (including staff–student, student–student and staff–staff relationships)

-

student culture (sense of connection, engagement and aspiration)

-

staff culture (values, vision, priorities, ethos, leadership)

-

physical environment (school grounds).

These stakeholders suggested that they would most value a synthesis of evidence on the effects of schools' ‘core business’ on student health in terms of (1) learning and teaching, (2) pastoral care and (3) discipline policies/practices. The mental health of teachers was also considered important by the stakeholders with whom we consulted.

Young people told us that being healthy and well meant feeling safe and secure, having personal confidence, feeling self-assured and having the support of friends and family. Young people suggested that schools affect their health and well-being in various ways and emphasised the importance of:

-

class size (e.g. large classes may mean less personal support, although some young people also thought small classes could be stifling)

-

staff attitudes (e.g. having to spend time with teachers in a ‘bad mood’ was unhealthy)

-

choice and empowerment at school (e.g. having a say in the running of schools)

-

social class composition (e.g. students from poorer backgrounds may feel or be made to feel out of place)

-

socialising (e.g. making friends, meeting people from different backgrounds)

-

teaching and learning (e.g. ‘making you smarter’, ‘opening your mind’)

-

hygiene (e.g. ‘disgusting toilets’)

-

school meal options and prices (e.g. healthy food is often more expensive).

Young people thought the following were the most important things that a school could do to improve student well-being:

-

reduce class sizes

-

foster a positive attitude in teachers and good relationships between staff and students

-

focus less on ‘league tables’ and more on ‘learning for learning's sake’

-

increase opportunities for students to focus on what they are interested in or good at

-

provide more sources of social support for students.

The young people we consulted with cited the following as important outcomes: good relationships (especially with teachers), anxiety, self-image and ‘overachieving’. This informed our decision to focus on aspects of schools' ‘core business’ of teaching, pastoral care and discipline. Based on these consultations we decided not to focus on school activities such as extracurricular activities, catering and vending of food and drinks, physical education (PE) and active transport to and from school.

Implications for stage 2: in-depth review

The findings from the evidence and theory map as well as the stakeholder consultations with young people and people working in policy, practice and research suggested that the most important school environment determinants and interventions to focus on concerned those relating to how schools are organised and managed and how they deliver teaching, pastoral care and discipline, as well as the physical environment of schools. Therefore, we focused on aspects of schools' organisation and management, teaching, pastoral care and discipline and the physical environment that may influence student health outcomes. We chose not to focus on catering, PE, extracurricular activities or active transport to and from school. Our decision not to focus on school environment interventions involving changes to school catering, PE and extracurricular activities was informed by a view that these areas are already well synthesised. 25,61 We also decided to review only references focused on student health and not teacher health despite this being recommended by some stakeholders, to make our review manageable.

Research questions for stage 2: in-depth review

Research question 1

What theories and conceptual frameworks are most commonly used to inform school environment interventions or explain school-level influences on health? What testable hypotheses do these suggest?

Research question 2

What are the effects of school environment interventions (interventions aiming to promote health by modifying how schools are organised and managed, or how they teach, provide pastoral care to and discipline students, and/or the school physical environment) that do not include health education or health services as intervention components and which are evaluated using prospective experimental and quasi-experimental designs, compared with standard school practices, on student health (physical and emotional/mental health and well-being; intermediate health measures such as health behaviours, BMI and teenage pregnancy; and health promotion outcomes such as health-related knowledge and attitudes) and health inequalities among school students aged 4–18 years? What are their direct and indirect costs?

Research question 3

How feasible and acceptable are the school environment interventions examined in references addressing RQ2? How does context affect this, examined using process evaluations linked to outcome evaluations reported under RQ2 above?

Research question 4

What are the effects on health and health inequalities among school students aged 4–18 years of school-level measures of school organisation and management, teaching, pastoral care and discipline, student attitudes to school or relations with teachers, and/or the physical environment (measured using ‘objective’ data other than aggregate self-reports of the same individuals who provide data on outcomes), examined using multilevel quantitative designs?

Research question 5

Through what processes might these school-level influences occur, examined using qualitative research?

The chapters that follow describe how references in the evidence map were screened against a priori criteria to determine whether or not they were included in the in-depth reviews addressing each of the above questions.

Additional searches

Additional searches were conducted by screening the reference lists of all reports from the evidence map that were included in the in-depth review; contacting authors of included references for additional references; and asking Cochrane review collaborators for additional references. References published before June 2011 from the additional searches were considered for inclusion in stage 2.

Stage 2 In-depth synthesis

Chapter 6 Research question 1: theory synthesis

Research question

Which theories are cited in the literature and what hypotheses do they suggest for this review?

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Thirteen stand-alone theory references were identified from the evidence and theory map as relevant to the theory synthesis. We included literature in the in-depth synthesis that theorised how the school social or physical environment (defined in terms of how schools are organised and managed, how they provide teaching, pastoral care or discipline, and schools' physical environment) affects students' health or well-being. An additional two references56,57 were sourced through reference checking. The full-text reports of these references were retrieved and the following exclusion criteria were applied independently by two reviewers (there were no discrepancies to be resolved):

-

exclude reports that do not propose an abstracted, generalisable way in which core features of schools and school environment interventions are causally related as (1) a stand-alone theory, (2) a general theory of school health or (3) a theory addressing school influences on health

-

exclude reports that are not written in English.

Quality assessment

The descriptions of the theories were extracted from included reports. We then obtained the original source of the theory and used this as a focus for quality assessing theories. The criteria for quality assessing theories are as follows:

-

whether or not the constructs are well specified

-

whether or not clear causal pathways are specified between constructs

-

whether or not it was a simple theory/model

-

whether or not it suggested which specific aspects of the school institution might influence health

-

whether or not it is applicable to multiple health domains

-

what the theory/model assumptions are

-

whether these assumptions are implicit or explicit.

We developed these ourselves having searched for but not found existing criteria to assess the quality of theories. Our criteria were intended to determine which theories to use to inform the development of overall hypotheses for the review; these focus on the internal logic of each theory (well-specified constructs; clear pathways; simple; explicit assumptions) and its applicability to understanding school effects on health (which specific aspects of an institution influence health; applicable to multiple health domains). Some of these criteria were necessarily subjective, calling for researcher judgements, for example about whether or not a theory was simple (i.e. parsimonious). The quality assessment criteria were piloted on a random sample of two theories by two reviewers (CB and HW) before being applied by one reviewer (CB) and checked by another (HW), with any differences being settled by discussion.

The quality criteria were used to categorise theories as either primary or secondary theories, which in turn inform our primary and secondary review hypotheses. Theories were not excluded based on quality scores. We used these quality criteria to form a judgement about which theories to draw on to define our primary and secondary review hypotheses. We did not simply require that a theory meet every criterion to be deemed ‘primary’ because our judgements were necessarily more subtle than this.

Data extraction

We extracted data related to the name of the theory, its originator, the year of origin, what constructs and pathways it involved, its disciplinary origins and whether it is linked to any higher-order or lower-order theories. The data extraction tool was piloted by two reviewers (CB and HW) on a random sample of two theories before being applied by one reviewer (CB) and checked by another (HW), with any differences being settled by discussion.

Synthesis

We summarised the primary and secondary theories in tables and used these to inform the development of hypotheses for our review, which we assess against the empirical evidence reviewed and report in Chapter 11.

Overview of included reports

Flow of literature

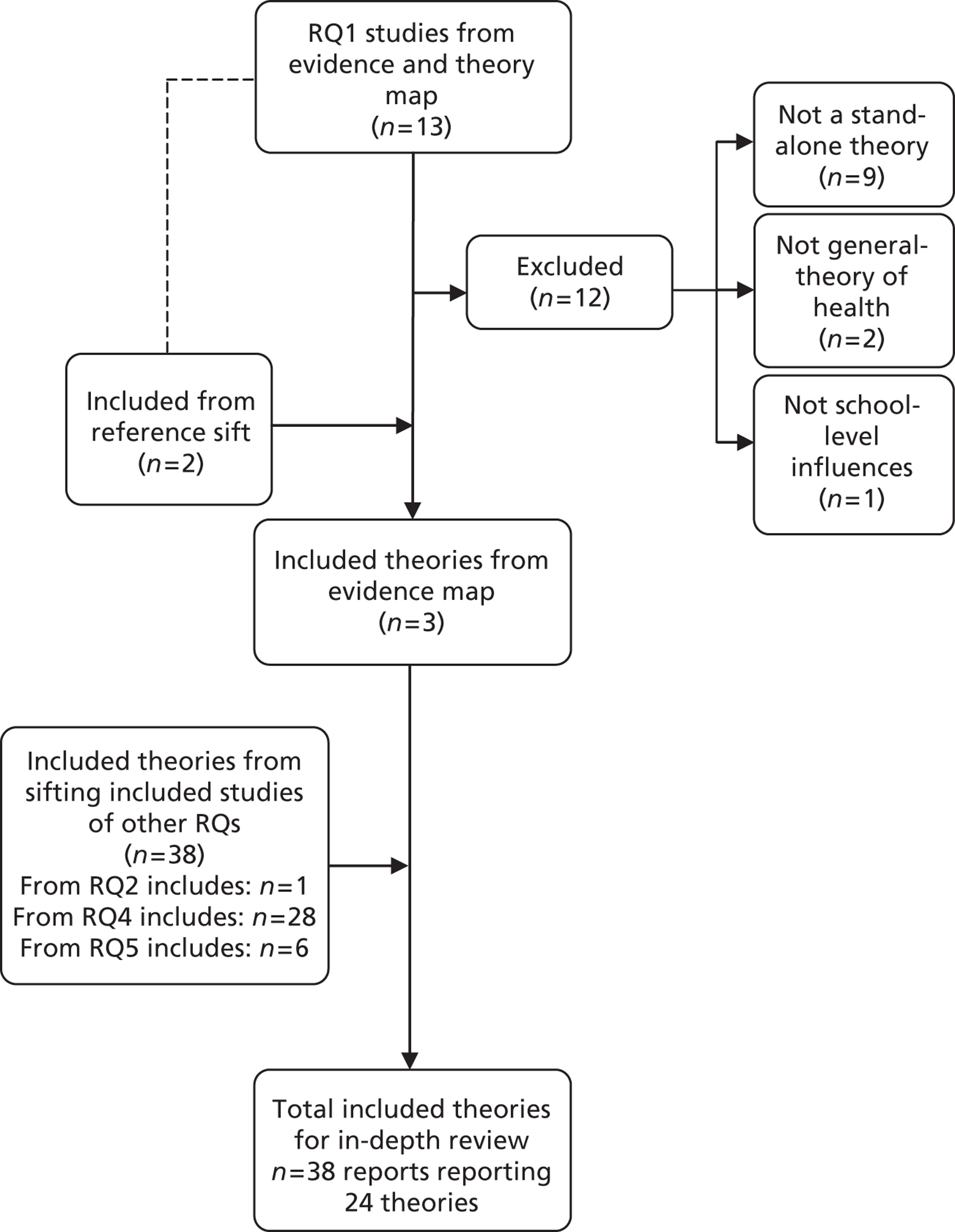

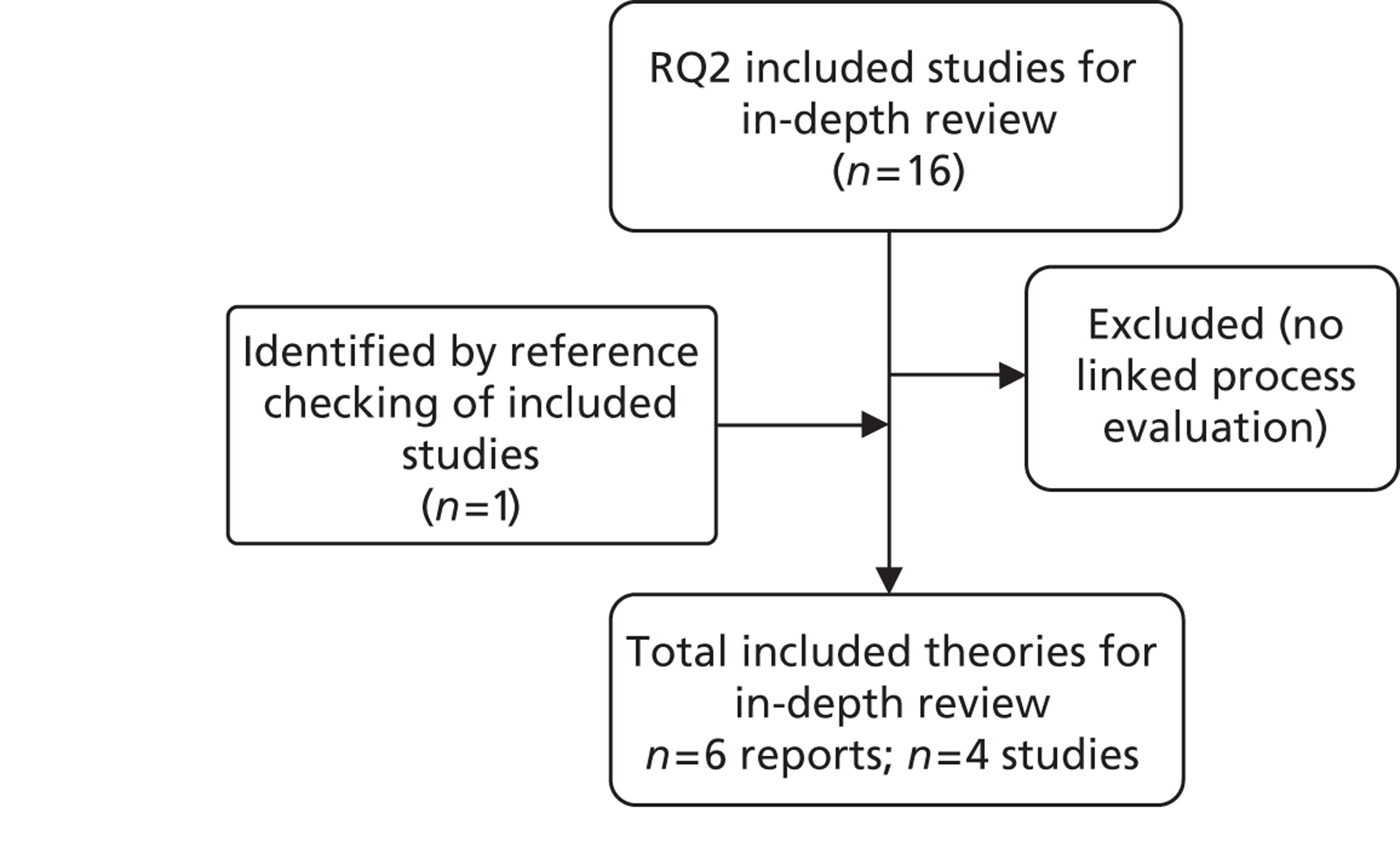

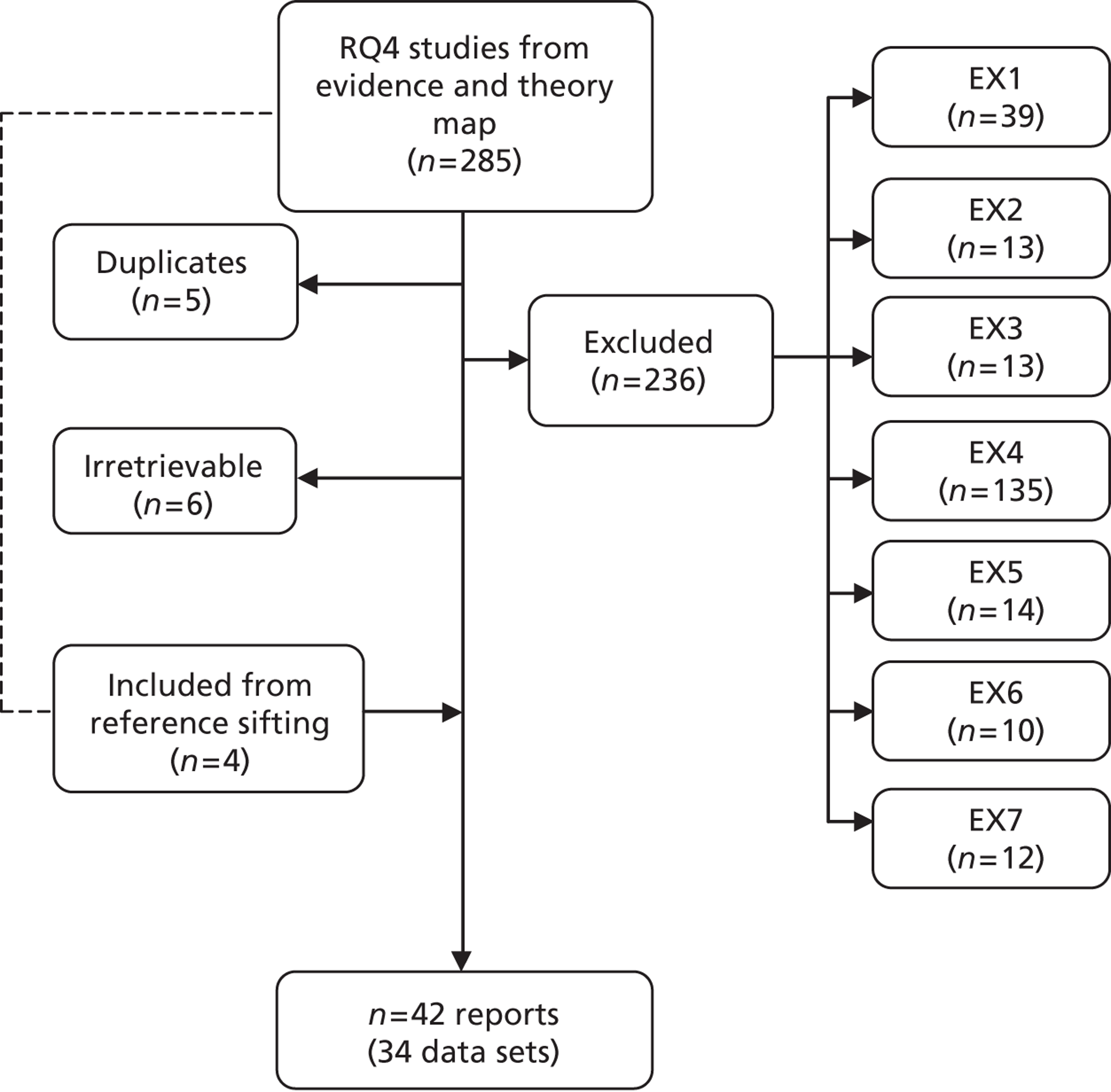

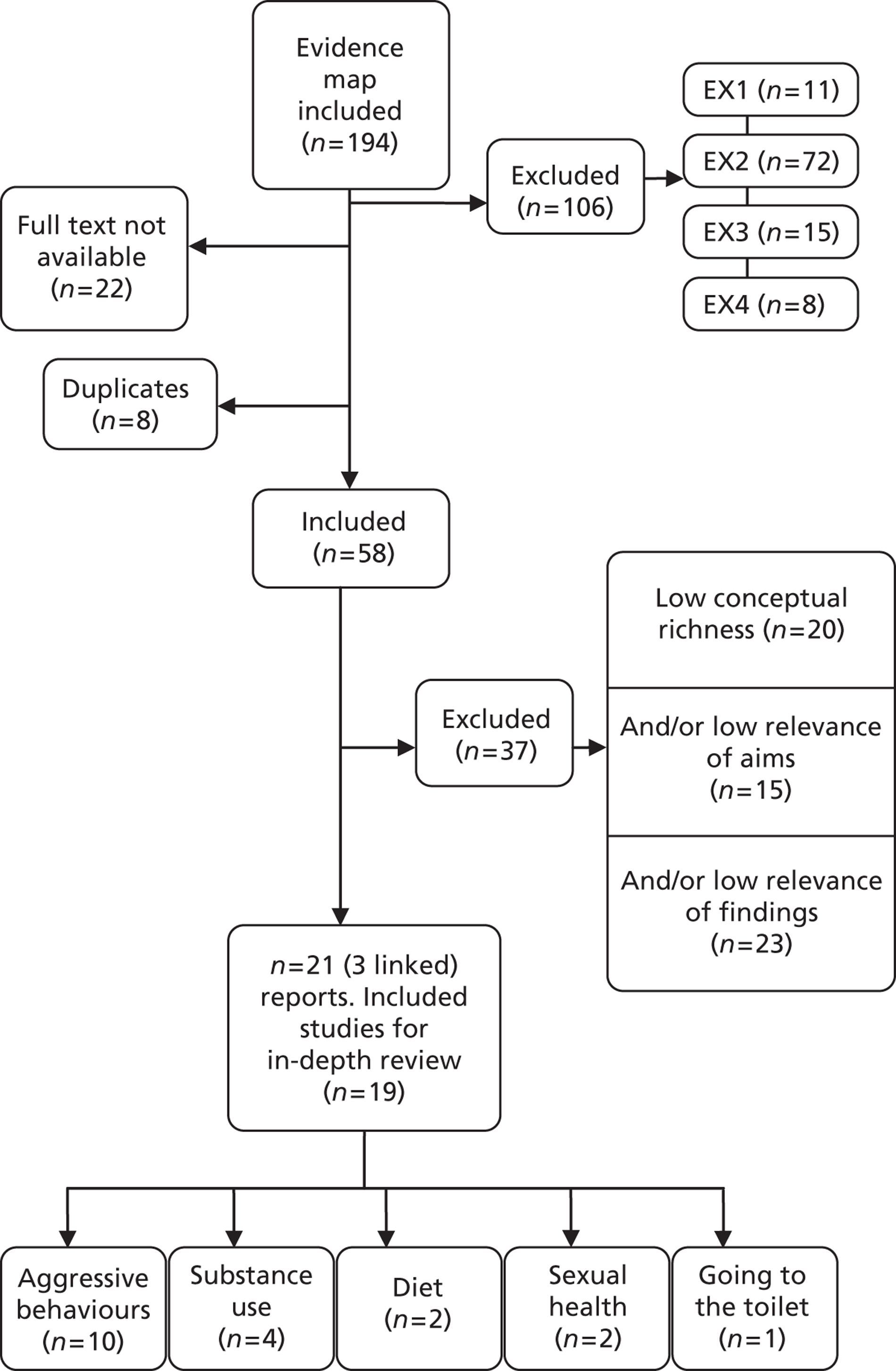

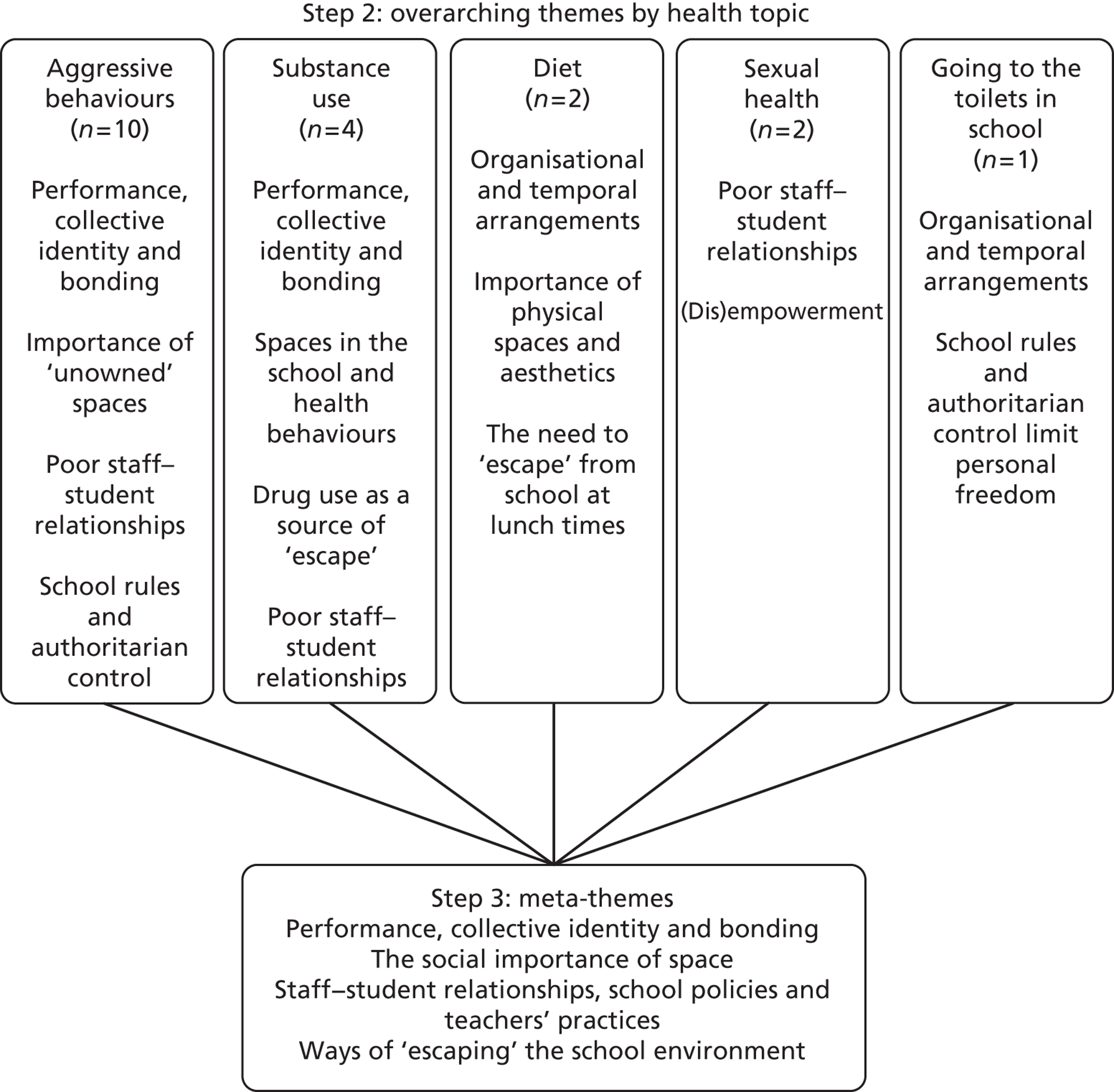

Of the 13 references identified from the evidence and theory map, only one62 was included. The other 12 references were excluded because they did not report a stand-alone theory (n = 9), did not report a general theory of school health (n = 2) or did not address school influences on health (n = 1). Two reports identified through citation chasing were included. 56,57 All empirical reports included in RQ2–5 were screened for reference to any theories. A total of 35 reports were identified through this search and were included in the in-depth synthesis. Thus, 38 reports, which reported on 24 theories, were included in the in-depth review (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Flow of literature: theory synthesis (stage 2: in-depth synthesis).

Quality assessment

We judged that three of the 24 theories (ecological systems theory, ecological model of co-ordinated school health programmes and theory of structuration) did not have clear or narrowly specified constructs in the sense that these might be operationalised in empirical research, but that the rest (n = 21) did. We judged that nearly all of the theories used a reasonably small number of components and a simple framework of inter-relations between them to understand potential school effects on health (n = 20). Four were categorised as more complex (ecological systems theory, ecological model of co-ordinated school health programmes, human functioning and school organisation and the theory of triadic influence). We judged causal relations between constructs as being clearly specified in all but three of the theories (contagion theory, ecological systems theory and ecological model of co-ordinated school health programmes). Fourteen of the 24 theories were judged not applicable to multiple health domains: 11 applied only to delinquency outcomes, two to public behaviour only and one to violence only. Moral authority theory, social control theory, deterrence theory, the integrated perspective on delinquent behaviour and strain theory were all judged as relevant to understanding health outcomes that are associated with antisocial behaviour (ASB) only. These theories are not relevant to understanding other health outcomes such as healthy eating and physical activity.

We judged that three theories fully met the criterion of whether or not the theory suggests which specific aspects of the school might influence health. Another 10 partially met it.

Study characteristics

Twenty-four theories were identified in the in-depth theory synthesis. These were cited in a total of 38 reports53,56,57,62–96. The theories most commonly cited in empirical reports were ecological systems theory68,75,77,78,80,83,85,90,96 (n = 10), social control theory71,73,80,82,97 (n = 6), social disorganisation theory70,79,88,89,97 (n = 5), social learning theory71,76,81,94 (n = 4), the theory of human functioning and school organisation53,64–66,95 (n = 5) and social cognitive theory63,76,77,83 (n = 4).

Results

Primary theories that explain the mechanisms by which schools determine health

We identified three theories to be most useful, informing the primary hypotheses to use in interpreting findings from the review's empirical studies. These met all of our quality criteria, with the exception of the theory of human functioning and school organisation, which did not meet our criterion of simplicity. However, we judged that this theory was very strong regarding our other criteria and so included it.

Social development model

The social development model is a social psychological theory developed by Hawkins and Weis,98 building on social learning and social control theories. This suggests that young people learn antisocial and prosocial patterns of behaviour from their immediate social environment by being provided with opportunities for involvement, opportunities to develop skills and reinforcements for actions. These processes build attachment to others engaged in these activities and, where these activities are prosocial, potentially build commitment to the conventional social order and conformity with social norms. This theory would lead us to expect that schools are more likely to foster attachment to the school and encourage healthy behaviours if they provide opportunities for students to participate in learning and institutional life; enable development of the skills necessary for such participation; and ultimately enable students to gain recognition and prosocial reinforcement for this.

Social capital theory

Social capital is conceived somewhat differently by different scholars; however, all conceptualise social capital as the product of social structures that facilitate group or individual actions. 99 The theory suggests that social networks characterised by reciprocity, trust and shared social norms will facilitate such actions, although whether such actions are health promoting or harming will depend on the specific nature of the norms. Theorists differ about whether social capital should be considered a property of groups, as Putnam100 suggests, or individuals, as Bourdieu and Wacquant101 argued. They also differ over whether it should be considered primarily as an adjunct to economic capital among elites, as suggested by Bourdieu and Wacquant,101 or as a distinct resource available for use by all, as Coleman102 suggested.

Social capital was theorised by Coleman102 as being strongest when the networks involved are stable, enclosed and intergenerational and involve norms of reciprocal obligation. Informed by Granovetter,103 Putnam100 introduced the distinction between bonding and bridging social capital, the former being strong ties between similar individuals and the latter being weaker ties between more disparate individuals and groups. Granovetter103 had earlier pointed to the importance of weak ties in communicating information and norms. Portes99 has pointed to the potential for bonding social capital to lower aspirations and reducing individual autonomy.

Drawing from these different perspectives we might therefore expect to find that the schools with more positive health outcomes are characterised by stability of the student and staff body, good relationships between staff and students and a positive school ethos of shared norms.

Theory of human functioning and school organisation

We judged this theory as offering the most specific guidance about the mechanisms by which schools might determine health. 62 It should be noted that this theory is not synonymous with the WHO guidance on HPS. It was produced by academic researchers not working with the WHO.

This theory asserts that a person's autonomy to make and enact good decisions is a necessary precondition for healthy behaviour. Informed by Nussbaum,104 this theory outlines how young people have various needs that must be met and capacities which must be built in order to achieve such autonomy. Enabling young people to develop ‘practical reasoning’ and ‘affiliation’ is key because fulfilment of all other needs and capacities will require a person to be able to think and form relationships. ‘Practical reasoning’ involves an ability to understand and manage one's own feelings, perspectives and emotions, and appreciate that other people also have their own feelings, perspectives and emotions. Practical reasoning also involves considering different options when making a decision on how to behave, including thinking about one's own and others' perspectives, feeling and emotions. ‘Affiliation’ involves an ability to form relationships with others.

A school can enable its students to fulfil these capacities through what Bernstein105 had previously called its ‘instructional’ and ‘regulatory’ orders. The instructional order is the way in which a school enables students to learn. It has traditionally involved developing students' practical reasoning through in-depth study of discrete academic subjects, but it can also refer to the development of life skills and emotional and social literacy. The regulatory order is the way in which a school aims to encourage norms of good behaviour and students' sense of belonging in the school community. Bernstein105 argued that schools should aim to ensure their students are ‘committed’: engaged with and able to meet the challenges of the instructional order, and accepting the norms of, and feeling a sense of belonging to, the regulatory order. However, students can become ‘alienated’, ‘detached’ or ‘estranged’ (Table 2).

| Accept and meet challenges of the ‘instructional’ order | Reject or unable to meet challenges of the ‘instructional’ order | |

|---|---|---|

| Accept values of the ‘regulatory’ order | Committed | Estranged |

| Do not accept values of the ‘regulatory’ order | Detached | Alienated |

Informed by Bernstein,105 Markham and Aveyard62 argue that alienated or detached students might instead seek alternative affiliation and self-development in other groups, such as anti-school peer groups, with consequences for health behaviours such as substance use, violence and teenage pregnancy. How students respond to school may depend partly on their social class and the extent to which school culture seems to connect with or contradict the culture that students experience in their families and communities. According to Bernstein,105 working-class students are more likely to become alienated, detached or estranged than middle-class students because they are more likely to feel that the school's culture does not resonate with their own culture and, therefore, that its instructional and regulatory orders are not aimed at meeting their own needs.

The theory of human functioning and school organisation suggests that schools will differ in how inclusive their culture is and the extent to which they enable different students to become committed. The extent to which schools are able to do this will depend on their modes of ‘classification’ and ‘framing’. 105 ‘Classification’ refers to how the school as an institution and its curriculum are organised and, within this, how rigidly ‘boundaries’ are set. These boundaries can involve those between staff and students and those within the student body (e.g. through academic streaming, those learning different academic subjects/studying for different qualifications). Some schools will reduce these boundaries and Bernstein105 proposes that these schools will be more successful at building student commitment and promoting student autonomy and health. ‘Framing’ refers to the style in which staff communicate with and teach students, either rigidly, in which communication is teacher centred and teaching is didactic, or more flexibly framed, whereby communication is more equal and students are able to contribute to decisions about how learning proceeds. 106 This theory suggests that schools that maintain rigid social boundaries, between staff and students and/or among students, and which frame learning in teacher-centred rather than student-centres ways will fail to ensure that their students are committed, so that these students reject the values of the school and seek affiliation elsewhere, including with peer groups that embrace substance use and other risk behaviours.

Secondary theories that explain the mechanisms by which schools determine health

We identified a further 10 theories that could be used to suggest our secondary review hypotheses. Several of these theories did not meet our quality criterion of addressing a range of health outcomes but we judged them to be sufficiently useful in understanding school effects on ASB-related outcomes, hence we included them. The theory of triadic influence was included despite not meeting our quality criterion of simplicity because of its clarity and comprehensiveness, while the ecological model of co-ordinated school health programmes was included despite not meeting our quality criteria of simplicity, operationalisable constructs and clear pathways because, unlike all other theories, it attended to certain aspects of the school environment, such as school safety and opportunities for physical activity.

Flay's56 triadic theory of health behaviours suggests that health behaviours are influenced by factors from three domains: intrapersonal factors (social competence and sense of self), socioenvironmental factors (behaviours of others and bonding to others) and the broader cultural environment (information and opportunities about behaviours and culture/religion). Each of these streams has distal and proximal elements moving from the social–personal nexus to expectancies and evaluations and to cognitions and affect, with dynamic inter-relationships between these. Attitudes, socially normative beliefs and self-efficacy determine decisions/intentions and behaviour. Although his theory offers a comprehensive framework for understanding how the influences on health behaviours inter-relate, it does not aim to offer a specific theory of how the school institution structures these factors. Nonetheless, it does suggest the hypothesis that schools may foster healthy behaviours by providing access to knowledge through health education, but also by reducing students' opportunities for engaging in risk and setting rules against risky behaviours, by providing opportunities for bonding with staff and other students, and enabling the development of social skills through health and general education.

Eight theories outline why certain young people may engage in antisocial or risk-taking behaviours. Social control theory107 suggests that individuals with a stake in a particular community will avoid committing acts considered deviant within that community. This might suggest the hypothesis that schools can reduce ASB by giving students some stake in their school community, perhaps by increasing their participation in decisions. The integrated perspective on delinquent behaviour108 suggests that delinquency will be greater among individuals who have experienced a failure to participate in conventional social settings. This would suggest the hypothesis that schools can reduce ASB by ensuring that all students experience success in school activities. Problem behaviour theory109 suggests that young people engage in behaviours such as drug use or risky sexual behaviour to cope with problems dealing with their wider system of conventional behaviour such as educational failure and low self-esteem. This would inform a hypothesis that schools could reduce ASB by ensuring that students' educational and social problems are addressed. Strain theory110 suggests that individuals may engage in ASB when they experience a strain between achieving what they regard as socially legitimate goals and their ability to achieve these through socially legitimate means. Thus, we might hypothesise that schools with lower rates of ASB are better at ensuring that students can achieve their broader goals through school activities.

None of the above theories considers the specific means by which schools may affect these mechanisms. Other theories go a little further towards suggesting what particular aspects of an institution might determine behaviour. For example, deterrence theory111 would suggest the hypothesis that individuals will be deterred from behaviours if these are met with certain, severe and rapid punishments. Similarly, although the theories of reasoned action112 and the theory of planned behaviour113 do not consider how the school environment is likely to influence health, they do suggest that behaviours that are the subject of clear sanctions within schools might be inhibited by encouraging students' acceptance of institutional norms and motivation to conform. This would suggest the hypothesis that schools with strict and strongly enforced codes against activities such as smoking, drinking and violence have lower rates of these outcomes. In contrast, moral authority theory114 argues that a prime aim of schools is to inculcate respect for the specific rules of the school as well as broader rules of social behaviour. However, this would not need to occur through strict enforcement and severe punishments, because acceptance of the rules can be internalised without recourse to such formal processes. This theory would suggest the hypothesis that schools with lower rates of ASB have a positive ethos and do not necessarily have strict rules, although the theory does not offer suggestions as to what system of organisation would be required to foster this positive ethos.

The ecological model of co-ordinated school health programmes,57 although not offering a very deep understanding of how institutions affect health, does direct attention to particular aspects of schools that might promote health across multiple domains. This model would suggest a hypothesis that schools can foster health by promoting a supportive psychosocial environment and safe facilities, as well as opportunities for physical activity within the school.

Discussion

Summary of key findings

Twenty-four theories were identified in the in-depth theory synthesis. The theories most commonly cited in empirical reports were ecological systems theory, social control theory, social disorganisation theory, social learning theory, the theory of human functioning and school organisation and social cognitive theory. We considered several criteria to decide which theories to use to inform our primary and secondary review hypotheses.

Table 3 indicates the testable hypotheses that the primary and secondary theories we identified might suggest.

| Theory | Hypothesis |

|---|---|

| Primary theories | |

| Social capital theory | Schools foster health by having a stable student and staff body, good relationships between staff and students and a positive school ethos of stable, shared norms |

| Social development model | Schools reduce ASB by providing opportunities for students to participate fully in learning and community life and develop the skills necessary for such participation and ultimately enabling students to gain recognition |

| Theory of human functioning and school organisation | Schools foster student autonomy and health by reducing social boundaries between staff and students and among students, and ensuring student-centred framing of learning, management and other school systems |

| Secondary theories | |

| Deterrence theory | Schools reduce ASB by setting certain, severe and rapid punishments |

| Theory of reasoned action | |

| Theory of planned behaviour | |

| Ecological model of co-ordinated school health programmes | Schools foster health by promoting a supportive psychosocial environment, good safety facilities and opportunities/requirements for physical activity within the school |

| Integrated perspective on delinquent behaviour | Schools reduce ASB by ensuring that all students experience success in school activities |

| Moral authority theory | Schools reduce ASB by inculcating respect and not necessarily setting severe punishments |

| Problem behaviour theory | Schools reduce ASB by ensuring that students' educational and social problems are addressed |

| Social control theory | Schools reduce ASB by giving students some stake in the school community, perhaps by increasing student participation in decisions |

| Strain theory | Schools reduce ASB by ensuring that students can achieve their broader goals through school activities |

| Theory of triadic influence | Schools foster health by providing health education, reducing students' opportunities for engaging in risk, setting rules/norms against risky behaviours, enabling bonding between staff and students and providing good general education |

Strengths and limitations

Our initial summary of theoretical literature in stage 1 was relatively unsystematic: we noted theories that recurred in the first half of our coding for the evidence map but not in the second. The preliminary summary identified only five of the theories that were identified in the in-depth synthesis. Nonetheless, this provided us with some insights into the range of theories informing the empirical studies. Along with the evidence map it enabled us to have a lively discussion with stakeholders about which types of evidence it would be most interesting and useful to review in depth in stage 2. We cannot rule out the possibility, however, that a more comprehensive summary of theory at this stage would have led to different priorities.

Our summary and assessment of theories in stage 2 was systematic, using a tool of our own devising. The judgements we made were to some extent subjective, for example in determining whether or not a theory was simple and had constructs that could be operationalised in empirical research. We used these multiple criteria to form a judgement about which theories to draw on to define our primary and secondary review hypotheses. We did not simply require that a theory meet every criterion in order to be considered primary because our judgements were necessarily more subtle than this. For example, the theory of human functioning and school organisation did not meet our criterion of simplicity; however, we judged that this theory was very strong regarding our other criteria and so included it. As a further example, several of our theories did not meet our quality criterion of addressing a range of health outcomes but we judged them to be sufficiently useful in understanding school effects on ASB-related outcomes and so we opted to use them to inform secondary review hypotheses. We think this balance between using clear criteria and making overall judgements is acceptable and appropriate given that these concerned the development rather than the testing of hypotheses.

Despite its subjectivity, this process was useful in determining which theories could most usefully provide hypotheses to assess against the empirical reviews. These theories enable us to develop hypotheses about how school environment interventions and school-level exposures might affect health, but did not enable us to focus on specific prehypothesised outcomes.

The theories themselves were biased towards those focusing on ASB, with six of our secondary theories but no primary theories having this focus. However, this reflects the theories that were used in empirical studies of the health effects of schools and school environment interventions and is an interesting finding of our review.

Chapter 7 Research question 2: outcome evaluations

Research question

What are the effects of school environment interventions (interventions aiming to promote health by modifying how schools are organised and managed, or how they teach, provide pastoral care to and discipline students, and/or the school physical environment) that do not include health education or health services as intervention components and which are evaluated using prospective experimental and quasi-experimental designs, compared with standard school practices, on student health (physical and emotional/mental health and well-being; intermediate health measures such as health behaviours, BMI and teenage pregnancy; and health promotion outcomes such as health-related knowledge and attitudes) and health inequalities among school students aged 4–18 years? What are their direct and indirect costs?

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

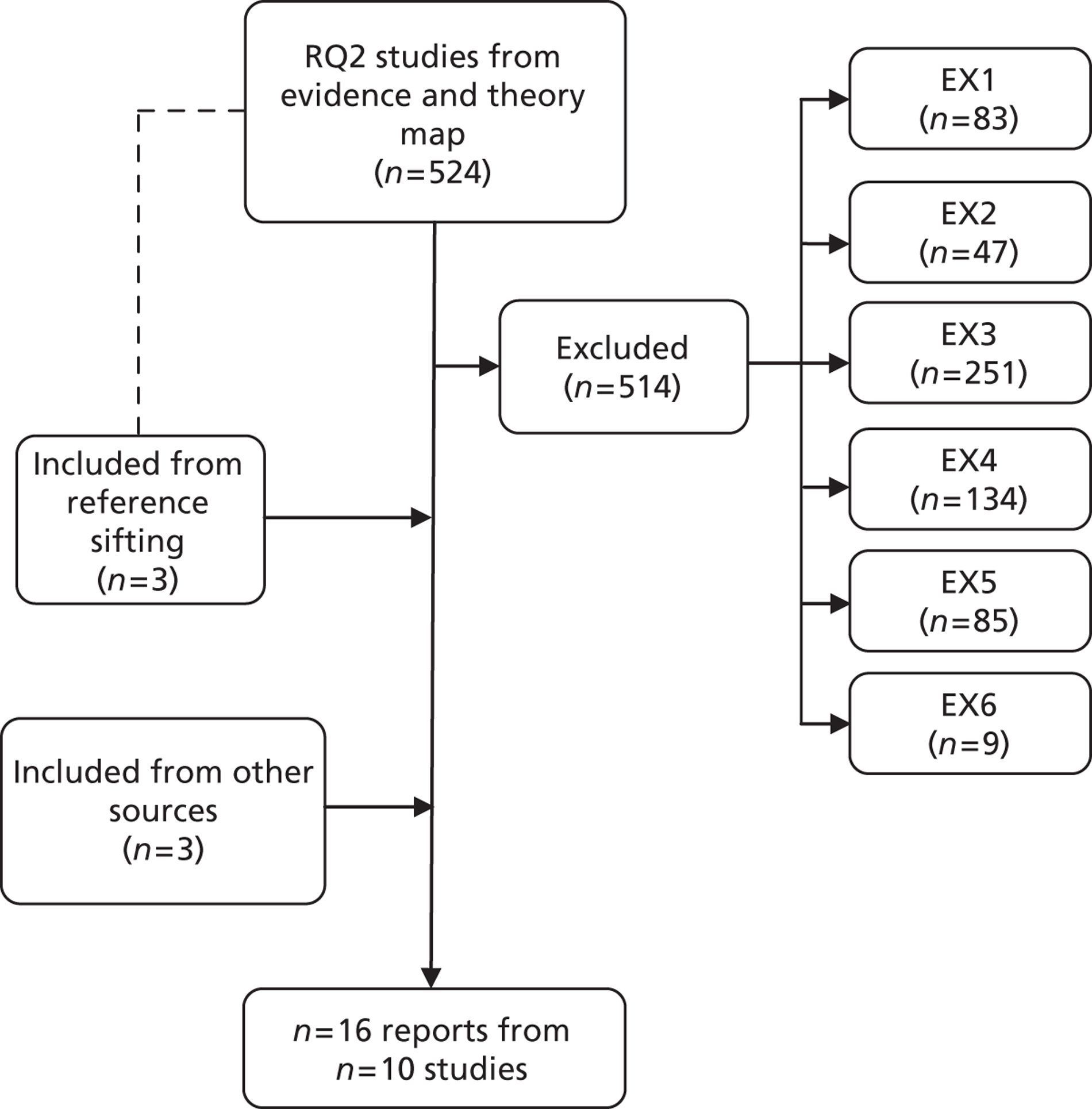

A total of 524 references were identified in the evidence and theory map as relevant to RQ2. We included experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations of the effects on health or well-being outcomes in students (aged 4–18 years) of school environment interventions that addressed how schools were led and managed, how they teach, support or discipline students, or schools' physical environment. Two reviewers (CB and HW) independently double-sifted these references based on title and abstract only and on full reports where necessary using the exclusion criteria in Table 4. It should be noted that all references coded as outcome evaluations were screened for inclusion because of the potential limitations of the accuracy of the coding in the stage 1 evidence map. Screening was not hierarchical or mutually exclusive. In other words, references may have been excluded based on multiple criteria.

| Exclusion criterion | Guidance |

|---|---|

| Exclude 1: not an evaluation | Exclude if study is not an evaluation study |

| Exclude 2: is a process evaluation only | Exclude if the study is a process evaluation |

| Exclude 3: based on intervention | Exclude if the study intervention does not address how schools are led and managed, or how they teach, support and discipline students, and/or the school physical environment (e.g. intervention merely involves extracurricular activities, catering, PE or active transport). Exclude if the intervention includes curriculum and community/parent components alongside school environment components |

| With intervention outcome evaluation studies we were interested in intervention studies in which the intervention aimed to modify student–student or staff–student relationships, as long as they did this by addressing the school environment and not merely through health education | |

| Exclude 4: not a cluster RCT +non-randomised prospective | Exclude the report if it is an outcome evaluation, but does not involve (a) a cluster RCT or (b) a non-randomised prospective cluster comparison design |