Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3000/14. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The final report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in April 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer:

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Lorenc et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The burden of mental health problems is immense. About 14% of the global burden of disease has been attributed directly to mental disorders; moreover, mental illness contributes to other health problems, including injuries and communicable and non-communicable diseases. 1 The National Service Framework for Mental Health2 also noted that, at any one time, one adult in six suffers from mental illness of one form or another, and it documents the immense costs in personal and family suffering and to the economy: mental illness costs in the region of £32B in England each year. Mental health problems are also strongly socially patterned and an important dimension of health inequalities. 3

The promotion of mental health and well-being can be located within current public concerns about the effects of places or neighbourhoods on health. Nationally, the need to undertake mental health impact assessments4 is emphasised in the National Service Framework for Mental Health,2 the public health White Paper Choosing Health5 and the health and social care White Paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say. 6 These policies prioritise improving mental health and well-being through local strategies. Identifying the links between the local environment and crime and fear of crime is also key to local mental health promotion strategies that aim to integrate mental health into local policy, sometimes referred to as creating ‘mentally healthy public policy’.

An important dimension of how place may influence mental health and well-being is through crime and the fear of crime. The World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health has emphasised that protection from crime is an important component of the healthy living conditions in which people are able to thrive,7 but the pathways through which crime and fear of crime influence individual and population health are only partially understood. Crime, particularly violent crime, obviously has direct effects on physical health through injury and death. However, the effect of crime and fear of crime on mental health and well-being, although less visible, may be just as important. As crime is highly unequally distributed at an area level, the well-being impacts of fear of crime may also be important drivers of social inequalities in mental health outcomes.

There is a lack of robust evidence syntheses on the broader effects of crime reduction interventions. Although there is a substantial amount of data on the effectiveness of crime reduction, particularly in the reviews conducted by The Campbell Collaboration Crime and Justice group, health and well-being are rarely included as outcomes in Campbell reviews (with the exception of interventions that target drug use). There is a need to understand how crime and the fear of crime may impact on mental health, and on well-being more broadly, including physical health, health behaviours and social well-being.

Objectives of the research

The objectives of the project are as follows:

-

to review theories and empirical data about the links between crime, fear of crime, the environment and health and well-being, and to develop from this a conceptual ‘map’ that underpins the types of interventions that stem from the theories

-

to synthesise the empirical evidence (quantitative and qualitative) on the effects on mental health and well-being of community-level interventions, primarily changes to the built environment (such as changes to local environments, ‘target hardening’, security measures, CCTV and other interventions)

-

to summarise the evidence on whether the interventions in question have the potential to reduce health and social inequalities

-

to produce policy-friendly summaries of this evidence that can be used to inform decisions about policy and disseminated to appropriate policy/practice audiences.

Structure of the project

The project contains four components:

-

a mapping review of theories and pathways, mainly directed towards objective (i)

-

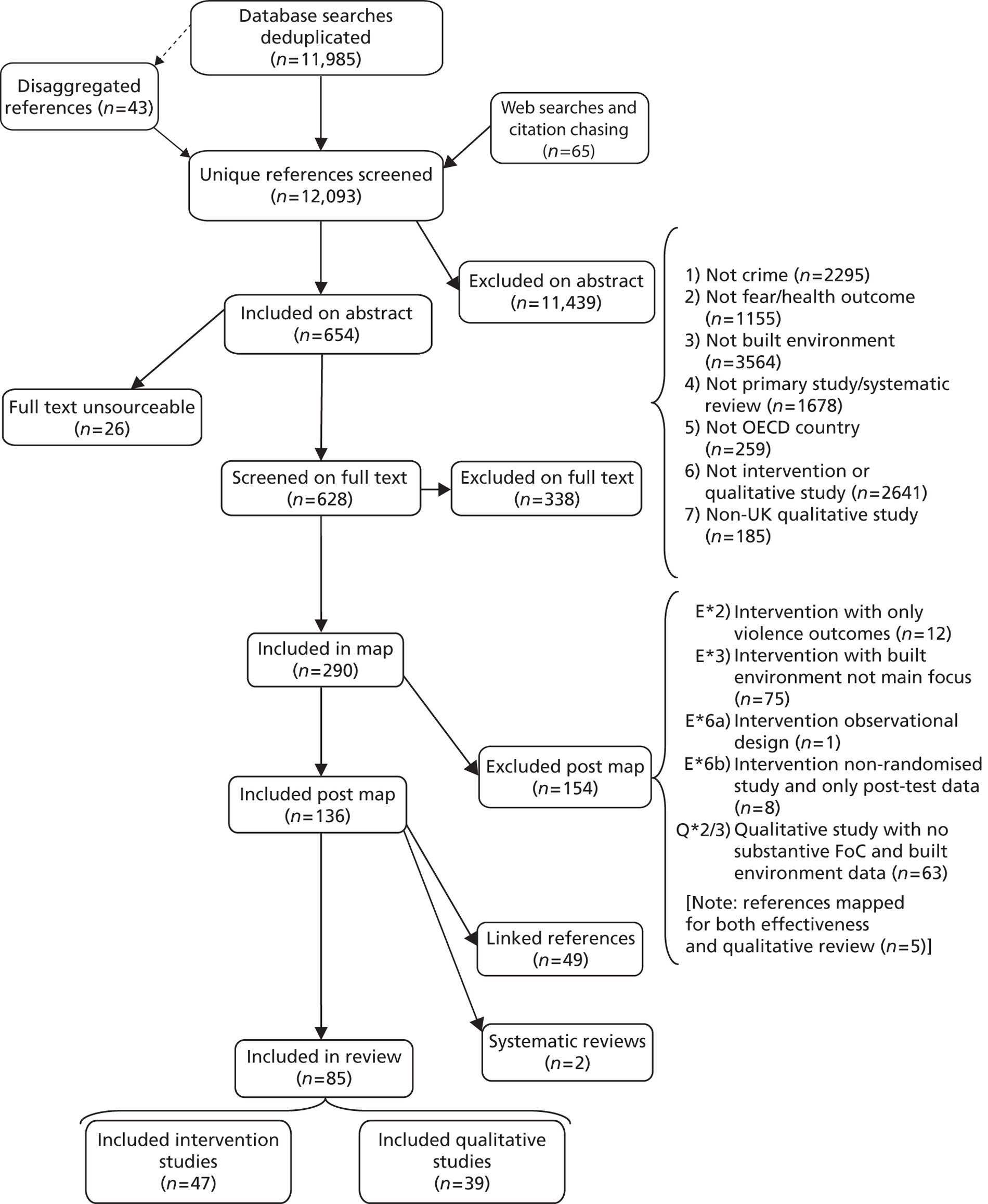

systematic reviews following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines8 for effectiveness and qualitative evidence, directed towards objectives (ii) and (iii)

-

consultation and interviews with stakeholders and the public, aimed at objective (iv) but also intended to inform the project as a whole.

Component (1) is reported in Chapters 2 and 3; components (2) and (3) are reported in Chapters 4–6; and component (4) is reported in Appendix 12.

Research questions (systematic reviews)

The research questions for the review of effectiveness are as follows:

-

What interventions in the built environment are effective in reducing fear of crime?

-

What crime reduction interventions in the built environment are effective in improving health status, health behaviour or social well-being outcomes?

The research question for the review of qualitative evidence is as follows:

-

What is known about the views and attitudes of the UK public with regard to fear of crime and the built environment?

Chapter 2 Review of theories and pathways: background and methods

The first stage of the project was to conduct a review of theories and pathways. The purpose of the review of theory is to provide an overview of the theoretical background and of relevant empirical data for the project as a whole. As set out below, a wide range of different fields, types of data and theoretical perspectives are covered in the review of theory.

The first section sets out the methodological background for the review of theory. In this section we outline current thinking regarding the use of theory in general, and causal mapping techniques in particular, to inform systematic reviews, and briefly set out some of the main issues and challenges involved. We then describe the methods used for the review of theory and set out the context and previous methodological work on which we drew in developing them.

Models and theories in evidence synthesis

Our thinking about the review of theory was initially informed by reflection on the use of causal models or maps to understand intervention effectiveness. By a model or map, we mean a schematic representation of the causal interactions between factors within a system. As used in this report, the term refers to qualitative models designed primarily to clarify theoretical or conceptual relationships, as opposed to statistical methods such as systems dynamics modelling that are designed to facilitate the analysis of quantitative data. 9 (There are emerging methods within statistics, particularly that of Pearl,10 which explicitly distinguish qualitative intuitions about causal relationships from quantitative statistical relationships and seek to develop more powerful tools by combining both; to our knowledge, there has been little contact between such methods and the more informal causal theories discussed here, and this may be a promising avenue for further research.) Causal models are often represented graphically using boxes and arrows. They can be seen as having two main dimensions: the identification of the key factors or concepts (the boxes) and the identification of the links between them (the arrows). The term ‘causal’ is used here in a loose sense: causal models are not limited to direct cause–effect relationships, but may, as we will see later (see Chapter 3, Fear of crime: measures and contexts, Background, and Built environment, social environment and fear of crime), include more complex and holistic linkages, as well as relations that are arguably conceptual or expressive, rather than narrowly causal.

The simplest type of causal model is the linear logic model of the following form: inputs ⇒ activities ⇒ outcomes ⇒ impacts. Such logic models have been widely used in the development and delivery of intervention programmes. 11 They seek to clarify the conceptual underpinnings of an intervention to guide its planning and evaluation. As such, they can be seen as expressions of the basic theory that underlies the intervention. They may be particularly valuable in the development of complex interventions as they make explicit the underlying model through which effects are expected. 12–14

The use of models in evidence synthesis builds on the logic model principle. However, in synthesising evidence on complex and/or heterogeneous interventions or factors, considerably more complex models are often required, depicting inter-relations between multiple factors on a wide range of scales from national and international policy to individual behaviour. These more inclusive models, which we will refer to as causal maps, are generally not linear in structure but include multiple overlapping relationships.

Causal maps have been identified as valuable for evidence synthesis, particularly of complex and/or heterogeneous interventions, for several reasons. By elucidating causal pathways at multiple levels, they can be used in the development and application of theories to categorise and evaluate complex interventions, hence clarifying the evidence landscape. 14–16 Causal maps have been identified as particularly promising in the field of public health, because the causal pathways involved in determining community- or national-level health outcomes are generally long and subject to unpredictable confounding. 17,18 Along similar lines, researchers in systems science have emphasised the value of mapping in making sense of dynamic, adaptive systems with multiple feedback loops, and have argued for the relevance of such approaches to public health. 19,20

Complex causal maps have been identified as particularly useful in synthesising evidence on the health impacts of policy21,22 and on the impact of interventions on health inequalities23–26 because of the nuanced and transdisciplinary approach required to address such questions. In particular, these questions often require the synthesis of diverse types of evidence because, for many relevant intervention types and outcomes, robust outcome evaluations are lacking. In this context, causal maps can help to assist researchers and policy-makers in putting together the ‘evidence jigsaw’. 27 By elucidating the pathways through which interventions or policy options may impact on health and well-being outcomes, causal maps can help to guide evidence syntheses in areas where robust outcome data are unavailable. 18,24,28

Several more specific advantages have been suggested from the use of causal maps as a priori guides to complex systematic review projects. First, they can help to identify promising points for intervention within the causal network and hence suggest innovative forms of intervention. 9,20,29 Vandenbroeck et al. 9 describe these points as ‘leverage points’ or ‘hubs’, where the focused application of effort and resources may bring about substantial change. Second, they can isolate ‘feedback loops’,9,22 which may act either to amplify or to frustrate interventions, depending on their place in the causal network. Third, they can be valuable tools in the exploration of policy scenarios, whereby the potential impact of high-level policy choices can be qualitatively explored in detail. 9 Fourth, they can assist in the development of recommendations for future research by identifying promising pathways that have not been subject to rigorous evaluation. 18 A final point, which has not been widely discussed in the literature, is that the use of causal maps may help to increase the transparency of the systematic review process by providing some insight into the process by which the review question was developed and refined.

The methodological question of how maps themselves should be constructed has not received focused attention in the literature. Some studies have used workshop or focus group methodologies, bringing together experts and stakeholders face-to-face. 9,13,20,29 Others, like this one, have been based primarily on non-systematic reviews of the published theoretical and empirical literature. 17,30 In either case, it is implicitly recognised in the literature that the construction of causal maps is a pragmatic process, without a clear a priori methodological framework (as part of the purpose of constructing the map is to provide such a framework). This means that it is generally impossible to construct maps in accordance with rigorous systematic review procedures. However, this is a developing field and there is limited methodological guidance available. Methods for the review of theory describes the methods adopted for this review and some of the reasoning behind our choice of methods.

Causal mapping in the evidence synthesis context is not without certain challenges and potential problems. Three of these are particularly relevant here. First, causal maps are themselves suggestive rather than descriptive in nature, and may draw on a wide range of data, including pure theory, empirical research of various types, policy documents and expert opinion. It is generally impossible to quantify the reliability of the evidence relating to particular links within the map. Of course, the links should be based on robust evidence as far as possible. However, especially with large or complex maps, this will not always be possible, and some links may be imputed on the basis of expert opinion or prima facie plausibility. Even when individual proximal linkages are well supported by evidence, the composite pathways between distant factors may fail to hold. In addition, as noted above, even when causal maps are evidence-based, they generally do not use full systematic review methods, which may limit the reliability of the findings. 18 Hence, although the pathways set out in the map can provide useful suggestions about the broader implications of particular research findings, they will usually not make robust empirical predictions. It has been observed that well-intentioned programmes can have negative effects;31 causal maps can help to mitigate this possibility by clarifying the pathways through which interventions may operate and the potential countervailing factors that may frustrate them, but they cannot remove it altogether.

Second, causal maps generally go beyond what is known from robust evaluation research; as noted above, this is one of their strengths. Of the potential pathways identified by the map, many may not be amenable to intervention for practical, ethical or political reasons. Of those interventions that have been attempted, not all will have been rigorously evaluated. Hence, the map may not correspond closely to the evidence landscape – particularly to that part of it concerned with the effectiveness of interventions – and cannot be used directly to delimit the scope of an evidence synthesis. Rather, the map provides a means of formalising and making explicit knowledge about the context of the review at multiple levels, and providing a framework for the evaluation of how and why interventions are effective. 17

Third, a reliance on causal maps may bring with it certain biases in terms of how the field of research is understood. The assumption that major causal factors can be identified in a context-independent and value-neutral way, and cleanly isolated from each other, may lead to a systemic failure to adequately integrate the insights of research using more contextually sensitive methods. For example, these insights may relate to the ways that the causal factors operate and are negotiated by individual actors in concrete situations; the social meanings and ethical values that may crystallise in particular factors; or the social and political commitments that may be embodied in methodological decisions. More specifically, causal maps tend to homogenise differences in terms of how factors are linked, and may perpetuate the assumption that these links can be conceptualised in terms of external cause–effect relations, when in some cases they may be better thought of as internal, hermeneutic or expressive relations. For this project this is particularly important as the value to be attached to many of the key outcomes of interest is not unquestionable; for example, reducing fear of crime, or increasing social cohesion, may not constitute positive outcomes in every case, even if this is true on the whole. To our knowledge, this issue has not been explicitly addressed in the causal modelling literature.

Methods for the review of theory

Aim and methodology of the review

The aim of the review of theory is to synthesise the available theoretical frameworks regarding the pathways between crime, fear of crime, health and well-being and the built environment, to develop a logic model for interventions and a causal map of relevant contextual factors. The findings of the review of theory were used to inform the design and interpretation of the systematic reviews that form the main part of the overall evidence synthesis.

The methodology employed for the review of theory was a pragmatic non-systematic review. The searching and selection of material were iterative, with phases of literature searching alternating with phases of synthesis and theory construction and testing. Search sources included Google Scholar, MEDLINE, Criminal Justice Abstracts and suggestions from subject experts within the review team. In addition, there was a strong emphasis on ‘pearl growing’ methods such as citation chasing. The selection of studies was purposive and context-sensitive and informed by the emerging theoretical picture at each stage; a priori inclusion criteria were not applied. As far as possible, selection was guided by the goal of theoretical saturation, although, because of the broad scope of the review, saturation could not be achieved in every area of the review. In the selection of theoretical studies, those with a scope similar to that of the present review and those that most adequately took into account the complexity of the relevant factors and their inter-relations were prioritised. In the selection of empirical data, studies with a robust methodology, particularly systematic reviews, were prioritised, as far as possible and appropriate. However, this prioritisation was purely informal in nature. Because of the widely varying quality of the evidence base in the different fields and questions investigated, consistent and explicit criteria could not be used.

The synthesis of data was based initially on an identification of similar theoretical concepts across the literature and an integration of these concepts into an overarching framework. The linkages between concepts were drawn initially from the most relevant theoretical literature and then filled out with reference to the empirical literature. As discussed in the following sections, our method was highly interpretive, with a strong emphasis on theory construction as an essential part of synthesis.

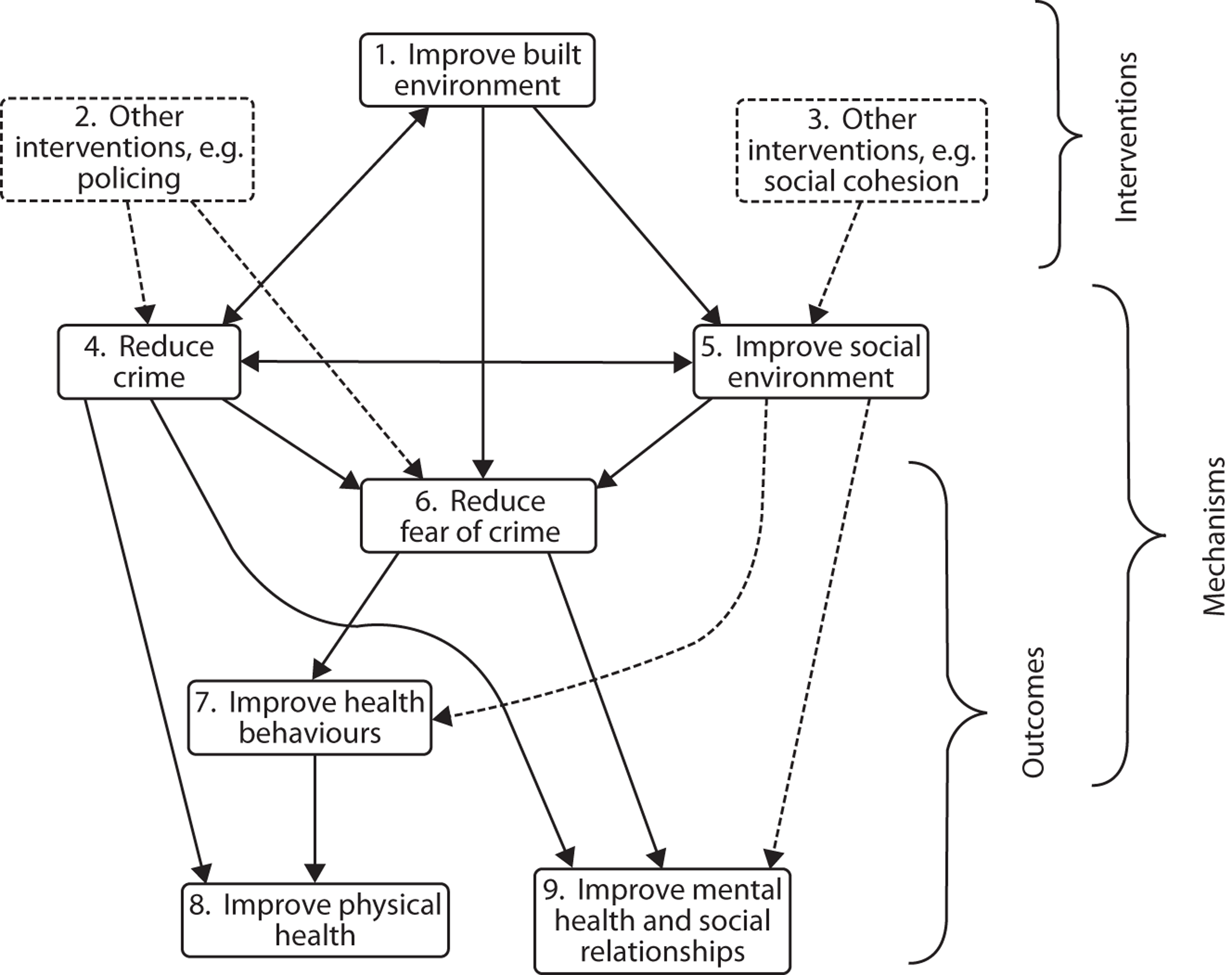

The synthesis resulted in two separate but linked models: a complex map of relevant contextual factors and a simpler and more linear logic model of interventions. This dual method of causal mapping has not been widely used in previous studies. It was adopted here because, owing to the scope and complexity of the larger map, intervention points and mechanisms could not be clearly identified within it. In addition, we had already made an a priori decision to focus on only one of the potential areas of intervention within the larger map, namely the built environment, so the logic model of interventions helped to clarify the consequences of this decision.

Appendix 1 includes a selection of theoretical models from previous research, with brief comments indicating how these have been utilised in the construction of our causal model. The selection of models focuses on those relating to fear of crime and/or crime and health; although we utilised causal models from the theoretical literature on other topics, such as the built environment and health, our use of these was generally more selective.

Methodological context

In this section we present some background to the choice of methods described in the previous section. We examine three methodological theories that have formed our thinking: realist synthesis, critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) and Baxter et al. ’s recent work on conceptual frameworks. 18 These theories are relevant, first, because all three have addressed the challenges of synthesising diverse types of evidence and, second, because they have all, in different ways, addressed the relation between evidence synthesis and theory construction. This section presents a brief overview of the three theories and then situates the methods used for this review with respect to these theories and the broader methodological landscape.

The realist synthesis approach has been recommended as particularly appropriate for the synthesis of disparate and complex data. 16,32,33 The characteristic feature of realist synthesis is an emphasis on the theory-laden and context-dependent nature of praxis within intervention programmes, systems and institutions. Hence, the synthesis of evidence about interventions or systems is inseparable from an engagement with the theories implicit in those systems. This engagement may frequently take the form of an analysis of causal pathways (although in most realist syntheses these analyses have been relatively linear, in the sense described in Models and theories in evidence synthesis). For proponents of this method, the synthesis of diverse evidence types (effectiveness data, qualitative data and theory), and the use of iterative searching and purposive selection, are required to understand ‘what works, for whom, how, and in what circumstances’. 33

Critical interpretive synthesis34,35 is similar to realist synthesis in some respects. One difference is that CIS emerged from the development of methods for qualitative synthesis rather than the synthesis of effectiveness data, for which there has generally been a stronger emphasis on theory construction as part of the synthesis process. 36 However, the proponents of CIS argue that it is not limited to the synthesis of qualitative data but can also be used for the synthesis of multiple types of evidence. CIS draws on Noblit and Hare’s37 method of meta-ethnography to develop the fundamental distinction between an ‘aggregative’ or ‘integrative’ approach, such as a traditional meta-analytic review of quantitative data, and an ‘interpretive’ approach, exemplified by CIS. Aggregative approaches seek primarily to draw together the available evidence and summarise it, and rely on the existence of well-specified concepts that can be used to carry out the summary without any deeper critical engagement. Interpretive approaches, by contrast, involve engaging critically with the conceptual frameworks found in the literature and developing overarching ‘synthetic constructs’. Here, CIS draws particularly on Noblit and Hare’s37 ‘lines-of-argument synthesis’, a type of synthesis in which the construction of new theoretical content is indispensable, by contrast with ‘reciprocal translational analysis’, which is limited to translating between studies to develop common concepts.

The third approach examined is that adopted by Baxter et al. 18 They present a methodology for developing a causal map for complex interventions (which the authors explicitly describe as integrative rather than interpretive in Dixon-Woods’ sense). 34 Initially the authors used a previously agreed framework38 to categorise the potential causal influences in the field under discussion. They conducted a non-systematic review of diverse types of evidence, consulted with an expert reference group and then coded the selected papers in depth using an approach derived from qualitative analysis. From these data, a causal map was constructed and revised using an iterative process. Although useful, Baxter et al. ’s methodology is less theoretically elaborated than those described above, and their description of the synthesis process is brief and does not draw on the methodological literature on qualitative synthesis (as reviewed by Barnett-Page and Thomas36).

Our methodology does not exactly line up with any of the three described above. It is closest to that of Baxter et al. 18 in the focus on causal mapping as the representation of theoretical content. However, our coding procedure was less formalised than that of Baxter et al. ;18 in addition, we would categorise our overall approach in Dixon-Woods et al. ’s terms34 as interpretive rather than aggregative (although see the discussion of this point below). On a practical level, the main item of guidance we draw from the three approaches described here is the use of iterative searching and purposive selection of studies, informed by emerging theoretical constructs. More broadly, we draw on their insights about the relation between synthesis and theory construction, and have sought to link these to relevant recommendations from the literature on causal mapping. (To our knowledge, few studies – with the partial exception of that by Baxter et al. 18 – have attempted to bridge these two distinct bodies of theory.)

However, our review diverges from these methodologies in two ways. The first point concerns the place of our review of theory in the overall evidence synthesis project. Like the methodologies described above, our review of theory includes diverse types of evidence including empirical data as well as theoretical constructions. However, unlike them, it is not designed to stand alone but to stand alongside the systematic reviews, which form a clearly separate phase of the project. Realist synthesis and CIS are comprehensive approaches explicitly designed to be an alternative to traditional systematic reviews, not a supplement to them (this point is less clear with regard to Baxter et al. 18). Hence, the greater synthetic power of these approaches must be set against the fact that they are substantially less transparent and reliable than systematic reviews, in those areas where systematic reviews are possible and appropriate. Our methodology represents an attempt to utilise the strengths of both approaches by combining a non-systematic critical review of theory with conventional systematic reviews in a way that maximises the potential to transfer insights and concepts from one to the other, while maintaining their methodological separation intact.

The second point of difference concerns the implicit assumption in all of these methodologies that the synthesis is different in kind from the primary materials included in the review, and that it stands, as it were, above rather than alongside the latter. Even in realist synthesis, with its emphasis on the theoretical content of interventions, it is clear that the theory developed in the synthesis is intended to be more inclusive and powerful than that implicit in the primary studies. By contrast, many of the ‘primary’ studies included in our review of theory are themselves exercises in wide-ranging theoretical mapping and hence of the same character as our review itself. The relation of the review to the included theories might be described as one of dialogue, rather than inclusion. Hence, the distinction between interpretive and aggregative approaches may not be applicable, as much of the primary material that is being synthesised consists itself of synthetic constructs, and so requires interpretation before it can be aggregated.

This was particularly true for our review of theory because we located no body of theory covering the whole scope of the review, or any shared consensus on the framework to be adopted. As set out in Chapter 3, there are highly sophisticated bodies of theory within particular areas, including crime prevention; the social and individual determinants of fear of crime; the links between the built environment and health; and the links between fear of crime and health or health behaviours. However, few researchers have attempted to map out the pathways between all of these factors simultaneously. Moreover, even within specific fields, consensus on the theoretical frameworks is often lacking. This is particularly true of theories of fear of crime (discussed in Chapter 3, Fear of crime: measures and contexts), on which researchers in the field frequently disagree on fundamental questions of methodology and definition.

Moreover, these diverse bodies of theory come from a wide range of disciplinary perspectives, including criminology and policing, sociology, psychology, public health and urban planning. Concepts in one field may not line up with those in another. For example, the concept of the built environment is only imperfectly translated to the policing field by the concepts of physical disorder, a narrower concept with a focus on visible problems, or place-based strategies, a concept that includes the social as well as the physical environment and is more closely linked to interventions. 39,40 More deeply, the theoretical bases underpinning work in different fields may be incompatible; for example, much recent fear of crime research has drawn on an expressivist paradigm that emphasises the social meanings of individual action,41,42 whereas the literature on environmental crime prevention largely remains within a rational choice perspective. 43

As a result, the synthesis could not proceed on the basis of a commonly defined vocabulary of concepts, as no such vocabulary was available, but had to proceed by drawing together heterogeneous theoretical constructs. In this context, the attempt to aggregate and translate between concepts to build a coherent causal map necessarily involved interpretation.

For reasons of space, this report does not present a systematic overview or glossary of all of the concepts used in the theories that form the sources for our synthesis, nor a full discussion of the deeper paradigms that underlie them. Hence, a full account of the issues raised above, and a record of all of the decisions made in constructing the synthesis, cannot be given. We have described specific issues in the relevant sections of Chapter 3 when they are consequential for the design or interpretation of the causal models.

Chapter 3 Review of theories and pathways: findings

Causal map: key concepts and definitions

This chapter presents the findings of the review of theory. This section presents an overview of the causal map; Fear of crime: measures and contexts outlines debates around the definition and measurement of fear of crime and relates them to the map; Causal map: relationships explores in more detail the relationships between the different factors in the map; and Intervention pathways (logic model) presents a simplified logic model based on the causal map, setting out how interventions might have an impact on health and well-being outcomes.

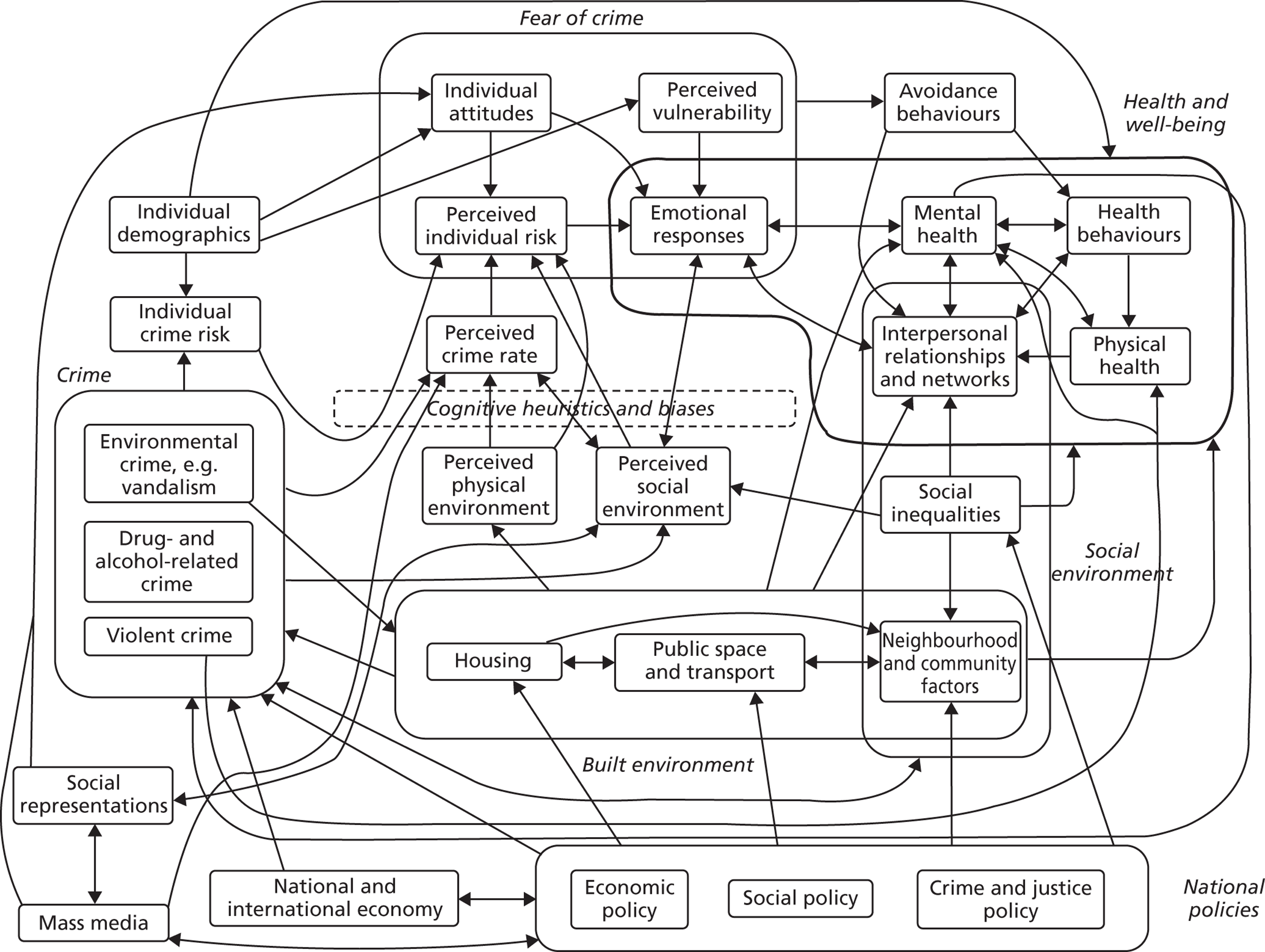

Figure 1 shows the overall causal map arising from the review of theory. The map shows six key concepts (the large hollow boxes) and a larger number of subconcepts (the smaller shaded boxes), together with the hypothesised relations between them. There are some areas where the key concepts overlap with each other. The map is broadly organised by scale, with individual (micro-level) factors nearer the top, meso-level factors in the centre and broad macro-level determinants nearer the bottom. In this section we summarise the six key concepts and provide definitions of the subconcepts; in the following section we consider some of the relationships that are important for the review.

FIGURE 1.

Causal map.

Crime and disorder

In principle, all types of crime are included in the theory review; however, three broad categories are likely to be especially relevant. For simplicity, only these are included as subconcepts in the model. Violent or potentially violent crimes against the person, such as rape, assault and mugging, are likely to cause substantial physical and/or psychosocial health harms for the victim and may often form the focus of fear. Drug- and alcohol-related crimes include a range of offences, such as violence, criminal damage, driving and public order offences, and crimes such as theft and burglary to fund drug habits; they often have a spatial patterning reflecting the locations of drug markets, alcohol outlets and the night-time economy. ‘Environmental’ crimes are those that impact directly on the quality of the physical environment, such as criminal damage, vandalism and graffiti; this category may also include non-criminal forms of antisocial behaviour such as littering. Of course, these are very different phenomena. In particular, the inclusion in the same concept of environmental crimes and serious violent crimes does not imply an endorsement of a punitive agenda towards the former. In general, the scope of this project precludes a fully critical perspective on the concept of crime and disorder.

[Two further points should be added here on the definition of crime. First, some non-violent crimes against property, such as burglary and car theft, are also salient in that they may have substantial psychological and emotional impacts and be widely feared44 (on the distinction between crimes against the person and crimes against property relative to the fear of crime, see Chapter 3, Emotional response: further considerations). Second, given the environmental dimension of the review project as a whole, ‘domestic’ crimes such as child abuse and intimate partner violence will be less salient than ‘stranger’ crimes. This is in no way to minimise the extent or impact of domestic crimes, only to observe that they are of less relevance within the overall conceptual framework adopted for the review.]

Fear of crime

Fear of crime is a complex concept that raises a number of challenging definitional and methodological issues and is discussed further in Fear of crime; measures and contexts. The two most important subconcepts here are the individual’s perceived risk of being a victim of crime and his or her emotional responses to crime, such as worry or anxiety. The model also includes individual attitudes (e.g. beliefs about the nature and extent of crime) and perceived vulnerability to crime, as these are known to be closely bound up with fear. However, the perceived and actual rates of crime in the local area, and the individual’s objective risk of crime, are not included within the fear of crime concept, although they are linked to it. As discussed in Fear of crime; measures and contexts, it is difficult to draw a clear boundary around the concept of fear of crime, given its complex linkages with the social environment and individual psychology, and our definition represents a particular theoretical position that is not shared by all researchers in the field.

Health and well-being

Our perspective on health and well-being is comprehensive, including all forms of physical and mental health outcomes; health behaviours such as physical activity, and social well-being broadly conceived, including interpersonal interaction and social capital. As such, our concept of health and well-being overlaps substantially with the concept of the social environment (see Social environment).

Built environment

The built environment includes factors relating to the physical environment insofar as they are shaped by human activity. In particular, it includes the design of public spaces such as streets and parks, land use policy more generally (e.g. zoning regulations), public and private transportation and the architecture and design of residential housing. In the model, these are summarised with the subconcepts ‘housing’ and ‘public space and transport’. It also includes people’s interactions with the environment and the physical and geographical distribution of social factors. This category includes, for example, the sociodemographic make-up of communities, or social or legal restrictions on people’s movement within the built environment. In the model this is represented by the subconcept ‘neighbourhood and community factors’, which overlaps with the social environment.

Social environment

The subconcepts in the social environment cluster are based on a previous review of theory. 45 ‘Neighbourhood and community factors’ are defined in the Built environment. ‘Social inequalities’ refers very broadly to the effects of sociodemographic factors such as socioeconomic status (SES), ethnicity and gender, including structural inequalities and individual discrimination. ‘Interpersonal relationships and networks’ includes more local-level dimensions of social interaction and can be taken to include measures such as social capital and social cohesion or integration. As such, it overlaps with the health and well-being concept, as we take the latter to include the social dimensions of well-being as well as individual physical and mental health.

National policies

The role of national policies is not specified in detail in the model as a full discussion of their effects, particularly on health and well-being outcomes, lies outside the scope of this project. For our purposes, the main influences of interest are on the built environment and on crime. However, it is important to bear in mind that all of the other factors and relationships are shaped, more or less directly, by government policy, as well as by other macro-level determinants such as the economy.

Fear of crime: measures and contexts

Background

In this section we explore fear of crime in further depth. Fear of crime receives particular attention here for two reasons. First, there are complex relationships between the subconcepts that may be relevant for understanding the evidence and specifying the scope of the project. Second, there has been considerable debate about the concept’s meaning and coherence, and about the appropriateness and interpretation of the measures used. In discussing the findings of the fear of crime literature in the following sections, we have not always been able to give detailed attention to these issues, so this section serves as an overall guide to interpretation. This section is itself limited in scope: we do not engage with the full body of evidence on the determinants of fear of crime, only those that are of relevance to the model. In addition, we cannot here engage with the broader context of the debates around fear of crime research, particularly its political role, although the highly politicised nature of many apparently technical debates should be borne in mind. 46–50 Some of these issues are addressed further in the following sections.

Because of its extent and the ongoing contestation of fundamental issues, it is difficult to give a clear and uncontroversial overview of the field of fear of crime research. One basic distinction might be between, first, an older tradition, going back to the 1960s, which has been based on a broadly positivist, data-driven model of research, and which has focused on using observational research to explore the determinants of fear; and, second, a newer critical tradition, drawing on psychology and symbolic interactionist sociology, and strongly influenced by feminist thought, to understand fear as expressive of a broad range of attitudes and anxieties, and as rooted in the day-to-day reality of individual lives. Broadly, the two research paradigms have tended to correspond to a methodological divide, with the older positivist tradition emphasising quantitative survey measures and the newer critical tradition emphasising qualitative and ethnographic research. Only relatively recently, particularly with the work of Stephen Farrall, Jonathan Jackson and colleagues,49,51 has a viewpoint that draws together these two perspectives, and which utilises both qualitative and quantitative methods, emerged.

Within the first, more data-driven tradition, four main theories, in the sense of perspectives emphasising particular causal factors, can be distinguished in the literature. 52–56 Different authors divide up the theoretical field differently (e.g. some would include sociodemographic factors as a theoretical perspective in its own right), but these four are the main theories identified in the literature. The first is vulnerability theory, which emphasises the role of vulnerability to crime (defined further in Perceived vulnerability) in producing fear of crime and focuses particularly on explaining differences in fear between sociodemographic groups. The second is social disorder theory or social disorganisation theory, a more ecological approach that emphasises the role of local physical and social environments in engendering fear. The third is victimisation theory, which sees fear of crime as primarily driven by actual crime victimisation, and holds that it can be explained by the same factors as crime itself. The fourth is social integration theory, which emphasises the role of strong social networks and attachments at a local level as protective factors that may reduce fear.

Researchers with a more synthetic perspective have seen these theories as reducing in turn to two paradigms, a rationalist and a symbolic paradigm. 57 A rationalist view of fear of crime would see it as based primarily on approximately correct estimates of the risks and potential consequences of victimisation, whereas a symbolic view would see fear as bound up with the social meanings and representations of crime and disorder. However, this division does not line up perfectly with the theories described above. Victimisation theory is clearly rationalist; vulnerability theory is rationalist to some extent, but may need to appeal to symbolic accounts in explaining how estimates of the consequences of crime spill over into assessments of risk. Social disorder and social integration theories are usually expressed in symbolic terms, but they may have a strongly rationalist component in that disorder and low social integration may be causally linked to crime and function as roughly accurate indicators of actual risk (see Social environment and crime). As discussed further below (see Chapter 3, Perceived risk and emotional responses), teasing apart the rational and symbolic, or cognitive and affective, components of people’s behaviour may frequently be difficult, particularly in the context of secondary research. More generally, some researchers in the critical tradition have questioned the construct of ‘rationality’ in this context, arguing that judgements of rationality or (implicitly) irrationality are difficult to justify with reference to fear58 and that the dichotomy is in any case a blunt instrument in understanding the place and meaning of fear of crime in individuals’ lives and social relationships. 59,60

In terms of our model, each theory can be seen to emphasise a different set of factors in terms of the strength of the hypothesised links to fear of crime outcomes. Accordingly, further information on the empirical grounding of each theory is divided between the relevant sections of the report. Vulnerability is discussed further in Perceived vulnerability; social disorganisation and social integration theories focus on the links between the social and physical environments and the fear of crime and are examined primarily in the section on these links (see Built environment, social environment and fear of crime); and victimisation, likewise, is examined in terms of the link between crime and fear of crime (see Crime and fear of crime). However, before examining these links, it is necessary to clarify what exactly is being measured in fear of crime research.

The unclarity in this central question has often been remarked on in the literature. Ferraro and LaGrange61 reviewed the measures used in fear of crime research, finding that many heterogeneous and not directly comparable measures had been used and that many measures were inadequately validated. Although considerable methodological work has been carried out since, the points that they make are still substantially valid today. 49,55 Studies that describe themselves as measuring ‘fear of crime’ may measure perceived risk of crime, perceived crime rate, feelings of safety, general anxiety or episodes of worry about crime (and many particular measures are possible for each type of outcome). This makes it challenging to interpret the findings of these studies, as apparently subtle differences or ambiguities in the measures used may have a substantial and unpredictable impact on the findings.

In addition, even when the measures themselves are valid, the responses may be subject to bias. For example, social desirability bias relating to gender roles has been argued to account for almost all of the observed gender difference in affective fear outcomes. 62,63 The immediate context in which questions are asked, such as the time of day, may have an impact on responses. 64

Because of these problems, some researchers have concluded that the concept of fear of crime, as used in these studies, is largely an artefact of the methods used to measure it, and that it does not correspond to a meaningful social reality. 65 Other researchers have argued further that the confusion is not purely adventitious but reflects the fact that fear of crime is an inherently vague and inclusive phenomenon that acts as an attractor for a wide range of ill-defined worries66 or for a general ‘urban unease’ engendered by the density and loose social controls of urban environments. 67

The critical tradition in fear of crime research has developed this latter point further, exploring how fear of crime may embody and express broader attitudes towards social change and diversity, politics and policy, and ‘security’ in a deeper sense than statistically low risk. 49,59,68–73 This work has emphasised the social construction of crime, risk and fear and argued that these high-level concepts may obscure the diversity and complexity of individual experiences of fear. It has also highlighted the way in which discourse about fear of crime in research and policy has functioned to perpetuate social hierarchies, by treating crime and fear in an uncritical fashion which occludes the social inequalities that underlie fear, especially the prevalence of male violence against women,70,71 and the question of whose interests inform the accepted definitions of fear. 72

Much of this theoretical work is rooted in detailed qualitative research, the findings of which cannot be engaged with in detail here; the more detailed findings are discussed in Chapters 6 and 7, to the extent that they overlap with our reviews of empirical data. In the context of this chapter, four theoretical points are particularly relevant. First, fear of crime is not a free-floating social phenomenon (as both abstract causal modelling and the more positivist tradition of research sometimes imply), but makes sense only when situated in particular physical locations, and in individuals’ lives and personal concerns. 68,70 Perceptions of space and the physical environment at a local level may interact with the broader determinants of fear in complex and unpredictable ways. 70 Second, this research suggests that some of the links hypothesised by the model between fear and other factors, such as the environment or individual attitudes, may be better thought of as expressive relations between social meanings than as cause–effect relations between really distinct factors (see also Chapter 2, Models and theories in evidence synthesis). In particular, the simplistic dichotomy between ‘subjective’ fear and ‘objective’ crime rates may obscure the social dynamics underlying both phenomena.

Third, as suggested earlier, the impacts of fear of crime are highly unequally distributed, and these inequalities tend to closely shadow the existing power relationships within society. The experience of fear of crime as a pervasive factor in one’s day-to-day existence is one that disproportionately affects women, ethnic minorities and people living in material disadvantage. For many people, fear of crime may refer as much to the latent violence that is implicit in discriminatory social structures as to the manifest violence that is measured by crime statistics; the inescapability of such fear, and its symbolic resonance with the marginalisation and devaluation of oppressed groups, may amplify its effect on mental health and well-being. Some scholars have utilised the concept of ‘spirit injury’ to encapsulate this link between individual victimisation and structural inequality. 74,75

Fourth, this literature provides a holistic sense of how fear of crime may act as a window into high-level social structures and dynamics, by acting as an illustration of how individuals’ deep psychological need for security is played out at the social level. Ulrich Beck’s76 thesis of the ‘risk society’, which suggests that risk is the central trope of contemporary societies, that the nature of risk transcends quantitative estimations of likelihood and that people tend to seek individual solutions for social or trans-social risks, has been a productive theoretical reference point for some of this work. 68 A somewhat different approach is represented by the work of Taylor and Jamieson,66,77 who see the fear of crime as a symbolic nexus that expresses concerns about national as well as personal status. We cannot here engage in any depth with these sociological theories, but one important potential implication is that the vague and inclusive nature of fear of crime may be as much a strength as a weakness, as it may enable researchers to grasp a complex domain of social and psychological reality with a single measure. 49,78

In any case, it is clear that any attempt to synthesise the findings on fear of crime, and draw them into a more inclusive theory, will need to carefully distinguish the subconcepts that make it up and the different measures that may be used to investigate fear. Our model includes four subconcepts: perceived risk, or the individual’s estimate of how likely he or she is to become a victim of crime; emotional responses, including the whole range of affective reactions to crime or the threat of crime; perceived vulnerability and individual attitudes. These subconcepts and their inter-relations are examined briefly in the remainder of this section. The research linking fear to the other factors included in the model is covered in Causal map: relationships.

Perceived risk and emotional responses

In our model, the central axis of fear of crime is made up of the two subconcepts of perceived risk and emotional response, or one’s estimation of the likelihood of victimisation and one’s feelings of anxiety or worry about crime, which can broadly be described as the cognitive and affective components of fear respectively. 79 [The action-oriented or ‘conative’ component, which some researchers include as a third dimension,55,79 is regarded as a separate concept (‘avoidance behaviours’) in our model.] The relation between them is complex. They may not always be closely linked: it is possible to know that one’s risk of crime is high without being emotionally concerned, or conversely to be highly worried while estimating the risk as low. At the same time, there may not always be a clear subjective separation between the two for individuals. Studies that have directly compared perceived risk and the emotional dimensions of fear have been inconsistent in their findings, but have generally found that they are never perfectly, and rarely very strongly, correlated;80–85 these findings are reviewed by Chadee et al. 85 The strength of the association between perceived risk and emotional responses has been found to vary substantially depending on demographic variables such as gender and on the specific crime types investigated. 81,83,86

Perceived risk and emotion have not always been clearly separated in the research. Given the weak correlation between them, this means that interpreting the findings of such research may be problematic. For example, questions such as ‘Do you feel safe in your area at night?’, which have been used in many fear of crime studies, could be interpreted as referring either to one’s affective ‘feelings’ of safety or danger or to one’s estimate whether one actually is safe. 61 In addition, even if risk and emotion could be cleanly separated (as, for example, in Ferraro’s87 risk interpretation model), there are numerous potential indirect links, as shown in the model: emotional responses may be driven by a number of factors that also influence perceptions of risk (e.g. perceptions of the environment) but in different ways. A further complication (which is not explicitly included in the model) is that, as well as individuals’ own risk, the perceived risk of others, particularly partners or children, may have an impact on fear and behaviour. This ‘altruistic’ or ‘vicarious’ worry appears to be widespread. 88,89

Given the inconsistency of the findings on perceived risk and affective fear, it is difficult to isolate factors that may help to explain the relationship. One complex of factors that may be relevant concerns the social and moral meanings of crime. Jackson et al. 42 observe that, unlike other negative outcomes that may be feared, crime represents a deliberate attack on social norms and the social order. The ‘how dare they’ factor involved in affective reactions to crime, then, may complicate the link to perceived risk. This may explain why other harms that have a negative impact and which have been found to form the focus of fear more often than crime, such as illness, accidental injury or unemployment,90,91 do not appear to have the same affective valence, because their social meanings are different. (However, Jackson et al. 42 do not explore the broader social meanings of ‘the “how dare they” factor’, for example in relation to social inequalities; see the discussion of ‘spirit injury’ in Background.) A related point is that anticipatory emotional responses, such as those involved in fear of crime, tend to relate to a repertoire of mental imagery more than to a detailed analysis of risk. 47,55 This may drive the tendency noted earlier for fear of crime to act as a point of articulation for broader social concerns. Some researchers have argued on this basis for much more complex multidimensional quantitative instruments to capture fear, although this proposal has not been widely taken up. 55

Emotional response: further considerations

Apart from the basic distinction between perceived risk and emotional response, a number of further refinements have been suggested regarding the measurement of the latter. The first is the temporal dimension of fear, particularly the distinction between ongoing ‘dispositional’ fear and ‘transitory’ or episodic fear. The second is the distinction between normal, reasonable fear and fear that is excessive or pathological. The third, which also bears on perceived risk, has to do with the specific types of crime that are feared.

Psychological research on fear and anxiety distinguishes ‘state’ anxiety, which is episodic in nature and responsive to particular situations, from ‘trait’ anxiety, which is a relatively stable and ongoing property of individuals. 92 State and trait anxiety are generally conceived in this research as intraindividual tendencies and, as such, have been found to be not strongly correlated with fear of crime. 93 More broadly, however, the distinction can be usefully adapted in the fear of crime context to distinguish ongoing ‘dispositional’ anxiety about crime and ‘transitory’ fear of crime, which is experienced as a discrete event. 79 These distinct constructs can then be accessed using general, non-time-specific measures of anxiety (e.g. ‘How much are you afraid of . . .’) and measures that ask about the frequency of worry in a given time period respectively. Several empirical studies show that measures of frequency give substantially different results from generic measures. 49,55,94–96 Using measures of frequency tends to lead to substantially lower estimates of fear, that is, a large number of respondents say that they are anxious in general, but report no or very few specific instances of worry. In addition, the two types of measure appear to be influenced by different factors, suggesting that two distinct constructs are in play. In particular, frequency of worry has been found to be fairly well predicted by perceived risk. 60

It has been further argued that transitory fear tends to occur in response to particular situations, particularly the immediate threat of victimisation, whereas dispositional fear is driven by broader factors beyond the particular situation. Some researchers have seen this as a way to distinguish ‘formless’ or ‘expressive’ anxiety from ‘concrete’ or ‘experiential’ fear,49,65,95,96 and thus to isolate that component of expressed fear of crime which is responsive to actual crime, rather than to broader social attitudes and concerns. The argument in these papers is highly sophisticated and draws on a wide range of evidence and cannot be adequately discussed here; briefly, however, one might question whether time-specific fears necessarily correspond to concrete threats (rather than, for example, to expressive concerns about particular places or people encountered) and non-time-specific fears correspond to broad expressive factors (rather than, for example, to concrete but ongoing indicators of high crime levels). In addition, as noted earlier (see Background), researchers in the critical tradition might argue that latent structural violence – such as that involved in maintaining gender or ethnic inequalities – is as important as manifest violence in explaining fear of crime and should not be dismissed as merely ‘expressive’.

The second clarification is to distinguish normal or ‘functional’ fear, which acts as a cue to behave in an appropriately cautious manner (e.g. by locking doors), from excessive or ‘pathological’ fear, which generates anxiety sufficient to lower one’s quality of life and which is not assuaged by routine precautions. 97,98 (It should be noted that this is not the same as the distinction between ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’ fear, as the focus is on the effects of fear rather than its relation to objectively measured crime.) The distinction is important, as normal or functional fear may well not be problematic or especially negative, contrary to the presumption in much research and policy discourse that all fear of crime is a problem per se. Many people who report worry about crime also report that this worry has no effect on their quality of life. 98 Across the population as a whole, 64% of respondents to the British Crime Survey report that fear has a low impact on their quality of life, 31% report that it has a moderate impact and 5% report that it has a high impact, although the proportion reporting a high impact is considerably higher for some groups in the population. 91

The third point regards what specific types of crime are feared. Many studies have used generic measures such as ‘Is there any area near where you live, that is, within a mile, where you would be afraid to walk alone at night?’99 Other researchers have criticised the lack of specificity of such questions and have preferred to use measures that can explore the differences between different crimes. For example, the British Crime Survey100 uses a multiple measure of worry that includes worry about the following crimes: burglary from the home; mugging, car theft; theft from the car; rape; physical attack by strangers; being insulted or pestered and being attacked because of skin colour, ethnic origin or religion.

Again, like the time-specific measures discussed above, crime-specific measures have received some attention as a means to distinguish realistic fears driven by crime risk from more formless expressive anxieties. However, as discussed in Crime and fear of crime, there appears to be relatively little reason to think that such measures do reflect more accurate judgements of risk.

There is also a debate in the literature about how many different crimes need to be measured to obtain an accurate picture of fear of crime. Some studies using multiple measures have found that fear of different crimes can largely be reduced to, first, fear of crimes involving physical harm and, second, fear of crimes involving loss of property. 101 Others argue that certain crimes, particularly rape and sexual assault for women, may be particularly salient in terms of fear and create a ‘shadow’ effect across fear of crime in general. 102 It is clear that crime-specific measures cannot be straightforwardly regarded as accessing different parts or aspects of fear of crime. Some findings show that substantially greater numbers of people report worry about specific crimes than report feeling unsafe in general. 103

In addition, decisions about which types of crime to investigate with respect to fear often depend on previous methodological decisions (often linked to broader sociological or criminological perspectives). The question of what counts as ‘crime’ is highly important for the interpretation of fear55 but has received limited attention, particularly in more data-driven quantitative research. In particular, most of the fear of crime literature has tended to focus on crimes committed by strangers in public places. The fear of violent crime in private spaces, committed by known offenders or intimate partners, has not been a salient theme in most fear of crime research, although research indicates that it is widespread and serious. 70,104

One general point that emerges from this literature is that the effort to distinguish realistic from expressive fear of crime on the basis of more precise quantitative measures, and thus resolve the ‘risk–fear paradox’, has had limited success overall, although research on this point is ongoing. Moreover, the critical tradition provides cogent reasons to think that the distinction itself may be based on a misconception (see Chapter 7, Fear and rationality). In terms of the model, it might be hypothesised that, if a sharp distinction were shown to be tenable, this would lead to stronger links between crime and realistic fear on the one hand, and expressive fear and health and well-being outcomes on the other, but a less coherent model overall, in the sense that realistic and expressive fear would themselves represent two substantially distinct phenomena. The resolution of the risk–fear paradox would thus tend to block any attempt to see fear as linking crime and well-being outcomes at a community level. However, the considerations in this section suggest that the paradox has not been satisfactorily resolved. If so, there may be more scope to see risk and crime as linked to well-being outcomes in a holistic way, even if the evidence for the individual links is frequently ambiguous.

We return in Fear of crime and health and well-being to the question of how different measures of fear relate to health and well-being outcomes. To anticipate, the distinction between cognitive and affective measures may, tentatively, be reflected in the research findings, which appear to suggest that emotional responses have a greater impact on health and well-being than perceived risk; this is intuitively plausible and is reflected in the model by the more direct connections of the former to health and well-being. Both dispositional and episodic measures of fear have been found to be associated with health outcomes. However, the other distinctions explored here do not seem to have been explored with regard to their health and well-being impacts. Intuitively, it might be expected that pathological fear is more damaging than normal fear, and fear of serious violent crimes more damaging than fear of less serious crimes and crimes against property. Further research would be valuable here.

Perceived vulnerability

Vulnerability has been seen as encompassing three concepts: risk, perceived negative consequences of crime and perceived control. 60,105 For our purposes, the concept of risk is not included in vulnerability, as it has its own subconcept in the model; vulnerability can then be seen as the combination of an individual’s perceptions of the severity of the consequences of crime and his or her ability to exert control, that is, to defend him- or herself against attack. These factors may relate to an individual’s ability to defend him- or herself physically, to the social resources on which one can draw to counteract crime, or to situational factors such as the presence of other people who may be able to assist. 105,106

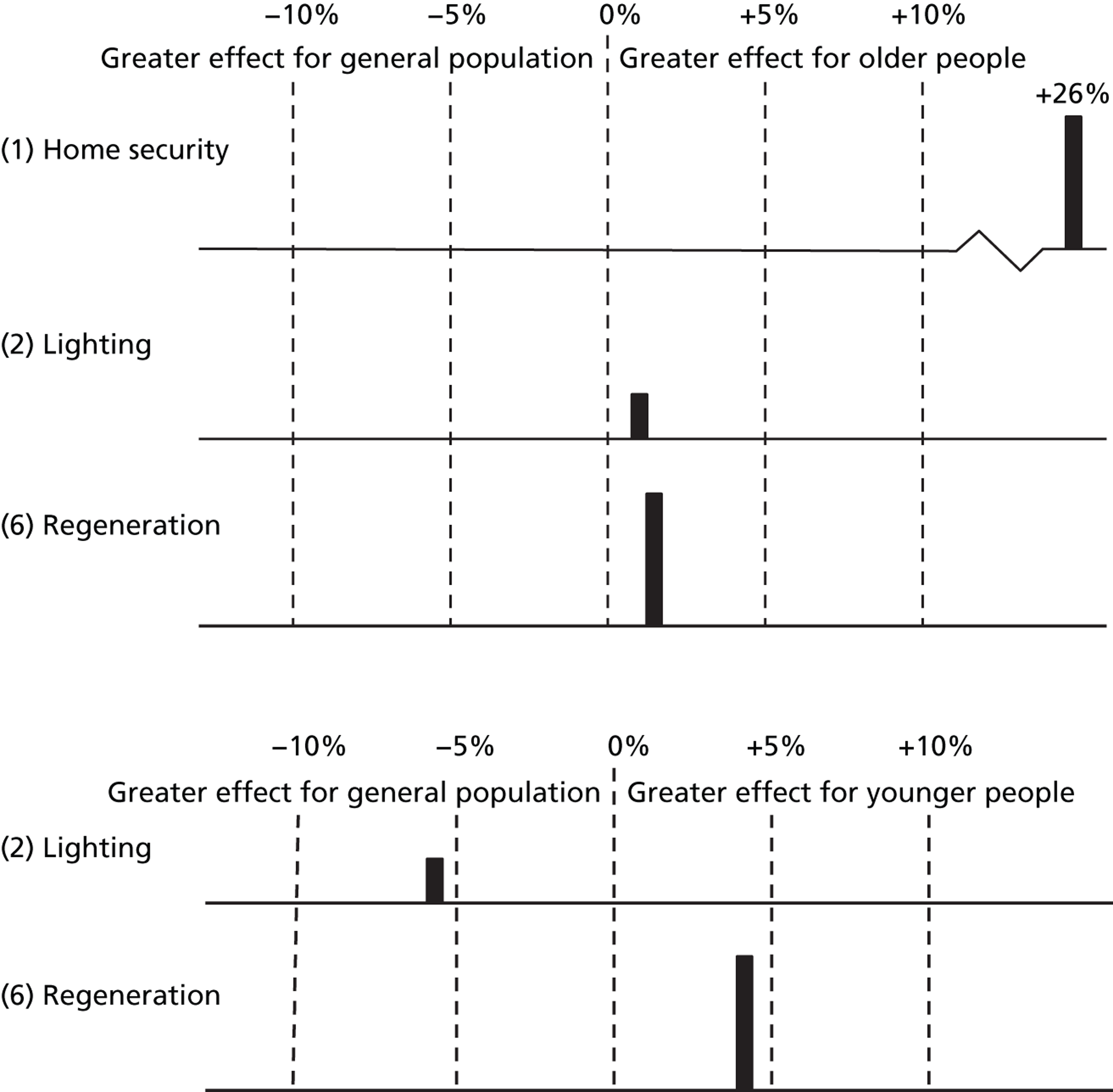

Vulnerability has been of interest particularly in explaining inequalities in the social distribution of fear. 103 That is, it may help to explain why certain groups, particularly women, older people and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, have a greater fear of crime but less objective risk of victimisation; their fear is a response to their greater vulnerability and the greater impact that crime has when it does occur. However, assessing the value of vulnerability in explaining these differences is challenging. Many studies have not sought to measure vulnerability directly but have used demographic variables directly as proxies for vulnerability. 56,103 However, when self-rated vulnerability has been measured, it has been found to be a better predictor of fear than age, gender or disability. 107 The effects of perceived consequences and control have been found to be substantially less important than those of perceived risk, which is not a dimension of vulnerability by our definition. 60 In addition, some of the findings on demographic differences in fear have been questioned. As noted earlier, some researchers have questioned whether differences between men and women may not be an artefact of the measures used;62,63 others have found that the purported difference between older and younger people tends to disappear, or even reverse, when the questions focus on fear of specific crimes. 87,108,109 As a result, although it remains true that vulnerability is associated with fear of crime and has a role in explaining the genesis of fear for individuals, its value in explaining the social distribution of fear remains open to debate. For our purposes, the most important insight of vulnerability theory is that factors other than perceived risk may have a substantial impact on fear, and hence reducing risk may have a limited impact on fear.

Individual attitudes

The model also includes an ‘individual attitudes’ subconcept. To some extent, this serves to capture the broader expressive factors outlined earlier, relating, for example, to the social meanings of crime as they impact on individual judgements and emotional responses. More specifically, a range of attitudes may be relevant in explaining the fear of crime, including perceptions of police effectiveness or attitudes to policing110 and broader political and social attitudes, such as those regarding law and order or social change. 111 Again, as with vulnerability, attitudes are included in the model primarily to indicate the halo of factors that may impact on individuals’ fear, and as a reminder that the central drivers in the model do not fully account for fear of crime outcomes.

Causal map: relationships

The map attempts to show the linkages between both the main concepts and the subconcepts. In some cases links are shown in detail, whereas in others they are more schematic. For example, the influence of individual demographics on health and well-being outcomes is not broken down according to the different outcomes of interest. In addition, not all potential pathways are shown, only those that are of interest for the review. In this section we summarise the theoretical bases of some of the key relationships and a selection of the relevant empirical evidence.

Crime and health

Crime may impact on health in a range of ways,112 which can broadly be grouped into two categories, namely direct and indirect impacts. 113 Direct impacts include physical injuries caused by violent crimes against the person and the psychological trauma that may accompany crimes involving violence or the threat of violence, or crimes such as burglary that involve intrusions into the private sphere. In the model, this is represented by the link from violent crime to physical and mental health. Indirect impacts include a wide range of negative effects that crime can have at a community level, for example by exacerbating social problems that impact on health. This distinction corresponds roughly to that between an individual perspective on crime and health and a social perspective.

The individual perspective, which focuses on the direct impacts of victimisation on individuals, has been the primary focus of the literature on crime and health. 113–115 These physical and mental health impacts on victims are often substantial and long-lasting. 116,117 ‘Domestic’ crimes, including child abuse and intimate partner violence, may have particularly serious health impacts. 118–120 However, at a community level, the health impacts are likely to be less substantial, because serious violent crime is relatively rare. In 2010–11 there were approximately 2.2 million incidents of violent crime in England and Wales,121 representing approximately 42 incidents per 1000 people per year. Dolan et al. 122 estimate the total health loss from the direct physical and psychological impacts of violent crime as being equivalent to 0.0024 quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) per person per year. However, this may be an underestimate as it includes costs relating to victims only rather than also including those relating to witnesses or victims’ families or friends, and the figures on which it is based may underestimate certain types of crime, particularly domestic crimes. In addition, crime and the health burdens of crime are highly unequally distributed, so the health impact is likely to be substantially higher than the average for some subgroups of the population.

The community- or social-level perspective on crime and health presents a more complex picture. Violent crime has been found to be associated with a wide range of negative health status outcomes at a neighbourhood level, including all-cause mortality,123 coronary heart disease124 and preterm birth and low birthweight,125 as well as health behaviour outcomes such as lower levels of physical activity. 126,127 Exposure to community violence is also known to be associated with negative physical and psychological health, particularly for children and young people. 128,129 However, although these associations are well established, the causal pathways involved remain open to debate in many cases.

Taking a social perspective on crime and health also demands a theoretical shift, analogous to that from the individual perspective of clinical medicine to the population perspective of public health and epidemiology. Perry130 argues that approaches to the prevention of violent crime still have much to learn from public health more generally, in that approaches known to be valuable within public health have not been widely applied to questions of crime. In particular, violence prevention has tended to focus on ‘high-risk’ subgroups in the population, rather than shifting the mean of the population as a whole, and on secondary rather than primary prevention. Taking a public health-informed approach to crime would imply de-emphasising questions of why specific individuals engage in criminal activities in favour of asking why crime rates and types vary across populations and areas. Perry also argues, drawing on Farmer,131 that it would imply a greater focus on the ‘structural’ violence latent in unequal and unjust social orders, not only on the manifest violence measured by crime statistics. This point relates to the idea of ‘spirit injury’ discussed earlier (see Background), and suggests that a population-based approach to crime and health will need to take into account the indirect as well as the direct impacts of crime, and to engage critically with the concept of crime itself.

As already discussed, such a population-level approach has been widely adopted in the observational epidemiological literature on crime and health. However, it has generally not informed the development of intervention strategies. Winett’s132 review on violence in the USA as a public health problem found that, although authors tended to identify social and structural causes for violence, the interventions that they proposed targeted individual behaviour change and improved public health practice and de-emphasised social factors. Winett’s132 findings suggest a need for a more contextually informed understanding of crime and health and of the potential for interventions to ameliorate the health impacts of crime.

A further body of research has examined the links between alcohol availability or use and violence. These links may be complex: alcohol consumption may increase risky behaviour, inhibit the ability to avoid violence, increase the risk of being a victim of violence and increase the risk of violent tendencies developing in those exposed to alcohol in utero. 133 A summary of the epidemiological and criminological literature134 notes that, although problem drinking is associated with intergenerational transmission of intimate partner violence and of violence perpetration and victimisation for both men and women, and is significantly related to violent offending, the causal link between alcohol consumption and violent behaviour remains questionable. (Throughout this report, when an association or finding is referred to as significant, we mean ‘statistically significant’ unless otherwise stated.) However, the author notes that the economic literature does suggest a causal link through studies examining price changes and alcohol outlet density. This potential link is of particular interest for our purposes. Two systematic reviews of studies examining the effects of changes in alcohol outlet density have found a positive association between alcohol outlet density and increased alcohol consumption and related harms, including injuries and violence. 135,136 The causal direction of the link between high outlet density areas and alcohol consumption rates is unclear,136 although outcome evaluations of interventions do exist in addition to observational studies.

Finally, as well as the pathways from crime to health described above, there may also be pathways in the other direction, insofar as people with health problems, particularly serious mental health problems, may be at greater risk of crime;137–139 this is represented in the model by the pathway from mental health to crime.

Crime and fear of crime

The link between crime and fear of crime is conceptually obvious but empirically complex. Until recently a long-standing truism of fear-of-crime research was that objective risk of crime was poorly correlated with perceived risk and affective fear outcomes. Victimisation theories of fear of crime posit that fear is largely driven by the lived experience of victimisation. However, this theory does not appear to be strongly supported by the data. Although research does tend to show some relationship between victimisation experience and fear, it is not as strong as might be expected. 140–142 However, this may depend on the measures used. Some researchers have found that victimisation is associated with frequency of worry, as opposed to dispositional measures. 49 Repeated or multiple victimisation may also be more strongly associated with fear than one-off or occasional victimisation,117 although it is less clear that it has more severe mental health impacts.

At a broader level, it is unclear to what extent individuals’ perceptions of their own risk represent accurate estimates of the probability of victimisation (as measured by area-level crime rates or individual-level predictors of risk), or are responsive to changes in the latter. Some studies have found that most individuals are ‘pessimists’ in that their estimated risk of crime is substantially higher than their actual measured risk. 143 However, other studies with a more specific focus have found the opposite result; for example, women’s estimations of the risk of sexual assault have been found to be relatively ‘optimistic’. 144 Such results have led some researchers to speak of a ‘risk–fear paradox’. 145,146

Empirical studies of the correlation between risk and fear tend to show that there is a relation between the two, but that it is not very strong. Most studies do find that there is a statistically significant relationship, but also that it explains only a small amount of the variation in fear. Again, there is considerable controversy about which measures of fear best access the relationship. For example, some researchers hypothesise that measures which access worry about specific crimes (as, for example, the British Crime Survey measure) may be more closely related to objectively measured crime rates than those that access anxiety about crime in general. However, there does not appear to be any trend towards a stronger relationship with objective risk in studies that use the former type of measure of fear147,148 than in studies using more global measures of anxiety. 149–151