Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3005/05. The contractual start date was in December 2010. The final report began editorial review in December 2012 and was accepted for publication in June 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catherine Law is Director of the NIHR Public Health Research Programme, Editor-in-Chief of the Public Health Research journal and a former member of the NIHR Journals Library Board. Helen Roberts is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Law et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Levels of childhood overweight and obesity have been rising steadily over the past decade. In 2010, 31% of 2- to 15-year-old boys and 29% of girls were overweight or obese; figures for obesity alone were 17% and 15% respectively. 1 Comparable figures in 1995 showed that 24% of boys and 26% of girls were overweight or obese, with 11% and 12% respectively classed as obese. 1 Although the rise in prevalence appears to be levelling off,2 rates of childhood overweight remain high.

Childhood overweight arises because of an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure. This is linked to increased sedentary behaviour (particularly related to screen-based entertainment), low physical activity and patterns of diet such as consuming high-fat and high-sugar foods and drinks. 3 These behaviours are potentially modifiable, but the causes of childhood overweight also need to be considered at a societal level as the features of ‘obesogenic’ environments which promote obesity often operate at levels largely beyond families’ control. 4,5

Compared with their peers with healthy weight, overweight children have a higher risk of a range of adverse health and other outcomes. These include fatty liver disease, childhood-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus, adverse cardiovascular risk profiles, impaired psychological health, low self-esteem and being a perpetrator and/or victim of bullying. 5,6 Both the prevalence and adverse consequences of childhood overweight and obesity are underestimated by parents. 7 This may reflect general desensitisation to seeing excess body fatness, such that overweight among children is seen as normal, fatalism (‘nothing can be done about it’), optimism (‘they’ll grow out of it’) or denial of a stigmatising problem. 8 Childhood obesity is a risk factor for adult obesity, and so is associated with an increased risk of premature mortality and morbidity from a range of adult conditions. 5,6 In addition to its substantial health impact, obesity is projected to have significant future cost implications for the NHS. Using a microsimulation model, it has been estimated that the NHS costs of managing obesity and its consequences in England will reach £9.7B by 2050,3 around 10% of NHS expenditure at 2007 levels. The societal costs of obesity, including those from lost productivity and premature death, are projected to be £49.9B in 2050. 3,9

Despite the scale of childhood overweight, and a large research endeavour, relatively few effective interventions for the prevention or treatment of childhood overweight have been described. Authoritative syntheses of evidence, both international10,11 and applied to UK settings,5,9,12 for treatment of childhood overweight and obesity have noted that there is insufficient evidence to recommend one programme over another, although principles of effective interventions have been established. In addition to the changes needed to the obesogenic environment,13 these principles include addressing diet and physical activity, behaviour change, involvement of the family and a positive emphasis on managing a healthy lifestyle for the whole family.

Evaluation of a scaled-up weight management intervention

In this study we examine a weight management intervention, Mind, Exercise, Nutrition, Do it! (MEND) 7–13 (www.mendcentral.org). It is one of a suite of interventions offered by MEND Central, a limited company delivering weight management interventions from early childhood to adulthood. MEND 7–13 is a multicomponent family-based intervention which aims to support families of overweight and obese children to adopt and sustain healthy lifestyles. Children are eligible for the programme if they are aged 7–13 years and are overweight or obese (referred to as overweight throughout this document, unless otherwise specified), defined as exceeding the 91st centile of the UK 1990 growth charts. 14 The programme was shown to be effective in reducing body mass index (BMI) and improving self-esteem after 6 months and 1 year in a randomised controlled trial (RCT). 15

The MEND 7–13 intervention meets the guidelines for weight management interventions outlined above. 9 It combines principles of nutritional and sports science with those from psychology, learning and social cognitive theories and the study of therapeutic processes. It seeks to address three components necessary for individual-level behavioural change – education, skills training and motivational enhancement16 – while recognising the need to engage multiple, interacting systems of influence within the family context. 17 It was developed on the basis of literature and expert guidance9 and to be delivered in community settings. Because of the importance of family involvement for behaviour change, the programme requires a parent or carer to attend all sessions.

The intervention was ‘scaled up’ rapidly across England from 2007. Scaling up has been defined as:

. . . a policy that builds on one or more interventions with known effectiveness and combines them into a programme delivery strategy designed to reach high, sustained, and equitable coverage, at adequate levels of quality, in all who need the interventions[.]

p. 154118

There is a lack of information about what happens when public health interventions deemed to be effective under research conditions are scaled up for delivery under service conditions. 19 This arises partly because outcome data are often not collected and/or collated during service delivery. We drew on data collected by MEND 7–13 delivery partners (individuals and organisations who co-ordinate and run local MEND programmes) and collated and held by MEND Central. Data were available for > 20,000 children referred to MEND 7–13, to examine characteristics of this scaled-up weight management programme.

Using quantitative and qualitative methods, we aimed to assess whether and how MEND contributes to tackling childhood overweight under service conditions, how it works in different contexts, for whom and why. We addressed these aims through the following specific research questions (which are addressed in Chapters 2–6).

-

What are the characteristics of children who take part in MEND, a family-based intervention for childhood overweight and obesity, when implemented at scale and under service conditions?

-

How do the outcomes associated with participation in MEND vary with the characteristics of children [sex, socioeconomic circumstances (SEC) and ethnicity], MEND centres (type of facility, funding source and programme group size) and areas where children live (in relation to area-level deprivation and the obesogenic environment)?

-

What is the cost of providing MEND, per participant, to the NHS and personal social services (PSS), how does this vary and how is it related to variation in outcome?

-

What is the salience and acceptability of MEND to those who commission it, those who participate in full, those who participate but drop out and those who might benefit but do not take up the intervention?

-

What types of costs, if any, are borne by families (and by which members) when participating in MEND, and in sustaining a healthy lifestyle afterwards?

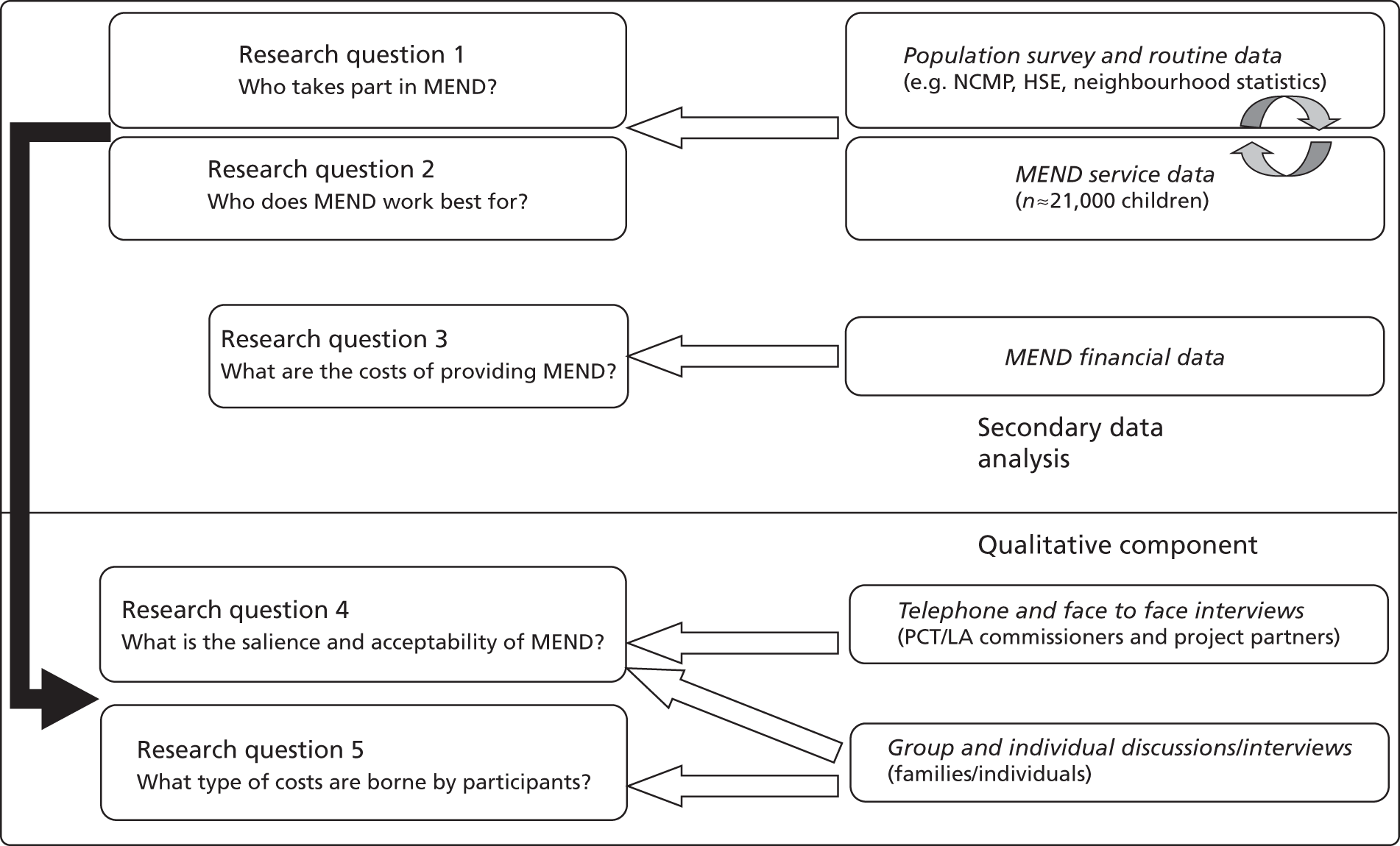

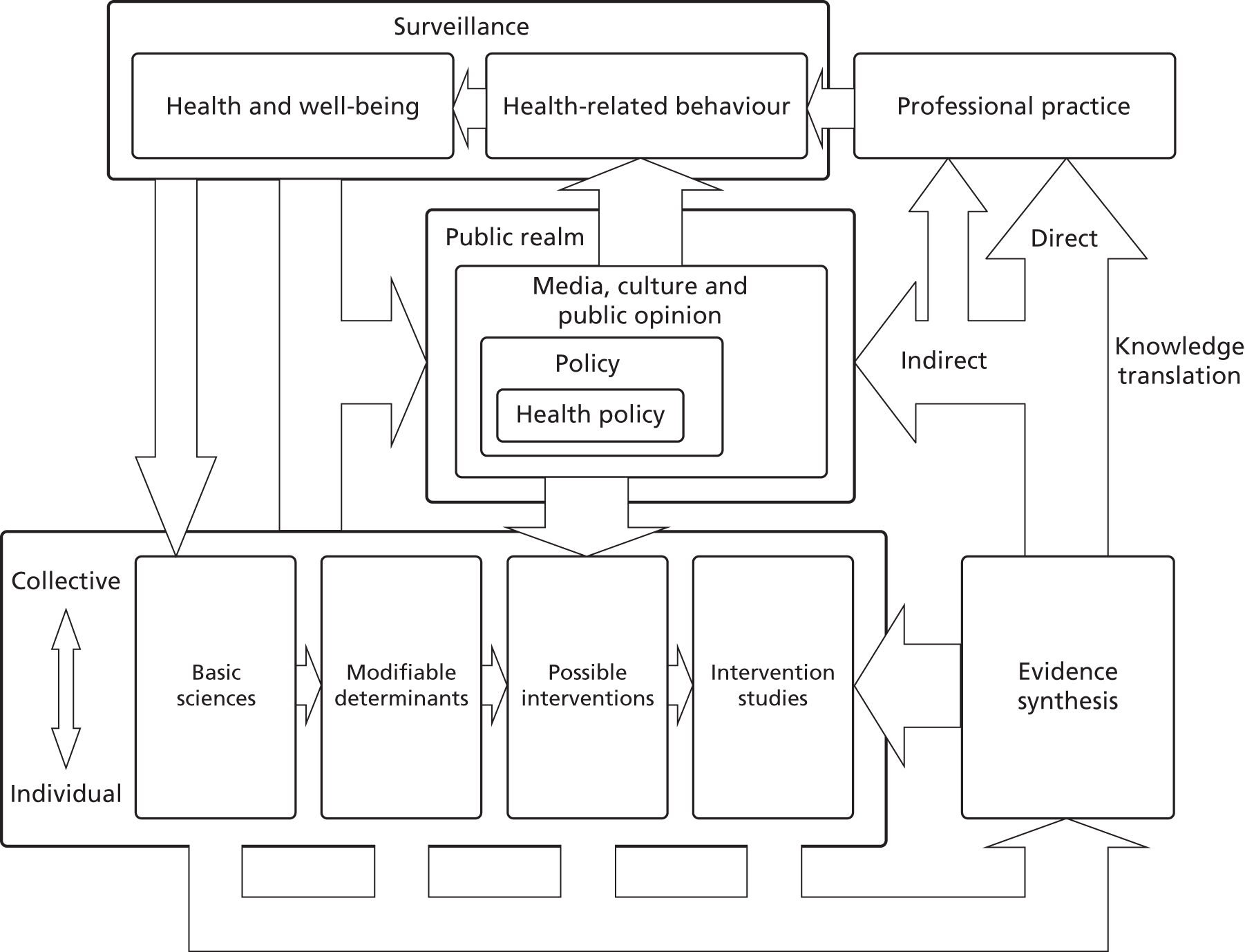

These questions, their rationale and the methods used to address them are summarised in Figure 1 and described briefly here. Further detail is given in Chapters 2–6.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of study design. HSE, Health Survey for England; LA, local authority; NCMP, National Child Measurement Programme; PCT, primary care trust.

Research question 1: Who takes part in MEND?

Children living in disadvantaged SEC are more likely to be overweight than their more advantaged peers. 20 In addition, the proportion of children who are overweight varies by ethnic group. 21 Research also suggests that some families (those in more advantaged SEC, for example) may be more likely to access or benefit from services which support behaviour change. 22

Given the socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in childhood overweight and potential inequities in the use of services (including weight management services), we examined the question of who takes part in the MEND 7–13 programme. To do this, we used service data from MEND 7–13 and information from routine data sources about the characteristics of children who would be eligible to take part in the programme. MEND 7–13 participants were described by their age, sex, ethnicity, SEC and characteristics of their residential neighbourhood. The MEND 7–13 participants’ sociodemographic profiles were then compared with those of respondents to three nationally representative surveys [the Health Survey for England (HSE), the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) and the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP)]. This analysis is described in full in Chapter 2.

Research question 2: Who does MEND work best for?

Interventions might work less well for some groups than others, and so create or exacerbate inequalities through differential effectiveness. 23 Research suggests that some groups (again, those with more favourable SEC) may be more receptive to interventions aimed at promoting healthy patterns of diet and physical activity. 24 MEND 7–13 (like some other weight management interventions) was evaluated in a relatively small (n = 116) RCT15 which (in common with similar intervention studies) was not designed to investigate whether effects varied by sex, ethnicity or SEC. Therefore, questions remain about whether outcomes associated with participation in MEND 7–13, weight management programmes more generally, and indeed public health programmes in general, vary with these characteristics. 23 We examined how changes in outcomes associated with participation in MEND 7–13 varied by the sociodemographic characteristics of participants and the places where they lived.

Interventions need to be understood as part of a complex system, rather than one-off events which can be understood in isolation. 25 The substantial variations in the contexts where the MEND 7–13 service was delivered, combined with the large size of the data set, allowed us to estimate how changes in outcomes varied by characteristics of programmes and contexts. We estimated whether outcomes associated with MEND 7–13 were moderated by obesogenic characteristics of the environment (such as the density of fast food outlets or access to green space in the local neighbourhood). We also estimated whether differences in programmes accounted for differences in outcomes.

Randomised controlled trials are often conducted with highly selected populations in academic settings,10 meaning that conclusions about effectiveness cannot necessarily be generalised for all groups in the population. 26 In the case of MEND 7–13, the RCT was delivered only to children who were obese, although both overweight and obese children are eligible for the MEND 7–13 service following its implementation into practice. Additionally, as discussed above, once scaled up, the service was delivered across a wide range of contexts. There was therefore significant potential for outcomes under service conditions to vary from those observed in the RCT.

Although the RCT of MEND followed children up for 12 months, such long-term follow-up of participants in large-scale service interventions is unusual and would be costly. Our analyses could only assess changes associated with participation in the MEND 7–13 programme from the first to the penultimate sessions (the time of the last measurement), a period of 10 weeks. We compared unpublished RCT data over a comparable period of follow-up with these service data.

These analyses are described in full in Chapters 3 and 4.

Research question 3: What are the economic costs of MEND?

Evaluations of this type are developed in part to inform decision-making by those considering whether or not to commission weight management interventions like MEND 7–13. The economic costs of interventions are clearly an important component of such decisions. We aimed to analyse cost data for MEND 7–13 to estimate the overall cost of delivery and to characterise the types of costs which were involved in running the programme, over and above the costs of the programme itself.

Although our initial intention (as illustrated in Figure 1, research question 3) was to conduct a de novo analysis of MEND financial data, in the course of reviewing the literature we identified work which had recently estimated these costs for MEND 7–13 on a national and local level. These sources were reviewed and used for our analysis rather than repeating work already undertaken. This analysis is described in full in Chapter 4.

Research questions 4 and 5: What is the salience and acceptability of MEND to those who commission and use it, and what types of costs are borne by participants?

Proponents of the evidence and effectiveness agendas27 have long understood the importance of collaborating with citizen, policy, funding and practitioner users if research is to influence practice. 28 Literature on the difficulties of implementation, the tension between programme fidelity and responsiveness to local needs and the importance of context29–31 informed our approach to research questions 4 and 5.

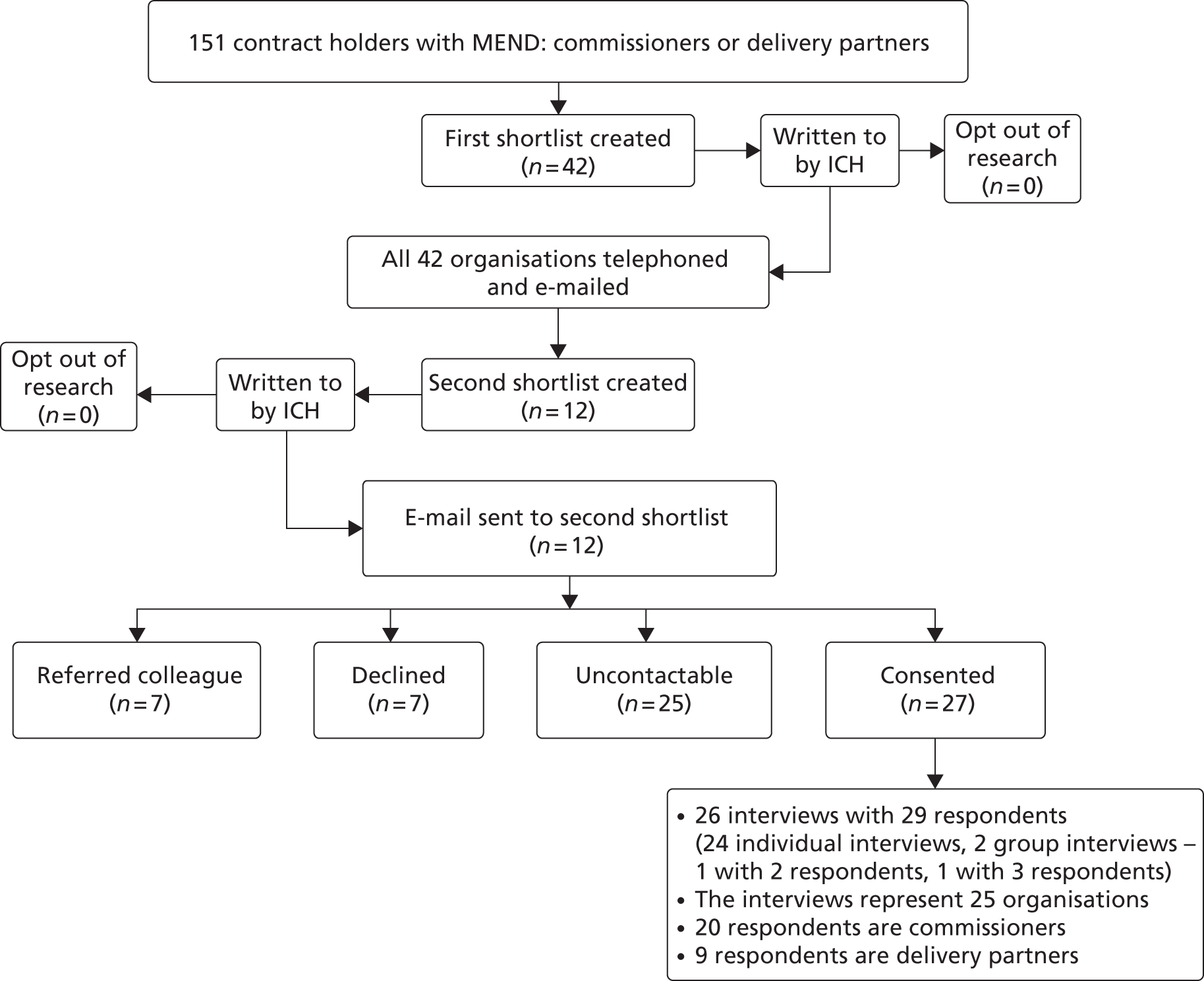

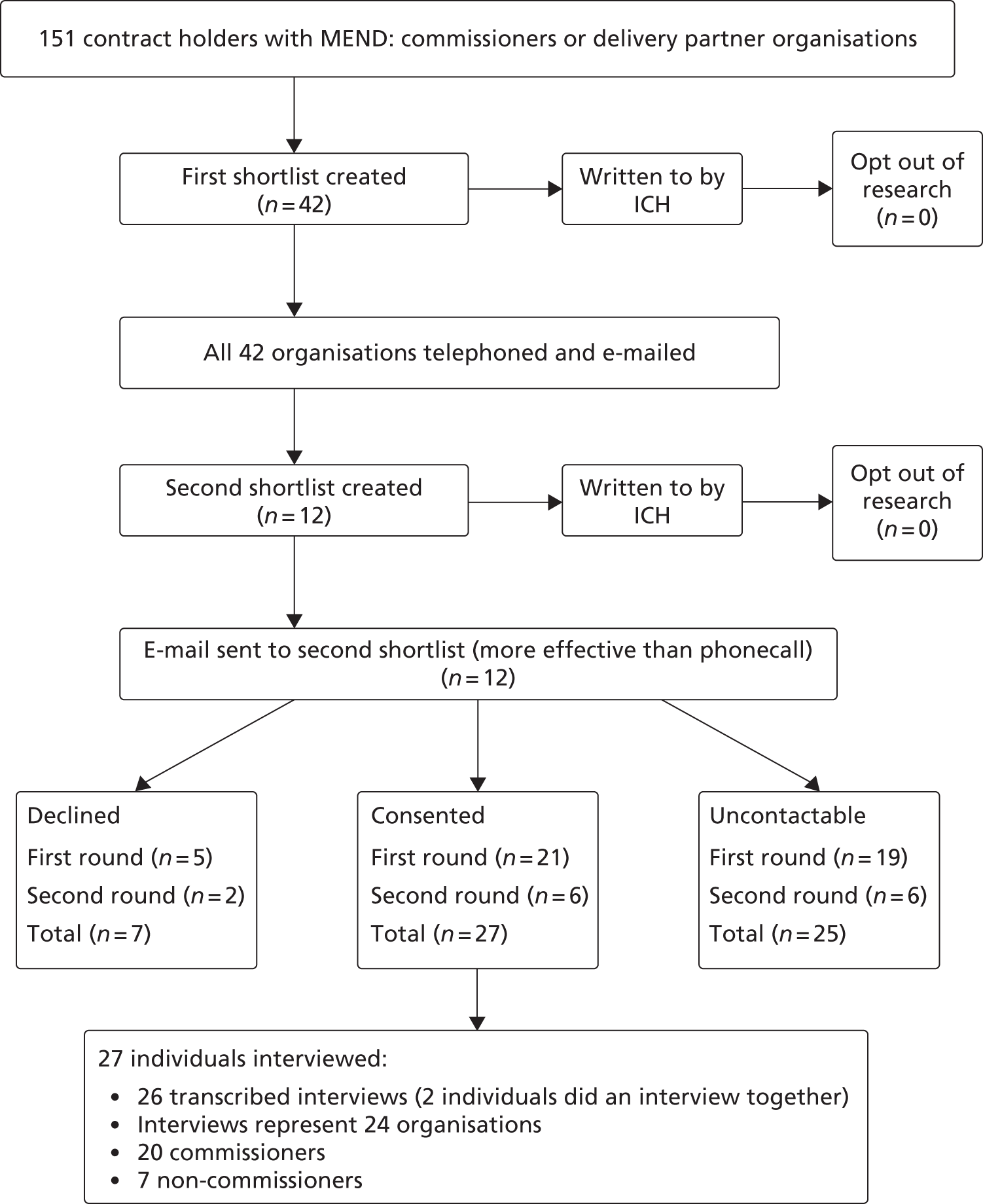

Our qualitative research was designed to address the salience and acceptability of the intervention to users, non-users and providers. Hawe et al. 32 point to the context-level factors which may affect intervention uptake, success, and sustainability and which include primary care agencies and local adaptation of an intervention. In the course of our study, the NHS was undergoing fundamental reorganisation as a result of proposals subsequently set out in the Health and Social Care Act 2012. Commissioners and service delivery partners, never professionals with time on their hands, were experiencing considerable churn in the system, and we were concerned to capture insights from these provider groups as early as possible in the study. They were selected from a database provided by MEND Central. The interviews were designed to explore the ways in which commissioning and recommissioning decisions were made, what worked well or less well, and the tension between programme fidelity and responsiveness to local context (see Appendix 14 for topic guide). Our findings from these interviews are set out in Chapter 5.

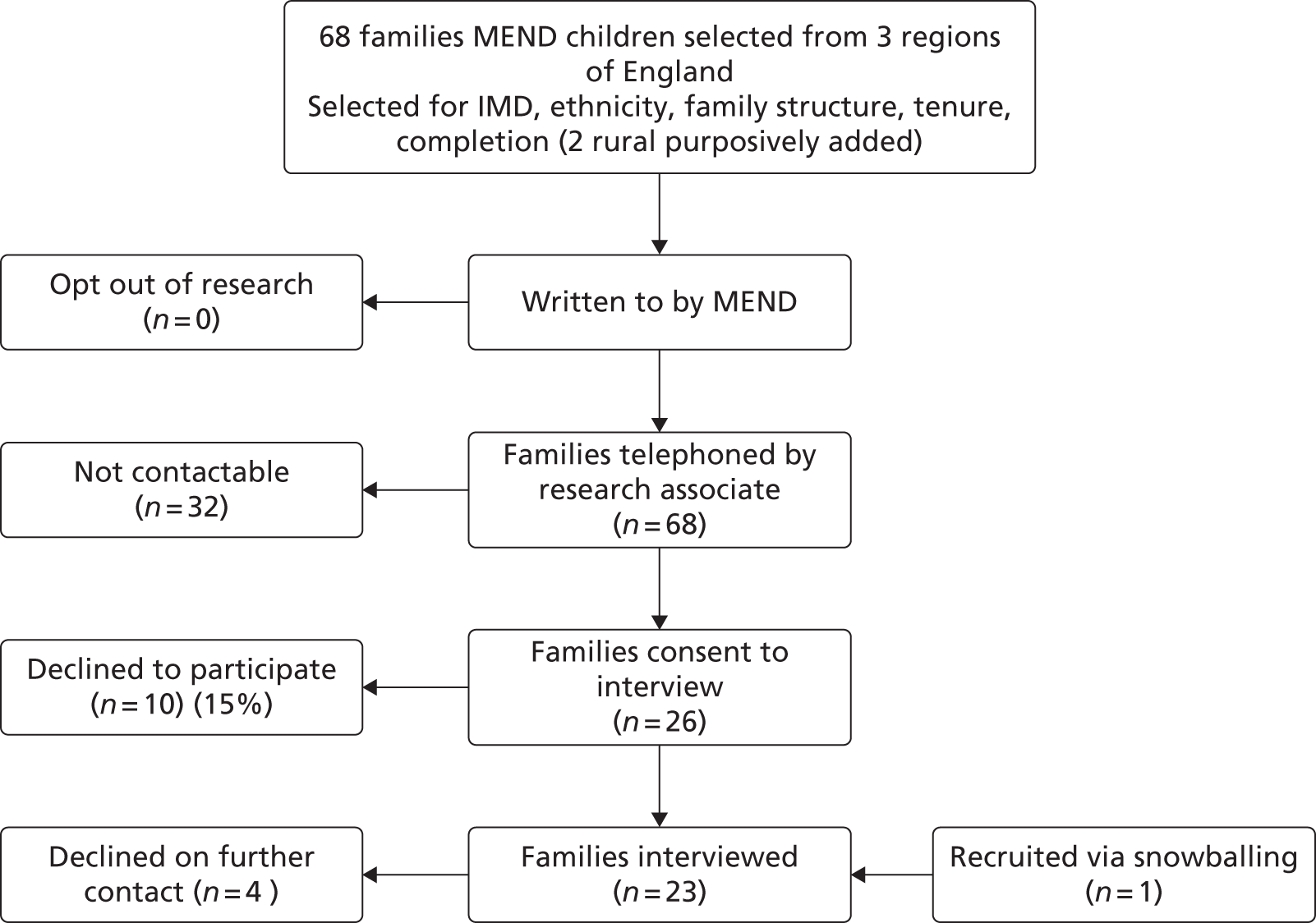

Families were selected from the same MEND database as that used in the quantitative analysis, up to 4 years after they had participated in a MEND 7–13 programme. Interviews began with open questions about family make up and memories about MEND, followed by discussions of barriers and levers to participation, costs and benefits within the family, and life after MEND (see Appendix 14 for topic guide). Our findings from these interviews are set out in Chapter 6.

Roles of the research team

The study was designed and planned by the investigators and project partners. Quantitative analyses were undertaken by Jamie Fagg, supported by team members with expertise in public health epidemiology, policy and health inequalities in childhood (Catherine Law), geographies of health and community evaluation (Steve Cummins) and statistical expertise in child growth, multilevel modelling and the handling of missing data (Tim Cole and Harvey Goldstein). The analysis of the costs of MEND 7–13 was co-ordinated by Steve Morris, a health economist.

Qualitative work was co-ordinated by Helen Roberts. Families and commissioners were purposively selected for recruitment using criteria set out in our grant application. The methods of operationalising these criteria were developed by Jamie Fagg in discussion with the qualitative research team. Families and commissioners were selected by Jamie Fagg, and Hannah Lewis contacted and recruited respondents to the study. Interviews were conducted and analysed by a team of four experienced qualitative researchers (Helen Roberts, Katherine Tyler, Patricia Lucas and Lisa Arai). Additional work on the analysis and report of the commissioner study was conducted by Sally Stapely.

The team members met regularly in the context of the project management group and within subgroups to take part in the planning, management and reporting of the project.

Data from MEND 7–13 were transferred to the Institute of Child Health research team by employees of MEND Central (Paul Sacher, Paul Chadwick and Duncan Radley). They also provided advice on some aspects of the design and development of the project and the technical details of the intervention but did not participate in the analysis of the data (see Management of competing interests). Analyses of the NCMP were commissioned from the National Obesity Observatory (NOO).

The project overall was managed by Catherine Law. Jamie Fagg co-ordinated and managed the project on a day-to-day basis, with support from Hannah Lewis and Chloe Parkin.

Public involvement

The protocol for the project was discussed with the National Children’s Bureau’s (NCB’s) young person’s Public health, Education, Awareness, Research (PEAR) group in 2009. The group’s suggestions (see Appendix 3) informed the successful grant application and the planning of the project. Findings from the study were presented to the comparable NCB Research Advisor’s Group in July 2012 for their feedback (see Appendix 3), which is reflected in the discussion of our results (see Chapter 7).

Ethical considerations

We applied for three sets of ethical approval reflecting the three distinct components of our study. The first two applications were to UCL Ethics Committee for the quantitative secondary data analysis and the qualitative study of families. The committee granted approval for the quantitative study in October 2010 (ref. 2677/002) and for the qualitative study in February 2011 (ref. 2842/001).

As the third element of the study involved a qualitative study of commissioners, many of whom were based in the NHS, we sought NHS Research Ethics (NRES) permission. The NRES committee that reviewed our application deemed this component of the study to be a service evaluation not requiring NRES permission (East London Research Ethics committee ref. 11/H0703/3). As a service evaluation it was also exempt from the need to seek ethics permission from UCL Ethics Committee. We conducted this component of the project with reference to the framework for research ethics produced by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). 33

Management of competing interests

MEND describes itself as a social enterprise – an ethical business which aims to benefit society in general. In the UK, MEND has two operating arms: MEND Central, a limited company, and MEND Places, a not-for-profit company originally set up to provide a route for donations to subsidise places for families on the MEND programme. To date, all those commissioning MEND 7–13 placed funding through MEND Central. As discussed above, three members of the project management group (Sacher, Chadwick and Radley) were employees of MEND Central Ltd. Sacher and Chadwick are also shareholders. They therefore had an interest in MEND Central’s success.

The MEND programme was aimed at 7- to 13-year-olds, based on research undertaken at the Institute of Child Health. Under a contractual relationship, the Institute of Child Health received a proportion of the revenues generated from this programme. These sums were less than £10,000 per annum between 2007 and 2010. The Institute used these funds to support nutrition research and none of the research team had access to these funds, nor works in the department where the funds were held.

Given that results from the project might support, threaten or have no effect on MEND Central’s success, our grant application and subsequent protocol set out governance measures to ensure that these competing interests, and the interests of project stakeholders, were managed appropriately. The project was run according to these measures, with minor variations approved by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Details of governance procedures were agreed with the project advisory group (PAG) (see Appendix 1 for PAG terms of reference). The policy on competing interests was also agreed with this group; see Appendix 2 for full details.

Chapter 2 Who takes part in the MEND 7–13 programme?

What are the characteristics of children who take part in MEND, a family-based intervention for childhood overweight and obesity, when implemented at scale and under service conditions?

Background

We were interested in how far the sociodemographic characteristics of children who were referred to and participated in MEND 7–13 reflected those of the population who were eligible for the intervention. As emphasised by Glasgow et al. ,34 assessment of the reach of interventions is, alongside effectiveness, an important step when considering the population-level impact on health. In particular, research should assess two aspects of reach. First, to what extent are participants in interventions representative of the target population? Second, how far do interventions reach their target population in terms of the percentage who are referred, take up the intervention and complete the intervention? We draw on MEND 7–13 service data and routine data sources to address these issues in this chapter.

Data

MEND 7–13 service-level data

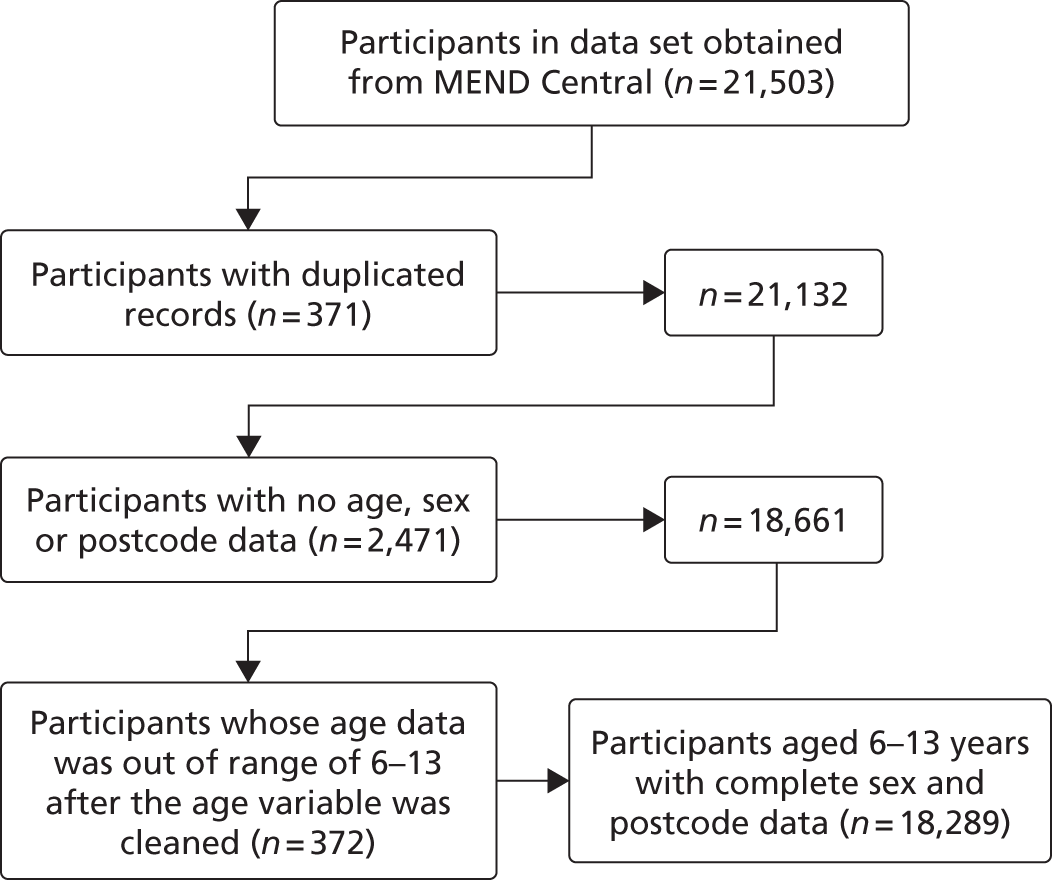

Service-level data about the MEND 7–13 programme were collected by local MEND programme managers and collated by MEND Central between January 2007 and December 2010. All analyses of service data (n = 21,503) were also restricted to those with no duplicate observations in the data set and those with completely observed information for age, sex and postcode (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Derivation of analysis sample, excluding participants with duplicate records, partially observed data on age, sex or postcode and those outside the age range 6–13 years.

Outcome variables: adiposity, psychosocial health and lifestyle

All outcome variables (Table 1) were measured at baseline (the first session of the programme) and follow-up (the penultimate session). The primary outcome used in the study was change in body mass index (BMI), calculated from height and weight [(weight/height)2] measured by MEND 7–13 staff. We also investigated change in age- and sex-standardised BMI (zBMI), self-esteem measured by a modified version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale35 (participant reported), participant psychological distress measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, parent-reported version),36 and questions devised by MEND Central about participants’ levels of physical activity and the healthiness of their diets (both parent reported). Analyses of these outcomes are reported in detail in Chapters 3 (changes in BMI and zBMI) and 4 (changes in psychosocial and lifestyle outcomes).

| Variable | Measured at baseline (B) or follow-up (F) | Data management of MEND Central data by the ICH team | Variable (coding) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birthdate | B | No additional data management at ICH | Date (day/month/year) |

| Measurement date | B and F | No additional data management at ICH | Date (day/month/year) |

| Age | B and F | Derived from birth and measurement dates | Continuous (accurate to day) |

| Sex | B | No additional data management at ICH | Girls (0)/boys (1) |

| Height | B and F | Outliers removed at ICH | Continuous (nearest 0.1 cm) |

| Weight | B and F | Outliers removed at ICH | Continuous (nearest 0.1 kg) |

| BMI | B and F | BMI calculated at ICH from height and weight | Continuous (kg/m2) |

| Change in BMI | F – B | Baseline subtracted from follow-up | Continuous (kg/m2) |

| zBMI | B and F | zBMI calculated at ICH from UK 1990 data, age, sex, height and weight | Continuous (standardised units) |

| Change in zBMI | F – B | Baseline subtracted from follow-up | Continuous (standardised units) |

| Self-esteem (on Rosenberg self-esteem scale) | B and F | Scale calculated at ICH using published instructions | Continuous (range 0–30) |

| Change in self-esteem | F – B | Baseline subtracted from follow-up | Continuous |

| SDQ | B and F | Scale calculated at ICH using published instructions | Continuous (range 0–42) |

| Categorical baseline SDQ score | B | Derived at ICH using published instructions | Categorical (normal = 0–13 symptoms, borderline = 14–16 symptoms, abnormal = 17–37 symptoms) |

| Change in SDQ score | F – B | Baseline subtracted from follow-up | Continuous |

| PA | B and F | Items (walking and cycling) selected and collated at ICH | Continuous (hours in last week spent walking or cycling) |

| Change in PA | F – B | Baseline subtracted from follow-up | Continuous |

| Diet | B and F | Scale collated by ICH staff using MEND coding matrix (provided in Appendix 12) | |

| Change in diet | F – B | Baseline subtracted from follow-up | Continuous |

| Ethnicity | B | Collated at ICH from multiple classifications provided by MEND Centrala | White (0), Asian (1), black (2), other (3) |

| Family structure | B | No additional data management at ICHa | Couple (0), single parent (1) |

| Housing tenure | B | Derived at ICH from rental status and owner-occupation variables provided by MEND Centrala | Owned (0), social rented (1), private rented (2) |

| Employment status of primary earner | B | No additional data management at ICHa | Yes (0), no (1) |

| Residential postcode of MEND 7–13 participants | B | Incomplete postcodes coded as missing; those with clear errors were cleaned with algorithms developed at ICH (e.g. WCI = WC1) | Standard postcode format |

| Attendance at MEND sessions | Each session | Did not differentiate between missing data and non-attendance. Cleaned using assumptions developed at ICH in consultation with MEND Central | Categorical: non-completers < 25% of sessions attended (0), partial completers 25–75% of sessions attended (1), completers > 75% of sessions attended (3) |

| Programme-level variables | |||

| Group size | B | Derived using participant and programme identifiers | Continuous (range from 1–20) and categorical: 1–5 (1), 6–9 (2), 10+ (3) |

| Number of programmes to date for programme manager | B | Derived using measurement date, programme and programme manager identifier | Continuous (ranging from 1–32) |

| Rounding of height measures | B | Derived using height, participant and programme identifiers | Binary (0 if < 20% of programme participants equal to 0 or 0.5 cm, 1 if > 20% rounded) |

| Rounding of weight measures | B | Derived using height, participant and programme identifiers | Binary (0 if < 20% of programme participants equal to 0 or 0.5 kg, 1 if > 20% rounded) |

Demographic and socioeconomic variables

Age at the first and penultimate sessions was used in the derivation of zBMI at baseline and follow-up. Otherwise, age at baseline was used as a covariate in the study. Sex and ethnicity (white, Asian, black or other, as reported by parents) were also used.

Socioeconomic circumstances were reported by parents. These included family structure, housing tenure and parental employment (whether the ‘primary earner’ in the household was employed or not at baseline). Employment status was not differentiated by subcategories, such as ‘self-employed’ or ‘retired’. It was only collected in 2009 and 2010 and so we used multiple imputation methods to impute values for 2007 and 2008.

Attendance

In theory, attendance was logged by MEND 7–13 local staff at each session. Where a value of 0 had been entered on the service database it was difficult to know whether this was because managers had not collected attendance data or because the child did not attend the session. To separate those who did not attend from cases where information had not been recorded, we derived a variable indicating valid entries for those observations where the programme manager had entered a value of 1 for at least one other child for every session in the programme (some sessions were completely blank; this was taken to indicate lack of data entry rather than lack of attendance). Out of 13,998 children who started the programme (and had age, sex, postcode, measurement year and BMI data recorded in the first session), 7862 (58%) had valid attendance data. Otherwise, attendance data were either missing or judged to be invalid and coded as missing. The number of MEND sessions per programme changed from 18 to 20 in 2008, because the two measurement sessions were not recorded as sessions prior to 2008. This means that the total number of recorded sessions differed, but that the times of measurement and the period from the first observation of outcomes to the last was the same. Attendance was measured as a percentage (not a count) of sessions attended.

There is little consensus on what constitutes completion and attrition in paediatric weight management interventions. 37 Reflecting this uncertainty, we drew three groups based on the percentage of sessions that they attended, which we called non-completers (< 25% of sessions attended), partial completers (25–75% attended) and completers (> 75% of sessions attended).

Programme-level variables

Variables which were constant within programmes but varied between them (hereafter called ‘programme-level’ variables) included participant group size, the number of programmes delivered by each programme manager to date, and rounding of height and weight data. Group size was derived by calculating the number of children in each MEND programme at baseline (Table 2 shows group size distribution within the data set). The number of programmes delivered by each programme manager was derived using the measurement date of the first session of each programme combined with the identification number of each programme manager. This variable was used as a proxy for the amount of experience a team had for running a programme. However, it is important to note that a programme manager did not necessarily have the same role at each venue at which MEND 7–13 programmes were delivered. Specifically, some programme managers do run programmes themselves but others may manage delivery teams who run programmes; programme managers may run teams across single or multiple venues; and having the same programme manager over time does not mean that delivery teams remain constant (Duncan Radley, MEND Central, 2012, personal communication).

| Programme group size (number of children at baseline) | Number of programmes | Total % | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 2.22 | 2.22 |

| 2 | 55 | 2.84 | 5.05 |

| 3 | 97 | 5.00 | 10.05 |

| 4 | 207 | 10.67 | 20.72 |

| 5 | 223 | 11.49 | 32.22 |

| 6 | 230 | 11.86 | 44.07 |

| 7 | 233 | 12.01 | 56.08 |

| 8 | 227 | 11.70 | 67.78 |

| 9 | 173 | 8.92 | 76.70 |

| 10 | 152 | 7.84 | 84.54 |

| 11 | 110 | 5.67 | 90.21 |

| 12 | 81 | 4.18 | 94.38 |

| 13 | 47 | 2.42 | 96.80 |

| 14 | 36 | 1.86 | 98.66 |

| 15 | 15 | 0.77 | 99.43 |

| 16 | 7 | 0.36 | 99.79 |

| 17 | 1 | 0.05 | 99.85 |

| 18 | 1 | 0.05 | 99.90 |

| 19 | 2 | 0.10 | 100.00 |

| Total | 1940 | 100 |

As a proxy for data quality we estimated the degree of rounding of height and weight measurements by programme staff. MEND Central recommend that height is measured to the nearest 0.1 cm, using a stadiometer accurate to 0.1 cm, and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg, using electronic scales accurate to 0.1 kg, following standardised procedures. They also provide training to all delivery staff in taking these measurements. To estimate whether there was rounding at the programme level, we calculated the percentage of baseline measures at 0 or 0.5 kg (for weight) or 0 or 0.5 cm (for height). We then calculated which programmes had > 20% of measures rounded to these intervals, indicating that there was possible rounding.

Comparator data – representing the ‘MEND-eligible’ population

The ‘MEND-eligible’ population comprised those children who were living in England during the period when MEND was scaled up (2007–10), who were overweight and within the observed age range for participants on the programme. We estimated the size and sociodemographic composition of the MEND-eligible population using three ’comparator’ data sets: the HSE, the MCS and the NCMP. From these data sets we derived subsets representative of children in the MEND-eligible population.

Health Survey for England 2007–10

The HSE is an annual, nationally representative cross-sectional survey of English children and adults. 2 In 2007–10 the survey was boosted with additional samples of 0- to 15-year-olds. We pooled information from the years 2007–10 for overweight children aged 6–13 years (n = 2799). It included information on sex, ethnicity, housing tenure, employment status of household reference person and family structure. Where subcategories for these variables were available (i.e. retirement in employment status) these were merged so that the variables could be compared with the MEND 7–13 data (see Table 27 in Appendix 5 for full details of coding in comparators and MEND). The survey design (a cluster randomised sampling strategy, booster sampling, inverse probability weights, pooling of 2007–10 data sets and restriction to a subpopulation defined by an age range of 6–13 years and overweight) was accounted for using survey commands in the statistical package Stata 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). This meant that prevalence and percentages calculated from the data were representative of overweight children aged 6–13 years and resident in England between 2007 and 2010.

Millennium Cohort Study wave four

The MCS is following the lives of 18,819 children born in the UK in 2000–2. We used information taken from children living in England in wave four of the study (n = 8728) when they were aged 6–8 years inclusive. This was restricted to those who were overweight (n = 1533). 38 MCS respondents were categorised by sex, ethnicity, housing tenure, employment status of the household reference person and family structure (see Table 27 in Appendix 5). As with the HSE, the survey design [a cluster randomised sampling strategy, booster sampling of socioeconomically deprived areas and those with high percentages of black and minority ethnic (BME) groups, inverse probability weights, attrition over time, and the use of a subpopulation who were overweight and resident in England] was accounted for using survey commands in the statistical package Stata. This meant that prevalence and percentages calculated from the data were representative of overweight children aged 6–8 years, born in England in 2000–1 and eligible for MEND 7–13 between 2006 and 2009.

National Child Measurement Programme 2007–10

The NCMP records height and weight measurements of children in Reception (typically aged 4–5 years) and Year 6 (aged 10–11 years) school classes. 39 We commissioned analysis of data from the NOO on 10- to 11-year-old children who were overweight in 2007–8, 2008–9 and 2009–10 (n = 379,756). Specifically, we obtained percentages of overweight children by sex and ethnic group. The NCMP does not collect SEC information other than at the neighbourhood level, where urban/rural status and deciles of the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) 2007 relative to England as a whole are available (see Routine small area-level data). Data from the NCMP were nationally representative. In the years between 2007 and 2009 participation rates were judged to potentially impact on calculations of prevalence or percentages, and therefore figures were adjusted. There was no adjustment in 2009–10 as analysis suggested that selective participation would not introduce appreciable bias to estimates. 40

Subsets of MEND data set used in this chapter

For the analyses in this chapter, the MEND service-level data were divided into three subsets of participants (MEND-HSE, MEND-MCS and MEND-NCMP), each drawn to be comparable with their respective comparator by age and time period. Thus, 18,289 children (all children with observed data for age, sex and postcode) were referred to and contacted MEND (discussed as ‘referrals’ throughout) and were comparable in terms of age (6–13 years) and time period (2007–10) with the HSE data. Of these, 13,998 had BMI measured at the first session and are discussed as ‘starters’, while 8311 starters completed > 75% of sessions and are referred to throughout as ‘completers’. This is the MEND-HSE subsample.

The MEND-MCS subset is made up of 4391 children referred to MEND Central when they were aged 6–8 years inclusive. This subsample was not restricted to the MCS data collection period (mainly in 2008) as this would have severely reduced the numbers, and hence the power for comparison. Of the 4391 referrals, 3360 were starters and 2010 were completers. Although MEND 7–13 was aimed at 7- to 13-year-olds, in practice 317 children (1.6%) who participated were aged 6 years, and we included these participants in our analyses to increase the statistical power to compare MEND participants with MCS respondents.

The MEND-NCMP subsample included 6004 children referred to MEND who would have been in Year 6 in 2007–8, 2008–9 or 2009–10, and who were therefore comparable with the pooled NCMP data. Of these, 4615 were starters and 2711 were completers.

Routine small area-level data

All the individual data sets (MEND, HSE, MCS and NCMP) contained the residential postcodes of respondents. These data were not routinely available for these data sets but were linked to the MEND 7–13 data set by the Institute of Child Health team, to the HSE by the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen), to the MCS by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies (based at the Institute of Education, University of London) and to the NCMP by the NOO. This was then used to describe which of 34,378 lower super output areas (LSOAs) across England the respondents and their families lived in. LSOAs are statistically designed to have a minimum of 1000 residents but average 1500 residents. Using the LSOA identifiers we linked in the IDACI 2007 deciles41 and an indicator of urban/rural status to the MEND and comparator data sets. For analyses reported in Chapters 3 and 4 we also linked in measures of the food and built environment (described below) to the MEND data sets. We decided not to use composite indicators of multiple deprivation such as the Index of Multiple Deprivation 200741 as we wished to assess which specific components were independently associated with our outcomes.

The IDACI 2007 measures the percentage of income-deprived households with children aged 0–15 years in the LSOA. Households are defined as income-deprived if they are in receipt of means-tested benefits such as Jobseeker‘s Allowance or child tax credits. 41 The majority of underlying data sources were collected in 2005, although some are based on 2001 census data. Therefore, this index slightly predates the MEND and comparator data sets. However, it is unlikely that the decile ranking of LSOAs would vary in the 2-year period between measurement of most of the IDACI data and the measurement of the individual data sets. Deciles of the index were calculated relative to the deprivation ranking of all English LSOAs. Thus, MEND participants and survey respondents living in a LSOA classified as decile 10 live in an area which is among the 10% most deprived areas in England (as opposed to within the data set) for children.

In addition to IDACI 2007, we used an index developed for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 42 The index divides England into grid squares, classifying those with more than 10,000 people as ‘urban’. Rural categories are assigned using geospatial statistics to categorise communities as ‘town’ and ‘fringe’ (described throughout this report as ‘suburban’), or as ‘villages’, ‘isolated hamlets’ or ‘dispersed communities’ (described here as ‘rural’). This index was available at the LSOA level and was linked into our data sets.

We also described the environmental characteristics of participants’ residential LSOAs, which might constrain physical activity or be associated with unhealthy or healthy diets, and so moderate the effect of MEND 7–13. We examined physical land use characteristics, specifically the percentage of green space and the percentage of roads in each LSOA. Land use data were linked from the Generalised Land Use Database constructed in 2005. 43 These land use components were inversely correlated (i.e. as the percentage of green space increases, the percentage of roads in an area decreases) and therefore would violate assumptions of collinearity in regression models. Therefore, we combined them into a single ‘built environment’ variable using factor analysis, with a low value indicating a LSOA with a high percentage of green space and low road density. The Local Index of Child Well-being44 includes a relevant measure of access to sports facilities as well as the percentage of green space as two of five underlying environmental measures. However, we decided not to use this composite indicator as we wished to assess which specific components were independently associated with our outcomes.

To examine the characteristics of the local food environment in the MEND data we linked in information from the national Ordnance Survey Points of Interest data set,45 which lists the postcode locations of all food retail outlets in England on an annual basis. Following previous work examining the relationship between food availability and overweight and obesity in 9- to 10-year-old children,46 supermarkets and fruit and vegetable stores were classified as ‘healthy’ and takeout/fast-food outlets and convenience stores as ‘unhealthy’. Population data downloaded at the LSOA level from the mid-year population estimates for England47 were used in conjunction with the Points of Interest data to derive two density measures of the number of healthy and unhealthy food outlets per 1000 population in the LSOA in 2007.

Methods

Percentage of MEND-eligible population referred to, starting and completing MEND 7–13

We estimate the percentages of the MEND-eligible population who were referred to, started and completed MEND 7–13 as the number of children referred to, starting and completing the programme divided by the size of the MEND-eligible population. We also calculated the percentage of the MEND-eligible population who started or completed the programme who were obese (as opposed to overweight or obese) when they started the programme.

The MEND-eligible population (the denominator) was estimated three times, using the HSE, MCS and NCMP. The HSE allowed us to estimate the prevalence of children aged 6–13 years who were overweight or obese between 2007 and 2010. We applied this prevalence to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) mid-year population estimates of 6- to 13-year-olds between the same years48 to estimate the MEND-eligible population aged 6–13 years.

Sweep four of the MCS was collected in 2007 and 2008, providing information about children who were born in England between August 2000 and September 2001. These children were aged 6–8 years when they were surveyed. We used the estimates of the MCS population size (537,000 children born between August 2000 and September 2001) as reported by Plewis et al. 49 As with the HSE, we applied the sweep four prevalences of overweight and obesity, which were adjusted for sampling design including attrition.

The NCMP measures the BMI of children in Year 6, predominantly aged 10–11 years. This population cannot be readily represented using ONS population estimates of 10- or 11-year-olds as the school year spans the period of interest for mid-year estimates. Instead, we used the observed population counts from the NCMP as our denominator.

Missingness and multiple imputation

Data were missing for sociodemographic and outcome variables to varying degrees (Table 3). This was attributable to systematic reasons for some variables; for example, parental employment status was only collected in 2009–10, and self-esteem was measured by the Harter personality profile instead of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale until mid-2008.

| Variable | Missing data (n) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 4595 | 32.8 |

| Family structure | 5028 | 35.9 |

| Housing tenure | 4949 | 35.4 |

| Employment status of primary earner | 8804 | 62.9 |

| Percentage of sessions attended | 5811 | 41.5 |

| BMI (follow-up) | 4435 | 31.7 |

| Self-esteem (baseline) | 5902 | 42.2 |

| Self-esteem (follow-up) | 8895 | 63.5 |

| SDQ score (baseline) | 1000 | 7.1 |

| SDQ score (follow-up) | 5760 | 41.1 |

| PA (baseline) | 8218 | 58.7 |

| PA (follow-up) | 11,821 | 84.4 |

| Diet (baseline) | 1389 | 9.9 |

| Diet (follow-up) | 5899 | 42.1 |

This number of missing data were considered to have the potential to introduce systematic bias to observed associations, and to reduce both the statistical power of models to detect associations and the precision of estimates. Therefore, we decided to impute missing values using multiple imputation. This is a general approach to producing valid inferences when analysing partially observed epidemiological data. 50 Multiple imputation assumes that data are missing at random (MAR), and that differences between the missing values and the observed values can be explained by differences in the observed data. Therefore, a multiple imputation approach will not, in theory, account for missing data arising from factors not included in the multiple imputation model [where data are missing not at random (MNAR)] or those where the participants with missing data do not differ from those with complete data [where data are missing completely at random (MCAR)]. However, it is important to note that whereas multiple imputation explicitly makes this assumption, other techniques, such as discarding cases with only partially observed data (complete case analysis), implicitly make similar assumptions (MCAR in the case of complete case analysis51). Furthermore, although it may be difficult to verify why data are missing (i.e. how far the MAR assumption is correct) in any given analysis, studies which simulate different missing data patterns have demonstrated that multiple imputation tends to be more robust to departures from these assumptions than available alternatives such as the complete case approach. 52

Multiple imputation for our data set was complicated by two characteristics of the missing data. Firstly, because data were multilevel, participants were not randomly distributed in the population but grouped through attendance at programmes. This meant that the reasons for the data to be missing might vary between participants but also between programmes (when, for example, staff did not input any responses for a particular programme). To take account of this we estimated multiple imputation models using the REALCOM-IMPUTE software (REALCOM, Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK). 53 This software imputed missing data while taking account of the multilevel nature of the missingness. The second complicating feature was that we had 15 variables which were only partially observed (i.e. had missing data) and these were a mixture of categorical and continuous variables. The imputation of the missing values needed to be conducted in a single model to ensure that the relationships between the variables were estimated as precisely as possible. Again, the REALCOM software allowed these joint models to be fitted, while taking account of the multilevel structure described above.

In summary, we assumed that the reasons for missing data could be explained by the variables included in the multiple imputation model (i.e. all outcomes, sociodemographic, attendance, neighbourhood and programme-level factors, height and weight rounding, and random variation between programmes).

Differences between sociodemographic characteristics of MEND 7–13 participants and the MEND-eligible population

Percentages for the MEND subsamples and comparators were calculated, taking into account survey design where necessary (see Comparator data – representing the ‘MEND-eligible’ population). Differences in percentages were calculated for each MEND subsample (MEND-HSE, MEND-MCS and MEND-NCMP) by subtracting from them the corresponding comparator percentage (HSE, MCS or NCMP). The statistical significance of the differences at the 5% level was then tested using tests of the equality of percentages for two independent samples.

Calculation of differences in percentages for the imputed variables was a three-stage process. First, 10 data sets were imputed from the master data set by the multiple imputation model described above (stage 1). Following this, 10 tests of the equality of percentages were conducted, producing 10 sets of differences (and their variances) in percentages (stage 2). Finally, these parameters were combined into final estimates using Rubin’s rules,54 which take into account the variation introduced by the imputation procedure (stage 3).

These calculations were repeated for all the imputed socioeconomic variables (i.e. ethnicity, family structure, housing tenure and employment status). The process was repeated for the MEND-MCS and MEND-NCMP data sets, which were also imputed and compared with the percentages in the MCS and the NCMP.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted with the MEND-HSE data set to examine whether the sociodemographic composition of MEND participants varied by year. We repeated comparisons of the MEND-HSE data and the MEND-eligible population for starters and completers using complete case data, imputed data for overweight children excluding obese children, and imputed data for obese children.

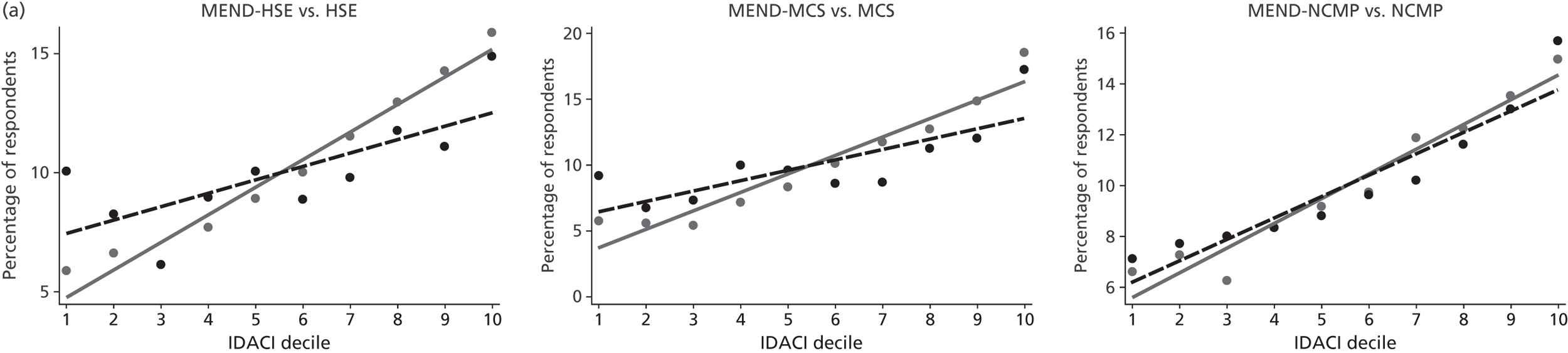

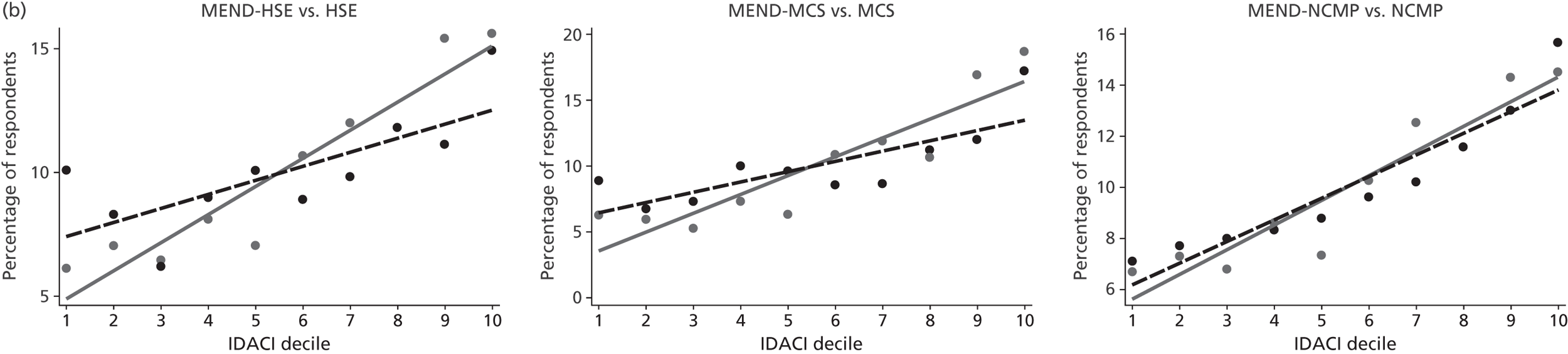

Differences in neighbourhood income deprivation gradient between MEND 7–13 participants and comparators

We tested for differences in the social gradients of participants in the MEND programme by examining IDACI 2007 deciles graphically. The statistical differences in slopes were tested using regression models where the outcome was the percentage of participants by deprivation in each MEND subsample (MEND-HSE, MEND-MCS and MEND-NCMP) and comparators (HSE, MCS and NCMP) (for further details see Appendix 7). This analysis was repeated, where data existed, for those referred to MEND 7–13, those who attended < 75% of sessions (low to medium attendance) and those who attended > 75% of sessions (high attendance).

Determinants of completion of MEND 7–13

A multilevel poisson regression model was used to estimate the relative risk ratios of children completing the programme. A multilevel model was needed because participants were nested within programmes and so were not statistically independent from each other (a violation of the assumptions of single-level regression models). Relative risks ratios were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We examined unadjusted and adjusted associations between completion and BMI at baseline (BMI at the first session), SDQ score at baseline, age, sex, ethnicity, family structure, housing tenure, employment status of the primary earner, IDACI 2007 decile, built environment, urban/rural status, group size and the number of previous programmes per programme manager.

We fitted the final multilevel model in MLwiN Version 2.25 (MLwiN, Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK),55 fitting a model for each of the 10 imputed data sets in turn before combining the coefficients and standard errors using Rubin’s rules54 as implemented by the Stata 11.2 multiple imputation commands.

The model was estimated using multiply-imputed data for 13,998 participants. As with the calculation of differences in percentages described above, the relative risk ratios and standard errors derived from analysis of all ten data sets were calculated using Rubin’s rules as implemented by the Stata 11.2 missing data (mi est) commands.

Age was grand-mean centred, subtracting the mean across the whole sample from each observation. This means that relative risk ratios from the model could be interpreted as ‘for each year of age greater than the average the risk of completion increases/decreases by . . .’

We categorised all continuous covariates apart from age as this facilitated interpretation. We categorised the SDQ as normal (0–13 symptoms reported), borderline (14–17 symptoms reported) and abnormal (≥ 17 symptoms reported), following the wording and guidance of the score’s developers. 36

Findings

What percentage of the MEND-eligible population are referred to, start and complete MEND 7–13?

Estimates of the size of the MEND-eligible population were calculated using prevalence and population estimates data presented in Table 4. The prevalences of overweight and obesity were smallest in the youngest children (in the MCS) and highest in the NCMP data (for Year 6 children).

| Percentage of 6- to 13-year-olds in 2007–10 (HSE) (95% CI) | Percentage of 6- to 8-year-olds in 2008 (MCS) (95% CI) | Percentage of 10- to 11-year-olds in 2007–10 (NCMP) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight | 23.3 (22.4 to 24.1) | 17.7 (16.8 to 18.7) | 25.4 (25.4 to 25.5) |

| Obese | 10.7 (10.1 to 11.4) | 8.0 (7.3 to 8.8) | 11.7 (11.7 to 11.8) |

Table 5 shows the population estimates by the age range of the comparator surveys. Across the entire age range of the MEND 7–13 programme (6- to 13-year-olds), 4.4 million children would have been eligible for the programme and just under half (2.0 million) of those eligible would have been obese.

| MEND-eligible population size | Number of 6- to 13-year-olds in 2007–10 (HSE) | Number of 6- to 8-year-olds in 2008 (MCS) | Number of 10- to 11-year-olds in 2007–10 (NCMP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All children | 18,804,500a | 567,000b | N/Ac |

| MEND-eligible: overweight | 4,372,080 | 100,566 | 379,756 |

| MEND-eligible: obese | 2,020,648 | 45,466 | 175,375 |

Of the 21,132 children who self-referred or were referred to MEND, 18,289 had complete age, sex and postcode data. These children constituted 0.42% of the MEND-eligible population (Table 6). A total of 13,998 started a MEND programme, constituting 0.32% of the MEND-eligible population; the 8311 who completed the programme constituted 0.19%. The percentages of those who were referred, started and completed were higher for 6- to 8-year-olds. The percentages who were referred, started and completed were estimated to be higher for 10- to 11-year-olds (Year 6 children), reflecting the high percentage of MEND 7–13 children in that age range (mean age of MEND children at baseline was 10.7 years). Percentages reduced from referral through starters and completers in the same way for the age ranges 6–13, 6–8 and 10–11 years.

| MEND 7–13 (n) | Percentage of MEND-eligible populationa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of 6- to 13-year-olds in 2007–10 (HSE) | Number of 6- to 8-year-olds in 2008 (MCS) | Number of 10- to 11-year-oldsb in 2007–10 (NCMP) | Percentage of 6- to 13-year-olds in 2007–10 (HSE) | Percentage of 6- to 8-year-olds in 2008 (MCS) | Percentage of 10- to 11-year-oldsb in 2007–10 (NCMP) | |

| Overweight | ||||||

| Referrals | 18,289 | 983 | 6004 | 0.42 | 0.97 | 1.58 |

| Starters | 13,998 | 919 | 4615 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 1.22 |

| Completersc | 8311 | 571 | 2711 | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| Obesed | ||||||

| Starters | 11,796 | 825 | 3795 | 0.58 | 1.81 | 2.17 |

| Completersc | 7024 | 508 | 2236 | 0.35 | 1.12 | 1.27 |

The percentages of obese children referred to the programme could not be calculated because anthropometry was not measured until participants started the programme. The percentages of obese children who started and completed MEND 7–13 were higher than when overweight (including obese) children were considered (see Table 6). Starters aged 6–13 years who were obese accounted for 0.58% and completers accounted for 0.35% of the MEND-eligible population who were obese.

Differences between the sociodemographic characteristics of MEND 7–13 participants and those of the MEND-eligible population

We investigated how MEND referrals, starters and completers compared with the MEND-eligible population. Characteristics of all data sets compared in the analyses are available for reference (see Tables 28 and 29). Differences between the MEND referrals and children in the MEND-eligible population are reported only in the text (only sex- and area-level data were available for referrals) and, for starters and completers, sociodemographic differences and the p-values of these differences are reported in Table 7. A negative value for the difference in the proportions indicates that proportionally fewer children of that group were in the MEND participant subsample than might be expected given the proportion of children in that group in the comparator data set (and, by extension, in the MEND-eligible population). Figure 3 presents graphs showing the distribution of MEND subsets and comparator data sets by deciles of deprivation. The results are discussed below.

| Variables | Section A: starters (attended at least one session) | Section B: completers (attended > 75% of sessions) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEND 7–13 vs. comparator | MEND 7–13 vs. comparator | |||||

| HSE difference in percentages (p) | MCS difference in percentages (p) | NCMP difference in percentages (p) | HSE difference in percentages (p) | MCS difference in percentages (p) | NCMP difference in percentages (p) | |

| Adiposity | ||||||

| Overweight excl. obese | –38.1 (< 0.001) | –40.0 (< 0.001) | –36.0 (< 0.001) | –38.0 (< 0.001) | –39.8 (< 0.001) | –36.3 (< 0.001) |

| Obese | +38.1 (< 0.001) | +40.0 (< 0.001) | +36.0 (< 0.001) | +38.0 (0.000) | +39.8 (< 0.001) | +36.3 (< 0.001) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Boy | –7.1 (< 0.001) | –11.2 (< 0.001) | –8.0 (< 0.001) | –9.6 (< 0.001) | –14.4 (< 0.001) | –10.3 (< 0.001) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | –2.3 (0.014) | –5.9 (< 0.001) | +2.3 (0.004) | –1.1 (ns) | –4.0 (0.007) | +3.6 (0.001) |

| Asian | +3.0 (< 0.001) | +7.3 (< 0.001) | +4.8 (< 0.001) | +2.4 (0.003) | +5.9 (< 0.001) | +4.1 (< 0.001) |

| Black | +0.2 (ns) | +0.3 (ns) | –4.6 (< 0.001) | –0.2 (ns) | –0.7 (ns) | –5.1 (< 0.001) |

| Other | –0.9 (0.025) | –1.7 (0.022) | –2.6 (< 0.001) | –1.1 (0.016) | –1.2 (0.100) | –2.8 (< 0.001) |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Lone parent | +4.0 (0.020) | +6.1 (0.002) | – | +1.0 (ns) | +3.3 (ns) | – |

| Housing tenure | ||||||

| Owned | –10.1 (< 0.001) | –12.6 (< 0.001) | – | –5.3 (< 0.001) | –6.7 (0.001) | – |

| Social | +6.7 (< 0.001) | +5.1 (0.007) | – | +2.7 (0.009) | +1.1 (ns) | – |

| Private | +3.4 (< 0.001) | +7.5 (< 0.001) | – | +2.6 (0.001) | +5.7 (< 0.001) | – |

| Employment status of primary earner | ||||||

| Unemployed | +5.5 (< 0.001) | +7.9 (< 0.001) | – | +2.2 (0.039) | +4.4 (0.012) | – |

| Urban/rural | ||||||

| Urban | +6.9 (< 0.001) | +5.4 (< 0.001) | +4.4 (< 0.001) | +6.0 (< 0.001) | +4.4 (< 0.001) | +3.1 (< 0.001) |

| Suburban | –2.5 (< 0.001) | –1.4 (ns) | –1.2 (0.003) | –1.9 (0.001) | –1.2 (ns) | –0.5 (ns) |

| Rural | –4.5 (< 0.001) | –4.0 (< 0.001) | –3.3 (< 0.001) | –4.1 (< 0.001) | –3.2 (< 0.001) | –2.8 (0.000) |

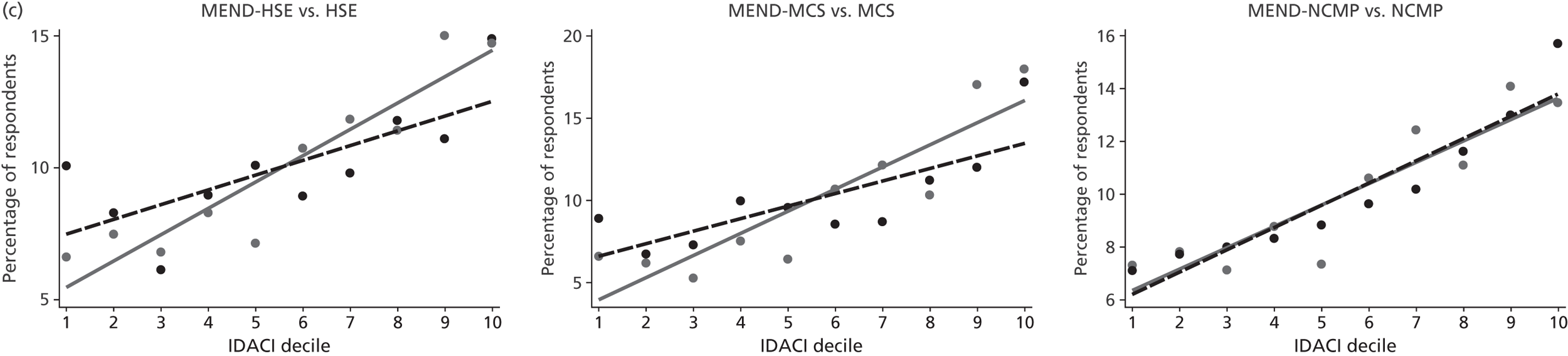

FIGURE 3.

Percentages of MEND participants and comparator respondents by decile of IDACI 2007, where decile 10 is the most deprived. The dashed black line is the socioeconomic gradient, estimated by linear regression of the MEND-eligible population (represented by HSE, MCS and NCMP). The solid grey line is the socioeconomic gradient of the MEND participants (MEND-HSE, MEND-MCS and MEND-NCMP respectively). Black and grey spots are comparator- and MEND-observed proportions respectively. (a) Social gradient by IDACI decile of MEND referrals vs. comparators; (b) social gradient by IDACI decile of MEND starters vs. comparators; and (c) social gradient by IDACI decile of MEND completers (> 75% of sessions attended) vs. comparators.

Who was referred to MEND?

Results for all three comparisons (MEND-HSE referrals vs. HSE, MEND-MCS referrals vs. MCS and MEND-NCMP referrals vs. NCMP) were broadly consistent. Fewer boys [−6.3% (p < 0.001) in HSE vs. MEND-HSE, −10.7% (p < 0.001) in MCS vs. MEND-MCS and −7.0% (p < 0.001) in NCMP vs. MEND-NCMP] were referred to MEND relative to the MEND-eligible population. Conversely, more girls were referred than might be expected.

More urban children [+7.1% (p < 0.001) in HSE vs. MEND-HSE, +5.0% (p < 0.001) in MCS vs. MEND-MCS and +4.4% (p < 0.001) in NCMP vs. MEND-NCMP] were referred to MEND relative to the MEND-eligible population. Conversely, children living in suburban and rural locations were less likely to be referred to MEND.

There was a steeper social gradient by IDACI 2007 decile in those referred to MEND 7–13 than in the MEND-eligible population (see Figure 3a). Broadly speaking, this means that proportionally more children were referred to MEND 7–13 from the most deprived areas than might be expected given the proportions of MEND-eligible children in those areas. These differences in gradients were statistically significant for those aged 6–13 years (HSE data) and 6–8 years (MCS data) but not for the Year 6 children (NCMP data). See the regression models in Appendix 7 (Table 33) for model coefficients.

Who started on MEND?

MEND starters were more likely to be obese than those in the MEND-eligible population. Specifically, 84% (95% CI 83.7 to 84.9%) of children aged 6–13 years who started MEND in MEND-HSE exceeded the 98th centile of the UK 1990 growth charts,14 whereas the comparable figure from the HSE was 46%.

Sociodemographically, in line with the analysis of those who were referred to MEND, there were lower proportions of boys in each of the MEND starter subsets than in the MEND-eligible population (see section A of Table 7). There were proportionally more MEND starters from Asian groups than in the MEND-eligible population (but not from black groups, where differences were non-significant), and proportionally fewer from white and other ethnic groups.

Proportionally more MEND starters than children in the MEND-eligible population lived with a lone parent (see section A of Table 7). The pattern was similar for housing tenure, where higher proportions of MEND starters lived in social or private rented housing; and also for parental employment, with higher proportions of MEND starters living in households where the primary earner was unemployed.

The results show that compared with the MEND-eligible population, MEND starters were more likely to live in urban neighbourhoods and less likely to live in rural and suburban neighbourhoods (although the suburban difference was non-significant for the MCS vs. MEND-MCS comparison).

As with referrals, there was a steeper social gradient by small-area deprivation among those who started MEND than in the MEND-eligible population (see Figure 3b). Proportionally more children from the most deprived areas started MEND than might be expected given the proportions of MEND-eligible children in those areas. These differences in gradients were statistically significant for those aged 6–13 years (HSE data) and 6–8 years (MCS data) but not for the Year 6 children (NCMP data). See the regression models in Appendix 7 (Table 33) for model coefficients.

Who completed MEND?

The sociodemographic distribution of the children who completed the MEND programme was, when compared with the MEND-eligible population, similar to that of MEND referrals and starters in terms of direction (see sections A and B in Table 7 and Who was referred to MEND?). That is, there were proportionally more girls and Asian children in the completers sample than in the MEND-eligible population, and proportionally fewer white children (although the HSE vs. MEND-HSE comparison was non-significant). There were proportionally fewer MEND completers than MEND-eligible children living in owner-occupied and proportionally more living in private rented housing. However, although proportionally more MEND completers lived with lone parents, with a parent who was unemployed or in rented accommodation, these differences were not statistically significant. As with the referrals and starters comparisons, MEND 7–13 completers were more likely to live in urban areas.

There were differences in the results between completers and starters in terms of the size and statistical significance of the results. The difference between the MEND-eligible population and MEND subsamples was greater for boys and girls when the completers findings were compared with the starters. The size of the differences was also smaller for the SEC in completers compared with starters.

Proportionally more MEND completers came from the most deprived areas than might be expected given the proportions of MEND-eligible children in those areas (see Figure 3c). These differences in gradients were statistically significant for those aged 6–13 years (HSE data) and 6–8 years (MCS data) but not for the Year 6 children (NCMP data). See the regression models in Appendix 7 (Table 33) for model coefficients.

Sensitivity analyses

The analyses described above were conducted for all MEND 7–13 referrals, starters and completers who were overweight. However, the majority of MEND participants were obese. To test whether the distribution of MEND 7–13 was steeper by IDACI 2007 decile because of the differential adiposity of the MEND 7–13 and comparator samples, we repeated analyses for obese children only (see Appendix 6, Table 30) and overweight children excluding those who were obese (see Appendix 6, Table 31). Results were very similar.

Some variables in the service data were only partially observed, so that the complete case data set was significantly smaller than the number of participants in MEND. Basing the analysis on this would have reduced the power to detect genuine variations in the outcome, and could have introduced bias. We addressed this limitation using multilevel multiple imputation, which relies on the assumption that the data were MAR. By making comparisons based on imputed data we were able to maximise power and minimise bias. While the MAR assumption could not be directly tested, we ran sensitivity analyses of the final multivariable models with complete case data (as recommended for this type of analysis50). Results were similar between the complete case and the multiple imputation models (see Appendix 6, Table 32), implying that bias introduced by missingness due to MAR was minimal. However, the multiple imputation findings are presented because the variation in the sample is more accurately estimated by these models. Sensitivity analyses suggested that the sociodemographic characteristics of the MEND starters and completers did not vary systematically by year of participation (data not reported).

Determinants of completion of MEND 7–13

The relative risk of completion (recorded as attending > 75% of sessions) varied by sociodemographic, neighbourhood and programme-level characteristics (Table 8). The second column of Table 8 presents the results from models of the unadjusted relative risks of completion. Covariates which were significantly associated with the relative risk of completing from these univariable models were carried forward to a multivariable model (presented in the final column). The unadjusted results show that SDQ score at baseline, sex, family structure, housing tenure, employment status of the primary earner, IDACI 2007 decile, programme group size and the number of previous programmes per programme manager were associated with the relative risk of completing. Conversely, BMI at baseline, age, ethnicity and urban/rural status were not. These variables were not carried forward to the multivariable model.

| Parameters | Single variable models uRR (95% CI) |

Multivariable model aRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | – | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.95)** |

| BMI at baseline (ref. 91st–95th centile) | ||

| 95–98th centile | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.14) | – |

| > 98th centile | 1.00 (0.92 to 1.10) | – |

| SDQ score at baseline (ref. ‘normal’) | ||

| ‘Borderline’ | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.02) | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.04) |

| ‘Abnormal’ | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.93)*** | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.97)** |

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.00) | |

| Sex (ref. girls) | ||

| Boys | 0.90 (0.86 to 0.95)*** | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.96\)*** |

| Ethnicity (ref. white) | ||

| Asian | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.00) | – |

| Black | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) | – |

| Other | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.08) | – |

| Family structure (ref. couples) | ||

| Lone parents | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.92)*** | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98)* |

| Housing tenure (ref. owner-occupied) | ||

| Social rented | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.85)*** | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95)*** |

| Private rented | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.92)*** | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.97)** |

| Employment status of primary earner (ref. employed) | ||

| Unemployed | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.89)*** | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.98)* |

| IDACI 2007 deciles [ref. decile 1 (least deprived)] | ||

| 2 | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.14) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) |

| 3 | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.09) | 0.99 (0.88 to 1.12) |

| 4 | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.08) | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.11) |

| 5 | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.04) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.08) |

| 6 | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97)* | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.03) |

| 7 | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.97)* | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.04) |

| 8 | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.95)** | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.05) |

| 9 | 0.81 (0.73 to 0.91)*** | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.02) |

| 10 (most deprived) | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.83)*** | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.96)** |

| Urban/rural status (ref. urban) | ||

| Suburban | 1.09 (1.00 to 1.20) | – |

| Rural | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.22) | – |

| Programme group size (ref. one to five participants) | ||

| Six to nine participants | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.01) | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.01) |

| ≥ 10 participants | 0.83 (0.76 to 0.90)*** | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.91)*** |

| Number of programmes per manager (ref. < 10) | ||

| ≥ 10 | 0.91 (0.85 to 0.98)* | 0.93 (0.86 to 0.99)* |

The multivariable model showed that, on average, children with higher than expected symptoms of psychological distress (‘abnormal’) at baseline were less likely to complete than those with ‘normal’ symptoms (see adjusted relative risk ratios in Table 8). Boys were less likely to complete the programme than girls.

All four markers of SEC were independently associated with completion (see the final column of Table 8). Children living with a lone parent were less likely to complete compared with those living with two parents. Children living in social or private rented housing were less likely to complete than those living in owner-occupied housing. Children living in households where the primary earner was unemployed were less likely to complete than those in households where the primary earner was employed. Finally, children living in the most deprived neighbourhoods were less likely to complete the programme.

Families who started MEND 7–13 programmes in groups with > 10 people were less likely to complete than those who started in groups of one to five children. However, there was no statistical difference in completion between those in groups of six to nine children and those in groups of one to five children. Children attending programmes where managers had run ≥ 10 previous programmes were less likely to complete than those where managers had run < 10 programmes.

As noted previously (see MEND 7–13 service-level data), there is no agreed definition of a completer. 56 We tested relationships between completion and covariates using a lower threshold of attendance at 60% of sessions to define completion (see Appendix 8 for results). The direction and statistical significance of relationships were similar.

Discussion

Percentage of the MEND-eligible population referred to, starting and completing MEND 7–13

Our analysis shows that only a small percentage of the MEND-eligible population were referred to, started and completed MEND 7–13 programmes. As MEND 7–13 has been reported as the largest intervention of its type in England in a recent mapping study of such schemes,57 this serves to illustrate the challenge for scaling up family-based lifestyle interventions to the population level.

Those who started and completed the programme were more likely to be obese compared with the MEND-eligible population, indicative perhaps that children and families principally self-refer or are referred when levels of adiposity are perceived by families or professionals as already particularly high. The percentage of MEND-eligible children referred to the scheme was slightly higher for 10- to 11-year-olds, which might reflect the role of the NCMP as a health promotion intervention which raises awareness of childhood overweight.

Differences between sociodemographic characteristics of MEND 7–13 participants and those of the MEND-eligible population

Our results showed that in comparison with the MEND-eligible population, proportionally more children who started or completed MEND lived in less favourable SEC (indicated by employment status of the primary earner, family structure and housing tenure). Relative to the MEND-eligible population, proportionally more of those who started or completed a MEND 7–13 programme were girls, Asian and urban-dwelling, and proportionally fewer were of white or other ethnicities. Finally, relative to the MEND-eligible population, proportionally more MEND 7–13 starters and completers were obese, rather than overweight but not obese.

We also found that there were socioeconomic gradients in referral to, starting or completing MEND 7–13 at the neighbourhood level. In the MEND-HSE and MEND-MCS comparisons, the proportions of MEND 7–13 participants were higher for those living in the most deprived areas relative to the MEND-eligible population. In the MEND-NCMP comparison, proportions of MEND 7–13 participants by deprivation were similar to the proportions in the MEND-eligible population. In none of the comparisons was provision of MEND 7–13 in the most deprived neighbourhoods less than expected. This is an interesting finding as it suggests that referral to MEND 7–13 was equitable, in the sense that children from more deprived communities were more likely to be referred or to self-refer to the scheme than those living in more advantaged circumstances.

Finally, MEND children were more likely to live in urban areas and less likely to live in suburban and rural areas than children in the MEND-eligible population. This applied to those who were referred to MEND and also to starters and completers.

Many of the differences between the MEND-eligible population and the MEND referrals, starters and completers were statistically significant but not large in magnitude. Therefore, we conclude that the provision and/or uptake of MEND 7–13 did not appear to compromise and, if anything, promoted participation of those from more disadvantaged circumstances and from ethnic minority groups. This suggests that participation in MEND 7–13, when it was implemented at scale across England, had the potential to make a contribution to tackling health inequalities.

The reasons for the differences between the MEND-eligible population and MEND referrals, starters and completers might be owing to factors related to the differential supply of the service (programmes may be more likely to be commissioned in deprived localities) and/or the differential uptake of the service (families in more disadvantaged SEC may be more likely to take up the programme). We were not able to examine these factors.

Determinants of completion of MEND 7–13

Completers differed from starters. Completers were less likely to be psychologically distressed at baseline than starters. This is consistent with the findings of previous work. 58 Specifically, girls were more likely to complete than boys. This finding was inconsistent with the results of previous research,59 which found no sex difference in dropout rates (dropout rather than completion was measured in previous work). Completion of MEND 7–13 was not associated with ethnicity in unadjusted models. This was in contrast to previous research suggesting that children from BME groups were more likely to drop out of paediatric weight management programmes. 58,59 The difference in findings might reflect the fact that the previous studies were based in different countries (the Netherlands59 and the USA58) with different ethnic, cultural and other contexts.