Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3010/06. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in June 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Peter Donnan has received research grants in the past from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Otsuka and Amgen Inc. He is also a member of the New Drugs Committee of the Scottish Medicines Consortium. Dr Adrian Brady has received research grants from Merck, Servier, AstraZeneca and Bayer, has provided consultancy to Merck USA and Bayer Germany, and been awarded lecture fees and/or honoraria from Merck, Servier, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer and Bayer. Eleanor Grieve has received unrestricted research funds from Cambridge Weight Plan.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language which may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Wyke et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The problem of obesity and male obesity

Rising levels of obesity are a major challenge to public health. There are expected to be 11 million more obese adults in the UK by 2030, accruing up to 668,000 additional cases of diabetes mellitus, 461,000 cases of heart disease and stroke, 130,000 cases of cancer, and up to 6.3 million lost quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), with associated medical costs set to increase by £1.9–2.0B per year by 2030. 1

In Scotland, more men (69%) than women (60%) are overweight or obese,2 and the UK prevalence of male obesity is among the highest in Europe1 and forecast to increase at a faster rate than female obesity in the next 40 years. It is likely that the link between obesity and socioeconomic deprivation, already evident in women, will soon appear in men. 2 Compared with women, men may be more vulnerable to adverse health consequences of obesity. At all ages, men are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus at lower body mass index (BMI) than women3 and adult men are more insulin resistant than women, a finding that is associated with difference in fat distribution. 4

Men, existing weight loss programmes and the potential of sporting organisations

Although 5–10% weight loss can produce significant health benefits,5 men are under-represented in trials of weight loss interventions (only 27% of participants are men),6 in referrals to commercial weight management programmes (between 11%7 and 13%8 of men) and in NHS weight management services (23% of men). 9 As a recent systematic review of approaches to the management of obesity in men concludes: ‘That men are under-represented suggests that methods to engage men in services, and the services themselves, are currently not optimal’. 10

Men’s reluctance to enrol in weight management programmes in part reflects a failure to recognise gender differences in societal processes that contribute to becoming overweight or obese. For example, greater body size is often associated with masculinity,11 leading some men to be concerned about being too thin and less likely to diet than women. 12–14 Indeed, men often view dieting as ‘feminine’15 and are more likely to use exercise to control their weight. 13 In addition, men tend to have poorer nutrition knowledge than women, to be resistant to healthy eating campaigns16 and to be less aware of links between diet and ill health. 13,17 Alcohol may pose an additional problem for weight management for men;18,19 Scottish men drink around twice as much as Scottish women. 20 However, evidence suggests that when gender issues are used to inform programme design, men will engage with appropriately gender-sensitised weight management interventions and lose weight. 10,21

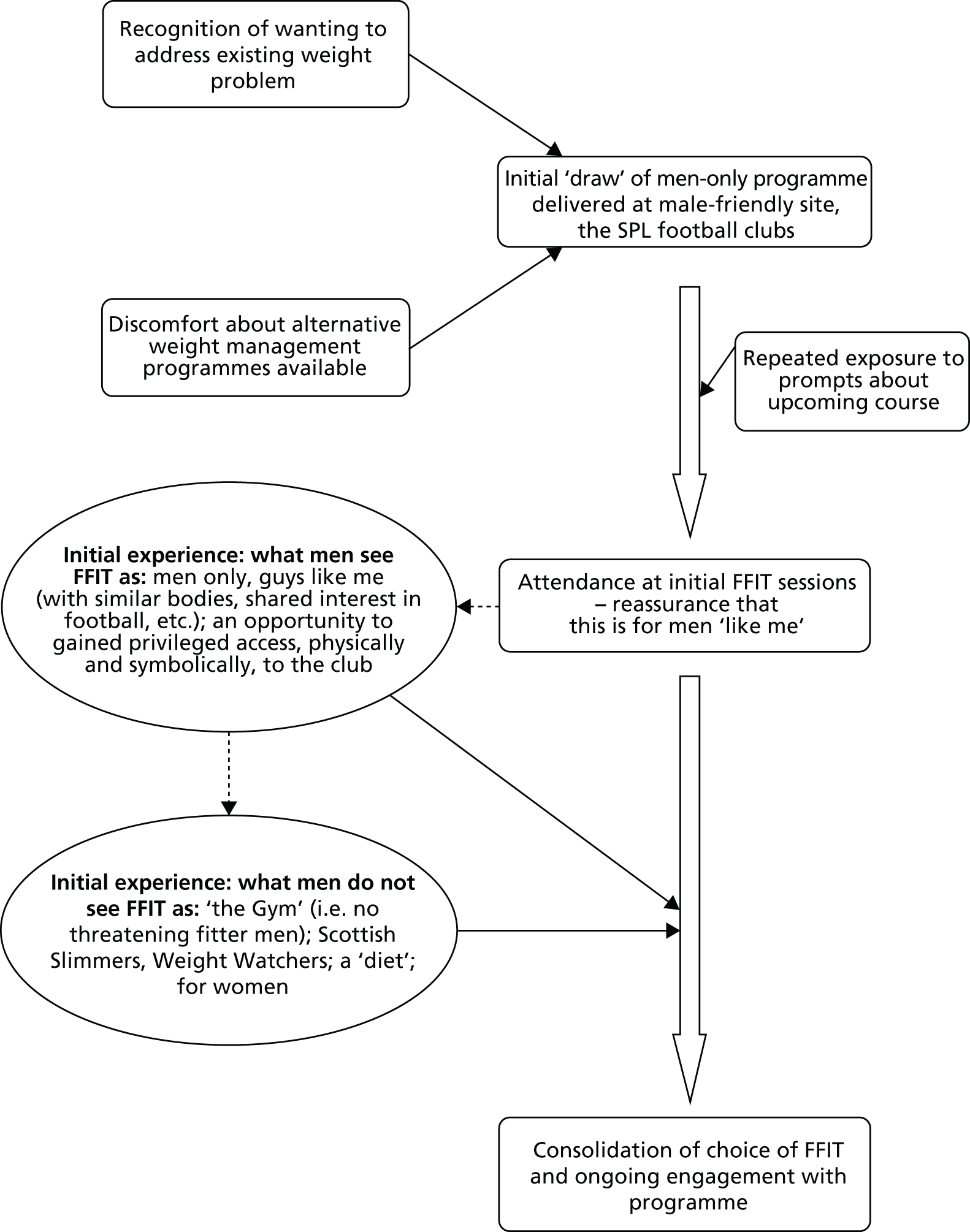

Another reason men may not enrol on weight loss programmes is the setting in which they are delivered. There is a common perception that commercial slimming groups are mainly for women. 22 However, recently the potential of professional sporting organisations to reduce health inequalities by providing access to hard-to-reach populations, including men, has been recognised. 23,24 Although some research has demonstrated the potential of professional sports clubs, particularly football clubs,24–26 to engage men in lifestyle changes, there have been no published controlled studies. 10,26

The Football Fans in Training (FFIT) intervention uses the traditionally male environment of football clubs,27 existing loyalty to football teams and the opportunity to participate in men-only groups to maximise men’s engagement with an evidence-based, gender-sensitised weight management programme. 28 FFIT is delivered under the auspices of the Scottish Premier League (SPL) Trust [which became the Scottish Professional Football League (SPFL) Trust in June 2013]. 29 During the 2011–12 season, nearly 2 million fans passed through SPL club turnstiles. 30

The FFIT is delivered in 12 weekly sessions at club stadia by community coaches trained in diet, nutrition, physical activity and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to a standard delivery protocol. This intensive weight loss phase is followed by a 9-month minimal contact weight maintenance phase including periodic post programme e-mail prompts and one face-to-face reunion session at the club. The programme’s development is described in Gray et al. 28 and its components are detailed in Chapter 2, Interventions.

Rationale for current study

Project team members have collaborated with the SPL Trust (now the SPFL Trust) to design, implement and evaluate FFIT since June 2009. This partnership has complemented the Trust’s remit to increase Scottish professional football clubs’ community engagement and this is wholly supported by premier league clubs. 29 We developed the evidence-based programme,28 conducted an initial evaluation of the delivery of the pedometer-based walking programme to ensure that it was appropriate for men31 and conducted a feasibility study funded by the Chief Scientist Office (CSO) (CZG/2/504). 32 The feasibility study was conducted in one small and one large club in 2010/11 and demonstrated that men could be recruited to a randomised trial in this context, FFIT was successful in recruiting the target group (mean BMI 34.5 kg/m2 ± 5.0 kg/m2), retention through the trial was good (> 80% at 12 weeks and 6 months; > 75% at 12 months) and men would be likely to engage with the programme (76% attended at least 80% of available programme delivery sessions, and qualitative data examined their enthusiasm for the programme and the context). 31,32 We also found that the programme was likely to be successful; by 12 weeks, the intervention group had lost significantly more weight than the comparison group (4.6% vs. –0.6%; p < 0.001) and many maintained this to 12 months (intervention group baseline 12 month weight loss: 3.5%; p < 0.001). 32

These results supported the decision to conduct the full randomised controlled trial (RCT) reported here.

Note: previous publication of some of the results

Some of the methods and results presented in this report have been previously reported. The design, methods and main results of the RCT were published in The Lancet. 33 The ‘draw’ of the football club setting to attract men to weight management who were at high risk of ill health and who would not otherwise have attended a weight management programme was published in BMC Public Health. 34

Chapter 2 Methods

Setting

A total of 13 professional football clubs in Scotland, including the 12 football clubs constituting the SPL in the 2011–12 football season, and the club relegated to Division 1 at the end of the 2010–11 football season participated in the study.

Overview of study design

We undertook a two-arm, pragmatic, RCT to evaluate delivery of the FFIT programme in 13 Scottish professional football clubs in 2011–12. Men were randomised to intervention or comparator in a 1 : 1 ratio, stratified by club.

Randomisation of individuals within clubs (rather than randomisation of clubs) was chosen for two reasons. First, individual randomisation is more efficient unless contamination is a major risk35 and, second, the SPL Trust was required to deliver the programme in all clubs at the same time.

Assessment of the primary outcome (mean difference in weight loss between groups at 12 months) was blinded.

A summary of the protocol is available at www.thelancet.com/protocol-reviews/11PRT8506. 36

Recruitment strategies and contact with men

At the time of the trial, funding from the Scottish Government and The Football Pools had been secured for three deliveries of the FFIT programme (August to December 2011, February to April 2012 and August to December 2012) in 13 clubs, and the funders required the SPL Trust to provide two deliveries of FFIT in the 2011–12 season. We needed to recruit sufficient men to fill all available places in the three deliveries because the trial design compares men randomly allocated to the FFIT programme in September 2011 with those randomly allocated to a waiting list comparison group starting the FFIT programme 12 months later and we needed to ensure that comparison group participants could not ‘leak’ into vacancies on the non-trial delivery programme. This meant that our recruitment target was inflated from 720 to 1080 (see Sample size for the calculation).

Formal recruitment commenced on 2 June 2011 and continued until the week before the baseline measurements in each club, which took place between 11 August 2011 and 20 September 2011. Participants randomly allocated to the delivery in August to December 2011 formed the intervention group and those randomly allocated to the August to December 2012 delivery formed the waiting list comparison group and undertook the programme after the 12-month trial outcomes had been completed. Those allocated to the February to April 2012 delivery did not participate in the trial.

Our multifaceted recruitment strategy was informed by the feasibility study, which suggested that club-based strategies were likely to be most effective and that men may need multiple prompts before signing up. 32 Box 1 lists the various strategies we adopted to recruit the numbers needed over a very limited time period. Club-based recruitment included advertisements on SPL, club and fans websites, in-stadia advertising (poster/flyers with endorsement from club personalities), active involvement of local supporters’ organisations, advertisements in the club and Scottish Football Association e-newsletters. We also employed fieldworkers to approach potentially eligible men on match days to ask if they would like to register an interest in FFIT. Between 16 July and 17 September 2011, our recruitment staff attended 25 pre-season ‘friendlies’, early-season home games and club open days.

Posters/flyers with endorsement from club personalities; end of season home match advertising (except at Hibernian); active involvement of local supporters’ organisations (Kilmarnock, Motherwell, Hibernian, Hamilton and Aberdeen).

Online publicity including SPL website, club websites, fan websites, some club e-newsletters.

Publicity in media NewspapersLocal papers: Evening Telegraph, 3 May 2011; The Courier, 6 May 2011; Evening Times, 31 May 2011; Paisley Daily Express, 18 May 2011; and The Inverness Courier, 9 September 2011.

National papers: The Sunday Times, 17 April 2011; Daily Record, 13 June 2011; Sunday Post, 10 July 2011; Metro, 11 July 2011; and Daily Record, 11 July 2011.

TV and radio coverageBBC Radio Scotland: John Beattie show, lunchtime, 2 May 2011; Call Kay, morning, 17 June 2011; ‘On the Ball’, 18 June 2011; FFIT documentary, 18 June 2011 and 9 July 2011; STV: The Hour, teatime 17 May 2011.

Workplace advertisingLocal councils: Perth and Kinross, Glasgow City, North, South and East Ayrshire, North Lanarkshire and Highland.

Other employers: Glasgow Benefits Office, Wiseman’s dairies, HBOS, Clydesdale Bank, Scottish Qualifications Authority, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education, Thomas Cook, Mahle (Kilmarnock), Aviva, BP, Longannet Power Station, Dell Scotland, HP Scotland, Microsoft Scotland, Oracle, Scottish Business in the Community, Scottish Enterprise, all companies at City Park in Glasgow, Morris and Spottiswood and Adecco (Scotland).

OtherFFIT Facebook® (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) page, FFIT website (www.spl-ffit.co.uk), FFIT participant online diary February to June.

BBC, British Broadcasting Corporation; BP, British Petroleum; HBOS, Halifax Bank of Scotland; HP, Hewlett Packard; STV, Scottish Television.

We made a concerted effort to achieve media coverage. We were successful in attracting articles in local and national newspapers (see Box 1), a video blog filmed by a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Scotland sports presenter who took part in one of the pilot deliveries of FFIT, a 1-hour-long documentary on BBC Radio Scotland and interviews with members of the research team and participants in the pilot FFIT programme on Radio Scotland and Scottish Television. As part of our recruitment drive, we ran a five-a-side tournament for ‘graduates’ of the pilot FFIT programme on 18 June 2011 at St Mirren’s home stadium, which formed an excellent focus for some of this publicity. We invited the BBC to contribute a team (made up of sports presenters and three former Scottish international football players) to participate and this event was the focus of live coverage on BBC Radio Scotland’s ‘On the Ball’ football programme. It is possible that articles and events attracted other media coverage that we were not aware of during the recruitment period.

Other strategies included e-mails to staff through local employers (see Box 1) and word of mouth. Men who took part in the pilot FFIT programme told their family, friends and work colleagues about the programme and some also put up leaflets in their workplaces. An incentive (a £50 football club shop voucher) was offered to the FFIT graduate who generated the highest enrolment rate of eligible men in the FFIT study.

All publicity invited men to contact the research team by short message service (SMS) text, e-mail or telephone to register their interest in the study by providing their contact details and self-reported weight, height, trouser waist size and date of birth. They were also asked where they heard about the study. Men who gave their name to recruitment staff on match days were subsequently telephoned by the research team to confirm their interest in the study and to collect full contact and self-report information. All men whose self-reported BMI (calculated from self-reported weight and height) and age suggested they were eligible for the study were invited to participating club stadia for formal eligibility assessment.

Participants

Men were eligible if they:

-

were aged 35–65 years in 2011/12

-

had an objectively measured BMI of at least 28 kg/m2

-

completed the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q)37

-

consented to randomisation and

-

consented to weight, height and waist measurements (this was a requirement for taking part in the FFIT programme imposed by Scottish Government, irrespective of the trial).

The age limits reflect recognition that overweight and obese men in their mid-to-late thirties may experience an attitudinal shift towards their health and weight,38 and focusing on men in the middle years can maximise the potential effectiveness of lifestyle interventions. 39 The older age limit reflects opinions that for those over the age of 65 years, physical activity programmes may be more effective when targeted specifically.

The decision to include only men with a BMI of at least 28 kg/m2 was made for three reasons. First, we had previously reported the power for men of being told that they were ‘obese’ as a motivator for them to want to lose weight40 and that those labelled ‘overweight’ were more likely to challenge the validity of BMI categories. 41 We thought that ‘approaching obese’ would be similarly motivational. Second, men with a BMI of at least 28 kg/m2 would also be more likely to benefit from weight loss. Third, in our feasibility study we had found that men liked being with others with similar weight loss goals. 28

The PAR-Q is a self-screening tool to help identify those who should seek medical advice prior undertaking exercise. If any of the men had answered ‘yes’ to any of the seven questions, fieldwork staff were instructed to recommend that men consulted their general practitioner (GP) prior to commencing the FFIT programme. Although answering ‘no’ to all questions was not an inclusion criterion for FFIT, with participants’ permission, copies of the PAR-Q forms were given to the community coaches so that they could check whether or not men had any pre-existing medical conditions and help the men exercise appropriately.

Because of the SPL Trust’s whole-hearted commitment to collaborating in a rigorous evaluation of FFIT, it was not possible for eligible men to access the FFIT programme unless they agreed to be randomly allocated to any one of the three programmes starting in September 2011, February 2012 or September 2012.

The SPL Trust also required participants to consent to weight, height and waist measurements, but men were free to opt out of additional measures/procedures relating to the trial’s secondary and process outcomes. Men were excluded if they had participated in FFIT previously.

If men’s blood pressure, as measured at baseline, contraindicated vigorous exercise (systolic ≥ 160 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 100 mmHg), they were initially able to take part in the classroom sessions only and the incremental, pedometer-based walking programme; they were advised that they would be able to take part in more intense in-stadia training once they had provided coaches with evidence of a reduction in their blood pressure.

Interventions

All men measured at baseline were informed of their weight and BMI, given a British Heart Foundation booklet, So You Want to Lose Weight?, which offered detailed advice on weight management,42 were advised to see their GP if baseline readings for blood pressure exceeded pre-specified levels, and met the coaches, who talked broadly about the FFIT programme and gave information of the timing of the programme at their club.

The FFIT programme was developed and optimised during our feasibility study and the content of the programme is described in detail elsewhere. 28 The programme adheres strictly to national guidance for weight management programmes. 5,43 The behavioural aspects of the programme were not based on any single theory of behaviour because, as Michie et al. 44 suggest, single theories contain so many overlapping constructs that there is no good basis for deciding which would be appropriate. Here we briefly describe the way in which the programme was gender sensitised, its dietary and physical activity components, the evidence-based BCTs45 used, the format through which it was developed and the training delivered to coaches.

Gender sensitivity

The FFIT was designed to work with, rather than against, prevailing conceptions of masculinity28,31,34 and gender sensitised in relation to the context, content and style of delivery. 31 The traditionally male environment of football clubs and men-only groups led by club community coaches provided a masculinised context for the delivery of key messages.

The programme content was developed to be attractive to men. It provided information on weight loss presented simply (‘science but not rocket science’), included a separate session on alcohol reinforced by demonstration of the size of units and discussion of alcohol’s potential role in weight management, and provided men with a physical representation of the amount of weight lost to date at week 7 for them to hold. In addition, materials ‘branded’ with club insignia were provided; for example, T-shirts in their club colours and with the FFIT logo were provided for men to wear when attending the programme and the programme notes were branded with club-specific insignia.

Finally, the style of delivery of the programme was participative, with coaches facilitating interactive learning through discussion of key points and encouraging camaraderie, ‘team bonding’ and ‘banter’ to facilitate discussion of sensitive subjects.

Dietary components

The dietary component of FFIT was designed to deliver a 600-kcal daily deficit (from estimated daily energy requirements)5,46 through the gradual adoption of more nutrient-dense foods and reduction of portion size, particularly of energy-dense foods, as well as the reduction of snacks, sugary and alcoholic drinks. Classroom activities were aimed at encouraging participants to make dietary changes that suited their individual circumstances and eating preferences, to weigh themselves each week and to keep a personal record of their weekly weight loss. Men were encouraged to make changes to their diet informed by the recommended balance of food groups indicated in the ‘Eatwell Plate’47,48 and make small, gradual and achievable changes to their normal diet. Key messages for dietary habits indicated in Cancer Research UK’s ‘ten top tips’49 were highlighted as the men moved towards a programme to maintain weight loss in the longer term.

Physical activity components

The FFIT had two physical activity components: an incremental pedometer-based walking programme shown to increase physical activity50,51 and pitch-side physical activity sessions led by club community coaching staff.

The men set individual daily brisk walking goals and recorded their progress each week in step count diaries provided in programme notes and reported back to the group during the weekly classroom sessions. Our feasibility work had shown that the walking programme was highly acceptable to men; participants described the pedometers as a very useful technology for motivation, self-monitoring and goal setting. In addition, the men reported finding they (re)gained fitness quickly through walking, which in turn enabled them to participate in other forms of physical activity that they also enjoyed (such as playing football). 31 As the programme progressed, they were encouraged to supplement walking with more vigorous activity (e.g. gym membership).

The pitch-side physical activity sessions taught men how to increase fitness through structured activities. Training was tailored to individual fitness levels and ability and included aerobic (e.g. walking, stair climbing, jogging), muscle strengthening (e.g. weight/circuit training) and flexibility (e.g. warm-up/cool-down activities) exercises. 52 Participants were taught to use the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale to ensure their activity was appropriate for their own fitness level and was performed at moderate intensity. The men were encouraged to consider how they could continue these activities in community settings using community resources, to continue to meet to train together post programme and to avoid compensatory behaviours (e.g. increased snacking or television viewing) that can undermine weight loss following physical activity. 53,54

Behaviour change techniques

Using the BCTs Taxonomy v1,45 37 specific BCTs are used in FFIT. 28 However, the programme draws most heavily on self-monitoring, implementation intentions, goal setting and review, and feedback on behaviour, all of which are associated with control theory55 and have been shown to be effective in physical activity and healthy eating interventions. 56–58 The programme also encourages social support, which has been shown to be effective in weight loss interventions57 and relapse prevention strategies. Further key techniques used in FFIT draw on other theoretical accounts of behaviour change (e.g. social cognitive theory and self-regulation)59 and include information on consequences, identification of barriers to change, verbal persuasion about capability, instruction in performing new behaviours, graded tasks to encourage increases in self-efficacy and social comparison.

Format of the programme

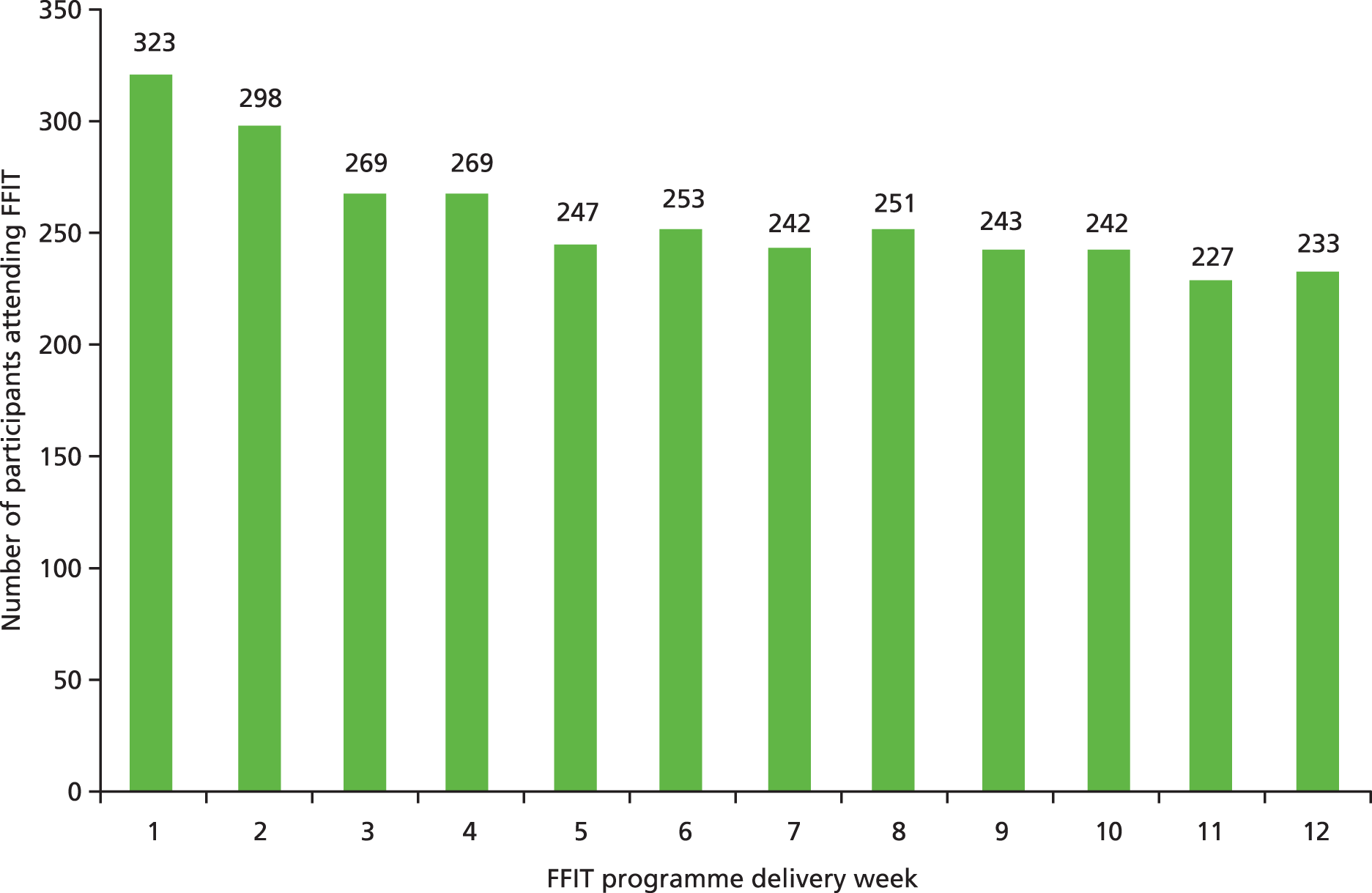

The FFIT was delivered free of charge by community coaching staff, employed by individual clubs and trained to standard protocols, to groups of up to 30 overweight/obese men (participant to coach ratio of 15 : 1) over 12 weekly sessions at the club’s home stadium. Each 90-minute session combined advice on healthy diet with physical activity. The balance of classroom and physical activity sessions changed over the 12 weeks; later weeks focused more on physical activity as men became fitter and the classroom element was shorter and focused on revision. 28 A club-branded information booklet (including tables to record self-monitored weight loss and step counts) was given to each participant.

Based on evidence from previous group-based physical activity programmes,60,61 we encouraged coaches to create a welcoming, supportive climate from the outset to encourage group cohesion. This included sharing some of their own experiences and allowing plenty of time for group interactions. Delivery notes reminded them which key tasks to deliver each week (summarised in Table 1). Nevertheless, the programme was cumulative in that each week built on what had been learnt in previous weeks and there was repeated practice of BCTs such as goal setting, self-monitoring and action planning with interactive problem-solving. Coaches were available at the end of each session if any man wanted to discuss issues individually.

| Session | Number of key tasks per session |

|---|---|

| Session 1. Getting started | |

| KT1. Introduce men to aim of programme ‘how to eat better, be more active and stay that way in the long term’ | 5 |

| KT2. Getting to know one another and sharing ideas and experiences | |

| KT3. Influences on choosing what to eat and control over food and eating | |

| KT4. Energy balance (intake vs. output) | |

| KT5. Food diary homework | |

| Session 2. What are we eating? | |

| KT6. Explanation of food groups and eating a healthy diet using Eatwell Plate (less fatty and sugary foods, more fruit and vegetables, whole-wheat bread and pasta and brown rice) | 3 |

| KT7. Food diaries compared with healthy eating recommendations and smaller portions | |

| KT8. SMART goal setting introduced | |

| Session 3. Making changes | |

| KT9. Review of SMART goals | 6 |

| KT10. Avoiding compensation | |

| KT11. Example of individualised healthy eating plans | |

| KT12. Health benefits associated with 5–10% long-term weight loss | |

| KT13. Personal weight loss targets | |

| KT14. Importance of support from others | |

| Session 4. Thinking about physical activity | |

| KT15. Review of SMART goals | 4 |

| KT16. Health benefits of physical activity | |

| KT17. Overcoming barriers to physical activity | |

| KT18. Local amenities for physical activity | |

| Session 5. Thinking about drinking | |

| KT19. SMART goal setting | 5 |

| KT20. Alcohol and weight gain | |

| KT21. Alcohol units | |

| KT22. Planning your drinking | |

| KT23. Cutting down on sugary drinks (fizzy and tea/coffee) | |

| Session 6. Halfway down | |

| KT24. Stages of change | 3 |

| KT25. Introduction to setbacks and strategies for dealing with them | |

| KT26. Measurements taken to review progress | |

| Session 7. How are we doing? | |

| KT27. Physical representation of individual weight loss to date (e.g. sandbag) | 3 |

| KT28. SMART goals and weight loss reviewed | |

| KT29. Reflection on how things are going so far | |

| Session 8. What to look out for | |

| KT30. Understanding food labels and choosing healthier foods | 2 |

| KT31. Importance of regular meals and breakfast | |

| Session 9. Practical stuff | |

| KT32. Making favourite meals healthier | 3 |

| KT33. Eating out sensibly | |

| KT34. Damage limitation for takeaways | |

| Session 10. Myths and moods | |

| KT35. Common ideas about healthy living | 3 |

| KT36. Triggers for setbacks and how to avoid them | |

| KT37. SMART goals reviewed | |

| Session 11. Making progress? | |

| KT38. Food diaries revisited | 3 |

| KT39. The energy balance and eating plans revisited | |

| KT40. Locus of control revisited | |

| Session 12. Looking forward | |

| KT41. Review of progress and next steps | 2 |

| KT42. Final measurements taken and recorded | |

| Total number of key tasks in the 12-week programme | 42 |

The 12-week active phase was followed by a ‘light-touch’, weight maintenance phase with six post-programme e-mail prompts over 9 months and a group reunion at the club 6 months after the end of the weekly sessions. E-mail prompts were designed to be easy to deliver and did not require coaches to interact with participants; however, this meant that they were largely passive and consisted of periodic reminders to enact some of the behavioural skills learnt on the programme. Table 2 provides some more detail of their content.

| Content | BCT reminded to use | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Football Fans in Training: how’s it going? | |

| Restatement that coach enjoyed working with them and hopes they are keeping the weight they lost off and keeping up lifestyle changes | Self-monitoring of behaviour and outcome of behaviour; goal setting for behaviour and goal setting for outcome; problem-solving | |

| Reminder to weigh themselves weekly or daily; to continue to monitor daily activity; to plan for set-backs and to remember to use SMART goals if going off-track | ||

| 2 | Football Fans in Training: still going well? | |

| Reminder to check current step count and consider whether or not it was as high as at the end of the programme | Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal; action planning; social support/encouragement | |

| Suggested ways to increase if not as high | ||

| Recommend getting in touch with others who had done FFIT via Facebook® (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) site to help get active again | ||

| 3 | Football Fans in Training: still on target? | |

| Reminder to check 5–10% weight loss target from baseline and current weight. Reminder of health benefits of losing weight | Goal setting for behaviour and outcome; discrepancy between current behaviour and goal; health consequences | |

| Reminder to set some SMART goals for eating well if off-track and suggested ways to make small dietary changes | ||

| Reminder that they will be meeting up again for 9-month reunion in club and will see other guys to discuss how will be doing | ||

| 4 | Football Fans in Training: looking forward | |

| Restatement that coach enjoyed seeing some people at 9-month reunion and reminder to keep in touch with other guys for support | Social support/encouragement; goal setting for behaviour and outcome | |

| Reminder to check their progress, set some goals if not achieving them and check their confidence to achieve goals | ||

| 5 | Football Fans in Training: reflecting on progress | |

| Reminder to check whether eating and exercise routines are still healthy and make SMART goals if no longer on track, reminder that has been successful in past and that has skills to be so again. Suggestion that other men have used use if-then plans to plan for difficult situations | Focus on past success; verbal persuasion to boost self-efficacy; goal setting for behaviour and outcome; problem-solving | |

| 6 | Football Fans in Training: FFIT for life? | |

| Consider how many ‘top tips for weight loss’ still use. Reminder to use SMART goals to achieve them if not using. Information about some people has found FFIT to be life changing. Good luck for future | Goal setting for behaviour and outcome | |

The 9-month reunion meeting was designed to allow men to share experiences of successes and difficulties in maintaining weight loss post FFIT, set new specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-limited (SMART) goals and take part in a group physical activity session.

Coach training

Coaches received group-based training over 2 days and detailed delivery notes. Within these notes, separate sections for each week of the programme described the ‘key tasks’ for the session (see Table 1), the equipment and preparation required, a suggested order of activities and the detailed content for that session. The coaches’ delivery notes incorporated and cross-referenced to the participant notes.

The length of the training was limited by the availability of the coaches. It was delivered face to face in a central location (although some coaches still had to travel for up to 4 hours to attend) and took place over a period of 2 days, timed to fit in the training around a full programme of other activities.

The aim of the training was to foster full competence in delivering the programme and a sense of ownership of the delivery of the programme in their own club while adhering to the delivery of key tasks. Training was designed to build on coaches existing strengths, to teach them how to deliver each element of the programme and how to use their existing skills to create a positive, welcoming climate. Training was interactive to allow coaches to discuss their experience of delivering each component and exchange practical tips. It highlighted key elements of the programme (the use of pedometers, the Eatwell Plate, the alcohol session, the ‘key tasks’ for each week) and emphasised the importance of applying BCTs, in particular self-monitoring, goal setting and action planning and relapse prevention; personalisation of each element of the programme to suit individual men’s abilities and circumstances; and encouraging mutually supportive interaction between participants.

The delivery of the programme, but not its core components, had to be flexible to allow coaches to adapt the programme to suit their club’s facilities, their own skills set, the limitations and abilities of the specific men enrolled on their programme and external factors such as the weather, the rearrangement of club match fixtures or the timing of the recommended ‘guest appearance’ of a club celebrity (recommended for week 6) to suit the club celebrity’s diary. Coaches were also encouraged to respond to group interactions and queries while ensuring that the key tasks in each session were covered.

In relation to physical activity, coaches were encouraged to use their own experience and the facilities available within their club to devise interesting and varied physical activity sessions. The training included a practical session in which coaches shared and demonstrated ideas about how to adapt flexibility, cardiac fitness and strength exercises for overweight, potentially very unfit men. Coaches were instructed that they should reinforce the use of the RPE scale in every session,62 to ensure that men were exercising at a moderate intensity level.

The coach and participant notes have been made available for others’ use. These can be requested from the FFIT research website, which can be accessed at www.ffit.org.uk. 63

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to determine whether or not FFIT, a gender-sensitised, weight loss, physical activity and healthy living programme delivered in SPL football clubs, can help men aged 35–65 years with a BMI of at least 28 kg/m2 achieve a reduction in body weight that is at least 5% more than any reduction seen in the comparison group 12 months after the start of their participation in FFIT.

Three further objectives related to the investigation of secondary, health economic and process outcomes:

Secondary outcomes to investigate whether or not involvement with FFIT:

-

reduces body weight by at least 5% at 12 weeks

-

reduces waist circumference and percentage body fat at 12 weeks and 12 months

-

increases physical activity and reduces sedentary behaviour at 12 weeks and 12 months

-

improves eating habits at 12 weeks and 12 months

-

reduces alcohol consumption at 12 weeks and 12 months

-

reduces blood pressure at 12 weeks and 12 months

-

increases positive affect and self-esteem, and improves quality of life (QoL) at 12 weeks and 12 months.

We also examined the difference in area under the trend line of weight loss from baseline to 12 months as a measure of the effect of the intervention across all time periods.

Cost-effectiveness to investigate whether or not FFIT has the potential to provide a cost-effective use of resources.

Process outcomes to investigate:

-

programme reach

-

participants’ reasons for continuing with or opting out of FFIT

-

the extent to which coaches deliver FFIT as designed

-

participants’ views of FFIT: including satisfaction, acceptability and any unexpected outcomes

-

coaches’ experiences of delivering FFIT: including satisfaction, acceptability and any unexpected outcomes

-

participants’ experiences of maintaining weight loss and lifestyle changes in the longer term.

Under Procedures below, we report on the measures and processes of data collection for primary and secondary trial outcomes. Chapter 3 reports the results of the trial, Chapter 4 reports the economic analyses, including methods and results, and Chapter 5 reports process outcomes.

Outcome assessment

Outcome measures are set with reference to National Obesity Observatory guidance for the evaluation of weight management interventions. 64

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was mean difference in weight loss between groups at 12 months, expressed as absolute weight and as a percentage.

Secondary outcomes

-

Weight loss at 12 weeks.

-

Reduction in waist circumference and body fat at 12 weeks and 12 months.

-

Physical activity: changes in self-reported frequency and duration of walking, moderate activity, vigorous activity and sedentary behaviour over the last 7 days at 12 weeks and 12 months as measured by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Short Form. 65

-

Eating habits: changes in self-reported intake of key contributors to weight gain (e.g. fast foods, chocolate bars, chips, pies, sugary drinks), expressed as estimated intake of fatty foods, sugary foods and fruit and vegetables at 12 weeks and 12 months.

-

Changes in self-reported alcohol consumption over the last 7 days at 12 weeks and 12 months measured using an alcohol diary over a week66 and expressed as units of alcohol per week.

-

Reduction in resting blood pressure at 12 weeks and 12 months.

-

Psychological outcomes: (1) changes in positive and negative affect as measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS),67 (2) changes in self-esteem as measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem (RSE) scale68 and (3) changes in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as measured by the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12),69 all at 12 weeks and 12 months.

-

Difference in area under the trend line of weight loss from baseline to 12 months.

Procedures

Timing of measurements

Outcomes were measured at baseline, 12 weeks and 12 months according to the measurement schedule shown in Table 3. Demographic characteristics were measured at baseline. Copies of the questionnaires are available on request.

| Time | Demographic characteristics | Height | Weight | Waist | BMI | Blood pressure | Modified DINE questionnaire | IPAQ | Self-reported alcohol | PANAS | RSE scale | SF-12 and resource use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 12 weeks | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 12 months | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

The fieldwork team

Data were collected by teams of fieldworkers, educated at least to degree level. Each team in each measurement session had a designated team leader and a fieldwork nurse responsible for blood pressure measurement. Staff were trained to standard measurement protocols by experienced research and survey staff in the Medical Research Council (MRC)/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit. Training took place over 2 days and emphasised strict adherence to protocol to minimise detection bias. Field staff wore T-shirts branded with FFIT research logos at all measurement sessions. Figure 1 illustrates the measurement team spirit that was encouraged.

FIGURE 1.

Fieldwork team arriving at a 12-month in-stadia measurement session.

Baseline data

All men who had registered an interest in FFIT prior to the baseline measures in their club (and whose self-reported BMI and date of birth suggested they were eligible to take part) were sent a letter of invitation to attend an appointment at an in-stadia measurement session at their club. They were asked to confirm or rearrange their appointment date and time by e-mail or telephone. Eligibility criteria were confirmed through objective measurement of height and weight.

Outcome measurement

The 12-week measures

The intervention group 12-week measurements were taken around the time of the final FFIT programme session. We telephoned participants to make appointments and sent written reminders in advance by e-mail or letter according to the individual’s preference. Men who did not attend the stadia for these measurements were telephoned to arrange individual measurements at home.

Men who had dropped out of the FFIT programme were invited to the measurement sessions by telephone and, if that was difficult for them, they were offered a home visit for measurement. Any men who had dropped out of the programme, and men in the comparison group, were offered travel expenses and a £20 club shop gift voucher in appreciation of their time. FFIT intervention group participants were not offered a club gift voucher because their 12-week measurements followed on immediately after the programme completed, but they were offered travel expenses if the made a special journey to take attend the 12-week measurements.

To avoid risk of contamination, 12-week in-stadia measurements for the comparison group were held on a different evening from the intervention group measurement sessions.

The 12-month measures

The 12-month measurement sessions for both groups were held at club stadia. To maximise retention at 12 months, the men were (1) sent an advanced reminder that follow-up measurements were imminent, using a personalised letter sent 4–5 weeks ahead of the measurement dates at their club; (2) telephoned within a fortnight of the reminder letter to arrange a personal appointment time; (3) sent an e-mail (or letter) around a week before their appointment and a SMS text reminder the day before; (4) offered a home visit if attending the stadium was difficult; and (5) offered a £40 club voucher to thank them for their time.

Measurement protocols: objectively measured outcomes

Weight (kg) was recorded using electronic scales (Tanita HD 352™, Middlesex, UK) with participants wearing light clothing, no shoes and with empty pockets. Height (cm) was measured without shoes using a portable stadiometer (Seca Leicester™, Chino, CA, USA). Waist circumference was measured twice (three times, if the first two measurements differed by 5 mm or more) and the mean of all recorded measurements calculated. Resting blood pressure was measured using a digital blood pressure monitor (Omron HEM-705CP™, Buckinghamshire, UK) by a fieldwork nurse. All equipment was calibrated prior to fieldwork.

Measurement protocols: outcomes based on self-report

Participants completed self-administered questionnaires. Fieldworkers assisted any participant who appeared to have literacy problems and, whenever possible, checked questionnaires before the participant left the measurement session to minimise missing data.

Measurement of adverse events

An adverse event was defined as any injury or newly diagnosed health condition (e.g. high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus) that occurred while a man was registered on the FFIT programme, whether or not it was related to his participation in FFIT. A serious adverse event was defined as an adverse event that included at least one of the following: an event requiring hospitalisation or prolonged medical attention, an event that is immediately life-threatening (such as a cardiac arrest), a fatal event. Any serious adverse events were reported immediately to the chairperson or the Trial Steering Committee. A report of all adverse events was provided at every meeting of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.

At the baseline and 12-week measurements, men were given a pre-paid postcard and details about how to report any adverse events. In addition, coaches (and the researchers who conducted the observations of the programmes) were also asked to report any adverse events that came to their attention. At the 12-month measurements, all participants were asked whether or not they had experienced any adverse events since their last contact with the research team.

All adverse events were categorised by a member of the research team according to their severity and whether or not they were related to participation in FFIT. When possible, serious adverse events and any adverse events for which relatedness to participation in FFIT was not clear were followed up by a telephone call to the participant. Adverse events that occurred before the baseline measurement period or after the August to December 2012 delivery of FFIT had started were not recorded.

Preparation of self-reported variables for analysis

Physical activity

Following standard procedures described in the IPAQ scoring protocol,70 we calculated and reported sedentary time, and metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week from self-reported walking, vigorous and moderate exercise and a measure of total MET minutes.

Diet

We used the adapted Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education (DINE) questionnaire to collect data on self-reported frequency of intake of different food types and the dietary question referred to the last 7 days. The full DINE questionnaire can take a considerable time to complete and can be difficult for some participants. Recent evidence on dietary factors influencing weight gain highlights items not included in the tool (e.g. sugary drinks); therefore, we adapted the DINE questionnaire to reduce participant burden and capture information on additional relevant markers. From these data, we calculated a fatty food score, a fruit and vegetable score and a sugary food score.

Description of items included in the adopted Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education questionnaire

Participants reported how many times (over the last 7 days) they had consumed a serving of cheese, beef burgers or sausages, beef, pork or lamb, fried food, chips, bacon or processed meat, pies, quiches or pastries, crisps and fast food. We also asked about the amount of milk used in a day (for drinking or in cereal, tea or coffee) and what kind of milk is usually used (full cream, semi-skimmed or skimmed). They also reported how many times a day they had consumed fruit and vegetables, chocolate or sweets, and biscuits and sugary drinks (fizzy drinks, diluting juice or fruit juice).

Scoring food frequencies

Food frequency categories differed for different food types and we converted the DINE questionnaire food frequency categories as described in Table 4.

| Food type | Scoring of frequencies |

|---|---|

| Cheese, beef burgers or sausages, beef, pork or lamb, chips and fried food | 0 times = 1 |

| 1–2 times = 2 | |

| 3–5 times = 6 | |

| ≥ 6 times = 9 | |

| Pies, quiches and pastries | 0 times = 1 |

| 1–2 times = 2 | |

| 3–5 times = 5 | |

| ≥ 6 times = 8 | |

| Bacon or processed meat and crisps | No times = 1 |

| 1–2 times = 2 | |

| 3–5 times = 5 | |

| ≥ 6 times = 6 | |

| Milk amount | Less than one-quarter of a pint = 1 |

| About one-quarter of a pint = 2 | |

| About half a pint = 3 | |

| ≥ 1 pint = 4 | |

| Sugary drinks | Less than once = 1 |

| 1–2 times = 2 | |

| 3–5 times = 3 | |

| ≥ 6 times = 4 | |

| Biscuits, chocolate and sweets | Less than once = 1 |

| 1–2 times = 2 | |

| 3–5 times = 4 | |

| ≥ 6 times = 6 | |

| Fruit and vegetables | Less than once = 0.5 |

| 1–2 times = 1.5 | |

| 3–5 times = 4 | |

| ≥ 6 times = 6 |

Alcohol intake

Following Emslie et al. ,66 we converted responses to the 7-day recall diary for alcohol to standard units equivalent to 8 g of pure alcohol (half a pint of ordinary beer, lager or cider, one small glass of wine and one measure of spirits each contain 1 unit of alcohol). We calculated total number of units reported in the last week.

Psychological outcomes

Scores for both the RSE scale and the short form of the PANAS were normalised so that values could be calculated for participants who had missed one or two items contributing to each scale. The PANAS-normalised scale scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher negative affect and higher positive affect. Similarly, higher scores on the RSE scale (normalised range 0–3) indicate better self-esteem.

Scores on QoL using the SF-12 were summarised scores for mental and physical health following standard algorithms. 69

Changes to outcomes after trial commencement

The protocol stated that the secondary outcomes of weight loss at 12 weeks and reduction in waist circumference and body fat at 12 weeks and 12 months would be reported as percentages. To be consistent with best statistical practice71 these were reported as absolute differences. All changes made, together with their rationale, are summarised in Table 5.

| Original outcome as expressed in the protocol | Changed outcome | Rationale for change |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage weight loss at 12 weeks | Weight loss at 12 weeks | To be consistent with best statistical practice, which recommends reporting absolute differences |

| Percentage reduction in waist circumference and body fat at 12 weeks and 12 months | Reduction in waist circumference and body fat at 12 weeks and 12 months | |

| Eating habits: changes in self-reported intake of key contributors to weight gain (e.g. fast foods, chocolate bars, chips, pies, sugary drinks) at 12 weeks and 12 months using questions adapted from the DINE questionnaire | Eating habits: we calculated dietary intake scores for fatty food, sugary food and fruit and vegetables | There were 17 separate variables included in our adapted DINE questionnaire; to reduce reporting burden we summarised these into three scores indicative of healthy changes that men could have made to their diets |

| Changes in self-reported alcohol consumption over the last 7 days at 12 weeks and 12 months measured using an alcohol diary over a week and expressed as units of alcohol per week, and changes in football-associated alcohol consumption | Changes in self-reported alcohol consumption over the last 7 days at 12 weeks and 12 months, measured using an alcohol diary over a week and expressed as units of alcohol per week | On reflection we realised that the questions we had developed to assess football-related alcohol intake lacked external validity and we focused our analysis only on total alcohol consumption |

Sample size

The study was powered to detect a 5% mean difference in percentage weight loss between the intervention and comparison groups at 12 months, with standard deviation (SD) of 19.9%, 80% power and a two-sided significance level. A total of 250 men were required in each trial arm and based on our feasibility study,32 the sample size was inflated to 360 men in each arm to allow for 30% attrition.

Randomisation

Following baseline measurement the randomisation sequence was generated by the Tayside Clinical Trials Unit (TCTU) statistician using SAS (v 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), blocked (block size between two and nine depending on how many participants were recruited at a club) and stratified by club. The allocation sequence was sent in a password-protected file to a database manager (not part of the research team) who assigned individuals to each group. All those allocated to the intervention group were telephoned within 3 weeks of baseline measurements at each club to notify them of their allocation and the date, time and place of the first FFIT session. This was confirmed in writing. Those allocated to the waiting list comparison group were informed of their allocation by letter and given information about when they should expect to hear from the research team over the following 12 months. They were reassured that they had a guaranteed place on the FFIT programme in their club commencing August/September 2012.

Blinding

To blind the measurement of the primary outcome at the 12-month measurement, session weight was the first measure taken and was taken by fieldworkers employed only for 12-month measures (and who, therefore, had not met the men before), who were trained to minimise interaction with men until weight had been recorded and was in a screened-off area to prevent interaction with others. Blinding for other measures was not possible.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted as intention to treat on randomised participants, with all available data in mixed models as recommended by White et al. 72 All outcome variables were continuous. If the distribution was not normal, we carried out a logarithmic transformation to achieve normality and results comparing intervention with comparators were subsequently expressed as the ratio of geometric means (RGM) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). We used multiple linear regression for all analyses and baseline measure, group allocation and club (to allow for stratification by club) were included as fixed effects in adjusted models.

To assess whether or not the intervention effect on the primary outcome and four selected secondary outcomes differed between subgroups of the study population we conducted pre-specified subgroup analyses by adding allocation group by subgroup factor interaction terms to the models. 73 The four selected secondary outcomes were total MET minutes/week, fatty food score, sugary food score and positive affect. Potential moderating variables were age, marital status, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) from postcode of residence, location of measurement (stadium vs. home), orientation to masculine norms, affiliation to football, whether or not attended a formal weight management programme in the last 3 months, smoking, housing tenure, education, ethnicity, employment status, joint pain, injuries and limiting long-standing illness (LSI).

Changes are presented as mean (95% CI) unless otherwise specified.

We conducted sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome (1) multiple imputation for missing data assuming data missing at random,72 (2) added club as a random variable to account for possible clustering74 and (3) repeated measures analysis using results from both 12 weeks and 12 months.

All analyses were conducted using SAS (v 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) by the TCTU statistician who was blinded to group allocation.

Changes to protocol

There were no changes to protocol except those concerned with the way that outcomes were expressed. See Table 5.

Public involvement

Extensive public engagement was built into the development of the FFIT intervention and the evaluation design. This principally involved ongoing engagement during the programme development phase with key stakeholders (the SPL Trust, the football clubs and the programme delivery funders) and consultation with men who took part in the first pilot deliveries of FFIT at 11 clubs in the 2010–11 football season. Input from the coaches, the SPL Trust and the target group of men thus all fed directly into the final shaping of the intervention and the research design.

Representatives of the SPL Trust were actively involved throughout the development of the delivery protocol for the pilot FFIT programme. Following these initial meetings, we also met with community managers from the football clubs who would be involved in the pilot programme prior to the finalisation of the pilot delivery protocol. These meetings allowed the community managers to input into the programme design and to discuss the importance of undertaking a programme that was evidence based and generalisable, and of gathering gold standard evidence of its effectiveness by conducting an evaluation using a randomised design. We also met with the coaches who were delivering the autumn 2010 pilot programme at a training workshop in October 2010 to ask for feedback on the initial sessions. At the end of the autumn 2010 delivery, we held in-depth interviews with coaches at the two clubs which took part in our pilot trial to obtain their views about the programme and research design and received written feedback from coaches at the other clubs. 28 In addition, CMG visited all clubs during spring 2011 to observe delivery sessions of the second pilot programme and to speak informally to the coaches and in April 2011 we fed back the emerging the pilot findings at a plenary meeting organised by the SPL Trust at the National Football Stadium, Hampden Park. All comments were carefully considered in the development of the final version of the FFIT programme that was delivered in the intervention arm of the trial as reported by Gray et al. 28

The views and experiences of the men who participated in the pilot deliveries also fed into the development of the intervention. All men taking part in the autumn 2010 pilot deliveries were asked to complete a programme evaluation form, which asked for their suggestions for changes. Men at the two clubs involved in the feasibility study also took part in focus groups following the autumn 2010 and spring 2011 pilot deliveries where they gave their views on the content of the programme and on the planned research procedures for the RCT. 28,32 In addition, when a reviewer of the grant application for this trial suggested that the evidence on men and health raised questions about whether or not men would engage with the pedometer-based walking programme, we undertook a series of semistructured telephone interviews (n = 27) with men from a number of clubs who had taken part in the autumn 2010 pilot deliveries, to ask them about their experience of this aspect of the programme. These interviews strongly reinforced our first hand experiences that men saw the pedometer-based walking programme as an appropriate way to begin to regain some fitness and (re-)engage with physical activity;31 furthermore, it demonstrated that this was a part of the programme that was highly valued by our target group (men aged 35–65 years with a BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2).

Participants in the pilot deliveries of FFIT in 2010/11 were also engaged in outreach work on FFIT prior to and during our intense period of recruitment to this trial. Many participated in various public engagement activities including the five-a-side football tournament held in June 2011 at St Mirren Football Club for ex-participants and a video diary made by a BBC journalist, Paul Bradley, who took part in the spring 2011 pilot FFIT programme, which illustrated week by week (each week being filmed at a different club) the atmosphere that the programme sought to foster in order to engage men. Throughout the summer of 2011 (July and August), participants from the pilot deliveries took part in TV, radio and newspaper interviews about their experiences of FFIT (including a 1-hour-long BBC Radio Scotland documentary about the programme that was first broadcast on 18 June 2011). They also played an active role in recruitment by telling their friends and family about the programme, advertising it in their workplaces and local community venues (e.g. libraries) and supporting fieldworkers during match day visits to home fixtures. In February 2012, a half-hour TV documentary on FFIT, which involved interviews with several participants from the autumn 2011 deliveries of FFIT (the intervention group in the trial), was screened on BBC 2 Scotland. Finally, in September 2013, representatives from each of the groups of men who undertook the intervention in autumn 2011 readily agreed to come to a bespoke event at Hampden Park to talk about their experiences of FFIT for future dissemination purposes, including the FFIT research website (www.ffit.org.uk). 63

Chapter 3 Results: the randomised controlled trial

Participant flow

Figure 2 shows participant flow through the trial. Of the 1231 men registering an interest during the recruitment period, 483 were excluded from the trial (101 decided against participation, 76 had a BMI < 28 kg/m2, 306 were allocated to the non-trial delivery of FFIT). Three hundred and seventy-four were randomly allocated to the intervention group and 374 to the comparison group. One comparison group participant subsequently withdrew and requested we destroy his data.

FIGURE 2.

Flow of participants through the FFIT RCT. a, After randomisation, one participant requested to have all of his data destroyed. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 2014, 383, 1211–21). 33

Recruitment

As described below (see Baseline data), formal recruitment commenced on 2 June 2011 (although preparations for recruitment had begun in anticipation of receiving the grant award) and continued until the week before the baseline measurements in each club, between 11 August 2011 and 20 September 2011. Figure 3 shows that recruitment started slowly, probably because in Scotland the 2010/11 season had closed and the 2011/12 season had yet to begin. As the clubs and media coverage geared up for the start of the season, and we were able to recruit men at games, recruitment speeded up so that we exceeded our target of 1110 men.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment to the FFIT study from May to September 2011.

Baseline data

Table 6 shows baseline characteristics of participants (n = 747), including total self-reported MET-minutes per week. FFIT attracted men from across the socioeconomic spectrum, but few from ethnic minority groups.

| Variable | FFIT (n = 374) | Comparison group (n = 373) | Total (n = 747) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 47.0 (8.07) | 47.2 (7.89) | 47.1 (8.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White – British/Scottish/Irish/other | 367 (98.1) | 368 (98.7) | 735 (98.3) |

| Other | 5 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) | 7 (1.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) |

| SIMD (% living in quintiles) | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 65 (17.4) | 66 (17.6) | 131 (17.5) |

| 2 | 69 (18.4) | 62 (16.6) | 131 (17.5) |

| 3 | 62 (16.6) | 60 (16.0) | 122 (16.3) |

| 4 | 82 (21.9) | 84 (22.5) | 166 (22.2) |

| 5 | 89 (23.8) | 99 (26.5) | 188 (25.1) |

| Missing | 7 (1.9) | 3 (0.8) | 10 (1.3) |

| Employment status | |||

| Paid work | 322 (86.1) | 304 (81.5) | 626 (83.8) |

| Education or training | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.4) | 8 (1.1) |

| Unemployed | 9 (2.4) | 18 (4.8) | 27 (3.6) |

| Not working due to long-term sickness or disability | 8 (2.1) | 8 (2.1) | 16 (2.1) |

| Retired | 14 (3.7) | 18 (4.8) | 32 (4.3) |

| Other | 17 (4.6) | 19 (5.0) | 36 (4.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Education | |||

| No qualifications | 37 (9.9) | 34 (9.1) | 71 (9.5) |

| Standard Grades/Highers | 115 (30.8) | 126 (33.7) | 241 (32.3) |

| Vocational or HNC/HND | 133 (35.6) | 107 (28.7) | 240 (32.1) |

| University education | 75 (20.1) | 81 (21.7) | 156 (20.9) |

| Other | 14 (3.7) | 25 (6.7) | 39 (5.2) |

| Housing tenure | |||

| Owner-occupied | 280 (74.8) | 283 (75.8) | 563 (75.3) |

| Other | 94 (25.2) | 90 (24.2) | 184 (24.7) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 249 (66.6) | 269 (72.1) | 518 (69.3) |

| Living with partner | 55 (14.7) | 40 (10.7) | 95 (12.7) |

| Other | 70 | 64 | 134 |

| Objectively measured outcomes | |||

| Weight (kg) | 110.3 (17.9) | 108.7 (16.6) | 109.5 (17.3) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 118.7 (12.3) | 118.0 (11.1) | 118.4 (11.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.5 (5.1) | 35.1 (4.8) | 35.3 (4.9) |

| Body fat (% total weight) | 31.8% (5.7) | 31.5% (5.2) | 31.7% (5.5) |

| Missing | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Blood pressure (mm/Hg) | |||

| Systolic blood pressure | 139.4 (17.6) | 141.2 (14.9) | 140.3 (16.3) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 88.2 (10.3) | 89.5 (10.1) | 88.8 (10.2) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Participants with BMI < 30 kg/m2 | 35 (9.4) | 40 (10.7) | 75 (10.0) |

| Self-reported outcomes | |||

| Total MET-minutes/week | 1188 (396–2559) | 1173 (396–2559) | 1188 (396–2559) |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| DINE-based measures | |||

| Fatty food score (range 10–58) | 23.3 (7.1) | 23.4 (7.1) | 23.3 (7.1) |

| Fruit and vegetable score (range 1–6) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.7) |

| Sugary food score (range 3-16) | 6.0 (2.7) | 6.2 (2.9) | 6.1 (2.8) |

| Total alcohol consumption (units per week) | 16.5 (17.4) | 17.0 (17.4) | 16.7 (17.4) |

| Self-esteem (normalised RSE score, range 0–3) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| Positive affect (normalised PANAS score, range 1–5) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Negative affect (normalised PANAS score, range 1–5) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) |

| HRQoL (SF-12) | |||

| Mental aspects | 48.9 (10.1) | 48.3 (9.2) | 48.6 (9.7) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Physical aspects | 47.0 (7.9) | 47.7 (7.5) | 47.4 (7.7) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Table 7 shows baseline levels of self-reported physical activity in relation to whether activity was vigorous, moderate or walking (reported in MET-minutes/week) or time spent sitting on a week day in the last 7 days.

| Variable | FFIT (n = 374) | Comparison group (n = 373) | Total (n = 747) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vigorous MET-minutes/week | 0 (0–720) | 0 (0–720) | 0 (0–720) |

| Missing | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Moderate MET-minutes/week | 0 (0–360) | 0 (0–360) | 0 (0–360) |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Walking MET-minutes/week | 462 (132–1188) | 396 (99–1039) | 445 (99–1188) |

| Missing | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Time spent sitting on a week day in last 7 days | 480 (300–600) | 420 (300–600) | 450 (300–600) |

| Missing | 75 | 72 | 147 |

Numbers analysed

After randomisation, one participant allocated to the comparison group withdrew and requested that all of his data be destroyed. This left 374 participants in the intervention group and 373 in the comparison group. Retention was high, although it varied between intervention and comparison groups (see Figure 2). At 12 weeks, measurements were obtained for 91% of participants: 330 out of 374 (88%) in the intervention group and 347 out of 373 (93%) in the comparison group. At 12 months, measurements were obtained for 92% of participants: 333 out of 373 (89%) in the intervention group and 355 out of 373 (95%) in the comparison group. All analyses were conducted as intention to treat on randomised participants with all available data.

Outcomes

Primary outcome: weight at 12 months

At 12 months, mean weight loss among men in the intervention group was 5.56 kg (95% CI 4.70 kg to 6.43 kg) and 0.58 kg (95% CI 0.04 kg to 1.12 kg) in the comparison group (Table 8).

| Variable | FFIT (n = 374) | Comparison group (n = 373) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Change in weight from baseline (kg) | 333 | –5.56 (–6.43 to –4.70) | 355 | –0.58 (–1.12 to –0.04) |

| % change in weight from baseline | 333 | –4.96 (–5.71 to –4.20) | 355 | –0.52 (–1.00 to –0.03) |

The mean difference in weight loss between groups, adjusted for baseline weight and club, was 4.94 kg (95% CI 3.95 kg to 5.94 kg) and the mean difference in percentage weight loss at 12 months, similarly adjusted, was 4.36% (Table 9).

| Variable | Difference between groups | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Change in weight from baseline (unadjusted) (kg) | –4.11 (–6.75 to –1.47) | 0.0023 |

| Change in weight from baseline (adjusted for baseline weight and club) (kg) | –4.94 (–5.94 to –3.95) | < 0.0001 |

| % change in weight from baseline (unadjusted) | –4.36 (–5.09 to –3.64) | < 0.0001 |

| % change in weight from baseline (adjusted for baseline weight and club) | –4.36 (–5.08 to –3.64) | < 0.0001 |

Sensitivity analyses on primary outcome: change in weight at 12 months

The sensitivity analyses gave similar results to the main analysis (Table 10). Using multiple imputation, assuming data were missing at random, to account for missing data the mean difference in weight loss between groups adjusted for baseline weight and club was 4.93 kg (95% CI 3.92 kg to 5.94 kg). Adding club as a random effect to account for possible clustering, the mean difference in weight loss between groups adjusted for baseline weight was 4.94 kg (95% CI 3.83 kg to 6.04 kg). Using repeated measures to make use of weight loss data from both 12 weeks and 12 months found that the mean difference in weight loss between groups at 12 months, adjusted for baseline weight and club, was 5.28 kg (95% CI 4.62 kg to 5.94 kg) (see Table 10).

| Model | Difference between groups | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple imputation model (adjusted for weight at baseline and club) | –4.93 (–5.94 to –3.92) | < 0.0001 |

| Club as a random effect (adjusted for baseline weight) | –4.94 (–6.04 to –3.83) | < 0.0001 |

| Repeated measures model (adjusted for weight at baseline and club) | –5.28 (–5.94 to –4.62) | < 0.0001 |

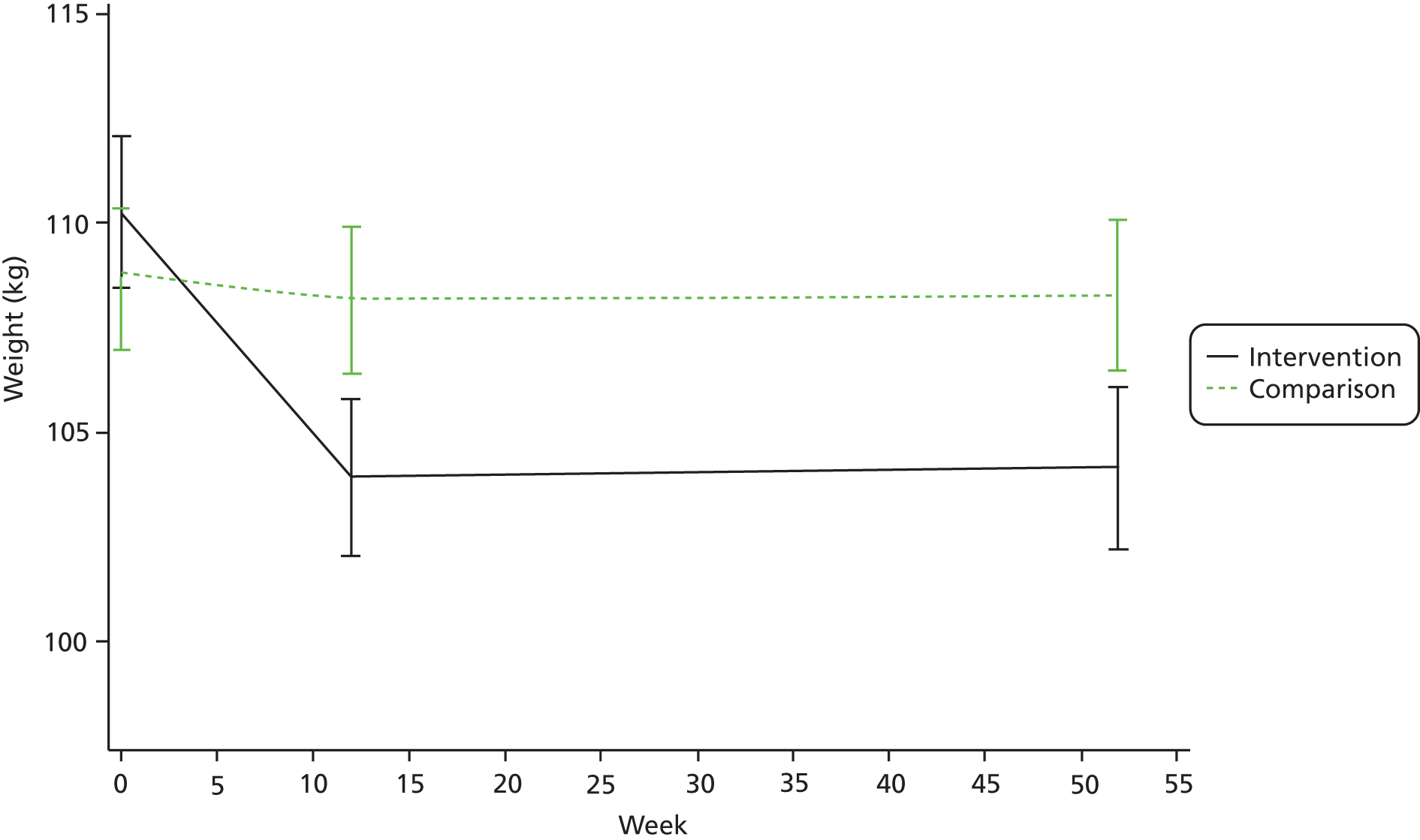

As shown in Figure 4, participants lost most weight over the period that coincided with the 12 weekly sessions delivered in the clubs.

FIGURE 4.

Mean weight (kg, 95% CI) in participants allocated to the FFIT weight loss programme or waiting list comparison group 12 weeks and 12 months after baseline measurement. Note that the y-axis (weight) does not start at zero. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 2014, 383, 1211–21). 33

Subgroup analyses on primary outcome

In order to investigate potential differential effects on the primary outcome by subgroup, we investigated associations between pre-specified subgroups (see Chapter 2, Statistical methods) and weight loss at 12 months. Table 11 shows which variables were significantly associated with weight loss in univariate analyses.

| Variable | ANOVA F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.02 | < 0.0001 |

| Number of long-standing illnesses | 9.88 | 0.002 |

| Fatty food score | 10.06 | 0.002 |

| Conformity to masculine norms | 5.81 | 0.016 |

| Employment status | 2.08 | 0.024 |

| Fruit and vegetable score | 4.63 | 0.032 |

| Joint pain | 4.82 | 0.029 |

| Housing tenure | 2.20 | 0.053 |

| SIMD (quintile) | 2.08 | 0.080 |

| Affiliation to football | 0.98 | 0.47 |

| Any attempts to lose weight in last 3 months | 0.26 | 0.61 |

| Ethnicity | 0.69 | 0.63 |

| Ever smoked | 0.24 | 0.79 |

| Highest educational status | 0.86 | 0.53 |

| Number of injuries | 1.78 | 0.18 |

| Marital status | 0.75 | 0.61 |

| SIMD (decile) | 1.32 | 0.22 |

| Sugary food score | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Trained at club they supported | 0.21 | 0.64 |

Table 12 demonstrates that in multiple regression analyses including only those variables which had shown significant association with weight loss in univariate analysis together with weight at baseline and treatment group, the only significant associations were weight at baseline and treatment group. That is, the pre-specified subgroup analyses found no significant additional predictors of primary outcome and the intervention effect did not vary significantly by age, marital status, deprivation of area participants’ residence, location of measurement (stadium vs. home), orientation to masculine norms, affiliation to football, whether or not attended a formal weight management programme in last 3 months, smoking, housing tenure, education, ethnicity, employment status, joint pain, injuries and number of long-standing illnesses.

| Variable | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment group (FFIT vs. comparison) | 0.94 (0.92 to –0.97) | < 0.0001 |

| Weight at baseline | –4.94 (–3.95 to –5.94) | < 0.0001 |

| Club | 0.637 | |

| Age (years) | 0.051 | |

| Fatty food score | 0.999 | |

| Fruit and vegetable score | 0.652 | |

| Number of long-standing illnesses | 0.182 | |

| Joint pain | 0.713 | |

| Conformity to masculine norms | 0.600 | |

| Employment status | 0.428 | |

| SIMD (quintile) | 0.311 |

Secondary outcomes

More men in the intervention group (39.04%, 130/333) than the comparison group (11.27%, 40/355) achieved at least 5% weight loss at 12 months (RR 3.47, 95% CI 2.51 to 4.78) and more had a BMI below 30 kg/m2 (Table 13).

| Variable | FFIT (N = 374) | Comparison group (N = 373) | Relative risk (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (%) | n | n (%) | |||

| Percentage who achieve at least 5% weight loss | 12 weeks | 329 | 154 (46.81) | 347 | 24 (6.92) | 6.77 (4.52 to 10.13) |

| 12 months | 333 | 130 (39.04) | 355 | 40 (11.27) | 3.47 (2.51 to 4.78) | |

| Percentage with a BMI < 30 kg/m2 | 12 weeks | 329 | 85 (25.84) | 347 | 44 (12.68) | 2.04 (1.46 to 2.84) |

| 12 months | 333 | 85 (25.53) | 355 | 48 (13.52) | 1.89 (1.37 to 2.60) | |

Table 14 shows changes in other secondary outcomes at 12 weeks and 12 months, before and after adjusting for baseline measure and clubs. These analyses show similarly positive results.

| Variable | FFIT (n = 374) | Comparison group (n = 373) | Mixed models, difference between groups, mean (95% CI) | Mixed models, difference between groups, mean (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (95% CI) or median (interquartile range) | N | Mean (95% CI) or median (interquartile range) | Unadjusted | p-value | Adjusteda | p-value | |

| Objectively measure outcomes | ||||||||

| Change in weight (kg) | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | 329 | −5.80 (−6.33 to −5.27) | 347 | −0.42 (−0.76 to −0.09) | −3.93 (−6.47 to −1.38) | 0.0026 | −5.18 (−6.00 to −4.35) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 329 | −5.23 (−5.69 to −4.78) | 347 | −0.37 (−0.67 to −0.07) | −4.72 (−5.45 to −3.99) | < 0.0001 | −4.71 (−5.44 to −3.98) | < 0.0001 |

| Change in waist circumference (cm) | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | 329 | −6.70 (−7.28 to −6.13) | 345 | −1.00 (−1.43 to −0.56) | −4.88 (−6.72 to −3.04) | < 0.0001 | −5.57 (−6.41 to −4.72) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 318 | −7.34 (−8.18 to −6.49) | 353 | −2.04 (−2.63 to −1.46) | −4.47 (−6.31 to −2.63) | < 0.0001 | −5.12 (−5.97 to −4.27) | < 0.0001 |

| Change in BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | 329 | −1.87 (−2.04 to −1.70) | 347 | −0.14 (−0.25 to −0.03) | −1.36 (−2.09 to −0.63) | 0.0003 | −1.66 (−1.93 to −1.40) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 333 | −1.79 (−2.07 to −1.51) | 355 | −0.20 (−0.38 to −0.02) | −1.27 (−2.00 to −0.54) | 0.0007 | −1.56 (−1.82 to −1.29) | < 0.0001 |

| Change in % body fat | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | 276 | −2.70 (−3.21 to −2.23) | 260 | −0.30 (−0.62 to 0.09) | −1.77 (−2.70 to −0.84) | 0.0002 | −2.16 (−2.81 to −1.51) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 271 | −2.20 (−2.88 to −1.60) | 312 | 0.00 (−0.40 to 0.43) | −1.92 (−2.83 to −1.00) | < 0.0001 | −2.15 (−2.78 to −1.52) | < 0.0001 |

| Change in systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | 295 | −7.50 (−9.14 to −5.89) | 280 | −3.50 (−4.97 to −2.00) | −5.41 (−7.70 to −3.12) | < 0.0001 | −4.51 (−6.36 to −2.67) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 318 | −7.90 (−9.54 to −6.25) | 351 | −6.60 (−7.98 to −5.31) | −3.58 (−5.76 to −1.39) | 0.0025 | −2.27 (−4.01 to −0.54) | 0.0171 |

| Change in diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | 295 | −3.70 (−4.77 to −2.70) | 280 | −1.50 (−2.53 to −0.54) | −3.10 (−4.56 to −1.64) | < 0.0001 | −2.51 (−3.71 to −1.32) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 318 | −4.60 (−5.63 to −3.60) | 351 | −3.80 (−4.74 to −2.96) | −2.16 (−3.55 to −0.76) | 0.0014 | −1.36 (−2.48 to −0.24) | 0.0102 |

| Self-reported physical activity | ||||||||

| Changes in total MET–minute/week (walking, vigorous and moderate exercise) | ||||||||

| 12 weeks | 325 | 1485 (IQR 339–3435) | 341 | 0 (IQR −840–747) | 2.43 (IQR 1.92–3.07) | < 0.0001 | 2.38 (IQR 1.90–2 .98) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 310 | 1219 (IQR 54–3111) | 347 | 375 (IQR −414–1800) | 1.51 (IQR 1.12–2.04) | 0.0.007 | 1.49 (IQR 1.11–1.99) | 0.008 |

| Self-reported eating and alcohol intake | ||||||||

| Change in DINE-based measures | ||||||||

| Fatty food score | ||||||||