Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3001/04. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rona Campbell is a director of DECIPHer IMPACT Ltd, a university-owned not-for-profit company that licenses and supports the implementation of evidence-based health promotion interventions, for which she receives fees paid into a grant account held by the University of Bristol used to support further research activities. She is also a population and public health member of the Wellcome Trust’s Expert Research Group; a fee was paid for the time spent reviewing applications and attending board meetings in London. Adrian Davis is an independent public health consultant on transport planning and health, promoting evidence-based transport policy and practice, and has been paid by Bristol City Council in this capacity.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Audrey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Physical inactivity increases the risk of many chronic diseases, including coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity and some cancers. 1 It is currently recommended that adults should aim to undertake at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more throughout the week. 2,3 There are concerns that many adults in the UK and other high-income countries do not achieve this,1,3,4 although allowing for the accumulation of 150 minutes in bouts of 10 minutes has led to an estimated 61% of adults in England self-reporting that they do achieve the recommended levels. 5 Increasing physical activity levels, particularly among the most inactive, is an important aim of current public health policy in the UK. 1,6

In addition, there is increasing interest in the relationship between time spent sedentary (defined as any waking sitting or lying behaviour with low energy expenditure [≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalent of task (METs)] and health outcomes. 7 A large amount of time spent sitting has been associated with greater risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. In addition, a high volume of objectively measured sedentary time has been associated with a poorer metabolic profile in healthy adults and those at risk of and having developed type 2 diabetes. It is of note that these associations are independent of the volume of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and consequently UK health guidelines recommend that adults should minimise the amount of time spent sedentary (sitting) in addition to increasing physical activity. 1

There is evidence of the link between adult obesity levels and travel behaviour, one indicator of which is that the countries with the highest levels of active travel generally have the lowest obesity rates. 8 Walking has been described as near-perfect exercise. 9 It is a popular, familiar, convenient and free form of exercise that can be incorporated into everyday life and sustained into older age. It is also a carbon-neutral mode of transport that has declined in recent decades in parallel with the growth in car use. 1 Even walking at a moderate pace of 5 km/hour (3 miles/hour) expends sufficient energy to meet the definition of moderate intensity physical activity. 10 Hence there are compelling reasons to encourage people to walk more, not only to improve their health but also to address the problems of climate change. 11–14

In the UK, there are substantial opportunities to increase walking by replacing short journeys undertaken by car. For example, the 2011 National Travel Survey showed that 22% of all car trips were shorter than 2 miles in length, while 18% of trips of less than 1 mile were made by car. 15 An opportunity for working adults to accumulate the recommended moderate activity levels is through the daily commute, and, in addition, replacing the car for short journeys is likely to reduce sedentary time. Experts in many World Health Organization (WHO) countries agree that significant public health benefits can be realised through greater use of active transport modes. 16 Furthermore, cost–benefit analysis for the UK Department for Transport suggests that the ratio of benefits to costs is high. 17

A systematic review comparing direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults found that self-report measures were higher than objective measures in some cases and lower in others. 18 This calls into question the reliability of self-report measures, and indicates that there is no approach to correcting for self-report measures that will be valid in all cases. However, very few studies have objectively measured the contribution of walking, particularly walking to work, to adult physical activity levels; more evidence is needed. 19

In Sweden, two studies examined the association between neighbourhood walkability [measured using a geographic information system (GIS)] and objective physical activity (measured using accelerometers). 20,21 Both studies demonstrate how increased walking rates translate directly to increased MVPA. In the USA, a cross-sectional study included 2364 participants enrolled in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study who worked outside the home during year 20 of the study (2005–6). 22 Associations were examined between walking or cycling to work and objective MVPA using accelerometers. Active commuting was found to be positively associated with fitness in men and women, and inversely associated with body mass index (BMI), obesity, triglyceride levels, blood pressure and insulin level in men. The authors concluded that active commuting should be investigated as a means of maintaining or improving health.

Systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in general,23–26 but there is less evidence about how best to promote walking to work. Available systematic review evidence has focused on interventions that promote walking; interventions that promote walking and cycling as an alternative to car use; and the effectiveness of workplace physical activity interventions. None focuses specifically on employer-led interventions that promote walking to work, although the studies that have been undertaken are included within the available systematic review evidence.

A systematic review of interventions to promote walking comprised 19 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 29 non-randomised controlled studies. 27 The review identified two general characteristics of interventions found to be effective: targeting and tailoring. Only six studies included even a rudimentary economic evaluation. A systematic review of promoting walking and cycling as an alternative to using cars26 identified 22 studies that met the inclusion criteria and found some evidence that targeted behaviour change programmes can change the behaviour of motivated subgroups. A systematic review of the literature regarding the effectiveness of workplace physical activity interventions, commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), graded 14 studies as high quality or good quality. 28 Three public sector studies provided evidence that workplace walking interventions using pedometers can increase daily step counts. One good-quality study reported a positive intervention effect on walking to work behaviour (active travel) in economically advantaged female employees. There was strong evidence that workplace counselling influenced physical activity behaviour, but the reviewers indicated that there was a dearth of evidence for small- and medium-sized enterprises.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence public health guidance on workplace health promotion concluded that although a range of schemes exist to encourage employees to walk or cycle to work, little is known about their impact. 29 Few studies used robust data collection methods to measure the impact of workplace interventions on employees’ physical activity levels (most use self-report) and there is a lack of studies examining how workplace physical activity interventions are influenced by the size and type of workplace and the characteristics of employees.

Benefits and risks of walking as active travel

Physical activity is an important element of a healthy lifestyle. In England, the Chief Medical Officer has stated that the target of 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity for adults on at least 5 days per week, in order to promote health, will best be achieved by helping people to build activity into their daily lives. 1 Experts in many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries agree that significant public health benefits can be realised through greater use of active transport modes. 16 Furthermore, the ratio of benefits to costs is high. 17 There are also potential benefits to walkers from reduced commuting costs and greater certainty about the timing of the journey to work. The potential benefits to employers who promote walking to work include a reduction in absenteeism; employees’ increased concentration and mental alertness, and better rapport with colleagues; a reduction in employees being late because of greater certainty about the timing of the journey; improved public image as a result of lowering the workplace’s carbon footprint; and savings in parking costs. 30

Despite the benefits, there are potential risks to pedestrians. For example, in Great Britain in 2008 there were 170,591 reported personal injury road accidents, of which 1 in 6 involved a pedestrian; 572 pedestrians were killed (23% of the total road accident fatalities); 6070 were seriously injured (23% of all seriously injured casualties); and 21,840 were slightly injured (11% of all slightly injured casualties). 31 In 54% of accidents, contributory factors were assigned to pedestrians only (‘pedestrian failed to look properly’ being the most common individual factor). In 25% of accidents, at least one factor was assigned to both a pedestrian casualty and a vehicle (the most common combination being both participants failing to look properly). In 21% of accidents, factors were associated only with vehicles involved (‘failed to look properly’ being the most common vehicle factor). There is also potential for harm in relation to personal safety of walkers where lighting is poor or there is potential for street crime.

Using behaviour change techniques to encourage active travel

Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) have been defined as the ‘active ingredients’ within an intervention designed to change behaviour that are observable, replicable and irreducible components which can be used alone or in combination. 32 A taxonomy of 26 BCTs was identified in 2008,33 with subsequent work undertaken to improve labels and definitions and to reach a wider consensus of agreed distinct BCTs. 32,34 The 2008 taxonomy has been successfully used to categorise the BCTs used in healthy eating and physical activity interventions, with ‘self-monitoring’ combined with at least one other technique identified as the most effective. 35 For walking and cycling interventions that have resulted in behaviour change, the most commonly used techniques are ‘self-monitoring’ and ‘intention formation’. 36 The UK’s NICE has recently issued recommendations advising that interventions should use BCTs based on goals and planning, feedback and monitoring, and social support. 37

The effectiveness of interventions to promote active travel tends to be measured using self-report surveys. Of the 46 walking and cycling controlled interventions coded for BCTs by Bird et al. ,36 21 reported a statistically significant effect using a mean number of BCTs of 6.43 [standard deviation (SD) = 3.92]. However, very few published studies have looked qualitatively at participants’ views of the BCTs used in the intervention.

The socioecological model

Individual behaviour does not occur in a vacuum, but is shaped by external factors. In acknowledging this, initiatives to encourage walking to work can be considered within a socioecological model,38 identifying and exploring intrapersonal, interpersonal, community and organisational factors within the overall policy context. Within this model, BCTs to encourage walking to work operate at the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels, but the ability to implement and act upon them is shaped by policies and practices in the workplace, the neighbourhood and wider society.

Rationale for a feasibility study focusing on walking to work

A number of high-profile active travel initiatives focus on cycling. 39,40 However, walking may be perceived by employees as a cheaper and safer option: it requires no special equipment and is less likely to involve direct competition with motorised traffic for road space. In addition, there is no requirement for employers to provide special parking facilities or changing and showering facilities. Compared with other forms of physical activity, walking is a popular, familiar, convenient, readily repeatable, self-reinforcing, habit-forming activity and the main option for increasing physical activity in sedentary populations. 9,26 There is a dose–response curve to physical activity, so that the greatest health benefits are achieved when the least active undertake some physical activity. In industrialised countries, higher levels of mortality and morbidity from obesity and physical inactivity-related diseases disproportionately affect those in poorer communities. Walking is the most obvious, low-cost, immediate and normative means by which to increase physical activity and may, therefore, help to address health inequalities as well as be beneficial to people across all socioeconomic groups.

At the time of writing the proposal, there was a paucity of information about the design and implementation of interventions specifically promoting walking to work (as opposed to walking for pleasure, walking as part of a rehabilitation programme for a specific health problem, or active transport initiatives which include cycling and walking but tend to promote cycling). This continues to be the case. There was also little, if any, information about differences between small and large workplaces in the delivery or receipt of such interventions. Under such circumstances, the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for the evaluation of complex interventions emphasises the importance of undertaking a feasibility study before embarking on a phase 3 RCT. 41,42

Phase 1 focuses on existing evidence and theory to inform the development of the intervention and ways to evaluate it. Phase 2 involves testing the feasibility of a full-scale trial, including the ability to recruit and retain participants, the acceptability of the intervention and the methods used for its evaluation. An exploratory trial also provides a sound basis for calculating the sample size for a main trial. As workplace interventions are targeted at the cluster level, an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) is needed. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) group has indicated that the conduct and reporting of cluster trials has been poor, including failure to account for clustering in the planning of trials or to account for clustering in the sample size calculations and analysis. 43 Without published data from a full-scale cluster RCT of a workplace intervention to promote walking to work, there was no estimate of the ICC. Estimates from other studies in different settings or using different outcomes may provide some information, but if the ICC is underestimated, then a full trial may be considerably underpowered. Consequently, there was a need to calculate an estimate of the ICC. Furthermore, in order to perform a formal sample size calculation for a definitive cluster trial, a good estimate of likely recruitment and adherence rates and feasible differences in outcome was required. Within a cluster trial, the average cluster size dramatically affects the inflation factor required for sample size.

As well as contributing to statistical analyses, an exploratory trial offers opportunities for process evaluation and estimations of costs. Conducting a process evaluation within a feasibility study enables the examination of the context and delivery of and response to an intervention. Consideration can also be given to the facilitators of and barriers to its successful implementation. In addition, an assessment of the costs and potential benefits of an intervention is required when considering if it is likely to be adopted into routine practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study aim and objectives

The overall aim of the research was to build on existing knowledge and resources to develop an employer-led scheme to increase walking to work and to test the feasibility of implementing and evaluating it in a full-scale RCT.

The objectives were:

-

to explore with employees the barriers to and facilitators of walking to work

-

to explore with employers the barriers to and facilitators of employer-led schemes to promote walking to work

-

to use existing resources and websites to develop a Walk to Work information pack to train work-based Walk to Work promoters

-

to conduct an exploratory RCT of the intervention to:

-

pilot workplace and employee recruitment procedures

-

determine eligibility and consent rates

-

examine retention rates

-

pilot cost and outcome measures

-

inform a sample size calculation for a full RCT with estimation of potential feasible differences in outcome

-

gather information regarding variablility within and between workplaces

-

-

to pilot the use of accelerometers and global positioning system (GPS) monitors to measure:

-

eligible employees’ levels of MVPA

-

daily steps taken in walking

-

temporal pattern of physical activity (to identify when activity has increased and whether or not there is a compensatory decrease in activity at other times)

-

route taken and physical activity associated with journey

-

-

to explore any social patterning in uptake of walking to work, particularly in relation to socioeconomic status (SES), age and gender

-

to examine whether or not the size or type of workplace influences uptake of walking to work

-

to assess intervention costs to participating employers and employees

-

to provide preliminary evidence on the cost and economic benefits of the intervention to employers, employees and society.

Research design

During phase 1, a review of current resources that promoted walking (and in particular the benefits of walking to work) was undertaken, and three focus groups with employees plus three interviews with employers were conducted in workplaces (small, medium and large) outside of Bristol to finalise the intervention design. Phase 2 comprised an exploratory randomised trial in Bristol. The trial included an integral process evaluation and an assessment of intervention costs to participating employers and employees.

Setting

The intervention took place in Bristol. With a population of 433,100 people, Bristol is the largest city in the south-west and one of the eight core cities in England, excluding London. 44 The areas of highest population growth are all concentrated around the city centre and nearly half (46%) of all jobs are located in the city centre. 45 A substantial number of people in Bristol make short journeys to work by car. The 2011 census indicated that there are 44,000 people who travel < 5 km to work yet still go by car, of whom 13,000 drive < 2 km. 46 The intervention was implemented in 17 workplaces (eight small, five medium and four large). Seven workplaces received the intervention, and 10 workplaces constituted the control arm.

Workplace recruitment and randomisation

Workplaces were approached through BusinessWest for initial expressions of interest, including willingness to allocate employee time for study activities. A publicly available list of major employers was also used to identify large employers who were not on the BusinessWest mailing list. The e-mail contact included an information leaflet giving details of the study and the expectations of participating employers and employees, with the contact details of the research team. In addition, paper copies were sent out, as it was felt that, for some employers who receive large numbers of e-mails, the e-mail invitation might be deleted as low priority. The paper copy included a pre-paid reply envelope. Workplaces expressing an interest were sent a short questionnaire to enable purposive sampling of pairs (one intervention, one control), with each pair containing workplaces as similar as possible with respect to total number of employees (up to 50, 51–250, 250+),47 location characteristics and type of business. Assignment of workplaces to the intervention group employed computer-generated allocation.

Study participants

Employees living within 2 miles of the workplace (‘walking distance’) were given information about the study, by e-mail or letter as appropriate, to be distributed through the workplace with an invitation to participate. As the study progressed, it was felt that this was too restrictive, and a second round of recuitment was undertaken to include people who lived further away and were willing to incorporate some walking into their daily commute.

The Walk to Work intervention

The socioecological model informed the Walk to Work intervention, which was designed to encourage employers and employees to consider, and where possible address, the facilitators and barriers at each level of the socioecological model (Table 1).

| Socioecological level | Objective |

|---|---|

| Intrapersonal: individual knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviour | Increase employees’ knowledge of the benefits of walking to work |

| Identify and address perceived personal barriers | |

| Personal goal setting | |

| Change in travel to work routines | |

| Increase employers’ knowledge of the benefits of walk to work schemes | |

| Increase employers’ support for employee walk to work schemes | |

| Interpersonal: influence family, friends, colleagues | Identify and address specific barriers, e.g. school run |

| Colleagues and friends encourage each other to walk to work | |

| Increase ‘culture’ of walking to work | |

| Institutional: workplace policies, procedures and facilities | Enhance employer/workplace support for walking to work |

| Community: built, natural and social environment and local resources | Identify safe, feasible walking routes |

| Identify local groups and organisations to support and enhance walking to work | |

| Public policies: national and local initiatives, policies and plans | Increase employee and employer understanding of national and local policy context, walking initiatives and websites |

The intervention was based on the idea of recruiting and training, with the permission and support of the employer, a ‘champion’ (Walk to Work promoter) within each participating workplace to promote walking to work. The role of these Walk to Work promoters was to promote walking to work with their employer and among eligible employees in their workplace, to be ‘role models’ for the Walk to Work intervention and to be the recognised ‘point of contact’ for the Walk to Work intervention in their place of work.

The intervention focused on nine BCTs which included three categories (goals and planning, feedback and monitoring, and social support) as recommended by NICE. 37 The nine BCTs and the contact points at which they were used are listed in Table 2.

| Contact | BCT | Walk to Work intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (at week 1) | Intention formation | Employee decides to participate in the Walk to Work intervention and try to increase the amount of walking during the journey to and from work |

| Barrier identification | Promoter works with participant to determine the benefits of and barriers to walking to work and some proposed solutions. Participant booklet contains some examples of barriers and possible solutions | |

| Specific goal setting | Promoter and participant agree short- (weeks 1–3), intermediate- (in 1 month) and longer-term (in 3 months) goals. Worked examples provided in employee booklet | |

| Provide instruction | Promoter issues participants with booklet containing practical information, websites and a 10-week diary. Promoter booklet provides instructions on how to support the walkers | |

| Provide general encouragement | Promoter and colleagues provide encouragement and affirmation | |

| Self-monitoring of behaviour | Participants asked to keep an optional record of walking behaviour in a diary. Promoter issues each employee with optional pedometer to monitor steps walked per day and allow them to record steps in the diary | |

| 2 (from week 3) | Techniques in contact 1 as appropriate | Participants encourage and support each other in changing their behaviour. Promoter offers assistance, encouragement, guidance and motivation to the employee. Participants encouraged to seek support from people outside the workplace, such as family and friends |

| Plan social support | ||

| 3 (from week 5) | Techniques in contact 1, 2 as appropriate | Promoter reviews intentions and short-, intermediate- and long-term goals to better suit the employee as necessary |

| Review of behaviour goals | ||

| 4 (from week 7) | Techniques in contact 1, 2, 3 as appropriate | Promoter identifies situations likely to result in participants readopting old behaviour or failure to maintain walking and helps to plan to avoid or manage them, recognising that it take several attempts before walking to work becomes a habit |

| Relapse prevention |

Following the resource review and focus groups during phase 1, members of the research team developed booklets for Walk to Work promoters and participating employees. The packs included information about the health, environmental, economic and social benefits of walking to work derived from, for example, Walk4Life (www.walk4life.info), Walkit.com urban route planner and Living Streets (www.livingstreets.org.uk). Specific BCTs used were providing information on the link between walking and health; identifying barriers and ways to overcome them; goal setting and review of goals; prompting self-monitoring by use of a travel diary and pedometer; providing social support and encouragement; and relapse prevention. There is evidence that these techniques can effect behaviour change. 33,36

There were four main stages of the intervention:

-

Eligible employees were identified through workplace records (matching postcodes of workplace and home address, and checking for disability status or other disqualifying factors, e.g. delivery drivers).

-

Walk to Work promoters, either volunteers or those nominated by participating employers, were trained by expert members of the research team about the health, social, economic and environmental benefits of walking to work and how to identify and promote safe walking routes for employees. This half-day training took place at the University of Bristol for those who were able to attend. Those who were not were given an individual training session at their place of work. All Walk to Work promoters were given a booklet to guide them in their role, as well as Walk to Work booklets and pedometers for participating employees. They were also trained to access relevant websites and toolkits (e.g. Walkit.com, Living Streets). The aim was a maximum of 25 participants to each Walk to Work promoter.

-

The Walk to Work promoters were asked to discuss the Walk to Work intervention with study participants in their workplace and to ask those who were interested in walking to work to ‘sign up’ at this stage. The promoters were also encouraged to identify safe, feasible walking routes for their colleagues and to help them to set goals for walking to work.

-

Further encouragement was to be provided through four contacts from the Walk to Work promoter over the following 10 weeks (face to face, e-mail or telephone, as appropriate for the workplace). The Walk to Work promoters were encouraged to focus on specific BCTs as outlined in Table 2.

During the first contact with the Walk to Work promoters, those who agreed to try changing their travel behaviour were asked to identify barriers, propose solutions and develop a plan of how they might increase walking. This involved setting short-, intermediate- and long-term goals, for example walking 1 day per week in the first week and then increasing it during the course of the intervention. Participants were issued with a Walk to Work booklet and pedometer. They were also encouraged to complete diary sheets and record whether or not they had walked and, for those using pedometers, how many steps had been registered.

The promoters were asked to make three further contacts with participants, in person, by e-mail or by telephone according to the needs of the workplace and employees. Week 3 (contact 2) focused on social support from other people, such as colleagues, family or friends; week 5 (contact 3) stressed a review of goals to see whether they had been achieved or needed to be adjusted; and from week 7 (contact 4) until the end of the intervention, the aim was to prevent relapse by supporting and encouraging participants to continue working towards their goals.

Assessment of harms

Although this was a low-risk intervention, the team were mindful of the potential for harm in terms of road traffic accidents; personal safety of walkers where lighting is poor or there is potential for street crime; difficulties experienced by Walk to Work promoters, including disrupting usual working relationships and employers’ attitudes towards time taken out of usual work activities; and costs to employers, including disruption to work routines, of permitting the intervention during working hours. It was also possible that people with low activity and no history of walking would suffer initial muscle stiffness. To address these issues, the Walk to Work booklets included advice about setting appropriate goals and personal safety. Participating employers were given information in advance about the level of time commitments and the potential benefits of the scheme. Employers and employees were given the contact details of the principal investigator to report any adverse incidents, which would then be recorded and kept on file, with any relevant participants informed immediately (e.g. other employees taking a similar route across a dangerous road or through a dimly lit area with a high rate of street crime).

Outcome measures

Because this was a feasibility study, the outcomes did not relate to the effectiveness of the intervention but to the feasibility of, and requirements for, a full-scale trial. Several items were identified relating to the trial design, physical activity measurement, the context, delivery and receipt of the intervention, and the assessment of costs. The main study outcomes are listed in Table 3.

| Category | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Trial design | Workplace recruitment and retention rates |

| Employee eligibility, recruitment and retention rates | |

| Sample size calculation with estimation of potential clustering within workplaces and potential feasible differences in outcome | |

| Physical activity | Overall level of physical activity (cpm) |

| MVPA | |

| Temporal pattern of physical activity (when activity has increased and any compensatory decrease) | |

| Physical activity associated with the journey to work | |

| Process | Context, delivery and receipt of the intervention from the perspectives of employers, Walk to Work promoters, employees |

| Evidence of social patterning in uptake of walking to work (SES, age, gender, location) | |

| Identified interpersonal, intrapersonal, community and organisational facilitators of and barriers to walking to work | |

| Costs | Costs and benefits to employers of implementing the scheme |

| Costs and benefits to employees of participating in the scheme | |

| Health service use for general health problems and specific commute-related adverse events |

Assessment and follow-up

At the baseline data collection (DC1), participants in the intervention and control arms were asked to complete a questionnaire giving basic personal data, including postcode (to assess distance from home to work), job title, mode of transport to work, before- and after-work ‘routines’ affecting travel mode (e.g. school run), typical commuting costs, household car ownership, commute-related adverse events, health service use and views about walking. Eligible employees were also asked to wear an accelerometer for 7 days from waking in the morning until going to bed at night to provide an objective measurement of physical activity (including intensity and step counts), and a personal GPS receiver during the journey to and from work to confirm the duration of the journey and quantify its contribution to overall physical activity. The GPS recorded location and speed at 10-second intervals while outdoors. Participants were required to turn it on at the start of the journey to work and off when the journey home ended, as the battery life was only 24 hours. Participants were also given small chargers for the monitors, with written instructions. A £10 gift voucher was given to participants who returned accelerometers and GPS receivers.

Immediately post intervention (DC2), questionnaires were administered in the intervention and control arms to explore attitudes towards and experiences of walking to work, including perceived barriers and facilitators and emotional and physical well-being. Additional questions about the acceptability of the intervention were included for the intervention arm only. At 1-year follow-up (DC3), questionnaires, accelerometers and GPS receivers were administered again in the intervention and control arms (as per baseline protocol).

Measuring physical activity

To address the potential for the time of year to confound differences in the trial arms, the outcome data were collected simultaneously in each ‘pair’ of workplaces.

Physical activity was measured objectively using accelerometers (ActiGraph GT3X+; ActiGraph LLC, FL, USA) worn on a belt around the waist during waking hours for 7 days and removed for swimming and bathing. Accelerometers were set to record data at 30 Hz. The protocol, decisions and outcomes for analysis of accelerometer data are listed in Table 4.

| Decisions | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Initialising | Accelerometers initialised to start on day after distribution for 7 days including a weekend |

| Data collection points | DC1, DC3 |

| Protocol | Single ActiGraph GT3X+ monitor, worn around the waist over the same hip during waking hours (except when swimming/bathing/showering) |

| Wear time | 6.00 a.m. to midnight |

| Valid length of day | 10 hours (600 minutes) |

| Days required | 3 working days |

| Epoch length | 10 seconds |

| Zero counts | Bouts of 20 minutes of continuous/consecutive zero counts excluded |

| Spurious data | > 15,000 cpm |

| Missing data | No imputation |

| Activity cut-point | Moderate: 2000 cpm |

| Outcomes |

|

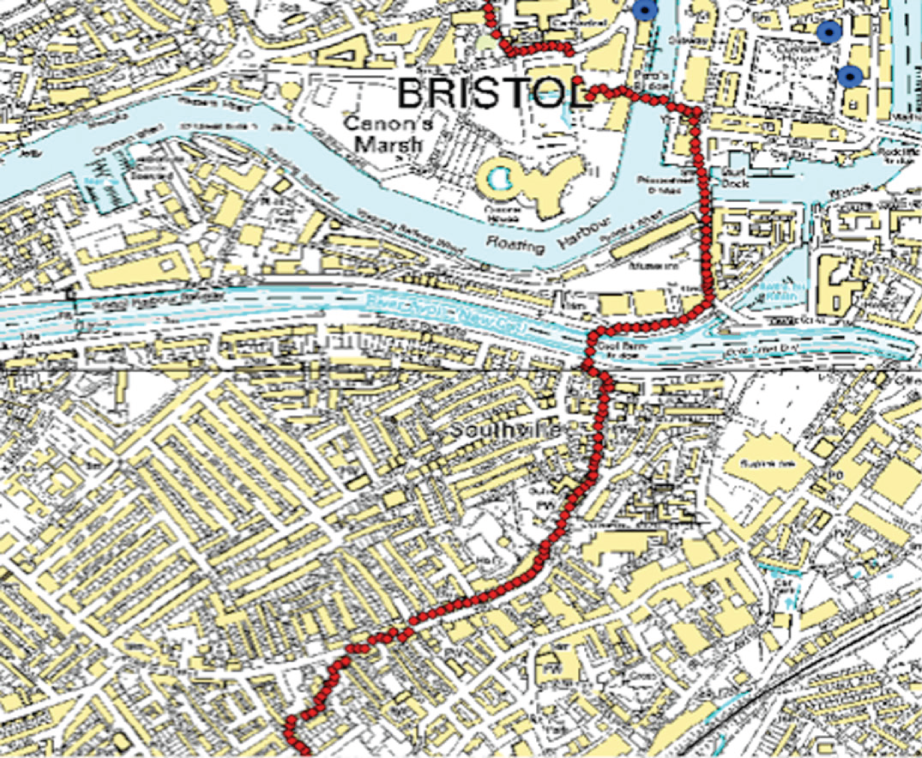

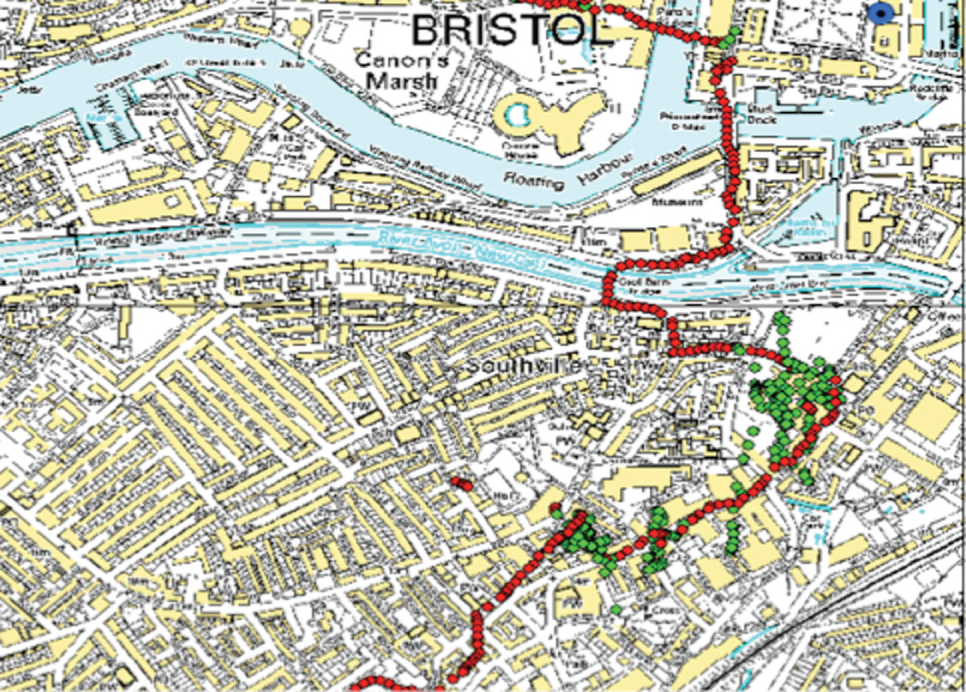

Participants also wore a personal GPS receiver (QStarz BT-Q1000XT, Qstarz International Co. Ltd, Taiwan) on the same belt during their commuting journeys for 7 days to allow the journey to and from work to be spatially described. GPS data were recorded at 10-second intervals and, where possible, the ‘assisted GPS’ mode was used to enhance the precision of the GPS location data.

Raw accelerometer data were downloaded using Actilife 6 software (ActiGraph LLC, FL, USA) and reintegrated to 10-second epochs for analysis and matching with GPS data. Reintegrated accelerometer data were processed using Kinesoft (v3.3.62; KineSoft, Saskatchewan, Canada) data reduction software to generate outcome variables. Continuous periods of 20 minutes of zero values were considered to be ‘non-wear’ time and removed. Outcome variables were physical activity volume [mean daily accelerometer counts per minute (cpm)] and intensity (MVPA and sedentary time) defined using validated thresholds (sedentary < 100 cpm; MVPA > 952 cpm). 48

Combining accelerometer and global positioning system data

Accelerometer and GPS data were combined (accGPS) based on the timestamp of the ActiGraph data. For measurement of the journeys to and from work, the participant’s workplace and home were geocoded using the full postcode, and imported into GIS software (ArcMap v10, Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). The merged accGPS files were then imported into ArcMap and journeys to and from work were visually identified and segmented from other accGPS data using the ‘identify’ tool. Journeys were identified as a continuous (or near-continuous) sequence of GPS locations between the participant’s home and workplace, and thus included trips to other destinations (e.g. supermarkets) if taken as part of the journey to or from work.

Baseline data analysis: the contribution of walking to work to physical activity

A cross-sectional study was undertaken using the baseline data to assess the contribution of walking to work to physical activity levels. 49 Analyses were confined to data recorded between 6.00 a.m. and midnight. Participants recorded travel mode to and from work for each day, and only days where participants used the same mode of transport both to and from work were included in the initial analyses, to allow classification as either an active commuter (walk or cycle) or a car user on each day. For participants who recorded using a mixed mode (e.g. walk and bus) for a journey, the mode of transport of the longest duration was considered to be their mode for that journey. If the modes were of equal duration, that day of data was excluded.

Participants who cycled to work (n = 19) were excluded from analyses because of the inability of waist-worn accelerometers to accurately record physical activity during cycling, as were the small number (n = 7) using ‘other’ modes of travel. Where a travel diary was not completed, usual travel mode was determined from the baseline behaviour questionnaire where possible (n = 10). Differences in physical activity between travel modes (walking/car) were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Paired samples t-tests were used to compare weekday and weekend values for total physical activity (cpm), MVPA and time spent sedentary, and to investigate differences in the volume of MVPA accumulated between overall accelerometer data and spatially segmented trips. Linear regression was used to explore the association between travel mode (walking/car) and total weekday physical activity (cpm) and MVPA (minutes per day). Models were adjusted for possible confounders [age, sex, education (educated to degree level or not)], and accelerometer wear time.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were largely descriptive. Reasons for non-eligibility, refusing consent and withdrawing from the study were fully documented. Within the intervention group, differences between employees who do and do not walk to work were explored, particularly in relation to SES, age and gender. Such exploration is hypothesis generating but may be investigated further in a full trial. In addition, such differences were examined to inform changes to the implementation or design of the ‘Walk to Work’ intervention and its evaluation prior to a full RCT.

Analyses of outcomes to be used as primary outcomes for a full trial were carried out at the employee level using multilevel regression models to account for the effects of clustering within workplaces. Models were adjusted for baseline and covariates including age, gender and SES. As an exploratory trial, the proposed study was not powered to provide a definitive comparison between the intervention and control groups. However, estimates of effect and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were generated. CIs informed feasible effect sizes to be incorporated into sample size calculations for a full trial. The intracluster correlation was estimated to provide some information about variability within and between workplaces to inform the sample size calculation for a full trial.

Process evaluation

The process evaluation examined the context, delivery and receipt of the intervention from the perspectives of employers, Walk to Work promoters and employees. Researcher notes were taken at each stage of the intervention, i.e. recruitment of workplaces, recruitment of study participants, and the recruitment and training of Walk to Work promoters. In addition, post-intervention interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of employees who increased walking to work and employees who did not. A senior manager and the Walk to Work promoter(s) in each workplace were also interviewed. Process data were also gathered through the behaviour questionnaires administered at baseline, immediately post intervention and at 1-year follow-up. An outline of the process evaluation is provided in Table 5.

| Stage | Method | Issues examined |

|---|---|---|

| Recruiting and randomising workplaces | Letter to all workplaces | Response rates Expressions of interest |

| ‘Matching’ and randomising | Ability to ‘match’ by size, type of workplace, location, proportion of eligible employees Randomisation process Response to randomisation |

|

| Baseline | Questionnaires | Interpersonal, intrapersonal, community and organisational facilitators of and barriers to walking to work |

| Interviews with employers | Views about employer-led schemes to encourage walking to work, perceived facilitators and barriers, context (including routes, working practices, car parking facilities at the workplace) | |

| Recruiting Walk to Work promoters | Baseline interview with employers in intervention arm | Rationale/method used for choice of Walk to Work promoter(s) |

| Training Walk to Work promoters | Researcher observations | Attendance Context Style and content of training Participants’ views of training/issues raised |

| Evaluation pro forma completed by trainers and Walk to Work promoters | ||

| Immediately post intervention | Questionnaires with all eligible employees (intervention and control arms) | As per baseline questionnaires for all eligible employees Additional questions for employees in workplaces that received the intervention about the context, delivery and receipt of the intervention |

| Interviews with purposive sample of employees who have increased walking to work and employees who have not | Views about the context, design, delivery and receipt of the intervention Interpersonal, intrapersonal, community and organisational facilitators of and barriers to walking to work |

|

| Interviews with manager in each participating workplace (intervention arm) | ||

| Interviews with Walk to Work promoters | ||

| One-year follow-up | Questionnaires with all eligible employees (intervention and control arms) | As per baseline questionnaires for all eligible employees |

Descriptive statistics were compiled, for example of recruitment and retention. Qualitative analyses employed the framework method of data management, with textual data placed in charts in relation to specific research questions and then scrutinised for differences and similarities within emerging themes, keeping in mind the context in which these arose.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Interviews with employers/managers from five workplaces, and focus groups with employees at three workplaces, were conducted during the phase 1 developmental work; these workplaces were not then recruited to the phase 2 exploratory trial. The aim was to explore the participants’ views of walking to work and, in particular, the proposed intervention and evaluation methods. During phase 2, baseline interviews were conducted with employers/managers (n = 12) of participating workplaces to understand the context of the workplaces, their views about travel to work, reasons for participating in the study and their opinions about the proposed intervention and its evaluation.

Immediately post intervention, 36 interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of participating employers and managers, Walk to Work promoters, and employees who had attempted to change their travel behaviour and those who had not. In addition, to further investigate issues relating to the recruitment of workplaces, semistructured interviews were conducted at six workplaces with employers/managers who had initially expressed an interest in the study but did not participate.

The focus groups and semistructured interviews were conducted in a private room at the workplaces of the participants. A topic guide was developed as part of the process evaluation to examine the context, delivery and receipt of the intervention. The topic guide allowed flexibility for participants to raise issues and follow their own train of thought, as well as including specific prompts. All interviews were audio recorded, fully transcribed and anonymised, and electronically stored in a secure folder.

The framework approach for data management was used to aid qualitative analysis. 50,51 The interview transcripts were read and reread, and textual data were placed in charts focusing on key research questions. The charts were scrutinised and each unit of data was subsequently coded. For example, the charts relating to the use of BCTs focused on barriers and enablers to walking to work, and the extent to which the BCTs facilitated change in travel behaviour. The charts relating to employers’ views of the intervention focused on employers’ views of the advantages and disadvantages of employer-led schemes to promote walking to work, and whether or not they felt that it was possible for employers to promote active travel.

Assessment of costs

Trainer time was costed using basic salary, national insurance and superannuation, and, where external consultants were employed, their day rate was divided by eight in order to identify a unit cost per hour. The number of promoters and number of individuals participating in the intervention at each workplace was recorded, which allowed us to estimate the number of promoter and employee booklets required. The booklets were printed by the University of Bristol print services and paid for by a small grant from Bristol City Council. The unit cost of pedometers, which were provided free of charge to the trial, was estimated from an online supplier (Be-Active Ltd, www.be-activeltd.co.uk/step-counter.htm).

The delivery of the promoter training day was planned to take place outside the workplace. However, it was not feasible for all of the promoters to attend these training days and therefore some promoter training was provided in the workplace. For training days outside the promoter workplace, costs included trainer and consultant time, lunch and drinks, and room hire. The unit cost of promoter time was calculated by dividing the upper quartile weekly earnings by the median number of hours worked per week. 52 The upper quartile was applied as it was believed that promoters were likely to be on a higher wage than the average worker. Promoter expenditure was also included with respect to travel to the promoter training day location. The cost per mile was calculated using the AA schedule of motoring costs. 53 Promoter training at the workplace included the cost of the trainer, travel costs to the workplace for the trainer, and promoter time.

Health service use in the past 4 weeks was self-reported by study participants at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Table 6 provides the unit costs that were used to value health service use. Primary care, including general practitioner (GP) visits, nurse visits, GP calls and nurse calls, was costed using national unit cost estimates. 54 All hospital-based care was costed using Department of Health reference costs. 55 Acupuncture and chiropractic care were costed using the NHS choices website. 56,57 Physiotherapy, chiropractic care, acupuncture, midwife visits, counselling and walk-in services were grouped together under ‘other care’ for the analysis. Routine dental and optician appointments were excluded from the analysis and a few health-care items were excluded because of lack of information on what service the participant had received. Medications were costed using the Prescription Cost Analysis. 58 Where medications could not be costed because of missing information on the number of days taken, it was assumed for chronic conditions and contraception that the medications were taken daily. For medications with missing information on the number of doses per day, an assumption of one dose was made. Any medications that could not be costed due to lack of sufficient information were excluded.

| Resource | Unit cost (£) |

|---|---|

| Face-to-face appointment with a doctor at the GP surgery | 43.00 |

| Face-to-face appointment with a nurse at the GP surgery | 13.69 |

| Telephone consultation with a doctor at the GP surgery | 26.00 |

| Telephone consultation with a nurse at the GP surgery | 8.28 |

| Hospital accident and emergency department | 108.00 |

| Hospital outpatient appointment | 106.00 |

| Hospital admission | 1096.00 |

| Face-to-face appointment with community physiotherapist | 33.00 |

| Face-to-face consultation with a counsellor at the surgery | 59.00 |

| Walk-in services not leading to admission | 41.00 |

| Antenatal or postnatal community midwife visit | 59.73 |

| Initial or further acupuncture session | 42.50 |

| Appointment with the chiropractor | 37.50 |

Self-assessed productivity based on the extent to which health problems affected it in the past 7 days was measured on a 10-point scale, where 1 indicated that health problems had no effect on an individual’s work and 10 indicated that health problems completely prevented work. Absence from work was also self-reported, whereby participants were asked to report the number of hours of work they had missed in the past 7 days because of health problems. 59

Information regarding the commute was recorded for 1 week at baseline and at 12-month follow-up in a travel diary. Time spent commuting by mode of transport, daily expenses (e.g. bus fare) associated with the commute and occasional expenses of commute (including bus and train passes and parking permits) were all recorded. A cost per mile of 0.665 pence53 and an average speed of 15.7 mph60 were used to calculate a cost per minute of driving, which was multiplied by the number of minutes driving in order to calculate the cost of commuting by car. Cost and duration of parking permits, bus and train passes were used to calculate weekly parking permit, bus and train costs. Car sharing was incorporated into the costs of car travel by dividing the cost of driving and the cost of a parking permit by the number of people in the car.

Study timetable and milestones

The study timetable is summarised in Table 7. To allow for seasonality, data collections took place concurrently in each ‘matched’ pair of workplaces (one in the intervention, the other in the control arm). In addition, baseline (DC1) and 1-year follow-up (DC3) data collections were undertaken in the same season (April to June).

| Milestone | October–December 2011 | January–March 2012 | April–June 2012 | July–September 2012 | October–December 2012 | January–March 2013 | April–June 2013 | July–September 2013 | October–December 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethics application and approval | ✓ | ||||||||

| Resource review | ✓ | ||||||||

| Phase 1 focus groups and interviews | ✓ | ||||||||

| Transcription and analysis | ✓ | ||||||||

| Phase 2 recruit and randomise workplaces | ✓ | ||||||||

| Prepare Walk to Work packs | ✓ | ||||||||

| DC1 | ✓ | ||||||||

| DC1 data entry | ✓ | ||||||||

| Identify eligible employees | ✓ | ||||||||

| Recruit and train Walk to Work promoters | ✓ | ||||||||

| Implement Walk to Work intervention | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Post-intervention data collection | ✓ | ||||||||

| Post-intervention interviews | ✓ | ||||||||

| DC2 data entry and transcription | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| One-year follow-up | ✓ | ||||||||

| DC3 data entry | ✓ | ||||||||

| Data analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Paper writing and dissemination | ✓ | ✓ |

Public involvement

The public were involved in shaping the intervention through the phase 1 focus groups with employees in three workplaces and the individual interviews with employers in five workplaces. Their views were sought on the design of the Walk to Work intervention and its evaluation, including the use of accelerometers and GPS monitors. Data from these focus groups and interviews shaped the intervention and its evaluation. Additional interviews were conducted with employers (n = 15) and employees (n = 33) following implementation of the intervention during the phase 2 exploratory trial. Participants identified a number of improvements that could be made, should an application for a full-scale trial be made: a simplified recruitment process, greater flexibility for attending the Walk to Work promoter training, and provision of additional information to employers in the intervention arm about changes they can make in the workplace to support employees who are attempting to increase walking to work. Representatives of non-academic organisations also influenced the study: a director of Sustrans advised on promoting active travel; a transport consultant with Bristol City Council helped to design and implement the training programme; and representatives of BusinessWest advised on, and supported, the recruitment of workplaces.

A feedback event was held in February 2014. Employees, employers and Walk to Work promoters attended a half-day event at which the research team presented findings, and participants were invited to give feedback on the intervention and its evaluation. Expressions of interest were collected for a public advisory group should a full-scale trial be funded for wider implementation.

Changes to protocol

There were no major changes to protocol. The number of workplaces recruited was increased because of the smaller-than-anticipated cluster size. Recruitment of employees was extended to include employees who lived further than 2 miles from the workplace. A request for a 3-month non-financial extension was granted towards the end of the study.

Chapter 3 Results

Wider context

Two important factors are likely to have influenced recruitment to the study and the actions and attitudes of participants. The study took place in the aftermath of a global banking crisis. 61 This resulted in economic insecurity, with businesses restructuring and an increase in unemployment. Under these circumstances, health promotion interventions may be seen as less important to employers and employees than the survival of businesses and the retention of jobs. Secondly, the intervention was implemented during the wettest summer in the UK for 100 years. 62 Weather conditions have been identified as an important barrier to walking and this is likely to have been exacerbated by the weather during the summer of 2012.

Workplace recruitment and retention

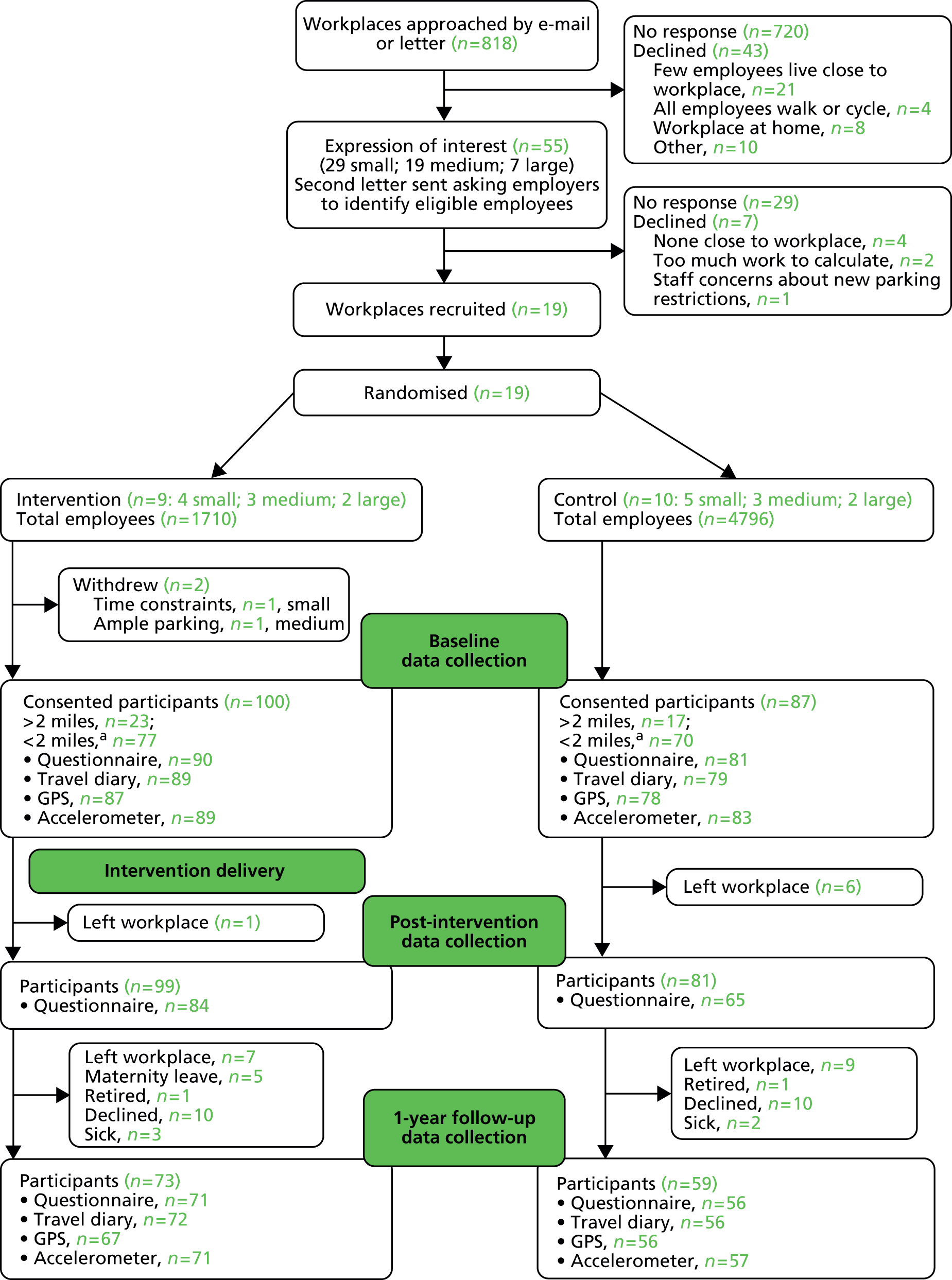

A summary of workplace recruitment is included in Figure 1. Following an e-mail sent through the Chambers of Commerce contact list, and a paper mailing to workplaces included in a publicly available list of large employers, 55 workplaces expressed an interest in the study. Small and medium-sized workplaces appeared more interested than large workplaces. A short questionnaire was sent to those expressing an interest, asking about the type of business and size of workplace, and with a request to assess the number of employees living within 2 miles of the workplace by inserting relevant postcodes into a calculator on the Walkit.com website. A list of the first four digits of postcodes likely to contain relevant employees was also supplied, to reduce the number of postcodes to be checked. Nevertheless, this task appears to have been too onerous for some employers, and 19 workplaces returned the completed questionnaire, of which 17 continued through to DC1 (Table 8). These workplaces were willing to continue throughout the study, although in one large factory in the control arm (workplace 28) there was only one participant, who retired before the 1-year follow-up data collection.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials: Walk to Work flow of workplaces and participants. a, Target participants were those living < 2 miles from the workplace who did not walk or cycle to work.

| Workplace ID | Sizea | Type of businessb | Location | Trial arm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Small | Professional, scientific and technical | City centre | Intervention |

| 12 | Small | Manufacturing | City centre | Control |

| 13 | Small | Professional, scientific and technical | City centre | Control |

| 14 | Small | Professional, scientific and technical | City centre | Intervention |

| 15 | Small | Professional, scientific and technical | City centre | Control |

| 20 | Small | Professional, scientific and technical | Suburban | Intervention |

| 21 | Small | Transportation | Suburban | Control |

| 22 | Small | Professional, scientific and technical | City centre | Control |

| 17 | Medium | Education | Suburban | Control |

| 18 | Medium | Professional, scientific and technical | City centre | Intervention |

| 19 | Medium | Accommodation and food services | City centre | Control |

| 23 | Medium | Manufacturing | City centre | Intervention |

| 24 | Medium | Education | City centre | Control |

| 25 | Large | Public administration | City centre | Intervention |

| 26 | Large | Manufacturing | City centre | Control |

| 27 | Large | Financial and insurance activities | City centre | Intervention |

| 28 | Large | Manufacturing | Suburban | Control |

Participant recruitment and retention

Characteristics of the 187 participants recruited are summarised in Table 9 and the flow of workplaces and participants through the study is described in Figure 1. There was a balance of males and females and an overall mean age of 37.8 years, with a range from 17.3 to 67 years. The participants were predominantly white (77%), well educated (with 60% having a degree or higher qualification) and employed in sedentary (desk-based) occupations.

| Characteristics | Control (N = 87), n (%) | Intervention (N = 100), n (%) | All (N = 187), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 46 (52.9) | 43 (43.0) | 89 (47.6) |

| Female | 41 (47.1) | 57 (57.0) | 98 (52.4) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 36.8 (± 12.4) | 38.7 (± 11.7) | 37.8 (± 12) |

| Range | 17.3–64.8 | 21.6–67 | 17.3–67 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White British | 65 (74.7) | 79 (79.0) | 144 (77.0) |

| White other | 11 (12.6) | 8 (8.0) | 19 (10.2) |

| Mixed ethnic group | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.1) |

| Asian or Asian British | 3 (3.4) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) |

| Chinese | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Not disclosed/missing | 7 (8.1) | 10 (10.0) | 17 (9.1) |

| Education | |||

| PhD, master’s degree, NVQ level 5 | 20 (23.0) | 17 (17.0) | 37 (19.8) |

| Degree, NVQ level 4 | 34 (39.1) | 41 (41.0) | 75 (40.1) |

| BTEC (Higher) or equivalent | 4 (4.6) | 3 (3.0) | 7 (3.7) |

| GCE ‘A’ Level, NVQ level 3 | 7 (8.0) | 13 (13.0) | 20 (10.7) |

| BTEC (National) or equivalent | 5 (5.8) | 2 (2.0) | 7 (3.7) |

| GCSE grades A to C or equivalent | 8 (9.2) | 9 (9.0) | 17 (9.1) |

| No formal qualifications | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 2 (1.1) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Not disclosed/missing | 9 (10.3) | 12 (12.0) | 21 (11.2) |

| Income | |||

| Up to £10,000 | 6 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.2) |

| £10,001–20,000 | 7 (8.1) | 9 (9.0) | 16 (8.6) |

| £20,001–30,000 | 7 (8.1) | 15 (15.0) | 22 (11.8) |

| £30,001–40,000 | 14 (16.1) | 15 (15.0) | 29 (15.5) |

| £40,001–50,000 | 11 (12.6) | 13 (13.0) | 24 (12.8) |

| More than £50,000 | 24 (27.6) | 26 (26.0) | 50 (26.7) |

| Don’t know | 9 (10.3) | 6 (6.0) | 15 (8.0) |

| Not disclosed/missing | 9 (10.3) | 16 (16.0) | 25 (13.4) |

| Occupation activity level | |||

| Sedentary | 57 (65.5) | 83 (83.0) | 140 (74.9) |

| Standing | 20 (23.0) | 4 (4.0) | 24 (12.8) |

| Manual | 3 (3.5) | 3 (3.0) | 6 (3.2) |

| Not disclosed/missing | 7 (8.0) | 10 (10.0) | 17 (9.1) |

Walk to Work promoters’ recruitment and training

Walk to Work promoters were recruited in each of the workplaces randomised to the intervention arm (Table 10). Of the 10 Walk to Work promoters trained, six were female and four were male.

A single half-day group training event for all Walk to Work promoters had been planned. However, it did not prove possible to timetable a training event to suit all workplaces. Consequently, two smaller training events were organised at the University of Bristol, and three visits were made to individual workplaces for on-site training.

| Workplace ID | Workplace sizea | Gender | Training venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Small | Female | Workplace |

| 14 | Small | Male | University |

| 20 | Small | Male | University |

| 18 | Medium | Female × 2 | University |

| Male × 2 | Workplace | ||

| 23 | Medium | Female | Workplace |

| 25 | Large | Male | University |

| 27 | Large | Female × 3 | University |

At the training, the Walk to Work promoters received general information about the benefits of walking to work and were taken through the stages of a Walk to Work promoters’ booklet outlining their role and the BCTs to be used with participants during each of the four contacts over the 10-week intervention period. The session ended with further information about publicly available resources and websites that could be also be accessed and used to promote walking.

Qualitative data from the post-intervention (DC2) interviews suggest that the promoters found the training day useful: ‘I thought it was useful, I mean a lot of it was sort of stuff I knew already but it all sort of brought it together really’ (male, aged 30, workplace 25); ‘It was good, it was really informative that day’ (male, aged 29, workplace 20). One promoter (female, aged 45, workplace 27) commented that ‘It was good to work with other people from other companies’. Overall, the promoters found that their booklets were ‘well set out’ (male, aged 38, workplace 18) and gave clear guidance on the role: ‘It’s not too intimidating, it’s quite accessible, it’s got a, sort of a structure you can work through, when the Walk to Work promoter meets with the employees to discuss and set goals and review them’ (male, aged 30, workplace 25). However, one promoter said that he was ‘disappointed with myself getting out of sync and not following it properly because it guides you well but I lost sight of which week I was on and what I was supposed to be achieving’ (male, aged 38, workplace 18). Another suggested that more support and encouragement for the promoters would have been helpful, for example ‘each week, like, e-mail a newsletter just to remind you about the entire thing and kind of give you more information to convince you to keep on doing it’ (male, aged 29, workplace 20).

Assessment of costs

Intervention costs

The fixed costs of the intervention are provided in Table 11.

| Equipment/printing | Number of units | Cost per unit (£) | Total cost (£) | Total academic cost (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Printing cost of employee booklet | 20 | 0.81 | 16.20 | |

| Printing cost of promoter booklet | 10 | 0.81 | 8.10 | |

| Pedometers | 20 | 9.80 | 196.00 | |

| Total | 220.30 |

A breakdown of the cost of each type of training is provided in Table 12.

| Number of units | Cost per unit (£) | Total cost (£) | Distance (miles) | Cost per mile (£) | Total cost (£) | Academic cost (£) | Business cost (£) | Promoter cost (£) | Total cost (£) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter training day at Bristol University | ||||||||||

| 31 May 2013 | ||||||||||

| Research associate | 3.5 | 28.86 | 101.01 | 101.01 | 101.01 | |||||

| Research fellow | 3.5 | 33.57 | 117.50 | 117.50 | 117.50 | |||||

| Consultant 2 | 3.5 | 87.50 | 306.25 | 306.25 | 306.25 | |||||

| Room hire | 1 | 395.00 | 395.00 | 395.00 | 395.00 | |||||

| Lunch and drinks | 1 | 60.50 | 60.50 | 60.50 | 60.50 | |||||

| Promoter workplace 18 | 5 | 19.05 | 95.25 | 10 | 0.665 | 6.65 | 95.25 | 6.65 | 101.90 | |

| Promoter workplace 14 | 5 | 19.05 | 95.25 | 10 | 0.665 | 6.65 | 95.25 | 6.65 | 101.90 | |

| Subtotal | 1184.06 | |||||||||

| 11 July 2013 | ||||||||||

| Research associate | 3.5 | 28.86 | 101.01 | 101.01 | 101.01 | |||||

| Research fellow | 3.5 | 33.57 | 117.50 | 117.50 | 117.50 | |||||

| Consultant 2 | 3.5 | 87.50 | 306.25 | 306.25 | 306.25 | |||||

| Room hire | 1 | 395.00 | 395.00 | 395.00 | 395.00 | |||||

| Lunch and drinks | 1 | 61.95 | 61.95 | 61.95 | 61.95 | |||||

| Promoter workplace 20 | 5 | 19.05 | 95.25 | 10 | 0.665 | 6.65 | 95.25 | 6.65 | 101.90 | |

| Promoter workplace 27 | 5 | 19.05 | 95.25 | 10 | 0.665 | 6.65 | 95.25 | 6.65 | 101.90 | |

| Promoter workplace 27 | 5 | 19.05 | 95.25 | 10 | 0.665 | 6.65 | 95.25 | 6.65 | 101.90 | |

| Promoter workplace 27 | 5 | 19.05 | 95.25 | 10 | 0.665 | 6.65 | 95.25 | 6.65 | 101.90 | |

| Promoter workplace 25 | 5 | 19.05 | 95.25 | 10 | 0.665 | 6.65 | 95.25 | 6.65 | 101.90 | |

| Subtotal | 1491.21 | |||||||||

| Promoter training day at workplaces | ||||||||||

| 12 July 2013 | ||||||||||

| Research associate | 1.5 | 28.86 | 43.29 | 2 | 0.665 | 1.33 | 44.62 | 44.62 | ||

| Promoter workplace 11 | 1 | 19.05 | 19.05 | 19.05 | 19.05 | |||||

| Subtotal | 63.67 | |||||||||

| 26 July 2013 | ||||||||||

| Research associate | 1.5 | 28.86 | 43.29 | 6 | 0.665 | 3.99 | 47.28 | 47.28 | ||

| Promoter workplace 23 | 1 | 19.05 | 19.05 | 19.05 | 19.05 | |||||

| Subtotal | 66.33 | |||||||||

| 6 August 2013 | ||||||||||

| Research associate | 1.5 | 28.86 | 43.29 | 4 | 0.665 | 2.66 | 45.95 | 45.95 | ||

| Promoter workplace 18 | 1 | 19.05 | 19.05 | 19.05 | 19.05 | |||||

| Subtotal | 65.00 | |||||||||

| Total | 2870.27 | |||||||||

Cost per employer and employee

The cost of the intervention per workplace and employee is presented in Table 13. Costs varied because of different numbers of promoters in each workplace and depending on the number of employees participating in the intervention from each workplace. The location of promoter training also had an impact on the cost per workplace and per employee. The cost of promoter training days at the workplace was lower, as the training was shorter and promoters took less time off work. The costs per workplace and per employee by workplace size demonstrate that there is no clear association between employer size and cost per participating employee, as some very large employers were not successful in recruiting a large number of employees to participate.

| Workplace size | Workplacea | Cost per workplace (£) | Cost per employee (£) | Cost per employee by workplace size (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large | 27 | 958.38 | 159.73 | 159.83 |

| 25 | 320.27 | 160.14 | ||

| Medium | 23 | 66.33 | N/Ab | 191.85 |

| 18 | 701.09 | 175.27 | ||

| Small | 20 | 341.49 | 85.37 | 130.16 |

| 14 | 624.67 | 208.22 | ||

| 11 | 75.09 | 75.09 | ||

| Average cost per employee | 154.37 | |||

| Average cost per workplace | 441.05 | |||

| Total cost | 3087.32 | |||

Health service use

Table 14 provides the mean number of units and cost of each service per participant, by group and time point, for each category. There were a total of 100 participants in the intervention group and 87 participants in the control group. At baseline, the response rate varied between 86% and 88% in the intervention group, and 91% and 93% in the control group, depending on the question asked. At follow-up, response rate varied between 70% and 71% in the intervention group, and 59% and 62% in the control group. On average, the response rate was 19% lower in the intervention group and 35% lower in the control group at follow-up.

| Health service | Mean units | Mean (SD) cost | Mean units | Mean (SD) cost | Incremental difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 86a) | Control (n = 79b) | ||||

| Baseline | |||||

| GP appointment | 0.17 | £7.41 (£18.79) | 0.15 | £6.53 (£18.33) | £0.88 (−£4.82 to £6.58) |

| Nurse appointment | 0.09 | £1.26 (£3.98) | 0.05 | £0.68 (£3.00) | £0.57 (−£0.51 to £1.66) |

| GP telephone call | 0.02 | £0.60 (£3.94) | 0.05 | £1.30 (£7.04) | −£0.70 (−£2.43 to £1.04) |

| Nurse telephone call | 0.01 | £0.10 (£0.89) | 0.00 | £0.00 (£0.00) | £0.10 (−£0.10 to £0.29) |

| A&E visits | 0.00 | £0.00 (£0.00) | 0.05 | £5.33 (£23.55) | −£5.33 (−£10.32 to –£0.35) |

| Hospital outpatient visits | 0.05 | £4.82 (£27.41) | 0.06 | £6.54 (£25.67) | −£1.73 (−£9.81 to £6.36) |

| Other care | 0.14 | £5.06 (£18.59) | 0.14 | £4.65 (£30.80) | £0.42 (−£7.33 to £8.17) |

| Medication | £4.29 (£18.99) | £2.47 (£5.72) | £1.82 (−£2.54 to £6.18) | ||

| Total | £20.94 (£40.58) | £26.80 (£63.18) | −£5.86 (−£22.29 to £10.56) | ||

| Intervention (n = 70c) | Control (n = 51d) | ||||

| Follow-up | |||||

| GP appointment | 0.09 | £3.69 (£14.16) | 0.30 | £12.98 (£24.71) | −£9.30 (−£16.29 to –£2.30) |

| Nurse appointment | 0.10 | £1.37 (£4.14) | 0.16 | £2.15 (£5.73) | −£0.78 (−£2.55 to £1.00) |

| GP telephone call | 0.07 | £1.86 (£8.07) | 0.04 | £1.02 (£7.28) | £0.84 (−£1.99 to £3.66) |

| Nurse telephone call | 0.00 | £0.00 (£0.00) | 0.00 | £0.00 (£0.00) | – |

| A&E visits | 0.03 | £3.04 (£18.00) | 0.02 | £2.00 (£14.70) | £1.04 (−£4.91 to £6.99) |

| Hospital outpatient visits | 0.10 | £10.60 (£40.95) | 0.02 | £1.96 (£14.42) | £8.64 (−£2.92 to £20.19) |

| Other care | 0.26 | £10.10 (£32.32) | 0.09 | £2.98 (£15.51) | £7.12 (−£2.93 to £17.18) |

| Medication | £7.05 (£23.21) | £2.52 (£4.82) | £4.53 (−£1.83 to £10.88) | ||

| Total | £36.89 (£77.50) | £18.45 (£30.91) | £18.44 (−£5.41 to £42.29) | ||

At baseline, the mean total cost of health services, including medications, in the intervention group was smaller than for the control group at £20.94 (SD £40.58), compared with £26.80 (SD £63.18). At follow-up, a larger mean cost of health service use was observed in the intervention group at £36.89 (SD £77.50) when compared with the control group at £18.45 (SD £30.91), but this difference was not statistically significant.

Commute

A summary of the commute data is presented below in Table 15.

| Mode of transport | Mean (SD) daily minutes | Mean (SD) daily minutes | Incremental difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 89) | Control (n = 79) | ||

| Baseline | |||

| Walked | 14.33 (12.43) | 12.03 (12.56) | 2.31 (−1.50 to 6.12) |

| Cycled | 1.49 (3.52) | 1.92 (4.34) | −0.44 (−1.64 to 0.76) |

| Bus | 2.14 (7.93) | 0.95 (4.49) | 1.19 (−0.81 to 3.19) |

| Train | 0.67 (6.36) | 1.22 (6.25) | −0.55 (−2.48 to 1.37) |

| Car | 7.16 (11.75) | 8.56 (12.05) | −1.40 (−5.03 to 2.23) |

| Other | 0.02 (0.17) | 0.33 (2.02) | −0.31 (−0.74 to 0.11) |

| Inactive travel | 10.00 (16.19) | 11.07 (14.61) | −1.08 (−5.80 to 3.64) |

| Total | 25.81 (15.48) | 25.02 (15.35) | 0.79 (−3.91 to 5.50) |

| Intervention (n = 71) | Control (n = 55) | ||

| Follow-up | |||

| Walked | 12.20 (10.40) | 9.21 (11.47) | 2.99 (−0.88 to 6.86) |

| Cycled | 1.81 (4.34) | 2.39 (5.12) | −0.58 (−2.25 to 1.09) |

| Bus | 3.67 (9.60) | 0.83 (3.38) | 2.84 (0.15 to 5.52) |

| Train | 0.56 (4.75) | 2.11 (7.78) | −1.55 (−3.77 to 0.68) |

| Car | 9.64 (16.23) | 10.88 (14.10) | −1.24 (−6.70 to 4.21) |

| Other | 0.12 (0.99) | 0.20 (1.52) | −0.09 (−0.53 to 0.36) |

| Inactive travel | 13.99 (18.73) | 14.03 (17.73) | −0.04 (−6.55 to 6.47) |

| Total | 28.00 (15.76) | 25.63 (16.22) | 2.37 (−3.31 to 8.04) |

At baseline, 89% of participants in the intervention group and 91% of participants in the control group provided information on their weekly commute to and from work. At follow-up, 71% of the intervention group and 63% of the control group provided this information. At baseline, the average time commuting to work daily was similar between groups, at between 25 and 26 minutes for both. Results showed that, at baseline, those in the intervention group spent around 2 minutes longer walking per day; however, this result was not statistically significant. Time spent on inactive travel, which included commuting by bus, train, car or other mode of transport, was around 1 minute longer in the control group; however, this was also not a significant result. At follow-up, there was a trend for higher mean daily minutes of walking [12.2 minutes (SD 10.4 minutes)] in the intervention group than in the control group [9.21 minutes (SD 11.47 minutes)], but this difference was not statistically significant.

As shown in Table 16, at baseline the mean daily commute cost was £1.79 (£3.59) in the intervention group and £2.57 (£5.81) in the control group, representing a –£0.78 (95% CI –£2.23 to £0.66) difference. At follow-up, the commute cost increased in both groups. In the intervention group, the mean daily cost was £2.66 (£4.32), and it was £3.64 (£12.16) in the control group. This represented a slightly larger difference than at baseline at –£0.98 (95% CI –£4.06 to £2.10), yet this difference was not significant.

| Time point | Mean (SD) daily cost | Mean (SD) daily cost | Incremental difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 90) | Control (n = 80) | ||

| Baseline | |||

| Daily commute cost | 1.79 (3.59) | 2.57 (5.81) | −0.78 (−2.23 to 0.66) |

| Intervention (n = 71) | Control (n = 55) | ||

| Follow-up | |||

| Daily commute cost | 2.66 (4.32) | 3.64 (12.16) | −0.98 (−4.06 to 2.10) |

Productivity

Response rates to the questions on self-rated productivity and absenteeism declined over the study period (Table 17). At baseline, approximately 85% of the intervention group and 91% of the control group answered these questions. At 1-year follow-up, response rates had fallen to approximately 70% in the intervention group and 61% in the control group.

| Time point | Intervention | Control | Incremental difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | ||

| Self-assessed productivity | |||||

| Baseline | 83 | 1.65 (1.73) | 80 | 1.55 (1.44) | 0.10 (−0.39 to 0.59) |

| Post intervention | 79 | 1.99 (2.00) | 61 | 2.05 (2.22) | −0.06 (−0.77 to 0.65) |

| Follow-up | 70 | 1.51 (1.41) | 54 | 2.07 (2.24) | −0.56 (−1.21 to 0.09) |

| Hours of work missed | |||||

| Baseline | 88 | 0.32 (1.43) | 78 | 0.32 (1.56) | 0.00 (−0.46 to 0.46) |

| Post intervention | 79 | 1.04 (3.81) | 60 | 0.58 (1.86) | 0.45 (−0.60 to 1.51) |

| Follow-up | 69 | 0.84 (4.58) | 53 | 0.17 (1.10) | 0.67 (−0.60 to 1.94) |

At baseline, the mean productivity score in both the intervention and control groups was low [1.65 (SD 1.73) and 1.55 (SD 1.44), respectively], indicating little self-perceived impact of health on productivity. There were no clear trends in productivity over the study period. While productivity scores were slightly lower (better) in the intervention group at 1-year follow-up, the difference was not statistically significant [1.51 (SD 1.41) and 2.07 (SD 2.24), respectively; p = 0.09].

The average number of hours missed from work because of health problems was the same across both groups at baseline at around 0.32 hours. Immediately post intervention and at 1-year follow-up, the mean number of hours missed was higher in the intervention group, at 1.04 hours (SD 3.81 hours) compared with 0.58 hours (SD 1.86 hours) post intervention and 0.84 hours (SD 4.58 hours) compared with 0.17 hours (SD 1.10 hours) at follow-up. However, neither of these differences was statistically significant.

Physical activity outcomes

Although the study was not powered to detect effectiveness, some statistical analyses were conducted to identify whether or not there was any evidence of promise that the intervention could increase walking to work and hence justify an application for a full-scale RCT.