Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3001/16. The contractual start date was in September 2012. The final report began editorial review in August 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Barber et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Physical activity and the preschool years

The preschool years are considered a critical period for establishing healthy lifestyle behaviours such as physical activity. 1 The benefits of engaging in regular physical activity in the preschool years are numerous, with one of the most significant being the promotion of healthy weight and prevention of obesity during childhood. 2–5 The prevalence of overweight and obesity in preschool children has doubled in recent decades,6 and in the mid-2000s over one-third of preschool children in the UK and USA were overweight or obese. 7 Despite the widespread belief that the prevalence of childhood obesity is still escalating, contemporary high-quality studies suggest a slowing in the rate of rise in some developed countries, including the UK. 8,9 Although this appears promising, levels still remain high and are heterogeneous within countries. 8 For example, in England childhood obesity is higher in urban areas, in children from deprived backgrounds and in certain ethnic minority groups including black and Asian populations. 10 South Asian school-aged children are reported to have substantially lower levels of physical activity than white Europeans. 11 These particularly low levels may contribute to the increased risks of obesity, coronary heart disease (CHD) and diabetes seen in South Asian adults living in the UK. 12 The cause of obesity has not been fully identified but it is probable that reduced physical activity and increased sedentary behaviour are important contributing factors. 3,4 Lower time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during the early years has been shown to be associated with higher fat mass (+0.75 kg for girls and +0.61 kg for boys in the lowest compared with the highest quartiles). 2 Additionally, reduced MVPA at age 5 years increases fat mass at age 8 and 11 years: for every 10 minutes per day of MVPA at age 5 years, fat mass has been reported to decrease by 0.2 kg at age 8 and 11 years. 2 Furthermore, levels of MVPA have been inversely associated with measures of central adiposity in children aged 3–8 years. 5

Observational and experimental studies have shown that regular physical activity has other important health and social implications for preschool children. Physical activity is valuable for developing motor skills, enhancing bone and muscle development and developing social competence. 13,14 Furthermore, regular physical activity in this age group may also have beneficial effects on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors such as blood pressure and blood lipids. 14–16 Finally, levels of physical activity track through early childhood17 and into adulthood;18,19 therefore, establishing habitual physical activity early in life may be key to remaining active throughout the lifespan.

Current levels of habitual physical activity in preschool children in the UK, and internationally, are unclear. Methodological differences in the objective measurement of physical activity have resulted in a wide variation of levels reported. Daily physical activity levels have been reported to be as low as 90 minutes20 and as high as 569 minutes21 in the UK. Levels of 127 minutes per day have been reported in Belgium, Australia and the USA22–24 and levels of 402 minutes per day have been reported in Portugal and the USA. 23,25 This large variation in reported physical activity behaviour, even within countries, is likely to be because of the application of different intensity cut-points to accelerometry data (i.e. cut-point non-equivalence26) between different research groups, rather than actual behavioural differences within and between countries. Despite the lack of clarity regarding the extent to which preschoolers engage in physical activity, it has been clearly identified that health-enhancing physical activity declines markedly during childhood,27 with this decline potentially beginning in the early years. 28 Therefore, the promotion of physical activity in the preschool years is critical to slow the rate of this age-related decline.

UK physical activity policy for preschool children

The importance of engaging preschool children in daily physical activity was brought to the forefront in July 2011 with the publication of the UK’s first physical activity guidelines for the under 5s in the Chief Medical Officer’s (CMO) report Start Active, Stay Active. 29 The report recommends 180 minutes of physical activity (light, moderate and vigorous intensity) each day and states that the volume of physical activity is more important than the intensity. Physical activity should be spread throughout the day and should include active play (activities that involve movements of all the major muscle groups) and the development of locomotor, stability and object-control skills.

These guidelines are a significant step towards recognising the importance of physical activity promotion for preschool children; however, guidelines themselves do not change behaviour. The determinants of physical activity in young children are unclear. One systematic review that studied correlates of preschoolers’ physical activity found that boys were more active than girls and that a parent’s level of physical activity and a child’s time spent outdoors had a positive association with physical activity. 30 Members of our team (SEB and DDB) are currently updating this systematic review. The preliminary findings confirm the results from the previous review with regard to sex and time spent outdoors. Additionally, the individual preschool that the child attends has been associated with physical activity level, suggesting policy and environmental impacts on preschool activity levels. This finding is further supported by a systematic review of physical activity in school-aged children, which suggests that environments allowing easy access to physical activity are important. 31 The CMO report states that a ‘concerted and committed action to create environments and conditions that make it easier for people to be more active’ is needed (p. 8). 29 The guidelines also highlight the need for activities to promote movement in the early years and the need to recognise that local communities can have a strong influence on behaviour. The report suggests that investment should be made in community-level programmes in settings such as school playgrounds. We have developed and pilot tested such an intervention, Preschoolers in the Playground (PiP), in the city of Bradford, an area of ethnic diversity and social deprivation in West Yorkshire, UK.

Components of successful interventions

The literature identifies several features likely to lead to successful physical activity interventions and these have informed the development of the PiP intervention.

Theoretical underpinning

The utility of basing health promotion interventions on sound theoretical frameworks is well expounded. 32 A systematic review33 conducted by members of our team (CDS, HJM) reported that the predominant behaviour change theory used in successful childhood obesity prevention interventions is Bandura’s social cognitive theory. 34,35 This theory describes behaviour change as an interaction between personal, environmental and behavioural factors. Personal and environmental factors provide the framework for understanding behaviour. The personal concepts include skills, self-efficacy, self-control and outcome expectancies whereas the environmental concepts include availability (e.g. provision of space for physical activity) and opportunity for social support (e.g. a group setting). The review also reported that providing information on behaviour–health links appeared to be an important component in childhood obesity prevention and physical activity interventions.

An outdoor setting

Enhancing environmental and cultural practices that support children to be more active throughout the day are thought to be promising strategies to prevent childhood obesity, particularly if the children perceive the activities as being fun. 36 Time spent outdoors has been shown to correlate with physical activity levels in preschool children30 and outdoor play is associated with a lower risk of overweight. 37 School and preschool playgrounds provided a potential opportunity to intervene to increase physical activity levels. Indeed, in school-aged children, outdoor playground interventions have been shown to increase daily physical activity. 38,39 Furthermore, some studies have reported that factors related to increased MVPA in playground interventions include greater provision of equipment38,39 and greater play space per child. 40 However, a recent systematic review concluded that further research is needed to elucidate which intervention strategies and playground characteristics are most effective. 41 Interventions in preschool playgrounds supervised by preschool teachers have had mixed success. Adding portable play equipment in a US preschool playground increased physical activity levels in 3- to 5-year-olds. 42 In contrast, in Belgium, no change in physical activity levels of 4- and 5-year-olds was reported after providing playground markings or play equipment or both in the preschool playground. 43 The authors concluded that creating an activity-friendly environment may not be sufficient to promote physical activity in preschoolers and regular infusions of different equipment with more guidance and encouragement from adults to play in an active way are required. Currently, there is no evidence regarding preschool playground interventions in the UK.

Seasonality and weather conditions can present barriers to participation in outdoor play for children. 44,45 Emerging literature is beginning to focus on the importance of season in physical activity promotion and weight management. Two recent studies in the UK21 and Denmark46 have examined seasonal variations in preschool children’s physical activity levels. In both studies, overall, children were significantly less active during the winter months than in the spring, summer and autumn. The Danish study also examined differences in activity patterns across seasons according to body mass index (BMI) status. Children in the highest tertile of BMI had a flatter activity profile throughout the year than children in the lowest tertile. Those in the lowest tertile showed a curved pattern, with activity peaking between June and August at around 200 counts per minute (measured via accelerometry) greater than their higher BMI counterparts. Although not statistically significant, these different activity patterns between normal and overweight people have also been observed in adult populations. 47 Thus, the establishment of annual patterns of physical activity, with levels peaking in the summer months, may begin during the preschool years and possibly track into childhood, contributing towards the prevention of childhood obesity. This emerging research highlights the need to consider seasonality when designing and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions. The PiP intervention was conducted in three waves that were staggered across the year to examine the impact of season on the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention.

Parental involvement

Parental engagement should be a key part of any intervention in the preschool years48 and the suggestion that adult encouragement is required to increase active play is supported by findings from a systematic review of preschool obesity prevention interventions. 49 The 12 interventions reported in this systematic review were conducted in a variety of settings (preschool/childcare, home, group, primary care and mixed settings) and included a physical activity component. Home-based interventions appeared to be the most successful at increasing physical activity despite the small sample sizes of studies and poor adherence to the interventions. This is perhaps because of parental involvement in the interventions, which has been suggested to be vital for facilitating behaviour change during the early years. 33 Mothers in particular are considered to play a major role in establishing a child’s healthy lifestyle behaviours50 and this, in part, may be indirectly through modelling of behaviours. 51

Since the PiP pilot trial started in September 2012 more physical activity interventions for preschoolers have reported a parent or family component. A recent German preschool physical activity intervention with strong and active parental involvement found statistically significant increases in physical activity, reductions in sedentary time and improved perceived general health and quality of life 1 year post intervention. 52 Using a participatory approach, parents were supported to develop and implement their own physical activity-promoting activities for their children in a preschool centre. This study is a good example of capitalising on a setting where preschool children and their parents congregate and involving parents in activities to promote and model physical activity. Another study from the UK demonstrated a statistically significant increase in preschoolers’ physical activity levels immediately after receiving a 10-week active play programme that targeted the whole family. 53 Families were invited to attend five sessions of active play and parent education. Although these recent studies are promising, the changes in physical activity have not been clinically meaningful and thus further research and intervention development is required for this age group.

A further intervention in Belgium (ToyBox) used a preschool-based curriculum plus passive family involvement (giving newsletters, tip cards and posters) approach. 54 This intervention demonstrated effectiveness for boys or children from high-socioeconomic status (SES) preschools only and not girls or children from low-SES preschools. Given that boys and children of a higher SES level have higher levels of physical activity,10,30 this intervention actually generated further health inequalities. These studies with a parental component indicate that active parental involvement rather than just passive parent education may be required to elicit improvements in preschoolers’ physical activity levels and prevent further health inequalities. The development of preschool physical activity interventions that focus on increasing physical activity levels in groups with particularly low levels, including girls, low-SES children and ethnic minority groups, requires particular attention.

Health inequalities and interventions

As demonstrated by the ToyBox study in Belgium,54 interventions aimed at improving public health outcomes can inadvertently exacerbate health disparities when they are differentially effective for those from different socioeconomic positions or ethnic populations. This can occur during a number of stages of intervention implementation including provision of, or access to, the intervention, uptake of the intervention and compliance to the intervention. For example, in the ToyBox study, the lower-SES families may not have read the newsletters provided or implemented changes from the ‘tips’ given, whereas the higher-SES families may have done so, thus widening the inequalities.

There is some guidance regarding the types of public health interventions likely to reduce inequalities. A rapid overview of systematic reviews55 concluded that ‘downstream’ interventions that seek to directly alter the adverse health behaviour are more likely to increase inequalities whereas ‘upstream’ interventions that focus on the wider circumstances that produce the behaviour are more likely to have a positive equality impact. Interventions that are targeted at the most disadvantaged groups may also reduce health disparities. A recent Canadian study demonstrated that a ‘whole school-based’ physical activity promotion intervention targeted at low-SES schools reduced inequalities in physical activity. 56 Furthermore, members of our group (HJM, CDS) have recently conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing inequalities in childhood obesity-related outcomes (including physical activity). 57 The review concluded that school-based interventions targeted at low-SES children may have some beneficial effects in reducing inequalities, although the evidence is not conclusive. It recommends that participants should be engaged in the development of interventions to prevent intervention-generated inequalities. Shared decision-making in interventions may be more beneficial to disadvantaged groups than to those with higher literacy or SES. 58

Successful early interventions that are effective and reduce health inequalities have a high potential return in terms of health, social and economic benefits for children throughout their lives. Early childhood problems often translate into lifelong inequalities in health and well-being, and the preschool period is seen as a key period for intervention. The Marmot review of health inequalities59 concluded that ‘giving every child the best start in life’ was its ‘highest priority recommendation’.

Development and description of the Preschoolers in the Playground intervention

The PiP intervention was developed in 2011 following the publication of the UK CMO’s guidance for physical activity in the under 5s,29 consideration of potentially effective intervention components, strategies to reduce health inequalities and focus groups with mothers of preschool children.

The predominant behaviour change theory used in successful childhood obesity prevention interventions32 is Bandura’s social cognitive theory34,35 and, therefore, social cognitive theory was used to direct the intervention development and appropriate behaviour change techniques utilised. The intervention was based in an outdoor environment, the primary school playground, and had strong parental involvement, with parents actively playing with their child during the intervention sessions. The intervention was an ‘upstream’ community-level intervention that focused on changing the traditional use of the local primary school playground and school play equipment, allowing groups of parents and their preschool children to use the facilities to play actively outdoors in a safe environment. It was also ‘downstream’, with direct engagement from preschoolers and their parents. The intervention was targeted at the two most deprived quintiles of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) in Bradford and at both white and South Asian families to tackle health inequalities in physical activity levels (see Appendix 1). The intervention was developed in conjunction with parents through focus groups that explored typical physical activity in preschoolers and the barriers to and facilitators of physical activity. 60 Six focus groups with a total of 17 white and Pakistani mothers and caregivers (English and Urdu speaking) were conducted at children’s centres in the poorest IMD areas in Bradford. Mothers reported that their children were innately active and enjoyed playing outside. Lack of time was a major barrier to physical activity. Mothers minimised the amount of ‘journeys’ that they made and were put off organised activity sessions, finding it inconvenient to leave the house with young children. Other barriers to outdoor physical activity included ‘feeling that their neighbourhood was an unsafe place to play outdoors’ and ‘needing help from another adult to take the children to the park’. Additionally, the season, the weather and having to take public transport to parks were also identified as barriers. Key facilitators for physical activity were having someone to help during activities and having activities available locally. There was little variation in the reported barriers and facilitators between ethnicities.

Site of delivery of the intervention and timing of the sessions

Local primary school playgrounds were chosen as the site for delivering the PiP intervention. It was anticipated that using the school setting for the intervention would overcome some of the barriers to participation in physical activity for preschool children reported by parents in the focus groups. For example, the intervention would be available locally and would fit into family routines and the playground is an enclosed space that can be supervised easily. Furthermore, the intervention would be accessible to hard-to-reach families, who often do not attend other community-based children’s activities such as those held at children’s centres. Primary school playgrounds (or children’s centre playgrounds when located on the primary school site) were made available to parents and preschool children at times when parents were likely to be attending school (e.g. dropping off or picking up older children from school or young children from nursery). These times were chosen to capitalise on times of the day that parents are already out of the house and minimised the number of journeys to activities that parents had to make (identified as a barrier in focus groups). Six PiP sessions per week for 30 weeks (three school terms) were available to families. This number of sessions was chosen to meet the need for flexibility, which was highlighted at the focus groups. Families were encouraged to attend at least three of these sessions each week. Each PiP session lasted for 30 minutes. There were two phases of the intervention, the initiation phase (10 weeks: one school term), which was supervised and facilitated by a member of school staff, and the maintenance phase, which was unsupervised (20 weeks: two school terms).

Intervention facilitators

Following consultations with two staff members from two schools, parental involvement workers or nursery teachers were suggested as appropriate facilitators to deliver the intervention. It was thought that by training existing staff the intervention would be more sustainable. The initiation phase (10 weeks) was facilitated by parental involvement workers and/or nursery teachers employed by schools/children’s centres. These facilitators undertook a 2-hour training session using the PiP manual and were accompanied during the first session by the lead researcher (SEB) who developed the PiP intervention. Subsequent telephone support from the lead researcher was offered to facilitators during the intervention period as and when they requested it.

The Preschoolers in the Playground manual

The PiP manual was developed as a resource for the facilitators. It included a background section explaining how the intervention had been developed, an explanation of the facilitators’ role and what was expected of them, an equipment list detailing the play equipment that would be required to deliver the intervention (all play equipment was standard school physical education equipment), information about the importance of physical activity in the early years, guidelines for physical activity in preschoolers and information about giving effective praise, encouragement and positive reinforcement. The manual also described the session timings and structure of the sessions. A guide on how to deliver the first session was also provided for support. The manual included a description of the ‘statue game’ used in sessions to gather the group together, a description of 20 structured play games called PiP-PoPs, five handouts to be photocopied for parents and instructions on facilitating 10 discussions (one per week) with parents about physical activity-related topics (more detail is given in Content of the Preschoolers in the Playground intervention and Appendix 2). At the back of the manual was a paperwork section that included a register of attendance and adverse event reporting forms. The manual was reviewed by five early years workers and minor revisions were made before the start of the intervention (e.g. changing the order of the contents in the manual). The manual was also modified during the delivery of the intervention following feedback from the facilitators delivering the intervention (e.g. language was clarified).

Structure of the Preschoolers in the Playground sessions

Each PiP session lasted for 30 minutes and included two 5-minute structured play activities (PiP-PoPs), 15 minutes of free play (during this time handouts were given out and guided discussions conducted) and 5 minutes for an active tidy-up. Play activities were designed to be of light physical activity (LPA) and MVPA. There is some evidence to suggest that as little as an extra 10 minutes per day of MVPA significantly reduces fat mass. 2 Furthermore, 56 minutes per day of MVPA in boys and 42 minutes in girls aged 5–8 years has been reported to improve metabolic status assessed from a composite score of various CVD risk factors. 61 Given the sporadic nature of physical activity in very young children, and that between 25% and 70% of total physical activity (TPA) in preschoolers has been classified as MVPA,23,62,63 it was estimated that during a 30-minute session the children would spend at least 10 minutes in MVPA and that this could contribute towards the amount of MVPA required for health benefits. Furthermore, it was thought that a 30-minute session would be more acceptable to both schools and families.

During the maintenance phase (20 weeks) playgrounds remained available to parents and their preschool children six times a week for 30 minutes at specific times to coincide with the ‘school run’, as allocated by the schools/children’s centres. For the purposes of the pilot trial, the PiP facilitator took a register of attendees at the beginning of the sessions but did not give formal supervision.

Content of the Preschoolers in the Playground intervention

The following sections provide a detailed description of the content of the PiP intervention. Table 1 summarises the content, evidence for the content and associated behaviour change techniques for both the initiation and the maintenance phases of the intervention.

| Content | Initiation (I) or maintenance (M) phase | Evidence to support content | Behaviour change technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of playground area at a time that coincides with families’ daily routine (dropping off at/picking up from school/nursery) | I, M | Social cognitive theory (environmental factors);34,35 focus group reports: activity sessions need to fit into other daily routines60 | Environmental changes |

| Provision of outdoor play equipment during sessions | I, M | Social cognitive theory (environmental factors)34,35 | Environmental changes |

| Facilitator to give telephone support and encourage families to attend the sessions | I, M | Social cognitive theory (behavioural factors)34,35 | Social processes of support/encouragement |

| Group sessions | I, M | Recommendation for preschool obesity interventions32 | Social processes of support/encouragement |

| Supervision at the session from the facilitator | I | Focus group reports: parents need extra support to feel confident and safe playing with their children outside60 | Social processes of support/encouragement |

| Facilitator to encourage children to be physically active and give rewards (praise and ‘well done’ stickers) | I | Social cognitive theory (behavioural factors);34,35 recommendation for preschool obesity interventions48 | Social processes of support/encouragement |

| Facilitator to support parents to give positive reinforcement to their child’s physical activity | I | Social cognitive theory (behavioural factors);34,35 parent involvement is important for children’s behaviour change49,52,53 | Modelling, social processes of support/encouragement, increasing skills, rehearsal of skills |

| Facilitator to encourage outdoor play between parent and child outside of the intervention | I | CMO report29 | Social processes of support/encouragement |

| Facilitator to provide information (verbally) and leaflets and facilitate parent discussions on the link between physical activity and health and provide guidelines for physical activity and sedentary behaviour in under 5s | I | Social cognitive theory (personal factors);34,35 recommendation for preschool obesity interventions32 | Provide information regarding behaviour, provide information on consequences, social processes of support/encouragement |

| Ideas for active games provided and these games and activities are fun for children | I (facilitator), M (instruction cards) | Social cognitive theory (personal factors);34,35 CMO report;13 recommendation for preschool obesity interventions48 | Increasing skills, skill rehearsal, modelling, graded tasks |

| Facilitator to teach two 5-minute structured parent and child games to develop children’s observational learning, locomotor, stability and object-control skills | I | Social cognitive theory (personal factors);34,35 CMO report29 | Increasing skills, skill rehearsal, modelling, graded tasks |

| Facilitator to modify play activities to suit the different needs of children in the group | I | CMO report29 | Graded tasks |

| Children have 20 minutes of free play | I | CMO report29 | Environmental changes |

| Facilitator to ensure regular infusions of different play equipment during free play | I | Recommendation for preschool playground interventions43 | Environmental changes |

| Play equipment given out once a week to support families to play at home | I (three schools only) | Social cognitive theory (environmental factors and behavioural factors);34,35 CMO report29 | Rewards/incentives, skill rehearsal |

Structured play activities

There were 20 different PiP-PoPs (structured play activities) and facilitators were asked to teach each PiP-PoP at least once during the 10-week period. The PiP-PoP activities were designed to promote active play (activities that involve movements of all of the major muscle groups) and the development of locomotor, stability and object-control skills (as recommended by the Start Active, Stay Active report29). Ideas on how to modify each PiP-PoP to make it easier or harder depending on each child’s ability were also given.

Free play

At the beginning of the free-play segment of sessions, facilitators were instructed to bring out two or three pieces of equipment and then bring out additional equipment later on in the segment to ensure a flow of different equipment. Facilitators were instructed to allow all of the children to decide what they would like to play with and then to support the parents to do this, encouraging all of the children to explore and use their imagination.

Guided discussions and handouts

The facilitators were asked to guide discussions with parents on physical activity-related topics each week during the initiation phase. For some of the discussions there were accompanying handouts for parents to take home. The discussion topics were:

-

what to wear for outdoor play (supplemented by a handout)

-

giving praise and encouragement (supplemented by a handout)

-

why physically active play is important (including physical activity guidelines for preschoolers; supplemented by a handout)

-

help your child move and play every day (supplemented by a British Heart Foundation leaflet)

-

active parents have active kids (supplemented by a handout)

-

outdoor spaces near me (supplemented by a handout)

-

playing as a family

-

couch potatoes

-

games I used to play

-

continuing to be active.

Active tidy-up

At the end of each initiation session families were encouraged to tidy up the playground in a playful and active way. For example, facilitators may have asked the group to collect all the balls up and jump back to put them in the carrier. It was anticipated that, by including an active tidy-up, when families began the maintenance phase with no facilitator this would continue and the school playground would be left tidy at the end of each PiP session.

Changes to the intervention

Before the PiP intervention commenced, a change was made to the duration of the intervention, from 36 weeks (12 weeks in the initiation phase and 24 weeks in the maintenance phase) to 30 weeks (10 weeks in the initiation phase and 20 weeks in the maintenance phase); blocks of 10 weeks were better suited to school term times. During the PiP intervention, changes were made to the content of the intervention. These included the addition of weekly, take-home play equipment during the initiation phase, with £15 spent per child. This action implemented the behaviour change techniques of providing rewards for participation and skill rehearsal. The take-home play equipment included items that would allow parents and children to recreate at home the PiP-PoPs that they had learned in the sessions. The kit included:

-

PiP kit bag

-

PiP-PoP game cards

-

hoop

-

skipping rope

-

beanbag

-

ball

-

bat

-

collector bag

-

chalk

-

water pot and brush.

A further change was the addition of telephone support provided by facilitators to parents who, for unknown reasons, had not attended three consecutive sessions (one week of the intervention). A change to the delivery of the intervention was also made: schools were given the option to reduce the number of sessions offered to four per week after the first 3 weeks of the intervention if two sessions were poorly attended.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

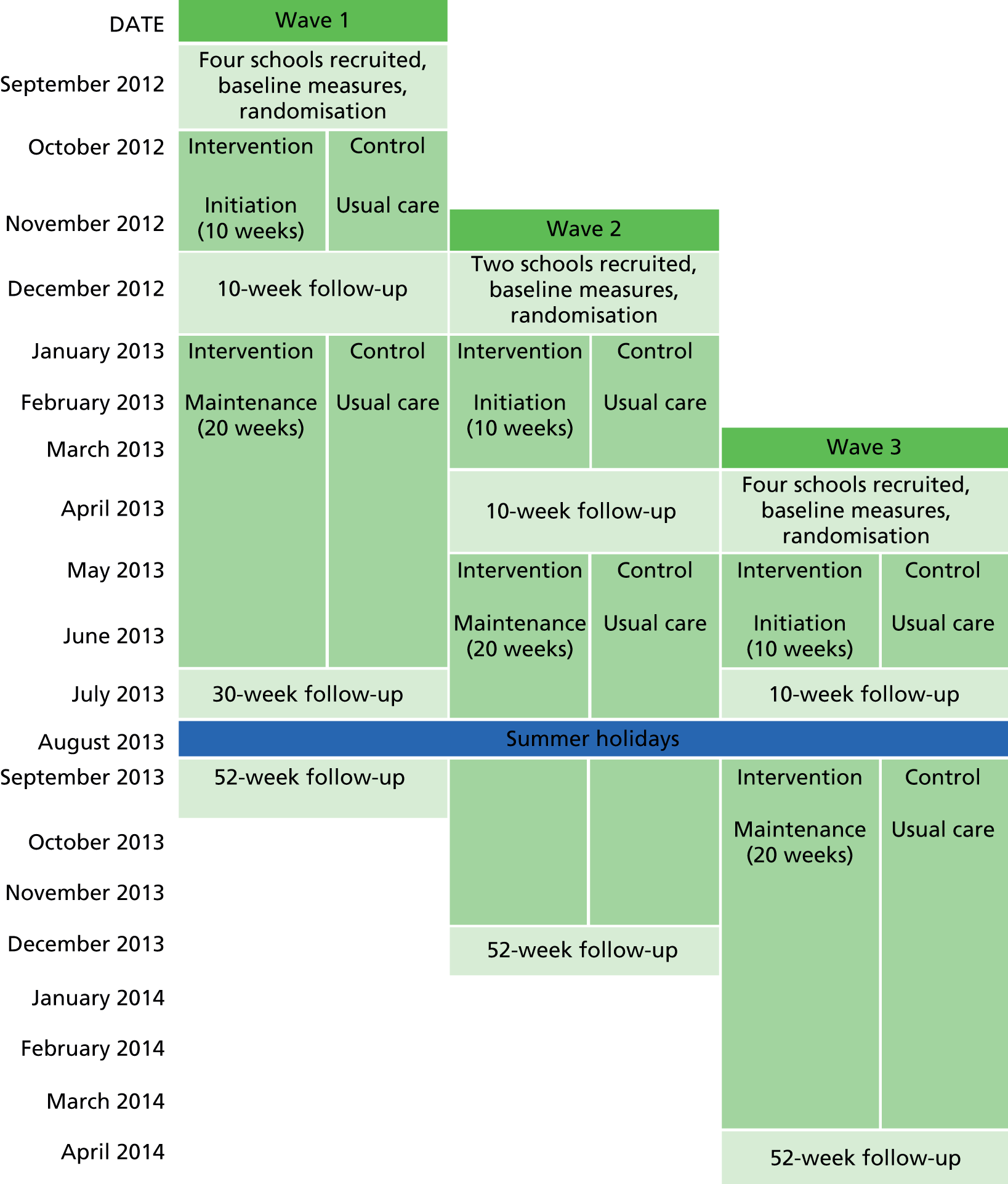

The design of this pilot study was based on guidance from the UK Medical Research Council for developing and evaluating complex interventions. 64 Figure 1 shows the trial design: a two-armed pilot cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) with economic and qualitative evaluations. The two arms were the PiP intervention and usual practice (control). Recruitment, randomisation and the intervention or control period took place in three waves. Wave 1 commenced in the autumn 2012 school term, wave 2 commenced in the spring 2013 school term and wave 3 commenced in the summer 2013 school term. This staggered approach allowed the examination of seasonal variations in the feasibility of the intervention as well as mimicking one approach that could be taken in a full cluster RCT. The intervention consisted of a 10-week initiation phase (one school term) followed by a 20-week maintenance phase (two school terms). Further details of the intervention are provided in Chapter 1 (see Development and description of the Preschoolers in the Playground intervention). Follow-up was at 10 weeks (mid-intervention), 30 weeks (at the end of the intervention) and 52 weeks. For waves 2 and 3, the follow-ups at 30 weeks (immediately after the intervention) and 52 weeks (1 year after baseline assessment) fell at the same time because of the school holidays occurring during the middle of the intervention period (see Figure 1); this meant that 30-week data were collected from wave 1 children only. It was not possible for schools, participants and facilitators to be blind to allocation because of the nature of the intervention. It was planned that researchers would be blind to allocation; however, many of the parents informed staff of their child’s trial status. It was also planned that the statistician and health economist would be blind to allocation; however, because of sickness of the blinded statistician an unblinded statistician conducted the analysis. The health economist was blinded. Ethics approval for the study was secured from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee Yorkshire and the Humber – Bradford (reference 12/YH/0334) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. 65

FIGURE 1.

Study design: a pilot cluster RCT conducted in three waves.

Setting

The high levels of deprivation in Bradford and the multiethnic nature of Bradford’s population made it an ideal setting in which to trial this preschool physical activity intervention. Bradford is the sixth largest metropolitan borough in England with a population of approximately 500,000 and includes some of the most deprived areas in the UK. 66 The National Child Measurement Programme for 2010–11 reported that 22% of Bradford’s children in reception classes (similar to the national average) and 35% in year 6 (higher than the national average) were overweight or obese. 67 In addition, overall there are very low levels of participation in school sport in the city. 67 Half of all babies born in Bradford are of South Asian origin68 and 60% of these are born into the poorest 20% of the population of England and Wales, based on the IMD. 66

Sample size

It was anticipated that at least 150 children from 10 schools with 15 children at each school would be recruited. This would give five schools with a total of 75 children in the PiP intervention arm and five schools with a total of 75 children in the control arm.

Recruitment of schools and participants

School recruitment

The study was initially publicised to primary schools through advertising and presentations at education conferences and events hosted for Bradford primary school staff. Letters were also sent to eligible schools (those located in the two poorest quintiles of the IMD for Bradford) (see Appendix 1). Schools were asked to contact the researchers if they were interested in taking part in the study. Interested schools were then contacted and visited to discuss the study further. Schools that were located in different areas of the city of Bradford (Bradford South, Bradford West, Bradford East and Shipley) were selected to take part. Each study site completed a study site agreement, which was signed by the head teacher and chair of governors. To express thanks for participating in the pilot trial, all schools received a donation of £200 towards play equipment. Because the children were of preschool age and were not attending the primary schools, those affiliated to the schools in the control arm did not have access to the play equipment during the trial period.

Participant recruitment

Families from participating schools, and families who used children’s services affiliated with the schools (e.g. nearby children’s centres or nurseries), were approached to take part in the trial. Recruitment was carried out through letters home with school-going children and through face-to-face conversations with community research assistants in school playgrounds and children’s centres or nurseries. A participant information sheet (see Appendix 3) was given to participants before they attended a baseline measurement appointment. Written informed consent was obtained before any data were collected at the baseline measurement session. To account for the linguistic diversity among the study population, research staff recruiting families and conducting measurements and questionnaires were bilingual and undertook these tasks in either English or Urdu. 68 Urdu is the language spoken and understood by Pakistanis; it is also spoken and understood in many parts of Bangladesh. For Bangladeshi participants who did not fully understand Urdu, the consent form was audio recorded in Sylheti and participants were asked to sign a paper copy of the consent form (translations and transliterations were prepared in collaboration with Born in Bradford staff, according to standard Born in Bradford procedures68). All families received a £10 voucher for a children’s shop (Mothercare or the Early Learning Centre) as a thank-you for attending each study measurement session (baseline and 10, 30 and 52 weeks’ follow-up) and for participating in a qualitative interview.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Children were included if they were aged between 18 months and 4 years and were available to complete three school terms of the intervention before going into the reception class (first year of school). For wave 1, children were eligible if they were born between 1 September 2008 and 5 March 2011. For wave 2, children were eligible if they were born between 1 September 2009 and 7 July 2011. For wave 3, children were eligible if they were born between 1 September 2009 and 6 November 2011. Children were excluded if a parent or legal guardian was unable to provide informed consent.

Randomisation

Randomisation was conducted by the York Trials Unit Randomisation Service using a secure computer system after baseline data were collected. Schools were allocated on a 1 : 1 basis to the intervention arm or the control arm. The first four schools (wave 1) were randomised using block randomisation with a block size of four. The remaining schools (two in wave 2 and four in wave 3) were allocated using minimisation. Minimisation is a largely non-random method of treatment allocation in trials and is particularly useful when there are a small number of units to be randomised and balance is desired across a number of variables. Treatment allocations are determined by which would lead to a better balance between groups in the variables of interest.

In Bradford ethnic groups tend to cluster in localities and thus the predominant ethnicity of pupils attending the schools was used as a minimisation factor with two levels (< 50% South Asian pupils and > 50% white pupils). When schools were recruited into the study, an assumption was made that the ethnicity of participants recruited at each school would reflect the ethnic groups of pupils attending each school. IMD was not used as a minimisation factor because all of the schools were in the two poorest quintiles of the IMD for Bradford. Furthermore, Bradford is particularly skewed towards a high IMD and, thus, this was not felt necessary.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the study was to undertake a pilot cluster RCT of an outdoor playground-based physical activity intervention (PiP) to assess the feasibility of a full-scale cluster RCT of the PiP intervention. The specific objectives were to determine:

-

the feasibility and acceptability of the recruitment strategy for schools and families and whether or not there was a difference in recruitment rate between ethnic groups

-

follow-up and attrition rates during the trial and whether or not there was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups

-

the acceptability of the trial procedures

-

the feasibility of collecting the outcome measures and whether or not there was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups

-

the influence of financial incentives on trial participation

-

attendance to, and acceptability of, the intervention, whether or not there was a difference between ethnic groups and whether or not attendance varied by season

-

the fidelity of programme implementation

-

the capability and capacity of schools to deliver and incorporate the intervention within existing services

-

the effect of participation in the intervention on health outcomes and whether or not there were any differences between ethnic groups

-

estimates of effect size, typical cluster sizes and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) to enable an accurate sample size calculation for a full trial

-

preliminary assessment of the potential cost-effectiveness of PiP and an estimate of the value of further research

-

whether or not links can be established between short-term outcomes and long-term quality of life, potentially including across sectors

-

whether or not it is appropriate to apply for further funding for a full-scale RCT.

Data collection and analysis

To answer each of the study’s objectives a multimethods approach was used to collect and analyse the data. The following three sections describe how the quantitative data, the health economics data and the qualitative data were collected. Methodology for each study objective describes how the data were analysed to answer each of the objectives. Throughout the report participants are grouped according to ethnicity. The predominant ethnicity of pupils attending the school is used to describe cluster-level ethnicity. At the participant level a child’s ethnicity (as reported by his or her parent) is used, except when data specifically relate to the parent [i.e. for the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), Comprehensive Quality of Life Scale – Adult (ComQol-A5) and General Self-Efficacy Scale questionnaires]. White refers to participants who were white European (white British, white Irish, white Polish) and South Asian refers to participants who were of Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Indian heritage; the other group included participants who were of African, Burmese and dual heritage (white and Asian and Chinese and Indian).

Quantitative data

Trial recruitment, attrition and follow-up

Community research assistants logged all trial contacts with participants and the outcomes of these contacts on a central database system. Data relating to trial recruitment, attrition and follow-up were captured.

Health outcomes

Each parent and his or her participating child were invited to attend a measurement session in a private room at their school to collect health outcome data at baseline and at 10, 30 (for wave 1 participants only) and 52 weeks’ follow-up. When families were unable to attend the appointment at the school, a community research assistant visited their home to conduct the measurement session. Community research assistants used standardised paper and electronic forms to record data from participants. The measurement sessions were child friendly with toys and play equipment available to entertain the children and put them at ease.

Child’s physical activity

At the measurement session a triaxial Actigraph GT3X+ accelerometer (15-second epochs; Actigraph Pensacola, FL, USA) was placed on the child on a belt around his or her waist (anterior to the iliac crest). Parents were asked to place the accelerometer on their child in this position during waking hours for the subsequent 7 days including at least 1 weekend day. 69 Parents were provided with a diary to record the times that the accelerometer was put on and taken off their child. Further details about the processing and analysis of accelerometry data are provided in Objective 4: feasibility of collecting the outcome measures and whether or not there was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups and Objective 9: the effect of participation in the intervention on health outcomes and whether or not there were any differences between ethnic groups, Physical activity.

Child’s height and weight and waist and upper arm circumferences

Body mass was measured in standard clothing conditions (lightweight clothing) using regularly calibrated Seca electronic scales (Medical Scales and Measuring Systems, Birmingham, UK). Height was measured using a Leicester Height Measure (Harlow Healthcare, Harlow, UK). Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the lowest rib and the iliac crest. Upper arm circumference was measured at the mid-point between the acromion process of the scapula and the olecranon process. Further details about the analysis of these data are presented in Objective 9: the effect of participation in the intervention on health outcomes and whether or not there were any differences between ethnic groups, Anthropometry.

Parent well-being and self-efficacy

Parents completed the ComQol-A570,71 to assess their well-being; they also completed the General Self-Efficacy Scale. 72 Details regarding how these data were analysed are provided in Objective 4: feasibility of collecting the outcome measures and whether or not there was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups.

Intervention attendance, fidelity and environment

Intervention attendance

The PiP facilitators completed a standardised register for each PiP session (both initiation and maintenance phases) to record attendance. This included recording who attended the PiP session with the child. Withdrawals from the intervention (i.e. parents who gave notification that they no longer wanted to attend the intervention) were also recorded by either the PiP facilitator or the study co-ordinator. Facilitators were provided with adverse event reporting forms and were instructed to contact the study co-ordinator immediately if an adverse event occurred.

Intervention fidelity

Fidelity was assessed in line with guidance from the National Institutes for Health (NIH) Behavior Change Consortium. 73 To assess adherence to the intervention protocol an observer attended two sessions in the initiation phase at each intervention school; intervention delivery was scored on a scale from 1 to 4 (with 1 relating to poor adherence and 4 relating to complete adherence) in relation to five key intervention factors:

-

delivery as per manual, which consists of four subcomponents

-

supervision

-

support given to parents

-

encouragement of children

-

infusion of play equipment.

Some sessions were observed by two individuals, with each scoring independently. When this was the case, the average score for each component was used.

Playground and local environment

To assess whether or not the school and local environment impacted on the intervention, the study co-ordinator visited each school before it was allocated to either the intervention arm or the control arm and completed a standardised form detailing the playground and the local environment.

Health economics data

Child and parent health-related quality of life

At each of the measurement sessions parents completed the EQ-5D instrument74 to report on their own health-related quality of life (HRQoL); they also completed the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL)75 regarding their child’s HRQoL. The PedsQL items were slightly different for infants (aged 13–24 months) and toddlers (aged 2–4 years). Further details regarding the analysis of the two instruments are provided in Objective 11: preliminary assessment of the potential cost-effectiveness of Preschoolers in the Playground and an estimate of the value of further research, Health-related quality of life outcomes.

Injuries and health service use

Parents were asked to recall their child’s use of hospital services [overnight stay, day hospital attendance, outpatient visit, accident and emergency (A&E) department attendance, day-case surgery] and contact with health professionals within the last 3 months. This was recorded on a standardised form (see Appendix 5). Further details about the analysis of these data are given in Objective 11: preliminary assessment of the potential cost-effectiveness of Preschoolers in the Playground and an estimate of the value of further research, Resource use and unit costs.

Qualitative data

Interviews were carried out with parents in both the intervention arm and the control arm and with PiP facilitators and head teachers in the intervention arm. The methods used to carry out the interviews are described here. How the data collected were used to meet each study objective is described in Methodology for each study objective.

All of the interviews used a semistructured topic guide (see Appendix 6) to ensure consistency. The questions were as open-ended as possible to enable participants to raise issues that were important to them. The wording and order of the topics covered also varied between interviews to ensure that each interview was informal and open-ended to suit individual participants. 76 Interviews were audio recorded digitally with the exception of the wave 1 interviews with parents (see the following section).

Parent interviews

The aim was to interview approximately 16–20 parents/carers (up to 15 parents/carers from the intervention arm and up to five from the control arm) at the 10-week follow-up time point. A maximum variation sampling strategy77 was employed to achieve diversity on three key characteristics for which views about the PiP study might be expected to differ. First, the wider PiP study was interested in understanding potential differences in feasibility between South Asian and white families; we therefore sought to include a mix of South Asian and white parents/carers in this qualitative component. Second, of parents/carers allocated to the intervention arm, we aimed to interview parents who had continued to attend the PiP intervention as well as those who had never attended or who had dropped out. Third, we intended to interview a mix of mothers, fathers, grandparents and carers. We found that it was only parents who were attending measurement and PiP sessions with their children and, thus, for the remainder of this report we refer only to parents.

Parents were asked to consent to take part in an interview when they were recruited to the PiP trial. From those who consented, the study co-ordinator purposively selected parents to be interviewed on the basis of their ethnicity, (non-) attendance at the PiP intervention (intervention arm only) and parental role. Parents were then recruited in one of two ways: either a community research assistant asked parents if they would be willing to be interviewed when booking the 10-week measurement session or the study co-ordinator telephoned the parents and requested them to take part in an interview. By this time both of these individuals were known to the parents and could vouch for the trustworthiness of the interviewer, hence facilitating recruitment. 78 Parents received a £10 gift voucher for Mothercare or the Early Learning Centre on completion of the interview.

Parents were interviewed after completing their 10-week measurement session. Interviews lasted between 6 and 19 minutes and were conducted in English. The wave 1 interviews were undertaken over the telephone in the week following the 10-week measurement session. This was because of very bad weather (snow) and the school Christmas holidays commencing immediately after the end of the 10-week initiation phase of the intervention. Because of a technical fault with the digital recorder these interviews were not recorded; instead, the interviewer took detailed notes whilst conducting the interview. The wave 2 and wave 3 interviews were conducted face to face immediately after the measurement session had been completed (either in the parent’s home or at the school).

Facilitator and head teacher interviews

In each of the five intervention schools we intended to interview the PiP facilitators with responsibility for delivering the intervention at the 10-week follow-up time point and the head teachers at the 52-week follow-up time point. The study co-ordinator contacted each PiP facilitator and head teacher by telephone/e-mail to arrange their participation in this qualitative component. This included providing a participant information sheet (see Appendix 7) and the consent form (see Appendix 8) and subsequently arranging a date/time for the interview.

The PiP facilitators were interviewed face to face in school. The exception was one PiP facilitator in a wave 1 school who was interviewed over the telephone (as with the wave 1 parents this was because of bad weather and the Christmas break). PiP facilitator interviews lasted between 13 and 31 minutes. Head teachers were interviewed on the telephone and these interviews lasted between 12 and 16 minutes.

Thematic analysis of the interviews

The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim with anonymisation of all personal data. The detailed notes taken for the wave 1 parent interviews were used as data. These interview data were then analysed using thematic analysis, which is a method of ‘identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within the data’ (p. 79). 79 This a useful approach for producing qualitative analyses suited to informing policy and programme development. 79 The six phases of thematic analysis were as follows.

-

Familiarisation. The researcher became immersed in the raw data by ‘repeated reading’ of the transcripts and listed key ideas for coding.

-

Generating initial codes. Initial codes and a coding framework were developed, informed predominantly by the objectives of this qualitative component (a deductive approach), although novel views expressed by participants were also captured (an inductive approach). 4 The interview data were then coded to this framework using the ATLAS.ti data management software package (version 6.2; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, Corvallis, OR, USA). Data from the three participant groups (parents, PiP facilitators and head teachers) were coded to the same framework with additional codes created for each particular group when necessary.

-

Searching for themes. The codes were then organised into potential themes and subthemes. At this point similarities and differences in views ‘within’ and ‘across’ the three participant groups were explored.

-

Reviewing themes. The coded data within each potential theme were reviewed and the themes modified to ensure that they formed a coherent pattern. Each theme was then reviewed to see if it ‘worked’ in relation to the entire data set.

-

Defining and naming themes. A short paragraph was produced for each theme and subthemes to define the ‘essence’ of the theme/subthemes and names were allocated.

-

Producing the report. The thematic analysis was written up.

Methodology for each study objective

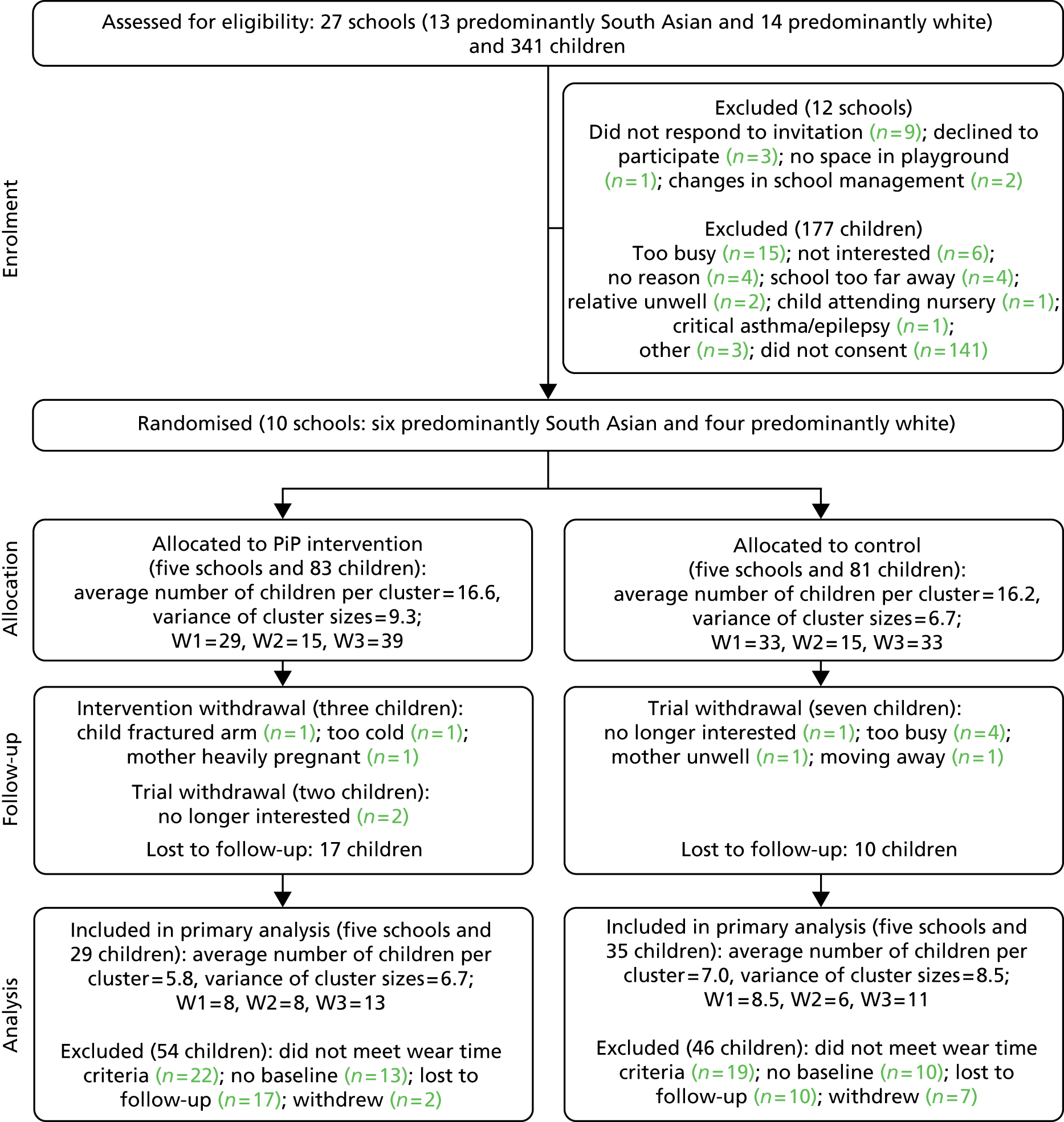

Objective 1: feasibility and acceptability of the recruitment strategy for schools and families and whether or not there was a difference in the recruitment rate between ethnic groups

The numbers (and percentages) of schools approached, recruited and randomly assigned were summarised, as were the number of children who were approached, the number screened, the number of parents who consented to further contact and the number taking part. The reasons for parents declining to be contacted further about the study were tabulated. The flow of schools and children through the study was presented in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. Consent status was also summarised by parents’ ethnicity. Characteristics of the schools (location, presence of children’s centre on site, number of pupils on roll, percentage free school meals (FSMs), percentage white, percentage South Asian and percentage with English as an additional language) were summarised alongside allocated trial arm. The characteristics of participating children and parents were summarised by trial arm both overall and as analysed. As analysed were those individuals who were included in the primary analysis who had baseline and week 52 MVPA data that both met the wear time criterion (see Objective 4: feasibility of collecting the outcome measures and whether or not the was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups).

The characteristics of the parents, PiP facilitators and head teachers who were interviewed for the qualitative component were tabulated. Parent and head teacher reasons for taking part in the study were explored, as were parents’ views on recruitment and the information that they were given about the study.

Objective 2: follow-up and attrition rates during the trial (in particular, whether or not there was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups)

A CONSORT diagram was produced to display the follow-up and attrition rates during the trial.

The numbers (and proportions) of children providing accelerometer data, questionnaire data (including anthropometry data) and both were summarised over time for the whole trial, by trial arm and by ethnicity. The numbers of children withdrawing from the trial were summarised alongside the reasons for withdrawal and ethnicity. The numbers of communications required for follow-up visits were also summarised.

Objective 3: acceptability of the trial procedures

Qualitative analysis of the interviews explored parents’ understanding of the trial procedure, including randomisation. The acceptability of randomisation, the accelerometer and the measurement sessions was also examined.

Objective 4: feasibility of collecting the outcome measures and whether or not there was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups

Physical activity data were downloaded from accelerometers and reduced using Actilife software version 5 (Actigraph Pensacola, FL, USA). Non-wear time was defined as consecutive zero counts of ≥ 10 minutes. 80 Parent-completed wear-time logs were checked for periods when the monitor was not worn and matched against Actigraph data. To determine the minimum wear time (i.e. daily wear hours and number of wear days) required to achieve a reliable estimate of habitual physical activity, that is, an ICC value of ≥ 0.8, the Spearman–Brown prophecy formula was applied to participants’ baseline accelerometer data. 81 This resulted in a wear-time criterion of at least 6 hours of wear time on any 3 days for data to be included in the analysis (see Appendix 9 for a table of these results). The number and proportion of data meeting the wear-time criterion were assessed overall, by trial arm, by ethnicity and over time.

Completion rates for anthropometric measurements (height, weight, BMI and waist and upper arm circumferences) and for questionnaires [children: infant (13–24 months) and toddler (2–4 years) PedsQL; parents: EQ-5D, ComQol-A5 and General Self-Efficacy Scale] were assessed. These summaries were presented overall, by trial arm, by ethnicity and over time.

Objective 5: influence of financial incentives on trial participation

Parent and head teacher views on the influence of financial incentives on trial participants were explored through qualitative analysis.

Objective 6: attendance to, and acceptability of, the intervention, whether or not there was a difference between ethnic groups and whether or not attendance varied by season

The number of schools and number of children providing attendance data to the PiP intervention sessions were summarised by initiation and maintenance phase and overall. For those children attending at least one session, the average number of sessions attended was summarised [mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum values]. The data were provided overall, by school (and wave/season) and by ethnicity.

Quantitative data were used to examine parents’ and PiP facilitators’ views on the acceptability of the PiP intervention, parents’, PiP facilitators’ and head teachers’ views on reasons why participants did not attend and parents’ and facilitators’ acceptability of the maintenance sessions. These data are presented alongside the qualitative data.

Objective 7: fidelity of programme implementation

Summary statistics were produced for the fidelity scores relating to each of the five key intervention factors: delivery as per manual, supervision, support given to parents, encouragement of children and infusion of play equipment. The delivery as per manual factor has four components; summary statistics were presented for each component separately and for the combined total score.

Objective 8: capability and capacity of schools to deliver and incorporate the intervention within existing services

Summary statistics were presented for the playground and local environment factors by trial arm and overall. Head teacher views on capability and capacity and benefits to the schools and suggestions for improving the PiP intervention were all explored through analysis of the qualitative interviews. PiP facilitators’ experiences of delivering the intervention, the training that they received and their views on the PiP manual were also examined and are summarised.

Objective 9: The effect of participation in the intervention on health outcomes and whether or not there were any differences between ethnic groups

Health outcome data were processed as detailed in the following sections.

Physical activity

After the application of the wear-time criterion (see Objective 4: feasibility of collecting the outcome measures and whether or not there was a difference between trial arms and ethnic groups), vaild accelerometer data were analysed and time spent in different physical activity intensity levels was calculated from the vertical axis activity counts using the thresholds shown in Table 2. These cut-points, which were derived by Pate et al. 82 for children aged 3–5 years, were selected as they have been cross-validated under free-living conditions and have been found to have better agreement with directly observed physical activity than other published Actigraph intensity cut-points in children aged 16–35 months. 83 The percentages of children meeting the physical activity guideline of 180 minutes per day (TPA) were also calculated.

| Physical activity level | Counts per 15-second epoch | Equivalent counts per minute |

|---|---|---|

| TPA | ≥ 38 | ≥ 149 |

| Light | 38–419 | 149–1679 |

| Moderate to vigorous | ≥ 420 | ≥ 1680 |

| Sedentary | ≤ 37 | ≤ 148 |

Anthropometry

Body mass and height were measured and used to calculate BMI. These were then converted to age- and sex-adjusted z-values relative to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2006 growth standard84 using the least mean squares method. The percentage of overweight children in each arm, defined as having a BMI z-value of > +1.04 (= 85th centile), was recorded. Waist and upper arm circumference were also measured.

Parent well-being and self-efficacy

Parent well-being was measured using the ComQol-A5. The questionnaire asked both subjective and objective questions relating to seven domains (material well-being, health, productivity, intimacy, safety, place in community and emotional well-being). A mistake was made when administering the questionnaire and one page relating to the subjective domains was not included. Thus, only the objective data were analysed. The objective score on each domain was the aggregate of the three objective questions on each domain. The General Self-Efficacy Scale consisted of 10 items, each with four levels. The final composite score was obtained by summing the response levels on all dimensions (lower values indicating better self-efficacy).

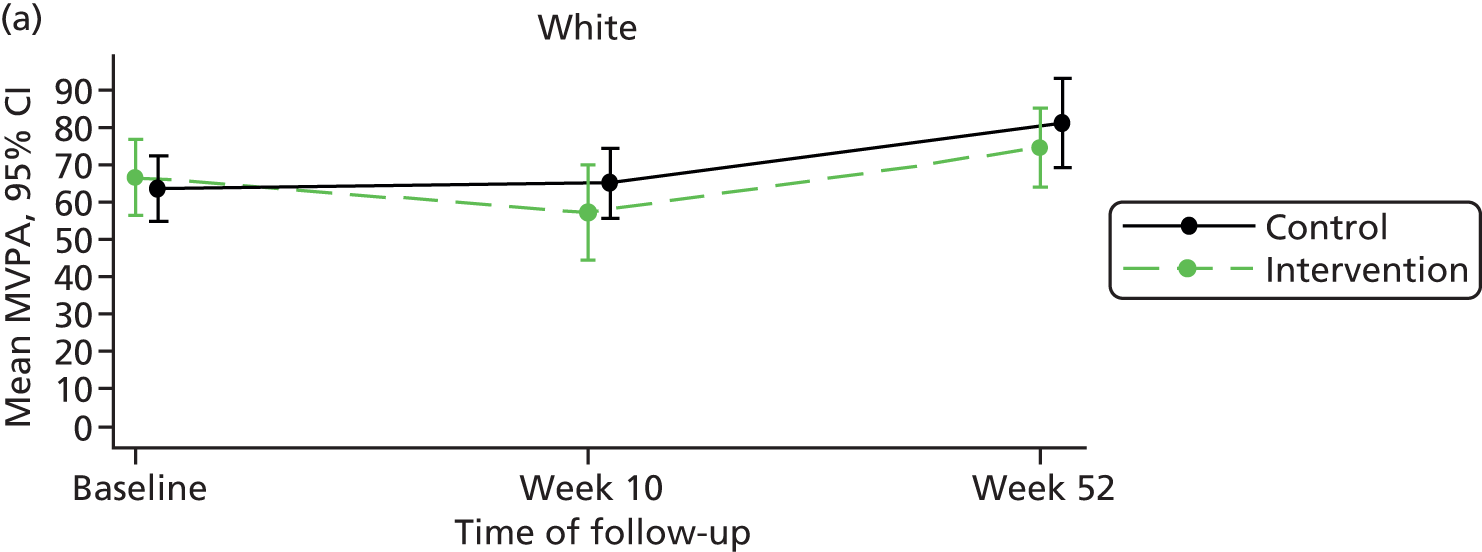

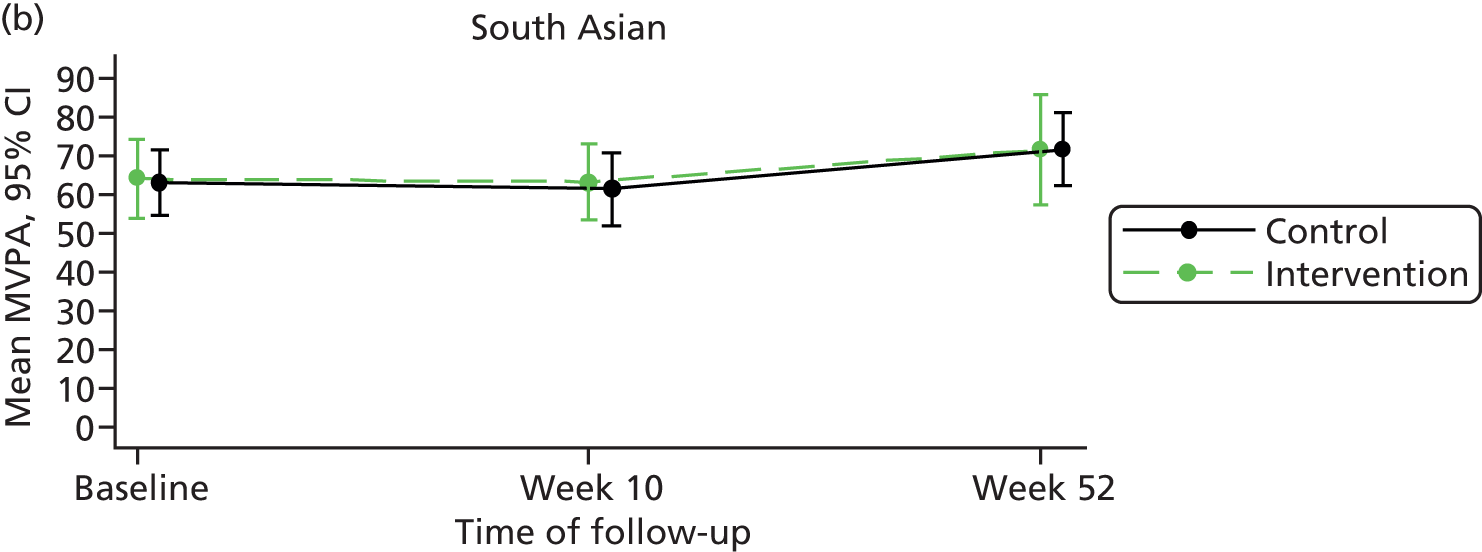

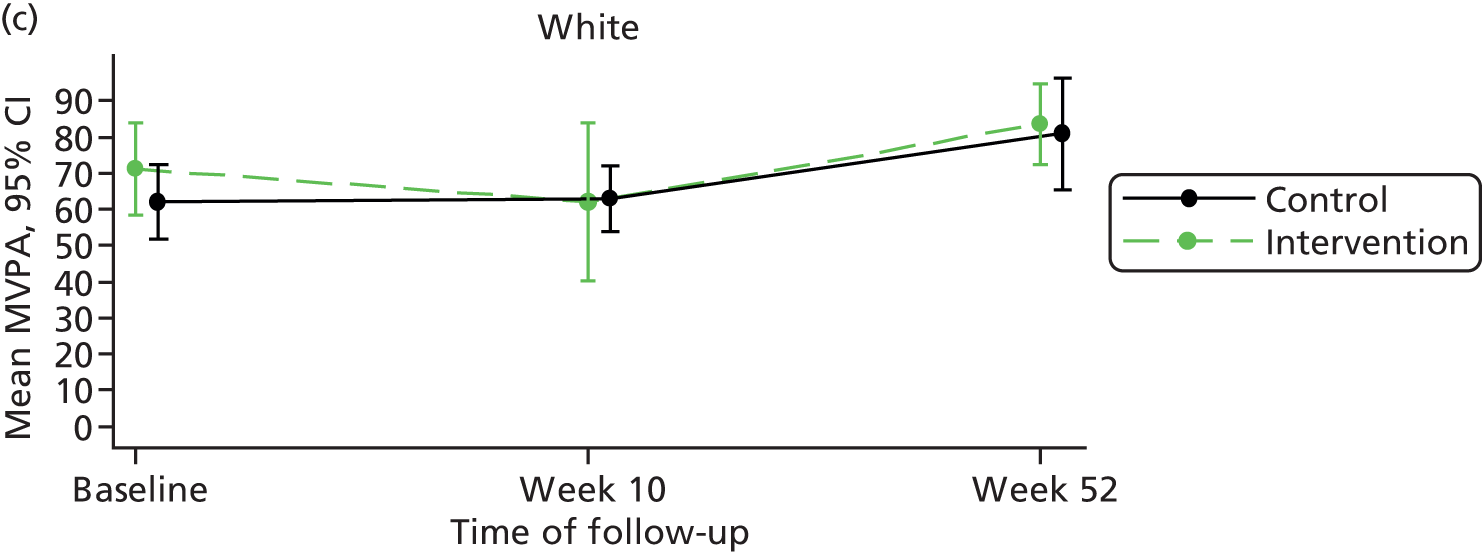

Health outcome analysis

Appropriate summary statistics were calculated in Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) following the intention-to-treat principle for each of physical activity, anthropometry, parent well-being and self-efficacy. Data were summarised for each time point overall, by trial arm and by ethnicity. A graph of the changes in MVPA over time by group and ethnicity was presented. When statistical testing was undertaken, statistical significance was assessed at the 5% level and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated where appropriate.

Objective 10: estimates of effect size, typical cluster sizes and intraclass correlation coefficients to enable an accurate sample size calculation for a full trial

The main aim of this study was to establish practicality, feasibility, recruitment rates and the sample size to inform a full-scale trial and, although it is unlikely that the small sample size would result in effectiveness being established, the primary outcome for a full trial, daily MVPA, was analysed to mimic practice in a full-scale trial. Results from this analysis must be treated as preliminary and interpreted with caution. 85,86 As the number of clusters is low, cluster summary statistics were utilised rather than multilevel modelling. 87,88 The analysis was carried out using school as the unit of analysis and the mean MVPA per day for the individuals in the school as the outcome variable. A weighted linear regression model was used to compare the PiP intervention arm and the control arm weighted by the number of participants followed up in each cluster and adjusted for the baseline average MVPA per day for each cluster. A sample size calculation was undertaken using the relevant information from the pilot study.

Objective 11: preliminary assessment of the potential cost-effectiveness of Preschoolers in the Playground and an estimate of the value of further research

Preliminary assessment of the potential cost-effectiveness

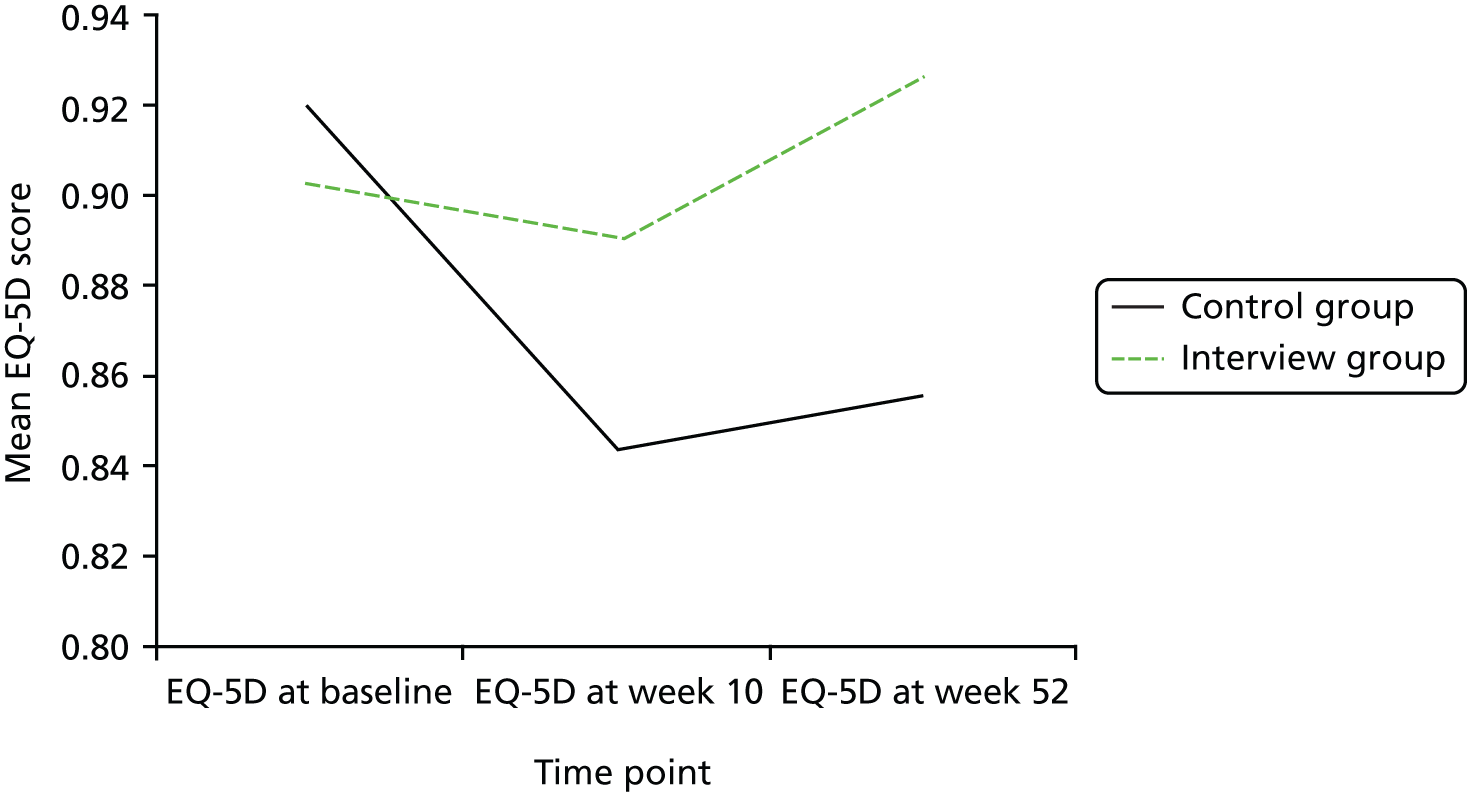

To make a preliminary assessment of the likely cost-effectiveness of the PiP intervention compared with usual practice in the context of the pilot trial, a cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted. When subgroup analysis was carried out, the whole group was analysed first and then the same analysis was repeated for both white and South Asian groups separately. The perspective was the NHS and Personal Social Services and 2012–13 costs were used. Costs and outcomes [as measured by quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and the PedsQL questionnaire] are not discounted as the time horizon was 1 year only, that is, the period that the study covered.

The outcome used to capture parents’ HRQoL was QALYs. QALYs are the product of the health state of each individual and the time spent in that state. The health state of each parent was evaluated using the EQ-5D instrument. The EQ-5D is a validated generic health-related preference-based measure consisting of five items that cover mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and anxiety and depression, each with three levels of severity. This generates 245 possible health states, including ‘death’ and ‘unconsciousness’. The EQ-5D scores collected at baseline and 10 and 52 weeks were transformed into HRQoL weights using the UK general population tariff, which assigns societal values to each health state. 89,90 Subsequently, QALYs accumulated over the 52 weeks of the trial period were derived for each individual applying the area under the curve (AUC) method. 91 In this approach, the HRQoL weights are multiplied by the respective length of time to produce the QALYs using the following equation:

where Q denotes the weight derived from the EQ-5D score at the time point t.

The HRQoL of children was assessed using the PedsQL questionnaire, which consists of four multidimensional scales, that is, physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning and school functioning, with a total of 23 items. Each item is assigned a value from 0 to 100 and a summary score is produced by summing all of the items over the number of items answered across all of the scales. Three summary scores can be estimated: total scale score (23 items), physical health summary score (eight items) and psychosocial health summary score (15 items). A higher score indicates a better health state. 92 For the purpose of this study the total scale score was used.

Parents recalled their child’s use of NHS services. All unit costs of the resources used were taken from the NHS reference cost database93 and the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU),94,95 adjusted to 2012–13 prices when necessary (Table 3).

| Description | Mean cost (£) | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital services | |||

| Overnight stay (short) | 735.59 | Per person per day | Weighted average of the costs of a non-elective inpatient (short stay) and an elective inpatient stay across paediatric services93 |

| Overnight stay (long) | 933.35 | Per person per day | Weighted average of the costs of a non-elective inpatient (long stay) and an elective inpatient stay across paediatric services93 |

| Day hospital attendancea | 799.61 | Per attendance | Weighted average of the cost of day cases93 |

| Outpatient appointment | 184 | Per attendance | Weighted average of the cost of outpatient attendances across paediatric services93 |

| A&E | 115 | Per attendance | A&E services93 |

| Day-case surgery | 1099 | Per attendance | Weighted average of the cost of paediatric surgery across all paediatric surgery services93 |

| Dentist | 38.15 | Per hour | Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration 201496 |

| Dermatologist | 140 | Per attendance | Paediatric dermatology93 |

| ENT | 95 | Per attendance | Paediatric ENT93 |

| Consultant for learning disabilities | 101 | Per hour | Consultant: psychiatric, PSSRU 201395 |

| Non-hospital services | |||

| General practitioner | 45 | Per patient contact lasting 11.7 minutes | PSSRU 201395 |

| General practitioner home visit | 114 | Per 23.4-minute consultation including travel | PSSRU 201395 |

| Practice nurse | 13.43 | Per 15.5-minute consultation | PSSRU 201395 |

| Practice nurse home visit | 21.53 | Per visit | PSSRU 201094b |

| Occupational therapist home visit | 47.36 | Per visit | PSSRU 201094b |

| Speech and language therapist | 45.21 | Per hour of client contact | PSSRU 201094b |

| Speech and language therapist home visit | 47.36 | Per visit | PSSRU 201094b |

| Physiotherapist | 45.21 | Per hour | PSSRU 201094b |

| Clinical/child psychologist | 134 | Per hour | PSSRU 201395 |

| Children’s social worker | 218 | Per hour | PSSRU 201395 |

| Health visitor | 59 | Per hour of patient-related work | Cost per hour of patient-related work, PSSRU 201395 |

| Special help teacher | 47.36 | Per visit | Speech and language therapist home visit, PSSRU 201094b |

| Family support worker | 49 | Per hour of client-related work | PSSRU 201395 |

| NHS Direct | 25.53 | Per call | |

Costing for overnight hospital stays was differentiated between participants who spent only 1 night in hospital and those who stayed for > 1 night, based on the distinction reported in the NHS reference costs database. 93 Those who were admitted for only 1 night were assigned a ‘short overnight stay’ cost, which was calculated as a weighted average of the cost of an elective inpatient stay and the cost of a short non-elective inpatient stay across paediatric services. Those who remained in hospital for > 1 night were attached a ‘long overnight stay’ cost, that is, a weighted average of the cost of an elective inpatient stay and the cost of a long non-elective inpatient stay across paediatric services (see Table 3). The cost per day of an inpatient stay was also varied substantially in the sensitivity analysis (see Chapter 3).

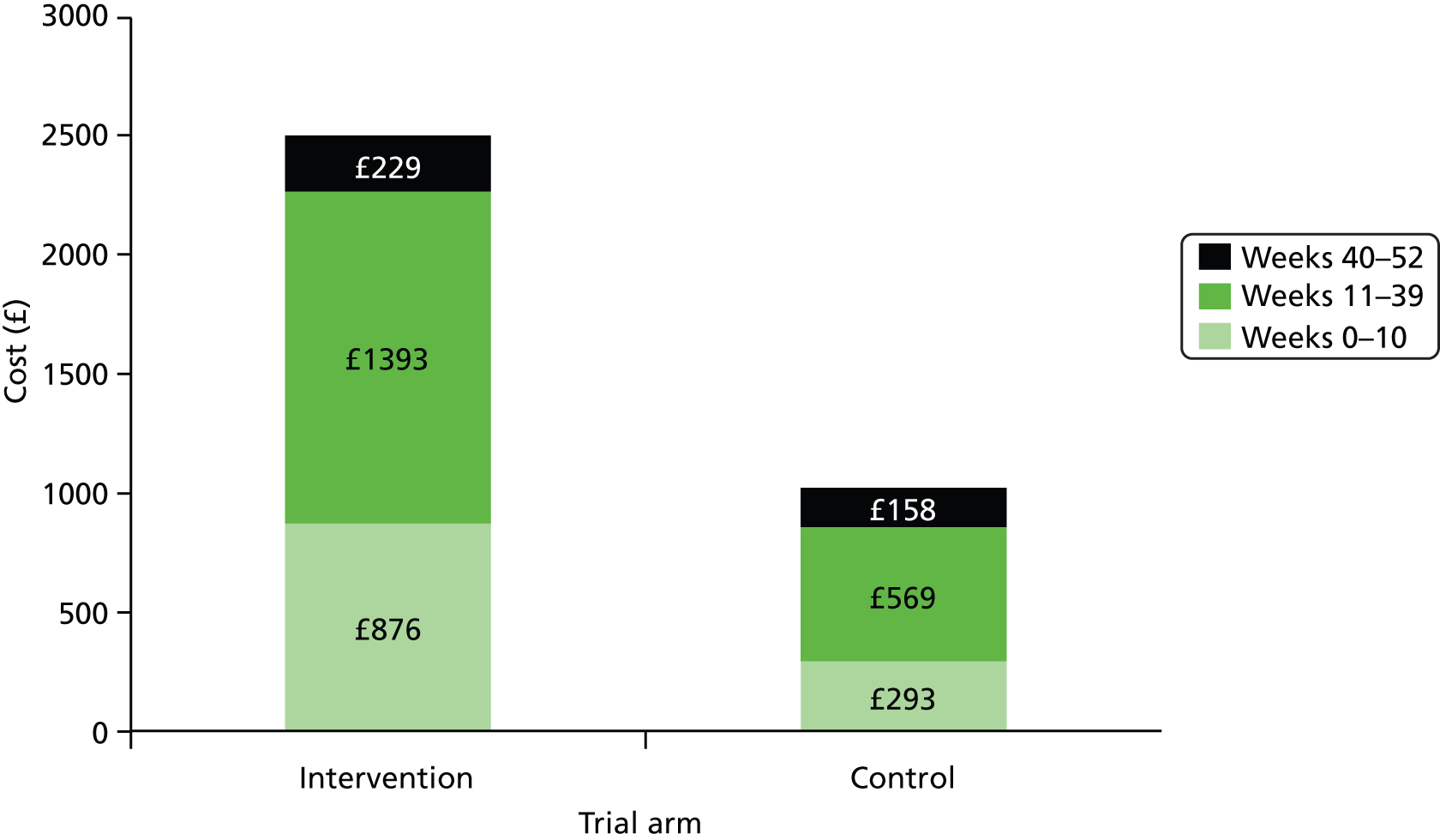

In addition, a detailed costing of the PiP intervention was performed (Table 4). The cost of the intervention consisted of two components: the salary of the PiP facilitator (based on the salary of a parental involvement worker) and the cost of training. A pro-rata annual salary of £18,144, increased by 25% to account for on-costs, was assumed for PiP facilitators, which resulted in a £14.69 hourly wage assuming that they worked for 30 hours per week over a period of 39 weeks and 10 days. 97 In total, 11 PiP facilitators were recruited in the trial, of whom five delivered six 30-minute PiP sessions per week for a period of 10 weeks. In future, the training of PiP facilitators would most likely be performed by experienced sports development officers and, therefore, would be costed using a £30,000 annual salary (37.5 hours per week for 42.7 working weeks per year),98 assuming £10,000 additional on-costs to account for national insurance and pension charges. The training involved a one-off session of 2.5 hours provided to each school. Furthermore, a total of three additional support visits to intervention schools were needed and telephone support was provided throughout the trial period. Forty 5-minute calls were included in the cost of training, that is, two calls per school in the initiation phase and two calls per school in the maintenance phase (Table 5). Alternative assumptions about the cost of the intervention were employed in the sensitivity analysis.

| Description | Mean cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| PiP facilitator | 14.69a | Prospects Online97 |

| PiP facilitator training | 24.98a | Prospects98 |

| Description | n | Use |

|---|---|---|

| PiP facilitator training | 5 | 2.5 hours |

| Telephone support to PiP facilitator | 40a | 5 minutes |

| Support visit to intervention school | 3 | 40 minutes |

| PiP facilitator | 5 | 60 × 30-minute PiP sessions |

Missing data arose when participants did not fully complete the follow-up questionnaires or missed one or more follow-up interviews. In the base-case analysis, missing data were imputed by multiple imputation (MI) using predictive mean matching. Complete-case analysis (excluding participants with missing data) was carried out as a sensitivity analysis.

The MI model included all variables related to costs, EQ-5D scores and PedsQL scores at the three data collection points. The total costs incurred by each individual at baseline, 10 weeks and 52 weeks were inserted in the model after being aggregated on two levels: total primary care costs and total secondary care costs.