Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3007/06. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The final report began editorial review in December 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

We confirm that there are no conflicting or competing interests in respect of DeltaNet International Ltd as the Anderson Peak Performance (APP) gateway and the companies responsible for website and logo design.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Stansfeld et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Background

There is empirical evidence, including several meta-analyses, showing that the psychosocial work environment impacts on employee well-being and mental health and risk of sickness absence. 1–4 Job strain, in terms of high demands and low decision latitude, low social support at work from managers and colleagues, effort–reward imbalance, organisational injustice and job insecurity have been related to an increased risk of common mental disorders, depressive disorders and sickness absence. Mental ill health at work has enormous costs to the economy: in 2007 the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health estimated that the total cost to UK employers of absenteeism, presenteeism and staff turnover was £25.9B. 5 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that mental ill health costs the UK economy £70B every year, of which 53% relates to loss of employment and productivity. 6 In the UK, 40% of overall sickness absence is a result of mental health problems, amounting to 70 million working days lost to psychiatric sickness absence per year. 5 There is consensus that employee health is a public health priority and the responsibility of employers and employees as well as health services. 7,8

Stress management interventions

Stress management interventions in the workplace target either the individual or the organisation9–11 and may act at primary, secondary or tertiary preventative levels. Most interventions to manage stress and mental illness at work have targeted the individual, usually at a secondary or a tertiary prevention level, using a clinical intervention such as cognitive–behavioural therapy or treatment of depressive illness with medication. 4,12 A meta-analysis of individually targeted health promotion13 has shown that it is not especially effective. However, the logic of the research findings linking the psychosocial environment to mental health suggests that primary preventative interventions are needed that can be delivered through the workplace. 14

Organisational interventions

So far, evaluations of organisational interventions for workplace stressors are limited, although there have been some process evaluations using qualitative methods and case studies to identify manager competencies needed for dealing with workplace stress and to examine how management standards are used in large organisations. 15–17 Three reviews of interventions within organisations11,18,19 showed mixed evidence of benefit in terms of health outcomes; van der Klink et al. ’s19 meta-analysis of 48 studies of occupational stress interventions showed that the majority of interventions were delivered to individuals rather than targeting the organisation and often involve cognitive–behavioural techniques. 20

Organisational approaches to improving mental health

Examining organisational-level interventions, Egan et al. 21 reviewed action research studies testing Karasek’s22 job strain model of the health effects of the combination of high job demands and low decision latitude or control over work. An elaborated version of this model includes the ameliorative effects of work social support on the health effects of job strain. Eight studies in this review reported benefits of the intervention for job control and participation; seven reported significant overall health improvements including for mental health questionnaire scores; and four studies reported decreased job demands post intervention accompanied by improved health outcomes in each instance. Improved support was also associated with improved health in the majority of studies in which it was measured. In those studies in which control, demand or support were recorded as unchanged or worsened, health outcomes often remained unchanged. 21 Furthermore, Bambra et al. 23 reviewed studies of workplace reorganisation involving increasing skill discretion, teamworking and decision latitude in diverse occupational groups. Nineteen of these studies included a control group but none was a randomised study. Again, the results were mixed; however, the teamworking interventions did improve the work environment by increasing support.

Organisational approaches to reducing sickness absence

Michie and Williams24 reviewed six studies and found that training and organisational approaches to increase participation and decision-making and increased work support and communication led to reduced sickness absence. The difference between ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ workplaces in terms of the psychosocial as opposed to the physical environment was attributed to the quality of leadership and the competence and awareness of management throughout the organisation. 24

Methodological problems in organisational interventions

Systematic and meta-analytic reviews conclude that there is a notable scarcity of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of organisational-level interventions. This partly reflects the difficulty in organising RCTs;25 the insufficient length of follow-up;19,26 and difficulties finding similar clusters for randomisation. 27 Nevertheless, these difficulties are not insurmountable, as exemplified by the WellWorks project, which included a RCT on cancer prevention strategies in 24 organisations in Massachusetts. 28 In summary, there have been insufficient methodologically robust RCTs to test whether or not organisational-level psychosocial interventions are effective in improving the well-being of employees and reducing sickness absence. In general, there is little knowledge of what works at an organisational level to improve employee well-being. A RCT of a participatory intervention involving action planning with nurses and sharing good practice and obstacles was associated with changes in work characteristics but not mental health29 and a participatory risk management intervention in an Australian public sector organisation was associated with significant improvements in job design, training and morale and a reduction in organisational sickness absence duration. 30 There are undoubtedly difficulties in carrying out RCTs in organisations in which there are many complex influences on the behaviour and well-being of employees and managers. However, although it may not be possible to adjust for all confounding factors, previous research has indicated that it is possible to execute RCTs in organisational settings. 24

This study aimed to build on the existing research to pilot an organisational-level management intervention to test the acceptability of a trial, the feasibility of recruitment, the components of the intervention, adherence and the likely effectiveness of the intervention before submitting it to rigorous RCT methodology.

Management standards

In this study we used an organisational-level intervention based on the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) management standards for work-related stress. 31,32 These psychosocial interventions were the first national approach that sought to reduce the incidence of work-related stress at source by applying a risk assessment process to triggers of work-related stress. An integral part of that process was the development of the management standards indicator tool. 31 This consists of 35 questions designed to assess adherence to the six management standards (change, control, demands support, relationships and role). The indicator tool provides a way for an organisation to identify potential hotspots where sources of stress exist and each of the six stressor areas is accompanied by a description of the desirable states to be achieved (the management standards), which are seen to reflect high levels of health, well-being and organisational performance. The basis of the management standards approach is to test or compare the states to be achieved with the actual conditions that currently exist within an organisation. This helps employers identify the underlying causes of workplace stress and think about how they might be prevented through practical improvements using organisational-level interventions. 33 We sought to test the benefits of using the management standards as a tool that can promote health in the workplace when used to improve management understanding and develop more effective competencies, rather than only as a method of assessing risk and compliance with standards. As the management standards are concerned with the prevention of work-related stress, it is apparent that the application of the six standard areas in the promotion of mental health is useful in the design of packages to improve well-being and reduce stress and sickness absence. Donaldson-Feilder et al. 34 found that previous competency frameworks for management did not cover all the six areas of the management standards.

Manager competencies

The HSE and the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development have worked together in a collaborative research programme with input from employers and employees to develop a set of competencies and behaviours perceived as being the most relevant and appropriate for helping managers to be better at managing work-related stress. The Management Competency Framework35 has four overarching competencies with an additional twelve subcompetencies. Each competency has associated behaviours, both positive and negative, which allow organisations to identify areas of management strengths and development needs around the skills necessary for tackling work-related stress. There has been significant interest and uptake of the Management Competency Framework by the human resources (HR) community, enabling new action plans for managers with regards to their current and future training needs. 36,37

An adapted version of the management standards for managers in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has been evaluated by Gaskell et al. ,38 who concluded that it offered ‘time-poor’ SME managers a quick and easy method for identifying problems and the mechanisms for dealing with them. This study focused on improving manager competencies to deal with stress at work within the framework of the HSE management standards.

Rationale for the pilot study

An efficient and potentially cost-effective way of improving the psychosocial work environment is training managers to provide more effective supportive management for employees; this support should make employees feel valued and help managers recognise stressful and unfair conditions in the workplace. When applied to managers at all levels, such interventions can be transmitted through work relationships to change the organisational culture. We decided to focus the intervention on line managers for employees, as these managers would have the most effect on employees and might be under most pressure from both above and below. We planned to test the acceptability, feasibility, risks and likely effectiveness of a primary preventative intervention that provides knowledge and skills about management standards and their implementation in terms of managing stress at work and promoting well-being. This is a pilot study and we did not expect to obtain definitive results on the effectiveness of the intervention as we were not powered to do so. Rather, we wished to assess the likely magnitude of the effect of the intervention as a guide for the future trial.

The intervention was delivered in the form of a guided e-learning education program provided as part of a continuing professional development (CPD) process. The advantage of targeting our intervention at managers who are line managers for a number of employees is that this is potentially a cost-effective way of influencing employees’ well-being. The study randomised the intervention to ‘clusters’ consisting of groups of managers and those employees whom they supervise. It has an advantage over approaching employees directly as managers have more power to change working conditions and these changes will apply to a number of employees in specific work groups. A cluster design allowed us to select managers and the employees working with them in service configurations in which they were carrying out the same types of tasks with similar groups of participants. Potentially, the cluster design also allowed us to recruit groups of managers who work in close proximity on similar tasks and who could share experiences in the facilitated meetings. We attempted to match up employees with their managers involved in the study.

The e-learning intervention allows managers to access the intervention at the most convenient time for them and to be supportive and perhaps facilitate change in working conditions. It can also be returned to again and again and was delivered in weekly or fortnightly instalments to make it more manageable to engage with within a busy working life. The hosting system for the e-learning package also enabled take-up (access, duration and frequency) to be measured so that the influence of intensity of package use could be assessed. The package is interactive (inviting reflection, requiring participants to make decisions during case studies, integrating real-life practical activities) and therefore is likely to engage the interest of the managers involved. The e-learning package could be applied to the whole cluster simultaneously. Thus, middle managers, who are particularly vulnerable to stress, benefit from the intervention directly through their own e-learning.

Several commercial organisations have developed e-learning programs based on management standards but there is no clear evidence of the effectiveness of such programs. In this pilot study we tested the likely effectiveness of an established e-learning program. We chose to use the Anderson Peak Performance (APP) e-learning package Managing Employee Pressure at Work [see www.andersonpeakperformance.co.uk (accessed 25 May 2015)], which is based on HSE management standards and addresses many of the aspects of workplace stress identified in observational research. It has been used in a number of public and private organisations by its originator Rosemary Anderson but its effectiveness has not been formally tested. A comparison of face-to-face stress intervention workshops led by an instructor with an e-learning format suggests that both formats can lead to significant reductions in reported stress, although attrition is significantly higher in the e-learning format. 39 Although there are a number of e-learning tools on stress at work, very few focus on what managers can do to reduce stress among their employees, which is a key feature of the APP e-learning package.

Objectives

The overall aim of the main randomised trial was to evaluate whether or not an e-learning health promotion intervention using management standards applied by managers improved employees’ well-being and reduced sickness absence in clusters selected from an organisation compared with similar clusters in the same organisation where it was not applied.

In this pilot study we tested within separate clusters of the same organisation:

-

the acceptability of the trial

-

the feasibility of recruitment

-

the components of the intervention

-

adherence

-

the likely effectiveness of the intervention.

With regard to adherence, in the protocol we stated that ‘The acceptability of the intervention to managers will be assessed by managers’ engagement with the intervention and their attitudes to the intervention using qualitative methods’. Adherence was not explicitly defined.

As the aim of a pilot study is to prepare for and improve on the design for a full RCT, we formulated a set of progression criteria to assess the likely success of such a future trial and identify measures for improvement. We hoped to see the following results for progression to the main trial to occur:

-

An increase in well-being scores of at least 3% among those employees whose managers completed the intervention compared with employees from the control cluster whose managers did not complete the intervention.

-

Recruitment of 80% of the eligible sample and 80% follow-up of the recruited sample of employees (up to 20% withdrawal from the study), with at least 60% of managers invited actively engaging with the intervention.

-

The acceptability of the intervention and the trial would be judged by the responses of managers to the intervention and the responses of employees to the trial, using data from the qualitative study.

-

The feasibility of the outcome measures and their collection would be assessed by the response rate to the online and paper questionnaires for employees, at least 60% coverage of recruited employees and the ease of availability of sickness absence data.

The decision to progress would also take into account whether or not simple procedures had been identified that are likely to improve rates of recruitment, retention and adherence, taking all measures together rather than in isolation. The overall costs and benefits of the pilot study intervention were also assessed to judge whether or not these would support a full trial.

In the protocol (version 3) our criteria for progression were as described in the following section.

Study progression

Progression to the main study will be assessed in terms of fulfilment of the pilot study objectives: sufficient trial recruitment; acceptability of, use of and adherence to the e-learning program by managers; acceptability of the trial to employees and managers; and the feasibility of the outcome measures and their collection. We estimate that progression to the main study would occur if there is an increase in well-being scores of at least 3% among those employees whose managers completed the intervention compared with those employees from the control cluster whose managers did not complete the intervention. We would aim for 80% recruitment and a 80% follow-up rate, with at least 60% of managers actively engaging with the intervention. The decision to progress will also take into account whether or not simple procedures have been identified that are likely to improve rates and taking all measures together rather than in isolation. We will also assess the overall costs and benefits of the pilot to judge whether or not these would support a full trial.

Patient and public involvement

Public involvement in the research was carried out through the steering group, which included a union member and a member of a mental health charity. Both contributed to fine-tuning the design of the study and to the management of the research. In particular, they were helpful in making suggestions about the content of the employee questionnaire and about ways to engage research staff and managers.

In addition, we held meetings with trust managers a month before the start of the study. As there were no ‘patients’ involved in this study and the relevant ‘public’ involved in this study were employees, we felt that managers and employees were the relevant groups to discuss the study with. This was very helpful in engaging the target audience and the discussion with the managers helped to refine the study methodology. Feedback was used to identify the best channels to communicate with managers during the intervention, for instance managers tended to favour telephone and face-to-face contact with the facilitator rather than web-based interaction. We also received helpful pointers about possible concerns regarding the understanding of cluster selection and randomisation and the confidentiality of the employee questionnaires, which helped us in the set-up of communications with the targeted participants.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction to the mixed-methods approach

The pilot study was designed as a ‘mixed-methods’ study, incorporating a qualitative component alongside a RCT. The benefits of a mixed-methods design are increasingly acknowledged40–42 in terms of helping to illuminate the processes of a trial, the acceptability of a trial and intervention and possible reasons why an intervention does or does not work and to draw out the learning from a study.

Trial methods

Trial design

This trial was designed as the precursor of a cluster, single-blind RCT of a site-level intervention. It was conducted at a single organisation with four clusters of employees and the managers who supervise them. Each of the clusters was equivalent to one service unit within the recruited organisation, either for a specific geographical location or for a separate organisational unit. Each cluster was expected to consist of about 10–15 managers responsible for 5–20 employees each. It was expected that 100 employees per cluster would give consent. The clusters were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group at a ratio of 3 : 1. In total, we expected to recruit 30–40 managers from three clusters randomised to the intervention and about 400 employees from all four clusters.

Participants

We recruited a single organisation to participate in the pilot study that was receptive to using a CPD approach to adopting management standards. Inclusion criteria included the organisation’s ability to provide usable data on sickness absence and to allow internet access at work for its staff.

The four clusters were identified and selected in collaboration with stakeholders at the organisation. Although no strict selection criteria were defined in the protocol, we sought to include clusters of comparable size, with similar organisational and hierarchical structures and areas of activity and with relative separation in terms of either geographical location or organisational structure, to minimise contagion effects between intervention and control group clusters.

Within the selected four clusters we aimed to invite all employees and their immediate line managers to participate in the study. Potential participants were identified with the help of the organisation’s own research team, who acted as local study champions, and with the use of the organisation’s electronic staff records. Participants were classified as either employees or managers for the purpose of the study. We excluded staff for whom the intervention was unlikely to have an effect because they would not remain in the organisation for the duration of the study: the long-term sick, those with a notified pregnancy and staff on fixed-term contracts due to expire during the course of the trial.

During recruitment, these exclusion criteria were amended to explicitly exclude managers as well as employees on long-term absences and to exclude managers and employees with other types of contracts known to expire or terminate during the course of the trial (e.g. because of retirement). This amendment was a clarification of the eligibility criteria that became necessary during the recruitment process and did not alter the pool from which the participants were recruited. Long-term sickness absence, often the result of severe illness or very entrenched work problems or both, was unlikely to be influenced by a short-term intervention such as that applied in the study and thus employees with long-term sickness absence were excluded.

Potential participants were invited to take part by the local research team and given a participant information sheet and asked to sign an informed consent form for participation in the study. There were two different information sheets, one customised for employees and one for managers. Participants who gave written informed consent to take part in the study were allocated a three-digit unique participant identification number for pseudo-anonymisation. Participants who were invited to take part in the qualitative research interviews or focus group were asked to give a short separate informed consent for the recording and use of the interview data.

Procedure for the follow-up of employees

Employees recruited to the study were invited to complete a work, health and well-being questionnaire at baseline (i.e. before the start of the study intervention) and at follow-up (after the end of the intervention). Questionnaires were completed online by employees but paper copies were offered to those who were unwilling or unable to complete online questionnaires.

After registration, employees received an automated e-mail with the questionnaire log-in instructions. In case of non-response, the reminder procedure was as follows:

-

two automated e-mail reminders were sent out to participants who had not completed the questionnaire, 7 days apart

-

one personalised e-mail reminder was sent by the trial manager if no response was received

-

local research staff then attempted telephone contact with the participants who had not responded

-

paper questionnaires were then offered to those employees who had not responded by this point.

Intervention

Name of the intervention

The intervention involved a guided application of the APP e-learning program Managing Employee Pressure at Work for managers. A summary of the intervention timeline is given in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Intervention timeline.

Aims of the intervention

The e-learning package Managing Employee Pressure at Work is an already established e-learning health promotion program for managers with a focus on the six management standards domains: change, control, demands, relationship, role and support. This psychosocial program aims to help managers identify sources of stress, understand the link with mental and physical illness and improve managers’ capacity for helping employees proactively improve their well-being and deal with stressful working conditions. The intended focus is on improving social support for employees, improving communication, improving organisational justice, providing more information about job change and making sure that employees’ work is valued. The intervention also involved guidance in the form of face-to-face sessions and support from a study facilitator.

The e-learning program was designed to help managers understand:

-

the concept of pressure at work, the link with mental and physical ill health, the need to take this seriously and the personal and team/organisational benefits for doing so

-

how to work proactively with their teams to identify collective problems and find solutions

-

how to spot if an employee has a problem and work with the individual to find suitable acceptable solutions

-

how to support individual employees who are experiencing problems

-

their legal duty of care

-

how to avoid personal injury claims and how to carry out a HSE-compatible risk assessment if required

-

how their own management style may add to or reduce pressure on their employees.

The intended mechanism of the intervention was as follows. Through participation in the e-learning program, the completion of e-learning activities and consultation with the facilitator, managers change their behaviour towards employees and the workplace conditions. The change in managers’ behaviour results in improved well-being and reduced stress among employees. Increased well-being is also related to employees subsequently being less likely to take sickness absence.

Incentivisation

Staff were incentivised to use the intervention through management ‘buy-in’, publicity and receiving a certificate of completion as part of CPD. The project was presented to senior managers and managers targeted for study participation at two local meetings a month before the start of recruitment, with the endorsement of executives within the organisation. Executives verbally agreed to allow allocated time for managers to complete the e-learning. Senior managers also received access to the same e-learning program as the targeted managers. We presented the program in a way that attempted to incentivise middle managers to participate, showing that this could improve their working life.

Content of the intervention and procedures

The intervention consisted of two face-to-face educational sessions with a facilitator, the modular e-learning program and ongoing e-mail or telephone support from the facilitator. The e-learning program consisted of a series of linked topics with case examples, additional activities that could be completed outside the e-learning environment and an assessment activity in the form of a quiz. The HSE management standard domains are dealt with across several of the e-learning program modules and are not distinct to any one module.

In module 1 pressure and demands are identified and discussed. In module 3 the Health and Safety at Work Act 197443 is explained as well as the need to carry out risk assessments for stress at work. Reference is made to the health and safety guidance on work-related stress44 and the indicator tool. 31 In module 4 each of the six risk factors is introduced and dealt with in terms of manager competencies. Modules 5 and 6 each take the HSE five-step approach [educate to understand the causes of stress, identify the problems, determine ways to improve, record (devise an action plan), take action and review]. In module 5 proactive solutions are suggested including increasing control and social support. The structure of the modules is described in Table 1.

| Title and content | Additional activities for managers to apply to their current work situation | Duration of e-learning module alone (without activities) |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction and benchmarking quiz This module explains how the program is structured. It introduces each module and how to navigate the program. It shows how to access extra information and activities. It also looks at the obstacles to successfully tackling stress at work and explains the benefits of taking part. The introductory quiz is introduced as being for research purposes only |

None | 10 + 10 minutes |

| Module 1: Why tackle employee pressure at work? Health issues The physiological, psychological and behavioural symptoms of stress, how they can affect an employee’s health and well-being and how to spot them; how to more effectively motivate employees |

Activity on motivation | 30 minutes |

| Module 2: Why tackle employee pressure at work? Economic issues The economic reasons why organisations need to address pressure at work |

None | 10 minutes |

| Module 3: Why tackle employee pressure at work? Legal issues The legal reasons why organisations need to address pressure at work and the legislation most commonly associated with this |

None | 10 minutes |

| Module 4: What can a manager do? A management competency topic What managers can do to reduce pressure for employees, the causes of pressure at work and how general management skills and behaviour can reduce pressure at work |

Management styles and behaviours including suggestions for working with teams and colleagues | 20 minutes; additional time to work with teams and colleagues |

| Module 5: Being proactive – helping your team How to identify problems common to a team, how to work with the team to make improvements and how to make an action plan for these improvements |

Developing an action plan | 10 minutes |

| Module 6: Being proactive – helping individuals Why it is important to be aware of an individual’s concerns at work, how to identify problems that employees might be experiencing and how to work with individuals to find solutions to problems at work and stressful situations that require managers to take action |

Interactive case study | 30 minutes; additional time to work with the team and produce an action plan (will vary) |

| Final quiz and confirmation of successful completion 15 randomised questions to check participants’ understanding |

None | 10 minutes |

For the purposes of defining the content and the amount of engagement that managers would show with the e-learning program, modules 1–6 were defined as the ‘main’ learning modules of the program.

The content of the e-learning program Managing Employee Pressure at Work is proprietary to APP and not publicly accessible. The content of the e-learning program was reviewed by the research team before the start of the intervention. The e-learning program was adopted for use in the study without any changes, with the exception of the quiz. The standard e-learning program contains a quiz only at the end of the program, consisting of 10 questions randomised from a bank of 40 questions. To make the assessment more demanding and to allow for an assessment of managers’ knowledge gained from the intervention, the questionnaire was extended to 15 questions from a bank of 75 questions, with additional questions based around the HSE management standards, and duplicated, so that participants would also complete an introductory quiz against which to benchmark their scores on the final quiz.

Duration and schedule of the intervention

The intervention was presented over a 3-month period. The same intervention, including the same e-learning package, was used for all managers in those clusters randomised to the intervention. Having provided written informed consent, the recruited managers were sent a welcome e-mail and invited to take part in an induction session.

The intervention started with the face-to-face induction session conducted by the study facilitator. Three separate induction sessions were held, one for each of the three clusters of managers randomised to the intervention, in separate geographical locations within the participating organisation, at a date convenient for the participating managers. The induction sessions lasted between 90 and 120 minutes. The principal aim of the induction session was to engage the managers in the program by motivating them to take part in the training, by initiating an exchange among their peers on the topic of stress and stress management and by introducing them to the content and technical aspects of the e-learning program. A detailed programme of these sessions is given in Appendix 3. Managers unable to attend the induction session were sent an introductory handout by the trial manager and were contacted by telephone by the study facilitator to brief them on the program, offer support and answer any questions. Attendance at facilitated sessions was documented by circulating an attendance register.

The e-learning program was then applied in weekly to fortnightly instalments:

-

weeks 1 and 2: completion of the introduction and benchmarking quiz after attendance at the induction meeting

-

week 3: completion of modules 1–3

-

week 4: catch-up week, time to carry out motivational activity contained in module 1

-

week 5: completion of module 4

-

week 6: catch-up week, time to carry out activity on management competency contained in module 4

-

week 7: completion of module 5

-

week 8: catch-up week, time to carry out group activity contained in module 5

-

week 9: follow-up face-to-face meeting with the facilitator

-

week 10: completion of module 6 and final quiz

-

week 11: catch-up week.

Participants were provided with a suggested timeline to follow when working through the program (see Appendix 3). During weeks 1 and 2, only the introductory module and the benchmarking quiz were accessible online, to prevent participants from accessing the main content modules before completing the initial benchmarking quiz. From week 3 onwards, all of the remaining modules were made available online and participants were essentially free to complete the program at their own pace, that is they could also complete the remaining modules in one session if they wished. It was, however, stressed that the activities should take place in adherence to the timeline so that they would be able to receive support and have the opportunity to discuss their experiences with the facilitator and at the follow-up meeting.

A second face-to-face session took place with the facilitator after the scheduled completion of module 5. Again, three sessions were held, one for each of the clusters randomised to the intervention. The aim of this follow-up session was to provide an opportunity for managers to discuss their learning, give feedback on the program and discuss their experience with the activities contained within the modules.

After completion of the e-learning program, participants were provided with a certificate of completion. A generic, electronic e-learning certificate automatically became available at the end of the final online quiz module if participants answered at least 10 out of 15 questions correctly. The quiz could be retaken an unlimited number of times. At the end of the study we provided a tailored, Guided E-learning for Managers (GEM) study-specific certificate in paper format to all participants who had completed all of the main e-learning modules, based on the final full uptake data report.

The e-learning program remained accessible to all participating managers until the end of the follow-up period (i.e. for an additional 3 months during which follow-up sickness absence data were collected and while employees completed the follow-up questionnaire), allowing managers to revisit any topics should they wish.

Completion of the e-learning program itself was expected to take around 2.5 hours without any interruptions. Including the completion of the embedded activities, it was expected to take around 4 hours, although more time could be spent on the activities if desired. Finally, adding attendance at the face-to-face sessions with the facilitator, the entire guided e-learning intervention would be expected to take between 7 and 8 hours.

Delivery of the intervention

The guidance for the intervention was provided by a study facilitator recruited especially for this project, a consultant and trainer in organisational health with experience in stress management and the provision of corporate training. The facilitator received 2 days of training from the developer of the e-learning program, a chartered psychologist with 18 years’ experience of working with organisations. The content of this training is summarised in Appendix 3.

The face-to-face induction and follow-up sessions were held on site, at facilities provided by the participating organisation. They were led by the facilitator and attended by the participating managers as well as the qualitative researcher. Care was taken to create an environment in which managers could discuss issues around work and stress freely and confidentiality.

The e-learning program was hosted by DeltaNet International Ltd (Loughborough, UK), who provided unique log-in usernames and temporary passwords for each participating manager. The trial manager sent an e-mail to each individual manager containing a link to the online log-in page for the program, together with log-in information. Managers were required to change their password at their first log-in. They were then free to access the program as many times as desired, from any location and web browser that supported the Adobe Flash plug-in and had JavaScript enabled. The program included a reminder function for any participants who might have forgotten their password and the trial manager was available by telephone and e-mail in case of any technical issues. Each learner’s personal e-learning program home page offered an overview and short description of the different modules and displayed the status of completion for each module, to allow participants to track their progress. Each individual module opened in a pop-up window.

Tailoring of the intervention

The e-learning program and the two face-to-face sessions form the core of the intervention. Additionally, guidance and support from the facilitator was adapted to the participants based on their needs, whether they were able to attend the face-to-face sessions and whether they could be reached for a follow-up telephone conversation. The facilitator would offer support to managers by telephone and/or e-mail to discuss any issues that came up and would attempt to contact managers who had fallen behind on their e-learning schedule. All participants received fortnightly e-mail prompts from the trial manager to complete modules when they became due; non-responders received additional weekly e-mail reminders to complete any overdue modules.

Lastly, we planned that the intervention should be embedded within the participating organisation’s existing policies on stress management. Participating managers therefore received information on existing internal sources of support for dealing with employee stress in the form of a handout entitled Health and Well-being Support Available to Managers, including contact details for various internal support services such as occupational health and staff support and psychological well-being services.

Assessment of adherence

Use of the program was monitored to measure uptake of the intervention by managers. The system logged the number of times each participating manager accessed each module, the duration of access per module and the score on each attempt at both quiz modules. The system automatically logged out users after 30 minutes of inactivity. Weekly uptake reports provided by the e-learning host detailed the number of modules that were completed, not started or incomplete. A final report provided at the end of the intervention additionally detailed the number of times and the length of time that managers spent accessing each module and the scores for each attempt at the baseline and follow-up quiz. The system recorded and reported only the overall scores for the quiz modules for each participant; individual answers to the quiz were not stored, neither was any information entered by participants in any activities integrated within the main learning modules (e.g. text boxes inviting reflection).

Control group treatment

Managers in the cluster allocated to the control group were not recruited to the study and were not given any form of control intervention. They were informed by the local research team of their cluster allocation and asked not to reveal their allocation to their teams. Managers in the control group were offered access to the e-learning program at the end of the study after all follow-up data collection was complete; one control cluster manager took up this offer. This control group access to the e-learning program was not monitored or evaluated in terms of uptake, as this was not within the scope of the study.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of this pilot study related to acceptability, feasibility and participation.

Adherence to the e-learning intervention

Manager adherence was defined in the protocol as the number of times that managers logged on to the e-learning program. Additionally, it emerged during the intervention that the protocol had not specified a minimum level of engagement to qualify as adherent for the purposes of measuring differing effects between employees whose managers did engage with the intervention and employees whose managers did not engage with the intervention. The number of times that a manager logged on to the program emerged as a poor measure of adherence or engagement, as non-adherent managers could log on without spending a meaningful amount of time with the program, whereas an actively engaged manager could log on once and complete the entire e-learning program in one sitting. Completing the modules contained within the program was a much more meaningful measure. Active engagement with or adherence to the intervention by managers was therefore operationally defined during data collection and before analysis and required managers to have completed at least 50% of the six main learning modules of the e-learning program.

Acceptability of the intervention to managers

The acceptability of the intervention to managers was assessed by managers’ engagement with the intervention and their attitude to the intervention, assessed in individual interviews with managers and in the focus group.

Acceptability of the trial to managers and employees

We assessed the acceptability of the trial to managers and employees using individual interviews with managers and employees and a focus group with managers post intervention.

Feasibility of the trial

The feasibility of the trial was measured for employees and managers by participation and retention rates in the study and the ease of availability of sickness absence data at the cluster level and economic data at the individual level.

Participation of managers

For managers, participation was assessed as the percentage of managers who gave written informed consent to take part in the study, the percentage of participating managers who attended the induction session and the number of times that managers logged on to the program (see Adherence to the e-learning intervention).

Participation of employees

For employees, participation was measured by the giving of consent to take part in the study (presented as the percentage of employees who were approached) and response rates to the baseline and follow-up questionnaires (presented as the percentage of those consenting). Additionally, demographic details in terms of age band, sex and salary band were collected for employees who dropped out of the study between baseline and follow-up and these were compared with the demographic details for the overall trust workforce.

The following are the outcome measures of the main randomised trial, which we also piloted in this study; all employee outcomes were assessed at baseline (i.e. for a period of 3 months before the start of the intervention) and at follow-up (i.e. for a period of 3 months, starting 1 month after completion of the intervention).

Managers’ knowledge gained from the program

This was assessed by comparing scores achieved by managers in the e-learning quiz at the beginning and at the end of the intervention. The quiz was based on a bank of 75 multiple choice questions, out of which 15 questions were randomly selected for each quiz selection. Scores were presented as percentages.

Employee well-being

Pre–post changes in levels of well-being were assessed using the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS),45 a brief 14-item scale assessing aspects of positive mental health, including both hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives. The score ranges from 14 to 70 with 70 representing perfect well-being. The WEMWBS score is presented as the mean [standard deviation (SD)] and the difference between baseline and follow-up comparing the intervention and control groups after adjusting for baseline. This is presented as an effect size with [95% confidence interval (CI)].

In this pilot study we estimated the SD of change in well-being over 3 months and the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) between the four clusters.

Sickness absence

Periods of sickness absence were requested for all employees who gave consent to the study, in an anonymised format, using the existing reporting system of the organisation recruited. Although it is not possible to link these individuals to their GEM study identification number, the number of individuals whose records were not found and hence who cannot be assumed not to be absent was reported back to the trial team.

The sickness absence data collected included the employee age group, sex, income band and dates of sickness absence. The sickness absence data were categorised as ‘short term’ (< 7 days), ‘medium term’ (7–21 days) or ‘long term’ (> 21 days). Sickness absence was calculated as the number of days absent between 1 May 2013 and 31 July 2013 for baseline and between 1 January 2014 and 31 March 2014 for follow-up. If an employee was sick over the weekend, the weekend days were included even though they may not have been working days lost. This was because employees worked for an NHS trust and many worked at weekends. Separate periods of sickness were added together to calculate the total number of days absent. Long-term sickness absence was defined as > 21 consecutive days within the data collection period. Employees with long-term absence were excluded from the overall analysis of sickness absence. Thus, some employees might have had the beginning or end of a long absence within the data collection period but not be coded as having a long-term absence.

Although we did not expect to see changes in sickness absence in this study, the pilot study allowed us to test the process of data collection.

Self-reported sickness absence

In addition to the sickness absence reported from the organisational reporting systems, we also asked employees in the employee questionnaire to report the number of days taken off sick, including weekends, over the previous 3 months. We did not ask about individual periods of sickness absence and so omitted anyone who had been sick for > 21 days in total from the self-reported sickness absence analysis.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was measured using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). 46 The GHQ-12 score is reported as a mean and percentage above 3, the threshold used to identify mental health problems.

Because of error, the wrong item responses were reproduced for question 12 (happiness) on the baseline questionnaire, with ‘not at all’/‘no more than usual’/‘rather more than usual’/‘much more than usual’ presented to the employees instead of ‘more so than usual’/‘about the same as usual’/‘less so than usual’/‘much less than usual’. For the main analysis the first 11 items were used and multiplied by 12/11 for both baseline and follow-up time points. Thus, the same method was used at both time points. Appendix 2 compares the GHQ-12 scoring based on 11 items with that based on 12 items and that based on 11 items with the 12th item classified as ‘missing’.

Psychosocial work characteristics

Psychosocial work characteristics were measured using the standardised assessment tools within the employee questionnaire based on the job strain model (control and demands),22 work social support47 and effort–reward imbalance48 using abbreviated versions for epidemiological studies. 49 Questionnaire items relating to these outcomes are reproduced in Appendix 1.

Job strain is defined as the combination of high psychological demands and low decision latitude. The GEM questionnaire has been designed to capture information on the following work characteristic dimensions: work demands, skill discretion, decision authority and social support. Decision latitude is derived as the sum of decision authority and skill discretion. Job strain is the decision latitude score subtracted from the work demand score. All items have been presented on a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 representing high support for support-related scales and high demand for demand-related scales. Job strain is measured on a scale from –100 to 100, with 100 representing highly demanding roles with low levels of autonomy and –100 representing highly autonomous jobs with low demand.

A modified version of the effort–reward ratio was computed for each employee according to the formula e/(r × c), where e is the sum score of the effort scale, r is the sum score of the reward scale (with reversed polarity, which means that low scores indicate high distress resulting from a lack of recognition) and c defines a correction factor for different numbers of items in the nominator and denominator. Effort uses the same items as work demand and reward uses the same items as supervisor relationship but both are scaled from 1 to 100 to avoid dividing by zero. The correction factor was set to 1 as both effort and reward are measured on the same scale from 1 to 100. As a result, a value close to zero indicates a favourable condition (relatively low effort, relatively high reward), whereas values > 1 indicate an effort–reward imbalance.

We also assessed additional work characteristics such as work conflict, change at work, supervisor relationships (five items from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development Employee Outlook surveys scored on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’), supervisor support (two items), job insecurity, clarity of information (with two items on sufficient and consistent information from supervisors) and stressfulness. All items except stressfulness are presented on a scale from 0 to 100, with job stressfulness presented on a scale from 0 to 10. For all scales mean scores are presented.

Additionally, we also assessed employee health behaviours (smoking and alcohol consumption) and social support outside work. Problems with drinking alcohol were assessed using the four-item CAGE (Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye-opener) instrument. 50 Participants who responded positively to two or more items were classified as having an alcohol problem. Perceived social support was assessed using four items (‘people who make me feel happy’/‘people who make me feel loved’/‘people who can be relied on’/‘people who give support’) out of the seven items used in the Health Survey for England. 51 Those responding positively to all items were classified as having perceived social support.

Safety considerations

The pilot study allowed us to study any risks of the intervention. Given the nature of the intervention and the absence of any routine clinical assessments or reporting procedures as part of this study, there was no systematic documentation of adverse events or adverse effects.

Potentially, we thought that managers could misinterpret the program and adopt maladaptive management strategies. However, the intervention was laid out in such a way that it was easy to comprehend, was organisationally supported and was sanctioned as being part of the HR and professional development strategies. Potentially, some managers could have become distressed by recognising that their previous management practices had not been ideal or that new techniques may be more time-consuming, requiring them to relinquish some control or be involved in more teamwork. We organised an e-mail or telephone-based discussion option for managers to discuss with the study facilitator any issues that arose with the program. The facilitator was asked to report any harms identified to the study team. Negative experiences by managers during the guided e-learning intervention, and by employees as a consequence of their manager’s participation, could be documented qualitatively in a sample of in-depth interviews.

The questionnaires for well-being (WEMWBS) and psychological distress (GHQ-12) are too non-specific to identify clinically significant distress reliably within individual distress. In case psychological distress was reported directly to the research team, protocol guidelines were in place to guide participants to relevant sources of support. Any such direct reports would be reported anonymously for the purposes of the safety evaluation of the study.

Sample size

The study was designed to recruit 120 employees from four clusters, expecting that 100 employees per cluster would consent. The response rate was estimated to within 3.8 percentage points, for example 76.1% to 83.9%. Measurements of intervention acceptability could be estimated from those managers who consented to the intervention, expected to be 40 individuals. If the take-up was 80% the 95% CI would be 64% to 91%. We envisaged recruiting 30–40 managers, each responsible for 5–20 employees. The pilot study was designed to provide evidence for the basic assumptions in our sample size calculations, to strengthen our calculations for the main study. From earlier literature on well-being measures52 the ICC was expected to have a value of about 0.07. Eldridge and Kerry53 showed that ICC estimates from small studies are dependent on the number of individuals and therefore four clusters provide a reasonable estimate. In this pilot study we estimated the likely effect size with its 95% CIs.

Randomisation

Three clusters, rather than individual participants, were randomly allocated to the intervention group and one cluster was randomised to the control group. This was to fit the aims of the trial, which were to test the recruitment process and obtain information about the implementation of the intervention. All managers within a specific intervention cluster were provided with the same intervention. One simple randomisation step was undertaken by an independent statistician. Randomisation of clusters was scheduled to take place after employees had been recruited and before recruitment of the corresponding managers, as only managers in clusters randomised to the intervention would be actively involved in the study.

Blinding

Employees were blinded to whether or not their managers had been randomised to the intervention or the control group. Managers in both groups were asked not to reveal their allocation to their teams.

As managers in the three intervention clusters only were recruited into the study, and as allocation to the intervention or the control group was self-evident, participating managers could not be blinded to their allocation. Likewise, the study facilitator and qualitative researcher were aware of the allocations.

As this was a cluster randomised study and no medical intervention was applied that would require emergency treatment, unblinding procedures were not applicable. Participants were informed of their allocation at the end of the study.

Members of the research team were kept blinded with regard to identification of the intervention and control group clusters and were unblinded only on a need-to-know basis. Members of the local team responsible for the recruitment of employees were not told of the allocation until the end of recruitment. Researchers performing analyses on the quantitative and economic data were blinded to the allocation until the main analyses had been performed.

On recruitment, each participant was allocated with a three-digit unique study identification number. These numbers were predefined and allocated in groups to one of the four clusters. This allowed for participants to be allocated to the correct clusters without identifying the cluster.

Statistical methods

The analyses were carried out using Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Pilot study analyses were descriptive and no formal statistical analyses were conducted to determine the effectiveness of the intervention,54 although CIs are presented. Participation rates are presented for each cluster and overall and 95% CIs for rates have been presented without adjustment for clustering. Effectiveness comparing the intervention and control clusters was estimated using a random-effects model with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. As the random-effects model assumes a large sample for the number of clusters, the CIs were calculated using the standard error from the model and the t-distribution with 2 degrees of freedom instead of the normal distribution. Post-hoc analyses were carried out to assess changes in well-being scores for employees of managers who did or did not engage with the intervention, as well as for employees of managers who changed position during the course of the study. This analysis used a random-effects model but did not adjust for the small number of clusters as the comparison was within rather than between clusters.

The same method was used to assess sickness absence but only employees who did not have an episode of sickness absence > 21 days were included.

Qualitative methods

Interviews with key informants

An aim of the qualitative study was to describe the policy and organisational context within which the overall study took place and the thinking behind the study and intervention. To address this, the qualitative study began by identifying ‘key informants’ for in-depth interview. We interviewed members of the study team and scientific steering committee, senior managers at the NHS trust and those involved with the development and implementation of the guided e-learning intervention. We followed up suggestions from these informants of additional key informants (e.g. other researchers in the field of work stress and well-being). We undertook 14 in-depth key informant interviews, using the topic guide in Appendix 4 as a basis for discussion. We were particularly interested in exploring what key informants identified as critical topics and questions for the study to ask managers and employees. We also asked informants to identify relevant literature, both published and ‘grey literature’. Most interviews were conducted face to face; when this was difficult to arrange (three cases) the interview took place by telephone. Ten of the 14 interviews were audio recorded and transcribed; in the others the qualitative researcher took extensive notes.

Interviews with managers

A key aim of the qualitative study was to explore managers’ views about the study and their experience of the guided e-learning intervention and of managing stress in the workplace. We adopted a narrative approach to interviewing,55 meaning that interview questions encouraged respondents to recount stories of specific (anonymised) cases and incidents, as a way of eliciting a rich and reflective account of the complexities of managing stress at work. A narrative methodology focuses on concrete and situated practice, rather than on abstract perspectives, as is typical of other interview methods. We asked managers to talk through a specific case in which an employee who they line managed had experienced stress and how they had managed that particular case. We took a similar narrative approach to asking questions about the managers’ experience of studying the guided e-learning intervention. The interview schedule is reproduced in Appendix 4.

We adopted a purposive approach to sampling managers for interview to ensure a heterogeneous sample, including men and women from across the intervention and control group clusters. In total, 21 managers (out of the 41 in the intervention clusters who had consented to participate in the GEM study) were approached for interview and of these 11 agreed (the remaining 10 did not respond to the e-mail invitation or a reminder), giving a response rate of 52% among managers in the intervention groups. Eight managers from the control cluster were invited to interview and two agreed (five did not respond to the e-mail and one replied that she no longer held a managerial position). Thus, we undertook a total of 13 in-depth interviews with managers (10 women and three men, which reflects the female–male ratio among the managers participating in the trial).

In total, 10 of the 11 managers interviewed from the intervention groups were defined by the trial as ‘adherent’ (i.e. had completed three or more of the main e-learning modules of the intervention). A limitation of the qualitative sample was therefore that it included only one manager from the ‘non-adherent’ group of managers. Furthermore, as consent had not been gained for this purpose, we were unable to approach managers in the trust who did not participate in the GEM study, although their views would have been of interest.

Manager interviews took place between March and May 2014 (≥ 2 months after they had participated in the guided e-learning intervention) and lasted between 17 and 38 minutes. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and anonymised.

Interviews with employees

An aim of the qualitative study was to build a picture of how employees conceptualised and experienced stress and well-being at work and their perceptions of their managers’ role in managing stress. The aim was that these qualitative data would help with interpreting the quantitative findings of the trial.

As with managers, we adopted a purposive approach to sampling employees for interview. To avoid possible influence on employees’ questionnaire responses, we approached employees for interview after they had completed their follow-up questionnaire. In total, 36 employees from across the four clusters in the study were invited for interview (from the sample of 163 employees who had completed their follow-up questionnaire by this time). Ten employees responded (a low response rate of 28%) but we were unable to fix interviews with two of these employees and subsequently undertook a total of eight employee interviews (six women and two men, again reflecting the male–female ratio in the trial employee sample). The sample consisted of two employees from each of the four clusters.

Interviews took place in March and April 2014. As with the manager interviews, we drew on a narrative methodology to elicit employee stories of specific instances of stress at work. Interviews lasted between 10 and 27 minutes. The interview schedule is reproduced in Appendix 4.

Additional data from employees

The baseline and follow-up questionnaires for employees included a free-text box in which employees were invited to make additional comments at the end of the questionnaire. In total, 59 employees out of the 350 who completed the baseline questionnaire provided additional comments and 56 out of the 291 who completed the follow-up questionnaire gave additional comments.

The original study proposal included a suggestion to conduct focus groups with employees. However, given the relatively low response rate to our request for individual interviews with employees, and the rich data that we collected from those who did agree to interview, a decision was taken to not collect focus group data. In total, 12 employees attended the study dissemination meetings (see following section) and contributed to the group discussions at these events.

Observation of study meetings for managers

Meetings between managers involved in the study provided an opportunity to collect observational data. The qualitative researchers and/or study facilitator took field notes, written up in full after the meetings. We observed 10 meetings:

-

A preliminary meeting at the trust in April 2013 to launch the study in the trust and introduce the study and intervention to managers, attended by approximately 20 managers.

-

Three facilitator-led induction meetings for managers in October 2013 to introduce the intervention (see Appendix 3 for details). A total of 26 managers attended these meetings. The meetings constituted the first of two face-to-face ‘educational sessions’ with a facilitator and as such were part of the ‘guided’ component of the guided e-learning intervention.

-

Three ‘follow-up’ facilitator-led meetings in December 2013. These meetings formed the second of the face-to-face educational sessions with the facilitator.

-

A ‘feedback’ meeting for managers in April 2014. This meeting was convened specifically as a qualitative focus group discussion and was audio recorded and transcribed. All interviewed managers from the intervention groups were invited, of whom six (out of 11) accepted and three (one from each of the intervention clusters) attended on the day. The qualitative researcher gave a short presentation of the preliminary interview findings and managers were then invited to comment on the validity of the research interpretations and to reflect as a group on their participation in the study. The trial manager and qualitative researcher facilitated the group discussion.

-

Two study dissemination meetings were held in September 2014 to disseminate the overall study findings to trust staff. Three managers and three employees attended one meeting and one manager and nine employees attended the other. In addition, the meetings were attended by trust staff who had helped manage the research and by the e-learning program developer.

Observation of steering committee and study team meetings

The qualitative researchers acted as participant observers at the two steering committee meetings held during the course of the study and the monthly study team meetings. Research notes, minutes of meetings and associated documentation were considered data sources for qualitative analysis. We were particularly interested in documenting and exploring how the relationship between the quantitative and the qualitative components of the study unfolded in practice and how the qualitative data were perceived as adding value to the trial (or not). Our findings on this aspect of the study will be reported in a separate paper.

Qualitative analysis

Data analysis took place concurrently with data collection, enabling progressive focusing on emerging themes. Two qualitative researchers were engaged in close readings of the transcripts of interviews and meetings, observational field notes and associated documentation. We individually and collectively identified themes emerging from the data, both within subsets of the data (i.e. themes emerging from key informant interviews, from manager interviews and from employee interviews) and across the data set. We discussed our preliminary findings with members of the study team, individually and at team meetings, and with the steering committee and drew on these discussions to interrogate our data further and develop our in-depth analysis.

In keeping with the narrative approach to interviewing, we drew on a narrative approach to analysis of the interview data. This meant that we paid particular attention to the story as a whole that respondents told rather than simply focusing on segments of text. The aim was that this approach would generate a rich picture of the subjective and situated experiences of workplace stress and the guided e-learning intervention.

Dissemination of the results

As part of this pilot study it was planned to disseminate our findings specifically among the study participants, as promised to them, to receive additional feedback. We designed a printed newsletter that was supplied to all participants and conducted two local feedback meetings for study participants at which we presented and discussed our findings. We have also presented the results at the following conferences: a Public Health England-sponsored conference on Work, Health and Wellbeing in Manchester (10 November 2014); the UK National Work-Stress Network annual conference in Birmingham (22–23 November 2014); and the European Association of Work and Organisational Psychology Conference held in Oslo, Norway (20–23 May 2015). Some parts of the GEM study were also presented at an ISER seminar at the University of Essex on 19 January 2015. Our website has been updated and will refer to published GEM study results in the future [see www.gemstudy.net (accessed 3 June 2015)]. Three papers are also in preparation: a mixed-methods paper reporting the results of the pilot study led by Stephen Stansfeld, which has been submitted for publication; a review paper of e-learning approaches in work stress management led by Tarani Chandola, targeted at an occupational medicine audience; and a mixed-methods paper with a qualitative focus co-led by Jill Russell and Lee Berney, aimed at a social science audience.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Participant flow

Inclusion of clusters

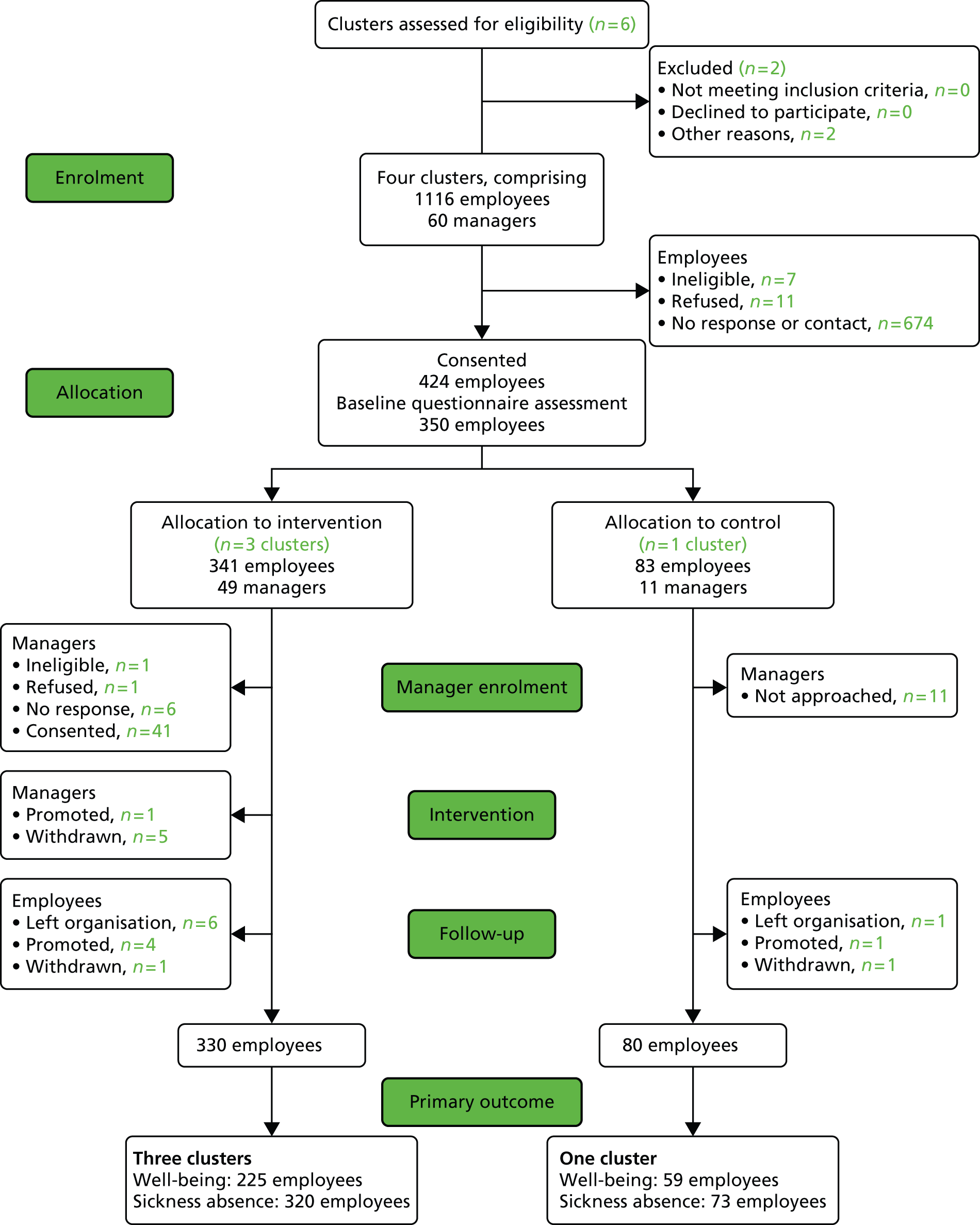

We recruited the clusters and participants from a mental health NHS trust in the north of England (participating organisation). The flow of clusters and participants is represented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow diagram.

Six clusters from within this organisation were considered for inclusion in the trial. In one cluster the workforce composition and organisational structure was considered too different for comparison with other clusters. Another cluster had insufficient availability of employment data. These two clusters are marked as not included for ‘other reasons’ in Figure 2.

The four selected clusters that took part in the study consisted of three adult mental health services working in separate geographical areas of the participating trust and the teams caring for adults with learning disabilities within the same trust. There were between 199 and 330 employees reported to be working in each cluster who were targeted for participation in the study (Table 2). It should be noted that the total number of targeted employees (n = 1116) is based on estimates given at the local sites on enquiry by the recruiting staff and is higher than the number of staff expected based on figures indicated by local stakeholders when we selected the organisation (n = 650). These employees were managed by between 11 and 19 managers per cluster (Table 3 and see Figure 2).

| Details of employees | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | All intervention clusters | Cluster 4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of employees invited (no. of employees approached personally by recruiting staff) | 323 (142) | 264 (174) | 330 (204) | 917 (520) | 199 (129) | 1116 (649) |

| Ineligible | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Refused | 2 | 7 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| Consented (% of those approached) | 100 (70) | 126 (72) | 115 (56) | 341 (66) | 83 (64) | 424 (65) |

| Baseline questionnaire (% of those consented) | 89 (89) | 101 (80) | 93 (81) | 283 (83) | 67 (81) | 350 (83) |

| Paper based | 21 (19 + 2a) | 14 (13 + 1a) | 28 (27 + 1a) | 63 (59 + 4a) | 10 | 73 (69 + 4a) |

| Online | 68 | 87 | 65 | 220 | 57 | 277 |

| Follow-up questionnaire (% of those consented) | 77 (77) | 86 (68) | 68 (59) | 231 (68) | 60 (72) | 291 (69) |

| Paper based | 20 | 27 | 22 | 69 | 10 | 79 |

| Online | 57 | 59 | 46 | 162 | 50 | 212 |

| Primary outcome analysis (% of those consented) | 74 (74) | 85 (67) | 66 (57) | 225 (66) | 59 (71) | 284 (67) |

| Sickness absence data (% of those consented) | 93 (93) | 120 (95) | 107 (93) | 320 (94) | 73 (88) | 393 (93) |

| Details of managers | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3a | All intervention clusters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managers invited | 19 | 17 | 13 | 49 |

| Ineligible | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Refused | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Consented (% of those invited) | 12 (63) | 17 (100) | 12 (92) | 41 (84) |

| Consented but no employees in the study | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Adherence to the intervention | ||||

| Completed fewer than three modules | 6 | 9 | 5 | 20 |

| Completed three or more modules | 6 | 8 | 7 | 21 |

| Primary outcome analysis: no. of employees whose managers | ||||

| Did not consent | 16 | 0 | 3 | 19 |

| Completed fewer than three modules | 20 | 38 | 28 | 86 |

| Completed three or more modules | 38 | 47 | 35 | 120 |

| Primary analysis: managers changing role during study | ||||

| No. of managers | 2 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| No. of employees of these managers | 12 | 28 | 12 | 52 |

Inclusion of participants

Employees were recruited by the local research team (clinical study officers and research facilitators), who visited the various teams across the four clusters and attended local team meetings to introduce the study. Many of the teams were visited several times during recruitment to meet the targets. Teams were spread over a large geographical area, many employees were working off site and the meetings were never attended by all staff at any given visit, so not all employees could be contacted personally. The local research team reported contacting 649 employees (58%) during these visits. In total, 424 employees gave written informed consent to take part and baseline questionnaires were completed for 350 (83%). Of these questionnaires, 277 were completed online, 69 were completed on paper only and four were started online and completed on paper. At follow-up, 291 of the employees who had previously completed the questionnaire at baseline completed the follow-up questionnaire and 284 of these also completed the WEMWBS, the primary end point. Thus, 67% (95% CI 62% to 71%) of employees consenting provided primary outcome data at follow-up.

Baseline and follow-up sickness absence data were available for 393 employees (93%, 95% CI 90% to 95%). Data for 368 employees were available from the participating trust HR database and data for an additional 25 employees were available from three local council HR departments, as these were social services employees working within the trust. Reasons for non-availability of sickness absence data were participant withdrawal (as a result of consent withdrawal, leaving the organisation or promotion); staff on service-level agreement contracts, student contracts or other specific contracts with no centralised sickness absence records or records being kept elsewhere; no response from one local council; and administrative failure (records could not be located).