Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3010/21. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Kerenza Hood is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Moore et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Structure of the report

Introduction

This trial aimed to determine the effectiveness of a novel, risk-led intervention delivered by environmental health practitioners (EHPs) to licensed premises across Wales. This was achieved by carrying out a pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT). However, trialling the intervention was only one element of the overall project. The project also included an intervention development component, an embedded process evaluation and a cost-effectiveness evaluation. The aim of these developmental and evaluative components was to document how the intervention integrates into the working practice of EHPs and to scrutinise and appraise the iterative design and implementation process.

Intervention development involved focus groups with senior EHPs, information sharing meetings between academic researchers, senior EHPs and stakeholders, and development meetings with design professionals. The purpose of this stage of the trial was to optimise the design of the intervention and to determine the most acceptable method of delivery. The findings from this element of the trial were also used to develop a logic model for the planned intervention.

This trial involved the randomisation of purposively sampled licensed premises into control and intervention arms. The premises in the intervention group were visited by an EHP, who undertook an audit that assessed operational risks associated with alcohol-related violence (ARV). The premises staff in the intervention group were also given access to a website with videos and educational material containing information designed to help the staff proactively identify and reduce the risk. The control group did not receive a visit from EHPs or intervention materials. If risks identified using the intervention audit were substantial or significant enough to warrant a formal notice, the premises were reaudited within 3 months of the initial audit taking place. The objective of this part of the trial was to determine, using police violence data, whether or not the audit, associated materials and follow-up audit (when implemented) could reduce incidences of ARV in and around premises.

The evaluative stage of the trial encompasses the imbedded process evaluation and cost-effectiveness analyses. The process evaluation aimed to understand the implementation of the intervention, to aid interpretation of outcomes and to improve future delivery. The aim of the process evaluation as a whole was to better understand all aspects of the trial and to identify opportunities to improve intervention delivery.

Report chapters

This report is laid out as a series of chapters that provide a description of the rationale, conduct and outcomes resulting from each of the trial components. The chapters are now summarised.

Chapter 2 begins with an introduction to the issue of ARV and provides the motivation for a premises-level risk-led intervention and the rationale for using EHPs to deliver the intervention to the premises.

Chapter 3 summarises the theoretical basis behind the main aspects of the trial, including the reason behind the choice of the primary outcome measure, and describes the processes and methods involved in designing the intervention.

Chapter 4 describes the trial stage methods, cost-effectiveness analysis methods and process evaluation methods.

Chapter 5 presents the main quantitative results, together with a brief summary.

Chapter 6 presents results from the embedded process evaluation along with a short discussion that summarises the main findings and examines their significance in the context of previous research.

Chapter 7 presents the findings from the cost-effectiveness evaluation and a brief discussion.

Chapter 8 synthesises the findings arising from the trial as a whole and assesses the extent to which the aims and objectives set out in the introduction were met. This chapter also identifies implications for future research and practice.

Chapter 2 Introduction

In the UK, the costs of ARV to public services, including the NHS, the economy and society, are substantial, estimated to be between £8B and £11B. 1,2 Between 2011 and 2012 there were over 910,000 violent incidents where the offender was believed to be under the influence of alcohol, accounting for 47% of all violent offences committed in that period. 3 An estimated 2 million emergency department attendances each year are thought to be alcohol related. These figures account for 70% of unscheduled accident and emergency (A&E) attendances during peak hours. 1 Medical treatment following alcohol-related assaults, therefore, places a considerable burden on the NHS. 4

Premises licensed for the on-site sale and consumption of alcohol are implicated in alcohol-related injury and violence. 5,6 ARV is commonly observed in alcohol-focused nightlife, with estimates suggesting that 20% of all violence in England and Wales occurs in or around pubs, bars or nightclubs. 7 Many premises licensed for the sale and consumption of alcohol target young adults, and feature minimal seating, loud music, late licences and other features associated with harm. 8,9 As such, there is a growing literature detailing environment-specific risk factors in the on-licensed trade8,9 and recognition that interventions to address these are required. 10,11

Previous evaluations have examined interventions that focus on single risk factors for alcohol-related harm such as responsible beverage service (RBS) training, licensee accords and staff violence-reduction training. 12 RBS training, the most commonly evaluated intervention type, typically deploys ‘off-the-shelf’ training packages that do not involve any consideration of premises’ underlying risk factors. These unfocused interventions are likely to be less effective than interventions that are responsive to the risks and needs of individual premises. Consequently, there is a need for robust, formally evaluated interventions that can be routinely adopted by partners involved with managing the night-time economy (NTE).

Interventions to reduce alcohol-related violence

The UK Licensing Act 200313 emphasises a harm-minimisation approach. While a number of promising premises-level interventions to promote a more proactive approach to harm reduction have been identified,8,14–16 evidence for their effectiveness is limited. There are very few evaluations employing robust methods such as a RCT design, and none of these interventions has been trialled in the UK. Disparate measures of violence have been used, including data from hospital A&E17 and the local police,18 yet it is unclear if outcomes from these studies can be attributed to interventions at the premises level.

A systematic review undertaken in 2007 examined server training interventions aimed at reducing ARV. This review concluded that interventions focusing on a single risk, such as RBS, fail to account for the complex relationships between staff (i.e. servers, security and management) and the premises environment. It was therefore suggested that research in the context of the NTE should be broadened to develop interventions that address more complex causation and multiple risk factors across the full socioecological environment. 12 Another review8 identified a broader range of approaches to prevention encompassing RBS training (n = 6), enhancing the enforcement of licensing regulations (n = 2), multilevel interventions (n = 6), licensee accords (n = 2) and a risk-focused consultation (n = 1). The review highlighted that, of the available RCT evaluations that have been conducted in this area, only Graham et al. 19 implemented a tailored intervention that was responsive to the idiosyncratic needs of premises, while Toomey et al. 20 evaluated a risk-led intervention using quasi-experimental methods. Both of these studies concluded that premises-level interventions that are designed to offset risk factors in each premises are feasible and potentially effective. However, many studies in this area8,12 were subject to a number of shortcomings, including (1) considerable variation in and poorly defined outcome measures, meaning that studies could not be compared, (2) follow-up periods were decided ad hoc and did not consider intervention sustainability, (3) studies often relied on inappropriate control groups, (4) many failed to achieve random allocation, and (5) participants or evaluators were not blind to trial conditions. The review concluded that, while interventions that address multiple risk factors and interventions that are designed and implemented by multiagency and community partnerships have the potential to be effective, there is little rigorous evidence of effective approaches. The recommendation was to develop and pilot complex interventions that address multiple risk factors as a prerequisite for rigorous evaluation and any subsequent implementation.

In response to these findings, Moore et al. 21 examined the feasibility and efficacy of a risk-led, premises-level intervention in reducing ARV. Using the evidence regarding efficacy in reducing ARV, Moore et al. 21 developed a premises-level risk audit designed to assess environmental risk in discrete areas of a premises with the view to providing bespoke advice designed to target, and reduce, risk where required. In line with reviews which have been critical of the methodology used to explore the efficacy of ARV reduction programmes, the intervention developed by Moore et al. was trialled using a RCT design and incorporated a nested process evaluation. 21 Findings from this feasibility study supported the intervention, strengthening evidence that tackling specific environmental risk factors within at the premises level can reduce the incidence of ARV. However, disappointing levels of intervention adoption within licensed premises led to further reflection, particularly on the need for statutory powers to enforce any intervention.

Identifying risk factors

Risk factors are those characteristics of licensed premises that are associated with an increased likelihood of severe intoxication and disorder. These factors are many and varied and may interact with one another. Furthermore, it is likely that many risk factors have not yet been described or that latent factors may offer a simpler explanation for clusters of the observed risk factors. The theoretical frameworks that motivated our approach were routine activity theory (RAT)22 and ‘broken windows’ theory (BWT). 23,24 Both theories describe factors that are necessary for, or increase, the likelihood of crime taking place. RAT is a situational approach to crime that emphasises three co-occurring phenomena: a motivated offender, a suitable target or victim and the absence of a capable guardian. When considering violence from the perspective of RAT it is understandable how licensed premises can play an important role in managing the convergence of these phenomena. Similarly, the recognition of a victim’s participation and the failure of guardians to prevent the incident also make RAT a suitable theory in which to ground prevention research, as it acknowledges determinants other than the presence and motivation of an offender. BWT suggests that offending is informed by situational cues that indicate an absence of social order such as graffiti, litter, vacant buildings and broken or boarded windows. An absence of social order indicates a lack of capable guardians, making it a convenient environment in which to commit crime. In ‘real-world’ experiments, Keizer et al. 25 have shown that individuals take cues from their environment to inform their behaviour. For example, the sound of fireworks being set off illegally was related to an increase in littering, and the presence of graffiti on a mailbox was related to an increase in opportunistic theft.

Social control is also a central component to our approach in understanding the way violence arises in licensed premises. Social control is defined as ‘. . . those organised responses to crime, delinquency and allied forms of deviant and/or socially problematic behaviour that are actually conceived of as such’ (p. 3). 26 Distinctions are made between ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ social controls, with the former relating to interventions enacted by agencies of the state usually under the auspices of legal authority (e.g. the police, environmental health officers), while the latter is concerned with the regulatory and social ordering functions performed by citizens (including bar staff and private security). Innes27 maintains that social controls are increasingly embedded within the physical environment. Further, Black28 proposed that the quantity of social control tends to stay relatively constant, the changing variable being the proportion of control delivered by formal or informal means. 27,29 Additionally, situational and individual factors contribute,30–34 including the opportunity to offend. 22,35–37

The wide variety of activities available in NTEs brings with them a range of risk factors for disorder and intoxication, and numerous studies have sought to identify those risk factors. These risks are summarised briefly below; for more detailed accounts see comprehensive reviews by Graham and Homel. 9,38

High outlet density

The distribution of licensed premises in urban centres has been identified as a key contributor to levels of alcohol-related harm. 39 Areas with high concentrations of licensed premises have disproportionately higher levels of disorder, suggesting a cumulative, non-linear effect of outlet density. 40–42 Clearly, there can be no causal association between outlet density and harm, as areas with a large number of premises but few patrons would be expected to exhibit low levels of alcohol-related harm. High density most likely encourages behaviours that are associated with harm, such as pub hopping and competition between premises that leads to inappropriate promotions. While outlet density is not in itself in the control of premises staff, it would be possible for premises to mitigate those features that are causally associated with harm and are correlated with heightened outlet density, such as crowding and competition. 15

Customer management

Generalising from BWT, the entrance and façade of a premises inform potential customers of the characteristics within. While it is unclear if customers can accurately predict the risk of disorder in a premises based simply on approach, it is likely that interpretations of social norms are informed by these external characteristics. Therefore, door staff behaviour, queue management and the management of intoxicated or disorderly customers are fundamental in providing cues about descriptive and injunctive norms within. Interactions outside premises also represent potential flashpoints for disorder. The congregation of people outside after closing time represents a considerable risk factor, as this usually occurs at times when staff have finished their shift and are busy emptying the premises of its last few customers. This leaves the external area of the premises without a designated guardian at a time when customers are likely to be most intoxicated.

Security and door management

Generalising the social control theory outlined above, door staff represent both the expression and the actuality of informal social control, or guardianship, in a licensed premises. It is, therefore, important that they are adequately trained and present a professional and welcoming demeanour. In England and Wales it is illegal, under the Licensing Act, to allow disorderly conduct on premises. Furthermore, any member of staff who is authorised to prevent disorder and allows it to happen on the premises is legally culpable. Therefore, the refusal of admission to disorderly customers is regarded as a main role of door staff in England and Wales. The deployment of sufficient numbers is essential and should be informed by the capacity of the premises, the number of expected customers and past history of disorder.

In order to obtain a door licence, applicants are required to complete an examined training course. Moreover, in the event of a violent incident, customer ejection or injury on the premises, all details of the incident should be recorded clearly, accurately and promptly in a log book and subsequently reported to the police and, depending on circumstances, to local authority (LA) environmental health officers. Recording events linked to disorder, extreme intoxication and violence also enables premises managers to explore trends in disorder and to determine how to best allocate door staff.

Vigilant serving staff

Premises serving staff play a key role in the safe service of alcohol and the prevention of disorder, as they are responsible for refusing service to underage customers and intoxicated customers and for identifying signs of disorder within the premises. It is essential that serving staff are aware of their legal responsibilities and that they take these responsibilities seriously. Server training has been shown to have limited, short-term effects in improving serving practices in respect of the refusal of service to intoxicated patrons. 8 As serving staff act as informal guardians, it is important that sufficient numbers of staff are deployed in order to facilitate this role. Insufficient numbers of serving staff are associated with increased levels of disorder in a premises, as this increases competition for service between customers,43 as well as crowding. 15 Furthermore, a premises with a high proportion of male staff is associated with disorder in licensed premises,44 although this phenomenon may be a reaction to past disorder as opposed to a causal factor. Clarke45 further suggests that an overly sexualised dress code for female serving staff can contribute to heightened levels of arousal in a premises and this is further implicated in disorder.

Environmental factors

A number of studies have aimed to identify the environmental aspects of a premises that influence the likelihood of disorder. Graham et al. 46 conducted a detailed multilevel analysis of risk factors for bars in Toronto, ON, while Green and Plant38 collated a detailed description of these risk factors. Evidence suggests that showing sport in premises increases the length of customers’ visits47 and is associated with increased levels of aggression. Music has also been related to levels of disorder and intoxication. For example, poor-quality bands can be an irritant,48 while slower tempo country music is associated with an increase in drinking speed. 49 Loud music may further impair communication between customers, preventing the de-escalation of fractious encounters. A range of other environmental factors can act as irritants such as poor air quality,43 increased temperature50–52 and uncomfortable furniture. 43,53 Moreover, dim lighting reduces the capacity for formal surveillance by premises guardians, impairs communication and increases the likelihood of collisions. Areas that are difficult to view and guard, such as thoroughfares and stairways, can also provide increased opportunities for collisions and injuries. Glassware also presents a significant risk factor for serious injury owing to its portability, accessibility and the level of harm that can be caused with a single blow. 12 Furthermore, the presence of empty glasses and other litter on tables may signal low levels of social order, and there is a relationship between untidy premises and disorder. 19,44,48,53,54

Promotions

Stockwell et al. 55 found that alcohol promotions were associated with intoxication but not associated with the risk of alcohol-related harm. More recently, however, studies suggest that promotions and becoming drunk are associated with police-recorded violence. 14

Customer behaviour and characteristics

Disorderly customer behaviour, according to BWT, contributes to perceptions of a permissive environment, thereby increasing the likelihood of further disorder. However, the relationship between gender ratio and disorder risk is unclear and evidence is scarce. 9 Although men are at far greater risk of violence,4 the presence of women may actually serve as a risk factor for violence owing to competition for sexual resources. Similarly, while a younger age is associated with increased risk of violence, customer age is not a strong predictor of disorder. However, age may interact with several other factors, such as premises type, which ultimately contributes to disorder. Typically, persistent offenders who are frequently violent when intoxicated56 are usually well known, emphasising the need for door staff and premises managers to share data across premises in an area.

The importance of partnerships

While identifying and addressing risk at the premises level may help to reduce violence, a part of any intervention is likely to require input from a range of organisations able to assist premises make the required changes. Accordingly, tackling alcohol-related harm and violence is a focus of partnerships involved with managing night-time environments,10,11 including the police, NHS, and local and national government. The aim of partnership-working is to mobilise a power base whereby politics and policy work smoothly together to enable change. 57 Partnerships that cross traditional organisational boundaries have become the accepted approach when addressing health and social problems that require complex solutions. 58 Indeed, Section 17 of the UK Crime and Disorder Act 199859 places an obligation on statutory bodies to work together in partnership to reduce crime and the UK government’s Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy for England suggests that tackling alcohol misuse and related harm relies on the creation of partnerships between national and local government and health care, policy services, individuals and communities. 60 For city-centre ARV, the Department of Health’s Alcohol Improvement Programme encourages partnership-working to address alcohol-related hospital admissions. 61 The importance of partnerships are further emphasised in the UK’s Alcohol Strategy,1 which sets out proposals to reduce alcohol-fuelled violence and excessive alcohol consumption.

In 2003 alcohol licensing systems were reorganised in England and Wales through the introduction of the Licensing Act 2003 (implemented in 2005). 13 This shifted responsibility to LAs, which were obliged to manage applications in relation to the sale of alcohol through a licensing committee comprising responsible authorities. These responsible authorities, which include the police, the fire service and Trading Standards, are expected to work towards four licensing objectives: the prevention of crime and disorder, public safety, the prevention of public nuisance and the protection of children from harm. Responsible authorities can comment on all applications and also call for the review of an existing licence if there are legitimate concerns that a premises has breached one or more of the licensing objectives. For the first time, through a 2013 amendment, the responsible authorities include the NHS and environmental health, a government agency that is chartered nationally but managed separately within respective LA boundaries.

The UK government has called on LAs to use existing powers to reduce alcohol-related harm. As statutory partners in reducing crime and disorder, and responsible authorities under the Licensing Act, EHPs are well placed to implement effective strategies to prevent workplace violence. EHPs are chartered environmental health professionals who have a history of enforcement and partnership-working and are trained to deliver risk-reduction interventions and advice to small and medium-sized businesses. The primary objective for EHPs is to promote positive relationships between regulators and those they regulate, to protect the public and to encourage business growth,62 and they are the only responsible authority with this remit. EHPs intervene proportionately to the evidence for risk, with the emphasis on a dialogue that helps those they regulate achieve compliance and reduce risk. 63

Given this, an opportunity exists for EHPs to become more involved in ensuring that the on-licensed trade works to reduce risk and maximise public safety. Assault data implicating a premises could be interpreted as an indicator of risk that the premises may not have done all that is reasonably possible to prevent that assault. These data could then be used to trigger an inspection to identify whether or not known causes of violence are present, the expectation being that EHPs would use their regulatory authority to determine whether or not licensed premises are meeting their obligations to maintain public safety. As the link between episodes of violence and risk of harm falls within the remit of the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 197464 (HSWA) and enforceable legislation, is it feasible for EHPs to identify the risks of harm within their statutory remit and work with premises to lessen those risks? This paper addresses that question.

The role of environmental health practitioners

All businesses with five or more employees are obliged under the HSWA to have a written policy that describes how risks are identified and managed. 64–67 The expectation is that all businesses conduct risk assessments and take reasonable actions to reduce risk. The risk assessment, therefore, provides the point through which formal control (i.e. the HSWA and the Licensing Act) can operate to increase informal governance, whereby premises managers work to identify areas in which harm (including alcohol-related harm and disorder) might arise and what can be done to minimise those risks. Risk assessments should be reviewed regularly and employees are expected to be aware of what measures are in place. Dissemination is through formal induction processes for new employees and regular refresher sessions for existing staff, which in turn are expected to increase informal governance within premises. The HSWA therefore provides an important opportunity to manage risk in licensed premises and to encourage appropriate informal governance across the entire premises environment.

The HSWA aims to ensure that business practices are safe for staff and customers. Evidence suggests, however, that some businesses focus more on profitability and ignore the potentially harmful effects of their operation. 68 The concept of social corporate responsibility acknowledges that staff attitudes and ethics can influence business management and practice. Attempts to implement interventions to combat ARV through a social corporate lens can thus lead to difficulties if costly changes are required without a mandate that obliges intervention adoption.

The process evaluation from an earlier feasibility study21 appears to corroborate the lack of enthusiasm and urgency in tackling health and safety issues. Feedback from those delivering the intervention indicated that due diligence was not overly apparent in many premises, indicating that enforcement was, therefore, both critical and necessary. This led to the logical conclusion that intervention implementation was likely to be improved if delivered by a statutory authority.

Of the groups able to enforce organisational change on premises (e.g. the police, LA licensing officers and EHPs), EHPs are most accustomed to surveillance-led activities, particularly in the case of food-poisoning outbreaks. However, unlike the police, they are accustomed to working with small businesses to proactively reduce harm. In the light of this, and given their knowledge, expertise and experience, EHPs may provide a foundation for the development of licensed premises interventions.

Currently, EHPs have no prescribed role in respect to violence reduction in licensed premises and are primarily responsible for enforcing the HSWA and related legislation. However, in upholding the HSWA, EHPs have, among other powers, a right of entry to a premises at reasonable times, the right to investigate and examine, the right to see documents and take copies, the right to request assistance from colleagues, including the police, and the right to ask questions under caution. Where enforcement is necessary, EHPs have several options available to them. They can give legal notices, which are written documents requiring persons to do/stop doing something of which there are two kinds. First, if an EHP is of the opinion that a person is currently contravening the HSWA, or has contravened it in the past, they can be serve that person with an improvement notice that details what is wrong and how to put it right within a set period of time. Second, if an EHP is of the opinion that activities are being carried on, or are likely to be carried on, that involve the risk of serious personal injury then they may serve a prohibition notice, which prohibits the use of equipment and/or unsafe practices immediately. In extreme circumstances EHPs can also prosecute both employers and employees; this can include unlimited fines and a jail sentence.

Implementing a risk-led intervention

As statutory partners in reducing crime and disorder, and responsible authorities under the Licensing Act, EHPs are well placed to drive local action and implement effective strategies that are designed to prevent workplace violence. We therefore sought to identify how risk reduction might be enforced by EHPs under the HWSA.

In order to enhance the ownership and agency of bar staff, the intervention was framed as a risk audit, findings from which informed a subsequent action plan (if necessary). The expectation is that, should the action plan be adopted, the risks linked to premises-level harm will have been addressed and a reduction in alcohol-related harm would be expected. The action plan would require premises to make changes to operating procedures (e.g. reducing capacity, changing how security staff are deployed, checking patrons’ age at the door) that have been identified as contributing to the risk of alcohol-related harm. Although this intervention is framed as a supportive process, designated premises supervisors (DPSs) are still under a legal obligation to respond to the audit action plans.

Furthermore, in an attempt to enforce change through the threat of punishment, parliament has increased the penalties for serving alcohol to intoxicated and/or disorderly customers. An element of the audit will therefore be to establish how much DPSs and servers understand about the behaviour of an intoxicated and/or disorderly individual, and to determine whether or not staff know how to identify and defuse potentially violent encounters. In line with the collaborative aspect of the intervention, premises staff will be encouraged to use an online educational tool developed to aid staff in acknowledging, understanding and addressing customer behaviour.

Rationale for the All-Wales Licensed Premises Intervention trial to reduce alcohol-related violence

The evidence thus far has indicated that interventions addressing multiple risk factors and designed and implemented by multiagency and community partnerships have the potential to be effective in reducing ARV. An evaluation of a UK pilot RCT made significant headway in the delivery and implementation of a risk-led intervention aimed at reducing ARV, while substantial progress was also made to better understand the theoretical mechanisms of a successful risk-led intervention. The All-Wales Licensed Premises Intervention (AWLPI) trial aimed to build on this earlier research by developing a context-based risk-led intervention and to determine its effectiveness in a RCT. If the intervention, designed to be implemented by EHPs, was to prove successful the potential benefits could be substantial. It was calculated that, if the potentially low-cost implementation of the AWLPI succeeds in reducing violence, there could be substantial tangible (e.g. reducing costs to health services and the police) and intangible (e.g. reducing fear of crime and the psychological impact of victimisation) benefits. Furthermore, the research team reasoned that this project could offer the prospect of implementing routine surveillance and proactive violence reduction in EHPs’ practice through engagement with the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

Overview of the All-Wales Licensed Premises Intervention trial

The trial described in this report was conducted in two stages. The first stage of the trial involved developing the intervention. The second stage of the trial encompassed training, site recruitment and randomisation, implementation of the intervention, data collection, and the process and economic evaluations.

Intervention development and refinement

In order to develop a suitable and workable intervention, the AWLPI trial incorporated an intervention refinement stage, which involved collaboration with senior EHPs, researchers and web media experts. The specific aim of this stage was to transfer the theoretical and empirical motivations for the intervention into a practicable and accessible evidence-based intervention programme. The intervention refinement stage of the trial is described fully below.

Trial stage

The effectiveness of the intervention developed in the intervention refinement stage of the trial was assessed using a RCT design described more fully in Chapter 4. The primary outcome in this trial was the difference in police-recorded violence between intervention and control premises over the follow-up period. Secondary outcomes were assessed using an embedded process evaluation (see Chapter 6) and economic evaluation (see Chapter 7).

Summary

The costs to society of violence associated with the on-licensed trade are substantial.

There is a statutory requirement of licence holders to reduce the risk of violence, research evidence suggesting that this is possible and strong theoretical positions indicating that an effective approach is feasible.

An earlier feasibility study indicates that, while a trial of interventions to reduce risk in premises is feasible, significant barriers include access to, and therefore the provision of intervention materials in, licensed premises.

Environmental health practitioners have both the skills required to deliver interventions in licensed premises and the statutory authority to gain access.

Environmental health practitioner-delivered interventions in licensed premises also have implications for the NHS, which is a responsible authority under the Licensing Act but has no formal representation on licensing committees or regulatory relationship with licensed premises.

Aims

-

To refine an intervention that can be mainstreamed into EHP usual practice.

-

To test EHPs’ capacity to reduce ARV in a RCT.

-

To determine the effectiveness, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of a risk-led intervention designed to reduce ARV.

Objectives

-

To develop intervention materials that:

-

translate formative work for use in EHP normal practice

-

encompass a risk audit to cover multiple risks and that are therefore responsive to each premises’ unique circumstances.

-

-

To map premises-specific police-recorded violence data across time to determine whether or not the impact of the intervention reduces violence and whether or not any effect changes over time.

-

To identify the costs associated with Safety Management in Licensed Environments (SMILE) implementation and delivery and to approximate the extent to which it can be regarded as an efficient use of public funds.

-

To use qualitative and quantitative data from the embedded process evaluation to:

-

understand intervention development and integration into normal practice

-

assess intervention reach, fidelity, dose and receipt

-

identify if and how the design and implementation of the risk-led intervention delivered by EHPs in this trial could be further optimised and

-

critically appraise the quantitative and qualitative outcomes alongside one another in order to develop a revised logic model of the intervention.

-

Chapter 3 Developing SMILE

Introduction

Overview

The previous chapter described the theory behind premises-level interventions and areas of premises operation that could be targeted so that improvements would bring about a reduction in alcohol-related harm. This chapter describes how formative work was translated for use by EHPs and into a format that would be acceptable to premises staff.

Key research findings from a feasibility study of a risk-led intervention showed that (1) an enhanced multiple risk-audit approach can successfully identify appropriate targets and approaches to prevention; (2) the engagement of licensed premises and intervention efficacy were maximised when implemented by statutory authorities; and (3) police-recorded data on violent incidents were a valid measure of harm, sensitive to change at the premises level. 69

The theoretical basis to the intervention was that identifying risk of alcohol-related harm and motivating changes in premises to mitigate those risks would be expected to reduce alcohol-related harm. This approach is enabled by current legislation. The Licensing Act 2003 places a requirement on DPSs to adjust premises operation if they become aware that their operation increases the risk of harm. 13 Therefore, practitioners who are able to identify and advise premises staff on such risks should expect their advice to be heeded and that premises will respond to such advice. Furthermore, and specific to EHPs, the HSWA facilitates practitioners’ access to premises and premises staff and also affords EHPs the statutory remit to investigate workplace violence. 64 Thus, EHPs provide formal governance and are able to require change in small businesses to reduce harm.

While EHPs were not susceptible to the intervention barriers identified in the feasibility trial, there still existed a need to translate formative theoretical work into a format that was both consistent with EHPs’ normal working practice and acceptable to premises staff. Intervention materials were coproduced with EHPs to translate formative work into a format that communicated premises, obligations to minimise harm in a way that was acceptable to all premises staff (e.g. via an accessible website and informative films). The expectation was that these materials would engage all staff in the premises hierarchy, from door security staff to servers and management. Second, a risk audit was developed that covered multiple risks. This comprised a written booklet that both outlined the statutory and research evidence for areas in which EHPs should attend and provided a uniform means of identifying and collating evidence for risk in premises (see Appendix 1). The risk audit was intentionally developed from earlier audits used by EHPs.

All-Wales Licensed Premises Intervention aims and objectives

The primary research aim for this component of the trial was to refine a risk-led intervention that aimed to identify environmental risks in premises and that could be subsequently mainstreamed into EHP usual practice.

Intervention development

During the first 6 months of the trial (March to September 2012), senior EHPs, industry representatives and web consultants were involved in a consultation process with the research team to develop intervention and training materials. These consisted of the risk audit tool, a website, short instructional films and additional materials such as incident reporting templates and health and safety guidance. Collectively, these were designed to facilitate the risk audit and to standardise the risk audit. The intervention development meetings with the senior EHPs were conducted separately from the meetings with the media and web consultants.

The intervention was planned and constructed during subgroup meetings using a framework structure to guide development. The framework adopted an iterative process informed by subgroup discussion and the literature.

A stakeholder intervention coproduction group was, therefore, established that consisted of four senior EHPs from across Wales and three academics involved in the initial feasibility trial. The first meeting focused on presentation and discussion of feasibility study results. Early on it was recognised that the intervention would map strongly onto current EHP work practices and that the underlying research aims and objectives met with those of the environmental health agency, an agency concerned with anything that was a risk or hazard to the environment generally or to members of the public specifically (see Chapter 4, Process evaluation). In initial meetings it was clear that the value of SMILE had been understood and the organisation was keen to be involved. The meetings also improved academic understanding of the organisational context and the remits of routine EHP practice, which was to investigate accidents, educate and work in partnership with groups and stakeholders who have an interest in public health or the health of the environment.

Three subsequent meetings focused around delivery systems for and design of SMILE. For delivery, EHPs suggested that health and safety EHPs should implement the intervention, as these specialists were likely to have gained useful experience and knowledge of RIDDOR (Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013), regulations that require employers, the self-employed and those in control of premises to report specified workplace incidents. 66 Further deliberation about possible changes needed to adapt the risk-audit intervention to the environmental health context resulted in the agreement of senior EHPs to coproduce SMILE with the aim of ensuring that the audit mapped on to existing work practice as closely as possible. Initial iterations of the risk audit tool were developed by the academics based on feasibility trail results and systematic review evidence. This was adapted by the EHPs to conform to existing audit tools used in normal practice. This was then piloted by the senior EHPs with their teams in three premises in each of their areas. Feedback resulted in a revised third and final iteration of the audit tool. For the video, an initial meeting between the stakeholder group, project advisory group and a design company identified potential aims and objectives and suitable content. A follow-up meeting of the stakeholder group reviewed draft videos and recommended revisions. The final videos were agreed by the stakeholder group in a third meeting but these were not piloted with the wider EHP organisation owing to time limitations.

The overall goal was to design an intervention that included a follow-up audit that was deliverable, effective and could yield the data needed to answer the research question. The framework used to structure the intervention development phase is now described.

Key questions:

-

What are the key elements of the intervention?

-

Which components of the current audit are currently performed by EHPs/other agencies?

-

Which components not currently captured by the audit should be included?

-

What policy documents already exist for licensed premises?

-

What supportive materials would be appropriate (i.e. content of videos)?

-

Should follow-up be included as part of the intervention and, if so, what should it assess?

-

-

When should the intervention take place?

-

Should audits take place during the day or at busiest periods?

-

When should follow-ups take place?

-

-

How should the intervention be implemented?

-

Should all aspects of the audit be conducted by EHPs?

-

How should action plans be delivered (e.g. in person/by e-mail/by post)?

-

What is the best format for the action plan (e.g. CD-ROM/hard copy/booklet/web upload)?

-

Should follow-ups be conducted by EHPs only, or in conjunction with other agencies, or solely by other agencies?

-

How should training videos be disseminated [e.g. YouTube (LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA; www.youtube.com), e-mail, newsletter, dedicated sessions at work, dedicated website]?

-

Secondary questions:

-

What will be the main challenges to implementation?

-

What will be the main barriers to premises implementing the action plans and can these be addressed in the development phase?

-

How will other EHPs react to the intervention – anticipated objections/resolutions?

-

What structures and resources would be needed to make the intervention sustainable if it were rolled out?

-

How will the implementation process be monitored? This includes issues such as type and frequency of contact with premises, acceptance of intervention from DPSs, barriers/facilitators to implementation.

-

Are there existing reporting structures that EHPs follow that could be adapted?

-

What are the best ways to capture issues with implementation (e.g. diary/log/telephone call/online form)?

-

Audit development

Three core members of the research team and five senior EHPs were involved in the AWLPI audit development. Development began initially by identifying the most pertinent indicators on an EHP health and safety audit that had previously been developed by EHPs. Selected indicators were translated into a series of items and mapped onto a spreadsheet to provide a comprehensive matrix whereby each item was associated with a potential response. This matrix was sent to the subgroup EHPs for feedback. This process was repeated during the development phase until all parties were satisfied. The finalised matrix was then formatted in the style of a health and safety audit (see Appendix 1). The AWLPI audit was then piloted by EHPs (naive to the AWLPI trial) to check for completeness, accuracy and ease of use. Final iterations of the audit were made as recommended in the piloting feedback.

Web-based training and instructional materials

Representatives from a web development company, a graphic design company, the British Association of Anger Management, an organisation representing door supervisors and a communications consultancy along with three core members of the research team were involved in the development of the AWLPI website and online training films.

The focus of the short films was explored during the developmental meetings between the research team and EHPs. The overarching topics chosen for the films were influenced by the literature, previous research conducted in licensed premises and industrial experience of both the researchers and the EHPs. The visual concepts of the films were developed using storyboards.

Once built, the system underwent user acceptance testing by the research team and all content on the website was checked by EHPs to ensure legal compliance.

Summary of website specifications

-

Technical specification:

-

four videos, each 5 minutes long

-

website and videos to be accessible to smartphones and tablets

-

bilingual (Welsh and English)

-

linked to HSE website (www.hse.gov.uk/)

-

internal database metrics (e.g. to determine usage).

-

-

Design concepts:

-

Enhancing practitioner engagement by:

-

catering for different levels of employee

-

catering for different types of premises

-

‘buy-ins’ for those using the website (e.g. opportunity to gain transferable skills).

-

-

-

Video content:

-

Need to engage audience in four areas:

-

security and communication

-

particular emphasis to be placed on pro-active de-escalation

-

environment

-

crowding/intoxication.

-

-

-

Website structure:

-

The homepage will direct the user to:

-

information about the issues

-

the short films

-

a ‘diligence’ page where users can demonstrate using a feedback mechanism that they have accessed and assimilated the information

-

contact page using a standard e-mail form.

-

-

-

Website design and function:

-

include references to involved parties – the university and funding body

-

function for premises staff to provide feedback/demonstration of diligence to content

-

include links to AWLPI trial Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) page and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) account.

-

Content of intervention materials

Risk audit

The risk audit included items that could be used to describe basic features of the premises being audited. This included the number of full- and part-time staff, whether or not food was served and whether or not the premises hosted live music. The date and time of the audit was also recorded as well as the distance travelled by the EHP to the premises.

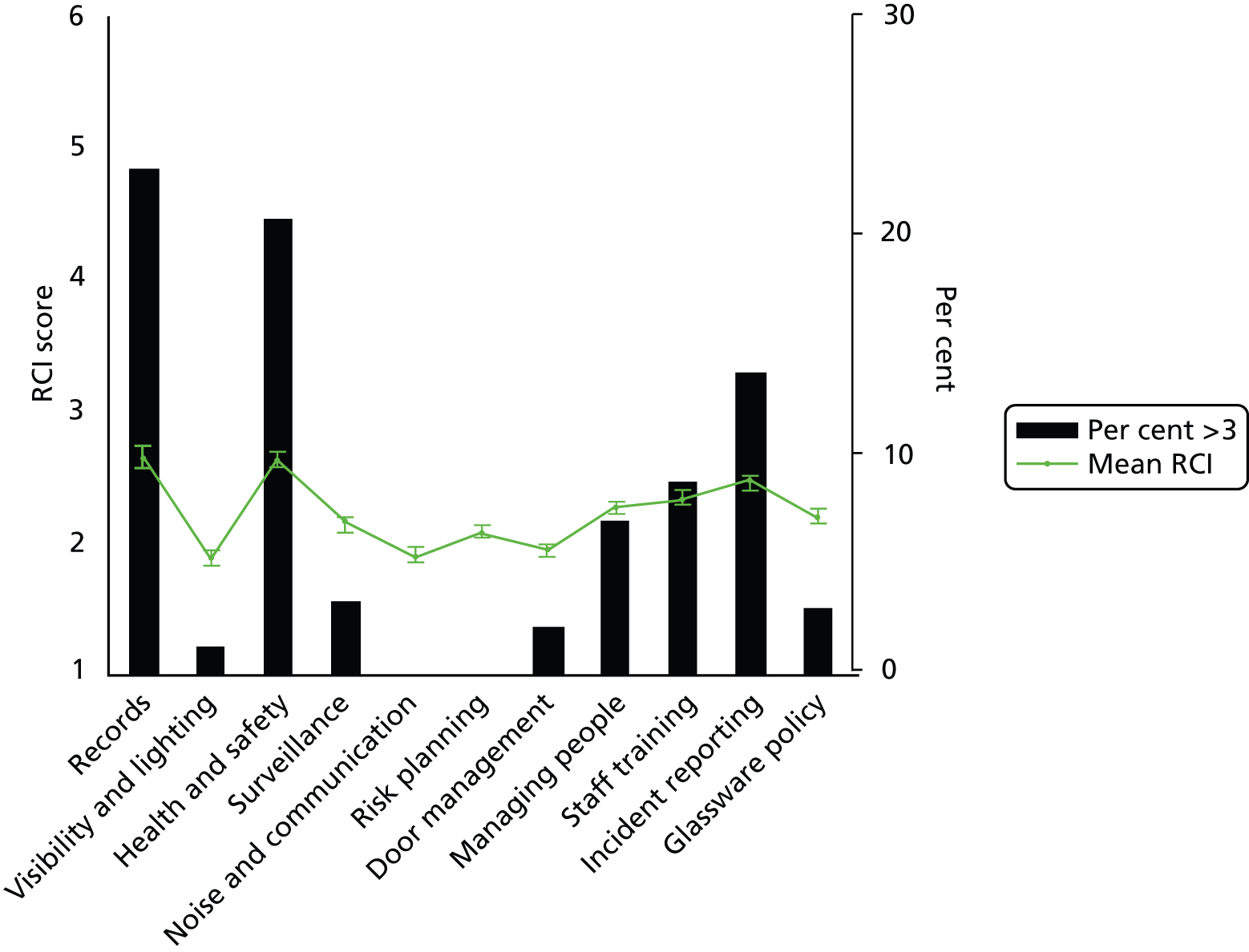

Eleven operational domains were examined and included:

-

Records management: written risk assessments, related policies, premises opening/closing logs and incident logs must be available and up to date. Incidents logged should be cross-referenced with policies and risk assessments to assess whether or not action had been taken to minimise the risk of further harm.

-

Visibility and lighting: visibility and lighting should be good throughout the premises. Blind areas can impede surveillance by premises staff, as can low levels of lighting.

-

Health and safety observations and checks: heating, ventilation and the overall condition of the premises were assessed.

-

Surveillance: surveillance arrangements should be sufficient to protect health and safety. This includes where security staff are usually located and the use of closed-circuit television (CCTV).

-

Noise and communication: staff should be able to communicate with each other effectively about potential risks during times when the premises is open.

-

Risk planning: there should be evidence of regular engagement with PubWatch (www.nationalpubwatch.org.uk) or similar. There should be no evidence of irresponsible drinks promotions. There should be sufficient numbers of front-of-house staff present during busy periods.

-

Door management: effective door management during busy periods should be in place. This includes maintaining appropriate door-staff registers and policies.

-

Managing people: visibly intoxicated and/or disorderly patrons should be effectively managed. Those who are disorderly must be escorted off the premises and those who are intoxicated must not be served alcohol.

-

Staff training: there should be evidence of staff induction and ongoing training that encompasses disorder, violence and aggression.

-

Incident reporting: it is a legal requirement to record violent incidents that have occurred on the premises, records that should inform future practice.

-

Glassware policy: literature suggests that the use of toughened glass or plastic reduces risk of injury.

Risk score and action required

Each of the 11 sections included a risk control indicator (RCI) score. The RCI is a standard instrument used by EHPs to record the perceived level of risk in the environment. Using the RCI, a score of 1 represents a situation where the EHP believed that no further improvements were possible (based on current legislation and guidance); scores of 2 and 3 represent situations where enforcement action may be appropriate; a score of 4 or higher denotes situations requiring legal enforcement. The guidance indicated that EHPs should give a RCI score of 0 to non-applicable areas of premises operation. Each section required EHPs to record any action they had taken (none, verbal advice, written advice, improvement notice or prohibition notice).

Web-based training and instructional materials

Films

Training and educational films were designed to increase awareness of the physical and social environment, and increase knowledge of policies and practices that prevent and reduce excessive alcohol consumption and violence (Figure 1 and Table 1). Each film included animations, summary text and a spoken script. The messages of the films were positively framed by focusing on the benefits to be enjoyed from implementing the techniques demonstrated in the films rather than dramatising the consequences.

FIGURE 1.

An example of a storyboard used to inform the design of the short films. ID, identification; VO, voiceover.

| Chapter One: the benefits of a safer environment | |

|---|---|

| Voiceover: creating a safe environment not only provides a better atmosphere for your customers; it can also help to improve staff retention by making your venue a more pleasant place to work. And with happy customers and happy staff, your reputation can bring you more business Everyone working at the venue can play a role to help reduce risk within your venue. And it needn’t be time-consuming; this video provides a quick snapshot of the ways staff can get involved and work together to provide a safer environment |

Visual: presenter piece to camera, walking through scene of happy customers, happy staff, and busy bar |

| Duration: 30 seconds | |

The training and educational films provided guidance in the following areas: premises environment, security, crowding and how to de-escalate fractious encounters between customers. The four film topics were:

-

safety and your colleagues

-

keeping them happy

-

tables and chairs

-

staggering crowds.

Angling the films towards depictions of emotions, and anger in particular, was felt to be a good inclusion, as staff may feel empowered to recognise and understand conflict at the bar more easily. The films also aimed to communicate that customers’ pride (or ‘power base’) needs to be kept intact throughout interventions in order to avoid escalating or displacing aggression.

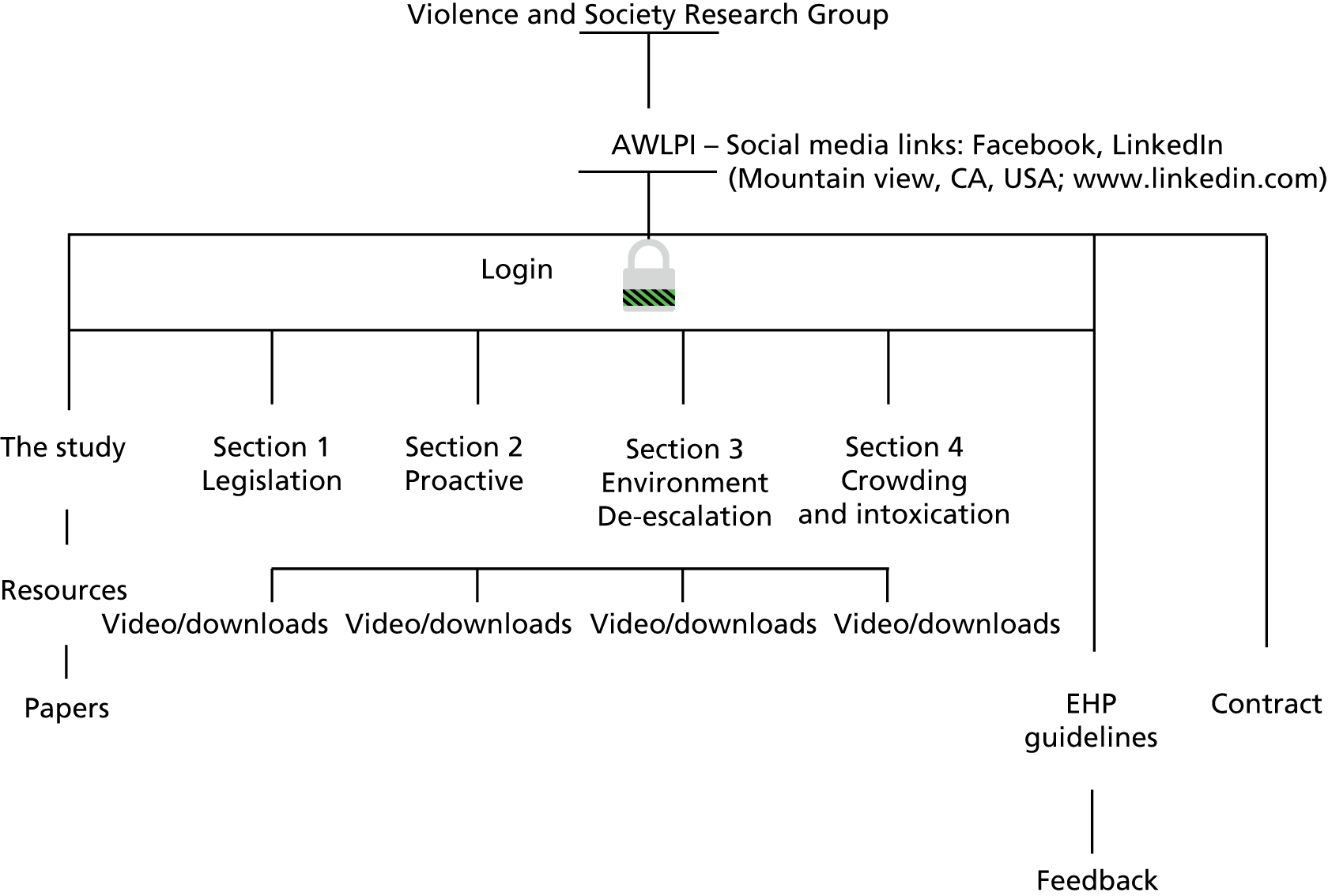

Website

The intervention website contained information about harm-reduction practices in licensed premises and provided guidance documents that could be downloaded and used by premises staff (Figure 2). The website also contained a due-diligence quiz that was designed to provide instruction on how premises staff can reduce excessive alcohol consumption and violence. The website was made available in English and Welsh. 70 A diagram of the site layout is in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 2.

The homepage of the SMILE website.

Due-diligence quiz

The due-diligence quiz comprised 25 questions that assessed understanding and knowledge gained through viewing training films. Members of premises staff answering ≥ 50% of questions correctly received a certificate of achievement that could be displayed in premises. Reference materials were also provided. These were downloadable guidance documents, document templates and posters that collectively aimed to help premises staff reduce ARV in their premises. Business cards were also used to advertise the website address. The quiz used is included in Appendix 3.

Intervention training

In order to enhance intervention fidelity, EHPs who were to deliver the intervention attended one of three training workshops held in North, West and South Wales. The training was mainly delivered by senior EHPs and academic staff with a research interest in reducing violence. However, presentations were also given by medical consultants, who were able to highlight the extent and severity of violence within the NTE.

The training sought to increase awareness of ARV in and around premises and to elucidate the potential impact EHPs could have on reducing ARV. Additionally, EHPs were presented with information about the AWLPI trial and the SMILE intervention tools. This part of the training entailed navigating the risk audit and associated website in detail, and advice on how to implement these tools to the best effect.

The finalised intervention

Prior to outlining the intervention for the AWLPI trial, it is worth highlighting that the professionals delivering the intervention were, to some extent, embedded within the intervention itself. The fact that EHPs have statutory powers in the area of workplace health and safety meant, in theory, that the intervention could be delivered with some authority and as such removed the need to gain consent from participating premises. In Wales, the intervention was adopted as EHPs’ annual project, which meant that all EHPs were committed to delivering the intervention as part of their standard practice for that year.

EHPs were programme advocates for the AWLPI trial and also delivered the intervention as auditors. During the training it was emphasised that those delivering the intervention should do so in a standardised manner, to ensure that the mechanisms through which the intervention worked functioned as intended. Figure 3 depicts a logic model of the intervention.

FIGURE 3.

Logic model of the intervention for the AWLPI trial.

Intervention input

The key ingredients during this phase of the intervention are (1) the auditor, (2) the audit and (3) the training films.

-

The auditor is an EHP who has been trained to conduct the audit in a systematic and standardised way.

-

The audit materials consist of:

-

the 11-point audit of the premises, this is grouped into:

-

– the physical environment

-

– policies and procedures

-

– staff training

-

– risk assessment and planning

-

-

guidance leaflets and notices, to be given at the end of the audit if necessary.

-

-

Training films, which were accessed using the SMILE website.

Activities

The audit was conducted in person with each premises’ DPS. The audit took place at a time suitable to both the auditor and the DPS, when they would not be interrupted. It was expected that the audit would take approximately 1 hour. The DPS from each premises should have been informed approximately 2 weeks prior to interview that the auditor would request to see as many of the following documents as possible:

-

health and safety policy

-

drugs and search policy

-

staff training records

-

incident log book

-

accident book (if appropriate)

-

door staff register

-

written procedures for opening/closing bar

-

health and safety checklists

-

fire alarm checks.

Intervention and control groups

In summary, intervention premises received SMILE as described above. Control and intervention premises both received ‘usual practice’, the normal regulatory attention ascribed by partners involved in managing harm in the night-time environment. While this may vary across LAs, in so far as LA licensing, the police and other agencies are differentially involved according to local requirements, such variance will be at the LA level. Because control and intervention premises were stratified by LA in this RCT, such local variation is expected to be balanced across groups.

Following the audit, auditors were asked to discuss the arising risk factors with DPSs to ensure that each risk factor was justified in relation to relevant legislation or evidence. During the audit visit EHPs were to provide the DPS with information about the SMILE website and how to navigate it effectively. DPSs were urged by the EHPs to cascade information about the SMILE website to all their staff and to encourage engagement with the website and its associated training films.

Expected output arising from the audit

The second component of the intervention is the generation of an action plan arising from the audit itself. The action plan given to the DPS should be tailor made for each premises as a result of the findings from the audit. There is a need for this to be a list of points (‘tell me what to do’) rather than a long document. The way the action plan is written should take HSE reports on how small businesses perceive and implement legislation into consideration.

Conducting a follow-up audit

Depending on the severity of the risks identified during the initial audit the EHP would serve an improvement notice or a prohibition notice, or arrange for a second audit to take place. When a formal notice is served the EHP would specify the provision(s) that had been contravened and give reason(s) why they feel these had been contravened. The requirements necessary to remedy the contravention should then be given followed by a reasonable time period in which to comply with the notice (not fewer than 21 days). A second audit would be arranged to ensure that premises had complied with directions.

As a part of the intervention, second audits were expected to have been completed within 3 months after the intervention to check that actions had been taken. In premises where no risks were found, no further visits would be necessary and usual practice would resume.

Expected outcome

It was expected that, through dialogue with auditors immediately following the audit, DPSs would feel some ownership over the action plan they receive. This was key in facilitating premises to carry out the action points, as any disagreement over risk factors should have been resolved and there should not have been any surprises in the action plan.

Summary

Developing and refining an intervention to be delivered by EHPs was undertaken through a period of preparation involving a multidisciplinary team. The basis of the intervention was developed through meetings between environmental health agency managers and academic research staff where the objectives of the intervention were developed from the rationale behind the trial, the literature and previous experience of working with licensed premises to reduce ARV. The underpinnings of the intervention, guided by the overall research objectives, were further developed by the core research team using key questions to guide and focus progression. Industry representatives and web consultants took the visual aspects of the website and video elements of intervention forward with the guidance and feedback from the research team. The audit was finalised between the research team and senior EHPs. With respect to time scales, development of intervention materials occurred concurrently to meetings concerning intervention delivery, data collection and overall trial design in order to maximise intervention feasibility and collecting the data needed to answer the primary research objective. Preparation to conduct the trial, which included intervention development and refinement, took 6 months. By the end of this period a premises-specific, risk-led intervention had been coproduced through collaboration with senior EHPs. This notionally gave the intervention the best chance of being mainstreamed into EHP usual practice. Additionally, consideration of the materials and their implementation alongside the overall trial design throughout this process increased the likelihood of successfully trialling the finalised intervention in licensed premises in Wales.

Chapter 4 Methods

Trial design

The project included a randomised controlled effectiveness trial, with licensed premises as the unit of randomisation. Figure 4 depicts the trial schema. The trial was preceded by an initial intervention refinement period and included an embedded process evaluation and economic evaluation. The trial received ethical approval from Cardiff University Dental School Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/08).

FIGURE 4.

All-Wales Licensed Premises Intervention trial schema.

Trial population

The population comprised premises licensed for the on-site sale and consumption of alcohol residing within any of the 22 Welsh LAs.

Premises eligibility

Licensed premises were eligible if, between the months May 2011 and April 2012, they had one or more violent incidents associated with them. Incidents inside and in the immediate vicinity of licensed premises were identified from police data. Other inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 2. In order to determine eligibility, premises were cross-referenced with licensing data and, where feasible, premises’ own online web pages.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| On-licence premises that are based within the 22 LAs in Wales | On-licence premises that are cafes, restaurants and entertainment venues such as sports facilities and concert halls |

| On-licence premises that are public houses, nightclubs or hotels with public bars | |

| On-licence premises that have one or more violent incidents recorded by the police (including Section 18/20, Section 47, common assault, affray, assault of a police officer) in the 12 months up to May 2012 |

Baseline violent crime data

In order to access police data, data sharing agreements were prepared and signed between Cardiff University and all four police forces in Wales. The agreements covered the period from May 2011 to the end of the trial follow-up period. These data were used to identify eligible premises (see above) and to provide baseline characteristics required for stratification.

All violence against the person data for Wales were requested from all four police forces in Wales. These data included incident location, coded as both Global Positioning System (GPS) co-ordinates (recorded by the attending police officer) and a free-text description of the incident location (also entered by the attending officer). The data from North and South Wales territories were extracted using the NICHE Records Management System. In the Dyfed and Gwent territories the data were extracted using the CIS Records Management System (Computer Information Systems, Inc., Skokie, IL, USA) and Guardian Records Management System (Victorville, CA, USA), respectively, which introduced minor coding differences between each police force data set. Data were handled according to the data sharing agreements in place; original data were encrypted, stored and accessed by two named individuals. Only anonymised data or data with premises details but not crime information were available to members of the research team for screening.

Baseline premises address data were manually checked by two independent researchers. All addresses that identified a licensed premises were marked as such. Licensed premises were identified using online search tools and LA licensing data. Contact (telephone number) and address information were appended to the data, as well as licensable hours of business. Premises were telephoned to ensure that they were open and this was rechecked through contacting LA licensing teams. Premises that were open at baseline and deemed eligible by the research team were then stratified (the variables used to stratify the premises are outlined below). This produced a total of 837 licensed premises with one or more violent incidents associated with them that were eligible for inclusion in the trial. The 600 premises selected for trial participation were chosen randomly, resulting in 300 premises in the intervention group and 300 in the control group. The remaining 237 premises were reserved as replacement premises in the event that intervention premises were closed by the time audits began. A list of intervention premises was then split by LA, weighted by LA size and sent to the respective EHP responsible for premises in that LA, along with intervention materials.

Closure and replacement premises

It was anticipated that a number of premises screened and allocated to the intervention or control groups might cease business or become ineligible (e.g. changing to a restaurant) before the intervention was to be conducted. If premises in the intervention arm became ineligible before the intervention phase began, it was replaced with a premises randomly selected from a list of any remaining premises in that LA, matched by strata. When a replacement premises meeting the necessary strata criteria was unavailable the premises was not replaced. Following the intervention period, the research team investigated closure of premises (in both experimental arms) by contacting LAs. Duplicate premises, or premises in the intervention arm that did not co-operate with EHPs or could not be accessed by EHPs in the allotted intervention period, were not replaced with any of the remaining premises.

Permission to participate

Permission for environmental health practitioners to deliver the intervention

Environmental health practitioners across Wales have allotted time to engage in projects each year. The All-Wales Technical Panel agreed in 2012 that the AWLPI trial would be that year’s project of choice.

Consent from environmental health practitioners

As the EHPs delivering the intervention have statutory powers in the areas of workplace health and safety, and assess risk in small and medium-sized businesses as part of their usual activities, the trial was essentially a natural experiment (albeit with allocation to group being randomised). Therefore, as a part of EHP routine practice, it was unnecessary for premises to provide consent to participate in the trial and/or to receive the intervention.

Trial procedures

Environmental health practitioner intervention training

At least one EHP from each LA attended one training workshop. The EHPs were provided with a training manual and were supported throughout the trial period by the research team.

Data collection

Audit data

Staff at intervention premises were contacted about their forthcoming audit by a letter which was sent by the EHP responsible for that premises. The letter provided information about the trial and explained that an EHP would contact the DPS to arrange a convenient time to undertake the audit. The same template letter was used across all LAs.

The audit was completed by an EHP at a mutually convenient time. Parts of the audits were completed through interactive discourse with the DPS and beverage servers in order to find out more about a particular procedure or when physical evidence of certain artefacts, for example certificates of training, were required. On completion, EHPs fed back to the premises staff on areas where further action was required, if any. Feedback on changes required was given verbally, by letter or through formal notices (prohibition or improvement notices).

Once the forms were completed the EHPs photocopied the completed parts of the form and returned the original version to the research team and kept a photocopy for their files. Inconsistencies or omissions in the audit were clarified with the EHPs before the audit was scanned electronically and stored within a password-protected domain of the Cardiff University shared drive. The paper versions of the audits were stored in a locked cupboard. Audit completion was tracked using a Microsoft Access® database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Responses from the audit forms were entered manually (using double data entry) into an Access database; these data were then converted into a Stata data file (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The researchers entering the data were provided with a metadata template enabling them to match each question/response field on the audit with its shortened variable name and providing them with information about what type of data should be entered (i.e. single response, integer, text, etc.) and how data should be labelled/transformed. The audits also included a section for EHPs to complete that consisted of a checklist and space for reflective feedback regarding each premises. This part of the audit was scanned/e-mailed/faxed/posted and entered into a separate spreadsheet to be used to inform the process evaluation.

The procedure for collecting, storing and entering follow-up audit responses was the same as that for the initial audit.

Feedback from the SMILE website

The SMILE website was coded such that usage statistics could be derived (unique visitors), providing an indication of use. In addition, the site was further coded so that it would not be included in search engines, to reduce the possibility that traffic had been generated from non-project activity.

Police outcome data

Between April and May 2014, data were received from four police forces, Dyfed-Powys, Gwent, North Wales and South Wales, in response to the original data sharing agreements with each. Data were received as four Microsoft Excel® files in different formats (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). All files contained information related to offence (classification), time (date) and location (GPS and street address). These files were amended so that the data from the four authorities appeared in the same format.

Premises closure

All premises were checked for closure throughout the follow-up period. Premises closures and reopenings were tracked on an Excel spreadsheet. In addition, intervention premises closures were also determined by EHPs reporting that premises were closed when they were unable to gain access to premises for audit visits.

It was initially planned to use LA licensing data to identify premises that were economically active. These data were not available in most LAs, with data quality being at best below the expected standards.

At the end of the follow-up period a freedom of information request to all LAs requested business rate information on all study premises. All businesses are required to pay business rates unless they temporarily or permanently cease trading. These data were accessed to determine temporary and permanent premises closures in both trial arms.

Premises that were closed at the time of intervention delivery (and did not receive an initial audit) were dropped from the study. Premises that received the audit but were temporarily closed had their outcomes censored.

Follow-up data

Police data from January 2013 for 455 days were accessed from the four Welsh police forces. Two data sets were created, one using similar manual search methods used with the baseline data and one using automated search algorithms trained using baseline data. Primary outcome data were in the data file generated using automated procedures; sensitivity analyses used the manually produced data and a combination of both manual and automated.

Manual data

All violence against the person data were manually screened, comparing each entry with the list of trial premises. For each police force, a random subset of entries was independently rechecked using similar methods by a second researcher. Both data sets were compared and inter-rater reliability was calculated as the proportion of records that were identically identified, where a score of 1 was assigned where both raters agreed and 0 otherwise.

Automatic data

The GPS co-ordinates associated with each trial premises, derived from the baseline data, were used to extract a second data set of follow-up data. Data were received from four police forces: Dyfed-Powys, Gwent, North Wales and South Wales. Data were received as four Excel files in different formats. All files contained information related to offence (classification), time (date) and location (address). In order to classify crimes within the violence against the person category, we used Home Office crime classifications. 71 First, different coding systems used by different police forces were normalised to the latest version of the Home Office crime codes. A document called Crime Tree: Mapping of Crime Codes sets out how individual crime codes map to the branches of the crime tree. Level 3 of the tree was used to extract offences related to the violence against the person category. All crime codes corresponding to the violence against the person category at levels 3, 4 and 5 were extracted from the tree and cross-referenced against the crime data.

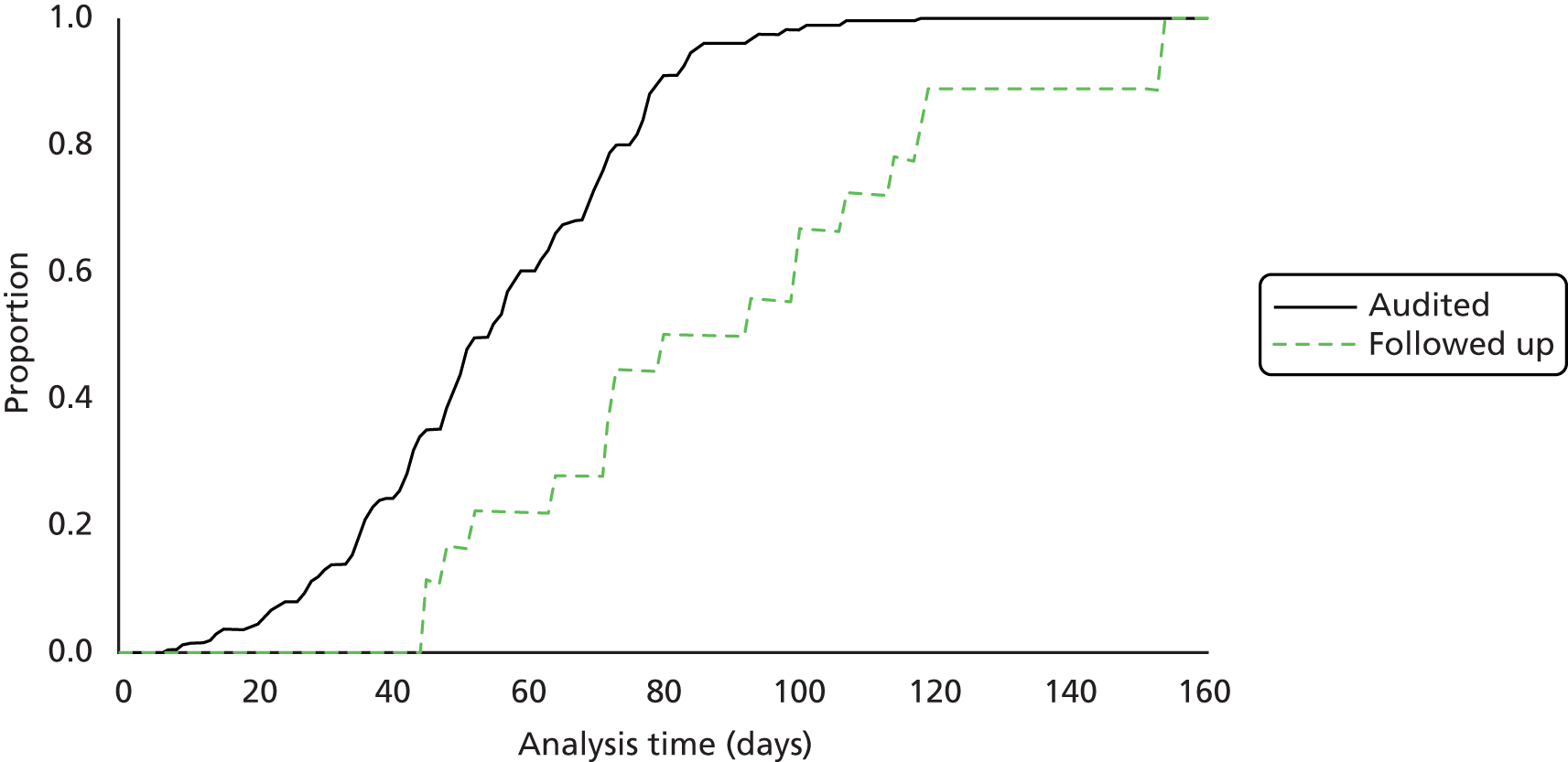

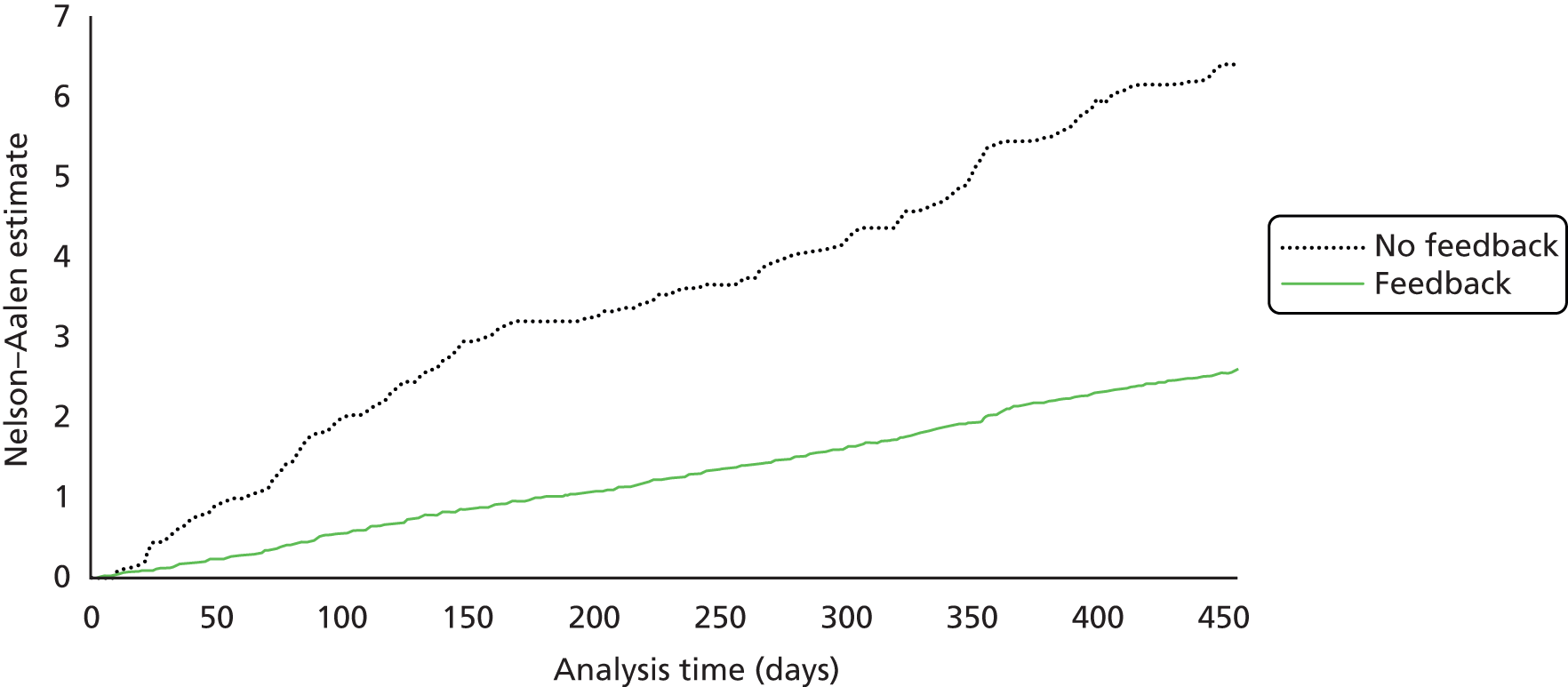

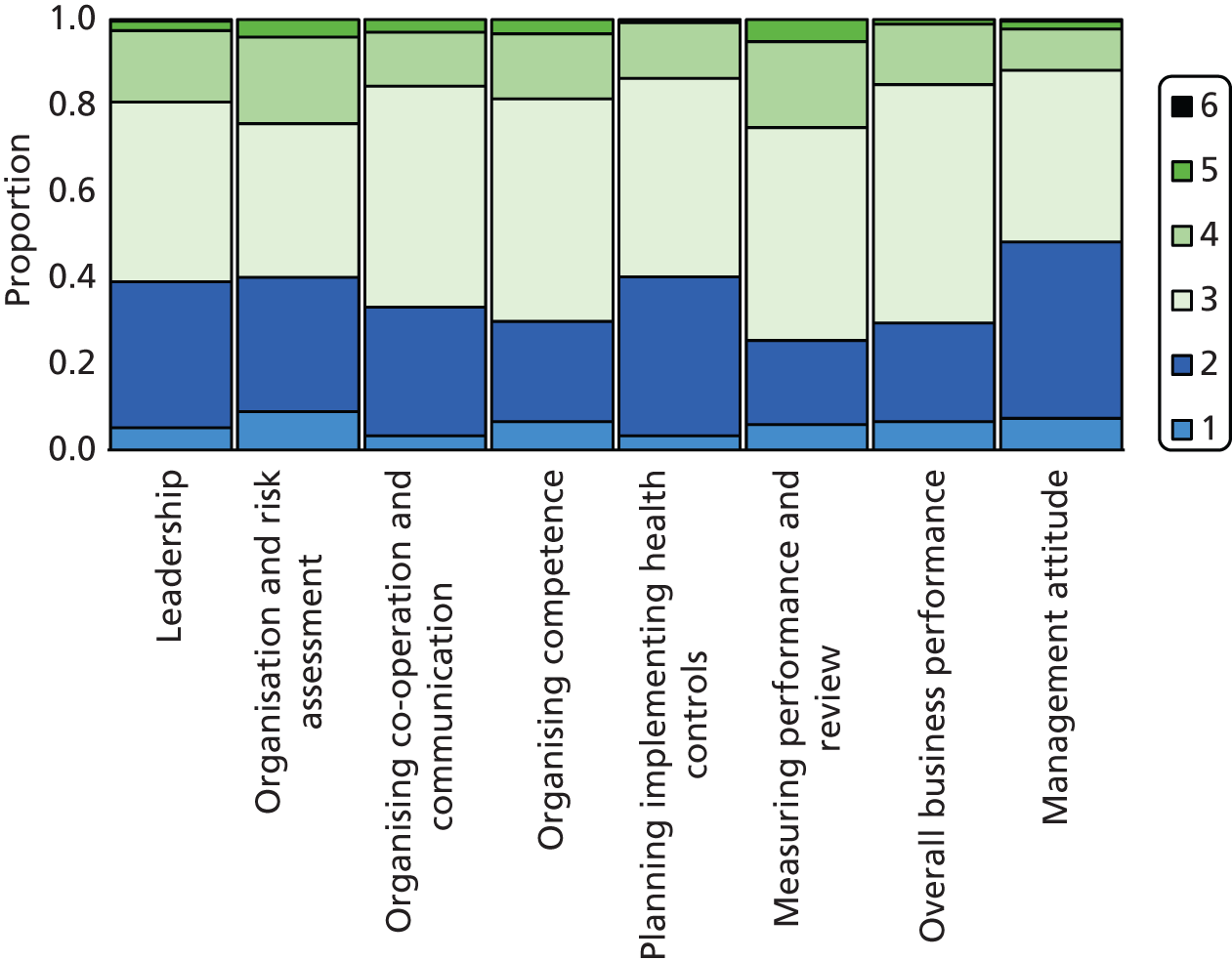

In the next step, offences not related to premises were removed from consideration. A list of lexical clues was assembled to automatically remove the bulk of the non-relevant data. Examples of such lexical clues include words and phrases such as car park, school, play area, road, footpath, mini market, etc.