Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3008/07. The contractual start date was in December 2011. The final report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in February 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Popay et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

This is the final report of a study that has explored the impact on health inequalities and their social determinants of the diverse approaches to community engagement (CE) adopted in the New Deal for Communities (NDC) regeneration initiative implemented between 1998/9 and 2010/11. This is the third of three closely linked studies. The Department of Health Policy Research Programme funded the first and second of these studies. The first, which ran from 2003 to 2005 considered the feasibility of evaluating the impact of the NDC initiative on health inequalities using secondary data sources [Popay J, McLeod A, Kearns A, Nazroo J, Whitehead M. New Deal For Communities And Health Inequalities: The Final Report of a Scoping Study. Submitted to the Department of Health (ref: RDD/018/063) 2005; unpublished report]. The second, which ran from 2010 to 2013, evaluated the impact of local NDC programmes on health inequalities and their social determinants. 1 The third study, reported on here, has built on this previous work in three ways: (1) by considering whether or not NDC approaches to CE had any independent impacts on a range of health and social outcomes; (2) by considering whether or not these approaches to CE contributed to the impacts of local NDC programmes reported in our previous study; and (3) by including an exploratory analysis of the cost-effectiveness of NDC CE approaches.

In this introduction we describe some of the challenges involved in evaluating action with the potential to reduce health inequalities and their social determinants, focusing in particular on initiatives to engage the public in policy decision-making. We then briefly consider the role of theory-based evaluations of complex interventions, such as the NDC, before describing the NDC initiative itself and providing an overview of previous evaluation of the impact of different types of local NDC programmes on a range of health and social outcomes. Some of this work is considered in more detail in Chapter 4. Finally, we outline how the rest of the report is structured.

Conceptualising health inequalities and action to reduce them

Health inequalities are systematic differences in health experiences/status between socioeconomic groups, areas of the country, women and men, and different ethnic groups that have their roots in unjust social arrangements. Repeated enquiries into the scale and causes of these inequalities have adopted a social model of health, which places the individual at the centre surrounded by ‘layers of influence’ relating to lifestyle factors, social and community networks, living and working conditions, and the general socioeconomic and cultural environment. 2 To reduce health inequalities action is required at all levels including the wider determinants of health such as unemployment, poverty, low educational attainment, poor housing and poor physical environments.

Despite the considerable effort and resources that have been invested in action to reduce health inequalities in the UK, these inequalities have remained largely unchanged over recent decades and in some instances have worsened. 3 Over the same period action aimed at reducing these inequalities has focused primarily on changing lifestyles among groups with the poorest health. Interventions have had a particular focus on proximal ‘risky behaviours’ including, in particular, poor diet, high alcohol intake, low physical activity, high smoking rates and risky sexual activity. When attempts are made to change environments public health initiatives typically continue to focus on the same ‘risky’ behaviours by, for example, creating environments to encourage greater physical activity, working with ‘fast food’ outlets to change menus and/or banning smoking in public places.

Evaluative research suggests that, although lifestyle-oriented approaches can improve population health overall, they do not significantly reduce health inequalities,4–6 and in some instances can increase them. 7 Part of the explanation for the failure to reduce health inequalities may be a lack of understanding about the meaning of what are commonly labelled ‘risky behaviours’. Research has shown, for example, that for some groups these behaviours may be better understood as ways of coping with difficult life circumstances. 8 From this perspective people experiencing disadvantage may have the capacity to change behaviours only if their social and economic circumstances change for the better. If the circumstances do not change in the face of lifestyle interventions, they may substitute one coping mechanism for another, which could have equally negative impacts on health and well-being.

Another part of the explanation for the enduring nature of health inequalities may lie with the failure of action to address the more distal causes – the causes of the causes as Marmot and colleagues4,9 have argued. For example, Phelan and colleagues6 have shown that historically new socially patterned proximal threats to health tend to replace the risks previously prioritised by public health policies, so continually reproducing health inequalities. These authors and others9,10 argue that this occurs because the fundamental causes of health inequalities – socioeconomic inequality or social injustice – are not being reduced. These ‘fundamental causes’ are assumed to operate through an unequal distribution of multiple resources, including income, wealth and power, which give groups/individuals differential capacity or ‘control’ to reduce proximal risks.

Control, community engagement and health inequalities

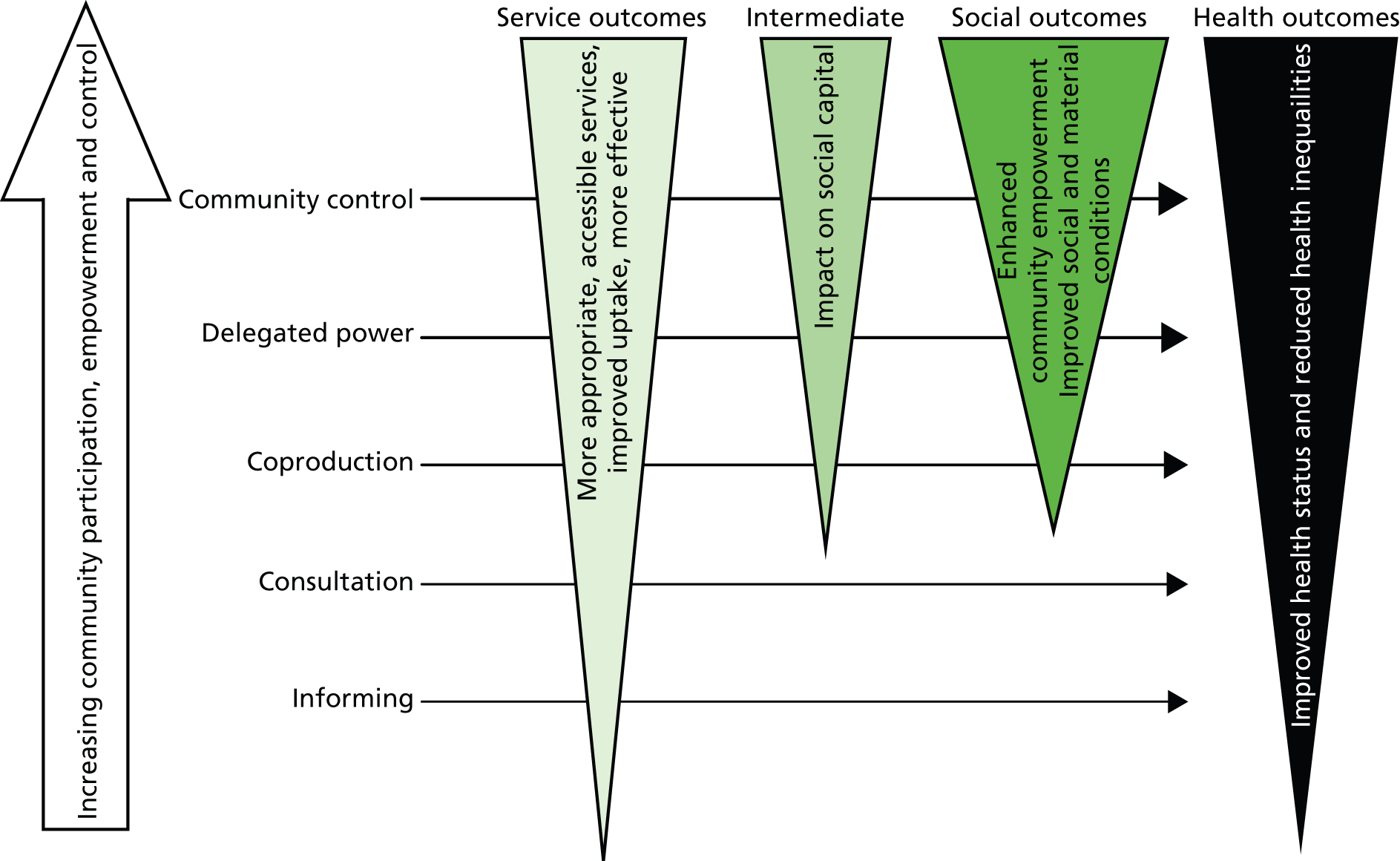

Community engagement is an eclectic arena. In the health field it may mean involving people living in particular areas in delivering (typically lifestyle) interventions designed by professionals. Other initiatives aiming to engage local people in action to improve health seek to give residents of a neighbourhood or group influence over which issues are to be prioritised for action, what the action is to be and who delivers it, and how it is to be delivered. In theory there are a number of possible interlinked pathways between the processes of CE, enhanced community control/influence and social and health outcomes (including both improved population health and reduced health inequalities). Some of these pathways are illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the initial conceptual framework that informed our study.

FIGURE 1.

Pathways from community empowerment and engagement to health improvement. Source: Popay. 11

The model proposes that, at one end of the spectrum, engagement that involves the more or less passive transfer of information between communities, professionals and/or organisations may impact on the appropriateness, accessibility, uptake and ultimately the effectiveness of services but is unlikely to increase social cohesion and solidarity among people living in a neighbourhood or result in significant empowerment of a community. Hence, the impact on health at the population or individual level is likely to be modest.

In contrast, the greater the emphasis on giving communities more power and control over decisions that affect their lives, the more likely there are to be positive impacts on service quality, social cohesion, socioeconomic circumstances, community empowerment and ultimately population health and health inequalities. It is also theoretically possible that engagement initiatives may have negative impacts on service use, social cohesion and individual and population health, for example if ‘engaged’ individuals are not appropriately supported and, at the population level, if community expectations of involvement, influence and/or control are not met. 12

There is a considerable body of research on the health and social outcomes of control at the individual level. Within social psychology, control is conceptualised at the individual level as the power to manage situations in the paid work environment, for example Karasek’s demand–control model13 and Siegrist’s effort–reward imbalance model. 14 There is also a literature on social identity, social relationships and membership of groups that links individual control to well-being and health outcomes. 15

Reviews of research evaluating the impact of CE,16–22 have found evidence of positive health and social outcomes for ‘engaged’ individuals including increased self-efficacy, confidence and self-esteem; improved social networks; a greater sense of cohesion and security; improved access to education leading to increased skills and paid employment; and self-reported improvements in physical and mental health, health-related behaviour and quality of life. There is also some evidence that CE can have unintended negative impacts on ‘engaged’ individuals including physical and emotional health costs, consultation fatigue and disillusionment. Additionally, some evidence points to potentially important relationships between the type or level of CE and intermediate social determinants of health outcomes at a community level including, for example, improved uptake and effectiveness of services,19 improved living conditions including housing quality20 and both ‘bonding’ and bridging social capital. 21

Research by Chandler and Lalonde23,24 found that the greater the degree of cultural continuity in British Columbia’s First Nations the lower the rates of youth and adult suicide. Cultural continuity was operationalised in terms of measures of the collective control that First Nations have over their ‘civic lives’ including securing ownership of their traditional lands; community control over educational services, police and fire protection services, and health care; having dedicated ‘cultural facilities’ to help preserve and enrich their cultural lives; women’s participation in local governance; community control over child custody and child protection services; and the proportion of children removed from parental care.

Emerging work by the New Economics Foundation on the concept of solidarity is also relevant to discussions about collective or community control. Coote and Angel25 argue that solidarity locates the sources of transformative action in civil society and recognises that moments for change arise from popular understanding of the structures and processes that reproduce inequalities. Qualitative research suggests that some of the strategies that people develop to manage their lives in difficult places, for example distancing themselves from others living in the same neighbourhood, can undermine the development of shared narratives and respect based on mutual understanding, which are prerequisites for collective action for change. 26,27 Research suggests that initiatives aiming to engage people in policy-making and implementation may help counter these processes and may have positive health and social outcomes for the people who get engaged. However, there is also a significant body of research highlighting the barriers to effective engagement of communities in policy and practice decision-making. 18,28 Formal evaluations of a number of English high-profile health-related policy initiatives in the first decade of this century, all with a strong emphasis on CE (such as Health Action Zones, Sure Start Centres and Healthy Living Centres), highlighted these barriers, reporting that, although community members participated successfully in specific health improvement initiatives and service delivery, there was little collective community control over the strategic direction of these initiatives. 12,29–38

It is also the case that much available research on the impact of CE is of poor quality and there are major gaps in the evidence, including an absence of evidence on the impact on health inequalities; poor descriptions of the CE interventions; a lack of evidence on the relative effectiveness of different CE approaches in engaging people from different social groups/communities, a lack of evidence on the impact of these different CE approaches on the individuals who are engaged and at the community level; and differential impacts of CE across population groups. There is also an absence of adequate information on resource use and especially the opportunity costs of CE to community members. 39 The research reported here has sought to address these problems and advance the evaluation of CE approaches and their impact on health inequalities.

‘Theory of change’ approaches to evaluation

Over the past two decades, theory-based approaches to the assessment of public policy and interventions have been elaborated in the general evaluation literature. 40–42 The idea, as originally proposed by Wholey,43 is to analyse, for the purposes of evaluation, the logical reasoning that connects intervention programme inputs to intended outcomes and assess whether or not there is any reasonable likelihood that programme goals could be achieved. This logical reasoning, called the ‘theory of change’ refers to how and why an intervention works. 44 This literature acknowledges that all intervention programmes are based on theories, whether implicit or explicit, of how the activities proposed in a programme are expected to have their impact. Making these programme theories explicit helps in the design of an evaluation, but also draws attention to the existing literature on the probable effectiveness of the proposed mechanisms for change.

Such theory-based approaches have been used in particular to evaluate the effectiveness of health promotion and risk prevention interventions,45 and latterly have been adopted for the evaluation of complex community interventions in the UK, such as the English Health Action Zones. 46 Their value lies in assessing the effectiveness of the various components of existing interventions, and also the design of future initiatives, by generating plausible programme theories and designing programmes to test them under real-life conditions. 42 The usefulness of ‘theory of change’ approaches is currently being explored for the assessment of the various endeavours to tackle health inequalities. 47 In this evaluation we have used this approach to help in the development of a typology of NDC approaches to CE and in the interpretation of our findings.

The New Deal for Communities Initiative and community engagement

In 2003, the then Labour government set the NHS and local authorities targets for reducing the gap in life expectancy and infant mortality between the most disadvantaged areas/groups and the average for the population as a whole in England. Although much activity was aimed at lifestyle and behaviour change, a National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal48 was also expected to contribute by improving the wider social determinants of these inequalities, for example reducing poverty and increasing housing and improving physical environments. The area-based regeneration initiative NDC was a central part of this strategy.

There were 39 NDC areas, launched in two waves: 17 pathfinder areas in 1998 and a further 22 areas in 1999. Each NDC area had a budget of around £50M (nearly £2B in total). The overall aim was to bridge the gap over a 10-year period between some of the most deprived neighbourhoods in England and the rest of the country in six outcome domains, three intended to improve the areas (crime, community cohesion, and housing and the physical environment) and three intended to improve outcomes for people (education, health and worklessness). However, the form that these local programmes took varied significantly as they sought to address local needs in very different socioeconomic, cultural and political contexts.

Various commentators argue that public participation under New Labour was grounded in theories of democracy and citizenship, and framed in rhetoric about building stronger communities through social cohesion and civic renewal. 49–51 Like other policy initiatives at the time, therefore, the NDC programme had a strong focus on CE, reflecting the wider trend of intensifying citizen participation in both UK and international public policy. 52

The theory of change underpinning CE in the NDC and other policy initiatives emerged from the Social Exclusion Unit in the Cabinet Office and assumed that engaging the communities of NDC areas in developing and delivering local programmes would overcome problems of social exclusion and promote social cohesion, hence reducing crime and incivilities, and would also make services more responsive to local needs and hence increase access and effectiveness. 48 An analysis of NDC policy guidance and strategy undertaken by Wright and colleagues51 midway through the programme positioned the NDC as ‘an attempt to reconnect deprived neighbourhoods with the rest of Britain . . . Herein the NDC partnership expresses the ideal of active citizens asserting their equality of status and demanding accountability from service providers’ (p. 351). To achieve these goals, empowerment was conceived of as a mechanism to support members of the public to develop capabilities to participate in and influence services, and shape the future of their neighbourhoods.

However, commentators have also noted the constraints of an empowerment model in the context of a government-led programme ultimately driven by policy-makers’ strategic goals, with policy-makers criticised for lacking an appreciation of the complexity of ‘community’. On the one hand the NDC’s model of engagement was concerned with the active participation in democratic and civic life of politically aware citizens. On the other hand, Wallace50 argues that policy-makers advocated for a very particular type of participation, creating structures for ‘responsible but apolitical actors’ to participate in decisions about neighbourhood life, with little scope to include social action resistant to or challenging of government agendas (p. 813).

In terms of the practice of engagement in the NDC initiative,53 the team conducting the national evaluation of the NDC reported that 18% of the total expenditure of local NDC partnerships (excluding management and administration) or approximately £248M went on ‘community-related interventions’ in the first 8 years of this 10-year programme. Almost one-fifth of this went on new or improved community facilities, but a substantial amount was also spent on involving local people and developing the skills and infrastructure of the community. 53 Although approaches to engagement varied (as discussed in Chapter 3 of this report), a wide range of engagement activities were implemented, including forums, festivals and events, NDC newsletters, funding for community development and involvement teams, training for resident representatives on NDC boards and providing resources for local action through the ‘Community Chest’ and other small grant programmes.

Predictably, only a minority of residents either had heard of the NDC or got engaged in NDC activities. For example, data from the four Market & Opinion Research International (MORI) household surveys conducted for the national evaluation suggest that the numbers who had heard of the NDC increased over time between 2002 and 2008 from 16% of residents to 22%, but declined a little by 2008. In the last of these surveys in 2008, 17% of all respondents said that they had been involved in NDC activities at some point in time (although this percentage was 44% among those respondents who had lived in a NDC area over the whole of the period). Of the 17% of all survey respondents who reported getting engaged in some NDC activities, 87% played a participative role, with most of them attending events or festivals. Only 14% voted in NDC elections and just over one-quarter (or 4% of all residents) had been involved in volunteering for the NDC partnership, although overall voluntary activity increased over the life of the NDC programme (albeit remaining lower than for England as a whole). However, in all 39 areas residents were a majority on the partnership boards that oversaw local programmes and were involved in most subcommittees overseeing thematic work (e.g. on environmental or health initiatives).

Previous evaluations of the New Deal for Communities

The government’s Neighbourhood Renewal Unit, in the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, funded a consortium of universities led by Sheffield Hallam University to carry out a national evaluation. The National Evaluation Team (NET) started work at the end of 2001 – almost 2 years after the first wave of NDC partnerships was approved (1999) and 1 year after the second wave was commissioned (2000) – and its funding ended in 2010/11. The evaluation involved an initiative-wide impact assessment, investigating the association between ‘effort’ and ‘change’ during two periods, 2001–5 and 2006–8, utilising 36 indicators developed to measure progress across the six outcome domains. The NET also explored factors influencing programme implementation. 54 The NET evaluation involved the identification of comparator areas matched to each of the 39 NDC areas by deprivation score and local authority area, and the collection and analysis of a wide range of quantitative and qualitative research data – both cross-sectional and longitudinal – some for all of the NDC areas and their comparators and some for selected NDC areas (see Chapter 2). The NET has produced a number of reports, which are available for download from http://extra.shu.ac.uk/ndc and journal papers (accessed November 2014).

In addition to the national evaluation, there has also been a number of smaller-scale evaluations of local NDC programmes, some undertaken by individual NDC partnerships and one by a team based at the Universities of Birmingham, Staffordshire and Central England. The latter study was exploratory, considering the availability and selection of health outcome measures relating to specific activities in six NDC local programmes in the West Midlands, but there have been no publications of impact on health or health inequalities.

Although the NET looked at some health outcomes (see Chapters 2 and 4), neither its work nor any of the smaller-scale evaluations focused explicitly on the impact of the NDC programme as a whole on health inequalities or their social determinants. In 2003, the Department of Health therefore commissioned us to assess the feasibility of undertaking such an evaluation using secondary data sources, including in particular the data sources compiled by the NET. The scoping study concluded that an evaluation of the impact of the NDC initiative on health inequalities using secondary data sources was feasible [Popay J, McLeod A, Kearns A, Nazroo J, Whitehead M. New Deal For Communities And Health Inequalities: The Final Report of a Scoping Study. Submitted to the Department of Health (ref: RDD/018/063) 2005; unpublished report]. The Policy Research Division subsequently funded this evaluation in 2010 and the findings were reported in November 2013. 1 Findings from our evaluation of the health and social impact of different types of NDC local programmes are summarised in Chapter 4.

About this report

The research reported here has built on our previous evaluation of the impact of the NDC on health inequalities and their social determinants. In the research described here we sought to evaluate the impact on a range of health and social outcomes of the approaches that NDC partnerships took to engaging their residents in the design and delivery of local programmes. In Chapter 2 we describe the study design, methods and sources of the largely secondary data that we have used. Chapter 3 describes the development of a typology of NDC approaches to CE, which we subsequently used in our analyses of what impact, if any, CE had on health and social outcomes. The findings of these impact analyses are reported in Chapters 4–6. Findings from our qualitative research are reported in Chapter 7 and our cost-effectiveness work is described in Chapter 8. In Chapter 9 we highlight some of the limitations of the research, summarise key findings and consider the implications for policy and practice of aiming to engage people in shaping and delivering action to improve their lives and the places in which they live.

Chapter 2 Study design and data sources

Introduction and research questions

Our research has involved collaboration between researchers at the Universities of Lancaster, Liverpool, Manchester and St Andrews, and the Medical Research Council Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing now at University College London. We have also engaged NDC residents and past workers in the research as described in the following section. Originally, the evaluation was to be conducted over 24 months from 1 September 2011. However, a 9-month no-cost extension was agreed to accommodate significant delays because of changes in staff, giving a new end date of 31 May 2014.

Public involvement in our research

The main mechanism for public involvement was through the advisory group. Professor Paul Lawless, who also led the national evaluation of the NDC, chaired this advisory group, which included residents of NDC areas, former staff of NDC areas [including a previous NDC Chief Office who was later the chairperson of the Neighbourhood Regeneration Agency (NRA)], academics with a range of expertise, representatives from the Department of Health and members of the project team. Advisory group members were able to comment on regular updates on the research and the debates and critiques were invaluable, helping to strengthen the study’s methods and interpretation of findings.

In addition to participating as members of the advisory group, NDC residents (including Ann-Marie Pickup who was a named co-applicant) and NDC workers (including Liz Kessler, a former NDC employee who was extremely helpful in our previous evaluation of the NDC initiative) contributed to our research in other ways. An example of this type of contribution (described in detail in Chapter 3) involved two public advisers participating in an exercise designed to help us allocate nine NDC areas, for which we had insufficient information, to one of our CE ‘types’. Some of the NDC resident members of the advisory group also acted as advisers to the fieldwork, helping to identify research participants, proofreading project information sheets, testing research tools (such as the interview schedule), and taking part as research participants. Additionally, our public advisers participated in a workshop to discuss the interim findings from the project and to inform aspects of the work to develop a CE typology for the NDC areas (described in Chapter 3). Specifically, discussions informed the design of the research tools for telephone interviews and helped to refine the dimensions to be used in the typology of approaches to CE. Public advisers were offered an involvement fee for their participation and we developed an information sheet based on INVOLVE guidance55 that set out what advisers could expect in terms of their participation.

The NRA was the successor body to an organisation set up to support and connect the NDC areas. Its board consisted of former chief executives of NDC areas. When the NDCs were running, the NRA organised conferences and workshops that brought representatives from the NDC areas together, enabling them to share knowledge and ideas. The chief executive of a NDC successor body in one of our fieldwork sites put us in touch with the NRA, and the chair, Sam Tarff, agreed to join the study advisory group. The NRA worked with project researchers to plan a workshop to discuss the study findings with a wider group of NDC area residents and former staff. This workshop was postponed because of the low take-up of places, but we continued to involve the former CE of the NRA as a member of the advisory group. We also circulated e-mail updates on study progress to a wider network of members of the public that included former NDC employees, residents of NDC areas and newer successor organisations. We plan to produce a lay summary of this report when it has been approved and will be discussing other dissemination options with relevant funders in due course.

Study design, methods and data sources

The study has considered whether or not different approaches to CE taken by the 39 local programmes that make up the NDC regeneration initiative had different impacts on health and social outcomes and whether or not some approaches were more cost-effective than others. The aim was not to evaluate the multitude of specific techniques and processes of engagement used in local areas, but rather to evaluate the different strategic approaches to engagement adopted at a local programme level. To do this we first had to develop a typology of these approaches and then evaluate the impact of these different ‘types’ of CE approaches. The study has therefore involved mixed methods and consisted of three linked elements: development of a typology of NDC approaches to CE; assessment of the impact of NDC approaches to CE on health and social outcomes; and an exploratory economic evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of NDC approaches to engagement.

Developing a typology of New Deal for Communities approaches to engagement

The development of a typology of NDC approaches to CE was undertaken in three phases. These are described in more detail in Chapter 3 and Appendix 1. During phase 1 of this work a preliminary typology was developed using secondary data sources collected by the NET. The main sources of secondary data used in the typology development are listed in Box 1. This work involved simple descriptive statistical analyses of household survey data and content analyses of documents.

-

Cross-sectional data from the MORI household surveys in all NDC areas and comparator areas (repeated in 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008), described in more detail in Assessing the impact of New Deals for Communities approaches to community engagement on health inequalities and their social determinants.

-

Partnership Survey reports on process and management in all NDC areas (2002/3, 2003/4, 2004/5).

-

Comprehensive project case studies in all NDC areas (2003).

-

Case study work with selected NDCs to look at specific issues in more detail, including case studies on engagement. 56

-

Local documents including delivery plans, CE strategies, progress reports and local evaluation reports.

a Data available from http://extra.shu.ac.uk/ndc/ncd_data.htm (accessed 9 August 2015).

A second phase of work involved the collection of new qualitative data from residents and workers in a purposive sample of NDC sites, which were analysed thematically, and collation of additional local documents identified during the fieldwork. Finally, the typology was revised on the basis of the data collected and its applicability to specific NDC areas tested through telephone interviews with key informants in a sample of NDC sites. This resulted in the following fourfold typology, which is described in more detail in Chapter 3:

-

type A: resident led and driven by strong CE values

-

type B: initially resident led and driven by strong CE values but this weakened over time

-

type C: balancing instrumental and CE values

-

type D: instrumental with approach to CE shaped by external priorities.

Assessing the impact of New Deal for Communities approaches to community engagement on health inequalities and their social determinants

Our impact analyses sought to answer five questions:

-

Which approaches to CE effectively engage which social groups in NDC populations?

-

Do different approaches to CE have different health and social outcomes for NDC populations?

-

Does the association between these outcomes and the NDC approach to CE vary across groups defined by age, ethnicity, gender and material circumstances?

-

Do different approaches to CE have any impact on the health gap between NDC areas and areas from across the socioeconomic spectrum?

-

Does the approach to CE help to explain any of the differential outcomes of local NDC programmes identified in our previous research?

Our previous evaluation of the health and social impact of local NDC programmes1 had categorised the 39 NDC areas into three theoretically derived groups based on the type of local programmes that they developed:

-

Local programme type 1 (transformational). This had a primary focus on changing the composition of the area population through major redevelopment of housing.

-

Local programme type 2 (incremental). This involved a more balanced approach, with smaller-scale housing redevelopment and environmental improvements combined with a focus on human capital development in the local population.

-

Local programme type 3 (strengthening). This had a primary focus on strengthening the skills and capacity of residents, and improving their living conditions.

This typology of local NDC programmes is used in some of our impact analyses alongside the fourfold CE typology described earlier and in Chapter 3.

In addition to the questions listed above we also indicated in our original proposal that we would examine health and social outcomes for those residents who were most actively engaged in the NDC, for example as members of local partnership boards. However, this has not proved possible. Although the NET undertook a survey of a subset of residents engaged in NDC board activities, collecting data on their time commitment and burnout as well as their positive experiences, it has not been possible to link these individuals to CE types as NDC identifiers were not retained within that data set. We also undertook an exploratory analysis of health and social outcomes by CE type among the subgroup of respondents to the MORI surveys who said that they were involved in NDC activities. This amounted to 11–12% of residents and initial analyses failed to find any interactions between CE type and engaged residents. We were concerned about the robustness of this analysis because of low statistical power and opted not to investigate this further.

Our impact analyses have used self-reported outcomes from the MORI household surveys conducted in the NDC areas and comparator areas, and the Health Survey for England (HSE) as well as outcomes based on routine administrative data. These data sets and the analytical methods used are briefly described in the following sections and the results are reported in Chapter 4.

The impact of New Deal for Communities approaches to community engagement on self-reported health and social outcomes from surveys: data and methods

These analyses utilised three different data sets, briefly described below.

-

NDC MORI survey cross-sectional data. This data set consists of data from four cross-sectional surveys of residents in NDC areas and the so-called ‘comparator’ areas that the NET commissioned MORI to undertake in 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008. The target sample size was 500 in each NDC area for 2002–4, which was cut by one-fifth in 2006–8. The cross-sectional response rate in 2002 was 74%, with top-up interviews conducted at each wave to compensate for attrition. The sample size varied between 12,000 and 15,000 respondents in each round for the combined NDC areas. These data were used in three sets of analyses: (1) to test the differentiated impact of the CE typology on measures of community cohesion and health-related outcomes in NDC areas; (2) to assess change over time in these outcomes in NDC areas adopting different approaches to CE relative to their comparative areas; and (3) to compare the change over time between 2002 and 2008 in measures of cohesion and health-related outcomes in the NDC areas against the change over time in the same outcomes in the comparator areas. These data can be found at http://extra.shu.ac.uk/ndc/ncd_data.htm.

-

HSE/NDC MORI survey cross-sectional data set. This data set consists of data from the HSE and the MORI survey cross-sectional data sets for 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008. This purpose-built data set was created to provide a more robust assessment of the impact of the NDC intervention than by simply matching NDC and comparator data. The HSE survey is an annual cross-sectional survey that is nationally representative of households in England. It adopts a multi-stage probability sampling design selecting a sample of postcode sectors from the Postcode Address File and households from each postcode sector. All adults (aged ≥ 16 years) in each household are selected for interview. Topics include general health, health-related behaviours and chronic diseases. Data from the core samples of the HSE in 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008 were used to measure health and its social determinants in areas drawn from across the socioeconomic spectrum. We considered four outcomes of interest that could be acceptably harmonised across the HSE and the MORI surveys: mental health, self-rated health, current smoker and not in paid employment. The HSE provides data from residents living in areas across the full socioeconomic spectrum. We classified postcode sectors with a deprivation score in the bottom two quintiles as ‘HSE low deprivation’, those with a deprivation score in the top two quintiles as ‘HSE high deprivation’ and the remainder as ‘HSE medium deprivation’. These data can be found at http://extra.shu.ac.uk/ndc/ncd_data.htm.

-

NDC MORI survey panel data. The four MORI surveys include a panel of people who responded to the surveys at two or more time points and who remained at the same address. This data set was used to look at within-person change in health and social outcomes in NDC areas grouped according to CE type and local programme type. Given our interest in the impact of extended exposure to the NDC local programmes, only respondents present at wave 1 were retained in analyses using these data. There were 10,638 observations at wave 1 with at least two records, but the longitudinal sample size for people with full records was 3554 in NDC areas. The outcome variables used from the MORI survey data are shown in Box 2. These data can be found at http://extra.shu.ac.uk/ndc/ncd_data.htm.

-

Three-category self-rated health with answers being ‘very good’, ‘fairly good’ or ‘not good’.

-

A five-item mental health instrument derived from the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36).

-

Whether or not a current smoker.

-

Whether or not eating five portions of fruit/vegetables at least three times a week.

Trust in the neighbourhood: three-item measure of trust in the local community:

-

‘Overall, to what extent do you feel part of the local community?’ (‘a great deal’, ‘a fair amount’, ‘not very much’, ‘not at all’)

-

‘On the whole, would you describe the people who live in this area as friendly or not?’ (‘very friendly’, ‘fairly friendly’, ‘not very friendly’, ‘not at all friendly’)

-

‘Would you say that you know most, many a few of, or that you do not know people in your neighborhood.

Trust in local services: three-item measure:

-

‘How much trust would you say you have in each of the following organisations?’ (‘a great deal’, ‘a fair amount’, ‘not very much’, none at all’):

-

the local council

-

the local police

-

the local health services.

-

-

Education, measured as a three-category indicator: National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) levels 4–5, 2–3 or ≤ 1.

-

Whether or not respondents lived in rented accommodation (public as well as private).

-

Whether or not respondents lived in a jobless household (this measure included retired respondents but it was assumed that controlling for age would account for potential bias).

-

Sex.

-

Age.

-

Whether or not respondents were non-white British (self-report).

Depending on the data set one of the following statistical approaches was used:

-

Analysis based on NDC MORI survey cross-sectional data relied on binary logistic regression, reporting odds ratios of dichotomised health and cohesion outcomes, adjusting for sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

-

Analysis based on the combined cross-sectional HSE/NDC MORI survey data set similarly relied on binary logistic regression.

-

Analyses of within-person change using the longitudinal panel from the NDC MORI surveys for 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008 used one of two modelling frameworks depending on the outcome variables of interest:

-

Discrete behaviour such as smoking or healthy eating was captured in dichotomised variables and modelled in survival (i.e. Cox) models in which the relative probability (also called the hazard ratio) of quitting smoking or taking up healthy eating at some point between 2002 and 2008 was estimated.

-

Latent growth modelling was used to model changes in mental health, self-rated general health and aspects of social cohesion. This approach allows us to estimate associations between demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, and baseline levels and change in outcomes. This approach also allows for multiple items capturing the same underlying ‘latent’ construct or factor to be modelled together in a two-stage (cohesion outcomes and mental health) or single-stage (self-rated general health) estimation process. For example, the latent variable ‘trust in the community’ was captured by three observed variables – ‘feel part of the community’, ‘describe people in the neighbourhood as friendly’ and ‘extent to which know people in the neighbourhood’ – which were summarised as a single latent variable using a latent trait model. The resulting predicted scores were then used as outcomes in the growth models.

-

Most of these models were fitted as follows: (1) CE type only; (2) demographic factors (gender, age, ethnicity) and socioeconomic factors (educational attainment, household employment status and housing tenure); and (3) interaction terms for CE types by education, CE types by joblessness and CE types by housing tenure were added to assess whether or not CE type moderated the impact of socioeconomic factors on outcomes. Some analyses included a fourth model exploring interactions with local NDC programme type.

In the quantitative analysis using individual MORI survey data, we also adjusted for residential mobility and for variables shown to predict mobility or the desire to move as potentially important explanatory factors in the relationship between CE and outcomes. Multilevel modelling, using a random-effects approach, utilises longitudinal data for those who participate in only some waves and so analysis is not restricted to those in all four waves. In addition, the longitudinal models were all fitted using full information maximum likelihood with Mplus version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA), to include all available information from participants with incomplete data, under a ‘missing at random’ assumption.

In addition to the above we also used the MORI survey cross-sectional data set to undertake a ‘difference-in-difference’ analysis. This is a relatively new way of evaluating the impact of large-scale interventions such as the NDC programme. The NDC is treated as a multiple before–after, case–control study, with the ‘cases’ being the 39 NDC intervention areas and the ‘controls’ being the 39 ‘matched’ comparator areas. Two assumptions underpin this statistical procedure:

-

that the intervention and comparator areas are well matched in terms of the factors influencing change so that any changes independent of the intervention should be similar in the control and intervention areas

-

if there is a positive impact of the intervention then the situation should have improved more in the intervention area and if there is a negative impact then the situation should have improved less in the intervention area.

Our difference-in-difference analysis therefore used the MORI survey cross-sectional data for 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008 to compare change over time on a number of social and health outcomes in the NDC intervention areas with change over time on the same outcomes in the NDC comparator areas.

The impact of New Deal for Communities approaches to community engagement on health and social outcomes using routine administrative sources: data and methods

The Oxford Social Disadvantage Research Group, a member of NET, also constructed time series data sets for each NDC area and its comparator using routine administrative data sources. When our evaluation began these time series, data sets ran from 1998 up to 2007 for some but not all variables and included data on health outcomes and social determinants of health from the census, NHS sources, Office for National Statistics (ONS) and government departments. In early summer of 2013, with additional funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), we requested data to extend this series of indicators. Table 1 shows which NET indicators have been extended and which have been specifically constructed for this work. Unfortunately, several of the original indicators relating to crime, education and exit rates from unemployment could not be extended because of shortage of time or restrictions on data access.

| Indicator | Source of data | Period covered by Oxford data | Period covered by indices computed for this project |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and morbidity | |||

| Six hospital admissions indicators (standardised for age and sex) for drug misuse, alcohol misuse, cancer, respiratory conditions, heart conditions and mental health | HES | 1999/2001–2001/3a | 2002–10 |

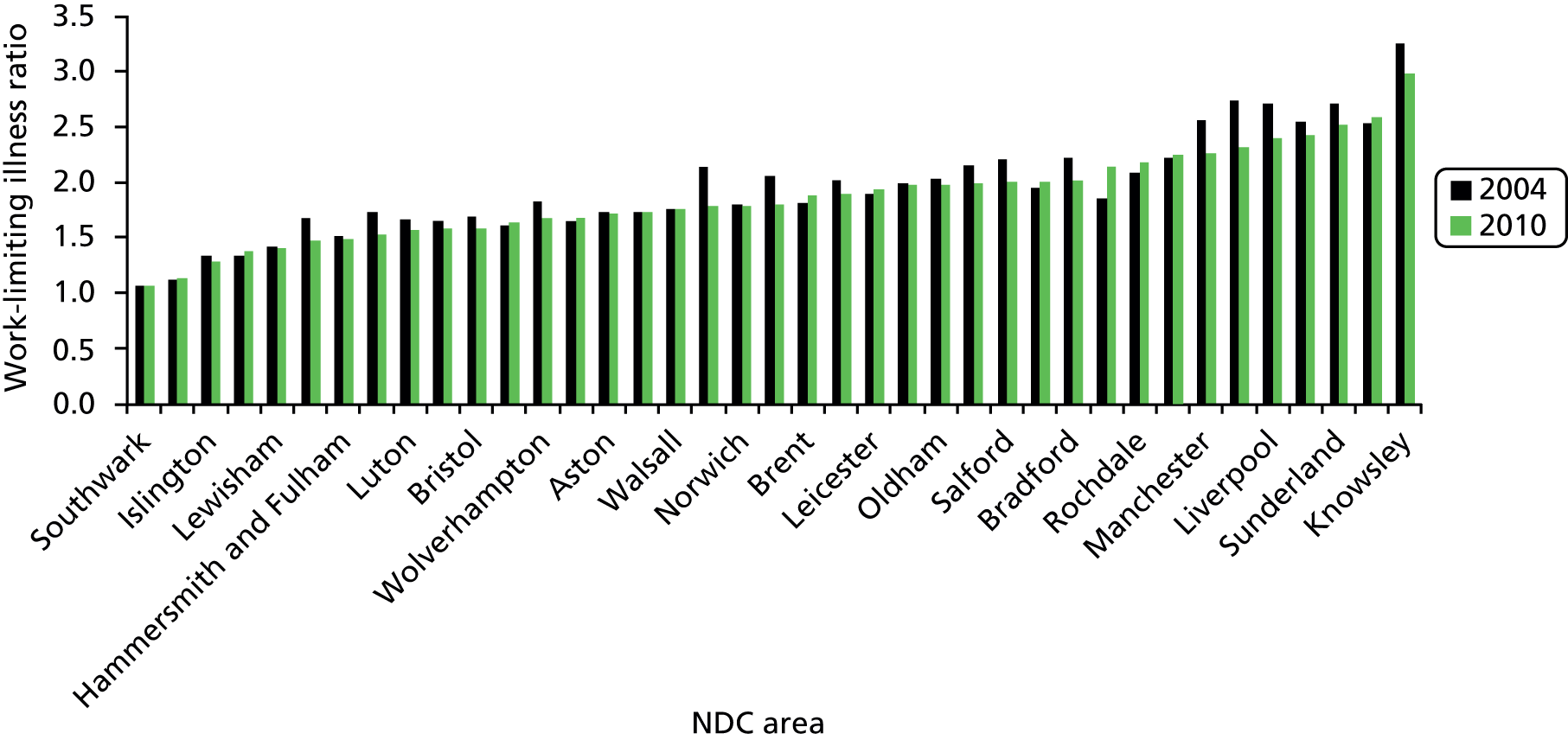

| Work-limiting illness | DWP | 1999–2008 | 2009–11 |

| Standardised illness ratio (based on individuals receiving at least one of AA, DLA, SDA, IB or ESA) | DWP | a | 2004–11 |

| Low birthweight: proportion of singleton births weighing < 2.5 kg, 5- or 3-year averages | ONS | 1997/2001–2001/5a | 2003/5–2008/10 |

| All-cause under 75 years mortality indicators (SMR, CMF and ‘shrunk’ CMF) – 5- or 3-year averages | ONS | 1998/2002–2001/5 | 2003/5–2009/11 |

| Unemployment and low income | |||

| Worklessness | DWP | 1999–2008 | 2009–11 |

| Unemployment | DWP | 1999–2008 | 2009–11 |

| Low income/poverty | DWP | 1999–2008 | 2009–11 |

| Other topics | |||

| Average house prices | Land Registry | 2001–8 | b |

| Educational attainment | DEF | 2002–8 | b |

| Entry to higher education | UCAS | 2002–8 | b |

Preliminary analyses of these data for our previous study found considerable diversity in trends within each type of NDC local programme and the same was the case when NDC areas were groups according to CE type. 1 We therefore decided to compute trends for individual NDC areas and their comparators separately and then summarise the individual results for groups of NDCs, rather than combine the NDC areas with the same CE type before computing trends. The high degree of variability of some indicators based on small numbers of events, such as low birthweight and under 75 years mortality, can produce instability in indicators for individual NDC areas, even when data are averaged over several years. Consequently, point comparisons are not a reliable guide to change and we therefore used the following linear regression approach to test for trends:

-

the difference in value of the indicator between each individual NDC area and its comparator area is computed for each of the years in the time series

-

this difference is regressed against time

-

unstandardised coefficients are reported when they are significant at ≥ 10%.

The results of these analyses are reported in Chapter 4.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A third strand of work explored the cost-effectiveness of different CE approaches using secondary data, new qualitative data collected during interviews with NDC workers and the results of the impact analysis. This work involved two phases. Phase 1 aimed to compile data to estimate the total costs of CE activities for individuals and at the level of local NDC programmes. Phase 2 sought to relate these costs to the categories defined in the CE typology. However, as we describe in Chapter 8, the economic strand of this project has proved to be much more challenging than originally envisaged. This is partly because of the limited nature of the cost data that we were able to identify and partly because of the diverse patterns of health and social impacts associated with different approaches to CE. Details of the methods used in this work are included in Chapter 8.

Data archiving

In addition to seeking to answer our research questions we aimed to provide a data archive making available programming codes and data for other users so that the typology development and analyses reported here can be replicated. This legacy will allow longer-term follow-up of the impact of the NDC on health inequalities and their social determinants, as well as comparison of health and social outcomes in NDC and similarly deprived areas.

The material in the archive includes:

-

Time series indicators – these include indicators derived from administrative data and are of two types: (a) hospital admission indicators, already produced and analysed, including but not limited to drug misuse, mental health and circulatory diseases for the period 2000–12 for NDC areas and their comparators; (b) social indicators: health and incapacity- and unemployment-related benefit claimant counts for NDC areas and their comparators. A user guide for these time series data sets, with careful documentation of how measures were constructed, is included so that they can be generated in a consistent way in the future.

-

A user guide and documented programming code for deriving the cross-sectional and longitudinal analytical sample and variables drawn from the NET MORI surveys and used in our impact analyses (see Chapter 4). This also includes micro-data for the comparative areas, currently not available.

-

A user guide and documented programming code for deriving the analytical sample and variables from the HSE as well as the derived data sets (see Chapter 4). This includes documentation and a programming code to code the data according to level of area deprivation.

-

Detailed documentation of our approach to classifying NDC areas in terms of local NDC programmes and NDC approaches to CE.

In addition to the above, the feasibility of archiving anonymised interview transcripts from the fieldwork reported in Chapter 3 is being explored. However, the preparation of these data for archiving will require additional funding.

This archive material is now available from http://dx.doi.org/10.17635/lancaster/researchdata/27.

Summary

In this chapter we have set out the questions addressed in our research and our study design. We have described the primary and secondary data sources we have used and the analytical methods adopted. In the next chapter we describe how we developed the typology of NDC approaches to CE, before moving on to report the results of our impact analyses and economic evaluation.

Chapter 3 Developing a typology of New Deal for Communities approaches to engagement

Introduction

To assess the impact of different approaches to CE, the NDC areas first needed to be categorised according to the approaches that they took. Rather than simply describing the myriad of CE activities taking place, the typology sought to understand the values and ethos underpinning different approaches to CE taken by local NDC partnerships and the factors that shaped the approaches that they adopted as well as the context that NDC partnerships operated in. The development of this typology built on the development of a typology of the local programme interventions implemented across the 39 NDC areas as part of our Department of Health-funded study (see Appendix 1).

Development of the typology consisted of three phases of work:

-

phase 1: identifying and reviewing secondary data on CE for all 39 NDC areas where possible

-

phase 2: primary data collection in 11 NDC areas and telephone interviews in another 10 areas

-

phase 3: synthesising findings from phases 1 and 2 to develop a typology, and categorising the 39 NDC areas according to this typology.

Methods for developing a typology of the New Deal for Communities approaches to community engagement

Phase 1: identifying preliminary dimensions of approaches to community engagement

The aim of this first phase was to identify aspects of CE approaches within NDC areas to be incorporated into a preliminary framework that would guide the primary fieldwork in phase 2, rather than to produce a definitive typology of engagement. Various data sources were therefore used to develop ‘thin’ descriptions of levels and types of CE, aspects of the local context, baseline levels of engagement, and processes and structures to support CE. Descriptions of baseline levels of engagement and some aspects of local context were produced for all 39 NDC areas using quantitative secondary data sources (e.g. the MORI surveys). It was not possible to describe processes and structures for all 39 areas because of a lack of documents in many NDC areas; however, we were able to identify sufficient documentation including CE strategies to produce ‘thin descriptions’ of CE structures/processes for approximately one-quarter of the NDC areas. The data and methods used in this phase, which was also informed by a number of published conceptual frameworks relating to CE,57–59 are briefly described in the following sections.

Levels and types of engagement and local context

The 2002 MORI survey data set provided data on levels and types of engagement from 2002 to 2008 in all NDC areas. We considered a wide range of other data sources but for a variety of reasons these could not be used (e.g. they were not disaggregated at NDC level). MORI survey data on aspects of community cohesion (e.g. feel part of the community), on engagement (e.g. involved in voluntary organisations, involved in NDC activities) and on levels of trust in various local organisations were analysed across four time points (2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008) for each NDC.

Values on these variables were categorised in 2002 and 2008 as ‘low’, ‘average’ and ‘high’ compared with the mean values for these variables across all NDC areas in that year, with ‘average’ values falling within the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the mean, ‘low’ values significantly lower than the NDC mean (p = 0.05) and ‘high’ values significantly higher than the NDC mean (p = 0.05). As NDC values were not compared with broader local, regional or national data, this meant, for example, that levels of trust were not necessarily ‘high’ but were higher than average for the NDC areas. The differences between the values in 2002 and 2008 were categorised in a similar manner. For some areas the percentage point change for a particular variable between 2002 and 2008 fell below the NDC average change value. Sometimes an area started with a higher value than the NDC average for a variable so that ‘low’ levels of change may not reflect a failure of the NDC per se, but rather the maintenance of an existing good.

The NET also gave us access to the non-aggregated data at NDC level from the NDC Partnership Surveys that it undertook regularly to collect data from NDC staff, members of the partnership board and other stakeholders. The Partnership Survey from years 2002/3 provided useful information on the context of the NDC areas at start-up, including information on whether or not respondents felt that their NDC areas had a dominant cultural identity, good networks and group activities, low levels of interethnic cohesion, moderate or high racial tension and/or other moderate/severe tensions. We used the data on perceptions of community cohesion in the selection process for fieldwork sites.

Mapping New Deal for Communities processes and structures for community engagement

To map structures and processes put in place to support CE we used documents already gathered in our previous Department of Health-funded study,1 searched NDC websites and contacted informants in local areas. We were particularly interested in identifying whether or not we could access CE strategies for NDC areas; however, the availability of documents was variable. In total, we found reference (i.e. on a website or in other programme documents) to a CE strategy in 11 areas along with evidence that the CE strategy had been evaluated. Seven more NDC areas made reference to a CE strategy in documents and provided information on CE projects, but it was unclear whether strategies were reviewed. The remaining 21 NDC areas did not explicitly refer to a CE strategy and additional information on CE was generally mixed. Even when strategies or evaluations of strategies were stated to have been produced, these were not often in the public domain. The availability of documentation could be argued to reflect differences in the level of commitment to CE, but as the NDC initiatives had ended by the time that we were doing this work it may simply reflect difficulties of access, as offices and websites had been closed down. We therefore used availability of documentation as one of the criteria for selecting sites for the fieldwork in phase 2 of the typology development.

The varying level of documentation meant that it was not possible to map CE structures and processes in all 39 areas. Therefore, we initially focused on reviewing documents in depth from 10 NDCs. These were read by researchers (EH and JT) to familiarise themselves with the documentation and consider whether or not there were key target documents that could be the focus of a content analysis. Documents were sampled to examine engagement over time and included delivery plans, CE strategies and evaluations. Notes were taken on issues and emerging themes related to CE. These were used to develop a data extraction framework and informed a content analysis of a smaller subset of documents from five of the 10 NDCs. The five NDCs were selected to reflect geographical spread and differences in CE identified from the initial document screening. Time constraints meant that we were unable to review multiple documents for all 10 areas but a content analysis was undertaken of at least one key document from each area (typically the 10-year NDC evaluation), providing some data on CE processes and structures in 10 NDCs at this stage.

This analysis extended the dimensions of CE used in the development of our typology of NDC local programmes to include existing levels of capacity for engagement at the start of the programme, relationships between residents and local agencies, and definitions of ‘community’. The analyses also sought to detect differences in engagement approaches, identifying, for example, NDC areas placing emphasis on increasing resident control over NDC activities and areas that placed a greater emphasis on consultation or engagement in governance structures.

A preliminary conceptual framework of dimensions of community engagement approaches

Through analyses of the data collated and drawing on the theoretical literature, reports from the NET and discussions in the research team, a set of key dimensions of CE were identified. These took into account the known variability of CE baselines and change over time, sought to reflect a more holistic understanding of how engagement ‘worked’ in the NDC areas beyond discrete CE activities and incorporated aspects of the social, economic and political context in which CE took place. This preliminary conceptual framework consisted of three dimensions of local relationships (trust, community cohesion and conflict/tension) as well as other elements of the local context. The rationales for the inclusion of these four dimensions are set out below.

Our typology is underpinned by the theory of community engagement most associated with social influence and the transformation of power relationships. This theoretical approach is highlighted in the quote from Laverack and Wallerstein. 60

It is only by being able to organize and mobilize oneself that individuals, groups and communities will achieve the social and political changes necessary to redress their powerlessness. This remains the domain of community empowerment as a political activity, which enables people to take control of their lives.

Various engagement frameworks or typologies have sought to classify the nature and levels of engagement. 61–63 The research team concluded that attempting to ‘type’ NDC approaches to CE by focusing primarily on engagement activities and their immediate goals (as these typologies tend to do) was likely to be problematic given the complexity of CE in a regeneration programme such as NDC. We felt that it was important to include other potentially salient issues, particularly dimensions of local relationships that have been identified as important factors shaping engagement processes in NDC areas, such as trust and tension between communities and public agencies,64,65 and between different community groups. 56

Trust

The importance of ‘trust’ between the public (variously defined) and formal agencies has become axiomatic with ‘engagement’ across a variety of disciplines and institutions. However, institutional attempts by, for example, local authorities and the NHS to engender trust in the context of CE activities have been criticised for being too instrumental. This can be defined as the use of engagement as a means to achieve institutional goals rather than as a route to genuine community empowerment. 28,66 Analyses of NDC documents revealed that trust was widely seen to be relevant and important in positively engaging residents, but MORI data showed pre-existing levels of trust varied significantly across NDC areas.

Community cohesion

Although the evidence base is relatively weak, in theory, at least, CE within regeneration programmes such as NDC could foster greater cohesion in populations of disadvantaged neighbourhoods, particularly if the approach is informed by an ethos of empowerment and community development. 11,67 It could be argued, for example, that an approach that invested in developing community ‘infrastructure’ and shared interests among residents could have greater positive impacts on trust between residents than an approach more focused on engaging residents in governance and strategic planning.

Conflict/tension

Conflict may be indicative of positive engagement but power imbalances can also have negative implications for relationships (in communities or between residents and agencies). There were tensions between the requirements of the national NDC policy and the expectations of NDC residents. For example, early policy documents were unclear about what was meant by ‘community leadership’. Communities were told that the money was ‘theirs’ to spend; this of course was not meant literally but was taken literally by some communities not used to working with government. 64,65 Pressures from central government to spend budgets and deliver outcomes were often incompatible with the time needed to establish effective CE processes. 65

Other dimensions of local context

Other dimensions of local context within which NDCs operated can also be expected to shape attempts to foster the genuine engagement of residents in decision-making. These factors include the area characteristics and population dynamics, previous experience of CE, local capacity to engage and the history of the area and its labour market. 56

Phase 2: primary data collection

The second phase of the typology development aimed to identify any gaps in the conceptual framework described in the previous section as well as to provide a more nuanced understanding of the dimensions of the framework and the relationships between them. This would enable us to begin to validate the main dimensions of CE to be included in our typology and to assess the relative emphasis placed on different approaches. We also aimed to collect information, and identify key informants, for the economic evaluation.

Sampling New Deal for Communities fieldwork areas, recruitment of respondents and data collection

The selection of fieldwork sites and the collection of data were informed by the conceptual framework developed in phase 1. We were aiming to select 10 NDC areas. The first four sites were selected on the basis of purposive and pragmatic criteria, including level of CE, availability of documents, the type of NDC local programme intervention and proximity to the researchers’ institutions. Sampling of additional sites also took account of level of relative deprivation, aspects of context and region. An 11th site was included to increase the total number of interviews (see later in this section). Initial entry to the sites was negotiated through key informants identified during our Department of Health-funded study and contacts working at NDC legacy organisations or relevant local authorities. Details of the sites and sampling criteria are provided in Table 2.

| NDC area | MORI QC05 – feel able to influence decisions locally? | MORI QC06 – involved in voluntary organisations? | Scoping of CE strategy and evaluations: current availability of documents | NDC type categoryb | Partnership Survey 2002/3: area with networking and group activities? | NDC area context at start-up | Geographical region | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002: % ’yes’ | Percentage point differencea 2008 – 2002 | 2002: % ‘yes’ | Percentage point differencea 2008 – 2002 | Relative deprivationc | Historical contextd | Residential mobilitye | |||||

| Site 1 | Average | Low | Low | High | High | 2 | Yes | 2 | 4 | 2 | North West |

| Site 2 | Average | Low | Low | Average | Low | 1 | Yes | 3 | 4 | 1 | North West |

| Site 3 | Average | High | Low | Average | Low | 2 | Yes | 3 | 4 | 2 | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| Site 4 | Average | High | High | Average | High | 3 | Yes | 2 | 4 | 1 | North West |

| Site 5 | Average | Average | Low | High | Low | 1 | No | 3 | 3 | 2 | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| Site 6 | High | Average | High | Low | Low | 1 | Yes | 3 | 1 | 2 | South West |

| Site 7 | High | Low | High | Low | Medium | 3 | No | 1 | 1 | 2 | London |

| Site 8 | Low | High | Low | High | Low | 3 | Yes | 1 | 3 | 3 | London |

| Site 9 | Average | High | Low | High | Medium | 1 | No | 3 | 4 | 1 | West Midlands |

| Site 10 | Low | High | Low | Low | Medium | 2 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 2 | East of England |

| Site 11 | High | Low | High | Average | High | 1 | Yes | 3 | 4 | 3 | North West |

We aimed for 50 semistructured interviews across 10 sites. In each site this was to include three residents active on NDC partnership boards or in CE activities and two former NDC staff. In most cases a primary contact in the site assisted in making initial contact with potential participants and sometimes snowball sampling was used to identify other informants.

Potential interviewees were invited to participate, typically by e-mail or by telephone, and were sent an information sheet. All participants were asked to sign a consent form after reading the information sheet and being given an opportunity to clarify issues/ask any questions. The consent form was securely stored and a copy of the form returned to the participant. Participants were informed that they could withdraw themselves or their data at any point up to the time when data analysis began; they were also reminded of this at the beginning of the interview. Resident interviewees were offered a £15 voucher as a ‘thank you gift’.

It was more difficult and time-consuming to identify resident interviewees in each site than originally anticipated. We therefore added an additional site to increase the number of resident interviews. In total, 47 interviews were conducted in these 11 sites between October 2012 and March 2013 (27 residents and 20 staff). Residents were either members or chairs of NDC partnership boards. Staff members interviewed primarily included NDC chief executives and CE managers, but also co-ordinators for NDC themes and projects. In two instances, staff members defined themselves as both a resident and staff.

The majority of interviews were conducted face-to-face during visits of 2–3 days. Interviews took place in a central location (e.g. NDC successor organisation office or community centre) or in the resident’s home or workplace. Two interviews were conducted by telephone. All researchers (JT, EH and SP) were involved in the conduct of the interviews. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed with the consent of the participant and adhered to Lancaster University ethical procedures for informed consent, data protection and fieldworker safety.

The interviews lasted for between 50 and 120 minutes and were semistructured but tailored to the role and experience of the respondents. The interviews covered local context, processes and structures of CE, perspectives on the level of engagement in the activities that respondents were familiar with and perceived impacts of these activities. Respondents were also asked about the specific examples of engagement selected to be the focus of the economic evaluation and whether or not they could suggest somebody who would be useful to speak to about the costs of engagement (see Chapter 8). The interview schedule was initially piloted with two of our public advisers (who were residents of fieldwork areas). As amendments to the initial schedule were minimal, full consent was obtained from these two pilot respondents for data from their interviews to be included in the study. The first few interviews with residents took much longer than anticipated, primarily because of the extensive experience that these respondents wished to share. It was therefore decided to make some sections of the interview much more structured to allow opportunities for respondents to talk about their experience of engagement within a reasonable time frame. The interviewers also sought documents, such as local evaluation reports, CE strategies, reports on CE activities and succession plans, when these had not already been obtained.

Analysis of fieldwork interview data

The project team agreed that for the purpose of typology development the analysis would use a deductive thematic framework based on the interview schedule and preliminary conceptual framework. The analysis was conducted manually with transcripts divided between the three researchers, who extracted data relevant to the themes onto an Excel 2010 spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Columns were included for researchers to note additional emergent themes and to highlight key differences in respondents’ perspectives across interviews within sites. A process of cross-checking took place for a sample of transcripts with a second researcher undertaking a second analysis to ensure consistency.

Interim findings from the analysis of transcripts from four fieldwork sites were taken for discussion to a reflective workshop with public advisors in May 2013. The aim of the workshop was to (1) obtain feedback on the preliminary findings and explore participants’ views on dimensions that would best enable different approaches to CE to be distinguished; (2) involve public advisers in the design of a telephone interview schedule (see following section); and (3) discuss dissemination plans. Discussions of preliminary findings also highlighted the ways in which national pressures had impacted on the ability/success of NDC areas in engaging residents in the programme, providing useful contextual information that aided the interpretation of our findings.

Telephone interviews

Following this workshop the analyses of interview transcripts focused on a smaller number of themes and a cross-site comparative analysis was undertaken. Alongside this we aimed to conduct telephone interviews with key informants in as many of the remaining 28 areas as possible to validate the dimensions of the CE typology emerging from the analysis of fieldwork data and fill gaps in knowledge about these NDC areas to support the process of allocating areas to types. We used the contacts made in our previous study and a variety of other means (contacting the legacy organisation and council departments, following the advice of our public advisers) to identify key informants. This was a time-consuming process as over the course of the study increasing numbers of staff/residents were no longer contactable and following an intensive period 10 interviews were conducted across 10 sites. The recruitment and consent process was the same as for the face-to-face interviews except that potential respondents were able to return their signed consent by e-mail.

The telephone interview schedule included structured items constructed to measure respondents’ perceptions of levels of control, trust, conflict/tension and cohesion among residents of their area prior to the NDC programme, during the early years of the programme (2002–4), mid-NDC programme (2004–8) and towards the end of the NDC programme (2008–10/11), with the same set of questions repeated for each time point. Our approach to ‘measuring’ change was informed by a study that had sought to develop indicators for the assessment of community participation in health programmes. 59 The methods used in this study aimed to position responses to questions on a continuum rather than to gather quantifiable data. We used scales from low to extremely high or extremely high to none. An example is provided in Box 3.

We are interested in the relationships within the area before the NDC funding took place between residents and residents, and residents and agencies. I am now going to ask you about these in relation to trust, conflict and levels of influence.

-

Thinking about the issue of trust – how would you describe the levels of trust between residents and residents?

1 – extremely high; 2 – high; 3 – fair; 4 – low; 5 – none.

And between residents and other bodies, for example the council?

1 – extremely high; 2 – high; 3 – fair; 4 – low; 5 – none.

-

Thinking about the issue of conflict – how would you describe the levels of conflict between residents and residents?

1 – extremely high; 2 – high; 3 – fair; 4 – low; 5 – none.

And between residents and other bodies, for example the council?

1 – extremely high; 2 – high; 3 – fair; 4 – low; 5 – none.

-

How would you rate the level of resident influence on matters affecting their community?

1 – extremely high; 2 – high; 3 – fair; 4 – low; 5 – none.

Respondents were also asked to indicate which of a series of statements about approaches and values associated with CE best described aspirations for their NDC programme. Participants were able to offer an alternative if none of the options given was perceived to be relevant. An example question is provided in Box 4. Finally, as with the fieldwork interviews in phase 2, the researchers asked questions about the costs of engagement and, if relevant, whether or not the respondent would be happy to participate in a short telephone conversation about costs conducted as part of the economic work (see Chapter 8).

Which of the following best describes the community engagement approach/model that your NDC programme aspired to/took?

-

Community led and individual and community capacity building.

-

The community was represented and consulted.

-

Council/agency led but direct community involvement.

-

Council led and representative democracy.

-

Other (if none of the above is relevant to your experience).

The telephone interview schedule was piloted with members of the research team and a NDC respondent. Telephone interviews were not recorded. The interviewer made detailed notes during and after the interview and these were used to populate data analysis templates that were then used in a final synthesis.

Phase 3: final synthesis and allocation of New Deal for Communities areas to the community engagement typology

The final synthesis consisted of four elements: (1) confirming patterns within and between the primary dimensions of control, trust and conflict/tension and agreeing the final CE typology; (2) a comparison of patterns in changes in MORI data on cohesion, engagement and levels of trust with qualitative data from fieldwork sites to see if the MORI data would be useful in typing areas where data were limited; (3) allocating NDC areas to a CE ‘type’ when information was judged to be sufficient; and (4) allocating NDC areas to a CE ‘type’ when data were insufficient.

Agreeing the final community engagement typology