Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3000/03. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2015 and was accepted for publication in August 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Stallard reports support from Pathways, the organisation that markets the FRIENDS programme, during project dissemination. Accommodation was paid for by Pathways whilst presenting the results of this study at the ‘train the trainer’ conference in Brisbane in August 2014.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Stallard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Nature, extent and course of emotional problems in children

Anxiety and depressive disorders in children are common. The American Great Smoky Mountain Study found that 2.4% of children aged 9–16 years fulfilled diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder and 2.2% for a depressive disorder over a 3-month period. 1 Similar rates were found in the British Mental Health Survey, where 3.7% of 5- to 15-year-olds had a current anxiety disorder and 1% had a depressive disorder. 2 Comorbidity between anxiety and depression is common,3,4 with cumulative rates suggesting that by age 16–17 years 15–18% of children will have experienced an impairing emotional disorder of anxiety or depression. 1,4

Emotional problems have a persistent and unremitting course, with longitudinal studies highlighting that child mental health disorders persist into adulthood. In the Dunedin birth cohort study approximately 52–55% of young adults with depression or anxiety met diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder before the age of 15 years, with 75% having a first diagnosis before the age of 18 years. 5 Childhood anxiety increases the risk of anxiety, depression, substance misuse and educational underachievement in early adulthood. 6,7 Similarly, childhood depression increases the risk of suicide, subsequent depression and substance misuse. The associated health-related burden and economic and societal costs are considerable and the need to improve the mental health of children is being increasingly recognised as a national and global priority. 8–10

Limited reach of treatment services

Improving the emotional health of children is an important public health issue that has become a major tenet of UK governmental policy. 11–13 Effective psychological treatments are available for children with mental health disorders, although few children actually receive them. 14,15 Surveys in the UK and USA found that approximately one-third of children with anxiety disorders and under half with depressive disorders had sought or received specialist help over a 1- to 3-year period. 16,17 Those with emotional disorders were less likely than those with other mental health disorders to have contact with specialist services. The limited reach and availability of specialist treatment services alongside a policy shift towards early intervention has led to a growing interest in preventative approaches and a move from clinical to community settings.

School-based preventative approaches

In the UK, almost eight million children and young people attend primary and secondary schools. 18 As such, schools provide an important environment for public health initiatives, offering the potential for delivering both primary prevention (i.e. promoting well-being and reducing the occurrence of new problems) and secondary prevention (i.e. stopping mild or moderate problems from worsening). Schools provide a familiar and natural environment, reaching a high percentage of children. Their central role in promoting emotional well-being has been emphasised in the national Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) initiative. 13

The effectiveness of school-based emotional health prevention programmes for primary school children has been the subject of two National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) reviews. 18,19 In the first, 31 studies were identified that adopted a universal approach (i.e. interventions were provided to all children regardless of need), with only one having been undertaken in the UK. 18 The second focused on targeted/indicated approaches in which interventions were provided to children at high risk or already displaying mild or moderate problems. 19 Ten studies that focused on internalising problems (anxiety and mood) were identified, but none was undertaken in the UK.

Both reviews found evidence that universal and targeted/indicated mental health programmes could have an effect on mental health. In terms of content, multicomponent programmes (i.e. teaching different skills such as relaxation, problem-solving and cognitive awareness) based on a clear theoretical framework, particularly cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), and which included some parental input (e.g. training/information) had the strongest evidence. This conclusion was also endorsed in a review of 27 randomised controlled anxiety prevention trials. 20 The results indicate that most universal, selective and indicated prevention programmes were effective in reducing anxiety symptoms. Although not formally tested, the authors note that the effects of CBT programmes were marginally larger than those of non-CBT interventions, with the median effect size for CBT programmes of 0.57 indicating a moderate effect. However, there was considerable variation in effect size between studies, suggesting that, although the content is important, mediating variables such as adherence to programme fidelity, leader rapport, levels of participation and audience appeal are also important factors that will influence effectiveness.

The reviews also identified a number of important methodological limitations, including small sample sizes, use of non-standardised mental health outcome measures and an absence of follow-up assessments. In addition, the comparative effectiveness of teacher-delivered and mental health-delivered interventions is unclear and has been directly investigated in only one study. 21 Before school-based emotional health programmes can be endorsed, implementation trials in which efficacious interventions are provided under diverse everyday conditions are required. The replication of treatment effects under everyday conditions cannot be assumed, with a number of recent school-based prevention studies failing to find positive effects on depression,22–25 anxiety26,27 and general emotional well-being. 28

The FRIENDS cognitive–behavioural therapy prevention programme

Cognitive–behavioural therapy is concerned with the way that children think about their world and the meanings and interpretations they make about the events that occur. It provides a framework for helping children to understand the link between what they think, how they feel and what they do. During CBT they are helped to explore and become aware of their cognitions and how these are associated with their feelings and affect their behaviour. This process allows unhelpful cognitions to be identified, tested and re-evaluated in more helpful ways that allow the child to experience more pleasant feelings and to become more motivated and able to face challenges and problems. In addition to understanding and challenging cognitions, CBT helps children to develop better emotional awareness, so that they can become better at identifying their different emotions, and a range of emotional management skills. Finally, CBT includes many behaviour techniques to facilitate behaviour change such as positive reinforcement, contingency management, monitoring and graded exposure.

Expected outcomes of CBT relate to each of the three core domains of the model: first, cognitive changes such as reductions in worries or negative thoughts; second, improved emotional management resulting in reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression; and, third, changes in behaviour resulting in improvements in self-esteem as the child learns to successfully overcome and cope with challenges. Another outcome that has been observed from the small group process that is an integral part of child CBT programmes such as FRIENDS is improvements in relationships and reductions in bullying.

Of the school-based CBT preventative programmes that have been developed, the FRIENDS programme is one of the better evaluated and has more consistent evidence of effectiveness. 20,29 This was noted by the World Health Organization,30 who identified the FRIENDS programme as having strong evidence of being effective as a school-based intervention for anxiety. The programme addresses a number of the issues identified in the previous reviews. It has a clear theoretical model, sufficient sessions, age-appropriate materials, enjoyable and fun activities, a structured leader manual with detailed session plans, standardised leader training, ongoing supervision to ensure fidelity, a parent session and weekly parent contact sheets.

In an initial randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving 489 children aged 10–12 years, significant post-intervention reductions in anxiety were reported following the FRIENDS programme. 21 These results were replicated in a subsequent study involving 594 children aged 10–13 years and were found to be maintained at 12 months. 31,32 The FRIENDS programme also had a positive effect on mood in the high-anxiety group. In terms of those with more significant problems, 85% of those in the FRIENDS group who initially scored above the clinical cut-off for anxiety and low mood were diagnosis free at 12 months compared with 31% in the comparison group. In the most recent study involving 692 children, the FRIENDS group demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety 3 years after the FRIENDS programme. 33 In addition, comparison between children aged 9/10 years and those aged 14/16 years showed that, although both age groups benefited from the FRIENDS programme, the younger group demonstrated the greatest changes in anxiety symptoms. 34 Although these results are promising, recent trials in Canada failed to find additional benefits for the FRIENDS programme, as either a universal or a targeted intervention. 26,27 Finally, no RCTs of the FRIENDS programme have been undertaken in the UK and so it is unclear whether the programme is effective when delivered in UK educational settings.

The current study

The systematic reviews summarised above indicate that school-based programmes can have benefits in terms of both secondary (post-intervention reductions in symptoms) and primary (preventing the development of significant symptoms) prevention. Programmes with a clear theoretical model based on CBT appear the most effective for anxiety and mood disorders. In addition, multicomponent programmes that teach children skills in different areas and which involve parents (e.g. relationship building/skill enhancing) appear particularly promising.

Of the available programmes fulfilling these criteria, the FRIENDS programme has a strong evidence base. Small-scale cohort studies of the FRIENDS programme have been undertaken in the UK and demonstrate the feasibility of delivering the programme within the UK educational system. These studies have found encouraging post-intervention results, with gains being maintained 1 year after the programme. 35,36 Similarly, a recent small-scale evaluation has found preliminary evidence to suggest that the FRIENDS programme may also have a primary preventative effect. 37

In the UK studies, the FRIENDS programme was delivered by trained school nurses from outside the school. This method of delivery is consistent with findings from a systematic review of school-based anxiety prevention programmes which noted that programme leaders were more likely to be mental health professionals. 20 However, the review also noted that, in one-quarter of studies, programmes were led by trained teachers and delivery by school staff also resulted in significant reductions in anxiety. 20 In terms of the FRIENDS programme, only one study has directly compared leader effects and found school leaders to be as effective as health leaders. 21 However, this study was underpowered and recent implementation trials of the FRIENDS programme delivered by trained school staff failed to find a positive effect. 26,27 It is therefore unclear whether school leaders are as effective as health staff in delivering the FRIENDS programme.

This trial compared the relative effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme delivered by trained school and health staff compared with usual school lessons (personal, social and health education, PSHE). The study addressed the methodological concerns identified above, had adequate power to detect predicted differences between groups and included an assessment of treatment fidelity; included follow-up at 12 and 24 months; and included an analysis of primary and secondary preventative effects and an evaluation of cost-effectiveness and acceptability. If found to be effective, the FRIENDS programme could be made widely available in the UK; it could be integrated within the school PSHE curriculum and would complement and build on other school initiatives.

Objectives

-

Primary outcome: to evaluate the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme in reducing symptoms of anxiety and low mood at 12 months.

-

Primary outcome: to evaluate the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme for children with low and high anxiety at baseline in terms of symptoms of anxiety and low mood at 12 months.

-

Secondary outcomes: to examine the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme in terms of self-esteem, worry, bullying and overall well-being at 12 months.

-

Medium term: to examine the medium-term effects of the FRIENDS programme on symptoms of anxiety and low mood at 24 months.

-

Medium term: to evaluate the effects of the FRIENDS programme for children with low and high anxiety at baseline in terms of symptoms of anxiety and low mood at 24 months.

-

Medium term: to examine the effects of the FRIENDS programme on secondary outcomes of self-esteem, worry, bullying and overall well-being at 24 months.

-

Cost-effectiveness: to assess the cost-effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme in terms of health-related quality of life (and cost–utility) at 6 months.

-

Acceptability: to assess the acceptability of the FRIENDS programme including participant perceptions of usefulness, examples of ongoing skill usage and satisfaction (6 months).

Chapter 2 Methods

The study protocols for the 12- and 24-month assessments have been published. 38,39

Design

Preventing Anxiety in Children through Education in Schools (PACES) was a pragmatic, cluster, three-arm RCT; the three arms consisted of the FRIENDS programme delivered by health staff or school staff and the usual school curriculum (Table 1). The key difference in the two FRIENDS conditions was the person leading the sessions. In the health-led FRIENDS programme the leaders were health professionals from outside the school whereas in the school-led FRIENDS programme the leader was the teacher or a member of the school staff with responsibility for delivering PSHE.

| Trial arm | Content | Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment as usual | Normal school curriculum | One member of the school staff (one person per class) |

| School-led FRIENDS | Structured CBT programme | School staff leader with two facilitators (three people per class) |

| Health-led FRIENDS | Structured CBT programme | Two health staff leaders with teacher (three people per class) |

Ethical approval, consent and trial monitoring

The study was approved by the Department for Health Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bath.

Six- and 12-month follow-ups

Consent/assent involved three stages. First, eligible schools were provided with information about the study and interested head teachers were required to provide written confirmation that their school wished to participate. Second, information was sent to the home address of the parents of all eligible children. Parents were invited to return a form opting out of the study if they did not wish their child to complete the study assessments. Finally, children were provided with information about the study and were required to provide signed assent before completing the baseline assessment. Dual carer/child consent/assent was therefore required for assessment completion.

Twenty-four-month follow-up

The PACES cohort transitioned to secondary school in September 2013. A new opt-in recruitment process was approved for the 24-month assessment, which required signed parent and child consent. Participants received a £30 financial incentive to compensate parents and children for their time in completing the assessments.

Trial monitoring

The ongoing conduct and progress of the trial was monitored by an independently chaired Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee and a Trial Steering Committee. The trial steering committee included a teacher and a parent representative.

Participants, recruitment and randomisation

Sample size

The study was powered to detect a difference between the FRIENDS programme (health and school led) and usual PSHE. Based on an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.02, 28 pupils per class, 90% consent and 80% retention, effect sizes in the range of 0.28–0.30 standard deviations (SDs) are detectable with 80% power and 2.7% Dunnett-corrected two-sided alpha with 45–54 schools (i.e. 1134–1360 consenting pupils). A standardised treatment effect size of 0.3 is equivalent to an estimated difference on the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) of 3.6 points based on a SD of 12.

Recruitment of schools

A list of primary schools in Bath and North East Somerset and Swindon and Wiltshire within a 50-mile radius of the University of Bath was compiled from local authority information (n = 268). Project information sheets were sent to the head teachers and meetings arranged with the 45 schools who expressed an interest. Four schools did not return signed letters confirming participation before randomisation and were therefore excluded. In total, 41 schools were randomised with one school subsequently withdrawing (usual school provision arm) before baseline assessments were completed. The cohort therefore consisted of 40 schools (1448 eligible children).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Interventions were provided during the school day as part of the school PSHE curriculum. All children aged 9–10 years (Years 5 and 6) were eligible unless they were not attending school (e.g. because of long-term sickness or because they were excluded from school) or did not participate in PSHE lessons for religious or other reasons.

Randomisation

Allocation of schools on a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio took place once all schools had been recruited. Balance between trial arms with respect to key characteristics [school size, number of classes, number of children in Year 5 classes, preferred term of delivery, preferred day of delivery, numbers of mixed Year 5 classes (i.e. classes that were Years 4/5 combined and classes that were Years 5/6 combined) and single Year 5 classes and level of educational attainment] was achieved by calculating an imbalance statistic for a large random sample of possible allocation sequences. 40 A statistician with no other involvement in the study randomly selected one sequence from a subset with the most desirable balance properties.

Interventions

FRIENDS: a universal cognitive–behavioural therapy programme

The FRIENDS programme is a manualised CBT programme designed to improve children’s emotional health. 41 Each child has his or her own workbook and group leaders have a comprehensive manual specifying key learning points, objectives and activities for each session. The intervention trialled in this study involved nine 60-minute weekly sessions delivered to whole classes of children (i.e. universal delivery). Written work is kept to a minimum and each session uses a variety of different materials and activities to engage and maintain interest. The feasibility and viability of delivering the FRIENDS programme in UK schools has previously been established. 35–37

The FRIENDS programme is based on the principles of CBT and develops skills to counter the cognitive, emotional and behavioural aspects of anxiety. Children develop emotional awareness and regulation skills to enable them to identify and replace anxiety-increasing cognitions with more balanced and functional ways of thinking and to develop problem-solving skills to confront and cope with anxiety-provoking situations and events. The programme therefore teaches children skills to identify and manage their anxious feelings, develop more helpful (anxiety-reducing) ways of thinking and face and overcome fears and challenges rather than avoid them. A detailed summary of each session is provided in Table 2.

| Session | Primary focus | Core tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to FRIENDS |

|

| 2 | Introduction to feelings |

|

| 3 | Identify feelings and learn to relax |

|

| 4 | Helpful and unhelpful thoughts |

|

| 5 | Changing thoughts and facing challenges |

|

| 6 | People who can help and problem-solving |

|

| 7 | Reward yourself for being brave |

|

| 8 | Practise the FRIENDS plan |

|

| 9 | Review and celebrate |

|

An additional session for parents/carers was conducted to provide parents with an overview of the programme, the CBT rationale and the skills that the children learned. In addition, parents received a summary sheet detailing the key learning points of each session and the skills that their child would be practising so that they were able to reinforce and encourage their use at home.

Health-led FRIENDS programme

The FRIENDS programme was delivered by two health facilitators (e.g. school nurses, psychology assistants) external to the school with the class teacher providing support. These were not mental health specialists but health professionals with a lower level of training and/or expertise. All 11 facilitators had at least an undergraduate university degree in a relevant discipline (psychology n = 3; art therapy n = 1) or an appropriate professional background (school nurses n = 6; teaching n = 1) and experience of working with children or young people.

School-led FRIENDS programme

Each participating school identified school staff members (e.g. class teachers, special educational needs co-ordinators, teaching assistants) to deliver the FRIENDS programme. In total, there were 14 school-led leaders (five class teachers; four PSHE co-ordinators; three learning support assistants and two head teachers).

School staff were assisted in delivering the programme by two health facilitators external to the school. This ensured that there were at least three adults present during session delivery. The health facilitators were not responsible for leading the session but for supporting the school leader. The school leader therefore led the session, introduced the session topic, planned the content and led the delivery of the exercises. The facilitators worked as class helpers, being organised and directed by the teacher to work with small groups or individual children to help them engage in the exercises and express their ideas.

FRIENDS programme training and supervision

The FRIENDS leaders from the health- and school-led arms attended a 2-day training event to familiarise them with the nature, extent and presentation of anxiety and depression in children and the CBT model. Participants worked through each of the FRIENDS sessions and practised the exercises to familiarise themselves with the materials and key learning points.

During delivery of the programme, fortnightly group supervision was provided by an accredited FRIENDS trainer. Health and school leaders attended together. During these sessions the aims and content of the FRIENDS sessions were reviewed and any problems with implementation were addressed.

Usual school provision

Children participated in their usual PSHE sessions provided by the school. All schools were following a UK national curriculum programme designed to develop self-awareness, management of feelings, motivation, empathy and social skills. 13 The sessions were planned and provided solely by the teacher and did not involve any external input from the research team.

To more specifically define PSHE within each school the head teacher and the school PSHE co-ordinator and/or the Year 5 class teacher participated in a semistructured interview. The interview was undertaken at the end of the school term and assessed whether the school was following the national curriculum and what additional interventions might be running in the school and their content. The interview clarified the PSHE topics covered by the 9- and 10-year-old children during the study period, the way that they were addressed (dedicated sessions, integration, circle time, etc.), the length of time devoted to the PSHE curriculum and the number of adults (e.g. teachers, assistants, volunteers, trainees) in the classroom.

Treatment fidelity

Treatment fidelity was assessed by randomly assessing audiotape recordings of 10% of the FRIENDS sessions. Sessions were rated by an independent assessor to determine whether core tasks (detailed in Table 2) were delivered.

Delivery of the FRIENDS programme

At the end of each FRIENDS session leaders rated a range of possible mediating variables including child engagement, participation and contributions, school support, personal confidence in delivering the FRIENDS programme, personal enjoyment of the group and their perception of group benefit.

Acceptability of the FRIENDS programme

All children who received the FRIENDS programme were asked at the end to assess the programme on 10 dimensions including enjoyment, acquisition and use of new skills and whether they would recommend the programme to another child.

Demographics and context

Family, demographic and socioeconomic status

At baseline children completed a questionnaire assessing age, sex, who they lived with, number of siblings and ethnicity. In addition, they completed the Family Affluence Scale (FAS), which provides an indicator of socioeconomic status. 42,43 This short questionnaire asks children to rate the following four items relating to family affluence: family ownership of a car, child has own bedroom, number of family holidays in the past year and how many computers the family own.

School context

Data on a number of socioeconomic indices that might be related to outcome were collected for each participating school. These included the number of children receiving free school meals, the number of children in care, the number of children with educational statements, the level of educational attainment on standardised assessment tests, class size and the number of teaching assistants in study classes. In addition, the dominant pedagogical orientation of each school was profiled.

Outcome measures

Assessments were completed at baseline and 6, 12 and 24 months and involved a combination of child-, parent- and teacher-completed questionnaires and semistructured interviews.

Child report questionnaires: psychological functioning

All child outcome data were collected by self-completed questionnaires administered by researchers blind to children’s trial allocation. Questionnaires were completed at school, in groups in classes, at baseline and 6 and 12 months. The researchers and any teaching assistants working in the class helped individual children with literacy problems. At 24 months they were completed individually by each child in the home.

Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale

This was the primary outcome measure. The RCADS44 is a recent modification of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale,45 which was revised to correspond more closely to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition criteria for anxiety and depression. 46 The 30-item scale was used (RCADS-30), which assesses anxiety in the areas of social phobia, separation anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder and also assesses major depressive disorder. The RCADS-30 has good internal consistency, test–retest stability and convergent and divergent validity. 47,48

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale49 is a self-completed questionnaire that assesses self-worth and acceptance and requires the child to rate each of 10 questions on a four-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity across a large number of different sample groups, including young children aged 7–12 years, and is one of the most commonly used and best-known measuring tools for self-esteem.

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Children

The tendency for children to engage in excessive, generalised and uncontrolled worry was assessed by the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. 50 Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale assessing how strongly it applies to the child (0 = ‘not at all’ through to 3 = ‘always true’). The original scale consists of 14 items although a subsequent evaluation found that with children aged 8–12 years it was preferable to remove the three reverse-scored items. 51 The 11-item version was used here, which has good psychometric properties with this age group.

The Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire

The degree to which children have bullied others or have been the victim of bullying was assessed with the two global items from the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. 52

Well-being

Overall life satisfaction and happiness with six aspects of everyday life were assessed on a 7-point scale. 53 These items were selected from the 12 domains identified within The Good Childhood Report54 and pragmatically seemed more relevant for our (younger) cohort. The items selected assessed satisfaction with school, appearance, family, home, friendships and health and overall life satisfaction.

The School Concerns Questionnaire

The School Concerns Questionnaire (SCQ)55 was completed by children at the 24-month assessment only. The SCQ is a 20-item scale assessing worries about starting secondary school. Items cover organisational (e.g. changing classes, remembering equipment), social (e.g. making new friends, being bullied) and academic (e.g. homework, being able to do the work) concerns. Each item is rated on a 10-point scale assessing the extent of worry.

Health-related quality of life: child health utility

Children completed the Child Health Utility 9 Dimensions (CHU-9D) (licensed by the University of Sheffield)56 at baseline and 6, 12 and 24 months. The CHU-9D, a validated measure of health-related quality of life, is short (nine items) and has been specifically developed for use with children aged 7–11 years. 57 The use of the CHU-9D allowed us to assess how improvements in mental health (anxiety and depression) might translate into changes in overall health-related quality of life.

Parent report questionnaires: child psychological functioning

Questionnaires for parents at baseline and 6 and 12 months were sent home and returned in a prepaid stamped addressed envelope. At 24 months, parents completed the questionnaires either over the telephone or during an interview with a researcher.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)58 is a brief, widely used behavioural screening questionnaire. The SDQ consists of 25 items that assess emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and/or inattention, peer relationship problems and pro-social behaviour. 58,59 Parents also rate overall distress and the social impact of their child’s behaviour on home life, friendships, classroom learning and leisure activities.

Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale – Parent Version

The parent-completed Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS-30-P)60 is a 30-item parent version of the primary outcome measure completed by children. The RCADS-30-P has high internal consistency and test–retest reliability and good convergent and divergent validity.

School Concerns Questionnaire

The SCQ55 is the parent version of the questionnaire completed by children. It was completed at the 24-month assessment only, after children had transitioned to secondary school.

Teacher report questionnaires: psychological functioning

Class teachers were asked to complete the overall distress and impact rating of the SDQ for all children in their class. This assesses the teacher perception of whether a child has a problem with his or her emotions, concentration or behaviour or being able to get on with other people. If so, the teacher completes questions about chronicity, distress, interference with peer relationships or classroom activities and burden.

Child interviews

Semistructured interviews were undertaken with a self-selecting group of approximately 10% of the children who received the FRIENDS programme to discuss their experience in more detail. The interview explored what they had learned, whether they had used any new skills, what aspects of the programme were most helpful and what could be improved. Areas of satisfaction and dissatisfaction were assessed and views about the materials, activities and specific sessions obtained.

Parent interviews

A letter was sent to all of the parents of participating children through their child’s school inviting them to participate in a semistructured interview. Those who agreed to be interviewed at baseline (n = 308) were invited to repeat the interview at 6 (n = 284) and 24 (n = 252) months. The interviews were thus conducted with a self-selected (non-random) subsample of all parents of trial participants. Parents were offered a cash voucher to cover the cost of their time. Interviews were conducted at the parent’s home or at a convenient location of their choice. A copy of the parent interview is provided in Appendix 1.

Client Services Receipt Inventory

The Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI)61 is a semistructured interview used for economic analysis that was used to assess children’s use of health, social and educational services over the past 6 months. The CSRI was adapted following experience from a previous study and further piloting, with more optional specification of the types of other professionals who may have been seen for worry, anxiety or unhappiness. There was also a revised question to capture how many days out of paid employment a parent or other adult may have taken off to look after their child and another to capture whether their child had received extra support or input at school to help with learning or because of their behaviour. Similarly structured questions elicited information about help or support from social services or help or support from voluntary organisations for their child.

Screen of parental health and mental health

Parents completed the mental health screening tools routinely used by the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) project. This includes a measure of anxiety (Generalised Anxiety Disorder seven-item scale, GAD-7),62 depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items, PHQ-9)63 and the IAPT phobia scale. 64

Parents also completed the 8-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-8)65 and the adult version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. 66 The SF-8 assesses eight aspects of health including pain, energy, everyday impairment and emotional problems.

Additional areas

Finally, parents completed an inventory of recent life events and were surveyed about the recreational and leisure time pursuits of their child.

The 24-month interview covered all of the above and in addition parents were asked to complete the SCQ, which provided their perceptions of how well their child had transitioned to secondary school.

School interviews

At the end of each FRIENDS programme the class and head teachers in the intervention schools were invited to participate in a semistructured interview to obtain their views about the programme. They were asked whether they had noticed any particular benefits, whether they had identified any problems in terms of delivery, materials and integration within the school curriculum and whether they felt that the programme was sustainable.

Assessment summary

A summary of the assessments completed at each assessment point is presented in Table 3.

| Assessment | Who | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child questionnaire | All participating children |

|

|

|

|

| Parent questionnaire | Postal questionnaire responders |

|

|

|

|

| Teacher questionnaire | All participating teachers |

|

|

|

|

| Parent interviews | Parents who opt in for interview |

|

|

|

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and was undertaken blinded to allocation. Analysis and presentation of data are in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines and in particular the extension to cluster randomised trials. 67–69

The effects on the primary outcome (RCADS score at 12 months’ follow-up) were assessed by intention-to-treat analysis without imputation. To take account of the hierarchical nature of the data, we used multivariable mixed-effects models to compare the mean RCADS score at 12 months for health-led FRIENDS with that for school-led FRIENDS and usual school provision, with adjustment for baseline RCADS score, sex and school effects. These analyses were repeated for secondary outcomes. Group comparisons were Bonferroni corrected for multiple testing.

For RCADS score we undertook a further planned analysis. We used repeated-measures mixed-effects analysis of variance models to investigate convergence/divergence between trial arms over time. We carried out preplanned subgroup analyses using interaction terms in the regression models between randomised arm and the baseline variable [RCADS score 0–48 (low anxiety), ≥ 49 (high anxiety)].

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the potential effect of missing data. Completion rates for all groups at 12 months were high (91.8–92.7%) although non-completers tended to be more symptomatic on our primary outcome measure (RCADS) at baseline (data not shown). Using multiple imputation methods 20 data sets were created and showed that imputation for missing data made no material difference to the overall results (see Table 10).

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative interviews were undertaken with staff from all 28 schools who received the FRIENDS programme. Children from 19 of these schools participating in the first two terms of the programme volunteered to take part in focus groups. A total of 115 children participated, a sample that was sufficient to ensure that all themes had been identified. Interviews followed topic guides informed by previous research on the FRIENDS programme to assess programme acceptability.

Interviews and focus groups were digitally audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were thematically analysed following the guidelines of Braun and Clarke. 70 Recordings were transcribed using NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The data were then openly coded, that is, without trying to fit them into the pre-existing coding frame. The coding was conducted at a semantic level, that is, by explicit or surface meaning of the data, without looking beyond what a participant said, and was allowed to form as many codes as appropriate.

Coding reliability and validity were checked by two researchers independently coding three randomly selected transcripts. Inter-rater reliabilities were calculated using NVivo 10. The coding agreement was in the range of 79–100%, indicating satisfactory agreement and consistency.

Transcripts were then independently coded and analysed by four researchers. A final coding framework was generated by discussion and consensus. The final analysis identified six distinctive themes relating to programme overview, programme content and delivery, the FRIENDS workbook, positive aspects of the programme, programme benefits and continued use of skills. The themes were checked for internal consistency. Further analysis involved building detailed data maps and examining data prevalence.

Economic analysis

An analysis comparing the two versions of the FRIENDS programme and treatment as usual was undertaken. The cost-effectiveness analysis was based on the primary outcome measure (i.e. cost per extra point reduction per child on the primary outcome measure RCADS) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) (i.e. cost–utility analysis). The analysis of costs and cost-effectiveness was conducted using prices from the year 2013. It was carried out according to current best practice methods for conducting economic evaluation alongside trials71,72 and alongside cluster RCTs. 73,74

Both the cost analysis and the cost-effectiveness analysis were from the joint perspective of the health sector (NHS) and the education/social services sector (e.g. capturing children’s within-trial contacts with mental health services as well as those opportunity costs incurred by schools in order to participate). They encompassed resources needed to provide the intervention (teacher and health professional time, training time and materials, recruitment of schools) and estimated resource impacts of altered outcomes (e.g. mental health service consultations and treatments). The study identified, measured and valued the resource consequences of each alternative (applying opportunity costs as the main principle for valuation), including the separate identification of those costs/resources associated with the provision and evaluation of the interventions within the context of a research trial (i.e. those costs that would probably not be incurred should the programme be more widely implemented). The opportunity cost of a consumed resource is the value of the benefits foregone by using the resource for the next best alternative; conventionally, in most circumstances, market rates (e.g. pay per hour) or prices paid are assumed to represent opportunity costs.

Service use data

Individual-level resource use data was collected during interviews with parents of a subsample of the trial participants, using an adapted version of the CSRI61 at baseline and 6 months’ follow-up. The range of services assessed is summarised in Table 4.

| Type of service use | Details recorded | Notes or limits |

|---|---|---|

| Overnight hospital stays | Number of days in hospital and reasons for stays | For up to three stays |

| Accident and emergency visits | Number of visits and reasons for visits | Up to three reasons |

| Hospital outpatient appointments | Number of visits and reasons for visits | Up to three reasons |

| Visits to the GP | Number of visits and number of visits for worry, anxiety or unhappiness | |

| ‘Has your child seen anyone else for psychological problems (such as worry, anxiety or unhappiness)’ | Number of times seen (for each of nurse at a GP practice, school nurse, counsellor, child mental health service, child psychologist, social worker or ‘Someone else, please say who’) | |

| Taking medication (for anxiety or depression) | Name of medicine and how long taken | Up to three medicines |

The unit costs applied to different types of health service use and for visits to different types of professionals or services because of anxiety or depression are provided in Table 5. The two main sources for the unit costs were the Department of Health’s NHS reference costs76 (for primary care trusts and NHS trusts combined) and the Personal Social Services Research Unit’s unit costs of health and social care75 (hourly costs of patient or client contact for various types of health or social care professional).

| Resource type and unit | Unit cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Visit to GP | 37 | aSection 10.8 (11.7-minute consultation)75 |

| GP practice nurse consultation | 12 | aSection 10.6 (nurse GP practice, per consultation)75 |

| School nurse time (per hour) | 60 | aSection 10.1 (community nurse, per hour with patient)75 |

| Counsellor (per hour)b | 63 | aSection 2.8 (counselling services in primary medical care, per hour with patient or per contact hour)75 |

| Child mental health service (per hour)b | 65 | aSection 10.2 (mental health nurse, per hour with patient)75 |

| Child psychologist (per hour)b | 134 | aSection 9.5 (clinical psychologist, per hour with patient)75 |

| Consultant psychiatrist (per contact)b | 261 | aSection 15.7 (consultant: psychiatric, per face-to-face contact)75 |

| Social worker (per hour)b | 55 | aSection 11.3 [social worker (children), per hour with client]75 |

Costing the intervention

The resource use involved in delivering the FRIENDS programme was costed using project records of staff time and other expenditure, based on as detailed a breakdown as possible of different resources used (i.e. a microcosting approach). This included the paid time of facilitators or teachers delivering the programme, the cost of their training and ongoing supervision and management, travel costs, printing costs for course booklets and an apportionment of the cost of recruiting schools. The calculated intervention costs excluded the costs of developing or adapting the new materials (these were treated as ‘sunk costs’ as it was assumed that they would not be incurred again). We also excluded the proportion of the facilitators’ delivery time that was spent completing additional research measures. The costs did, however, include the initial training costs of the facilitators (time of trainers and facilitators, room hire and subsistence). Usual school provision involved no intervention costs.

All costs were calculated as either the amount of resource used multiplied by a unit cost or the total amount incurred over the trial period divided by the number of pupils in participating classes, the number of sessions delivered or the number of schools, depending on the level at which the cost was incurred. Teacher time costs were based on hourly average pay rates for mid-grade primary school teachers, whereas the cost of the health facilitators was based on hourly actual salary costs of those employed over the relevant period of intervention delivery (see Appendix 2).

Economic analysis

The cleaning and correction of resource use and CHU-9D data and the calculation of service use costs were conducted in PASW Statistics v21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Some educational resource use data that were collected were not costed, for example additional help and support for maths and literacy (spelling, reading), because it was considered unlikely to be associated with changes in low mood or anxiety. Similarly, although child absence from school because of worry, anxiety or unhappiness was reported, we did not estimate any cost impact associated with this.

The models for analysing incremental cost-effectiveness were fitted using Stata 12 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Given the short time frame of the trial and follow-up, neither costs nor outcomes were discounted to present values.

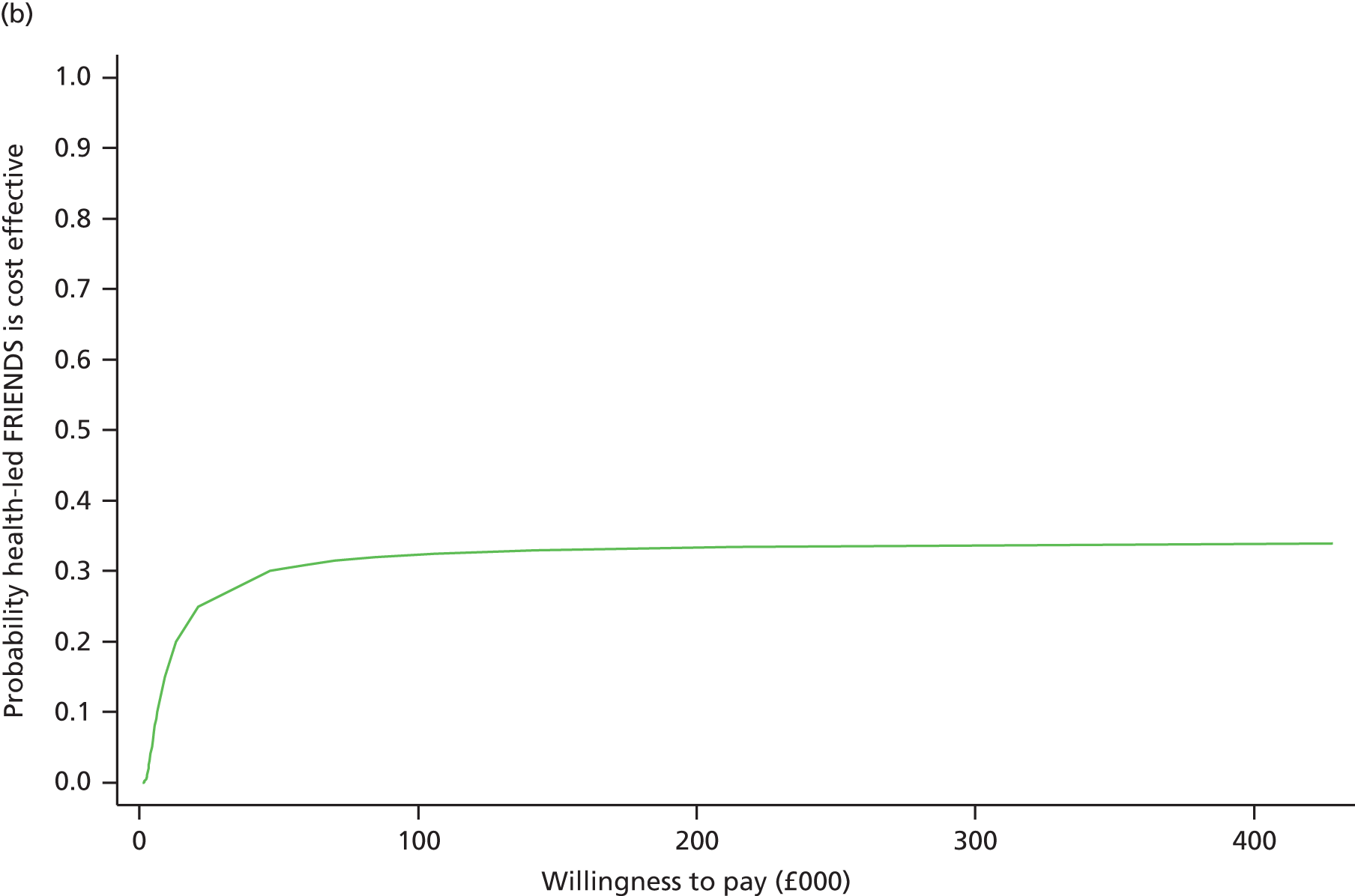

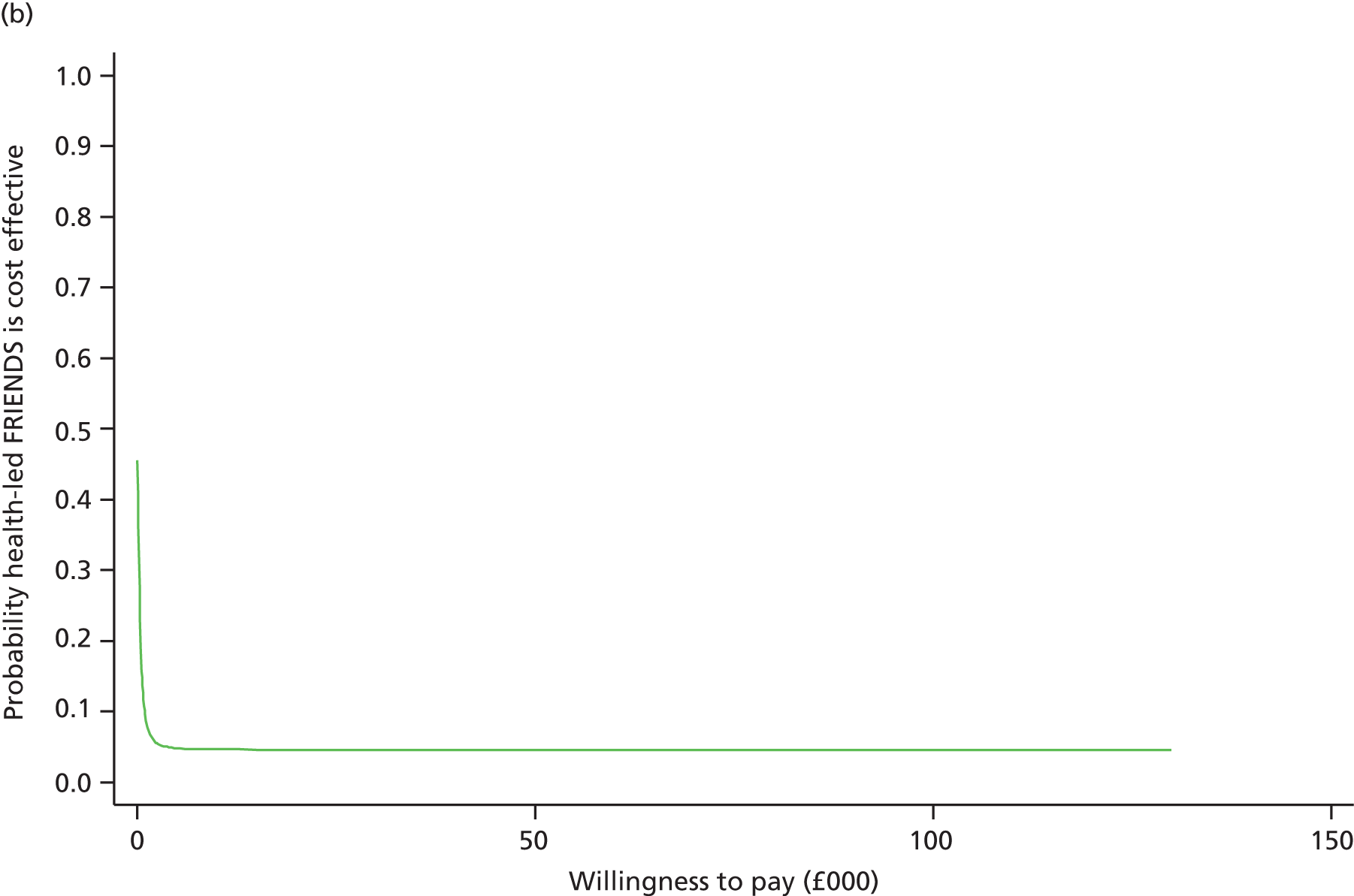

Two cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted, one using the RCADS score and another using QALYs based on responses to the CHU-9D questionnaire. The derivation of the per-person QALYs from baseline to 6 months for each child involved (1) converting complete CHU-9D raw responses into CHU-9D utility values using the established algorithm57 and (2) estimating the mean of the CHU-9D utility at baseline and at 6 months and dividing this by two (i.e. half a year). QALYs were therefore calculated only for children who had complete CHU-9D data at both time points.

Incremental costs, incremental effects and, when relevant, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were estimated, comparing the classroom-based CBT arm with the usual school provision arm. The incremental cost per unit decrease in RCADS score (as lower scores on the RCADS indicate better outcome) and the incremental cost per unit QALY increase were estimated. Both unadjusted and adjusted analyses were carried out, adjusting for year level for all outcomes and additionally for RCADS score at baseline when analysing the RCADS outcome. The remaining factors used to balance the randomisation were not adjusted for because of the relatively small number of clusters.

Random-effects bivariate linear regression models were fitted to model cost and effectiveness (RCADS or QALY) simultaneously, allowing for correlation within randomised clusters and correlation between cost and effectiveness score within participants. 77 These models produced estimates of the mean difference in cost and its standard error; the mean difference in effect and its standard error; and (indirectly through the variance–covariance matrix of the regression coefficients) the correlation between the mean cost difference and the mean effect difference.

Both the RCADS- and QALY-based cost-effectiveness results are based on those in the economic subsample who had valid cost and outcome data. A sensitivity analysis combining the cost data from the economic subsample with the effectiveness data from the whole sample was also conducted.

The findings reported here are based on analyses of complete cases. Within the economic subsample levels of missing data for the key outcomes were low. Also, the economic subsample was deemed too small to justify imputation of any missing data.

The potential value of extrapolating the trial results using a decision model was originally suggested. This was proposed when our follow-up was going to be 12 months and would have been valuable if there was a convincing between-group difference in effectiveness and/or service use costs at 6 and 12 months. However, at 24 months, after the trial extension, our results showed no between-group differences in effectiveness and, as such, we felt that no model-based extrapolation would be plausible.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and participant flow

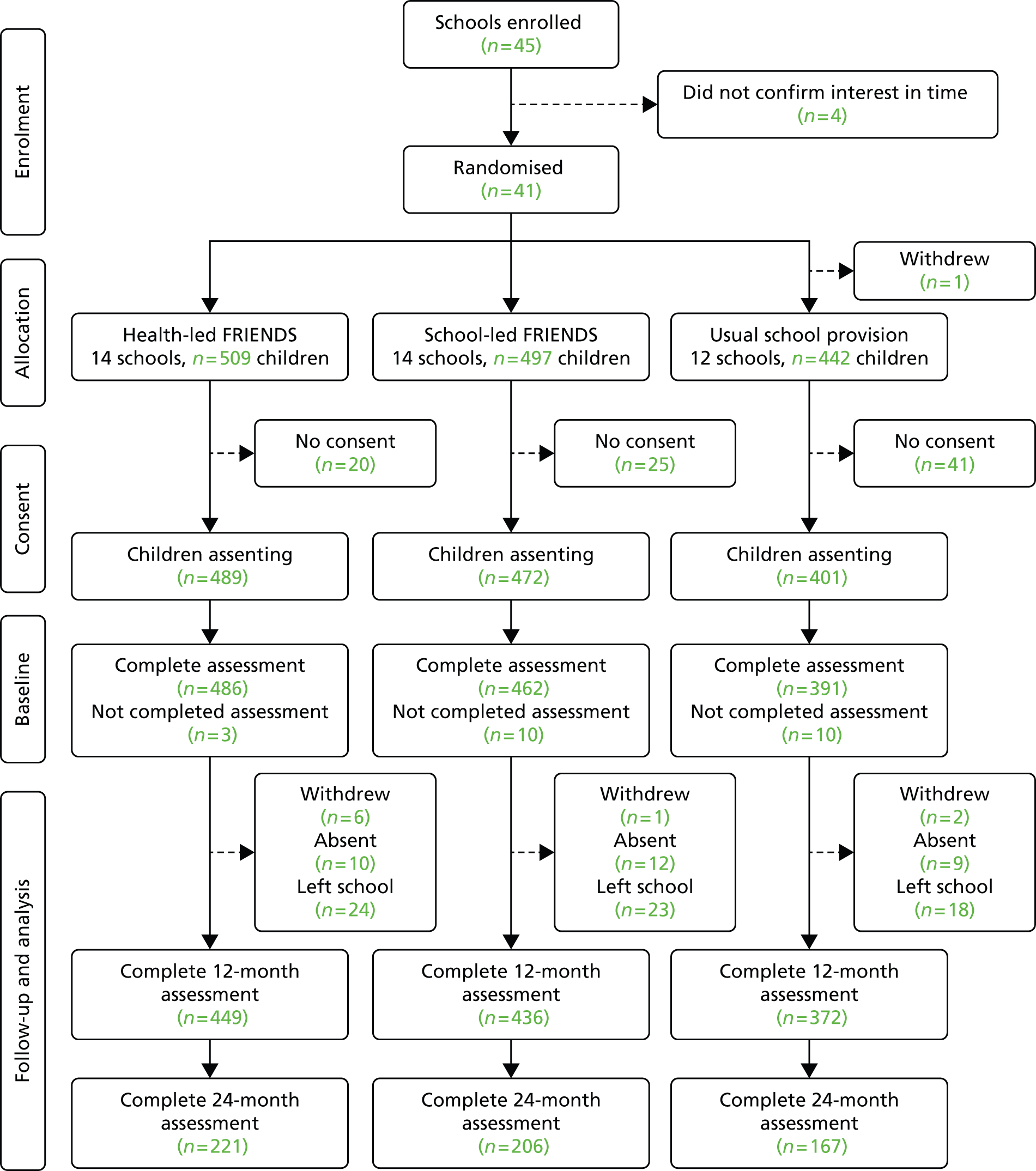

In total, 45 primary schools were enrolled in the study, with 41 providing signed consent by the specified deadline. Following randomisation, one school allocated to the usual school provision arm withdrew before the baseline assessment. The remaining 40 schools were retained throughout the study and the flow of participants is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PACES CONSORT flow diagram.

Of the 1448 eligible participants, 1362 (94%) consented to participate in the study with 1339 (98%) completing baseline assessments. Of these, 489 were allocated to health-led FRIENDS, 472 to school-led FRIENDS and 401 to usual school provision. Interventions were delivered to all participating schools in the academic year September 2011–July 2012.

At 12 months, 65 (4.8%) children had left school, nine (0.7%) withdrew consent and 31 (2.3%) were absent on the day(s) of assessment, resulting in 1257 children (92.3%) being assessed.

By the 24-month assessment children had transitioned to secondary school. For this assessment we had to initiate a new recruitment and consent process. We wrote to all of our initial cohort and asked parents to opt in to this assessment by returning a signed consent form and contact details. Data were obtained from 594 children, 43.6% of those who initially consented to participate. The 24-month assessments were completed by 221 (45.2%) in the health-led FRIENDS arm, 206 (43.6%) in the school-led FRIENDS arm and 167 (41.6%) in the usual school provision arm.

School demographics

Table 6 summarises the 40 participating schools by trial arm. On average, the schools were representative of the UK in terms of academic attainment (i.e the percentage of children achieving Key Stage 2 level 4 in maths and English). However, there were more children with special educational needs [23.2% vs. 17.1%; t = 4.180, degrees of freedom (df) = 39; p < 0.001] and lower rates of pupil absence (4.4% vs. 5.1%; t = –4.513, df = 38; p < 0.001) and eligibility for free school meals (12.4% vs. 18.2%; t = –3.540, df = 39; p < 0.001) in the study cohort than the national average.

| School ID | Trial arm | Number of pupils | Last Ofsted ratinga | Eligible for free school meals (%) | Educational needs (%) | Overall absence (%) | % achieving Level 4 English and maths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 183 | 1 | 2.2 | 15.8 | 2.8 | 96 |

| 8 | 1 | 215 | 3 | 9.5 | 27.4 | 4.9 | 67 |

| 38 | 1 | 149 | 2 | 0 | 34.9 | 3.6 | 95 |

| 13 | 1 | 394 | 3 | 11.3 | 26.1 | 3.8 | 64 |

| 29 | 1 | 50 | 2 | 6.4 | 18.0 | 3.8 | n/a |

| 4 | 1 | 126 | 2 | 9.5 | 11.9 | 6.8 | 79 |

| 15 | 1 | 108 | 4 | 45.4 | 49.1 | 4.5 | 71 |

| 24 | 1 | 288 | 2 | 9.3 | 18.4 | 2.7 | 95 |

| 40 | 1 | 220 | 3 | 30.5 | 33.2 | 5.0 | 71 |

| 19 | 1 | 274 | 1 | 4.4 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 91 |

| 25 | 1 | 258 | 2 | 8.2 | 20.9 | 3.9 | 85 |

| 11 | 1 | 253 | 2 | 10.6 | 34.0 | 5.0 | 64 |

| 34 | 1 | 354 | 2 | 8.9 | 29.1 | 4.8 | 73 |

| 32 | 1 | 238 | 1 | 7.2 | 15.1 | 3.6 | 98 |

| 1 | 2 | 260 | 2 | 22 | 39.2 | 6.0 | 73 |

| 37 | 2 | 381 | 3 | 6.7 | 12.1 | 4.5 | 88 |

| 3 | 2 | 188 | 1 | 2.7 | 18.1 | 3.0 | 87 |

| 14 | 2 | 49 | 1 | 2 | 26.5 | 3.6 | 67 |

| 27 | 2 | 205 | 2 | 17.1 | 16.1 | 3.5 | 87 |

| 30 | 2 | 140 | 2 | 32.2 | 30.0 | 6.2 | 94 |

| 18 | 2 | 346 | 1 | 7.8 | 16.2 | 3.0 | 81 |

| 21 | 2 | 182 | 4 | 27.8 | 36.8 | 6.8 | 58 |

| 6 | 2 | 117 | 2 | 10 | 24.8 | 4.8 | 57 |

| 39 | 2 | 239 | 2 | 19.2 | 18.4 | 3.6 | 79 |

| 9 | 2 | 488 | 1 | 4.5 | 22.5 | 4.2 | 88 |

| 5 | 2 | 107 | 2 | 1.9 | 11.2 | 4.3 | 88 |

| 7 | 2 | 405 | 3 | 11.4 | 15.1 | 4.5 | 85 |

| 36 | 2 | 411 | 1 | 11.9 | 18.7 | 3.4 | 94 |

| 28 | 3 | 356 | 2 | 10.3 | 21.3 | 4.8 | 81 |

| 16 | 3 | 183 | 2 | 7.1 | 16.9 | 3.4 | 100 |

| 26 | 3 | 150 | 2 | 27.5 | 20.0 | 4.9 | 81 |

| 17 | 3 | 396 | 2 | 5.6 | 18.2 | 4.2 | 81 |

| 23 | 3 | 94 | 3 | 6.3 | 22.3 | 4.1 | 91 |

| 33 | 3 | 348 | 2 | 4.8 | 17.8 | 4.1 | 85 |

| 31 | 3 | 180 | 3 | 7.7 | 16.7 | 4.1 | 70 |

| 35 | 3 | 414 | 2 | 16.2 | 32.9 | 4.9 | 76 |

| 41 | 3 | 119 | 2 | 27.7 | 30.3 | 4.6 | 73 |

| 22 | 3 | 93 | 2 | 16.8 | 32.3 | 5.9 | 67 |

| 20 | 3 | 197 | 2 | 1.5 | 25.9 | 3.7 | 78 |

| 12 | 3 | 243 | 3 | 22.6 | 33.3 | 5.1 | 88 |

| Average | 235 | 12.4 | 23.2 | 4.4 | 78.7 | ||

| National average | 18.2 | 17.1 | 5.1 | 79.0 | |||

| Average by trial arm | |||||||

| 1 | 222 | 2.1 | 11.7 | 24.0 | 4.3 | 74.9 | |

| 2 | 251 | 1.9 | 12.7 | 21.8 | 4.4 | 80.4 | |

| 3 | 231 | 2.3 | 12.8 | 24.0 | 4.5 | 80.9 | |

There were no significant differences for any variable between trial arms.

Balance between trial arms

Demographic and baseline symptomatology for the three groups is summarised in Table 7. The proportion of boys in the usual PSHE group (42%) was lower than that in each of the other two trial arms (52% and 50%) but otherwise the arms were well balanced at baseline.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Health-led FRIENDS | School-led FRIENDS | Usual PSHE | |

| No. of children | 489 | 472 | 401 |

| No. of schools | 14 | 14 | 12 |

| No. of schools with two or more classes | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| Class size of schools, mean (SD) | 19.56 (6.56) | 18.15 (7.68) | 20.05 (8.29) |

| Missing baseline assessment, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 10 (2.1) | 10 (2.5) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 255 (52.1) | 237 (50.2) | 170 (42.4) |

| Female | 234 (47.9) | 235 (49.8) | 231 (57.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| British white | 455 (94.2) | 439 (95.2) | 359 (92.1) |

| Non-white | 28 (5.8) | 22 (4.8) | 31 (7.9) |

| Living situation, n (%) | |||

| Mum and dad | 347 (71.4) | 315 (68.2) | 268 (68.5) |

| Parent and partner | 43 (8.8) | 55 (11.9) | 37 (9.4) |

| Single parent | 67 (13.8) | 68 (14.8) | 58 (14.8) |

| Other | 29 (6.0) | 24 (5.2) | 28 (7.2) |

| Number of siblings, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 49 (10.1) | 30 (6.5) | 32 (8.2) |

| 1 | 221 (45.5) | 214 (46.5) | 184 (47.1) |

| 2 | 129 (26.5) | 134 (29.1) | 92 (23.5) |

| 3 or more | 87 (17.9) | 82 (17.8) | 83 (21.2) |

| Family affluence, n (%) | |||

| Low (0–2) | 6 (1.5) | 11 (2.4) | 13 (3.3) |

| Medium (3–5) | 142 (29.4) | 139 (30.1) | 128 (32.9) |

| High (6–8) | 331 (69.1) | 311 (67.5) | 249 (63.8) |

| Child-reported assessment | |||

| Child total RCADS score, mean (SD) | 26.24 (15.56) | 24.91 (14.32) | 26.78(16.32) |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Children score, mean (SD) | 10.63 (8.14) | 10.99 (8.24) | 10.46 (8.35) |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale score, mean (SD) | 18.94 (5.34) | 19.43 (5.39) | 19.57 (5.98) |

| Total life satisfaction, mean (SD) | 14.21 (6.77) | 13.32 (5.71) | 13.76 (6.82) |

| Bullied more than two or three times a month, n (%) | 142 (29.3) | 124 (26.8) | 112 (28.6) |

| Parent-reported assessment | n = 217 | n = 201 | n = 153 |

| Total RCADS score, mean (SD) | 12.55 (8.81) | 10.99 (8.60) | 12.52 (9.34) |

| Total SDQ score, mean (SD) | 9.09 (6.32) | 8.31 (6.28) | 9.00 (6.24) |

| Total SDQ threshold | |||

| Abnormal ≥ 17, n (%) | 22 (10.5) | 25 (13.0) | 21 (14.4) |

| Teacher-reported assessment | n = 487 | n = 466 | n = 396 |

| Teacher-rated SDQ impact | |||

| Difficulty, n (%) | 119 (24.4) | 125 (26.8) | 109 (27.5) |

Usual school provision

Semistructured interviews were completed with each school in the usual PSHE arm to determine the nature, extent and content of the PSHE that was provided. An overall rating of the emphasis that each school placed on academic attainment and social and emotional well-being on a 10-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not important’; 10 = ‘very important’) was obtained. Data are summarised in Table 8.

| School | Main PSHE model | Dedicated PSHE sessions | Time per Week | No. of PSHE leaders | PSHE content covered | Academic attainment importance | Social and emotional well-being importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | SEAL | Yes | 5 hours per term | 1 + TA | New beginnings; getting on and falling out | 8 | 10 |

| 26 | Learning 4 Life | Yes | 45 minutes | 1 + TA | My family and friends; healthy bodies, healthy minds | 9 | 10 |

| 17 | SEAL | Yes | 45 minutes | 1 | New beginnings; getting on and falling out | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| 23 | Learning 4 Life | Yes | 45 minutes | 1 | Going for goals; my family and friends | 7 | 10 |

| 33 | SEAL | Fortnightly assembly | 40 minutes | 1 | Getting on and falling out; good to be me | 8 | 8 |

| 31 | Interpersonal Curriculum model (SEAL based) | Weekly assembly | 30 minutes | 1 | Adaptability; communication | 8 | 8 |

| 35 | Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural Development model (not SEAL based) | Yes | 30–60 minutes | 1–2 | Caring and sharing; staying healthy; safety first | 9 | 8 |

| 22 | Learning 4 Life | Yes | 60 minutes | 1 | Our happy school; out and about | 8 | 8 |

| 20 | SEAL | Yes | 60–90 minutes | 1 | New beginnings; getting on and falling out | 9 | 8 |

| 12 | SEAL | Yes | 30 minutes | 1 | Going for goals; new beginnings; good to be me | 9 | 9 |

| 41 | SEAL | Yes | 60 minutes | 1 | Good to be me; going for goals | 9 | 10 |

| 28 | SEAL | Yes | 30–40 minutes | 1 | Could not recall | 10 | 8 |

The PSHE lessons were typically delivered by a single teacher as dedicated weekly sessions of 30–60 minutes. Academic attainment and social and emotional well-being were both rated equally highly by the schools.

In terms of content, all but one school were following the national SEAL curriculum13 or a programme informed by it (Learning 4 Life). 78 The SEAL curriculum aims to develop the underpinning qualities and skills that help promote positive behaviour and effective learning. It focuses on five social and emotional aspects of learning: self-awareness, managing feelings, motivation, empathy and social skills. SEAL is organised into seven main themes: new beginnings, getting on and falling out, say no to bullying, going for goals, good to be me, relationships and changes. Each theme is designed for a whole-school approach and includes a whole-school assembly and suggested follow-up activities in all areas of the curriculum.

The Learning 4 Life programme was developed in Wiltshire. It is based on the SEAL curriculum and includes a range of emotional literacy materials that can be integrated within the wider PSHE curriculum. The programme has six main themes that closely map onto the SEAL curriculum. The SEAL and Learning 4 Life programmes are summarised in Table 9.

| Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning | Learning 4 Life |

|---|---|

| New beginnings: exploring feelings of happiness, excitement, sadness, anxiety and fearfulness. Learning to calm down and problem solve | Our happy school: working in a group, respect others, personal responsibility for own behaviour |

| Getting on and falling out: developing social skills for friendships; learning to work well in a group, manage anger, resolve conflict | Out and about: keeping safe and managing risk, discrimination and stereotyping, protecting oneself online |

| Say No to Bullying: antibullying work | |

| Good to be me: understand effect of feelings on behaviour, feel good about self; manage feelings, relax, cope with anxiety, stand up for yourself and assertiveness | Healthy bodies, healthy minds: healthy lifestyles (diet, alcohol, drugs) and promoting positive physical and mental well-being; managing risk, building resilience, making safe choices around drugs, work/life balance |

| Going for goals: reflecting on self and strengths, taking responsibility, building confidence and self-efficacy | Looking forward: looking at choices with reference to finance, saving, budgeting |

| Relationships: exploring feelings in terms of important relationships (family and friends) and coping with loss | My family and friends: coping with issues such as loss, self-image and media influence; pubertal changes and sex education and relationships |

| Changes: understanding different types of change (positive and negative) and responses to it | Ready, steady, go: exploring difficult changes around loss and bereavement; planning to transition to secondary school |

Within the usual provision schools, PSHE had a wide focus. During the intervention phase PSHE addressed issues including personal safety, healthy eating, coping with loss and social skills, as well as emotional awareness and management. Although the focus on emotional regulation and problem-solving overlapped with the focus of the FRIENDS programme, the specific PSHE focus on anxiety was less systematic and intensive.

Intervention dosage and fidelity

The complete nine-session FRIENDS programme was delivered to all classes in the health-led and school-led groups. Session attendance was not recorded although average school absence rates in participating schools were very low (health-led 4.25% vs. school-led 4.4%).

To assess intervention fidelity, 49 sessions (one from each class in the 28 schools delivering the FRIENDS programme) were audio recorded and independently rated to determine how many core tasks had been delivered. All specified core tasks and home activities were delivered in the 24 health-led sessions assessed. In the 25 school-led sessions, 15 (60%) delivered all of the core tasks and the home activity, eight (32%) delivered all except the home activity and the remaining two (8%) did not deliver one core task and the home activity.

Outcomes

Objective 1: to evaluate the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme in reducing symptoms of anxiety and low mood (primary outcome) at 12 months

At the 6-month asssessment, data were available from 1317 children, 96.7% of those who completed the baseline assessments. Our analysis revealed no significant between-arm differences in total RCADS score (health-led FRIENDS: baseline 26.24 (SD 15.56) vs. 6 months 22.99 (SD 14.52); school-led FRIENDS: baseline 24.91 (SD 14.32) vs. 6 months 24.32 (SD 15.95); usual school provision: baseline 26.78 (SD 16.32) vs. 6 months 24.70 (SD 15.84).

Our primary outcome was the child-reported RCADS score at 12 months. Data at 12 months were available for 1257 children, 92.3% of those who completed the baseline assessments (health-led FRIENDS 91.8%; school-led FRIENDS 92.4%; usual school provision 92.7%). Tables 10 and 11 summarise the total and subscale scores by trial arm at baseline and 12 months.

| RCADS scale | Health-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | Adjusted difference (95% CI), health-led FRIENDS vs. usual school provision | Usual school provision, mean (SD) | Adjusted difference (95% CI), health-led FRIENDS vs. school-led FRIENDS | School-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 489) | 12 months (n = 449) | Baseline (n = 401) | 12 months (n = 372) | Baseline (n = 472) | 12 months (n = 436) | ||||

| Depression | 4.04 (2.60) | 3.15 (2.53) | –0.36 (–0.76 to 0.04) | 3.85 (2.77) | 3.47 (2.,72) | –0.34 (–0.82 to 0.14) | 3.68 (2.34) | 3.34 (2.51) | 0.120 |

| Social anxiety | 5.28 (3.28) | 4.39 (3.32) | –0.41 (–0.94 to 0.12) | 5.13 (3.26) | 4.68 (3.37) | –0.79 (–1.42 to-0.16) | 5.05 (3.23) | 5.04 (3.43) | 0.013 |

| Separation anxiety | 3.81 (3.34) | 2.48 (2.94) | –0.42 (–0.97 to 0.12) | 4.23 (3.45) | 3.07 (3.14) | –0.42 (–1.07 to-0.23) | 3.68 (3.14) | 2.89 (2.96) | 0.190 |

| Generalised anxiety | 5.79 (3.80) | 4.43 (3.56) | –0.77 (–1.40 to –0.14) | 5.97 (3.94) | 5.15 (3.70) | –0.89 (–1.64 to-0.14) | 5.64 (3.54) | 5.19 (3.64) | 0.011 |

| Panic | 2.85 (2.87) | 2.03 (2.56) | –0.34 (–0.78 to 0.09) | 2.97 (3.11) | 2.42 (3.00) | –0.37 (–0.89 to 0.15) | 2.68 (2.79) | 2.33 (2.74) | 0.157 |

| OCD | 4.56 (3.31) | 3.43 (3.10) | –1.99 (–0.71 to 0.31) | 4.61 (3.22) | 3.79 (3.20) | –0.51 (–1.12 to 0.10) | 4.45 (3.12) | 3.99 (3.20) | 0.124 |

| Total RCADS | 26.24 (15.56) | 19.49 (14.81) | –2.66 (–5.22 to –0.09) | 26.78 (16.32) | 22.48 (15.74) | –3.91 (–6.48 to-1.35) | 24.91 (14.32) | 22.86 (15.24) | 0.009 |

| RCADS scale | School-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | Adjusted difference (95% CI), school-led FRIENDS vs. usual school provision | Usual school provision, mean (SD) | Adjusted difference (95% CI), school-led FRIENDS vs. health-led FRIENDS | Health-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 472) | 12 months (n = 436) | Baseline (n = 401) | 12 months (n = 372) | Baseline (n = 489) | 12 months (n = 449) | ||||

| Depression | 3.68 (2.34) | 3.34 (2.51) | –0.02 (–0.43 to 0.38) | 3.85 (2.77) | 3.47 (2.,72) | –0.34 (–0.82 to 0.14) | 4.04 (2.60) | 3.15 (2.53) | 0.120 |

| Social anxiety | 5.05 (3.23) | 5.04 (3.43) | 0.38 (–0.16 to 0.91) | 5.13 (3.26) | 4.68 (3.37) | –0.79 (–1.42 to-0.16) | 5.28 (3.28) | 4.39 (3.32) | 0.013 |

| Separation anxiety | 3.68 (3.14) | 2.89 (2.96) | 0.00 (–0.54 to 0.55) | 4.23 (3.45) | 3.07 (3.14) | –0.42 (–1.07 to-0.23) | 3.81 (3.34) | 2.48 (2.94) | 0.190 |

| Generalised anxiety | 5.64 (3.54) | 5.19 (3.64) | 0.12 (–0.52 to 0.75) | 5.97 (3.94) | 5.15 (3.70) | –0.89 (–1.64 to-0.14) | 5.79 (3.80) | 4.43 (3.56) | 0.011 |

| Panic | 2.68 (2.79) | 2.33 (2.74) | 0.03 (–0.41 to 0.47) | 2.97 (3.11) | 2.42 (3.00) | –0.37 (–0.89 to 0.15) | 2.85 (2.87) | 2.03 (2.56) | 0.157 |

| OCD | 4.45 (3.12) | 3.99 (3.20) | 0.31 (–0.21 to 0.83) | 4.61 (3.22) | 3.79 (3.20) | –0.51 (–1.12 to 0.10) | 4.56 (3.31) | 3.43 (3.10) | 0.124 |

| Total RCADS score | 24.91 (14.32) | 22.86 (15.24) | 1.28 (–1.30 to 3.87) | 26.78 (16.32) | 22.48 (15.74) | –3.91 (–6.48 to-1.35) | 26.24 (15.56) | 19.49 (14.81) | 0.009 |

Our analysis was adjusted for school, baseline symptomatology (RCADS score) and sex. There was a significant difference in adjusted mean total RCADS score at 12 months between health-led FRIENDS and school-led FRIENDS [–3.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) –6.48 to –1.35; p = 0.0004] and usual school provision (–2.66, 95% CI –5.22 to –0.09; p = 0.043). The 95% CIs include our predefined clinically important difference of 3.6 points on the RCADS. Analysis of the RCADS subscales (see Table 11) showed a difference in generalised (p = 0.011) and social (p = 0.013) anxiety but not depression (p = 0.12).

Missing data analysis

Although data completion at 12 months was very high (93.9%), an analysis of missing data was undertaken to compare baseline RCADS scores of those who did and those who did not complete the 12-month assesments (Table 12). On our primary outcome measures (RCADS), child non-completers at 12 months had higher baseline scores (indicating more symptomatology) on the total RCADS and all subscales.

| Characteristic | Health-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | School-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | Usual school provision, mean (SD) | p-value (interaction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completers, n (%) | 449 (91.8) | 436 (92.4) | 372 (92.8) | 0.867 |

| Non-completers, n | 40 | 36 | 29 | |

| Sex male, n (%) | ||||

| Completers | 234 (52.1) | 220 (50.5) | 159 (42.7) | 0.649 |

| Non-completers | 21 (52.5) | 17 (52.8) | 11 (37.9) | |

| Child-reported RCADS score | ||||

| Depression | ||||

| Completers | 4.01 (2.58) | 3.62 (2.31) | 3.73 (2.68) | 0.001 (0.140) |

| Non-completers | 4.41 (2.89) | 4.46 (3.04) | 5.43 (3.45) | |

| Separation anxiety | ||||

| Completers | 3.84 (3.43) | 3.63 (3.15) | 4.07 (3.36) | 0.015 (0.012) |

| Non-completers | 3.54 (2.18) | 4.24 (3.04) | 6.29 (4.03) | |

| Social anxiety | ||||

| Completers | 5.24 (3.28) | 4.97 (3.14) | 5.00 (3.20) | 0.001 (0.298) |

| Non-completers | 5.72 (3.24) | 5.97 (4.13) | 6.79 (3.65) | |

| General anxiety | ||||

| Completers | 5.71 (3.76) | 5.65 (3.56) | 5.76 (3.79) | 0.001 (0.010) |

| Non-completers | 6.64 (4.13) | 5.54 (3.35) | 8.64 (4.75) | |

| Panic | ||||

| Completers | 2.85 (2.89) | 2.65 (2.72) | 2.84 (3.01) | 0.020 (0.045) |

| Non-completers | 2.84 (2.70) | 3.00 (3.54) | 4.64 (3.88) | |

| OCD | ||||

| Completers | 4.49 (3.26) | 4.42 (3.10) | 4.48 (3.17) | 0.002 (0.361) |

| Non-completers | 5.38 (3.84) | 4.91 (3.38) | 6.18 (3.47) | |

| Total RCADS score | ||||

| Completers | 26.10 (15.66) | 24.63 (14.13) | 25.88 (15.78) | 0.001 (0.025) |

| Non-completers | 27.87 (13.53) | 28.21 (16.32) | 37.96 (18.99) | |

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the potential effect of missing data. Twenty imputed data sets were created using imputations based on RCADS total and subscale scores (Table 13).

| RCADS scale | Health led FRIENDS (n = 489), mean (SD) | School led FRIENDS (n = 472), mean (SD) | Usual school provision (n = 401), mean (SD) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 3.10 (2.85) | 3.39 (2.87) | 3.44 (2.84) | 0.163 |

| Separation anxiety | 2.55 (3.78) | 2.952 (3.82) | 2.900 (3.77) | 0.209 |

| Social anxiety | 4.34 (3.74) | 5.04 (3.69) | 4.62 (3.69) | 0.021 |

| General anxiety | 4.36 (4.27) | 5.20 (4.28) | 4.94 (4.23) | 0.013 |

| Panic | 2.03 (2.99) | 2.38 (3.00) | 2.32 (2.96) | 0.170 |

| OCD | 3.47 (3.43) | 4.03 (3.45) | 3.69 (3.42) | 0.052 |

| Total RCADS score | 19.79 (17.18) | 23.01 (17.23) | 21.89 (17.00) | 0.020 |

Imputation for missing data made no material difference to the overall results. There continued to be a between-group difference in total RCADS score and on the generalised and social anxiety subscales.

Objective 2: to evaluate the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme for children with low and high anxiety at baseline in terms of symptoms of anxiety and low mood at 12 months

We were interested to explore the effects of the programme on those children with elevated symptoms of anxiety. Within community surveys 3–4% of children will be suffering with an anxiety disorder. In addition, a further group of children will have significant symptoms but may not fulfil all diagnostic criteria. We therefore chose to identify the 10% with the highest RCADS scores to cover both of these groups.

The distribution of child-reported total RCADS scores at baseline was examined. A total RCADS score of ≥ 49 identified 10.1% of children and was used as a cut-off to categorise children as having either high anxiety (n = 130) or low anxiety (RCADS score of ≤ 48, n = 1151). Using this cut-off, 99 high-anxiety and 1029 low-anxiety children completed the RCADS at 12 months. Table 14 summarises the total RCADS score at baseline and 12 months by trial arm for the high- and low-anxiety subgroups.

| Subgroup | Health-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | School-led FRIENDS, mean (SD) | Usual school provision, mean (SD) | p-value overall group effecta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High anxiety (RCADS score of ≥ 49) | n = 36 | n = 31 | n = 32 | |

| Baseline | 57.59 (8.18) | 55.66 (7.16) | 57.57 (7.90) | 0.288 |

| 12 months | 35.31 (19.24) | 40.65 (21.40) | 33.97 (21.15) | 0.368 |

| Low anxiety (RCADS score of ≤ 48) | n = 374 | n = 360 | n = 295 | |

| Baseline | 22.78 (11.86) | 22.01 (11.05) | 22.51 (12.03) | 0.623 |

| 12 months | 17.68 (13.40) | 21.06 (13.42) | 20.74 (14.12) | 0.006 |

There were significant within-group reductions for the high-risk group at 12 months but no between-group effects. For the low-risk group, there were significant within-group reductions and between-group differences in mean RCADS scores at 12 months (p = 0.006). Adjusted mean differences showed an effect for health-led FRIENDS compared with school-led FRIENDS (–3.78, 95% CI –6.16 to –1.40; p = 0.003) and for health-led FRIENDS compared with usual school provision (–3.13, 95% CI –5.61 to –0.65; p = 0.015). Post hoc analysis indicated that this related to a reduction on the social (p = 0.013) and generalised anxiety (p = 0.006) subscales in the health-led FRIENDS group.

Objective 3: to examine the effectiveness of the FRIENDS programme in terms of self-esteem, worry, bullying and overall well-being (secondary outcomes) at 12 months

At the 6-month assessment, data were available from 1317 children and 479 parents. Analysis of our secondary outcomes revealed no significant between-group differences (data not reported here).

Our primary assessment point was 12 months post baseline assessment. Table 15 summarises the secondary outcomes (child-reported outcomes and parent and teacher assessments) at baseline and 12 months by trial arm.

| Outcome | Health-led FRIENDS | School-led FRIENDS | Usual school provision | p-value overall group effecta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months | Baseline | 12 months | Baseline | 12 months | ||

| Child reported | |||||||

| n | 489 | 449 | 472 | 436 | 401 | 372 | |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Children score, mean (SD) | 10.63 (8.14) | 8.19 (7.93) | 10.99 (8.24) | 9.62 (8.30) | 10.46 (8.35) | 9.03 (8.52) | 0.0136 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale score, mean (SD) | 18.94 (5.34) | 20.90 (6.22) | 19.43 (5.39) | 20.77 (5.82) | 19.57 (5.98) | 20.87 (5.95) | 0.639 |

| Total life satisfaction, mean (SD) | 14.21 (6.77) | 13.87 (6.00) | 13.32 (5.71) | 13.73 (6.08) | 13.76 (6.82) | 13.95 (5.88) | 0.770 |

| Bullied more than two or three times a month, n (%) | 142 (29.3) | 74 (16.5) | 124 (26.8) | 98 (22.5) | 112 (28.6) | 86 (23.2) | 0.156 |

| Not bullied or bullied once or twice, n (%) | 343 (70.7) | 374 (83.5) | 338 (73.2) | 337 (77.5) | 279 (71.4) | 285 (76.8) | |

| Parent reported | |||||||

| n | 217 | 173 | 198 | 159 | 152 | 119 | |

| Total RCADS score, mean (SD) | 12.55 (8.81) | 10.76 (8.90) | 10.99 (8.60) | 9.82 (7.13) | 12.52 (9.34) | 10.03 (7.31) | 0.816 |

| Total SDQ score, mean (SD) | 9.09 (6.32) | 7.06 (6.00) | 8.31 (6.28) | 6.67 (5.62) | 9.00 (6.24) | 7.32 (9.95) | 0.767 |

| Total SDQ threshold ≥ 17, n (%) | 22 (10.5) | 15 (9.3) | 25 (13.0) | 11 (7.3) | 21 (14.4) | 9 (7.9) | 0.333 |

| Teacher reported | |||||||

| n (%) | 487 (99.6) | 454 (92.8) | 466 (98.7) | 445 (94.3) | 396 (98.8) | 375 (93.5) | |

| Teacher SDQ impact, mean (SD) | 119 (24.4) | 131 (28.9) | 125 (26.8) | 143 (32.1) | 109 (27.5) | 117 (31.2) | 0.538 |

There were no between-group differences on any measure after adjusting for baseline, sex and school-level effects.

Objective 4: to examine the medium-term effects of the FRIENDS programme on symptoms of anxiety and low mood (primary outcome) at 24 months

A total of 594 children completed assessments at 24 months. A comparison of the baseline characteristics of those who did and those who did not complete the 24-month assessment is shown in Table 16.

| Characteristic | Completers (n = 594) | Non-completers (n = 768) | p-value |