Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/133/20. The contractual start date was in February 2014. The final report began editorial review in April 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Gail Mountain is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Baxter et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

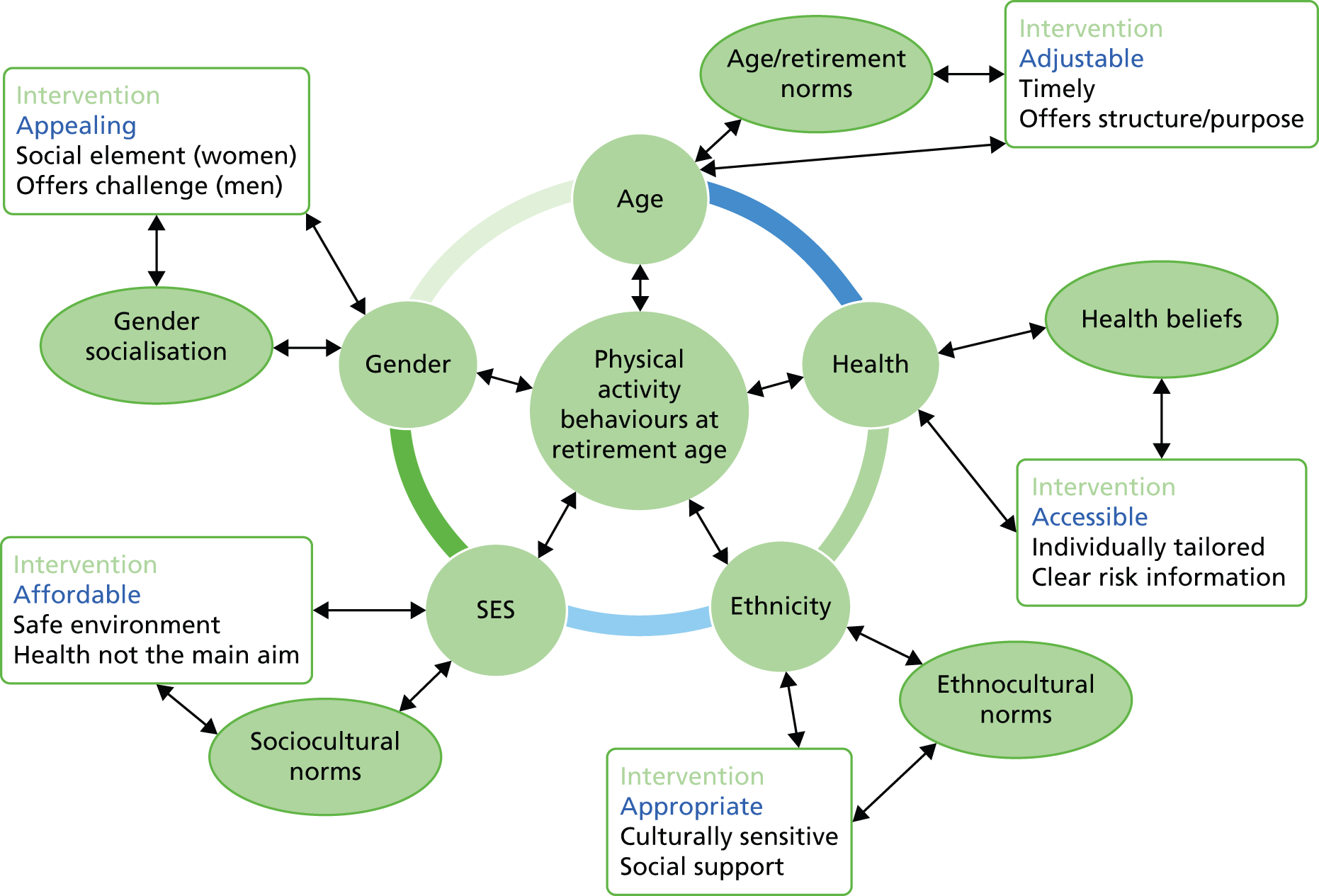

With a growing proportion of the population approaching the age of retirement, there has been an increasing focus on how this sector of society can maintain their independence and mental and physical well-being as they age. The potential future demand for health care in this population suggests that this stage of life would be an opportune time at which to intervene with health-promotion activities.

It has been argued that transition points in life, such as the approach towards and the early years of retirement, present key opportunities for interventions to improve the health of the population. 1 In particular, the transition to retirement is associated with changes in physical activity levels as a result of changing lifestyle, and this period is thus a particularly important time at which to intervene in order to increase or maintain levels, especially in lower socioeconomic groups. 1

With the increase in the numbers of retired adults within the population, and the established link between exercise and health, interventions that may increase or preserve activity levels around the time of retirement have the potential to provide benefits in terms of increased health and well-being for people in later life. There are also potential economic benefits from a reduction in health-service use. The nature of the retirement transition has undergone considerable change in recent years, with varying patterns of work, the abolition of the compulsory retirement age and increases in the numbers of people in part-time employment. 2 These changes may all blur the boundary between working life and retirement, making the process of retirement transition potentially more complex.

It has been recognised for some years that a large proportion of people aged over 50 years are sedentary (i.e. take < 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week), and few people take the recommended levels of activity for improving health (30 minutes of moderate physical activity, such as brisk walking, household chores or dancing, at least five times a week). 3 Physical activity is known to have a wide range of health benefits, including the potential to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, some cancers, disability and falls,3–8 and to improve overall quality of life in older people. 4–8 In view of these important benefits, the generally low levels of physical activity in this population are a cause for concern. 9,10

The transition to retirement may provide a significant opportunity to encourage people to maintain or increase their activity levels. Retirement can represent a major life change for individuals, with changes or disruptions to daily routines and self-perceptions. Retirement may, therefore, enable individuals to make changes to their activity levels that are much more difficult to make or sustain when their circumstances or environment remain the same. Interventions that provide the opportunity or motivation for individuals to maintain or increase physical activity at the point of retirement therefore have the potential to make an important contribution to establishing a healthier older adult population.

The number of people aged 65 years and over is projected to rise by nearly 50% (48.7%) in the next 20 years to over 16 million people worldwide. 11 It is therefore increasingly important to maintain a healthy older population with individuals who are able to contribute to society (e.g. by engaging in voluntary work or by acting as carers for spouses or grandchildren). Thus, there is a need to examine interventions that aim to increase or maintain physical activity in older people during and shortly after the transition to retirement and to identify how positive changes in activity levels at this key transition point can be effectively (and cost-effectively) encouraged, without exacerbating health inequalities in later life.

In addition to the need to encourage physical activity in the older adult population, recent systematic reviews have highlighted health inequalities in response to physical activity interventions and inequalities in levels of physical activity and health status in the retired population. 12,13 Appropriately targeted interventions have the potential to encourage physical activity at this life transition and to ensure that inequalities in health and well-being are not widened at retirement. This is particularly true where retirement is a positive choice (i.e. for those with more resources and/or better health) rather than an enforced and negative change in employment and financial status (i.e. for those with fewer resources and/or poorer health).

Recent systematic reviews of evidence (summarised later in this report) suggest that, without intervention, physical activity levels after retirement tend to increase in older people from higher socioeconomic groups, but decrease in those in lower socioeconomic groups. Socioeconomic status (SES) may moderate the impact of retirement on physical activity levels (with only higher social classes associated with increases in physical activity at retirement). Studies have also described that particular barriers among those from low socioeconomic backgrounds may include a lack of time owing to increased family responsibilities and the attachment of low personal value to recreational physical activity. Inequalities may also be the result of wider environmental or ecological factors or differing access to technology between populations. Therefore, the point of retirement appears to present a risk for widening health inequalities across different socioeconomic classes.

Aims and objectives

We aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-synthesis of UK and international evidence on the types and effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity among people around the time of retirement, including data regarding factors that may enhance or mitigate outcomes. The results of the review could inform the development and delivery of interventions to promote physical activity in the transition from paid work to retirement. Specific research aims were:

-

to systematically identify, appraise and synthesise UK and international evidence reporting outcomes resulting from interventions to maintain or increase physical activity in older adults in the period immediately before or after their retirement from paid employment

-

to determine how applicable this evidence might be to the UK context

-

to identify factors that may underpin the effectiveness or acceptability of interventions by exploring qualitative literature reporting the perceptions of older people and service providers with regard to facilitators or obstacles to successful outcomes

-

to explore how interventions may address issues of health inequalities.

The specific objectives to meet these aims were:

-

to identify the most effective interventions to maintain and/or increase physical activity in older people during and shortly after the transition to retirement by conducting comprehensive and systematic searches for published and unpublished effectiveness evidence (including grey literature)

-

to determine the best practice principles for effective physical activity interventions in this population by considering the qualitative evidence to provide context and examination of social and cultural issues surrounding intervention effectiveness and acceptability

-

to examine any evidence regarding the impact of interventions in different populations and/or the potential for retirement to increase health inequalities

-

to generate a critical meta-synthesis of the evidence suitable to inform policy decisions and disseminate to relevant audiences.

The population (patient) group

This systematic review considered older adults who were about to retire or who had recently retired.

The intervention

Interventions examined had the reported aim of maintaining or increasing physical activity, delivered in any context and by any method.

Comparator

The review included studies with any comparator or no comparator.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest were those relating to physical activity levels recorded by validated measures/scales, or other indirect measures such as hours of activity, well-being or measures of physical or mental health.

How this study has changed from protocol

At the outset of the review we had not intended to specify an age range for inclusion, as retirement age may vary and the length of the transition period could also differ between individuals. In the protocol we stated that we would revisit this decision as the review progressed. We were able to identify only one paper that specifically referred to the study population as being about to retire or newly retired, with the majority of studies describing populations of older adults by average age or age range only. We therefore took the decision to develop an applicability categorisation based on age, which we used as a proxy for the retirement transition period, as described in Chapter 2.

Owing to the nature of the identified literature, we were unable to carry out our planned meta-analysis. Although there was a good number of studies with experimental designs, the heterogeneity in outcomes measured and the small number of studies with no-intervention comparators precluded an examination of effectiveness by meta-analysis. We therefore completed a narrative summary and used Harvest plot visual summaries.

We also carried out an alternative form of meta-synthesis across the quantitative and qualitative literature to that originally planned. The lack of quantitative studies relating to specific interventions precluded use of the qualitative data as explanatory insight into intervention outcomes. Instead, we combined the two sets of data via a comparison of intervention content reported in effectiveness papers, versus optimal content as reported in the qualitative papers.

In the original proposal we had stated that we would provide audio summaries for each of the included papers in order to enhance accessibility of the research to a lay audience. Owing to the extensive volume of included literature, we have instead produced an accessible screencast presentation which summarises the background to the study, the methods and the findings (see http://youtu.be/47jA4OUWfdQ).

Chapter 2 Methods

A number of reviews of physical activity interventions for older adults have been carried out. However, a broad-based systematic review examining both qualitative and quantitative evidence across all forms of intervention in adults around the point of transition to retirement was needed. We adopted a review method that was able to combine multiple data types to produce a broad evidence synthesis. We believe that this approach was required to best examine the international evidence on interventions and to ascertain whether or not and how these interventions would be best applied in a UK context, in order to inform future guidelines and the development and implementation of effective interventions across the population.

Development of the review protocol

A review protocol was developed prior to beginning the study. The protocol outlined the research questions, and detailed methods for carrying out the review in line with guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 14 The protocol encompassed: methods for identifying research evidence; method for selecting studies; method of data extraction; the process of assessing the methodological rigour of included studies; and synthesis methods. The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database as CRD42014007446.

In the scoping phase of the project, we consulted with a range of stakeholders including older people, professionals working with older people and researchers with expertise in the field, in order to assist in the development of the scope of our review and the search terms used. In total, 35 people contributed to the consultation process in informal focus-group settings.

All participants were asked to discuss the following three questions:

-

What characteristics best describe an older person? How old is ‘older’ and how does this relate to retirement?

-

What activities do you think would help an older person to remain healthy in retirement?

-

What might stop an older person from being active in retirement?

Overall, there was a considerable degree of consensus between participants in the group discussions. In terms of describing an older person, all respondents took the view that it was inappropriate to define being older in relation to a particular numerical age. Professionals did note that many services (such as in the NHS/social care) define older age as starting at 65 years, although they did not necessarily consider that this criterion should be applied throughout society. Many participants highlighted that the definition of ‘older’ has changed over time, as people are living longer and working longer (by choice or necessity). In relation to this, it was noted that retired people are not necessarily ‘old’.

‘Old’ seemed to be defined as ‘someone older than you’ and was described as being dependent on underlying health conditions. For example, a 60-year-old person with a chest condition might seem older than a 90-year-old in good health. It was also described as being dependent on ‘who you are as a person and the life you have lived’. Older people in the groups highlighted that you were only old when you felt that you were old, suggesting that definitions are related to individual state of mind as well as to physical health.

A broad range of activities were reported in respect to staying healthy in retirement. These ranged from activities that were clearly defined as physical activity (e.g. walking, cycling, swimming, tai chi), but also activities such as volunteering, running a social group, getting a dog and being a carer, which all required physical activity, but in which this was not seen by participants as being the main purpose of the activity. Participants also mentioned the importance of motivation to staying active and that participating in a group activity (such as a walking group) might improve motivation owing to the social aspects of such activities. Reducing isolation or replacing the loss of interaction with work colleges was described as important.

Factors that were outlined as potential barriers to remaining active in retirement were ill health (including the side effects of prescribed drugs), feeling tired, the physical environment, poor access to public transport or leisure facilities, having to care for someone else (such as a partner or grandchildren) and a lack of confidence, or depression. There was also discussion regarding expectations of how a retired person should behave; for example, the expectation that when you retire you slow down makes it acceptable to do so. The groups also highlighted the influence of the way in which retirement had come about (forced retirement vs. choosing to retire); for example, in situations where ill health or an accident had forced retirement, it was harder to then be active.

The results of these consultations influenced how we defined the parameters of the review. The input that we received confirmed the need to have broad inclusion criteria in relation to the types of intervention that we would consider, ensuring that activities such as volunteering, which may not be considered physical activity traditionally, were eligible for the review and specifically included in search strategies. This consultation also provided valuable input regarding age inclusion criteria, with the emphasis that retirement did not mean a specific age, but instead could occur over a range in time. This underpinned our decision not to set age-limit parameters to the review at the outset of the work.

Involvement of patients and the public

In addition to the involvement of patients and the public during the scoping phase described above, the advisory group for the project also had representation from retired people. This was of benefit to the study in terms of providing advice on the application prior to submission, providing advice during the ongoing review regarding key terms during the searching phase of the work, and later input into the process in order to assist the team in understanding and interpreting the review findings. The inclusion of patient and public members on the advisory group was also valuable in terms of identifying avenues for dissemination and translating the key messages of the work for a lay audience.

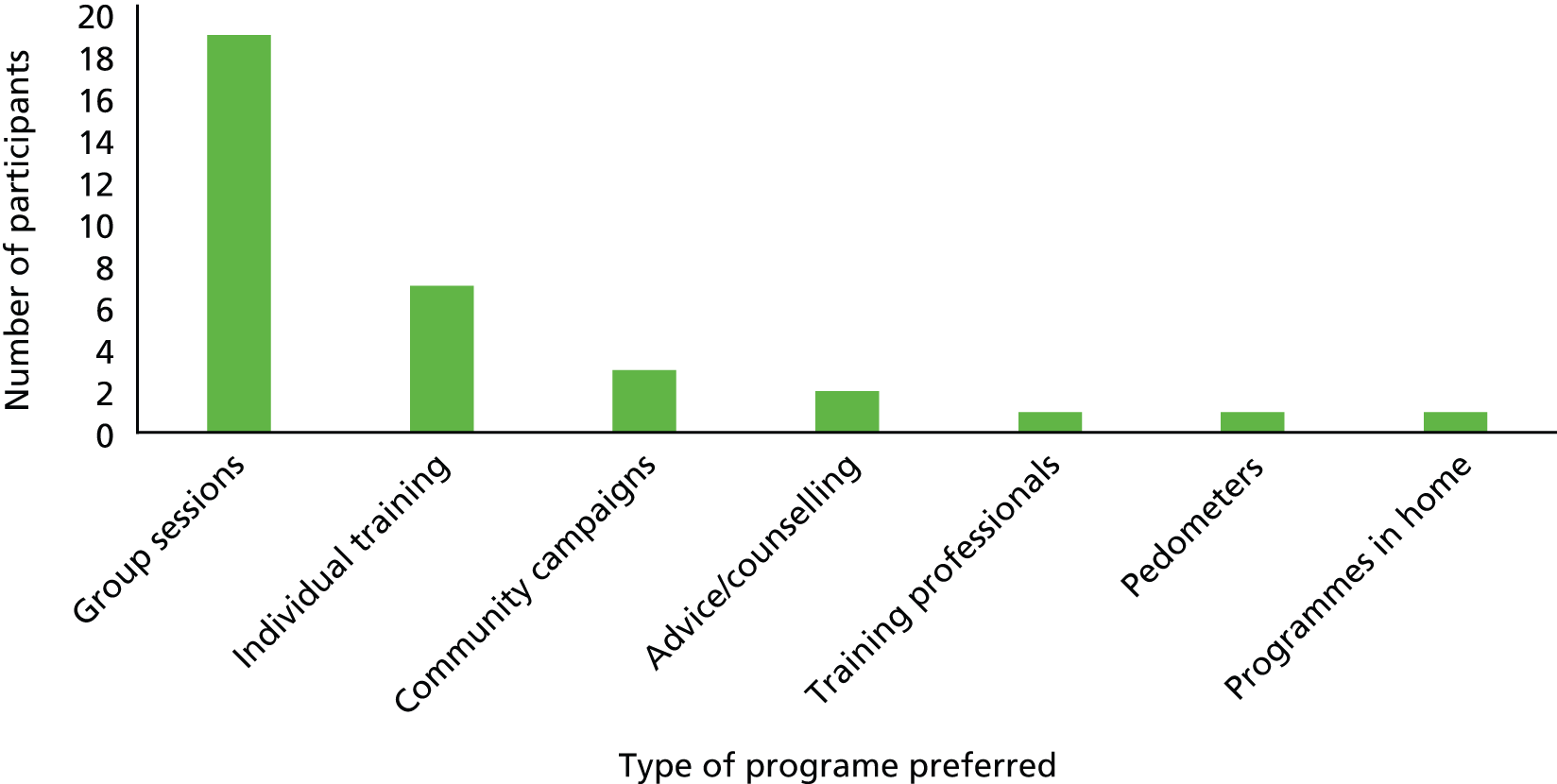

Following completion of the review, we presented and discussed the findings at a series of sessions with groups of retired people and staff providing services to older adults. We sought views regarding whether or not there may be issues of applicability of the evidence to the retirement transition in terms of if any of the interventions described in the literature may not be suitable for people around retirement; how far the factors reported in the qualitative literature may influence the amount of physical activity people close to retirement may do; and if elements of interventions reported may influence whether or not someone around retirement would take part in them. This phase of the work provided valuable insights into the translation and applicability of the study findings to the retirement population.

Identification of studies

Search strategies

A systematic and comprehensive literature search of key health and medical databases was undertaken from March to December 2014. The searching process aimed to identify studies that reported the effectiveness of interventions for people around the transition to retirement, as well as studies that reported the views and perceptions of older adults and staff regarding interventions. Searching was carried out for both reviews in parallel, with allocation to either effectiveness or qualitative reviews at the point of identification and selection of studies for potential inclusion. The search process was recorded in detail and included lists of databases searched, the dates on which searches were run, the limits applied, the number of hits and duplication as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. 15 The search strategy is provided in Appendix 1.

The search strategy was developed by the information specialist on the team (Helen Buckley-Woods) who undertook electronic searching using iterative methods to create a database of citations using Reference Manager version 12 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA). The searching process was both iterative and emergent,16 with the results of an initial search informing the development of a subsequent search strategy (and so on), in order to explore fully the evidence relevant to the research questions. Database searching alone is not sufficient to provide the necessary evidence for a systematic review17,18 so ‘supplementary’ searching techniques, such as citation searching, were employed to ensure a comprehensive approach to identifying the evidence. As public health evidence is typically dispersed across a number of disciplinary fields, a wide variety of data sources were searched to include medicine and health, social science and specialist bibliographic databases (such as SPORTDiscus). Sources to identify grey literature were also explored. Searches were limited to 1990 to present where sources allowed.

First search

An initial search was developed using terms that reflect the concept of the transition into retirement combined with terms that reflect the concept of physical activity. ‘Retirement’ terms were broad to reflect the population of interest and the varied circumstances of ‘retirement’ (i.e. not only from full-time employment). Hence, terms for redundancy, ‘empty-nest’ and other similar circumstances of role change (such as becoming a mature student) were included. The search strategy was informed by an existing scoping search and incorporated suggestions for terms and concepts from the project team and as a result of consultation in stakeholder workshops.

Second search

The initial search retrieved a limited number of papers that specifically referred to the transition to retirement or to retirement as a concept. In order to assess whether or not this was a true reflection of the published literature, a new search was developed which used terms for older age to reflect the population of interest. These terms were combined with the terms for physical activity that were used in the initial search. Combining only these two facets of the question would retrieve unmanageable numbers of papers, so a modified study filter was applied to identify quantitative studies of either clinical trial or observational design.

Citation searching

In addition to standard electronic database searching, citation searching was undertaken later in the project (November–December 2014). Two sets of papers were used for citation searches. First, citations to a small set of existing reviews on the topic of interest were retrieved. Second, citations to both qualitative and quantitative included papers were identified, producing a further substantial set of results.

Grey literature

Searches for grey literature were undertaken in order to identify any reports or evaluations of ‘grass roots’ projects or other evidence not indexed in bibliographic databases and also to minimise problems of publication bias. These searches were either in specific grey literature sources such as ‘Index to Theses’ and ‘OpenGrey’ or by searching specific topic-relevant websites.

Sources searched

The following electronic databases were searched for published and unpublished research evidence from 1990 onwards:

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (via ProQuest).

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (via EBSCOhost).

-

Cochrane Library, including Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Health Technology Assessments and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (via Wiley).

-

Health Management Information Consortium (via Ovid).

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid).

-

Science Citation Index via Web of Knowledge (Thomson ISI).

-

Social Science Citation Index via Web of Knowledge (Thomson ISI).

-

Sociological Abstracts (via ProQuest).

-

PsycINFO (via Ovid).

-

Social Policy and Practice (via Ovid).

-

SPORTDiscus (via EBSCOhost).

-

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre Databases: Bibliomap, Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews, Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions.

-

The database on Obesity and Sedentary behaviour studies: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/.

-

Open Grey: www.opengrey.eu/.

-

Index to Theses: www.theses.com.eresources.shef.ac.uk/default.asp.

-

Conference Papers Index Science and Social Science (via Web of Science).

-

Department of Health: www.dh.gov.uk.

-

BHF national centre for physical activity: www.bhfactive.org.uk/.

-

U3 A: www.u3a.org.uk/.

-

Web search (Duck Duck Go): https://duckduckgo.com/.

All citations were imported into Reference Manager (version 12) and duplicates deleted prior to scrutiny by members of the team.

Search restrictions

Searches were limited by date (1990 to present), as the review was aiming to synthesise the most up-to-date evidence. The searches did not set an English-language restriction. We included studies published in developed countries and, although we intended that the review would be predominantly limited to work published in English to ensure that papers were relevant to the UK context, we aimed to search for and include any additional key international papers that had an English abstract and that we were able to obtain.

Selection of papers

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

We aimed to include studies that were carried out with people during and shortly after the transition to retirement. However, we also considered studies of other populations for which we might be able to make an association with the recently retired population, for example, people who have been made redundant or who have given up work to become a carer. Our key population was therefore older people who were not in paid employment (part- or full-time), and those about to leave paid employment.

Following input during our initial consultation phase, which emphasised that retirement did not begin at a particular age, we aimed to be flexible in our definition of ‘retired people’, as there is no clear and universally accepted definition. We did not, therefore, initially intend to impose age restrictions on our searching beyond an inclusive definition of ‘older adults’ as being 50 years and over (thus ensuring that retirement in different professions such as the police force were included). As outlined in our study protocol, further on in the process we intended to consider the relevance and applicability of including studies of older adults of any age in the synthesis.

Following completion of the initial phases of searching, as a result of the types of study that we were finding, we developed a system of applicability criteria with age serving as a proxy for retirement transition (see Process of selection of studies). These criteria excluded studies with participants below the age of 49 years or over 75 years, as these were furthest from statutory retirement ages and were considered to have limited applicability to the about-to retire or recently retired population.

We excluded study populations in which the intervention was provided for a specific clinical condition (e.g. people with coronary heart disease or following specific cardiac events such as heart attack, diabetes, cancer or osteoarthritis). We also excluded papers that described the study sample as being elderly and frail or as having limited mobility. We did not exclude patients who visited their general practitioner (GP) for a consultation and were recruited via this means to a non-clinical physical activity intervention.

Interventions

We included studies of any intervention aiming to increase and/or maintain levels of physical activity which could be applied to those older adults in the transition to retirement. We did not place any limitations regarding the setting/context in which interventions were conducted. Physical activity interventions delivered in any setting that were targeted at, or had the potential to affect, older people in the transition to retirement were eligible for inclusion, for example, health settings, community settings and residential/supported care settings and community/voluntary sector groups.

We excluded interventions that had the purpose of improving a clinical condition rather than increasing physical activity more generally. We excluded interventions that were described as aiming to increase stretching/flexibility or balance rather than activity and those described as specifically aiming to reduce falls in older people.

Outcomes

Physical activity is defined by the World Health Organization as ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure’. 19 We therefore adopted a broad inclusion criteria in terms of outcomes. This included outcomes that measure physical activity directly using a validated scale or other tool, as well as those that report indirect measures related to physical activity, such as hours of gardening or participating in walking groups. We also included papers reporting other relevant outcomes such as social, psychological, behavioural and environmental factors related to increasing and/or maintaining physical activity in older people. We excluded papers that reported exclusively clinical outcomes such as cardiac function tests and blood sugar levels (papers with both clinical and physical activity outcomes were eligible for inclusion). We excluded studies concerned solely with stretching and flexibility outcomes.

Comparators

All comparator conditions were considered, as well as interventions with no concurrent comparator.

Study design

With the increasing recognition in the literature that a broad range of evidence is needed to inform the depth and applicability of review findings, experimental, observational and qualitative studies were included in the review. The review included designs that may be termed randomised controlled trials (RCTs), randomised crossover trials, cluster randomised trials, quasi-experimental studies, non-RCTs, cohort studies, before and after (BA)/longitudinal studies, case-control studies and qualitative studies. We excluded studies using a survey design. In order to maximise relevance, we included grey literature from the UK.

Other inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included studies from any developed country that is a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). As outlined above, we included studies published in English, and considered translations of those studies with relevant English abstracts. As noted above, the cut-off date for studies was 1990.

Process of selection of studies

Citations retrieved via the searching process were uploaded to a Reference Manager database. This database of study titles and abstracts was independently screened by two reviewers and disputes were resolved by consulting other team members. This screening process entailed the systematic coding of each citation according to its content. Codes were applied to each paper based on a categorisation developed by the team from previous systematic review work. The coding included categorising papers that fell outside the inclusion criteria (e.g. excluded population, excluded design, excluded intervention) as well as citations potentially relevant to the clinical effectiveness review and those potentially relevant to the qualitative review.

Full-paper copies of all citations coded as potentially relevant were then retrieved for systematic screening. Papers excluded at this full-paper screening stage were recorded and details regarding the reason for exclusion were provided.

Following our two large electronic database searches, we examined the scope of the literature that we had identified, and revisited our study questions and population age inclusion criterion. We had identified a large number of papers that described study populations as being older adults and/or those aged 40 years and over. However, we had found only one paper that specifically referred to the participants as being recently retired. Apart from this one paper, all other literature we identified provided only age bands or average ages for their study populations, with a minority including references to numbers in employment/not in employment and a smaller number still making reference to retirement. The nature of the identified literature therefore led us to further consider which types of papers provided data from older adult study participants that would best answer our research question and were therefore most applicable to those in the phase of retirement transition.

We adopted an approach to the selection of papers for review based on using age as a proxy for the period of retirement transition, where this was not specifically reported. We developed a grading system of applicability for the papers, whereby A1 papers had populations described as recently retired or about to retire, A2 papers had a population mean or median age of 55–69 years, A3i papers had a population mean/median in the range of age 70–75 years, and A3ii papers had a population mean/median of age 49–54 years. Owing to the large volume of literature identified (see Figures 1 and 2) we took the decision to exclude papers that had study participants with an average age of over 75 years or below 49 years, as these adults were furthest from retirement age and the data may have had limited applicability to our research question. A report from the OECD20 provides the statutory retirement age for men and women in each OECD country. It outlines that the age is either 65 or 67 years in all but three countries (68 years in two countries and 69 years in one). Further information regarding this selection process is detailed in the results section.

Data extraction strategy

Studies that met the inclusion criteria following the selection process above were read in detail and data were extracted. An extraction form was developed using the previous expertise of the review team to ensure consistency across the data retrieved from each study. The data extraction form recorded authors, date, study design, study aim, study population, comparator (if any), details of the intervention (including who provided the intervention, type of intervention and dosage). Three members of the research team carried out the data extraction. Data for each individual study were extracted by one reviewer and, in order to ensure rigour, each extraction was checked against the paper by a second member of the team.

Quality appraisal strategy

Quality assessment is a key aspect of systematic reviews in order to ensure that poorly designed studies are not given too much weight so as not to bias the conclusions of a review. As the review included a wide range of study designs, assessment required a sufficiently flexible and appropriate tool. Quality assessment of the effectiveness studies was therefore based on the Cochrane criteria for judging risk of bias. 21 This evaluation method classifies studies in terms of sources of potential bias within studies: selection bias; performance bias; attrition bias; detection bias; and reporting bias. As the assessment tool used within this approach is designed for randomised controlled study designs, we adapted the criteria to make them suitable for use across wider study designs including observational as well as experimental designs (Table 1). The detailed assessment for each study is provided in Appendix 2.

| Potential risk of bias | Bias present? | Detail of concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Selection bias | ||

| Method used to generate the allocation sequence, method used to conceal the allocation sequence, characteristics of participant group(s) | Y/N/unclear | |

| Performance bias | ||

| Measures used to blind participants and personnel and outcome assessors, presence of other potential threats to validity | Y/N/unclear | |

| Attrition bias | ||

| Incomplete outcome data, high level of withdrawals from the study | Y/N/unclear | |

| Detection bias | ||

| Accuracy of measurement of outcomes, length of follow-up | Y/N/unclear | |

| Reporting bias | ||

| Selective reporting, accuracy of reporting | Y/N/unclear | |

Assessment of quality for the qualitative papers was carried out using an eight-item tool adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative studies (Table 2). 22 The quality scoring for each study is presented in tabular form across each of the eight items (see Appendix 3).

| Quality appraisal tool for qualitative studies | |

|---|---|

| 1. Was there a clear statement of the aim of the research? | Y/N |

| 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Y/N |

| 3. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Y/N/unclear |

| 4. Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Y/N/unclear |

| 5. Has the relationship between researcher and participant been adequately considered? | Y/N |

| 6. Have ethical issues been taken into account? | Y/N/unclear |

| 7. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Y/N |

| 8. Is there a clear statement of findings? | Y/N |

Data analysis and synthesis strategy

Effectiveness studies

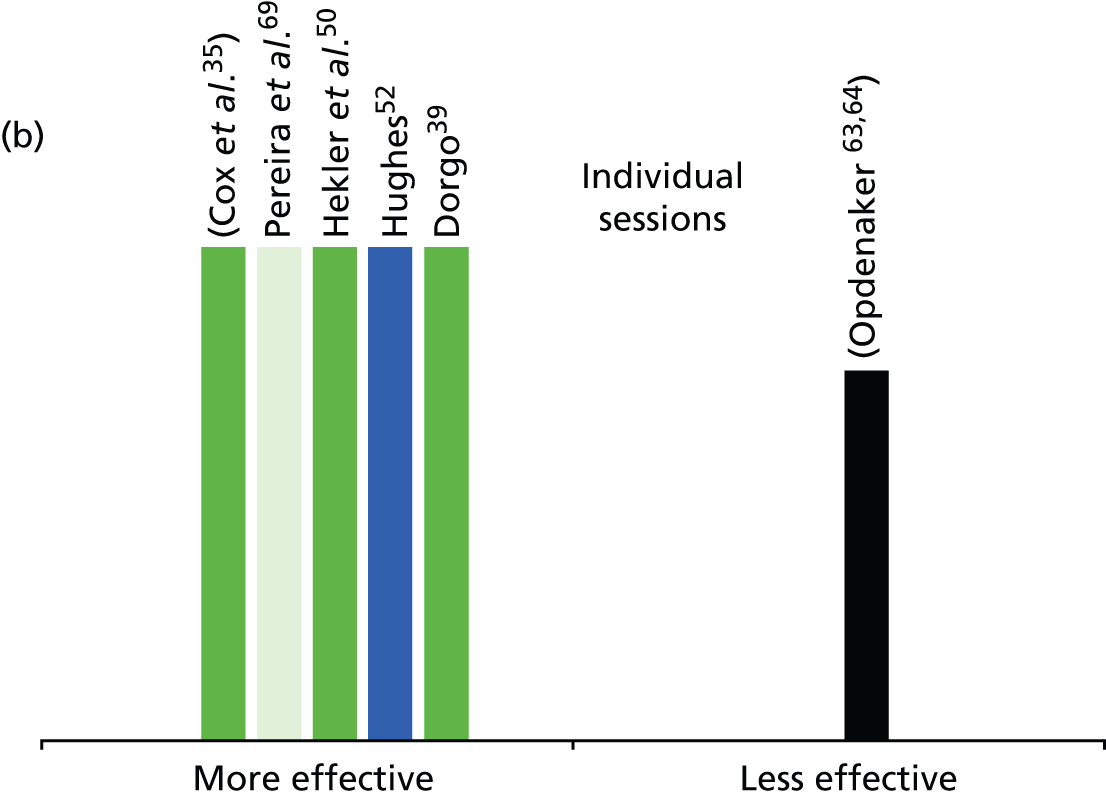

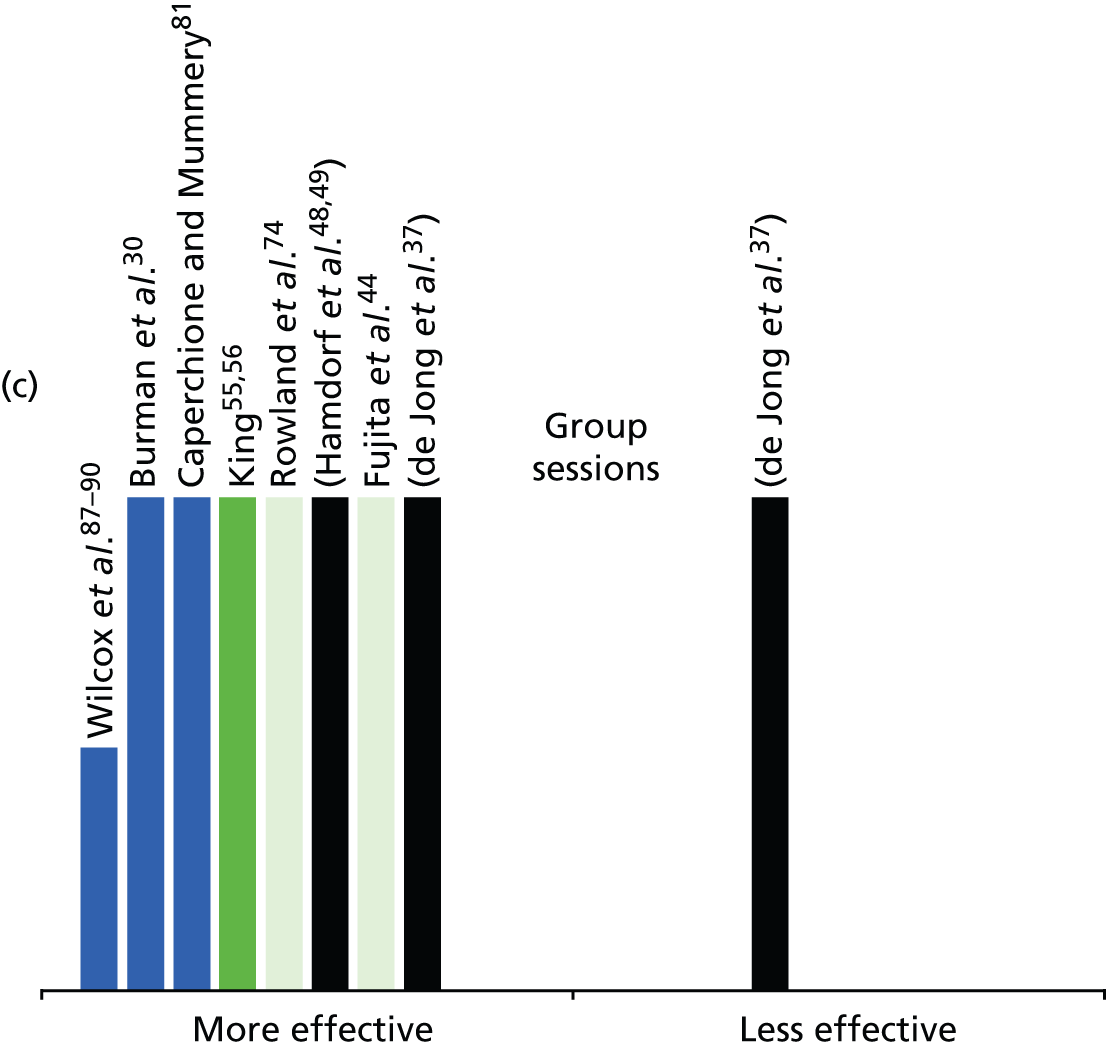

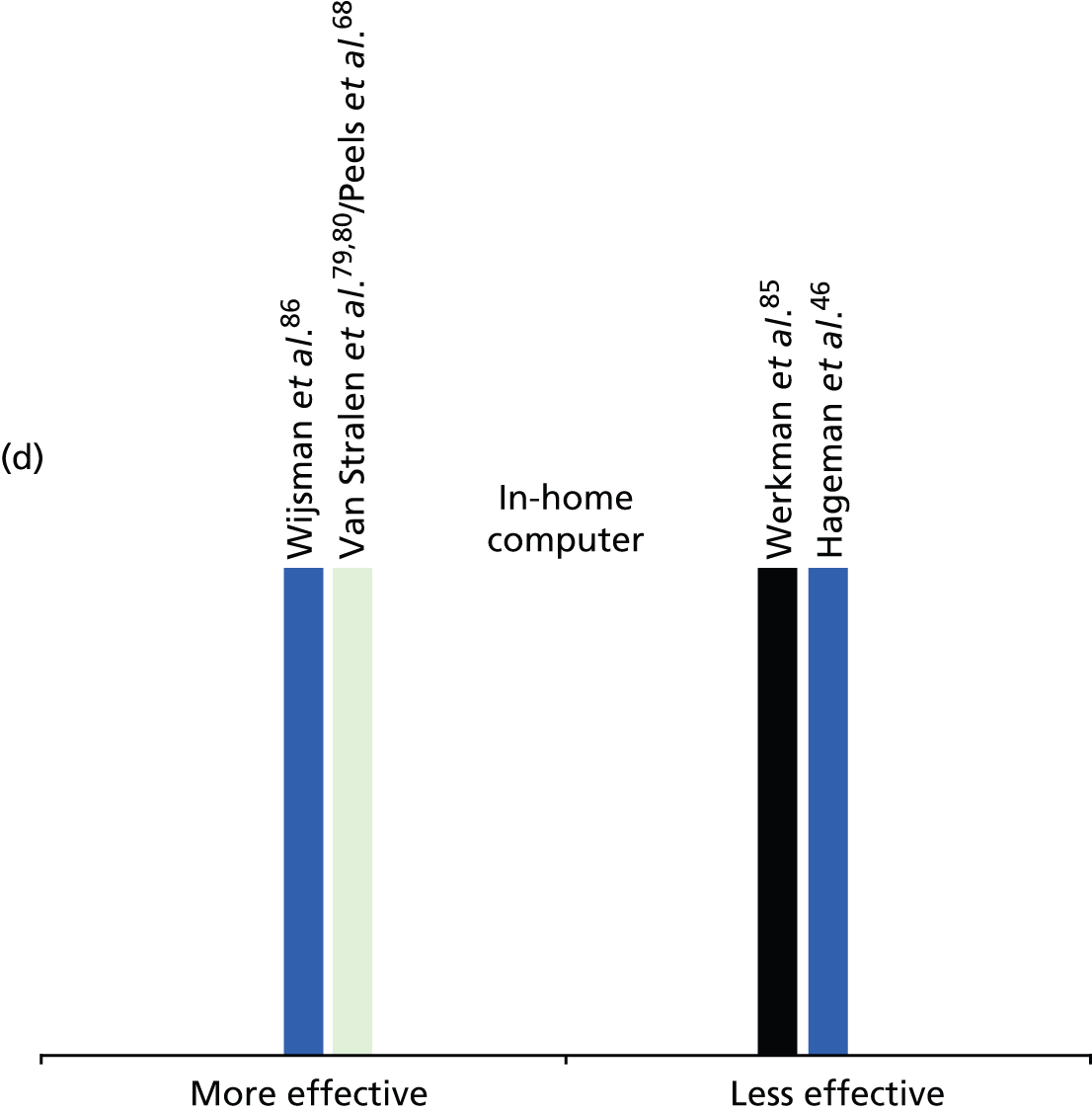

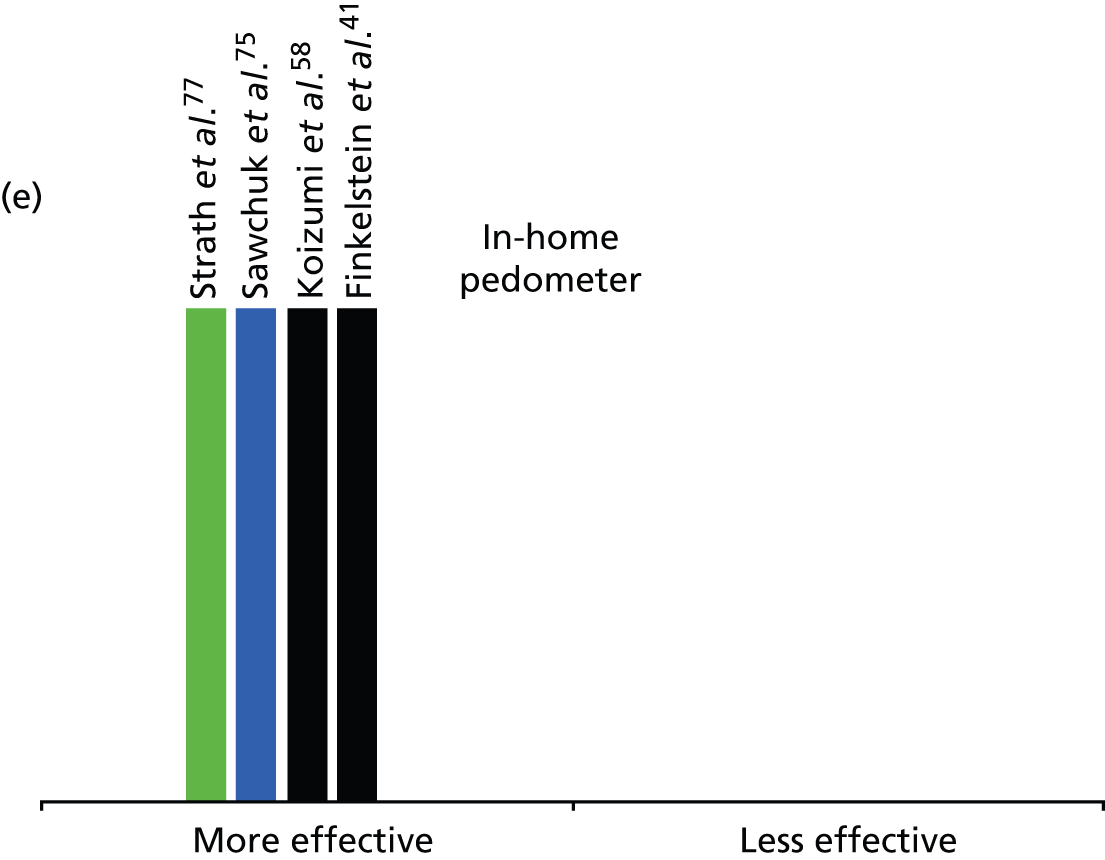

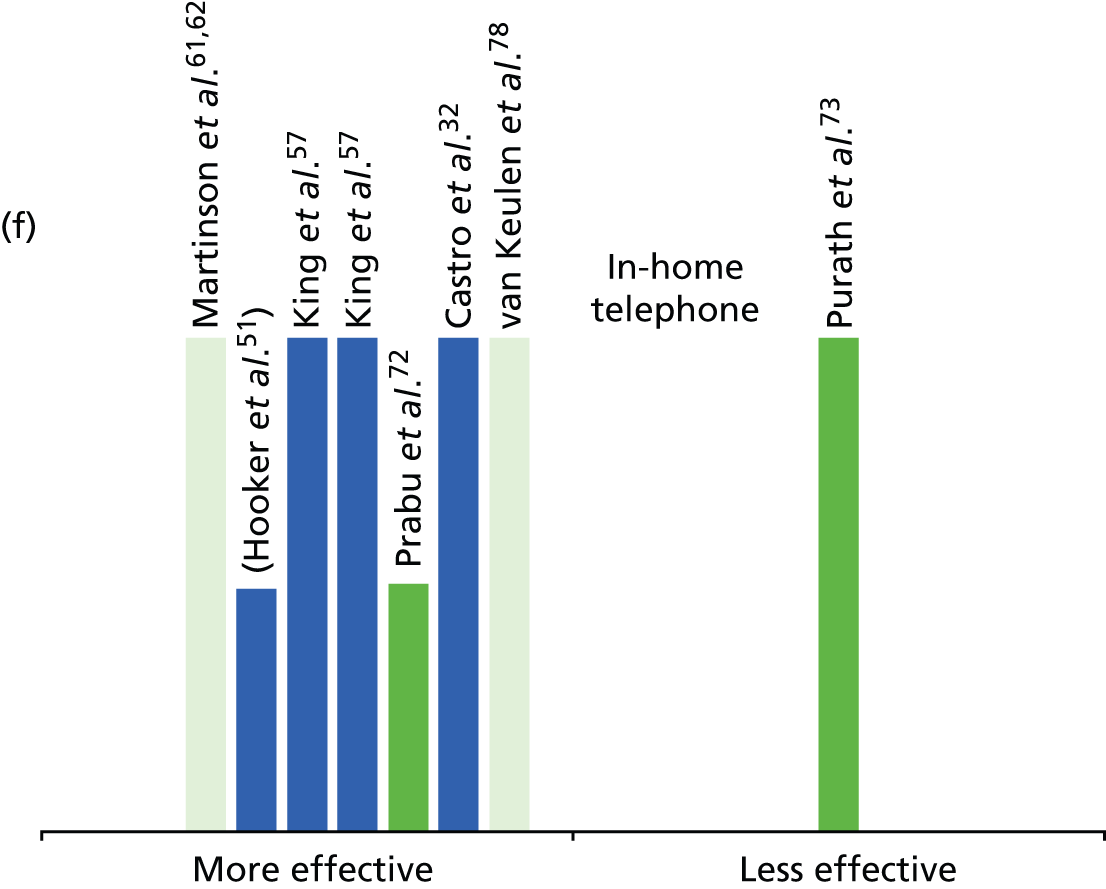

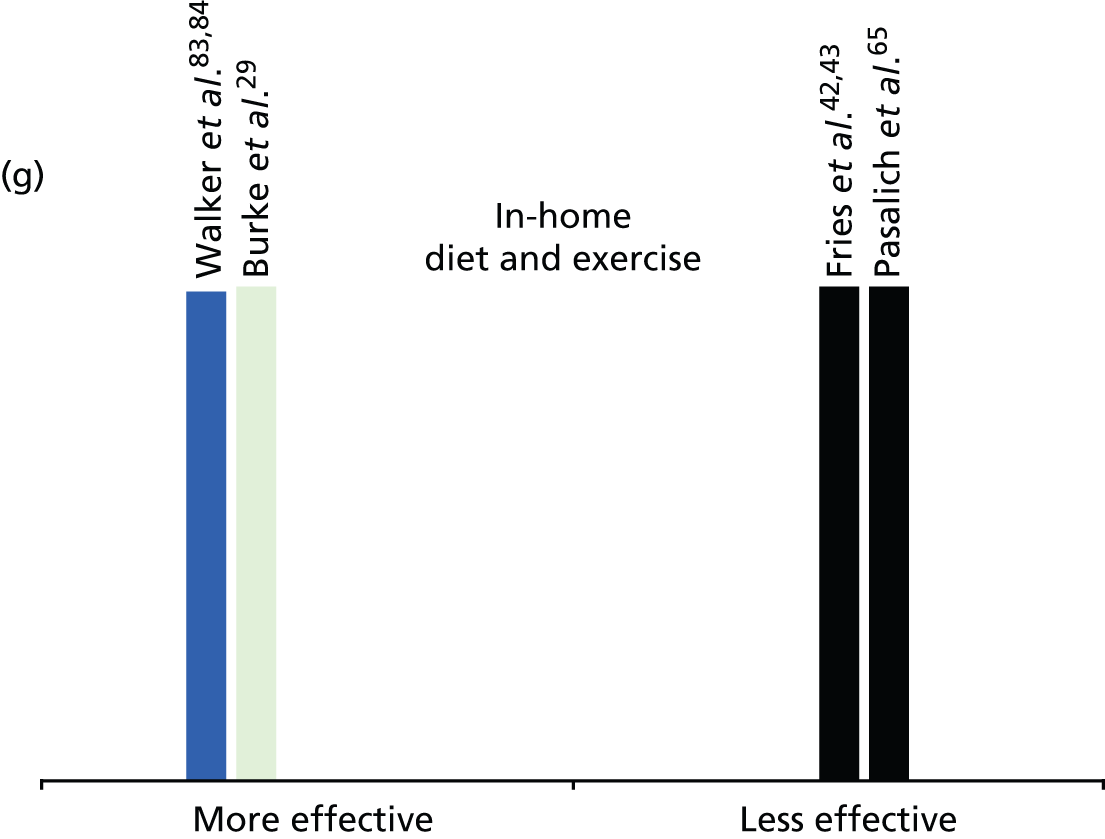

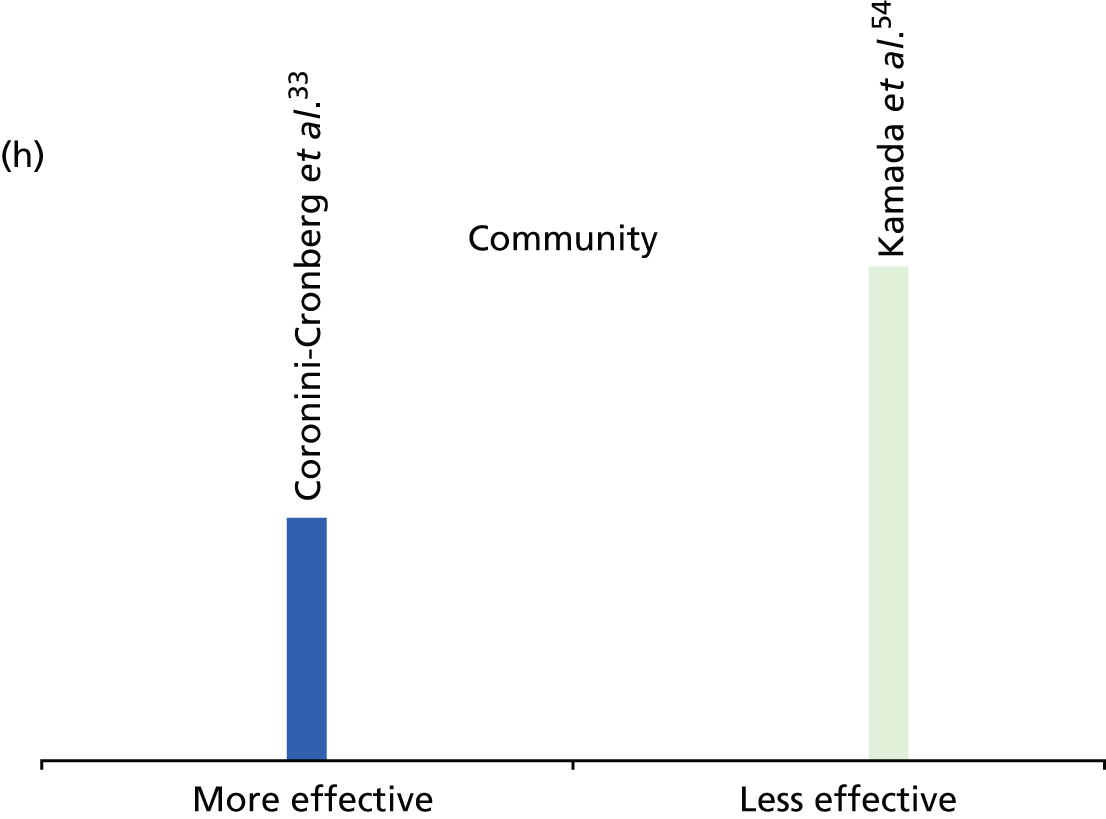

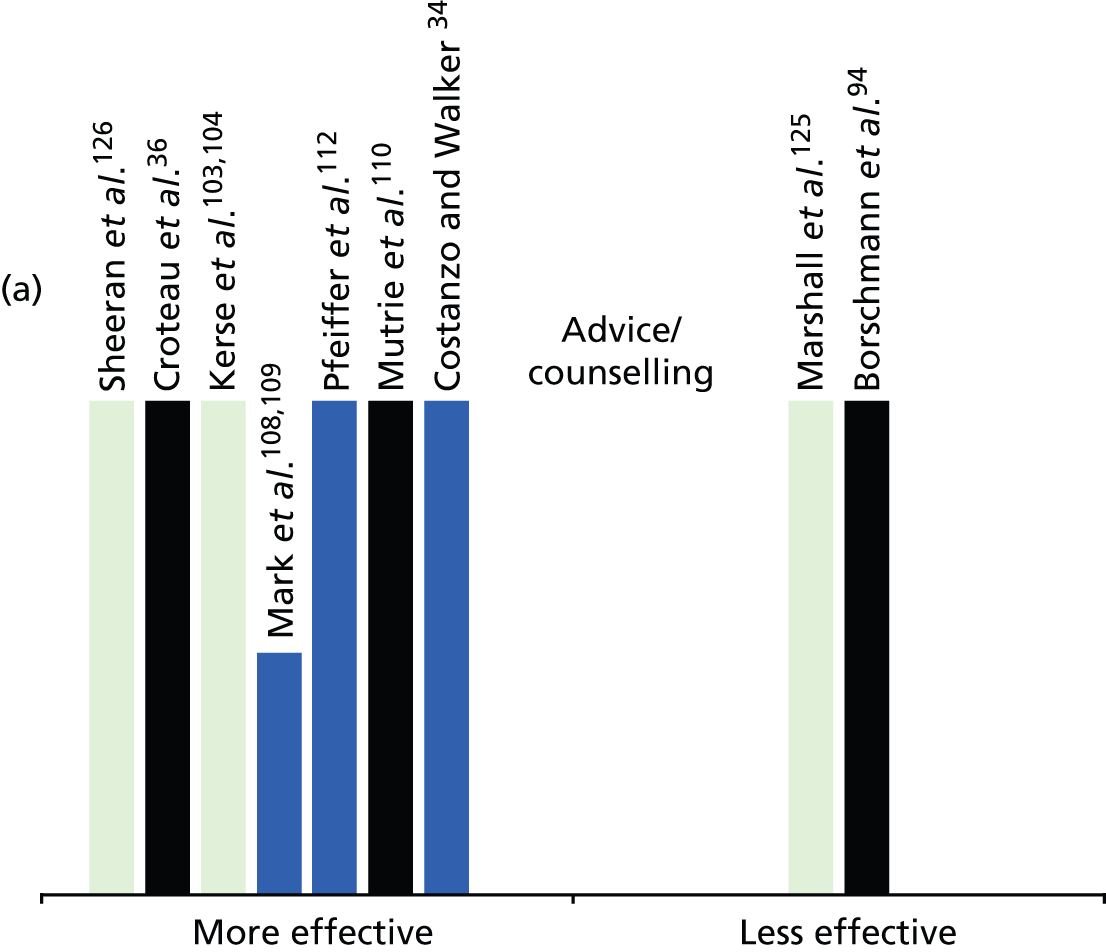

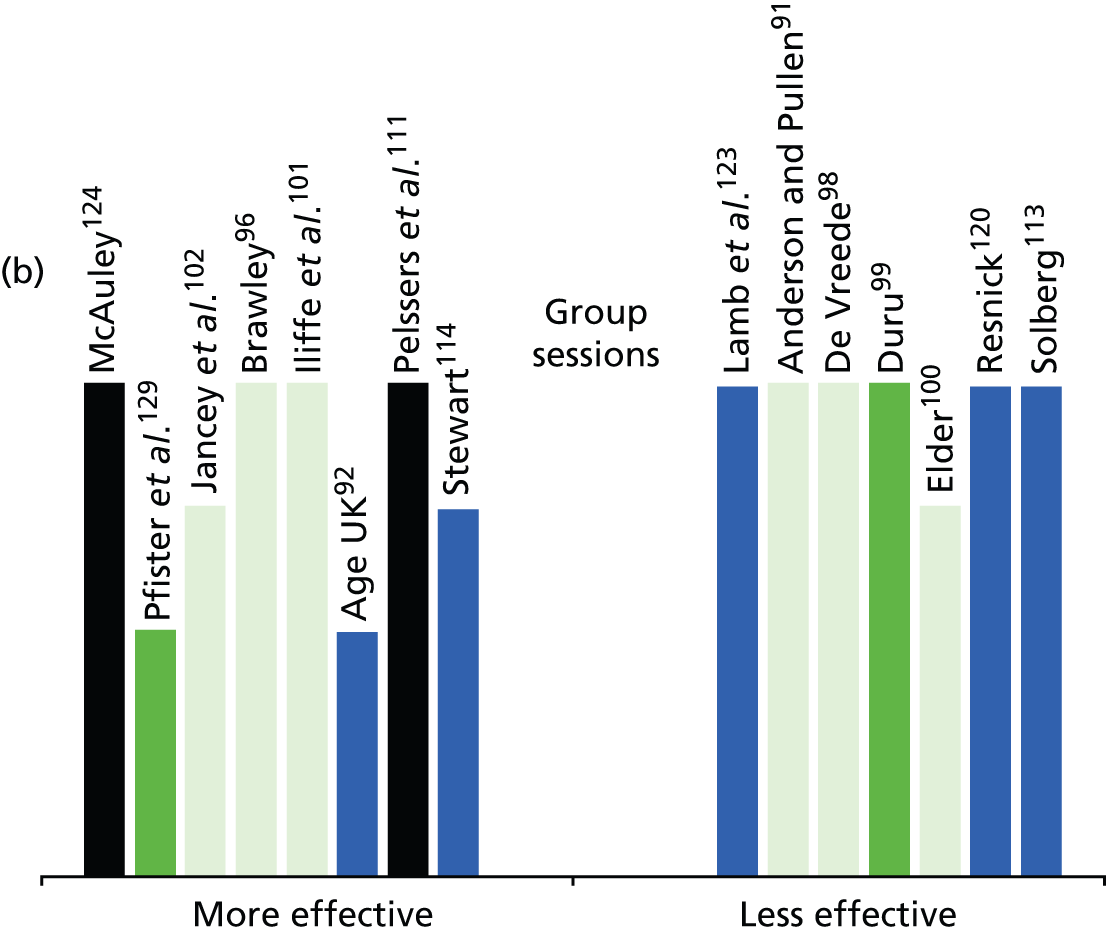

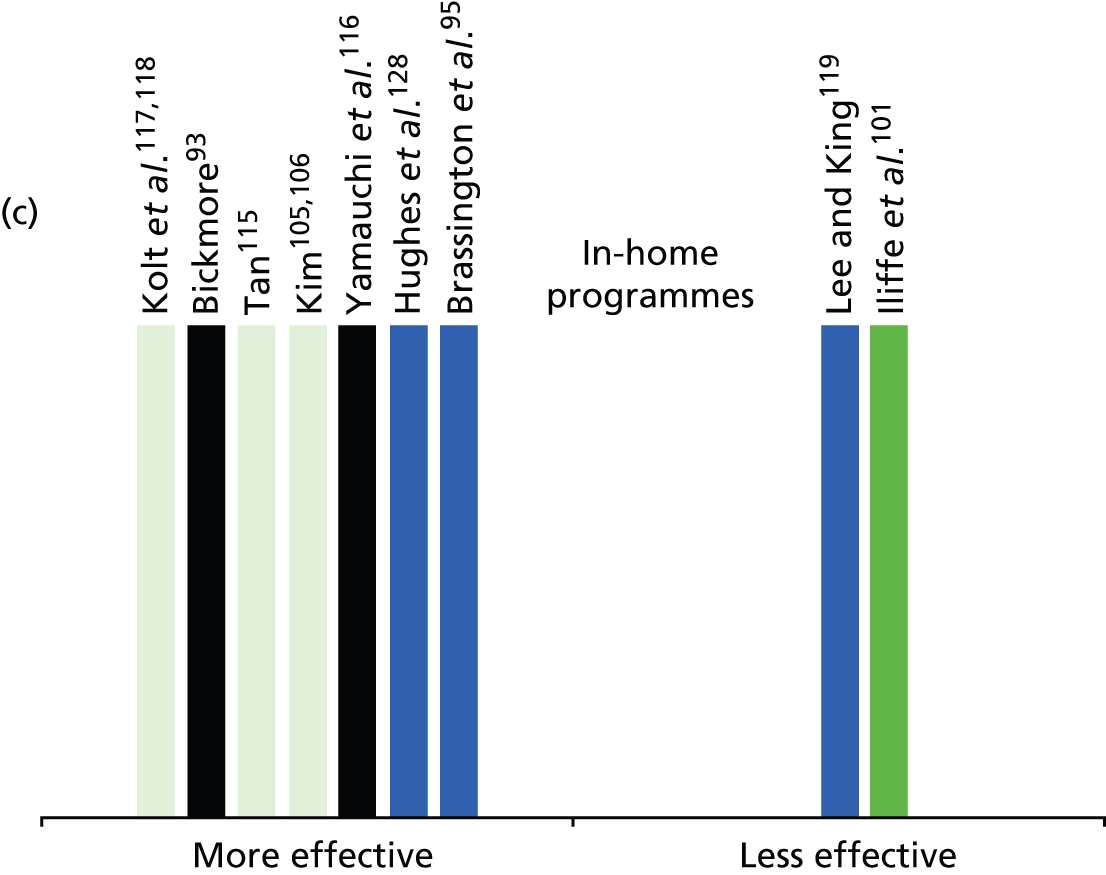

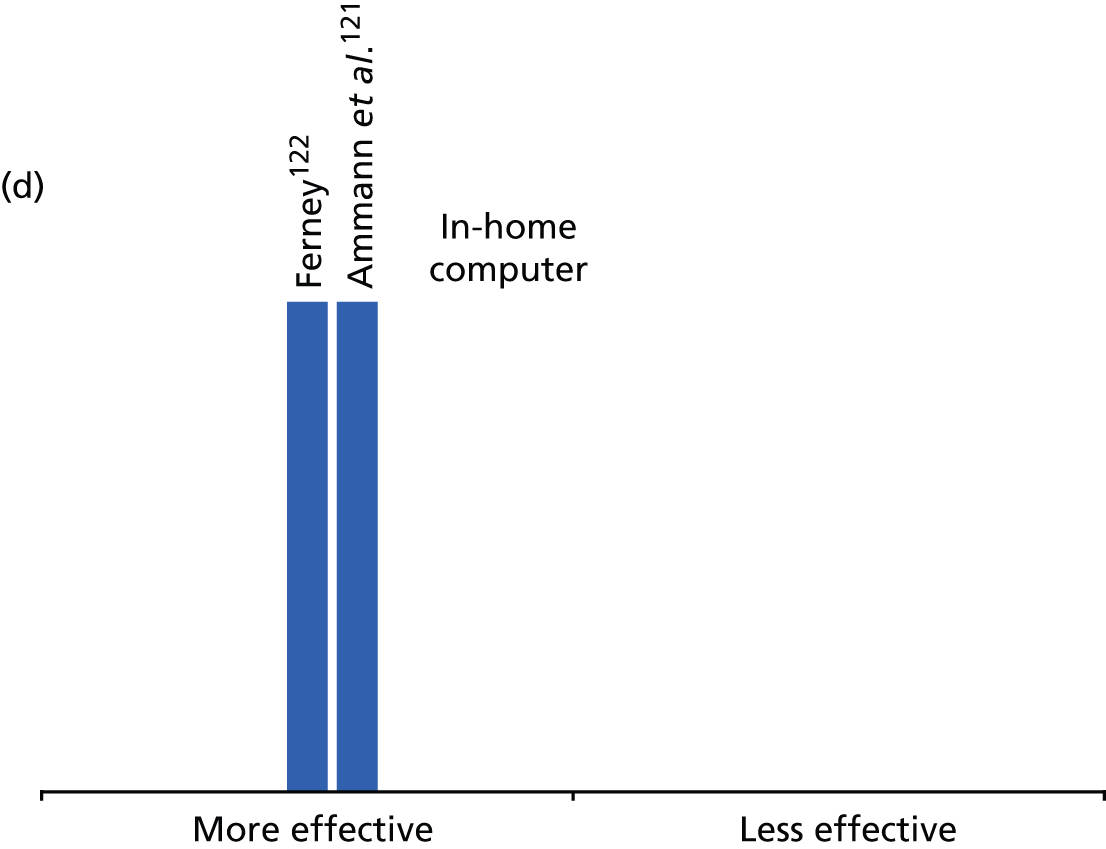

Data were synthesised in a form appropriate to the data type. It was proposed that meta-analysis calculating summary statistics would be used if heterogeneity permitted, with use of graphs, frequency distributions and forest plots. It was anticipated that subgroups including age of participants, learning disability, intervention content and delivery agent would be examined if numbers permitted. The heterogeneity of the included work precluded summarising the studies via meta-analysis, as described in Chapter 3, Intervention effectiveness by typology. In order to provide a visual summary, we drew on Harvest plot techniques to examine intervention outcomes across the different types and to perform comparison of where there was greater evidence of rigour. 23

Effectiveness review findings were reported using narrative synthesis methods. We tabulated characteristics of the included studies and examined outcomes by characteristics such as intervention content, agent of delivery, intervention dosage and length of follow-up. Relationships between studies and outcomes within these typologies were scrutinised.

Qualitative studies

Qualitative data were synthesised using thematic synthesis methods in order to develop an overview of recurring perceptions of potential obstacles to successful outcomes within the data. 24 This method comprises familiarisation with each paper and coding of the finding sections (which constitute the ‘data’ for the synthesis) according to key concepts within the findings. Although some data may directly address the research question, sometimes information such as barriers and facilitators to implementation has to be inferred from the findings, as the original study may not have been designed to have the same focus as the review question. 24

Combining quantitative and qualitative data

We had intended to use a meta-synthesis method which uses the qualitative data to add explanatory value to effectiveness study findings. 25,26 However, we found little of the qualitative literature referred specifically to interventions; instead, it tended to report more general views and perceptions of physical activity in retirement and/or older age, as well as elements of activity that may be most appealing. We therefore used a meta-synthesis method whereby themes relating to facilitators of engagement in physical activity were used to examine the content of interventions included in the review of effectiveness.

Chapter 3 Results of the effectiveness review

Quantity of the evidence available

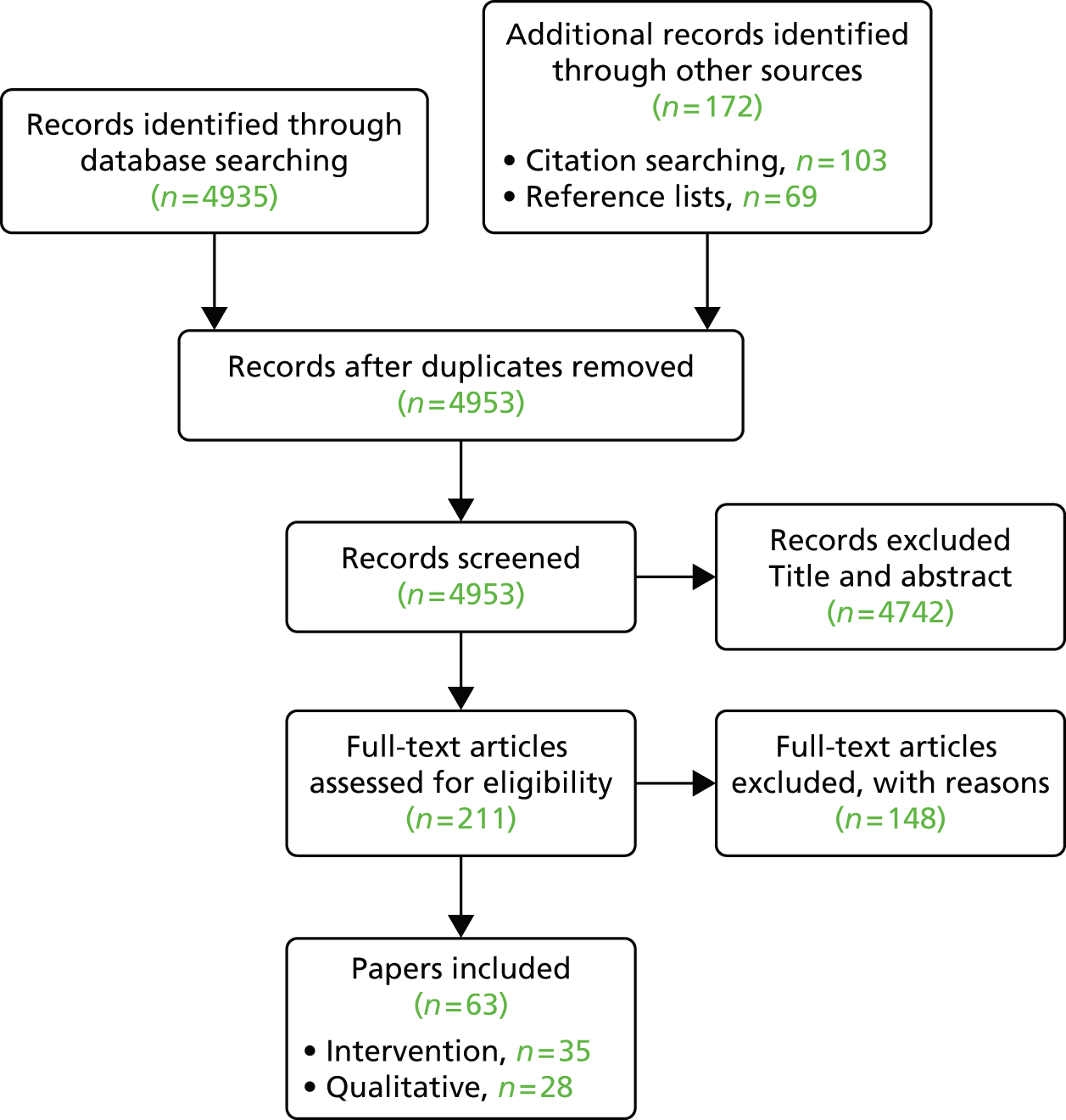

The initial electronic database searches using terms related to retirement/life transition identified 4935 citations following de-duplication. From this database of citations, 809 potentially relevant papers were retrieved for further scrutiny. We developed a grading system of applicability for the papers, in which A1 papers had populations described as recently retired or about to retire, A2 papers had a population mean or median of 55–69 years, A3i papers had a population mean/median in the range 70–75 years of age, and A3ii papers had a population mean/median in the range of 49–54 years of age. Detailed examination of these articles resulted in 19 A1/A2 and 16 A3 papers that met the inclusion criteria for the review of clinical effectiveness. Sixteen further papers relating to the review of effectiveness were identified from additional searching strategies (citation searching or reference list scrutiny), giving a total of 35 A1/A2 and 16 A3 papers included from this first search.

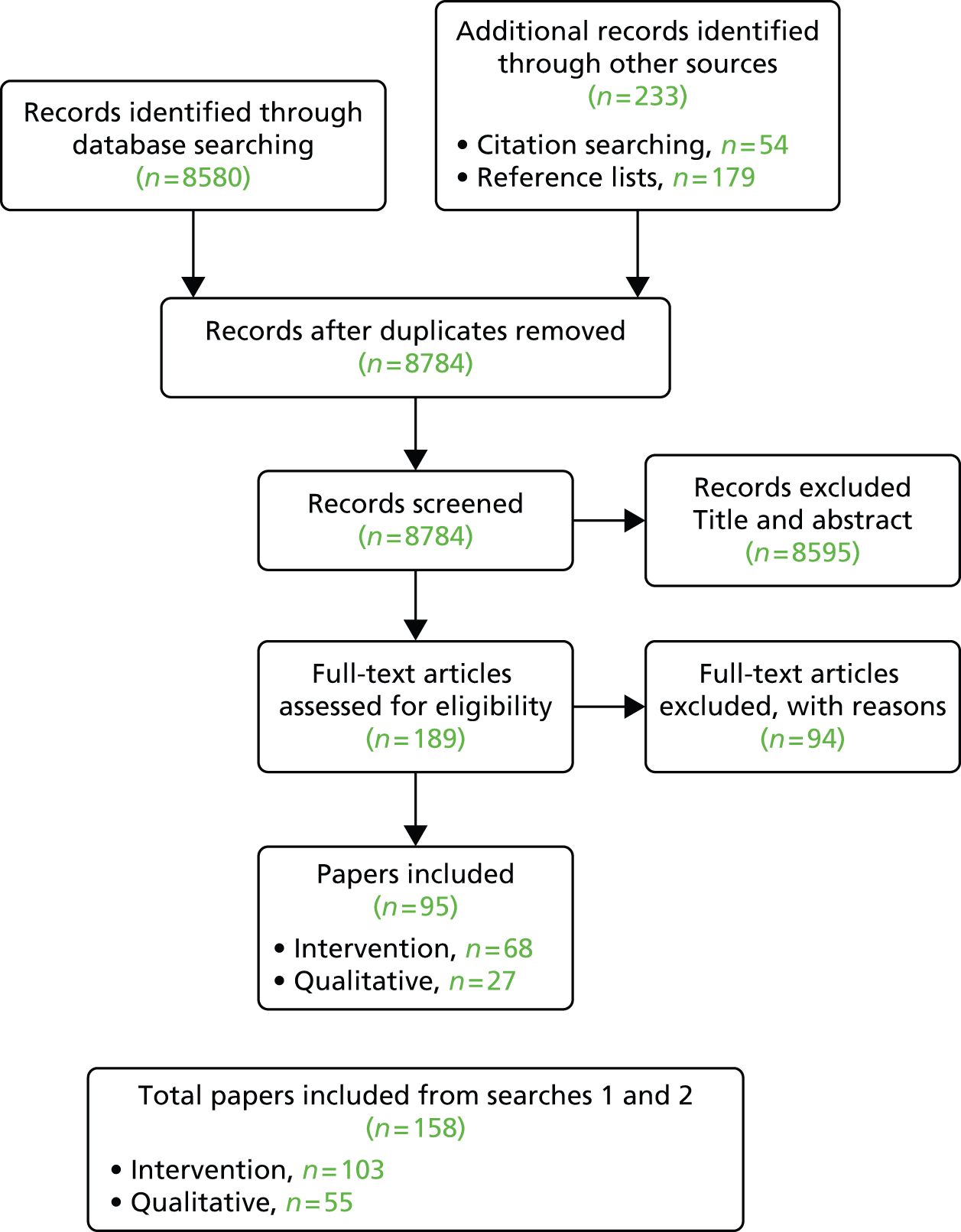

The second electronic database search using terms related to older adults identified an additional 8318 citations that had not already been retrieved. From these, 169 potentially relevant papers were retrieved for further scrutiny. Examination of these articles resulted in an additional 45 A1/A2 papers and 14 A3 papers that met the inclusion criteria for the review of clinical effectiveness. Twelve further A1/A2 papers relating to the review of effectiveness were identified from additional searching strategies (citation searching or reference list scrutiny). Figures 1 and 2 provides a detailed illustration of the process of study selection for each of our two phases of electronic database searching.

FIGURE 1.

Process of selection of studies: first search.

FIGURE 2.

Process of selection of studies: second search.

As outlined previously, there was little literature that described study participants as being our key population of interest, namely those about to retire or recently retired. A total of 63 papers fell within our proxy retirement transition age range (A2 papers) and 39 further papers fell within the wider age range (A3 papers).

There were a number of papers that reported data from the same study, either follow-up data in a later paper, or different aspects of a study including development of the intervention or implementation data. Of the 64 included A1/A2 papers, there were 48 unique studies.

Quality of the research available

We considered the potential for bias within included studies using the quality appraisal tool described earlier. Table 3 provides an overview of the quality assessment for the included intervention studies, with further detail provided in the expanded table in Appendix 2. The most frequent areas of concern related to limited reporting regarding the process of randomisation; the recruitment of volunteer participants; studies having two intervention arms with no control condition; the wide use of self-reported data for levels of physical activity; high rates of ineligible participants; and high rates of dropout in some studies.

| Study | Selection bias | Performance bias | Attrition bias | Detection bias | Reporting bias | Number of criteria met |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ackermann et al. (2005)27 | Y | Unclear | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Armit et al. (2005)28 | Unclear/not fully random | Unclear | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Burman et al. (2011)29 | Unclear | Unclear | Y | Y | N | 1 |

| Burke et al. (2013)30 | Unclear | Unclear | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Caperchione and Mummery (2006)31 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Castro et al. (2001)32 | Unclear | N | Y | Y | N | 2 |

| Coronini-Cronberg et al. (2012)33 | N | N | Y | Y | N | 3 |

| Costanzo and Walker (2008)34 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 1 |

| Cox et al. (2008)35 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | 2 |

| Croteau et al. (2014)36 | Y | N | Y | N | N | 3 |

| de Jong et al. (2006)37 | Unclear | Unclear | Y | N | Y | 1 |

| de Jong et al. (2007)38 | Unclear | Unclear | Y | N | Y | 1 |

| Dorgo et al. (2009)39 | Unclear | Unclear | N | Unclear | Y | 1 |

| Elley et al. (2003)40 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| Finkelstein et al. (2008)41 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| Fries et al. (1993)42 | Y | N | Y | N | N | 3 |

| Fries et al. (1993)43 | Y | N | Y | N | N | 3 |

| Fujita et al. (2003)44 | Y | N | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Goldstein et al. (1999)45 | Y | N | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Hageman et al. (2005)46 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| Halbert et al. (2000)47 | Unclear | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| Hamdorf et al. (1992)48 | Y | Unclear | Y | Y | N | 1 |

| Hamdorf et al. (1993)49 | Y | Unclear | N | N | N | 3 |

| Hekler et al. (2012)50 | Y | Y | N | N | N | 3 |

| Hooker et al. (2005)51 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Hughes et al. (2009)52 | Y | N | Y | N | N | 3 |

| Irvine et al. (2013)53 | Y | N | Y | N | N | 3 |

| Kamada et al. (2013)54 | N | N | N | Y | N | 4 |

| King et al. (2002)55 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| King et al. (2000)56 | N | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| King et al. (2007)57 | Unclear | N | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Koizumi et al. (2009)58 | Unclear | N | Unclear | N | N | 3 |

| Lawton et al. (2008)59 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| Marcus et al. (1997)60 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Martinson et al. (2010)61 | N | N | N | Y | N | 4 |

| Martinson et al. (2008)62 | N | N | N | Y | N | 4 |

| Opdenacker et al. (2011)63 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 2 |

| Opdenacker et al. (2008)64 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 2 |

| Pasalich et al. (2013)65 | Y | N | N | Y | N | 4 |

| Peels et al. (2012)66 | Unclear | Unclear | NA | NA | N | 1 |

| Peels et al. (2012)67 | Unclear | Unclear | NA | NA | N | 1 |

| Peels et al. (2013)68 | Unclear | Unclear | Y | Y | N | 1 |

| Pereira et al. (1998)69 | Unclear | N | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Petrella et al. (2010)70 | Unclear | Unclear | N | N | N | 3 |

| Pinto et al. (2005)71 | Y | Unclear | N | N | N | 3 |

| Prabu et al. (2012)72 | Y | N | Y | N | N | 2 |

| Purath et al. (2013)73 | N | N | Y | N | N | 4 |

| Rowland et al. (1994)74 | Y | N | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Sawchuk et al. (2008)75 | Y | Unclear | N | Y | N | 2 |

| Stevens et al. (1998)76 | Y | Unclear | Y | Y | N | 1 |

| Strath et al. (2011)77 | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| van Keulen et al. (2011)78 | N | N | Y | Y | N | 3 |

| van Stralen et al. (2009)79 | N | N | N | Y | N | 4 |

| van Stralen et al. (2010)80 | N | N | Y | Y | N | 3 |

| van Stralen et al. (2011)81 | N | N | Y | Y | N | 3 |

| van Stralen et al. (2009)82 | N | N | Y | Y | N | 3 |

| Walker et al. (2009)83 | N | N | N | Y | N | 4 |

| Walker et al. (2010)84 | N | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Werkman et al. (2010)85 | N | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Wijsman et al. (2013)86 | Y | N | N | Y | N | 3 |

| Wilcox et al. (2008)87 | Unclear | Y | Y | Y | N | 1 |

| Wilcox et al. (2009)88 | Unclear | Y | Y | Y | N | 1 |

| Wilcox et al. (2009)89 | Unclear | Y | Y | Y | N | 1 |

| Wilcox et al. (2006)90 | NA | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA |

| Total of numbers | 13 | 38 | 33 | 26 | 59 |

As shown in Table 3, only three studies56,84,85 met all five quality criteria. A total of 14 studies reported in 15 papers were judged as having a single area of potential bias. 40,41,46,47,54–56,59,61,62,65,73,77,79,83

Type of evidence available

Study design

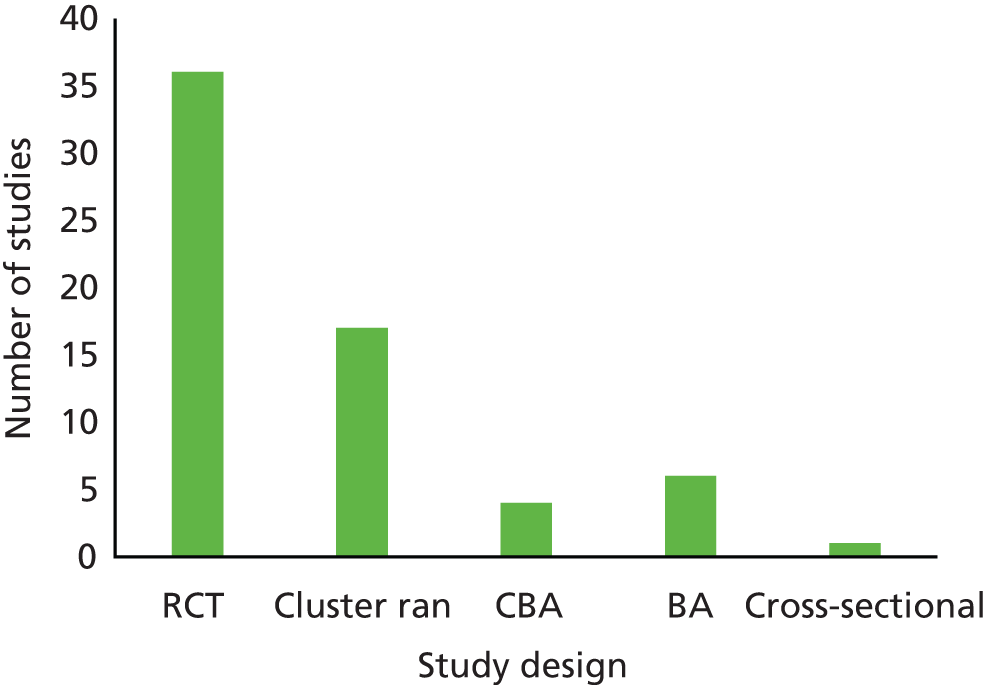

Figure 3 shows that the identified literature was of a reasonably high quality in terms of study design, with a large proportion (36) of the papers reporting studies using a randomised controlled design,28–32,34–36,39,41,44,46–50,52,53,55–59,61,62,69,71,73–78,83,84,86 and 18 papers reporting studies using a cluster randomised design. 27,37,38,40,42,43,45,54,66–68,70,79–82,85 See Appendix 3 for lists of the studies within each category.

FIGURE 3.

Number of intervention studies of each design. CBA, controlled before and after.

Population

Country of origin

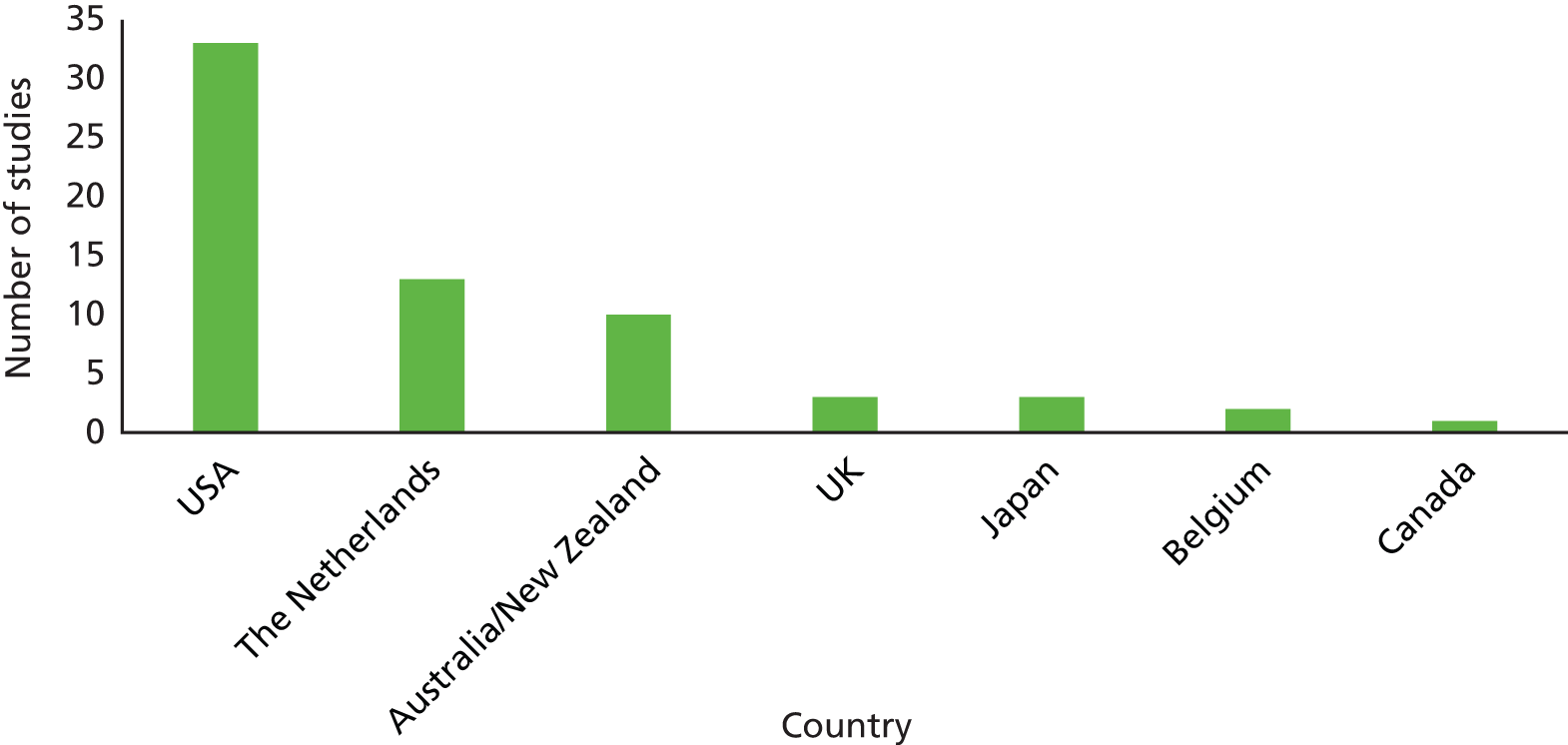

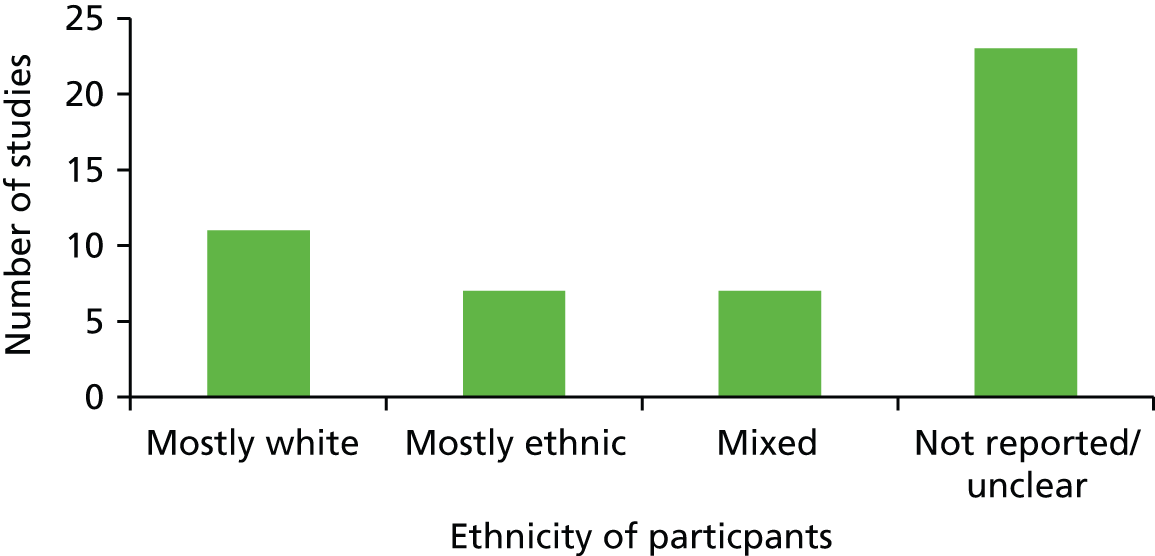

An overview of included studies by country of origin is provided in Figure 4. The greatest proportion of work was reported by authors based in the USA (33 papers),27,30,32,34,36,39,41–43,45,46,50–53,55–57,60–62,69,71–73,75,77,83,84 followed by authors based in the Netherlands and in Australia/New Zealand. Three of the papers were from the UK. 33,74,76 (See Appendix 3 for the list of studies within each category.)

FIGURE 4.

Number of intervention studies from each country.

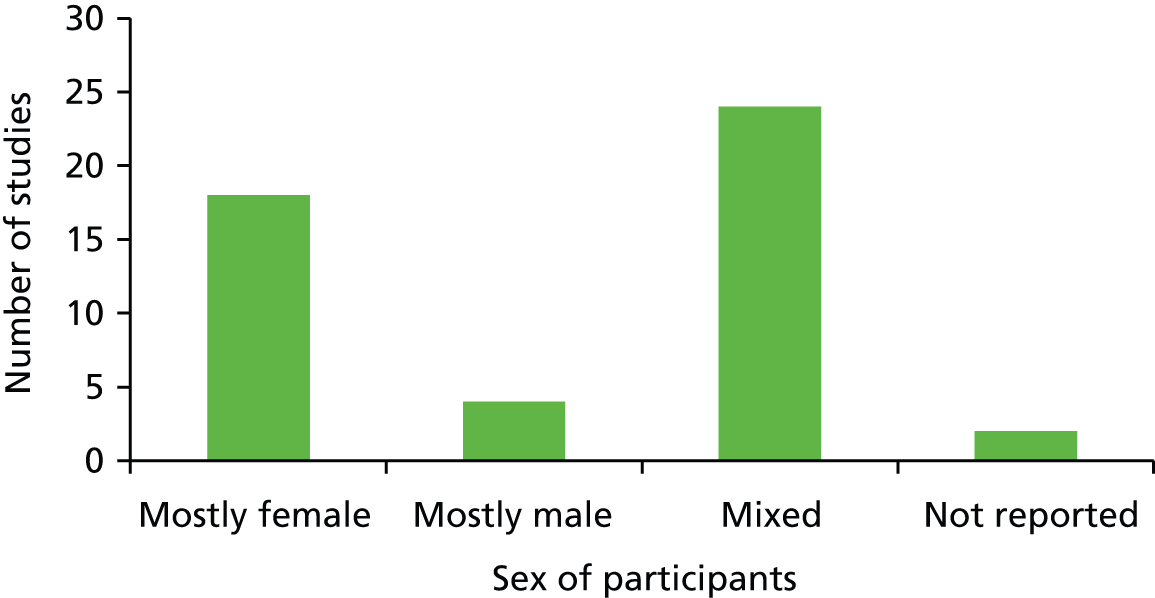

Sex

The literature contained 34 papers with either all female participants or a majority of female participants28,30,31,34–36,40,41,46,48–53,55–59,61,62,69,72–75,77,83,84,87–90 (Figure 5) (see Appendix 3 for a list of studies). This contrasted with only two studies that recruited only males. 27,85

FIGURE 5.

Number of intervention studies by sex of participants.

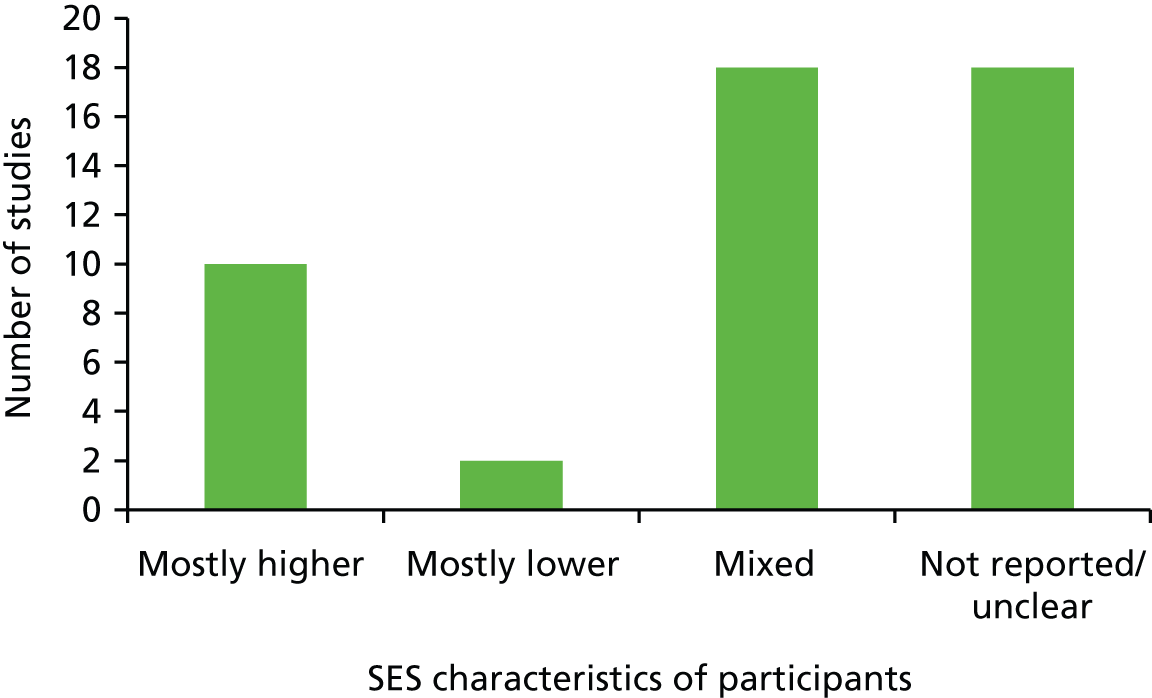

Socioeconomic/educational status

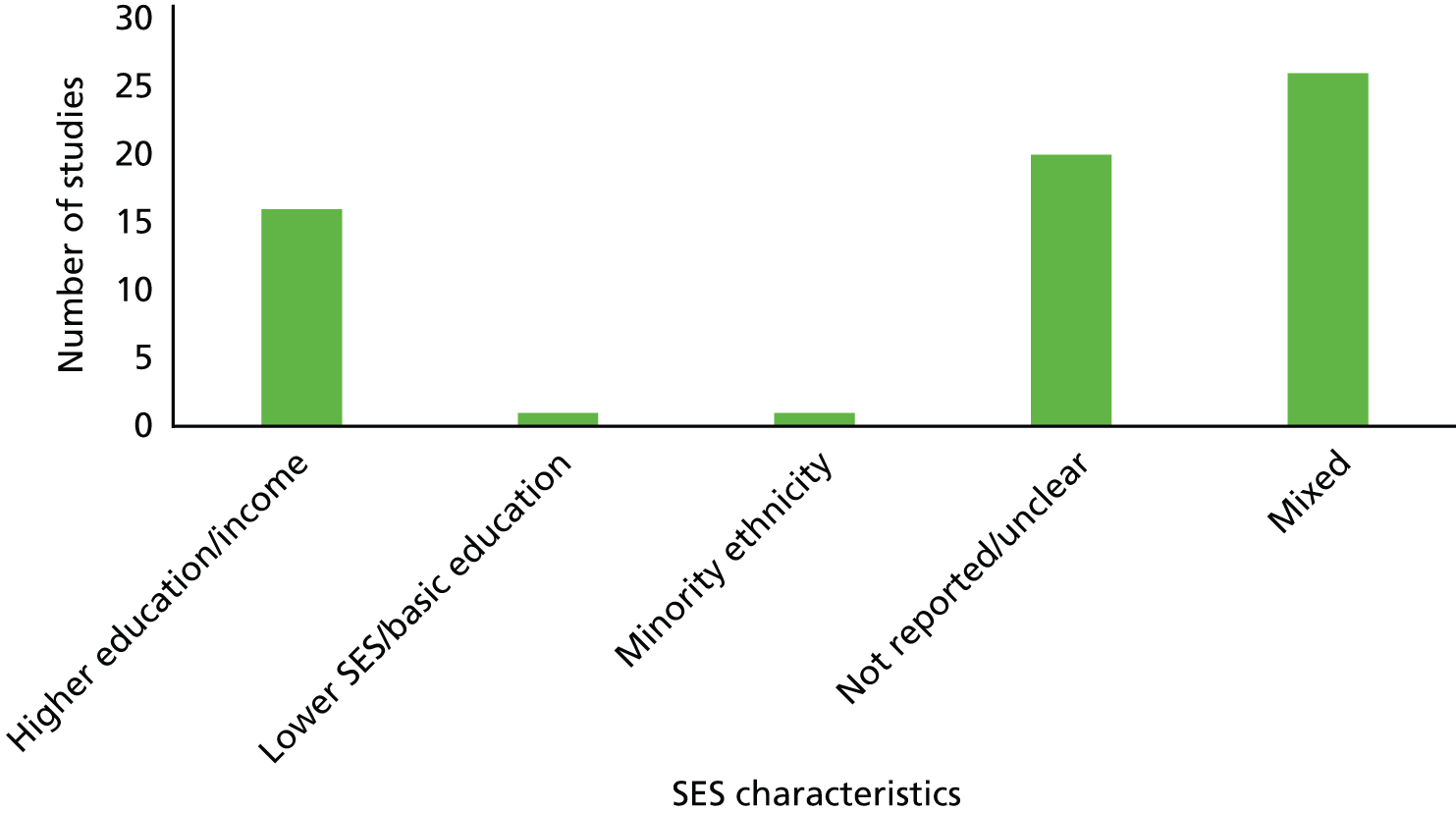

We identified only one study that described participants as being of predominantly low SES29 and one paper that described participants from a minority ethnic population. 75 Sixteen papers described their studies as being in predominantly more highly educated/higher income participants. 30,32,34–36,41,46,50,52,53,61,62,65,69,73,77 The majority of studies were either unclear regarding education/SES or included diverse/mixed participants. See Figure 6 for a summary graph and Appendix 3 for lists of studies within each category.

FIGURE 6.

Number of studies reporting socioeconomic characteristics of participants.

Physical activity level

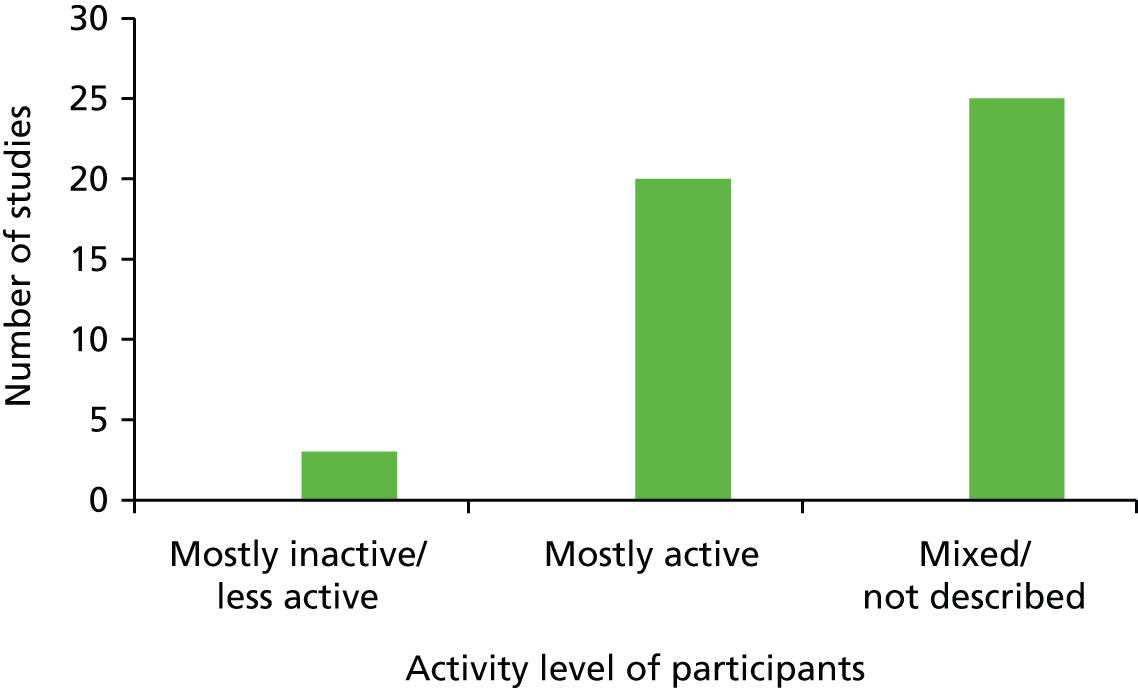

Approximately half of the studies (34) recruited participants who were below recommended activity levels, with the majority of these using higher activity level as an exclusion criterion. 27–31,34–36,40,41,46,50,52,53,55–57,59–65,70,71,73,75,77,86–90 The other 29 papers32,33,37–39,42–45,47,48,51,54,58,66–69,72,74,76,78–85 did not detail inactivity as being an inclusion criterion, and therefore in the absence of any other reporting it is assumed that these participants were most likely to be of mixed activity levels. (See Appendix 3 for detail of the studies within these categories.)

Age of participants

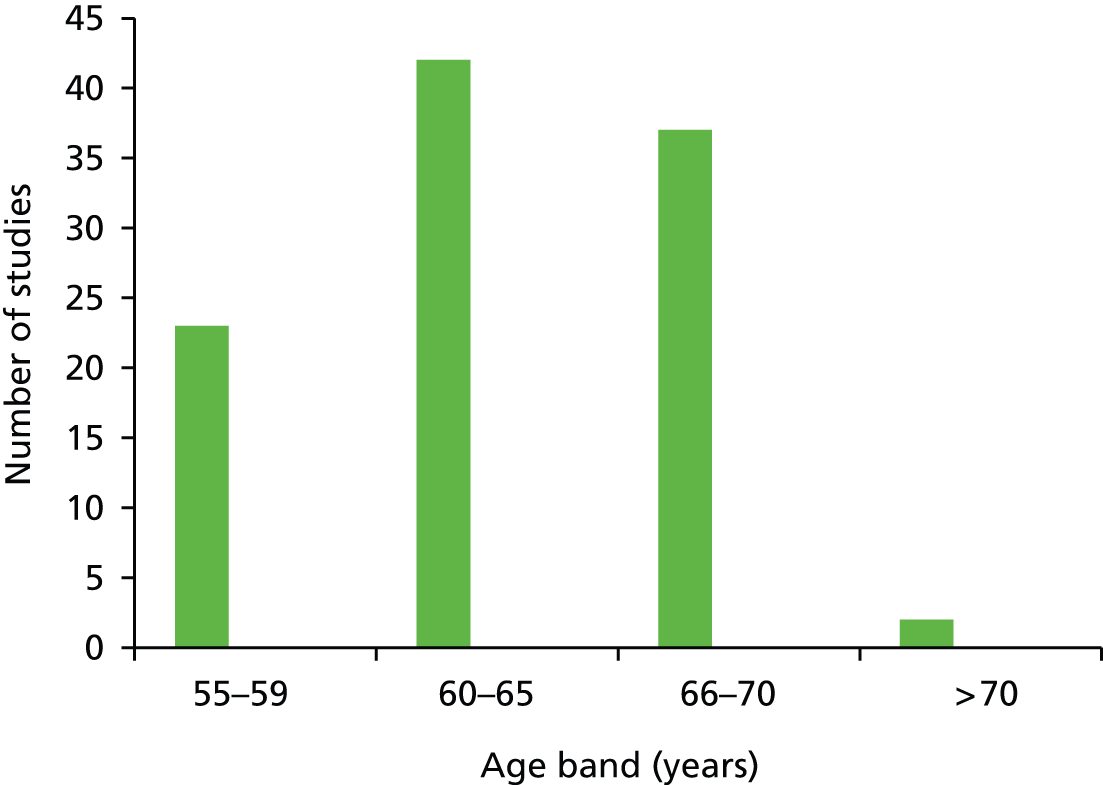

As outlined above, in the absence of literature specifically examining people at retirement transition, we took the decision to grade the applicability of other papers that reported interventions in older adults, with the average age of participants standing as a proxy for retirement age. We developed a four-point applicability rating system, in which A1 studies were those that referred to participants as immediately before or after retirement, A2 studies were those with an average participant age in the most common retirement transition age range of 55–69 years, and A3 studies were those that were less likely to be applicable to the retirement transition period, having an average age of either 50–54 years (A3i) or 70–75 years (A3ii).

This rating system was based on the most common statutory retirement ages across OECD countries of 65 or 67 years. The band 55–69 years was, therefore, most likely to include those approaching retirement (and those taking early retirement) together with those in the period immediately following retirement, and was of most relevance to our research question. The A3 papers, although potentially relevant, were considered to be of lower applicability. These papers were identified and examined to ascertain whether or not there were any studies of particular significance to the review. Table 4 presents the papers rated A1 and A2, categorised by age range. In this report, we intend to focus our synthesis on these A1/2 studies, as those most relevant to the retirement transition. However, we will provide an overview of the A3 studies and also consider any similarities and differences between the A1/A2 group and A3 studies.

| Average age | Studies |

|---|---|

| 55–59 years | Caperchione and Mummery (2006)31 (> 50 years) Castro et al. (2001)32 (50–65 years) Costanzo and Walker (2008)34 (50–65 years) Cox et al. (2008)35 (50–70 years) de Jong et al. (2006)37 (55–65 years) de Jong et al. (2007)38 (55–65 years) Elley et al. (2003)40 (40–79 years) Finkelstein et al. (2008)41 (50–85 years) Hageman et al. (2005)46 (50–69 years) King et al. (2007)57 (45–81 years) Lawton et al. (2008)59 (mean 58.9 years, SD 7 years) Martinson et al. (2010),61 (2008)62 (50–70 years) Pereira et al. (1998)69 (50–65 years) Prabu et al. (2012)72 (average 57 years) Sawchuk et al. (2008)75 (50–74) Stevens et al. (1998)76 (mean 59.1 years) van Keulen et al. (2011)78 (mean 57.15 years, SD 7 years) Walker et al. (2009),83 (2010)84 (50–69 years) Werkman et al. (2010)85 (mean 59.5 years) |

| 60–65 years | Armit et al. (2005)28 (55–70 years) Burman et al. (2013)29 (50 years and older) Burke et al. (2013)30 (60–70 years) Croteau et al. (2014)36 (51–81 years) Goldstein et al. (1999)45 (50 years and above) Hamdorf et al. (1992),48 (1993)49 (mean 64.8 years) Hekler et al. (2012)50 (50 years or older) Irvine et al. (2013)53 (mean 60.3 years) Kamada et al. (2013)54 (40–79 years) King et al. (2007)57 (55 years and over) Peels et al. (2012),66 (2012),67 (2013)68 (over 50 years) Petrella et al. (2010)70 (55–85 years) Strath et al. (2011)77 (55–80 years) van Stralen et al. (2009),79 (2010),80 (2011),81 (2009)82 (average 64 years, SD 8.6 years) Wijsman et al. (2013)86 (60–70 years) |

| 66–69 years | Ackerman et al. (2005)27 (50 years and older) Dorgo et al. (2009)39 (60–82 years) Fries et al. (1993),42 (1993)43 (all retired) Fujita et al. (2003)44 (60–81 years) Halbert et al. (2000)47 (60 years and over) Hooker et al. (2005)51 (48–90 years) Hughes et al. (2009)52 (50 years or older) King et al. (2002)55 (over 65 years) Koizumi et al. (2009)58 (mean 67 years) Marcus et al. (1997)60 (over 50 years) Opdenacker et al. (2011),63 (2008)64 (60–83 years) Pasalich et al. (2013)65 (60–70 years) Pinto et al. (2005)71 (mean 68.5 years) Purath et al. (2013)73 (60–80 years) Rowland et al. (1994)74 (mean 66 years) Wilcox et al. (2008)87 (mean 68.4 years, SD 9 years) Wilcox et al. (2009),89 (2006)90 (50 years or older) Wilcox et al. (2009)88 (50 years or over) |

| No average | Coronini-Cronberg et al. (2012)33 (over 60 years) |

Retirement/employment

As described above, only a minority of papers made reference to the employment/retirement status of the older adults included in the studies. The 22 papers that provide this detail are listed in Table 5. As can be seen, four of the interventions were carried out in populations in which all individuals were described as retired. Where percentages of those employed are provided, it is not clear if the other non-employed participants were unemployed or retired or working part time. The challenge in identifying the retirement status of study populations in these papers was further highlighted by Hooker et al. 51 This study makes an interesting distinction between those participants that are categorised as ‘retired and working’ and those categorised as ‘retired and not working’. A further point of interest relates to the only paper we identified to describe the study population as recently retired. This paper85 gives the mean age of study participants as a seemingly young age of 59.5 years, which supports our decision to include those in their late fifties in our A2 applicability band.

| Study | Reported participant characteristics |

|---|---|

| Armit et al. (2005)28 | 81% retired |

| Burke et al. (2013)30 | 40% working |

| Costanzo and Walker (2008)34 | 1 (of 51) not employed |

| Cox et al. (2008)35 | 52–80% employed |

| Croteau et al. (2014)36 | 16 (of 36) employed |

| Finkelstein et al. (2008)41 | 28% retired |

| Fries et al. (1993),42 (1993)43 | All retired |

| Goldstein et al. (1999)45 | 36% employed |

| Hageman et al. (2005)46 | 6.7% retired |

| Halbert et al. (2000)47 | All retired |

| Hekler et al. (2012)50 | 56% employed |

| Hooker et al. (2005)51 | 49% retired, not working; 17.7% retired, working; 20.9% employed |

| Kamada et al. (2013)54 | 64% employed |

| King et al. (2007)57 | 48.5% working full-time |

| Martinson et al. (2010),61 (2008)62 | 77% employed |

| Opdenacker et al. (2008)64 | All retired |

| Pasalich et al. (2013)65 | 42% employed |

| Rowland et al. (1994)74 | All retired |

| Sawchuk et al. (2008)75 | 27% employed |

| Stevens et al. (1998)76 | 55% economically active |

| van Stralen et al. (2009)79 | 47% employed |

| Werkman et al. (2010)85 | Recently retired |

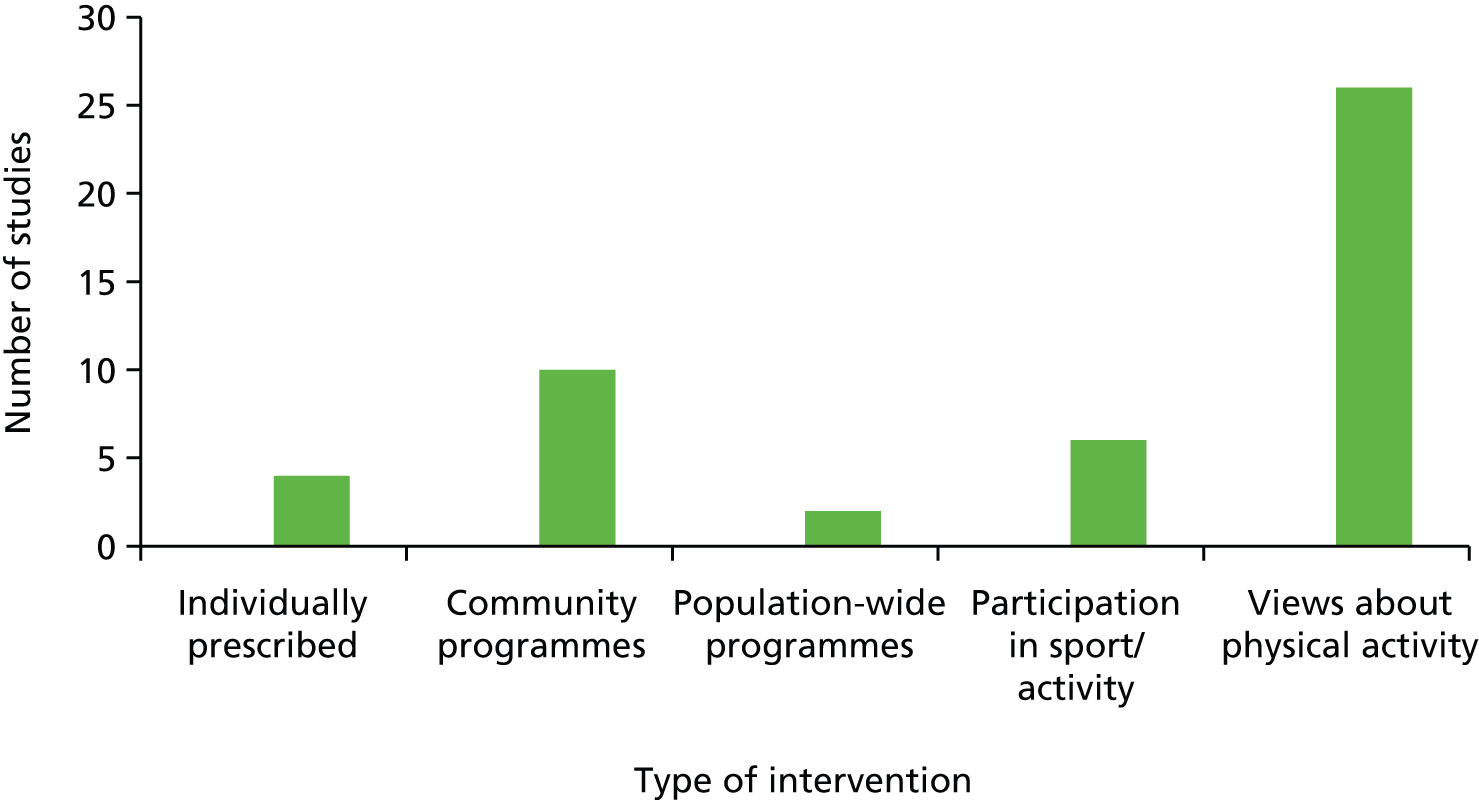

Intervention typology

The papers reported a varied range of intervention approaches, and included one study that intervened with health-care professionals in order to enhance the content of consultations,57 one that evaluated a community campaign54 and a further study that analysed the effect of providing free bus passes to older adults. 33 The remaining papers were divided into those that evaluated interventions provided to participants within their home (content was delivered via the telephone, via e-mail/internet or via post) and those where participants either travelled to their local community health centre/surgery for advice/counselling, attended classes/workshops, or took part in organised walks/swimming sessions. For many of these away-from-home interventions, it was unclear where exactly the sessions were held.

The in-home interventions often included multiple elements such as advice, pedometer use, keeping an exercise diary, and/or information. A number of the papers examined different variants of interventions rather than comparing with a control group. The Peels et al. 66–68 studies, for example, varied the delivery method (via the internet vs. via mail), and the content (additional environmental information vs. none). Croteau et al. 36 examined the addition of group sessions to a standard intervention, Sawchuk et al. 75 evaluated the addition of a pedometer to their programme and Strath et al. 77 included telephone calls for a subgroup of participants.

Outcomes measured

The included literature measured a wide range of outcomes, encompassing those that were self-reported via completion of questionnaires, in person, via telephone or via postal questionnaire. Outcomes that were measured by the research team included weight, body mass index (BMI) and fitness tests, together with data downloaded from pedometers or accelerometers. Table 6 outlines the physical activity measures that were used within the set of papers. Of note are only two papers which measured inactivity in addition to activity. 29,55 The first of these29 collected data on reported sitting time (minutes per week), and the second55 used a questionnaire (Measure of Older Adults’ Sedentary Time), with television viewing time considered to be the primary outcome of interest. In addition to these measures relating to physical activity, many papers also included a raft of other measures such as strength, balance, flexibility or falls, which we have not included as not directly relating to activity levels.

| Type of measure | Specific outcomes assessed |

|---|---|

| Objective measures | Activity Accelerometer Pedometer (daily steps/aerobic minutes) Retention and participation in programmes |

| Fitness 1-mile walk time 12-minute walk test 12-minute swim 1.6-km walk time Record of illness and injury Health benefit company data on claims made Rockport Walking Fitness Test |

|

| Biophysical Blood pressure Body fat Cardiovascular risk Body composition BMI Weight Waist circumference Biotrainer data Senior fitness tests of muscle strength, endurance and balance |

|

| Self-reported | Activity 7-day activity recall questionnaire (or modified version) Achievement of recommended minimum levels of moderate-intensity physical activity CHAMPS questionnaire used to calculate calorific expenditure Compendium of Physical Activity Tracking Guide Dutch Short Questionnaire to Assess Health-Enhancing Physical Activity Exercise history questionnaire Exercise Habits Scale Health Habits questionnaire Human Activity Profile International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire Maximum current activity Measure of older adults’ sedentary time Minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity National Travel Survey Older adults sedentary behaviour Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly Paffenbarger Sports and Exercise Index Reported level of regular physical activity Self-report daily log of activity Sitting time (minutes per week) Time spent walking Total weekly days and total weekly minutes of physical activity Travel diary |

| Fitness Comparative fitness rating Perceived fitness score |

|

| Psychosocial correlates Barriers to Self-Efficacy Scale Benefits and Barriers Scales Exercise Motivation Scale Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale Family Support for Exercise Habits Scale Friend support Physical activity group environment questionnaire Physical activity readiness questionnaire Physical improvement programme perceptions Physician-based assessment and counselling for exercise questionnaire Quality-of-life scales (SF-36) Reported awareness, attitude, social influences, motivation, intention, commitment, perceived environment, strategic planning, action planning and coping planning Satisfaction with the intervention Self-efficacy for Exercise Habits Scale Social Support and Exercise Survey Stage of change instrument |

|

| Health correlates Behavioural Risk Factors Surveillance system Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Normative Impairment Index Nottingham Health Profile questionnaire Perceived Stress Scale Satisfaction with body functioning Self-reported physical performance, perceived functioning and well-being Vitality Plus Scale |

Follow-up periods

Whereas 10 studies carried out outcome assessment immediately following the intervention,27,29,34,41,50,57,58,73,75,77 nine studies reported follow-up periods of > 12 months30,32,43,59,61,63,64,69,78,85 (Table 7).

| Length of follow-up | Studies |

|---|---|

| Immediate follow-up | Ackermann et al. (2005)27 Burke et al. (2013)30 Costanzo and Walker (2008)34 Finkelstein et al. (2008)41 Hekler et al. (2012)50 King et al. (2007)57 Koizumi et al. (2009)58 Purath et al. (2013)73 Sawchuk et al. (2008)75 Strath et al. (2011)77 |

| Up to 6 months | Armit et al. (2005)28 de Jong et al. (2006)37 Dorgo et al. (2009)39 Fujita et al. (2003)44 Hageman et al. (2005)46 Irvine et al. (2013)53 Marcus et al. (1997)60 Martinson et al. (2010)61 Pasalich et al. (2013)65 Peels et al. (2012)67 Pinto et al. (2005)71 |

| Up to 12 months | Caperchione and Mummery (2006)31 Cox et al. (2008)35 Croteau et al. (2014)36 de Jong et al. (2006)37 Elley et al. (2003)40 Fries et al. (1993)42 Goldstein et al. (1999)45 Halbert et al. (2000)47 Hamdorf et al. (1992),48 (1993)49 Hooker et al. (2005)51 Hughes et al. (2009)52 Kamada et al. (2013)54 King et al. (2002),55 (2000) 56 Peels et al. (2013)68 Petrella et al. (2010)70 Rowland et al. (1994)74 Stevens et al. (1998)76 van Stralen et al. (2009),79 (2010)80 Walker et al. (2009),83 (2010)84 |

| Over 12 months | Burman et al. (2011)29 Castro et al. (2001)32 Fries et al. (1993)43 Lawton et al. (2008)59 Martinson et al. (2010)61 Opdenacker et al. (2011),63 (2008)64 Pereira et al. (1998)69 van Keulen et al. (2011)78 Werkman et al. (2010)85 |

Intervention effectiveness by typology

As outlined above, there was a wide range of outcomes examined in the included studies. These ranged from those that were self-reported, including activity diaries and self-efficacy questionnaires, to those that were measured by research staff, including weight, BMI, blood pressure and fitness. The range of outcomes (see Table 9), as well as the limited number of studies comparing no-intervention control groups (rather than comparing several intervention arms), precluded the use of meta-analysis to provide a statistical summary of intervention effectiveness. We have therefore completed a narrative summary of the papers together with visual summaries to enable comparison between study findings. In the following section, studies within each intervention typology are briefly outlined and their key findings described.

Education of health-care professionals

One paper57 evaluated an intervention with staff which trained primary care providers to offer referrals to community exercise programmes for patients who reported before their clinic visit that they were ‘contemplative’ about regular exercise. This cluster RCT study found that patients were more likely to receive exercise advice from trained GPs. However, there was no significant difference in patient-reported regular exercise for the intervention group compared with controls.

Counselling and advice

Eleven included papers28,34,36,40,45,47,59,60,70,71,76 (10 studies) assessed the effectiveness of interventions comprising the giving of advice or counselling with seven of these providing stronger evidence of effect. One of these interventions was delivered by peer mentors, one by trained physicians, one by a nurse, two by exercise professionals, two encouraged patients to prompt their physician, and the final four papers examined combined physician and exercise professional input.

The Stevens et al. 76 paper from the UK evaluated both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a 10-week programme, in which inactive people were invited to a consultation with an exercise professional. They were given information on physical activity and health and the local opportunities available to them to be more active. This study had a participant mean age of 59 years and found a net 10.6% [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.5% to 16.9%] reduction in the proportion of people classified as sedentary in the intervention group compared with the control group. In addition, the study found an increase in the mean number of self-reported episodes of physical activity per week in the intervention group compared with the control group (an additional 1.52 episodes, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.95 episodes) at 8 months’ follow-up. The cost of achieving the recommended level of activity for each person was estimated at £2500.

A study evaluating physician exercise prescriptions in Canada70 had two intervention arms, with prescription only and prescription plus counselling programmes. Around half the participants in this cluster RCT study were retired, with all having an inactive lifestyle. Cardiorespiratory fitness increased significantly (p < 0.001) at 12 months’ follow-up for both groups [prescription + counselling 3.02 ml of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute (ml/kg/minute) (95% CI 2.40 to 3.65 ml/kg/minute), and prescription only 2.21 ml/kg/minute (95% CI 1.27 to 3.15 ml/kg/minute) with no significant difference between the groups]. Physical activity was measured by 7-day recall, with estimated kilocalories/kilograms per day significantly increasing in both groups. However, the prescription plus counselling group increased significantly more than the prescription-only group (p = 0.006). A sex difference in response was noted, with women responding significantly better (improved predicted maximal oxygen consumption p < 0.001) to the prescription plus counselling intervention than prescription-only, and men benefiting equally from the interventions.

Lawton et al. 59 examined outcomes following a brief advice session led by a nurse for women with low activity levels (mean age 59 years). The counselling session was supplemented by monthly telephone support and a follow-up session after 6 months. Mean self-reported physical activity levels were higher for intervention participants than for controls (p < 0.001) and a greater proportion in the intervention group than the control group reached the target of physical activity at 12 months [233 (43%) vs. 165 (30%); p < 0.001]. Levels declined but were still significantly different at 2 years [214 (39%) vs. 179 (33%); p < 0.001]. There was no difference between groups with regard to clinical outcomes and it was noted that falls/injuries were higher in the intervention groups.

The third study providing stronger evidence of effectiveness36 had two intervention arms, with one consisting of counselling, pedometer use and self-monitoring over 6 months, and the other consisting of the same interventions plus monthly mentoring meetings with a fitness professional. Participants in this small-scale evaluation (described as a pilot study) were inactive, with a mean age of 64 years, and 16 of 36 participants were employed. The study found a significant intervention effect [p = 0.015; effect size (ES) 0.611] with both groups significantly increasing step count at 6 months, with no significant difference between groups (p = 0.151). The group that received additional mentoring maintained the effect at 12 months (ES 0.606), whereas there was fading of effect for the standard intervention group.

Another paper comparing two interventions71 evaluated advice from a physician and physician advice supplemented by telephone counselling from a health educator, for patients with a mean age of 68 years. At 3 months, 7-day recall self-reported data indicated significantly increased minutes of moderate physical activity for the advice plus counselling group (p < 0.05), increased moderate exercise kilocalories per week (p < 0.05) and biotrainer physical activity counts (p < 0.01) for this group from baseline. These improvements were maintained at 6 months. The physician advice-only group also increased on most measures, although the changes were not statistically significant.

In a small-scale pilot study, Armit et al. 28 randomised participants to three intervention arms: advice from a GP; counselling and telephone calls from an exercise scientist; or counselling and telephone calls with the addition of pedometer use. The participants were inactive patients recruited from physician waiting rooms with a mean age of 64 years. At 12 weeks, there was an overall increase of 116 weighted minutes of self-reported physical activity per week (p < 0.001) across the three groups. The paper describes no significant difference between groups, although the data presented indicate no change in the GP advice group compared with significant differences in average physical activity levels pre–post for the other two groups.

Another similar intervention with GP advice, supplemented by telephone support from an exercise specialist,40 increased self-reported mean total energy expenditure by 9.4 kcal/kg/week (p = 0.001) and leisure exercise by 2.7 kcal/kg/week (p = 0.02). This equated to 34 minutes per week more in the intervention group than in the control group (p = 0.04). The proportion of the intervention group reporting undertaking 2.5 hours per week of leisure exercise also increased by 9.72% (p = 0.003) more than in the control group. The participants were sedentary patients visiting their GP/nurse (mean age 57 years), and the intervention was designed to prompt practitioners to give advice and an exercise programme to patients on being given a form by patients.

A paper from Australia47 provides more limited evidence of effect. This study examined the provision of an advice session with an exercise specialist to sedentary adults (mean age 67 years). Although physical activity increased in both intervention and control groups, there was a significantly greater increase (p < 0.05) in self-reported frequency and time of vigorous exercise in the intervention group than in the control group (who received a nutritional pamphlet). Self-reported intention to exercise also increased significantly more in the intervention group (p < 0.0001). Although the paper reports these positive effects on vigorous exercise and intention to exercise, self-reported walking time and frequency of walking did not improve significantly more in the intervention group. However, a sample of the participants wore an accelerometer during the intervention period, and, with this measure (rather than self-reported data), there was no intervention effect on the daily number of steps. There was also no difference between groups with regard to physiological measures (such as body weight, blood pressure). Quality-of-life scores decreased for all participants over the 12-month study period, with the greatest decrease in women in the intervention group.

Costanzo and Walker34 provide weak evidence of effect following a behavioural counselling intervention. This study, which compared one session versus five sessions of counselling, reported an effect on self-efficacy, although no direct influence on physical activity. The change in self-efficacy (ES 0.19) was attributable to a decrease in the one-session group rather than change in the five-session group.

The other two papers reporting limited effects were the Marcus et al. 60 paper, which describes the pilot phase of work, and the Goldstein et al. 45 paper, which further outlines this. The evaluated intervention consisted of a physician training session and one physical activity counselling session provided to patients with one follow-up appointment 4 weeks later. Participants in the main study were an average age of 65 years and 36% were employed. At 6 weeks, participants in the intervention group were more likely to be in advanced stages of motivational readiness for physical activity than participants in the control groups [preparation or action 89% vs. 74%, odds ratio (OR) 3.56, 95% CI 1.79 to 7.08; p < 0.001]. However, the effect was not maintained at 8 months. There was no significant difference between intervention and control groups with regard to the number reporting meeting the recommended guidelines for physical activity at 6 weeks or 8 months. Both groups increased at 6 weeks and decreased by 8 months.

Group sessions

A total of 13 papers30,31,37,38,44,48,49,55,74,87–90 evaluated group-based programmes, with 11 of these reporting stronger evidence of effectiveness. 30,31,44,48,49,55,74,87–90 In total, four studies (reported in seven papers)30,31,55,87–90 compared differing forms of interventions rather than having no-intervention control groups.

The first of these, outlined in four papers,87–90 compared telephone-based counselling calls for 6 months to a 12- or 20-week group-based programme. Participants had a mean age of 68 years and were 80% female. The Wilcox et al. 87,88 papers present immediate follow-up data from one and three cycles, respectively, of the programmes. Results for the first implementation showed a significant increase from pre test to post test in self-reported moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity (p < 0.001) and total physical activity (p < 0.001) for all participants, with both programmes having significant effects. Across three cycles of the intervention, the telephone programme led to a significant increase in reported moderate and vigorous physical activity [Cohen’s d (d) = 0.62/0.66/0.75], and all reported physical activity also increased significantly (d = 0.55/0.6/0.63) in each of the 3 years in which the programme was run.

Similarly, for the group programme the study reported that moderate and vigorous physical activity increased significantly (d = 0.74/0.66/0.58), as did all physical activity (d = 0.79/0.56/0.63). For both programmes the proportion of participants reportedly reaching exercise recommendation levels increased significantly (p < 0.001). The papers present no data comparing effectiveness between the interventions beyond reporting the ESs for each, which were similar. The first Wilcox et al. 88 paper reports 6-month follow-up data and found a significant increase from pre test to post test for both programmes in self-reported physical activity, which was maintained at follow-up (p < 0.001). The second Wilcox et al. 89 paper analyses predictors of response to the intervention and reports that older participants (> 75 years of age) and those with less social support responded less well. It is noteworthy that those with lower activity levels at baseline improved the most.

Another study in this group that had two intervention arms30 assessed a programme which comprised access to a community exercise facility, a pedometer, peer mentors and group sessions. The participants were inactive and had an average age of 63 years, and 82% were female. The group sessions in one arm involved general health education, whereas the other arm received sessions on support for physical activity change. At the end of the intervention (16 weeks) both groups self-reported significantly more activity than at baseline [p < 0.001 (ES 1.38)], with no difference between the interventions. At 18-month follow-up, the intervention group receiving physical activity change sessions reported significantly more moderate to vigorous activity minutes per week than the general health education intervention arm [p = 0.04 (ES 0.32)].

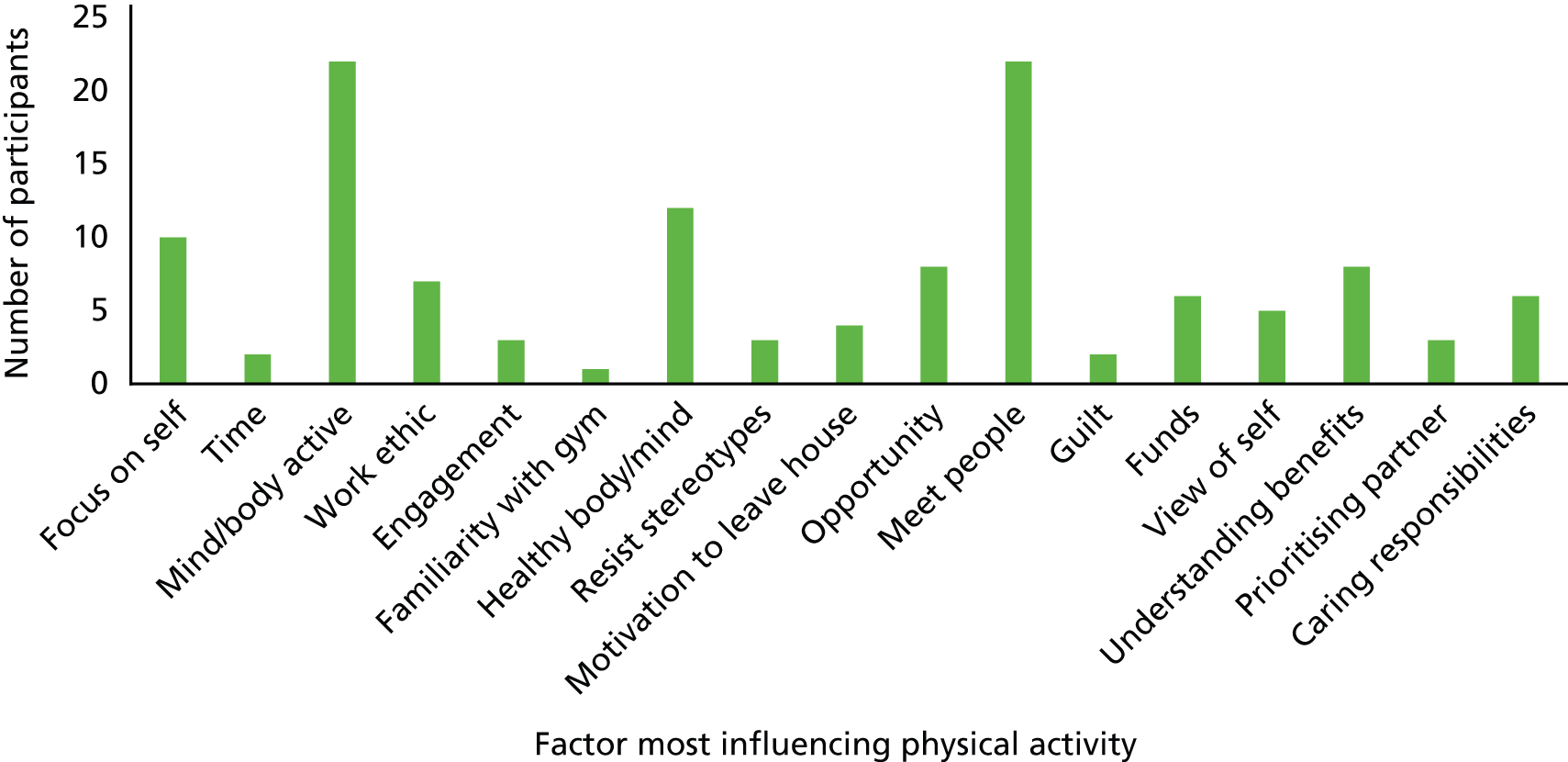

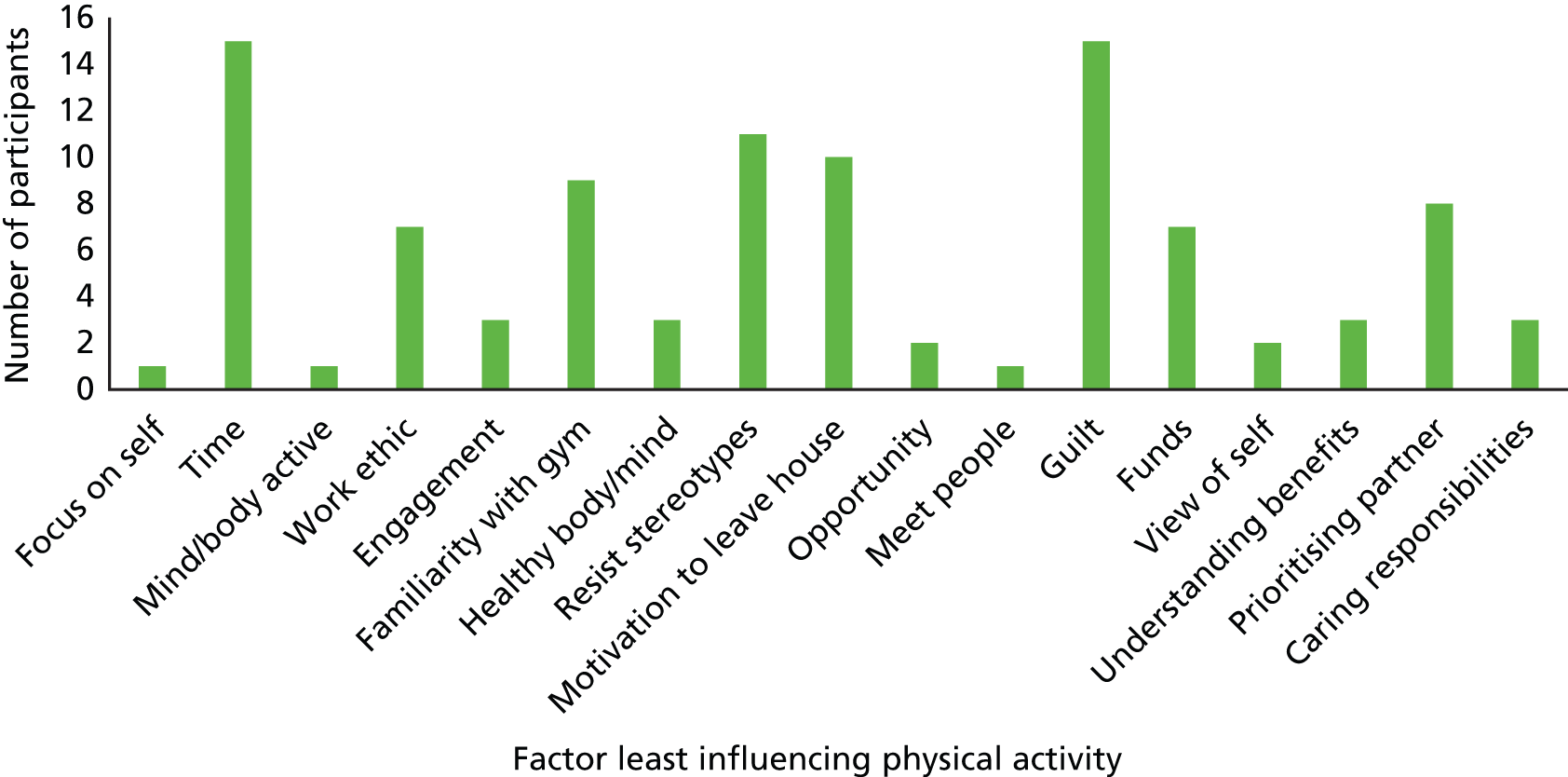

Caperchione and Mummery31 similarly compared a standard intervention to an enhanced programme. The 12-week lifestyle intervention comprised instructor-led group walks and group education sessions incorporating cognitive–behavioural strategies and health-related information. The enhanced package also included education sessions on group process. Participants had a mean age of 58 years; 38% were retired and 50% were employed and were inactive. The study found a significant increase in self-reported physical activity behaviour (as measured by calorific expenditure) at time points up to 12 months’ follow-up for both groups (p < 0.05), with no significant difference between the standard and enhanced intervention.