Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/153/19. The contractual start date was in October 2013. The final report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rona Campbell reports grants from University of Bristol during the conduct of the study and is a Director of DECIPHer Impact Limited, a not-for-profit company wholly owned by the Universities of Bristol and Cardiff whose purpose is to maximise the translation and impact of evidence-based public health improvement research and expertise. It does this by selling goods and services starting with the DECIPHer-ASSIST (A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial) smoking prevention programme. Rona Campbell received modest fees in payment for her work as Director which are paid into an account held at the University of Bristol and used to fund research-related activity. Elizabeth Oliver reports grants from the University College London Institute of Education during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Bonell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Health-risk behaviours and young people in the UK

The health of young people in the UK is among the worst in Europe, with marked inequalities across the social scale. 1,2 Health-risk behaviours increase during adolescence3 and lead to high rates of later chronic disease and other problems, and to substantial economic costs. 4 Child poverty is currently increasing, raising the possibility of upwards trends in young people’s risk behaviours, with worrying implications for future chronic disease rates and NHS costs. 5 Smoking, drinking alcohol and using illicit drugs (henceforth termed substance use), as well as violence, are highly prevalent and damaging to young people’s long-term health. Rates of youth smoking, drinking and illicit drug use in the UK are among the highest in Europe. 6,7 Despite significant declines since the 1990s, 17% of 15-year-old boys and 20% of 15-year-old girls are regular or occasional smokers, and around one-quarter of 15-year-olds drink alcohol every week, while 15% of 15-year-old boys and 11% of 15-year-old girls report drug use in the past month. 8 Recent estimates suggest that more than 11,500 under-18-year-olds access drug treatment services each year. 9 There are short- as well as long-term public health threats arising from young people’s substance use. For example, adolescent use of cannabis is associated in the short term with increased sexual risk behaviour and injury. 10 Young people’s use of substances is associated with social disadvantage across studies,11 and reinforces existing socioeconomic inequalities in health across the life course. This raises key equity considerations: substance use is most prevalent among socially disadvantaged young people and frequent use at a young age is strongly associated with more harmful use and chronic illness in adulthood. 12–14 Aggression and violence are similarly challenging, and preventing youth violence continues to be a public health, education and criminal justice priority. 15–17 One survey reports that by 15–16 years of age, one-quarter of young people have carried a weapon, and 19% reported attacking someone with the intention to hurt them seriously. 18 Violence is subject to marked social inequalities19 and is associated with an increased risk of physical health problems;20 engaging in other health-risk behaviours such as substance use;21–23 long-term emotional, behavioural and mental health problems;20,24,25 and self-harm and suicide. 26 Moreover, gang involvement is associated with acute health risks and strongly correlated with later-life offending and serious, adverse mental health outcomes in longitudinal studies. 27 The economic costs associated with youth substance use and aggression are extremely high. 12,28,29

Youth programmes to reduce health risks in young people

Primary prevention interventions to reduce health risks in adolescence are potentially highly cost-effective. 30 There are increasing calls for adolescent health interventions to address multiple- rather than single-risk behaviours because such behaviours cluster together31,32 and because such interventions are potentially more feasible and efficient. 33 Positive Youth Development (PYD) is one such intervention to address interclustered risk behaviours among young people. PYD is the dominant paradigm in youth work in the UK.

The National Youth Agency (NYA), the major youth-work organisation in the UK, defines such interventions as voluntary and informal educational activities aiming to bring about generalised youth development rather than merely remedying ‘problem behaviours’. Such development is defined in terms of the promotion of positive skills, attitudes, relationships and identities. 34 A literature review published by the NYA developed a complex definition of PYD in terms of philosophy, constructs, domains and processes but similarly emphasised young people’s positive attributes and competencies through structured voluntary activities. 35

Similarly, in the USA, PYD is defined in terms of its goal of developing a range of positive development assets, such as bonding, resilience, social, emotional, cognitive, behavioural or moral competence, self-determination, spirituality, self-efficacy, clear and positive identity, belief in the future, recognition for positive behaviour, opportunities for pro-social involvement and/or pro-social norms,30 academic, cognitive or vocational skills, confidence, connections to peers and adults, character in terms of self-control, respect and morality and caring for others. 36

Although one aim of this review is to synthesise existing literature on the theory of change underlying PYD interventions, it was apparent to us in planning the review that PYD has the potential to reduce substance use and violence through various complex pathways. First, PYD can address some of the underlying social determinants of these outcomes, such as disengagement from education, lack of social support and low aspirations for the future. 30 Second, PYD can divert young people away from substance use and violence through engaging them in more positive forms of recreation. 36 Third, PYD can promote social and emotional competences, some of which are important protective factors against adolescent health-risk behaviours. 5 Fourth, PYD providers can provide credible health messages and signpost health services. 37

Even in the context of public-sector cuts, there is major investment in such interventions. The UK government’s Positive for Youth38 report announced a multimillion pound investment in youth work, youth centres, the National Citizen Service and other youth volunteering projects. The most recent public health White Paper39 cited such work as a key element in promoting young people’s health. The Mayor of London and local government across the UK are also investing millions of pounds in various PYD interventions. 40 The devolved governments in Scotland and Wales also emphasise these principles and promote investment in PYD. 41,42

However, despite this widespread investment and potential, the evidence base for the public health benefits of such interventions is unclear. Although a systematic review examining non-health outcomes43 reported benefits for self-confidence and self-esteem, school bonding, positive social behaviours, school grades and achievement test scores, the review did not systematically examine health effects. Systematic reviews of health outcomes have, so far, focused only on sexual health44,45 and have not attempted to meta-analyse evidence of effects. They have, however, reported sustained effects, albeit with considerable unexplained variability between programmes. For example, the Children’s AID Society Carrera programme reduced teenage pregnancy in some US sites but not others,37 whereas two evaluations of PYD interventions in the UK suggested adverse and no effects on sexual health, respectively. 46,47 US researchers have argued that some youth programmes that target ‘delinquent’ young people and that are insufficiently well structured may actually reinforce violence and antisocial behaviours via peer deviancy training. 48 Others have disputed this, referring to meta-analyses of interventions addressing youth delinquency49 which suggest that the targeting and structure of sessions do not moderate effects. However, no systematic review focusing on PYD interventions has examined these questions. Non-systematic reviews of PYD effects on violence and drug use30,50 have reported benefits as well as variability, but their findings must be treated with caution, given that they were unsystematic and are now quite old.

Rationale for this review

This review aims to fill two timely and important knowledge gaps and to provide important evidence to local government commissioners of youth services and public health. First, it aims to synthesise evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PYD interventions delivered outside school as a means of primary prevention in reducing substance use and violence. Second, it aims to examine how effects vary according to the characteristics of participants, in order to assess what works, for whom and in what settings (to inform assessments of generalisability), as well as to estimate effects on health inequalities. Addressing intervention effects is important because, as described above, UK young people have among the worst health in Europe, with marked inequalities across the social scale. Moreover, PYD interventions are receiving significant policy attention and investment, despite a lack of evidence of health benefits from systematic reviews. Addressing moderators of effects is also important given the possibility discussed above that PYD effects will vary and given our interest in assessing the potential of PYD to reduce health inequalities.

Review aims and objectives

The overarching aim of this systematic review is to systematically search for, appraise the quality of and synthesise evidence on PYD programmes that address substance use or violence and that examine the extent to which these effects vary and/or are moderated by characteristics of participants and contexts.

These aims have been addressed by focusing on the following objectives:

-

conducting electronic and other searches for studies of PYD interventions

-

screening references and reports for inclusion in the review

-

extracting data from and assessing the quality of included studies

-

synthesising thematically theories of change relating to PYD interventions to produce a taxonomy and theory of change for PYD interventions

-

synthesising process evaluations of PYD interventions

-

consulting with policy-makers and practitioners and youth to validate the resultant taxonomy and theory of change

-

synthesising outcome and economic evaluation data and undertaking metaregression and qualitative comparative analyses

-

drawing on these syntheses to draft a report addressing our review questions (RQs)

-

consulting with policy-makers and practitioners and young people on the draft report to inform amendments and dissemination.

Review questions

The following RQs were addressed:

RQ1: what theories of change inform PYD interventions delivered to young people aged 11–18 years addressing substance use and violence?

RQ2: what characteristics of participants and contexts are identified as barriers and facilitators of implementation and receipt in process evaluations of PYD?

RQ3: what is the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PYD compared with usual or no treatment in reducing substance use (smoking, alcohol, drugs) and violence (perpetration and victimisation)?

RQ4: what characteristics of participants and contexts appear to moderate, or are necessary and sufficient for, PYD effectiveness?

Chapter 2 Review methods

About this chapter

This section outlines the methods used in this systematic review. They were described a priori in a research protocol51 (see Appendix 1). The study is registered as PROSPERO CRD42013005439 (see www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/). Although there are no checklists for a complex, multimethod review such as the one undertaken, we have adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (the PRISMA checklist can be found in Appendix 2). 52

Design

The project is a multimethod systematic review of known existing research. This chapter describes the flow of studies through the review as well as the characteristics of included studies. This is followed by four chapters presenting our various syntheses:

-

A thematic synthesis of the literature describing the theory of change of PYD interventions.

-

A thematic synthesis of process evaluations.

-

A narrative synthesis and meta-analysis of experimental [randomised controlled trials (RCTs)] and quasi-experimental studies (employing non-randomised prospective comparison groups) of the effectiveness of PYD interventions on substance use and violence outcomes. We found no economic evaluations.

-

An overview bringing together all three syntheses outlined above.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

The criteria and definitions used for considering which studies to include in this review are outlined below. These inclusion criteria were operationalised into exclusion criteria to inform our screening of studies found (see Appendix 3). The results of this screening process are detailed in Chapter 3.

Date

We included only studies published in and after 1985, as this is when PYD interventions first began to be developed. 30,44 Our original proposal did not restrict included studies by date; we added this exclusion criterion at an early stage in the review, including this in our registered protocol. 51

Language

We included only studies published in English because PYD interventions appear to be a phenomenon particular to anglophone countries. 30,44 Our original proposal did not exclude studies published in other languages; we added this exclusion criterion at an early stage in the review, including this in our registered protocol. 51

Types of participant

We included studies in which the majority of participants were aged 11–18 years. Although the World Health Organization defines adolescents, the target group for PYD, as those aged 10–19 years,53 to increase this review’s UK policy relevance, we chose 11–18 years as our age range as this encompasses those engaged in secondary education in the UK. We excluded studies of populations targeted on the basis of pre-defined physical and mental health conditions (because we are interested in PYD as primary prevention) but not those that targeted participants on the basis of pre-existing risk behaviour or other forms of targeting (e.g. area-level deprivation). We also excluded interventions that targeted parents/carers alongside young people in order to focus on family functioning.

Types of intervention and setting

Informed by existing theoretical frameworks,30,44 PYD interventions were defined as programmes that involve voluntary education with the aim not merely of preventing problem behaviour but also of promoting generalised (beyond health) and positive (beyond avoiding risk) development, which were defined as promoting:

-

bonding (developing the child’s relationship with a healthy adult, positive peers, school, community, or culture)

-

resilience (strategies for adaptive coping responses to change and stress and for promoting psychological flexibility and capacity)

-

social competence (developmentally appropriate interpersonal skills and rehearsal strategies for practising these skills, including communication, assertiveness, refusal and resistance, conflict-resolution and interpersonal negotiation strategies for use with peers and adults)

-

emotional competence (identifying feelings in self or others, skills for managing emotional reactions or impulses, or skills for building the youth’s self-management strategies, empathy, self-soothing or frustration tolerance)

-

cognitive competence (cognitive abilities, processes or outcomes including academic performance, logical and analytic thinking, problem-solving, decision-making, planning, goal-setting and self-talk skills)

-

behavioural competence (skills and reinforcement for effective verbal, non-verbal and other actions)

-

moral competence (empathy, respect for cultural or societal rules and standards, a sense of right and wrong or a sense of moral or social justice)

-

self-determination (capacity for empowerment, autonomy, independent thinking or self-advocacy, or their ability to live and grow by self-determined internal standards and values, which may or may not include group values)

-

spirituality (beliefs in a higher power, internal reflection or meditation; supporting youth in exploring a spiritual belief system or sense of spiritual identity, meaning or practice)

-

self-efficacy (personal goal-setting, coping and mastery skills, or techniques to change negative self-efficacy expectancies or self-defeating cognitions)

-

clear and positive identity (healthy identity formation and achievement in youth, including positive identification with a social or cultural subgroup that supports young people’s healthy development of a sense of self)

-

belief in the future (belief in his or her future potential, goals, options, choices or long-range hopes and plans were classified as promoting belief in the future, including guaranteed tuition to post-secondary institutions, school-to-work linkages, future employment opportunities or future financial incentives to encourage continued progress on a pro-social trajectory; or optimism about a healthy and productive adult life)

-

recognition for positive behaviour (response systems for rewarding, recognising or reinforcing children’s pro-social behaviours were classified as using recognition for positive behaviour)

-

opportunities for pro-social involvement (activities and events in which youths could actively participate, make a positive contribution and experience positive social exchanges) and/or

-

pro-social norms (clear and explicit standards for behaviour that minimised health risks and supported pro-social involvement).

Included interventions either needed to address at least one of these forms of asset but could be applied to different domains such as family, community, school, or needed to address more than one of these assets in a single domain.

Our original funding proposal defined PYD interventions in terms of voluntary education provided by youth workers and addressing generalised, positive development in terms of vocational, academic, social or cognitive skills; self-confidence; positive identities, attitudes and aspirations; and/or relationships with adults or peers. However, we used the more theoretically informed definition listed above from an earlier stage in the review, which was included in our registered protocol. 51

We included studies in which interventions were provided in community settings (which could include schools) outside of normal school time. Our definition excluded PYD delivered in school time because this involves a distinctive theory of change and has been the subject of recent reviews. 54,55 It also excludes interventions delivered in custodial or probationary settings, clinical settings or employment training for school leavers, again because such interventions will involve distinctive theories of change, and, in the case of clinical and employment training settings, will feature participants not meeting our inclusion criteria.

Types of studies

We included multiple types of studies based on whether or not they could answer the individual RQs. In order to address RQ1, we included studies describing a PYD intervention theory of change in relation to our outcomes. We defined theory in the same way as in our previous National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)/Public Health Research (PHR)-funded review of the effects of schools and school-environment interventions on health. 56 Included studies either dealt exclusively with theory of change or addressed it alongside the reporting of empirical data.

In order to address RQ2, we included studies reporting on process evaluations of PYD intervention. Included studies reported on how the planning, delivery, receipt or causal pathways of PYD varied or were influenced by characteristics of place or person using quantitative and/or qualitative data. These studies either reported exclusively on process evaluations or reported process data alongside outcome or economic data. In order to address RQ3, we included studies reporting on outcome and economic evaluations of PYD interventions. We included experimental (RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies (employing non-randomised prospective comparison groups). Control groups needed to receive usual care or no treatment. Economic studies addressing RQ3 were defined in terms of their comparison of the costs and consequences of two or more interventions or, where there was good reason to believe that outcomes were similar, involved cost-minimisation analyses. In order to address RQ4, we have drawn on the syntheses of all of the above study types.

Types of outcomes

This review included studies addressing substance use (i.e. smoking, alcohol use and/or drug use) or violence (i.e. perpetration and/or victimisation involving physical violence aimed at person(s) as opposed to damage to property).

Informed by existing systematic reviews that focus on substance use and violence among young people,57–60 outcome measures could draw on either dichotomous or continuous variables and/or self-report or observational data. They could use measures of frequency (monthly, weekly or daily), the number of episodes of use or an index constructed from multiple measures. Alcohol measures could examine alcohol consumption or problem drinking. Drug outcomes could examine general or specific illicit drug use. Measures of violent and aggressive behaviour could examine the perpetration or victimisation of physical violence including violent crime.

Search strategy

Database search strategy

Search terms

A sensitive search strategy using both indexed and free-text terms was developed and tested by an experienced information scientist (CS). These searches were run on 7 November 2013. Key search terms were determined by the RQ and the inclusion criteria and were developed and tested against papers already known to the research team in writing the research proposal. The search strategy involved developing strings of terms and synonyms to capture three core concepts in the review:

-

Concept 1: population (e.g. youth or young people or adolescents).

-

Concept 2: intervention (e.g. after-school clubs or community-based programme or informal education).

-

Concept 3: population and intervention (e.g. youth work or youth development or youth club).

These concepts were combined in searches as follows: concept 1 and (concept 2 or concept 3). The initial free-text search terms generated for concepts 1 and 2 were broad and could identify non-relevant literature (e.g. volunteer, development, etc.). Thus, to balance specificity with sensitivity, where possible we required that intervention terms were adjacent or near to population terms (e.g. after ‘school’ N12 ‘young people’ OR ‘adolescen*’ OR ‘youth’). An example of a search string from PsycINFO can be found in Appendix 4.

Databases

Searches were undertaken on the following 21 electronic bibliographic databases:

-

Applied Social Science Abstracts via ProQuest

-

Australian Educational Index via ProQuest

-

BiblioMap health promotion research via EPPI-Centre

-

British Educational Index via ProQuest

-

Child Data via Ovid

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials via The Cochrane library

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCOhost

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

-

Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews via EPPI-Centre

-

Health Technology Assessment Database

-

EconLit via Ovid

-

Education Research Index Citations via ProQuest

-

International Bibliography Social Sciences via ProQuest

-

MEDLINE via EBSCOhost

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database

-

PsycINFO via EBSCOhost

-

Sociological Abstracts via ProQuest

-

Social Sciences Citation Index via Web of Knowledge

-

Social Policy and Practice via Ovid

-

Social care online via Ovid The Health Management Information Consortium via Ovid

-

Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (via EPPI-Centre).

Other search sources

The following websites were also searched to identify relevant studies:

-

The Campbell Library

-

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

-

OpenGrey

-

The Health and Safety Information Centre of the International Labour Office

-

Drug and Alcohol Findings Effectiveness Bank

-

Dissertation Abstracts/Index to Theses

-

Schools and students health education unit research archive

-

Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA)

-

Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA)

-

US Center for Substance Abuse Prevention

-

Northern Ireland Online Research Base

-

US Food and Drug Administration–Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Tobacco Prevention

-

Tobacco Use Behaviour Research

-

UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio

-

Personal Social Services Research Unit Discussion Papers (see www.pssru.ac.uk/)

-

Cost-effectiveness Analysis Registry

-

National Youth Agency

-

Social Policy Digest

-

Drug database (see www.drug.org.au/)

-

Smoking and Health Resource Library

-

Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit

-

Children in Scotland

-

Children in Wales

-

Children’s Research Centre

-

Welsh Government Social Research

-

Scottish Government website

-

Young Minds

-

Social Issues Research Centre

-

European Commission – Community Research and Development Information Service library

-

Centre for Prevention Research and Development

-

Joseph Rowntree Foundation

-

Childhoods Today

-

The Children’s Society

-

National Youth Agency

-

National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts.

Website searches were run between 7 and 16 January 2014. Depending on the functionality of each website interface, searches were undertaken using a combination of medical subject headings (if available) and/or free-text search terms to capture the key concepts of the intervention (e.g. ‘positive youth development’; ‘youth work’; ‘youth clubs’). Citations were screened online based on their title, title and abstract or full text when available. Potentially includable studies were cross-referenced with the electronic searches imported to EPPI-Reviewer version 4.0 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK) to identify any unique references. As is customary with searching of this type, only included references were recorded.

We also hand-searched those journals that (1) contained studies that we included; (2) were found only via reference checking; and (3) were not indexed on databases that we had searched. We hand-searched these initially for the past 5 years and if these elicited > 1 new included study we hand-searched for a further 5 years. Our original proposal stated that we would hand-search the five journals that yield the highest numbers of studies meeting the inclusion criteria. However, we decided very early on in the review that this approach would have low specificity in identifying studies not already identified by our other methods of searching and was thus not a good use of resources. We therefore amended this aspect of our search so that hand-searching was much more targeted towards studies that were unlikely to have been identified through other means, including this in our registered protocol. 51

We also sought to contact subject experts to identify unpublished or ongoing research. We pursued this by contacting the authors of all included studies to seek their advice on other studies that we might consider for inclusion. As stated above, the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform was also searched to identify any relevant ongoing and unpublished trials on PYD. Finally, we searched reference lists of all included studies for further relevant studies.

Information management

All citations identified by our searches were uploaded and managed during the review process using the EPPI-Centre’s specialist online review software, EPPI-Reviewer version 4.0 software. 61 This software records the bibliographic details of each study; where studies were found and how; reasons for their inclusion or exclusion; descriptive and quality assessment codes; text about each included study; and the data used and produced during synthesis. The software also enables us to store and track electronic documents (e.g. portable document format files).

Study selection

An exclusion criteria worksheet, informed by our inclusion criteria and with guidance notes (see Appendix 3), was prepared and piloted by four reviewers (CB, KD, KD, LM), who screened 100 references in pairs, on title and abstracts. We increased the number of studies on which to pilot the screening from 50 studies as originally set out in our proposal to 100, in order to facilitate greater discussion on the application of the exclusion criteria by ensuring that we had a wider variety of citations to compare. Pilot screening results were discussed by pairs of reviewers involved in screening to ensure consistency in applying the criteria. A 90% agreement rate was required before proceeding to independent screening of the full set of references. Between submitting the proposal and finalising the protocol51 we piloted the search. Initial yields indicated that the use of sensitive and comprehensive terms to capture literature seeking to answer theory, process and outcome RQs would lead to a high number of studies to screen (e.g. above 10,000). It was decided that double screening of the search would therefore not be feasible and a better use of resources would be to pilot the exclusion criteria and screen independently, an approach taken in most EPPI-Centre reviews. 62 The remaining references were divided between five reviewers (CB, KD, KH, KL, LM) with each reference being screened independently by one reviewer. If a single reviewer could not reach a decision regarding inclusion of a specific article, judgement for selection was referred to a second reviewer. If these reviewers could not reach a consensus then a third reviewer was consulted. Full reports were obtained for those references judged to meet our inclusion criteria based on title and abstract or where there was insufficient information from the title and abstract to judge inclusion. References thus passing this first round of title and abstract screening were subject to a second round of screening using the same approach, but based on full study reports in order to determine which studies were included in the review. The principal investigator [PI (CB)] made a final check of all studies identified as potential included in the review, as a final check to determine inclusion, to identify which RQ they answered and to determine cases in which multiple reports were ‘linked’, that is, reporting on the same study.

Data extraction

Coding tools

Data were extracted using coding tools developed for the review components relating to each RQ (see Appendices 5–7). Each drew on and supplemented the codes used in the EPPI-Centre classification system for health promotion and public health research. 63 For studies describing a theory of change (either as a purely theoretical study or an empirical study addressing a theory of change), we extracted data on aim; description of theory of change; links to other theories; description of how PYD is intended to act on the individual or their environment; and description of how PYD is intended to reduce substance use or violence. For both process and outcome evaluations, we extracted data on study location; intervention/components; intervention development and delivery; timing of intervention and evaluation; provider characteristics; target population; sampling and sample characteristics (where relevant by wave of follow-up); data collection and analysis. For process evaluations, we also extracted data on findings relevant to our review, including verbatim qualitative data plus author descriptions and interpretations. For studies reporting on outcome evaluations, we also extracted data on the nature of the control group(s); research design; unit of allocation; generation and concealment of allocation; blinding; adjustment/control of clustering and confounding; outcomes; and effect sizes overall and by age, sex, socioeconomic status (SES) and ethnic subgroup. No economic evaluations were found, so no economic data were extracted.

Data extraction process

Data extraction tools were piloted on two studies. Reviewers met to compare extraction and to identify any differences that might inform refinements of the coding tools or how these were applied. All study reports were then extracted by two reviewers who worked independently before meeting to discuss and agree their coding, to ensure quality and consistency in their interpretations. If reviewers could not reach a consensus, judgement was referred to a third reviewer. The data extraction tool for theory was adapted slightly after it had been piloted on two papers.

Missing data

Where missing data might have affected our ability to assess the quality of studies or synthesise findings, we contacted study authors to request additional information (see Appendix 8). When authors were not traceable or sought information was not forthcoming within 2 months of contact, we recorded that the study information was missing on the data extraction form, and this was captured in our risk-of-bias assessment of the study.

Quality assessment

The quality of each study was assessed independently by two reviewers, with differences in opinion resolved by discussion without the need for recourse to a third reviewer. Given that no economic studies were found, no economic quality appraisal occurred.

Theory studies

The quality of studies reporting on theory was assessed using a new tool which was informed by a tool used in a previous NIHR review56 as well as by other recent work on theory synthesis. 64,65 Quality was assessed in terms of clarity of constructs, clarity of relationships between constructs, testability, parsimony and generalisability. We pre-specified how we would apply each of these criteria as follows:

-

Construct clarity: are the constructs clear, either because they are well-established constructs such as self-esteem or because they are more novel theoretical constructs such as cultural pride or spirituality for which the authors provide a definition?

-

Relationships between constructs: do the authors explain the relationships between their constructs? Do they describe each step in the theory of change?

-

Testability: would it appear possible in principle to test the theory of change within our review by drawing on experimental or quasi-experimental evaluations of intervention that were informed by these theories of change? For example, a theory of change involving improving young people’s social competence to reduce violence would be testable, whereas a theory of change involving improvements to the way young people are treated in society overall would not be.

-

Parsimony: is the theory of change as simple as it can be without losing its value? This is a subjective decision but we could probably agree that some theories of change involve so many constructs and/or have so many interconnections between these constructs that it detracts from their ability either to inform an intervention or an empirical evaluation of whether an intervention informed by that theory of change is effective.

-

Generalisability: does the theory of change apply across: (1) behaviours; (2) populations; and (3) contexts, or is it relevant only to smoking but not drug use, or only to young men or Native American peoples but not to women or Asian peoples, or only to the USA but no other country, for example?

Process evaluations

Process evaluations were assessed using standard Critical Appraisal Skills Programme and EPPI-Centre tools for qualitative studies. 66 Quality tools for qualitative studies address the rigour of sampling, data collection, data analysis, the extent to which the study findings are grounded in the data, whether or not the study privileges the perspectives of participants, the breadth of findings and the depth of findings. A final step in the quality assessment of qualitative studies was to assign studies two types of ‘weight of evidence’. First, reviewers assigned a weight (low, medium or high) to rate the reliability or trustworthiness of the findings (the extent to which the methods employed were rigorous/could minimise bias and error in the findings). Second, reviewers assigned an additional weight (low, medium, high) to rate the usefulness of the findings for shedding light on factors relating to the RQs. Guidance was given to reviewers to help them reach an assessment on each criterion and the final weight of evidence.

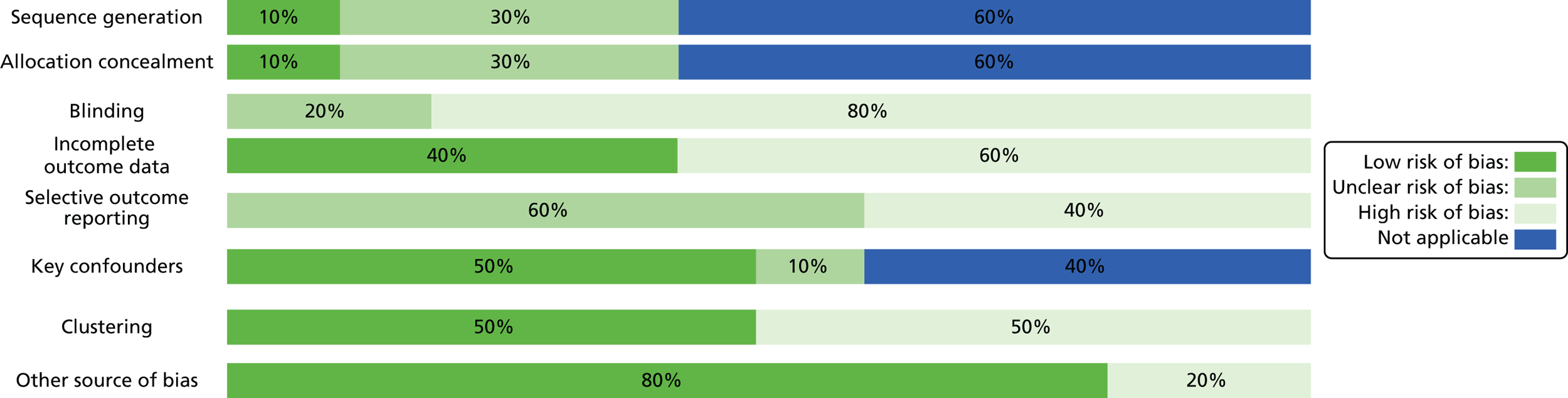

Outcome evaluations

Outcome evaluations were assessed for risk of bias using the tool modified from the questions suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 67 For each study, two reviewers independently judged the likelihood of bias in seven domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding (of participants, providers or outcome assessors); incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias (e.g. recruitment bias in cluster-randomised studies); and intensity/type of comparator. Each study was subsequently allocated a score of ‘high risk’, ‘low risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ within each domain.

We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions68 to present the quality of evidence and ‘Summary of findings’ tables. The downgrading of the quality of a body of evidence for a specific outcome was based on five factors: limitations of study; indirectness of evidence; inconsistency of results; imprecision of results; and publication bias. The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality (high, moderate, low and very low).

Synthesis of results

Theory

We synthesised descriptions of theory of change using a form of thematic content analysis known as template analysis. 69–72 Theory synthesis is not the same as synthesis of qualitative research for two reasons. First, theory synthesis analyses theoretical constructs rather than interpretive concepts. Theoretical concepts have been developed anew by theorists and are not necessarily based on prior concepts used by those who are the objects of theory. In contrast, interpretive concepts are interpretations of the concepts used by participants in qualitative research. Thus, theoretical concepts are first order, whereas qualitative interpretations are second order. Second, syntheses of theory bring together theoretical concepts that are often described using fairly consistent terminology across included reports and that may often be informed by similar assumptions. In contrast, syntheses of qualitative research bring together interpretive concepts which originate from quite diverse data and study designs, employ different terminology and are often informed by different epistemological and ontological assumptions. For these reasons, it would not be appropriate to use metaethnographic methods in synthesising theory. We instead used thematic content analysis. It may even be inaccurate to discuss the elements of the emerging synthesis in terms of ‘themes’, as this word suggests a label that has been given to help interpret a diverse array of qualitative data, whereas theory synthesis will more often need to proceed via the development of more tightly defined constructs and inter-relations. Nonetheless, we still believed that it would be useful to employ thematic content analysis to synthesise the theoretical literature, because the goal was to compare and contrast how constructs and the inter-relations between constructs are described across diverse sources in order to build theory that goes beyond what is present in each individual source.

The coding template was developed in three stages.

First, two reviewers developed an initial coding template based on theoretical concepts that were already apparent within the protocol or which occurred to them during their data extraction of the theoretical literature (Table 1). The codes were arranged hierarchically, going from broad themes to more specific codes and subcodes.

| Themes | Codes and subcodes |

|---|---|

| Definition of PYD interventions | PYD vs. prevention science/traditional youth programmes Definition in terms of developmental assets vs. programme atmosphere Characteristics of programmes |

| Taxonomy | Individual vs. environment/community emphasis Pro-social development vs. critical conscious raising General ‘pile up’ of assets vs. specific ‘molecular’ effects of specific assets on specific outcomes |

| Mechanism of action | Action on risk of substance use/violence Action on thriving |

| Possible moderation by context | Moderation by person/population Moderation by setting |

Second, using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to manage data, the two reviewers independently used the initial template to code the same two theory papers (which were chosen on the basis that both researchers had earlier assessed these as high quality). In applying the coding template to code these two papers in turn, the researchers could each refine or add to the template as new theoretical ‘themes’ arose or existing ones were reformulated. Where codes were refined or added, the reviewers wrote short ‘memos’ explaining their thinking. Each kept a record of the coding template as it stood at the end of coding each paper. The reviewers also noted how each study contributed to their development and refinement of the coding template. The reviewers then discussed the refined coding template that they had each produced, developing an agreed new common template.

Third, the reviewers then coded the rest of the theory papers using the template refined in the previous stage, coding the most recently published study reports first. As they did so, they could again refine or add to the coding template as new themes arose. In the course of analysing the papers, each reviewer wrote an overarching memo which presented the emerging overall synthesis as they saw it. This reflected the evolving coding template, expanding on it to describe emerging ideas about how PYD is defined and categorised and its intended mechanisms of action, as well as to hypothesise about possible moderators of intervention effects. Each reviewer recorded how each paper contributed to the emerging overall synthesis. Again, as reviewers coded each paper they kept a record of the coding template and the overall synthesis as it stood at the end of coding each paper.

In this way the researchers gradually developed a synthesis of PYD theory which attempted to develop a common and overarching definition, taxonomy, theorised mechanism of action and set of hypothesised contextual moderators for PYD. When the two researchers finished coding all the theory papers, they wrote up a summary drawing on their individual templates and memos. The text was organised under the four headings of the initial coding template, namely, definition of PYD, mechanism of action, moderation by context and taxonomy.

The reviewers then combined their efforts, producing an overall summary of their analysis by discussion and iterative drafting. The resulting text was then edited in response to verbal and written comments from co-investigators. These processes of refining the analysis did not fundamentally change the substance of the synthesis but did enable it to be presented in a conceptually clearer manner. For the initial templates that two reviewers created, see Appendix 9; these have been included to enable readers to judge the extent to which our final report of the synthesis tallies with our initial attempts at coding the theoretical literature.

Process evaluations

We aimed to produce a qualitative metasynthesis of process evaluations using thematic synthesis methods. 73–75 Qualitative metasynthesis aims to develop interpretative explanations and understanding from multiple cases of a given phenomenon by using qualitative research reports. Two reviewers independently read and reread all study reports to gain a detailed understanding of the findings and then undertook line-by-line coding of the findings sections using EPPI-Reviewer version 4 software. 61 They first applied in vivo codes to what Schutz76 termed first-order (verbatim quotes from participations) and second-order constructs (authors’ descriptions or interpretation of the data). Reviewers wrote memos to summarise their interpretations of these first- and second-order concepts. Axial codes were then applied which aimed to make connections between in vivo codes in order to deepen analysis, with reviewers writing memos to describe emerging ‘metathemes’. Each reviewer developed an emerging coding template, a hierarchical organisation of the codes that were applied in the course of the analysis. The two reviewers then met to compare their coding templates and to agree a common template which would form the basis for the drafting of the synthesis, which represented a set of third-order constructs developed by the reviewers.

As the coding template was developed, the reviewers referred to tables summarising the methodological quality of each study, so that this could be taken account of in the synthesis, with findings from more reliable or more useful studies being given more weight.

The two reviewers met to compare and contrast their draft coding templates and memos in order to develop consensus about the development of a single, coherent, overall synthesis. One reviewer then drafted the overall synthesis drawing on each reviewer’s coding template, memos and the assessment of the quality of each study. This was then commented upon by the second reviewer, with comments incorporated by the first (see Appendix 10).

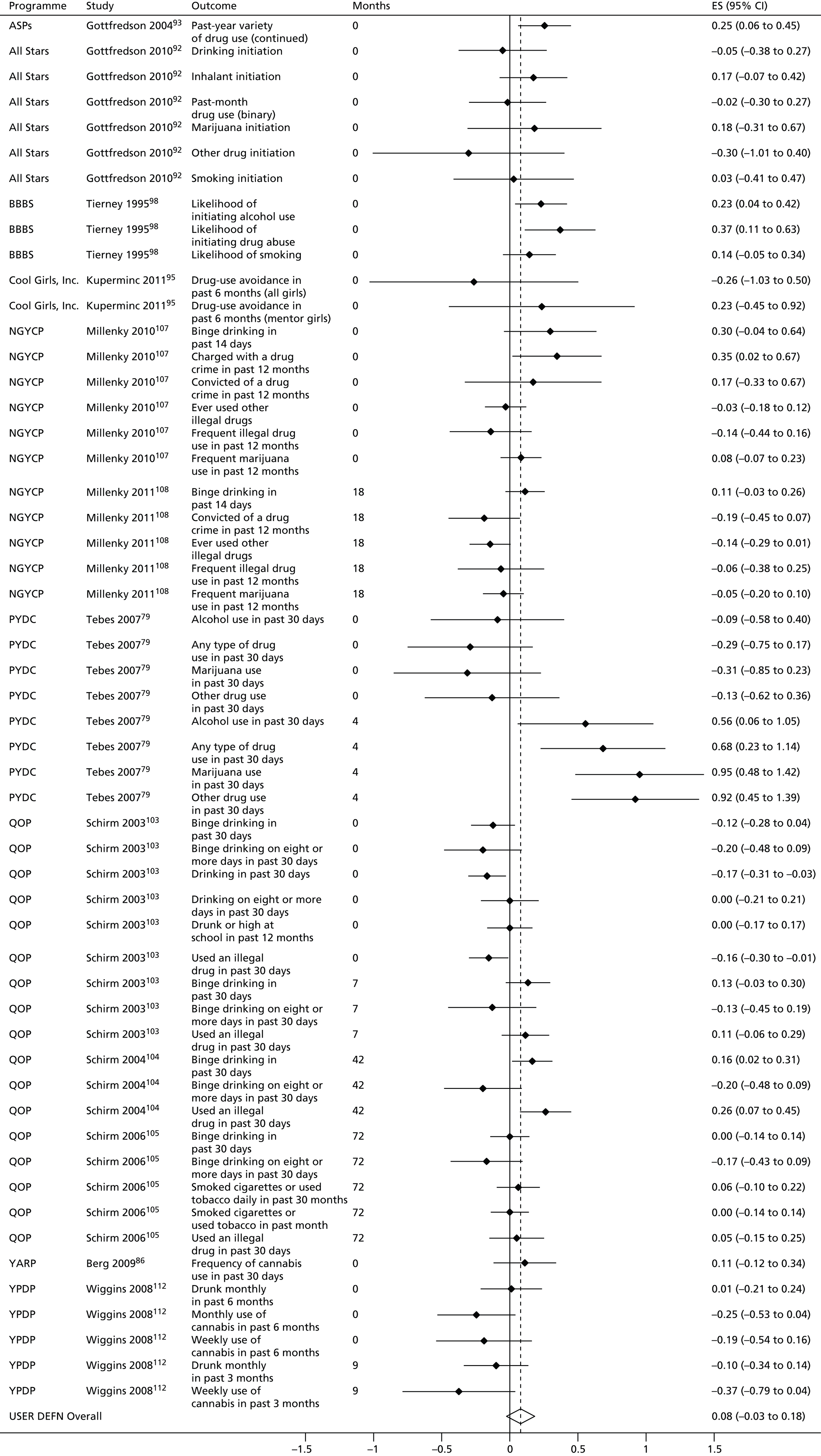

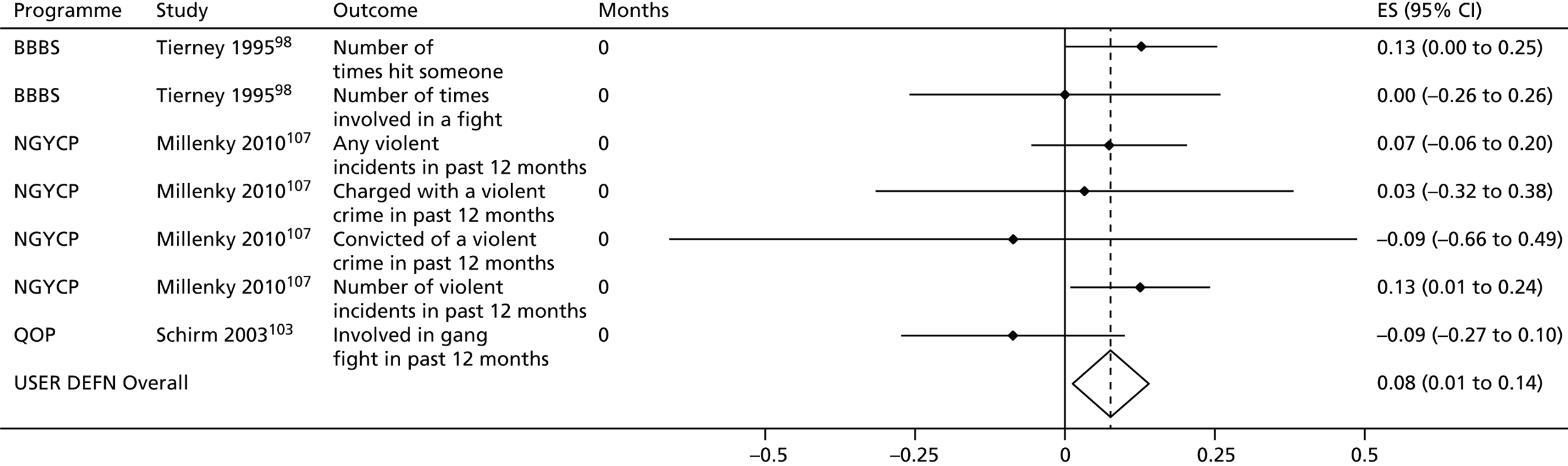

Outcome evaluations

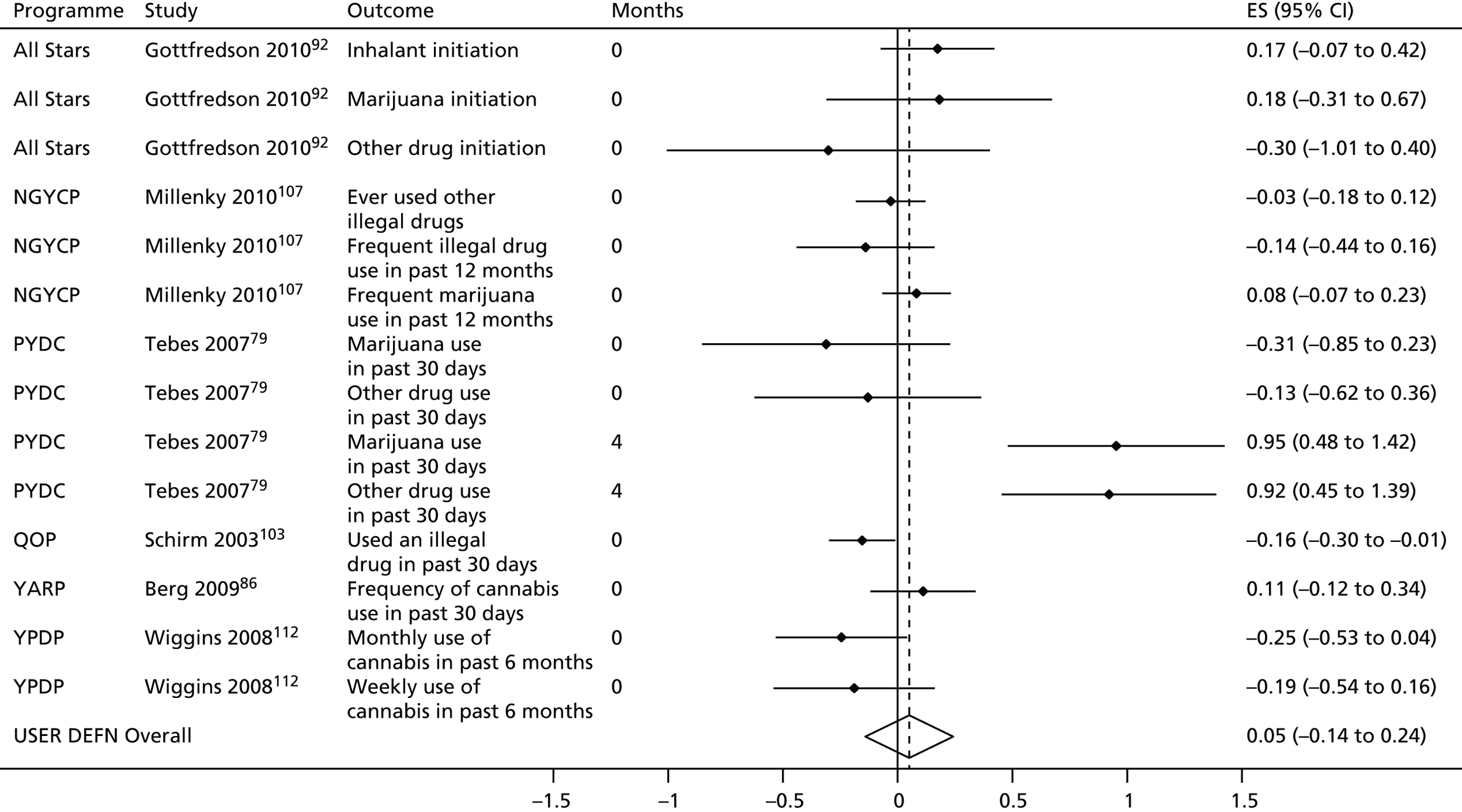

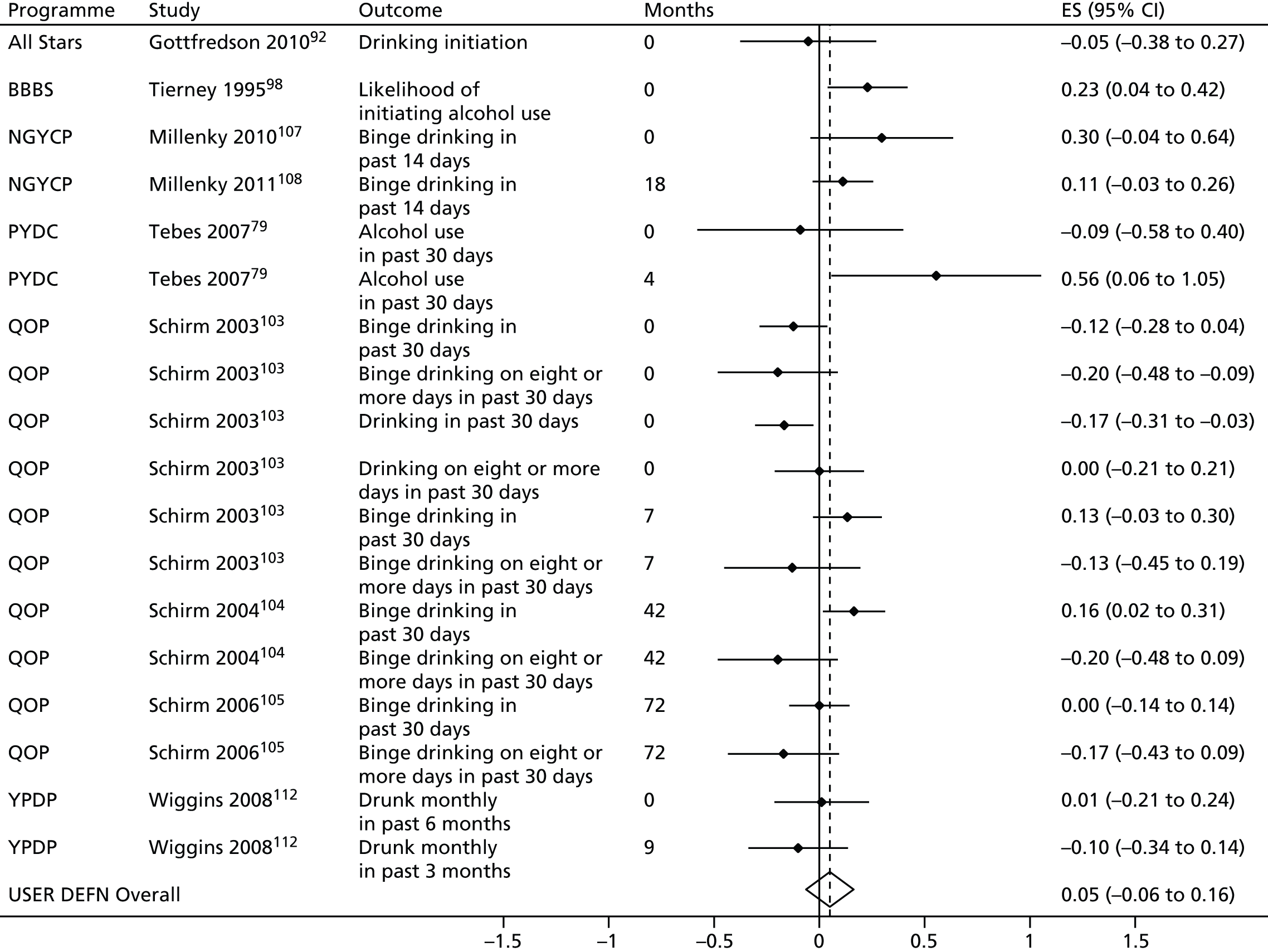

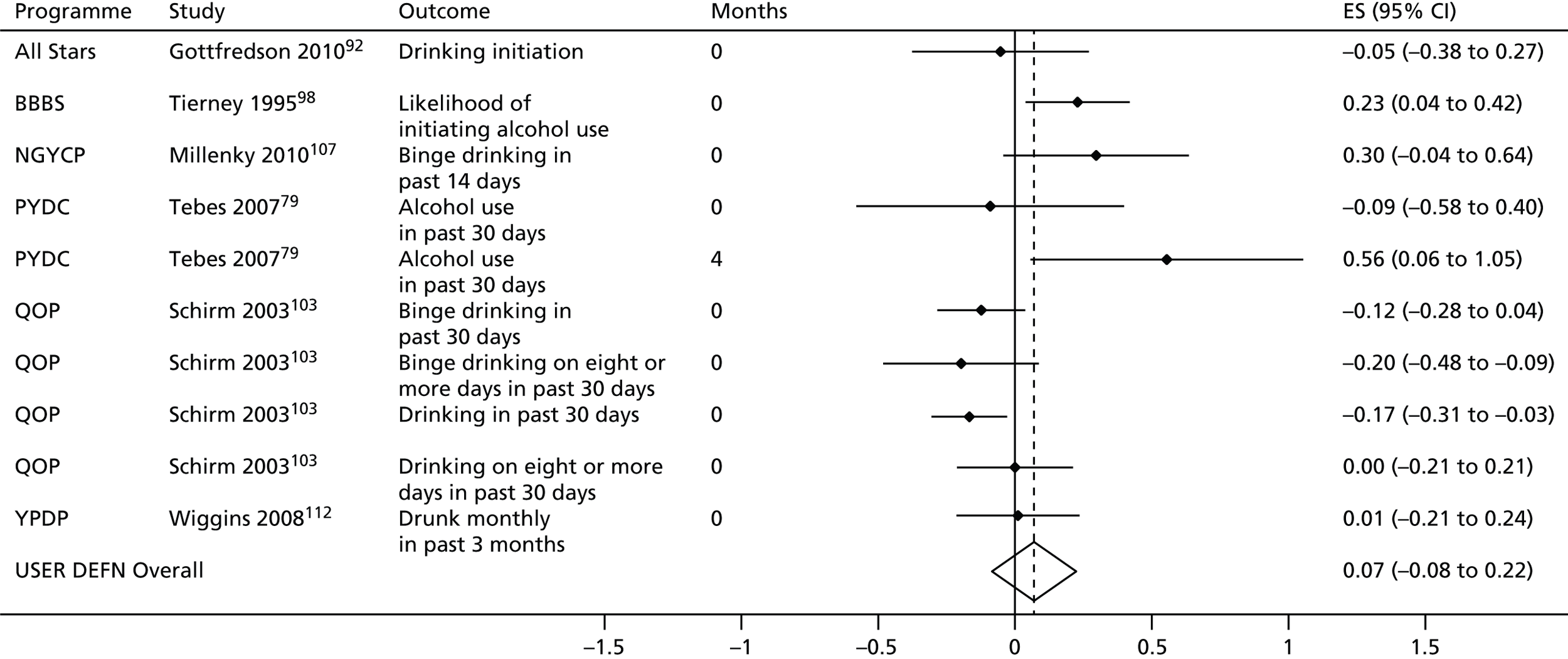

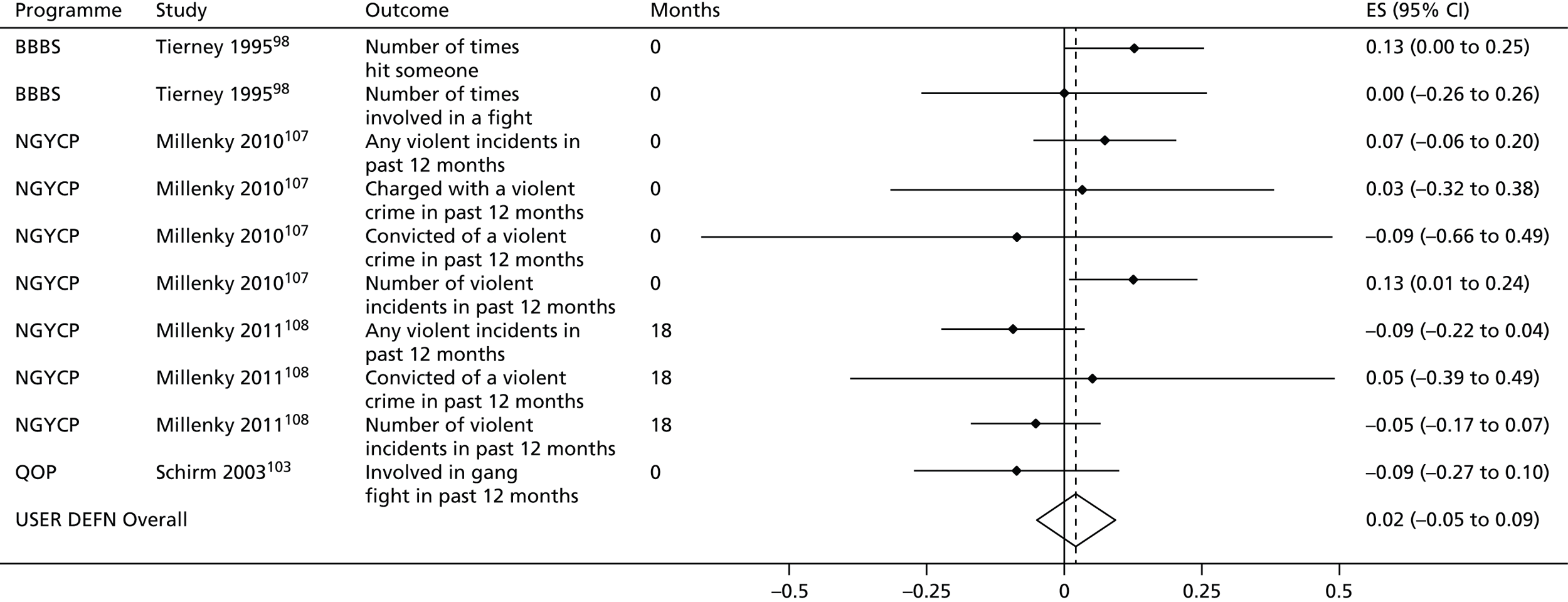

We undertook both narrative and meta-analytic synthesis of the results of outcome evaluations. Effect sizes from included study reports concerning substance use (smoking, alcohol or drugs) or violence as defined in the protocol51 were extracted into a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet and converted into standardised mean differences (Cohen’s d) using all available information as presented for each study. As recommended by the Cochrane Handbook,67 when the evaluation was designed as a RCT, we extracted the ‘least adjusted’ effect size estimates from each evaluation (i.e. uncontrolled estimates, or estimates controlling for baseline scores). When the evaluation was a matched or otherwise non-randomised design, we extracted the most adjusted effect size estimates (i.e. estimates in which the full vector of control variables was included). In interpreting the results of meta-analyses, we followed the standard rule for interpretation of Cohen’s d that 0.2 is a small effect, 0.5 is a medium effect and 0.8 is a large effect. Positive effect sizes indicate an effect favouring the intervention.

Because of the variation in reporting across studies, some degree of data transformation and imputation was necessary (see Appendix 11). Where the method of analysis was a linear probability model, as was the case with the National Guard Youth ChalleNGe Program (NGYCP)77 and the Quantum Opportunity Program (QOP),78 we took the group means on each outcome and used the sample sizes for each group to estimate odds ratios (ORs). In one case, an evaluation of after-school programmes (ASPs) reported by Tebes et al. ,79 we used gain scores to adjust for baseline differences. In this case, we estimated that the pre-test to post-test correlation was r = 0.5 and sensitivity analysed our estimates with r = 0.1 and r = 0.9. This was done to render all effect estimates in the same metric as recommended by Morris and DeShon. 80 Although we also intended to impute intracluster correlation coefficients for studies in which clustering was not appropriately addressed, we were unable to do so because of the small number of studies and the lack of any comparable estimate from other reviews. We note in the results where studies did not adequately address clustering in analyses.

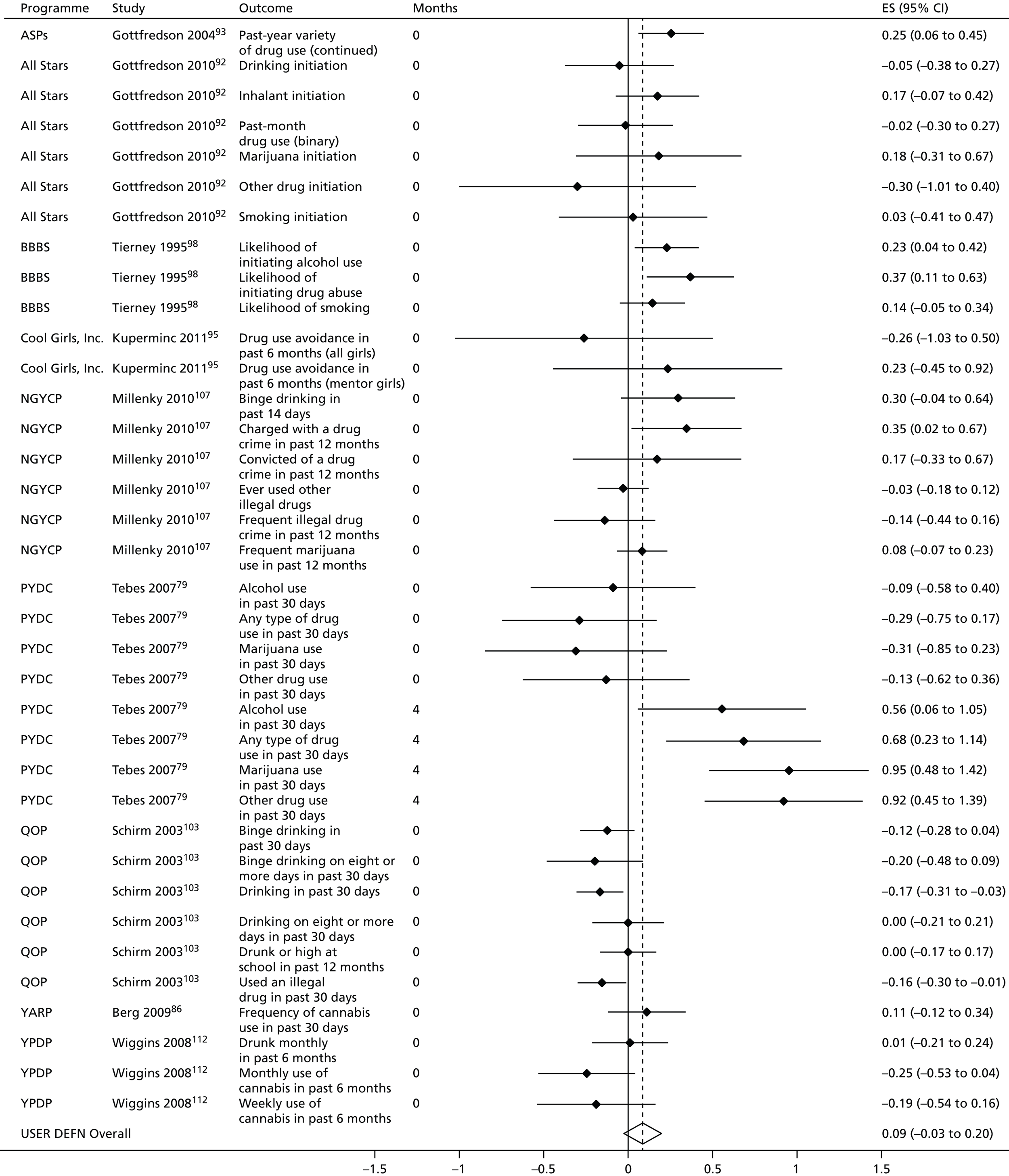

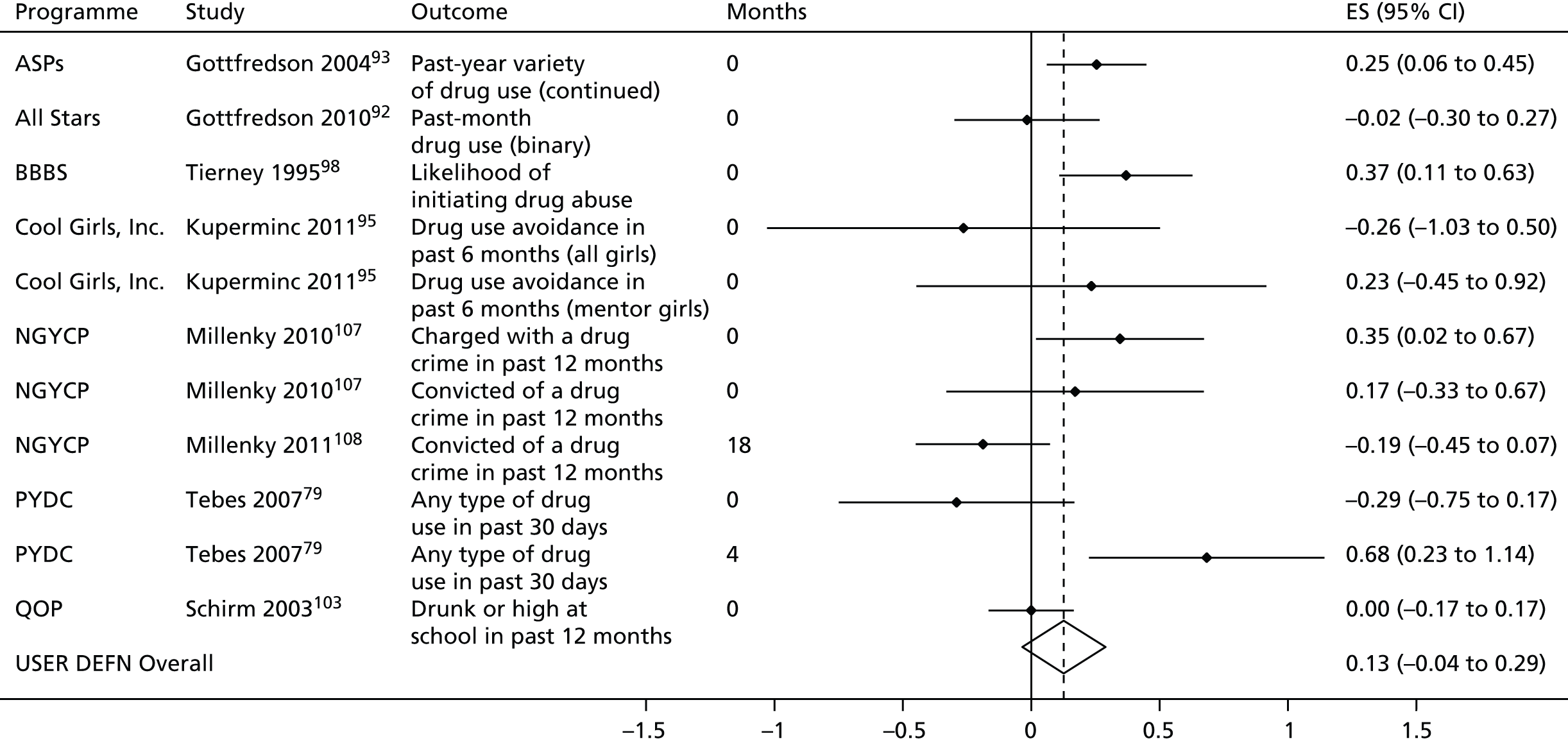

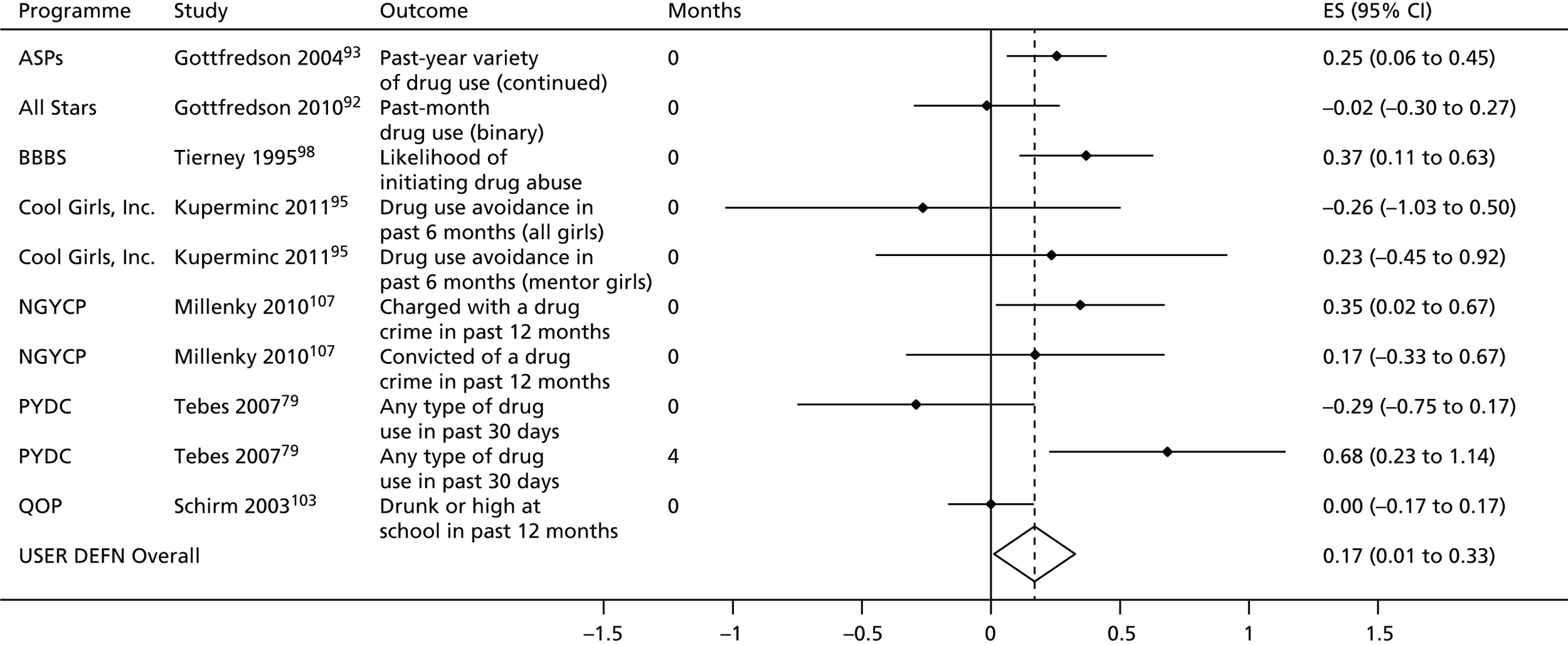

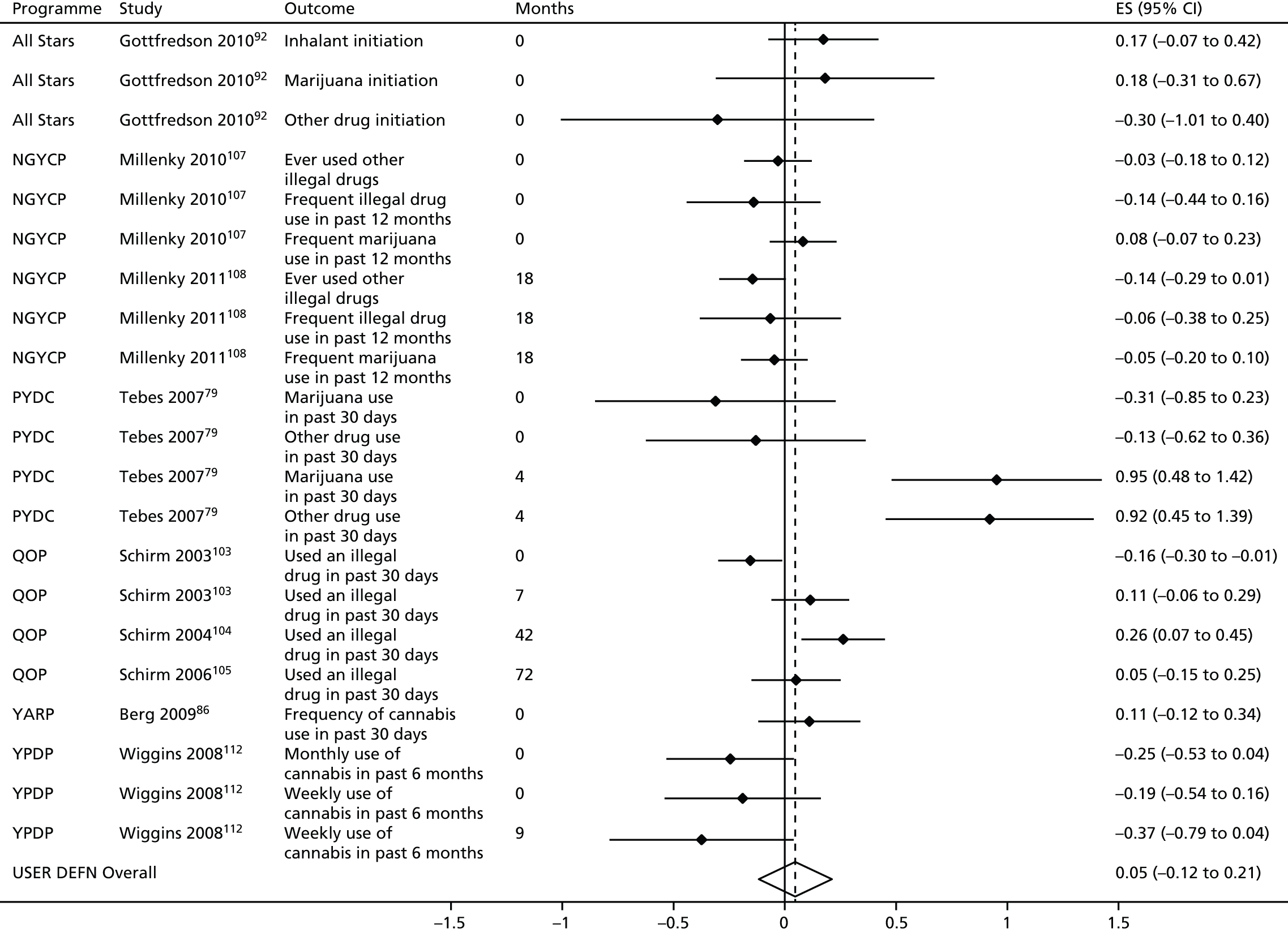

Most studies reported several substance use and violence outcomes at several measurement time points. As indicated in the protocol51 we intended to use multivariate meta-analysis or another method to synthesise effect sizes in this situation. However, this was not possible because of the heterogeneity of outcomes and the lack of availability of a variance–covariance matrix for reported outcomes. Instead, we used multilevel meta-analysis as set out by Cheung81 with random effects at both the outcome and study level. Multilevel meta-analysis accounts for dependencies between outcomes from the same study by partitioning the variance (τ2-statistic) between outcomes into a within-study level and a between-study level. The final effect size estimate includes all information that the multiple effect size estimates contribute while correcting for the non-independence of multiple effect size estimates from each study. This method indicated that using a random-effects model to synthesise the evidence was appropriate.

We used a standard three-level model, with level one being the ‘hypothetical’ participants who contributed to the effect sizes, level two being the within-study outcome-specific effect size estimates with sampling error, and level three being the ‘between-study’ level [two programmes (NGYCP,77 QOP78) having multiple study reports contributing to the analysis]. We did not run a four-level model to account for clustering within study reports because multiple reports from the same study involved similar personnel and methods.

Because we did not know the covariance between violence and substance-use outcomes in this context, we ran two separate sets of analyses. First, as specified in the protocol51 we ran an overall model capturing all violence outcomes, a model capturing all substance-use outcomes, and individual models for smoking, alcohol and illicit drug-use outcomes. Second, because studies often reported ‘omnibus’ outcomes covering a variety of substance-use behaviours across smoking, alcohol and illicit drug use, we also examined these generic substance-use outcomes in a separate model.

In our protocol51 we planned to examine subgroup effects according to the timing of follow-up assessment: post intervention to 3 months, 3 months to 1 year and > 1 year. However, this would have been inappropriate given the right-skewed distribution of the measurement time points in included studies, so we decided to examine a subset of short-term outcomes captured between post intervention and 4 months in separate models. We did not examine outcomes beyond 4 months because this would have included an extremely broad range of follow-ups.

For each model, we estimated an overall effect size expressed as a standardised mean difference with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We tested overall heterogeneity using Cochran’s Q, and we estimated I2 for the outcome level and the study level of the model using formulae published elsewhere. 81 Interpretation of I2 at the level of the study is most comparable to interpretations of I2 in ‘standard’ meta-analyses that include one effect size per study.

We intended to estimate metaregression models both to examine how intervention effects varied by participants’ SES, sex and ethnicity, to examine how intervention effects varied by area deprivation, and to test hypotheses on other moderators of effects. These other hypotheses were derived from the syntheses of theory and process evaluations, and consultations with young people and policy/practitioner stakeholders. However, such analyses were not possible because of the absence of meaningful heterogeneity in effects between studies as well as the lack of consistency of reporting of subgroup effects within studies. We also intended to run a qualitative comparative analysis to examine the causal combinations of conditions that predict intervention effectiveness. However, because of the absence of meaningful differences across our qualitative assessments of the outcomes of each intervention, this was not possible. We also found insufficient studies (≥ 10 per outcome) to draw funnel plots to assess the presence of possible publication bias. Full details of these methods may be found in our protocol. 51

Economic evaluations

Given that no economic evaluations were found, we did not synthesise economic data.

User involvement

We consulted with policy-makers, practitioners and young people during the course of the review. We convened a policy advisory group of the following stakeholders: Public Health England (Eustace de Sousa, Deputy Director, Children, Young People and Families); Department of Health (Geoff Dessent, Deputy Director, Health and Wellbeing); National Youth Agency (Jessica Urwin, Head of Policy); Association for Young People’s Health (Ann Hagell, Research Lead); and Project Oracle/London Metropolitan University (Georgie Parry Crooke, Professor of Social Research and Evaluation). Young people were also consulted via the Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) young people’s public health research advisory group based in the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a research collaboration between the universities of Cardiff, Bristol and Swansea.

Both groups were consulted at project inception as part of the protocol-development stage to gauge their interest in the work and identify additional priorities. 51 This consultation informed our view that synthesising evidence on PYD was a priority and that this should include assessments of process alongside outcomes in order to consider the feasibility and acceptability of interventions and what contextual factors affect transferability across settings. This consultation also informed our decision to prioritise evidence of effects on substance use (smoking, alcohol and drugs) and violence (perpetration and victimisation).

Feedback from the policy advisory group and young people was also obtained in October 2014 and April 2015. In October 2014, the policy advisory group was provided with information about the review’s aims, RQs and methods together with a draft synthesis of theory and process evaluations plus a list of potential hypothesis generated from these (see Appendix 12). Because a date for a meeting that everyone could attend proved impossible to find, consultation was undertaken via bilateral telephone conversations with a reviewer or via written e-mail feedback. Stakeholders’ views were sought on the clarity of the draft syntheses, whether or not these resonated with their experiences in the UK and their views on the hypotheses that we had developed on the basis of our syntheses. The ALPHA group also met in October 2014, in person. A total of eight young people aged between 15 and 19 years took part in a group discussion, facilitated by two researchers, one of whom took notes. After providing a Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentation distilling the main findings of the theory and process syntheses, the group provided feedback and engaged in a ranking exercise about the importance of various aspects of PYD interventions (see Appendix 12). In March 2015, both groups were contacted during the write-up of the final report to inform how the research outputs were structured and to inform the dissemination strategy.

Ethical arrangements

This project was approved by the research ethics committee of the Institute of Education’s Faculty of Children and Learning (ethics approval reference number FCL 544). The project complied with the Social Research Association’s ethical guidelines82 and guidance from the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement. 83

Chapter 3 Included studies

About this chapter

This chapter reports the results of our systematic search and screening process and gives a brief overview of the included studies.

Results of the search

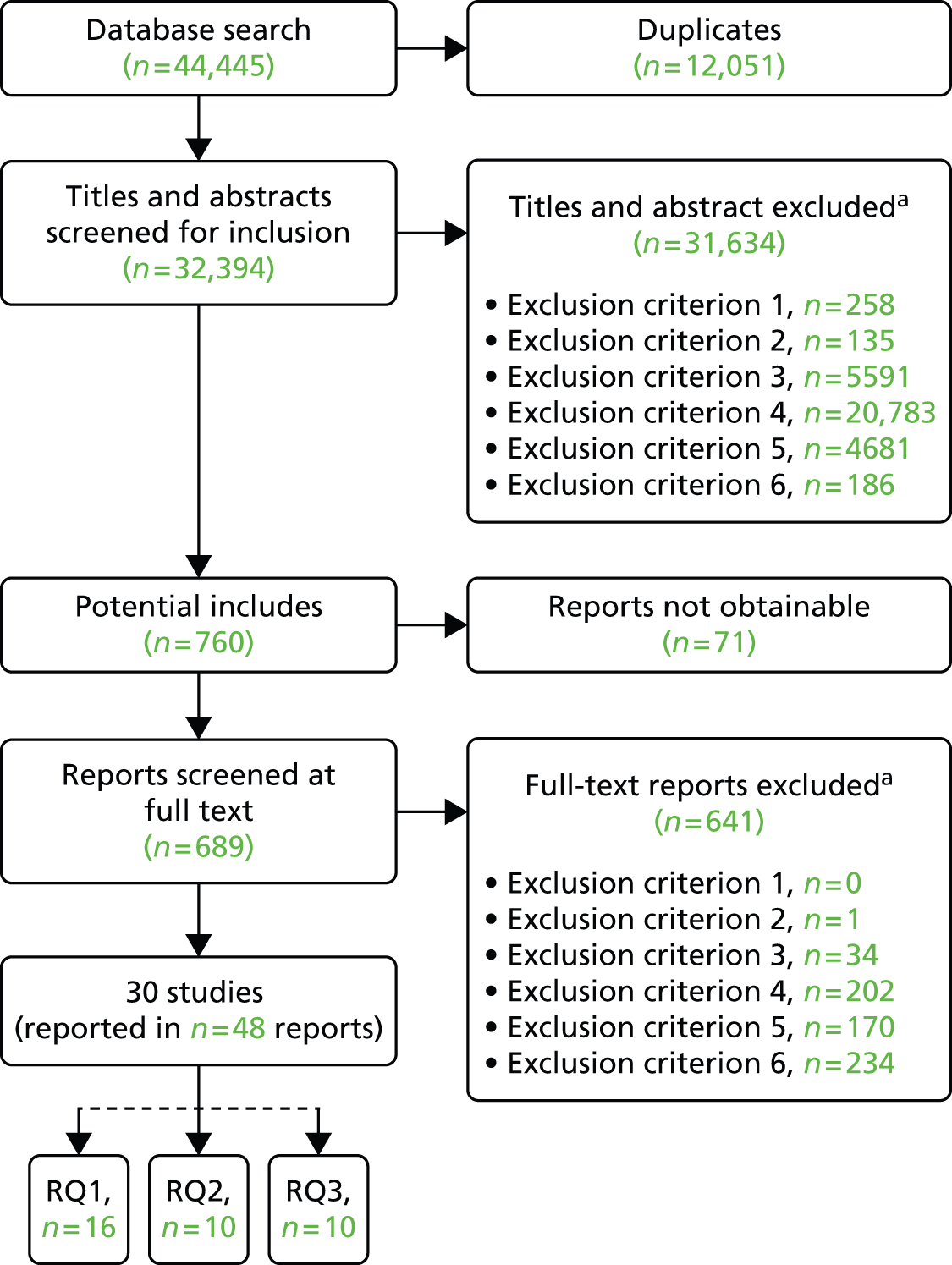

A total of 44,445 references were identified from the searches. Of these, 12,051 (27%) were identified as duplicates. The remaining 32,394 references were screened on title and abstract and, of these, 31,634 (97.6%) were excluded using the criteria listed in Appendix 3.

When piloting the process for screening on title and abstract, initial screening agreements between reviewers varied slightly but were consistently above 90% on whether or not a study should be excluded. Agreement was lower on the question of which particular criterion should be cited in excluding a particular reference, varying from 45% to 77% among five different pairs of reviewers. Discussion between reviewers established that this reflected the multiple criteria that could be used to exclude many studies and, therefore, the choice of which particular criterion to cite in each case was somewhat arbitrary. Given that agreements were above 90% on whether to exclude or not, we moved to a system of one reviewer independently screening each reference, as set out in our protocol. 51

Of the 760 remaining references included at this stage, we were able to obtain the full-text reports of 689, with the remainder not accessible online or in local libraries. Piloting the application of same exclusion criteria used at the title and abstract screening stage on full-text documents, screening agreements between two pairs of reviewers also reached above 90% on whether a study should be excluded or not. The agreements on which criterion to apply still remained lower, varying between 37% (KD and CB) to 66% (KD and KH) for the same reason of multiple possible criteria to apply in many cases. However, similar to the first round of screening, as agreement overall was above 90%, individual reviewers (KD, KH, CB) moved to independent screening of documents, consulting with a second reviewer when a decision could not be easily reached. The PI (CB) also made final checks of all the studies included by reviewers. This process led to a further 641 studies being excluded at this stage in the review screening process.

The remaining 48 reports deemed eligible for inclusion in the review were coded according to which RQ they answered. A total of 30 distinct research studies were included in the review. Five research studies contributed more than one study report to our set of included reports, together providing 23 reports that we needed to link to other reports from the same study. Furthermore, five study reports provided answers to more than one RQ. In presenting the number of studies and study reports, we have not double counted those that address more than one of our review questions. Where appropriate, we clarify whether or not a study or report addressed more than one of our RQs. Figure 1 summarises the flow of references, reports and studies through the review, providing a breakdown of the exclusion criteria at both title and abstract and full document stages and the number of studies included in each synthesis. Table 2 provides an overview of the interventions that were subject to process or outcome evaluation included in this review.

| Interventions examined in the review | Included theory studies | Included process evaluations | Included outcome evaluations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised ASP | Armstrong and Armstrong84 | ||

| A violence, delinquency and substance abuse prevention programme | Baker et al.85 | ||

| YARP | Berg et al.86 | Berg et al.86 | Berg et al.86 |

| Chicano Latino Youth Leadership Institute | Bloomberg et al.87 | ||

| Stand Up Help Out: leadership development ASP | Bulanda and McCrea88 | ||

| All Stars prevention curriculum: an enhanced ASP | Cross et al.89 Gottfredson et al.91 |

Cross et al.90 Gottfredson et al.92 Gottfredson et al.91 |

|

| MAPs | Gottfredson et al.93 | ||

| Community Youth Initiative | Lee et al.94 | ||

| Cool Girls, Inc. | Kuperminc et al.95 | ||

| BBBS | Rhodes et al.96 Grossman and Tierney97 Tierney98 |

||

| QOP | Maxfield et al.99 Maxfield et al.100 |

Rodriguez-Planas78 Maxfield et al.100 Rodriguez-Planas101 Rodriguez-Planas102 Schirm et al.103 Schirm and Rodriguez-Planas104 Schirm et al.105 |

|

| NGYCP | Schwartz et al.77 Bloom et al.106 |

Schwartz et al.77 Millenky et al.107 Millenky et al.108 Millenky et al.109 Perez-Arce et al.110 |

|

| PYDC | Tebes et al.79 | ||

| Stay SMART programme | St Pierre and Kaltreider111 | ||

| YPDP | Wiggins et al.112 | Wiggins et al.112 Wiggins et al.46 |

Study characteristics

A descriptive overview of the 30 studies and 48 study reports included in the review is provided below. It includes details of the rate of publication, geographical location of study publication, the age group targeted by PYD programmes and the age of actual sampled populations.

Rate of publication

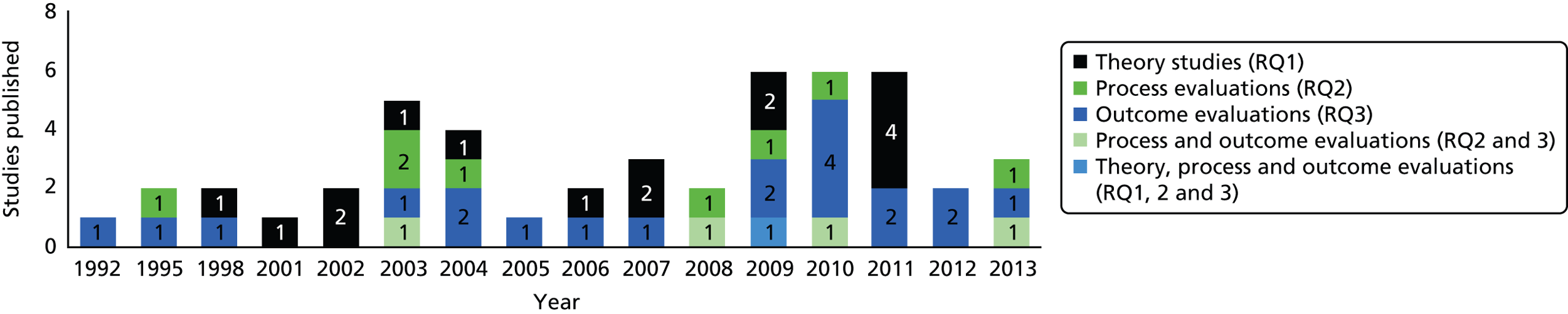

Figure 2 provides a breakdown of rate of publication, based on the 48 reports included in the review according to which RQ they answered. The data indicate that there was an increase in studies being published in this area from 2002–2011 (n = 37) reaching a peak in 2003 (n = 5) and another in the period 2009–2011 (n = 6 per year) with few studies published before 2001 (n = 6).

FIGURE 2.

Rate of study publication.

Geographical location

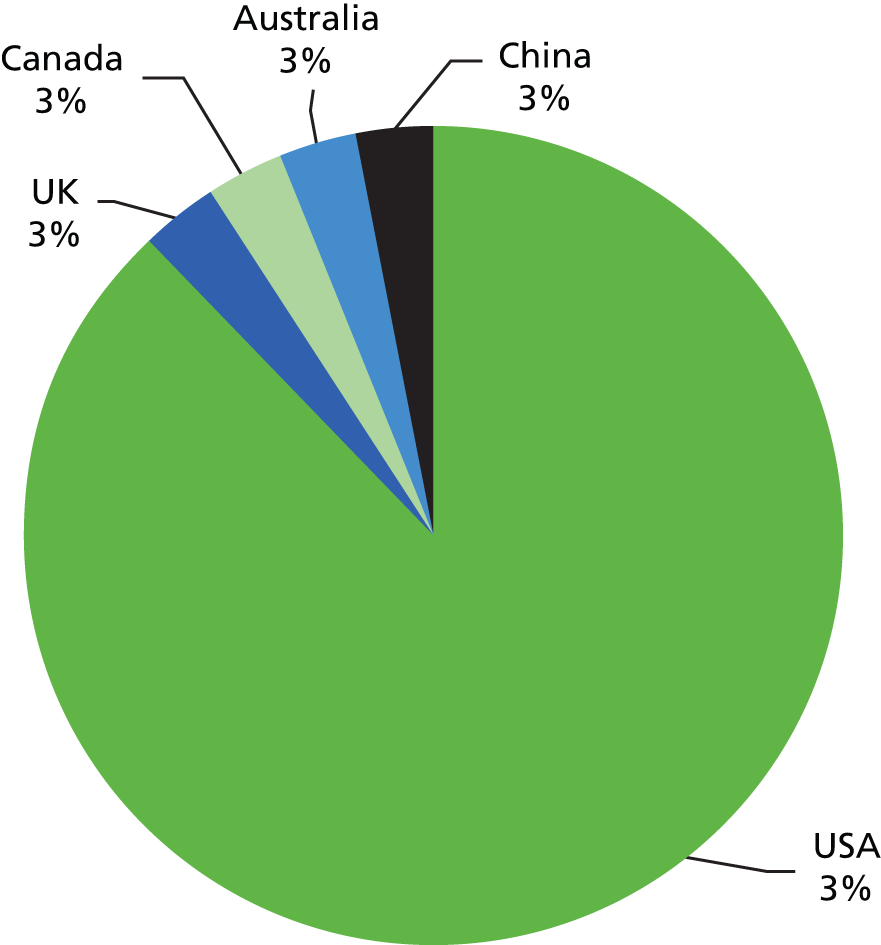

Figure 3 provides a summary of the geographical origin of studies. Of the 30 included studies, the vast majority were written and published in the USA (n = 26), reflecting the origins of the programme. Only a few studies were conducted in other countries; one each from the UK, Australia, Canada and the Hong Kong province of China.

FIGURE 3.

Spread of studies by country (mutually exclusive).

Target age group of Positive Youth Development programmes

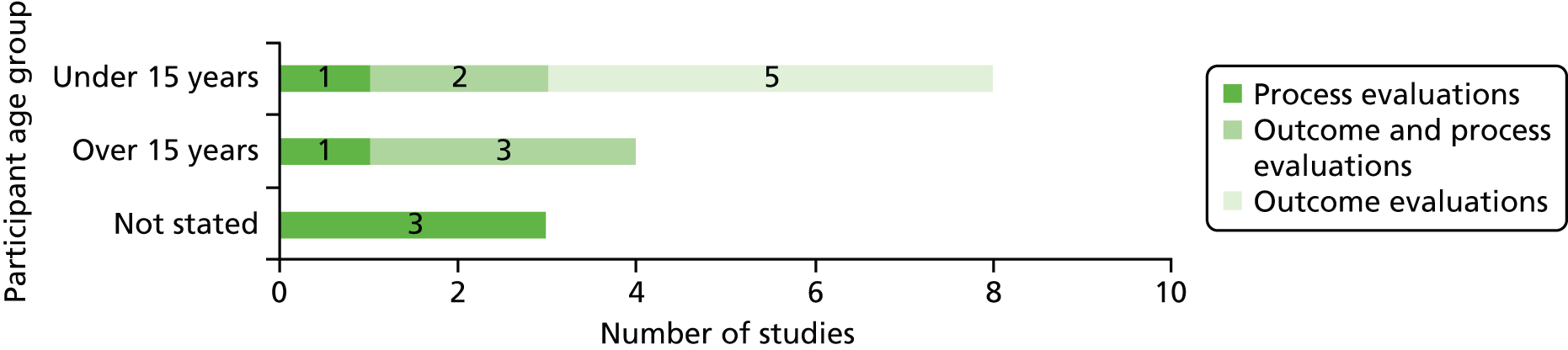

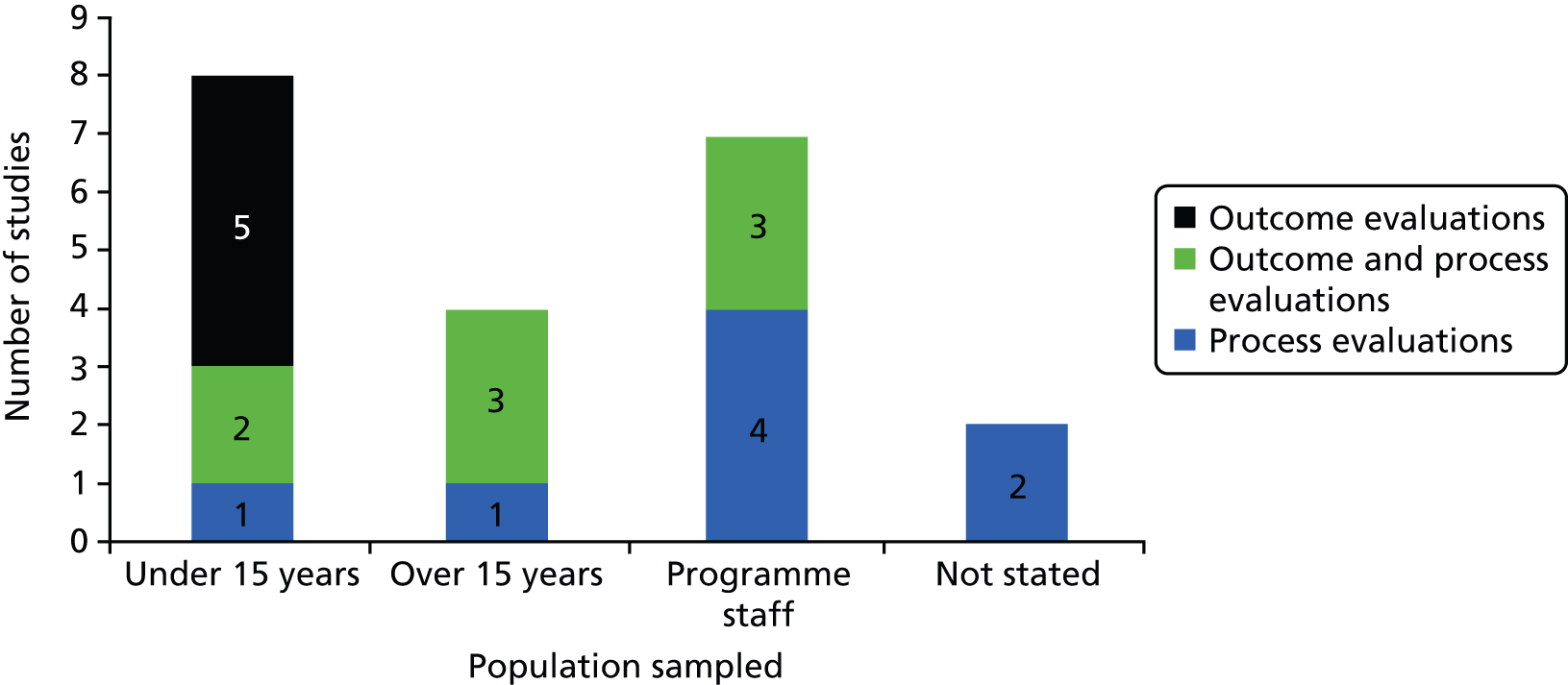

The majority of process and outcome evaluation studies (n = 15) focused on programmes delivered to children and young people under the age of 15 years (n = 8) rather than to those over 15 years of age (n = 4) (Figure 4). Three process evaluations did not explicitly report the age group of their target population of interest, simply stating that programmes were eligible to all young people or for those young people considered to be ‘at risk’ in their community.

FIGURE 4.

Target age group of programmes according to study type (mutually exclusive).

Sampled population

Figure 5 summarises the populations sampled. The outcome evaluations sampled the same population targeted by the programmes under investigation. However, as would be expected, the studies containing process data sampled both programme providers (n = 7) and young people (n = 7). Of the seven studies with process data sampling young people, three sampled those under 15 years of age and four sampled those aged over 15 years. The remaining two studies failed to provide a breakdown of the age of young people in their sample.

FIGURE 5.

Population sampled in outcome and process evaluations (not mutually exclusive).

Chapter 4 Synthesis of theories of change

About this chapter

This chapter describes and reports the quality of the included studies which describe theories of change for PYD interventions. It also reports our thematic synthesis of these studies, which aimed to produce a taxonomy and theory of change of PYD interventions and which uses this synthesis to develop some hypotheses about the factors that might moderate the effectiveness of PYD interventions. Characteristics of theory studies and an assessment of their quality are tabulated in Appendix 13.

Included studies

A total of 16 reports were judged to set out a theory of change for PYD and were thus included. 50,86,113–126 One report was led by Canadian authors117 and one by authors from Hong Kong. 122 All other reports were led by authors from the USA. 50,86,113–116,118–121,123–126 One report which described theory of change was also included in our review of process and outcome evaluations,86 but all other theory reports did not report on empirical evaluations of PYD interventions. Four reports were led by Benson113–116 and two by Lerner and Lerner. 123,124

During the process of coding studies, reviewers determined that the included reports engaged in two types of theorising, namely ‘normative’ (what things should look like) and causal (how things are causally interconnected). Nine of the reports largely focused on developing normative theory,113–116,119,122–125 which asserted the value of PYD in focusing on the development of assets rather than merely the prevention of risk behaviours, albeit with some discussion of causality too. Six reports largely focused on causal theory, which aimed to describe the mechanisms by which PYD might promote benefits,50,117,118,120,121,126 and one report gave attention to both normative and causal elements. 86 Rather than limit synthesis to causal theories, we decided to broaden this to include normative theorising because we felt that this enabled a clearer specification of the assumptions that lie behind PYD interventions. Most of the reports drew on established psychological theories to describe and/or assert the value of PYD. These included bio-ecological theory,127 referenced by Benson et al;113 social learning theory,128 referenced by Berg et al;86 and identity development theory,129,130 referenced by Busseri et al. 117 We identified only one novel theory that was explicitly presented as a theory of PYD, namely that developed by Benson et al. 113 called ‘developmental assets theory’. This is predominantly a normative theory rather than a causal theory, in that it asserts the importance of developing positive youth assets rather than describing a causal theory of change explaining how PYD interventions might achieve their impacts.

Although all studies gave some attention to how PYD might reduce risk behaviours, only nine studies did so in any depth,50,86,115,118,120–122,125,126 and, of these, only Catalano et al. 118 presented a comprehensive assessment of the causal mechanisms involved. Thus, many studies only narrowly met the inclusion criteria for this element of our review and did not present detailed causal pathways by which PYD interventions might reduce substance use and violence. Nonetheless, our synthesis of these studies succeeded in drawing on these disparate reports to develop a synthesis which offers a somewhat more comprehensive analysis of how PYD intervention might aim to reduce these risk behaviours than is presented in any single included study.

Quality of studies

Assessing the quality of theory reports proved challenging despite the use of criteria informed by previous literature. 64,131 As shown in Appendix 13, there was very little agreement on the scores given by the two reviewers and, thus, with the exception of three studies, we decided not to develop an overall agreed score. The utility of the assessment of the quality of theory reports is considered further in Chapter 7.

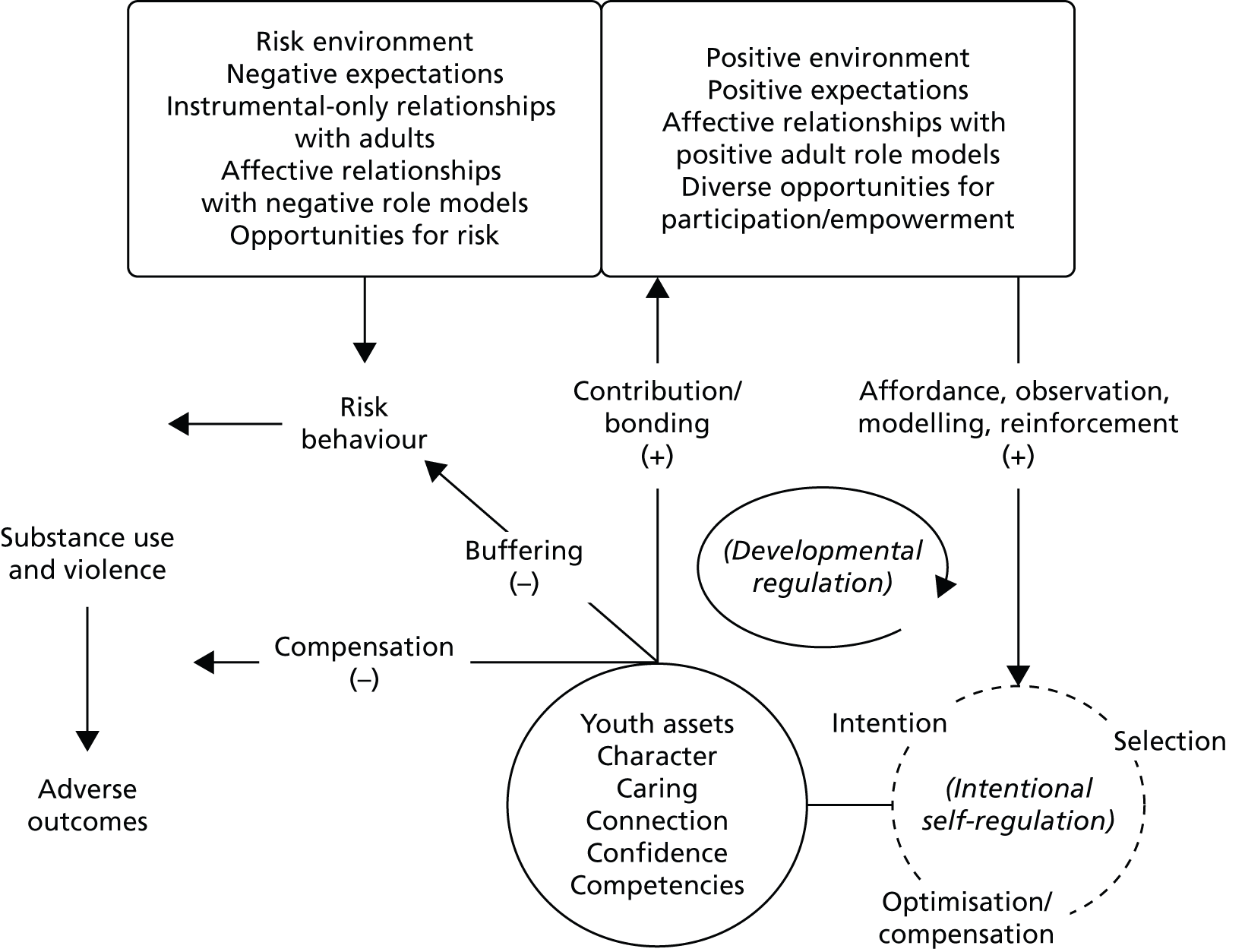

Synthesis of theories of Positive Youth Development

The two reviewers differed in how they coded and interpreted the theoretical literature (see coding templates in Appendix 9). One attempted to bring the theories together to create an overarching theory of change from PYD intervention to risk reduction, even where the lack of clarity and attention to the question of risk reduction in primary sources did not make this task very easy. The other reviewer focused on highlighting that the PYD theoretical literature gives more attention to asserting what PYD is and why it is superior to prevention science, rather than on theorising the causal pathways by which PYD interventions promote positive assets or how these then help to reduce risks. This reviewer also focused on how the PYD literature did not put forward a novel theory of change but rather relied on a number of existing psychological theories. Nonetheless, it was possible to produce an overall analysis which drew on these different elements, and this is summarised below.

The original focus for the synthesis was to define, produce a taxonomy of and identify a theory of change for PYD interventions. However, our thematic analysis led us to expand our examination of PYD definitions to develop a synthesis of what we term a ‘normative’ theory of PYD in addition to our focus on causal theories of change. Normative theories set out ideal conditions, or as Sayer132 argues, what alternative, better, social conditions might be possible. In addition, our synthesis examined the potential generalisability of PYD and the factors that might moderate its impacts.

Normative theory of what is Positive Youth Development

Within the theme of normative theory, we identified subthemes including the principles and assumptions which underlie PYD; a normative vision of what positive development should look like for young people and their environments; and the required characteristics of PYD interventions. 133

Principles/assumptions that underlie Positive Youth Development

Included reports suggested a number of principles and assumptions that appeared to underpin PYD interventions.

All young people have potential

The first assumption of the PYD literature is that all young people have the potential to develop healthily rather than this being dependent on innate or other fixed factors. This assumption was at the heart of a number of concepts and assertions made in included reports. Lerner and Lerner,123 for example, suggest that PYD ‘conveys the adults’ beliefs in youth as resources to be developed rather than as problems to be managed’ (Roth and Brooks-Gunn,134 cited in Lerner and Lerner123), a sentiment echoed by Kim et al. 121 and Schwartz et al. 126 In addition, Schwartz et al. 126 and Lerner et al. 123,124 assert that PYD is possible because young people’s development is subject to ‘plasticity’. 126 Benson et al. 114 and Benson and Scales115 similarly set out an assumption that all youth have the inherent capacity for optimal development given appropriate opportunities and ecologies. Berg et al. ,86 Kia Keating et al. ,120 Lerner and Lerner,123 Roth and Brooks-Gunn50 and Lee122 all describe how hope is central to the atmosphere of PYD programmes. Lerner and Lerner123 and Kim et al. 121 stress that the optimism expressed by adults in the strengths and potentials of young people is an important contributor to the fostering of hope. This might stand in contrast to traditional prevention programmes that explicitly present to young people the belief that they may experience adverse outcomes.

Amelioration is required because of deteriorating environments

Another assumption, apparent within reports by Benson et al. 114 and Kim et al. ,121 is that PYD interventions are necessary because of deteriorations in young people’s environments. Addressing this matter from a conservative political position, Benson et al. 114 refer to the erosion since the 1960s of what they describe as the ‘traditional’ supports for youth development, such as stable families and communities characterised by intergenerational relationships and good-quality school systems. 114 Kim et al. 121 similarly refer to deficits in parenting arising from social mobility and transiency which erode neighbourhood stability. 121 Roth and Brooks-Gunn50 state that ‘when circumstances prevent . . . families, schools, and communities from providing their youth with fundamental . . . resources, youth development programs offer one avenue for fulfilling these needs’. Moreover, Kim et al. 121 suggest that the separation of youth from adults in modern society is denying young people adult models and potentially increasing the alienation and isolation of young people.

In considering deteriorating social contexts, only a minority of authors emphasise increasing social inequalities; Berg et al. 86 and Ginwright and Cammarota119 both describe young people’s environment as toxic to healthy development because of inequalities relating to SES, ethnicity and sex. Ginwright and Cammarota119 criticise what they regard as mainstream ideas of youth development in their neglect of the inequalities present in existing social arrangements. These authors maintain that it is not sufficient to understand challenges to young people’s development only in terms of the individual, their family and community and that attention must also be given to the larger social and economic forces that impact on and limit healthy development.

Normative vision of what positive development should involve

Another subtheme within our coding template concerns what positive development should involve.

Thriving and positive assets

The major emphasis across nearly all the literature was on the importance of enabling young people not merely to reduce problem behaviours and adverse outcomes but to achieve ‘normal development’. 50 This is emphasised for example by Roth and Brooks-Gunn,50 Schwartz et al. 126 and Lerner and Lerner. 123 Kim et al. ,121 Catalano et al. ,118 Busseri et al. 117 and Roth and Brooks-Gunn,50 for example, all state that ‘problem free is not fully prepared’50 – in other words that a young person needs more than merely to avoid risk in order to thrive. Lerner and Lerner123 and Kim et al. 121 all contrast PYD with the risk factor approach characteristic of prevention science, arguing that PYD defines the positive assets that should be promoted and not merely the risks and problems that should be avoided. Benson et al. 114 describes PYD as a ‘strength-based approach’:

The theory and research undergirding developmental assets and asset-building community are designed, in part, to reframe the targets and pathways of human development around images of strength and potential. We posit that this shift is crucial for mobilising both personal and collective efficacy on behalf of child and adolescent development. By so doing, we ultimately seek to balance paradigms so that communities pursue deficit reduction and asset building with equal vigour.

Benson et al. 113

Kia-Keating et al. 120 argue that PYD is also distinct from the resilience literature in that PYD focuses more on what is actually required for thriving (whether adversity is experienced or not), whereas the resilience literature often continues to emphasise the avoidance of harms in the face of adversity. Roth and Brooks-Gunn,50 Busseri et al. ,117 Lerner et al. ,123,124 Schwartz et al. 126 and Perkins et al. 125 all build on this idea of thriving by suggesting what particular ‘assets’ PYD might aim to develop, terming these the ‘5 Cs’:

-

competence in academics, social, emotional and vocational areas

-

confidence in who one is becoming (identity)

-

connection to self and others

-

character that comes from positive values, integrity and a strong sense of morals

-

caring and compassion. 125

The Search Institute, Benson et al. 113,114,116 and Roth and Brooks-Gunn50 propose an alternative categorisation of 40 assets. These comprise 20 ‘internal’ assets (in four groups) which relate to young people’s positive development and 20 ‘external’ assets (also in four groups) which describe the assets that environments should possess to enable young people’s positive development.

Internal (individual) assets include:

-

‘commitment to learning (achievement motivation, school engagement, homework, bonding to school, reading for pleasure)

-

positive values (caring, equality and social justice, integrity, honesty, responsibility, restraint)

-

social competencies (planning and decision-making, interpersonal competence, cultural competence, resistance skills, peaceful conflict resolution skills) and

-

positive identity (personal power, self-esteem, sense of purpose, positive view of personal future)’. 113

External (environmental) assets include:

-