Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3050/01. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The final report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Jago has been a member of the Research Funding Board for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) board since October 2014. Professor Powell was a member of the NIHR PHR Funding Board from June 2011 to September 2015.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Jago et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction/background

Benefits of physical activity

Regular physical activity (PA) can improve a number of risk factors for chronic disease, including body composition, lipoprotein profiles, insulin sensitivity, glucose levels and blood pressure in children and adults. 1,2 PA is also associated with positive emotional well-being and self-esteem among young people. 3 Despite these benefits, a large number of young people in the UK do not meet the PA recommendations of 60 minutes on most days of the week. 2 The number of young people meeting this guideline fell between 2008 and 2012. 4 There is an age-related decline in PA levels during childhood and adolescence, with the start of secondary school being a key period of downwards transition. 5,6

Girls’ physical activity

The percentage of girls who meet government recommendations of 60 minutes of PA per day is low. 4,7,8 Throughout childhood and adolescence, girls spend less time in moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) than boys, with reports of > 60% of girls’ time being spent on sedentary behaviours. 7 Therefore, there is a need for effective strategies to attenuate this decline in PA among girls and to reduce the amount of time spent being sedentary.

A number of reasons have been proposed as possible explanations for the age-related decline in girls’ PA. Research conducted by the Women’s Sport and Fitness Foundation9 found that girls’ attitudes towards PA are positive and that 76% of 15-year-old girls want to do more PA. Girls perceived more barriers to being active than boys, ranging from disinterest and boredom to a lack of opportunity for the desired sport in school. 10 Self-presentation issues also affect participation, with 76% of girls agreeing that they are conscious of their body image. 9

Sport competence has emerged as a common theme relating to the PA levels of girls. Sports competence declines with age in boys and girls, but is consistently lower for girls and falls faster between 17 and 18 years of age. 11 Physical education (PE) in school can expose anxieties and make girls feel embarrassed about their perceived lack of skill, further deterring them from participation. Focus groups based on girls’ attitudes towards PA have reported that girls are often disinclined towards PA because they do not like to appear tired or ‘sweaty’ in front of peers, especially males. 10,12 Girls also worry about not looking ‘cool’ and being teased by boys and girls about not being feminine,9,10 leading to an increased likelihood of giving up sport. During adolescence, girls begin to form their own self-perception of sporting ability, which contributes to the decision-making process about whether or not to participate. 11 Therefore, the factors that contribute to the decline in PA must be handled delicately and be considered when designing interventions to increase girls’ PA.

Interventions to increase girls’ physical activity

A recent meta-analysis concluded that interventions designed to increase girls’ PA levels have a minimal, yet significant, effect (g = 0.314; p < 0.001). 13 On average, girls in intervention groups accrued 12.17% more PA than girls in control groups. The authors suggested that the results led to the belief that behaviour change in this population is challenging but possible. A subgroup analysis found that interventions developed specifically for girls and interventions with multiple components were more likely to produce a significant treatment effect. For example, an intervention that worked with Girl Scout troops to foster healthy behaviour resulted in girls in intervention troops accumulating significantly more MVPA than girls in control troops, with 7.4% of girls meeting MVPA daily targets versus 1.6%, respectively (χ2 = 18.4; p < 0.001). 14

A number of approaches have attempted to help girls overcome their anxieties around PA. Intervention approaches have included allowing schools to develop bespoke action plans to prevent the decline in girls’ MVPA. 7 The Nutrition and Enjoyable Activity for Teen Girls intervention15 provided enhanced school sports sessions for 12- to 14-year-old girls, held seminars and workshops, and used various tools to help self-monitor activity. The choice of music and appealing activities during the sports sessions were incorporated to engage girls. The results suggest that these elements may have contributed to the favourability of sessions (41.7% of participants reporting it as the most enjoyable component of the intervention). However, it was found that MVPA did not significantly differ between the intervention and control groups [adjusted difference in change –4.28 minutes/day, 95% confidence interval (CI) –13.82 to 5.25 minutes/day; p > 0.05]. 15 It is important to note that the authors did not reflect on elements of the intervention that were successful or unsuccessful.

Taymoori and Lubans16 used theoretical constructs to aid the development of educational and counselling sessions for girls in order to identify potential mediators of PA behaviour change. Both interventions showed an intervention effect on self-reported PA. However, PA was not measured objectively. The authors concluded that certain behavioural strategies, such as goal setting and activity monitoring, were mediators for behaviour change. This suggests that interventions that focus on these components could be effective in increasing PA. Few studies have focused on increasing girls’ PA as well as on attempting to overcome barriers such as low levels of competence and providing choice. Therefore, there is need for an intervention to be tailored to address these issues.

In summary, research suggests that adolescent girls are less active and experience greater declines in PA than boys because they have disengaged from and/or lack confidence in the types of PA that are traditionally offered. Increasing girls’ perceived competence, strength of identity and interest in activities may help to sustain girls’ participation in PA throughout adolescence.

Dance as a method to improve girls’ physical activity levels

Dance is popular among UK and US adolescent girls. 12,17,18 Dance also provides an opportunity to socialise. 19 The proportion of girls who dance remains high throughout adolescence, with 31.9% engaging at 12–13 years of age and 33.1% at 18 to 19 years of age. 20 This interest in dance indicates that it could be a useful medium through which to help improve girls’ participation in PA.

In order to promote dance as a medium for increasing girls’ PA, it is important to understand what attracts girls to dance. It appears that the style of dance is important. In particular, modern, high-energy dances are seen as more fun. 19 Girls particularly enjoy the opportunity to input into the dance moves that they learn and perform. 19 The type of music (contemporary and upbeat) is a key factor that appeals to girls. 19 Opportunities to socialise and support from peers contribute to whether or not girls participate. 19,21 Dance provides an opportunity for all of the above and can be used as a tool to help overcome barriers to girls’ participation in PA. Dance is usually group-based (and is thus less likely to lead to individuals being on public display), non-competitive and takes place indoors where weather is not particularly important. 10,12,22

Dance interventions

Numerous studies have examined the effects of dance interventions on physical and psychological factors in females. A dance intervention focusing on the ‘joy of movement’ successfully improved self-rated health scores among girls (aged 13–18 years) with internalising problems at 8-, 12- and 20-month follow-up (8-month difference in mean change 0.30, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.61; 12-month difference in mean change 0.62, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.99; 20-month difference in mean change 0.40, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.77). 23 Aerobic capacity (p = 0.001) and upper body strength (p = 0.002) has also been found to significantly increase for girls attending contemporary dance classes. 24 These studies were limited by the absence of a control group, the small sample size and the fact that, although recruitment took place within a school setting, two of the interventions were carried out in the community.

The ‘Dance 4 your life’ intervention improved self-esteem (p = 0.01) from pre to post intervention among females aged 14 years. 24 Burgess et al. 25 found improvements in factors that contribute to self-esteem, which supports the findings from ‘Dance 4 your life’. A total of 6 weeks of aerobic dance classes reduced body image dissatisfaction and enhanced physical self-perception. However, girls were recruited selectively based on their scores for these variables. 25 Zander et al. 26 found that participants in a dance intervention were likely to form mutual affective and collaborative ties with peers, indicating that dance can be used as a socialising medium. Limitations to this trial include the lack of evaluation of the project and the non-random assignment to control or intervention arms. These studies provide evidence for many health-related benefits of dance; however, few studies have focused on the effect of dance on PA levels. There is a need, therefore, to test the applicability of a large, robust, UK dance-based intervention to increase PA levels among girls.

Dance has been established as a valid alternative to traditional sport and exercise, as it has been proven to elicit physical and psychological health benefits. It has also been found to contribute up to 29% (95% CI 25.9% to 31.6%) of girls’ total MVPA and to reduce the amount of time that girls spent on sedentary behaviour (p < 0.001). 27 Moreover, girls enrolled in dance classes accumulated more MVPA on days on which they danced (28.7 ± 1.4 minutes) than on non-dance days (16.4 ± 1.5 minutes) (p < 0.001). However, the cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to attribute increasing MVPA solely to dance.

Girls who may drop out of other activities during secondary school are more likely to engage in dance. 28 Dance has the potential to increase the intrinsic motivation for PA and to improve perceived autonomy, competence and relatedness. 21,28 Recent media coverage that demonstrates the benefits of dance has increased its popularity with the public and heightened awareness of dance as a form of exercise. 24 Therefore, dance interventions may be more appealing to girls and may function as an effective means by which to increase girls’ MVPA.

There is little current dance provision within UK schools. Over 50% of primary schools in the UK do not provide dance as an extracurricular activity29 (equivalent data are not available for secondary schools). In secondary schools in England, there is no requirement for the arts to be taken as part of the English Baccalaureate, meaning that access to the arts (including dance) in schools is limited. In addition, only 4% of PE teachers hold a post-Advanced-level qualification in dance,30 restricting the quality of dance offered as part of PE.

After-school interventions

The extended schools policy,31 in which all UK secondary schools are encouraged to stay open for additional activities, provides an opportunity to alleviate some of the problems associated with dance provision in schools. A benefit of interventions being held after school is that they take place in a safe environment in which children can be active and spend time with peers and adults, who may act as role models. 32 The majority of after-school programmes have been well received by parents and children, meaning that the hours after school provide a good opportunity for children to have fun and be active. 32,33 Atkin et al. 34 found that the most effective after-school interventions were located on school sites, where they are easily accessible, and this eliminated some of the reliance on transport and parents/carers. The authors suggested that after-hours interventions may be more successful if the focus is on changing only one behaviour and if the intervention is relatively short in duration (two effective and four non-effective studies were < 12 weeks), as many longer interventions faced implementation and fidelity issues.

Organised after-school PA programmes that focus on increasing PA opportunities for a wide group of adolescents could be an effective means by which to engage inactive adolescents in PA. 35 Previous systematic reviews report that the evidence for interventions to increase PA in young people is weak. This is, in part, a result of poor design, weak methodology and insufficient statistical power. There is a need for additional well-controlled studies that incorporate a theoretical rationale to produce trustworthy results. 32–34,36,37 A recent literature search revealed that since these reviews, there have been five randomised controlled trials38–42 that employed objective measures of PA in evaluating the effectiveness of a school-based intervention to increase PA levels. Of these, two were feasibility trials38,39 and one was a cross-sectional study. 40

Looking at the five studies, withdrawal and drop-out rates were low (< 20%); however, attendance varied widely, thus compromising intervention integrity. Two studies38,39 reported on the long-term impact of the intervention on PA once the programme had finished. Only one study41 monitored intervention consistency, making it difficult to establish whether or not the other interventions were delivered as intended. The use of psychological theory was found to contribute to the success of behaviour-change theories. 43 All but one42 of the five studies used either social cognitive theory or self-determination theory (SDT) to aid the development of their interventions, thereby allowing the appropriate mediators of PA to be targeted.

The five studies suggest that there is some evidence that school-based interventions were successful in increasing objectively assessed MVPA among certain subsets. Our own feasibility work [Bristol Girls Dance Project (BGDP) feasibility trial], in which girls in intervention schools received a 9-week programme consisting of two 90-minute dance sessions per week increased MVPA among intervention participants at 3 months after the completion of the dance sessions (8.7 minutes per weekday, 95% CI 5.5 minutes per weekday to 11.9 minutes per weekday) compared with a control group. 38 The Action 3 : 30 trial trained teaching assistants to deliver after-school PA sessions to 9- to 11-year-old children; weekday MVPA for boys increased by 8.6 minutes per day (95% CI 2.8 minutes to 14.5 minutes). 39 Both Madsen et al. 42 and Dzewaltowski et al. 40 found a significant increase in MVPA in an overweight subsample of children. The SCORES programme used soccer to support the development of skills and competencies among 9- and 10-year-old students and resulted in an increase in MVPA of 3.4 minutes per weekday (95% CI 0.3 minutes per weekday to 6.5 minutes per weekday; p-value not reported) among students with a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 85th percentile. 42 The HOP’N trial aimed to develop the skills and efficacy of adults and children (aged 9–10 years) to build a healthy after-school environment. Overweight/obese children in the HOP’N trial obtained 5.92 minutes more MVPA per day (95% CI –13.00 minutes to 1.17 minutes; p = 0.10) than overweight children in the control group. 40 Finally, Wilson et al. 41 conducted the Active by Choice Today trial among adolescents from low-income and ethnic minority backgrounds, which consisted of a 17-week programme delivered three times a week for 2 hours. The programme entailed a homework and snack element, MVPA activities chosen by students and a behavioural skills/motivational component. MVPA declined less among students in the Active by Choice Today trial intervention group than in the control, resulting in 4.87 minutes (95% CI 1.18 minutes to 8.57 minutes) more MVPA per day than those in the control group. 41

It is important to recognise that, although these five studies indicate that after-school programmes hold promise for increasing children’s PA levels, they have limitations. The Active by Choice Today trial found that fidelity and dose were not adequate during the first year of the trial, potentially weakening the overall effect. 41 The other studies did not monitor fidelity38–40,42 and at least one39 emphasised this as a limitation. The need for new strategies to keep attendance levels high to improve intervention integrity also emerged from the studies.

Theories of behaviour change: self-determination theory in physical activity research

Interventions based on psychological theory have proved more successful than those not based on psychological theories. 43,44 SDT45 is particularly illuminating in examining adolescents’ motivation for PA46 (e.g. how self-determined their reasons for PA are). The underlying principles of SDT are that self-determined (autonomous) motivation is behaviourally and psychologically adaptive and that it develops to the extent that individuals perceive a sense of ownership or autonomy over their PA, feel able and competent and are supported in their PA by meaningful social relationships. 45,47 This hypothesis is supported by empirical research in the PA/exercise domain among children,48 adolescents49 and dancers. 50

Six motivation types are proposed in SDT, varying in their degree of self-determination or autonomy. Each is hypothesised to be differently associated with individuals’ engagement in a given behaviour (e.g. being active), cognitive processes and affective outcomes. 51 The more self-determined motivational types (intrinsic, integrated and identified behaviours) are grouped as autonomous. Intrinsic motivation sees an individual engage in an activity for inherent satisfaction or enjoyment. Other forms of motivation involve doing the behaviour for a reason(s) distinctive from inherent satisfaction. Integrated regulation is when engaging in a behaviour is in line with an individual’s broader self (e.g. being active as part of a person’s identity). Identified motivation is driven by an outcome, such as health benefits or friendship. The less self-determined motivational forms (introjected and external) are broadly grouped as controlled motivation. Introjected regulation refers to motivation based around internalised pressures, like avoiding feelings of guilt. External regulation is characterised by prods and pushes that are external to the individual, such as avoiding punishment.

Previous research suggests that autonomous motivation for PA is positively associated with an increase in young people’s PA behaviour. 48,52 In addition, autonomous motivation is seen to positively affect psychological outcomes such as quality of life and physical self-concept. 53 Girls with autonomous motivation for exercise have been found to exhibit a greater sense of competence and achievement, and tend to remain involved in PA, whereas those without this form of motivation lose interest and look elsewhere for investment of their efforts. 54 Evidence suggests that social aspects motivate girls to engage in PA, with > 50% of girls being active because of peers. 9 Peer support is an important factor in the participation and retention of after-school dance programmes. 19 It has been shown that children cluster in groups with similar activity levels,55 suggesting that friendship is important for PA participation. As such, an intervention that addresses these factors may be successful in engaging girls in PA and encouraging lifelong attitudes towards being active.

Self-determination theory is particularly amenable to inclusion in behavioural interventions because it specifies the psychological and socioenvironmental conditions that underpin autonomous forms of motivation. 56 In SDT, it is important to note that for interventions delivered by practitioners (e.g. dance instructors), people’s psychological needs can be supported or undermined by the motivational climate that an authority figure creates through their interpersonal or teaching style. 57,58 Needs-supportive motivating styles are underpinned by the provision of autonomy support (i.e. providing a meaningful rationale, offering choice and avoiding the use of controlling language), structure (i.e. setting out clear expectations and providing guidance) and involvement (i.e. being empathic and showing genuine interest for others). 58,59 A controlling motivating style is characterised by strategies such as tangible rewards, feedback aimed to manipulate rather than to inform and the use of controlling language. 60 Among children, PE teachers’ use of autonomy-supportive versus controlling motivation styles has been associated with pupils’ psychological need satisfaction and autonomous motivation for PE. 49

Formative work

Extensive formative work was conducted to inform the design of the current study. This included: (1) qualitative work with Year 7 girls and their parents on how to design an after-school dance programme and recruit children;19 (2) interviews with teachers and dance specialists to identify key elements to incorporate into the intervention;61 and (3) a feasibility trial38 and economic evaluation. 62

Focus groups (including 65 girls) and telephone interviews (with 16 parents) were conducted in four secondary schools across Bristol. 19 Some issues were suggested to affect recruitment. The intervention needed to be marketed as fun and enjoyable (as well as something that provides an opportunity to socialise). To encourage participation, taster sessions were considered useful. Parents suggested that attracting groups of friends and stressing the health benefits of dance may also increase interest. Views on sustaining participation differed for girls and parents. Girls highlighted the importance of dance styles and music (and being allowed to input on both) for keeping them motivated, and parents suggested that setting achievable goals throughout the programme would help retention. Parents also cited enjoyment and teaching style as important.

Interviews were conducted with 11 PE teachers from secondary schools in the local area and 11 dance instructors. 61 PE teacher interviews covered logistical issues of a dance intervention within a school setting and structure, content and recruitment concerns for an after-school dance programme. Dance instructor interviews explored barriers to participation, strategies to aid progression, content of dance sessions and how to retain participants. PE teachers pointed to a lack of dance in school and suggested that they were not confident to deliver dance. All dance instructors concurred that dance sessions should cover a number of dance genres and be structured in a way that helps foster friendships, enjoyment, ownership and a rapport between instructor and pupils.

The BGDP feasibility study63 was a three-arm, parallel-group, cluster randomised controlled study and economic evaluation, with schools as the unit of allocation. The intervention content was informed by the focus groups and interviews discussed above. Seven secondary schools were recruited and all Year 7 girls who were physically able to participate in PE were invited to participate. For practical reasons the sample was limited to 30 girls per school. Three intervention schools received two 90-minute after-school dance classes per week, for 9 weeks. The feasibility trial demonstrated that it is possible to recruit Year 7 girls and record the cost of the programme. The study also showed that girls would attend dance sessions and that it was feasible to collect PA data from the girls at three time points. The feasibility work suggested that it is possible to achieve a mean increase of 10 minutes of MVPA per weekday if the session intensity was increased and inactive creative time reduced. An embryonic resource use checklist was developed for use in the main trial economic evaluation. 62

Summary and rationale for the Bristol Girls Dance Project trial

Physical activity is important for the prevention of a number of diseases and also enhances mental well-being. PA declines during youth, with the start of secondary school being a crucial period of change. Girls are less active than boys at all ages and there is an absence of effective interventions to encourage PA in girls. Dance provides an opportunity for high levels of PA; it is also social and enjoyed by girls. As such, dance has the potential to function as a source of PA across the life-course. After-school dance programmes may be an effective means by which to increase the PA levels of girls. However, dance provision in schools is limited, and in the current economic climate schools have reduced funds to support after-school programmes. The goal of this study was to test whether or not after-school dance programmes can be effectively delivered in UK secondary schools.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Aims and objectives

The specific research aims of the BGDP (locally known as Active7) trial were as follows.

Primary aim

-

To determine the effectiveness of the BGDP intervention to improve the objectively assessed (accelerometer) mean weekday minutes of MVPA accumulated by Year 7 girls 1 year after the baseline measurement (T2 = T0 + 52 weeks).

Secondary aims

-

To determine the effectiveness of the BGDP intervention to improve the following secondary outcomes among Year 7 girls at T2:

-

mean weekend day minutes of MVPA

-

mean weekday accelerometer counts per minute (CPM) (providing an objective measure of the volume of overall PA in which girls engage)

-

mean weekend accelerometer CPM

-

the proportion of girls meeting the recommendation of 60 minutes of MVPA per day

-

mean accelerometer-derived minutes of weekday sedentary time

-

mean European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions Youth survey (EQ-5D-Y) scores

-

programme costs (school-level).

-

-

To determine the effectiveness of the BGDP intervention during the intervention period (T1) on all primary and secondary outcome variables.

-

To determine the extent to which any effect on the primary outcome was mediated by autonomous and controlled motivation towards PA and perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness in PA. 45

-

To determine the cost-effectiveness/utility of the intervention from a public-sector perspective over the time frame of the study.

Research design

The trial was a two-armed, cluster randomised controlled trial conducted in 18 secondary schools across the greater Bristol area. The trial included process, economic, quantitative and qualitative evaluations.

The study was granted ethical approval from the School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol, and was sponsored by the University of Bristol. The trial was registered with International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register under the reference number ISRCTN 52882523. The original study protocol was sent to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) on 26 April 2013 and published as a journal article. 64 A small number of revisions were made to the protocol during the study. A summary of changes that were made to the original protocol paper are given in Table 1.

| Change to protocol | Date |

|---|---|

| The recruitment target was increased from 30 to 33 girls in each school | 17 July 2013 |

| Girls in intervention schools were be given a ‘dance diary’. They were encouraged to complete this between sessions. Diaries required girls to reflect on their learning and set personal goals The questionnaires that girls answered include a section that measures self-esteem The process evaluation incorporates audio-recording of dance instructors. Observers rated the degree to which the instructors delivered the core components of the session. The audio-recordings were rated, using a validated tool, to measure the extent to which dance teachers’ teaching styles were autonomy-supportive |

20 September 2013 |

A recommendation from the March Trial Steering Committee meeting was to reconsider the inclusion criteria for the secondary analyses. The protocol was subsequently amended to reflect these changes:

|

1 May 2014 |

Study population and recruitment

The study sought to recruit 18 mainstream secondary schools (excluding special educational needs providers, dance academies and privately/independently funded schools) operating within three local authorities (Bristol City Council, North Somerset Council and Bath and North East Somerset Council). To participate, schools needed to have at least 30 Year 7 girls and be able and willing to allocate space for two after-school sessions per week for 20 weeks between January and June/July 2014. All schools fulfilling the inclusion criteria were invited to participate and the first 18 schools that agreed to participate were enrolled. Additional schools were placed in a reserve pool. We aimed to recruit between 25 and 33 Year 7 girls from each school (450–594 girls). To participate schools had to recruit at least 25 girls to the study. In the case of five schools, it was not possible to recruit the minimum number of girls, so reserve schools acted as replacements. This extended the recruitment period into November 2013.

Following school recruitment, a participant recruitment campaign was initiated in all 18 schools. A taster session was provided for all Year 7 girls who were able to engage in PE classes. Taster sessions were delivered by external dance instructors within school time (usually in a PE session). At the end of the taster session pupils were told about the study (including details of the randomisation and data collection commitments). The only exclusion criterion applied at pupil recruitment was that girls were able to participate in standard PE lessons.

Where more than 33 consent forms were returned, pupils were randomly ranked, with the first 33 pupils being selected at random using a computer-generated algorithm. Any girl dropping out of the study prior to baseline data collection was replaced by the subsequent pupil in rank order. This process was repeated as necessary. No replacements were made after baseline data collection.

School contacts signed a ‘school study agreement’, which stated that the school contact was happy for their school to take part in the study and for data to be anonymously stored in data sets and be used for publication. The form also collected contact details and basic demographic information of Year 7 girls. Written informed parental consent was obtained for all girls, and school contacts and dance instructors (taking part in the end of study qualitative work) also provided written informed consent. Following each taster session, all girls were given information packs for themselves and their parents/guardians. Girls wishing to participate had to return a completed parental informed consent form to school.

Our pilot work63 indicated that small reimbursements enhance data provision. As such, all girls received a £10 gift voucher on completion of each data collection phase (£30 in total). Control schools were each given a £500 donation to offset any costs incurred in facilitating data provision, which was received after the third stage of data collection.

Public and patient involvement

A Local Advisory Group (LAG) was formed to improve the relevance and delivery of the intervention for the schools and girls taking part. The LAG consisted of a variety of individuals in order to address the views of as many stakeholders as possible. The group met on three occasions during the study and played an important part in informing the intervention materials (dance diaries), behaviour management and attendance. The LAG also provided extensive input into the dissemination materials, which were developed in consultation with them. The group consisted of local council staff, school teaching staff, dance instructors, creative directors, school sport development managers and parents.

Baseline data

Both objective and self-reported data were collected from various stakeholders. A summary of the data collected can be found in Box 1.

The local authority to which each school belonged.

Percentage deprivation (based on the Department of Education’s Pupil Premium, a measure of the number of girls receiving free school meals in each school).

Total number of pupils in school.

Total number of Year 7 girls in school.

Baseline mean MVPA per school (for randomisation purposes).

Details on after school activity provision available to Year 7 girls in school.

Participant level Parent reportedHome postcode.

Age of child (years and months).

Number of siblings.

Highest level of education in household.

Child reportedObjectively assessed:

-

Accelerometer data for 7 days (see Table 4 for PA measures derived from accelerometer data).

-

Height (cm) and weight (kg) to calculate standardised BMI z-score (kg/m2).

Self-reported:

-

EQ-5D-Y score.

-

Psychosocial questionnaire (tablet device).

-

Dance classes attended outside school (child questionnaire).

Randomisation

Schools were randomised to control (n = 9) or intervention (n = 9) in a 1 : 1 ratio after baseline data had been collected using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) code specifically designed to balance the two arms by minimisation, which took account of four school-level factors, namely local authority, school size, baseline mean MVPA (%) and deprivation (based on the percentage of children with free school meals). Deprivation was assessed as the percentage of pupils in the school eligible for the Department of Education’s Pupil Premium (additional funding given to schools to support disadvantaged pupils and bridge the attainment gap between them and their peers). Randomisation was conducted by Keeley Tomkinson. Mark J Edwards made schools aware of their allocation soon after randomisation was conducted.

Intervention group

The nine schools that were randomised to the intervention arm received a 20-week dance intervention, consisting of two 75-minute after-school sessions per week (maximum 40 sessions), which were provided between January and June/July 2014. Dance sessions were led by 10 professional self-employed dance instructors who delivered a standardised programme which was developed in the feasibility trial. Instructors attended an induction session before the intervention began (December 2013) and a ‘booster session’ after the first term of intervention delivery (April 2014).

The dance programme focused on building girls’ autonomous motivation to be active and perceived dance autonomy, competence and relatedness through an autonomy-supportive environment. The programme provided exposure to a wide range of dance styles (instructors were given flexibility in what they delivered) (see Appendix 1). Girls in intervention schools were each given a ‘dance diary’ (see Appendix 2) which they were encouraged to complete between sessions. The diaries were intended to help children reflect on their learning and to encourage them to set their own goals.

Development of dance instructor training and manual

The BGDP aimed to increase girls’ autonomous (mainly identified and intrinsic) motivation for both dance and PA more broadly by providing them with fun and need-satisfying dance sessions led by an autonomy-supportive instructor. This was targeted through the ‘Guide for dance instructors’ (‘session-plan manual’) (see Appendix 1 for excerpts), the session design and content, and dance instructor intervention training. The ways in which the dance instructor manual and session content mapped on to the theoretical targets of the intervention are presented in Table 2. Dance instructors received a 1-day training session prior to the start of the intervention. The training was developed collaboratively between a dance instructor who had been involved in the feasibility study and study team. From the theoretical perspective it included a 2-hour session on SDT that highlighted the key features of the training manual (i.e. definitions and descriptions of motivation types, need-satisfaction and autonomy-supportive motivating styles) and how it can be applied in after-school dance sessions. Practical activities were used throughout the training to provide dance instructors with the opportunity to practice autonomy-supportive styles, ask questions and receive feedback. At the mid-point of the intervention, dance instructors attended a half-day booster session where the central tenets of the SDT-based teaching style were revisited and instructors were able to share their experiences of delivering the intervention and collaborate with study staff to resolve any problems they were facing.

| Theoretical target | Guide for dance instructors/‘motivation toolkit’ | Dance session design and content |

|---|---|---|

| AS |

|

|

| CS |

|

|

| RS |

|

|

| Structure |

|

|

| Promoting autonomous motivation |

|

|

Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist

In an attempt to standardise the reporting of interventions, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide has been proposed. 65 The 12-item checklist aims to improve the reporting and replicability of interventions. Table 3 summarises the BGDP trial in accordance with the TIDieR checklist.

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Name (1) | BGDP (locally known as ‘Active7’) |

| Why (2) | The primary aim was to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an after-school dance intervention in increasing mean weekday minutes of MVPA among 11- to 12-year-old (Year 7) girls. The proportion of adolescent girls who meet the recommended levels of MVPA per day is lower than for boys. PA levels among children decline as they progress through to adolescence Girls lose interest in PE, face barriers to being active and lack opportunities for other desired PA. Competence in PA declines throughout school and self-presentational concern can deter girls from PA. Dance is a desirable activity for girls and can contribute to MVPA. It provides opportunities for peer support and socialisation and is perceived as enjoyable The Active7 intervention is based on SDT, which suggests that satisfying individuals’ sense of freedom and choice, and helping them feel competent in PA and supported by others, will help nurture more self-determined forms of motivation to be physically active Research and current PA trends suggest that there is a need for effective strategies to attenuate the decline in girls’ PA levels. A dance intervention has the potential to be a cost-effective way of engaging girls in PA |

| What: materials (3) | Training was provided for dance instructors who delivered the intervention. The content focused on the philosophy of the BGDP and how to deliver dance sessions underpinned by SDT. Specifically, the session covered different motivation and communication styles, how to create an autonomy-supportive environment, how to build a sense of belongingness among the group and how to increase competence. A booster training session (mid-way through the intervention) included a refresher on motivating children and managing problem behaviour, as well as covering the remaining session plans All instructors were provided with a ‘Guide for dance instructors’, detailing the aims and objectives of the study and how to deliver sessions successfully. It also included 40 session plans. A gradual progression was incorporated into the intervention design All intervention school girls received a dance diary. This was a booklet in which girls could reflect on their progression and the dance sessions (encouraging girls to reflect on what they had learnt and enjoyed, what they would like to do in future sessions and goals they wanted to achieve) |

| What: procedures (4) | Secondary schools were recruited through a letter of invitation. A meeting was held between the school contact and BGDP trial manager to discuss logistical issues and to obtain a signed study agreement form. A taster session was then delivered to all Year 7 girls who were able to take part in PE. The taster sessions most often took place instead of PE lessons and were led by one of the study’s trained dance instructors. Students were told about the study and given information packs for themselves and their parents. Children had to return signed consent forms a few days later in order to sign up to the study There were 33 intervention places available per school. If more than 33 girls provided consent, girls were randomly selected to participate. Reserves were used if a girl dropped out prior to baseline data collection Schools were randomly assigned to ‘intervention’ or ‘control’ groups and were made aware of their allocation shortly after baseline data collection (in order to allow sufficient time to organise the after-school sessions) Intervention schools received dance sessions led by an external dance instructor. The dance sessions were free to the school and girls A process evaluation was conducted throughout the study to assess the implementation and mechanisms of intervention impact. The process evaluation reported on the dose, implementation and theory fidelity, and intervention receipt. Attendance was recorded by the instructor. Observations occurred at four occasions within a randomly chosen session within each quarter of the intervention to assess theory fidelity and intervention receipt. Girls recorded their perceived levels of enjoyment and exertion on four occasions |

| Who provided (5) | Freelance female dance instructors from the local area were recruited to the study In total, 10 instructors delivered the intervention. One instructor delivered the intervention in two schools. Halfway through the intervention period one instructor withdrew and was replaced by a reserve. Instructors covered one another’s absences. Instructors were paid for each session they delivered. All instructors completed a half-day training session, specific to the BGDP, before the intervention began. Instructors also attended a half-day ‘booster session’ after the first term of programme delivery |

| How (6) | Dance sessions were open to a maximum of 33 girls, who consented to participate at the beginning of the study |

| Where (7) | Dance sessions were delivered after school in the nine intervention schools. Schools were located across the greater Bristol area. The sessions were delivered in school facilities, usually a dance studio or school hall |

| When and how much (8) | Intervention schools received two 75-minute dance sessions per week (term-time only) for a period of 20 weeks (a total of 40 sessions), starting in January and finishing in June/July 2014. Sessions began 5–10 minutes after school (usually between 15.00 and 15.40) |

| Tailoring (9) | All instructors received the same training and materials to aid delivery. All were also encouraged to adopt an autonomy-supportive environment in line with SDT |

| Modifications (10) | No modifications were made to the intervention; however, after 4 months delivering the programme, one dance instructor was unable to continue. This instructor was replaced by a reserve instructor who had delivered some taster sessions |

| How well: planned (11) | Fidelity to the intervention manual was reported by dance instructors. Instructors indicated the extent to which the session was similar to the main features from the manual as either ‘very’, ‘somewhat’ or ‘not at all’ |

| How well: actual (12) | In total, 93 (26.80%) sessions were reported as being ‘very’ similar to the manual, 164 (47.26%) were ‘somewhat’ similar and 90 (25.94%) were ‘not at all’ similar [one session had missing data (0.29%)]. Instructor interviews revealed that adherence to the manual was initially high but reduced over time in response to the needs and skill levels of the girls. No instructor fully adhered to the manual. On the whole, instructors reported adhering to the principles of SDT during the delivery of sessions by offering need-support; this aligned with the girls views, although there was room for improvement in theoretical fidelity |

Control group

Schools in the control arm did not receive the dance intervention and continued with their normal practice (no data were collected regarding what was offered during the intervention period in control schools). Control schools received a £500 donation to the school fund after all data had been collected from girls.

Measurements

Data were collected from all girls (intervention and control) at three time points:

-

Time 0 [T0 (baseline)]: September to November 2013.

-

Time 1 [T1 (weeks 17–20 of the intervention)]: June 2014.

-

Time 2 [T2 (baseline + 52 weeks)]: September to November 2014.

To assess any contamination of the control group from dance classes locally, we collected data on the extracurricular provision (including dance) offered by all 18 schools. This was done at each measurement point. In addition, girls were asked if they attended dance classes outside school at each measurement point. At baseline, parents completed a demographic questionnaire which included the free-text item ‘Does your Active7 child take part in any other after-school clubs?’. To assess differences between the intervention and control girls at T1 and T2, and to minimise any burden on parents beyond baseline, girls were asked to complete one questionnaire item at T1 and T2 measuring the types of activities (active and sedentary) that they had performed in the after-school period, in the evenings and at the weekend over the past 7 days. This item was intended to help understand the PA behaviour of the girls in both groups at all time points. All data were collected during school time on school premises.

Accelerometer-determined physical activity

Girls were asked to wear an Actigraph GT3x+ (Actigraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA) accelerometer for 7 days. Periods of ≥ 60 minutes of zero values were defined as accelerometer ‘non-wear’ time and excluded from analysis. Girls were included in the primary outcome analysis if they provided 500 minutes of valid data on at least 2 weekdays. Mean minutes of daily MVPA were defined as ≥ 2296 CPM, which was established using the threshold developed by Evenson et al. 66 This has been shown to be an accurate threshold for this age group. 67 The derived accelerometer measures are listed in Table 4.

| Variable | Period of time (average minutes) | Time point | Reason assessed: to determine the effectiveness of the BGDP to improve the following variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| MVPA | Weekday | T0, T1, T2 | Mean weekday minutes of MVPA per day |

| Weekend day | Mean weekend minutes of MVPA per day | ||

| Overall | The proportion of girls meeting the recommendation of 60 minutes of MVPA per day | ||

| Counts | Weekday | T0, T1, T2 | The volume of activity in which girls engage in on weekdays |

| Weekend day | The volume of activity in which girls engage in on weekend days | ||

| Sedentary time | Weekday | T0, T1, T2 | Mean weekday minutes of sedentary time per day |

Psychosocial questionnaire

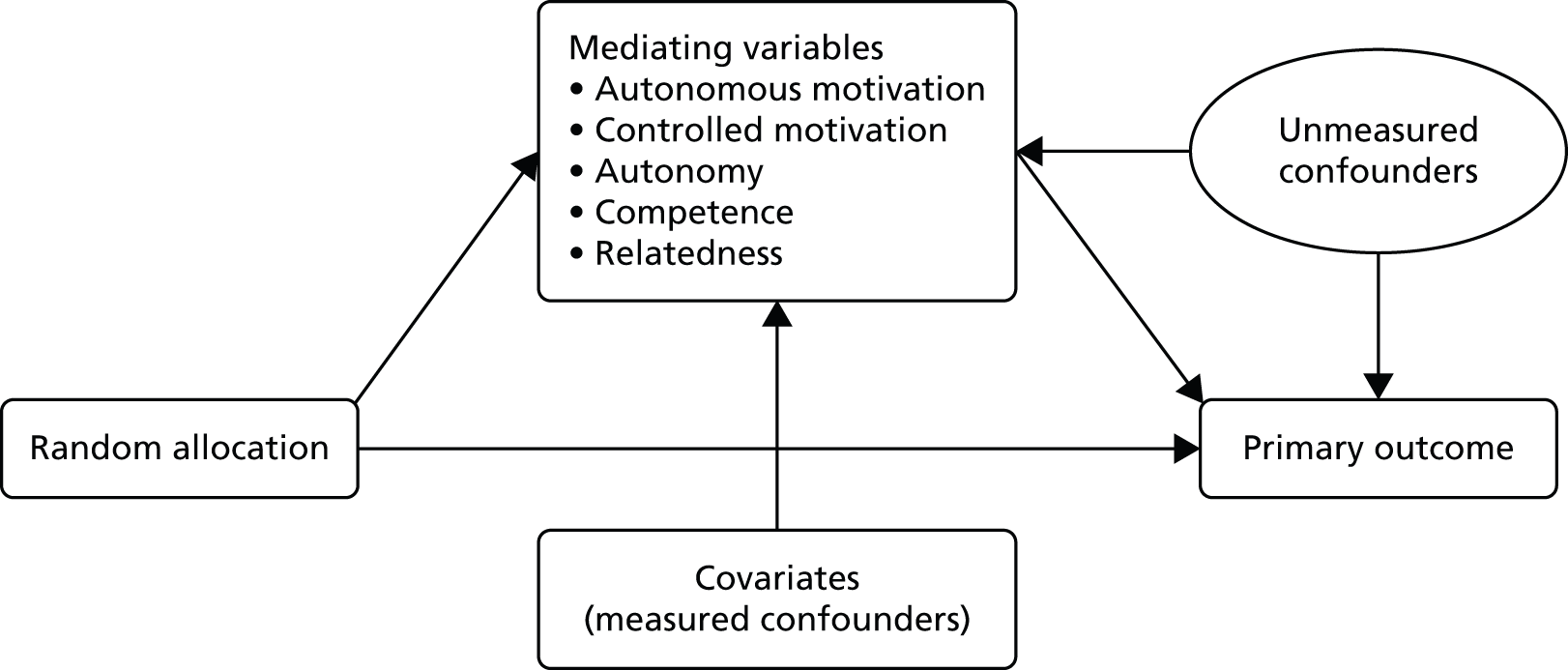

At each time point girls were asked to complete a psychosocial questionnaire. Questionnaires were completed on a Google Nexus 7 (ASUSTek Computer Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) tablet. We hypothesised that the variables below would mediate the effect of the intervention on girls (Figure 1). The psychosocial questionnaire was therefore designed to provide all the information that would be needed to address this question, specifically the following constructs were assessed:

-

motivation for dance and PA

-

perceived autonomy, competence and relatedness in PA.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesised mediation model.

All girls were asked to complete a 67-item questionnaire at T0. The questionnaire assessed psychosocial variables that could be influenced by the intervention and/or mediate the effect of the intervention on MVPA. Questionnaires assessed autonomous and controlled motivation for dance and PA,68 perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness69,70 within PA and self-esteem. 71

A modified questionnaire was used at T1 and T2. The girls were asked about the after-school activities in which they took part and whether or not they took part in organised dance outside school. At T1 only (during the intervention), girls rated the degree to which they perceived their dance instructor to be autonomy-supportive on a seven-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Items were based on the Health Care Climate Questionnaire72 and have been adapted for use in an activity setting. 73 At T2 these six questions were removed from questionnaires, as they were relevant only at T1 when girls were taking part in the intervention. A summary of the variables that were assessed at each time point can be found in Table 5.

| Items assessed | T0 (baseline, September to November 2013) | T1 (weeks 17–20 of the intervention, July 2014) | T2 (follow-up, September to November 2014) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDT-derived questions (67 items) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Weekday and weekend day activity questions (8 items) | ✓ | ||

| Sport climate questionnaire (6 items) | ✓ |

Height and weight

Girls’ height and weight were measured at each time point. Girls were asked to remove footwear and any bulky clothing they had on before being measured. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Seca Leicester stadiometer (HAB International, Northampton, UK). Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Seca 899 digital scale (HAB International, Northampton, UK). Data were recorded on paper by two study team members and cross-checked when being entered into study databases. BMI (kg/m2) was then calculated and converted to an age- and sex-specific standard deviation (SD) score. 74

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions Youth survey

All girls completed a paper-based EuroQol EQ-5D-Y scores at each time point. The EQ-5D-Y, recently validated for use in adolescents,75 was applied as a secondary outcome measure of health-related quality of life.

Sample size

Sample size calculations were performed to detect a mean difference of 10 minutes of weekday MVPA between the intervention and control groups. The uninflated sample size required for analysis to detect a difference of 10 minutes/day MVPA, assuming a SD of 18 minutes63 with 90% power and a 5% two-sided alpha of 68 per arm. We estimated the 95% CI for the school-associated intraclass correlation (ICC) in the pilot study to be < 0.001 to 0.087. On the assumption that 20% of girls would not provide primary outcome data, the mean cluster size for analysis would be 24, resulting in a design effect of 3.0 using the upper 95% confidence limit for ICC. Thus, we aimed at (and succeeded in) recruiting a total of 18 schools and at least 450 girls.

Summary of changes made to the sample size

After incorporating lessons learnt in a similarly designed feasibility cluster RCT,39 we anticipated a 10% dropout between baseline data collection and intervention start. To account for this difference we increased the maximum recruitment to 33 at the school level (from an initial maximum of 30 pupils per school).

Blinding

All project staff, excluding the Trial Manager and Process Evaluation Research Associate, were blinded to the allocation of intervention arms. Primary and secondary analyses were conducted blind by the statistical analysis team. Blinding was broken at the presentation of the main trial results to the Trial Management Group on 2 February 2015. Statisticians were unblinded at this point in order to undertake the per-protocol analysis which examined the intervention effect for girls who had adhered to the intervention and the statistical elements of the process evaluation which was conducted only in intervention schools.

Process evaluation methods

Overview

A process evaluation, reporting on consent, recruitment, dose, implementation fidelity, theory-based fidelity and intervention receipt, was conducted in the nine intervention schools. It included both qualitative and quantitative components. The aim of the qualitative component of the process evaluation was to explore the views of girls, dance instructors and intervention school staff to: (1) identify elements of the intervention that worked well; (2) identify potential improvements; (3) examine dance instructors’ experiences of delivering and girls’ experiences of receiving an intervention based on SDT76 and their psychological responses; and (4) identify considerations for dissemination/rollout of the project. 64

The quantitative element of the process evaluation was conducted using self-report questionnaires and instructor observations. To conduct these measures, visits were made to all nine intervention schools on four randomly chosen occasions during the intervention. No visits were made during the first four sessions to avoid adversely affecting the settling in period for dance instructors and girls. Similarly, no visits were made during the last four sessions of the intervention to avoid clashes/overlap with the T1 data collection.

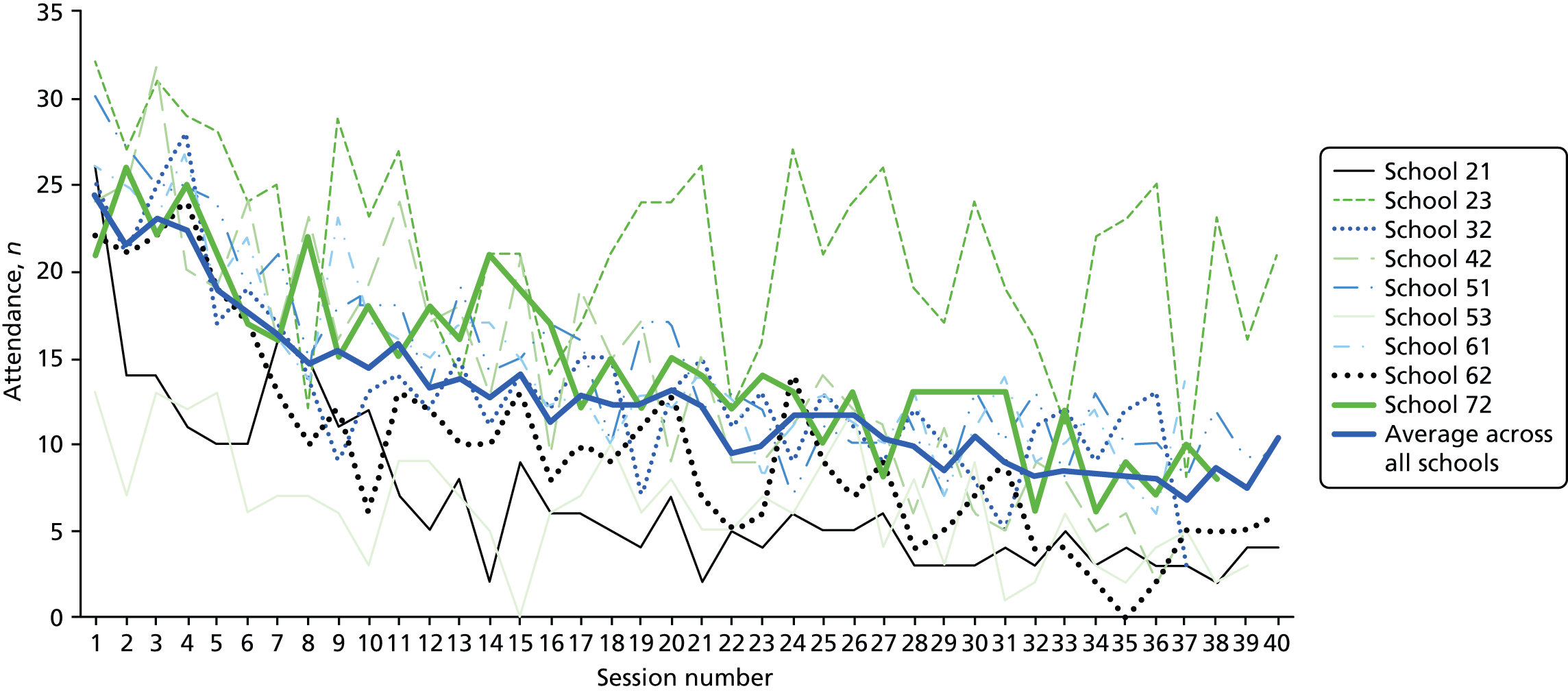

Dose

The dose of the intervention (number of sessions delivered) was recorded at each school as a percentage of the intended 40 sessions.

Attendance at the dance sessions was recorded in registers provided to the dance instructors. These data were used to calculate compliance adherence to the intervention, defined as girls attending two-thirds of the total sessions available at their school.

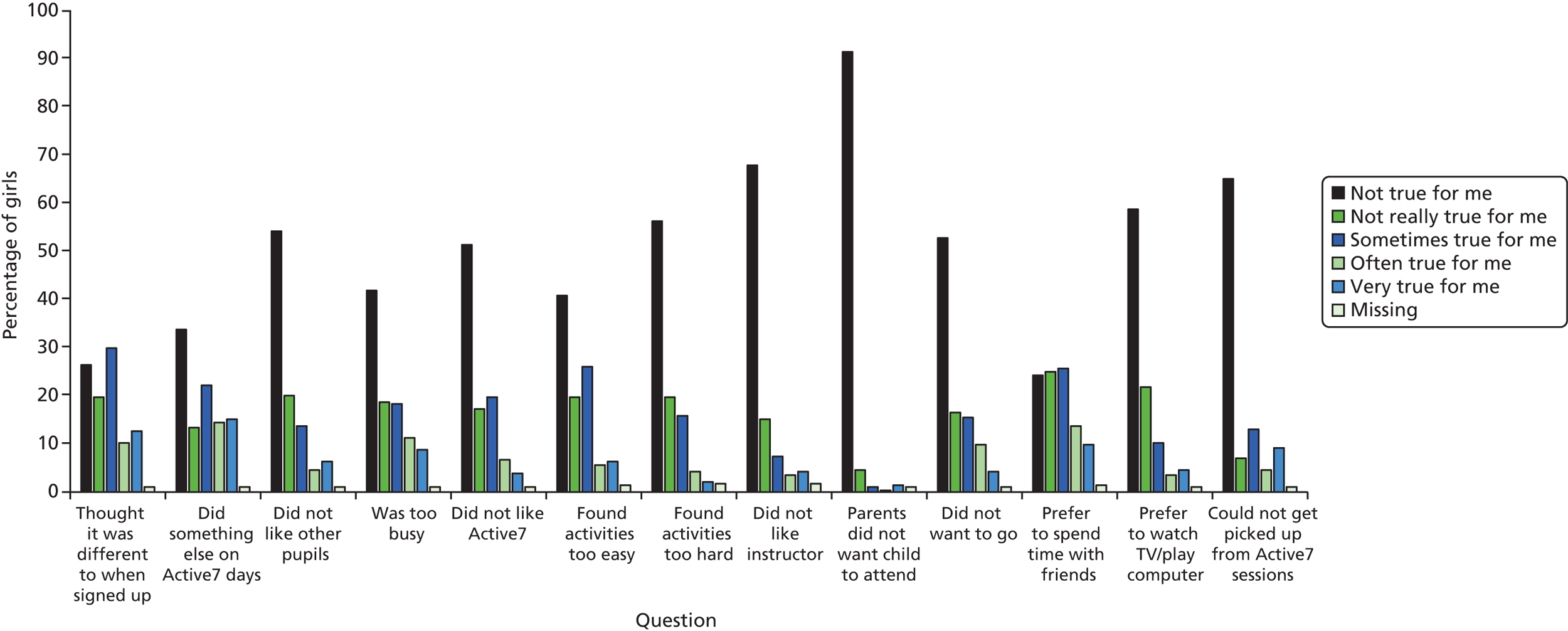

At T1, girls receiving the intervention completed a questionnaire to understand the reasons for the level of attendance. For dance sessions with fewer than three girls, the relevant instructor was asked if there was a reason for the low attendance (e.g. school camp, sports day). The instructor’s response was recorded as ‘no reason’, ‘school or year event’ or ‘communication breakdown’ to help explain any low levels of attendance in analyses.

The following definitions were applied to identify three types of withdrawal.

-

Pre-intervention withdrawal: a child who attended no dance sessions but attended data collection at T1 and T2.

-

Withdrawal during intervention period: a child who attended only one dance session and still attended data collection at T1 and T2.

-

Complete study withdrawal: a child who may have attended some dance sessions but notified project staff that they wished to withdraw from the study and future data collection.

Implementation fidelity

Implementation fidelity was assessed by instructors indicating the extent (‘very’, ‘somewhat’ or ‘not at all’) to which each session delivered reflected the session plan in the manual.

Theory-based fidelity

The intervention was based on the premise that supporting the girls’ psychological needs would lead to increases in autonomous motivation and PA (see Chapter 1, Theories of behaviour change: self-determination theory in physical activity research). To assess the extent to which the intervention was delivered consistently with the tenets of SDT, a team member observed four randomly selected sessions in intervention schools using a measure developed by Haerens et al. 59 During the observations the extent to which the dance instructors’ teaching styles were needs-supportive was rated. Five teaching practices were rated, and an average of these five measures were calculated to provide an overall score. The original procedure adopted a video rating system. For ethical and practical reasons, the observation system was adapted to use a combination of visual and audio recordings. The first observation in each school was conducted by two researchers to allow the main rater to reflect on their interpretations in the observation scoring process. A subsample (6/36 sessions) of the audio recordings was double coded (by the main rater and a team member with expertise in SDT) to check inter-rater reliability. Only the scores of the main rater were used in the analysis.

As noted above (see Psychosocial questionnaire), to measure perceptions of autonomy support provided by the dance instructor, all girls in intervention schools were asked to complete six items from the Sport Climate Questionnaire at T1. 72,73

Intervention receipt

At the end of the four observed sessions in each school, girls were asked to complete a perceived exertion77 and enjoyment78 questionnaire.

Qualitative process evaluation design

At the end of the 20-week intervention, semistructured interviews were conducted with the dance instructors who delivered the intervention and school contacts. School contacts were individuals within schools who facilitated the intervention and were the main contact for study staff. A focus group with participant girls was conducted in each intervention school.

Recruitment

All dance instructors (n = 10) and school contacts (n = 9) took part in semistructured interviews. A sample of 10 girls (six to eight girls and two reserves) per intervention school were purposively selected to reflect the views of girls from different thirds of dance session attendance within each school. To ensure that the focus group girls were able to share intervention experiences, girls who attended fewer than three sessions were excluded. Three individuals from the middle and highest attendance thirds and two individuals from the lowest third were randomly selected and invited to interview. Finally, across all thirds, two reserve girls were randomly selected. Girls absent from school on the day of the focus group were replaced with a reserve where possible.

Interview topic guides

Interview topic guides were developed for each informant group (three guides in total). The focus group guide (see Appendix 3) explored factors that encouraged or discouraged participation, elements that were enjoyed or not, views on dance instructors’ teaching styles and experiences of how the group worked over time. The guide also explored the receipt of the intervention in terms of the theoretical constructs of SDT. In particular, questions probed perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness, how these were supported by the dance instructor and participants motivational experiences. 76

The dance instructor interview guide (see Appendix 4) explored experiences of intervention training and potential improvements, implementation and dissemination. In relation to implementation, interviews addressed successes and challenges associated with intervention delivery. Fidelity to the session-plan manual and experiences of delivering the SDT-underpinned intervention were also explored [including how instructors supported the girls’ basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness)].

School contacts discussed the logistical issues of the project within school, including recruitment, intervention delivery, data collection and improvements (see Appendix 5). Views were also sought on considerations for the dissemination of the intervention.

Interviews and focus groups were recorded using an encrypted digital recorder [Olympus DS-3500 (Olympus UK, Southend-on-Sea, UK)] and audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and fully anonymised. Transcripts were compared with the audio recordings and amended as necessary to ensure accuracy. Written informed consent was gained from school contacts and dance instructors before the interview and written consent was gained from children’s parents when they signed up for the study.

Qualitative analysis

The framework method, a form of thematic analysis defined by the systematic production of a matrix which reduces data into a series of codes, was used. 79 This method is useful for condensing and summarising large qualitative data sets. It is an approach that does not exclusively align with a particular theoretical or epistemological perspective and, therefore, can be applied using an inductive or deductive approach. 79 Analysis consisted of the following six steps.

-

Transcripts were read and reread to form preliminary impressions of the data.

-

Initial codes were created to summarise and interpret data. Both inductive and deductive coding was used. Deductively, the analysis probed data to understand whether or not the intervention was delivered in line with SDT. Pre-defined codes were created from the central tenets of SDT. 45 In addition, a pre-defined code ‘school context’ examined the potential interaction between school context (e.g. participant- and area-level demographic factors and school culture) and intervention delivery and experience. The pre-defined codes were broad, with the primary purpose of categorising relevant information, which was further interrogated. Initial codes were inductively produced independently by four researchers (JK, ME, SS and TM) who each coded three transcripts (one from each informant group).

-

Initial codes were discussed, refined and combined to produce three coding frameworks, one for each informant group.

-

The coding frameworks were applied to all remaining transcripts by three researchers (JK, ME and TM). New and redundant codes were discussed in frequent meetings of the analysis group (JK, ME, SS and TM) and iterative amendments were made to each framework.

-

The coded data were then entered into a framework matrix in NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The framework condensed the volume of data and summarised codes with illustrative quotations. This process facilitated reflections on salient codes between participants within each informant group.

-

The three frameworks were triangulated using the convergence coding matrix approach,80 in which the codes for informant groups were compared to assess the degree of convergence as either: ‘Agreement’, ‘Partial agreement’ and ‘Silence’ or ‘Dissonance’ (see Appendix 6). In total there was agreement between informant groups in 22 themes, partial agreement in 26, silence in 39 and dissonance in 6 out of 77 themes.

To ensure trustworthiness, we applied four criteria: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (see Appendix 7). 81 The main themes elicited from the interviews are presented in Chapters 6–8 and are supported by illustrative, relevant and representative quotations.

Statistical analysis

The analysis and presentation of the trial was carried out in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines, with the primary comparative analyses being conducted on an intention-to-treat basis and due emphasis placed on CIs for the between-arm comparisons. To take appropriate account of the hierarchical nature of the data, we used multivariable, mixed-effects, linear regression to estimate the difference in the primary outcome for intervention group versus control, adjusting for baseline MVPA and randomisation variables.

For the baseline (T0) summary statistics, the mean (SD) was reported for normally distributed variables and the median [interquartile range (IQR)] for skewed variables. Normality was determined by the Shapiro–Wilks test, histograms and normal probability plots. Proportions were reported as percentages. Summary statistics were reported for each group. A kernel density estimation was used to calculate the probability density function of non-parametric continuous variables, and, thus, kernel smoother plots were used to describe such distributions.

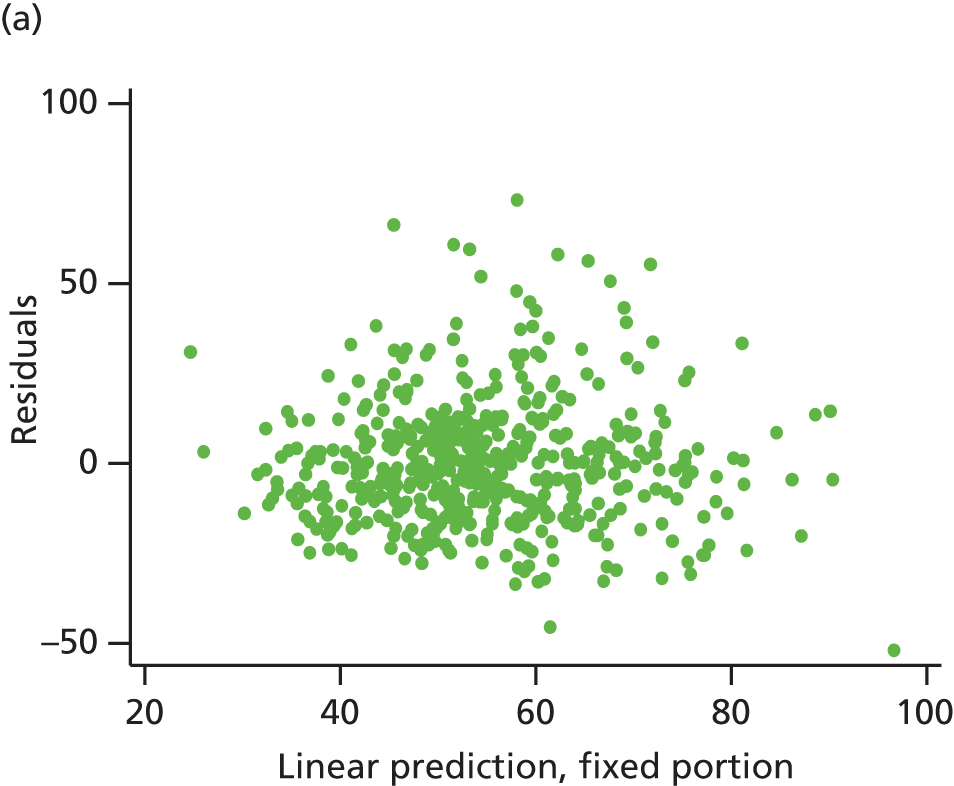

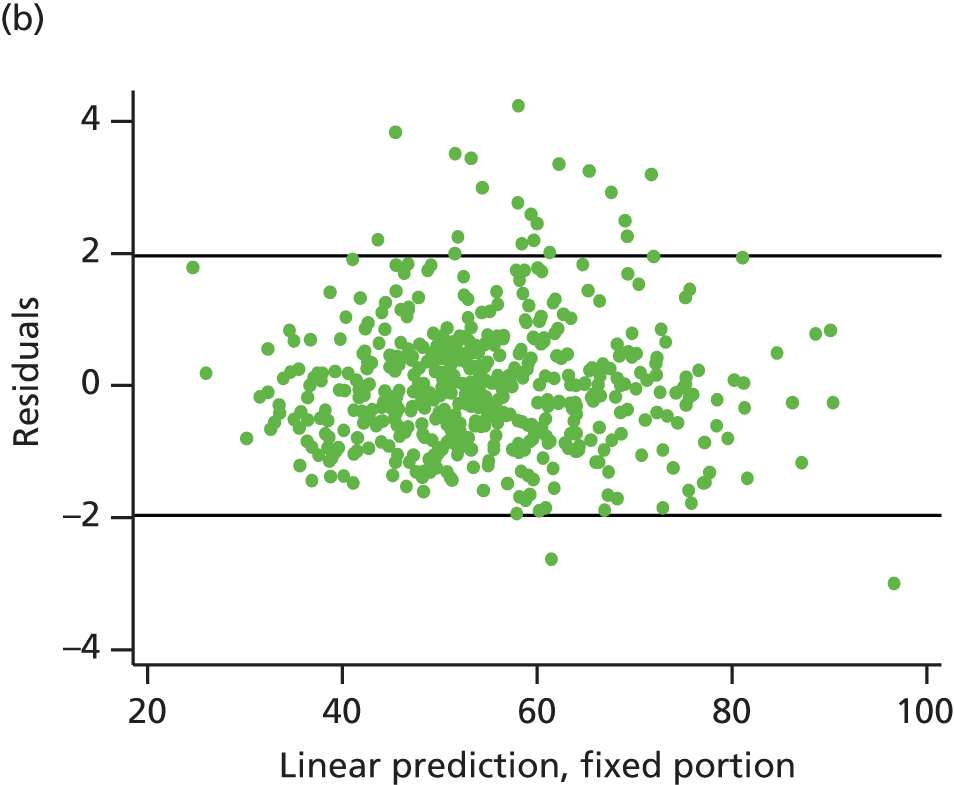

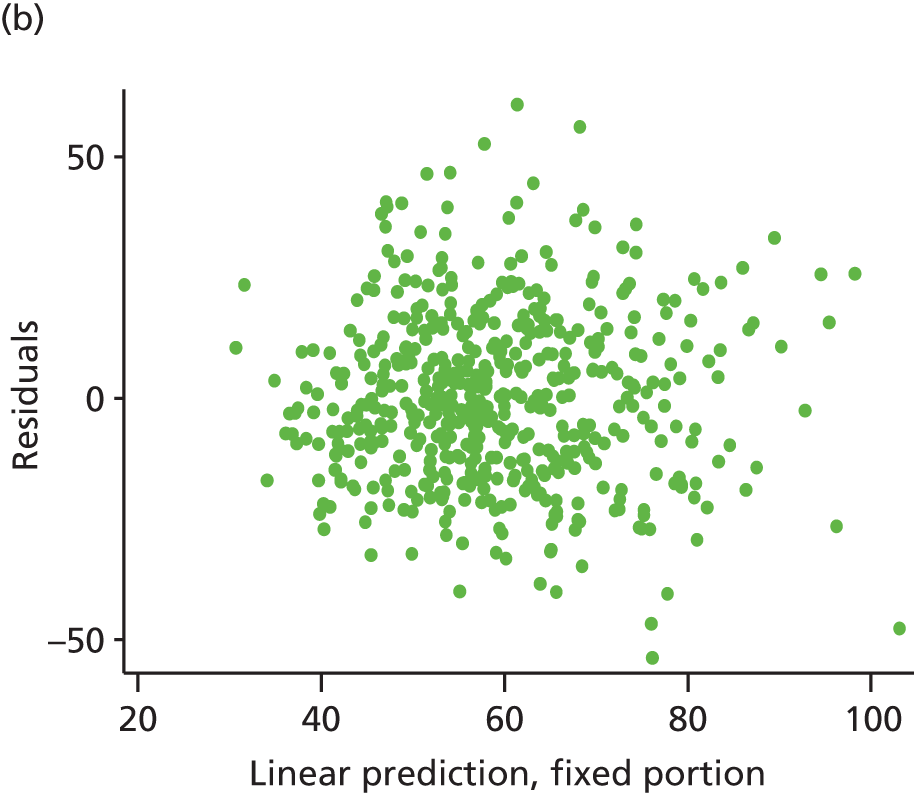

Linear mixed models were used to assess the primary and secondary outcomes, and a logistic model was used for proportional data. The variables to be included in the regression models were predetermined in the analysis plan. A typical model included the outcome at T2 as the dependent continuous variable (e.g. weekday MVPA at T2), whereas the independent variables consisted of the main variable of interest (the two arms of the trial) adjusted for T0 (e.g. weekday MVPA at T0), the number of valid weekdays at T0, the number of valid weekdays at T2 and the variables used in the randomisation process. Model assumptions were checked by testing the residuals for normality and plotting the linear predictor against the residuals to ensure that no trend was present.

After the statistician was unblinded, a per-protocol analysis was performed. The trial allocation and attendance data were merged with the accelerometer data and a new variable ‘adherence’ was generated. For the T2 analysis, all girls who had not adhered to the intervention in the intervention arm were dropped from the data set and the regression model for outcome ‘weekday MVPA at T2’ was rerun on this data set. This type of analysis was repeated for ‘weekend MVPA at T2’, ‘weekday MVPA at T1’ and ‘weekend MVPA at T1’. Owing to the bias introduced by dropping girls who did not adhere in the intervention group in the per-protocol method, a complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis was conducted, which included all girls, regardless of whether or not they adhered. Each girl in both groups was given a new variable of adherence (0 = no, 1 = yes) whereby all girls who adhered in the intervention group were coded 1 and all girls who did not adhere were coded 0, and all girls in the control group who adhered to the control (i.e. did not move to an intervention school and start a dance class) were also coded as 0. Instrumental variable regression was then conducted to identify whether or not there was any difference between the two arms with respect to adherence.

We intended to explore whether or not any effect of the intervention on the primary outcome was mediated by autonomous and controlled motivation for PA and/or perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness need satisfaction in PA, using the methods described by Emsley et al. 82 However, as there was no effect on the primary or secondary outcomes, we did not conduct the mediation analysis.

Quantitative process evaluation data (e.g. attendance rates) were analysed using appropriate descriptive statistics for normally distributed variables (using the mean and SD) and variables without such a distribution (using the median and IQRs). Ratings of instructors’ teaching styles were made from visual observations and audio recordings of 21 items. Each item was rated in 5-minute intervals during the session, these values were summed and divided by the number of intervals in the session across five teaching elements: relatedness support; structure before the activity; structure during the activity; autonomy support; and controlling teaching behaviour. A rating of the overall impression of the session was also given for autonomy-supportive teaching style, structure and instructor relatedness support. All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Economic evaluation

Full details of the economic evaluation are shown in Chapter 4.

Chapter 3 Trial results

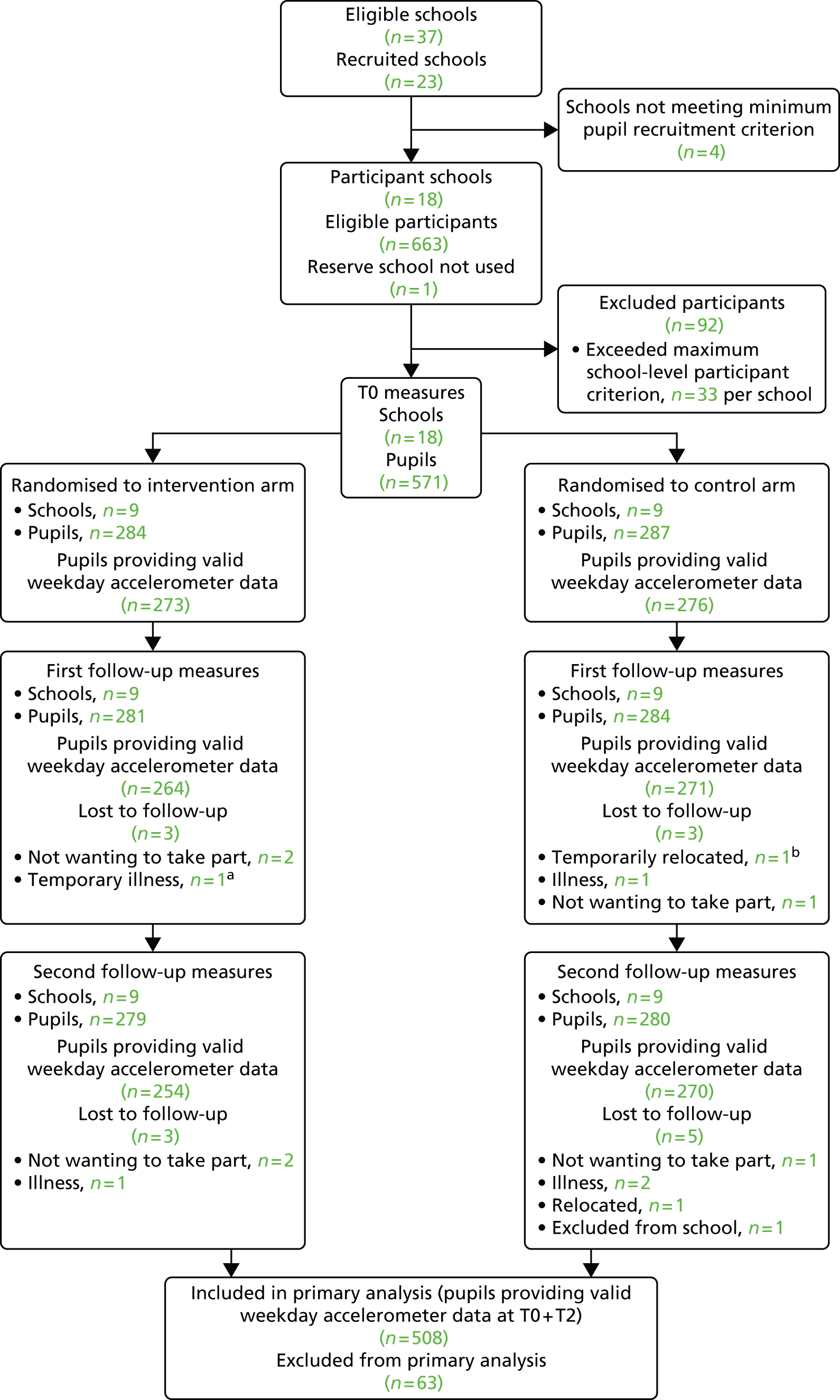

In total, 571 girls were recruited to the BGDP trial. 284 girls from nine schools were randomly allocated to the intervention arm and 287 girls from nine schools were allocated to the control arm. Figure 2 presents the CONSORT flow diagram for the trial and summarises participation in the three measurement time points (T0, T1, T2) and withdrawals (with reasons) from the study.

FIGURE 2.

Trial profile for the BGDP (CONSORT flow diagram). a, Participant had suspected long-term illness, but returned for T2 measures; b, participant temporarily relocated at T1 and returned at T2.

Recruitment

Dance instructor recruitment

It was possible to recruit dance instructors to deliver a relatively long duration after-school intervention in secondary schools. Recruitment of instructors was more difficult for schools that were not located close to an urban centre (Bath or Bristol). The more isolated a school was, the more difficult it became to find willing and able instructors to deliver sessions on the desired days. Four dance instructors could not participate when approached. Reasons dance instructors cited for not participating included travel time (worsened by city centre traffic) and distance to the school (from home or other venues). Reserve instructors were recruited to cover absences.

School recruitment

There were 41 mainstream secondary schools in the three local areas: Bristol City Council, Bath and North East Somerset Council and North Somerset Council. Four schools were ineligible (one school was male only, three schools had fewer than 30 registered Year 7 girls). The remaining 37 schools were sent postal recruitment materials (a brief study flyer, detailed study information and an expression of interest form). Follow-up telephone calls and e-mails were sent shortly after postal materials (including relevant attachments). The principal investigator and trial manager also spoke at a PE teachers’ meeting in one of the local areas.

Recruitment materials were sent to schools both by post and electronically. It is difficult to ascertain whether or not the materials made it to a suitable staff member (e.g. head teacher or PE teacher). It is often difficult to identify the most appropriate staff member to receive recruitment materials. In certain circumstances this may mean that recruitment materials do not reach the most relevant individual.

Of the 37 schools eligible to participate, 18 initially signed up. The recruitment campaign continued in order to ensure that there were reserve schools if needed (five reserve schools were recruited in all). An additional school wanted to participate but withdrew owing to geographical and transport restrictions. As such, from those schools eligible to participate (n = 37), just under two-thirds (n = 24) expressed an interest to participate.

After attempts were made to recruit the minimum number of Year 7 girls (n = 25) in each school, four schools had to be replaced with reserves as they were unable to fulfil the minimum recruitment criteria. Sufficient numbers of girls were recruited from these schools.

Child recruitment

At the point of school recruitment, dates were arranged on which pupil recruitment could take place. All schools received the same recruitment procedure: (1) a taster session; and (2) detailed information (verbal and written) on what participation in the study would entail. Taster sessions were usually arranged in place of PE lessons, thus enabling all Year 7 girls eligible to take part in PE lessons to have the opportunity to participate (the sessions were for females only). Taster sessions opened with a brief introduction to the study (by study team members). After this, a dance instructor led the girls through a standardised dance session so the girls could experience what the intervention sessions would be like. Between two and six taster sessions were received in each school depending on school size.

At the end of the taster session a study team member explained what participation in the study would entail (focusing particularly on school randomisation, data collection and what girls would be asked to commit to in order to participate). Following the briefing girls were given recruitment packs for themselves (including detailed information on the study) and for their parents (including a study information sheet, informed consent form and a demographic questionnaire). If a child wanted to participate they had to return a completed informed consent and demographics form by an arranged date.

The child recruitment campaign began in the same month in which the Year 7 girls began high school (in some cases recruitment began in the first week of term). As such, the girls were new to the school and in the process of forming social ties. This was a notably busy and often confusing period for the girls, especially in some schools.

Issues encountered during recruitment

A less conventional aspect of the recruitment campaign was the provision of taster sessions in schools. Organising taster sessions was logistically difficult. A total of 65 taster sessions took place within a short time period. These were delivered by six instructors and study staff made recruitment presentations at each taster session. Schools were largely confined to scheduling taster sessions in place of PE lessons, meaning that there was little flexibility on their part.

When schools withdrew from the study (owing to insufficient pupil sign-up) there were time pressures on recruiting replacements. Data collection was planned to take part between September and October 2014; thus, when replacement schools were sought they had to be recruited quickly (as taster sessions had to be arranged and necessary information handed out and returned).

No adverse events were reported during the intervention delivery.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Data provision

Table 6 shows the number of girls who provided valid data, including those who returned an accelerometer (and therefore for whom there were accelerometer data available) at each time point. Valid weekday data were defined as data from ≥ 2 valid weekdays; valid weekend data were defined as data from ≥ 1 valid weekend day. At T0 height/weight data were available for 571 girls, that is, 284 in the intervention and 287 in the control group. Accelerometer data were available for 568 girls (99.47%), with 282 and 286 girls in the intervention and control groups, respectively. Of those girls for whom accelerometer data were available at T0, 549 (96.15%) had valid weekday data and 431 (75.48%) had valid weekend data. At T1, 561 (98.29%) girls returned an accelerometer, 535 (94.69%) had valid weekday data and 347 (61.42%) had valid weekend data. At T2, 557 (99.64%) girls returned an accelerometer; of these, 524 (93.74%) had valid weekday data and 320 (57.25%) had valid weekend day data. There were 508 (88.97%) girls who had valid weekday data at both T0 and T2, and 521 (91.24%) girls who had valid data at both T0 and T1; these figures are shown in the ‘T0 + T2’ and ‘T0 + T1’ sections in Table 6. A breakdown by group is also provided.

| Variable | Control, n (%) | Intervention, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | |||

| Height (cm) | 287 (50.26) | 284 (49.74) | 571 (100.00) |

| Weight (kg) | 287 (50.26) | 284 (49.74) | 571 (100.00) |

| Psychosocial questionnaire | 287 (50.26) | 284 (49.74) | 571 (100.00) |

| EQ-5D-Y | 287 (50.26) | 284 (49.74) | 571 (100.00) |

| Accelerometer returned | 286 (50.08) | 282 (49.39) | 568 (99.47) |

| Valid weekdaya | 276 (48.33) | 273 (47.81) | 549 (96.15) |

| Valid weekenda | 221 (38.70) | 210 (36.78) | 431 (75.48) |

| T1 | |||

| Height (cm) | 284 (50.27) | 281 (49.73) | 565 (100.00) |

| Weight (kg) | 284 (50.27) | 281 (49.73) | 565 (100.00) |

| Psychosocial questionnaire | 284 (50.27) | 281 (49.73) | 565 (100.00) |

| EQ-5D-Y | 284 (50.27) | 281 (49.73) | 565 (100.00) |

| Accelerometer returned | 282 (49.91) | 279 (49.38) | 561 (98.29) |

| Valid weekdaya | 271 (47.96) | 264 (46.73) | 535 (94.69) |

| Valid weekenda | 188 (33.27) | 159 (28.14) | 347 (61.42) |

| T2 | |||

| Height (cm) | 280 (50.09) | 279 (49.91) | 559 (100.00) |

| Weight (kg) | 280 (50.18) | 278 (49.82) | 558 (99.82) |

| Psychosocial questionnaire | 280 (50.09) | 279 (49.91) | 559 (100.00) |

| EQ-5D-Y | 280 (50.09) | 279 (49.91) | 559 (100.00) |

| Accelerometer returned | 280 (50.09) | 277 (49.55) | 557 (99.64) |

| Valid weekdaya | 270 (48.30) | 254 (45.44) | 524 (93.74) |

| Valid weekenda | 170 (30.41) | 150 (26.83) | 320 (57.25) |

| T0 + T1 | |||

| Accelerometer returned | 281 (49.21) | 277 (48.51) | 558 (97.72) |

| Valid weekdayb | 265 (46.41) | 256 (44.83) | 521 (91.24) |

| Valid weekendb | 159 (27.85) | 130 (22.77) | 289 (50.61) |

| T0 + T2 | |||

| Accelerometer returned | 279 (48.86) | 275 (48.16) | 554 (97.02) |

| Valid weekdayb | 262 (45.88) | 246 (43.08) | 508 (88.97) |

| Valid weekendb | 145 (25.39) | 124 (21.72) | 269 (47.11) |

Baseline data

Table 7 describes the baseline data. Medians (with IQRs) were reported for continuous accelerometer outcomes, as the data were skewed. Of the 282 girls who returned accelerometers in the intervention group, 273 (96.81%) provided valid weekday data. For the control group, 276 (96.50%) girls provided valid weekday data. The intervention group had 74.47% of girls with valid weekend data compared with 77.27% of girls in the control group.

| Variable | Control | Intervention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | IQR | n | Mean | SD | IQR | |