Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/182/14. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The final report began editorial review in November 2015 and was accepted for publication in March 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Karl Atkin is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research Funding Board. Chris Hatton’s salary is part-funded by Public Health England through his role as a codirector of their Learning Disabilities Public Health Observatory.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Berghs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Note on terminology

In this project, we tried to be inclusive of all theories and models of disability. The language used reflects this. Impairment and disability are used interchangeably. In doing so, we acknowledge that these words assume different meanings depending on the paradigms or social movements with which they become associated. It is equally important to acknowledge that disabled people might wish to choose their own definitions, which may or may not accord with standard classifications. We did not want to impose contested definitions on the experiences of people with disabilities, although, to be helpful, we provide a summary of common approaches, reflected in the literature and with which our report engages.

Medical models tend to define disability in terms of a biological pathology located in an individual body, which requires medical technology, medicine or rehabilitation to make a person well. Human rights approaches use person-first definitions, such as ‘persons with disabilities’, and are keen to establish legal, political, cultural, social and economic rights, consistent with the normative values associated with the society within which a disabled person lives. A social model of disability makes a distinction between disability as the experience of oppression and disadvantage and impairment as a physical, sensory, cognitive or mental health condition. Therefore, when a person refers to himself or herself as a disabled person, they are referring to his or her identification with the experience of disablement. Critical disability studies approaches use terminology such as ‘differently able’ or view disability along a continuum of human diversity. This includes people who might take pride in their specific form of disability or their social experiences of disability, such as ‘psychiatric system survivors’. Finally, there are people who have impairments but who do not define themselves as having disabilities or do not want to be associated with disability. They might prefer to use a medical description, which can be linked to cultural, social and political understandings (as in the case of people with dementia), or they may wish to connect with other identities associated with family, kinship, ethnicity, religion or other social or political movements.

Chapter 1 Background to the study

The research was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme in response to a call, ‘Implications for public health research of models and theories of disability’ (see www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129559/CB-12-182-14.pdf). Consistent with the scope of this commissioned call, the project presents a critical and informed discussion of how best to encourage more inclusive research practices, in a way that enables public health research evidence to better reflect the diverse experiences of people with a range of different disabilities. This introductory chapter explains why the research is important.

Disability and public health

According to the Family Resources Survey,1 estimates of disability in the UK have remained stable, at 19% of the population. Consequently, 10 million people in England experience significant difficulty with day-to-day activities linked to long-term conditions; this population includes those with lifelong and later-life conditions. 1 As ageing is associated with functional decline, nearly half of those living with impairments are aged 60 years or over. 2 Many disabled people also live with other physical conditions, such as coronary heart disease, diabetes and respiratory conditions, alongside mental health problems. 1

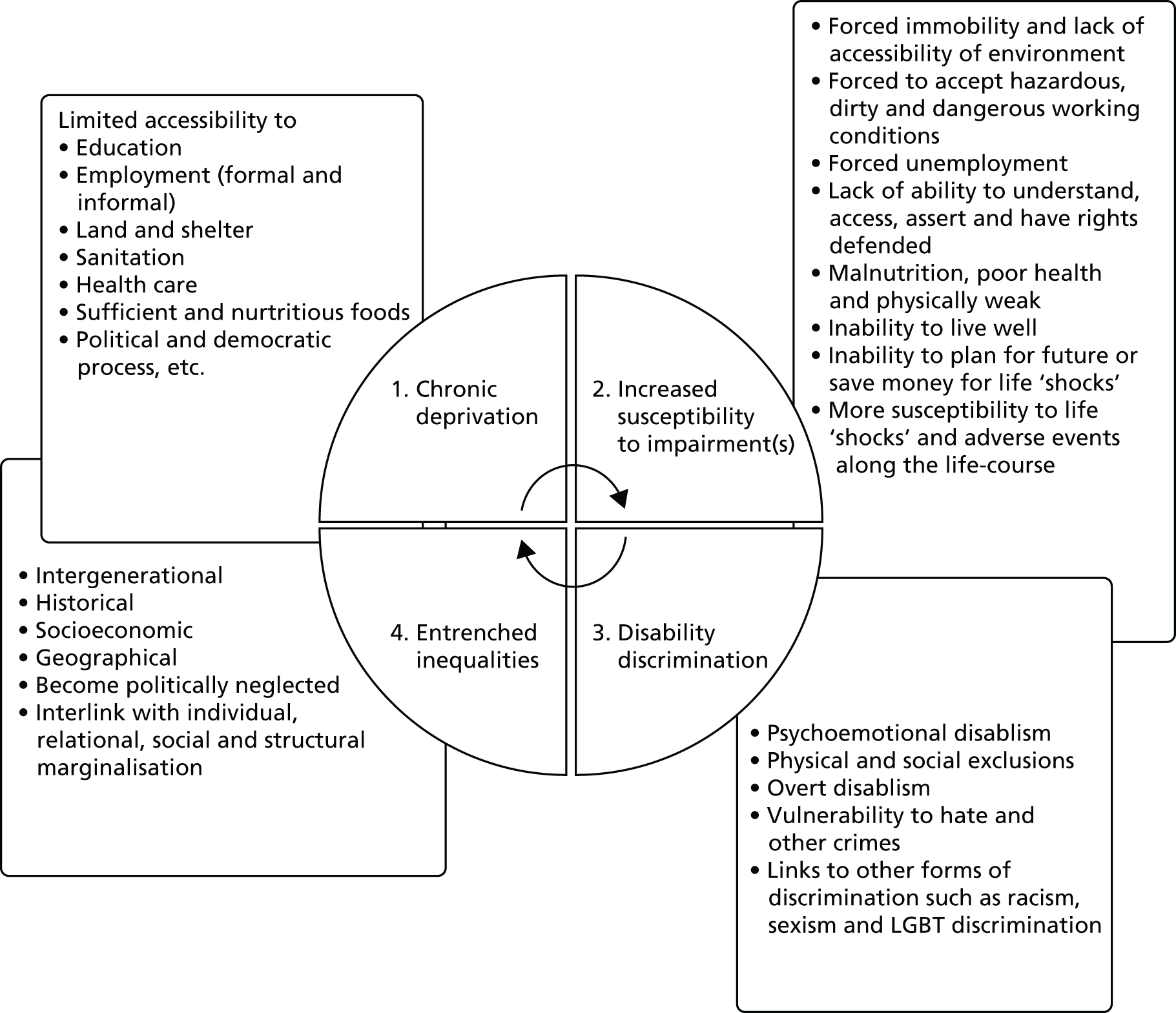

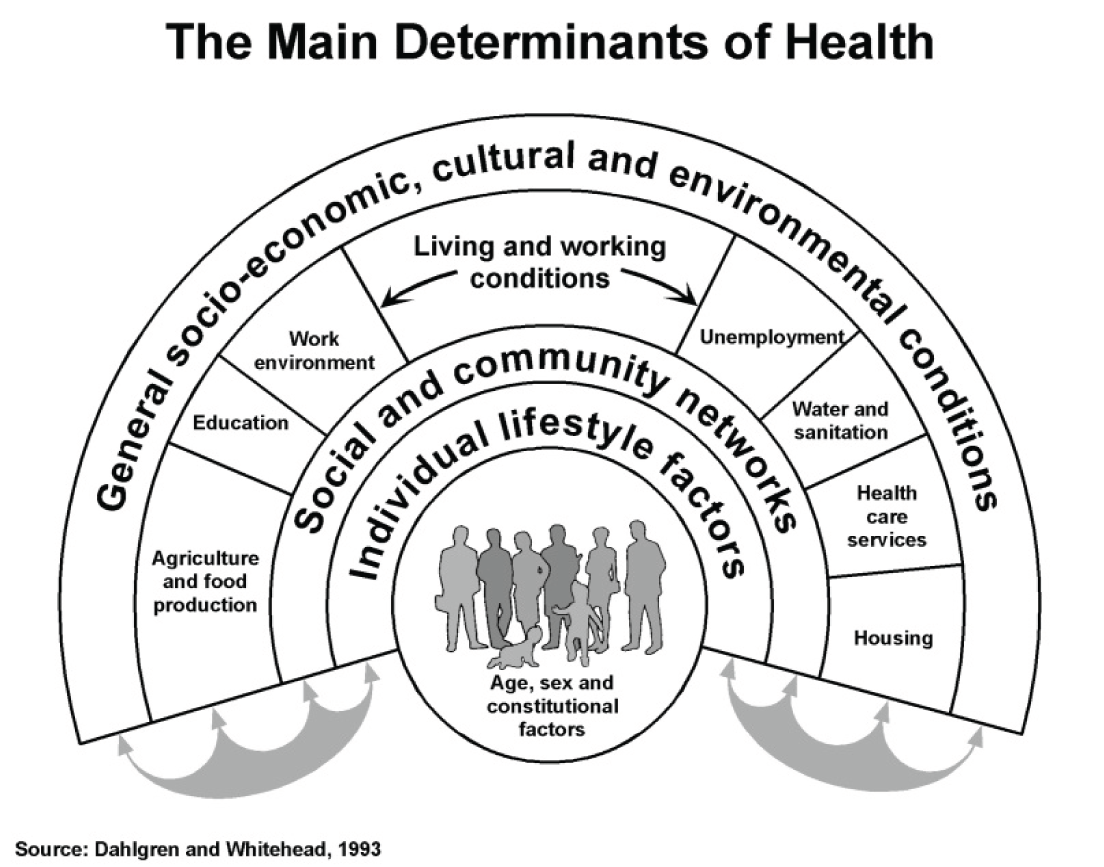

There are marked social gradients in disability across the life-course, with evidence of enduring effects associated with childhood circumstances. 3–10 In addition, and at each stage of the life-course, people with disabilities are disproportionately exposed to the social factors that contribute to health inequalities, including proximal risk factors such as smoking, obesity and lack of physical activity,11,12 alongside broader determinants associated with educational and employment opportunities, poverty and poor housing, and inequitable access to services. 6,13,14 These environmental disadvantages are, in turn, disabling and create further barriers to social inclusion. 12,15,16

There is growing appreciation of the diversity of disabling experiences, with different impairments having their own aetiologies and trajectories, acquired in a wide range of circumstances, and mediated by individual, social and political contexts. The public face of impairment is also challenging previous perceptions by encouraging a more encompassing understanding of ‘being disabled’. 17 Disability, although socially patterned, can affect anyone, including those with pre-existing chronic conditions, mental health problems and intellectual and cognitive impairments. 6,18–20 Furthermore, international understandings have moved away from a strictly medical definition, where ‘disability’ is ‘caused’ by functional deficits (such as physical injury or intellectual disability), to one that is sensitive to environmental determinants and in tune with how people experience disability as they go about their day-to-day lives. 21 This shift is a fundamental aspect of our analysis.

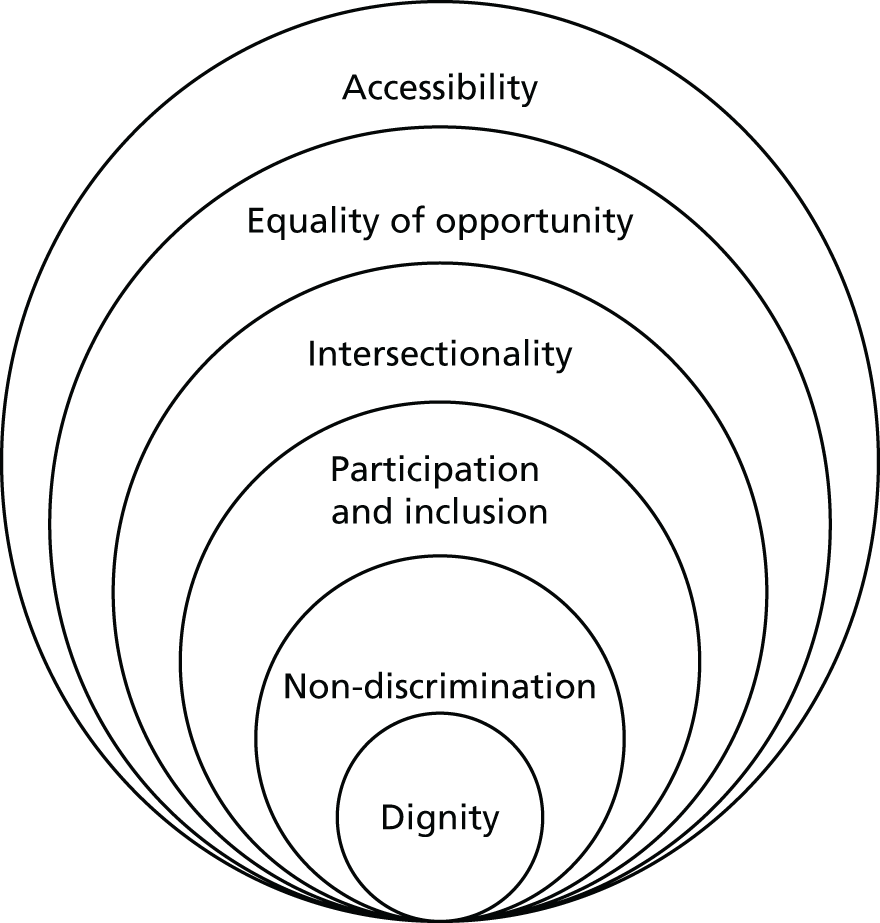

The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) reflects these changes, such that disability is understood to result ‘from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinders their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’. 22 Human rights and equality frameworks are also increasingly employed to articulate the moral claims and service needs of people with disabilities,12,23,24 in order to reflect impairment complexity. 25,26 The CRPD, for example, sets out an international framework for citizens’ rights and state obligations on health-care provision, rehabilitation, accessibility and research with and for disabled people. 22 The UK is a signatory to this framework, which is further supported at a national level by the Human Rights Act (1998)27 and the Equality Act (2010)28 which make discrimination on the basis of disability illegal, while also requiring an equality duty in health-care provision. 29 The duty to involve and support people in decisions linked to their health and well-being is also defined in the Mental Capacity Act (2005)30 and the Care Act (2014),31 respectively.

Public health research

Public health interventions have a critical part to play in advancing the status and well-being of people with disabilities. Interventions to tackle underlying causes of ill-health and reduce health inequalities have the potential to transform lives. 6 These interventions also support wider policy objectives to promote independent living and care at or close to home. 32 However, there are significant challenges to developing an evidence base,33 and four broad inter-related concerns can be identified: a lack of engagement with more theoretical conceptualisations of disability; a lack of methodological sophistication in including and capturing the experiences of disability; limited public engagement; and failing to ensure that research findings produce evidence that reflects the diverse experiences associated with disabling conditions. These challenges explain why public health research has been criticised for largely overlooking the experiences of disabled people and has been slow to accommodate shifts in understandings of – and the politics around – disability,34–39 despite equity being an increasingly salient feature of public health interventions. 40 Perspectives and assumptions can, for example, be outmoded and inappropriate, with disability represented as a ‘burden’ and a ‘cost’ to society. 41–43

Consequently, there is limited evidence on the types of public health interventions that are likely to be effective and on the kinds of measures that should be used when evaluating effectiveness. 44 There remains a dearth of public health material discussing intervention design, methods, including economic evaluation, and strategies to actively make mainstream disability-sensitive research by adapting universal and inclusive designs. 45–48 There is also little debate about how best to actively engage disabled adults, young people and children, particularly when trying to identify interventions consistent with disabled people’s preferences. 49–54 Further difficulties are associated with accommodating the differences generated by lifelong, acquired or fluctuating conditions, where experience is further mediated by sociodemographic factors such as gender, social class, ethnicity, sexuality and age. 10,55–57 Few studies, for example, assess the impact of public health interventions aimed at specific groups of disabled people, with diverse circumstances across the life-course. 58,59

This report seeks to fill these gaps by facilitating a discussion on the most appropriate ways in which to generate research evidence that is sensitive to a broad range of disabling experiences. 21,60 This is challenging. Nonetheless, disability studies and allied perspectives offer alternative ways of defining and engaging with disability, which can improve future intervention research. 61–66 However, these perspectives typically derive from a different epistemological and ontological starting point to that informing mainstream public health research and policy. 67–70 They might, for example, encourage a suspicion of any public health interventions that seek to ‘rehabilitate’ or ‘normalise’ behaviour, believing them to be a form of oppression and to deny the rights of disabled people. 23,71

Such perspectives – aligned to social and political movements – conceptualise disability as generated by the wider structures of social inequality and as a human rights issue. 72 Research perspectives and methods that have been built from these perspectives are grounded in an appreciation that disability is – and is experienced as – a dynamic interplay between impairment, attitudes and the environment. 73 Consequently, disability seen to be generated by normative values and assumptions, embedded in discursive practices, where failure to accommodate diversity and difference denies the experiences of people with disabilities, generates oppression and produces inequalities.

These approaches have generated a rich literature on disability – including that developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) – which accommodates social, relational, ecological, economic and medical models. 12 Recent international reviews, for example, have examined the application of different theories to public health interventions in terms of measurement, applicability and standardisation. 62,63,74 These reviews challenge mainstream practices and generate alternative ways of doing research. Some reviews, for example, have examined how public health theories could connect to specific disability measurements. 75 There are also studies assessing the relevance of public health outcome measurements to the experiences of people with disabilities. 43,61,76–79 Other work, although oriented to specific forms of impairments or groups, such as intellectual disabilities, mental health or younger populations, explores how disability impacts on and is affected by public health interventions,55,58,80–82 including health information;83 health-promotion interventions;57,84,85 health checks;86 self-management;87 personalisation;88 self-advocacy;89,90 and access to health care. 82,91 Despite providing valuable insights into more inclusive research strategies,36,51,65 this disparate literature has yet to be synthesised in a way that makes it accessible to those commissioning and undertaking public health research. 92 Connecting this more critical literature on the experiences of disability to the models and theories associated with public health is an important starting point, from which more inclusive research may emerge.

Why do the research?

Public health interventions aim to improve population health and reduce inequalities. As we have seen, people with disabilities are at particular risk of poor health and are disproportionately disadvantaged vis-à-vis the social factors that contribute to health inequalities. Although people with disabilities constitute a major recipient group for public health interventions, research has not engaged in any systematic way with the experiences of people with disabilities. 93 This undermines the ability of public health research to promote equity and social inclusion. 40

An appreciation of how different models of disability can inform the development and evaluation of public health interventions, together with the provision of guidelines on the most appropriate ways in which to incorporate the perspectives and experiences of those with disabilities, could be especially beneficial to research and policy. 94,95 It can help connect evidence-based practice to the diverse needs of those with disabilities, while also being sensitive to broader concerns about social disadvantage, accessibility and inclusion.

It is against this background that the NIHR PHR programme commissioned research on the public health implications of models and theories of disability. Public health interventions have been a key feature of successive governments’ policies, with a focus on developing interventions that both improve overall population health and reduce health inequalities. This drive has occurred against the backdrop of an ageing and increasingly diverse disabled population, and a cost-saving agenda that places a premium on people with impairments remaining in the community and accessing – and remaining in – the labour market, supported by effective health- and social-care interventions.

Increasing attention is being given to understanding how public health can deliver appropriate models of support and ensure better outcomes for disabled people, in which their rights are respected. 96 The Department of Health, for example, began a partnership with the Disability Rights Commission (now part of the Equality and Human Rights Commission) to ‘improve information and services, communications and levels of awareness of disability issues’. 97,98 Such strategies promote the inclusion of disabled people, their rights and needs in all public services,99 including public health. 100–102

There are particular advantages of integrating current public health research to emerging ideas that see those with disabilities as active citizens, part of wider social networks (such as partners and parents) and as stakeholders in the services that they use. 56,103 Incorporating such perspectives, while maintaining a commitment to understanding what – and how – interventions work, can lead to a range of public health benefits. 104 These include the promotion of health, social inclusion and equality. For example, the life expectancy of those with mental health problems is 20 years lower than the population norm. 105 One of the reasons for this includes the difficulty of maintaining a healthy lifestyle. 106,107 Smoking cessation raises particular challenges, particularly given that evidence suggests that current interventions are not sensitive to the experiences of those with mental health problems or the ways in which people have to negotiate social disadvantages associated with their disability. 108 A more inclusive approach, committed to ensuring that differences do not become the basis of inequalities, not only would empower people but would also have the potential to achieve significant public health gains. 109

Aims of the study

As we have argued, the complex and nuanced nature of disability is rarely considered in public health debates, especially when evaluating interventions. With a large and growing population of disabled people, the UK needs a strong evidence base on which to build future intervention research, and one that specifically offers advice on how to reconcile established research designs with those informed by more inclusive models. Without this, we shall continue to know little about what will work, for whom and under what circumstances. In line with the commissioning brief, our research questions are:

-

How can different models and theories of disability appropriately inform research into the effectiveness of public health interventions? To what extent can intervention research be sensitised to accommodate different configurations of diversity within and among general and disabled populations?

-

How do different models of disability map on to current research on public health interventions? What are the implications of commissioning research into public health interventions that are inclusive of, or for, disabled people in a way that accommodates appropriate terminology and measurement and takes account of different causes and types of impairment, while being sensitive to the experience and needs of different demographic groups associated with gender, socioeconomic position, ethnicity, sexuality and age?

-

How should participants, the public and stakeholders be involved in research and what does inclusive research practice look like?

-

What study designs and relevant outcomes best capture the experiences of impairment and disability in a way that maximises health benefits and that ensures that mainstream research reflects the experiences of people with disabilities?

To answer these questions, the project was organised in two parts (see Appendix 1). First, we scoped models and theories of disability and explored their relevance for public health paradigms; and, second, we assessed their implications for public health by reviewing a sample of systematic reviews of public health interventions, explored how far current intervention designs incorporated approaches consistent with disability models and theories. Our analysis, along with discussions with politically active disabled people and professionals working in public health, informed the iterative development of a decision aid. The decision aid aimed to critically evaluate current research practices and evidence bases, while looking to the future by enabling commissioners to assess the likelihood that commissioned public health research will produce more inclusive evidence relevant to the experiences of those with disabilities.

Conclusion

This opening chapter established the context for the research and the reasons why it is necessary. To be relevant, public health research needs to reflect a diverse range of disabling experiences. Otherwise, current evidence will struggle to engage with social disadvantage, accessibility and inclusion and thereby will risk generating inappropriate responses and wasting valuable resources. Our research explores how mainstream public health research can be more sensitive and inclusive of disability, in terms of how research is commissioned and how interventions are developed and researched. This includes connecting theoretical debates about how disability is conceptualised with current research practice to assess how current research design captures, engages and explains the experiences of disability. Our final conclusions will enable commissioners to judge the likelihood that research on a particular intervention will apply to a range of different disabilities, as experienced in different social contexts. It will also encourage researchers to adapt more inclusive approaches, including examples of best practice, from which successful public health interventions can be developed. Chapter 2 outlines how we operationalised our research questions by discussing the methodological basis of our work.

Chapter 2 Methods

The previous chapter established the broad aim of the project, which is to explore whether or not, and how, current research on public health interventions captures a diverse range of disabling experiences. Our analysis has to connect the more theoretical and sometimes polemical literature on the experiences of disability, in which various critical voices question the underlying assumptions of the research and policy process, with the mainstream public health literature, concerned with generating an evidence base on effectiveness. This required us to provide an overarching account of the different ways in which disability is conceptualised and to translate this into a language accessible to those engaged with public health. In this chapter, we explain:

-

how we carried out a two-stage scoping review to investigate what implications differing theories and models of disability could have for understanding the effectiveness of public health interventions

-

how we generated and analysed public health interventions of two types:

-

generic public health interventions potentially relevant to the lives of disabled people, in order to gain insights into the ability of mainstream research to capture the experiences of disability

-

specific public health interventions targeted at people with disabilities, which enabled us to explore the potential of more inclusive designs

-

-

how our analysis informed the development of a decision aid/toolkit

-

how we organised a consultation with politically and socially active disabled people and public health professionals to deliberate our findings.

Our first scoping review identified the range of disability theories and models and considered their strengths and possible limitations in generating inclusive approaches and capturing diverse experiences. We assessed the potential contribution of these theories and models to public health research and policy by developing a decision aid to evaluate and inform more inclusive research practice. The second stage of the project examined purposively selected public health reviews from the Cochrane (international) Library of Intervention Reviews and, to further support diversity, relevant databases held by the Campbell Collaboration and Joanna Briggs Institute. A total of 30 Cochrane reviews deal with mainstream, generic interventions. This enables the research to consider the potential for more inclusive designs. Another 30 Cochrane reviews include people with disabilities as a key target group, thereby enabling the research to assess the extent to which a more inclusive research question was able to capture the experiences of disabled people. Two reviews from each arm of the review were then purposively sampled and subjected to more detailed analysis. Finally, deliberation panels with socially and politically active disabled people and public health professions helped to refine our conclusions.

In preparing the chapter – and consistent with our iterative approach – we had an awareness of how the different stages of the project influenced each other. We have, however, adapted a pragmatic approach in describing this. This chapter outlines the different stages of the project, while acknowledging the difficulties of providing a conventional and discrete methodological account. This is why we introduce our initial reflections of the literature, as way of explaining why certain decisions were taken.

Stage 1: scoping different models of disability

We sought to identify, appraise and summarise relevant works on disability according to an explicit and reproducible methodology. Typically, scoping reviews are inclusive, and encompass relevant literature, concept or policy mapping, in addition to stakeholder consultations. 110–112 This can be a strength when assessing the depth and breadth of a research field and particularly one characterised by diverse approaches. 113–115 However, it can also be a potential weakness, which underplays specificity and encourages imprecision,112 while the perceived lack of defined quality assessment can affect empirical robustness and, in turn, policy uptake. 114,116

Aware that we had to provide a broad (theoretical) overview of a research field, while mindful of potential weaknesses in our approach, we relied on Arksey and O’Malley’s110 widely used framework to establish transparency, which helpfully parallels those used for more conventional systematic reviews. This framework informs a structured approach to reviewing, while incorporating an iterative searching process, with search terms subject to refinement in the light of the studies identified. The framework also enables us to contextualise our discussion in broader debates. We further supplemented our approach with reference to Levac et al. ’s115 and Daudt et al. ’s117 recommendations of enhancement, which include (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results; and (6) a consultation exercise.

To this extent, our approach is more akin to a knowledge review. Such reviews, developed by the Social Care Institute for Excellence (see www.scie.org.uk/), provide a thematic, explanatory exploration of the relevant literature. Knowledge reviews are especially useful in informing more reflexive commissioning, policy and practice112,114 and more broadly in assessing theory and models. 118 They also allow an appraisal through ‘mapping’ the literature rather than giving an ‘assessment’ of the ‘quality of the individual studies’, while highlighting gaps in current available reviews. 112 Moreover, knowledge reviews do not take the available evidence at face value but generate important questions about, for example, what research is commissioned and whose priorities it reflects. 112

Aims of first scoping review

The stage 1 scoping review offers a critique of different (largely theoretical) understandings of disability and explores six inter-related themes by:

-

identifying and summarising the range of disability models, definitions and theories and assessing their potential contribution to public health research and policy

-

locating different definitions, models and theories within the field of disability studies and the social and political movements of disabled people

-

appraising how well different definitions capture the diverse range of experiences associated with disability, with a particular focus on how different causes, aetiologies and trajectories mediate this experience, including a consideration of the impact of comorbidities

-

assessing whether or not, and how, the different consequences of impairment and the context in which it is realised inform debates, including a focus on how well different theories of disability take account of broader sociodemographic variables and experience

-

investigating the consequences of adapting particular terminologies, study designs and outcome measures when evaluating public health interventions

-

examining different approaches to public/stakeholder involvement.

We began by developing a protocol, outlining all major methodological decisions taken. Identified references were entered into an EndNote (version 7.4, Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) library. This enabled studies to be retrieved by key word, subject heading or medical subject heading (MeSH) searches. We intended to identify relevant studies through:

-

searches of major electronic databases

-

cross-checking with major publications in the field of disability studies, history and policy

-

scanning reference lists of relevant papers

-

internet searches

-

searches of key books and book chapters (an important source of literature on this subject)

-

examining major policy documents

-

consulting experts in the field by cross-checking key texts with members of the project steering committee.

As can be seen in Initial inclusion criteria, we had to refine our initial approach to one that was more focused and consistent with the aims of the project. We next explain the development of our thinking and how we arrived at our eventual methodological approach.

Initial inclusion criteria

All resources were searched from 1990 onwards, as this is when critiques and new models begin to appear in the UK (as seen in the work of writers such as Nasa Begum and Gerry Zarb,66 Colin Barnes and colleagues,67 Mike Oliver72 and Jenny Morris119). These authors also capture the history of the various disability and civil rights movements, thereby adding further context, enabling us to locate material within broader social movements.

We then set about identifying MeSH terms. In doing so, we included a range of different physical, intellectual and mental impairments, while reflecting the different political, economic and cultural disabling consequences of having a lifelong, acquired or fluctuating condition. These were cross-referenced against those terms used in disability studies, sociological literature and public health policy. Our MeSH terms included: ‘model*’, ‘theor*’, ‘disab*’, ‘handicap*’, ‘persons with disabl*’, ‘mentally disabled*’, and ‘chronic disab*’. We used Boolean operators such as ‘AND’ to widen or narrow the searching in our databases. Our search strategy included the following electronic databases: Scopus, MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO and Social Sciences Citation Index. We set an inclusion and exclusion date (1990 and 2014, respectively). We supplemented the electronic database searches with hand-searching of key journals, along with website and grey literature searches (such as the Conference Proceedings Citation Index).

Our inclusion criteria mean that an output was considered relevant only if it was in English; informed by one or more of the key guiding issues highlighted in the review questions; clearly focused on models and theories; and met our operationalisation of the study objectives/review questions. Studies were excluded if they were not in the English language. Studies published before 1990 or after May 2014 were excluded. If the studies did not incorporate our MeSH terms, they were also excluded. Box 1 illustrates preliminary results when using the SCOPUS database.

(1990 to May 2014) AND (‘disabilit*’ AND ‘theor*’) = 4970.

(1990 to May 2014) AND (‘disabilit*’ AND ‘model*’) = 26,415.

(1990 to May 2014) AND (‘model* of disabilit*’) = 26,415.

We had a large number of ‘hits’, but closer scrutiny revealed that many of the included studies were not unequivocally discussing models or theory linked to ‘disability’. We realised that the scoping in the databases was rather unwieldy, as the overview of theories and models of disability was too extensive. We checked if this would be the case in the PubMed database using the same MeSH terms. ‘Hits’ were still in the thousands. On further analysis, the way in which ‘theory’ could be defined was too diffuse for the purposes of our review. There were also different conceptual levels of theories, comparisons and meta-analysis, based in a plethora of paradigms evident across psychology, law, social sciences, medicine, statistics and public health. We discussed this as a team and with our project steering committee.

Following these discussions, the research team decided to refine and refocus our scoping approach to ensure that we adequately captured the theoretical richness and diversity of ‘disability’ in a way that was consistent with our aims. 118,120 Consequently, we oriented our search towards specific journals in which we felt that this diversity would be reflected. This not only offered a more manageable approach, but also ensured the inclusion of different disability theories and models. Following discussions with the project steering committee, we made a list of the 10 most influential peer-reviewed journals considered likely to contain articles about theories or models of disability and, at the same time, to capture the experiences of various impairments, different social and political experiences of disability and perspectives that took account of intersectionality.

Using this more focused approach, we hand-searched 10 journals and followed up key papers, reports and texts. The 10 journals were Disability & Society; Scandinavian Journal for Disability Research; Disability Studies Quarterly; Journal of Intellectual Disability Research; British Journal of Social Work; Human Rights Quarterly; Journal of Disability Policy Studies; Social Science & Medicine; Ethnicity & Health; and Social Theory and Health. We did not include journals such as the Disability and Health Journal or Disability and Rehabilitation, as we wanted to avoid a focus on rehabilitation. We also wanted the selected journals to ensure representation across not only impairments, age, socioeconomic class, geography and ethnicity but also the political and social spectrum.

We searched the archives of each of these journals from January 1990 to May 2014. For each journal, we kept a record of the possible articles of interest. In keeping with both a conceptual and genealogical approach, we decided to make our MeSH terms more flexible and inclusive to accommodate the historically changing language and policy landscape. The abstract or title of a paper thus had to include at least one of the following search terms: ‘model’, ‘paradigm’, ‘perspective’, ‘approach’, ‘formulation’, ‘conceptual frame’, ‘discourse’, ‘definition’, ‘understanding’, ‘theory’ or ‘framework’. We were especially aware that early articles may not use the word ‘model’. There also had to be an explicitly named perspective of viewing disability in the title or abstract. If we were unsure, but the title included possible MeSH terms that could be linked to a specific way of viewing disability, we included it. For example, we included papers that were about ‘human rights’, ‘social understanding’, ‘United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’, ‘International Classification of Impairments, Disability and Handicap’ (ICIDH), ‘International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health’ (ICF), ‘ecological’, and ‘critical disability studies’ (CDS). Finally, we tried to be inclusive of language that was applicable to specific disabilities or language that may now be considered politically incorrect, such as ‘normalisation’ or ‘retardation’.

Ideally, we would have liked to have included a journal with an explicit focus on childhood disability. However, potential journals such as Archives of Disease in Childhood had a biomedical focus, whereas more specialist journals, with a large number of papers on childhood, such as Autism, were too broad in scope. The 10 journals selected, however, did include papers on childhood disability, although we acknowledge a potential gap in our approach, which we attempted to address when interrogating reviews of intervention studies.

Data selection

We located 182 articles from the 10 journals and printed these for further hand-searching. We mapped these papers according to the guidelines of Arksey and O’Malley110 by providing a summary of each paper. 110 Methodologically, Campbell et al. 118 noted that there are no real guidelines linked to theoretical reviews. Particular challenges include charting the relationship of a model vis-à-vis a theory, theoretical explanation and/or development. 121 We also realised that, in order to understand the applications of some models, we had to be methodologically inclusive of how they had been translated. As we have seen, scoping reviews are especially useful in allowing an appraisal through ‘mapping’ of the literature rather than giving an ‘assessment’ of the ‘quality’ of the individual studies. They are also useful in highlighting gaps in current available reviews. 112

Conceptually, we wanted to understand theory development and implications of use. This informed our approach to charting. A data extraction sheet was designed to quickly map details on the five inter-related themes (see Appendix 2). This enabled us to identify and summarise a range of disability models, assess their potential contribution to public health research and policy, and appraise how well different definitions capture the diverse range of experiences associated with disability. Following discussions with our project steering committee, we wanted to ensure balance in how we represented theories and models, by illustrating both their strengths and their weaknesses.

Refinement of inclusion criteria

In charting each article, we further refined the explicit discussion of theoretical models by offering an analysis of a particular model, paradigm or perspective; a comparative analysis or comparison between models, paradigms or perspectives; and a meta-analysis of models, paradigms or perspectives. We included grey literature if relevant, for instance, an extensive book review presenting a critique of a particular model and any subsequent rebuttals. We excluded applications of a model to a specific impairment or group of impairments, research-based papers or testing of a model or paradigm. We also excluded sociocultural understandings of disability, statistical approaches and in-depth theoretical or philosophical analyses unless specific to a model, paradigm or perspective. Although some commentaries and editorials were interesting, we excluded them if they referred to a study that was already included or critiques made more extensively elsewhere.

The refinement of the inclusion criteria through the mapping exercise meant that we were left with 121 articles. After scoping by the primary reviewer (MB), a second reviewer (KA) examined the validity of the findings of the primary reviewer. The second reviewer also checked and charted the 27 articles about which the first reviewer was unsure. As most of these articles were concerned with explicit discussions about disability and were not research-based, the first and second reviewer did not have to engage in an analysis of the methods and methodology or robustness of the research undertaken.

The results of our initial search strategy finally identified 104 articles explicitly about disability models, paradigms and theories (Figure 1). We used these articles to identify relevant secondary sources and grey literature such as major books and theories on disability theory and sociological theory linked to disability (such as that on chronic and long-term illness) as well as public health policy documents from national and global institutions such as the Human Rights Commission, the WHO, the UN, the UN Children’s Emergency Fund, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. An initial list was drawn up largely based on the volume of citations. We also discussed and agreed with our project steering committee what the more influential and most important texts (books and chapters) on disability theory, models and definitions were. This literature provided important and nuanced theoretical context to our analysis, while reflecting current debates about disability and how these have changed over time. To this extent, our account is a broad and extensive map of current theories and models of disability.

FIGURE 1.

Scoping flow chart.

Reflections on the literature

When looking across the set of papers, we noted four distinct models: medical models; human rights models; social models; and CDS models. Although the core elements of the models demonstrated a degree of consistency over time, perhaps not surprisingly, the definitions, terminology and theoretical background of the models kept changing and were dynamic, gradually becoming more reified – and perhaps less innovative – over time. Our analysis reflects this.

More theoretically informed articles were found in two journals, namely Disability & Society and Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. Furthermore, although we assumed that journals such as Human Rights Quarterly would include discussion about disability rights, our review suggested otherwise. Ethnicity & Health had no discussions of models and Social Theory & Health, for example, contained only one article that was relevant (Table 1). The journal Disability & Society was largely UK focused, although it published foundational work on the social model and functioned as a genealogical review through which to find books, articles and grey literature. The Scandinavian Journal for Disability Research focused on Scandinavian or European thought on disability with well-established international academics and was especially strong on linking more relational and psychological accounts of disability.

| Journal | Number of articles |

|---|---|

| Disability & Society | 49 |

| Scandinavian Journal of Disability Studies | 16 |

| Journal of Disability Policy Studies | 12 |

| Social Science & Medicine | 8 |

| Disability Studies Quarterly | 7 |

| Journal of Intellectual Disability Research | 5 |

| British Journal of Social Work | 2 |

| Human Rights Quarterly | 2 |

| Social Theory and Health | 1 |

| Ethnicity & Health | 0 |

The most geographically diverse journal was the Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. By way of contrast, the Journal of Disability Policy Studies was completely US based. Social Science & Medicine was heavily biased towards the international application of more medical models of disability and Disability Studies Quarterly was the most innovative by linking disability with cultural studies. We would have expected there to be a lively debate on models of disability in the British Journal of Social Work or Social Theory and Health; however, this rarely occurred. Furthermore, despite an interest in disability and human rights, especially in an international context, ‘disability’ tended to be undertheorised in Human Rights Quarterly. Although research on disability had been published in Ethnicity & Health, no conceptual discussions were found.

Geographically, most discussion of theoretical models were located in the Global North (the UK, the USA and Europe) rather than the Global South, where, it is argued, more disabled people are located. 12,122 Across our review period, we found only one article discussing a rights-based model from the Global South (Table 2).

| Region | Number of articles |

|---|---|

| UK | 44 |

| USA | 26 |

| Europe | 15 |

| International | 7 |

| Canada | 6 |

| Australia | 5 |

| India | 1 |

Stage 2: reviewing public health interventions

We now turn to the second stage of the scoping review and explore its relationship with stage 1. Our second stage explored three components, namely:

-

broader public health interventions potentially relevant to the lives of disabled people, in order to gain insights into the ability of mainstream research to capture the experiences of disability (n = 30 reviews)

-

public health interventions targeted at people with disabilities, which enabled us to explore the potential of more inclusive designs (n = 30 reviews)

-

an analysis of the applicability and feasibility of a decision aid applied to the two reviews of interventions, to assess the potential for a more inclusive approach, reflecting the diverse experiences of disability.

Key analytical questions, applied to both reviews, included:

-

Was an inclusive approach considered and used to inform the design and conduct of studies?

-

Did the study design privilege the inclusion of some impairment types and disability groups over others and, if so, what types of disabilities are more likely to be accommodated?

-

What possible accommodations could be identified to make for a more inclusive research design?

-

Were accommodations – potential or otherwise – identified by authors as having the potential to jeopardise the scientific integrity of the research evidence?

-

Were communication difficulties used to justify the exclusion of certain people and to what extent could these be regarded as legitimate?

-

How were those with disabilities treated when recruiting to the study?

-

How was disability discussed in the findings?

-

Did the authors consider the extent to which their findings could be generalised to include the experiences of those with disabilities?

-

To what extent could the findings produce relevant and universal evidence?

-

To what extent could study designs be perceived to be disablist (excluding disabled people) or ableist (premised on able bodied norms).

Similarly to in stage 1, we followed Arksey and O’Malley’s110 framework. This provided a structured and iterative searching process, with search terms subject to refinement in light of the studies identified. We did an initial pilot search using The Cochrane Library before beginning our formal full searches. The combined MeSH terms of ‘disability’ and ‘interventions’ generated > 5000 hits. However, the joining of the MeSH term of ‘disability’ AND ‘intervention’ generated a more manageable 643 results. We used this to generate a sample of 30 reviews; each, on average, included 16 studies (with a range of 3 to 51 studies). This potentially gave us material on 480 studies. However, when we reviewed these studies in more detail, we found that many of these interventions were not reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that were sufficiently specific to the public health policy context or inclusive of ‘disability’. We checked to see how many studies were specifically about ‘public health’ AND ‘disability’ and found only 13 results out of a possible 8664 records. The pilot search, therefore, demonstrated the feasibility of our approach but also the importance of assuming a more iterative approach to the literature, particularly given the broad and flexible use of terms such as ‘public health’, ‘intervention’ and ‘disability’. To further facilitate this approach, we compared an expansive search with a theoretically specific search to assess how best to proceed.

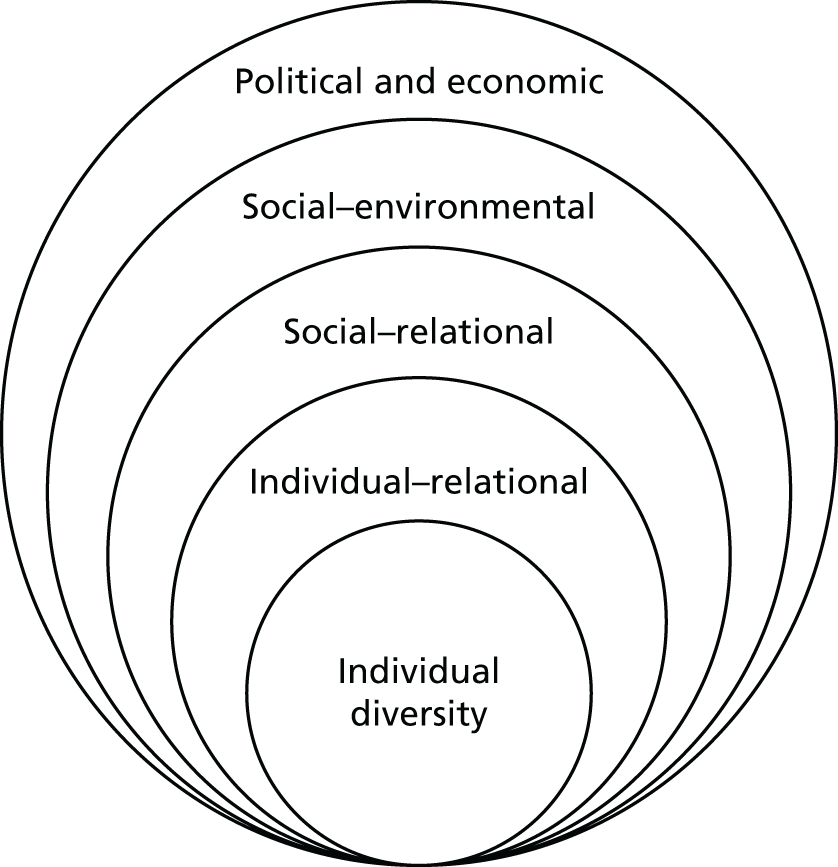

The expansive search was extensive to the extent that it identified how many interventions were linked to public health and how many interventions were linked to disability in The Cochrane Library. The theoretically specific approach was informed by an analysis of disability theory and models linked to both ecological public health and disability rights models, in addition to reflecting differing impairments, intersectionality and life-course (see Chapter 3). This approach also had the advantage of focusing on individual, social–relational, social and macrostructural levels, linked to differing public health issues as well as to disabilities. Contrasting an expansive with a theoretically informed searching process also allowed a check of The Cochrane Library in terms of what would be identified by the Library as relevant.

Our focus on public health interventions and their evaluation using RCTs offered a good reflection of current policy, research and funding priorities in the UK. Furthermore, policymakers, researchers and professionals frequently used The Cochrane Library to inform decision-making. The Cochrane Library, although not covering a broad range of evaluative methodologies, does provides a good account of mainstream public health research and this is what we wanted to capture.

The results of our expansive approach allowed us to gain an overview of and to identify relevant systematic review studies for our topic of interest (see Appendix 3). We found 181 results from 8660 records from a search on ‘public health’ in the title, abstract or keywords, and we found 541 results from 8660 records from a search on ‘disability’ in title, abstract or keywords in The Cochrane Library. We printed out a list of the first 40 studies for public health interventions to check mainstreaming and the first 40 most relevant disability interventions to check inclusion. We had a list of studies for public health and a list for disability, and two reviewers (MB and KA) checked each study for relevance.

Having undertaken the expansive scope, we cross-checked the findings by means of a theoretically specific scope to find out how that would compare. When scoping the disability literature, we found that disability concepts such as ‘theory’ and ‘model’ were rarely linked to evaluation of reviews. 118,120 Bonner123 argues that theory-based evaluations can be of great use in identifying why interventions do or do not work in specific contexts and can be linked to realist pragmatic outcomes. Moore et al. 124 note the greater importance of theory and its contribution to how the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance of complex interventions was framed. This is why we decided that it was important to understand the role of theory in public health interventions. We used the theoretical paradigms of the different but interconnected levels on which public health and disability interventions should ideally be working.

We combined our search on interventions with insights generated from our theoretical search to guide the scoping and to ensure that it covered issues across individual, social, institutional and policy perspective, both in terms of a ‘public health’ and a ‘disability’ focus. Furthermore, and to ensure consistency with the NIHR PHR brief, we decided that our scoping should be guided by individual public health policy priority issues (such as obesity) as well as by areas in which we thought that future individual public health issues would probably lie (such as gambling, new forms of infectious diseases and disaster preparedness) or more social public health issues (such as the use of green and public spaces, urban renewal and impact of environmental change). We cross-referenced for possible variations on terminology and to ensure consistency with the brief, and included current public health themes as reflected in recently funded interventions by the NIHR PHR, such as health literacy, binge drinking, physical activity and smoking cessation (Table 3).

| Individual | obesity | cardiovascular disease | gambling |

| respiratory health | diabetes | sexual health | |

| mental health | alcohol | maternal health | |

| dental | smoking | cancer | |

| injury | violence | substance abuse | |

| Relational/life-course | pregnancy | infant | teenager |

| adult | older person/elderly | ||

| Social | education | housing | employment |

| recreation | transport | ||

| Macrostructural | socio-economic | environmental | political |

| historical/policy | cultural |

We printed out the first three hits for each of the headings. The first (MB) and second (KA) reviewer went through the results to assess relevance for public health. Although there was a plethora of material on public health priorities such as obesity and smoking cessation, there was, perhaps not surprisingly, not much evidence on effectiveness of interventions on possible future public health policy issues such as gambling, the environment or recreation. This is an important consideration when interpreting our findings.

Our review of public health and disability followed the same approach (Table 4), although we additionally conducted a mapping exercise identifying common forms of impairment by noting the number of hits when we cross-checked with public health (i.e. ‘public health’ AND ‘intellectual disab*’).

| Individual | intellectual disabilities | hearing impairment | chronic conditions |

| dementia | stroke | ADHD | |

| frailty | spinal cord injuries | pain | |

| visual impairment | arthritis | depression | |

| musculoskeletal (back pain) | HIV | autism | |

| Relational/life-course | pregnancy | infant | teenager |

| adult | older person/elderly | ||

| Social | education | housing | transport |

| employment | recreation | ||

| Macrostructural | socio-economic | environmental | political |

| historical/policy | cultural |

To ensure consistency with the brief, we checked our findings against common forms of ‘disability’ in Britain,1 alongside what we thought would be future public health priorities in terms of improving health, well-being and quality of life (QoL) (e.g. dementia, depression and mental health). Terminology often had to be clinical to access the interventions we were looking for. We tried to be exhaustive by cross-checking interventions on disability issues (i.e. work disability and behavioural interventions), while also including terms such as ‘sustainable’, ‘investment’ and ‘social protection’. We had, however, few public health and disability hits, despite disability models and theories indicating that public health research was moving in this direction. This explained our use of supplementary databases.

Many of theories and models of disability identified disability as an affirmative identity and examined disabling barriers that impede independence and health. The idea of ‘independence’ was foundational to the creation of many disability theories and models. To ensure that such paradigms were not excluded, we further verified our approach against the Derbyshire Coalition for Inclusive Living’s ‘seven needs for independent living’. 125 This approach consists of information, peer-support, housing, technical aids, personal assistance, transport and access. 125 Unfortunately, we could not find sufficient public health evidence linked to peer-support, technical aids, communication and personal assistance.

To conclude, neither an expansive nor a theoretical scoping on disability was as relevant as the combined, more focused, results that we gained from MeSH terms such as ‘public health’ AND ‘disability’. We increased hits a little by adding variations of (disab*). Additional piloting indicated that the Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews and Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Studies were important in accessing more specific information on public health and disability, particularly with regard to future priorities. We decided to use these three databases (the Cochrane Library, the Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews and the Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Studies) together to build our review of specific interventions about disability and public health. The results of the theoretical scoping were slightly better for public health, in that this ensured a more general overview in terms of accessing public health issues in accordance with an ecological model on several levels from policy implementation to individual physical interventions. 126 However, the two reviewers found that the same results were obtained within an expansive scoping by rejecting doubles, or reviews of interventions that were on the same theme. To guide the scoping, the two reviewers decided to keep the idea of multilayered framework – combining expansive and theoretical scoping – and use it as an implicit guide (Figure 2). We also note the importance of rejecting interventions on the same theme to ensure an overview of policy issues, while reflecting areas in which research was lacking.

FIGURE 2.

Mapping theoretical approaches on to reviews of interventions.

Scoping public health interventions

In scoping relevant studies, we first assessed how inclusive 30 randomly selected generic public health interventions found in the Cochrane database were of the disability theories or models we identified (see Chapter 3). The piloting demonstrated that the Cochrane database was sufficiently comprehensive to ensure that we accessed a wide variety of reviews of public health interventions. Second, we gathered information about ‘public health’ interventions inclusive of disability for 30 specifically sampled studies. When undertaking the more specific review of disability and public health we checked the Cochrane database first but found insufficient studies (n = 13) and had to supplement this information with studies from the Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews and Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Studies. We manually searched the online archives of the Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews from 2004 to 2015 (Volume 11). We manually searched the online archives of the Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Studies from 1998 to 2014. These searches generated seven reviews. Apart from the use of databases, the methodological principles informing the generic reviews and the reviews more inclusive of disability were similar.

Inclusion criteria

We randomly selected relevant peer-reviewed studies based on our MeSH terms. The review studies had either an explicit public health focus for the generic review or a specific public health and disability focus for our second, more focused, review. The review had to be located in developed or middle- to high-income countries so that they would have relevance to the UK. We were particularly interested in reviews of public health interventions (RCTs). Reviews located in mainly low-income countries were excluded. Reviews that had not been completed and could present only a protocol were also excluded, as were studies still in progress, being updated or withdrawn by the database we were using. If there were reviews in which themes overlapped, we chose the most relevant review and rejected the other review as a ‘double’. When scoping for reviews of disability and public health, we excluded studies about self-care, peer-support, rehabilitation and information unless they had an overt public health focus.

Nonetheless, some of the excluded reviews provide useful analytical insights, which were useful in refining our decision aid. For example, although Godfrey et al. 127 had a relevant and potentially interesting review on intervention strategies across disease and impairment groupings, we had to exclude this because the focus was on ‘self-care’ activities. However, they noted challenges of data synthesis linked to differing ‘types of outcomes measured’; ‘methods of measurement’; and types of ‘priority’ given to outcome measures, preventing comparison of heterogeneous data. 127 This review also raised important issues about scientific rigour and the reporting of systematic review methodologies and appraisal of ‘risk of bias’. 127 The authors point out, for example, that risk of bias is considered internally to a study and does not focus on real-world maintenance or sustainability of an intervention. Similarly, Balogh et al. 82 and Robertson et al. 128 focused on interventions in health and health-care services that fell outside our scoping. Nonetheless, they identified differences not only in outcome measures used by different studies but also the jurisdictions and way that the provision of care would be organised.

Data selection and analysis

The formal content of reviews was appraised by adapting the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool recommended by the Cochrane Public Health Review Group (see Appendix 4). For the purposes of this study, we operationalised the assessment tool to include an examination of how the research question was formulated; sampling strategy; response and follow-up rates; intervention integrity; statistical analyses; and assessment of adjustment for confounders. We used quality appraisal criteria for descriptive rather than exclusion purposes and to highlight variations between reviews (and studies). We also used the Cochrane–Campbell Equity Checklist for Systematic Reviews (or Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-Plus) to evaluate the extent to which studies included in the reviews engaged with equity, thereby providing evidence for good research practice, which has successfully engaged with the diverse experiences of disability.

To facilitate this, we used scoping charting methods to help us organise the material selected. 110 We focused on trying to understand if inclusion of disability was linked to the theoretical paradigm being used and if that influenced the methodology and the use of outcome measures. We developed a data extraction table to enable us to scope and review this quickly (see Appendix 5). To aid analysis, we decided to colour code the results similarly to a traffic-light system: red (no inclusion); amber (nominal inclusion); and green (inclusion). 129,130 The term ‘nominal’ indicated that, although disability had been included, there was often no real attempt to define disability theoretically and inclusion appeared to be in name only. 131

In analysing the selected reviews, we became aware of a difference among ‘active exclusion’, in which people with disabilities were excluded from interventions; ‘passive exclusion,’ where the study was designed in such a way to be exclusionary (i.e. owing to exclusions set around ‘literacy’);59 or ‘partial exclusion’ where some – but not all – categories of impairments were seen as problematic (such as mental health). We wanted to keep the scoping open at this stage of the process and focus mainly on categories of inclusion, paradigms used and outcome measures. We initially thought that identifying disability paradigms would be indicative of type of inclusion or exclusion. This was not the case. We discovered that there had been very little theoretical integration of disability paradigms; often, we had to examine the outcome measures or diagnostic definitions of impairment to understand the models being used.

The initial screening of identified reviews was conducted by two reviewers (MB and KA). Discussions resolved any discrepancies. A data extraction sheet collected details on the intervention being evaluated; study designs; target populations; inclusion and exclusion criteria; measures used and their appropriateness to understanding different types of disability; user and public involvement; and relevance of findings to broad and diverse experiences of disability. We noted where reviews included studies with participants from poorer backgrounds, ethnic minority populations and other marginalised groups. We also commented on the extent to which studies – either generic or specific – accommodated the different circumstances in which disability is negotiated and experienced.

The first reviewer (MB) did the initial piloting, scoping and charting of the material. By mapping the reviews, the charting offered a critical commentary on the models and theories of disability (or lack thereof) underpinning (implicit or explicit) evaluations of public health interventions. It also explored whether or not ‘disability’ was included, how it was being defined and what the connection was to the outcome measures and more general concerns of public health. In any review, there is a risk of bias, and, to offer a counter to this, a second reviewer (KA) reviewed the charted data and checked for public health relevance. This was also important in ensuring our iterative process and considering the broader heterogeneity of our approach.

To be consistent with the initial brief, we kept thresholds for inclusion of ‘disability’ as low as possible, but this can be viewed as a limitation to the extent that it might not accord with the lived experiences of disability. We relied mainly on the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews but had to interrogate other databases in order to ensure that we had sufficient research evidence. This could be indicative of a lack of ‘disability’ evidence or that we were too narrowly focused on RCTs as providing ‘evidence’. 132 Nonetheless, a more inclusive approach would have generated too much material and greater heterogeneity, thereby making it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions. We were also aware of how our definitions of public health research were influenced by current NIHR practice in terms of research priorities and previously commissioned research. This might have provided a more narrowly defined approach to public health, but was necessary in order to set boundaries consistent with the commissioners’ needs. Furthermore, we were aware that we were assessing reviews of studies on interventions. This is why we decided to select two papers from the different arms of stage 2 scoping and subject them to a more detailed analysis.

Interrogating two selected reviews in more detail

We interrogated the individual studies included in two selected reviews of interventions. We developed a simple charting diagram to collect material (see Appendix 6). Using insights from our earlier scoping, we were especially interested in life-course and fluctuating conditions, the role of intersectionality, and the use and relevance of outcome and effectiveness measures.

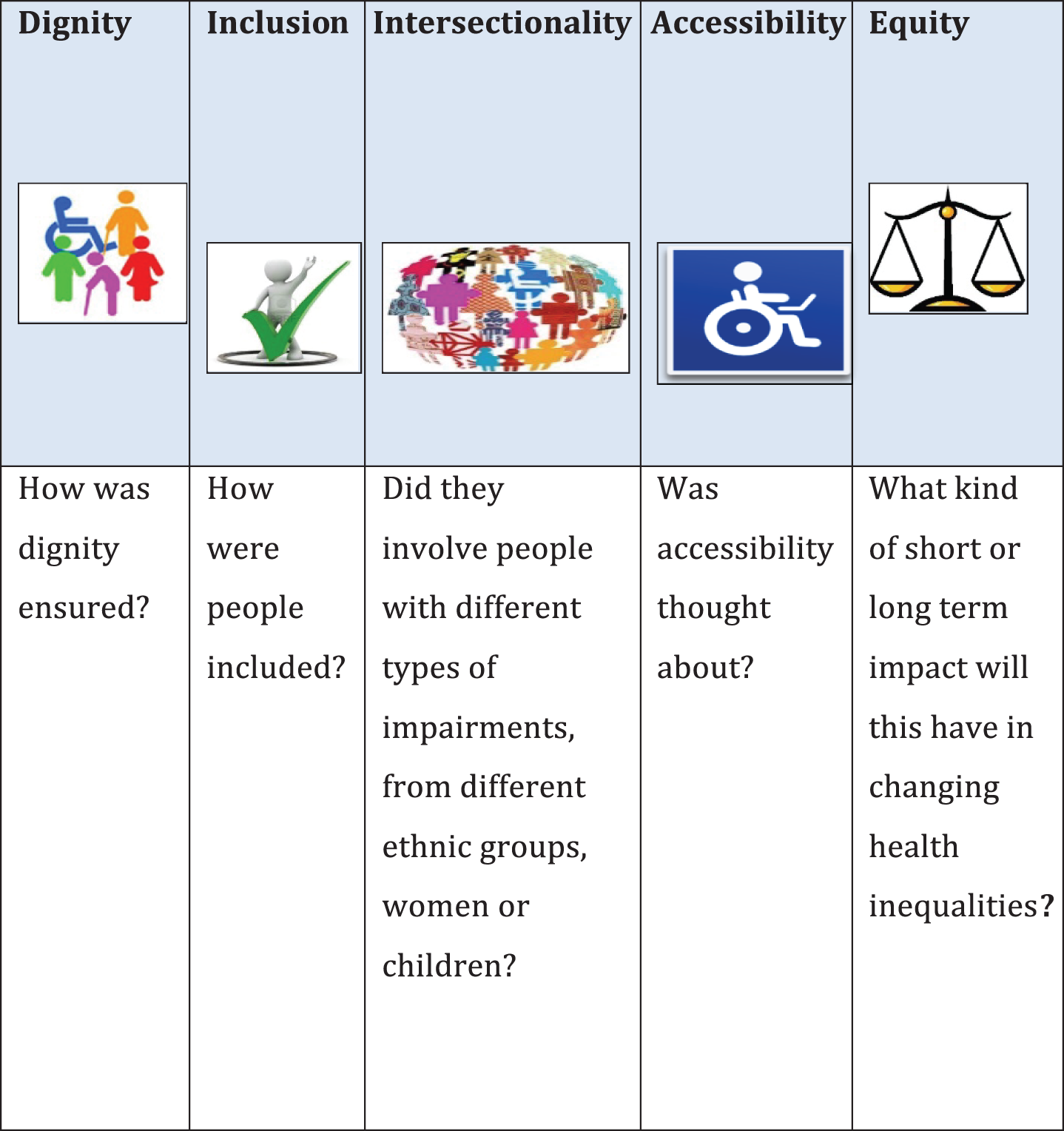

In selecting the reviews, we decided to focus on an important cross-cutting public health and disability issue, that is, physical activity. We reasoned that studies would be easy to access and would include a wide variety of outcome measures. Following discussion among the review team, we identified two reviews. The first was a generic physical activity intervention, including 44 studies. 133 The second review focused on physical activity for older people with dementia and included 17 studies and was more purposively specific. 134 The reviewers (MB and KA) read through each article cited in each of the reviews. They were especially sensitive to any reference to disability, including those that might seem more tangential, such as ‘morbidity’. The reviews also explored if any theoretical framework – implicit or explicit – informed the research and, if so, the extent to which this was linked to research design. When formally charting the material, we appraised the extent to which each study was inclusive of the following concepts (see Chapter 4); dignity, inclusion, intersectionality, accessibility and equity in design.

To supplement our material, a member of the project team (MB) e-mailed the corresponding author of each public health study to check whether or not people with disabilities were included and, if so, how. In assessing their responses, the reviewers adapted Feldman et al. ’s92 methods to compare studies; this included asking whether or not the study could have made reasonable accommodations to include disability; the extent to which it could account for intersectionality (such as gender, ethnicity, comorbidities and so on); and if equity was a part of the research design (see Appendix 7). The ‘reasonable accommodation’ question was deliberately ‘open’, as we wanted to get a feel for what authors saw as the key issues. We also asked how easily the intervention could be taken up and whether or not any identified change was sustainable. We gave the corresponding authors 1 month to answer our questions. We received 39 replies out of 44 trials or RCTs which made up the review.

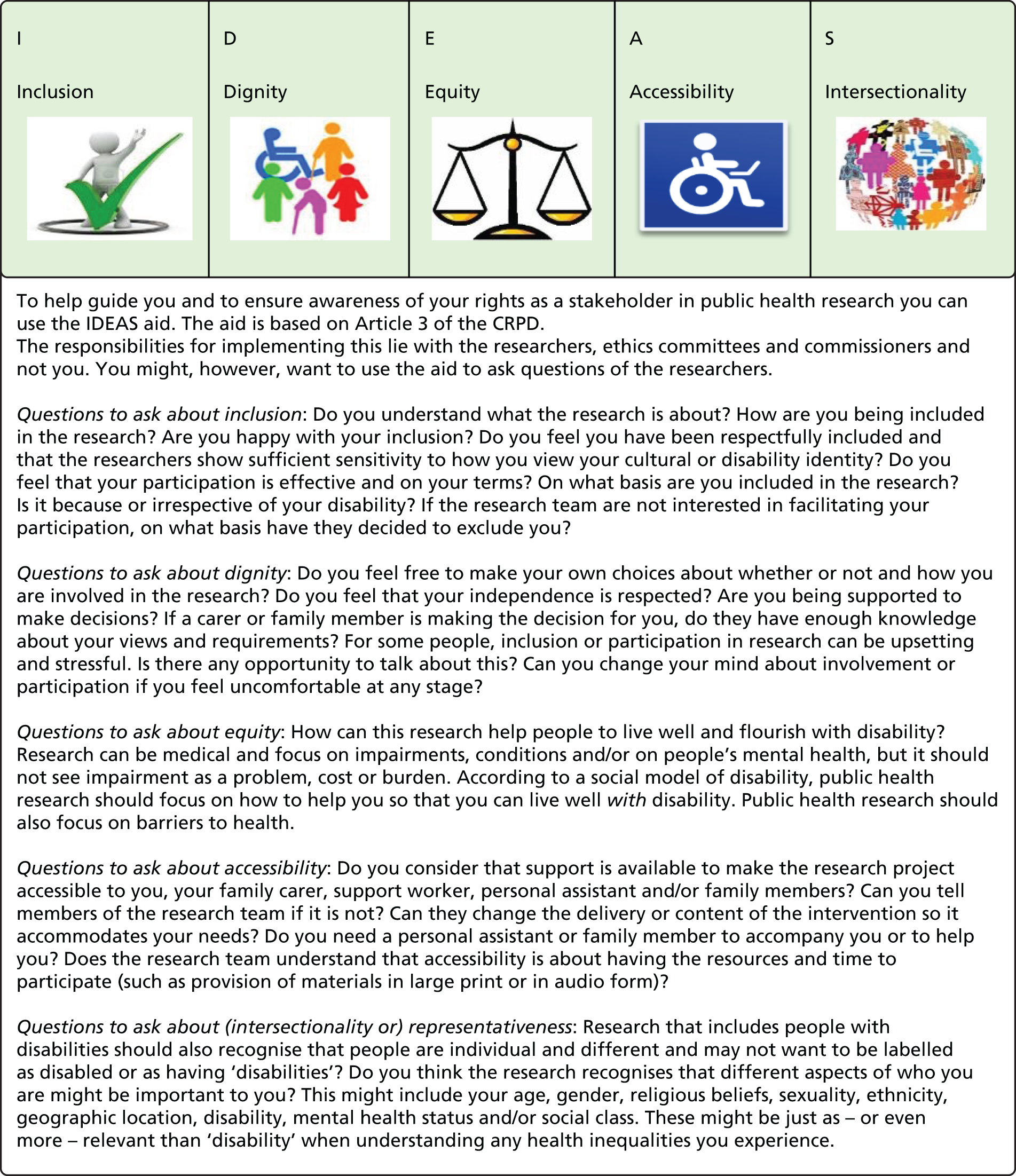

Developing a decision aid and checklist

Our initial analysis suggested the importance of developing a decision aid which could:

-

provide a framework by which to offer a critique of current research practices

-

build capacity and support a more inclusive public health research agenda.

In analytical terms, the decision aid can be seen as an outcome of the first scoping review, which was further developed when evaluating material generated during the second stage of the scoping review and in consultation with our deliberation panels. Our scoping review indicated a need for a greater connection between the disability literature and public health interventions. The lack of explicit engagement with disability that we identified in the public health reviews made this challenging. Nonetheless, we were able to use the material to generate an informed and critical discussion, which connected more theoretical approaches to the more practical, methodological questions raised by the commissioning brief. Chapter 5 provides a more detailed account of our findings, but, as some important themes informed our analysis, we briefly discuss them here.

A study may have been inclusive of ‘disabled people’ but may not have thought about offering a meaningful analysis of disabling experiences by mainstreaming ‘disability’; engaging with disability culture; or considering (dis)ableism in research design. Similarly, most studies had a rudimentary discussion of ethical issues, often confining discussions to confirmation of gaining ethical consent and formal approval. Few, if any, studies engaged with broader ethical issues associated with ensuring ‘inherent dignity’. Only one study, for example, discussed how disability had been ‘dignified’ in terms of inclusive practices. 135 As anticipated, the participation of disabled people in a study’s development and inclusion in samples was rare. Nonetheless, understanding the reasons for inclusions or exclusions was valuable in developing the decision aid. Intersectionality, accessibility and equity assumed similar analytical importance.

Intersectionality was often defined in terms of descriptive categories and reported as such, with little attempt to offer explanatory accounts. It was rare, for example, for sociodemographic categories to be theoretically linked to specific paradigms. Offering an explanation of inequalities was, therefore, the exception rather than the rule. Overall, most studies had examined certain issues of intersectionality but very few put them all into practice, especially comorbidities. For example, papers would note that disability was linked to diabetes and chronic conditions but did not explore this during analysis. More often than not, comorbidities were used as a reasons for exclusion. 136 Accessibility and the broader accommodation of study participants with disabilities were poorly articulated too, with few attempts made to offer a theoretical engagement or to connect to study design. 137,138 Most authors noted that accommodations could have been possible but were not applicable to the study, that study settings, such as schools, would have mainstreamed participants with disabilities and, therefore, did not have to consider it, or ignored the question. Equity was a particularly difficult issue to define. Many of the problems were linked to the empirical design of interventions and, although most studies had theoretically considered equity, they could not provide evidence of long-term sustainability, sensitive to the needs of disabled people or how their intervention could be maintained in the long term. We thus had to focus on methodological design in terms of equity, particularly given that inclusion could occur within an ethical and empirical environment not conducive to equity. 136

Deliberation panels

Consultation with stakeholders is an essential but often neglected part of scoping methodologies. 115,117 We were committed to debating our findings with key stakeholders, particularly given that we believed it would prove useful in identifying gaps in the accommodation of disability in public health. Such consultation would also enable our research (and public health) to reflect the social and political context of disability. 139–141 We first deliberated our findings with politically and socially active disabled people. This ensured that our findings had some grounding in the expectations and experiences of different stakeholders, including those likely to be critical of our approach. We felt this to be especially important, as we wanted our account to reflect the challenges facing public health research when engaging with people with disabilities. We also recruited participants from different regions, to reflect the local dynamics of disability politics. Our agenda was deliberately broad, and the deliberation panels offered expertise, criticisms and advice on the relevance of our work. 142 A fifth deliberation panel comprised researchers, public health professionals and commissioners. The purpose of these deliberation panels was to ensure that our discussion was located in the practicalities and challenges of undertaking public health research. We could also contrast the priorities of professional stakeholders with those of politically active disabled people.

We engaged four partner organisations to help us organise and recruit people to these panels. These voluntary organisations were geographically spread across the country in London (Inclusion London), Manchester (Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People), Sheffield (BME Network) and Leeds (Sisters of Frida). The organisations were very small, locally run and located in areas linked to social disadvantage and deprivation, such as Brixton (London) and Moss Side (Manchester). Potential participants were all given information sheets explaining the study and a copy of the ethical decision-aid to discuss before the panel happened (see Appendix 8). The voluntary organisations were given recruitment fees and the participants were paid a fee plus travel expenses for participation.

Although we wanted the deliberation panels to reflect diversity, we did have issues in terms of how inclusive we were of various impairments and identities. Initially, we contacted the Mental Health Foundation/Joseph Rowntree Foundation (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project)143 with regard to organising a group with people in the early stages of dementia. We wanted to capture the experiences of people not yet politically organised as ‘disabled’. 96,144 Owing to time constraints, this was not possible. We also wanted to capture the recommendations of people with various types of impairment who may not ascribe to an identity of ‘disabled’ or ‘disability’ but who may be socially and politically organised. We had more success in achieving this.

Five deliberation panels took place during late July and early August of 2015. A total of 34 participants were involved. Formal ethical approval (see Appendix 9) was granted by the Department of Health Sciences’ Governance Committee (University of York). In gaining approval, we were aware that our work occupied a grey area between consultation and research. We decided to gain ethical approval, however, as it would enable us to publish our findings.

Before each deliberation panel began, participants were asked if they had any questions about the information sheet or study. Participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. The consent process and form was also explained to participants. A moderator from the partner organisation was always present and ensured oversight of the deliberation process. The deliberation panels were recorded and lasted between 60 and 100 minutes. The deliberation was structured into three parts: the meaning of public health; how to conduct public health research; and the relevance of our decision aid. Our sampling strategy attempted to be as inclusive and diverse as possible. In total, 30 disabled people participated in four panels. They had a wide range of backgrounds and impairments (Table 5). These included social activism within an organisation or community work, in addition to political activism, lobbying and representation. Parents of disabled children were involved, alongside young people with disabilities. Adults participating included those with hidden disabilities, undiagnosed conditions, fluctuating conditions, multiple impairments and mental health issues. We did note a slight predominance of people with visual impairments and wheelchair users. People with hearing impairments were under-represented, whereas people with learning disabilities were not represented. We also noted a slight gender bias, with more women than men in all but one of the panels. The panel with health-care professionals recruited four people. When we explored this low uptake further, we found that many public health professionals thought that disability was a specialised issue or not directly linked to public health. Many, therefore, declined because they thought that they would have nothing to say.

| Panels | Participants | Gender | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 4 | 3 women, 1 man | Professionals |

| London | 8 | 4 women, 4 men | Disability |

| Manchester | 8 | 4 women, 4 men | Disability |

| Sheffield | 8 | 6 women, 2 men | Disability |

| Leeds | 6 | 6 women | Disability |

Deliberation panels were digitally recorded, transcribed, anonymised and analysed using NVivo (version 10, QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia). Analyses were conducted using a constructionist grounded theory. We started data analysis using line-by-line coding, then developing categories, which we coded thematically. The object of the thematic stage of coding was not to develop a theory per se, but to assemble the insights of our participants to refine the decision aid. 145

Role of the project steering committee