Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3010/02. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in October 2015 and was accepted for publication in April 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Laura Jones receives personal fees from the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training, outside the submitted work. Sarah Lewis is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme researcher-led board.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Szatkowski et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Harms caused by smoking in young people

Cigarette smoking is a significant preventable cause of morbidity and mortality. In 2013 in England, 17% (78,200) of all deaths of adults aged 35 years and over were estimated to be attributable to smoking, a proportion that has remained largely unchanged in more recent years. 1 Approximately half of all current smokers will die prematurely as a consequence of smoking unless they quit, on average 10 years earlier than if they had never smoked. 2 The total cost of smoking to society in England is approximately £12.9 billion a year, including the cost of treating smoking-related diseases and productivity losses attributable to premature mortality, smoking breaks and smoking-related work absences. 3

Most smokers become addicted to smoking before they reach the age of 18 years, with nearly 40% becoming addicted before the age of 16 years,4 predominantly during their years in secondary education. Smokers who start smoking at an early age tend to smoke more cigarettes per day in adulthood,5 smoke for longer,6 are less likely to quit7 and are more likely to die from a smoking-attributable cause. 6 Smoking in adolescence impedes lung growth and causes a premature decline in lung function,8 is linked to early signs of heart disease and stroke8 and is a major driver of inequalities in health; children in lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to start smoking and to do so at a younger age. 4 Intervening with young people to prevent them smoking is thus a crucial public health priority.

The prevalence of smoking among young people

Uptake and ever smoking

In the past 10 years there has been a steady decline in the number of students aged 11–15 years in England who report having tried smoking at least once, from 39% in 2004 to 18% in 2014. 9 The proportion of students who have ever smoked increases with age; in 2014, 4% of 11-year-old children reported ever smoking, increasing to 35% of 15 year olds. 9 In 2014, 3% of 11- to 15-year-old students smoked regularly (at least one cigarette a week), a decrease from 9% in 2004. 9 The proportion of children smoking regularly also increases with age, reaching 8% among 15 year olds. 9

Susceptibility to smoking

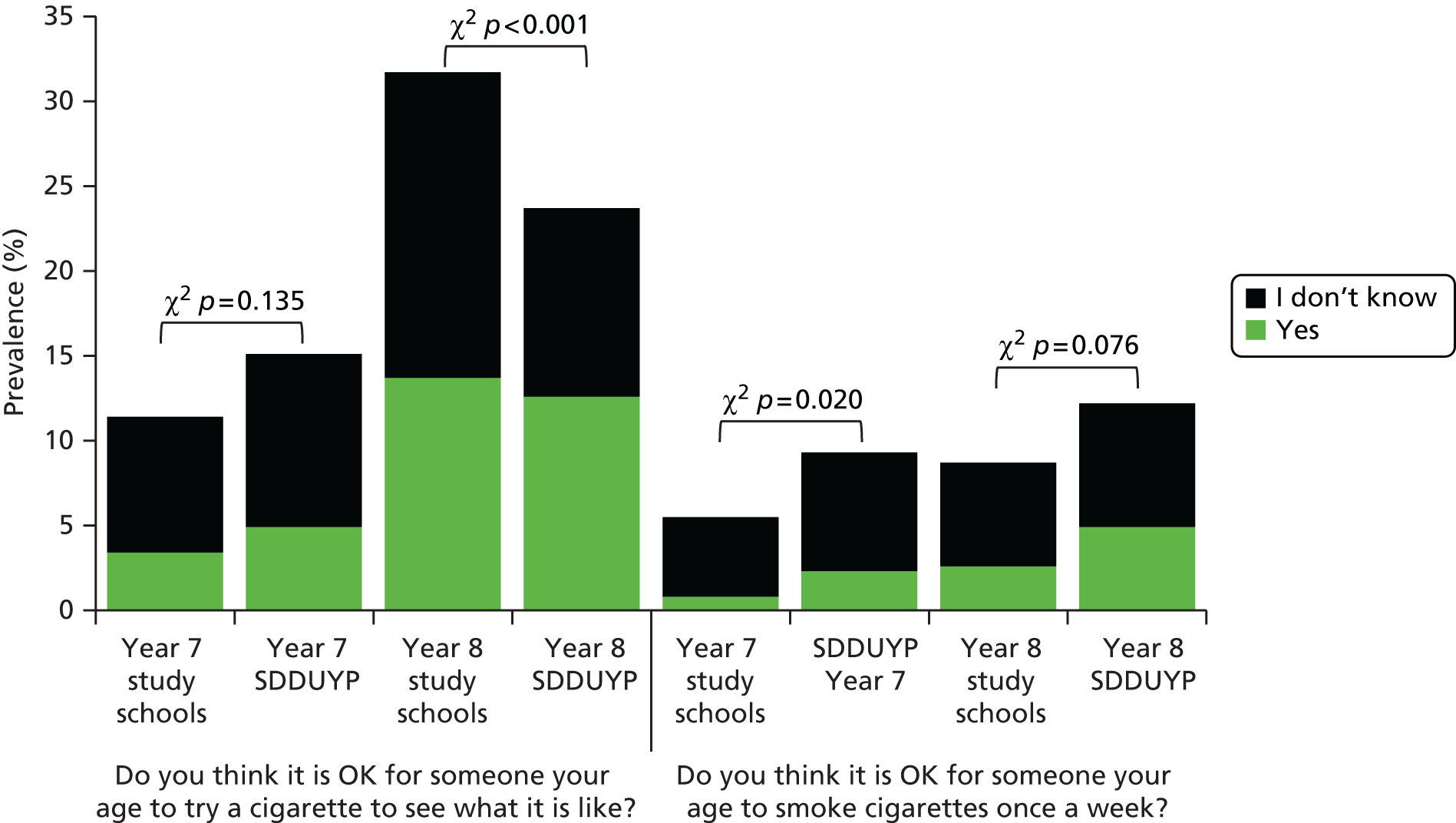

It has been suggested that initiation of smoking among adolescents is preceded by a shift in attitudes when young people begin to entertain the possibility that they might try a cigarette and no longer hold a strong cognitive commitment not to smoke. 10 This cognitive shift has been described as the development of a susceptibility to smoking. 11 There are no national data on susceptibility to smoking in England, although in one local study 27.2% of 11- to 15-year-old students were deemed to be susceptible. 12 In 2014, 26% of students aged 11–15 years nationally thought that it was OK to try smoking to see what it was like, and 10% thought that it was OK to smoke once a week. 9 Both figures have declined steadily over time, from 48% and 25%, respectively, in 2003. 9

Existing research evaluating approaches to preventing adolescent smoking uptake

Systematic reviews of the design, implementation and effectiveness of interventions to reduce uptake of smoking in young people conclude that, although there is some (although by no means conclusive) evidence that school-based interventions may have short-term positive effects, there is little robust evidence that these interventions prevent young people from taking up smoking in the longer term. 13–15 However, as noted by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), given that very little of this work has been carried out in the UK, these findings may not be applicable in the context of the UK education and health-care systems. 15 In addition, much of the existing evidence dates from the 1980s and 1990s, when the tobacco control environment and public attitudes towards smoking were very different from those of the present day. However, in the absence of relevant and recent UK data, evidence from older studies and those conducted elsewhere is useful to inform key questions surrounding the design and implementation of a successful intervention to prevent smoking uptake in young people in the UK today.

Effectiveness of existing interventions

Existing studies have tested a variety of interventions, differing in theoretical approach, design, intensity and mode of delivery and utilising different outcome measures and follow-up periods in evaluation. Therefore, given the substantial heterogeneity between studies, evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of this literature is difficult to interpret. Although there is no definitive evidence regarding interventions that do not work and should thus be avoided, there is also no clear evidence for what may be effective.

There is no conclusive evidence that any one theoretical approach or conceptual framework is superior to others in preventing smoking uptake. 15 Interventions that involve providing young people with information about the prevalence and consequences of smoking, enhancing their social competence (e.g. teaching skills to increase self-esteem and cope with stress) and addressing social influences (e.g. increasing awareness of peer and media influence and teaching refusal skills) have all been tested with inconsistent results in terms of their effects on smoking uptake. 14

In the UK the A Stop Smoking In Schools Trial (ASSIST) programme trains students in Year 8 (aged 12–13 years) as peer supporters who are able to intervene in their friendship groups to encourage non-smoking. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) of ASSIST, the results of which were published in 2002, found a significant reduction in reported recent smoking (in the past 2 weeks) up to 2 years later. 16 In the only other UK study, carried out in the late 1990s, a RCT in 52 schools in the West Midlands tested the effectiveness of a 1-year-long programme in which students in Year 9 (aged 13–14 years) received three classroom-based and three computer-based sessions to encourage them to refrain from or to stop smoking. 17 This study found no significant effect of the intervention on the proportion of adolescents smoking one or more cigarettes per week 12 months later.

There is good evidence that ‘booster’ sessions are useful in the months and years after the delivery of a main intervention to strengthen and maintain its effectiveness, and, therefore, NICE recommend their use. 15 Booster components that have been trialled in previous smoking-prevention interventions have included classroom-based sessions,18 tailored letters,19 telephone calls,20 videos21 and magazines. 22

Some young people may experiment with smoking intermittently over many years before they identify and report themselves as a smoker, whereas others show signs of dependence very early in their smoking career. 23 For this reason it is recommended that school-based interventions contain elements of both smoking prevention and cessation and that a school smoke-free policy should include efforts to promote local NHS stop smoking services to both students and staff. 15

What constitutes a cost-effective intervention?

There is limited evidence for the cost-effectiveness of smoking-prevention interventions in UK schools; studies carried out elsewhere are also of limited relevance here given differences in their populations and health-care and education systems. 24 ASSIST was judged to reduce adolescent smoking at a modest cost; the incremental cost of the intervention per student not smoking at 2-year follow-up was £1500 [95% confidence interval (CI) £669 to £9947]. 25

Who should deliver an intervention?

Existing studies have utilised a range of people to deliver anti-smoking interventions to young people, including teachers, school nurses, project staff external to the school and students themselves. However, there is no consistent evidence regarding which of these providers gives the best results, and it is impossible to compare across studies given the probable confounding by other factors such as the content of the intervention itself. A Canadian study carried out in the 1990s found that teachers and school nurses were equally effective in delivering a classroom-based intervention to students in Grades 6 to 8 (ages 11–14 years) and there was no differential effect based on whether staff were formally trained in organised workshops or were provided with self-preparation materials. 26 The ASSIST study trained students as peer supporters and, as noted earlier, found a significant impact on student smoking up to 2 years later. 16 This positive effect was not restricted to the students trained as peer educators but was also extended to the non-trained students with whom the peer supporters were intervening. The ASSIST intervention was most effective in schools in the Welsh valleys, and the authors attribute this to the existence of clearly defined, close-knit communities in which the trained students were able to diffuse new behavioural norms. This suggests that the use of peer educators may be less effective in more poorly defined communities. Peer educators may also be counter-productive among students who already smoke. Other studies in the USA and Europe not using ASSIST have identified a ‘boomerang effect’, whereby over the course of a study smoking prevalence increased more in those exposed to anti-smoking interventions than in controls who did not receive the intervention. 18,27

At what age should you intervene with young people to prevent smoking uptake?

Age is a strong predictor of smoking behaviour, and existing studies have intervened across the age spectrum from the earliest years of primary school28,29 to the later years of secondary school. 30 The majority of interventions have been aimed at young people between the ages of 11 and 14 years; ASSIST intervened with students in Year 8 (aged 12–13 years). 16 There is no conclusive evidence on the age at which it is best to start delivering school-based interventions to prevent young people from smoking, but Years 7 and 8, the years in which smoking experimentation and the prevalence of regular smoking begin to increase dramatically,9 are arguably a logical point at which to intervene.

How do other student and school characteristics influence the effectiveness of an intervention?

There is conflicting evidence over whether or not school-based interventions have a differential impact according to gender and, indeed, the direction in which this effect might operate. 15 Similarly, students’ ethnicities and social groups may or may not influence the effectiveness of an intervention. The ASSIST intervention was most effective in the Welsh Valleys, a deprived area, and, in particular, was effective in reducing smoking only among girls. 31 In contrast, an intervention with 13-year olds in the Netherlands was significant only among young people whose parents had high levels of education and who worked full time, and particularly among boys with high levels of parental education. 21 Previous work by the authors of this report32,33 has shown that young people are more likely to begin smoking if they attend a school at which smoking prevalence among senior students is high; therefore, school smoking prevalence may influence the effectiveness of an intervention. Students who are smokers are also more likely to be absent from school and less likely to engage fully with an intervention than non-smokers. 17

What do schools and teachers want?

An intervention must be acceptable to teachers if it is to be delivered as intended and have the hoped-for consequences. At present, the National Curriculum for Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education (PSHE) in England, although non-statutory, suggests that schools teach facts and laws about tobacco use and misuse, and the personal and social consequences of smoking for the smoker themselves as well as for others. 34,35 However, a wide variety of approaches to teaching this material is seen across schools and, although the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) concludes that the quality of PSHE delivery is generally improving, there are variations in coverage and quality. 36 In many secondary schools PSHE is taught by form tutors, although many of these may lack the training, skills and experience to deliver content effectively; only 22% of PSHE teachers have any relevant training, and half of secondary schools have no staff with continuing professional development accreditation in the subject. 37 Therefore, an intervention needs to be accessible to teaching staff with no subject-specific training. In addition, schools face an increasing number of demands on their time and, thus, any intervention must be suitable for implementation with little preparation. A process evaluation of the ASSIST intervention suggested that teachers are receptive to new ideas and ways of teaching the difficult topic of smoking prevention and cessation, but that this must fit in with a school’s existing ethos and organisation. 38 The inevitable added workload for teachers involved in trialling a new intervention means that it should arguably be delivered before students reach Year 9 when they have often begun work towards external General Certificate of Secondary Education examinations (summative school-leaving exams taken at the age of 16 years) and when teachers may be occupied with Standard Assessment Tests (progress assessments completed during Year 9) teacher assessments. 38

How can young people’s families be engaged to help prevent young people from smoking?

The NICE recognises that no one intervention alone will succeed in preventing the uptake of smoking among young people, but that a wider approach tackling individual, family, community and societal influences is needed. 15 The strong association between parental and child smoking9 suggests that the addition of a family component to a school-based intervention might help both to encourage young people not to smoke but also to encourage cessation among any parents who smoke themselves. A recent Cochrane review found there to be moderate-quality evidence from RCTs that family-based interventions can have a positive effect on preventing young people from starting to smoke. 39 The strongest evidence was for intensive interventions, delivered independently of a school-based intervention, which encouraged authoritative parenting (defined as showing an interest in and care for the adolescent, often with rule setting), although the limited numbers of studies and participants made conclusions difficult to draw for other types of interventions. 39

A promising literature is developing around the effectiveness of interventions to encourage parents to talk with their adolescent children about smoking. 40 Various approaches to prompt discussions between parents and children have been trialled, including the provision of pamphlets and quizzes,41 booklets,42 newsletters43 and postcards44 mailed to parents, homework activities for the child to complete with their parents,44 videos43 and financial incentives. 43 These have demonstrated some positive effects on the degree to which children report talking to their families about smoking, although their effectiveness in reducing smoking uptake remains unclear. As expected, interventions prompting communication may be most effective when the parent is a non-smoker. 40 Most of these studies were carried out in rural, middle-class areas of the USA and their relevance to the UK is not clear.

To our knowledge, no work has been undertaken with secondary school-aged children themselves to understand their views on whether or not, and how, their families should and could be engaged to support them to remain non-smokers. Focus groups with primary school-aged children after they had received a smoke-free homes intervention suggested that they were confident in talking to their parents about the issue, although the children themselves were not involved in designing the intervention. 45

What does existing smoking-prevention education look like in the UK?

To the best of our knowledge, there are no existing publications summarising the state of existing smoking-prevention education in the UK. A systematic-style literature and internet search conducted by a University of Nottingham medical student during the course of this study identified 19 smoking education resources available for use in the UK; these varied in content and delivery style, and, although they all received positive feedback from teachers and students, formal evaluation of effectiveness was lacking. A survey of East Midlands secondary schools also conducted as part of this project suggested that schools dedicated little time to smoking education (especially with older students) and concentrated on teaching about the health effects of smoking, and that a large proportion of staff leading sessions had not received any training in delivering PSHE. Further details on this work are included in Appendix 1.

The Truth® campaign

Evidence from the USA suggests that a focus on the ethics and exploitative tactics of the tobacco industry may be effective in encouraging young people not to smoke. 46,47 Through mass media campaigns and additional online content, the Truth® campaign48 has been credited with producing declines in youth smoking prevalence by countering the tobacco industry’s deceptive marketing strategies and denial of the addictive nature and health effects of cigarettes, and by focusing attention on the negative effects of the industry on the environment and society. Although not specifically a school-based intervention, the relevance of the approach of the Truth® campaign to the UK has been identified by NICE as an area for further research. 15

Operation Smoke Storm

The emphasis of the Truth® campaign was adopted by Kick It, the NHS Stop Smoking Service for Hammersmith and Fulham, Kensington and Chelsea, Westminster, Kingston upon Thames and Richmond upon Thames49 in designing (prior to the start of this project) Operation Smoke Storm, a novel educational package for use in schools to increase awareness of tobacco industry practices. A short description of Operation Smoke Storm is given in Box 1; for a more detailed description of the intervention, see Appendix 2.

Operation Smoke Storm is a web-based educational package designed for delivery by teachers as part of a school’s PSHE curriculum. Teachers are provided with detailed lesson plans for three 50-minute classroom sessions (although the material can also be delivered as one longer session). Multimedia presentations, streamed over the internet, are used to guide teachers and students through the lessons. Students act as secret agents to uncover the tactics of the tobacco industry and share what they find with others. The sessions also cover the health effects of tobacco, passive smoking, nicotine addiction and the economic cost of smoking.

Sessions 1 and 2 include video clips followed by individual and group-based quizzes, and discussion activities in which students learn about the harmful and addictive nature of smoking and methods used by tobacco companies to encourage young people to smoke. Students are provided with a workbook to record their answers. In session 3, they then use this information to ‘spread the word’ in a group presentation to their class, in a format of their choice, such as drama or song.

In a small-scale evaluation in two London schools of changes in students’ awareness and attitudes, as well as acceptability and ease of use, Operation Smoke Storm was very positively evaluated. 50 Although data were collected from just 53 students, students who received Operation Smoke Storm reported an increased knowledge of smoking and the tobacco industry, 89% liked the resource, 98% thought that it was easy or very easy to understand, and 72% went on to tell their friends and/or parents about their lessons. The staff (two teachers and two members of staff from Kick It) who delivered the intervention in this small-scale evaluation also gave very positive feedback; Operation Smoke Storm comes with detailed lesson plans and thus requires minimal teacher preparation, making it suitable for use by busy staff who have many competing demands on their time and who may have little or no subject-specific knowledge or training. 37 To date, there has been no evaluation of the effectiveness of Operation Smoke Storm in preventing smoking uptake among students who receive the intervention.

Summary

Existing literature highlights a lack of recent, UK-specific evidence regarding how best to design and implement interventions to prevent youth smoking uptake. However, a successful intervention would be likely to involve a booster and family component, make few demands on busy teachers with little subject-specific knowledge, and be evaluated for both short- and long-term effectiveness. In this study, the existing Operation Smoke Storm resource was used as the basis of the intervention. Qualitative work was undertaken to refine Operation Smoke Storm and to develop additional components to maximise the potential for the intervention to be effective in reducing smoking in young people. The final multicomponent intervention was then formally evaluated for its effectiveness in preventing smoking uptake in order to gain evidence to inform whether a fully powered cluster RCT to evaluate effectiveness and cost-effectiveness was warranted.

Objectives

The overall purpose of this research was to assess whether or not a multicomponent intervention involving educational resources for use in schools, alongside family components, is effective and cost-effective in preventing the uptake of smoking in school-aged children. Specific objectives were to:

-

pilot Operation Smoke Storm to gain preliminary evidence for its acceptability and effectiveness.

In the first year of the study, Operation Smoke Storm was trialled with Year 7 students (aged 11–12 years) in two schools. Student questionnaires and qualitative work with students and teachers evaluated the acceptability of the intervention (see Chapter 3).

-

develop an effective and acceptable booster intervention for use with students in Year 8 to maintain and strengthen the effects of Operation Smoke Storm.

Qualitative work with Year 7 students and teachers was used to explore views about what the booster element should include, how it should be delivered, as well as probable uptake by students (see Chapter 3). This feedback was used to develop the booster intervention (see Chapter 4).

-

identify and develop acceptable and effective intervention components for use by families which build on Operation Smoke Storm to prevent the uptake of smoking in young people and to promote and signpost support for cessation to students, their family members and school staff who smoke.

Focus groups with Year 7 students explored if, and how, their families could be engaged to help them not to start smoking, or to quit if they already smoke. Opinions on the variety of family interventions that have been used previously were mapped so as to design a family-based intervention for use here which was both acceptable and likely to be effective (see Chapters 3 and 4).

-

provide preliminary evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the combined school and family intervention on which to base a decision on whether or not to continue to a fully powered trial.

The proportion of students reporting smoking or susceptibility to smoking was compared with control data from an existing local survey (see Chapter 5). An independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) made a recommendation to the Study Steering Committee about whether or not to proceed to a full trial based on this evidence of effectiveness alongside qualitative evidence of the acceptability of the intervention to schools, teachers, students and parents (see Chapter 6); the readiness of the intervention for immediate implementation; and the likelihood of willingness to take part in the trial from a sufficient number of schools (see Chapters 5 and 6).

Chapter 2 Overview of research design and methods

This chapter provides a summary of the study, giving an overview of the different phases and processes, and signposts readers to the relevant chapters in the main body of the report in which further details can be found.

The study was split into two phases. In phase 1, conducted between September 2013 and August 2014, the original Operation Smoke Storm was piloted with students in two schools; results from qualitative work conducted with students and teachers were used to refine the resource and to extend it with booster and family components. In phase 2, conducted between September 2014 and May 2015, the refined and extended intervention package was delivered in the same two schools, with accompanying quantitative and qualitative evaluation. Figure 1 summarises the research processes across the two phases.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of research processes.

At the end of phase 2, the Study Steering Committee, informed by the recommendation of a DMEC, determined whether or not the intervention showed sufficient promise of effectiveness to justify progression to a fully powered, cluster RCT, for which funding for a 1-year follow-up had been provisionally agreed with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Funding for longer-term follow-up would be sought at a later date if initial results looked promising.

School recruitment and participants

Two out of six schools approached agreed to participate in the study. Although the other schools showed interest in the resource, time pressures resulted in them being unable to participate. Both participating schools were located in Nottinghamshire, UK, but had contrasting sociodemographic profiles. School 1 served a relatively affluent catchment area in a market town, with 6.1% of students eligible for free school meals (used as a measure of deprivation; the national average in January 2014 was 16.3%51). School 2 served a less affluent catchment area in a former coal-mining town, with 10.2% of students eligible for free school meals.

Research design

In phase 1, Operation Smoke Storm was delivered to all Year 7 students (n = 585) in two schools during their PSHE lessons. Kick It has previously delivered Operation Smoke Storm to students in older year groups, but the decision was made here to deliver the first part of the intervention in the first year of secondary school, before the majority of students have begun to experiment with tobacco. The research team provided a brief training session to teachers prior to their delivery of Operation Smoke Storm which outlined how to access and navigate the resource and provided information about the research processes (questionnaires, interviews and focus groups).

In total, 585 Year 7 students (aged 11–12 years) received Operation Smoke Storm (School 1: 347 students in 14 classes; School 2: 238 students in eight classes). School 1 had shorter lessons (40 minutes per week) and so some classes required more than three sessions to cover the material. School 2 had 1 hour of PSHE per fortnight, so delivery was possible over three lessons but over a longer period of time than in School 1. In both schools PSHE was taught by form tutors in mixed-ability teaching groups.

Questionnaires were administered before and immediately after the delivery of Operation Smoke Storm to gather data on students’ smoking behaviour and susceptibility (a composite measure assessing likelihood of smoking soon or if offered a cigarette by a friend, defined in full in Chapter 5) and their impressions of the intervention (see Appendix 3). Eight focus groups with 79 students in total were then carried out (two groups of boys and two groups of girls in each school) to explore views on the effectiveness and acceptability of the intervention and to suggest any necessary improvements. Using examples of existing resources to facilitate discussion, students’ views on the design of a booster component for use in Year 8, and a family component to engage their parents, were also sought. In-depth interviews with 18 teachers who delivered the intervention and the Head of PSHE at each school were conducted to elicit their views of the effectiveness and acceptability of the intervention, covering aspects such as how easy it was to take the package and deliver it as an ‘off-the-shelf’ resource, and whether or not it fitted in with timetabling and the existing curriculum (see Chapter 3).

Based on the qualitative feedback from students and teachers gathered in phase 1, the Operation Smoke Storm lessons and resources were refined, and booster and family components were developed. The booster component consisted of a flexible, ‘off-the-shelf’, lesson for teachers to deliver in PSHE lessons during Year 8. The family component consisted of an interactive take-home booklet to complement the Year 7 lessons. The take-home booklet was piloted with two external public research groups, the National Children’s Bureau’s (NCB’s) group of Young Research Advisors and the Nottingham Smokers’ Panel, which resulted in further refinements (see Chapter 4 for further details on the development of the booster and family components and a full description of these resources).

In phase 2, the same students who had received Operation Smoke Storm when they were in Year 7 received the booster intervention when they were in Year 8 (n = 538). In one school, students were taught in PSHE teaching groups streamed according to ability. Two of the teachers delivering the intervention were specialists in teaching PSHE; the remainder had other subject specialisms. In the second school, students were also taught in streamed groups, but by specialist science teachers during science lessons. Students again completed a questionnaire to gather data on smoking behaviour and susceptibility (see Appendix 3). The primary quantitative analysis compared the combined prevalence of ever smoking and susceptibility to smoking in Year 8 in students who received the intervention with the prevalence and susceptibility in students from local schools who did not receive the intervention but who were asked identical questions in a separate study (see Chapter 5 for a more detailed description of this quantitative analysis). A composite outcome measure was used, because, at this age, relatively few children have actually experimented with tobacco, and very few are established, regular smokers. The composite measure allowed identification of those students who were most likely to go on to smoke, plus those who became smokers between the baseline and follow-up data collection, as well as afforded benefits in terms of study power. Qualitative work in phase 2 comprised four focus groups in each school with 51 Year 8 students in total, and interviews with seven Year 8 teachers, to assess the effectiveness, appropriateness and acceptability of the booster component.

At the same time, the refined version of Operation Smoke Storm was delivered to a new cohort of Year 7 students (n = 350) in School 1 only; students also received the new take-home family booklet. Changes to the PSHE curriculum at School 2 meant that it was not able to accommodate delivery of the Year 7 resource. Questionnaires were again completed to gather quantitative data (see Appendix 3). Qualitative work comprised two focus groups with 16 Year 7 students in total, nine in-depth interviews with 10 Year 7 teachers, and nine paired student–parent in-depth interviews to assess the reach, acceptability and perceived impact of the revised Operation Smoke Storm and family component, and to identify any aspects that could be improved (see Chapter 6).

Progression to a cluster-randomised trial

At the end of phase 2 an independent DMEC considered all the available evidence on the potential effectiveness of Operation Smoke Storm, the acceptability of the intervention, and the ability to deliver a full trial, and made a recommendation to the Study Steering Committee and NIHR on whether or not progression to a fully powered cluster RCT was warranted. This evidence, discussed in more detail in the following chapters, suggested that, although the intervention was, on the whole, acceptable to students, parents and teachers, there was no proof that it was effective in preventing smoking uptake. There was also evidence that it would be extremely difficult to successfully complete a trial in this setting. Therefore, the DMEC’s recommendation, agreed with by the Study Steering Committee, was to not progress to a cluster RCT.

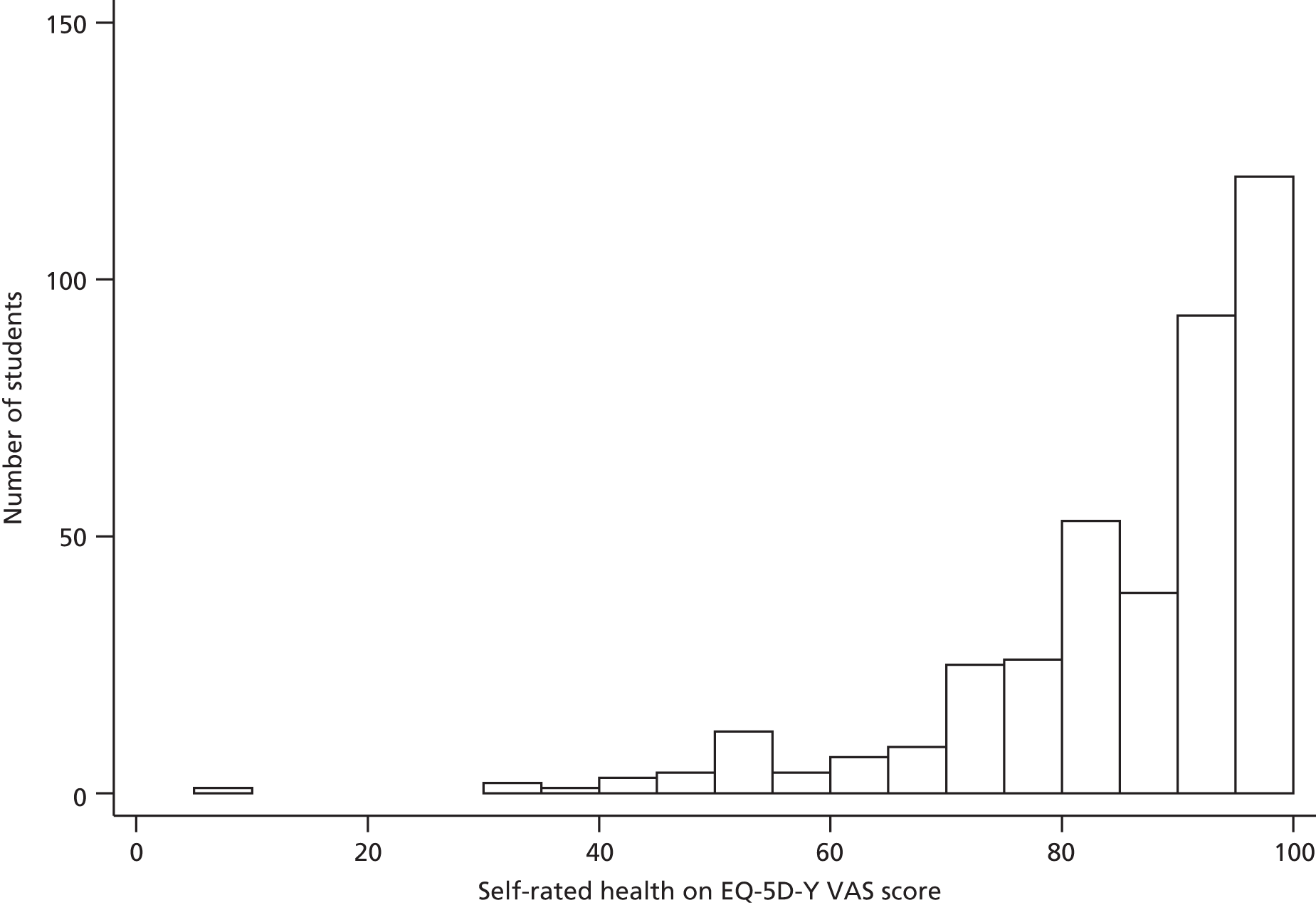

A full cost-effectiveness analysis was planned as part of a definitive trial of Operation Smoke Storm, but, given the lack of quantitative evidence indicating potential effectiveness, and the resulting recommendation of the DMEC not to progress to a full trial, a cost-effectiveness analysis was no longer possible. Instead, Chapter 7 describes the costs incurred in developing and delivering the intervention. This chapter also uses questionnaire data collected from students to assess the feasibility of gathering data in a school setting for a health economic evaluation of health-promotion interventions and uses these data to estimate the health-care costs associated with smoking in the study population and to quantify the state of students’ health.

Ethics approval

This project was reviewed and approved by the University of Nottingham Medical School Research Ethics Committee (reference C13122012 CHS EPH Smoking), which is compliant with the Economic and Social Research Council’s Research Ethics Framework,52 to ensure that the work was conducted in accordance with the highest standards of ethics.

Public involvement

Feedback was elicited from qualitative research with teachers, students and parents to help further develop and refine the intervention. Two other pathways to enable relevant lay people to contribute to the research were also employed. The University of Nottingham Smokers’ Panel, comprising active and former adult smokers from the local area, meets every 6 months to discuss tobacco control research and policy. One of these panel meetings, in June 2014, was devoted to discussing the research. A session was also run with the NCB’s group of Young Research Advisors to explore their views on the new intervention components. More detailed discussion of these aspects of public involvement is included in Chapter 4.

Management of competing interests

Kick It’s expertise in designing multimedia resources and bringing them to fruition was invaluable as we sought to develop the proposed booster intervention and materials for use with parents. However, Kick It had no involvement in the recruitment of schools, the delivery of the intervention, the data collection and analysis or the interpretation of results. Nor did it play any part in the preparation of academic papers for publication or in the preparation of this report.

Chapter 3 Initial delivery and evaluation of Operation Smoke Storm

This chapter reports the qualitative methods and findings from phase 1 of the project, namely students’ and teachers’ views on the initial delivery of the existing Operation Smoke Storm and how to extend this further to include a family and booster component.

Methods

Study design and participant recruitment

Focus groups with students in Year 7 and interviews with teachers were used to explore the acceptability and effectiveness of Operation Smoke Storm and to provide feedback to inform refinements and extensions. Separate focus groups for boys and girls were planned, as research suggests that smoking has become increasingly gendered, with the UK having one of the most pronounced gender differences in regular smoking behaviour in Europe (with girls having the higher prevalence). 53 Qualitative research with 15- and 16-year-old smokers in Scotland concluded that differences in smoking behaviours and attitudes according to gender could be attributed to individuals’ social worlds and relationships, interests, meanings attached to smoking and the role smoking had in dealing with the everyday experiences of being a girl or boy in her or his teens. 54 Therefore, gender-specific groups were used both to encourage honest discussion and to allow us to explore any potential differences according to gender. We aimed to run four focus groups in each school, two for each gender, with between 8 and 12 students in each, in line with recommendations for focus group size. 55,56 We also attempted to recruit all of the teachers who delivered the package in each school and the two PSHE teaching leads. However, recruitment remained flexible with the option to cease if recruitment targets proved difficult to meet but data saturation had been reached.

Parents of all Year 7 students in the two schools were sent a letter by the research team notifying them about the Operation Smoke Storm sessions and the associated evaluation. Parents were asked to return an opt-out slip if they did not wish their child to complete a questionnaire or participate in a focus group. Teachers explained the purpose of the focus groups to students after the first Operation Smoke Storm session. Those who wished to take part provided their name, gender and class on a piece of paper to the teacher. Students were told that up to 12 participants would be selected at random if more people volunteered than were needed. This sampling technique ensured that adequate numbers would be interviewed even if some individuals chose to withdraw or failed to attend, and would help individuals to feel sufficiently comfortable to contribute equally. In School 1 the research team randomly selected students from a list of volunteers’ names provided by the Head of PSHE; students from School 2 were randomly selected by the PSHE teaching lead.

All teachers who delivered Operation Smoke Storm, and the PSHE teaching lead from each school, were invited via e-mail to take part in a one-to-one semistructured interview (face to face or via telephone) after they had delivered all their sessions, with repeat invitations sent as necessary.

Focus group and interview procedures

Semistructured focus group guides (for students) and interview guides (for teachers) were developed to explore the acceptability and perceived effectiveness of Operation Smoke Storm (see Appendix 4). Given the limited time available for the focus groups and interviews, our choice of topics was driven by a need to gather responses to key questions in order to inform the refinement of the Year 7 sessions and development of the booster and family components. Focus groups considered students’ views of the Operation Smoke Storm sessions and their awareness of, and attitudes towards, the tobacco industry. Students’ were asked for their opinions on what a booster component and family component might look like and what they would be likely to enjoy and engage with the most. Examples of existing resources were used to stimulate discussions around these topics. As a potential booster activity, students were asked to consider the acceptability and potential effectiveness of playing a game (either paper-based, such as a board game, or an electronic game on a computer, tablet or mobile telephone) or producing their own short film, with the example of Cut Films57 being shown to students in their focus groups. The acceptability and potential effectiveness of printed materials and online resources were also discussed.

Interviews with teachers focused on the design, suitability and usability of Operation Smoke Storm, the extent to which it was an ‘off-the-shelf’ resource, how well delivery integrated with the school’s existing timetable and curriculum, and their suggestions and preferences for the content and format of the booster and family components. The interview guide for the PSHE teaching leads also sought information about how smoking education was usually taught in the school.

Before the start of the focus groups and interviews, it was explained to participants that their responses would not identify them and would be confidential, and that they had the right to withdraw at any point if they wished to. Following this, written informed consent was obtained. Focus groups took place in the schools, during school time. They were facilitated by JT or AT, supported by MB, LS or LJ, and lasted 35 minutes on average (range 27–50 minutes). Face-to-face interviews took place at the respective schools (conducted by JT or AT), and telephone interviews were conducted from a private room (by AT), at a time that was convenient for teachers. Interviews lasted 34 minutes on average (range 24–50 minutes). The focus groups and interviews were digitally audio-recorded to aid transcription.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were approached using a realist paradigm. As such, data were viewed as telling us about, in a fairly straightforward way, what the participants thought about Operation Smoke Storm, which subsequently helped to inform the development of the resource. Given that this was the first time that Operation Smoke Storm had been evaluated, this approach was deemed appropriate. An external specialist transcription company transcribed the digital audio recordings generated from the student focus groups and teachers’ interviews clean verbatim. Transcripts were then checked for accuracy (by JT and AT) and any personal identifiers were removed. Each was assigned a unique code that identified the school (1 or 2) and focus group (male or female) or teacher number. These data were analysed using the framework approach58,59 to examine emergent themes. To aid familiarisation, data from the first four focus groups and four teacher interviews were initially read several times by JT, AT and MB who independently summarised these data [using Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)] and identified initial codes, themes and subthemes. This stage also allowed the researchers to identify any contradictory cases or any within- or between-group differences (according to school and gender). As the codes identified from both the focus groups and teacher interviews were similar (apart from an additional teacher theme about preparation to deliver the resource), data were analysed together. Initial codes, themes and subthemes were discussed between the researchers in order to reach consensus on an initial analytical framework. This framework was then applied and refined following analysis of the remaining transcripts by JT and AT. JT and AT met at regular intervals to discuss their respective coding decisions and continued to refine the framework as required. Data were then indexed according to the final framework using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) version 10 software and the transcripts were charted into matrices according to each theme to facilitate synthesis and interpretation. These charts were rich in terms of detailing the data that we had, which enabled us to map, interpret and report findings in a succinct manner. Data presented reflect the overall views of the participants from both schools and extracts from the transcripts are included to illustrate the main findings.

Results

We conducted eight focus groups in total (four at each school) with 79 students (39 males, 40 females), an average of 10 students per group (range 8–11 students). Of the 23 eligible teachers and PSHE leads, 20 were interviewed (18 face to face and two by telephone). Three teachers (all from School 2) declined to take part owing to time constraints.

Four core themes were generated from the data: (1) teachers’ preparedness and delivery of Operation Smoke Storm; (2) raised awareness; (3) students’ engagement with Operation Smoke Storm; and (4) options for developing Operation Smoke Storm.

Teachers’ preparedness and delivery of Operation Smoke Storm

Teachers from both schools indicated that they had attempted to address smoking during Year 7 PSHE classes, typically focusing on smoking-related harms and strategies to resist pressure from peers to try smoking. Teachers from School 2 also covered how celebrities and role models can influence smoking uptake by young people.

Yes we do, and how, exactly, bringing up what they might see on soaps or in films, and how that’s not really something to be led by. We talk about that, yeah.

School 2, Teacher 1

Operation Smoke Storm replaced what the schools would have otherwise delivered around smoking. Most teachers reported having had no prior training or experience in teaching students about smoking. Thus, a number felt that the introductory training session about the resource increased their confidence in delivering the sessions.

The initial session [training session], yeah. I think that was definitely useful in terms of setting it up. It would have been quite difficult in my opinion otherwise, if we didn’t know the concept and the ideas behind it. I think that helped in terms of delivering it.

School 1, Teacher 5

Generally, teachers found the fact that Operation Smoke Storm was an ‘off-the-shelf’ resource highly beneficial, as it meant that background knowledge about the topic or lengthy preparation time was not required.

I think in respect that everything was just there for you, you didn’t really need a huge amount of knowledge yourself beforehand because there were the videos and the resources just meant that that was already structured.

School 1, Teacher 7

I think it was brilliant. The pack that I received is excellent. Everything was so easy to plan out. It was fantastic.

School 2, Teacher 2

However, the amount of preparatory work teachers undertook varied. Although many teachers felt confident to deliver Operation Smoke Storm with minimal preparation, others reported spending more time doing their own research around the topic.

I felt like I had to do a bit of research on my own, which wasn’t ideal, but if we had an information pack or something that said to us these are the kinds of things you’re going to come across.

School 1, Teacher 2

As well as feeling the need for more background information about the topic, some teachers reported wanting more guidance on steering discussions. In addition, although many teachers felt able to address students’ concerns about family members who were smokers, others suggested that the resource should have come with specific guidance on how to advise and support young people, especially when they were worried or upset about issues raised by the sessions.

It did upset a few of my form whose parents heavily smoke. I think it upset them, so maybe more, what’s the word, like help with knowing how the kids are going to react.

School 1, Teacher 9

In School 1, teachers struggled to complete all the set tasks because they had 10 minutes fewer than the recommended 50 minutes for each session. Subsequently, many admitted that they spent less time on some of the discussions; they felt that more time devoted to this would have helped to consolidate students’ learning.

Some of the discussions we cut down quite a lot . . . it would have been lovely to have had more time.

School 1, Teacher 4

Sometimes it might have been nice to have a little bit more discussion with the children and I felt like I was moving them on quite quickly.

School, 2, Teacher 4

Teachers were concerned about not being able to navigate through the resource so that they could deliver material according to the needs of their class and the length of their lessons.

There needs to be a bit more of, a teacher can override what is happening . . . so that it can suit the class.

School 1, Teacher 7

Not being able to skip particular sections or revisit areas if a recap was needed was a particular issue reported by some teachers.

The main thing would be a back button, without a shadow of a doubt.

School 2, Teacher 3

Just making it a bit more useable with being able to skip ahead, and if there was a menu or something like that, that would be perfect because then you could just, if that one’s optional choose to go onto the next one and continue from that point.

School 1, Teacher 15

One teacher suggested that having guidance on how to split the sessions to cater for different lesson lengths would be helpful. Another wondered if it would be possible to combine the three sessions into one file to aid flexibility and ease of navigation.

I think it would have been easier if you’d told us how to split it up into a 40-minute lesson rather than say this is session one, just stop where it ends kind of thing.

School 1, Teacher 13

Some teachers felt that they needed to be able to stop the countdown timer and move on if their students had answered the question within the allotted time.

So the timer ticking down was an issue when they knew the answer and having to wait; you want to be able to control that yourself.

School 1, Teacher 3

In addition, teachers found that not being able to view other websites on their computers while Operation Smoke Storm was running, without having to shut down and restart the programme, was frustrating.

Raised awareness

Many students mentioned that they had some existing knowledge about smoking from sessions in primary school, but that Operation Smoke Storm provided insight into the extent of the harms of smoking and the huge array of chemicals in cigarettes, which seemed to make some of them appreciate the associated dangers more.

Back at primary school I did about three lessons on it, but when we did this it gave a lot more detail showing you what not to do and what was in it, so we can see how dangerous it was.

School 1, Male

A lot of students were shocked and surprised by the information and many went on to state that smoking was worse than they had previously thought.

I learnt that it’s actually more harmful than people think . . . it’s got loads of different poisons and stuff that we would never expect to be in it.

School 1, Female

Subsequently, students expressed that this knowledge had strengthened their desire to remain smoke-free.

I didn’t want to smoke to start with . . . but now I know I definitely, definitely don’t want to smoke.

School 2, Female

However, a few students suggested that introducing the topic of smoking to those who had not given it any thought previously might make some curious about trying it.

In a way I don’t think it’s that clever because kids are going to go home and talk to their parents about cigarettes, and because they know about it they might want to try it and it could encourage them.

School 1, Male

Although students seemed to learn the most about the ingredients found in cigarettes and the health effects of tobacco, a few students did report having learnt new information about the tobacco industry. In particular, these students felt that the tobacco industry is motivated by profit, that it lacks concern for people’s health and that it targets young people to maintain its customer base.

They only do it just to make money; they don’t really care if people die.

School 1, Female

I’ve learnt that they try and make different kind of flavoured cigarettes to get different people, like they made, they tried testing chocolate flavoured cigarettes to get like young kids to smoke.

School 2, Female

Students’ engagement with Operation Smoke Storm

Most students reported that they enjoyed the Operation Smoke Storm sessions. Students found appeal in the interactive nature of the resource and in the fact that it was novel compared with their usual PSHE lessons.

It was mostly different to another PSHE lesson because mostly you would do group work . . . and learn lots of new things. So it would probably be better than another one.

School 2, Male

Generally, teachers agreed that the format involved students, which helped to keep them engaged.

I liked how it was more on them [the students]; it wasn’t me at the front just talking to them. It was them watching stuff and then answering questions about it. So it really got them involved.

School 2, Teacher 5

Furthermore, some teachers appreciated the fact that Operation Smoke Storm was taking a novel approach to education about smoking which was different from the usual the anti-smoking messages.

It wasn’t just ramming down the kids’ throats that they shouldn’t smoke, it was so much more to it than that and I think that was really good for them.

School 1, Teacher 7

For the most part, students bought into the secret agent theme, which served to keep them motivated and focused throughout the sessions.

It was really amazing because it felt like you were actually a secret agent; like you were actually there . . . it makes you involved with it so that you don’t get bored of it.

School 1, Male

However, many of the students found the female spy handler character annoying and distracting.

There was this woman after everything who kept on saying weird things that gets right on your nerves.

School 2, Male

The variety of activities seemed to further contribute to maintaining students’ engagement.

They were doing something different each week. They did seem quite excited to be doing it.

School 1, Teacher 6

Students enjoyed sharing ideas in group work and the freedom to create a presentation in the style of their choice.

You can use your imagination to create it [presentation] and make it what you want to make it.

School 2, Male

However, some teachers felt that having to split the class into four groups for the presentation resulted in too many students per group.

The final activity of session 2 required students to recall facts learnt in session 1 and earlier in session 2 which they would need as the basis for their presentations. Both teachers and students reported that this recall was difficult, especially when the lessons were more spread out. Teachers thought that incorporating a plenary session or providing students with an answer sheet to which they could refer if they needed help remembering certain facts or scoring their answers would be helpful.

The facts flashed up and then left, and flashed up and then left, but you needed like a review or some kind of plenary or something that had it all written down.

School 1, Teacher 2

In the main, teachers reported that the resource catered well for students of different academic abilities, particularly because it allowed for group work in which higher- and lower-ability students could be mixed. However, there were a couple of instances in which teachers felt that some differentiation in the activities could be beneficial to assist less able learners.

I’ve got a couple of kids in my class who are dyspraxic and dyslexic, because there’s not a lot of reading it was really good for them, they liked the tick box stuff, but then when we got to this section of ‘remember all this information and now create your own’, they found that more difficult because they hadn’t retained the information as well.

School 1, Teacher 1

There were mixed feelings about the appropriateness of a swear word within a quotation cited in the resource: ‘We don’t smoke that shit we just sell it. We reserve the right to smoke for the young, the poor, the black and the stupid.’ Several students thought that the language was inappropriate, and some teachers reported that it disrupted the class considerably. Although teachers felt that not all students had appreciated the meaning of the quotation, others reported that it had had an impact.

They didn’t like the [Chief Executive Officer] CEO quote, the one about the poor, black . . . they really hated that; that really got under their skin.

School 1, Teacher 4

The teachers felt that some of the language and concepts were at too high a level for the age group being targeted, such as references to smoking potentially causing impotence and affecting menstruation. Some students did not understand these terms, and teachers felt that having to take time to explain them disrupted the flow of the lesson.

I didn’t have time to go into what impotence was, so it was a bit like, ‘OK, so we’re going to move on very quickly from that point’, and then they get a bit confused.

School 1, Teacher 1

Options for developing Operation Smoke Storm

Both students and teachers were receptive to the idea of a booster session, delivered 1 year after the initial sessions when students are in Year 8 (aged 12–13 years), to reinforce their learning about how the tobacco industry targets young people. In general, teachers felt that a classroom-based session would probably be more successful than asking students to complete a homework activity.

I don’t think the engagement would be as good with home-based learning as within a classroom.

School 1, Teacher 4

They felt that it would be necessary for the booster to begin with a reminder of Operation Smoke Storm but that the secret agent theme would be too juvenile for a Year 8 student.

I don’t think that [secret agent undercover] would fly again. It would maybe have to be something a little bit different.

School 1, Teacher 10

Students were enthusiastic about the idea of the booster activity involving playing an electronic game or making a short film. Some felt that an anti-smoking message delivered by peers of their own age in a short film would be effective.

I think it will encourage other people who are watching it to not smoke because they’ll know that other people around their age are saying it and they’ll be persuaded more to not do it.

School 1, Male

Teachers also endorsed these ideas, but felt that in practical terms they would be challenging to deliver in school. For instance, it was suggested that access to equipment (such as video recorders) and computer room space is often limited.

They’re not allowed to bring mobile phones into school so they wouldn’t do it on their own phones. PSHE . . . doesn’t have tablets and . . . getting in the computer room is a bit of a nightmare.

School 1, Teacher 7

However, a teacher-led game was considered feasible with students playing in groups to answer questions and score points, with breaks for discussion. Teachers did not believe that engagement with an electronic game played at home would be optimal, partly because not all students have a mobile phone or tablet. As well as having limited access to film-making equipment, students also expressed concern that some people might post films on the internet in which they appeared but that some parents might not be happy with this.

But then some people’s mums and dads might not allow them to go on the internet and post it, because of their face.

School 1, Male

Teachers also felt that film-making in groups may be largely driven by some students only, and getting students together out of school would be as difficult as a homework activity.

Especially around here where the catchment areas are so spread out, then sometimes they do start struggling to get together to do group activities.

School 1, Teacher 12

Irrespective of the content of a booster session, teachers recommended that a teacher-led ‘off-the-shelf’ resource similar to the existing Operation Smoke Storm resource should be developed.

PSHE – because you’ve got non-specialists, if you say ‘go away and plan something’, it’s additional work for someone who it’s not their subject, so I think they would prefer something sorted for them.

School 1, Teacher 14

Another idea suggested by teachers was students working together on a research task to create something to teach younger children about smoking. However, this would require some guidance on structure and perhaps examples, such as existing anti-smoking adverts.

Students and teachers were also asked to consider ways in which to engage families in discussions about smoking. In particular, participants were asked to consider the idea of a take-home booklet containing information about the anti-smoking message and tobacco industry tactics, in line with the material delivered in class, containing activities that parents and guardians could complete with their child. In principle, students were in favour of a booklet, but opinion was divided in terms of whether their parents would actually read it or have time to complete the activities with them.

Also some people’s parents work a lot, because my mum’s a nurse so she works nights, and it would be quite hard for me to get her to fill it out if she was working.

School 2, Female

Teachers believed that involving parents and guardians in students’ learning would be beneficial but recognised the difficulties of engaging parents in school activities. They were generally in favour of a take-home booklet, as long as it was worded so as not to alienate or offend any parents who smoked.

The students don’t always . . . speak to their parents about what they’ve done in the school, so that’s a physical reminder of what they’ve done and there’s more opportunity for parents to engage.

School 1, Teacher 5

Summary

The qualitative data described above demonstrate that Operation Smoke Storm is generally acceptable to Year 7 students and teachers, can be delivered by teachers with relative ease, and appears to raise awareness about tobacco-related issues.

However, based on student and teacher feedback, a number of changes were subsequently made to the Operation Smoke Storm lessons to improve their flexibility and ease of use. Broadly, these revisions sought to provide teachers with additional background information about the topic as well as guidance on how to steer discussions, especially in situations in which students were worried or upset. Revisions also sought to make the resource more versatile to enable use in lessons of differing lengths and with students of different academic abilities. Lesson objectives were made more obvious and some of the language contained within the resource was revised. For further description of the changes made, see Chapter 4.

In order to ensure optimal engagement with a booster component, teachers felt strongly that this should be classroom-based rather than a homework activity and pitched at a level appropriate to the Year 8 students. In line with the Year 7 Operation Smoke Storm lessons, the preference of most teachers was that the resource should be designed to be ‘off-the-shelf’, incorporating lesson plans, timings, background information and learning outcomes. The development of the booster session is described in more detail in Chapter 4.

In the absence of any feasible alternatives being suggested by teachers, a take-home booklet to accompany Operation Smoke Storm was considered to be the best option to engage families in the anti-smoking message. Although teachers highlighted that schools do struggle with parent engagement and that, as such, complete uptake could not be guaranteed, the qualitative work suggested that most students would take a booklet home and that parents would find it interesting. The development of this booklet is described in more detail in Chapter 4.

A summary of the findings from phase 1 of the research was sent to the Head of PSHE at each school for distribution to the teachers who had participated in the research (see Appendix 5).

Chapter 4 Revisions to Operation Smoke Storm and development of booster and family components

From the qualitative feedback from students and teachers in phase 1 of the project, a number of suggested changes to the Year 7 Operation Smoke Storm lessons, and ideas for the booster and family components, were identified. Here we describe the changes that were made and the booster and family components that were developed. This work was carried out in collaboration with Kick It, who developed the original version of Operation Smoke Storm and who will distribute and support the delivery of the revised and extended intervention package beyond the end of the project. Also involved were additional collaborators specialising in graphic and flash design, video production and the design of educational resources (all of whom had been involved in the development of the original Operation Smoke Storm resource). Changes and developments were made through iterative discussions between all parties, taking into consideration what was feasible within the timeframe and budget; this meant that it was not possible to implement all suggested changes and ideas.

Feedback was sought from two independent public groups (the NCB’s Young Research Advisors and the Nottingham Smokers’ Panel) on the appropriateness of exploring tobacco industry marketing strategies in the booster component and the design of an early version of the take-home family booklet. This feedback is described in the second part of this chapter.

Changes made to Year 7 lessons

Resource flexibility

The overall impression from teachers was that more flexibility in the delivery of the resource was needed, primarily to accommodate different lesson lengths and needs of a class. In particular, some teachers felt that they needed to find more time to allow the student groups to discuss their opinions and to prepare properly for their presentations. To increase flexibility, a menu bar, back button and the ability to stop the countdown timer were added to allow swifter navigation and to enable the teacher to skip to sections of priority if they were not able to deliver the whole content in the time available.

Guiding students

Learning objectives were added in audio format at the beginning of each session and the accompanying teacher notes were modified to remind teachers to highlight these. Teachers were provided with written answers to all questions to which they could refer if students could not remember answers. In line with requests from teachers, an initial page was inserted in the teacher booklet providing background information about smoking and setting the scene for teachers about the importance of preventing youth smoking uptake. An overview of Operation Smoke Storm was also provided, as well as information on how to use the new navigation menu bar and suggested timings for shorter lessons. Also included in the teacher booklet was advice on the questions that students might ask and how they could respond if students got upset or were worried by any of the resource content.

Teachers had suggested that students needed more guidance on the group presentation that was prepared and delivered in the final session. The student handbook was amended to make it clear that the content of the presentation was more important than the format of delivery, and that the content should be based on their learning from Operation Smoke Storm. The score sheet students used to mark each other’s presentations was amended to match the assessment criteria, with the following specific question being added: ‘How well do you think the group’s presentation will convince people of your age not to start smoking?’.

Enhancing student engagement

After much deliberation the decision was taken to overdub the expletive (‘shit’) with the word ‘rubbish’ and similarly to replace it in the student handbook (in quotation marks to signify that this was a substitute for the original word). It was too costly to remove words such as ‘impotence’ and ‘menstruation’ from the video recordings, although the activities in the student workbooks were changed so that the students were not required to recall this information.

For a full description of the final Year 7 lessons, see Appendix 2.

Development of the booster component

A number of considerations were taken into account in the process of designing and developing a booster session for use with Year 8 students 1 year after they had received the original Operation Smoke Storm intervention.

To ensure optimal engagement, the booster component was designed as a classroom-based session, suitable for use ‘off-the-shelf’, with a clear lesson plan and learning outcomes. Despite being endorsed by students and teachers, it was felt that an individual electronic game or making a film in small groups could not be delivered in school owing to equipment constraints. Although teacher-led games were considered, it was felt that these would be costly to produce and might not engage enough students simultaneously or serve the purpose of providing the important educational content needed.

Kick It and the research team were keen to build on the main premise of Operation Smoke Storm, namely educating young people about the ways in which the tobacco industry operates, especially the methods it uses to target young people as its future customers. There was some concern that the secret agent theme would be too juvenile for Year 8 students. However, continuing the Operation Smoke Storm narrative in an age-appropriate form was considered to be a useful way to link the booster to the Year 7 resource which, it was hoped, would prompt students to remember their earlier learning.

After much discussion it was felt that one classroom session would be sufficient to cover the intended material adequately while not placing too high a demand on schools’ time. Care was taken to ensure that the resource developed was as sustainable as possible, particularly given the rapidly changing tobacco control environment.

Description of the final booster session

The booster component was designed to create classroom discussion and debate about tobacco industry practices that may be targeting young people. Specifically, it focuses on tobacco marketing strategies from the perspectives of a tobacco industry executive and marketing company, as well as a health campaigner, seen through the eyes of a teenager and reported directly to camera in the form of a social media blog.

The session begins with a video recap of the Year 7 Operation Smoke Storm lessons to remind students of what they did the previous year and to orientate teachers who had not delivered the Year 7 lessons.

This is followed by an introduction to a new character, Kiara, who explains on her online blog that she is going on work experience with a marketing company. The storyline follows Kiara into an encounter with a tobacco industry executive in a meeting in which she is asked to sit in. In this meeting the tobacco industry executive discusses with the marketing company ways in which they might improve the company’s public image. This meeting prompts Kiara to investigate more about tobacco and the way it is advertised to young people, including speaking to a health campaigner to find out his perspective.

Students are asked a series of questions relating to the tobacco industry at key moments in the storyline. They are prompted to write their answers in an individual workbook and then to discuss their views with the rest of the class.

There are also two further activities, which teachers can choose to complete if they have sufficient time. The first asks students to write a slogan for a billboard poster, advertising a fake cigarette brand, targeting young people. The purpose of the activity is for students to consider how tobacco companies may portray smoking to young people and raise their awareness of being targeted.

The second activity asks students to write a Tweet (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) about the tobacco industry, sharing their opinion with peers. The aim of this activity is for students to consider what they have learnt about the tobacco industry and their personal thoughts and feelings about this.

For a full description of the booster session see Appendix 2.

Development of the family component

As discussed in Chapter 3, there was general agreement that a take-home booklet to accompany the Year 7 Operation Smoke Storm lessons would be the best method to engage the largest number of parents in discussing the anti-smoking message with their children. Teachers highlighted that parental engagement is already difficult in schools and that they felt that parental participation should not be compulsory and should be worded sensitively; this would also serve to avoid any offence being taken by parents who were smokers themselves. There was consensus that the booklet should not be so long that busy parents would be put off reading it.

Description of the final family component

The final booklet comprised 10 pages designed to stimulate discussions about smoking between parents and students at home. The booklet contains a series of informative and interactive activities, each of which covers a different smoking-related issue pertinent to young people. The booklet is intended to be given to students after their first Operation Smoke Storm lesson in Year 7 for them to take home and share with their parents. An introductory page acts as a reminder for the students of their mission as a secret agent, as well as an overview of Operation Smoke Storm for parents.

The first activity, Involve Your Family, is a repeat of quiz questions that students completed in class, ascertaining knowledge about areas such as the chemicals in cigarettes and the health effects of smoking. Students are encouraged to ask their family members to answer the questions to ascertain their level of knowledge and the subsequent level of seniority at which they might be recruited to a job in a tobacco company.

The second activity, Know the Industry, contains new information about the marketing practices that the tobacco industry has employed in the past and at present. The activity prompts students to think about how they might be targeted by the tobacco industry, to consider their feelings and to consider their families’ feelings about it.

The third activity, Supporting Others, asks students to give advice to other young people in various scenarios relating to smoking in which they might find themselves. It encourages students to discuss with parents or friends what they might say in these situations. Signposts to cessation support services were also included in the booklet.

A prototype of the family booklet was reviewed by two public groups (see Public and patient involvement) and their feedback was taken into account when finalising the resource. For a full description of the family booklet, see Appendix 2.

Public and patient involvement

The involvement of users was a crucial element of this project. In addition to the qualitative research with students, teachers and parents to inform the development and refinement of Operation Smoke Storm, two public groups were used to enable relevant lay people to contribute to the research.

National Children’s Bureau

The NCB is a charity that aims to improve the lives of children and young people. 60 As part of its work the NCB runs a Young Research Advisors group, a group of 12- to 21-year-old young people who consult and collaborate on research projects relevant to children and young people. Members of the research team (AT and LS) led a meeting of 17 Young Research Advisors (aged 12–18 years) in June 2014. The aim of this meeting was twofold: to gain an insight into young people’s perceptions and levels of understanding of tobacco marketing in order to inform the level of detail to include in the booster and family intervention components, and to gather young people’s opinions on the acceptability of the family booklet to inform the refinement of the resource before piloting it in schools.

In the warm-up activity, each Young Research Advisor introduced themselves and was asked to give one reason why a young person might try a cigarette to encourage their thinking about the issues surrounding smoking. They were then split into three groups, facilitated by either AT, LS or a member of NCB staff, for the two main activities.

Activity 1

In the first activity, each group was presented with a set of images associated with the marketing of tobacco to young people, including images of cigarette packages, screenshots from social media and pictures of celebrities smoking in films and music videos. Participants were given 20 minutes to discuss what they could see, how they felt about the images and what influence they might have on young people. Each group then fed back their thoughts to the whole group and a short whole-group discussion took place. The aim of this activity was to explore young people’s abilities to understand how marketing may influence them and other young people to smoke; findings were used to inform the level of detail to include in the resources being developed.

Activity 2