Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/153/26. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The final report began editorial review in May 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Lohan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Research aims and objectives

Introduction

This chapter details the aims and objectives of the research study, ethics approval, study relevant documents, Steering Group arrangements, stakeholder representation and public and patient involvement (PPI) in the research.

Aims and objectives

Primary aim

The aim of the study was to determine the value and feasibility of conducting an effectiveness trial of the If I Were Jack Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE) intervention in post-primary schools.

Secondary objectives

The research aimed to achieve the following secondary objectives:

-

assess the acceptability of the intervention to schools (school principals and RSE teachers), male and female pupils and parents

-

identify optimal delivery structures and systems for the delivery of the resource in the classroom

-

establish participation rates and reach including equality of engagement across schools of different socioeconomic and religious types

-

assess trial recruitment and retention rates

-

assess variation in normal RSE practice across the participating schools

-

refine survey instruments as a result of cognitive interviews with male and female pupils

-

assess differences in outcomes for male and female pupils

-

identify potential effect sizes that might be detected in an effectiveness trial and estimate appropriate sample size for that trial

-

identify the costs of delivering If I Were Jack and pilot methods for assessing cost-effectiveness in a future trial.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) (reference 04.02.02.V2).

Study protocol, participant letters of invitation, information leaflets, consent forms and data collection instruments

For the protocol (version 2), see or http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2014.08.003.

For participant letters of invitation, information leaflets and consent forms, see Appendix 1.

For data collection instruments, see Appendix 2.

Protocol amendments

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Protocol version two changes (20 April 2015) included the following:

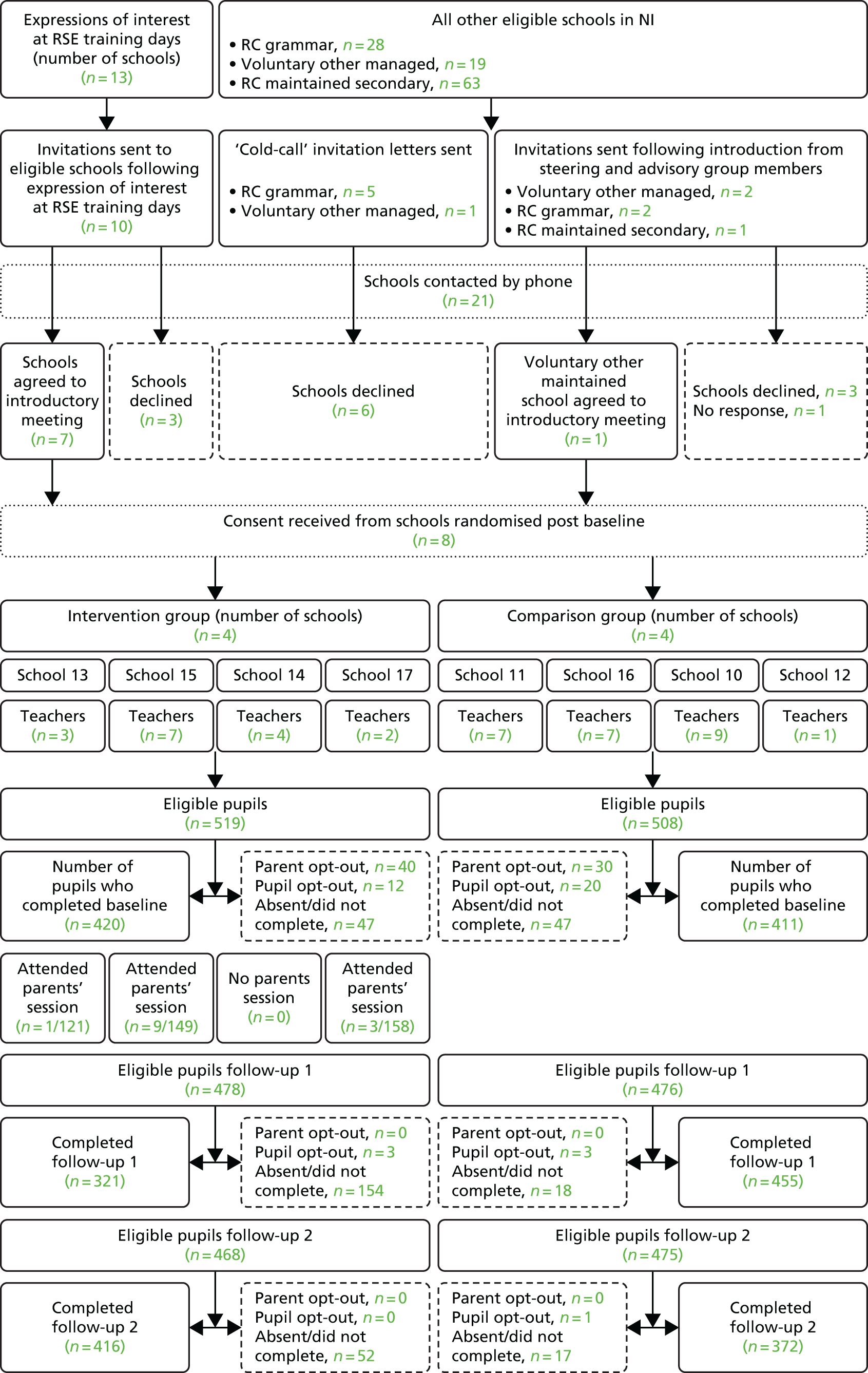

-

Updated version number.

-

Updated date of version.

-

Changed Clinicaltrials.gov registration number (NCT02092480) to an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN99459996).

-

Changed all references to seven schools to eight schools in the text and the flow chart.

-

Changed all references to three control schools to four control schools in the text and the flow chart.

-

Adjusted the sample size calculation from 630 to 720 to reflect the increased number of schools.

-

Added in a stratification subsection in section 5.b.

-

Added in a randomisation subsection in section 5.b.

-

Updated Appendix 3 (outcome measures) by removing the ‘Beliefs about Consequences’ outcome and the ‘London measure of unplanned pregnancy’ which occurred post pilot. These changes were due to low variability in responses and the low numbers of pregnancy, respectively. The newly developed Intention to Avoid Unintended Teenage Pregnancy (UTP) scale was added.

-

In this section Process evaluation, the following line was removed: ‘Inquire into teacher trainer’s views on the training materials for teachers’. This is because the researcher is delivering the teacher training.

-

Added the information video on YouTube (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) to the Parents Information Evening section.

-

Changed the sample size estimate for parent focus groups from 25–95 to eight-20.

Stakeholder representatives, international advisory group, trial steering group and details of meetings

Stakeholder group

Ms Joanna Brown, RSE and Local Area Coordinator, Sexual Health Training Team, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust (BHSCT), Northern Ireland (NI), UK.

Dr Bernadette Cullen, Consultant in Public Health, Public Health Agency (PHA) of NI.

Ms Kathryn Gilbert, Curriculum and Assessment Programme Manager, Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (CCEA), NI.

Dr Naresh Chada, Senior Medical Officer, Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS), NI.

Ms Janet Moore, DHSSPS.

International Advisory Group

Trial Steering Group

Professor Vivien Coates (Independent Member and Chairperson), Institute of Nursing and Health Research, School of Nursing, University of Ulster, NI.

Dr Suzanne Guerin (Independent Member), School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Ireland.

Dr Liam O’Hare (Member), Centre for Effective Education, School of Education, QUB.

Master Patrick Lynn (Independent Public Member/School Pupil).

Miss Chloe Templeton (Independent Public Member/School Pupil).

Dr Darrin Barr (Independent Public Member/School Principal).

Ms Grace McCarthy (Independent Public Member/School Teacher).

Ms Lisa Barr (Independent Public Member, Parent).

Dr Maria Lohan (Member and Chief Investigator), School of Nursing and Midwifery, QUB.

Dr Áine Aventin (Member), School of Nursing and Midwifery, QUB.

Dr Hannah-Rose Douglas (Independent Member), National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health, NI.

Trial Steering Group meetings

The Trial Steering Group met three times, on 9 October 2014, 11 May 2015 and 24 November 2015. For Trial Steering Group minutes see Appendix 4.

Public and patient involvement

The study was informed by several stakeholders:

-

Survey research with adolescents evaluating the If I Were Jack interactive film and a qualitative study with teachers. 1

-

In the intervention development phase (see Chapter 3), we convened a professional stakeholders’ group (see above) of senior representatives from key government departments [Health and Safety Executive, PHA, DHSSPS, CCEA (Belfast, UK), and Department of Education Ireland] who, alongside teachers and pupils, were involved in designing the intervention. 2

-

Prior to the pilot study for questionnaire development, we liaised with a young people’s research group. This was an ad hoc group comprising the young people from the Trial Steering Group and additional members of a Young People’s Advisory Group working on a similar study at QUB, in which Dr Lohan (Chief Investigator) was involved.

-

During the pilot study for questionnaire development (see Chapter 4).

-

During the feasibility trial through consultation with the Trial Steering Group, which included relevant independent and public lay membership (see above).

-

During the feasibility trial through process evaluation whereby we sought the views of teachers, pupils and parents regarding potential refinements to the intervention (see Chapter 7).

Chapter 2 Background and rationale for the study

Existing research: understanding unintended teenage pregnancy

Teenage pregnancy remains a worldwide public health concern. 3,4 The UK has the highest rate of adolescent pregnancy in Western Europe. 4 Although rates of teenage pregnancy have been gradually falling across the UK since 2002, the birth rate for girls aged under 20 years in England and Wales remains high, at 37.4 per 1000 in 2014. 5 In real terms, just under 26,000 women under the age of 20 years became pregnant in England and Wales in 2014 and approximately half of these pregnancies ended in legal abortion, reflecting the potentially unintended or unwanted nature of these conceptions. 6 The conception rate for Scotland was 37.7 per 1000 in 2013. 7 In NI, abortion is illegal and is considered lawful only in exceptional circumstances in which the life of the pregnant woman is at immediate risk or if there is a risk of serious injury to her physical or mental health. Reflecting this different legal framework, government targets around reducing teenage pregnancies in NI relate to births and not conceptions. In NI, the birth rate to teenage mothers per 1000 of the female population aged 13–19 years in 2014 was 10.3 per 1000 young women (a total of 839 births). 8 The rate for young women in the most deprived areas was nearly 30 per 1000. 9

Although the life course for teenage parents is not universally negative,10,11 the social disadvantage and exclusion that are linked to teenage pregnancy are considered problematic. 12 UTP can lead to considerable adverse health problems for teenagers and their infants, as well as generate enormous emotional, social and economic costs for adolescents, their families and society. 13 Although UTP is a complex phenomenon that cannot be prevented through RSE alone,14–20 high-quality RSE is an essential component in the process of reducing unintended pregnancy rates, as well as being a vital aspect of improving holistic sexual health and well-being. 21–27 Reflecting the importance of RSE, the governments of NI, England and Scotland all emphasise the policy importance of the reduction of teenage pregnancy rates via the implementation of RSE in schools as a key objective in current sexual health policies. 26–28

Unprotected sex during teenage years is well established as the main proximate behavioural determinant of teenage pregnancy and is a commonly measured behavioural outcome in studies examining the impact of RSE interventions on teenage pregnancy. 17,27,29 Research indicates that, although other behavioural determinants (such as frequency of sexual intercourse and number of sexual partners) are important, avoidance of unprotected sex via consistent use of contraception is central in explaining variation in levels of adolescent pregnancy. 22

A number of systematic reviews have identified the characteristics of effective RSE programmes that may have an impact on sexual risk-taking behaviours. 19,30–36 These include the use of theoretically based interventions targeting sexual and psychosocial mediating variables such as knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, intentions, perceptions of risk, and perceptions of peer norms which are linked to sexual behaviour change; the use of culturally-sensitive and gender-specific interventions; the use of interactive modalities that promote personal identification with the educational issues and engagement of young people; the use of skills-building components; the involvement of parents in the RSE process; and facilitating linkages with support services.

Evidence supporting a theory-based approach

Providing a theoretically informed foundation for sexual health education programmes is considered key to effectiveness because it ensures that the most important determinants of young people’s sexual behaviour are targeted. 22,32,34,37–39 The underpinning theoretical framework for the intervention used in this study combines the well-established theory of planned behaviour40,41 and recent updates to this theory,42,43 which focus on the individual behavioural antecedents of an unplanned pregnancy along with an understanding of the broader socioenvironmental factors (such as social class) and underlying values (such as religiosity and gender ideologies) associated with the occurrence of teenage pregnancy. 18 Interventions should target six psychosocial mechanisms that research indicates are related to a reduction in risk-taking behaviour: knowledge, skills, beliefs about consequences, social influences, beliefs about capabilities and intentions. 19,44,45

Evidence supporting the use of culturally relevant and gender-specific interventions

The World Health Organization (WHO),46,47 recent systematic reviews commissioned by the US-based National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy,48,49 and the NIHR,50 among others,1,22,51–54 recognise that adolescent men have a vital yet neglected role in reducing teenage pregnancies, and that there is a pressing need for RSE interventions designed especially for them.

In relation to cultural relevance, research suggests the need to engage with young people both empathetically and cognitively in order to increase the relevance of the issues being raised. 14,23,30,31,55 As Ingham and Hirst24 have noted, it is important to harness the potential for sex education to be keenly anticipated, especially by those who are less engaged in the wider school curriculum, a factor that was identified as a possible barrier to impact. 50

Evidence relating to socioeconomic position and inequalities

Research suggests that interventions targeting only schools in disadvantaged areas are insufficient for achieving population-level reductions in teenage pregnancy. 56,57

Evidence supporting the use of interactive computer-based interventions

Recent systematic reviews have shown the value of interactive-computer-based interventions,34,35,55 and a meta-analysis examining these reviews in relation to the theoretical mediators of safer sex36 concluded that they were successful in impacting knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy relating to sexual health.

Evidence supporting the use of skills-building components

Reviews and trials of health promotion and educational interventions show that simply providing information does not lead to behaviour change and that instead it is necessary to support young people to develop their own communication skills in relation to preventing risky sexual behaviours. 14,17,19,21–23,30,34,47,58 A recent NIHR Health Technology Assessment systematic review19 of the effect of interventions aiming to encourage young people to adopt safer sexual behaviour found that school-based interventions that provide information and teach young people sexual health negotiation skills can bring about improvements in behaviour-mediating outcomes such as knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy. The authors noted that these variables are no less valuable than behavioural variables because they provide young people with a solid foundation on which to make sexual decisions.

Evidence supporting the involvement of parents in Relationship and Sexuality Education

Although evidence suggests that schools are an important context for sex education,14,48,59 recent systematic reviews have also shown that programmes that reach beyond the classroom (including multifaceted approaches with a parental or community component) are more effective,19,25,60 particularly with adolescent men. 48 In particular, factors such as parental monitoring and supervision and familial communication have been associated with adolescent sexual behaviours. 61,62 Teenagers who can recall a parent communicating with them about sex are more likely to report delaying sexual debut and increased condom and contraceptive use. 63–65

Most parents do, however, recognise the importance of speaking to their children about sex and most would like more resources to help them in this regard. 66 Furthermore, many teenagers report parents as a primary source of information on sexual health matters. 67 The unprecedented growth in the use of online and mobile technology over the past few decades by people of all ages presents opportunities for increasing the reach (and decreasing the perceived embarrassment) of parental involvement in sex education. 68 More than 20 years ago, Miller et al. 66 found that a home-based video sex education intervention designed to make it easier for parents to talk to their teens about sex was effective in increasing the frequency of parent–teen communication regarding sexual topics. The use of ‘education entertainment’ for addressing health issues has become increasingly common since then69 and, in recent times, studies61,68,70 have demonstrated the importance of embracing such modalities as engaging adjuncts to school-based education.

Rationale for the feasibility trial

The study is justified on the following grounds.

Previous research by members of the study team

When we used an earlier version of this interactive video drama (IVD), a component of the intervention in this study (see Chapter 3) as part of a research project on teenage males and unintended pregnancy, 85% of a sample of male pupils in Ireland (n = 360) and 72% in Australia (n = 386) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that it ‘helped me understand the effect an unplanned pregnancy would have on a guy like me’. In Ireland and Australia, 79% and 69%, respectively, agreed or strongly agreed that the IVD ‘made me realise that I should never get myself in that situation’. 71

The public health concern of teenage pregnancy and the potential reach of targeted school-based interventions to provide young people with a solid foundation on which to make sexual decisions

The core aim of the If I Were Jack intervention is to use an evidence-based process to allow schools to provide pupils with opportunities for exploring the issues surrounding teenage pregnancy and parenthood with reference to the individual, family, community and society. If it is acceptable and effective, it has the potential to be rolled out to large numbers of boys and girls attending schools across the UK and to be of benefit to several groups of people. In 2011/12 there were 24,251 pupils in Year 11 in the 216 mainstream post-primary schools in NI72 and 551,800 pupils in the 3268 state-funded secondary schools in England. 57 Pupils will benefit from an engaging educational resource. Parents will benefit from a process designed to involve and support them in communicating with their child. RSE teachers will benefit because the resource will provide them with a stimulus for engaging pupils in an immersive decision-making experience from the point of view of a teenage male, followed by guided classroom-based activities.

Teenage pregnancy is both an outcome of, and a contributor to, inequalities in health. 12 The aggregate projected spend for 2013–20 for treating both unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (for all ages) across the UK is estimated to be between £84.4B and £127B. This is based on a projected spend of £11.4B of NHS costs as a result of unintended pregnancy and STI costs, and between £73B and £115.3B of wider public sector costs. 73 The NI government estimates the cost to the Exchequer of teenage pregnancies at £20,000 per teenage mother on the basis that a teenage pregnancy effectively withdraws the mother from the labour market (not in education, employment or training) for at least 18 months and accounting for unemployment benefits and administration, plus tax revenue forgone. 26 Our population-based approach is consistent with the evidence that universal interventions are necessary to achieve population-level reductions in teenage pregnancies. 56,74–76

This study will begin a process of robust evaluation that may also lead to the roll-out across the UK and international applications of the intervention

Internationally, policy-makers and researchers have called for scientifically evaluated school-based RSE interventions. 16,21–25,77,78 A successful feasibility would underpin the development of a UK-wide Phase III trial. The intervention has been designed specifically for use in NI, but it is based on international research regarding effective RSE interventions. Although the video drama features NI actors, there is no specific reference to NI in the video and we believe that it would have strong cultural resonance in the rest of the UK. Furthermore, although the accompanying materials make specific reference to the NI curriculum and legislation in NI governing termination of pregnancy, the costs of making changes to these references so that the materials could be used in contexts across the UK would be negligible.

The need to develop and evaluate age- and gender-specific Relationship and Sexuality Education resources

The need for gender-sensitive interventions to address teenage pregnancy has been highlighted as a global health need by the WHO46,47 and has been recommended in systematic reviews. 19,48,49 Addressing teenage males’ RSE is an important mechanism for promoting positive development and improving the lives of all young adults, especially those suffering the effects of various types of disadvantage. 48,51–53,79

A recent inspection by the Education and Training Inspectorate of RSE implementation in post-primary schools in NI identified the need for RSE resources for older adolescents, especially at Key Stage 4 (age 14+ years). 80 The absence of such resources is thought to be a demotivating factor, making RSE more difficult for some schools to implement. Internationally, there has also been demand for age-appropriate school-based RSE interventions. 16,21–25,77,78

We aim to initiate a process of robust scientific evaluation, which will ultimately produce generalisable findings especially relating to gender-specific interventions. The intervention we propose is gender-inclusive in terms of intent and impact and it can be used in mixed-sex classrooms, but is gender-specific in that it specifically targets the inclusion of adolescent men by developing an interactive film from a man’s point of view.

The strengths of the If I Were Jack intervention

The If I Were Jack intervention is grounded in empirical research on adolescent men’s attitudes to UTP; was developed in consultation with key health and education experts, pupils, teachers and parents; and is informed by the best available evidence regarding the development of classroom-based RSE interventions. It is predicted to impact on a number of behavioural and psychosocial mediating variables, which research suggests decrease sexual risk-taking behaviour. It uses an innovative combination of intervention components which address deficits in existing RSE interventions and aim to maximise potential impact.

The right place for this study

This research is necessary to address the deficit of research on high-quality RSE interventions in NI. Although RSE is mandatory in NI, its provision in schools is known to be underdeveloped and highly variable. 9,80–83 In addition, given that RSE in NI is underdeveloped, we are more likely to be able to test the efficacy of the intervention in NI as a prelude to a Phase III trial to test its effectiveness. In our preliminary research and in working through a partnership model to develop this study, we believe that we are in a strong position to overcome the problems in implementing RSE in NI and have already found the resource to be culturally sensitive and acceptable to statutory stakeholders and schools.

The educational and policy demands for such an intervention

The letters of support from across the health and educational sector of the UK (including, in NI, the Chief Medical Officer, PHA NI, DHSSPS and CCEA) identify the need for and support this study. Several stakeholder organisations are also offering in-kind contributions in terms of membership of a study stakeholder’s group along with a contribution of £20,000 co-funding from PHA. This stakeholder investment in this project attests to the widely held need to evaluate evidence-based, theory-informed RSE resources that clearly target boys as well as girls in relation to unintended pregnancy and improving sexual health and well-being.

Chapter 3 The intervention

Overview of the intervention

The If I Were Jack intervention2 is a classroom-based RSE resource intended for use by teenagers aged 14–15 years, based around a core component – a culturally sensitive interactive IVD to immerse young people in a hypothetical scenario of a week in the life of Jack, a teenager who has just found out that his girlfriend is pregnant. It is designed to be delivered by teachers over 4 weeks, and also incorporates communication with parents/guardians within the RSE process.

It is composed of a number of components:

-

the If I Were Jack IVD, which asks pupils to put themselves in Jack’s shoes and consider how they would feel and what they would do if they were Jack

-

classroom materials for teachers containing four detailed lesson plans with specific classroom-based and homework activities including group discussions, role-plays, worksheets and a parent–pupil exercise

-

a 60-minute face-to-face training session for teachers wishing to implement the intervention

-

a 60-minute information and discussion session for parents/guardians delivered by RSE teachers (also presented as a brief 6-minute YouTube video delivered by the principal investigator (PI) containing an overview of the key points, for those who were unable to attend)

-

detailed information brochures and factsheets about the intervention and UTP in general for schools, teachers, teacher trainers, young people and parents.

The IVD is interactive in that the film pauses throughout with questions that invite users to imagine being Jack. On individual computers, they watch Jack as he thinks about what his friends and parents might say, chats to his girlfriend and attends a pregnancy counselling session. The user answers questions about how they would think, feel and react in these situations and ultimately decide upon a pregnancy resolution option. Although targeted specifically at young men, through the presentation of the case scenario of an UTP from a teenage male’s point of view, it can also be used by young women and in mixed-sex classrooms. By asking both girls and boys to empathise with Jack and ask themselves how they would think and feel if they were in his situation, it is designed to make explicit the gender assumptions around roles and responsibilities for teenage pregnancy while opening them up for reflection and negotiation.

The face-to-face teacher training session lasted for 60 minutes and was mandatory for those delivering the intervention. It included an overview of the If I Were Jack feasibility trial and the components of the intervention, its underlying theory and key messages. Teachers were given a full demonstration of the IVD and detailed information on the accompanying activities and how they should be implemented. They were advised that they should stick as closely as possible to the implementation guidelines detailed in the ‘information for teachers’ booklet. However, as implementation processes were being piloted as part of the study, they were informed that they could vary implementation if necessary and were asked to record any variation in implementation in the implementation log booklets.

The development of the intervention was informed by empirical research on adolescent men’s attitudes to UTP and the best available evidence regarding the components of effective RSE interventions. It was designed to fit with the RSE curriculum by a team of researchers working with experts from the DHSSPS, PHA, and CCEA, as well as teacher trainers, teachers, parents and adolescents.

The intervention includes an innovative combination of different components, content and educational objectives which provide pupils with educational information and opportunities for communication with peers and parents, skills practice, reflection and anticipatory thinking (see Appendix 5). The design and development of the If I Were Jack intervention is detailed in full in Aventin et al. 2 and addresses identified deficits in existing RSE interventions. Additional intervention components, which are based around the IVD, include classroom materials, a comprehensive training session for teachers/RSE facilitators and an information and discussion session for parents. For the feasibility trial this information was also presented as a brief 6-minute YouTube video delivered by the PI containing an overview of the key points, for those who were unable to attend. Further information about the intervention, including excerpts from the film and feedback from end users regarding the acceptability of the IVD, is also available from the project website (see www.qub.ac.uk/IfIWereJack). 84

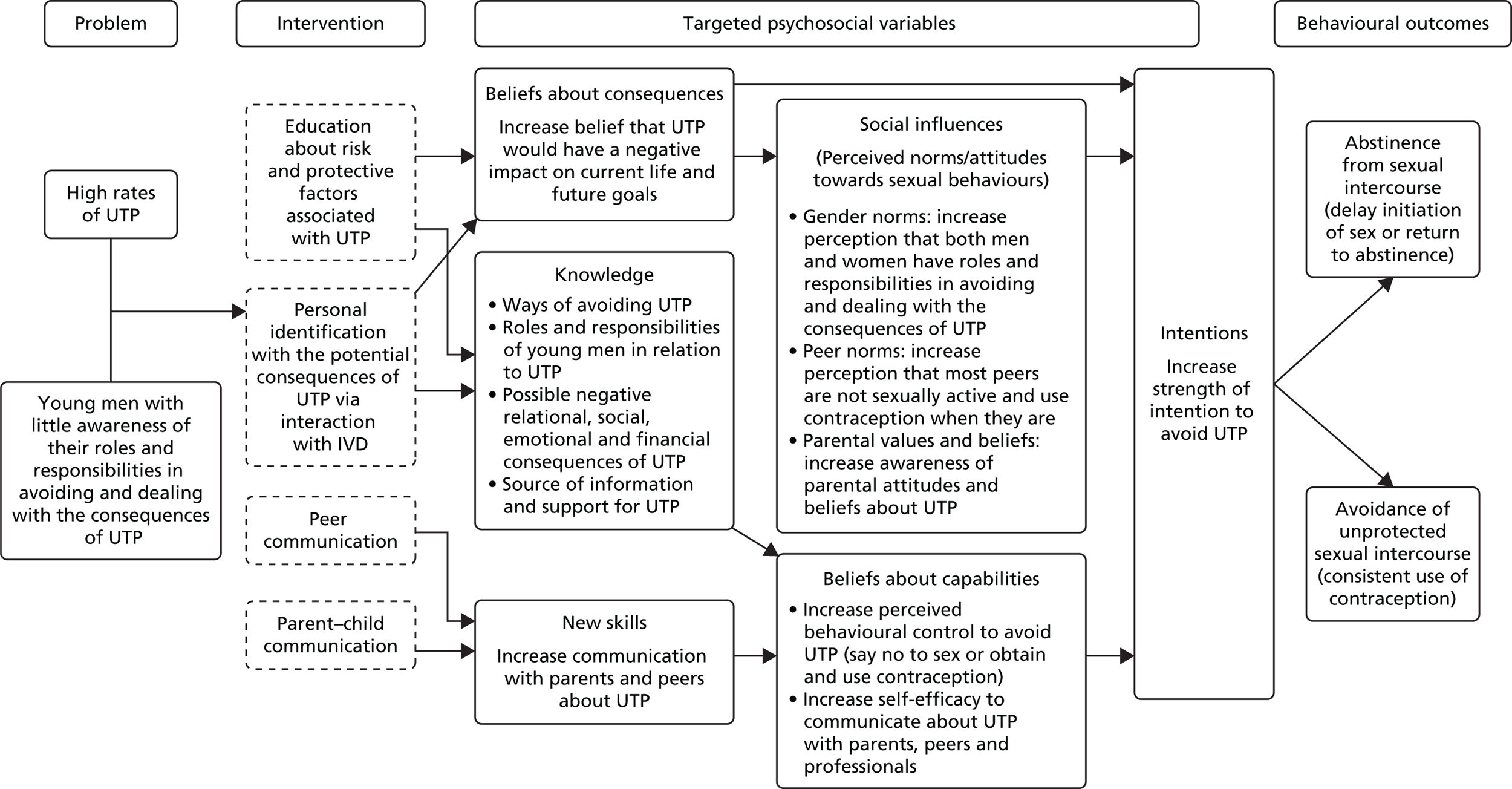

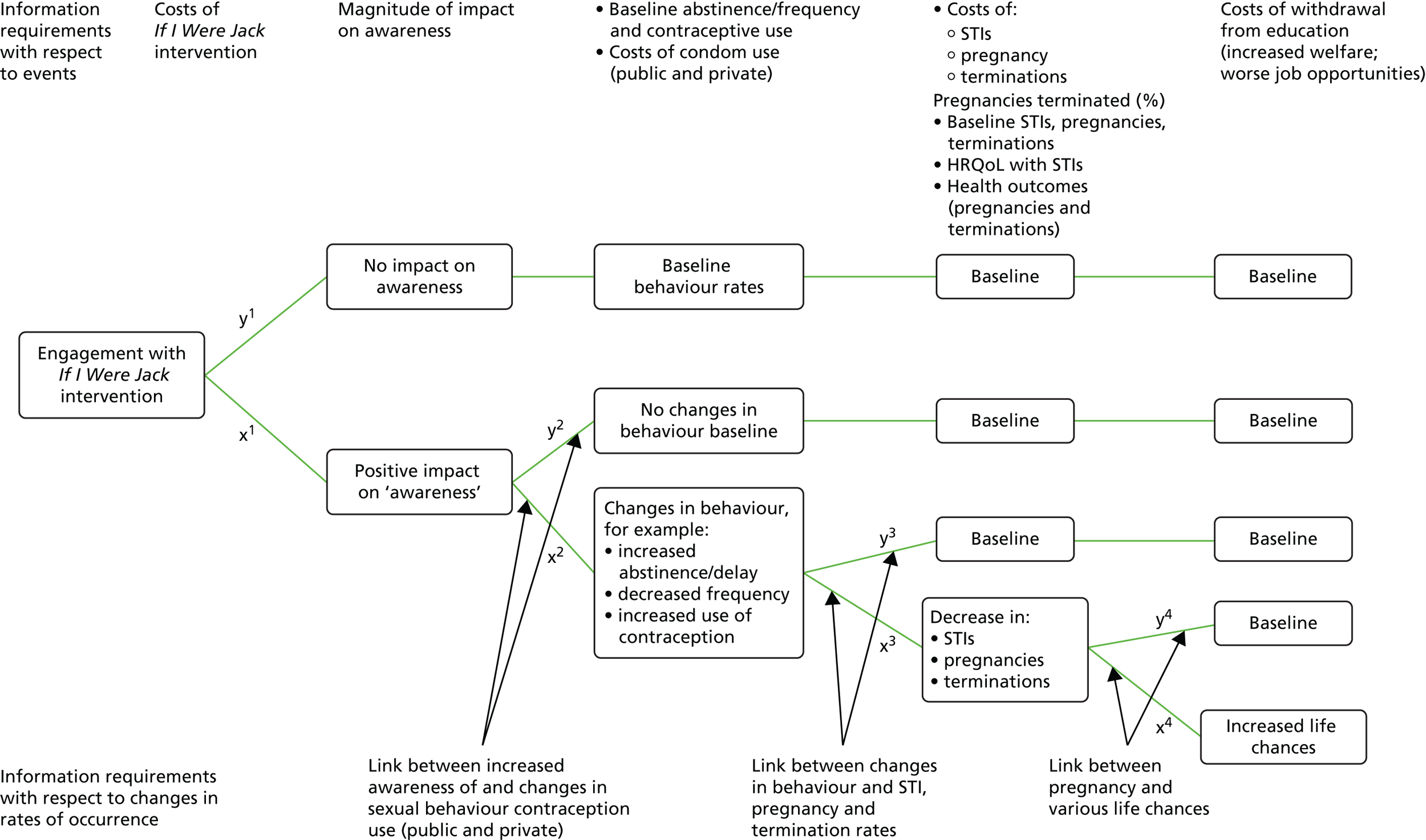

The intervention is designed to increase adolescents’ intentions to avoid an UTP by delaying sexual intercourse or consistently using contraception in sexual relationships. To achieve this impact, it targets six psychosocial mechanisms (see Appendix 5), which theory and research suggest are key to decreasing sexual risk-taking behaviour: (1) knowledge; (2) skills; (3) beliefs about consequences; (4) other sociocultural influences such as peer norms, gender norms and parental values and beliefs; (5) beliefs about capabilities; and (6) intentions. 40,85–87 The If I Were Jack theory of change model is detailed in Figure 1. The intervention aims to maximise potential impact by incorporating components, which some studies have indicated are key elements of effective RSE interventions (e.g. interactive media,34,35 peer discussion25,37 and parental involvement). 88 In brief, we hypothesise that by encouraging personal identification with the UTP scenario in the IVD, we engage pupils in an exercise of the imagination whereby they stop and think about the consequences that an UTP might have on their current life and future goals. This identification and reflection process is reinforced by providing knowledge about the risks and consequences of UTP and ways to avoid it and offering opportunities to practice communicating about UTP with peers and parents/guardians (activities that also increase awareness of peer norms and personal and familial values and beliefs about sexual behaviour and unintended pregnancy). We hypothesise that by targeting these psychosocial factors, we impact on teenagers’ sexual behaviour via pathways through their intention to avoid UTP.

FIGURE 1.

If I Were Jack theory of change model.

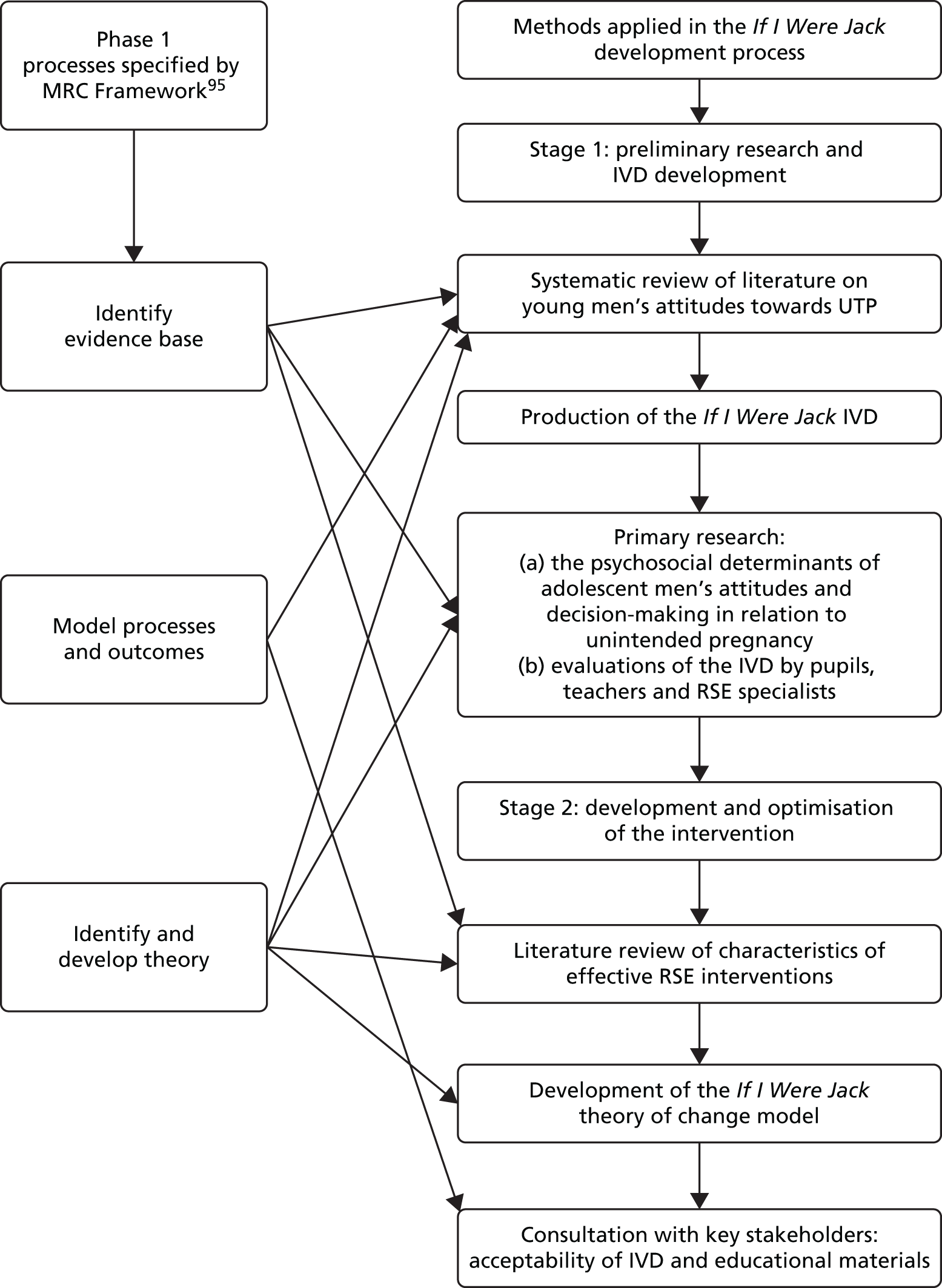

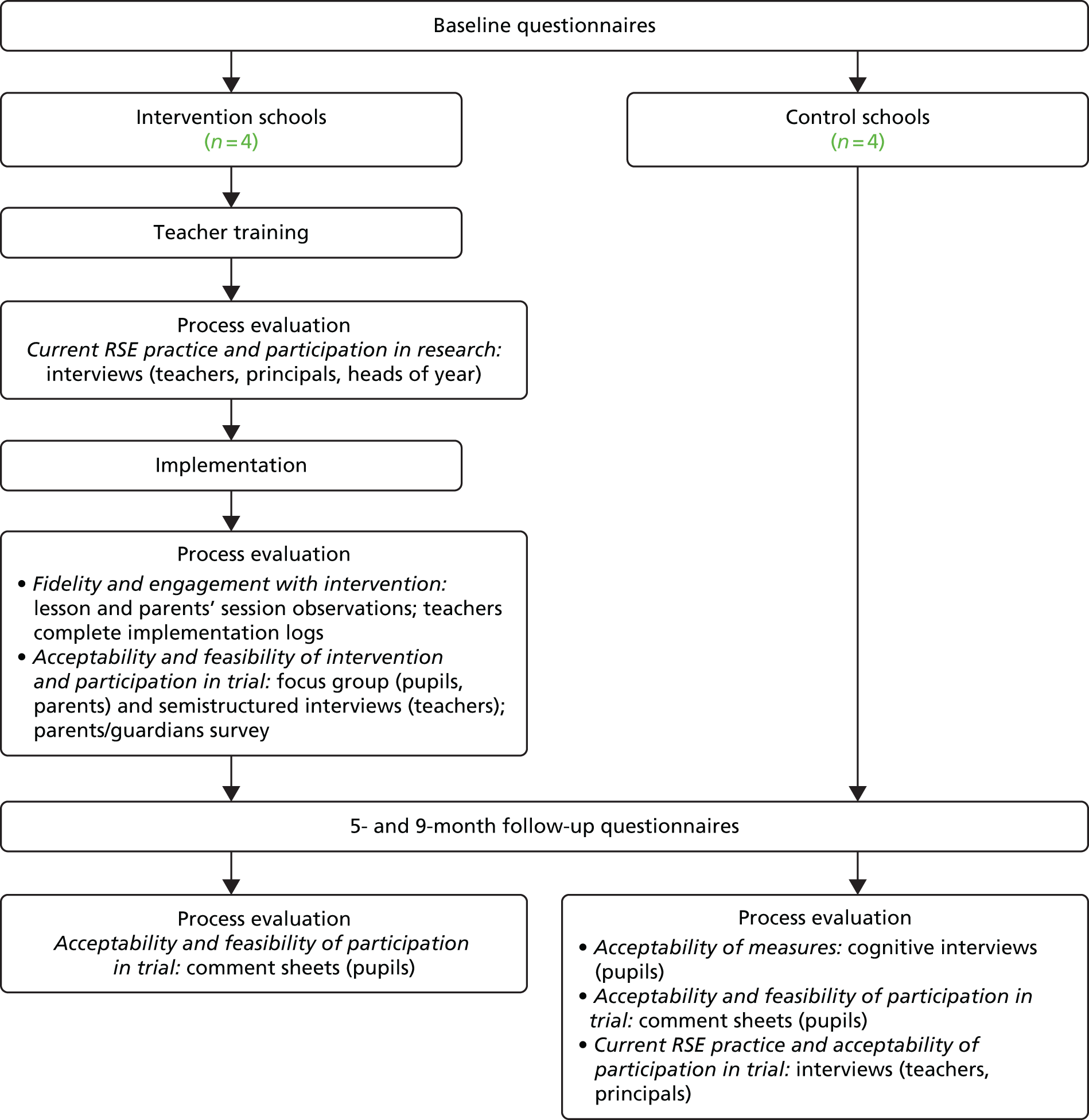

Methods

Development of the intervention was a two-stage process (Figure 2) informed by the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework. 89 The process began with a systematic review of the literature on adolescent men and UTP. 90 Following this, a version of the IVD was developed as a data collection tool and used to develop the empirical evidence base on adolescent men’s attitudes and decision-making in relation to an UTP (see Chapter 2, Previous research by members of the study team). 1 Feedback from pupils, teachers and educational specialists indicated that this version of the IVD had potential to be redeveloped as part of an intervention. This resulted in stage 2 of the process, in which a further systematic review of the literature on the characteristics of effective RSE was conducted. The IVD was redeveloped, which involved the filming of a new Northern Irish version (for the purposes of cultural relevancy) and the development of additional intervention materials informed by the theory of change model depicted in Figure 1 and by consultation with stakeholders.

FIGURE 2.

The If I Were Jack development process.

Results

Stage 1: preliminary research and development of the interactive video drama

Systematic review

A systematic review of the literature on young men’s attitudes towards UTP and parenthood indicated a number of potential psychosocial influences on young men’s attitudes towards UTP and pregnancy outcome decisions. 90 These included social class, religiosity, gender identity, masculinity, the idealisation of pregnancy and parenthood, and attitudes and subjective norms regarding how significant others (such as parents, friends and partners) would expect them to behave in such a situation. The If I Were Jack intervention targets these psychosocial influences as key mechanisms.

The If I Were Jack IVD was inspired and modified (with permission) from a version used in an Australian study of adolescent men and pregnancy. 91 Irish and Northern Irish versions were filmed (to be more culturally and contextually relevant), informed by previous Irish research92 and in consultation with an expert advisory group and youth drama groups, first for use as a data collection tool in a study examining influences on young Irish men’s attitudes and decision-making in relation to a hypothetical UTP. 1 A significant change included the addition of a third pregnancy outcome choice, namely ‘adoption’, in addition to ‘keeping the baby’ and ‘abortion’. Evaluation supported the notion of developing it as an educational resource and offered suggestions for how it might be optimised for use in the classroom. 71 There was agreement among participants that it was authentic in its representation of a believable UTP scenario; engaging to users because of its interactive modality; unique in its representation of the male role in UTP and use of high-quality drama; easy to use; and held potential for inclusion within broader RSE curriculum. 71 Formative evaluation of the original Australian version indicated that the IVD had potential for achieving key educational and health promotion outcomes in relation to raising awareness around UTP in young men’s lives. 93 Further development and evaluation of the existing Northern Irish IVD into an educational intervention ensued in stage 2 of the production process.

Stage 2: development and optimisation of the intervention

Stage 2 focused on developing the intervention. This involved redevelopment of the IVD and design of accompanying classroom materials based on evidence regarding the characteristics of effective RSE interventions and theoretical understanding of the determinants of behavioural change. Also central to stage 2 was consultation in relation to the content (see Chapter 1, Public and patient involvement).

Identifying the evidence and modelling theory

A number of systematic reviews have identified the characteristics of RSE interventions that have been effective in changing sexual risk-taking behaviours. 19,30,33–35 The If I Were Jack intervention represents an innovative combination of these different elements. Providing a theoretically informed foundation for sexual health education programmes is considered key to effectiveness because it ensures that the most important determinants of young people’s sexual behaviour are targeted. 21,34,37 The If I Were Jack intervention is broadly based around the theory of planned behaviour40 but also draws on other psychosocial theories which emerged as important during the systematic review stage described above. The If I Were Jack theory of change model is depicted in Figure 1, the development of which (informed by Kirby et al. 94) included four steps:

-

identification and selection of the health goal (reduction of UTP rates)

-

identification and selection of important related behaviours (abstinence from sexual intercourse and avoidance of unprotected sexual intercourse)

-

identification and selection of important risk and protective factors (targeted psychosocial variables as indicated by theory and research)

-

identification and selection of intervention components (see below).

Developing the content and components

Educational outcomes were defined for each of the user groups (pupils, teachers, teacher trainers and parents) based on the targeted psychosocial variables detailed in the theory of change model (see Figure 1) and then considering possible activities that might help young people to achieve this outcome. An overview is provided in Appendix 5.

Refining the content in consultation

The draft IVD and educational materials were reviewed by a steering group and amended following feedback. Further consultation with relevant stakeholders – teachers, pupils and parents – regarding their acceptability was also undertaken. This is described in full in Aventin et al. 2 Notable refinements made as a result included the following.

Addressing the issue of abortion

Although the intervention is non-directive in terms of pregnancy outcome options, stakeholders were concerned that the mention of ‘abortion’ might negatively impact on uptake, in particular in schools that have an anti-abortion ethos. This issue was addressed by changing the order in which the pregnancy outcome options were displayed in the IVD; including information about the legal status of abortion (locally); and changing wording that might be interpreted as pro-abortion. In addition, teachers were reminded repeatedly during the teacher training session and in the classroom materials that they have the opportunity to state the school ethos and RSE policy and that the intervention allows for this flexibility.

Making it gender sensitive

Although the intervention was developed specifically for teenage males, preliminary research suggested that it would also be suitable for use by teenage women. The learning objective was to introduce the topic of UTP through the male perspective, arguably a fresh perspective, but to use this as a starting point to discuss both male and female perspectives and to explore similarities as well as differences. Thus, girls are also asked through this intervention to imagine ‘If I Were Jack’. Following consultation, additional amendments made to address this issue involved the addition of three questions to the IVD which referred to how the female character may be feeling (i.e. ‘If I were Jack, how do I think Emma would be feeling now?’). Such questions allowed for further exploration of the female partner’s perspective while retaining the focus of the exercise on the perspective of the male character.

Increasing credibility

Increasing the credibility of the intervention to gatekeepers (schools, teachers and parents) was achieved by developing a dedicated website for the intervention. The website includes, among other features, expert stakeholders’ and teachers’ audio- and video-recorded testimonies.

Increasing accessibility

The IVD was developed for the internet, adapting the previous version, which was delivered to the end user on digital versatile disc (DVD), and transforming it into the online environment.

Discussion

Effective RSE interventions require rigorous development processes and transparent reporting to ensure both substantive and process-related knowledge transfer. The design and development of the If I Were Jack intervention benefited from the guidance provided by the MRC framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions87 and followed the recommended process of identifying the evidence base, identifying theory relating to the phenomenon of young men and UTP and modelling the processes and outcomes of implementing the intervention through preliminary research and consultation with key stakeholders. In applying the framework in the real world we learned lessons, which both complement and extend beyond the guidance that accompanies it, and gained practical insight into a development process that might be useful for others. Three key lessons are detailed in full in Aventin et al. 2 and are summarised below:

-

Know and involve your target population and engage their gatekeepers in addressing contextual complexities:

-

systematic reviews

-

primary research

-

development/adaptation of film script, storyboard and interactive questions

-

consultation

-

participation.

-

-

Know the behaviours you wish to target and model the process of change:

-

psychosocial theory

-

characteristics of effective interventions

-

logic modelling.

-

-

Look beyond development:

-

consider evaluation, implementations and knowledge transfer from the start.

-

Limitations

A recent systematic review of effective sexual health interventions19 indicated the importance of building connections with community-based sexual health services and providing longer-term programmes. The If I Were Jack intervention was unable to address such components owing to the strategy employed to develop and test an existing IVD. Such issues and other evidence-based components could be addressed in future development work.

As the If I Were Jack intervention strongly emphasises the potential negative consequences that having a child might have on a teenager’s current life or future goals, another potential limitation of the intervention is that it may have a possible negative impact on teenagers who have had, or are about to have, a child. It has the potential to reinforce or indeed instigate stigmatisation processes. Design features of the intervention aim to off-set this potential negative impact through the teacher training process, which emphasises the importance of reminding and discussing with pupils that the resource refers to UTP (i.e. a pregnancy that is unexpected and unwanted) rather than a teenage pregnancy in general, which for some young people can be a planned and positive experience. Pupils are also informed by the teachers and researchers involved that they can and should contact the school counsellor/pastoral care (PC) officer should they find any part of the intervention upsetting.

Conclusions

The If I Were Jack intervention is a unique, evidence-based, theory-informed intervention that to date has been found to be acceptable to statutory stakeholders, teachers, pupils and parents in diverse geographical and cultural settings (Ireland, NI and Australia). The intervention is based on existing evidence-based RSE programmes targeting UTP and includes key behaviour change techniques that are influential in changing sexual behaviour and incorporates sociological understandings of gender norms relating to pregnancy. The If I Were Jack intervention is the first to be documented in the scientific literature2 that specifically addresses teenage males and UTP.

Although the MRC guidelines89 suggest a very useful framework for conducting Phase I research, they provide little description of how this should proceed (relative to guidance provided on Phases II–IV). This effectively relegates the importance of this phase to considerations of summative evaluation, despite growing consensus that the development of conceptually based, acceptable interventions is of vital importance before proceeding to trial. This is compounded by a dearth of published literature reporting the development of complex interventions in practice. The result is an increased potential for misallocation of research labour and resources on what is already a costly and time-consuming process. More broadly, as the new mantra of knowledge translation spreads across the academic community there is ever more need to report intervention development processes and intervention components in detail for others seeking to bridge the gap between research and interventions. Reporting on these methodological processes has already directly inspired a research team to develop and evaluate a similar IVD-based educational resource on young people and marijuana use for British Columbia, Canada, entitled Cycles (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada). 95 Consequently, the model of intervention development reported in this report and elsewhere2 is presented not as an ideal, but as an exemplar that other researchers might utilise, modify and improve.

Chapter 4 Developing and evaluating the questionnaire

Introduction

The study endeavoured to conduct a qualitative and quantitative validation of a questionnaire developed for the study to ensure its reliability and acceptability to participants. The questionnaire incorporated validated questions from the Sexual Health And RElationships (SHARE) questionnaires18 and items from a number of standardised measures to provide broad estimates of effect size and the feasibility and acceptability of the questions. The measures were chosen because the constructs they measure map closely to the theoretical framework underpinning the intervention (theory of planned behaviour; see Chapter 3) and they are widely used measures with robust reliability and validity (see Appendix 6). The questionnaire also incorporated a measure of intention to avoid UTP, developed as part of the research process (see Feasibility study below). A prior intention in relation to development was that the questionnaire should aim to take no longer than 30 minutes to complete, as this is the average length of RSE lessons in NI. Effort was made to ensure that the study team consulted with the sexual health and education expert members of the project Stakeholders Group and end users who are members of the Trial Steering Group (see Chapter 1) regarding the acceptability of the questions in the long version of the instrument. The structure of the chapter will describe the following stages in development and evaluation.

Pilot study

Rationale

A key outcome of this study was to pilot test the feasibility, usability and acceptability of providing demographic data and answering questions measuring the proposed primary and secondary outcomes of a future Phase III trial (see Chapter 6), that is, sexual behaviour data, including engagement in sexual intercourse, contraception use and diagnosis of STIs; data regarding knowledge, attitude, skills and intentions relating to avoiding UTP; and data on socioeconomic status (SES). The pilot study was not intended to assess the design and usability of the format of the questionnaire itself.

Methods

Unlike the finalised version of the questionnaire (for the feasibility study), the pilot version was of a basic format using the SurveyMonkey™ (Palo Alto, CA, USA) platform as the feasibility trial website was still in design.

To pilot test the questionnaire prior to the beginning of the feasibility trial, a school was approached that had been identified as willing to use the questionnaire, through prior liaison, with 50–60 of their Year 11 students (male and female, aged 14–15 years), who had proactively volunteered. In order to facilitate completing the questionnaire online, the Year 11 students were spilt into two groups across two different computer rooms and a researcher and a Learning for Life and Work (LLW) curriculum teacher (see Appendix 7) were present at all times in both groups. The session lasted for 1 hour. The data were analysed quantitatively by use of descriptive statistics and analysis of the reliability and spread of the scales.

Qualitative analysis was also made possible via focus group methodology. Focus group interviews are used extensively within social sciences to elicit information, perceptions, beliefs and attitudes. The group dynamic allows for a more natural conversational style rather than a traditional rigid interview technique. Researchers often use this technique to engage the end user in instrument design. Pupils who had completed the questionnaire were asked to participate in the focus group session regarding the acceptability and feasibility of the questions. These interviews lasted for 25 minutes. The students gathered around in a circle and the discussion was audio-recorded to facilitate note taking at a later stage. To begin with, the researchers reminded the students of the purpose (i.e. to find out what they thought about the questionnaire and not to be afraid of giving their honest opinions). The researchers also went over some ground rules, following the Respect, Involvement, Confidentiality, Equality (RICE) rules below:

R: Respect for an individual’s contributions, which we can demonstrate by listening to one another’s views.

I: Involvement in the discussions and activities.

C: Confidentiality – we are not going to talk about our own personal/individual stories but we can talk about relationships in general.

E: Equality – we want to acknowledge that everyone’s experience and opinions are equally valid.

The questions asked during the course of the cognitive interviews are listed below.

-

Would you prefer to complete the questionnaire on the computer or on paper?

-

What did you think about the length of the questionnaire?

-

What did you find useful or interesting about the questionnaire?

-

What did you find difficult or confusing about the questionnaire?

-

Is there anything that you think should be removed from the questionnaire?

-

When you talk about these issues with your friends what terms do you tend to use?

-

I have some specific terms that I wanted to check your understanding of. Ask what would that mean to you? Do you think there are some people your age who would not understand what it meant?

For invitation letters, information sheets and consent forms for schools, teachers, parents/guardians and pupils regarding questionnaire development, see Appendix 2. For the focus group topic guide, see Appendix 3.

Results

The participating school was a grant-maintained integrated co-educational secondary school (which did not go on to be involved in the feasibility trial). The school was located in an urban area and 17.8% of its students were eligible for free school meals. In total, 38 students (mean age of 14.72 years) agreed to take part (in two rooms containing 22 and 16 pupils, respectively), provided parental consent and completed the questionnaire.

Quantitative analyses

The estimated time taken to complete the questionnaire was 40 minutes; the actual time taken was around 25 minutes, including time taken to log in. The first section contained sociodemographic questions. The sample of respondents comprised 55% male and 45% female students and was spilt between 14- and 15-year-olds (26% and 68%, respectively). All students completed these questions, although two incorrectly inputted the date of the pilot study instead of their date of birth. Owing to this error, the online questionnaire was developed to bring up an error message if the year of birth does not equate to a Year 11 student. Sixteen students skipped the question that asked them to write in their postcode. As this information is important for a check to ensure that questionnaires can be correctly linked across the trial and potentially used for gathering multiple deprivation score, it was necessary to keep this in but it was accompanied with more explanation as to why this information was being collected. One question asked about the educational achievement of the respondent’s mother and father (or guardian) and was broken down into six questions asking specifically about General Certificates of Secondary Education (GCSEs), Advanced levels (A levels), degrees, apprenticeships, diplomas or no qualifications. Five participants skipped these questions and 18 did not know the answer. It was therefore decided to incorporate these questions into a single item referring to highest achieved qualification.

Owing to limited variation in responses received to the categorical tick box responses for the question ‘Whose responsibility is it to prevent unintended pregnancy?’, it was decided to change the response format of the question to the following visual analogue scale (Figure 3), with the following instructions: put an X on the line below to show how much responsibility you think boys and girls should have. For example, if you think that girls have more responsibility than boys, put an X on the line closer to girl; if you think that boys have more responsibility than girls, put an X on the line closer to boy; if you think that boys and girls should have equal responsibility, put an X in the middle of the line.

FIGURE 3.

Whose responsibility is it to prevent unintended pregnancy? A visual analogue scale.

Only 14% (five participants) of the sample said that they had experienced penetrative sex and only three answered the question regarding their age at which they first had sex, which was 15 years. When asked how many times they had had sex, two participants responded that they had had sex once; however, one participant said that they had had sex 30 times. It could be likely that they have been sexually active 30 times in the past but it could also be the case that this may have been an error and was perhaps meant to say ‘three’. To minimise this type of error and therefore to ensure that we could correctly interpret the data, it was decided to use fixed-category responses rather than free responses.

As the pilot study sought to determine participants’ level of comfort in answering potentially personal questions about a sensitive topic, the question ‘how comfortable do you feel in answering these questions?’ was added to the pilot questionnaire to assess this. Most participants felt comfortable answering all or most of the questions (n = 18), but some did report experiencing discomfort (n = 7).

Reliability and spread of pilot results

The decision to include or exclude scales or items was based on internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha), and the overall variability of the data produced (standard deviation). Those values > 0.70 were considered acceptable (Table 1). The internal consistency for the Sexual Stereotyping scale did not meet the threshold; this measure was included because it produces a high degree of variability in the data. This was replaced by the Male Role Attitude scale instead, which can be used by both sexes. The attitude items were excluded owing to their unacceptable levels of internal consistency and low degree of variability.

| Measurement scales or knowledge items | Cronbach’s alpha | Number of items | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexual Self-Efficacy | 0.922 | 13 | 110.8 | 11.7 |

| 2. Intentions to Avoid Teenage Pregnancy | 0.869 | 16 | 127.4 | 18.0 |

| 3a. Comfort Communicating about Sex (boys) | 0.812 | 6 | 84.0 | 25.7 |

| 3b. Comfort Communicating about Sex (girls) | 0.721 | 6 | 88.2 | 23.0 |

| 4. Costs of Unintended Pregnancy | 0.699 | 6 | 75.2 | 17.5 |

| 5. Sexual Stereotyping | 0.611 | 11 | 59.7 | 22.8 |

| 6. Attitudes | 0.364 | 4 | 56.5 | 4.4 |

The knowledge items (Table 2) employed a true/false response format rendering a check on internal consistency inadvisable. However, closer examination of the individual items revealed that some were producing ceiling effects, indicating that the questions were too obvious. A decision was made to exclude items 2, 4, 9 and 10 and to retain all other items.

| Knowledge items | True, n (%) | False, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Washing the vagina after penetrative sex will help to prevent pregnancy (false) | 12 (31.6) | 25 (65.8) |

| 2. A girl cannot get pregnant the first time she has penetrative sex (false) | 7 (18.4) | 28 (73.7) |

| 3. A girl can get pregnant if the boy withdraws his penis (pulls out) before ejaculation (coming) (true) | 22 (57.9) | 15 (39.5) |

| 4. When a teenage boy and girl have a baby together, they will likely get married to each other eventually (false) | 7 (18.4) | 30 (78.9) |

| 5. Contraception (when used correctly) provides as much protection against pregnancy as not having sex (false) | 22 (57.9) | 15 (39.5) |

| 6. The rhythm method (only having sex during the few days before and after a woman’s period) is as safe as using a condom in preventing pregnancy (false) | 18 (47.4) | 18 (47.4) |

| 7. When teenagers have penetrative sex for the first time, the majority of them use condoms (false) | 14 (36.8) | 22 (57.9) |

| 8. Teenage males can seek advice from pregnancy counsellors (true) | 20 (52.6) | 16 (42.1) |

| 9. An advantage of using condoms is that they help prevent sexually transmitted diseases (true) | 33 (86.8) | 2 (5.3) |

| 10. An advantage of using condoms is that they can be bought in shops and chemists by either boys or girls (true) | 35 (92.1) | 1 (2.6) |

| 11. More than half of all teenagers in Northern Ireland have had penetrative sex by the time they are 16 (false) | 31 (81.6) | 5 (13.2) |

The Cost of Unintended Pregnancy scale had an acceptable level of internal consistency (α = 0.699; see Table 7); however, on account of the three-point Likert scale, it produced very little variability in participant responses (Table 3). A decision was made to exclude the scale on this basis.

| Costs of unintended pregnancy (α = 0.699) | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Teenagers avoid pregnancy because their parents would not approve | 1.80 | 0.871 |

| 2. Teenagers avoid pregnancy because they are not ready to be a parent | 2.46 | 0.373 |

| 3. Teenagers avoid pregnancy because having to decide whether to keep the baby or not might be a very difficult decision | 2.31 | 0.398 |

| 4. Teenagers avoid pregnancy because having a baby might really change their life | 2.51 | 0.375 |

| 5. Teenagers avoid pregnancy because it might mess up their future plans for college, school or a career | 2.51 | 0.316 |

| 6. Teenagers avoid pregnancy because their friends would not approve | 1.32 | 0.771 |

Qualitative analysis

All 38 pupils who answered the questionnaire participated. The questions asked during the course of the cognitive interviews are listed below, along with the responses given by the students.

-

Would you prefer to complete the questionnaire on the computer or on paper?

In this pilot, all pupils completed the questionnaire using the online SurveyMonkey™ format. However, they were asked if they would prefer to do this on paper or computer. There was general agreement with the students that they would prefer to do this online, that it would be more confidential.

because once you click the button it is away

-

What did you think about the length of the questionnaire?

Most said it was too long. Others said:

‘too much reading’; ‘frustrating’; ‘it was all right’; ‘too personal’; ‘I thought it was all right’; ‘very detailed’; ‘too many details in some parts’.

One student noted that:

it was shorter than the other one we did.

-

What did you find useful or interesting about the questionnaire?

Responses to this varied:

‘not really’; ‘it was all interesting’; ‘it was useful’.

One student felt that the questionnaire would help give teenagers the opportunity to think through issues:

it’s a good mind set for teenagers – gives them an idea of what sex is actually like and what pregnancy can do. It can ruin your life if you want to have a scholarship or go to college or something like that.

As this was a pilot and not part of the trial, students were given an answer sheet to the true and false knowledge questions after they had finished. They really liked getting this information, although this would not be offered to students in the main trial.

-

What did you find difficult or confusing about the questionnaire?

The length of the questionnaire was mentioned as a disadvantage:

just the number of questions that kept coming up and up after every single question.

There was also confusion over the difference between likely and somewhat likely. Other comments made included:

‘some didn’t make sense’; ‘it was weird’.

It was not possible to clarify the meaning of these terms in either case but the researcher present thought that they were trying to say that they could not understand why some of the questions were part of a questionnaire about UTP.

-

Is there anything you think should be removed from the questionnaire?

Both groups agreed that asking for the postcode should be removed and queried why it was in there.

I don’t like giving my postcode.

Some pupils thought that the question ‘have you ever had sex’ should be removed. One pupil said this was too personal; however, this point of view did not garner much agreement from others. Another student felt that the question relating to family finance was also too personal to ask.

I didn’t understand why there were questions about your financial circumstances. Just the financial stuff is a bit personal.

Some said that the set up with everyone sitting so close made them feel uncomfortable and others said that they did not mind. They suggested that we could make it more private by asking them to do it at home (some said they would not feel comfortable doing this), one suggested a sheet of paper, talk to each pupil privately, interview them (others disagreed with this); do it on your phone.

-

When you talk about these issues with your friends what terms do you tend to use?

It was reported that they would not use the terminology in the questionnaire when talking with friends. The discussion then moved to a discussion of what terms they did not understand, which were stated to be ‘legal highs’, ‘sexual advance’ and ‘rubber Johnny’.

-

I have some specific terms that I wanted to check your understanding of. Ask what would that mean to you? Do you think there are some people your age who would not understand what it meant?

Feedback on participants understanding of key terms used is detailed in Table 4.

| Phrase for clarification | Student response to phrase | Altered phrase |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Future sexual encounter’ | No problem | – |

| ‘Resist peer influence’ | No problem | – |

| ‘In a relationship’ | No problem | – |

| ‘Sexual advance’ | Did not understand | Added a definition: can be used to describe an attempt by one person to gain sexual favour with another (also called ‘come on to’ or ‘pull’) |

| ‘A sexual encounter’ | No problem | – |

| ‘Feeling obliged to have sex’ | Did not understand | Changed to ‘feeling you have to’ |

| ‘Control your sex urges’ | No problem | – |

| ‘Peers’ | No problem | – |

| ‘Most women cannot be trusted’ | No problem | – |

| ‘dating relationship’ | Outdated | Changed to ‘boyfriend/girlfriend’ |

| ‘manipulate’ | Did not understand | Added a definition: to control or influence (a person or situation) cleverly or dishonestly |

| ‘highly regarded’ | Did not understand | Change |

| ‘easy/sexually easy’ | Had some problems | Added a definition: can mean someone who agrees to have sexual intercourse with others without difficulty |

| ‘multiple sexual partners’ | No problem | – |

| ‘sexually active’ | Did not understand | Added a definition: can be used to describe a person who participates in sexual intercourse |

| ‘sexual exploits’ | Did not understand | Added a definition: the people you have had sexual intercourse with in the past |

| ‘sexuality’ | Had some problems | Added a definition: can be used to describe a person’s sexuality or preference (e.g. whether you are sexually attracted to males, females, both males and females, or have never been attracted to anyone) |

| ‘Other drugs’ | Had difficulties thinking about other types of drugs | Added: ‘e.g. ecstasy, magic mushrooms, LSD, cocaine, heroin’ |

Observations made during questionnaire completion

Although there were two groups completing the questionnaire independently in different rooms, the two researchers administering the questionnaire observed similar issues. The major difficulty observed by both researchers was that friends sat side by side and many openly and audibly discussed their answers and the meanings of words/questions/response sets. This was even more of an issue in the group that had the least personal space. To combat this the possibility to play music via the internet to keep the students focused and minimise the opportunity for discussion was examined. Ultimately this would not be possible, owing to issues such as the selection of music, the availability of headphones in schools and the ability of the software. Emphasis was placed at the beginning of the questionnaire that this questionnaire addresses private and sensitive issues and that respondents should remember to respect each other’s privacy when completing the questionnaire and not to discuss their answers. Other issues that were noted during the observations were:

-

One female, in reference to the Intentions scale, said that she could not answer the questions because she felt that they were too personal. The researcher reminded her and the rest of the group that they could skip any questions they were uncomfortable answering. A decision was made to emphasise this more clearly in writing on the questionnaire and in the verbal introduction.

-

Some queried the Likert-scale responses on the Intentions scale:

What’s the difference between likely and somewhat likely?

-

Other questions or comments included:

‘what is penetrative sex?’; ‘what is a legal high?’; ‘what is contraception?’; ‘I don’t remember my post code’.

-

One male said that he did not have a father so should he put ‘not sure’ in response to the paternal education question. It was decided that the questionnaire employed in the feasibility trial should include a ‘not applicable’ option.

Summary of changes made to questionnaire for feasibility study

In conclusion, the Year 11 students who assisted with the pilot development stage of the questionnaire were mostly positive about their experiences in completing the questionnaire. Feedback on their understanding of key terms used was critical to ensure that future participants can understand what is being asked and also to enable reliable estimates of effects. A number of changes were made to the questionnaire in light of this work, which are summarised below.

-

changes made to terminology used

-

‘hover over’ definitions used on terms on the online questionnaire and a separate definitions page on the paper version of the questionnaire

-

response format from one questionnaire changed to a visual analogue scale

-

more description about a Likert scale and how to answer them

-

removed Cost of Unintended Pregnancy scale

-

the knowledge items two, four, nine and 10 were removed

-

changed ‘How many times have you had sex?’ question from free response to fixed-category tick boxes

-

included ‘not applicable’ option to question on paternal and maternal education?

-

greater explanation of why we are asking for postcodes

-

inserted reminders in the online questionnaire if any items are left blank unintentionally

-

validity checks for date of birth inserted into online questionnaire

-

explained why the questionnaire contains questions relating to parental education and finances

-

broke up how longer scales are displayed – no more than six questions per page

-

added progress bar to online version.

Feasibility study

Further exploration and analyses of how well the questionnaire performed after baseline data collection, after follow-up 1 (second data collection wave) and post trial after follow-up 2 (third wave of data collection) were conducted. The following sections detail this, in addition to any further proposed changes thought necessary to bring forward to a main trial.

Rationale

The aim was to further refine the survey instruments by assessing their acceptability and usability among the pupils now completing them within the setting of the feasibility study.

Methods

An electronic version of the questionnaire was developed post pilot and offered to the schools as an alternative to the use of paper-based questionnaires.

The data were analysed quantitatively following baseline data collection, by use of descriptive statistics and analysis of the reliability and spread of the scales. The research team also made minor amendments to the survey instruments to aid user understanding after each data collection wave; these changes were based on analysis of responses and qualitative experiences of watching the pupils complete them.

As with the pilot study, qualitative analysis was also made possible via focus group methodology. This was conducted post trial. Two separate focus groups were conducted within two of the control group schools. The focus groups were audio-recorded to ease transcription and lasted no longer than 45 minutes. Soft drinks and snacks were provided and the interviewer tried to create a relaxed atmosphere to facilitate a discussion in which everyone had a voice. The focus groups were timed to coincide with the end of data collection for the feasibility trial and occurred either directly after data collection or within a few days of this. This timing ensured that issues the participants may have had and the survey instrument itself would be fresh in their minds. Although they were already familiar, sample questionnaires were given out to all participants so that they could examine it in detail.

Participants were given an overview of what a focus group is as well as a topic guide (see Appendix 3). They were reminded that although they would be discussing the questionnaire, for example, whether the questions were easy or difficult, they would not be asked to discuss their own personal answers. For relevant invitation letters, information sheets and consent forms for schools, teachers, parents/guardians and pupils, see Appendix 2.

The focus group schedule (see Appendix 3) was divided into five topics: questionnaire instructions, questionnaire design, terminology used, individual questions and other issues.

Results

Quantitative analysis

Baseline data collection was conducted during December and November 2014 in eight schools with 831 pupils (mean age 14.45 years) completing the questionnaire across the eight participating schools. Three of the eight schools elected to use the electronic questionnaire at baseline data collection. The paper version of the questionnaire only was available for use at follow-up 1 and 2 data collection owing to technical software problems.

Analysis of demographic variables

Table 5 details the questions in the ‘about yourself’ and ‘your family’ sections. Within this section we tried to assess social class in a variety of ways. A surprisingly small percentage of pupils aspired to attend university or college upon leaving formal schooling, suggesting that the wording of this question might require amendment. The majority of girls and boys categorised themselves as heterosexual. There was a range of living arrangements reported and a wide range of responses to respondents families’ financial situation, although ‘average’ was the most common answer.

| Survey questions | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Future aspirations, n (%) | ||

| At college/uni full-time | 63 (15.1) | 46 (11.4) |

| At college/uni and working part-time | 32 (7.7) | 54 (13.4) |

| Working full-time | 186 (44.7) | 180 (44.7) |

| Working part-time | 106 (25.5) | 90 (22.3) |

| On a training scheme | 15 (3.6) | 19 (4.7) |

| Unemployed | 4 (1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 10 (2.4) | 13 (3.2) |

| Sexuality, n (%) | ||

| Female | ||

| I have never felt sexually attracted to anyone | 32 (18.3) | 24 (12.1) |

| Only to males, and never to females | 132 (75.4) | 165 (82.9) |

| More often to males and at least once to a female | 9 (5.1) | 8 (4.0) |

| About equally often to females and to males | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.0) |

| More often to females and at least once to a male | – | – |

| Only to females, never to males | – | – |

| Male | ||

| I have never felt sexually attracted to anyone | 13 (5.9) | 6 (3.0) |

| Only to males, and never to females | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| More often to males and at least once to a female | – | 2 (1.0) |

| About equally often to females and to males | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| More often to females and at least once to a male | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| Only to females, never to males | 204 (92.7) | 184 (92.0) |

| Live with, n (%) | ||

| Both parents in same household | 272 (65.2) | 297 (72.4) |

| Mother only | 81 (19.4) | 65 (15.9) |

| Father only | 8 (1.9) | 7 (1.7) |

| Mother and partner or stepfather | 30 (7.2) | 28 (6.8) |

| Father and partner or stepmother | 9 (2.2) | 2 (0.5) |

| Grandparents only | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Foster care | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Others | 14 (3.4) | 9 (2.2) |

| Well off, n (%) | ||

| Not at all well off | 2 (0.48) | 2 (0.5) |

| Not very well off | 11 (2.7) | 30 (7.4) |

| Average | 198 (47.7) | 189 (46.9) |

| Well off | 147 (45.4) | 140 (34.7) |

| Very well off | 35 (8.4) | 18 (4.5) |

| I do not know | 22 (5.3) | 24 (6.0) |

Analysis of primary and secondary outcomes

Sixty pupils (7%) surveyed reported that they had had sex and the average age at which they had sex for the first time was 13.7 years in the intervention group and 14 years in the control group. In the ‘Age First Time’ question one pupil entered 20 and another entered 21. As these are impossible values given the age of the pupils filling in the questionnaire, they were excluded from the summary calculations for this question. Of those who reported ever having sex, the most common number of partners was one; however, 42% reported having had more than one partner. A complete breakdown of these responses can be viewed in Table 6.

| Survey questions | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Ever had sex, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 35 (8.5) | 25 (6.4) |

| No | 376 (91.5) | 367 (93.6) |

| Age first time | 13.7 (0.184) n = 34 | 14 (0.096) n = 20 |

| How many people have you ever had sex with, n (%) | ||

| One | 20 (58.8) | 13 (54.2) |

| Between 2 and 5 | 7 (20.6) | 7 (29.2) |

| Between 6 and 10 | 4 (11.8) | 4 (16.7) |

| More than 10 | 3 (8.8) | – |

| Number of times had sex in past 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Once | 17 (53.1) | 5 (22.7) |

| Between 2 and 5 times | 11 (34.4) | 7 (31.8) |

| Between 6 and 10 times | 2 (6.3) | 5 (22.7) |

| Between 11 and 20 times | – | 1 (4.6) |

| More than 20 times | 2 (6.3) | 4 (18.2) |

| When last had sex, n (%) | ||

| < week ago | 5 (14.3) | 7 (29.2) |

| > week ago but < month ago | 9 (25.7) | 7 (29.2) |

| 1–6 months ago | 16 (45.7) | 7 (29.2) |

| > 6 months ago | 5 (14.3) | 3 (12.5) |

| Number of sexual partners in past 6 months (girls), n (%) | ||

| One | 5 (71.4) | 6 (85.7) |

| Between 2 and 5 | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) |

| Between 6 and 10 | – | – |

| More than 10 | – | – |

| Number of sexual partners in last 6 months (boys), n (%) | ||

| One | 12 (60.0) | 9 (69.2) |

| Between 2 and 5 | 6 (30.0) | 2 (15.4) |

| Between 6 and 10 | – | 2 (15.4) |

| More than 10 | 2 (10.0) | – |

| Had sex when you did not want to in past 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 7 (21.9) | 7 (28.0) |

| No | 25 (78.1) | 18 (72.0) |

| Had sex when you did not want to in past 6 months (girls), n (%) | ||

| Yes | 1 (11.1) | – |

| No | 8 (88.9) | 7 (100) |

| Had sex when you did not want to in past 6 months (boys), n (%) | ||

| Yes | 6 (26.1) | 7 (38.9) |

| No | 17 (73.9) | 11 (61.1) |

Table 7 shows the responses to the contraception questions. Fewer than half of those participants who reported sexual activity (either in the intervention or control group) stated that they always used contraception (48%). Twenty-two pupils reported that they had been unprotected in the last sexual encounter they had had. They reported using a range of contraception types, the most common of which was condoms. Twenty-six (45%) reported that they had sex without using a condom at least once in the past 6 months.

| Survey questions | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| How often has sex been protected, n (%) | ||

| Never | 5 (14.7) | 3 (13) |

| Not very often | 4 (11.8) | 4 (17.4) |

| About half the time | 3 (8.8) | – |

| Most of the time | 3 (8.8) | 6 (26.1) |

| Always | 19 (55.9) | 10 (43.5) |

| Contraception used the last time you had sex, n (%) | ||

| None for me, do not know about partner | 8 (22.9) | 3 (12.0) |

| None for either of us | 5 (14.3) | 6 (24.0) |

| Yes | 22 (62.9) | 16 (64.0) |

| Type of contraception used the last time you had sexa | ||

| Pill, patch or vaginal ring | 5 | 5 |

| Condoms | 19 | 14 |

| Emergency contraceptive pill | 2 | 1 |

| Injection | 1 | – |

| Implant | – | – |

| Withdrawal method | 2 | – |

| Intrauterine device | – | – |

| Diaphragm/cap/spermicide | – | – |

| Natural family planning | – | 1 |

| Do not know name | – | – |

| Other | 1 | – |

| Number of times you had sex without a condom in past 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Never | 19 (57.6) | 13 (52.0) |

| Once | 4 (12.1) | 5 (20.0) |

| Between 2 and 5 times | 7 (21.2) | 4 (16.0) |

| Between 6 and 10 times | 2 (6.1) | 2 (8.0) |

| Between 11 and 20 times | 1 (3.0) | – |

| > 20 times | – | 1 (4.0) |