Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3005/07. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David Ogilvie, Richard Prins, Andy Jones, Hilary Thomson and Shona Hilton report additional funding from the Medical Research Council. David Ogilvie, Louise Foley, Richard Prins and Andy Jones report additional funding from the UK Clinical Research Collaboration. Andy Jones is a member of the Research Funding Board of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme. Nanette Mutrie reports additional funding from the NIHR.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Ogilvie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Urban regeneration and public health

A variety of urban regeneration initiatives have been pursued in recent decades, often driven by a view that promoting economic growth is key to improving the health and prosperity of deprived urban populations. Urban regeneration refers to myriad activities, including housing improvements, broader changes to neighbourhood public spaces and other forms of inward investment. 1 The case for such interventions is consistent with a social ecological model of health in which economic conditions, as well as physical and social environments, are seen as important influences on the health and well-being of individuals and populations. 2–4 Research indicates that some forms of urban regeneration do indeed have the potential to improve the well-being of local residents. 5–7 However, the evidence that such initiatives have produced the economic or population health outcomes claimed for them in practice is far from conclusive, and different aspects of urban regeneration may have different effects. 8,9 Urban regeneration in deprived neighbourhoods may have further implications for health inequalities, as deprivation is itself associated with poorer health and well-being. 10,11 Previous regeneration projects have been associated with modest improvements in socioeconomic outcomes, but the effects were not larger than corresponding national trends. 8

Urban mobility, transport infrastructure and public health

One specific approach to improving access to employment, education and other opportunities involves increasing people’s mobility. However, the societal costs attributable to traffic congestion, poor air quality, physical inactivity, injuries, noise and other impacts of motor transport in English urban areas have been estimated at £40B per annum. 12 Furthermore, the benefits and harms of a pattern of mobility dominated by motor transport are inequitably distributed. Serious injuries to child cyclists and pedestrians are three and four times more frequent, respectively, in the most deprived areas of England than in the least deprived, and people without cars make fewer trips than those with cars, but travel 50% further on foot. 13,14 Less affluent groups or areas are therefore disadvantaged in terms of overall mobility and injury risk, although they may gain benefits from additional physical activity as a result.

Physical activity is important for health and well-being, and can help to prevent a wide range of non-communicable diseases,15 whereas sedentary behaviour is associated, independently of physical activity, with both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. 16–18 Physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour are particularly prevalent in more affluent countries; the UK data included in a recent global study suggest that 63% of the population is physically inactive,19 and other data suggest that British adults sit for an average of 5.5 hours per day. 20

Recently, research and policy attention has been drawn to the potential of active travel (walking or cycling for transport) to contribute to daily physical activity and to promote good health. 21–23 Active travel can become a habitual, sustainable part of everyday life, as well as having important co-benefits such as helping to limit carbon emissions through reduced reliance on motorised transport. 24 In tandem, reducing car use has been identified as an important policy objective because of the relationship between motor vehicle use and poor health via physical inactivity, air pollution and injuries from road traffic accidents. 25–27 Reducing car use has also been promoted on equity grounds. People from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to have access to motor vehicles, but deprived areas bear a disproportionate burden of traffic-related injuries and air pollution. 28 A population shift towards more sustainable transport offers a potentially winning combination of an increase in physical activity coupled with reductions in traffic congestion and use of fossil fuels, and is therefore increasingly regarded as desirable on public health, environmental and equity grounds. 29

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour are partly shaped by local physical environmental conditions, such as the availability of recreational facilities and infrastructural design. 4,30 Although cross-sectional studies indicate associations between features of the built environment and both physical activity31,32 and sedentary behaviour,33 there is little longitudinal evidence to show whether and how changing the environment changes these behaviours. In particular, in a series of systematic reviews, we have shown a lack of good evidence from intervention studies as regards how to achieve this;34–36 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance has drawn particular attention to a lack of robust controlled longitudinal studies of the behavioural impacts of environmental changes,37,38 and a House of Lords report has identified a specific need for more evidence on the effects of interventions on car use. 39

One particularly contentious type of intervention is the construction of new major roads. On the one hand, infrastructure projects of this kind may improve mobility, including improving (road) access to more distant recreational amenities, which may facilitate their use for physical activity40 and may contribute to the economic revival of local communities. On the other hand, they have the potential to degrade the local environment, contributing to a process of ‘deprivation amplification’41 in vulnerable communities and widening existing inequalities. Exposure to roads and traffic has been shown to contribute to noise disturbance and severance, whereby residents are separated from the amenities that they use (such as shops and parks) or their interpersonal networks and social contacts are disrupted. 42–44 Other studies indicate an association between noise disturbance from traffic45 or living in industrial areas characterised by noise disturbance and air pollution46 and poorer quality of life or well-being. Furthermore, providing new or improved major roads has been shown to increase traffic47 and may contribute to making sedentary travel by car a more attractive option,26 and more traffic in local streets may make it less safe and attractive for people to be physically active outdoors, thereby promoting increases in other more sedentary activities. 48 In contrast, a growing body of evidence suggests that changes to the environment such as traffic calming, charging road users and constructing routes for walking or cycling can be effective in promoting active travel. 37,49,50

Egan et al. 51 showed in a systematic review that new major roads in urban areas are associated with noise disturbance and severance effects. However, that review found no evidence for the effects on physical activity or health inequalities, and little evidence to support a common assertion that new roads reduce the incidence of injuries. In the decade since that systematic review was completed, we are not aware of any new longitudinal studies examining the effects of motorways on physical activity, sedentary behaviour or well-being in local residents.

The extension of the M74 motorway in Glasgow

The intersection between urban mobility, transport infrastructure and public health is exemplified in Glasgow, a conurbation characterised by extremes of affluence and deprivation.

A longstanding project to extend the 1960s urban motorway network was resurrected by the new Scottish Government following devolution in 1999. The new motorway was intended to relieve congestion on the M8, an existing motorway built in the 1960s, which traverses the city centre. It also formed part of a wider strategic initiative to regenerate the ‘Clyde Gateway’ area, and changes in the local built environment were not limited to motorway construction. As described in more detail in Chapter 2, Characterising the environmental changes and refining the study design, the core of the intervention comprised the construction of a new 5-mile, six-lane section of motorway, which is mostly elevated above ground and runs through a predominantly urban, deprived area of south-east Glasgow. This was associated with a variety of changes to the urban built environment, including the insertion of highly visible viaducts and embankments, as well as junctions and slip roads intersecting with local streets in residential areas; the realignment of feeder roads; and the redevelopment of former open space, the demolition of old housing stock and the construction of a new residential development on a brownfield site adjacent to one of the new motorway junctions.

Numerous health-related claims were made for and against the new motorway. It was claimed that the new motorway would relieve congestion, improve conditions for pedestrians and cyclists on local streets, reduce traffic noise and bring new local employment opportunities, helping to regenerate some of the most deprived and least healthy urban communities in Europe. Objectors claimed that the new motorway would largely benefit freight traffic and workers and other motorists from outside the local area, and would encourage car use, degrade the quality of the local environment, and reduce the safety and attractiveness of local routes for pedestrians and cyclists. We summarised these issues into contrasting narratives and articulated them as two equally valid, competing, testable, overarching hypotheses about the effects of the intervention, expressed in the form of vignettes of two alternative extreme cases, a ‘virtuous spiral’ and a ‘vicious spiral’ (Table 1). 52,53

| Virtuous spiral | Vicious spiral |

|---|---|

| The opening of the motorway encourages inward investment to the area, providing new local opportunities for work | The opening of the motorway displaces some local businesses, whose employees now have to travel further to work, and gives easier access between the motorway network and the local area |

| Traffic on local roads is reduced, which makes conditions more pleasant for pedestrians and cyclists, and encourages people to spend more time out and about on local streets | This increases traffic on local roads and encourages local people to travel further and by car, not just for work but also for shopping and leisure |

| Local businesses thrive | At the same time, the motorway and its junctions degrade the local environment, making conditions less pleasant or safe for people in their homes and for pedestrians and cyclists |

| People perceive the local environment to have more positive attributes | The combination of fewer people out and about on local streets and the tendency to travel further afield to amenities leads to a decline in local shops and other amenities, which reinforces the decline in the attractiveness of the area and the car-bound exodus in search of alternatives |

| Any noise or air pollution produced by the motorway is not noticed against the background of existing urban conditions | |

| The well-being of local people and opportunities for physical activity both increase |

An independent Public Local Inquiry (PLI) in 2003 considered the arguments for and against the construction project. The inquirers concluded that the claimed benefits were likely to be ‘ephemeral’ and that the new motorway ‘would be very likely to have very serious undesirable results’ for local communities, and, therefore, recommended against the proposal. 54 With this advice having been overruled by the government of the day, construction began in 2008 and the motorway was finally completed and opened to traffic on 28 June 2011 at an eventual cost of approximately £800M. The intervention was funded by a public-sector partnership comprising Transport Scotland, Glasgow City Council, South Lanarkshire Council and Renfrewshire Council, and was delivered by Interlink M74 Joint Venture, a consortium of civil engineering contractors.

The new motorway runs between Tradeston (close to Glasgow city centre) and Cambuslang (on the south-east edge of the city), passing through or adjacent to several established residential areas such as Govanhill, Toryglen and Rutherglen: some homes are < 50 m from the carriageway (Figure 1). The most affected neighbourhoods are among the most deprived in the UK, reflecting a local history of rapid deindustrialisation in the late twentieth century. Car ownership is low, and part of the route lies in the Shettleston constituency, which at the time of construction had the lowest life expectancy for males in Scotland (68.2 years): > 7 years below the national average.

FIGURE 1.

Route of the M74 extension. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2016.

Rationale and approach for the study

The opening of the M74 extension presented an opportunity to examine the health impacts of a new major road infrastructure in a natural experimental study, using the developing situation in Glasgow to understand more about the positive and negative effects of the changes to the urban landscape from which more general lessons could be learned for the planning and implementation of future initiatives. In anticipation of the planned motorway extension, a baseline cross-sectional study was carried out in 2005. This study included a postal survey of travel and physical activity behaviour, neighbourhood perceptions and general health and well-being in adult residents of the intervention area, and two matched control areas in Glasgow and a preliminary qualitative interview study. Contact was maintained with the original study participants by means of annual mailings, and the baseline study produced a Doctor of Philosophy thesis,55 four scientific publications,52,56–58 and hypotheses and research methods to inform the follow-up study described in this report. Key baseline findings included the observations that access to local amenities was the most significant quantitative local environmental correlate of active travel;57 that the new motorway might cause inequitable psychological or physical severance of routes to those amenities, for example by reducing the perceived safety of walking routes to local shops;58 and that people might not use local walking routes or destinations such as parks and shops if these were considered undesirable, unsafe or ‘not for them’. 58 The follow-up study built on our previously collected baseline data to examine if and how a major set of changes to the urban environment affected key aspects of the health and health-related behaviour of the local population.

It is not easy to parse urban regeneration ‘interventions’ into their components and establish causal relationships with behaviour or health, because such interventions are typically both complex and ill-suited to evaluation using randomised study designs. However, they can be seen as natural experiments, that is, interventions that are not designed for research purposes but that can nevertheless be used to evaluate the population health impacts of environmental or policy changes over time. 59 Interventions of this kind are often not primarily intended to improve health, although health-related claims were implicit in the case of the M74 extension and subsequently aired explicitly by both proponents and opponents of the project (see Table 1). The indirect or implicit nature of these health effects poses a problem if evaluation research is understood in simple terms of ‘what works?’ or, in other words, whether or not an intervention has achieved its stated aims and objectives. In this context, it may be at least as important for public health researchers to focus on investigating indirect or unintended effects on aspects of health and well-being of particular interest. No research study could conceivably evaluate effects across all possible domains identified in the public discourse about the motorway. We therefore chose to focus on the comparatively under-researched questions of the effects of this type of major change to the urban landscape on active travel, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, road traffic accidents and well-being, while acknowledging the potential importance of other effects – notably on employment and the economy – that were beyond the scope of our study.

Main research questions

The aims of the study were to address the following primary research questions:

-

What are the individual, household and population impacts of a major change in the urban built environment on travel and activity patterns, road traffic accidents and well-being?

-

How are these impacts distributed between different socioeconomic groups?

The study also aimed to address the following secondary research questions:

-

What environmental changes have occurred in practice?

-

How are the effects of the environmental changes experienced by local residents?

-

How are any changes in behaviour or well-being mediated and enacted at individual and household levels?

This report

This report summarises a considerable body of research, some of which has already been published – or submitted or prepared for publication – in other open-access academic journals, and to which an extensive study team has contributed in various ways (see Acknowledgements). Further details of the methods and results of the various analyses summarised in the report can be found in these publications, which are referred to in the text and are available via the Centre for Diet and Research Activity (CEDAR) study website (www.cedar.iph.cam.ac.uk/research/directory/traffic-health-glasgow). 60

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

Introduction

In this chapter, we describe the development of our final study design and methods. We begin by describing the key geographical areas, populations and outcomes of interest, after which we outline our specific study objectives and overall study design. We then describe the methods and results of a series of activities to characterise the specific environmental changes that had been proposed and that actually occurred, along with discussions and interviews with relevant stakeholders to develop a preliminary understanding of issues currently of concern in local communities, including views about the motorway’s environmental and economic impacts. Together, these activities laid the groundwork for the final, realised study design. The remainder of the chapter is devoted to describing the sampling and data collection methods, the derivation of variables and the overall approach to analysis.

Overall research design

In this section we describe the population and outcomes of interest, the study objectives and the overarching study design and logic model.

Study population and outcomes

To address the questions outlined in Chapter 1, Main research questions, we conducted a mixed-method longitudinal study with the elements outlined in Table 2.

| Study design element | Operationalisation |

|---|---|

| Population | Householders living close to the route of a new urban motorway |

| Intervention | Construction of a new urban motorway |

| Comparator | Householders not living close to the route of a new urban motorway |

| Primary outcomes | (1) Walking for transport, (2) cycling for transport, (3) car use and (4) MVPA within the neighbourhood |

| Secondary outcomes | (1) Road traffic casualties, (2) perceptions of the neighbourhood environment, (3) well-being and (4) overall MVPA |

We combined this with the analysis of routinely available population data on road traffic accidents and travel behaviour.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were:

-

to characterise the context, content and implementation of the intervention by means of an environmental survey

-

to follow up a cohort of residents of the intervention and control areas had who previously responded to a postal survey at baseline [2005; time point 1 (T1)]

-

to draw new repeat cross-sectional samples of residents of the intervention and control areas for a postal survey at follow-up [2013; time point 2 (T2)]

-

to objectively measure the travel and activity patterns of a subsample of survey participants

-

to estimate changes and differences in the primary and secondary outcome measures between the intervention and control areas, and by level of exposure to environmental changes within those areas

-

to examine the extent to which any changes in outcomes were mediated by changes in perceptions of the neighbourhood environment

-

to examine the extent to which any changes in behavioural outcomes were associated with changes in well-being

-

to interview a further subsample of participants to elicit how the effects of the environmental changes were experienced by local residents and how any changes in behaviour or well-being were mediated and enacted at individual and household level

-

to examine changes in the incidence and sociospatial distribution of road traffic accidents on the road network

-

to explore trends and spatial variation in travel behaviour using existing national population data sets

-

to examine the extent to which the results of the different analyses supported either of the two competing overall hypotheses regarding the cumulative effects of the intervention (see Table 1).

Study design

The study used a combination of quantitative [cohort, cross-sectional, repeat cross-sectional and interrupted time series (ITS)] and qualitative (documentary analysis and interview) research methods to evaluate both individual- and population-level changes in health and health-related behaviour, and to develop a more in-depth understanding of how these changes were experienced and brought about.

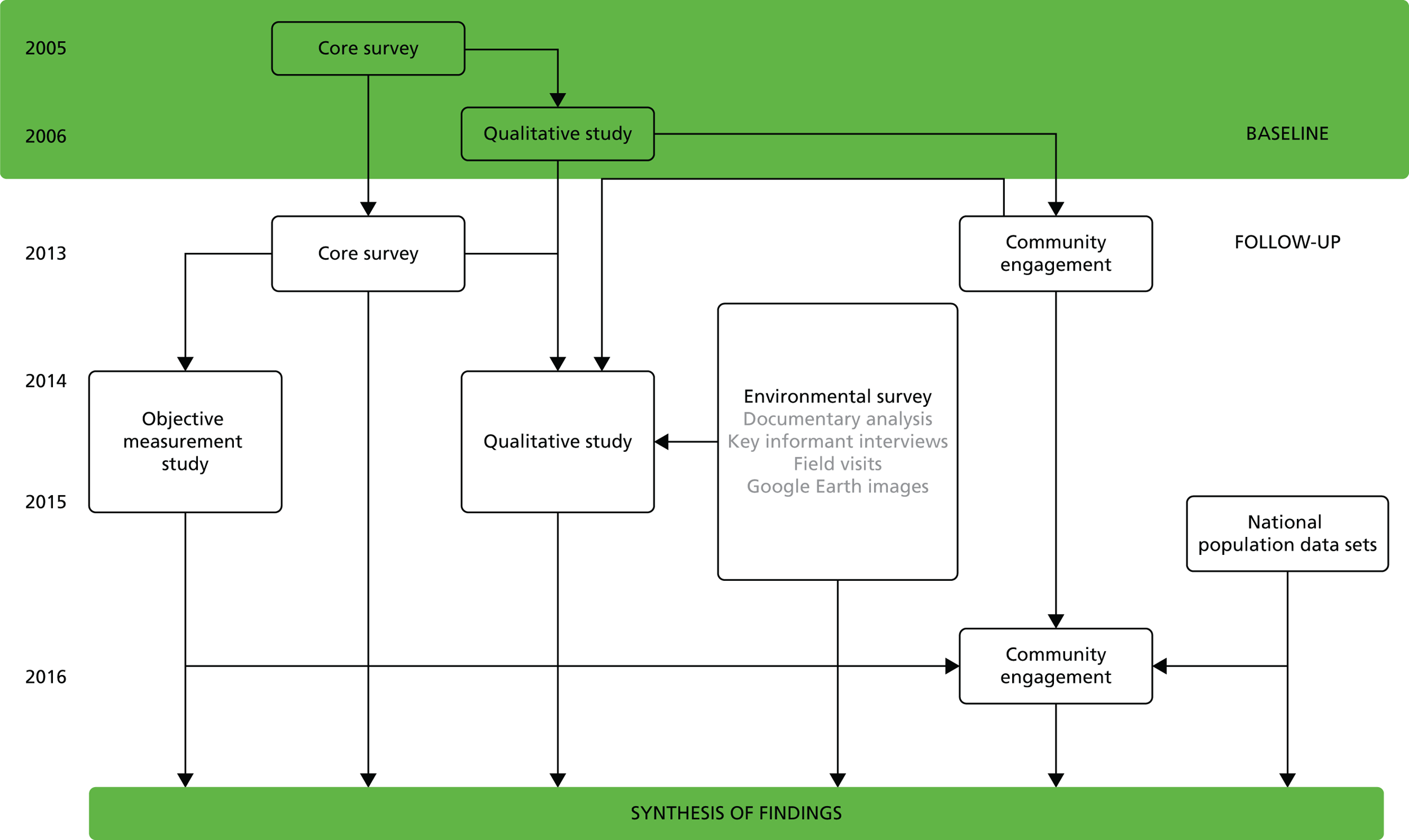

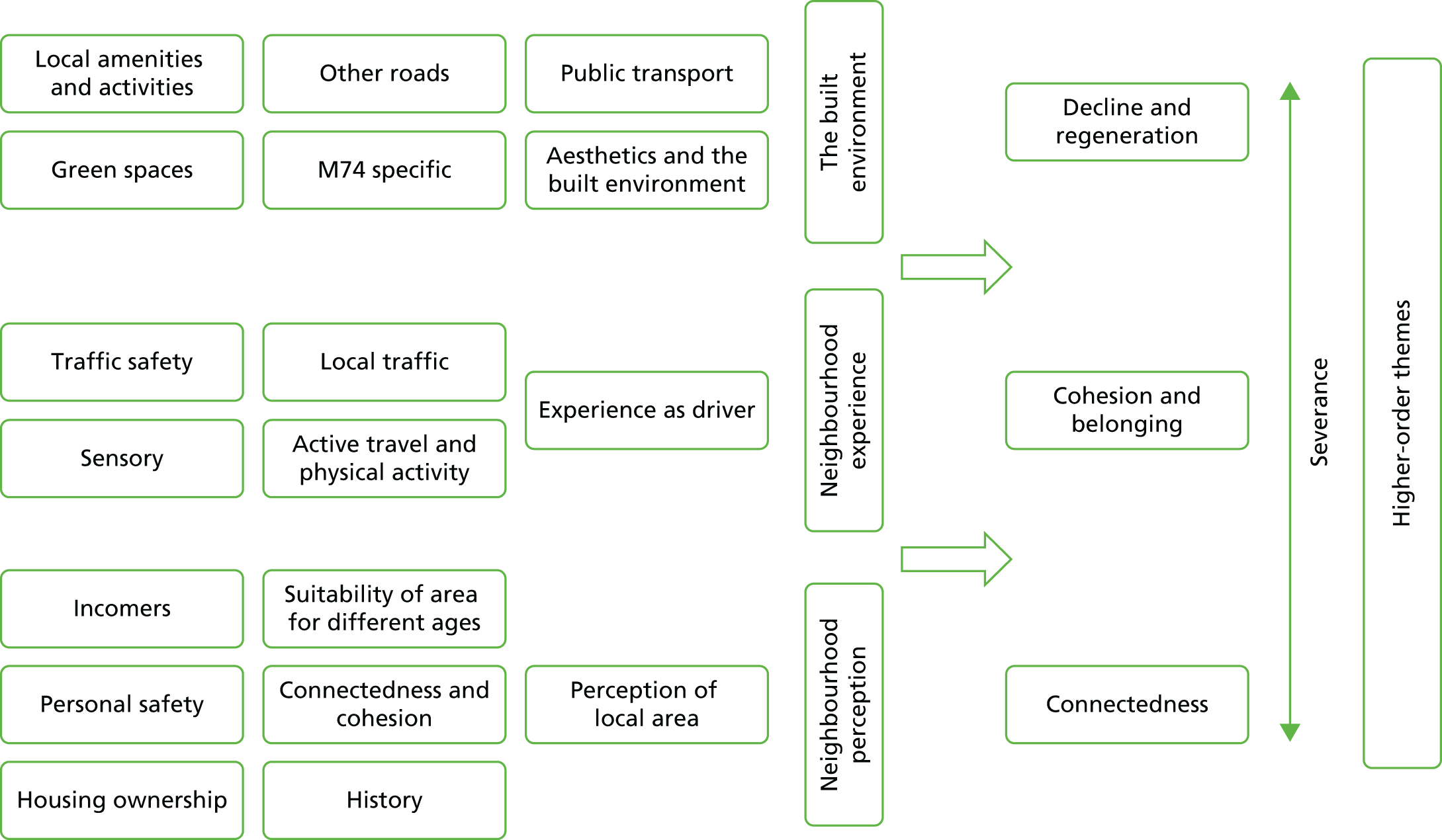

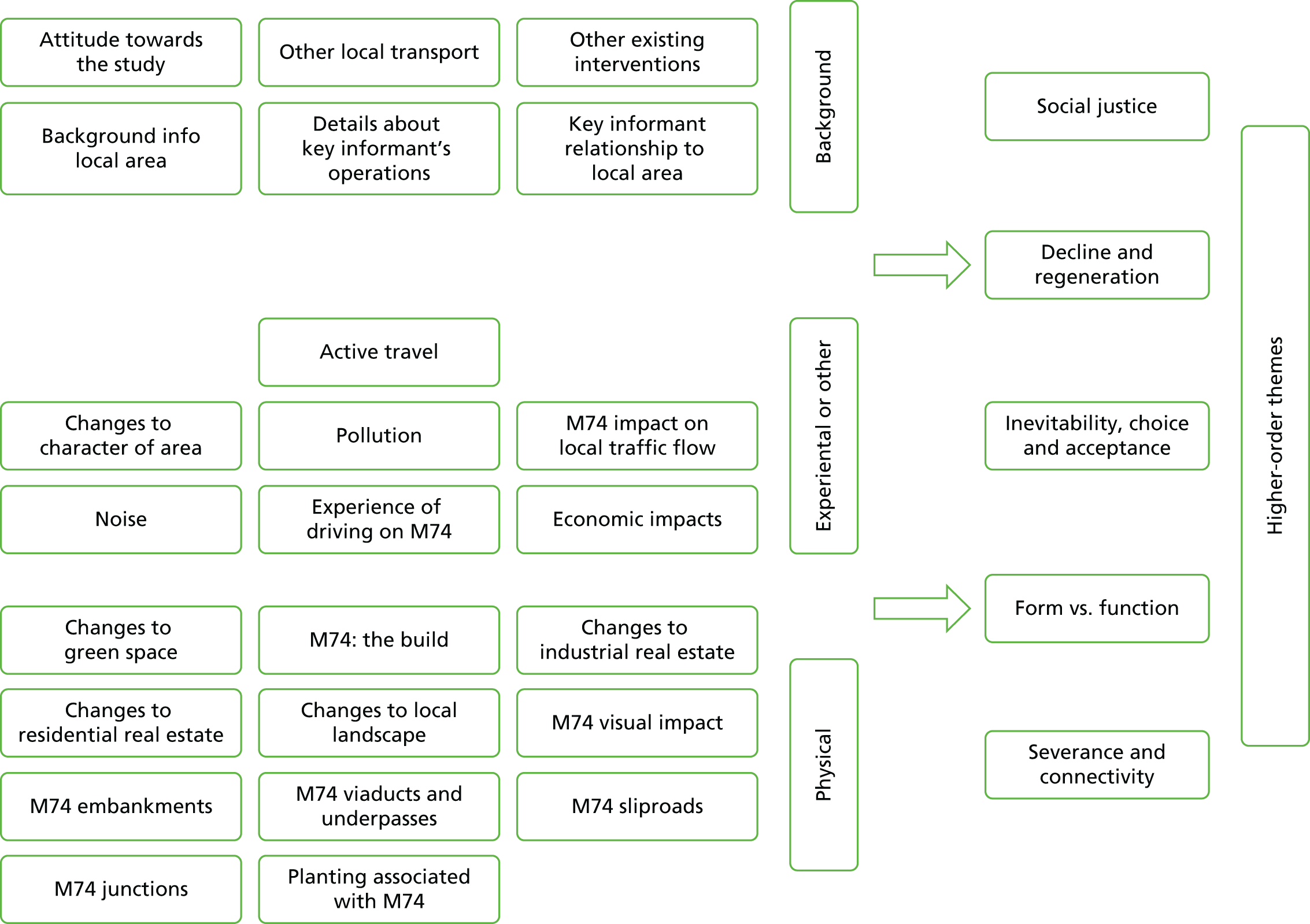

The study comprised six main components (Figure 2):

-

an environmental survey consisting of documentary analysis, interviews with key informants, field visits and use of Google Earth (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) images (objective 1)

-

core surveys of local study areas to compare changes in neighbourhood perceptions, travel behaviour, physical activity and well-being in the intervention and control areas by means of combined cohort and repeat cross-sectional follow-up surveys of local residents (objectives 2, 3, 5, 6 and 11)

-

an objective measurement study of a subsample of core survey participants to quantify any differences in physical activity between intervention and control areas (objectives 4, 5, 6 and 11)

-

a qualitative study of a subsample of core survey participants to elucidate their experiences of environmental changes and the mechanisms through which these may have influenced behaviour (objectives 7, 8 and 11)

-

an analysis of existing national population data sets to evaluate the impact of the intervention on road traffic casualties and to describe concurrent regional and national trends in travel behaviour (objectives 9–11)

-

running alongside all other components, a programme of community engagement to help shape the final study design, elicit a wider range of accounts and develop a shared understanding and interpretation of the emerging findings (objective 11).

FIGURE 2.

Study components.

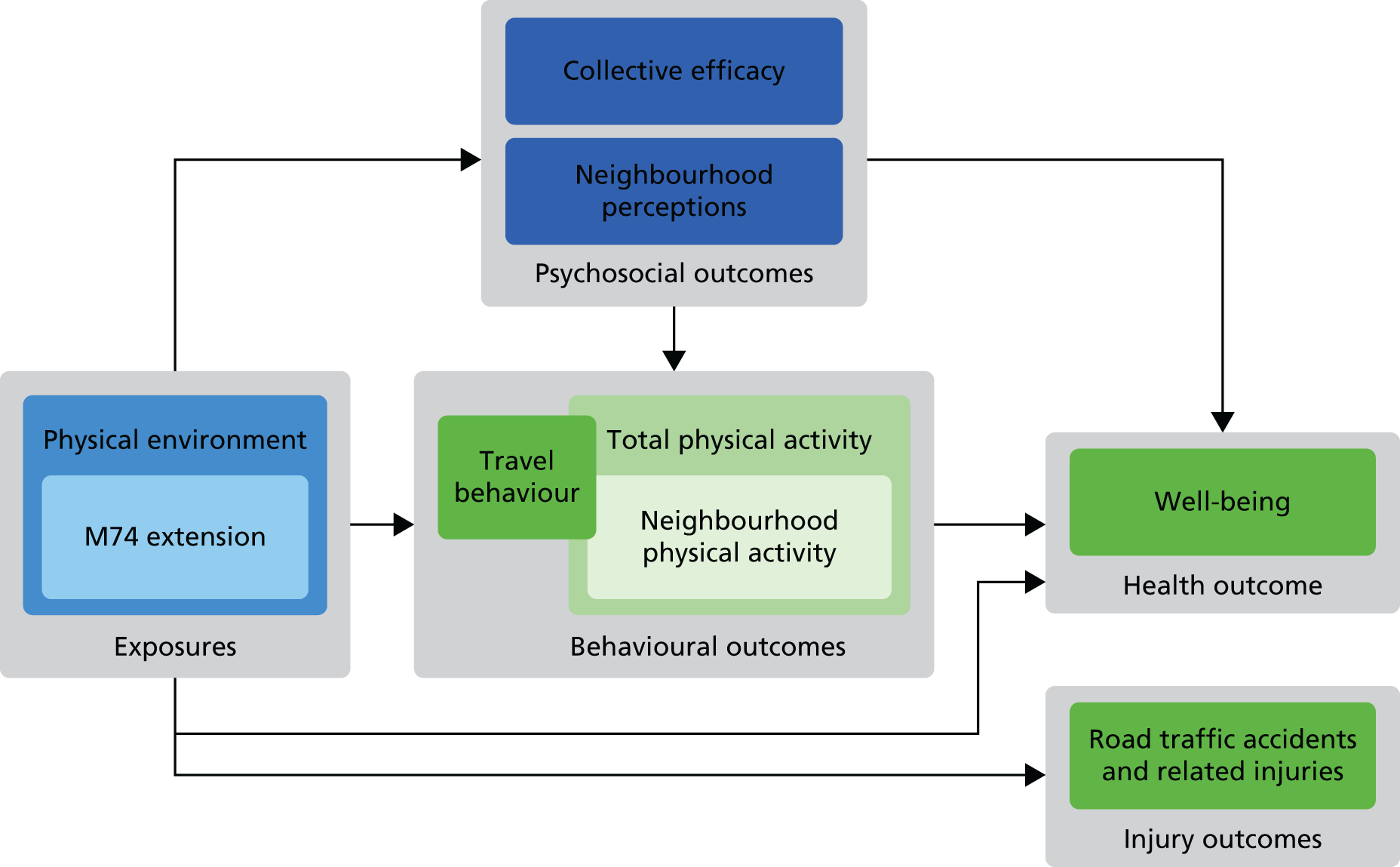

Logic model

As discussed in Chapter 1, we summarised the contrasting narratives about the motorway into vignettes describing two competing overarching hypotheses about the effects of the intervention. In order to operationalise the relationships of interest and refine our analytical priorities, these were further developed into an overarching logic model describing the main putative causal relationships to be investigated at follow-up (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Overarching logic model.

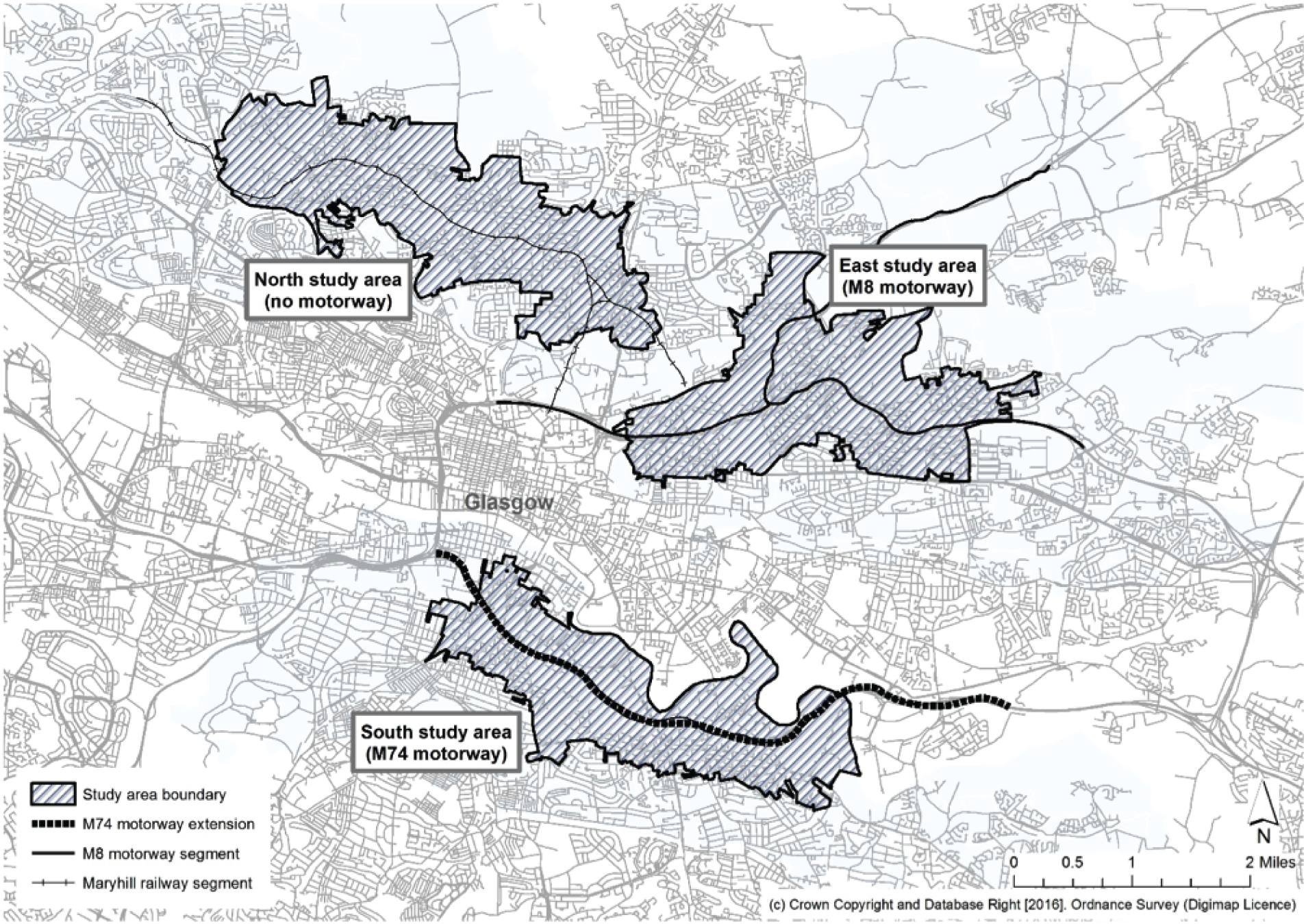

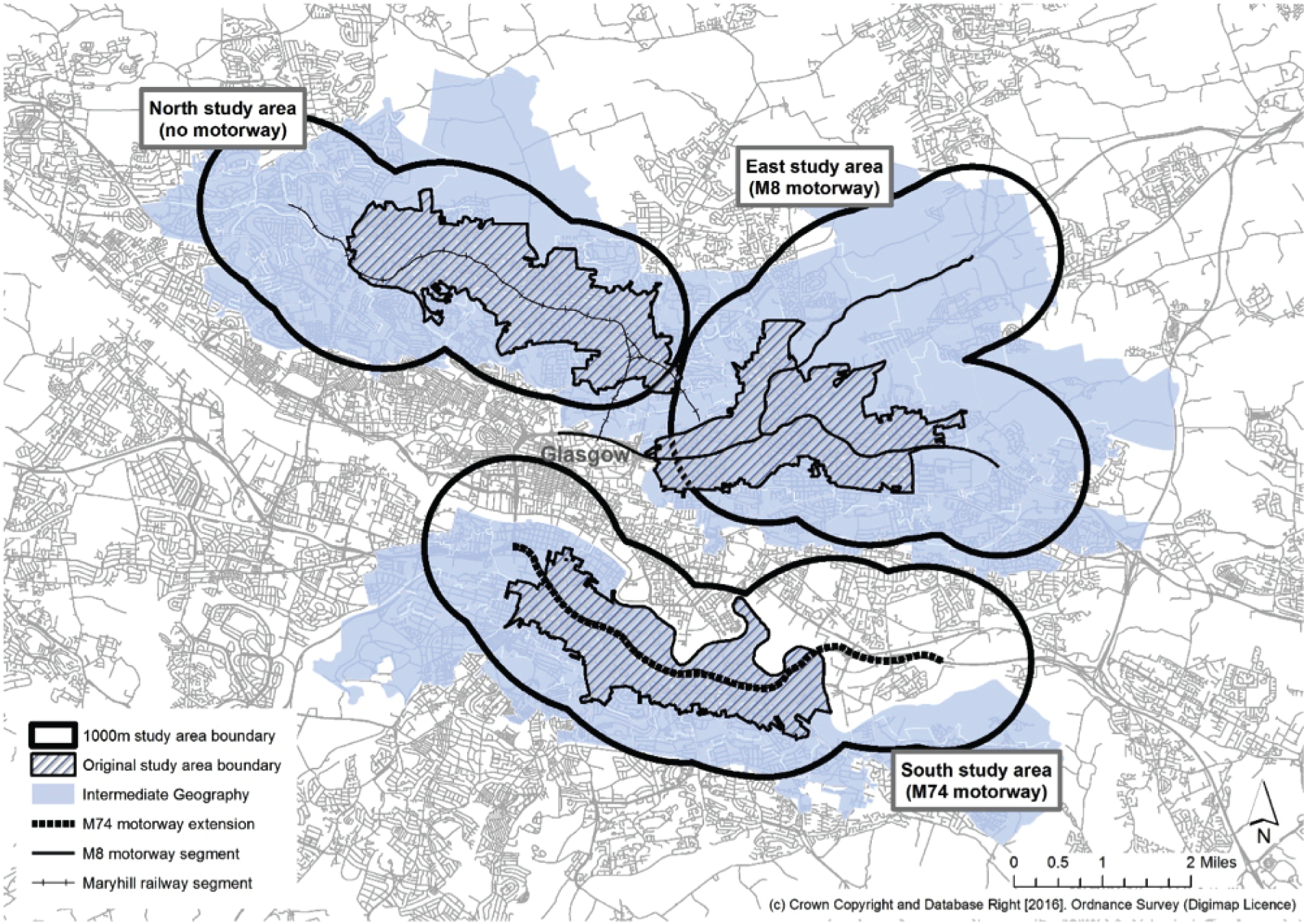

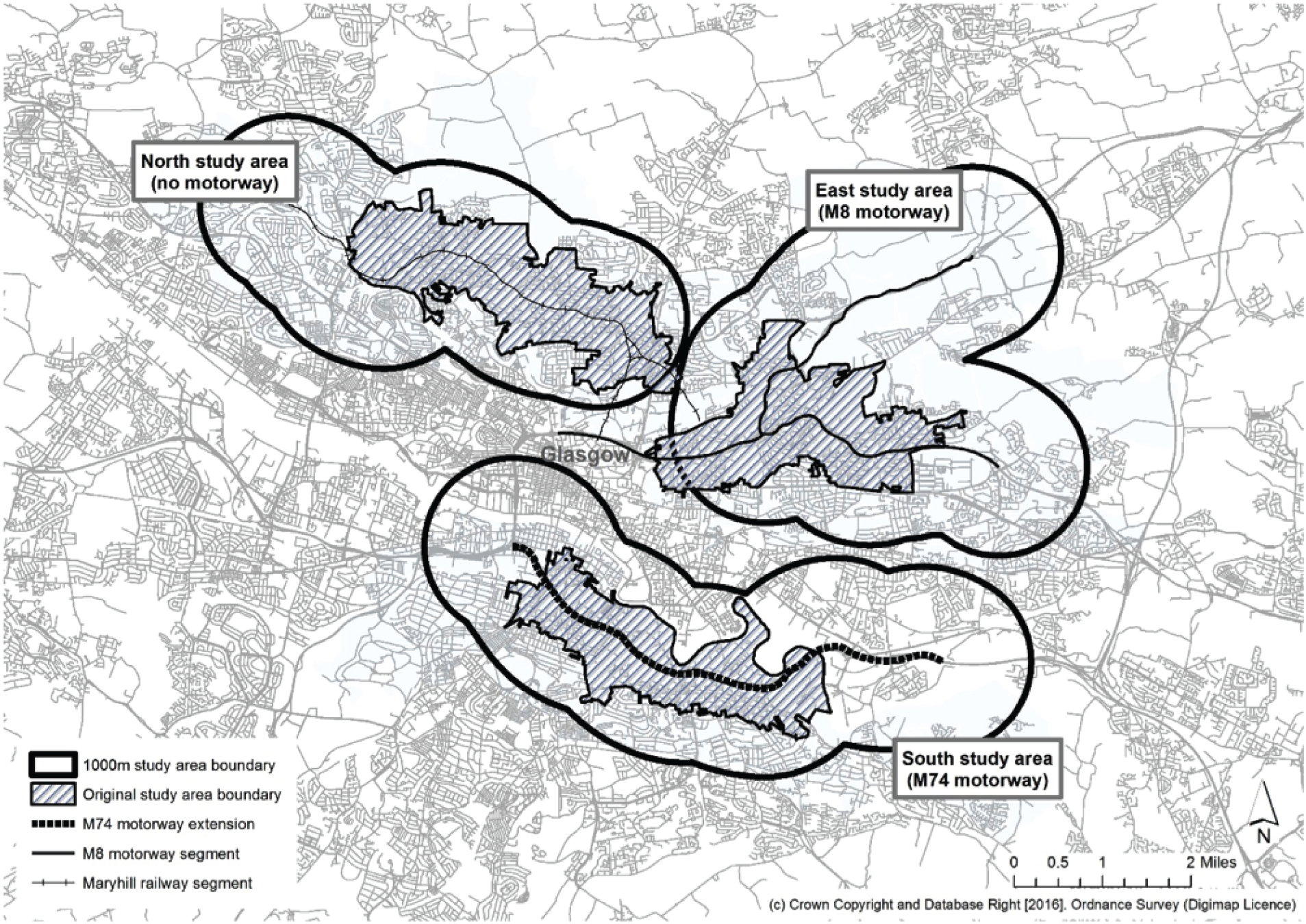

Study areas

At baseline, three local study areas were defined: the ‘M74 corridor’ intervention area (South) and two control areas, one of which surrounded the existing M8 and M80 motorways (East) and one of which had no comparable major road infrastructure (North) (Figure 4). These study areas were carefully and iteratively delineated at baseline using spatially referenced Census and transport infrastructure data combined with field visits to ensure similar aggregate socioeconomic characteristics and broadly similar topographical and urban morphological characteristics apart from their proximity to urban motorway infrastructure (Table 3). 55 Baseline analysis confirmed no significant differences between the achieved survey samples in these three areas on any socioeconomic or behavioural summary measures apart from a minor difference of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.053) in the distribution of housing tenure. 57 All three study areas extend from inner mixed-use districts close to the city centre to residential suburbs, contain major arterial roads other than motorways and contain a mixture of housing stock including traditional high-density tenements, high-rise flats and new housing developments.

FIGURE 4.

Study areas for the core survey. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2016.

| Study area | Definition |

|---|---|

| South | A set of Census output areas encroaching within 500 m of the proposed route of the new M74 motorway |

| East | A set of Census output areas encroaching within 500 m of the routes of the existing M8 and M80 motorways |

| North | A set of Census output areas encroaching within 500 m of the route of the railway between Cowlairs and Maryhill and not encroaching within 500 m of the route of any existing or proposed motorway |

Characterising the environmental changes and refining the study design

In this section, we describe the environmental survey and preliminary community engagement (components 1 and 6 of the study design described in Overall research design), in which we aimed to understand more about the context, content and implementation of the intervention, thus addressing research question 3. This process consisted of (1) a documentary analysis; (2) preliminary community and stakeholder engagement, leading to (3) a series of in-depth interviews with key informants; and (4) field visits combined with the analysis of current and historic aerial imagery in the public domain. This information informed the final study design, outlined in the remainder of this chapter.

Documentary analysis

During the pre-construction planning and consultation phase, two key public documents outlined the proposal for the M74 extension and described its potential effects. The first of these, the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), was published in December 2003. 61 This document, led by proponents of the scheme within the Scottish Executive, outlined the plans for the new motorway and detailed the hypothesised positive and negative impacts on traffic flows, the environment and the community in the immediate area. After a significant number of objections to the compulsory purchase orders for land required for the scheme, and general public protest, an independent PLI was conducted by a senior planner within the Scottish Executive. The second key document, the report of findings from the inquiry, was published in March 2005. 54

To analyse and compare these two documents, the hypothesised impacts of the new motorway were organised according to the categories defined by the EIA and broadly used by the subsequent PLI (Table 4). As described in Chapter 1, Rationale and approach for the study, the study was limited to examining selected impacts of living near a new urban motorway. Further work on the environmental survey was therefore focused on the categories of impact that were most relevant and feasible for our study:

-

land use and landscape appraisal

-

visual impacts

-

noise and vibration

-

pedestrian and other community effects

-

economic effects.

| Impact | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Planning policy | Alignment of the new motorway with published transport or other policy aims (e.g. road construction, public transport, economic development, social justice) |

| Land use | Original land uses in the area lost to motorway construction (e.g. green space, wildlife corridors, industrial, residential) and the impact of these changes in land use |

| Geology, soil and contaminated land | Impacts on the environment resulting from the disturbance during motorway construction of land previously contaminated by industry |

| Water quality and drainage | Impacts on water quality attributable to road runoff or flooding, and proposed drainage systems |

| Ecology and nature conservation | Destruction of animal or plant habitats and the impact on local biodiversity and endangered species |

| Landscape appraisal | Temporary and permanent impacts on the character of the area through which the new motorway passes |

| Visual impacts | The visual effect of the new motorway, given that it is elevated above the townscape for much of its length |

| Cultural heritage | Destruction or demolition of sites of archaeological and cultural interest close to the new motorway |

| Disruption owing to construction | Impacts limited to the construction period, including traffic disruption, noise and vibration |

| Noise and vibration | Impacts related to ongoing traffic noise from the new motorway, mainly for nearby residential properties |

| Air quality | Impacts on air quality from dust and pollutants from the new motorway |

| Pedestrian and other community effects | Impacts on community journeys made by pedestrians and cyclists including severance effects attributable to increased traffic and the need to cross slip roads and junctions |

| Vehicle travellers | Impacts on travel time and stress for drivers on the new motorway |

Where a distinction was made between impacts predicted in the short term (e.g. 1 year) and in the long term (e.g. 15 years), our documentary analysis focused on the short-term impacts because these were more congruent with the time frame of our study, which examined impacts approximately 2 years after the opening of the new motorway. Although disruption attributable to the construction period was potentially relevant to our study, we had no way of verifying such impacts because we were unable to collect data during construction and, therefore, did not explore this category of impact further in the documentary analysis. Effects on vehicle travellers were important, in that changes in travel times may have influenced travel decisions. However, the measurement of traffic flows was beyond the scope of our study and was therefore not explored further in the documentary analysis. The potential economic effects of the new motorway were mostly explored with reference to the PLI, because this topic was not covered in detail in the EIA.

The two documents examined projected impacts in a number of key local areas in the M74 extension corridor (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Key local areas in the M74 corridor. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2016.

Findings from documentary analysis

Land use and landscape appraisal

The EIA emphasised a general pattern of potential adverse effects on residents at the western end of the development (notably in Tradeston and Eglinton), the demolition of existing commercial and industrial sites through the middle of the development, and the loss of green space, particularly in Auchenshuggle Woodland, at the eastern end of the development. The PLI described the majority of potential adverse impacts on townscapes as being concentrated in four residential areas: Eglinton, Toryglen, Rutherglen and Farme Cross. These residential areas would bear a combination of effects, including community severance, visual intrusion and noise.

Visual impacts

The projected visual impacts were considerable, as the new motorway is elevated above the townscape for much of its length. The EIA predicted adverse visual impacts in varying degrees across the entire development, with the most substantial occurring in Eglinton and Rutherglen and where the motorway crossed the River Clyde. In the long term, some potential beneficial impacts were described, whereby new planting associated with the scheme would replace existing views of derelict land or industrial estates.

Noise and vibration

The EIA assumed that a number of mitigation strategies would be in place to combat noise and vibration from the motorway, including low-noise road surfacing and noise barriers. Despite the mitigation strategies, the EIA predicted ongoing major adverse noise impacts in Toryglen. Modest positive benefits were predicted on certain streets in Eglinton and Rutherglen because of forecast traffic reductions on these streets. The PLI further commented that the River Clyde walkway and cycleway had not been included in the noise assessment presented in the EIA. However, this semi-rural area was remote from main roads, and the construction of the new motorway across the River Clyde could therefore result in significant adverse noise impacts.

Pedestrian and other community effects

The EIA described an existing north–south divide between communities on either side of the West Coast Mainline railway. The EIA summarised key intercommunity pedestrian journeys and identified the routes used to undertake these journeys. Rutherglen and Govanhill were identified as two communities attracting inward journeys from neighbouring communities because of their high concentration of facilities. These journeys would often, but not always, involve crossing the railway line.

The new motorway follows the West Coast Mainline for much of its length and, therefore, crosses existing roads that provide important north–south pedestrian linkages between the communities on either side. Although it does not physically sever any of these links, because crossing points such as underpasses are provided, pedestrians are nevertheless now required to pass over or under the new motorway.

The main proposed adverse severance effects on pedestrian journeys were at the site of the new junctions, because of the need to cross the new slip roads and increased traffic on these roads. This would be particularly salient for those with mobility difficulties. The EIA also proposed some severance relating to reluctance to use the new underpasses owing to unpleasantness or safety concerns, which would be heightened at night. However, beneficial effects on pedestrian journeys were projected on certain streets, particularly in Rutherglen, because of a forecast reduction of traffic on these streets.

The PLI agreed that these severance effects would occur and predicted that they would be substantially more serious than outlined in the EIA, to the extent that they would ‘devastate communities’ on either side of the M74. In particular, travel between Farme Cross and Rutherglen was identified as a key community journey on which severance effects would occur. In addition, pedestrian journeys on local streets would become more difficult and hazardous because of increased traffic flow on slip roads.

The PLI further explored the wider effects of M74 construction on social inclusion and environmental justice, which were not covered in the EIA. The PLI noted that, owing to a comparatively low level of car ownership, the motorway would be of limited use to the local population. Increased provision for car users would undermine the provision of public transport options, leaving those without cars ultimately more disadvantaged. Those who did own cars might subsequently travel further afield to access facilities, which would undermine local community facilities and further increase inequalities. The PLI criticised the use of public funds for the scheme, commenting that they might have been better spent on public transport and direct assistance for disadvantaged communities.

Economic effects

One of the key objectives of the motorway was to stimulate wider economic regeneration in the local area. Although this was mentioned only briefly in the EIA, the PLI examined the proposed economic benefits of the M74 construction. The key potential benefits identified were short-term employment during construction, time savings for vehicle journeys, cost savings from reduced vehicle accidents and associated injuries, the redevelopment of nearby vacant or derelict sites near the new motorway and the provision of new local jobs at these sites. However, the PLI highlighted the uncertainty of these effects on long-term economic regeneration, and identified potential adverse effects on the local economy, whereby loss of employment or income would arise from the demolition of existing industrial and commercial sites.

Discussion

The primary purpose of the M74 extension was to relieve traffic congestion on other motorways and main roads, particularly the M8 motorway. Both the EIA and the PLI agreed that it was likely to produce an initial reduction in traffic congestion, amounting to an average 5- to 10-minute reduction in journey time during peak periods. However, the documents differed in their prediction of the longevity of these effects. The EIA predicted that beneficial effects would remain until 2020 and beyond, whereas the PLI described a gradual erosion of these benefits owing to increasing traffic and increasing attractiveness of car journeys. Although the measurement of traffic flows was beyond the scope of our study, projected impacts of this kind were nonetheless important because they had been used to justify the construction of the new motorway on the assumption that the beneficial effects on congestion would outweigh the considerable drawbacks for those living nearby identified in both documents.

For the most part, the EIA and PLI were in agreement on the nature and scale of both positive and negative probable impacts of the new motorway on the landscape, visual and noise effects, and severance in the local area. The PLI identified additional potential positive and negative effects on the local economy. However, the EIA and the PLI fundamentally disagreed on whether or not the long-term benefits on traffic and congestion were sustainable and, therefore, on whether the benefits of the new motorway would outweigh the harms. The PLI concluded that the distribution of benefits and drawbacks was both unequal and inequitable, that the claimed benefits were likely to be ‘ephemeral’ and that the new motorway ‘would be very likely to have very serious undesirable results’ for local communities. 54

Preliminary community and stakeholder engagement

A complementary programme of community and stakeholder engagement ran alongside the study. This was brokered by the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) and the Scottish Community Development Centre (SCDC), which are established centres working with community organisations in Glasgow. Between March and May 2013, initial contact was made with 18 key organisations in the M74 corridor, the interests of which may have been affected by the new motorway. These included local housing associations, development trusts, community councils, residents’ associations and public-sector development agencies. Organisations were invited to comment on whether or not any issues associated with the new motorway were of importance to local communities, and, if so, what these issues were. The process and outcomes of subsequent community and stakeholder engagement in the study are described in Chapter 8.

Findings from preliminary community and stakeholder engagement

For most of the organisations approached, the agenda had moved on and the M74 extension was not seen as an issue of concern, although in several cases organisations reported that they had originally been opposed to the development. A single community organisation in Eglinton that owned housing stock directly overshadowed by the new motorway reported ongoing issues with noise, dirt and deterioration in neighbourhood quality. In contrast, for several of the organisations the new motorway was regarded as having had a beneficial effect on neighbourhood quality, particularly where it acted as a bypass for streets that were previously congested (e.g. in Rutherglen town centre). In addition, a number of the organisations saw it as having facilitated other developments, each of which may have had a positive or negative effect on local quality of life and opportunities, particularly for employment. These included the development of the site for the 2014 Commonwealth Games and other industrial, commercial and housing developments near the new motorway.

Interviews with key informants

The interviews with key informants were intended to provide an overview of the environmental, economic and social impact of the new motorway. Informants were recruited purposively, based on their involvement with the local groups identified through the preliminary community engagement described in the previous section in combination with snowball sampling. Informants represented a variety of organisations, including local development groups, local community councils, local housing associations, local charities, organisations involved in the planning and development of the motorway and an anti-M74 protest group [Joint Action against M74 (JAM74)].

Between March 2014 and April 2015, information sheets and invitations were either e-mailed or posted to key informants’ organisations and followed up by either e-mail or telephone call. In cases in which an individual informant had already been identified by initial community engagement work, that informant remained the contact for that group. Twenty-five invitations were sent and 12 key informants consented to take part.

Key informant interviews were carried out using a semistructured format, based on a topic guide that could be applied flexibly to informants’ varying roles and levels of involvement with the local area. As key informants held a variety of roles, some were able to give an overview of issues, whereas others addressed local changes in more specific detail. Interviews were conducted in a variety of locations depending on the informants’ preferences, including their homes, places of work, cafés and the offices of the Medical Research Office/Chief Scientist Office (MRC/CSO) Social and Public Health Sciences Unit. All but one were recorded using a digital voice recorder and transcribed verbatim. One participant declined to be recorded; their interview was attended by two researchers, of whom one conducted the interview and the other wrote notes that formed the material for subsequent analysis. These key informant interviews were much more specifically focused on the M74 than the main programme of qualitative research with local residents described in Chapter 7. The topic guide focused on a number of themes, including the impacts of the physical structure of the motorway and associated engineering features, and its wider economic impacts (see Appendix 1).

Walkalong interviews, in which an interviewer and participant conduct their interview while walking through a particular space, were not originally envisaged as a method for interviewing key informants. However, two key informants suggested that they would be better able to address the main themes of their interview by showing their local area as well as describing it. We therefore conducted walkalong interviews with these two participants. More information on this method can be found in Evaluating the intervention.

Findings from interviews with key informants

Key informants were asked about their views on the environmental impacts of the motorway in general, as well as specific physical changes related to the structure of the motorway itself, including slip roads, embankments, junctions, viaducts and underpasses. Overall, views on the environmental impact of the motorway were mixed, with some key informants feeling that the motorway had been detrimental to the local environment and others feeling that it was a valuable part of local environmental regeneration. Specific impacts are discussed in more detail below.

Environmental impacts

Key informants’ views on the visual impact of the extension ranged between negative (‘ugly’ and ‘aesthetically, I think it’s awful’) and neutral (‘it’s had a reasonably minimal impact’). Perceptions of visual impact appeared to be related primarily to two factors: (1) how the new motorway looked in contrast to what had been there before; and (2) whether or not a particular section of the new motorway was elevated. A number of respondents mentioned that the new motorway sympathetically followed the existing line of the railway and was built on predominantly post-industrial, vacant or otherwise unattractive land, and therefore did not detract from a previously picturesque landscape. Others, however, felt that the motorway had visually ‘carved up’ the residential land and had added another unattractive feature to an already post-industrial residential landscape.

I mean, it’s not great to suddenly have these enormous concrete structures, particularly the flyovers. But on the other side, a lot of the land is now being developed as a result, you know, and wasteland versus, I suppose, not magnificent architecture but something happening as opposed to wasteland I think is good.

Key informant, local development trust

In areas where the motorway was elevated, key informants were more likely to describe negative visual impacts and, in particular, several of them drew attention to areas where they felt this visual disturbance was most acute, namely around Eglinton Street and Devon Street, and around the junction at Tradeston. In areas where the motorway was not elevated, however, key informants were more likely to describe visual disturbance as minimal.

Perceptions of pollution from noise and fumes were also related to whether or not the motorway was elevated and whether or not it was perceived to have diverted traffic away from local streets. A number of key informants felt that the new motorway had been highly successful in achieving the latter in certain areas, to the benefit of local people; however, there was less consensus about whether or not this had occurred in Govanhill. In streets such as London Road that were described as having experienced a significant decrease in traffic, the area was described as now being ‘lighter and more open’ as well as more appealing and safer for active travel. In other areas such as Rutherglen, some key informants drew attention to a recent Friends of the Earth report publicised in the media, indicating high levels of pollution in Rutherglen Main Street:

I think most damaging of all is the area around Rutherglen. I mean, it’s obviously not criminal in a legal sense but I think what was done there was very, very poor. [. . .] I mean, it’s an urban motorway – but it’s very, very close to the community of Rutherglen and now people are wringing their hands about the air quality in the Main Street. Well, you know, it’s stating the bleeding obvious.

Key informant, local community council

There seemed to be a lack of consensus around whether the motorway had reduced pollution in these areas by diverting traffic from (some) local streets or if pollution from traffic had merely been shifted to the motorway, which was sufficiently close to these areas to be a cause for concern. Several key informants called for detailed evidence on pollution to be gathered as a key indicator in evaluating the motorway’s impact. In addition, key informants discussed existing contaminated land related to the area’s industrial past. Several key informants felt that the construction of the M74 extension had been instrumental in ‘capping’ and covering up a number of pieces of land contaminated with industrial waste, whereas others had concerns that industrial wastes in the soil had been disturbed by the building process.

In terms of noise, negative impacts on the tranquillity of natural green spaces were described by several key informants, with particular reference to Malls Mire woodland in Toryglen (which is directly adjacent to the motorway) and Auchenshuggle Woodland to the east of Glasgow (through which the motorway runs; see Figure 5). However, the new motorway was also credited by one key informant with having being instrumental in creating the necessary accessibility to secure funding for a major new green space development, the Cuningar Loop.

Other aspects of the new motorway discussed by key informants included underpasses, which were described alternately as being ‘clean, modern . . . reasonably well lit’ or as being bare, unused spaces. Key informants discussed ideas for improving these spaces with interest, describing plans for urban parks, art works or well-planted green spaces. Existing planting along the new motorway was described as a positive aesthetic development by some, and as insufficient by others.

Although the majority of key informants agreed that the motorway had reduced journey times for car users, a few described the new motorway junctions as problematic, for example Polmadie junction near Govanhill, which was described as causing tailbacks in the local area at peak commuting times. Features such as slip roads were described as being mostly well designed, but with some problematic areas where traffic was required to filter abruptly into fewer lanes, causing tailbacks.

Key informants also described changes in both residential and industrial land use as a result of the new motorway. They discussed the removal of older housing stock as being related to the new motorway both directly (having been demolished to make way for the route) and indirectly (forming part of a broader regeneration plan). The creation of new housing (including the athletes’ village for the Commonwealth Games) was also discussed, with some key informants stating that the new motorway might attract new people (‘commuters’) and others stating that it might make journeys shorter for existing commuters. The attraction of new commuters to the area was described by one resident as having uncertain implications for community cohesion.

They also described a number of changes in industrial land use that they perceived to be related to the new motorway. Many of these were considered to be positive, for example the removal of an old processing plant [‘getting that bit of quite industrial stuff off their doorstep was quite nice’ (key informant, local development trust)] and the aesthetic overhaul undertaken by some companies that now found their premises directly overlooked by passing traffic. Other changes received a more mixed reception, such as a new recycling centre and incinerator, which was described by one key informant as facilitating the importation of waste from other areas [‘they’ve built it . . . right next to Govanhill ‘cos no one gives a shit about Govanhill’ (key informant, local development trust)]. Generally, several respondents felt that these new industrial developments were positive for the local economy, but others expressed concerns about encouraging more industrial development (reindustrialisation) in residential areas.

Economic impacts

The majority of key informants viewed the M74 extension as forming part of a package of economic regeneration that intertwined with other initiatives, including those associated with the Clyde Gateway development company and the Commonwealth Games. The new motorway was credited by some with making the area more accessible and therefore more attractive to investors, and one key informant considered it a factor that had helped their organisation to ‘ride out’ the recession. Several developments were described as already either in place or under construction, including new offices and the recycling facility mentioned previously. For the most part, key informants acknowledged the beneficial potential of these developments for local jobs, but some mentioned that this potential had yet to be realised. Others questioned the investment in road transport, wondering if a similar level of investment in active travel or public transport might have been preferable. It was acknowledged that the economic downturn, as well as a perception of instability that may have accompanied the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, may have contributed to slower than projected economic investment along the motorway corridor, and that a longer evaluation timeline might be needed to capture these potential benefits.

Competing changes

Key informants were also asked about any other changes that might have diminished, intensified, complicated or otherwise altered the effects of the new motorway on the local area. In addition to the changes referred to above, respondents also mentioned recent welfare reforms, initiatives encouraging local people to cycle and changes to the configuration of local streets.

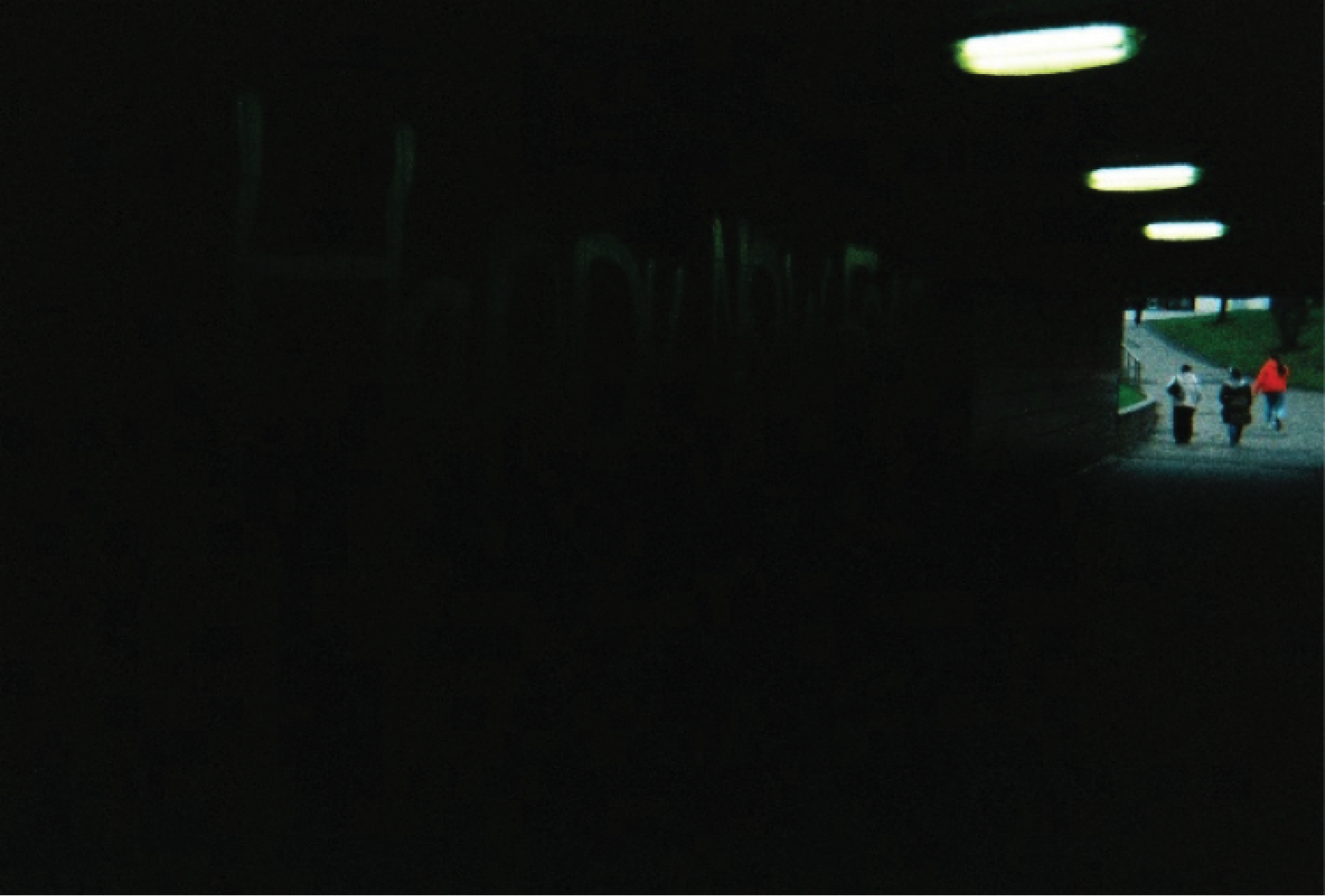

Field visits and analysis of aerial imagery

In 2013, a member of the study team examined various aspects of the motorway infrastructure using Google Street View. In 2014, another member of the study team undertook several field visits to inspect the motorway and its relationship with the wider cityscape. Examples are shown in Figures 6–9.

FIGURE 6.

M74 extension crossing the Tradeston area on a viaduct. Photograph © Amy Nimegeer and reproduced with permission.

FIGURE 7.

M74 extension crossing the Eglinton area on a viaduct. Photograph © Amy Nimegeer and reproduced with permission.

FIGURE 8.

Noise barriers along the M74 extension at Rutherglen. Photograph © Amy Nimegeer and reproduced with permission.

FIGURE 9.

Underpass beneath the M74 extension at Rutherglen. Photograph © Amy Nimegeer and reproduced with permission.

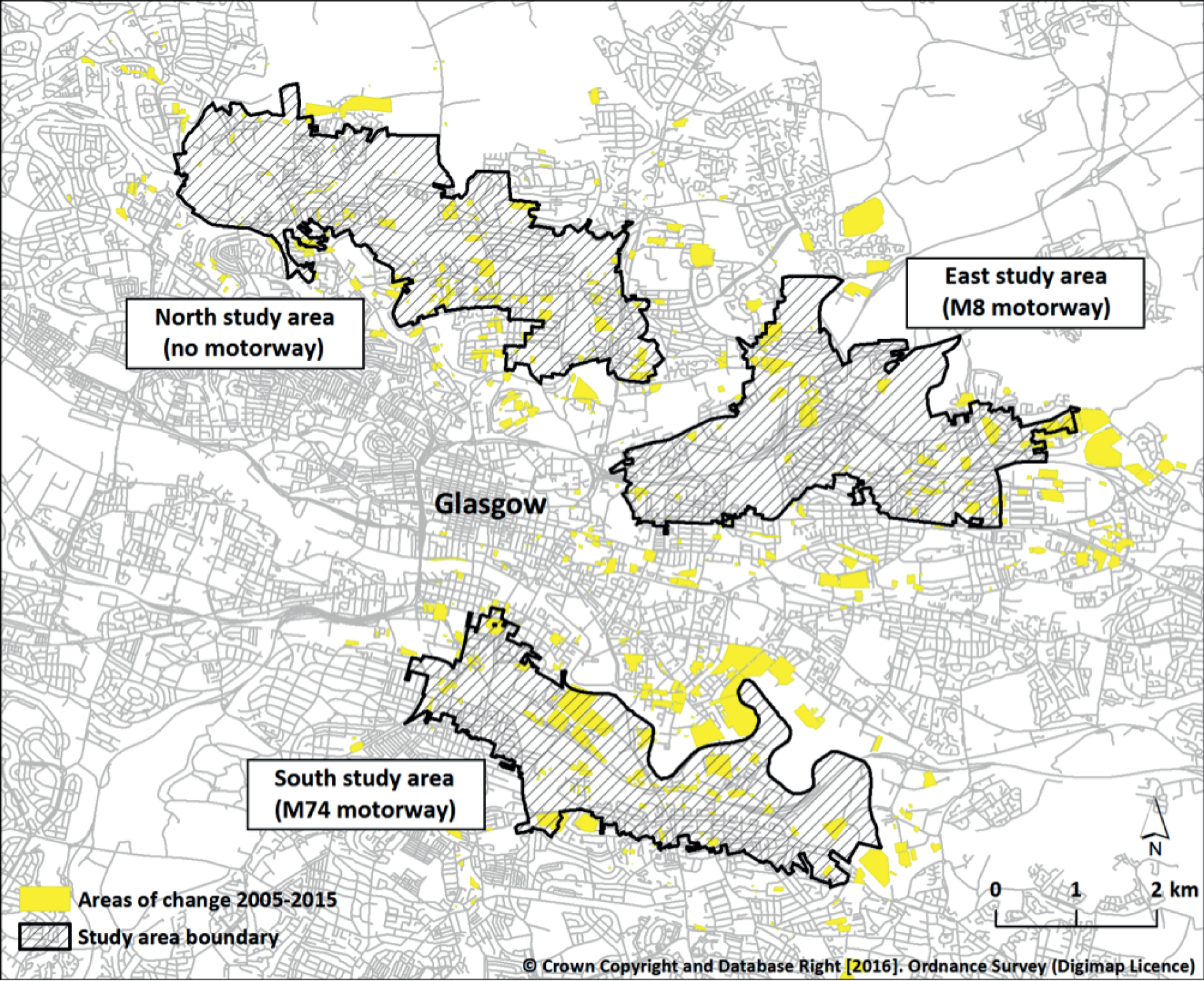

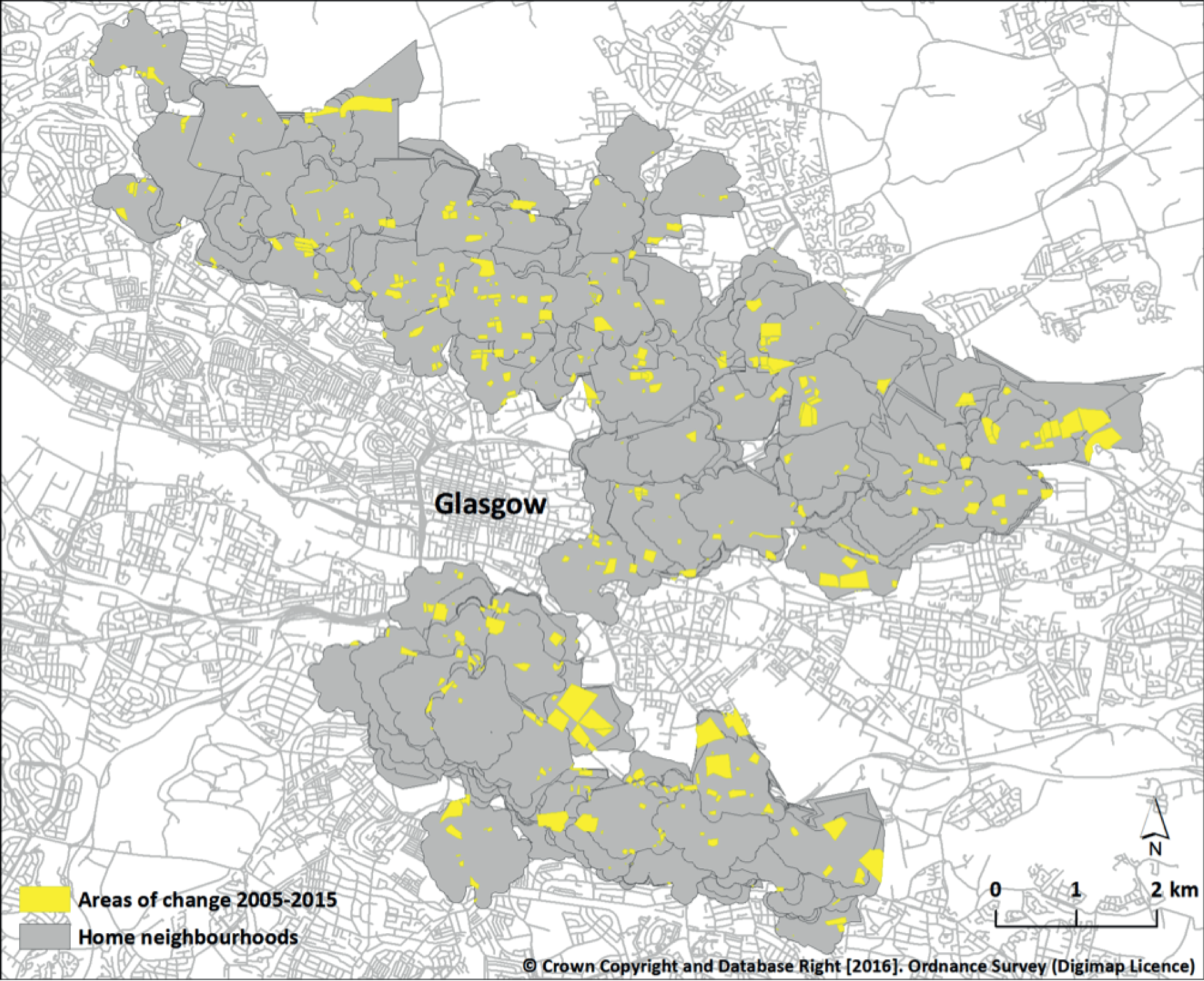

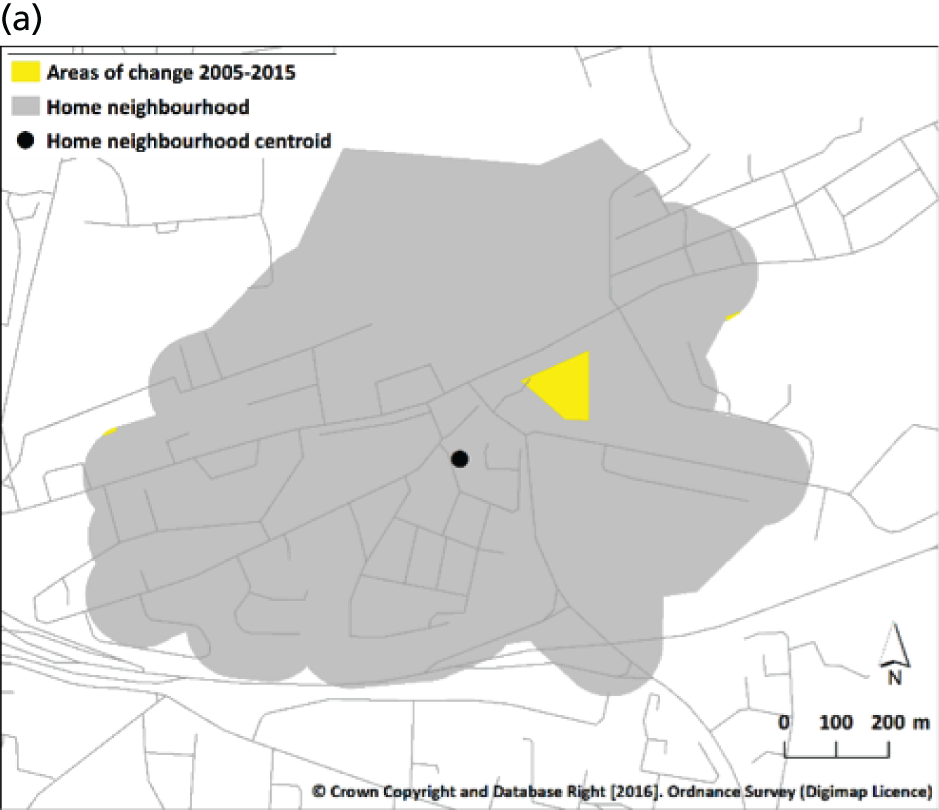

The new motorway formed one component of a wider strategic initiative to regenerate the local area. We therefore wished to identify other concurrent major changes in the built environment. We developed bespoke software to display side-by-side aerial images of the same location taken at different times, using the Google Earth time slider function. The software allowed the operator to zoom the images and move them in tandem, comparing them in order to identify areas of difference and delineate each area with a polygon. The changes identifiable using this method included the construction or demolition of buildings, and the loss or gain of green space (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Example of environmental change identified by comparing aerial images. (a) 2015; and (b) 2005. Source: Google Earth.

We used this method to identify (but not to characterise) all visible changes occurring between 2005 and 2015 in each of the three study areas and extending to approximately 1 km beyond their boundaries (Figure 11). As expected, large changes had occurred in the South study area during this time, but substantial changes were also identified in the other two areas.

FIGURE 11.

Areas of change within and surrounding the study areas. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2016.

Evaluating the intervention

The information from the environmental survey further crystallised the relationships and outcomes of interest and contributed to shaping the final design of the study, particularly the qualitative fieldwork and analysis. In this section we describe the final study design in terms of the sampling and collection of data from participants, the derivation of variables and the overall approach to analysis.

Participant sampling

Core survey

Inclusion criteria

At baseline (2005; T1), eligible participants were adults aged ≥ 16 years residing in one of the three study areas, who responded to a postal survey delivered to their home address. If more than one householder was eligible, the individual with the most recent birthday was asked to complete the survey. At follow-up (2013; T2), eligible participants were (1) those who had responded to the postal survey at baseline, had not moved out of the UK, and responded to a subsequent postal survey at follow-up; or (2) adults aged ≥ 16 years residing in one of the three study areas, who responded to a postal survey delivered to their home address.

Recruitment

At both time points, eligible unit postcodes (the smallest unit of postal geography in the UK, corresponding to approximately 15 addresses on average) were identified for each of the three study areas. A random sample of 3000 private residential addresses in each area – 9000 in total – was drawn using the Royal Mail Postcode Address File. A survey pack was posted to each of these households, addressed to the householder. Participants were given the option to return a consent form giving permission to be contacted again in the future. Contact with these participants was maintained via yearly mailings between 2005 and 2012. At follow-up, a further 3000 postal surveys were issued in each study area. The recipients comprised all those baseline participants who could still be contacted, including those who had moved between or out of the study areas but not out of the UK, together with a newly drawn random sample of households to bring the total up to 3000 in each area. All follow-up participants were given the option to return a consent form giving permission to be contacted again for the objective measurement or qualitative substudies.

We followed evidence-based practice to maximise responses to the postal survey. 62 Potential participants were sent a notification postcard, which was followed by the survey 1 week later. The survey packs were posted in the first week of October at both time points, to account for potential seasonal variation in responses, and a repeat survey pack was sent to all non-responders approximately 1 month later. All mailings were staggered over multiple days to ensure that surveys were received and completed on a variety of days of the week. Responses received > 3 months after the first mailing were excluded from analysis.

Data collection

Core questionnaire

The core questionnaire collected information relating to demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and the main outcomes of interest: perceptions of the neighbourhood environment, travel behaviour, physical activity and sedentary behaviour, and well-being. In particular, it incorporated the following at both time points:

-

A 1-day travel record, adapted from similar instruments used in the Scottish Household Survey (SHS)63 and the National Travel Survey. 64 For each journey made the previous day, participants reported the purpose, the mode(s) of transport used and the time spent using each mode. Both single and multimodal journeys could be reported. Participants were asked not to report journeys made in the course of work, or purely for recreation.

-

The short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), an extensively validated instrument in which participants estimated the number of days and the average daily duration of walking, moderate and vigorous physical activity, as well as the average daily time spent sitting, in the previous 7 days. 65

-

The Short Form 8 Health Survey (SF-8) scale, an extensively validated eight-item instrument assessing health-related quality of life in the previous 4 weeks. 66

-

A 14-item instrument assessing perceptions of the conduciveness of the neighbourhood environment for physical activity, developed for the study and assessed for its factor structure and test–retest reliability at baseline. 56

At follow-up, the following items were added to the core questionnaire:

-

The short version of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS), a seven-item instrument assessing positive mental well-being in the previous 2 weeks. The original long version of the instrument has been shown to have acceptable psychometric properties. 67,68

-

A nine-item instrument adapted from Sampson et al. 69 to assess collective efficacy, defined as the norms and networks that enable collective action and comprising informal social control (the willingness of community members to look out for each other and intervene where necessary) and social cohesion (feelings of belonging, shared values and mutual trust).

The full questionnaire issued at follow-up is reproduced in Appendix 2.

Objective measurement study

At follow-up, all core survey participants who had provided consent for recontact, and who currently lived in one of the three study areas, were eligible to take part in the objective measurement study. Information about this study and an invitation to take part was posted to these potential participants in a rolling recruitment exercise between October 2014 and July 2015. Those who responded were then contacted to agree a start date for their monitoring. Once this had been confirmed, participants were mailed an accelerometer [Actigraph GT3X+ (Actigraph, Pensacola, Florida, USA)] and global positioning system (GPS) receiver [Qstarz BT Q 1000XT (Qstarz International Co, Taipei, Taiwan)] attached to an elastic belt, along with written instructions for their use, a log sheet and a consent form.

The Actigraph GT3X+ is a small, lightweight triaxial waveform accelerometer. It detects normal human motion and rejects motion from other sources. It measures acceleration at a user-specified rate of between 30 and 100 Hz, and stores raw, unaccumulated data. Depending on the sampling rate, it has a battery life of 16–31 days and can store 12–43 days’ worth of data in on-board memory. The GT3X+ provides detailed information about the intensity, frequency and duration of activity and has been extensively validated in both laboratory and free-living conditions. However, it has well-documented limitations for assessing water-based activities or those dominated by upper body movement. 70

The Qstarz BT Q 1000XT data logger uses signals from satellites to determine the spatial co-ordinates (i.e. latitude and longitude) of participants at 5-second intervals. It is the size of a match box, has a battery life of 24–48 hours in normal use, can store up to 10 days’ worth of data in on-board memory and does not suffer from the loss of satellite signal when in a vehicle or under tree canopy that affects some alternative GPS devices.

Participants completed a 7-day protocol of accelerometer and GPS monitoring. They were asked to wear the two devices on an elastic waistband on the right hip during waking hours for 7 days, removing them only for bathing, showering and swimming. Participants used the log sheet to record times at which the devices were removed and reattached, and the reasons for removal. They were asked to switch off the GPS receiver while it was not being worn, and to recharge the batteries overnight.

At the end of the monitoring period, a field worker organised a face-to-face meeting with the participant at their home, workplace or other mutually convenient location. At this meeting they retrieved the devices, and collected and checked the completeness of the log sheet and consent form. Alternatively, participants could elect to return their devices and study documents by post. Following the retrieval and download of devices, participants received a thank-you letter containing a summary of their own activity data. During download, accelerometer data were scanned to identify participants who had completed less than four 10-hour days of monitoring. Those whose devices had recorded less than this quantity of data were offered the opportunity to rewear the devices for a further 7-day period.

Qualitative study

At follow-up, core survey participants who had provided consent for recontact and who lived in the South study area within 400 m of the M74 extension formed the sampling frame for the qualitative study. This substudy aimed to elicit how the effects of the environmental changes were experienced by local residents and how any changes in behaviour or well-being were mediated and enacted at individual and household level. A pilot study was conducted prior to the main period of data collection.

Pilot qualitative study

An initial review of methods for collecting qualitative spatial data revealed several methods that showed promise. We piloted two of these methods, namely photovoice and walkalong interviews, between March and August 2014 to assess whether either or both would be suitable for our needs and acceptable to our participants. Each participant in the pilot study undertook an initial semistructured interview and was then given the option of a second interview, which could be either photovoice or walkalong. As the initial interviews were held indoors, the second interviews were intended to provide additional insight into specific features of the outdoor built environment that participants viewed as key to their neighbourhood experience, as well as giving insight into their typical journeys through their local area.

For the pilot study, batched quota sampling was employed in a rolling recruitment exercise to achieve a sample that reflected a variety of characteristics, including area and duration of residence and distance from the new motorway, age, sex, socioeconomic status, presence or absence of impaired mobility, car ownership and household composition. Information about this study and an invitation to take part was posted to these potential participants, and followed up with a telephone call or e-mail to confirm willingness to participate and to arrange an initial interview. Willingness to participate in a second interview was established at the initial interview; the second interview was arranged either at that time, or by a subsequent telephone call if the participant wanted more time to make their decision. Consent forms were completed by participants immediately before each interview, except in the case of photovoice interviews, in which case consent was sought prior to the participant receiving their camera or taking their photographs.

In order to investigate participants’ perceptions, experiences and uses of their local neighbourhood in general, the initial interview followed a semistructured format using a topic guide (see Appendix 3). This included questions about residents’ perceptions of the local area as a place to live, their feelings towards the area, the activities they undertook in the local area and the extent to which any of these had changed. If a participant did not mention the M74 extension, the researcher raised the issue – but only at the end of the interview – in order to better understand the relative importance of the motorway and other sources of change in the lives of the participants. Interviews took place, depending on participants’ preferences, in homes, the offices of the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit or in other (public) places. All interviews were recorded using a digital voice recorder and transcribed verbatim, and field notes were written in all cases.

Walkalong interviews were intended to illustrate a typical journey made by a participant, to consider more deeply the features of the local built environment (including the motorway) that affected their experience of place and to observe their interactions with their environment, including the microdecisions made as part of everyday journeys. This method proved unpopular, however, with only one participant in the pilot study opting to take part. Their walkalong interview followed a very loosely semistructured format, falling somewhere between Carpiano’s71 semistructured question-based approach and Kusenbach’s purely participant-led discussion. 72 Prior to the walkalong interview, the researcher re-examined the transcript of the initial interview and noted key topics and potential follow-up questions. The walking route was negotiated between researcher and participant based on the initial interview, and the participant was prompted to vocalise whatever came to their mind while moving through the neighbourhood and acting as a guide to the researcher, describing anything they viewed as particularly ‘bad’ or ‘good’ about the environment. If conversation faltered, the researcher introduced questions or prompts based on the previous interview (e.g. ‘in your interview you said . . . tell me more about that’). At key points when the participant made specific reference to a physical feature, additional photographs were taken by the researcher. The interview was recorded using a digital voice recorder and transcribed verbatim, and a wrist-worn GPS receiver was used by the researcher to record the route and waypoints. Walkalong interviews with key informants (see Interviews with key informants) followed a similar structure in that the participant selected the route and used environmental interactions to illustrate and stimulate their discussions; given the absence of a prior semistructured interview in these cases, the walkalong discussion was more closely based on the predetermined topic guide.

Photovoice interviews, like walkalong interviews, were used to further investigate how participants interpreted and interacted with their surroundings. The subjects of potential photographs were discussed between participant and researcher at the end of their initial interview. Most participants chose to photograph a typical journey, or to further illustrate points made during their initial interview, on the understanding that they would take additional photographs if they encountered anything else that they would like to raise with the researcher. They were given the choice of either using their own digital camera or smartphone, or using a disposable camera and posting it back to the researcher. There are currently no legal restrictions on taking photographs in public places, including photographs of people. 73 However, participants were instructed to take other people’s wishes for privacy into consideration, to refrain from taking photos of children (other than their own children) and to avoid taking close-ups of people’s faces. The photographs were developed by the researcher (if necessary) and formed the basis of the discussion for the second interview. This began with the researcher asking the participant to sort their photographs into their preferred order and then discuss each in turn. Participants linked their photographs together through different narratives (e.g. a journey, a theme such as traffic or a contrast such as ‘new vs. old’) and organised them into groups or a narrative flow based on the order in which they were taken. As with all other interviews, the photovoice interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim, and a digital copy of all photographs was kept for reference. Participants retained the copyright of their photographs, but as part of the consent process they were asked to give permission for their photographs to be used to illustrate the findings of the research (as in this report).

Main qualitative study

The main qualitative study fieldwork was conducted from September 2014 to April 2015, having been deferred to avoid collecting data around the time of the Commonwealth Games (23 July to 3 August 2014). Recruitment and data collection followed similar procedures to those used in the pilot study, with two important exceptions. First, following the pilot study we concluded that the walkalong method had proven too unpopular and time-consuming to be continued and therefore limited the main study design to an initial semistructured interview with each participant, followed by the option of a follow-on photovoice interview. Second, it became clear in the pilot study that most participants coming forward lived in one of two main areas, Govanhill and Rutherglen, and that experiences of the new motorway differed between these areas. We therefore decided to focus on these two areas as qualitative case studies and accordingly limited recruitment for the main study to participants living within 400 m of the M74 extension in either of these two areas.

Existing national population data sets

STATS19

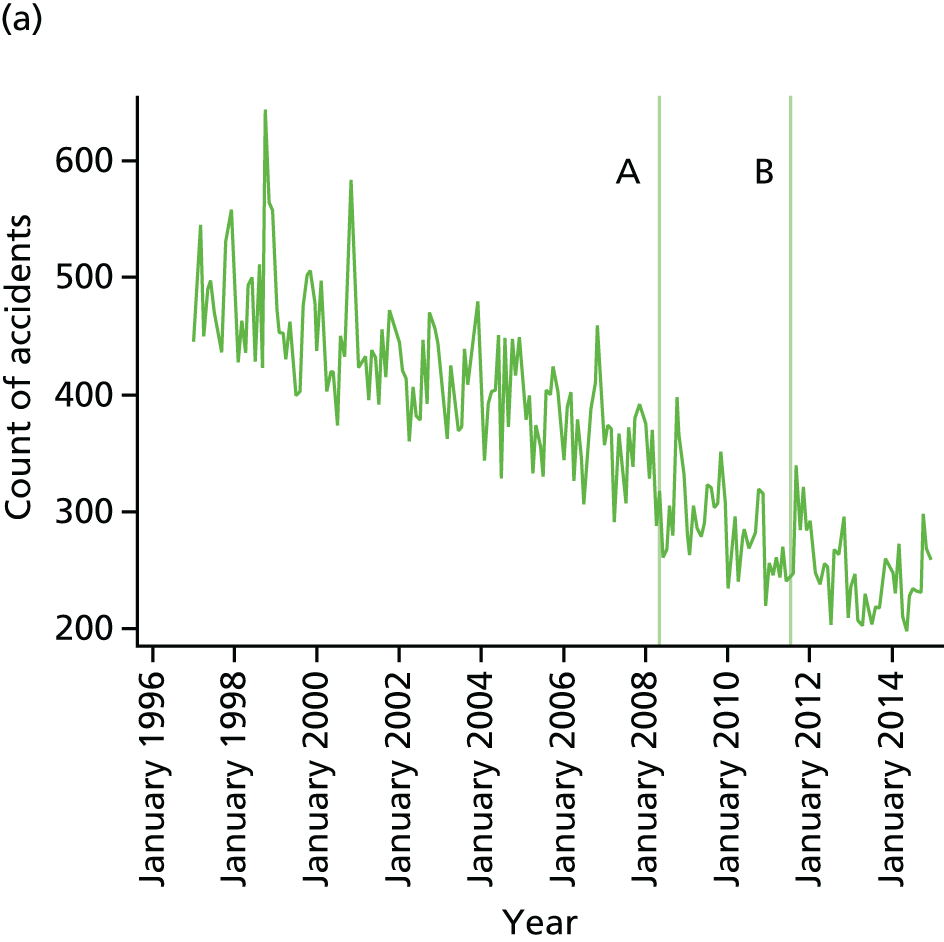

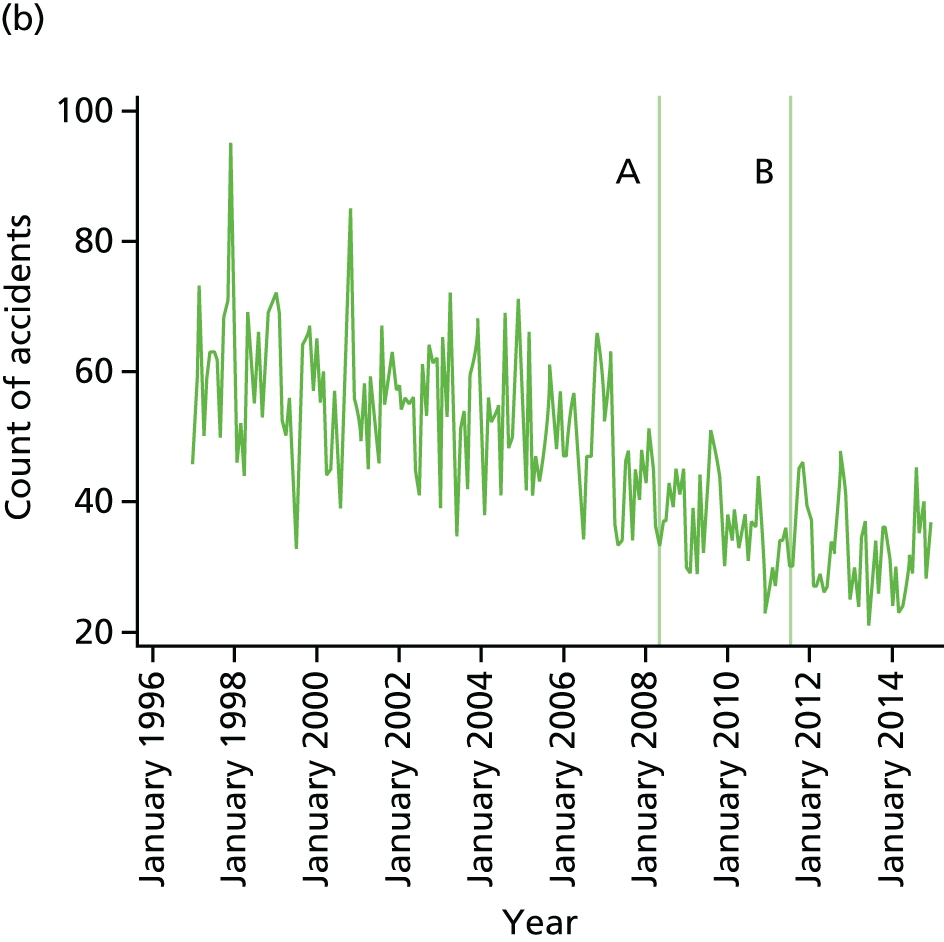

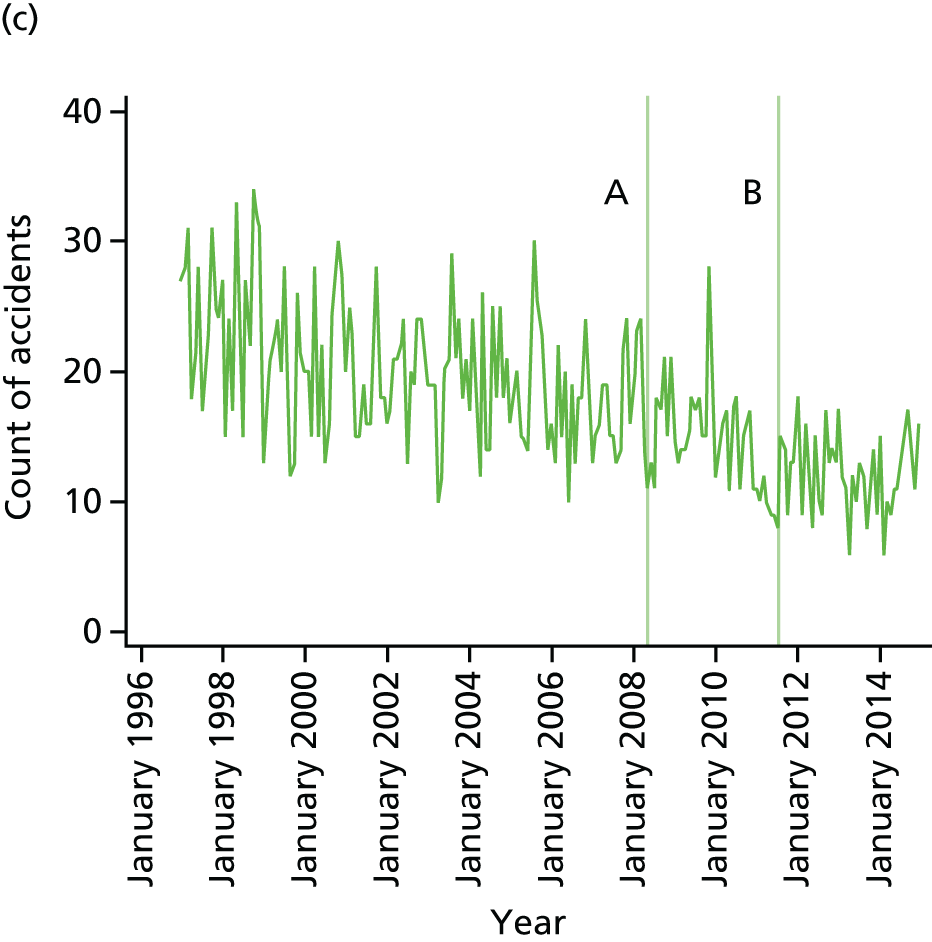

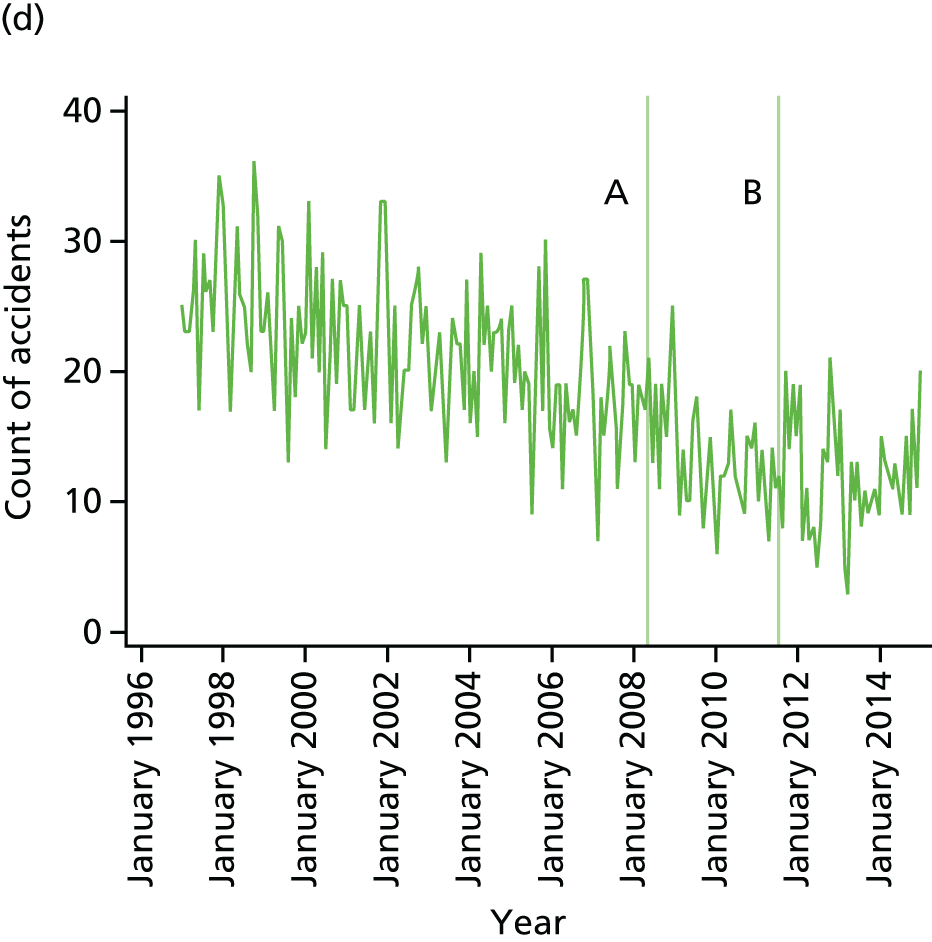

Data from STATS19,74 a detailed data set of road traffic accidents, were obtained for the period 1997–2014 from the UK Department for Transport. STATS19 contains routinely collected information about all road traffic accidents in the UK that have resulted in a casualty and have been reported to the police. Detailed data are provided about each accident including the date, the casualty severity and the precise co-ordinates of the location. Each accident can be linked to a more detailed data set describing the type of road user (pedestrian, driver, passenger or cyclist) and to more information on the accident and the casualty. Multiple casualties can be assigned to each accident. The casualty severity of each accident is pre-classified using the following definitions: slight, an accident in which at least one person is slightly injured but no one is killed or seriously injured; serious, one in which at least one person is seriously injured but no one is killed; and fatal, one in which at least one person is killed. To increase the sample size of accidents available for analysis, we expanded the boundaries of the South, East and North study areas using 1000-m buffers rather than the 500-m buffers originally used to define these areas (see Overall research design and Chapter 5, Introduction). We also used the larger area covered by Glasgow City Council and its surrounding local authorities as a reference area for these analyses, partly because the intervention area spanned two local authority areas (Glasgow City and South Lanarkshire) and partly to provide a mixture of urban and rural areas, and varied designs and densities of road networks for comparison.

Scottish Household Survey

Travel diary data were obtained from the complete SHS63 data set for the whole of Scotland from 2009 to 2013. The SHS is a nationally representative rolling cross-sectional survey of adults aged ≥ 16 years selected from a geographically representative cluster-random sample of households. 63 Face-to-face interviews were conducted and participants completed a travel diary detailing all journeys completed during the previous day, including the origin, destination and purpose of each journey, and the mode of transport used on each stage of each journey. The distance of each journey was calculated by Transport Scotland in a geographical information system (GIS) using the straight-line distance between the origin and destination.

Incentives and feedback for participants

For the core survey, participants were entered into a £50 prize draw (at baseline) or received a £5 voucher (at follow-up). At follow-up, those who participated in the objective measurement study received a second £5 voucher, and those who participated in the qualitative study received an additional £10 voucher for each interview conducted.

Derivation of key variables

In this section, we describe the derivation of the key variables used in our quantitative analyses.

Travel behaviour

Core survey

We excluded the travel records of participants who returned a completely blank record, reported not having been at home on the day in question, returned a record so implausible that they appeared to have misunderstood the question or returned non-numeric values (such as ticks) instead of minutes values. However, we retained records in which participants had reported no journeys but had completed other parts of the record (e.g. specifying the day of the week), treating these as a positive indication of ‘no travel’ rather than as missing data on travel behaviour. Participants were instructed to report neither journeys made in the course of work (such as driving a bus or making deliveries), because these were not personal travel, nor those made purely for recreation (such as going for a bike ride) rather than to get from place to place, because recreational physical activity of this kind was captured in the physical activity questionnaire. If such journeys were reported, they were deleted from the travel behaviour record. Time spent using each mode of transport was summed and used to derive the following variables:

-

total travel time (minutes/day)

-

bus travel time (minutes/day)

-

car travel time (minutes/day)

-

walking time (minutes/day).

Summary variables were not derived for time spent on the train or using a bicycle, because fewer than 6% of participants at follow-up reported using these modes of transport.

Scottish Household Survey