Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/3060/03. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Laurence Moore and Rona Campbell are Scientific Advisors to DECIPHer IMPACT, a not-for-profit organisation that licenses the ASSIST smoking prevention programme. Adam Fletcher, Rona Campbell, Matthew Hickman and Chris Bonell are members of the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research Research Funding Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by White et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background to the research

Definitions of illicit drug use and legislative framework governing use

Illicit drugs are those for which non-medical use is prohibited by international drug control treaties. 1 This includes plant-based substances (e.g. cannabis, cocaine, heroin) and synthetic substances such as amphetamine-like stimulants, novel psychoactive substances and prescription opioids. In the UK, illegal drugs are controlled substances defined in the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act2 or determined to be capable of producing a psychoactive effect and not exempted by the 2016 Psychoactive Substances Act. 3 Glues, gases and aerosols (GGAs) also face restrictions on sales to those aged < 18 years under the Cigarette Lighter Refill (Safety) Regulations 19994 and Anti-social Behaviour Act 2003. 5 Henceforth, GGAs will be classified as illicit drugs.

The prevalence of illicit drug use in school-age adolescents

In the UK, over the past 10 years there has been a steady decline in the number of students aged 11–15 years in England who report ever having tried drugs, from 26% in 2004 to 15% in 2014. 6 In 2014, 10% of 11- to 15-year-olds had used drugs in the last year, a decrease from 18% in 2004. The proportion who have ever used drugs increases with age: in 2014, 6% of 11-year-old children reported having used drugs, which increased to 24% for 15-year-olds. 6 The proportion of children using drugs in the last month increases with age, reaching 12% in 15-year-olds. In total, 8% of 11- to 15-year-olds had tried cannabis, 6.8% had tried GGAs and 1% had tried cocaine, ecstasy and magic mushrooms. 6

Direct harms to health associated with illicit drug use

The latest Global Burden of Disease Study found that the risk factors for disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) attributable to drug use disorders in young people had increased between 1990 and 2013. 7 One DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of 1 year of full health. Across 188 countries, drug use disorders were ranked 14th in the causes of DALYs in 10- to 14-year-olds; fifth in 15- to 19-year-olds (behind alcohol misuse, unsafe sex, iron deficiency and unsafe water), up from sixth in 1990; and second in 20- to 24-year-olds (behind alcohol misuse), up from fourth in 1990.

In the UK, the direct harms to health associated with drug use in school-age children are mainly attributable to cannabis and GGA use. Around 10% of cannabis users will become dependent on it8 and it is the primary reason for seeking specialist drug treatment in the UK in those aged < 18 years. 9 In 2014/15, 13,454 (73%) 11- to 18-year-olds receiving specialist drug treatment did so primarily for cannabis use. 9 The proportion of young people seeking treatment for cannabis use has been on an upwards trend since 2005/6 (from 55%, n = 9043). The median age at first treatment was 16 years. 9

A number of cohort studies have shown that regular cannabis users have lower attendance rates and are more likely to leave school10,11 and have a lower level of educational achievement. 12 In the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) birth cohort,13 lifetime cannabis use by 15 years of age was associated with a 2-point lower mathematics General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) score, a 48% increased risk of not attaining five or more GCSEs and a threefold increased risk of leaving school, or having no qualifications, after adjusting for prior key stage 2 results, parental substance misuse, gender and concurrent drug and tobacco use. Stronger associations were found for weekly cannabis use. 13 This is consistent with case–control studies, which have found poorer verbal learning, memory and attention in those who regularly use cannabis than in those who do not. 14

Indirect harms of drug use for health

Illicit drug use may indirectly affect health by limiting opportunities for employment and educational attainment resulting in exclusion from school.

In the UK, in 2014/15 there were 607 (3% of all offences) proven offences (defined as a reprimand, warning, caution or conviction) that were drug related among 10- to 14-year-olds, increasing to 6922 cases (10.3%) in 15- to 17-year-olds. 15 There were 142 guilty verdicts delivered at courts attributable to drug offences among 10- to 14-year-olds (5.5% of all indictable offences), increasing to 2480 (17.2%) among 15- to 17-year-olds. 15 All offences and convictions are subject to disclosure to a potential employer under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 197416 if the role requires, such as when working with children or vulnerable adults, within law, health-care and pharmacy professions and in some senior management posts and when matters of national security are involved. The exact impact of drug convictions on employment is not known.

In 2014/15 there were 480 permanent (10%) and 7900 fixed-period (3.3%) drug- and alcohol-related exclusions in state-funded secondary schools in England. 17 These data do not disaggregate between illicit drug use and alcohol use.

Evidence on the effectiveness of school-based drug prevention

In response to a commissioning brief published by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) inviting applications to examine using peer support to prevent illicit drug uptake in young people (reference 12/3060), we conducted a scoping review of relevant systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The effectiveness of school-based drug prevention has been examined in a 2014 Cochrane systematic review. 18 In this review, 51 RCTs of universal (i.e. provided to all) school-based prevention interventions were identified, with only two studies from the UK. The interventions reviewed showed, on average, no protective effect on drug use after 12 months. In terms of what types of interventions are effective, interventions that aim to increase knowledge did not lead to changes in drug use behaviour, whereas those aiming to increase social competences (i.e. teaching self-management, social skills, problem-solving, skills to resist media and interpersonal influences, how to cope with stress) or based on social influence theories (i.e. correcting overestimates of the prevalence of drug use, increasing awareness of media, peer and family influences, practising refusal skills) increased knowledge about drugs but had small and inconsistent effects on drug use at ≥ 12 months. The six studies that examined interventions using components from both social competence and influence approaches had a small beneficial effect on preventing cannabis use, but no effect on hard drug use (defined as heroin, cocaine or crack) after 12 months. The authors noted that many studies did not describe the randomisation method or account for clustering (non-independence between children in the same school) in their analyses, despite all being cluster RCTs (cRCTs). 18

A second systematic review examined the effectiveness of peer-led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol or illicit drug use in 11- to 21-year-olds. 19 Pooled data from the three school-based RCTs reporting a drug use outcome (976 students, 38 schools) suggested that peer-led interventions had a small protective effect on cannabis use at ≥ 12 months. One study in this review, the Towards No Drug Abuse Network (TND-Network) study, which involved nominated peers delivering lessons on drug use, found a small reduction in monthly cannabis use. 20 In a subgroup of students whose friends had already used substances (calculated as a composite of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and cocaine use), an iatrogenic effect was found whereby monthly cannabis use slightly increased. Contamination was potentially an issue in this study, as classes rather than year groups or schools were allocated. Another school-based drug abuse prevention trial, the European Drug Addiction Prevention (EU-Dap) trial, reported no effect on drug use at 18 months in the peer-led intervention arm,21 but implementation of the intervention in this arm was poor, with only 8% of centres implementing all seven sessions and 71% not conducting any meetings at all.

These reviews identified a number of methodological weaknesses in the evidence base, including small sample sizes, contamination, inadequate reporting of randomisation and outcomes and a failure to account for clustering in cRCTs. 18 Interventions using a combination of social influence and social competence training have had small beneficial effects on knowledge and cannabis use at 12 months’ follow-up. 18 Two peer-led RCTs have shown a small beneficial effect of peer-led interventions on preventing and reducing cannabis use. 19 There were some limitations in the design of these interventions, including the iatrogenic effects in one peer-led study20 and low levels of implementation in another study. 21 This suggests that a more careful approach to intervention design and refinement is needed. In these reviews, no drug prevention interventions were implemented in a UK educational setting.

Rationale for the current study

The rationale for this study was to develop, refine and conduct a pilot cRCT of a new school-based peer-led drug prevention intervention. Specifically, in our study we aimed to adapt an existing, effective, peer-led smoking prevention intervention (ASSIST) that uses components of social influence and competence programmes to deliver information on illicit drug use from the UK national drug education website [see www.talktofrank.com (accessed 29 August 2017)].

ASSIST

The ASSIST intervention is an evidence-based, informal peer-led smoking prevention intervention based on diffusion of innovations theory22 that aims to diffuse and sustain non-smoking norms via secondary school students’ social networks in Year 8 (age 12–13 years). 23 It is part of the tobacco control plans of the Scottish24 and Welsh25 Governments and is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 26 In the UK, > 120,000 students have taken part in the ASSIST intervention and an estimated 2200 young people have not taken up smoking because of ASSIST who otherwise would have done so. The five stages of ASSIST, as currently delivered, are listed in Table 1.

| Stage | Primary focus | Core tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nomination of peer supporters |

|

| 2 | Recruitment of peer supporters |

|

| 3 | Training of peer supporters |

|

| 4 | Intervention period |

|

| 5 | Acknowledgement of peer supporters’ contribution |

|

Talk to FRANK

The Talk to FRANK website (see www.talktofrank.com) was set up by the UK Department of Health and the Home Office in 2003 to provide up-to-date, youth-friendly information and advice on the risks of illicit drug use. Between January and December 2014 there were 5.1 million visits to the FRANK website. 27 In 2013, 18% of 11- to 15-year-olds (increasing from 5% of 11-year-olds to 33% of 15-year-olds) reported that the website was a source of helpful information about drugs. 28 The FRANK website is the most commonly cited source of information by teachers (78%) for preparing lessons on drugs. 6

Information is provided using a number of interactive methods including videos showing the effects of specific drugs, regular updates on the legality and mechanism of effect of new drugs, an A-Z guide of drugs and a frequently asked questions (FAQs) section. Highly rated FAQs include those on the long-term effects of cannabis, the levels of drug use associated with dependence, criminal consequences and the half-life of specific drugs. FAQs are also tailored to young people, parents and health professionals. Support is offered through the website with instant messaging, live chat (available at specific times during the day), an online forum, a confidential 24-hour telephone service and an e-mail or text service. Trained advisors operate this free service and local help can also be found by entering a postcode.

CASE+

There was a previous attempt to adapt the ASSIST intervention to prevent cannabis use. An unpublished feasibility trial (CASE+) in six Scottish secondary schools found little change in intentions to use cannabis in 732 students aged 12–13 year over a 3-month follow-up (Munro A, Bloor M. A Feasibility Study for a Schools-based, Peer-led, Drugs Prevention Programme, Based on the ASSIST Programme: the Results. Centre for Drug Misuse Research Occasional Paper. Glasgow: University of Glasgow; 2009). The intervention included an extra day of education solely on cannabis use in addition to the 2 days of training on smoking in the ASSIST intervention. However, the study had several limitations: (1) no drug use data were collected, (2) 3 months’ follow-up is not long enough to ascertain a likely effect of the intervention over longer periods and (3) the intervention content was solely related to cannabis use.

The process evaluation indicated that, although implementation fidelity and acceptability to school staff was high, students were overwhelmed with the amount of information that they received in the extra day of training on cannabis. The peer supporters also rarely had conversations about cannabis but focused on smoking, because only a few students were experimenting with cannabis at age 12/13 years and there was sensitivity around discussing cannabis use as it is illegal. We decided to adapt the ASSIST model to deliver the information from the FRANK website rather than CASE+ as it has a database of information on illicit drugs and not just cannabis. The FRANK website has demonstrated a large number of hits per year and teachers and young people use it, such that it provides an accessible drug education resource that updates.

Study design

This study was conducted in three stages. Stage 1 involved the development of two new school-based peer-led drug prevention interventions: ASSIST + FRANK (+FRANK) and FRANK friends. Stage 2 involved the delivery of the interventions in one school each, conducting a process evaluation and using this information to refine the interventions. Stage 3 was a four-arm pilot cRCT (+FRANK, FRANK friends, ASSIST and usual practice) with an embedded process evaluation. The ASSIST arm was used to investigate any potential indirect effects of a smoking prevention intervention on drug use.

Aim and objectives

The overall aim of this study was to assess the feasibility, acceptability and fidelity of delivery of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions to inform a full-scale RCT.

The objectives were to:

-

refine the ASSIST logic model to drug prevention and develop the ASSIST + FRANK and FRANK friends interventions

-

test the feasibility of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions in one school each and

-

assess the acceptability of the intervention to trainers, students, parents and school staff and explore the barriers to and facilitators of implementation

-

explore the fidelity of intervention delivery by +FRANK and FRANK friends trainers and peer supporters

-

refine the interventions

-

-

conduct a pilot cRCT of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions to

-

assess the feasibility and acceptability of the refined interventions to trainers, students, parents and school staff

-

assess the fidelity of intervention delivery by trainers

-

compare the feasibility and acceptability of the interventions

-

assess trial recruitment and retention rates

-

pilot outcome measures

-

record the delivery costs and pilot methods for assessing cost-effectiveness

-

-

determine the design, structures, resources and partnerships necessary for a full-scale trial to take place.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

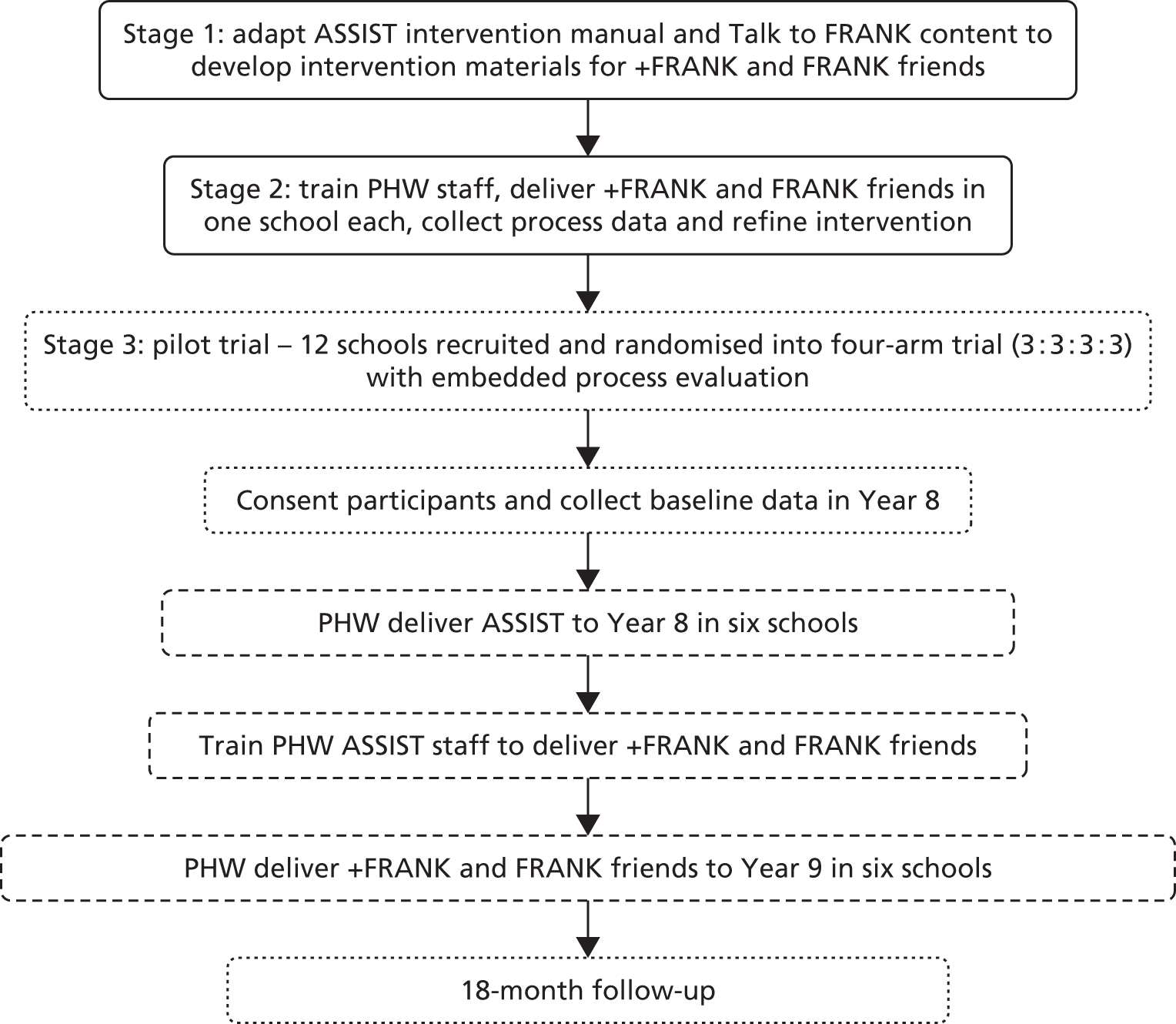

The three stages of the project are described in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study schema. Note: stages did not take place in chronological order. The ASSIST intervention was delivered in Year 8 and the baseline data collection for the pilot trial (stage 3) took place before the piloting of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions. Dashed lines indicate stages that were part of the pilot cRCT. PHW, Public Health Wales.

Setting

The study took place in seven local authorities in South Wales (Cardiff, Newport, Torfaen, Blaenau Gwent, Rhondda Cynon Taf, Merthyr Tydfil and Caerphilly). With a projected population of 1,155,800 in 2016, these local authorities represent 36.9% of the Welsh population. 29 Fourteen out of the 72 secondary schools across the seven local authorities participated. Two schools received one of the interventions each in stage 2. Twelve schools were involved in stage 3, the pilot cRCT.

Ethics approval and monitoring

The study was granted ethics approval by Cardiff University School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (reference SREC/1103). NHS research and development (R&D) approval was also granted, as Public Health Wales (PHW) staff delivered the interventions (reference 2013PHW0015).

Trial monitoring

The ongoing conduct and progress of the study was monitored by an independently chaired Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The membership included independent scientific experts, representation from the Department of Health, policy leads for children and young people in PHW and a parent representative.

Interventions

We present here an outline of each intervention provided at the time of the submission of the proposal for funding. The content of the activities and the method of delivery had yet to be developed. Both interventions underwent revision during stages 1 and 2.

+FRANK: an informal peer-led drug prevention adjunct to ASSIST

+FRANK is an informal peer-led intervention to prevent drug use in UK Year 9 secondary school children. A summary of the +FRANK intervention is provided in Table 2.

| Stage | Primary focus | Core tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Re-engagement of ASSIST peer supporters |

|

| 2. | Recruitment |

|

| 3. | Training of peer supporters |

|

| 4 | Intervention period |

|

| 5 | Acknowledgement of peer supporters’ contribution |

|

FRANK friends: an informal peer-led drug prevention intervention

FRANK friends is a standalone informal peer-led intervention to prevent drug use in UK Year 9 secondary school children. It replicates the format of the ASSIST intervention in the peer nomination process, the 2 days of off-site training and the four face-to-face follow-up visits. The +FRANK intervention includes only 1 day of off-site training. The additional day of training in the FRANK friends intervention is mainly spent developing communication skills, which are covered in training for the ASSIST intervention. A summary of the FRANK friends intervention is provided in Table 3.

| Stage | Primary focus | Core tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nomination of peer supporters |

|

| 2. | Recruitment |

|

| 3. | Training of peer supporters |

|

| 4 | Intervention period |

|

| 5 | Acknowledgement of peer supporters’ contribution |

|

Stage 1: development of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions

We used a three-phase multimethod framework to guide the adaptation of the ASSIST smoking prevention intervention to develop content, resources and delivery methods for the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions (Figure 2). 30 The methods used at each stage allowed for integration of the scientific literature with key stakeholders’ knowledge and expertise. Key stakeholders included people with direct experience or knowledge of youth drug taking, recipients of the existing ASSIST smoking prevention intervention, intended recipients of the newly developed interventions and those who delivered any existing drug prevention interventions within the setting (i.e. schools) or who provided intervention resources (e.g. financing, staffing).

FIGURE 2.

Framework for intervention coproduction and prototyping. a, Stakeholders comprise those within or external to the delivery setting (e.g. school-based: school teachers, head teacher, contact teacher, head of year, receptionist, head of personal, social, health and economic education; national and local policy leads; and parents/guardians/carers.

Phase 1: evidence review and stakeholder consultation

Evidence review

We conducted a scoping review of systematic reviews and RCTs of school-based drug prevention. We also examined the latest population-based randomly sampled surveys on the prevalence of illicit drug use in school-age children in the UK.

Consultations with young people

We gathered multiple perspectives about drug use and existing drug education to tailor the intervention content to increase acceptability within the school context and population. Our aim was to maximise acceptability and reduce problems with implementation. This involved a range of methods.

Focus groups with young people

Six focus groups were conducted with 47 young people aged 13–15 years, who were purposively sampled from three schools, a youth centre and a student referral unit. A semistructured topic guide was used with broad open-ended questions relating to participatory task-based activities using resources based on the Talk to FRANK website.

Interviews with the ASSIST intervention delivery team

Interviews were conducted with five members of the PHW ASSIST delivery team.

Structured observations of current practice

Structured observations of all five stages of ASSIST intervention delivery were conducted (n = 8), as well as one observation of the ASSIST ‘Train the Trainers’ course.

Stakeholder consultation

A range of informal consultations was also conducted with young people and practitioners, one with five volunteers from a young people’s public involvement group aged 16–19 years; one with seven young people aged 13–15 years; one with five recipients of the ASSIST intervention aged 12–13 years; and nine individual consultations with health professionals working for drug agencies (n = 4), with young people (n = 4) or both (n = 1).

Audio recordings from interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. Researcher field notes from observations and informal consultations were combined with the data from the interviews and focus groups. An a priori coding framework focused on assessing the acceptability of the content and delivery of the intervention. An element of flexibility was maintained in coding such that data that did not fit the framework were also captured in an inductive manner. This approach to analysis has been described in detail elsewhere. 31 The findings from the analyses fed into the coproduction of intervention content during phase 2.

Phase 2: coproduction

An intervention development group (IDG) was established consisting of members of the research team and the PHW ASSIST delivery team. The PHW team had delivered the ASSIST intervention to > 350 schools over a period of 7 years and so had extensive experience of intervention delivery within schools. The aim of the IDG was to adapt the ASSIST intervention materials to deliver information from the Talk to FRANK website, informed by the findings from phase 1.

Coproduction of intervention content took the form of an action research cycle over a series of meetings of the IDG at which findings from stage 1 were considered, ideas were presented by all members, feedback on ideas was sought and refinements were made and presented again, until the final content was agreed. Five face-to-face meetings were held over the course of a 4-month period. These were supplemented by communications by e-mail when face-to-face meetings were not possible or when matters arose that required discussion between meetings.

Phase 3: prototyping

After a first draft of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions had been developed, the manuals and resources (e.g. fact sheets on the effects of cannabis on mental health) underwent expert review. Two experts were asked to examine key uncertainties identified during phases 1 and 2. The lead author of the ASSIST cRCT23 examined the fit of the activities with diffusion of innovations theory,22 on which the ASSIST intervention was based. The lead trainer of DECIPHer IMPACT (Bristol, UK), the company that licenses ASSIST, and reviewers examined the age appropriateness of the activities and the suitability of the timings and sequencing of activities.

Preliminary feedback on acceptability and feasibility was collected during training of the PHW intervention delivery staff. Training involved the delivery of the two interventions to the IDG. Feedback was also sought from ASSIST trainers at a DECIPHer IMPACT ‘Train the Trainer’ course. The interventions were also delivered to a young people’s public involvement group (aged 16–19 years). Feedback was sought from young people on each activity, with a particular emphasis on relevance for their age group and interest in and engagement with the content.

Stage 2: delivery and refinement of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions

The +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions were delivered in one school each. The aim was to conduct a detailed process evaluation examining the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention from the perspective of teachers [contact and school management team (SMT) members], peer supporters and trainers within the school context.

Figure 3 provides an overview of the process and methods used to refine the intervention content and delivery mechanism.

FIGURE 3.

Framework for refining the intervention content and delivery mechanism.

Public Health Wales identified eligible +FRANK schools for the initial feasibility testing as the schools were required to have received the ASSIST intervention in Year 8. Eligible FRANK friends schools were required to have not received the ASSIST intervention in Year 8. The order of invitation was not determined by any defined method. The interventions were delivered over two different terms because of a lack of capacity in the PHW team to deliver them concurrently. The +FRANK intervention was delivered first followed by the FRANK friends intervention. Information was collected to determine acceptability and feasibility to inform refinements to the intervention manuals and associated resources in preparation for the pilot trial. This involved a range of methods.

Structured observations, evaluation forms and interviews

Independent structured observations were undertaken by two researchers of all intervention activities, including recruitment, re-engagement, training and follow-up visits. Observation forms captured whether or not objectives for the sessions and learning outcomes for activities were met using a traffic light system. Green indicated that the activity had been fully delivered with all objectives met, amber indicated minor deviations in delivery and red highlighted that activity objectives had not been met. The timings of the activities delivered were also recorded along with notes on any deviations to the timetable and/or activity instructions. Trainers completed self-assessment forms following each delivery episode to capture their perceptions of the delivery for each aspect of intervention delivery and training.

Evaluation forms were completed by peer supporters and trainers at the end of the off-site training days and final follow-up visit. Interviews were conducted with peer supporters, trainers, contact teachers and members of the SMT after the last follow-up. Interviews with peer supporters were conducted individually, in pairs or in small groups, to suit the requirements of the school. Additional interviews were conducted with trainers and students after delivery in the two schools that took part in the initial feasibility testing.

Interviews were conducted with peer supporters using a semistructured topic guide to explore all parts of the interventions, particularly what did and did not work, with a view to identifying areas for potential refinement. Interviews with school staff explored the intervention delivery, methods and processes. Interviews with SMT members explored their awareness and understanding of the interventions, the information that they had received and their overall impressions of the intervention. Audio recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymised at the point of transcription. This included removing personal names, school names and any other identifying information. Qualitative data analysis was facilitated by the use of NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), a qualitative data analysis software programme.

A framework analysis was employed. 32 A coding matrix was used to index and categorise data, with categories and themes being predetermined based on the research objectives (e.g. feasibility of delivery of the intervention components, acceptability of the intervention components to peer supporters) and with any unexpected themes identified being added. Data collected from the structured observations and self-assessments were organised in descriptive ‘chunks’ for each component/activity within the interventions. Identification of recurring and salient themes was examined against this framework. Two coders agreed on the framework and then referred to an additional two independent members of the research team to discuss/resolve any discrepancies and reach a consensus. To agree on refinements to intervention resources and delivery mechanisms, the results were shared with the Trial Management Group (TMG) and IDG.

Stage 3: external pilot cluster randomised controlled trial

The external pilot trial was a parallel, four-arm cRCT with school as the unit of randomisation. The investigator team, students and staff were unblinded and fieldworkers were blinded. The primary aim of the pilot trial was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial methods and gather data to plan a future full-scale trial. This included estimating rates of eligibility, recruitment and retention at the 18-month follow-up, as well as the acceptability, reliability and rates of completion of pilot primary and secondary outcome measures.

Eligibility criteria and recruitment

The pilot trial was embedded within the 2014/15 delivery of the ASSIST intervention by PHW. As part of the Welsh Government’s Tobacco Control Action Plan, PHW was funded to deliver the ASSIST intervention to 50 schools a year. The Welsh Government provided PHW with a list of approximately 160 schools eligible for the ASSIST intervention out of the 220 secondary schools in Wales. The Welsh Government informed PHW that schools were selected on the basis of having a high percentage of children in receipt of free school meals (FSMs) and schools were in relatively deprived areas according to the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD). 33 The Welsh Government did not provide the exact cut-off points applied for FSMs or the WIMD to exclude schools. From this list PHW recruited schools from the counties of Cardiff, Newport, Torfaen, Blaenau Gwent, Rhondda Cynon Taf, Merthyr Tydfil and Caerphilly, inviting those that had not received the ASSIST intervention in the past 2 years. Out of the 72 schools in these counties, 40 had not received the ASSIST intervention in the last 2 years and formed our sampling frame. These schools were sent a project information sheet, reply envelope and form asking them to contact PHW or the principal investigator if they wished to be involved in the study. Non-responders were followed up with a reminder and telephone call from the study manager (KM). All interested schools were visited by the study manager to discuss the study in more detail.

Consent

Head teachers signed a memorandum of understanding before taking part in the study describing the roles and responsibilities of both the intervention delivery and the research teams and the timeline of intervention delivery and assessments. Letters were sent to parents/guardians asking them to contact the school if they did not wish their child to participate in the trial. Parents who did not wish their child to participate were able to opt their child out of data collections. Written consent detailing the right to withdraw was sought from all participants. At all data collection points, age-appropriate information sheets were provided, together with a verbal explanation by researchers on the right to withdraw.

Sample size

As this was a pilot trial a power calculation was not required. The estimated sample size at baseline was 1440 students across 12 schools (n = 360 per arm), chosen to provide some information on variability within and between schools at baseline and follow-up. This sample was not anticipated to provide adequate power to detect a statistically significant difference across groups. However, the sample was used to indicate the likely response rates and permit estimates [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] of intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of drug prevalence in anticipation of a larger cRCT. 34

Randomisation

Schools agreed to take part prior to randomisation. The study used an assignment ratio of 1 : 1 : 1 : 1. Allocation was conducted by the study statistician, blind to the identity of schools, and minimised on the median percentage of students in receipt of FSMs (below/above median) and median school size (below/above median) to balance the randomisation. Optimal allocation was used to carry out the randomisation. 35

Interventions

The +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions delivered in the external pilot cRCT are described in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Delivery of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions occurred between September and November 2015. In the +FRANK arm, peer nomination was repeated to examine the proportion of students nominated in Year 8 who were renominated in Year 9.

Usual practice

Children participated in their usual personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE) lessons provided by the schools. All schools followed a national PSHE curriculum, which may include education on drug use and smoking.

Quantitative data collection process

The consent procedure and questionnaires were self-reported. All data were collected by fieldworkers. Questionnaires were completed in school halls or classrooms under examination conditions. Researchers, fieldworkers and dedicated school staff helped children with literacy problems and special educational needs. Baseline data collection took place between 17 September and 20 October 2014, prior to randomisation. Follow-up data collection took place 18 months later between 22 March and 5 May 2016. To increase response rates, additional collections were made for students who were absent. Schools were paid £300 for staff cover for the data collections after the 18-month follow-up.

Outcome measures

The main study outcomes were operationalised as progression criteria. Progression criteria were agreed by the TMG, TSC and NIHR Public Health Research (PHR) Research Funding Board. Assessment methods used a mix of quantitative and qualitative data. Table 4 shows the research questions that the progression criteria addressed, the data collection methods and the sources of data used.

| Research question | Progression criteria | Data collection method | Data examined |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was it feasible to implement the +FRANK intervention in (at least) two out of three intervention schools? | ≥ 75% of Year 8 ASSIST peer supporters are recruited and retrained as +FRANK peer supporters in Year 9 | Attendance records | Percentage of students who completed ASSIST training in Year 8 attending the recruitment and training sessions for +FRANK |

| PHW staff delivered the +FRANK training in full in all three intervention schools | Structured observations of training and follow-up sessions | Number of predefined learning outcomes met at training and follow-up sessions | |

| Interviews with trainers | Facilitators of and barriers to delivering the intervention activities | ||

| 2. Was it feasible to implement the FRANK friends intervention in (at least) two out of three intervention schools? | ≥ 75% of Year 9 students nominated are recruited and trained as FRANK friends peer supporters | Attendance records | Percentage of students who were nominated to be FRANK friends peer supporters attending the recruitment and training sessions |

| PHW staff delivered the FRANK friends training in full in all three intervention schools | Structured observations of training and follow-up sessions | Number of predefined learning outcomes met at training and follow-up sessions | |

| Interviews with trainers | Facilitators of and barriers to delivering the intervention activities | ||

| 3. Was the intervention acceptable to students trained as +FRANK peer supporters? and 4. Was the intervention acceptable to students trained as FRANK friends peer supporters? | ≥ 75% of +FRANK and FRANK friends peer supporters report having at least one or more informal conversations with their peers at school about drug-related risks/harms |

|

|

| ≥ 75% of +FRANK and FRANK friends peer supporters report ongoing contact with PHW staff throughout the year through follow-up visits |

|

|

|

| 5. Was the +FRANK intervention acceptable to the majority of SMTs, other school staff and parents? and 6. Was the FRANK friends intervention acceptable to the majority of SMTs, other school staff and parents? |

|

|

|

|

|||

| 7. Were the trial design and methods acceptable and feasible? | Randomisation occurred as planned and was acceptable to SMTs | Interviews with SMT staff |

|

| A minimum of five out of six intervention schools and two out of three schools from the comparison arms participate in the 18-month follow-up | Study records |

|

|

| Student survey response rates are acceptable at baseline (80%+) and follow-up (75%+) | Attendance records |

|

Self-reported outcome measures

The self-report questionnaires included items to assess the anticipated primary outcome in a future full-scale trial, the lifetime prevalence of illicit drug use, using questions from the ALSPAC cohort. 36 At baseline, students were asked whether they had ever tried 10 drugs that had a > 1% prevalence in 13- to 14-year-olds in the 2013 Smoking, Drinking and Drug use survey,37 with an additional ‘other’ open response category. At follow-up an additional seven drugs were added. Street names were also provided for all drugs and a fictitious drug (semeron) was used to examine false responding. We also examined a number of potential secondary outcomes in this population: frequency of use of each drug in the past 12 months, last 30 days and last week; cannabis dependence using the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST);38,39 lifetime smoking and weekly smoking status (weekly defined as smoking at least one or more cigarette a week40); number of cigarettes smoked every day; nicotine dependence using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)41 and Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI);41,42 lifetime alcohol consumption; the frequency of heavy episodic alcohol use using the Adolescent Single Alcohol Question (A-SAQ), which is a modified version of the modified Single Alcohol Screening Questionnaire;43 and health-related quality of life, using the Child Health Utility-9 Dimensions (CHU-9D) measure. 44,45

Self-reported measures of intermediary factors

To examine the hypothesised mechanisms of action described in the logic models, we examined a number of intermediary factors. These included the perceived lifetime prevalence of drug use in Year 9, the frequency of drug offers, conversations with friends about drugs and visiting the Talk to FRANK website, ever having talked to a peer supporter about drugs, whether students would get help for themselves or a friend from the Talk to FRANK website if they had a problem and knowledge about drugs calculated as the number of correct answers from eight true or false questions about drugs (see Appendix 1, Table 16).

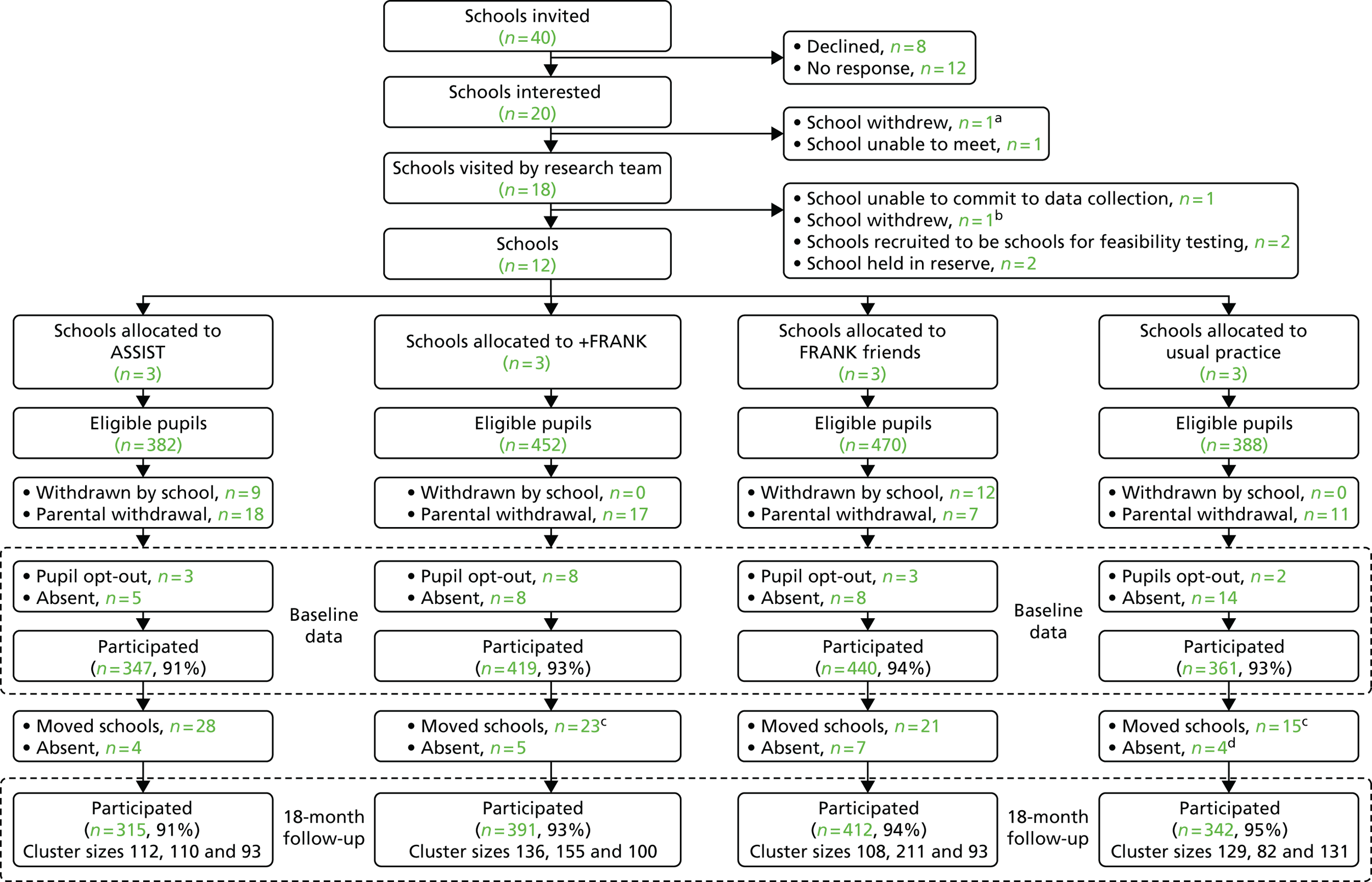

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were largely descriptive. The eligibility, recruitment and retention rates for schools and students were summarised using a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (see Figure 7). 46,47 The data collected for trial participants were summarised by trial arm and combined across arms. To examine the acceptability of potential outcome measures the percentage of missing values are reported for all variables. Categorical variables were summarised using the percentage in each category. Numerical variables were summarised using the mean, standard deviation (SD) and a five-number summary (minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, maximum). We present mean and median values to examine the shape of each distribution. We estimated the percentage of recanted responses, whereby individuals indicated having never used a drug at follow-up but indicated that they had used at baseline, as a measure of reliability. Comparisons were made between those who completed the study and those who dropped out of the study. ICCs were calculated. Exploratory effectiveness analyses using multilevel linear and logistic regression models adjusting for gender, age, FSM entitlement and residence with an adult in employment were conducted for indicative outcome and intermediary variables. We fitted an interaction term to examine effects in students who had and had not used drugs at baseline. If the ICC was < 1 × 10–8, a single-level model was used. All analyses used intention-to-treat populations.

Cost analysis

We estimated the cost of delivering the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions. The cost and cost-effectiveness of the ASSIST intervention has been previously reported. 48 We aimed to provide preliminary evidence on the likely affordability of these interventions and also pilot methods of data collection. We focused on additional costs, over and above those of usual practice, that would be incurred by the public sector (i.e. PHW and schools/education authorities). We did not track or cost the resources used in development or the feasibility testing of the +FRANK or FRANK friends interventions (i.e. stages 1 and 2) as once manuals and resources are developed these are sunk costs. We also excluded the costs of the ‘Training the Trainers’ session as these are artificially high in a pilot trial setting where the training costs are spread over a small number of schools. However, it is important to recognise that some costs associated with updates to the intervention and PHW staff training, because of staff turnover, would be needed if the intervention is used routinely.

We recorded the time spent and other costs of administrating (e.g. contacting schools, arranging venues) and delivering (e.g. intervention days and follow-up sessions) the intervention. The cost of delivering the intervention was predominantly for room hire, catering, PHW staff time, transport costs and intervention consumables (e.g. text messaging service). PHW estimated unit costs for PHW staff time and transport, as well as expenses incurred for room hire, catering, student transport (i.e. coach hire) and consumables.

Process evaluation

The process evaluation examined the feasibility and acceptability of the two interventions from the perspectives of peer supporters, schoolteachers, intervention delivery staff, parents and a public health commissioner. Researcher notes were taken at each stage of intervention delivery, including the training of intervention delivery staff, nomination of peer supporters, training of peer supporters and post-intervention delivery (to assess objectives 3a–c; see Chapter 1).

Two staff members conducted structured observations to assess whether the defined learning outcomes of all intervention activities were met. Observations of the delivery of all intervention activities, across all sites, were made by two members of the research team to examine the fidelity of intervention delivery.

In each school, one member of the SMT plus the contact teacher, head of year or PSHE lead were interviewed. Post-intervention interviews were also conducted with a purposive sample of peer supporters in schools with the highest and lowest prevalence of drug use. All interviews were audio recorded, fully transcribed and anonymised and electronically stored on a secure server. Table 5 provides an outline of the methods used at each stage of the process evaluation in the external pilot, as well as the issues examined.

| Stage | Method | Issues examined |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment and re-engagement of influential students | Record of participation | Response rates |

| Researcher observations | ||

| Trainer feedback form | ||

| Peer supporter training | Record of participation | Attendance/engagement |

| Researcher observations | Intervention fidelity | |

| Post-training evaluation form completed by peer supporters | Acceptability to peer supporters | |

| Interviews with trainers | Explore acceptability and feasibility of delivering the intervention training | |

| Follow-up visits | Record of participation | Retention rates/engagement |

| Researcher observations | Intervention fidelity | |

| Post-intervention evaluation form completed by peer supporters | Acceptability of content and role as a peer supporter | |

| Post intervention | Interviews with peer supporters | Acceptability of intervention content, delivery method and role of peer supporter |

| Interviews with teaching staff | Acceptability of intervention content and delivery method and feasibility of intervention delivery | |

| Interviews with trainers | Acceptability of intervention content and delivery method and feasibility of intervention delivery | |

| Interviews with parents | Acceptability of intervention content, delivery method and role of peer supporter |

Qualitative data analysis

Thematic analysis was employed in the qualitative analysis. 32 The deductive coding framework developed in stage 2 feasibility testing was adapted to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention against progression criteria. We used a coding matrix to index and categorise data, with categories and themes being predetermined based on the research objectives (e.g. feasibility of delivery of the intervention components, acceptability of the intervention components to peer supporters), with flexibility maintained so that any unexpected themes identified from the data could also be added. A sample of six transcripts was coded and compared and regular data analysis meetings were held by the qualitative research team to discuss emerging themes and ensure consistency in coding. Analysis was conducted using NVivo 10 software to assist with the systematic coding of data to identify patterns in the narrative provided by teachers, peer supporters, students, parents and schools.

Changes to the protocol

There were no major changes to the protocol. 49 In the statistical analysis section we stated that we would adjust for baseline levels in the analysis of lifetime drug, smoking and alcohol use at the 18-month follow-up. However, we did not adjust for lifetime measures of use at baseline or conduct subgroup analyses in baseline users. This is because with lifetime measures adjustment creates a situation of perfect prediction. As baseline users can only remain users at 18 months, estimates for students who report lifetime use at baseline cannot be calculated. A request for a 3-month non-financial extension was granted towards the end of the study.

Chapter 3 Results

This chapter presents the results of the study, which are organised according to the three stages of the study: (1) development of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions, (2) feasibility testing of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions and (3) external pilot cRCT.

Stage 1: development of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions

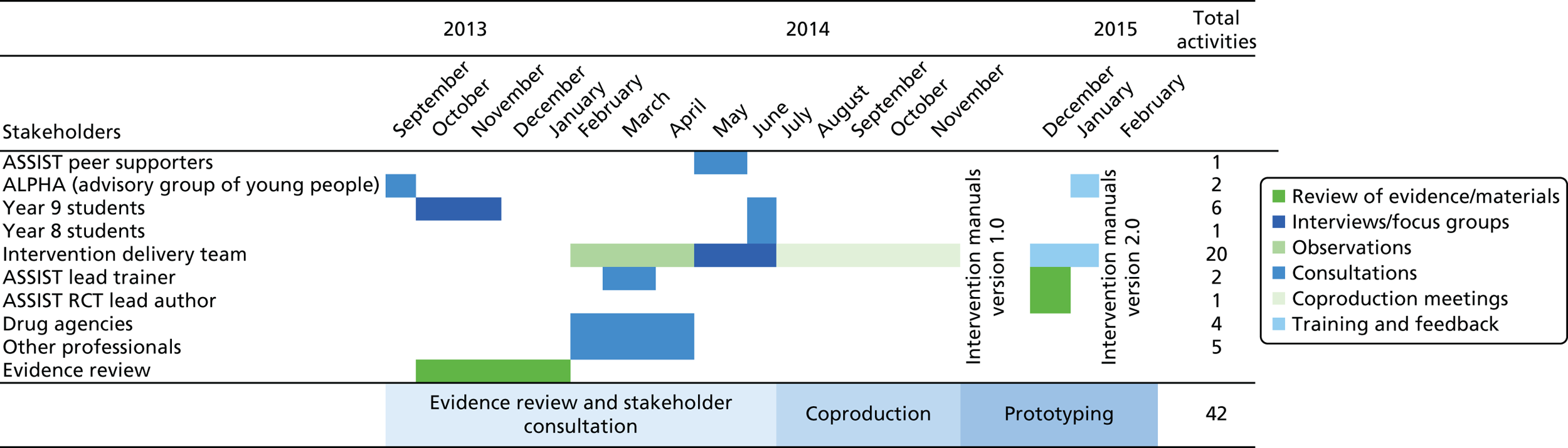

The development process took 18 months and consisted of 42 activities (Figure 4 shows the frequency and timeline of each activity). The process was iterative and cumulative, with refinements made before proceeding to the next stage.

FIGURE 4.

Frequency and timeline of each activity in the development of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions. ALPHA, Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement.

Table 6 summarises the results from stage 1.

| Activity | Objectives | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: evidence review and stakeholder consultation | ||

| Evidence review | Identify target age group for the interventions and identify target drugs to focus the intervention content on |

|

| Consultation with young people’s involvement group | Explore thoughts about drug education in school, young people’s conversations about drugs with friends, awareness of Talk to FRANK and opinions of the website |

|

| Consultation with Year 9 students | Explore views about drug use in their age group and ideas about content for a drug prevention intervention |

|

| Focus groups with Year 9 students | Explore knowledge and risk perceptions of drug use and perceptions of drug use prevalence in their age group and the acceptability and age appropriateness of drug education messages on the Talk to FRANK website |

|

| Consultations with stakeholders (drug agencies and professionals who work with young people) | Explore awareness of drug education resources and support and views on appropriate content for a drug prevention intervention |

|

| Consultations with Year 8 recipients of the ASSIST intervention | Explore ideas about peer supporter training and content for a drug prevention intervention |

|

| Observations of current ASSIST practice | Identify aspects of the intervention that work well and could be adapted for use to deliver a drug prevention intervention and with a Year 9 population |

|

| Interviews with the intervention delivery team | Identify possible influences on intervention feasibility and acceptability, for example explore aspects of the ASSIST intervention that could be adapted to deliver a drug education intervention and for use with 13- to 14-year-olds, as well as those that might not lend themselves to adaptation |

|

| Phase 2: coproduction | ||

| Meetings of the IDG | Action research cycle of assessment, analysis, feedback and agreement on the core components of the intervention required to educate peer supporters on the harms of drug use and the skills required to communicate these to their peers |

|

| Phase 3: prototyping | ||

| Expert review of intervention materials | Identify potential problems or weaknesses in the intervention materials prior to piloting |

|

| Testing of intervention materials with young people | Delivery of the intervention. Identification of issues around the feasibility and acceptability of the newly developed intervention content |

|

| Training of the intervention delivery team | Simulation of intervention delivery. Identification of issues around the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention content |

|

Phase 1: evidence review and stakeholder consultation

In line with Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on developing complex interventions,50 we reviewed the existing literature. Two systematic reviews of school-based drug prevention programmes found small effects on cannabis use in the short term. 18,19 Researchers working on one RCT noted evidence of poor implementation of interventions21 and, in another peer-led programme, evidence was found of iatrogenic effects20 (see Chapter 1, Evidence on the effectiveness of school-based drug prevention, for further details).

Population-based studies on the prevalence of drug use in secondary school-aged children in the UK have shown that the lifetime prevalence of any illegal drug use in England doubled from 6.8% to 12.4% and then to 23.1% from 13 to 14 to 15 years, respectively. 28 The lifetime prevalence of drug use was > 1% only for cannabis, GGAs, ecstasy, poppers, cocaine, ketamine, mephedrone and magic mushrooms. Cannabis had the highest lifetime prevalence, which increased from 2.7% to 7.5% and then 18.7% from age 13 to 14 to 15 years, respectively. GGA prevalence was 3.5%, 4.0% and 4.4% for 13-, 14- and 15-year-olds, respectively. No equivalent data were available in Wales. This informed our decision to deliver the intervention to UK Year 9 students (aged 13–14 years) and focus the intervention content on cannabis and GGA use.

Consultations with young people and practitioners in drug charities noted a local issue with steroid use in older age groups, which was not apparent in prevalence data as these were gathered in England and did not sample from Welsh schools. This led us to include information on steroids in the interventions.

The consultations and focus groups with young people suggested that 13- to 14-year-olds were relatively familiar with the potentially harmful effects of drugs on health:

Like we all know weed is bad, we all know what it does to you as well.

Young person 6

Young people were less familiar with the potential legal consequences of being caught in possession of an illegal drug in the UK:

When it says unlimited fine, does that mean the police can just charge you?

Young person 9

The familiarity of young people with the harmful effects of drugs on health prompted us to expand the focus to include the harms associated with drugs being illegal and therefore unregulated. These included the possibility of unexpected effects brought about by consuming an unknown compound, of unknown purity and dose. Other concerns that young people voiced included the potential harmful effects of drug use on family relationships, future education and employment:

I mean that’s your mum, that’s one of your parents, they put a roof over your head. If you get drove away from them you don’t get food for yourself, you don’t get a roof over your head, you’re out on the streets. You don’t have anyone to get you a meal or look after you ‘cause you’re on your own.

Young person 29

’Cause then you’re getting a criminal record that’s stopping you from getting a job and loads of stuff.

Young person 19

A number of factors that might influence the engagement of students during peer supporter training were found in both the interviews with the ASSIST delivery team and the independent observations by the research team of the delivery of the intervention. In particular, flexibility in delivering intervention activities to different groups and the need for engaging, interactive content were noted:

We work to the same objectives, but in terms of how we run some activities, we might change them a bit . . . with different groups you know, how they react to a certain activity you might change it round to help the running of it.

Trainer 2

Making sure that they’re interactive . . . so they’re up and about, they get moving around, break off activities, um, just making it as interactive as possible.

Trainer 6

Phase 2: coproduction

During coproduction, the IDG reflected on findings from stage 1 to adapt the content from the ASSIST intervention or develop new content. In interviews with the ASSIST team it was noted that it was important to provide peer supporters with interesting and memorable facts about smoking that they could use in conversations with their peers:

So if we can give them facts that sort of link into what they could be talking about with their friends, it makes it easier for these conversations to happen. In ASSIST, one of the facts they always remember, is that smoking could affect your ability to get an erection. That is the one that sticks with them, and you might not have done the training for 10 weeks, and they will still remember that.

Trainer 2

In ASSIST, we know that young people will leave knowing the ingredients of a cigarette, long-term, short-term health effects, is it guaranteed. We know that you’d go up to any young person that had done the training and you’d ask them how many ingredients are in a cigarette and they’d be able to tell you.

Trainer 2

This led us to adapt information from the Talk to FRANK website about the risks of drug use into memorable factual statements. These key statements were then used across several activities within the peer supporter training and were added to the peer supporter diaries as a reminder.

Phase 3: prototyping

Expert peer review, independent from the IDG, by the lead author of the ASSIST RCT23 and the lead trainer at DECIPHer IMPACT, was used to examine and address key areas of uncertainty. The feedback led to refinements in the timing of the intervention activities and the presentation of instructions in the intervention manual.

Feedback provided by the trainers at the end of the two training sessions indicated that the training was well received and that some of the issues that were raised at the end of the first training session, such as concerns about the need for an encyclopaedic knowledge of drugs, had been addressed during the second training session. This was achieved by providing additional drug education during the session along with the inclusion of a ‘new to trainers’ worksheet that trainers could use to demonstrate to peer supporters the difficulty of keeping track of new drugs and street names. Suggestions raised by trainers for improving activities were added to the intervention materials during refinement prior to stage 2. A final training session was delivered to run through the finalised intervention materials and schedules in advance of stage 2 delivery in two schools so that trainers could become more familiar with the running order of the +FRANK and FRANK friends training days and the resources required for carrying out the activities.

Stage 2: feasibility testing of the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions

+FRANK intervention

Seven structured observations of delivery were completed for the +FRANK intervention, eight self-assessments were completed by the trainers and 14 +FRANK peer supporters completed an evaluation form at the end of the off-site training day. At the end of intervention delivery (i.e. after the final follow-up), 12 peer supporters completed evaluation forms. Interviews were also conducted after intervention delivery with six peer supporters, three trainers (at the end of the off-site training and the last follow-up), two of the contact teachers and two members of the SMT.

Recruitment

Of the 18 students invited to be retrained, 13 attended the re-recruitment meeting and 14 attended the off-site training day.

In total, 78% of Year 8 ASSIST peer supporters were recruited and retrained as +FRANK peer supporters in Year 9. Although only 13 students attended the recruitment session, one student who was absent was provided with details about the programme and was given an opportunity to attend the training via the contact teacher. The contact teacher stated that those who did not take part did so for a variety of reasons, including one peer supporter not wanting the responsibility, one not enjoying the ASSIST training, one having too many commitments and another being absent from school too frequently.

At the recruitment stage of the ASSIST intervention, if a nominated student or his or her parent/guardian did not want him or her to attend the off-site training, trainers worked down the ranked list of students with the most nominations and invited the student with the next highest number of nominations. With the +FRANK intervention it was not possible to substitute students because they must have trained as an ASSIST peer to be invited to take part in the intervention. This feature of the +FRANK intervention increases the risk that less than the required 17.5% of the year group are trained as peer supporters.

Acceptability of the +FRANK intervention to peer supporters

Peer supporters felt that the peer nomination process was an acceptable method of recruiting. They thought that students in receipt of the most nominations were more likely to be listened to.

Recruitment meeting

Most peer supporters noted that having previously participated in the ASSIST intervention was a positive influence when deciding whether or not to participate in the +FRANK intervention. Familiarity with the trainers and the peer supporter role encouraged students to become +FRANK peer supporters:

. . . ’cause I like I liked doing it last time and . . . I thought it would be good to do it again.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 5

A few peer supporters indicated that they would have benefited from receiving more information at the recruitment meeting, about what to expect and the content of the new programme:

I don’t know, made a bit more detail of what we were doing then maybe we like, we’d have more . . . we’d know whether we’d want to go or not.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 2

Training day

Most of the peer supporters and trainers reported that the +FRANK intervention activities delivered on the training day were acceptable. Some peer supporters noted that a lot of new information was provided, which could be challenging for some:

Loads of facts like, I can remember like parts of them, but I can’t remember which one goes where like.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 1

But maybe it sounds like you need ways of remembering some of that information?

Yeah . . . like writing it down and then just . . . like stick it in my bag so I can remember it.

Some trainers also noted that too much information was being delivered during the training sessions:

Yeah. And probably there was too much information there because I found they needed a lot of prompting for that activity. Some of the groups worked quite well and others, unless you were kind of stood there helping them with the activity they were kind of like what do I do.

Trainer 2

Some peer supporters compared the +FRANK training with their experiences of the ASSIST training, noting the lack in the +FRANK training of activities related to practising conversations about drugs and that they would have liked more opportunities for this:

And they did give us conversation skills like on the smoking course as well but they just didn’t really explain how to give on the information. And really I think that like . . . like I think what would have been cool is because on the smoking course we did like an acting thing and I think, even on the drug course or even on the smoking course as well we could have like acted like bringing up drugs in conversation. That would have been like a good thing.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 2

Peer supporter conversations and use of the diaries

Eleven out of 14 peer supporters returned their diaries. All 11 diaries noted at least one or more informal conversation. The majority of conversations were reported as being face-to-face and easy to initiate. Peer supporters felt that the diaries were helpful in providing a space to record their conversations and could also be referred to to remind themselves of facts and be shown to others:

They were like, good like easy to talk about, like it wasn’t like, like they always listened, like I had like my say, they had their say about it.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 1

Um, well obviously in the diaries you had lots of facts in there so if you forgot any while you were talking just take it out and read through it.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 3

Follow-up sessions

Twelve peer supporters attended the in-person follow-ups 1 and 4. Ten of the 14 peer supporters provided either an e-mail address or a mobile number for the e-follow-up sessions but students indicated that they tended not to use their e-mail. Of the peer supporters who provided contact details, five were e-mailed a task as part of the e-follow-up session. One peer supporter engaged with each of these e-follow-up sessions.

Structured observations, trainer self-evaluation forms and interviews with peer supporters and trainers suggested that there were a number of factors influencing the poor attendance at the e-follow-up sessions. First, there was uncertainty among the peer supporters about why their contact details were needed. One peer supporter noted that they were not allowed to provide their own mobile number so gave their parent’s. Others could not remember their number or forgot to complete the tasks. Second, the school did not provide students with a designated e-mail address and so there was no unified method of contacting students. Third, one teacher also noted that some students would not have permission from their parents to provide their e-mail address. Fourth, during observations of delivery by the research team it was noted that the collection of the details was rushed because of the timing of the follow-up session at the end of the school day. Fifth, the school also had a no homework policy, which meant that students were not familiar with completing tasks out of school. Finally, no text messages were sent by the PHW intervention delivery team because of technical problems with the messaging service. This came to light only after follow-up 4. Peer supporters indicated that they would have preferred to have someone to supervise a designated session for completing the e-follow-up tasks and to be able to work as a group, rather than being left to complete the e-follow-up by themselves:

I didn’t leave anything because I didn’t know my number and I couldn’t remember my e-mail address.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 4

So many of them haven’t got e-mail addresses . . . asking them for e-mail addresses, you’ll only get a handful, or they’ll use Mum’s or Dad’s, and it’s not always appropriate.

+FRANK school, teacher 2, SMT

Yeah if we like we all done it at the same time, ’cause like, no one would probably bother to do it, ’cause no one’s here telling us to actually do it.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 1

One peer supporter who completed the e-follow-up tasks indicated that they enjoyed using the website and was able to think and provide answers in their own time.

I enjoyed answering the questions and reading the information on the website . . . I didn’t feel put on the spot, I could answer in my own time.

+FRANK school, peer supporter 4

Fidelity of implementation

Of the 15 activities in the +FRANK training day, five were delivered in full, eight had minor deviations from the manual and two were not delivered at all. Observations highlighted the need to change the timing of some of the activities as well as amend some of the instructions for trainers, to indicate which tasks are essential and which are optional.

FRANK friends

Fifteen structured observations were made of delivery of the FRANK friends intervention, nine self-assessments were completed by the FRANK friends trainers and 26 FRANK friends peer supporters completed an evaluation form at the end of the second off-site training day. At the end of intervention delivery, 21 peer supporters completed evaluation forms. Interviews and focus groups were also conducted after intervention delivery with 20 peer supporters, five trainers (at the end of off-site training and the last follow-up), two contact teachers and two members of the SMT. Five focus groups were conducted in the FRANK friends school.

Recruitment

Of the 30 students invited to be peer supporters, 29 attended the recruitment meeting and 26 attended both off-site training days.

Acceptability of the FRANK friends intervention to peer supporters

The peer nomination process was perceived as inclusive and fair as it reflected the opinion of everyone in the year group.

It was a positive experience for peer supporters as they felt respected by their peers and believed that they were suitable for the role as they had a wide social network.

Recruitment meeting

Peer supporters mentioned that they were given sufficient and clear information about the study and the role of a peer supporter. They noted the informal and friendly setting of the recruitment meeting, which put them at ease to speak freely and decide whether or not to participate in the study:

It was sort of an introduction because if people didn’t feel like they were right for what they were doing or they didn’t – wouldn’t enjoy it then they could just leave, and I think that was important ’cause it’s a comfortable environment where you’re not forced to do anything.

FRANK friends school, peer supporter 1

Training days

In general, peer supporters enjoyed the 2-day training and were keen to increase their knowledge about drugs. Most of them felt that they had received the right amount of information. Some peer supporters commented that it was easy to learn and retain facts on drugs as the facts were short and relevant for their age:

. . . wasn’t complicated, long-worded facts that we’d easily forget about by the next day, it was like short facts that would stick in our mind and they clearly have from the training.

FRANK friends school, peer supporter 2

And the fact that we concentrated on the most likely ones for our age, it wasn’t like all loaded on us, it was just the three ones ones that we were probably gonna be dealing with.

FRANK friends school, peer supporter 3

Most peer supporters found the training on conversation skills particularly useful because it increased their confidence in initiating conversations with their peers. It also taught peer supporters ways to bring up drugs in conversations and respond to the reactions of their peers in different situations:

There was this one activity where we had like a piece of paper and it gave us a situation to talk to them about and like how we had to act so then we knew how to respond to what they were feeling like or what they were acting like.

FRANK friends school, focus group 3, peer supporter 15

However, a few supporters thought that the conversations felt forced and might not be practical in the real world:

. . . but I think the techniques that we got taught you couldn’t really do it in real life and like we were practising conversations, it just felt awkward and like forced.

FRANK friends school, peer supporter 5

Follow-up sessions

Attendance at the four in-person follow-up sessions ranged from 16 to 21 peer supporters out of the 26 who were trained. The content and duration of the follow-up sessions were acceptable to peer supporters. Peer supporters used the follow-up sessions to reinforce the knowledge that they had gained during training and also to obtain support around conversations from trainers and fellow peer supporters:

Some conversations like people didn’t think that the facts were true. But then like we spoke to the people [trainer] and they explained what we could do if that happened.

FRANK friends school, peer supporter 4

Peer supporters were required to visit the Talk to FRANK website to complete some activities in a couple of the follow-up sessions. The activity was well received by peer supporters as it was interactive and fun:

I think the video [health effects of cannabis] was very helpful as well because it’s, more people prefer to watch videos than be told all the time and if they wa, like watch that it was quite appealing to other people as well.

FRANK friends school, focus group 5, peer supporter 20

However, a few peer supporters mentioned that the follow-up sessions were less engaging than the 2-day training session and that that might have a negative impact on attendance:

I think some of the follow ups were quite, quite slow . . . I was just waiting for something . . . And I think less people started turning up and then it felt, it didn’t feel as special then.

FRANK friends school, focus group 1, peer supporter 9

Peer supporter conversations and use of the diaries

Twenty out of the 26 peer supporters returned their diary. All diaries noted at least one or more informal conversation. The majority of peer supporters recorded that they had had face-to-face conversations. This allowed peer supporters to gauge and respond to the reactions of their peers through reading their facial expressions and body language:

Face to face you can react like on the spot of what they’re thinking and what they’re looking like, so you can see if they’re look – if they’re looking scared or if they’re looking nervous then you can try and support them through whatever they’re going through.

FRANK friends school, peer supporter 3

Some peer supporters felt that text messages and social media were not an appropriate medium by which to communicate information about drugs:

It was easier to bring it into the conversation, whereas like when you’re [text] messaging them it comes out like of nowhere.

FRANK friends school, peer supporter 4

Peer supporters used the diaries in several ways, including to reflect on conversations that they had had and remind themselves of the facts that they had learned:

The diaries helped a lot because they could see how the conversations went and if they didn’t go well then we were able to write what didn’t go well and what did go well.

FRANK friends school, focus group 5, peer supporter 19

It had like the facts on, top five facts so we could always go back to there if we forgot to say something, to remember it so that was really good for reminding us.

FRANK friends school, focus group 5, peer supporter 19

Fidelity of implementation

In the FRANK friends training days, across the 25 activities, 13 were delivered in full, nine had minor deviations from the manual and three were not delivered at all.

Refinements to the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions: what changed from stage 1

The outcomes of the process evaluation were presented to the TMG. The TMG then agreed some amendments to the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions. Nearly all of the refinements were made to both the +FRANK intervention and the FRANK friends intervention as a result of the process evaluation undertaken at stage 2 (Table 7). Peer supporters were contacted by e-mail or text message after training with the contact details for the Talk to FRANK website and were sent updates when news items or new drugs were added to the website. Peer supporters were also sent reminders to have conversations and bring their diary to follow-up sessions. The training day agenda was reordered and the timings of activities were amended to accurately reflect the time recorded during observations. Activities deemed to be non-essential were changed to be ‘optional’ and could be delivered at the trainers’ discretion if time allowed.

| Intervention element | Refinements made |

|---|---|

| Recruitment meeting |

|

| Training day |

|

| Follow-up sessions |

|

Refinements unique to the +FRANK intervention included e-follow-up sessions 2 and 3 changing to in-person follow-up sessions in which trainers go into the school to deliver tasks. Follow-up session 4 was dropped and the content was covered in follow-up session 3.

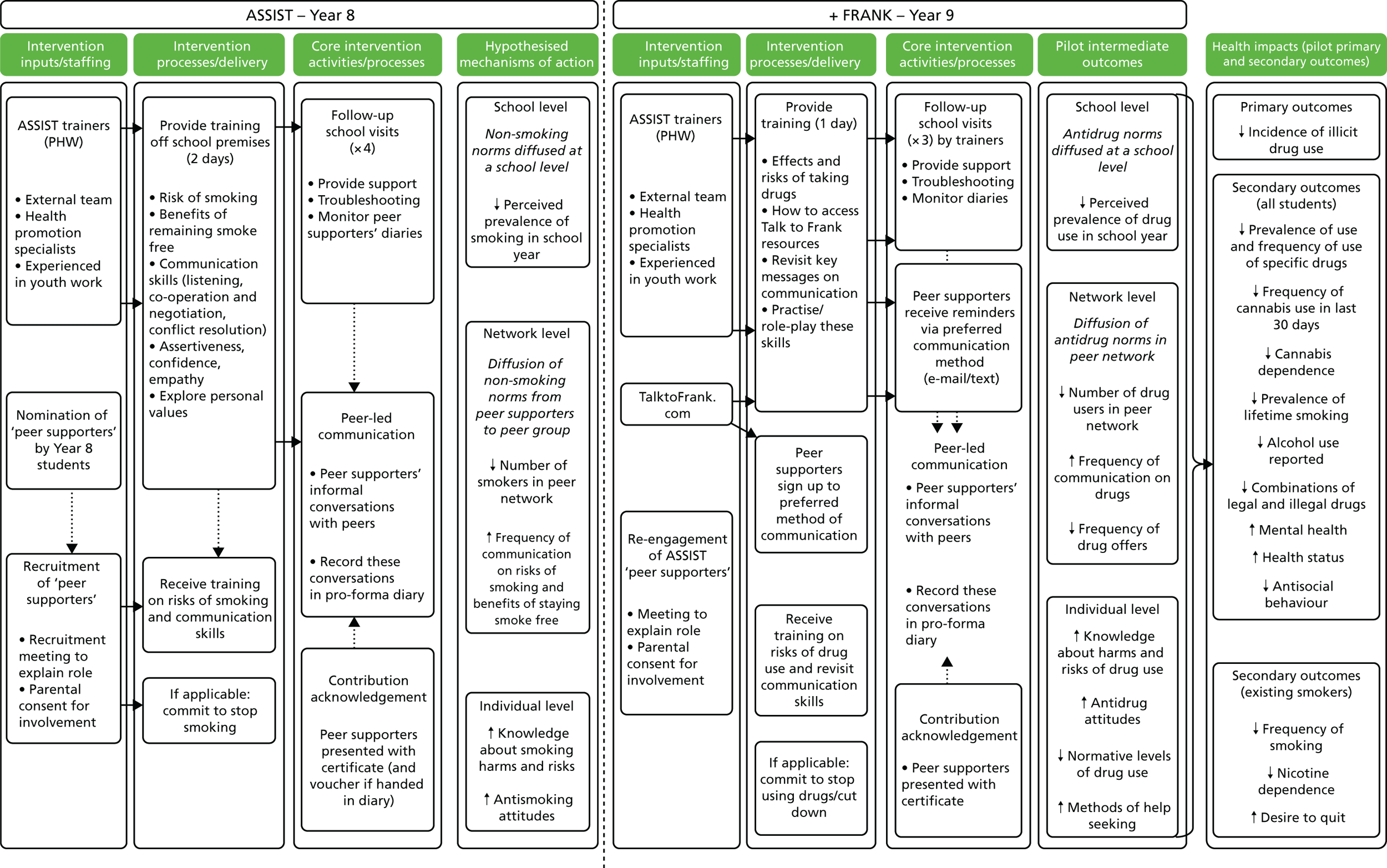

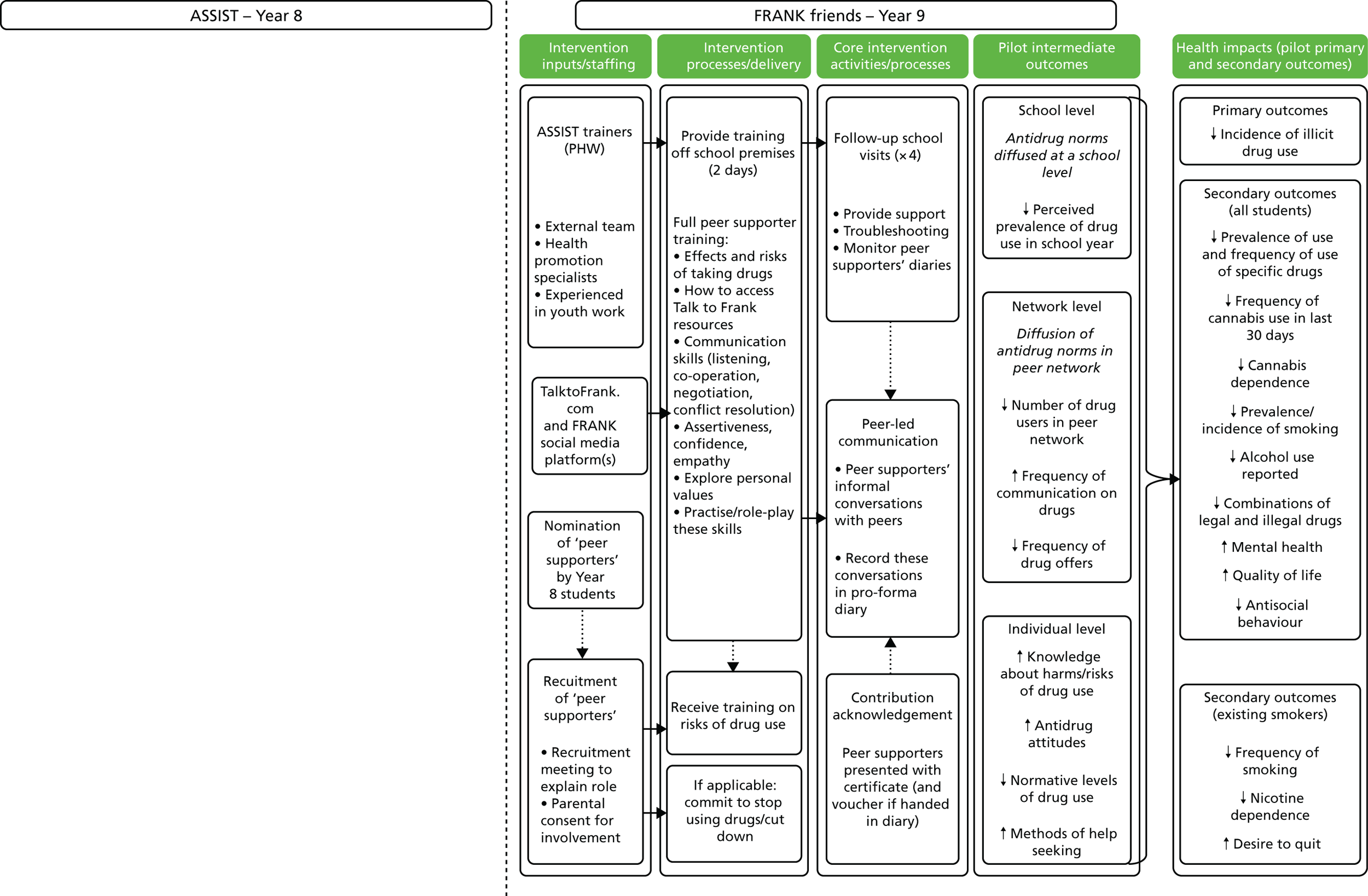

Figures 5 and 6 show the refined intervention logic models for the +FRANK and FRANK friends interventions, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

+FRANK logic model.

FIGURE 6.

FRANK friends logic model. The ASSIST intervention is not given as part of the FRANK friends intervention.

Stage 3: external pilot trial

The external pilot trial was a parallel-group, four-arm cRCT with school as the unit of randomisation.

Recruitment and retention