Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/42/02. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The final report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Adam Fletcher, Graham Moore and Chris Bonell are members of the Public Health Research (PHR) Research Funding Board. Rona Campbell is a member of the PHR Research Funding Board, and reports grants from the University of Bristol during the conduct of the study and personal fees from DECIPHer Impact Limited, outside the submitted work. Note that the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer) and DECIPHer Impact Ltd are separate entities, the latter being a not-for-profit organisation.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Fletcher et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Youth smoking: a public health priority

Smoking is a major cause of preventable illness, premature death and health inequalities in the UK. Preventing young people from taking up smoking is vital to maintain and accelerate recent declines in smoking rates. Although much research has been undertaken to develop and evaluate school-based prevention interventions targeting 11- to 15-year-olds,1 the General Lifestyle Survey Overview: A Report on the 2010 General Lifestyle Survey (GLS) illustrates that smoking continues to grow rapidly among older adolescents. 2 The GLS does not differentiate those in or out of education; however, with > 1.5 million British 16- to 18-year-olds now enrolled in further education (FE) courses, new smoking prevention interventions are required that target FE settings (e.g. general FE colleges, ‘sixth form’ colleges attached to secondary schools, etc.). 3 As well as being a period in life when smoking often begins, the transition to FE itself may also increase the risk of smoking as young people are exposed to new sources of peer influence and have more independence from their parents.

Health improvement in further education settings

Research evidence about smoking prevention interventions delivered in FE settings is sparse. Two recent systematic reviews of health improvement interventions in educational sites contain no reference to such studies in FE settings. 4,5 This finding supports calls from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for more evidence regarding smoking prevention interventions in secondary schools and in other youth settings such as FE institutions. 3 Furthermore, the failure of the two reviews4,5 to identify any cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs) undertaken within FE settings highlights the lack of rigorous health improvement evaluation in this context to date.

A search of bibliographic databases undertaken in 2013 identified a further 14 relevant reports about smoking prevention and other health improvement interventions in FE settings. 6–19 Among these, six non-systematic literature and policy reviews reported increasing policy interest in health improvement interventions targeting young people within FE settings, but noted the absence of any evidence regarding appropriate or effective interventions in FE settings. 6,7,9,10,12,14 No examples of effective smoking prevention interventions delivered in this context were identified. Three studies evaluated single-session motivational interviewing interventions in English FE settings,8,11,17 finding that it is feasible to deliver brief interventions within FE settings. 11 These studies also found that motivational interviewing targeting high-risk students engaged in drug use may reduce their use of cigarettes, alcohol and drug use. 8 However, it was not an effective method for preventing the uptake of smoking among 16- to 19-year-olds in FE. 17 One quasi-experimental study of a multicomponent intervention combining health education, counselling and nicotine therapy in French vocational colleges was found to be effective in supporting smoking cessation. 19

Effective smoking prevention methods and approaches

With no evidence of effective smoking prevention methods or approaches in FE settings, the findings of five recent systematic reviews of smoking prevention interventions delivered in other educational and/or community contexts were identified and synthesised to inform the pilot intervention. 20–24 The reviews suggest that the following smoking prevention methods and approaches are effective: reducing the illicit sale of tobacco products to under-18s;20–23 initiating tobacco-free policies and environmental change;22 age-appropriate, interactive educational messages delivered via intensive, long-term mass media campaigns;21 and social competency and skills development interventions to support young people to resist peer influence. 24 A recent systematic review of school effects/environment interventions also found that initiating tobacco-free policies and environmental change can be effective, especially in permissive contexts,4 which is likely to be the case in some FE settings.

This evidence highlights the relevance of multilevel smoking prevention interventions and identifies a set of intervention methods and approaches that may underpin intervention efficacy:

-

restricting the availability of tobacco and opportunities for smoking

-

restructuring environmental contexts

-

educating and persuading young people about the harms of smoking and social norms via multiple methods and communication channels

-

modelling social/situational resistance skills.

Systematic reviews also consistently find that ‘multilevel’ interventions, which address both individual and environmental determinants of behaviour simultaneously, are most effective for improving young people’s health outcomes. 20,23,25,26 These interventions, which include ‘higher-level’ environmental components, also tend to be more cost-effective,27 and are less likely to generate inequalities than individually focused components alone. 28,29 However, if such interventions are to deliver major public health gains, they must also be feasible to deliver and sustain. 30

‘The Filter FE’ intervention design and logic model

‘The Filter FE’ intervention was co-designed by Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) Wales and the research team following a commissioned call from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme in 2013. It is a smoking prevention intervention managed and delivered by trained staff working on ASH Wales’ ‘The Filter’ youth project, who apply existing staff training, social media and youth work resources in FE settings. Informed by the socioecological theory of health,31 and evidence of effective smoking prevention methods and approaches (summarised in Effective smoking prevention methods and approaches), Filter FE aimed to integrate multiple intervention activities within a multicomponent, multilevel intervention for FE settings.

The intervention design and hypothesised mechanisms are summarised in the logic model (Figure 1) and described in more detail in Chapter 2, Intervention components. In summary, five areas of synergistic activity were planned to augment any existing activities already undertaken in FE settings: (1) working with local shops to restrict the sale of tobacco to under-18s; (2) implementing tobacco-free campus policies; (3) training FE staff to deliver smoke-free messages; (4) publicising The Filter youth project’s online campaigns, advice and support services via FE websites and social media; and (5) on-site youth work activities to provide credible educational messages and promote social/situational resistance skills, as well as signposting cessation services. As described in the logic model (see Figure 1), it was hypothesised that these components would prevent the uptake of smoking via the restriction of the availability of tobacco; restructuring the institutional context to prevent smoking on site and promote non-smoking behaviour as normative; education and persuasion of young people regarding the harms of smoking and social norms via multiple interactive methods and channels of communications; and modelling social/situational self-efficacy and resistance skills.

FIGURE 1.

Intervention logic model. AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption; EMCDDA, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; EMQ, European Model Questionnaire; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, 5-level version; ESFA, European Smoking Prevention Framework Approach; HSI, Heaviness of Smoking Index; IT, information technology; ONS, Office for National Statistics; QoL, quality of life.

In order to enable scalability across different types of FE settings (including large institutions), as well as sustainability and fidelity, the intervention was designed so that it involved standardised processes and activities balanced with opportunities for a degree of local tailoring of activities. Some flexibility to allow for local adaptation can support universal adoption, institutional ownership and sustainable implementation of multiple activities. 32,33 The intervention was also designed to allow the ‘dose’ of staff training and youth work activities to vary according to the size of institutions.

Public involvement

As well as co-designing the pilot intervention, staff working on ASH Wales’ The Filter youth project were involved in designing all aspects of the pilot trial and process evaluation prior to bid submission. The research team also worked with the Involving Young People Officer based in the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement to organise two consultations with the Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) youth group at the project development stage. ALPHA is a group of young people aged 14–21 years who advise researchers on intervention design, logic modelling and data collection methods by discussing and debating their views on the proposed research. Staff from Public Health Wales and FE teachers were also consulted on the intervention design, logic model and research strategy.

Three further consultation meetings with the ALPHA group took place post commissioning to enable the researchers to consult with young people during the project on recruitment and survey methods (e.g. advice on the design of publicity materials, information sheets and e-questionnaires), strategies for increasing retention/follow-up, and public engagement and knowledge exchange activities.

Study aim, objectives and research questions

The aim of the pilot trial was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of implementing and trialling a new multilevel smoking prevention intervention in FE settings. The study had three objectives.

The first objective was to assess whether or not prespecified feasibility and acceptability criteria were met, which were agreed with the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre and Trial Steering Committee, and deemed necessary conditions for progressing to a Phase III trial. The progression criteria are listed in full in Chapter 2, Progression criteria. In order to meet this objective, data were collected and analysed to address the following research questions (RQs):

-

Did the intervention activities occur as planned in (at least) two out of three intervention settings?

-

Were the intervention activities delivered with high fidelity across all settings?

-

Was the intervention acceptable to the majority of FE managers, staff, students and the intervention delivery team?

-

Was randomisation acceptable to FE managers?

-

Did (at least) two out of three colleges from each of the intervention and control arms continue to participate in the study at the 1-year follow-up?

-

Do student survey response rates suggest that we could recruit and retain at least 70% of new students in both arms in a subsequent effectiveness trial?

The second objective was to explore the experiences of FE students, staff and the intervention delivery team to refine the intervention and study design prior to a potential Phase III trial. In order to meet this objective, data were collected and analysed to address the following RQs:

-

What are students’, college staff’s and intervention team members’ experiences of the intervention and views about its potential impacts on health?

-

What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, implementation and how do these vary according to college context and/or other factors?

-

Were there any unexpected consequences?

-

How acceptable were the data collection methods to students and staff, and do participants think that longer-term follow-up via e-mail or telephone interview would be feasible?

-

What resources and partnerships are necessary for a Phase III trial?

The third objective was to pilot primary, secondary and intermediate outcome measures and economic evaluation methods prior to a potential Phase III trial. It was not an objective of the pilot study to assess intervention effects nor was it powered to do so, but data were collected and analysed to address the following RQs:

-

Does the primary outcome measure (smoking weekly or more) have an acceptable completion rate, adequate validity and minimise floor/ceiling effects?

-

Do cotinine concentrations of saliva samples indicate any evidence of response bias between arms in self-reported smoking status?

-

Was it feasible and acceptable to measure all the secondary and intermediate outcomes of interest at baseline and follow-up?

-

Is it feasible to assess cost-effectiveness using a cost–utility analysis within a Phase III trial?

Chapter 2 Methods

In this section of the report we provide an overview of the study design, including the specific intervention components examined. Details are then provided of the sampling and recruitment of the FE settings and randomisation. We then describe the methods used to assess the ‘progression criteria’ (objective 1), explore participants’ experiences of the process of implementing and trialling the intervention (objective 2) and examine pilot trial outcomes (objective 3). Details of the pilot economic analysis and trial registration, governance and ethics are provided at the end of this chapter.

Study design: overview

A cluster randomised controlled pilot trial was undertaken in six FE settings in south-east Wales with allocation to the Filter FE intervention (three settings) or continuation of normal practice (three settings). In order to assess the feasibility and acceptability of delivering and trialling the intervention according to prespecified criteria (objective 1), we collected a range of quantitative and qualitative data via semistructured observations of the intervention delivery, interviews with FE college managers and the intervention team, and documentary evidence (e.g. college policies, intervention team records, etc.). The retention of FE settings and response rates were assessed using student survey data.

To explore participants’ experiences of implementing and trialling the Filter FE intervention (objective 2), data were collected via semistructured interviews with FE managers and the intervention team, focus groups with students and staff, as well as additional process and contextual data via observations of intervention settings, staff training and youth work activities.

Primary, secondary and intermediate (process) outcomes, and economic evaluation methods were also piloted in this study (objective 3). Surveys of new students enrolling at the participating FE settings in September 2014 (baseline) and September 2015 (1-year follow-up) were used to examine the pilot primary, secondary and economic outcome measures. Informed by the intervention logic model, multiple sources of data were also collected at baseline and follow-up to pilot intermediate (process) outcomes at multiple levels: the restriction of the availability of tobacco in local shops was assessed via ‘mystery shopper’ audits; changes to the institutional environment and policies were assessed via structured observations and analysis of college policy documents; and students’ knowledge, norms and social/situational self-efficacy and resistance skills were assessed via the student survey.

Intervention components

This section describes how each of the pilot intervention components were intended to be delivered, by whom, and their logic.

Prevention of the sale of tobacco to further education students aged < 18 years

To restrict availability locally, the intervention manager would map and contact all shops selling tobacco within 1 km of the intervention setting (i.e. within a 10-minute walk). Information letters would be distributed to these retailers to inform them that a new project (Filter FE) was taking place at their local FE institution, explain why reducing supply is an important component of prevention and remind them about the penalties for selling tobacco to under-18s. The letter focused only on sales of legal tobacco through the retailers. Posters, stickers and other materials would also be supplied for these shops to provide information to their customers about the legal age for purchasing tobacco products and the requirements to produce statutory identification to purchase tobacco.

Institutional policy review to promote a tobacco-free environment

To restrict opportunities for smoking and promote non-smoking as the norm via modifying the institutional context, the intervention manager would work with FE managers to review institutional policies using the tobacco-free campus guidance developed by ASH Australia. 34 This tool uses a three-stage process to promote a tobacco-free environment, including advice on advertising, the supply of tobacco and support services, as well as information on maintaining smoke-free public areas, buildings and vehicles. First, current policies and practices are reviewed using this tool to develop a new whole-campus tobacco-free policy. Second, the revised policies are implemented and launched. Third, policies are monitored, evaluated and updated/refined if required.

Further education staff training

To train staff to deliver smoke-free educational messages and support institutional change, training officers employed on The Filter youth project [accredited by the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and Agored Cymru] would organise and deliver training sessions on site using modules and teaching resources developed and piloted by ASH Wales in schools and other youth settings. Interactive, 2-hour training workshops would be delivered to approximately 10 staff per session, with FE staff trained to integrate activities about smoking into their lesson plans and other routine work (e.g. via body mapping the health harms of smoking, exercises on how tobacco companies recruit young smokers). All staff attending these sessions would also be encouraged to champion new tobacco-free policies (see Institutional policy review to promote a tobacco-free environment) and intervene to prevent smoking on site. The number of sessions to be delivered would vary depending on the size of the FE setting to ensure that resources are distributed appropriately: one session to be delivered at smaller ‘sixth form’ sites (i.e. to reach a total of approximately 10 members of staff) and 2–4 sessions to be delivered at medium and large FE campuses, respectively (to reach up to 20–40 members of staff).

Social media

To educate and persuade students about the harms of smoking, social norms and the relevance of support services, The Filter youth project’s web and social media officers would work with staff and students to integrate it online social marketing campaigns, advice and support services (e.g. The Filter text/instant messaging services) with institutional websites and social media channels maintained by staff and/or students [e.g. the college Facebook (www.facebook.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) page, institutional Twitter (www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) feeds, Instagram (www.instagram.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), etc.]. As well as embedding information on each intervention setting’s home/index webpage, the web and social media officers would work with the college information technology staff and consult students to identify opportunities for publicising key information and messages via frequently accessed webpages/micro-sites (e.g. online learning portals, e-mail login pages).

Youth work activities

To educate and persuade students about the harms of smoking and model social/situational resistance skills, qualified youth workers from The Filter project would work with college staff and students to plan and deliver a range of youth work activities on site (e.g. smoke-free message film-making, graffiti walls and/or other arts-based activities). Youth workers would launch the project in the autumn term, and then work with staff and/or student groups to identify 5, 10 or 15 groups (depending on institutional size) of 10–20 students to take part in locally tailored group-based activities. As with the staff training, the numbers of sessions delivered would vary according to the FE setting’s size to ensure resources are distributed appropriately. These group-based youth work activities would be provided on site during college time and typically last 1–2 hours. Students would not be targeted based on their smoking status or any other characteristics, as the aim is to recruit as many newly enrolled students as possible. Information about online support/advice services would also be provided to current smokers, when appropriate.

Sampling and recruitment of further education settings

The following diversity and matching criteria were used to purposively sample six FE settings in south-east Wales: large FE college campuses (new intake of > 500 students) (n = 2), small FE college campuses (new intake of < 500 students) (n = 2) and ‘sixth form’ colleges attached to schools (n = 2).

Purposive sampling ensures a diversity in contexts at the intervention piloting stage so that a realist lens can be applied to address questions regarding not only what is feasible and acceptable in general, but also for whom and under what circumstances, and place much more emphasis on exploring potential mechanisms of action and how these may vary by context prior to large-scale RCTs. 35 To avoid contexts in which implementation may be less challenging (or atypical in other ways), private institutions, small sites (with < 100 students) and ‘sixth forms’ at schools where < 10% of students are entitled to free school meals were not included. To minimise the potential for contamination across arms, no more than one FE setting was recruited from any middle-layer super output area, nor were FE settings recruited in neighbouring middle-layer super output areas.

The intervention team identified and contacted school and FE managers in the summer term of 2014, with recruitment complete by July 2014. A total of 10 FE settings in south and mid-Wales were contacted by ASH Wales’ staff in May and June 2014. Those who first expressed an interest were visited by researchers between June and July 2014, until six FE settings had been recruited according to the sampling criteria, above. Participating FE settings are listed in Table 1 according to recruitment strata (pseudonyms).

| Sampling/randomisation strata | FE setting (pseudonyms) | Allocation | Estimated new students aged 16–18 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large FE college campuses (n = 2) | Valeside College | Intervention | 1027 |

| Middledale College | Control | 760 | |

| Small FE college campuses (n = 2) | Laurelton College | Intervention | 130 |

| Glynbel College | Control | 175 | |

| School ‘sixth form’ colleges (n = 2) | Athervale Sixth Form | Intervention | 110 |

| Afonwood Sixth Form | Control | 161 |

Randomisation

Colleges agreed to take part in the study prior to randomisation. This study used a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. Allocation to intervention and control arms was conducted by the study statistician and stratified by the size and type of FE settings. The three strata were large FE college campuses with a new intake of > 500 students, small FE college campuses with a new intake of < 500 students and sixth forms within secondary schools. Table 1 reports the outcome of the random allocation to trial arm by sampling strata, including the size of each FE setting’s new intake.

It was not possible for colleges, the intervention team and researchers to be blinded to allocation throughout the study. However, colleges were randomised after baseline data collection to ensure that all students, staff and researchers were blind at the time of the recruitment of colleges and baseline data collection.

Progression criteria

In line with Medical Research Council guidance,36 data collection during the pilot trial focused on assessing acceptability and feasibility, and allowing us to judge progress against the agreed criteria for progression to a subsequent trial of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The first objective was specifically to assess whether or not the criteria deemed necessary in order to progress to a larger cluster RCT were met (Box 1). These were agreed by the investigator team, the NIHR Evaluation, Trial and Studies Coordinating Centre and Trial Steering Committee prior to commencing the pilot trial as evidence of feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial methodology.

-

Did the intervention activities occur as planned in (at least) two out of three intervention settings? This will be assessed according to the extent to which the following intervention activities occurred:

-

tobacco retailers within 1 km of the FE setting were contacted in writing within 3 months of the start of the intervention

-

institutional policies and practices were reviewed, updated using the tobacco-free campus guidance, and changes communicated to staff and students within 6 months of the start of the intervention

-

a minimum of one, two or four staff training sessions were delivered as planned (according to institutional size), with a minimum of five staff attending each session

-

The Filter youth project’s web-based information, advice and support services were embedded on the FE institution’s homepage during the intervention and online information, advice and support services are promoted through at least one local social media channel maintained by staff and/or students (e.g. the college Facebook page, Twitter feed, etc.)

-

a minimum of 5, 10 or 15 youth work sessions were delivered as planned (according to institutional size) with a minimum of eight different students attending each session.

-

-

Were the intervention activities delivered with high fidelity across all settings?

-

Was the intervention acceptable to the majority of FE managers, staff, students and the intervention delivery team?

-

Was randomisation acceptable to FE managers?

-

Did (at least) two out of three colleges from each of the intervention and control arms continue to participate in the study at the 1-year follow-up?

-

Do student survey response rates suggest that we could recruit and retain at least 70% of new students in both arms in a subsequent effectiveness trial?

Data sources

In order to answer RQ 1 (see Box 1), quantitative and qualitative data were collected from multiple sources. To assess if tobacco retailers within 1 km of the FE setting were contacted in writing within 3 months of the start of the intervention, data collected via intervention team records were examined and cross-checked through interviews with the intervention team. To assess if institutional policies and practices were reviewed and updated using tobacco-free campus guidance, with changes communicated to staff and students within 6 months of the start of the intervention, data collected via intervention team checklists were examined and cross-checked with documentary analyses of college policies and structured observations of the FE environments at follow-up. To examine the fidelity and reach of staff training, data collected via intervention team checklists and semistructured observations of training were examined. Integration of ASH Wales’ The Filter online resources by intervention setting was assessed using intervention team checklists and cross-checked via semistructured observations of college websites and social media channels. To examine the implementation of youth work activities, data collected via intervention team checklists were examined and cross-checked in interviews with FE managers.

In order to answer RQ 2 (see Box 1), semistructured observations of staff training sessions (n = 1 per intervention setting) and group-based youth work sessions (n = 1 per intervention setting) were used to assess fidelity of delivery of those components across settings and the fidelity of other intervention components (activities aiming to prevent the sale of tobacco to under-18s in shops near the intervention site, institutional policy review and revision, social media integration) were examined via intervention team checklists and interviews with the intervention team and FE managers. To answer RQ 3 (see Box 1), intervention acceptability and whether or not this was reported by the majority of participants, was assessed via data from semistructured interviews with FE managers and the intervention team, and student and staff focus groups. Data from semistructured interviews with FE managers were used to examine RQ 4 (see Box 1). In order to answer RQs 5 and 6 (see Box 1), the retention of FE settings and response rates were assessed using student survey data.

Data analysis methods

The quantitative and qualitative data collected to answer RQs 1–6 were managed and analysed separately. For example, the standardised checklist data from the mystery shopper, environmental observation and policy audits were collated and analysed in Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), whereas data from focus groups and interviews were analysed using NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The emergent results from each data source were shared and discussed among the research team. Individual results were collated according to a framework derived from key RQs and relevant progression criteria to ensure that data from all sources were used when pertinent to answer the RQs, and to facilitate triangulation. When data from one source contradicted data from another source, this was noted and discussed.

Evaluating participants’ experiences of the process

In addition to examining intervention delivery according to prespecified criteria (objective 1), a second objective was to explore student, staff and intervention team experiences of implementing and trialling the intervention, and how this varied in different FE contexts, in order to refine the intervention and trial methods. RQs 7–11 addressed this objective (Box 2).

-

What are students’, college staff’s and intervention team members’ experiences of the intervention and views about its potential impacts on health?

-

What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, implementation and how do these vary according to college context and/or other factors?

-

Were there any unexpected consequences?

-

How acceptable were the data collection methods to students and staff, and do participants think that longer-term follow-up via e-mail or telephone interview would be feasible?

-

What resources and partnerships are necessary for a Phase III trial?

To answer RQs 7–11, multiple sources of qualitative data collected via semistructured observations, semistructured interviews and focus groups were analysed to explore student, staff and intervention delivery team experiences in depth, and how and why these varied.

Qualitative process data

Semistructured interviews and focus groups were conducted with a range of stakeholders to explore in detail the process of planning, implementing and receiving the intervention. Table 2 summarises the process evaluation data collected at each FE site. Each method of data collection is described in more detail below.

| Trial arm and FE setting | Data collection method (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semistructured observations of | Student focus groups | Staff focus groups | FE manager/staff interviews | ||

| Staff training sessions (total delivered) | Youth work sessions (total delivered) | ||||

| Intervention arm | |||||

| Valeside College (large FE college campus) | 1 (1) | 1 (10) | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Laurelton College (small FE college campus) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Athervale Sixth Form (school sixth form college) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Comparison arm | |||||

| Middledale College (large FE college campus) | N/A (0) | N/A (0) | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Glynbel College (small FE college campus) | N/A (0) | N/A (0) | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Afonwood sixth form (school sixth form college) | N/A (0) | N/A (0) | N/A | N/A | 0 |

Semistructured observations

Semistructured observations of staff training and youth work sessions were conducted to provide contextual detail on the delivery, and receipt, of the intervention and to provide data on potential barriers to, and facilitators of, implementation. Observations focused on the way in which sessions were delivered, the content and activities included, and the way in which they were received by staff and young people. Semistructured observations (of staff training and youth work sessions) were recorded on templates devised a priori, documenting the content of sessions, the number and types of participants, and the dynamics among the group, allowing for observation of intervention acceptability and fidelity.

Whenever possible, the same researcher conducted the observations, interviews and focus groups in each FE setting, and observations of staff training and youth work sessions were carried out before focus groups to maximise the opportunity to respond to issues that arose from observations and preliminary analyses in focus groups and interviews. This depth of fieldworker immersion and data triangulation enabled unexpected and emergent issues [e.g. attitudes and beliefs around electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes)] to be tested and clarified.

One staff training session in each of the three intervention sites was observed between April and June 2015. Sessions lasted a maximum of 2 hours. A total of 28 members of staff attended the three sessions observed (Table 3). Participants included both teaching and support staff.

| Intervention setting | Participants (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Teaching staff | Support staff | |

| Valeside College (large FE college campus) | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Laurelton college (small FE college campus) | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Athervale Sixth Form (school sixth form college) | 13 | 10 | 3 |

Three observations of youth work sessions were undertaken, one in each intervention site, between March and May 2015. The largest observed group had 22 students, the smallest had six participants; a member of teaching staff sat in on each of the observed sessions (Table 4). It is not known what proportion of participants identified as smokers, as it was not the intention to target students based on smoking status.

| Intervention setting | Participants (n) | Teachers present (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Female | Male | ||

| Valeside College (large FE college campus) | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Laurelton College (small FE college campus) | 6 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Athervale Sixth Form (school sixth form college) | 22 | 16 | 6 | 1 |

Focus groups with students and staff

Focus groups were conducted with students and staff at all the intervention settings to explore their views on student smoking norms and behaviour; their awareness and/or experiences of participation in Filter FE project activities at their college, including their views on how successfully each component was implemented and barriers to implementation; their perceived impact of the intervention activities on student and staff smoking norms, and behaviours at their college; and the acceptability and feasibility of recruiting and collecting multiple waves of e-survey data from students. Focus groups with students were chosen for both pragmatic and methodological reasons. First, focus groups allowed us to quickly capture a range of views from a relatively largely number of students (n = 69 in all focus groups). Second, we wished to gain insights into students’ shared (or contested) understandings of the smoking culture within FE settings; focus groups were, therefore, the most appropriate method.

The number of student focus groups varied according to the size of the college (see Table 2). The aim was to recruit six student focus groups (three smokers groups, three non-smokers groups) at the large FE college campus, four in the medium-sized college campus and two in the sixth form college. This was almost achieved: in the large FE college, five student focus groups were taken, with four and two undertaken as planned in the other intervention colleges. FE managers recruited students to attend the focus groups. They were asked to recruit both students who identified as smokers and those who identified non-smokers, from a range of courses. In practice, it was difficult to purposively sample and stratify students into groups by smoking status as some young people identified as non-smokers but revealed that they smoke (e.g. ‘social smoking’) during the focus group; other groups were mixed because the students were recruited through friendship groups or through a convenience sample of one tutor group. Although managers were briefed about how to recruit students, this mode of recruitment meant that there was potential for students to come along without a clear understanding of the purpose of the focus groups. We were therefore careful to provide a clear introduction before each focus group started, allowing participants to withdraw if they wished.

Student focus groups took place between April and June 2015. Most were in June 2016, and were conducted only after all intervention activities were completed at the site. A total of 69 students participated in the focus groups, of whom 31 were female (45%) and 18 explicitly identified themselves as smokers (26%); some additional participants identified as non-smokers but during the focus group discussion revealed they sometimes smoked. The smallest focus group had two students and the largest had 13 participants. The focus groups included part-time and full-time students from a range of courses, including Advanced level (A-level), Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC) and vocational students. Student focus groups lasted between 40 and 80 minutes, and were all conducted in private rooms at the intervention college sites using topic guides. Topic guides covered their views on student smoking norms and behaviours; awareness of and participation in The Filter FE project; how successfully each component was implemented and why implementation may have been limited; perceived impact on student and staff smoking norms behaviours; and the acceptability and feasibility of recruiting and data collection methods piloted. All participants were provided with a £10 ‘Love2shop’ voucher for taking part in the focus groups.

We conducted two staff focus groups at the two larger intervention sites: one focus group with staff who had received training from The Filter team as part of the intervention, one with staff who had not. Only one staff focus group took place at Athervale Sixth Form because of the smaller number of students and staff based there. We aimed to include approximately eight staff in each focus group but, in practice, it was difficult to recruit staff to attend the focus groups, especially those who had not attended the training. In total, 19 staff participated across the five focus groups (including eight staff trained by The Filter team); the size of focus groups ranged from two to six participants. Focus groups were conducted in private rooms on each site using semistructured topic guides that covered the same broad areas as the one used in the student focus group (see above paragraph). Participating staff represented a range of teaching, management and support positions within each setting.

Semistructured interviews with further education managers

Semistructured interviews were conducted with FE managers at both intervention and control sites to explore their experiences of participating in a trial, including the acceptability of randomisation and data collection methods; perceived benefits and challenges of the Filter FE intervention on student and/or staff smoking behaviours; and, at intervention sites, managers’ experiences of implementation in their college context, including activities completed/not completed and barriers to, and facilitators of, implementation. Interviews were used as FE managers were the person (or in the case of one paired-interview, people) who could offer the best insight into their experience of participating in the research.

A member of the management staff at each of the six participating FE settings was recruited to participate in a semistructured interview at the end of the intervention. Interviews were conducted with FE managers at both intervention and control sites between June 2015 and February 2016, after the completion of the intervention. One (control) FE manager declined to participate in the interview. One interview was face to face with two staff members who had been working jointly as the lead FE manager for the study and four interviews were conducted over the telephone at the participants’ request. This may have affected the data collected as the face-to-face interview was longer and the interviewees and interviewer had an established rapport. However, the telephone interviews were conducted by two experienced qualitative researchers (one was the researcher who conducted the face-to-face interview) and we ensured that all data were included in the analysis and contributed to the findings. We were careful to provide prompts to aid the recall of managers who were interviewed. The time between recruitment to the study and the interviews may have affected some interviewees’ accounts and led to difficulties in recall, although two of the interviewees were particularly keen to provide feedback about the recruitment process and the early stages of the study, suggesting that the interviewees had time to reflect on the process even if they could not remember fine details. Interviews lasted between 20 and 60 minutes. Topic guides included questions and prompts regarding our a priori progression criteria, their experiences of being involved in the pilot RCT and of planning, implementing and receiving the intervention (if they were an intervention site).

Semistructured interviews with the intervention team

Semistructured interviews were conducted with the intervention team to explore their experiences of implementing the intervention; facilitators of, and barriers to, implementation; potential changes to be made to the intervention; and their experience of delivering the Filter FE within a trial context. Two of these interviews were conducted before the end of the intervention because the members of staff were leaving the organisation. Recruitment to these interviews was based on whether or not the individual had been involved in intervention implementation and aimed to encompass a range of different staff roles (project managers, staff trainers, youth workers and social media team members); researchers recruited these staff directly.

Interviews were conducted with six members of the intervention delivery team between April and September 2015. All interviews were conducted face to face; five of the six interviews were conducted in private rooms in the ASH Wales offices and one was conducted in a private space at an intervention site after a staff training session. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. The interview topic guides covered their experiences of implementing The Filter in FE settings; facilitators of, and barriers to, implementation; what they would change about the intervention if they could; and their experience of delivering the intervention within a trial context.

Data analysis methods

Qualitative data collected via focus groups and semistructured interviews were transcribed verbatim and entered into NVivo software to aid data management and analysis. Qualitative data were analysed using techniques associated with thematic content analysis and grounded theory. Transcripts were initially divided into four groups to assist manageability: student focus groups, staff focus groups, FE manager interviews and intervention team members. First, one of the research team (MW) read each of the groups of transcripts to familiarise herself with the data. All transcripts for each group were then reread and coded line by line to identify emergent themes, and an initial coding framework was developed to identify key themes and subthemes. The coding framework included both deductive codes, derived from key RQs and relevant progression criteria, and inductive codes, identifying other relevant themes emerging from the data (e.g. e-cigarette use in FE settings). Micky Willmott and a second researcher (RL) independently applied this coding framework to three transcripts, then met to discuss and further refine the coding framework. The final agreed coding framework was applied to all subsequent manuscripts by Micky Willmott, noting and discussing any substantial additions or modifications with the research team, as necessary. The way in which themes inter-related and how they varied between different groups and contexts was carefully scrutinised throughout the analysis process and recorded using detailed memos.

The quotations presented in the report were selected because they best illustrate the common and/or interesting ideas and themes emerging from the data. These were discussed and agreed among the research team. When contradictory data were identified (e.g. the difference between school sixth forms and colleges, or when some students identified that they felt that they had been bullied into smoking), these are noted in the report.

Observation records of staff training and youth work sessions were analysed separately from interview and focus group data by Micky Willmott, with NVivo used to support cross-checking and data triangulation. Records were coded line by line, then grouped according to whether they related to the framework described above or inductive, emergent themes.

Most of the qualitative data collected for the process evaluation were collected by experienced qualitative researchers who were independent of the trial management or baseline data collection. Although this added an additional layer of contacts for FE managers to liaise with, it meant that the researchers had minimal knowledge or preconceptions about the sites. The researchers were all white professionals (three female and one male), which reflected the predominant ethnicity in FE sites. They had little knowledge of the areas in which the FE sites are based, and all were English, not Welsh or Welsh speakers, which may have had an impact on how the students and staff responded to them in focus groups. Researchers shared their reflections on data collection to aid analysis and an interpretative approach.

Pilot outcome measures

The final objective was to pilot primary, secondary and intermediate outcome measures and economic evaluation methods. The pilot cluster RCT design enabled a range of outcome measures and data collection methods (student surveys, policy audits, environmental observations and mystery shopper visits) to be piloted at baseline (September 2014) and at the 1-year follow-up (September 2015) to answer RQs 12–15 (Box 3).

-

Does the primary outcome measure (smoking weekly or more) have an acceptable completion rate, adequate validity and minimise floor/ceiling effects?

-

Do cotinine concentrations of saliva samples indicate any evidence of response bias between arms in self-reported smoking status?

-

Was it feasible and acceptable to measure all the secondary and intermediate outcomes of interest at baseline and follow-up?

-

Is it feasible to assess cost-effectiveness using a cost–utility analysis within a Phase III trial?

The pilot outcomes are described first in Pilot primary and secondary outcome measures and Pilot intermediate outcome measures, followed by a description of the data sources used to operationalise these measures to assess change at the student, college and community levels (see Data sources). These pilot outcomes are also summarised in the intervention logic model (see Figure 1). Finally, the methods for analysing the student survey data and other quantitative data sources are described in Statistical analyses.

Pilot primary and secondary outcome measures

All the pilot primary and secondary outcome measure data were collected via student surveys at baseline and at the 1-year follow-up, which are described in more detail later (see Data sources).

The pilot primary outcome was prevalence of weekly smoking (defined as smoking at least one cigarette weekly or more) at the 1-year follow-up, which was assessed using an item adapted from the GLS. 2 Students were asked: ‘Do you smoke cigarettes at all nowadays?’ and given four response options: ‘Yes, every day’, ‘Yes, at least once a week’, ‘Yes, occasionally but less than once a week’ and ‘No, never’. Those who responded ‘Yes, every day’ or ‘Yes, at least once a week’ were considered weekly smokers.

The pilot secondary outcomes were lifetime smoking, using the Office for National Statistics (ONS) GLS item;2 use of cannabis in the past 30 days and frequent cannabis use (four or more times in the past 30 days), using the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction European Model Questionnaire items;37 high-risk alcohol use, using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) measure;38 and health-related quality of life, using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, 5-level version (EQ-5D-5L) measure. 39

The following three measures were additional pilot secondary outcomes at follow-up for baseline smokers only: self-report smoking cessation, using the ONS GLS item;2 number of cigarettes smoked per week, using the ONS GLS item;2 and nicotine dependence as measured using the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI). 40

Pilot intermediate outcome measures

As illustrated in the intervention logic model (see Figure 1), it was hypothesised that the intervention components would prevent the uptake of smoking through triggering changes at the individual (student), college and community levels. For this reason, intermediate outcome variables were piloted at each of these three levels by collecting a range of additional quantitative process data at baseline and at the 1-year follow-up via college policy audits, environmental observations and mystery shopper visits, as well as via the student surveys at each site.

At the individual level, baseline and follow-up student surveys assessed self-reported changes over time to attitudinal and knowledge-based precursors to smoking, including perceived prevalence of smoking (i.e. perceived norms), by adapting NatCen items;41 social and situational self-efficacy and skills, using the European Smoking Prevention Framework Approach (ESFA) items;42,43 and awareness of The Filter project.

At the institutional level, two measures of college environmental change were piloted. First, progress towards a tobacco-free environment, determined via an audit of FE college policies and structured observations at both intervention and comparison settings pre and post intervention. Second, staff commitment to smoking prevention and delivery of smoke-free messages, assessed via student survey items at follow-up.

At the community level, the availability of tobacco to students aged < 18 years from local retailers was assessed via a pre- and post-intervention mystery shopper audit of retailers within 1 km of intervention and comparison sites and items on the student follow-up survey.

Data sources

Quantitative data were collected at baseline (September 2014) and follow-up (September 2015) via the following methods: student surveys, college policy audits, structured observations of the college environment and mystery shopper visits. These methods are described in detail in turn below. All baseline data collection was completed prior to randomisation (October 2014). The investigator team was unblinded to allocation at follow-up, but all fieldworkers remained blinded throughout the study.

Student surveys

Students were eligible to participate at baseline if they were aged between 16 and 18 years on 1 September 2014 and had enrolled into FE studies in the 2014–15 academic year (i.e. they were new FE students, aged 16–18 years). Students who were older or younger than 16–18 years and completed the survey were excluded from analyses.

As this was a pilot trial, a power calculation was not required. The estimated sample size at baseline of 2500 students in six FE settings was chosen to provide some information on variability within and between settings at baseline and follow-up. This sample was chosen to indicate the likely response rates and permit estimates [with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] and intracluster correlations (ICCs) of weekly smoking prevalence in advance of a potential effectiveness trial involving a larger number of clusters (colleges) and students.

At baseline and follow-up, the consent form and survey were completed using an e-questionnaire for ease of delivery and completion in all areas of college, including social spaces without desk access, with paper copies available if necessary (e.g. requested by student, because of technical problems, etc.). Use of incentives is considered fair recompense for time in work with young people. 44 Here, student participation was incentivised via prize draws for an iPad (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) and shopping vouchers at both baseline and follow-up.

In the first week of September 2014 (i.e. the first week of the new term), students at each participating FE setting that used an e-mail system (four out of six institutions) were contacted directly via their new e-mail account and asked to complete the baseline survey directly via a weblink, they were also sent a reminder e-mail 3 weeks later. Those students who did not complete the survey online directly via this e-mail link, or who attended an institution without a student e-mail system, were given multiple opportunities to complete the e-questionnaire on site during September 2014 via: (1) timetabled classroom periods dedicated to survey completion, in which students used either college computers, their own devices (laptop, tablet computer or smartphone) or Google Nexus tablet computers (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) provided by the fieldworkers; or (2) informal data collection sessions (using Google Nexus tablet computers and/or quick layered response codes) in common areas at break periods. Hard copies were available as a backup (e.g. if the internet connection was too slow or could not be accessed temporarily) and were entered online once fieldworkers returned to the office. All baseline collection occurred between 1 and 30 September 2014. Detailed contact information (name, personal e-mail and mobile phone number) was collected at baseline to help track students who left or were on work-based placements at follow-up.

The 1-year follow-up took place when students had begun the next college year in September 2015 and used the same methods (i.e. e-mails to all students with a college e-mail account, classroom sessions, informal data collection sessions in common areas). To increase response rates, participants were also telephoned up to three times in September 2015 to collect follow-up survey data. All follow-up data collection occurred between 1 and 30 September 2015. Participants who left college or were unable to be contacted were lost to the trial at follow-up.

After the follow-up survey, all students were contacted and asked to provide a saliva sample in order to examine the reliability and validity of the self-reported smoking outcome via cotinine and anabasine testing. However, it was not feasible to recruit sufficient students to provide these samples, despite the use of £10 vouchers as incentives, and we do not report the results of this validation substudy here.

College policy audits

Institutional policies were obtained in September 2014 (baseline) and September 2015 (follow-up). Researchers requested all relevant tobacco policy documents directly from the management teams at each participating FE setting. Data were extracted into an online pro forma to capture the following information about each setting:

-

whether the institution has a specific tobacco policy in place or if tobacco use is covered in other institutional policies

-

the date of the policy and how often reviewed

-

whether or not students and/or staff are allowed to smoke or use e-cigarettes on site according to current policy

-

whether or not college policies make provisions for cessation services and other ‘quit resources’ on site

-

other details, including whether or not careers events, funding and financial connections are covered by existing institutional policies.

Structured observations of the college environment

One researcher completed a structured observation of each college environment (n = 6) at baseline and follow-up using a tablet computer. These observations aimed to assess student and staff practices (e.g. smoking outside of designated areas, where e-cigarettes are used, etc.) and the extent to which the physical environment at each site communicated tobacco-free messages (e.g. through signage) and/or supported institutional policies (e.g. directed people to designated smoking areas off site). Photographs were also taken on the tablet computers to illustrate the information recorded in the observational schedule.

Mystery shopper visits

Tobacco availability to students aged < 18 years was assessed at baseline and follow-up using a mystery shopper audit of all retailers within 1 km (i.e. within a 10-minute walk) of all six participating FE sites. These were the shops that were in the target area for intervention. The aim of the visits was to assess whether or not local shops were compliant with the restriction of tobacco sales to under-18-year-olds at baseline and/or follow-up, and to explore differences over time overall and by arm. The protocol for the mystery shopper activity was developed with input from Caerphilly Trading Standards officers in line with best practice guidance for test purchasing methods.

Mystery shopper exercises were carried out by two young people aged 17 years (one in 2014, one in 2015) who were (1) aged < 18 years and (2) not students at any of the sites included in the study. At both baseline and follow-up the mystery shoppers were male. The shoppers were accompanied by an adult fieldworker, who remained outside the shops and out of sight. The shopper entered the shop and asked to purchase cigarettes while the fieldworkers waited outside. They then completed an online, standardised checklist with the fieldworkers that covered type of shop visited, whether or not they were able to purchase cigarettes and the presence of age restriction warning posters or materials in the shop. There was one instance at baseline (none at follow-up) in which the shopper was unable to recall whether or not there was additional signage in the store regarding smoking or age restrictions.

A total of 18 shops were followed up at both baseline and follow-up; seven shops were also visited only once (either baseline or follow-up) because of closure or because their identity could not be verified at follow-up (e.g. name changed). In Chapter 3 we therefore report the results when data are available for shops at both baseline and follow-up (n = 18).

Statistical analyses

The primary aim of the pilot trial was to assess feasibility and acceptability, and gather data to plan a future definitive trial. This included estimating rates of eligibility, recruitment, retention at the 1-year follow-up, as well as the acceptability, reliability and rates of completion of pilot primary and secondary outcome measures.

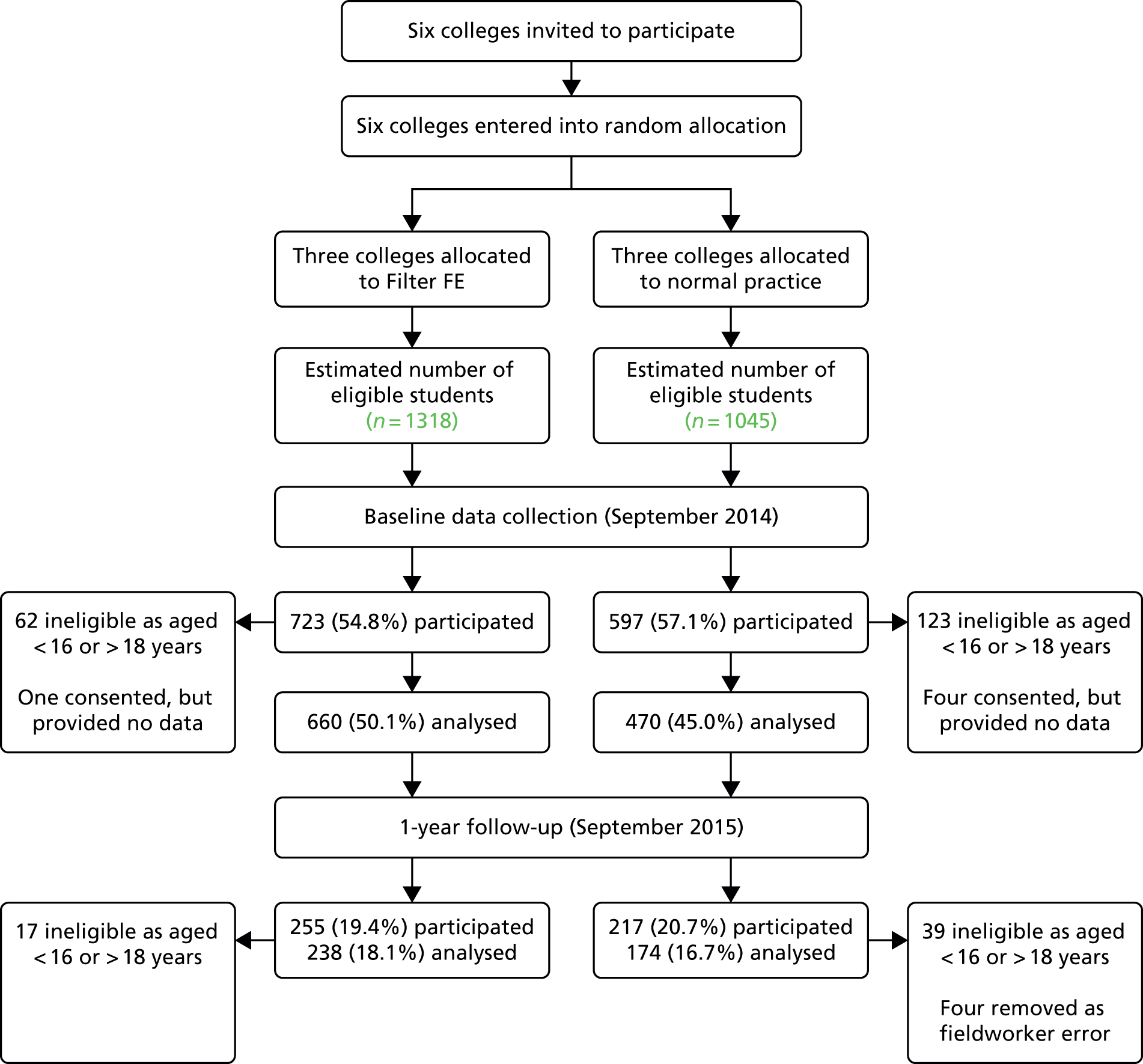

The eligibility, recruitment and retention rates for colleges and students are summarised using a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram (see Figure 2). The data collected for trial participants were summarised by trial arm and combined across arms. The aim was to examine the acceptability of potential primary and secondary outcome measures for a future trial, as well as describing the baseline characteristics of participants. The percentage of missing values was reported for all variables. Categorical variables were summarised using the percentage in each category. Numeric variables are summarised with the mean, standard deviation (SD) and a five-number summary (minimum, 25th centile, median, 75th centile, maximum). We present mean and median values to examine the shape of each distribution. All analyses used intention-to-treat populations.

We used chi-squared and t-tests to examine differences between students who did and did not provide data at baseline and follow-up. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to examine the internal consistency of measures. Multilevel logistic regression models adjusting for baseline weekly smoking status, age, gender, residence with an employed adult, ethnicity and educational attainment [five or more General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) at A*–C] were used to conduct exploratory effectiveness analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted with Stata® version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Data from the mystery shopper, policy audit and environmental observations were collated and analysed using Excel spreadsheets. For the mystery shopper survey, shops visited at both baseline and follow-up were matched in the spreadsheet and the data for each survey item (e.g. whether or not cigarettes were successfully purchased) compared. For each site, items on the policy audit were compared at baseline and follow-up, with differences between intervention and comparison sites scrutinised. Similarly, environmental observation items were compared between intervention and control site, noting any changes between baseline and follow-up.

Economic analysis

We piloted a brief health service use survey for student completion and the EQ-5D-5L (pilot secondary outcome) to record preference-based health-related quality of life. 39 These measures were piloted because it was anticipated that, if feasible to collect data from students in these settings, they could be used in any subsequent Phase III trial to measure any short-term impact of smoking on health-care use and/or health-related quality of life.

Trial registration, governance and ethics

The study was funded by the NIHR PHR programme (13/42/02). The trial protocol was registered with Current Controlled Trials (ISRCTN19563136). The study was overseen by a Trial Steering Committee, comprising an independent chairperson (Professor Paul Aveyard, University of Oxford) and three other independent members (Professor Angela Harden, University of East London; Professor Rob Anderson, University of Exeter; and Dr Julie Bishop, Public Health Wales). The Trial Steering Committee met every 6 months throughout the study (three times in total) to examine the methods proposed and monitor data for quality and completeness. With the agreement of the Trial Steering Committee and NIHR PHR co-ordinating centre, a separate Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee was not established because this was a pilot trial with no interim analysis.

The study was approved by the Cardiff University School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee prior to recruitment and data collection commencing. The validation substudy (saliva testing) was approved by the School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee, liaising with Cardiff University Human Tissue Act managers as necessary. The pilot trial protocol was approved by the South East Wales Trials Unit and the Trial Steering Committee.

Chapter 3 Results

In this section of the report, we first describe the student response rates at baseline and follow-up and the characteristics of the students participating in the study. The findings related to the primary objective are then presented, which was to assess the prespecified ‘progression criteria’ considered to represent evidence of feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial methodology. We then present student, staff and facilitators’ experiences of the intervention and trial process. Finally, we report the quantitative data analyses examining the pilot primary and secondary outcomes, including the pilot economic outcome measure and the pilot intermediate outcome measures.

Description of pilot trial sample

Six colleges were assessed as being eligible to participate in the trial and participated in the study, including random allocation (three intervention and three control; Figure 2). Colleges could not always know or provide exact ages of enrolled students before data collection, which is discussed further in Chapter 4.

FIGURE 2.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

Flow of participants in the pilot trial

Of the target population of 2363 students at baseline, 1320 (55.8%) participated in baseline data collection. Of those 1320 participants, five students (0.4%) provided consent information but did not answer any questions on the survey and 185 (14.0%) were ineligible because they were aged < 16 years or > 18 years. Of those excluded as a result of age, around half (49.7%) were aged ≥ 21 years. The remaining 1130 students, 470 in the control arm and 660 in the intervention arm, equated to a baseline response rate of 47.8% based on the estimated total population of new students aged 16–18 years at these college campuses.

At the 1-year follow-up, 472 (35.7%) baseline respondents participated in the repeat survey. Fifty-six of these participants (12.0%) were students who were ineligible to take part in this study at baseline because they were aged < 16 years or > 18 years. Four participants’ responses were removed because of concerns about the quality of data collected on 1 day at one site, based on fieldworker reports (Laurelton College). Out of the 2363 potentially eligible students at baseline, 412 (17.4%) students who were eligible to participate provided valid survey data at baseline and at the 1-year follow-up. This comprised 238 students in the intervention arm and 174 students in the control arm.

Student characteristics

The categorical baseline characteristics for eligible and non-eligible participants are summarised and compared in Table 5.

| Variable | Baseline data: distribution over categories by eligibility, %a | |

|---|---|---|

| Eligible (aged 16–18 years) (n = 1130) | Not eligible (aged < 16 or > 18 years) (n = 185) | |

| Gender | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Male | 37.1 | 38.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Missing | 0.1 | 0 |

| White British | 92.8 | 91.4 |

| White not British | 0.9 | 2.7 |

| Mixed race | 3.1 | 1.1 |

| Asian or Asian British | 0.9 | 1.6 |

| Black or black British | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Other | 1.1 | 2.2 |

| Is the adult you live with in paid work? | ||

| Missing | 2.7 | 34.5 |

| Yes | 76.8 | 46.0 |

| No | 14.2 | 15.1 |

| Not sure | 6.4 | 4.3 |

| Studying full or part time? | ||

| Missing | 1.3 | 2.7 |

| Full time | 95.3 | 85.4 |

| Part time | 3.5 | 11.9 |

| Working full or part time? | ||

| Missing | 1.5 | 3.2 |

| Full time | 6.7 | 12.4 |

| Part time | 26.4 | 27.6 |

| I do not work | 65.4 | 56.8 |

| Do you have five or more GCSEs? | ||

| Missing | 0.9 | 2.2 |

| Yes | 74.0 | 51.9 |

| No | 19.0 | 33.0 |

| Not sure | 6.1 | 13.0 |

| Qualification(s) studying at college | ||

| Missing | 1.2 | 2.7 |

| AS/A level | 34.5 | 8.11 |

| BTEC | 32.9 | 29.7 |

| Access level course | 7.4 | 12.4 |

| GCSE | 5.1 | 7.0 |

| Other vocational award, certificate or diploma | 4.1 | 4.9 |

| Welsh Baccalaureate | 0.4 | 0 |

| Other | 5.7 | 15.1 |

| Apprenticeship | 1.4 | 3.7 |

| Essential skills | 2.4 | 5.4 |

| HNC | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| HND | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| NVQ | 4.4 | 8.2 |

The eligible participants (i.e. those aged 16–18 years) who completed the baseline survey were predominantly female (62.9%), white British (92.8%), living with an adult in paid work (76.8%), studying full time (95.3%) and had five or more GCSEs (74%). They were enrolled on a wide range of courses, although the two most common FE pathways reported by participants at baseline were AS (Advanced Subsidiary level)/A-level courses (34.5%) and BTEC courses (32.9%).

The distribution of gender was similar in eligible and non-eligible participants. Ethnic group was evenly distributed across the two groups (eligible and non-eligible participants), with few non-white participants. Non-eligible participants were more likely than eligible participants to study part time, have a full-time job and be studying for an access level course, but less likely to have five or more GCSEs and study AS/A levels.

The categorical baseline characteristics of eligible participants by trial arm are summarised in Table 6. Gender was not evenly distributed across the trial arms: the control group comprised 44.7% males and the intervention group 31.8% males. Participants in the control group were older than intervention group students, with 15.1% of participants at control sites aged 18 years, compared with just 8.2% at intervention sites. Ethnicity was evenly distributed, with very few non-white participants in either arm. Control group participants were more likely to study part time and live with an adult in paid work, but less likely to have five or more GCSEs, and be studying for AS/A-levels than intervention group participants.

| Variable | Baseline data: distribution of categories by trial arm, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 470) | Intervention (n = 660) | Overall (N = 1130) | |

| Gender | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Male | 44.7 | 31.8 | 37.1 |

| Age (years) | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 60.4 | 69.1 | 65.3 |

| 17 | 24.5 | 22.7 | 23.4 |

| 18 | 15.1 | 8.2 | 11.0 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Missing | 0.2 | 0 | 0.1 |

| White British | 91.3 | 93.9 | 92.8 |

| White not British | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| Mixed race | 2.6 | 3.5 | 3.1 |

| Asian or Asian British | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Black or black British | 2.6 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Other | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Is the adult you live with in paid work? | |||

| Missing | 4.1 | 1.7 | 2.7 |

| Yes | 68.9 | 82.4 | 76.8 |

| No | 18.7 | 10.9 | 14.2 |

| Not sure | 8.3 | 5.0 | 6.4 |

| Studying full or part time? | |||

| Missing | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Full time | 93.4 | 96.7 | 95.3 |

| Part time | 5.7 | 1.8 | 3.5 |

| Working full or part time? | |||

| Missing | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Full time | 7.7 | 6.1 | 6.7 |

| Part time | 23.8 | 28.2 | 26.4 |

| I do not work | 67.2 | 64.1 | 65.4 |

| Do you have five or more GCSEs? | |||

| Missing | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Yes | 63.0 | 81.8 | 74.0 |

| No | 26.4 | 13.8 | 19.0 |

| Not sure | 9.6 | 3.6 | 6.1 |

| Qualification(s) studying at college | |||

| Missing | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| AS/A-level | 24.8 | 41.4 | 34.5 |

| BTEC | 30.4 | 34.7 | 32.9 |

| Access level course | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.4 |

| GCSE | 8.3 | 2.9 | 5.1 |

| Other vocational award, certificate or diploma | 5.3 | 3.2 | 4.1 |

| Welsh Baccalaureate | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Other | 8.5 | 3.6 | 5.7 |

| Apprenticeship | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Essential skills | 3.8 | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| HNC | 0 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| HND | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| NVQ | 7.4 | 2.3 | 4.4 |

Progression criteria assessment

The first objective was to assess if prespecified feasibility and acceptability criteria were met to determine whether or not to progress to a larger, Phase III trial to examine effectiveness (RQs 1–6). Intervention feasibility and acceptability addresses RQs 1–3: did the intervention activities occur as planned in (at least) two out of three intervention settings?; were the intervention activities delivered with high fidelity across all settings?; and was the intervention acceptable to the majority of FE managers, staff, students and the intervention delivery team? The questions regarding the acceptability and feasibility of trial methods (RQs 4–6) are then addressed in Trial feasibility and acceptability.

Intervention feasibility and acceptability

First, each of the five intervention components is considered in turn to understand whether or not they were delivered as planned (RQ 1) and with high fidelity across multiple settings (RQ 2). At the end of this section, the question of overall acceptability is addressed briefly (RQ 3) prior to presenting participants’ views in more detail in Process evaluation: participants’ experiences.

Prevention of the sale of tobacco in local shops

With the aim of restricting the local availability of tobacco at each intervention setting, the Filter FE intervention included a community-level component targeting local retailers. The aim was for the intervention manager to contact all shops selling tobacco within 1 km of the intervention setting (i.e. within a 10-minute walk). This component was intended to be delivered immediately post randomisation (early October 2014) via letters sent to these retailers to inform them that a new smoking prevention project (The Filter FE) was taking place at their local FE institution. Posters, stickers and other materials about The Filter and ASH Wales were also to be distributed to these shops to provide additional information to them and their customers about the legal age for purchasing tobacco products and the requirements to produce statutory identification to purchase tobacco. Owing to the location of the intervention settings in rural and suburban areas, in total there were only five shops within 1 km of all the intervention sites; one rural site had no tobacco retailers within 1 km (Laurelton College).

The results indicate that the criteria for RQs 1 and 2 were not met for this component at any of the three intervention sites. Despite the low number of retailers, the intervention team checklists were not recorded consistently and intervention team members reported that resources were not sent out to these retailers as planned. Various factors appeared to contribute to this, but the most common factors appeared to be the relatively short time available to identify and work with local community settings, as well as poor management of intervention implementation. There was also no evidence of changes in practices from the mystery shopper audit at follow-up in September 2015. In two out of the three shops close to intervention sites that were audited by a mystery shopper at baseline and follow-up, it was possible to buy cigarettes at follow-up but not at baseline (i.e. local availability of tobacco to students aged < 18 years may have increased; the findings of mystery shopper audit are reported in Pilot intermediate outcome measures). There was some observational evidence that age restriction signage increased in local shops between baseline and follow-up, although this was consistent across shops in both intervention and control arms.

Policy review to promote a tobacco-free environment

Five policies were audited and recorded at baseline. In one (control) site, Afonwood School, there was no written policy, but if students were caught smoking on site, a letter was sent to their guardian (a copy of the letter was obtained). With the aim of restricting opportunities for smoking and promoting non-smoking as the norm at each intervention setting, it was intended that the intervention manager would develop new whole-campus tobacco-free policies with each intervention setting. This component was intended to be delivered immediately post randomisation (early October 2014) by the intervention manager who would work with FE managers at each intervention setting to review their institutional policies using the tobacco-free campus guidance developed by ASH Australia. 34