Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3002/02. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The final report began editorial review in August 2016 and was accepted for publication in January 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elizabeth Allen, Joanna Sturgess and Diana Elbourne report grants from the NHS National Institute for Health Research Public Health Programme to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine during the conduct of the study. Geraldine Macdonald is in the process of completing a Cochrane Review of home-visiting programmes that will include studies of nurse–family partnership. Two predecessor reviews were withdrawn in response to a criticism by David Olds. The criticism did not materially affect the results or conclusions of the reviews, but it was deemed appropriate to correct these and republish. This work is in progress, but the results are not yet available.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Barnes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report describes the evaluation in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the Group Family Nurse Partnership (gFNP) programme, compared with usual care, as a strategy to reduce the likelihood of child abuse and neglect.

Background

Recent estimates show that suboptimal parenting of infants is a major public health issue. As of 31 March 2012, infants (children aged up to 1 year) accounted for 13% of those who were subject to a child protection plan in England. 1 The most common initial category of abuse for infants was neglect (49%), followed by emotional abuse (22%) and physical abuse (16%). Infants also face four times the average risk of homicide, perpetrators being parents in most cases. 2 Non-accidental head injuries are common, resulting in up to 30% mortality and significant neurological impairment for survivors. 3 Furthermore, the abuse of very young children may be up to 25% higher than indicated by official estimates. 4

In addition to preventing childhood injury and abuse, sensitive caregiving during the first year is important for promoting optimal child outcomes because brain development at that time is rapid and vulnerable to negative influences. Brain development is strongly influenced by the environment, the key component being the interactions with primary caregivers. Early research in the field of developmental psychology has, for example, highlighted the significant role that the infant’s primary caregiver plays in regulating the infant. 5 Maternal sensitivity has been shown to be a significant predictor of infant attachment security,6 and recent research has identified the importance of the specific nature or quality of the attunement or contingency between parent and infant,5 and the parent’s capacity for what has been termed ‘maternal mind-mindedness’7 or ‘reflective function’. 8 Research also shows that infant regulatory and attachment problems can best be understood in a relational context, and that disturbances to the parent–child relationship and parental psychosocial adversity are significant risk factors for infant emotional, behavioural, eating and sleeping disorders. 9 Trauma and adverse parent–child interactions in infancy elevate cortisol, a strong indicator of stress, and can lead to attachment difficulties, hyperactivity, anxiety and impulsive behaviour. 10,11

Policy context

A range of cross-party policy documents has now explicitly highlighted the importance of promoting children’s well-being during pregnancy and first 2 years of life,12–14 and recent key documents include Conception to Age 2: The Age of Opportunity15 and The 1001 Critical Days: The Importance of the Conception to Age Two Period. 16

Fair Society, Healthy Lives. Independent Review Into Health Inequalities in England Post 201017 focused on the importance of pregnancy and the first 2 years of life in terms of equalising the life chances of children, and Healthy Lives, Healthy People18 similarly points to the importance of ‘starting well’, focusing in particular on the health of mothers during pregnancy and parenting during the early years. Recent research has identified that this period is key because of the ‘biological embedding of social adversity’ that takes place during sensitive developmental periods. 19,20 This research showed that toxic stress caused by high levels of anxiety and depression during sensitive developmental periods (e.g. pregnancy and the postnatal period) can disrupt the developing brain architecture and other organ systems and regulatory functions, impacting the fetal/infant physiology in terms of hyper-responsive/chronically activated stress response; their resulting behavioural adaption; and the long-term cognitive, linguistic and socioemotional development. The long-term impact occurred in terms of increased stress-related chronic disease, unhealthy lifestyles and widening health disparities.

Evidence context

There is limited evidence available about ‘what works’ to support vulnerable parents during pregnancy and infancy. Although evidence concerning the effectiveness of home-visiting programmes in general in reducing child maltreatment is inconclusive,21 the US-developed Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) was one of nine home-visiting programmes identified as effective by the US Department of Health and Human Services as part of their Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness Review. 22 It is commonly named when examples of programmes with high-quality evidence for success are sought. For instance, the US coalition for evidence-based policy, responding to a Congressional directive that funds be directed to programmes with top-tier evidence of effectiveness identified only two programmes for children aged 0–6 years and their families that could be thus categorised, one of which was the NFP. 23 The Blueprints mission of the ‘Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence’ was charged with identifying outstanding violence and drug prevention programmes that meet a high scientific standard of effectiveness and, out of 800 with published research, found 12, one of which was NFP. 24 A similar conclusion was reached by academics seeking evidence-based home-visiting programmes likely to reduce child abuse and neglect. 25 The NFP was found to be effective in both decreasing child maltreatment and improving parenting practices. 22 Long-term follow-up of the NFP in the USA suggests a 48% reduction in cases of child abuse and neglect by the age of 15 years. 26

The NFP curriculum has strong theoretical underpinnings, in terms of both risk and protective factors, and the mechanisms through which change may be produced,27 drawing on ecological,28 self-efficacy29 and attachment30 theories. Ecological theory emphasises the importance of interactions between the characteristics of individuals and their contexts; self-efficacy theory focuses on an individual’s beliefs that they can successfully carry out behaviour required for good outcomes; and attachment theory highlights the importance of the early interactions with the primary caregiver in terms of the child’s later capacity for affect regulation. The cornerstone of the NFP model is the therapeutic nurse–client relationship. Beneficial outcomes found in the US trials included improved prenatal health, fewer childhood injuries, fewer subsequent pregnancies, increased intervals between births, increased maternal employment and improved school readiness;23,26,31–33 it has also been shown to have the potential to be cost-effective. 34 Results from the US trials of NFP found that it was particularly beneficial for women with ‘low psychological resources’, namely a combination of lower intelligence, mental health problems and low self-efficacy. 35

The NFP programme was introduced into England in 2007, renamed the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP),36 and has been offered to first-time teen mothers in more than 70 locations in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland,37 although recent RCT evidence has failed to support it as a way to reduce child abuse and neglect in the UK. 38 An implementation evaluation in the first 10 areas to provide FNP found that the programme was perceived in a positive light by potential clients and the nurses responsible for its delivery and uptake was high, with delivery close to the stated US objectives. 39 Nevertheless, potential sustainability issues were identified and in particular local concerns about its cost set against long-term rather than immediate gains. 40,41 Issues of eligibility were also examined, with the conclusion that, over time, the criteria might have to be changed to include additional risk factors beyond young age, although this could cause difficulties in identifying women early in their pregnancy. 42

In addition to being trained according to the US requirements, UK nurses are trained in ‘motivational interviewing’43 so that they can develop in-depth engagement with families to achieve change. As is the case in the USA, fathers are encouraged to be present for home visits and they have reported positively about the programme, in particular that the nurses invested time in developing relationships with them and identified their strengths in addition to areas that needed support, and that the programme was holistic in its approach. 44

Developing Group Family Nurse Partnership

In response to enquiries for a programme that could be offered to women who are ineligible for FNP, a group-delivered structured-learning programme based on FNP was developed in England by the Family Nurse Partnership National Unit (FNP NU) in collaboration with the NFP National Office at the University of Colorado, Denver. 45,46 gFNP was developed as a way to use the expertise of the FNP nurses, and the learning from the FNP, to reach women whose children were at risk of poor outcomes, but offered in a different context, and to reach those not eligible for FNP. The programme has the same theoretical basis as the home-based programme but is delivered in a local children’s centre (or similar community location). gFNP is, like FNP, aimed at helping young parents develop their health, well-being, confidence and social support in pregnancy and their children’s health and parenting in the first year of life, and at raising aspirations about future education and employment to increase support for the family in the future. 45

The programme was designed on the basis that group care prenatally can improve pregnancy outcomes47,48 and may be less costly than individual support,49 and that postnatal groups are a way of supporting potentially vulnerable mothers. 50,51 Meeting in a group with other mothers can be perceived by non-teenage mothers as more helpful than one-to-one support. 52 However, young mothers can be uncomfortable in groups and are less likely than older mothers to attend, especially if the group includes predominantly older mothers. 53 The main difference from existing group support in the UK for pregnant women or women with new babies, such as that offered by midwives and health visitors delivering the universal Healthy Child Programme (HCP)54 and other support provided in Sure Start Children’s Centres,55 is that gFNP spans both pregnancy and infancy, with ongoing support from the same practitioners over 18 months and ongoing contact with a group of families whose babies are of a similar age. Other group services are more time limited and focus either on pregnancy well-being, preparation for labour and birth or on specific infant issues such as sleep problems or breastfeeding, although the Preparation for Birth and Beyond materials56 are designed to address this by incorporating approaches to supporting families in pregnancy that are holistic and practical.

The gFNP programme uses the materials and approach of the NFP programme,23 aiming to improve maternal and infant health, promote close mother–infant attachment, develop sensitive parenting and effective family relationships, and help women to explore life choices as they become parents. 57 In addition, the programme includes aspects of ‘Centring Pregnancy’, an intervention developed in the USA, which provides groups of between 8 and 12 women with antenatal care during nine 2-hour sessions, with time for discussion about issues such as smoking, healthy eating and breastfeeding, and enables women to understand their own health status by encouraging them to be actively involved in all of the health checks. 47 The group-based Centring Pregnancy is said to be preferred to traditional (individual) antenatal care,47,58,59 and has led to improved prenatal outcomes such as fewer preterm births among high-risk women. 48,60 Experience of Centring Pregnancy in the UK context is limited to a feasibility study carried out in South London. 61 As part of the gFNP programme, during pregnancy clients receive routine antenatal care in accordance with UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,62 and in the postnatal phase infants are monitored according to the HCP54 guidelines. To allow for this, one of the practitioners delivering the programme had to have also notified his or her intention to practise as a midwife and the FNP nurses had to have training in the delivery of the HCP.

Although NFP23,26,31 and Centring Pregnancy47,59,60,63 have substantial evidence outside the UK, it was necessary to provide evidence for gFNP, and for the merger and adaption of the two approaches to supporting mothers and their infants. The gFNP programme is a complex intervention made up of many components that have been designed, through education, nurse contact and peer support, to change parent behaviour. 64,65 According to Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines,64,65 and in line with a framework proposed for developing and evaluating NFP innovations,66 the stages for effectively evaluating and implementing complex interventions are (1) programme development; (2) piloting for feasibility; (3) evaluation of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, ideally with a RCT; and (4) translation into mainstream practice.

Following programme development and prior to this RCT, the UK Department of Health (DH) and the FNP NU commissioned two feasibility evaluation studies of gFNP. 57,67 The feasibility of delivering gFNP was established68 by asking if there were barriers to reaching the intended population; whether or not any client factors were related to attendance; if programme delivery could be sustained over 18 months; and if gFNP was acceptable to different stakeholders.

Each feasibility study used a mixed-methods design69 involving the parallel collection of quantitative information on attendance, and client characteristics and qualitative data from semistructured interviews or focus groups (depending on resources and participant availability) to provide contextual understanding of the specific study questions. Quantitative data documented the outcome of referrals to gFNP, characteristics of clients and their attendance. Qualitative data covered experiences of the programme and reflections on programme delivery from a range of stakeholders.

Variability in attendance was identified, despite clients reporting strong commitment in interviews. Across the six sites delivering gFNP in the two feasibility studies, the mean number of sessions delivered by sites was 38 out of a potential 44 in the curriculum. 68 Although some clients had attended almost the maximum number of sessions, two never attended any meetings. An examination of whether or not any client factors could be linked to attendance found only that low attendance overall was related to mothers having never been employed (vs. employed full-time), whereas attendance in pregnancy was significantly lower for women living alone than for those living in a household with other adults. 68

Acceptability was high, with clients reporting support from others and enjoying the fact that they could share their baby’s progress with other parents. They also believed that coming together as a group with the babies and mothers helped in their baby’s developmental progress. The majority of clients considered that the inclusion of routine midwifery care in the group was a positive aspect to the programme.

Study aims

Following the results of the two, generally positive, feasibility studies, it was decided, in line with the MRC guidelines for evaluating complex interventions,64,65 to evaluate gFNP’s impact with the highest quality of evidence, in a RCT. The First Steps study’s objective was:

-

to determine whether or not gFNP, compared with usual antenatal and postnatal care, could reduce risk factors for maltreatment in a vulnerable group (namely expectant mothers aged < 20 years who already had a child, and expectant mothers aged 20–24 years with no previous live births and low/no educational qualifications).

In addition, the study aimed to answer the following questions:

-

Would provision of gFNP enhance maternal physical and mental health in pregnancy and the experience of pregnancy and delivery for mothers and fathers?

-

Would provision of gFNP enhance infant birth status and health status in infancy, breastfeeding and immunisation uptake during the first year?

-

How feasible and acceptable would gFNP be as part of routine antenatal and postnatal services?

-

How cost-effective was gFNP as a means of providing antenatal and postnatal services, compared with usual care?

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The study comprised a multisite randomised controlled parallel-group trial in which eligible women were allocated (minimised by site and maternal age group) to one of two arms: (1) gFNP delivered via 44 sessions over 76 weeks or (2) usual care.

Participants

The participants were young (aged < 25 years) pregnant women.

Eligibility criteria

The requirement of the UK FNP NU was that gFNP should be offered to women who were not eligible for FNP, but who would be likely to benefit from the content of programme, based on research in the USA. 23,26 Women eligible for the trial, based on criteria defined by the FNP NU, were expectant mothers with expected delivery dates (EDD) within approximately 10 weeks of each other, for each group in each site. The range of EDDs was specified in relation to the expected date of the first meeting per site so that the majority would be 16–20 weeks pregnant when programme delivery commenced in that site. Specific criteria, beyond similar EDDs and gestation, were that participants should be either:

-

aged < 20 years at their last menstrual period (LMP) with one or more previous live births; or

-

aged 20–24 years at their LMP with no previous live births and low educational qualifications [defined as not having both mathematics and English language General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) at grade C or higher or, if they had both, no more than four GCSEs at grade C or higher].

Exclusions were:

-

expectant mothers aged < 20 years who had previously received home-based FNP

-

mothers in either age group with psychotic mental illness (defined as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia)

-

mothers who were not able to communicate orally in English.

Study setting

Family Nurse Partnership teams are located around England, but with various dates of starting ranging from 2007 to the time that the study was being planned (October 2012). FNP teams were eligible to be part of the trial if:

-

the team had delivered the home-based FNP programme in its entirety (from birth to age 24 months) to a cohort of women

-

the team included at least one family nurse (FN) practitioner who had notified their intention to practise as a midwife.

Invitations were sent by the FNP NU to eligible teams, noting that they could take part if, in addition:

-

they could demonstrate from birth records that sufficient women of the relevant age and parity in the local area had given birth in the previous year for recruitment of two groups of 16–20 women (8–10 intervention, 8–10 control), each recruited within approximately 6 weeks, assuming that at least three times that number would need to be identified to gain sufficient agreement

-

they could confirm good links with community midwifery such that they also signed the expression of interest.

Seventeen teams expressed initial interest and eight sent in formal expressions of interest. Following site visits to discuss the likelihood of sufficient birth data and good midwifery collaboration, seven teams agreed to take part in the trial, located across England in Barnsley, Dewsbury, Lewisham (London), Nottingham, Sandwell (Birmingham), South Tyne and Wear and Waltham Forest (London). The eighth site found that their birth rate would not support the numbers needed for the trial.

The selection of FNs within sites to be involved in the trial was the responsibility of FNP teams. FNs, all of whom had substantial experience of delivering FNP, in general volunteered, and the majority had previous experience of running other types of group. At least one FN at each site had to have an intention to treat (ITT) as a midwife. The FNs received several days of training specific to delivering gFNP, which focused on group dynamics and the different aspects of the curriculum designed to generate interactions between group members. The training, from FNs who had developed the programme materials and been involved in feasibility research, covered topics such as using communication and motivational interviewing skills within a group context. 70 Although in theory FNs could have withdrawn from involvement, any FN withdrawing during the study did so owing to illness. Most sites were not able to send to training more than the two FNs needed for the programme. In cases of short-term absence, the supervisor or another FN from the team usually deputised.

Study intervention

Group Family Nurse Partnership is designed to run from the first trimester of pregnancy until infants are aged 12 months, with 44 group meetings in the curriculum (14 covering pregnancy and 30 covering infancy). 57 It was delivered to a group of women living in relatively close proximity, with similar EDDs (within 8–10 weeks). 46 Meetings lasted around 2 hours and were held in children’s centres, health centres or other suitable community facilities in the local areas served by the FNP teams. Sessions were facilitated by two experienced FNP FNs, one of whom had notified their intention to practise as a midwife. The two FNs exchanged the roles of active leader (facilitating a topic and activity) and active observer, noticing behaviours and body language of members and stepping in to support the leader and maintain a positive and inclusive group environment.

The gFNP programme includes content to improve maternal health and pregnancy outcomes; to improve child health and development by helping parents provide more sensitive and competent care; and to improve parental life course by helping parents develop effective support networks, plan future pregnancies, complete their education and find employment. 23 The curriculum domains were mother’s personal health, the maternal role, maternal life course, family and friends, environmental health and related health and human services, with referrals made when necessary. The gFNP curriculum materials and activities were modified from those used to deliver FNP to reflect group administration. They were designed to avoid a lecture context and to facilitate interaction between group members and between group members and the nurses, providing a range of engaging, often ‘hands-on’ activities. In particular, gFNP had a particular focus on enhancing social support and social networks through dialogue between group members, which is not a specific focus of home-based FNP. 46,57

Specific to the gFNP programme and following NICE guidelines,62 the family nurse midwife (FNMW) provided routine antenatal care during the meeting, taking an approach based on the Centring Pregnancy Programme,47,59,61 which encourages women to monitor their own health (e.g. by testing their own urine or listening to the fetal heartbeat). The Centring Pregnancy approach was perceived to correspond well with the gFNP aims in that both focus on developing self-efficacy and encouraging women to be more self-aware. 46 Once infants were born, both FNs were involved in routine infant checks, conducted in accordance with the UK NHS HCP. 54

An appreciation of the diversity of group members is central to thinking about how the content is delivered, especially for some emotive topics such as ‘safe relationships for our children’. 46 Although there was a curriculum for each meeting, the nurses were sensitive to the need for ‘agenda matching’ related to particular issues raised; this requires the practitioners to listen to the issues that are uppermost for the group members and agree how these can be met, while at the same time ensuring that the session agenda is realised and behaviour adaptation is progressed for everyone. In addition to modelling of infant care, they model respectful relationships and turn-taking,71 which are expected to be of benefit to any group members with poor social skills, especially if they are experiencing difficult interpersonal relationships. 46 Study participants allocated to gFNP could also access any aspect of the HCP usual care that they wished, independently or with the guidance of the gFNP nurses.

Control: usual care

Complete details of the care offered through the NHS to pregnant women and those with infants up to the age of 1 year at the time that the research was conducted can be found in the Healthy Child Programme. Pregnancy and the First Five Years. 54 The HCP, led by health visitors, is delivered through integrated services that bring together Sure Start Children’s Centre staff, general practitioners (GPs), midwives, community nurses and others. In summary, it offers every family a programme of screening tests, immunisations, developmental reviews, and information and guidance to support parenting and healthy choices. There are core universal elements provided for all families with additional progressive, preventative elements for those with medium or high risk. The universal programme includes a neonatal examination, a new-baby review at about 14 days, a 6- to 8-week baby examination, and a review by the time the child is 1 year old and at 2–2.5 years.

It aims to develop strong parent–child attachment and positive parenting, resulting in better social and emotional well-being among children; care that helps to keep children healthy and safe; healthy eating and increased activity, leading to a reduction in obesity; prevention of some serious and communicable diseases; increased rates of initiation and continuation of breastfeeding; readiness for school and improved learning; early recognition of growth disorders and risk factors for obesity; early detection of – and action to address – developmental delay, abnormalities and ill health, and concerns about safety; identification of factors that could influence health and well-being in families; and better short- and long-term outcomes for children who are at risk of social exclusion.

There is a focus on supporting mothers and fathers to provide sensitive and attuned parenting, in particular during the first months and years of life. From the 12th week of pregnancy, women are encouraged to see a midwife or maternity health-care professional for a health and social care assessment of their needs, risks and choices.

Primary outcome measures

Two primary outcome measures of parenting were used because of the difficulties associated with the detection of low frequency events such as child abuse. One is a self-report measure of parenting opinions and the other is an objective measure of maternal behaviour during a parent–infant interaction. Both are known to be able to identify mothers at risk for abusive parenting.

-

The Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory Version 2 (AAPI-2)72 is a 40-item self-report measure able to discriminate between abusive and non-abusive parents. The total raw score is converted to a standard 10 score, with low scores indicating a higher risk for practising abusive parenting practices. Subscales are also available: ‘inappropriate’ expectations of children (seven items); inability to demonstrate empathy to children’s needs (10 items); strong belief in the use of corporal punishment (11 items); reversing parent–child family roles (seven items); and oppressing children’s power and independence (five items). Responses are on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Internal reliability of the subscales ranges from 0.83 to 0.93, Cronbach’s alphas range from 0.80 to 0.92. The scales were constructed based on factor analysis to demonstrate construct validity and the inventory has discriminant validity comparing abusive and non-abusive parents.

-

The observational CARE-Index73,74 is based on a video recording of 3–5 minutes of mother–child play, and measures three aspects of maternal behaviour (sensitivity; covert and overt hostility; unresponsiveness) and four aspects of infant behaviour (co-operativeness; compulsive compliance; difficultness; and passivity). For this study only maternal sensitivity has been used as the co-primary outcome and has been shown to differentiate between abusing, neglecting, abusing and neglecting, marginally maltreating and adequate dyads. 75 Scores can range from 0 to 14, higher scores indicating better maternal sensitivity and/or infant co-operation. Scoring was conducted blind to allocation. Reliability scoring was completed on a random 10% sample of the recordings.

Secondary outcome measures

Eight secondary outcomes assessed socioemotional aspects of parenting and family life and service use.

-

The observational CARE-Index infant co-operativeness.

-

Maternal depression was assessed (at baseline and at 2, 6 and 12 months post partum) using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS),76 a well-validated 12-item measure of postnatal depression with high reliability (0.88) and internal consistency (0.87), 86% sensitivity and 78% specificity. This questionnaire was scored within 24 hours of its administration so that any woman with a total score above the recommended cut-off indicating a risk of depression, or who responds affirmatively to the question asking about self-harm, could be identified and a health-care professional contacted to give appropriate support.

-

Maternal stress was assessed (at 2 and 12 months post partum) using the Abidin Parenting Stress Index (PSI), Short Form,77 a well-validated 36-item measure of perceived stress in the parenting role with sound test–retest reliability (r = 0.84) and internal consistency (α = 0.91). High scores on the PSI have been associated with abusive parenting,78,79 with some evidence that parenting stress is higher in women with five or more risk factors for child abuse. 80

-

Parenting sense of competence was assessed with the Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) scale81 at 2 and 12 months. This 17-item measure has three factors – satisfaction, efficacy and interest – established by factor analysis in a normative non-clinical sample, each with acceptable internal consistency (from 0.62 to 0.72). 82

-

The extent of social support available to the mothers was assessed (baseline and 12 months) using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), Social Support Survey. 83 The 20-item scale measures four dimensions of support, established using confirmatory factor analysis (emotional support, tangible support, positive interaction and affection), each with internal consistency of 0.91 or higher, and also provided a total support score (Cronbach’s alpha 0.97); stability over time is also high for each scale (ranging from 0.72 to 0.78). 83

-

Brief questions designed for the study and based on those developed for use when delivering FNP40 asked about maternal smoking and alcohol and drug use.

-

Brief questions designed for the study and based on those developed for use when delivering FNP40 asked about relationship violence.

-

Brief questions designed for the study asked about infant feeding.

Information other than for the primary and secondary outcome at different time points was collected and is shown but was not formally tested (e.g. baby demographics; immunisations; maternal smoking, alcohol and drug use).

Data collection

The trial commenced in February 2013, recruitment and baseline data collection commenced in July 2013, continuing to July 2014, and data collection was completed in March 2016. Data collection was conducted by researchers making four visits to participants’ homes (baseline in early pregnancy, when infants were 2, 6 and 12 months of age), when they administered structured questionnaires, and (at 12 months) made a 3- to 5-minute video recording of the mother and infant together, presented with a standardised set of toys.

At a Project Management Committee meeting (31 October 2014), it was agreed that the target windows for data collection were 2–3.5 months (60–105 days) for the 2-month outcomes, 6–7.5 months (180–225 days) for the 6-month outcomes and 12–14 months (365–425 days) for the 12-month outcomes, although data would still be collected outside those windows if the participant was available. It was also agreed that interviews with mothers whose babies were premature would be timed as much as possible according to their chronological age. The participants were given ‘High Street’ vouchers for £20 at each home visit data collection point to acknowledge their time for participation. All reasonable attempts were made to contact any participants lost to follow-up during the course of the trial to complete the assessments.

Data management

Each participant was allocated a unique identifier (UID) prior to the baseline interview and this UID was recorded on each questionnaire completed for that participant. All questionnaires were anonymous. The researchers sent completed questionnaires by post directly to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) and checks were made for receipt. The questionnaires received at the LSHTM CTU were reviewed for errors and omissions and, when possible, these were resolved via communication with the researchers. The questionnaires were stored in a locked cabinet. The data were double entered into a database by trained data personnel. All electronic trial data from questionnaires and electronic management data with personal participant content stored at the LSHTM CTU were password protected and held on secure servers at the LSHTM.

Video-taped play interactions were transferred by the fieldworkers from the camera to encrypted USB flash drives with Advanced Encryption Standard 256-bit military-level security, sent by recorded delivery to the principal investigator (PI), with files deleted from the camera by the fieldworkers. Recordings were decrypted by the PI and saved with full anonymisation of filenames on a dedicated drive separate from any other study information. Copies of recordings were sent on DVDs to the coder by special delivery and codings returned on a password-protected Microsoft Excel (2010; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) file to the study PI via e-mail. These were converted to a Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS version 22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) data file once all codings had been received and sent by the PI as a password-protected file by e-mail to the trial statistician at the LSHTM CTU.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated for the two primary outcomes: the AAPI-272 and maternal sensitivity from the observational CARE-Index. 73–75 The standard deviation (SD) of the AAPI-2 based on a total sum of the raw scores of 40 items (range 40–200 items) is 10, with differences of 6.7 identified in the normative sample between abusive and non-abusive adult females. 72 The SD for the CARE-Index sensitivity scale (range 0–14) was expected to be around 2.3. 73

For this individually randomised trial, we initially proposed to recruit sufficient mothers and babies (families) to allow the trial to detect a difference between groups of 0.5 SD, with 90% power at a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed), considered to represent a moderate size of effect. 84 Basing calculation on the AAPI-2, very conservatively assuming a correlation of 0.4 between pre- and post-intervention scores, at least 71 families were needed in each arm of the trial to detect this difference. Allowing for an expected 30% dropout rate (based on the first two applications of the programme in England), we planned to recruit a minimum of 84 families per arm of the trial. We therefore proposed, conservatively, to recruit a minimum of 100 families per arm (n = 200). The proposed sample size would similarly allow us to detect a change of approximately 0.5 SD in the CARE-Index maternal sensitivity score. 73–75 If this was achieved, we expected to be able to detect a difference at follow-up between arms of the trial of approximately 1.2 with 90% power and a 5% level of significance.

However, owing to ongoing slow recruitment, and because two of the Phase I groups with very low numbers were discontinued prematurely, the allocation ratio was changed during the trial from 1 : 1 to 2 : 1 in favour of the intervention arm. As a result of this and the actual recruitment rate, sample sizes were revised to 100 families in the intervention arm and 65 families in the control arm. With the expected dropout rate of 30%, we would still have 82% power to detect the planned differences in the primary outcomes.

Recruitment and consent

Community midwives were initially involved in identifying potentially eligible women based on their age, parity and gestation,85 giving them a study leaflet describing the study (see Report Supplementary Material 1) and asking for written agreement to give their names and contact details to the local researcher as part of a staged consent process, using an ‘agreement to contact’ form (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Owing to a range of factors,86 the identification of potentially eligible participants subsequently involved both Clinical Local Research Network (CLRN) midwives and FNP FNs who generally gained oral agreement for research contact, as approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) (amendment #1).

The first research contact was by telephone to confirm eligibility. Women who were not eligible were thanked for their time. Those eligible were given an information sheet about the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 2), and time to think about participation. After at least 24 hours, researchers arranged a home visit, so that written consent could be obtained (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and baseline data could be collected.

Randomisation procedure

The process was overseen by the LSHTM CTU. The UID (which included a site identifier) and age at the LMP of eligible consenting mothers-to-be were passed by the researchers to the central randomisation service at the Health Services Research Unit, Aberdeen, using an automated telephone procedure. Minimisation criteria [site and age group (< 20 years and 20–24 years)] were used to ensure a balance of key prognostic factors. Allocation to one of two arms was securely computer generated and delivered by e-mail to the LSHTM, which conveyed the information to study participants by post and conveyed to each gFNP team the names and contact details of women allocated to the intervention arm by fax or password-protected e-mail, receiving confirmation of receipt by e-mail.

Blinding

The research team collecting the data and the psychologists scoring the videos were blind to treatment allocation.

Statistical analyses

The primary analyses were by ITT and included adjustment for baseline measure of the outcomes when possible (analysis of covariance; ANCOVA). When outcomes were collected at multiple time points to gain power, random-effects models, using a likelihood-based approach, were fitted to the outcomes at all the time points they were measured at simultaneously (Table 1 and see Appendix 1). This has the additional advantage that the data from all participants contribute to the analysis, even if there are missing data at some follow-up time points.

| Measure | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, pregnancy | Infant, 2 months | Infant, 6 months | Infant, 12 months | |

| AAPI-2 | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CARE-Index | ✗ | |||

| Demographics | ✗ | ✗ (update) | ✗ (update) | ✗ (update) |

| EPDS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Infant feeding | ✗ (plans) | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Infant immunisations | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Maternal drug use | ✗ | ✗ (update) | ✗ (update) | |

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Maternal smoking and alcohol use | ✗ | ✗ (update) | ✗ (update) | |

| PSI, Short Form | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| PSOC | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Relationship violence | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Social networks (MOS) | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Service use | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

Reflecting the discussion at the Project Management Group (31 October 2014), about appropriate time windows for data collected at 2, 6 and 12 months, the statistical analysis plan as agreed with the Data Monitoring Committee in December 2014 was for the primary analysis to exclude all data outside the windows (i.e. after 12 months + 60 days; 6 months + 45 days; and 2 months + 30 days). A sensitivity analysis was then conducted including all data, even those outside the windows.

For the primary outcome of the AAPI-2,72 a linear regression model was used to estimate a mean difference in AAPI-2 score between the two arms of the trial. For the primary outcome maternal sensitivity score, a mixed-effects model was used with a random effect at the mother level (to allow for multiple births), to estimate a mean difference in maternal sensitivity score between the two arms of the trial. However, only one set of twins was available for this analysis and their responses were identical. Therefore, it was not possible to include a random effect and the analysis was carried out at the mother level using a linear regression model.

For the secondary outcomes, appropriate generalised linear models were used to examine the effect of the intervention. Odds ratios (ORs) and mean differences are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When continuous measures were available at baseline, they were adjusted for in the analysis.

When there was evidence of non-normality in the continuous outcome measures, the non-parametric bootstrapping, with 1000 samples, was used to estimate the effect of the intervention and bias-corrected CIs are reported. 87 When this was done, p-values were estimated using permutation tests.

An adjusted analysis, adjusting for site and maternal age group, was also carried out. A pre-specified subgroup analysis was planned based on ‘looked-after’ history, but, as there was only one participant in the intervention arm (see Chapter 6), this was not carried out.

It was planned that the impact of being a twin would be explored by including a covariate in all models, but owing to the low number of twins this was not carried out. However, exploratory analyses were carried out to examine the impact of premature birth on all outcomes. Further exploratory secondary analyses were also carried out, in which the small group in which the intervention was delivered was fitted as a random effect to allow for any potential clustering by group.

A complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis88 was also carried out. The CACE analysis estimates a measure of the effect of the intervention on those participants who received it as intended by the original allocation.

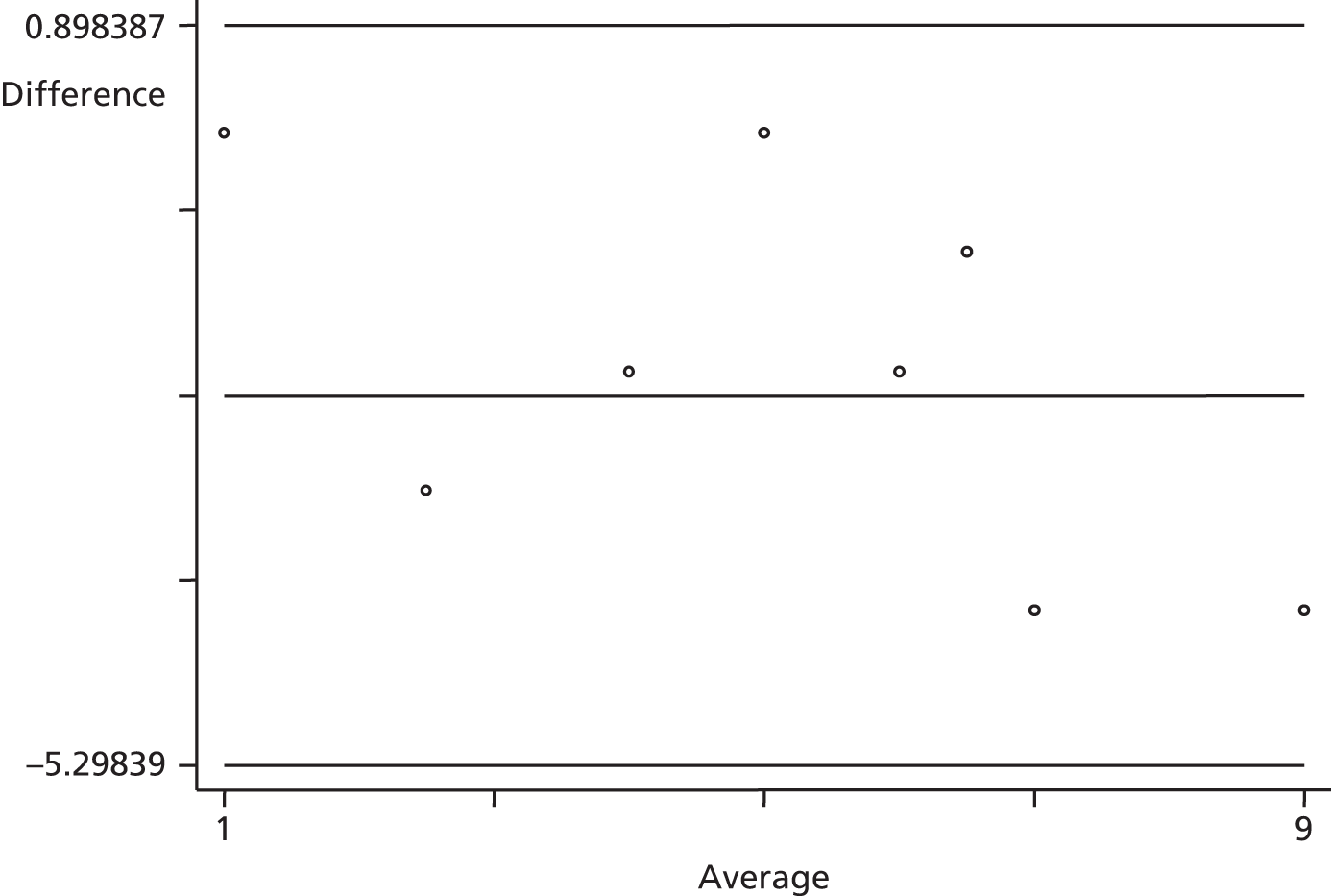

A reliability analysis was carried out for the CARE-Index. Ten randomly selected videos (stratified by site) were scored by a second scorer and Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient was calculated and Bland–Altman plots were produced to assess reliability.

Health economic study

A prospective economic evaluation, conducted from a NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective, was integrated into the trial. The economic assessment method adhered as closely as possible to the recommendations of the NICE reference case. 89 Primary research methods estimated the costs of the delivering gFNP, including development and training of accredited providers, the cost of delivering the group sessions, participant monitoring activities and any follow-up/management. Broader resource utilisation was captured through participant questionnaires administered at baseline, 2, 6 and 12 months post partum. Maternal health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) measure90 at baseline and at 2, 6 and 12 months post partum. This contains a visual analogue scale (VAS) asking patients to rate their current HRQoL on a scale from 0 to 100, and a five-dimension health status classification system, which can then be converted to a multiattribute utility score by applying a UK tariff. 91

In addition, information was collected about service use that could indicate a risk factor for abuse or neglect, namely contact with a social worker and the child’s attendance at hospital accident and emergency (A&E) departments (all based on maternal reports at 2, 6 and 12 months). Confirmation was to be from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) records, but these could not be obtained. The unit costs for health and social care resources were largely derived from local and national sources and were estimated in line with best practice. For further details, see Chapter 4.

Process study

The uptake rate of women who agreed to the intervention involved an assessment of the ratio of women randomised to receive the intervention who then attended at least one session relative to those who either refused after meeting with the FN or agreed but never attended any sessions based on standardised data forms completed by FNs.

The study attrition rate was estimated in terms of the proportion of women who dropped out relative to those who continued in either arm of the trial and also those who may or may not have taken part in research visits, but ceased to receive the intervention, based on information provided by the nurses delivering the programme. This included both women who stopped attending and women in areas where the programme delivery ended prematurely.

The extent to which the programme was delivered with integrity was assessed through an analysis of data from the programme’s standardised data forms, documenting attendance and the content domains covered in sessions.

A parallel qualitative appraisal was concerned with understanding ‘how’ the gFNP service:

-

was implemented based on data collated by the FNP NU on sessions delivered and attendance of clients, to develop evidence for future roll-out and potential fidelity measures

-

was experienced by families and practitioners, to develop recommendations for improvement

-

impacted on established roles to understand how barriers to and drivers of change manifest in distinct professional knowledge, practice and cultural domains.

The appraisal was informed by both quantitative data and qualitative interviews, which are further detailed with the results in Chapter 5.

Focus on mothers with a ‘looked-after’ history

After the programme concluded, delivery interviews were sought with participants who had identified at 6 months post partum that they had spent time away from their parent(s) during childhood, in the care of social services. Interviews were also conducted with FNs involved in delivering gFNP in sites, which included the self-identified ‘looked-after’ participants, and with other professionals involved in providing support to young parents who had in their childhood or adolescence been ‘looked after’. For further details, see Chapter 6.

Study harms/adverse events

Information was collected on any hospitalisation of mother or infant other than for delivery; congenital anomaly or birth defect; persistent or significant disability; and death identified by information from participants at data collection points or using pre-paid change of circumstances cards. All events were reported to the REC, which gave a favourable opinion within 15 days of the PI becoming aware of the event.

Ethics

Ethics approval for the main study was granted in May 2014 by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee South West – Frenchay (REC reference 13/SW/0086). Six substantial amendments to the study protocol were also approved, as follows, most of which were changes that were designed to boost the poor recruitment.

October 2013: approval of –

-

FNs with access to midwifery records and Comprehensive Clinical Research Network midwives (when available), having access to midwifery booking lists to identify potentially eligible participants

-

contact with potentially eligible participants to be by telephone to gain ‘agreement to research contact’

-

a study poster to highlight the study in GP clinics and midwifery waiting rooms

-

extending the recruitment period by 2 months

-

adding one additional exclusion criterion – any woman already enrolled in the trial who experiences fetal death and becomes pregnant again within the recruitment period

-

a letter to be sent to any participant experiencing fetal death

-

a change in the original analysis plan, with a CACE analysis to be carried out after the ITT analysis to determine the effect of the intervention on those who received gFNP as intended.

November 2013: approval of –

-

including in the groups a small number of women who are not part of the research study (called in subsequent sections ‘buffer clients’). They were women not eligible for the research because they were aged 20–24 years but had more educational qualifications than were allowed for eligibility. This was to facilitate the groups being of the minimum size (set at eight), which had become a concern with slow recruitment. The presence of buffer clients has been taken into account in the analyses.

December 2013: approval that –

-

owing to ongoing slow recruitment and two of the Phase I groups with very low numbers being discontinued prematurely, the allocation ratio be changed from 1 : 1 to 2 : 1 in favour of the intervention arm (this was predicted to lead to a reduction in the power of the study from 90% to 80%)

-

additional questions added to the process qualitative interviews so that the experience of a group being discontinued could be examined.

April 2014: approval of –

-

a simplification of the eligibility criteria for 20- to 24-year-olds for the final (third) phase of recruitment, removing the requirement for low/no educational qualifications

-

a slightly revised study leaflet removing mention of the educational requirement.

June 2014: approval that –

-

contrary to the original proposal, the 6-month data collection would be by a home visit rather than a telephone call, a change based primarily on feedback from clients when visited at 2 months, that they did not want to talk extensively on the telephone when coping with a baby, and also as a strategy to maximise study retention

-

participants would be provided with a £20 voucher at 6 months rather than the planned £10, as it was a home visit, rather than the original plan of a telephone call and a voucher to be sent in the post

-

one final question be added to the 6-month interview so that participants could identify whether or not they had any history of being ‘looked after’ by the local authority.

November 2014: approval of –

-

all of the study materials (consent form, information sheets, interview guides) to conduct the qualitative interviews with study participants who had been allocated to receive gFNP and with FNs who had delivered gFNP; interviews to begin once gFNP delivery was complete in the area.

Chapter 3 Results: main study

Participant flow and recruitment

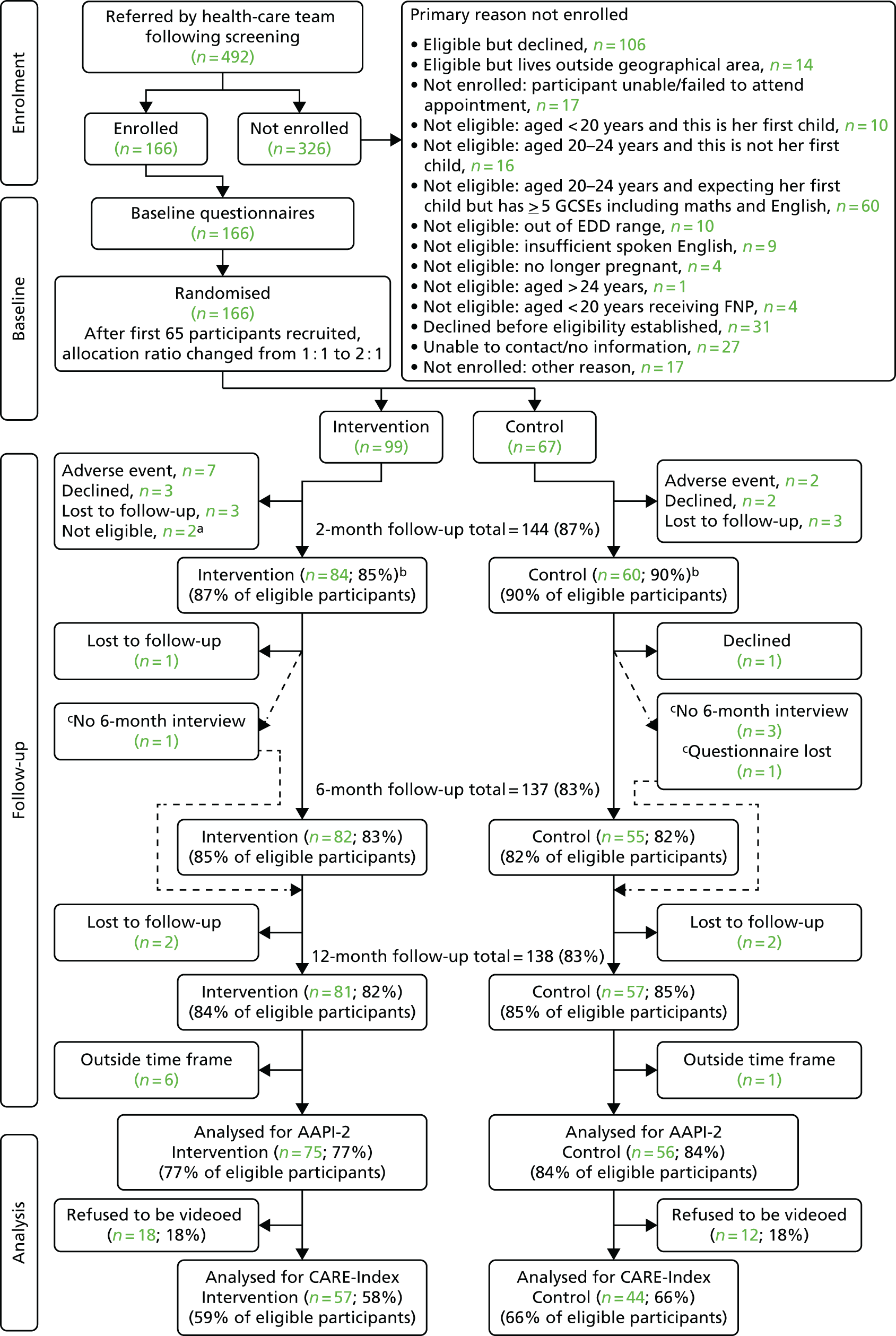

Of the 492 women who agreed that the research team could contact them about the study, after their initial eligibility was ascertained on the basis of their age, parity and EDD, 166 were enrolled (99 to the intervention group and 67 to the control group). The full details of the reasons for non-enrolment can be seen in Figure 1. Some (n = 31) declined when they were contacted by researchers before their eligibility could be established and others (n = 27) could not be contacted. Among the 137 found by researchers to be definitely eligible for the study, the main reason for non-enrolment was that they declined (n = 106), whereas other eligible women agreed to consider taking part in the study but then were not available for an interview (n = 17) or were found to live outside the area served by the FNP team (n = 14). Ineligibility was determined for 114 women and was primarily for women in the 20–24 years age range who had more educational qualifications than were specified (n = 60) or were not expecting their first child (n = 16). A small number of the women aged < 20 years were found to be expecting their first child (n = 10), and other women (n = 10) were not within the specified EDD range or could not communicate adequately in spoken English (n = 9).

FIGURE 1.

First Steps Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. a, Identified as ineligible after recruitment: one participant outside gFNP service area, one participant previously received one-to-one gFNP; b, includes one 2-month questionnaire (in each arm) completed at the 6-month time point; and c, no 6-month interview data but followed up at 12 months. Figure reproduced from Barnes et al. 92 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

After recruitment, it was found that two women in the intervention arm were ineligible (one was outside the service area and the other had received FNP), and so baseline information is provided for 97 women in the intervention arm and 67 in the control arm. Although information from the follow-up at around 2 months post partum was collected for 144 participants (84 in the intervention arm and 60 in the control arm), 16 participants (nine in the intervention arm and seven in the control arm) were outside the agreed time window, leaving 128 participants (75 in the intervention arm and 53 in the control arm). From the follow-up at around 6 months post partum, information was collected for 137 participants (82 in the intervention arm and 55 in the control arm); however, 16 participants (12 in the intervention arm and four in the control arm) were outside the agreed time window, leaving 121 participants (70 in the intervention arm and 51 in the control arm) (see Figure 1). Although 138 12-month interviews were carried out (81 in the intervention arm and 57 in the control arm), seven (six in the intervention arm and one in the control arm) were outside the agreed time window, leaving 131 interviews (75 in the intervention arm and 56 in the control arm) eligible for the primary analysis. The primary analysis for the CARE-Index (co-primary outcome) was based on 101 videos (57 in the intervention arm and 44 in the control arm) (see Figure 1).

Baseline

The participants in the two randomised arms appear comparable at baseline in terms of their demographic characteristics (Table 2), partner’s demographic characteristics (Table 3), smoking, alcohol consumption and drug use (Table 4) and questionnaires documenting parenting attitudes, depression symptoms, social networks and relationship violence (Table 5). In all tables the denominator is the whole sample, but also given, when relevant, are numbers of missing data and the number of data available when the denominator depends on the answer to a previous question (e.g. if yes, has GCSEs, then how many? If yes, a smoker, then how many cigarettes per day?).

| Category | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 97) | Control (N = 67) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 21.7 (1.9) | 21.9 (1.6) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 |

| Age at LMP, mean (SD) | 21.0 (1.8) | 21.2 (1.8) |

| Educational qualifications: GCSEs or equivalent? | ||

| Yes | 73 (75.3) | 55 (82.1) |

| No | 24 (24.7) | 12 (17.9) |

| Number of GCSEs, mean (SD) | 6.7 (3.1) | 6.4 (2.7) |

| Data available, n | 70 | 54 |

| Number of GCSEs at grade C or higher, mean (SD) | 3.8 (3.6) | 3 (2.5) |

| Data available, n | 69 | 53 |

| Educational qualifications: other? | ||

| Yes | 79 (82.3) | 56 (83.6) |

| No | 17 (17.7) | 11 (16.4) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White: British | 61 (63.5) | 48 (71.6) |

| White: Irish | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Any other white background | 2 (2.1) | 3 (4.5) |

| Asian British: Indian | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian British: Pakistani | 5 (5.2) | 5 (7.5) |

| Asian British: Bangladeshi | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Black British: Caribbean | 14 (14.6) | 6 (9.0) |

| Black British: African | 3 (3.1) | 2 (3.0) |

| Any other black background | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Chinese | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mixed | 8 (8.3) | 3 (4.5) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Current partner? | ||

| Yes | 83 (85.6) | 59 (88.1) |

| No | 14 (14.4) | 8 (11.9) |

| Current partner: biological father? | ||

| Yes | 83 (100.0) | 59 (100.0) |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 10 (10.4) | 8 (11.9) |

| Unmarried/cohabiting | 43 (44.8) | 37 (55.2) |

| Separated | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Widowed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Single | 43 (44.8) | 22 (32.8) |

| Number of people currently living with, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.6) |

| Missing, n | 1 | |

| Currently living in household | ||

| Own mother/parents | 11 (11.7) | 7 (10.9) |

| Husband/partner | 24 (25.5) | 24 (37.5) |

| Husband/partner and others, not including maternal mother | 10 (10.6) | 6 (9.4) |

| Own mother/parents and others, not including husband/partner | 14 (14.9) | 10 (15.6) |

| Own mother/parents and others, including husband/partner | 6 (6.4) | 5 (7.8) |

| Foster parent | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Husband/partner and others | 2 (2.1) | 3 (4.7) |

| Other adults (own father, aunt, grandmother, older sibling, friend, etc.) | 12 (12.8) | 6 (9.4) |

| Live alone | 15 (16.0) | 3 (4.7) |

| Where are you living? | ||

| House or bungalow | 68 (70.1) | 49 (73.1) |

| Flat, low rise | 12 (12.4) | 5 (7.5) |

| Flat, high rise, first three floors | 5 (5.2) | 12 (17.9) |

| Flat, high rise, above third floor | 4 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Room or bedsit | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.5) |

| Hostel | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Supported housing | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| In a group home/shelter | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Confined to an institutional facility | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Homeless | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Enrolled in any school or educational programme? | ||

| Yes | 12 (12.4) | 9 (13.4) |

| No | 85 (87.6) | 58 (86.6) |

| What course? | ||

| School, up to year 11 | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| School, year 12 or 13/sixth form college | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Access course | 1 (8.3) | 1 (11.1) |

| Vocational course | 6 (50.0) | 2 (22.2) |

| University | 3 (25.0) | 6 (66.7) |

| Ever worked? | ||

| Yes | 76 (78.4) | 56 (83.6) |

| No | 21 (21.7) | 11 (16.4) |

| Currently working? | ||

| Yes, full-time | 30 (39.5) | 28 (50.0) |

| Yes, part-time | 14 (18.4) | 8 (14.3) |

| No | 32 (42.1) | 20 (35.7) |

| Category | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 97) | Control (N = 67) | |

| Partner’s educational qualifications: GCSEs or equivalent? | ||

| Yes | 52 (54.7) | 39 (58.2) |

| No | 10 (10.5) | 12 (17.9) |

| Don’t know | 20 (21.1) | 8 (11.9) |

| No partner | 13 (13.7) | 8 (11.9) |

| Number of GCSEs, mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.9) | 7 (2.9) |

| Data available, n | 32 | 28 |

| Number of GCSEs at grade C or higher, mean (SD) | 3.8 (3.0) | 4.3 (3.6) |

| Data available, n | 28 | 24 |

| Educational qualifications: other? | ||

| Yes | 60 (72.3) | 43 (72.9) |

| No | 8 (9.6) | 12 (20.3) |

| Don’t know | 15 (18.1) | 4 (6.8) |

| Ever worked? | ||

| Yes | 73 (88.0) | 56 (94.9) |

| No | 9 (10.8) | 2 (3.4) |

| Don’t know | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.7) |

| Currently working? | ||

| Yes | 56 (76.7) | 38 (67.9) |

| No | 17 (23.3) | 18 (32.1) |

| Don’t know | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Current job | ||

| Managers and senior officials | 1 (1.6) | 2 (4.3) |

| Professional occupations | 3 (4.7) | 1 (2.1) |

| Associate professional and technical occupations | 3 (4.7) | 1 (2.1) |

| Administrative and secretarial occupations | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) |

| Skilled trades occupations | 17 (26.6) | 19 (40.4) |

| Personal service occupations | 4 (6.3) | 2 (4.3) |

| Sales and customer service occupations | 11 (17.2) | 6 (12.8) |

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 6 (9.4) | 7 (14.9) |

| Elementary occupations | 12 (18.8) | 1 (2.1) |

| Don’t know | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| N/A | 7 (10.9) | 7 (14.9) |

| Category | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 97) | Control (N = 67) | |

| Ever smoked? | ||

| Yes | 56 (57.7) | 43 (64.2) |

| No | 41 (42.3) | 24 (35.8) |

| Smoked during pregnancy? | ||

| Yes | 42 (75.0) | 32 (74.4) |

| No | 14 (25.0) | 11 (25.6) |

| Number of cigarettes per day, mean (SD) | 3.7 (4.6) | 3.8 (4.6) |

| Data available, n | 41 | 31 |

| Anyone else in household smoke? | ||

| Yes | 43 (44.8) | 29 (44.6) |

| No | 53 (55.2) | 36 (55.4) |

| Alcohol consumption in the last month? | ||

| One or two times a week | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.0) |

| One or two times a month | 4 (4.1) | 4 (6.0) |

| Less than once a month | 4 (4.1) | 4 (6.0) |

| Never | 89 (91.8) | 57 (85.1) |

| Last month typical? | ||

| Yes | 60 (61.9) | 37 (55.2) |

| No | 37 (38.1) | 30 (44.8) |

| Typical monthly alcohol consumption (if no)? | ||

| Three or four times a week | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| One or two times a week | 15 (41.7) | 16 (55.2) |

| One or two times a month | 12 (33.3) | 7 (24.1) |

| Less than once a month | 6 (16.7) | 5 (17.2) |

| Never | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.5) |

| Number of units per day, mean (SD) | 4.6 (6.3) | 4.5 (5.4) |

| Data available, n | 69 | 51 |

| Marijuana use in last month? | ||

| Three or four times a week | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.0) |

| One or two times a week | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| One or two times a month | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Less than once a month | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Never | 95 (97.9) | 63 (94.0) |

| Refused to answer | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| In the past month, on how many days did you use any street drugs? | ||

| Never | 97 (100.0) | 67 (100.0) |

| Plan to breastfeed baby? | ||

| Yes, definitely | 63 (65.0) | 40 (59.7) |

| Possibly, not certain | 22 (22.7) | 15 (22.4) |

| No, definitely not | 12 (12.4) | 12 (17.9) |

| Category | Trial arm, mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 97) | Control (N = 67) | |

| AAPI-272 (higher = positive) | ||

| Total (/10) | 7.2 (0.8) | 7.2 (0.9) |

| Missing, n | 9 | 2 |

| Inappropriate expectations (/35) | 21.6 (4.2) | 21.8 (4.0) |

| Empathy (/50) | 36.3 (5.0) | 36.3 (5.4) |

| Corporal punishment (/55) | 43.2 (5.5) | 42.3 (6.1) |

| Role reversal (/35) | 24 (4.1) | 23.9 (4.5) |

| Power independence (/25) | 18.6 (2.1) | 19.3 (2.3) |

| EPDS76 (higher = more depressed) | ||

| Total (/30) | 6.9 (4.7) | 7.7 (5.0) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 |

| Possible depression (EPDS ≥ 10) | ||

| Yes | 24 (24.5) | 20 (30.3) |

| No | 74 (75.5) | 46 (69.7) |

| Social networks83 (higher = more support) | ||

| Total (/100) | 85.8 (15.6) | 85.3 (16.4) |

| Missing, n | 2 | |

| Tangible support (/100) | 85.5 (18.1) | 86.4 (17.5) |

| Emotional support (/100) | 85.1 (16.4) | 83.3 (18.9) |

| Affectionate support (/100) | 91.8 (16.4) | 90.8 (17.7) |

| Positive social interaction (/100) | 83.9 (20.6) | 85.1 (19.4) |

| Relationships40 (higher = more abuse) | ||

| Total abuse (/8) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.8) |

| Lifetime abuse (/2) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.8) |

| Physical aggression (/2) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.3) |

| Verbal abuse (/2) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.4) |

| Sexual abuse (/2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.2) |

Attendance at Group Family Nurse Partnership groups

Programme delivery and attendance is covered in detail in Chapter 5 so it is only summarised here. In total, the 97 trial participants were allocated to 16 planned groups; five sites planned to offer two groups (A and B) and two sites planned to offer three groups (A, B and C) (Table 6), although in some cases no sessions were delivered for a planned group. In addition, one participant attended sessions offered in groups A and B as the first group was terminated prematurely.

| Site | Group | Number allocated to group | Mean number of sessions attended (SD) | Median number of sessions attended | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 117a | 11.8 (13.8) | 3 | 0–44 | |

| 1 | A | 7 | 12.1 (10.2) | 11 | 0–23 |

| 1 | B | 12 | 6.8 (11.7) | 1 | 0–31 |

| 2 | A | 7 | 30 (12.7) | 33 | 15–44 |

| 2 | B | 7 | 15.1 (13.1) | 13 | 0–32 |

| 3 | A | 5 | 1.4 (1.3) | 2 | 0–3 |

| 3 | B | 10 | 17.1 (13.4) | 23.5 | 0–33 |

| 4 | A | 6 | 3.3 (2.4) | 4 | 0–6 |

| 4 | B | 13 | 17.6 (15.0) | 24 | 0–38 |

| 4 | C | 6 | 0.3 (0.5) | 0 | 0–1 |

| 5 | A | 7 | 12.7 (11.1) | 16 | 0–26 |

| 5 | B | 7 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 6 | A | 7 | 29.3 (13.9) | 35 | 0–39 |

| 6 | B | 10 | 15.1 (14.3) | 14 | 0–34 |

| 7 | A | 5 | 1.2 (2.2) | 0 | 0–5 |

| 7 | B | 5 | 4.2 (4.1) | 5 | 0–9 |

| 7 | C | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

The mean number of gFNP sessions attended by the 117 clients allocated to groups (see Table 6), comprising 99 trial participants (97 allocated to gFNP and two control group participants mistakenly offered gFNP as buffers by FNP teams) and the 18 buffer clients who were not eligible for the trial owing to educational qualifications but were offered gFNP to boost group sizes to a viable number, was 11.8 (SD 13.8).

Overall, the 97 trial participants in the intervention arm attended a mean of 10.3 sessions (SD 13.4), but a substantial proportion (39, 40%) did not attend any sessions (Table 7). Of the 97 randomised to the intervention, 17 were never allocated a gFNP UID number by the relevant gFNP team and did not attend any sessions. The reasons for this are given in Chapter 5 (see Uptake of the programme). Twenty-two of the remaining 80 participants registered for gFNP did not attend any sessions, 10 of whom were allocated to groups that did not offer any sessions. Five of those were offered one-to-one FNP, but no information was available about how much of that service was received and others were referred back to existing services. Thus, of the 97 study participants allocated to the intervention arm, 58 took part in at least one gFNP session. A summary of attendance overall and by group is given in Table 6 (trial participants and buffer clients), Table 7 (only intervention arm trial participants), Table 8 (only intervention arm trial participants, pregnancy sessions) and Table 9 (only intervention arm trial participants, infancy sessions).

| Site | Group | Number allocated to group | Mean number of sessions attended (SD) | Median number of sessions attended | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 97a | 10.3 (13.4) | 2 | 0–44 | |

| 1 | A | 3 | 2.3 (3.2) | 1 | 0–6 |

| 1 | B | 12 | 6.8 (11.7) | 1 | 0–31 |

| 2 | A | 4 | 36.3 (11.7) | 41 | 19–44 |

| 2 | B | 6 | 15.5 (14.3) | 15.5 | 0–32 |

| 3 | A | 5 | 1.4 (1.3) | 2 | 0–3 |

| 3 | B | 8 | 20.6 (12.6) | 25.5 | 0–33 |

| 4 | A | 6 | 3.3 (2.4) | 4 | 0–6 |

| 4 | B | 9 | 19.7 (15.4) | 26 | 0–38 |

| 4 | C | 6 | 0.3 (0.5) | 0 | 0–1 |

| 5 | A | 5 | 12.2 (10.6) | 16 | 0–24 |

| 5 | B | 7 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 6 | A | 4 | 22.8 (15.9) | 28 | 0–35 |

| 6 | B | 9 | 13.1 (13.6) | 13 | 0–34 |

| 7 | A | 5 | 1.2 (2.2) | 0 | 0–5 |

| 7 | B | 5 | 4.2 (4.1) | 5 | 0–9 |

| 7 | C | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| Site | Group | Mean number of sessions attended (SD) | Median number of sessions attended | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 4.5 (5.1) | 2 | 0–15 | |

| 1 | A | 2 (2.6) | 1 | 0–5 |

| 1 | B | 2.9 (3.8) | 1 | 0–10 |

| 2 | A | 13 (2.0) | 14 | 10–14 |

| 2 | B | 8.3 (7.1) | 10.5 | 0–15 |

| 3 | A | 1.4 (1.3) | 2 | 0–3 |

| 3 | B | 7 (4.9) | 8 | 0–14 |

| 4 | A | 3.3 (2.4) | 4 | 0–6 |

| 4 | B | 7.9 (6.4) | 11 | 0–14 |

| 4 | C | 0.3 (0.5) | 0 | 0–1 |

| 5 | A | 6.4 (5.3) | 7 | 0–12 |

| 5 | B | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 6 | A | 8.5 (6.0) | 10 | 0–14 |

| 6 | B | 4.9 (4.4) | 6 | 0–12 |

| 7 | A | 0.8 (1.3) | 0 | 0–3 |

| 7 | B | 4.2 (4.1) | 5 | 0–9 |

| 7 | C | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| Site | Group | Mean number of sessions attended (SD) | Median number of sessions attended | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 5.8 (8.2) | 0 | 0–30 | |

| 1 | A | 0.3 (0.6) | 0 | 0–1 |

| 1 | B | 3.8 (8.3) | 0 | 0–22 |

| 2 | A | 23.3 (9.7) | 27 | 9–30 |

| 2 | B | 7.2 (7.7) | 5 | 0–17 |

| 3 | A | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 3 | B | 13.6 (8.6) | 16.5 | 0–22 |

| 4 | A | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 4 | B | 11.8 (9.5) | 14 | 0–24 |

| 4 | C | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 5 | A | 5.8 (5.7) | 7 | 0–13 |

| 5 | B | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 6 | A | 14.3 (9.9) | 18 | 0–21 |

| 6 | B | 8.2 (9.4) | 7 | 0–23 |

| 7 | A | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 7 | B | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

| 7 | C | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0–0 |

Baseline demographics for all intervention arm trial participants and for those who attended at least one group session are given in Table 10. There are no apparent differences between the demographic characteristics of women who attended at least one group session and those of the intervention arm trial participants as a whole.

| Category | Intervention (N = 97), n (%) | Attended at least one group session (N = 58), n (%) | Control (N = 67), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 21.7 (1.9) | 21.6 (1.8) | 21.9 (1.6) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Age at LMP, mean (SD) | 21.0 (1.8) | 20.9 (1.7) | 21.2 (1.8) |

| Educational qualifications: GCSEs or equivalent? | |||

| Yes | 73 (75.3) | 46 (79.3) | 55 (82.1) |

| No | 24 (24.7) | 12 (20.7) | 12 (17.9) |

| Number of GCSEs, mean (SD) | 6.7 (3.1) | 6.5 (3.3) | 6.4 (2.7) |

| Data available, n | 70 | 44 | 54 |

| Number of GCSEs at grade C or higher, mean (SD) | 3.8 (3.6) | 3.9 (3.6) | 3 (2.5) |

| Data available, n | 69 | 43 | 53 |

| Educational qualifications: other? | |||

| Yes | 79 (82.3) | 47 (81.0) | 56 (83.6) |

| No | 17 (17.7) | 11 (19.0) | 11 (16.4) |

| Ethnicity? | |||

| White: British | 61 (63.5) | 34 (59.7) | 48 (71.6) |

| White: Irish | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Any other white background | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (4.5) |

| Asian British: Indian | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian British: Pakistani | 5 (5.2) | 1 (1.8) | 5 (7.5) |

| Asian British: Bangladeshi | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Black British: Caribbean | 14 (14.6) | 10 (17.5) | 6 (9.0) |

| Black British: African | 3 (3.1) | 3 (5.3) | 2 (3.0) |

| Any other black background | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Chinese | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mixed | 8 (8.3) | 5 (8.8) | 3 (4.5) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Current partner? | |||

| Yes | 83 (85.6) | 51 (87.9) | 59 (88.1) |

| No | 14 (14.4) | 7 (12.1) | 8 (11.9) |

| Current partner: biological father? | |||

| Yes | 83 (100.0) | 51 (100.0) | 59 (100.0) |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Marital status? | |||

| Married | 10 (10.4) | 6 (10.3) | 8 (11.9) |

| Unmarried/cohabiting | 43 (44.8) | 25 (43.1) | 37 (55.2) |

| Separated | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Widowed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Single | 43 (44.8) | 27 (46.6) | 22 (32.8) |

| Number of people currently living with, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.6) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | |

| Currently living in household? | |||

| Own mother/parents | 11 (11.7) | 4 (7.1) | 7 (10.9) |

| Husband/partner | 24 (25.5) | 16 (28.6) | 24 (37.5) |

| Husband/partner and others, not including maternal mother | 10 (10.6) | 5 (8.9) | 6 (9.4) |

| Own mother/parents and others, not including husband/partner | 14 (14.9) | 8 (14.3) | 10 (15.6) |

| Own mother/parents and others, including husband/partner | 6 (6.4) | 3 (5.4) | 5 (7.8) |

| Foster parent | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Husband/partner and others | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (4.7) |

| Other adults (own father, aunt, grandmother, older sibling, friend, etc.) | 12 (12.8) | 9 (16.1) | 6 (9.4) |

| Live alone | 15 (16.0) | 9 (16.1) | 3 (4.7) |

| Where are you living? | |||

| House or bungalow | 68 (70.1) | 38 (65.5) | 49 (73.1) |

| Flat, low rise | 12 (12.4) | 9 (15.5) | 5 (7.5) |

| Flat, high rise, first three floors | 5 (5.2) | 2 (3.5) | 12 (17.9) |

| Flat, high rise, above third floor | 4 (4.1) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Room or bedsit | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.5) |

| Hostel | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Supported housing | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| In a group home/shelter | 2 (2.1) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Confined to an institutional facility | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Homeless | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Enrolled in any school or educational programme? | |||

| Yes | 12 (12.4) | 9 (15.5) | 9 (13.4) |

| No | 85 (87.6) | 49 (84.5) | 58 (86.6) |

| What course? | |||

| School, up to year 11 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| School, year 12 or 13/sixth form college | 1 (8.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Access course | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Vocational course | 6 (50.0) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (22.2) |

| University | 3 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) |

| Ever worked? | |||

| Yes | 76 (78.4) | 46 (79.3) | 56 (83.6) |

| No | 21 (21.7) | 12 (20.7) | 11 (16.4) |

| Currently working? | |||

| Yes, full-time | 30 (39.5) | 17 (37.0) | 28 (50.0) |

| Yes, part-time | 14 (18.4) | 9 (19.6) | 8 (14.3) |

| No | 32 (42.1) | 20 (43.5) | 20 (35.7) |

Primary outcome

A total of 131 12-month interviews were carried out within the agreed time frame and 101 mothers agreed to be videoed for the CARE-Index. 73,74 The reasons for not agreeing to video recording were as follows: self-conscious about appearing on video (five of these participants were in a later stage of pregnancy) (n = 14); baby not well (n = 4); no time after the interviews and did not want a second appointment (n = 4); family pressure (n = 3); just did not like the idea (n = 3); interview not in the home so not practical (n = 1); and failure of recording and no wish for another appointment (n = 1). The primary outcome data and estimated intervention effects are shown in Table 11.

| Measure | Intervention (n = 75), mean (SE) | Control (n = 56), mean (SE) | Unadjusted effect estimatea | Adjusted effect estimateb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-value | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| AAPI-272 (higher = positive) | ||||||

| Total (/10) | 7.5 (0.1) | 7.5 (0.1) | 0.05 (–0.17 to 0.24) | 0.68 | 0.06 (–0.15 to 0.28) | 0.59 |

| Missing, n | 5 | 1 | ||||

| Inappropriate expectations (/35) | 23.5 (0.6) | 22.9 (0.6) | 0.58 (–0.71 to 1.96) | 0.44 (–0.89 to 1.78) | ||

| Empathy (/50) | 38.0 (0.6) | 37.0 (0.7) | 1.2 (–0.11 to 2.49) | 1.21 (–0.03 to 2.57) | ||

| Corporal punishment (/55) | 43.3 (0.7) | 43.3 (0.7) | –0.63 (–2.17 to 0.84) | –0.45 (–1.96 to 1.02) | ||

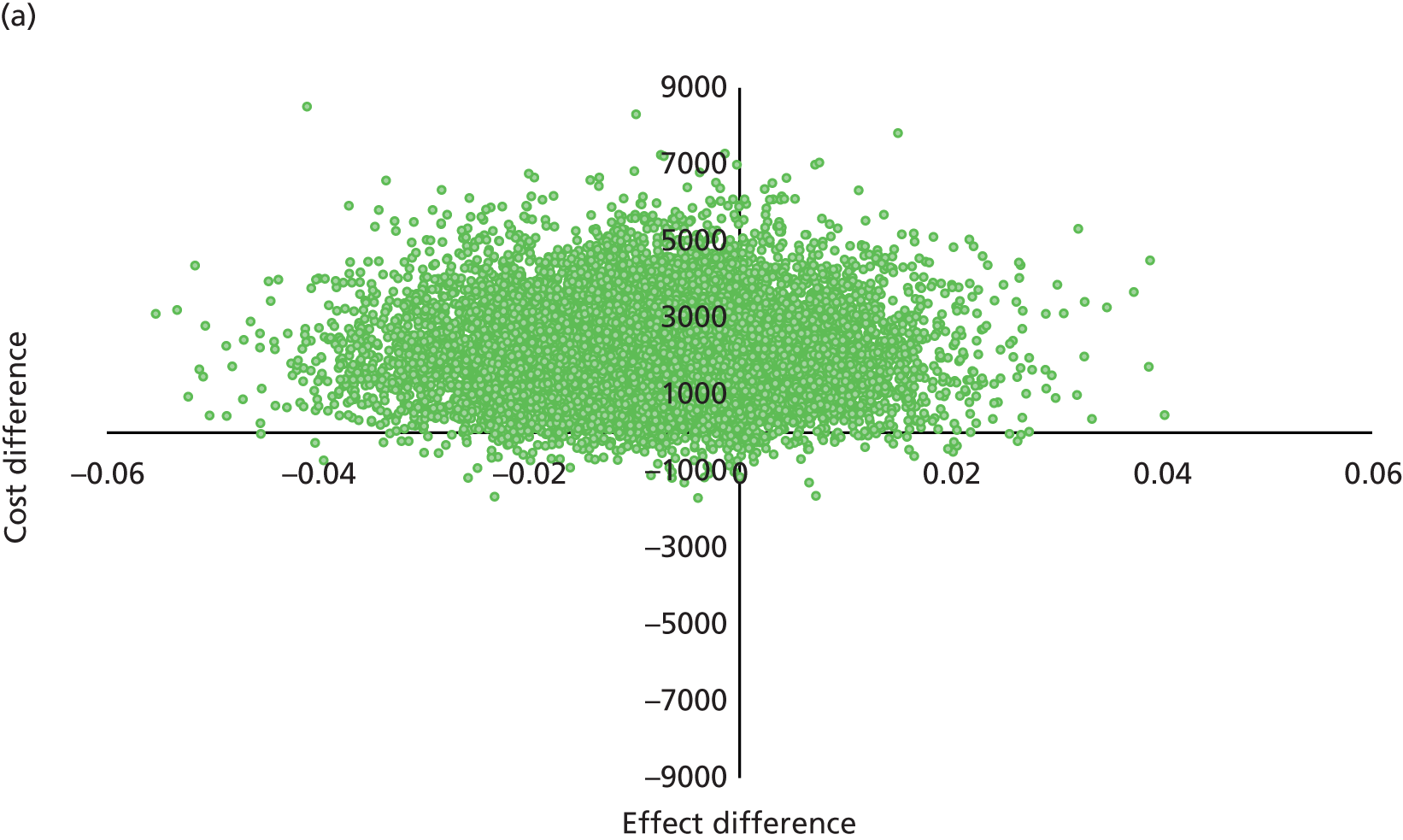

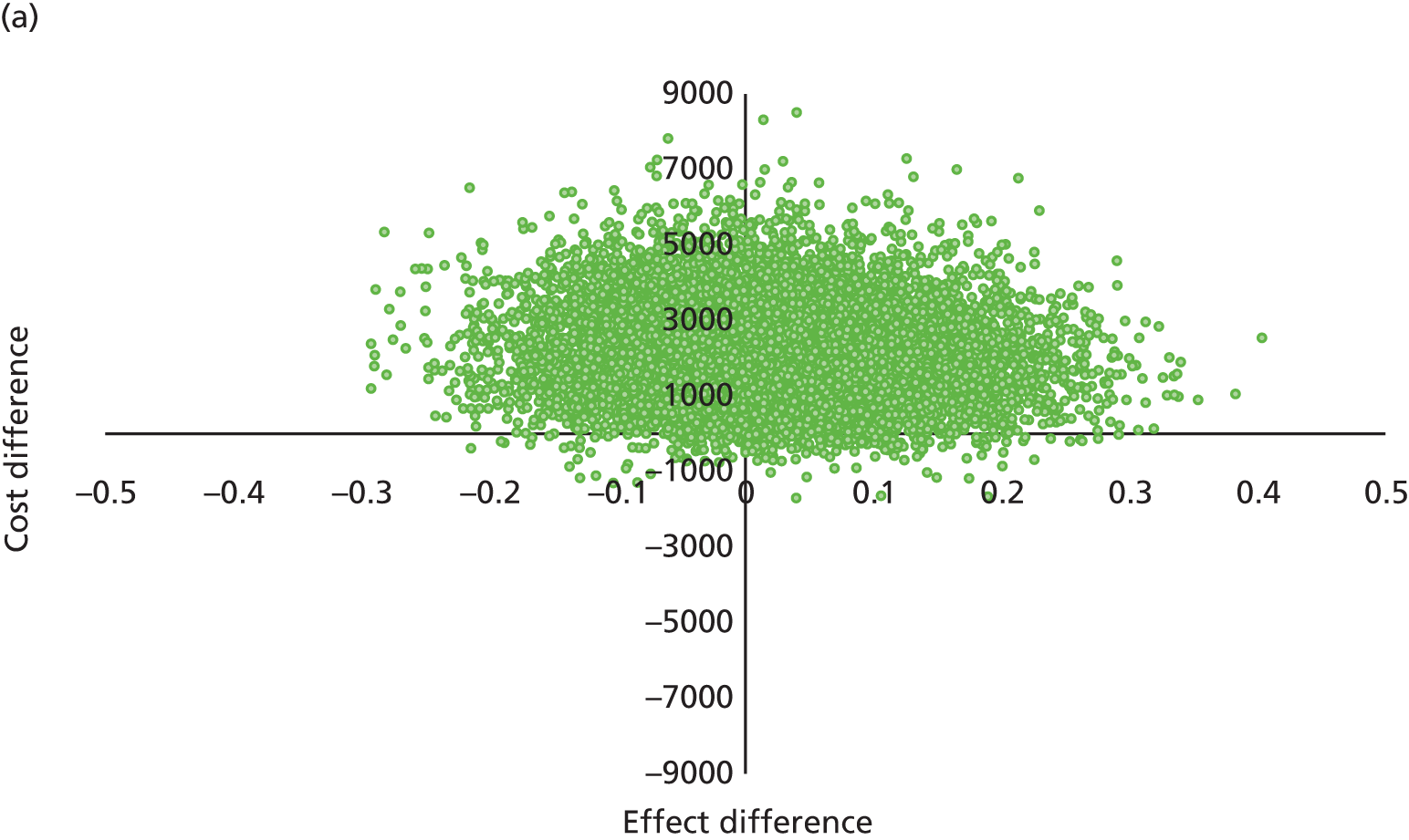

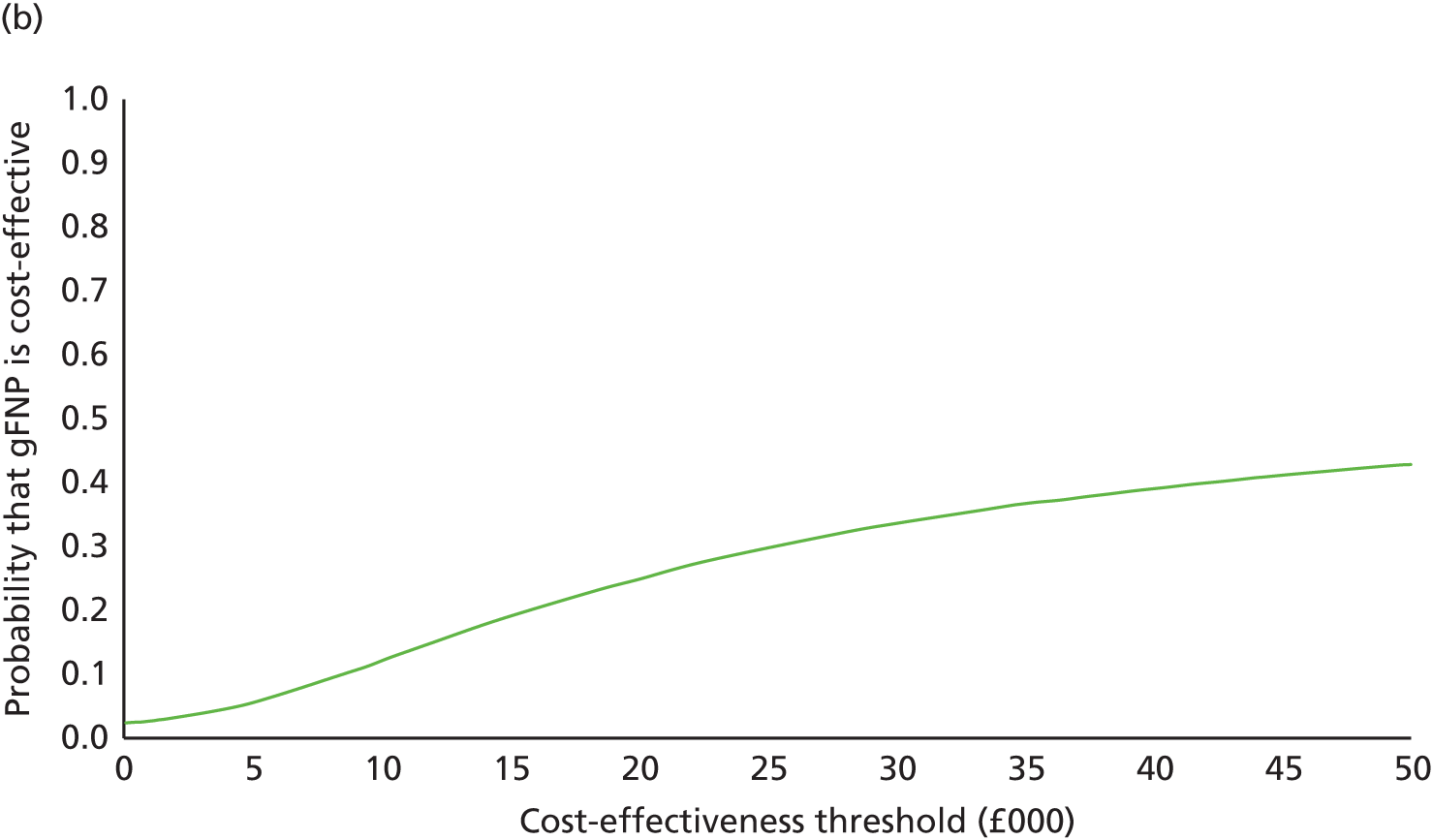

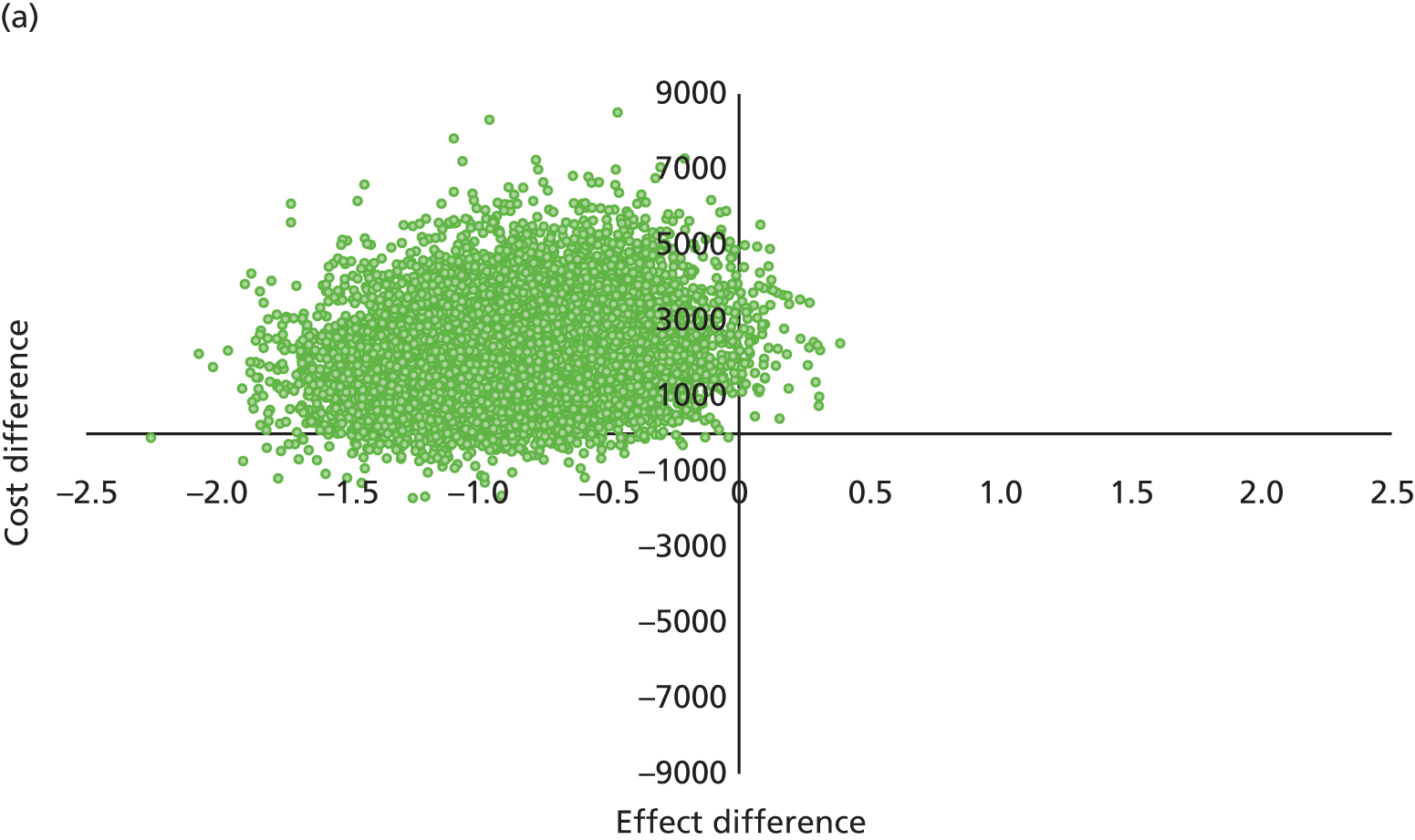

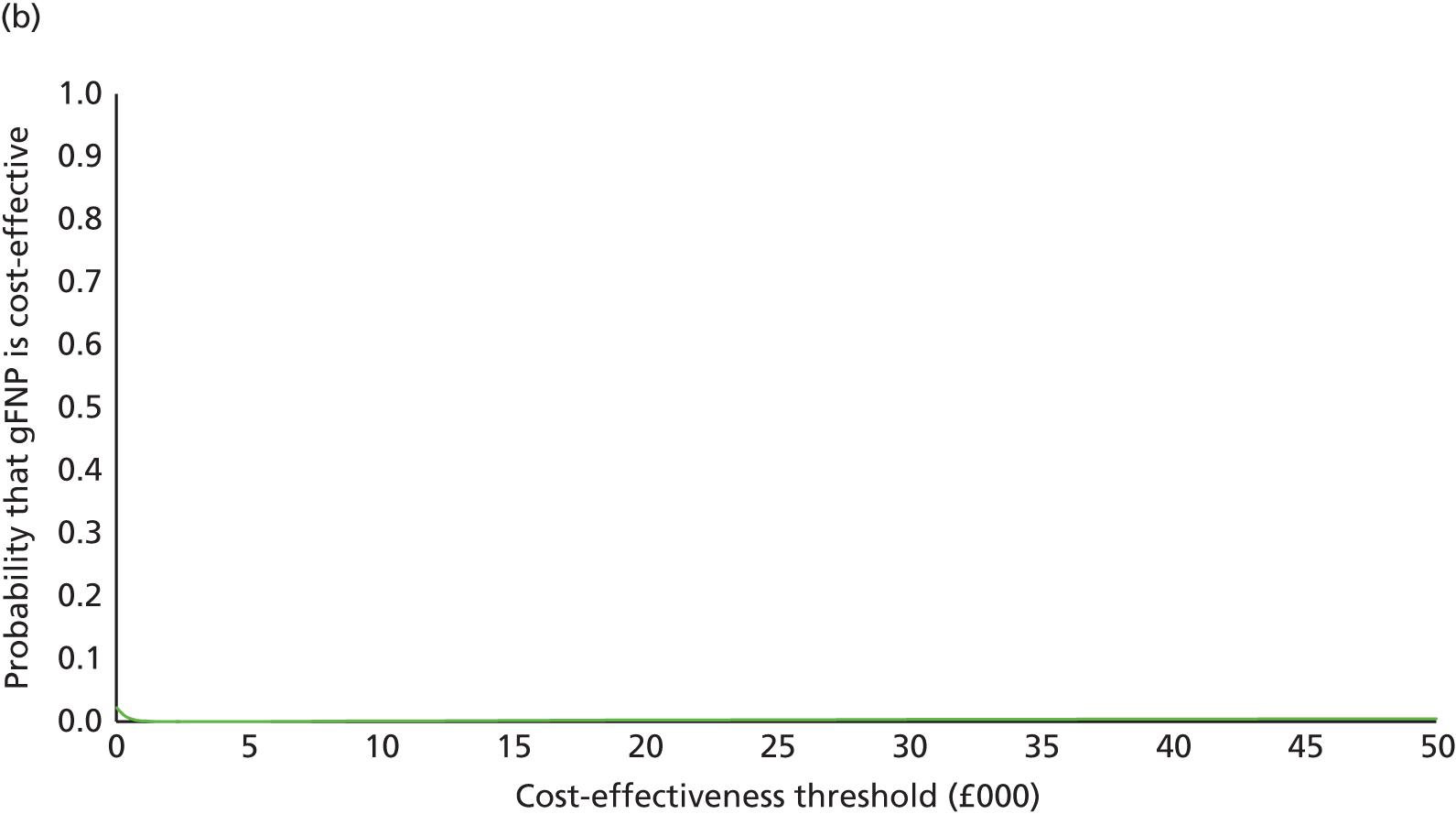

| Role reversal (/35) | 25.6 (0.5) | 26.1 (0.6) | –0.5 (–1.54 to 0.53) | –0.47 (–1.53 to 0.60) | ||