Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/3070/04. The contractual start date was in November 2013. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Judy Hutchings reports personal fees from the Incredible Years Company, the Children’s Early Intervention Trust training company and Early Intervention Wales Training Ltd during the conduct of the study. She is a certified trainer for the Incredible Years® parent programmes and has occasionally been paid by that organisation to deliver training overseas. She also trains parent group leaders for the Children’s Early Intervention Trust, a registered charity, the profits from which fund research activity in Bangor University. Judy Hutchings was principal investigator (PI) on two included trials. Stephen Scott reports that he was an investigator and author of four of the trials contributing data in the work. Sabine Landau reports grants from the UK National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study. Frances Gardner was PI on one of the included trials. Patty Leijten reports that she was an investigator and author of one of the trials contributing data to this project.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Gardner et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In this report, particularly in the methods and results, the headings are structured and, when appropriate, numbered according to the most relevant and up-to-date guidelines, the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of individual participant data’ (PRISMA-IPD Statement). 1

Disruptive behaviour in children

Persistent disruptive or antisocial behaviour is a major public health issue, not least because it is the most common mental health problem in children. Two terms are used when employing diagnostic criteria to apply a cut-off point for the level of disruptive behaviour: oppositional defiant disorder, which is more commonly seen in younger children (defying requests, tantrums, blaming other people for their mistakes, physical aggression and so on), and conduct disorder, usually seen in adolescents, which includes, for example, more serious behaviour such as assault, theft and forcing people to have sex. Together, oppositional and conduct disorders affect 5% of the population. 2 In this report we use the term ‘disruptive behaviour’ synonymously with oppositional and conduct problems, as they refer to the same phenomena. We prefer this to the terms oppositional/conduct problems/disorder, as the these are often not widely understood beyond the relatively narrow confines of the mental health field, and so may not have meaning for teachers, social workers and the general public. This grant was for parenting trials primarily outside the UK NHS child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHSs), so terminology is particularly important.

There are high health burdens into adulthood. For example, for the most disruptive 5% of 7-year-olds, by the age of 25–27 years there is a 5- to 10-fold risk of alcoholism, drug abuse, criminality, domestic violence, sexually transmitted infections, unemployment, psychosis and early death. 3–5 As with poor parenting, there is a strong association with social and socioeconomic disadvantage, with a four- to fivefold higher rate of disruptive behaviour in the most disadvantaged groups in the population. 2 The extra public cost of early-onset disruptive behaviour is £225,000 (USD 335,000) per person by the age of 27 years, which is 10 times that of control participants. 6 Cost savings appear to apply to children with mild and moderate problems, as well as to those with more severe disruptive behaviour who are at greatest risk for long-term problems. 7

Parenting interventions

Parenting interventions potentially form an important public health strategy for preventing disruptive behaviour and other poor outcomes in children for a number of reasons. First, poor parenting skills are strongly predictive of youth disruptive behaviour. 8,9 Second, because the public health and financial burden of child disruptive behaviour and its later consequences are very high, it provides an excellent opportunity for early preventative intervention. Serious, enduring disruptive behaviours in adulthood nearly all always begin in childhood, particularly in early childhood: in < 10% of persistent cases does the disruptive behaviour begin after the age of 18 years. 10 Third, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Cochrane reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs)11–13 clearly show that parenting interventions help prevent child disruptive behaviour problems and enhance parent and child mental health. Many policy bodies worldwide have recognised this (e.g. World Health Organization,14 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime15 and US Centers for Disease Control16). The National Research Council and Institute of Medicine17 has issued a strong call for early preventative intervention trials to explore how mental health disorders can be prevented. These calls are echoed in UK policy. Thus, the Department of Health states the need to promote evidence-based parenting programmes in several 2011 policy documents (e.g. No Health Without Mental Health: A Cross-Government Mental Health Outcomes Strategy for People of all Ages - a Call to Action;18 Talking Therapies: A Four-Year Plan of Action19). The NICE report13 recommends parenting interventions. Its meta-analysis found an effect size of 0.6 standard deviation (SD) on child problem behaviour in the 3–8 years age range, with good long-term effects, which is an extremely worthwhile effect in public health terms. On 27 February 2013, NICE launched its full guideline for prevention and management of antisocial behaviour and conduct disorders, a further recognition of the public health importance of this problem. The guidance confirmed the previous health technology assessment analyses and recommended the use of high-quality evidence-based parenting programmes to prevent the development of antisocial behaviour and conduct disorders. Similar to the economic modelling study by members of our own group,20 and by Lee et al. ,21 the NICE guidance13 shows good financial returns from investment in evidence-based programmes.

Moderators: understanding for whom interventions are effective and their ‘equity’ implications

Given a strong body of evidence showing beneficial main effects of parenting interventions on child outcomes in various trial populations, it is important to understand any effect of heterogeneity between and within study populations. Investigations that aim to establish whether or not there are differential effects for different subgroups in the population are referred to as moderator, effect modifier or subgroup analyses. Importantly, we distinguish moderator from ‘predictor’ analyses, which we define as those that do not examine interaction effects, but instead analyse predictors of outcome in a treated group only, making no comparison with change in the control group. This is a significant distinction, as without this comparison it is not possible to know whether or not any differential effects are related to the intervention per se, or if they merely reflect naturally occurring subgroup differences in prognosis. Understanding treatment effect heterogeneity is vital for a number of reasons, including (1) assessing equity effects of interventions, and whether or not they work for those at greatest risk of poor outcomes, (2) ensuring that interventions are targeted appropriately, (3) understanding for whom intervention strategies may need to be improved or altered and (4) exploring possible differential intervention mechanisms.

Assessing equity effects of interventions

Health inequities have been defined as unfair and avoidable differences or inequalities in health between subgroups in populations. Subgroups might be defined by social or socioeconomic disadvantage, gender or ethnicity (e.g. Tugwell et al. ,22 Welch et al. 23 and Whitehead24). Most health and well-being outcomes are strongly patterned by social and socioeconomic disadvantage, and there are multiple biological and environmental reasons for these observed inequalities. However, an over-riding concern for public health policy and practice is to ensure that interventions that may be effective at improving the mean level of a health outcome across the population do not, at the same time, have the unintended effect of increasing inequalities between groups. For several reasons interventions may serve to increase inequalities, for example if there is differential screening, diagnosis, access, uptake, compliance or effectiveness of interventions22 by different groups in the population. Such effects were inferred from observational epidemiological data relating to a child public health programme in rural Brazil,25 suggesting that in this context, despite good programme access and coverage for the very poorest people, health outcomes for this group were slow to change and occurred only subsequent to improvements in wealthier children. It is important to note that, although inequalities may be magnified (or reduced) at any of these stages on the pathway from screening to intervention effectiveness, moderator analyses generally deal with differential effectiveness, subsequent to intervention access and uptake. It is this aspect of health equity that the current study is able to investigate; different approaches and methods are needed to examine differential access.

These equity considerations are highly relevant to parenting interventions; poor parenting and disruptive behaviour are patterned by social and socioeconomic disadvantage and are linked to diminished life chances in key areas of schooling, employment and health. 5,26 The question then arises whether or not disadvantaged children are also at higher risk of poorer outcomes from parenting interventions than more advantaged children. With the increasing availability of parenting interventions as a public health measure across the population, this becomes a hugely important question. It is a risk well recognised in public health, albeit often poorly defined,27 and which is termed the ‘inverse care effect’, that interventions may sometimes have greater benefits for more advantaged families. 28 This ‘inverse’ effect was found in the early Sure Start evaluations. 29 If it were the case that more disadvantaged families were failing to access or benefit from parenting interventions, then roll-out of these programmes would have the unintended consequence of increasing social inequalities in parenting and disruptive behaviour, and potentially in subsequent life chances, in the very groups at highest risk for these problems. Such an unequal effect could occur despite average beneficial effects of an intervention across the population. Conversely, if an intervention were to have differential effects that conferred greater benefit on the most disadvantaged families, then it would potentially serve to narrow social inequalities in the intended outcome.

Equity effects by ethnicity are also important to understand for several reasons. First, it is important not to increase any social inequalities that may arise from ethnicity, if there were to be differential effects of parenting intervention by ethnicity. Second, investigating whether or not there are ethnicity effects can help to illuminate questions about the generalisability of interventions developed (and often delivered) by people from an ethnic majority, and then applied to minority families. Questions such as these about transportability of interventions across cultures and countries are of wider global importance, as countries seek to enhance child outcomes through parenting and other psychosocial interventions. 14,30,31

Ensuring that interventions are targeted appropriately

A second reason for examining moderator effects is to establish for which subgroups interventions might be most efficiently targeted. In the parenting literature, there is mixed evidence and opinion about the effectiveness of interventions for children at different levels of risk for conduct disorder. Yet this evidence is vital for prevention policy and determining the most appropriate targets for scarcer-indicated prevention and treatment delivery. When interventions are targeted at children showing early signs (indicated prevention) or diagnoses (treatment) of conduct disorder, are parenting interventions most effective for those at higher or lower levels of severity?

Understanding for whom interventions strategies may need to be improved or altered

If it were found to be the case that parenting interventions are less effective for children with high levels of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), in addition to conduct problems, or for those whose parents are depressed, then it would be vital to develop and test improved versions of parenting programmes or to provide other effective interventions that are more suited to the needs of these families. For example, if parents who are depressed show less benefit, then it might be important to modify the approach or add additional strategies that address the ways in which depression may affect parenting and behaviour change. 32 Equally, if low-income or ethnic minority families were found to benefit less, then content or delivery features would need to be modified to ensure fairer access to effective interventions, for example by use of cultural or practical adaptations. 33

Moderator analyses may also provide pointers towards differential intervention processes

When there are differential effects on child behaviour outcomes by subgroup, this may be a sign of potential subgroup differences in the underlying mechanisms of change. Hypotheses about mechanisms, drawn from existing theory and process evaluations, can then be tested in analyses of moderated mediation. 34–37

Prior literature on predictors and moderators of parenting intervention effects

Existing literature points to a number of putative treatment effect moderators. The main categories are:

-

social and socioeconomic disadvantage

-

ethnicity

-

child characteristics: behavioural and emotional problems; age and gender

-

parents’ clinical and parenting practices

-

contextual factors.

We will review these in turn.

Social and socioeconomic disadvantage

The wide dissemination of parenting interventions in the UK makes it urgent to determine the effectiveness of these interventions across a range of social groups. Early poor parenting is patterned by social and socioeconomic disadvantage and in the absence of intervention is predictive of child behaviour problems and diminished educational and health outcomes, which suggests that it is a key mechanism for perpetuating health and social inequalities across generations (e.g. UK birth cohort data, Ermisch8 and Kelly et al. 38). Prospective studies39,40 of high-risk samples support the hypothesis that poor parenting mediates intergenerational transmission of adverse child outcomes. Furthermore, UK cohort analyses suggest that social inequalities in both child and parent mental health appear to be widening over time. 41,42

These observational studies suggest that parenting may be an important mechanism in promoting inequalities and that, with current policies, inequalities in mental health do not appear to be lessening over time. Instead, intervention studies are needed to examine whether improving parenting will have an adverse or beneficial effect on inequalities in child outcomes. Despite a large number of high-quality trials and systematic reviews on the topic, conclusions from the literature are mixed on the question of whether or not there are differential benefits of parenting interventions by family social and socioeconomic disadvantage. A number of trials and systematic reviews have found weaker effects of parenting interventions for more disadvantaged families, including two of the largest meta-analyses of predictor effects. 43,44 On the other hand, other reviews draw more uncertain conclusions. 12,45 Some of the few individual trials testing moderator effects46–48 find that these parenting interventions are equally or sometimes more effective for the most disadvantaged families, which, without intervention, tend to do worse, suggesting the potential for reversing some of the poorer child outcomes associated with family poverty. It is worth noting that most trials have not used their data to ask these questions. However, this limitation aside, there are a number of methodological reasons for these conflicting results, and we argue (in Methodological limitations of current moderation literature) that such moderation questions cannot adequately be answered from individual trials or aggregate-level meta-analyses alone.

The qualitative literature on parents’ experiences can also help identify putative moderators. A systematic review by Kane et al. 49 found five qualitative studies of the views of (mainly disadvantaged) parents who had participated in parenting interventions; our searches found several more recent studies of the Incredible Years® (IY) programme, two of which were embedded within a trial. 50,51 Barriers to uptake and success in intervention included stresses related to time pressure, financial pressure, the influence of antisocial neighbourhoods, reluctance to share problems with others and lack of support from family members. These findings show congruence between parents’ views of barriers and those factors drawn from the literature on moderators and risk factors for child disruptive behaviour. 52

Ethnicity

Few trials in the UK or elsewhere have been able to examine effects of parenting interventions on families from different ethnic backgrounds. This is vital in order to assess whether such services are likely to reduce or widen inequalities by ethnicity in child and maternal outcomes. 53 This is becoming increasingly important in the UK, and, for example, recent population data in London suggest that in some of the more disadvantaged boroughs one-third of children or more (over half in Tower Hamlets) belong to an ethnic minority. When there is evidence from other countries, mainly from the USA, the picture is quite mixed about whether or not there are differential effects of parenting interventions. Measuring a very wide range of parent and child outcomes, as well as parent engagement and satisfaction, Reid et al. 54 found surprisingly little evidence of differential effects of the IY parenting intervention by ethnicity in a predictor analysis; when there were differences by ethnicity, they tended towards greater engagement and uptake by some minority groups. On the other hand, much theoretical and prevention literature from the USA focuses on the need for interventions to be specially adapted for different ethnic groups. 55,56 Even leaving aside the controversial question of which is most effective,57 approaches involving substantial adaptation by culture would imply the need to run parenting groups that are separated by ethnicity, and this raises critical questions about what would be appropriate service delivery patterns for multiethnic UK inner cities. 58 There have been very few studies of outcome differences in parenting trials by ethnicity in the UK or other European countries, or qualitative studies alongside trials. One exception is the trial by Scott et al. ,59 conducted in a highly deprived London borough. They found considerable baseline differences in parenting practices by ethnicity, but, intriguingly, no ethnic differences in attendance, or in intervention effects on parenting skills. This trial therefore suggested that despite large initial differences in parenting style by ethnicity, parenting programmes apparently based on ‘Western’ family values are equally effective with ethnic minority parents, when sensitively delivered, using a programme with an underlying philosophy that is collaborative and parent centred. 60 A Manchester study of parents’ views of a similar programme, Triple P,61 suggested that Asian and African parents are most inclined to take up a parenting intervention, but that white and African Caribbean parents are somewhat less likely to do so.

Child characteristics: behavioural and emotional problems – age and gender

Relatively little is known about how child characteristics, such as age, gender and initial severity and comorbidity of problems, and parent characteristics, such as depression and parenting style, influence the effects of parenting interventions.

Age

Whether or not intervention effects (and cost-effectiveness) vary by age of the child is a particularly salient policy issue. Current policy thrust is towards earlier interventions being thought to having more powerful and longer-term effects on child outcomes, based apparently on evidence from neuroscience62 and from intervention studies. For example, Heckman’s63 broadly conceived synthesis of a range of youth interventions at different ages concluded that early interventions are more cost-effective than later ones for improving subsequent ‘human capital’ outcomes. In the UK, the 2011 Allen Report on early intervention62 strikingly proposed that resources should be taken away from later intervention and redeployed to earlier age groups. Yet there are surprisingly few conclusive data on the most effective age for targeting preventative interventions for disruptive behaviour, with small trials providing conflicting results. For example, one recent trial found no age effects,48 whereas another found a slight advantage of younger age46 but it was limited by including only a narrow preschool age range in the trial. Systematic reviews have also produced mixed findings; two reviews of age effects on parenting interventions found no differential advantage of young age,12,43 and two found greater effects for older children. 64,65 However, most of these reviews are not up to date, and are severely constrained by lack of data on age at an individual (rather than trial) level. Moreover, the number of trials is rarely large enough to be able to control for baseline severity of child problems, which is important because age is often confounded by severity (as it is with gender, such that older children, and boys, tend to have more severe problems), and there is evidence that children with more severe behaviour problems may gain more from these interventions.

Gender

The picture from existing literature is complex: when girls present with severe disruptive behaviour problems, they often show more marked comorbidity than boys. However, in prevention samples, they often have less severe behaviour problems, and this might contribute to finding stronger intervention effects in boys in some studies (e.g. moderator analyses in the Wales Sure Start Trial46). However, other prevention trials find no such gender effects. 54,66,67 Therefore, it is important that studies are able to investigate whether or not gender moderates intervention outcomes, while also controlling for initial severity and comorbidity, as it may be likely that these are associated with gender. If there are weaker effects for girls, programmes may need adjusting to take account of their needs.

Initial severity of behaviour problems

Systematic reviews of parenting interventions again provide conflicting results, albeit based on contrasting meta-analytic methods for synthesising moderator effects. One review found that children with higher levels of behaviour problems did better,43 another that they did worse44 and a third review50 found no difference. As with other moderators with mixed findings, this may be because of programme differences, and especially methodological weaknesses and differences. These are vital issues for making public health decisions about the most appropriate targeting of parenting intervention by level of severity.

Comorbid child problems

Linked to initial severity is the question of whether or not child comorbid problems moderate intervention effects. Some studies suggest that children with high levels of other mental health problems (e.g. ADHD) do less well in parent training, but others have found as good a response in these children. 68,69 If severe ADHD does moderate treatment response adversely, then this might suggest that, before parent training is undertaken with this population, stimulant medication (as recommended by NICE) should be considered. The impact of comorbid child emotional problems, such as anxiety and depression, which, for example, reduce the effectiveness of some interventions for ADHD, is worth examining in the context of disruptive behaviour, as these problems have been found to sometimes diminish intervention effects (e.g. Beauchaine et al. 66).

Parents’ clinical and parenting characteristics

Parent depression

Parental depression is related to children’s behavioural problems,70 with as many as 50% of mothers of children with disruptive behaviour showing clinical levels of depression. Thus, many parents who participate in a parenting intervention to reduce children’s conduct problems may suffer from mild to moderate levels of depression. Policy-makers and practitioners may worry that these families are harder to treat because of the complexity of the family problems. Earlier findings about the extent to which parental depression actually impacts parenting intervention effectiveness are highly inconsistent. Some suggest that families with parental depression are harder to treat,44 whereas others suggest that parenting interventions particularly benefit families with higher levels of parental depression. 46,71 For example, skill deficits such as poor problem-solving and an inability to recall specific events are commonly associated with both depression and inadequate parenting of children with disruptive behaviour problems. 72,73

Parenting behaviour

Parenting interventions aim to reduce children’s conduct problems through improvement of parenting behaviour. Parents’ knowledge and skills at the start of the intervention may impact the extent to which their parenting behaviour improves as a result of the intervention. Perhaps surprisingly, therefore, baseline levels of parenting behaviour are rarely studied as putative moderators of parenting intervention effectiveness. Alternatively, parenting behaviour may have been included in moderator analyses but not reported because of non-significant outcomes (i.e. reporting bias74). The present study seeks to determine more conclusively if parents’ baseline levels of parenting skills impact the extent to which families benefit from a parenting intervention.

Contextual factors

Relevant contextual factors that the literature suggests are likely to affect implementation and effectiveness of parenting interventions can be coded at the level of the trial, because they are the same for all families within the same trial. 75,76 These include type of service provider organisation, level of professional training of the staff delivering the intervention, level of attention to fidelity of implementation, university efficacy compared with ‘real-world’ service effectiveness setting, and geographic factors (e.g. UK vs. other countries, city vs. rural). It is largely unknown whether any reduction in effectiveness is better accounted for by family-level variables (e.g. income and lone parenthood) or, even after taking these into account, whether there are still contextual factor effects. As contextual factors are measured at the trial level, power will be limited for these analyses. In addition, variation between trials on these factors may be limited. For example, the IY parenting intervention was mainly delivered in towns, with few groups in rural areas.

Methodological limitations of current moderation literature

Across these studies of child- and family-level risk factors as moderators of parenting intervention effects, there are common methodological issues arising. Data come from secondary moderator analyses of individual trials, from narrative synthesis of such findings across trials or from metaregression as part of an aggregate-level meta-analysis of parenting trials. We first describe the current methods used in the literature, and then discuss how pooled individual-level data can overcome these drawbacks.

The authoritative paper by Lambert et al. 77 comparing these usual meta-analytic methods with pooling individual data concluded that: ‘[m]eta-analysis of summary data may be adequate when estimating a single pooled treatment effect or investigating study-level characteristics. However, when interest lies in investigating whether patient characteristics are related to treatment, individual patient data analysis will generally be necessary to discover any such relationships’. A conventional aggregate/summary data analysis approach is likely to be less powerful and miss important moderating effects, as it can detect effect moderation only by trial-level summaries rather than individual-level variables. For example, the mean age of children in a range of trials may be similar, and the average effect sizes may also be similar, so that using trial-level comparisons, such as metaregression or subgroup analysis of effect sizes, age would not be predictive of intervention effect. However, often within trials there is age variation, and, by combining them at an individual case level, we will have requisite information to see whether or not there is effect modification by age, and by the socioeconomic variables that we plan to investigate.

Second, as is well established from the statistical multilevel modelling literature, effects operating at the (aggregate) trial level need not be the same as those operating at the level of the individual. Basing inferences on the equality of between- and within-trial effects when in reality this is not the case is known as the ecological fallacy. 78 Thus, aggregate-level metaregression can inform us only about between-trial effects. We should not use these trial-level results to infer effect moderation by individual-level variables, such as child age, maternal depression, and so on; however, this is what most meta-analyses do. Our study will serve to illustrate the extent of this fallacy, as we will be able to directly compare trials and individual-level moderator effects.

A further problem that stems from the use of trial-level predictors of treatment effects is that predictors are prone to confounding by a common cause,79 making it hard to interpret their meaning. An example of this can be seen in the subgroup analyses in the Furlong et al. review. 12 There, trials conducted in research settings, or with more affluent parents, were also those more likely to be conducted by the developer: all factors that tend to produce larger effect sizes. Thus, it is unclear which of these factors is the cause of the observed treatment effect moderation.

Finally, a second but less commonly used meta-analytic approach to investigating moderators is one that synthesises the published findings of predictor analyses from trial data across trials,44 that is, a meta-analysis of predictor effects. This approach has the advantage of making use of within-trial variability in socioeconomic characteristics, therefore not committing the ecological fallacy and mitigating somewhat the problem termed as ‘those confounded moderators’ by Lipsey,79 and does not require labour-intensive pooling of individual data. However, this approach also suffers from serious drawbacks, leading to researchers recommending against its use. 80,81 A key drawback is that most trials do not report predictor or moderator data, raising the possibility of reporting bias, or, at best, resulting in meta-analyses that can summarise only an incomplete picture. In addition, trial outcome data are rarely broken down by equity factors; when trials do test socioeconomic or other predictors of treatment effects, statistical models are specified in varying ways,80 for example, some calculating interaction effects but others only within-group predictors, which renders synthesis meaningless. 23,82 These problems apply no less to parenting intervention trials,46,50 and can be overcome by use of pooled data. Pooling individual-level data is an exciting new approach to data synthesis,80,83 increasingly common in medicine in recent years,84 but rarely used in public health or psychosocial fields. This study is the first to pool individual-level data from multiple independent trials of a parenting intervention (the IY Basic parenting series) in order to investigate moderator effects in a large, well-powered sample, and making use of individual rather than aggregate trial-level measurement of moderator variables.

Wider health benefits and potential harmful effects

In addition to assessing child disruptive behaviour, typically the primary outcome, parenting interventions may have wider benefits for family well-being. First, these include improving parenting skill and parent–child relationships, with increases in positive involvement with children, and reductions in harsh parenting and abusive practices. Although these are termed secondary outcomes in most trials, they are also seen as crucial mediators between intervention and outcome. 46 Second, programmes have been shown to improve adult mental health and well-being, including parental depression, confidence in their ability to be a successful parent and partner relationships. Third, some studies show generalisation to improved behaviour of other children in the family. 85

The inclusion of these wider health benefit measures, however, is far from systematic across trials. It is often unclear why certain trials include some measures of wider health benefits, whereas others do not. Moreover, reporting bias may exist in that authors report only wider health benefit outcomes that were significantly altered by the intervention,74 although the recent trend to publish trial protocols (e.g. Chhangur et al. 86) will hopefully diminish this. Reporting bias is problematic because it may overestimate the effects that parenting interventions have on wider health outcomes. Alternatively, if relevant wider health benefits are not assessed, the policy impact of parenting interventions on family well-being may be underestimated. There is, thus, a need for a systematic investigation of the extent to which parenting interventions designed to reduce conduct problems improve family well-being more broadly. A systematic investigation would require (1) authors to share data on all measures of wider health benefits they included in the study and (2) sufficient numbers of participants for greater power and precision to estimate the magnitude of effects. This would allow for more conclusive results that include a wide range of possible health benefits (e.g. more elaborate than previous reviews, such as Barlow et al. 11) and, that is, more up to date (e.g. building on Furlong et al. 12).

Wider health benefits

Negative (i.e. harsh and inconsistent) parenting, and a lack of positive parenting (i.e. positive reinforcement and monitoring) are of particular importance for child well-being and quality of life; in prevention trials, in which many of the children show quite low levels of behaviour problems, these interventions impact public health by reducing levels of harsh or abusive parenting and family stress. This has been found in universal and selective prevention trials,32,87 and in studies of parents at high risk for abusive parenting. 88,89 The Triple P trial87 showed that widespread implementation of a similar parenting programme reduced admissions to hospital for abuse, measured by county-level indicators. Recent reviews confirm that even mildly harsh parenting is associated with harmful biological effects on children, including, for example, dysfunctional cortisol secretion patterns and raised C-reactive protein, which in turn are associated with increased cardiovascular disease and mortality. 90

Parental well-being (i.e. depression or stress) has been shown in some trials to be improved by parenting interventions, and this will be an important public health benefit to document. Parents with young children spend many or most of their waking hours caring for them, and qualitative studies suggest that failure to succeed in controlling child behaviour is a major source of lack of confidence and depressive cognitions. 51 Improving parent–child dynamics, including more positivity and improved communication, may contribute to parents’ sense of well-being and fulfilment in the parenting role. Some previous work suggests that parenting interventions designed to improve the parent–child relationship and children’s conduct problems also reduce parental symptoms of depression. 12

Although parenting interventions primarily aim to reduce children’s conduct problems, there is evidence to suggest that they may have a wider impact on children’s mental health, including children’s ADHD symptoms, ADHD being the most prevalent comorbidity of conduct problems. 91 Recent findings about the extent to which parenting interventions reduce ADHD symptoms in children are inconsistent, and may in part depend on the type of instrument used (e.g. Daley et al. ,92 Jones et al. 68 and Sonuga-Barke et al. 93). The extent to which parenting interventions designed for reducing conduct problems may benefit children’s emotional well-being, however, remains understudied. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are common in children with conduct problems. 94 Some studies evaluating the IY parenting intervention indicate effects of the intervention on reduced emotional problems in children (e.g. Herman et al. 95). Others, however, have failed to replicate these findings (e.g. Leijten et al. 96) or emotional problems are not measured. These inconsistent findings suggest that more thorough investigation is needed of the extent to which parenting interventions for conduct problems also impact children’s emotional problems.

Potential harmful effects of parenting interventions

As well as benefits, it is important to consider potential harms, especially as they are rarely studied in parenting intervention trials. When harms have been studied in psychosocial trials, they have mainly involved youth-focused interventions and have been defined as main effects in the unintended direction. 97,98 Recent systematic reviews of parenting interventions have not found evidence of harmful effects defined in this way. 12 Parents rarely report potentially harmful outcomes in qualitative studies; Morch et al. 51 mention none, despite interviewing many parents for whom intervention was not successful. A few parents in the study by Furlong and McGilloway50 were concerned about increased conflict with partners related to trying new parenting techniques and the lack of privacy in group interventions that discuss family problems. The Cochrane review by Furlong et al. 12 planned to examine two potential adverse effects, namely the burden on families in attending (e.g. child-care issues) and increased family conflict, but found no studies reporting these outcomes. Given this weak state of evidence on harms from parenting interventions, cautious, exploratory (hypothesis generating, rather than hypothesis driven) analyses are needed to see if there is evidence of main effects in the adverse direction.

Parent satisfaction data

Data on parents’ views are rarely presented in detail in trial reports or reviews12 and the rate of missing data is often high. These are available only for parents in the intervention group, and not the control group, but if numbers are sufficient, and instruments comparable, they could potentially be synthesised.

The Incredible Years parenting programme

The IY Basic parenting programme is a 12- to 14-session programme, delivered to groups of between 6 and 15 parents, in weekly sessions of 2–2.5 hours. 32 It has been widely rolled out throughout the UK, as well as in some other European countries. It has been identified in many systematic reviews11,12,99 as effective for preventing disruptive behaviour in children, and improving parenting quality and parental mental health. The programme has received UK government funding for training as part of the Pathfinder Early Intervention programme and Welsh Government funding as part of the Parenting Action Plan for Wales, and as a result of its widespread dissemination, eight community-based RCTs have been completed [sited in London,59,100,101 Plymouth,101 Oxfordshire,102,103 Wales85,104 and Birmingham. 105

The content of the programme106,107 is derived from social learning theory and attachment theory. More specifically, the techniques that parents learn are designed to break coercive cycles of parent–child interaction in which parents and children reinforce negative and aggressive behaviour in each other. 108 The following topics are covered: relationship-building through playing or spending special time with the child, providing praise and rewards as reinforcements of positive behaviour, effective limit-setting, adequate disciplining techniques (e.g. ignore and time-out techniques), and coaching children in social, emotional and academic skills. The content of the IY parenting programme is very similar to the contents of programmes based on social learning theory (e.g. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy and Parent Management Training – the Oregon model).

What is different from other programmes, however, and potentially important for reaching and benefiting socioeconomically disadvantaged families, is the approach of the IY programme. As opposed to a didactic style in which the therapist teaches the parent how to change his or her behaviour, IY therapists (i.e. ‘group leaders’) use a collaborative approach in which parents are seen as the experts on their own children. Parents are guided to set weekly goals, which fit with their cultural and personal needs and values. Moreover, as opposed to the therapist ‘talking’ about the kind of parenting behaviour that is considered to be appropriate, video-taped scenes showing examples of parent–child interactions are central in the sessions and parents are guided to identify key parenting behaviours or principles that might be useful for their own family context. There are also discussions about programme-driven and parent-initiated topics, brainstorms about different parenting techniques and role-plays in which parents practise different techniques. There is also an important focus on home practice, and parents receive weekly check-in telephone calls. The group format is essential here, because the group leaders try to let most of the ideas and solutions come from the parents themselves. The group format further allows for normalisation and social support.

Rationale for the current study (PRISMA-IPD #3)

This study addresses the following broad question: how far could widespread dissemination of parenting programmes improve child disruptive behaviour and reduce social inequalities? Combining data sets from trials in different communities to establish for whom programmes are effective: an individual participant-level meta-analysis.

To answer this question, we combine individual participant data (IPD) from 14 randomised trials of the IY parenting intervention across Europe. Our study brings to bear four important design features that increase power, value and generalisability, compared with single trials and compared with conventional meta-analysis. First, we analyse RCTs, thus overcoming the risks of biased estimates of treatment effectiveness that may arise from observational studies of public health strategies, in which differences seen between populations do not necessarily translate into benefits when these are rigorously tested in intervention experiments.

Second, rather than combining trials at the study level as is usual in meta-analytic studies using aggregate data, we combine data from 14 trials at an individual participant level, thus greatly enhancing the opportunity to detect moderating (interaction) effects of social and socioeconomic disadvantage and other risk factors. A particularly key advantage is that combining individual-level data makes full use of the rich variation within (as well as between) trials. This information is completely lost when testing moderators in a conventional meta-analysis, for which participants can be characterised only at the aggregate trial level and not as individuals. Our design represents a unique opportunity to overcome the problems of low power and reporting bias that beset subgroup analyses in most individual trials, and hence to enhance our understanding of how parenting interventions may reduce or widen health and social inequalities. 82,109,110 Moreover, our study will illustrate the extent of this ‘ecological fallacy’, which can arise when aggregate-level data are used to infer individual-level effects, as we will be able to directly compare trials and individual-level moderator effects.

However, it is important to note that pooling data from multiple trials, although bringing unique advantages, also brings challenges and compromises, primarily in that different trials do not use the same measuring instruments, and variables thus need harmonising across trials. In conventional, aggregate-level meta-analysis, combining outcome data by converting aggregate scores to standardised mean differences is relatively straightforward but this is not applicable to individual-level data meta-analysis. 109

Third, we draw upon qualitative research and public involvement, soliciting parents’ views on factors affecting intervention success, to inform hypotheses for testing and help interpret the findings.

Fourth, by accessing a complete set of trial data, irrespective of whether or not findings from secondary outcomes have previously been published, and analysing using a consistent and preplanned strategy, we aim to obtain a less biased and more precise estimate of the wider benefits and potential harms of the intervention.

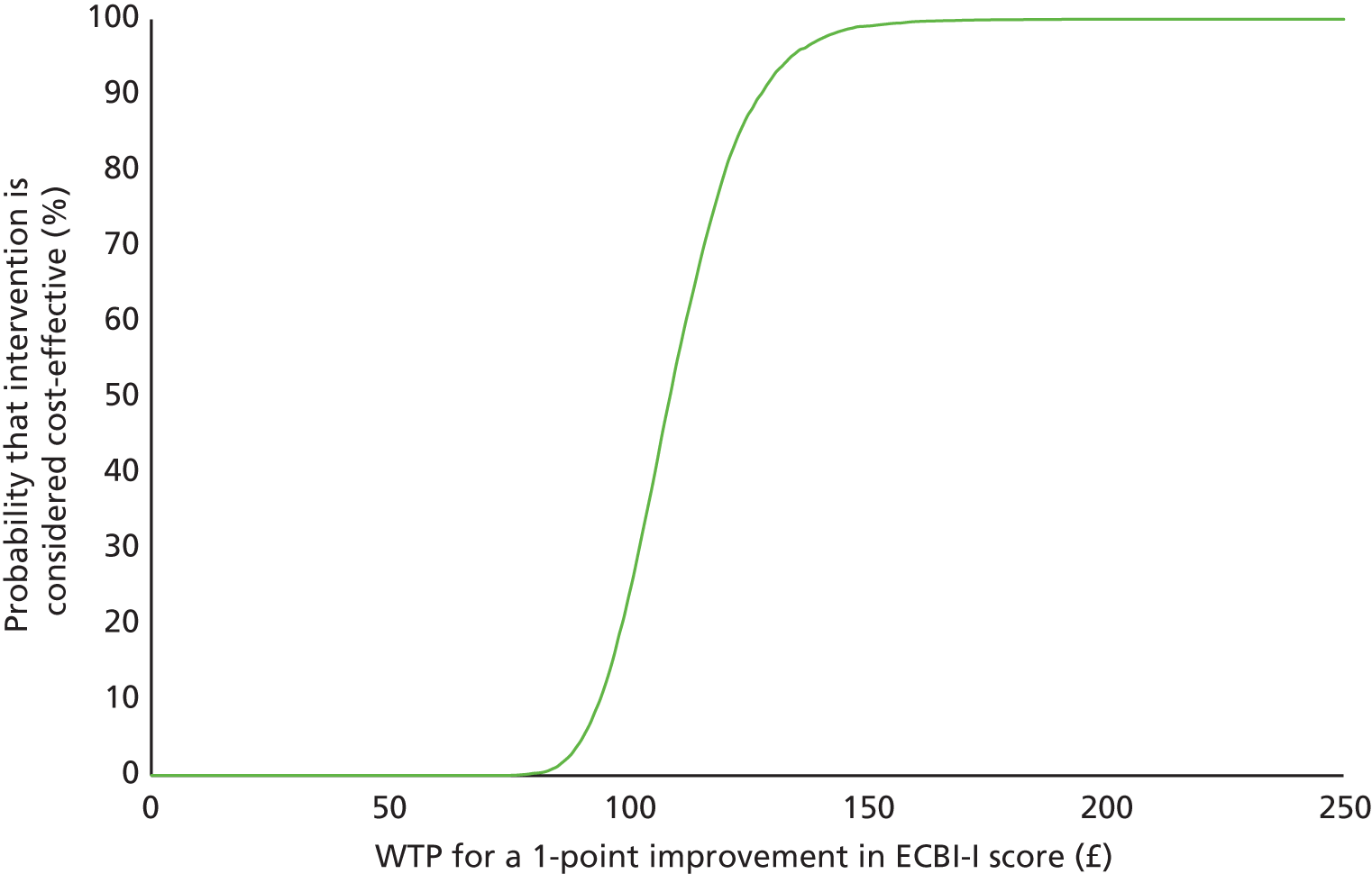

Fifth, we apply cost and cost-effectiveness approaches by health economists to enable potential benefits to public health to be predicted as accurately as possible.

This unique study based on pooled individual data is the largest of its type in the world and will considerably advance our understanding of differential intervention effects, and cost-effectiveness of parenting interventions for families with differing levels of social and socioeconomic disadvantage and child risk factors. This will help to determine whether or not such programmes are likely to reduce or widen social inequalities, which is an important public health question because of the damaging and expensive effects of disruptive behaviour. It is of direct relevance to the NHS, which is investing heavily in programmes to prevent disruptive behaviour. It will also generate a more precise estimate of the wider benefits of the IY parenting programme, which may be at least in part generalisable to the effects of other parenting programmes with a similar background in social learning theory. Perhaps most importantly, if there are groups for which programmes work less well, it will stimulate change in working practices to try to improve availability and effectiveness of these programmes for such groups.

By pooling all available baseline and outcome variables across trials, our analyses will help to reduce selective reporting and publication bias, whereby positive secondary outcomes are reported more than those showing null or harmful effects, or non-significant moderator analyses (if conducted) may potentially not be published. 80 Reporting bias is known to be a considerable problem in many areas of health care; systematic reviews find it to be linked to higher effect sizes. 111,112 It is especially problematic in this field, in which there are typically multiple secondary outcomes and multiple measures of the same construct within and between trials. 12

Our analyses will also allow for wider generalisability across community service contexts, regions and countries. As the trials were conducted in a range of service settings (non-governmental organisations, Sure Start services, day nurseries and primary schools), samples and regions, inferences will be generalisable. This will potentially allow us to examine contextual effects on outcome, and their interaction with individual-level factors. However, it should be noted that power for examining contextual effects, as these operate largely at trial level, is likely to be very limited as the sample size is only as large as the number of trials.

Finally, our evidence is up to date. It is unlikely that we have missed any relevant European trials of IY, as we conducted extensive literature searches and contacting of experts, which revealed many trials, which, at the outset of the study, were recently completed and not yet published.

Research questions (PRISMA-IPD #4)

Underlying population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design (PICOS) question for main effects in the pooled trials:

-

Population: families with children aged 2–10 years

-

Intervention: IY parenting programme

-

Comparison: waiting list, minimal intervention or care as usual

-

Outcome (benefit): child disruptive behaviour post test

-

Study design: RCT.

Specific questions for this IPD meta-analysis:

-

To what extent does the IY parenting intervention benefit the most socially disadvantaged families compared with average families?

-

To what extent does the IY parenting intervention benefit families from ethnic minorities compared with those from the ethnic majority?

-

To what extent does the IY parenting intervention differentially benefit children with different levels of characteristics, including age, gender, severity of conduct problems and comorbid problems, at baseline?

-

To what extent does the IY parenting intervention differentially benefit children whose parents have different levels of depression and parenting skill at baseline?

-

To what extent do trial-level effects predict outcome, including contextual variables (country, rural vs. urban) and intervention factors that indicate level of intervention fidelity (level of staff training, certification and supervision); and number of sessions offered?

-

What are the wider public health benefits and potential harms of the IY parenting intervention?

-

What are the costs, cost-effectiveness and potential longer-term savings of the IY parenting intervention?

Chapter 2 Methods

In this report, the numbered headings are structured according to the most relevant and up-to-date guidelines, the PRISMA-IPD Statement. 1

Protocol and trial registration (PRISMA-IPD #5)

The protocol for this study is available on the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research website (project number 12/3070/04).

Eligibility criteria (PRISMA-IPD #6)

We sought to include all completed RCTs of the IY parenting programme in Europe for children aged 1–12 years. Non-RCTs were excluded because no causal inference about the effects of the IY programme can be drawn from non-randomised designs. No restrictions were placed on the years in which trials were conducted, required minimum follow-up or included outcome measures. Within each RCT we included individuals who had received the IY (or a combination of IY and a reading intervention that focused on similar parenting behaviour) and individuals in control conditions. We excluded trials with additional non-parenting programmes, as well as excluding individuals who had received additional treatment for disruptive behaviour such as the IY child programme, because the focus of this project was to examine the effect of the parenting programme as a sole intervention. We excluded programmes that were much more minimal than the standard IY programme of 12–14 sessions, for example highly abbreviated non-standard versions. We also excluded individuals who received only a reading intervention.

Identifying studies: information sources (PRISMA-IPD #7)

Studies were identified in 2013 through (1) a systematic literature search in the following databases, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, Global Health, MEDLINE and PsycINFO; (2) the IY website, which provides information on trials evaluating IY; (3) the European IY mentors’ network; and (4) asking experts. Searches in January 2015 revealed no further completed trials.

Identifying studies: search (PRISMA-IPD #8)

EMBASE, Global Health, MEDLINE (< 1946 to present) and PsycINFO were searched via Ovid using the following search terms:

-

incredible year$.mp

-

webster-stratton.mp

-

1 or 2.

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature was searched via EBSCOhost using the phrase ‘incredible years’.

Study selection processes (PRISMA-IPD #9)

Eligibility was assessed by the first author and double-checked by four additional authors (SS, JH, PL, JM). There were no differences of opinion.

Data collection process (PRISMA-IPD #10)

Anonymised data for 15 RCTs were requested for all families randomised. Investigators were first e-mailed to ask whether or not they would be willing to collaborate and share their data for this project. They were then sent a detailed guideline on how to anonymise their data and an overview of the variables we were hoping to collect. Investigators uploaded their data set to a University of Oxford web service that supports the exchange of large data files. The data transfer was encrypted and password protected. Files were deleted from the web server once the transfer had taken place. Raw (i.e. not recoded) individual-item level (i.e. not total scale scores) were supplied in SPSS format (SPSS statistics version 21; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and were checked for missing items and consistency with trial protocols and published reports. Copies of the original questionnaires were requested and received to check for consistent use of similar questionnaires across trials and the order in which questions were asked.

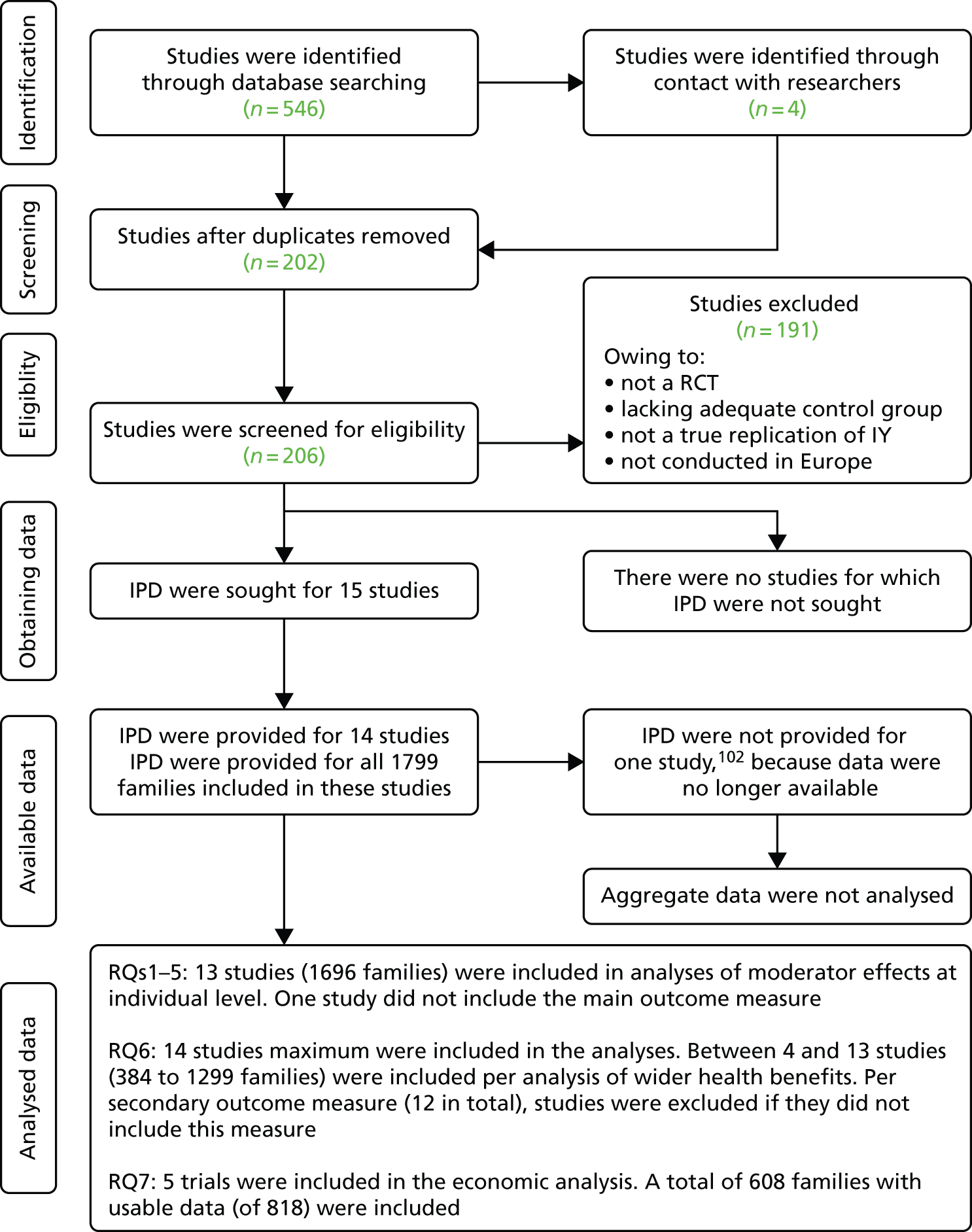

Individual participant data were available and received for all randomised participants in 14 trials (see flow diagram, Figure 1). Investigators were contacted in cases for which additional information was needed about the interpretation of the IPD. All investigators signed a data sharing agreement (see Appendix 1). IPD for the 15th trial102 were reported by the investigators to be no longer available. The pooled data set consisted of records on 1799 families.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of search results. RQ, research question.

Overview of trials

An overview of the trials is listed in Table 1. Detailed information about trial characteristics is provided in the results (see Chapter 3, Description of included trials), including fuller tables (see Table 7 and Appendix 2).

| Trial number | Country | Trial acronym | n | Brief description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Norway | NOR | 75 | Referred children in psychiatric clinics | Larsson et al.113 |

| 2 | Sweden | SWED | 62 | Referred children in psychiatric clinics | Axberg and Broberg114 |

| 3 | Portugal | PORT | 124 | Parent-referred children in university clinics, screened for conduct problems | Homem et al.115 and Azevedo et al.116,117 |

| 4 | Ireland | IRE | 149 | Mixed community services, children screened for conduct problems | McGilloway et al.48 |

| 5 | The Netherlands | NL-BS | 99 | Mothers released from incarceration (non-governmental organisation for former incarcerated mothers) | Menting et al.118 |

| 6 | The Netherlands | NL-SES | 156 | Socioeconomically disadvantaged and immigrant families (clinics and community services) | Leijten et al.96 |

| 7 | Wales | WL-SS | 153 | Sure Start services; preschoolers, screened for conduct problems | Hutchings et al.85 |

| 8 | Wales | WL-FS | 103 | Flying Start services, toddlers in highly socioeconomically disadvantaged areas | Hutchings et al.104 |

| 9 | England | BIRM | 161 | Mixed community services in Birmingham, children screened for conduct problems | Morpeth et al.105 and Little et al.119 |

| 10 | England | LON-SPO | 112 | Socioeconomically disadvantaged primary schools in London, children screened for conduct problems | Scott et al.100 |

| 11 | England | LON-PAL | 174 | Socioeconomically disadvantaged primary schools in London | Scott et al.59 |

| 12 | England | LON-HCA | 214 | Primary schools in London and Devon, children screened for conduct problems | Scott et al.101 |

| 13 | England | OXF | 76 | Referred children in voluntary sector service, children screened for conduct problems | Gardner et al.103 |

| 14 | England | LON-NHS | 141 | Referred children in NHS psychiatric clinics | Scott et al.120 |

| 15 | England | – | 116 | Data not available, children screened for conduct problems in general practice and NHS | Patterson et al.102 |

Individual patient data integrity (PRISMA-IPD A1)

We checked each trial data set to identify missing data and assess data validity (e.g. we double-checked individual item formulation and scores for all constructs). To assess randomisation integrity, we checked patterns of treatment allocation and balance of baseline characteristics by treatment group. Any queries were resolved in collaboration with each trial investigator.

Risk of bias assessment in individual studies (PRISMA-IPD #12)

We used the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool. 121

Harmonisation of individual-level data

Three different data harmonisation strategies were used.

-

Combining similar classification systems to harmonise data for different socioeconomic status (SES) indicators. Indicators of SES were screened for comparability. Fortunately, most trials used similar indicators that were operationalised in similar ways. For example, whether or not a family had low income was defined by receiving financial benefits (10 trials), receiving financial benefits and having below-median income (one trial), scoring below the low SES threshold on the Hollingshead Index (one trial) or living in social housing or with family/friends (two trials). Indicators of families’ (risk for) low income were dichotomised. Educational-level categories used across trials were compared with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics International Standard Classification of Education 2011. 122 Although some categories had to be combined (e.g. less than primary education and primary education) because these had already been combined in some trial data sets, five main categories (primary education or less, lower secondary education, upper secondary education, postsecondary education and university degree) were present in data from all trials and used in the final pooled data set.

-

Using norm deviation scores to harmonise scores on child behaviour problems (disruptive, ADHD and emotional problems) and parental depression. A primary measure (i.e. the most frequently used measure) was selected for each construct. If data on the primary measure were unavailable, data from similar measures were converted into scores on the primary measure using norm deviation scores (i.e. number of SDs the individual scores are above or below the population mean). This approach assumes that both instruments measure the same construct with the same measurement error on different instruments and thus the scores can be converted using known population characteristics.

The advantages of using norm deviation scores are that (1) absolute scores can easily be interpreted, because they are on the original scale of the primary measure – this allows for interpretation of clinical significance of intervention effects – and (2) the scores of individuals remain the same after adding data from new trials, because harmonisation is done on an individual family level.

In contrast, integrative data analysis using latent variables based on the different measures included across trials, although strong in its use of multiple measures within trials, has the disadvantage of scores that are hard to interpret on an absolute level, as well as scores that depend on the model tested and thus the trials or families included in the model. Norm deviation scores were used to harmonise data from the following constructs: parent-reported disruptive child behaviour, children’s comorbid ADHD symptoms, children’s comorbid emotional problems and parental depression.

-

Using item-level harmonisation based on face validity and correlations to harmonise scores on self-reported parenting practices. When no norm scores were available for measures, scores on similar items across scales that aimed to measure the same construct were selected. Response scales were harmonised to reflect the response scale used most frequently. For example, if most measures used a 1–7 Likert scale, scores from a measure using a 0–3 Likert scale were converted such that 0 = 1, 1 = 3, 2 = 5, 3 = 7. This approach makes assumptions based on face validity: items that are formulated similarly will measure a similar construct.

Relatively similar response scales were used across the instruments. Response scales varied between ‘never and always’ or ‘not at all likely’ and ‘extremely likely’. For the items in relation to the last 2 days, response scales vary from ‘never’ to ‘not with my child in the last 2 days’ and from ‘none’ to ‘more than 4 hours’.

Somewhat different time periods were covered by the different measures. The Parenting Scale (PS) asks parents to reflect on the last 2 months; the Parenting Practices Inventory (PaPI) asks parents ‘how often do you do each of the following?’ or ‘within the last 2 days how many times did you?’ or ‘about how many hours in the last 24 hours did . . .?’ or ‘within the last 2 days, about how many total hours was your child . . .?’ and ‘what percentage of the time do you know . . .?’. The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) asks parents to reflect on what typically occurs at their home. The interview used in trials 10–12 asks parents to reflect on what occurred in the last week (rewards) or yesterday (praise). The interview used in trial 14120 did not define a time point. We were able to check actual correlations between scores from different measures for a few constructs based on a small sample (N = 44). These varied between 0.30 and 0.87. We used item-level harmonisation for the following constructs: self-reported parenting practices (seven constructs).

Data items (PRISMA-IPD #10)

Design variables: trial level

Trial identifier

Indicating the trial from which the observation is taken.

Family identifier

Denoting the family number for each observation.

Type of control condition

Whether or not the trial used a waiting list (10 trials), no treatment control condition (two trials) or a minimal intervention control condition (two trials).

Incredible Years sessions offered

Number of sessions of the intervention offered to the participant.

Design variables: individual level

Randomisation ratio applied to each participant

Where the randomisation ratio varied with the trial, this variable denotes the batch of randomisations in which the participant was randomised.

Cluster used for randomisation

Trials 11 and 14 used cluster randomisation. This variable denotes the cluster to which the participant belonged.

Stratification variables used within the trial

If stratified randomisation was used, this variable denotes those variables that were used in the stratification [e.g. trial site, sex, age, recruitment cohort and/or score above the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory Intensity scale (ECBI-I) 97th percentile].

Baseline measures: individual family level

Child gender

Gender of the target child was coded as male or female.

Child age

Age of the target child at baseline was described in months.

Primary parent gender

Gender of the child’s primary caregiver was coded as male or female.

Primary parent age

Age in years of primary caregiver at birth of target child was described in years. Primary parent is defined as the parent responsible for the majority of the care of the target child.

Secondary parent gender

Gender of the child’s secondary caregiver was coded as male or female.

Secondary parent age

Age in years of secondary caregiver at birth of target child was expressed in years.

Child was referred

Denoting whether or not the child was referred to the service for behaviour problems.

Low income

Indicators of families’ (risk for) low income were dichotomised. Low income was defined as receiving income-dependent financial benefits (10 trials: trials 3, 4 and 7–14); receiving financial benefits or having below-median income if financial benefits were not income dependent (one trial: trial 1); scoring below the low SES threshold on the Hollingshead Index (one trial: trial 2); or living in social housing or with family/friends (two trials: trials 5 and 6). Categorised as a binary variable (0 = no; 1 = yes).

Educational level

Highest educational level of the primary parent. Educational level was categorised according to an amended version of the International Standard Classification of Education 2011:122 1 = primary education or less, 2 = lower secondary education, 3 = upper secondary education without qualifications, 4 = post-tertiary education and 5 = bachelor-, master’s- or doctoral-level education. In addition, a binary variable was created because of low numbers in some of the educational-level categories in some of the trials: 0 = upper secondary-, tertiary- or university degree-level education; 1 = primary or lower secondary educational status.

Lone parenthood

The primary parent does not live with a partner or spouse. Categorised as a binary variable (0 = no; 1 = yes).

Teenage parenthood

Primary parent was younger than 20 years at birth of the target child. Categorised as a binary variable (0 = no; 1 = yes).

Parental unemployment

No employed parent in the household. Categorised as a binary variable (0 = no; 1 = yes).

Ethnic minority status

Binary categorisation of the primary parent’s ethnic background into ethnic majority status or ethnic minority status based on the adapted Office for National Statistics (ONS)123 classification (see Ethnic background). Value 1 (white) was scored as 0 = ethnic majority status. All other values (2–10) were scored as 1 = ethnic minority status.

Ethnic background

Categorisation of the primary parent’s ethnicity according to adapted ONS123 classification. We adapted the ONS classification to include categories that are relatively common in our pooled data set, such as Mediterranean, but were not included in the original ONS classification. This variable included the following categories: 1 = white, 2 = black, 3 = Middle Eastern, 4 = South-East Asian/Chinese, 5 = Indian, 6 = Pakistani, Bangladeshi, 7 = Arabian (North African), 8 = Mediterranean (Turkish, Greek and Italian), 9 = Latin American and 10 = other.

One trial (trial 12) had many missing data on parent ethnicity. We therefore used child ethnicity to approach parent ethnicity (e.g. if a child was coded as white, we coded the primary parent as white). However, this was done only if (1) the child was coded as white or black (e.g. not when child was coded as ‘other’ or ‘mixed’) and (2) the child and parent were known to be biologically related.

Baseline measures: trial level

Urban or rural

The percentage of therapy groups within the trial that were held in a rural setting.

Country

Whether the trial was held in the UK or Ireland (coded as 0) or in another European country (coded as 1).

Efficacy or effectiveness

Type of clinical setting. Whether the trial was carried out under optimal conditions (efficacy, coded as 1) or under a real-world context (effectiveness, coded as 0).

Percentage of staff who were clinically trained

Percentage of the staff within the trial who provided the therapy groups and had formal clinical training and education, for example in clinical psychology, psychiatry or mental health nursing.

Percentage of staff Incredible Years certified

Percentage of the staff within the trial who provided the therapy groups and were formally certified as an IY group leader.

Service context

Whether the therapy groups were held within health services (e.g. NHS or a similar service in other countries) (coded as 1) or in community or voluntary sector services (coded as 0).

Type of trial

Whether the trial was a selective prevention trial (i.e. families targeted were at risk of conduct problems but not necessarily currently experiencing problems, coded as 0) or a indicated prevention or treatment trial (i.e. children with reasonably high levels of conduct problems were targeted, coded as 1).

Checklist

Did staff complete the IY checklist after sessions (coded 1 for yes and 0 for no)?

Mentor

Whether or not a mentor was part of the trial (coded 1 for yes and 0 for no).

Video

Were sessions video-taped (coded 1 for yes and 0 for no)?

Video supervision

Were video-taped sessions used in supervision (coded 1 for yes and 0 for no)?

Supervision

Was there weekly/fortnightly supervision (coded 1 for yes and 0 for no)?

Fidelity

Did independent ratings of session fidelity take place (coded 1 for yes and 0 for no)?

Workshop

Whether or not any group leaders in the trial attended an international workshop (coded 1 for yes and 0 for no).

Number of Incredible Years sessions offered

Number of IY sessions offered in the active arm.

Primary outcome: individual family level

Disruptive child behaviour

The ECBI-I124 was used to assess disruptive child behaviour, primarily conduct problems. The ECBI-I is a widely used 36-item measure that rates parent-reported frequency of disruptive child behaviour on a 7-point scale. The ECBI-I has shown good convergent125 and discriminant validity. 126,127 If a trial did not include the ECBI-I we chose the measure that best captured the same construct and used norm scores to convert scores on the alternative measure to ECBI-I scores (see Harmonisation of individual-level data). Three trials did not include the ECBI-I (trials 3, 8 and 14). For two of these trials (trials 3 and 14) scores on the Parental Account of Children’s Symptoms (PACS128) were converted into ECBI-I scores using norm deviation scores. One trial (trial 8) did not include a measure of parent-reported disruptive child behaviour because of the young age of the children.

Parental Account of Children’s Symptoms scores and ECBI-I scores correlated (r = 0.71) in our sample, based on data from four trials (trials 10–13) that included both the ECBI-I and PACS. The internal consistency of ECBI-I scores was α = 0.94 at time point 1 (T1) and α = 0.95 at time point 2 (T2). The internal consistency of the PACS scores was 0.82 at T1 and 0.79 at T2. Data were available from 13 trials (all except trial 8).

Secondary outcomes and baseline moderators: individual family level

Comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to assess parent-reported comorbid ADHD symptoms in children. If a trial did not include the SDQ hyperactivity/inattention subscale, we chose the measure that best captured the same construct (child ADHD symptoms) and used norm scores to convert scores on the alternative measure to SDQ scores.

Original SDQ scores were used for trials 2–4, 6, 7, 9–11 and 14. Scores were converted for trials 1 (from the Child Behavior Checklist, CBCL129), 12 (PACS) and 13 (CBCL). Original US male aged 4–18 years norm scores129 were used to convert CBCL scores into norm deviation scores. Original UK norm scores130 were used to convert PACS scores into norm deviation scores. American male aged 4–17 years norm scores were used to convert norm deviation scores into SDQ scores. 131 Trials 5 and 8 did not have a parent-reported measure of child ADHD.

Converted SDQ scores above the maximum or below the minimum possible score on the SDQ scale were altered to the maximum or minimum possible score, respectively. If, after harmonising, scores were outside the theoretical range (0–10), they were changed to either the theoretical minimum (n = 0 at all time points) or maximum (n = 68 at T1 and n = 40 at T2).

Comorbid emotional problems

The SDQ was used to assess parent-reported comorbid emotional problems in children. If a trial did not include the SDQ emotional problems subscale, we chose the measure that best captured the same construct (children’s emotional problems) and used norm scores to convert scores on the alternative measure to SDQ scores.

Original SDQ scores were used for trials 2–4, 6, 7 and 9–11. Scores were converted for trials 1 (from the CBCL129), 12 (PACS), 13 (CBCL) and 14 (PACS – for participants for whom SDQ scores were missing). Original US male aged 4–18 norm scores129 were used to convert CBCL scores into norm deviation scores. Original UK norm scores130 were used to convert PACS scores into norm deviation scores. American male aged 4–17 years norm scores were used to convert norm deviation scores into SDQ scores. 131 Trials 5 and 8 did not have a parent-reported measure of children’s emotional problems.

If, after harmonising, scores were outside the theoretical range (0–10), scores were changed to either the theoretical minimum (n = 21 at T1; n = 7 at T2) or maximum (n = 12 at T1; n = 4 at T2).

Parental depression

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)132 was used to assess parental depressive symptoms. The BDI is a 21-item measure of depressive symptoms and has shown good concurrent and convergent validity. 133

If a trial did not include the BDI we chose the measure that best captured the same construct (parental depression) and used norm scores to convert scores on the alternative measure to BDI scores. BDI scores were included for trials 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 13 and 14. More specifically, BDI version IA scores were included for trial 13 and BDI version II scores were included for trial 8. Scores were converted using norm deviation scores for trials 2 (from the Brief Symptom Inventory – depression subscale;134 see Francis et al. 135 for norm scores), 5 and 6 (from the Symptoms checklist – depression subscale;136 see same reference for norm scores), 10 and 11 (from the General Health Questionnaire;137 see Booker and Sacker138 for norm scores) and 12 (from the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale;139 see Crawford and Henry140 for norm scores).

Internal consistency for the BDI was 0.93 at T1 and 0.93 at T2. Internal consistency of the General Health Questionnaire was 0.86 at T1 and 0.87 at T2. Internal consistency of the Symptoms checklist – depression subscale was 0.93 (T1 only).

Parental stress

The Parental Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF)141 was used to assess symptoms of parental stress. The PSI-SF is a 36-item measure of parental stress. Data were available from trials 1, 4, 7, 8 and 10. Internal consistency of the PSI-SF was 0.95 at T1 and 0.96 at T2. Trials 3 and 6 used a subset of the items of the PSI-SF. Data from these trials were therefore not included.

Parental self-efficacy

Parental Sense of Competence (PSOC) scale142 was used to assess parental self-efficacy. The PSOC scale is a widely used 16-item measure of parental self-reported self-efficacy scored on a 6-point scale. The PSOC scale was used in trials 3, 8, 11 and 13.

Trials 3, 8 and 11 used a 5-point rating scale for the PSOC scale and trial 13 used a 6-point rating scale. Trials 3, 8 and 11 were therefore recoded to a 6-point scale using the following recoding: 1 = 1, 2 = 2.25, 3 = 3.5, 4 = 4.47 and 5 = 6.

Trial 12 included parental self-report data on ‘confidence in managing child behaviour’ but it was decided not to include these data, as they consisted of one item on a 6-point scale. Internal consistency on the PSOC scale total score was 0.84 at T1 and 0.90 at T2.

Self-reported positive parenting practices (use of praise, use of tangible rewards, and monitoring)

Across measures, items theoretically fitted three different constructs of positive parenting (Table 2). Praise was defined as any verbal compliment in response to the child’s behaviour. Tangible rewards were defined as any rewards for the child that are not verbal or physical, for example privileges, stickers on a chart, special food, small toy or money. Monitoring was defined as parental supervision and knowledge of the child’s whereabouts when the child is out of the parents’ sight, including knowing the child’s friends.

| Instrument | Construct | Original subscales |

|---|---|---|

| PS | Monitoring (one item) | Items was an extra item for the total score on the PS and was not part of any subscale |

| PaPI | Praise (two items) | Items are part of ‘praise and incentives’ subscale |

| Tangible reward (four items) | Items are part of ‘praise and incentives’ subscale | |

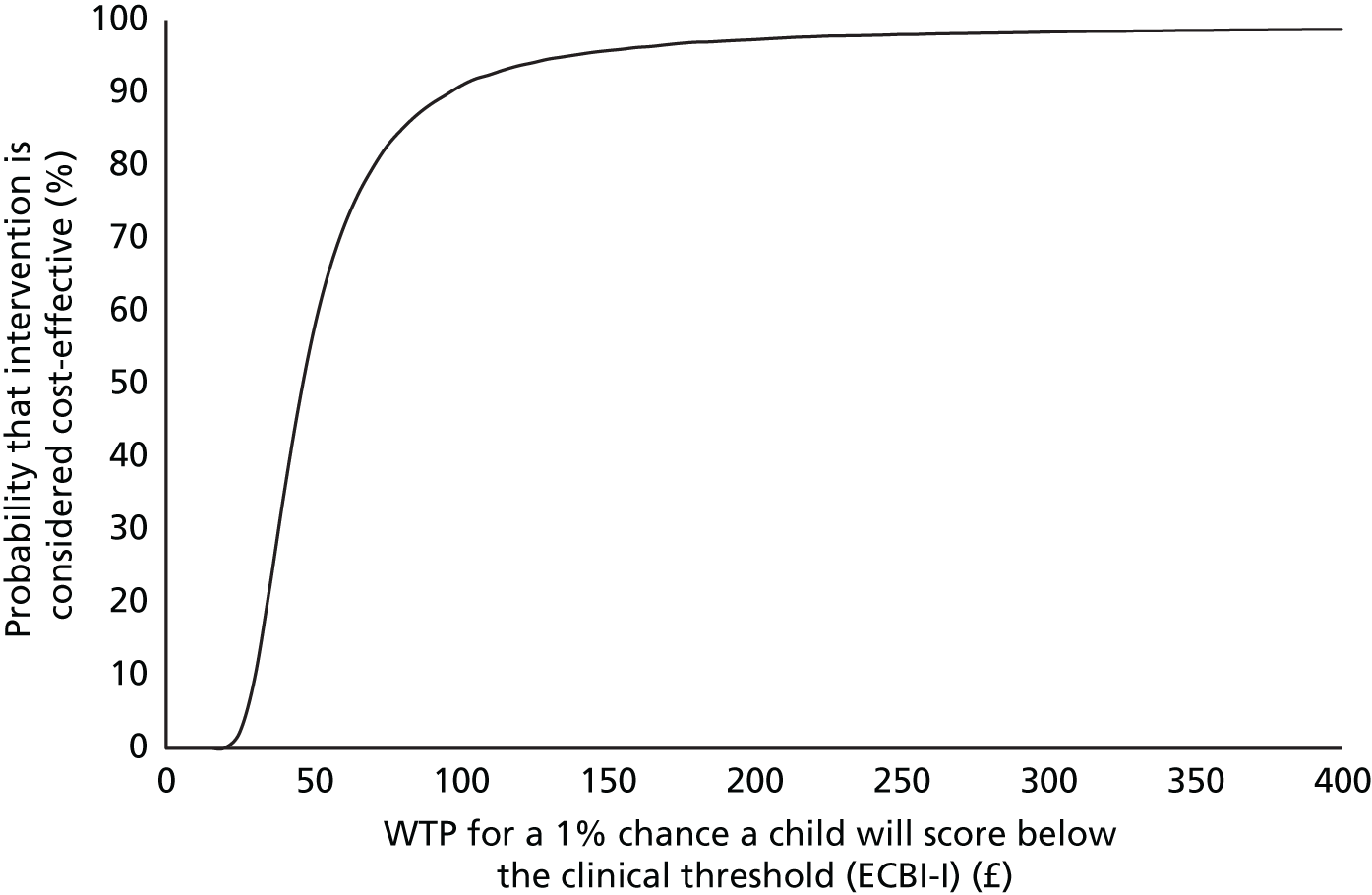

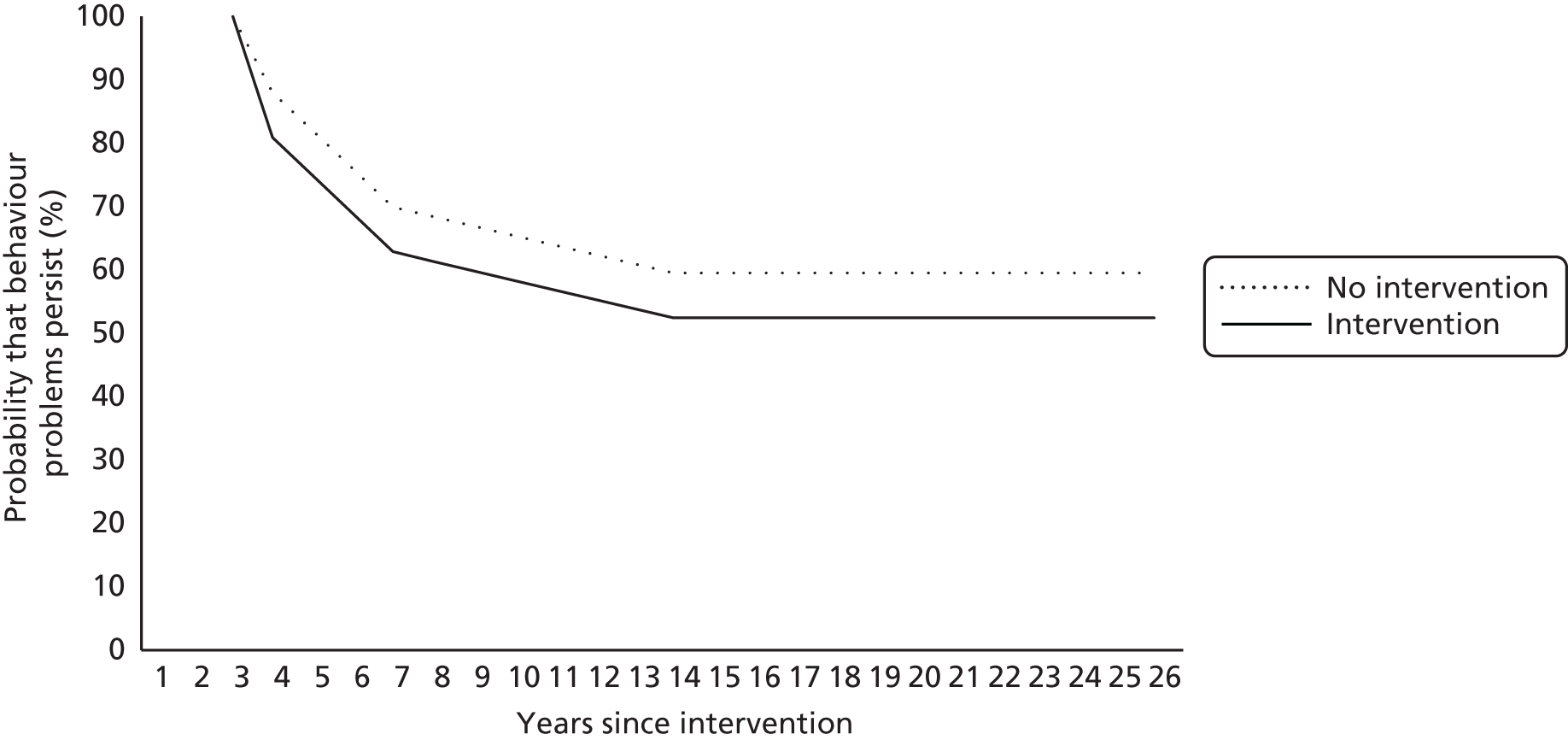

| Monitoring (five items) | Items are part of the ‘monitoring’ subscale | |