Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/3090/05. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Kenning et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Background

Despite relatively high levels of employment among working-age adults in the UK, there is still a significant minority who are off work with ill health at any one time (so-called ‘sickness absence’). Figures for the UK show that 131 million days were lost as a result of sickness absences in 2013. 1 Although this is down from around 175 million days before the turn of the century,2 sickness absence still has huge economic implications.

More than 2.5 million people claim health-related benefits (Incapacity Benefit and Employment and Support Allowance – 2013/14 data), costing the government £12B a year. 3 Furthermore, employers pay around £9B per year in sick pay and associated costs. 3

Office for National Statistics figures show that, in 2013, minor illness (e.g. colds and coughs) accounted for around 27.4 million days lost, typically short-duration absences. The greatest numbers of days lost were attributable to musculoskeletal problems (30.6 million days of work lost) and mental health problems such as stress, depression and anxiety (15.2 million days of work lost). 1 Although most absences are of 4 weeks or less, many absences last longer than they need to, and every year over 300,000 people fall out of work and claim health-related state benefits. 3

People with long-term health conditions can and do work. Around one-quarter of the 28 million people in work in the UK have a long-term condition. 3 Employees who suffer significant periods of sickness absence are at increased risk of longer-term problems, with profound implications for their long-term health, wealth and social inclusion.

Policy and current initiatives

Dame Carol Black’s 2008 review of the health of Britain’s working-age population, Working for a Healthier Tomorrow,2 cast light on the scale and impact of sickness absence on the economy, as well as the personal impact on individuals. The report outlined the changes in attitudes to work and health that were required to manage the problem of sickness absence more effectively, and the organisational and service delivery challenges that such changes would be likely to introduce. 2

The report also listed a number of key priorities for the government. One of the recommendations from this review was the introduction of a new service to offer support for people in the early stages of sickness absence. Funded by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department of Health, a proof-of-concept pilot study was set up in 11 localities across the UK to test different locally determined models for delivering services to help employees to return to work. These were known as Fit for Work (FFW) services and the pilot ran from 2010 until 2013. The results of the pilot study were published by the DWP in June 2015. 4

In all pilots, the client journey included five separate stages, but practice at each stage varied from site to site. The stages were (1) referral, (2) screening, (3) assessment and case management, (4) support and (5) discharge.

Although not intended to be rolled out nationally, models of best practice from the pilot study were used to inform the implementation of the new national independent health and work advice and referral service (also named the FFW service) launched at the end of 2014.

Another recommendation from the Black review2 was the need to focus on the benefits of work for health and on getting away from the notion that a person needs to be 100% fit to work. Replacing the old ‘sick note’ system with a new ‘fit note’ system in 2010 was intended to encourage general practitioners (GPs) to include advice on how a person ‘may be fit’ to work with reasonable workplace adjustments.

Recommended by the Black–Frost review,3 the FFW scheme is a new independent assessment and advisory service aimed at getting people back to work and away from long-term sickness benefits. It is proposed that the scheme will save employers up to £160M a year in statutory sick pay and increase economic output by up to £900M a year. 5 Currently, only 10% of employees in small firms have access to an occupational health (OH) service, compared with more than half of staff in larger firms. The new service will enable employers of all sizes to access expert advice to help them manage sickness absence in the workplace.

Current evidence on return-to-work interventions

Research into the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs) commissioned by the British Occupational Health Research Foundation6 (BOHRF) concluded that there was a lack of evidence about the clinical effectiveness of EAPs. Despite the prevalence of EAPs, no studies were found that could empirically demonstrate that EAPs were more effective than no intervention on a range of outcomes, including sickness absence. However, EAPs have continued to be used, and a more recent review by Mellor-Clark et al. 7 provides some evidence towards the efficacy of these programmes. Looking at clinical improvement, the study included a data sample of 17,520 clients. For all clients with valid pre–post therapy Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) data, the mean pre-therapy clinical score was 17.40 [standard deviation (SD) 6.01] and the mean post-therapy clinical score was 8.80 (SD 6.09) (pre–post effect size 1.43). The results provide some evidence that EAP counselling provision may be an effective intervention for employees experiencing common mental health problems. However, this was a retrospective observational study with no comparator, so we cannot be sure how much of the observed effect was as a result of the intervention.

A review of long-term sickness absence interventions conducted for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)8 to support public health guidance in this area identified 45 evaluations of the effectiveness of interventions, targeting mainly musculoskeletal interventions. The evidence base was heterogeneous but identified three intervention strategies that merited further investigation: early intervention, multifaceted approaches and interventions with a workplace component. Economic modelling based on this review found that any intervention which returns at least an additional 3% of employees to work and costs less than an additional £3000 per employee is likely to be considered economically attractive compared with usual care, relative to other interventions routinely funded by the NHS. 9

A further review of the evidence for workplace involvement on return-to-work rates following long-term sickness absence10 found that only a particular type of workplace involvement intervention was consistent in achieving positive return-to-work results. The evidence was limited to employees with back pain and found that active, structured consultation among employee, employer and OH practitioners, and agreements regarding subsequent, appropriate work modifications, appear to be more effective at helping employees on long-term sickness absence to return to work than those interventions which lack such components. 11 This type of intervention was also more cost-effective than other workplace-linked interventions, including exercise. These findings are further confirmed in other reviews focusing on the characteristics of successful return-to-work interventions that highlight the importance of early intervention (i.e. in the first 6 weeks of absence) and the use of multifaceted interventions (particularly those including a workplace consultation component). 12,13

A report on vocational rehabilitation suggested that a variety of responses were required to better manage different patterns of workplace absence and the needs of different groups. Simple, low-cost workplace interventions might be sufficient for those with short-term absence, with effective vocational rehabilitation programmes combining health and occupational assistance for those with longer-term absences. 14 The delivery of a range of interventions of different intensity according to need echoes the adoption of ‘stepped-care’ services in the NHS to manage some long-term conditions, including depression. 15 The report also highlighted the need for systematic adoption of ‘basic principles’ related to the management of these problems, irrespective of whether they were work related or comparable health conditions. 14 However, the significant challenges associated with effective implementation of such principles in routine practice were also highlighted.

Since the current study began there have been a number of new reports published in this area. A review by Nieuwenhuijsen et al. 16 focused on return-to-work interventions for people with depression. The authors reported that adding a work-directed intervention to a clinical intervention reduced the number of days on sick leave compared with a clinical intervention alone [effect size –0.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.66 to –0.14]. Another Cochrane review, by van Vilsteren et al. ,17 assessed the impact of workplace interventions compared with usual-care or clinical interventions. They reported that workplace interventions reduce time to first return to work (hazard ratio 1.55, 95% CI 1.20 to 2.01), and that workplace interventions reduce the cumulative duration of sickness absence (–33.33 days, 95% CI –49.54 to –17.12 days). However, the authors also reported a single study demonstrating that workplace interventions increased recurrences of sick leave (hazard ratio 0.42, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.82).

Current approaches to the management of people with long-term conditions

The call for adoption of core ‘basic principles’ is in line with current thinking in chronic disease (or ‘long-term condition’) management in health care. 18,19 There has been significant development in our understanding of the nature of long-term conditions. It is widely acknowledged that many long-term conditions raise common challenges for patients, and that the organisational and therapeutic interventions required involve the following common elements:

-

individualised assessment of behaviour

-

collaborative goal-setting

-

skills enhancement

-

proactive follow-up

-

self-management support for healthy behaviour change

-

access to resources. 6

As noted previously, the bulk of long-term sickness absence relates to musculoskeletal or mental health problems, and both of these areas have proven themselves amenable to adoption of these ‘basic principles’. 20,21 Depression and distress are common features of long-term sickness absence. The application of the principles of chronic disease management in depression has been demonstrated through the literature on so-called ‘collaborative care’ models. 22–24

Historically, conventional approaches to depression were oriented to the management of depression as an acute problem, where patients seek help when they deem it necessary, and professionals respond to those patients seeking help. 25,26 However, depression is a disorder that results in low motivation to seek, and adhere to, care, and services that respond only to patient presentations are unlikely to be optimal for managing depression in the community. 27 The full range of interventions employed in collaborative care models varies but generally includes education of primary care professionals (through short courses and provision of clinical guidelines), systematic screening to identify depression in the wider population, enhanced patient education and self-management support, and consultation between specialist and primary care provider to ensure that specialist and generalist approaches to management are aligned (a health-care analogue of the ‘workplace consultation’ identified in earlier reviews). However, a critical component is ‘case management’. Case management involves specific professionals taking responsibility for the assessment, support and follow-up of individual patients in an integrated and proactive fashion. 28

Given that the problems faced by employees on long-term sickness absence are likely to involve a complex mix of physical and psychological symptoms, this suggests that the broad ‘collaborative care’ model could be highly relevant to this population.

Collaborative care in occupational health

Although chronic disease management models and collaborative care for depression were developed in health settings, there is evidence for the relevance of these models in an OH context. Vlasveld et al. 29 developed a version of collaborative care including many of the conventional elements described above (6–12 sessions of problem-solving treatment, manual-guided self-help, and antidepressant management monitored by an occupational case manager and supported by a mental health specialist). The programme also included elements specific to the OH context, including workplace assessments and adjustments, with the case manager mediating between employee and employer. The study randomised 126 patients with depression to either collaborative care or usual care, and reported a significant difference between four groups in the proportion of clients achieving a 50% reduction in depression symptoms (50% in the collaborative care group and 28% in the usual-care group; odds ratio 2.50, 95% CI 1.04 to 6.10). However, there was less evidence of benefit in measures of return to work. 30

A second trial recruited 604 workers from diverse sectors of the US economy, and randomised them to a telephone-led case management programme or usual care (which included encouragement to enter existing treatment programmes). Case management included brief interventions direct from the case manager for patients who refused to seek help elsewhere, including eight sessions of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for those with persistent symptoms. 31 The results showed improvements in depression as a result of case management interventions similar in magnitude to existing evidence on collaborative care (approximately one-third of a SD), and better rates of recovery (31% vs. 21%) at 12 months. Patients in case management also reported two additional hours of work per week (approximately 2 weeks of additional work over a 12-month period). The potential of collaborative care models in OH has been demonstrated, but the case is far from proven. It is unclear whether or not these models will generalise to a UK OH context and whether or not the benefits found in patients with diagnosed depression will generalise to a broader mix of problems reported by employees currently on long-term sickness absence. A definitive trial of the potential of these models in the OH setting in the UK is thus indicated. The FFW pilot scheme also adopted a collaborative care model, the results of which were published during the course of this research. The findings are discussed later (see Chapter 5) in comparison with our own findings.

Summary

It is evident from the literature that employees who suffer significant periods of sickness absence are at increased risk of longer-term problems, with profound implications for their long-term health, wealth and social inclusion. Long-term absences also result in considerable financial implications for the government and for employers.

The body of evidence for intervention with people on or entering long-term sickness absence is growing, but results appear mixed. There is good evidence for collaborative care models in the care for long-term conditions and, as stated previously, around 25% of the working population currently have long-term conditions. Collaborative care in an OH setting has been trialled in the Netherlands and the USA, but a definitive trial has not taken place in the UK, which has a markedly different system.

Bringing this literature together, this study aims to adapt a collaborative care model for use in OH and conduct a pilot study to see how it might work in this setting. The pilot study will determine if it is feasible to recruit and deliver the new model to working adults on longer-term sickness absence and if it is acceptable to both employees and employers.

Research objectives

Phase 1: development

-

Adapt a collaborative case management intervention to the needs of UK employees, in a range of occupations and organisations, who are entering or experiencing long-term sickness absence.

Phase 2: internal pilot

-

Conduct a pilot study to test:

-

recruitment of employees on long-term sickness absence to a trial

-

delivery of the intervention in an OH setting

-

adherence and acceptability among employees on long-term sickness absence

-

appropriateness of inclusion criteria and outcome measures

-

evaluation of the rate of return to work in those receiving a collaborative case management intervention compared with those receiving care as usual.

-

Chapter 2 Phase 1

This chapter describes phase 1 (development), which was conducted to meet the objective of adapting a collaborative case management intervention to the needs of UK employees, in a range of occupations and organisations, who are entering or experiencing long-term sickness absence.

Scoping review

First, a scoping review was conducted to see what could be learned from previous trials. A database search was carried out using OVID and searching the following databases: CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials), MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO.

Search terms: the following broad search terms, key words and BOOLEAN operators were used in the searches: case management, collaborative care, co-ordinated care, collaboration, multidisciplinary care, employees, OH, workplace interventions, sickness absence, sick leave, return to work and absenteeism.

Suitable studies were selected and data extracted on methods, results and, in particular, on barriers to, and limitations of, the research.

The review looked at key existing research in three areas:

-

OH-based interventions that were not case management

-

case management interventions that were not based in OH

-

case management interventions that were based in OH.

Similarities and differences from the identified trials were considered. Key points were identified from the literature and discussed in relation to the content and delivery of an intervention.

Expert consultation

Second, a full trial meeting was held with all co-applicants and collaborators, with patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) input. The results of the review were presented to the group along with the existing intervention model that we proposed using. These were then discussed by the group to see how the model might need amending to better fit an occupational setting, and how to best set up and run the trial in light of the findings and expertise of those in the group.

Development of materials

Following the initial work, we developed materials for the intervention, including the intervention manual and case manager training.

Manual development

Following the meeting, the existing case management intervention was adapted to focus more on work issues and to include the option for workplace facilitation. Example case studies were written, in consultation with the FFW team, as real-life stories for the manual to help participants engage in the intervention. The manual was designed and sent to our PPIE representative for their feedback, and then amended where needed. A copy of the finalised manual can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Case manager training

To support case managers, a 2-day training course was developed that introduced the principles of case management and provided training in the brief psychological interventions employed in the patient manual. The case managers took part in role play sessions to aid learning and were encouraged to ask questions. The course was based on similar courses run by applicant Karina Lovell for other trials,32 but was modified appropriately.

As well as training in the intervention, case managers also received training delivered by the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre Clinical Trials Units (MAHSC-CTU) (www.mahsc-ctu.co.uk/) in the trial methods and reporting procedures, and also completed Good Clinical Practice (GCP) training.

Summary of the results of the review

Occupational health-based interventions that were not case management

The studies carried out in OH settings33–40 were heterogeneous. They encompassed a wide range of interventions from psychological interventions, problem-solving and return on reduced hours, to interventions with occupational physicians and adherence to guidelines. The interventions were also aimed at a wide range of participants: some were sick-listed, some had recently returned from sickness absence, and other interventions were preventative and, therefore, not targeted to those on sickness absence. The index condition tended to be specific and aimed at common mental disorders or musculoskeletal disorders, with no studies targeting both, or other, conditions. Trial outcomes in those studies with sick-listed participants tended to focus on time to return to work, number of days’ absence and quality-of-life measures (Table 1).

| First author and date of publication | Title | Intervention | Sample | Outcome/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arends et al., 201433 | Prevention of recurrent sickness absence in workers with common mental disorders: results of a cluster-randomised controlled trial | Problem-solving intervention vs. usual care | 80 workers recently returned to work after sickness absence for CMDs | Incidence of recurrent sickness absence. Adjusted OR of 0.4 (95% CI 0.2 to 0.8) TG compared with control |

| Delivered by physicians | The Netherlands | Time to absence: adjusted hazard ratio of 0.53 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.86); TG compared with control | ||

| Aelfers et al., 2013;34 protocol only | Effectiveness of a minimal psychological intervention to reduce mild to moderate depression and chronic fatigue in a working population: the design of a randomized controlled trial | Over 4 months patients receive between 1 and 10 sessions | 124 workers with chronic mental fatigue or mild to moderate depression | Primary outcome: symptom measures; secondary outcomes: sickness absence, quality of life |

| Intervention: teaches workers to take responsibility for the day-to-day management of problems | The Netherlands | Protocol | ||

| Trained occupational nurse | ||||

| Feicht et al., 201335 | Evaluation of a 7-week web-based happiness training to improve psychological well-being, reduce stress, and enhance mindfulness and flourishing: a randomised controlled occupational health study | Web-based happiness training | 147 out of 1050 employees (15%) volunteered (not sick-listed) | Happiness (d = 0.93), satisfaction (d = 1.17) and quality of life (d = 1.06) improved; perceived stress was reduced (d = 0.64); mindfulness (d = 0.62), flourishing (d = 0.63) and recovery experience (d = 0.42) also increased significantly |

| Germany | ||||

| van Beurden et al., 2013;36 protocol only | Effectiveness of guideline-based care by occupational physicians on the return to work of workers with common mental disorders: design of a cluster-randomised controlled trial | Guideline-based training to improve occupational physicians’ understanding of and adherence to the national guidelines | 232 sick-listed workers with CMD | Protocol but primary outcome will be full RTW. Secondary: partial RTW, number of sick leave days, symptoms and work ability |

| The Netherlands | ||||

| Linden et al., 201437 | Reduction of sickness absence by an occupational health care management program focusing on self-efficacy and self-management | OHMP to improve the health status of employees, increase work ability and reduce absence time | Not clear | Rate of sickness absence in the intervention group decreased from 9.26% in the year before the OHMP to 7.93% in the year after the programme |

| Germany | ||||

| Rantonen et al., 201238 | The effectiveness of two active interventions compared to self-care advice in employees with non-acute low back symptoms: a randomised, controlled trial with a 4-year follow-up in the occupational health setting | Three groups: rehabilitation, exercise or self-care | 143 employees with LBP | Among employees with relatively mild LBP, both interventions reduced pain, but the effects on sickness absence and physical impairment were minor |

| Occupational physician | Finland | |||

| Lagerveld et al., 201239 | Work-focused treatment of common mental disorders and return to work: a comparative outcome study | Work-focused CBT vs. CBT | 208 workers on sick leave for CMD (168 included in analysis) | Duration to RTW. Full RTW occurred 65 days earlier for TG, partial RTW occurred 12 days earlier in TG |

| Delivered by psychotherapists | The Netherlands | |||

| Viikari-Juntura et al., 201240 | Return to work after early part-time sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders: a randomized controlled trial | Randomised to part- or full-time sick leave (workload and work time reduced by about 50%) | 63 workers with MSDs and unable to perform regular work | Time to return to regular work > 4 weeks: shorter in part-time sick leave group (12 days vs. 20 days) |

Case care interventions that were not based in occupational health settings

The majority of collaborative care trials have been carried out in a health-care setting and they tend to be targeted at depression and anxiety disorders32,41–48 (Table 2). Accordingly, most outcomes were condition-specific measures. Although some looked at impact on disability and function, none reported on work-related outcomes.

| First author and date of publication | Title | Intervention | Sample | Outcome/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coventry et al., 2015;32 | Integrated primary care for patients with mental and physical multimorbidity: cluster randomised controlled trial of collaborative care for patients with depression or comorbid with diabetes or cardiovascular disease | Collaborative care that included patient preference for behavioural activation, cognitive restructuring, graded exposure, and/or lifestyle advice, medication management and relapse prevention | 387 primary care patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease and depressive symptoms | Mean depressive scores were 0.23 SCL-D13 points lower (95% CI –0.41 to –0.05 points) in the collaborative care arm, equal to an adjusted standardised effect size of 0.30 |

| Delivered by IAPT workers | UK | |||

| Stewart et al., 201441 | Effect of collaborative care for depression on risk of cardiovascular events: data from the IMPACT randomized controlled trial | IMPACT: collaborative care programme involving antidepressants and psychotherapy | 235 primary care patients with depression or dysthymia with or without CVD (119 with) | Treatment × baseline CVD = significant interaction (p = 0.21). TG patients without CVD had a 48% lower risk of an event than UC |

| USA | ||||

| Von Korff et al., 2011 42 | Functional outcomes of multicondition collaborative care and successful ageing: results of randomised trial | TEAMcare: integrated treat to target programme | 214 patients with diabetes, CHD or both, and moderate depression (88% completed all six sessions) | Improvements from baseline on the Sheehan Disability Scale (−0.9, 95% CI −1.5 to −0.2; p = 0.006) and global quality-of-life rating (0.7, 95% CI 0.2 to 1.2; p = 0.005) were significantly greater at 6 and 12 months in patients in the intervention group |

| Intervention nurses and primary care physicians | USA | |||

| Richards et al., 201343 | Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): cluster randomised controlled trial | Collaborative care including depression education, drug management, behavioural activation, relapse prevention and primary care liaison delivered by case managers | 581 primary care patients with depression | After adjustment for baseline depression, mean depression score was 1.33 PHQ-9 points lower (95% CI 0.35 to 2.31 PHQ-9 points; p = 0.009) in participants receiving collaborative care than in those receiving UC at 4 months, and 1.36 PHQ-9 points lower (95% CI 0.07 to 2.64 PHQ-9 points; p = 0.04) at 12 months |

| UK | ||||

| Fortney et al., 201344 | Practice-based versus telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression in rural federally qualified health centres: a pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness trial | Practice-based collaborative care delivered by on-site primary care provider and nurse care manager | 364 patients with depression | Significant group main effects were observed for both response (OR 7.74, 95% CI 3.94 to 15.20) and remission (OR 12.69, 95% CI 4.81 to 33.46) |

| USA | ||||

| Muntingh et al., 201445 | Effectiveness of collaborative stepped care for anxiety disorders in primary care: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial | Collaborative stepped care (CSC) including guided self-help, CBT and antidepressants | 180 patients with panic disorder or generalised anxiety disorder | On the BAI, CSC was superior to CAU (difference in gain scores from baseline to 3 months: –5.11, 95% CI –8.28 to –1.94; 6 months: –4.65, 95% CI –7.93 to –1.38; 9 months: –5.67, 95% CI –8.97 to –2.36; 12 months: –6.84, 95% CI –10.13 to –3.55) |

| Care managers – 31 psychiatric nurses | The Netherlands | |||

| Oosterbaan et al., 201346 | Collaborative stepped care vs. care as usual for common mental disorders: 8-month, cluster randomised controlled trial | Collaborative stepped care | 163 patients with CMD | At 4-month mid-test CSC was superior to CAU: 74.7% (n = 68) vs. 50.8% (n = 31) responders (p = 0.003). At the 8-month post test and the 12-month follow-up no significant differences were found |

| GPs and psychiatric nurses | Holland | |||

| Morgan et al., 201347 | The TrueBlue model of collaborative care using practice nurses as case managers for depression alongside diabetes or heart disease: a randomised trial | Nurse-led collaborative care model for depression in patients with diabetes or heart disease | 400 patients with depression, diabetes and CHD | Mean depression scores after 6 months of intervention for patients with moderate to severe depression decreased by 5.7 ± 1.3 points compared with 4.3 ± 1.2 points in control, a significant (p = 0.012) difference |

| Australia | ||||

| Huijbregts et al., 201348 | A target-driven collaborative care model for Major Depressive Disorder is effective in primary care in the Netherlands. A randomized clinical trial from the depression initiative | Web-based tracking and decision aid system that advised targeted treatment actions | 93 patients with major depression | CC more effective on achieving treatment response at 3 months (OR 5.20, 95% CI 1.41 to 16.09; NNT 2) and at 9 months (OR 5.60, 95% CI 1.40 to 22.58; NNT 3). Not statistically significant at 6 and 12 months |

| The Netherlands |

Case management interventions that were based in occupational health

There have been a of number collaborative care interventions carried out in OH settings, although none in the UK30,31,49–54 (Table 3). Interventions were generally targeted at specific conditions, including mental health problems such as depression30,31,49 or musculoskeletal disorders. 51–53 One study focused on women after gynaecological surgery50 and one study included people with a range of conditions. 54 Return to work was the primary outcome in most studies except for Vlasveld et al., which had clinical outcomes. 30 Content of the interventions varied but often incorporated a brief psychological intervention along with medical intervention and, in some cases, workplace intervention.

| First author and date of publication | Title | Intervention | Sample | Outcome/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vlasveld et al., 201330 | Collaborative care for sick-listed workers with major depressive disorder: a randomised controlled trial from the Netherlands depression initiative aimed at return to work and depressive symptoms | Collaborative care provided by OP. 6–12 sessions: problem-solving, self-help, workplace intervention, antidepressant medications (optional) | 126 sick-listed workers with MDD (4–12 weeks’ absence) | Outcome: depression response (reduction of symptoms by 50%) |

| The Netherlands | Shorter time to response by 2.8 months in TG. No difference in remission or RTW | |||

| Volker et al., 201349 | Blended E-health module on return to work embedded in collaborative OH care for common mental disorders: design of a cluster randomized controlled trial | E-health intervention (decision aid for OP and personalised modules for points) delivered as part of a collaborative care programme | 200 workers with common mental disorders (4–26 weeks’ absence) | Study protocol only |

| The Netherlands | Primary outcome = RTW | |||

| Vonk Noordegraaf et al., 201450 | A personalised eHealth programme reduces the duration until return to work after gynaecological surgery: results of a multicentre randomised trial | Described as multidisciplinary but not sure there is a case manager? | 215 women who had gynaecological surgery Secondary care |

Primary = RTW |

| The Netherlands | Mean 39 days TG, 48 days control | |||

| Jensen et al., 201151 | One-year follow-up in employees sick-listed because of low back pain: randomized clinical trial comparing multidisciplinary and brief intervention | Case management; one or more sessions depending on progress: tailored rehabilitation plan | 351 participants with LBP (3–16 weeks’ absence) | RTW achieved in 71% multidisciplinary intervention, 76% in brief intervention |

| Control = clinical examination, reassurance treatment and rehabilitation by GP | Denmark | |||

| Jensen et al., 201252 | Sustainability of return to work in sick-listed employees with low-back pain. Two-year follow-up in a randomised clinical trial comparing multidisciplinary and brief intervention | As above | As above: 2-year follow-up | 1 year RTW: multidisiplinary intervention, 61%; brief intervention, 66% |

| Denmark | 2 years RTW: multidisiplinary intervention, 58%; brief intervention, 61% | |||

| van Beurden et al., 201253 | A participatory return-to-work program for temporary agency workers and unemployed workers sick-listed due to musculoskeletal disorders: a process evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial | Stepwise process guided by independent RTW co-ordinator | 79 sick listed as a result of musculoskeletal disorders | Satisfaction with RTW co-ordinator; barriers: administrative time investment, no clear information about programme |

| Feasibility study | The Netherlands | |||

| Martin et al., 201354 | Effectiveness of a coordinated and tailored return-to-work intervention for sickness absence beneficiaries with mental health problems | Co-ordinated and tailored RTW programme vs. conventional case management | 196 sick-listed workers (not employed – job centre intervention) | Time to RTW |

| Denmark | CRW: returned slower than CCM | |||

| Wang et al., 2007 31 | Telephone screening, outreach and care management for depressed workers and impact on clinical and work productivity outcomes | Telephone-delivered case management | 604 workers (not sick-listed) with evidence of depression and psychological distress | TG had significantly higher job retention, more hours worked and lower QIDS score (relative odds of recovery) |

| Master degree-level mental health clinicians | USA |

The majority of studies reported positive outcomes for the intervention group compared with control. However, two studies51,52,54 did not report improvement in primary outcomes for the intervention groups. Martin et al. 54 compared a co-ordinated and tailored return-to-work (CTRW) intervention to conventional case management, and reported that people in the conventional case management group returned to work more quickly than those in the treatment group. It may have been that, as the CTRW intervention was more in-depth, it took longer for employees to work through the different aspects of the intervention and return to work. It may have been useful if data had been collected on recurrent sickness absence in the groups to see if the CTRW intervention resulted in slower return to work but affected further sickness absence. The second study51,52 also showed slower return to work in the treatment group at both the 1- and 2-year follow-ups. The case management intervention in the Jensen et al. 52 trial did not include workplace intervention or any liaison between the employer and employees, which may have affected return-to-work rates.

These case management trials had many elements in common, such as consensus-based care plans and access to brief interventions such as problem-solving, self-help, pain management and brief psychotherapy. Not all interventions included a fully collaborative model including the employee, a general practitioner (GP)/occupational physician, employer and case manager. Another key point for many of the trials was the low adherence to the intervention by participants.

The key findings from the review are summarised in Box 1.

-

Participants: length of sickness absence varied but tended to be relatively short, with most between 2 and 12 weeks. Only one trial49 included employees absent for a longer period, and then only up to 26 weeks of absence.

-

Intervention: access to brief interventions such as problem-solving, self-help, pain management and psychotherapy was common but not all had a workplace component. Those that did include a workplace component identified it as a key aspect of the intervention.

-

Most studies agreed on the need for consensus-based action/care plans, making the intervention patient centred, and that the employee should be involved in all discussions about their health and capacity for work.

-

Many reported low adherence to intervention by participants.

-

Most trials focused on specific conditions, such as ‘common mental disorders’ or musculoskeletal disorders, but were not inclusive of both.

Developing the intervention

Phase 1 suggested several key aspects to the intervention. These constituted the need for:

-

an intervention that addresses multiple needs, supported by medical intervention where necessary

-

patient-centred assessments and care plans

-

a workplace component to the intervention

-

signposting to other services and support

-

interaction between employee, case manager, employer and GP/occupational physician.

The review and discussion from the meeting suggested the need for a three-component intervention that addresses multiple needs, supported by medical intervention where necessary. In usual care there may be little interaction between those involved in helping an employee return to work. The patient will have contact with their GP and/or an OH physician if their employer provides OH support. Other than producing a fit note, the GP will not have contact with the employer and, as a result of the format of the fit note, may not even know what their patient’s job role is. If the employer has OH support, then there may be interaction with the employer.

The usual sickness absence relationships are presented figuratively in Figure 1. A new model, based on that used in case management, was further adapted to include the workplace in the relationships (Figure 2). The model describes a cyclical route with the employee/patient at the centre, with co-ordinated contact and support provided by a case manager. As a cyclical model, other agencies or other support services could also be incorporated in it, for example if an occupational physician is employed by the employer.

FIGURE 1.

Usual sickness absence relationships.

FIGURE 2.

Collaborative care relationships.

As well as altering the usual sickness absence care relationships, the intervention aimed to improve employee feelings of well-being and to support return to work. A collaborative care approach was developed, comprising a client-centred approach including partnership working and proactive follow-up with integrated communication and care between the case manager, client, GP and employer.

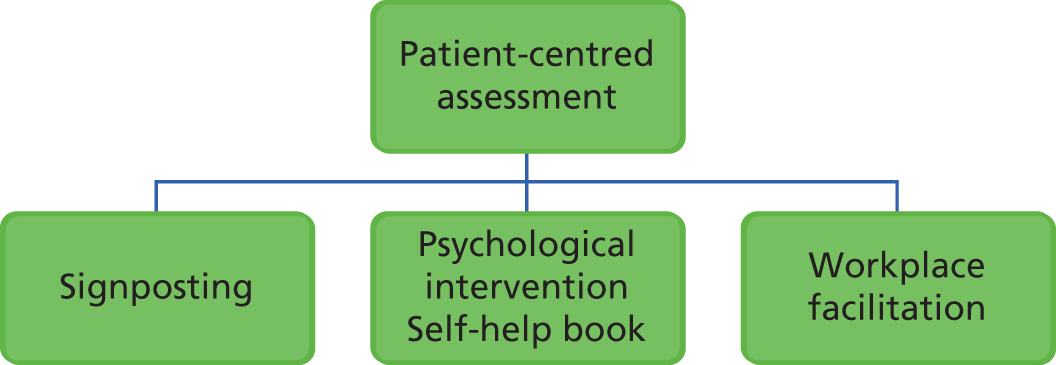

Adapted from an existing psychological intervention trialled previously in primary care, the intervention is client-defined and goal-orientated to improve mental and physical health outcomes. Within this framework, each employee is offered a client-centred assessment followed by a choice of intervention(s) including the psychological intervention, signposting and/or workplace facilitation (Figure 3).

-

Psychological interventions based on brief CBT interventions including behavioural activation and cognitive restructuring. The format is guided self-help, supported by a self-help client manual and telephone sessions with a case manager.

-

Workplace facilitation involving negotiation with the employer about workplace adjustments to assist the employee returning to work.

-

Signposting: providing information or encouraging employees to contact local/national agencies to help in other areas of their lives (e.g. debt advice, domestic violence services, self-help groups, health- or social-care services).

FIGURE 3.

Intervention model.

Intervention delivery

The intervention was to be delivered by a case manager specially trained for the trial and with specialist supervision. Case managers were provided with a therapist manual to support intervention delivery and adherence to the model (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

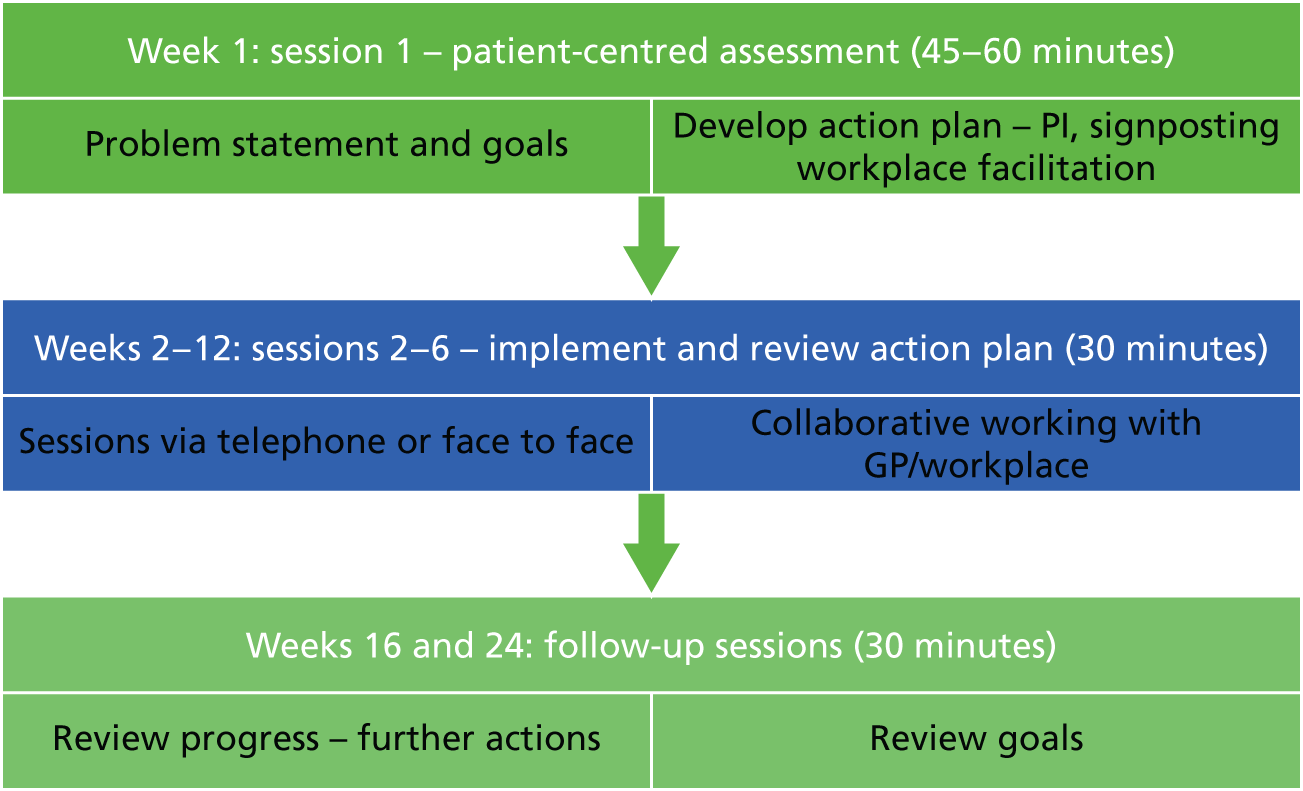

Participants would receive up to six telephone sessions with their assigned case manager, delivered over a 12-week period, with two follow-up sessions, at weeks 16 and 24, to check on progress (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Overview of the intervention sessions. PI, psychological intervention.

Case managers

The case managers were recruited from existing advisors at the two collaborating sites. Two were recruited from the OH provider site to deliver the intervention to trial participants for their customers, and one from FFW. We had intended to have at least two from each site to share the workload and to provide cover for annual leave or staff changes, but FFW was not able to facilitate this as it was a small team and they did not think it was necessary with the small number of cases (10) that they would be assigned.

All case managers attended an initial 2-day training course developed and delivered by applicant Karina Lovell. The training included an overview of collaborative care and specific sections on key psychological principles. The case managers took part in activities and role-playing sessions to facilitate their understanding. During these sessions, they were encouraged to ask questions and to reflect on aspects that were the same as, or different from, their current roles. Case managers were given copies of the therapist manual (see Report Supplementary Material 2) to support them, as well as the client manual (see Report Supplementary Material 1) so that they could support participants in using it.

Supervision

Case managers received supervision from applicant Karina Lovell. Sessions were delivered individually by telephone approximately every 2 weeks for around 15–30 minutes, dependent on the number of cases being managed by case managers. Supervision consisted of discussing problem summaries and goals, discussing selection and application of interventions, and problem-solving any difficulties or barriers that clients or case managers faced.

Chapter 3 Phase 2

In this chapter we present the methods for the second objective: to conduct a pilot study to assess feasibility for a full-scale trial and the acceptability of the newly developed intervention.

Internal pilot objectives

Conduct a pilot study to test:

-

recruitment of employees on long-term sickness absence to a trial

-

delivery of the intervention in an OH setting

-

adherence and acceptability among employees on long-term sickness absence

-

appropriateness of inclusion criteria and outcome measures

-

evaluation of the rate of return to work in those receiving the intervention.

Trial methods

The protocol for the pilot study was developed with input from the research team, the PPIE representative, MAHSC-CTU and the collaborating sites.

Design

The study was a two-arm randomised controlled trial evaluating a collaborative case management intervention for employees who have been on long-term sickness absence. The collaborative care intervention was delivered by existing OH staff with supervision from the research team.

Setting

The study was carried out with two partner organisations. One of our partners (OH provider) had links with several large commercial organisations with approximately 250,000 clients and up to 2000 new referrals per month. To access small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs – with 250 or fewer employees), our other partner organisation was Leicester FFW.

Recruitment of sites: OH provider

Existing customers of the OH provider were approached and given information on the trial by the company, and were offered a consultation with the research team to explain the aims and methods of the trial in further detail. We aimed to recruit at least two large private or public sector companies.

Recruitment of sites: Fit for Work

As the FFW team currently utilises a similar case management approach for people in Leicestershire, but not in Leicester city (as a result of funding boundaries), it was decided that recruiting from Leicester city would provide a better context with less potential for contamination.

As FFW did not currently operate in the city, identification of people on long-term sickness absence was done through GPs in the area. Support costs were provided by East Midlands Clinical Research Network (CRN) to recruit up to 15 GP practices to conduct mail shots to eligible patients identified through fit notes.

Participants

Recruitment remains the major challenge to successful delivery of trials, especially in mental health,55–58 which highlights the need for the pilot.

Recruitment of patients with long-term conditions has been strongly supported by the method of screening routine records containing relevant information, followed by mass mailing of invitations to participants. 32,43,59 The proportion of patients entering the study can be low (10–30%), raising some concerns about external validity. However, this method is robust, facilitates the planning of larger trials and has been adopted by a number of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded trials in primary care. 32,43,59 The CAse Management to Enhance Occupational Support (CAMEOS) study was based on this model, and the pilot was adopted to test whether or not the model would translate to a new patient population (long-term sickness absence) and a new context (OH).

Eligibility

Employees experiencing or entering long-term sickness absence were identified using routine recording systems in their employing organisations, or through their GP. Long-term sickness absence was defined as having been off work for at least 4 weeks or being in receipt of a fit note from a GP for at least 4 weeks and up to 12 months.

Participants had to report a minimum level of baseline distress, defined as a score of 11 or more on the CORE-OM of general health and well-being. A minimum level of distress on the CORE-OM was required to ensure that there was significant room for improvement in outcomes associated with intervention.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Box 2.

-

Adults aged 18–65 years.

-

Adults who have been off work for at least 4 weeks or who have been signed off for sickness absence for at least 4 weeks and for up to 12 months.

-

Minimum baseline distress level (CORE-OM score of ≥ 11).

-

Currently attending formal psychotherapy through NHS or private services.

-

Requires palliative care.

-

Absent because of bereavement.

-

Suffering from a severe and enduring mental disorder, or at risk of suicide, and requiring immediate care.

-

In advanced stage of pregnancy (defined as > 24 weeks’ gestation).

Identification: occupational health provider

Initial identification of participants was undertaken by human resources (HR) representatives of the employer. Each month their systems were updated to flag anyone who has been absent for 21 days or more. They were asked to check the system for employees who had been off for ≥ 4 weeks to match the inclusion criteria.

Once they had the list of names, HR staff screened the list to exclude those who they did not feel were eligible, those undergoing grievance proceedings or whose employment was to be terminated. The remaining employees were sent an information pack containing a participant information sheet (PIS), consent-to-contact form and participant consent form (Appendix 1).

Identification: Fit for Work service

Initial identification of participants was undertaken by GP Patient Identification Centre (PIC) sites facilitated by the Local Clinical Research Network (LCRN). General practices that agreed to take part were asked to identify patients requiring fit notes. A basic search strategy was developed by the LCRN to be run on practice databases (Box 3), to identify potentially eligible patients. The majority of fit notes are given for short periods of around 2 weeks, and they need to be reviewed and reissued after that time. This meant that identification of patients who had been absent from work for 4 weeks or more was problematic. Furthermore, GP records do not always record employment status of patients. Letters had to be sent to all patients with fit notes and then eligibility was assessed during screening. All patients with fit notes were sent an information pack containing a recruitment pack cover, PIS, consent-to-contact form and participant consent form (Appendix 1).

-

Age – > 18 years.

-

Event location – here (including branch site).

-

Select numerics – and numeric reading of duration of sickness certificate (days) (Read code: Y1712) > = 28days (**you can use the Read code search for MED3 – doctors statement, but that will include all MED3, i.e. less than 28 days as well.)

-

Run search – GP/staff to check MED3.

Participant consent

As information packs were mailed out, participants had as much time as needed to consider participation. The information pack asked them to either contact the research team directly by telephone or e-mail or to return the consent-to-contact form along with the consent form.

Once the employee details were received, a member of the research team contacted them by telephone. Participant consent to participate in the trial was taken after a full explanation had been given, with the opportunity to ask questions in accordance with the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care (RGFHS) guidelines. 60 The right of the participant to refuse to participate in the trial without giving reasons was emphasised and respected. If they had not done so already, they were asked to sign and return the participant consent form. If the participant consented, they were assigned a non-repeatable unique identifier (Screening Log ID).

Participants from both centres were also asked to indicate on the consent form if they would be willing to be considered to take part in an interview at the end of the study exploring their thoughts on, and experiences of, the intervention.

All participant materials including the PIS, response and consent forms were edited by the PPIE representative to ensure the language was easily understandable and clear.

Screening for eligibility

Once an employee contacted the research team, with the employee’s consent, they were screened for eligibility. This was done by telephone and took around 15 minutes. The researcher completed the screening case report form (CRF), which included key demographic eligibility criteria and also included the CORE-OM.

Employees who met all of the inclusion criteria were asked if they would like to take part in the trial, and were reminded that they may be randomly assigned to either care as usual or the trial intervention.

Outcome measures

Eligible consenting participants were sent a questionnaire containing the outcome measures (Box 4). Participants were also advised that they could complete these measures by telephone with the researcher if they preferred. Participants received a £20 gift voucher to thank them for completing the baseline questionnaire.

-

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation Outcome Measure. The CORE-OM is a 34-item measure of psychological distress and comprises four dimensions: subjective well-being, symptoms, functioning and risk. 61

-

The Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) (version 2) is a brief version of the well-known SF-36 (Short Form questionnaire-36 items). The scale uses 12 questions to measure functional health and well-being over the past 4 weeks. 62

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which is a nine-item scale recording core symptoms of depression. 63

-

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) is a short, five-item measure of impairment in functioning across five domains (work, home management, social leisure, private leisure and relationships). 64

-

Self-reported actual and effective working hours quantified by the absenteeism and presenteeism questions of the World Health Organization’s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire. 65

-

Client health- and social-care utilisation was included for cost-effectiveness calculations (adapted from the Client Service Receipt Inventory). 66

-

EQ-5D-5L (EuroQol-5 Dimensions, Five-Level version) measure of health-related quality of life. The five-item scale covers mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain; and anxiety and depression. Each has five levels of severity, and the scale provides a utility value based on a population tariff. 67

-

The Bayliss measure of multimorbidity was used to assess the impact of physical symptoms and associated long-term conditions. The measure assesses the presence and impact of 22 common problems (baseline only). 68

-

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8): an eight-item assessment of client/patient satisfaction with mental health interventions (follow-up only). 69

The primary outcomes for the study were well-being and return to work. However, we collected data on a number of different measures, such as client health- and social-care utilisation (via the Client Service Receipt Inventory), although no economic analysis was planned during this pilot phase. The main function of economics in the pilot study was to explore our ability to collect relevant data.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised by the research team via a central telephone-based system provided by the MAHSC-CTU. The method of randomisation was permuted blocks within strata, with block sizes themselves varying randomly between prespecified limits. There were two stratification factors: partner organisation (OH provider, the FFW team) and baseline CORE-OM score (11–17.9, 18–23.9 and 24–40).

As a result of the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants to the arm of the trial they were in. After randomisation they were sent a letter informing them of the outcome: that they would either continue with their usual care or receive a copy of the patient manual along with an explanation that they would soon be receiving a telephone call from a case manager. As a small-scale pilot study, blinding of the single researcher involved in the study was not considered feasible.

Intervention: collaborative case management

The intervention was collaborative case management. The intervention involved core aspects of published ‘collaborative care’ models, including:

-

a 60-minute client-centred assessment

-

collaborative goal-setting (to agree on what support is needed)

-

evidence-based low-intensity interventions (such as behavioural activation, problem-solving and cognitive restructuring)

-

effective liaison and information sharing with key health-care personnel such as GPs and other primary care providers (where appropriate, and with patient consent).

These elements are central to all effective collaborative care interventions and the principles of effective chronic disease management. Following the assessment session, the intervention consisted of up to five 45-minute sessions to assess progress and solve problems that may arise in achieving their goals. To maximise the ‘reach’ of the intervention, the sessions were delivered by telephone. The intervention also involved the option for workplace facilitation, where the case manager (with client agreement) mediates between employer and employee to identify barriers to return to work. The case managers, in collaboration with the participants, were free to give the most suitable forms of interventions as described above.

Participants completing the 12-week intervention were monitored further and contacted by their case managers at 16 and 24 weeks after the start of the intervention. The case monitoring was considered part of the intervention and done through telephone calls to enquire about participant well-being and any progress made towards return to work, but no data were collected from these monitoring calls for this pilot trial.

Care as usual

The intervention was assessed against ‘care as usual’ in the organisations where we recruited. Variation in care as usual was expected, dependent on a number of factors such as reason for absence (predominantly physical, mental or work related), or whether they were receiving care mainly from primary care or through employer-provided OH packages. Although such variation in the trial reflects usual practice, data were collected about any care received during the 3-month intervention period on the follow-up questionnaire.

Follow-up measures

The outcome measures listed above were repeated, with the addition of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8), an eight-item self-administered questionnaire. Questionnaires were posted to participants at either 12 weeks (care as usual) or on completion of the intervention (treatment group). Participants were asked to complete and return the follow-up questionnaire in the pre-paid envelope provided to receive a £20 gift voucher as recompense for their time. A reminder was sent by post if the questionnaire was not returned within 2 weeks of posting.

Participants who dropped out of the intervention before 3 months were asked if they would still be willing to complete the measures and if they wanted to give a reason or take part in a short interview about why they had withdrawn from the study.

Nested qualitative study

The aim was to interview a subsample of around 20 participants who received the trial intervention to get feedback on their views and experiences of the intervention and trial participation. At the time of consent, participants were asked if they would be willing to be contacted for an interview. If they consented, a note was made and this was checked when selecting participants for interview. If they were selected, the research team then contacted them by telephone. The purpose of the interview was explained and they were asked for further verbal consent to confirm that they were happy to take part in the interview. With agreement, the interviews were recorded over the telephone and later transcribed or, if preferred, written notes were made by the researcher during the telephone interview.

Data management and analysis

Quantitative

Data were input into a database by MAHSC-CTU from the CRFs completed by a researcher and questionnaires completed and returned by participants.

Relevant data were recorded on the CAMEOS CRFs provided by the MAHSC-CTU. All entries on the CRF, including corrections, were made by an authorised member of trial staff. Screening and follow-up data collected by the research team were collected directly on to the CRF and, therefore, treated as source data. Participant-completed questionnaires were also treated as source data.

Data provided to the MAHSC-CTU were checked for errors, inconsistencies and omissions. If missing or questionable data were identified, the MAHSC-CTU requested that the data be clarified. On completion of relevant data management processes, the data were passed directly to the trial statistician for analysis (MH).

All data handling and analysis were conducted in line with RGFHS guidelines60 and the Data Protection Act 199870.

As a result of the limited data we were able to collect, analysis consisted of simple descriptive statistical analysis using Stata® [version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA)].

Qualitative

All interviews were transcribed and analysed thematically.

This study was reviewed and approved by NHS Research Ethics Committee: North West – Greater Manchester Central on 25 July 2014 (reference number 14/NW/1008).

Chapter 4 Results

Phase 2 (internal pilot phase)

As well as feasibility and acceptability outcomes, baseline and follow-up data were collected through self-report questionnaires. The primary outcomes were well-being and return to work.

During this phase we tested the following:

-

recruitment of employees on long-term sickness absence to the trial

-

delivery of the intervention in an OH setting

-

adherence and acceptability among employees on long-term sickness absence

-

appropriateness of inclusion criteria and outcome measures

-

evaluation of the rate of return to work in those receiving the collaborative case management intervention compared with those receiving care as usual.

Recruitment to the trial

Evaluation of site recruitment: OH provider

The aim had been to recruit at least two large private or public sector companies that were current customers of the OH provider. Specifications for the companies were outlined and negotiations to begin recruitment were conducted with the OH provider at the first trial management group meeting in June 2014. Feedback from the OH provider was that they had difficulty recruiting suitable customers, and this was, at least in part, due to funding issues. Customers can purchase different levels of support for their employees but, in most cases, the delivery of the trial case management intervention resulted in increased time per employee, which, in turn, increased costs. In a NHS setting, this would be an ‘excess treatment cost’. These are often problematic for trusts and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), but they are more used to them. Most companies would have had to invest financially if they agreed to take part in the trial. Five large organisations were approached and all felt unable to take on the extra costs associated with participating in the trial. This process took around 9 months and it failed to engage a company to take part.

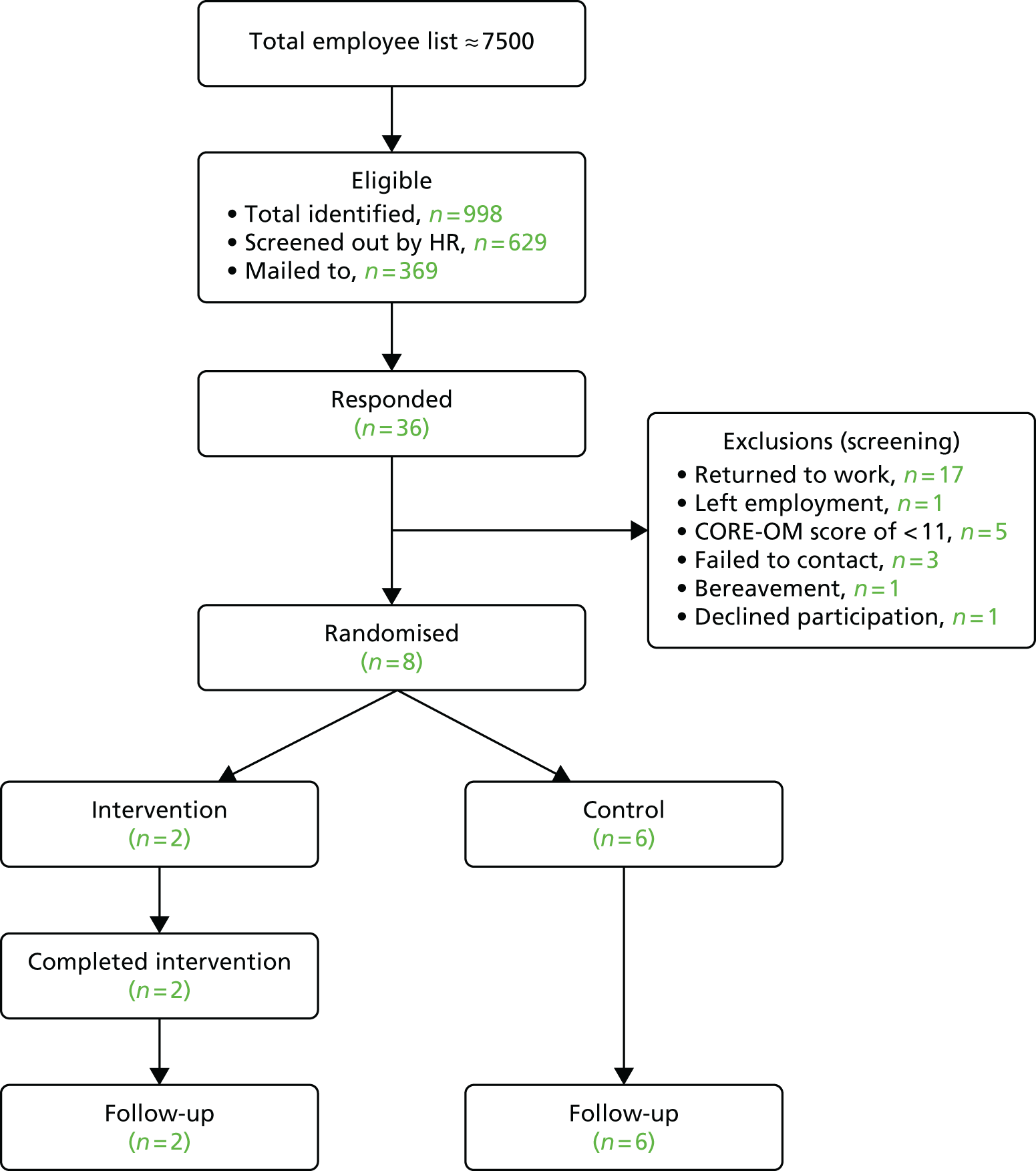

After this delay we recruited a NHS trust that was an existing customer of the OH provider. We found that it was more willing to engage in research and had support costs available to it that facilitated participation. The process for getting the funding and contracts agreed for its participation took a total of 6 months. The trust was not as large as desired, with around 7500 full-time equivalent staff. It projected that around 4.4–6.0% of its workforce would meet our inclusion criteria, giving us a potential pool of 330–450 employees. Details of the study held on the CRN portfolio resulted in a number of expressions of interest from other NHS trusts, but unfortunately they were not existing customers of the OH provider and, therefore, could not take part in the pilot study. However, this showed that it is an area of research that interested employers, and that long-term sickness absence appears to be a significant concern in the NHS.

The difficulties associated with recruiting customers to the trial were what led to the 9-month delay in starting recruitment. There is a need to ensure that funding is available from the customer themselves or financial support is available from another source in order to get companies involved in this type of research.

Evaluation of site recruitment: Fit for Work

Funding was agreed with Public Health England to support the clinical activity involved in delivering this intervention through the FFW organisation, as it is a non-profit social enterprise. Therefore, there were no funding issues holding up recruitment. In order to identify potential participants for the FFW site, it was decided to use recruitment of patients through GPs in Leicester. This was how they often received referrals, and many of the GPs were familiar with this process. To support practices as PIC sites, we applied for support costs from East Midlands CRN. Using the network, they identified eight GP PIC sites. It was initially planned to recruit up to 15 sites in Leicester.

Although site set-up and recruitment through GPs was quickly arranged, we were unable to begin recruitment of participants as a result of the delays with the OH provider site. As we had designated a 6-month window for all recruitment, the clock would have started once we began with FFW, and as the OH provider site was not ready this would have resulted in the 6-month period expiring before recruitment could even begin with the OH provider. It was decided, therefore, to delay the start of recruitment until both sites were activated.

Recruitment of participants took place between October 2015 and September 2016. Follow-up took place 12 weeks after randomisation, ending in December 2016.

Evaluation of participant recruitment: OH provider

Delivery in an occupational health setting

Negotiations took place to discuss how best to set up the study within the participating organisation. Several points for intercepting employees on sickness absence were considered. However, it was decided that, rather than the OH provider recruiting participants directly, which would affect targets and agreed contractual obligations between the OH provider and customer, recruitment should instead take place at the host organisation. The HR department would identify employees who met the criteria of being absent for 4 weeks or more when they were updated on their monitoring systems, once a month.

As a result of the system update only occurring once a month, there were delays in sending out letters. In the first mailout there was a substantial delay of 5 weeks between the database being updated, the search being done and the letter being mailed out. The result of this delay was that, of the nine responses we received, all employees were ineligible (eight had returned to work and one had left employment). This resulted in us going back to the HR team to discuss how the process could be improved. It was agreed that searches of the database would happen as soon as possible after the database had been updated from the roster and that letters would be sent out immediately following the screening process.

Even with the implemented measures to try and speed up the process, it took 2–3 weeks before employees received their information packs.

Response rates

To assess likely response rates and assess the allocation of resources needed, an initial mailout restricted to 100 employees identified as meeting the study search criteria was conducted.

Screening identified 240 employees (3.2%, slightly below the projected 4.4–6.0%). Of the 100 letters sent out to employees, only nine responses were received, a rate of just 9% (in comparison to the 20% normally experienced with primary care studies). Testing the search and mailout process revealed that there were considerable delays that resulted in the information being outdated by the time responses were received from employees. As a result, none of the nine respondents was eligible to take part in the trial, mainly as a result of return to work. No participants were randomised from the initial mailout (see Table 4).

| Search number | Month/year | Identified, n | Screened out, n | Mailed to, n | Responses, n (%) | Randomised, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | September 2015 | 240 | 140a | 100 | 9 (9) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | December 2015 | 166 | 65 | 101 | 9 (8) | 3 (3) |

| 3 | April 2016 | 132 | 56 | 76 | 8 (11) | 3 (4) |

| 4 | May 2016 | 101 | 67 | 34 | 6 (18) | 2 (6) |

| 5 | June 2016 | 96 | 74 | 22 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 6 | July 2016 | 111 | 96 | 15 | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| 7 | August 2016 | 152 | 131 | 21 | 3 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 7 months | 998b | 629c | 369 | 36 (10) | 8 (2) |

A further mailout was conducted in December 2015, which identified an even smaller number of eligible employees (2.2% of staff). After excluding ineligible employees and those who had already been sent a letter in the first mailout, 101 letters were sent (see Table 4). Again, we received just nine responses, of which three were randomised.

At this point, we reviewed our methods and reported back to the Trial Steering Committee, which consisted of a triallist/methodologist, a statistician and a PPIE representative. At the meeting, we discussed the delays, likely causes of delays and possible courses of action to rectify the low identification and response rates. Following this meeting, a full trial management meeting was held with co-applicants, collaborators and a PPIE representative to feed back the steering committee’s comments and reflect on how the barriers could be addressed by incorporating the expertise of the wider team. An action plan was developed based on the outcome of these two meetings.

Key points from the action plan and how they were addressed

Improving the identification of potential participants:

-

We had hoped that it would be possible for weekly searches to be conducted by the HR team at the employer organisation but as a result of its internal procedures for updating its records, this was not possible. Negotiations with the employer organisation resulted in improving the system so that every month, as soon as its own systems were updated with absenteeism in the company, they would run the search and mail the invitations to eligible employees.

-

To widen the potential pool of participants, the search criteria were changed to identify employees who had been absent for 21 days and over (this is the internal marker for long-term sickness absence and thus integrates with their systems more effectively), instead of the 4 weeks or more previously agreed. The inclusion criteria for the trial remained the same.

-

The company would regularly send internal updates to managers and team leaders. Details about this research were to be included in those updates, raising awareness of the trial and asking senior staff to mention it to any staff who were currently on long-term sickness absence.

Increasing patient response rates and recruitment to the trial:

-

It was felt that some people may have been self-excluding from the study as they did not consider themselves ‘long-term’ after just 4 weeks’ absence. We amended the participant materials, looking at the language used, to make them more inclusive (see Appendix 2). The altered materials were again reviewed by a PPIE representative. These changes had to be approved by the NHS Research Ethics Committee.

-

Instead of sending a whole information pack to employees, a two-stage process was tested. Employees were initially contacted by the employer by letter with a brief flyer that also directed them to the intranet site. If they were interested or wanted more information, they could then contact the research team directly, and the PIS and consent forms were mailed out to them after a verbal explanation had been given and any queries were answered.

-

An internal website on the company’s intranet system was set up. The site was accessible to all employees and it provided them with information about the study. The site also encouraged employees to contact the research team, either through the site, by e-mail or by telephone, if they had any questions or wanted to know more.

-

The LCRN there also offered to provide an experienced band 5 research facilitator from the CRN team to make follow-up telephone calls to potential participants a week or so after they have been sent the recruitment materials. The aim of the call was to ensure that the employee had received the materials and to see if they would be willing to have a member of the research team contact them to discuss the study. As this was not part of our protocol, a further ethics amendment had to be submitted, which took some time to get approval.

The effects of the implemented changes

Following the changes to the methods as described above, we continued recruitment in April 2016 and five further mailouts were conducted (Table 4). Immediately following the changes, the response and randomisation rates both improved, peaking at an 18% response rate and a 6% randomisation rate. The improved response rates may have been a result of increased awareness of the trial following inclusion in briefings and the introduction of the website. However, this improvement appeared temporary and rates reduced again.

One of the main changes we made was the introduction of telephone calls from an independent party to aid the recruitment process. Unfortunately, because of a delay in getting ethics approval for this amendment, we were only able to implement it on the last mailout in August 2016. Telephone calls were made by a band 5 research facilitator from the CRN. Approximately 1 week after the letters had been sent to the 21 identified employees, the facilitator tried contacting them by telephone.

The information fed back from the research facilitator was that:

-

13 had answered neither their mobile nor their landline telephone

-

two had already returned to work – they were ineligible

-

two opted out – they did not want to take part in CAMEOS study

-

three stated they had not yet received the study pack – the information was sent again

-

one potential participant gave verbal agreement to forward personal details.

As Table 4 shows, a large proportion of potentially eligible employees were screened out by HR before mailout. The main reasons for this were that they were employees:

-

who had been sent an invitation in previous mailouts

-

who were involved in a grievance action with the employer

-

who were unlikely to remain with the employer, for example if their contract was ending and not likely to be renewed.

Recruitment had to close in September 2016 in order to meet the project end dates and allow delivery of the intervention. Any participants randomised to the intervention group required up to 12 weeks to complete participation. Therefore, the study closed with just eight participants randomised from OH Assist, reflecting just 10% of the total 80 we had intended to recruit (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram 1: occupational recruitment.

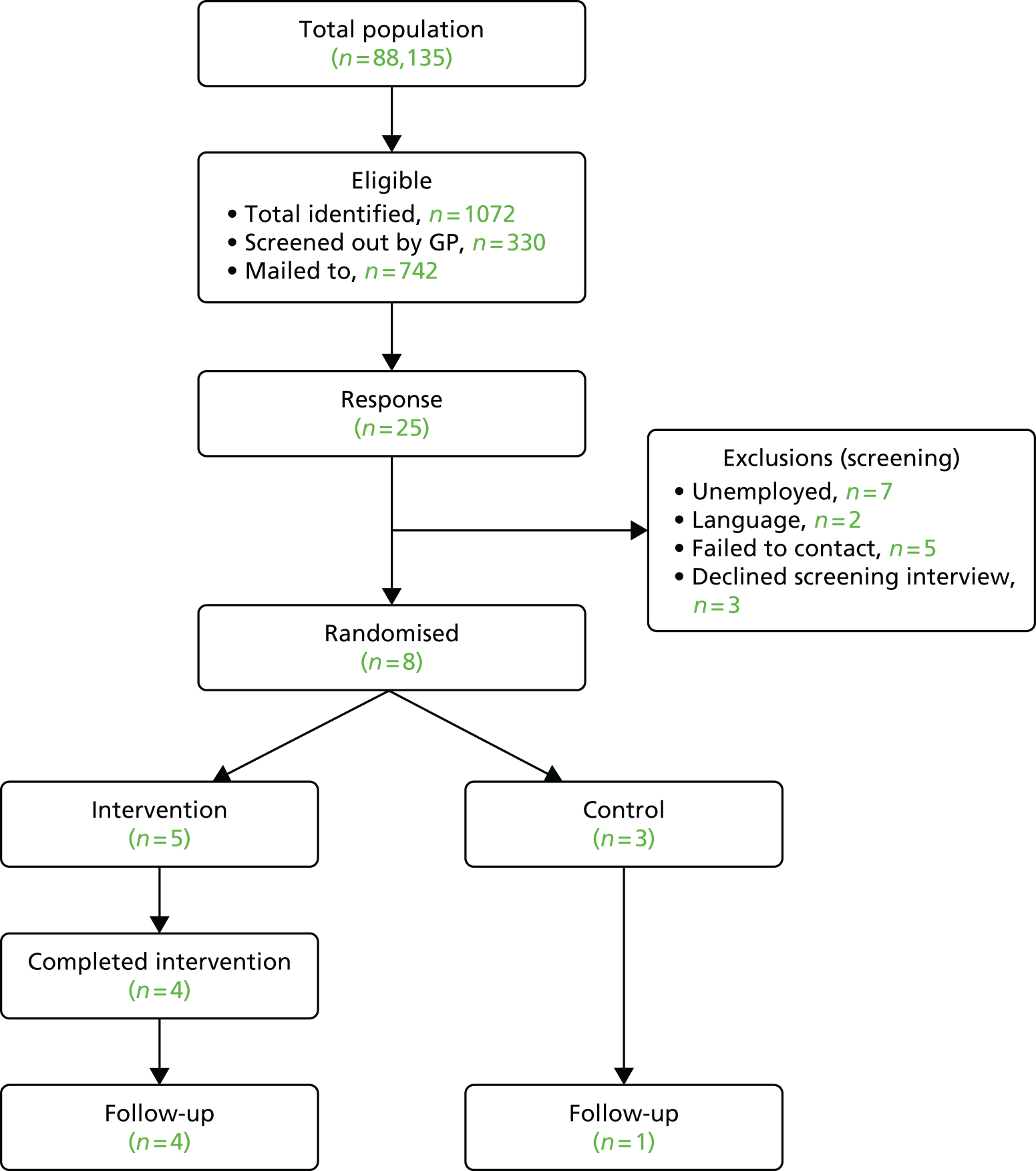

Evaluation of participant recruitment: Fit for Work

Delivery by the Fit for Work team

As the FFW team was providing its own case management approach for clients, we had to recruit people from outside its coverage. To do this it was decided that recruitment through the GP, one of the ways they generally receive referrals, would be the most efficient method.

Recruitment of GP practices was slow, with East Midlands CRN able to identify only eight practices to take part. A further five practices were recruited from Nottingham. GPs seemed to show little interest in taking part in the research even though it was relatively light-touch with just a single screenshot and mailout. Some of the reasons for this may be the introduction of the new FFW service and the updated fit note system. It is possible that GPs felt that this increased the burden or they felt that working within these new systems provided their patients with enough support.

Response rates