Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3006/02. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Frank Kee reports that he chairs the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme Research Funding Board. Emma McIntosh reports that she is a member of the NIHR PHR programme Research Funding Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Connolly et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report presents the findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial evaluation of the Roots of Empathy (ROE) programme. This chapter provides the background for the study and a description of the programme. The methodology for the evaluation is outlined in Chapter 2. The quantitative findings from the trial regarding the impact of the programme on pupil outcomes and the cost-effective analysis are reported in Chapter 3 and the findings from the accompanying qualitative process study are set out in Chapter 4. Key issues emerging from the findings are set out in Chapter 5.

Rationale for current study

There is a growing consensus in academic and policy circles regarding the importance of attending to young children’s social and emotional well-being. There is substantial evidence that links early social and emotional development to later academic performance1 and a number of key health outcomes, such as stress and mental health. 2 Deficits in basic skills, such as the ability to identify emotions, tend to have wide-ranging implications, including being rejected by others and excluded from peer activities and being victimised. 3 Such deficits are also related to lower peer-rated popularity and teacher-rated social competence. 4,5 Chronic physical aggression during primary school also increases the risk of violence and delinquency throughout adolescence in boys. 6,7 In turn, this can lead to destructive forms of emotion management, such as alcohol abuse.

In recognition of this, a comprehensive set of public health guidelines was published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2008, the aim of which was to encourage the promotion of social and emotional well-being in primary school children. 8 According to the guidelines, child well-being not only is important in its own right but can also be a determinant of success in school and physical health. The guidelines recommend that schools create an ethos that supports positive behaviours for learning and successful relationships, and also provide an emotionally secure and safe environment that protects against bullying and violence and offers teachers and practitioners the support they need in developing children’s social and emotional well-being.

However, perhaps the most significant recent development has been the publication of the Marmot Review in England. 9 At the heart of the review’s key recommendations is the policy objective of giving every child the best start in life. Of the six policy objectives identified by the review, this one was held up as its ‘highest policy recommendation’ and reflected the review’s life course perspective. Alongside a call to increase the proportion of overall expenditure allocated to the early years, the review also placed an emphasis on reducing inequalities in the early development of physical and emotional health and cognitive, linguistic and social skills, and thus building resilience and well-being among young children. This should be done, according to the Marmot Review, through investment in ‘high quality maternity services, parenting programmes, childcare and early years education to meet need across the social gradient’ (p. 16). 9

A second, linked, policy objective identified by the review is to enable all children, young people and adults to maximise their capabilities and have control over their lives. This, in turn, should be achieved by ensuring that schools, families and communities work in partnership to improve health, well-being and resilience. Among some of the key recommendations made in this regard is the need to prioritise developing the capacity of schools to address and improve children’s ‘social and emotional development, physical and mental health and well-being’ (p. 18). 9

Most recently, a report commissioned by the Early Intervention Foundation in the UK (March 2015) explored the relationship between social and emotional skills in childhood and long-term effects into adulthood. 10 The authors found that self-control and self-regulation are the most important childhood social and emotional skills in relation to positive adult outcomes. Similarly, they found that self-perception, self-awareness and social skills were important influences on many adult outcomes. There was no clear evidence linking motivation or resilience to adult outcomes; however, emotional well-being in childhood was found to be important for mental well-being as an adult. An equally important finding from this report was that social and emotional development is just as important as cognitive development, if not more so, in some respects, for future life.

Scientific background

A substantial body of evidence now exists to suggest that well-designed school-based prevention programmes can be effective in improving a variety of social, health and academic outcomes for children and young people. 11,12 Several reviews have been conducted in the area of social and emotional learning (SEL) programmes and, although the types of intervention, participants and outcomes have varied between reviews, the consensus is that well-designed universal school-based programmes have a positive impact on child outcomes. 13–16

The most relevant and recent of these reviews is Durlak et al. ’s17 meta-analysis, which focused exclusively on school-based universal SEL programmes and their impact on a number of pupil outcomes, including SEL skills, attitudes, positive social behaviour, conduct problems, emotional distress and academic performance. The analysis comprised 213 programmes and 270,034 pupils. The mean effect sizes for each outcome ranged from –0.22 (conduct problems) to 0.57 (SEL skills), which, the authors note, is consistent with effect sizes reported by other studies and reviews of similar programmes and outcomes. The most effective SEL programmes in this review (defined as those that had a significant and positive impacted on all six outcomes) were those that did not experience implementation problems and, consistent with Payton et al. ’s14 conclusions,14 also incorporated the following four recommended practices commonly referred to as ‘SAFE’:

-

Sequenced – applying a planned set of activities to develop skills in a step-by-step fashion

-

Active – using active forms of learning (i.e. role plays, behavioural rehearsal with feedback)

-

Focused – devoting sufficient time to developing social and emotional skills

-

Explicit – targeting specific social and emotional skills.

Durlak et al. 17 concluded that SEL programmes tended to have a significant and positive impact on students’ social and emotional competence, increase prosocial behaviour, reduce conduct and internalising problems, and improve academic performance. They also reported that in those studies that followed up participants, these effects remained statistically significant for at least 6 months post intervention.

However, only a small number of studies in this review (15%) reported follow-up data that met the inclusion criteria, and so little is known about the long-term effects of SEL programmes. Adi et al. ,18 whose review informed the NICE guidelines, reinforced this view and observed that, although programmes teaching social skills and emotional literacy show promise, there remains a need for good-quality trials to assess these programmes’ long-term effectiveness.

More recently, the Early Intervention Foundation’s second of three reports on social and emotional skills in childhood focused on what works in the UK to promote such skills in childhood and adolescence. 19 The authors found that school-based and targeted programmes were most effective, along with those interventions that adopted a ‘whole school’ approach, involving staff, parents and the wider community. The evidence of the effectiveness of UK out-of-school programmes was less clear-cut.

Existing impact evaluations of the Roots of Empathy programme

The ROE website (www.rootsofempathy.org) reports a number of evaluations that have been conducted to date. To provide further context for this present study, an attempt has been made to identify these existing studies and to synthesise the data. Full details of the studies identified and of the methods used for the meta-analysis are provided in Appendix 1.

In total, 10 studies20–29 were identified that had reports that provided sufficient information to assess their eligibility for the meta-analysis. A further six studies were referenced but it was not possible to locate the full report or the data for these. Although the authors of these were contacted directly, the research team had not received a response at the time of writing. Of the 10 reports found, three were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria (i.e. employed an experimental or quasi-experimental design, quantitatively measured at least teacher-rated prosocial and aggressive/difficult behaviour, and collected outcome data at both pre and post test).

Of the seven eligible studies,20–26 only one20 was a (cluster) randomised controlled trial that also tracked children for 3 years following the end of the programme. The remaining six studies employed quasi-experimental designs with pre- and immediately post-test data only. Four of the studies,20–23 including the cluster randomised controlled trial, were conducted in Canada, two were conducted in Scotland24,25 and one was conducted in Australia. 26

A total of 4140 primary school aged children from 145 schools took part in the seven eligible studies. 20–26 Sample sizes ranged between 132 and 785 children, with an average sample size of 591. All of the evaluations measured teacher-rated prosocial and aggressive behaviour using valid and reliable instruments. A range of other teacher and child rated outcomes were also measured, but this meta-analysis focuses only on synthesising the effects for the most commonly measured outcomes:

-

teacher-rated prosocial behaviour immediately post test (all seven previous studies)

-

teacher-rated aggressive behaviour immediately post test (all seven previous studies)

-

child-reported empathy immediately post test (five studies)

-

child-reported emotional regulation immediately post test (two studies).

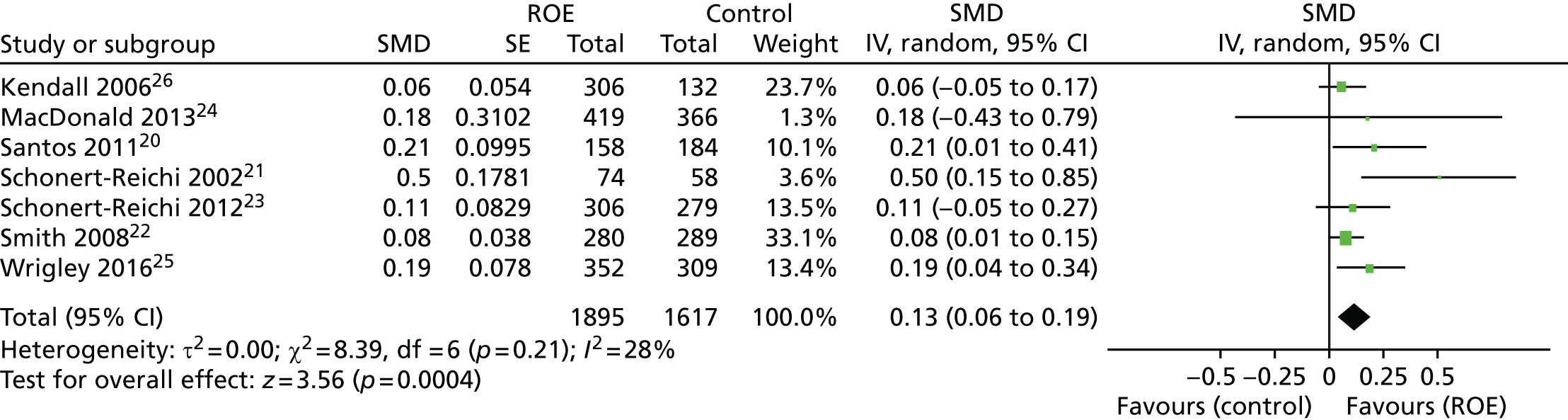

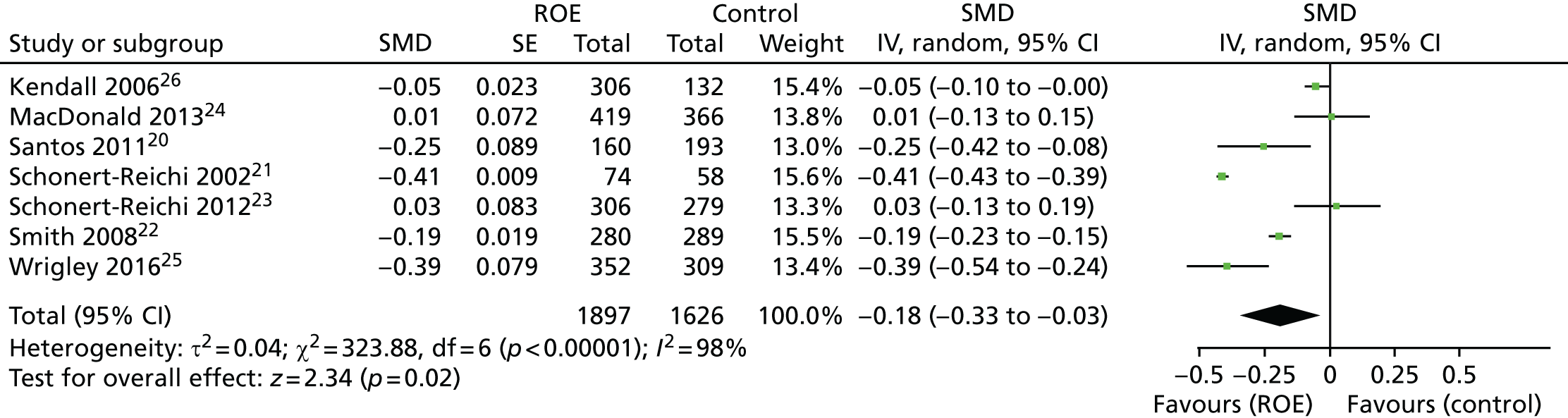

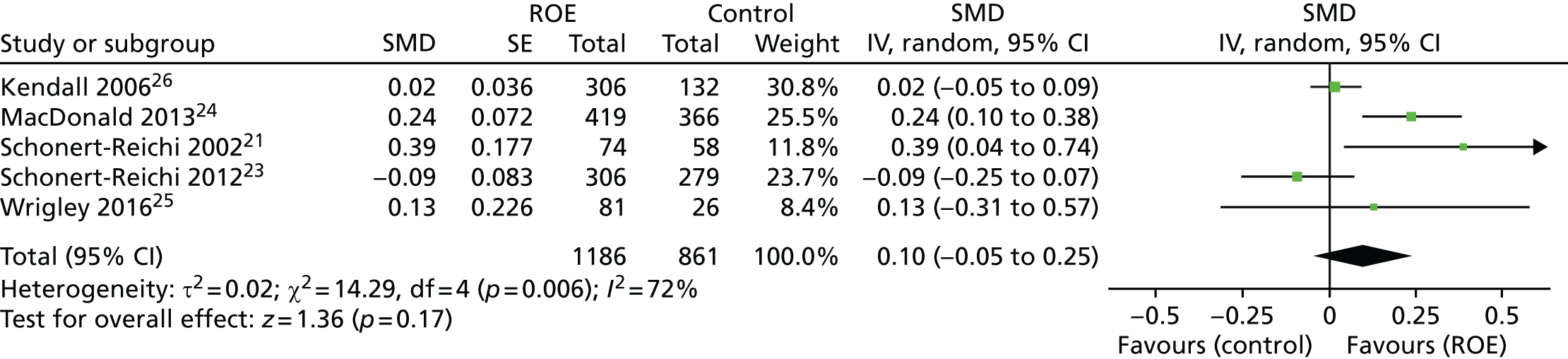

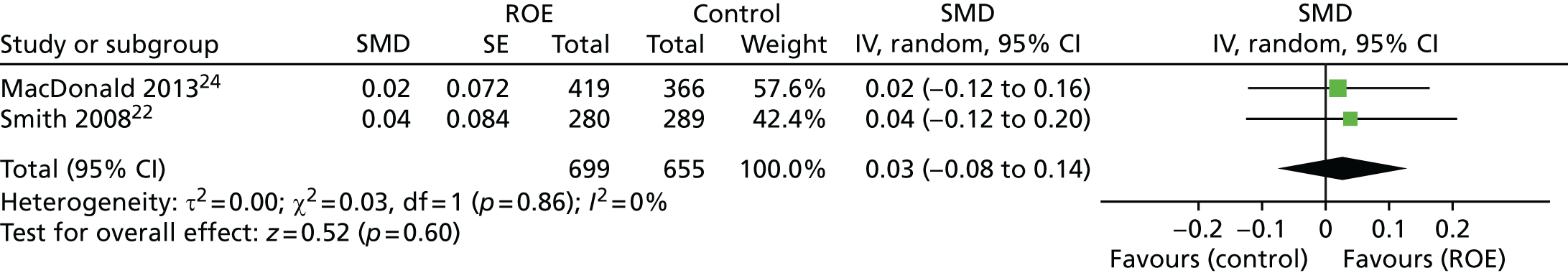

Full details of the studies included and excluded, and also of the methods used for the meta-analysis, are provided in Appendix 1. The findings are summarised in Table 1. As can be seen, when the available data from the seven studies are pooled there is evidence that ROE is effective in leading to small improvements in prosocial behaviour [standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.13] and reductions in aggressive behaviour (SMD –0.18). However, and interestingly, there is no evidence to suggest that it is effective in improving other SEL outcomes among children, in this case empathy and emotional regulation.

| Outcome | Pooled sample | Pooled SMD (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher-rated prosocial behaviour | 1895 ROE, 1617 control (seven studies) | 0.13 (0.06 to 0.19) |

| Teacher-rated aggressive behaviour | 1897 ROE, 1626 control (seven studies) | –0.18 (–0.33 to –0.03) |

| Child-reported empathy | 1186 ROE, 861 control (five studies) | 0.10 (–0.05 to 0.25) |

| Child-reported emotional regulation | 699 ROE, 655 control (two studies) | 0.03 (–0.08 to 0.14) |

As noted, only one evaluation20 studied the longer-term impact of the programme. This is the only pre-existing randomised controlled trial for which there are data, and it suggests that after 3 years the intervention group had poorer prosocial behaviour than the control group [SMD –0.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.17 to –0.07]. With respect to aggressive behaviour 3 years post intervention, the intervention group were displaying only slightly less aggressive behaviour than the control group (SMD –0.06, 95% –0.09 to –0.03) and, although statistically significant, this effect was much reduced compared with that observed immediately post test (SMD –0.25).

Overall, therefore, although the findings from existing evaluations of ROE are promising, they raise interesting questions regarding the apparently mixed effects of the programme immediately post test and also about whether or not such effects are sustained in the longer term. Moreover, the current evidence base is limited to only one randomised trial that is also the only study to date that has considered the longer-term effects of the programme. In addition, no study to date has included a cost-effectiveness analysis. This, then, provides the rationale for the present evaluation.

Objectives

The aims of the current evaluation are to:

-

evaluate the immediate and longer-term impact of the ROE programme on social and emotional well-being outcomes among pupils aged 8–9 years

-

evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the programme.

The purpose of the research is to answer the following research questions.

-

What is the impact of the programme post test and up to 3 years following the end of the programme on a number of specific social and emotional well-being outcomes for participating children?

-

Does the programme have a differential impact on children depending on their gender, the number of siblings they have and their socioeconomic status and/or the socioeconomic profile of the school?

-

Does the impact of the programme differ significantly according to variations in implementation fidelity found?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of the programme in reducing cases of aggressive behaviour and increasing prosocial behaviour among school-aged children?

The full protocol for this trial, published in August 2011 before ethics approval was sought for the study and, thus, before the recruitment of schools and pre-testing, can be found at the National Institute for Health Research Evaluation, Trials and Studies website. 30

Chapter 2 Methodology

Introduction

This chapter begins by setting out the methodology for the trial in relation to sampling, outcomes and measures, data collection and analysis plan. It then describes the methodological approach adopted for the qualitative process evaluation and the approach being taken for the cost-effectiveness analysis. It concludes by identifying a small number of minor changes to the evaluation from the original published protocol.

Trial design

This study is based on a cluster randomised controlled trial and qualitative process evaluation undertaken in four of the five health and social care trust areas in Northern Ireland. The random allocation of schools to either the intervention or the control condition was carried out on a 1 : 1 basis. Ethics approval was granted by the School of Education, Queen’s University Belfast, Research Ethics Committee on 2 September 2011.

Deviations of the evaluation from the original protocol

The protocol for this evaluation was published in August 2011, before ethics approval was secured and, thus, before the recruitment of schools and pre-testing. It has not been amended since and is available online. 30 The trial was also registered with an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) in December 2011 (ISRCTN07540423). The original aims and objectives of the evaluation have not been altered and the overall approach to the research design in relation to the cluster randomised controlled trial, the process evaluation and the cost-effectiveness evaluation have also remained unchanged. The specified primary and secondary outcomes, with their accompanying measures, have also remained the same, as has the proposed analysis plan.

Within this, a small number of minor deviations to the original protocol, published in 2011, have been made, and these are detailed below.

Missing secondary outcome measures

It was not possible to collect data on two of the secondary outcomes specified in the original protocol: educational attainment and class detentions. With regard to education attainment, and at the start of the trial in 2011, the use of standardised InCAS literacy and numeracy tests became compulsory for children in Years 4–7 in Northern Ireland (www.cem.org/incas). Before this, there was no statutory testing in Northern Ireland primary schools. The evaluation planned to take advantage of this new statutory testing as a convenient means of collecting (directly from schools) literacy and numeracy attainment data for the sample immediately post test (June 2012) and for follow-up data sweeps in June 2013 and 2014 while the children were still in primary school. However, schools raised serious concerns about the reliability of the tests (and not related to this present trial), and these were abandoned the following year, 2013. Moreover, this had an impact on data collection in 2012. Unfortunately, therefore, only partial data were available from schools in 2012, with InCAS data available for only approximately 300 pupils in our sample collected in 2012.

Principals advised the research team to, instead, collect the results from the Progress in English and Progress in Maths tests that some schools use with their Year 6 children (our cohort in 2013 and at the 12-month follow-up). Unfortunately, not all schools used this test, and so the team have these data for only around 850 pupils in the sample immediately post test. There was no resource within the study budget for the purchase and administration of independent attainment tests and, for these reasons, it has not been possible to include a reliable measure of educational attainment.

In relation to the other outcome, the team originally intended to collect a class-level measure of behaviour via class detention rates. However, this proved not to be possible, as primary schools did not use detention as a means of punishment for poor behaviour, this being more common in post-primary schools. Primary school pupils may be suspended or expelled, but the instances of these events are extremely rare. For this reason, it was not possible to collect valid (or any) data on this outcome.

Missing and additional covariates for the main analysis

The original proposal stated that, for the main analysis, a series of covariates would be added to each statistical model representing the baseline (pre-test) scores for each of the outcome measures used, as well as measures representing the child’s core characteristics. As detailed by the models in Appendices 2 and 3, this approach to the analysis was followed. However, there were a small number of covariates not included in these main models associated with data that were collected on the children’s core characteristics. More specifically, these were:

-

the parents’ highest qualifications received

-

the parents’ occupations

-

the number of siblings in the family home.

Data for these three variables were collected from the parents directly, but, given the lower response rates from parents, it was decided not to include these as covariates in the final model, as the number of missing data would have reduced the effective sample size by half. However, a separate sensitivity analysis in relation to the primary outcomes was undertaken to compare the findings of the main analysis with those of an alternative analysis that included these three additional covariates. This sensitivity analysis is provided in Appendix 3. As can be seen, the sensitivity analysis suggests that the exclusion of these three covariates did not have a notable impact on the findings presented in this report.

In addition, and following advice from the Trial Steering Committee, the decision was taken to add an additional covariate to all of the statistical models consisting of three dummy variables representing the location of each school in relation to the four health and social care trusts participating in the trial. Because the randomisation of schools occurred within each of the four trusts, it was felt appropriate to control for any possible design effects resulting from this by the inclusion of these dummy variables.

Missing assessment of external validity using propensity scores

Finally, the original protocol included a proposal to assess the external validity of the findings arising from the trial using propensity scores to compare the characteristics of trial participants with those of the population as a whole in Northern Ireland. Such an analysis would have required individual-level data not only for children participating in the trial but also for children from the wider population in the region. Unfortunately, the data required to undertake such an analysis were, subsequently, found not to be readily available and there was no resource in the project budget to cover the costs required to collect these. Therefore, the research team decided to assess the external validity of the trial through aggregate comparisons of the characteristics of the sample of children participating in the trial with those of the population as a whole.

Participants

Seventy-four primary schools (clusters), from four of the five trust areas in Northern Ireland, were originally recruited to and enrolled into the trial [Belfast Health and Social Care Trust (HSCT), South Eastern HSCT, Southern HSCT and Western HSCT] by trust personnel between March and June 2011. All primary schools were eligible to take part and all Year 5 children within each school were also eligible to participate. Before randomisation, school-level consent was sought from the principal of each participating school. Parental consent was sought post randomisation for each child participating in the trial. Teacher- and child-rated data were collected in the school setting and parent-rated data were collected via a postal questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for copies of the research instruments used).

Intervention

Roots of Empathy is among a small number of named universal school-based SEL programmes that has an existing evidence base regarding its effectiveness. It is a universal programme that has been developed and implemented in Canada, and it has only recently been introduced into the UK. It is delivered on a whole-class basis for one academic year (October to June). It consists of 27 lessons, which are based around a monthly classroom visit from an infant and parent, usually recruited from the local community, whom the class ‘adopts’ at the start of the school year. Children learn about the baby’s growth and development through interactions with and observations of the baby during these monthly visits.

Each month, a trained ROE instructor (who is not the class teacher) visits the classroom three times for a pre-family visit, the visit of the parent and infant, and a post-family visit. Instructors undergo a total of 4 days’ intensive training that is delivered directly by a specialist ROE trainer from Canada. The specialist trainer also provides ongoing mentoring support to all instructors via regular telephone calls. In addition, ongoing support is available to each instructor through the health and social care trust’s lead ROE co-ordinator. Each ROE lesson takes place in the classroom, and the class teacher is present but not actively involved in delivery. The programme provides opportunities to discuss and learn about the different dimensions of empathy, namely emotion identification and explanation, perspective-taking and emotional sensitivity. The parent-and-infant visit serves as a springboard for discussions about understanding feelings, infant development and effective parenting practices. The intervention is highly manualised, and any adaptation or tailoring of either the content or the method of delivery is discouraged by the ROE organisation.

Roots of Empathy seeks to develop children’s social and emotional understanding, promote prosocial behaviours, decrease aggressive behaviours, and increase children’s knowledge about infant development and effective parenting practices. At the heart of the programme is the development of empathy among young children. Empathy is the capacity to recognise and, to some extent, share the feelings experienced by others. Baron-Cohen31 describes empathy as spontaneously and naturally tuning into the other person’s thoughts and feelings. It is believed that the existence of empathy lays the basis for helping other people and for other forms of prosocial behaviour because it underpins the motivation to respond to the feelings of others. Similarly, it is suggested that the absence of empathy leaves a person to consider their own needs without reference to the feelings of others, which results in asocial or antisocial behaviour, depending on the degree of impact on the other person.

Baron-Cohen31 suggests that there are two major elements to empathy: cognitive (perspective-taking) and affective (sharing the feeling of the other person). The cognitive element of empathy is less problematic in some respects because the capacity for perspective-taking occurs as part of a wider developmental pattern of growth (as described by Piaget32,33). The feeling element, on the other hand, is considered to develop mainly in response to close personal relationships, the prototype for which is the attachment bond between mother and child. The centrality of the attachment relationship was first established by Bowlby34 and developed later by Ainsworth et al. 35 to include patterns of attachment between caregiver and child. For Ainsworth and many subsequent researchers, secure attachment is regarded as the basis for sound psychological development.

The means through which attachment has beneficial effects on development is still not fully understood. Fonagy et al. 36 argue that securely attached individuals tend to have more robust capacities to represent the state of their own and other people’s minds. This ability to perceive and interpret human behaviour in terms of intentional mental states (e.g. needs, desires, beliefs, goals, purposes and reasons) is known as mentalisation. The concept of mentalisation is receiving increasing empirical support as a core process in the attachment relationship. It appears, however, that mentalisation can be acquired outside infancy and, indeed, there is a form of mentalisation therapy used in adults for which an evidential basis has been developed. 37

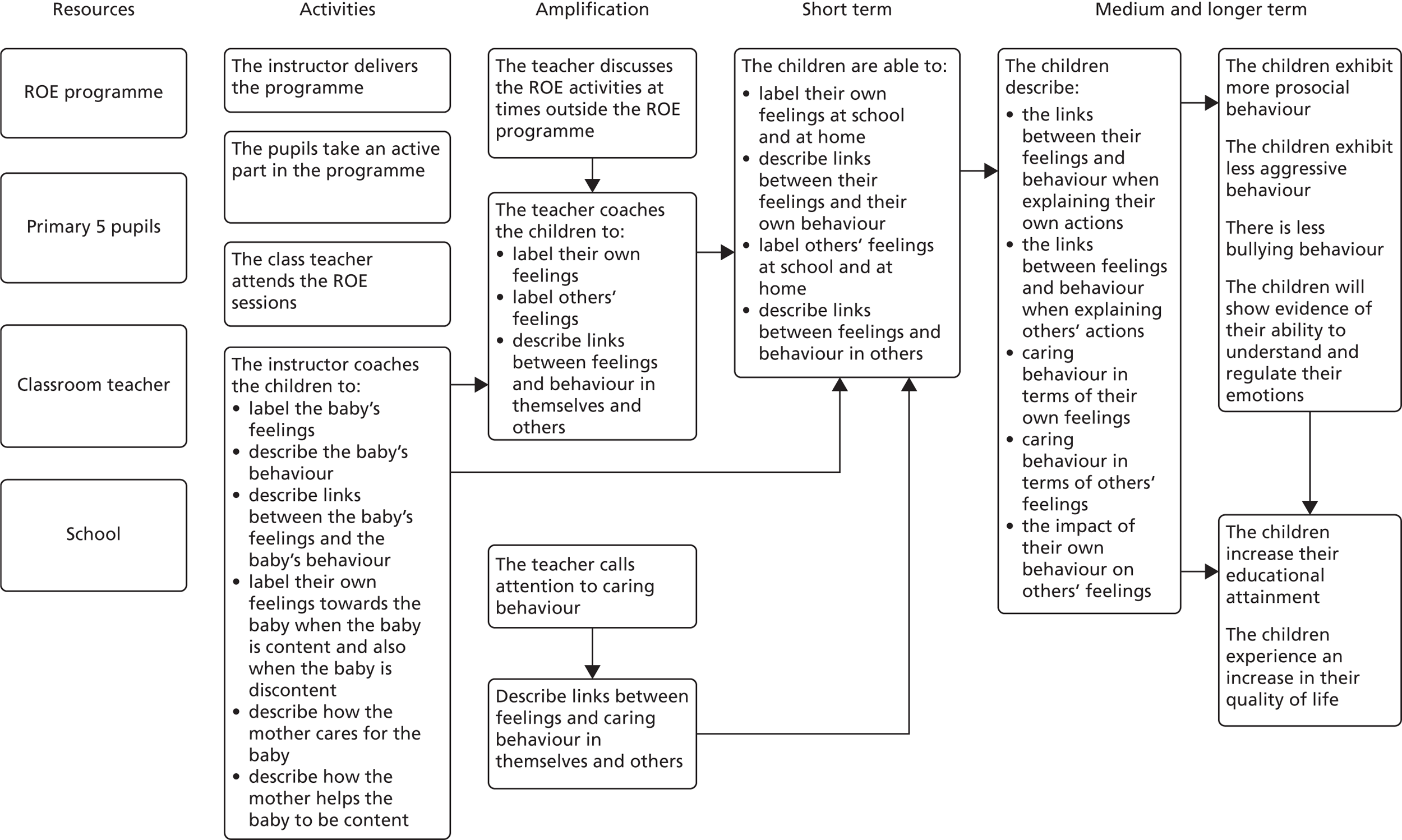

A characteristic of ROE is that it is a mentalisation-based programme with the principal aim of developing empathy in children. The labelling of feelings and the exploration of the relationship between feelings and behaviour is achieved through the mother–infant interaction that is observed by the children in the classroom. Clearly, the baby cannot communicate in words and can only express his or her feelings through behaviour. For this reason, the baby provides an ideal opportunity for the children to learn mentalisation skills through interpreting and labelling the baby’s emotions and, by this means, to learn the affective and cognitive components of empathy, which will enable them to empathise with others. If and when children learn empathy, they then have the basis for developing positive social partnerships with others, as depicted in the logic model, shown in Figure 1, that has been developed by the present authors to summarise the implicit theory of change underpinning the programme.

FIGURE 1.

Logic model for the ROE programme.

Outcomes

The outcomes measured in this trial are based on the logic model (see Figure 1). The primary child outcomes are increases in prosocial behaviour and decreases in difficult behaviour as measured by the teacher-rated version of the SDQ. Additional data from alternative sources (parent- and child-rated SDQ) and alternative measures [teacher-rated Child Behaviour Scale (CBS)] were collected to allow the triangulation of the data and to confirm the reliability of the primary outcome measures (i.e. the teacher-rated SDQ). This is discussed further in Chapter 3.

The secondary outcomes largely reflect the key precursors expected to lead to behavioural change. The exceptions to this are bullying and quality of life, for which it is hypothesised that improvements are likely to flow from improved behavioural change. A description of the measurement of each outcome is given in Table 2.

| Outcomes | Measures | Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||

|

Prosocial behaviour Difficult behaviour |

SDQ38

|

Teacher ratings

|

| Secondary outcomes | ||

|

Understanding of infant feelings Understanding of how to help a baby who is crying |

Infant Facial Expression of Emotions Scale21

|

|

| Recognition of emotions | ERQ40

|

Emotion recognition = 0.58–0.61 |

| Empathy | IRI41

|

Total empathy = 0.85–0.86 |

| Emotional regulation | CAMS44

|

Anger management = 0.69–0.77 |

| Bullying | Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire45

|

Bullying = 0.83–0.84 |

| Quality of life | CHU9D46

|

Quality of life = 0.71–0.74 |

Alongside completing the SDQ for their child, parents were asked to provide additional contextual information: their home postcode, the number and age of siblings, their education qualifications and their occupation. A proxy measure of socioeconomic status was determined from the Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure (NIMDM) 2010,47 derived from the child’s home postcode. Although entitlement to free school meals is often used as a proxy indicator of deprivation, concerns have been raised about its robustness, as it reflects only low income. 48 The NIMDM 2010, on the other hand, provides a relative measure of deprivation by collating information across a spectrum of factors (e.g. income deprivation, health deprivation, employment deprivation and living environment). The geographic areas corresponding to each home postcode are ranked according to overall deprivation. Rankings can range from 1 (most deprived) to 890 (least deprived), and in the current sample ranks ranged from 1 to 889.

Data collection

The research instruments used for data collection are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1. Initial pre-test data [time (T) 0] from the children, parents and teachers were collected in October 2011 across all participating schools before the first sessions of ROE were delivered in the intervention schools. The first (immediately) post-test data (T1) were collected in June 2012 and again, annually, at 12 (T2), 24 (T3) and 36 months (T4). The final sweep of data collection took place in June 2015 when children were 11–12 years of age and at the end of their first year in secondary school.

Teachers were asked to complete questionnaires, which included the SDQ and the CBS, for each participating child in their class at each time point. When children were attending primary school, their class teacher completed the questionnaire. At the final sweep of data collection, when children were completing their first year of secondary school, their form teacher (or the teacher who knew the child best) was asked to complete the questionnaire. Thus, a different teacher completed the questionnaire at each sweep of data collection.

Consenting parents were contacted by post and asked to complete a questionnaire, which included the SDQ and background information on family composition, parental education and employment, and return it to the research team in a freepost envelope. Parents were given the option of completing the questionnaire via telephone interview, but none chose this.

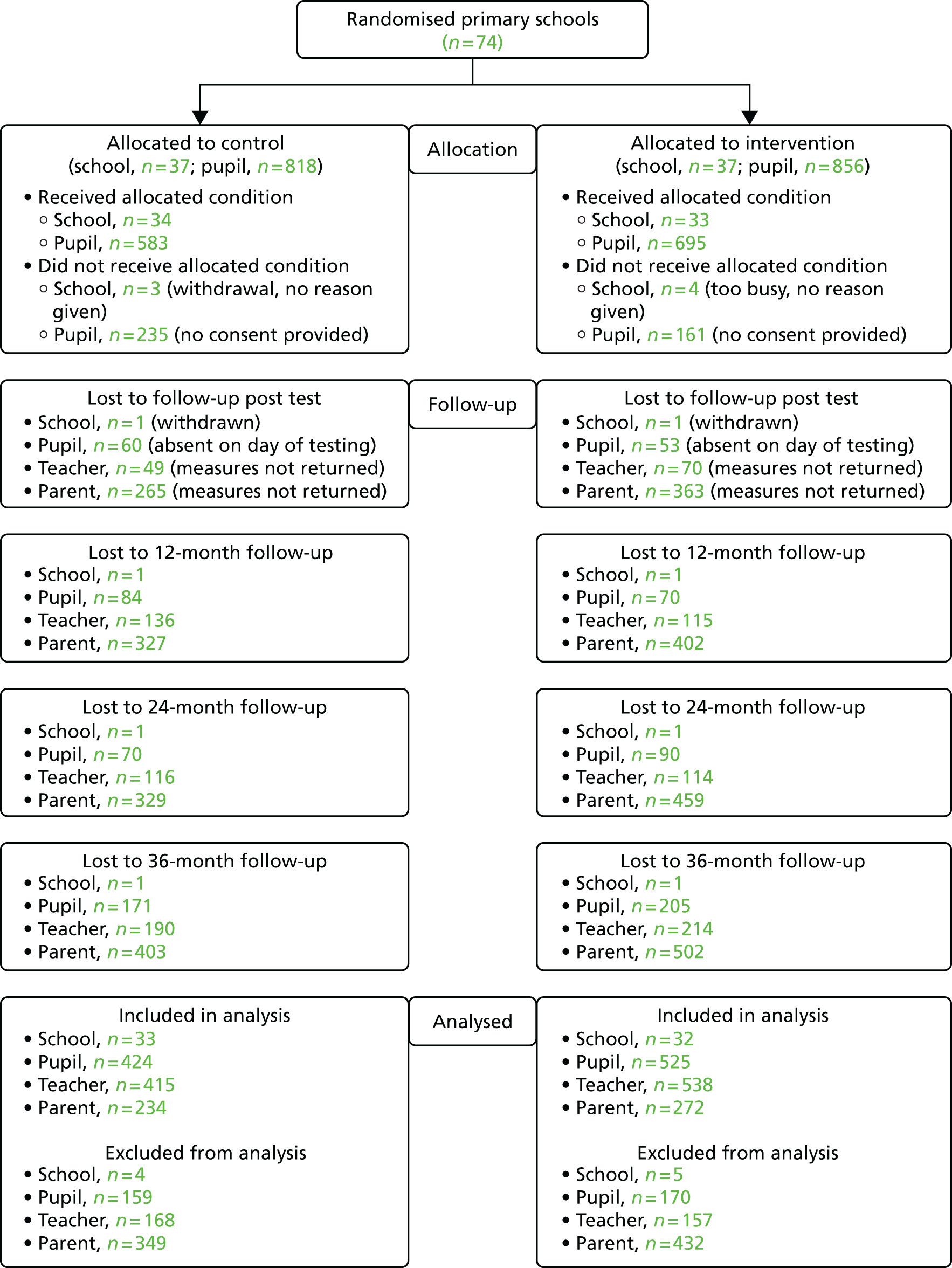

Experienced field workers visited each school and administered questionnaires to the children on a whole-class basis. Fieldworkers were fully trained and co-ordinated by the research team. The children’s questionnaires covered the secondary outcomes detailed in Table 3 (emotional regulation, empathy, recognition of emotions, understanding of infant crying, bullying and quality of life). Children were asked not to confer, and this was ensured by the field worker and the class teacher. Each question was read aloud to the class and any difficult words/phrases were explained. Depending on the ability level of the group, testing took between 30 and 40 minutes. If a child was absent on the day of testing, efforts were made to return to the school at a later date and test these children separately. The procedure and materials were pilot tested by the research team during an earlier, feasibility study of ROE implementation. Figure 2 presents a flow diagram of teacher, pupil and parent responses through the trial. As can be seen, barring the seven schools that withdrew before the start of the trial, retention rates were good overall, with 1278 pupils tested pre test (583 control and 695 intervention pupils) and 949 remaining in the study at the final 3-year follow-up (76.3%) and included in the analysis (424 control and 525 intervention pupils, i.e. 74.3%). However, parental engagement was less successful, with only 686 returning data pre test (53.7% of the sample of 1278 children tested), reducing to 506 at the end of the study that were included in the analysis (234 control and 272 intervention parents, i.e. 39.6%).

| Region | Group, n | Withdrawn pre test, n | Withdrawn post test, n | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Belfast HSCT | 11 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| South Eastern HSCT | 12 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Southern HSCT | 8 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Western HSCT | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 37 | 37 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of recruitment and testing of children.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on the following assumptions.

-

Previous evaluations of ROE, together with the wider meta-analysis of SEL programmes, suggested effects that would range in magnitude between d = 0.22 and d = 0.57.

-

For the primary outcome measure (SDQ), typical intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) have been found to range between 0.05 and 0.15.

-

With the inclusion of the relevant pre-test scores and other covariates, it is also reasonable to assume that the multilevel models used to estimate the effect sizes of the intervention will be able to account for approximately 20% of the variation in post-test outcome scores.

Thus, it was estimated that for the trial to be able to detect the lower bound anticipated effect size of d = 0.22 with between 85% power (for ICC = 0.05) and 60% power (for ICC = 0.15), a sample size of 70 schools with an average class size of 33 children [i.e. 630 children per arm (1260 in total)] would be required. For the highest estimate of ICC = 0.15, the trial would achieve sufficient power (80%) for effects of d ≥ 0.28. These estimates were calculated using Optimal Design (version 2.0) (https://sites.google.com/site/optimaldesignsoftware/).

Randomisation

An independent statistician from the Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit undertook the (1 : 1) random allocation (stratified by health and social care trust area) of enrolled schools and assigned 37 schools to either the intervention or the control group (Table 3).

The schools that were randomly allocated to the intervention group received the ROE programme in their selected Year 5 class for one academic year (2011/12). When there were parallel classes in any specific school, one Year 5 class (8- to 9-year-olds) was randomly selected from these to take part in the trial.

The remaining schools in the control group did not receive the ROE programme but continued with the regular curriculum and usual classroom activity. Schools in the control group were placed on a waiting list to receive the programme in 2012/13, but this was on the understanding that ROE would not be delivered to their current Year 5 cohort as they progressed through Years 6 and 7.

The Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit informed the research team of the allocation outcomes and the research team passed this information to the relevant HSCT personnel, who in turn informed the school.

Statistical methods

Data were entered into IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for preparation and preliminary exploration before being analysed using Stata® version 14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Data preparation involved checking the proportion of missing data, and checking that minimum and maximum values were within the appropriate range. Descriptive statistics were generated for each variable, and the distribution was checked. The validity of measures [the SDQ,38 the CBS,39 the Interpersonal Reactivity Index,41 the Emotion Recognition Questionnaire40 and the Child Anger Management Scale44 (CAMS)] was assessed using factor analysis, and internal reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha. The core characteristics (gender, parental education and familial deprivation) of the control and intervention groups were compared (controlling for clustering) using binary logistic multilevel modelling for categorical data and linear multilevel modelling for continuous data. Differences in mean scores for outcome variables between the control and intervention group were tested using multilevel models to control for effects of clustering.

Owing to the clustered nature of the data, the statistical analysis involved the use of multilevel models with children (level 1) clustered within schools (level 2). This was done separately for the immediately post-test data and then for each subsequent time point. For each of the outcome measures, a linear multilevel model was estimated, with the relevant post-test score being set as the dependent variable and its related pre-test score added as an independent variable together with a dummy variable for whether the child was a member of the control or the intervention group. A series of covariates, including child characteristics (gender and familial deprivation score) and mean pre-test scores for all other outcome measures, were also included in the models.

Before the analysis, all of the outcome variables (pre test and post test) were standardised, as were the covariates. The only exception to this was the dummy variable representing group membership, which remained the same (coded ‘0’ for control group and ‘1’ for intervention group). This meant that the constant in each of the main models represented the standardised group mean for the control group and the coefficient for this dummy variable represented the difference between that and the standardised group mean for the intervention group. As all of the variables had been standardised, this coefficient also represented the effect size associated with the programme for that particular outcome. The effect sizes reported in Chapter 3 were calculated with the formula for Hedges’ g and using the estimated post-test mean scores for the control and intervention groups from the statistical models, the standard deviations (SDs) for both groups pre test and their corresponding sample sizes. Not surprisingly, given the sample sizes involved, the effect sizes calculated were essentially the same as those estimated in the models (barring some minor differences due to rounding). Evidence of the effects of the programme is indicated by the statistical significance of the coefficient for the variable for intervention status.

The multilevel models were used to calculate the predicted mean post-test scores for the intervention and control group for the average child such that:

Beyond these main models that were used to estimate the overall effects of the ROE programme, exploratory analyses were also undertaken to assess whether or not the programme was differentially effective for differing groups of pupils in terms of gender, familial deprivation and number of siblings. These analyses were undertaken by extending the main pre-test/immediately post-test models to include an interaction term between the contextual variable of interest and group membership. Evidence of differential effectiveness of the programme was indicated in relation to the statistical significance of this interaction term. Full details relating to all of the multilevel models estimated are provided in Appendix 2.

Sensitivity analyses

Two sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the reliability of the findings arising from the main analysis outlined above. The first involved comparing the effects of the programme that were estimated with regard to the two primary outcomes using the teacher-rated SDQ with the effects estimated using the alternative parent- and child-rated forms of the SDQ and also the CBS child-rated measures for prosocial behaviour and aggressive behaviour. This analysis assessed the robustness of the findings for the two primary outcomes and, also, with the parent- and child-rated measures, whether or not there was any evidence of bias introduced as a result of the use of teachers’ ratings, given that the teachers were not blind to the children’s participation in the evaluation.

The second sensitivity analysis explored how the findings may have been affected by attrition and, thus, by missing data. This was undertaken by rerunning the main analyses, conducted using only observed data, using multiple imputation.

Qualitative process evaluation

A qualitative process evaluation was conducted alongside the trial to provide in-depth qualitative data on both the implementation and the outcomes of the ROE programme. The delivery process of the programme was monitored and tracked across all schools and then a more detailed inquiry of underlying broad patterns outlined from across the schools was the focus of an in-depth case study approach conducted in six of the intervention schools.

Selection of the sample

A sample of six of the intervention primary schools were selected purposively from across four of the five health and social care trust areas in Northern Ireland. One of the selected schools declined to take part and another school was substituted, matched as closely as possible to the characteristics of the original school. The six schools selected were all intervention schools. The six case study schools were selected purposively to represent:

-

the main types of schools (controlled, Catholic maintained and integrated)

-

the trust areas (Southern, South Eastern, Belfast and Western)

-

a mix of urban/rural schools

-

size (large versus small)

-

different catchment areas in terms of socioeconomic background.

School personnel

To explore the impact of the programme on the pupils and the school, interviews were carried out in all six schools with the ROE instructor, the class teacher and the principal (18 interviews). Interview schedules focused on the interviewees’ perceptions of the following: the programme’s perceived impact; the benefits of the programme; how the children responded to the programme; the value added to the class/school from the ROE programme; what worked well and what worked less well; the main challenges in implementing the programme; and the school’s engagement strategy and experience of participation of parents with the programme. Interviews lasted no longer than 60 minutes.

Local programme co-ordinators

The four key point people from the health trusts were interviewed about their role in the implementation of the ROE programme. This included their experiences of schools in which programme implementation had been challenging or straightforward in terms of recruitment, curriculum, strengths and limitations of the programme, engagement of all participants and strategies used to ensure smooth roll-out of the programme in promoting the engagement of schools.

Volunteer mothers

The volunteer mothers from each of the six participating schools were interviewed about their experience of the family visits. The interview schedule focused on how they had heard about the ROE programme; what influenced their decision to participate; how comfortable they felt with the circumstances of the classroom visits; if they had experienced any challenges; their commitment to the programme; what they thought were the main benefits for the children, for them and for their baby; and how the children responded to their baby.

Children

The research team included staff who were very experienced in working with young children and it was proposed that children’s views be sought about school and the ROE programme. This was undertaken on a group basis in each of the participating six schools. Six focus groups were conducted, with 6–10 pupils in each, and with specific children purposively selected to represent a range of observed responses to the programme (from resistance/non-response to active engagement). The group sessions were used for exploratory discussion of children’s views of ROE, what they learned, what they liked and did not like about the programme and whether or not they talked to their families about it.

Parents

Parents in the intervention schools were invited to participate. They were asked about their views and experiences of the ROE programme and its impact on/contribution to their engagement with the child and the school; what benefits it brought and what the drawbacks were, if any; and whether or not they would recommend the programme to others.

Observational analysis

In total, there are 27 ROE lessons in the school year and there is a plan for every lesson. Nine themes are covered and each is addressed over three visits (pre-family visit, family visit and post-family visit). During the programme delivery (October 2011), classroom observations were conducted on three ROE lessons in each of the case study schools (18 observational visits). Three lessons were observed in each of the case study schools. Observational visits were selected to ensure that a variety of these lessons were observed in each of the case study schools. All of the lessons were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. During direct observation, field notes were taken to provide a descriptive summary of the lesson and record a time log of each lesson and written up in detail. The researcher interpreted the data immediately after collecting the field notes.

Ethics, consent and data analysis

Organisational consent was sought via a letter to the principal of each of the six case study schools, informing them of the purpose and nature of the research and outlining what taking part would mean for them and their school. This letter was followed by a telephone call to each principal to address any concerns or queries and to determine principals’ levels of interest in taking part. After principal consent had been obtained, parental and participant consent was sought.

To explain the study to the parents of the Year 5 children, the research team wrote a letter that was sent to parents via the school. The letter explained the study in non-technical terms and invited the parent and child to take part. It outlined the aims of the study, explained what was involved if the parent agreed that their child could take part and highlighted that fact that the participation of the child was voluntary.

Informed verbal consent was sought directly from the children. Children were provided with clear information on consent and confidentiality. Care was taken to make the information understandable, and the children had the opportunity to ask questions about the study. Following this, they were given the opportunity to consent to take part in or to withdraw from the study.

The data from the interviews were analysed using thematic analysis following the approach outlined by Braun and Clarke. 49 Thematic analysis is a flexible and descriptive method that allows the emergence of a narrative to formulate the important features relevant to the research questions. With prior consent, the qualitative interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and field notes were written up from the lesson observations. To perform the thematic analysis adequately, the coding programme MAXQDA 10 (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used. Six initial categories were created to reflect the research questions of this evaluation, namely:

-

benefits

-

programme content

-

mentoring and support

-

limitations

-

main challenges

-

parental involvement.

Themes that emerged were identified, and illustrative quotations have been used in the report. The observational data were analysed in a similar way to those from the interviews and focus groups, with a thorough process of reading, categorising, testing and refining that was repeated by the researcher until all emerging themes were compared against all of the observations.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Economic evaluations of school-based population health interventions such as ROE are relatively uncommon, and yet there is growing consensus on the value of investing in children’s health. 50,51 By improving a child’s overall health and well-being, that child may perform better in school, reduce their use of costly health-care services and, ultimately, be better prepared for and successful in adulthood in terms of labour and employment outcomes. 50,51 Furthermore, having good social, emotional and psychological health can affect physical health and can also protect children against emotional and behavioural problems, violence, crime, teenage pregnancy and drug misuse. 8,18 Beyond the health and social benefits to the individual, such outcomes have long-term economic impacts that need to be evidenced so that investment in such interventions can be justified.

The purpose of the economic evaluation was to answer the following research question:

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of the programme in reducing aggressive behaviour and increasing prosocial behaviour among school-aged children?

The aim of this economic evaluation was to determine the cost-effectiveness of the ROE programme compared with usual classroom activity. Specifically, we aimed to conduct a:

-

cost–utility analysis comparing costs and utilities of the two groups over a 3.75-year period

-

cost-effectiveness analysis comparing costs and effects such as decreases in difficult behaviour and increases in prosocial behaviour as measured by the SDQ between groups.

Usual classroom activity was chosen as the most appropriate comparator, as this is what would normally occur in the absence of ROE.

Methods overview

The base-case analysis compared the ROE intervention group with the usual classroom activities control group in terms of (1) costs incurred over the 3.75-year period and (2) quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained over the 3.75-year period. Data were collected at five time points:

-

pre test (baseline)

-

post test (after intervention completion)

-

1-year follow-up post test

-

second-year follow-up post test

-

third-year follow-up post test.

The analysis had a time horizon of 3.75 years (45 months), which equates to 3 years’ follow-up after intervention completion, as described above. A cost–utility analysis was undertaken, with costs considered from a public sector perspective (2014 GBP) and health outcomes measured by QALYs. Health utilities were measured using the Child Health Utility – 9D (CHU9D),46 a health-related quality-of-life measure designed specifically for children. All analyses were performed on individual patient-level data, taking clustering into account, and collected from the ROE trial. Table 4 describes the data collected for the economic evaluation.

| Data type | Description of data | Time points |

|---|---|---|

| Costs of intervention | Fees, training, personnel and materials to run ROE | During trial |

| NHS/PSS resource use | NHS/PSS service use and medications | FU2, FU3 |

| Cost to society | Social worker, school nurse and police visits | FU2, FU3 |

| Health-related quality of life | CHU9D | Pre test, post test, FU1, FU2, FU3 |

| Demographics | Gender, school, NIMDM 2010, number of siblings | Pre test |

Costs and QALYs were discounted using NICE’s recommended public health economic evaluation discount rate of 1.5%. 52 Missing data on costs and QALYs were handled by multiple imputation with chained equations. 53 Regression methods were used to obtain incremental cost and effect estimates. Multiple regression methods that ignore clustering (e.g. the within-school clusters as in this trial) can lead to biased coefficients and, especially, biased standard errors. 54 Multilevel models have been proposed as a method to address issues surrounding clustering in economic evaluation,9 and their use was explored. On recognition of the model being a poor fit for costs in this particular data set, regression with robust standard errors was conducted to adjust standard errors by indicating that observations within schools may be correlated but are independent between schools.

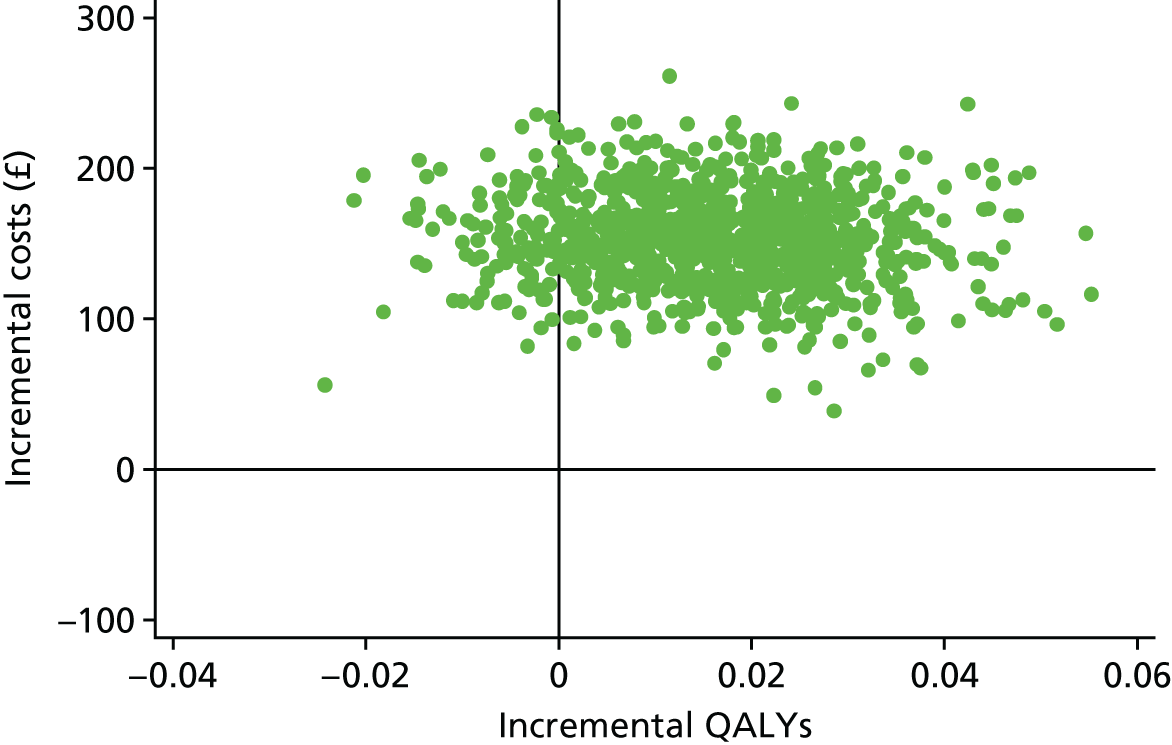

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were estimated by dividing the difference in mean costs between groups by the difference in mean effects between groups:

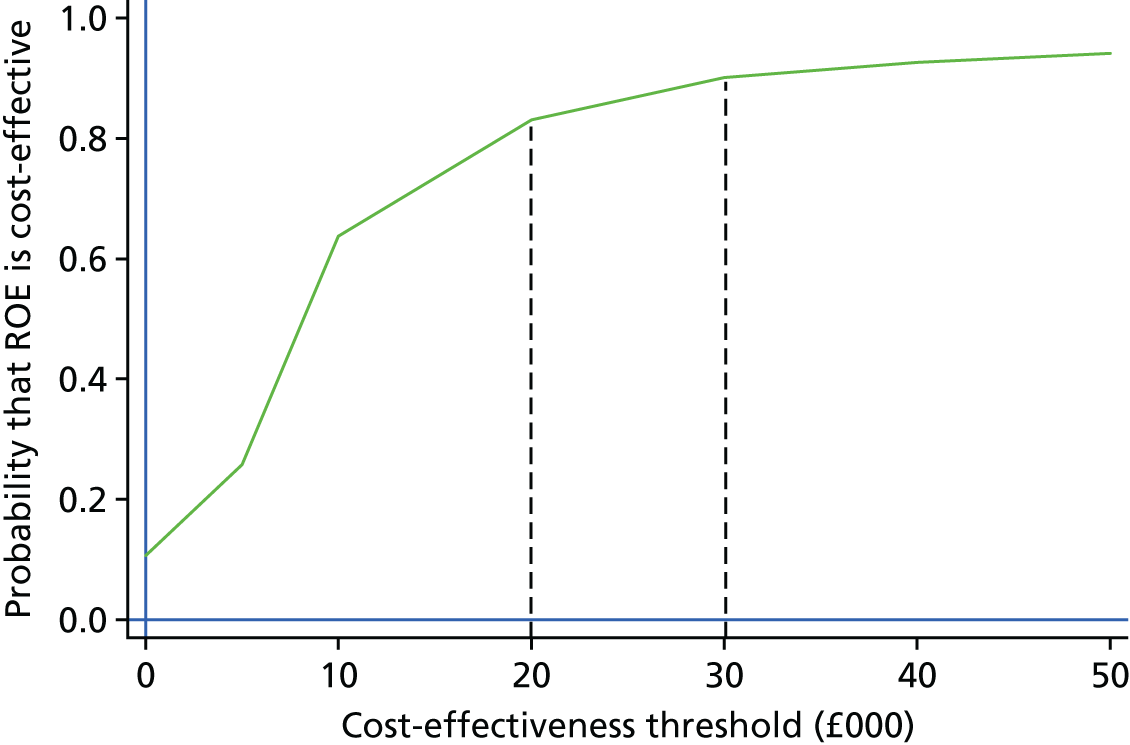

The uncertainty surrounding the ICER was investigated by use of a non-parametric bootstrap of 1000 iterations. This uncertainty was then presented on the cost-effectiveness plane and summarised on the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. ICER estimates were compared with the £20,000–30,000 per QALY threshold generally accepted by NICE. 55 To allow for uncertainty, a series of sensitivity analyses were performed. All analyses were conducted as intention-to-treat analyses and performed in Stata/SE version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Methods

Resource use

Resource use was identified through early discussions with the trial managers and their contacts with the school to identify likely resource use. Resource use was then measured over the duration of the trial and was made up of the following data collection: (1) resource use due to the delivery of the intervention including personnel, training, materials, fees and other costs; (2) NHS resource use, including service use and medications; and (3) societal costs such as social worker, school nurse and potential contacts with the police. These broad-ranging costs were considered from a public sector perspective, as per NICE public health guidance. 52

Cost of the intervention

Personnel costs (salary costs) were classified by NHS band and were taken from the 2011/12 Agenda for Change pay scale. 56 Personnel costs included key point people (band 7), who are health trust employees who co-ordinate ROE in each of the four participating trusts; administrative support (band 3); and ROE instructors (band 6). Salaries were based on mid-spine points for each respective band range, including 25% for on-costs, and adjusted for the time spent delivering ROE. An instructor fee was included, which was a one-time fee paid to each instructor.

The costs of time spent training instructors and of the training materials were also included. Other costs were made up of fees paid to the ROE programme in Canada for use of the programme in the UK. These included programme support costs, materials shipping, trainers and mentoring expenses. The programme fees were originally purchased in 2011 Canadian dollars and converted to the current price year using Purchasing Power Parities reported by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 57 When required, costs were inflated to our base year of 2014 (GBP).

Annuitisation was carried out to spread the costs over the expected 5-year life span of the ROE intervention fixed costs. Annuitisation is typically performed for capital costs such as buildings and equipment; however, other costs such as training and materials may also be annuitised if they are incurred at the start of the programme and yet have a useful life longer than the initial period. 58 Training, materials and other programme costs were one-time costs and were annuitised over the expected life of the intervention. 58 The base-case assumption of the expected life of the intervention was assumed to be 5 years; therefore, costs were annuitised over 5 years at a discount rate of 1.5%. The equivalent annual cost was estimated using the annuitisation formula given below, where K = the initial outlay, E = the equivalent annual sum, n = the time period and r = the interest rate:

Resource use

Resource use was collected at the second- and third-year follow-ups. To account for resource use over the entirety of the trial period, resource use questionnaires at the second-year follow-up asked parents to recall health and social care resource use from when their child started Primary 5, which relates to the beginning of the study. In the third-year follow-up, resource use questionnaires asked parents to recall their child’s resource use from the previous 12 months. The resource use measured was deliberately broad-ranging and included various types of health and social service use, and potential contacts with the police. Resources were valued using UK national unit costs. 59

Quality-adjusted life-years

The QALY is a generic measure of health that combines life expectancy with health-related quality of life and is defined as a year lived in full health. 60 QALYs are calculated by weighting length of life by health-related quality of life. In this trial health-related quality of life was measured using the CHU9D, which is a generic preference-based measure specifically designed for use with children to estimate QALYs for economic evaluation of programmes/interventions for young people. 61 It was originally developed for younger children (aged 7–11 years) and scored using weights based on UK adult general population values (n = 300). 46 Since then, an alternative value set has been developed for use with adolescents (aged 11–17) using weights based on Australian adolescent population values (n = 590). 62 For our base-case analysis, the CHU9D was scored using the original UK value set. In this context, QALYs should be interpreted in the same way as the outcome of any population health intervention. ROE QALYs reflect the quality-of-life gains achieved from the intervention’s aims to increase social and emotional understanding, empathy, promote prosocial behaviours and decrease aggressive behaviours.

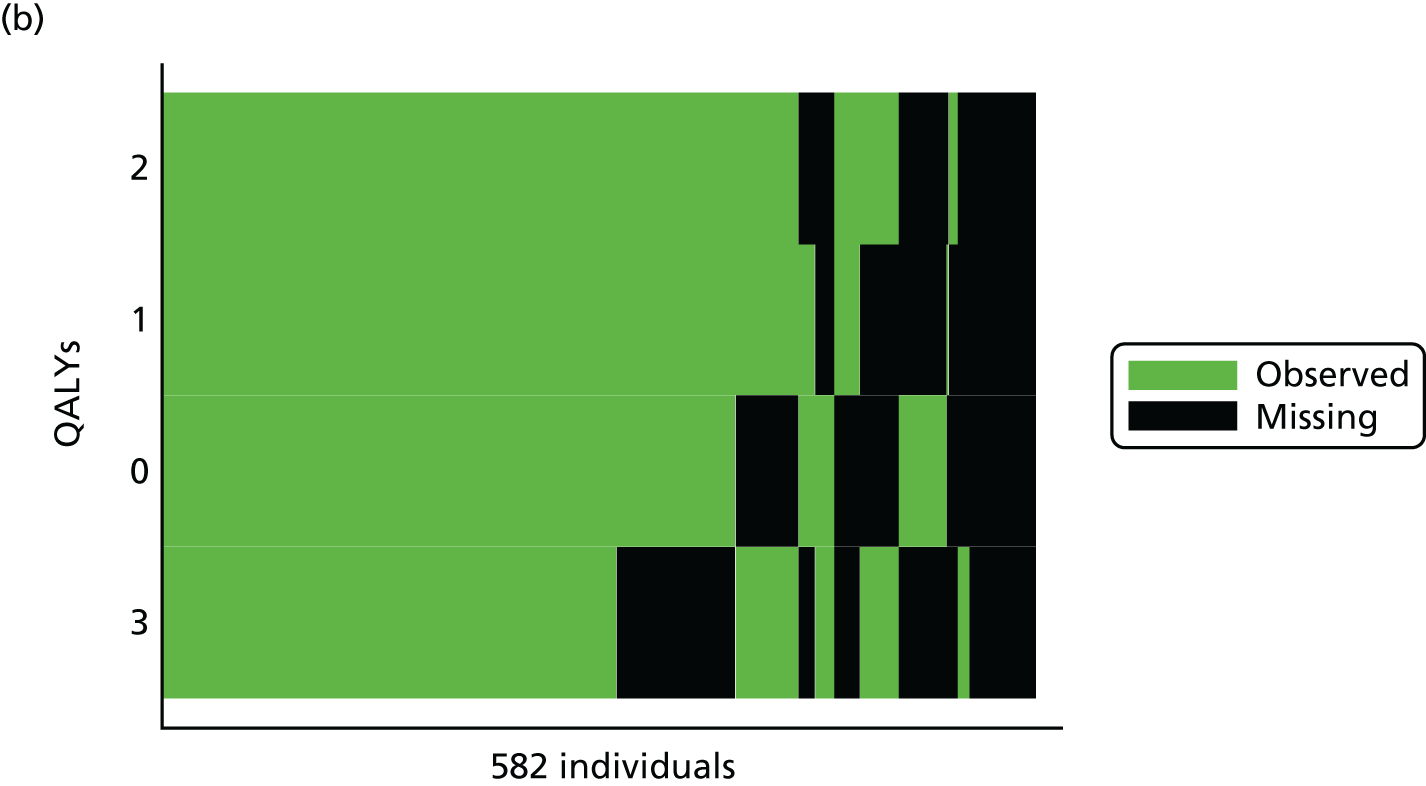

Missing data

Health and resource use costs for children were measured using parental self-report. The health and resource use questionnaire (see Appendix 4) was posted home to parents, who were asked to fill it in and return it in a stamped, addressed envelope. Health and resource use data were available for the second- and third-year follow-ups. A descriptive analysis of missing data was first undertaken to identify an appropriate analysis method to deal with the missing data. The missing data analysis follows recommendations set out by Faria et al. 63 for handling missing data in a cost-effectiveness analysis.

Missing data mechanisms are often categorised using Rubin’s framework for missing data. 64 ‘Data missing completely at random’ assumes that missing data do not depend on the observed and unobserved data values, and thus that the missing data vary indepedently of these. If data are missing completely at random, a complete-case analysis is valid. In complete-case analysis, only individuals with complete data at each follow-up point are included in the analysis. This is an inefficient use of the data because any individuals with missing follow-up data are dropped from the analysis. 63 Available case analysis makes more efficient use of the data by calculating costs and QALYs by treatment group at each follow-up point. They are then summed by treatment group over the whole time horizon of the study. A limitation is that different samples of costs and QALYs may be used, which can lead to non-comparability and affect the covariance structure. 65 ‘Data missing at random’ is a less restrictive assumption, as missing data depend only on the observed data and not the unobserved missing data. Multiple imputation is an appropriate analysis strategy for dealing with missing at random data. Data are not missing at random when the probability that data are missing depends on unobserved values.

A descriptive analysis of the proportion of missing values by group and in total was undertaken, along with the range, mean and SD of the observed data. Patterns of missing data were explored using the Stata ‘misspattern’ command. Logistic regression was performed to explore if baseline covariates were associated with the probability of data being missing. A dummy variable indicating missing data was created for overall costs and QALYs. Logistic regression was conducted with baseline covariates including gender, year group, multiple deprivation and number of siblings. A significant association between a baseline covariate and missing data indicates that data are not missing completely at random. 63 Dummy variables were created for costs and QALYs at each time point to explore the association between missing data and observed outcomes. Each indicator variable was then regressed on all other costs and QALYs observed in each year (i.e. missing baseline QALYs were regressed on costs and QALYs in each subsequent follow-up). Data were then assumed to be missing at random, in which case multiple imputation is an appropriate method of analysis for missing at random data.

Multiple imputation

Multiple imputation was employed using chained equations to handle missing cost and QALY data. Costs were imputed at the total cost level and QALYs were imputed at the index score level for each time point. Owing to advances in computational feasibility, a rule of thumb has been proposed that ‘the number of imputations should be similar to the percentage of cases that are incomplete’. 53 Missing data on resource use costs were particularly high, so 75 imputations (m = 75) were performed. Predictive mean matching was used for continuous, restricted range, and skewed cost and QALY variables. Predictive mean matching is useful as it avoids predictions that lie outside the bounds of each variable;53 however, it can produce predictions that closely match observed values. The uncertainty in these values is incorporated into the mean costs and QALY estimates using Rubin’s rules.

Multiple imputation was implemented separately by group allocation (ROE intervention and control), as is recommended to be good practice. 63 Covariates included in the imputation model were the same as those used during the estimation step and included gender, year in school, intervention allocation, number of siblings, school, trust and deprivation level. After imputation, three passive variables were created to allow total costs, total QALYs and QALY decrements to be classified as imputed variables to be analysed during the estimation stage. The total cost and QALYs variables generated were the sum of the imputed costs and QALYs at each time point. The QALY decrement was defined as the maximum QALYs that could possibly be accrued within the time frame minus the actual QALYs gained.

Analysis

Regression methods were used to estimate the incremental difference in cost and QALYs while simultaneously adjusting for baseline characteristics that were the same covariates used in the imputation model. Generalised linear models were selected because of their advantage over ordinal least squares and log models, in that they model both mean and variance functions on the original scale of cost. 66 They also take into account the typically skewed nature of cost and QALY data. 67 As cost data are typically right-skewed, a right-skewed gamma distribution is appropriate. As QALYs are typically left-skewed, the QALY decrement (described in Quality-adjusted life-years) was analysed with a gamma distribution. Thus, both costs and QALYs were analysed with a generalised linear model specifying a gamma family and identity link. Cost and QALY decrements were adjusted for the following covariates: gender, year in school, intervention allocation, number of siblings, school, trust and deprivation level. Baseline health-related quality of life was also included to adjust for any imbalance of health-related quality of life between groups. 68

The mean costs and QALYs for each group were presented using the method of recycled predictions. 66 Incremental costs and QALYs, along with their corresponding robust standard errors, were reported from results of the generalised linear model. The ICER was estimated, and uncertainty surrounding the estimate of incremental costs, QALYs and ICERs was investigated by use of a non-parametric bootstrap of the cost and effect pairs for 1000 iterations. This uncertainty was then presented on the cost-effectiveness plane and a 95% CI of the bootstrapped ICER was calculated. The results were summarised using a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve to reflect the probability of ROE being cost-effective at various willingness-to-pay thresholds. The thresholds varied from £0 to £50,000 per QALY, reflecting the range generally accepted to be considered cost-effective by NICE (£20,000–30,000 per QALY gained).

Clustering within economic evaluation

Roots of Empathy was a cluster randomised controlled trial, and so randomisation took place at the cluster (school) level rather than at the individual level. Therefore, it is important to take the effects of clustering into account in the economic analysis. 54 Cluster randomisation tends to reduce statistical power and precision69 because, in the case of ROE, individual pupils from the same school will be more similar than pupils from different schools. This non-independence is referred to as the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). 70 The ICC could be thought of as the proportion of variance due to between-cluster variation, or the correlation between members of the same cluster. 54 For sample size calculation, an ICC of 0.05 was assumed. 71

Clustering was accounted for by use of a multilevel model72 and the true ICC was estimated. It was expected that a multilevel model may not actually be the best-fitting model for this analysis (owing to having collected cost at only two time points). With this in mind, the ICC was examined to determine if clustering had a design effect on the economic outcomes. If the ICC was < 0.01, then a more practical approach to reflect clustering would be employed by reporting robust standard errors73 for the generalised linear model regressions.

Sensitivity analysis

Extensive sensitivity analyses were undertaken to allow for, explore and assess the uncertainty around the cost-effectiveness results in this economic evaluation. Thorough exploration through sensitivity analysis strengthens the external validity and generalisability of our results. All sensitivity analyses were derived from the base-case analysis described above and a description of each variation is provided in Table 5. To answer the main research question of the trial, outcomes were varied by conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis on the primary outcome, the SDQ. The SDQ has two components: the total difficulties score (which comprises difficult and aggressive behaviour) and the prosocial behaviour score. A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted on both. For the cost-effectiveness analyses, differences in effect were measured as the difference in scores from year 3 to baseline by group (Table 6).

| Sensitivity analysis | Element | Description of variation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Base case | Multivariate analysis of cost and QALY public sector perspective, 1.5% discount rate, child health utility, MAR assumption and multiple imputation |

| 1 | Outcomes | SDQ total difficulties (CEA) |

| 2 | SDQ prosocial behaviour (CEA) | |

| 3 | CHU9D computed with alternative tariff | |

| 4 | Costs | Training and material costs not annuitised |

| 5 | Training and material costs annuitised over 3 years | |

| 6 | Discount rate | Use of more traditional 3.5% discount rate for costs and outcomes |

| 7 | Missing data | Available case analysis assuming MCAR |

| Group | Total cost (mean) | Baseline score | Score at final follow-up (mean) | Difference in score | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | a | c | e | (e – c) | (a – b) / [(e – c) – (f – d)] |

| Control | b | d | f | (f – d) | |

| Difference | (a – b) |

The cost of the intervention was a main cost driver, so annuitisation assumptions about the useful life of the intervention were varied to account for no annuitisation and annuitisation over a shorter useful life of 3 years versus 5 years. The discount rate was also varied to reflect a more traditional rate of 3.5% versus the 1.5% public health rate. The level of missing resource use and health-related quality-of-life data from the trial was particularly high, and so a sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore the uncertainty surrounding the missing at random assumption and use of multiple imputation. An available case analysis was conducted, assuming that data were missing completely at random, to assess the impact that multiple imputation had on the incremental costs and QALYs. The main analysis is referred to henceforth as the base-case analysis.

Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement in this evaluation – particularly in relation to policy-makers, commissioners and programme providers, as well as teachers and pupils – has been a key element throughout this study. The purpose of such engagement has been to:

-

inform aspects of study design (data collection processes, procedures and dissemination)

-

raise stakeholders’ awareness, support their involvement and develop their capacity to coproduce research into the practice of school

-

encourage active involvement in the interpretation of the trial findings and process evaluation

-

help identify the practical significance of the findings from the trial and implications for the further delivery of the ROE programme.

-

help plan a dissemination strategy, including a national dissemination seminar in Belfast.

This engagement has taken five forms, as described in the following sections.

Partnership meetings

From the outset of the trial, the research team has attended and fully engaged with the partnership meetings with staff from the health trusts, staff from education library boards and principals from schools participating in the trial. Each meeting has been attended by the lead health programme co-ordinator from the health trust, the pupil personal development officer for the education and library board and usually 6–8 principals from intervention schools. This forum has maintained a schedule of twice-yearly meetings throughout the trial (5 years). The research staff established links at the start and then continued to have consultations with the forum attendees throughout the research period. The aim has been to help influence the research at an early stage of development, to raise awareness of the research and to support the schools’ involvement in the process.

Stakeholder members of the Trial Steering Committee

Alongside the above partnership meetings, key stakeholders, comprising staff from the health trusts and staff from education and library boards, as well as the Public Health Agency, have also contributed directly to the evaluation as members of the Trial Steering Committee. Critically, this has included contributing to the emerging interpretation of the findings and the development of the dissemination strategy.

Process evaluation

The research team has given particular prominence to the process evaluation element of the study. As described above, this has involved in-depth engagement with all of the key stakeholders to ascertain their experiences and perspectives of the programme. The rich qualitative insights gained from the teachers, ROE instructors, parents and pupils are demonstrated clearly in Chapter 4 of this report.

End-of-project consultation meetings

Towards the end of the trial (May–June 2016), discussion groups were conducted in three of the intervention schools to provide preliminary feedback on the findings of the study in order to ensure stakeholder engagement in the interpretation and dissemination of the core findings. The consultations involved nine interviews, and, in addition, a focus group was held with pupils. Overall, as part of this phase, the research team talked with three principals, two teachers, two ROE instructors, two parents and a group of eight pupils. A purposive quota sample of three schools was recruited, which, within the available budget and time frame, represented the different subsectors of the diverse primary school population in Northern Ireland. The sample was chosen to include schools of different sizes, schools from rural as well as urban locations and schools from three of the education and library boards. These key stakeholders continue to be consulted regarding the development of a regional dissemination strategy, including a national dissemination seminar in Belfast.

Dissemination events

A regional launch of the findings of this evaluation took place in September 2016. This attracted over 100 attendees representing participating schools and a range of voluntary and statutory organisations in the region. This event was planned with the Public Health Agency and in ongoing consultation with members from the Partnership Meetings and those recently engaged through the end of project consultation meetings.

A further regional event, aimed at schools, was held in November 2017, by the Centre for Evidence and Social Innovation at Queen’s University Belfast. This event was also co-organised with the Public Health Agency and the Department of Education and included presentations on the findings of this evaluation and another evaluation of an SEL programme undertaken by the Centre for Evidence and Social Innovation. Further regional events are planned for 2018.

In addition, the PHA has funded members of the present research team to undertake a broader systematic review of school-based universal SEL programmes for children aged 3–11 years who have been registered with the Campbell Collaboration. 74 The findings of this present evaluation, together with the forthcoming findings of the systematic review, will be used to inform future policy and practice with regard to the promotion of children’s social and emotional development in Northern Ireland.

Chapter 3 Results from the trial and cost-effectiveness analysis

Introduction

This chapter presents the findings from the trial element of the study and its associated cost-effectiveness analysis. It begins by describing the sample and comparing the differences between the intervention and control groups pre test. It then sets out the findings in relation to the impact of the programme immediately post test and then at each of the follow-up time points. It concludes with an outline of the findings of the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Participant flow

Before pre testing, seven schools withdrew from the trial: four from the intervention group and three from the control group. Sixty-seven schools participated pre test (October 2011). Two further schools withdrew post test, one each from the intervention and control groups, and, thus, 65 schools participated in the post-test data collection (June 2012). At the 12-month follow-up (June 2013), one further school (from the control group) did not take part in data collection; however, this school did not permanently withdraw from the study and will take part in the subsequent data sweeps. No other schools withdrew from the study. The flow of individual children and parents through the study is described in detail in Figure 2.

Recruitment

Seventy-four primary schools (clusters), from four of the five trust areas in Northern Ireland, were originally recruited to and enrolled in the trial (Belfast HSCT, South Eastern HSCT, Southern HSCT and Western HSCT) by health and social care trust personnel between March and June 2011.

In total, 1278 pupils aged between 8 and 9 years were recruited to the study: 695 in the intervention group and 583 in the control group. It can be seen from Table 7 that the proportions of controlled, Catholic-maintained and integrated primary schools recruited to the sample were broadly representative of the population of Northern Ireland primary schools as a whole.

| School type | Population,a n (%) | Sample, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled | 378 (44) | 27 (40) |

| Catholic maintained | 392 (46) | 31 (46) |

| Integrated | 42 (5) | 6 (9) |

| Other | 42 (5) | 3 (5) |