Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 09/3009/02. The contractual start date was in December 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2016 and was accepted for publication in October 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All authors received a grant of £28,000 from the North East Strategic Health Authority in 2012 to cover the costs of delivering the intervention, associated training and other non-research costs of this study. Elaine McColl has been a subpanel member of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research and Programme Development Grants since June 2008. She was also an editor for the NIHR Journals Library Programme Grants for Applied Research programme from July 2013 to March 2016. Luke Vale has been a panel member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Board since 2014, a panel member for NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research from March 2008 to June 2016, and Director of the NIHR Research Design Service for the North East of England since April 2012. Martin White is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Board. He is Programme Director of the NIHR Public Health Research programme and Editor-in-Chief of the NIHR Public Health Research journal (he has held both roles since October 2014).

Dedication

We dedicate this report to Emma Noble, the lead researcher on this project, who died tragically, aged 46, in the second year of the study. Emma was a registered general nurse who worked in the NHS for 14 years prior to her appointment to Newcastle University in September 2004. Emma worked as a researcher in the School of Neurology, Neurobiology and Psychiatry, and the School of Education, Communication and Language Sciences, before she was appointed as a Research Associate in the Institute of Health & Society. Emma worked on the Do-Well study from its inception and was central to establishing the trial. She was a highly valued member of the team. Her sudden and unexpected death was a shock, not only to her family, friends and colleagues, but also to study participants to whom she was a great source of support. She is greatly missed.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Haighton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from our study protocol,1 published under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/). In addition, some text, boxes, figures and tables have been reproduced from Howel et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International license (CC BY 4.0), which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Socioeconomic inequalities in health among older people

A vast body of observational evidence on socioeconomic inequalities in health suggests a close relationship between access to resources and health status that is positive, progressive and has no apparent thresholds. 3,4 Health inequalities are universal across time, nations, societies and the human life course. Socioeconomic differences in health persist into old age, and socioeconomic inequalities in self-reported physical and mental health widen in early old age. 5,6 Individuals with mild cognitive impairment exhibit poorer financial and health literacy. 7 Low household wealth is strongly associated with poorer life satisfaction and quality of life. 8 The poorest older people have inadequate access to services essential to health and well-being. 9 Older people, especially those in poor health, therefore often need additional income and support to maintain their independence, including payments for care, domestic help and aids and adaptations to the home. 10–12

Resource-based interventions to promote health

Research into the differential provision of welfare across nations has shown that it can exert an influence on subjective well-being, morbidity and mortality. For example, older people are emotionally better off13 and at lower risk of suicide in welfare states more generous than the UK. 14 Almost half of the reduction in excess winter mortality since 1999/2000 has been attributed to winter fuel payments. 15 Key theories that explain how money influences health include materialist explanations (e.g. money buys health-promoting goods and the ability to engage in a social life in ways that enable people to be healthy, and enables the avoidance of health risks in the environment); psychosocial mechanisms (e.g. the stress of not having enough money may adversely affect health, and having adequate resources may relieve stress); behavioural factors (e.g. people living in disadvantaged circumstances may be more likely to have unhealthy behaviours); and being in poor health may affect education and employment opportunities in ways that affect subsequent health. 16

In theory, increasing individual or group access to material, social or financial resources (so-called ‘assets-based’ approaches)17 should result in improved health,4,18,19 yet little research has directly evaluated the impact of increasing resources on health. 20 Ecological studies following the reunification of Germany have suggested important impacts of increased income on mortality, although a range of other factors may have played a part. 21,22 A systematic review20 of 10 North American randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of income supplementation experiments targeting a range of age groups, carried out in the late 1960s and 1970s, showed that none had reliably assessed the effects of increased income on health. The authors pointed out that, although such experiments are unlikely to be repeated, one way of assessing the health impact of increasing financial resources on health would be to evaluate the impact of assisting claimants to obtain full welfare benefit entitlements. 20

Tackling health inequalities has become a major policy priority for the UK, highlighted, for example, in the White Paper on public health (Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation). 23 Following publication of the Acheson report24 and the advent of Health Action Zones in the late 1990s,25 there was an increase in welfare rights advice projects linked to primary care in the UK. Welfare rights advice provision in primary health-care settings can reduce, by an estimated 15%, the time general practitioners (GPs) spend on benefits issues, and leads to fewer repeat appointments and fewer prescriptions. 26 In 1999, Reducing Health Inequalities: An Action Report27 highlighted welfare rights advice as a potentially effective intervention for reducing health inequalities. This proposal was endorsed by the UK government’s Marmot review in 2010. 3

Social welfare for older people and the underclaiming of entitlement

In the UK, a range of financial and non-financial welfare benefits is available; these benefits have different purposes and different criteria for entitlement. Some are means-tested (income-related) and others are dependent on an assessment of health or other needs. Means-tested benefits include income-replacement benefits (e.g. income-related pension credit, and income-related financial support with housing costs). Non-means-tested benefits are intended to help meet the additional needs of those with health or social care problems (e.g. meeting the extra costs associated with ill-health or disability, carer’s benefits to supplement/replace earnings for people who provide support or bereavement benefits for people whose legal partner dies). In addition to financial benefits, material support can be offered to those in need (e.g. mobility aids and housing adaptations, such as rails, ramps and bathroom aids). Financial and non-financial benefits are variously administered through the Department for Work and Pensions, local authorities, housing associations and charities. Welfare rights advisors (WRAs) in local authority social services departments and third-sector organisations (e.g. Citizens Advice Bureaux, Age UK and other charities) help by undertaking financial assessments, recommending whether or not a client might be eligible for a benefit and sometimes offering active assistance with completing claims. Active assistance may also involve liaising with health or social care professionals for evidence of diagnosis or care needs.

The non-claiming of welfare entitlements among older people is a long-standing problem, which is currently increasing. 28 A large proportion of eligible welfare benefits remains unclaimed,28 and many of these are health-related benefit entitlements of vulnerable groups, such as older people. 28,29 Failure to claim entitlements is associated with a number of factors including the complexity of the benefits system,30 lack of knowledge about entitlements and difficulty in making claims. 12,31–33 In recent British studies, the bureaucracy associated with applying and uncertainty regarding the outcome of any claim, the amount of the award, autonomy and independence were reasons cited by people who were entitled to but did not claim benefits. 12,31–34 In addition to the state pension, there are a number of means-tested and non-means-tested benefits that can be awarded to older people if entitlement conditions are fulfilled. The level of underclaiming varies depending on the benefit concerned, but it is estimated to be at least 33% for Pension Credit and 40% for Council Tax Benefit. 35 Entitlement to one benefit can often act as a ‘passport’ to others, as many of the benefits aimed at people over the state retirement age are linked together in a complex network of entitlements that is often difficult for people to access without expert assistance.

Welfare rights advice services and their evaluation

Our systematic review of the health, social and economic impacts of welfare rights advice services in health-care settings32 identified numerous studies that demonstrated the financial and material benefits of such services. Welfare rights advice provided by local authorities and third-sector organisations is known to increase the uptake of benefits among those eligible, particularly when this involves ‘active assistance’ with benefit claims. 24,36 Studies have also shown that the receipt of benefit entitlements can be increased by providing information and advice in general practice, particularly in relation to those benefits that are health related. 37–41 However, our systematic review identified only two studies that investigated the health impact of welfare rights advice,42–44 one of which found an improvement in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in some of the subscales of the Short Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36). 42,43 However, both studies demonstrated the difficulties of identifying and measuring appropriate health outcome measures when assessing the health effects of welfare rights advice in primary care. Neither study used a randomised controlled design, and both suffered from significant methodological weaknesses that rendered them inconclusive. Both studies evaluated a model of welfare rights advice delivery that was based in primary care, required referral from practice staff and did not offer a domiciliary service or active assistance with claims. Qualitative studies exploring the impact of welfare rights advice on clients in primary care have identified a range of health-related outcomes that can potentially result from the receipt of welfare rights advice, including changes in the physical, behavioural and, in particular, psycho-social domains of health. 12,31–33

Since 2006, few studies have added substantively to this literature. Two papers updated analyses included in our systematic review but yielded no new conclusions. 45,46 A study in a hospice setting audited referrals for welfare rights advice and found inconsistency in referral practices and a heavy workload for WRAs, but valuable potential of such referrals in terms of benefit eligibility. 47 A study in a UK musculoskeletal clinic48 examined the use of the Health Assessment Questionnaire49 as a tool to identify patients’ eligibility for welfare benefits. Although the authors found relatively high levels of eligibility for new benefits among those identified, there are inconsistencies in the numbers in the paper that make it difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, it does identify a potential screening tool for use in health care that might be of value in the future. Another study from some of the authors of this report (Moffatt, Noble and White) examined the use of welfare rights advice among 1174 cancer patients, assessing the viability of a service linked to clinical teams using qualitative methods. 50 The service proved feasible, with exceptionally high levels of successful claims (96%) and median benefits returned (£70/patient). Patients and staff valued the service highly, and health outcome evaluation was felt to be warranted. Krska et al. 51 used a cohort study with qualitative interviews among 148 patients in primary care to evaluate a Citizens Advice Bureaux-delivered welfare rights advice service. 51 They reported a decrease in prescription of hypnotic/anxiolytic medications 6 months after referral for advice, compared with 6 months before, but their analysis was uncontrolled. Practitioners felt that the service benefited patients and reduced workloads.

We conducted a pilot RCT to prepare for the definitive RCT described here, evaluating the impact of a domiciliary welfare rights advice service offered to people aged ≥ 60 years identified via primary care in disadvantaged areas. 11,12,52 In this pilot trial, 58% of participants were awarded either financial (median gain £55/week), non-financial (e.g. aids and adaptations to the home) or both types of benefits,11 confirming the feasibility and success of the intervention from the point of view of accessing unclaimed benefits. It also provided vital information on the feasibility of such a trial, which has helped in planning the definitive RCT reported here. In reporting on the pilot trial we identified a number of key design and methodological issues that would need to be addressed in a definitive evaluation. These are discussed below.

Study design, level of randomisation, contamination and dilution

An appropriate trial design was required, preferably with both randomisation and concurrent controls. Individual-level randomisation was considered preferable to cluster randomisation (e.g. at general practice level), as it required a smaller sample size. The potential problem with individual-level allocation was that there could be ‘contamination’ between intervention and control participants in the same general practice. This was more likely to be the case when welfare rights advice was available from an open-access service delivered in the general practice. However, by using a WRA who only saw patients in their own homes, we found in our pilot RCT that contamination did not occur; no control participants reported independently seeking welfare rights advice during a follow-up period, albeit a period of only 6 months. 11

Equipoise and the control condition

A key consideration in designing the proposed trial was whether or not there was genuine equipoise. Welfare rights advice is known to increase access to financial and material resources for eligible clients. However, our systematic review of published and grey literature indicated that there was no conclusive evidence that welfare rights advice leads to positive or negative changes in health. 32 We discussed these findings with WRAs, with directors of adult social services, with a selection of GPs and with members of the public in our target age group. We found each of these groups to be in equipoise with regard to the proposed trial health outcomes. Having established this, we also carefully considered the issue of study design and the ideal and feasible control conditions.

We considered that, ideally, controls should be adults as similar as possible to intervention group participants, but should not receive welfare rights advice, nor claim or receive new benefits, during the period of outcome follow-up. In clinical trials, it is usual to withhold the intervention from the control group because the health benefits of the intervention are not proven (i.e. clinical equipoise exists). Although this is the case with regard to the health impacts of welfare rights advice, as indicated above there is adequate evidence that welfare rights advice leads to significant financial and material gains for a proportion of recipients. Thus, it was considered ethically problematic to identify that control group participants were eligible to receive additional financial benefits, but either to keep this information from them or to tell them of their eligibility but not give them advice or help with claims. To circumvent this dilemma, we proposed that control participants should not receive a welfare rights assessment until the end of the trial period (i.e. following final outcome measurement). The full intervention (i.e. a full benefit assessment and active assistance with claims until resolved) would then be offered.

We had concerns that the WRAs might feel tempted to offer benefits advice to control participants before the 2-year ‘wait period’ had elapsed. We planned to avoid this by not informing the WRAs of the names of control participants until a few weeks before their benefits assessment was due (i.e. 2 years after their baseline assessment). The study team would hold control participants’ names securely during this period.

The design would thus avoid unfairly raising expectations among control participants. It would also help to avoid the potential problem of contamination, which could have arisen if control participants independently sought welfare advice (leading to dilution of the outcome effect), although we did not propose attempting to prevent this as we found little evidence of it in our pilot RCT. The proposed control condition is, therefore, in effect a ‘wait-list’ control, whereby the control group waits to receive the intervention 24 months after the intervention group.

It is, of course, possible that some members of both the intervention and control groups will die during the proposed 24-month follow-up period, which we would expect in the course of any prospective study of this age group. In our pilot study, we recorded seven deaths (four in the intervention group and three in the control group) out of 105 after 24 months’ follow-up. 11

One of the reasons that such interventions to date have not been rigorously evaluated for health impacts is in part because such research has previously been deemed unethical by researchers considering undertaking such evaluations,53 on the grounds that one cannot withhold benefits to which people are entitled. The proposed design of this RCT is fair because, at present, this kind of intervention is not routinely available to primary care patients and is generally only available to those who seek such services or are referred to them by a health or social care professional (e.g. a hospital social worker); these options remain open to patients in this trial. When targeted services are available in primary care, they tend to be short term and ad hoc. If we find any general practices in participating local authority areas with access to such services, they will be excluded from this trial. Genuine uncertainty exists about the proposed health-related outcomes because participants will not be denied any entitlement that they would otherwise receive and, at the time of the study, the health impact of the proposed intervention remains unknown. 32 We have determined that the research team and key stakeholders from health and social services are in equipoise about the proposed health outcomes.

Pragmatic versus explanatory

In the proposed trial, we know that not all participants in the intervention group will be eligible for additional benefits, and that those who are will receive variable amounts of financial and non-financial benefits. Ideally, we wish to examine the health impact of receiving versus not receiving such benefits, as well as examine the potential for a gradient of effect (‘dose–response’ relationship) by the amount of benefit received. However, to do so will require a substantially larger sample size than that proposed. In practice, therefore, the receipt of welfare rights advice is the intervention we will be evaluating (rather than receipt of specific benefits), as ‘welfare rights advice’ is the service being delivered. The proposed trial is, therefore, a pragmatic (intention-to-treat) RCT of this ‘complex’ intervention. 54 Nevertheless, we will also assess the potential for exploratory subgroup analyses looking at differential effects by participant characteristics (such as age and sex), and receipt/non-receipt of and levels of any benefits received. We anticipate that the trial will therefore contribute both to answering the question of whether or not the welfare rights advice intervention is effective in improving health and to providing new evidence on the more fundamental question of whether or not increasing resources leads to better health. 4

Length of follow-up

To enable the accurate assessment of the health and social effects of welfare rights advice, an appropriate length of follow-up is required. Our previous work suggested that considerable time may elapse between the first advice session and the receipt of new financial or material benefits. Often this is between 3 and 6 months, but it can be longer if the case is not straightforward or if there is an appeal. For example, in our pilot RCT, 45% had received their entitlements by 3 months after their welfare assessment, 85% after 6 months, 95% after 9 months and 100% by 12 months. 11 Given such delays in receipt of benefits, as well as the fact that any financial benefits may not be spent immediately, it seemed unlikely that the benefits would have substantial impacts on health within the first 12 months. In our pilot, which was not adequately powered for substantive analyses, we found no suggestion of differences in health-related outcomes between the intervention and control groups after 6, 12 or 24 months (although in the pilot trial control participants did receive the intervention after 6 months). 11 Nevertheless, it seemed likely that the longer the delay between receipt of intervention and measurement of outcomes, the greater the chance of demonstrating a substantive effect on health.

To assess the acceptability of a range of delays in receiving the intervention among control group participants, we undertook an experiment in the context of a focus group discussion with a representative sample of low-income older people. To achieve this, simulations of the RCT randomisation procedures were undertaken. The first simulation concerned a typical drug trial, and participants were given sweets whose colour depended on whether they were randomised to the intervention or the control group. Then, randomisation for the proposed trial was simulated. The concept of equipoise, with regard to the health impacts of welfare rights advice, was explained. Next, each group member was given an envelope from which they found out whether they were in the control group or the intervention group. If in the intervention group, they were allocated various types of benefit (e.g. Attendance Allowance plus Council Tax Benefit plus Housing Benefit), and the monetary value of these was revealed to them. We then talked through the various possible time delays until the control group would also receive their welfare rights assessment and advice. The time delays used were 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36 and 60 months. The initial response to the design was that it was unfair to those in the control group. However, when it was explained that (1) although such services exist, they are not routinely targeted at or delivered to all people aged ≥ 60 years but are only available on referral or demand, (2) the findings of this study could influence the development of such services, involving collaboration between health and social services, and (3) that a substantial ‘wait’ between intervention and control groups is needed to establish any differences in health outcome, the consensus of the group was that a delay of 24 months would be acceptable in the context of the proposed trial. We therefore opted for a wait-list design for the proposed RCT, with a 24-month follow-up period for the main outcome assessment, followed immediately by delivery of the full intervention to the control group.

Selection bias

In our pilot RCT, GPs wrote to random samples of people aged ≥ 60 years, inviting them to respond with an indication of their willingness to participate in the trial (i.e. to ‘opt in’). 11 Using this method, 36% initially agreed to participate, 14% declined to participate and 50% failed to respond. Low levels of positive response to an ‘opt-in’ approach carries a risk of participation bias. 55,56 In their work on evaluating the impact of welfare rights advice for the Department for Work and Pensions,57 Corden et al. 58 routinely use an ‘opt-out’ method of recruitment for similar populations. With the approval of the NHS Research Ethics Service (NRES), we proposed using this type of recruitment method in this trial; this should have reduced the potential recruitment bias associated with ‘opt-in’ recruitment methods and increased the efficiency of trial recruitment.

Choice of outcome measures

Previously reported studies of the health effects of welfare rights advice have restricted reported health outcomes to general measures of health or psycho-social functioning (such as the SF-3642,59), together with measurement of financial gains.

In our qualitative research among recipients of welfare rights advice,12,33 we identified a range of potential benefits of advice, including:

-

health (improvements in anxiety, depression, insomnia; reductions in medication or consultation)

-

health-related behaviours (health-promoting changes in smoking, diet, physical activity and alcohol consumption)

-

social (improvements in family or other relationships, reduction of social isolation, increased ability to work, ability to care for relatives, etc.)

-

financial (debt rescheduling and receipt of new benefits, e.g. Attendance Allowance, Disability Living Allowance, Disability Living Allowance mobility component, Invalid Care Allowance, Incapacity Benefit, Housing Benefit, Income Support)

-

material (e.g. access to free prescriptions, Council Tax exemption, entitlement to respite care, Meals on Wheels, rehousing or home modifications).

The qualitative findings of our pilot study12,33 summarised these perceived benefits of the intervention in terms of:

-

increased affordability of necessities

-

increased capacity to manage unexpected future problems

-

decreased stress related to financial worries

-

increased independence, including ability to travel, shop, visit the GP, etc.

-

increased ability to participate in family life and society.

These findings are corroborated by a recent evidence synthesis undertaken to develop a logic model for the health outcomes of welfare rights advice services. 19 The resultant logic model has been used as the basis for a realist evaluation of the health impact of Citizens Advice Bureaux services, for which a protocol has recently been published. 60

In addition to qualitative work with study participants in our pilot RCT, we collected proposed outcome measures and relevant potential confounding factors. 12 The pilot trial was not sufficiently powered for substantive analyses, but the feasibility of measurements was good, and well tolerated by older people. The main outcome measure we assessed was the SF-36 instrument, as used in several previous studies. 42,59,61,62 Although this had demonstrated some potential, albeit in uncontrolled or non-randomised studies (e.g. positive changes in the mental health and emotional role domains),59 we were concerned that its domains did not sufficiently encompass the substantially wider range of reported impacts of welfare rights advice identified in qualitative studies, including our own (see Welfare rights advice services and their evaluation). 12,33 We therefore sought an alternative HRQoL measure that might best encompass key domains, such as independence, social participation and mental health. There is no single, ideal outcome measure that captures all of these domains, but the CASP-19 (Control, Autonomy, Self-realisation and Pleasure) instrument,57,63 developed specifically with a view to measuring quality of life in older people, comes close and has been recommended by Corden et al. 58 as a composite measure of the impact of welfare rights advice. 57 It is a self-reported summative index, comprising 19 Likert scale items in four domains: control, autonomy, self-realisation and pleasure. 63 Its performance has been examined in several prospective studies, including the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). 64,65

Generalisability

Our pilot trial was undertaken in one social services district (Newcastle upon Tyne) and in four general practice populations. 11 However, we know, from other work and discussions locally, that service delivery in welfare rights advice varies from area to area, as do general practice populations. To enhance the potential generalisability of the results, the RCT was, therefore, undertaken across a range of geographical and local authority areas (including urban and rural) and general practices. It seemed possible, indeed likely, that the present welfare regime would change during the course of the trial. The proposed intervention was not dependent on any particular set of benefits and was adaptable to any new regime. This added to its future generalisability.

Target population

Although we recognised that isolated older people who are eligible for benefits may live in all areas, in order to maximise the efficiency (and impact) of welfare rights advice services provided through primary health care, this RCT focused on practice populations in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. Eligibility for health-related benefits (and failure to claim) increases with age, particularly post retirement; although there are other key target groups, such as single parents, non-claimants most likely to be accessed through primary care are predominantly in older age groups. 33,66–68 This trial therefore focused on a predominantly post-retirement population (those aged ≥ 60 years), residing in areas of economic deprivation.

The North East has some of the poorest health outcomes in England, coupled with high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage. From the 19th century, the regional economy was based on heavy industries such as deep coal mining, shipbuilding and steel making. Since the 1970s and the demise of heavy industry, the area has suffered economic decline due, in particular, to the closure of shipbuilding, coal mines and other heavy manufacturing. The post-retirement population of interest in this trial were born in the pre-and post-Second World War years (from 1920 to 1950), and many would have worked in these industries, which are associated with industrial-related conditions such as musculoskeletal injuries and diseases of the lung.

Nature of the intervention

The intervention delivered in this trial was based on standard advice services of the type found across local authorities in England when this study was designed. Welfare rights advice is not a statutory service, and provision varies across all local authorities in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Conventionally, however, these services are available only on demand or by referral. Thus, for example, an older person admitted to hospital may be referred by a hospital social worker, doctor or nurse for benefits assessment prior to discharge. Only some services have undertaken the targeting of welfare rights advice at a population level. 32 Those that have done so have found that there is a significant level of underclaiming in the general population and, in particular, among older people. 29 The proposed intervention is, therefore, a modification of a standard welfare rights advice service to target proactively a particularly vulnerable population in which we anticipated there would be high levels of underclaiming (i.e. those aged ≥ 60 years in disadvantaged areas). The only reliable population registers in England at a local level are the primary care patient registration lists held by GPs, which were used to sample this target group selectively.

In our pilot RCT, we identified that effectiveness and efficiency (in terms of successful claims) could be maximised by making the service domiciliary, as a substantial proportion of those aged ≥ 60 years have limited mobility, and during assessments clients often need access to information they keep at home. 33 Domiciliary visits also proved more popular with clients. In addition, we found that WRAs need to provide ‘active assistance’ with claims, for example completing claim forms for clients, as being unable to complete the forms is a key barrier to people claiming. 12,31,32 Finally, GPs need to have appropriate awareness of welfare entitlements and, for health-related benefits in particular, an understanding of the medical criteria on which decisions are made, so that they can support reasonable claims effectively in medical assessments requested by the Benefits Agency. Good communication between GPs and WRAs is essential to facilitate this. In our pilot RCT, we delivered education and training on these issues to all GPs in participating practices,11,12 another feature that is included in the proposed definitive RCT.

Process evaluation

Process evaluation is an essential element of designing and testing complex interventions. Process evaluation is used to assess the fidelity and quality of implementation, clarify causal mechanisms and identify contextual factors associated with variation in outcomes. 54 When evaluating the impact of an intervention, the emphasis of process evaluation is on providing greater confidence in conclusions by assessing the quantity and quality of what was delivered, and assessing the generalisability of its findings by understanding the role of context. 69

To draw conclusions about what works, process evaluations aim to assess fidelity (whether or not the intervention was delivered as intended) and dose (the quantity of intervention implemented). Intervention fidelity relates to adherence to the content of the study protocol and the process of ensuring quality and consistency in intervention delivery to all study participants. 70,71 This includes ensuring a clear intervention model, developing an intervention protocol, selecting appropriate staff to deliver the intervention, ensuring adequate training in the implementation of the intervention and providing staff with ongoing supervision. 70 In complex interventions, fidelity is not a straightforward process. In pragmatic trials the standardisation of the intervention to the study protocol will promote internal validity, but limiting variation may affect generalisability. 54

In addition to what is delivered, process evaluation can investigate how the intervention is delivered. This can provide vital information about how the specific intervention might be replicated, as well as generalisable knowledge on how to implement other complex interventions. Issues considered may include training and support, communication and management structures, and how these structures interact with implementers’ attitudes and circumstances to shape the intervention. Process evaluations also investigate the reach of interventions (whether or not the intended audience comes into contact with the intervention, and how). 69

Exploring the mechanisms through which interventions bring about change is crucial to understanding both how the effects of the intervention occurred and how these effects might be replicated by similar future interventions. Process evaluations may test hypothesised causal pathways using quantitative data as well as using qualitative methods to better understand complex pathways or to identify unexpected mechanisms. Context includes anything external to the intervention that may act as a barrier to or facilitator of its implementation, or its effects. Implementation will often vary from one context to another, however; an intervention may have different effects in different contexts even if its implementation does not vary. Complex interventions work by introducing mechanisms that are sufficiently suited to their context to produce change, while causes of problems targeted by interventions may differ from one context to another. Understanding context is, therefore, critical in interpreting the findings of a specific evaluation and generalising beyond it. Even where an intervention itself is relatively simple, unlike welfare rights advice, its interaction with its context may still be highly complex. 69 In the proposed RCT, we collected both quantitative and qualitative data to assess the process of intervention delivery, allowing us to explore the reach, uptake, fidelity and quality of the intervention, as well as provide contextual information that may prove valuable in explaining the observed outcomes.

Chapter 2 Methods

In this chapter we present the objectives of the study and then describe the methods that were used to achieve the objectives. The methods are divided into three main sections: quantitative (trial) methods, embedded qualitative study methods and economic evaluation methods. We conducted a process evaluation, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data, and the methods for this are presented in relevant sections below, and drawn upon in the corresponding results chapters. The process evaluation aimed to evaluate the trial procedures, assess the fidelity of the intervention and ascertain the reasons for the intervention’s success or failure. It drew on quantitative data collected to assess the fidelity, dose and reach, including socioeconomic patterning, of the intervention, as well as qualitative data to assess the acceptability and perceived impacts of the trial and intervention, and the reasons for success and failure of each component thereof. An initial analysis of process data was conducted before the main outcome analysis to avoid biased interpretation of process data. This allowed process data to provide prospective insights into why we might have expected to see positive or negative overall effects and generate hypotheses about how variability in outcomes may have emerged. 69 They thus informed our secondary, exploratory analyses.

The proposed methods for all analyses were documented in our protocol. 1 Statistical and economic evaluation analysis plans were further pre-specified in greater detail and approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) prior to the analyses being commenced.

Objectives of the randomised controlled trial

The overall aim of the study was to evaluate the effects on health and well-being of a domiciliary welfare rights advice service for independently living, socioeconomically disadvantaged older people (aged ≥ 60 years), recruited from general (primary care) practices.

Primary objective

To establish the effects on HRQoL of a domiciliary welfare rights advice service targeting independently living, socioeconomically disadvantaged older people (aged ≥ 60 years) identified via primary care, compared with usual practice.

Secondary objectives

-

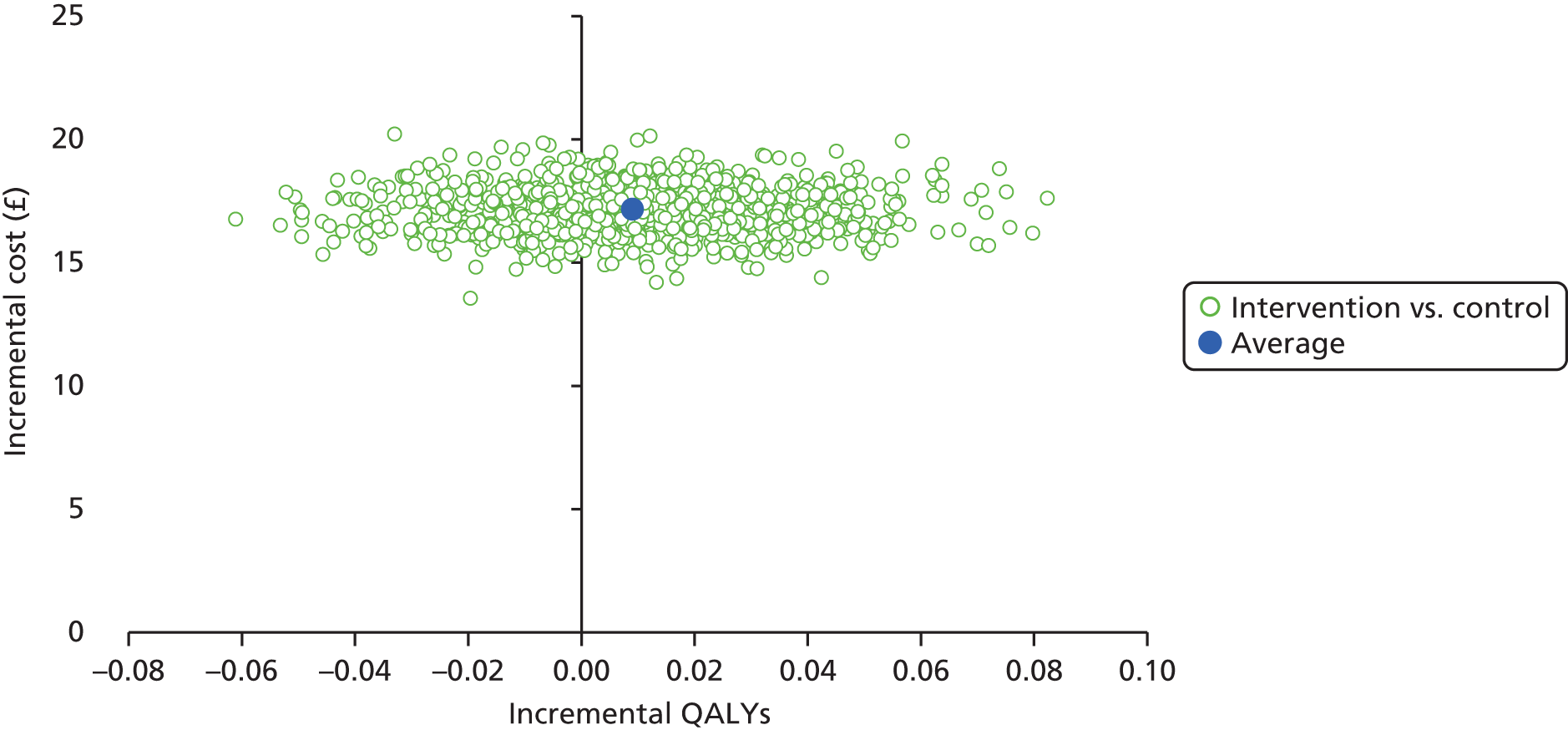

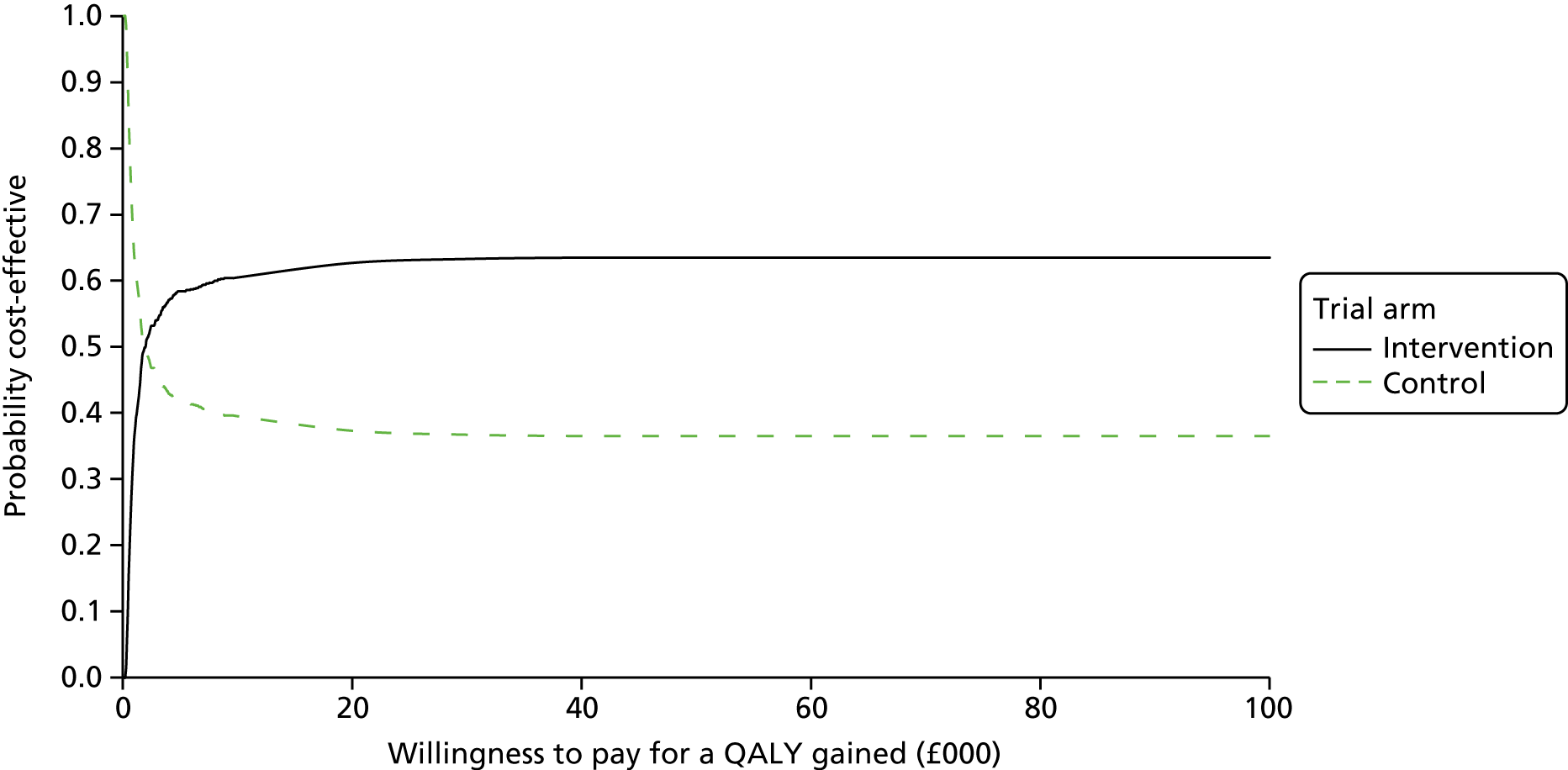

To establish the cost consequences and the cost-effectiveness of a domiciliary welfare rights advice service targeting independently living, socioeconomically disadvantaged older people (aged ≥ 60 years) identified via primary care, compared with usual practice.

-

To establish the acceptability to trial participants and relevant professionals of a domiciliary welfare rights advice service targeting independently living, socioeconomically disadvantaged older people (aged ≥ 60 years) identified via primary care.

-

To identify the unanticipated consequences (positive or negative) of a domiciliary welfare rights advice service targeting independently living, socioeconomically disadvantaged older people (aged ≥ 60 years) identified via primary care.

Trial design

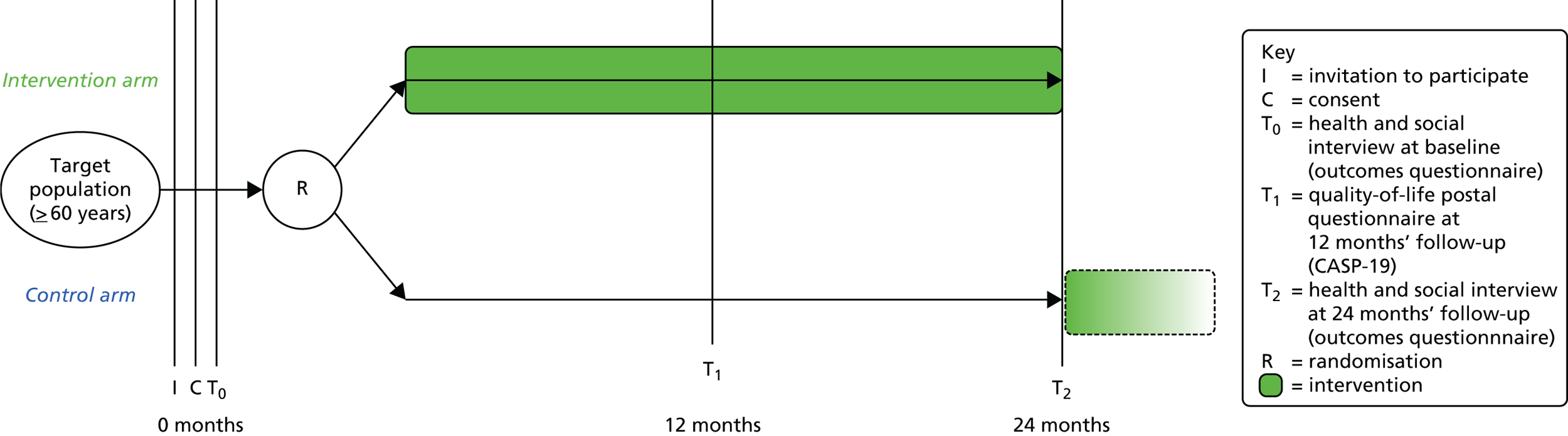

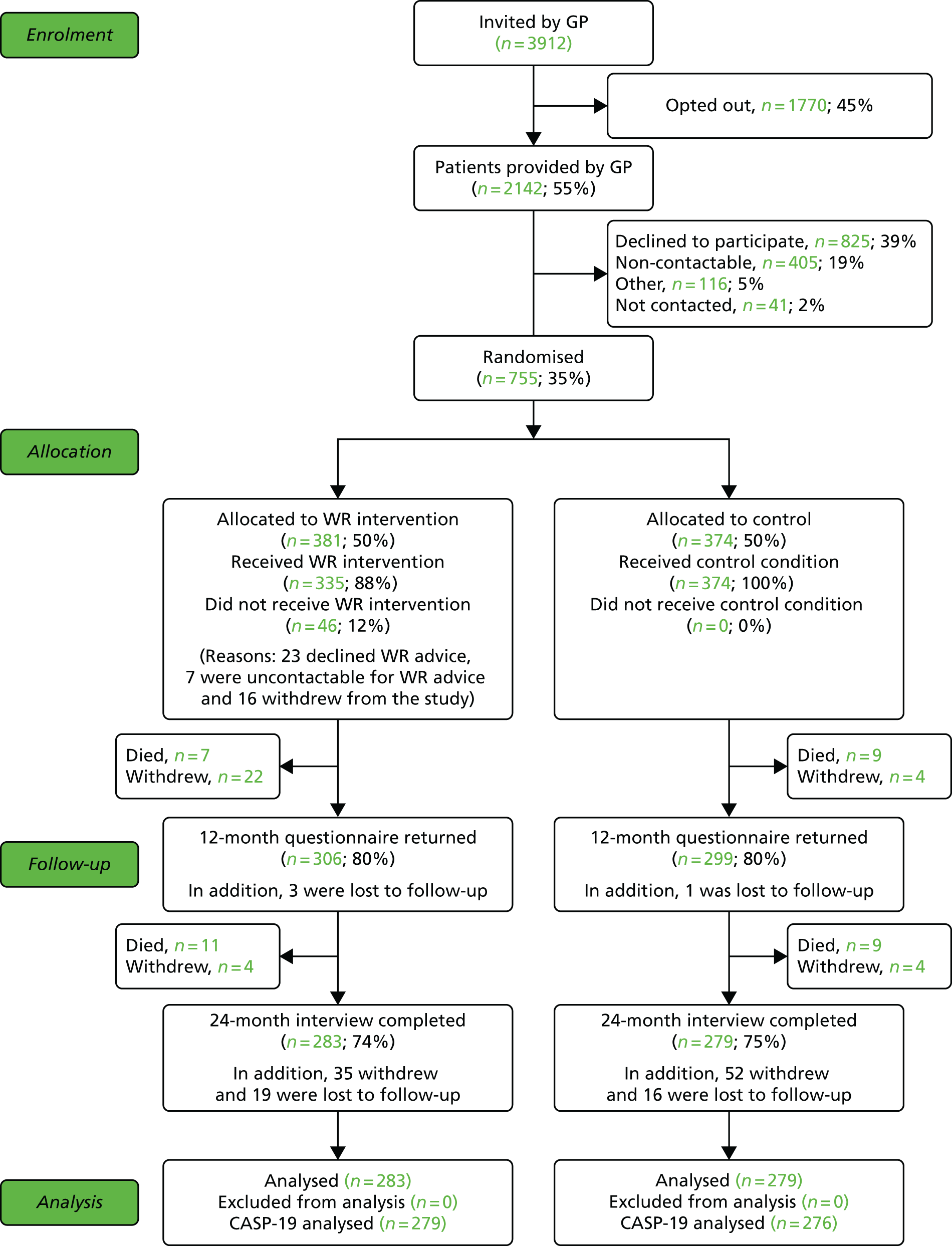

A pragmatic, individually randomised, single-blinded (researchers), parallel-group, wait-list controlled trial of domiciliary welfare rights advice versus usual care, with embedded economic and quantitative and qualitative process evaluations (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of study design.

Setting

The trial took place in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas in the North East of England, which included urban, rural and semirural areas, with no previous access to welfare rights advice services targeted to primary care patients.

The study was planned to take place in 10 of the 12 local authority districts in the North East of England (Stockton, Darlington, Middlesbrough, County Durham, Sunderland, South Tyneside, North Tyneside, Newcastle, Northumberland and Gateshead). Social services departments in these local authorities had agreed in principle to provide domiciliary welfare rights advice services. The intention was to recruit two general practices per local authority district with the help of the Primary Care Research Network – Northern and Yorkshire (PCRN-NY). Lists of all general practices from the local authority districts were obtained from the PCRN-NY and ranked according to deprivation score using the 2010 English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) calculated at middle-layer super output area (MSOA) level for practice premises (main surgery) postcodes, in accordance with the method of Griffin et al. 72 Deprivation covers a broad range of issues and refers to unmet needs caused by a lack of resources of all kinds, not just financial. The English Indices of Deprivation attempt to measure a broad concept of multiple deprivation, made up of several distinct dimensions, or domains, of deprivation. Super output areas are geographical units for the collection and publication of small area statistics. There are currently two layers of super output area: lower-layer super output areas (LSOAs) and MSOAs. LSOAs have an average of 1500 residents and 650 households. MSOAs have a minimum of 5000 residents and 2000 households, with an average population size of 7500, and fit within local authority boundaries. WRAs established whether or not any of the practices in the most socioeconomically deprived two-fifths of the IMD distribution had existing dedicated or targeted welfare rights advice services. Those practices in the lower two-fifths of the deprivation ranking distribution, without existing dedicated or targeted welfare rights advice services, were eligible for inclusion and were sent a letter by the PCRN-NY inviting them to participate (see Appendix 1), along with an information sheet describing the study (see Appendix 2) and an expression of interest form to return directly to the PCRN-NY.

The PCRN-NY provided the study team with a list of all eligible practices that had indicated a willingness to participate in research. If more than two general practices per local authority expressed willingness to participate in the research, the intent was to list the practices randomly and then contact them sequentially until two practices from each local authority district had agreed to participate in the trial. Fourteen eligible practices originally volunteered to participate in the research, representing only eight of the local authority areas for which we had secured the services of domiciliary WRAs. As we did not achieve our target of two general practices per local authority area immediately, we took two further courses of action: (1) we asked those practices that had originally volunteered if they would be willing to recruit additional patients (specifically, twice the number originally requested); and (2) we attempted to recruit further eligible practices through informal research networks across the North East of England. The latter strategy resulted in three further practices volunteering to participate from local authorities already involved in the study. However, it was also necessary to ask three general practices that had expressed willingness to do so, to recruit double the number of participants (Table 1). Owing to the problems with general practice recruitment, the welfare rights advice services in two local authorities that were willing to provide them were ultimately not required and the study took place in eight local authority districts.

| Local authorities (12 approached, 10 offered WRA services, 8 participated) | Domiciliary welfare rights advice services available | First-wave practices volunteered | Second-wave practices volunteered | Number of patients invited to participate by general practice | Number of patients invited to participate by local authority (N = 3912) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First mailing (N = 1700) | Second mailing (N = 2212) | Both mailings (N = 3912) | |||||

| A | N | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| B | N | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| C | Y | b | b | b | b | b | b |

| D | Y | b | b | b | b | b | b |

| E | Y | 1 | 200 | 187 | 387 | 387 | |

| F | Y | 2 | 100 | 195 | 295 | 695 | |

| 3 | 200 | 0 | 200 | ||||

| 4 | 100 | 100 | 200 | ||||

| G | Y | 5 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 600 | |

| 6 | 100 | 0 | 100 | ||||

| 15 | 0 | 200 | 200 | ||||

| H | Y | 7 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 400 | |

| 8 | 100 | 0 | 100 | ||||

| 16 | 0 | 200 | 200 | ||||

| J | Y | 9 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 600 | |

| 10 | 100 | 200 | 300 | ||||

| K | Y | 11 | 200 | 0 | 200 | 400 | |

| 17 | 0 | 200 | 200 | ||||

| L | Y | 12 | 100 | 230 | 330 | 330 | |

| M | Y | 13 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 500 | |

| 14 | 100 | 100 | 200 | ||||

Participants and recruitment

Participants were volunteer patients aged ≥ 60 years (one individual per household) who were not resident in a nursing home or in hospital, were not terminally ill (as assessed by their GP) and were fluent in written and spoken English.

The PCRN-NY and the Comprehensive Local Research Networks offered personnel and financial resources to participating general practices in the North East of England to identify and approach research study participants. Each participating practice was asked to generate a random sample of up to 300 people aged ≥ 60 years from their practice register. Practice staff scrutinised their list to identify any patients terminally ill or known to be resident in hospital or long-term care, who were excluded. Those who were assessed as not able to participate in the research due to poor mental or physical health, as assessed by their GP, were excluded from the study. Practice staff also checked to ensure that only one person per household had been selected for this list. If two people from the same address were found, one was selected by practice staff at random (by flipping a coin) to be retained and the other was removed from the sample list. Not all practices had sufficient patients registered to be able to generate a list of 300 people aged ≥ 60 years from their practice register; in these circumstances, they listed as many as possible.

This list of up to 300 names (of people believed to meet the eligibility criteria) per practice was randomly ordered and the first 100 patients on the list were sent a letter (see Appendix 3) and patient information sheet (see Appendix 4) signed by the senior GP partner on behalf of the practice, inviting them to participate in the trial. The figure of 100 patients was determined on the basis of the recruitment rate in the pilot study and anticipated to yield the required sample in an optimistic, best-case scenario. The letter on practice-headed paper explained that, unless the participant objected by returning the opt-out form (see Appendix 5) to the practice in the stamped addressed envelope within 2 weeks, their name and contact details would be passed to the research team, who would then contact them directly to discuss the trial further and seek informed consent.

After 2 weeks, the names, addresses and telephone numbers of those who had not opted out were passed to the research team. Research interviewers contacted these individuals by telephone to arrange, if acceptable, a face-to-face meeting at a mutually convenient time in the participant’s own home. At the initial appointment, research interviewers sought written informed consent (see Appendix 6) and then proceeded to collect baseline data.

We monitored recruitment continuously to assess whether or not and when further patients should be invited by each practice. When it became apparent that we would need to approach more than 100 patients to achieve our proposed sample size, practices were asked to write to additional patients from their original list of 300. In two cases, practices contacted all remaining patients aged ≥ 60 years. In these cases, the total number of patients invited was 387 and 330 (practices 1 and 12, respectively). In the three practices that had offered to recruit additional participants, recruitment numbers were doubled at each stage of the process.

Randomisation

Following written consent and baseline assessment, participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to intervention or control condition, stratified by practice. Research interviewers notified the project administrator after each baseline assessment that a new participant had been successfully recruited. The administrator held sequential allocation tables for each practice, independently generated from random numbers prior to recruitment [generated by a statistician (AB) using Stata version 12 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA]. The administrator allocated all participants to the intervention or control group in the chronological sequence in which they were recruited and immediately sent each participant a standard letter (see Appendix 7) informing them of their group allocation. Only the project administrator had access to the allocation tables, and the allocation was thus concealed from the research team, data collectors and statisticians. The allocation was revealed to the participant and (in the case of intervention group participants) the relevant WRAs. The administrator immediately informed the appropriate local WRA team member of the contact details of each newly allocated intervention group participant and requested that they should be visited for a welfare assessment within 2 weeks. The WRAs were sent lists of control group participants to assess 24 months later, once follow-up had been completed.

Blinding

Research interviewers, who collected data from participants at baseline and 24 months, were not notified of the allocation status of participants to ensure that they remained blinded for the duration of the study.

Intervention

Here the intervention is described as designed and intended, according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guidelines. 73,74 In Chapter 3, variations of this intention are documented and the implications are identified. The rationale underpinning the intervention components was rehearsed in Chapter 1.

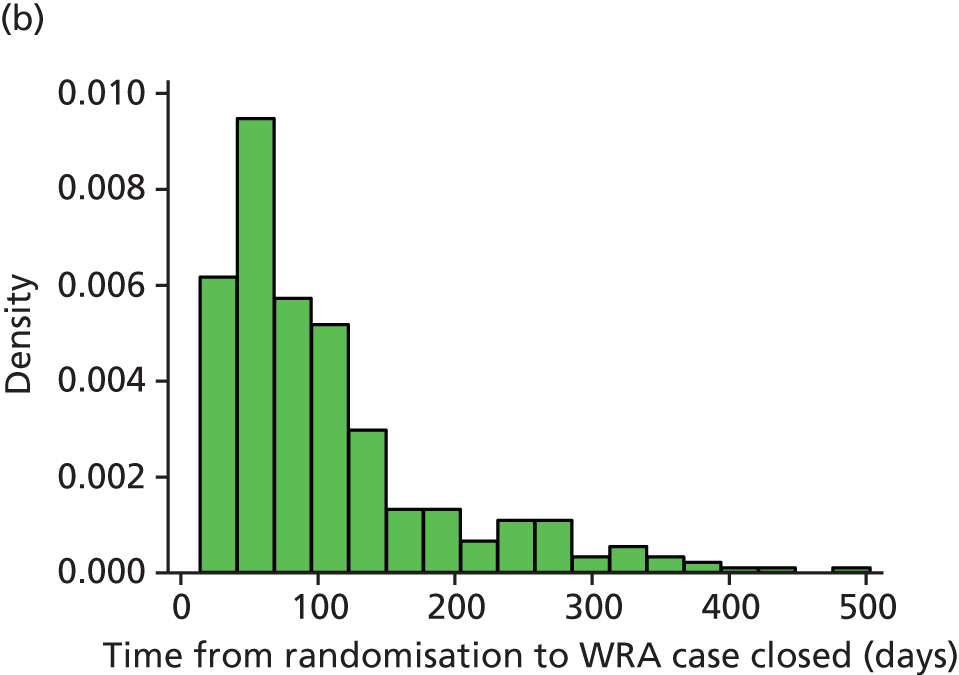

The domiciliary welfare rights advice service comprised face-to-face welfare rights advice consultations and active assistance with benefit claims, delivered in participants’ own homes and tailored to their individual needs by a qualified WRA employed by local authority departments, or their contracted services, in the North East of England. In one local authority, welfare rights advice services were contracted and delivered by a third-sector organisation. Following randomisation, intervention group participants were given an appointment in their own home with a WRA within 2 weeks, during which participants underwent a full benefit entitlement assessment involving assessment of financial, material and welfare status; assessment of previous benefit entitlement and claims; discussion of current entitlement and options for action, including new claims (financial and non-financial). Active assistance with benefit claims and other welfare issues was given, which included completion of benefit application forms on behalf of the participant. Complex claims or those referred for further assessment or tribunal were managed as per their usual practice by WRAs. It was anticipated that initial assessments would last up to 60 minutes. Participants were followed up at home or by telephone as required by WRAs until they no longer required assistance (cases are usually ‘closed’ once all claims and appeals have been concluded), which could take several months. 11

In area K, one local authority WRA provided the intervention from the start of the project until April 2013, when budget reviews restricted the availability of the WRA for the Do-Well study. A freelance WRA took over and completed the intervention in this area. In area G, the local authority WRA volunteered to provide the intervention for the Do-Well study but withdrew before recruitment began; therefore, a freelance WRA provided the intervention in this area. In area J, a local authority WRA provided the intervention at baseline but was unable to continue at 24 months (i.e. to deliver the intervention to control participants) because welfare rights posts had been lost and a new team had been formed that combined local welfare provision with supported housing. One WRA was retained by the local authority to deal with complex welfare cases but did not have the capacity to continue providing the intervention for the Do-Well study; therefore, a freelance WRA provided the intervention at the 24-month follow-up. In area L, three local authority WRAs provided the intervention throughout the study. In area M, the intervention was provided by paid staff from the Citizens Advice Bureau. In areas H and F, one local authority WRA within each area respectively provided the intervention for the duration of the study. In area E, two local authority WRAs provided the intervention for the duration for the study.

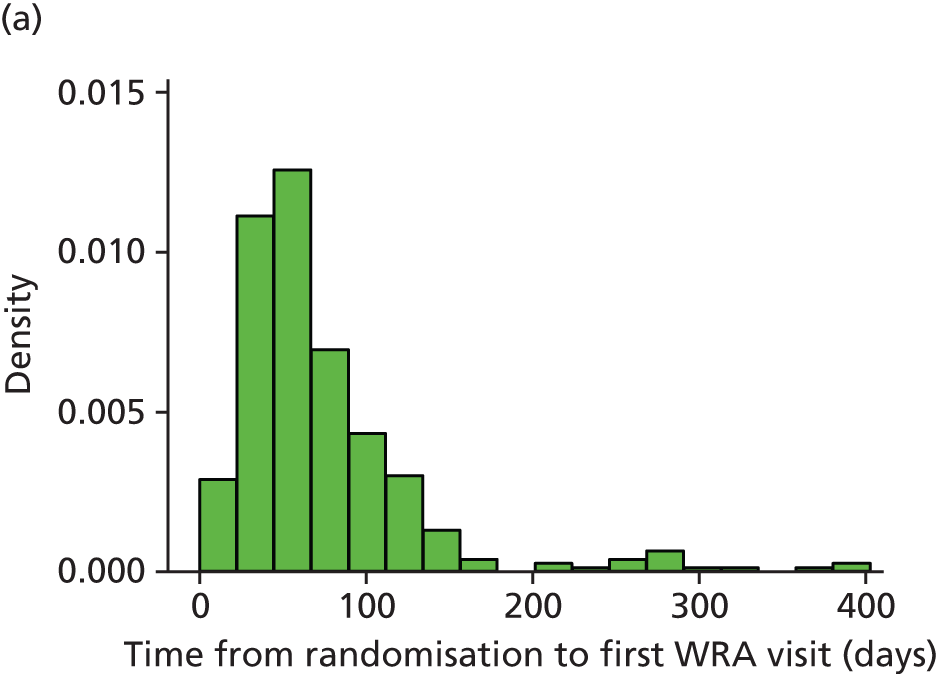

Intervention reach

Intervention reach was assessed as the proportion of those eligible to receive the intervention who actually received it. Causes of participants not receiving the intervention as intended (e.g. participants withdrawing, refusing or being lost to follow-up) and reasons given by participants (in interviews and questionnaires) were recorded when available. We also analysed the socioeconomic patterning of receipt of the intervention, and receipt of welfare benefits using IMD 201072 scores assigned at household level by matching postcode to IMD score at LSOA level.

Eligibility and receipt of welfare benefits was assessed, by type of benefit, as a proportion of those assessed by WRAs in the intervention group at baseline. This was also assessed in the control group at the 24-month follow-up.

At the outset, the intervention was primarily to be funded and provided by welfare rights advice services in the 10 participating local authority areas in the North East. However, a contingency fund of ≈£28,000 was also secured from the North East Strategic Health Authority in 2012, prior to the start of the study, to fund any excess intervention costs and the costs of any training for WRAs and GPs to ensure the effective delivery of this service with a high level of fidelity.

Training and quality control

To ensure consistent approaches to medical assessments related to relevant claims, each participating general practice was visited by a member of the research team and provided with an information pack and guidance on the completion of medical information on benefit application forms (see Appendix 8). This information was developed by the study team, with the help of a senior WRA who was involved in training and quality control in our pilot RCT, and a GP who was a member of the study team for the pilot RCT.

All participating WRAs were invited to attend information sharing events prior to intervention delivery to agree the intervention protocol, which specified the procedures for delivering welfare rights advice and the follow-up actions in a standardised manner. Intervention procedure checklists (see Appendix 9) were then given to all WRAs prior to the commencement of the study to ensure consistent delivery. Study staff closely monitored the progress of intervention delivery and maintained regular contact with all WRAs.

Fidelity assessment

We assessed the fidelity of the intervention in a number of ways. First, we asked WRAs to record the date and time of each initial welfare rights advice assessment, so we could assess whether or not these were delivered on time (within 2 weeks of the baseline study data collection). Second, we assessed whether or not initial welfare rights advice assessments were delivered as intended. This assessment was carried out, as unobtrusively as possible, by analysing audio-recordings of WRAs undertaking this aspect of intervention delivery with a small subsample of study participants. We aimed to analyse one initial welfare advice consultation per WRA (i.e. n = 19). Audio-recorded consultations were assessed by a senior WRA from a local authority not involved in the Do-Well study, selected for her extensive experience as a WRA, supervisor and welfare advice team manager. Each WRA was contacted shortly after the start of the study and asked to audio-record the next consultation undertaken with a consenting participant, and to record a brief commentary explaining the case and the actions recommended. We explained to WRAs that, as part of the research, we needed to understand how they interacted with clients and how outcomes were achieved. We avoided explicit reference to judgements about their practice, as this might have led to practice that was different from usual. Each participant was informed about the nature of the fidelity assessments, and written consent was obtained for audio-recording of the consultation. If a participant refused consent, the WRA was advised to ask the next participant they were due to visit for an initial assessment. The fidelity assessments took place between December 2012 and February 2013. Each consultation was analysed against a checklist of criteria developed by the study team (see Appendix 10). This checklist assessed the overall quality of the consultation, whether or not the correct assessment of needs had been made and that, if warranted, the correct benefits were applied for according to standard procedures. The senior WRA who listened to the recordings completed a confidentiality agreement prior to assessment, as it was felt not possible to fully anonymise the recordings. All data were held in accordance with the Data Protection Act 199875 and all sound files were individually password protected. After analysis of the fidelity assessment, all recorded files were destroyed. The research team was provided with a summary of each consultation based on assessment against the criteria of needs assessment, appropriate benefits applied for and a brief commentary on the justification for the outcomes achieved.

Comparator (wait-list control condition)

Participants randomised to the control group received ‘usual care’ (standard practice) from both health and welfare rights advice services after randomisation until they had completed their 24-month follow-up assessment. They were given no advice regarding welfare rights as a part of the study intervention during this period. However, they were free to seek welfare rights advice independently from their local authority or any third-sector provider at any time. Participants who sought independent advice remained in the trial and were analysed in the control arm on the intention-to-treat principle, and details of any advice and ensuing claims and outcomes were recorded at the 24-month follow-up assessment. Following the 24-month follow-up assessment, participants in the control arm received the intervention, as delivered to the intervention group (described above), including all follow-up visits by WRAs and assistance with claims and appeals over the following months, until all claims had been resolved.

The participants were informed during recruitment, via the patient information sheet (see Appendix 4), that we wanted to recruit 750 people into the study. They were told that one group of 375 people would be given an appointment with the welfare advice service straight away and another group of 375 people would be given an appointment around 24 months later. Potential participants learned that the group they would be put in would be decided by chance, like tossing a coin, but that everyone would receive an appointment within 24 months. Once individuals agreed to participate in the study and completed baseline assessment, they were sent a letter (see Appendix 7) detailing which group they had been assigned to. Wait-list control participants were told that the group they had been assigned to would mean that they would see a WRA approximately 24 months after they entered the study.

Both intervention and control group participants remained clients of the welfare advice service beyond the end of the trial, if necessary, until such time as their help was no longer needed, as per usual welfare rights advice service protocols.

Data collection

Primary outcome measure

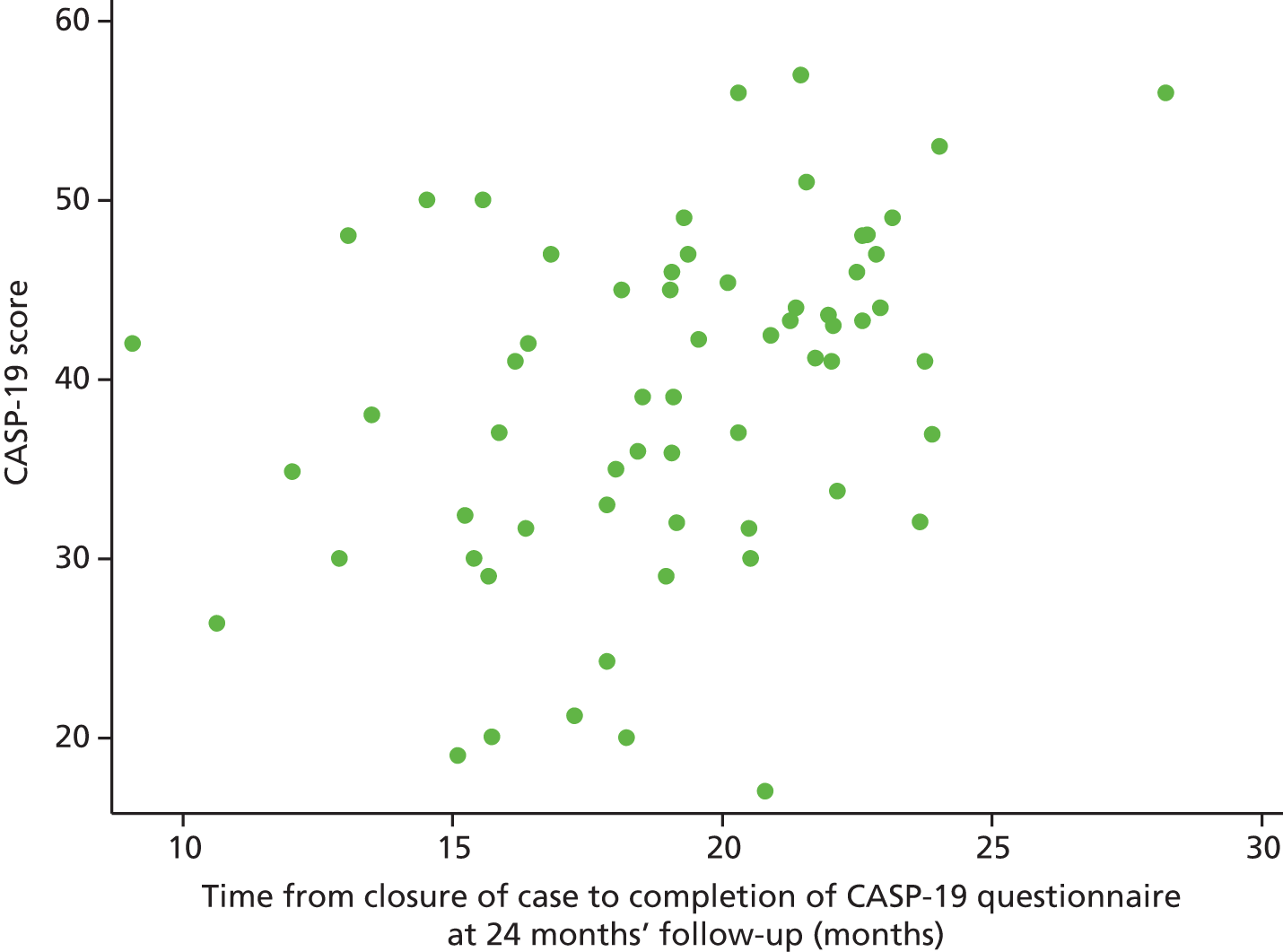

The primary outcome measure was HRQoL, measured using the CASP-19 questionnaire. 57,63 CASP-19 comprises 19 questions in the four domains of control, autonomy, self-realisation and pleasure. The range of the scale is 0–57, with higher values indicating better quality of life. 63 CASP-19 was administered by face-to-face interview at baseline (pre randomisation) and at follow-up 24 months post randomisation, and by postal questionnaire (with two reminders at fortnightly intervals including one duplicate questionnaire) at 12 months post randomisation (see Appendix 11).

Secondary outcome measures

The following secondary outcomes were collected by face-to-face interview at baseline (pre randomisation) and at follow-up 24 months post randomisation (see Appendix 11).

Mental health

Mental health was measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression scale. 76–78 The PHQ-9 examines nine mental health problems. The potential range of the scale is 0–27, with lower values indicating fewer depressive symptoms.

Perceived financial well-being

Perceived financial well-being was measured by the Affordability Index. 79 The 13-item Affordability Index has a potential score range of 4–20, with lower scores indicating fewer financial problems.

Standard of living index

The standard of living index is a 0–24 scale assessing ownership of 24 household items, based on questions used in the British General Household Survey. 80 A higher score indicates a higher standard of living. The items enumerated are listed in question 42 in Appendix 11.

Social support and participation

Social support and participation was measured by social interaction and strength of confiding relationships. 11 The social interaction score has a potential range of 0–27, with higher scores indicating a higher level of social engagement and support. An isolation indicator was created from one item on this scale, categorising whether or not participants reported that they did not see friends and relatives as often as they wished.

General health status

General health status was measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions-3 Levels (EQ-5D-3L) instrument. 81,82 The EQ-5D-3L is a five-item scale with three levels of response. The tool has been extensively used in studies and full details are reported on the website of the EuroQoL Group (www.euroqol.org/).

Health-related behaviours

Health-related behaviours were assessed by self-report, to measure change in key indicator behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol consumption,83 diet (consumption of key food groups) and physical activity [Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE)],84 as in our pilot RCT. 11 The diet score had a potential range of 15–75, with higher scores indicating a healthier diet in terms of salt, fat and sugar consumption. The physical activity score had a potential range of 0–400+, with higher scores indicating higher levels of activity.

Mortality

Mortality was assessed by identifying deaths at 12 months and 24 months from GP records. General practices were sent a list of participants and asked to check their status. This was carried out prior to commencing the 12- and 24-month follow-up assessments, in order to avoid distressing any recently bereaved relatives.

Financial status

Financial status was measured using an assessment tool developed and used in our pilot RCT. 11 This included data on all sources of household income, including benefits, major outgoings (rent/mortgage, fuel bills, etc.), debts and capital assets (i.e. home and savings). As well as these data, at follow-up detailed data were collected (by WRAs) on new benefits received since baseline, including one-off (lump sum) payments and regular, weekly or monthly income.

Independence

Independence was measured by assessing living arrangements and carer status using the following categories: living independently or with carer support, in own home, with relations, in a care home or hospital. We also assessed (by self-report) the number of hours of home care received per week.

Harms

At the outset, we were not aware of any major risks or harms associated with the delivery of the intervention. However, it was possible that older people could spend additional resources in ways that would be potentially harmful. These might include spending additional financial resources on alcohol or tobacco (with known risks of chronic diseases), ‘luxury’ foods, high in fat and sugar (e.g. chocolate), or gambling, which can be addictive and financially ruinous. It was also possible that the increased independence and mobility (which we hypothesised would be associated with access to additional resources) could result in greater environmental exposures outside the home, resulting in infectious diseases or accidental injury. Furthermore, the intervention could lead to greater use of car travel, resulting in lower levels of physical activity. It was also possible that older people would feel obliged to share any additional income with family members, who may be equally socioeconomically disadvantaged, thus negating the beneficial impacts on themselves. Older people may also be more vulnerable to external pressures, such as cold-calling from salespeople. We assessed potential adverse outcomes by (1) identifying negative (unhealthy) changes in all primary and secondary outcome measures; and (2) including additional, semistructured open questions in follow-up questionnaires and interviews on other, potential, unanticipated outcomes in order to document these and develop explanations.

Other quantitative data collected

Demographic variables were collected to characterise the trial participants and adjust for potential confounding in analyses, including age, sex, ethnicity, educational level attained, employment status and living arrangements (number of household members, paying for accommodation, and whether or not emotional support was available). In addition, two scales were used.

Functional ability was measured by the modified Townsend Activities of Daily Living scale,85 which assesses a person’s ability to perform eight activities. The possible range of scores is 0–16, with higher values indicating a greater ability to perform activities of daily living.

Life events score was measured by recording eight potentially serious events, including bereavement and significant illness, that might have occurred in the past 7 months, as well as their impact on the individual. 86

Sample size

A minimum of 318 participants needed to be followed up in each of the intervention and control arms (a total of 636) to provide 90% power at 5% significance level to detect a 1.5-unit difference in mean CASP-19 score57,63 at 24 months between the intervention and control groups, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 8.7 and a correlation between baseline and 24 months of 0.74. The estimates of SD and correlation coefficients came from the results of ELSA (wave 4) restricting the analyses to those aged ≥ 60 years. 87 Estimating an attrition rate between baseline and 24-month follow-up of 15% (as experienced in our pilot RCT),11 we needed to recruit 750 participants to the study (375 to each group).

There has been no published work to establish a meaningful or clinically important difference on the CASP-19 scale. However, we based the above acceptable difference on data from waves 1 and 2 of the ELSA in those aged ≥ 60 years. We investigated the adjusted mean difference in CASP-19 at wave 2 between groups whose social or health circumstances had changed. 64 Examples of changes in CASP-19 score associated with changes in health or social circumstances that we might have expected to see in the proposed trial included ‘developed limiting illness’, –2.8 units; ‘developed depression’, –2.7 units; ‘lost access to car’, –1.8 units; and ‘increased chance will not meet financial needs’, –1.1 units. These differences on the CASP-19 scale suggest that a difference of 1.5 units would represent a minimally clinically important difference. 65 The chosen sample size also provided power to demonstrate some clinically significant differences in secondary outcomes. For example, 750 participants would provide 90% power to detect a difference between a prevalence of 11% and 4% of clinically significant depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10).

Data handling, record keeping and sharing

Baseline and 24-month data were entered directly during interviews, via a tablet computer, into a secure custom-built database for processing and management using a bespoke content management system on Microsoft SQL® Server and ASP.NET (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). A record was maintained of any changes made to the data post entry. All personal information obtained for the study was held securely at Newcastle University and was treated as strictly confidential. The project administrators undertook entry and verification of data from 12-month posted self-completion questionnaires into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet, with a 10% random sample checked for data entry accuracy. The data collection and transfer in this study complied with NRES88 and Caldicott guidelines89 and the Data Protection Act 1998. 75

All patients were allocated a unique study identifier, which was used on all data collection forms and questionnaires to preserve confidentiality; names or addresses did not appear on completed questionnaires or on other data collection forms. Only a limited number of members of the research team were able to link the unique identifier to patient-identifiable details (name, address and telephone number) that were held on a password-protected Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database. All study documentation was held in secure offices that were not open to the public, and all members of the research team with access to identifiable or anonymised data operated to a signed code of confidentiality. Transmission of original or hard copy records (e.g. questionnaires, interview recordings) was by secure fax, post or hand delivery by members of the research team or by the WRAs. Participants were informed in the patient information sheet (see Appendix 4) about the transfer of information to the research team and about levels of access to patient identifiable data, and were asked to consent to this.

At the end of the study, original questionnaires, interview transcripts, consent forms and final versions of all data sets will be securely archived in the Institute for Health & Society for 5 years following publication of the last paper or report from the study, in line with sponsor policy and Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit standard operating procedures. This also allows any queries or concerns about the data, conduct or conclusions of the study to be resolved. Anonymised data will subsequently be securely archived and made available for secondary analysis as appropriate. Details of data sharing arrangements are available from the corresponding author.

Trial data analysis

In this section, the methods used to organise and analyse the data are described. This is divided into three sections, covering the quantitative study, economic evaluation and qualitative analysis.

Statistical analysis

Analysis populations

The analysis used the intention-to-treat population, which comprised all participants in the group to which they were randomised, regardless of the intervention that they received. The number of participants who did not receive the intervention to which they were randomised is reported.

Analysis data sets

As interviewers collected most of the data, it was not expected that there would be many missing data on items in particular scales. However, unless specified otherwise by the scale developers, when no more than 20% of items were missing or uninterpretable on specific scales, the scores were calculated by using the mean value of the respondent-specific completed responses on the rest of the scale to replace the missing items. 90

Depending on the extent of missing data on the primary outcome at 24 months, the use of multiple imputation was considered for the primary outcome CASP-19. It was decided that multiple imputation using iterative chained equations was appropriate to obtain a complete data set for the primary outcome at 12 and 24 months, conditional on survival to 12 or 24 months. 91 The variables considered for the multiple imputation model were those thought a priori to be associated with CASP-19 at 12 and 24 months, as well as variables that were predictors of missingness of CASP-19 scores. 92 The final model included baseline characteristics (e.g. age, gender, education, living alone), and CASP-19 at baseline and 12 months. Twenty multiple imputation data sets were produced.

The primary analysis of study end points (listed in the next section) was after the use of the simple imputation method described above to estimate missing items. A sensitivity analysis was carried out to explore the effect of this simple imputation approach. The results of the CASP-19 are also reported after using multiple imputation.

Descriptive analyses (baseline)

Baseline characteristics of the study population were summarised separately within each randomised group. This included primary and secondary outcome variables and covariates. Continuous variables were summarised by numbers of observations and mean and SD, or median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on whether or not the distribution was symmetric. The numbers of observations and percentages are reported for categorical variables. No significance testing for any baseline imbalance was carried out, but any noted differences are reported descriptively.

When covariates were available in both the Do-Well data set and the national ELSA (wave 4),87 their distributions were compared to determine the representativeness of the Do-Well participants.

Analyses of study end points

Descriptive analysis of benefits received

The numbers and percentages of any financial and non-financial benefits (e.g. aids and adaptations) received since baseline were summarised separately within each of the randomised groups.

Primary effectiveness end point

The primary end point, CASP-19, was compared at 24 months between the intervention and control groups using multiple linear regression with adjustment for baseline value and general practice (the stratification variable). The results are reported as a difference in means with a 95% confidence interval (CI). An adjusted analysis included the life events score and functional ability score at 24 months, and baseline covariates age, gender, education and whether or not living alone in the regression model. Bootstrap estimation was used if the distribution was skewed. A similar comparison was also made at 12 months (in this analysis, the life events and functional ability scores at baseline were used instead of those at 24 months).

Secondary effectiveness end points

The following continuous outcomes were assessed at 24 months:

-

mental health PHQ-9

-

Affordability Index

-

Standard of Living Index

-

social interaction score

-

alcohol (timeline follow back)

-

dietary intake score

-

physical activity (PASE)

-

receiving care – hours per week.